* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Marlborough His Life and Times--Volume VI

Date of first publication: 1937

Author: Winston Spencer Churchill (1874-1965)

Date first posted: August 19, 2025

Date last updated: August 19, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20250825

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

MARLBOROUGH

HIS LIFE AND TIMES

VOLUME VI

1708-1722

BY WINSTON S. CHURCHILL

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1911-1914

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1915

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1916-1918

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1911-1918 (Abridged, in one volume)

THE AFTERMATH

A ROVING COMMISSION

THE UNKNOWN WAR

AMID THESE STORMS

THE RIVER WAR

MARLBOROUGH

MARLBOROUGH

From an engraving after a painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller

MARLBOROUGH

HIS LIFE AND TIMES

By

The Right Honourable

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL, C.H. M.P.

VOLUME VI

1708-1722

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Copyright, 1938, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this book

may be reproduced in any form without

the permission of Charles Scribner’s Sons

This volume upon the fall of Marlborough completes the story of his life which I began nearly ten years ago. It exposes and explains the lamentable desertion by England of her leadership of the Grand Alliance, or League of Nations, which had triumphantly broken the military power of Louis XIV. It shows how when victory has been won across measureless hazards it can be cast away by the pride of a victorious War Party and the intrigues of a pacifist reaction.

In the spring of 1709 we see England, or Great Britain, as she had recently become, at the summit of power and achievement. Queen Anne, seated securely upon her throne, was the centre of the affairs of the then known world. The smallest incident at her Court was studied with profound respect or attention by all civilized countries. Louis XIV, old, broken, bereaved, brooded disconsolately amid the stricken splendours of Versailles. The tyrant of Europe, who had let loose a quarter of a century of war upon his neighbours, had become a suppliant. The Whig Party in England, possessed of majorities in the Lords and Commons, had forced themselves into power. They no longer sought the liberation of Europe, but the destruction of France. They lost the victorious peace which might have closed the struggle. In France they roused the patriotism with which Frenchmen have always defended their soil, and in England they fell a prey to the designs of their party foes. The terrible battle of Malplaquet, the bloodiest and best contested for a hundred years, marked the climax of their efforts. Thereafter all became shameful and confused. Queen Anne abandoned the purposes of her reign. Abigail led Harley up the backstairs. The Queen devoted her great power to driving out the Whigs. England was dominated by party politics and the jealous emulation of great nobles. Marlborough and Godolphin were undermined. The Whigs were ejected and chased from office, and a Ministry was installed resolved upon peace at any cost. But by these very facts the French were incited to continue their resistance, and after three more years of conflict they found themselves, though exhausted, still erect.

This process depended upon the political drama in London, which in its various acts and scenes illustrates vividly the life of a Parliamentary nation, and reveals at many points the foundations of our Constitution. Marlborough was hunted down. His wife was driven from the Court. He himself, though he served the Tories faithfully in the field, was subjected to the cruellest humiliations and vile, undeserved reproach. The British army was forced to abandon its comrades in the field, and a peace was made contrary to every canon of international good faith. All Europe, friend and foe, was staggered by the perfidy of the Tory Ministers; but while the Queen lived they ruled with unchallengeable authority. Marlborough chose exile rather than the ill-usage he must receive in his native land. The name of England became a byword on the Continent, and at the moment of Queen Anne’s death the Protestant Succession itself was in danger, and our island on the verge of a second Civil War. This supreme disaster was averted, but when Marlborough returned to his native land and to a great position, time and age, which cast their veils over the fierce impulses and scenes of action, had led him to the dusk of his life.

I have tried to show Marlborough in his wonderful strength, without concealing his faults. I am not aware of any charge brought against him that has not been fully exposed and discussed. My impression of his size and power has grown with study. His genius in war, his statecraft, his virtues as a man, may be judged by these pages; nor is it necessary to dwell further upon them here. Happy the State or sovereign who finds such a servant in years of danger!

I have followed the method used in earlier volumes of always endeavouring to make Marlborough speak whenever possible. I have drawn upon the admirable foreign histories of this period—Klopp, Salomon, Von Noorden—and have been guided by them to the vivid reports of Hoffmann, Gallas, and other ambassadors and envoys to the English Court. From these sources a more intimate picture can be obtained of the political life of our country than in any of our domestic records.

The Blenheim archives have been found more fertile than in the preceding volume; in particular the reports of the British spy in Paris seem of high interest.

I must express my acknowledgments to the authorities of the Rijksarchief at The Hague for the courtesy with which they have laid their archives open to me; and also to the Huntington Library in California, to the Hon. Edward Cadogan, Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon Halswell, and others who have contributed original material.

I have been greatly assisted in the necessary researches by Mr F. W. Deakin, of Wadham College, Oxford, and again by Brigadier R. P. Pakenham-Walsh and Commander J. H. Owen, R.N., in technical matters. I accord my thanks to all those who so kindly allowed me to reproduce pictures and portraits in their possession, and to the present Duke of Marlborough for continuing to give me the freedom of the Blenheim archives.

WINSTON SPENCER CHURCHILL

Chartwell

Westerham

August 13, 1938

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | “00” | 17 |

| II. | The Whigs and Peace | 30 |

| III. | The Great Frost | 46 |

| IV. | The Fatal Article | 62 |

| V. | The Lost Peace | 80 |

| VI. | Darker War | 93 |

| VII. | Tournai | 110 |

| VIII. | The Investment of Mons | 127 |

| IX. | The Battle of Malplaquet | 142 |

| X. | The Ebb-tide | 172 |

| XI. | The Queen’s Revenge | 196 |

| XII. | Mortifications | 209 |

| XIII. | Sacheverell and Shrewsbury | 222 |

| XIV. | The Ninth Campaign | 234 |

| XV. | Sunderland’s Dismissal | 259 |

| XVI. | The Alarm of the Allies | 282 |

| XVII. | The Fall of Godolphin | 295 |

| XVIII. | Marlborough and Hanover | 308 |

| XIX. | Dissolution | 320 |

| XX. | The New Régime | 333 |

| XXI. | The Gold Key | 352 |

| XXII. | The Death of the Emperor | 371 |

| XXIII. | Harley and St John | 384 |

| XXIV. | General Only | 405 |

| XXV. | Ne Plus Ultra | 421 |

| XXVI. | Bouchain | 440 |

| XXVII. | The Secret Negotiations | 458 |

| XXVIII. | Hanover Intervenes | 472 |

| XXIX. | The Political Climax | 489 |

| XXX. | The Visit of Prince Eugene | 506 |

| XXXI. | The Peculation Charge | 521 |

| XXXII. | The Restraining Orders | 535 |

| XXXIII. | The British Desertion | 551 |

| XXXIV. | Marlborough leaves England | 567 |

| XXXV. | Exile | 578 |

| XXXVI. | Utrecht and the Succession | 594 |

| XXXVII. | The Death of the Queen | 612 |

| XXXVIII. | Marlborough in the New Reign | 623 |

| XXXIX. | At Blenheim Palace | 639 |

| Bibliography | 653 | |

| Index | 657 |

| PLATES | |

| PAGE | |

| Marlborough | Frontispiece |

| The Old Pretender | 28 |

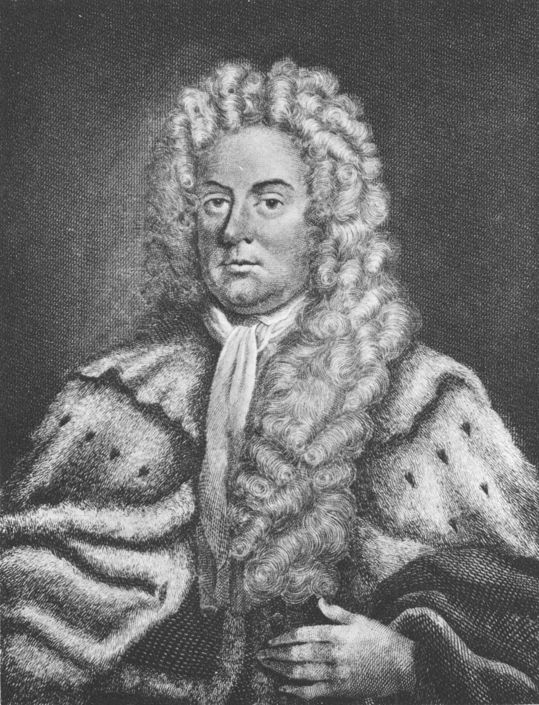

| John, Lord Somers | 32 |

| Charles, Second Viscount Townshend | 66 |

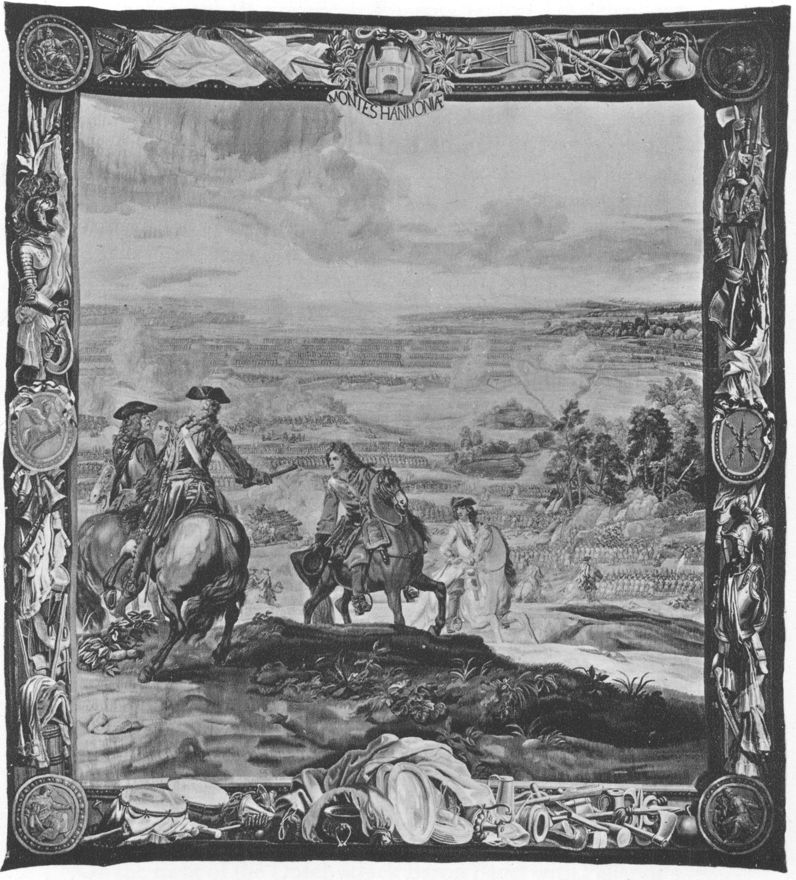

| Tapestry of the Battle of Malplaquet | 150 |

| James Craggs the Younger | 186 |

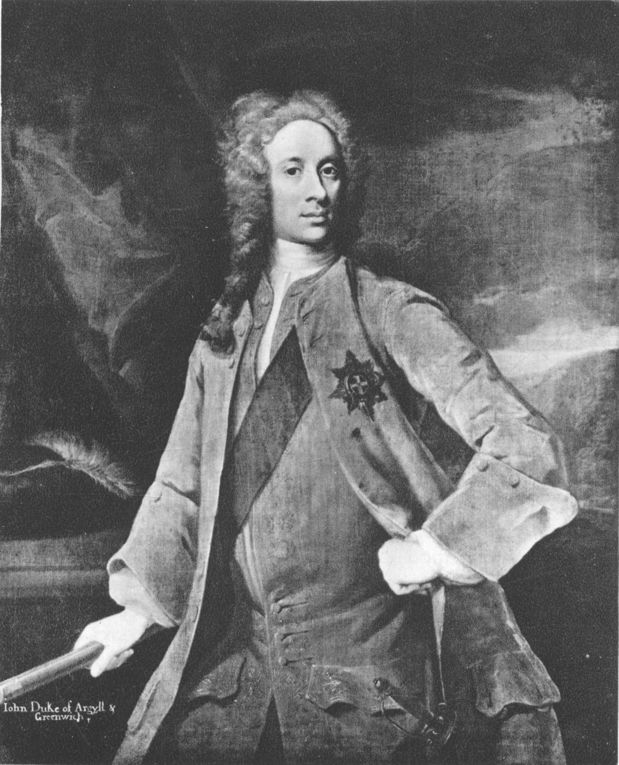

| John Campbell, Second Duke of Argyll | 190 |

| Charles Seymour, Sixth Duke of Somerset | 204 |

| Henry Sacheverell | 224 |

| Charles Boyle, Fourth Earl of Orrery | 252 |

| Robert Walpole | 270 |

| William, First Earl Cowper | 324 |

| Sir John Vanbrugh | 338 |

| The Emperor Charles VI | 374 |

| John Dalrymple, Second Earl of Stair | 414 |

| The Duke of Marlborough and Colonel Armstrong | 444 |

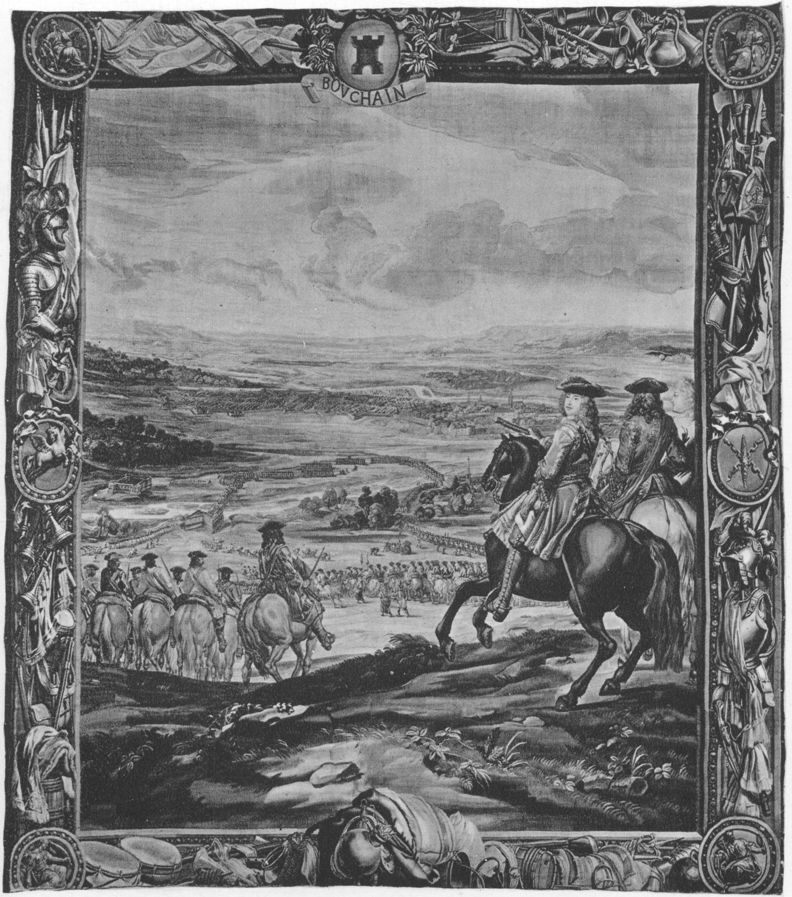

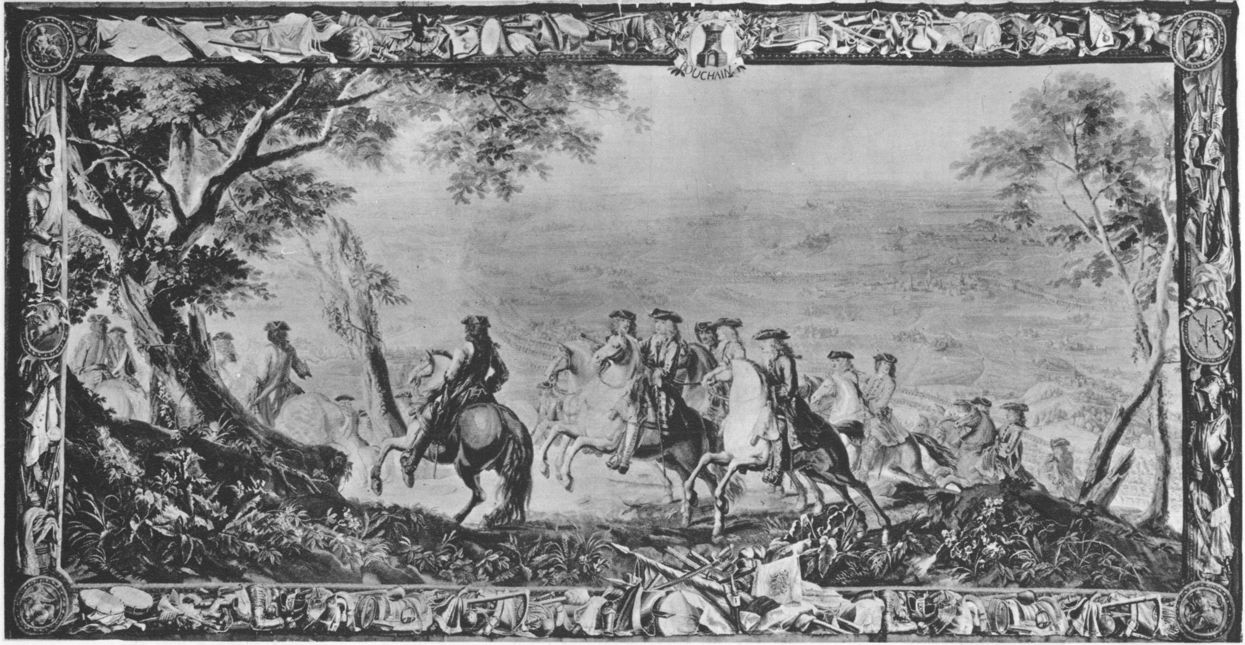

| Tapestry of the Capture of Bouchain | 448 |

| Tapestry showing Marlborough at Bouchain | 454 |

| Thomas Wentworth, Third Earl of Strafford | 514 |

| James Brydges, First Duke of Chandos | 530 |

| James Butler, Second Duke of Ormonde | 538 |

| John Sheffield, First Duke of Buckingham and Normanby | 614 |

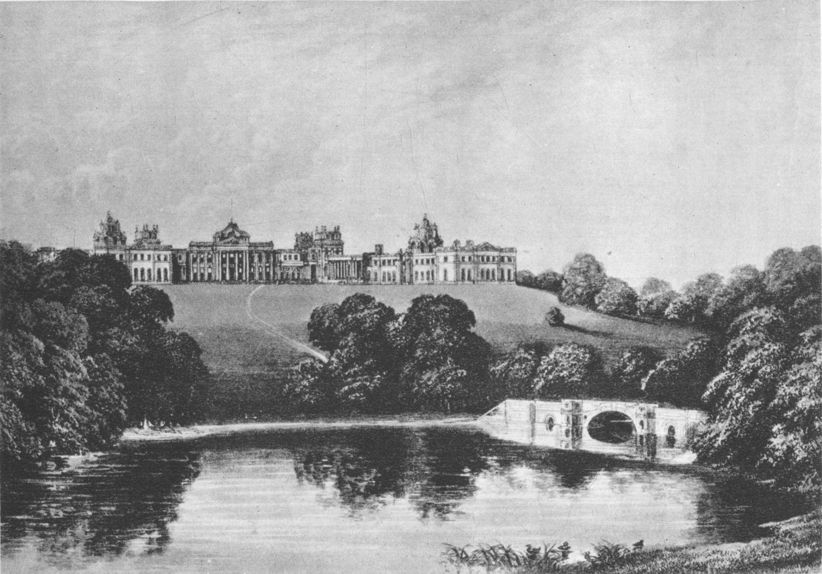

| Blenheim Palace | 642 |

| Marlborough as a Young Officer in the French Army | 652 |

| FACSIMILES OF LETTERS | |

| PAGE | |

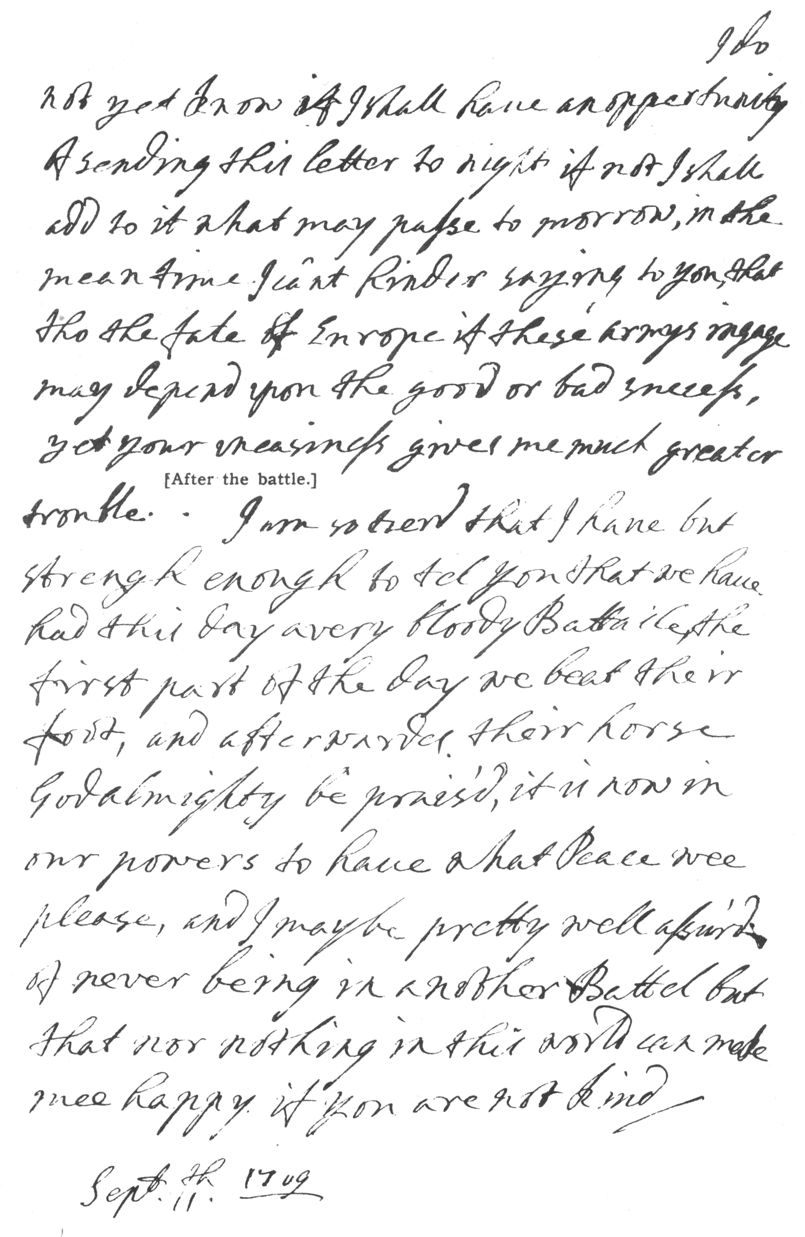

| John to Sarah after Malplaquet | 171 |

| MAPS AND PLANS | |

| PAGE | |

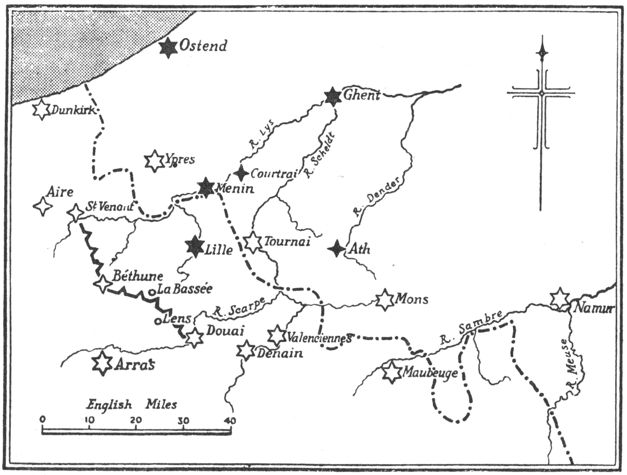

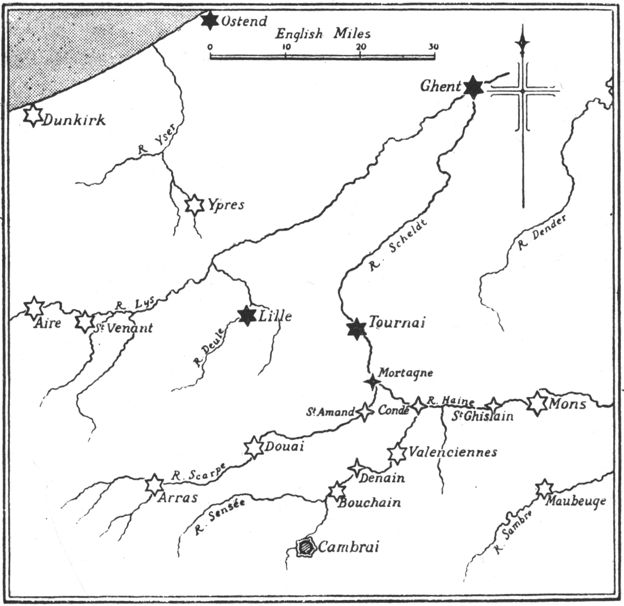

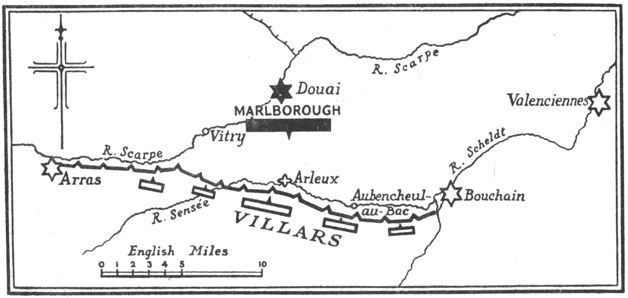

| The Situation Early in 1709 | 103 |

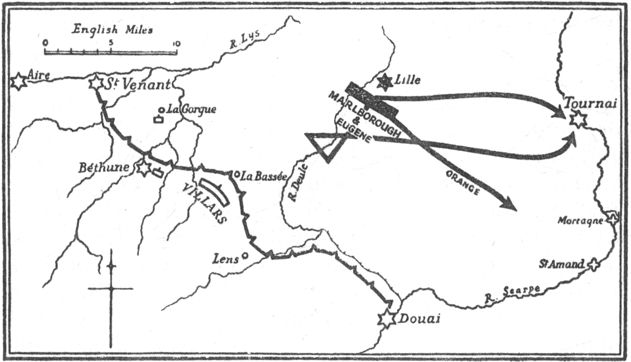

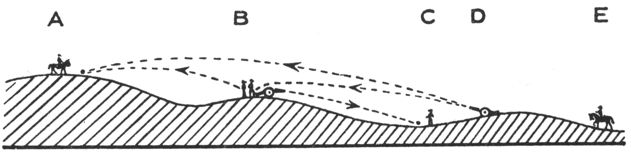

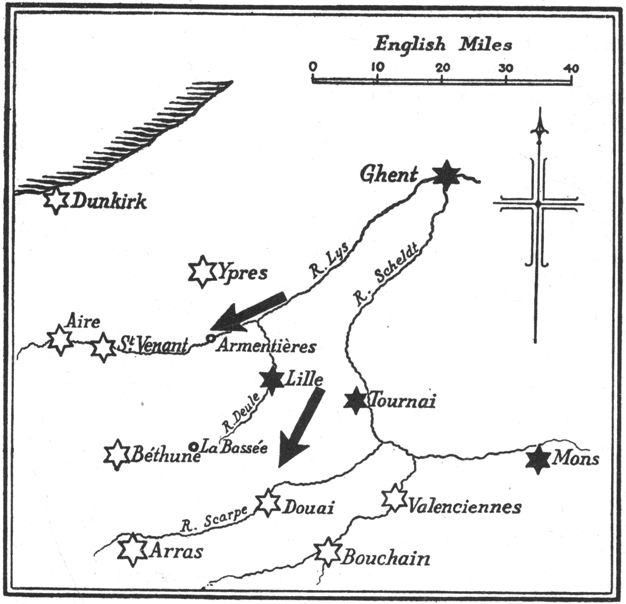

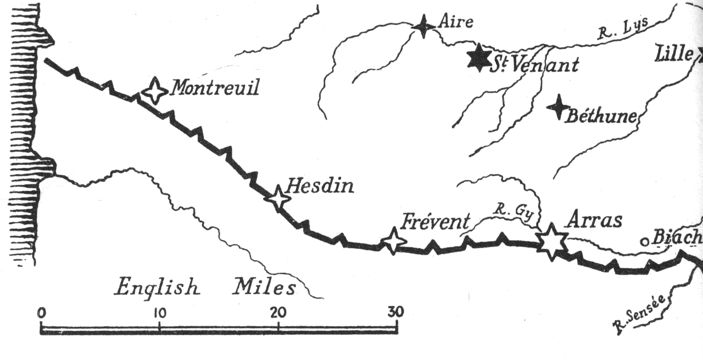

| The Feint before Tournai | 111 |

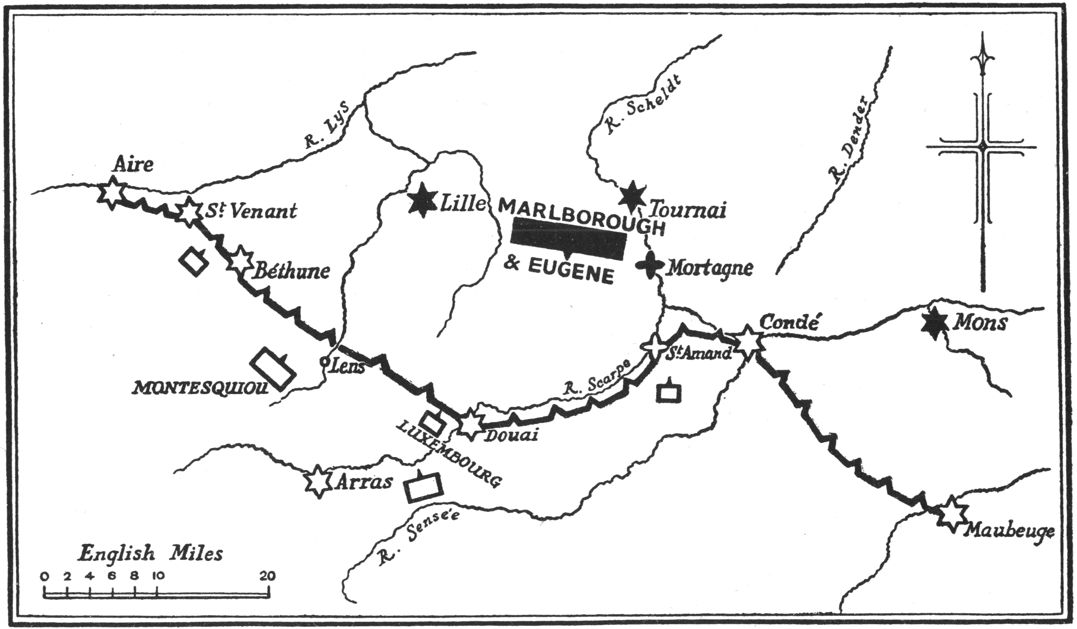

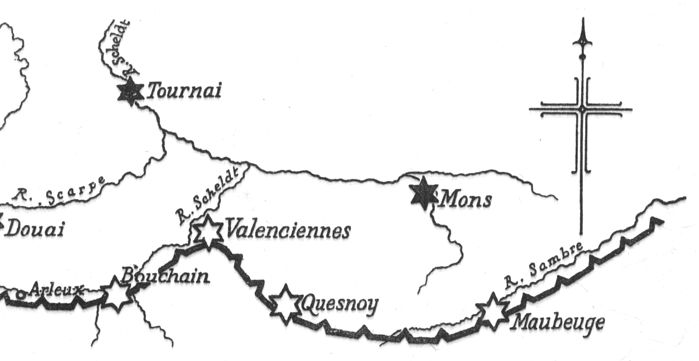

| Fortresses after the Fall of Tournai | 129 |

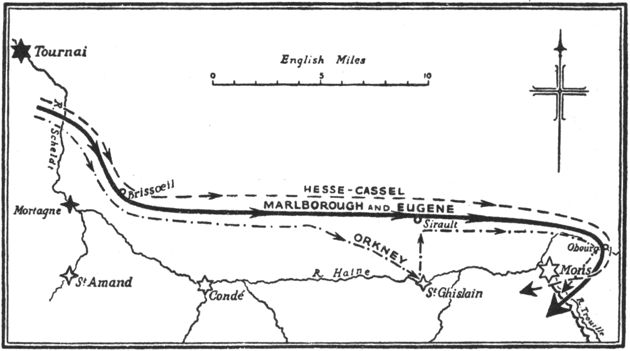

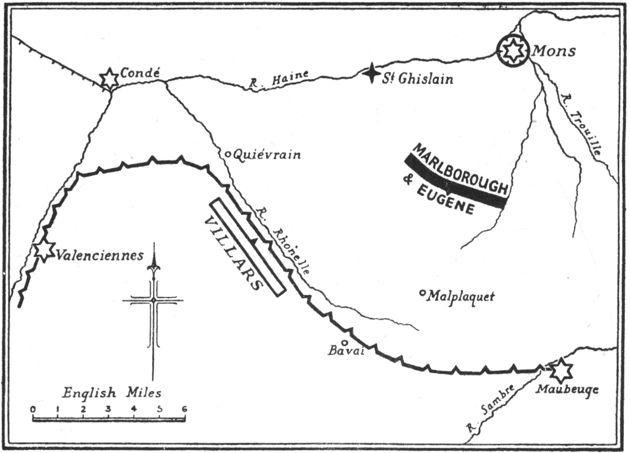

| The March from Tournai to Mons | 131 |

| Evening of September 7, 1709 | 133 |

| Evening of September 8 | 135 |

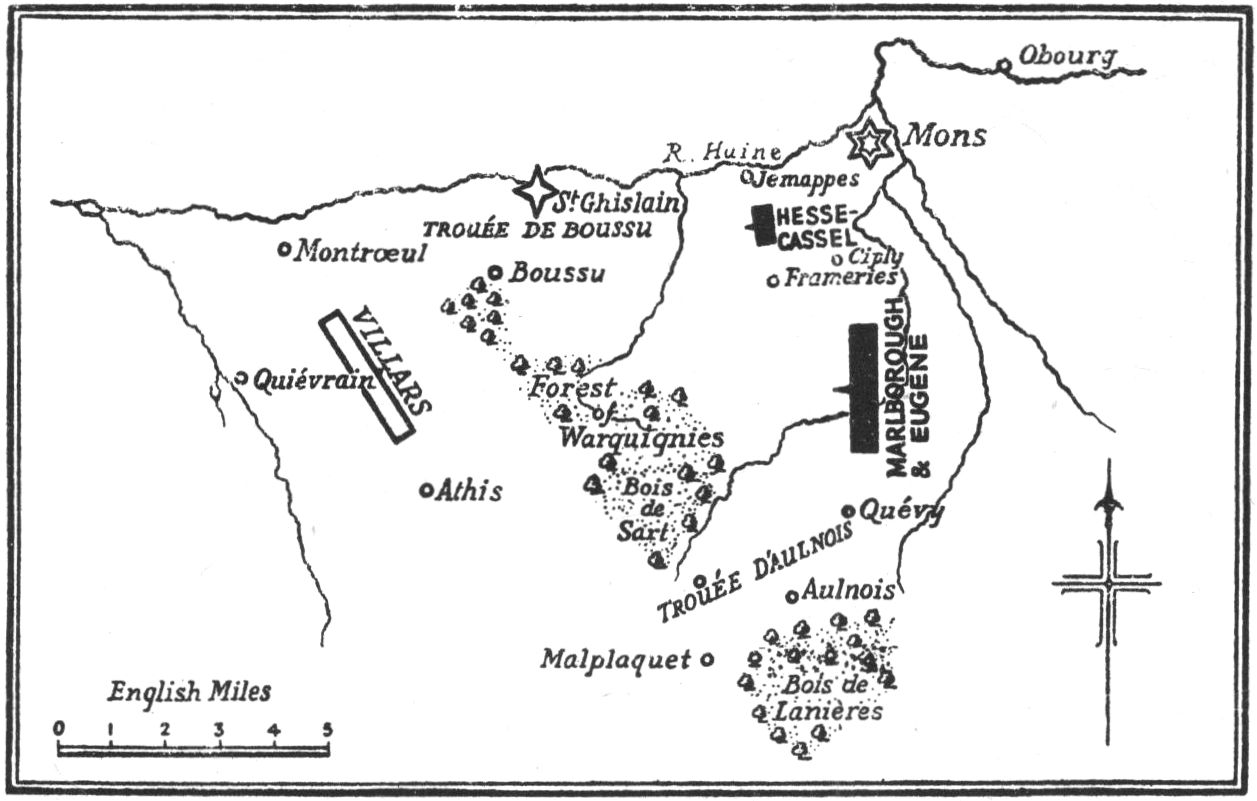

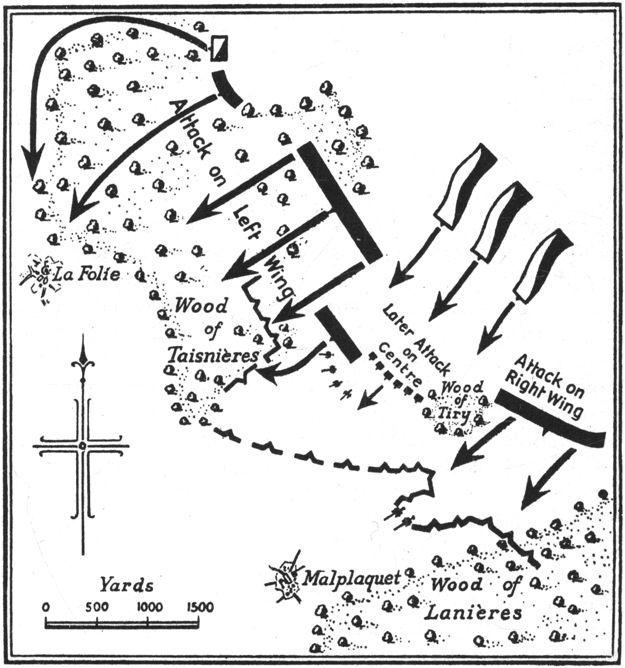

| Marlborough’s Plan of Attack | 143 |

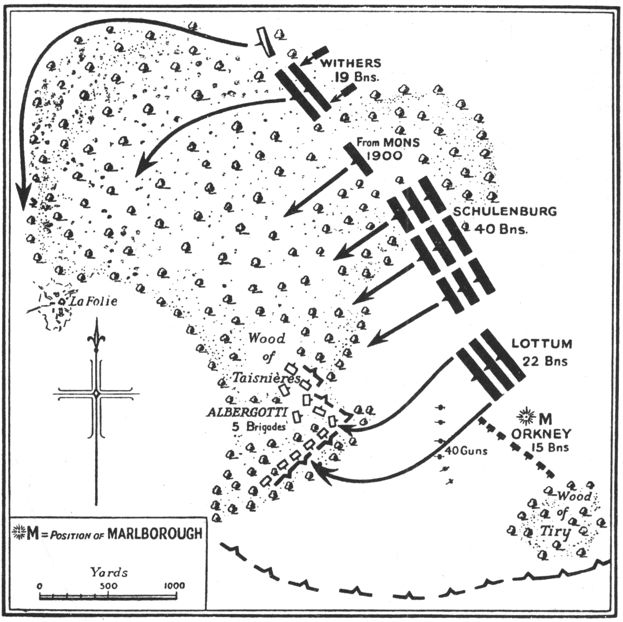

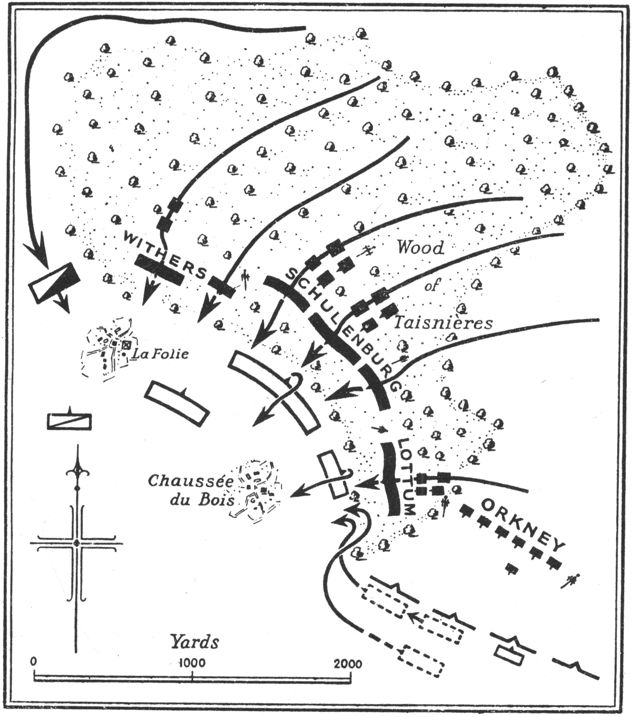

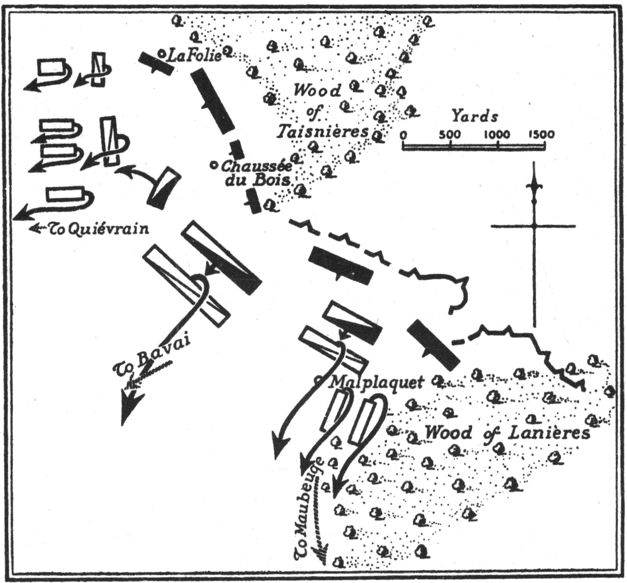

| The Attack on the Wood of Taisnières | 147 |

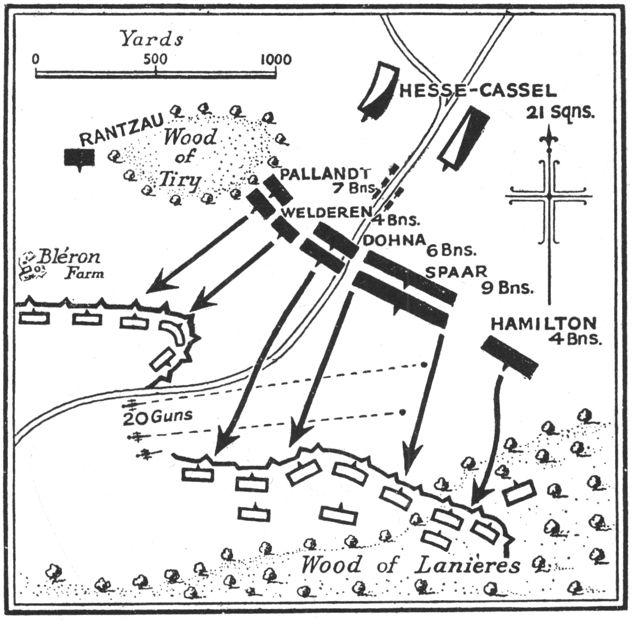

| The Dutch Attack | 149 |

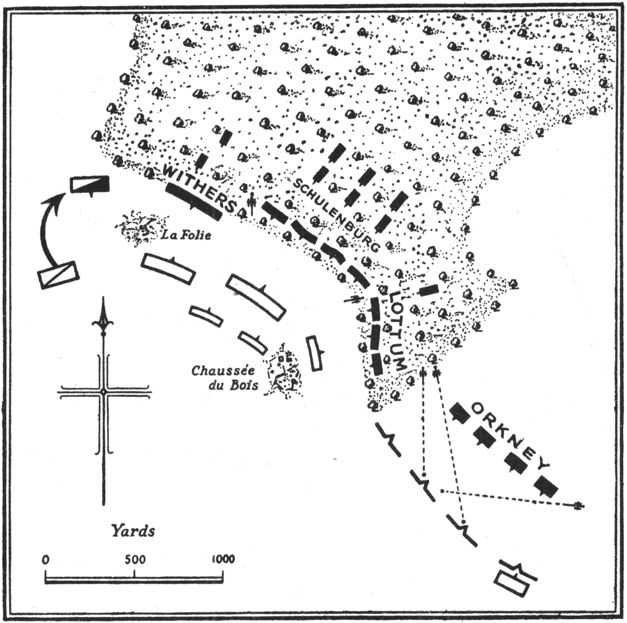

| The Allied Right in the Woods | 157 |

| The Allies reach the Edge of the Woods | 158 |

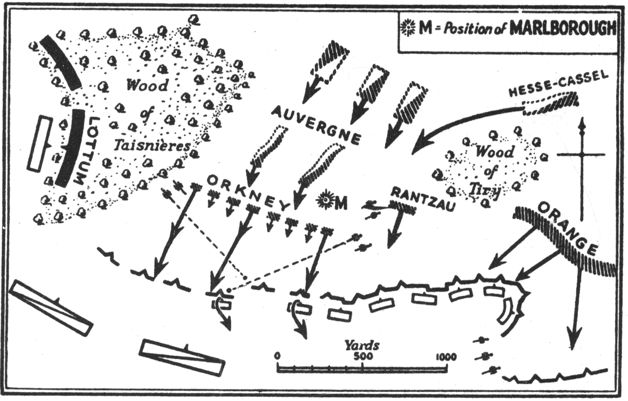

| Orkney’s Attack | 162 |

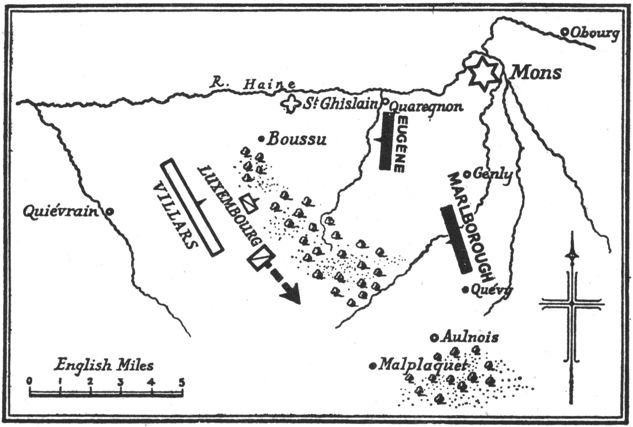

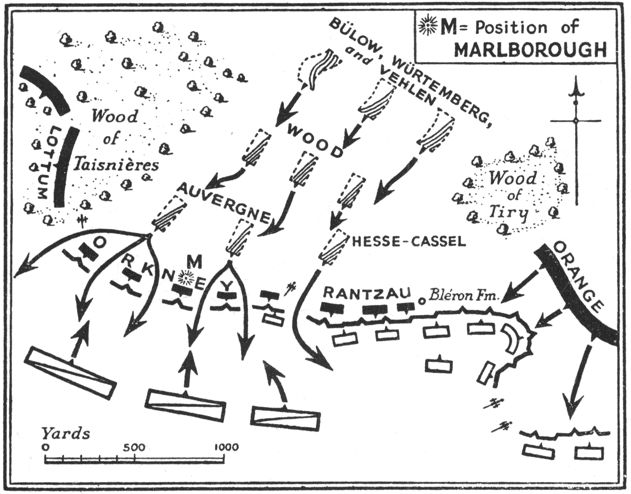

| The Cavalry Attack | 165 |

| The Battle of Malplaquet | 166 |

| Artillery Fire at Malplaquet | 168 |

| The French Retreat | 170 |

| The Siege of Mons | 180 |

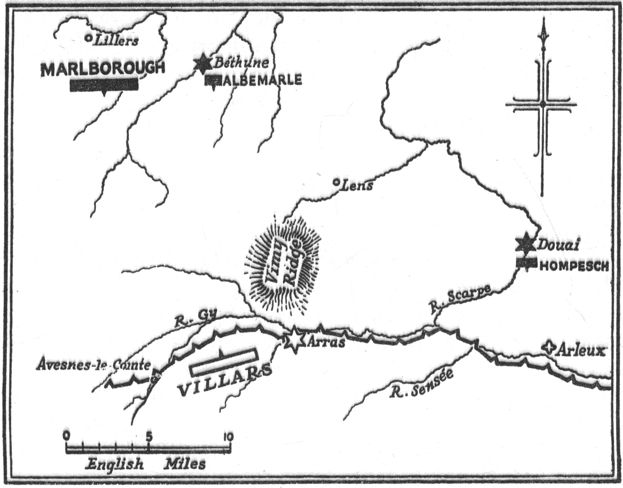

| The Choice in 1710 | 239 |

| The Situation in April 1710 | 241 |

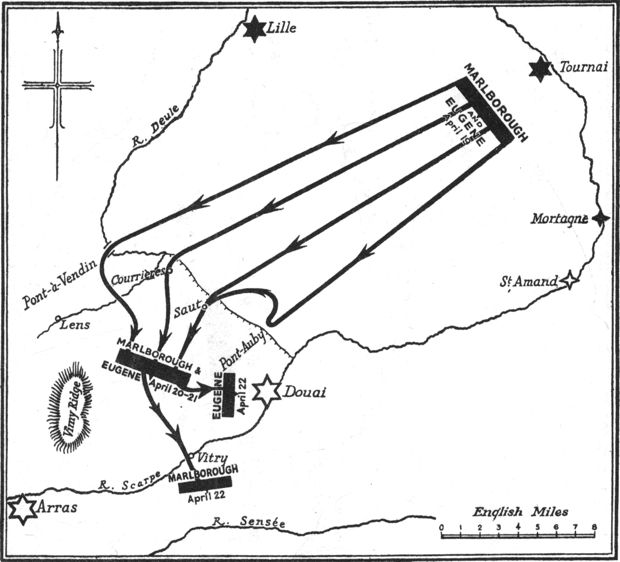

| The Advance: April 19-22, 1710 | 242 |

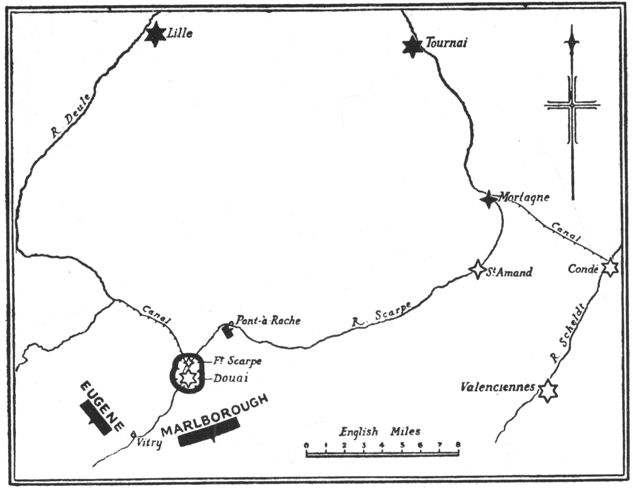

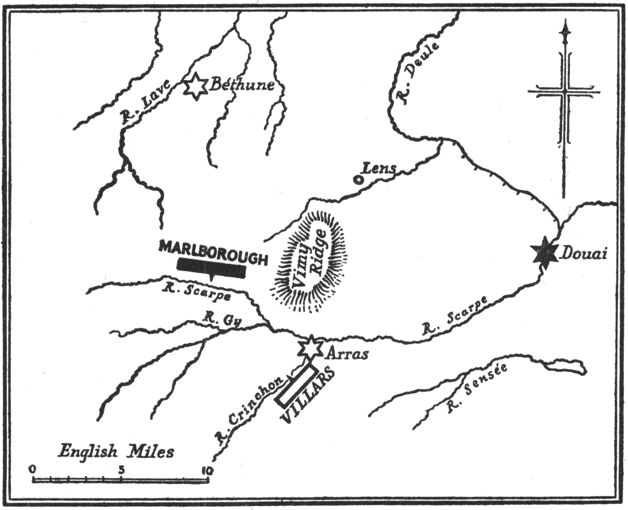

| The Siege of Douai | 244 |

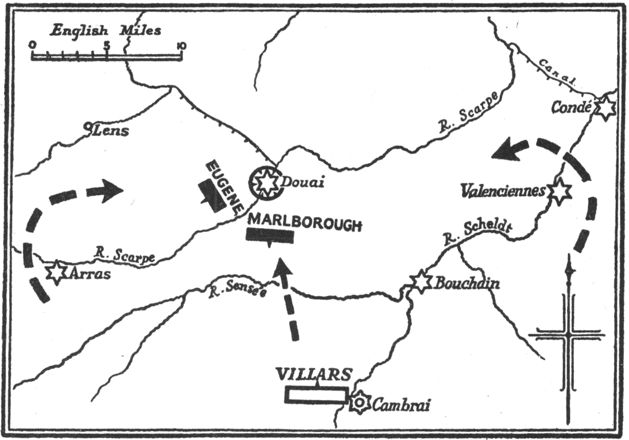

| Villars’s Choice of Action (May 1710) | 246 |

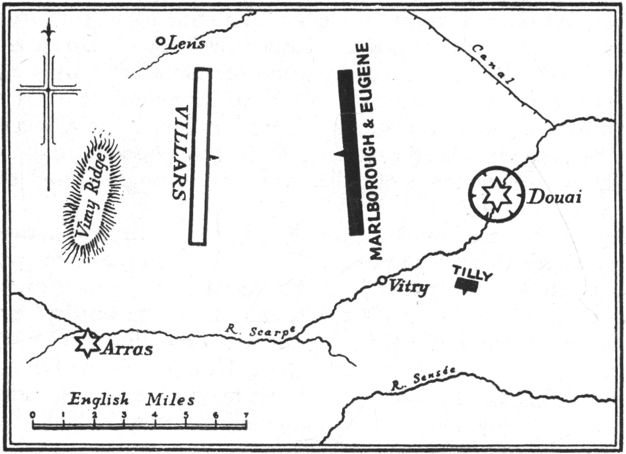

| May 27-30, 1710 | 248 |

| July 12, 1710 | 254 |

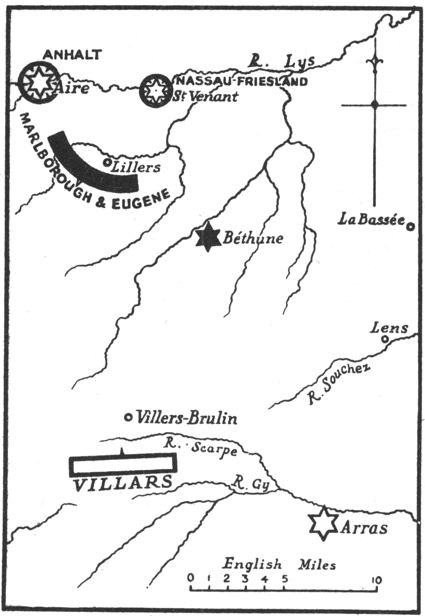

| Sieges of Aire and Saint-Venant | 257 |

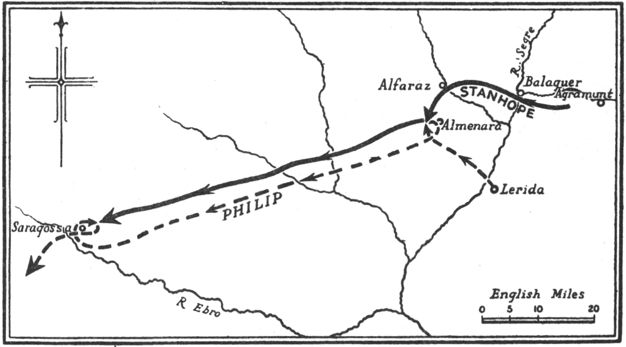

| Almenara and Saragossa | 347 |

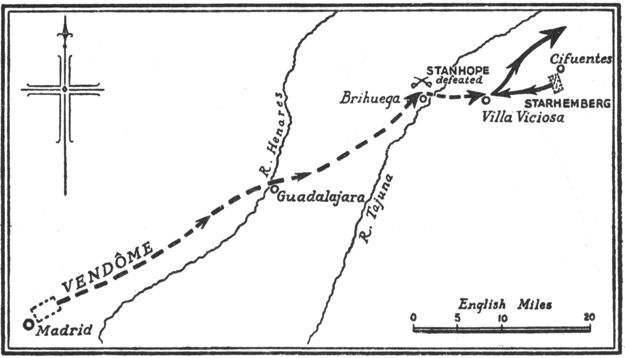

| Brihuega and Villa Viciosa | 350 |

| May 1711 | 411 |

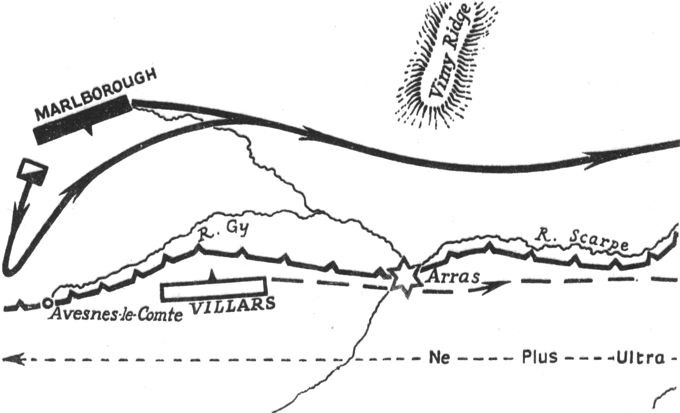

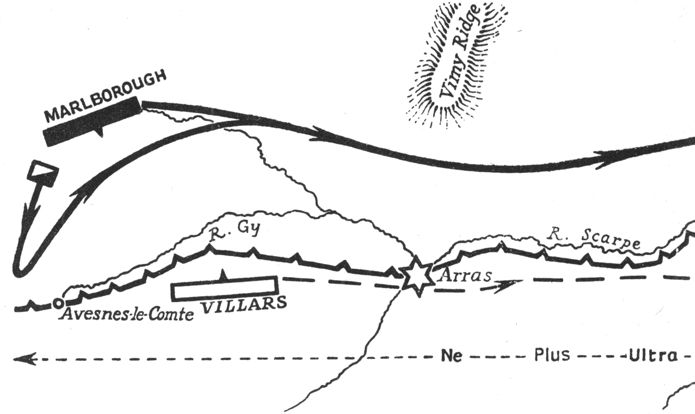

| The Ne Plus Ultra Lines | 416-417 |

| July 26, 1711 | 424 |

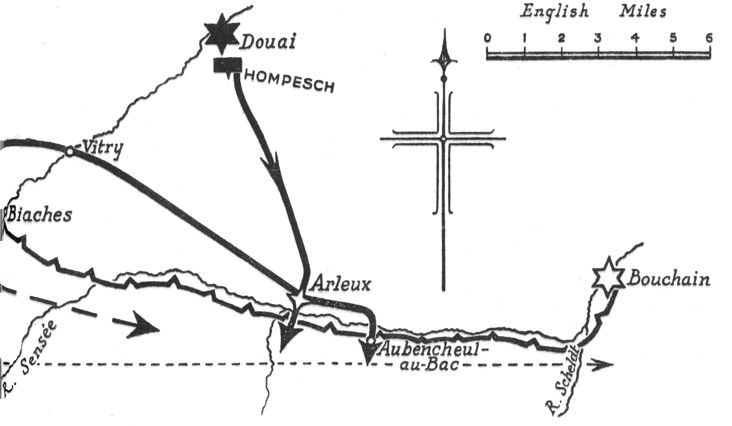

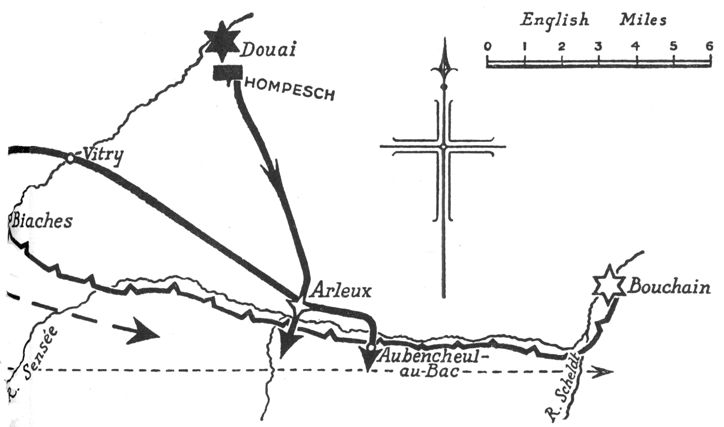

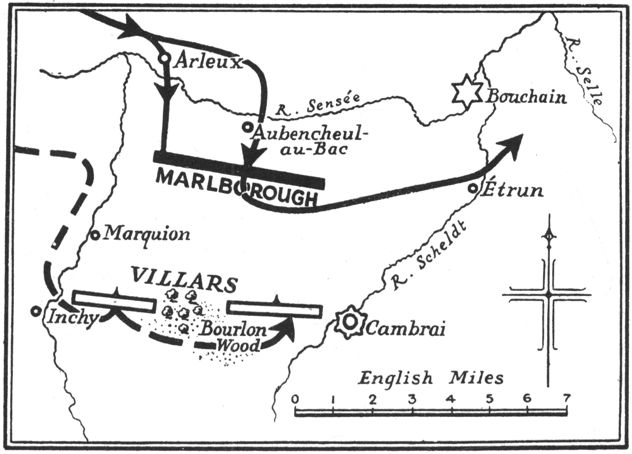

| The March to Arleux | 428-429, 430-431 |

| August 6, 1711 | 438 |

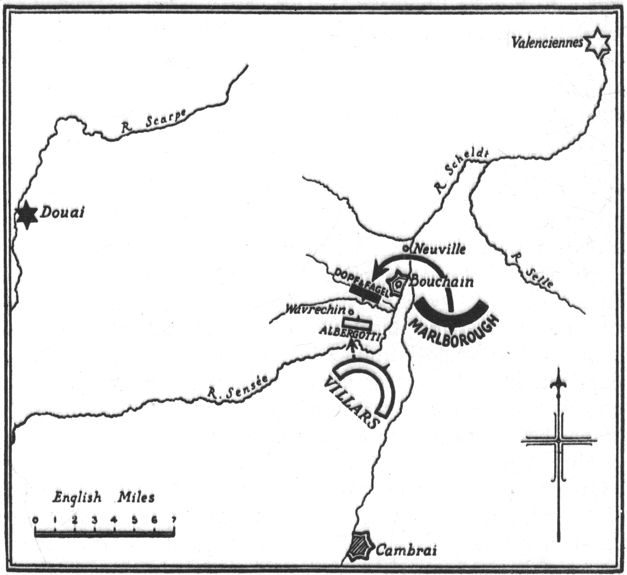

| August 9, 1711 | 441 |

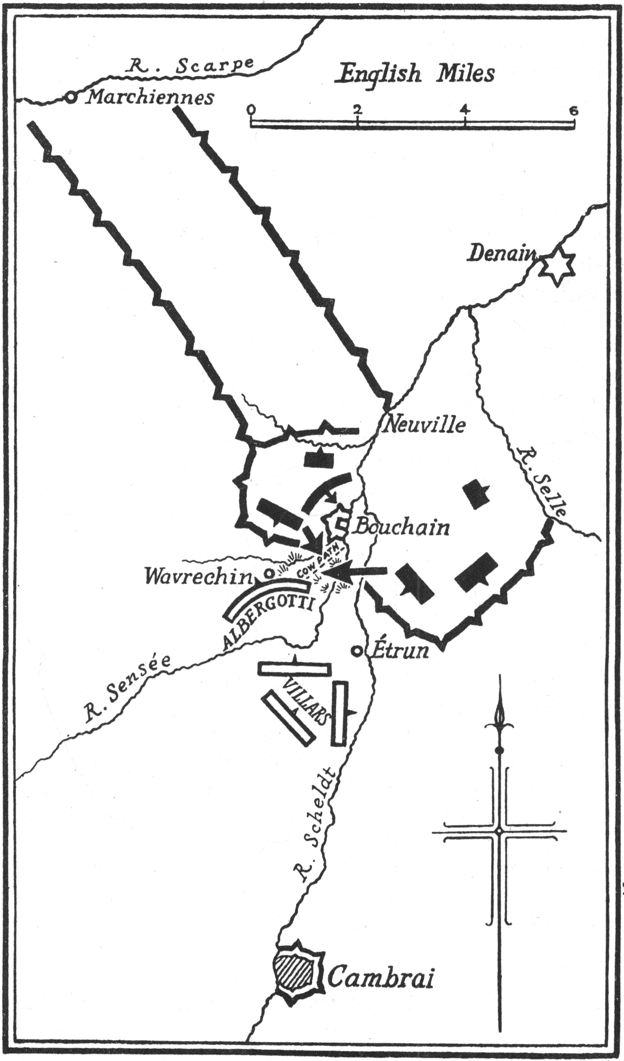

| The Siege of Bouchain | 447 |

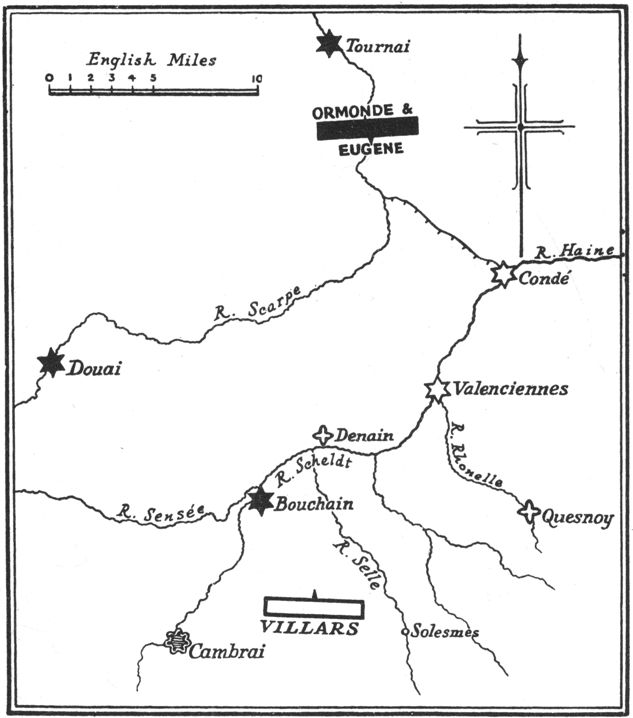

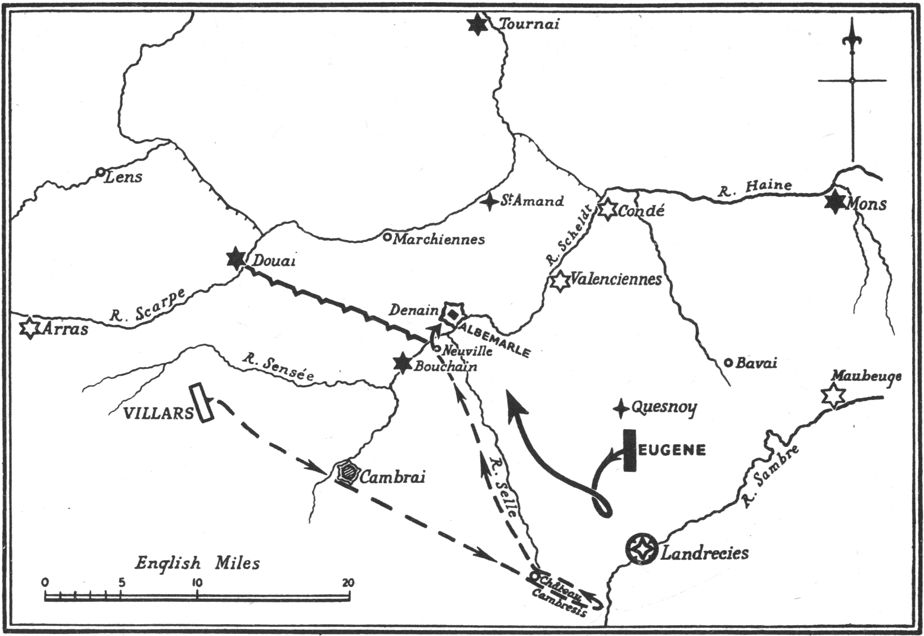

| May 1712 | 540 |

| The Surprise of Denain | 559 |

| The Western Netherlands | 656 |

| General Map of Spain | 656 |

B.M. = British Museum Library.

H.M.C. = Report of the Royal Historical Manuscripts Commission.

P.R.O. = Public Record Office.

S.P. = State Papers at the Public Record Office, London.

Documents never before made public are distinguished by an asterisk (*).

All italics are the Author’s, unless the contrary is stated.

In the diagrams, except where otherwise stated, fortresses held by the Allies are shown as black stars and those occupied by the French as white stars.

Until 1752 dates in England and on the Continent differed owing to our delay in adopting the Reformed Calendar of Gregory XIII. The dates which prevailed in England were known as Old Style, those abroad as New Style. In the seventeenth century the difference was ten days, in the eighteenth century eleven days. For example, January 1, 1601 (O.S.), was January 11, 1601 (N.S.), and January 1, 1701 (O.S.), was January 12, 1701 (N.S.).

The method used has been to give all dates of events that occurred in England in the Old Style, and of events that occurred abroad in New Style. Letters and papers are dated in the New Style unless they were actually written in England. In sea battles and a few other convenient cases the dates are given in both styles.

It was also customary at this time—at any rate, in English official documents—to date the year as beginning on Lady Day, March 25. What we should call January 1, 1700, was then called January 1, 1699, and so on for all days up to March 25, when 1700 began. This has been a fertile source of confusion. In this book all dates between January 1 and March 25 have been made to conform to the modern practice.

The whole of Europe was now weary of the almost unceasing wars which had ravaged its peoples for twenty years. Peace was desired by all the warring states. It was in all men’s minds. The Allies wished to reap the fruits of victory. Louis XIV, resigned to the decision of arms, sought only a favourable or even a tolerable escape. The enormous quarrel had been fought out, and the exorbitant power of France was broken. Not one of the original objects of the war was not already gained. Many further advantages were open. Why then was this peace not achieved in the winter of 1708 or the spring of 1709? Upon Marlborough has been cast the responsibility for this lamentable breakdown in human affairs. How far is this censure just? The issue is decisive for his fame. Before it can be judged his authority and the foundations on which it stood in Holland and in Britain must be measured.

From the day in 1706 on which the Emperor had first offered him the Viceroyalty of the Netherlands a sense of divergent interest had arisen between the Dutch leaders and their Deputy Captain-General. Although Marlborough had at a very early stage refused the offer, the Dutch could not help suspecting first that he owed them a grudge for having been the obstacle, and secondly that he still hoped to obtain the prize. It was known in Holland that both the Hapsburg brothers were intent upon this plan. After Oudenarde Marlborough had been sent a patent for life of the Governorship of the Netherlands. In August 1708 King Charles had written, “I do not doubt but that you will never allow the Netherlands, under the pretext of that pretended Barrier, to suffer any diminution either in their area or as regards my royal authority in them, which authority I wish to place in your hands.”[1]

In reporting the arrival of the patent to Godolphin Marlborough had written, “This must be known to nobody but the Queen; for should it be known before the peace, it would create inconveniences in Holland.” But, he had added, if when the time came Anne “should not think it for her honour and interest that I accept of this great offer, I will decline it with all the submission imaginable.”[2]

Nothing, indeed, could be more correct than his conduct. But the Dutch increasingly regarded him as the interested supporter of Hapsburg and Imperial claims rather than of their own. Rumours of the arrival of the patent were rife in The Hague in December. There is a report in the Heinsius Archives of an interview in December 1708 between Marlborough and the Dutch Intendant at Brussels, a certain Pesters, with whom he was particularly friendly and from whom he gained much information. Marlborough spoke with vehemence.

“In God’s name, what have I to expect from King Charles? He has more than once bestowed on me the government of the Low Countries. I have the patent” (pointing to his strong-box). “No, I have left it in England. But when I learned that it was displeasing to your Republic I renounced the idea, and I renounce it for ever. No, in truth, Pesters” (he always calls me “Pesters” when he wishes to speak with sincerity), “if they offered me in Holland the office of Stadtholder, I swear by God and by my own damnation I would not accept it. I am greatly misjudged. I know of what I am suspected; but my sole thought, after I shall have done my utmost to secure a good and durable peace, is to retire into private life. Nevertheless, if a Governor were required for the Low Countries I do not know why I should be less agreeable to the Republic than another, but I assure you that I have no thoughts of it.”[3]

During the summer of 1708 a correspondence sprang up between Heinsius and Torcy, the French Foreign Minister, the tendency of which was a separate understanding between Holland and France which might well bring about a general peace conference. This was irregular, but not necessarily disloyal. The preliminaries of the Treaty of Ryswick, in spite of the passionate resentment of England, had been arranged for the whole coalition by Holland, and the Dutch Republic conceived itself upon this precedent practically entitled by custom to test for itself, without consulting its allies, the readiness of the enemy to make peace. Louis XIV also was obstinately convinced that the path to peace lay through an initial and separate understanding with The Hague. A means of communication had long existed in the person of Herman von Petkum. Petkum, “Petithomme,” as Marlborough once, perhaps accidentally, spelt his name, was officially the agent at The Hague of the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, but he was in fact the Pensionary’s servant, reserved for just this kind of work. Although he was paid not only by Heinsius and Vienna, but by Torcy,[4] his faithful and skilful labours for peace none the less deserve respect. At the end of May 1708, even before the battle of Oudenarde, Torcy had invited Petkum secretly to Paris, and in August, with the knowledge and approval of Heinsius,[5] he had conversations with Torcy at Fontainebleau. Torcy complained of the obduracy of the Allies. Petkum said this was due to the shifting propositions of France through different channels, and insisted that France must as preliminaries agree to yield Spain and the Indies, and all allied conquests in Brabant, Flanders, and Alsace; must recognize Queen Anne and undertake not to interfere with her or with the order of succession established by Parliament; must restore English trade in France to its former footing, and accord to Holland the tariff of 1664 and a satisfactory Barrier.

Torcy said that France would hazard everything sooner than submit to these excessive demands. On the other hand, he contemplated the partition of the Spanish Empire, was prepared to yield the bulk of it, and also declared that “the maritime Powers should receive security for their trade, and the Low Countries their tariff and their Barrier.”[6]

Having remained at Fontainebleau for five or six days, Petkum returned to Holland and reported everything to the Pensionary. But Heinsius told Marlborough nothing.[7]

It was not proper nor did it prove possible to keep all this from the vigilant Captain-General. During August the news of Petkum’s Paris visit leaked out in high circles at The Hague, and it cannot be doubted that it soon reached Marlborough. In fact, at the beginning of 1709 his Secret Service obtained the whole file of the current Torcy-Petkum correspondence. It was in cipher; but one of his agents, Blencowe,[8] a gentleman from Northampton, succeeded in penetrating the code, and translations of eleven letters are now in the Public Record Office.[9] In the autumn of 1708, however, Marlborough was dependent mainly on oral accounts. He was conscious that his relations with Heinsius were far from sure. He was not willing that Heinsius should pursue separate negotiations behind his back or that of the British Government, and in his turn he sought contact with France.

Throughout the long campaigns Marlborough had maintained correspondence, written in English and under his secret sign “00,” with his illustrious nephew Berwick. In the main this had been concerned with the courtesies of war, and cherished kinship amid national quarrels. It also served to keep alive that link with the exiled family at Saint-Germain which had persisted for so many years. But Marlborough’s civilities, although they always excited tremors of hope, had long ceased seriously to deceive the Shadow Court. It was not till 1708 that the correspondence touched any serious matter. Communication was easy, for Berwick at Château l’Abbaye was but a day’s ride from Marlborough’s headquarters at Helchin, and there was much traffic between the hostile commanders upon the exchange of prisoners, safeguards, and complaints of various kinds. To and fro went the messengers with their trumpets and flags of truce, bearing letters of routine, and other letters also, in their sabretaches. Marlborough took every possible precaution. He enjoined secrecy. He requested Berwick to return each of his letters with the answer. He seems to have trusted him absolutely, and as it proved rightly. Nevertheless, he ran a very high degree of risk in confiding himself to those upon whom he was inflicting such grievous injuries when, without consulting the Queen or the Cabinet, Sarah or Godolphin, Heinsius or Eugene, he at last, in mid-August 1708, definitely set on foot a peace negotiation.

Marlborough to Berwick

August 24

00. I had not had time when I returned your trumpet to answer your last letter. You have no doubt heard of the commotion caused by the respite accorded to mylord Griffin, and that the malcontents say that they will raise the matter when Parliament meets. However, you may be sure that at the first opportunity I shall render a similar service to my lord Middleton’s sons.[10] I would also assure you that no one in the world wishes for peace with more sincerity than I. But it must be stable and lasting, and in conformity with the interests of my country. Circumstanced as I am, I am inclined to think that the best way to set on foot a treaty of peace would be for the proposal to be first made in Holland, whence it will be communicated to me, and then I shall be in a better position to help, of which you may assure the King of France. And if there is anything which he wishes me to know upon this, I beg him that it may not be by other hands than yours, for then you may rest assured that I will tell you my opinion frankly. 00.[11]

It will be seen that Marlborough’s intervention took the form, not of superseding any negotiations already in progress between France and Holland, but rather of broadening their basis, and bringing himself and Britain into them. Berwick replied cordially to this letter, and sent it to the King. Louis and his advisers Chamillart and Torcy were all set on dealing with the Dutch alone. They did not welcome the intervention at this stage of Marlborough, and still less of Britain. They also inclined to regard Marlborough’s letter as only another of his innumerable traps and stratagems. Chamillart thought that it confessed a precarious military position. The answer which Berwick was at length directed to send reflected these views. “It is not now for his Majesty to make such overtures, but for the Dutch.”[12] He invited Marlborough to continue to use him as a channel, and thanked him for his efforts to save the lives of Lord Griffin and Middleton’s sons. Marlborough could only reply, “The King is alone the judge of what is best for his honour and his interest. . . . If ever the King wishes to let me know his intentions about peace, I desire that it should be by your agency, for I shall have no reserve with you, being sure of the care you will have for my safety and my honour.”[13] And a day or two later: “I beg you to believe that I have no other reason for asking you for the return of my letters than the fear of accidents, for I will always trust you willingly with my life and my honour. So pray return me in your first letter that which I wrote you on the 14th.”[14]

During the next two months Petkum continued his activities: “I have promised Heinsius,” he wrote to Torcy (September 11), “to treat with him alone and let him communicate to Marlborough no more than he thinks fit.” But Marlborough had already heard many things. Petkum wrote (September 25), “Marlborough suspects some secret negotiation, and will do what he can to thwart it.”[15] By the end of October the Duke feared that the Dutch were about to quit the Alliance.[16] No answer had been returned to his urgent request for an augmentation of their army for the campaign of 1709, and he saw that the fall of Lille would encourage the Dutch to a quick separate negotiation. Boufflers[17] beat the chamade on October 25, and on the 29th Marlborough received an unsatisfactory reply from Heinsius about the augmentation. Confronted with a grave menace to the Alliance and to British interests, he made a renewed and far more direct effort to gain control of the peace negotiations, and to bring London and Vienna into them.

On October 30, the night that the capitulation terms of Lille were finally agreed, and the day after receiving Heinsius’s refusal to increase the Dutch army, he wrote again to Berwick. This time he proposed that France, counting on his aid, should ask for an armistice and openly seek a peace.

Marlborough to Berwick

October 30

. . . You know that I have formerly assured you of my desire to contribute to peace whenever a favourable occasion should present itself. In my view it is at this moment in our power to take such a step as will produce peace before the next campaign. . . .

My opinion is therefore that if the Duke of Burgundy had the King’s permission to make proposals by means of letters to the deputies, to Prince Eugene, and to me, requesting us to communicate them to our masters, which we should be bound to do, that would have such an effect in Holland that peace would certainly ensue.

There follows this remarkable passage:

You may be assured that I shall be wholeheartedly for peace, not doubting that I shall find the goodwill [amitié] which was promised me two years ago by the Marquis d’Alègre [i.e., the douceur of two million livres]. If the King and the Duke of Burgundy do not feel that this time is suitable for peace proposals, I beg you to have the friendship and justice to believe that I have no other object than to end speedily a wearisome war.

As I trust you without reserve I conjure you never to part with this letter except to return it to me.[18]

It is indeed amazing that any man should have the hardihood to write such a letter to those who regarded him as their most terrible foe—indeed, their only foe. Marlborough is justified before history in pursuing these unauthorized negotiations. In his supreme position, both military and political, he was entitled, on his own judgment and at his own peril, to act for the best for his country, for the Alliance, and for Europe, all bleeding and ravaged by interminable war. It is often inevitable that the first overtures of peace should be made by secret and informal means. Marlborough, for his part, combined all the qualities both of the military and the civil power; he was the soul of the war, and if he thought it was time to make peace he was right before God and man to do so. But to introduce into this grave and delicate transaction a question of private gain, a personal reward of an enormous sum of money, however related to the standards of those times, was, apart from moral considerations, imprudent in the last degree. Yet this conduct has a palliative feature curiously characteristic of several of Marlborough’s most questionable acts. It served interests national, European, and personal at once and equally. It was the one thing capable of convincing the French King and Cabinet of his sincerity. It affected Berwick in this sense immediately. “Although naturally,” he wrote to Torcy on November 2, “I am not taken in by all he says, nevertheless I am inclined to believe in his good faith on this occasion, all the more because he speaks in it of a certain matter by which you know he sets great store.”[19]

It certainly shook the advisers of Louis XIV. “If he is sincere,” wrote Chamillart to Torcy (November 2), “use should be made of his goodwill, which would not be bought too dearly at Monsieur d’Alègre’s figure.”[20] The dreaded conqueror placing himself in their hands in this way, and revealing his personal weakness so nakedly, went far to sweep away their inveterate suspicions. They addressed themselves with renewed concern to his proposal. In the course of their anxious confabulations a memorandum was written, assembling all the arguments for and against the project, which throws a revealing light upon the inmost thoughts of the hard-pressed yet mighty monarchy.

The Duke of Marlborough must amidst all his prosperity fear the envy and antagonism of his own class, the general hatred of his countrymen, whose favour is more inconstant than that of any other people, the fickleness of his mistress and the credit of new favourites, perhaps the death of the Princess [Queen Anne] herself, the resentment of the Duke of Hanover[21] and the residence of his son in England, and lastly the breaking up of the Alliance. . . . If the war could last for ever, a man like Marlborough, who rules absolutely the councils of the principal European Powers and who conducts their armies, might have to make up his mind whether the fear of the future should induce him to abandon so fine a personal position. But in one way or another the war is drawing towards its end. . . .

He might well be satisfied with his glory if he could win peace for his country. . . . He will be no less satisfied upon the point of possessions, which the war has procured him in plenty. It is not just that peace should deprive him of all the advantages which the command of the armies brings him. We might well, therefore, give him to understand, and that without undue circumlocution—scarcely necessary, indeed, with him—that if he worked sincerely for peace he would be rewarded on its conclusion with a sum of two or even up to three million livres, payable at the earliest date, which would be a matter of arrangement.

The influence which Cardonnel has upon his mind is such that it is absolutely necessary to persuade the secretary in order to succeed with the master. The sum of three hundred thousand livres would be usefully employed to this end, and the King agrees to the Duke of Berwick proposing this by the person whom he chooses to speak to the Duke of Marlborough.[22]

In the end, however, King Louis and his councillors could not bring themselves to take the momentous step which Marlborough required. They still saw plainly the shattering effects upon French prestige and French means of resistance which were involved in suing for an armistice or initiating a peace proposal to Holland on the morrow of the fall of the city of Lille. It spelt defeat, acknowledged for all time in letters of fire. Well might they believe that Marlborough was sincere; for what better conclusion could the war hold for him? His sword would have struck the final blow. They would have surrendered beneath its impact, and he would quit the field of war loaded alike with glory and booty. More grievous distresses were needed to bring them to their knees. So, hearkening principally to Chamillart and his false ideas about the immediate military situation, clinging to the hope that the French armies could winter on the Scheldt and that Lille could be regained in the spring, the King directed Berwick to say in reply:

November 5, 1708

You know that the Kings of France and Spain desire peace. . . . You are aware that so far [the Allies] have made no response indicating a genuine desire for a settlement. Their situation, although most brilliant in appearance, cannot prevent those who have experience of war from perceiving that it is strained in all sorts of ways, and may at any moment be so transformed that even if you took the citadel of Lille you might be thrown into extremities which would destroy your armies and put it out of your power to supply with munitions and food the strong places you occupy beyond [depuis] the Scheldt, to recruit and re-establish your forces, and to put your armies in a state to resume the war in the next campaign.

I cannot but think that these reflections, joined to the desire which you have always shown me to contribute to a peace, have led you to write me the letter which I have received from you, which I will send you back if it has no happy results, and which I would return with great pleasure if it proved to have hastened the moment for me to thank you for the part you have allowed me to play in this important negotiation. . . .

If you think it would help the negotiation that the proposals for an armistice should come rather from the Duke of Burgundy than from the Allies, but without any mention of peace proposals, it is for you to bring us to that step in the best way. But in my opinion the conditions under which a suspension of arms could be arranged with your armies still in the midst of territories in his Majesty’s rule, and Prince Eugene besieging the citadel of Lille, will be more difficult to settle than those of a general peace, and it is in this last case that you would receive all the marks of friendship of which the Marquis d’Alègre has given you assurances on behalf of the King.[23]

Berwick was sorry to have to send such an answer. He had arrived by very different paths at the same estimate of the war facts as Marlborough. “Nothing,” wrote Berwick,

could have been better for all than this idea of the Duke of Marlborough’s. It opened to us an honourable doorway to finish a burdensome war. . . . Monsieur de Chamillart from political excess made himself believe that this proposal of Marlborough’s was extorted only by the plight in which the allied armies stood. I confess that this reasoning was beyond me; and from the manner in which Marlborough had written to me I was sure that fear had no part in his action, but only his wish to end a war of which all Europe began to weary. There was no sign of bad faith in all that he said to me, and he only addressed himself to me so as to make the negotiation pass through my hands, believing that this would be helpful to me. Monsieur de Chamillart prescribed the answer for me to make, and I thought it so extraordinary that I sent it in French in order that the Duke of Marlborough might see that it did not come from me. He was, in fact, so affronted by it that nothing fruitful for peace could be gathered from this overture. I even believe that this was the main cause of the aversion which the Duke of Marlborough always showed afterwards to a friendly settlement.[24]

That Berwick was right upon the personal and military issues cannot be disputed. Marlborough felt himself violently rebuffed. He does not seem to have minded at all asking the King of France to give him a fortune if he brought all things to a happy conclusion. He had no consciousness of how disdainfully posterity would view this incident. But he was deeply angered that the other side should dispute his opinion upon the military situation. He was sure he could beat their armies wherever they chose to stand. His peace proposals had been sincere. He had made the French what he deemed a fair offer. They had rejected it. Let them, then, since they were so proud, learn the consequences. In a few weeks he had broken their lines along the Scheldt, recaptured Ghent and Bruges, and driven Burgundy and Vendôme helter-skelter into France. “I am much mortified,” he wrote to Berwick,

to see that you believe I had any other motive for my letter except a wish for peace and the promise which I had given to let you know when I thought the proper time had come to take the steps necessary to secure it. . . . If the King and the Duke of Burgundy feel that secret conferences would be a surer and quicker path, they can propose this to the Pensionary and to some of the States at The Hague, so that when the campaign is finished and I arrive there, I can be informed of what has passed.[25]

He would, he added, continue to do his best to reach a just and lasting peace before the next campaign, “and meanwhile the two armies will be free to make the best use of the advantages which they each suppose they possess. Please send me back my letters with your next.” Marlborough’s request for the return of his letters was evidently complied with by Berwick. The French archives contain only unsigned, undated translations from Marlborough’s English in Middleton’s[26] hand, with comments by Berwick.[27] This fact has a bearing on a future transaction.

THE OLD PRETENDER

A. S. Belle

National Portrait Gallery

So failed Marlborough’s personal effort for peace. That it was wisely and justly founded at the time few can doubt. It is tarnished for us by the alloy of a sordid pecuniary interest. But this, indeed, in that age added to its chances of success. Some writers have actually maintained that Marlborough only inserted this suggestion in order to convince the French Court of his sincerity; and they point to his refusals, to the astonishment of Torcy, of all bribes when these were eventually offered. But the suspicion remains. It reflects more upon Marlborough as a man than upon Marlborough as a worker. He was a greater worker than man. No personal interest or failing turned him from his work. He toiled and schemed with all his power for a reconciled and tolerant Europe, a chastened France, and a glorious England to inherit the New World. As a part in these purposes he delighted in military success. All these conditions being satisfied, and without prejudice to their achievement, he would take pains and stoop for a commission. Supreme sanity, profound comprehension, valiant, faithful action, and if all went well large and punctual money payments!

|

Charles to Marlborough, August 8, 1708; Brussels Archives, quoted in L. P. Gachard, Histoire de la Belgique, p. 337. |

|

W. C. Coxe, Memoirs of John, Duke of Marlborough (second edition, 1820), iv, 246. |

|

H. Pesters to Heinsius, December 17, 1708; Heinsius Archives. See also R. Geikie and I. Montgomery, The Dutch Barrier (1705-19), pp. 93, 373. |

|

Eugene’s report to Vienna, Vienna Archives; W. Reese, Das Ringen um Frieden und Sicherheit (1708-9) (1933), p. 16. See also O. Klopp, Der Fall des Hauses Stuart, xiii, 217. See also Recueil des instructions données aux Ambassadeurs de France, tome xxiii. Petkum received from France 3000 livres a year after 1703; on October 6, 1709, 4000 livres, on March 6, 1720, 3000 livres (French Foreign Office Archives, “Correspondance de Hollande,” tome 200, ii, 117). |

|

Klopp, xiii, 219. |

|

Round Papers, H.M.C., p. 329. |

|

Marlborough to Heinsius, November 6/17, 1708 (Heinsius Archives); Marlborough to Wratislaw, September 25, 1708 (Vienna Archives); Reese, pp. 27-28. |

|

William Blencowe was a Fellow of All Souls and barrister-at-law. He received two hundred pounds a year from the Secret Service fund for his decoding work. Hearne, the Oxford antiquary, calls him “a proud fanatical Whig.” He lost his employment on the arrival of the Tories in office, and shot himself in August 1712. See Remarks and Collections of Thomas Hearne (edited by C. E. Doble, 1889), iii, 439. |

|

B.M., Add. MSS. 32306, 34518. |

|

Lord Griffin and Middleton’s sons were among those captured in the Jacobite descent of 1708. Marlborough had exerted himself to save the aged Lord Griffin from the scaffold. See Vol. V, p. 363. |

|

French Foreign Office Archives, “Angleterre,” tome 226, f. 121; A. Legrelle, La Diplomatie française et la succession d’Espagne, v, 381. |

|

Loc. cit. |

|

Dépôt de la Guerre, tome 2083, p. 68. |

|

Loc. cit. |

|

Round Papers, H.M.C., p. 330. |

|

Marlborough to Heinsius, October 6, 1708; Hague Archives; Reese, p. 28 n. |

|

The governor of Lille. |

|

Legrelle, v, 385. |

|

Ibid., 387. |

|

Legrelle, v, 386. |

|

The Duke, or Elector, of Hanover was offended at not having been fully consulted in the Oudenarde operations. |

|

Legrelle, v, 674 et seq. |

|

Legrelle, v, 390-391. |

|

Memoirs, ii, 51-53. |

|

Legrelle, v, 392. |

|

Secretary of State to the Pretender. |

|

Legrelle, v, 664-665. |

The Lords of the Junto had held together through many baffling years. They now formed the core of a party Cabinet which controlled ample majorities in both Houses. We must not underrate their contribution to the course of public affairs. For years in their splendid country houses, in their clubs, in their party groupings and assemblies, they had examined and discussed every aspect of British politics and of the European war. They conceived themselves the heirs to the majestic estate which Marlborough’s sword and their policy had raised for Britain. They proposed to manage it in their own way, and in accordance with the matured and defined principles of their party, and, above all, in accordance with its interest. On no point did the Whigs ever consciously diverge from that.

The arid, pedantic Sunderland was no longer their chief representative in the Cabinet. Somers had become Lord President of the Council. His outstanding ability, his experience, his learning, his eloquence and aptitude in speech and writing, once joined to a great office, ensured him leadership in the political world. Godolphin, divorced from the Tories, evidently weakened with the Queen, was, in spite of his Treasurership, eclipsed at the council board. His political authority, apart from his long fame, amounted to no more than his unbreakable association with Marlborough.

On the other hand, the fact that the Whigs were now effectively in power, and for the first time satisfied with their treatment by the Crown, removed for the moment all Parliamentary difficulties. For the first time in Anne’s reign the organized dominant forces in the Cabinet and in Parliament had a clear-cut, coherent policy upon the war, upon peace negotiations, and in domestic affairs. The Whig leaders regarded Marlborough as their most valuable instrument. They were at last also contented with Godolphin. Few scruples had governed the pressures they had exerted upon the Crown or upon the Captain-General and Treasurer in order to gain office; but it must be admitted that, once installed, they showed themselves resolute, efficient, and helpful in all the processes of government. They managed the Parliamentary machine with deft and sure touch. Queen Anne had hoped that in practice the Whig Party would be split between the Junto and its moderate elements; but the Junto showed themselves too clever for this. They withdrew their own nominee for the Speakership in favour of the candidate of the moderates, and carried him with a solid party vote. The Royal Speech in November breathed inflexible resolution to continue the war with the utmost vigour. The addresses in reply from both Houses praised the Queen’s conduct of affairs in glowing terms. The successes of the campaign were extolled, and the thanks of Parliament were once again voted unanimously to the Duke of Marlborough for his latest successes and for the energy which he was displaying in the national service. Since he was still abroad, a delegation was sent to present these tributes to him. Without waiting for any similar decision by the Dutch, an augmentation of ten thousand men was voted for the army in Flanders.

Finance was the field in which the Whig mastery was greatest. The whole force of the City, of the Bank of England, of the moneyed classes, obeyed the Ministerial requirements with the enthusiasm of confidence and interest. The largest estimates yet presented were cheerfully accepted by the House of Commons. All Europe marvelled that in the seventh year of so great and costly a war, when every other state was almost beggared, if not bankrupt, the wealth of England proved inexhaustible. Indeed, it seemed that the Government held a magic purse. The yield of high taxation was reinforced by internal borrowing upon the largest scale yet known. The Bank, in exchange for a twenty-one years’ extension of their charter, bound themselves to provide four hundred thousand in cash and issue two and a quarter millions of bank-bills. The lists were opened on February 11. Within four hours of nine o’clock the whole amount was subscribed, and eager would-be lenders were turned away in crowds.[28] Hoffmann dilated to the Emperor upon these prodigies, as they then seemed to the world. “Outside England,” he wrote,

it would appear incredible for this nation, after it has provided four hundred million Reichsthaler during nearly twenty years of war, to be able to produce a further ten millions in a few hours at the low rate of interest of 6 per cent. It must be observed that this has not been done in cash, which is now difficult to obtain, but in paper, particularly banknotes. Indeed, not a penny of these ten millions was paid in cash, but all in banknotes. These banknotes circulate so readily here that they are better than hard coin. So the whole of this wealth appears to be based almost entirely upon the credit of the paper money and the punctual payment of the interest.[29]

In the ordinary tactics of party also the Whigs easily out-manœuvred the Tory Opposition. They freed Marlborough and Godolphin from the minor annoyances which they had so long endured while unprovided with a disciplined majority. If there were losses and arrears in the yield of the Land Tax they would allow no censure to fall upon the Treasurer. Godolphin’s name was deleted from the hostile motion by 231 votes to 97. If there were reproaches that the measures to defend Scotland at the time of the invasion had been inadequate, these were converted into votes of confidence and thanks to the Queen’s Government for the great and effectual precautions they had taken and for their success. If “warm speeches were made against him, and he was roasted, as they call it,”[30] the Whigs hastened to his aid. There was another little matter in which the Whigs made themselves obliging to the two non-party or super-Ministers. An act of general pardon was passed for all correspondence with the Court of Saint-Germain, and, indeed, for all past treasonable actions of any kind except treason upon the high seas. This last provision was designed to exclude the Jacobites who had actually sailed in the invading fleet the year before. Thus the slate was cleaned, and a very large number of Tories and Jacobites both in England and Scotland, who lay under anxieties for what they had done or planned to do if the Pretender landed, were generously released by those who might have been expected to be their chief prosecutors. Gratitude from this quarter was neither expected nor received.[31]

JOHN, LORD SOMERS

From an engraving after a painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller

Marlborough had always pursued his devious way serene and imperturbable. He did not concern himself with the Amnesty Bill. But Godolphin, whom Wharton had recently confronted with one of those customary sentimental letters to Mary of Modena which the Treasurer persisted in writing, was certainly well pleased to have an Act of Parliament between him and future reprisals by his enemies. It is perhaps of significance that the Queen gave consent to the Bill on the very day of its passage. To have the Whigs showing themselves so accommodating to her Tory and Jacobite friends and to Mr Harley, lately harried again over the Greg affair, was at any rate some compensation for their presence at her Council.

But the incident most illustrative of these times concerned the Queen herself. A number of young Whig Members moved an address to the Queen urging her to marry again. This striking proposal was not only supported by the House of Commons, but endorsed by the Lords. At this time Queen Anne was in the depths of mourning for her husband. She had already been eighteen times disappointed of an heir by death or miscarriage; she was within a few days of her forty-fifth birthday. It had, in fact, been decided to omit from the accession service the prayer that the Queen might be “an happy mother of children, who, being educated in Thy true faith and fear, may happily succeed her in the Government of these kingdoms.” What wonder then that many regarded such a suggestion to the Queen as ill-timed and indecorous? Indeed, Mordaunt, Peterborough’s younger brother, who sat in the Commons, raised a general laugh when he suggested impudently that the address should be presented only by Members who had not yet reached their thirtieth year. The explanation was, however, simple to those who were behind the scenes. The bitterness which the Whig triumph aroused in the Tory Opposition had led them once again to bait the Queen with the prospect of bringing over the Electress of Hanover or her son to visit or, perhaps, to reside in England. The Whig counter-move was to urge the Queen to marry again, for she could hardly be urged to do this one day and to bring over the existing heir the next. It seems certain that the Queen fully understood the tactics of both the attackers and the defenders. She replied by message sedately the next day: “The subject of the address is of such a nature that I am persuaded you do not expect a particular answer.”[32] But if the Queen, weighed down by her grief and increasing infirmities, was thus quaintly protected by the Whigs from a Hanoverian intrusion, and might even recognize their Parliamentary dexterity, she nevertheless sought their expulsion from office as her chief desire.

At this time one would suppose Marlborough and Godolphin had all they could ask in Britain for themselves or for their policy. Yet their intimate letters reveal their profound misgivings and discouragement. Godolphin harps again on vexations to which “the life of a slave in the galley is paradise in comparison.”[33] Marlborough replies that nothing but his loyalty to his colleagues and his duty to the Queen would make him endure the burden and hazards of his command. There is so much bewailing in the Marlborough-Godolphin correspondence, written for no eye but their own, that many writers have questioned the sincerity of these tough, untiring personalities who, in the upshot, held on with extreme tenacity and to the last minute to every scrap of power. It was surely, then, no mere desire to keep up appearances before each other, but rather to fortify their own minds for action by asseverating their own disinterestedness, that made it worth while to set all this on paper? It is certain that neither was deceived by the favourable surface which British politics had assumed. Both knew too much of what was hidden from Parliament and even from the foreign envoys in London. They knew Queen Anne with the knowledge of a lifetime. They knew the Tory Party to its roots. They had enjoyed the best opportunities of measuring ex-Secretary of State Harley. Thus their eyes were necessarily fixed upon Abigail and the visitors she brought to the Queen by the backstairs.

Party government in time of war might show management and efficiency, but it lacked the deep-seated, massive strength of a national combination. This was revealed only too clearly upon the question of conscription. The fighting had lasted so long in 1708 that the regimental officers concerned in recruiting not only for reinforcements, but even for drafts, were very late in coming over. Parliament had voted an extra ten thousand men for the coming campaign, but had not yet faced the difficulties of recruiting them. Several proposals had been put forward in Ministerial circles. One was the Swedish plan that owners of houses and land should be organized in groups, each group being responsible for the maintenance of a recruit. Walpole, the Secretary-at-War, proposed recruiting the English Army after the French pattern, based on the obligations of each individual parish. But the Cabinet did not feel strong enough to adopt either scheme in the face of high Tory and Whig opposition. Even the tightening up of the existing recruiting laws upon the unemployed and idle was not carried through.[34] In fact, apart from hired foreign contingents, the proportion of British soldiers in the allied ranks was smaller in 1709 than ever before.

Neither could the Whigs bring to the peace negotiations the real force of a national decision. A Whig Government might in 1707 and earlier years have been most helpful to vigorous war. In 1709 their peculiar qualities, prejudices, and formulas were a new obstacle to the peace now within reach. England had little to ask for herself. The recognition of the Protestant Succession, the expulsion of the Pretender from France, and the demolition of the harbour and fortifications of Dunkirk seemed modest requirements for the State and nation which had formed, sustained, revived, and during so many years led to victory the entire coalition. But upon the general objective of the war the London Cabinet was implacable. The whole of the original Spanish Empire—Spain, Italy, and the Indies—must be wrested from Philip V, the Duke of Anjou, and given to Charles III. As early as 1703 Rochester and the high Tories, intent upon colonial acquisition, had raised the cry “No peace without Spain.” The Whigs, while holding a different view about strategy, were for their part more than willing to associate themselves with this sweeping demand. What had become for years a Parliamentary watchword was now to be made good. This was not only an extension of the original purposes of the war; it was a perversion of them. The first aim had been to divide the Spanish inheritance; now it was to pass it in a block to the Austrian candidate, himself the direct heir to the Imperial throne of the Hapsburgs. From the rigid integrity of this policy there was not to be even the slightest concession. Nothing was to be offered to the Duke of Anjou. Nothing was to be offered to Louis XIV. In order to carry into history their English Parliamentary slogan, the British Government, with Parliament behind them, were ready to shoulder all the demands of the Empire upon the Rhine, including Strasburg, all the demands of the Duke of Savoy, and almost all the demands of the Dutch for their Barrier.

There is no doubt that responsibility for the loss of the peace in 1709 lies largely upon England, and that the cause arose unconsciously out of her Parliamentary stresses. In Parliament the Spanish theatre always commanded vivid and abnormal interest. Money for Spain; troops for Spain; ships for Spain; a base for the fleet in Spanish waters; war in the Peninsula; no peace without its entire surrender—these were phrases and ideas popular not merely for a session but year after year, and enlisting a very general measure of active support. Marlborough throughout regarded the whole of this Spanish diversion as a costly concession to wrong-headed but influential opinion. By one device or another he had contrived to reduce it to the least improvident dimensions. He scraped away troops and supplies on various pretexts. He sought his results in Flanders or at Toulon. Nevertheless, as in the famous debate of December 1707,[35] he found it necessary to his system to humour Parliament in these ideas which were so strangely cherished by them. No doubt he found it convenient to gather support for the general war by adopting and endorsing the watchword “No peace without Spain.”

Indeed, at this juncture in 1709 we find Marlborough mouthing this maxim, to which he had become accustomed, as fervently as its ill-instructed devotees. He was committed to it by the shifts to which he had been put to gain supplies from precarious majorities in former years. It had become a sort of drill, a parade movement, greatly admired by the public, of doubtful value on the battlefield, but helpful in recruiting. So now, at the culmination of the war, Marlborough marched along with the Cabinet and Parliament upon this Spanish demand; and the whole influence of England, then paramount, was used to compel the Dutch and incite the Empire and German states to conform. The Whigs in the brief morning of their power invested this demand with their own sharp precision. Upon it was placed an interpretation which certainly had not been adopted by any English party at an earlier stage. ‘Spain’ was made to include not only the Indies, but Italy. The interests of the City and of the Whig merchants in the Levant trade now found full expression in the Cabinet. “Let me tell you,” said Sunderland in April to Vryberg, the Dutch envoy, “that any Minister who gave up the Sicilies would answer for it with his head.”[36] There could be no compromise with the Whigs about Sicily and Naples.

It has been remarked as curious that each side in the great war, while remaining in deadly conflict, had in fact largely adopted the original standpoint of the other. The English, who under King William had seen their safety in the partition of the Spanish Empire, now conceived themselves only served by its transference intact to the Hapsburg candidate. The Spanish nation, which at the outset cared little who was their king so long as their inheritance was undivided, were now marshalled around their Bourbon sovereign, and were almost indifferent to what happened outside the Peninsula. The insistence by England upon her Parliamentary formula destroyed the victorious peace now actually in her grasp. The incidents of the negotiations which will presently be recounted followed inevitably from this main resolve. But although England with her wealth and Marlborough’s prowess could, as the event showed, over-persuade the Allies to her point of view, her resulting position was unsound and even absurd. Neither the Dutch nor the German states had the slightest intention of making exertions to conquer Spain after they had made a satisfactory peace with France. Austria, at once famishing and greedy, was impotent for such a purpose. Upon England alone and the troops she paid must have fallen the burden of conquering not only Spain but, as it had now become, the Spanish nation. It is certain that this was a task of which she would soon have been found incapable.

The Dutch demands were more practical, but no less serious. They had fought hard and long for their Dyke against France. It was now certain they would gain it. Exactly which fortresses, how many of them, where the flanks of the line should lie, were to be matters of sharp discussion with the French, with the English, with the Prussians, and still more with the Empire. But in all that concerned military security friend and foe were agreed that the Dutch rampart should be established. During the course of the war the Dutch trading interests had come to regard the conquest of the Barrier of fortress towns as carrying with it control over the commerce of the whole countryside between the fortresses. The Empire, the Allies, King Charles III, several of the most important German states, and also England had rights or interests which this Dutch demand affronted. In those days the wishes of the local population, with their charters and long-established customs, also counted. The Belgian people, Flemings and Walloons alike, were no friends of France. They were prepared in the circumstances to be ruled by Charles III of Spain, by the Elector of Bavaria, or, if that could be brought about, by the Duke of Marlborough. The one solution which was abhorrent to them was the intimate exploitation of their Dutch neighbours. We have seen how, as Marlborough predicted in 1706, eighteen months of Dutch rule over the Belgian cities had produced a universal disaffection, culminating in the treachery of Ghent and Bruges. A hundred and thirty years later the severance of Belgium from Holland arose from the very same antagonisms which surged within the victorious Grand Alliance and beat upon the head of Marlborough. It was not only fortresses the Dutch wanted, but the trade of Belgium. The London Cabinet was, however, in no position to read the States-General a lecture. In the summer of 1707 Stanhope had induced King Charles III to give special trading rights in the Indies—ten ships a year—to England. This was a minor, though none the less vexatious, breach of the pledge binding on all signatories of the Grand Alliance not to seek special favours at the expense of their confederates. The Dutch might claim that this liberated them from their own undertakings.

The Tories were prepared to make a stand for British trading interests in the Low Countries. But the Whig Junto dwelt upon the Dutch guarantee of the Protestant Succession which assured their ascendancy in Great Britain. Marlborough, whose outlook was European and covered at the least the whole compass of the Grand Alliance, saw from the beginning that if the Dutch had their way in the Spanish Netherlands, not only about the Dyke but about trade and government, the Empire would be fatally estranged. Charles III would be virtually stripped of his dominions in the north, Prussia would be indignant, the cohesion of the Alliance would be ruptured, and the English Tories would make the satisfaction of Dutch pretensions at the expense of British trade a mortal grievance against the Minister responsible. The argument which Marlborough used so often, that, once satisfied about their Barrier, the Dutch would desert the war, was disproved by the event. After the Barrier Treaty, which gave them their fill, had been signed by the Whig Ministers, the Dutch, so far from abandoning the war, fought all the harder for this dear prize. Indeed, it was only England who quitted the field.

Why did Marlborough not see that it would always be possible for England in conceding the Dutch demand about the Barrier to stipulate, as was in fact done, for a still more vigorous prosecution of the war by the Republic? His contention, though valid in the controversy of 1709, was stultified by the final outcome. He had, however, broad as well as particular reasons for opposing the Barrier Treaty. It seemed to him the highest unwisdom to give one of the members of the Alliance all that they desired, thus offending and unsettling the others, before the military power of the common enemy was decisively broken and it was certain the war could be ended. Moreover, his personal influence upon events must be seriously prejudiced. He saw, with his customary clarity, that if his were the hand that signed this invidious pact the wrath of all the disappointed members would be vented upon himself. His own countrymen were turning against him. The Dutch found themselves able, and preferred, to deal over his head with the Whigs. Must he then break with the Empire, with the two Hapsburg sovereigns who wished to make him almost a king, and with Eugene, his faithful comrade? Must he, by accepting the Dutch view of the Prussian claim to Guelderland, alienate that jealous Prussian Court, with whom his influence stood so high, for whose splendid troops he was in constant entreaty? Thus smitten, how could he conduct the war, if after all it had to be resumed? Whatever else a Barrier Treaty agreeable to the Dutch might mean, it was certain that Marlborough could not make it without destroying the whole system upon which he had hitherto led the Alliance through so many perils and shortcomings to what in the spring of 1709 seemed to be almost unbridled victory. For all these reasons, public and also more personal, which nevertheless on the whole corresponded to the essential needs of Europe, Marlborough, as we have seen, had hitherto delayed the Barrier Treaty and was bent on persevering in that course.

The divergence between Marlborough and Heinsius was thus inevitably serious. The Pensionary had been vexed by Marlborough’s obstruction of the Barrier negotiations in 1706. He had for months been conducting secret parleys with France on the basis that Marlborough was not to be told about them. Already in December 1708 Heinsius had gone so far as to instruct Vryberg to discuss the Barrier Treaty directly with Somers[37] and to appeal to the new Whig Ministers apart from Marlborough. In December Vryberg reported that he had done so, and had found the Whig leader very desirous of a settlement with Holland on the basis of a reciprocal guarantee about the Barrier and the Succession. Godolphin wrote to Marlborough that he agreed with Somers. The formal proposals for a Barrier Treaty which he was expected to negotiate reached Marlborough on his way from Ghent to The Hague, and on arrival he was officially told about the French peace offers through Petkum.

At this time he believed that any peace offer from France would only be an attempt to amuse and cheat the Allies. Accordingly when the Pensionary harped upon the Barrier Marlborough diverted the discussions to the Dutch quota of troops for the new campaign. As the mails from England were weatherbound, he was able to profess himself without sufficient instructions. Heinsius had, however, already threatened Godolphin that he would send Buys, the Amsterdam leader and a friend of Harley, to London to conduct the Barrier negotiations there if Marlborough proved obdurate. He appealed to the Whig Junto over Marlborough’s head, and with success. The Cabinet, and especially Godolphin, who feared Buys’ Tory contacts, was anxious to prevent a Dutch mission arriving in London. Sunderland did not hesitate to criticize Marlborough to Vryberg, the Dutch Ambassador. When he was told that Marlborough pretended to have no powers Sunderland said, “I cannot imagine what reasons my Lord Duke can have for doing so.”[38] Vryberg lost no time in telling Heinsius that Marlborough was disavowed by the Secretary of State, “who does not hesitate even to gainsay his father-in-law’s opinions when he thinks they are not right.”[39] Thus at the outset of these all-important negotiations Marlborough found himself to a large extent isolated. He was divided both from the Dutch and from his own Government upon large issues of principle and procedure.

His main wish was to convince the Dutch that he cared more for their confidence in the conduct of the war than for the Viceroyalty of the Netherlands. For this he took during the spring and summer a series of steps which were painful to him. The question of the Viceroyalty did not slumber. In February Charles pressed him further.

Charles III to Marlborough

February 2, 1709

* On the return of Mr Craggs I have received yours of October 29 in answer to that which I had entrusted to him upon his departure for England. He has given me an ample account of all you had commissioned him to say, and in particular of your zeal in working for all that can help my interests. . . . I am sure you will continue to respond in the same manner as you have always done. Indeed, you could not better employ your zeal than for a Prince whose interests are always and will ever be so tightly bound up with those of your Mistress, the Queen. . . . As to what I have written you formerly concerning my Low Countries, you will find me always ready to keep my word. I should indeed feel a keen regret [déplaisir] if by any accident or consideration you should be turned from accepting this mark [marque: this word is added in Charles’s own handwriting] of my gratitude and of the esteem which I have formed of your merit. I approve, however, the prudent dissimulation which you have used up till now in the direction of the Dutch; although it would be equally useful to the Common Cause, and necessary for the repose and comfort of my Low Countries, if the States-General would allow them at least to take the oath of fidelity. I need not desire you to uphold my interests in the present session of Parliament, because your own zeal will lead you to do that yourself, and particularly in all that can re-establish our affairs, and put us in condition to wage an offensive war in Spain. . . .[40]

Marlborough conveyed through Stanhope, with whom he had relations of close confidence and friendship, an account of the difficulties which prevented him from accepting the Viceroyalty.

King Charles replied (June 16):

I had thought to give you some evidence of my goodwill in this matter in the message which I sent you formerly by the resident Craggs, but what General Stanhope has just told me on your behalf has caused me trouble and disquiet. I hope none the less that the consideration which you wish to have for the Dutch in this juncture will soon cease to carry weight with you, and that in other circumstances you will have the pleasure of enjoying this small mark of my gratitude—to put it better, that I shall myself profit by your good government and the good order which you would bring into the Low Countries.[41]

Up to this moment Marlborough had still nourished hopes of ultimately receiving the appointment. But in the middle of 1709 he took a decisive step to exclude himself. At all costs to himself he must regain the confidence of the Dutch. A letter from Charles III to Wratislaw on June 30, 1709, shows how far he went. Not only did he three times specifically refuse this magnificent office, but he urged that it should be conferred upon Eugene. He thought that only by the substitution of another name for his could the misunderstandings between him and the Dutch be finally removed. Reluctantly he had reached the conclusion that only this sacrifice would preserve that Anglo-Dutch unity, the keystone of the whole Alliance, which was now in jeopardy.

Charles III to Wratislaw

June 30, 1709

[As to] what concerns the person of the Duke of Marlborough, to whom I alone upon the advice of Moles[42] have given the patent of the Governor in the Netherlands, which he has three times resigned and bidden me rather to name another ‘actualen’ [in order] to placate the jealousy of the Dutch. He has also written about this matter to the Emperor to ask if he does not think that it would be better to send Prince Eugene himself there, for he is very popular with the Dutch, and it is at the moment very necessary to bring order into the whole Barrier affair, and thereby to animate the Dutch further.[43]

It would no doubt have been agreeable to Marlborough, since he was resolved not to accept the Viceroyalty himself, to have it conferred upon his friend and comrade Prince Eugene. With Eugene in control of the Spanish Netherlands, he could be sure that the treatment of the Belgian inhabitants and the general course of the government would be no hindrance to the military operations. But to propose Eugene for the appointment was by no means to secure it for him. The question became a burning one as soon as Eugene reached Vienna. The Prince himself was anxious to accept. He had been baulked by internal jealousies in 1706-7 of his desire to remain Viceroy of the Milanese. Here now was the opportunity of gaining a finer kingdom, where he would be more closely knit with Marlborough for any further campaigns in the Low Countries. His enemies, however, were as persistent as ever against him. They were now reinforced by the apprehensions of his friends, who saw themselves likely to be deprived in the future of his leadership and protection in Vienna. Thus Marlborough’s proposal was never made public by the Emperor or by Charles III, and it was only after a lapse of a hundred and fifty years that the fact became known.

|

Boyle to Marlborough February 9, 1709 * . . . At a general court held this morning they [the Bank] agreed to open their banks for an additional subscription of two million two hundred thousand pounds. We shall make the way easy for them to supply the Government with any amount my Lord Treasurer proposes. P.S. February 11.—The subscription of the bank was filled to-day, not lasting for four hours. [Blenheim MSS.] Sunderland to Marlborough February 11, 1709 * This day was appointed for taking the subscriptions of the Bank, and the whole sum was subscribed by twelve o’clock; the like I believe was never known in any country. I hope it will have its weight in France. [Ibid.] |

|

Hoffmann’s dispatch, March 5, 1709; Klopp, xiii, 206-207. |

|

Peter Wentworth to Lord Raby, March 1, 1709; J. J. Cartwright, The Wentworth Papers (1705-39) (1883), p. 77. |

|

Ibid., p. 83. |

|

Parliamentary History of England (Hansard), edited by William Cobbett and J. Wright, vi (1810), 778. |

|

Coxe, iv, 356. |

|

Report of L’Hermitage, January 1 and February 1, 1709; C. von Noorden, Europäische Geschichte im achtzehnten Jahrhundert, iii, 385. |

|

Vol. V, pp. 342-345. |

|

Vryberg to Heinsius, April 26, 1709; Heinsius Archives. |

|

Heinsius to Vryberg, December 14; Hague Archives. |

|

Heinsius Archives, quoted in Geikie, p. 104. |

|

Loc. cit. |

|

Blenheim MSS. |

|

Ibid., and Geikie, p. 373. |

|

The Duke of Moles was Charles’s principal councillor and Austrian representative at Barcelona. |

|

Ritter von Arneth, Prinz Eugen von Savoyen (1864), ii, 467. |

The campaign of 1708 had ended according to Marlborough’s “heart’s desire,” and although it had been protracted beyond all custom into the depth of winter and over the end of the year, his warlike energy was entirely unabated. “This has been,” he wrote to Godolphin (January 31, 1709), “a very laborious campaign, but I am sensible the next will be more troublesome; for most certainly the enemy will venture, and do their utmost to get the better of us; but I trust in the Almighty that he will protect and give success to our just cause.”[44] Neither his own fatigues and worries nor his deep desire for peace had slackened his preparations for 1709. While peace negotiations regular or secret, now by this channel, now by that, made The Hague a whispering-gallery, Marlborough had already for two months past been concerting with Godolphin, the British Cabinet, and throughout the Grand Alliance the marshalling for 1709 of the largest armies yet seen in Europe. In order that the whole movement of the Alliance towards its goal should be unfaltering, it was planned that he and Eugene should take it in turns to remain in Holland driving forward the gathering of men, munitions, food, and forage, and making sure that no signatory state fell out of the line. Eugene’s presence in Vienna being judged at first indispensable, Marlborough stood on guard in Holland during January and February. As soon as the fall of Ghent liberated the confederate armies for what remained of the winter he repaired to his headquarters at Brussels, and thence, with occasional visits to The Hague, began to pull all the levers of the vast, complicated, creaking machine of which he was still master.[45]

He seems to have quartered himself when at The Hague upon the Prussian commissary, General Grumkow, who wrote some droll accounts to his master:

My lord Duke has obliged me to take a furnished house opposite the Orange palace and is living there himself. This costs me twenty louis d’or a month, and as I have very good Tokay, qu’il aime à la fureur, I gave his Highness a supper yesterday, which was attended by Prince Eugene, my lord Albemarle, Cadogan, and Lieutenant-General Ros. They were all in the best spirits in the world. I recommended the matter of exchanging the prisoners to my lord Duke in the most pressing manner yesterday; he was almost angry and said to me, “I will stake my fortune on what you want; you will have your people before the end of this month.” “Good,” I said; “I will wager you ten pistoles.” “Done,” replied the Duke, and soon afterwards, with a violent gesture, “Mordieu, if these people make me lose this money I will make them suffer so much that they will have cause to regret their surliness.” Prince Eugene laughed loudly over the effect which a bet of ten pistoles had upon the spirits of my lord Duke, and I cannot help assuring your Majesty that if I had foreseen that my lord Duke would take this matter so much to heart I should have offered him fifty pistoles and gladly lost them so that your Majesty should be more certain of getting back two battalions and two squadrons. The bet has at any rate resulted in the Duke’s sending precise and threatening commands to the French commissary over the matter.[46]

Marlborough lavished his flatteries and persuasions upon the King of Prussia, using exactly the kind of arguments which were most likely to appeal to a military monarchy.

Brussels

January 31

“Imagine for a moment,” said my lord Duke in the further course of the conversation, “that we make a celebrated campaign and conclude peace, would not the King of Prussia be held in greater esteem if he had had twenty thousand men in the field than if he had had fourteen thousand? And in what ultimately does the greatness of a king and his might consist except a large army and good troops—le reste n’est que chimère!”[47]

Brussels

February 17