* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

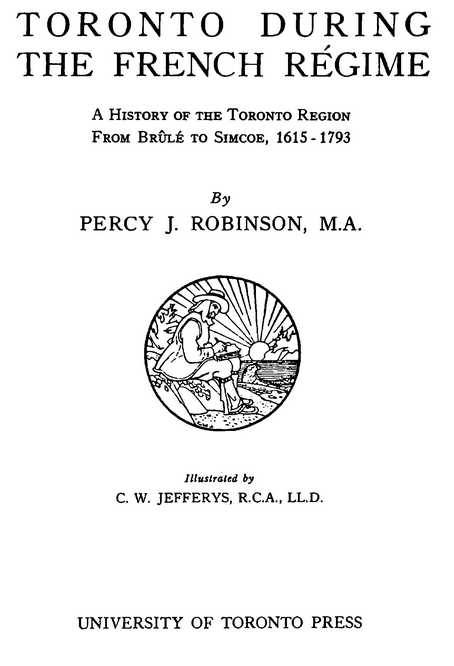

Title: Toronto During the French Régime, 1615-1793

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Percy J. Robinson (1873-1953)

Illustrator: C.W. Jefferys (1869-1951)

Date first posted: February 12, 2026

Date last updated: February 12, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260220

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

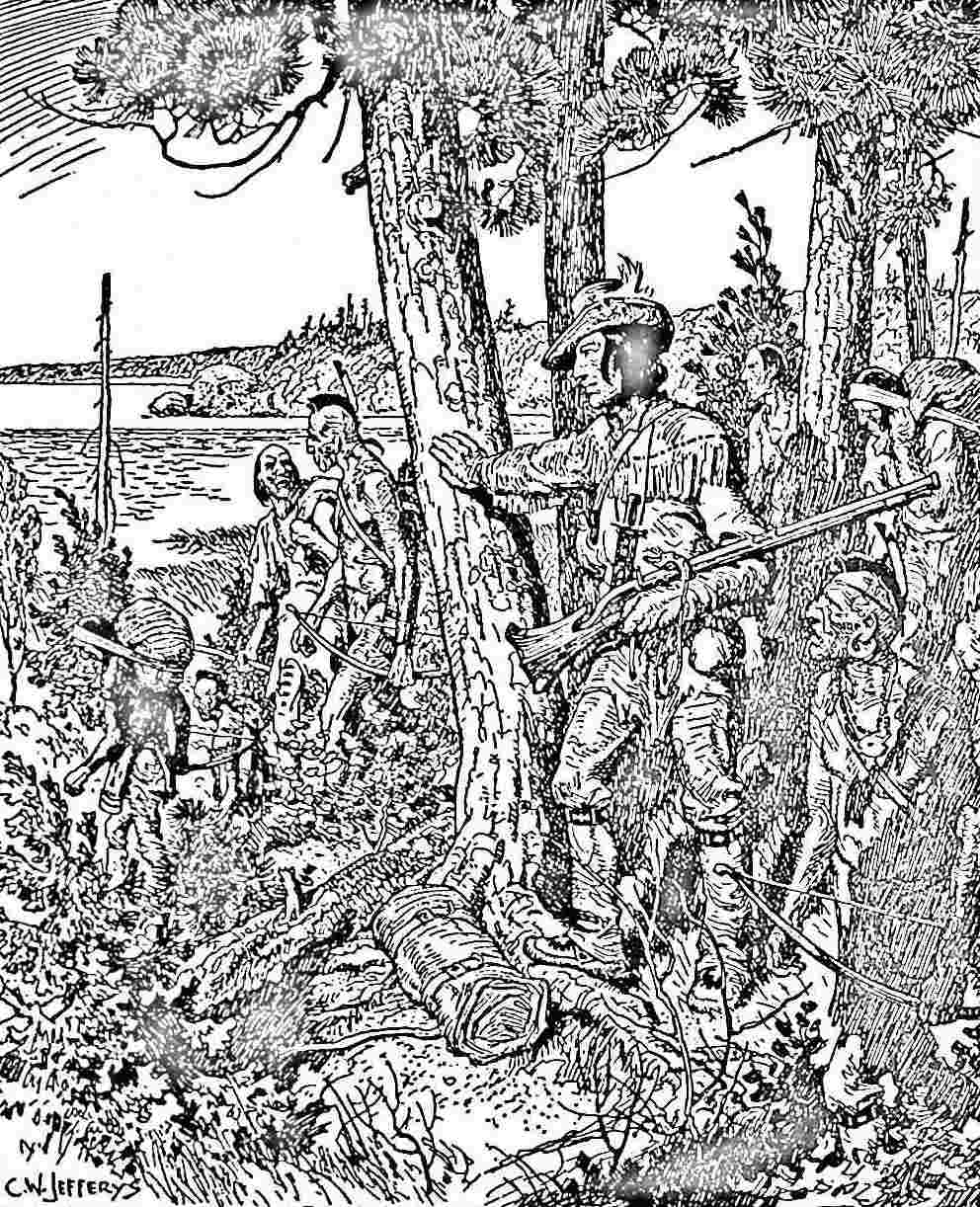

Étienne Brûlé

At the mouth of the Humber, 1615.

First published 1933 by The Ryerson Press, Toronto

and University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Second edition

© University of Toronto Press, 1965

Printed in the U.S.A.

To

MY WIFE

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The University of Toronto Press is happy to present this new printing of a classic in the history of Toronto, long unavailable. The author had made many marginal notes in a precious personal copy of the first edition, and these were examined when the present edition was planned. The notes reveal the author’s continued fascination with the subject and his careful attention in his reading of early Canadian history to every new bit of information about early Toronto. He continued to write about it, and, in addition to correcting a few typographical errors and adding several notes (indicated in the text proper by asterisks), the present edition offers as an additional appendix section several important summaries of his later research. The first is from an article which appeared in the Toronto Evening Telegram, August 27, 1938; it corrects the account given in the book of the Toronto Purchase. The second selection printed here is an excerpt from an article “Montreal to Niagara in the Seventeenth Century,” Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, 1944, Section II; the passage deals with the name “Toronto.” The third selection, “More about Toronto,” originally appeared in Ontario History, 1953, and is the author’s final word about the city. He died at Toronto on June 19, 1953.

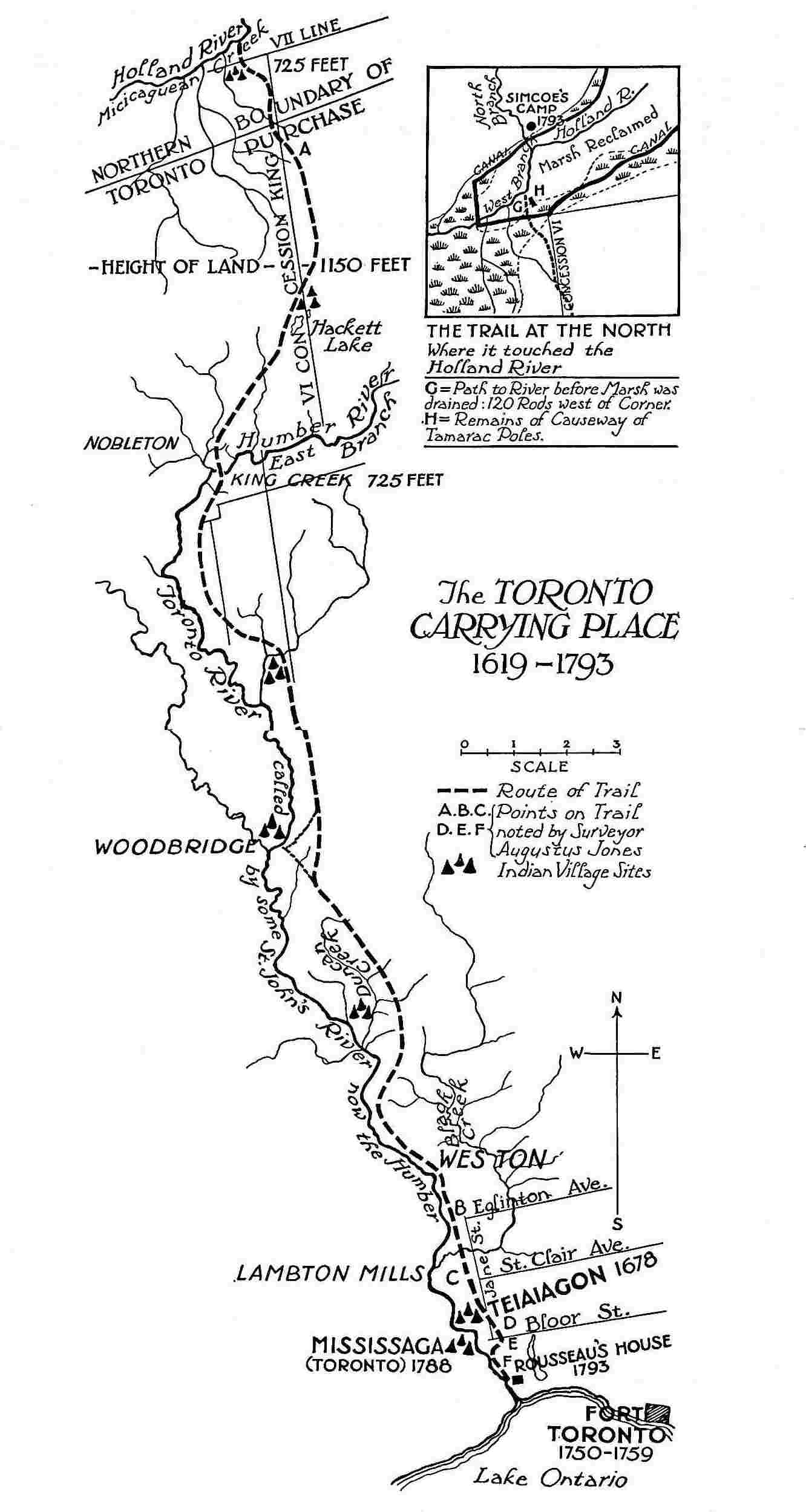

The TORONTO CARRYING PLACE 1619-1793

The centenary of the city of Toronto seems an appropriate time for gathering together whatever is known of the history of the region during the French régime and down to the founding of York in 1793. Dr. Henry Scadding, in his Toronto of Old, first published in 1873, sketched the outlines of this period. Only a few documents were at that time accessible. Since the appearance of his classic work, the publication of very many documents and maps, and the researches of numerous investigators, have made a more detailed picture possible. The plan adopted in the present study has been to record all known facts and wherever possible to allow the original documents to speak for themselves, bridging any gaps in the continuity of the narrative by historical comment. Except in one or two cases the original spelling and punctuation of the documents quoted has been retained. Only an arbitrary standard in the spelling of Indian place-names would reduce, for example, the fifty-five variants of Cataraqui to uniformity; the infinite and picturesque variety of the originals has not been sacrificed.

Younger by two hundred years than Montreal and Quebec, Toronto, at first sight, does not seem to possess that heritage of history and romance which flings a glamour about the traditions of the older cities. Nevertheless the Toronto Carrying-Place for a century and a half before the arrival of Simcoe, possesses a history which, though little known, is always dramatic and picturesque; it is the history of the wilderness, of the fur-trade, of the wars and cruelties of the Iroquois, of the adventures of explorers and missionaries, of the discovery of the Mississippi Valley and of the great North-West. Sometimes intimately, sometimes remotely, the Toronto Carrying-Place was touched by the struggle for the control of the continent waged so long between the French on the St. Lawrence and the Dutch and the English on the Hudson.

The reader will observe two omissions in this record. The story of the Huron Mission has been told so often and told so well that it does not require to be retold; but it ought not to be forgotten that the events of that dramatic and tragic episode took place within the Toronto region, for, as we shall discover in the course of our study, the name “Toronto” was at one time or another applied to all parts of the pass between the Georgian Bay and Lake Ontario. Neither will the coming of the United Empire Loyalists find a place in the narrative, except to mark the limits of investigation. Very happily the hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the arrival of the Loyalists in Ontario coincides with the centenary of the city of Toronto. The history of the Province of Ontario begins with that event, but the Loyalists themselves did not settle in the Toronto region till the founding of York. Their coming exercised too profound an influence upon the destiny of Canada to be discussed within the limits of a local history. It was, however, an eminent Loyalist, Sir John Johnson, proposed by Lord Dorchester as the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, who in his capacity of Indian Agent arranged the purchase from the Missisauga Indians of the tract of land known as the “Toronto Purchase,” within which lies the city of Toronto, and to which all land titles trace their legality.

Much of the present volume is composed of entirely new matter. A continuous history of the locality from 1615 to 1793 is now for the first time possible. The site of the Seneca village of Teiaiagon, visited by Hennepin and La Salle, has been identified. Joliet is shown to have been the first to record the position of Toronto Island, as Raffeix in 1688 was the first to trace the course of the Don. The existence of a French post at Toronto in 1720, hitherto unsuspected, and built by the Sieur Douville, is now for the first time established by documentary evidence. The results of the recent discoveries of M. E.-Z. Massicotte, the learned archivist of Montreal, proving that two forts were built by the French at Toronto in 1750 and 1751 on different sites, have been included. Hitherto unpublished letters from Fort Rouillé have been translated. An accurate restoration of Fort Toronto, officially called Fort Rouillé, is now for the first time possible. Biographies of the Sieur Douville, the Sieur de la Saussaye, Captain René-Hypolite La Force, Captain J. B. Bouchette and Philippe de Rocheblave, all connected in one way or another with Toronto, have been prepared; as de Rocheblave was the first to point out the value of the site of the city of Toronto, a special article by the Hon. E. Fabre Surveyer of the Superior Court of Quebec, has been included in an appendix. Surveyor Aitkin’s account of the first survey of the Toronto Purchase in 1788 is now published for the first time; this recently-discovered document establishes the fact that Toronto was laid out by Lord Dorchester as a town five years before York was founded by Simcoe. Many new facts about Col. J. B. Rousseau, the last of the French traders at Toronto, have come to light and have been included. The etymology of the word “Toronto” has been discussed from a fresh point of view, and a cartography of the Toronto region has been prepared. The Toronto Carrying-Place has been mapped and its course through the city of Toronto indicated.

In collecting the details of our local history, sources of information too numerous to mention have been laid under contribution. More especially the writer is indebted to the researches of Dr. Scadding, Miss Lizars, Mr. F. D. Severance, the historian of Fort Niagara, and Professor Louis C. Karpinski of the University of Michigan. Grateful acknowledgment is made of the generous assistance of Mr. L. Homfray Irving of the Ontario Department of Archives, Mr. N. A. Burwash of the Ontario Surveys Department, Major Gustave Lanctot, M. F.-J. Audet, Mr. N. Fee of the Public Archives, Ottawa, M. E.-Z. Massicotte of the Montreal Archives, M. Ægidius Fauteux, Chief Librarian, Montreal, and Mr. Justice E. Fabre Surveyer of the Superior Court of Quebec. The author wishes to thank Dr. F. N. G. Starr, of Toronto, for permission to reproduce a photograph of the astrolabe found on Christian Island, and Miss Margaret Rousseau and Miss Muriel Rousseau, of Hamilton, for access to the papers of Col. J. B. Rousseau. Mr. J. M. Walton, of Aurora, by his knowledge of local topography, and Mr. A. J. Clark, of Richmond Hill, by his thorough acquaintance with the archaeology of the district, have rendered invaluable assistance. Professor W. B. Kerr, of the University of Buffalo, has given me the results of his examination of the Amherst Papers. The author is indebted to Mr. R. Home Smith for permission to reproduce several of the illustrations in Miss Lizars’ The Valley of the Humber.

P. J. R.

| CONTENTS | ||

| Preface | xi | |

| I. | Shadows on the Street | 1 |

| II. | The Gateway of the Huron Country: 1615-1663 | 5 |

| The Carrying-Place the link between Lake Ontario and the Georgian Bay. The Huron Country and the Huron Mission. Brûlé and the Carrying-Place. Brûlé’s route to the Andastes. Other travellers over the Carrying-Place. The Gate to the Huron Country closed by the Iroquois. Early maps and the astrolabe found on Christian Island. | ||

| III. | Hennepin and La Salle at the Carrying-Place: 1663-1683 | 14 |

| The French reach Lake Ontario. Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario. The Sulpicians. Joliet and Péré. De Courcelles on Lake Ontario. Teiaiagon. The founding of Fort Frontenac. Hennepin at Teiaiagon. Site of Teiaiagon. La Salle’s traders at Teiaiagon. La Salle at Teiaiagon and the Carrying-Place. Du Lhut. | ||

| IV. | From the Return of La Salle to de Callières’ Treaty with the Iroquois: 1683-1701 | 43 |

| French and English ambitions. Position of the Iroquois. A chain of posts proposed. Denonville and Toronto. Meaning of the name. Rooseboom and MacGregorie. Denonville at Toronto. Ganatsekwyagon and the eastern arm of the Carrying-Place. Return of Frontenac and the progress of the Missisaugas. | ||

| V. | From the Founding of Detroit to the Building of Fort Toronto: 1701-1750. The Magasin Royal at Toronto: 1720-1730 | 61 |

| A Period of Trade Rivalries. Projects of de Vaudreuil. The Douvilles appear in the lake. A Royal Magazine at Toronto. Oswego and the “Castle” at Niagara. The Sieur de la Saussaye’s lease cancelled. Toronto a Dependency of Niagara. | ||

| VI. | Fort Toronto or Fort Rouillé: 1750-1759 | 93 |

| Projects of de la Galissonnière in the Ohio Valley. Chouéguen. The Post at Toronto restored by Jonquière. Portneuf’s first fort. Dufaux’s second fort. Sites of the two forts. Troubles of the Contractor. Fort Toronto restored. Visit of the Abbé Picquet. Various references to Fort Toronto. Letters from Fort Rouillé. Fall of Niagara and the Burning of Fort Toronto. Captain Douville. | ||

| VII. | From the Fall of Niagara to the End of the Conspiracy of Pontiac: 1759-1764 | 141 |

| Sir William Johnson. The Missisaugas surrender to the English. Major Rogers at Toronto. Illicit liquor at Toronto. Alexander Henry at Toronto. | ||

| VIII. | From the Conspiracy of Pontiac to the Quebec Act: 1764-1774 | 151 |

| Sir William Johnson virtual ruler of the West including Ontario. He diverts the trade to Albany. Interview between Norman McLeod and Wabecommegat at Niagara. St. John Rousseau at Toronto. | ||

| IX. | From the Quebec Act to the Founding of York: 1774-1793 | 155 |

| The War of American Independence. Visit of Captain Walter Butler to Toronto. Kaskaskia and Philippe de Rocheblave. De Rocheblave asks for the site of the city of Toronto. Frobisher interests himself in the Portage. The Toronto Purchase. The first Survey of the site of Toronto. Details of de Rocheblave’s application for land at Toronto. Other applicants for land at Toronto. Fate of de Rocheblave’s scheme. Captain La Force. Captain J. B. Bouchette. | ||

| X. | The Founding of York and the Last Phase of the Carrying-Place: 1793 | 185 |

| Bouchette’s description of Toronto. Arrival of Simcoe; he is piloted into the Harbour by Rousseau. Mrs. Simcoe’s account of the trip over the Carrying-Place. Alexander Macdonell’s diary of the expedition. Simcoe’s party. | ||

| XI. | Retracing the Trail | 195 |

| The course of the Carrying-Place lost. Various sources of information. Notes made by Augustus Jones. Where the Carrying-Place crossed the streets of Toronto. Site of Rousseau’s house. Northern terminus of the Carrying-Place. | ||

| XII. | Jean Baptiste Rousseau | 209 |

| APPENDICES | ||

| I. | The Etymology of “Toronto” | 221 |

| Various theories, “Place of Meeting,” “Trees in the Water,” “Lake Opening or Pass.” The Huron name of Lake Simcoe. | ||

| II. | Cartography of the Toronto Region from 1600-1816 | 226 |

| III. | Philippe François de Rastel de Rocheblave | 233 |

| By The Honourable Mr. Justice E. Fabre Surveyer, F.R.S.C., the Superior Court of Quebec. | ||

| IV. | Iroquois Place-Names on the North Shore of Lake Ontario | 243 |

| By J. N. B. Hewitt, the Smithsonian Institute, Washington. | ||

| APPENDICES TO SECOND EDITION | ||

| The Toronto Purchase | 247 | |

| The Name Toronto | 255 | |

| More About Toronto | 257 | |

| Notes to the Original Text | 263 | |

| Index | 265 | |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| 1. | Frontispiece: Étienne Brûlé, at the Mouth of the Humber, 1615 | |

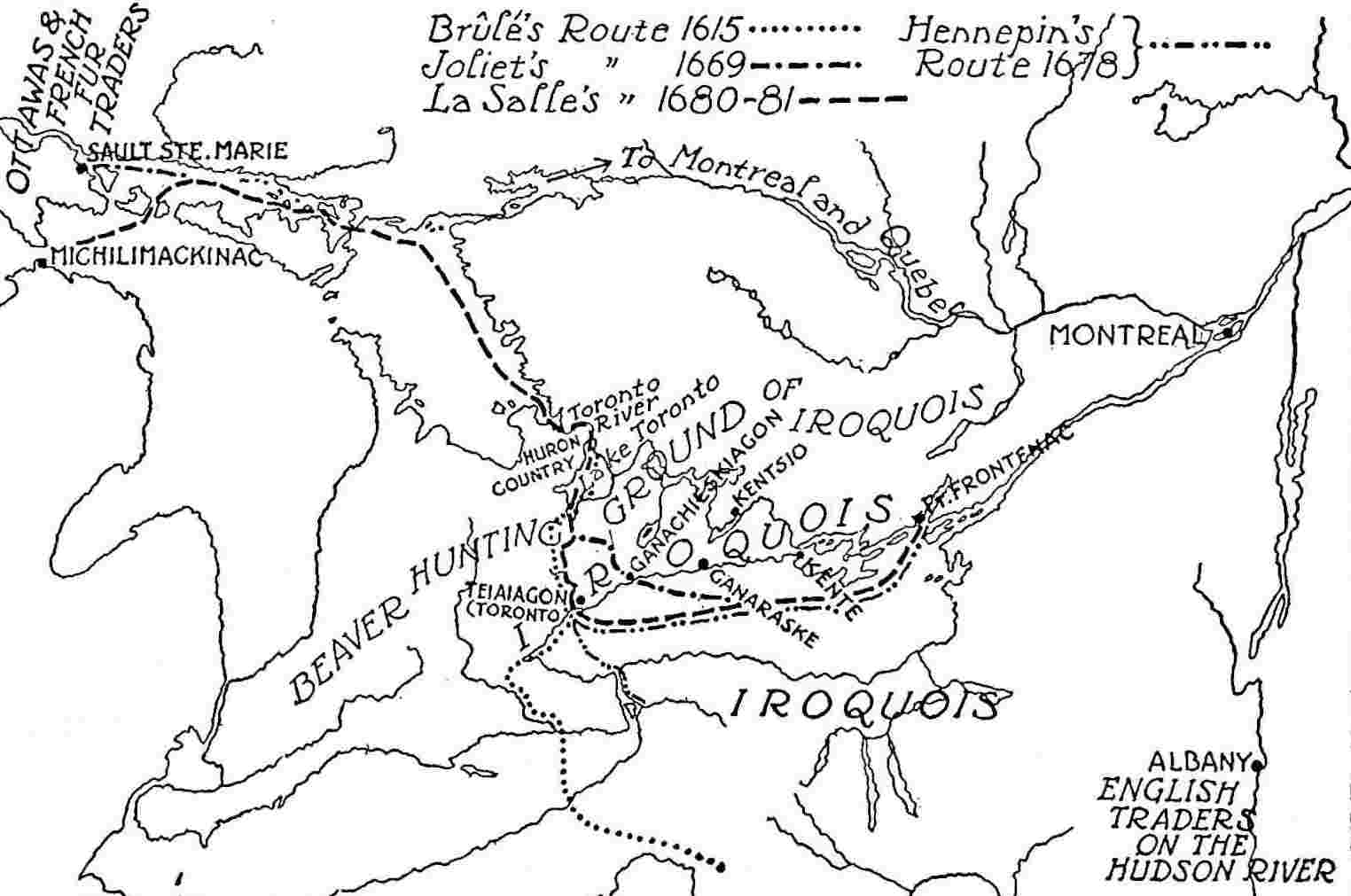

| 2. | The Toronto Carrying-Place, 1615-1793 | viii-ix |

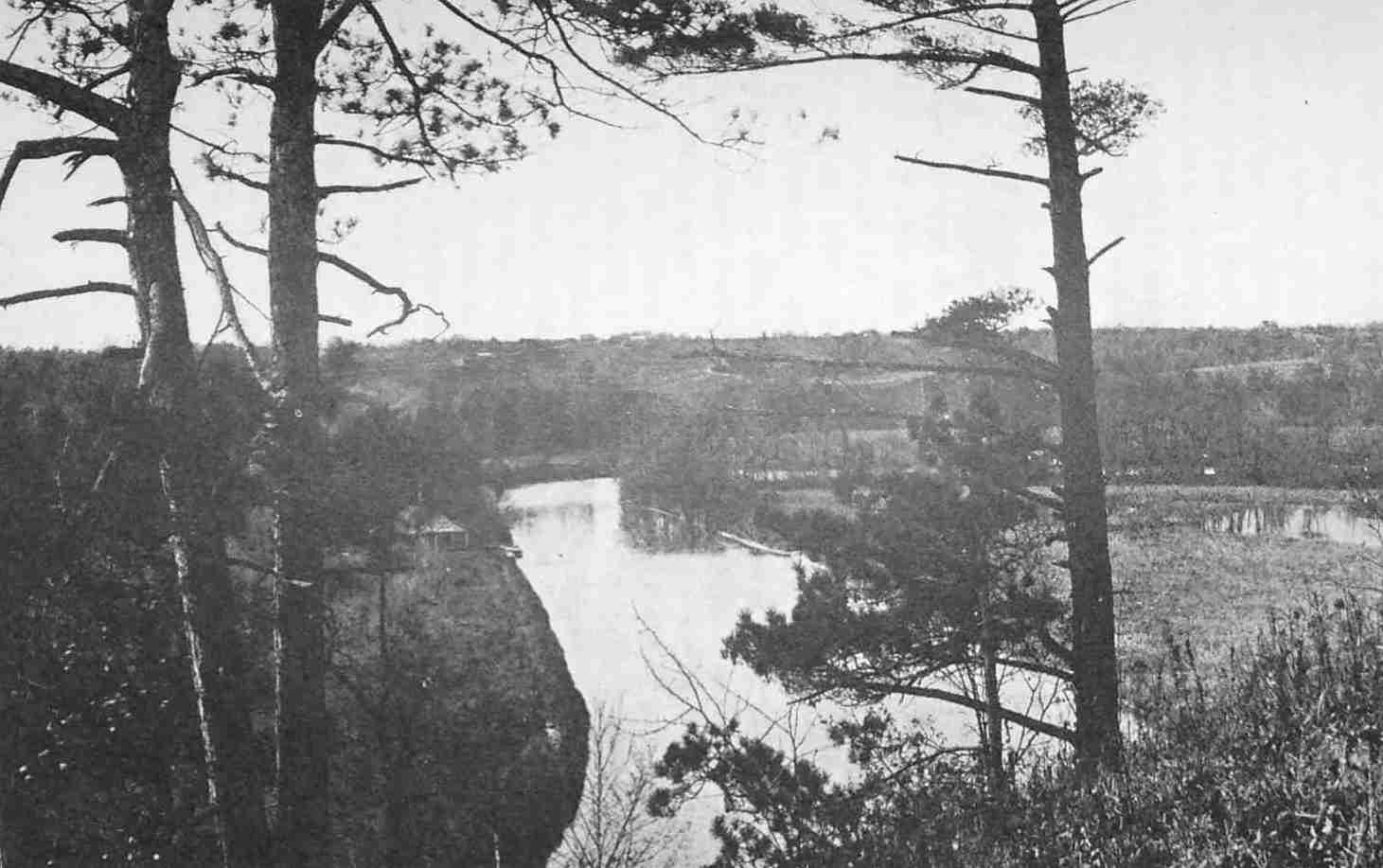

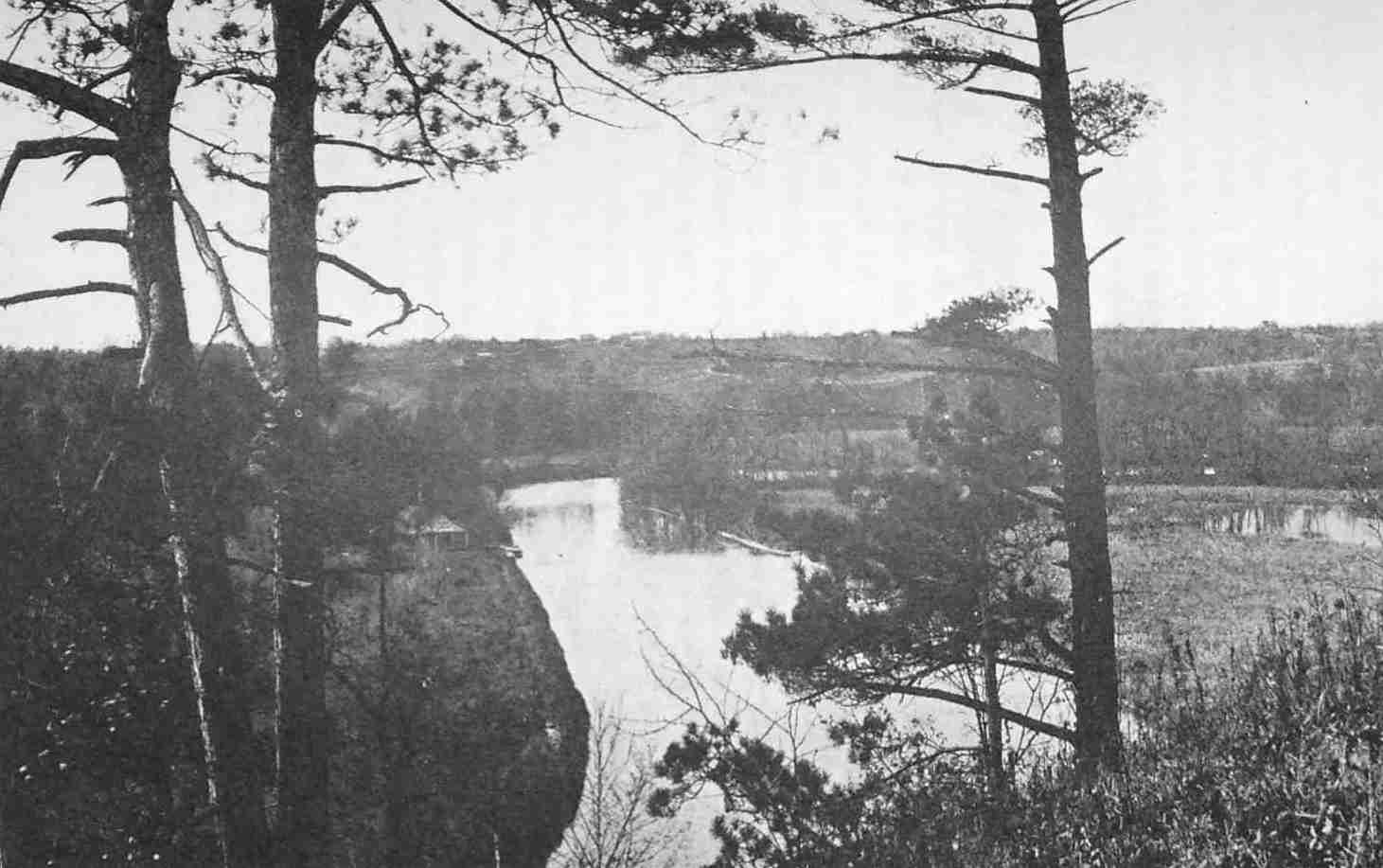

| 3. | Mouth of the Toronto or Humber River[1] | 2 |

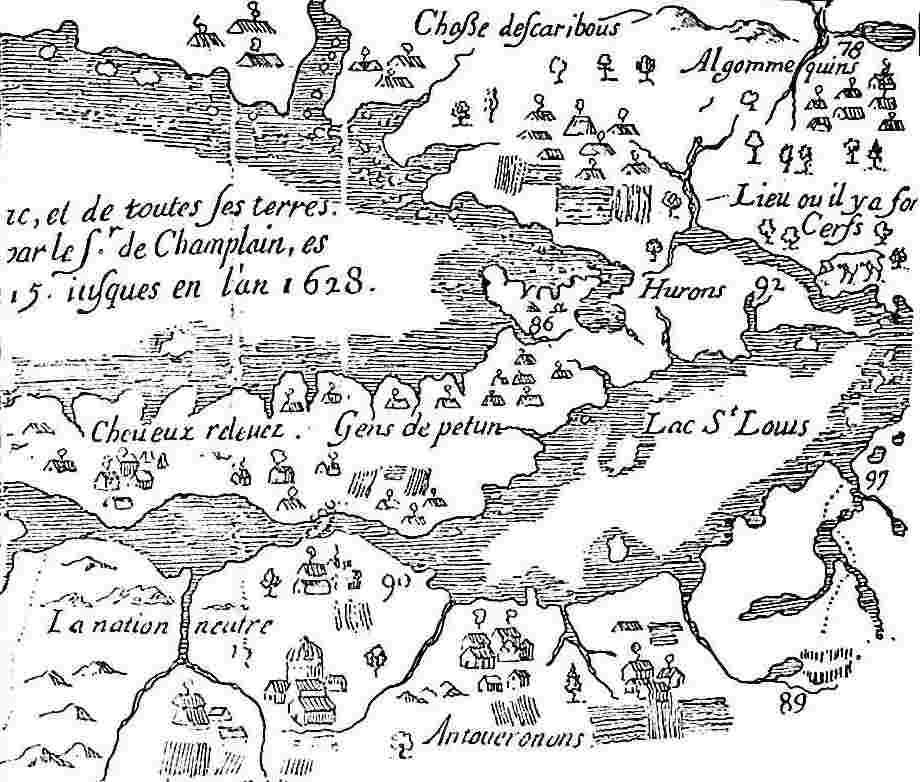

| 4a. | Champlain Map, 1632 | 10 |

| 4b. | Sanson Map, 1650 | 10 |

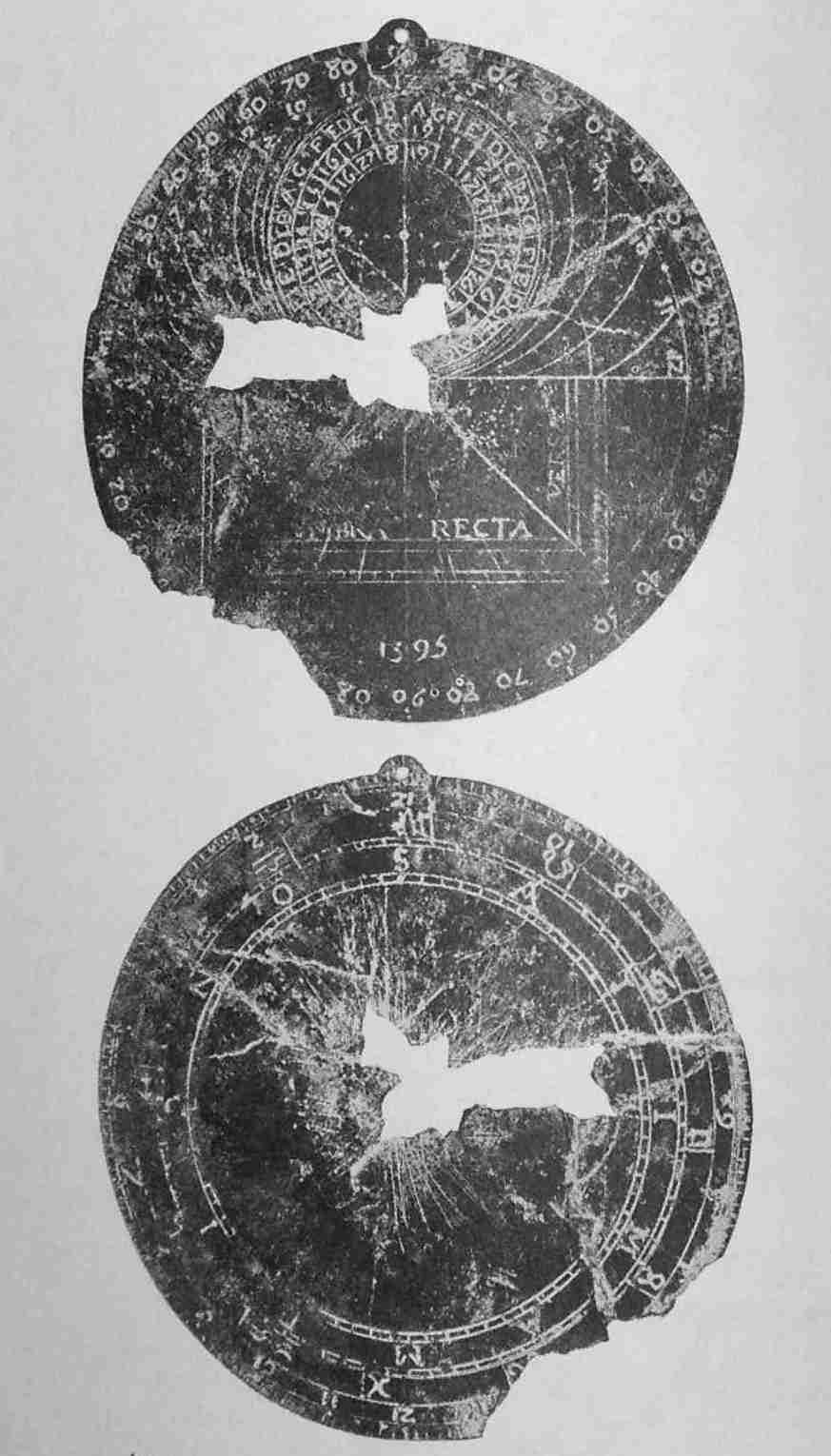

| 5. | The Jesuit Astrolabe | 10 |

| 6. | La Salle Crossing the Toronto Portage, 1681 | 14 |

| 7. | Routes Followed by Brûlé, 1615; Joliet, 1669; Hennepin, 1678; La Salle, 1680-1681 | 19 |

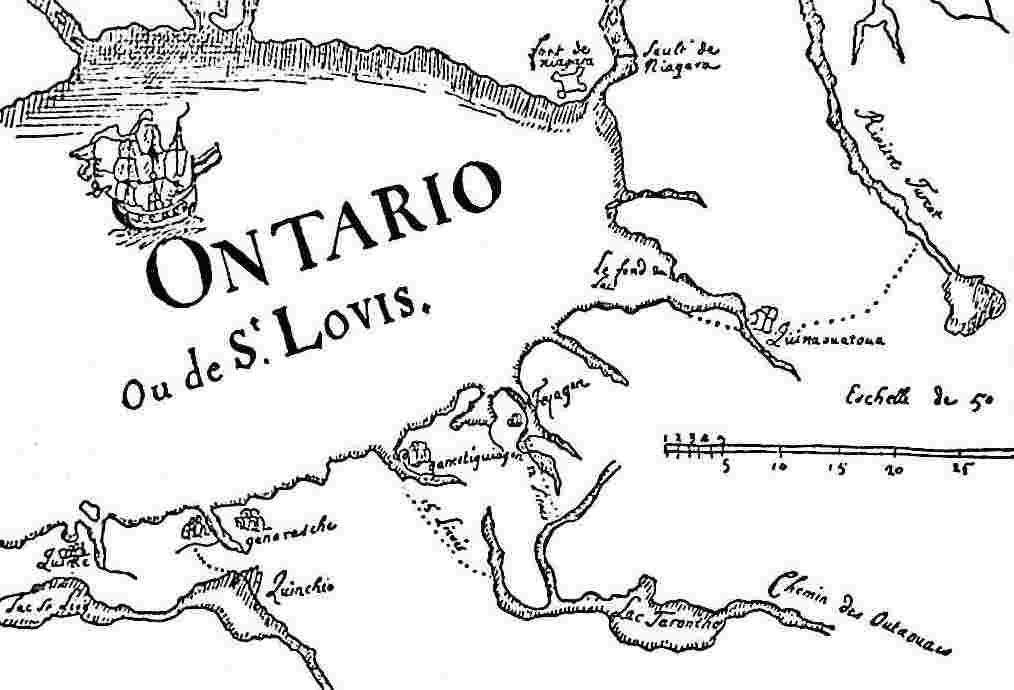

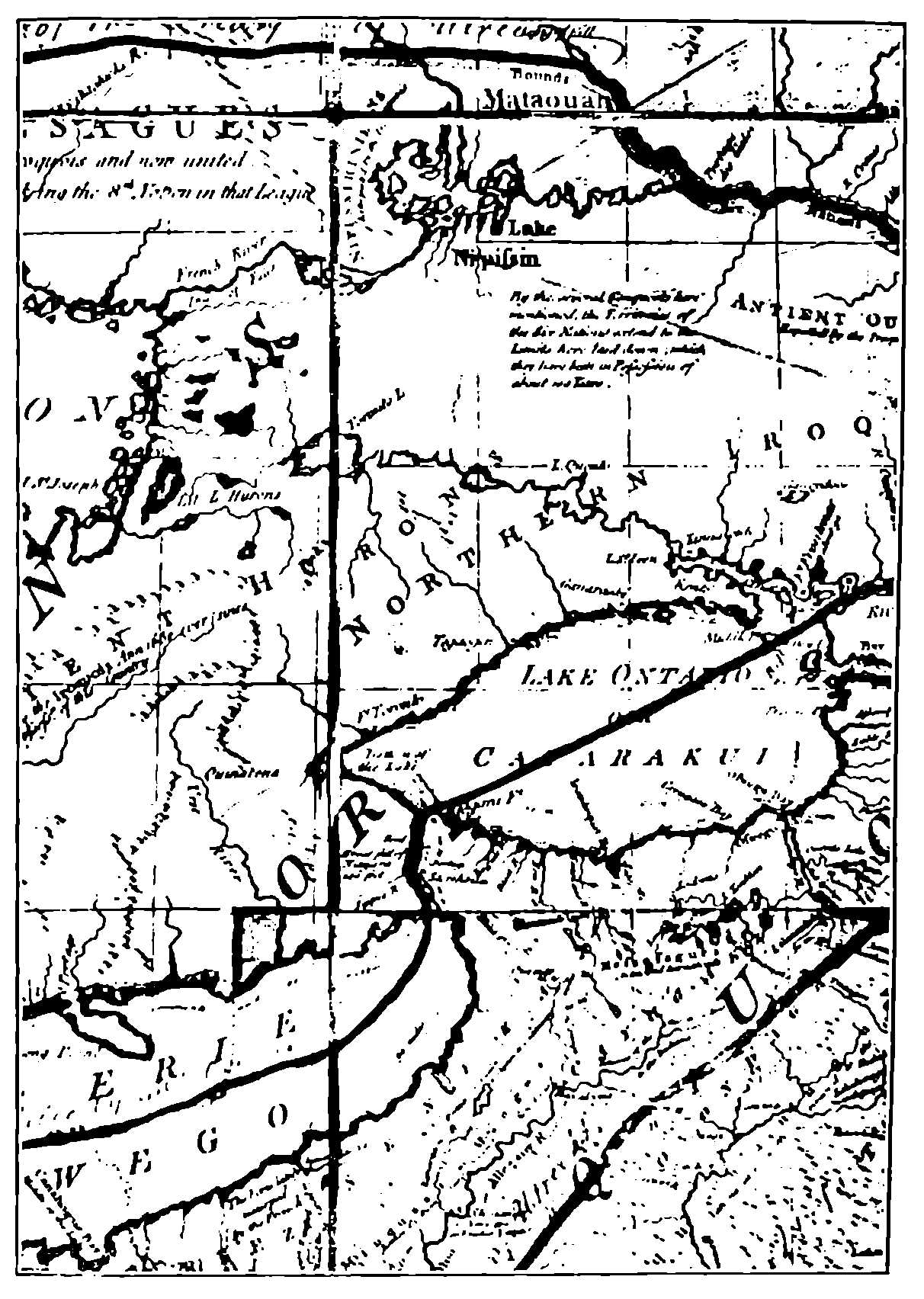

| 8a. | Joliet Map, 1674 | 20 |

| 8b. | Du Creux Map, 1660 | 20 |

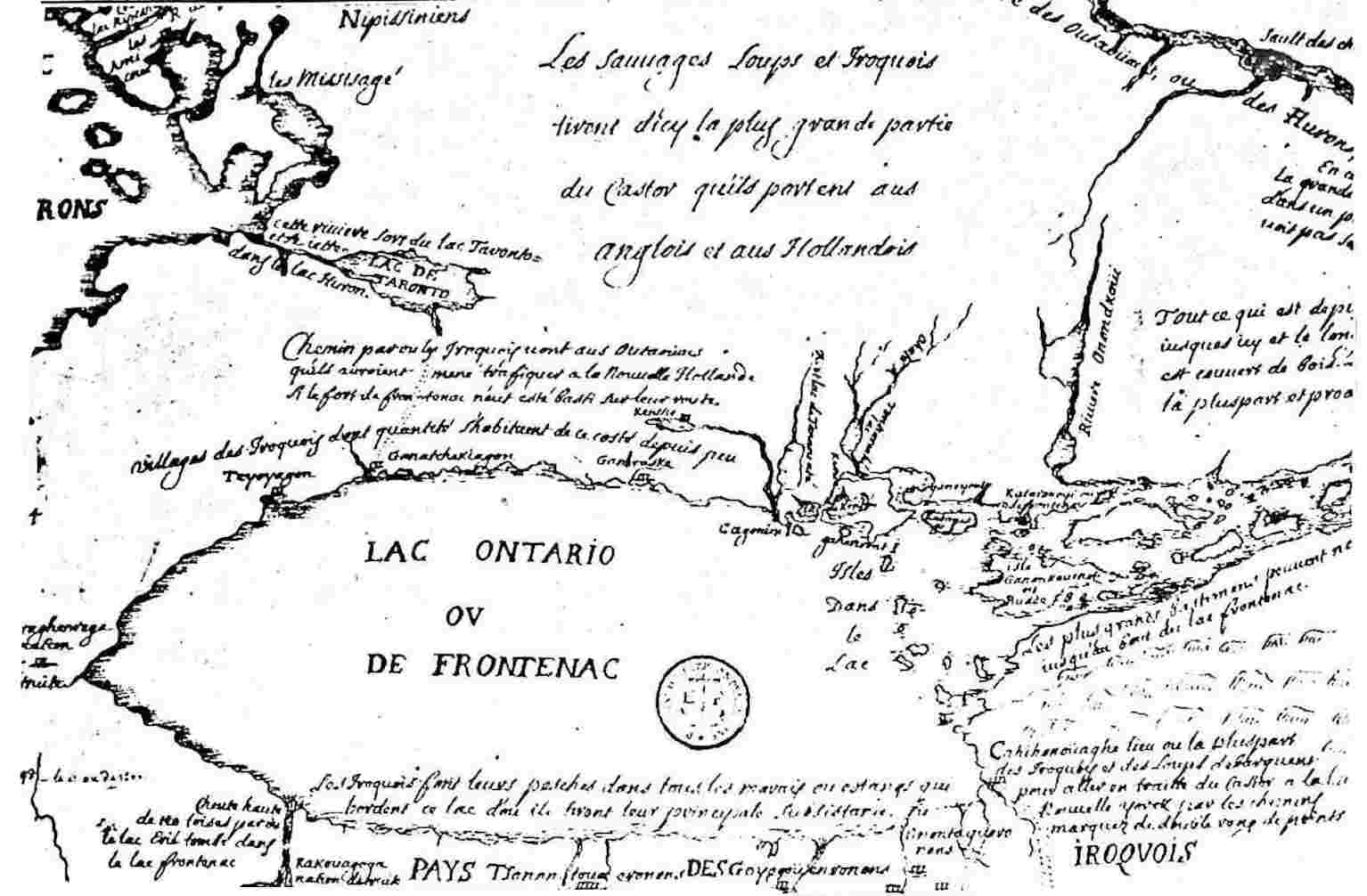

| 9. | The First Detailed Map of Lake Ontario | 20 |

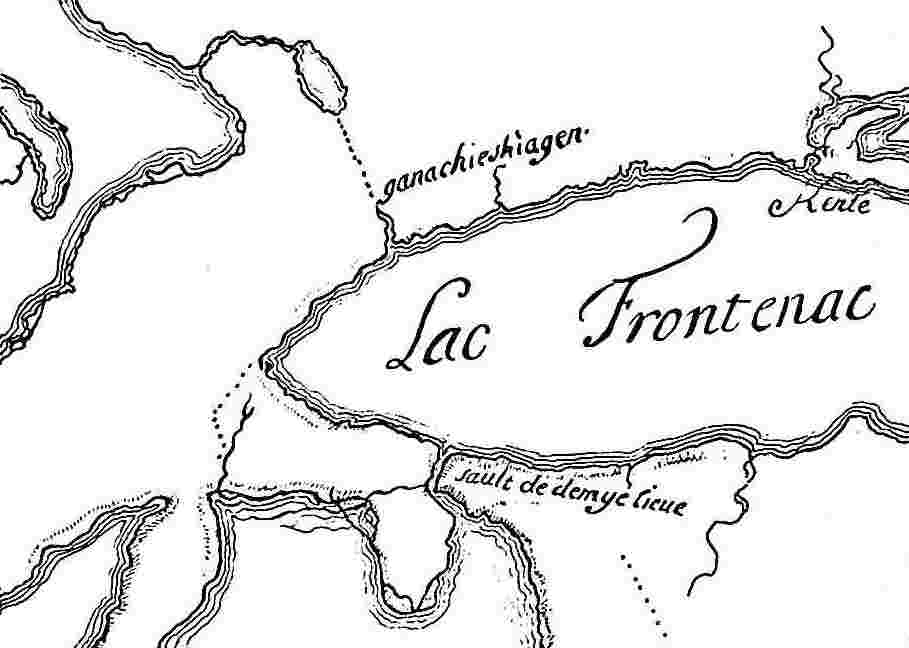

| 10. | Part of Raffeix Map, 1688, Showing Position of Teiaiagon | 32 |

| 11a. | The Stone House at Niagara | 62 |

| 11b. | Baby Point, the Site of Teiaiagon | 62 |

| 12. | Mitchell Map, 1755 | 74 |

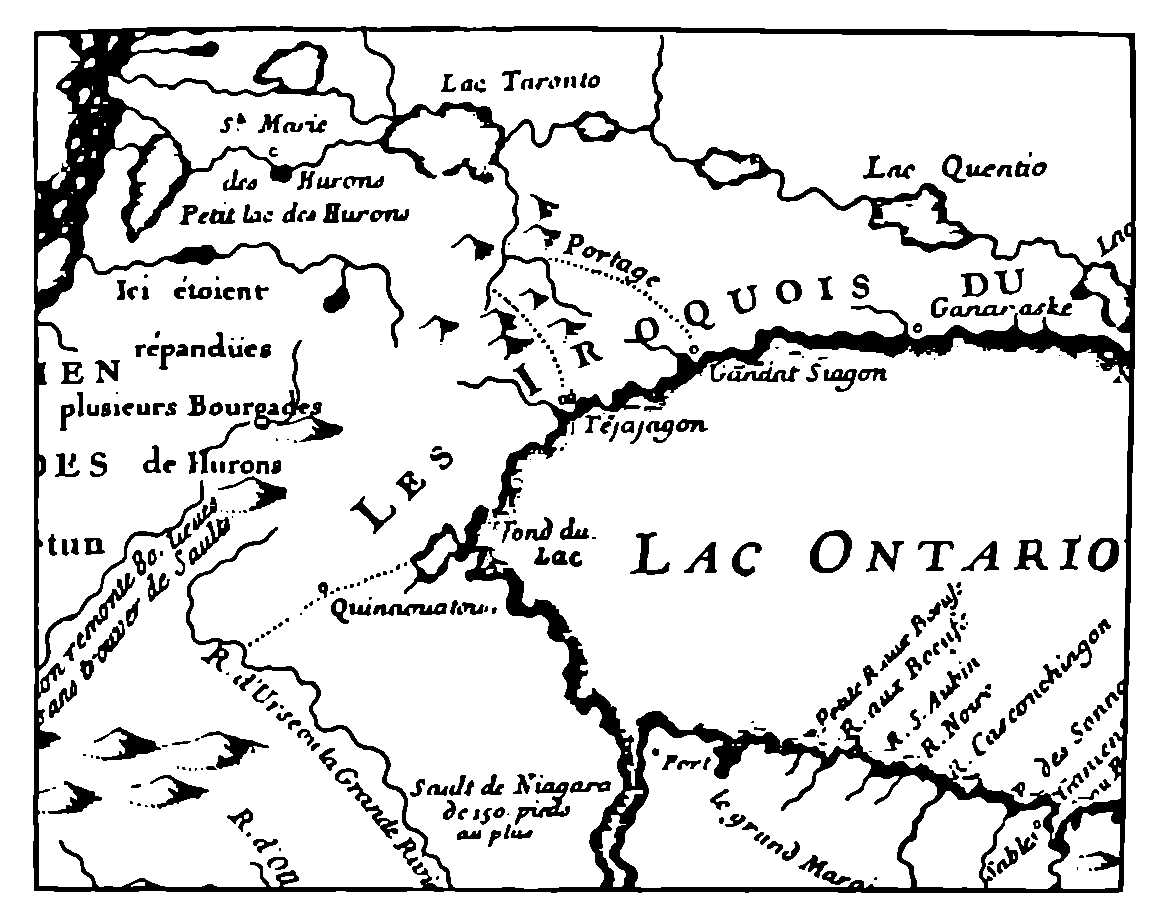

| 13a. | Charlevoix-Bellin Map, 1744 | 76 |

| 13b. | Danville Map, 1755 | 76 |

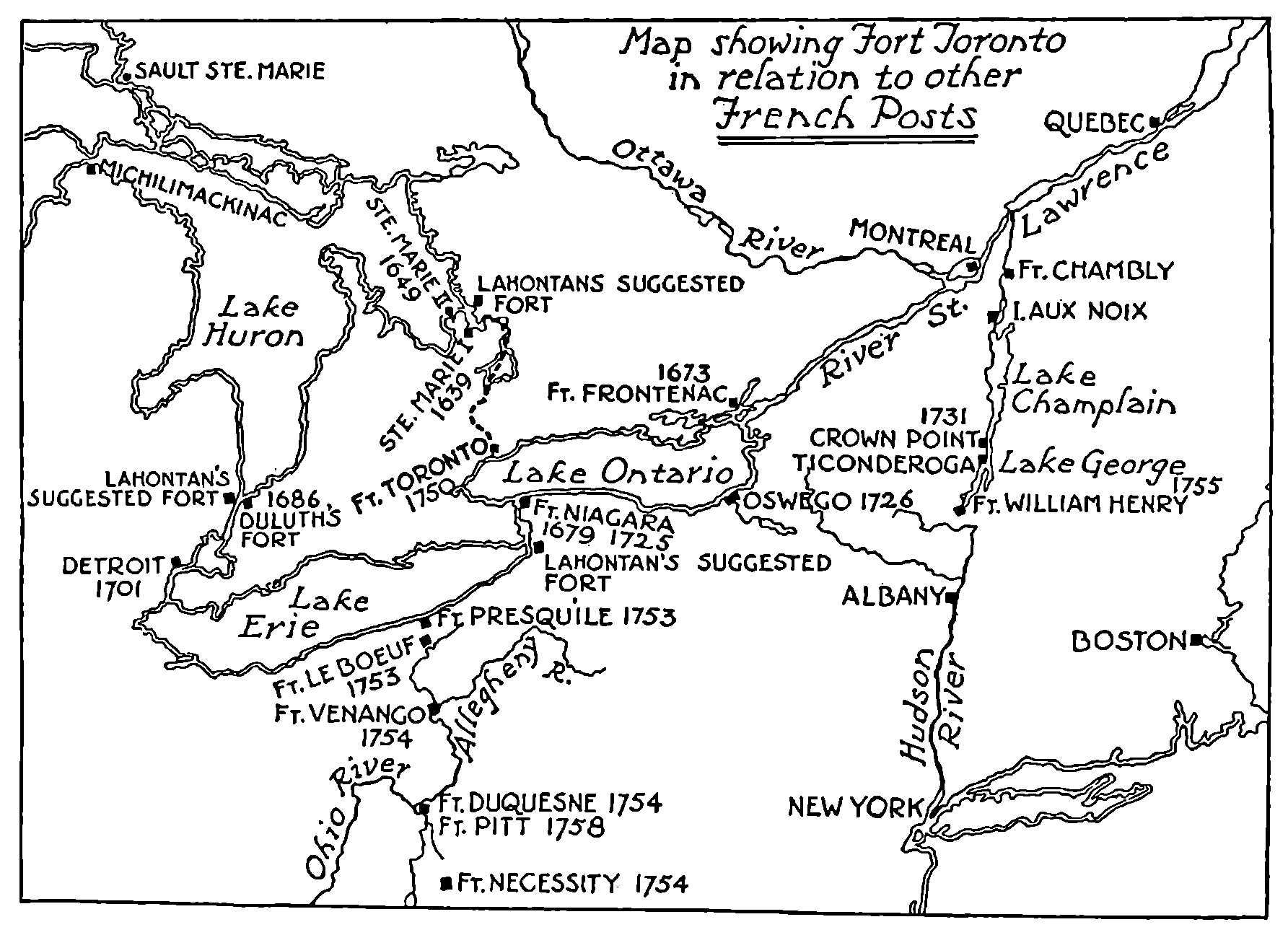

| 14. | Fort Toronto in Relation to Other French Posts | 95 |

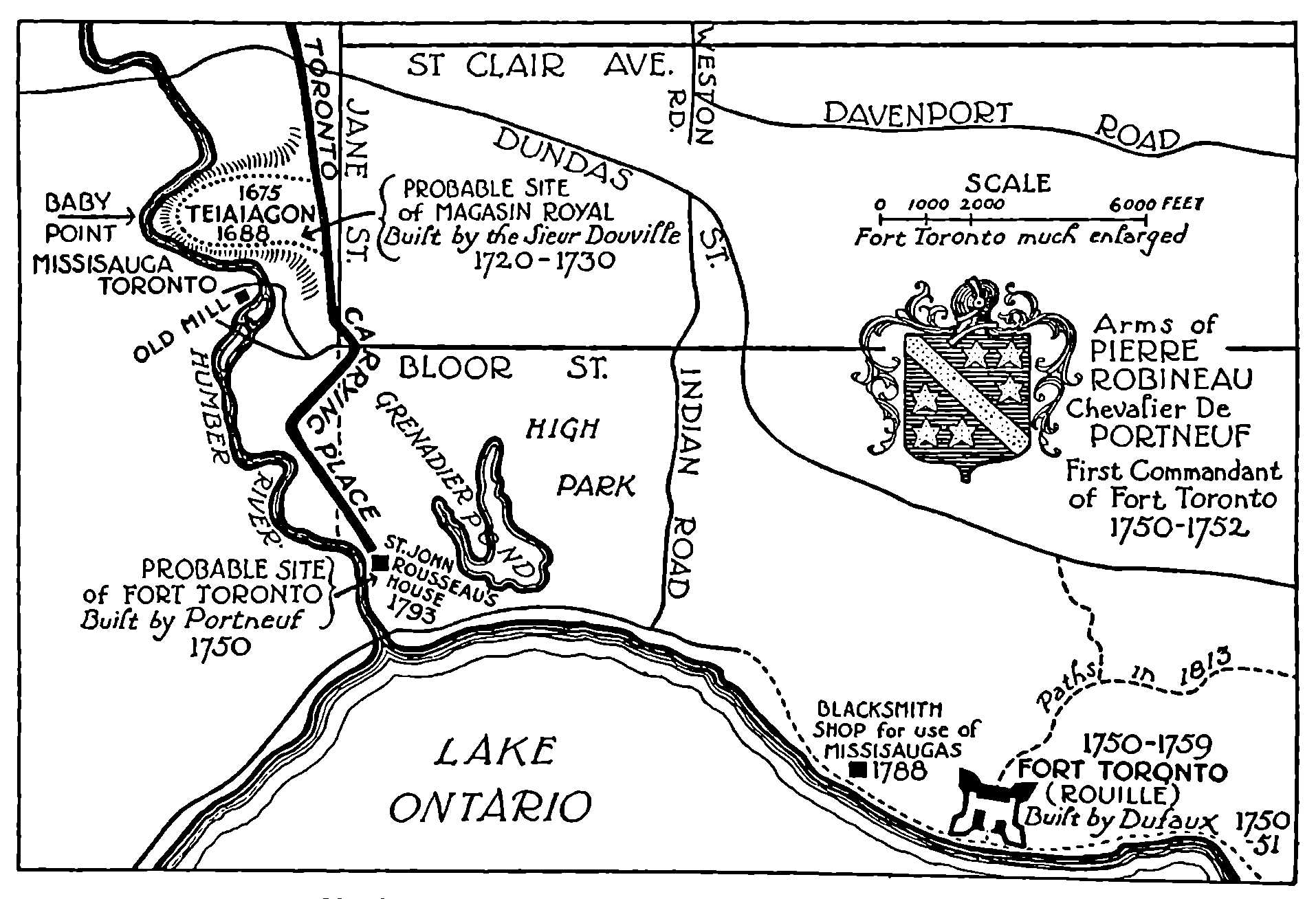

| 15. | Map Showing Position of the Three French Posts at Toronto | 111 |

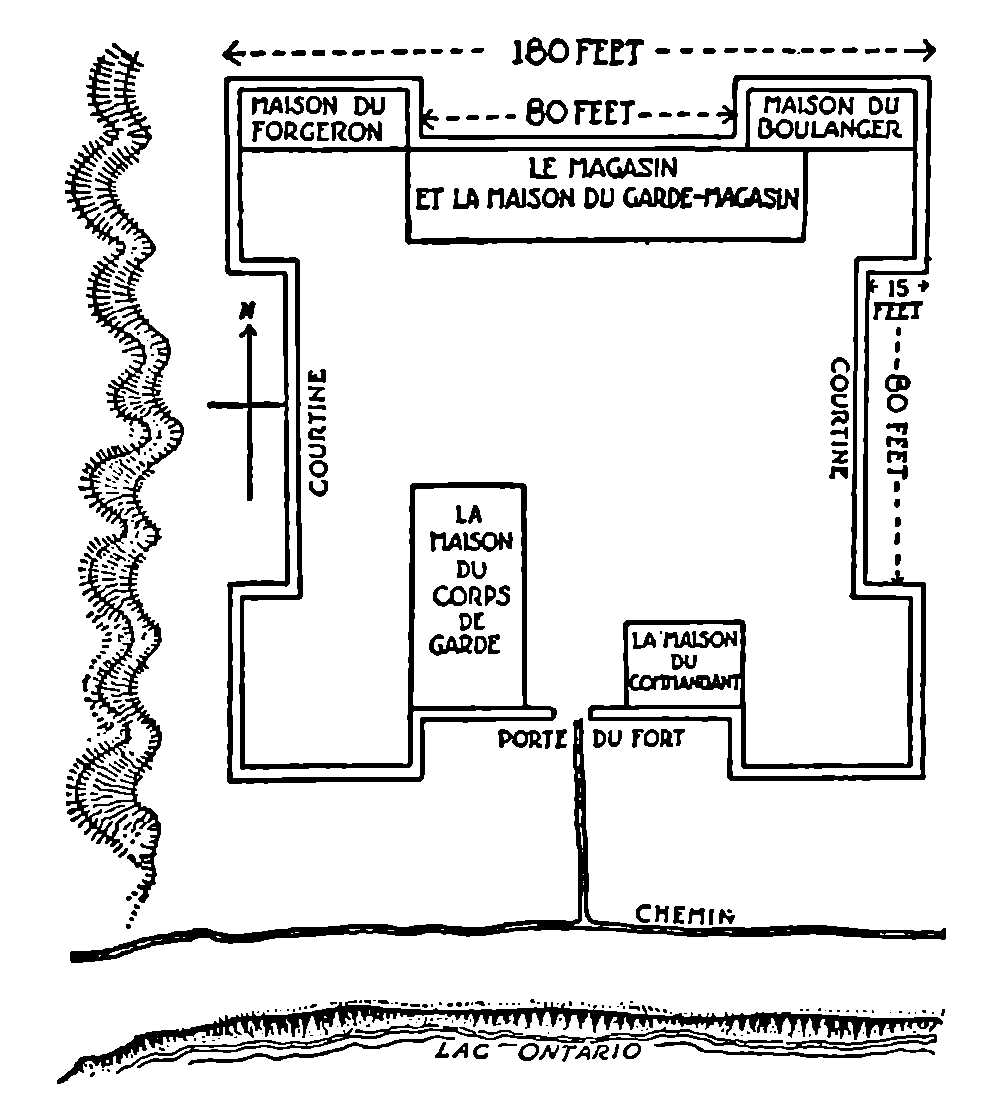

| 16. | Fort Rouillé or Toronto (reconstructed) | 115 |

| 17. | The Toronto River; the Second Bend[2] | 134 |

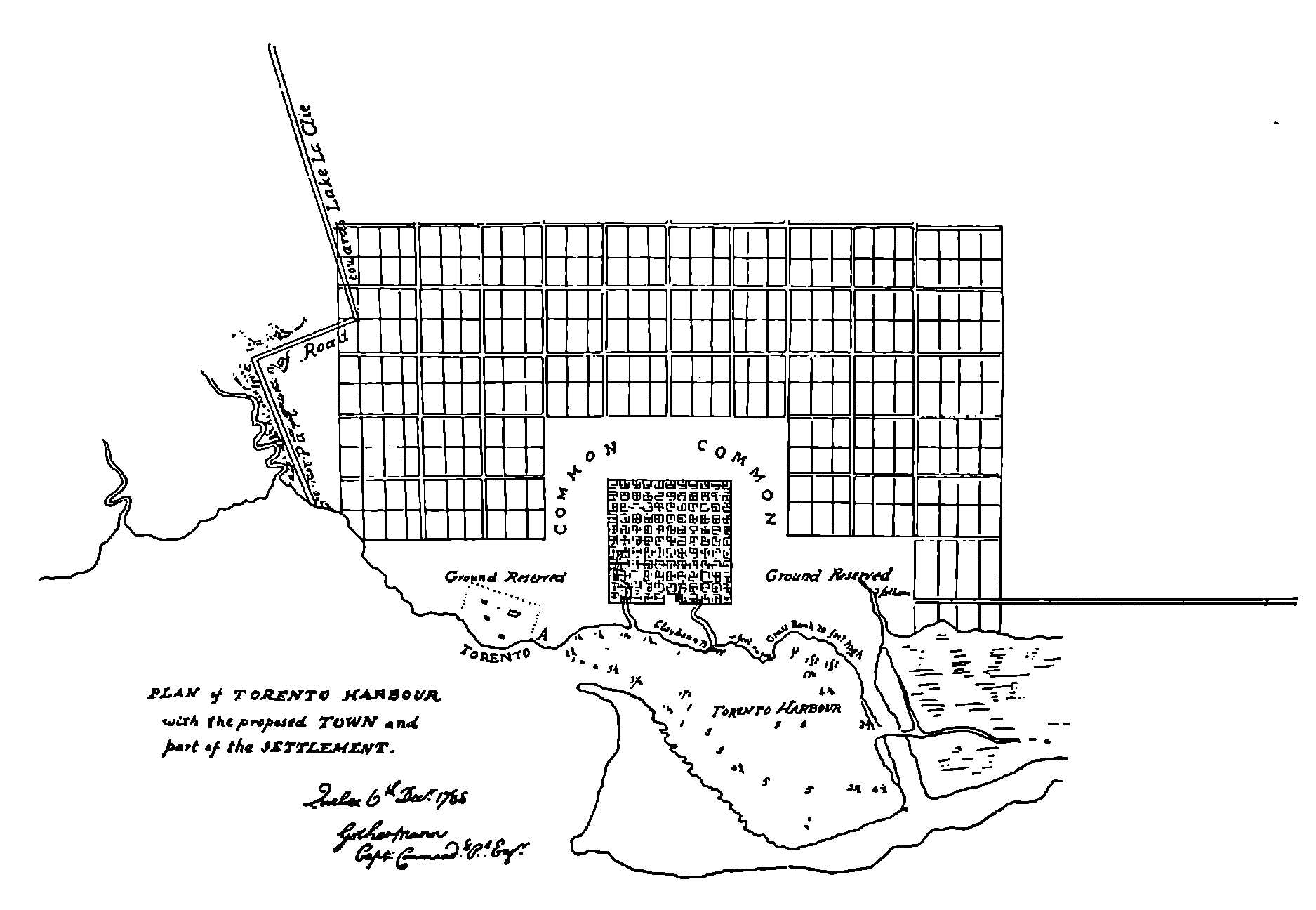

| 18. | Proposed Plan of Toronto, 1788 | 166 |

| 19. | The Toronto or Humber River[3] | 188 |

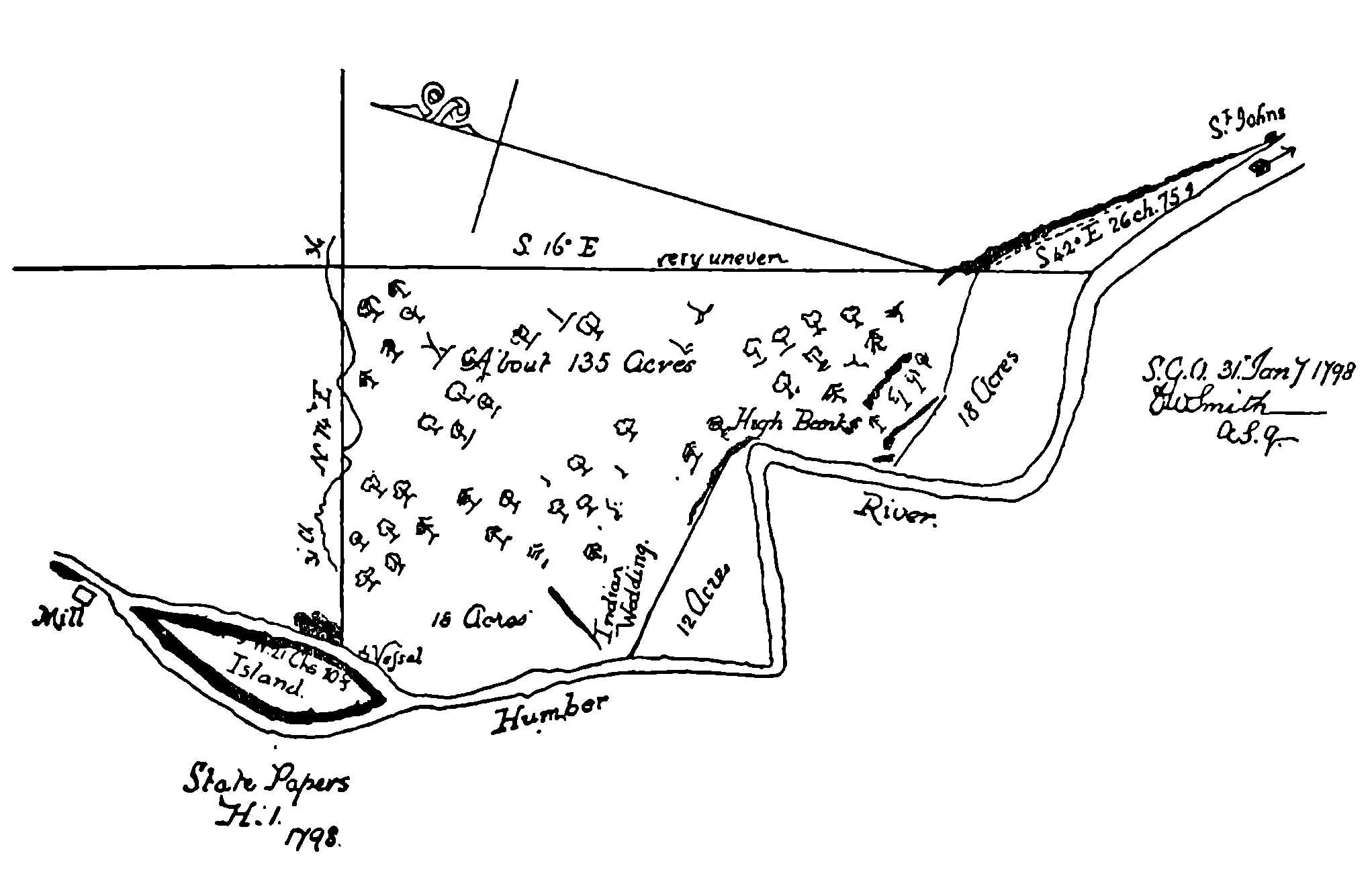

| 20. | Map of 1798, Showing Site of Rousseau’s House | 201 |

| 21a. | The Northern End of the Carrying-Place | 208 |

| 21b. | Crossing the Marsh | 208 |

| 22. | Relics of Colonel J. B. Rousseau, the Last of the French Traders at Toronto | 210 |

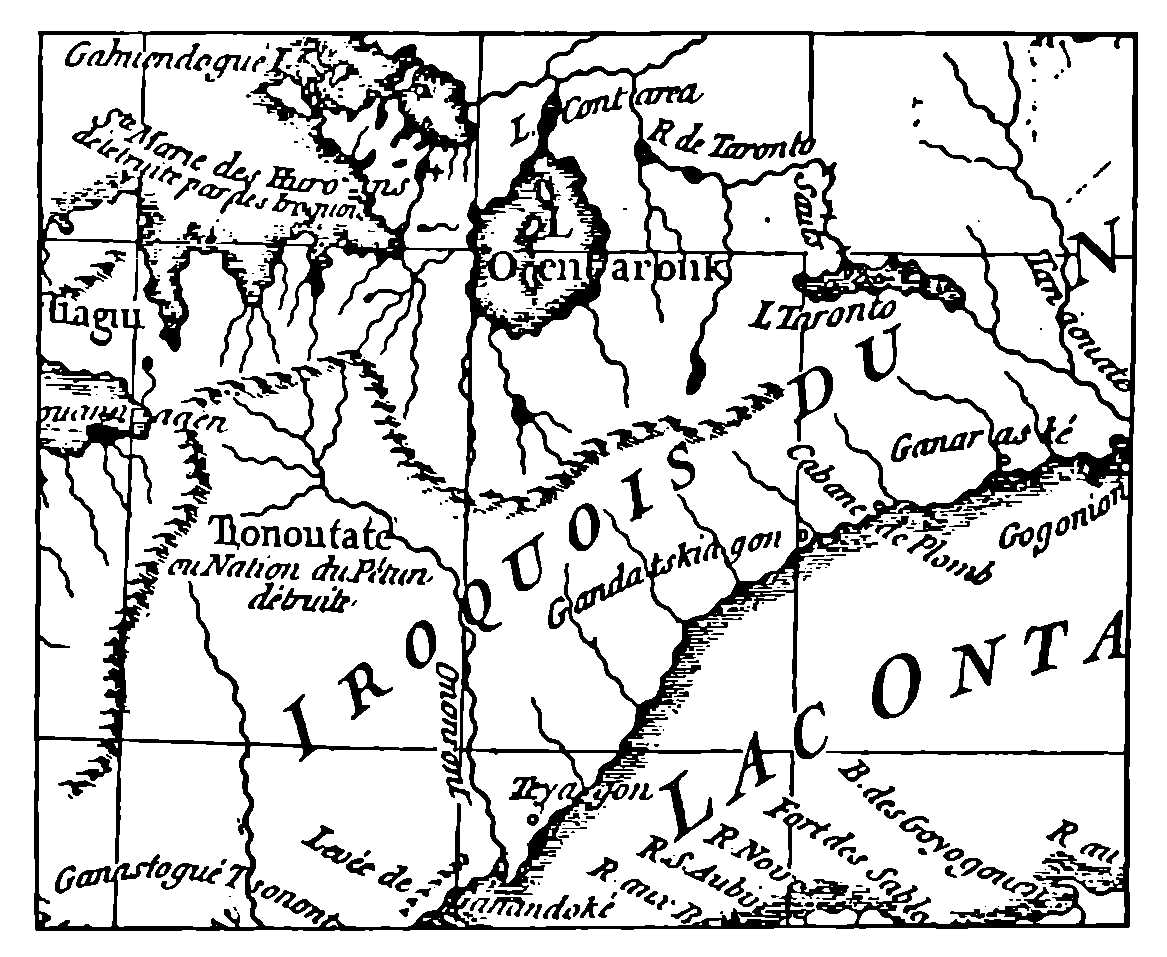

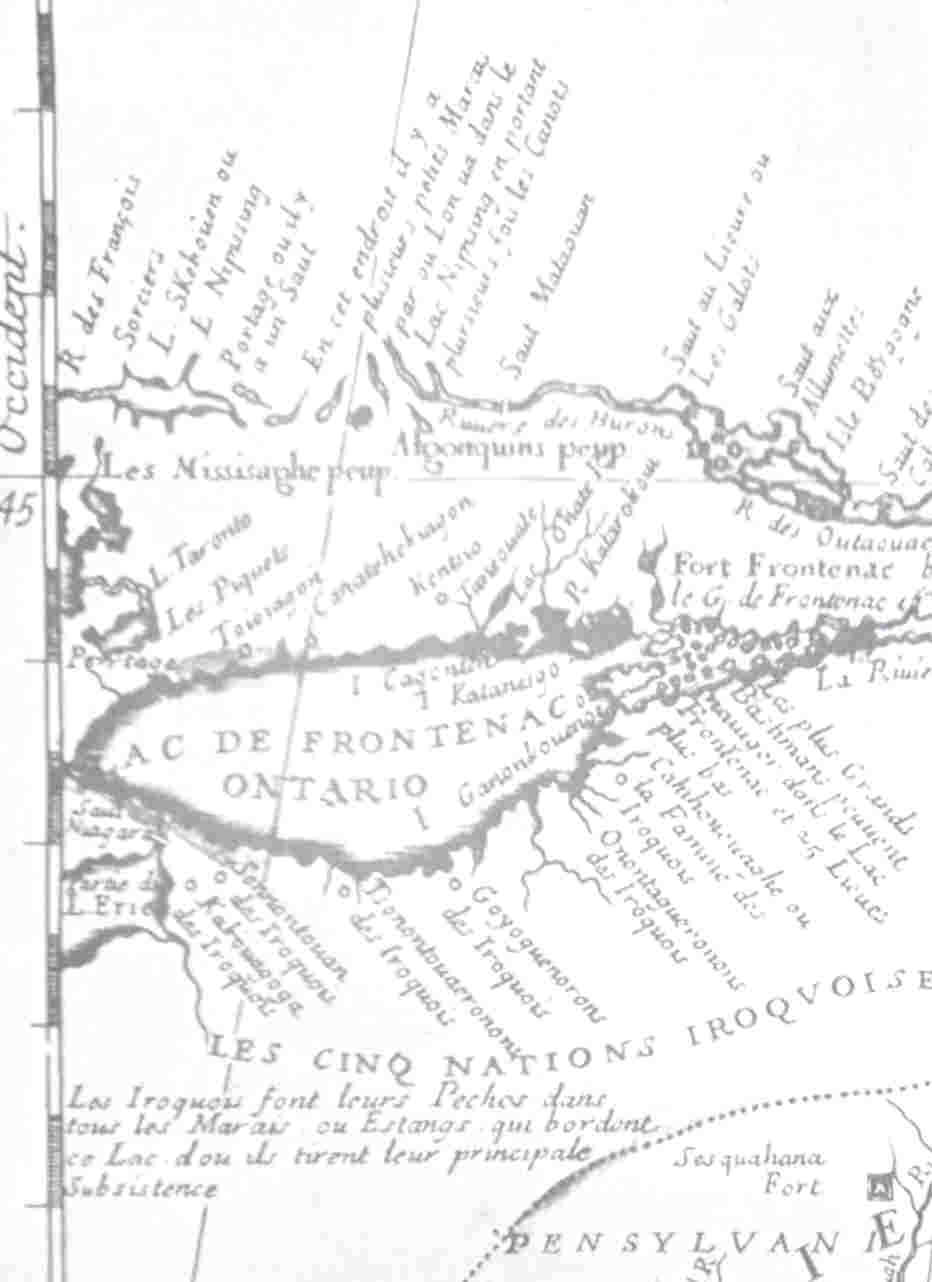

| 23. | Coronelli Map, 1689 | 222 |

|

From Miss K. M. Lizars’ The Valley of the Humber. |

|

Ibid. |

|

Ibid. |

The east bank of the Humber, where it flows into Lake Ontario, is formed by a ridge whose steep sides are still clothed by vestiges of the original forest. Along the crest of this ridge Riverside Drive winds among the trees with scarcely room here and there for the houses. Occasional glimpses are to be caught of the river meandering as pleasantly through marshy ground for the modern motor boat as for the canoes of the Senecas and Missisaugas. Less picturesquely in the valley to the east and screened by a growth of trees, runs the Kingsway, pulsating with the traffic of a modern highway. Riverside Drive enjoys a peculiar seclusion. The forest seems to be making a last stand against the intruder. The hum of the adjacent city scarcely penetrates this isolated region, and when it does it is not loud enough to break the mood of musing and reminiscence so easily evoked. There is no monument to recall the past, but this is one of the most historic spots in the lake region, and here we may go back three centuries to the beginning of Canadian history. This is the foot of the Toronto Carrying-Place with memories of Simcoe and Joliet, of La Salle and Denonville, of Brûlé and St. Jean de Brébeuf.

In the centuries when all travel was by canoe and trail, the Carrying-Place was the link between Lake Ontario and the upper lakes. Running from the mouth of the Humber to the west branch of the Holland, it was always traversed on foot. It was a long portage, but the road was good and it saved the traveller a detour of hundreds of miles over the exposed waters of the Great Lakes. The oldest maps indicate that its course was always the same. This was no ordinary trail; it was a main thoroughfare, a trunk line of communication with distant regions definitely determined by the contours of the country traversed. The Carrying-Place possessed a permanence very different from casual paths through the forest. It was as old as human life in America.

May we for a moment anticipate research and weave the shadows of this modern street into a brief pageant of forgotten traffic along the old trail? A midsummer night and moonlight would be the best setting for this reunion of the ghosts of bygone days, but the trail was trodden for so many centuries by human feet on so many errands, that if anything of outworn humanity clings to our material surroundings, here at least at any time imagination may evoke the past.

Along this street, when it was only a narrow foot-path in the woods, how many grotesque and terrible figures passed in the long years before and after the coming of the white man: war parties of painted braves; lugubrious trains of miserable prisoners destined to the stake; embassies from tribe to tribe on more peaceful errands; hunters wandering into the distant north in quest of furs; Hurons and Iroquois, Ottawas and Menominees, Shawanoes and Sacs and Foxes and last of all the debauched Missisaugas, spectators of the white man’s progress and participating with him in cruel and dramatic events; raids into New York, the defeat of Braddock, the tragedy of Fort William Henry, the fall of Quebec, the massacre of Wyoming!

Traders, too, of every description knew the mouth of the Humber and bargained here for the precious peltries; Dutchmen from the Hudson before the French themselves had gained access to Lake Ontario; French traders from Fort Frontenac; English freebooters from Albany, they all knew the Carrying-Place, and with or without license robbed the poor Indian. How various and picturesque they were, these rascals from the Hudson and these lawless coureurs-de-bois from the St. Lawrence, wild hearts and children of the wilderness as truly as the aborigines whom they beguiled. To-day there is a dance-hall on the bank of the Humber on a knoll overlooking the lake; it stands at the foot of the Carrying-Place; below it is a cove where hundreds of these gentry landed for their nefarious trade. Time has shifted the scene.

Mouth of the Toronto or Humber River

The Carrying-Place ran along the top of the bank on the right.

Here, too, in sombre contrast with the war-paint of the savages and the gay garments of the coureurs-de-bois were seen the black robes of the Jesuits and the less gloomy garb of the Récollets and Sulpicians. Hennepin was here, and Raffeix mapped the shore and traced the course of the Don as early as 1688; and Fénelon and d’Urfé came from the mouth of the Rouge to preach at Teiaiagon.

Du Lhut and Péré, Tonti and La Forest, Henry and Frobisher, and many of the French pioneers of the West passed this way. None of whom stand out so vividly as the great explorer of the Mississippi with his crowd of Shawanoes and his great canoes, three feet wide, to be carried over the long portage and the “high mountains” between Teiaiagon and Lac Toronto. Great days those for the old trail when the dream of empire was maturing in the brain of La Salle, a dream which in the end was to expel the French from America!

And there are memories of Pouchot exploring the shores of Lake Ontario and perhaps already dimly conscious that he would be the last to defend the flag of France at Niagara; of de Léry carefully mapping a region so soon to slip into the hands of the English; and of all who came and went to the fort to the east, the soldier-abbé Picquet, and that Captain Douville whose wife was a niece of Madeleine de Verchères. How many of these sojourners idled a summer afternoon on the Toronto river or wandered up the enticing trail into the unbroken woods!

How the Missisauga chiefs from their village near by must have wondered at the fallen fortunes of the French when they saw the smoke of the burning fort rising above the trees, and what tales of a new order did they bring back to the river after they had sworn allegiance to the British and to Sir William Johnson at Niagara! Strange subjects these of the Crown, these first citizens of a British Toronto!

Here too, at the foot of the old trail, Surveyor Aitkin and Colonel Butler debated with the Missisaugas the limits of the land purchased the year before at Quinte. The Indians had sold more than they intended or they had forgotten the limits of the sale. Here they are, the white men strong in the destinies of their race, and the red men fated to disappear and relinquishing with reluctance the lands of their fathers. Herodotus loved local history and he would have made a striking picture of so dramatic an incident.

Yonder is Jean Baptiste Rousseau, the last citizen of the old French Toronto and the first of the new York, putting out in the early dawn of a midsummer morning from his house at the foot of the trail to pilot the Mississaga into the bay. The vessel carries Governor Simcoe and his lady and numerous officials. They have crossed the lake in state to found the new town. The band of the Rangers is on board, and for the first time British martial music is heard in these savage wilds.

A few weeks later, the Governor’s gentle wife is to be seen taking her rides along the ridge where the trail ran; and in the autumn of the same year the Governor himself setting out with a well-equipped party on horseback to explore the communications to the north. And then the trail vanishes from history. The story of the Carrying-Place comes to an end, for a great highway called Yonge Street presently takes its place.

Like a huge spearhead, the peninsula of Ontario projects into the heart of the lake region. More than two-thirds of the isthmus between the Georgian Bay and Lake Ontario is intersected by navigable river and lake. A portage of thirty miles, known as the Toronto Carrying-Place, completes this historic communication. Near the northern end the French established themselves early in the seventeenth century at Fort Ste. Marie, and failed in their first attempt to control the interior. At the southern end, on Lake Ontario, Simcoe in 1793 founded his town of York, which was to grow into the city of Toronto.

Flanked on all sides by magnificent waterways, the peninsula of Ontario occupied a strategic position long before the coming of the French. With the advent of the fur-trader, the explorer and the missionary, the country of the Hurons became the key to the continent. Adjoining the Hurons on the south-west were the Petuns; north of Lake Erie were the Neutrals; further south on the southern shores of Lake Erie were the Eries, or Nation of the Cat; southward on the Susquehanna lived the redoubtable Carantouans or Andastes, old allies of the Hurons; east of the Hurons were the Upper Algonquins, the Ottawas and the Nipissings, differing from the Hurons in customs and language and independent one of another, but all of them united in a common hatred of the Iroquois, whose rich and populous country lay south of Lake Ontario and extended east to the Hudson River. “The Huron Mission,” writes Bressani in his Relation Abrégée, “included all these countries. Our purpose was always to march on to the discovery of new peoples, and we hoped that a settlement among the Hurons would be the key.”[4]

Champlain himself desired the establishment of this mission not only from the point of view of religion, but because he appreciated the immense advantages which the French would derive from it from the point of view of commerce and conquest. The Huron Mission was, in Champlain’s opinion, an advance post towards the west, which was to assure to France the freedom of her communications in the heart of North America. He hoped to attach the fur-trade to the mission, and to make himself master in the Huron country of all the commerce with the peoples of the interior, to the exclusion of the English and the Dutch.[5] He was not long in allying himself with the Hurons and visiting their country.

Accordingly on the eighth of September, 1615, we find Champlain at the northern outlet of Lake Simcoe ready to set out with the Hurons on an expedition against the Iroquois, and accompanied by his interpreter, Étienne Brûlé, whom he despatched with twelve Hurons and two canoes to the Carantouans or Andastes to summon their assistance. It is at this point that the “Toronto Carrying-Place” comes into history, for it was by this route that Brûlé and his companions set out on their long and devious journey to the Andastes. We have, however, to rely upon inference and tradition, for Champlain has little to say about Brûlé, and the dotted line on Champlain’s map, which seems to indicate Brûlé’s trail to the country of the Carantouans, begins south of Lake Erie and gives no hint of the route followed before reaching that point. The tradition which connects Brûlé with the Humber has, however, the support of all historians, including Parkman and Butterfield; and since Brûlé parted with Champlain at the Narrows it is reasonable to infer that he would follow the most direct route to his destination.

Butterfield remarks: “There were two streams, one from the southward emptying into Lake Simcoe, another the Humber, from the northward flowing into Lake Ontario, which were to be their highway of travel, there being a short portage from one to the other, across which two canoes could easily be carried.”[6] Butterfield is mistaken as to the length of the portage; the Toronto Carrying-Place, twenty-eight miles in length, ran from the west branch of the Holland to the mouth of the Humber, and there is no indication that it was ever traversed otherwise than on foot. This, however, would be no obstacle to the nimble Hurons, nor to Brûlé, who had now been five years in their country, and was by this time as active and nimble as themselves.

We may follow, in imagination, Brûlé and the Hurons, swinging along at a rapid rate through the September woods with their canoes on their heads. Possibly they reached the mouth of the Humber some time after sundown on the ninth. Brûlé was the first white man to behold the site of the city of Toronto; and the scene which met his gaze as he and his twelve Huron companions emerged from the woods by the foot-path which until recent years still followed the east bank of the Humber, must have been a noble and impressive sight. East and west the forest clothed the shores, and before him, extending to the horizon, lay the lake which has borne in succession the names, Tadenac, Lac Contenant,[7] Lac St. Louis, Lac des Entouhonoronons, Lac des Iroquois, Cataraqui, Contario, Lac Ontario,[8] Lac Frontenac, but which the Iroquois themselves called “Skaniadorio”[9] or the “beautiful lake”—a fair scene of primitive and virgin beauty, very different from the animated picture which the bathing-beach at Sunnyside presents to-day with its Mediterranean brilliancy of colour backed by the skyscrapers of a modern city.

What route Brûlé followed from the mouth of the Humber to the country of the Andastes has been the subject of considerable conjecture. It has been thought that the party crossed Lake Ontario in their canoes; others have maintained that they followed the shore to the end of the lake and coasted the southern shore to the mouth of the Niagara River; others have asserted that Brûlé turned westward from the mouth of the Humber and followed the valley of the Thames to the neighbourhood of Detroit and then reached the Andastes by a long detour south of Lake Erie. All this is conjecture; but it seems probable, if the dotted line in Champlain’s map represents the route followed after the party had crossed Lake Erie, that Brûlé on this historic occasion took the trail which appears on the earliest Joliet map, from the head of the lake to the Grand River, and that Brûlé, descending that river to its mouth, crossed Lake Erie and followed the route indicated by Champlain.

Posterity has not done Brûlé justice; he was the first of Europeans to master the Algonquin and Huron languages; he was bold enough and hardy enough to risk his life among these tribes for many years; he was the first to make the long journey from Quebec to Lake Huron by way of the Ottawa River; the first to enter what is now the Province of Ontario; the first in all likelihood to sail Lake Ontario and to visit the Niagara Peninsula, and the first to cross over northern New York and to descend the Susquehanna River, passing on his way through parts of Pennsylvania and Maryland and touching the soil of Virginia; he was the first also to stand upon the shores of Lake Superior. Although research has revealed much about this extraordinary man, he remains a shadowy figure; it is likely that his explorations covered a much wider area than we know. He was illiterate and possibly irreligious. His contemporaries, with the exception of Sagard, do not speak well of him.[10] Champlain, while making use of the information which Brûlé obtained, ignores his discoveries. Brûlé’s unpopularity with the Jesuits may be due to the fact that he “went native”; the missionaries alleged that his life among the Hurons was a disgrace to the French and to Christianity. Brûlé avenged himself by siding with the Huguenot traders and afterwards with Kertk; he shared the infamy of Marselot, another of Champlain’s “boys,” in piloting the English from Tadoussac to Quebec. He was sharply rebuked by Champlain, and was murdered some years later by the Hurons; they killed and ate him when they heard that the French had returned to Quebec. Poor Brûlé! It is impossible to form a very just estimate of an adventurer whose character has been painted in the darkest colours by his contemporaries. The discoveries which he made alone and unaided in the interior of America are a title to honours which he has not received. The investigations of Dr. A. F. Hunter make it almost certain that the skull and bones of Étienne Brûlé, together with his weapons, his pipe and other personal belongings, lie buried according to the custom of the Hurons somewhere in Lot 1 of the 17th Concession of the township of Tay.

Du Creux’s formidable indictment of Brûlé—more formidable still in the stately Latin—lies like a monument of obloquy upon the memory of the intrepid explorer.

It is clear that Brûlé was a bad man, and guilty of every vice and crime. He had served as interpreter for the French among the Hurons, and the wretch had not been ashamed to disgrace himself by betraying the French and passing over to the English when they took possession of the citadel of Quebec. Champlain taunted Brûlé with this perfidy, and pointed out how disgraceful it was for a Frenchman to betray king and country, and for an orthodox Catholic to ally himself with heretics, share their foul intoxication and eat meat on days when, as he well knew, Catholics were forbidden to do so. The impious man answered that he knew all that, but since a comfortable future was not before him in France, the die was cast, and he would live with the English. Brûlé returned to the Hurons. It cost him nothing to give up his country. Long a transgressor of the laws of God and man, he spent the rest of his wretched life in vile intemperance, such as no Christian should exhibit among the heathen. He died by treachery; perhaps for this very reason, that he might perish in his sins. Deprived of those benefits by which the children of the Church are prepared for a happy issue from this mortal life, Brûlé was hurried to the Judgment Seat to answer for all his other crimes and especially for that depravity which was a perpetual stumbling-block to the Hurons, among whom he should have been a lamp in a dark place, a light to lead that heathen nation to the Faith. Let us return to our story.[11]

It is not unlikely that there were others who travelled the trail early in the seventeenth century; French missionaries and traders or adventurous Dutchmen from Fort Orange on the Hudson. It is possible that Brébeuf and Chaumonot passed this way in the spring of 1641, on their return from the country of the Neutrals where they had spent the winter; they reached Fort Ste. Marie on March 19th, and since the Relation for that year informs us that Brébeuf broke his left shoulder-blade in a fall on the ice on Lake Simcoe, the missionaries may have returned to Huronia by the Carrying-Place and not by the long inland trail up the valley of the Grand River. The finding of an ovoidal stone on Lot 24 of the fifth concession of the township of Vaughan, inscribed with the date 1641 and now in the Royal Ontario Museum, seems to indicate that there were Frenchmen in that vicinity in that year.[12] Sagard, however, makes it plain that when the Petun chief conducted Father de la Roche d’Aillon[13] into the country of the Neutrals in 1626 the party followed the long trail across country and not the more direct route of the Carrying-Place. Although there were many Frenchmen in Ontario from 1610 to 1650, we learn little from the Relations about the geography of any part of the Province except that district in which the French were conducting their missions. Yet it is incredible that bold and adventurous spirits should face all the dangers of the journey from Quebec to Huronia and then remain inactive within the confines of that somewhat restricted area; there were at times as many as sixty men engaged in one way or another in the work of the mission, and Lake Ontario and the Toronto Carrying-Place must have had many visitors in the intervals of peace with the Iroquois.

Champlain—1632

The dotted line on the left is Brûlé’s trail.

Sanson—1650

The two lines from the Georgian Bay to Lake Ontario are probably the Quinte and Toronto routes.

Astrolabe Discovered in 1925 on Christian Island, Georgian Bay, and now in the Possession of Dr. F. N. G. Starr, Toronto

This instrument was no doubt employed by the French missionaries in constructing the earliest maps of the lake region. It bears the date 1595 and is 4¼ inches in diameter. Champlain’s astrolabe, discovered on the portage from the Ottawa River to Muskrat Lake in 1867, is dated 1613.

There are only two specimens of this rare Instrument in America.

To the Iroquois is due the fact that the country south of Lake Simcoe and along the north shore of Lake Ontario remained a no-man’s land during this period, with no permanent settlements and traversed only by raiding parties from the north or from the south. The evidence seems to show that most of the attacks of the Iroquois upon Huronia came from the region of the Narrows above Lake Simcoe, and that the Iroquois availed themselves of the Trent Valley waterways as the most convenient approach; but it is more than probable that they occasionally employed both of the trails leading from Lake Ontario to the Holland River, and it is certain that, as soon as they had expelled the Hurons from the country, they began immediately to make use of these routes. We may suppose, too, that the Hurons often sent their raiding parties along both these trails, more especially when attacking the Senecas, the most westerly of the Iroquois. There is no record of the routes followed by the numerous embassies to and from the Andastes, but if the Toronto Carrying-Place was avoided, it was avoided because it was the obvious route and would be closely watched by the implacable enemies of the Hurons. The Toronto Carrying-Place was the front door of the Huron country, and the French, though compelled to follow the toilsome trail up the Ottawa, had learned at an early date of this route from Quebec to Huronia, for the Hurons informed them in 1632 that they knew of a trail by which they could come to the French trading place in ten days. So formidable, however, were the Iroquois who barred the St. Lawrence that not one single Frenchman ascended that river till the year 1657. Had it not been for the Iroquois it is probable that there would have been a French settlement at Toronto even before the founding of Montreal; the Jesuits would certainly have ascended to the Hurons by the shorter and more direct route, and the rich peltries which were collected at Fort Ste. Marie would have descended to Quebec by le passage de Toronto instead of by the long and perilous portages of the Ottawa.[14]

From the first the fur trade determined the history of the Carrying-Place. The French had hoped by still further estranging the Hurons and the Iroquois to possess for themselves the peltries of the former, and the Iroquois had bent themselves to the destruction of the Hurons in the hope of acquiring the whole trade for themselves and the Dutch. Supplied by the latter with firearms, and stimulated with Dutch brandy, the Iroquois by a policy of terrorism expelled the Hurons, the Petuns and the Neutrals from the whole of the peninsula lying between the lakes, and acquired hunting grounds far richer than any south of the lake. Ontario appears on the maps for a century after the expulsion of the Hurons as “the beaver hunting ground of the Iroquois.”[15]

In 1638, while these wars were raging, a people known as the Ouenrohronnons,[16] who lived east of the Niagara River, abandoned their country and took refuge with the Hurons. The Relation for that year informs us that they arrived in an exhausted condition and that many of them died on the way. As the statement is made that the distance which they had covered was more than eighty leagues, and since this corresponds roughly with the following route, we may assume that the Ouenrohronnons, escorted by the Hurons, skirted the western shores of Lake Ontario till they reached the mouth of the Humber, and then by way of the Carrying-Place arrived eventually at Ossossane, where they were to find a new home.

Between 1600 and 1663 the maps of the lake region are not numerous, but some of them are more detailed than the maps of the succeeding period. The Hakluyt map of 1600 merely indicates a great inland sea called “The lake of Tadenac whose bounds are unknown.” This map is described by Hallam in his Introduction to the Literature of Europe as “the best map of the sixteenth century.” It is in all probability the new map referred to by Shakespeare in Twelfth Night, Act III, Scene 2. More is to be learned from Champlain’s map of 1612. No white man had as yet ascended the St. Lawrence above Montreal, and Champlain’s information was derived from the Indians. In this map the falls of Niagara are indicated for the first time. Three villages are marked on the north shore of Lake Ontario. Champlain gives no name to Lake Ontario, but describes it as a lake of fifteen days’ journey by canoe, Lac Contenant 15 journées des canaux des sauvages. The Dutch, supposing that Contenant was a proper name, perpetuated this error in their maps for fifty years. The Quinte Peninsula and the Trent Valley route are indicated.

In Champlain’s smaller map of 1613, Lake Ontario appears for the first time as Lac St. Louis. In his much more detailed map of 1632 there are no place names or sites along the north shore; Lake Simcoe is shown, and the Humber River and Brûlé’s trail to the Andastes south of Lake Erie. Jansson’s map of 1636 shows that the Dutch knew the hills north of Toronto. Sanson’s map of 1650 has lines which may be the Toronto and Quinte routes. His map of 1656 gives Lake Simcoe as Lake Oentaron. Du Creux in 1660 gives this lake as lacus Ouentaronius and marks the Holland and the Humber rivers and other streams flowing into Lake Ontario. Sanson and Du Creux probably based their maps upon Jérôme Lalemant’s map of 1639, which has not been discovered. Du Creux’s map is the more detailed in the Toronto region, and both these maps show a surprising knowledge of the lakes, although Lake Michigan and Lake Superior are still imperfectly delineated. We may believe that observations were taken in many places with the astrolabe found within recent years in the neighbourhood of Fort Ste. Marie II on Christian Island.

|

rochemonteix, Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle France, Tome I, p. 321. |

|

rochemonteix, Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle France, Tome I, p. 335. |

|

butterfield, Brûlé’s Discoveries and Explorations, p. 48. |

|

visscher’s map, 1680. |

|

potier, Radices Huronicae, I, p. 156; ontare—ils appellent ainsi tous les lacs (à l’exception du Lac Superior, qu’ils nomment okouateenende) + io, “beautiful, good, large,” ibid., II, p. 236. |

|

coronelli, map, 1688. |

|

du creux, Historia Canadensis, pp. 119, 120, 161, 172. |

|

du creux, Historia Canadensis, p. 160. Consult also a paper by Mr. J. W. Curran, of Sault Ste. Marie, read at St. Catharines, June, 1932. |

|

Ontario Archaeological Report, 1897-1898, p. 32. |

|

“Many of our Frenchmen,” says the Jesuit Relation of 1640-1641, “have in the past made journeys in this country of the Neuter nation for the sake of reaping profit and advantage from furs and other little wares that one might look for. But we have no knowledge of any one who has gone there for the purpose of preaching the Gospel, except the Rev. Father Joseph de la Roche Dallion, a Récollet.” |

|

“It is true that the way is shorter by the Sant de St. Louys and the Lake of the Hiroquois (Ontario), but the fear of enemies, and the few conveniences to be met with, cause that route to be unfrequented.” Brébeuf, Relation of 1635. “If once we were masters of the sea nearest the dwelling of the Iroquois we could ascend by the river St. Lawrence without danger, as far as the Neutral Nation and far beyond with considerable saving of time and trouble.” Jérôme Lalemant, May 19, 1641, St. Mary’s in the Huron Country. |

|

wraxall, New York Indian Records, McIlwain, Introduction. |

|

du creux, Historia Canadensis, p. 238. |

La Salle, “un homme devenu grand par ses actes, par leurs conséquences et avant tout par le sacrifice de sa personne.”[17]

In 1663 Canada became a Royal Province; the period of romance was at an end; there were to be no more dreams of spiritual empire. But with the coming of the Carignan-Salières regiment in 1665 there was peace, and the French for the first time began to find their way to Lake Ontario, to explore its shores, and to lay their plans for recapturing from the Iroquois the fur-trade, which the latter had diverted to the English and the Dutch on the Hudson, and to the Swedes in New Jersey. The first steps had already been taken; for the Jesuits, abandoning the Huron country and the rest of Ontario to the Iroquois, had pushed farther into the west, and as early as 1660 had discovered Michilimackinac in the heart of the continent at the juncture of three great inland seas, where they established a post which was to continue for a century to be the citadel of the French in the interior. With the establishment of Fort Frontenac at the eastern extremity of Lake Ontario in 1773, the French found themselves at last in a position to impose an effective curb upon the Iroquois, and to collect at their leisure the peltries from the north and south sides of the lake. Le passage de Toronto,[18] which but for the Iroquois would have been the main avenue of approach to the Huron country, now became the link between Fort Frontenac at the base of the St. Lawrence and Michilimackinac and the Sault in the heart of the west, and began in a measure to replace the route by the Ottawa which had been the only available approach to the interior since the days of Champlain.

La Salle

Crossing the Toronto Portage, 1681, on his way to the Mississippi.

But hardly had the French resumed control of the fur-trade when France began to play a new rôle in America. With La Salle and Frontenac, the empire-builder appears upon the scene, and no longer content with the banks of the St. Lawrence, the French conceived that grandiose scheme of securing the valley of the Mississippi, which was to end in tragedy a century later. It is an altered scene. If the old actors continue to play a part, it is upon a larger and a more varied stage. Le passage de Toronto becomes not only a link between Fort Frontenac and Michilimackinac, but a highway to the Mississippi.

The Jesuit, Le Moyne, who undertook a diplomatic mission to the Onondagas in the year 1654, was the first white man to follow the St. Lawrence from Montreal to Lake Ontario. From that time missionaries began to find their way into the Iroquois country south of the lake. But it was not till the year 1668, when the Sulpicians of Montreal began their mission among the scattered Iroquois on the north shore of Lake Ontario, that the district once so thickly peopled by the Hurons, the Petuns and the Neutrals again comes into history. From the spring of 1650, when the miserable remnant of the Hurons fled northward along the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, the whole of the peninsula between the lakes had been in the hands of the Iroquois. “Succurrebat animis,” writes Du Creux, “Huronicos tractus deinceps aliud nihil esse nisi locum horroris, et vastae solitudinis, theatrumque caedis et cladium.” For almost twenty years the Iroquois, in the intervals of warlike expeditions, had gathered the rich peltries and sold them to the Dutch and English on the Hudson. Gradually, too, after 1666, they had migrated in small bands to the north shore of the lake, and had established themselves where the trails led off into the interior, to the richer hunting-grounds of the north. Beginning at the eastern end of Lake Ontario, the names of these Iroquois villages are as follows: Ganneious on the site of the present site of the town of Napanee, a village of the Oneidas; Kenté on the Bay of Quinte, Kentsio on Rice Lake, Ganaraske on the site of the present town of Port Hope, villages of the Cayugas who had fled from the menace of the Andastes to a securer position beyond the lake; Ganatsekwyagon at the mouth of the Rouge and Teiaiagon at the mouth of the Humber, villages of the Senecas who had established themselves at the foot of the two branches of the Toronto Carrying-Place and were thus in command of the traffic across the peninsula to Lake Simcoe and the Georgian Bay.[19] It is probable that there were other villages of the Iroquois here and there in the interior, but it is only possible to surmise their situation.[20] De Courcelles, who visited the eastern end of the lake in 1671, observed that the Iroquois never hunted the beaver on the south side of Lake Ontario for the very sufficient reason that they had exterminated them there long ago, and that it would be extremely difficult to discover a single specimen in the Iroquois country; they did all their hunting on the north side of the lakes, where the Hurons had formerly hunted.[21] On the first arrival of the French in Lake Ontario, they found the Dutch in possession of the trade. These enterprising traders from Fort Orange and Manhatte, les Hollandois[22] who appear so often in the records of the period, had long been en rapport with the Iroquois and could speak their language, and seem to have swarmed over the lake and the adjoining territory, debauching the savages and carrying off their furs. In the years between the fall of Huronia and the return of the French to the lake region, these Dutch traders must have frequented Ganatsekwyagon and Teiaiagon and the shore between these two villages where Toronto now stands.

Dollier de Casson, in his Summary of the Quinté Mission, describes its origin.

It was in the year 1668 that we were given the task of setting out for the Iroquois, and Quinté was assigned to us as the centre of our mission because in that same year a number of people from that village had come to Montreal and had definitely requested us to go and teach them in their country, this embassy reached us in the month of June. As, however, we expected that year a superior from France, it was deemed fitting that they should be asked to come back again, as it seemed inadvisable to undertake a matter of this importance without waiting for his counsel, so that nothing should be done therein save as he decided. In September the chief of that village did not fail to appear at the time set for him, to try and lead back into his country a number of missionaries. The request was placed before M. de Queylus, who had come to be superior of this community, and he gave his approval of the plan very willingly. After that we went to see the bishop, who supported us with his authority. As for the governor and intendant of the country, we had no difficulty in obtaining their consent, as they had from the first thought of us in connection with such an enterprise.[23]

M. de Trouvé, from whose letter the above extract is taken, and M. de Fénelon, the fiery half-brother of the famous Archbishop of Cambrai, and author of Télémaque, were the first missionaries; the latter, in company with another missionary, M. d’Urfé, passed the winter of 1669 and 1670 in the village of Ganatsekwyagon,[24] a fact which is commemorated by the name Frenchman’s Bay, which clings to the inlet near the mouth of the Rouge.[25] This is the first recorded residence of white men in the neighbourhood of Toronto.

Routes Followed by Brûlé, 1615; Joliet, 1669; Hennepin, 1678; La Salle, 1680-1681

Frontenac, in his letter to the Minister under date of November 2, 1672, makes it very plain why the Sulpicians were selected for the new mission on Lake Ontario. It was felt that a new policy must be adopted with the Indians. The Jesuits had made no effort to turn them into Frenchmen or even to teach them the French language. It was hoped that the Sulpicians would render them more useful allies of the French.

It was in the year 1669, possibly before the arrival of Fénelon and d’Urfé in the village of Ganatsekwyagon, that two notable explorers, Péré and Joliet, camped for a time in that village before crossing le passage de Toronto[26] to the Georgian Bay. They were on their way to Lake Superior in search of the great copper mine reported to exist in that region. It has been thought that this was not the first visit of Péré to the locality, and that he visited the site of the city of Toronto in the preceding year;[27] he was the first French trader on Lake Ontario, and the few facts which have been ascertained about him serve to stimulate curiosity. On November 11, 1669, the sieur Patoulet wrote to Colbert from Quebec, “The sieurs Joliet and Péré to whom M. Talon has had paid 400 and 1,000 livres respectively, to go and find out if the copper mine which exists above Lake Ontario, and of which you have seen several samples, is a rich mine, and easy to work, and accessible, have not yet returned.” They had left Montreal in May or June of 1669, and there is a legend on the Dollier-Galinée map attached to the village of Ganatsekwyagon, “It was here that M. Perray and his party camped to enter Lake Huron—when I have seen the passage I will give it; however, it is said the road is very fine, and it is here the missionaries of St. Sulpice will establish themselves.” This information must have been obtained from Joliet and Péré, whom Dollier and Galinée met on September 24, 1669, at the village of Tinawatawa on the portage from the head of Lake Ontario to the Grand River. Similarly at the head of Matchedash Bay there is this legend on the Galinée map: “I did not see this bay, where was formerly the country of the Hurons, but I see that it is even deeper than I sketched it, and apparently the road over which M. Perray travelled terminated here.” There is thus good evidence to prove that Joliet and Péré passed over the passage de Toronto from Ganatsekwyagon to the mouth of the Severn River in the year 1669, and that they found the road good and likely to prove an excellent alternative to the long and dangerous route by the Ottawa River.[28] We may conclude also that the Abbé Fénelon and the Sulpicians decided to establish themselves at Ganatsekwyagon because that village was situated at the foot of one arm of the passage de Toronto.[29] On several maps of this period the Ganatsekwyagon portage is indicated and the Teiaiagon portage is not marked, though the village itself is shown; the French seem to have selected the former because it was nearer to the eastern end of the lake, and for those travelling by canoe there would be no need to go on twenty-three miles to the better anchorage at the mouth of the Humber. We shall hear once more in Denonville’s time of Ganatsekwyagon, and then the preference seems to have been given to Teiaiagon and the western branch of the portage, which became definitely known as the Toronto Carrying-Place.

Joliet—1674 This is the earliest map of the Toronto Carrying-Place.

Du Creux—1660 In an inset map of the Huron country Lake Simcoe is Lacus Ouentaronius.

From a copy in the Public Archives, Ottawa.

The First Detailed Map

This map (4044 B: No. 43, Service Hydrographique Bibliothèque, Paris.) has been ascribed to Joliet; it is not earlier than 1673. It is the first map on which the name Toronto appears, and the first to show Teiaiagon and Toronto Island. This map indicates that before 1673 the route of the English and Dutch trade with the Ottawas was round the eastern end of Lake Ontario to Ganatsekwyagon. The building of Fort Frontenac resulted in a new trade route from Chouéguen (Oswego) round the western end of the lake to Teiaiagon, with the Senecas as middlemen.

Péré and Joliet had been despatched not only to search for a copper mine but also to find a new route to the west; they were the first white men to pass through the straits at Detroit. Dollier and Galinée had embarked on a similar errand in the same year, but they tell us nothing about the Toronto region; they followed the south shore of Lake Ontario and returned next year by the Ottawa. With the exception of Péré, the names of all these men are too well known to students of history to require further comment. Péré[30] remains a shadowy figure; choosing the life of a coureur-de-bois, he seems to have laid aside the loyalties as well as the restraints of civilization and to have conceived an ambitious plan for disposing of the furs of the coureurs-de-bois to the English at Albany. Arrested by the English and detained in England, he returned to America. There is ground for supposing that he was the discoverer of the Moose River flowing into Hudson Bay; it bears his name in some early maps. At any rate, he was one of those many Frenchmen attracted by the wild life of the woods who disappeared into the wilderness.[31]

On August 29, 1670, Talon sent to Colbert, by the hands of the Abbé Fénelon, a map showing the communication between Lake Ontario and Lake Huron. “Another missionary,” he wrote, “also from the Seminary of St. Sulpice, has penetrated farther than he in order to find out for me about a river for which I was looking in order to establish a communication between Lake Ontario and Lake Huron where they say there is a copper mine. This missionary made a map of his journey a copy of which is in the hands of the said Abbé Fénelon. It will form un assez juste sujet de vostre curiosité.”

Hardly had the results of these explorations been ascertained when the Intendant Talon wrote to Colbert explaining his plans for curbing the Iroquois, who were hunting the beaver on the lands of those savages who had placed themselves under the protection of the king and plundering them of their own peltries. He proposed to establish two posts, one on the north and the other on the south side of Lake Ontario, and to build a small vessel which could be either sailed or rowed and which could show itself wherever there was trading on the lake; he explained that the English from Boston and the Dutch from Manhatte and Orange secured from the Iroquois and other tribes in their neighbourhood more than 1,200,000 livres of beaver skins of the best quality, all of them secured on the dominions of the king, and that he thought he saw the way to direct the greater part of this commerce, naturally and without violence, into the hands of His Majesty’s subjects.[32] The two posts which he proposed to establish would protect the Ottawas when they came down with their rich beaver skins. It is likely that Talon had in mind an establishment at Niagara on the south side of the lake and at Cataraqui on the north, for though the Ottawas were in the habit of employing the Toronto Carrying-Place, it was thought at first that these two posts would be sufficient.

In 1671, the year after Talon wrote to the king urging an establishment on Lake Ontario, the governor, de Courcelles, visited the lake. It seemed to him une pleine mer sans aucunes limites, and he, too, speedily formed the opinion that the best means of preventing the trade between the Iroquois and New Holland, lately become New York, would be the establishment of a fort at the entrance of Lake Ontario, “which would occupy the passage by which the Iroquois passed on their way to trade with the Dutch when they had secured their furs.” He, too, observed that the Iroquois did all their hunting on the north side of the lake, and there were fresh expressions of indignation that the profits of this trade, drawn from what the French regarded as their own territory, should go to their rivals, the Dutch and the English.[33]

It was in 1672 that Frontenac, in writing to the Minister, proposed for the first time the erection of a post on Lake Ontario. He alludes to the post which de Courcelles had projected on the lake to frustrate the efforts of the Iroquois to capture the trade with the Ottawas for the Dutch, and expresses the hope that the Sulpician missionaries would prove of assistance. In November, 1673, in writing to Colbert, he remarks: “You will remember, my Lord, that several years ago you were informed that the English and the Dutch were doing all they could to prevent the Ottawas, the tribes from which we draw all our peltries, from bringing them to us, and that they wanted to get them to come to Ganacheskiagon, on the shores of Lake Ontario, where they offered to bring for them all the goods that they needed. The apprehensions of my predecessors that this would utterly ruin our trade, and their desire to deprive our neighbours of their profitable trade with the Ottawas through the Iroquois, made them think of establishing some post on Lake Ontario which would give them control.” The Governor then proceeds to describe the founding of Fort Frontenac. It is plain from these remarks and from the legend on the unsigned map shown on page 22 of this volume, that Fort Frontenac was founded as a rival to the trade at Ganatsekwyagon, the Seneca village at the terminus of the eastern arm of the Toronto Portage. In November, 1674, in writing to Colbert, Frontenac returns to the same subject: “They (the envoys of the Iroquois) have promised to prevent the Wolves of Taracton, a tribe adjoining New Holland, from continuing their hostilities with the Ottawas, of whom they had killed seven or eight, which might have had grave consequences, and they have given their word not to continue the trade, which, as I informed you last year, they had commenced to establish at Gandaschekiagon with the Ottawas, which would have absolutely ruined ours by the transfer of the furs to the Dutch.”[34] It is apparent, then, that the reason for the building of Fort Frontenac was to destroy the trade of the English and Dutch along the eastern arm of the Toronto Portage. It would seem that the English and the Iroquois, foiled by Fort Frontenac in their trade at Ganatsekwyagon, which they had reached along the north shore of Lake Ontario, now began to trade at Teiaiagon, which they reached by following the south shore round the western end of the lake.

There was a serious obstacle, however, to the realization of these plans. The traders in Montreal discouraged every attempt to establish a post in the interior; trading was forbidden in the upper country and the Indians were encouraged to bring their furs to Montreal to a great annual market held there. The matter of a fortified post on Lake Ontario was deferred till 1673 when Frontenac, in the teeth of much opposition, founded his fort at Cataraqui. Next year, in 1674, the seigniory of Fort Frontenac was granted to La Salle as a reward for discoveries already made, and, although Montreal continued to oppose the development of the west, La Salle held his ground. We shall find him almost immediately at the Toronto Carrying-Place.

The inhabitants of Teiaiagon,[35] the Seneca village on the site of Toronto, are not mentioned among those who sent envoys to confer with Frontenac at Cataraqui in 1673.[36] Possibly, being the farthest towards the west, they thought they might be excused from making the arduous journey. The deputies of Ganatsekwyagon, Ganaraske, Kenté and Ganneious had been rounded up by the missionaries, but too late to be present on the occasion when Frontenac addressed the Iroquois nations from the south of the lake, and the Governor seems to have been a little put out that he had to go through the performance again. However, after sharply rebuking them for their absence, he exhorted them to become Christians, to keep the peace and to maintain a good understanding with the French, all of which they promised to do with as much readiness as their kinsmen from the south of the lake, whose spirit and willingness to obey they professed to share. But though Teiaiagon was not represented on this important occasion, Frontenac and La Salle seem soon to have become aware of its existence. Its situation at the southern terminus of the Toronto Carrying-Place was strategic, and accordingly, in the remarks appended to the statement of expenditures incurred by La Salle between 1675-1684, we find this statement:[37]

It (Fort Frontenac) has frustrated and will continue to frustrate the designs of the same English, who had undertaken to draw away to themselves by means of the Iroquois, the nations of the Outawas. They have to go to them by the road which leads to Lake Huron from the village of Teiaiagon, and they would have succeeded had not M. de Frontenac placed this fort in their path; the whole country has felt the benefit, not only in the protection of the trade and in maintaining peace, but in checking the license of our deserters, who had an easy road there by which to make their way to strangers.

We may be sure that La Salle, when he established himself at his seigniory at Fort Frontenac, in 1675, took pains to acquaint himself still more thoroughly with the shores of the lake, and especially with the north shore, where the fur trade was most active.[38] It is likely that he visited the villages along the shore and gathered all information available about the trails leading into the interior. He would, no doubt, accompany the small vessels sent from the fort to collect the furs at these places, and it would not be long before he would learn about the Toronto Carrying-Place; he may even have passed over it on some unrecorded exploring expedition prior to 1680. It is more than likely that he was quite familiar with Teiaiagon and the Carrying-Place long before he employed that route in his western explorations. As we shall presently see, La Salle was the first traveller to describe in his own words a trip over the portage; he was also the first to record the place name “Toronto” in its accepted spelling.[39] Before La Salle, the maps indicate that the eastern trail from Ganatsekwyagon was the route usually followed. La Salle’s choice of the trail from Teiaiagon must have been deliberate and may have been due to the fact that there was better anchorage for larger vessels. Experience had probably proved it the better path; also it may have been easier to elude the vigilance of the Iroquois at Teiaiagon than at Ganatsekwyagon, for La Salle was anxious to conceal the fact that he was carrying ammunition to the Illinois, with whom the Iroquois were at war. According to Raffeix’s map of 1688, the western route from the Humber mouth was much shorter.

But before following La Salle on the various occasions on which he traversed the Carrying-Place, we have to recount the visit which Father Hennepin paid to Teiaiagon and the mouth of the Humber in the late autumn of 1678; for it is in the company of this remarkable person that documentary history arrives for the first time at the foot of the trail and at the site of the present city of Toronto. Hennepin had joined the Récollet mission at Fort Frontenac in 1675, so that in 1678 he was no stranger on Lake Ontario. The barefooted follower of St. Francis is famous for his thirst for adventure and glory, and for his lukewarm attachment to the truth. But on this occasion when he was visiting an obscure Indian village, there need be no reason to suspect his veracity. He will be allowed to tell his story in his own words; it is contained in the beginning of the fourteenth chapter of his New Discovery of a Large Country in America, which the author published in an English edition in London in 1698 with a dedication to “His Most Excellent Majesty William III,” a fact which will not be without significance to those who recall the subsequent devotion of the city of Toronto to that monarch. Hennepin writes:

That same year, on the Eighteenth of November, I took leave of our Monks at Fort Frontenac, and after mutual Embraces and Expressions of Brotherly and Christian Charity, I embarked in a Brigantine of about ten Tuns. The Winds and the Cold of Autumn were then very violent, insomuch that our Crew was afraid to go into so small a Vessel. This oblig’d us and the Sieur de la Motte, our Commander,[40] to keep our course on the North-side of the Lake, to shelter ourselves under the Coast, against the North-west Wind, which otherwise wou’d have forc’d us upon the Southern Coast of the Lake. This Voyage prov’d very difficult and dangerous, because of the unseasonable time of the Year, Winter being near at hand.

On the 26th, we were in great danger about two large Leagues off the Land, where we were oblig’d to lie at Anchor all that night at sixty Fathom Water and above; but at length the Wind coming to the North-East, we sail’d on and arriv’d safely at the further end of Lake Ontario, call’d by the Iroquoese, Skannadario. We came pretty near to one of their Villages call’d Tejajagon, lying about Seventy Leagues from Fort Frontenac, or Catarokuoy.

We barter’d some Indian Corn with the Iroquoese, who could not sufficiently admire us, and came frequently to see us on board our Brigantine, which for our greater security, we had brought to an anchor into a River, though before we could get in, we run aground three times, which oblig’d us to put fourteen Men into Canou’s, and cast the Ballast of our Ship over-board to get her off again. That River falls into the Lake; but for fear of being frozen up therein, we were forc’d to cut the Ice with Axes and other Instruments.

The wind turning then contrary, we were oblig’d to tarry there til the 15th of December, 1678, when we sail’d from the Northern Coast to the Southern, where the River Niagara runs into the Lake; but could not reach it that Day, though it is but Fifteen or Sixteen Leagues distant, and therefore cast Anchor within Five Leagues of the Shore, where we had very bad Weather all the Night long.

On the 6th, being St. Nicholas’s Day, we got into the fine River Niagara, into which never any such Ship as ours enter’d before. We sung there Te Deum, and other Prayers, to return Thanks to God Almighty for our prosperous Voyage. The Iroquoese Tsonnontouans inhabiting the little Village, situated at the mouth of the River, took above Three Hundred Whitings, which are bigger than Carps, and the best relish’d, as well as the wholesomest Fish in the World; which they presented all to us, imputing their good Luck to our Arrival. They were much surprized at our Ship, which they call’d the great woodden Canou.

We have quoted at some length from Hennepin; he is an interesting person whose talents have been somewhat obscured by his lack of veracity, for did he not attempt to appropriate the glory of the discovery of the lower Mississippi, incorporating for that purpose in his own book a passage from Le Clercq’s l’Établissement de la Foy, describing La Salle’s journey from Fort Crèvecœur to the mouth of the Mississippi in 1682 and so twisting it as to refer to himself? Nevertheless Hennepin’s is a vivid personality; we can easily picture the barefooted, brown-habited friar, with the cord of St. Francis about his waist, in the autumn of 1678 at Teiaiagon. He confesses himself that he loved adventure and travel as much as religion, and in truth he is far removed from the earnest Jesuits who preceded him, who believed in the conversion of the Indians as a reality and a possibility, and were ready to suffer tortures to attain that object. Father Hennepin took his religion less seriously; it was all very well to preach the Gospel to the savages, but he tells us himself that it was idle to expect their conversion; the savages were too fickle and too degraded. Meantime he devoted himself to exploration. We find him on this occasion storm-stayed at Teiaiagon for nearly three weeks, and we may be sure he did not devote all that time to the spiritual welfare of the inhabitants. Very likely he had been in Teiaiagon before, as it was an outlying post of the mission at Fort Frontenac, and we can imagine him, when he had satisfied his conscience with a little mission work in the lodges, exploring the shore, or reading his breviary by the banks of the Humber, where he would be more sheltered from the wind which was lashing the lake, and impatient to proceed on his journey to the Niagara River and so on to the great falls, of which he was to give us the first detailed picture which we possess. While he tarries reluctantly and the ice begins to form in the Humber and the first scuds of snow chase one another over the black ice, let us try to see Teiaiagon as it must have presented itself to his eyes.

Indian villages as a rule did not remain longer than about twenty years in one place; a change would be necessary, not only for sanitary reasons, but also because the supply of wood for the fires in the lodges would become exhausted. But there were reasons why Teiaiagon should remain more permanently where it was. It was an Iroquois village and there were cultivated fields near by, and the labour of clearing away the forest would be too great to encourage frequent changes. Moreover, Teiaiagon was at the foot of the Toronto Carrying-Place and commanded the route by which the Iroquois from the south of the lake passed to the rich beaver hunting-grounds formerly enjoyed by the Hurons. Teiaiagon, once established, could never move far from the mouth of the Humber. It was tied to this locality by another excellent reason. Like their neighbours at Ganatsekwyagon at the mouth of the Rouge, the inhabitants of Teiaiagon depended for part of their sustenance upon the salmon fisheries which were especially abundant at the mouths of the Humber and the Rouge. Everything combined to give permanence to a village once established at so strategic a point, and indeed the name “Teiaiagon” appears attached to the mouth of the Humber on the best maps of the district for a hundred and thirty years after La Salle and Hennepin; though no mention of the place has been found in any document later than 1688.[41]

Would that the versatile friar had devoted some of his time to a more detailed description of Teiaiagon; undoubtedly he would have done so had he divined that a great city was one day to spread itself for miles along that sandy shore where the waves beat so mercilessly that autumn. There is no likelihood, however, that Teiaiagon differed very much, except in situation, from a score of other Indian villages with which Hennepin was familiar, and since he has told us a good deal about what he observed of the life of the savages during his two and a half years at Fort Frontenac, it will not be difficult to reconstruct the scene. We may be sure that Teiaiagon was protected by a stout palisade[42] and fortified with all the skill which the Iroquois could command; this would be equally true of all the Cayuga and Seneca villages on the north shore of the lake, for they were outposts, cut off from assistance in case of raids from the north. Teiaiagon in this respect would have much to fear. What was left of the Huron and Algonquin enemies of the Iroquois had concentrated themselves at Michilimackinac and the Sault where the French had recently formally declared their ownership of the country; the Jesuits were there and the fur-traders, and to all the savage hordes who roved the northern wilderness Teiaiagon was within easy striking distance by way of the Toronto Portage. It would be well palisaded, and inside it would not differ in general pattern from other Iroquois villages. There would be long-houses[43] in place of the conical lodges of the Algonquins, and there would be the usual filthy squalor of those miserable abodes; the narrow streets would be a playground for naked children; there would be groups of women and girls gossiping or performing the simple tasks incident to savage life; there would be young men gambling in the shade and old men comforting their age with tobacco; possibly there would be Dutch traders or furtive coureurs-de-bois, anxious to escape the observation of the emissaries of La Salle; coming and going there would be hunters from the woods, or old hags bringing in faggots from the forest, or braves returning from a scalping party with prisoners to be tortured; for in Teiaiagon, no doubt, were enacted those horrible scenes of torture and cannibalism which seemed to the missionaries so like their imagined conceptions of inferno. Hennepin does not say so, but the hopelessness of reforming such places was due in large measure to the traffic in brandy and to the loose living of the white men who undid and gave the lie to all the efforts of the missionaries.

Although the visit of Father Hennepin to Teiaiagon in 1679 is the first visit to Toronto personally recorded, it is not the first glimpse which history gets of the place. Some time in the ’70s a party of La Salle’s men from Cataraqui were at Teiaiagon and engaged in a drunken debauch; this is the first definitely recorded visit of white men to the site of the present city; a rather melancholy beginning for Toronto the good! The incident is recorded in an obscure tract entitled Histoire de l’eau de vie en Canada, under the heading, “Sad Death of Brandy Traders”: “The Carnival of the year 1676—six traders from Katarak8y[sic] named Duplessis, Ptolémée, Dautru, Lamouche, Colin and Cascaret made the whole village of Taheyagon drunk, all the inhabitants were dead drunk for three days; the old men, the women and the children got drunk; after which the six traders engaged in the debauch which the savages call Gan8ary[sic], running about naked with a keg of brandy under the arm.” The writer of the tract then proceeds to point out that each of the traders met a tragic end.[44] The same document mentions the fact that two women were stabbed at Tcheiagon (Teiaiagon) in 1676 as the result of a drunken brawl, possibly the same occasion. In 1682 the Mémoire de la guerre contre les Iroquois informs us that the Iroquois having resolved “to put Onontio in the pot,” began the year by plundering three Frenchmen at Tcheyagon (Teiaiagon): Le Duc, Abraham[45] and Lachapelle.[46] Apparently Teiaiagon had the characteristics of a frontier post.

Part of Raffeix’s Map—1688

From a copy in the Public Archives, Ottawa. This is the first map to show the Don River.