* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Bishop Bompas

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Emily Murphy (1868-1933)

Illustrator: C. W. Jefferys (1869-1951)

Date first posted: November 26, 2025

Date last updated: November 26, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20251138

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE RYERSON CANADIAN HISTORY READERS

Are designed to meet a real need of the schoolroom. Every wide-awake teacher has long recognized the value of supplementary readers, simple and interesting enough to be placed in the hands of the pupils.

Each reader contains a wealth of historical information, and completely covers the history of our country through its great characters and events. These books are written in a charming and vivid manner, and will be valued, not only as history readers, but also as lessons in literary appreciation, for the teaching of history and literature ought to go hand in hand.

“I am very interested in these booklets and should like to place a set in every school in the province.”—Henry F. Munro, M.A., LL.D., Superintendent of Education, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

“We have prescribed several of the Ryerson History Readers for use in our elementary schools . . . I believe they will become more and more popular as time passes.”—S. J. Willis, LL.D., Superintendent of Education, Victoria, B.C.

“These little books are admirably adapted for use in our schools. They provide a fund of interesting information arranged in very readable form, and should prove a real help in arousing and maintaining interest in the events that constitute the history of our country.”—A. E. Torrie, M.A., Principal, Normal School, Camrose, Alta.

“From my point of view these little booklets fill admirably the purpose for which they were designed. They say enough—but not too much. Big books are tiresome to young people. There are so many outside distractions for them these days and we must conform to circumstances. Your booklets are excellent in every way and will, I hope, be very cordially received.”—M. Pierre Georges Roy, Provincial Archivist, Quebec.

“We would like 350 sets—each set to contain 40 numbers published, as marked with an asterisk on the enclosed leaf.”—A Maritime Department, of Education.

“Children will really know and learn to love Canadian History when it is introduced by such charming booklets. They meet the real need of the schoolroom.”—The Canadian Teacher.

Copyright, Canada, 1929, by The Ryerson Press, Toronto

When William Carpenter Bompas, a young Anglican clergyman from Regent’s Park, London, went as a missionary, in 1868, into the great polar desolation known as the Arctic Circle, the Eskimos took him for a descendant of Cain.

According to their legends, there were two brothers in the first family of mankind and one killed the other, the murderer afterwards disappearing into the frigid parts of the world. How many years ago this was they could not calculate, but, at any rate, it was quite evident that the young man, who had now come into their more pleasant region, was the son of Cain. This does not seem to have caused any hostility toward him, for, in writing of these people later, Bompas said that in all the world there was nothing warmer than the grasp of an Eskimo’s hand. Indeed, the Eskimos partook with him of the amerquat, that is to say they ate off the same bone, each man taking a bite and passing on the bone to the next man, a ceremony equivalent to our agape or love-feast.

In his great adventure for humanity, Bompas spent forty years in the north, coming out only twice. On the first occasion, he went to England to be elevated to the episcopate. The second was shortly before his death. Taking into consideration his loneliness, as well as his hardships and sufferings, the statement made by one of his associates, that he was the most self-sacrificing bishop in the world, is probably correct. Be this as it may, no name looms larger in the missionary annals of our Canadian North.

Truly, these forty years spent by Bompas in northern latitudes may properly be compared with the forty years Moses tarried in the wilderness, except that, to Bompas, these were never accepted in a spirit of bondage. Giving all, he asked nothing. He was a man great in his service, great in his faith, and great in his love.

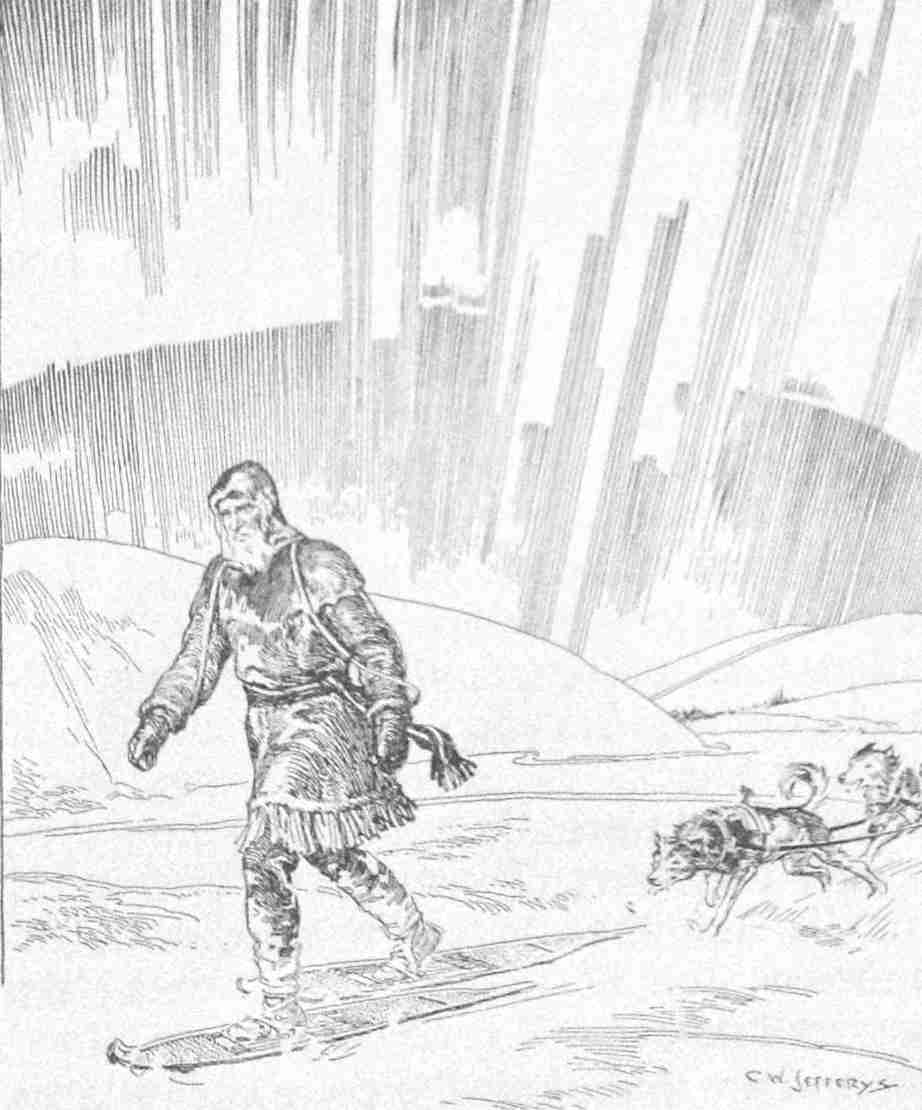

BISHOP BOMPAS IS HERE SHOWN MAKING HIS PASTORAL ROUNDS UNDER THE NORTHERN SKIES. NOT ONLY DOES THE LONELINESS OF HIS LIFE IMPRESS ONE, BUT ALSO THE ENDLESS DEMANDS MADE UPON HIS STRENGTH AND ENDURANCE. THE SNOW-SHOES ARE OF A TYPE WORN IN THE NORTH, LONG AND NARROW, PERMITTING ONE TO SLIDE DOWN THE HARD-PACKED SURFACE OF THE BARE HILLS. THE BISHOP SWINGS AHEAD MAKING A TRACK FOR HIS WEARY DOG-TEAM.

The ecclesiastical domain of William Bompas was known as the Diocese of Athabasca, and contained about one million square miles. Like Bobbie Burns’ “cauld, cauld kirk,” there were “in’t but few,” these few being Eskimos, Indians, missionaries and the fur-traders known as the “Gentlemen Adventurers of England Trading into the Hudson Bay.” These fur-traders lived at forts, each fort being a collection of log buildings used for storehouses, residences and trading shops. The forts, in some instances surrounded by palisades of wood known as stockades, were usually built on the riverways, at a distance of from one hundred to three hundred miles apart.

There would be fewer people in the area of this vast diocese than young Bompas had in his second parish at New Radford, England. Ah, well; it was a northerner who boldly said, “The world is large that men may take it in possession.”

This land of adoption was a cold and ill-nurtured one. Its people, “the lean men of the lone shacks,” were, for the most part, ungentle and uncouth, but to the young missionary they were of intense and vital interest. To him, the whole of this empty northland was full of things that attracted the keenest interest.

Nowhere in the world is there such silence and inscrutability as in these large lands of the north, where the world stretches wide ’neath the midnight sun. Isolated from civilization, and thrown upon his own resources, this was how the rare and great-souled prelate came to look upon material things with spiritual eyes, and to record his observations in the volume entitled Northern Lights on the Bible.

Here was a land which he described as having no money, mails or markets; no streets, carriages or railways; no villages, farms, flocks or herds; no government, police, soldiers, lawyers or physicians; no hospitals, prisons or even any taxes. While in a sense a new land, yet it was primeval in that the life and customs of the people had changed but little. Their food, dress and habits were almost the same as a thousand years before, few white men having penetrated these regions. Yet, in his book, William Bompas wrote of the compensations of the land as no one had ever dared to write.

Does he sleep in the woods? . . . He tells us that to sleep in the woods is much easier than to sleep without woods. Does he speak of the isolation from civilization, and of the scarcity of happenings? He tells us the opportunities for study, meditation and research are long and plentiful.

That he took advantage of these opportunities is shown by the fact, that he came to be acknowledged by the savants as the foremost living authority in Syriac.[1] Although it took two or three years to get an answer, mooted points in the translation of this language were frequently referred to him from Europe for explanation.

It may be that this lonely young missionary studied diligently to keep himself at his best, just as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, stationed in Arctic regions, observe a stricter discipline in order to preserve their morale and general self-command. It must have been this, for once he says: “The dangers to a genial character in a solitary life are manifold. The mind is apt to become warped, narrowed, conceited, gloomy, morose, self-opinionated and obstinate. . . .” Again, he says, “Should circumstances oblige a life of loneliness, then welcome occasions of intercourse.”

Be this as it may, Bompas came to know the land by heart, and to see goodness in all its varying phases. He was a true lover of the north, and like the picture of the British bulldog standing resolutely on the flag, what the north has it holds. The north may whiten a man’s hair, harden his voice, and wrinkle his skin, but it pours a magic into his veins so that he dies with longing for it in any other land. They failed to grasp this, the genial hosts of Bishop Bompas in Vancouver, when, in his latter days, he paid his second visit to civilization. They were both amazed and amused when, night after night, the aged prelate, finding himself unable to rest in houses made by hands, was wont to steal silently out of his bedroom; make his way to the dockyards; wrap himself in his blankets, and there to sleep without fear of hurt or hindrance.

The thing was whispered among the clergy with bated breath, for fear of the shock that might come to the laity had they known that so high a dignitary as a bishop was nightly identifying himself with those weird folk who sleep out o’ nights! As for the Bishop, ah well! besides securing the necessary rest, His Lordship was effectively practising the fine maxim of Aristippus,[2] that it is better to adapt circumstances to yourself than to adapt yourself to circumstances.

On one occasion, however, William Bompas must have enjoyed amusement at the expense of a western host. It was in July, 1873, when he travelled overland for several months, covering a distance of two thousand miles, and stopped to rest awhile at the Red River Settlement (now Winnipeg) before continuing his journey to England, where he was to be elevated to the episcopate.

Arrived at the settlement, Bompas made his way to the See House of his friend, Bishop Machray of Rupert’s Land. Because of his rough travelling clothes, the serving-man took Bompas for a tramp and refused to let him in, but the traveller from the north was so insistent in demanding admittance, the Bishop had to be informed.

“Take him to the kitchen, James, and feed him,” said the prelate, thinking thus to rid himself of a troublesome vagrant.

But after the vagrant had eaten his dinner at the lazy side of the stove—that is to say at the back thereof—and being a stiff-minded fellow, the Bishop-elect still persisted in requesting to see his host, so His Lordship of Rupert’s Land was finally persuaded to come into the kitchen. He was there suddenly stricken with a mortifying malady which affects the whole system, and which has been aptly described by the half-breed woodsmen of these districts as “a crisis of the nerves!”

William Carpenter Bompas was born on January 20th, 1834, at 11 Park Road, Regent’s Park, London. It is believed that his forbears were of French extraction, having settled several centuries ago in England. One of these was knighted by Edward, the Black Prince, for valour on the field of Crécy. His great-grandfather was Lord of the Manor of Longden Heath, in Worcestershire. His father, Charles Carpenter Bompas, was a distinguished jurist and is generally understood to have been the original of Dickens’ character, Sergeant Buzfuz, in The Pickwick Papers.

On his mother’s side, the family were also scholars and men of parts. One of them was private secretary to John Hampden, and another performed a like office for Queen Henrietta Maria, he being hanged, alas, by the Roundheads for aiding her husband, Charles the First.

William Bompas was educated at home. We do not know much of his early years under the paternal roof except that he was deeply religious. He had a retentive memory, was retiring by nature and liked to go sketching. He was also a good gardener and a fine walker. These qualities and habits doubtless contributed in no small measure to his ultimately becoming the greatest circuit rider of his age.

In the year 1852, the youth was articled to a firm of solicitors, in whose office he worked for five years. Later, he was attached to another firm for two years. Because of his sympathetic temperament, and the consequent strain of court work, Bompas had a nervous breakdown. During the three months that followed he became a student of the Greek Testament and, as a result, decided to enter the ministry of the Church of England.

After his ordination as a deacon by the Bishop of Lincoln, the young preacher was appointed curate at Sutton-in-the-Marsh, where he had the distinction of being the first resident clergyman since the days of the Reformation. This parish is described as having “a rough and primitive population, most of the men having been smugglers in former times.”

Much of the curate’s work was devoted to establishing a school, there being none of any kind. In this, he was at first opposed by the people, who had a poor opinion of “schoolbook learning,” but, in the end, their approval and co-operation were secured. In his tireless work for the people of Sutton, it may truly be said of Bompas, what Elbert Hubbard said of a great American reformer, “He gave his services as the night gives its dew, as the flower gives its perfume, as the sun gives its light.”

In 1862 Bompas moved to the parish of New Radford, Nottingham, his parishioners being chiefly engaged in the industry of curtain-making. For a short time he ministered to the parish of Alford, in Lincolnshire, where he enthused the people with the story of foreign missions. Indeed, this story had made so deep an impression upon himself, that he desired to go either to India or China, but the Church Missionary Society rejected him, believing a man of thirty too advanced in years to become proficient in an oriental language. Shortly afterward, the way opened for him to another field under the auspices of the very society that had rejected him.

It happened like this. Bishop Anderson of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land, speaking at St. Bride’s Church, London, in 1865, told in the course of his address, of an isolated station on the Yukon River in Canada, where Robert McDonald, the missionary in charge, was failing rapidly in health, and refused to leave his post until relieved by a substitute from England. William Bompas walked straight into the vestry and offered his services. It might seem he had little idea of the distance or the difficulties that were before him, and of the often perils. But, perhaps, he had too, for they were rovers—these Bompas fellows—one of them having crossed the Atlantic in the ship Fortune so long ago as 1623.

It was on July 1st, 1865, that Mr. Bompas left London for his journey of eight thousand miles, the greater part of which was through an untenanted wilderness. In less than a year he had reached Fort Simpson, on the Mackenzie River, where he stayed with William West Kirby, afterwards Archdeacon Kirby. Here word was received that McDonald, the missionary at Fort Yukon, had regained his health and required no substitute.

When Bompas reached the western plains of Canada he was told the Indians were on the warpath, and that he could go no farther. The plainsmen, seeing that he was still bent upon going, told him to take a British flag and, perhaps, the Indians would respect it. But there was no flag for sale, nor any to give away, so the missionary was obliged to make one. It was by no means an exact specimen of “the jack,” but it proved effective enough, for later, when the Indians encircled his party on the trail, and saw the flag, they wheeled their horses and rode away.

On this occasion the guide of the party was Dr. Schultz, a merchant of the Red River district, who afterwards became Sir John Schultz, Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba.

Bompas “travelled light.” His brother, Judge Bompas, declared that, “William decided to take nothing with him that would lead his thoughts to home and he gave away all his books and other tokens of remembrance, even the paragraph Bible he had always used.” Truly, this was a paring to the quick, for a clergyman’s paragraph Bible is almost equivalent in value to a woman’s wedding ring, or the compass of a sailor.

Two months later, at Portage La Loche, he found that the last boat of the year had left for the North. There would be no other until the following summer. So, hiring a canoe and a couple of French Crees, he pushed forward till he came to Fort Chipewyan, on Lake Athabasca. He was invited by the Hudson’s Bay Company’s factor to spend the winter there, but still the young curate decided to push on to the north.

The story of his terrific struggle through the northern rivers for sixty days, and of his overland journey with dog trains for another thirty days until, at length, he reached Fort Simpson on the Mackenzie River, is one of almost incredible heroism. With little food and no shelter, cutting their way through the ice with axes, drenched until their bodies became encased in frozen spray, Bompas and his half-breeds made a journey which, for hardships and speed, broke all records to that time.

It was Christmas morning when the intrepid traveller arrived at Simpson, and so the “Gentlemen Adventurers” of the Hudson’s Bay Company called him their Christmas-box. His sermon, too, was appropriate for the day: “Behold I bring you tidings of great joy which shall be to all people.”

By the following Easter, when he left Simpson for Fort Norman, farther north on the Mackenzie, he had become sufficiently versed in the native language to be able to address the Indians in their own tongue. Forty years later he had not only mastered the seven dialects of the country, but had published manuals, hymns, prayers and catechisms for the use of these people. He had also printed the gospels in Chipewyan, Slavi, and Tukudh. The Indians believed he had learned their language by “big medicine,” that is to say by magic.

The comments of Mr. Bompas concerning these languages show that, while a tireless student, he was no mere bag of books. He could sense the unique word or phrase which gave a glimpse into the minds of the Indians or Eskimos. Speaking of the language of the Athabasca Indians he says: “Sometimes, I think they were the first people that were made, because they call a finger ring ‘o’ and a star ‘sun’.” “Flour is known by the Tukudh Indians as ‘ashes from the end of heaven.’ Tobacco is ‘warmth and comfort,’ and a pipe ‘the comforting stone.’. . . A watch is called ‘the sun’s heart.’ A bat is known as ‘the leather wing’ because of its appearance.”

Besides the seven dialects of the North, William Bompas also studied the Bible in Greek, Hebrew and Syriac. Indeed, he translated a large portion of the Bible from the Syriac.

In the year 1880, the Bishop published a book in England, The Diocese of Mackenzie River, in order to raise funds for his missionary work. This volume contained much about the geography, resources, prospects, flora, fauna, dress and habits of the North.

Later he published Northern Lights on the Bible. It is a book of delights, in which unique features of the Arctic regions are used to illustrate passages in the Bible. A few of the striking things dealt with are “Mock Suns,” “Skins,” “the Aurora,” “Earth’s Bounds,” and “Gold.”

Everywhere, in these regions, he sees the hand of Providence at work. “It is a singular provision of nature,” he says, “that the fur of the polar bear is such that no snow can adhere to it, and a mitten of Polar bear skin is used by the Eskimos as a snow whisk to clear their deer-skins, or other furs, from the snow that may casually cling to them.”

The following year Bompas journeyed on to Fort McPherson, on the Delta of the Mackenzie River. Travelling still northward with two Eskimos, he studied their language that he might be able to instruct the people in the Christian religion. When, at length, he reached the Eskimo camps on the rim of the Arctic Ocean, he was suffering intensely from snow blindness. In one of his books he speaks of this incident, but does not relate it as a personal experience. “A traveller, starting to visit the Eskimo camps at the Arctic coast, toward spring, in company with an Eskimo boy, was overtaken on the way by snow-blindness. The man he was travelling with deserted him, but not so the boy who led him by the hand ’till, on the sixth day of his march, hauling a small sled of necessities, they reached the first Eskimo camp.” There can be little doubt that Bompas must have derived happiness from the devotion of the boy, with whom he could not converse, but yet who refused to desert him. Maybe, it was such a devotion Victor Hugo had in mind when he said, “To be blind and to be loved—What happiness!”

This was the first time Bompas had lived in a snow hut, which structure he later described as, “a white beehive about six feet across with the way a little larger than that for bees.” It was in these huts, or igloos, that he became acquainted with the language, habits, food and traditions of the Eskimos. There, too, he heard their snuffling, monotonous songs of five or six notes, always rendered in the same tune and time, and with a weird accompaniment of bladder drums.

But, on the whole, Bompas had little complaint to make. Writing, on one occasion, of these igloos he said: “A kind Creator adapts men’s homes to their tastes, and it would seem that few natives are so homesick when removed from their native land as the Eskimos.” In these places, with their long airless passages, there hangs what someone has described as “the odour of paganism.” However, they stand for home and shelter.

It is true that, in the winter, the people have little water and no soap, but then one’s skin may be cleansed by currying or scraping, and a mother may always wash her infant’s face by licking it with her tongue, just as a cat washes her kitten. Snow melted over a little lamp with a tiny wick is far too precious to be wasted in washing one’s face! In the summer, when the ice has passed out of the river, the family moves to a tent made of skins. Then, if not afraid of catching one’s death of cold, it is not at all unreasonable to wash one’s hands, and ears, and neck.

But in the winter the ice is everywhere. The bleak winds wail; the fishes are in the caves of the sea far under the ice. In the winter, the white bear is hidden in the snow and the wolves have denned in the rocks. In the winter, the land is dark. Everything is dark, except the lamp in these igloos or snow bubbles—the whale-oil lamp with its heart of fire. There is no doubt of it, this tiny blubber torch is the real sanctuary lamp of the North. It stands for light, warmth, food, and even for life itself.

When, at last, the spring had fairly come, Bompas travelled south with the Eskimos to Fort McPherson, where they did their annual trading with the Hudson’s Bay Company. They carried walrus tusks for ivory, leather, fish, and seal oil to barter with the Company in exchange for axes, kettles, tobacco, tea, ammunition and flour. On each of their flat-bottomed boats were the family, the dogs, a tent, sledges, harness, arrows, bird nets, fish nets, stone lamps, water pans, and the peltry of seal, and bear, and deer.

All might have been well on the journey southward had it not been for the unusual amount of ice encountered. The Eskimos attributed it to the baneful presence of the white man. Therefore they decided to take his life. Fortunately for Bompas, the Chief of the Eskimos had come to appreciate the missionary. So, during the night, he changed the purpose of his tribesmen, telling them how he had dreamed that the white men, at Fort McPherson, were waiting on the river bank to shoot them, because the young man with the ashy face was missing. By morning the angry looks of the Eskimos had entirely disappeared, and so the missionary’s life was saved. This incident seems to prove Carlyle’s comfortable doctrine, that there is always life for the living one!

From Fort McPherson Bompas travelled south in a canoe to Fort Vermilion, on the Peace River, in order that he might preach to the residents. The journey occupied sixteen weeks, and totalled a distance of 4,700 miles, including the curves of the waterways. Of the journey we have little account. Probably the missionary’s greatest inconvenience came from the mosquitoes and biting flies, which may frequently have reminded him that the word Beelzebub means literally “the Lord of Flies.”

Among his other duties at Fort Vermilion, Bompas vaccinated approximately five hundred Indians, as many as two thousand tribesmen having died from smallpox, at one post, on the previous summer.

The next seven years he continued his ministrations to the natives of the Athabasca District, after which he decided to travel on to Fort Yukon in order to teach the Indians there.

Because of this life of continuous travel, the missionary liked to describe himself as a “detached cruiser.” Indeed, as the Indians travelled almost constantly, it was necessary for their teacher to travel also. Presently we find him among the Tukudh Indians of the Yukon. These people, the nearest neighbours to the Eskimos, are commonly designated the Loucheux, or Squint-eyed, because their eyes resemble those of the Chinese. Long ago they were a proud and intelligent race, of formidable appearance—veritable “Cocks of the North.” Writing of these people he says: “The Tukudh language is spoken in its purity by only a few hundred families, and these located in the Arctic Circle, yet, it possesses forms of conjugation of its verbs at least as complicated as those of the Greeks, and in some respects more difficult.”

The following year Bompas visited the Upper Yukon, baptizing the Indians, some of whom had been Christians for nearly ten years. While here, he was summoned to England to be consecrated as Bishop of this diocese, the area of which was more than half as large as all Canada. In July, 1873, Bompas set out for the Old World. The following May, he was elevated to the Episcopate, the service of consecration taking place at Lambeth with the Archbishop of Canterbury officiating.

A few days later Bishop Bompas was married to Miss Charlotte Selina Cox, daughter of Joseph Cox, M.D., Montague Square, London. Within the week, the newly-wed couple set sail for Canada, it being fated that the Bishop was never again to return to his birth land. They arrived in September at Fort Simpson. Here the “Bishop’s Palace” was erected, and a school started for Indian children.

Visiting this place thirty-four years later, Agnes Deans Cameron said:

“There is something in the picture of this devoted man writing gospels in Slavi, printing in Dog Rib, and a prayer book in syllabic Chipewyan, which brings to mind the figure of Caxton bending his silvered head over the blocks of the first printing press in the old Almonry so many years before. . . . What were the ‘libraries’ in which this Arctic Apostle did his work? The floor of a scow on the Peace, a hole in the snow, a fetid corner of an Eskimo hut. His ‘Bishop’s Palace’ when he was not afloat, consisted of a bare room, twelve by eight, in which he studied, cooked, slept, and taught the Indians.”

That would seem excellent advice a Roman gave his country some centuries ago, “Avoid great things: under a mean roof one may outstrip kings, and the favourites of kings in this life.”

From Fort Simpson Bompas travelled out to the trading posts and encampments, which dotted his diocese of a million square miles. On his way along the Indians brought their sick to him, and, because of their irregular food and uncleanly habits, there were many to be healed. On one occasion the Bishop was called upon to amputate a man’s leg, which task he performed with success. Often the Eskimos became despondent and seemed to die without cause. Life would become heavier than death. What they called “the pain of sorrow” was in their hearts, and this required healing as well.

A few years later the Bishop and Mrs. Bompas adopted a little Indian girl, who had been deserted and left to perish by her father when he murdered her mother. Her Indian name was Owindia, that is to say, “the Weeping One.” The Eskimos believe a child cries at birth because it wants its name. Be this as it may, Owindia was baptized under the name of “Lucy May.” Later the child was sent to London to be educated, but, as one expressed it, “the wee red plant would not flourish in that soil and so she sickened and died.” It is related that the little northern girl, like other of her tribal folk, carried “a compass in the head,” or was possessed of what we call “the homing instinct.” Once, when lost in London, she made her way across the metropolis with unerring accuracy.

In St. David’s Cathedral, at Fort Simpson, a baptismal font was erected by Mrs. Bompas, and remains to the present. It bears the inscription: “In dear memory of Lucy May Owindia, baptized in this church, 1879.”

Owing to the rigorous climate, loneliness, and lack of proper diet, Mrs. Bompas fell seriously ill, in 1887, and was obliged to leave the Bishop and return to England.

It was in 1892 that husband and wife met again, and in the Yukon. The Diocese having been divided during her absence, the Bishop selected the northerly half for his field of labour. Here a new school was opened, and a more comfortable home provided for Mrs. Bompas. For the most part the Bishop did the carpentering; but alas! “the beautiful cupboards and shelves,” which Mrs. Bompas describes, had to be taken down to make coffins for the Indians. “The Indians,” writes Mr. H. A. Cody, “would also beg packing boxes from the Hudson’s Bay Company’s officers, and, as these were generally too small, arms and legs would often be seen hanging out of the box as it was lowered into the grave.”

About this time the gold miners flocked into the Yukon, and Dawson City sprang into existence, changing very materially the nature of the Bishop’s work. Writing of Mrs. Bompas, in 1903, Bishop Ridley of Caledonia said, “She is accomplished far beyond the standard one meets in London drawing-rooms.” One of her favourite pastimes was the study of Dante in the original. Oftentimes she may have read aloud The Divine Comedy, and, while her husband listened, perhaps he beheld her as his Beatrice. It may be, too, that he said of her even as Dante said:

“Here is a deity stronger than I

Whose coming shall rule over me.”

There existed a deep affection between these two. Years later, when Bishop Bompas had been laid to rest in the little cemetery at Carcross, Yukon Territory, his aged wife came back to Canada to spend the remainder of her days on the soil that also shrouded him. It is reported that she was obliged to steal secretly away from her friends in England because they would not agree to her leaving.

. . . Because of the crime that followed the influx of the gold miners into the Klondyke, Bishop Bompas urged the Federal Government that a detachment of the Royal North-West Mounted Police be sent for the preservation of peace and for the safety of the people. Even after the arrival of “the Mounted” serious fights took place and, on one occasion, the Bishop separated two Indians who slashed at each other with long sharp knives. It was only natural that the Red men, suddenly becoming rich, should imitate the white man in “language,” drunkenness, and irreligion generally.

With the arrival of the white man food became more plentiful, and famine no longer stared the people in the face. When the Bishop summoned his first Synod, in 1891, there had been a great scarcity of food. Some said that the steamboat, which came in that year, injured the fish; others declared it to be caused by the white folk bathing in the river.

Of his sufferings during these periods of scarcity William Bompas, “the Pine-tree Chief,” seldom spoke, and then usually with a sense of humour. In writing of these famines he said: “The Indians had to eat a great many beaver skins . . . imagine an English lady taking her supper off her muff. The gentleman now here with me supported his family for a while on bear-skins. Can you fancy giving a little girl, a year or two old, a piece of Grenadier’s cap, carefully singed, boiled and toasted? Mr. McAulay’s little girl has not yet recovered from the almost fatal sickness that resulted. This scarcity brings out the strange contrast between this country and others. Elsewhere money ‘answereth all things’ . . . yet, it would do us no good, as for digestion we must find it ‘hard cash’ indeed.”

Because of these famines the Bishop established a mission-farm at Dunvegan and another at Vermilion, the latter being in charge of Mr. Sheridan Lawrence. He also proposed to build a steam launch to supply the missions with produce, but this task was shortly afterwards assumed and carried out by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

There is much that might be written about the varied works of William Bompas in his forty years of service for the North, but always it may be said what his hand found to do, he did it with his might. Speaking of the fact that he, for the most part, had to work without a programme, Bompas says: “The work of a missionary is perhaps less systematic than of any other avocation. There is no textbook of a missionary’s duties, or of counsels for his direction and guidance besides the Scriptures. ‘Preach the gospel to every creature’ is the Divine word.”

His wife, in after years, wrote concerning her husband’s physical labours: “We believe that God’s servants have been given a premonition of the approach of death. The Bishop laid his plans some months ahead, and made necessary preparations for a winter down the river. He had always been remarkable for physical strength and energy. For his winter travelling he was always seen running with the jaunty pace of the northern tripper ahead of his sledge. He was ever ready to help the men hauling up a boat at some of the portages, or in pushing it down the bank into the river.

“Among our party it was always the Bishop who insisted on charging himself with the heaviest articles, and it was only within the last two years that he abstained from hauling water from the lake for the whole of our household.

“But symptoms of some diminution of strength and vigour in this strong man were beginning to show themselves. The eyes that had pored so long with imperfect light over the pages of Hebrew and Syriac, in which he so delighted, were failing and had to be strengthened with glasses stronger and yet stronger still. Since his last attack of scurvy he had lost all sense of smell or taste. . . . No one could be with the Bishop many hours without observing an expression of weariness and dejection in his countenance, which was as intense as it was pathetic. He was often heard whispering, ‘Courage, courage’.”

Whether or not Bishop Bompas adopted a programme, as one follows his labours in the northern hinterlands of Canada, and sees him working as translator, writer, teacher, doctor, voyageur, geologist or administrator, it gradually dawns upon the mind that “the romance of the north” is a term often used but seldom understood. The term is not properly applicable to the country itself, but to peerless men like William Carpenter Bompas, who have been romantic in spite of their setting.

At the age of seventy-two, while engaged in writing a sermon, the great and gentle prelate, with only a cry, and without a struggle, passed out and beyond to the ever-during exile of death. These words, sung by Horace, the Roman poet, are true of Bishop Bompas: “Him shall enduring fame bear on pinions that refuse to droop.”

|

A dialect spoken in Mesopotamia. It flourished as a literary language in the thirteenth century. |

|

A Greek thinker and friend of Socrates founded a School of Happiness, about 370 B.C., which taught that pleasure is the end of human life. |

Misspelled words and printer errors have been corrected. Where multiple spellings occur, majority use has been employed.

Punctuation has been maintained except where obvious printer errors occur.

A cover which is placed in the public domain was created for this ebook.

[The end of Bishop Bompas, by Emily Murphy]