* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

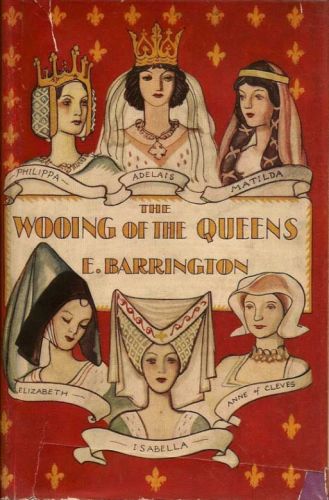

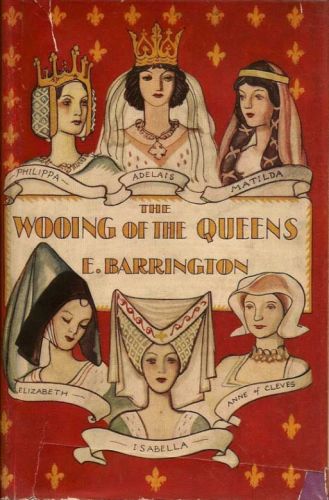

Title: The Wooing of the Queens

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Elizabeth Louisa Moresby (as E. Barrington) (1865-1931)

Date first posted: January 7, 2026

Date last updated: January 7, 2026

Faded Page eBook #20260112

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

By the Same Author

Anne Boleyn

The Duel of the Queens

The Great Romantic

The Irish Beauties

The Graces

THE WOOING

OF THE QUEENS

by

E. BARRINGTON

CASSELL

AND COMPANY, LIMITED

London, Toronto, Melbourne

and Sydney

First Published 1934

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

EBENEZER BAYLIS AND SON, LIMITED, THE

TRINITY PRESS, WORCESTER, AND LONDON.

F50.634

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| 1. | THE HEART OF MAUD | 1 |

| 2. | THE LADY OF THE ENGLISH | 43 |

| 3. | ADELAIS THE LOVELY | 79 |

| 4. | PHILIPPA THE CHIVALROUS | 119 |

| 5. | THE LITTLE QUEEN | 161 |

| 6. | THE QUEEN OF MODESTY | 199 |

| 7. | THREE KATHARINES, TWO ANNES, AND A JANE | 243 |

(MAUD, QUEEN OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR.

KNOWN AS MAUD IN ENGLAND,

AND AS MATILDA BY THE NORMANS)

The Princess Maud stood before her father the sovereign Earl of Flanders as a culprit had up for judgment, and she looked him as straight in the eyes as he in hers. Indeed they were hewn out of the same marble, strong and daring, haters of the weakness of human nature, lovers of its strength. But she was young and had not yet had time to weave and wear the cloak of astute diplomacy with which her father was obliged to hide his own feelings among warlike neighbours. He hated it, but he wore it, and Maud too must be trained to docility for her country’s sake as well as his own. What good are daughters else?

“I have said and I repeat,” said Earl Baldwin glowering at her, “that you will marry the reigning Duke William of Normandy. And if you refuse it is in my power to have you whipped until the blood runs!”

“And I have said, and I repeat, that I will not marry him. I carry a dagger in my girdle” (she drew it out—a pretty slender thing, but sufficient) “and I will stick it in my throat before I marry a man fit only to wipe my shoes if they were muddy.”

Earl Baldwin invoked St. Ursula and her twenty thousand virgins, though he had found one a match for him. The Princess Maud had been a handful since she had kicked him in the face but an hour after her birth, as she lay on her nurse’s knee and he had brought his short-sighted eyes close to see the queer little specimen of womanhood. Now she was a tall girl, brown-eyed and haired, with a full red mouth, a handsome blunt nose and a throat like a pillar of sunburnt ivory, and she did the same—but figuratively. She had reason for headstrong pride if beauty, quick wit, wealth, and the highest birth in Europe are permitted stilts to vanity, and she stalked with the best.

“Normandy,” said the earl playing on that string, “is a glorious country, fat and fertile. The King of France is overlord, true—but Duke William is a prouder and stronger man than he. And now listen, Maud, and shut your jaws on what I tell you. There is more than that. Much more. Duke William is cousin to the King of England, Edward the Confessor, the saint—a man by far too godly to have children of his own and makes a sister of his wife Edith——”

“The old fool!” said the princess.

“True enough, but listen. In a most secret message, not written, but whispered in my ear by a bird who sings at night, William the Norman tells me that Edward will choose him for his successor—has sworn it by the relics of St. Peter in his new Abbey of Westminster. Therefore William the Norman will be King of England—and Conqueror of France. He can spring on France from Normandy with England behind him. I salute the Queen of England and France in my daughter!”

“That you do not!” retorted the princess sturdily, “and for two excellent reasons. There is Harold the Saxon prince, the true heir of that throne. He will be King of England. I love the brave Saxon men, all gold and white and ruddy—big giants of men. That is one reason. The other is that I will not marry William of Normandy. His father was Duke of Normandy—yes—but his mother—oh, the good God!”

She screwed up her face as if at a pungent smell and went on:

“Arlotte, the daughter of the tanner of Falaise! A light-heeled wench that the duke took as one eats a hearty dinner to quench an appetite. I smell raw leather when I hear her name. And he thrust her brat on his nobles as heir because there was no other of his own blood. And am I to marry a man with a big black bar across his coat-of-arms—if he has one? Am I to see every knight’s wife turn up her saucy nose—‘There goes Maud, the wife of the Mamzer of Normandy!’ That’s what they call him!—and say, ‘Poor slut, her father could find no decent match for her so he took the Mamzer, the tanner’s grandson, and glad to get him.’ I tell you, my father, I will not. Blessed Lady, are we come to this!”

Her astute father looked at her in dismay. It was true—too true. Duke Robert of Normandy had omitted the ceremony which would have made his son William a match for the best in the world. But women are sticklers on such points and will not realize that circumstances alter cases. But why has Providence created women and made them a necessity in continuing the race? Earl Baldwin in a frantic moment had asked that question of his confessor, who had replied:

“They were created so that men who would otherwise doubt the truth of hell may see its visible proof on earth and foretaste its torments.”

Earl Baldwin agreed with him now. Duke William’s suit had a note in it that said “Beware!” as with a clash of swords, and Flanders is near to France and to Normandy, and it is well to be civil when swords talk. Said he, deliberately mixing religion with politics as was the fashion:

“Such pride is hateful to God and man, my daughter. Repeat it and I shall have you guarded in your chamber and fed on bread and water. Your dagger of which you boast shall be taken from you and your hands bound. And I myself will flog you with a scourge of knotted cords until you agree to what is needful. You have it now, short and sweet. Choose.”

In a second out flashed her dagger, and the point was at her throat beneath the ear. A drop of blood sprang where it pressed and trickled down her neck to the pearls. So they remained for a second or two—the duke with fallen jaw, the young woman with a steady hand, and a look that concentrated volumes in one defiant word—Death. At last she spoke.

“I will not be flogged nor put on bread and water. And now I tell you, my father, that you waste breath. Four days ago I sent a messenger riding to Normandy, and not your swiftest can overtake him. He carried my answer to the Mamzer.”

“Holy St. Peter!” gasped the earl and collapsed into his great chair.

His daughter knew she had the heels of him and composedly thrust the dagger into its gay velvet sheath, where it hung at her dropped girdle among half a dozen charming trifles. She leaned against the wall, hung with arras—the duke’s tapestries were famous,—waiting his recovery. He slowly pulled himself together and asked with a gulp:

“I trust in God you at least wrote with civility?”

“Very little!” she admitted carelessly. “I gave my reason as I gave it to you. He will not trouble us again with offers.”

The occasion was too serious for parental bellowing. Earl Baldwin’s voice was small and cold as he said bitterly:

“No. No offers. He will come with sounding trumpets and drums and trample Flanders and take you in your smock and you may pray God in vain that he marries you when all is done. But he will not. The proudest man alive, and you have trampled his pride where it is tenderest! What did you say?”

“I said: ‘My lord Duke of Normandy, our forefathers were princes when your mother’s folk were skinning beasts to make shoes for their betters. I counsel you to seek your like. If my husband is to wear a black bar across his shield he must win me by some deed of courage that shall blind my eyes to it, and this you cannot. I recommend you heartily to God.’ And now, my lord and father, may I go? You and I were always good comrades between our quarrels and the thing is done and over. I will not marry unless I love. And I believe I am in love already, though I am not certain.”

Her audacity terrified her father; he blustered and questioned no more. He could only hope that if she had a passion it might serve his ends. He said almost beseechingly:

“And which of the kings and princes has my beauty chosen?”

Maud laughed. She knew she was no beauty in a picture but merely a handsome girl with the face that sparkles with character and courage, the face which some men fear and some worship, but all will pick out and remember long after they have tired of golden-haired languishers and mincers, and have sought entertainment elsewhere. She slipped into the huge chair beside her father and put her arm about his neck for all the world as if there had been no dagger flashing a few minutes back and rubbed her nose gently against his ear.

“Now that I shall not tell you, my father, nor do you expect it. Did you tell your father the first time you cast sheep’s eyes at golden curls and red lips? Oh, no—nor do I. Besides—I do not expect to marry this man. I will not make trouble for you there. It is a charming distraction. He is to love me for ever, and I am to forget him when I please.”

A handful indeed! The earl’s only clear thought was that he wished William of Normandy had the handling of her instead of her poor bewildered father. She answered the look of horror he gave her.

“No—it will not go too far. I have drawn a line; beyond it I do not step. But—I like love. It is warm. It is a decoration to life. It——”

“If your name is tossed in the dirt none will marry you and into a convent you go,” the earl ejaculated, and wrested his neck free from her.

She laughed like a carillon of bells.

“I am told that one may be very merry in certain convents. No—do not kill him Father, if you guess. Trust me and when I am tired I will perhaps marry who you will.”

On this the earl was obliged to go, for he could get no other satisfaction. His mind worked like a yeasty sea brewing storm. Would the Bastard of Normandy declare war on a girl’s impudent letter? If he did, could France be coaxed to an alliance which might crush Duke William and divide Normandy between France and Flanders? And what about England? A girl’s whim to have such fearful consequences! He shut himself into his innermost chamber to plot a course and could think of none.

But Maud mounting her jennet, hung like a window with purple velvet and silver fringes, rode through the narrow streets of Bruges smiling upon all and sundry as they greeted their princess with frantic applause. She took the quietest ways, but still many welcomed her and the frank gay smiles she shed among them like rosy flowers. Also she dipped a generous hand in the embroidered silk purse that dangled at her side, and to the poorest she gave silver coins and to one poor cripple a bit of shining gold. Some she recognized, and hailed by name—never a franker, more cordial princess won the hearts of her people—and so under narrow eaves and strange high-pitched roofs and barred lattices she rode to the Convent of St. Catherine among its willows, and by its canal. Leaving her train and pride outside as befitted a daughter of the Church, she went in with one confidential lady to make her prayers in the chapel.

The princess was received by the prioress attended by two nuns who, with her lady, were dismissed after the formalities were over. This prioress was a remarkable lady both in and out of religion, and tall and beautiful even though her hair was now white and her blue eyes sunken. For she was cousin to that Countess Godiva, wife to Earl Leofric of Coventry, who was held a saint in Europe for her great deed of mercy in riding clothed only with her long golden hair through the streets of Coventry, when her husband made that deed the cruel condition of his remitting the fierce taxation imposed upon his people there. The prioress herself was famous not only for the noblest blood of England, but also for the strange and dreadful austerities which had won her the rule of this convent in a foreign land. The Princess Maud herself knelt and kissed her hand, and asked her benediction as humbly as any woman in the street outside would have done it.

The blessing was given, and immediately there was a startling change in their manner to one another. The prioress Elswitha seated herself in an almost regal chair surmounted with the Cross and Maud, pulling a cushion to her, sat on the floor before the prioress and leaned one arm on her coarse black serge habit.

“I have a story to tell my reverend Mother,” she said, “and if I was wrong I will ask pardon, but I think I was not wrong.”

So with the nun’s hand laid on her nut-brown hair the princess told what had passed between her father and herself. She looked up at the end to find the stern face smiling down upon her with amusement—even with relish at the dash and glitter of the escapade.

“You are a minx and more,” she said, “but a royal minx, and if you can have your way it is a good way. Women must show they are strong if they are to rule. The meek woman creates tyrants and turns herself into a servile liar. Our women in Saxon England are no slaves. I sat in the castle in Coventry the day the Earl Leofric dared his wife, my Lady Godiva, to ride naked through Coventry if she wanted the taxes removed from the half-starved people. The poets have painted her all shrinking modesty and wifely meekness—both of which are excellent good things, but there are better. For Godiva was all flame and courage. She looked at him with eyes that should have scorched the brute where he stood—the great hulking master—and then she laughed.”

“Laughed? I like her for it. I know how she laughed!” said Maud with coldly sparkling eyes. “To-day I also laughed.”

The prioress herself laughed.

“But she said nothing, except that it was a hard condition and he slouched whistling to his dogs to ride to his hunting grange at Tamworth, and I said to her: ‘You will do it?’ And she laughed again but very differently, for we loved one another. And she said: ‘I would do it if I knew I must drop dead in the street, for the people are right and my earl is wrong. But also, he will dare no more tyranny after that with me for the world shall hear of it. He will fear me because I am a saint who sticks at nothing, and I shall master him. Two birds may be killed with one stone.’ ”

“Her story has certainly been heard,” said the princess. “And two birds may be killed with one stone—I know it.”

“And so when he had ridden off secure in his tyranny she sent out her proclamation to Coventry that no man or woman should stir next morning in the streets until the bell in the gable should ring from the great house. And in the dawn I was with her when she stood robed in yellow hair from crown to ankle, and I held her bridle while she mounted and rode slowly like a queen through the empty city. And I was there when she told Leofric her deed, and he quailed before her and she triumphed like one of the Valkyrie our forefathers worshipped—the maids who choose the slain. And from that day the world sainted her and he was her slave and had he crossed her will all England had risen against him. She had killed her two birds.”

The prioress halted, almost breathless for a moment, then added:

“And it is in England you should reign, Maud, my daughter, for I love you and know that the English love a proud free woman. And that is why I have permitted you to meet the Saxon lord Brictric who comes from England to woo you for Harold, son of Earl Godwin. Harold is the chosen king for England when Edward the Confessor dies, and though his family and mine were enemies, for him I would do all. Also—I have seen in a dream that you will be Queen of England.”

“And I have seen it too,” said Maud clasping her hands upon her knee. “I am as sure I shall be Queen of England as that I sit here and love you. But my father must not know yet—not yet. And I will be brave as Godiva. Will Harold do my will? I must have an Englishman.”

“I think your wills will be one and that is the best. It is a good thing when man and wife are of one mind in a house. Their foes despair. Their friends rejoice. And Harold is a man any woman might desire for her children’s father—tall and fair and mighty and a natural worshipper of good women——”

“And if they are not good?” the princess asked mischievously.

“Still their worshipper for what he hopes in them. But you are good enough,” said the prioress. She had loved the girl for years and trained her to more than prayers.

She touched a little bell of silver that stood on a table beside her, and into the room came a grave old nun, her wrinkled face half hidden by coif and veil. The prioress made a sign with her hand and she went out. Meanwhile the princess rose and stood beside the great chair waiting with a visible flutter of feeling until the heavy curtain swung aside and the nun reappeared with a young man behind her, and then slipped noiselessly away again.

He was a very splendid young man in a dark blue tunic—short to the bare knee; his arms, bare also, tattooed with stars, fishes and animals after the fashion of the English, and laden with great gold bracelets like fetters. He was well able to defend them. His skin was fair as snow—they called him Brictric the White. He was mighty in the shoulders and had great limbs, and a splendid height. Saxon crossed with Dane, he was a man to catch any woman’s eye with his golden hair and the golden moustache that clothed his short upper lip disclosing teeth white as a hunting hound’s. In short, a Norse god with Victory to perch on his shoulder like a tamed falcon when he handled his huge bow and arrows for war. The Princess Maud was a tall girl but she could only have laid her head as high as his heart.

Duke William himself had some of the same blood in him on his father’s side, though he did not show it, for the name of his Normandy commemorates the land of the Northmen who, coming down from the cold North, seized the land and called it after themselves.

This Brictric bent his knee and kissed the hand of the prioress as she blessed him. And then, without a word, like one who follows an expected ritual, she went out and left the young man and woman together.

They were as safe as in the sanctuary. Kings dared not penetrate convent secrets. Armies would have halted at those gates. And this they knew.

The princess, smiling, stretched out her hands and the young man knelt and kissed them, burying his face in them not like an envoy, but a lover. She slipped one away and sitting in the great chair put her arm about his neck so that he knelt beside her, and she could lay her head upon his breast. Half mad with love he kissed her hair and what could be reached of her face—rose-red with happiness and love. Harold of England had chosen his messenger ill.

Yet the Saxon lord had been honest after a fashion. He had drawn a splendid picture of Earl Harold, the king-to-be, of his loveless political marriage with the cold-hearted Welsh princess, so easily to be dissolved, of the glories that would await the Flemish princess when she was his wife.

“For he will kiss the ground your little feet touch,” had said Brictric the Englishman. “In England we do this when our wives are brave and beautiful. And the English people will worship their queen, and your sons will be sturdy and long-lived as oaks, and your daughters lovely as the fairies who dance beneath them.”

Tempting enough, but from the first minute he appeared at her father’s court, an envoy of good-will from the English king-to-be, the princess had taken very much more interest in the messenger than in the message. Did she love him? She really did not know. She was only certain that he must love no one else, and that certainly appeared to be his own opinion.

An ardent lover; Harold of England was forgotten, and the two talked of themselves in the quiet room which looked out into the green cloud of linden boughs and did not even speak of marriage, but only of the delightful dream in that earthly paradise where lips touch lips, and youth is eternal and death a nightmare to be forgotten in love’s surprise.

She told him now of her father’s wrath and her repulse to the mighty Norman, and felt his start of dread. She raised her head and looked at him—his face had paled.

“You fear for me, my dearest, and why?” she asked.

He clasped her hands in his.

“Because of all men living, this Norman is the mightiest. Were it not for the wide sea between Normandy and England I dread that even Harold the earl could not face him. I have seen the man and know. How shall I describe him! He is dark, not over-tall, but most strongly built. Great shoulders and yellow eyes like a dragon’s or lion’s, as they say. And when he fixes those eyes on a man, sparkles flash from them as from red iron when the smith hammers. And then men wither. It is true, my princess! He does not roar or storm as a warrior should in anger, but passion turns him white and silent as though the blood ran back on his heart to swell it with power. You should not have dared him—never, never!”

“Then should I have submitted?” Her own voice was quiet now, and it was observable that she drew one hand away to settle her neck pearls.

“No, my princess—could your lover say such a horror? But you should have won your father and fawned and wiled and slid out of it like a snake. A woman has a hundred ways of escape. I fear for you very greatly. The Mamzer of Normandy never forgets an insult. He sits still and thinks, and his rage grows like a toad with its swelled sides full of death. God and Our Lady only can meet him!”

“Then the Mamzer of Normandy is a greater man than your Harold?” said the Princess Maud thoughtfully.

“How shall I say that?” answered the Englishman. “But I would say to Harold—‘Keep the wide sea between you,’ as I would keep it between myself and Harold if I had offended my overlord.”

The princess turned a curl of his hair about her finger where it shone like a gold ring and smiled her brightest smile.

“So now I understand!” she said. “You are a strong man, but Harold is stronger, and William of Normandy is strongest. And Harold must wear the sea for his shield! Well—it is best I should know the truth. Now let us forget our masters and tell me—have you ever loved any English woman? Be true. I know you love me now.”

He laughed and blushed like the great boy he was, half denying, and half confessing, and fondled her hands, caressing them like a dog with all the love in his body. And at last she pressed him.

“Why, yes, my princess! Young men are young men. I own it. But I have forgotten her now.”

“What like was she?”

Old love rekindled in his eyes as he answered musing.

“A girl of Dane’s blood. Swanhild her name. White as a whale’s tooth. Eyes like a midsummer sea. Hair of the true red-gold the dwarfs find in the Dovrefeld. Lovely. Deep-breasted. Sweeter than sweet, proud to all but me; but to me—a dog fawning—she——”

But the princess interrupted softly with a most beguiling smile: “Does a man ever forget his first love?”

“Never, never!” he answered in a dream, kissing her hand softly. But she knew that his lips caressed a hand over the sea and that memory put it in his own. She withdrew hers, and whispered again softly:

“And shall I be forgotten?”

Again he answered:

“Never—never!” and tried to recapture her hand. But she rose.

“Then you are vowed to me in life and death and out beyond both? You will never hold another in those strong arms? You will never wed. You swear yourself mine for ever. I do not forgive a false heart. No!”

He answered eagerly:

“For ever. Who can forget the princess of the world when she stoops to her slave? I am your man while my heart beats and my blood flows. For ever and ever—and ever and out beyond life.”

“Blood may flow in more ways than one,” said the princess. “Well, do not forget me for Swanhild. That I could not forgive. I have claws! I warn you! Remember I am a woman.”

“Soft hands!” he whispered in a rapture and kissed them with passion.

They went together into the room where the prioress sat attended by her old nun, and she looked eagerly at Maud for some good word of Harold the English king-to-be. Maud said not a word, but her smile was like that of the saint over the great archway, who having been a sinner is now smiling, holy among the holy, but he remembers both sides of life.

Thus the princess rode back through the blessings of the people, and her father commended her pious visit to the convent.

Later, the messenger returned from his errand to William the Norman duke, and was ushered to the room where the princess sat in a great Byzantine brocade of red and gold with wheels and birds in the design. She leaned her round chin upon her hand, looking sidelong at him over the arm of her chair and asked:

“The message?”

“None, my princess. I rode to Rouen—a great city where the Norman sits in state, and to a castle up-towering which armies could not break, and I said: ‘Tell my lord Duke I am come from the Princess Maud of Flanders’—and when that reached him everyone was thrust aside and I went up proudly to the great stone hall where he sat with his councillors in armour.”

“What like was he?”

“He stood a moment before settling himself to hear and I saw. Not over-tall, but mighty. His shoulders like a bull’s; he has a round head, an eagle’s beak for a nose, and beyond all that—oh, a face of clenched iron!—a terrible fighting face indeed! So I knelt and offered my princess’s letter and—a strange thing—he stretched his sword and spitted it on the point—I aiding—and so he took it. Princess, my heart beat like a bird’s! So he read and stood thinking awhile.”

“And then?”

“Madam, he laughed. Not angrily. But softly. And he said this: ‘Had this letter come from a hand less lovely, the tanner girl’s son would have flayed the bearer alive and made his skin into gloves for it. But since it is so, ride back in safety.’ ”

She mused a little on that and asked:

“No more?”

“He called Taillefer his minstrel and bid him sing the song of King Cophetua and the beggar-maid. And that man sang so that my eyes moistened for the fair beggar-maid who kissed the king’s feet. Then my lord duke said ‘Go,’ and I went, but I do not know his meaning.”

She dismissed him and sat awhile pondering, then went to Earl Baldwin and told him the story.

“He took it as a jest. We have got off cheaply. Do not play such a trick again, young fool!” he said eagerly.

Maud was silent.

Again time went by and all the world knew of Duke William’s great doings in Normandy. The princess had bid the prioress send Harold’s messenger back to England without any promise. She was young, she must consider, she said. But she kissed Brictric passionately on the mouth in saying good-bye, and clung to him awhile but with no tears in her eyes, saying:

“Remember! None but me—but me while life lasts!”

And again he swore on the Passion of God.

The princess rode one day to hear Mass at the Convent of St. Catherine. She rode her white horse, with a side-chair saddle inlaid with gold and silver by great craftsmen of Flanders. Her robe was white and gold with a rich border of jewellers’ work about the bosom. Her nut-brown hair rolled back in ripples from her forehead and was bound by a noble golden band with fleurs-de-lis of pearls. She looked a queen in an old romance, her damsels two by two riding behind her.

A shout—a roar—her horse reared violently, and all but fell on the back of the two behind, throwing them into confusion. The girls shrieked. The crowds on either side fell back. A man unarmed, except for his sword, broke from a side-street followed by two companions. Their horses trampled the shrieking crowd. He made for the princess as she frantically tried to control her horse.

“A capture—a capture! Save our princess!” yelled the crowd, huddling together in panic. But it was no capture.

In the wild uproar the stranger rode furiously to the princess, and when she saw his face she dropped her bridle and sat like marble, staring at him.

He towered over her a second, black as a thunder-cloud, then sprang from his horse and winding his hand in her long hair dragged her from her mount. Down into the foul roadway he dragged her, trampling her brocades and flowing hair in the black mud. His followers seized the horses and looked on tranquilly. Along the street he dragged her, silent as death. He flourished a strirup leather above her and thrashed her with it as a man does a stubborn horse. Blood broke on her arm, her face was vile with mud, her hair dabbled with it.

All went in a flash. A man raised a yell of “The Duke of Normandy” and in terror of his name the crowd fled along the side alleys—away—away! The street was suddenly empty, though a few citizens still stared aghast from their windows.

Then he released her, and she lay half swooning in the mud.

“You sent your message. I brought mine!” he said, and mounted with never a look at her as she lay, and so vanished, stooping over his horse’s neck and riding like the wind. It seemed that the thing could never have been. And yet it had been, and the bedraggled princess lay trampled in the mud.

Men-at-arms stormed into the street. Her shuddering ladies returned and men brought a litter, and she was laid in it and brought to the palace and bathed and restored. She was not wounded, except in spirit, but there the wound was heart deep. Earl Baldwin came to her trembling: “My daughter—my daughter! The foul villain!” expecting a Fury, her hair all snakes clamouring for vengeance. Instead she sat humped together like a cat, though not showing her teeth, in a stupor of broken pride, and her father put his arm about her and cursed the Mamzer.

“But it will be forgotten, my child. The world will cry shame upon him.”

She flashed:

“It will not be forgotten. I shall not forget!” she said. “My anguish—my anguish! He did not take me with him.”

Duke Baldwin nearly fell from his chair.

“What?” he screamed. “You would have gone with the brute beast!”

“I would follow him to the world’s end!” said the princess with glittering eyes.

“Yes, to stab him, to drive your dagger in his foul face. To——”

“To kiss his feet. He is the only man I will ever marry. The only man on earth. To ride into my father’s city and flog me in sight of the cowards, to drag me in the dirt; to punish me rightly for the foul shame I did him. I love him—I worship him! I tell you I kiss his feet.”

She was aflame with passion.

“But, God in Heaven!—you refused him!” cried the earl, believing her mad with pain and disgrace.

“I did. I did not know him. Oh, the agony! He despises me, he does not want me. Oh, that he had taken me with him.”

“Women—women!” groaned the earl. “Does even their Creator know them? If I had laid a finger on you——”

“I would have stabbed you,” said Maud, “but he is different. Write to him. Tell him——”

But here the earl sturdily refused. The city was in an uproar. Men were arming. Drums were beating. Soldiers started in pursuit. The princess raved. Trusted women were set to watch her lest she should disgrace herself by writing to William of Normandy. And the tale circled Europe.

A month went by, and the princess agonized under the close guard of these women. No word, apology or defiance, from Normandy. Silence. The physicians feared for her reason and still she repeated:

“I will marry no other—no other. Oh, I see his face—all scorn and hatred, and no wonder! A god among men!”

One day rode into Bruges heralds and men-at-arms, splendid in gold and scarlet, the Lion of Normandy on their banners and pennoncelles—“In the name of the high and mighty Prince, William Duke of Normandy.”

The princess did not hear the confusion where she sat pale and weeping. Her father hesitated to receive the letter, for all Europe knew the insult. But it might be a much-belated apology. In full council, in full armour, he opened it while his barons scowled about him.

It was a beautifully worded, courteous demand for the hand “of my very distant and highly honoured cousin, the Princess Maud. I have heard reports of her excellent beauty and courage——” and so on in the usual manner, through some gratifying details of the provision to be made for her in widowhood, to the end. Not a hint, not an allusion to the “Harrying of Bruges” as the people called it. That might have been a dream. This, the placid reality.

He carried it to the princess and it broke like a sunburst through her gloom. She would hear nothing, would say nothing, would not argue, but repeated her father’s first eager entreaties for the match.

“You desired it once. I desire it now,” she said. “And I tell you this—if you stop it I will run away barefoot to his arms. He is my man to me.”

There could be nothing done against her madness and the match was a splendid one apart from the “Harrying of Bruges.” Therefore a gracious acceptance was sent, and on a given day the bridegroom rode to Bruges for the marriage. The meeting of a bride and bridegroom is always interesting to bystanders, but on this occasion a breathless crowd watched it, and wagered on the issue.

She might fling him off at the last moment, revealing her real heart of pride. He might drag her to her knees and throw the once-scorned ring in her face and ride away to Normandy. Anything might happen.

But what really happened was this. The Earl Baldwin led his daughter forward and William of Normandy advanced to meet them. The bride dropped her father’s arm and fell on her knees before her bridegroom and with her hair sweeping the ground kissed his feet. Those who forgot for a moment to look at her expression—and it was worth considering—were rewarded by his. Steel-hard and ice-cold, it broke up in a moment as the Polar ice might break if all the summers of æons together poured a sudden glow upon it. He raised his kneeling princess and held her to his heart.

This all the world saw. They neither saw nor heard what was said when they were alone; the Queen of England told it to her eldest daughter when she was about to be wed.

For she held him off at arms’ length with her two hands locked in his and whispered:

“I am forgiven or we should not have met to-day. But tell me—is it possible you should love the girl you dragged in the mud and saw disgraced before the people? Tell me your true mind. Better break our marriage than promise to live together with that between us. For never was woman so won before.”

The light of the lamp fell on his dark face. Its pride and resolve were incomparable. But he was used to action rather than thought, and in all this matter he had not reasoned but felt. Now he hesitated, holding her hands.

“I do not know how to use words,” he said. “Even when I fall in a passion I am silent, they say. But you speak sense. We should know each other before I make you mine.”

“And you mine?” she said. But it was a question. His was not. His face was grave, earnestly bent on the problem.

“That I scarcely know. I do not promise you fidelity as the Church calls it. How can I promise even a year ahead? But this I say. I am a man and the fruit of a lawless passion. You taunted me with that and—I cannot tell you why—your scorn won me. I think it is right a woman should feel this, though we men know differently—and if you sinned thus I should kill you. But I have great dreams. Briefly, I shall be King of England and more. My plans are made for many things. Now, if I am away from you or drawn that way it is very possible I may be unfaithful to you. As possible as that I should ride out hunting when you wish to hold me in your bower. Why should I not? I am no churchman. But unfaithful as I count faithlessness I shall never be. I cannot. By the splendour of God, I swear it! Your letter made us one. Your silence, when I saw your white face in the mud and you bit your lips till the blood ran, and made no sound, I loved you. That made us one. We are flesh indeed—the same blood moves our heart. You shall be my crowned duchess and shall be also crowned queen, and my every thought a book for you to read. If you die I will take no other wife. We will lie side by side in the church as in our bed, and when the Trumpet sounds we will face God together hand in hand. Is this fidelity sufficient?”

They looked at each other, held apart still by their arms’ length in a silence.

She dropped her hands, and slipped the great sleeve of splendid stuff up her arm disclosing a white ridge across its warm snow.

“There is your mark, my heart,” she said. “See, I kiss it. I bless it. That fidelity you promise is sufficient. It is such riches that tears blind me reckoning it.”

He opened his arms and she clung to him. Then putting his two hands behind her head he pressed her lips to his.

Great and glorious was the marriage—the bride glowing like a rose of fire in her pride. It conferred loveliness on her. The people stared at her beauty. Her bridegroom sat beside her, still and strong as a sleeping sea hiding its secrets beneath calm.

The Pope commanded them to separate when they reached Normandy, because though remotely cousins they had begged no dispensation, and Holy Church must have her share in so wealthy and royal an alliance.

“We must humour the churchmen. I have reasons,” said William to his duchess, and therefore he built a great monastery to St. Stephen, and she a noble convent to the Holy Trinity, both at Caen. So the Church was bought to their interests, and to-day these two buildings stand to commemorate their wedded passion.

In ancient Roman days brides vowed fidelity to their husbands in this fashion: “Where you are Caius I am Caia”—and of Maud it may be said that where William was lion, she was lioness. She plotted with him to trap Harold to their Norman castle, and to force him to swear on the huddled relics of saints that he would never claim the English throne but would be William’s man, and let him climb to it from his back, so to speak.

“I long to see England,” the duchess said thoughtfully, before Harold left them. “I have never seen an Englishman but I liked and trusted him! There was one at my father’s court—a very brave and worthy man—Brictric, I think, his name. Is he still your man, Earl Harold, as he was then?”

She made no reference, nor did Harold, to that old hope so long forgotten. He smiled with her child upon his knee.

“Brictric, madam? A gracious memory yours! Yes, a rich man, great in lands and King Edward’s favour, and married to a lovely Danish woman, Swanhild, called by the people, the Fair. All is well with Brictric. Shall I give him your commendations when I cross the Channel?”

“My commendations and kind memories!” she said smiling, and added pleasantly, “I could wish to be Queen of England. It must be a fair country.”

Harold smiled also—from the teeth outward.

It was the Duchess Maud who, when Harold broke his oath and had himself crowned King of the English, fanned the sullen flame in William’s heart until it roared heavenward, she who gave him the glorious ship the Mora that led his conquering fleet, and the stroke of her lion-paw was swift and sure as Norman regent for him as his stroke on England.

And so came the great battle of Senlac, or Hastings, and the Duchess Maud, Regent of Normandy, sat with her ladies and stitched with them at her roll of history-pictures which may still be seen at Bayeux, a roll of canvas sixty-seven yards in length. There King Harold sets sail for Normandy from little Bosham in Sussex. There the great three-tailed comet of A.D. 1066, which predicted the humbling of England, glares at the Saxon princes. Over these pictures of needlework the Norman ladies paused to mutter prayers for their men. And when William the Duke conquered and—

Harold, Earl, shot over shield

Lay alone the autumn weald,

to Maud came his hurrying messengers. She was praying for him then in the Benedictine Priory of Our Lady, and rising like a queen she commanded that the priory should be henceforth called “Our Lady of Good Tidings,” and thus it is to this day.

So to England in triumph came the first Queen of England—for before that the wife of the king had been styled always the Lady of England, but William chose otherwise. And in the young April of 1068 she was crowned in the royal and ancient city of Winchester in robes that shamed the sunshine, and her William was crowned again with her.

But when that pomp was past, Maud the Queen came to her husband where he sat alone and said:

“My lord, like the Queen Esther of old I have a petition to make to you.”

And he replied:

“Like her king of old I answer—‘Ask, even to the half of my kingdom.’ What is it?”

And sitting beside him, and holding his sword-hand in one of hers she said:

“This. There is a man in England who has done me a great displeasure. His name is Brictric—and he is an English lord. He came to Bruges to ask my hand for Harold Godwinsson the dead king. But he dared also to make love to myself—then a maiden. And not content with this, when I scorned him he taunted me with his love for one more beautiful than I—a Danish woman called Swanhild. Now you and I are King and Queen in England—what shall we do?”

William sat swearing softly. This was a woman’s matter and perplexed him, but certainly it could not be let pass. He knew his Maud by this time, though it was seldom that she was not dove to him—whatever she might be to others.

“It is in your hands, my dove,” he said presently, “and, by the splendour of God, I pray you to make an example of him! We must grind these English to powder and make roads of their bones before this land can know peace. Stay, I will find out his possessions.”

“But I know them already!” said Queen Maud with composure. “He is lord of the city of Gloucester and much land round about it, and elsewhere. Are he and his possessions mine, and will you take what I do as your own deed?”

“I take it for mine, as you are mine,” replied the Conqueror.

Later she sent for Brictric the Englishman to her palace of Winchester, and with her ladies out of earshot, and sitting in her great carven chair with her hands laid on the two arms like an image, she spoke to him thus, he kneeling before the step of her chair:

“Once we were lovers and you swore to me on the Passion of God that you would be true man to me in life and death and beyond it. That you had done with this Swanhild, and had cast her aside like a used shoe. But you wedded her. What have you to say?”

Nothing apparently. He all but writhed before her.

“Then there is nothing to be said, unless indeed you drive Swanhild out with contempt for the foul thing she is,” said the queen. “That done, and submission made I will let things rest as they are. You are so far below me that it matters little if it were not that queens do not easily bear insults. Those are my conditions.”

There came a silence. The soft voices of the women outside talking gently over the great roll of the Bayeux tapestry, recording the king’s deeds, broke it no more than the distant singing of birds in the garden of the palace.

Then from his crouched kneeling with clasped hands like fear incarnate, Brictric the Englishman rose and stood leaning upon the cross-handle of his sword. So great was his height that as he stood he looked level into the eyes of the Norman queen as she sat uplifted. And so he spoke.

“Once we were lovers, and to my thinking when once man and woman have touched lips there should be no hatred between them, even if the fire is ash. I thought you then a noble young woman—a goddess strong and frank and overmastering. Now I do not know what you are. But this I say, Lady of the Normans—if I leave my wife, the mother of my sons, may she and you despise me together. But I will not put her away. I love her, and she shall not despise me, nor will I bear your contempt. Were I to yield, you would rightly smile and call me niddering, and to the English that is a word for swine and cowards and all foul weak things. I will not be niddering. Now, do with me what you will.”

Pale as death, Queen Maud still kept her long hands on the arms of her stately chair, not a tremble in them.

“To me the king has given all your lands and the city of Gloucester to do with them what I will. I am Lady of Avening, Tewkesbury, Fairford, Whitenhurst, all that stands written yours in Domesday Book. Do you still hold by Swanhild? Do you remember your oath?”

Still looking her in the eyes: “I have answered,” he said.

With the light crown of golden fleurs-de-lis binding her beautiful brows, and the white transparent veil flowing from it, she might have been an image of the crowned Madonna seated to receive homage. More than one sculptor indeed had the queen in mind in carving the gracious statues of her noble Abbey of Caen. That was not now the resemblance which impressed itself on the Englishman. At last she spoke:

“I deprive you of all your lands. They are mine. I deprive you of liberty. You are mine. You have chosen. I accept your choice.”

She clapped her hands to summon a lady—and she the guard. That day Brictric was chained in the strong castle of Winchester and his end none knows, for no man knew it but those who inflicted it, and buried him secretly in the castle. And still in William’s great Domesday Book where the lands of Brictric the White are entered, stands this note: “But afterwards held by Queen Maud.”

Songs were made of this story in the reign of Maud’s son Henry Beauclerc, for many pitied Brictric. As thus:

The Queen Maud

Who when she was a maiden

Loved a count of England.

Brictric the White they called him.

Except the king no man was richer.

To him the maiden sent messengers.

But Brictric refused Maud.

No doubt she was a great queen and lady, but at her heart of hearts very woman, and of this heart another reading also.

Once the stern heart of the Conqueror swerved a little—but a very little—from his royal wife. A canon of Canterbury Cathedral had a niece, beautiful, brown-haired and hazel-eyed, delicate and tender, and upon her the Conqueror swooped as an eagle upon a lamb, trusting in the secrecy of his men with sins of their own to hide. Smiling, they were silent. But women will dare where men hold back, and there was one woman in England who would have dared Hell for vengeance on William—the Lady Gyda, mother of Harold, the last King of the Saxons, he who had fallen fighting at Hastings.

To her the girl fled shamed and sobbing. Immediately, carried swinging in her litter by sturdy Saxon peasants along rough tracks and up hill and down dale, Gyda came to the palace of Winchester, and found Queen Maud sitting under green trees, placidly watching her children at play. To her the fierce, gaunt old woman seemed a ghost set free from the churchyard with her grey hair about her face, and eyes eagle-keen and cruel.

“And you sit here, Maud the Queen, watching children at their games when your lord dishonours Englishwomen and you. You avenged yourself once. Has the fire gone out of you or do you not dare to face your master?”

The queen rose and faced her:

“And what has happened?” she asked, listening in silence very disappointing to Lady Gyda.

The chroniclers relate that she ordered the girl’s jaws to be slit, that “She shall kiss none, nor they greatly desire to kiss her.”

It was vain for William to plead that he had warned her that a man’s heart can be true though his flesh is weak. His Maud smiled and was silent. The story was told, the episode ended. She did not argue.

The centuries roll by and Maud sleeps in her great Abbey of Caen. William made her a glorious tomb of gemmed sculpture and recorded her life thus:

Here she lieth, friend indeed

To the hungry heart of need.

Poor herself, enriching all

Who her gentleness did call

To their aid, and therefore she

Blest to all eternity

Passed to peace most peacefully.

The ancient chronicler writes of her:

This princess, descended from the Kings of France and Germany, was even more famous for the purity of her mind and manners than for her great descent. She united beauty with gentleness, and all the graces of Christian holiness. While her glorious lord subdued all things she never wearied of alleviating distress in every shape. All hearts loved her.

It might be interesting to determine how much of history is fiction, and how much of fiction is truth. Only the gods can know. But there can be no two opinions as to the omissions in obituary notices whether ancient or modern, royal or private, and their effect on the composite picture history presents to the admiring reader.

(MAUD, FIRST QUEEN OF HENRY THE FIRST)

“Maud and Edith are my names,” said the princess, “and both are Saxon and if I needed a further cause to hate the Normans—which I do not—it is that they call me Matilda! But Saxon and English I will be if the Normans leave me not so much as nine inches, the length of my foot, of English ground to stand on. What! am I not of the royalest Saxon blood, of the same stock as the great King Alfred and Edward the Confessor, and am I to listen to the boasts of the verminous Normans that overrun England, feeding on the blood of my people? Thank God and Our Lady I am in free Scotland and not fettered England and can speak my mind!”

Turgot the priest listened to the girl with amusement which he did not hide. The Princess Maud had been committed to his care as a child by her mother, Margaret, the sainted Queen of Scotland. As tutor to an especially wilful child he had more than once beaten her with his own sacred hand, and many had been her meals of bread and water eaten under his austere eye. To the scowls he paid not the least attention, nor did her teeth-clenched endurance under the rod mitigate one blow of the number judged necessary. But in his heart he loved the child beyond her sister Mary, also in his care, and well-behaved and docile. There were times when he felt obliged to lay his hard case before the Heavenly Court of Assize, imploring the Eternal Judge to forgive his preoccupation with a little demon when he might far more Christianly have set his affections on a golden-haired cherub who was never known to have disobeyed orders.

Yes, it was the rebel Maud whom he loved—Maud who never obeyed, who was more intent on catching a little shaggy Scots pony by the mane to swing herself on his back and so away over the moors, than on any prayer and book. Maud who would keep him hunting until she collapsed with laughter, and was caught and led in to receive the attentions of the rod with a meal of bread and water to follow.

“A princess in adversity such as yours and with a royal saint for a mother should set an example of piety to all!” said the good Turgot. “Consider, madam! Your royal grandmother fled with her children from England where most certainly the usurper William the Conqueror would have murdered her and hers, and by God’s gracious providence her ship was driven ashore in Scotland. The good King Malcolm Canmore saw and pitied their sorrowful plight, and married your lovely mother. A saint indeed! Should you not be a very different girl from what I weep to see?”

Princess Maud looked at him out of eyes as blue as the ocean on a midsummer day. Her self-willed hair curled in tendrils opinionated as a vine’s over a milk-white forehead and golden brown eyebrows drawn as straight and fine as if a geometrician had ruled them. A Saxon beauty indeed. She answered laughing:

“If God does not like me as I am it is not my fault. You blame the potter and not the pot if it does not stand steady on its legs. How can I stand steady on legs that must always be dancing or running? Yet, Father, do you think I do not know you love me best?”

“God forgive me, I do. But that is only the sinner in me and when——”

“Never be a saint or you and I part company!” said the inveterate Maud. “When I remember my mother! She kept the pattern of sainthood before her and stitched her copy after it like a girl at a sampler, and my poor father and ourselves were all pressed into the service of adoration.”

For once the good Father Turgot was indignant with his darling.

“Princess I will not call you!” he said, “but rebel against all sacred things. The daughter of a saint whose virtues——”

“I have noticed,” replied Maud competently, “that the daughters of saints are often rebels. And that is as it should be. It holds the balance even. Now when the balance tips one way or the other the world turns a somersault which is not as it should be. My daughter shall be a saint. It is necessary, for I am a sinner.”

Father Turgot shook his head sadly:

“You will never have a daughter, and that brings me to what I came to tell you. Now that your parents are dead and your father’s brother has seized the throne of Scotland he desires to be rid of you and your sister Mary. The Norman king, William Rufus, has demanded it and the King of Scotland will not protect you.”

The colour fell from her bright face. She loved Scotland and to see England under the Norman heel of the sons of William the Conqueror hurt her Saxon heart with agony like the thrust of cold steel. This was the second time the Normans had rendered her and hers homeless. It took a moment’s silence to recover her courage, but presently it flashed in cold fire.

“And where will our Norman masters fling the garbage of the royal family of England?” she asked.

The good father spoke sadly:

“The Normans desire that you and your sister Mary should leave no heirs to injure their succession to the English Crown, and it is agreed that you two shall be sent to the Abbey of Romsey in England as novices. There your aunt, the Princess Christina Atheling, is abbess of the black Benedictines. You shall be placed under that stern rule and you will both become professed nuns when you reach the proper age. The Norman king hopes in this way to quiet the English clamour for their own royal family and to convince them that you prefer the Cross to the Crown. So I say truly you will never have a daughter.”

His words are cold, written, but in reality they were warm with kindliness and pity in his eyes. The truth was, as I have said before, he loved the ground Maud walked on, and could he have seen her sitting crowned as rightful Queen of England would have died for it any day, and taken his chance of Purgatory. It was because she also loved the old man as truly that she spoke her mind to him. With others she could be cold and silent as her mother’s wonder-working image in the church hard by.

“Now, Father, you challenge me!” she said with a brightening eye, “and I challenge you! What will you wager that I have no daughter? It is only my will against William Rufus’s—the bestial Norman! Which will you back? I will have a daughter. I swear it in the face of the Normans themselves!”

Father Turgot threw up his hands in the necessary horror. That concession made to propriety, he lowered them and proceeded:

“My daughter, the future is dark and doubtful. My own heart’s desire is that you should marry a Norman prince and so unite the Conqueror’s claim with the ancient right. If you did this he would perhaps restore your brother to the Scots throne and so all be peace throughout the island. But William Rufus is bestial, and go to England you must. But I will find some place within reach of you and we will pray for better days.”

“You shall pray, Father, and I will work for them.”

There was a moment’s silence. It grew so emphatic that Father Turgot turned and faced the princess almost in suspense. She suddenly threw up her right hand and held it palm out.

“I swear before God and His holy Apostles that I will not be a nun—no, not if they drag me to the altar. You are my witness! May I have a thousand thousand years in Purgatory if I abase myself to the Norman will.”

She lowered her hand, dropped her tragedy air as suddenly as she had shown it and said with humour:

“Set a thief to catch a thief! I match myself against my Aunt Christina and the Normans, and she is worse than they. Well!—when is it the Norman pleasure that we ride to Romsey?”

It was the pleasure of the usurping King of Scotland and of the Norman, King William the Second, that it should be soon, and the two disinherited princesses arrived at Romsey Abbey, were duly frozen by the icy eye of their abbess aunt, and jolted uneasily into the conventional routine. To the Princess Maud it was a minor hell. Every cyclone has its centre, and in her case the cyclone revolved about the terrible black horsehair veil, which the abbess with her own hands placed upon their heads and dared them to remove. Mary obeyed her and went about—a little pale moth in a black chrysalis. When the sacred hands of the abbess placed it on the head of Maud it met a different fate. The princess took it in her two stalwart little hands and wrenched it off, leaving her golden vine-tendrils in wild disorder and with one foot on the veil glared at her aunt the abbess.

“You dare!” she choked out. “I tell you I will never be a nun. No—not if you beat me till my back is raw!”

The great abbess did not argue. People obeyed without argument and if they did not she had other means. A stalwart nun of peasant extraction was called and not unaided administered a discipline to the princess not more minutely to be described than in her words above. She took it in grim silence. The abbess replaced the veil and the moment her back was turned Maud danced upon it with language at which history blushes and passes mutely by. This is the solemn historical truth.

The years slipped by. The abbess was promoted to the great Abbey of Wilton near the royal city of Winchester, and never were the Normans so soundly hated as in Wilton. Nor was there ever a conventual rule so strict as that the Abbess Christina wielded, or two princesses in a fairy tale more rated and driven by any cruel witch than the unfortunate Maud and Mary by their pious aunt. Maud found her sole joy in her books and teachers, her sole hope the steady growth of a secret purpose in her heart. But of that she spoke to no one.

There came at last a certain heavenly October day, when not a russet leaf fluttered to its fall, and no bird sang. It was early morning and silent—the earth’s orisons not yet finished. The princess had walked (with her veil flung over her arm) through the abbey garden under apple trees stripped of fruit but still lovely with red leaves, through the herb and flower garden tended by chaste hands, and she had now come to the forbidden door in the wall leading to the vast forest outside. It was kept locked with a great key, and the key hidden. The abbess’s lips had tightened and her frown blackened as she spoke of the Normans who haunted those forest glades, for hunting even within the convent acreage. They were clad in green. They carried bows and arrows. They rode swift horses who would make nothing of a shrieking maiden bound behind the rider. And these men had the glance and gaiety that appeal to all that is sinful in the heart of a woman. Well might the key be massive and the door fast locked!

The Princess Maud arrived at the gate and remembered and despised the warnings of her aunt. Then she sighed, and in sighing her eye fell on a hole in the wall and in it—the key. The abbess said afterwards that the Father of Lies had undoubtedly placed it there himself where a kindred eye would catch it.

Let us do Maud the justice to say that she put on her black veil before she applied the key to the lock, peering cautiously through its slits as she turned the key. It revolved as smoothly as infernal keys have always done. She opened the door, closed it behind her and stood in a woodland glade where a few innocent grey rabbits hopped in peace. The glades, sparkling with dew on the russet leaves, were peaceful as the glades of Paradise. Where could be the harm in a thickly veiled religious taking a few steps into the loveliness of the free world?

She walked with resolution down the glade for at least twenty minutes, rounded a great oak and came upon a man sitting beneath it notching an arrow with diligence. His unstrung bow lay across his knee. He heard her black robe rustle among the rosy carpet of leaves and saw a grave religious advancing. He sprang to his feet, snatched off his cap of green and bowed deeply. To be courteous to any religious was an easy short-cut to heaven’s favour. He addressed her in Norman-French—a mixture of French and Danish, and as “Ma mère.” The Princess Maud bowed, her eyes through the slits in the veil were attentively surveying the young man.

He was tall and extremely well-formed and the low morning sun shot an arrow through the glades that lit gold in his brown curling hair. His eyes were brown as the forest pool by the oak and gay with quick-witted glances. Instinctively Maud hunched her shoulders under her black. In that young man’s company fifty years would be a much needed fence. She could not jar the young silver of her voice with age’s quaver, but she could do her best to appear an old woman otherwise, and did. She bowed again and turned towards the abbey. The young man carelessly, as it were, placed himself in her way.

“Ma mère, I see you are a nun of the black Benedictines of Wilton Abbey. May I ask three questions of your sanctity? If I say I have left the hunt and sat here three days in succession in hopes of seeing some person connected with the abbey you will believe I am in earnest.”

His voice was very pleasant to the ear, deep and with possibilities of hidden laughter. Keeping her young hands hidden in the great dropping sleeves, the Princess Maud began to enjoy herself. A breeze of youth went singing down the glade and stirred her heart. But again she only bowed in silence. The young man looked embarrassed for a moment.

“Madam, I am a squire attached to the train of Prince Henry, son of William the Conqueror of England, and brother to the present King William, known as Rufus from his ugly red head. My master Prince Henry is a fighting man, but is also most learned in all the arts and sciences. Indeed, because he is thus a learned young gentleman (though a fighter and a huntsman) we Norman-French call him Henry Beauclerc.”

Under her veil Maud’s heart beat quicker. Could it be possible that Providence had played traitor to Aunt Christina and William Rufus and lured her through the locked door for its own wise purposes? She bowed in silence, but her supple body listened and her expression was alert and keen beneath her veil. The young man went on cheerily:

“Madam, you have in Wilton Abbey the heiress—on the English side—to the Crown of England. If my master has a curiosity on earth it is to know what that demoiselle is like? First question. Dark or fair? Willow or scrub? Second question. Is she skilled in the arts and sciences or a niminy-piminy doll? Third question, dependent on the others. Is she a charmer of hearts? For it is possible to have beauty, grace and knowledge and yet be a frost piece, a cold, haughty shrew. You see the royal demoiselle daily. I beg you to answer as to your confessor.”

There was something in this young man’s manner which disarmed anger, even allowing for his impudence, which was superlative. There is no doubt that had the lady before him been in truth an ancient nun she still would have answered and with a smile. Maud cleared her throat for business and replied in Norman-French pure as his own.

“Sir, it is true that I see the princess daily. But may I ask the name of the gentleman who questions so boldly, and his reasons?”

A quick look, instantly quenched, darted from the young man’s eye. He replied courteously:

“Madam, you may. My name is Henri de Selby and I am English born and have a smattering of Saxon. The Prince Henry Beauclerc is very kindly to me on those grounds, for, unlike his father and brothers, he loves the English, who in return hate him as affectionately as they do the rest of his family. My reason could only be told frankly to a holy and experienced person like yourself. I wish with all my heart that a liking could arise between this prince and the princess, for she is the root of the royal tree of England, and it would quiet the English, who are now very turbulent, if that demoiselle sat on the throne with my master. See!—I am frank! In the holy cause of peace be you the same.”

The young man stooped and picked up his bow and settled the loose arrow into his quiver, for the religious made no answer. Was he going? She answered hurriedly:

“Sir, in the abbey our concern is less with ladies’ faces than with their virtues. The princess has two besetting sins, pride of her great family and anger with the Normans. She would not marry an oppressor of her people—no, not though he were shod with gold and crowned with diamonds! She is the descendant of Alfred the great king who loved his subjects, and loved mercy and justice like God the Father and His Son. William the Conqueror loved the tall deer as if they were his children, and for the pleasure of murdering them he drove out the English to make his great forests. And William Rufus is the same—and is Henry Beauclerc any better? And even if he should be, he has two elder brothers and is only a landless prince. He is not worth a glance of her royal eyes!”

“Landless!” The young man threw up his head. “He may be now, but he is rich in treasure and his brains would buy and sell his two elder brothers. William Rufus has no wife and is drinking himself to death. Robert is a good-natured fool that would sell England or Paradise for hunting horses and hawks. My good mother, the next King of England is Henry Beauclerc as sure as I stand here and swear it. Tell me, I beseech you, what is the Princess Maud to look at?”

The nun considered a moment. She slid a more soothing note into her words.

“Sir, a woman cannot judge of beauty. But I can say this—she is golden-haired and blue-eyed, and the monk Leofric of Gloucester, the great illuminator of missals, thought fit to copy her face for that of St. Lucy of the lovely eyes in the jewelled book he made for the Abbey of Romsey. She can be seen there in blue robe and white veil flowing from her martyr’s crown. But again I warn you, sir, that the royal demoiselle loves the English better than her own flesh and blood, and the man who desires her must be good lord to them or he will never see her face.”

The young man smiled quaintly.

“I will certainly see her face, for I will ride to Romsey to-morrow. And I do not dislike the pride of the demoiselle. The English are rough stuff—knotted oak—but I judge they would wear well if they liked a man’s behaviour, and my master would sooner win a man’s heart than lash him into submission.”

“He will not lash the English into submission. There is not the man living who could do it! The country will be a boiling pot until the Normans learn manners, and Henry will yet scald his fingers.”

She forgot her hunched back and stood straight before him as a sapling pine. Through the slits he had a flashing glimpse of angry blue eyes. Her voice rang. Whatever else the lady might have under her veil, she had youth’s zest and fire.

“Ha! A Saxon!” he said.

She turned and walked away rapidly towards the door, gripping the key in her hand. He followed cap in hand.

“Madam, I am English born. I honour any man who fights for his country. I bid you good day and,” he added this in pure mischief, “I beg that you will lay the compliments and commendations of Henri de Selby before the feet of the royal demoiselle—a man who would most willingly do homage to her as his queen provided her king were his master Henry of Normandy.”

Without another word the princess marched to the door. She unlocked it without a backward look, went in and slammed it in his face. He heard the key turn inside.

If, like many another abbey in England, the boundaries of Wilton had been straight wooden palings what happened next could not have been. But, it so chanced, that the walls were of English stone. Over them drooped the boughs of beech and elm not yet stripped for winter.

The young man reflected for a moment—then, with perfect woodcraft, shaped his lips and made a blackbird’s whistle that might deceive the very king of the blackbirds. Another young man slipped snake-like from among the golden bracken. They interchanged signs and Henry of Selby mounting on his shoulders got a grip on the rough stones that soon brought him comfortably atop of the wall and among the flaming beech boughs. Looking down and onward he saw a sight worth seeing.

A black horsehair veil lay on the ground. A girl in black with the morning sun tangled in the tendrils of her hair till they gleamed like a saint’s aureole, stood staring at the door with clasped hands. To set her at her ease and give himself leisure to examine her, he made a sign to his friend below, who walked off immediately, crashing through the bracken with some ostentation of going. She relaxed the tension at once, unclasped her hands and smiled beautifully. Presently another mood. Her face clouded. She clenched her right hand and shook it furiously at the door. She spat at it like an angry cat. She picked up the veil, threw it over her arm and marched away through the trees.

Maud went in unveiled to the refectory where the oldest of the nuns, an ancient of good Saxon family, was preparing the tables, and put her question bluntly:

“My sister, where was the Norman prince Henry born, and is he a dark man like his father?”

“Lady of the Saxons, he was born at Selby in Yorkshire, and for that reason the English in Yorkshire call him Henry of Selby, and say that had he an English right to the Crown he would be a good king, for he is learned and wise and gay. He is brown-haired, they say, and walks like a prince. But why does a royal nun give a thought to a man?”

“I am not a nun and never will be. There is not a soul in this abbey but knows it from my aunt downwards and——”

A gliding step and the abbess lifted the curtain. Her cold eyes pierced the guilty pair.

“Chattering instead of prayers—and chattering of men! Good manners for the Abbey of Wilton! Put on your veil, rebel, and I dare you to remove it. Get you to your work, sister, and take a penance of three days’ bread and water to tame a loose tongue.”

Maud put on her veil in a hot fury that matched the abbess’s cold one. But when she was in her own retreat she dragged it from her head and trampled it. That had become a sacred rite never to be missed. Then sat down to think.

Meanwhile Henry Beauclerc, Henri de Selby, rode slowly and thoughtfully down the wood-ways towards the royal city of Winchester. His wits were like diamond and they lit a dull horizon. He loathed his brother William Rufus, the king, and there the whole world sided with him. He despised his elder brother Robert the Unready—the careless good-natured fool always a day behind the fair—whom all liked and none respected. And Henry’s eyes were so firmly fixed on the throne of England that its dazzle blinded him to the difficulties of a third son with not a rood of land to call his own. Policy fixed his eyes on the Princess Maud. Here she was in England, and the English adored her and what she represented—the freedom and justice of the good old days in England. Had she been thirty, with a squint and a hump, still Henry would have married her and found his solace in quarters to which he had already a well-trodden way. And now he had seen her and found her altogether seductive with her young pride and audacity and beauty. Heavens!—if he could ride into Winchester with her on his right hand as Lady of England or, as his Normans would call her, Queen of England—not an Englishman but would fall on his knees to kiss the hem of her robe. “And what I will, I do!” he said in his heart, and burst into carolling like a troubadour, making his horse curvet and leap for mere pride of heart. She would be a companion—no doll decked out in a crown and jewels. A rare girl indeed! Most surely luck was on his side this blessed day, for he had never hoped to get a sight of her.

“Down this way, beau sire,” his companion said, pointing down a faint track through a coppice, and they rode in silence now under clipped boughs which showed men used it, however seldom. Henry the prince had much to think of. A beautiful girl to sit on a throne and trail her crimson velvet robes furred with royal ermine. That golden head would set off a coronal of gold and pearl trefoils—the most beautiful setting in the world for unbound tresses. He re-read much into that brief talk and her look and threat at the door when she thought herself alone. And what a lineage! Her ancestors were kings when his were rough sea-hawks—Vikings blown on a lucky wind to Normandy—no more.

A hut stood before the two riders, a rough hut of wattled boughs and osiers—as bare a place as human being could seek shelter in. But an old woman crouched before it warming trembling limbs in the sun. It is likely enough that Shakespeare many centuries later drew his witches in the story of Macbeth (not so long dead then in Scotland) from this woman, for this story is no less true than famous in England. When she saw the prince coming she rose on her trembling legs and pointed a skinny finger, and said in a voice like the piping of wind in the keyhole of a long deserted house:

“Stop, Henry of Normandy—Stop! For I have news to make your ears ring!”

His horse swerved and nearly unseated him, but he laughed and tossed her a coin that would keep her for a month, and so made to ride on. She laid a cold hand on his bridle with swollen veins like blue worms crawling on it, and to his amazement and that of the man behind him, broke into verse little suited to the rage that fluttered about her. Her voice gathered strength and in a moment he knew that Fate had met him in the forest.

“Hasty news to thee I bring

Henry, thou art now a king!

Mark the words and heed them well

Which to thee in truth I tell,

And recall them in the hour

Of thy royal state and power.”

He would have thrown her hand off, but gazing into her bleared eyes they widened on him as the grey rings spread when a boy throws a stone into still water. Enlarging, they grew in power and numbed his resistance. The bridle dropped from his hand. He sat and stared into grey that veiled the earth and air and hid all but itself.

“What?—How?” he muttered, and did not know his own voice from a stranger’s. The bounds of personality were wiped clean out for a moment, and he merged into her will.

“Your brother William the Vile lies dead in this wood. Ride, ride for Winchester lest they outride you for the Crown. Go! King of England!”

She flung her hand outward as if she struck the horse, yet did not touch him, and carried away like a sack of wheat, Henry felt the wild speed beneath him and heard the thundering hoofs and saw clods of turf flying, and knew not what he did until he turned and looked back and saw no hut, no woman, but only the empty coppice and the rabbits loping about it and rubbing their grey noses in the sun. It seemed that a laugh followed him, but nothing more. His squire was not in sight.

It was a time uncountable before his brain cleared and he knew he was riding a horse that could race the north wind and win. Shouts and cries rang in the air about him, coming from everywhere and the forest confused him so that he could not tell any direction. “The King!—the King!” they shrieked, and one man yelled: “Wat Tyrrell!—the king-slayer!” and still he rode. A man burst from a thicket with great eyes and the sweat rolling down his ghastly face.

“Sir, the king lies dead, shot by a chance arrow. Stay—stay!”

But still he rode—why stay? He had hated his brother since they were children together. Dead? He rode—not faster, for that could not be—but wildly like the huntsman who follows the ghostly hounds through dark midnight. He did not spur nor urge the horse, for he went beneath him with speed that swept the breath from the prince’s mouth. Now he heard the racing speed of another horse following him through the woods for awhile, then lost it, and so, riding like a man the devil drives, he came into Winchester and to the door of the Treasure House, and as he reached it and leaped down the horse staggered with bleeding nostrils and blood that welled from his mouth and fell dead beside him.

Henry drew his sword and stood before the door where a few men of his following gathered about him, and to them, now wholly clear-brained, he told his tale. Even as he ended, the following horse burst into sight along the street and de Breteuil, the Treasurer of William Rufus, leaped off beside him, frantic with haste.

“Sir, the king is dead. Tyrrell’s arrow glanced off a tree and shot him dead, and your brother Duke Robert is King of England,” he gasped, giddy, with his hand on the saddle. Henry laughed aloud.

“My brother Duke Robert is crusading in the Holy Land and I am here and the man who holds Winchester and the Treasure House is King of England. Do homage to the King, de Breteuil!”