* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: What’s Past Is Prologue

Date of first publication: 1963

Author: Vincent Massey (1887-1967)

Illustrator: Al Beaton (1923-1967)

Date first posted: July 24, 2025

Date last updated: July 24, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20250734

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

What’s Past Is Prologue

the tempest: Act 2, Scene 1

© Vincent Massey 1963

All rights reserved—no part of this book may be

reproduced in any form without permission in writing from

the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief

passages in connection with a review written for inclusion

in a magazine or newspaper.

Printed in Canada by the T. H. Best Printing Company Limited

In dulci memoria A.V.M.

The author and the publisher wish to thank the following for permission to use quotations from copyrighted material:

The University of Toronto Press, Toronto, for extracts from The Mackenzie King Record, vol. 1, by J. W. Pickersgill; The Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, for extracts from The Second World War, vol. 2, by Winston Churchill and The War Speeches of Winston S. Churchill, vol. 1;

Lord Beaverbrook and the Bonar Law-Bennett Library of the University of New Brunswick, for a short quotation from the Bennett Papers; and Kathleen P. Milne, executrix of the David B. Milne Estate, for excerpts from letters from the late David B. Milne to Alice Massey.

The author also wishes to thank those who gave him permission to quote correspondence and the many persons who in different ways—by writing letters, answering questions, checking facts and sources—helped him to settle problems that arose in the preparation of the manuscript.

A book of memoirs does not, perhaps, require an apology, but it probably does call for an explanation. Why should it be written? Henry Thoreau said he wrote about himself because he knew himself better than anyone else. An author thus finds a ready source of material; but we still have to ask why he writes. Perhaps this is the answer: his views can be seen best in the context of personal experience.

For this reason I was persuaded by my friends to write this book. I claim no merit for the opinions expressed in its pages, but I know that the subjects themselves are often important; the more we ponder them the better.

I have been fortunate in those who were interested in the book and gave me wise and generous counsel. I can mention but a few. Mr. W. H. Broughall, Mr. Robertson Davies, and my son Lionel read the text with a discerning eye. Mr. T. A. Stone, Senator Norman Lambert and Mr. John Holmes were kind enough to apply their special knowledge to certain sections. Sir John Wheeler-Bennett perused a number of chapters critically and helpfully. Professor James Eayrs of the University of Toronto was of the greatest assistance through his researches. My secretary, Miss Joyce Turpin, through her devotion to her task and her skill in its performance has earned my sincerest gratitude.

The reader deserves his meed of thanks. If a book is a personal narrative, those who read it forge links with the author; he in turn can only respond with warmth and appreciation.

V. M.

Batterwood,

nr. Port Hope, Ontario

September, 1963

| Contents | |

| Chapter | |

| one | Roots: 1887-1906 |

| two | Branches: 1906-1919 |

| three | Business: 1919-1925 |

| four | Politics: 1925-1926 |

| five | Washington I: 1926-1927 |

| six | Washington II: 1927-1930 |

| seven | Batterwood I: 1930-1935 |

| eight | London I: 1935-1939 |

| nine | London II: 1939-1942 |

| ten | London III: 1942-1944 |

| eleven | London IV: 1944-1946 |

| twelve | Batterwood II: 1946-1952 |

| thirteen | Ottawa 1952-1959 (I) |

| fourteen | Ottawa 1952-1959 (II) |

| fifteen | Batterwood III: 1959-1962 |

| Index | |

| Illustrations | ||

| 1. | The author, aged five | Photograph by J. Fraser Bryce, Toronto |

| 2. | The author as Pius VII in Paul Claudel’s play, L’Otage, Hart House Theatre, 1924 | |

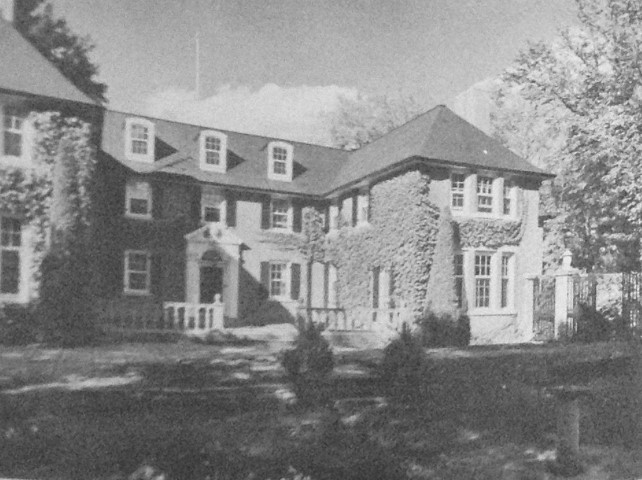

| 3. | Hart House | University of Toronto—Max Fleet |

| 4. | Lionel and Hart in front of the foundation-stone of Hart House, 1920 | |

| 5. | The Canadian Legation in Washington, 1927 | Harris and Ewing |

| 6. | President Coolidge and the Canadian Minister with Canadian guard of honour, Washington, 1927 | |

| 7. | The High Commissioner with senior members of his staff: Major-General Georges Vanier, Mr. Lester Pearson, and Mr. Ross McLean, London, 1936 | |

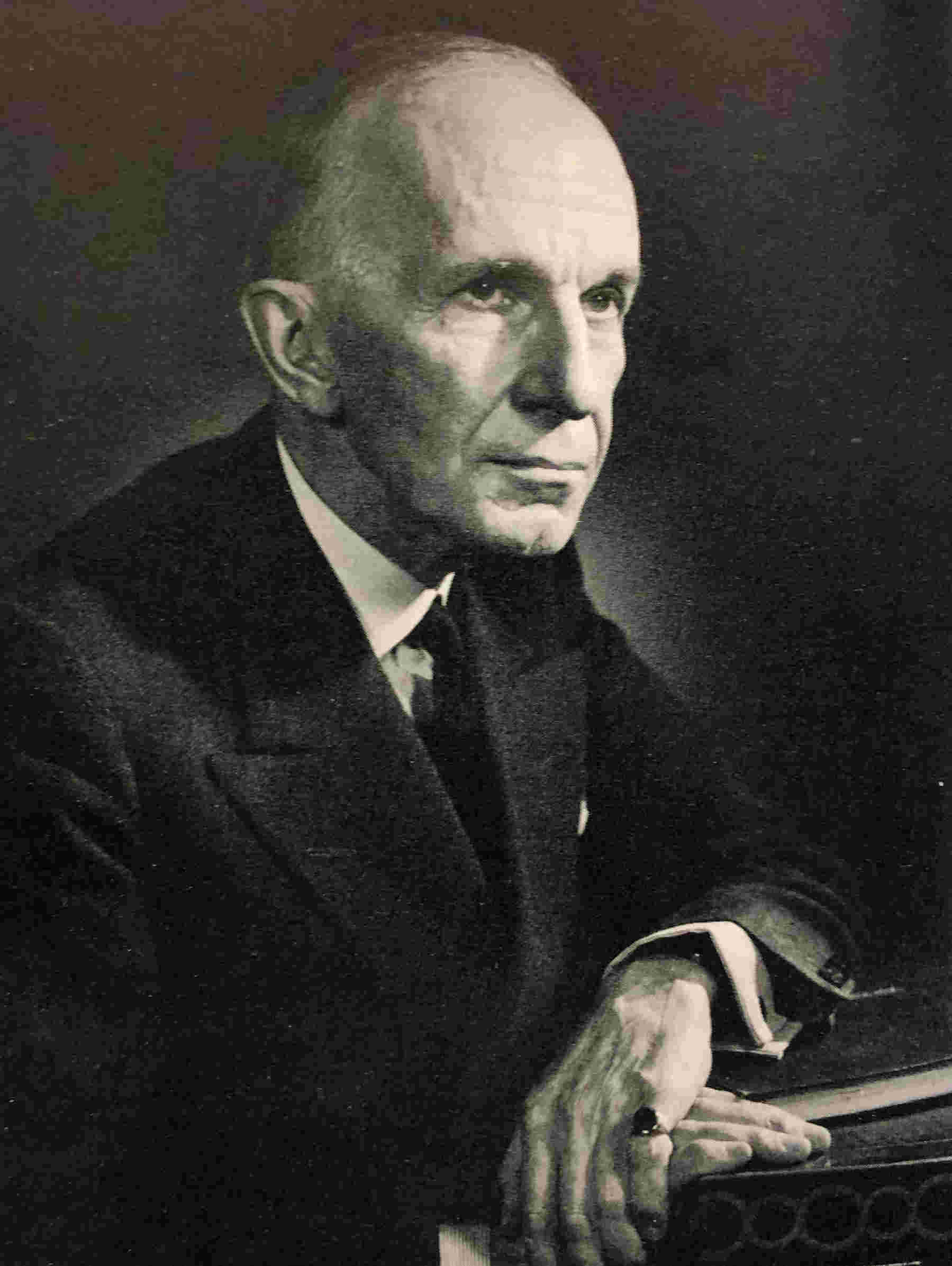

| 8. | The Author | Karsh, Ottawa |

| 9. | Alice Vincent Massey | Fayer, London |

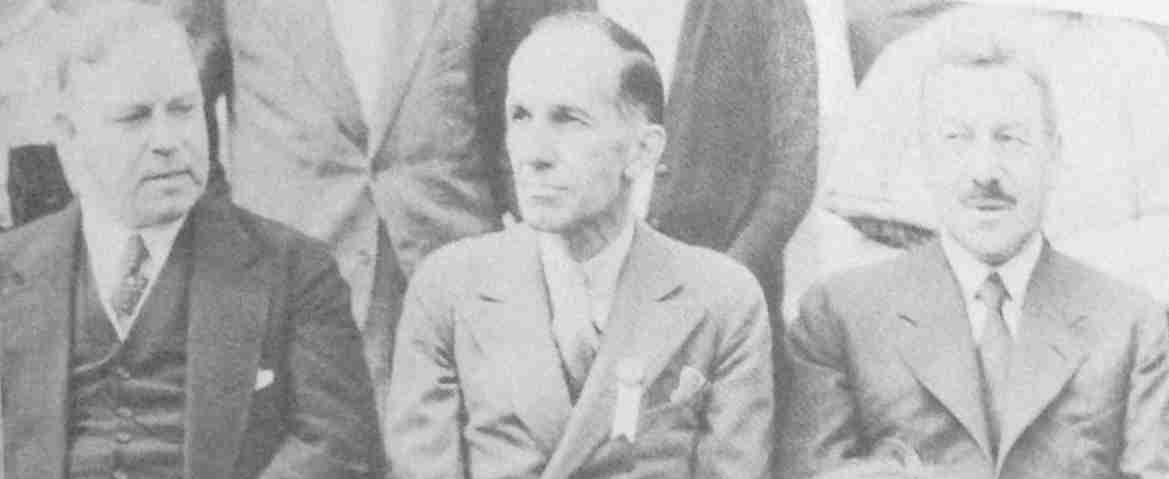

| 10. | Mackenzie King, the author, and Sir Herbert Samuel at the Liberal Summer Conference, Port Hope, 1933 | |

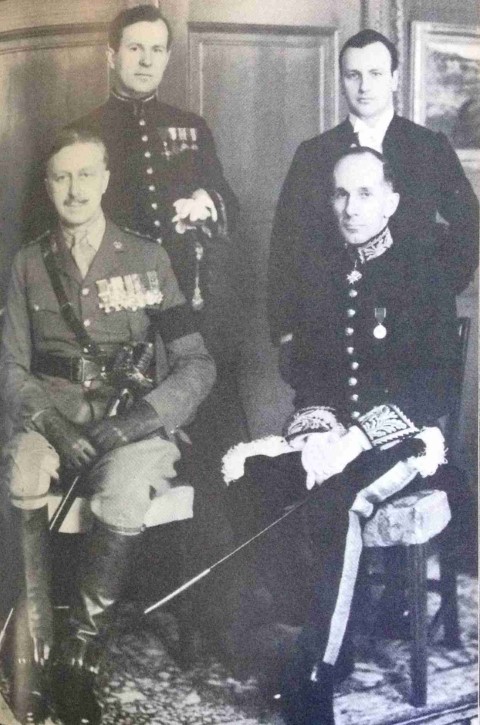

| 11. | The High Commissioner and General Sir Alan Brooke, 1940 | The Bystander |

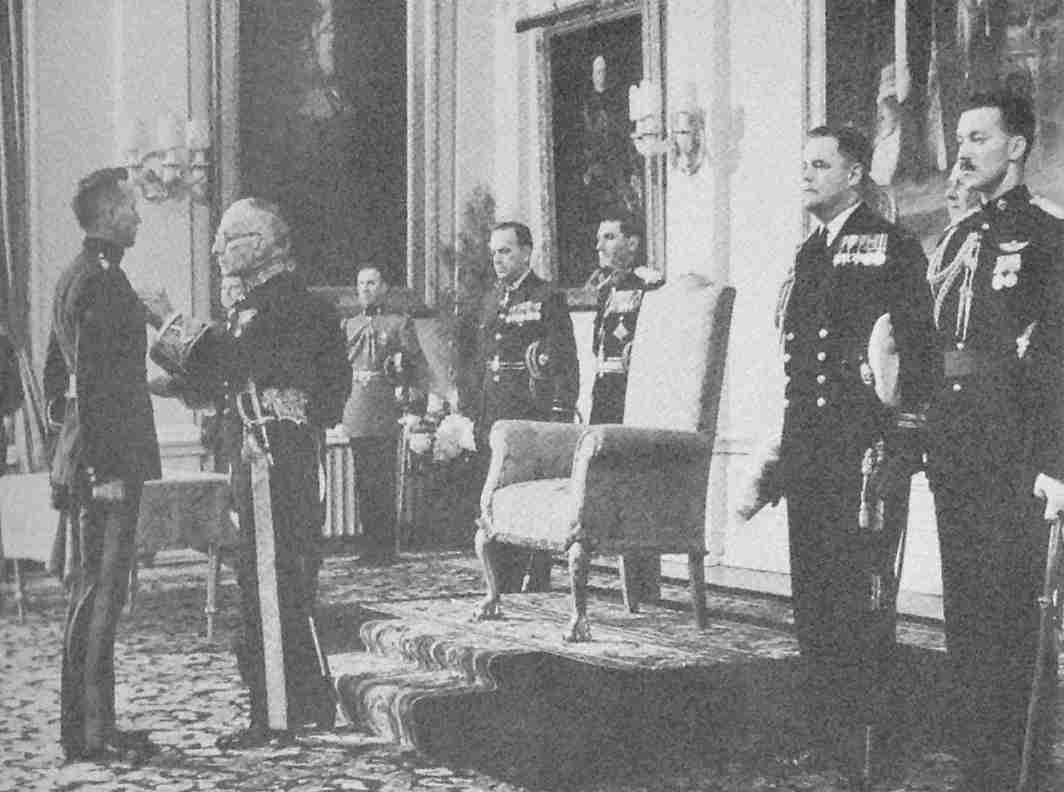

| 12. | The King and Queen with the High Commissioner at the reopening of the National Gallery, London, 1946 | R.C.A.F. |

| 13. | F/L Hart Massey, R.C.A.F. | Fayer, London |

| 14. | Capt. Lionel Massey, K.R.R.C. (60th Rifles) | Fayer, London |

| 15. | Mrs. Hart Massey | Karsh, Ottawa |

| 16. | Mrs. Lionel Massey | Karsh, Ottawa |

| 17. | The author and Mrs. Massey, London, 1939 | Dorothy Wilding, London |

| 18. | The Royal Commission on the Arts, Letters, and Sciences, 1949-51 | |

| 19. | Batterwood House | Lazlo Udvarhelyi |

| 20. | Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip with the Chancellor of the University of Toronto at Hart House, 1951 | Globe and Mail |

| 21. | Jonathan, Jane, Susan, and Evva with their grandfather | Fednews |

| 22. | In the State carriage on Coronation Day, 1953 | National Film Board |

| 23. | With Sir Anthony Eden and his goddaughter Susan at Government House, Ottawa, 1956 | National Film Board |

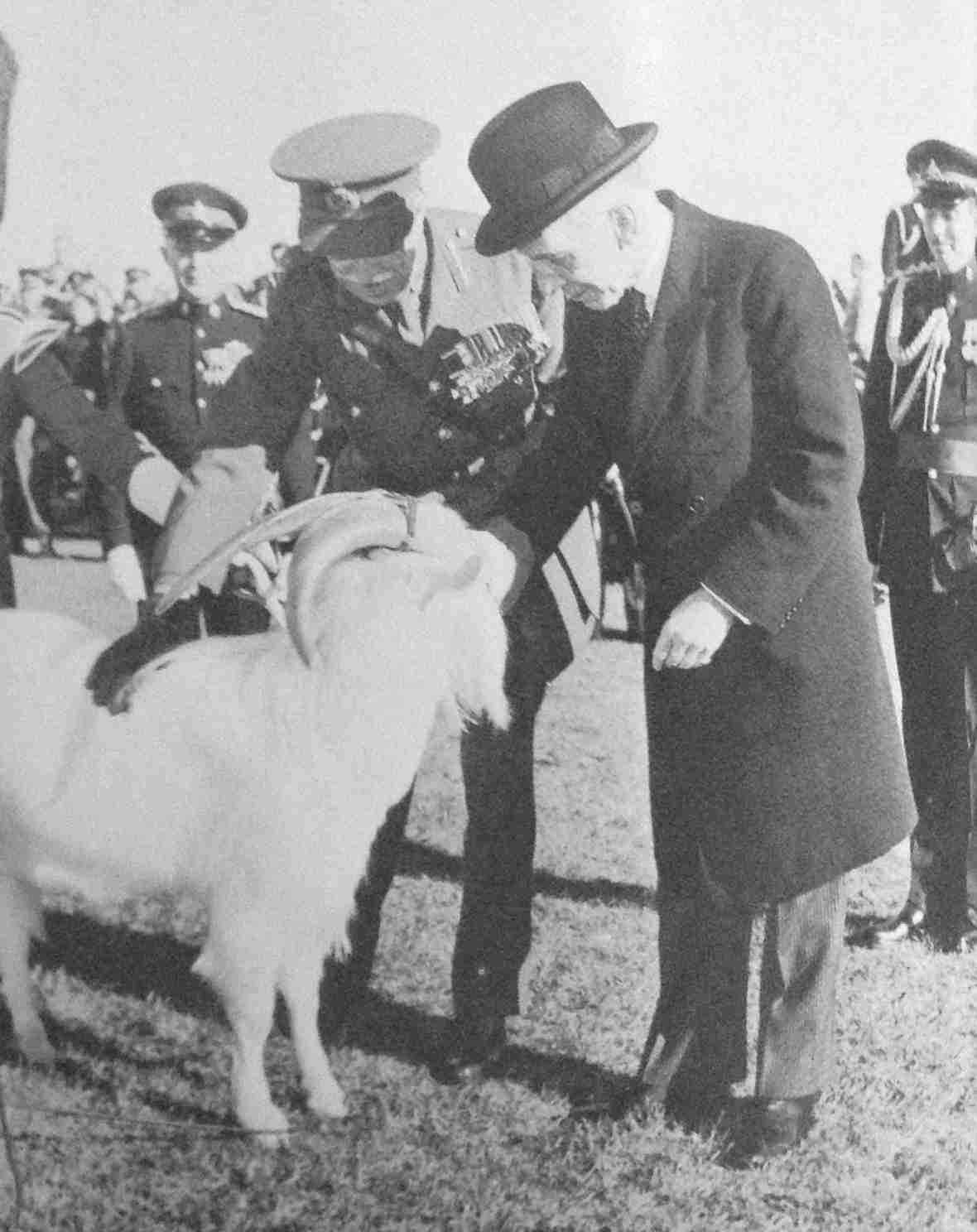

| 24. | Presentation of mascot, ‘Batisse’, to Royal 22e Régiment | Canada Wide |

| 25. | An investiture at Government House | National Film Board |

| 26. | The Governor-General becoming Chief Running Antelope of the Blood Indians | Lethbridge Herald |

| 27. | With the Eskimoes on Baffin Island | National Film Board |

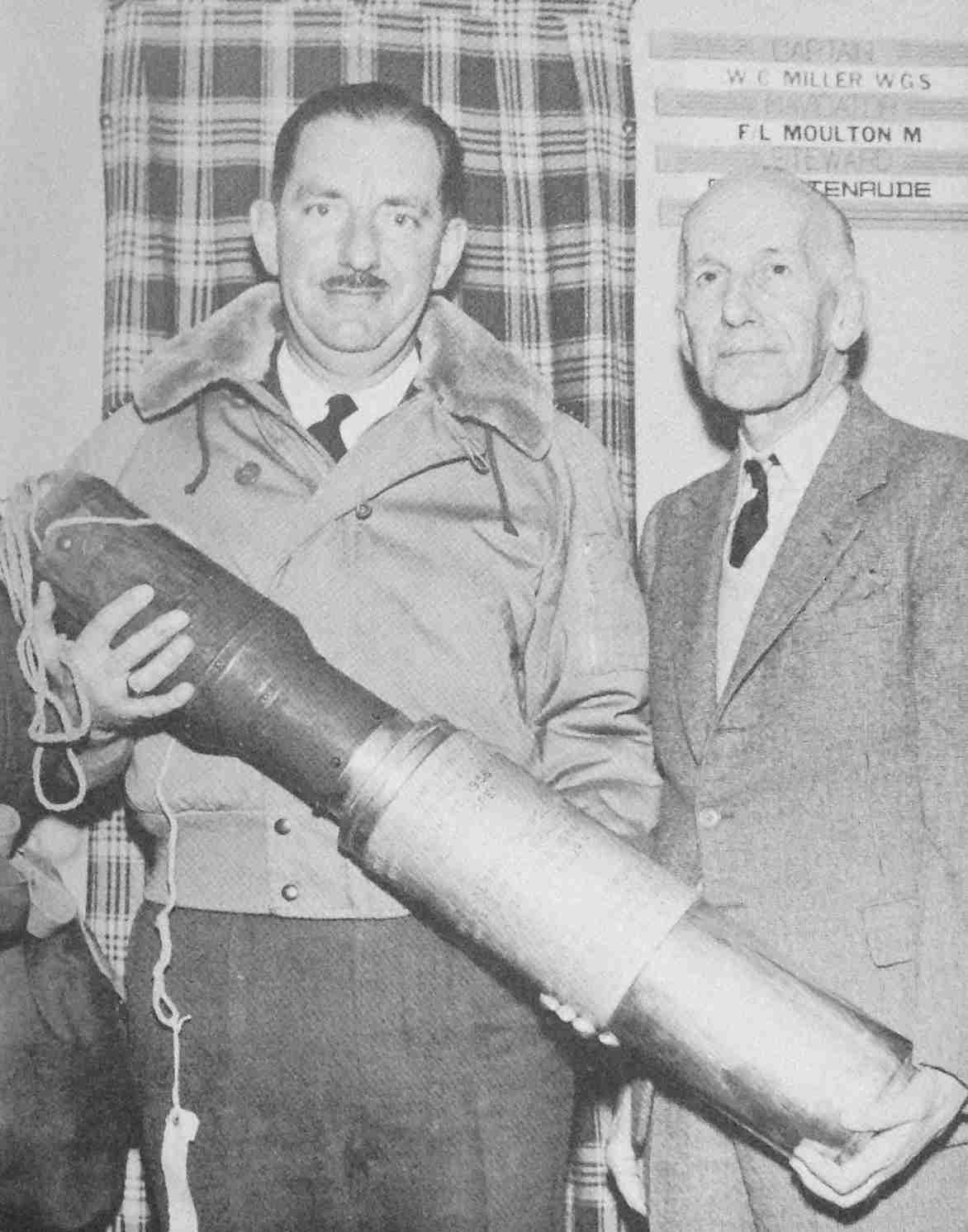

| 28. | In the ‘Saucy Sally’ from H.M.C.S. Buckingham | National Film Board |

| 29. | In the aircraft over the North Pole | Fednews |

| 30. | On tour (Wolf Cubs) | Lethbridge Herald and Fednews |

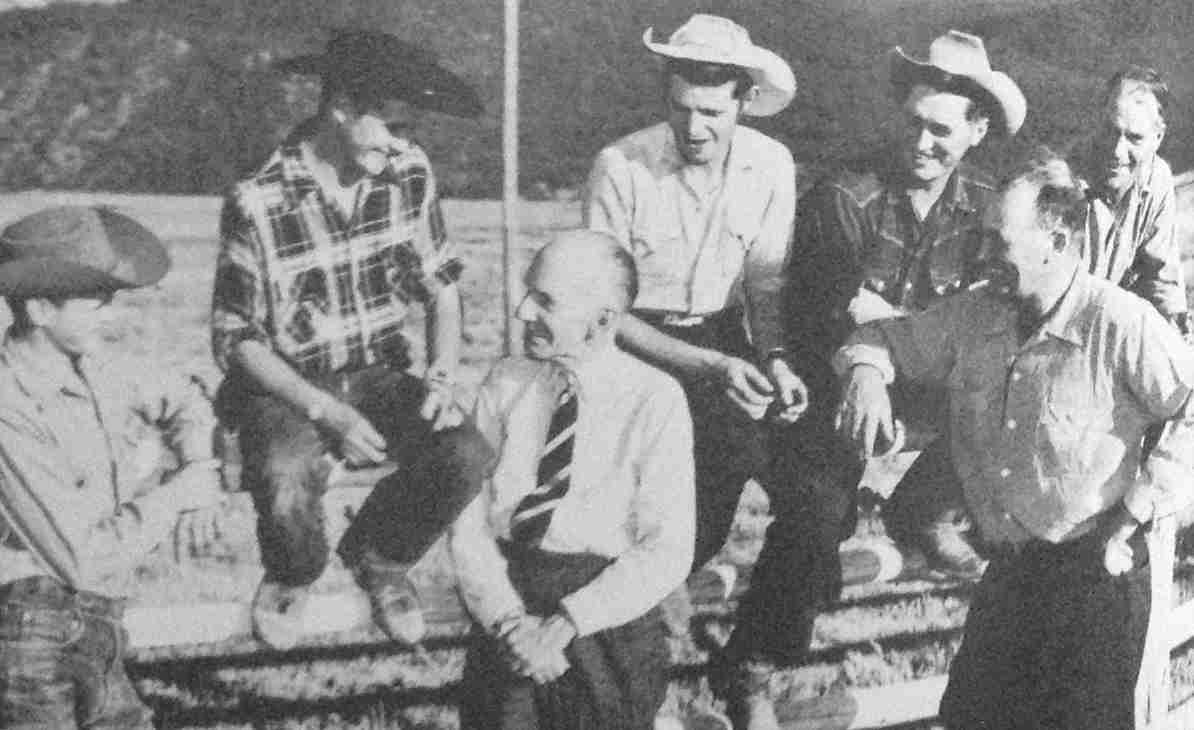

| 31. | On tour (Cowboys) | Lethbridge Herald and Fednews |

| 32. | Aboard H.M.C.S. Cayuga | National Defence, Ottawa |

| 33. | The Queen and the Governor-General at Batterwood House, 1959 | Maria Schartner |

| 34. | Review of 1st Canadian Infantry Division, Gagetown, New Brunswick, July 1, 1956 | Fednews |

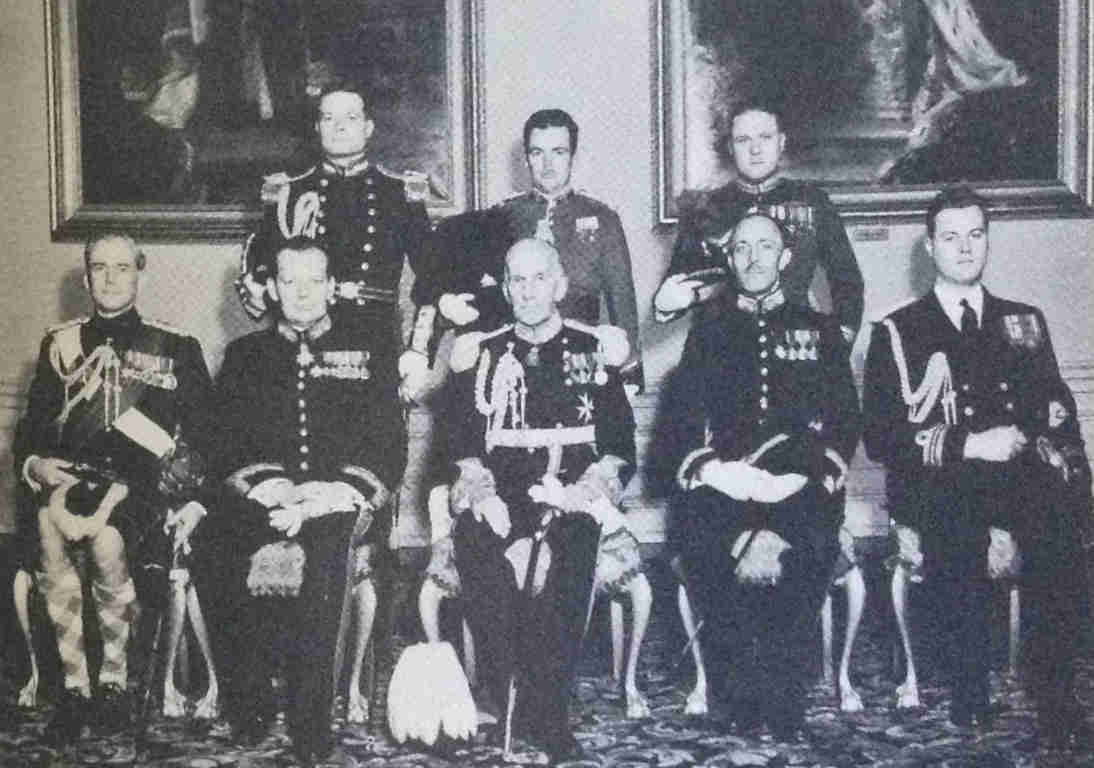

| 35. | The Governor-General and his personal staff, 1956 | National Film Board |

| 36. | The President of the University of Toronto and the author with model of Massey College | University of Toronto—Ken Bell |

| 37. | Massey to Visit the North Pole (cartoon) | |

What’s Past

Is

Prologue

The big house was a paradise for children. A Victorian mansion with a massive staircase, and a spacious hall. A little fountain played there, and goldfish darted in and out of miniature castles. On the top floor was a room laden with the treasures of family tours such as ostrich eggs, a model Swiss chalet, Arab costumes, and African assagais. They recalled tales we had heard of an uncle we were too young to have met who once brought an Arab home from Egypt and who introduced several monkeys into his father’s house on Jarvis Street. In the attic was a ‘magic lantern’. There were no moving pictures in those days, but there were animated slides. One was in constant demand. It showed an old man in a nightcap, asleep and snoring, with his mouth wide open; a mouse crawled up the sleeping figure and disappeared in the mouth. That gave us unfailing delight. In an ample conservatory flourished orchids and other tropical plants; a greenhouse was given over to grapes. The gardener, a strict man, once caught me red-handed among them. It is a curious thing that gardeners seem so often to be short-tempered, while men who work with horses are generally amiable. The coachman, unlike the gardener, was a friend; the enormous carriage horses in his care were a source of fascination.

The author, aged five

The big house was the home of my grandfather, Hart Massey. He was a stern man, but an indulgent grandparent. He would occasionally take me to ‘The Works’, the factory where farm implements were made in the family business. This was always an exciting experience. You passed from the quiet of the office through a single door into the din and murk of the machine shop. The transition was rather frightening. Farther on, in the foundry, you saw molten metal being poured into moulds and, in the paint shop, great machines being dipped into enormous vats of vermilion paint. There was a haunting smell.

A visit to ‘The Works’ generally involved lunching with members of the Board. There was nothing very elegant about this meal, served in the basement of the caretaker’s house, but to a small boy it was a resplendent and overpowering occasion.

A great day in our year was when our grandfather took my little cousin Ruth and me to the Exhibition, the annual fair still permanently embedded in Toronto life. The family company in those days always had an exhibit designed to interest and amuse visitors from the country. A favourite was ‘the vegetable wedding’, wherein carrots, beets, lettuces, and other produce, fashioned into figures of life size, took part in a mock marriage ceremony.

Ruth lived across the street from us. As very small children—she was a couple of years younger than I—we were constant playmates. We created a world of our own out of the large and shaggy garden in which our grandfather’s house stood. We were both fairly determined characters. Difference of opinion would arise, and often Ruth with a toss of her head would disappear to return to her parental roof. That gave me an early sense of the unpredictability of women. Later in life, as Mrs. Harold Tovell, Ruth became an able historian of art, and she will be remembered for her important study, Flemish Paintings of the Valois Courts.

Overlooking our grandfather’s garden was a convent school. We could occasionally see the sisters in their coifs, framed in the windows. Our attitude to the nuns was uncharitable and, indeed, deplorable. We were convinced that the children had been captured and were kept in the convent against their will. Such was the influence of the Puritan strain in our family.

Puritanism is an important stream in Canadian social history. There were really three Puritan streams which merged: from New England (whence we came), from Scotland, and from the evangelical England of the nineteenth century. With it came principles, convictions, and standards of life, and the determination to maintain them. But it had its obvious weaknesses:

The Puritan, as down life’s path he goes,

Gathers the thorn and casts away the rose,

Thinking to please, by this peculiar whim,

The God who fashioned it and gave it him.

Geoffrey Massey, my immigrant ancestor nine generations ago, came to Salem, Massachusetts, from Cheshire in the late 1620s. (When I visited Knutsford in that county, I found the family name repeatedly, in the churchyards of neighbouring villages.) Geoffrey had better-than-the-average education of his day. I have seen his copperplate handwriting on documents in Salem drawn up by him. The Masseys, like many pioneering families, moved into the wilderness from the coast, not once but several times. The last migration took place in 1800, when they left New York State for Upper Canada. I cannot claim that the family possessed any special eminence, but always, in the period of pioneering and later in the management of a growing business, its members had the qualities of integrity and diligence. It was not a bad legacy to pass on.

My father was a semi-invalid for most of his life, as a result of an early illness. He was unable to read without suffering severe headaches, and I remember his saying, in a perfectly matter-of-fact tone, ‘When I go to Heaven I expect to spend the first thousand years in reading.’ Despite ill-health and a sombre outlook on life, he had an affectionate temperament and an engaging sense of humour—the kind that lets one laugh at oneself. My father could generally see the funny side of his eccentricities, as when, in certain weather, he would wear three overcoats on a drive, taking off one after another as he got warmer. He had neither recreations nor hobbies, except his collection of pictures. These were nearly all the work of minor painters of the Barbizon School, or of Dutch artists of his day. They gave him intense pleasure not because of any pride of possession but simply because he liked living with them. I well remember seeing him in a black velvet jacket sitting alone in the room where most of them hung, deriving quiet enjoyment from these works. He always showed great personal generosity. He enjoyed giving money away, although the objects of his philanthropy were not always wisely chosen. Rarely could he resist an emotional appeal, and he was especially susceptible to the pleas of coloured parsons. I thought on one occasion of blackening my face and asking my father for a subscription for ‘de workers in de vineyard’: I am sure I would have come away with a handsome cheque! And when the disguise was discovered my father would have enjoyed the hoax as much as its perpetrator.

My mother, Anna Vincent, was of Huguenot ancestry. Members of her family had played a very creditable part in the church, at the bar, and in business. An historian of the Vincent family says this about my maternal grandfather: ‘My father in his early life worked on a farm and inherited all the American democratic dislike for mere privileged aristocracy. Accordingly once, in his later life, on being asked whether he had a family coat-of-arms he replied, “Oh! yes, of course.” “But what is it, Mr. Vincent?” he was asked; “we have never seen it.” “It is very simple,” he said, “just a currycomb and a sawbuck—both rampant!” ’

My mother came from Pennsylvania. She was a gay person, with warm and gentle manners. People in the shops in Toronto that she frequented spoke of her with affection for many years after her death. She had been brought up in a community that must have been attractive to a young woman with a charming temperament and high spirits. She was devoted to my father and adapted herself loyally to the habits of a family steeped in the Puritan tradition, accepting very sweetly the restrictions imposed on her life.

When I was about sixteen, I went with my parents on a visit to London. My mother was very anxious to attend a performance at the opera. My father relaxed his self-imposed rules about the theatre sufficiently to agree to their going. The regulations of Covent Garden, however, offered a difficulty—evening dress was obligatory. This presented no problem to my father, who looked rather distinguished in white tie and tails, but it did involve a low-cut dress for my mother—foreign to my father’s taste. However, a compromise was reached by adding net to the bodice of her dress. From what I remember, it was a very happy evening for them both.

I have often been asked how a family with our austere background could have produced actors and actresses. Perhaps my father’s power of mimicry and love of charades provides an answer. But the theatre, as an institution, was on the proscribed list. I got him to go a few times to the theatre—once, as I have already said, to the opera in London; once to hear Parsifal, because it was a drama with a religious theme; once to the London Hippodrome, because it was not called a theatre (some of the jokes were startling, but my father didn’t understand them); and once to see one of Shakespeare’s plays, which were acceptable as classics. I was well on in my teens before I was allowed to enter a theatre. The play was Beerbohm Tree’s production of Richard II at His Majesty’s in London. The presentation by a theatrical actor of a theatrical king was most satisfying to my juvenile mind.

If the theatre was barred to me in my early years, so were many other things. Our family recognized no place in life for dancing, playing cards, tobacco, or alcohol in any form. Sunday was a day of unbroken austerity.

Most of my father’s friends were ministers of his Church. One of these was a southern American by the name of Goucher, commemorated by a college for women in Baltimore which he founded. He once told us a moving story about Abraham Lincoln which, as I remember it, ran as follows: as a boy, Dr. Goucher was in Pittsburgh with his family when Lincoln was to be given a public reception on his way to Washington for his second inauguration. Little Johnny Goucher was told that he could not be exposed to the crowds on that occasion and had to remain at home. He escaped and, joining a long line of city dignitaries making its way into the Monongahela House, young Goucher slipped, with others, into the great parlour where the President was greeting his friends and admirers. So entranced was he by the scene that before he knew it the room was empty save for Mr. Lincoln, and himself hidden in the corner. As Lincoln was about to retire into his private apartments, he heard the sound of a foot and, startled, turned round quickly to see the diminutive figure advancing towards him. The boy said more or less what he had heard his elders say a few minutes before, ‘I wish you all success in your great mission, Mr. President,’ and put his hand out. Lincoln grasped it, along with most of the boy’s arm and, leaning over, said, ‘My boy, love your God and your Country and you will be all right,’ and disappeared.

My father, because of his health, was unable to be a companion to my brother and myself; that role was played by a fabulous uncle—the sort of uncle every boy should have. He was an exciting person: he had one of the first motor-cars in Canada; he had travelled widely and brought home the most astonishing things from the South Pacific and the Middle East; he organized a family camp on a northern lake where he performed the most prodigious feats like shooting a water snake with a revolver. Uncle Walter meant a good deal to me. On warm summer evenings his little daughter Ruth and I would go for a ‘spin’ with him on our ‘safety bicycles’. I still can remember the pungent smell of the newly-laid asphalt with which a few of the streets were paved.

During my early years my enterprising uncle bought a farm not very far from Toronto on which my father built a house. The farm had plenty of interest for a small boy. It had a dairy herd from which pasteurized milk was produced (I think this was the first experiment of the kind in Toronto), but the farm possessed amenities too. A tiny stream fed a chain of ponds in which lethargic trout lay awaiting capture; a rough little golf course wound its way through the pastures; there were horses to ride and drive. Here we used to spend the summers.

Toronto, where I was born in 1887, was in my early years a small, quiet, coherent town; it was far from today’s shapeless city, with its pulsating, insistent activity. Then, as now, it escaped the guidance of the planner. Motor-cars had, of course, not yet made their appearance, and there were countless horses. In the older parts of Toronto, known as ‘residential’, you can still see, behind many of the houses, buildings that were at one time stables, and later were converted into flats. As a boy I could hear, after I was tucked in bed, the romantic sound of trotting horses on the pavement and I knew that there must be a special party that night, probably a ball at Government House, round which the social life of the city revolved. I could imagine a scene of gaiety still far beyond my years.

The Lieutenant-Governor in those days had little concern with the province outside Toronto, and there was a preferred list of those who had the entrée to Government House, which then stood in pleasant grounds on King Street. There were four buildings on this corner—Government House itself, Upper Canada College, a church, and a saloon (to use the venerable term); a pale little joke of the time was that the four buildings represented legislation, education, salvation, and damnation.

The winter climate has not changed, although our approach to it has. In those days there was no snow removal; runners took the place of wheels on all vehicles. Everyone had sleighs of one sort or another. Loads of hay on sledges, coming from farms to stables in the city, offered good sport to boys and girls who clambered aboard them and stole rides. Men so inclined indulged in racing on Sunday afternoons between trotting horses drawing light cutters. Mounted policemen made a half-hearted effort to stop this form of sport, possibly because of its danger to pedestrians, but particularly because of the desecration of the Sabbath. The city policemen wore black Persian lamb caps of an attractive cut; their uniforms were not yet defaced by garish shoulder badges in an alien tradition. We went to school in moccasins, wearing on our heads knitted tuques. On Saturday afternoons a driving club had its meet at ‘The Guns’ in Queen’s Park, and a long line of cutters and sleighs of all sorts, some drawn by tandems, wound its way through the city to the pleasant chime of sleigh-bells on the horses. Winter brought many pleasures. New Year’s Day, under the prevailing Scottish influence, was a festival of importance. Those of us who were old enough would hire sleighs and call on the young ladies of our acquaintance. Mamma was always in the drawing-room; tea was probably the best we could hope for. Our aim was to accomplish as many calls as possible, and the climax was reached at Government House where there was always something stronger than tea.

Sunday sixty years ago was a sombre day. Paterfamilias, in top hat and frock coat, with his domestic brood, found his way to one or other of the many churches (as many as there were saloons, it was said)—generally on foot, because for long no streetcars ran on Sunday. The sidewalks, for the most part, were made of boards. The streets were generally paved with wooden blocks, sections of logs, with a persistent inequality of surface. Red brick was the prevailing material for buildings. Electricity was far from universal. Our house, like many, was lit by gas. I can remember my father generating current by rubbing his shoes on the carpet and lighting the jet by touching the burner with his finger and creating a spark. The streets in those days were rich in trees not yet sacrificed to the demands of the motorist, the traffic engineer, or the hydro-electrician. Their loss has made Toronto streets in our subtropical summer hotter than they need be. They were always hot; one way of cooling off in the evening used to be to ride on an open streetcar. I remember the circular run on the four streets which constituted the ‘belt line’ through which we passed (for a single fare) at an unbelievable speed. Motor-cars began to appear as a startling innovation while I was still at school; ours was among the first. Nowhere in Toronto were you far from open country. I could reach it on foot from my father’s house on Jarvis Street in a few minutes. The country meant much to us, especially on holidays. Of these, the twenty-fourth of May was the entrance-gate to spring. It had the aroma of tradition. It brought the excitement of fireworks. No one today seems to know its meaning any more.

The story of my family would not be complete without some account of a legendary figure who played a part in our affairs over many years. His name was Walter Seldon. There is a certain mystery about his background. I think he was originally employed in the factory as a wood-carver making ‘patterns’ in wood as models for use in the foundry. I knew him as someone in the family service in an entirely nondescript capacity. My father was unable to define his functions, and referred to him as ‘my man Friday’. His duties extended from mending electric bells to performing simple transactions at the bank, and supervising, or at least reporting on, some of the building activities in which the family was engaged. Seldon was very tall and had the moustache and goatee and the bearing of a Southern colonel. He was an excellent photographer for those days—both expert and prolific. In his correspondence with my father when he was away, about subjects that covered a wide range, he would frequently drop into the third person. ‘Seldon did this,’ he would say; or, ‘it is Seldon’s view.’ He had views on most things. He was often moved to write portions of his letters in verse. He had one overwhelming obsession and that was his unflagging loyalty to the family in whose service, in one capacity or another, he spent his entire life. He lived in a small house which he owned, beautifully kept and full of a nightmare of objects he had acquired as gifts from various members of the family, such as unwanted wedding presents. The house was alive with clocks, all kept in perfect order, which proclaimed the hour perpetually in various accents; one of them, it may be hard to believe, was equipped with running water and electric light. For years he was a pensioner; when he died we felt that something important had passed out of our lives.

My early education might be called chequered—I was sent to five schools. First a tiny kindergarten, with a population of three. Then a public school of the standard pattern which my father thought would exercise a democratic influence on his offspring. My dear mother very nearly undermined this carefully planned educational move by insisting that in inclement weather I should be driven to the school in the family brougham. The horror of this to the unfortunate boy concerned was something of which she had no conception. The situation was saved by collusion between the coachman and the boy, as a result of which I was dropped several streets away from the school. No one ever discovered my guilty secret. The school was, of course, for both boys and girls; the classes were too big; the school yard was sordid; my teacher for most of the time was a pleasant young woman who did me no good by paying more attention to me than she should, so that inevitably I was called ‘teacher’s pet’.

My father and mother insisted upon removing me from school now and then to go with them to some winter resort. This was not very helpful to a schoolboy—let parents take heed! There was one journey, however, sad though it was, for which I was most grateful (one of several visits to England when I was old enough to have some conception of what I observed). At this time my mother was very ill, and for three or four months I was free to explore London, about which I journeyed on the top of a horse-drawn bus. I was fascinated by all I saw and those months served to consolidate and deepen a love of England which remained with me from the time I was taken there as a child.

I have never felt away from home in England. This cannot be explained by heredity. My ancestors left Cheshire in the seventeenth century, but my feeling for England could hardly have been much stronger if I had emigrated to Canada myself. As was natural, I was first enchanted by the pictorial England—the ancient villages and the old buildings of London. Then I began to relate what I saw to the history I had read. Later on, of course, I began to acquire an understanding of English life and to appreciate its quality. There is nothing un-Canadian in this. We are North Americans in Canada, and much of our thinking and manner of living is shaped by this fact. But it is a platitude to say that we are the better Canadians if we remember the legacy of England—and, of course, Scotland.

There is no word that properly includes both these mother countries. Britain? No. It’s a useful and indeed an inescapable term to employ in most contexts, but it’s a blue-book word; it does not come from the heart. We can put it to the test by substituting ‘Britain’ for ‘England’ in certain well-known lines of poetry:

Oh, to be in [Britain]

Now that April’s there,

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In [Britain’s] green and pleasant land.

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever [Britain].

For several years after my mother’s death in England, our house was presided over by a cousin of my mother who had been brought up on a pre-Civil War plantation in Alabama. She had all the graces of a Southern lady—charm, dignity, and sweetness of character. ‘Cousin Kate’, as we called her, brought to the Scottish-Canadian town where she lived the sentiments and convictions of a Southerner which she never lost. If anyone strummed ‘Marching through Georgia’ on the piano she would slip quietly out of the room. She was a perfect hostess and loved gaiety; my much younger brother, Raymond, and I were very grateful for her influence as a foster-mother as we appraised it in later years.

Raymond and I are rather more than nine years apart in age. From the early days we were always very close, as our mother died when he was seven and it fell to me to play some part in his upbringing. As a child, a schoolboy, and always, he has been the most charming of companions. He was an enthusiastic amateur actor from his earliest years: at school and in the army when, during a tedious period with the Canadian Forces in Siberia after the Armistice, he organized dramatic entertainment for the troops. After the War when he was making an effort, under parental pressure, to become a business man in the family firm, he often appeared in the cast at Hart House Theatre.

When Raymond declared his intention to become a professional actor he came into head-on collision with my father, whose attitude to the theatre I have already described. It was obviously my duty to intervene on Raymond’s behalf; I did my best and learned what it is like to be placed between an irresistible force and an immovable object. Happily, my father relented and withdrew his objection to Raymond’s becoming a professional actor, but expressed the hope that he would not ‘practise’ (rehearse) on Sunday! Raymond first appeared on the professional stage in 1922, in London, and my father lived long enough to enjoy seeing him and to share the family’s pride in his success.

Phase three in my school education was the bright one. It carried me to what was called the Provincial Model School—an impressive name for a school in the state system like any other one except that the parents of the pupils paid a nominal fee and, as it was connected with the local institution for the training of teachers, its standards were rather higher than those of other schools. ‘The Model’ had a special character in another respect—it was not co-educational. The classrooms for the boys were on one side of the building and those for the girls on the other; the playing-fields were separate—we never saw one another at all at work or play. The boys were taught by men and the girls were taught by women, and I am sure we all worked harder as a result.

It is hard to understand why this school appealed to the boys in it. The building was gloomy and depressing; the scholastic year included few amenities. The rather drab routine that we followed can be understood when I say that a moment of delirious excitement came when we were all marshalled into what was known as the ‘theatre’ (which alluring name was applied to the school auditorium), probably to hear the Minister of Education deliver an address, never very thrilling, on Empire Day. The curriculum was dull and conventional but, although not decorative, it had its own fibre. It was far removed from what an American educationist has called ‘the playpen conception of education’. We were given not what we were expected to like but what was thought to be good for us. Arithmetic and English grammar played a large part in our programme and our infant minds were stiffened by the task of wrestling with both. We memorized quantities of verse. The drawing master induced us to pursue our ways through the bypaths of art by drawing cubes and spheres with a very hard pencil. The teaching of music was equally unrewarding. After the failure to conquer a problem in arithmetic or to parse an English sentence, we were ‘kept in’ until we did what was asked of us. We somehow realized that the master who imposed this ordeal on us was also keeping himself in for our benefit. We were made to take our hurdles, and that was the reason why most of the boys who passed through this school looked back on their years with satisfaction and pride. Our masters were gifted men, with a genuine vocation for teaching. We would not have put it that way but we sensed it. I am very glad to have learned from personal experience that what matters most in a school is the teacher. We cannot be too often reminded as we build educational palaces that the people who work in them are more important than the place in which they work. When we left the school we were somehow drawn back to it, and old boys used to return now and then to see the men under whom they had been persuaded or dragooned into doing their best, and to sit proudly at the back of the classroom to observe for a few minutes the new generation facing the tasks that they vividly remembered. No former pupil of the Model School (pupils were not called students in those days) could say anything about it without expressing his admiration, gratitude, or just plain awe of a master whose name was Porter—‘Tommy’ Porter, as we called him. How well I can remember his piercing steel-blue eyes—there was nothing he missed. He lived only for the boys he taught; their success was his. No one I ever knew so completely embodied the qualities of the great schoolmaster.

When I left the Model School I moved to the local high school called, romantically, the Jarvis Street Collegiate Institute. It was in sharp contrast with the school I had just left. It was co-educational—very co-educational. I have only one or two recollections of that period, which was brief. The principal used to visit the classes. On one occasion he came to ours when the lesson was devoted to French. He interrupted the teaching and informed us, as if this were a new discovery, that certain letters should produce a different sound in French from that in English, illustrating this graphically by the word bon, which he said in French was not pronounced ‘bonn’ but quite differently—‘bong’. We were suitably impressed.

I left the Collegiate Institute, not without some efforts of my own, after, I think, one term, and was entered at St. Andrew’s College, which had been modelled on the English public school without, I fear, a very accurate understanding of the principles on which it was based. For instance, the prefects, if I remember correctly, had privileges without corresponding responsibilities. A powerful secret society known as a ‘fraternity’ was allowed to exist in the school, having a divisive effect on what ought to have been a community. (The school I am speaking of is the one I knew over fifty years ago and not the excellent institution it is today.) Some of the masters were very able. The best of them was the history master, William Grant, who later held a professorship at Queen’s University and after that became principal of Upper Canada College. He made history live. Later I got to know him very well because he became my wife’s brother-in-law. He once told me that he never was as pleased with the results of his teaching as when he encountered two boys fighting fiercely because one of them said that a certain seventeenth-century figure in Scotland was ‘Bloody Claverhouse’ and the other maintained that he was ‘Bonnie Dundee’. No history master could be paid a greater compliment.

Not all the masters were of his calibre. I recall a lesson about Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner in which we were told that the date of the action in the poem could be determined by the cross-bow with which the albatross was shot: the cross-bow came into use at a certain time, and therefore this incident must be thought of as having taken place not earlier. No better example could be given of how not to teach poetry.

It would be an understatement to say that I did not excel in games. I hoped to be a cricketer, but my aspiration to be in the eleven was soon shattered. I was told I held my bat like a broomstick. The only award I ever won in any sport was for fencing; as there were only three contestants and the other two were really boxers by choice, my medal represented no great achievement.

St. Andrew’s was and is one of a number of independent schools which play a very important part in Canadian education. They give the pupil a rounded life that the state system, for obvious reasons, cannot provide. There was a time when such institutions, although they offered amenities and advantages of various kinds, left much to be desired when it came to scholastic standards. Now, for many years, that has not been true. Most of them compete satisfactorily with schools in the provincial systems. They have their critics, but the adverse comments they receive would be modified or would disappear if the critics had some first-hand knowledge of the life in the schools they criticize. They are no longer the preserves of the ‘privileged’—although those fortunate enough to attend them are privileged in the exact sense of the word. The progressive educationist will tell you that ‘the whole child’ goes to school; the independent school, as we know it in Canada, ministers to the whole child in all aspects of his being.

I left St. Andrew’s to enter University College, an integral part of the University of Toronto. The transition from school to university was complicated by the existence of fraternities, societies that had spread into Canada from the United States. The practice of a fraternity is to entertain schoolboys before they enter the university and, in sharp competition with their rivals, to commit them as potential members. Nothing could be more natural or useful in a large university, particularly one almost wholly non-residential, than clubs formed by undergraduates of either sex; but there are some features of fraternities as they exist today that are, in my view, undesirable. For one thing, they are mutually exclusive, and members are recruited, not as in ordinary clubs, but only on invitation and on a highly competitive basis. They are secret societies where new members are subjected to an initiation, sometimes involving public humiliation. Again, the fraternities in Canadian universities are nearly all branches of a larger society similarly represented in numerous universities chiefly in the United States. The theory is that everybody belonging to this chain of ‘chapters’ is the ‘brother’ of everybody else, singing the same songs, wearing the same badge, and using the same fraternal ‘grip’ in shaking hands. But these things symbolize an entirely artificial relationship between persons generally with no common interests at all. In some American universities the fraternities, as I have described them, have been converted into normal clubs. But where they continue on the old basis, they create little communities far too narrow in the tastes and sympathies of their members.

The author

In my last year at school I was entertained at several fraternity houses. (To use the technical term, I was being ‘rushed’.) In one of these I had two very close friends. I was asked whether I would like to join it, and without adequate reflection, judging the group only from my two friends, I agreed, and then in a solemn ceremony I pledged myself not to join any other. I was then given the freedom of the house. I discovered that, on the whole, the undergraduates who were members were not people with whom I had many interests in common, and I was not happy about the decision I had made. Two other freshmen were similarly involved. We decided that we would not go through with it and made it known that we did not wish to join. At that point a crisis developed. We were told that what we intended to do was like jilting a girl at the altar. Every conceivable kind of pressure was put on us to join what we no longer wished to join. Graduate members were enlisted to influence us. In my case, a girl—a friend of one of the members—was asked to do what she could to dissuade me from doing such a terrible thing. However, the three of us were immovable. We didn’t join, and after the storm was over I was very grateful that I was quite free in the University, without any ties at all, to find my friends where I wished.

I was lucky in my friends. The one I saw most of was Murray Wrong, the son of the professor of history. We were together at school and at University College and Balliol, and often I was a very happy guest in his father’s house at Murray Bay. Murray had a really distinguished mind. His ‘First’ in history was well-earned. He had inherited some of the finest qualities of his grandfather, Edward Blake, with just a touch of his intellectual coldness. He became a don at Magdalen, Oxford, and died very prematurely. He and I and others formed ourselves into a little group we called ‘The Seven Seekers’; we met quite often to take the universe apart and put it together again—not that we agreed on how it should work.

In 1909 I began to keep a diary. The first entry reads: ‘I resolve for the fourth or fifth time to keep a common-place [book] and with the inspiration afforded by Brown Brothers’ excellent book binding (witness this volume) I am determined to succeed better than in past attempts. . . .’ I managed to keep the diary regularly, and still do; but it is not like the famous diary kept so meticulously throughout his life by Mackenzie King. Nevertheless, though there are gaps here and there, without such a record this book would have been almost impossible.

University College in my time was really a non-collegiate body—it had no residence and little to give it the cohesion of a community, but it did include in its faculty some persons in the best academic tradition. They were talented men, highly individual, often eccentric in their habits. Standardized practice and overwork had not yet threatened academic life with uniformity. Our professors were good teachers and possessed for the most part very personal qualities. We were able to know them; the contacts between teacher and student were not yet smothered under the weight of numbers. We were spared the dreary and futile machinery of compulsory lectures and the ‘credit’ system. The standard of teaching was high, but the curriculum was muddled. There is something wrong with the pattern of one’s studies when failure to pass in experimental psychology might be atoned for by success in an examination on the minor prophets—which was my experience. My curriculum was a potpourri of unrelated subjects. In our English studies we were forced to acquire some knowledge of Anglo-Saxon. I expressed my views on this in an adolescent outburst in the undergraduate newspaper, concluding as follows:

Of course there are charms proper to Old English. In Germany they often spend an hour on a single vowel in a troublesome word. It must be thrilling, no doubt, to see a ‘mutating diphthong’ started from its lair in Anglo-Saxon philology, pursued relentlessly past the northern dialects, hounded on through the mazes of Anglo-Frisian, and finally pinioned in some dark corner of the Gothic language.

The professor concerned was a tolerant man and accepted my ‘undergraduate mutiny’, as he called it in the classroom, with humorous benevolence.

I was involved in the production of the inevitable undergraduate magazine, which we called Arbor, taking its name from the motto of the University. As one of its editors I wrote to ask whether Mr. Goldwin Smith would contribute something to our magazine. He wrote back to say that he could not do that, but would two or three of us come to lunch? He was living at the time in dignified retirement in a distinguished and venerable house in the Georgian style, ‘The Grange’ (later part of the Art Gallery of Toronto). We were much impressed to be in the presence of the great scholar, and in this perfect setting. His manner of living was very rare in the Canada of the day. We were struck by the ritual of his handing the keys of the wine-cellar to the butler, who was asked to bring up a bottle of sherry. After lunch we sat in his study and heard him talk about the great nineteenth-century figures whom he knew before he came to Canada. (He lived to write the obituaries of most of them.) He told us that on one occasion he had met a colleague of Pitt and had dined with one of Napoleon’s marshals. Later I came to deplore Goldwin Smith’s hope that Canada would become part of the United States, but as a kindly elderly host to three eager young men, he could not have been more charming. He said nothing of his pessimistic views about our country, although in his talk he reflected many of the opinions with which he will always be associated. He spoke with deep sadness about Gladstone ‘going over to Home Rule and leaving us’; he said that O’Connell was a blackguard; he gave expression to his pro-Boer sympathies and his hatred of party government. A remark of his, characteristically pungent, was that ‘the artifice to which Joseph Chamberlain would not stoop has yet to be invented’! He thought that Chamberlain’s illness was partly feigned. Goldwin Smith’s legs were the thinnest I had ever seen—I suppose then I did not realize that it was a mark of extreme age.

Alfred De Lury had the thankless task of trying to teach me mathematics. He had a hereditary love of Irish literature and was able to combine trigonometry and Yeats with ease. I shall be always grateful as well to W. S. Milner, who guided us through the landscape of ancient history. I remember the comment he used to make, in his rather nasal voice, on some impulsive observation one of us might make: ‘Now let’s stay with that a moment.’ Malcolm Wallace opened the doors of seventeenth-century English literature and the history to which it belongs: John Milton walked through them, alive. Dr. VanderSmissen, with his monocle, his enormous moustache and old-fashioned clothes, introduced us to Goethe. Of one of our French professors, St. Elme de Champ, who had a huge black beard and wore a violet rosette, it was rumoured incredulously among the undergraduates that he was a French baron. He lived in a club for members of the faculty in a rather sordid old building, and managed to smuggle into those inelegant and teetotal precincts contraband in the form of French wine.

I wish more people over the years had had his courage. The University suffered, and still suffers, from a convention under which it is ordained that no alcohol in any form shall be consumed on its premises. There is no statute to this effect—it is purely a tradition which gallant efforts have not succeeded in breaking. The authorities have tried to prevent cocktail bars from being established within a certain distance from the university grounds, somehow overlooking the fact that the enterprising undergraduate could always go a few hundred yards farther to find all the cocktails he wants, available, to use the parlance of the day, in licensed ‘outlets’. This recalls the advertisement of a school in the south-western States, proclaiming that its precincts were ‘six hundred feet above sea level and seven miles from any form of sin’!

I cannot overstate my debt to one member of the faculty—the professor of history, George Wrong. I learned much from him as a teacher; for two years I was happy to have him as my chief. In my view, George Wrong has never received adequate recognition. He was not a great scholar, though the books he wrote were urbane and distinguished contributions to Canadian history. With his great resourcefulness, energy, and imagination, he was largely responsible for the creation of the Champlain Society (which for many years has reproduced important documents relating to Canadian history), for The Canadian Historical Review, and for the Historical Club of the University, consisting of undergraduates, which since 1904 has met at the houses of hospitable citizens to read and discuss papers. But George Wrong’s greatest contribution was the organization of the Department of History. Under his direction was firmly established the tutorial system based on the Oxford model. Appointments to the staff were of a high order of ability and always included a few distinguished young historians from England. It is greatly to the credit of this department that when, after the Second World War, the number of undergraduates reached a peak of nearly 18,000, overcrowding classes and lecture halls, its staff refused to give up the tutorial system bringing teacher and student into close personal touch. It continues today as a result of great effort and self-sacrifice on the part of the teaching staff.

During my later school and university years, I seem to have been almost as much in the Wrongs’ house as in my own. The atmosphere was enchanting. Mrs. Wrong had Victorian manners but also a quiet, never-failing sense of humour. I can well recall the picture of the old-fashioned drawing-room, with the Scottish maid Lizzie putting the oil lamp on the table (Lizzie lived to be one hundred and three); Mrs. Wrong reading a volume of Trollope (she herself might have come from the pages of Barchester Towers); Mr. Wrong probably lying in front of the fire, occasionally using his snuff-box, and making remarks that his wife may have regarded as somewhat too frivolous; the children sitting about the room reading. A far distant cry from cocktails and T.V.! George Wrong was a robust Canadian but a great lover of England as well—as Canadians should be. Sometimes after studying some episode in our history he would display a rather prickly nationalism, but on his return from visits across the water, his assistant on the history staff would say with humour and affection, ‘The Chief’s come home completely feudal.’

As I have said, I often stayed with the Wrongs at Murray Bay. They were among the first English-speaking Canadians to spend summers there, where life in those days was both simple and civilized—plenty of books, good talk, life close to the wilderness, happy relations with the habitant population. Sometimes we would picnic up the river. We would reach the chosen spot, generally on the shore of the St. Lawrence, in canoes, and build a generous fire—the evenings, even in summer, were cool. There would be reading aloud in the firelight—J. M. Synge’s latest play perhaps being introduced to us by Will Blake in his fine voice reminiscent of County Galway in Ireland. Years later, when my wife and I had taken a house at Murray Bay ourselves, Blake arrived one day with the proofs of his translation of Hémon’s Maria Chapdelaine. It is not really a translation, it is more than that—a retelling of the story in exquisite English. He read us some of the chapters, the broad St. Lawrence and the blue hills making a perfect setting for the tale. Blake did nothing that he did not do well—with a trout-rod or a rifle, or in a canoe. He loved Murray Bay and had countless friends among the habitants. One of them said, when he heard of his death, ‘Il était le seul étranger qui était de notre paroisse.’

Will Blake’s daughter Nell, who later became Mrs. Philip Mackenzie, inherited her father’s knowledge of woodcraft and love of the wilds. She was a friend of mine since we played together as children in her father’s garden. Later I was often a guest at her place near Montebello in Quebec, with a tract of forest and two gleaming little lakes on one flank and a superb view over the Ottawa Valley on the other. Her death was a sad blow to her many friends.

I spent some very happy holidays in Georgian Bay where friends of mine had a house known widely as ‘Longuissa’. The establishment was really a matriarchy, with our hostess, Mrs. Archibald Campbell, presiding over it, following traditions that have disappeared long since. Longuissa had a routine—inflexible, even monumental. Some of it was inherited from Scotland, some of it belonged to Canada. At breakfast, porridge was consumed peripatetically—all of us moving slowly about the veranda. This habit has long since disappeared (you can’t eat corn flakes moving round!). Chaperonage was unshaken. If we were gathered in the evening and two young people were missing, their absence would be noted by our hostess and commented on. Lunch took place on an island or a point some distance away from the house—a delicious cold meal, at which everyone was required to choose an implement (never two, still less three), knife or fork or spoon; no more. In addition to the hampers for lunch, there was always a basket for books—the book you happened to be reading, or some spares, and always Blackwood’s and The Cornhill. In due course, we would return to the house and engage in whatever activity we wished—or almost what we wished. Our hostess and her family were determined that the house party at Longuissa should not be disturbed by invasion. If anyone was so ill-advised as to pay an impromptu visit to the family, whoever saw them approaching would sound the alarm and the entire family and guests would disappear from the house into the adjoining woods. The visitors might well be intimate friends in Toronto, but the friendship was not exportable. No motor boats were permitted in the bay; no irritating noise from engines; no gasoline fumes.

Under the influence of two or three Oxford men who had been at Balliol, I was determined to follow in their path. Here, not for the first time in my education, I met parental resistance. A young friend of my father’s, neither helpfully nor accurately, described the dissipated life he believed was led by Oxford undergraduates. Fortunately, there were countervailing influences. Among those on my side of the issue was a college servant at Balliol—scout, to use the time-honoured term—employed during the summer months as a waiter in an hotel in Devonshire where I was staying with my family; his affectionate description of the College strengthened my desire to get there and was not without some effect on my father.

Hart House

I was admitted to Balliol in 1910 but delayed my entrance until 1911. While I was an undergraduate, I had realized that the University of Toronto was sorely in need of equipment for the extra-curricular life of the students and it seemed that a considerable sum of money from my grandfather’s estate, of which I had been made an executor, could appropriately be applied to the erection of a building for this purpose. My father concurred, the University agreed, and we got to work on the plans. We decided to call the building Hart House, using my grandfather’s Christian name. It was of great importance that someone who understood the idea behind the project, which in many ways was novel, should work with the architect in the early, critical period. To do this I postponed my arrival in Oxford for a year to collaborate as a layman with him. Henry Sproatt was a man of real genius and a master of the Gothic form—the last of his kind in Canada. Gothic to him was not a language to be acquired—it was his own vernacular. He was unfamiliar with university life and the purpose to be served by Hart House, but he and I worked together—very happily—and the plans of the building grew under our joint efforts. These sometimes involved tiresome details such as the arrangements of the kitchens, about which my diary states that the problem was ‘household science versus household sense’. Cooking is a science, but it is also an art. If this were better understood we would be spared institutional cooking in which taste is neglected in favour of calories and protein—important but not supreme. I travelled a good deal, visiting students’ unions in Great Britain and the United States, the study of which had a bearing on the plans of Hart House.

At this time I journeyed also extensively in Canada. Undertaking a trip in 1911 to the West Coast, on this journey I was, so the record runs, made aware of only three subjects: real estate, crops, and reciprocity with the United States—in that order. The manager of one of the branches of our family business struck a melancholy note: reciprocity, according to his way of thinking and that of many others, would involve grave changes in our national destiny, morals, mode of living, religious life, and spiritual welfare.

One of the most interesting things in our country is the meeting of traditions, such as those coming from the ‘old country’ and those springing out of our North American soil. In Regina I stayed as the guest of the Lieutenant-Governor, a picturesque ‘old-timer’ who was determined that the office he held should remain true to British tradition. I remember driving to the Methodist Church in Regina from Government House near the city in a landau drawn by two splendid coach horses, with perfectly liveried coachman and footman on the box. We rocked and bumped over the bald prairie on our way to the church several miles away.

A few months earlier I had had the pleasure of meeting the Governor-General, Lord Grey, at Government House in Ottawa. I recorded:

The atmosphere there is more like that of a simple English country house than that of a Vice-Regal residence. Had quite a talk with the volatile Lord Grey who impressed upon me the necessity of arousing in Newfoundland a sentiment favourable to annexation to Canada. He is a delightfully affable, democratic sort of man with boundless enthusiasm. . . .

[Diary entry. May 7, 1911.]

I became a member of Balliol in the autumn of 1911 and commenced two of the happiest years I can remember. How many men have talked of the spell under which the undergraduate lives. Quiller-Couch understood it when he wrote of Oxford:

Know you her secret none can utter?

Hers of the Book, the tripled Crown?

Still on the spire the pigeons flutter;

Still by the gateway flits the gown;

Still on the street, from corbel and gutter,

Faces of stone look down.

• • • •

Still on her spire the pigeons hover;

Still by her gateway haunts the gown;

Ah, but her secret? You, young lover,

Drumming her old ones forth from town,

Know you the secret none discover?

Tell it—when you go down.

The College was what a college ought to be—a community. There was a great variety among its undergraduates—the great English public schools were fully represented and the smaller ones too, also the grammar schools, and there was a fair number from other parts of what we then called the Empire and a few from the United States and Germany. The undergraduates in Balliol were more varied in their background and tastes than in any other college in Oxford during my time, which gave life at Balliol a healthy versatility. The dons in those days were not nearly as numerous as they are now and formed a very close group dedicated to the College and its life. Their outside interests then were few and their devotion to Balliol gave it strength and cohesion. According to the local tradition they were, in most cases, addressed by their Christian names or nicknames by the undergraduates. It was a striking custom for those days and reflected the family atmosphere of the College. The Master, Strachan-Davidson, was an Olympian figure—remote and awe-inspiring. No one minded his eccentricities—if you come from Olympus these things do not matter. My recollection is that he knew hardly any undergraduates by name, although he made a gallant effort to do so. Innumerable stories are told of his confronting some junior member of the College from time to time and saying, ‘Your name is Thompson, isn’t it?’ ‘No, Master, Higgins.’ ‘You come from Scotland, don’t you?’ ‘No, Master, South Africa.’ There the conversation would end. We dined at the Master’s lodgings in groups. At twenty minutes past nine the custom was that the senior undergraduate would make the move and we would leave, relieved that the evening had come to an end, because it was never riotously gay. The Master had a cat, Tiberius, who used to stroll round the room, and when there was no obvious subject of conversation, someone was certain to say, ‘Tiberius is looking very well, Master’—and that always kept us going for another three or four minutes.

I read modern history. My tutor for the whole time was A. L. Smith. Countless old Balliol men will, I know, share my gratitude to this gifted teacher. Teaching was more important to him than the writing of books, and his counsel was always wise. I am particularly grateful to him for one piece of advice. ‘Don’t concentrate’, he told me, ‘too closely on your academic work. You are not here to get first-class honours, you are here to get everything you can out of Oxford life—enjoy it to the full.’ I got a second, having followed unknowingly a dictum of the Oxford don, Sir Walter Raleigh: ‘Final Schools and the Day of Judgment are not one exam but two.’ I would have read ‘Greats’ but I hadn’t the necessary preparation in the classics. ‘Greats’, I have no doubt, provides the finest training a mind can receive. But I had, as a matter of fact, become very much attached to history at the University of Toronto. A well-organized course in this subject, the study of the cause and effect of man’s actions, provides an intellectual discipline of rare value.

Among the dons one remembers at Balliol, ‘Sligger’ comes high on the list. Urquhart was his real name and why he was called ‘Sligger’ we never knew. His subject was history. He was not an outstanding scholar, but he was the sort of man to whose rooms (he was a bachelor) undergraduates would be drawn as by a magnet, and the talk that took place in those long evening sessions meant as much as lectures and essays. Far different was the historian H. W. C. Davis—austere, remote, indeed, rather frightening. In an inspired moment someone gave him the nickname ‘Fluffy’, by which he was known always but by which he was never addressed. The Junior Dean in my time was Neville Talbot, a clergyman of enormous physique—jolly, almost boisterous in his manner. He was quite capable of pouring a jug of cold water, with a gale of laughter, on an undergraduate proceeding under his window to the baths rather late in the morning. With the spirits of a schoolboy went great qualities which were to reveal themselves during the First World War. He was the brother of Gilbert Talbot, whose name is commemorated in Talbot House, known universally as Toc H.

It is natural that in so human an institution as Balliol, friendships should be many and should last. Harold Macmillan reminded me not long ago that we had been friends for fifty years. My recollection of Harold as a fellow undergraduate is entirely consistent with his most distinguished career. We have kept in touch over the years and have often stayed in each other’s houses. In the early 1920s, Harold was an A.D.C. to the Duke of Devonshire, the Governor-General of the day. When the Duchess stayed with my wife and me for a few days in Toronto, Harold was in attendance. Shortly after that he became engaged to the Duke’s daughter, Dorothy; Alice and I were happy that in later years we saw much of them both in London.

A contemporary of mine who has become over the years one of my greatest friends was Alister Wedderburn. He came up from Eton as a formidable figure. He had rowed in the Eton boat; he was very tall and extremely good-looking; he was in the Oxford eight, and became president of the Union. Alister was a frightening person to those who didn’t know him well, but I soon became aware of his modesty, great reserves of affection, and all that can make anyone a close and valued friend.

One of the men who lived on my staircase was Cyril Asquith, known to his friends as ‘Cys’. He had the diamond-like brilliance of his family, and subsequently became a distinguished High Court judge. When I was ‘up’, Mr. Asquith (the Prime Minister) came to the principal annual dinner of the College, at which the health of the guest of honour was always proposed by the senior scholar. The senior scholar was ‘Cys’ Asquith, and he took that occasion to pull his father’s leg in a witty and elegant speech. He complained very solemnly of the food he had been given as a small boy in the Asquith household, and he charged his father with heartless neglect when he suffered from the measles.

Robin Barrington-Ward was one of my greatest friends in the College. He was the son of the rector of a small Cornish parish, his father having taken orders late in life. I had one or two charming holidays with him in that most delectable of counties. We were to see much of each other in later life.

One of my most brilliant contemporaries was Walter Monckton. He was perhaps best known to undergraduates as a first-class cricketer, having as I remember played in the Harrow eleven. He is one of the most versatile men I know, as his career has amply demonstrated—soldier, barrister, public servant, cabinet minister, banker, Visitor of Balliol, of which last-named office I am sure he is as proud as of any in his career.

We were fortunate in Balliol in having some first-class undergraduates from the United States. One of these, who became a great friend of mine, was Whitney Shepardson. Like all the best representatives from his country, he made a well-rounded contribution to the College and grew to love Oxford and to acquire a deep feeling for England itself. This was shown in after years through his active interest in Anglo-American relations, as an able contributor to the Round Table magazine, and as a senior member of the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

A fellow undergraduate of whom I was very fond was Spenny Compton. (Lord Spencer Compton seems too formal a designation for one so unassuming.) He won the affection of everyone with his quiet modesty and natural capacity for making and keeping friends. Later he came to Canada as an A.D.C. to the Governor-General. His name appears in the memorial window at St. Bartholomew’s (the little Government House church), which the Duke of Connaught had put in in memory of the members of his staff who had fallen in the First World War.

Spenny Compton’s sister Margaret, now the Dowager Lady Loch, has been a lifelong friend. She possesses both enterprise and courage: she received her licence as a pilot in the year in which she became a grandmother. She has for some time lived half the year in Cyprus, and during the turbulent times no governor was able to get her to leave her isolated villa except Sir John Harding who persuaded—or I should perhaps say ordered—her to stay for a time in the shelter of a town. Not long ago when I had to undergo a serious operation, I was faced with a lonely period of recovery. Margaret, who was on a visit to the United States, as an act of real friendship, altered her plans in order that she could come to Batterwood for three or four weeks to provide company for a convalescent.

A student going from the new world has much to learn before he can adjust himself fully to English college life. One evening as a freshman I had dined with a second-year man. Next morning we met in the Quad. My instinct, coming from a country where salutations are very common, was to say good morning, or offer some form of greeting. He, on the other hand, looked straight through me. I wondered whether I had done something to put him off, but I realized very soon that you didn’t address anybody unless you had something to say—it was a time-saving habit. But I should not be surprised if the difference in practice, represented by this tiny incident, has not caused some people from abroad to wonder, and even to worry. Perhaps not enough attention has been paid over the years to the importance of informing young men about to go to an English college about the difference in habits and manners they will find.

I was lucky enough to dine once or twice with a Fellow of All Souls on the guest night, which that famous College observed on Sundays. It was an exciting experience for a green undergraduate—dinner in the beautiful hall, port and dessert in an adjoining room, coffee and tobacco in a third room, and post-prandial drinks in a fourth. At one stage in the evening, one of the college servants stood behind me and said, ‘The Warden wishes to have a glass of wine with you, sir.’ I frankly didn’t know what he meant, but a glance at the Warden himself at the far end of the table enlightened me. I saw Sir William Anson looking at me with a glass in his hand. We drank each other’s health with due gravity.

There were in Balliol at the time three Societies—the Annandale, the Brakenbury, and the Arnold. The current joke was that the Annandale washed but didn’t work, the Arnold worked but didn’t wash, while the Brakenbury made an ineffective effort to do both. As in all ‘mots’ there was an element of fantasy in this—I enjoyed my membership in the Brakenbury!

I was one of the editors of a magazine—The Blue Book we called it—which, like countless others, had a short, eventful, and, on the whole, satisfying life. The name was ill-chosen because the language of the magazine was, happily, far removed from that of government publications. There was good writing in it—an example of the fact that undergraduate magazines often reach a level of style that, for some reason, the writers seldom achieve later on. Perhaps it is because they are ‘on their toes’ and uninhibited. One of our board was poetry editor. I fancied myself as a poet—he did not. I produced a piece of verse and sent it to him anonymously; he passed it for publication—and never forgave me. The appearance of the magazine was celebrated by a memorable dinner. The menu, which follows, was superbly printed by the Clarendon Press and, as a result of earnest research in the Bodleian, records a choice of food more historical than digestible:

BILL OF FARE

Broth

Som Playses

A Sirloin of Beef

A Roast Duck

A Pie of Eels and Lampreys

A Venison Pasty

Hearbs & other Country Messes

A Tipsie-Cake & other Sweetmeats

Seasonable Fruits

A Stilton Cheese full ripe

Segars, Tobacco & Snuff

Dishes of Bohea to taste

Strong Ale of a triple Brew Small-beer

Audit Ale of Cambridge, Sherry-wine & Bristow-milk

On the reverse side of the sheet, recorded irrevocably, are the exuberant signatures of some of the diners, in a state of elation which in after years they might perhaps be willing to forget!

I was one of a small group, Spenny Compton was another, who founded a university society that lasted much longer than the magazine. The Ralegh Club survived two wars and is still going strong. The purpose of the Club was to discuss the affairs of the British Commonwealth, and its membership was restricted to undergraduates from Commonwealth countries. Our juvenile enthusiasm was guided by one or two dons who helped us find speakers, especially for the annual dinner which was, and I believe still is, a distinguished event attended by public men of eminence as guests. We engaged in a great deal of research on the best way to spell the name of the great Sir Walter which, because of the various combinations, can be written in over a hundred different ways. On the menus of the club dinners we printed this invocation, taken from Milton’s ‘Of Reformation’: ‘Thou who of thy free grace didst build up this Brittanick Empire to a glorious and enviable heighth, with all her daughter islands about her, stay us in this felicitie. . . .’ Oxford is a fertile soil for traditions; some of them can be artificial. We established one practice which, considering the name of the Ralegh Club, seemed to be appropriate—the use of churchwarden pipes at our meetings. An absent-minded Canadian professor upset the box containing the pipes and broke them all. This was perhaps a good thing, because we were becoming a bit bemused by tradition.

I recall a stay I made at this time with Sir Horace Plunkett in his house outside Dublin; he was very kind to Oxford undergraduates. Sir Horace was a great figure in the Ireland of his day. His special interest was the organization of Irish agriculture, to which it can be said he devoted his life; he was a practical visionary. On this visit, I met the famous George Russell (‘Æ’) who combined in his active life economics, poetry, and painting; Mrs. John Richard Green (the widow of the historian) who, I was told, was at the moment engaged in gun-running in preparation for ‘trouble in Ireland’; and other people representing various aspects of the Irish issue.

My athletic life—using the term in the broadest sense—was, as always, limited. Tennis, country walks, yes, and the Oxford countryside had unlimited resources for that, and for the bicycle. In organized sports I contented myself with the role of a cox in the ‘torpids’, the winter races on the river. If anyone thinks that that function is comfortable or automatic in its performance, he should make further inquiries. The study of the currents, particularly in that serpentine section known as the ‘Gut’, was an intellectual exercise, and the negotiation of these gave no small satisfaction to the humble person in the stern in whose hands eight hearty oarsmen had placed themselves. The weather that generally prevailed I do not care to remember. My modest performance as cox of a College boat pales into insignificance beside that of my younger son, Hart, who coxed the Oxford eight many years later and won well-merited acclaim.

Nothing is harder than to describe what a college means to you. Its influence is always intangible; the life within its walls is always complicated. What you want to describe seems to dissolve under the impact of description. One whose description did not dissolve it is Harold Macmillan. Here is the conclusion of his memorable speech before the Balliol Society in 1957.

. . . if I have ventured to speak a little of the Balliol that I knew, it is because I feel sure it is the way to renew in each of your minds your affection for the Balliol of your time and of all time. For that of course never changes. Balliol still retains its unique character among all Oxford Colleges and, I was going to say, among all human institutions. . . . And so, because in spite of all the affected cynicism, the passion for epigram, the very natural cult of extreme views—sometimes on the right, sometimes on the left—that youth properly pursues, because after all Balliol is something greater than can be described except in very simple words, I will—greatly daring—go back to Belloc—

Balliol made me, Balliol fed me,

Whatever I had she gave me again;

And the best of Balliol loved and led me,

God be with you, Balliol men.

This year, 1963, we celebrate our 700th anniversary.

As an undergraduate I fell under the influence of Lionel Curtis—influence is, perhaps, too weak a word, for he was the most persuasive and magnetic of men. The Round Table group in England had taken shape by that time, composed almost entirely of men who had worked with Lord Milner in South Africa in the early years of the century—a group that will go down in history under its nickname ‘Milner’s Kindergarten’. I had the privilege of seeing something of Lord Milner both in England and Canada and I remember how touched I was that, when we arranged to discuss some matter, he insisted on coming to my club in London, which was an unusual compliment for one of his eminence to pay a young man. I could understand what he meant to the group who worked with him in South Africa before Union was achieved.

Lionel and Hart in front of the foundation-stone of Hart House, 1920

Lionel Curtis was my guest in Toronto several times, and I often stayed with him in Herefordshire. I recall happily those week-ends and the walks we took together in that lovely countryside with its red (and very adhesive) soil. Curtis was deeply engaged in applying to the Commonwealth the principles that had lain at the back of the South African Union. Studies on a project to federate the Commonwealth of Nations were emerging from his library in great profusion. These were given close examination by his friends in London, whose meetings were known as ‘Moots’, and in due course were dispatched to other Round Table groups organized in various parts of the Commonwealth for their criticism. The original and most important document for this purpose was known as ‘The Green Memorandum’, which embodied a careful and well-written statement describing a system of Imperial Federation. It was a private document, entirely anonymous, and printed with alternate pages blank, on which the recipients were invited to write their comments. The plan was to form groups on a very wide scale. When I returned to Canada from Oxford in 1913, it fell to me to play an active part in the organization of the Round Table movement in the Dominion.

This work was from the outset complicated by a certain ambiguity in the purposes of the movement. Was it (and I and most of our Canadian members came to wish it to be) a purely disinterested study of what we then called ‘the Imperial problem’, to which those of greatly differing points of view would be not only admitted but welcomed? Or was it less an attempt to examine the problem of Empire than an effort to persuade, to convince, as many as would listen that its solution lay in Imperial Federation?