* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Life and Letters of the First Earl of Durham Vol. 2 (Lord Durham—Life and Letters #2)

Date of first publication: 1906

Author: Stuart Johnson Reid (1848-1927)

Date first posted: November 29, 2025

Date last updated: November 29, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20251144

This eBook was produced by: Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

LIFE AND LETTERS

OF

THE FIRST EARL OF DURHAM

Vol. II.

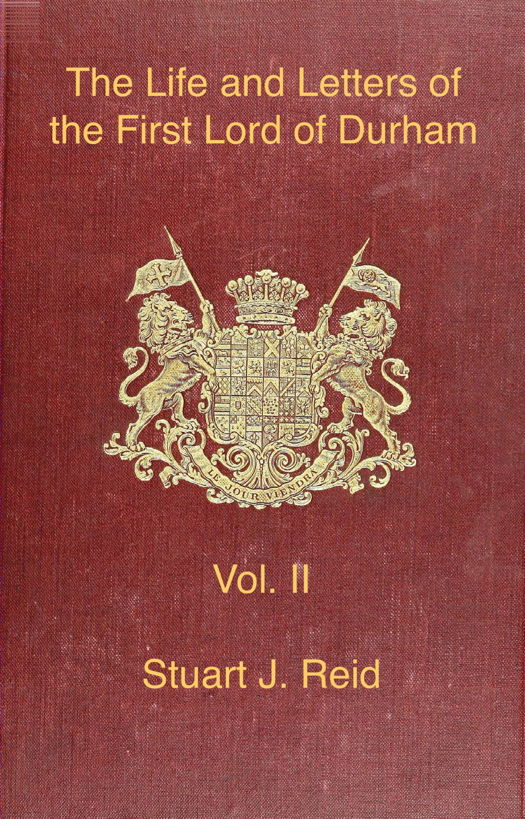

Sir Thomas Lawrence, P.R.A.

Walter L. Colls, Ph. Sc.

Louisa

Countess of Durham

Life and letters

of the first earl

of Durham

1792-1840

BY

STUART J. REID

AUTHOR OF ‘THE LIFE AND TIMES OF SYDNEY SMITH’

‘LORD JOHN RUSSELL’ ETC.

‘Canada will one day do justice to my memory’

Dying words of Lord Durham

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. II.

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1906

All rights reserved

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| DURHAM AS AMBASSADOR TO ST. PETERSBURG | |

| 1835 | |

| PAGE | |

| Durham’s friendliness towards France—Peel’s Ministry—The Marquis of Londonderry and the British Embassy in Russia—The Melbourne Government and Durham’s exclusion from it—Durham appointed Ambassador to Russia—A visit to Athens—An audience of the Sultan—Journey through Russia to the capital—The question of the Russian occupation of Constantinople—Death of Lady Frances Ponsonby—Attacks on Russia by the English Press—Russia’s sources of weakness—Fête at the Winter Palace—Durham’s relations with the Tsar | 1 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| REPORT ON THE STATE OF RUSSIA | |

| 1836 | |

| Inability of Russia to engage in a war—Groundless suspicions of the Tsar’s intentions—Changed phases of the Eastern question—Over-estimation of Russia’s power—Weakness of the Tsar’s Army and Navy—Financial resources—Effect on the Empire if Russia conquered Turkey—Influence of the aristocracy—Fatalism in the Army—Lord Grey on Durham’s Report—Austrian occupation of Cracow—Efforts on behalf of the Poles—Palmerston on Russian policy—Durham’s guiding principles in Russia | 28 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| DURHAM’S DIPLOMACY | |

| 1835-1837 | |

| Combating British prejudice—Russia’s fiscal policy—The case of Mr. Grant—Russian aggression—King William’s jealousy of Russia—Durham’s illness—The right attitude of England—The Tsar’s tariff reforms—The affair of the Vixen—The Emperor’s designs in Central Asia—The route to India | 53 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| SIDE LIGHTS ON ENGLISH POLITICS | |

| 1835-1837 | |

| The influence of Parkes on British politics—Passing of the Municipal Reform Act—‘Brougham like a tiger in a jungle’—Radical estimate of Durham—Founding of the Reform Club—Correspondence with Parkes—Comments on public men—Durham’s relations with the Duchess of Kent and the Princess Victoria—The Melbourne Cabinet in difficulties—Durham ‘thrown over’ by the Whigs—Pamphlet on Russia by ‘A Manchester Manufacturer’—Durham’s prophecy about Cobden | 70 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| THE WHIGS BEGIN TO DRIFT | |

| 1836 | |

| Correspondence with Bulwer Lytton—Lady Blessington at Gore House—French view of the ‘essence of liberty’—Gossip at dinner parties—Letters from Leslie Grove Jones on the political situation—Grey and O’Connell—Irish Tithe Bill—Correspondence with Sir Charles Wood, Henry Bulwer, and Edward Ellice—Radical dissatisfaction with the Government—Melbourne’s ‘mixed set’—The question of Peerage Reform—Schism between Whigs and Radicals—Durham exhorts the Radicals to support the Whigs | 95 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| THE NEW REIGN, AND DURHAM’S POSITION | |

| 1837 | |

| Durham repudiates his alleged rivalry of Palmerston—Roebuck ‘scatters wild-fire in the constituencies’—The Melbourne Cabinet ‘living from hand to mouth’—Banquet to Durham in St. Petersburg—Conferment of honours—Death of William IV. and accession of Victoria—The Countess of Durham, and her admirable qualities—Results of the General Election—Durham’s appearance, manner, and temperament—‘The Queen and Liberty’—Durham’s fidelity to his early political creed—His sympathy with Ireland—On England’s foreign alliances—Lord Grey’s attitude towards Durham | 120 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| THE CLOUD IN THE WEST | |

| 1837-1838 | |

| The rebellion in Canada—Durham offered the post of Governor-General—Melbourne’s disregard of Colonial expansion—‘Little England’ ideas prevalent in 1837—Supremacy of permanent officials at the Colonial Office—A patriotic appeal to the electors of England—Wise and unwise Reform—Attitude of the Tory party towards Ireland—Durham accepts the Governor-Generalship of Canada—Bill to suspend the Constitution of Lower Canada—Durham’s speech in the Lords on his appointment—Charles Buller—Edward Gibbon Wakefield, and Thomas Turton | 136 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| POLITICAL CRISIS IN CANADA | |

| 1838 | |

| Durham’s departure for the West—Sydney Smith and the ‘overtures’—Work on board the Hastings—Hostility of French Canadians—Suspicious movements of the United States—Dissensions of British settlers—Outline of the political history of British North America—The Clergy Reserves—Defiant conduct of Mackenzie and Papineau—Lord John Russell’s narrow Colonial views—Rule of Lord Gosford and Sir John Colborne—The political prisoners—Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act | 163 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| AN EVIL BEQUEST—THE POLITICAL PRISONERS | |

| 1838 | |

| A glimpse of the ‘Dictator’ from Buller’s pen—Durham issues his Proclamation—Enthusiastic reception given to him—Members of his Executive Council—Sentiments of French Canadians—Influence of the British party—The ‘Family Compact’—Sir George Arthur and the condition of Upper Canada—Threats of the refugees—The United States’ support of the outlaws—Burning of the Sir Robert Peel—Criticism at home on the appointments of Wakefield and Turton—Durham’s challenge to the Melbourne Government—Establishment of a police system—Crown Lands—Encouragement of emigration—The question of the political prisoners and their banishment—Durham’s Ordinance and Proclamation—Letter to the Queen | 181 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| THE CONDUCT OF THE MELBOURNE GOVERNMENT | |

| 1838 | |

| The humanity of Durham’s policy—Approval in England of the Ordinance—Attack in the House of Lords on the Ordinance and the Proclamation—Brougham’s spite—Lord John Russell’s support of Durham—Brougham and the daguerreotype picture—Macaulay and Sir George Otto Trevelyan on the persecution of Durham—Abandonment of Durham by his political allies—Tour through the Canadian Provinces—At Niagara—Letter to Melbourne on the possibilities of Canadian development—‘Go on and prosper’—Melbourne’s cowardly surrender | 208 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| DISALLOWANCE OF THE ORDINANCE | |

| 1838 | |

| Durham’s work of pacification—‘A bolt from the blue’—Durham determines to resign—Burning of Brougham in effigy—Meeting of Maritime Delegates—Ovation at the theatre—Address to the Delegates—Lord John Russell’s advice—A Ministry ‘utterly weak and incapable’—Resolutions of confidence and sympathy—Despatches to Lord Glenelg—Melbourne’s treachery—The Indemnity Bill—The Bermuda imbroglio—Durham’s defence of his policy | 230 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| THE QUESTION OF THE PRISONERS AT BERMUDA | |

| Examination of objections to the Ordinance—Criticism in England of the Proclamation—Reception of the Proclamation at Quebec—Address of confidence to Durham, and testimonies of respect—Dr. Kingsford on the Proclamation.—The objects which Durham had in view—Charles Buller’s comments on the banishment of the prisoners—The danger of the Canadian Provinces separating from Britain—Signs of renewed rebellion—Durham’s final acts in Canada—The Guards’ farewell dinner—Scenes in Quebec on Durham’s departure—Arrival at Plymouth | 266 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| LORD DURHAM’S REPORT | |

| Mill’s vindication of Durham—Addresses of welcome in Devonshire—Melbourne keeps aloof—Lady Durham resigns her place in the Queen’s Household—Presentation of the Report to Parliament—Its keynote, and analysis of contents—Scheme for the future government of Canada—Durham’s advocacy of the union of Upper and Lower Canada—Urges State-aided emigration, and the formation of an inter-Colonial railway—The application of Durham’s views to the problem of Colonial Government—Allegations as to the authorship of the Report—Brougham’s slander—The part taken by Buller and Wakefield in the preparation of the Report | 306 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| ‘THE SUNSET GUN TOO SOON’ | |

| 1840 | |

| Resignation of Lord Glenelg—Anti-Corn Law agitation—Melbourne resigns and re-assumes office—Lord John Russell at the Colonial Office—Durham’s interest in the New Zealand Company—Outbreak of another rebellion in Canada—Consideration in Parliament of the Canadian problem—Durham’s last speech in Parliament—Appointment of Poulett Thomson as successor of Durham in Canada—Durham’s welcome in the north—The Duke of Sussex on Durham’s services—A meeting with Brougham—The Canada Bill—Durham’s illness and death—‘The dead man lives in the hearts of the people’—Expressions of sorrow and sympathy—Death of Lady Durham—The verdict of history—Durham’s prominent characteristics—Tribute of Bulwer Lytton | 343 |

| INDEX | 377 |

| LOUISA, COUNTESS OF DURHAM. By Sir Thomas Lawrence, P.R.A. | Frontispiece | |

| From a Picture at Lambton Castle in the possession of the present Earl. | ||

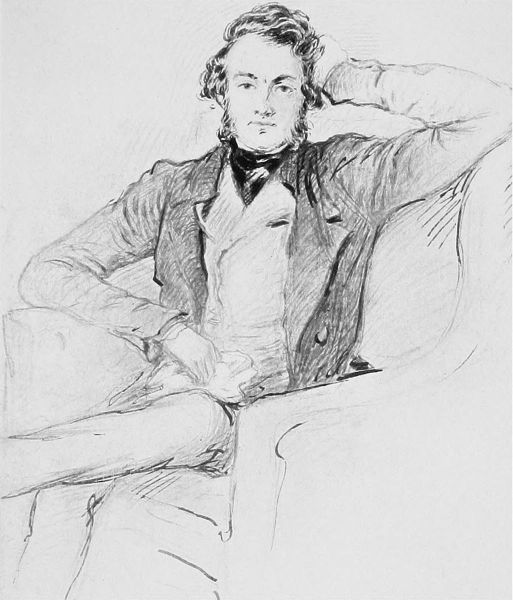

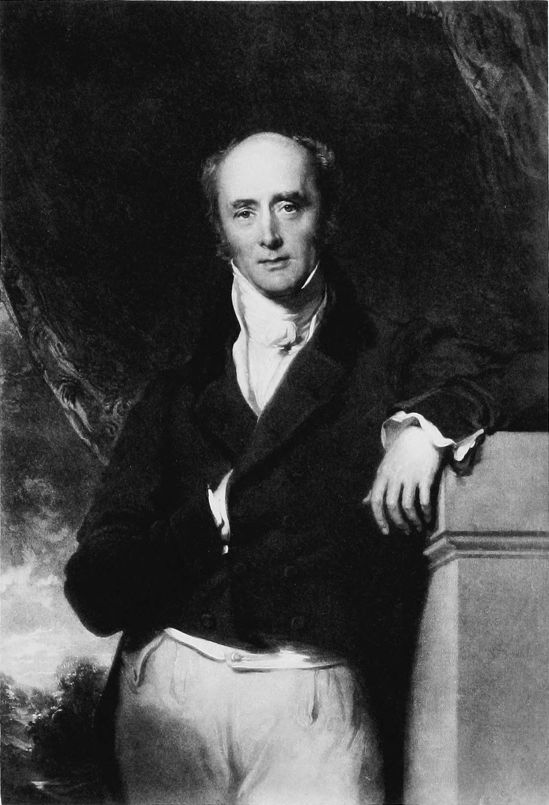

| LORD DURHAM, at the age of thirty-six | To face p. 32 | |

| From a Miniature in the possession of Stuart J. Reid. | ||

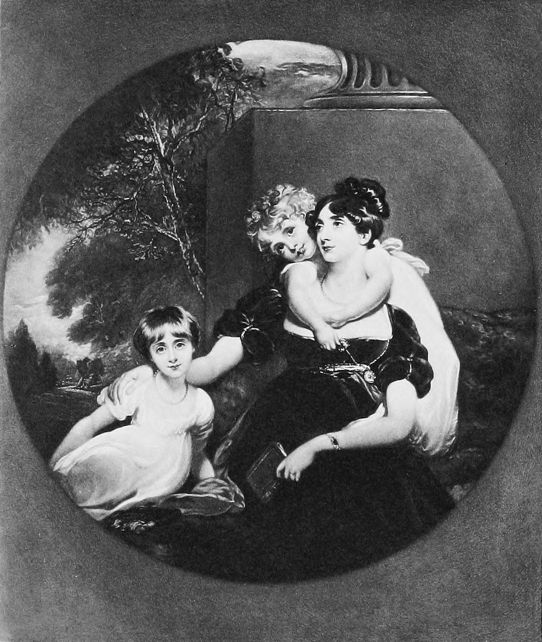

| THE COUNTESS GREY AND HER DAUGHTERS. By Sir Thomas Lawrence, P.R.A. | To face p.„ 59 | |

| The child in the foreground is Lady Louisa, afterwards Countess of Durham. | ||

| LAMBTON CASTLE FROM THE BANKS OF THE WEAR. By John Glover, P.W.C.S. | To face p.„ 130 | |

| From a Water-colour Drawing. | ||

| CHARLES BULLER, M.P. | To face p.„ 182 | |

| From a Black and White Drawing from life in the possession of Stuart J. Reid. | ||

| CHARLES, EARL GREY. By Sir Thomas Lawrence, P.R.A. | To face p.„ 216 | |

| From a Picture at Howick in the possession of the present Earl. | ||

| ‘THE DESERTER’ | To face p.„ 274 | |

| From a Cartoon by ‘H. B.’ (Richard Doyle). | ||

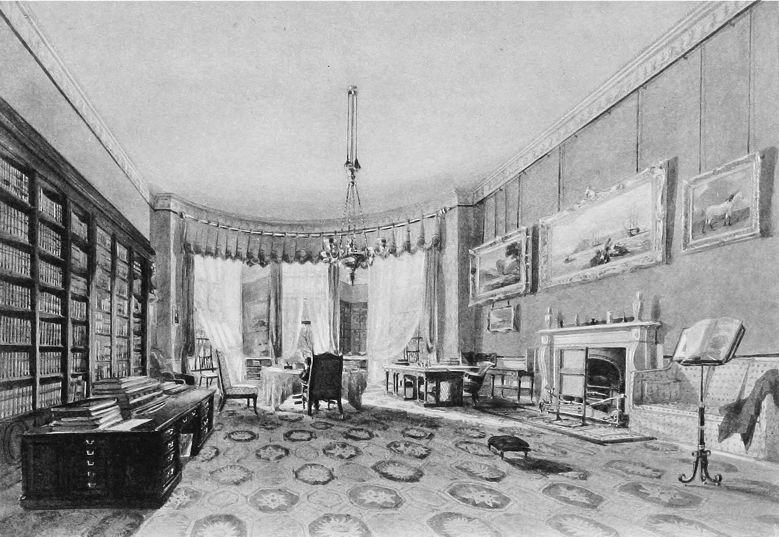

| LORD DURHAM’S LIBRARY, 13 Cleveland Row, London, S.W. | To face p.„ 309 | |

| From a Water-colour Drawing in the possession of the present Earl. | ||

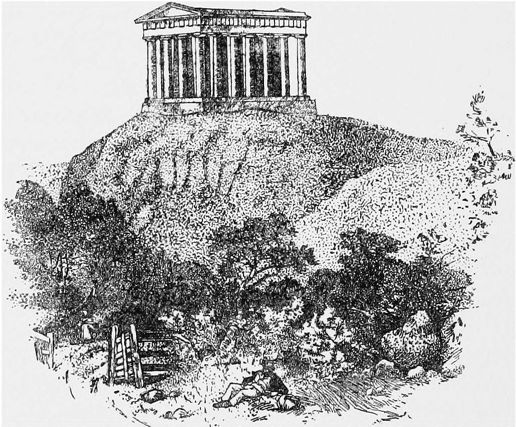

| THE DURHAM MONUMENT, on Penshaw Hill, Durham | page 376 | |

| From a Sketch at the time of its erection in 1844. | ||

LORD DURHAM

Everything with the Russians is colossal rather than well proportioned, audacious rather than well planned; and if the end is not attained, it is because they overshoot it.—Madame de Staël.

1835

Durham’s friendliness towards France—Peel’s Ministry—The Marquis of Londonderry and the British Embassy in Russia—The Melbourne Government and Durham’s exclusion from it—Durham appointed Ambassador to Russia—A visit to Athens—An audience of the Sultan—Journey through Russia to the capital—The question of the Russian occupation of Constantinople—Death of Lady Frances Ponsonby—Attacks on Russia by the English Press—Russia’s sources of weakness—Fête at the Winter Palace—Durham’s relations with the Tsar.

Durham was not left in any doubt as to the popular verdict up and down the kingdom on his speeches in the north. The Radicals in every town and village were delighted, and even Whigs of the more cautious school were forced to admit the eloquence and courage which marked them. Sir John Bowring and Sir Henry Bulwer were both in Paris at the moment, and their letters to him show in what high esteem he was held, as a statesman, in France. No public man of that period was more anxious than Durham, as his speeches show, to bring about a close commercial alliance between this country and France. He used to say that, if he was in power, it would be one of the foremost objects of his ambition to make the mutual dependence of the two countries, the shores of which were only five-and-twenty miles apart, so certain and so strong that war between them would be impossible. He never lost an opportunity of trying to dissipate the prejudice against the French nation, then just rising into political freedom, a prejudice which was one of the worst bequests which the war with Napoleon transmitted to this country. He never concealed his opinion that Napoleon, whom he denounced as a cruel despot, had done his best to excite feelings of hatred against England, in order the more successfully to carry out his own selfish designs in Europe.

Meanwhile, Sir Robert Peel, travelling in hot haste, in obedience to the King’s summons, arrived in London from Rome on December 9, 1834, and was accorded an instant audience, and accepted the office of Prime Minister. His first Administration was tentative and short-lived, but it brought him at the age of forty-seven into the front rank of English statesmen, and introduced to office for the first time, in the capacity of Under-Secretary for the Colonies, that ‘stern and unbending Tory’—as Lord Macaulay described him a few years later—W. E. Gladstone, a statesman who was destined to leave a more splendid mark than any other on the political history of the Victorian Era.

Peel coquetted with the Whigs when he formed his Ministry at the close of 1834. He made overtures to Stanley and Sir James Graham to join the new Cabinet, but they declined. His address to his own constituents was a striking example of vacillation, and Lord Wharncliffe was responsible for a bon mot which flew round the town—‘Peel wrote the first half of his Tamworth address at Brooks’s, and then hurried across to the Carlton, and there scribbled the rest.’ Part of it undoubtedly reflected the prevailing opinion of the Whig club, whilst the other part was perfectly in accord with the sentiments uppermost at the headquarters of the Tory party. The result was that it satisfied nobody, and was deemed more in the manner of a man halting between two opinions than as the statement of a Prime Minister’s claims to national confidence. ‘Peel’s address is humbug,’ exclaimed Joseph Parkes, with brusque honesty, and there were a great many people, not as a rule sharing his way of thinking, who were much of the same opinion.

A General Election followed in December, and Durham, as his correspondence shows, threw himself with characteristic energy into the struggle by aiding and abetting the Liberal candidates at Newcastle and throughout his own county. ‘The great nail to drive home,’ he declared, ‘is the formation and organisation of political associations in every town and village of the Empire. With these in existence, we can never be betrayed again by mad Tories or timid Whigs.’ His own position in the country at that crisis is sufficiently clear from the fact that the ‘Times’ and the Tory journals held him up, as he himself put it, as the ‘alarm-creating alternative of the Duke and Peel.’ But he had foes in his own camp, with whose hostility he did not sufficiently reckon, for, if the Tories feared him, high-and-dry official Whigs, who pinned their faith to Grey, were alarmed by his outspoken speeches at Glasgow and Newcastle, and were not in the least prepared to endorse the bold and progressive programme to which he stood pledged.

The elections went in favour of Peel, but they did not place him in a majority. The Whigs lost ground, because nothing seemed to delight them more at that juncture than throwing a wet blanket on popular enthusiasm. Parkes wrote to Durham when the contest was in progress: ‘It seems to me that for four years the Whigs have never tried to rally talent or zeal to themselves, and that now things may take their chance. What they most fear are candidates professing your creed.’ As it was, a great many Radicals were returned, but not enough to make the Durham party master of the situation.

Peel quickly showed his hand. One of the first diplomatic changes, consequent upon the accession of the new Ministry, was the proposal to send the Marquis of Londonderry as Ambassador to St. Petersburg. ‘Londonderry has announced,’ wrote Durham, ‘that he is to go as Ambassador to Russia. This is a pretty commentary on Sir Robert Peel’s declaration that he does not intend to change our foreign policy; Londonderry having declared in every speech in the Lords that his object is to perpetuate his brother Lord Castlereagh’s Continental system.’ The wrongs of the Poles at that time excited as much indignation in England as was afterwards evoked by the Bulgarian atrocities of the Turks. Londonderry was not only a man of slender capacity, but an avowed opponent of the just claims of this oppressed race, and so great was the storm raised by his appointment that he had the good sense to decline the post.

All through the spring of 1835 Durham pursued a waiting policy. Some of his best friends told him to beware of the Whigs, since they were jealous of his influence in the country. He himself was beginning to realise by this time that the powerful influence of his father-in-law was not likely to be cast in his favour. The collapse of the Peel Government was brought about by that rock of offence, the Irish Church. Lord John Russell carried his motion for the appropriation of its surplus revenues to the religious and moral instruction of all classes of the community, and on April 8 the Government resigned. Lord Melbourne was once more called to power, but not before Lord Grey had been sent for, only, however, to decline the task of forming an Administration. Grey’s attitude to Durham at this juncture determined the latter’s fate. Early in the spring of the same year, when it became plain that the Peel Administration was not likely to outweather the storms of the session, Grey and Melbourne were in active correspondence in view of approaching political changes. Grey made no secret that, in his opinion, Durham was impossible. He declared that, even if he felt able to take up the burden of office again, which was not the case, he could not join forces with his son-in-law, since he was opposed to the ‘three additional articles of faith’—the Ballot, Triennial Parliaments, and a further instalment of Political Reform—which Durham had publicly announced as his programme. This constituted, to borrow his own phrase, an ‘insurmountable obstacle.’

Melbourne, who cordially disliked Durham, and recognised him as the statesman who, of all others, was his most powerful rival, quickly seized the hint, with the result that the latter was not even offered the portfolio of Foreign Affairs, a position which he was known to covet, and for which he had sedulously trained himself. He was checkmated, in truth, by Melbourne in one direction, and by Palmerston in another, both of whom represented Whig traditions, and neither of whom, at that period, was in touch with popular sentiment. There is no use concealing the fact—it stands revealed in his private letters—Durham felt keenly the manner in which his claims were passed over, and the reflection that Lord Grey was a party to his exclusion naturally heightened his chagrin.

‘Lambton has formed bad connections,’ was Lord Grey’s assertion at the moment when Cabinet changes were under discussion, a certainly contemptuous allusion when applied to men of the stamp of Grote, Molesworth, Duncombe, Bulwer, and Parkes, who could at least claim to represent the new aspirations of the Liberal party, to which the Reform Bill had given so splendid an impulse. It was this obstinate attitude of the official Whigs to new men, and to popular aspirations, in the closing years of William IV., which did more than anything else to provoke the Chartist movement, which menaced England early in the reign of Queen Victoria.

Apart from Durham, Melbourne had other difficulties, for, as Sheil bluntly put it, there were also ‘a bully and a buffoon,’ who had to be considered. In the end, O’Connell was won over to temporary, though uncertain, co-operation without office, and Brougham was left out in the cold. ‘O’Connell,’ wrote Greville, ‘has behaved admirably well, and the difficulty with regard to him is at an end. Brougham is to be set at defiance; his fall in public estimation, his manifold sins against his old colleagues, and his loss of character, all justify them and enable them—as they think—to do so with impunity.’ Palmerston, whom Melbourne would gladly have seen in another position, absolutely refused to join the new Administration except on his own terms. He went accordingly to the Foreign Office, though, in view of his overbearing attitude, not without some trepidation on the part of his colleagues. Grey, even more than Melbourne, recognised the danger of such an appointment. He declared that the tidings would be received with an unpleasant shock of surprise throughout Europe, but both the old Whig Premier and the new felt that, under all the circumstances, there was no alternative except to gratify Palmerston’s ambition.

Meanwhile Durham’s exclusion from office in the Melbourne Administration was warmly resented by the Radical section of the party. The common opinion of the moment attributed it to personal antipathies, and the King’s jealousy of his position—it was always confidential—with the Duchess of Kent and the Princess Victoria. It was also hinted that his political integrity stood in the way of the just recognition of his unquestionable claims. His health—always an uncertain quantity—was a matter of concern to his friends, even more than to himself, in the late spring of 1835, when he was seriously ill. He might well have refused, on that plea alone, to fill one of the most important and difficult diplomatic posts, which were now urged upon him. The gossip of the hour ran that he would be the next Viceroy of India, but it was to another, and even more difficult post just then, that he was sent. The first hint of the proposal to ask him to accept the position of Ambassador to St. Petersburg occurs in a letter of Lord Grey, written on the 15th of May, to the Princess Lieven. ‘I don’t know yet anything certain as to the person destined for St. Petersburg. But I believe it is intended to send Lord Durham there. My only objection to this appointment arises from my fear that neither his own health nor that of my daughter and her children will be found equal to the severity of the climate.’

Durham might easily have shirked so arduous a mission. He owed nothing to Melbourne, but no man of that period was more sensitive to the claims of public duty. ‘Now that I am getting better,’ he wrote from Cowes on June 7, ‘which I am every day, I am overcome with horror at my hopeless idleness and inactivity.’ His reasons for accepting the offer, which a few days later was definitely made to him, are best expressed in his own words, ‘I cannot be employed at home, and don’t like being idle. The only language I have heard from those who profess to be my friends is, “We don’t wish to see you in office—your time has not yet come.” This feeling has been acted upon by the Government also, and I am thus put out of the pale of home politics.’ He was gazetted as Ambassador to St. Petersburg on July 8, and on the 26th of that month set out for Russia. He went by way of Constantinople, as he wished to consult with Lord Ponsonby on the Eastern Question. The newspapers declared that Durham had accepted St. Petersburg on account of his health. ‘If health was my object,’ was his quiet but amused comment, ‘I would have remained at Cowes,’ where his yacht, one of the chief pleasures of his life, at that moment lay anchored.

Some of his friends openly expressed their disappointment at his acceptance of this diplomatic mission to St. Petersburg. They felt that he had been badly treated by the official Whigs, and thought—perhaps they were right—that it would have been more to his interests to remain in England, even if compelled to fight for his own hand. They thought he had been shelved, and told him that he underrated his influence with the party; but, whatever happened, the Radical section of it looked to him—and would continue to look—as its real leader.

Durham resolutely put aside such counsels. He was proud, sensitive, at times impatient, and even irritable, but he was, in truth, a magnanimous man. He felt a slight keenly, but could rise above it, especially if he thought that the interests of the nation demanded the sacrifice of personal feeling. He was not at any period of his life vindictive, and he went to Russia at this crisis because he believed—and the event proved it—that his personal influence with the Emperor Nicholas was of a kind which made for the peace of Europe. His one ambition was the patriotic desire to serve England, and, not for the first or the last time, he renounced all else for that end in the summer of 1835. He made no secret that he felt that he had been put on one side by the Liberal party; ‘perhaps it was necessary,’ he said quietly, and then added: ‘I owe them no grudge, and am ready at a moment’s notice to do whatever is deemed right!’

He went by sea on board H.M.S. Barham, and was accompanied by his secretaries, Mr. Edward Ellice, jun., and Mr. Arthur (afterwards Lord) Kinnaird. In his private journal, Lord Durham gives a lively account of the voyage, describes his mode of life on board ship, his rubbers of whist with the officers, the Welsh chaplain who had never been at sea before, the progress of the ship, his attempt to catch a shark which followed it, his impressions of the Rock, his desire to land at beautiful Cadiz, which he was forced to forego, as it meant seven days’ quarantine at Malta, and, in short, the usual incidents at sea. Malta was reached on August 17. He landed under a salute, went to the Governor’s palace, saw the usual sights, and foregathered with Mr. Dawkins, late Minister in Greece, slept on board, and on the following day was present at a large dinner given by the authorities in his honour—‘like all great dinners, was very dull and tiresome, and also very hot.’ On Monday, August 24, the coast of Greece was well in view. ‘I have just been on deck, and seen Athens, with the Acropolis and Parthenon, to the left Ægina, with the Temple of Jupiter, on the right Cape Colonna, with the Temple of Minerva. All these are distinctly visible with the telescope, and, with the Gulf of Athens and the high land about Corinth, form one of the most beautiful panoramas in the world.’ Next day he landed five miles from the capital, and was met by Sir E. Lyons, and, under a broiling sun, ‘jolted up to Athens.’ He took up his quarters at Sir E. Lyons’s house, where he met his old friend General Church, and later in the day was presented to the King, who promised him a private audience on the morrow.

‘Otho is a young man, not good-looking or intellectual, and seemed very shy at first. He had his throne in a room about thirty by twenty, and his Court about him of his Ministers and aides-de-camp, all in uniform. It appears he had wished to make the reception as solemn and imposing as his little means would allow him. I presented the “suite” to him, and then we had a conversation of about ten minutes, after which we departed. Taking off our harness, it being the cool of the evening, we went to see the Temples of Theseus and of Jupiter Olympus. The first is nearly all standing. A delightful sea breeze had set in, and was very cool and pleasant.’ Up at sunrise the next morning, Lord Durham and his secretary spent the day exploring the Acropolis, and stood, he states, on the very spot where Demosthenes harangued the Athenians. His visit to the Parthenon was a mixed delight. ‘It is horribly disfigured by Venetian fortifications, Turkish mosques, and Christian erections of all kinds, but still it is splendid and the situation incomparable.’

The following day, August 27, he was received in private audience by the King. ‘It lasted two hours, during which I had to explain to him most minutely the theory and practice of the British Constitution, the powers of the Sovereign and of the Ministers, the House of Commons and the people—in short, all the machinery of our institutions. He seemed very anxious to be informed, but not very bright. I then returned home, and sat with Sir E. Lyons, discussing our mutual business, until dressing time. At seven we went to the palace, where there was a formal official dinner of Ministers, generals, &c. This lasted until eleven, was very hot, but went off well, and they all said they had never seen the young King so pleased or animated. They tell me I have made a most favourable impression on him. At twelve I was in bed, having been nineteen hours in constant action.’ More sight-seeing followed next day, another dinner, with the Greek Chancellor and a large circle of officials, a visit to General Church, and a final audience of the King, who was extremely gracious, and gave him, on taking leave, the Grand Cross of the Greek Order. The modern condition of Athens did not impress Durham. He declared that the new town looked almost as dilapidated as the old.

Constantinople was duly reached on September 3. ‘It is a splendid place. The finest situation for a capital I ever saw, and, if it was only under good and free government, it would be one of the most prosperous cities in the world. The Dardanelles, the Bosphorus, and the entrance to the Black Sea are surpassingly beautiful. I am staying at Lord Ponsonby’s house at Therapia, where the Embassy is situated. As the plague is raging in Constantinople, I fear I shall not see much of the town. I am to have an audience with the Sultan in a day or two. He sent one of his pachas to congratulate me on my arrival. This is supposed to be a great mark of favour.’ In spite of the plague, he managed to see a good deal during the next few days, had long conversations with Lord Ponsonby on the Eastern Question, and especially the attitude of Russia, and made the acquaintance at receptions and dinners of most of his host’s colleagues of the Corps Diplomatique. His description of his audience with the Sultan, on September 11, may perhaps be quoted. It took place at the palace, about a mile from Scutari:

‘At half-past ten we landed from two barges at the gate, and were conducted into an apartment at the entrance, where we found the Ministers. I was introduced to each separately, made a variety of civil speeches, and then sat down on the sofa with them. Pipes and coffee were brought in, and I went through the form of smoking and drinking. We remained about ten minutes, and then started in procession, the pachas and officers of the Porte preceding and accompanying us. We passed through several fine rooms, beautifully painted and decorated, and found the Sultan (Mahmud II.) in a small cabinet, looking on the Bosphorus. He was seated on a sofa at the end, with his back to the window. He is a dark man, of strong, coarse features, not intellectual, but marked with determination and energy. His officers lined the side, we occupied the centre of the room. I then advanced with the dragoman, and addressed him in English as was agreed upon beforehand. This was interpreted first by a dragoman and then by the Sultan’s Minister.

Lord Durham took the opportunity of assuring his Majesty of the goodwill of the English Government, and laid stress on the fact that the commercial interests of England and Turkey were identical. The Sultan replied, through his dragoman, in courteous terms, and begged that his sentiments of friendship might be conveyed to the English Court, as well as to the Tsar of Russia. He declared that he regarded Durham’s presence in Constantinople as a proof of the friendship of the British nation. He was at a loss to know who was now Premier, and asked significantly whether Lord Palmerston was still at the Foreign Office. He told Durham that he had given instructions that everything that he deemed worthy of inspection at Constantinople was to be shown him. ‘He then desired me to present to him all the suite, which I did separately, even to two little midshipmen of the Barham who had smuggled themselves in.’

Next day Durham was shown the Turkish fleet, and the new military college, and had much close talk with the Sultan’s Ministers. ‘I took every opportunity I could of giving them the best advice in my power for the carrying out of new plans of improvement. The chief Ministers of the Porte were afterwards entertained on board the Barham, a compliment which they evidently appreciated. ‘The result of all this has been to replace our influence on that footing from which our false policy has lately suffered it to fall, and Lord Ponsonby feels himself strengthened.’

After seeing the sights of Constantinople, and receiving many marks of attention, Durham resumed his journey on September 15, and arrived at Odessa on the 18th after a voyage in which, thanks to an equinoctial gale, he was ‘knocked and tumbled about’ to a degree that he had never experienced in his life. At Odessa he was promptly put into quarantine, because of the plague in Constantinople. It was a new experience for Durham to be held up in this fashion, but he made the best of the situation. He describes his picturesque quarters in the Lazaretto, the scrupulously clean and neatly furnished apartments, the little courtyard of the house filled with acacias, through the foliage of which he could see the ships tossing in the bay.

Always a great reader, he spent much of his time during this enforced pause with his books; but in the afternoons, when the weather was fine, he and Mr. Kinnaird, Captain Brinkwater, or others of his suite, went down to the harbour and rowed about in a six-oared boat, which had been placed at their disposal. ‘The Governor of Odessa comes every now and then to pay me a visit, and sends me all the papers, “Galignani,” “Journal des Debats,” “Temps,” and the “Morning Post,” so I get regular and late news from England.’ Once out of quarantine, in the four or five days during which he remained, entertainments of all kinds were got up in his honour. He held what he describes as a kind of levée at the Hôtel de Richelieu, since all the consuls at Odessa came to pay their respects in uniform. He saw the cathedral, visited the opera, which was excessively crowded with the fashion and beauty of the city, and met, in familiar talk, all sorts of official people, from Count Woronzow, who had come specially from the Crimea to meet him, and the Admiral in command of the Russian fleet in the Black Sea, to his late custodians at the Lazaretto.

He started for his long journey to Moscow on Saturday, October 10, Count Woronzow taking leave at the carriage door. He was escorted out of the town by a guard of Cossacks, and then, as he puts it, left to his fate on the Steppes. The weather was miserably bad, and just after nightfall the unexpected happened. ‘By some means or other the postillions lost their way, although the lamps were lit. At length I perceived it, and called to them, when they confessed that they had lost the road altogether. After several attempts in vain, I made them draw up under a haystack, took out my compass, and found that the heads of the carriages were exactly the wrong way. I then ordered a lamp to be hoisted on the top as a sort of lighthouse, and sent out four postillions north, south, east and west to hunt for the road. In about an hour they returned, having found it, five miles off.’ The next post was reached at two o’clock on Sunday morning—the result of being lost for eight hours in the dark on the Steppe. He reached Kieff on October 15, where he was received in audience by the Tsar, who arrived towards the end of his stay to inspect the troops quartered in that city. ‘I had the honour of an audience at three o’clock, which lasted until four. I was received by his Majesty in a manner so cordial and friendly that I feel convinced that he still entertains those gracious feelings, the prevalence of which during my former Embassy was of such material advantage to me.’

The journey was resumed on October 24, and he pushed on, along roads that were at times almost impassable, to Orel. He was thoroughly exhausted by the last stages of this tedious progress across Russia, ‘through seas of mud’ and along ‘primitive roads.’ The jolting was so bad that Durham states that he had to ‘hold on as if he were in the Bay of Biscay.’ Once more the postillions lost their way, and were seven hours in traversing twelve miles. Eager as he was to push on, it was almost a relief to him to find that the postillions demanded a halt at Orel for repairs to the carriages. It gave the tired Ambassador the first chance with which he had been favoured for a whole week of sleeping in bed.

Moscow was reached on October 30, and there, as indeed everywhere on his journey, Durham was received with marked attentions. He spent two or three days in the ancient capital, and found the time all too short to do justice to the half-Asiatic, half-European splendour of the city. The Kremlin, the great cathedrals and churches, the palaces, monasteries, picture-galleries, libraries, museums, and arsenal, all were visited. Then the last stage of the journey was accomplished, and at the end of the second week of November he set foot in St. Petersburg. Lady Durham and his daughters were the first to greet him. They had come by the direct route, and were comfortably established in a ‘beautiful though rather small house.’

Almost immediately the opportunity came of presenting his credentials to the Tsar, who had just taken up his residence at the Winter Palace, on his return from the southern provinces. In one of the first letters that Durham wrote from St. Petersburg—it bears date November 16, 1835—the following statement occurs, not merely as to his reasons for accepting the post of Ambassador to Russia, but also what had induced him to make the long and difficult journey by which he approached the capital:—‘Not liking to be idle, I took the opportunity offered me of employment, and I am happy to think that I have done the State some service. When I accepted the Embassy here, I imagined that the circuitous route by Constantinople would be the most advisable one for me to take. It gave me the opportunity of becoming personally acquainted with the state of affairs in Greece and Turkey, and of being able subsequently to judge of the correctness of the representations made to me. I knew that at St. Petersburg I should derive great advantage from the possession of this knowledge, and, besides, I wished to re-establish our influence at Constantinople, which had been suffered to lapse into discreditable abeyance. In all this I have succeeded to the utmost extent of my hopes, and it will be the fault of the Government and of their future policy if we are not all-powerful with the Sultan and throughout the East.’

Durham was convinced that this was the true way to arrest Russian ambition in the near East. He declared that we had left the field open to them so long, that it was not surprising they had availed themselves of such an advantage. He added that, as England was now beginning to show herself on the alert, statesmen at St. Petersburg were inclined to say that they had enough to do at home, and even the possession of Constantinople, far from being an advantage, would be a calamity to Russia. Whether Russian diplomacy was sincere in all this mattered little, he argued, provided it acted up to such declarations, and thus staved off political confusion, misunderstanding, and, ultimately, war. His own language to them was: ‘I do not believe that you entertain the designs attributed to you, because you are too wise and too clever to attempt impossibilities. The retention, nay, the occupation of Constantinople, is an impossibility. We never could and never would permit it, whilst there was a shilling in our treasury, or a drop of blood in British veins.’ They always reply, ‘You are right, we do not entertain the design. Alexander and Catherine did. The Emperor does not; he has enough to do at home.’

During his journey by coach of fifteen hundred miles across Russia, Durham used his eyes to some purpose. He inspected the Russian outposts on the Black Sea, and in the southern provinces of the Empire, and declared that he saw no symptoms of any preparations for war, nor even the power to make them. He was convinced, from all that he had seen in the south of Russia, that the Tsar had not the power, even if he had the will, to call suddenly into action a sufficient force to take possession of Constantinople. His Majesty said to him at Kieff, ‘Vous verrez La Russie dans toute son étendue, et vous verrez que j’ai plutôt à consolider ce que j’ai qu’à chercher de nouvelles conquêtes.’ All classes of Russian society with whom Durham came in contact avowed the same sentiments, and volubly disclaimed any policy of conquest in the East; whilst politicians of the Moscow party went so far as to assert that the taking of Constantinople would be the signal for the dismemberment of the Russian Empire, as it had once been of the Roman. England, Durham held, needed to keep Russian opinion in the same virtuous mood by showing the great Northern Empire that, whatever policy she chose to follow, our own determination was unalterable, namely, never to permit the occurrence of such an event.

Durham was in high spirits during the first two or three weeks after his arrival at St. Petersburg. He felt that his visit to Constantinople and the opportunity which it had afforded him, not merely of talking over the political situation with Lord Ponsonby and other diplomatists, but of forming his own impressions on the spot, had given him a new insight into the Eastern Question. His subsequent journey, in his own carriage, across Russia had enabled him, at every place at which he halted by the way, to gather fresh information as to Russia’s preparations for war and to form his own conclusions concerning the Tsar’s military designs. No Plenipotentiary could have been sent to a foreign Court with more splendid credentials than those which were given to Durham by Palmerston, under the sign-manual of William IV.

In that document it was expressly set forth that the King, being desirous of giving to his Imperial Majesty, the Tsar of All the Russias, an ‘unequivocal and public testimony of our true regard, esteem, and brotherly affection,’ had nominated ‘our right trusty and right well-beloved cousin and councillor, John George, Earl of Durham, Viscount Lambton, Baron Durham,’ as Ambassador-Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary. Lord Durham, it was added, had received the King’s command to repair with all possible diligence to the Russian Court, in order to give the Tsar the ‘strongest assurances’ of the King’s ‘unabated desire to strengthen and improve the harmony and good understanding happily subsisting between us and your Imperial Majesty.’ Finally, the hope was expressed that the Tsar will ‘receive our said Ambassador in the most favourable manner, and give entire credence to everything which we have ordered him to declare in our name,’ not merely when presenting his credentials, but ‘upon every subsequent occasion which may require his opening our sentiments to your Imperial Majesty.’

Whether the Tsar gave ‘entire credence’ to everything that Durham was commanded to say may be doubted, but personally his Majesty, who felt instinctively that he was a statesman he could trust, always received him in the most ‘favourable manner.’ It was, in fact, the confidence which Durham, by his character, much more than his address, inspired in the mind of Nicholas I. that enabled him to accomplish the great work which rendered his mission to Russia during the years 1835-37 so beneficial and memorable.

By the middle of December, finding the house which Lady Durham had taken before his arrival in St. Petersburg much too small, he removed to another, large enough to accommodate, in addition to his family, the members of his suite, whom he wished to have within call. Although the cold was excessive, it was bracing, dry and exhilarating, and though he afterwards felt it severely, and declared that only a man of granite could endure such a climate, there is evidence enough that, during his first months in St. Petersburg, he enjoyed life to the utmost in the brilliant society of the capital. He thought that nowhere did people understand how to warm a house better than in Russia. There were no draughts in the drawing-rooms like those at home, where guests were half toasted on one side and chilled to the marrow on the other. He did not go out much, in spite of all the balls and parties to which he was summoned, for he neither danced nor cared much for cards, though nothing delighted him better than a dinner-party at which talk touched high levels. Everybody in Russia, he remarked, from Tsar to the noble and peasant, did his best to set him at his ease, and just as he was beginning to feel entirely so, and was getting into close touch with Nesselrode on questions of international moment, a bolt from the blue fell upon him in the announcement that his daughter, Lady Frances Ponsonby, was dying at Bessborough in Ireland, after a brief married life, which had scarcely outlasted the honeymoon.

Lady Frances was the only one of the three daughters of his first marriage who had fairly crossed the threshold of womanhood, and up to the time of her marriage she had been her father’s constant companion. Her union with the Hon. J. G. Ponsonby, afterwards fifth Earl of Bessborough, and the son of Durham’s old colleague and friend, Lord Duncannon, took place in London on September 8, 1835. It was a marriage which had his entire approval. It seemed to promise to both husband and wife deep and settled happiness; but the end came quickly, on Christmas Eve in the same year, to the young wife, at the age of twenty-three. Lord Durham’s brother, Hedworth, went to Ireland as soon as he knew that his niece’s illness was critical, and wrote a note to St. Petersburg, to prepare her father for the tidings which he feared must follow. News in those days travelled slowly, and Lady Frances had passed away six days before the following pathetic letter was penned:

‘St. Petersburg: December 30, 1835.

‘My dear Hedworth,—I am very, very grateful to you for going to Ireland. It is a great comfort to me to know that you were there, and I add this to the many other proofs you have given of your affection for me and mine; with you it does not end in words. You may conceive my wretchedness; I cannot describe it. Every post-day I tremble at the thought of receiving the fatal intelligence. If God has spared her life when you get this, give her a million loves. I cannot write to her, for I fear saying anything which might alarm her, and I can say nothing about our life here, for since I got intelligence of her danger we have not been out. If she remarks on this, ascribe it to the cold, but don’t let her think we know of her danger. All this anxiety and misery has made me quite unwell again, and I write to you from my bed after a very violent attack in my head. But what is that I endure to the sufferings of my poor dear child! God bless you, my dear Hedworth.

‘Ever yours affectionately,

‘Durham.’

When those words were written, letters of condolence from a wide circle of relatives and friends were already on their way, for everyone who knew Durham at all intimately recognised that this fresh blow was one which would fall with peculiar severity. Out of such expressions of sympathy it is perhaps enough only to cite one—the letter which Lord Grey wrote to him between the death and burial of his daughter.

‘Howick: December 26, 1835.

‘My dear Lambton,—Though I am well aware of the impossibility of saying anything on such an occasion which can afford any real comfort or consolation, I hope, at least, for an excuse, from the sincere affection which I bear you, for expressing how much and how deeply I have felt for the loss which you have sustained. You must have been prepared for the event, which for some weeks there seems to have remained no hope of averting. But the blow would hardly be less severe when it fell, and I sympathise with you from the bottom of my heart under this new affliction. Could anything lessen its weight, it would be the assurance of the heavenly state of mind in which poor Fanny left this world, with all the prospects of happiness which had so lately been opened to her. Nothing could be more beautiful and affecting than the accounts which we have received of her truly religious feelings, and of the resignation and piety which supported her under the separation from all she loved on earth. She has pointed to us all the way to obtain the same support, under whatever dispensations it may please the Divine Providence to visit us with, and I feel confident that this reflection will at length afford you the comfort which no earthly aid can bestow.

‘Lady Grey writes constantly to Louisa, who will have seen the deep anxiety with which she has watched the approaches of this event, and the sincere sorrow with which she received the account of its arrival. Our best and most affectionate wishes attend you both, with our sincere prayers that the blessings which you still possess may long be preserved to you.

‘At such a time I cannot enter upon any other subject. Indeed, in the complete seclusion in which I live, hearing and knowing nothing, I could have little to say on any public subject; but, from all I can observe, the continuance of Melbourne’s administration appears to me very precarious.

‘Yours most affectionately,

‘Grey.’

The year 1836 opened darkly for Durham, but it was not until the first week of it had passed that his worst fears were fulfilled. When he heard the evil tidings he was reduced almost to the same condition of physical collapse as in 1831, when the boy on whom he built his hopes was snatched away. ‘Poor Lambton is very miserable!’ wrote Lady Durham on January 9. ‘Little did I forebode, in parting from Fanny on the night of her marriage, that I was never to see her again.’ Two days later, Durham wrote himself to his brother, having received a letter from him in the interval, written from Bessborough immediately after the death of his daughter:

‘St. Petersburg: January 11, 1836.

‘My dear Hedworth,—I have received your letter, with all the heartrending details of my poor darling child’s death. Can I tell you how wretched I am! Impossible! You know what she was to me—my companion, above all, from her earliest childhood. Oh God! it seems a frightful dream.

‘I did not look for such a renewal of past afflictions; it makes me tremble for the future. I dare not write on, or I shall go mad.

‘Believe my assurances once more that I am very sensible of your affectionate zeal in all that concerns me. It was a great consolation to me your being there.

‘God bless you.

‘Your ever affectionate

‘D.’

Happily, the duties of his position quickly asserted themselves, and prevented him from brooding over a loss which, to the end of his life, he never ceased to lament. The despatches which he wrote to Lord Palmerston in those sorrowful weeks at the beginning of 1836 reveal how fully he was alive to the necessity of keeping the English Government informed of all that was happening just then in Russia. He assured Palmerston that he was convinced Russia was powerless just then to disturb the peace of Europe, even if she had the inclination. He was in constant communication with Count Nesselrode, and had assured him repeatedly and firmly that England would never consent to the occupation of Constantinople by Russia.

‘I am on the best terms with Nesselrode,’ he wrote, in a letter to Lord Grey, ‘but at the same time I have invariably held the same language to him, namely, that we never could or would permit Russia to occupy Constantinople, or take any portion of Turkey. Once convinced of this, and that it never can become theirs, I can easily convince them that it is for their advantage to make that Power strong and independent. For Russia to conquer Turkey she must be weakened—as an ally (against Austria for instance) she must be strengthened. So conscious of this is Metternich, that he would oppose to the utmost of his power the restoration of Egypt to the Porte. In that I think he is right. The welfare of the Mediterranean and the security of its commerce is much safer with Mahomet Ali acting as a check on the Sultan, than it would be if the ancient Ottoman Empire was restored in all its former extent and strength. With reference to that object, in my opinion, Turkey, as it is now, should be supported and consolidated; but I am against any reformation of the old.’

Durham always held that this country was in danger of showing too much distrust, suspicion, and jealousy of Russia, and he urged on Palmerston that it was to our own interests to cultivate a strict alliance. One of his great difficulties arose out of constant and often virulent attacks on Russia in the English newspapers, all of which quickly found their way, through Count Pozzo di Borgo, Russian Ambassador at the Court of St. James’s, to the knowledge of the Tsar, and were in due course brought before the English Ambassador by Count Nesselrode, as a matter of complaint. Durham, of course, did not for one moment attempt to deny the existence of such sentiments, and declared that they had arisen as the result of a long series of events, concerning the policy and justice of which the two nations held opposite views. He assured Nesselrode that there was nothing for it but to trust to time and future intercourse for the removal of such a feeling. He added that he had already contributed not a little to so desirable a result by informing the English Government of the entire absence of any hostile designs against Turkey on the part of Russia—a matter on which he had satisfied himself by personal observation.

He felt, so he assured one of his most intimate friends, that it was his business to make himself acquainted with the powers and resources of the Russian Empire, as well as with the intentions and declarations of statesmen at St. Petersburg. Russia, he declared, is a great, unwieldy giant, of immense power, with his back against the wall which nature and barbarism have erected behind him. The giant was powerful so long as he remained in that position, as Napoleon had discovered to his cost, but weak and assailable the moment he advanced into an open arena. ‘Russia has, besides, three sources of weakness, inherent and irremediable—Poland, the Caucasus and the Fleet. All these deprive her of immense sums of money and large masses of men. I find weakness where the world imagines strength, and the latter where the former is believed.’ His letters show that he was keenly following public events in England. ‘The municipal elections have produced a great effect, and must show to all but the wilfully blind what are the opinions of the people of England. If the Crown will only go with them in good faith and harmony, Monarchy is invulnerable.’

Sometimes, though rarely, gossip invades his letters. He describes in one of them a New Year’s fête at the Winter Palace, in which all the world, so to speak, was admitted, as well as a supper for officials of high and low degree, to which the Tsar did not sit down, but walked about talking to the guests. His Majesty had heard that one of them was a notorious gourmand. Nicholas, with malicious humour, stepped up to this particular man whenever a plate was put before him, and entered into conversation with him. Instantly the attendants, who were in the secret, whipped off the appetising portion, and this happened all the way through the banquet, so that the unfortunate guest had to be content with the marked and quite unusual attention of his Sovereign. ‘This is not bad fun, to be sure,’ was Durham’s comment, ‘but rather “infra dig.,” as Jonathan would say.’

‘Personally, I am on the best terms with the Tsar, but I daresay he does not relish the plain language I always address to his Ministers on their Eastern policy. Is not mine a singular fate? In 1834 I am received with favour, nay affection, by thousands of the “people.” In 1835 I am equally well and confidentially treated by Sultans and Emperors. I can only account for this in one way—for my principles are the same and cannot suit both parties—namely that they both believe I am honest. I hope this is the true solution. If it is not I must be a great impostor. I own I am a little puzzled.’ Those words of course could not have been published at the time they were written, but, after the lapse of more than half a century they may escape into print, if only as a tardy answer from Durham’s own lips to the old taunt of certain Radicals of his day, that they were at a loss to understand how he, as a champion of democracy, could ingratiate himself at foreign Courts. It was not merely the transparent honesty of the man, but his habitual and conscientious attempt to do justice to the point of view of those from whom he differed, and not less the courage and conciliation which he manifested, which made him welcome wherever he went, as a statesman of the Crown.

Lady Durham’s letters at this period are full of allusions to her husband’s frequent attacks of illness, and his own show how constantly the thought of his recent bereavement oppressed him. All his life he was subject to deep fits of depression, but, happily, like other men of his impressionable temperament, he was able, when occasion demanded, to rise above them. Early in the spring he found himself called upon to play the part of consoler to his son-in-law, the Hon. J. G. Ponsonby, who, after four brief months of wedded happiness, came, utterly broken down, to St. Petersburg, in order to be with those who knew and loved his young wife best. He afterwards became fifth Earl of Bessborough, lived for many years, but never married again; and, though he kept a journal which is now in possession of his nephew, the present Earl, the pages in it which refer to his short married life were removed by his own hand from the manuscript as too sacred for other eyes.

Erratum

Vol. II. page 27.

Bessborough, Ireland, October 11, 1906.

I find that I have unwittingly fallen into error in the last sentence of this chapter, and will, of course, see that the matter is put right in all but the first copies of this edition. After I sent the book to press I came here on a brief visit to Lord and Lady Bessborough, and at once discovered that the statement that the fifth Earl ‘never married again’ was incorrect. The fact is he remained a widower for fourteen years, but in the autumn of 1849 he took as his second wife Lady Caroline Gordon Lennox, daughter of Charles, fifth Duke of Richmond and Lennox. The fifth Earl died in 1880, but the Countess survived until 1890.

S. J. R.

The end of politics is the application of a moral law to the civil constitution of a nation in its double activity, domestic and foreign.—Mazzini.

1836

Inability of Russia to engage in a war—Groundless suspicions of the Tsar’s intentions—Changed phases of the Eastern Question—Over-estimation of Russia’s power—Weakness of the Tsar’s Army and Navy—Financial resources—Effect on the Empire if Russia conquered Turkey—Influence of the aristocracy—Fatalism in the Army—Lord Grey on Durham’s Report—Austrian occupation of Cracow—Efforts on behalf of the Poles—Palmerston on Russian policy—Durham’s guiding principles in Russia.

Early in 1836, in response to Palmerston’s request for an exact account of the political situation at St. Petersburg, Lord Durham prepared his luminous and remarkable ‘Report on the State of Russia.’ It is a document of considerable length, and the outcome of knowledge derived during his first Embassy, as well as from personal investigations made during his journey from Constantinople to Moscow, and ‘diligent inquiry,’ not in one, but in every direction, during the four or five months which had elapsed since his arrival at the Russian Court. It is written with great ability—a skill and felicity in the marshalling of facts, which suggests comparison with his more famous achievement three years later—the historic ‘Report on British North America’—a State paper which has been termed the Magna Charta of the Dominion.

The Russian Report was avowedly an attempt to unravel a political problem which directly concerned the interests of England and the peace of Europe, namely, whether Russia was likely to make a hostile movement for her own security or for territorial expansion. He disclaimed, at the outset, all confidence in verbal assurances on the part of Russia, except in such cases where they were corroborated by facts, accessible to witnesses with no predilections in her favour. His aim was to prove that the Tsar was as much prevented by incapacity as by inclination from going to war, or from seeking to obtain, directly or indirectly, that which was once the object of his ambition, the possession of Constantinople. In defiance of the policy of Canning, we had allowed Russia, in 1828, to pour her armed masses into Turkey without remonstrance or opposition, and then, when war and disease had nearly annihilated her army in the following year—a fact which was now admitted by the most eminent Russian generals—we had allowed her to conclude the Treaty of Adrianople with all the honours and advantages of a triumph, which in reality did not exist, and was within measurable distance of a defeat. Our policy at that time was ignorant and short-sighted, and resulted in the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, the military abandonment of the whole of Roumania, the opening of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, which gave access to the Black Sea, the right of commerce by Russia throughout the Turkish Empire, and the payment of a huge indemnity for the expenses of the war, which practically compelled Turkey, in lieu of money, to resort to further political concessions.

Durham was at a loss to understand why in 1836 we should reproach ourselves with our blindness in 1829, when Russia was allowed by Europe to advance within a few days’ march of Constantinople, and why we ought now to regard with suspicion and doubt her desire for peace, when she had retired within her own frontiers, when no aggressive tendency was visible, when she had without pressure withdrawn her army from the Bosphorus. Navarino had spelt Russia’s opportunity. Metternich endeavoured to intervene, but neither France nor Prussia at that crisis was prepared for concerted action with Austria, whilst England, under Wellington, was not inclined to take any decisive measures to arrest the advance of Russia. ‘It was comparatively easy, therefore, for Russia at that time to march against her sole antagonist, the Sultan, enfeebled as he was by the successive separations of Egypt and of Greece from the Empire, by the loss of the fleet, and deprived of the cordial and fanatical support of his remaining subjects, who were bewildered by the novelty of changes and reforms, which they then considered impious and impracticable.

‘But the state of things is now very different. These internal ameliorations are not only submitted to by the Turks, but their further prosecution is admitted to be essential to the prosperity and salvation of the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan’s army is rapidly organising on European principles. His fleet is restored. No drain on his resources exists either for Greece or Egypt, and, with common prudence and discretion, a few years will exhibit the Ottoman Empire as powerful and independent as it was then weak and degraded. On the other hand, England, which, in 1829, looked on stupefied or indifferent, has unequivocally declared that any attempt on the independence of Turkey will be resisted to the uttermost.’

Russia, Durham contended, recognised that a fresh and formidable change had come over the Eastern Question. It was no longer possible for her to measure swords with Turkey alone. Any hostile movement against the Ottoman Empire would now bring England against her, and probably France and Austria as well. But this, after all, was only one side of the question. Russia’s external difficulties, great as they were, did not stand alone. There were other obstacles, and they concerned her internal resources. Peter the Great had done wonders, and since he founded the great capital which he called after himself, though little more than a century had elapsed, great strides had been made in civilisation, so much so, in fact, that the Russians themselves had been not merely dazzled but deceived. The power of Russia, in Durham’s opinion, was greatly over-estimated. ‘The difficulties of communication, the vast extent of territory, the inclemency of the climate, prevent, except in isolated cases, all acquaintance with the internal state of Russia, and we are therefore compelled to accept and act upon the representations of her own subjects. Such, in my mind, are the causes of the inflated tone which misrepresents the real position of the Russian Empire. It is not wilful, but it is exaggerated.’

Lord Durham proceeds to show, by an analysis of the population, the military and naval resources of the Russian Empire, and of its economic conditions, that there is not a single element of strength which is not counterbalanced by a corresponding degree of weakness. The Tsar’s subjects in 1836, it is interesting to learn, numbered forty-eight millions in Europe and ten millions in Asia. This vast population—it is of course far greater to-day—was scattered over an area of millions of square miles of territory, an almost insuperable difficulty in days when there was no railway communication. The population of the Russian Empire, moreover, was at that time shorn of all moral force and national unity by the barriers of various climates and customs, as well as by the universal lack of education amongst the middle and lower classes. The Army at that time was strong enough to be a menace to the peace of Europe, for it consisted of no less than eight hundred thousand men; but here again the whole truth of the situation had to be taken into account. Frontiers had to be guarded more than ten thousand miles. Poland on one side of the Empire had to be held in subjection by 60,000 soldiers, whilst on the Asiatic side 70,000 more were required in the military operations in the Caucasus.

Nor was this all; along the southern line of the Russian frontiers it was necessary to keep military watch and ward against the predatory incursions of Tartar tribes, as well as to maintain unsleeping vigilance over the movements of the Persians and Chinese. Even this did not exhaust the demands made on the Russian Army, for all the fortresses from St. Petersburg to Archangel, along the Baltic and on the shores of the Black Sea, had to be garrisoned. Durham held that, when these facts were taken into account, Russia’s military force of 800,000 men was reduced, for any aggressive movement, to less than 150,000. Russia knew perfectly well that, if she attacked Turkey again, and England, in consequence, took up arms against her, another Polish insurrection would immediately follow, which, with such a union of forces against her, would be difficult, if not impossible, to suppress. This, in itself, was one reason, out of many, which made for peace. As to the navy, the Russian fleet made a brave show on paper, and even rode well at anchor, but it was not as formidable at sea as was commonly supposed.

Walter L. Colls, Ph. Sc.

Lord Durham,

at the age of thirty-six

From a miniature in the possession of Stuart J. Reid

‘The genius and spirit of the Russians are not maritime. The service is forced on officers and men, is not congenial to the tastes and habits of the one or the other, and is, moreover, destitute of the best and only supply from which it can be efficiently recruited—a commercial navy. There is, no doubt, to be seen at Cronstadt as splendid a collection of line-of-battle ships, frigates, corvettes, gun-boats, &c., &c., as can well be imagined, but they are firmly embedded in the ice seven months out of the twelve, and when at sea for a summer’s cruise of three months the men exhibit all the symptoms of rawness and inefficiency, which must naturally be expected from crews thus circumstanced. In this light is the Russian navy considered by almost every official person with whom I have conversed on the subject. They all declare it to be a “toy,” and a very expensive toy, with which the Emperor delights to occupy himself, but not one of them, from Prince Menschikoff downwards, anticipates the possibility of its ever being made use of as a means of attack or defence, and all openly deplore the expense which it occasions, as weakening their financial resources, and withdrawing large sums annually from more useful national purposes.’

But it is time to turn from what Durham has to say concerning the position of the Russian army and navy to what he added as to the financial means which the Tsar’s Government possessed for putting either or both in motion—in other words, what about the sinews of war? ‘In 1835 the revenue amounted to 472,457,975 roubles, the expenditure to 520,670,050 roubles, leaving a deficit of more than 48,000,000 roubles. The debt, bearing interest, amounts to 1,000,000,000 roubles at 5% and 6%, in addition to which there is an issue of 600,000,000 roubles of paper money on which no interest is payable. The expenditure of the War Department was 181,862,047 roubles, that of the navy 37,534,999 roubles. Of the receipts, 81,500,000 roubles were derived from the customs; 131,285,539 roubles from the capitation tax and Crown dues; and 119,171,550 roubles from the brandy and salt monopolies. There has been an annual deficit since 1831, amounting on an average to upwards of 30,000,000 roubles, and if the receipts have increased, so has the expenditure. Receipts and expenditure reveal a gradual increase under both heads, but that of expenditure exceeds that of income. It is true that an increase of the capitation tax, from a new revision, is expected, but, on the other hand, it is certain that the customs will fall short of the sum anticipated.

‘It appears then, on this view of the Russian finances, that no extended military operations could be undertaken without an increased expenditure, which could alone be supplied by means of a loan. In what money market in Europe, after a declaration of war against the most influential portion of it, Russia could be accommodated, I am at a loss to conjecture. The more probable event would be such a depreciation of her credit as would render any pecuniary advance from capitalists, however speculative, impossible. But even these statistics based on the latest official returns do not exhaust the economic obstacle to war. There are other difficulties which spring out of the trade and manufactures of the country, and the landed interests of the nobles, and the commercial interests of the merchants. Russian exports in 1834 amounted to 230,000,000 roubles, against imports 218,000,000 roubles. Out of this the extent to which Russia would be crippled by a war with England in her trade alone is at once apparent when it is stated that, out of her total exports, just cited, 105,000,000 roubles represent her export trade with this country.’

Durham proceeds to show that manufactures have been established, involving a capital of 250,000,000 roubles, but, in spite of the ‘forced and unnatural protection’ which is given, worse articles are produced than could be imported and higher prices are demanded for them. Russia, moreover, is absolutely dependent on foreign countries for raw material. ‘She is dependent on England, America, Italy and Persia, for cotton, cotton-twist, indigo, raw sugars, dyes, silk, &c., and the supply would be cut off in the event of a war with England.

‘There is yet another view of this branch of the subject well worthy our attention when we are closely examining hidden as well as open difficulties, which render a war, especially an Eastern war, improbable. What would be the effect on the Russian Empire itself by the conquest of Turkey and the occupation of Constantinople? How long would St. Petersburg remain the capital of this new and extended Empire? Would it ever be transferred to Moscow, which is now the great object of the Russian nobility? No, but to Constantinople. All the advantages of climate and situation are so notorious, that the natural consequence must inevitably be the transfer there of the Court and Government. Russia therefore—real Russia—would become a province. The estates of the nobility, placed at such a distance from their residence and superintendence, must inevitably suffer to the greatest degree, and unless the nobles were to be indemnified by grants of land in Turkey—which again would render the Turkish population discontented and hostile—they would be reduced to the verge of ruin.’

Durham next points out that even the Autocrat of All the Russias is not omnipotent. The power of the nobles is real, though it does not manifest itself, as in former times, in drastic measures of deposal or assassination. The Russian nobility are, moreover, becoming every day more enlightened, and their intercourse with the rest of Europe, in spite of all prohibitions to the contrary, is more frequent. The younger Russian nobility are, in fact, often as well educated and independent as men of their class in other countries nominally more civilised. ‘It is a great mistake, therefore, to suppose that those schemes of visionary ambition which dazzled the imagination of barbarous Tsars and nobles are equally attractive now, when civilisation and education have inspired both with sounder and more rational notions.’ After describing the wide range of the inquiries on which he based his conclusions, Durham alludes to the Tsar’s emphatic declaration to himself, the sincerity of which he sees no reason to doubt, that he had enough to do in the way of consolidation and improvement at home to prevent him from seeking conquest abroad.

This remarkable Report on the state of Russia is finally summed up in the following words: ‘In these circumstances and with the evidence of these facts before me, I humbly conceive that I am justified in reporting to his Majesty and to the Government my conviction that the peace of Europe is not likely to be disturbed by any ambitious or hostile enterprises on the part of Russia, for which she has neither the inclination nor the means. In fact her power is solely of the defensive kind. Leaning on, and covered by, the impregnable fortification with which nature has endowed her—her climate and her deserts—she is invincible, as Napoleon discovered to his cost. When she steps out into the open plain, she is then assailable in front and rear and flank—the more exposed from her gigantic bulk and unwieldy proportions—and exhibits, as in Poland and Turkey, the total want of that concentrated energy and efficient organisation which animates and renders invincible smaller but more civilised bodies.

‘Abroad her soldiers fall by thousands, sullen and dispirited, evincing the passive devotion of fatalism, but neither the brilliant chivalry of the French, nor the determined unyielding courage of the English. At home they fight with desperate, unconquerable fury, for national and domestic objects, consecrated by religious feeling and patriotic traditions. Such a nation therefore cannot be successfully led over her frontiers. Her wants, her weaknesses, her peculiar strength, all demand concentration at home. Once impressed with the conviction of this truth ourselves, and with the belief that it is also apparent to her own rulers, we shall then no longer entertain that jealousy of all the movements of Russia which, in other circumstances, would be wise and necessary, but feel justified in courting openly, and assiduously cultivating, that alliance between the two countries which is so imperatively demanded by common unity of national interests, and by the soundest principles of European policy.’

Lord Grey was quick to recognise the importance of this masterly survey of the position of Russia. In a letter of thanks for birthday congratulations which Durham had sent him, and dealing largely with purely family matters, he alludes to the ‘very interesting despatch’ which he had just seen, and expresses the hope that, in view of Durham’s impaired health, he will not see it his duty to remain much longer in Russia. The letter, it will be seen, throws into relief what was only too apparent to all who knew him at this juncture, the writer’s antipathy to politicians of advanced opinions, and especially the more immediate following of O’Connell, a man to whom he naturally bore a grudge for the collapse of his own Government, and to whom, both by temperament and conviction, he was opposed.

‘Berkeley Square: April 12, 1836.

‘My dear Lambton,—This (the kind feeling so strongly manifested in your letter) has afforded me the same pleasure as your other communications of the same nature. The information it contains of the state of Russia is most important, and affords better means of judging of the policy which requires to be pursued on our part than anything I have yet seen. In the conclusions you deduce from it I entirely concur, and have not the least doubt that a firm but conciliatory spirit is that which ought to prevail in all our discussions with the Court of St. Petersburg. Your conduct appears to have been most judiciously directed to the preservation of peace for the present, and to our being placed in such a position that, whatever may happen in the future, our means of counteracting any designs that might be prejudicial to our interests will be improved and strengthened.