* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

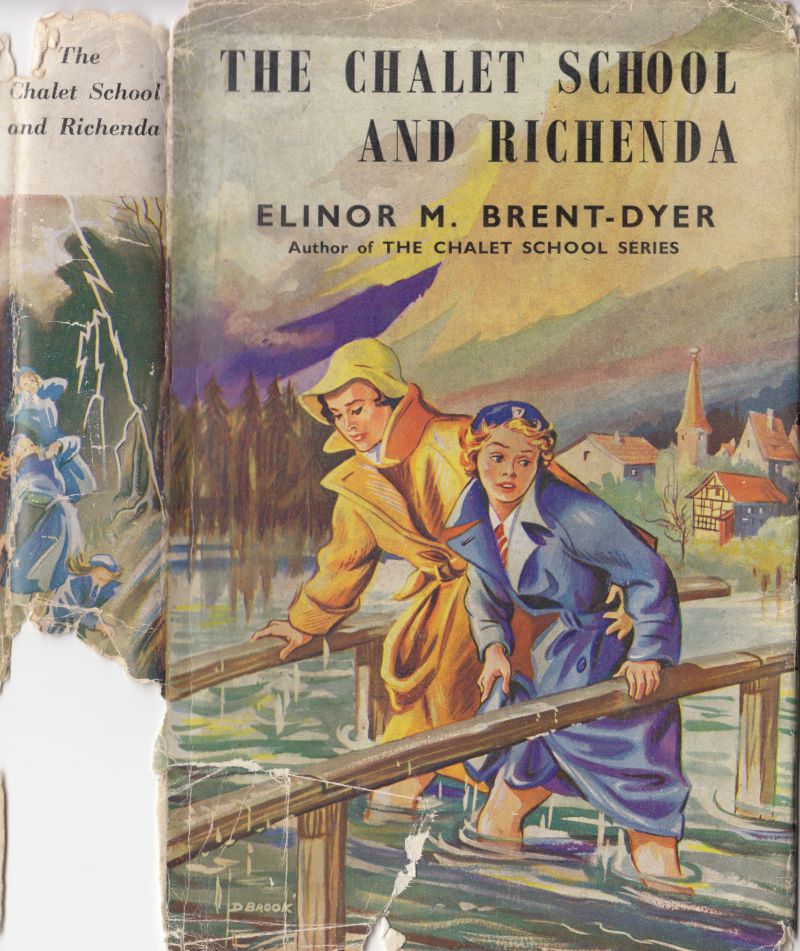

Title: The Chalet School and Richenda (Chalet School #40)

Date of first publication: 1958

Author: Elinor Mary Brent-Dyer (1894-1969)

Date first posted: January 22, 2026

Date last updated: January 22, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260126

This eBook was produced by: Alex White, Hugh Stewart & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE CHALET SCHOOL AND RICHENDA

By

Elinor M. Brent-Dyer

First published by W. & R. Chambers, Ltd. in 1958

To

My Dearest Cissie

(A. F. J. Warren-Swettenham)

with much love from

Elinor

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Khang-he Vase | 7 |

| II. | Richenda takes the Plunge | 18 |

| III. | New Experiences for Richenda | 32 |

| IV. | In Form Vb | 48 |

| V. | Plans for Richenda | 61 |

| VI. | A Different Outlook | 70 |

| VII. | Joey puts Her Oar In | 81 |

| VIII. | Taking Odette in Hand | 92 |

| IX. | Thunder in the Offing | 106 |

| X. | Racing the Storm | 117 |

| XI. | The Staff at Leisure | 130 |

| XII. | The Professor upsets Things | 140 |

| XIII. | Joey | 152 |

| XIV. | Joey has a Crack at It | 165 |

| XV. | Monday’s Trip | 176 |

| XVI. | A Terrible Accident | 189 |

| XVII. | Professor Fry | 201 |

| XVIII. | All’s Well! | 215 |

“Richenda!”

There was no reply, Richenda being not only miles but centuries away as she stood dreamily in the Chinese Room, long, sensitive fingers running lightly over the paste of the vase she held, eyes feasting themselves on the rich red hues of the sang-de-bœuf glaze with which it glowed so gorgeously.

“Rich—en—da!”

This time it came in a bellow that would not have disgraced one of the famous bulls of Bashan; and this time it penetrated. Richenda started so violently that she came within an ace of dropping the vase. Sheer instinct made her hands tighten their grasp on it, but she had no time to replace it on the shelf whence she had lifted it, for the bellow was followed by the furious irruption of her father into the room, and she was well and truly caught. It was bad enough that she was there at all, seeing that she had been strictly forbidden ever to go there alone. What made it ten times worse was the fact that she was standing there holding his very latest acquired treasure—the valuable Khang-he vase. She had committed a sin in his eyes in being where she was at all. Just what he would think or do about her touching his beloved porcelain, she couldn’t imagine.

“Oh, Christmas!” she thought to herself as she turned to face him, the vase still hugged against her.

“So here you are—again!” he roared. “Didn’t I strictly forbid you to come here unless I was with you? Didn’t I. . . .” At which point his eyes fell on the vase, and he suddenly changed his tactics. “Put—that—down,” he said in a low tone, infinitely more terrifying to his daughter than his earlier efforts. “Put—that—DOWN!—right in the middle of the table!”

For once in her life Richenda obeyed him implicitly. She was quaking inwardly, for her disobedience had been deliberate in even coming to the room. Twice before, he had caned her for a similar offence when he found that talking seemed to do no good. The last time, the punishment had been so severe that her hands had been sore for days. What he would do this time, she simply couldn’t imagine; and yet she found it impossible to keep away. Why, oh, why couldn’t he understand that she, too, loved the beautiful things he kept in the Chinese Room? She would never hurt them—or not so long as he didn’t startle her nearly into a fit by appearing suddenly and shouting at her. This last, because she remembered the occasion when he had found her with a little blue crackle jar in her hands, and had startled her so badly that she had dropped and smashed it. There had been a fine old row then!

She had no time for further thought, for, once the vase was safe, he laid a heavy hand on her shoulder and marched her before him to the study where he wrote the books on Chinese ceramics which were bringing him fame among connoisseurs. A considered judgment by Professor Ambrose Fry was regarded by people who knew with deep respect.

By the time he got her there, she was feeling resentful as well as frightened. If he was as clever as everyone said, he might have taken time to think that her passion for the porcelain was an inheritance from himself and she couldn’t help it. He never seemed to think of that!

He kicked the door to after them, and it slammed loudly, which did not improve matters. He set her free, went to the swivel chair behind the big desk, and pointed to the place opposite.

“Stand there!” he said in tones that literally vibrated with rage.

Richenda took up her position with outward meekness and inward fury. Then she faced the glower he bestowed on her with head up for she was not going to let him see how frightened she really was. The two pairs of grey eyes, so alike in shape, colour and intelligence, met and locked, and there was silence for a few seconds. Then he spoke.

“Well? And what, pray, have you to say for yourself?”

Richenda remained silent. She could think of nothing that would mitigate her crime in his eyes. He waited. Then, seeing that he was likely to get nothing from her that way, he began his inquisition. It was brief, but to the point.

“I have forbidden you to go into that room unless I take you myself, haven’t I?”

“Yes, Father.”

“And in any case, it is a strict rule that you never—never, I say—handle anything there, isn’t it? And you’ve known that most of your life?”

Richenda went red. “Yes, Father,” she said.

“But you chose to disobey me—you deliberately chose to be disobedient.”

“Ye—yes, Father.” Despite herself, her voice quavered a little on the last reply. She guessed she was in for it this time.

“Why?” he shot at her.

But though he was giving her a chance to defend herself, Richenda could think of nothing to say. In fact, she was far too scared to think clearly at all. She only wished he would cane her, or whatever it was he meant to do to her by way of punishment, and get it over. Whatever it was, it would be bad; she knew that. Waiting and wondering about it made no better of it.

“If you were a boy,” he said slowly while his unhappy daughter squirmed inwardly and wished herself a thousand miles away, “I’d give you such a flogging as you’d remember to the last day of your life. How dare you defy me like this?” His voice rose to a furious bray. “You have the audacity to ignore one of my strictest rules. How dare you go into my private room and actually pick up and handle one of the choicest pieces of porcelain there? Do you realise that if you had dropped it you would have destroyed one of the finest specimens of its kind that I have ever even seen? How dared you—how dared you?”

Richenda remained silent, which was as well. He was so angry that, girl or not, if she had ventured to defend herself, she might have got the flogging. She simply stood there, staring at him in silence. She was white and her lips were trembling, though she pressed them together as hard as she could. Her father was also wordless, glaring at her until she was ready to burst into frantic yells or equally frantic tears. At last he spoke.

“Go to your room,” he said, “and stay there. Don’t dare to come near me until I send for you, either. And don’t think you’ll escape any further punishment, Miss! I’m going to make sure that in future you obey me. When I give an order, you’ll do as you’re told, or I’ll know the reason why. Now go!”

Richenda fled, thankful for the respite, though her heart was in her mouth at the thought of what he might do to her. She was sure it would be horrible, whatever it was. He very rarely did rouse himself to interfere with her upbringing, preferring to leave it to Nanny and her school—she had lost her mother when she was still little more than a baby—but when he did, he did it with a vengeance. She was due to go to tea with her chum, Susan Mason, the doctor’s daughter, but Susan must just think what she chose. Perhaps if her father went out later she might be able to slip down to the study and ring Susan, but that would all depend on circumstances.

She reached the haven of her room, and, as she went in, she heard the telephone bell and knew he was ringing someone. He had known she was going to the Masons’ that afternoon, so perhaps he was ringing them himself to explain. Oh, Heavens! What on earth would he say to them? Would he just say she couldn’t go, or would he go into detail? There was never any telling where he was concerned. But it gave Richenda something more to worry about as she sat down in the wicker chair by the window.

“Oh, dear!” she thought to herself. “If only there was someone to take my part and make him see that it isn’t ordinary disobedience! I just can’t help it! When I see beautiful porcelain like that, I’ve just got to touch it and look at it. I get it from him—everyone says I’m as like him as can be! Why can’t he see I’m like him in that, too?”

That way of thinking got her nowhere. There was no one to stand between them and explain her to him, since her mother was dead and her only aunt had long ago quarrelled with him, and no one knew exactly where she was now. Nanny adored her, but though she saw to it that her charge was well cared for and brought up with good manners, she had no understanding of the passion for ceramics which Richenda had indeed inherited from her father. She would merely say that it was a pity that the girl couldn’t do as she was told. Nanny was one of the old school and great on the virtue of obedience.

However, at one o’clock, the old woman arrived to say that the professor had told her to tell his daughter that he was out and she might come down, but she was not to leave the premises. He would be back by half-past six when she was to go to the study to learn what her punishment would be.

“And what have you been doing to need punishment?” Nanny demanded severely.

“The usual,” Richenda told her laconically.

She needed no further explanation. “You’ve been into that room of his again in spite of all he’s said to you about it? Then you’re a very naughty girl, Richenda, and you deserve all you’ll get. I’ve no pity for you. You’re only a child, and a child does as she’s told or takes the consequences,” she scolded. “You’re too old to be spanked nowadays, but your pa’s got a fine rod in pickle for you, or I’m much mistaken! You take and tell him you’re very sorry for all your naughtiness and maybe he’ll let you off a bit.”

“But I’m not sorry,” Richenda returned calmly. “I just can’t help it. It’s part of me. And anyhow, I’ll be fifteen in less than a week’s time, and that’s not a child. He ought to listen to me and try to understand instead of bawling——”

“Now that’s quite enough!” Nanny broke in sharply. “Hold your tongue at once, Richenda, and don’t expect me to stand here listening to you talking about your pa like that, for I won’t do it, and well you ought to know it!”

“I wasn’t doing any harm in his old room,” the culprit said rather more calmly.

“That’s neither here nor there. He told you to stay out, and you’ll stay out if you know what’s good for you! And I’ve no time to stand here talking to you. Go and make yourself tidy, and then come down to the schoolroom and get your dinner. Your pa’s gone off to London, he said. I’m not going to be bothered laying the dining-room table just for you. Hurry up, now!” With which valediction she stumped out of the room, leaving Richenda to wash her hands and face and tidy her hair before she ran down to the sunny back sitting-room which had been the nursery in her baby days and was now dignified by the title of schoolroom.

Nanny had the table ready, and as she passed a plate of tongue and ham and salad to her nursling, she gave her a further message from the Professor.

“Your pa says you’re to ’phone Masons’ and tell them you can’t go to tea with Susan this afternoon. And you’re not to set foot outside the garden, so mind that. See if you can obey for once. Now hurry up and get started. I’ve got to go into the town this afternoon to pay the bills, and I don’t want to be late and all the shops busy. I’ve got to oversee that Iris at the washing-up. If I’m not there, she just holds the things under the tap and sets them to drain. Such laziness!”

“Will you be in for tea?” Richenda asked.

“I’ll be back by half-past four—unless you and Iris between you make me late for the shops. Eat up your lettuce, Richenda. I’ll have no saucy ways.”

Well aware that she was in dire disgrace, Richenda said nothing, but finished her lettuce and bread and butter. However, as usual, Nanny’s tongue was a good deal worse than her bite, and she had provided tinned apricots and a large dollop of ice-cream for a sweet. Her charge finished her meal with a good deal of relish.

When they had done, Nanny sailed off to the kitchen to attend to the morals of Iris, the daily help. Richenda went off to the study to ring up the Mason house. She was lucky enough to raise Susan herself who was all that was sympathetic to her friend, though she bewailed the punishment, since it affected herself as badly as Richenda.

“Don’t you worry! This isn’t the punishment,” Richenda assured her. “This is only by the way. I’m most awfully sorry, Sue. I was looking forward to coming. But Nanny says Father has a fine rod in pickle for me. Goodness only knows what it is! Nanny didn’t say—I don’t think she knows. But I’m not looking forward to half-past six, I promise you!”

Susan, whose parents were very easy-going, repeated her sympathy, and then had to ring off. In a doctor’s house you can’t monopolise the telephone for a private conversation for any length of time. Richenda hung up, and went to seek a book before going off to the garden and the standing hammock, where she spent the afternoon alternately reading Mist Over Pendle and wondering just what ghastly punishment her father was evolving for her. She frightened herself badly, and got little good of her book so, on the whole, it was a wasted afternoon.

Nanny returned at half-past four and called her to tea. Whatever she might say, she was deeply sorry for her charge, and she had provided eclairs to follow more of the apricots and cream. Richenda wished she hadn’t had that awful interview looming ahead of her. She could have enjoyed the treat so much better if it hadn’t been for that!

Tea over, Nanny sent her to change into a clean frock and make herself tidy.

“And mind and see your nails are clean,” she finished. “Then you can take your book into the garden again and sit quiet till half-past six. You’ll hear the church clock chiming, and if you don’t, I’ll call you. But you’d best be in good time, so I’d listen, if I was you.”

Richenda did as she was told; but now that the time was so near, even the adventures of Margery and the witches of Pendle failed to hold her attention. The question of what her father meant to do to her would come bobbing up between her and the story, and she thought that half-past six would never come. When she heard the chimes from the nearby church clock, she stood up and smoothed down her skirts with hands that were suddenly clammy. Then she set off for the house, leaving the book in the hammock to take care of itself. She was met by Nanny with the information that her father had just rung up to say that he would not be at home till eight and she had better have her supper at the usual time. There was nothing for it but to go back and wait till Nanny called her at half-past seven for supper. But now the book lay where she had tossed it, and she gave herself up unreservedly to a gloom which even Nanny’s information that she had provided sardine sandwiches for supper did nothing to relieve, though normally, it would have been greeted with a cheer. But she couldn’t think of anything until she knew her fate.

She made such a poor supper that Nanny was secretly worried and wished that her master had seen fit to catch the earlier train. But it was twenty past eight before they heard him come in, and ten minutes more before the study bell trilled sharply through the quiet house. Nanny looked her over swiftly, and then sent her off. Richenda, now that it was upon her, simply crawled along the passage to the door and her tap was so faint that he never heard it and she had to knock again.

He heard her this time, and his voice bade her enter. She took a long breath, threw up her head and stuck out her chin, determined not to let him know how scared she was feeling, and went in. He was at his desk again, looking over something before him, and, as she shut the door, he glanced up at her.

“Come in and shut the door. Now come here. Stand there and listen to me. You’re evidently getting beyond Nanny, and it’s quite plain that tinpot school of yours isn’t doing you much good, either. It’s high time you were at a larger one where you’ll learn to obey orders. I’ve seen Miss Hilton, and I’ve told her you’re leaving.” He stopped and glared at her.

Richenda said nothing, but inwardly she was feeling as if the bottom had dropped out of her world. Was he going to send Nanny away? But he couldn’t! Who would look after the house and buy her clothes, and see to all the thousand and one things that Nanny took on so capably? And what was this about taking her away from St. Margaret’s House? She had been there ever since she was seven. She and Sue had gone up the school side by side, always in the same form, always disputing in a friendly way for the top places. It was a small school—only about forty girls, but she loved it and had been very happy there. And if he took her away as he threatened, then she would be parted from Susan, and they had been friends ever since the day when, as two very new little Juniors, they had met in the cloakroom and chummed up. She knew that in another year’s time they must both leave, as Miss Hilton took no girls over fifteen; but then the pair had made a plan that Susan’s mother was to offer to save the Professor trouble and hunt up a school for both of them. Now, it seemed, she was to leave after this term. And then she found that there wasn’t going to be even one last term. He had paid a term’s fees in lieu of notice, and she had left!

“You need something else and you’re getting it—and at once! When the new term begins, you’re going to a big boarding school where you’ll be one of over two hundred girls, which means you’ll have to toe the line pretty strictly; and that’s what you need. I met Professor Dunne’s wife some weeks ago, and she told me what a good school it is. Her younger girl has been there, but she left last term. I happened to see in The Times at the beginning of the week that the Head would be in London this week-end for interviews, so I went to see her, and I’ve made all the arrangements, so please spare me any appeals to change my mind. They’ll get you nowhere!” He stopped and fished among the papers with which his desk was littered, until he found a long envelope, which he passed to her. “Here; give this to Nanny and tell her she’s to get you everything on the list there. Here’s a cheque for her. If it isn’t enough, she can come to me for more.”

Richenda grasped the envelope and cheque mechanically. She had no thought of appealing against her sentence. She was far too stunned to say anything just yet. But he had not finished what he had to say.

“I hope, Richenda, that when you have come to your senses, you’ll be properly grateful to me for all I’m doing for you. When you come home at Christmas, I hope to find you a very different girl. At the moment, I expect nothing from you but unquestioning obedience. See that I get it!”

There was one thing that had to be said now, and, somehow, Richenda managed it, though it was all she could do to keep from crying, and that she was determined not to do in front of him.

“But—but what about half-term? Don’t I come home for half-term?”

“No; it’s much too far and very expensive into the bargain.”

“Too far? But—but where is the school, then?”

“It’s in Switzerland, in the Oberland. You’re going to a Swiss boarding school. Now you may go. I’ve seen all I want of you for one day. Good night!”

Somehow Richenda contrived to reply. Somehow she got herself from the room. She even remembered to close the door behind her though she had a tiresome habit of leaving doors open. She went to seek Nanny, not very sure whether she was on her heels or her head. A Swiss boarding school! She was going among foreigners who probably didn’t know a word of English, who would never play hockey or netball or cricket! And she knew no German and her French was still rather of the “my-aunt-has-the-pen-of-the-gardener’s-mother” variety!

Really, if her father had tried with both hands for six months on end, he could not have devised a more awful punishment for poor Richenda!

Richenda stood on the platform at Victoria Station, clad in smart coat and beret of gentian blue. Beneath the coat she wore a skirt to match, and an irreproachable shirt-blouse with the tie of her new school knotted beneath the collar. Her hands were in tan gloves, and her shoes and stockings matched the gloves.

“Just a trim schoolgirl,” one might have said at first glance. At the second, one would have withdrawn that. There was more than that to her. Her clothes were certainly all that they ought to be. Her face, as Nanny had told her once this morning, was enough to turn any milk sour!

Her fine black brows were drawn together in an outsize in frowns. Her lips were set in a straight line, and the hand that held what the school inventory called “a night-case”, gripped it as if she would like to sling it up and slug someone over the head with it.

The Professor had gone off to Harrogate to a conference of fellow connoisseurs. He had departed the day before, so Nanny had brought the victim up to London, and was to hand her over to the escort mistress.

The pair had said farewell after breakfast the day before, and it had been icy in the extreme. Once she had got it firmly into her head that there was to be no reprieve for her, Richenda had lapsed into a prolonged fit of what Nanny called “the black sulks”. She had only opened her lips to her father when she couldn’t help it. When they said good-bye, she had jerked her head back from his kiss and put her hands firmly behind her back. She would neither kiss him nor shake hands with him. He had treated her abominably and she would never forgive him!

“Oh, very well!” he had said, “but it’s to be hoped this new school of yours does something to bring you to your senses pretty quickly.”

It was hardly a soothing farewell, but it was his last word to her just then. He had to hurry off to catch his train and she was left to stare sullenly out of the window and wish that she’d never been born or else that she had been born different. He had kept the door of the Chinese Room locked ever since he had caught her, and she resented it fiercely. So, what with one thing and another, her behaviour during the three weeks that had followed his fiat had been somewhat that of a sulky tigress.

Nanny had seen it all, and once her master was away, she called her nursling to account with a point and vim that had its effect.

“Richenda, you’re behaving disgracefully! The master is spending a small fortune on you, and you don’t deserve it, in my opinion—behaving like a naughty sulky baby. Let’s have no more of it, if you please! You’re going tomorrow, and at the rate you’re carrying on, we’re all going to be thankful to be rid of you. Stop it at once!”

She accompanied her diatribe with a sharp shake which shook Richenda out of her mood into a weepified one. She cried until poor Nanny was nearly at her wits’ end to know what to do with her. However, it ended at last, and for the rest of the day the girl behaved more or less like a Christian.

As a matter of fact, she had been growing rather tired of her sulks herself. They got her nowhere, and for all the notice her father took of them, they might not have existed. She was very mournful when the Masons arrived after tea to bid her good-bye, but they contrived to cheer her up between them. The doctor produced an envelope and told her to put it into her bag and not open it until she was safely at the school. Mrs. Mason had a three-pound box of chocolates for her, and Susan had a new book. But perhaps the best of all was the news that Susan told her just as they were saying good-bye. In two more terms’ time Susan herself was going to the same school, and they would be together again.

Richenda had been almost herself for the remainder of the evening, but when she came down to breakfast next morning, Nanny felt her heart go down with a thump, for the black dog was sitting firmly on her back.

“Oh, dear!” thought poor Nanny. “Whatever will the ladies that keep the school think of her if she goes on like this? They’ll say I’ve brought her up very badly. And after me promising her blessed mother I’d do my best for her baby! But there! I dursen’t say a word now. It’d only make her go off in a rage. I wish,” as she watched her charge’s black face, “she were young enough for me to take and give her a good spanking. It’s what she needs!”

At this point, a young lady came up to them with a smile, and Nanny eyed her with approval. She was small and slight and very trig and fresh-looking. When she spoke, her voice was clear and musical and very distinct. Nanny, though she would never own to it, was distinctly “hard of hearing” and it was a treat to deal with someone who neither mumbled nor shouted at her.

“Good morning,” she said, with another of those pretty smiles. “I think this is another new girl for the Chalet School. What is your name, dear?”

“Richenda Fry,” the owner of the name muttered.

“And I’m Miss Ferrars, one of the mistresses at the school. You must be Professor Fry’s daughter. Is your father here with you? We’re just going to take our seats, and you’ll want a last word with him I expect.”

Nanny looked imploringly at her nursling, but Richenda remained dumb, so she had to explain. “The Professor has had to go to Harrogate on business, madam. I’m Richenda’s old nurse—at least I was. I’m the housekeeper now. I hope you will find Richenda’s things all right, madam. I think we got everything the list said. But if there’s anything more she wants, the master said to ask you to write to him, and he would tell me and I’d get it and send it.”

“If you’ve stuck to the inventory I’m sure she has everything she needs,” Miss Ferrars said, laughing. “It’s a most comprehensive document! Our senior mistress, Miss Derwent, is over there if you’d like to have a word with her.”

Nanny shook her head. “Oh, no, madam! That will be all right. I’ll just say good-bye to Richenda and then she can go with you.”

Miss Ferrars nodded with another of those quick vivid smiles. “Then when Nanny has done with you, Richenda, join up with that group of girls over there, will you? They’re all people of around your age, and they’ll look after you.” She nodded a smiling good-bye to Nanny and moved off to speak to someone else.

“That’s a nice young lady,” Nanny said emphatically, when she was too far off to overhear. “I hope she’ll have some of the teaching of you, Richenda.” She put an arm round her sulky charge. “We must say good-bye now, my dear. Be a good girl and do your best. Write to me sometimes and let me know if you want any more hankies or stockings or things like that. And now, my dear, remember it’s your pa’s wish you should go to this school and he knows what’s best for you. Give me a kiss for good-bye and try to cheer up! It’s only three months, and then you’ll be coming home for the holidays—and able to talk all the foreign languages, too, I make no doubt.”

She pulled down the curly red head which was well above her own, since Richenda was a long-legged creature, and bestowed a loving kiss on the sulky mouth. “God bless you, my dear, and bring you safe home to us at Christmas!”

“Good-bye!” Richenda muttered. She was in one of her worst moods and enjoying it at the moment. Nanny sighed to herself, but wisely left it to the new experiences immediately before the girl to put an end to it. She kissed her again and stepped back. Richenda suddenly dropped her case, flung both her arms round the comfortable figure in a mighty hug, and kissed her old nurse warmly. Then she picked up the case, all without a word, and went over to join on to the little group of girls Miss Ferrars had pointed out to them.

One of them, a tall girl with a thick rope of black hair dangling to her waist, promptly moved over to Richenda and spoke to her. Then they were joining on to the long line of blue-clad girls which was moving slowly and steadily, without fuss or scrambling, into the train in single file.

Nanny nodded to herself as she stood watching. “As smart and clean as if they were soldiers,” she said to herself. “And a very nice happy lot they look, I must say. Let’s hope Richenda settles down soon. Bless her! She’s miserable enough just now, but she’s only a child when all’s said and done. Children get over their troubles fast enough. I’ve thought the Master a bit too hard on her, but maybe he’s in the right after all. Likely she’ll come home all the better and she did need a bit of disciplining!”

She gave her eyes a quick dab with her handkerchief as tears suddenly dimmed them. Richenda, glancing back as she waited for her turn to climb into the carriage, saw her and felt a sudden wild longing to break away and go rushing to her and return home with her to all the things she knew and loved. She bit her lips hard and blinked away the sudden rush of tears to her eyes. Then the girl who had taken charge of her gave her a gentle push.

“Go on, Richenda,” she said. “We’re holding everyone else up.”

Richenda turned and clambered in. By the time she had reached the compartment she was to share with seven other people of her own age, the parents and friends who had come to see them off were gathered round the window and her old nurse had vanished in the crowd. So her last link with home had gone. Then she was aware that her “sheepdog”, as she found later the girls called it, was speaking, and she turned to see what she wanted.

“Your case goes on the rack, Richenda, until we’re well away from Victoria.” She gave a sudden infectious gurgle as she added, “That’s been the rule ever since Heather Clayton dropped hers between the platform and the carriage three terms ago, and there was a lovely performance before it could be fished up! Give it to me and I’ll heave it up with mine, shall I?”

She took it and “heaved” the two cases on to the rack and then sat down, pulling Richenda down beside her. “By the way, I’m Rosamund Lilley. The rest, when they’ve finished saying good-bye, are Joan Baker, Betty Landon, Alicia Leonard, Eve Hurrell and the two Dawbarns, Priscilla and Prudence. They’re twins,” she added.

Richenda looked gloomily at them. Yet to an unprejudiced eye, they were as pleasant-looking a set of girls as you could find anywhere. Two or three of them were exceedingly pretty, and all wore friendly expressions. At present, they were engaged in making final remarks and requests to the little crowd milling around before the compartment window. But when the train finally began to move and they had finished waving, they all sat down and the chatter began.

“I heard Rosamund telling you our names,” Eve Hurrell said. “Tell us yours, won’t you? We can’t go on just calling you ‘you’. It sounds most icy!”

“Richenda Fry,” Richenda told her shortly.

Then she stood up, took down her case, opened it and picked out a book, after which, she returned the case to the rack and settled herself to read.

The girls glanced at each other. Was the new girl homesick and afraid to talk in case she began to weep? They had known that happen before. But as she clearly wanted to be left alone, they kindly fell in with her wishes and began to gossip among themselves about holiday doings and left her to it. Silly Richenda, having got what she wanted, promptly began to think them very unkind to leave her out. As for her father, she reflected once again that he was cruel and most unfair.

Halfway to the coast, Eve produced a great slab of chocolate which she broke up and passed round. When it came to Richenda’s turn, she eyed it stonily and said, “No, thank you.” Eve raised her eyebrows, but she said nothing, merely offering it to Rosamund who accepted with gratitude.

But if Eve could hold her tongue, it was too much to expect that Prudence Dawbarn would do so. That young woman was very badly misnamed and discretion formed no part of her character. She helped herself when her turn came, gave a giggle, and then addressed Richenda directly.

“I say, are you afraid of being seasick when we cross? You needn’t be. The weather forecast this morning said that everything in the garden would be lovely—or words to that effect, anyhow.”

Richenda didn’t trouble herself to look up from her book as she replied, “I hadn’t thought about it, thank you.”

Her tone was so crushing that Prudence was utterly snubbed for once in her life. She shut up and said no more. Rosamund gave her charge a quick, inquisitive look, but she changed the subject deftly by initiating a discussion about which of them was likely to go up a form this term and in the interest of it, they forgot Richenda who sat turning the pages of The Adventure of the Amethyst without taking in anything of what she was supposed to be reading.

“I won’t, for one,” Prudence said with certainty. “I was seventeenth in form last term and eighteenth in exams. It’s Inter V for me again this year. But Pris was ninth and seventh, so she’s safe for Vb and we’ll be parted, alas!”

Betty giggled. “Well, that’ll be some relief to the Staff and prees!” she remarked.

“What on earth do you mean?” Priscilla herself demanded with some heat.

“Only that one of you in a form ought to be enough for anyone,” Betty explained sweetly. “I wonder if all three of the Maynards will go up, by the way?”

“Len and Con for certain,” Rosamund said. “Len was bracketed second with Jo Scott and Con was eighth. They’re safe for a remove.”

“What about young Margot?” Eve queried. “Thirteenth, wasn’t she? You know, she ought to be a lot better than that. She’s got heaps of brains.”

“Yes, but she still doesn’t use them all the time,” Rosamund said. “Len and Con work steadily, but you can’t always rely on Margot. She does the maddest things on occasion. Anyhow,” she added cheerfully, “she’s just a kid still.”

“So are Len and Con, if you come to that,” Joan Baker put in. “Not fourteen till November, are they?”

“November fifth,” Rosamund agreed. Then she giggled. “Len once told me that her mother always says their arrival was her big bang on that day.”

The others joined in her giggles and, despite herself, Richenda, who had been listening with all her ears, nearly gave herself away by gasping aloud. She had heard of triplets, of course, but she had never met any before. Were there really triplets in this school? How simply weird! And there were twins, too, because Prudence and Priscilla were twins. Rosamund Lilley had said so. She began to wonder about the Maynard trio. Were they all as alike to look at as the Dawbarns?

She stole a brief glance through her lashes at the pair sitting side by side. They were very alike with wavy brown hair, hazel eyes and short, uptilted faces. She fancied it would take her some time to know them apart. Three girls as alike would be something of a problem. But at least, as she now realised, one part of her difficulties had melted away. There were a tremendous number of English girls in the school so she supposed they would be allowed to speak their own language occasionally. That was something to be thankful for!

By this time, the others had all produced sweets or chocolate. They were punctilious in offering her a share, but she refused everything. She was not going to make friends in this ghastly school! Susan would remain her only friend—and every minute she was going further and further away from Susan. She glanced down at her watch. St. Margaret’s began today and by this time, they would all be hard at it. How was Sue getting on? What new girls were there? Had Miss Coulson really left? There had been rumours about it last term, but no one seemed to know for certain. It would be ages before she could hear anything. She had very vague ideas about how long it would take a letter from home to reach the Görnetz Platz, but at least a week, she felt sure! Sue wasn’t in the least likely to write by airmail. Oh, why must her father send her right away from everything and everyone she loved just because she hadn’t been able to resist the Chinese Room and that wretched Khang-he vase.

If she had been alone, this was where she would probably have burst into tears. As it was, she swallowed hard and concentrated on her book, deliberately shutting her ears on the gay chatter that was going on round her.

Presently Rosamund, feeling guiltily that the new girl was being left out, spoke to her again. “Have you ever travelled by this line before, Richenda?”

“No, never,” Richenda replied briefly.

“It’s rather decent country, isn’t it?” Rosamund went on perseveringly. “Kent is a pretty county, don’t you think?”

“I don’t know anything about it,” Richenda told her, still in that brusque manner. Her tone added, “And I don’t want to, so let me alone!”

Rosamund gave it up. If Richenda wouldn’t talk, she wouldn’t talk and there was nothing to be gained by trying to make her. No more than anyone else did she like being snubbed so downrightly. A question from Alicia Leonard gave her the excuse. She replied to it and Richenda was left to herself once more.

Illogically, she thought that it was very unkind. But then, if Rosamund had continued making conversation, she would have thought that very unkind. Nanny would have said that she was “fit to fight with a feather”, just now. It would have done her all the good in the world if someone had given her a good shaking or a smart slap at that moment. She certainly deserved it. There was no one to do it, so she sat there, looking like a thundercloud and feeling more and more miserable.

Presently, there came the sound of light footsteps and a tall girl looked in on them to be hailed by a delighted chorus of greeting from the others, who called her “Mary-Lou”, and rained questions on her.

Mary-Lou leaned up against the door into the corridor, beaming benignantly on them all. Richenda glanced up at her long enough to realise that she was exceedingly attractive, tall and slim, with a shapely head covered by a fuzz of brown curls that were full of golden gleams. Her very blue eyes were dancing behind their long fringe of black, up-curled lashes. She had a perfect complexion, and her smiling mouth was beautifully cut and her best feature. She replied to their vociferous greeting in clear, bell-like tones.

“Hello, folks! Glad to see you all again. I had jolly decent hols, thank you. The people on Inchcarrow, that Hebridean island where Clem and Tony were living just before Clem and Verity and I first came to the school, had invited those two to go there for three weeks or a month. Clem wrote back saying that Tony could go, but she couldn’t as she wanted to be with us, since we only saw each other in the hols now. They wrote back and told her to bring us two along as well, so we all went and had a gorgeous time. It fitted in very nicely, for Dad had to go to see that specialist lad in Glasgow who keeps an eye on him, and Mother always goes with him. So we all went up to Glasgow and they picked us up there and took us along.”

“The Hebrides?” Betty asked. “That’s quite a trip by sea, isn’t it?”

“It is,” Mary-Lou replied feelingly. “Inchcarrow’s in the Outer Hebrides. It’s a duck of an island. Quite tiny, with white-washed cottages with great bushes of fuschias growing right up to the roofs. We fished and boated and bathed—there’s gorgeous bathing in one bay—and Clem made some jolly good sketches. She’s come on a lot since she went to Art School.” Then her voice changed. “Hallo! A new girl! Welcome to our midst! What’s your name?”

Richenda had to look up at this. Nanny’s rigid training in good manners held, even in her present black mood. “Richenda Fry,” she said.

“Richenda? What a jolly pretty name! And absolutely uncommon! I’ve never met it before. Well, Richenda, I’m one of the prefects. If ever you want a spot of help, mind you come along and ask me and I’ll do what in me lies. That’s one thing we prefects are for—besides making all you people toe the line!” she added with an infectious grin at the others, who broke into loud protests—all but Prudence Dawbarn, who looked sheepish and said nothing. “Well, I’m just going the rounds to remind everyone that Dover’s getting near and you must make sure you have all your possessions handy. There isn’t any too much time between the train and the boat, and if we miss it, we’ll hold up all the people in Paris. You can guess how dearly we should all be loved if we did that!” She flashed another grin round and added, “You have been warned!” Then she removed herself from the doorway and vanished into the next-door compartment.

The younger girls set to work at once, rather to Richenda’s amazement. She had expected them to take their time about preparations. But in five minutes’ time, everyone was sitting with her night-case on her knee, beret pulled on, any other impedimenta such as umbrella, hockey-stick, raincoat, leaning against her and all ready to leave the train on the word. Rosamund had seen to it that she herself was as ready as the others and her book had been put into the case.

When they had done everything, they sat waiting, and the talk turned on the prefects—and especially Mary-Lou. Richenda gathered that she was something rather particular in the school. The girls all spoke of her with affection and admiration, even if they criticised her.

“Think she’s slated for Head Girl this year?” Alicia demanded presently.

“I expect so,” Betty returned. “It’ll be either her or Hilary—or there’s Vi Lucy, of course,” she added.

“It won’t be Vi, anyhow,” Eve said with decision.

“How d’you know that?” Priscilla Dawbarn asked. “She could do it all right. She just like Julie and Betsy, and look what decent Head Girls they both were. I like Vi. I think she’d made a jolly decent Head Girl. She’s got what it takes.”

“I’m not disputing that,” Eve said calmly. “All the same, she won’t be it this year. She hasn’t been a full-blown prefect for a year—only last term when Amy Dunne left. Mary-Lou and Hilary have. When those two are available, the Abbess and Bill aren’t very likely to fall back on someone who’s had only a term of prefecting.”

“And if you think it’ll be Hilary, you’ve another guess coming,” big Joan Baker shoved her oar in.

“Why ever not?” Prudence demanded, wide-eyed.

“Well, won’t she be slated for Games? She was Second Games last year and she’s the best all-rounder of the prefects. If you ask me, I’d say there’s no question about it—it’ll go to Mary-Lou. She’ll be jolly good, too.”

“She’ll always be too jolly on the spot, you mean!” Prudence said gloomily.

“Don’t go making a silly ass of yourself and then it won’t matter to you,” Betty told her briskly. “The more on the spot she is, the better, I should say. We’ve our own fair share of demons among the Middles.”

“Listen to the pot calling the kettle black!” Eve giggled. “I’ve always heard you were never a little angel yourself in your Middles days!”

“That,” Betty said sedately, “is why I know what Middles need in the way of a Head Girl. I hope it is Mary-Lou. She’ll make a real go of it.”

“You’re quite right, Bets.” This was the thoughtful Rosamund. “I don’t know how she does it, but she seems to be able to see all round everyone else’s point of view almost before they get there themselves. And she’s always just and kind and—and helpful.”

Betty nodded. “Exactly! Look at the way she got round Jessica Wayne.”

“She’s too jolly on the spot for me,” Prudence reiterated gloomily.

“Then just take a pull on yourself this term!” Betty retorted. “Come off it, Prue! So far, you’ve jolly well asked for all you’ve got! You try asking for something different and then it won’t matter to you how much on the spot Mary-Lou is. After all, you’re fifteen now—nearly sixteen, isn’t it? Time you gave up acting like a kid!”

“Hear—hear!” Alicia chimed in.

Richenda took no part in the chatter, of course, though she listened with all her ears. In spite of her determination to loathe everyone and everything connected with her new school, she couldn’t help feeling the attraction that Mary-Lou radiated so unconsciously. She could never have said what it was that seemed to draw her, even on first sight, to the tall, handsome girl, but there it was! Whatever she might have made up her mind to do, she knew, in her heart of hearts, that she couldn’t help liking the prefect who, to judge by the gossip of the rest, was going to hold one of the most coveted posts in the school.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me!” she told herself crossly. “I won’t like her! I won’t like any of them! I loathe the place and the people and everything and I’ll go on loathing them! And Father’s a cruel pig to treat me like this!”

The result was that when she followed the others on to the boat, Francie Wilford, who had travelled in the next-door compartment, stared at her with interest, and then demanded of Betty Landon and Priscilla Dawbarn if they knew just why that new girl looked as if she had committed a murder and didn’t know what to do with the body?

“Have you all got your cases and other oddments ready?” Miss Ferrars demanded as the motor-coach in which Richenda was sitting beside Rosamund Lilley swung round a wide curve in the road. “Make sure, please. We’re terribly late, thanks to that wash-out, and the men have to get the coaches back to Interlaken tonight. You’ve all got to be ready to pour out the moment it’s our turn, and waste not one moment! Prunella and Clare, just see that the racks are quite cleared, will you?”

Two Seniors rose from their seats and examined the luggage-racks from end to end before reporting that they were clear. The remaining forty-six had hurriedly collected all their belongings and were all sitting looking very alert, and though no one said anything just then, very thankful that the ordeal was so nearly over. For it had been an ordeal for once. Usually, they got into the train at the Gare du Nord at Paris, changed at Basle for the Berner express, and left the train there for the big motor-coaches always chartered by the school for the beginning and end of term, without any major incident happening. On this occasion, however, Fate had seen fit to vary the programme.

They had reached Basle without any trouble, though Richenda, for one, had felt very muzzy as she clambered down the steps of the east-bound express to the lamp-lit platform of the station and met the chill air of six o’clock on a September morning, after the distinctly fuggy atmosphere of the carriages. There was time for coffee and rolls in the station restaurant, and, for the first time, she tasted the luscious black cherry jam of Switzerland and found it all fancy could paint. They had taken their places in the train for Berne and then—it happened!

The express runs from Basle to Berne with about two stops. On this occasion, however, they were held up at Meinsburg where information had been received, that thanks to recent heavy rains, there had been a landslide, and part of the embankment had collapsed ten minutes previously. All trains in the area were being stopped and sent round, where possible, to Solothurn. Theirs would be backed there and thence they must go by a very roundabout route to Berne.

The Staff has looked very blue at this. It meant at least two hours added to their journey. That meant that they would reach the Görnetz Platz somewhere about twenty o’clock as the startled Richenda overheard them all saying, instead of eighteen. As soon as a telephone was available, Miss Derwent, head of the party, sent little Miss Andrews flying to ring up the school and warn them of what had happened. She only just managed it. In fact, the train was on the move out of Solothurn station as she scrambled up the high steps to the carriage where she was caught by Mlle Lenoir, one of the junior music mistresses, and yanked to safety to a chorus of shrieks from the girls.

The Seniors were mostly old enough to realise what difficulties this diversion would make, and some of them grumbled over the extra length of the journey. The Middles and Juniors thought it huge fun—then. Later, as they became more and more stiff and cramped, they began to growl on their own account. No one but the smaller ones had slept too well during the night and quite a number of people thought longingly and affectionately of the comfortable school beds and the peace and quiet of the Platz.

The change to the motor-coaches, when at long last they reached Berne, roused them all, but was not much help where comfort was concerned. They were much more cramped than the railway carriages, and it had been a fairly silent and thoroughly tired-out set of girls for the last hour of the run through the mountains, going higher and higher as they went. At last, they reached a level road which ran through two or three tiny villages where lights twinkled at them from the chalet windows and very few people seemed to be about. By this time it was dusk and they could see very little. Then, as they swung round a wide curve in the road, Rosamund nudged Richenda, who was nearly asleep, and pointed to the left where a tall bulk loomed up, with lights showing at several windows.

“That’s Freudesheim where the Maynards live,” she said. “It’s next door to the school, so we shan’t be long now.”

Richenda roused with difficulty. “Oh?” she said, little interest in her voice.

Rosamund gave it up for the time being. During the whole of the journey she had loyally done her best to make the new girl feel welcome among them. She had tried to bring her charge into the gay chatter which had enlivened the first part of the journey. She had pressed sweets and magazines on her, and done every single thing she could think of to help Richenda over what she and the rest had diagnosed as an extra-violent case of homesickness. Nothing seemed to have the slightest effect. Richenda refused the corner seat Rosamund self-sacrificingly offered her, declined sweets and papers, and only opened her lips when she was asked direct questions. She had asked none herself, though her “sheepdog” had begged her to ask anything she wanted to know, and had tried to impart various pieces of information about life at the Chalet School. For about the tenth time since they had left Victoria station, Rosamund decided disgustedly that you couldn’t do a thing with her. Let her stew in her own juice! She’d have to come out of it some time soon, for no one in charge was going to allow this kind of attitude to go on. Perhaps when that happened she’d be a little more grateful and forthcoming than she had proved so far!

By this time it was quite dark. They turned in at some gates and rolled up a short drive, and Richenda couldn’t avoid seeing the girls from the coach immediately before theirs, marching steadily and smartly round the building which was glowing with lights from every window, swing round and be lost to sight. Even as their own vehicle slowed up, the other moved off, and they came to a halt before a wide door where a tall, slim woman in the mid-thirties, with the light from the lamp in the wide entrance shining on her fair hair, waited to direct them.

The girls greeted her with delighted cries of, “Oh, Miss Dene!” and Richenda wondered if she was one of the mistresses. Then she remembered that Rosamund had told her that Miss Dene was the school secretary, and an Old Girl herself. She was evidently regarded as a good friend by everyone judging by the way they greeted her. She replied to their clamour laughingly, but remained firm all the same.

“We’ll be seeing plenty of each other during the next three months or so. It’s terribly late, and there are two coaches after yours. Hurry up and get out of the way as fast as you can. Splasheries first and then to your common rooms until the gong sounds for Abendessen—and that won’t be many minutes. There’s no time for gossip now. We can talk later.”

They calmed down at once, and each clutched her possessions and set off. Rosamund forgivingly saw to it that Richenda went with them, and three minutes later, that young woman found herself entering a side-door and being steered along a passage to a long, narrow room, with pegs on the two side-walls, a peg-stand running down the centre, two big windows with toilet basins beneath, and at the far end, lockers built right up to the ceiling. This, she was informed, was the new Splashery for the three Fifth forms. A door beside the lockers led into a much smaller room which contained four more toilet basins and more lockers. Rosamund made straight for the wall opposite the main door and hunted along it. Then she gave a cry.

“Here we are! This is your peg, Richenda, next door to mine. Hang up your coat and beret, and put your gloves in one of your pockets. Take the small towel with the loop from your case and hang it on the lower hook. Then change your slippers, and I’ll show you where to put your shoes.” She turned to the girl on the other side of Richenda. “Hello, Primrose! I didn’t see you on the train! This is Richenda Fry, a new girl. If I’m not ready in time, show her where her locker is, will you?”

Primrose, a fair, pretty girl with hair as rampantly curly as Richenda’s own, and a wicked twinkle in her blue eyes, nodded. “O.K. Someone’s on the yell for you, Ros! Better scram! I’ll see to—what did she call you?” turning to Richenda as Rosamund vanished among the mob.

“Richenda Fry,” the owner of the name replied curtly.

“Gosh! That’s a new one on me!” Primrose was frankly slangy at this end of the term. “Well, better get cracking. We haven’t a moment to spare and Matey is the outside of enough when it comes to being late for anything!”

With this piece of advice, Primrose yanked off her own coat and beret and hung them up, tucked her gloves into a pocket and proceeded to unstrap her case and produce slippers and towel. She had kept one eye on Richenda to make sure that she followed suit, and when both stood up in their slippers, tucked a hand through the arm of the new girl, who by this time, wasn’t sure if she were on her heels or her head, and steered her through the throng to the lockers, shoes in hand.

“Now, let’s see! Oh, here you are! This is yours—‘R. Fry’—and here’s mine just below. This one next to you belongs to Ros—and here she comes! Hello, Ros! Here’s your locker all safe. And here’s your stray lamb! Let’s shove our shoes in and get washed and clear out of this place. It sounds like a looney-bin!”

Rosamund grinned. “That’ll soon stop, thank goodness! Don’t be scared, Richenda. Tomorrow, rules come into full force, and you’re either silent in the Splashery or talk in whichever language for the day it is.”

Richenda stared. What on earth did she mean? There wasn’t time to ask, however, even if she wasn’t still determined to make no advances to anyone. Primrose and Rosamund saw to that. They marched her back to her peg to get her towel and then to one of the toilet basins where, by main force of wriggling and pushing, they contrived to make places for themselves and were able to wash.

Richenda thankfully splashed her hot face with the cold, velvety-feeling water and then set to scrubbing her hands which were filthy. Primrose gave her a matey grin as she, too, did her best to remove the dirt.

“Filthy stuff they use on the steam trains abroad, isn’t it? Soft coal it is, and no matter how careful you are, you just can’t help getting dirty. Baths at bedtime, though—unless they decide that we’re too late, we’d better wait till the morning. Got your comb handy? Better tidy your wig. It looks wild!”

“Your own’s nothing to write home about!” Rosamund told her. “Thank goodness mine’s a pigtail and stays tidy!”

Richenda had forgotten her comb, but Primrose offered hers when she had reduced her fair curls to something like order. Once it had been run through the ruddy mop she began to feel better and ready for her supper—if that was what Miss Dene had meant by that weird word. Foreign, she supposed. Would they have foreign food as well? Would they have——Richenda handed back the comb, hastily searching her memory for any foreign foods of which she had heard. Only one came and she actually forgot her vow of silence long enough to ask Primrose if they would be having sauerkraut—she called it “soarkrort!”—for their meal. Primrose first stared at her blankly, and then went off into fits of laughter.

Richenda stared at her offendedly. “I don’t see anything to laugh at,” she said stiffly.

“Sorry,” Primrose gasped, “but it sounded so awful! And I couldn’t think what you were getting at at first, anyhow. My lamb, it’s called ‘zourkrowt’ and we don’t have it at all. It means ‘sour cabbage’ and we don’t go in for exotic dishes of that kind! Whatever else we have for Abendessen, it certainly won’t be that! Much more likely to be cold meat and salad and fruit and cream. We’ll know in a minute or two. Rosamund’s in charge of you, isn’t she? Come on then! She’s gone, and anyhow, you can’t find a soul in this Black Hole of Calcutta. We’ll pick her up in the common room. This way!”

She steered Richenda through the crowd, along the passage, down another and into a third where she opened a door halfway along and ushered her charge into the Senior common room where Rosamund was waiting near the door.

“Oh, there you are!” she exclaimed, coming to claim her “lamb”. “Sorry I had to leave you, but Virginia Adams simply shoved me aside and then the crowd came between. But I knew Primrose would look after you. This is our common room, Richenda, where we spend our free time when we can’t go out. Rather jolly, isn’t it?”

Before Richenda could do more than glance round, a deep, booming sound rang out and at once everyone stopped chattering and hurried to form into line by the door. Two of the elder girls who were clearly prefects, appeared and took command and they marched out “decently and in order”, to quote Rosamund later, back down the corridor, along another and so into a very long room which Primrose, just behind her, hissed over her shoulder was the “Speisesaal”.

They took their places behind the pretty peasant chairs standing along the sides of the lengthy refectory tables which ran down the room in three rows with another across the top of the room. When everyone was present, a tall, stately woman in a green dress with masses of brown hair coiled low on her neck in a big knot, said a short Latin Grace in a deep, musical voice which had something of the quality of the ’cello in it. They all sat down and plates of cold, stuffed veal were placed before them.

Richenda could scarcely eat her share for looking round and taking in all she saw. And it was quite a good deal. She filled a page of writing pad with her description of the room when she wrote to Nanny on Sunday. The tables were spread with gaily-checked cloths and they all had napkins to match. The glasses at each place were of different colours—ruby, sapphire, emerald, topaz, garnet—and under the electric light, they glowed like the jewels they resembled in colour. Down the centre were great platters of peasant ware, as gay as the cloths, and piled high with delectable salad. Salad dressing was in glass jugs which matched their tumblers. Hand-woven baskets held crisp rolls on which they spread ivory butter, firm and sweet. The chairs delighted her, too, with her passionate love of colour. They were of white wood, enamelled and varnished cream, and on the back of each was painted a posy of Alpine flowers, all different. Later, she heard that the Senior art classes were responsible for the floral decoration.

She was so absorbed in it all that her neighbours had to jog her more than once or her plate would still have been full when the Head signalled to the maids beside the hatch to change the plates. Thanks to Rosamund and Primrose, however, she did finally clear it and then came a new thrill. She had never tasted anything more delicious than that veal.

“What is it?” she whispered to Primrose, since Rosamund was talking to Joan Baker at the moment.

“Kalbsbraten,” Primrose said solemnly, though her eyes danced wickedly.

“Kalbsbraten? What, exactly is that? I don’t know any German.”

“Roast veal, my child. Karen does it gorgeously, doesn’t she? Karen—the cook, of course. She’s one of the foundation stones of this establishment. She was with the school when it was in Tirol—ages and ages ago. Before the war, in fact. I once asked her what she did to make it taste so marvellous and she said garlic. But I don’t know just how she uses it. She wouldn’t tell me.”

“Oh, goody!” broke from the girl sitting at Primrose’s right hand. “Bricelets! I do love them!”

“Oh, we all know what your middle name is, Emmy,” Primrose said with a chuckle. “Sugar-baby! Not that I don’t like them myself,” she added as her plate was passed to her.

Richenda tasted her portion cautiously. Then she set to work to finish it. It consisted of a square, sweetened wafer, fried in olive oil and sprinkled with sugar and, as she told Sue Mason in one of her letters, luscious beyond words. They had either milk or still lemonade to drink with it. Rosamund advised the lemonade and Richenda found it a very different thing from Nanny’s, which was made with crystals from a bottle. Karen’s was from fresh lemons, sliced thinly and powdered with sugar before boiling water was poured over them.

As the meal was ending, a bell rang through the room and at once the hum of chatter and laughter ceased, and everyone turned expectantly to the top table where the lady in green had risen and was smiling at them.

“One moment, girls,” she said. “It is very late, thanks to the accident to the railway line. I will leave my usual talk till after Prayers tomorrow morning. You all have—or ought to have—all you need for the night in your night-cases. As soon as you have finished and cleared the tables, you are to go straight to Prayers—Protestants to Hall and Catholics to the gym, as usual. After Prayers, you go upstairs to bed—everyone! You must all be very tired and we can leave everything until the morning. I’ll just take this opportunity of welcoming every one back to school and saying that I hope all the new girls will settle in among us as soon as possible and be very happy with us. In the morning, when Prayers are over, you will unpack and those not required by Matron first will come to Miss Dene in the office to report. There has been no time for it this evening.

“Now that is all for the moment. Finish your meal and don’t loiter over clearing the tables. The Juniors are all very sleepy, I know, and the rest of you will welcome your comfortable beds after last night in the train.” She smiled at them again and sat down, and they set to work to clear their plates and glasses before the bell at the high table rang again and they stood for Grace.

Richenda, considering the number of girls there, had been wondering however they managed to stand without colliding with each other. She found out now. At the peal of the bell, everyone stood up and every girl slipped out of her place to the right hand, pushed back her chair into its place and stood behind it. When Grace ended, each girl seized her plate, glass, spoon and fork and went to pile them on one of the big, three-tiered trolleys waiting. As each trolley was filled, a prefect pulled up wire sides which kept everything safe, and they were left for the maids to wheel out later. They had to take their napkins and put them in one of the drawers of a great armoire built into the wall at one side and the prefects at the head and foot of the tables, folded up the cloths and added them to their own drawer—one for each table. When it was all done, the girls went to join one of two long lines forming at the head of the room behind the high table which the Staff had left as soon as Grace had been said.

Rosamund turned to her charge and asked, “Which are you—C. of E. or R.C.?”

“Why—C. of E., I suppose,” Richenda said doubtfully.

“Don’t you know?” Rosamund asked involuntarily.

“Yes, it’s C. of E. all right.”

“Then join on to this line after me.” Rosamund led the way and presently someone said, “March!” and they all marched quietly down the corridors and into an enormous room with a dais at the top end. On the dais stood a lectern, a beautiful William and Mary chair in carved walnut and canework, and behind these, a semi-circle of ordinary chairs. A piano stood at one side and a mistress was already seated at it, turning the pages of a hymn book on the desk.

Richenda might have resolved to talk as little as possible, but she was only human, and by this time she was nearly bursting with questions. She conveniently forgot her resolve and turned to Rosamund as soon as they were sitting on one of the long, green-painted forms which filled the upper part of the room.

“Who was that that spoke at supper?”

“The Head, of course—at least, one of the Heads. That’s Miss Annersley. She’s Head here and Miss Wilson is Head at St. Mildred’s. But they work in together most of the time. This school has two Heads.”

“St. Mildred’s? Which is that?”

“The finishing branch where most girls go for their last year. But it’s all in the prospectus. Didn’t you see it?” Rosamund demanded, startled.

“No,” Richenda said with a sudden guilty memory of the way she had treated it. She was rather sorry about that now. She felt ignorant and she need not have been. However, there was nothing she could do about it now.

“Oh, well,” Rosamund said, inwardly delighted that this new girl seemed to be coming round a little, “you’ll soon know all about it. Ask me anything you want to know and I’ll tell you if I can.”

“Well, why do we have two lots of Prayers?” Richenda demanded.

“Because we have nearly as many Catholics as Protestants—or quite as many I should think, nowadays. When Bill—er—I mean Miss Wilson—is here, she takes Prayers for the Catholics. When she isn’t, Mlle de Lachennais does. It mostly is her. Miss Wilson has to be with her own girls at St. Mildred’s as a rule. Miss Annersley always takes us unless she’s away or engaged.”

“Do you always call Miss Wilson ‘Bill’?” Richenda asked curiously; and a deep red flooded Rosamund’s clear skin.

“We oughtn’t, of course. But she always has been, they say.”

“Then what do you call Miss Annersley?”

But before Rosamund could answer, a bell pealed out from somewhere overhead, and even the very quiet talk which had been going on among the girls was hushed on the instant. Prefects appeared with piles of prayer-books which they handed out. Mary-Lou appeared on the platform to announce, “The beginning of term hymn!” in her clear ringing tones. Then the mistress at the piano began to play softly—a Bach prelude, if Richenda had only known—and everyone sat very quietly.

“Almost like one of our Meetings,” Richenda thought as she glanced round.

Her father was, of course, a Quaker, but she herself had mostly gone to the parish church with Nanny who was staunch Church of England. But she had attended a few Quakers’ Meeting and now once more she began to feel the same hush which had always pervaded them. She had yet to learn that this interval of peace was intended to help the girls to a devout mood before Prayers actually began.

The top door opened and the mistresses entered quietly, headed by Miss Annersley, who wore her M.A. gown flung over her pretty jade-green dress. She took up her stand behind the lectern and the Staff went quietly to their seats before Miss Lawrence, at the piano, modulated from Bach into the hymn, which was sung with gusto by everyone. When it ended, they sat down and Mary-Lou, looking for once in her life rather discomposed, read the parable of the Talents, after which they all knelt while Miss Annersley repeated two or three collects, led them in the Our Father which belongs to all Christians; then Gentle Jesus for the little ones and, finally, the lovely old Antiphon, “Oh, God, keep us waking, watch us sleeping that awake, we may watch with Thee and asleep, we may rest in peace.” It was new to Richenda, but she listened as Rosamund and Primrose on either side of her repeated it devoutly, and she liked it immensely.

The blessing followed and they all remained on their knees for a few moments. Then they stood up and Miss Annersley wished them all good night and sweet sleep. The girls returned the wish and then, to the tune of a quiet march, they left Hall and went upstairs to the dormitories, Richenda keeping close to Rosamund who had already consulted dormitory lists and found that her charge was in Pansy with her.

There was no talking on the stairs, but once they were in the dormitory, Rosamund spoke again. “This is Pansy. Let’s see which is your cubey. Here you are!” as she led the way along the narrow aisle made by curtains at one side and the green wall of the room at the other. “This cubey is Betty’s and I’m on your other side. The rest of us are Heather Clayton, Len Maynard, the eldest of the Maynard triplets—eldest by half-an-hour,” she added with a sudden chuckle, “and two new girls, Odette Mercier and Carmela Walther. Half a tic till I see who’s our pree.”

But before she could move, the curtains of the big cubicle at one end of the dormitory were swept apart, and a girl of their own age in dressing-gown and bedroom slippers with her thick pigtail of reddish hair twisted up on top of her head appeared, towel in one hand and sponge bag in the other.

“Jo Scott!” Rosamund exclaimed. “Are you our dormy pree this term?”

“Looks like it,” Jo said with a grin. “You’re no more surprised than I am, Ros. But now our one and only Mary-Lou has the Head Girl’s room, someone had to take her place, and believe it or not, they’ve pitched on me!”

“They might have done worse,” commented Betty, poking a tousled head between her own curtains. “Supposing they’d chosen ME!”

“Don’t you worry!” A long-legged individual with curling chestnut hair tumbling about her to her waist, dashed into the fray. “No one on this Staff is either blind, deaf, or crackers! Hello, Ros! Haven’t had a chance to see you before. And there’s not going to be much chance now,” she continued, pushing the heavy waves of hair out of her eyes. “Lights Out will go in precisely twenty minutes, so I’d advise you to get cracking. Who’s this?” She turned a frankly interested gaze on Richenda and beamed at her.

“This is Richenda Fry,” Rosamund said. “Richenda, this is Len, one of the Maynard triplets. Now come on into your cubey. You can talk tomorrow. There isn’t time now. This peg is for your dressing-gown and this is your bureau. Mirror here and you keep your brush and comb in this little locker affair beneath. Your clothes go into those drawers—all but your frocks and coats and so on. You have three pegs and hangers in the closet at the far end for those. I’ll help you fold your counterpane and then I must fly. I’ll come to show you the bathroom in five minutes, so mind you’re ready. I’m just next door if you want me.” And having instituted the new girl into her cubicle, she scurried out, and to judge by the sounds, undressed in a frantic hurry.

Richenda was so sleepy by this time that she was yawning almost continuously. She was unaccustomed to lengthy journeys and she had had a whole bunch of new experiences on top of that, so small wonder that she was weary! She tossed off her clothes and contrived to be ready when Rosamund arrived to take her to the bathroom. She was told that she might have a cold or a lukewarm bath in the morning and she would use the same bath cubicle all the time. She washed her face and hands, but nearly forgot to brush her teeth, so drowsy was she. However, she remembered in time and was ready when Rosamund appeared to escort her back to the dormitory.

“Finish undressing, and do your hair,” Rosamund said. “The bell for private prayers will ring in less than ten minutes and it’ll be lights out five minutes after that. Good night, Richenda. I hope you’ll sleep well.”

“Good night,” Richenda mumbled, repressing a yawn with difficulty. “Thanks for all your help.”

“That’s all right,” Rosamund said. “When I was new I was helped, and next term it may be your turn. We all do it. Goodnight!”

She slipped through the dividing curtains and Richenda was left to discard the rest of her clothes and pull on her pyjamas. A bell rang just as she finished buttoning the jacket and she contrived to remember about the prayers. But though she knelt at the side of her bed, it is to be feared that they got all mixed up and when the second bell rang, she just dived into bed under the sheet and blankets and pretty, pansy-powdered couvrepied. Then she fell down, down, down until she was drowned in sleep and knew nothing more till the morning.

Richenda slept like a log all night. She didn’t even dream. She was roused at half-past six next morning by the loud pealing of a bell. Still half-asleep, she bounced up in bed and stared wildly round her. Where on earth had she got to? And how did she get here, anyway? As the fog left her brain, she began to remember. But before she could remember everything, she also took in the appearance of her cubicle and a spontaneous exclamation of, “Oh, what a pretty room!” was jerked out of her before she could stop it.

A pleased voice from behind the curtains on her right replied at once. “Yes, rather nifty, isn’t it? Sorry I can’t come in to you, but visiting is strictly forbidden unless it’s an emergency. And talking of emergencies, we’re both likely to run head-on into one if we don’t get up at once! Matey’s dead nuts on punctuality, let me tell you!”

A thud followed this speech, showing that Betty had suited her actions to her words, and Richenda felt she had better imitate her. She was not devoid of common sense and she saw no common sense in getting into a row the very first moment. She threw back her bedclothes, swung her feet to the floor, made a long arm and grabbed her dressing-gown from the hook where it seemed to have found its own way. She had a hazy memory, but quite distinct, of tossing it down somewhere last night. She was not to know that Rosamund had peeped in on her last thing, and seeing the mess in her cubicle, had broken rules and tidied it up.

The front curtains swayed apart as she pulled the blue gown on and Rosamund’s black head was poked between them. Her hair was screwed up on top of her head and she nodded cheerfully at the new girl.

“You’re up! Oh, good! I just called in to tell you that you’re after me on the bath-list, so be ready to fly when I come back. There are people after you, you know. Strip your bed while you wait—Betty or someone will show you if you’re not sure——”

“I will, Ros,” said Len Maynard’s pretty voice behind her.

“Oh, good for you, Len! Thanks a lot! You’ll be all right with Len, Richenda.” The black head was withdrawn as Rosamund scuttled off to the bathroom and Richenda was left to wonder why someone should have to show her how to strip a bed. Nanny had taught her that years ago! What is more, she saw to it that it was done properly every morning.

There came the patter of light feet and Len Maynard peered in at her. “Shall I show you what to do, Richenda? Matey’s rather sticky about beds being stripped in the one way she thinks best.”

Richenda took firm hold of her wits. “Thanks, but I can strip a bed,” she replied. And she pulled off couvrepied and blankets and flung them over the back of a chair, followed them with her sheets and pillows and finally turned the mattress over the foot of the bed.

Len watched her approvingly until she came to the mattress. There, she interfered. “I hope you don’t mind me telling you, but Matey makes us hump it up in the middle—like this—to let the air pass under it.” She “humped” the mattress and then grinned at the new girl. “Matey insists on doing it this way and it’s always best to fall in with her ideas. She’s a perfect poppet when she likes; but get across her and you know all about it!”

“Len Maynard! What are you doing in someone else’s cubey?” Jo Scott’s voice demanded firmly from the aisle. Then she came in, looking well-washed and glowing, with her mane of reddish hair beginning to tumble down from the screwed-up knot into which she had tied it on top of her head.

“Only showing Richenda the way Matey likes us to strip our beds,” Len explained. “She doesn’t need any showing, really, except about the mattress. Here comes Ros! Grab your things and scram, Richenda! There isn’t time to breathe in the mornings here! D’you know where to go, by the way?”

Richenda nodded as she snatched up her belongings and shot off down the dormitory, urged to instant flight by everyone else’s insistence. Betty Landon came flying behind her as if wolves were after her. Clearly dilly-dallying was not encouraged here!

As they met at the bathroom door, Betty panted, “Cold or lukewarm, but not hot! And for pity’s sake don’t splash or you’ll have it to clear up!”