* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: A Sturdy Young Canadian

Date of first publication: 1915

Author: Frederick Sadleir Brereton (1872-1957)

Illustrator: Charles M. Sheldon (1866-1928)

Date first posted: Sept 16, 2025

Date last updated: Sept 16, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20250912

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GEORGE AND HIS MATES SNOWED UP IN THE FREIGHT CABOOSE

By CAPTAIN BRERETON

With Wellington in Spain: A Story of the Peninsula. 6s.

Kidnapped by Moors: A Story of Morocco. 6s.

The Hero of Panama: A Tale of the Great Canal. 6s.

The Great Aeroplane: A Thrilling Tale of Adventure. 6s.

A Hero of Sedan: A Tale of the Franco-Prussian War. 6s.

How Canada was Won: A Tale of Wolfe and Quebec. 6s.

With Wolseley to Kumasi: The First Ashanti War. 6s.

Roger the Bold: A Tale of the Conquest of Mexico. 6s.

The Great Airship. 5s.

A Boy of the Dominion: A Tale of Canadian Immigration. 5s.

Under the Chinese Dragon: A Tale of Mongolia. 5s.

Indian and Scout: A Tale of the Gold Rush to California. 5s.

John Bargreave’s Gold: Adventure in the Caribbean. 5s.

Roughriders of the Pampas: Ranch Life in South America. 5s.

With Roberts to Candahar: Third Afghan War. 5s.

A Hero of Lucknow: A Tale of the Indian Mutiny. 5s.

Jones of the 64th: Battles of Assaye and Laswaree. 5s.

Tom Stapleton, the Boy Scout. 3s. 6d.

A Soldier of Japan: A Tale of the Russo-Japanese War. 3s. 6d.

With Shield and Assegai: A Tale of the Zulu War. 3s. 6d.

Under the Spangled Banner: The Spanish-American War. 3s. 6d.

With the Dyaks of Borneo: A Tale of the Head Hunters. 3s. 6d.

A Knight of St. John: A Tale of the Siege of Malta. 3s. 6d.

Foes of the Red Cockade: The French Revolution. 3s. 6d.

In the King’s Service: Cromwell’s Invasion of Ireland. 3s. 6d.

In the Grip of the Mullah: Adventure in Somaliland. 3s. 6d.

With Rifle and Bayonet: A Story of the Boer War. 3s. 6d.

One of the Fighting Scouts: Guerrilla Warfare in South Africa. 3s. 6d.

The Dragon of Pekin: A Story of the Boxer Revolt. 3s. 6d.

A Gallant Grenadier: A Story of the Crimean War. 3s. 6d.

LONDON: BLACKIE & SON, Ltd., 50 OLD BAILEY, E.C.

A Sturdy

Young Canadian

BY

CAPTAIN F. S. BRERETON

Author of “With Wellington in Spain”

“The Great Airship” “Kidnapped by Moors”

“The Hero of Panama” &c. &c.

Illustrated by Charles M. Sheldon

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

1915

| CONTENTS | |

| I. | George Instone’s Bad Luck |

| II. | Ike Lawley’s Hold-up |

| III. | Repairing Damages |

| IV. | Aboard a Locomotive |

| V. | A Record Snowstorm |

| VI. | In Great Difficulty |

| VII. | Winter Quarters |

| VIII. | Señor Enrico Gonvalezaro |

| IX. | Hike Entertains the Party |

| X. | Snowploughs in Action |

| XI. | The Shushanna Goldfields |

| XII. | A Capsized Freighter |

| XIII. | George Saves the Cargo |

| XIV. | Fritz, George, and Scotty |

| XV. | “Diamondfield” Bill |

| XVI. | The Sheriff’s Posse |

| XVII. | A Thorough Scoundrel |

| XVIII. | The Partners Prosper |

| XIX. | A Hazardous Calling |

| XX. | Run to Earth |

| XXI. | Simple Justice |

| Illustrations | |

| 1. | George and his Mates snowed up in the Freight Caboose |

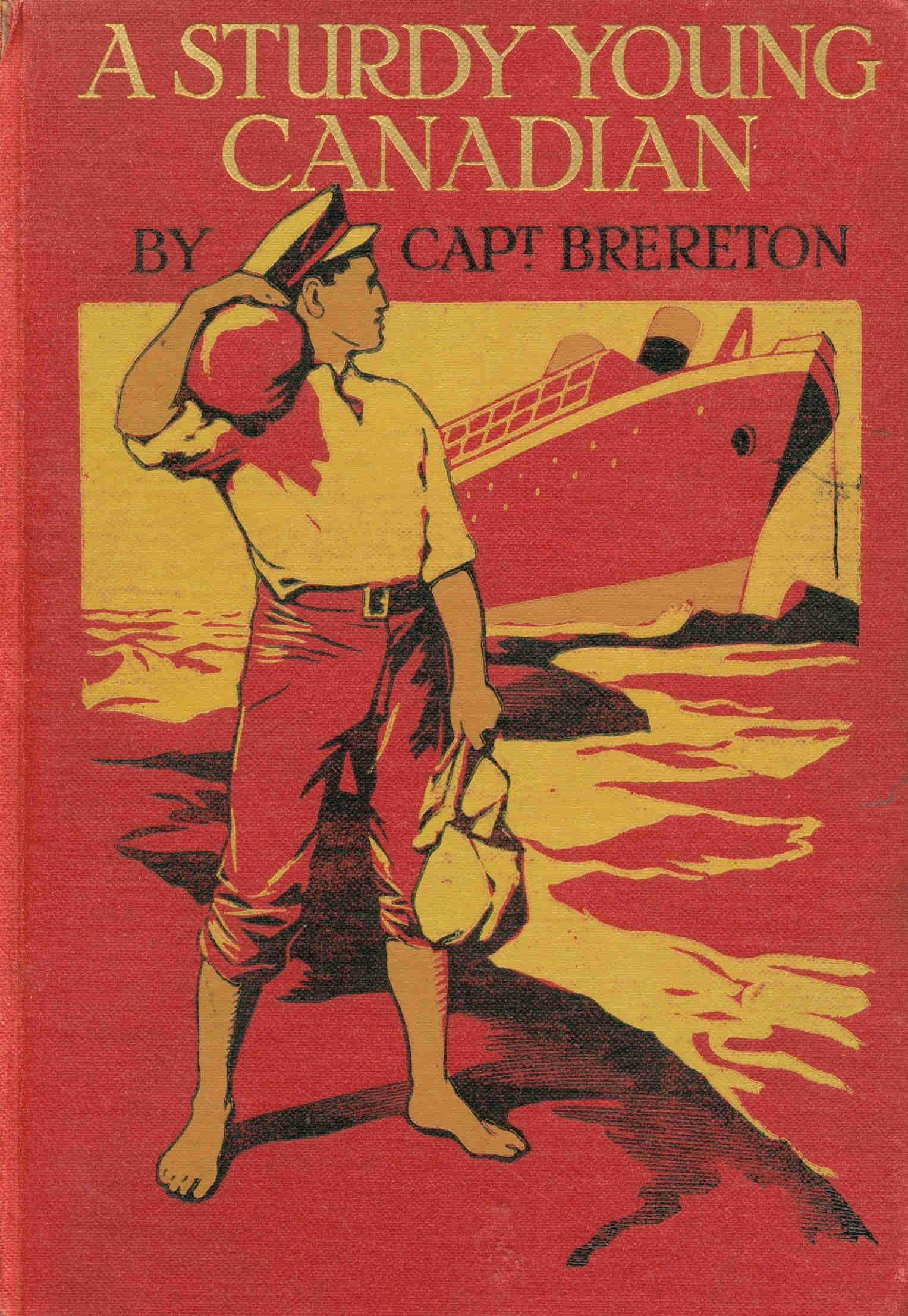

| 2. | George Instone is “held up”, but his Pluck brings him out on Top |

| 3. | “George realized that Tom had been shaken out of the window, and that he was alone on the runaway engine” |

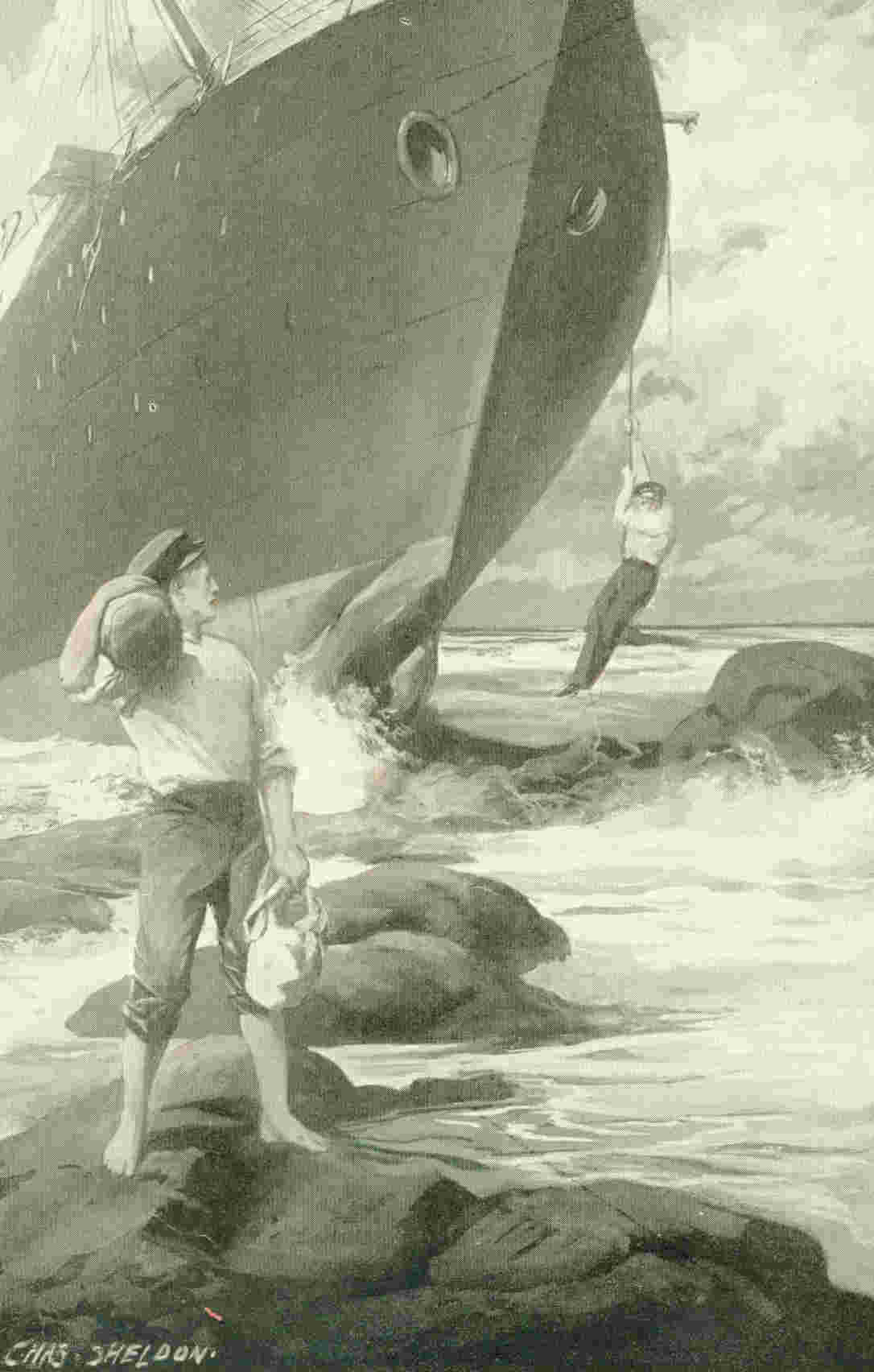

| 4. | George Instone and Scotty lower themselves from the Wrecked Vessel |

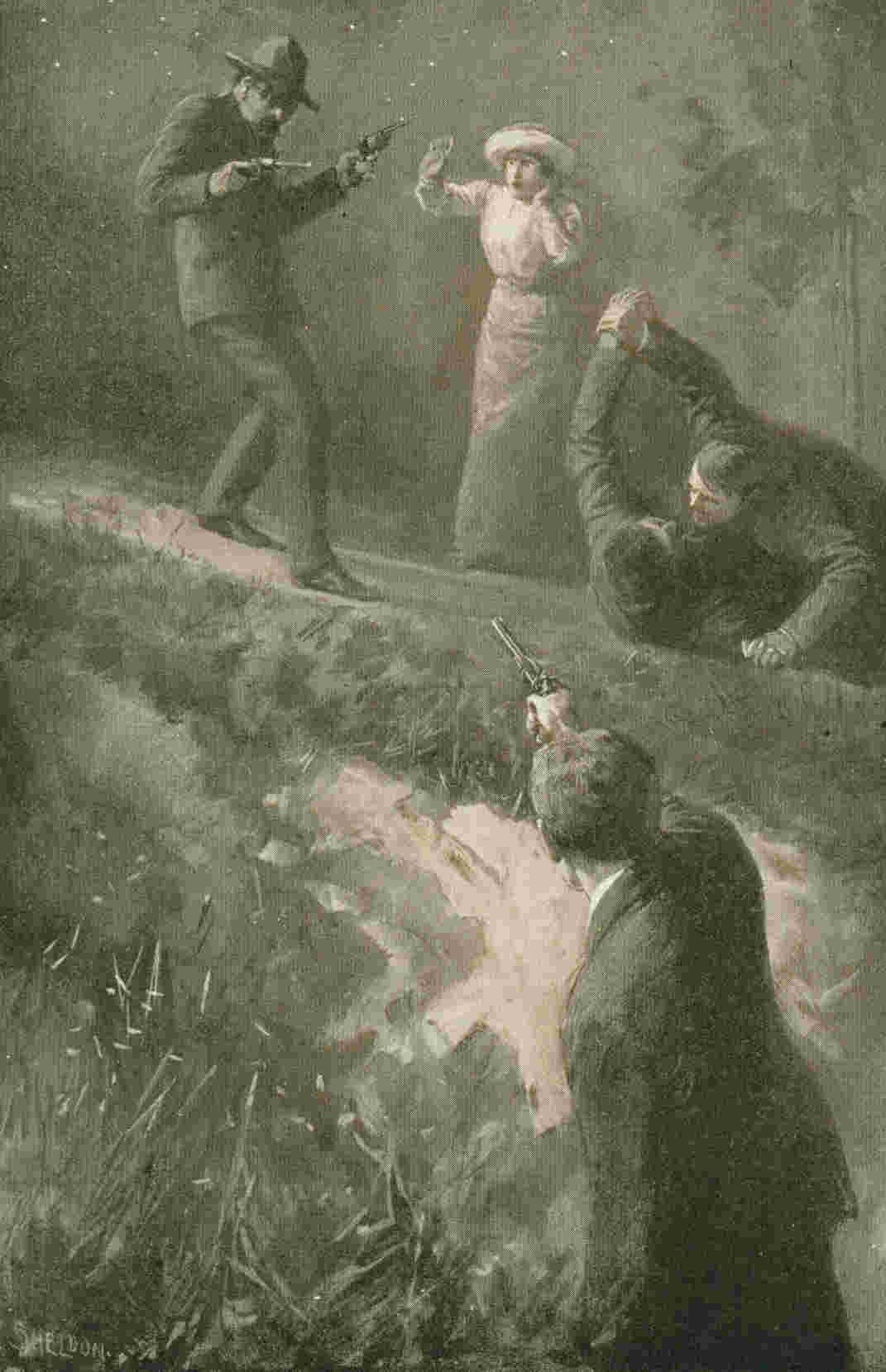

| 5. | George and Scotty hear the Robbers outside their Shack |

| 6. | George Instone explaining his Scheme for Sluices to work his Gold Claim |

A Sturdy Young Canadian

“Fact is, you can’t make a silk purse out o’ a sow’s ear, and that’s all there is to it, lad,” observed Carl Ossler, as he leaned against the doorpost of the shack (hut) and sucked at a pipe which had seen better days. “You can’t no more expect to take a city man, what was born and raised inside city limits, and make a success of him on the land than you can take a tarnation muskeg (swamp) and turn it slick away into wheat-raising land.”

“But—but it oughtn’t to have been muskeg,” said George somewhat dismally. “It was advertised as first-class land, as well-drained, fenced, and improved property, and Dad bought it as such.”

“In course; and I ain’t saying as he didn’t,” replied Carl, though there was an ugly frown on his face as he did so. He looked keenly at his youthful companion from beneath a pair of shaggy eyebrows, withdrew his pipe, inspected it critically and with some amount of affection. For Carl was an inveterate smoker, and carried about his person, whether on the farm or within the shack, an aroma of strong tobacco to which his wife had long since become resigned, but which other more delicate nostrils found at times somewhat overpowering. Then, as if to gain time, he sought for a match in the pocket of his somewhat tattered and frayed waistcoat, struck it on the seat of his trousers, and slowly sucked in the flame.

Carl Ossler was a queer-looking fellow. His name would have led you to the belief that he was a foreigner, and so he had been at one time, for Carl had, years before, cut himself adrift from his kith and kin, had wrenched up the many stakes which exist to tie every man to his homeland, and had become one of the mighty and ever-increasing army of immigrants who enter the Dominion of Canada. Tales of promise, of a free country, of free grants of land, of high wages and fine living, had attracted him, and he had set out. But that was years ago. In the process of time Carl had become a typical Canadian, a Westerner, and had also suffered many a disillusionment. Not that he had not found Canada filled with opportunities. He had discovered there the land of freedom indeed, the country where a poor man—a working man—is welcomed with widespread arms, and where social distinctions do not exist to keep him irrevocably chained down. Carl had, in a measure, made good, and was now the possessor of a fine property not far from Calgary, close up by the Rocky Mountains, with a house upon it which was infinitely superior to the shack which had first of all accommodated his family. In fact, though a working man when he first arrived in the Dominion, and still one too, as a person could easily see for himself by the simple process of inspecting his horny hands, Carl was, nevertheless, a man of some wealth and position, who could claim acquaintance with the best in the neighbourhood, and whose advice was sought by the most prominent people in that part of the country. But Carl had met with difficulties; he had run heavily up against snags, and more than once had with difficulty saved his barque from foundering.

For the rest, Carl was tall, and big, and bony. A little bent about the shoulders, clean-shaved every Saturday evening, and a scrubby individual when the week had gone round. He was dressed in a blue shirt which had seen better days, and which had sadly lost its colour. No collar nor tie troubled his sunburned neck, while his nether limbs were clad in a pair of corduroy breeches which had seen many a day’s work, and which had needed Mrs. Carl’s industrious needle on frequent occasions. A broad-brimmed hat sheltered a massive head covered thickly with fair-yellow curls, while a fine face, one which showed determination, acuteness, kindness, and consideration, was set off by a pair of excessively blue eyes which flinched at nothing.

“I ain’t saying as Mr. Instone didn’t buy it as good fenced land, land what’d been improved,” he repeated, when he had set his pipe going again to his satisfaction, though, to speak the truth, he was actually paying far more attention to the young fellow before him than to his beloved pipe. But then, in his own way, Carl was a diplomatist. Appearing to centre his interest on his pipe gave him an opportunity to watch, unobserved, the face of his companion. And George Instone was a young fellow who was quite worth inspection. For he, too, was a typical Canadian. Born and raised in Toronto, he was one of Canada’s big boys, or, rather, young men, for he was more than seventeen years of age, and wellnigh six feet in height. But he was no weed. Even the most critical could not call him that. He was broad shouldered and powerful, though a little fine drawn, for he had been growing fast. His trousers showed that, for they hardly reached his ankles, while his arms protruded quite a long way through the sleeves of his somewhat dilapidated jacket. Round his waist was a belt which was hardly more than half long enough for Carl, lean though he was, while the remainder of his equipment was completed by a black shirt, such as is worn by mechanics and engineers in Canada, by a cravat of the same hue, and by a squash hat which had had many a battering. But, as in the case of Carl, it was the face which attracted.

“He’s just the manliest, likeliest, good-lookingest young fellow around here,” Mrs. Carl had often remarked since the coming, a year ago, of the Instones. “That George’ll make a man, he will, and a fine one at that. Pity is his father’s so weak and ailing, for what with his ill health and the thing he’s bought for a farm, why, George’ll have the world up against him before many months have gone.”

George was manly, without shadow of doubt. Also he was possessed of quite tolerable looks. Not a hair as yet graced his lip or chin, but that was no disadvantage in a land where clean shaving is the rule rather than the exception. He was dark, was possessed of a somewhat prominent nose and forehead, and when he smiled displayed a set of white teeth which did credit to the country of his origin. And as a rule George was a smiling, happy, contented, and plucky fellow. Just now, however, the world was up against him, to use Mrs. Carl’s expression, and George was undoubtedly downcast. Not tearful, though. Young fellows of George’s age are not generally that, whatever the trouble. But he was despondent, and for the while at least his face had lost its smile. He, too, leaned against the wall of the shack, glancing now and again at Carl, but more often staring out across the broad acres which were his—his by right of descent from his father—broad acres of muskeg, useless for any sort of purpose.

“I kin understand the whole of the proposition,” said Carl at last, when he had sucked thoughtfully at his pipe for some few moments. “You’re hit hard, young fellow; but there’s this to console you. You ain’t the only one as has been taken in and swindled.”

“More’s the pity,” George interjected tartly. “Father was fooled as well as swindled.”

“Which only follows up what I was a-saying. You can’t make a farmer—speaking generally you’ll understand—out of a man that’s been born and raised in city limits. It’s clear up agin common sense. But, bless you, you can’t no more preach that and have folks believe than you can keep down them skunks that prey on the city feller. Them real-estate men are the curse of this country.”

So saying Carl sucked hard again at his pipe, and, finding the weed had gone out, beat the bowl irritably against his boot heel. He was in a bad temper; you could see that clearly. His forehead was seamed and furrowed, his eyebrows drawn down, and his mouth set firmly. Carl at that precise moment looked as if he would bite.

“They’re the curse of the country, them real-estate men,” he asserted angrily; “the cause of the downfall of many a poor fellow.”

“But—but surely they are not all alike?” George asked.

“All? Not by a long way. It’s the same with farmers, tinkers, tailors—any sort of fellers. There’s a sight of ’em as is real, honest, hard-working folks; but there’s others, too, as is scoundrels. And the real-estate bunch has got a whole crowd of wrong ’uns with ’em. It’s like this, George. This here’s a new country, and there’s thousands of acres to be had. Those acres can be had pretty nigh free in most cases, so as people can come out and take up a holding without paying out the little capital they’ve got. That lets ’em use what they’ve saved to work their land, and in time, when the acres begin to get under cultivation, and gets paying money to the settler, why, he can set by a bit to square the Government for his grant. What’s more, a newcomer, one, you understand, who has been long enough in the country to know something about it—for a man’s a fool to settle right down when he’s a stranger—a newcomer wanting a free grant can set to work and fix on his own location.”

“Then why is there need for the land agent?” asked George.

“Well, there’s folks who want to sell their land, and agents is wanted for that. But, when all’s said and done, there ain’t the need for the hosts of fellers as calls themselves real-estate men. And it’s like this all along the road. Land’s cheap in Canada, speaking generally. So men with a little capital invest in that land, and, since they mostly know the country, they buy where people are gathering, where a railway’s likely to come, or where a town’s about to spring up. Not that they always buy outright. They ain’t got the dollars. They pay so much down, and then set to work to advertise for buyers, calling their land the finest in the Dominion, first-class farm land if it’s outside a city’s limits, and first-class building land, even if it’s four or five mile outside a settlement that’s got no more than a couple of thousand inhabitants. That place’ll be a city in their advertisements, and the chaps who buy believe, often enough, that they’re buying something that’s bound to increase rapidly in value. That is when they buy without seein’, and that’s often enough the case.”

“Like Father,” observed George. “He heard of this farm when in Toronto, and bought. It was too far to run over and see it.”

“Sure. Two thousand miles if it’s an inch, and a costly journey at that. So he got swindled. The rascal as called this a farm ought to ha’ been tomahawked,” declared Carl, with some feeling. “But there ain’t no getting after him. He’s gone, after swindling and ruining a whole bunch of simple fellers. The thing is this: What are you going to do now? What move are you figuring?”

George took a long look round at his possessions—some forty acres of useless muskeg—and forbore to reply to Carl. For at the moment he had no plans. One could hardly blame him either, though starvation almost stared him in the face. For he had gone through an exceedingly troublesome time. As the reader will have gathered, Mr. Instone had been swindled, a common enough proceeding in the Dominion in connection with the purchase of land. Possessed of some means, for he had saved steadily, he had decided to throw up his position in Toronto and come west, for he was assured that thereby his health would be benefited. And George recollected with bitterness their good spirits when leaving Toronto. Then had come the awakening. Their high hopes, their plans for the future, had been shattered by the discovery that the forty acres bought in Toronto—forty acres of land said to be fenced and drained and in full bearing—were composed of swamp and rock and sedges almost without exception. Indeed, the shack, described by the rascally land agent as a commodious and modern dwelling, occupied almost the only dry and firm spot on the holding. Then had followed the downfall. Efforts to bring the swindler to book had failed, as they almost invariably do. Then Mr. Instone’s health had broken down entirely. But for a year George had stood by him, working on Carl’s neighbouring farm and earning their sole means of sustenance. Now it was over. The late owner of the swamp lay in his narrow grave, his troubles ended for ever. George had to think of the future.

“Well, you ain’t answered,” said Carl, sucking by force of habit at his empty pipe, and scowling because the soothing smoke was not to be coaxed from it. “I kin see as it’s a conundrum in a way, ’cos you ain’t meant for sitting down. You’re one o’ the go-aheads, George, and you’ll be figuring to get clear away from this here ranch and farm and try your luck elsewhere. Well, I ain’t saying as that isn’t wise. A young feller has to carve his own way in the world, and he ain’t as likely to do it quick ’way out in the country as he will in the towns. There’s hardships he kin put up with as don’t come pleasant to a man o’ my age, and he jest makes light of difficulties and misfortunes. So I’m kinder expecting as you’ll hike it off to some o’ the cities. But you ain’t got no call to do so. You kin stay right on here, and sence you’re a good lad, and has learned a deal of things, why, you kin ask fer forty dollars a month besides yer lodging and keep.”

“You’d be offended if I declined?” asked George, for Carl was a good friend, and he feared to hurt his feelings.

“Offended ’cos a young feller has got the grit and push to strike out for hisself! Here!” called Carl gruffly.

“Sorry. But I wouldn’t do that for anything.”

“And ain’t likely to do so neither. I’ll say right here what I’d do ef I was in your shoes,” said Carl, stepping away from the shack and surveying the surroundings. Indeed, he looked so long and so intently at those forty acres of miserable swamp that George’s thoughts returned promptly to the scoundrel who had swindled his father so outrageously.

“You’d follow that man up?” he asked, astonished, for had not Mr. Instone lost the last of his savings in a similar attempt?

“I’d be right down crazy,” asserted Carl vehemently. “Jest leave him out altogether, boy. Get him outer yer head right now at this instant, ’cos he ain’t never likely to be useful to you. I don’t say as you mayn’t, one o’ these days, drop across him, for though Canady’s big, men hits up agin one another most unexpectedly. Ef you do, don’t holler. Jest fix tight onter him and see as he don’t get outer sight till he’s paid up handsome. It ain’t likely, I say, but ef it happens, why, you’ve got the papers, and you remember the feller.”

“Well,” said George bitterly. “A smooth-spoken, jovial individual.”

“They mostly is,” observed Carl dryly. “Fine clothes that’s cost wellnigh thirty dollars, a clean collar, and a tie to make ’em handsome, and hot air (talk)—my! you can’t jest get in a word edgeways. Their holdings is mostly hot air too, though they keeps a few good things for clients as insists on investigating. But jest you drop him from this moment and get down to business. Now you was asking whether I’d be offended if you was to quit the farm.”

“And you were going to tell me what you’d do under the same circumstances,” said George, nodding.

“Then I’d quit, I would, right now, and look for a job in a busier part, where there was more things doing.”

“But—but how?” asked George, rather dismally. This, in fact, was the very question which most troubled him.

“How? It ain’t hard. You kin find a job.”

“When I get to it. But I’m here, out in the country, and I’ve not a cent,” said George desperately. “See here. Empty! I paid the last away for the funeral.”

He dragged at the pockets of his trousers, turning them inside out, and then repeated the process with the pockets in his other garments. “Dead broke,” he said bitterly, “like the poor old father.”

“Fine!” declared Carl, much to his astonishment. “See here, boy, you ain’t got nothing to lose now, save yer good name. But you’ve got everything to make, and one o’ these fine days, when the clouds has lifted, you’ll be able to turn round and say: ‘I made this here out of nothing, nothing but the fine health and strength which the good God gave me, and hard work and determination.’ When you’ve made good, George, you’ll be prouder for the fact that this day’s seen you with empty pockets. Now, I’ll tell you. You’ll want a job, and you ain’t got a cent right now. Then you kin put in a week’s work on the farm, and so earn ten dollars. By then I’ll have set to and made enquiries. You’ll make west, eh? That’s where things is moving. The Pacific coast’s the place fer young fellers.”

George lapsed into silence for the next few seconds, and again took to viewing his useless property. Young though he was he could see that there was common sense in what Carl had said, for in the country, without capital with which to buy a holding, and with the very limited experience of farming which he then possessed, he could not expect to advance his fortunes very rapidly. At the most he might earn some fifty dollars (ten pounds) a month—not a great wage as things are in Canada—and it would take years to save an adequate sum with which to start a business of his own. But in a city, where pay was higher and where there would undoubtedly be greater opportunities, he might do far better for himself. In any case he could not be poorer. His empty pockets were strong evidence of that fact, while, as Carl had said so truthfully, if he made good—and George was fully determined that if hard work and honest dealing would help, as undoubtedly they would, he would certainly make a success of his life—then he would have the happiness of turning round one day and congratulating himself on the fact that he had virtually started as a pauper, and had made his way simply by his own strength and determination.

“I’ll do it!” he exclaimed.

“What? Work here for me, lad? I’d be glad. Or make west to the Pacific coast?”

“Make west, Carl. But I’ll have to work more than a week to earn the transport money. When I’ve got that, and a little in hand, then I’ll set out.”

“Then the first thing to do is to sell off what there is in the shack, and the few tools outside,” said the practical Carl. “See here, George, I’ll take the tools, and I dare say the missus’ll want some of the things inside. We’ll get Mike Davis to value the things. He’s due out on the farm to-morrow or next day, and seeing that he’s an auctioneer, why, he’ll be able to do what we wants. Then I’d hand over the rest of the things to him, and let him run them into Calgary on his rig (cart) and sell ’em. They’ll fetch a better price in the city, and the money you get’ll be a little nest-egg with which to set out. Say now, how’s that?”

“Fine. And I’ll do it.”

Now that George was face to face with the future, and had had the opportunity of discussing it with such a wise head as Carl, he felt infinitely better and happier. The old smile returned to his face very soon, and that very evening, when, having accompanied Carl back to his house, he entered the parlour, Mrs. Ossler held up her hands in amazement.

“What have you been a-doin’ with the lad, Carl?” she called out gaily, shaking George’s hand warmly. “Glad you’ve come, George; but what’s this man o’ mine been a-sayin’? Why, I declare, if you ain’t smilin’ all over yer face, and looking better’n I ever saw. Welcome, lad; and sence you’ve come along to work, jest get in right now as chore boy (general work). There’s coals wanted for the kitchen stove, and chips’ll come in handy by early mornin’. Time was when I did most of them things; but a body’s gettin’ old these days, and it’s good to have a lively young feller around to lend a help.”

Mrs. Ossler was just a type of the Canadian woman to be met with the length and breadth of the Dominion. Very womanly, proud of her house, her husband, and children, she was a marvel at management, for there are few servants in Canada. The entire household work of a house has to be done by the wife, and she is busy and about from early dawn, cooking for the family and often enough for the hands on the ranch or farm, cleaning the rooms, and tidying up, besides seeing to the clothing of the children. Not that she does not receive help. There is scarce a house in the Dominion where the man does not see to the fires, and if the wife is up at dawn, then the husband or one of the boys is about before the light has come, getting the stoves going, cutting wood, and drawing water where necessary. That now became George’s work, and being accustomed to it, for he had done that and everything besides at the shack, even to cooking, he made light of it. In addition he had his work on the farm, and no sooner were the fires going than there was milking to be done. Then, when the milk had been carried to the dairy and poured into the refrigerator, George made his way in to breakfast. And what a meal he could eat! for the sharp morning air on the foothills of the Rocky Mountains gave him a tremendous appetite. Cups of steaming coffee disappeared rapidly, while each one of the hands—of whom there were four—tackled an enormous plate of mush (porridge). After that Mrs. Carl always had a dish of bacon or of meat for the men, and sometimes, too, a dish of trout caught by her husband that same morning in the stream which bubbled down through the centre of the farm.

See George, then, content after breakfast, issue forth for further work, dressed in the customary suit of overalls adopted by workmen up and down the Dominion. Perhaps there was carting to be done, perhaps Carl gave orders for some ploughing, while on occasion there were fences to be mended, or the huge stacks of hay to be cut and bundled and pressed ready for transport to the railway.

“And you may jest as well take ’em in, lad,” said Carl, when more than a week had passed since George came back to the farm. “You had better put Pat and Sassy Sue in the cart, ’cos they always runs well together, and don’t ferget to take yer beddin’. A gun (revolver), too, ain’t a bad thing to lift along with you, ’cos there’s bad men about these hills, and hold-ups (robberies) ain’t altogether unknown—not as they’re common. In the fust place, the farm is so out o’ the way that precious few hoboes (tramps) comes this way; and then what travellers there are ain’t always rolling in wealth. Still, there has been hold-ups, so you look lively, and hike off with that gun that’s hanging in the parlour. Don’t ferget that you’ve to call on the auctioneer and draw your dollars, and keep your tongue quiet about it.”

“I’ll take a look round for a job too, Carl,” said George. “There may be something suitable to be had, and it’d be foolish to waste the opportunity a visit to Calgary is likely to give.”

It was a crisp, early morning when George set out for his destination. Pat and Sassy Sue, the two draught horses usually employed for haulage purposes, were hitched to the four-wheeler farm cart, and from the first streak of dawn George and one of the hands had been busy swinging bales of hay on to it till they were piled high in the air. Then the roll of bedding, which no Canadian goes without on such a journey, was tossed up on to the front, and, with a crack of his whip and a shout of farewell to the Osslers, George set the horses in motion. And though he kept very wideawake throughout the day, for this was almost his first experience of transporting goods to Calgary, and he felt the responsibility, not a single suspicious person did he see. At noon he pulled his horses up outside a roadside shack, watered the beasts, and gave them a feed, while he himself entered the shack to ask for a meal.

“In course, stranger,” was his greeting. “Sit right down. You’ve come handy at the right moment, for we was ready ourselves. You’ll be from Carl Ossler’s farm?”

“Yes,” admitted George, taking his seat, for such is the custom, wayfarers of George’s class being always welcome to a meal and even to a night’s rest. “I’m taking hay into the railway depot.”

“And you’ll be young George Instone, I’ll bet, son of the one as was swindled?”

George nodded. It did not surprise him to discover that he was known, for in such small communities there are few matters which do not soon become public property, however scattered the homesteads may be.

“Then it ain’t no use fer me to tell you what I think of them thieves of real-estate men,” grunted the farmer. “You’ve been bit. So was I. There’s a sight of men about as has paid dear for stuff that those ruffians sold, stuff that wasn’t worth buying; and there’s a sight of people away out of Canady as ain’t got no more satisfaction for their money than a piece of paper. Their block of land ain’t of no use whatever.”

It was late in the evening when George drove his team into Calgary, and, remembering the instructions which Carl had given him, made direct for the freight yard of the railway. Pulling in alongside the freight cars, which stood empty in a siding, he asked an employee which one was reserved for the hay he had brought. Then he unhitched Pat and Sassy Sue, and, taking them over to an open shed, tied them up there, watering and feeding them promptly. Later on he groomed them, and covered them with blankets, for the nights were getting cold. It was nine in the evening when he himself obtained a meal at a little café frequented by railway men. Then, as he needed exercise, he went for a sharp walk through the city, and, turning north, was soon clambering the heights which overlook the business portions of Calgary, where the houses of the richer inhabitants are situated. It was perhaps half an hour later, when returning down the hill, that George was suddenly startled by an individual who sprang from a hollow beside the road and accosted him abruptly:

“Hands up!” he heard. “If yer move I’ll put daylight through yer. Hands up! Now, where’s your stuff? I want every penny of it.”

That hold-up of which Carl had spoken had come, come most unexpectedly, and right in the heart of the city. George found himself facing a masked individual who looked wonderfully forbidding and burly beneath the rays flung by an electric arc lamp dangling a great distance away, and, worse than all, discovered that a plated revolver was grinning directly at him.

“Hands up!” the ruffian repeated. “No hankey. There ain’t no time fer delay in this matter.”

As George Instone looked into the grinning mouth of that plated revolver which was held presented at him, and from the muzzle to the masked face of the ruffian who had accosted him in the dark street in Calgary, consternation at first took hold of him. And then, so rapidly do our thoughts chase through our minds, and so swiftly is the human being capable of forming plans and resolutions, he found himself with hands stretched over his head, apparently yielding to the superior force of this rascal, yet restraining himself with an effort from suddenly launching himself at the robber.

“Why not?” he asked himself. “He’s no bigger than I am, and one leap will get me close to him. I could knock his weapon up, and then——”

“Turn round!” commanded the man. “What’s yer work? Where’s yer dollars?”

George turned. To have resolutions is one thing, to carry them out beneath the grinning muzzle of a loaded revolver another, altogether and entirely another. For George knew, as others know in the Dominion, that footpads and robbers are not possessed of over nice feelings. Out there they are usually desperate men—many of them with a long score of misdeeds already to answer for, and with life sentences awaiting them. In any case they have a particularly evil reputation, and shoot on the smallest provocation. So it is not to be wondered at that George turned.

“I’m a farm hand,” he said.

“Ah! Been selling stuff down at the yard?”

“No. I only reached in to-night.”

“Where’s yer dollars?”

“I’ve five dollars on me, that’s all. It’s in my purse, in the right-hand hip pocket.”

He felt the muzzle of the revolver touch his neck, and its cold chill sent a shiver down his spine. Then the man’s fingers groped at his pocket, and he felt his purse being dragged out into the open.

“You kin hop right now,” said the robber. “You was going down to the depot. Then cut, and don’t you look back, my son, or I’ll send a bullet after you. And mind this, git right off to yer bed, and don’t stand talking to the cops and other fellers. Hear that? Then git! Ike Lawley ain’t the feller to play with.”

George at once faced down the hill, and strode away rapidly. Nor did he venture to look behind him. A glance round would certainly have brought a bullet, and he had sense enough to know that that bullet would strike him.

“It’s Ike Lawley, the desperado,” he told himself, hardly repressing a shiver. “The fellow who has infested the cities this side of the Rockies for the past six months. The ruffian who is wanted for three cold-blooded murders. And he’s got my dollars.”

That stung. George was a careful fellow, for his had been a life of struggle just recently, and dollars meant much to him. What right had Ike to relieve him of them?

“None; and I’m not going to hike right off and leave him with them,” said George stubbornly. “Why did he order me to make direct back to the depot and not get talking? Simply because he means to hold up others. That’s it. My five dollars are nothing to him. He’ll wait for someone else, and as the spot he chose is good—for I didn’t see him till he jumped out of the ditch—why, he’ll be waiting there certain.”

George was not the lad to let the grass grow once he had come to a decision, and no sooner had he reached the foot of the hill, and judged himself to be beyond Ike’s view, for the electric lights were spread far apart, than he took to his heels and raced along till he reached the car line. The ding-dong of a tramcar bell reached his ear, and running again he reached the stopping-point just in time to leap upon the vehicle. It sped on into the city, so that within a few minutes he was back at the depot.

“With just ten cents left to pay for my car fare out again and home,” he told himself, fumbling in his pocket. “Lucky I had a few loose coins in another pocket. Now for the gun which Carl loaned me.”

It was somewhat big and antiquated, and had been honest Carl’s companion for many a year. Not that such a weapon is necessary throughout the Dominion, for the country has become wonderfully settled. Still, out in the open some weapon of defence may be advisable at times, while weapons are habitually carried during the night by railway servants engaged in freight yards and depots.

George strapped the weapon round his waist, pulled the brim of his slouch hat down over his eyes, and turned his coat collar upward. That was all the disguise he could think of in case of his suddenly being accosted by the ruffianly Ike Lawley.

“Got to chance it,” he thought. “If he’s moved down the hill he’ll jump out again just as unexpectedly. Well, I’ll give him the revolver instead of dollars. Now for a car back to the place I came from.”

For a moment he wondered whether he ought to apply to the police, and had he met an officer on his way to the car line he would undoubtedly have given immediate information. But there did not happen to be a single person about, while delay was obviously a thing to be avoided. George reached the car line, signalled for the vehicle to stop, and leaped on.

“Going home, sonny?” asked the motorman, a lively fellow.

“Yes,” said George, fibbing for the moment.

“Where do you live then? Up west?”

George nodded. Then, so that he should not be asked more awkward questions, he promptly dived into the body of the vehicle and mingled with the passengers. It was some ten minutes later when he commenced to clamber up the hill to the spot where he had been accosted.

“Three hundred yards farther up, I guess,” he told himself, “and just to the right of the sidewalk. That fellow was hiding in a ditch, and as this is on a hill it is likely enough that the ditch runs clear down to the bottom. Good! I’ll leave the path and enter.”

He was on the point of slipping into it when he observed two figures on the sidewalk in advance of him. They had just come down a side street and turned up the hill.

“Likely victims,” thought George. “I’ll hurry.”

He dived into the ditch promptly, finding that it was almost dry. Perhaps a little water had descended during the day, and as it happened that this part of the city of Calgary was not yet paved, save for its sidewalks, the bottom of the ditch was covered with soft earth, and not cemented, as, no doubt, would be the case later on as this part developed. It was therefore quite silently that he clambered up the hill, his feet not making the smallest noise as he went. He had occasion, too, to congratulate himself on this fact a little later, for he had scrambled over only a few yards when he heard a sharp command and then the crack of a revolver.

“Ike,” he thought, while his pulses suddenly thudded and his heart beat against his ribs. George had hardly ever experienced such excitement before. True, the meeting he had already had with Ike had not been too pleasant—and we wish to portray our hero in the truest of colours, and to do so must mention the fact that George did not find that meeting altogether to his liking. To commence with, there was that uncanny feeling produced by the plated muzzle of the revolver when thrust in his face. Then the top of his scalp was decidedly interested in the matter. It was positively sore now, and George had the distinct impression that, had his head been bare and the light a strong one, Ike would have been entertained by the vision of his, George’s, hair rising. What wonder, too? The robber had pounced upon him quite unawares, and his manner had been so threatening. However, George’s sensations now were decidedly different. This was pure excitement from which he was suffering, though very inconvenient. His breath came in gasps, which he vainly struggled to silence, while it made scrambling along the ditch difficult. Then his heart thumped so heavily against his ribs that it positively shook him. With an effort he forced himself to be calmer. Then, racing on till he judged he had gone far enough, he lifted his head cautiously above the edge of the ditch.

Phew! So that was the situation! Ike was not the only ruffian abroad in Calgary that evening. He had a friend, an accomplice, who, no doubt, had hidden himself in the ditch also. And fortune had favoured the two rascals, for they had held up two sets of people. There were the two whom George had seen walking in advance, and three others who had been coming in the opposite direction. It was from one of these, too, that Ike and his rascally companion had met with opposition, for a man lay stretched out on the sidewalk near his companions, his head downhill, and his legs mingled with the feet of the others. George lifted his head cautiously, his revolver gripped in his right hand, and his left on the edge of the ditch. And very rapidly he took in the whole situation. Ike stood with his back to him, swinging slowly from side to side, his elbows tucked into his body, and his two hands gripping revolvers. Directly in front of him were the lady and gentleman who had been ascending the hill, the former supported on one arm of her companion, and obviously on the point of tumbling, while the man himself held his free arm over his head. A little higher was the prostrate figure of the one who had been shot, with two burly men standing over him, their hands in both cases being elevated. As for Ike’s accomplice, the rogue had tucked his own weapon into the pocket at his hip, and was carefully going through the clothes of his victims. George took steady aim at Ike.

“Can’t do it,” he told himself, with a feeling of dismay. “He’s a rascal; but I can’t shoot a man in the back in cold blood. I’ll have to shout or do something.”

“Out with it, me livelies, out with dollars and everything. It ain’t no use to hide ’em up,” Ike’s companion began cheerily, addressing the two men he was then searching, “ ’cos we ain’t likely to miss nothing, and ructions’ll sure bring trouble. Ho, ho! This here’s one of the city bosses. Ike, this here’s Andrew Shere, storekeeper, hotel owner, boss of the moving pictures. What’s this? A roll of ’em, Ike! A whole roll of bills, and twentys, every one of ’em!”

Not a word came from the unhappy victims of these two footpads, though the lady was now sobbing. It made George grind his teeth.

“Got to do something,” he told himself desperately. “But, supposing there’s shooting, that lady might be injured. I know. I’ll hold ’em up myself. Wait till they’ve gone through the pockets of these people, and then make after them.”

But Ike and his friend were in no hurry. They had chosen an excellent site for this attempt, and knew it to be almost deserted at this hour of night. Police patrols were few and far between, while the steepness of the hill kept people from promenading in that direction. But there were always people visiting friends in that part of the city, and seeing that all the best houses were there, and the most prosperous individuals lived in them, why, the citizens they might accost when returning from some convivial little evening would probably be birds who were worth plucking.

“Stripped him as clean as ever he stripped one o’ the jays he’s sold stuff to in the city,” chuckled Ike’s companion, when he had finished going through the pockets of Andrew Shere. “Taken five hundred and forty cool dollars from him, a pin that was in his tie, and that’s pure diamond or I’m a Dutchman, and a ring with a stone in it big enough for the foundations of one of his hotels. Say, Ike, this is a haul! We’ve struck it rich with a vengeance.”

“Get in at it,” growled the other, swinging still, and turning his weapons now on one of the groups and then on the other. “You ain’t got no call to drop that right arm, sir. One’s enough to support the lady, ain’t it? Then keep the other up or I’ll drop you and her, so that’s all there is to it.”

“Ho, ho!” came again from his accomplice, and this time his tones were even more joyful. “Why, bless us, it we didn’t come out on jest the right sort of evening. This here’s John Hill, railway boss, the chap who’s come away west to inspect the far side of the Rockies. I seed in the papers that he was coming. Now you ain’t got no call to get fidgety, John Hill. This here’s the pocket in which you carry dollars in bill form, and—why—here’s a shooter!”

He brought it out from the hip pocket of the second victim, inspected the weapon without the smallest trace of hurry, and transferred it to his own pocket. Then, rapidly completing his search, he stepped downhill to the gentleman and lady.

“Been through the pockets of the man he’s shot,” thought George. “Wonder whether he’ll be brute enough to search the lady.”

In his eagerness he raised his head rather high above the edge of the ditch, and in moving his left hand along it set a stone rolling. Instantly Ike turned round, and though George ducked swiftly it was evident that the ruffian’s suspicions were aroused.

“Joe,” he called sharply, “see if there’s anyone in the ditch behind. I’ll cover these fellers. If it’s a cop, shoot straight off. You don’t need to ask any fancy questions.”

George crouched low in the ditch, the brim of his hat pulled well over his face, and his hands hidden. But the one gripping the revolver pointed that weapon upward, the muzzle just protruding from beneath the flap of his coat.

“Mayn’t see me,” he thought. “It’s dark in here, and with face and hands covered I may escape. If not, I’ll shoot. Ah! He’s looking down.”

It was an extremely uncomfortable position for George, and we tell the truth when we say that he found it difficult to decide whether to remain as he was or to chance everything by suddenly leaping from the ditch. There was the fear, too—an awkward feeling—that the rascal staring into the depths of the ditch might fire downward just to save himself the trouble of clambering into it. And, as it happened, that was his intention.

“Don’t see a thing. Guess it’s empty,” he grumbled, stuffing the rolls of bills he had just filched from the pockets of his last victim into a capacious sack carried beneath his coat. “But there ain’t nothing like making sartin, and sence it’ll only cost a bullet, and there’s bills here to pay for heaps more of ’em—why——”

“Hold! Guess you’d better quit firing,” said Ike, sharply. “There’s been one shot already, and you can never say as a patrolman ain’t heard it. If he has, he’ll fetch another cop, ’cos they ain’t fond of meeting Ike Lawley when by their selves, and that’d just fix us. Get finished with the search, Joe. Then we can get a move on.”

They were really the coolest of ruffians, and evidently accustomed to such proceedings. For Ike never altered his position, save for the time when he had swung round suddenly. He still covered the two groups of Calgary citizens, sweeping his two weapons round first upon one and then upon the other, using the muzzles indeed as if they were the nozzles of a couple of hoses, and he directing water first in one and then in the other direction. As for Joe, he was a short, lightly-built rascal, and pocketing the weapon with which he had been about to probe the depths of the ditch, he leaped back on to the sidewalk, and again approached the lady and gentleman.

“Plucked as clean as a chicken,” he grinned, running his hands through the pockets of the latter. “He ain’t never been poorer. Now, ma’am, we comes to you. Rings fust, I’m thinking.”

He seized the hand of the lady roughly, and endeavoured to tear off her gloves. And then it was that the struggle which George had been anticipating commenced with a vengeance. For the gentleman suddenly let go of his burden, and, springing at the rascal Joe, gripped him by the collar. At once the two became locked together and went staggering across the sidewalk, edging downhill as they struggled. It was obvious, too, that Joe was likely to have the worst of the argument, for he was small, as we have said, and his opponent larger. He lifted Joe as if he were a boy, and swung him from side to side. Then he brought him down with a bump, the robber’s rubber-covered shoes thudding heavily against the sidewalk. As for Ike, probably he had never faced a similar situation. For his weapons were useless. He could not fire at Joe’s antagonist for fear of hitting his own friend; while he dared not remove his weapons from the two men standing a little higher up the hill, those who had already been relieved of their valuables. He edged a little downhill, his eyes fixed on the men above, but darting sudden glances over his shoulder.

“Jest let me see one o’ you wink as much as an eye, and, bosses or no bosses, I’ll drill yer,” he growled.

GEORGE INSTONE IS “HELD UP”, BUT HIS PLUCK BRINGS HIM OUT ON TOP

“Hold him, Joe. Give him a shake, and get a grip of yer shooter. I’ve got these here chaps, and you ain’t got no call to fear anyone else.”

But there was George, and our hero had no intention of looking on only. He had his own five dollars to recover and a duty also to perform. The knowledge that earlier action would have been rashness, and would have seen him shot like a rabbit, had alone kept him crouching at the bottom of the ditch. But he was never more determined to bring Ike to justice, and now seemed to be the opportunity. With a bound he leaped out of the ditch on to the sidewalk. Then, just as Ike heard him and swung round with his weapons, George gave him a terrific buffet. His left fist flew out, and, striking Ike on the cheek, sent that worthy flying. A second later George had his weapon levelled at him as he lay on the sidewalk.

“Move an eyelid,” he called harshly, unconsciously mimicking the robber, “move a finger, and I’ll drill you. Now, sir, kindly secure this fellow. Ah! Reach out for a gun, will you?”

Back went the trigger and the hammer of his weapon rose. George sighted it on Ike’s body and made ready to fire; for he knew well enough that he had a desperate man to deal with. Indeed, Ike was the class of man who would have dared anything to escape capture, well knowing that once he was apprehended his chances of escape were not worth considering. But George’s revolver staring at him restrained the movement he had attempted. He lay on his back on the sidewalk, his arms outstretched, his two revolvers just within reach of him, but lying opposite his knees where George’s lusty blow had caused him to drop them.

“Now, sir,” said the latter, addressing the gentlemen who had been held up by the two footpads, but keeping his eyes on Ike all the while; “kindly hasten and secure this fellow. Keep to the far side, so that I can fire at him at any moment, and kick those weapons out of his reach.”

Had both of these worthy citizens been as cool and circumspect as George, matters might have gone smoothly for the whole party, and Ike would certainly have been secured within the minute. But one was too upset by excitement to follow the instructions given. He came down the sidewalk, crossing between George and the prostrate robber, and in an instant the latter had taken advantage of the situation. Meanwhile Joe and the other citizen fought for the mastery, the man who had gripped him retaining the little rascal in such a position that Joe was helpless. He could not free a hand to seek for his revolver, and without that Joe was as good as captured.

With weapons he and Ike were capable of intimidating a carload of people, and Ike promptly proceeded to make use of such powers of persuasion. With a swing he brought his arms downwards, and instantly fixed his fingers on his weapons. Then, not attempting to rise, but merely lifting his head to aim, he fired direct at our hero, for by then the incautious citizen had crossed, and there was a clear path for the bullet. As for George, he felt as if he had been struck by a hammer. He received a terrific blow on the chest which doubled him up like a rabbit and sent him sprawling across the sidewalk and into the ditch, where he tumbled headlong. But, to his own amazement, he was still cool and collected, though horribly winded. He gasped for air, struggling all the while to rise, and still gripping his weapon. Ike, too, had made the most of the situation. He had scrambled to his feet, and was now backing uphill, away from his victims.

“Hands up!” George heard him calling. “You two fools as come to hold me when that young chap chipped into this business, you two just move, that’s all I’m wanting. You know what you’ll get, and I ain’t so sure as I won’t put a bullet into you now jest for punishment. Anyways, you can expect to hear again from Ike Lawley, you two bosses, Andrew Shere and John Hill. Not as I’ll hold you up. But I’ll write yer, and you’ll have need to answer. Then you’ll have a bank at your back, and will be able to draw the cash I shall want for your safety. Jest you speak to the cops about it, too, and put the ’tecks on me, sure, there’s nothing I like better. But, you two, it won’t be specially healthy for you.”

He was staring at Joe now, wondering whether he would desert his friend or go to his assistance. For Joe’s affairs had not progressed in the last few seconds. Indeed but a little more than a minute could have passed since George had leaped from the ditch, and yet see what a great deal had happened. Ike had been worsted. For a while, just a few brief seconds, he had been as near being a captive as ever he would be without being actually taken. And then suddenly, most unexpectedly, he had again become master of the situation. Joe, however, had been sadly battered. The man who had so pluckily fastened upon him had the little robber by the two wrists, and held him as if in a vice. Ike sighted one of his weapons on him.

“Couldn’t be done,” he said, coolly enough, squinting along the sights. “They’re moving about too much. Guess I’d better go to him.”

Slowly he began to descend the hill, his weapon still turned on the two citizens he commanded. Then he halted again and levelled a weapon at Joe’s antagonist. The lady screamed, while someone called loudly in the distance. Ike gave vent to an exclamation of annoyance and would have pulled his trigger promptly, had not the man then gripping Joe seen his intentions and swung the little robber round between himself and Ike’s weapon.

“Hi, police!” someone called in the distance, while a shrill whistle was blown from the doorstep of one of Calgary’s fascinating bungalows quite close at hand, and within sight of the hold-up.

“Then there ain’t nothing more for it,” growled Ike, glaring around him.

For the moment the ruffian considered the advisability of abandoning his comrade, for, after all, Joe was a fool to have allowed himself to get into such a situation. Then, seeing that he could hear no one approaching, and that it would be easy enough to lose themselves in the darkness, the rascal went steadily downhill towards Joe’s lusty antagonist, his intentions written clearly on his scowling face.

Meanwhile George had been puffing and blowing heavily. Doubtless those near at hand took the sounds and his struggles for death movements. Ike smiled grimly, for he had seen men flop down before beneath his bullets and kick and flounder for a while.

“Dead as mutton,” he told himself. “It’s that young fool of a cuss as I relieved of five dollars. At least I guess it is, though there ain’t no saying for certain. But he won’t want five dollars nor five cents after this. He’s drilled through as sure as ever.”

But if George were drilled through, then he was an extremely lively fellow after such an occurrence. Now that his breath was returning he felt actually as strong as ever, though there was a terrible sharp pain in his side, a stabbing pain as if a sword were being driven into him.

“Can’t help it,” he said to himself angrily. “If it does hurt a bit I’ve got to get a move on. Ah! That’s better. I don’t gasp now. I’ll still fix that fellow Ike Lawley or get killed in trying.”

He was on his knees in an instant, and by then Ike was quite close to his victim, while Joe was calling to his comrade.

“Shoot the fool!” he shouted. “Shoot him, Ike, and let’s quit. There’s people coming, and I can hear a cop running up the hill towards us. Put your gun to his head and blow the fool’s brains out!”

“Stop!” shrieked the unhappy lady, the centre all this while of the situation. “Stop; he is my husband!”

But what cared Ike or Joe for husbands or for women or for children? They were rogues of the worst description, and Canada possesses a few of them. And the Dominion is no stranger to shooting incidents, to hold-ups and deeds of violence, though for the most part the country is wonderfully settled, and people can lead as tranquil a life as anywhere else. The two footpads were, as we have said, desperate fellows, with a price on their heads, and one murder more, one additional shooting outrage, made no particular difference to them. Ike seemed to be unmoved by the thought of the deed he was contemplating, unless, indeed, he were just a little amused. For he was grinning as he descended towards his comrade, a wolfish grin, while every now and again he swung round to threaten the men above him.

“In a moment or two he’ll have reached Joe,” thought George, “and then the brute will murder that fine fellow. Well, he won’t, ’cos I’m here. That’s better, for I’ve got my breath and am steadier.”

He lifted his weapon and shouted “Ike!” Instantly the robber stopped and swung round.

“Hands up!” shouted George, still stooping below the edge of the ditch. Two sharp reports rang out instantly, while a couple of bullets swept over his head. Not that Ike had aimed at him. He couldn’t see our hero yet, though he guessed that the one he imagined to be lying dead in the ditch was the cause of this new interruption.

“Raise a hair and I’ll shoot it,” he growled, watching intently and warily. Then George did a clever thing, and marvelled afterwards that the idea should have come to him at such a moment. He pitched his broad-brimmed hat on to the very edge of the ditch and hurried downhill at his fastest pace, his body bent almost double. Crash! Bang! Two more shots rang out, and the bullets thudded into the far side of the ditch some five yards above George’s new position. As for the hat, it performed the most curious evolution. It rose suddenly, spun round like a teetotum, and then hopped a foot downward along the edge of the ditch. Indeed its movements were so natural, as if George’s head had been within it, and he only grazed by the bullets which Ike’s sure aim had certainly sent through it, that the rascal instantly opened fire once more at the very top of the hat, all that was now visible to him. George raised his head sharply. Levelling his own weapon he fired swiftly at Ike, but not so swiftly that the other did not see him. Indeed the two shots rang out simultaneously, and again George experienced a most unpleasant and painful sensation.

“Hit! Bang through the arm this time,” he told himself, while everything about him became suddenly blurred. Indeed a misty film seemed to have become stretched between himself and the other participators in this adventure. He could see Joe still gripped by the plucky fellow who had seized him, the two staggering this way and that and steadily descending the sharp incline. He could hear the shouts and oaths of the helpless robber. Then there was the lady, now rushing to help her husband, her hat awry, her skirt blowing in the wind, her voice frightened and penetrating. Higher up the hill were the two whom Ike had designated bosses. They were coming towards him, stepping swiftly along the sidewalk, their arms no longer raised above their heads, the sign and symbol of all who are the victims of a hold-up.

“Rummy that,” thought George dully. It really didn’t seem to matter very much to him what anyone was doing. Even Ike didn’t concern him very much just now, though to be sure he was wondering how that individual was faring. But it was so difficult to see through that mist, and, besides, try as he would, his legs were so strangely unsteady that he had no time to be looking about him. George celebrated the occasion, and marked the end of this sensational conflict, by falling backward and sliding unconscious into the ditch which he had but just quitted. As for Ike, he lay on his face, his fingers still gripping both of those terrible weapons.

“Dead!” declared Andrew Shere, bending over him. “Let’s look at the other fellow. John Hill, that stranger deserves our best thanks for his most plucky action. But I have doubts that he’s alive. You go down and help with that other rascal while I get into the ditch.”

Whistles were sounding in all directions then, and the usually sedate and select district of Calgary was already in a ferment. There were men and women on the balconies of the majority of the houses within sight and sound of the occurrence, while people were running along the sidewalk. Then a motor horn sounded, strong electric headlamps lit up the scene, while a powerful police car dashed up the hill from the business part of the city. They do things well in Canada. The municipalities have the latest of everything, and their police and fire appliances seem to be worth copying. Here was a sample of up-to-dateness. The car came to a standstill opposite the scene of the conflict, and half a dozen men tumbled out of it.

“Two down,” said one in uniform, who seemed to be in command. “Boys, lift them into the nearest house, and, Doctor, take a look at them. Hallo! What’s this? I was called upon on the ’phone and told that two were killed. Why, here’s another.”

The second individual, styled a boss by Ike, was at that moment dragging George’s limp figure from the ditch into which he had tumbled.

“Huh! Dead?” asked the police official, coming forward instantly. “Who is he?”

“Don’t know, officer,” came the answer. “But he’s the plucky fellow who saved our lives and the whole situation. He shot Ike there and then went down himself. Is he dead? Can’t say. Let the doctor come along immediately.”

Thus ended George’s first attempt to break away from the peace and quietness of the country.

“Recover! Certainly, my dear sir, certainly. The fellow’s as hard as nails, and young, Mr. John Hill—young, let me remind you. He has the constitution of an ox and the robustness of an elephant. Die! Pooh; he’ll live to make Canada proud of him!”

George heard it all vaguely. He had the idea that the words referred to himself, and was just a little pleased. After all, it was nice to hear that he would live, for at the age of seventeen life is, perhaps, dearer than when more years have been added and troubles have come along. It was amusing, too, even gratifying, to learn that he had the constitution of an ox and the robustness of an elephant, if elephants may be said to possess such a thing. But, really, it didn’t matter very much. George was very sleepy, very comfortable, and quite inclined to leave matters as they were and enjoy present comforts. He sighed, then yawned, and, rolling over, attempted to gather the bedclothes about him. It was then that his troubles commenced.

“Can’t,” he grumbled. “Here! who’s holding my arm? and someone’s digging something into my side. Shut up, will you!”

“A little delirious, perhaps,” said an anxious voice. “That wound is enough to account for it, eh, Doctor?”

“Fiddlesticks! Delirious! no. Just dreaming. But look at that, Mr. Hill. I ask you, did you ever see such a sight before? Saved his life, sir. Saved his life, and will make him the most unpunctual fellow in the Dominion. He’ll get into trouble, he will. He’ll be fired from every job he accepts. Ha, ha! He’ll perhaps take a job on your railway and then all the trains’ll be late, the passengers will be inconvenienced, and the manager will be discharged. Mr. Hill, this is a very serious matter.”

He was a very jovial fellow, whoever was talking, and George managed just to open one eye—the other was beneath the bedclothes and so he didn’t bother with it—and stared hard at the man. He was short, at least George thought so, but he himself was so deliciously sleepy that he wasn’t certain, and then again the fellow who had been hanging on to his arm, and the other idiot who had been poking him in the ribs, much to his discomfort, had ceased their practical joking. Yes, the fellow outside the bed looked short, and round, and fat, yes, very plump, and seemed to have a very red face. It reminded George of Carl’s. He was laughing, too. Seemed to be laughing all the while, and intensely pleased with himself. Why? Was he the practical joker? George glared at the man.

“Better give it up,” he grumbled threateningly, though really he couldn’t bother to do more than grumble. But wait.

“Decent-looking chap,” thought George, managing to prop his heavy eyelid open again. “Who is he? Ah! Ike!”

It was the first time for quite a while that his thoughts had returned to Ike Lawley, the hold-up, the footpad, the terror of the Calgary district; the rascal who had committed three brutal murders, and now had more to answer for. Yes; Ike had been masked, and that would hide his face. The clean-shaven fellow with the red, smiling face, the stout, little fellow standing outside the bed, who had had the audacity to torment our hero, must be Ike.

“Suppose he’s got me as well as those dollars,” George mumbled. “But it don’t matter, for I seem to be pretty comfortable, and then he don’t look very dangerous. Wonder whether I hurt him? Carl always did advise me to practise shooting, and said that I couldn’t hit a haystack even if I tried. So I suppose I missed. Well, I ain’t sorry, for Ike, now that he’s got rid of his mask, isn’t a bad-looking fellow. Heigho!”

“Sleepy. The shock affects him,” said the stout little man. “He’ll be better and more like himself in a couple of days. But that thing’s worth preserving, Mr. Hill. It saved his life; even if it will make him late for the rest of his existence. Ha, ha! That’s a joke we’ll have to reserve for him when he’s better.”

The other man laughed; rather an irritating laugh George thought it. He managed to elevate that refractory eyelid again, and glared at the second individual who had the temerity to enter his room. He was tall, clean-shaven, it appeared, and really he looked quite decent. But so did Ike; quite respectable, even gentlemanly, as if he belonged to some profession. And he, too, was laughing, while he leaned over Ike’s shoulder and inspected something which shone in the sunlight. Yes, sunlight!

“Crikey!” exclaimed George, a little more animated. “Sunlight now! Why, it was half-past ten, perhaps, when that shindy finished. I had to return to the freight yard, and spread my bed in the freight car. It’s morning, then? There are the horses to water and feed, and that hay to be loaded. Carl’ll be after me if I’m not slippy. Here, you let go! None of yer monkey tricks for me! I’ve had enough of yer teasing.”

The stout little man had placed a plump finger on George’s wrist, and at that precise moment had poised himself beside the bed, his head a little on one side, his eyes half-closed. He looked like a bird; very wise, very thoughtful, full of understanding. George shook his hand off roughly.

“Here! Leave go, Ike!” he tried to shout. Then, following the train of thought which had swept across his brain, he threw the clothes off with the only arm which seemed to be unfettered, and endeavoured to rise.

“There’s those hosses,” he told the two. “They ought to have been fed and watered at dawn. Let go, will you? I’ve had enough of this fooling!”

The little man giggled. “Lie down,” he said kindly, and George was lost in amazement now, for the voice was not Ike’s. He propped that lid open again.

“And this fellow’s short,” he told himself aloud. “Ike was tall. It was Joe who was short; but this one’s stout, fat—as fat as a bullock.”

“Ho, ho, ho!” came from the second man. Looking up, George saw him laughing uproariously, while the stout one was pretending to scowl, and was actually shaking his fist at him.

“John Hill, John Hill,” he said sternly, “you’re incorrigible! First you whine and plead with me to come here, when I have told you time and again that there is no actual need; and then, when I have reassured you, you make the worst of my misfortunes. You laugh and ridicule me. Now, perhaps, you will be satisfied. ’Pon my word, the young ruffian shows fight. He’s ready for another encounter.”

That set them both laughing, and brought our hero to a sitting position. He was wideawake now—quite active, in fact—but bewildered.

“Please explain,” he said curtly. Indeed, George was quite irritable. His sleep had been disturbed, and someone had said something about lateness. Well, he was late, for the sun was shining strongly upon him and flooding the room. He ought to have been up and about hours ago. But here was something else that was strange. The room was wonderful. It reminded him of the home in Toronto, only it was larger, more magnificent, better furnished, and evidently part of a house of huge proportions. He squinted round.

“I say,” he began.

“Then don’t,” snapped the stout man abruptly. “Lie down and sleep. Your horses have been attended to, and the hay loaded. You’ve got to rest, my friend, and Mr. John Hill will take charge of you.”

“Who’s he?” demanded George suspiciously, eyeing the second individual, and rather liking his looks.

“Oh, who’s he? Well, a railway servant,” laughed the stout man. “The fellow who carries so many dollars about with him that Ike Lawley gladly holds him up. That’s John Hill.”

There was more merry laughter, in which both joined, though the second man pushed the stout one promptly aside.

“Don’t listen to him, George,” he said. “This is Dr. Cramer, a noted wag, one who’s never serious. The wonder is that he ever has a single patient. But he’s fixed you up.”

“Why? Am I ill, then?” asked George, surprised. “I feel as fit as a fiddle, but frightfully sleepy. Who says I’m ill?”

He glared at the doctor, sending that stout and merry individual into another peal of laughter.

“No one,” he managed to reply at last. “But let’s be serious. Lad, you’ve been hurt in that business with Ike Lawley. The ruffian sent a bullet through your arm, and if it hadn’t been for this he’d have drilled a hole clear through your body.”

He held up a shining object, and, inspecting it narrowly through eyes which were not more than half-open, George discovered it to be a watch—his own watch. The thing was badly damaged, dented deeply, and had lost a portion of the outer case.

“Father’s,” he murmured. “Kept splendid time. Descended to him from his father, who brought it out from England. Eighteen-carat gold, sir; jewelled, and all the rest of it.”

“Then it’s fit for a museum now, lad,” laughed the doctor, “though you’ll no doubt miss it, and be sorry for the damage done. But it saved your life. Ike’s bullet struck it, and stopped short. Here it is, embedded in the works. The two ribs lying beneath the watch were broken.”

Slowly the whole affair began to dawn on George. He felt about his waist with the one hand that was free, and discovered that bandages were about him. Yes, there was a decidedly tight feeling about his chest, and now that he had sat up for a few moments he began to cough, and there was a little faintly bloodstained matter on his lips. As to the other arm, it was tied up fast at a right angle. The elbow was firmly secured, and——

“It’s in a splint,” he cried, beginning to get brighter.

“Broken, like the watch,” said Mr. Hill. “But lie down, lad. As to the watch, we’ll see what can be done. If new works can be put in, and the case repaired, why, it shall be attended to; if not, then you shall have another just as good, though it can hardly have the same sentimental value. But I’ll not have Dr. Cramer prophesying continual unpunctuality in the case of any of my friends. There, lie down, George. Don’t listen to the doctor.”

It was really all very pleasant and nice, and George didn’t mind if he did obey the order. For it was an order. Mr. Hill meant what he said, and very obediently George lay on his back. He hadn’t to use any effort to close his eyes, for they shut of themselves. The lids were so desperately heavy that it would have required a strong man to hold them up. So George made the best of a bad matter, and gave in. It wasn’t like him to give up a struggle; but, then, things seemed all right.

“Hosses fed and watered, and Carl’s hay loaded,” he mumbled. “Then a chap may as well sleep.”

“Just shock,” he heard a fat voice say, while someone giggled aimlessly. But it reassured George. “Let him rest. In a week we’ll have him about and kicking. There’ll be a court case, eh, Mr. Hill? And he’ll be wanted. Well, he’s in your hands now. Ring me up on the ’phone if you’re worried.”

When our hero next opened his eyes the sun was low in the heavens and wonderfully bright. It flooded the broad acres of wonderful wheat-growing land which stretch for nine hundred and more solid miles between Winnipeg and Calgary in an east-and-west direction, and for hundreds more miles to the north of the Canadian-American frontier. Could one see all that land, who could fail to be impressed with the possibilities of the Dominion? And who, travelling southward over the frontier, and sitting for hour after hour in an American train, could fail to wonder and admire at nature’s provision for future generations? For the North American continent is vast—so huge that a description of it fails to do more, perhaps, than merely interest the reader. To appreciate to the full the vastness of the open spaces, still untenanted, still vacant and waiting, one must visit the Dominion or America for oneself, and there see all that is spread before one. All? That is impossible. A man might live his life out there and never see more than a proportion of the country. Let him, however, board the train at Quebec and travel on during day and night for a solid week, till he comes to Vancouver, and he may have some idea, remembering that he might, were the railway tracks laid, commence a similar journey from New Orleans, in America, and travel north for a similar number of days, and still have miles of solid land to cover.

That sun flooding George’s room was the same which had attracted his attention on the previous occasion when he awoke; but it, too, like the traveller, had sped along in the interval. It heralded another day, and all over those thousands of miles men and beasts obeyed its summons. From city homes, from shacks, from the rough shelters of lumbermen and hunters, and from the lean-to’s attached to many a farmhouse, men and cattle issued into the open; the city man to hasten to his office, the farmer to his crops, the lumberman to again set the woods ringing with his axe. Hunters, no doubt, cleared up their camp, stamped out the fire with which they had cooked their morning meal—for fires start easily in Eastern and Western Canada, and carelessness leads to terrible loss of timber—and took the trail for mountain or river. Thousands of reapers were working already, without a doubt, while in a host of places men of the Dominion, hardy settlers who had come to carve out wealth for themselves, were already engaged in clearing their virgin land of roots, tearing them out by sheer force, thanks to the aid which engineering science has given. Yes, on many a quarter-section there could by now be heard the blast of dynamite and the thud, thud of the donkey engines used to haul at the tree roots. And what bonfires blazed out there in the wilds! Stacks of roots fifty feet in height shed their heat broadcast, for in that way does the settler rid himself of useless lumber, of wood which, in the older countries of Europe, would be gratefully received in many a house and cottage.

“Hallo!” said George.

“Hallo yourself!” someone answered.

“Good morning, Mr. Instone!” a pleasant voice chimed in. It was a musical voice, a lady’s voice, and set George blushing.

“I say,” he began, and then sat up. No, he didn’t cough. George, you see, had the constitution of an ox and the robustness of an elephant. Oxen don’t make much of fractured ribs, and why should our hero?

“You’ll do,” said Dr. Cramer cheerily, for he it was. “He’ll get along nicely now, Mrs. Hill. Let us get the dressing done and he’ll be more comfortable.”

Comfortable. George was that, quite. “Thanks!” he said. “I’m all right. But I suppose I’d better get up and dress if——”

He looked towards the lady. “Oh, you’ve mistaken the doctor!” smiled Mrs. Hill. “You are to have your wounds dressed, and I am here to help. I’m your nurse, you know, and you’ll have to be very good and obedient. Now, Doctor.”

George submitted. He was bright, and had his full wits about him now, and fully understood the whole situation.

“What about Ike Lawley?” he asked, when the dressing of his wounds was in process. “We fired at the same moment, I think. Then, somehow, I couldn’t see him. Things were blurred. There wasn’t anyone else to fire at. And how about Joe, the other rascal?”

Dr. Cramer chuckled. “Joe’s a sore man,” he laughed. “He’s in the jail at this moment waiting for your evidence. Ike’ll never work a hold-up again. He’s gone to the great beyond, lad. Your bullet struck him square between the eyes, and he’ll cease now from being a terror to the district of Calgary.”

“Ah!” gasped George. It made him feel queer to learn that he had killed a man. It was disagreeable information. It left a nasty taste in his mouth. The doctor looked up sharply, and then nodded secretly in Mrs. Hill’s direction.

“And a good riddance, say I and every other good citizen of Calgary, and every wayfarer and every farmer in the district,” he said cheerily, proceeding without pause with his work. “There. That hurt? Of course it don’t. Ike’s bullet struck the outside bone of the forearm, and chipped a piece out of it as big as a walnut. Talking of Ike reminds me you’ve no cause to fret because you killed him, lad. Someone had to do it some day, and the sooner the better. If he hadn’t been shot out there on the hill, he’d have killed other people, and some day, as I’ve said, someone would have had to hang the rascal. So there it is. He was a ruffian and a murderer, and the man—for you’re a man, George, ain’t you——?”

“Certainly,” declared Mrs. Hill sharply. “It requires a man to do what he did.”

“Ma’am,” said the doctor, smiling and probing, at which George winced, “you’ll make the boy conceited. Besides, I was asking him the question.”

“As if you could expect him to answer,” replied the lady indignantly.

“Please be careful,” the doctor cautioned her severely. “You’re moving the arm, and at the moment I’m performing a somewhat delicate operation. Yes, as I was saying, when Mrs. Hill interrupted——”

“Really, Doctor,” protested the lady, laughing nevertheless.

“Yes, really. There, George, that don’t hurt, does it? No! Certainly not! Give him a drink of water, Mrs. Hill. That’s better, lad, eh? A wounded arm’s always a little tender, and you stood it well. But, dear me, I was saying something. Oh yes, about Ike! There are hosts of people, quite peaceful fellows I do assure you, quiet, well-conducted citizens, fathers of families, responsible individuals, you understand, who would willingly have shot Ike Lawley at sight, and been glad of the opportunity. You don’t quite appreciate the situation, Mrs. Hill.”

“I? I don’t. Why——” began the lady, for it was hard to tell when this jovial doctor was serious and when merely teasing. “It’s George you’re speaking to,” she said severely.