* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

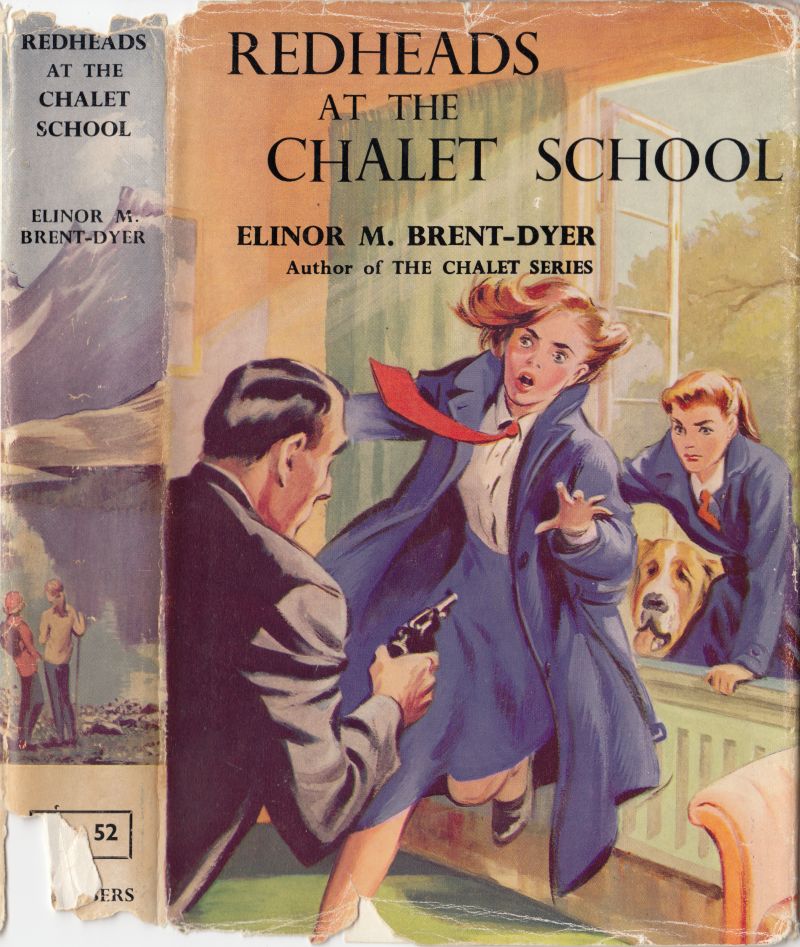

Title: Redheads at the Chalet School (Chalet School #52)

Date of first publication: 1964

Author: Elinor Mary Brent-Dyer (1894-1969)

Date first posted: February 6, 2026

Date last updated: February 6, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260212

This eBook was produced by: Alex White, Hugh Stewart & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

REDHEADS AT THE CHALET SCHOOL

By

Elinor M. Brent-Dyer

First published by W. & R. Chambers Ltd. in 1964.

To

JULIE EASTLAND

With Much Love

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Copper Asks Why | 9 |

| II. | Early Days for Copper | 20 |

| III. | Things Begin to Move | 32 |

| IV. | Len Wonders | 41 |

| V. | Miss Annersley Decides | 53 |

| VI. | Upper IV | 63 |

| VII. | An Odd Encounter | 74 |

| VIII. | Another Queer Episode | 84 |

| IX. | Joey Takes a Hand | 97 |

| X. | Prudence is Tactless | 106 |

| XI. | Val | 115 |

| XII. | A Clue at Last | 124 |

| XIII. | Val is Returned | 133 |

| XIV. | Nemesis! | 145 |

| XV. | Half-Term | 153 |

| XVI. | Reckoning the Casualties | 166 |

| XVII. | Inspector Letton Explains | 177 |

| XVIII. | Joey Does them Proud | 187 |

| XIX. | The Christmas Play | 198 |

The lean, dark man and the solemn-faced schoolgirl had sat side by side in silence for some time. Suddenly he spoke softly without turning his head—almost without moving his lips. “Copper! No; don’t move. Keep on looking out of the window. Now listen! You understand that you must use your proper name. I know you’ve always been called Flavia Letton, but from now on you are Flavia Ansell. Got that?”

“Yes, Dad.” Copper was staring out of the carriage window, her back turned squarely to the man, her long red pigtails dangling over her shoulders. Her words were almost as inaudible as his, but he caught them.

“That’s how you’ve been entered at this school and all your things are marked ‘Ansell’. I gave the order when I bought them. So no more ‘Letton’, remember. As far as possible you are to go nowhere alone. I wish,” he added, half to himself, “that there was no need to tell you anything, but for your own good you must know certain things. Please listen! You are never to go anywhere with any stranger, no matter what message they may say they’ve brought from me or anyone.”

“O.K., Dad.” Copper still spoke in that undertone. “There’s something up, isn’t there?”

“Quite right, but I’m telling you no more than I must—not yet, anyhow.”

“No; but I do wish I knew the why of all this!” It came with heartfelt fervour.

“You shall some day; but not yet. And Copper, it may be some time before I see you again. Write to me as often as you can and don’t be disappointed if you don’t hear from me as often. I’ll write when I can but—well, you’ve been a policeman’s daughter for most of your life and you know that we can’t always call our time our own. It may be impossible for me to manage even a postcard. Don’t worry if that happens. It will simply mean that I’m too occupied with my job at the moment. You’ll hear sooner or later.”

Copper nodded and one of the pigtails swung out, catching a warmer gleam from the September sun which was pouring through the window of their compartment. The man’s eye was on it and he frowned quickly.

“Your hair! Those bellropes of yours are pretty conspicuous. I’m not sure——” he broke off. Then he went on: “Yes, I am, though. Sorry, old lady, but you’ll be better off without them.”

The deep grey eyes still obediently fixed on the flying landscape, widened. “Have them cut off, you mean? Oh, Dad, must I? But why?”

“Better, I think. Once all this—well, later on, anyhow, you can grow them again if you want to. For the present you’ll be safer without them. I’ll give you a chit to hand over to whoever sees to that sort of thing.” He pulled out a notebook, scribbled for a minute or two and then tore out the page, sliding it along the seat towards her. “Here you are. Mind you hand it over as soon as you can.”

Copper’s face was gloomy but all she said was, “O.K., Dad!” as she took it and tucked it into her handbag. He took no notice but went on: “Don’t forget to read those papers I gave you. They tell you all you should know about your own father—all your mother told me when she married me. Learn it by heart and fix it in your mind. That is your story and the only one you know. Forget you have a stepfather as far as you can. Keep turned!” he added sharply.

In her surprise at his last remark, Copper had half-turned towards him, but his quick ears, already alerted for any new sound, had caught the noise of advancing footsteps in the corridor outside. She was back in her old position in a flash; her shoulders well hunched, her eyes fixed unseeingly on the flying landscape, one hand clutching at the tell-tale plaits dangling to her waist.

The man who strolled past the windows at the other side, casting a casual glance at the occupants of the compartment as he went, would never have imagined that there was any connection between the man buried in the outspread sheets of the newspaper he held and the sulky-looking schoolgirl in the far corner, whose blue-bereted head was bent over the book she had held on her lap all the time. He passed on without a pause and once his steps had died away, Chief Inspector Detective Letton laid his paper down, leaned out of the doorway and looked sharply after him. He had vanished into the next door carriage and all seemed to be safe enough.

“O.K.,” the Inspector said. “Go on listening to me. You know what happens when we reach Besançon. You leave the train and you’ll be met by two ladies.”

“I know,” Copper recited in an undertone. “One is big and fair and will be wearing brown; the other is small and darker and is in green. Both will have sprays of yellow flowers pinned to their jackets. I’m to go with them.”

“Right! And whatever you do, you must not—not!—turn back to look at the train or take any notice of me whatsoever. Yes; I know it isn’t going to be easy. We’re pretty close pals, aren’t we? But this is an order.”

Copper nodded silently. His final statement had clinched matters for her. When he said that she knew that all she had to do was to obey him to the letter.

“We’re getting near Besançon,” he said. “Get your traps together. Then go to the door and be ready to jump out as soon as the train stops.”

She stood up and took down the nightcase and rug from the rack. Hockey stick, raincoat and umbrella were already strapped to the case. She rummaged in her handbag for her ticket and finally stood erect, case in one hand, handbag and rug over her arm, and turned to the corridor.

“Go on,” he said from behind his paper. “No; don’t kiss me! Take no notice of me. We’re nearly in,” as a lady went past to the outer door. “Off you go!”

She went out and as she turned from him she caught, very faintly, the words, “God keep you, my darling!” A choky feeling came into her throat and tears pricked the back of her eyes, but she had her orders and she must obey without argument. Already the train was slowing down. In another minute it had stopped and the door was swung open by a porter. The lady she had followed went down the steps and turned towards the luggage-van. Copper jumped down, almost into the arms of a small lady in a green knitted suit and hat, with a spray of yellow flowers pinned to her coat.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” she began, but was stopped at once.

“You’re Flavia Ansell, aren’t you?” the lady said. “Good! I’m Miss Ferrars, and Miss Wilmot is over there by the barrier. Give me your case. That’s right! Got your ticket? Come along, then!”

With an effort, Copper marched off beside Miss Ferrars without looking back at the train. It was bad enough having to leave her stepfather for months at a time; to have to go without even waving to him was almost too much for her. She never knew that Inspector Letton, apparently busy jotting down something in his notebook, was really watching the erect little figure as it went to the barrier and was lost in the crowd there.

She gave up her ticket and they passed through, to be seized on and greeted by a big, pretty woman in brown who took her rug from her at once, saying: “Come along, Flavia! I’m Miss Wilmot. We’re going to a pâtisserie for coffee and then we’ll collect the car and be off to the mountains. This way!”

She led the way out of the station and presently they turned in at a pâtisserie. Here Copper was presented with a plate and cake-fork and introduced to the pleasant continental custom of going to the counter, where tempting cakes and rolls and twists of fancy bread were heaped up in long trays, and helping herself to whatever she liked. She had felt that she could not eat a bite, but the mistresses saw to it that when they reached their table her plate was well-filled, and when she had nibbled the first twist and drunk some of the delicious coffee, rich with cream, which their waitress brought she had found an appetite. When they left her plate was as empty as the others.

“Now for the car!” Miss Wilmot exclaimed. “Along here, Flavia.”

They went along the busy street, turned down another and presently came to a small hotel in a side street. In the courtyard at one side stood two or three cars. The mistresses made for a small dark-blue Citroën and Copper’s possessions were tucked into the back seat beside Miss Ferrars while she herself was commanded to sit in front beside Miss Wilmot. Copper knew that the rule of the road on the Continent is the opposite to the British, but it was quite a shock to find herself sitting on the righthand side while Miss Wilmot, in the driver’s seat, was on the left.

By the time she was growing accustomed to it they were rolling over a long bridge across a wide river towards which Miss Wilmot nodded. “The Doubs—mainly a French river, though it flows through a corner of Switzerland, too. You’ll see it again later on when we enter Switzerland at Les Brenets, though we shan’t have time to stop to show you the Saut-au-Doubs waterfall, which is a really lovely sight at any time of the year. However, we have a good many expeditions from school and the chances are one may go there in the spring and you may be with it.”

“That’s really the best time to see it,” put in Miss Ferrars, leaning forward from the back seat to join in the talk. “The river’s full from the melting snows then and the fall is a magnificent sight—nearly 100 feet of falling water crashing down at full pitch!”

“It sounds fabulous!” Copper said.

By this time they were out of the town and speeding along one of the great motorways, but before long they turned off and Miss Wilmot drove them along an obvious second-class road—very second-class, Copper thought—as they bumped over certain ruts and pot-holes. Miss Wilmot kept her eyes and attention on her driving but Miss Ferrars explained.

“We could go all the way by the motor road, but Miss Wilmot knows the short cuts and as it’s a longish journey in any case and we don’t want to land up about midnight, she’ll take the lot. This won’t last long, though I admit it’s—more than a little—jerky!”

The last words were literally shaken out as they bumped out of a big pot-hole and Miss Ferrars finished on a laugh. Copper laughed, too, as they swung round a sharp bend and she grabbed frantically at the strap. Then they ran through a little village, turned another corner into a lane, and emerged from this on to the motor road once more.

“Saved three kilometres there,” Miss Wilmot said complacently as she guided the Citroën into the long stream of traffic. “The main road curves out widely at that point, but the one we took goes direct. Still all together, Flavia?”

“I—I think so!” Copper gasped. “Gosh! What a difference!”

“Oh, in France that often happens. Besides we’re among the Juras and now we go on up for a time. Ever seen mountains like this before?”

No; Copper had not. “I went with my form for a weekend in Paris last Easter, but that’s the only time I’ve been abroad. Mostly, we go to the coast for holidays—Broadstairs or Bournemouth, and once we went to Cromer. It’s all pretty flat country. Aren’t these marvellous? Are any of them snow-capped or do they have glaciers?”

“No; for that you must wait till we reach the Alpine country,” Miss Ferrars told her. “You’ll see plenty of snow-caps and glaciers once we’re at school. We aren’t far from the Jungfrau there; and on clear days we look right across the valley to the true Bernese Oberland and have magnificent views. You’ll see!”

“It sounds fabulous!” Copper said, turning back to gaze at the view ahead.

On and on and up and up they climbed, now turning aside from the main road for two or three kilometres into another rutted way; then coming out again to the great motor road where the running was like a billiard-table. At last they reached their summit and then they began to go down steadily till they reached the frontier. A mile further on they ran into a busy little industrial town where they halted for lunch, or “déjeuner” as both mistresses called it.

“This is Le Locle,” Miss Ferrars said when they had parked the car and were walking along a busy street to a restaurant. “It’s a busy little place and quite an important one. This is where Daniel Jeaurichard, the man who invented the very first pocket watch, lived. Look over there. That street is named in honour of him. They still turn out the high-precision clocks and watches that have made Switzerland famous for its timepieces.”

“How jolly interesting!” Copper exclaimed. “When did—I forget his name—live?”

“He died in 1741 at seventy-six—so he had a good run for his money,” Miss Wilmot said, as she turned in at the swingdoor of a restaurant. “Heard of turnip watches, Flavia? That’s what the first pocket-watches were like—round, you know, and definitely weighty. They were carried in specially-made pockets at the waist. Coats were cut with very long skirts in those days and just as well, or gentlemen might have lost their watches to pickpockets all too easily. They cost the earth, of course. And there were none for women for years, of course. Watches definitely belonged to men.”

Miss Ferrars laughed. “I remember reading a book when I was your age, Flavia, in which the heroine, who was a girl in the eighteen-forties, was given a watch, and it said how rare they were, even in those days. Here comes our soup, and I expect you’re ready for it.”

Copper was ready, and she enjoyed the delicious soup followed by cold stuffed lamb served with tiny potato balls all crisp and golden outside and melting and savoury within, and artichokes with a delicate creamy sauce. They topped up with something that was pink and fluffy and delectable and wound up with cups of coffee blanketed with mounds of whipped cream.

“I like Swiss cooking,” Copper decided as they went to collect the car once more. “I wonder if we get this sort of thing at the school?”

Before long she had forgotten it, however, in the excitement of all there was to see. Miss Wilmot avoided the busy streets of Neuchâtel, but they had a glimpse of the lake as they raced round the little golden city and away to Berne which they reached with time to stop for more coffee and cakes—called here “Kaffee und Kuchen,” as the mistresses informed her.

“This is a German canton,” Miss Ferrars explained when they were once more on the road. “Neuchâtel is French. By the way, Flavia, do you speak French or German?”

“French a little,” Copper replied. “German hardly at all.”

“Ah! Then I’d better break it to you at once that at the Chalet School we speak three languages day about,” Miss Wilmot said blandly but with a wicked twinkle in her pansy-blue eyes. “So pick up all you can of either language.”

“Speak them? You mean—all the time, lessons and everything?” Copper gasped, appalled at the prospect. “But I can’t—not German, anyhow.”

“You’ll soon learn,” Miss Ferrars told her soothingly. “When you hear nothing but one language round all day for a whole day and must do your best to speak that language, you very soon pick up enough for everyday work. When it comes twice a week you find that you’re gathering a vocabulary together. Once that happens, you go ahead.”

Miss Wilmot laughed. “My dear girl, don’t look so pussystruck! As Miss Ferrars says, you do pick it up quickly—unless you’re a complete dullard—which you certainly aren’t. Besides, everyone is willing and ready to help you out; and, apart from that, after the first fortnight of school you’re fined if you use the wrong language. By the time you’ve been penniless for a few weeks, you soon learn enough to carry you through, believe me! I’ve been through it myself—I’m an Old Girl of the Chalet School and I know from experience.”

Copper still looked dismayed. “It sounds awful! I’ll never be able to do it!”

“Oh yes, you will,” Miss Ferrars assured her. “I’m not an Old Girl of the school and I could speak after a fashion before I joined the staff, but I had a hopelessly British accent which isn’t noticeable now. Being in the middle of it all has done that for me. You’ll find it’ll do the same for you. Don’t worry about it. Instead, look at the river. That’s the Aar, which flows out of Lake Thun where we have swimming and boating in summer and sometimes skate in winter when it’s possible to get down from the Görnetz Platz.”

“Is that where the school is?” Copper asked, diverted from future troubles by this. “I didn’t know. Where is it exactly?”

“It’s a shelf up on the mountain—a big one,” Miss Wilmot said. “The school is at one end and the big Görnetz Sanatorium three miles or so away at the other. Usually, we go up the mountain by train, but as we have the car today, we’ll take the coach road which goes up near Därligen on Lake Thun. Not so far now, as I expect you’ll be glad to hear. You must be growing tired after all your travels.”

Copper was wearying by this time. Her travels had begun the evening before when she and her stepfather had flown to an airfield near Nemours in Central France, taking the train from there to Besançon where the long car journey had begun.

“If Dad’s pal had only been able to fly us the whole way we’d have done it in half the time,” she thought sleepily. “What a pity that he had to get back. Then Dad could have come the whole way with me.”

She drowsed off to sleep after that. In fact, so tired was she that when they finally reached the school she had to be shaken awake before they got her out of the car and into the big entrance hall. There Miss Ferrars led her through corridors to a pleasant room where she was warmly greeted by a lady with a most attractive face and voice before she was handed over to a small, middle-aged woman in Matron’s uniform. Of the simple supper she kept sufficiently awake to eat, and the subsequent journey upstairs to a little cubicle where Matron helped her to undress and finally tucked her up in bed, she never really remembered a thing. She was half-asleep, and before Matron left her she had fallen fathoms deep in a slumber which lasted until the rising-bell next morning managed to reach her. She awoke to realize that she was in her new school with home and Dad hundreds of miles away, and she might not even call herself Flavia Letton as she had always done, but must begin her new career with a new surname and remember that henceforth she was Flavia Ansell.

It took Copper exactly ten days to settle down and decide that she was going to like her new school. At first, she was not so sure. For one thing, despite her pleading, she found that Flavia was her name and Flavia she would be called—by the staff, at any rate.

“It’s such a—a soppy name!” she protested to Miss Dene, the school secretary. “It sounds just like Mummy’s darling daughter, all curls and fancy frocks. It isn’t me.”

Miss Dene rested her chin on her clasped hands and looked seriously at her. “Is that how it strikes you? Myself, I should call it stately rather than soppy. I’m sorry. We do permit abbreviations of names, but not nicknames—not officially. What your future little playmates may call you among yourselves will lie between you and them. In form, my dear, it must be Flavia.”

Something in her tone kept Copper from further protest and, on later consideration, she realized that the staff of the Chalet School would have had to be very different from the general run of staff if they had given in to her.

French and German were another snag. French wasn’t too bad. The lessons at her high school helped her there. German was quite a different story. When you are still at the “Ich habe das Buch meines Bruders” stage, to have to try to understand whole conversations in nothing but German—as well as doing your best to produce remarks also in German that would pass muster with most folk—did not help to make life easier. However, Copper did not lack sense and though she might—and did—growl about it to herself she did pay attention to what she was taught, and by the end of the second week of term she discovered that she was beginning to understand a fair amount of what was said. Talking herself was another matter.

She had handed over her father’s note to Matron the day after her arrival and that lady had proceeded to clip off the long thick pigtails on the spot and trim the untidy ends into neatness. On the Saturday Copper had been marched off to the school’s hairdresser, Herr Fritz Beschannen, who kept an establishment in Interlaken. By the time he had finished with her head Copper had ceased to regret her thick mane. It had been a bother to brush and comb and plait. Now she would have more time for other things in the mornings and at night, and at least there would be no ghastly tangles to wrestle with.

“It suits you,” remarked Miss Ferrars, who had brought her. “The only thing is you must remember to brush it thoroughly night and morning until it’s settled down to the new parting. Still, that probably won’t take long.”

Herr Beschannen had given her a side parting instead of the centre one she had always had, and Miss Ferrars had bought her a couple of slides to keep the hair in place.

Copper peered at herself in the big mirror. “I look—different,” she said. “I think I’m going to like it, though. My head feels pounds lighter and it won’t be nearly such a bother to keep neat.”

Miss Ferrars, whose own brown hair was also cut, nodded. “So I imagine. And when it comes to washing it, it won’t be half such a trial.”

Copper’s “little playmates”, to quote Miss Dene, were intrigued by the change when she rejoined them just before Mittagessen, as she was learning to call the midday meal. She had been put into IVa and found them a friendly crowd. There were five other new girls besides herself, and one “old” girl took charge of one new, saw that she had all her books and stationery, knew about the various clubs and societies and was ready to explain anything that needed explanation.

Copper’s own “sheepdog” (as she discovered they were called unofficially) was a short, dark girl a little younger than herself, with black hair cropped like a boy’s and offhand, boyish ways which were brusquely kind. Jack Lambert was one of a crowd of six or seven girls who more or less led their own form by the nose. Since Form IVa was the top form in the Middle school, it looked rather, as Len Maynard, one of the prefects, had remarked, as if they would also lead all the Middles.

“And Heaven send that Jack and Co. don’t take any mad ideas into their heads,” she added piously, “or we shall have a sweet time of it this term.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” Len’s own special friend, Ted Grantly, rejoined. “We all know what Jack is when she has an inspiration!”

It was to this promising gang that Copper was first introduced, though Jack saw to it that she knew everyone in the form—twenty-three other girls. Quite a number of them were from other countries, including France, Holland, Belgium, Germany and Italy as well as the U.S.A., Canada and even Australia. Switzerland, of course, was well represented. Most of them spoke the school’s three languages more or less fluently, though one Italian girl who was new that term could manage only some French and neither German nor English.

Copper was not given to making friends quickly. She was pleasant to everyone, but while quite a number of the new girls were already beginning to join up conspicuously with one or more, she sat back, considering the various people. Jack she liked, though she shrewdly guessed that Miss Jack was a good deal of a featherhead. Jack’s special chum, Wanda von Eschenau, attracted her more. Wanda was small, dainty and unusually lovely, with long golden curls, deep violet eyes and perfect features. Copper soon saw that quiet as Wanda was in general, she frequently acted as a brake on Jack’s wilder exploits. Two more of the same gang—they were known as the Gang by most folk—were Dutch girls, Arda Peik and Renata van Buren, the last-named famed for a habit of looking angelic when she was contemplating the wickedest deeds. There were also Barbara Hewlett, generally considered the most level-headed of them, and Valerie Gardiner, a red-head usually to be relied on to be up to the neck in every mischief that was going. Strictly speaking, Valerie was more or less a hanger-on, for she had her own chum, Celia Everett, who was not one of the Gang. The rest of IVa were more or less law-abiding creatures, who regarded the Gang with awe and admiration, but preferred to keep clear of their wilder efforts at livening up things.

So far as work went, Copper found that she was well up to the standard of the form in most things. In one or two subjects she was even slightly ahead of them. Science, for instance, in which she was deeply interested, was one, and her mathematics were good. On the other hand, her essays were on the bald side and languages were a stumbling-block at present. Still, she felt that she had no need to worry about keeping her place so long as she worked steadily during lessons and preparation.

What Copper enjoyed most of all were the games. She had been doubtful about these at first. How could such a hodgepodge of nationalities as the Chalet School contained produce players of the same calibre as the First and Second XIs at the High School? On the first Saturday afternoon Miss Burnett, the games mistress, arranged for inter-form games for all the hockey players; the weather looked doubtful and no one was going to risk the girls being caught in a heavy shower when they were at some distance from the school. Netball games were also arranged for those who preferred the milder game. Others might look on or, in the case of the Juniors, join in a game of rounders. Copper elected to watch the Sixth forms versus the Fifths and the play of the two teams made her open her eyes. There was little or nothing to chose between the Chalet girls and those of the High School.

Later on, when she moved with Gretchen von Ahlen of her own form to watch the tussle between the Fourths, she found the same thing. Everyone in the teams played up for all she was worth, and Arda Peik was quite equal to Jack Lambert or Barbara Hewlett, who were both good for their age.

“What do you play?” she asked Gretchen as they stood watching.

“Netball; but I am not very good,” Gretchen replied. “I get tired so quickly and then they do not allow me to play, you see.”

“Oh, hard luck!” Copper said.

Gretchen grinned at her. “I do not mind. I think I am not fond of games. I like better to read and sew and knit. But I like to watch,” she added. “Shall we walk? The wind is cold.”

Lacrosse did not begin till the following week, but her first two practices thrilled Copper, who made up her mind then and there that it was the game for her when the time came for choosing which she would do. Altogether, she was finding life very full and she had no time for worrying about what her father had said. She wrote him a long letter on the second Saturday, giving him all the news and so plainly showing that she was settling down happily that he heaved a sigh of thankfulness when he read it.

“She should be safe enough there,” he said to himself as he folded up the closely-written sheets and put them away in a safe place. “And thank Heaven! I believe we got her away without anyone finding out where she had gone.” Then his work claimed his attention and he set further thought of her aside for the time being.

It was on the second Saturday that Copper enjoyed her first long walk at the school. The first part of the morning was always given up to preparation, home letters and mending. At 10.30 they had elevenses and, after that, games from 11.00 to 12.00. Mittagessen came at 12.30. After that, so Jack Lambert informed the new girl, if there were no matches and it was a fine day, the school divided up into parties and went for a ramble.

“How a ramble?” Copper asked. “Do you mean a walk?”

Jack grinned. “I do not. I said ‘ramble’, and I meant ‘ramble’.”

Wanda, who was with her as usual, explained. “When we walk, we go in croc: two and two, you understand. But if it is a ramble we may break line as soon as we have left the Platz and go in groups. And as it is Saturday, we may talk as we wish. I mean in what languages we wish.”

“But I thought Saturday was one of the English days,” Copper objected.

“But no; only the morning. After Mittagessen we may speak in any language, as I told you.—Jack, do you know who will be our escort?”

Jack shook her black head. “Not me! Haven’t had a moment to look at the lists since Prayers and they weren’t up then. Let’s go and have a dekko now. Coming, anyone?”

They went in a body, Wanda slipping a hand through Copper’s arm and pulling her along with them. She went cheerfully and they marched into Hall, making a beeline for the great school notice-board on which the lists were pinned up.

“Here’s ours,” said Renata, pointing. “Oh, good! We’ve got Willy and Ferry for staff, and Len Maynard and Rosamund Lilley and Ted Grantly for prees. That’s all right. Oh, and look at that, Jack! ‘Take rucksacks and call at the kitchens.’ That means a picnic.”

“Smashing!” exclaimed Copper. Then she saw they were all looking at her. “What’s wrong?”

“Only that ‘smashing’ is one of the words that’s utterly verboten here,” Barbara explained. “You know that we’re fined if we’re caught using certain words. That’s one of them, so cut it out if you don’t want to find yourself penniless by Saturday.”

“Gosh! How awful!” Copper gasped. “I knew we were fined if we didn’t try to use the language for the day, but I never thought of slang.”

“Len Maynard explained it to me,” Jack said. “You see, no one wants foreigners—oh well, folk from other countries, since you’re all so fussy!”, as an outcry rose at this. “Well, anyhow, we’re not to teach them our slang, Copper,”—IVa had taken to Copper’s nickname with acclaim—“and they’re not to teach us theirs. So don’t tell anyone to ‘ferme le bec’ if you want them to shut up, or you’re for it.”

“Shut the beak?” Copper repeated in puzzled tones. “Is that how you say it in French? I’d never have thought of it on my own.”

“Well, you forget it now,” Barbara advised her.

“What are you people doing in here?” demanded a fresh voice from the doorway and the party swung round with one accord.

“Oh—Len,” Jack said. “We just came to see who we were to have for escort this afternoon.”

“Yes; well, now you know. You clear out and go and make yourselves fit to be seen. The gong will sound for Mittagessen in less than ten minutes,” Len said with a glance at her watch, “and you’re all looking pretty wild about the head. Scram, everyone!”

They sped off. Len Maynard was a beloved prefect, largely because she seemed to be able to understand the point of view of her juniors and make certain allowances accordingly; but when she gave a direct order, she saw to it that she was obeyed—or else! as Jack Lambert had observed feelingly on one occasion.

Copper washed her hands and face and then produced her pocket comb and tidied the smooth red locks which she found so much easier to deal with than her pigtails. Barbara, similarly engaged, glanced at her and chuckled.

“When you come to think of it, what a lot of red tops we’ve got in the school,” she remarked. “There’s Len and her sister Margot—only she’s reddy-gold and Len’s hair is very dark red. Then we’ve young Val who’s a regular carrots, and now you’ve come. And there are others as well.”

Copper gave a final touch to her hair and pocketed her comb. “There are lots more people with black or brown or fair hair,” she said. “You’re brown yourself; and Jack is black, and Wanda is golden and Gretchen’s hair is so fair it’s nearly white.”

“It is not,” observed Gretchen herself in offended tones. “It is flaxen and that is not white.” She gave a toss to the long braids she wore dangling over either shoulder.

“Oh, I didn’t mean anything,” Copper said quickly. “I was just pointing out to Barbara that there aren’t all those many red-headed people in the school.”

“Oh, what does it matter?” demanded Jack, who never cared about looks so long as she was clean and tidy enough to pass muster. “It’s a lot of rot, anyhow. I’m ready if you folk are. Come on! Let’s go to the commonroom. The gong will sound in half a tick.”

She marched out of the splashery, the school’s name for a cloakroom, and the rest followed her to the commonroom. Copper was very quiet, although the rest chattered like starlings. Barbara’s remark had reminded her of her father’s insistence on her having her own plaits cut off. She wondered why he had said it would be better. Why did he think so? She had heard that some people thought girls were better off with short hair while they were growing. Was that it? Or was it something else? Why had she been rushed off to Switzerland so suddenly. Why had Dad spoken so quietly in the train and ordered her to speak quietly, too? And why had he made her turn away from him and not even kiss him goodbye?

“Copper—Copper—Flavia Ansell! Stop mooning and listen! What’s biting you?” Jack’s voice cut across her puzzled thinking and she gave herself a mental shake and turned to see what was wanted.

“Did you speak?” she asked. “Sorry, but I was thinking and I didn’t hear.”

“Didn’t hear? I’ll say you didn’t! I’ve called your name three times,” Jack said sarcastically. “What were you mooning about anyhow?” Her sharp eyes were bright with curiosity as she looked keenly at the new girl.

Copper flushed. “Oh—just something my father said to me,” she replied.

“Well, you give it a miss and listen to us,” Jack commanded. “D’you know what? Renata says she thinks our crowd are to take the train and go up to the Rösleinalp and picnic up there. Jolly good, isn’t it?”

“I don’t know. Well, how could I? What is the Rösleinalp, and why is it so smash—er—decent—to go there?” Copper asked.

“It’s a shelf quite a bit higher than this,” Barbara explained. “There’s a decent village up there with two shops where you can buy things like chocolate and wood-carvings and so on. And you get a fabulous view of the Alps towards Geneva at one end. I say, let’s ask if we can go along there and show it to Copper. Len would come with us if we asked her.”

The door burst open before anyone could reply, and Mollie Rossiter and Margaret Twiss, two more of IVa, dashed in.

“News!” Mollie shrieked. “Gorgeous news! What d’you think?”

“That you’d better pipe down or someone will be coming to ask who’s making all the row!” Jack retorted smartly. “What a silly clot you are, Moll! D’you want us to have a row?”

Mollie went red. “Sorry, everyone, but it really is rather good,” she apologized. “Listen to this! St Hilds is coming along to join us so we’ll have Gillie and Kitty and Mary and all that crowd. Now then!”

“Ferry told us just as we left the splashery,” Margaret put in rather more calmly. “She said, ‘You people will be glad to hear that your St Hild friends are joining us for the ramble. You may tell the others, but warn them not to make too much noise about it.’ ”

Jack’s face was alight. “I say! That’s fabulous! I’ve rather missed that crowd this term. I’ve quite a lot to say to Gillie and the rest—including what I think of Gil for not writing more than once during the hols. She is a blight!”

“How often did you write yourself?” someone demanded.

“One letter and two p.c.’s and all I had from her was one p.c. of Oban with ‘Having a gaudy time. Wish you were with us.’ I don’t call that writing to a chap. Did Ferry say when they began, Meg?”

“This week—on Tuesday. I’m aching to hear what they think of their new place,” Margaret replied.

Wanda, seeing that Copper felt rather out of all this, turned to her. “It is a school that were—no, was—burnt out this time last year before ever they began. Their Head was very badly hurt and was at the Sanatorium at the other end of the Platz for a long time. They came here to join us until something could be planned for them and they stayed the whole year. But now they have their own house at Ste Cecilie further along the motor road, so, you understand, they are not here and we all want to hear about it. Gillie and Kitty and Mary and the others were in our form last year and we really became very friendly with them.”

“Anything but, at first,” interjected Val Gardiner with a giggle. “Then Jack and Gillie rescued their cat—at least we thought it was their cat though no one’s ever been sure of it——”

The gong rang at that point and all talking must cease. Rules at the Chalet School were not many, but what there were had to be obeyed. Val stopped short in the middle of her sentence and the girls quickly formed into line and were all ready when Rosamund Lilley, the Head Girl, came to give them the signal to march to the Speisesaal, where Mittagessen was awaiting them. Copper had to wait until grace had been said and they were all sitting in their places before Val and the rest could enlighten her about the mystery of the Chalet School cat, Minette, and St Hilda’s cat, also Minette, as well as the story of the hair-raising adventure on which Jack and her chum, Gillie Garstin, had embarked on finding that one of the pair was out on the school’s roof on a bitter winter night and too terrified to get back to safety by herself.

This exciting narrative lasted them until the end of the meal. After that, they all rushed to get into blazers, berets and stout walking shoes before shouldering their rucksacks and going to the kitchens for their picnic parcels. By the time this was done and they were out on a sidepath the sound of voices reached them from the motor road and, five minutes later, the girls from St Hilda’s had arrived and were joining up in their proper forms, so Copper had to wait to hear the rest of the saga.

“Hello, Gillie! You’re a nice one!” Jack Lambert’s greeting drew a broad grin from the St Hilda’s girl she had addressed.

“What’s biting you?” she replied amiably. “Hello, everyone! Nice to see your ugly old mugs again!”

“Ugly old mugs yourselves!” retorted Meg Walton, another of IVa’s redheads, with a toss of her long pigtail. “What cheer, Moira! Glad to have you back. What’s your new place like? Walk with Val and Celia and me when we break and give us all the gen, will you?”

Copper, standing beside Jack who was partnering her for the moment, looked rather shyly at this new crowd of girls who had joined them. She knew by this time that it was hopeless to expect Jack to introduce her. That young woman was apt to be careless about such things unless she was reminded. Wanda, however, was not and she came up at that moment with a girl who was greeted by the rest of the Gang as “Anne Crozier! Gosh! Haven’t you grown!”

Anne, a leggy creature with a page’s bob and sparkling brown eyes, laughed. “Oh, my lambs! I fell out of a tree on to my head the second day of the hols and got concussion. I was in bed for three weeks and I grew then. You should have seen Mum’s face when I did get up and all my frocks were yards above my knees! Every single hem had to be let down and even then most of them were on the short side. Believe it or not, I grew an inch and a half in the time.”

They laughed and Wanda, coming to Copper, said, “Oh, everyone! This is one of our new girls, Copper Ansell. Copper, these are Gillie Garstin, Mary Candlish, Anne Crozier and Kitty Anderson from St Hilda’s.”

The four stared. Gillie was the first to speak.

“Is your name really Copper?” she demanded. “How come?”

“Oh, I’ve been called that since I was an infant,” Copper said. “My real name is Flavia. Can you beat it?”

“What’s wrong with it?” Kitty asked. “Jolly pretty and not common, I call it. Oh, we’ll call you Copper if all the rest do——”

“Not the mistresses, I’ll bet,” Mary interrupted.

“You win,” Copper said laconically.

“But why Copper?” Kitty inquired. “Is it—is it your hair?”

“It was in the beginning,” Copper explained. “When I went to school, though, the others found out that my dad’s a copper, so they stuck to it.”

“Is he? I say, what a yell! Does he tell you all about his fights with criminals?” Kitty asked eagerly.

“Not much! He rarely talks about his job—well, you don’t when you’re C.I.D. any more than a doctor natters about his cases or—or a bank manager about the people who have accounts at his bank,” Copper told her.

“Don’t they—bank managers, I mean?” Jack demanded.

Anne, whose father was in a bank, exclaimed in shocked tones: “Of course they don’t! It’s all private between him and—and the other people. Surely you know that, Jack?”

“I didn’t. Never thought of it,” Jack replied cheerfully.

“Girls, get into line!” Len Maynard and her chosen companion, Ted Grantly, had arrived and the sixty odd girls who made up the party hurriedly found their partners and formed up in line. By the time the two mistresses had arrived they were ready and waiting, berets at the proper angle, rucksacks on backs and alpenstocks gripped firmly. Miss Ferrars and Miss Wilmot were distinctly popular with their charges of both schools and they were greeted by welcoming grins from everyone.

“Got your sandwiches, etcetera?” Miss Wilmot queried. “All got clean hankies, Kodaks—and other oddments? Excellent! Lead on, Meg and Kitty. Keep a good steady pace and the rest of you, keep up with them. Len, you and Ted go to the head and Miss Ferrars and I will do sheepdog at the rear.”

Then they were off. Copper found herself and Jack third couple immediately behind Gillie and her partner, Mary Candlish; Wanda and her partner followed them. Down the motor road they went at a smart pace. The station was some distance away, lying midway between the school and the great sanatorium which brooded over the other end of the Görnetz Platz. The girls chattered as they went, but always with an ear open for any loudly-raised voices. The rule was that so long as they were on the road they must talk quietly. Not only were there a good many chalets scattered about, but there were a couple of guest houses where people with friends or relations in the Sanatorium might stay, and no one was anxious for Chaletians to get a name for rowdiness.

Arrived at the little station itself—a mere roofed shed—they found they were just in time for the train which was gliding up the long steel rail that rose from the plain below right up to Wahlstein where the great glacier that wound down the mountain from the eastern summit ended. The Rösleinalp lay halfway between the Görnetz Platz and Wahlstein. The girls filed into the two glassed-in coaches and then they were gliding on, up the steep slopes with a glorious view of the mountains beyond the twin lakes between which on the one hand stood Interlaken, on the other was a high, grassy bank where late summer flowers still lingered in places.

“What lies behind that?” Copper asked Jack.

“Mountain path. Actually, we usually walk the whole way, but I heard Deney say to the Head that we had so many new girls this term, especially in Lower IVa, that it would be better if we went by train and then walked down. You see,” went on Jack with the condescension of a very recent member of IVa, “some of them are quite kids and they might find it a bit much for them.”

“Oh, I see.” She suddenly remembered something and changed the subject. “Jack, why do you call Gillie that? Shouldn’t it be Jillie—or Jill? Her name’s Gillian, I suppose?”

Jack grinned. “Not it! Don’t tell her I told you for she just loathes her proper name, but she’s Gilbertine, after her dad. No one ever calls her that, of course, and if any of us did, sparks would fly.” She gave a chuckle. “You ought to understand, seeing you prefer Copper to Flavia, which really is quite harmless and, if you mind about that sort of thing, even pretty.”

Copper screwed up her face. “Soppy and penny-novelettish. Come to that, what’s your proper name? Jacqueline?”

“No; but it’s quite as bad. They named me after my two aunts, Jacynth Gabrielle. I s’pose they thought I’d be like that but I never have been, so I’m Jack which can be short for Jacynth. The school doesn’t mind short names, but they don’t call you by your nicknames—and here we are! Grab everything and be ready to bound. The trains don’t hang about much, I can tell you.”

Thus warned, Copper was ready when the train stopped, and bounced out after Jack on to the short, sweet turf with an alacrity which drew an approving, “Good, Flavia!” from Miss Ferrars, who had been first out and was standing watching to see that no one was left behind. Miss Wilmot had gone to the other coach on the same errand. The two prefects remained till the last and the empty coaches were delayed only to allow a party of tourists to clamber in, when, with a warning hoot, the train set off again on its upward journey.

The girls stood watching as it went and Copper was too much engaged in listening to Jack’s conversation to notice that one of the women in the party had turned on the steps of the back coach to stare at them. Her eyes dwelt particularly on Meg Walton, Val Gardiner, Kitty Anderson and Copper herself. They stayed longest on Meg, who had pulled off her beret and stood with the fresh breeze stirring the flying ends of her red hair. In fact, no one noticed, and no one would have thought anything of it if they had. Miss Ferrars and Miss Wilmot were busy counting their charges to make sure that all was well and the prefects were talking to a little bunch of Lower IVa and had their backs to the railway.

“All present and correct,” Miss Ferrars said suddenly. “Well, what do you all want to do? No, Arda; you may not start on your eats. We’ll have those at 16.00 hours and no one is to interfere with her packets or flask until then. So how do you propose to fill in the time?”

“May some of us go to the other end?” Jack asked eagerly. “We want to show the new girls the view from there.”

“By all means, so long as Len or Ted goes with you. Well, you two?”

“I’ll take them,” Len said. “Ted is going to organize a walk round the alpe through the pines for anyone who likes it but she can do that without me.” She cast a fleeting grin at Ted who returned it. “How many want to go round the outer edge with me? Don’t all speak at once, please.”

“Which way are you going, Ted?” Renata asked.

Ted, a tall dark girl with black hair cut in a deep fringe over equally black eyes, laughed. “Through the pines over there and round the back to the chalet under the mountain wall. We’ll meet there, shall we, Len?”

“O.K.” Len agreed. “Sort yourselves and hurry up. We’ve just nice time for it if we set off at once. Who’s going with Ted and who’s coming with me? Hurry up and decide.”

Thus urged, the girls divided into three parties, the largest going with Ted, the next joining up with Len, and the fifteen or so left remaining to enjoy sketching, photography or quiet chatter among themselves. The two mistresses settled themselves on a convenient log with books and knitting, reminded the prefects that their picnic would begin at 16.00 hours, and then shooed them off.

“Come along,” Len said to her party. “This way. We walk round by the edge of the cliff. Not too near, please, Val,” as that young person, with Celia in tow, made for the outer edge. “And no monkey tricks, either. I don’t want to have to go back and tell the Head I’ve left you in bits and pieces halfway down the mountain!” Whereat Val giggled, but came farther in.

The walk was a revelation to Copper, who had never seen any real mountains until she came to Switzerland. Jack and Co chattered all the way as they went, but Copper was almost silent. Len, keeping a watchful eye on her followers, noticed it. Presently, she joined up with the younger girl.

“Aren’t the mountains wonderful?” she said quietly.

Copper turned to her quickly. “Fabulous!” she said. “Somehow I never thought they would be like this.” She waved her hand towards the great ranks of mountain peaks standing out clear against the blue September sky. “How far you can see! And yet some of those mountains look quite near.”

“It’s the clear air,” Len said. “And, of course, we are so much higher here than down on the Platz that we can see far more. Luckily,” she added, “it’s an extra clear day. I’ve been up when you could scarcely see a thing for heat haze—Jack Lambert! What are you doing? Come back at once! Now listen, all of you,” as Jack obeyed her, “you are not to go nearer the edge than two feet. If you do, I’ll turn round and go back. Understood?”

“Oh, yes, Len!” “Mais oui, certainement!”—“Aber gewiss!” they chorused in a hurry. No one wanted to turn back and sundry meaning looks were cast at Jack and Co and one or two others who might be expected to forget their limits unless they were reminded.

When they went on once more Len laughed. “I thought that would do it! I must go and talk to Kitty and Mary from St Hilda’s. Don’t you become so absorbed in the view that you forget and do a neat walk over the edge yourself,” she added with another chuckle before she left Copper, who was instantly claimed by Wanda and had little more opportunity to feast her eyes on the wonderful picture before her until they reached the far end of the shelf. There Len halted them and, for the sake of newcomers, pointed out various important landmarks before collecting them together again and marching them round the side of the shelf to a little chalet which seemed to nestle under the shoulder of the mountain. Here they met Ted Grantly and her party, who complained bitterly that, late September though it was, the flies were simply ghastly in the pinewoods.

“Well, tomorrow is the first of October, so they’ll all be gone in another week,” Len said cheerfully. “It’s getting much cooler at nights now. Haven’t you noticed it? We may expect night frosts, once October comes in. That puts paid to the flies.—I beg your pardon?” This last to a smartly dressed woman who had emerged from the woods and come over to them. “Can we do anything for you?”

“I wondered if you could tell me the nearest way to the station,” the stranger said, speaking with an unmistakable American twang. “I guess I’ve missed the road, way back in the woods. I don’t want to be benighted up here, and wandering alone among trees don’t appeal to me. Which way is the shortest to the railway?”

Len considered while the younger girls moved aside in groups and stood waiting. “The quickest way is straight across the grass in that direction. Keep on till you reach the Gasthaus——”

“Pardon?”

“The—the little hotel.” Len hurriedly corrected herself. “There’s a path going round to the left of it. Follow that and it takes you straight to the Bahnhof—I mean station.” She looked at her watch. “You’ve plenty of time; the next train down is due in less than ten minutes so you’ll miss that. But there’s another in less than an hour’s time so you ought to catch that easily.” She wound up with a pleasant smile before turning to collect up her party. Ted had already gone on, considering that her friend was quite capable of giving directions without any help from either her or the thirty girls in her charge.

“Well, that’s pretty nice of you,” the stranger said. “Thanks a lot.” She glanced at the Middles nearby and added, “I guess you’re a school, aren’t you? Up for the day, maybe?”

Some queer instinct warned Len to say as little as possible. “Yes,” she replied. “And we must go on or our mistresses will be wondering why we’ve loitered so. Lead on, girls!”

The stranger nodded. “I guess school-ma’ams are all alike—fussing half the time,” she said. “Well, thanks again. Maybe we’ll be meeting if your school is in Interlaken or round there. I’m staying around with a party and we’ll likely be here quite a while yet.”

“It’s quite possible,” Len agreed. “Excuse me, please. I must go or those young demons may be up to anything. Good afternoon. I hope you enjoy the walk and catch your train all right.”

She smiled and went after her flock who were strolling along between the pines, waving their berets at the clouds of flies that still haunted them though, as she had remarked to Ted, another week or so would see the end of them. Her interlocutor stood where she was, gazing after them until Valerie’s flaming curly crop had disappeared round a bush and she could see them no more. A queer little smile was on her lips.

“Now have I been lucky or have I?” she remarked aloud. “What was it Dwight said about that kid? Long red pigtails—and they’re easily cut off—was that it?” She considered as she began to walk slowly back across the short, summer-burnt turf. “I guess maybe I’ll make a little surer before I say anything to him. Dwight sure has a hair-trigger temper for all he’s such a smoothy in public. I wouldn’t want a fight with him and especially if I’m wrong—as I could be. Red pigtails—phooey! Guess there’s a million kids like that around here. But I’ll hang around if I meet them and try to find out about some of those kids. Come to think, the big one I spoke to had red hair herself. But it can’t be her. She must be seventeen or eighteen and Dwight said the one they were after was twelve or thirteen, maybe a bit more; but not all that much. That settles it! Nix on telling Dwight—not until I’m a lot surer than I am. You watch your step, Lou Manley. Dwight’s no man’s pet when he gets mad.”

Meanwhile, having caught up with her band, Len had little time for meditation on the encounter. She was just in time to stop Val and one or two other choice spirits from trying to climb a specially tall pine. Things had happened before through similar efforts. Only the previous term there had been a near accident which might have been very nasty through just that sort of escapade. The Head had said then that she had a good mind to forbid all tree-climbing. She had relented, but she had warned the school at large that one more episode of the kind would bring down the ban on them.

“And I’ll be gumswizzled if it happens while I’m in charge!” Len thought, even as she shouted, “Val Gardiner! What do you think you’re doing? Come down at once! Remember what happened last term when Jack got stuck?”

Jack was not there to hear this, having gone on with the rest of the Gang. Valerie, however, knew all about it and she scrambled down in haste while the others tried to look as if climbing pine trees was the thing farthest from their thoughts. Len waited until the Middle was safely on the ground before she said more mildly: “Honestly, Val! Do you want to make us all late, quite apart from risking an accident?”

Val flushed to the roots of her hair. “I—well, I just didn’t think.”

“Then give thinking a chance another time,” Len remarked. “If you go on like this,” she added with a sudden grin, “no one is going to agree to taking you out unless you’re on a collar and lead. All right, we’ll say no more.”

She nodded at Valerie and turned to speak to Kitty Anderson, who had come racing back accompanied by Jack. “Well, what’s the latest?”

“Oh, Len, we’ve found a snake—coiled up under a tree!” Jack gasped.

“Has anyone touched it?” Len asked sharply. There are harmless snakes in Switzerland, but some are venomous as she knew. They saw little of them, and in any case it was growing late for them. But there was always the odd one about at this time of year, growing torpid with the long winter sleep which was facing them.

“No—oh, no!” Kitty assured her earnestly as the prefect set off at a run, the Middles keeping pace with her with some difficulty. Len had long legs and was a good runner.

They soon reached the party which had found the creature. Mercifully, they had had the sense to keep well away from it for, as Len realized as soon as she saw the black diamonds on its yellow body, they had found a viper. The thing had reared up, hissing furiously, and the Middles were backing from it looking scared.

“Move off, girls,” the prefect said sharply. “Get as far off as you can!”

“Is—is it poisonous?” Gillie faltered, her face white.

“Could be. You could have a nasty time if it bit you,” Len replied, searching hurriedly for a stout stick. “Keep back there, all of you! Ah!” as her eye lighted on a pine bough which someone must have wrenched off, for it was still green and fresh. Gripping it firmly, she brought it down with all her force across the back of the furious creature as her father had taught all the older members of his family years before. She was lucky. Still hissing and writhing violently, it collapsed among its coils limply, its back broken, the stony, lidless eyes dulling. But it was not safe, even now. She dared not let the girls who had been with her come on until she had removed the thing from the path. Setting her teeth, for she had a horror of snakes, she got the end of her bough among the coils, lifted them and tossed bough and snake as far as she could among the pines. Only then when the still writhing reptile was gone did she call the Middles to come.

“Safe enough now,” she said, “but watch how you tread. We’re not likely to encounter another, but——”

“But tha-that one was th-there,” Jack put in shakily.

Copper’s eyes had gone to the prefect’s face. Len was white as a sheet and her chin was quivering. For all her self-possession, she was a highly strung girl and the danger had been so sudden and so frightening.

“I say, are you all right?” she asked anxiously.

Len looked down at her and gave a tremulous laugh. “Perfectly, thanks. It was just that it all happened at once and I hate snakes. I’m all right, Flavia. Don’t look so worried.” Whereat Jack darted a quick look at her and another, rather less friendly than usual, at Copper.

Len caught both looks and managed to forget her fright a little in hastening to pour oil on what might become troubled waters. Jack Lambert had a tendency to regard the prefect as hers specially and she was a jealous young thing. Only last term there had been trouble with her and the elder girl was not anxious to have the same sort of thing repeated.

“We’d better get on,” she said, tucking a hand through Jack’s arm. “Two and two until we’re clear of the pines, I think. Come along, Jack. You and I will lead. Join up, you folk, and follow us—and keep to the path,” she added as she marched Jack off.

They met with no other adventures, but Len was a thankful girl when they finally reached the end of the woods and were out on the sunny herbage once more. Ted and Co had beaten them and already people were squatting round on logs or their raincoats which Matron had insisted on their bringing, fishing in their rucksacks for flasks and the neat packages the kitchen staff had put up for them.

“Just in time!” Miss Wilmot remarked. “Find seats for yourselves and begin. We want to catch the train down at 17.00 hours and that doesn’t give us much more than three-quarters of an hour to feed, pack up, and reach the Bahnhof.”

They obeyed at once, and presently sundry members of the party were listening breathlessly to a highly coloured version of the viper episode retailed by Renata van Buren. It reached the mistresses, of course. They requested Renata to stick to the bare truth but they shuddered inwardly at the thought of what might have happened.

It was Len herself who put a stop to the chatter by asking Miss Ferrars if either she or Miss Wilmot had seen anything of the American who had accosted them at the other end of the little shelf.

“Was she American?” Miss Ferrars asked, thankfully grasping at the new topic. “How do you know that, Len?”

Len grinned—she was feeling more like herself now, with one of Karen the cook’s delicious sandwiches already inside her and a good drink of hot coffee on top—before she replied. “You could have cut her accent with a knife, not to speak of the way she talked. She said she’d missed her way in the woods and wanted to know how to reach the railway.”

“When was this?” Ted demanded. “Do you mean that female who was prancing across the grass just as we met? What on earth was she doing alone in the woods? And how, by the way, did we miss her? She must have come through the trees. She certainly wasn’t anywhere on the path.”

“We saw her hurrying past near the cliff edge,” Miss Wilmot said as she skinned a banana. “She glanced at us, but she didn’t address herself to us and naturally we didn’t say anything to her. Like you girls,” she laughed, “both Miss Ferrars and myself were heavily warned not to speak to strangers in our long ago girlhood. Don’t think you’re the only ones to be told that.”

They went into peals of laughter which redoubled as Jack said daringly: “I’ll bet your girlhood wasn’t so long ago as that—or else you’ve both got marvellous memories.”

“Oh, thank you, Jack! That’s quite a compliment,” Miss Wilmot nodded at Jack. “Did she say anything else to you, Len—apart from asking the way?”

“Asked if we were up for the day,” Len replied.

“And wanted to know if our school was in Interlaken,” Mary Candlish put in.

Miss Ferrars suddenly looked anxious. “What did you tell her?”

“Nothing,” Len replied. “Most of the crowd had gone on. I said I must catch them up. I didn’t know you were hanging round, Mary. Why weren’t you with the rest?”

“I’d got a bit of bark in my shoe and I was shaking it out,” Mary explained. “I was a bit to one side of you, and I heard her say that. Then I tied my shoelace and hurried after the others. Did she say anything more, Len?”

“Only that we might perhaps meet again as she and her party were staying in Interlaken. I came after you folk to see what you were up to and I suppose she headed for the railway. I advised her to take the straight cut across the grass in case she missed the train. I suppose that’s why you scarcely saw her, Ted.”

“Just her back, though I can’t say she was hurrying herself,” Ted returned. “What a mass of food Karen packs! I couldn’t eat another thing if you paid me. Any of you folk got room for an extra banana? You, Renata? Here you are, then.”

She tossed the banana over to Renata who was first to speak and then turned to address a remark to Len. That young person was munching a slice of cake and ruminating. She had seen the two mistresses exchange glances over the account of the American woman. It was unlikely that even Ted would have noticed anything, but Len was abnormally quick and there was an inwardness in those looks which roused her curiosity at once. However, she saw no hope of satisfying it just then, so she put it at the back of her mind as something to be debated later and answered with every appearance of calm Ted’s query as to exactly where they had encountered the snake.

“It was rather more than halfway along to this end. How come your crowd didn’t see it?”

“I imagine because it wasn’t there to see,” Ted replied. “Miss Wilmot, surely it’s getting late for snakes to be around? I thought they were hibernating creatures and curled up in holes earlier than this.”

“So they do hibernate; but this is still September, remember. I’ve seen them about as late as October if we’ve had a warm autumn.”

“How did you know it was dangerous?” Kitty Anderson asked.

“By its colouring and markings,” Len told her. “Those greeny affairs with rings round them are harmless enough, but avoid yellow snakes like poison for that’s what they are.” She gave a little shudder. “I’m thankful none of you touched it.”

“And I’m thankful that you knew what to do and did it at once,” Miss Ferrars remarked. “From what Renata has told us even taking her account with a very large pinch of salt, something had angered it. Snakes are, as a rule, timid creatures who prefer to slide away so long as they’re not molested. When they are, they can be really nasty.”

“This one was all right,” Jack said. “Why did you chuck it right away like that, Len? It was dead, wasn’t it?”

“Dead all right; but the muscles go on reacting for a time even after the thing has been killed and anyone getting bitten that way might be made ill. Dad warned us all about that ages ago. Oh well, it’s gone now. Change the subject, please.”

“I certainly will,” Miss Wilmot said, beginning to collect up her rubbish to stow away in her rucksack. “Finish, girls, and clear up. We haven’t too much time left before the train arrives, and we don’t want to miss it.”

There was an instant scramble and under cover of it the head of the maths department murmured to her colleague: “Choke the little blights off if any of them raise the topic again. It was a nasty experience for Len and she’s still looking rather white. Thank goodness it wasn’t Con! We’d have had her sleep-walking all over the place after a doing like that!”

Miss Ferrars laughed and agreed. Len Maynard was the eldest of triplet sisters. Con, the second one, had been given to walking in her sleep since she was a very tiny girl. In these days she had largely outgrown it, but any extra excitement was apt to set her off again and she had given one or two people bad frights during her peregrinations.

“This ramble hasn’t been without incident, has it?” Miss Ferrars asked. “First this snake business and then the American woman who spoke to the girls.”

“Oh, I don’t suppose that meant anything. It’s the sort of thing that might happen anywhere. Don’t you begin imagining horrors, Kathy. What a lurid yarn young Renata made of the snake! That child’s reading ought to be vetted.”

“Oh, just the natural tendency to exaggeration you can expect at her age,” Kathy Ferrars said. “She’s no worse than a dozen others. Most of them do it—I did it myself at that age.”

“Did you indeed? I can truthfully say that I never did.”

“Oh, you! You haven’t an ounce of imagination, my dear, and well you know it. But to be serious, I didn’t like those questions this person seems to have asked Len. You know what the Head said about that new girl, Flavia Ansell.”

“Yes, but I honestly do feel that you’re making far too much of it. After all it was natural to be interested in a school in a place like this. Oh, we must let the Head know, of course, but I don’t suppose she’ll let it worry her.”

This commonsense view soothed Kathy Ferrars’ feelings. She agreed that Miss Annersley must be told and then turned to look over the picnic ground to make sure that every scrap of paper or banana skin had been picked up. All the same, when they were all strolling along to the little Bahnhof she glanced across to the group in which Copper was with a tiny feeling of apprehension. Miss Annersley had warned them all to keep a look-out for curious strangers who might question them, however apparently idly. So far, no one had done so. There could be no real reason why a stray American who had lost her way should be anything but what she seemed. All the same, Kathy Ferrars didn’t like it.

“I’ve a good mind to speak to Joey Maynard about it,” she thought. “She knows everything, of course, and if she felt suspicious she would speak to Dr Jack. But if Nancy and I tell the Head, she’ll almost certainly tell them, anyhow. Better let it alone. I don’t want to be officious.” Then she gave it up and turned to answer an eager question from someone as to when they were likely to have another ramble.

As for Nancy Wilmot, she honestly thought that her friend was making too much of the whole thing. They must report to the Head, of course, but she didn’t think this was the sort of thing Miss Annersley had had in mind.

“Besides, if the weather reports are to be believed, we’re to have a bad winter and that will keep the girls very much to quarters,” she told herself, with a memory of the blizzards they had had the previous winter. “I don’t think we need worry much just yet. Anyhow, who’s to know which of the girls is Flavia Ansell? She’s quite ordinary-looking on the whole and we’re a biggish school. All the same it’s a responsibility. I’ll keep my eyes open when she’s in my escort and more no one can do. The great thing is to do that and also to see that the girls don’t get wind of it.”

By this time they had reached the Bahnhof and the train was in sight. The girls were forming into line, ready to pass into one or other of the coaches as soon as it stopped and she began to hope that there were no other passengers down. Their own crowd would pack the coaches and she had no wish to divide up the party and have to wait with some of them for the next train.

In the event there were only two people, a young Swiss woman who came from one of the upper shelves and was known to both her and Kathy Ferrars, and an old herdsman. Somehow they managed to crowd everyone in and then they were off and she could hear Copper remarking on the smoothness of the downward slope.

“It’s a lovely feeling,” she said. “Just the careful gliding down. Oh, the clicking, of course, from the—the trolley. Is that what you call it? Anyhow, I do like it.”

“You ought to try going in a chair-lift,” Barbara responded. “That really is a thrill when you look down and see the valley miles below you.”

“Do you know what?” came Mary Candlish’s voice. “Mrs Rosomon came to see us yesterday—one of your old girls, you know. She and Dr Rosomon are living not very far away. Isn’t she nifty?”

“Is she a very old girl?” Copper asked. “I don’t think I’ve heard about her. Is Dr Rosomon at the San?”

Jack chimed in. “Oh, I know quite a bit about her. She’s Mrs Maynard’s niece or something. I know she used to live at their house when they were in England. Len told me so once. She’s a doctor, too, you know, only she doesn’t do it any more because she’s got three little kids so she hasn’t time. Len was one of her bridesmaids and so were the other two—I mean Con and Margot.”

“I remember Daisy.” Miss Wilmot joined in the talk. “She was one of the wickedest Middles I ever knew. But she grew up to be an excellent prefect and Head Girl. So there’s hope for some of you later on.” She chuckled while a chorus of protests rose at this. “All right! Calm down! I didn’t mention any names, so if you like to wear the cap, well, it’s only proof that it fits you.”

They were suddenly quiet at this and she turned to Gillie who was sitting beside her. “Have you seen her family yet, Gillie? We were all delighted when she had a little girl after two boys. I haven’t seen the baby yet, though she’s a year old now. Daisy and her husband were living in Devonshire when she arrived. They only came out this summer and what with one thing and another, including the summer holidays, there’s been no time for a trip to Ste Cecilie. Who’s the baby like, Gillie? Fair like her mother or darkish like her father?”

“She’s got black hair,” Gillie said, “but her eyes are blue. Her name’s Mary, you know. Tony and Peter are like their mother, though. If we see her shall we tell her you’re coming?”

“Better not, seeing I can’t say exactly when. But you may tell her I was asking about her and the family. It’s high time she paid us a visit, anyhow. I must give her a ring sometime and insist that she comes along and brings the family. None of you people know her, but some of the Sixth do. They were Kindergarten when she was Head Girl. That was when we were in England. Or let me see. I believe they weren’t. Still, they’ve seen her at Speech Days and Sports and so on.” She caught Copper’s eye and added: “We believe in keeping in touch with our old girls as far as we can, Flavia. We have record books that were started three years ago. Ask someone to show them to you if you’re interested. We have photos and written records there. Some of our girls are quite well known—Dr Eustacia Benson, for instance. And Mrs Maynard herself for another. You’ve read some of her books, haven’t you?”

Copper nodded. “Rather! I was thrilled when I knew that Len and the rest belonged to her. She’s almost my favourite author. I’m longing to meet her.”

“So you will when the babies get over this go of chickenpox. Until that ends she’s tied up with them. But as soon as quarantine is over she’ll be coming to school. She is the oldest of our old girls and, in fact, in some ways she’s never left. And here we are at the Platz. Out you get, girls, and don’t loiter. Trains hereabouts are like time and tide—they wait for no man.”

The girls giggled as they seized their rucksacks and made for the door. Knowing what would happen if they were slow, they poured out in short order and, since this was the Platz, formed into lines with the two mistresses leading and Ted and Len tailing off to act as whippers-in if anyone lagged behind. Two or three people were waiting at the Bahnhof and as the last girl jumped out they hurried to take their places. But not before Len, glancing incuriously at them, gave a tiny gasp. Among them was the American they had met up at the Rösleinalp.

The mistresses duly reported to the Head on the events of the afternoon. Miss Annersley was startled and horrified by the viper episode. The other she treated more lightly.

“My dear, don’t let your imagination run loose,” she said to Miss Ferrars. “If you are going to suspect every stranger who asks you the way or the time, you’re going to have grey hairs before term ends. You were quite right to tell me; Flavia is a big responsibility; but keep your sense of proportion whatever you do. As for the snake business, thank heaven Len Maynard was in charge. That girl has her head well screwed on and Jack Maynard has seen to it that those three and the elder boys know how to deal with such things. All the same, we must think twice before we go rambling in those quarters again. Not,” she added, “that another ramble is likely immediately. The glass is going down and the weather forecast spoke of rain. If it comes, rambles will be off.”

Knowing the kind of rain the Alps can produce, the pair fully agreed with her. They left the Head with feelings of relief and retired to change for the evening. She herself only waited until the sound of the steps had died away. Then she went to the telephone and rang up Joey Maynard, mother of the long Maynard family and herself the first pupil in the school.

“Joey? Oh, thank goodness! How are your patients?”

“All very cross and well on the way to recovery,” Joey replied. “None of them have been really ill. They’ve had it as lightly as possible. But quarantine remains the same, worse luck! You don’t know how thankful I am all my school people were nowhere near the infection. What with Margot in Australia; Len and Con with Simone in France; the boys with the Emburys; the three Richardsons in England with their granny-people and Felicity and Felix gone off with the Morrisons to Scotland, we’ve managed to keep it to the nursery and at least that’s one thing that’s over.”

“I don’t suppose any of your elder six would have caught it in any case,” Miss Annersley said. “They’ve all had it and that’s supposed to frank you for the rest of your life, I’ve always understood.”

“So Jack says. But why did you ring me up? Something gone wrong?”

“That’s what I can’t say. You remember what I told you about that new girl, Flavia Ansell?”

“I do. Do you mean someone’s got on the trail?”

“I can’t be sure. I hope not. But listen, Joey.” And Miss Annersley told her about the afternoon’s events. “You see, it may be all imagination. It would be the natural thing for a stranger to take some interest in what was obviously a school party. I told Kathy Ferrars so, for the girl was looking really worried. On the other hand, we do know that some of them were American and, to be honest, I’m not sure which way to take it.”

“Better be safe than sorry,” quoth Jo. “I’d keep an unobtrusive but firm eye on Flavia and make sure that she never goes far from school by herself. Tell me again what it was her dad told you.”

“He said he’d had a note saying that the friends of—what was the man’s name?—Walter Manley—would see that his death did not go unavenged and sooner or later he would feel it where it hurt most. There was no clue to the writer and it had been posted in Liverpool which might mean anything. Inspector Letton had had threats before about what would happen if Manley was hanged, but he had taken no notice of them. I gather that sort of thing is done sometimes, though as a rule nothing comes of it. But these are a particularly nasty crowd who stick at nothing—witness their shooting that poor young constable in cold blood.”