* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Scottish-Canadian Poets

Date of first publication: 1907

Author: William Wilfred Campbell (1860-1918)

Date first posted: August 9, 2025

Date last updated: August 9, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20250814

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by the Canadian Research Knowledge Network.

Scottish-Canadian Poetry

By WILLIAM CAMPBELL

ARTICLE I

(The Canadian Magazine, April 1907)

The personality and work of Scottish poets in Canada.

cotland is known, the

world over, as the Land of

Song. It has been estimated

that “the Land of

Brown Heath and Shaggy

Wood” has given birth to two hundred

thousand poets. This seems like an

exaggeration, but that the statement has

been made is quite true. Is it a matter

for wonder, then, that this vast army of

poets has continued to overflow into

other lands, and that the members are

scattered abroad over the whole earth?

Canada has welcomed many of those

wanderers to her shores; and in their

new surroundings they have not ceased

to cultivate the muses. The Scot has

a happy faculty of getting reconciled to

new environments; and time has proved

that he can sing—if not as blithely, certainly

as ably and as sweetly, under the

shade of the Canadian maple as when

he trod his native heath. Scottish-Canadian

poets, which include native-born

Scots, and their descendants, have

written in recent years, say during the

past half century, some very fine poems

and songs. The theme of their lays has

in numerous instances been found in

Canada—in the forest, on the farm, and

in the busy city; yet it has to be admitted

that some of the tenderest and most

heart-stirring among their productions

have been inspired by scenes and faces

of other days in the dear home-land. It

could not well be otherwise. Those of

us who have spent our early days in Scotland,

however strong the ties we form

in this new land, a land literally “flowing

with milk and honey,” be it said, cannot

forget the mother-land, and the expatriated

Scot’s pent-up feelings have found an

outlet in describing, in glowing language,

the scenes of his happy boyhood and

the faces of those who were dear to him

in the “days o’ Lang Syne.” “Absence

makes the heart grow fonder,” and

cotland is known, the

world over, as the Land of

Song. It has been estimated

that “the Land of

Brown Heath and Shaggy

Wood” has given birth to two hundred

thousand poets. This seems like an

exaggeration, but that the statement has

been made is quite true. Is it a matter

for wonder, then, that this vast army of

poets has continued to overflow into

other lands, and that the members are

scattered abroad over the whole earth?

Canada has welcomed many of those

wanderers to her shores; and in their

new surroundings they have not ceased

to cultivate the muses. The Scot has

a happy faculty of getting reconciled to

new environments; and time has proved

that he can sing—if not as blithely, certainly

as ably and as sweetly, under the

shade of the Canadian maple as when

he trod his native heath. Scottish-Canadian

poets, which include native-born

Scots, and their descendants, have

written in recent years, say during the

past half century, some very fine poems

and songs. The theme of their lays has

in numerous instances been found in

Canada—in the forest, on the farm, and

in the busy city; yet it has to be admitted

that some of the tenderest and most

heart-stirring among their productions

have been inspired by scenes and faces

of other days in the dear home-land. It

could not well be otherwise. Those of

us who have spent our early days in Scotland,

however strong the ties we form

in this new land, a land literally “flowing

with milk and honey,” be it said, cannot

forget the mother-land, and the expatriated

Scot’s pent-up feelings have found an

outlet in describing, in glowing language,

the scenes of his happy boyhood and

the faces of those who were dear to him

in the “days o’ Lang Syne.” “Absence

makes the heart grow fonder,” and

“Time but the impression stronger makes,

As streams their channels deeper wear.”

The number of poets who have cheered and charmed their countrymen and countrywomen, and their descendants, on this side of the Atlantic can be reckoned by hundreds. And it can be truthfully stated that many of the poems and songs written by “the Scot abroad” will compare very favourably with the products of the Scot at home.

Up to the year 1905 no anthology of purely Scottish-Canadian poetry had been compiled, although numerous books of poetry had been published by authors, among whom may be mentioned Alexander McLachlan, Evan MacColl, Robert Reid, Rev. Wm. Wye Smith, John Imrie, Alexander H. Wingfield, Andrew Wanless, Rev. A. J. Lockhart, Donald McCaig, John Macfarlane and others. Among those who have distinguished themselves as poets, but who have not published their writings in book form, the following call for special mention: John Simpson, Dr. John Murdoch Harper, Rev. Andrew Macnab, John Mortimer, Mrs. Mary A. Maitland, Mrs. Jessie Wanless Brack, Mrs. Margaret Beatrice Burgess, Dr. Daniel Clark, Miss H. Isabel Graham, Thomas Laidlaw, Mrs. Isabelle Ecclestone MacKay, Agnes Tytler, William Telford, Edwin G. Nelson, William Murdock, Alexander Muir, Rev. G. Bruce, D.D.; Robert Boyd, Malcolm MacCormack, W. M. MacKeracher, John Steele, Allan Ross, Mrs. Georgiana Fraser Newhall, and George Pirie. This does not, by any means, exhaust the list, but it includes the more prominent amongst those of the past two generations.

EVAN MacCOLL

The Scottish muse does not pose as a classical beauty, but is rather a “simple country lass, fresh, buoyant, buxom and healthy, full of true affections and kindly charities; a barefooted maiden that scorns all false pretence, and speaks her honest mind. If sometimes indiscreet in her language, her heart is pure; she never jests at virtue, though she sometimes has a fling at hypocrisy. Her laughter is as refreshing as her tears, and her humour is as genuine as her tenderness.” And with these characteristics has the Scottish muse been transplanted in Canadian soil, where it has taken deep root, and bravely flourished.

The task of collecting and publishing a truly Scottish-Canadian book of poems and songs was left to the Caledonian Society of Toronto, and the idea originated with Dr. Daniel Clark, who was president of the Society in 1898. The work of collection fell to the writer of this article, who was then, and for five years subsequently, secretary of the Society. The reasons given for undertaking the work are set forth in the preface to the book which was the outcome of the movement, published in 1900.[1] It was felt that “besides what had already been published there was much meritorious poetry scattered throughout the country, which had never passed through a printer’s hands, and a desire was expressed that all the richer specimens be collected and printed in book form, and thus preserved to posterity.” Thus ran the preface, and it clearly sets forth what the Caledonian Society had in view when the enterprise was entered upon. From a financial standpoint, the book was not a success; but the critics all spoke of it in kind and exceedingly complimentary terms. Had the sales of the first volume been sufficiently encouraging, a second volume, and probably a third, would have followed. There was no lack of material.

Evan MacColl, called familiarly the “Bard of Lochfyne,” because born on Lochfyne-side, Argyllshire, will be best known to posterity as a Gaelic poet, although many of his English productions are very popular, and justly so. MacColl, like Burns, drew inspiration for his muse from familiar objects in everyday life, and whatever he touched he turned into gold. The great bens which encircled his birthplace, and the shady glens lying between; the mountain torrent as it foamed and fretted on its headlong career to the ocean; the lark carolling i’ the lift, and “the red heather hills of the Highlands” were all illumined by his genius. Like Burns, too, MacColl sang the praises of “Woman, charming woman, O,” and many of his most charming songs are inspired by the maidens whom he came in contact with in his early life. Here is a specimen in part:

BONNIE ISABEL

Give fortune’s favoured sons to roam

However far they please from home,

And find their eventide delights

’Mong Rhenish groves or Alpine heights;

But give to me, by Shira’s flow—

With none to see and none to know—

Love’s tryst to keep, love’s tale to tell,

And kiss my bonnie Isabel!

Many more songs follow on the same theme: “The lass of Leven-side,” “Jeanie Stuart,” “The lass wi’ the bricht gowden hair,” “The lass of Glenfyne,” “Sweet Annie of Glenara,” etc. Those earlier productions all prove how susceptible was the poet’s heart to the tender passion. One of MacColl’s favourite poems, “The child of promise,” has been translated from the author’s Gaelic by the late Rev. Dr. Buchanan, Methven, Scotland. Here are two stanzas of the translation:

She died—as die the roses

On the ruddy clouds of dawn,

When the envious sun discloses

His flame, and morning’s gone.

She died—like waves of sun-glow,

By fleeting shadows chased;

She died—like heaven’s rainbow,

By gushing showers effaced.

MacColl came to Canada in 1850, and died in Toronto on July 24th, 1898, in the ninetieth year of his age. His remains were interred in Cataraqui Cemetery, Kingston. The poet’s muse was not dormant during his long residence in Canada. On the contrary many of his finest poems, songs and sonnets were written in the land of his adoption, although it has to be admitted that the bard had often recourse to his “mind’s eye” in the choice of a theme for his creations. His heart remained ever true and loyal to his native land, and to those he left behind in bonnie Scotland; and it is no cause for wonder, therefore, that long after he had settled in Canada he continued to write on scenes and subjects of other days, before the exigencies of human needs or aspirations called him into exile. Among these later poems may be mentioned two on Burns, sonnets descriptive of the scenery of Argyllshire, “My own dear romantic countrie,” and a fine collection of songs, most of which have been set to popular airs. The marriage of the Princess Louise and Lord Lorne is also sung in a patriotic strain, and a satirical poem, “Macaulay versus Scotland,” holds up the historian to ridicule.

In writing on Canadian subjects MacColl exhibits the same beauty of style, and variety in expression, the same poetic fire, the same descriptive powers, that characterise his earlier productions in the midst of native environment. His verses on “The Chaudière,” a well-known scene on the River Ottawa, are a fair sample of his descriptive work. One verse will suffice for the purpose of illustration:

Where the Ottawa pours its magnificent tide

Through forests primeval, dark-waving and wide,

There’s a scene which for grandeur hasscarcely a peer,—

’Tis the wild roaring rush of the mighty Chaudière.

The poet’s susceptibility to female charms appears to have broken out afresh on Canadian soil as is shown by his tribute to

CANADIAN GIRLS

Canadian girls—the truth to tell

Sly arts coquettish practise well;

Yet must we own them not the less

Unrivalled in their loveliness.

In an article of the dimensions of this one it is impossible to do justice to the powerful and versatile genius of MacColl. His works will prove a lasting monument. Hugh Miller dubbed him the “Moore of Highland Song,” and no one qualified to form a true estimate of his Gaelic productions will dare dispute his title to wear the honour.

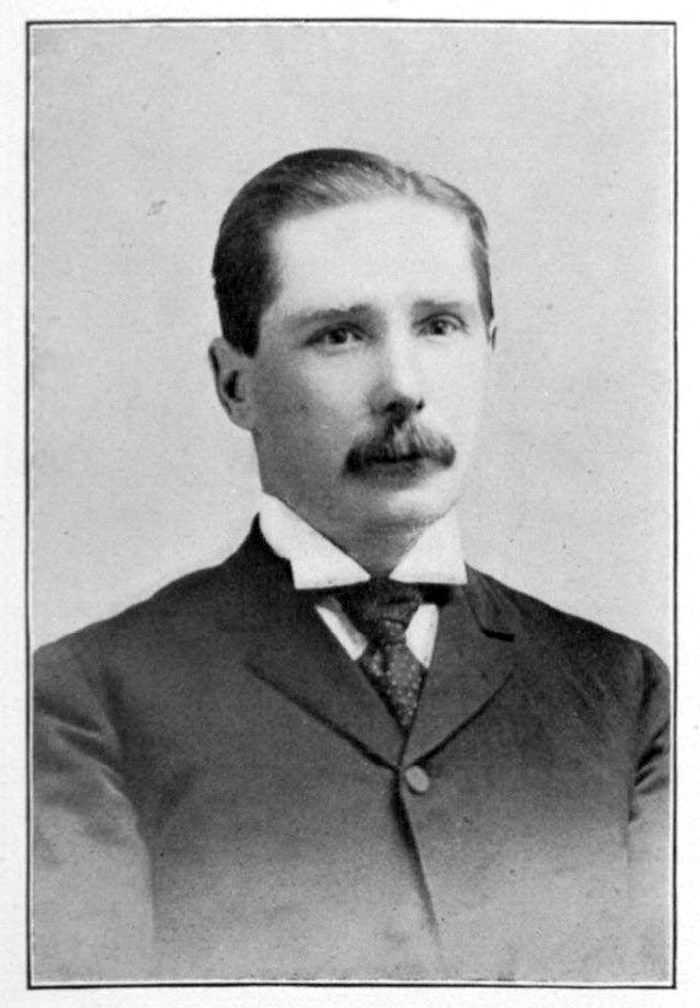

Alexander McLachlan occupies a first place among Scottish poets who have made Canada their home. Measured by what may be called the Burns standard, he is almost the equal of his great prototype; certainly he comes nearer to the Ayrshire bard than any other. Rev. Dr. Dewart in his “Selections from Canadian Poets,” said of McLachlan: “It is no empty laudation to call him the Burns of Canada,” and nearly a quarter of a century later he expressed himself as being still of the same opinion. McLachlan’s poems stamp the man as a born genius, possessing a lofty mind and a pure heart. His poems are alike inspiring and inspiriting, and a perusal of them cannot fail to do one good. Like many other poets before and after him, McLachlan had no great lineage to boast of. His parents were not possessed of worldly wealth and the education their offspring received was of a somewhat rudimentary character. The poet’s budding genius early manifested itself; and it is not unlikely that his inability to express his thoughts in suitable language was the incentive that led him to seek to supplement the somewhat scanty education he received when a boy. That he did improve himself is evidenced by the literary style which is everywhere shown in his writings. While possessed of a rich fund of humour, as his “Lang-Heided Laddie” shows, and while he sang of the objects of nature around him in simple, soulful numbers, true to life as he was accustomed to it, some of his finest productions are intended to lift us above sublunary things, and transport us into the unseen. His poem entitled “God” is a masterpiece of its kind, and had he written nothing else it would have brought him into prominence. Here are two stanzas:

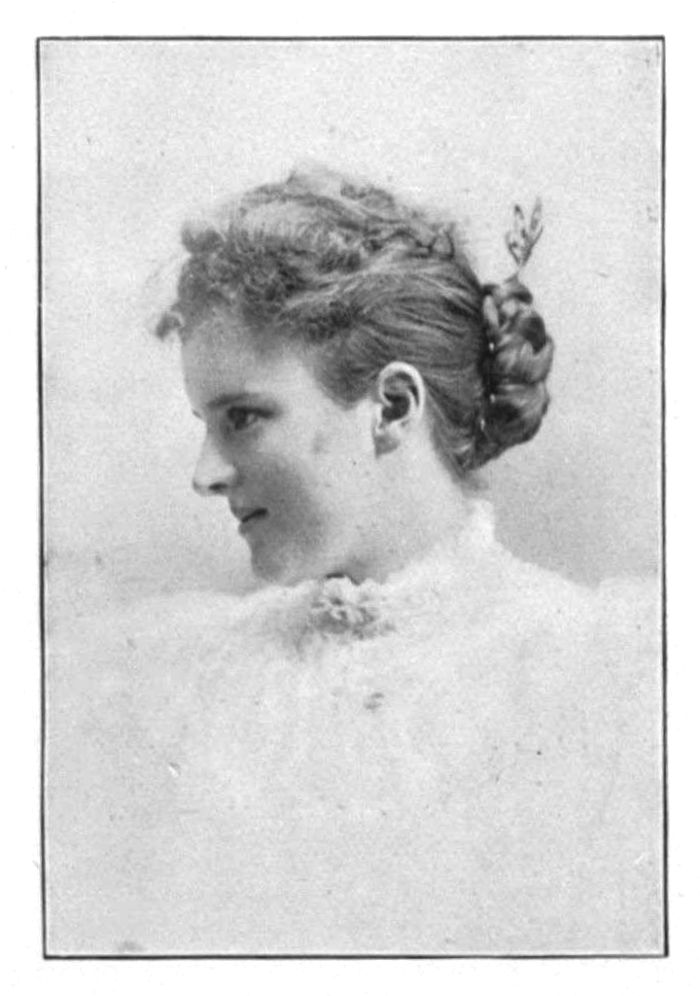

ALEXANDER McLACHLAN

God of the great old solemn woods,

God of the desert solitudes,

And trackless sea;

God of the crowded city vast,

God of the present and the past,

Can man know thee?

From out Thy wrath the earthquakes leap

And shake the world’s foundations deep,

Till Nature groans;

In agony the mountains call,

And ocean bellows throughout all

Her frightened zones.

Another poem in the same class reveals a desire in the heart of the author for a knowledge of the unseen. It is entitled “Mystery,” and is indicative of profound thought on the mysterious in nature. It is fine poetry, but it is more, as may be seen in even one stanza:

Mystery! Mystery!

All is a mystery,

Mountain and valley, woodland and stream;

Man’s troubled history,

Man’s mortal destiny,

Are but a phase of the soul’s troubled dream.

JOHN IMRIE

Rural scenery comes in for a large share of the poet’s attention, and he has a fine conception of the beauties of nature, as he shows in such poems as “Indian Summer,” “Far in the Forest Glade,” “The Maple Tree,” “Spring,” etc. Things animate and inanimate alike arrest his eye, and the murmur of the brook, the warbling of the birds, the rustling of the leaves, and the buds and blossoms that gem the greensward and bedeck the surrounding trees all come in for a share of his love, and are painted in the language of a true poet. One is tempted to give examples of this style of the poet’s descriptive powers, but the space I have left must be given to but two stanzas of one of McLachlan’s finest and most popular poems:

OLD HANNAH

’Tis Sabbath morn, and a holy balm

Drops down on the heart like dew—

And the sunbeams gleam

Like a blessed dream

Afar on the mountains blue.

Old Hannah’s by her cottage door,

In her faded widow’s cap;

She is sitting alone

On the old gray stone,

With the Bible in her lap.

An oak is hanging above her head,

And the burn is wimpling by;

The primroses peep

From their sylvan keep,

And the lark is in the sky.

Beneath that shade her children played,

But they’re all away with Death,

And she sits alone

On that old gray stone

To hear what the Spirit saith.

Alexander McLachlan was born in the village of Johnstone, Renfrewshire, Scotland, in the year 1820, and he died on March 20th, 1896. He engaged in farming in Canada. His farm was in the Township of Amaranth, and among his intimate friends he was called the poet of Amaranth. Farming did not prosper well with McLachlan, and as a consequence he had not over-much of this world’s goods. His many friends raised a sufficient sum to provide a steady income for him during the closing years of his simple life, which was ended peacefully at the home of his daughter in Orangeville, where his remains rest under a monument erected to his memory by his many admirers.

In taking up the poems of John Imrie, the writer experiences a peculiar pleasure, inasmuch as for about thirty years he was intimately associated with the poet and “lo’ed him like a vera brither.” Imrie’s was a kindly nature. His humanity was wide, tender and full of sympathy for everything in nature. He was eminently a poet of the people, and he was loved and respected by his fellow-creatures. His poems, apart from their merit, revealed the man in his varied moods perfectly. Although, perhaps, his muse did not soar quite so high as McLachlan’s, yet he filled his own niche in the Temple of Fame, and he filled it well. It may truthfully be said that Imrie’s poems are more familiarly known around the firesides of the Dominion than those of any of his compeers. Five editions of his poems have been issued. These facts furnish indisputable evidence of the popularity of the poet’s works. Imrie’s mission, as he declared it in the preface to the second edition of his poems, was “to please and encourage the toiling masses,” and in this he was successful in a marked degree. His zeal never flagged, his pen was ever busy, and notwithstanding the fact that he had a large business claiming much of his time and attention, he gave to the world an extensive and varied collection of poems. He was an enthusiastic Scot, while still a loyal Canadian, and he divided his attention fairly between the land he left and the land of his adoption. His verses entitled “Scotty” exemplify at once his modesty and his estimate of the Scottish character. One here will serve to give the key-note:

Yes! ca’ me “Scotty” if ye will,

For sic’ a name can mean nae ill,

O’ a’ nick-names just tak’ yer fill,—

I’m quite content wi’ “Scotty.”

* * * *

His verses entitled “Our Native Land—Fair Canada,” have a healthy, hopeful, and patriotic ring about them. Witness the first:

God save our native land,

Free may she ever stand,

Fair Canada;

Long may we ever be,

Sons of the brave and free,

Faithful to God and thee,

Fair Canada.

* * * *

Imrie was particularly happy in the home circle, and many of his popular pieces may be described as fireside lyrics. He was deeply religious, and many of his compositions are of a sacred character. His sonnets, also, of which he wrote quite a number, are mostly on sacred subjects.

John Imrie was a native of Glasgow. He made his home in Toronto when he first came to Canada in 1871, and in Toronto he died on the 6th November, 1902.

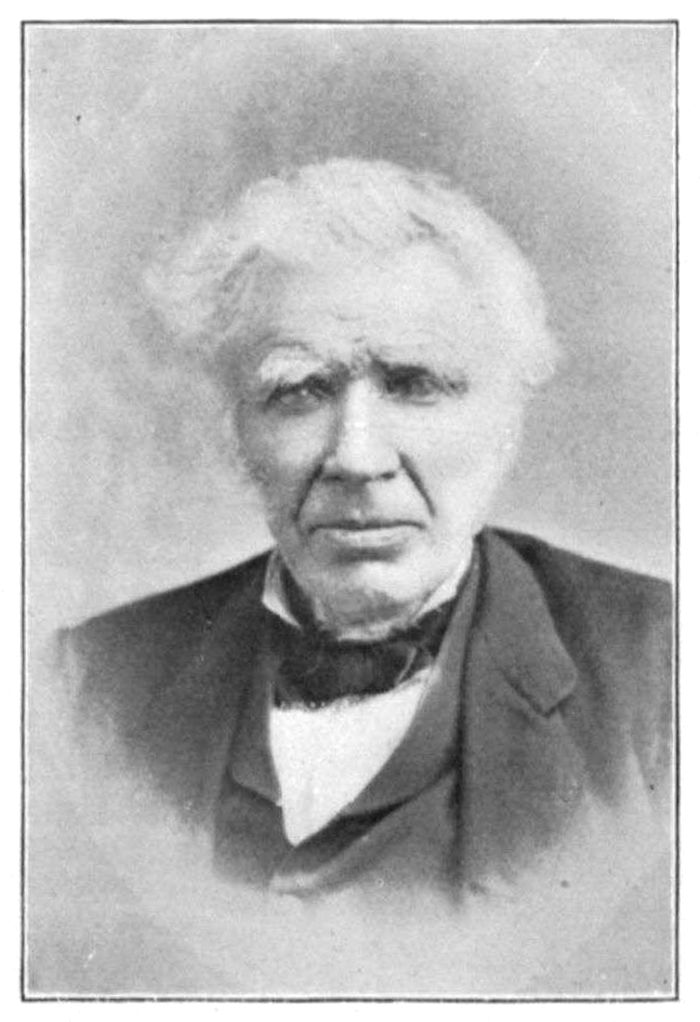

DR. JOHN MURDOCH HARPER

Dr. John Murdoch Harper, a well-known educationist in Canada, Inspector of Superior Schools for the Province of Quebec, in addition to many other fine qualities of head and heart, has distinguished himself as a poet.

Like Alexander McLachlan, Dr. Harper first saw the light in Johnstone, Renfrewshire, Scotland. His education was imparted first in the parish school, and afterwards in Glasgow E.C. Training College, which he entered as a Queen’s student of the first rank. After he had resided in Canada for some years, he became a graduate of Queen’s University, and later Illinois University conferred on him the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. His writings were not confined to poetry. His “History of the Lower Provinces” is a well-known text-book. In fiction, too, his name has a place, and he has written a number of sketches and essays which have attracted attention.

Dr. Harper’s poetic works breathe out a nobility of sentiment and a robustness typical of the man. At the same time he writes with a sweetness and tenderness which stamp him as a true poet. His lines “To a Sprig of Heather” are charmingly suggestive of other days:

My bonnie spray o’ pink and green,

That breathes the bloom o’ Scotia’s braes,

Your tiny blossoms blink their e’en,

To gi’e me glimpses o’ ither days—

The days when youth o’er-ran the hills,

A-daffin’ wi’ the life that’s free,

’Mid muirland music, and the rills

That sing their psalm o’ liberty.

The temptation to quote the other verses of the poem is strong, but one stanza must suffice.

Another dainty little poem attracts attention. It is entitled “Woo’d and Wed,” and is a pretty conception, of which any poet might feel proud. The first verse reads:

The east wind blustered in her ear,

The daisy, shuddering, drooped her head;

Such wooing pinched her heart with fear,

She closed her eye and said:

“No lover true would think to harm

A wee bit thing like modest me;

I’ll crouch me down and keep me warm

Till summer set me free.”

Dr. Harper’s masterpiece is perhaps a group of poems strung together under the general title of “Lays of Auld Lang Syne.” A finer collection of Scottish poetry one would not wish to read.

A poem of a serious nature, and one that has a charm all its own, though clothed in mournful words, is “The Old Graveyard.” There is room only for two verses, and with them this sketch must close:

The summer’s day is sinking fast,

The gloaming weaves its pall;

As shadows weird the willows cast,

Beyond the broken wall;

And the tombstones gray like sentinels rise,

To guard the dust that ’neath them lies.

* * * *

Then silken silence murmurs rest,

And the peace that reigns supreme

Seems but awaiting God’s behest,

To wake it from its dream;

While yet it soothes the hearts that weep

lament for those that lie asleep.

The name of Andrew Wanless is well known throughout Canada as a poet and a man. Mr. Wanless began his Canadian career in Toronto. He was a brother of Mr. John Wanless, of Toronto, and a native of Longformacus, Berwickshire, Scotland, where his father was parish schoolmaster for more than fifty years. His poetry was almost invariably of a happy, and very often of a decidedly humorous character. To those who knew him as intimately as did the writer, this was to be expected. A happier or a more cheery disposition was seldom met with, and his poems were an embodiment of the man. His popularity made him welcome, apart from his poetic attainments, and much of his time was spent in visiting the leading cities and towns of the United States and Canada.

Mr. Wanless had an intense love and veneration for his native land. He was decidedly domestic in his tastes also, tender in sentiment, and fanciful in the extreme. As already stated he seldom wrote in gloomy or sorrowful numbers. When he did his muse responded in the desired strain as is shown in the verses entitled “My Bonnie Bairn.” Here are three stanzas:

In my auld hame we had a flower,

A bonnie bairnie sweet and fair;

There’s no’ a flower in yonder bower

That wi’ my bairnie could compare.

* * * *

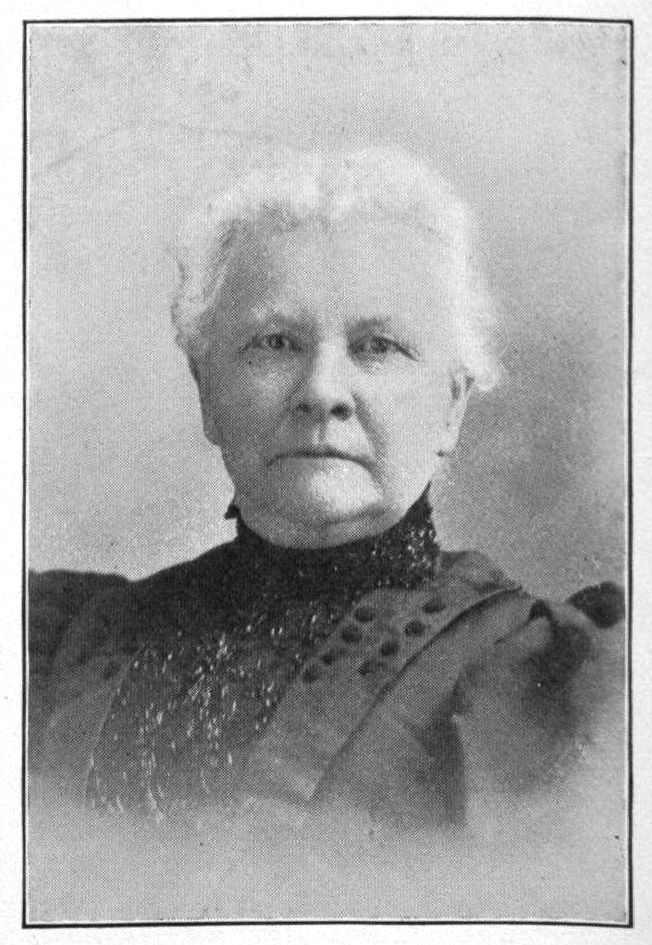

DR. DANIEL CLARK, WHO HAS DONE MUCH TO FOSTER SCOTTISH POETRY IN CANADA

I’ll ne’er forget the tender smile

That flitted o’er his wee bit face

When death came on his silent wing,

And clasped him in his cold embrace.

* * * *

At midnight’s lone and mirky hour,

When wild the angry tempests rave;

My thoughts—they winna bide away—

Frae my ain bairnie’s wee bit grave.

ANDREW WANLESS

Mr. Wanless was a prolific writer, and many of his best pieces will live through coming ages among his countrymen.

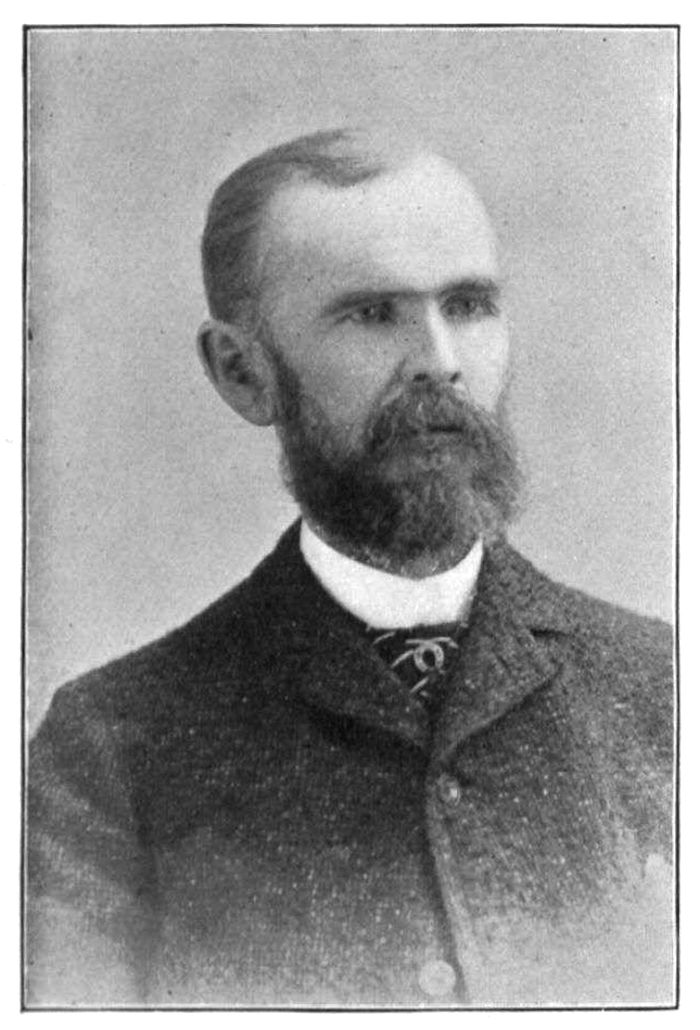

Robert Reid, of Montreal, who, in his younger days, loved to be known as “Bob Wanlock”—so named after the place of his birth, Wanlock, Dumfriesshire, Scotland—is a poet who ranks among the best among those sons of Scotland who have found a home in this country. Brought up beside the moors, his poems are laden with the perfume of the heather and the sweet briar. As a boy he seems to have revelled in the beauties of nature as disclosed on his native hills. His descriptions of the scenes in which his youthful lot was cast are admirable. There is a warmth of tone and a depth of feeling present in all his writings about Scottish scenery that have a strong fascination, especially for the Scot abroad. His heart and head are both those of a true poet: in fact, no Scottish-American poet of the present generation has been more highly complimented than Robert Reid.

ROBERT REID

A poem of peculiar beauty, and one that has attracted a great deal of attention, is entitled “The Whaup.” Here are the first and two last verses:

Fu’ sweet is the lilt o’ the laverock

Frae the rim o’ the clud at morn;

The merle pipes weel in his mid day biel’,

In the heart o’ the bendin’ thorn;

The blythe, bauld sang o’ the mavis

Rings clear in the gloamin’ shaw;

But the whaup’s wild cry, in the gurly sky

O’ the moorlan’, dings them a’.

What thochts o’ the lang gray moorlan’

Start up when I hear that cry!

The times we lay on the heathery brae

At the well, lang syne gane dry;

And aye as we spak’ o’ the ferlies

That happened afore-time there,

The whaup’s lane cry on the win’ cam’ by

Like a wild thing tint in the air.

And though I ha’e seen mair ferlies

Than grew in the fancy then,

And the gowden gleam o’ the boyish dream

Has slipped frae my soberer brain;

Yet—even yet—if I wander

Alane by the moorlan’ hill,

That queer wild cry frae the gurly sky

Can tirl my heart strings still.

While eminently distinguished for his command of the Doric, Mr. Reid is no less successful in his purely English compositions, among which might be mentioned “Here and Hereafter,” “The Poet and his Theme,” “The Two Gates,” “Looking Back,” “Retrospect,” “Only a Dream,” and many others which no minor poet could create.

Mr. Reid has published two volumes of poems—“Moorland Rhymes” and “Poems, Songs and Sonnets,” both of which have commanded an extensive sale, and have made their author famous at home and abroad.

To do justice to Scottish-Canadian poetry in a single article is an impossibility, as the field is a very large one. There are many writers of merit yet to be recognised, and that an effort may be made to include at least the best of them, a second article is in course of preparation, and will appear later in The Canadian Magazine.

|

Selections from Scottish-Canadian Poets, being a collection of the best poetry written by Scotsmen and their descendants in the Dominion of Canada, with an introduction by Dr. Daniel Clark. Printed by Imrie, Graham & Harrap; 320 pp., price $1.00. |

Scottish-Canadian Poetry

By WILLIAM CAMPBELL

ARTICLE II

(The Canadian Magazine, June 1907)

The personality and work of Scottish poets in Canada.

he subject of Scottish-Canadian

poetry was dealt with,

in part, in the April number.

It is now proposed to

take up the writings of as

many more of those poets who come within

the scope of these articles as will fairly

present the claims of Scottish-Canadian

poets before the public. At most it is

possible only to give examples. To attempt

to review the whole Scottish-Canadian

anthology of poetry would be beyond

the writer’s intention. Besides, a review

that would aim to cover so wide a field

might prove somewhat monotonous.

he subject of Scottish-Canadian

poetry was dealt with,

in part, in the April number.

It is now proposed to

take up the writings of as

many more of those poets who come within

the scope of these articles as will fairly

present the claims of Scottish-Canadian

poets before the public. At most it is

possible only to give examples. To attempt

to review the whole Scottish-Canadian

anthology of poetry would be beyond

the writer’s intention. Besides, a review

that would aim to cover so wide a field

might prove somewhat monotonous.

Among the poets whose pens are still kept in practice, John Macfarlane, widely known by his nom-de-plume “John Arbory,” is entitled to a prominent place. Mr. Macfarlane has given to the world many fine poems and lyrical pieces. Perhaps his fame will rest largely on what he has done to perpetuate the memory of the Scottish martyrs. Having martyr blood in his veins, and being possessed of a deeply religious nature, his heart went out in sympathy to those heroes of covenanting times, and he was constrained to sing their praises in such burning words as the following:

Chased frae his hame, an’ the bairns he lo’ed,

Far frae the luv o’ his kith an’ kin,

He still was leal to the grand auld league,

For he couldna bide in the tents o’ sin;

An’ the croun was his that the sainted wear,

For it glinted aft on his broo o’ care

Abune was the treasure he lang had hained,

Abune wi’ the host o’ the pure an’ just,

Sae he didna flee frae the hour o’ doom,

His father’s God was his only trust;

An’ his saul’s ta’en flicht to the realms sae blest,

Tho’ his shroud was a shroud o’ mornin’ mist

Of other poems by Macfarlane on the Covenanters and their times may be specially mentioned “Auchensaugh,” “Dowie Howms o’ Bothwell,” “The Nameless Martyr” and “The Last o’ the Hillmen.”

With a heart always warm for the mother-land, Macfarlane is fully alive to the magnificence of Canadian scenery, as some of his verses show.

The poet’s birthplace was the village of Abington, situated near the source of the River Clyde. When he came to Canada, Macfarlane took up his abode in Montreal, and there he still resides. That his muse is not dormant is evidenced by frequent contributions to The Scottish American, and other publications.

JOHN MACFARLANE

Donald McCaig, Public School Inspector for the District of Algoma, has not responded to his poetic aspirations in vain. In a little book published by him some years ago, under the title of “Milestone Moods and Memories,” he proved to the world his title to a place among Scottish-Canadian poets. Before venturing on a printed collection of his writings, Mr. McCaig was a frequent contributor to local newspapers, and he wrote the prize poem for the Toronto Caledonian Society in 1885, “Moods of Burns.” The poet’s father was a Highlander, and his mother came from Ayrshire. He was born in Cape Breton in 1832. His fondness for the land of his fathers is shown in his verses, “My Island Home,” a poem which displays literary ability of a high order.

WM. MURDOCH

His poem entitled “Eastern Twilight” paints the downfall of Brahma before the Christian religion. The concluding verses are as follows:

Gautama’s lamp is burning low,

The incense lost, the perfume shed

From censers idly swinging now,

Where soul of Brahma’s life lies dead!

O sages! waiting, watching still,

For Him who prophets saw afar,

Behold a light breaks o’er the hill,

Behold a newly-lighted star!

O priestess! looking to the skies

For coming tokens of the morn,

For you this brighter star shall rise,

For you this nobler Prince be born!

Of Him the herald angels sing,

“He knows, His children feel like them,

A Sun with healing in His wing,

A Star, the Star of Bethlehem!”

At the time when Mr. McCaig’s published poems appeared, they came under review, in these columns, at the hands of Mr. David Boyle.

As a man and a poet, Thomas Laidlaw, of Guelph, has scarcely come in for that mode of praise which his merits call for. If ever a man was filled with that burning love for Scotsmen and for Scotland, which is so characteristic of his countrymen, that man was Thomas Laidlaw. Although only six years of age when he came to Canada, he had within his nature, in large measure, that ingenium perfervidum Scotorum possessed, more or less, by every true Scotsman.

DONALD McCAIG

Mr. Laidlaw’s verses on “The Old Scottish Songs” are true to nature; brimful of descriptive power worthy of our best poets; and breathing out a spirit of patriotism which can only spring from the purest of sources. The poem consists of eleven stanzas, of which the following are fair samples:

With the sweet-scented gowan the meadows are gemmed,

And the lark sings its song from the sky;

All nature rejoices, and the hills have the voices

Of freedom that never will die.

* * * * * * * *

Yes, the spirit that stemmed the invasion that sought

To wrest from the kingdom its crown;

That spirit untamed down the ages has flamed

With untarnished, unsullied renown.

Robert Boyd, who was a pioneer as well as a poet, wrote some excellent poems, and no man within a radius of fifty miles of Guelph was better known or more highly respected. In his writings Mr. Boyd made everything very real. In his “Song of the Backwoodsman,” one fancies he sees the gleam of the axe, and hears the crash of the proud oak as it measures its length on the sward. A striking contrast is furnished by a love-lilt which follows, the opening stanza of which is well worthy of preservation, for its sweet and tender imagery:

The dark e’e o’ e’ening’s beginning to drap

The tears o’ its kindness in Nature’s green lap;

Ilk wee modest gowan has faulded its blossom

To sleep a’ the night wi’ a tear in its bosom.

THOMAS LAIDLAW

“The Herd Laddie” is a pastoral poem, redolent of the heather hills and gowany braes of Auld Scotland, and affords unmistakable proof of the author’s love for his native land, after an absence of well-nigh half a century.

REV. WM. WYE SMITH

That Mr. Boyd was possessed of a keen sense of humour, is shown in a lengthy poem entitled “The Bachelor in His Shanty,” in which he relates his experience as a pioneer, and the hardships he endured while hewing out a home for himself in the heart of the primeval forest. His experiences with wolves and bears in winter; and mosquitos and “bull-frogs brawlin’ ” in the summer, are graphically described, along with many more ills, to wit:

And oh! the mice are sic a pest,

They eat my meat and spoil my rest;

Whatever suits their palate best,

They’re sure to win it;

Blast their snouts, they e’en build their nest

In my auld bonnet!

The crickets squeak like sucking pigs,

And dance about my fire their jigs,

Syne eat my stockings, feet and legs,

The hungry deevils;

Sure Egypt e’en wi’ a’ her plagues

Had ne’er sic evils.

JOHN MORTIMER

Rev. William Wye Smith, of St. Catharines, was born in Jedburgh, Scotland, and came to Canada with his parents while yet in early boyhood. Mr. Smith’s name has been before the Canadian public, as a writer of both prose and verse, for well-nigh fifty years. His poetry, with which alone this article has to do, is characterised by originality, a masterly style and a winning tenderness, at times, that is quite captivating. Many of his lyrical pieces are beautiful, their outstanding features being simplicity and sweetness, alike in thought and expression. Coming from the border-land of Scotland, Mr. Smith naturally evinces a keen interest in border incidents of by-gone times. In a quaint poem, “The Ghost that Danced at Jethart,” he recalls an episode in the history of Jedbury which is familiar to the student of Scottish history. During the revels following the marriage of Alexander III, the assembled guests were startled by the appearance of an unbidden guest—a thing of dry bones, a skeleton, in fact—whose movements were marked by time and seeming sense—a something “uncanny” whose visit has never been explained. A few stanzas are given here because of their peculiar style, and to show Mr. Smith’s familiarity with the Scottish words in use in those days when the abbots of Jedburgh “had fat kail on Friday when they fasted”:

When gude King Alysander was marriet,

’Twas lang syne, kimmer, i’ the town o’ Jethart;

Stane-biggit, Abbey-crowned, auld Border clachan,

Whiles I ha’e thocht on greetin’, and whiles lauchin’,

Just as fond memory wi’ the past forgather’t,

And down Time’s stream was carriet.

MALCOLM MacCORMACK

The poem goes on to describe the marriage feast, the music and then the dancing. The merry guests are treading a lively measure—

“When sudden cam’ a stand!”

But still the patter o’ a pair o’ feet

Was heard fu’ right!

The lad had fainted wi’ the lang bassoon,

An’ kettle-drums an’ fifes were in a swoon,

An’ harpers glowered atween their silent thairms

On sic a sight!

It jos’l’t wi’ it’s elbucks e’en the King—

And maskers fled—

For ne’er in masquerade had sic a thing

Been seen or read!

It wasna leevin’, yet ’twas dancin’, loupin’,

An’ ower the provost it was nearly coupin’,

Sic swirls it led!

It had a plume an it had been a baron,

Wi’ feathers hie—

A kilt wi’ gold brocade an’ siller lacin’,

An’ dainty doublet wi’ braw, braw facin’,

But Och-hon-a-rie!

It was an atomy, a thing o’ banes,

That wadna dee!

It lightly trod the airy min-e-wae,

An’ crackit its fleshless thooms;

An’ linked wi’ unseen partners down the floor,

A country dance was never danced before!

An’ girned an’ boo’d to leddies on the dais—

Then flittit frae the place!

Here is a sample of Mr. Smith’s style on another theme, in which he shows his poetic fancy to advantage:

Wi’ the laverock i’ the lift, piping music i’ the skies

When the shepherd lea’s his cot, and the dew on gowan lies—

Up, up, let me awa’ frae the dreams the night has seen

And ask what is the matter wi’ my heart sin’ yestere’en?

The laverock i’ the lift, i’ the wildest o’ his flight,

Sees whaur his love abides, wi’ throbbings o’ delight—

But I behold her cot, and awaken to my pain—

It canna sure be love, or I’d sune be weel again!

JOHN SIMPSON

ROBERT BOYD

Adown the sunny glade, there’s a bower that cottage nigh

Whaur the flowers aye are sweetest, and the burn gangs singin’ by—

’Twas there we pairtit late, wi’ a kiss or twa between,—

But what can be the matter wi’ my heart sin’ yestere’en?

I’ll to yon garden hie, ere the gloamin’ close it’s e’e,

I’ll tell her o’ my pain, and ask what it can be;

It may be she can cure wha gar’t me first compleen,

For ah! there’s something wrang wi’ my heart sin’ yestere’en!

Another good example of Mr. Smith’s versification is a sweet, breezy poem entitled, “O, the Woods.” The verses have a true poetic ring in them and they are here reproduced, omitting the first stanza:

O, the woods! the woods! the Summer woods,

And the coolness of their shade!

Where in wildwood dell all the Graces dwell,

There to wait on a sylvan maid!

I’ll seek for flowers to deck her bowers,

And twine in her golden hair;

And, I wonder much if she thinks of such

As I, when the Winter’s here.

O, the woods! the woods! the Autumn woods,

And the chestnuts ripe and brown!

When the leaves hang bright in the changing light,

Like the banners of old renown!

And south-winds ripple across the lake,

Like chiming of marriage bells;—

O, I wouldn’t much grieve, if I’d never leave

These wildest of woodland dells!

O, the woods! the woods! Canada’s woods,

And the sweet flowers nourished there!

O, the beechen shade, and the sylvan maid

That garlands her golden hair!

Her name may change with the magic ring—

Her heart is the same for aye!—

In my little canoe there is room for two,

And sweetly we glide away!

Mr. Smith has been a prolific writer of poetry and his muse awakes at times, even yet.

WM. MURRAY

Among the many Scottish-Canadians who have sung in a minor strain, John Mortimer has a prominent place. Mr. Mortimer comes of Aberdeenshire stock. His father and mother settled on land immediately adjoining the town of Elora, and on the old homestead the poet still dwells.

Mr. Mortimer has exhibited in his writings a deep love of nature as it appears to him in his rural surroundings; his descriptive powers are above the average; he is possessed of a somewhat brilliant fancy, and a vivid imagination; in short, he is by nature well equipped for poetry, especially in its simpler forms. His lines entitled “A Tribute to the Toads,” appeals to us because of their simplicity and naturalness. Here are the first two verses:

The Spring has reached our Northern clime,

Crows in the air abound;

The snow is melting, and the time

For toads will soon be round.

I’m glad the Spring will turn them out,

I love so much to see

Those sober creatures hop about

Upon the grassy lea.

The short poem “Song” is a neatly written appeal to our common humanity and is one of Mr. Mortimer’s favourite pieces. It is as follows:

Some seem to think our mission here

Is only to be glad;

And the way to bless the sons of men

Is bid them ne’er be sad.

I claim not mirth should rule the earth,—

No prejudice have I,—

Nor reckon those but friends or foes

Who make me laugh or cry:

He who would share my joy or care

Is still the friend for me,

For the heart, you know, where’er you go

Is won by sympathy.

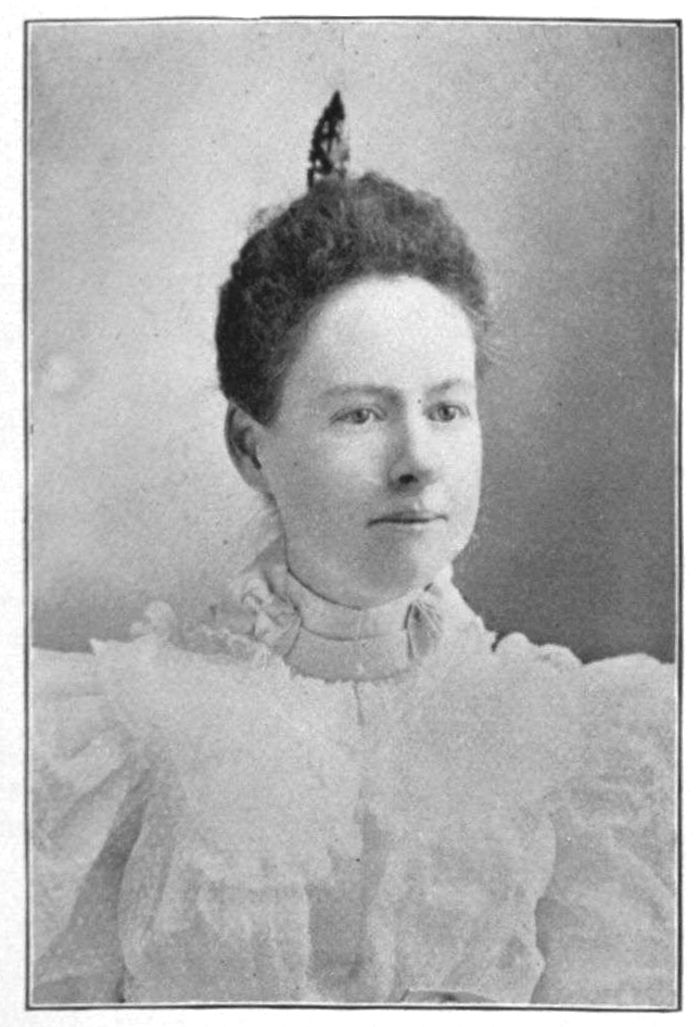

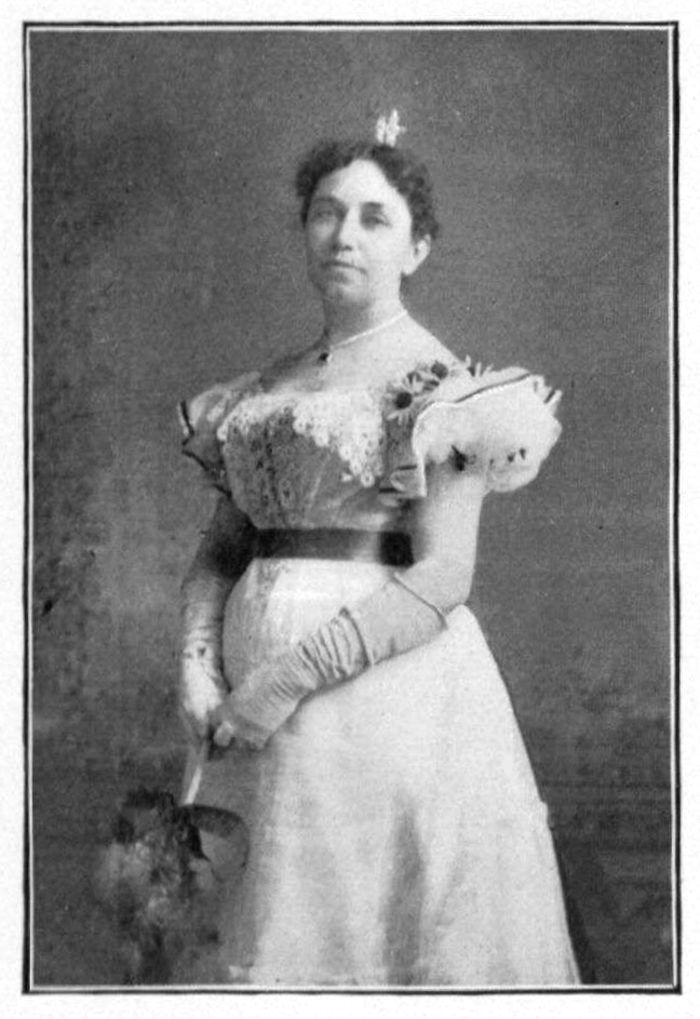

MRS. JEAN BLEWETT, AUTHOR OF “THE CORNFLOWER AND OTHER POEMS”

Is won by sympathy,

Is won by sympathy;

The heart, you know, where’er you go

Is won by sympathy.

When sounds of mirth and gladness fall

In vain on Sorrow’s ear,

Then strive to comfort those who weep

And give them cause for cheer;

We may impart to every heart

Some sunshine if we try;

’Twill hasten on the joyous dawn

We hope for bye-and-bye,

Till comes to stay that happy day

When all shall brothers be,

For the heart, you know, etc.

Another poem, “The Felling of the Forest,” brings out Mr. Mortimer’s descriptive powers. The poem is too long for reproduction here, but the temptation to give an extract from it is too strong to be resisted:

MISS H. ISABEL GRAHAM

But slowly did the work advance: to tell

How, thrown with skill, the forest monarchs fell,

To me were pleasant—prone and parallel;

This way and that, their huge boughs interlaced,

Tier over tier, for giant bonfires placed,

With terrible descent; but fearless all

We laid them low and climbed each swaying wall

To cut the higher trunks and boughs, and lay

Compact for burning at some future day.—

And listening now I hear those bonfires roar,

And see great sheets of flame that skyward soar,

Triumphant beacons of thy future, great,

Oh, Canada! our dearly loved estate!

* * * * * * * *

Thus fared the noblest of our forest trees,

Whose branches mingled, bending in the breeze

For broad, unmeasured leagues on every side,

All green and glorious in their summer’s pride!

The home of rustling wings and nimble feet,

The Red Man’s shelter, and the deer’s retreat.

MRS. ISABELLE ECCLESTONE MacKAY

Others of Mr. Mortimer’s poems that are deserving of special mention are “Somebody’s Child,” “After a Hundred Years,” a tribute to Burns; “Nelly and Mary,” a well-conceived and cleverly-written dialogue; “A Dream,” being a vision in which is a graphic and awe-inspiring description of the Deluge; “A Woodland Vision,” etc.

Malcolm MacCormack, as his name indicates, comes of pure Highland extraction, his parents having both come to Canada from Argyllshire. The poet was born in the village of Crieff, Wellington, Ontario. He early evinced a poetic tendency, which was stimulated and encouraged through coming in contact with McColl, Laidlaw, McCaig and others.

MacCormack’s verses entitled “The Gael’s Heritage,” are a tribute to Fingal and Ossian. Following are some verses which indicate pretty clearly the scope of the poem:

MRS. GEORGINA FRASER NEWHALL

Sons of the Gael! ’tis yours, with proud elation,

To guard the fame of the unconquered brave

Who stood erect, disdaining subjugation,

And scorned to own the hateful name of slave

’Tis yours to claim the heritage of splendour,

That gilds with light the old historic page,

Whereon your fathers’ deeds remain to render

Their fame undying to the latest age.

’Tis yours with grateful homage to remember

Their glorious deeds in those heroic days,

When Fingal fought his foeman without number,

And tuneful Ossian sang immortal lays.

The name of John Simpson is not so well known in Canada as it deserves to be. This may be accounted for in two ways. In the first place, he has not published his writings in book form; and in the second place he has resided for many years in the United States; at present he is understood to be living in British Columbia. Mr. Simpson was born in Elora, Ontario, on July 2nd, 1855, of good Aberdeenshire stock, his father’s name being Peter Simpson, and his mother’s maiden name, Janet Catanach. On his mother’s side, his progenitors were of a decidedly literary turn of mind, and distinguished themselves in the halls of learning. Mr. Simpson obtained his education at the Elora public and high schools, and at Toronto University, where he took his B.A. degree in 1884, and his M.A. degree in 1887. He has followed in the footsteps of his maternal grandfather, becoming a successful teacher. This enlargement on Mr. Simpson’s career is justified by the fact that he has written some of the best poetry of which Canada can boast; and it can confidently be said that he has not yet given to the world the best that is in him. His is the true poetic temperament and his genius is of that soaring kind behind which there lurk great possibilities. Here is what may be called a prayer for his native land. It is given in almost its entirety, as it breathes out a spirit which should animate every true Canadian heart:

AGNES TYTLER

THOU GOD OF NATIONS, GUARD OUR LAND!

Thou God of nations! guard our land,

Thy blessings on our country pour!

Our shield and succour evermore

Be Thine Almighty hand!

Thou high and mighty King of kings,

Thou Maker of all earthly things,

Support us with thy leading-strings,

Alone we cannot stand!

The mighty empires of the past

Have fallen, and in ruins lie;

Their walls, that towered once on high,

Upon the earth are cast:

Great Babylon is lying low,

Proud Carthage is a scene of woe,

In Rome corroding lichens grow

On ruins that are vast.

No human hand can shackle time:

Though Petra from the rocks was hewn,

In heaps its fragments now are strewn

Within a desert clime:

O Lord, lest such a direful fate

Our land and nation should await,

To Thee we fain would consecrate

Our lives with faith sublime.

Our nation ever shall be free,

No dweller in our broad domain

Shall ever guiltless wear a chain,

Or pine in slavery:

In praising Thee each shall alone

The guidance of his conscience own;

Our land shall never hear the groan

Of dying liberty.

A prolific writer of poetry is Mr. William Murray, of Hamilton, a kindly Scot from Finlarig, Perthshire, who, for thirty years or so, has been the honoured bard of the St. Andrew’s Society of Hamilton, and of the Caledonian and Gaelic Societies as well. Mr. Murray has written poetry sufficient to fill two volumes, but he has never ventured on the publication of his works, although many of his poems have appeared in print. Here is a specimen—not his best, but selected as being within available space:

THE SCOTTISH PLAID

The plaid amang our auld forbears

Was lo’ed ower a’ their precious wares,

Their dearest joys wad be but cares

Without the plaid.

And, when the auld guidman was deid,

’Twas aye, by a’ the hoose agreed,

That to his auldest son was fee’d

His faither’s plaid.

Ah! gin auld plaids could speak or sing,

Our heids and hearts wad reel and ring,

To hear the thrillin’ tales that cling

To Scotia’s plaid.

To hear hoo Scottish men and maids,

’Mang Scotland’s hills and glens and glades,

Baith wrocht and fought wi’ brains and blades

In thae auld plaids.

The star o’ Scotland n’er will set

If we will only ne’er forget

The virtues in our sires that met

Aneath the plaid.

Amang the Scottish sichts I’ve seen,

Was ane that touched baith heart and een,—

A shepherd comin’ ower the green

Wi’ crook and plaid.

And i’ the plaid a limpin’ lamb,

That on the hill had lost its dam,

And, like some trustfu’ bairnie, cam’

Row’d i’ the plaid.

Anither sight I think I see—

The saddest o’ them a’ to me—

The Scottish martyrs gaun to dee

I’ their auld plaids.

But let’s rejoice, the times are changed,

The martyrs hae been a’ avenged—

An English princess has arranged

To wear the plaid.

Wm. Murdoch, a native of Paisley, Scotland, came to Canada in 1823, and settled in St. John, N.B., where he engaged in various occupations, his later years being devoted to journalism. In his youth Mr. Murdoch was intimately acquainted with Walter Watson, who wrote the well-known song, “Sit Ye Doon My Crony and Gi’e Us Your Crack.” A day or two before Mr. Murdoch’s departure for Canada, Mr. Watson walked all the way from Kilmarnock to Paisley to bid farewell to his brother poet. The following stanzas from “A Prayer” will show what Mr. Murdoch could do in the way of versification:

From the depths of the ocean to earth’s utmost bound,

In ravine and valley, O God, Thou art found

By all who would seek Thee aright;

Could we penetrate earth to its innermost cave,

Or were mountains on mountains laid over our grave,

Were the floods of the ocean above us to rave,

We could not be hid from Thy sight.

Oh, Father of worlds—omnipotent God!

Support us, Thy creatures, who groan ’neath a load

Of transgressions by nature our own;

When Thy thunders shall over this universe boom,

And awake all who are, or have been, from the tomb,

May we number with those who in glory shall bloom

Eternally around Thy white throne.

It seems a noticeable and well-established fact to those who have given the subject of poetry any thought, that the proportion of the gentler sex who have wooed the poetic muse in Canada is greater than in the Old Land. Scotland may not have produced, proportionately, so large a number of poetesses; but what has been lacking in quantity has been made up in quality. Some of the finest songs in the language have been created by women in Scotland, and their popularity will go down through the ages.

Several ladies have distinguished themselves in the realm of poetry on this side of the Atlantic. Of these Mrs. Jean Blewett is perhaps the most widely read. As her work is well known to those who read The Canadian Magazine, but little need be said for her here. Her latest volume of verse was reviewed in the January number. Miss H. Isabel Graham, of Seaforth, a daughter of the Manse, has written many poems that will live. Miss Graham is a daughter of the Rev. Wm. Graham, for thirty years minister of the Presbyterian Church at Egmondville, and a native of Comrie, Perthshire, Scotland. Miss Graham is not unknown to public fame, as several of her poems have found their way into the public press. One little poem of hers entitled “There’s Aye a Something,” furnishes a moral clothed in everyday apparel, with a due proportion of embroidery in the shape of mother wit. Here is a sample of Miss Graham’s work in a familiar strain, bearing the title of “The Prodigal Child”:

Far from the light and the comfort of home,

Out where the feet of the desolate roam,

Wanders a son from his parent astray,

Bruised by the thorns of life’s rough, weary way;

Father, have mercy, the night’s dark and wild,

Save in his weakness Thy prodigal child.

Fall’n like a star from the firmament bright,

Hiding in darkness, away from Thy sight;

Gone are the false, fleeting pleasures of earth,

Dim are the marks of his right royal birth;

Yet Thou dost love him where’er he may stray,

Bidding him come to Thy bosom to-day.

Mrs. Isabella Ecclestone MacKay is a daughter of one of Woodstock’s best-known citizens, Mr. Donald MacLeod MacPherson, Scottish to the core, as his name indicates. Mrs. MacKay has the true gift of song, with a style of expression that is all her own. She has contributed quite a number of poems to Canadian and American publications, and these have attracted considerable attention. Her verses on “Hallowe’en” are unlike all other poems on that subject. Hallowe’en is suggestive of frolicsome fun, with a spice of something “no’ canny” thrown in. Mrs. MacKay’s poem is in the nature of a reverie—an appeal to the past, with a glimpse of

“Old friends whose comradeship my age has missed,

Dear faces whom death’s cruel lips have kissed;

One long-lost love whose face for weary years

I have not seen save through a mist of tears—

I see them all so plain. Ah, yes, I ween

I need no other guests on Hallowe’en.”

In “The Apple-parin’ Bee,” Mrs. MacKay strikes a different chord. Here are two verses:

My gals is struck on parties, the kind that’s known as “balls,”

They spend their lives in dancin’ an’ returnin’ dooty calls;

They never seem to get much fun, in fact it ’pears to me

We were a sight more jolly at an apple-parin’ bee.

* * * * * * * *

I asked the gals one mornin’ “Look here, I’d like to know

Jes’ what you think you’re gettin’ from this everlastin’ show?

We didn’t wake with faded eyes and headaches—no, siree!

The days our greatest frolic was an apple-parin’ bee!”

Mrs. Georgina Fraser Newhall, a native of Galt, of good Scottish stock, has distinguished herself both by her poetic and prose writings. Her “Fraser’s Drinking Song” has been adopted as the “Failte,” or welcome of the Clan Fraser Society of Canada, and it has been set to a stirring martial tune. The first and last verses, or toasts, are as follows:

All ready?

Let us drink to the woman who rules us to-night,

To her lands, to her laws, ’neath her flag we will smite

Ev’ry foe,

Hip and thigh,

Eye for eye,

Blow for blow—

Are you ready?

All ready?

A Fraser! A Fraser forever, my friends;

While he lives how he hates, how he loves till life ends,

He is first,

Here’s my hand,

Into grand

Hurrah burst—

Are you ready?

All ready!

All ready!!

All ready!!!

Agnes Tytler, whose poems, though comparatively few in number, have won for her a place among Scottish-Canadian poets, was born in the Township of Nichol, County of Wellington. Her father came from Aberdeenshire and her mother from Banff. Most of Miss Tytler’s poems are couched in a somewhat serious vein. The following verses from “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” are a fair sample of what she has written:

Even in youngest baby-days

The dark shade hovers nigh,

As oft we are reminded

There is none too young to die.

* * * * * *

The world was fair and beautiful

When I was young and gay;

I find much that is sorrowful

When I am turning gray.

* * * * * *

Tired, from this weary, weary world

I turn my thoughts on high,

Where dwelleth holy peace and love,

And naught can fade or die.

We need not wealth or power

To reach the heavenly shore;

Freely God gives us, day by day,

And bids us ask for more.

In making the foregoing selections from poems by women, only the writings of Scottish-Canadians have been drawn upon. Quite a number of native-born Scotswomen, resident in Canada, have contributed largely to the poetry of this land. Among the more prominent of the latter are: Mrs. Mary A. Maitland, Mrs. Jessie Wanless Brack, Mrs. Margaret Beatrice Burgess, and Mrs. J. R. Marshall.

There is one other poet to whom a tribute may well be paid—Rev. R. S. G. Anderson, who was, some years ago, in charge of the Presbyterian congregation at Wroxeter, but who is, at present, living in Scotland. Mr. Anderson has produced poetry that will compare very favourably with that of any of his compeers. “The Young Minister,” and “The Precentor,” are vivid pen-pictures. Both are written in “braid Scots,” with which Mr. Anderson is quite familiar; and they are brimful of that pawky humour which is characteristic of the Scot in his best moods. The Dominion is well remembered by this poet. “The Crofter’s Song,” “Sugar Making,” and “Canada,” all bear the stamp of a loyal and warm-hearted citizen. That Mr. Anderson is an Imperialist, as well as a patriot, is evidenced by the closing verse of “Canada,” which reads as follows:

Blest be our land that has written in story

Names that are worthy, and deeds that inspire!

Long may her place in the roll-call of glory

Wake a true pride with the patriot’s fire.

God ring the Empire round;

But let our sons be found

Marching, breast forward, the first of the free.

True to the larger house

Still shall we give the rouse,—

“Canada! Motherland! Our hearts beat for thee.”

What has been spoken of as “the flowery field of Scottish song” may be said to have been well cultivated in Canada. A few samples—among thousands—have been given in this and the previous article. But these will suffice to prove that the product, so far, has not only been plentiful, but excellent. With the making of history—the development of the country and the gradual building up of this great Dominion—will come a purely national poetry; but those who write that poetry will not be less successful that they have had as their model those poems and songs which have contributed, in so marked a degree, to popularise Scotland among the other nations of the earth.

Misspelled words and printer errors have been corrected. Where multiple spellings occur, majority use has been employed.

Punctuation has been maintained except where obvious printer errors occur.

A cover which is placed in the public domain was created for this ebook.

[End of Scottish-Canadian Poets, by William Wilfred Campbell]