* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Child's Auction and Other Stories

Date of first publication: 1869

Author: Oscar Pletsch (1830-1888)

Illustrator: Oscar Pletsch (1830-1888)

Illustrator: Harrison Weir (1824-1906)

Illustrator: Hammatt Billings (1818-1874)

Date first posted: August 7, 2025

Date last updated: August 7, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20250809

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Google Books

THE

CHILD’S AUCTION,

AND

OTHER STORIES,

FOR YOUNGEST READERS.

With more than One Hundred Illustrations

BY

OSCAR PLETSCH, HARRISON WEIR, HAMMATT BILLINGS, AND OTHERS.

BOSTON:

JOHN L. SHOREY, No. 13 WASHINGTON STREET.

NICHOLS & HALL, No. 43 WASHINGTON STREET.

1869.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by

JOHN L. SHOREY,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

Electrotyped and Printed by Geo. C. Rand & Avery, Boston.

CONTENTS

| IN PROSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| The Children’s Auction. By Ida Fay | 1 |

| A Story Small, but True | 4 |

| The Snow Cord and the Rain Cord | 6 |

| The Walnut Fleet By Sandy Bay | 7 |

| A Morning Call. (Oscar Pletsch) | 9 |

| Give Heed to Little Things | 12 |

| The Boy and the Nettle | 13 |

| About a Tame Tiger. By Trottie’s Aunt | 14 |

| Blowing Bubbles | 16 |

| The Professor. (Oscar Pletsch) | 17 |

| What we owe to the Sheep | 21 |

| The Show of Wild Beasts | 24 |

| What Harry found out | 25 |

| Chasing a Butterfly. By E. C. | 26 |

| A Secret.—Don’t Tell | 27 |

| Perseverance and its Reward | 28 |

| The Swallow and his Mate | 29 |

| Think Twice before you Shoot | 31 |

| The Turtle-doves | 32 |

| You can’t come in. (Oscar Pletsch) | 33 |

| The Power of Goodness | 37 |

| Beg, Sir | 40 |

| How the Ape, &c. By Trottie’s Aunt | 42 |

| Sunbeam | 45 |

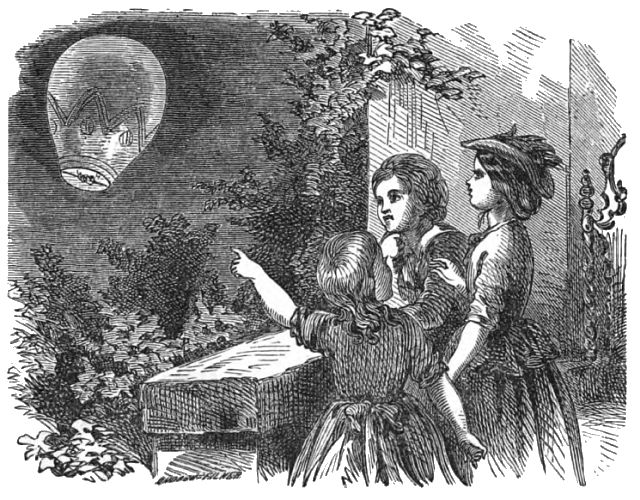

| The Fire Balloon | 48 |

| Robert the Organ-grinder | 49 |

| Help One Another | 51 |

| Our Dog. By Mrs. Ogden | 54 |

| Cooking Dinner. (Oscar Pletsch) | 56 |

| Getting Ready. (Oscar Pletsch) | 57 |

| Pop-corn | 59 |

| The Brother and Sister | 60 |

| The Goat | 61 |

| How the Dog, &c. By Trottie’s Aunt | 62 |

| What Lucy found out | 64 |

| Don’t touch this Baby. (Oscar Pletsch) | 65 |

| Do not take. By Col. Woods | 67 |

| The Grateful Tiger | 70 |

| The Stormy Petrel | 73 |

| How the Cat, &c. By Trottie’s Aunt | 74 |

| The Dove’s Nest | 77 |

| Sister and Brother Playing | 80 |

| Tit for Tat. By E. Carter | 81 |

| About the Air | 84 |

| Of what Use can I be? | 86 |

| James’s Ride | 88 |

| Under the Umbrella. (Oscar Pletsch) | 90 |

| Red or Black. By Uncle Charles | 95 |

| What a Lazy Boy! (Oscar Pletsch) | 97 |

| Brightening all it can | 99 |

| How the Swans, &c. By Trottie’s Aunt | 100 |

| The Child who fell | 102 |

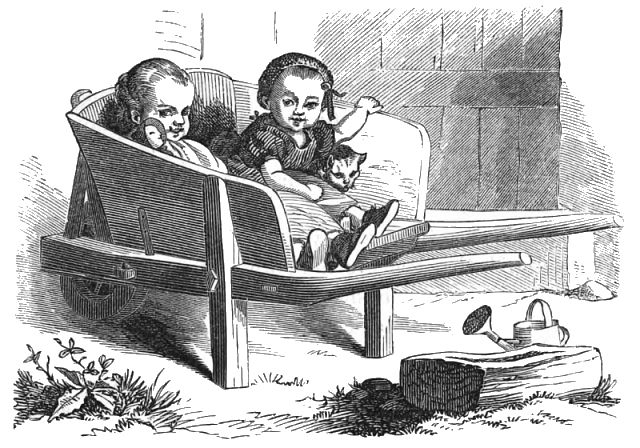

| In the Wheelbarrow. (Oscar Pletsch) | 105 |

| The Dog who had no Home | 109 |

| Hold on, Boy! | 112 |

| Teasing Willie | 114 |

| Coal | 116 |

| Wheat | 117 |

| The Bantam Hen | 118 |

| The Great Tea-party. (Oscar Pletsch) | 121 |

| How the Twins, &c. | 122 |

| The Two Little Bluebirds | 125 |

| The Child’s Carriage | 127 |

| Our Sail down the Bay | 128 |

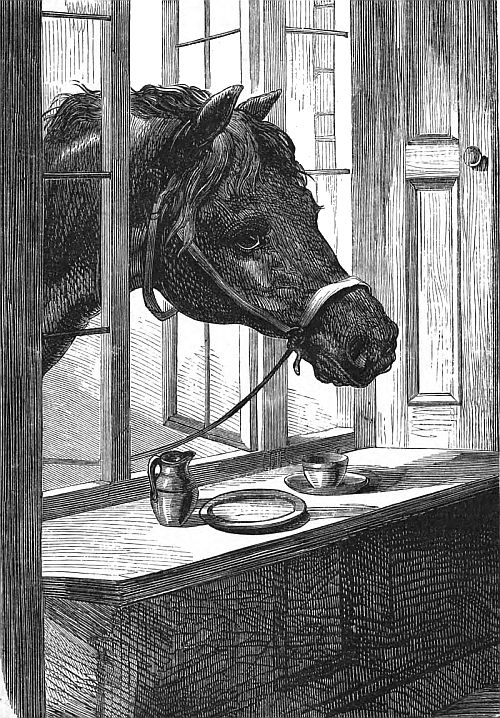

| I want a Lump of Sugar | 129 |

| The little Monkey | 135 |

| Pat and his Pig | 137 |

| Our Autumn Games | 139 |

| The Proud Cat By Trottie’s Aunt | 141 |

| The Young Neighbors | 145 |

| Arthur’s Schooner | 148 |

| The Pear on the Ground | 150 |

| Safe bind, Safe find | 151 |

| The Grand Concert (Oscar Pletsch) | 153 |

| Our Home in Georgia | 155 |

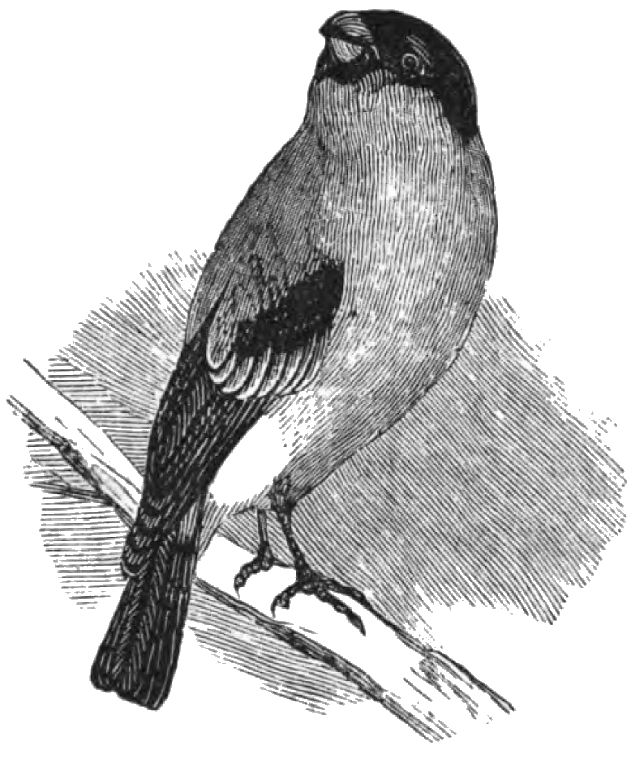

| The Piping Bulfinch | 157 |

| John the Green-house Man | 160 |

| Hide and Seek | 162 |

| Lost in the Grove | 164 |

| Little Anna. By W. O. Cushing | 168 |

| Charles and his Ducks. (Oscar Pletsch) | 169 |

| Our Friend Carlo. By Mrs. Ogden | 174 |

| Aunt Julia’s Gift | 177 |

| The Sailor-boy | 179 |

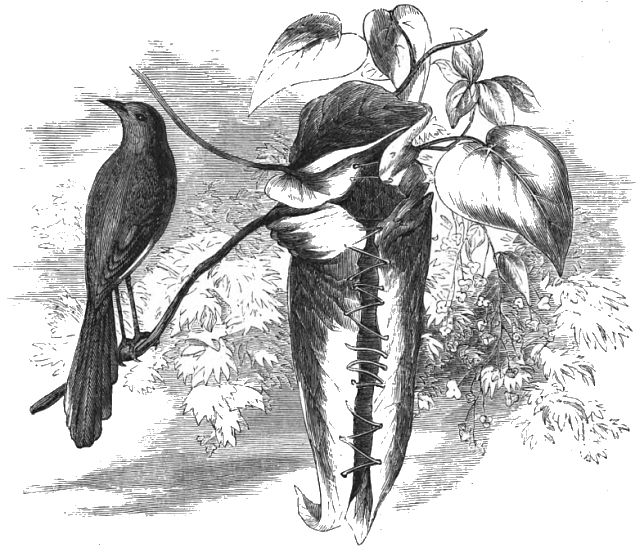

| The Tailor-bird | 181 |

| Out on the Snow | 185 |

| How the Dog got the Stick | 187 |

| IN VERSE. | |

| A Good Rule. By Emily Carter | 11 |

| The Bath-tub. By Mrs. Wells | 20 |

| Under my Window | 23 |

| The Hare | 27 |

| The Slothful Shall Come to Want | 31 |

| Evening Song | 36 |

| The Heavenly Father | 39 |

| The Fox and the Goose | 43 |

| The Cunning old Cat By E. C. | 44 |

| The Stag and the Wolves | 47 |

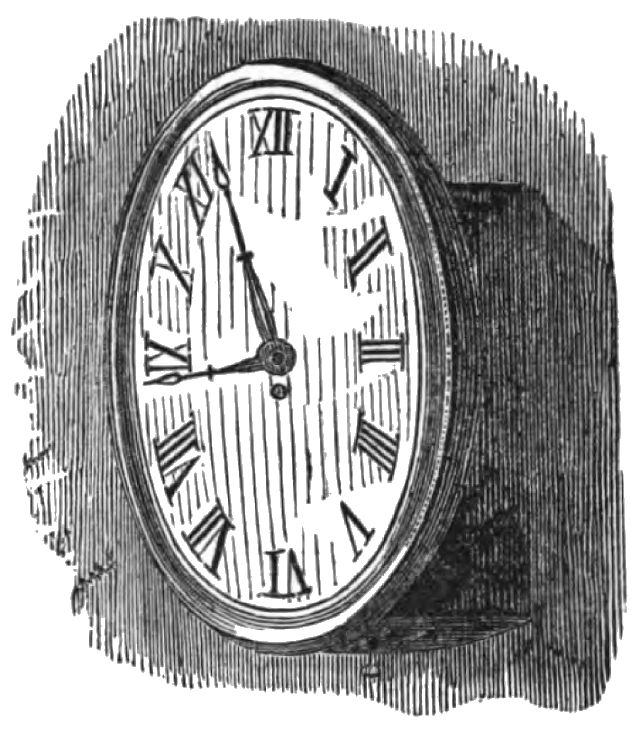

| What says the Clock. By E. C. | 52 |

| Little Voices | 53 |

| The Hunter’s Horn | 69 |

| Mary’s Rhymes. (Oscar Pletsch) | 72 |

| Washing. By M. S. C. | 79 |

| The Holly. By M. S. C. | 83 |

| The Woodman | 85 |

| The Anxious Mother | 92 |

| The End of the Bow. By Emily Carter | 93 |

| The Mother’s Lullaby. By M. S. C. | 96 |

| Good Wine | 103 |

| Lucy takes Care of the Flowers | 104 |

| In the Attic. By Mrs. Wells | 106 |

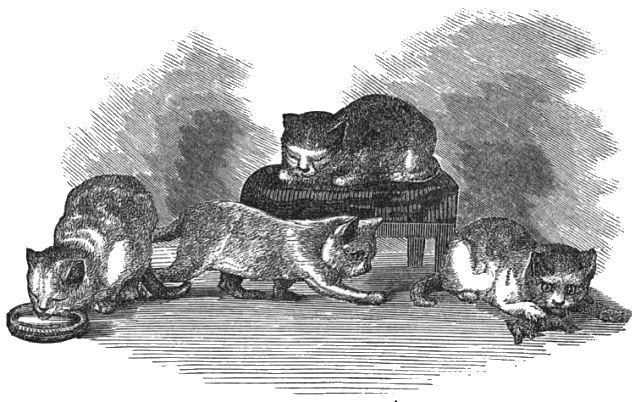

| The Kittens. (Otto Specker) | 108 |

| Baby’s Song | 109 |

| The Quail. By Emily Carter | 116 |

| Bed-time. By Edith Renshaw | 120 |

| Keep Trying | 132 |

| The Skipping-rope | 133 |

| Harry on his Horse | 134 |

| The Yellow-bird. By Mrs. Wells | 143 |

| The Honey-bee | 144 |

| Picture Rhymes | 147 |

| Little Molly. By Marian Douglas | 149 |

| Mabel’s Resolve. By Mrs. H. F. Harrington | 167 |

| The Seasons. By L. F. | 172 |

| Winter has come | 173 |

| The Blackbird. By Mrs. Wells | 176 |

| Song of the Bee. By Marian Douglas | 183 |

| Table Rules | 183 |

| A Wintry Day. By E. Taylor | 187 |

“How much for this fine apple?” said Arthur Lane, as he stood upon a stump near the fence, and held up an apple.

“One cent!” said little Julia, as she stood leaning against her sister Ruth, and holding her doll.

“Only one cent for this fine apple!” cried Arthur.

“Two cents,” said Martin, the boy who drove the cows.

“Thank you, sir,” said Arthur. “I am offered two cents. Going for two cents. Going—going”—

“Three!” cried Charles, who sat with his dog on the sod.

“The bid is three cents,” said Arthur. “Only three cents for this beautiful apple! I hope, miss, you will not let it go at so low a price. Going for three cents—only three!”

But, before Arthur could say “Gone,” Ruth, the elder sister, who sat with a basket in her lap, and the cat by her side, cried out, “Four cents!”

“Thank you, miss,” said Arthur. “I am offered four cents for this very superior apple.” Then, turning to Julia, he said, “Would not Dolly like it, ma’am? You must bid for her. You need not tell me you can’t afford it.”

“Well, then, I bid five cents,” said Julia, laughing.

“That is right,” said Arthur. “Five cents. Going—”

“It isn’t worth two cents,” said Martin.

“Look here, mister,” said Arthur, “if you mean to run down my goods, you must leave this auction. See how well the cat and dog behave.”

Martin leaned upon his stick, and was silent.

“The bid is five cents,” said Arthur. “Going for five cents! Five cents only! Only five cents! This is your last chance. Five cents! Going—going—gone! To Miss Julia Lane.”

Now, you may like to know why it was that these children were willing to pay so much for an apple; for it was quite true, as Martin said, that it was not worth two cents.

I will tell you how it was. There was a little girl of the name of Rachel, who went to the same school with these children; and this little girl was quite poor, for her father and mother were both ill.

The next Friday was to be the birthday of this little girl; and Ruth said, “Poor little Rachel wants a new pair of shoes. Let us make her a present of a nice new pair of shoes.”

“Let us do it by all means,” said Arthur. “How much will a pair of shoes cost?”

“We can get a good pair for two dollars,” said Ruth.

“Here are twenty cents,—all I have,” said Arthur.

“I will add ten to that,” cried Charles.

“I will add fifteen to that,” said Julia.

“I will add five to that,” said Martin.

“And I will add fifty to that,” said Ruth. “So now we have a dollar promised. How shall we get one more?”

“Let us have an auction,” said Arthur, “and sell as many things as we can get. I will be the auctioneer. See me sell this apple, and say if I cannot act like an auctioneer.”

So Arthur mounted the stump, and sold the apple.

The next day, the children told all the boys and girls of the school, that they were going to have an auction in the summer-house, to get money to buy a present for Rachel.

The boys and girls were all glad to lend their help. One gave a ribbon, one a top, and one a bag of marbles. One little boy gave a nice penknife, and another a bat and ball. One little girl gave a doll, and another a pencil. Many more things were given,—more than I can tell you about.

Arthur was once more the auctioneer. Some of the old people, learning what was going on, came to the auction, and made bids for the things that were sold.

When the auction was over, Arthur and Ruth counted up the money, and how much do you think they had made by the sale? They had made just seven dollars!

This was money enough to buy, not only a pair of shoes, but a calico dress and a pair of stockings, for little Rachel, besides food enough for her parents for a whole week.

How happy the children were when they took the things to Rachel! and how happy she and her parents were, to see the children so good and kind!

Ida Fay.

I have thought that some of the children might like to hear about a squirrel I used to know when I lived in Mississippi. It will not be a long story to tell; for he was a very small squirrel, and died quite young.

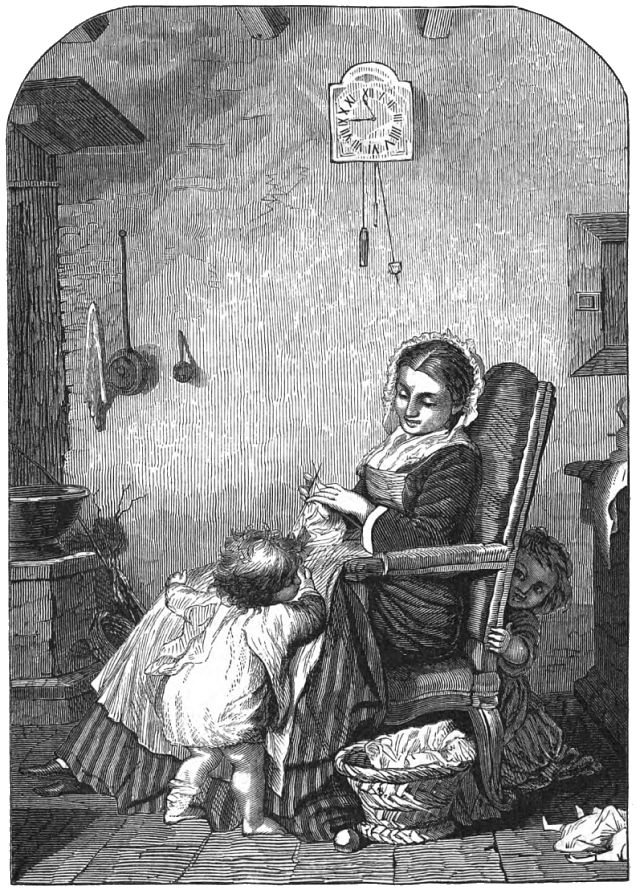

Oh, dear! I must not tell you the end of the story before I you know the beginning. Well, one bright May morning I was sitting sewing at the window; and Rhoda and Teresa, two dear little girls who were living with me, were playing in the yard.

Presently they came scampering into the parlor in a great flurry. Two eager faces were turned up to mine, a hand was seized by each of the children, and both cried out in a breath, “Oh! dear Aunt, do please just come and see what Uncle Jacob has brought for us!”

Uncle Jacob was a black man, and, of course, not their uncle at all; but Southern children always call a colored person uncle or aunt, because they think it more kind and respectful.

When we reached the back piazza, there was Uncle Jacob, holding in his hand the tiniest little squirrel that ever was seen. It was not more than two or three days old, and had not learned even to open its eyes.

“O Jacob!” said I, “how could you be so cruel as to take that baby-squirrel away from its mother?”

“ ’Deed, ma’am,” said Jacob, “I didn’t take him away from his mother. De ole snake take him away; an’ I take him away from de snake, an’ kill de snake. I fotch de squirrel home to de young ladies, so dey could raise ’im. Mighty fine pets dey is, so peart and lively.”

“Well, children,” said I, “it seems we shall have to adopt this little fellow; but how shall we feed him? It would not be the right sort of kindness, to save him from the snake only to let him starve. Run to the kitchen, and ask Aunt Lucy to please send me some warm milk.”

The milk was soon brought. I dipped a small sponge into it, and then held the sponge close to the squirrel’s mouth. He must have been hungry; for, as soon as he smelt the milk, he caught at the sponge, and began to suck it as fast as he could.

When he had finished his breakfast, Rhoda put him in a blanket on a nice bed of cotton, and he went to sleep as comfortably as if he had been in his own little nest in the hollow tree.

It would take too long to tell you how Bunny grew and grew; how, after he had had enough of sucking milk from a sponge, he took to helping himself to biscuits and lumps of sugar from the table; how at last he learned to get at the kernel of a nut, as cleverly as any of his little wild brothers and sisters. I must haste to the end.

One day in October, I went with Teresa to gather some bright autumn leaves. Rhoda stayed at home because she had a hard lesson to get; and we left her, on the steps of the piazza, at her books.

We got the leaves, and were almost home, when we heard a loud cry of lamentation, and soon saw Rhoda running to meet us, and weeping bitterly.

“O Aunty! O Tressy!” she cried: “our dear Bunny is killed. A horrid snake caught him as he was jumping about. I heard him cry. I ran to him. I screamed as loud as I could for help. But the snake would not let him go; and nobody would come for such a long time! And when Uncle Jacob came, and killed the old snake, poor Bunny was all crushed and dead. Oh! I wish there was not a snake in the world—so I do!”

Rhoda refused to be comforted, and Teresa mingled her tears with hers. Uncle Jacob, as he leaned thoughtfully on his spade, uttered his thoughts thus: “ ’Pears as if dat ar squirrel was bound to be killed by a snake.”

Mrs. E. H. Downing.

I know a little boy named Edwin, who likes snow very much. He has a pair of India-rubber boots with which he can wade through the melting snow. He also has a sled with which he can coast down hill.

Sometimes he will harness his dog to the sled; and then the dog will run like a reindeer over the snow and ice, dragging the sled with Edwin on it.

This little boy wishes very often that it would snow. Sometimes he springs out of bed, and looks out of the window to see whether any fresh snow has fallen through the night; and he will be vexed if, instead of that, he finds the rain pouring down.

What do you think he said, one day? “I wish,” said he, “that a snow cord and a rain cord hung down from the clouds; so that, if I pulled the snow cord, it would snow, and, if I pulled the rain cord, it would rain. Oh, how I would pull the snow cord, and make the snow fall down!”

Now, I would say a word to all little boys who wish that they had a snow and a rain cord. God holds all the cords in his hand. He sends the rain and the snow. He knows what is best for us. Do you not think, then, that we should be content with what he sends?

Uncle Charles.

Here are four children having a nice time sailing boats. Each boat, you see, is the half of a walnut-shell.

Charles, the eldest boy, cracked the nuts neatly into halves, picked out the meat (I wonder what he did with it), and then fitted out each boat with a wooden tooth-pick mast and a paper sail.

Then he and Mary launched the boats; and off went the whole fleet to sea in the wash-tub. Johnny sat in his little chair close beside the tub, looking at the fun; and little Annie was busy all the while trying to rig a boat with her own hands.

How well the boats floated on the water! “This,” said Mary, “is the sloop ‘Mary Jane,’ bound for Cape Ann.”

“This,” said Charles, “is the fast clipper-ship ‘Eagle,’ bound on a voyage round the world.”

“The Mary Jane has on board a fine lot of fresh mackerel,” said Mary.

“The Eagle is not in the fish-trade,” said Charles.

Little Johnny said nothing, but puffed out his lips, and blew a long breath upon the water.

“The wind is rising,” said Charles, laughing. “There’s a stiff breeze from the north-east.”

Here Johnny gave another puff. “It is getting rough and squally,” said Mary. “We shall have a gale of wind before long. The ‘Mary Jane’ will have to take in sail.”

“Let the gale come,” said Charles. “The good ship ‘Eagle’ will not take in sail. The harder it blows, the faster she goes!”

Just then Johnny gave a third puff, and aimed it right upon the sail of the good ship “Eagle.” Over she went.

“Capsized!” said Charles. “Get out the boats! Cut away the masts! Hoist a signal of distress!”

“Never fear,” said Mary: “the ‘Mary Jane’ is bearing down to the rescue. I told you there was a gale coming.”

“Yes,” said Charles; “but I didn’t expect a hurricane.”

“It was nothing but a squall,” said Johnny. “Look out for another!”

And he gave another puff, which capsized the whole fleet, including the “Mary Jane.” So the play ended in a roar of laughter; both Charles and Mary declaring that no ship could live in such a sea.

Sandy Bay.

Ah! here are our little friends, Bertha and Mary!

Why, I mistake: these are Mrs. Rose and Mrs. Lily! Mrs. Rose has come to pay Mrs. Lily a visit.

“Dear Mrs. Rose, how glad I am to see you!” says Mrs. Lily, as they shake hands. “You will stay to tea with me,—will you not?”

“Thank you, Mrs. Lily; but—ah! your little dog! Will he not hurt me?”

“Oh, no! Frisk never harms any one, though he does open his eyes so very wide at you. Do you not see how he tips his head on one side, and looks at you as much as to say, ‘Oh! I know who you are. You are my mistress’s dear friend, Mrs. Rose. I am glad to see you.’ ”

“Well, Mrs. Lily, he is not like Ellen Lee’s dog. When I met Ellen on the street the other day, and wanted to put my arm in hers, to walk with her, Jip sprang upon my dress, and barked at me so hard I was afraid of him. He would not let me touch her.”

“I like my little dog better than Jip, Mrs. Rose; for, though he cares most of all for me (don’t you, Frisk?), he is very fond of my friends. Now, make a bow, Frisk. Did you ride, Mrs. Rose?”

“No: the day was so fine, I thought I would give Amy a walk through the fields. Such beautiful butter-cups and daisies as we picked! But I feel very tired, for I had to take Amy in my arms, as you see. Ah! my hat has fallen on the floor.”

“I will pick it up, my dear. Throw off your cloak, too, and let me take Amy’s things; and do sit down and rest yourself. I will call Mary to bring in some more tea, and another cup and saucer.”

“Do not give yourself that trouble, Mrs. Lily. Ah! it is very warm. I will throw off my cloak a moment.”

“I hope you will excuse this basket on the floor, Mrs. Rose. I have been so busy to-day; and Katie has just come home from a visit to her cousin Susan! You see I have her hat in my lap. How old is your little girl?”

“Amy is three years old.”

“Why, Katie is only two years old, and yet she seems almost as large as Amy. But do take a seat at the table, Mrs. Rose.”

“I think I cannot stay to tea to-night, Mrs. Lily; for it is quite a long walk to my house, and I fear it will be dark before I get home. I like to have Amy go to bed before dark.”

“Let me order my carriage, then, for you. Mary, tell John to bring the carriage to take Mrs. Rose and her little girl home.”

“You are very kind, Mrs. Lily. I hope you will return my visit soon; and Katie must come, too, to see Amy. Good-by.”

“Good-by, Mrs. Rose. I am glad you called.”

h. l.

One rule to guide us in our life

Is always good and true:

’Tis, “Do to others as you would

That they should do to you.”

When urged to do a selfish deed,

Pause, and your course review;

Then do to others as you would

That they should do to you.

When doubtful which is right, which wrong,

This you can safely do:

Yes, do to others as you would

That they should do to you.

O simple rule! O law divine!

To duty thou’rt a clew.

Child! do to others as you would

That they should do to you.

Emily Carter.

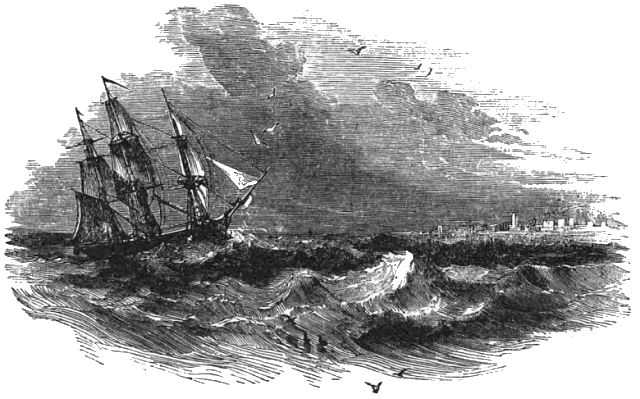

Two men were at work together one day in a yard where ships were built. They were hewing a stick of timber to put into a ship. It was a small stick, and not worth much. As they cut off the chips, they found a worm,—a small worm, not more than half an inch long.

“This stick is wormy,” said one: “shall we put it in?”

“I do not know,” said the other: “yes, I think the stick may go in. Of course it will never be seen.”

“That may be; but there may be other worms in it, and these may increase, and hurt the ship.”

“No, I think not. To be sure, the stick is not worth much; yet I do not wish to lose it. But, come, never mind the worm: we have seen but one; put it in.”

And so the stick was put in. The ship was built and launched. She went to sea, and for ten years she did well. But at last it was found that she grew weak and rotten. Her timbers were much eaten by worms.

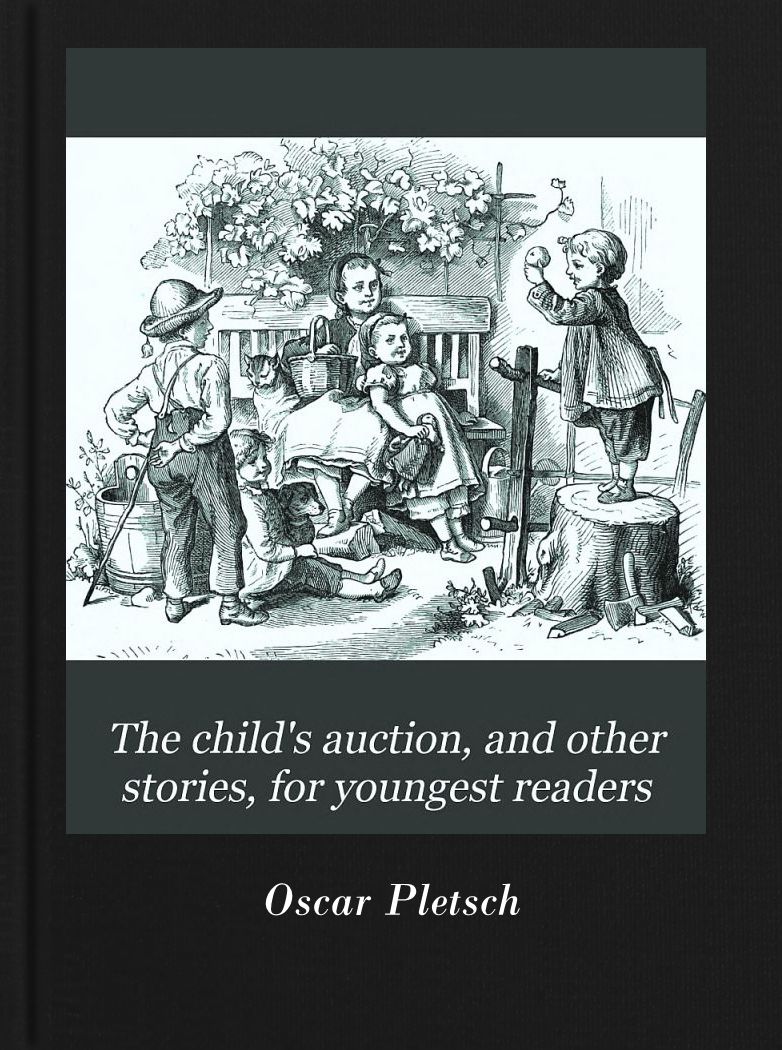

But the captain of the ship thought he would try and get her home. He had a costly load of goods in the ship,—such as silks, teas, &c.,—and a great many passengers.

On their way home, a great storm came on. The ship for a while climbed up the high waves, and then plunged down, creaking and rolling very much. At last she sprang a leak.

They had two pumps, and the men worked at them day and night; but the water came in faster than they could pump it out. She filled with water, and went down under the blue waves, with all the goods and all the people on board. Every one perished.

Oh! what a loss there was of life and of goods! and all because that little stick of timber with the worm in it was put in when the ship was built.

How much mischief may be done by a little worm! and how much evil may a man do, when he does a small wrong, as that man did who put the wormy timber into the ship!

Sandy Bay.

A boy came crying to his mother because he had been stung by a nettle.

“I am sure I never thought it would hurt me,” said he, “for I only touched it as gently as possible.”

“That is just why it stung you,” replied his mother: “if you had only grasped it firmly, it would have done you no harm.”

It is thus in life. Evils that are boldly met will not harm us so much as those which we meet with a faint heart and a feeble hand. It is always best to “grasp the nettle.”

“I have just heard a true story of a tiger. I think you would like to hear it. Shall I tell it to you?”

“Oh, yes! for you have never yet told me about a tiger.”

“Well, there was a man named Brown, who lived in India, and who had a tiger; and this tiger was so fond of Mr. Brown, that he was as tame as a dog with him. The tiger’s name was Tim.

“Tim would run and jump and play with Mr. Brown, and lick his hands and his face, and come when Mr. Brown called him, and go when Mr. Brown told him to go, and, in fact, do all that Mr. Brown told him to do.

“But, though Mr. Brown was fond of Tim, I cannot say that Mr. Brown’s friends were quite so fond of Tim. Tim was kept in a yard near the house; and, when these friends came to call on Mr. Brown, they could not but stand in fear of the tiger.

“They thought to themselves, ‘What if the great beast should spring here, and spring there, and spring this way, and spring that, until his next spring would be at us! He may love Mr. Brown, but he does not love us; and how do we know but Tim may strike us with his claws, and hurt us or kill us?’

“Now, Mr. Brown had to leave his own home, and go to a land far, far away; and though his friends were sad that Mr. Brown should go away, yet it must be said they were glad to think that now they should get rid of Tim.

“But Mr. Brown was not glad. Oh, no! it made him sad to think that he and Tim must part; for he could not take Tim with him. So Mr. Brown thought the best thing he could do for Tim was to put him into a place where wild beasts were kept. He begged the man who took care of the beasts to be kind to Tim; and then he said ‘Good-by’ to his dear Tim, and went to the land that was far, far away.

“Now, when Tim found that Mr. Brown was gone, Tim was so sad, that he would not run nor jump nor play nor frisk. He did not seem to care for any one at all. He would sit all day long at one end of the cage, and would just eat what they gave him, and sleep when the time for sleep came. But life was sad to poor Tim. His dear, kind friend was gone, and there was no one else whom Tim cared to see.

“Some years went by, and still Tim was just in the same sad state, when, one day, what should Tim hear but a step that he knew right well! Up sprang Tim, and with one bound was by the bars of his cage.

“Tim looked and looked to the side from which the sound had come: and at last he gave a bound and a spring, and a roar of joy; for Tim had heard the footstep right, and it was in truth his own dear friend and master who was once more by his side.

“Poor Tim! He did not know how best to show his joy. He rubbed his head on Mr. Brown’s hand; he licked his face; he purred out his joy like a cat; and all the time he seemed to want to say, ‘Oh! do not leave Tim again. My heart has well-nigh broken, you have been away so long. And, now you have come back, how glad I am!’ ”

“And did Mr. Brown leave Tim again?”

“That I do not know. I only know that Mr. Brown was very glad to see Tim once more; and that Tim, for some weeks, saw Mr. Brown once a day, and was happy.”

Trottie’s Aunt.

On a rainy day in June, Paul said to his sister Ann, “Now, if you will get a bowl of soap-suds, I will show you something.”

Ann ran and got the bowl of soap-suds, and John took from his pocket a pipe. Then he sat down on a stool, and began to blow bubbles.

Little Jane came in to see him.

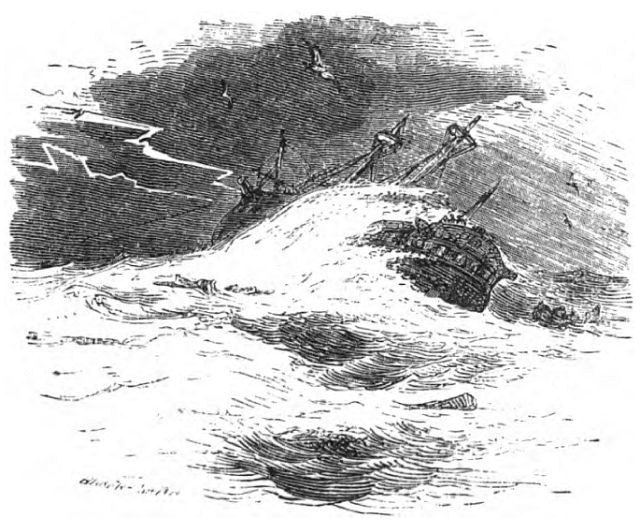

THE PROFESSOR.

John has put on his grandfather’s spectacles and cap. He calls himself “Professor Noodle, lecturer on Mother Goose.” He has a book in his hand, and he tries to look quite wise and grave; but in this I do not think he succeeds.

“Now, children,” he says, “you will please be still, and hear my lecture. Ahem! My subject, ladies and gentlemen, is Mother Goose. How the heart thrills at that name! Homer was great; Milton was great; but Mother Goose”—

“Look here, Professor: what will you take for that cap?” cried little Edwin Potter.

“Silence!” cried the Professor, in a loud voice. “Hear me for my cause, and be silent that you may hear. I shall divide my lecture into ten heads. First, who was Mother Goose? and where was she born? Second,”—

But here one of the Professor’s hearers, little Susan Ide, cried out, “I don’t want to hear about Mother Goose. I want to hear a story.”

“The young lady wants to hear a story,” said the Professor, shutting up his book. “Well, a story it shall be. But shall it be a true story, or a story made up out of my head?”

“Let it be a true story,” said Susan.

“If it is to be a true story,” said the Professor, “I must take off my spectacles and my cap. There! the Professor has left the chair; and now it is I, John, who speak.

“Not long ago a Mr. Webb, a friend of my teacher, was walking on the bank of the river in Paris, when he saw a man who held a dog by a chain. The dog seemed frightened, as if he knew what the man was going to do.

“ ‘Poor beast!’ said the man. ‘See how he fawns about my feet! He knows I am going to drown him.’

“ ‘But why will you drown him? Are you his master?’ asked Mr. Webb.

“ ‘Yes, I am his master,’ said the man, ‘and he is old. Poor Ponto! I am sorry, but it must be.’

“The dog gave a low whine, as if he understood what was said; and, trembling, he crouched down close to his master.

“ ‘He does not seem so very old; and it is too bad to drown so bright a dog,’ said Mr. Webb.

“ ‘Sir, he is of no use to me,’ said the man; ‘and, besides, I cannot afford to pay the tax for keeping him.’

“Thus speaking, the man put the dog into a boat, and rowed to the middle of the stream. When he came to where the water was quite deep, he all at once lifted up the dog, and threw him with great force into the stream.

“If the man had thought that the dog’s age would prevent his struggling for life, he was much mistaken; for Ponto rose to the surface, kept his head well up, and trod the water bravely.

“The man then began to push him away with an oar, and at last struck out so far as to deal the dog a blow. By this the man lost his own balance, and fell into the river. He could not swim, and cried loudly for help.

“What did poor Ponto do? Why, he swam straight to the man who had been trying to drown him. With his teeth he took hold of the man’s collar, and held him up till a boat could put off from the shore and save him.”

“And did they save poor Ponto, too?” asked Susan.

“Oh, yes! they saved the dog too. He was in great joy, and jumped up to lick his master’s face and hands.”

“The master did not deserve so good a dog.”

“That was just what Mr. Webb told him, but the man seemed sorry for what he had done, and said to Mr. Webb, ‘I was wrong,—I was wrong. Poor Ponto returned good for evil,—didn’t he? As long as I have a crust of bread, I will give half to my poor Ponto.’

“A woman, who had a basket on her arm, came up at the time, and said, ‘I should think you would be ashamed to look the brave dog in the face;’ and out of her basket she took a piece of meat, and gave it to the dog.

“You may be sure that Ponto had a good time of it after that. Mr. Webb would often meet him in the street; and, as the story of the dog’s brave act was soon well known, he had many friends to feed and pet him. And so his old age was no doubt the happiest part of his life.”

The first thing in the morning

When little Bessie wakes,

All full of life and gladness,

A pleasant bath she takes.

She frolics in the water

With childish glee and grace;

She dashes it and splashes it

About her neck and face.

Just three years old was Bessie,

When, on a summer day,

They took her to the sea-side

Along the sands to play.

They took her to the smooth beach

Where rolls the ocean flood;

They thought the salt sea-water

For Bessie would be good.

The beautiful sea-water!

She claps her tiny hands;

She loves the salt sea-water,

The hard and shiny sands.

She pulls the slimy seaweed,

The shells and pebbles wet;

She laughs to see the pretty mark

Her little toes have set.

“Come now, my little daughter,

And go into the sea;

A cool and pleasant bath for us,—

For Bessie and for me!”

“I’d rather not,” lisps Bessie,

And her lip begins to curl;

“I think it is too big a tub

For such a little girl.”

Mrs. A. M. Wells.

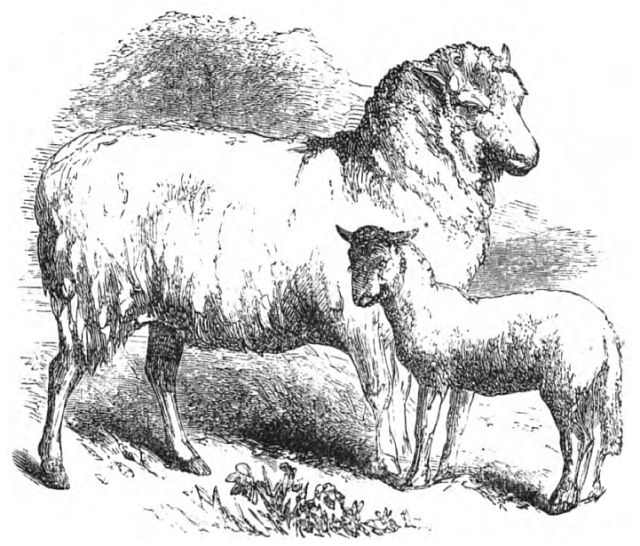

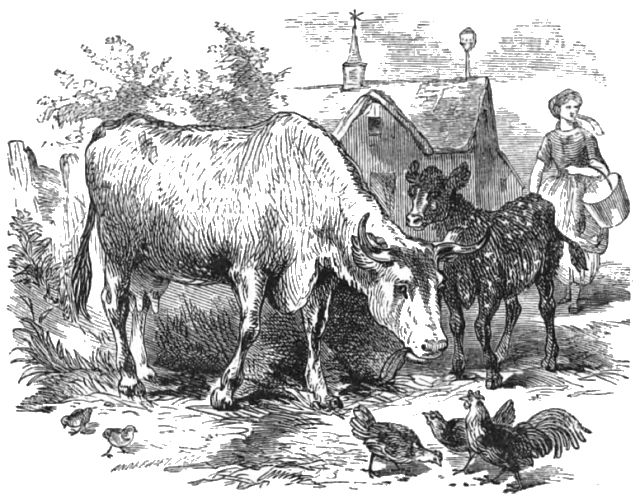

Dear Charlie, or Annie, or Willie, or Mabel,—I wish I were a fairy, and could guess your name!—have you a hood or cap to keep your ears warm when you play in the snow? have you mittens for your hands, and stockings for your feet? and do you sleep at night under a warm blanket? Then I think you will like to hear something about the sheep that give the wool out of which all these nice garments are made.

If you had wings, and could fly like a bird, you would be able to look down upon a great many different countries, and almost everywhere you would see sheep feeding on the mountains or the hills or the plains.

These sheep are not all alike, any more than boys and girls are alike. Some are black, some white, some brown, some yellow. But they all give wool, to keep little folks and big folks warm in the winter; and if you will run all over the house you live in, up stairs and down, and, every time you see any thing made of wool, say, “Thank you, dear little sheep!” you will say it over and over again a great many times; for there are carpets and rugs and shawls, and many more things, in the different rooms, made of wool. And, if I were you, I would keep my little feet trotting till I had found them all.

But do not go yet: I have something more to tell you. Mr. Whiteflock has a large farm in the country, and owns sheep; and, when the hot days of summer come, he takes down his big shears, and goes out among them. First he sends the little lambs away; then he cuts all the wool off the backs of their mothers.

Do you think this is cruel? Oh, no! The sheep like to have their wool cut off: it makes them cool. But you cannot think how queer they look after it is done. Oh, how you would laugh if you were to see them.

But the poor, dear little lambs do not laugh: they cry. They left their mothers looking nice and comfortable in their white coats of wool; but now they look naked and strange and miserable, and the little lambs do not know them.

Their mothers call them; and the lambs run with joy, just as you do, when your mother calls you. But they are frightened the moment they see their mothers,—so frightened, that they bleat in distress, and scamper away as fast as they can. This makes the poor mother ewes very unhappy, and they call again and again. Then the lambs come, and take another peep, and run away this time as fast as before.

At last the silly little lambs begin to find out that it is really the voice of their own dear mothers; and so they come and stay with them.

Do you think this is strange? If your own dear mother should come to you all at once with her hair cut off close to her head, and try to take you in her arms, do you not think that you would be frightened, and run away, just like the little lambs?

Elizabeth Harrington.

Under my window, under my window,

All in the mid-summer weather,

Three little girls, with fluttering curls,

Flit to and fro together;

There’s Bell, with her bonnet of satin sheen;

And Maud, with her mantle of silver green;

And Jane, with the scarlet feather.

Under my window, under my window,

Leaning stealthily over,

Merry and clear, the voice I hear

Of each glad-hearted rover:

Ah! sly little Jane, she takes my roses;

And Maud and Bell twine wreaths and posies,

As busy as bees in clover.

Under my window, under my window,

In the blue mid-summer weather,

Stealing slow, on a hushed tip-toe,

I catch them all together,—

Bell, with her bonnet of satin-sheen;

And Maud, with her mantle of silver-green;

And Jane, with the scarlet feather.

Under my window, under my window,

And off through the orchard closes,

While Maud she flouts, and Bell she pouts,

They scamper, and drop their posies:

But dear little Jane takes nought amiss;

She leaps in my arms with a loving kiss,

And I give her all my roses.

Thomas Westwood.

John and Mary, Thomas, Ruth, and Julia, have been to see the wild beasts that were shown in the great tent on the open lot in Main Street, in our town.

These children saw the lion and the lioness, in a cage with iron bars. John had read the story of the bad boy who kicked at the bars of a lion’s cage to vex him, till at last the lion put out his claw, and caught the bad boy by the boot.

“I will not try such a game as that,” said John. “It is not well to fool with wild beasts. I once saw some boys plague a wild cat that was chained to a post. I could not find fun in seeing the poor beast tormented.”

After they had seen the lion, these children went to see the tiger and the elephant. Then they saw a camel and an ostrich. The children were much pleased; and, when they went home, they read stories of the habits of all these animals.

Aunt Mary.

Here are six pictures; and, of the objects they show, three begin with A, one with B, one with C, one with D, and one with Q. Harry found them all out. Can you do as much?

William and his sister Emily went out on a fine day in June to see the men cut the grass. But soon the little girl saw a yellow butterfly, and cried out, “O William, do help me to catch that beautiful, beautiful butterfly!”

So the two started in chase of the bright little thing. William took off his cap, and held it so he could put it over the butterfly, if the butterfly would only be so good as to light on one of the dandelions, and wait.

But the butterfly did not choose to do this. He flew high up, where neither William nor Emily could reach him. And at last they sat down on a rock, and then William said,—

“On the whole, I am glad we did not catch the butterfly; for we did not want it, and we should only have hurt it. Why should we harm a bird or a butterfly just to please ourselves? We ought to know better.”

Just then the butterfly lighted on a blade of grass close by; and William quickly pulled off his cap, and was about to catch the butterfly, when Emily held his arm, and said, “Why should we harm a bird or a butterfly just to please ourselves?”

William laughed, and said, “You are right, Emily. Those who preach ought to practise. Now, I will tell you what will be better than chasing butterflies. Let us go and pluck some harebells.”

“Oh, yes!” cried Emily: “why didn’t we think of it before? Mother is so fond, you know, of having harebells in her little vase!”

And so the brother and sister did a much wiser thing than chasing butterflies. They went and made a nice little nose-gay, all of harebells, and took it to their mother, who kissed them both, and thanked them for the gift.

Emily Carter.

Scamper, scamper, little hare!

Scamper, scamper, little hare!

Of the cruel dogs beware!

They are swift upon your track:

Run, and stop not to look back.

A friend asked a pretty child of six years of age, “Which do you love the better,—your cat or your doll?” The little girl thought some time before giving an answer, and then whispered in the ear of the questioner, “I love my cat best, but please don’t tell my doll.”

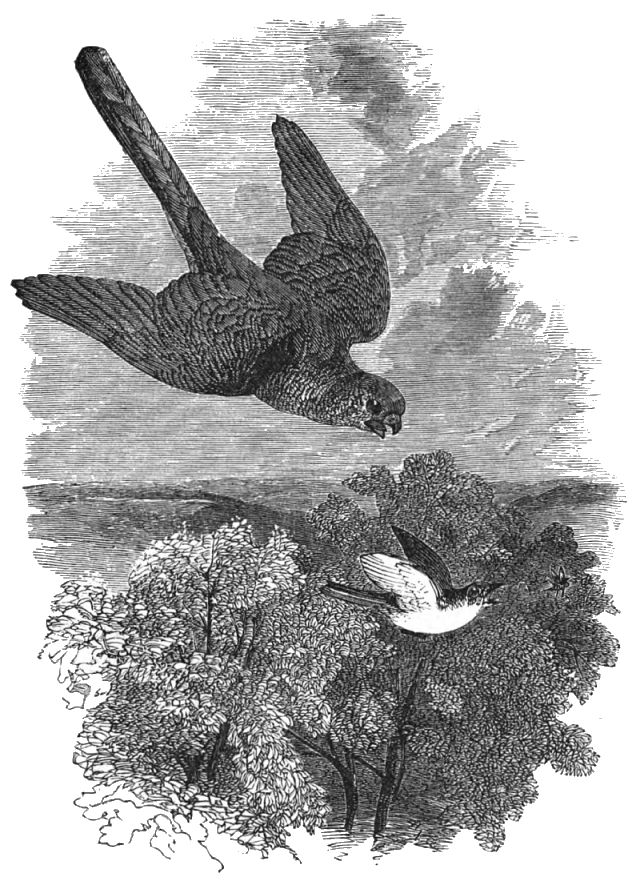

I once knew a man whose name was James Audubon. He had made up his mind to write a great book about the birds of America.

He could draw and paint well: so he went out into the woods, and shot wild birds of bright plumage, and of these he made colored drawings while the tints on their feathers were yet fresh and gay.

He went on with his work for years, and at last had made a thousand drawings. But by accident a fire broke out, and all the nice pictures were burnt.

Here was a misfortune! But what did Audubon do? Instead of complaining, he went to work and made new drawings, till he produced a great book, by which he got fame and wealth. Thus perseverance had its reward.

Among the drawings that Audubon made, were several of eagles. Here is a copy of one of his pictures; but it has not the fine colors he put in.

As I was taking a walk the other day, I saw a nice cottage with spruce-trees in front. Near by, two boys were at play swinging under a tree, while their sisters sat on the bank.

It was a pleasant scene; and, as I was tired, I stopped and began to talk with the children. The boy who was in the swing jumped down, and came to the spot where I stood.

We talked of trees, of flowers, and of birds. Then the larger of the two girls, who sat on the bank, said, “I think that birds must have some way of making known their wishes to one another.”

“What makes you think so?” I asked.

“Why, sir, this last spring, some swallows built their nests under a piazza of the house of a friend of mine. They were so tame, that the mother-bird would let us come up to her and touch her as she sat on her eggs. We gave her the name of Cozy.

“Now, the lower windows of my friend’s house have large panes of French glass, pure and clear as crystal; and sometimes, as you look at them from the outside, they reflect the waving trees and the blue sky so as to deceive the birds.

“Our poor little Cozy was deceived in this way. She left her warm eggs, and flew out for a few moments; and seeing, as she thought, a nice tree waving in the breeze, she flew towards it, when she hit her head against the glass, and was killed.

“She fell dead on the piazza. Soon the male bird found out what had happened. He seemed in great grief. He flew down to where his mate lay, and twittered as if to wake her. Then he flew up, and looked at the eggs. He acted as if he did not know what to do.

“At last he flew off, and we did not see him for three or four hours. Then he came back, and (will you believe it?) he had a new mate with him. He flew up where the eggs were, as if to show them to her; and she sat down on them, and sat till she hatched out four little swallows.

“Now, I think that the male swallow must have gone to some young hen-swallow, and told a pitiful story of how his dear Cozy had been killed, and how four little birds couldn’t get out of their eggs for want of a mother to keep them warm, and hatch them.

“And then the young hen-swallow must have said in reply, ‘I will be a mother to the little dears. Come, guide me to them swiftly.’ ”

Thus ended the little girl’s story. I laughed, and bade the children good-by; and the boys placed one of their sisters in the swing, and began to set it in motion.

Edward P. Carter.

Ralph Snow owns a brood of young chickens. He also has a pet owl he calls Downy. The other day some of Ralph’s chickens were killed, and Ralph thought that Downy killed them.

So Ralph loaded his gun; and, one night when the moon shone, he went out to watch. “I will kill Downy on sight, if I find he is to blame,” said Ralph.

“Think twice before you shoot,” said Ralph’s father.

Ralph had not watched long when he heard a noise among the chickens, and saw Downy come out with something in his claws. “Ah! you bad owl! Now I’ll shoot you!” cried Ralph.

So he raised his gun; but as he did so the thought came to him, “My father told me to think twice. Let me look closer at poor old Downy.” So he looked closer, and then found that Downy did not have a chicken, but a great fierce rat, in his claws.

The rat had done all the mischief in killing the chickens; and now Downy had caught him in the act, and the rest of the chickens would be safe. “How glad I am I did not shoot Downy!” said Ralph. “My father was right in telling me to think twice.”

Wm. C. Godwin.

He that hath it and will not keep it,

He that wants it and will not seek it,

He that drinks and is not dry,

Shall want the means wherewith to buy.

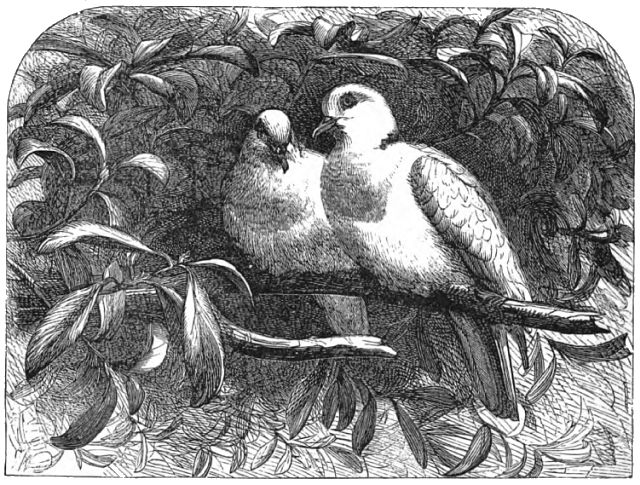

See them on the bough of the tree. Two little turtle-doves, sitting side by side! They never quarrel. If one gets a nice seed, the other does not try to get it away. “Coo,” says one; and “Coo,” says the other.

“Look at the doves on the high branch there,

Brother and sister, always a pair:

In sunshine bright, and in rainy weather,

They love each other, and keep together.

“Little children, in child-like love,

You should be like the gentle dove,—

Ever ready in peace to live,

Slow to offend, and quick to forgive.”

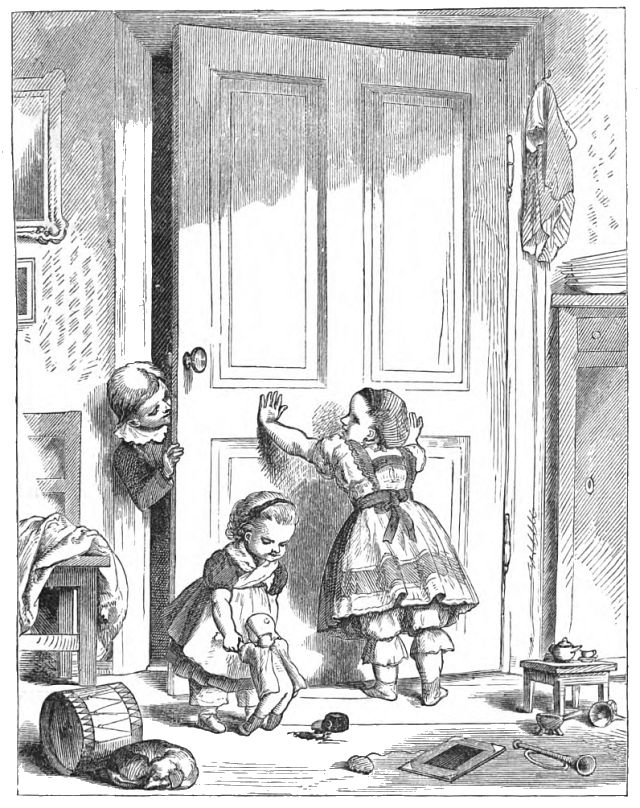

“YOU CAN’T COME IN.”

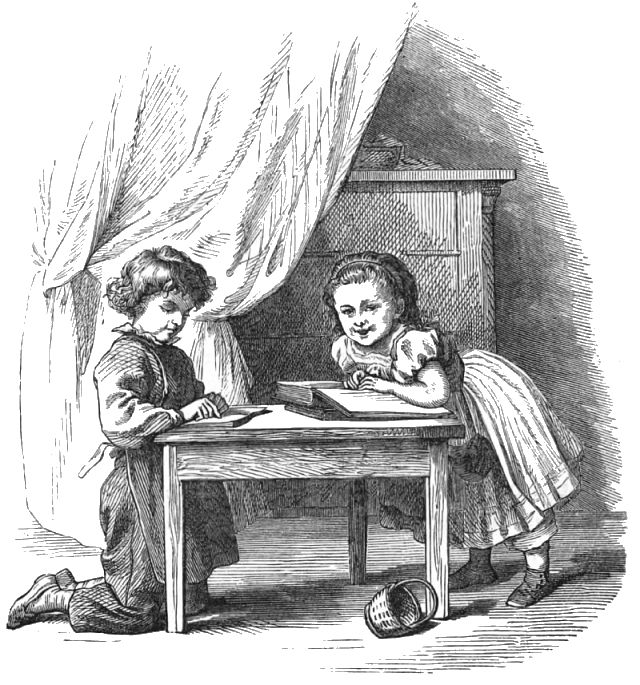

Once there were two little girls whose names were Jane and Mary. Jane was seven years old, and Mary was four. They had a brother whose name was Frank. He was a year older than Jane.

Mary and Jane used to have good times in the play-room, but John would sometimes come and tease them. So one day, when Jane heard him coming, she pushed with both hands against the door, and said, “You can’t come in.”

“Is tea ready?” said John; for he saw the doll’s tea-things on the doll’s little table. But Jane knew that he came to make fun of her and Mary and the doll; and so Jane said, once more, “You can’t come in.”

“Oh! but I must come in,” said Frank. “It is raining out of doors, so that I cannot fly my kite; so I must come and play with you and the dog.”

“Will you promise to be good, and not plague us, if I let you in?” said Jane.

“Yes: I will be very good,” said Frank.

“Then you may come in,” said Mary, letting him open the door.

“Now, I’ll tell you what we’ll do,” said Frank. “There’s a drum on the floor, and there’s a tin trumpet. We’ll get up a procession in honor of the doll; not of your poor rag-doll, Mary, but of the fine lady-doll that belongs to Jane. Where is she, Jane?”

“She is in the next room in her little carriage,” said Jane. “I will drag her in.”

So when the lady-doll was brought in, Frank roused up Trip, the dog, and harnessed him to the carriage. Then Frank took the rag-doll, whose name was Polly, and he tied her so that she sat upright on the dog’s back.

“Stop, sir, stop,” said Frank, as Trip tried to run away. “You must not start till the procession is ready. We must now get some flags.”

So they got two broomsticks, and tied ribbons to them, and hung them with pictures.

Mary carried one of the broomsticks, and Jane the other. Then Frank got his sword, and put his cap, with a feather in it, on his head.

Then he took the trumpet and the drum, and said, “Now, Mary, you shall see what a procession is. I am the band of music, and I go first. Then you shall follow with the flag; then Jane shall come; and, last of all, Old Trip shall come with the rag-doll on his back, and the lady-doll in the carriage. Now form in a line; and, when I sound the trumpet, we will begin to march.”

So they formed in a line; and Frank blew the trumpet and beat the drum. What a noise he made! Trip, at the same time, began to bark.

First they marched all round the room, three or four times. Then they marched from corner to corner. Then they ran. Then they walked slow; and at last they stopped, and gave three cheers.

This made Trip bark all the more. He did not know what it all meant. But the dolls behaved well.

It was a famous procession; but I am sorry to say that it was so noisy that the mother of the children came in to see what was the matter.

As soon as the door was opened, Trip broke loose from the carriage, and ran down stairs, and hid in the cellar. And so the great procession came to an end.

Ida Fay.

Here are some lines our Jamie learnt to say

While down the west sank the bright summer day:

I hope, dear child, that you will learn them too,

And in this hope I give them here to you.

Now the golden beams of day

In the west are fading,

Evening’s tints of sober gray

Fairest scenes are shading;

Sweet repose on all around

Silently is stealing,

Hushed is every busy sound,

Softened every feeling;

And my joyous song ascends,

Gratitude expressing,

For my home, and health, and friends,

And each daily blessing.

Lord, thy love I still would share

As the day is closing;

Guard me with thy tender care

While I am reposing:

Let my slumbers, calm and light,

Free from care and sorrow,

Make me feel all fresh and bright

When I wake to-morrow;

And in happier worlds above

May I dwell forever,

Where the Saviour reigns in love,

And night cometh never.

Once there was a good man whose name was John Kant. He lived at Cracow, in Poland, where he taught and preached. It was his rule always to suffer wrong rather than to do wrong to others.

When he got to be quite old, he was seized with a wish to see once more the home of his childhood, which was many miles distant from where he now lived.

So he got ready; and, having prayed to God, set out on his way. Dressed in a black robe, with long gray hair and beard, he rode slowly along.

The woods through which he had to pass were thick and dark; but there was light in his soul, for good thoughts of God and God’s works kept him company, and made the time seem short.

One night, as he was thus riding along, he was all at once surrounded by men,—some on horseback, and some on foot. Knives and swords flashed in the light of the moon; and John Kant saw that he was at the mercy of a band of robbers.

He got down from his horse, and said to the gang, that he would give up to them all he had about him. He then gave them a purse filled with silver coins, a gold chain from his neck, a ring from his finger, and from his pocket a book of prayer, with silver clasps.

“Have you given us all?” cried the robber chief, in a stern voice: “have you no more money?”

The old man, in his confusion, said he had given them all the money he had; and, when he said this, they let him go.

Glad to get off so well, he went quickly on, and was soon out of sight. But all at once the thought came to him that he had some gold pieces stitched into the hem of his robe. These he had quite forgotten when the robbers had asked him if he had any more money.

“This is lucky,” thought John Kant; for he saw that the money would bear him home to his friends, and that he would not have to beg his way, or suffer for want of food and shelter.

But John’s conscience was a tender one, and he stopped to listen to its voice. It seemed to cry to him in earnest tones, “Tell not a lie! Tell not a lie!” These words would not let him rest.

Some men would say that such a promise, made to thieves, need not be kept; and few men would have been troubled after such an escape. But John did not stop to reason.

He went back to the place where the robbers stood, and, walking up to them, said meekly, “I have told you what is not true. I did not mean to do so; but fear confused me; so pardon me.”

With these words he held forth the pieces of gold; but, to his surprise, not one of the robbers would take them. A strange feeling was at work in their hearts.

These men, bad as they were, could not laugh at the pious old man. “Thou shalt not steal,” said a voice within them. All were deeply moved.

Then, as if touched by a common feeling, one of the robbers brought and gave back the old man’s purse; another, his gold chain; another, his ring; another, his book of prayer; and still another led up his horse, and helped the old man to remount.

Then all the robbers, as if quite ashamed of having thought of harming so good a man, went up and asked his blessing. John Kant gave it with devout feeling, and then rode on his way, thanking God for so strange an escape, and wondering at the mixture of good and evil in the human heart.

Mary F. Lee.

Can you count the stars that brightly

Twinkle in the midnight sky?

Can you count the clouds, so lightly

O’er the meadows floating by?

God the Lord doth mark their number

With his eyes, that never slumber:

He hath made them every one.

Can you count the insects playing

In the summer sun’s bright beam?

Can you count the fishes straying,

Darting through the silver stream?

Unto each, by God in heaven,

Life and food and strength are given:

He doth watch them every one.

Do you know how many children

Rise each morning, blithe and gay?

Can you count the little voices,

Singing sweetly, day by day?

God hears all the little voices,

In their infant songs rejoices:

He doth love them every one.

From the German.

Now, Dash, if you want this bit of meat, you must sit up on your hind legs, and act like a good dog. You must not say “Bow-wow,” till I tell you to speak.

The cat sits by the wall, and she can see you. Sam is here with his cart, and Kate’s doll is in it. If you sit still, and do not bark till I tell you to, you shall have the meat; and then you shall drag the cart for Sam.

Look at Dash. How still he sits! He tries to be a good dog, and he shall have this bit of meat; for I told him he should have it, and we must be true in all things. Here, sir! Here, Dash! Now speak!

He says, “Bow-wow.” Take the meat, sir. See him eat it. He likes it. Pat him, Sam. He has been a good dog. The cat says, “Mew.” She, too, wants a bit of meat; but I have no meat for her. Wait, old cat, and you shall have some fresh milk.

Now come here, Dash, and let me tie you to Sam’s cart. There! Now drag it out on the grass. Do not run fast. Be good.

“Now I will tell you a story of an ape.”

“Oh, do! I like to hear of apes. Apes are so sly.”

“Yes, that they are; and this ape was sly, as you will hear. His name was Ned. He was so sly as to take what was not his; and in this way he did so much harm, that his master had to tie him up with a big chain.

“Now, Ned did not like that they should tie him up; and he did all he could to get rid of his chain, but it was of no use: he could not get it off.

“Now, his master had a pet dog who loved cakes and good things as much as Ned did; but the dog did not steal them.

“No: he would sit up on his hind legs, and put up his paws, and beg, as much as to say, ‘Will you give me a nice cake? I should like a nice cake so much.’

“And so Jack the dog got more cakes than Ned. Ned would have been a wise ape to ask for a cake in the same way; then Ned would have got one too.

“One day Ned saw Jack with a plate of nice things, and Ned put out his paw to try to take some for himself. But the plate was too far off.

“Ned tried, and tried; but, try as hard as he could, he could not get at the plate. So Ned had to sit still, and see Jack eat the nice food; and by and by he saw Jack put his paw in the plate, and take hold of the plate.

“Then Ned must have thought, ‘Now is my time. If I could but get Jack to pull back that plate, then the plate would be near to me, and I could put in my paw, and get the nice food. What if I take hold of Jack’s tail, and give it a hard pull? Will not that make Jack pull the plate, so that it will be near to me? I will try.’

“So Ned put out his paw, and took hold of Jack’s tail, and gave it a hard pull; such a hard pull that Jack cried out with pain, but did not let go the plate.

“So Ned pulled Jack, and Jack pulled the plate, till the plate was so near to Ned that the sly ape could put his paw in the plate, and eat the nice food at his ease.”

“Oh, what a sly ape, and what a bad ape too!”

“Yes, he was a bad ape to eat up the nice food that was not his own.”

Trottie’s Aunt.

FOX.

“Mrs. Goose, it is such lovely weather,

We ought to take a walk together.”

GOOSE.

“Mr. Fox, I prefer to remain at home.

Just now ’twas so fine I was tempted to roam;

But, since you’ve been standing near my door,

I don’t think it so fine as it was before.”

The weather was fine enough, ’twas true:

The sun was shining, the sky was blue;

But the goose, you must know, was a little afraid,

For she knew what tricks Master Fox had played;

And, had she consented with him to roam,

Never again would she have come home.

Out came three young mice

From a hole in the wall;

Then back, in a trice,

They ran, one and all;

For there sat the cat,

And to seize them she meant:

They did not like that,

So back they all went.

The cunning old cat,

Who knew she could peep,

Lay down on the mat

As if fast asleep.

She shut up her eyes,

And kept very still:

“Now, now,” thought the mice,

“We may get what we will.”

So forth they all crept,

As sly as could be:

They thought the cat slept,

And so could not see.

And there, on the floor,

Lay a nice bit of cheese,

And some crumbs by the door:

Oh! could they get these!

So, near and more near

The little mice went;

But, ah! with a tear

Their fate I lament.

Up sprang the old cat,

And caught them all three,—

Three mice, nice and fat,

Thought the cat, “good for me!”

Emily Carter.

I do not believe you know what I am going to write about, though Sunbeam stands all alone as the name.

“Yes, yes, I do!” I hear little voices saying. “Why! I know what a sunbeam is: of course, I do.”

“Why! I have seen one ever so many times, on the carpet, shining brightly.”

Well, children, so have I; and sometimes I have stooped to pick up a sunbeam, thinking it was something I could touch; but I could never move it.

That is not the kind of sunbeam I am thinking of now; for our little sunbeam I have often caught up from the floor, and hugged and kissed it, till, in return, I felt my hair pulled rather sharply.

“Well, now,” you ask, “what do you mean? What is your little sunbeam.”

Why, children, it is a dear little baby-boy! He has many pet names, but I think the sweetest one is Sunbeam; for he is just like a sunbeam, ever shedding light on all, because he is so good tempered, and so full of fun and play.

He is only one year old; but we called him Sunbeam long before his first birthday. He has bright blue eyes and flaxen hair; his cheeks are red like little roses, and no one can help kissing them.

But what makes him look most pretty is his sweet little mouth, which has ever a smile on it; and this is why we call him Little Sunbeam.

He loves flowers dearly, though he is so very young. When only eight months old, if any one gave him a flower, he would seem almost wild with joy. He would press his little fat hands together, and hold it fast, so that no one could take it from him.

Sometimes Sunbeam would wake up in the night, and lie awake, and laugh and play till he was tired; and then he would nestle down to sleep. Was it not nice to have a sunbeam in the night-time?

Our little Sunbeam’s real name is George. I know in one home there is a little sunbeam whose name is Ma′tie; in another home, one is called Gertie; another, Nelly; and another, Alice.

Dear children, what is Sunbeam’s real name in your home? Or is there no sunbeam there,—no such little sunbeam as I have been telling you about?

Mother and father could tell me, I know. Now, I will tell you how each one of you, children, may know whether you are a sunbeam in your home.

If you are good and obedient, kind and pleasant to your brothers and sisters, always trying to make others happy, and thus always happy yourselves, why, then I am sure that your father and mother must think that they, too, have a little sunbeam.

Children ought ever to be little sunbeams; but I know of some that are not. What shall we call them? Shall we call them little clouds, shade-spots? Children, which are you? sunbeams or clouds? Which shall we call this little pouting girl—a sunbeam or a cloud?

Aunt Mary.

Three fierce old wolves saw a stag on their way:

Three fierce old wolves saw a stag on their way:

Ah! now we’ll have a good dinner, thought they.

So they ran and ran with all their might;

But the stag was swift, and the stag was bright:

“You may pick my bones, old fellows,” thought he,

“If you can come up to-day with me.”

The wolves they ran till they gave it up:

“Ho! ho!” thought the stag, “now where will you sup?”

Hot air is lighter than cold air. So, if we fill a balloon with hot air, it will rise high up through the cool air around us.

We use gas now for balloons. We use the same kind of gas that is burned to give light; but, when balloons were first used, they were sent up by hot air.

Three of my little friends, on the Fourth of July, thought they would send up a balloon in the old way, by the use of hot air.

So they made a balloon of paper; and, as soon as the night grew dark, they lighted a fire inside of the balloon, fixing it so that the fire would heat the air without at once burning the paper.

Up rose the balloon, and it made a fine show for some minutes. But at last the paper caught fire, and then some of the burning pieces fell on some dry hay near the barn. Soon it was in a flame.

If we had not run out, and put the fire out, much harm might have been done. So I hope you will not try to send up a balloon with fire in it. In your plays, do not run the risk of doing harm to yourself or to others.

Uncle Charles.

ROBERT THE ORGAN-GRINDER.

Come, and hear what I have to tell you of the left-handed organ-grinder. His name is Robert. He is well known in our town. He was once a brave soldier, and his right hand was shot off in battle.

Before he went to the war, he had worked on a farm. Few men were so quick as Robert with the spade or the hoe, the scythe or the rake.

But when he lost his right hand, and came home from the war, he did not know what to do to maintain himself and his poor old mother. He could not mow, he could not dig.

Robert wished he had been taught, when he was young, to read and write and cipher; but his parents had been too poor to send him to school, and so, while yet a boy, he had been kept at work on a farm.

Mr. Wilton, a rich, kind man, who had learnt of Robert’s good conduct in battle, came to him, and said, “Robert, I will fit you out with a hand-organ, and you shall go round, and play for all the poor children.”

“But how shall I pay my way?” asked Robert.

“I will take care of that,” said Mr. Wilton. “I will see that you and your mother have enough to live on. Should people that are able give you money for playing, so much the better. What you get you can lay by for a rainy day.”

So Robert now goes round with a hand-organ. All the children in our town love him dearly, and he loves the children too. He loves them so well, that I think he spends too much of his money in buying toys and books for them, instead of “laying it by for a rainy day.”

But, if this is a fault, it is one I shall not blame him for. You should see the smile that lights up his face when he sees a troop of children running to hear him play, and to gaze on the wonderful little figures which move on his organ as he turns the handle.

The babies all stop crying when they see Robert coming; and I think there are many people in our town who send presents to Robert and his mother, just to pay him for the good he does in amusing our little ones.

Anna Livingston.

A poor lame boy was walking along one of the muddy streets of the city, trying to find a good place to cross. The heavy rains had fallen, and the mud was quite deep.

While he was waiting to cross, and afraid to venture, because of his lameness, another lad saw him, and cried out, “Stop, stop. I’ll carry you over.”

In a moment he took the little cripple in his arms, and bore him over to the other side of the street. In doing this, he got quite wet and muddy; but he did not mind it, for he felt glad in doing a good act. A good act is its own reward.

It was a pleasure to him to see the smile on the face of the little lame boy as he was set down on the clean sidewalk. “I thank you ever so much,” said the little lame boy. “You are quite welcome,” said the other.

Uncle Charles.

“Tick,” the clock says,—“tick, tick, tick!”

What you have to do, do quick.

Time is gliding fast away:

Let us act, and act to-day.

If your lesson you would get,

Do it now, and do not fret:

That alone is hearty fun

Which comes after duty done.

When your mother says, “Obey,”

Do not loiter, do not stay;

Wait not for another tick:

What you have to do, do quick.

If my little boy will mind,

And be prompt and good and kind,

Time to him will be a friend,

Time for him will sweetly end.

Emily Carter.

What says the little brook?

“I am but a little brook:

Yet on me

The stars as brightly gleam

As on the mighty stream;

And, singing night and day,

I sparkle on my way

To the sea.”

What says the little ray?

“I am but a little ray,

Sent to earth

By the sun so great and bright,

Giving food and heat and light;

Yet I gladden every spot:

The palace and the cot

Hail my birth.”

What says the little flower?

“I am but a little flower

At your feet:

Yet, on the path you tread,

Some joy and grace I shed;

So I am happy too

For the little I can do

When we meet.”

What says the little lamb?

“I am but a little lamb,

Soft and mild:

Yet in the meadows sweet

I ramble and I bleat;

And soon my wool will grow

To clothe you with, you know,

Darling child.”

What says the little bird?

“I am but a little bird,

With my song:

Come, hear me singing now,

As I hop from bough to bough;

For I cheer the old and sad

With my voice, and I am glad

All day long.”

What says the little child?

“I am but a little child,

Fond of play;

Yet in my heart, I know

The grace of God will grow,

If I try to do his will,

And his law of love fulfil

And obey.”

Our dog’s name is Carlo. Father bought him when he was only ten weeks old, and with him his little brother. Carlo is black. He has long ears, and his paws are spotted with white.

The first night that father brought him home, Carlo was well content, for his brother was with him; but, when his brother went to live on the next farm, Carlo felt very lonely, and cried so all night that he kept us all awake.

But he soon became used to being alone, and slept in his warm bed in the barn very happily. He was a playful little dog. He would pull the slippers from my father’s feet, and carry them out in the snow, and shake them till he almost shook them to pieces.

If any one of the girls got down before the stove to put wood into it, Carlo would take the end of her dress in his mouth, and run as far as he could; and, when he found she could not get up, it would please him very much.

He was fond of running away with towels and entry mats, and he would often shake or tear them quite to pieces. The hens did not like Carlo, and I will tell you why.

The hens, you must know, dread very much to step on the snow. In winter time, Carlo would run into the shed where the hens were; and he would bark at them, and drive them out on the snow, till you might see them all standing on one foot, and shivering.

Then mother would rap on the window, and shake her head at Carlo; and he would look up, with an innocent look, as much as to say, “Why, what have I been doing, that you should shake your head at me?”

When he was first brought to the house, the cat went away, and spent a day under a rock in the field; but, when she found that he had come to stay, she came home.

She never liked Carlo; but she had a kitten not so old as the dog, and this kitten and Carlo were great friends. Sometimes they would make such a noise playing in the house, that we would have to put one of them out; and then both of them would cry so that we would have to put them to bed.

One Sunday all the folks went to church. The dog and the kitten thought they would have a nice time. Mother had left her closet-door open, and what do you think these little rogues did?

Why, they dragged all the things out of the closet, across the chamber floor, through the entry, down the front stairs, to the front door. What a high time they had!

When the family came home from church, they found the hall strewn with slippers, boots, and dresses, and pieces of all kinds of cloth, that had been in a large bag in a corner of the closet.

The first time Carlo heard thunder he was not a year old. He seemed to think it was the sound of carriages, and he barked well at it.

When the swallows flew close to the ground, Carlo would chase them, and bark when he found he could not catch them.

Carlo is a wise old dog now; but he still does some cunning things, and I may tell you of them one of these days.

l. o.

What a hard life of it these little housekeepers do have! Here are Bertha and Mary once more hard at work; so hard at work, that they do not see that poor Dolly is lying flat on her back on the floor.

Mary is busy mixing pancakes, and Bertha is warming the soup on her little toy stove. I do not see any smoke come out of the chimney,—do you?

Let us now take a peep into the children’s little kitchen. I can see a ladle, a pestle and mortar, and a mug. I wonder what sort of pancakes Mary is mixing, and whether the soup will be nice. I wish they would ask me in to dinner.

“Why! they are only making believe,” says a little girl, as she looks at the picture. “I, too, can look busy when I am dressing my doll, and yet I am all the while only making believe that it is a baby.”

Ida Fay.

What have we in this picture? Let us look at it closely. Is it not a pleasant room to look into? See the nice bed with curtains all around it, and the looking-glass on the wall.

Master Ned is having his morning bath. Nurse has washed and dressed Mary and Frank, who are at play by her side.

She has just taken Ned into her lap from the tub where he has had a good plunge, and she is washing his face with a sponge. As she dips the sponge into the bowl on the table, and puts it to his mouth, see what a fuss he makes about it!

Ah! Master Ned, you need not throw your head back, and your hands up in that style, and try to scream “Oh, oh, oh!” Nurse will hold you fast till she makes your little mouth as sweet as roses, ready for papa and mamma to kiss when you go down to your breakfast.

“Hold still a minute longer,” Nurse says, “till I wipe your face dry with the towel. And don’t kick your socks off into the water again. See, I have hung up one pair on the stove-door to dry already. There are your little shoes by the tub, and soon you will be as clean as clean can be. Who so sweet as my baby?”

Mary thinks it is very funny to see Ned; but her doll Bess must be made ready for breakfast too.

So she takes dolly out of the crib, and puts her into the little tin bathing-tub on the floor. First, Mary filled the tub with water from the watering-pot you see there.

“Lie still, Bess, while I get your dress to put on,” says Mary.

I wonder where Mary keeps her dolly’s clothes. Oh! I see a drawer in that table where the bowl is,—don’t you? It has a knob on it; and I think Mary will go there for dolly’s clothes, when she has put the crib down.

How smiling she looks as she turns her head round to see if Bess likes her bath!

Mary is six years old, and is a dear good little girl, whom everybody loves. You can tell how good she is by looking at her face as she stands there, with her clean apron on, and boots so neatly buttoned up.

It is very easy for us to know about little girls and boys, if they are good or not. Good thoughts show out in the face. They make the eyes bright and sparkling, and the mouth all smiles; and these are what we like to see in our darlings.

Let me take a peep into your eyes now, little reader, and see what is written in them. Is it love and goodness? Always have kind thoughts in your hearts, and then you may be sure people will love you as they did Mary.

Now look at Frank. Frank is four years old. He does not seem to notice Mary or Ned or Nurse. He is playing with his wagon and horses. He has loaded his wagon with blocks, and is packing them down with one hand, while the other is on his knee.

“There, you are about full, old wagon,” he says. “Now for a start.”

“Get up, Tom and Dick,” he shouts; and the wheels roll over and over, and away the wagon goes.

Make haste, Master Frank, with your load, or Mary and Ned will be off down stairs without you.

When Nurse says, “Come, now, we are ready,” how quick they will all jump, and drop their toys! Then such a scampering to see who will bid papa and mamma a “good morning” first.

Ned’s little feet cannot keep up with Mary and Frank; so Nurse takes him up in her arms, and a little chorus of sweet voices greets the parents of these good children.

h. l. n.

Last May, when the pear-trees were all full of white blossoms, a little boy, who had never seen them before, but who had lately eaten some “pop-corn,” ran in from out-of-doors to his mother, and cried out, “O mother, come and see! come and see! The trees are all full of pop-corn!”

One day James and Ann found themselves alone in the house, and James said to his sister, “Come, Ann, we will try and find something nice to eat.”

Ann said in reply, “If you will take me to a place where no one can see us, I will do as you ask me to.”

“Oh, well!” said James, “come with me into the dairy, there we can taste of the cream.”

“No,” said Ann; “for look! there is a man chopping wood before the door, and he will be able to see us.”

“Then come into the kitchen; there is a jar of honey in the closet, and we will dip our bread in it: that will be good.”

Ann replied, “But consider, there is the neighbor who always sits with her work at the window of the next house.”

“Well,” said James, “we will go into the cellar where we shall find some nice pears; and it is so dark there that surely no one can see us.”

“O my dear brother!” said Ann, “you do not really believe there is any place where no one can see us. Do you not know that there is an Eye above, which can see through any wall, and see well in the thickest darkness?”

James was silent for a moment, and then said, “You are right, my dear sister. God can see all that takes place in the world he has made. He sees us when no mortal eye can see; then let us try to do no wrong.”

Glad was Ann to find that James, though quite young, could learn the great truth she had tried to teach him. She took a large card, and wrote on it these words, in large letters, and gave it to James to hang over his bed:—

“God sees us always. Let this thought keep us from sin.”

See the goat and her kid. A kid is a young goat. He will play like a lamb. He likes to play.

The milk of a goat is good. Some folks like it as well as they do cow’s milk, and drink it in their tea.

I know a baby who lives on the milk of a goat, and sucks it from the goat. The goat seems to love this baby.

A goat can climb well. I once saw five goats on a high rock. It was so high that men could not climb it.

A man tried to shoot one of these goats; but he did not do it, and I was glad that he did not do it.

Goats like the fine grass and the sweet herbs which they find high up on the hills and in the seams of rocks.

The flesh of some goats is good to eat, but I do not think it is as good as the flesh of sheep.

Some of the poor folks in our town, who cannot keep a cow, keep a goat that they may have milk.

The goat can butt with his horns; so you must not tease him, or go too near him unless you know he is kind.

“My friend Mr. Ray has a dog whose name is Max. This dog has one queer way of his own: he will not let a man sit in a room with his hat on.

“A few weeks back, Mr. Wade, who lives in our street, went to call on Mr. Ray; and, as he knew Mr. Ray well, Mr. Wade did not take his hat off when he came into the room, but just sat down in a chair, and began to talk to Mr. Ray.”

“But that was rude—was it not?”

“Yes: I think it was rude; and Max must have thought so too; for, when he had waited some time for Mr. Wade to take off his hat, he went up to Mr. Wade, and gave a loud bark.

“By this bark he meant to say, ‘Why do you sit down in this room with your hat on? Do you not know that it is rude to do so? Take your hat off, you rude man, or I shall take it off for you.’

“But, though Max knew what he meant by his bark, it was more than Mr. Wade knew; so Mr. Wade sat quite still, and kept his hat on.

“Then Max must have thought, ‘This will not do. If you do not know better than that, I must teach you. If you will not take your hat off with your own hands, I must take it off for you.’

“So Max walked round to the back of Mr. Wade’s chair, and stood up on his hind legs, and, with his fore-paws, lifted the hat from Mr. Wade’s head, and took it by the rim in his mouth, and ran off with it, and put it in the hall, on the stand where the hats were kept.

“Then Max came back, and looked up in his master’s face, and gave a short, glad bark, as much as to say, ‘Am I not a good dog? I have taught this rude man that he must be polite.’

“Then Max turned to Mr. Wade, and gave a low growl, as much as to say, ‘Now, sir, the next time you come to see my master, I think you will take your hat off in the hall. But, if you do not take it off, I shall take it off for you: you may be sure of that. I will not let a man be so rude as to sit in this room with his hat on, and talk to my master.’

“And then, when Max had growled at Mr. Wade, Max lay down on the rug, and went fast to sleep.”

“I shall not forget to take my hat off when I go into a room where there is a lady or a gentleman.”

“That is right. You must not forget the story of the dog who knew better than to let a man be so rude.”

Trottie’s Aunt.

There’s not a leaf within the bower,

There’s not a bird upon the tree,

There’s not a dew-drop on the flower,

But bears the impress, Lord, of Thee!

Who never tries will win no prize;

Who cannot work must fail;

Make your hay on a sunshiny day,

Wait not for storm or hail.

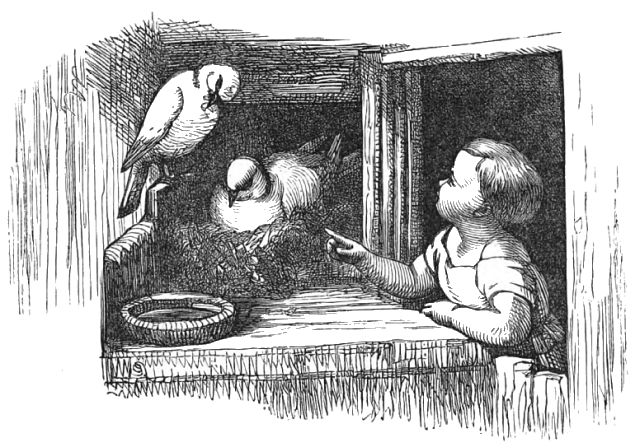

Here are six pictures, and Lucy counted nine objects they represent. The name of one begins with S, two with K, four with W (watering-pot, wall, wicket, well), two with B. Lucy is six years old. Can you do as well as she did?

I am a dog, and my name is Nip. I am put here to take care of this ba′by. You must not touch this ba′by: if you do, I shall bark and bite.

Oh! I am such a fierce dog, and I have such sharp teeth! You should see me chase the geese when they stray off too far from the barn! You should hear me bark at the old bull when he runs at the boys who throw stones at him in the field!

The old cat does not like me, and so I get out of her way as fast as I can; but Tit likes me. Tit is a tame bird who comes and eats out of my plate. I am good to Tit. No one must hurt Tit when I am by.

But I must tell you of the ba′by. This ba′by’s name is No′ra. She has a doll, and the doll’s name is Tiz′zy. That’s a queer name, isn’t it?