* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Spanning the Atlantic

Date of first publication: 1931

Author: Franklin Lawrence Babcock (1905-1960)

Date first posted: January 10, 2026

Date last updated: January 10, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260117

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

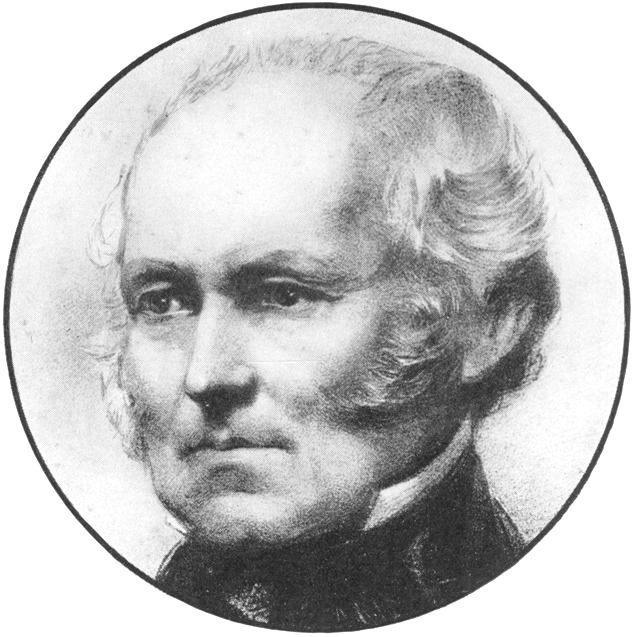

SAMUEL CUNARD

Copyright 1931 by Alfred A. Knopf · Inc.

All rights reserved—no part of this book may be reprinted in any form without permission in writing from the publisher

FIRST EDITION

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

IN THE interest of the general reader, the author has attempted to eliminate from the text all unnecessary technicalities and specifications. Foot-notes also have been avoided, with a view to subordinating details and minor controversial points to the purposes of a general narrative history of the Cunard Steamship Company. In compensation for these omissions is given a bibliographical list which will suggest further reference sources for such information.

The author wishes to express his gratitude for the many kindnesses extended to him during the preparation of the manuscript. Professor Archibald MacMechan of Halifax generously supplied the keys to some interesting biographical data. Mr. E. Francis Hyde, who for more than sixty years has crossed the ocean on Cunarders, gave him the benefit of his recollections and provided him with valuable material. Miss Alida M. Stephens, Assistant Librarian of Williams College, kindly extended him certain privileges in the use of books which he was unable to obtain elsewhere. Finally, special acknowledgments are due to the many officials of the Cunard Line, in the United States and Canada, who gave their patient co-operation and made available information otherwise inaccessible. The author assumes, however, full responsibility for all of his statements and conclusions, in which he has preserved complete independence of judgment.

F. Lawrence Babcock

| Preface | v | |

| I. | Samuel Cunard, Merchant | 3 |

| II. | The Development of the Steamship | 15 |

| III. | The Foundation of the Line | 36 |

| IV. | The Ocean Ferry | 50 |

| V. | Early Cunarders and Boston | 68 |

| VI. | Competition by Sail and Steam | 78 |

| VII. | The Struggle with the Collins Line | 91 |

| VIII. | The Great Migration | 107 |

| IX. | The End of the Paddle Wheelers | 124 |

| X. | Ocean Travel in the Seventies | 136 |

| XI. | The Mauve Decade | 155 |

| XII. | Twentieth Century Liners | 174 |

| XIII. | Cunarders in the World War | 188 |

| XIV. | Reconstruction and the Tourist Trade | 199 |

| XV. | The Tenth Decade | 210 |

| Bibliography | 219 | |

| Index | 228 | |

| Samuel Cunard | Frontispiece | |

| The Ships of Columbus | Facing Page 4 | |

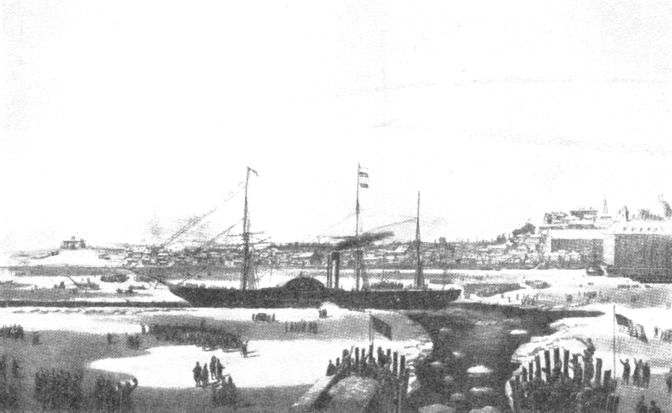

| Halifax Harbour in 1840 | 8 | |

| John Fitch’s Paddle Steamboat | 16 | |

| The clermont | 20 | |

| The Docks at Liverpool | 40 | |

| The britannia | 50 | |

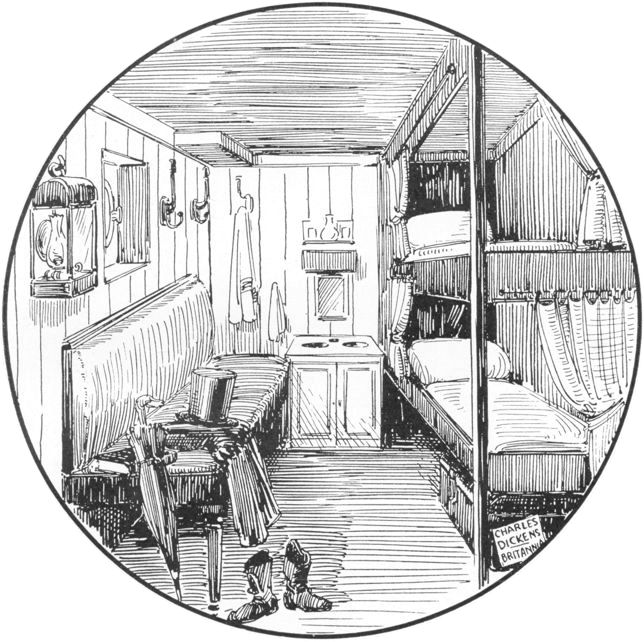

| Charles Dickens’s Cabin on the britannia | 54 | |

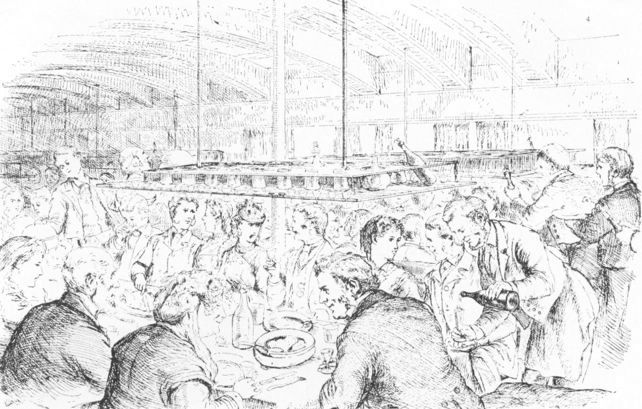

| Old-time Travel | 58 | |

| The First Day | ||

| The Second Day | ||

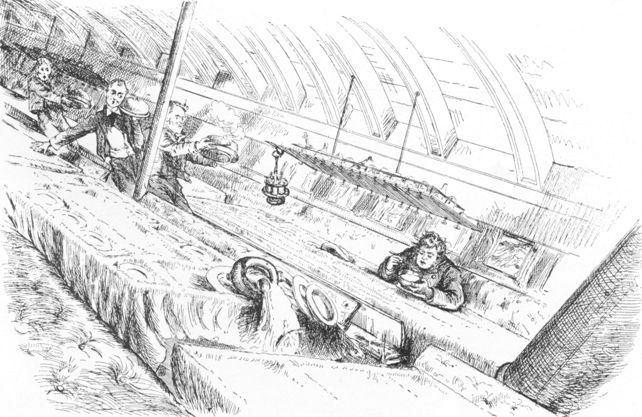

| The britannia in the ice | 72 | |

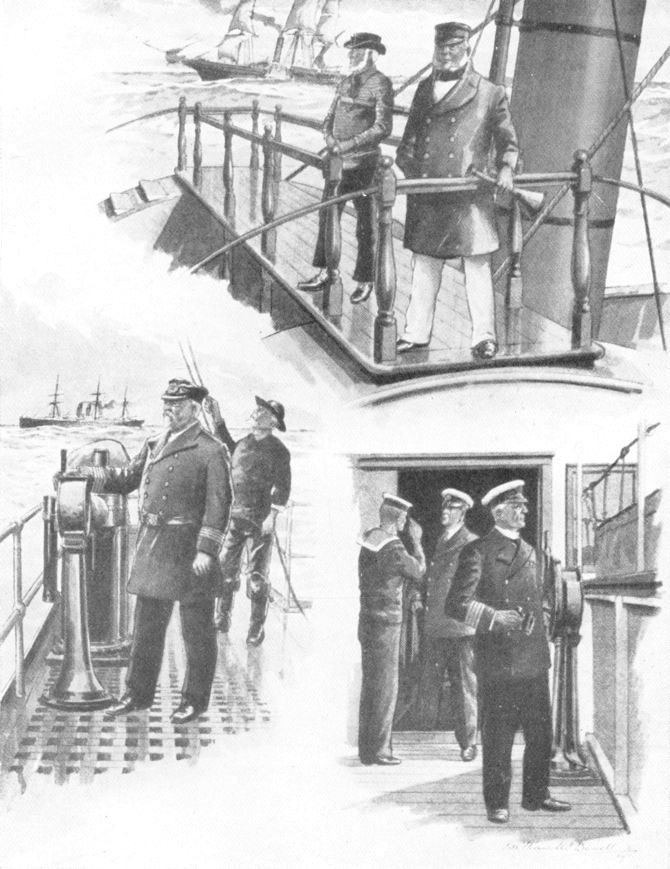

| Fashion in Captains’ dress | 78 | |

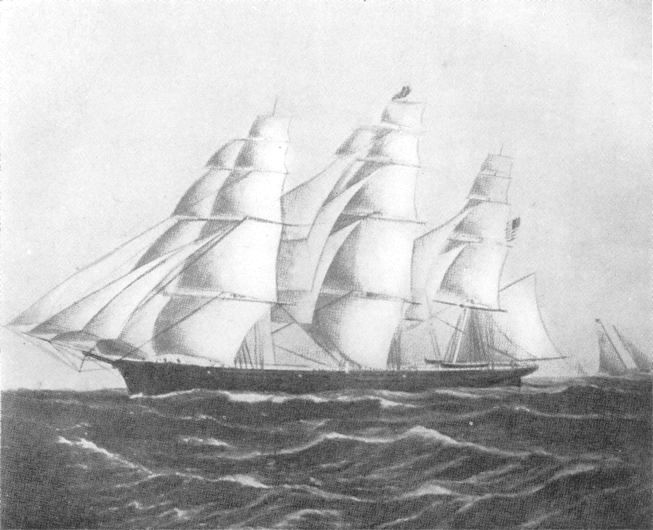

| The Clipper-ship westward ho | 88 | |

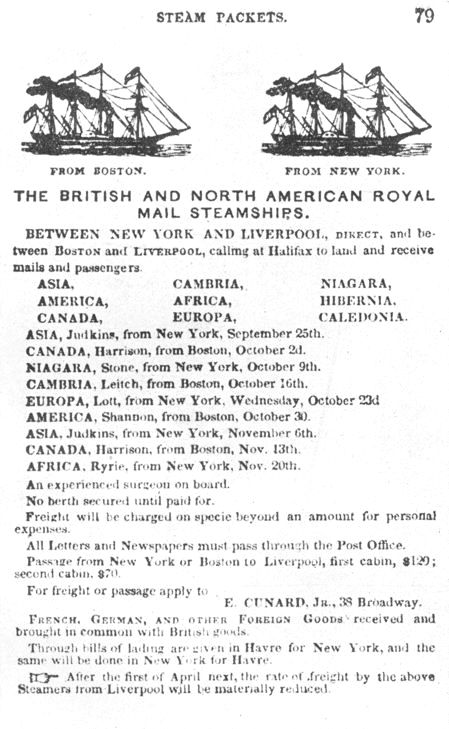

| An Early Cunard Advertisement | 92 | |

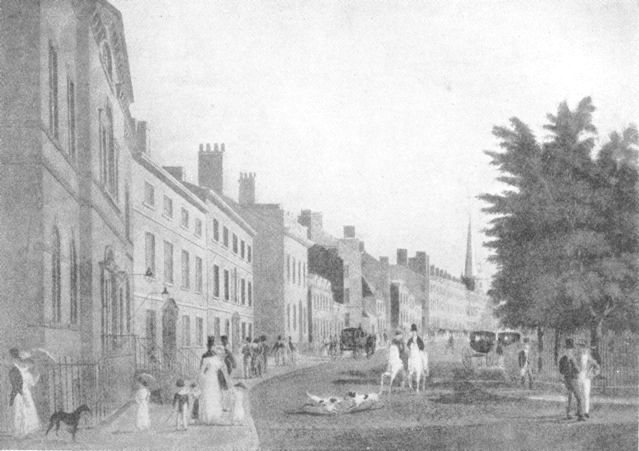

| The Broadway Site of the Present Cunard Building | 96 | |

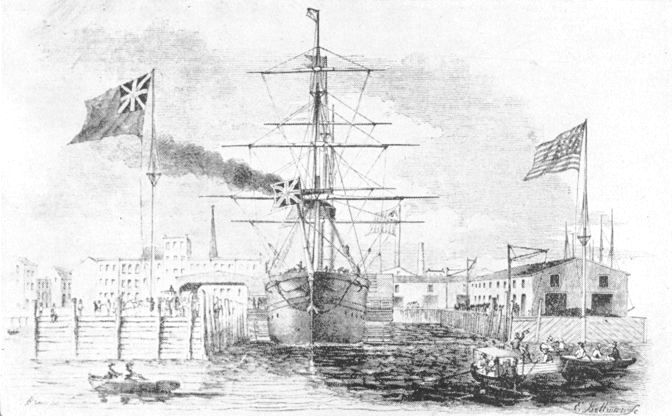

| The Jersey City Docks | 100 | |

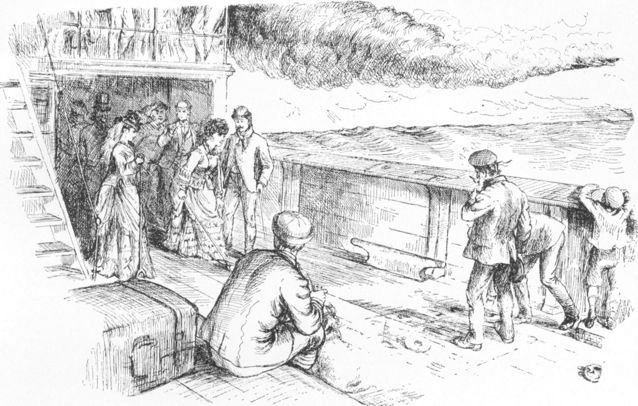

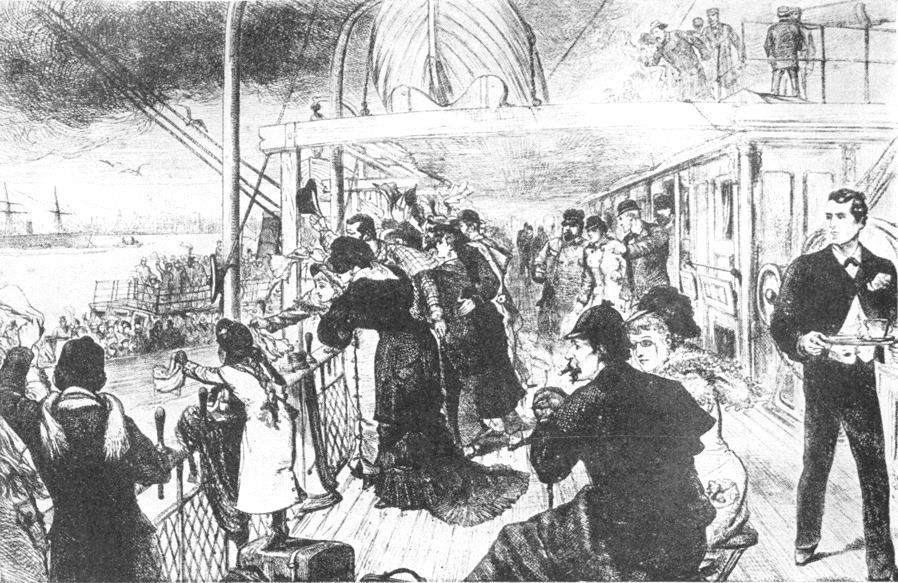

| Old-time Travel | 108 | |

| Shuffle-board | ||

| A Gale | ||

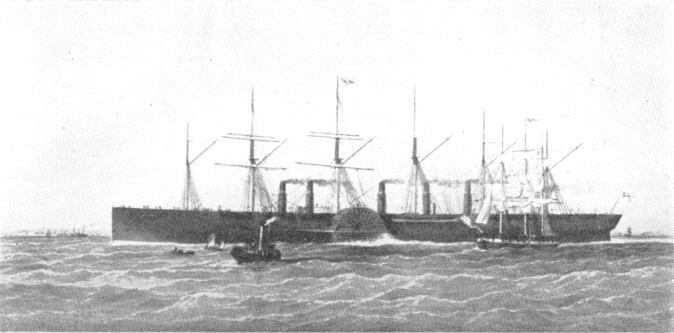

| The great eastern | 112 | |

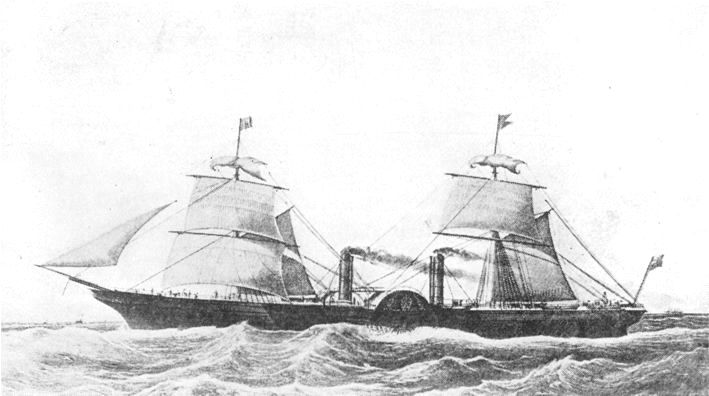

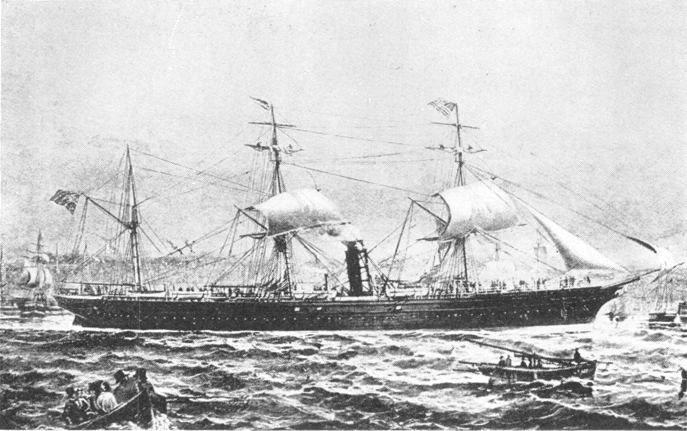

| The persia | 116 | |

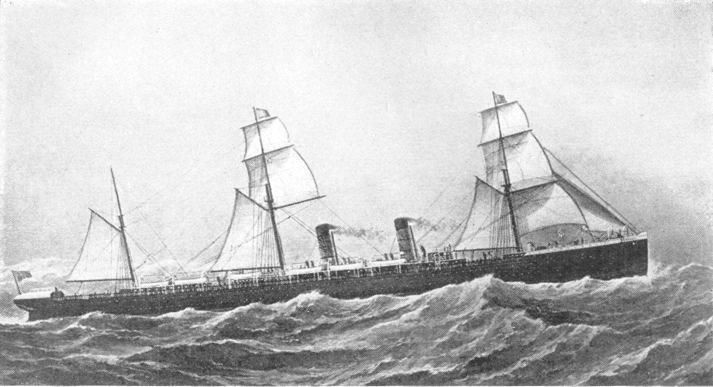

| The russia | 130 | |

| The bothnia’s Menu | 136 | |

| The servia | 148 | |

| A Deck Scene in the Eighties | 156 | |

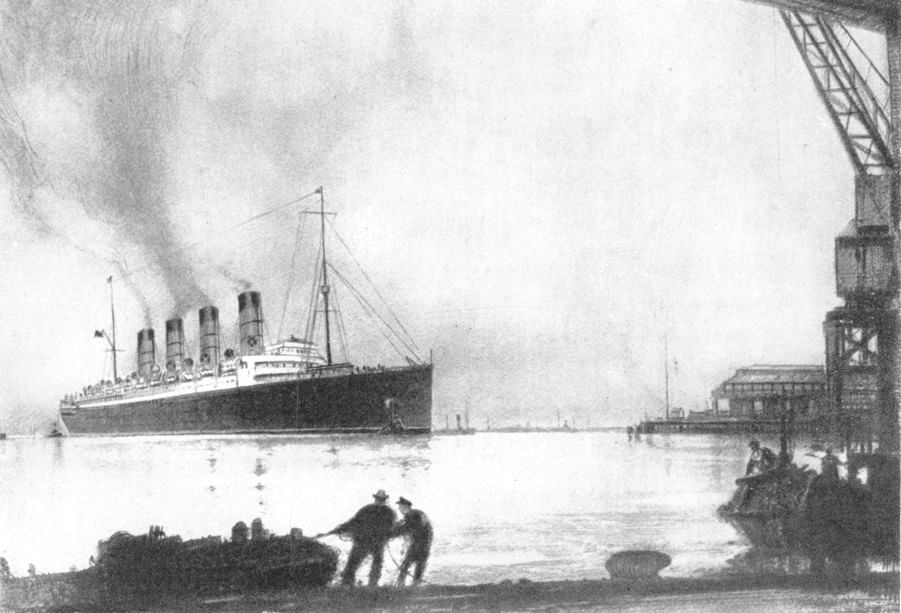

| The mauretania | 186 | |

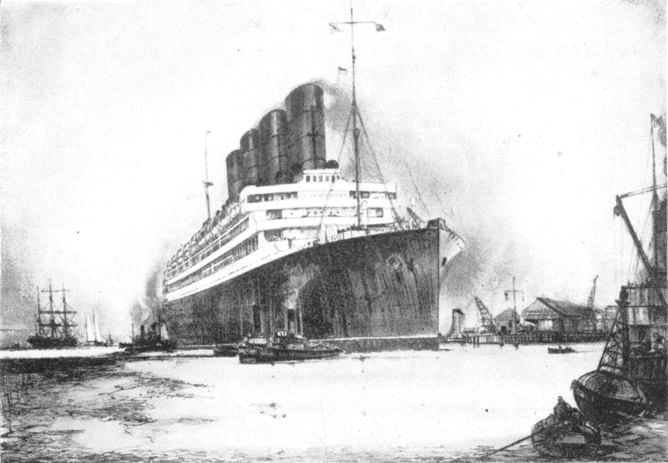

| The aquitania at Southampton | 190 | |

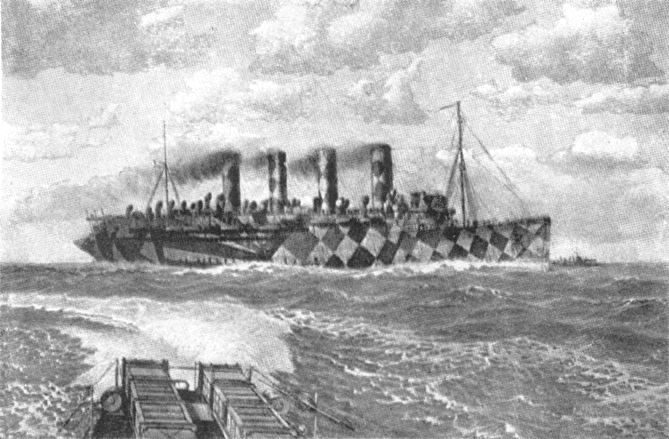

| The mauretania in Camouflage | 194 | |

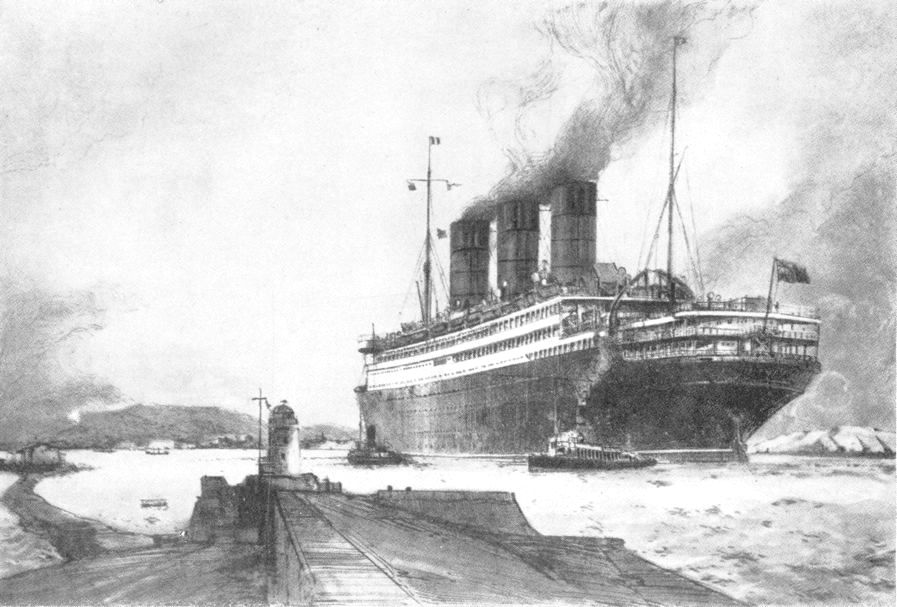

| The berengaria at Cherbourg | 202 | |

| “Number 534” as she will look against the Lower New York Sky-line—Scale Drawing of the britannia in the Foreground | 212 | |

SPANNING

THE ATLANTIC

IT SEEMS that into the epochal events of history are mingled the most remotely related factors—expansion of population and discovery of wealth; whim of royalty and conscience of artisan; rapacity of adventurer and courage of pioneer. Galaxies of accidents, tricks, coincidences and personalities miraculously appear to give these impulses common direction.

No combination of causes has a more astonishing variety than that which led to the discovery and colonization of America. The Mohammedans had cut off the eastward route to India just at the time that Europe was learning to dress in silks and to spice its meats. Gunpowder and the printing-press were invented at the moment when feudal states were beginning to draw themselves together into nations and to dream again of overseas empire. Luther and Calvin initiated the Reformation, while political philosophers were beginning to question the divine right of kings. And, finally, had it not been for the improvement of navigational instruments, Columbus’s feat of making an egg stand upright for the amusement of Queen Isabella of Spain would probably have been lost to history.

In the same way the establishment of steam navigation across the Atlantic and its growth to its present proportions have a history which, to be understandable, goes back to a period before the steamboats of John Fitch and Robert Fulton, before James Watt’s adaption of steam power, and before the American continent had revealed to Europe its great wealth and potential power. Perhaps Noah’s ark, the first known ship of the Mediterranean-Atlantic peoples, should be included, and the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria, the Greek discoveries in astronomy, and the invention of the compass. But the history of bridging the Atlantic properly begins with the origins of the man by whose influence the most dangerous and most travelled ocean was transformed from a perilous obstacle into a link between two continents. Not that the great movements of history can be attributed solely to the men who first happened to realize them, but the romantic impulse in human nature prefers to associate important events with illustrious names. And, for that matter, history could not have been made without leaders, even though leaders seem to have been made by history.

Out of the fermentation of ideas and impulses which the seventeenth century brought to our shores emerged the elements which gave us great men to fulfil our national destinies. From the gentry of Virginia sprang our first political genius; from Massachusetts came the founders of a world-wide commerce; New York gave to the New World its Flemish prodigality; and Pennsylvania taught our continent the sober ideals of peace and solvency.

THE SHIPS OF COLUMBUS

It was these same qualities of peacefulness and solid prosperity, brought to this country by the Quakers and Mennonites, that were instilled into the being of Samuel Cunard and translated by him into the matchless record of safety and dependability which has been realized by the line of steamships that bears his name. During the early decades of the Cunard Line, competitors’ ships, designed “to sweep the Cunarders off the sea,” offering more speed and greater luxury, challenged the existence of the enterprise. Yet, sailing over the same seas, in struggles for supremacy, and enduring the same perils, none survived with a career unblemished. Some lines gambled for huge stakes and, forgetting that each trip should be profitable, failed. Somewhere deep in the history of the Cunard Line lies a reason for the fact that for nearly seventy-five years, until the torpedoing of the Lusitania, it has contributed neither life nor letter to the great toll of loss the Atlantic trade has taken. Something in the Philadelphia Quaker ancestry of Samuel Cunard has endured through the two and a half centuries which separate the establishment of his family in this country and the modern Leviathans which fly the company’s emblem.

The first we know of the forbears of Samuel Cunard is that his great-great-grandfather, Thones Kunders, was a prosperous dyer in Crefeld, Germany, a town on the lower Rhine near the Dutch frontier. It is probable that his family came to Crefeld as refugees during the religious persecutions of the seventeenth century. Until Calvinists and Separatists fled from other German states, and Friends and Mennonites emigrated from Great Britain and from France, whence they were driven by the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Crefeld had been an obscure village. This influx of religious rebels brought new trades, with their new beliefs and the village became a town famous for the weaving and dyeing of linens and silks, for which it is still known. Finally, however, a huge grant of land by Charles II of England to William Penn opened a free country to the Quakers, who had been scattered over Europe, and gave them a leader to the New World. The Frankfort Company was formed to promote the emigration to America of the Friends who had gathered along the basin of the lower Rhine. In Crefeld thirteen families, thirty-three persons in all, were found that, preferring God’s wilderness to men’s wars, dared to exchange their properties and business for the unseen and uncleared acres in Penn’s Woods. The heads of these thirteen families were to draw lots for equal shares in six thousand acres which Penn had granted them. Among them was Thones Kunders, who, with his wife, Ellen, and three sons, embarked on the Concord July 24, 1683. After a passage of seventy-four days they landed at Philadelphia on October 6. Here, in addition to his share of the six thousand acres, Thones Kunders had for ten pounds bought from Lenant Arets, in Crefeld, a warrant for five hundred acres which had been purchased from William Penn.

These transactions were evidently profitable, for we next find him the owner of a house (in what is now Germantown) which must have been large for those days, as it was used by the Quakers as their place of worship before their first meeting-house was built. It was also well built, for some of its walls are said to be still standing as part of the house known as number 4537 Germantown Avenue. Besides working their new lands, the colonists continued in their trade of weaving and dyeing what an account of the Pennsylvania colonies describes as “very fine German lines such as no person of quality need be ashamed to wear.” By diligent industry and frugality Kunders evidently earned a considerable competence and won for himself a leading part in the community. He served as recorder of the courts, as juryman, and, when the town was incorporated, in 1691, as burgess. He is recorded as having contributed ten pounds and eight shillings towards the building of a stone meeting-house in 1705. And it is of special interest to note that he was one of the signers of the first protest against slavery of which there is record in America. Proud described him in his History of Pennsylvania as “an hospitable, well-disposed man, of an inoffensive life and good character.” In 1729, having spent forty-six years in America, he died, leaving a considerable property to be divided among his seven children, Cunrads (or Cunræds) Cunrads, Mathias Cunrads, and John Cunrads, who were born in Crefeld, and Henry Cunrad and three daughters, born in Germantown. Here it is curious to observe the fact that not only did the children of Thones use the name Cunrads, and variations of it, but he himself during his lifetime was sometimes referred to as Dennis Conrad. This may admit the possibility that the family originally came from Great Britain and that their name, having been Germanized, reverted to something like its original spelling during their early years in America. Nothing positive is known in support of this theory except the general belief that the Cunard family originally emigrated from Worcestershire or Wales in the early seventeenth century.

Henry, the sixth child of Thones Kunders, was born in Germantown on December 6, 1688, and on June 28, 1710, married Katherine Streepers, the daughter of another colonist from Crefeld. Shortly afterwards he bought, for £175, 220 acres and 110 perches of land in the township of Whitpain, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. The Quakers of Germantown recommended him and his wife to those of Whitpain as “both of a sober and honest conversation.” Here he established a home and evidently prospered, for he later acquired more land and, when he died, left a considerable estate to his seven sons, of whom Samuel, being the youngest, received only the modest “sume of Seventy Pounds.” This second generation born in Pennsylvania took, some of it, the name of Conrad, while others chose that of Cunard. Samuel, the son of Henry Cunrads, was known by the latter name, and it was his second son, Abraham, who, after the American Revolution, removed to Halifax, where was born Samuel Cunard, the founder of the Cunard Line. Abraham Cunard, father of Samuel, was the only descendant of Thones Kunders to cast his lot with the British Empire. Others rose to prominence in Philadelphia. Their pioneer blood must have contained a will to succeed tempered by the Quaker background of sober industry and fearless independence of thought.

Thus we come to Abraham Cunard, who, remaining loyal to King George III, effected the second, or probably the third, great change of residence in the history of his family. In 1780 he embarked for Halifax, the chief remaining British seaport on the Atlantic coast. He was a master carpenter by trade and easily found employment in the Dock Yard, which contributed to Nova Scotia’s mercantile fame. So finally the Cunard family looked seaward.

With a great-great-grandfather under whose roof William Penn had probably “sat in silence,” with three generations of forbears “of sober and honest conversation,” engaged in the handicrafts and in tilling the soil, and with a father who was a master carpenter, no one would have expected Samuel Cunard to become an irresponsible roustabout and spendthrift. But neither would one look to him for the originator of a daring, epochal enterprise, a diplomat in negotiation, or a charming figure in London society. His father had married in 1783, however, a Margaret Murphy who had fled to Halifax with a band of United Empire Loyalists from South Carolina. She, no doubt, brought her son the Gaelic imaginativeness which complemented his Quaker heritage of energy, method and perseverance.

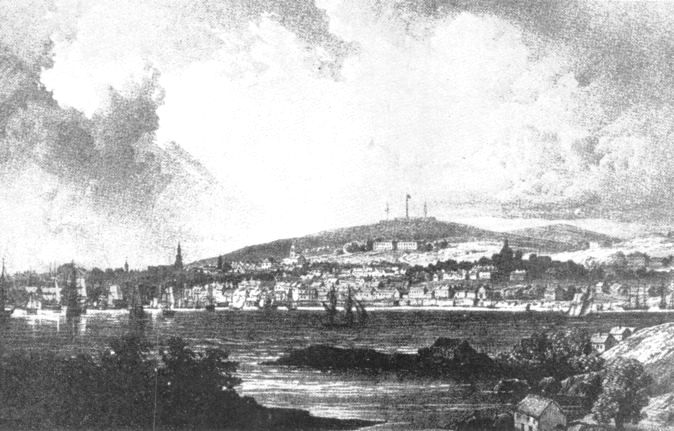

HALIFAX HARBOUR IN 1840

In a small house on New Brunswick Street, overlooking the then busy harbour of Halifax, Abraham Cunard’s second child, a son, was born on November 21, 1787. He was christened Samuel after his grandfather. Little is known of his boyhood and of his early education except the meagre accounts preserved in the local traditions of Halifax. Stories about his youth leave one the choice of supposing him either a prig or a dreamer with an overwhelming ambition. At the age at which other boys are apt to hope to grow up into firemen or policemen, young Sam knitted socks while driving the family cow home from the pasture, and “turned an honest penny” selling herbs he grew in his mother’s garden. While other boys might have spent their earnings in the acquisition of pocketable odds and ends, Samuel took his gains to auction and bought in bargains to sell again at a profit.

During the period of Samuel Cunard’s youth Halifax was a stimulating place to grow up in, filled with a variety of impulses to a boy’s imagination and challenges to a man’s mettle. First it was a haven for Tories emigrating from the United States. Then it began to expand as a great British seaport, a commercial entrepôt for trade between England, Canada, Newfoundland, and the West Indies. England’s needs, during the Napoleonic Wars, stimulated the great shipbuilding industry which made Nova Scotian sailing-ships famous and gave to the seas the “bluenose” boast of “wooden ships and iron men.” Crowded with garrisons, sailors, and a port’s cosmopolitan throngs, Halifax became both notorious and famous, and strongly conscious of its position in the Western hemisphere. It offered pleasure to those who sought it, and rewarded enterprise with wealth, and behind it lay the confidence and hope of a rich new continent and a pioneer people.

However slight may have been Samuel Cunard’s formal education, of which there is no sure record, he evidently had somehow schooled himself for exacting clerical duties; during his teens he obtained a post in the Civil Branch of the Engineering Establishment, a scientific service of the Army which must have required of its employees considerable personal attainments. Here, while drafting and making plans, he must have felt the throb of an empire struggling for its life, and when the town was illuminated to celebrate Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar he may have realized that across the Atlantic the New World had contributed to the history of the Old. When he left the government service he went to Boston and served in a ship-broker’s office. Soon he emerged from his apprenticeship in shipping and himself participated in the expansion of Nova Scotian commerce. Whatever were his earliest enterprises as a merchant, they must have been successful, for when he was but twenty-five years old he received from the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia a permit to trade with any port in the United States during the War of 1812. This bears witness to Samuel Cunard’s early success as a merchant, for it is rare to find such youthful owners of cargo in those days when fortunes were made more slowly. It is also notable as the indication of the bond which already existed between Canada and the United States. Long before the war between Great Britain and America there had been formulated the Anglo-American doctrine that war automatically prohibits all commercial intercourse between opposing belligerents. The fact that notwithstanding this the Lieutenant Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Nova Scotia authorized a Halifax merchant to buy cargoes of foodstuffs and naval stores in New England and promised his ship safe conduct, and the fact that the New England states, bitterly opposed to the war with England, evidently acquiesced, suggest that already the rancours produced by the American Revolution had been forgotten in a new sense of common interests in North America. It was no doubt the fruition of this tendency which eventually made the establishment by a Halifax merchant of a transatlantic steamship company “a landmark in the history of our country”—to use the phrase of Ezra Gannett, a famous Bostonian. Two years later Cunard came into further contact with the United States in the execution of a contract for the conveyance of His Majesty’s mails between Halifax, Newfoundland, Boston, and Bermuda. This important responsibility, undertaken at his own financial risk when he was but twenty-seven, was fulfilled to the entire satisfaction of the Government, and to his great credit.

In the meantime Samuel Cunard was winning for himself an important place in the commercial life of Halifax. Before the city was awake he would be at the wharves, buying cargoes from the United States and the West Indies. When Halifax was yawning to go to bed he was probably planning a larger career in terms of the two hemispheres. Some vision seems to have inspired the dogged progress of his twenties. His father, having for more than thirty years watched Halifax rise to its mercantile pre-eminence, must have seen a brighter future in commerce than in carpentering, and in his eldest son, Samuel, a suitable partner in the firm of Abraham Cunard and Son. Their joint enterprise, thus styled, was founded upon Samuel’s reputation for energy and reliability and aided by Abraham’s broad acquaintanceship, through his position in the Dock Yard, with the commercial and official circles of Halifax. In the space of twenty years it developed into a powerful organization controlling forty sailing-ships. Its first great success came from the purchase, at a bargain, of a prize ship, the White Oak. On July 2, 1813, they advertised “good accommodation” on her, sailing for London with the first convoy (for war still menaced lone merchantmen on the Atlantic). This marked Samuel Cunard’s entry into transatlantic shipping and was probably the shrewd stroke which thrust his name into history, for from that day his personal fortune rapidly increased until, in 1830, it was estimated at the then great sum of two hundred thousand pounds. In 1820 he bought his parents a huge farm on which to retire, changed the name of the firm to Samuel Cunard and Company, extended his shipping-business to whale-fishery, and set up his brothers, Joseph and Henry, in the timber and shipbuilding industry in New Brunswick. These expansions of his activities and his large purchases of land on Prince Edward Island, where he established ironworks, were undertaken despite the crisis which threatened the prosperity of Halifax that year. The depression which followed the close of the Napoleonic Wars and the removal of the Dock Yard to Bermuda, at the whim of an admiral, had already started the famous port on its long decline. Yet his company continued to grow, keeping the local shipyards busy supplying its fleet, and dispatching ships eastward to Newfoundland and England, southward to Boston and to the West Indies, and up the Saint Lawrence to Quebec and Montreal. His wharf became the focal point of the city’s commercial life.

To his own commercial enterprises Samuel Cunard added the agency for the Honourable East India Company, which he undertook in 1825 and which, through his initiative, brought to Halifax the first direct shipment of tea from Canton in the Countess of Harcourt. Two years later he also acquired the agency of the General Mining Association, which had purchased important coal-fields in Cape Breton. This organization, incidentally, eventually supplied the coal for the Cunard steamers calling at Halifax. (At the present day the original firm in Halifax of Samuel Cunard and Company, no longer connected with shipping, still deals in coal and advertises its wares with the inevitable slogan that it “answers the burning question.”)

During these years Cunard had shed some of the plodding austerity which seemed to dominate his boyhood. After his marriage to Susan Duffus, in 1815, he made a place for himself in the gay social life which was at its zenith in Halifax during his thirties. This in those days meant membership in the exclusive Sun Fire Company and a commission in the fashionable Second Halifax Regiment of Militia. As captain of the “dashing” flank company of the latter, known as the “Scarlet Runners,” he is described as “a bright, tight little man with keen eyes, firm lips and happy manners.” Later he became colonel of the regiment. Contemporary newspapers in Halifax are filled with more about the dinners and balls given by these genial groups than with accounts of fire or war. He became successively Fire Ward, Commissioner of Lighthouses, administrator of a bounty for the relief of destitute emigrants, and, finally, the Honourable Samuel Cunard, as member of the “Council of Twelve.” This was then the powerful chamber of the legislature, composed of the most influential merchants and officials. He was also one of the founders of Cogswell’s Bank, still important as the present Halifax Banking Company. In 1828 his wife died, leaving him charged with the education of two sons and seven daughters.

Cunard’s spectacular career in Halifax was marked by only one failure, which entailed serious loss to its promoters. For years enterprising spirits in Halifax had been considering a plan to build a Shubenacadie Canal to link the Bay of Fundy with the Atlantic. The project would facilitate the exploitation of resources from the interior and would prove useful in case of war. Although inspired by an age of canal-building in both Europe and America, the project was long deferred, owing to its great cost. It involved the engineering problems of digging an adequate passage fifty-three miles across the peninsula, and of overcoming the difficulties presented by the tides in the Bay of Fundy. These, being over fifty feet, are the highest in the world. Finally, in 1826, a company was incorporated to undertake the task, with Samuel Cunard as vice-president and as subscriber of a thousand pounds. At that date steam had made its power more felt on land than on the sea, and, like many such projects of the period, the Shubenacadie Canal was marked for failure by the potential competition of the railroad. Perhaps, however, this disaster had some influence upon the future of Samuel Cunard, as it taught the lesson of the revolution in transportation which steam was inevitably to introduce. Cunard was evidently not slow to learn from this experience, for in the year of the failure of the canal he also invested a thousand pounds in a company formed to operate steamboats between Halifax and Quebec. He came to the conclusion that “steamers properly built and manned might start and arrive at their destination with the punctuality of railroad trains on land.” He was evidently not yet ready, however, to coin his famous metaphor of “an ocean railway,” for as late as 1829 he wrote the following letter to Messrs. Ross and Primrose of Pictou, Nova Scotia, declining an offer to participate in a steamship enterprise:

Dear Sirs:—We have received your letter of the twenty-second instant. We are entirely unacquainted with the cost of a steamboat, and would not like to embark in a business of which we are quite ignorant. Must, therefore, decline taking any part in the one you propose getting up.

We remain yours, etc.

S. Cunard and Company

Halifax, October 28th, 1829

With Cunard’s rôle as the pioneer of continuous, safe, and dependable ocean steam navigation in mind, and his remarkable prophecy that “the day would surely come when an ocean steamer would be signalled from Citadel Hill every day in the year,” it is interesting to review the reasons for the disinclination evident in that letter. For what might have been recklessness in 1829 became daring foresight ten years later. Cunard’s ability to distinguish between the two was probably the chief reason for the establishment and survival of his “Atlantic ferry.”

Jonathan Hulls

With his patent skulls

Invented a machine

To go against wind with steam;

But, being an ass,

Couldn’t bring it to pass

And so was afraid to be seen.

NOTWITHSTANDING the quantities of controversial articles which have attempted to bestow upon this inventor or that the credit for originating steam navigation, it cannot be said to have been invented. Steam navigation grew out of centuries of experimentation with mechanical propulsion of boats. The Romans are said to have used the paddle-wheel, motivated by oxen; and the French, Spanish, and English devised substitutes for oar and sail long before steam power was discovered. Even steam was tried as early as 1543 in Barcelona by Blasco de Garay, in France by Papin in 1707, and in England by Jonathan Hulls in 1736. When James Watt finally produced a successful steam engine in 1769, however, several minds in different countries perceived a fresh possibility of releasing navigation from the caprices of the winds. Many of them applied to the problem ingenuities which, although failing through a lack of sufficient engineering knowledge, laid the foundations of future successes. In Great Britain were three notable experimenters, Miller, Taylor, and Symington, who built the Charlotte Dundas in 1802, a steam-driven craft, fifty-six feet long, capable of towing barges at over three knots. America, however, assumed the leading rôle in the development of the steamboat because, although it still lacked trained engineers comparable to those of Europe, its many rivers provided a great incentive to the improvement of water-borne commerce, and its pioneer condition was particularly conducive to experimentation. The credit for the final achievement of a practicable steamboat, popularly accorded to Robert Fulton, has often been questioned by the partisans of other inventors, among them James Rumsey, John Fitch, Colonel John Stevens, Nathan Read, Nicholas Roosevelt, Captain Samuel Morey, Elijah Ormsbee, Robert L. Stevens, and Robert R. Livingston. Among these John Fitch stands out as the one whose claim to glory rivals, if it does not exceed, Fulton’s, for not only did he experiment, with varying success, with the paddle-wheel and screw, as well as the mechanical oar, as means of applying steam to boat propulsion, but he actually operated a regular steam passenger service on the Delaware River seventeen years before the triumphal voyage of the Clermont up the Hudson. But his career was blighted by a series of misfortunes, of which not the least was the prematurity of the faith in the future of the steamship he expressed in a letter requesting a personal loan:

I am of the opinion that a vessel may be carried six, seven or eight miles an hour by the force of steam, and the larger the vessel the better it will answer, and am inclined to believe that it will answer for sea voyages as well as for inland navigation which would not only make the Mississippi as navigable as tide-water, but would make our vast territory on those waters an inconceivable fund in the treasury of the United States. Perhaps I should not be thought more extravagant than I already have been when I assert that six tons of machinery will act with as much force as ten tons of men, and should I suggest that the navigation between this country and Europe may be made so easy as shortly to make us the most popular empire on the earth, it probably at this time would make the whole very laughable.

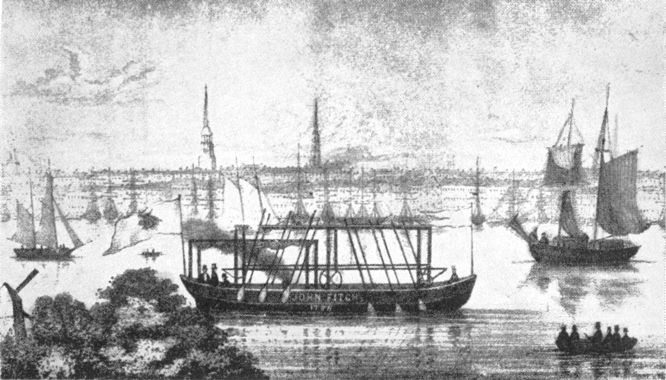

JOHN FITCH’S PADDLE STEAMBOAT

This was in 1786, and in 1792 experience had turned his belief into the conviction that “This, sir, will be the method of crossing the Atlantic, whether I bring it to perfection or not.”

Once, John Fitch came near to the success which would have fulfilled his dream and given him the place of honour Fulton was to occupy in his stead years afterwards. After the partial success of his Perseverance in 1787 he built the Pennsylvania, propelled by twelve oars, acting alternately on each side as paddles. She was intended to run on the Delaware between Philadelphia, Burlington, Bristol, Bordentown, and Trenton. On the day of her maiden voyage, June 16, 1790, Congress, which was then in session in Philadelphia, adjourned to witness the trial. Among those present was Benjamin Franklin, who was one of the shareholders in this enterprise. The boat amazed Fitch’s critics by a performance which fulfilled his every prediction, including the maintenance of a speed of eight miles an hour. After it had been tested by two months’ regular operation, steaming with passengers from both Philadelphia and Trenton three times a week, a correspondent of the New York Magazine reported that “Fitch’s steamboat really performs to a charm.” The support he won with this achievement was soon lost, however, when a larger boat he was building to sail on the Mississippi was destroyed by a storm. The meagre profits accruing from his enterprise were wiped out, and his financial backers, receiving no dividends from their investment, withdrew their assistance. Nevertheless, John Fitch persevered whenever he managed to acquire the means necessary, and he built other boats, including one driven by both a screw propeller and paddle-wheels, which he successfully tested on Collect Pond on lower Manhattan. His every mechanical triumph, however, was defeated by lack of funds, and he finally retired to an obscure village in Ohio and in 1798 ended his life by suicide. He requested that he be buried on the banks of the Ohio River, where he might hear “the music of the steamboats passing up the river.” Friends used to say of him without intentional malice: “Poor fellow, what a pity he is mad!”

There were others after John Fitch who believed in the future of the steamboat and who contributed to its final apotheosis, but it was Robert Fulton who realized with practical success the dreams of his predecessors. He possessed what the others had lacked—a well-disciplined knowledge of engineering and the gift of patient and precise experimentation where others had brilliantly blundered. Even as a boy in Pennsylvania he had devised paddle-wheels to be turned by a crank to propel the flat-boat in which he went fishing. Later he witnessed several of Fitch’s experiments in Collect Pond, and finally, while in England to study art, he made the acquaintance of Symington and others who were interested in the development of steam. When he went to France to continue his painting he must already have believed in steamboats, for it is related that Prince Talleyrand, after having sat next to Fulton at a dinner, expressed delight with his charming personality, but said that he was overwhelmed with sadness, for he could not but feel that he was mad. On another occasion he met the Duchesse de Gontaut, who was returning to revolutionary France under an assumed name, and soon asked her to marry him. When she replied that she already was married, he exclaimed: “Oh, what a pity, what a pity! I would make you rich. I am going to make my fortune in Paris. I have invented a steamboat and I am going to set the whole world going.”

In Paris he took up the study of higher mathematics and physics, and in 1800 he commenced to experiment with a submarine boat and with torpedoes for destroying warships. He also worked out plans and models for a steamboat. At that time France was fresh from victories on the Continent and in Egypt. Only England, with her matchless Navy and inaccessible situation, opposed Napoleon’s ambition for the hegemony of Europe. “A fair breeze and thirty-six hours” were all that the French thought necessary to place an army on British soil. Fulton wrote the First Consul a letter which, although somewhat over-confident, attracted the attention of the Government:

The sea which separates you from your enemy gives him an immense advantage over you. Aided in turn by the winds and the tempests, he defies you from his inaccessible island. I have it in my power to cause this obstacle which protects him to disappear. In spite of all his fleets, and in any weather, I can transport your armies to his territory in a few hours, without fear of the tempests and without depending upon the winds. I am prepared to submit my plans.

A commission was appointed to investigate his proposals. The result was the rejection of his plans for steamships, but he was given a grant of money to defray the cost of experiments with a plunging boat and torpedoes. This he developed with partial success, which was sufficient to cause grave anxiety in England. His progress was checked by the discontinuance of official support, which occurred partly because the Government thought it impossible to give naval commissions to the crews of submarines, as they would surely be hanged as pirates if they were captured.

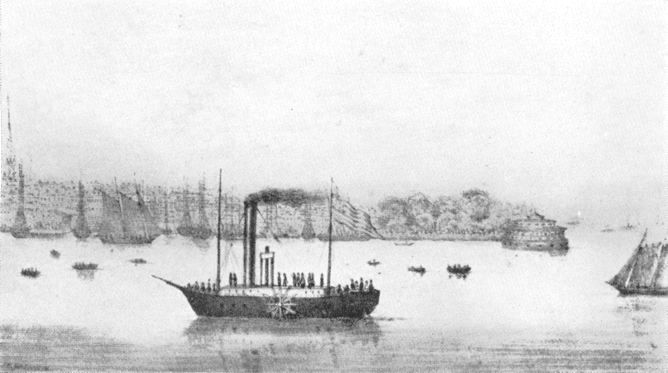

In the same year, 1801, Chancellor Robert R. Livingston was appointed American Minister to France. He had already paid for the construction of an unsuccessful steamship in New York and had procured from the State Legislature an exclusive grant to operate steamships on the Hudson River. Robert Fulton made the acquaintance of this far-sighted gentleman, who put sufficient sums at his disposal for the development of his plans for steamships. The result of their co-operation was that in 1803, after several failures which he carefully corrected by the construction and observation of working scale models, Fulton launched on the Seine a successful steamer. Her performance was sufficiently encouraging to induce Livingston to promise to pay for the construction of a larger boat to run on the Hudson River. He returned to America and built, at Charles Brown’s shipyard on the East River, a ship with a length of one hundred and thirty feet, sixteen and a half feet of beam, and a draft of seven feet. Her capacity was one hundred and sixty tons. Boulton and Watt of Birmingham, England, constructed her engines after Fulton’s specifications. The result was the Clermont, which startled the world by her voyage from New York to Albany and back, starting September 11, 1807, and making an average speed of over five miles an hour. This famous paddle-wheeler eclipsed her predecessors, and her years of successful service on the Hudson definitely established the future of commercial steam navigation. She was not so much an invention as she was a demonstration of the perfectibility of the less careful works of others. Fulton never claimed to have invented the steamboat, but he is entitled to the honour of producing the first ship which once and for all silenced the gibes of the sceptics.

THE Clermont

The following year was another landmark in the history of shipping. John Stevens had built in Hoboken a steamship he called the Phœnix. Unable to contest the monopoly which Fulton and Livingston had obtained on the Hudson, he decided to put her on the route John Fitch’s Pennsylvania had followed eighteen years before. She consequently made the first ocean voyage by steam on her run from New York to Philadelphia, where she was to engage in the river trade. This trip, made under stormy conditions, vindicated Fitch’s predictions that steamers would “answer for sea voyages as well as inland navigation.”

The conclusively happy union of financial and mechanical success represented by the Clermont was blessed with numerous offspring. Several river and coastwise steamers were established in America before the first successful passenger steamship in Europe—the Comet, built in 1812 for Henry Bell. She was a diminutive boat of twenty-four tons with a length of forty-two feet and an engine which developed all of four horse-power. Yet, plying the Scotch coast until 1820, when she was wrecked, she generated in England a steam-mindedness which eventually was to break the power of America’s splendid sailing fleet and to make England more than ever mistress of the seas.

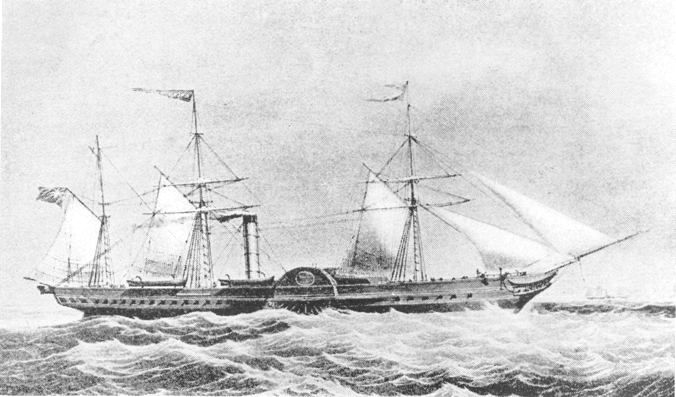

By 1819 the sea-voyage of the Phœnix had been followed by still more daring coastwise trips, and the feeling grew that Fitch’s misfortune was less madness than incredible foresight. Finally a three-masted full-rigged clipper-built ship of three hundred tons burthen was bought in New York by a Savannah firm, with a view to equipping her with a steam engine. Stephen Vail of Morristown constructed it, with a forty-inch cylinder carrying a pressure of twenty pounds. Her paddle-wheels were constructed with joints, so that they could be taken in when the engine was not running, to allow her free sailing. Under steam she had a speed of six miles an hour. She was built with a fuel capacity of only seventy-five tons of coal and twenty-five cords of wood. Captained by Moses Rogers, who had commanded the Phœnix, and navigated by John Stevens, she sailed to Savannah, for which port she was christened. Although her sailing from there to Liverpool was advertised in the local papers, the voyage seemed too chimerical to enlist any passengers, and she finally set out in ballast on May 25, 1819. Her owners had not destined her for transatlantic service but dispatched her in the hope of selling her to the Czar of Russia, who was a steamship enthusiast. She used her engines sparingly in order to save fuel for the finish, and the trip was uneventful until she sighted the Irish coast, on June 17. Her approach was marked by an episode which recalls the story of Sir Walter Raleigh’s servant who, when he first saw his master smoking, dutifully drenched him with water to keep him from burning up. The Savannah was sighted off Cape Clear by a King’s cutter. Seeing clouds of smoke rising from the American ship, which had steam up, the cutter followed in the hope of rescuing the crew of a burning ship. When the Savannah not only failed to stand by to receive assistance but, under bare poles, even outdistanced the government boat, the latter became both mystified and suspicious and fired several shots across her bows until she stopped her engines and received the visit of the amazed British captain. She finally steamed on to Liverpool, where she was greeted by a fleet of boats decked for a holiday, and crowds of enthusiastic and marvelling people. During her prolonged stop there, while her officers were being fêted, there was an amusing incident of bullying versus bluff. A boat from a British sloop of war came alongside of the Savannah, and one of its occupants asked of John Stevens, who was on deck: “Where is your master?” Stevens replied that he had no master. The Britisher demanded to see the captain; then, just as Moses Rogers was appearing from below, he shouted at Rogers: “Why do you wear that pennant, sir?” to which Rogers answered: “Because my country allows me to.” The Englishman replied: “My commander thinks it was done as an insult to him, and if you don’t take it down, he will send over a force to do it!” The American’s retort was to call to his crew to “get the hot water engines ready.” Picturing some infernal device to scald them all, the English boat pulled frantically out of danger, and Rogers had won the skirmish.

From Liverpool, with several passengers, the Savannah proceeded to St. Petersburg, stopping at Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Kronstadt. Among those aboard was Sir Thomas Graham, who presented Captain Rogers with a gold-lined tea-kettle, inscribed as follows:

Presented to Captain Moses Rogers of the Steam Ship Savannah (being the first steamship that had crossed the Atlantic) by Sir Thomas Graham, Lord Linedock, a passenger from Stockholm to St. Petersburg. September fifteenth, 1819.

In Russia the ship attracted great interest, especially on the part of the Czar, who already owned a river steamer for his private use. But, although he presented John Stevens with a handsome gold snuff-box, the Savannah did not find a purchaser who would offer the price her owners had hoped for. She returned to her home port that year, largely under sail, and her engines were removed. Reverted to a sailing-ship, she was wrecked off Long Island in 1822.

The voyage of the Savannah was generally considered more in the light of a novel experiment than as a revolution in ocean navigation. Her passage of twenty-five days was not particularly faster than the averages of the best sailing-packets; and the merely intermittent use of her paddles, rather than demonstrating their value, seemed to imply their relatively small importance. Although she was the first steamer to cross the Atlantic, it was not until eight years later that a vessel undertook the voyage under the continuous propulsion of steam power.

The next venture in the navigation of the Atlantic by steam was a more decisive success, which might have stimulated the earlier establishment of regular transatlantic steamers had it received more notice in England and America. But the fact that the Curaçao is even now largely ignored in the standard histories of steam navigation in circulation in English indicates that the voyages of this Dutch ship, remarkable though they were, did not encourage new enterprises in the two nations most interested in bridging the ocean. In fact there is no evidence that they were then even known of outside of Holland. Nevertheless, despite their isolated place in history, the several trips between Antwerp and the Dutch Island off South America made by the Curaçao gave Holland the distinction of having initiated practical transatlantic steamer navigation. She was a steamer of only 438 tons register, with three schooner-rigged masts, and paddle-wheels driven by independent engines. She was built at Bristol and at first called the Calpe, but was sold to the Netherlands Navy soon after her completion. Converted into a warship and under her new name, she sailed for South America in 1827, continually under steam, and during the next two years she made several passages across the Atlantic, carrying passengers, mails, and valuable freight. In 1830 the revolts in Belgium caused her withdrawal from commercial service and required her use as a man-of-war, in which capacity she continued until 1848.

The distinction which justly belongs to the Curaçao is generally credited to a ship whose career was, indeed, more picturesque and whose voyage across the Atlantic was destined to mark an epoch in the history of navigation. She was the Royal William, built in Quebec in 1830 and sailed from that port to London in 1833. In the Canadian House of Parliament at Ottawa there is a tablet which bears the following inscription:

In Honour of the Men

by whose enterprise, courage and skill

The Royal William

The First Vessel to Cross the Atlantic by Steam Power was wholly constructed in Canada and navigated to England in 1833. The pioneer of Those Mighty Fleets of Ocean Steamers by which Passengers and Merchandise of all Nations are now conveyed on every sea throughout the World.

Ordered by

The Parliament of Canada, June 13, 1894

She is described by one writer as “the first ship to cross the ocean by continuous steam power and the first war steamer.” Another calls her “the Herald of the Canadian Confederation and the pioneer of the Cunard fleet and of Ocean steam navigation.” Although some of these claims for her, made in the prevailing ignorance of the Curaçao’s precedence, are not strictly correct, the Royal William undoubtedly has the distinction of having convinced Great Britain and America of the practicability of transatlantic steamships. The cruise of the Savannah had stimulated no efforts to perfect marine steam engines, and until 1833 none of the energy devoted to the improvement of the sailing-ship was applied to the problem of attempting practical ocean steamers. In fact, the statements of Dr. Dionysius Lardner, a famous English scientist of the day, had had great circulation among the men interested in shipping and had served to convince them that, although coastwise steamers were already numerous, “men might as well project a voyage to the moon as to attempt steam navigation across the stormy Atlantic Ocean.” Besides those sceptics who agreed with Dr. Lardner that the plan would be “perfectly chimerical,” there were those who, being concerned with sailing-ships or believing the innovation of steam a potential menace to naval defence, supported the Duke of Wellington’s statement that “he would give no countenance to any schemes which had for their object a change in the established system of the country.” Just as Fulton’s Clermont had served to prove to England the practicability of steam propulsion twenty-four years before, it required the success of another ship from the New World to shake the inherent conservatisms represented by Wellington and Lardner.

Although the Royal William was not actually the “pioneer of the Cunard fleet,” she occupies an especially interesting place in its history as its forerunner, for the list of her stockholders is headed by the name of Samuel Cunard and includes those of his brothers, Joseph and Henry. The Quebec and Halifax Steam Navigation Company was formed to build her, in response to the Legislature’s offer of three thousand pounds to the first company which should operate between Quebec and Halifax a vessel of not less than five hundred tons burthen. Her keel was laid in Quebec in 1830, and on April 29, 1831, she was launched. This occasion attracted enthusiastic throngs of people, who saw in her the instrument of a closer relationship between Old Canada and the Maritime Provinces, and possibly of the eventual confederation of Canada. The port was decked with flags, military bands played, and the cannons of the fort saluted her. Lady Aylmer, the wife of the Governor General, christened her after the reigning sovereign, King William IV. She was rigged as a three-masted topsail schooner, with 830 tons displacement, length of deck 176 feet, a 44-foot beam including paddle-boxes, and a depth of hold of 17 feet 9 inches. She is described as of “a magnificent appearance, the prow and stern quarter galleries being particularly tasteful and the underdeck cabin fitted out with taste and elegance, containing some fifty berths, beside a splendid furnished parlor.” After the launching she was towed to Montreal, where she received engines of two hundred horse-power. Her total cost was sixteen thousand pounds, a great sum at that time.

In August, 1831, she opened her regular service from Quebec to Halifax, which latter destination was changed, during the fall, to Pictou. The Honourable Samuel Cunard took the opportunity of her calls at Halifax to study every particular of her sea qualities, speed, and fuel-consumption. Although she suffered damages, she proved both her seaworthiness and the reliability of her engines during the severe storms of that year, especially when she was called upon to rescue some people shipwrecked on Green Island.

In the spring of 1832 the Asiatic cholera, then rampant in Europe, burst out in Canada, especially in Quebec, where three thousand inhabitants were stricken. Business was paralysed, and when the Royal William came out of winter quarters her owners were threatened with failure. Finally, on June 16, she started on her first and only trip to Halifax that year, with eleven cabin and fifty-two steerage passengers. When she arrived at Miramichi three days later, the engineer dead and six of her crew showing choleraic symptoms, a panic seized that port, and the ship was quarantined. All passengers and the sick men were landed on Sheldrake Island. A boat manned by men armed with muskets guarded the ships and threatened to fire on anyone who might try to enter the ship’s boat, which Captain Nicholls had refused to surrender to them. The fireman finally went ashore in it to ask Mr. Cunard, her agent there, for sufficient coal to enable the Royal William to proceed on her journey, but the town’s magistrate not only refused to permit the request but seized the boat, after landing the man on the island. Finally, released from quarantine a month later, she sailed for Pictou, only to be turned back by an armed ship guarding the harbour. There was nothing to do but proceed to Halifax, where she was again quarantined. After an absence of fifty-five days she returned to Quebec with a few passengers and was laid up without a further attempt to run her that year. This season’s inactivity plunged the Quebec and Halifax Navigation Company deep into debt, and she was finally sold at a sheriff’s sale before a church door. Among those who joined to purchase her were some of her original shareholders who were willing to risk further investment in the hope that she eventually could be sold at a profit.

Under her new ownership she made a trip to Boston in June, 1833, touching at Gaspé, Pictou, and Halifax. There, as the first British steamer to enter the port, she received salutes from Fort Independence and was greeted at the wharfs with a military band playing God Save the King. Upon her return to Quebec after this triumphal voyage her owner determined to risk dispatching her to England for sale or charter. Cabin-passage for London was advertised for twenty dollars, exclusive of wines. She left early in August and stopped at Pictou to recoal and to await passengers from Prince Edward Island. Finally, captained by John McDougall, she sailed for London on August 18, with an extraordinary cargo consisting of 254 chaldrons (330 tons) of coal, a box of stuffed birds, and six spars, produce of Nova Scotia; one box, one trunk, household furniture, and a harp, all British; and seven passengers. Off Newfoundland she struck a gale which carried away the head of the foremast, disabled the starboard engine, and so battered her that the engineer reported she was sinking. She survived, however, and continued under steam until her crippled engine was repaired. Nineteen days from Pictou she sighted Land’s End and put in at Cowes for repairs. Despite a stormy voyage and serious delays, she finally completed her passage to London in twenty-five days from Pictou, having maintained steam all the way. Although it was not a triumph of speed, the successful voyage of the Royal William disproved the theory that a steamer could not carry enough fuel to propel her across the ocean—a notion which, had it not thus been disproved, might have delayed much longer the foundation of an “Atlantic ferry.” Thus it seems that two misfortunes—the failure of the Shubenacadie canal and the cholera epidemic in Quebec—were linked to produce a blessing. These two lessons in steam helped to make Samuel Cunard the engineer for an ocean bridge.

Ships seem to be ruled by curious destinies, however, and the St. Lawrence passenger ship ended her historic career as a Spanish battleship. Soon after her arrival in London she was sold for ten thousand pounds to a shipowner who chartered her to the Portuguese Government to carry Dom Pedro’s troops. Later she returned to London with invalided soldiers, and finally, still under the command of Captain McDougall, she was sold to the Spanish Navy and renamed the Isabel Segunda. As the flagship of Commodore Henry’s British auxiliary squadron employed against Dom Carlos, she fired the first hostile shot in the history of steamship warfare, in support of the British legion opposing the Carlists along the Bay of San Sebastian. Shortly afterwards, while she was laid up for repairs at Bordeaux, it was found that her timbers were decayed beyond repair, and the hull became a coal-hulk, while her engines were installed in a new Spanish man-of-war of the same name. In 1860 the new Isabel Segunda was wrecked in a storm off the coast of Algeria, and her Montreal-made engines, their purpose fulfilled, came to rest in the Mediterranean.

Up to this point the New World had led in the development of steam navigation, from the rudimentary successes of John Fitch to the successful crossing of the Royal William. This was a natural consequence of the fact that while mechanical ingenuity was absorbed in Great Britain by her growing manufactures, in America its most fruitful application was in the development of inland resources through the improved navigation of our great rivers. The early steamships were at a relatively greater advantage over sailing-vessels in inland waters. While river and coastal steamers were rapidly being developed in America, the fast sailing-ships of New York and New England were breaking records for speed on every ocean. The most glorious chapter of American sea-borne commerce was written by the sailing-ships between the years which saw Fulton’s success with steam and the final collapse of the clipper-ships, about 1860.

Great Britain, on the other hand, was quick to perceive the importance of the American invention and of the Canadian demonstration of its applicability to transatlantic travel. Although Boston merchants had discussed such projects as early as 1825, and Samuel Cunard was revolving the scheme in his mind, it was Bristol which built the first steamer intended for regular passenger service to America. The financial crisis in England of 1837 provided a powerful incentive, for it was believed that many of the substantial firms which failed might have survived the panic had remittances from America not been delayed by the prevailing easterly winds. This resulted in a strong pressure upon commercial interests, which hitherto had been apathetic towards steam navigation, to lend it their active support, in the desperate hope of accelerating the processes of international finance. Junius Smith, an American, having failed to muster sufficient support in his native country, had gone to England in 1832 in the hope of instituting a transatlantic steamship service. He was finally successful in organizing the British and American Steam Navigation Company, which ordered of Messrs. Curling and Young, of Limehouse, a ship of 1,700 tons burthen, to be engined by a Glasgow firm and to be named the British Queen. Her construction was seriously delayed by the failure of the engineering firm, and she was not launched until the Great Western of Bristol and the Sirius had already made passages across to New York and back. The former was built by Mr. Patterson of Bristol for the Great Western Steamship Company, which was formed to supplement the Great Western Railway by a transatlantic steam packet-ship. She was completed in 1837 and sailed for New York on April 7 of the following year, commanded by Lieutenant Hoskins, R.N. The passage was accomplished in fifteen days, with five days’ coal-supply left in her bunkers. Although, to their amazement, the passengers and crew of the Great Western found that another British steamer had arrived in New York just twelve hours before them, they received a frenzied ovation. Twenty-six salutes were fired from the harbour guns, and a fleet of river steamers and tugs came out to greet her. New York had not shown such excitement since the War of 1812. This time England was not the enemy, but the benefactress, the bearer “of all that relates to the communication of intelligence, to the spread of literature, and to the certainty and convenience of travelling.” Even then New York dailies were avid for foreign news, and the people had a sort of nostalgia for the Europe their forefathers had left behind.

The other ship which had arrived from Great Britain was the Sirius, which had sailed from Cork four days earlier than the departure of the Great Western. This was a small ship of only 703 gross tons, which had served on the Irish coast until she was chartered by the British and American Steam Navigation Company to take the place of the delayed British Queen. The impatience of the promoters had led to the hasty departure of the Sirius on April 4. Her voyage was four days slower than that of the Great Western, although she followed a shorter but much more adventurous route. Like Columbus, her captain was obliged to quell a mutinous crew, which, thinking the ship would never succeed in her crossing, demanded that she turn back. Although its weight nearly swamped her, the 450 tons of coal she carried were insufficient, so that she had to burn some of her spars for fuel during the last part of her voyage. Nevertheless, her passage had marked another step in the progress of steam navigation, and during the twelve hours before the Great Western appeared she held the record for crossing.

Both vessels returned to their ports with passengers, the Great Western making an eastward passage of fourteen and a half days. Passage on the Sirius cost $140, including wines and provisions, in the first cabin, and $80 in second cabin. The Great Western charged thirty guineas for a first-class passage, or fifty for a state-room reserved for one person. These steamers were followed by others in the same year. The Atlantic Steamship Company chartered a vessel named after the Royal William and ran her between Liverpool and New York for several trips. She was the first steamer divided by iron bulkheads into watertight compartments. The same company replaced her late that year with the Liverpool, which was nearly the size of the Great Western, but not so fast. In the following year the British Queen, with her engines finally completed by Robert Napier of Glasgow, was launched. She was not only the largest ship afloat, of 1,863 tons burthen, deck length of 245 feet, and 500 indicated horse-power, but she was equipped with unprecedented luxury, possessing shower-baths and a smoking-room. She made a few trips from Cork to New York, but failed to realize the speed expected and was finally sold to the British Government. The Great Western still easily held the best record for speed, cutting down her passage-time to twelve days and ten hours eastward and to thirteen days and three hours westward. The nine-per-cent profits she earned during her first year in service and her comparative regularity definitely established the superiority of steam over sail for transatlantic passenger service.

In the meantime Samuel Cunard had been receiving His Majesty’s mails from Falmouth in slow sailing-ships, popularly known as “coffin brigs,” and conveying them in his own schooners to and from Halifax to Newfoundland, Boston, and Bermuda. The numerous disasters which overtook these ten-gun brigs during the six or eight weeks required for their voyages from England and the irregularities they imposed upon the shipment of mails became more and more galling as Cunard’s far-flung business relations increased. Since his participation in the Royal William he was no longer “entirely unacquainted” with the steamship business; in fact he had become financially interested in coastal steamers. He discussed the project of a regular transatlantic mail service by steam several years before the Great Western entered the passenger trade, but the capital to build several large steamers for the purpose was forthcoming neither in Halifax nor in Boston. Both ports were improving their famous sailing-packets, and their surplus profits were being absorbed by the creation of new industries.

The first step towards the realization of Cunard’s plans came about through a providential coincidence. Two of his most illustrious fellow-townsmen, Joseph Howe and Sir Thomas Chandler Haliburton, the Nova Scotian Mark Twain, better known as Sam Slick, were bound for England on the brig Tyrian in April, 1838, just at the time that the steamer Sirius was returning from her first trip to New York. One of the passengers describes in a letter an incident which, indirectly, had much to do with the foundation of the Cunard Line.

A moment full of excitement . . . when, to our astonishment, we first saw the great ship Sirius steaming down directly in the wake of the Tyrian. She was the first steamer, I believe, that ever crossed the Atlantic for New York, and was then on the way back to England. You will, I dare say, recollect the prompt decision of Commander Jennings (of the Tyrian) to carry the mail bags on board the steamer, and our equally prompt decision not to quit our sailing craft, commanded as she was by so kind and excellent an officer; and the trembling anxiety with which we all watched mail bag after mail bag hoisted up the deep waist of the Tyrian; then lowered in the small boat below—tossed about between the vessels, and finally all safely placed on board the Sirius.

Howe visited the Sirius and “took a glass of champagne with the Captain.” He was particularly impressed with the relative luxury and spaciousness of the steamer, and when he saw her finally leave the Tyrian behind to await a better wind he agreed with his fellow-passenger that “they should bestir themselves, and not allow, without a struggle, British mails and British passengers thus to be taken past their very doors.” These Haligonians decided to discuss the matter of a steamship service to Halifax with the Colonial Secretary. Upon their arrival in England Howe and Haliburton joined two acquaintances from New Brunswick in addressing a letter to Lord Glenelg, urging upon the British Government the advisability of establishing a line of mail and passenger steamers to Halifax.

The result was that in November of that year the Admiralty advertised for offers for the conveyance of mails by steamship of not less than three hundred horse-power each, between England, Halifax, and New York. All tenders for the contract were to be received by December 15 of that year. Two offers were filed on time, by the Great Western Steamship Company and by the St. George Steam-Packet Company, owners of the Sirius. The Admiralty found neither of them acceptable. A copy of the advertisement somehow reached Samuel Cunard that year, probably through Haliburton, and he saw in the proposal the chance of fulfilling his cherished hopes. Although too late to present an offer to the Admiralty within the time-limit required, he set sail for England at once on the possibility that there would still be time to arrange matters.

IT SEEMS curious that the provincial merchant who registered at a Piccadilly hotel in January, 1839, should have snatched from powerful and established rivals the lucrative monopoly of the carriage of British mails across the North Atlantic. He possessed neither steamships adequate for the service nor funds sufficient to found a line on the scale intended. Although he was favourably known to the Admiralty for his excellent performance of the contract for the conveyance of mails between Halifax, Boston, and Bermuda, this enterprise was an essentially local one which did not produce for him a substantial patronage in London. The nature of his business relations in England, notably with the East India Company, was such that he might receive any necessary introductions, but hardly sufficient to procure him preferential consideration by the Government.

Although he was already fifty-two years of age, his portrait of that period, presented to him by Robert Napier, his associate in the foundation of the Cunard Line, shows a rather handsome man evidently still enjoying the full vigour of his prime. His cast of features was what has become known as characteristic of the New World—more that of the pioneer than of the local magnate, with an alert eye, daring nose, and decisive mouth. A fellow Haligonian describes him in a letter:

He was a skilful diplomatist—I have thought, looking at little Lord John Russell, whom he personally resembled (though of a larger mould), that he was the abler of the two. . . . In early life he was somewhat imperious. He believed in himself,—he made both men and things bend to his will.

Certainly to overcome the odds against his success in England he must have possessed all of these qualities and the aid of a generous measure of the sort of good fortune by which daring plans are so often rewarded.

Perhaps before all other circumstances which contributed to the realization of his enterprise must be mentioned the part played by the favour of London’s reigning beauty. Fanny Kemble, the famous actress and authoress, who eventually captured the American stage by storm, describes in her Records of a Girlhood how Cunard made the acquaintance of the persons of influence in London:

Mrs. Norton . . . was living with her uncle, Charles Sheridan, and still maintained her supremacy of beauty and wit in the great London world. She came often to parties at our house, and I remember her asking us to dine at her uncle’s, when among the people we met were Lord Lansdowne and Lord Normanby, both then in the ministry, whose goodwill and influence she was exerting herself to captivate in behalf of a certain shy, silent, rather rustic gentleman from the faraway province New Brunswick, Mr. Samuel Cunard . . . of the great mail-packet line of steamers between England and America. He had come to London an obscure and humble individual, endeavouring to procure from the government the sole privilege of carrying the transatlantic mails for his line of steamers. Fortunately for him he had some acquaintance with Mrs. Norton, and the powerful beauty, who was kind-hearted and good-natured to all but her natural enemies (i.e., the members of her own London Society), exerted all her interest with her admirers in high places in favour of Cunard, and had made this dinner for the express purpose of bringing her provincial protégé into pleasant personal relations with Lord Lansdowne and Lord Normanby, who were likely to be of great service to him in the special object which had brought him to England.

Fanny Kemble’s account marks a certain metropolitan condescension towards a provincial, which was probably not the least disadvantage which Cunard had to overcome. It is probably no more true that he was humble and rustic than it is that he hailed from New Brunswick, for his business career denotes a supreme self-confidence, and the part he eventually took in London’s social life was that of a man of the world. Fanny Kemble herself gives us a more gallant picture of him in a later volume in which she describes a stop in Halifax aboard one of the early Cunarders, bound for Boston. After days of deathly seasickness she had arrived at Halifax, where she was entertained for a few hours by Cunard at his house there, “whence,” she writes, “I returned to the ship for two more days of misery, with a bunch of exquisite flowers, born English subjects, which are now withering in my letter-box among my most precious farewell words of friends.”

While Mrs. Norton was initiating him into the charmed circle of her famous admirers Cunard was seeking a builder for his mail steamers. He was too astute to duplicate the tactical error committed by his chief rival bidder, the Great Western Steamship Company. This company had responded to the Government’s advertisement with a timid offer to enter into a contract for the carriage of monthly mails to Halifax, specifying, however, that the building of adequate ships would require two years. The St. George Steam-Packet Company offered to convey mails from Cork to Halifax in the steam vessels it already possessed, of which the Sirius was the largest, and from British ports to Cork and from Halifax to New York in still smaller steamers. Neither tender had suited the Admiralty. Cunard, on the other hand, intended to order for early delivery several ships to be built especially for the trade and, with this contract with the builder in his pocket, to approach the Government with a proposal which should be neither vague nor insufficient for its requirements.

James C. Melvill, the secretary of the East India Company, recommended Messrs. Wood and Napier of Glasgow as “highly respectable builders,” although Liverpool and London firms, probably out of jealousy for the growing shipyards on the Clyde, assured him that up there he would have “neither substantial work nor completed in time.” In February, 1839, Cunard consequently wrote to friends from Halifax who had settled in Glasgow, Messrs. William Kidston and Sons, asking them to do him the favour of interviewing Wood and Napier in his behalf. He explained that he should want “vessels of the very best description, and to pass the inspection and examination of the Admiralty . . . plain and comfortable, not the least unnecessary expense for show.” If these gentlemen were found likely to meet his requirements, he was to proceed himself to Glasgow to make arrangements with them.

Robert Napier at that time was becoming the most famous marine engineer in Great Britain. For ten years he had engined the coastwise and Isle of Man packets, in which he had improved and developed the side-lever engines employed in the early steamships. John Wood, whose firm Napier finally absorbed, had provided his hulls, and together they rose to pre-eminence in their complementary professions. One of their ships, the Queen of the Isle, served as model for the first Cunarders, and the mixture of bright ochre and buttermilk with which they painted their funnels produced the red colour which has always distinguished the Cunard ships. Thus not only has a long line of famous Cunarders carried on the traditions of their workmanship, but they have each thus been stamped with their individuality long after the obsolescence of their mechanical ingenuities.

THE DOCKS AT LIVERPOOL

Cunard’s proposal was nothing new to Napier, even though British shipowners were not yet disposed to make more strenuous efforts to secure the Admiralty contract for the carriage of mails to America. As early as 1833 he had engaged in a correspondence with Mr. Patrick Wallace of London regarding the establishment of a steamship service “betwixt Liverpool and New York” and he had foreseen the possibilities with surprising shrewdness. He had even then, in the infancy of the steamship, suggested to Mr. Wallace the system for the management of steamships which is still in use:

I would endeavour to get a very respectable man, and one thoroughly conversant with his business as an engineer. I would appoint this man to be master engineer, his duty being to superintend and direct all the men and operations about the engines and boilers, but to be accountable to the captain for his conduct, namely, to be under the captain. All other men for working the engines should be regular bred tradesmen, and all the firemen boiler-makers. A workshop, with a complete set of tools and duplicates of all the parts of the engines that are most likely to go wrong, should be on board.

He continued:

I would have everything connected with the machinery very strong and of the best materials, it being of the utmost importance to give confidence at first, for should the slightest accident happen so as to prevent the vessel making her passage by steam it would be magnified by the opposition and thus, for a time at least, mar the progress of the Company. But if, on the other hand, the steam vessels are successful in making a few quick trips at first, beating the sailing vessels very decidedly, then you may consider the battle won and the field your own.

Probably not even the companies which dispatched steamers for America five years later, in 1838, had considered the details of the project as closely as Napier had. He alone foresaw the profits to be made in the emigrant trade as well as from cabin-passages, and he estimated every expense of operation, even to a hundred pounds annually for advertising, and a hundred and four pounds for a ship’s doctor. His suggestions were too advanced for the conservative London capitalists, and nothing came of them until Cunard’s inquiry offered him a better opportunity to put them to use.

Napier immediately sent Cunard a favourable reply, and the latter proceeded to Glasgow at once. Their first interview found them in such ready agreement that a contract between them was soon made, and was ratified on March 18, 1839.

The contract provided for the construction of:

Three good and sufficient steamships, each not less than 200 ft. long, keel and fore-rake, not less than 32 ft. broad between paddles, and not less than 21 ft. six inches depth of hold from top of timbers to underside of deck amidships, properly finished in every respect . . . with cabins finished in a neat and comfortable manner for the accommodation of from 60 to 70 passengers or a greater number in case the space will conveniently and commodiously permit thereof; each of which vessels shall be fitted and finished with two steam Engines having cylinders 70 inches in diameter, and 6 ft. 6 inches stroke. . . . The said Robert Napier hereby Binds and Obliges himself . . . to finish and complete, to the entire satisfaction of the said Samuel Cunard, equal in quality of hull and machinery to the steamer Commodore or the steamer London, both constructed by the said Robert Napier, and equal to the City of Glasgow steamer in the finishing of the cabins.

These ships were to be of 960 tons each, 375 horse-power; and were to cost £32,000 each. In a letter to Melvill thanking him for the introduction to Cunard, Napier wrote: “I am of the opinion that Mr. Cunard has got a good contract and that he will make a good thing of it. From the frank and off-hand manner in which he contracted with me I have given him the vessels cheap and I am certain that they will be good and very strong ships.” Frank dealing and strong ships—these always seem to have run through the history of the Cunard Line.

But Cunard was not frank without shrewdness, and the keels of these ships were never laid. While Napier was engaged in completing the engines he was building for the British Queen, Cunard was making good use of his acquaintanceships in London through his friend Mrs. Norton, whose name the gossip of the time connected with that of Lord Melbourne, then Prime Minister. He had come into friendly contact with the members of the Government and he took the opportunity to discuss the mail contract with the Lords of the Admiralty. With his agreement with Napier in his pocket he was able to assure the Government that his ships would be “the finest and best ever built in this country.” Finally, on May 4, 1839, the negotiations resulted in a contract in which he undertook to convey Her Majesty’s mails twice every month from Liverpool to Halifax and return, in three ships of at least three hundred horse-power each; he further agreed to carry mails from Halifax to Boston and, when the St. Lawrence River should be ice-free, from Halifax to Quebec, twice a month in smaller steamers to connect with his transatlantic ships. He also assumed certain fines to be paid in the event of his failure to fulfil the various provisions of the contract, which was to remain in force seven years. The remuneration was to be £55,000 annually.

Here it is interesting to note that the original advertisement issued by the Government had called for tenders for the monthly conveyance of mails between England and Halifax, and also between England and New York via Halifax. Boston had not been mentioned as a western terminus. Cunard was aware that a line between Liverpool and Halifax alone would find difficulty in securing enough passengers and freight to be profitable, as Halifax had not recovered the commercial importance it enjoyed when he was a boy. He had seen and taken part in the rapid development of Boston’s commerce and he perceived in it great opportunities for a steamship service between that port and England. Moreover, the run from England to New York, via Halifax, was a much longer one than to Boston, and this route would place him at a disadvantage in competition with ships which crossed the ocean directly to New York without calling at Halifax. With this in mind he had written in March of that year to shipping friends in Boston, Messrs. Dana, Fenno and Henshaw, outlining his plan to bid for a mail contract between Liverpool and Halifax, with two branch lines of small steamers from Halifax serving Boston and Quebec. This plan had suited the Admiralty as a substitute for service to New York.