* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

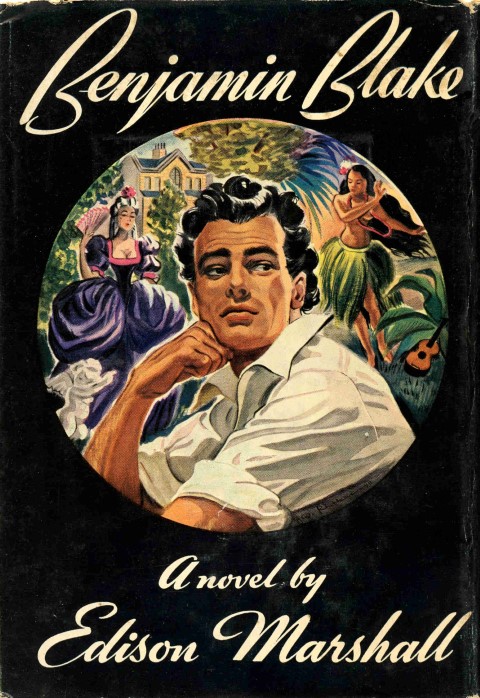

Title: Benjamin Blake

Date of first publication: 1941

Author: Edison Marshall (1894-1967)

Date first posted: January 18, 2026

Date last updated: January 18, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260122

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Books by Edison Marshall

Adventure Stories

THE VOICE OF THE PACK

THE FAR CALL

THE MISSIONARY

THE DOCTOR OF LONESOME RIVER

THE DEPUTY AT SNOW MOUNTAIN

THE LIGHT IN THE JUNGLE

DIAN OF THE LOST LAND

THE STOLEN GOD

Short Stories

THE HEART OF LITTLE SHIKARA AND OTHER STORIES

Novel

BENJAMIN BLAKE

COPYRIGHT, 1941, BY EDISON MARSHALL

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To

Nancy Silence Marshall

and

Edison Marshall, Jr.

| Contents | |

| 1. | GUNSMITH’S FORGE |

| 2. | BREETHOLM |

| 3. | HUE AND CRY |

| 4. | VOYAGE TO THE ISLES |

| 5. | DESERT ISLE |

| 6. | PARADISE ISLAND |

| 7. | PARADISE BESIEGED |

| 8. | OYSTER ONIONS |

| 9. | OLD PATHS |

| 10. | OLD FRIENDS |

| 11. | OLD SCORES |

| 12. | BREETHOLM BESIEGED |

| 13. | FAREWELL |

I,

BENJAMIN BLAKE

Dedicate to

TRUE MEN

Here and in Other Lands

This Account of Sundry Unusual

HAPPENINGS

in My Life as

COMMONER and GENTLEMAN

in the Disturbed Times of His Majesty

GEORGE III

Which Sets Forth the True Facts Causing

Me to Adopt for my Own the Motto

Non Quam Me Dedo

and Which has been Taken down in the

New Short Hand

by a Scrivener and Clerk of this Parish

Gentle Readers—and some of you are not so gentle, I’ll be bound—pray do not seek herein such elegant expression, polished diction, and learned syntax as you find in the immortal writings of Lord Bolingbroke and Horace Walpole; neither will you find sentences long and involved as a Dutch fish net. Kent, in my favorite play, proclaimed himself a plain, blunt man. I shall do the same, and have done with it. But I will confess at once—and soon you shall know why—that the character that moved me most in that thunderous tragedy was Edmund. To me, his story was a sadder one than the vain old King’s.

The proper beginning should be the date and place of my birth. Then I must be guilty of an impropriety at first blush, for even now I do not know the date, although Saint Bartholomew’s Day, 1751, has been chosen for me by an itchy-palmed gentleman in London. Certainly he had as much to do with it as had Toby Mallow, who otherwise would have occupied an important place in my history, having been my mother’s lawful husband. Nay, if Toby Mallow had done his duty by her, which God forbade, neither this tale nor its teller would have ever been. Neither did I know my native land until I was passed twelve, almost thirteen most likely, and still I do not know what corner of it heard my first wail.

In these tepid times, a boy of twelve is still nigh a babe in arms. It was not so in my young days: unless he grew tall and tough as ash, he was crushed underfoot, and at twelve he had seen a hanging, wagered a farthing on a cockfight, hardened his heart at a bear-baiting, and knew well that no stork had hatched him in this lewd world. I was even riper than most, counting myself almost a man, and already afraid of the press gangs, when I came home to Bristol from Master Chandler’s Grammar School at Bath. On the night these chronicles begin, I was reading by candlelight one of the lesser known plays of William Shakespeare. In those days I had barely peeped into the spacious mind of that glover’s son, honored less in this brutal age than the least fox-killing duke, but I was lost in the noble tale of a wicked uncle and an abused heiress, when I came to the lines:

’Tis far off,

And rather like a dream than an assurance,

That my remembrance warrants. Had I not

Four or five women once that tended me?

Only Master Shakespeare himself could describe the sensations coursing over me then. At first, I thought that the vision conjured up so dimly in the small end of the horn of my memory was no more than a waking dream inspired by the story, until it grew plainer, the broken lines filling in and sharpening. So I threw down my book and approached my grandfather, knitting in his big chair.

Until now there had been a conspiracy of silence between him and me. He knew that I had more knowledge of my situation than I pretended; I knew that he had more than he had ever revealed. One of the sorrows of childhood is what children know, unknown. Whether their rosy lips are locked by pride—for pride spares the pitifully young no more than pitiably old, growing fast and rank in that warm, sweet earth—or by love or fear of their elders, I know not.

My grandfather looked at me, and I at him. He saw a gangling boy, with the curly black hair, heavy brows, hooky nose, and cleft squire chin so meaningful to him, and the big feet and hands that in a stripling foretell great stature among men. I saw what I had never seen before in that chair, a mortal man instead of my grandfather. Faith, I can say it no better. You know how children take their old folk for granted. So I had taken Amos Kidder, my mother’s father.

He was older than I thought, smaller, frailer. I knew well the silver-rimmed spectacles that were his pride, but I had not known that behind them his eyes were pale blue, peering further than he could see, seeing more than he could attain to. He had sandy hair, thin on the crown. His neck was somewhat long and stringy-looking. His lower face came to a pointed chin like the bow of a boat, beardless except for three days’ stubble, although his forehead was broad and high. His ears flared as though he were listening for a trumpet sound. His hands were delicate, adroit, and strong.

When I gazed straight at him, he shrank a little from me, which I remembered he had often done before. His chin wabbled somewhat, as when he was distressed.

“What is it, Ben, lad?” he asked.

“Grand-dad, was I born here?”

“Why do ye ask that? Oh, isn’t it good enough for ye?”

It was a snug place, I warrant, and clean. My grandfather would never suffer dirt or litter. Even the gunshop next door, where my grandfather made dueling pistols and fowling pieces for the gentry, was so clean you could eat off the floor.

“ ’Tis good enough, but I was not born here.”

“Ah! Who told ye so?”

“No one told me. I remember. I was born in a house with a white ceiling-cloth, where snakes had their nests. There were trees outside with leaves big as a bushel, that rustled when the wind blew. There were women with dark skins to feed and bathe me, and one that I called—Nanna.”

My grandfather leaned back in his chair as though heart-stricken. Then he asked, “Was there a white woman, too?”

“Aye. She was always singing, and playing with me, and laughing. She was my mother.”

“A pretty wench, I warrant?”

“I don’t remember.”

“And a white man, too?”

“A tall white man.”

“That was your father, Godfrey Blake. The wench was my daughter.”

He said nothing more for a long time. Then he asked, his voice thin and very gentle:

“Are ye going back to your book? Not many lads of your age can read a primer, let alone William Shakespeare. Not many grandsons of an old gunsmith may go to Master Chandler’s Grammar School in Bath.” He was consoling himself more than me.

“I have read enough now.”

“Why do ye look at me so, Benjamin, my boy? Is it man more than boy at last? Ye are only twelve, or at the most, thirteen. What do ye want to know?”

“Only what the boys in school have not told me, and I have not guessed.”

“The boys at school? Did they—oh, Ben, I clean forgot the boys at school! Did ye hear from them the term ‘natural son’?”

“Nay, but I heard the name ‘bastard’.”

I did not tell him that this was not the first time I had heard the name, or yet the fortieth, and of how I knew it was a term of shame before ever I knew its meaning, and of how when I did know, even then I began to resist and not submit. Aye, the battle was long already—and I not yet thirteen. Half unaware, I was a war-scarred rebel against all that deemed me base, whether the God of the Churches, or the King, or the Law, or the settled order. Nor did I tell him what I know now was the most woeful thing of all—how part of me was a rebel against the other part, because I hated those above me with half my heart, and with the other half, craved their smiles. Even while I mocked and sneered at them to my little neighbor, Molly Shelton, I would have given my right hand to be like my schoolfellows, each safe in his seat. Nay, I did not tell him of my pantings when lords and ladies and gentlefolk came to visit or inspect the school, or stopped in their coaches outside the shop—how hateful they looked to me, and yet how beautiful.

“Oh, did your schoolfellows call ye a bastard?” my Grand-dad asked.

“Aye.”

“What did ye do then, Ben?”

“I fought them, and was beaten for it by the master. I still fight them, the biggest or the smallest, but choose the place and time to fight, so my back is almost well from the stick-welts. Few of them have called me that, of late.”

My grandfather’s eyes lighted behind his spectacles. “Your father was a good fighter, too.”

“Maybe he was a good lover, as well.”

“That he was!” A change came over my grandfather; he leaned forward and spoke with spirit. “A good lover was the right term for the scamp, and you are a knowing boy, far more knowing than I thought. And my Bessie was the right lass for him, who could give him as good as he sent.”

I was not ashamed of her. Although her justification was not yet clear in my mind—her babe’s right to prime begetting—yet I knew that only pride would save my soul. If I had no noble words of my own devising, at least I had learned by heart that bold speech of wicked Edmund, Gloucester’s natural son. “Thou, Nature, art my goddess!” No Latin-mouthing, horse-faced schoolmaster need tell me what he meant, and half-blindly, though with a burning heart, I sought to kneel at the same shrine. It had saddened me, though, that after his brave boast, he should show base.

“What had she to do with a muff like Toby Mallow?” my grandfather went on. “A good marriage, aye, for a poor gunsmith’s daughter. The vicar said so, Sir Samuel Haddock, my landlord, said so, and even her poor mother, may her soul rest in her Savior, said so too. He owned this snug little house and the land it stands on, and his shop had the best custom hereabouts. Better born he was by a long shot, the vicar said, but what did that froze-spit know about true life?”

My grandfather was talking more to himself than to me, and I did not divert him.

“They say the good Lord wanted it so, or ’twouldn’t be so,” he told me, shaking his head, “but between ye and me and the gatepost, ’tis rotten unfair. She was pretty as any lady, and clever, with a shape trim and neat as a French carbine, and she had sweet, gentle ways for all the sparkle in her eye, but because she was a poor gunsmith’s daughter, she must marry Toby Mallow, and who was I to interfere?”

“And then—?”

“Then comes in Godfrey Blake, to order a fowling piece, and who should wait on him but my Bessie? How could she help but take his eye, and he take hers, if all the vicars in England stood in the way? Tall, he was, and broad in the shoulder, with heavy black brows and a square cleft chin—” My grandfather stopped, appalled by his own words.

“Go on, Grand-dad.”

“ ’Tis not fit for ye to hear, my lad.”

I laughed at him, and he blushed.

“They’d say I should be whipped for telling of it. But ’tis a blessed relief, to get it off my tongue.” His tongue was reveling in it, as in a cup of syrup.

“The oldest son, he was, and though ’tis not always so, the rightful heir. He had the good, bold looks, and the big laugh, and the eye for a pretty lass that the old Squire had afore him. Son of Squire Blake of Breetholm he was, but then and there he declared he would have my Bessie, and faith, he’d have lain her on the workbench—” And again my grandfather grew silent.

“He ran away with her instead? Was that it?”

“He didn’t meet her in holes and corners, not he. He loved her enough to look ruin in the face, and the frowns of all the gentry in North Wiltshire, and while his brother Arthur shook with joy in his ugly boots, he carried her off on a tall ship to India!

“What did Toby say, ye may well ask?” Grandfather went on, with ill-concealed satisfaction. “ ’Twas cruel hard on him, aye—on his twopenny pride, I mean, for he had never loved my Bessie, hated her in his heart for being above him when she was born below him, and ye’ll see plenty more of that before ye’re through. So he went off to Virginia, leaving me to keep the shop. There was a fair profit for a good gunsmith among those ’Giny planters. And he’s been there ever since, getting rich.”

“He owns our shop?” I had always thought it belonged to my grandfather.

“Aye, he owns it, and I send him a fair half what I make from it.”

“We’ve lived, and kept a maidservant, and I’ve gone to Master Chandler’s Grammar School on half the profit?”

“Should Godfrey Blake’s son black his own boots? Should he grow to manhood and not write his own name, Ben Blake?”

“His natural son!”

“His son, just the same, by my Bessie. Oh, I’ve no head for figures, lad. I’ve kept the accounts well as I could, but there was no use putting in some little money I made after hours, or a few shillings some gentleman gives me for an extra handsome job.”

“He owns the cottage, too?”

My grandfather shrank back. “Aye, Ben Blake.”

“And he lets his wife’s bastard sleep in his bed? My fellows at school asked that, I remember.”

“He’s away in America, Ben. Could I call to him, as though he was at work at the next bench, when the ship that brought ye home from the Indies put in at Avonmouth? A gentleman of the East India Company put ye in my charge, with a letter from Godfrey Blake. Could I tell him I couldn’t take ye, because ’twas my son-in-law’s shop?”

“You’ve never told Master Mallow that I’m here?” I own that I scarce had breath to put the question.

“Mayhap I would, if he’d make bold to ask. Not a bold hair in his head, has Toby Mallow.

“You told me my parents are dead. ’Tis true, I warrant. I’d not like to think they’d both forsaken me.”

“They died of the fever. Rotten bad is the air in the Indies. The gentleman saw ’em bled by the company doctor, but they both died, and he helped bury ’em. And now Arthur Blake is the lawful Squire of Breetholm.”

“My father left me nothing?”

“Naught but his bold eye and brawn. He made money like a wool-merchant out there, but spent it as fast. A natural son can’t inherit by English law, so Arthur Blake’s the Squire, and his son will be after him. That’s the whole story, Ben.”

“Nay, ’tis hardly the beginning.”

“What makes ye tremble so, my boy?” My grandfather was trembling, too.

“I, too, ’ll go to India, when the time comes, and I’ll make money faster than any wool-merchant, but I’ll scrimp and save it, and when I have a bagful, I’ll bring it home.”

“ ’Tis a long way—but what makes your eye glitter and glimmer so, Ben Blake? Like a silver gun sight in the sun!”

“I’ll have a castle and a coach, and a coat-of-arms, and two princesses will want to marry me, the same as Edmund. But when the lawful heir fights me, I won’t be killed, and I’ll kill him instead.”

“I wish ye wouldn’t look so, Ben; I do indeed. Ye’ll learn the gunsmith trade, and some day have a shop of your own—maybe this shop, if Toby would be good enough to die out in America—with the gentry coming in to order pistols—”

“I’ll make pistols, that I will, but I’ll shoot ’em myself.”

What I now reveal occurred the following summer. I was standing outside the shop, talking to Molly Shelton, who was my own age, when a chaise drawn by a team of bays stopped at the door. When I saw the coat-of-arms emblazoned on the harness, I thought another of the county gentry had come to order a piece.

The lass curtsied quickly. And here I had best describe what welled within me from some bitter spring tapped long before, when my companions paid homage to gentlefolk. It was more than discomfort. It was envy and black rebellion mingled. I desired to be noticed by such people, to have their smiles and see them whispering that I had blood in me, which desire I would not have them know for all the world. . . . Nay, I cannot describe the sentiment, though I bite my tongue off. It had as many curves and bays and promontories as a floating cloud.

I was prepared to doff my cap and give the stranger my best bow, if he would smile or speak to me, and meanwhile feigned not to see him. Perhaps I did not see him clearly, his black brows and his square, cleft chin, for I was watching him sideways. Speak to me! I own he did. I had never heard such a voice, and well-nigh jumped out of my smallclothes.

“You, there! Take off your cap!”

“You mean I, sir? I didn’t see your lordship—”

Devil take me, I had not meant to say this. I had fancied myself showing little Molly that I was as wellborn and proud as any booted squire. His voice jumped it out of me, as the noise of a fowling piece will jump a hare hiding in its bed. It was a big voice, and deep, but there was no music in it.

He was an ugly man. Faith, he should have been handsome enough, with his broad shoulders and powerful neck and dark face and curly black hair and flashing dark eyes, but vile ugly he remained, which he knew the whole world saw, although few dared tell him. How I ached to tell him myself! “Blackguard Pretender, I’d liefer uncover to a chimney sweep!” If I could have said that, or some such noble thing, instead of merely thinking it in my shut head! Perhaps I did not even think it at the time—only afterward, when I lived the scene over, not as it happened but as I had wanted it to happen. At the time I was too busy snatching off my cap, and bowing like Punch at the fair.

“You didn’t see me, eh? So you’re a liar as well as too big for your breeches! What’s your name?”

“Ben, my lord.”

“Your whole name, you oaf. Don’t you call yourself Ben Blake? Answer me that.”

I nodded, because I could no longer speak. There was something about this man that dried the spit in my mouth.

“I thought so. And you’re just the insolent, lewd young guttersnipe I expected. You haven’t got a name, do y’hear me?”

He turned to enter the shop, then stopped. In the doorway stood my grandfather, who had heard it all. His face looked pinched and gray, like a cadaver’s, and his dim blue eyes were popping and blinking and moist. Aye, it was my grandfather, the one I leaned on ever, my inner fortress, quaking in terror and humility before this man. I was ready to cry then, and I must have cried inside, for I felt salt in my mouth.

“Oh, your honor,” my grandfather was wailing. “He’s big for his age, but he’s only thirteen or so. Was he disrespectful to ye? He’s a good boy—”

“A good boy! I came to order a pair of pistols, to give you a little custom to help support your daughter’s bastard, and what does he do but insult me on the street? ’Fore God, I’m a mind to have him ordered to the almshouse.”

“Oh, Squire Blake! I’ll make ye the pistols. I’ll charge ye only for the substance, and if ’tisn’t the best workmanship in the shire, ye needn’t pay me a farthing. I’ll do it gladly, for ye are the brother of—”

Meanwhile my grandfather had backed into the shop, crowded close by the choleric figure of the squire. When I would have crept away—it seemed that my grandfather was imploring me to do so, with his wabbling eyes—Squire Blake gave me a shove on the back of the neck that shot me through the door and half across the room. There I fetched up, panting.

“Don’t call the adulterer’s name, in my hearing,” Squire Blake cut my grandfather short. “He’s a disgrace to it, and to his blood. Why have I waited nigh ten years to find out the brat is here?”

“Oh, I wouldn’t trouble your worship. ’Twas not your fault, just the fault of that whore, Bessie, who I’m shamed to call my daughter, and ye’re not bounden to him in any way. She brought disgrace on us all, your honor, and if ye’ll tell me what bore you want, and let me measure your hand and arm—”

“Where’s Toby Mallow?”

“He’s not here, sir—”

“Don’t I know he’s not here? Didn’t he have to flee to the colonies from the disgrace? Out there ever since, by God, while his wife’s bastard eats his substance!”

“But he’s doing well, your worship. I run this shop for ’m—”

“Almighty queer, he’d buy bread for his wife’s bastard. Are you sure he knows he’s here? I didn’t know.”

“Oh, he knows it well. A forgiving soul has my dear son, Toby Mallow; in that he’s like the gentry, please your honor. I have a letter from him here in the shop, commending the boy to a Christian life, if I could put my hand on’t.”

“What schooling are you giving the boy?”

My grandfather peered about like a cornered rat. “A little, please, sir. Not enough to make him look above his station. He’ll turn out a good gunsmith—”

Squire Blake laughed then. It was a loud, not a hearty laugh, an ugly imitation of some one’s hearty laugh he had once envied. “Blast me, if I don’t think he’s safe enough with you, Master Kidder. He’s got the devil in him, you know, and if you’ll not spare the rod—”

“You should look at his back, your worship. It fair makes me cringe—”

“He’ll need a few stripes for forgetting his manners out there in the street. I wasn’t harmed by it, but he’ll be harmed unless the lesson is rubbed in. Where’s your whip, Master Kidder?”

“My whip?” My grandfather’s voice almost failed and his eyes were like china marbles, but no soldier fleeing in battle, then suddenly turning to front the foe, ever rallied braver than my grandfather then. “Why, it’s gone from the nail. Ben, you knave—”

“Oh, I didn’t take it—”

My grandfather turned to Squire Blake. “I’ll settle with him, never fear,” he said, speaking with great energy. “My daughter’s bad blood crops out in him at times, though ’tis not his fault. Wait till we’ve settled about the pistol, please your worship, so ye won’t be vexed with his howls.”

“You can go ahead now, Master Kidder. I’m in the way of being his uncle, and I’ll put up with him blasting my ears, to be sure you’re bringing him up the way he should go.”

“Well, I’ll give him a taste—and save the rest till I can put my mind on’t. Ben”—and he turned to me with a grim face—“get me that ramrod, and bend over the bench.”

“Oh, Grand-dad, don’t do that—”

“Obey me at once, d’ye hear me? I’ll teach ye not to raise your cap to the gentleman.”

“Oh, not with him looking on—”

Squire Blake started to speak, but for once in his life, when gentry spoke, my grandfather raised his voice and drowned him out.

“Why shouldn’t he look on? Shouldn’t he know I’m raising ye right, to know what ye are and be humble to your betters?”

There seemed nothing left, and I would have shot myself if I could have seized a loaded pistol. But this was the only time, before or since, I’ve looked down that road! I was a boy, then, hardly fourteen. Only the promise of my future strength was in me, and the will to live and conquer only beginning to be forged. Many times since I’d have given much for the will to die.

Crying, I could not see my grandfather’s face. Otherwise I solemnly believe that, boy though I was, I would have understood what was going on, and been saved all pain save the flesh. His eyes would have spoken to mine as the eyes of animals speak to one another on the moors. Squire Blake would be watching like a hungry hound, but would not hear a word. Then I was led blind and unbelieving, to the bench, and five times the wooden ramrod descended, for I cannot say fell. Thereafter I need have little fear of ordinary pain.

On the fifth blow the rod broke, causing Squire Blake to laugh.

“Ye’ll settle with me for that, too,” my grandfather said, gasping. “Now go to your room, and wait.”

I stumbled out, too stricken to cry; and time passed, as it always will at last, and then my grandfather was leaning over the bed, trying to draw my gangling body into his arms. His face was sticky with tears and slobber, but it was heaven to have it pressed against mine, for I knew that he loved me, always.

“Will ye forgive me, lad?”

“Aye, but I don’t understand. To strike me in his sight—”

“Great God, why should I strike ye save in his sight, ye the beat of my heart?”

“You did it to please him?”

“Aye, to please him, but he won’t be so pleased at last, if I know my boy. He had to think I was a cruel master—or he’d find ye another.”

“But why did you say what you did? Oh, did you have to say it?”

“About my Bessie? She knew I didn’t mean it, Ben, and ye know it too. She’d want me to say it. What would words matter to her up there, if one hair of your head was saved? She’d write down on the book she was a whore, if ’twould help ye a whit.”

“Did he order the pistols?” My heart was beating and pounding in my ears.

“Why do ye ask, Ben Blake?”

“Couldn’t you make them so they’d blow up the first time he fires ’em?”

“Oh, Ben!”

“Blow back, not to the side or before, the whole charge in his eyes? A weak lock, and a strong closed chamber filled with five drams of powder and a two-ounce ball, and a little hole left to prime the charge, and to let light through so he’d not suspect too soon? ’Twould kill him dead. He’d be dead. Couldn’t you do that? I’d show you how.”

“Ben— Ben Blake!” He put his hand over my mouth. “Don’t talk so.”

“Couldn’t you do it? Think hard, Grand-dad!”

My grandfather rose and went to the window. For a space I saw glory strike his eyes; then it died away, and he shook his head.

“He’d give ’em to his poor gamekeepers to try first,” my grandfather said.

“I can’t think of anything else. ’Tis no use to pray that he dies, is it, Grand-dad?”

“Nay, that’s no better than making a waxen man to melt in the fire. None of them things work against the gentry. But ye can pray that Toby Mallow dies, in the Americas. I’ve prayed till my throat’s sore, without ary answer.”

“So he won’t come back? Is that what you mean, Grand-dad?”

“Aye, Ben Blake. So he won’t come back. He’s not gentry—as ye are, in the eyes of God—and maybe ’twill work on him.”

Yet my grandfather and I lived at peace in our Bristol cottage for three more years. I learned something about gunsmithery, but more about the ships in Bristol Harbor, most of them bringing sugar, although no sugar could sweeten their stinking holds, and all the vicars in England could not bless their voyages. They loaded in Africa to trade in the West Indies.

When I was sixteen, I joined the Methodist Society at Horse Fair. If I had kept on with it, God only knows how my life would have been changed. Instead, I found that to make Heaven’s port I must live humbly in the station in which God had chosen to place me, which I could not do with an angel at either elbow, so I soon went back to my docks and my narrow, crooked, crowded streets I loved so well. Be it so, I had heard John Wesley preach, an event that did not impress me so greatly at the time, although a few years later a female missionary swooned in my arms at the thought.

That year the beam was layed for the stout ship I was later to sail. What I mean by this fancy language is that I gained most of my stature and a fair share of my weight. I could no longer enter a six-foot doorway without bowing, or sit in a pretty chair without hearing it crackle and complain beneath me. I do not know how strong I was, for I would not fight the riffraff of the port—I must confess they never pressed me very hard—and the gentry that I saw bewhiles were tolerably civil. I do know that I could take a handful of the brown nuts called Brazils and make them crack one another.

It was late summer, and I was about seventeen years old, when Squire Blake visited us again. I was not in the shop when he called. Except for the accident of a broken gallus, causing me to go there for a bit of leather, I might not have seen him at all, or—what was far more important—he seen me.

Molly Shelton, the daughter of the wainwright who lived next door, called to me as I approached, and came fast as her bare feet could fly. Later I learned that my grandfather had set her on watch for me, not to suffer me to enter the shop. What followed was heaven’s reward for my modesty in her sight. I had never ceased to be modest with her, much to the disappointment of the hot-blooded minx, and was ashamed to have her see me holding up my breeches, so I rushed on. By my troth, the Devil could preach a sermon on it! To flee from the wench, I walked through the door almost into the arms of Squire Blake.

I was whistling. The blithe sound was cut off as though a blower had left his bellows. In the three years or so since I had seen that dark face, with its Roman nose and cleft chin and forehead framed with black curls, I had forgotten to hate it and had almost forgotten to fear it, and had day-dreamed him out of my life. Maybe I did not remember fully until I saw Grand-dad’s face.

“Back already, boy?” my grandfather began, his poor Adam’s apple jumping up and down his stringy neck, and his voice, trying so hard to be hearty, with a crack in it. “Why, ye finished the job quicker than I thought.”

“Aye, I’m back.” I had been on no errand, except the desire of my heart. Then I turned to Squire Blake and gave him my best bow. “Good day, your honor, and good health to you.” But I fear my voice was but little stronger than my grandfather’s, for the squire’s glistening eyes were going over me, feature by feature, muscle by muscle, and his countenance darkened the whiles.

“I see you’ve better manners since I was here last.”

“Thanks to you, your honor.”

I would like to say that the words came hard, but this chronicle must be honest as my memory and my blind spots will permit, and I slobbered in my eagerness to please him.

“Grown well, too, I see. Nearly tall as I—and I’m the tallest man in the parish. Master Kidder, he had something richer than brown bread and curds, to put that meat on his bones.”

“Lentils, your worship. No end fond of ’em, he is.” Lentils were cheap in Bristol that year.

“Prime beef, I’ll swear. Wiltshire mutton and bacon and pies. By God, Master Kidder, your shop must pay well. You take only half, you said?”

“A fair half, no more. Toby Mallow, in Virginia, is mightily pleased with the accounting. I have a letter from him, somewhere about—”

“Can you read letters?”

“I stumble over the words, and the boy tries to help me—”

“So he learned nothing at Master Chandler’s Grammar School. Now there’s a pity.” Squire Blake’s eyes were gleaming. “Or maybe he’s forgotten his lessons. No wonder, when the last time I was here, he’d forgot he attended the school.”

“Ye ’re a great one for a joke, Squire Blake.” My grandfather tried to smile with his starched lips, chuckle through his gasps, but I was too deep in my own fears to pity him, let alone to hate his tormentor.

Squire Blake slapped his boot with his riding crop. He looked on my grandfather as he must look on a mutton pie when he came in hungry from hunting. He looked at me as at the stag he hunted, escaping him yet, but tall-horned and ripe for his hounds.

“Well, ’tis not my concern,” he said. “We’ve completed our business, Master Kidder, and I’ll bid you goodby.”

“Thank ’ee, your worship, and good health to ye.”

“My health is tolerably good, thanks.” He said this as though it were a great, cruel joke on my grandfather. “As for you, Ben—you are my brother’s son, a bit irregular ’tis true, and there is always a place for you at Breetholm.” And greatly pleased within, he took himself off.

When I looked at my grandfather he had climbed to his high stool, beside his engraver’s bench, the perch he always took when his soul was oppressed. His silver-rimmed spectacles had slipped down on the end of his nose. I gazed at the three-day growth of stubble on his pointed chin, thinking that if he had shaved that morning, he might have confronted Squire Blake with better spirit. But my grandfather was always unlucky in his shaving.

“Gave me a fine order, he did,” my grandfather said. “A fowling piece with engraved lockplate and brass mounts. Maybe ’twas his only reason for coming here.”

“Never believe it.”

“Who does better work? Why shouldn’t he come to me, though it’s nigh two days in the saddle from Breetholm?”

“Why does he hate me, Grand-dad?”

“Why, he doesn’t hate ye, lad. Ye’ve never harmed him. Ye never can harm him. Here ye stand, keeping out of his way, learning the trade of a gunsmith, not costing him a penny—”

“Why is it? Tell me.”

“Why, blast me, Ben—because your name’s Ben Blake.” My grandfather scrambled down from his stool, and put his hands on my arms, and his hands were trembling. “Because ye have the blood, and he throws back like a broken breach to some long-dead swineherd. Because ye look like your father, and he like a farrier. Because he knows ’tis only your lack of a parson’s mumbling that makes him cock of the Breetholm walk, and your birth was far more blessed than them of his spindly daughter and his puny sons by his wedded wife, who lies in his great canopied bed, and hates every hair of his head. ’Fore God, what better reasons do ye want, Ben Blake?”

“ ’Tis hard to climb into another man’s heart and look out.” How often since have I tried to do this, in vain! “But what can he do to me?”

“He’s high, and I’m low. He’s a magistrate, and on any quibble, he may go to the court and have ye taken from me. But he’d raised a good ’un afore now, if he’d had a mind to it. And he won’t—I know he won’t—” My grandfather’s voice failed.

“Write to Toby Mallow?”

“Oh, did ye think of that, yourself, or did ye pick it out of my head, like a jackdaw picks corn from a dish?”

“But he won’t—will he? What good would it do him?”

“He asked me of Toby Mallow. Where was he in ’Giny, and I told him he’d lately moved his shop, and would let me know on the next boat, where to reach him. No, the squire’s satisfied to keep you here, out of his way. No, no, he won’t write Toby Mallow, no fear of that.”

But we were happy only six months more. If the poor did not learn to live from day to day, blind to the march of days beyond the next bend in the road, they would lie down and die from pure fright. Six months was the time needed for a letter to reach Virginia, and a man to collect his goods, and make passage home. Then we listened for every footstep on the threshold—I alone, and my grandfather alone—denied even the comfort of listening together, I know not why.

There were many ships in those days, some of them manned by crews from the colonies. I could watch those that sailed into Avonmouth, but there were Plymouth, and Portsmouth, and Southampton, and even London, where a Bristol-bound passenger might disembark. But a month passed, and another month, and because I was young, and the days were bright, and the first flush of my strength was upon me, I began to think our fears were all in vain.

Then, one fine afternoon in late spring, came Toby Mallow.

My grandfather was busy engraving Squire Blake’s gun, so I had answered the bell. Because I expected a big sunburned man, a commanding presence, the thought that this weazened pale-faced fellow might be Toby Mallow, never entered my head. He was dressed like a prosperous tradesman, bound for church. Without stretching my neck, I could lay my chin on his pow. I have always noticed men’s hands, which speak far clearer than their eyes and nearly as clear as their mouths, and I saw that this visitor wore a fine gold ring, as well as a chain and seal on his patterned waistcoat; still I thought he had come on some twopenny business with my grandfather. He gazed at me as though to speak, thought better of it, and brushed by.

Then I looked at my grandfather. If he had had a weak heart, he would have died there on his stool. I protest he had a strong heart, a true English heart. I saw him break, and then I saw him mend. It was as though he took himself in his two strong, delicate hands, and set his shoulders square, and pushed his jaw in place, and thrust his pale eyes back into their sockets, and smoothed his sagging face muscles, and stiffened his neck so that his head shot up. In no great hurry, it seemed, he climbed down from his stool and stood as tall as I had ever seen him.

“Why, Toby,” my grandfather said. “So ye’re back.”

“Aye, I’m back.”

“And looking well, too, I’ll be bound.”

“Very like, but do not feel so well.”

“Quite a surprise to see ye, that it is.”

“A great surprise, Amos Kidder, I don’t doubt.”

“A good trip, I’ll warrant. The seas are smooth and the wind fair this time of year, so sailors say.”

“But rough and stormy enough, Amos Kidder.”

“Why do ye call me that? Why not ‘papa,’ as ye used to call me?”

“You’re not my father. You are Bessie’s father, devil take me.”

“She’s been gone many years, Toby—dead many years. They say, and ’tis true, that time heals all wounds.”

“There be some that neither time nor medicine can cure, Amos Kidder. I too have been gone many years. Have you thought of that?”

“So ye have, Toby. And prospered greatly in the Americas, I’ll be bound.”

“Not so much but that I sold my shop there, and came home to stay.”

“And a good price for it, to be sure. Well, Toby, the trade here is not so good—”

“So I thought, from the accounts I had from you, but judging by the shop and the cottage, maybe I was mistaken.”

“What do ye mean by that, Toby Mallow?”

“We shall see. Yes, we shall see. What gun is that you work on now?”

“A fowling piece for Squire Blake.” My grandfather’s tone fell a little.

“A choleric man, Squire Blake, but good. He has always felt for me. I’m glad he’s come into his own. I shall deliver the gun myself, for I see ’tis ready.”

“Nigh ready, but the work not paid for yet.”

“You have an apprentice, I see. What’s his name?” And Toby Mallow tried to speak calmly.

“Ye may call him Ben.” My grandfather did speak calmly, with desperate calmness.

“I did not ask what to call him. I asked what was his name. This is my shop, Amos Kidder. Do not forget that. There’s a place for you here as long as I require you, and no longer, although I’d thought to keep you, all your days. What is the young man’s name, I say?”

“He has no name, by law, except Ben,” my grandfather answered, and no peer of the realm could speak better. “He’s my grandson.”

“So, then, ’tis true.”

“I don’t deny it, Toby.”

“What use to deny it, when I saw it in his face the instant I stepped in the door? Have I forgotten Godfrey Blake? Think you I could forget, if I’d stayed in America till doomsday?”

“If ye’ve not forgotten, then the sight of my grandson’s face need be no shock to ye, or pain. It was not his fault, Toby. What could I do, when he’s Bessie’s son?”

“What could you do, but bring him here to feed on my carcass! First the father steals my wife, and the son my substance. I can scarce believe it, Amos Kidder.”

“Yet ye were forewarned, I trow.”

“ ’Twas only by accident. I might yet be living at Norfolk in the Virginnies, making guns for the gentry, and never known, if Squire Blake had not asked me to learn of the new boring used for deer-rifles in the Americas. In the course of that letter, he praised me for my forgiveness and charity in letting my wife’s and his brother’s bastard eat at my table.”

“ ’Tis well to practice forgiveness and charity, Toby Mallow. Let not your left hand know what your right hand doeth.”

“By God, Amos Kidder, will you quote Scripture at me? ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’—that is all the Scripture I need know, and ‘visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children.’ When I practice charity, I want one of my hands to know it, I do vum!”

“I fed and clothed him out of my half of the profit.”

“I doubt not the books will show it, but there’s a new order here now. As for the young man—he may stay on awhile. I must journey to Marlborough delivering Squire Blake his gun on route. When I return—unless he shows himself smart to learn the trade, and diligent, and agreeable to his station, away he goes!”

The threat was so much milder than my grandfather had expected that he was shorn of speech. As for me—I had felt no fears for myself from the moment Toby Mallow began to speak, and was glad that my mother had not lain long with such a trivial man. I had expected to hear a nine-pounder, and had heard a popgun. Alas, I reckoned without my host. Not much more than a boy at the time, trustful of fortune and the future, I did not know what even the clergy’s strong consciences make them confess—that poor men’s rewards are in heaven, with strings on them even there, and not on this miserable earth. Or did I know that the most dangerous men are not burly fellows, who storm and clench their fists, but little white-faced wights, who move in the dark.

Toby Mallow had been gone hardly a week, and my grandfather’s eye was bright again, and we had barely begun to talk over, and in and out, the good or bad luck in prospect, when he came again. And now he came riding in a carriage like a gentleman, with outriders, for beside him in the seat was Squire Blake. And in the squire’s hand was a document with a waxen seal, new and red as though the parchment bled.

Toby Mallow busied and bustled and bowed Squire Blake into the shop. I would as lief see him rub his nose on the floor, as men do for Kings in Cathay. I knew then, and I know still, that this is an indecent world and a wicked time, wherein men may gain favor or avoid disaster by such antics unto their fellows; and there is no worse insult to the God who made us. To me it was given to see more clearly than many wiser, older men, either the poor or the rich, the high or the low, because I looked down and I looked up; I got a sight on it from two points, as surveyors locate a corner; except for a clergyman’s blessing, I was a squire; and except for unlawful seed sewn in my mother’s womb, I was nothing.

There was triumph in the countenance of Squire Blake, and spite on the ratty face of Toby Mallow. But fear was mixed with that spite. Toby would have gotten between Squire Blake’s legs, if he could, like a poodle at sight of a sheep dog; as it was, he moved from one side to the other, always in his shadow. I stood by the wall. My grandfather rose before them, very calm.

“Will your worship tell him, Squire Blake?” Toby asked.

“I think I’ll give you the pleasure, Master Mallow.”

“Well, Amos Kidder, ’tis good news in a way, though I fear you may take it ill, until you’ve had time to think it o’er. It was no way possible for your grandson to remain here. What would our customers think, to see a wronged husband and his wife’s bastard working at the same bench? It would be rubbing it in the faces of the good people hereabouts.”

“Ye may get to it, if ye please, Toby Mallow,” my grandfather said.

“It would drive away all our trade. If I could forgive and forget, which is asking more than human flesh can bear, the gentry want no such winking at the disgrace, and ’twould corrupt the morals of all the good wives in the neighborhood. Be is so, before I spoke a word to the boy of my decision, I made sure he’d be provided for, and though I want no thanks for’t, and expect none, how many men in my boots would ha’ done it?”

“And now will ye make an end to it, Toby Mallow?” my grandfather asked. “When I would hear sermons, I’ll go to the church.”

“You take it in damned bad part, Amos Kidder. But like it or lump it, Squire Blake, who is next o’ kin to the boy, bastard though he is, has generously offered—”

“Plague take me, Master Mallow, you are long-winded,” Squire Blake broke in. “The long and short of it is this. By law, I’m not responsible for the young man, but he’s my brother’s son, and I shan’t let him starve.”

“Your worship, he won’t starve,” my grandfather cried. “Him and me’ll go away, where Toby here will never see him again, and I’m a good gunsmith, ye know that yourself, and I’ll see he comes not to want. There’s no call on you, Squire Blake. Was it your fault your brother disgraced your name? Ye need not have a reminder of it, in your very house. Aye, Ben, I’ll get my tools, and ye your kit-bag—”

“Not so fast, Master Kidder. Do you see this paper?”

My grandfather leaned against the bench. “Aye.”

“ ’Tis an order from the court putting the custody of Godfrey Blake’s natural son in my care.”

“You couldn’t let him go if you wished to, now, could you, Squire Blake?” Toby Mallow asked.

“Aye, I’ve agreed to feed and clothe and work him, and teach him his place and station, and if he should run away, to notify the sheriff, so he’d be brought back in chains.”

It took more than the word “chains” to break down my grandfather. “For how long, Squire Blake?”

“Why, damn my eyes, till he’s eighteen.”

“Then the time’s up already. Ben was eighteen six months gone. To look at him, ye’d think he’s twenty-one.”

I tried to look old, and with the help of all the angels, I tried to look brave.

“None o’ that, Amos Kidder. ’Tis a bald-faced lie, and you know it.” It was Toby Mallow speaking now, or rather squeaking. “Are you trying to tell us that the brat was born less than six months after Bessie ran away? Why, she’d never laid eyes on Godfrey Blake, until the month before. Why, in that case, Ben’s my own son.”

“Oh, but they met often before ye knew of it, Toby. I knew of it, but never told ye. Look at him there. Is that fine strapper your son?”

“Hell and Fury!” Until now the scene had been queerly calm, the men speaking as though a new gun were being ordered, Toby’s voice like oil to hide his fears; but suddenly the air was powder needing only a spark to explode, and Toby turned white with rage, and Squire Blake turned red. “You throw it into my teeth, Amos Kidder? You let her cuckold me, and never told me? I’d’ve throttled the bitch while she slept.”

“Take care, Master Mallow.” It was I who had spoken. “I’ll kill you too dead to skin, if you use that name again.”

“Nay, you shouldn’t use it in front of the boy,” Squire Blake broke in. “He’s got sensibilities, the same as anyone. But you’re all up the tree. ’Tis true, that if the boy was born within nine months after your wife left your bed, you’d have to claim him as your son—that’s the law—but be thankful ’tis not so.”

“What do you say, then, Squire Blake?”

“I’ve had letters from the East India Company. The boy was born in India, with a good three months’ margin for bastardy. He may be close on eighteen, but I’ve counted him even seventeen, with a full year in my care. If you don’t think that’s time enough to season him, Master Kidder, I’ll get this court-order changed to read till he’s twenty-one.”

“Then seventeen he is,” my grandfather answered, “with a year in your charge.”

“ ’Tis a foolish thing to quarrel over, when he’s going to the richest squire in North Wiltshire,” Toby Mallow whined.

“Ye’re right at that, Toby Mallow,” my grandfather said, while Squire Blake smiled like a cat. “And I’ll be leaving too, to work in a shop in Exeter, where I’m wanted.”

“What need of that, Amos Kidder? You’re wanted here.” My grandfather was well-liked by the gentry, and was the best gunsmith in Bristol. “I’ll take back my words, if you’ll take yours.”

“ ’Tis agreed, then. Squire Blake, do ye mean to take the lad now?”

“That’s what I came for, Master Kidder.”

“Then, Ben, run to the house and get ready your things. I’ll be along in a minute, to tell ye goodby.”

I tried not to go too quickly out the door, but as soon as it closed behind me, I ran like a terrier. I would not stop to collect my clothes, I thought, only to get the fine silver watch that had belonged to my father, a Sheffield clasp-knife that was my pride, and five shillings my grandfather kept in an old teapot, then I would run away and hide until I could board a ship bound for the Indies. As I was taking the teapot off the shelf, my grandfather entered the kitchen.

He came to me, and put his arms around me, and I went weak and cold all over, and could scarce stand on my feet.

“Were ye running away, my boy?”

“Aye. Let me go.”

“ ’Twas my first thought, too, but ’tis no use. They’d search every ship.”

“I’ve friends on the water front. They’ll hide me.”

“Not where ye won’t be found. If ye must run, wait till the road’s clear, and no one knows what port to look for ye. But best to stand it awhile. ’Tis only a year.”

“Oh, only a year.”

“Not so bad, Ben. Twas bound to come in the end, but we’ve held it off till ye’ve got your growth and strength. A man, as God’s my judge. Not a boy, who can’t fight back.”

Then I felt the breath rush into my lungs, and with one hand I could have picked up my grandfather and set him on the shelf with the old teapot. The fear went out of me as the strength and the glory came in, and I was laughing and crying both at once, and my grandfather was crying, too.

“There’ll be fighting, then? The more, the better.”

“Not open fighting, Ben. There must be none o’ that, no matter what comes. The law is on his side. But all the time ye’ll be lying in wait. Ye’ll be learning how to do, the way gentry talk, and the way they act. Oh, ye’ll be a lamb around ’em, Ben, bowing and doffing your cap, and holding their horses for ’em. Ye’ll not cross him in ary word.”

“What if he beats me? I can’t stand it.”

“ ’Twill be only a blow or two, which ye can write down in the book. He’ll shame ye every way he can, and goad ye, for no man could hate another worse than he hates ye, but ye must never answer him, and if ye can make show that your spirit is broken, all the better. Ye’re strong enough in the body, Ben, and ’tis your head that must strengthen now.”

“I hear you, Grand-dad.”

“ ’Tis only a year, unless he can make a charge against ye, for debt or stealing or assault, and he’ll not do that as long as ye’re a plaything in his hands. Let him play, Ben Blake! If ye watch and wait, by God, ’twill be your turn before many years.”

“I’ll watch and wait, Grand-dad, but I won’t submit.”

“Why do ye say that, Benjamin? I’ve heard ye say it in your sleep, the very words, and it frights me.”

“I know not. Speak on.”

“Ye know Pale Tom, the carter. He goes by Breetholm every third week, and ye’ll speak to him alone. If there’s a ship that’ll give ye passage, he’ll tell ye, but ye’re not to run for the first ship or the second, only the last ship, when flesh and blood can endure no more. Do ye hear me, Ben Blake?”

“I hear you, Grand-dad.”

“The chance of being caught’ll be two to one against ye, at the best. So say goodby to me, Ben. My tongue is stuck.”

I could not say it, either. Some have loved me since, and some I have loved, but always there was something to gain or lose, if it were only the spring of a maid’s nipple against my palm, or the feel of my ear-lobe in her fingers. Giving and taking there was, in my other love affairs, but this was the pure juice of our hearts.

I was not to ride in the carriage. To give the devil his due, Squire Blake did not lead me on with false hopes of my future station, that of a servant of the meaner sort; or perhaps he had waited too long already to begin teaching me my place. It mattered not to me. One of his outriders was to remain in Bristol on some business, and Squire Blake told me I could use his horse.

“Can you ride?” he asked.

“Aye.”

At least I had made friends with horses. It had come about from my fondness for courtyards and stables, and for the mellow-voiced, steady-handed men who dwelt there. The footmen gave themselves airs—they were not real horse handlers and liked to imitate their betters—but I had never found such hearty fellowship and truth as among the hostlers and grooms and drivers, true Englishmen all, or such peace as in the dim stalls, with the big honest doorways showing as bright rectangles, and every hole under the eaves, and in the walls, shining like a star. Manure was perfume to me, I’ll be bound.

“Blast me, where did you learn?” Squire Blake demanded.

“I’ve mere picked it up, your worship.”

“Get on the mare, and we’ll see. No, mount the dun gelding, he’s the better beast. Paddy, get down off Buck, and hold stirrup for the thruster!”

He spoke to a heavy-chested, red-haired man with greenish eyes, Welch I took him to be. The man glanced quickly at his master, and his bad mouth made a straight hard line, like a crack in his broad face. The other outrider—Enoch Skinner was his name—looked gray and ill, except for some dark ocean of rebellion in his eyes. Enoch had started toward me with the white mare, and his lips moved, muttering something about the rein. I could not hear what he said.

“I’ll not need you to hold stirrup,” I told Paddy. And getting the reins and the dun’s mane in a good grip, I swung in the saddle.

By God, I knew then what the squire had been up to! There are bully-horses, just as there are bully-men, and Buck was one of them. Perhaps he hated the world for the lack of his stones, as I might learn to hate it for lack of a name; more like it was pure meanness, that base sort that lickspittles the great and tramples down the lowly. Unless I could master him, he would kill me, he thought.

Well, I was no horseman in the gentleman’s sense of the term, or a daffodil either. When he twisted, I pulled down his jaw till it was like to break off, and thank heaven the reins were new cowhide; and when he reared and plunged, I pressed my knees so hard against the saddle, that he could not dislodge me. It was sheer brute strength rather than horsemanship, but this fact was no comfort to Buck; and when Paddy handed me the crop, I laid it on not gently with my right hand.

Buck grew frantic as he began to realize I was his master, and turned and twisted and plunged like a crazy thing; but the glory of victory was rising in my heart, and I stuck there. Suddenly he stopped and began to tremble all over like a coward.

“I’m sorry to delay your worship, but the horse was fractious.”

A well-turned remark, I’ll be bound! I wish I had devised it, with malice aforethought, instead of spitting it out like a peach seed. Now it was Squire Blake’s turn to give a word of praise, by the sporting code of his class. Instead he fingered his riding crop, and I feared that broad, dark face.

He signaled for us to start. I doubt if he could trust himself to speak. My grandfather had not come into the street to see us off, but Toby Mallow was standing there, his face as pinched and blue as though it were winter weather. Molly Shelton was watching, too, her eyes big with wonder at my good riding, and perhaps with regret that I had not proved it on a pretty filly much nearer home. I could not forebear from waving my cap at them, as I rode away.

We were past Hanham, before Squire Blake spoke a word. “So you’re a good hand with horses, Ben,” he burst out.

I longed to tell him what my grandfather had told me, that my father’s hand on a horse was known in half Wiltshire. With his black eyes fixed on me, I refrained.

“Thank’ee, your worship.”

“Don’t thank me. If you’ve got it, you got it where you got your devilish pride, which for your own good must be broken out of you, as you broke the heart of Buck. Well, we’ll kill two birds with one stone. You’ll be under Paddy, in the stables.”

If he thought to gall me, he had duped himself. If he did not know I would rather clean stables than his chamber pots, or trim his blasted box, or grow flowers for his dame, he was a fool as well as a knave. Horses are clean beasts. I had feared he would put me in the dining hall, to watch him chew. ’Fore God, it would have fluxed me.

“Can you teach him to be a hostler, Paddy?”

“That will I.” Seeing the lay of the land, he gave his master a glance that was supposed to speak worlds.

“You’re not to be too rough on him, mind, if he shows himself willing to learn. Now, Ben, don’t be down-hearted. From hostler to carriage-driver is a big step, but a bright lad can take it. Many a groom moves up to the kennels, and from there a ready, smart, well-spoken fellow can become gamekeeper. That’s almost a gentleman’s job.”

You can’t hang poachers any more in England, thank God, I wanted to tell him—and the words I want to say and dare not, scorch my tongue—but I kept silent.

I cannot describe the journey from Hanham to Marshfield, where we stopped for the night. Other chroniclers would remember every stone of the road, the cozy cottages and the apple-cheeked farm wives, and the gracious blessings of poverty upon the field hands, but I remember only the mudholes, and a sick sheep by a fence. I do recall a trifling incident in the inn stables.

Paddy thought the time had come to begin his good work. I was slow and awkward, and when I unbuckled the wrong strap, he raised his big freckled hand and slapped me in the face before the hostler. Then he looked at me sideways to see how I took it, and indeed I seemed to take it wondrous well. This greatly emboldened him, until the hostler was out of hearing.

“Paddy, you slapped me just now.”

“What if I did? Give me some of your lip, and ye’ll get another.” He employed the Cardiff dialect, thicker even than our country folk’s, but I marked him well.

“No, don’t ever do it again. Other men would fight you for it. I’ll kill you for it.”

He went back a step. “None o’ that, now. Now, now, none o’ that.”

“Not at the time. I shan’t be hanged for killing a Welch manure-fly. I’ll wait for the right time and place. Tell Squire Blake, if you want. He’ll curse me and maybe beat me, but that won’t save you, if you put hand on my face again.”

“I was only trying to give ye a lesson about yon strap, so ye’d remember it, that’s all I was trying to do, as the master told me.”

“I’ll learn as quick as I can. I’ll work for you, and obey you, as long as you’re over me. I’ll even be friends with you, if you’ll show yourself worth it. Will you shake hands on it, or will you try to find out if I mean what I say?”

Paddy shook hands with me, and we made out well enough thereafter. Indeed, I became rather fond of the fellow before the end. He would horsewhip his own mother to please Squire Blake, but that was only a sign of what poverty and subservience can do to a freeborn man. Although his heart had been hardened by the times, more than once I heard it crack and pour out love, as he sang his wild Welch songs.

Whether I would have kept the threat is, as Cap’n Greenough used to say, an Indian of another skin. I certainly thought so at the time, with such intensity that Paddy thought so too, so it came to the same in the end.

By the village of Stempot, not far from the town of Wootton-Bassett, lay Breetholm Manor. The gatekeeper bowed himself down until I thought he would burst his navel, and his pop-eyed wife curtsied till I almost could hear her knee bones squeak under her gingham. A pretty custom, curtsying, I hear folk say. I can forgive the gentry for enforcing it, for vanity and love of power are human enough, but blast me if I can forgive the poor for thinking it virtuous.

“How is your young nephew, Mistress Wheatly?” Squire Blake asked.

“He’s up and around now, thank ’ee, your worship,” the woman answered with dreadful mirth, “and a fair good lesson he’s had, thanks to ’ee.”

When we had passed through the gate, Squire Blake saw fit to explain this conversation. “You’ll hear of it from the stable hands,” said he, “so I’ll tell you the straight of it. Her nephew, George, has been wayward. He’s fourteen stone of brawn and bone, and takes the girls’ eyes, and in his pride he left his cap on his head, when he saw me riding by. ’Twas no skin off my bones, mark you, but until a boy learns to respect his betters, he don’t respect himself.”

“What did your worship do?” For he was waiting for me to ask this.

“I got off my horse, and beat him to a bloody pulp with my two fists.”

I had seen Mistress Wheatly laugh. She had loved that great lump of a boy, had told in shocked tones but with shining eyes of his haymow loves, and had wept in the silence of the night over his battered flesh—and she had laughed! What did I do? Did I curse Squire Blake? No, God save my soul, I laughed too. My mouth took the same hideous shape, that horrid, twisted, narrow opening, that her mouth had taken.

I was sick with shame and mazed with wonder, as we rode under the great beeches of Squire Blake’s park, but my strength returned to me, and with it such heart-fire as I had never felt before, as I saw Breetholm Hall take shape among the trees.

If I had tried to write down what I saw, I could not have told then whether the house was marble or Portland stone, gabled or flat-roofed, fifteenth century style or eighteenth. Later I was to know it was a rather typical Jacobean manor house, with mullioned windows and a stone-tiled cupola, surrounded by yew trees and flower beds edged with box, and with wide lawns and a bowling green; but at the time I gazed upon it as a predestined sinner might gaze through a chink in St. Peter’s gate upon Paradise.

Out of it came an angel. If this be extravagant language, still it is inadequate to my sentiment, falling woefully short of my design, so I had best speak plainly, sticking to the solid facts as I had stuck on Buck’s back, trusting to your wits to unbosom me. What happened was that Squire Blake’s daughter came out of the mansion, and stood on the white steps to greet him.

I saw her plain. By accident or purpose, Squire Blake had left me a moment to hold the horses, while Paddy drove the carriage to the shed. I was scarcely ten steps away, and the light was fair. Would you have a description of her, as though she were a filly? Well, then, she stood about three inches over five feet. In build she was on the slender side, weighing scarcely more than eight stone, although I could not help but see, half-shamed though I was to look, that her breast was fair full for so young a maid, and later I discovered that her calves were fine and round. The shape of her face was oval. I vow I had never seen so sweet a mouth, her lips tender and rounded but not too full, and there was a little dimple in her chin, and how so lovely a mark could come of the great ugly cleft in Squire Blake’s chin, quite moidered me.

I have never lingered over noses, and indeed have skipped them as much as possible, perhaps because they are so reminiscent of the snouts of beasts, and at least they seemed to lack what I have liked to fancy was human dignity, even more than do ears that bristle forth from the noblest human head; but as noses go, the maid’s was beautiful. I mean, it was in harmony with her other features and the contours of her face, neither small like a button, nor so large that the prospect of kissing her was o’ershadowed by it, as would have been the case with some noses I have seen; in few, it was neat, inconspicuous, and shapely. And wide on either side of its upper bridge (for her profile had a suggestion of the Classic Greek, not dented in under the brows like most English profiles) were eyes blue in color, large, and brilliant.

I would that I could describe her forehead. King Solomon could have done so, for he described his sweetheart’s very belly ravishingly, although to save my life I could not picture “an heap of wheat set about with lilies.” I can say only that it was white, and round, and most lovely. And her throat was so slim and sweet, and her fine hair, with a wave in it rather than a curl, light brown in color.

Can you see her yet? Is she still no more than a pretty young girl of the manor, who gathered simples, could sew a fine seam, sing a little song and speak a few words of French? Then how can you believe I had fallen in love with her, I not passed eighteen, and she no more than fifteen, and at first sight?

Is love so hard to fall in? Nay, even for men like clods and women like cattle, it is a yawning pit under a greased footbridge. It is a house with a thousand beckoning entrances, but woefully few exits. If you like not one of its shapes, it will quickly take another, to snare and entice the heart. A blind man may love a silver-throated bird. A lame man may love a stout tree.

As she stood between Squire Blake and his wedded wife, who also had come to the steps to greet him, she proved her lawful birth. Her ale-brown hair was halfway in color between the jet curls of her father and the ashen tresses of her dam. She stood on the stone steps of Breetholm Hall. The late sunlight shone full upon her, revealing her hands and feet small, and her features delicate, from gentle breeding. Now I have ridden the facts down, may I speak in love’s language of my love? To my thinking, it was lonely as the seas I had crossed, forsaken, between India and Avonmouth, hot as the fire of an old gunsmith’s forge, stinging as an insult, and blinding as a boy’s tears, shed at night alone.

“I won’t submit,” I heard myself whisper, that strange battle cry that ever and again rose on my lips, although its meaning in this instance, I knew not.

“Ben?” Squire Blake called.

“Aye, your worship.” For I’d bow my head low enough, and bend my great knees, until my time came.

“This is your new mistress.” He gestured toward the tall, pale-haired woman, standing beside him.

“I hope you’ll be happy with us, Ben,” the lady said.

I did not want my heart to be softened by her. I wanted to hate her, because she was another obstacle between me and my desire. When she spoke so gently, and tried so hard to keep pity out of her voice—not through fear of Squire Blake, but because she knew how pity stabs and burns, pity all the deeper because of my great bone and brawn, and the blood mark of the Blakes all over me—I could feel my face draw up, fit to cry.

“Thank ’ee, my lady.”

“You see he knows his place, my dear,” Squire Blake said to his wife. “If he ever forgets it, let me know, for I have his welfare at heart.”

“I’ll not need to call on you, Arthur, I know.”

No, she was not afraid of him. I saw this with my inner eye, or smelled it like a dog, or heard it in the way she pronounced his name. If I had been a saint instead of a man, I could have almost felt pity for him for his rage at it, that he could trample down so many others and not his very chattel, whose body and soul were his lawful own. It was no use to beat her. There was nothing he could say to her, to make her gaze flinch from his.

This was second hell, I warrant. Perhaps it was only one deep chamber of his first, which was his holding Breetholm by trick of law, instead of birth and worth. But if he could not make her acknowledge his false claim, he had high hopes of wringing it out of me, on my knees.

“These are my sons,” said he: “Master Herbert and Master Alfred.”

I had hardly noticed the puny brats, one about twelve, the heir to Breetholm, and the other seven or eight. Now I gave them bows.

“And this is my daughter, Miss Isabel.”

The girl was looking at me, and I could hardly draw breath to speak.

“Good health to you, Miss Isabel.”

I heard her voice, then. If it were harsh as a jackdaw’s, I’d not have complained, and perhaps taken heart at the imperfection, but I deemed it pretty as the rest of her.

“Father, am I to call him Ben?” she asked dutifully. “I didn’t hear his surname.”

“He has none.”

“But I never heard—”

“You never heard of a stableboy with only one name? By law he can acquire one, not inherit one. If he’s a good lad, some day his name may be Ben Coachmen—or even Ben Warden.”

“Why, when I first saw him holding the horses, I thought he was kin to us.”

I was not sickened, or even abashed, only touched to the heart by her innocence. Tenderling that she was, how could she know in what fence corners and on what roadsides, the human seed is sewn?

I expected the squire to be angry. Instead he uttered his unsonorous laugh.

“Bless me, but you’re an observing Miss. But you must know sooner or later, and I’ll not speak behind a man’s back what I won’t say to his face.”

“He’s only a boy, Arthur,” his wife protested, “but speak on.”

“Maybe you’d rather the boy tell her himself?” Squire Blake had set his great jaw. “Damme, that might be the way of kindness. Ben, tell your young mistress who you are.”

“Aye, I’ll tell her. Miss Isabel, I am the son of your father’s brother, Godfrey Blake.” I spoke clearly enough, in that big silence, for my heart was burning.

“There, you see—” Then Mistress Blake interrupted her husband, and silenced him, although he spoke loud, and she spoke soft.

“You must let him tell the rest, Arthur, now you’ve appointed him the task,” she said. “Ben, my daughter has seldom, if ever, heard of your father. Will you tell her about him?”

“Why, he was the oldest son, and the heir to Breetholm,” I said, for the devil himself could not have stopped me then. “He had a merry heart and a handsome face, and was beloved by all the people, but most of all by Bessie, who was a lady by her own gifts. She returned his love, and for sake of it, ran away with him from her unworthy husband, and bore him a son.”

There was a brief silence, where Isabel looked bewildered, and Mistress Blake stood very white and still; then Squire Blake took his breath and spoke.

“What a talker he is! By God, he would make a good clergyman, if the laws permitted a bastard to wear the cloth. Well, now you have spoken so finely, Ben, see how well you can rub down the horses.” Then he turned on his heel and entered his great hall.

I knew that Isabel looked after me, if only in uneasy wonderment, as I turned away. In good enough fettle, I went to the stables, which with the kennels, the poultry run, the dairy, and the dovecot, lay beyond the kitchen garden. It was now after feeding time, and between then and dark I was being looked over by the other hands, a game that two could play at. They were all greatly excited by my coming. It was no little thing to see the son of their former young master, born on the wrong side of the blanket though he might be, brought lower than their lowest.

One or two of them thought I deserved it. These were the squire’s lickspittles, although they took their stand on the most pious and self-righteous grounds, which I have seen support most human meanness. If you break the law of God and Man—and the traditions of Old England were in the bargain—you must pay the penalty, said they—as though I had hopped of my own free will, like a jumping bean from Spanish America, from my father’s stones into his mistress’ womb. Then there was an old dairymaid, maid being a truthful name for this thin-shanked, dry-papped old body, who was shocked within an inch of her life to see a life-size bastard.

Mostly they were like other poor I had known, glad to like me if I would like them, requiring nothing of me but my humanness—as sheep in a flock ask nothing of one another but a nuzzle now and then and the smell of wool—joyful to help me out with one pence of their six when the rich would not give ten guineas of their thousand to a broken friend, but too troubled and hard-driven to think of me twice, when I was out of their sight. Finally, there were a couple of oldsters who had loved my father, one of them Purdy, the hostler. (I would like a more exact term than “love” for feelings of a servant for a kind, admirable master, but can not think it through.) These knew well that I was the rightful heir, yet when Purdy doffed his cap to me before he thought, he pretended it was just to scratch his head.

Indeed, all of them but one addressed me warily in one another’s presence. God knew I could not blame them; I was here for the squire to kick, and they did not want to catch disfavor from me. The only exception was another of the so-called dairymaids, as different from the scrawny St. Agnes as I am from a bishop, and her name was Tilly. Either the lass did not know my position, or did not care. At first blush—and I trow she had not blushed since she was thirteen—she set out to charm me. I wanted none of her, then—my head and heart were mazed with Isabel—but as she was a sleek young wench, with flaxen hair and a sparkling eye and a rosy, smiling mouth, I took it not amiss.

I was in haste to go to my straw in the carriage shed, to be alone with my thoughts of Isabel. It was no remissness on my part that in five minutes I was asleep—a child of nature, I had never been able to refrain from rest and victuals, regardless of the state of my mind and heart—and I dreamed of her full boldly. Then I was awakened by old Purdy. His toothless gums were scraping from excitement. A lady wished to speak to me, he whispered.

Reckoning he meant Tilly, I wondered why the gaffer was so flurried. Heaven knew I had small cause to be vain, but I had known the alleys of Bristol, where life is too hurried and hard for leisurely wooing, life that must prolong itself from one horizon to another of time no matter what vicars frown, a need beyond denying, a law beyond repeal; and if the man will not go, the woman must needs come to him. But when I marked Purdy’s white face, I knew it was no dairymaid waiting outside.

Still the thought did not enter my head that it might be Isabel. It could not, out of the kind of love I bore her. I did not know what kind it was, and only its seed was planted in my heart, but that seed would rot could I picture Isabel in the least impropriety, or even unconventionality, let alone her white flesh craving the touch of mine. By God, I would as lief cut off my hand, I thought.

So when I put on my outer garments, and went forth into the moonlight, I was as ignorant of what to expect as a dog on a journey. The lady was standing in the shadow of an oak tree, and when the pale light sifted through the branches, I recognized Mistress Blake.

“Ben?”

“Aye, m’lady.”

“This is your first night here, only your second away from home, and I couldn’t bear for you to have no hope at all.”

“Thank ’ee, m’lady.”

“I thought of you lying there all night, afraid and friendless—Godfrey’s son. Well, I want you to know I’m your friend. I’ll do everything I can to help you.”

Why I know not, for I had not brooded over my lot since I had seen Isabel, and brooding had always come hard to me, if anger easy, but my eyelids smarted, and then my tears flowed too fast to wink away. Because I was under or barely eighteen at the time, I was ashamed. Blast me, but I would be proud enough now, if my parched fountains would flow at so sweet and tender a thing.

“When you can’t stand it any more, and must try to escape, there’ll be money hidden for you, and clothes, and friends if I can find them.”

“But he’ll make you smart for it. Oh, I couldn’t stand it, my lady! I’ll stand anything, rather than let you come to harm.”

“I’m not afraid. I alone need not be. Don’t let that keep you from being afraid, Ben, sore afraid. I can’t warn you enough. You don’t know him, yet.”

Then I said a bold thing. It is hard to relate because it will seem so hard to believe by those who did not stand there, hiding in the tree shadow, to behold this woman with her lantern eyes, and me with my drowned eyes.

“Why will you do this for me, Mistress Blake? I pray that you tell me.”

“If my prayers had been answered, I’d have been your mother.”

She walked away quickly. My tears dried fast, for they were only tears, not Avon Water. When I had come out the shed door, I had no thought of running away, until I could bear Isabel before me on my saddle to some house as fine as Breetholm, but when I entered the door again, the prospect was so firmly lodged in my mind that it seemed a premonition of inevitable event, a refuge throughout long months to come.

Within a fortnight I understood Mistress Blake’s warning. Until then, the squire had done no worse than assign me the meanest tasks—I must begin at the bottom of the hostler’s trade, quoth he—and this troubled me not a whit. Then on the morning that the Shuttlecock Hunt met at Breetholm, I let his horse splash mud on his buckskin breeches. As he took his seat, he struck me across the face with his hunting-crop.

I knew then why Mistress Blake was afraid for me. It was not the sting of the lash, although punishments made for beasts hurt a man full hard. A man will not die of one red stripe on white, or of white on red, but for perhaps sixty seconds I stood in imminent danger of the hangman.

It happened there was a mattock leaning by a tree. The lash had hardly ceased to whistle, before I had visioned snatching up the tool, striking, and watching Squire Blake topple down, his head like a broken jar of raspberry jam. But his arm had hardly dropped to his side, before I was fighting myself, the two sides of me lined up in clean array, whether or not that vision would come true.