* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Elizabeth the Queen

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Maxwell Anderson (1888-1959)

Date first posted: February 8, 2026

Date last updated: February 8, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260214

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

Elizabeth The Queen

A PLAY IN THREE ACTS

BY

MAXWELL ANDERSON

Copyright, 1930, by Longmans, Green & Co.

Copyright, 1934 (acting edition), by Maxwell Anderson

Copyright, 1957 (in renewal) by Maxwell Anderson

CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that “ELIZABETH THE QUEEN,” being fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, the British Empire, including the Dominion of Canada, and the other countries of the Copyright Union, is subject to a royalty, and anyone presenting the play without the consent of the owners or their authorized agents will be liable to the penalties by law provided. Applications for the acting rights must be made to Samuel French, at 25 West 45th Street, New York City, or at 811 West 7th Street, Los Angeles, Calif.

SAMUEL FRENCH, Inc.

25 West 45th Street, New York, N. Y.

811 West 7th Street, Los Angeles, Calif.

SAMUEL FRENCH, Ltd., London

SAMUEL FRENCH (Canada), Ltd., Toronto

ELIZABETH THE QUEEN

STORY OF THE PLAY

In this new drama by the author of “Saturday’s Children,” and the co-author of “What Price Glory,” we see Elizabeth, Queen of England, and Essex, royal favorite and popular general, in love with each other. This is an extraordinary situation, for Essex is barely thirty and Elizabeth an aging woman. Yet even more extraordinary is the character of their love. Each is passionately devoted, yet passionately opposed, to the other. The root of the trouble is power. Elizabeth delights in Essex, the courtier and lover, but is jealous of Essex, the military leader and hero. Her constant effort is to keep him quietly at Court under her own control. On the other hand, Essex, the last of a proud family, longs for action, glory, and power. He despises Elizabeth’s crafty, cautious statesmanship. He is for strength and decision, with himself as hero. Finally, through the plotting of Cecil and Raleigh, Essex is sent to Ireland, juggled out of favor, and, insultingly summoned home, arrives with an army, determined to get his way by force. This situation is resolved by Mr. Anderson with an ending of extraordinary poignancy and power.

Program of the first performance of “ELIZABETH THE QUEEN,” as produced at The Guild Theatre, New York:

THE THEATRE GUILD, INC.

Presents

THE THEATRE GUILD ACTING COMPANY

AND GUEST PLAYERS

In

ELIZABETH THE QUEEN

A new play in Three Acts

By MAXWELL ANDERSON

The production directed by Philip Moeller

Settings and costumes designed by Lee Simonson

CAST

(In order of appearance)

| Sir Walter Raleigh | Percy Waram |

| Penelope Gray | Anita Kerry |

| Captain Armin | Philip Foster |

| Sir Robert Cecil | Arthur Hughes |

| Francis Bacon | Morris Carnovsky |

| Lord Essex | Alfred Lunt |

| Elizabeth | Lynn Fontanne |

| Lord Burghley | Robert Conness |

| The Fool | Barry Macollum |

| Mary | Mab Anthony |

| Tressa | Edla Frankau |

| Ellen | Phoebe Brand |

| Marvel | Royal Beal |

| A Man-at-Arms | John Ellsworth |

| A Courier | Charles Brokaw |

| A Captain of the Guards | Edward Oldfield |

| A Courtier | Robert Caille |

| A Herald | Vincent Sherman |

| Burbage | Whitford Kane |

| Hemmings | Charles Brokaw |

| Poins | Curtis Arnall |

| Ladies-in-Waiting | { | Annabelle Williams |

| { | Louise Gerard Huntington |

Courtiers, Guards, Men-at-Arms:

Michael Borodin, George Fleming, Stanley Ruth, Nick

Wiger, Henry Lase, Guy Moore, James Wiley, James

A. Boshell, Thomas Eyre, Perry King, Curtis Arnall,

Charles Homer.

SYNOPSIS OF SCENES

| ACT I |

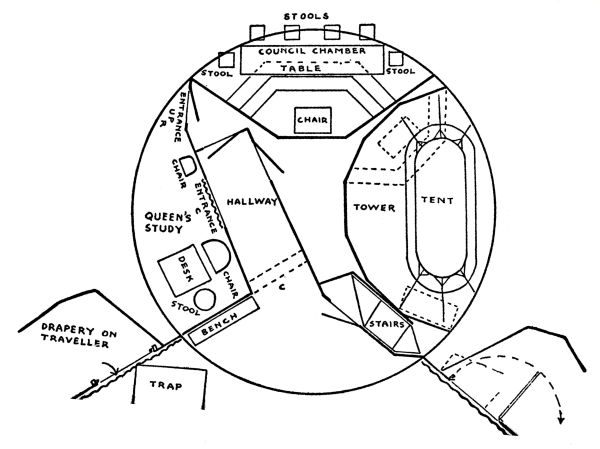

| Scene I. An entrance hall before the Council Chamber. In the palace at Whitehall. |

| Scene II. The Queen’s study. |

| Scene III. The Council Chamber. |

| ACT II |

| Scene I. Interior of Essex’s tent in Ireland. |

| Scene II. The Queen’s study. |

| Scene III. The Council Chamber. |

| ACT III |

| The Queen’s apartment in the Tower. |

An entrance hall before the palace at Whitehall.

The entrance to the Council Room is closed and

four Guards with halberds stand at either side.

All the Guards but one stand immobile. This

latter is pacing up and down the corridor. There

is an offstage call of “Change the Guard!” At

this, the Guard who is pacing comes to attention.

A Fifth Guard enters from corridor.

They salute and change places.

Raleigh enters from down R.

Raleigh. Has the Queen come forth yet?

First Guard. No, Sir Walter.

Raleigh. The Earl of Essex—is he here?

First Guard. He is—expected on the moment, my lord.

Raleigh. When he comes, send me word. I shall be in the Outer Corridor. (He crosses to L.C.)

First Guard. Good, my lord. (Exits R.)

(Penelope Gray comes in from down L.)

Raleigh. (Crossing to down L.) Greetings, lady, from my heart.

Penelope. (With a curtsey) Good-morrow, Lord, from my soul.

Raleigh. I take my oath in your face that you are rushing to the window to witness the arrival of my Lord of Essex.

Penelope. And in your teeth I swear I am on no such errand—but only to see the sun rise.

Raleigh. The sun has been up this hour, my dear.

Penelope. The more reason to hurry, gracious knight. (Starts to cross in front of him. He stops her.)

Raleigh. (His arm around her) Do you think to pull the bag over my head so easily, Penelope? On a day when the Earl returns every petticoat in the palace is hung with an eye to pleasing him. Yours not the least.

Penelope. I deny him thrice.

Raleigh. (Pushing her away—she takes a step back) I relinquish you, lady. Run, run to the window! He will be here and you will miss him!

Penelope. Is there a lady would run from Sir Walter in his new silver suiting? You dazzle the eye, my lord, with your flashing panoper. It is more brilliant than the sunrise I have missed!

Raleigh. (Looking himself over) Twit me about my armor if you will, my wench—there is no other like it in the kingdom—and not like to be.

Penelope. Heaven knows I have seen none like it, and none so becoming.

Raleigh. Is there no limit to a woman’s deception? Would you go so far as to appear pleased if I—— (He kisses her.)

Penelope. And no deception. I call the gods to witness—did I not blush prettily?

Raleigh. And meant it not at all. Tell me, did the Queen send you to look out the casement for news of her Essex, or did you come at the prompting of your own heart?

Penelope. Shall I tell you the truth?

Raleigh. Verily.

Penelope. The truth is I cannot answer.

Raleigh. (Quickly) Both, then?

Penelope. (Taking a step back) Both or one or neither.

Raleigh. (Following her) Fie on the baggage.

Penelope. Is it not a virtue to be close-mouthed in the Queen’s service?

Raleigh. If you kept the rest of your person as close as your mouth what a paragon of virtue you would be!

Penelope. (Crossing directly in front of Raleigh and curtseying) Indeed, my lord, I am.

Raleigh. Indeed, my lady? Have there not been certain deeds on dark nights?

Penelope. (Taking a step to his R.) Sh! Under the rose.

Raleigh. Meaning under covers——

Penelope. (Another step to R.) Fie on my lord, to make me out a strumpet!

Raleigh. (Following her) It is my manner of wooing, fair maid. I woo by suggestion of images—

Penelope. Like small boys on the closet wall—

Raleigh. Like a soldier——

Penelope. Aye, a veteran—of encounters——

Raleigh. I will have you yet, my love; I will take lessons from this Earl——(He puts his arms around her.)

Penelope. Take this lesson from me, my lord: You must learn to desire what you would have. Much wanting makes many a maid a wanton. You want me not—nor I you. You wear your silver for a queen. (Takes a step back to R.C.)

Captain Armin. (Enters from hallway, C. At entrance of corridor) Good-morrow, Sir Walter. Is the Queen still under canopy?

Raleigh. I know not.

Captain Armin. The Earl is here and would see her.

Raleigh. Bid him hurry if he wishes to find her abed as usual.

Penelope. (To Captain) She is dressed and stirring, Captain, and awaits my lord. (To Raleigh as she goes off, hallway C.) You make yourself so easily disliked.

(Captain Armin signals to the Guards, who go off, Two down L. and Two down R. respectively. Captain Armin goes off, hallway C. Raleigh is laughing as Cecil enters from stairway.)

Cecil. (Pointing up hallway) He is here.

Raleigh. (Crossing to R. of door down L.) So. The heavenly boy, clad in the regalia of the sun, even now extracts his gallant foot from his golden stirrup and makes shift to descend from his heaving charger. Acclamation lifts in every voice, tears well to every eye—with the exception of mine, perhaps, and yours, I hope——

Cecil. (A step down to Raleigh’s R.) I am at a pass to welcome him, myself. This Elizabeth of ours can be difficult on her good days—and there have been no good ones lately.

But in truth, I no longer

Stomach Lord Essex. Every word he speaks

Makes me feel queasy.

Raleigh. Then why put up with him?

Cecil. (Slyly)

The Queen, my friend. What she wants,

She will have,

And she must have her Earl.

Raleigh.

Which does she love more,

Her Earl or her kingdom?

Cecil. Which?

Raleigh.

Then you’re less sapient

Than I’ve always thought you, Cecil. She loves her kingdom

More than all men, and always will. If he could

Be made to look like a rebel, which he’s close to being——

And she could be made to believe it, which is harder,

You’d be first man in the council.

Cecil. And you would be?

Raleigh.

Wherever I turn he’s stood

Square in my way! My life long here at court

He’s snatched honor and favor from before my eyes——

Till his voice and walk and aspect make me writhe—

There’s a fatality in it!

Cecil.

Had it ever occurred to you that

If he could be sent from England—there might be a chance

To come between them?

Raleigh. Would she let him go?

Cecil.

No—but if he could be teased

And stung about his generalship till he was

Too angry to reflect—— Let us say you were proposed

As General for the next Spanish raid?

Raleigh. (Very quickly)

He would see it.

And so would she.

Cecil.

Then if you were named

For the expedition to Ireland?

Raleigh. (Crossing down L.)

No, I thank you.

He’d let me go, and I’d be sunk in a bog

This next three hundred years. I’ve seen enough

Good men try to conquer Ireland.

(Crosses back to L. of Cecil.)

Cecil.

Then how would this be?

We name three men for Ireland of his own supporters;

He will oppose them, not wishing his party weakened

At the court. Then we ask what he suggests

And hint at his name for leader——

Raleigh. Good so far.

Cecil.

He will be angry and hint at your name; you will offer

To go if he will.

Raleigh. No. Not to Ireland.

Cecil. (Topping him)

Yes!

Do you think he’d let you go with him and share

The military glory? It will go hard,

Having once brought up his name, if we do not manage

To ship him alone to Dublin.

Raleigh.

We can try it, then,

Always remembering that no matter what

Is said—no matter what I say or you—

I do not go. You must get me out of that,

By Christ, for I know Ireland.

Cecil. I will.

Raleigh. When is the council?

Cecil. At nine.

Raleigh. You’ll make these suggestions?

Cecil. Yes.

Raleigh. At nine, then.

Cecil. Be easy.

(Two Men-at-Arms enter from hallway with silver armor in their arms. They come only as far as the entrance.)

Raleigh. And what is all this, sirrah?

First Man. Armor, my lord. From my lord of Essex.

Raleigh. For whom?

First Man. We know not.

Raleigh. (Crossing to First Man) Now by the ten thousand holy names! Am I mistaken, Robert, or is this armor very much like my own?

Cecil. (Touching armor) Very like, I should say. Is it sterling?

Raleigh. And the self-same pattern. Has the Earl gone lunatic?

(Bacon enters down R. and stands in doorway.)

Cecil. (To Raleigh) He means to outshine you, perhaps.

Raleigh. Has it come to this? Do I set the style for Essex? That would be a mad trick—to dress himself like me. (Crosses to down R. and sees Bacon) What do you know of this, Sir Francis?

Bacon. They are Greeks, my lord, bearing gifts.

Raleigh.

To hell with your Greeks!

The devil damn him! This is some blackguardy.

(Turns away from Bacon toward

C. and two more Men-at-Arms

enter from hallway, carrying armor.)

There’s more of it!

(Still two more Men-at-Arms enter,

carrying armor.)

Good God, it comes in bales!

I say, who’s to wear this, sirrah? Who is it for?

(Essex enters from hallway between the two files of Men-at-Arms, pushing them aside as he does so, and crosses down to R. of Raleigh, speaking as he enters. Cecil has crossed to R. of door L.)

Essex.

Their name is legion, Sir Walter. Happily met—

Felicitations on your effulgence, sir!

You’re more splendid than I had imagined! News came of your silver

Even in my retreat! I was ill, and I swear it cured me!

Raleigh. I’m glad you’re well again, my lord.

Essex.

You should have heard the compliments I’ve heard

Passed on you! Sir Walter’s in silver! The world has been outdone

They said—the moon has been out-mooned.

Raleigh. You need not trouble to repeat them.

Essex.

The Queen herself has admired it—the design—

The workmanship—

And I said to myself— The great man—this is what we have needed—

More silver everywhere—oceans of silver!

Sir Walter has set the style, the world will follow.

So I sent for the silver-smiths. And by their sweat

Here’s for you, lads, tailored to every man’s measure—

Enough for the whole Queen’s Guard.

Shall Raleigh wear silver alone!

Why, no—the whole court shall go argent!

Raleigh. (Crossing to Essex) Take care, my lord. I bear insults badly.

Essex.

And where are you insulted?

For the Queen’s service you buy you a silver armor.

In the Queen’s service I buy you a dozen more.

A gift, my friends, each man to own his own.

As you own yours. What insult?

Raleigh.

Have your laugh,

Let the Queen and court laugh with you! Since you are envious

You may have my suit. I had not thought even Essex

Bore so petty a mind.

Essex.

I misunderstood you,

Perhaps, Sir Walter. I had supposed you donned

Silver for our Queen, but I was mistaken—

Keep these all for yourself. The men shall have others—

Some duller color.

Raleigh.

I have borne much from you

Out of regard for the Queen, my Lord of Essex—

Essex. And I from you—

Raleigh. My God—

Cecil.

You have forgotten, Sir Walter,

A certain appointment—

Raleigh. And you will bear more, by Heaven!—

Cecil.

He is going to the Queen,

Remember. And we have an errand.

Essex. (Taking a step down C.)

You presume to protect me,

Master Secretary?

Cecil. I protect you both, and our mistress. There can be no quarreling here.

Raleigh. That’s very true. Let us go. (Both bow. Raleigh goes out L. Cecil stops a moment, bows, then follows.)

Essex. (To Men-at-Arms) Go. Follow your bright example. (The Men-at-Arms go off L., following Raleigh and Cecil.)

Bacon. And this armor? What becomes of it?

Essex.

I have given it.

Would you have me take it back?

Bacon.

There has seldom been

A man so little wise, so headstrong, but he

Could sometime see how necessary it is

To keep friends and not make enemies at court.

But you—God knows.

Essex.

Let him make friends with me.

He may need friends himself.

(Crossing toward door down L.)

Bacon. You are going to the Queen?

Essex. Yes. God help us both.

Bacon. (Crossing to end of bench R.) Then hear me a moment——

Essex. (Crossing back to Bacon’s L.)

Speak, Schoolmaster Bacon,

I knew it was coming. You’ve been quiet too long.

Bacon.

Listen to me this once, and listen this once

To purpose, my Lord, or it may hardly be worth

My while ever to give you advice again

Or for you to take it. You have enough on your hands

Without quarreling with Raleigh. You have quarrelled with the Queen

Against my judgment—

Essex.

God and the devil! Can a man

Quarrel on order or avoid a quarrel at will?

Bacon. Why, certainly, if he knows his way.

Essex. Not I.

Bacon.

You quarrelled with her, because she wished to keep peace

And you wanted war—

Essex.

We are at war with Spain!

But such a silly, frightened, womanish war

As only a woman would fight—

Bacon. She is a woman and fights a womanish war.

Essex. But if we are at war, why not let some blood—

Bacon.

But ask yourself one question and answer it

Honestly, dear Essex, and perhaps you will see then

Why I speak sharply. You are my friend and patron.

Where you gain I gain—where you lose I lose—

And I see you riding straight to a fall today—

And I’d rather your neck weren’t broken.

Essex.

Ask myself

What question?

Bacon.

Ask yourself what you want:

To retain the favor of the Queen, remain

Her favorite, keep all that goes with this,

Or set yourself against her and trust your fortune

To popular favor?

Essex. (Crossing down L.) I’ll not answer that.

Bacon. Then—I have done. (Starts off up hallway, C.)

Essex. (Stopping him, crossing back to Bacon’s

L.)

Forgive me, dear friend, forgive me.

I’ve been ill of mind, and this silly jackanapes

Of a Raleigh angers me with his silver mountings

Till I forget who’s my friend. You know my answer

In regard to the Queen. I must keep her favor.

Only, I cannot endure—it maddens me—her everlasting dilly-dallying.

(Sits upstage end of bench R.)

This utter mismanagement, when a man’s hand and brain

Are needed and cannot be used.

Bacon. (Sits downstage end of bench R.)

Let me answer for you:

You are not forthright with yourself. The Queen

Fights wars with tergiversation and ambiguities—

You wish to complete your record as general,

Crush Spain, make a name like Caesar’s,

Climb to the pinnacle of fame. Take care,

You are too popular already. You have

Won at Cadiz, caught the people’s hearts,

Caught their voice till the streets ring your name

Whenever you pass. You are loved better than

The Queen. That is your danger. She will not suffer

A subject to eclipse her; she cannot suffer it.

Make no mistake. She will not.

Essex. And I must wait—hold myself back—

Bacon. Even so.

Essex.

Why? I come of better blood than Elizabeth.

My name was among the earls around King John

Under the oak—

(Bacon looks off R. apprehensively.)

What the nobles have taught a king

A noble may teach a queen.

Bacon. (Quickly and forcefully)

You talk treason and death.

The old order is dead, and you and your house will die

With it if you cannot learn.

Essex.

So said King John

Under the oak, or wherever he was standing.

And little he got by it, as you may recall.

What the devil’s a king but a man, or a queen but a woman?

(WARN Curtain.)

Bacon.

King John is dead; this is Elizabeth.

There is one man in all her kingdom she fears, and

That man’s yourself, and she has good reason to fear you.

You’re a man not easily governed, rebellious,

Moreover, a general, popular and acclaimed,

And, last, she loves you, which makes you the more to be feared,

Whether you love her or not.

Essex. I do love her. I do.

Bacon. My lord, a man as young as you—

Essex.

If she were my mother’s kitchen hag,

Toothless and wooden-legged, she’d make all others

Colorless.

Bacon. You play dangerously here, my lord.

Essex.

I’ve never yet loved or hated

For policy nor a purpose. I tell you she’s a witch—

And has a witch’s brain. I love her, I fear her,

I hate her, I adore her—

Bacon.

That side of it, you must know

For yourself.

Essex. I will walk softly—here is my hand. Distress yourself no more—I can carry myself.

Bacon. Only count not too much on the loves of queens.

Essex. I’ll remember. (Raleigh enters down L. and starts to cross up to hallway. He sees Essex and stops. He is wearing ordinary clothes, having dispensed with his armor. Essex rising and crossing to Raleigh’s L.)

What! Have you thrown your silver in the mud

After your cloak, Sir Walter? Take care!

(Crosses front of Raleigh and says the following as he goes off down L.)

Take care! She stepped on your cloak to some purpose,

But on your armor, she might slip.

CURTAIN

The Queen’s study. It is a severe little room. In the upper L. corner is a desk and chair. To the L. of this is a stool. There are entrances through curtains both down L. and down R. There is also an entrance up C. and up R. There is a chair between the two entrances. On the desk are various state papers, some books and a deck of cards and a calendar. Penelope is seated on the stool L. She crosses to door R. as she hears steps outside and listens. She then crosses back to C. Essex enters R.

Penelope. Good-morrow, my lord. (She curtseys.)

Essex. Good-morrow, Penelope. Have I kept the Queen?

Penelope. Would I acknowledge Her Majesty would wait for you?

Essex. (At R. of chair up R.) I commend me to your discretion.

Penelope. (At L. of chair up R.) Only to my discretion?

Essex. Take her what message you will—only let it be known that I am here.

Penelope. May I have one moment, my lord? She is not quite ready.

Essex. As many as you like. What is it, my dear?

Penelope. Do you love the Queen?

Essex. Is that a fair question, as between maid and man?

Penelope. (Very quickly) An honest question.

Essex. Then I will answer honestly. Yes, my dear.

Penelope. Dearly?

Essex. Yes.

Penelope. I would you loved someone who loved you better.

Essex. Meaning—whom?

Penelope. (Not looking at him)

Meaning—no one. Myself, perhaps. That’s no one.

Or—anyone who loved you better.

Essex. Does she not love me, sweet?

Penelope. She loves you, loves you not, loves you, loves you not—

Essex. And why do you tell me this?

Penelope. Because I am afraid.

Essex. For me?

Penelope. I have heard her when she thought she was alone, walk up and down her room soundlessly, night long, cursing you—cursing you because she must love you and could not help herself—swearing to be even with you for this love she scorns to bear you. (Looks off R. door) My lord, you anger her too much.

Essex. But is this not common to lovers?

Penelope. No. I have never cursed you. And I have good cause.

Essex. But if I were your lover, you would, sweet. So thank God I am not.

Penelope. I’ll tell her you are here. (She starts to go off C., then turns and comes down to him. He, in the meantime, has crossed down R. She lifts her face to be kissed. He kisses her.) Will you beware of her?

Essex.

Lover, beware your lover— That’s an old song.

I will beware.

Penelope. For I am afraid.

Essex. (Kisses her hand) Thank you, my dear. (She goes off C. Two Ladies-in-Waiting enter C. and hold the draperies back.)

First Lady-in-Waiting. Her Majesty.

(Elizabeth enters C. The two Ladies-in-Waiting go out C.)

Elizabeth. (Crossing down to L. of Essex)

When we met last it was, as I remember,

Ill-met by moonlight, sirrah.

Essex. (Who has knelt before her entrance and

who now takes her hand and kisses it)

Well-met by day,

My Queen.

Elizabeth.

I had hardly hoped to see you again,

My Lord of Essex, after what was vowed

Forever when you left.

Essex.

You are unkind

To remind me.

Elizabeth.

I think I also used

The word forever, and meant it as much, at least—

Therefore, no apology. Only my Penelope

Passed me just now with eyes and lips

That looked the softer for kissing. I’m not sure

But I’m inopportune.

Essex. She’s a crazy child.

Elizabeth.

These children

Have their little ways with each other!

Essex. (Rising, releasing her hand)

Must we begin

With charges and counter-charges, when you know—

Elizabeth.

Do I indeed?—

You have gone a week, at this Wanstock of yours—

And a week’s a long time at court. You forget that I

Must live and draw breath whether I see you or not—

And there are other men all fully

Equipped for loving and being loved!

You find Penelope charming. And as for me

There’s always Mountjoy—or Sir Walter—the handsome,

Sir Walter, the silver-plated—

Essex.

He’ll wear no more

Silver at your door.

Elizabeth.

What have you done—come, tell me.

I knew this silver would draw fire. What happened?

Essex. Nothing. But the fashion’s gone out.

Elizabeth. No, but tell me!

Essex.

He was unfortunate enough to be in the way when the upstairs crock

Was emptied. He has gone to change his clothes.

Elizabeth. (Laughing)

You shall not be allowed

To do this to him—

Essex. (Moving toward her. Putting his arm

around her)

You shall not be allowed

To mock me, my Queen.

(Kisses her.)

Elizabeth. (After the kiss)

Isn’t it strange how one man’s kiss can grow

To be like any other’s—or a woman’s

To be like any woman’s?

Essex.

Not yours for me,

No, and not mine for you, you lying villain,

You villain and queen, you double-tongued seductress,

You bitch of brass!

Elizabeth.

Silver, my dear. Let me be

A bitch of silver. It reminds me of Raleigh.

Essex. (Releasing her) Damn you!

Elizabeth.

Damn you! And double-damn you for a damner.

(Crosses to above desk)

Damn him, not me.

Come some day when I’m in the mood. What’s today? (Looks at calendar)

—Thursday? Try next Wednesday—or any Wednesday

Later on in the summer— Any summer

Will do. Why are you still here?

Essex. (Turns toward door R.)

Oh, God, if I could but walk out that door

And stay away!

Elizabeth. It’s not locked.

Essex.

But I’d come back!

Where do you think I’ve been this last week? Trying,

Trying not to be here. But you see, I am here.

Elizabeth. Yes, I see.

Essex. Why did you plague me without a word?

Elizabeth. Why did you not come?

Essex.

You are a Queen, my Queen.

You had prescribed me—let it be known I would

Not be admitted if I came.

Elizabeth. I may have meant it at the time.

Essex. I think I have a demon, and you are it!

Elizabeth.

If ever a mocking devil tortured a woman

You’re my devil and torture me! Let us part and quickly,

Or there’ll be worse to come. Go.

Essex. I tell you I will not.

Elizabeth.

Come to me, my Essex.

(Essex crosses and kneels at her R.

They embrace.)

Let us be kind

For a moment. I will be kind. You need not be.

You are young and strangely winning and strangely sweet.

My heart goes out to you wherever you are.

And something in me has drawn you. But this same thing

That draws us together hurts and blinds us until

We strike at one another. This has gone on

A long while. It grows worse with the years. It will end badly.

Go, my dear, and do not see me again.

Essex.

All this

Is what I said when last I went away.

Yet here I am.

Elizabeth.

Love someone else, my dear.

I will forgive you.

Essex. You mean you would try to forgive me.

Elizabeth. Aye, but I would.

Essex.

What would you have to forgive?

I have tried to love others. It’s empty as ashes.

Elizabeth. (Angry) What others?

Essex. No one.

Elizabeth. (More angry) What others?

Essex. (Rising) Everyone.

Elizabeth. Everyone?

Essex.

That too has been your triumph! What is a cry

Of love in the night, when I am sick and angry

And care not? I would rather hear your mocking laughter—

Your laughter—mocking at me—defying me

Ever to be happy—

Elizabeth. You have done this to me?

Essex.

You have done this to me! You’ve made it all empty

Away from you! And with you too!

Elizabeth. And me—what of me while you were gone?

Essex. (Crosses down a step—then turns to her)

If we

Must quarrel when we meet, why then, for God’s sake,

Let us quarrel. At least we can quarrel together.

Elizabeth.

I think if we are to love we must love and be silent—

For when we speak—

Essex.

I’ll be silent, then.

And you shall speak—

Elizabeth. (Her finger to her lips, sits at desk)

Shhh!

Essex. (Crosses to stool L. of desk and sits)

If you would sometimes heed me—

Elizabeth. Shh!

Essex. Only sometimes—

Elizabeth. Shh!

Essex. (Taking up cards and dealing them)

Only when I’m right—if you would

Say to yourself that even your lover might be

Right sometimes, instead of flying instantly

Into opposition as soon as I propose

A shift in policy!

Elizabeth.

But you were wrong!

(She glances over his shoulder at his cards)

A campaign into Spain’s pure madness, and to strike at Flanders

At the same moment—think of the drain in men

And the drain on the treasury, and the risks we’d run

Of being unable to follow success or failure

For lack of troops and money—!

Essex.

But why lack troops—

And why lack money?

There’s no richer country in Europe

In men or money than England! It’s this same ancient

Unprofitable niggardliness that pinches pennies

And wastes a world of treasure! You could have all Spain,

And Spain’s dominions in the new world, an empire

Of untold wealth—and you forego them because

You fear to lay new taxes!

Elizabeth.

I have tried that—

And never yet has a warlike expedition

Brought me back what it cost!

Essex.

You’ve tried half-measures—

Raids on the Spanish coast, a few horsemen sent

Into Flanders and out again, always defeating

Yourself by trying too little! What I plead for

Is to be bold once, just once, give the gods a chance

To be kind to us—walk through this cobweb Philip

And take his lazy cities with a storm

Of troops and ships!

If we are to trifle we might better sit

At home forever, and rot!

Elizabeth.

Here we sit, then,

And rot, as you put it. (Throwing her cards down.)

Essex. I’m sorry—

Elizabeth.

It seems to me

We rot to some purpose here. I have kept the peace

And kept my people happy and prosperous. They

Have had time for music and poetry—

Essex.

And at what a price—

What a cowardly price!

Elizabeth.

I am no coward, either.

It requires more courage not to fight than to fight

When one is surrounded by hasty hot-heads, urging

Campaigns in all directions.

Essex.

Think of the name

You will leave— They will set you down in histories

As the weasel queen who fought and ran away,

Who struck one stroke, preferably in the back,

(She hits Essex on the back.)

And then turned and ran—

Elizabeth.

Is it my fame you think of,

Or your own, my lord? Have you not built your name

High enough? I gave you your chance at Cadiz,

And you took it, and now there’s no name in all England

Like yours to the common people. When we ride in the streets

It’s Essex they cheer and not their Queen.

What more would you have?

Essex.

Is it for

This hollow cheering you hold me back from Spain?

Elizabeth.

It’s because I believe in peace, and have no faith

In wars or what wars win.

Essex. You do not fear me?

Elizabeth.

I fear you, too! You believe yourself

Fitter to be king than I to be queen! You are flattered

By this crying of your name by fools! You trust me no more

Than you’d trust—Penelope—or any other woman

To be in power! You believe you’d rule England better

Because you’re a man!

Essex.

That last is true. I would.

It’s because I love you that I can see

Wherein you fail—and why you fail and where

You fail as sovereign here. It’s because

You cannot act and think like a man.

Elizabeth. (Rises)

By God, I’ll make you sorry

(Throws the cards in his face)

For those words! Act and think like a man—!

Why should I

Think like a man when a woman’s thinking’s wiser?

What do you plan? To take over the kingdom, depose me?

Essex. (Smiling)

You are a touchy queen. (Picking up the cards.)

Elizabeth. (Laughing)

I had bad bringing up.

I was never sure who my mother was going to be

Next day, and it shook my nerves.

Essex. (Crosses to above desk)

You’re your father’s daughter.

I’ll swear to that. I can tell by your inconstancy.

Elizabeth.

I wish you had need

To fear it—or at any rate that I’d never

Let you see how much I’m yours.

Essex. But why?

Elizabeth. (Holds her hand out to him and he

crosses to her L.)

Tell me, my dear,

Do I tire you—do I wear upon you a little?

Essex. Never.

Elizabeth.

But you’d have to say that, you can see—

You’d have to say it, because you wouldn’t hurt me,

And because I’m your queen. And so I’ll never know

Until everyone else has known and is laughing at me,

When I’ve lost you.

(He starts to speak.)

Wait, let me say this, please—

When the time

Does come, and I seem old to you—

Essex. You are not old. I will not have you old.

Elizabeth. (Continues)

—and you love

Someone else, tell me, tell me the first—

Will you do that, in all kindness, in memory

Of a great love past? No. You could not, could not.

It’s not in a man to be kind that way, nor in

A woman to take it kindly. I think I’d kill you,

In a first blind rage.

Essex. Kill me when I can say it.

Elizabeth.

Love, will you let me

Say one more thing that will hurt you?

Essex. (Kisses her hand) Anything.

Elizabeth.

Your blood’s on fire to lead a new command

Now that you’ve won so handsomely in Spain,

And when I need a general anywhere

You’ll ask to go. Don’t ask it—and don’t go.

You’re better here in London!

Essex.

Was this all you wanted? (Stepping back)

To make me promise this?

Elizabeth.

Not for myself,

I swear it, not because I think you reckless

With men and money, though I do think that,

Not because you might return in too much triumph

And take my kingdom from me, which I can imagine,

And not because I want to keep you here

And hate to risk you, though that’s also true—

But rather—and for this you must forgive me—

Because you’re more a poet than a general—

And I fear you might fail, and lose what you have gained,

If you went again.

Essex. God’s death! Whom would you send?

Elizabeth. I asked you not to be angry.

Essex.

Not to be angry!

How do you judge a leader except by whether

He wins or loses?

(Crosses front of her down R.)

Was it by chance, you think,

That I won at Cadiz?

(WARN Curtain.)

Elizabeth.

Very well. You shall go.

Go if you will. Only I love you, and I say

What would be wiser.

Essex.

You choose the one thing I must have

And ask me not to ask it! No. Forgive me.

Elizabeth. I’ll not say it again.

Essex.

But if I’m more poet than

General, then poets, on occasion, make better generals

Than generals do.

Elizabeth.

You’ve proved it so

On more than one occasion.

(The CHIMES strike nine. There are four offstage

CALLS of “The Council is met!”)

Now we shall hear about Ireland,

If Cecil has his way. One thing remember,

You must not go to Ireland.

Essex.

No. That’s a war

I’m content to miss.

Elizabeth.

Thank God for that much, then. I’ve been afraid

Ireland might tempt you. And will you understand—

I’ll have to oppose you on

The Spanish hostages— You’ll have your way—

But I’ll have to oppose you.

Will you understand—?

Essex. I’ll play my part perfectly. (Kisses her hand.)

Elizabeth.

Now what can come between us, out of heaven or hell,

Or Spain or England?

Essex. Nothing—never again. (Kisses her.)

(A Councillor enters from R. He stops in the entrance.)

Councillor. (Bowing) Your Majesty, the Council’s met.

(Elizabeth and Essex, still kissing, pay no attention.)

CURTAIN

The Council Chamber. It is a large room with entrances

down L. and down R. respectively, the

doors of which are closed. Up C. in the room is

a three-stepped platform, on the top of which

is a chair of state. In front of this platform, on

stage level, is a long council table with four

stools in front and two at either end. The

Queen is seated in her throne, holding her ball

and mace. Essex is at the R. end of table and

Cecil at the L. The other Councillors are

seated in front of table, from L. to R., as follows:

First Extra Councillor, Burghley,

Raleigh, Second Extra Councillor. The

Fool sits cross-legged on a pillow on the top of

the platform at the Queen’s L. There are two

Guards, one below of entrance and one in

front of entrance both down R. and down L.

respectively. There are also Two Guards, one

at either side of the throne. A step below these

latter, on the platform, is a Man-at-Arms at

either side. Below these, on either side, is another

Man-at-Arms, each carrying a small

cushion.

As the Curtain rises there is a general ad lib.

among the Councillors which Elizabeth interrupts

with:

Elizabeth. (Interrupting)

Then the issue lies between the queen

And her soldiers—and your lordship need feel no

Concern in the matter.

Essex.

When I made these promises

I spoke for your Majesty—or believed I did.

Cecil.

My liege,

It is well known a regent may repudiate

Treaty or word of a subject officer.

The throne is not bound.

Essex.

If it comes to repudiation,

The throne can, of course, repudiate what it likes.

But not without breaking faith.

Elizabeth.

I fear we are wrong, Sir Robert;

And what has been promised for me and in my name

By my own officer, my delegate in the field,

I must perform. The men may have their ransoms.

The state will take its loss; for this one time

Only, and this one time only. In the future a prisoner

Is held in the name of the state, and whatever price

Is on his head belongs to the crown. Our action

Here is made no precedent. What further

Business is there before us?

Cecil.

There is one perpetual

Subject, your Majesty, which we take up

Time after time; and always leave unsettled,

But which has come to a place where we must act

One way or another. Tyrone’s rebellion at Ulster—

(Essex and Elizabeth

exchange glances.)

Is no longer a smouldering goal, but a running fire

Spreading north to south. We must conquer Ireland

Finally now, or give over what we have won.

Ireland’s not Spain.

Elizabeth. I grant you.

The Fool. I also grant you.

Elizabeth. Be quiet, Fool.

The Fool. Be quiet, Fool. (The Fool slaps his own mouth.)

Elizabeth.

Lord Burghley,

You shall speak first. What’s to be done in Ireland?

Burghley.

If my son is right, and I believe him to be,

We can bide our time no longer there. They have

Some help from Spain, and will have more, no doubt,

And the central provinces are rising. We must

Stamp out this fire or lose the island.

Elizabeth.

This means

Men, money, ships?

Burghley. Yes, madam.

Cecil.

And more than that—

A leader.

Elizabeth. What leader?

Cecil.

A Lord Protector

Of Ireland who can carry sword and fire

From one end of the bogs to the other, and have English law

On Irish rebels till there are no rebels.

We’ve governed Ireland with our left hand, so far,

And our hold is slipping. The man who goes there now

Must be one fitted to master any field—

The best we have.

Elizabeth. What man? Name one.

Cecil.

We should send,

Unless I am wrong, a proved and able general,

Of no less rank than Lord Howard here,

Lord Essex, Sir Walter Raleigh, Knollys, or Mountjoy—

This is no slight matter, to keep or lose the island.

Elizabeth. I grant you that also.

The Fool.

I also grant you. Be quiet,

Fool! (He slaps his mouth.)

Elizabeth.

I ask you for one and you name a dozen,

Sir Robert.

Raleigh.

Why should one go alone, if it comes

To that? Why not two expeditions, one

To Dublin, one into Ulster, meeting halfway?

Elizabeth. Are there two who could work together?

Cecil.

Knollys and Mountjoy.

They are friends and of one house.

Essex. Yes, of my house.

Elizabeth. Essex, whom would you name?

Essex.

Why, since Sir Robert

Feels free to name my followers, I shall feel free

To name one or two of his—

Elizabeth.

In other words,

You would rather Knollys and Mountjoy did not go?

Essex.

I would rather they stayed in England, as Sir Robert knows.

I have need of them here. But I will spare one of them

If Sir Robert will let Sir Francis Vere go with him.

Elizabeth. Let Vere and Knollys go.

Cecil.

Lord Essex names

Sir Francis Vere because he knows full well

I cannot spare him, my liege.

Elizabeth.

Is this appointment

To wait for all our private bickerings?

Can we send no man of worth to Ireland, merely

Because to do so would weaken some house or party

Here at court?

The Fool. Your Majesty has said—

Elizabeth. Be quiet—

The Fool. Fool!

Elizabeth. Be quiet!

The Fool. Fool!

Elizabeth. Be quiet!

(The Fool forms the word “Fool” with his lips, but makes no sound.)

Cecil.

I hope I betray no secret, Sir Walter,

If I tell the council that I spoke with you

Before the session, and asked you if you would go

Into Ireland if the Queen requested it—and that you said

Yes, should the Queen desire it.

Burghley. (To the Man at his L.) That would answer.

Cecil.

But I believe, and Sir Walter believes, there should be

More than one hand in this—that if he goes

Lord Essex should go with him.

Elizabeth. With him?

Essex.

In what

Capacity?

Cecil.

Leading an equal command. Two generals

Of coeval power, landing north and south

And meeting to crush Tyrone.

Essex.

Would you set up

Two Lord Protectors in Ireland?

Cecil.

It was my thought that we name

Raleigh as Lord Protector.

Essex. And I under him?

Cecil.

Since the Azores adventure

Which my Lord Essex led, and which came off

A little lamer than could be wished, but in which

Sir Walter showed to very great advantage,

It has seemed to me that Raleigh should receive

First place if he served in this.

Essex.

This is deliberate,

An insult planned!

Cecil.

It is no insult, my lord,

But plain truth. I speak for the good of the state.

Essex.

You lie! You have never spoken here or elsewhere

For any cause but your own!

Elizabeth. No more of this!

Essex.

Good God!

Am I to swallow this from a clerk, a pen-pusher—

To be told I may have second place, for the good of

the state?

Cecil. Were you not wrong at the Azores?

Essex. No, by God! And you know it!

Elizabeth. (A threat and a warning)

Whoever makes you angry has won

Already, Essex!

Essex. They have planned this!

Cecil. (Lifted. As though the matter is settled)

I say no more.

Raleigh will go to Ireland as Lord Protector

And go alone, if the Queen asks it of him,

And since you will not go.

Essex.

I have not said

I would not go. But if I were to go I would go

Alone, as Lord Protector!

Elizabeth. (Topping them all)

That you will not.

I have some word in this.

Essex.

If this pet rat,

Lord Cecil, wishes to know my wind about him,

(Cecil’s arm over back of stool.)

And it seems he does, he shall have it!

(Essex rises; leans over table)

How he first crept

Into favor here I know not, but the palace is riddled

With his spying and burrowing and crawling underground!

He has filled the court with his rat friends, very gentle,

White, squeaking, courteous folk, who show their teeth

Only when angered; who smile at you, speak you fair

And spend their nights gnawing the floors and chairs

Out from under us all!

Elizabeth. My lord!

Essex.

I am

Not the gnawing kind, nor will I speak fair

To those who don’t mean me well—no, nor to those

To whom I mean no good! I say frankly here,

Yes, to their faces, that Cecil and Walter Raleigh

Have made themselves my enemies because

They cannot brook greatness or power in any but

Themselves! And I say this to them—and to the world—

I, too, have been ambitious, as all men are

Who bear a noble mind, but if I rise

I hope it will be by my own effort, and not by dragging

Better men down through intrigue!

Burghley. Intrigue, my lord?

Raleigh. Better men, my lord?

(A Councillor raises his arm to stop Essex.)

Essex.

I admit

Sir Walter Raleigh’s skill as a general

And Cecil’s statecraft! I could work with them freely

And cheerfully, but every time I turn

My back they draw their knives!

Elizabeth. My lord! My lord!

Essex.

When Cecil left England

I watched over them as I would my own

Because he asked me to!—but when I left,

And left my affairs in his hands—on my return

I found my plans and my friends out in the rain

Along with the London beggars!

Cecil. I did my best—

Essex. Yes. For yourself! For the good of the state!

Raleigh. (Rising and leaning over table toward Essex)

If Lord Essex wishes

To say he is my enemy, very well—

He is my enemy.

Essex.

But you were mine first—

And I call on God to witness you would be my friend

Still, if I’d had my way! I take it hard

(Raleigh sits)

That here, in the Queen’s council, where there should be

Magnanimous minds if anywhere, there are still

No trust or friendship! (Essex sits.)

Elizabeth. (Very quickly)

I take it hard that you

Should quarrel before me.

Essex.

Would you have us quarrel

Behind your back? It suits them all too well

To quarrel in secret and knife men down in the dark!

Burghley. (Lifted)

This is fantastic, my lord. There has been no kniving.

Let us come to a decision. We were discussing

The Irish protectorate.

Cecil. (Lifted)

And as for Ireland,

I am willing to leave that in Lord Essex’s hands

To do as he decides.

Essex.

Let Sir Walter Raleigh go

To Ireland as Protector! And be damned to Ireland!

(Raleigh looks quickly to Cecil.)

Cecil. (Insidiously)

As the Queen wishes.

It is a task both difficult and dangerous.

I cannot blame Lord Essex for refusing

To risk his fame there.

Essex.

There speaks the white rat again!

Yet even a rat should know I have never refused

A task out of fear! I said I would not go

As second in command!

Cecil.

Then would you go

As Lord Protector?

Elizabeth.

You have named your man—

Sir Walter Raleigh.

Raleigh.

With your Majesty’s gracious permission

I’ll go if Essex goes.

Essex.

Is Sir Walter

Afraid to go alone?

Raleigh.

I don’t care for it—

And neither does our Essex!

Essex. (After a pause—turning front)

Why, what is this

That hangs over Ireland? Is it haunted, this Ireland?

Is it a kind of hell where men are damned

If they set foot on it? I’ve never seen the place,

But if it’s a country like any other country, with people

Like any other people in it, it’s nothing to be

Afraid of, more than France or Wales or Flanders

Or anywhere else!

Cecil. We hear you say so.

Essex. (Impetuously)

If I

Am challenged to go to Ireland,

(Rises)

Then, Christ, I’ll go!

Give me what men and horse I need, and put me

In absolute charge, and if I fail to bring

This Tyrone’s head back with me and put the rebellion

To sleep forever, take my sword from me

And break it— I’ll never use it again!

Elizabeth. Will you listen—?

Essex. They’ve challenged me!

Elizabeth.

If you volunteer

To go to Ireland there is none to stop you.

Essex.

Your Majesty, I can see that Raleigh and Cecil have set themselves

To bait me into Ireland! They know and I know

That Ireland has been deadly to any captain

Who risked his fortunes there; moreover once

I’m gone they think to strip me here at home,

Ruin me both ways! And I say to them “Try it!”

Since this is a challenge, I go,

And will return, by God, more of a problem

To Cecils and Raleighs than when I went!

Burghley. (Lifted)

If Essex will go,

It solves our problem, Your Majesty.

We could hardly refuse that offer.

(The Fool rises and approaches Essex from behind.)

Elizabeth. No.

Essex.

I will go,

And I will return! Mark me!

(The Fool crosses down to below Essex.)

The Fool. (Touching Essex) My lord! My lord!

(Raleigh, Cecil and Councillor at L. by table ad lib. at each other, quietly.)

Essex. (Turning suddenly with an instinctive motion that sweeps the Fool to the floor) You touch me for a fool!

The Fool. Do not go to Ireland!

Essex. (Impatiently) You too?

The Fool.

Because, my lord, I come from Ireland.

All the best fools come from Ireland, but only

A very great fool will go there.

Essex. Faugh!

(The Fool crosses up to R. of Elizabeth again, terrified, after Essex is about to strike him.)

Elizabeth.

No. Break up the council, my lords.

We meet tomorrow.

Burghley. Then there is no decision?

Essex. Yes! It is decided.

Elizabeth. Yes. Go to Ireland. Go to hell.

(She rises and motions them to go. The Council rises when Elizabeth does and files out L. silently, leaving Essex and Elizabeth.)

You should have had

The Fool’s brain and he yours! You would have bettered

By the exchange.

Essex. I thank you kindly, lady.

Elizabeth.

What malicious star

Danced in my sky when you were born?

Essex.

What malicious star danced

Over Ireland, you should ask.

Elizabeth.

You are a child in council. I saw them start

To draw you into this, and tried to warn you—

But it was no use.

Essex.

They drew me into nothing.

I saw their purpose and topped it with my own,

Let them believe they’ve sunk me.

Elizabeth.

You will withdraw.

I’ll countermand this.

Essex. And let them laugh at me?

Elizabeth.

Better they should laugh

A little now than laugh at you forever.

Essex. And why not win in Ireland?

Elizabeth.

No man wins there.

You’re so dazzled

With the chance to lead an army you’d follow the devil

In an assault on heaven.

Essex.

That’s one thing

The devil doesn’t know,

Heaven is always taken by storm.

Elizabeth.

I thought so as you said it,

Only sometimes here in my breast constricts—

I must let you go—

And I’ll never see you again.

Essex. (Taking one step up toward the throne)

Mistrust all these

Forebodings. When they prove correct we remember them.

But when they’re wrong we forget them. They mean nothing.

Remember this when I return and all turns out well.

That you felt all would turn out badly.

Elizabeth. Come touch me, tell me all will happen well.

Essex. And so it will. (Crosses up another step toward throne.)

Elizabeth. Do you want to go?

Essex. (His arms around her)

Why, yes—

And no.

(He kisses her)

I’ve said I would and I will.

Elizabeth.

It’s not yet

Too late.

Remember, if you lose, that will divide us—

If you win, that will divide us too.

(WARN Curtain.)

Essex.

I’ll win, and it will not divide us. Is it so hard

To believe in me?

Elizabeth.

No— I’ll believe in you—

And even forgive you if you need it. Here.

My father gave me this ring—and told me if ever

He lost his temper with me, to bring it to him

And he’d forgive me. And so it saved my life—

Long after, when he’d forgotten, long after, when

One time he was angry.

Essex.

Darling, if ever

You’re angry, rings won’t help.

Elizabeth.

Yes, but it would.

I’d think of you as you are now, and it would.

Take it.

Essex. (He does so and steps down one step)

I have no pledge from you. I’ll take it.

To remember you in absence.

Elizabeth.

Take it for a better reason. Take it because

The years are long, and full of sharp, wearing days

That wear out what we are and what we have been

And change us into people we do not know

Living among strangers. Lest you and I who love

Should wake some morning strangers and enemies

In an alien world, far off; take my ring, my lover.

Essex.

You fear

You will not always love me?

Elizabeth.

No, that you

Will not let me, and will not let me love you.

CURTAIN

Essex is seated back of the camp table. This table is L.C. in front of the tent. Dispatches and maps, a money-bag, and a mug of water are on the table. R.C. in front of the tent is a tying-post with ropes. Back of this on a long pole is Essex’s standard. Inside the tent are two chests, a saddle, and a suit of armor. There is also a lighted lantern on the table. There are two TRUMPET CALLS off stage. Essex rises with dispatches in his hand. He paces back and forth in front of table. As he reaches R.C. he calls:

Essex.

Marvel!—Marvel!—

(Crosses to L.C. Marvel enters from down R. and crosses to directly in front of table.)

There have been no other losses?

Marvel. Only at the landing.

Essex. There was ambush there.

Marvel. Yes, my lord.

Essex. (Crossing in front of Marvel to between

table and post)

It’s not losses we should fear now.

Though we have lost more than I should like to think of.

It’s going on against a retreating enemy,

Venturing further from our base

When we are not supplied.

This country’s barren—festering with fever bogs.

There are no roads—no food.

I think we have been forgotten in London.

Nay, worse than forgotten.

Marvel.

My lord, if I may make so bold,

There must be some reason for such strange policy.

The Queen has written.

Essex. Aye. She has written. “Lord Essex will confine his invasions to the near coast. Lord Essex will prepare to shorten his campaign.” And that is all. If she had wished Tyrone to win she could not have done better. (Crosses front of Marvel to L.C.) In the name of God can one fight thus?

Marvel. (Taking a step toward Essex) My lord.

Essex. (Pushing him away. Marvel goes to front

of post)

Stand away from me.

We all smell putrid here.

Has the valley been cleared of the corpses?

Marvel. Yes, my lord.

Essex. What is this stench?

(Essex crosses to back of table; takes a sip of water from the mug; sits; feels nauseous; rises and spits out the water, leaning over the table to the L. as though vomiting)

Even the water stinks.

(After a slight pause he sits again)

How many did you say lost at the landing?

Marvel. Thirty or so. Not many.

Essex.

There’s thirty less to wonder

Whether they’ll see their wives again.

Marvel. (Taking a step toward Essex) My lord.

The men have not been paid.

Essex.

Are they muttering?

My revenue’s been stopped.

Let them know that.

If we face Tyrone again it’s because Southampton

Has gone my surety. This is not the Queen’s war,

Not now. Are they deserting?

Marvel. They want one thing: to follow you to London.

Essex. And why to London?

Marvel.

Forgive my saying this—

They wish to make you King.

Essex. (After a pause) Have they forgotten the Queen?

Marvel. They are willing to forget her.

Essex. But I am not. We wait here.

Marvel. We cannot wait longer without supplies.

Essex. Word will come. We wait here—until—

Marvel. Shall I give this out?

Essex. Yes.

(A Man-at-Arms enters down R. and crosses to R. of Marvel.)

Man-at-Arms. There is a courier from the Queen, my lord.

Essex. At last, then.

Marvel. (Anticipating good news) You will see him at once?

Essex. Yes. (Marvel starts to go off R.) Wait. (Marvel stops.) Bring him in and stay here while I read the dispatches. If I give orders to torture or kill him—— You understand?

Marvel. You will not torture him?

Essex. Am I not tortured? (Marvel starts to protest, but instead goes off R. To the Man-at-Arms, who has taken his place upstage of the tying-post) You too, sirrah. You hear this?

Man-at-Arms. Yes, my lord.

Essex. Good.

(The Courier enters down R., followed by Marvel. He crosses to between table and post and falls to his knees. Marvel takes a position downstage of post.)

The Courier. My Lord of Essex?

Essex. Yes.

The Courier. I come from the Queen.

Essex. When did you leave London?

The Courier. Four days ago, my lord. We were delayed.

Essex. What delayed you?

The Courier. Thieves.

Essex. And they took what from you?

The Courier. Our horses and money.

Essex. And letters?—

The Courier. Were returned to me untouched.

Essex. When did this take place?

The Courier. This side of the ford. There were four armed men against us two.

Essex. (Grabbing the dispatches) Give me the letters. (There is only one dispatch, which Essex reads briefly) This is all?

The Courier. Yes, my Lord.

Essex. You are sure you lost nothing?

The Courier. Indeed, yes, my Lord. There was but one missive and the seal was returned unbroken. The cutthroats told us they cared the less about our letters for they could not read.

Essex. You are a clever liar, sirrah, and you are the third liar who has come that same road to me from London. You are the third liar to tell this same tale. You shall pay for being the third.

The Courier. My Lord, I have not lied to you.

Essex. Take his weapons from him, Lieutenant. (Marvel obeys.) Set him against the post there. (Marvel and the Man-at-Arms place him against the post. Marvel downstage—Man-at-Arms upstage.) Not so gently. Take out his eyes first and then his lying tongue.

The Courier. Your Lordship does not mean this.

Essex. (Rising and crossing to Courier, he slowly wrenches his arm backwards) And why not? We shall break him to pieces—but slowly with infinite delicacy.

The Courier. No, no, no, no! Oh, my Lord! My Lord!

Essex. (To Marvel as he lets go of the Courier’s arm) What are you waiting for?

Marvel. We must tie him to the post first, sir.

Essex. Then tie him! (Marvel and the Man-at-Arms do so.)

The Courier. My Lord. I have not lied to you. There was but one dispatch. There was but one—

Essex. We know too well what you have done, sirrah. We need no evidence of that. What we ask is that you tell us who set you on—and your accomplices. Tell us this and I want no more of you. You shall have your freedom—and this—— (Indicates the money-bag.)

The Courier. My Lord, if I knew——

Essex. Truss him up and cut him open. (They complete their binding.)

The Courier.

My Lord, I am not a coward, though it may seem to you

I am, for I have cried out—but I cried out

Not so much for pain or fear of pain

But to know this was Lord Essex, whom I have loved

And who tortures innocent men.

Essex. (To Marvel) Have you no knife?

(Marvel takes the knife he has taken from the Courier and during the next speech prepares to cut out the Courier’s tongue. Essex places his hands over Courier’s face as though to open his mouth.)

The Courier.

Come, then. I am innocent. If my Lord Essex

Is as I have believed him, he will not hurt me;

If he will hurt me, then he is not as I

And many thousands have believed him, who have loved him,

And I shall not mind much dying.

(Essex pushes Marvel’s knife away and releases the Courier.)

Essex. Let him go. (Marvel and the Man-at-Arms unbind him. Courier falls to the ground.) I thought my letters had been tampered with. (He lifts the Courier up) You’d tell me if it were so.

The Courier.

My honored Lord.

By all the faith I have, and most of it’s yours,

I’d rather serve you well and lose in doing it

Than serve you badly and gain. If something I’ve done

Has crossed you or worked you ill I’m enough punished

Only knowing it. (His head drops from weakness.)

Essex. (Lifting the Courier’s head so that he

may see his eyes)

This letter came

From the Queen’s hands?

The Courier.

It is as I received it

From the Queen’s hands.

Essex. There was no other?

The Courier. No other.

Essex. Then go.

The Courier. I have brought misfortune——

Essex. (Crossing front of table to L. of it) You have done well. We break camp tomorrow for London. Go. Take that news with you. They’ll welcome you outside. Remain with my guard and return with us. (Courier salutes and goes off R., followed by Man-at-Arms.)

Marvel. (Taking a step toward Essex, who has crossed to back of table) We march tomorrow?

Essex. Yes. (WARN Curtain.)

Marvel. Under orders from her Majesty?

Essex. No. (He reads the dispatch) “Lord Essex is required to disperse his men and return to the capital straightway on his own recognizance, to give himself up.” (Looking up) To give himself up.

Marvel. And nothing but this?

Essex.

There is a limit to my humiliation.

Give out the necessary orders.

We embark at daybreak.

Marvel. Yes, my Lord.

Essex.

And it is

As well it falls out this way!

Marvel.

By right of power and popular voice

It is your kingdom—this England.

Essex.

More mine than hers,

As she shall learn. It is quite as well.

Marvel.

There is victory in your path,

My Lord. The London citizens will rise

At the first breath of your name.

Essex. (Crossing to Marvel, putting his hand on

his shoulder)

And I am glad for England.

She has lain fallow in fear too long.

Her hills shall have a spring of victory.

Go, then.

(Marvel goes off down R.)

And for this order,

I received it not. (Tears the order to pieces.)

(A TRUMPET is heard off stage.)

MEDIUM CURTAIN

Penelope is sitting on chair up R., reading. The Fool enters L. She does not see him.

The Fool. (Crossing to L. of Penelope) Sh! Make no noise.

Penelope. What do you mean?

The Fool. Silence! Quiet!

Penelope. I am silent, Fool.

The Fool. You silent? And even as you say it you are talking!

Penelope. You began it.

The Fool. (Crosses to desk) Began what?

Penelope. (Still reading) Talking.

The Fool. Oh, no. Talking began long before my time. It was a woman began it.

Penelope. Her name?

The Fool. Penelope, I should judge.

Penelope. (She goes back to book) Fool.

The Fool. (Warmly) No, for with this same Penelope began also beauty and courage and tenderness and faith—all that a man could desire or a woman offer—and all that this early Penelope began has a later Penelope completed.

Penelope. It lacked only this—that the court fool should make love to me now.

The Fool. (Kneels and puts his hands on the pages of her book) I am sorry to have been laggard. But truly I have never found you alone before.

Penelope. (Pushing him away) How lucky I’ve been!

The Fool. Are you angered?

Penelope. At what?

The Fool. At my loving you.

Penelope. (Laughing) I’ve learned to bear nearly everything.

The Fool. (Mysteriously) A lover’s absence.

Penelope. Among other things.

The Fool. (Leaning toward her) The presence of suitors undesired?

Penelope. (Again pushing him away) That, too.

The Fool. (Rising and crossing to R. of desk) I am not a suitor, my lady. I ask nothing. I know where your heart lies. It is with my Lord Essex in Ireland. I do not love you.

Penelope. (Going back to her book) Good.

The Fool. (Crossing to her and kneeling) I lied to you. I do love you.

Penelope. (Very tenderly) I am sorry.

The Fool. You will not laugh at me?

Penelope. No.

The Fool. Then there is yet some divinity in the world—while a woman can still be sorry for one who loves her without return.

Penelope. A woman is sadly aware that when a man loves her it makes a fool of him.

The Fool. And if a fool should love a woman—(Rises and steps back) would it not make a man of him?

Penelope. (Quickly) No, but doubly a fool, I fear.

The Fool. (Quickly) And the woman—how of the woman?

Penelope. They have been fools too.

The Fool. (Very mysterious and sinister) The more fool I, I tried to save Lord Essex from Ireland—but he needs must go—the more fool he.

Penelope. (Rising) Let us not talk of that.

The Fool. (A step toward her) May I kiss you?

Penelope. No.

The Fool. (Pleadingly) Your hand?

Penelope. Yes.

The Fool. (Kneels and kisses her hand) I thank you.

Penelope. (Puts her arms around him as she would a crazy child) The more fool you, poor boy.

Cecil. (Enters L. Crossing to L. of desk) This is hardly a seemly pastime, Mistress Gray.

(The Fool laughs and exits L., repeating: “This is hardly a seemly pastime, Mistress Gray.”)

Penelope. And are you now the judge of what is seemly, Sir Robert?

Cecil. The Queen is expecting Master Bacon here?

Penelope. I am set to wait for him.

Cecil. You will not be needed.

Penelope. Excellent. (Goes out C. after an elaborate curtsey. Raleigh enters L.)

Cecil. This Bacon keeps himself close. I have been unable to speak with him. She has this news?

Raleigh. (Who is down L.) Yes.

Cecil. She believes it?

Raleigh. Beyond question. (Bacon enters from door up R., his book in his hand.)

Cecil. Good-morrow, Master Bacon.

Bacon. (Who has crossed down R.C.) And to you, my Lords.

Cecil. I have sent everywhere for you, sir, this three hours—and perhaps it was not altogether by accident that I could not find you.

Bacon. I was not at home. You must forgive me.

Cecil. You are here to see the Queen?

Bacon. (Bowing) The Queen has also been good enough to send for me.

Cecil. It was my wish to speak with you first—and it is my opinion that it will be the better for all of us if I do so now—late as it is.

Bacon. I am but barely on time, gentlemen.

Cecil. You need answer one question only. (Cecil motions Bacon to sit. He does so in chair up R. Cecil sits stool L. of desk. Raleigh crosses to above desk.) You have been in correspondence with Lord Essex in Ireland?

Bacon. Perhaps.

Cecil. The Queen has this morning received news warning her that Lord Essex is allied with the Irish rebels and is even now leading his army back to England to usurp her throne. Had you heard this?

Bacon. No.

Cecil. Do you credit it?

Bacon. It is your own scheme, I believe.

Cecil. That Essex should rebel against the Queen?

Bacon. Even so.

Raleigh. (A step toward Bacon) You accuse us of treason?

Bacon. If the Queen were aware of certain matters she would herself accuse you of treason.

Cecil. What matters?

Bacon. (Reading his book) I prefer that the Queen should question me.

Cecil. Look to yourself, Master Bacon. We know what the Queen will ask you and we know what you may answer.

Raleigh. (Another step toward Bacon) Come, there’s no time for this. Take your head out of your book, and if you’ve any interest in living longer keep it out. (To Cecil) Speak it out with him. (Crosses back to above desk.)

Cecil. Softly, softly. In brief, if you intend to accuse any man of the suppression of letters—(Bacon snaps book closed) written by Essex to the Queen, or of the suppression of letters sent by the Queen to Essex, you will be unable to prove these assertions and you will argue yourself very neatly into the Tower.

Bacon. (Looking up from book) My Lord—I had no such business in mind.

Raleigh. What then?—

Bacon. I hope I can keep my own counsel. The truth is, my Lords, you are desperate men. You have over-reached yourselves, and if wind of it gets to the royal ears you are done.

Raleigh. We shall drag a few down with us if we are done, though, and you the first.

Cecil. You have but a poor estimate of me, Master Bacon. If you go in to the Queen and reveal to her that her letters to Essex have not reached him—as you mean to do—the Queen will then send for me, and I will send for Lord Essex’s last letter to you, containing a plan for the capture of the city of London. It will interest you to know that I have read that letter and you are learned enough in the law to realize in what light you will stand as a witness should the Queen see it.

Bacon. I think it is true, though, that if I go down I shall also drag a few with me, including those here present.

Cecil. I am not so sure of that, either. I am not unready for that contingency. But to be frank with you.

Bacon. Ah! Frank! Frank!

Cecil. It would be easier for both you and us if you were on our side.

Bacon. (Opening his book) You must expect a man to side with his friends.

Cecil. And a man’s friends—who are they?

Bacon. Who?

Cecil. Those who can help him to what he wants.

Bacon. Not always.

Cecil. (Threatening) When he is wise. You have served Lord Essex well and I believe he has made you promises. But the moment Essex enters England in rebellion, he is doomed, and his friends with him.

Bacon. (Closing book quietly) One word from the Queen to him—one word from him to the Queen—one word from me revealing that their letters have been intercepted—and there can be no talk of rebellion. Your machinations have been so direct, so childish, so simple—and so simply exposed—that I wonder at you!

Cecil. My friend, he has spoken and written so rashly, has given so many handles for overthrow, that a child could trip him.

Raleigh. (In anger) We have news this morning that Lord Essex has already landed in England and set up his standard here. He is a rebel.

Cecil. (Quickly topping Raleigh) And when a man is once a rebel, do you think there will be any careful inquiry into how he happened to become one?

Bacon. (Puzzled) Essex in England!

Raleigh. (Quickly) In England. And has neglected to disband his army.

Cecil. (As quickly)

You speak of explanations between the Queen and Essex.

Unless you betray us,

There will be no explanations. They are at war now.

They will never meet again.

Bacon. That is, if your plans succeed.

Cecil. (Rising)

Very well, then. You have chosen your master.

I have done with you.

Bacon. (Not moving, but a quick glance to door

C.) And if she learns nothing from me?

(Cecil and Raleigh exchange glances.)

Cecil. (Very obsequious) Then—whatever you have been promised, whatever you have desired, that you shall have. (Bacon rises, takes a step down and bows. Cecil bows and continues) There is no place in the courts you could not fill. You shall have your choice. If you need excuse, no one should know better than you that this Essex is not only a danger to our state but also to you.

Bacon. If I need excuse I shall find one for myself. (Turning front and taking a step down. Penelope is heard off stage.)

Penelope. Yes, Your Majesty, he is here.

Elizabeth. Why was I not told? (Raleigh crosses down L. below Cecil. Two Ladies-in-Waiting enter C. and hold back the draperies. Elizabeth enters and comes C.) Is this an ante-chamber, Sir Robert? Am I never to look out of my room without seeing you?

Cecil. Your pardon, your Majesty. I——

Elizabeth. (Stopping him) You need not pause to explain why you came. I am weary of your face!

Cecil. Yes, your Majesty. (Cecil and Raleigh bow and go off L., Raleigh first.)

Elizabeth. (Crossing and sitting in chair above desk) I have heard that you are a shrewd man, Master Bacon.

Bacon. Flattery, Majesty, flattery.

Elizabeth.

I have heard it,

And in a sort I believe it. Tell me one thing—

Are you Cecil’s friend?

Bacon. I have never been.

Elizabeth.

He is a shrewd man; he’s

A man to make a friend of if you’d stand well

In the court, sir.

Bacon. It may be.

Elizabeth.

Why are you not

His friend, then?

Bacon. We are not on the same side.

Elizabeth. You follow Lord Essex.

Bacon. Since I have known him.

Elizabeth.

There’s

A dangerous man to follow.

Bacon. Lord Essex?

Elizabeth. Lord Essex.

Bacon.

I am sorry, madam,

If I have displeased you.

Elizabeth. You have displeased me.

Bacon.

I repeat, then—

I am sorry. (He bows.)

Elizabeth.

Good. You will change, then? You will forget

This Essex of yours?

Bacon. If you ask it—if there is reason—

Elizabeth.

There is reason! He has taken up arms

Against me in England.

Bacon. You are sure of this?

Elizabeth. Is it so hard to believe?

Bacon. Without proofs, it is. You have proofs?

Elizabeth.

Proof good enough. You know the punishment

For treason? From what I have heard

Of late both you and Essex should remember

That punishment.

Bacon.

Madam, for myself I have

No need to fear.

Elizabeth. You reassure me, Master Bacon.

Bacon.

And if Lord Essex has

I am more than mistaken in him.

Elizabeth. (Threatening)

But all friends of Essex

Go straightway to the Tower.