* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Maple Leaf, Vol 3, no. 5, November 1853

Date of first publication: 1853

Editor: Eleanor Lay (1812-1904)

Date first posted: January 9, 2026

Date last updated: January 9, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260114

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

| CONTENTS | |

| 1. | Legend of the Pyrenees (continued) |

| 2. | To the Parents of Caroline W. |

| 3. | To November |

| 4. | The Governor’s Daughter; or Rambles in the Canadian Forest |

| 5. | Natural Bridges |

| 6. | The Seasons in Canada: The Fall |

| 7. | To my Dear Sister Mary, in England, on the Morning of her Birthday |

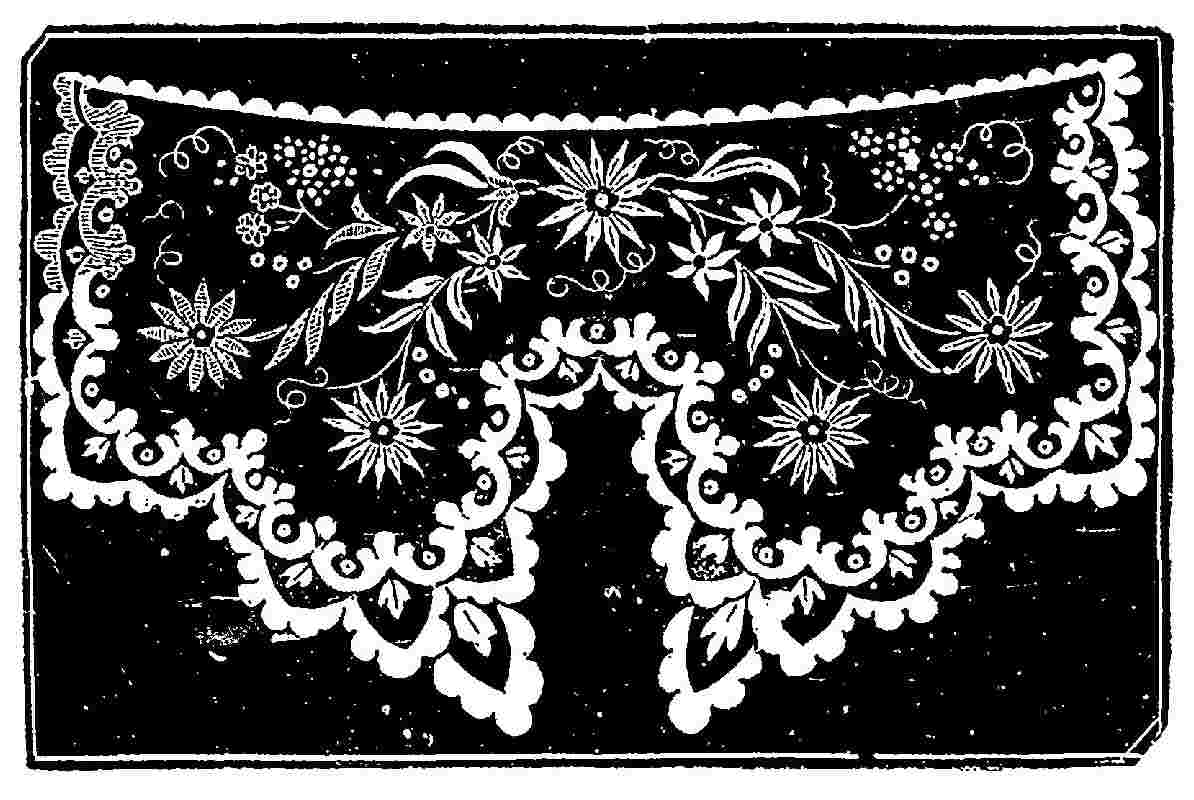

| 8. | Mousquetaire Cuff in Muslin Embroidery |

| 9. | A Day’s Fishing |

| 10. | Sleeps, in Christ’s Fear, Faith, and Love: My Sister Jane |

| 11. | Frankfort Cemetery |

| 12. | Things Useful and Agreeable. |

| 13. | Reply to Charade by Oscar, in October Number |

| 14. | The Cracker for Oscar’s Nut |

| 15. | Charade |

| 16. | Enigma |

| 17. | An account of the depth of the ocean |

| 18. | Editorial |

(CONTINUED.)

[Written for the Maple Leaf.

aking a position on some

stand point in the lapse of

time, the present for instance,

climbing it may be

one of the peaks that dot

the western Continent,

and

looking

over the vast scene, the human mind is bewildered

at the sight, and lost in wonder at the thought, of the youthful

fame and splendor that already cluster around America. In

1492 all was yet in the future. Then no trace of ocean

highway was visible, by the dim light that twinkled across

the waste of waters, and investigation folding her wings essayed

not to pierce the uncertain West. Around the limitless

expanse which stretched beyond Spain, popular description

had gathered vague forms. Superstition peopled the

caverns of the deep with genii, and wandering gnomes,

who held wild dances among the coral rocks, or rose on the

waves in magic circles, hovering phantom-like in the wake

of vessels that dared to venture near their domains. To

enter these unknown seas with frail barks, to brave the spirits

of the deep, and the revel of the winds and waves, uncertain of

the distance to be accomplished, argued great courage and hope

of success. Few embarked with Columbus comprehending

the greatness of the scheme; they went, because life had few

charms for them; or because they were pressed into service.

Conjecture exhausted itself in trying to account for the foolish

plan, as people deemed the project, and Columbus needed all

his faith to bear up under the ridicule and incredulity which

assailed him. Henri Baptiste stood by him in all his emergencies,

and it was with peculiar interest that he looked upon

this noble minded youth, and his offer to share the perils of the

voyage.

aking a position on some

stand point in the lapse of

time, the present for instance,

climbing it may be

one of the peaks that dot

the western Continent,

and

looking

over the vast scene, the human mind is bewildered

at the sight, and lost in wonder at the thought, of the youthful

fame and splendor that already cluster around America. In

1492 all was yet in the future. Then no trace of ocean

highway was visible, by the dim light that twinkled across

the waste of waters, and investigation folding her wings essayed

not to pierce the uncertain West. Around the limitless

expanse which stretched beyond Spain, popular description

had gathered vague forms. Superstition peopled the

caverns of the deep with genii, and wandering gnomes,

who held wild dances among the coral rocks, or rose on the

waves in magic circles, hovering phantom-like in the wake

of vessels that dared to venture near their domains. To

enter these unknown seas with frail barks, to brave the spirits

of the deep, and the revel of the winds and waves, uncertain of

the distance to be accomplished, argued great courage and hope

of success. Few embarked with Columbus comprehending

the greatness of the scheme; they went, because life had few

charms for them; or because they were pressed into service.

Conjecture exhausted itself in trying to account for the foolish

plan, as people deemed the project, and Columbus needed all

his faith to bear up under the ridicule and incredulity which

assailed him. Henri Baptiste stood by him in all his emergencies,

and it was with peculiar interest that he looked upon

this noble minded youth, and his offer to share the perils of the

voyage.

The humble port of Palos, on the Atlantic coast, was the one from which they were to sail. Preparations hastened to a close, at last all were ready, and the little band repaired to the Church, that they might leave fortified by sympathy and prayer.

The three little vessels rode quietly in the harbor, rocked gently on the rising swell; little dreamed the idle gazers on their humble equipments of the figure they were to make in the annals of the world. The moment came when anchors were weighed, sails unfurled, and the barks sped away. Columbus, whose heart was too full of prophetic hope to allow him to falter, directed their course with a steady voice, while the mariners now fairly embarked upon this uncertain enterprise, and overawed by the strangeness of their situation, yielded to his influence. Every sail was set, a propitious wind hurried them on; and ere the evening star lighted the ocean, the adventurers bade adieu to Spain. What thoughts were theirs!—how sublime was their mission!

How desolate must the ocean have appeared—how narrowed their hold upon the world, as with solemn hearts and voices, those lonely sailors sang their evening song, and from vessel to vessel resounded the answering watch-word; while sinking over the billows fell the veil of night.

Columbus paced the deck of the foremost barque,—the moment was too intensely fraught with emotions of sublimity to admit of sleep. He had launched upon the unknown ocean, and was steering away from land. No human power could aid him,—no human heart could assume the responsibility that rested on him,—how could he sleep with the gushings of that enthusiastic spirit heaving his whole frame? Now he looked out on the silvered furrow ploughed by his vessel, and saw in her wake the lights of the sister vessels, glimmering and dancing, ignis fatuus-like—apt illustration of the uncertainty of his success. Again he cast his eye upon the glorious host of the stars; they shone upon the water, as upon the land; sentinels they seemed, beacons scattered in the grand concave, to remind of that Power who never slumbered or slept; and then to calm his mind he stood by the binnacle light, and watching the needle, called out the passing bells as the night wore on.

Among the adventurers was one, who, gathering up the thread of pleasant associations, ventured to weave a few golden colors into his web of life, and vary their bright hues with shades of purple and violet; for in those times, as now, “telegraphic communications” were kept up between hearts, and no insulator had been discovered to retain the subtle fluid which cupid delighted to spread far and wide. No sleep pressed Henri’s eyelids during that first momentous night. He would scarcely leave the deck of the little Caravel a moment, but watched the wind, while the sailors tacked and steered, aiming at the distant light in the foremost vessel, where they knew wakeful eyes were guiding their course.

If a spot can be conceived where the idea of vastness and human nothingness in the midst of such overwhelming extent, fully takes hold of the mind, it must be amid the sands of the pathless desert, or when tossing in a small vessel on the mountain billows of the ocean. A watch on the quarter-deck of a noble merchant vessel is another thing; yet, even there, at midnight, the sturdy sailor gladly cheats the monotonous hour of its weariness, by spinning the yarn of wonderful incident, or picturing loved scenes and memories to his mind. Thoughts of the danger of the enterprise occupied Henri’s mind for a long time, the uncertainty that hung over it fired him with resolution, and left ample space for pictures of a sanguine character. Gradually, however, as the vessels glided prosperously onward, Henri’s feelings lost their anxious tone, and turned with fervor to the distant mountains and sunny vallies of his native Navarre, to the home of his childhood, and the villagers, in whose merry vintage songs he had often joined. New thoughts had struggled up into light, within his yearning bosom, since those careless days. He felt that he could never sing those songs as he once did; he had caught glimpses of the higher, inner life; he had learned that immortal mind cannot be satisfied with the circumscribed routine of mere physical enjoyment. Imagination bathed that home landscape in golden splendor, and filled that native air with sweetest harmony; and as the home of his beloved rose vividly before him, the currents round his heart thickened, then quickly receded like the ebbing tide, leaving bare and stranded, for a moment, the hopes of his life. It was only for an instant that he suffered himself to doubt, ere rushing into every avenue of his heart, wave after wave of love encircled and buoyed up his spirit.

The little fleet proceeded directly from Palos to the Canary Islands, from whence Columbus intended to sail westward. There they remained while one of their vessels was repairing; luxuriating in all the delightful accompaniments of that soft climate, and lingering with peculiar tenderness at those out-posts of life and society, on the borders of an unknown wilderness of waters. The repairs were soon completed, and laying in a supply of fruits and fresh water, they steered away. As the Peak of Teneriffe and the lofty heights of Ferro faded from their view, they were overwhelmed with their desolate situation, and gave themselves up to mournful forebodings, from which Columbus, with all his tact and versatility in devising expedients, could scarcely rouse them.

Days succeeded nights, and nights followed days, for weeks, and still the vessels held on their westward route, wafted by the propitious Trade winds, which blow in a direct line from the Canaries. The sailors were kept in constant excitement by the novelties they encountered. The curious variation of the magnetic needle filled them with astonishment. Columbus looked with wonder upon this phenomenon, and passed many an hour in meditating upon the probable reason.

The mild breeze that gently urged them on, alarmed the sailors from its unvarying sameness; they fancied that they could never return in the face of a breeze that blew ever towards the west. Flocks of birds alighted on the ships, sure indications, as they thought, of land, and then every eye was strained to catch the first indications of the wished-for shore. Now a floating piece of carved wood reassured them, or distant piles of vapor, mirage-like, deceived them into the hope that a magnificent city was near. In the latitude of the tropics, the air is so clear, that objects can be discerned at a great distance, and this beautiful serenity and freshness of the atmosphere kept them in happy expectation. These expectations were destined to be fully met. The grand repose of primeval forests was about to be invaded; the voice of civilization was soon to disturb the fainter sounds of savage life. The curtain was about to be rolled back and disclose the beauteous western world, with all its wonderful variety of scenery and climate. Land did indeed lie before them. “Land! land!” was the joyful chorus on every tongue.

Brightly beamed the morning sun upon the wooded shores and flowery summits of that lovely island, which reposed in the solitude of the ocean, like a gem of variegated colors dropped from the hand of Omnipotence. The little ships anchored before it, while the joyful adventurers stepped gratefully on shore. Those ships transported, it may be, leaves from the Tree of Life, germs of future glory, which the All-Wise would spread over the western world, until, in ages to come, light and knowledge and truth should meet and embrace on the Pacific shore, and the east and west, the north and south, be illuminated with celestial light.

It was a gala day in the Spanish capital. The church bells rung forth a merry peal, the streets were thronged with cheerful multitudes in their holiday garb, while the inspiriting notes of martial music lent a bewitching loveliness to their steps. From balcony and tower and lordly castle, floated gay-colored flags and banners. The fair and beautiful crowded the windows and porticos, and eagerly tried to catch a glimpse of the splendid procession which was passing through the principal streets. Conspicuous in front rode Ferdinand, whose nodding plumes were lifted with profound gallantry to the ladies; by his side rode the Queen of Castile, the idolised Isabella, her serene beauty partly concealed by a superb veil, which was fastened upon a jewelled tiara, and fell back in graceful folds round her royal person. As the cavalcade came in view, the crowd perceived the majestic form of Columbus, with a select retinue, near the king and queen, and bursting forth into ecstasy they raised the rejoicing shout, “Ferdinand and Isabella forever!”

It was a happy day to Isabella; she regarded herself as a steward of Heaven’s bounty, and felt that she ought to honor God with the most magnificent exhibitions of joy. It was a proud day to her, for she commemorated the discovery of a new world! That morning the court celebrated high thanksgivings for the prosperity of the little armament that sailed away from Palos amid so many trials, and now the king and queen, with the nobility and principal inhabitants, were on their way to honor the event in feast and tournament. Many feats were performed by bold Cavaliers, anxious to gain a glance of approbation from the fair beholders; many a lance had been broken, and many a rider unhorsed in the broad arena where they fought mimic battles. On a raised platform, the queen reclined, beneath a gorgeous canopy, surrounded by her ladies. A young man, of interesting appearance, advanced and knelt reverently at her feet, while a noble and beautiful lady threw over his shoulders an embroidered scarf, and presented to him a sealed packet. Henri, for it was he, gracefully kissed her hand, while he poured forth his thanks for the gift bestowed.

Columbus had represented Henri’s constancy and services during the voyage, his resolute adherence to the squadron when one of the vessels deserted, and his subsequent bravery when another was wrecked. Isabella was so pleased with this history, that she resolved to signalise the day by conferring upon him the honor of knighthood, and presenting him with a small estate, which had just reverted to the crown, by the death of the last heir. He had realised a large share in the golden favors of the savage chieftain on the Island of Hispaniola, a sufficiency to enable him to improve this estate, which was situated in the fertile province of Valencia, not far from the sea. He was not destined, however, to attain the summit of happiness at once, or even to revisit at this time his Irene. His country had claims upon his devotion and energy, in prosecuting the series of discoveries that promised to open to Spain the wealth of the Indies, and an empire whose greatness should overshadow all other European powers. So, repressing his ardor, he despatched a letter to the lady Irene, detailing his fortunes, and remained with the courtly circles of Barcelona, while the monarchs matured their negotiations with Portugal, and arranged the outfit for a second voyage of discovery. Longingly as he turned his eyes toward his home, he felt that it did not become the patriot to falter in the service of such sovereigns, or the Christian to seek his own ease, when such men as Columbus called upon him to aid in spreading the light of the gospel among the heathen; for the great aim, the great motive that sustained Columbus, was the hope of being the means of illuminating the pagan multitudes that he should find peopling the vast regions of the Western World. Still there were times, when the irrepressible longings of the heart, the desire for companionship, would assert their sway, when the beauty and splendor of the court contrasted painfully with his isolation of spirit, and he felt alone, though surrounded by all that could improve his mind and charm his senses.

The spirit is free in the midst of a crowd,

Sweet voices, lov’d voices, oft murmur aloud,

They tell of the absent, the cherish’d, the few,

Of joys in the future, of hopes bright and true.

Montreal, October, 1853.

(To be continued.)

TO THE PARENTS OF CAROLINE W.

Weep not for your little darling,

Though her tender spirit’s fled,

Though the cold damp earth’s the pillow

That supports her infant head;

Soft she slumbers,

Far from pain, and grief, and dread.

True it is, that she hath tasted,

“ ’Tis a bitter thing to die;”

How her little form was wasted!

Touching was her mournful cry;

But her spirit

Soar’d to dwell with God on high.

When with agonized feeling,

Round her dying form ye drew;

Had heav’n’s light, your eyes unsealing,

Then presented to your view,

Guardian Angels—

As from heav’n they downward flew.

Had ye seen them bear her spirit,

To the portals of the skies;

There made welcome to inherit

Joy that never, never dies;

Would ye murmur?

No! but gaze with glad surprise.

Let not grief o’erspread your faces,

Say “Our Father though thou hast

Borne her from our fond embraces,

May we meet in heaven at last;

And together,

Sing our woes and suff’rings past.”

E.S.O.

St. Andrews, C.E.

BY PERSOLUS.

[Written for the Maple Leaf.

Chill and surly as thou art, yet I love thee, November; thou season of the “sere and yellow leaf.” The young but seldom wish for thy coming; for thou wearest not an aspect promotive of pleasurable sensations, and thy gloomy and lowering skies accord not with the sunny hopes and towering aspirations of the springtide of life; and yet, though young, I love thee. I love thee for thy ever shifting clouds, which now are piled together in solid grandeur, and anon dispersed, in drifting flakes, sweep through the ærial vault. I love thee for thy fitful gales that rise like the fretful sleeper’s dream—there is the rush of the tempest, ’tis but for a moment, and all is quietness and peace. Oh, I love those chilling blasts, which in mournful cadence make musical the solitary forest. And I have heard, Oh joy, the low wild meanings of thy viewless winds which flit across the dreary heath. The beaming month of May comes to us rejoicing in its sprouting buds and opening blossoms, and her gentle violets peep from the verges of their chill beds of snow—the last and fading relicts of departed winter’s power. We hear the humming of the busy bee; the grove is vocal with the early songster’s warblings; and the summer months succeeding shed around us the rich fragrance of maturing fruits and flowers, and all the earth appears to revel in the calm and cloudless skies of June. And yet, November, I love thee far the best; thy season lulleth not to forgetfulness; for in thy whirling vapors I mark the evidences of wild excitement and of powerful emotion; and I love thee because that I, so unlike the noblest or the meanest sons of time, have found in thee a sympathising friend—a loved companion; thou art my natal month, and dear as a mother thou art indeed to me. Thou imagest my life, nay, more, thy frequent and fitful changes, thy decaying leaves which rustle in my path, teach me that life is fleeting; from the midst of thy general gloom and despondency thou leadest me to drink, yea, to bathe my weary limbs in that river of life, whose waters are pure as crystal, and whose streams make glad the city of our God; and when troubled with the ills of life, to seek for shelter where it only may be found, even with Him who is “as the shadow of a great rock in a weary land.”

Montreal, 1853.

GARTER SNAKES—RATTLESNAKES—ANECDOTE OF A LITTLE BOY—FISHERMAN AND SNAKE—SNAKE CHARMERS—SPIDERS.

urse, I have been so much frightened;

I was walking in the meadow, and a big

snake,—so big I am sure,” and lady Mary

held out her arms as wide as she could,—“came

from under a tuft of grass. His

tongue was like a scarlet thread, and had

two sharp points; and do you know that

he raised his wicked head and hissed at

me, and I ran away, I was so much

afraid of him. I think, Mrs. Frazer, it

must have been a rattlesnake. Only

feel how hard my heart beats;” and the

little girl took her Nurse’s hand and laid it

on her heart.

urse, I have been so much frightened;

I was walking in the meadow, and a big

snake,—so big I am sure,” and lady Mary

held out her arms as wide as she could,—“came

from under a tuft of grass. His

tongue was like a scarlet thread, and had

two sharp points; and do you know that

he raised his wicked head and hissed at

me, and I ran away, I was so much

afraid of him. I think, Mrs. Frazer, it

must have been a rattlesnake. Only

feel how hard my heart beats;” and the

little girl took her Nurse’s hand and laid it

on her heart.

“What color was the snake, my dear?” asked her Nurse.

“It was green and black; all checkered over; and it was very large, and spread its mouth very wide, and showed its red tongue. It would have killed me, if it had bitten me; would it not, Nurse?”

“It would not have harmed you, my lady, or, even if it had bitten you, it would not have killed you. The checkered green snake of Canada is not poisonous. It was as much afraid of you as you of it, I make no doubt.”

“Do you think it was a rattlesnake, Nurse?”

“No, my dear; there are none of that sort of snake in Lower Canada, and very few below Toronto. The winters are too cold for them. There are plenty in the western part of the Province, where the summers are warmer and the winters milder. The rattlesnake is a dangerous creature, and its bite causes death, unless the wound be burned or cut out. The Indians apply different sorts of herbs to the wound. They have several plants, known by the names of rattlesnake root, rattlesnake weed, and snake-root. It is a good thing that the rattlesnake gives warning of its approach before it strikes the traveller with its deadly fangs. Some people think that the rattle is a mark of fear, and that it would not wound people, if it were not afraid that they were coming near to hurt it.

“I will tell you a story, lady Mary, about a brave little boy. He went out nutting one day with another boy about his own age, and while they were in the grove gathering nuts, a large black snake that was in a low tree dropped down and suddenly coiled itself round the throat of his companion. The child’s screams were dreadful; his eyes were starting from his head with pain and terror. The other, regardless of the danger, opened a clasp-knife that he had in his pocket, and, seizing the snake near the head, cut it apart, and so saved his friend’s life, who was well nigh strangled by the tight folds of the reptile, which was one of a very venomous species, the bite of which generally proved fatal.”

“That was a very brave little fellow,” said lady Mary. “You do not think it was cruel, Nurse, to kill the snake?” she added, looking up in Mrs. Frazer’s face.

“No, lady Mary; it was to save a fellow creature from a painful death, and we are taught by God’s word that the soul of man is precious in the sight of his Creator. We should be cruel were we wantonly to inflict pain upon the very least of God’s creatures; but to kill them in self-defence, or for necessary food, is not cruel, for when God made Adam, he gave him dominion or power over the beasts of the field and the fowls of the air, and every creeping thing. It was an act of great courage and humanity in the little boy who periled his own life to save that of his helpless comrade, especially as he was not naturally a child of much courage, and was very much afraid of snakes; but love for his friend overcame all thought of his own personal danger.[1]

“The large garter snake—that which you saw, my dear—is comparatively harmless. It lives on toads and frogs, and robs the nests of young birds and the eggs also. Its long forked tongue enables it to catch insects of different kinds. It will even eat fish, and for that purpose frequents the water as well as the black snake.

“I heard a gentleman relate a circumstance to my father once, that surprised me a good deal. He said that he was fishing one day in a river near his own house, and that being tired he had seated himself on a log or fallen tree, where his basket of fish also stood; that a large garter snake came up the log and took a small fish out of his basket, which it speedily swallowed. The gentleman seeing the snake so bold as not to mind his presence, took a small rock-bass by the tail and held it towards him, half in joke, when, to his great surprise, the snake glided towards him and took the fish out of his hand, sliding away with its prize to a hole beneath the log, where it began by slow degrees to swallow it, stretching its mouth and the skin of its neck to a great extent, till, after a long while, it was fairly gorged, and then slid down into its hole, leaving its neck and head only to be seen.”

“I should have been so frightened, Nurse, if I had been the gentleman when the snake came to take the fish,” said lady Mary.

“The gentleman was well aware of the nature of the reptile, and knew that it would not bite him. I have read of snakes of the most poisonous kinds being tamed and taught all manner of tricks. There are in India and in Egypt, people that are called snake charmers, who will contrive to extract the fangs that contain the venom, from the cobra capella or hooded snake; they then become quite harmless. These snakes are very fond of music, and will come out of the leather bag or basket, that their master carries them in, and dance and run up his arms, twining about his neck, and even entering his mouth, when he plays on a sort of flute. They do not tell people that the poison teeth have been extracted, so that it is thought to be the music that keeps the snake from biting. The snake has a power of charming birds and small animals by fixing its eye steadily upon them, when the little creatures become paralyzed by fear, either stand quite still, or come nearer and nearer to their cruel enemy, till they are within his reach. The cat has the same power, and can, by this art, draw birds to her, and also mice. These little creatures seem unable to resist the temptation of approaching her, and even when driven away, will return from a distance to the same spot, seeking, instead of shunning, the danger which is certain to prove fatal to them in the end.

“Some writers assert, that all wild animals have this power in the eye, especially those of the cat tribe, as the lion and tiger, leopard and panther. Before they spring upon their prey, the eye is always steadily fixed, the back lowered, the neck stretched out, and the tail waved from side to side; if the eye is averted, they lose the animal, and do not make the spring.”

“Are there any other kinds of snakes in Canada, Nurse,” asked lady Mary, “besides the garter snake?”

“Yes, my dear, several. The black snake, which is the most deadly, next to the rattlesnake, it is sometimes called the puff adder, as it inflates the skin of the head and neck when angry. The copper-bellied snake is also poisonous. There is a small snake, of a deep grass green color, that is sometimes seen in the fields and open copse-woods, I do not think it is dangerous, I never heard of its biting any one. The stare-worm is also harmless. I am not sure whether the black snakes that live in the water are the same as the puff or black adder. It is a great blessing, my dear, that these deadly snakes are so rare and do so little harm to man. I believe that they would never harm him, were they let alone; but if trodden upon, they cannot tell that it was accident, and so put forth the weapons that God has armed them with in self-defence. The Indians in the north-west eat snakes, after cutting off their heads, I have been told. The cat also eats snakes, leaving the head; she will also catch and eat frogs, which is a thing I have witnessed myself, so I know it to be true.[2] One day a snake fixed itself on a little girl’s arm, and wound itself around it; the mother of the child was too much terrified to tear the deadly creature off, but filled the air with cries; just then a cat came out of the house, and quick as lightning sprung upon the snake, and fastened on its neck, which caused the reptile to uncoil its folds, and it fell to the earth in the grasp of the cat; thus the child’s life was saved and the snake killed. Thus you see, my dear, that God provided a saviour for this little one when no help was nigh; perhaps the child cried to Him for aid, and He heard her, and saved her by means of the cat.”

Lady Mary was much interested in all that Mrs. Frazer had told her; she remembered having heard some one say, that the snake would swallow her own young ones, and she asked her nurse if it were true, and if they laid eggs.

“The snake will swallow her young ones,” said Mrs. Frazer; “I have seen the garter snake open her mouth and let the little ones run into it when danger was nigh; the snake also lays eggs, I have seen and handled them often; they are not covered with a hard brittle shell, like that of a hen, but a sort of whitish yellow skin, like leather; they are about the size of a black-bird’s egg, long in shape, some are rounder and larger. They are laid in some warm place, where the heat of the sun and of the earth hatches them; but though the mother does not brood over them as a hen does over her eggs, she seems to take great care of them, and defends them from their many enemies, by hiding them out of sight, in the singular manner I have just told you. This love of offspring, my dear child, has been wisely given to all mothers, from the human mother down to the very lowest of the insect tribe. The fiercest beast of prey loves its young, and provides both food and shelter for them; forgets its savage nature to play with and caress them. Even the spider, which is a disagreeable insect, fierce and unloving to its fellows, displays the tenderest care, and the greatest wisdom in providing a safe retreat for them: the finest silken cradle she spins, in which to wrap the eggs, and leaves it in some warm spot, where she covers them from danger; some glue a leaf down and overlap it, to secure it from being agitated by winds, or discovered by birds. There is a curious spider, commonly known as the nursing spider, which carries her sack of eggs with her, wherever she goes; and when the young ones come out they cluster on her back, and so travel with her; when a little older, they attach themselves to the old one by threads, and run after her in a train.”

Lady Mary laughed, and said she should like to see the funny little spiders all tied to their mother, trotting along behind her.

“If you go into the meadow, my dear,” said Mrs. Frazer, “you will see on the larger stones some pretty shining little cases quite round, they look like grey satin.”

“Nurse, I know what they are,” said lady Mary; “last year I was playing in the green meadow, and I found a piece of granite with several of these little satin cases; I called them silk-pies, for they looked like tiny mince-pies. I tried to pick one off, but it stuck so hard that I could not, so I asked the gardener to lend me his knife, and then I raised the crust, it had a little rim under the top, and I slipped the knife in, and what do you think I saw? The pie was full of tiny black shining spiders, and they ran out, such a number of them, I could not count them, they ran so fast. I was sorry I opened the crust, for it was a cold, cold day, and the little spiders must have been frozen coming out of their warm house, that was glued down so tight.”

“They are able to bear a great deal of cold, all insects are; and even when frozen hard, so that they will break to bits if any one tries to bend them, yet when spring comes again to warm them, they revive and are as full of life as ever. Caterpillars thus frozen will become butterflies in due time. Spiders, and many other creatures, lie torpid during the winter, and then revive in the same way that dormice, bears and marmots do.”

“Nurse, please will you tell me something about tortoise,” said lady Mary, “and porcupines;” but Mrs. Frazer was obliged to attend to other things, so lady Mary could not hear any more that day.

The Origin of “Paul Pry.”—The origin of Mr. Poole’s comedy of Paul Pry is not perhaps generally known. Its construction was suggested to the author in the following manner. An old lady, living in a narrow street, had passed so much of her time in watching the affairs of her neighbours, that she acquired the power of distinguishing the sound of every knocker within hearing. She fell ill and was confined to her bed. Unable to observe in person what was going on without, she stationed her maid at the window as a substitute for the performance of that duty.—“Betty, what are you thinking about? Don’t you hear a double knock at No. 9? who is it?”—“The first-floor lodger, ma’am.”—“Betty, Betty, I declare I must give you warning; why don’t you tell me what that knock is at No. 54?”—“Why, Lor ma’am, it is only the baker with pies.”—“Pies, Betty, what can they want with pies at 54? they had pies yesterday.”

|

A fact that was related to me by an old gentleman from the State of Vermont, as an instance of impulsive feeling overcoming natural timidity. |

|

I saw a half grown kitten eat a live green frog, which she first caught and brought into the parlor, playing with it like a mouse. |

The mountain chains of America are distinguished from those of Europe by perpendicular rents or crevices, which form very narrow vales of immense depth. Those which occur in the Andes are covered below with vegetation, while their naked and barren heads soar upwards to the skies. The crevices of Chota and Cutaco are nearly a mile deep. These tremendous gullies oppose fearful obstacles to travellers, and the task of crossing them is one of great toil and danger. Travellers usually perform their journeys sitting in chairs fastened to the backs of men called cargueros or carriers. These porters are mulattoes, and sometimes whites, of great bodily strength, and they climb along the face of precipices bearing very heavy loads.

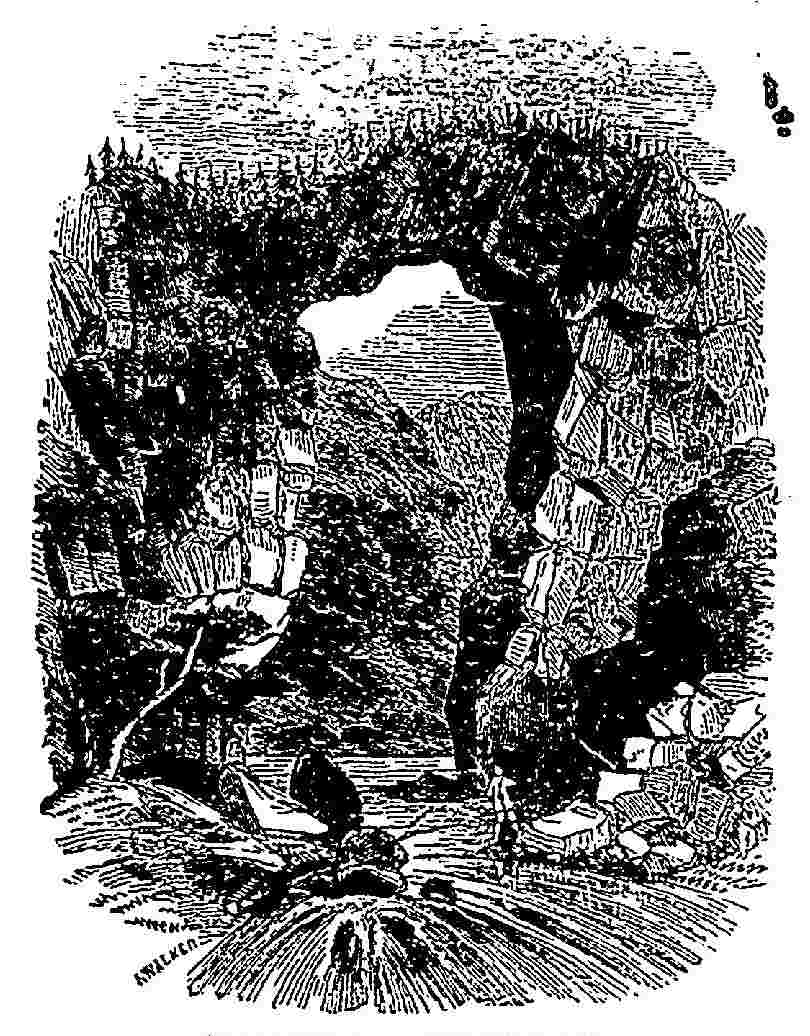

But sometimes these crevices are crossed by natural bridges which seem to be peculiar to the new world. Those of Iconozo, or Pandi, in New Grenada, are very remarkable: they have lately been described by Baron Gros, from whose account the following particulars are selected.

This valley of Iconozo, or of Pandi, is situated twelve or fifteen leagues to the north-east of Bogota. It derives its name from two Indian villages situated near the chasm, which is crossed by the Natural Bridges, and through which rolls the torrent of Summa-Paz. The nearest village to the bridges is Mercadillo: from this a descent of some five and twenty minutes brings the visitor to the bottom of the ravine through the thick woods which hang on the slope of the mountain. Before ascending the opposite side, his eye here catches sight of a small wooden bridge constructed after the fashion of the country by flinging trunks of trees from brink to brink, and covering them across with branches, supporting a floor of earth and flint stones about a foot in depth. A slender balustrade placed on each side of the bridge, at first excites some surprise; for on arriving at Mercadillo the traveller has crossed many impetuous torrents, by bridges of the same description scarcely three feet in width, spanning their chasms where the rocks upon which they rest rise many feet above the level of the rapids; yet, not the slightest lateral protection is afforded in any other case. The tread of the mule communicates to those long rafters an oscillation which occasions some alarm; and the more so because the path is so narrow, that in bestriding the animal, a plummet dropped from the foot of the rider, would reach the water without touching the edges of the bridge. The necessity for the balustrade is soon apparent, and although the thick brushwood encumbering the precipice at first completely conceals the gulf; yet, when the traveller stands on the centre of the bridge he sees through its tangled foliage an abyss of immense depth, from which arises a deadened sound like that of some torrent flowing leagues away. A bluish reflected light, and long lines of dirty white foam slowly sailing down the stream, and disappearing under the bridge, give evidence of a deep black water, flowing between those close and narrow walls. A stone flung into the gulf is answered by a screaming noise, and when the eye is accustomed to the obscurity of the chasm, thousands of birds are seen in rapid flight above the waters, uttering cries like those of the monstrous bats so common in the equinoctial regions.

This imposing spectacle presents itself to the traveller as he looks eastward, or up the stream. Underneath the wooden bridge, and at the perpendicular level of its edge, rocks of about sixty feet in thickness, and which are the continuation of those forming the sides of the abyss, fill up the cleft from side to side at intervals, and constitute three distinct Natural Bridges. One of these is formed of an enormous block of freestone, of nearly a cubical form, which has fallen from the upper strata, or has been torn, perhaps, out of that in which it is found, and rests suspended in the narrowing of the fissure. It forms, as it were, the key-stone of an arch between the projections of the rocky walls which are inclined towards each other at this place. On each side is a ledge or sort of cornice of several feet in width.

It is by a small path on the right, pierced at the head of the wooden bridge, at the side of Mercadillo, that the visitor may descend on the inclined plane forming the upper part of the thickness of this bridge. There are two other bridges equally accessible, over which a pedestrian might cross from one bank to the other if the wooden bridge did not exist. That immediately below the wooden bridge is also formed by masses of freestone, extending from either bank to meet in the centre. Thus, there are three stone bridges in the cleft: the first, lowest, and principal one being that beneath which the torrent flows at a vast depth; the second formed over the first by the great freestone block stretching from side to side; the third between that block and the wooden bridge; and if we add the latter, too, which is the continuation of a highway, there are four bridges over the gulf of Pandi, one rising above the other, and any one of which might serve for its passage in the absence of the others.

The total perpendicular height from the level of the water to that of the wooden bridge, was found to be two hundred and sixty-two feet; the depth of water underneath the bridges about seventeen feet. The cleft itself is about a league in length, and its mean width from thirty to thirty-five feet. According to Humboldt, there are two different kinds of sandstone in the crevice, the one hard and compact, and the other soft and slaty; he supposes the crevice to have been formed by an earthquake, which tore away the softer stone while the harder resisted the violence of the shock; and the blocks of stone falling into the crevices became suddenly fixed against its sides, thus forming the Natural Bridges in question.

A beautiful natural arch crosses the Cedar Creek in Rockbridge county, near Fincastle, in the higher district of Virginia. The rock, which is of pure limestone, is tinted with various shades of grey and brown. The chasm is about ninety feet wide, and the walls two hundred and thirty feet high: these are covered here and there with trees and shrubs, which also overhang from the top, and numerous gay flowers adorn the dazzling steeps. The bridge is of such solidity that loaded waggons can pass over it.

A recent writer, describing a visit to this bridge, says:—“It was now early in July; the trees were in their brightest and thickest foliage; and the tall beeches under the arch contrasted their verdure with the grey rock, and received the gilding of the sunshine, as it slanted into the ravine, glittering in the drip from the arch, and in the splashing and tumbling waters of Cedar Creek, which ran by our feet. Swallows were flying about under the arch. What others of their tribe can boast of such a home?”—Selected.

[For the Maple Leaf.

The Autumn in Canada—or, as it is here beautifully and poetically expressed, the Fall—has a loveliness peculiar to it, which we in vain seek for in other climes. Many indeed prefer this season here to Spring, speaking as the latter does of hope and the halcyon days of Summer. One reason may be, that often when chilled by the equinoctial gales and blasts, and already in imagination the long winter has set in, again we are gladdened by soft balmy airs, and Summer seems to smile once more upon us, rendered more delightful by the late dreariness. The exquisite clearness of the atmosphere, the grand serenity in the gorgeous tinted woods, rich even in the very signs of change and decay, insensibly sheds a feeling of calmness, not regret, over those who witness it. The skies so rich in golden sunsets, or that softened tinge bespeaking the Indian Summer, and the kind delay, and clinging to us of balmy days, even in November, make the Canadian Autumn a season of rare and deep enjoyment. It is as the lingering of some beloved one, on whose pale brow death has set his seal, yet, the spirit in winging its way heavenward, would by its own ineffable serenity, shed peace on the mournful beings so soon to be bereaved of that which to them formed earth’s brightest, purest joy. The fiat has gone forth; they know it; but as they gaze on those eyes already irradiated with heavenly visions, however afterwards human sorrow may triumph, at present it is stilled under the peace-shedding influences of the departing one.

Nature, in all thy seasons so wrought with sweet blendings of future hope, how should our hearts cling to thy softening influences. A word on the joyousness of the Autumnal foliage, surpassing all a painter or poet could imagine; indeed the former would be laughed at, did he venture to introduce tints of so brilliant a hue in his forest scenery. Description fails me, as I would attempt to portray the innumerable shades, from the deepest copper to the brightest scarlet, the darkest orange to the most brilliant yellow, with varied tints of vivid green, giving the mighty forests the air of one gigantic flower garden. My first introduction to the giant woods on this continent was at this season of the year, and how well I recall the sensations of that hour. Standing in the solitude of one of these primeval forests, an indescribable feeling of awe steals over the spirit, which communes with past ages. Gazing at the mighty array of stately columns, proudly erect, you feel the storms which have passed over them, and see them as erect in the sweeping hurricane. The sheddings of ages have fallen on the soft floor beneath your tread. Broken trees lie scattered on the ground, or with their wattle trunks uprooted, others throw their gaunt bleached limbs high in the air, some broken by the hurricane, others smouldering away or riven by the lightning’s flash, some covered with fungi and rare and beautiful mosses, astonishing you by the space they cover when fallen. The height of those forest kings could not otherwise be comprehended. All is still, save the tapping of the woodpecker. Such a scene creates a solemn influence over the heart, standing in the dim hallowed light of nature’s cathedral as it came fresh from the hand of its Divine architect.

C. Hayward.

Raven’s Court, near Port Hope, October, 1853.

Hail! to the day that bringeth back again

Thy much loved recollection, sister cherished!

’Tis not indeed, that other days pass over me,

Forgetful of thyself,—since such I’ve never known;

But this, a day, of more than usual interest,

In my heart’s calendar is marked;—’tis one of note!

Thy happy birthday!—and I wish thee joy!—

I’ll pledge thee here, my own beloved Mary,

In tankard rich and rare!—The wine shall be

The generous gushing streams of love!—the toast!—

Thine everlasting happiness! . . . . For thee,

This morn and e’en last night I craved,

At God’s high altar, “Bless her! gracious Heaven!

Replenish her with piety and Virtue’s draughts!—

Oh! may she prove a pattern to our band,—

A prop to our dear parents!—and beloved

Of Thine exalted Son!— . . . When she, unarmed

And terror-stricken, at Thy bar shall stand,—

O God! be merciful!—and welcome her

Into Thine arms of love,—then deck her brow

With jewels bright,—and let her wear a crown!”

Thus have I ceased not for four long years,

That time had written ’twixt our last embrace,

Tho’ not between our hearts;—and so I’ll pray.

Things have much altered,—many a relative,

Ay! many a chosen friend hath ope’d the tomb,

Since last we met; and we have tears affectionate

To their sweet mem’ries dropped!—still, plenty more

Are fleeting fast, and hearts will ere long ache!

Nay, all are hastening home! . . . Howe’er, the Star

Of Heaven beams kindly yet,—and will, I hope,

Bless thee, and smile on this thy natal day!!!

William.

Montreal, 4th August, 1853.

Mousquetaire Cuff in Muslin Embroidery.

Materials.— French Muslin, and Messrs. W. Evans & Co.’s Royal Embroidery Cotton, No. 60.

This is one of the newest Parisian patterns for a Mousquetaire sleeve, which is worn, more than any other style, in morning dress. The sleeve itself is a full plain bishop, with a narrow band at the wrist, and to this the cuff is attached. It falls back over the arm. It is particularly becoming to a small hand, besides being both more elegant and more suitable for morning wear than the mandarin and pagoda sleeves which leave the entire arm, up to the elbow, unprotected.

The design must be enlarged to the size required, exactly to fit the wrist. It should be fastened by double gold buttons.

It is worked almost entirely in raised button-hole stitch, the centres of the flowers, and the clusters of eyelet-holes only being pierced with a stiletto. The holes in the border are pierced, and worked round in button-hole stitch. The flowers in satin-stitch.

Our readers will, we think, be pleased with the novel and beautiful design which is now submitted to their appreciation.

[For the Maple Leaf.

here are few youths, from twelve and

upwards, who do not discover their ambition

to possess a gun, or a fishing-rod.

The love of sport seems inherent in

youthful humanity, and is developed at a

very tender age. From this fact, I am

inclined to think that the poet spoke only

plain prose when he talked of “teaching the

young idea how to shoot.” Indeed, I think he

would have added, “how to fish,” could he have

introduced the three words without marring his

metre. But, for my own part, I never could

endure the gun;—the exercise is so excessive, the

fruits generally so very small, and the sport altogether

of a very dubious character. Just think of walking

all day for a couple of brace of skeleton birds, called

woodcocks. The bare idea is enough to make one yawn. I

can see much more substantial sport in stepping into a poultry

yard and “bagging” a pair of serviceable shanghaes. Oh no,

give me the rod, and a clear running stream for real sport.

here are few youths, from twelve and

upwards, who do not discover their ambition

to possess a gun, or a fishing-rod.

The love of sport seems inherent in

youthful humanity, and is developed at a

very tender age. From this fact, I am

inclined to think that the poet spoke only

plain prose when he talked of “teaching the

young idea how to shoot.” Indeed, I think he

would have added, “how to fish,” could he have

introduced the three words without marring his

metre. But, for my own part, I never could

endure the gun;—the exercise is so excessive, the

fruits generally so very small, and the sport altogether

of a very dubious character. Just think of walking

all day for a couple of brace of skeleton birds, called

woodcocks. The bare idea is enough to make one yawn. I

can see much more substantial sport in stepping into a poultry

yard and “bagging” a pair of serviceable shanghaes. Oh no,

give me the rod, and a clear running stream for real sport.

You will have discovered, dear reader, that I am an enthusiast in Isaac Walton’s “noble science.” Well, I am,—but unfortunately, I am also a very unlucky disciple; whether the fault lies in the stupidity of the fish, or in my own bungling, I don’t know; but I never yet committed very serious inroads upon the finny tribe. In fact, entre nous, I am rather twitted on this score, and frequently bantered on my ill luck. It has even been asserted that all my fish could be weighed on the little finger! Now, the worst of all is, I am obliged to acknowledge the truth of this. What can be the reason that the water is always too high or too low—the weather too cold, or not cold enough—the season too advanced, or too early? Ill luck all of it; yet, all these misfortunes don’t dispirit me. On the contrary, and fishermen will understand me when I say it, an unsuccessful day only increases my anxiety to test the truth of the old saw, “better luck next time.” If we could all stick as determinedly to disagreeable duties, as we can to agreeable amusements, we might accomplish some grand end.

From these preliminary remarks, you may perceive, that the prospect of a day’s trout fishing, amid the wild scenery of Windsor and Compton, was very acceptable to your humble servant. For several days I had feasted on this prospect, and made hearty breakfasts on imaginary trout. I was to be accompanied by two friends, one a stranger to our wild Canada, who had come all the way across the Atlantic to see us and our notions, and to get plenty of fishing and shooting. I was glad of this—I could show him what real fishing was, and I determined to put my best foot foremost. Our friend had a superb “get-up” of tackle; a trout rod tapering to a shadow,—a line of the most airy, yet, strong material,—and flies of every color, size, and brilliancy. Indeed, the whole of the ornithological kingdom had been taxed, and its whole brilliancy centred in his fishing hook. My own tackle, though not consisting of a “pole, pack string, rusty hook, and bait of red flannel,” was immeasurably inferior to this old country outfit, but perhaps, was better suited to brave the roughness of a Canadian backwoods stream.

A drive of six miles brought us to the mouth of the brook, in whose pleasant waters were placed our piscatorial hopes. Its waters, just before entering the St. Francis, tumble down a chasm of rocks in miniature grandeur. To an admirer of nature, and especially of nature in the shape of falling water, their appearance that day would have been highly imposing; to us, whose sympathies were directed rather to animated nature, the immense volume of water which tumbled down the rocks was horribly suggestive of an overflowing river, and no fish. And, to be sure, there had been a fortnight’s previous rain which we had entirely overlooked. We remembered that only after we had come six miles. This was an unexpected misfortune, so we called a council of war. An old gentleman, who lived in the neighborhood, told us very decidedly that it was needless to attempt fishing while the water was so high. I felt the truth of the oracle, and the senior of our party, who didn’t seem very eager, probably on account of a recent attack of rheumatism, advised us to defer our trip till next week; but H——, with a keen appetite for sport, would go on; he remembered having caught trout in the old country, in swollen streams, and why not in Canada? So on we went.

Did you ever walk through a newly opened backwoods road after heavy rains? I can give my experience in two words—avoid them. The road we now found ourselves scrambling over was a newly opened outlet to some settlements in the interior. The settlers, however, must have reached their settlements in a very unsettled condition. Just imagine a narrow strip of opening in the dense forest,—full of holes, ruts, snags, stumps, stones, and mosquitos—during the dog days, and without a breath of air! Well, we had to walk some miles through this, and now and then caught a peep of the brook, rushing far beyond its proper limits. Soon the sound of running water became “beautifully less,” and we began to wish for a soda water fountain, or some such oasis in the desert. There is something cooling in the sight even of running water; so that when we lost all sight or sound of the brook, we felt very much oppressed with the heat, and the frequent use of a handkerchief told that we were in the “melting mood.”

As we had now walked several miles without coming to the fishing grounds, we felt undecided what to do. None of us knew the locality, and whether we were walking parallel with, or at right angles from the brook, was a problem which, with all our knowledge of mathematics, we couldn’t solve. H—— having sagely remarked that this wasn’t fishing, and both of us agreeing with him,—a very unusual thing,—M—— proposed to make a vigorous push for the brook, through the woods. H—— dissented, no doubt frightened by the thick and rugged nature of a Canadian soft wood forest; but he had to follow; so in we all went, and commenced a sort of scramble, half on all fours, through bushes, over logs and fallen hemlocks. Every one knows that walking in a thick wood implies walking in an eccentric course. We offered no exception to the general rule, notwithstanding the pocket compass, of which H—— discovered himself possessed, but which, the bearings of the brook not having been previously ascertained, was of very little use. H——, however, trusted more to it, than to his own, or our sagacity; and this division in the camp did not tend much to straighten our course. At last we came to a spot that fairly tried our tempers. It was a hemlock swamp, full of holes, rotten logs, covered with slippery moss, fallen hemlocks, always too high to get over, and too low to scramble under, thick bushes, and regiments of mosquitos. The picture is certainly not very inviting, but not being poetical, it bears no flights of imagination. We got very slowly through this swamp, and it was only after an hour’s walking that we came in sight of the water. We had next to search for a place free from bushes, from which to cast our lines. This involved a second tramp. At length, with the discomfort of wet feet, we gained a small rock, and prepared our tackle. H——’s first scientific cast was rather unfortunate. The rock upon which we all stood was rather small, and M——, being immediately behind, and also in the act of “throwing in,” the two lines caught and forthwith resolved themselves into a series of twists and knots, not unlike a dilapidated spider’s web. Here was a fine chance for me to get the first fish, so I waited patiently for that premonitory symptom—a nibble. “You may call spirits from the vasty deep, but will they come?” I am sure our bait was very enticing and varied, yet, no trout seemed inclined to meet us halfway. In vain we changed the bait,—in vain we offered flies of every hue and brilliancy, all calculated to allure the most fishy gourmand,—in vain we stood under a hot sun, every now and then asking each other the eager question, “have you had a bite yet?” We gave up at last, and winding up our lines, turned homewards.

The day was beginning to wane, and we had the disagreeable necessity before us, of walking through the same labyrinth in order to reach the road; so we started in rather a sulky mood than otherwise. This temper was not improved, when we found the wood thicker and more impassible than where we had passed in the morning. To step upon a fallen tree, green with age, was synonymous with a thumping fall, while the foot had to be planted with great care lest it might suddenly disappear a yard or two out of sight. The heat too, was intense—that damp muggy heat, which, with the concomitant of mosquitos, is terribly oppressive. Tumbling seemed the order of the day. H—— fell and tore his coat, while M—— injured his nose and his beauty in the same moment. We walked, I think, about an hour,—it seemed four,—and still without hitting the road. The sun was going down, darkness was coming on, and the prospect of a night’s bivouac in such a pleasant camping ground was anything but cheering. This hastened our steps, and of course increased our tumbles in an equal ratio. H—— brightened up so much as to be the first to descry the road. I don’t remember whether we exhibited our joy in three such cheers as only Britons can give, yet, I think I could have found vent for my joy in any expressive manner.

All our troubles suddenly vanished, and we felt so glad to have got out of the woods that the absence of fish was forgotten. We arrived home about 9 o’clock, and after a refreshing bath, sat down to an excellent supper; and while engaged in discussing its merits, we individually declared that we would never again venture into a soft wood forest.

A. T. C.

Montreal, 13th Oct., 1853.

“There had whispered a voice; ’twas the voice of her God,—

I love thee—I love thee—pass under the rod.”—Mrs. Sigourney.

“And they shall walk with me in white, for they are worthy.”—Promise.

Speak to me, sister,—as when last

Thou whisperedst in my ear.

When time on rapid wing sped past

And pointed to thy bier.

I hear thee not; doth the cold grave

Deny thee words to name?

Can the dull earth in justice crave

More than thy weary frame?

Oh no! for now I hear thy voice

In swelling tones of joy;

’Tis murmuring, Rejoice! rejoice!

Oh bliss without alloy.

In unison with golden harps

Struck by seraphic hands,

Melodiously thy voice imparts

A song of other lands.

A cheerful song of glorious bliss,

The product of the Tree;

A deep-toned song of thankfulness

To Him who died for thee.

I see thee in thy robes of white,

Once crimson like mine own,

By Him made pure,—bathed in that light

Which radiates round the throne

I see thee in thy bright attire,

Thou—a lost sinner—found

And in thy hands thou bear’st the Lyre,

The harp of solemn sound

Thy face is calm,—of light, a ray

Sleeps on thy placid brow;

Thou smil’st upon me, call’st away

From this bleak world below.

Sister,—we mourn, but not as these

To whom no hope is given;

Thy bliss is perfected, and glows

With matchless joys in Heaven.

Persolus.

Montreal, October, 1853.

The dead house, where corpses are placed in the hope of resuscitation, is an appendage to cemeteries found only in Germany. We were shown into a narrow chamber, on each side of which were six cells, into which one could distinctly see, by means of a large plate of glass. In each of these is a bier for the body, directly above which hangs a cord, having on the end ten thimbles, which are put upon the fingers of the corpse, so that the slightest motion strikes a bell in the watchman’s room. Lamps are lighted, and in winter the rooms are warmed. In the watchman’s chamber stands a clock with a dial-plate of twenty-four hours, and opposite every hour is a little plate, which can only be moved two minutes before it strikes. If then the watchman has slept or neglected his duty at that time, he cannot move it afterwards, and the neglect is seen by the superintendent. In such a case he is severely fined, and for the second or third offence, dismissed. There are other rooms adjoining, containing beds, baths, galvanic battery, &c., nevertheless, they say there has been no resuscitation during the fifteen years it has been established.

We afterwards went to the end of the cemetery to see the bas-reliefs of Thorswalden in the vault of the Bethmann family. They are three in number, representing the death of a son of the present banker, Moritz von Bethmann, who was drowned in the Arno about fourteen years ago. The middle one represents the youth drooping in his chair, the beautiful Greek Angel of death standing at his back, with one arm over his shoulder, while his younger brother is sustaining him and receiving the wreath that falls from his hand. The young woman who is there, told us of Thorswalden’s visit to Frankfort, about three years ago. She described him as a beautiful and venerable old man, with long white locks hanging over his shoulders, still vigorous and active for his years.

The cemetery contains many other monuments—with the exception of one or two by Launitz, and an exquisite Death Angel, in sandstone, from a young Frankfort sculptor—they are not remarkable. The common tomb-stone is a white wooden cross; opposite the entrance is a perfect forest of them, involuntarily reminding one of a company of ghosts, with outstretched arms. These contain the names of the deceased with mottoes, some of which are beautiful and touching, as for instance:—“Through darkness into light:” “Weep not for her; she is not dead but sleepeth:” “Slumber sweet!” &c. The graves are neatly bordered with grass and planted with flowers, and many of the crosses have withered wreaths hanging upon them. In summer it is a beautiful place; in fact the very name of cemetery in German—“Friedhof,” or, “Court of Peace”—takes away the idea of death. The beautiful figure of the youth with his inverted torch makes one think of the grave only as a place of repose.—Extract from J. Bayard Taylor’s Works.

The setting of a great hope is like the setting of the sun,—the brightness of our life is gone. Shadows of evening fall around us; the world seems but a dim reflection, itself a broader shadow. We look forward into the coming lonely night. The soul withdraws into itself. Then stars arise, and the night is holy.

How often the phantoms of joy regale us, and dance before us,—golden-winged, angel-faced, heart-warming,—and make an Elysium in which the dreaming soul bathes and feels translated to another existence, and then sudden as night or a cloud—a word, a step, a thought, a memory will chase them away.

Light is transmitted in all directions in straight lines, and traverses about 192,500 miles in a second of time. The color of bodies is due to the absorption of light. A body that absorbs all the rays will appear black, while one that reflects them will seem white; but some substances absorb some of the rays and reflect others. A yellow surface reflects the yellow rays, and absorbs the others; a blue surface reflects the blue; a scarlet surface absorbs all the rays except the red. Light is the cause of color in animals, plants, and minerals; but what becomes of the light that is absorbed by bodies is not known: it may possibly be latent or hidden, the same as color or heat, and enter into combination with them; for it is evident that light may be extracted from some bodies without any change being produced, as in pyrophori, or substances which absorb light, and emit it again when carried back into a dark place.

The yearly income of one firm in San Francisco, arising from ground-rents alone, is the large sum of $250,000. In no part of the world can a better position be found for witnessing what effect the “infernal thirst for gold” has upon poor humanity, than in this city. Fine specimens of our kind may every day be seen, fretting themselves to death to add to their stock of yellow metal, which is as much needed to further their happiness, or add to their comfort, as water would be to make a fire burn,—just as if people were born for no other purpose than to make themselves the meanest slaves in striving to possess quantities of gold, which, when got, appear to cost more anxiety to keep, than it did to amass it.—Extract from a Letter written in California.

Casco Bay.—Few sheets of water compare for romantic and beautiful scenery with Casco Bay, an arm of which makes the harbor of Portland. Its surface is broken up with more than three hundred islands, scattered irregularly, so as to present to the tourist who may be drifting over its summer wave, an ever varying series of enchanting views. Now his boat glides safely along under some rocky shore, so near that one may seize the down-stooping forest branches and swing himself upon the jutting points,—anon some tranquil inlet opens, revealing the fisherman’s snug cottage, with its grassy slope, fruit trees, and sheltering wood in the rear, and his trimly painted skiff curtseying in the waves in some protecting nook. Again the scene assumes more wild and primitive features, craggy ledges, grown gray in opposing the gale and billow; bold promontories surmounted by trees of gigantic proportions, above which, high in the blue empyrean, perchance sails the bold eagle; long reaches of glimmering sand-beach, upon which the weary waves, journeying in from the broad sea, throw themselves as if glad to find a resting place; and then there are forest, embowered coves, and grassy openings. In short, the adventurer may sail on for days amidst ever varying, but always interesting scenes.

Ah! well do I remember,

Not many years agone,

One bright night in September

I wandered,—not alone;

A manly voice beside me,

Enchained my list’ning ear—

Sure harm could ne’er betide me

With that strong heart so near.

We gazed into the moonlight,

And watched the floating cloud,

And thought how soon the midnight

Would come with pall and shroud.

We parted—Oh! ’twas sad to part,

Though hope with fear was mix’d;

My parting words, devoid of art,

Were “come,” with “do” prefix’d.

And oft do I bethink me

Of that sweet summer ev’n

When I asked you to “Tea,”

’Neath the blue arch of heav’n.

The zephyrs soft were dancing

In the boughs of the glade,

And a strange light came glancing

Through the deepening shade.

We arose from our feasting,

But wandered not far,

When, our vision arresting,

Blazed a wonderful star;

Like a ball of fire it gleamed

Amid the starry host;

Sun-like, radiant it seemed,

Wand’ring like some spirit lost;

On its trackless course it sped,

Trailing rays of wondrous light;

Till, through far off space it fled,

Vanishing from mortal sight.

As our steps we homeward turned,

Thought we of some minds of light,

That with brightest lustre burned,

But to sink in deeper night.

“Comet”-like their genius shone

As they ran their wayward way,

Till, like “Comets,” left alone,

Downward sank, and sank for aye.

Edla.

Montreal, October, 1853.

Oscar, what a sly fellow you are,

To write so pathetically,

About meeting clandestinely

With “blushes,” “fair tresses,” and eyes on a par;

If you didn’t feel happy it would be queer,

When “blushes” said “do come again Oscar, dear.”

“Love thinks” of the time when, “late in the eve,”

You rather more openly,

And very romantically,

Took some supper before you took leave!

Now come, Oscar, between you and me,

Wasn’t the celestial herb you sipped, green tea?

As you directed, I looked to the sky,

And in the deep profundity,

Of vast immensity,

I twigged the comet,—not “all in my eye,”—

A celestial long-tailed swaggering “ranger,”

In short, good Tom M’Ginn’s, “illustrious stranger.”

A. T. C.

Montreal, Oct. 1853.

See’st thou that form supremely fair—

That lofty brow—the raven hair

In curling ringlets wound?

Mark’st thou that eye, whose gentle light,

Dispels the deepest shades of night?—

It rises on thy rapturous sight,

And now my “First” you have found.

Simple sign of magic power.

Who can estimate thy dower?—

Who thy worth portray?

Far as the heaving billows roll

Thy mute voice cheers the weary soul,—

Points the young mind, perfection’s goal,

My “Second” leads the way.

Hast thou in gloom and sadness wept—

Thy chamber paced when others slept,

And wished for opening day?

In absence hast thou friends—although

Thy thoughts were present—yet, how slow

The postboy’s wheels—they come—and lo!

My “Whole” thy joys display.

Oscar.

Montreal, November, 1853.

I am a word of 11 letters.

My 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, a very useful animal.

My” 6, 5, 8, a color.

My” 5, 7, 6, part of the human body.

My” 11, 7, 9, 6, the ladies’ pride.

My” 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, is a root,

And my whole is a root.

P. R. Mc.

Montreal, Sept. 15, 1853.

The following account of the depth at which the ocean has been sounded will give some idea of the vast valleys that exist in its bed. The sounding was performed in the Atlantic in 36° 49′ S. lat., 36° 6′ E. long., in a voyage of the British ship Herald, from Rio Janeiro to the Cape of Good Hope. The depth at which bottom was reached was 7,706 fathoms, or 12,412 yards, being nearly eight miles. The highest mountains on the surface of the globe do not exceed five miles, and the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada are not more than 4,660 yards, so that the bed of the ocean has depths which far surpass the elevation of the highest points on its surface. The time required for this immense length of line to run out was about nine hours and a half.

“Oscar” will see that we have kept our promise. We insert two answers to his Charade in the October number, which were sent from different sources, and differ widely in their manner of solving it.

This number contains Mrs. Traill’s eleventh chapter of “The Governor’s Daughter,” &c., in which she relates some curious things of the reptiles of Canada. “Lady Mary’s Nurse” is a perfect treasure, a woman of practical information, and quite an observer of matters and things.

Poetry from Chambly has been received. Mrs. Hayward, our valued correspondent, proposes to send a series of original articles on the Seasons in Canada. The first appears in this number. The charming autumn weather which she describes so beautifully continues to shed its softening influence around our city, and almost cheats us into the belief that the storm-clouds have passed away to the North. The heavy shades piled up with gayer colors, blending and fading away in the sunset of our autumnal evenings, harmonize finely with the indescribable feelings which come, as if wafted to us on the heart-touching tones of its mournful winds, or the soothing music of its sighing breeze. The season is in unison, too, with refined and purifying emotions; suggestive, it is true, of decay and mortality, yet shadowing forth in a comforting manner the great doctrine of resurrectional beauty and glory, for the spiritual as well as the natural world.

Publisher’s Notice.—In answer to various inquiries, the Publisher begs to say, that all moneys sent by Mail, if the letter containing the same is marked “Money,” will be at the Publisher’s risk.

Misspelled words and printer errors have been corrected. Where multiple spellings occur, majority use has been employed.

Punctuation has been maintained except where obvious printer errors occur.

When nested quoting was encountered, nested double quotes were changed to single quotes.

A Table of Contents has been added for reader convenience.

A cover was created for this ebook which is placed in the public domain.

[The end of The Maple Leaf, Vol 3, no. 5, November 1853, by Eleanor H. Lay]