* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Canada and its Provinces Vol 14 of 23

Date of first publication: 1914

Author: Adam Shortt (1859-1931) and Arthur G. Doughty (1860-1936) (editors)

Date first posted: July 15, 2025

Date last updated: July 15, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20250722

This eBook was produced by: John Routh, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

Archives Edition

CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES

IN TWENTY-TWO VOLUMES AND INDEX

| (Vols. 1 and 2) | (Vols. 13 and 14) |

| SECTION I | SECTION VII |

| NEW FRANCE, 1534-1760 | THE ATLANTIC PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 3 and 4) | (Vols. 15 and 16) |

| SECTION II | SECTION VIII |

| BRITISH DOMINION, 1760-1840 | THE PROVINCE OF QUEBEC |

| (Vol. 5) | (Vols. 17 and 18) |

| SECTION III | SECTION IX |

| UNITED CANADA, 1840-1867 | THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO |

| (Vols. 6, 7, and 8) | (Vols. 19 and 20) |

| SECTION IV | SECTION X |

| THE DOMINION: POLITICAL EVOLUTION | THE PRAIRIE PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 9 and 10) | (Vols. 21 and 22) |

| SECTION V | SECTION XI |

| THE DOMINION: INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION | THE PACIFIC PROVINCE |

| (Vols. 11 and 12) | (Vol. 23) |

| SECTION VI | SECTION XII |

| THE DOMINION: MISSIONS; ARTS AND LETTERS | DOCUMENTARY NOTES GENERAL INDEX |

GENERAL EDITORS

ADAM SHORTT

ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

| Thomas Chapais | Alfred D. DeCelles | |

| F. P. Walton | George M. Wrong | |

| William L. Grant | Andrew Macphail | |

| James Bonar | A. H. U. Colquhoun | |

| D. M. Duncan | Robert Kilpatrick | |

| Thomas Guthrie Marquis | ||

VOL. 14

SECTION VII

THE ATLANTIC

PROVINCES

PART II

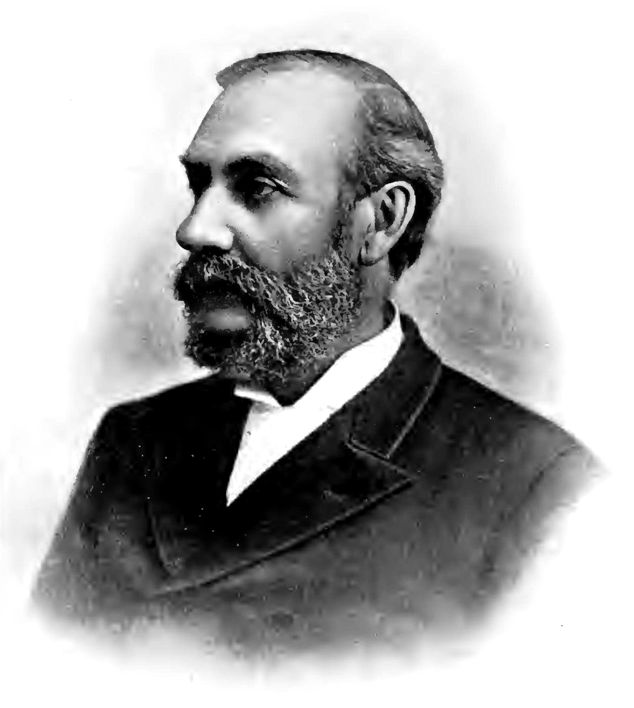

SIR CHARLES TUPPER, Bart.

From a photograph by Elliott and Fry, London

Copyright in all countries subscribing to the Berne Convention

| PAGE | |||

| NOVA SCOTIA: POLITICAL HISTORY, 1867-1912. By Archibald MacMechan | |||

| CONFEDERATION UNPOPULAR | 379 | ||

| THE CLOSING YEARS OF JOSEPH HOWE | 381 | ||

| HOWE'S CHARACTER | 383 | ||

| THE AFTERMATH OF CONFEDERATION | 384 | ||

| SIR WILLIAM FENWICK WILLIAMS | 388 | ||

| PARTIES AND POLITICS | 389 | ||

| RESOURCES AND INDUSTRY | 393 | ||

| NOVA SCOTIA AND THE GREAT BOER WAR | 396 | ||

| NEW BRUNSWICK: POLITICAL HISTORY, 1867-1912. By W. O. Raymond | |||

| THE EVE OF CONFEDERATION | 403 | ||

| AGITATION FOR RAILWAYS | 406 | ||

| THE CONFEDERATION CAMPAIGN | 410 | ||

| IN THE DOMINION | 418 | ||

| THE STRUGGLE FOR FREE SCHOOLS | 419 | ||

| MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT | 424 | ||

| A DISASTROUS CONFLAGRATION | 425 | ||

| SIR LEONARD TILLEY | 427 | ||

| A PROSPEROUS CITY | 428 | ||

| RECENT POLITICAL EVENTS | 431 | ||

| PROVINCIAL AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT. By Charles Morse | |||

| I. | NOVA SCOTIA | 435 | |

| Beginning of Representative Government—The Office of Lieutenant-Governor—The Executive Council—The Legislature—The Public Departments of Government—The Judicial System and Courts of the Province—The Provincial Revenue—Municipal Institutions in the Province | |||

| II. | NEW BRUNSWICK | 480 | |

| The Provincial Government—The Provincial Revenue | |||

| III. | PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND | 495 | |

| The Lieutenant-Governor—The Executive Council—The Legislature—The Public Departments of Government—The Judicial System and Courts—The Provincial Revenue—Municipal Institutions | |||

| HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN NOVA SCOTIA AND PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND. By A. H. MacKay | |||

| I. | EDUCATION IN NOVA SCOTIA | 511 | |

| Educational Beginnings—The Rise of the Colleges—University Statistics, 1911—Other Independent Colleges and Schools—The Public Schools and Government Institutions—Conspectus of Public School Statistics in Nova Scotia—Conspectus of Education Statistics in Nova Scotia—The Teachers—Salaries of Teachers—Devotional (Religious) Exercises—Classification of Public School Pupils according to Sex and Grade, 1911 | |||

| II. | EDUCATION IN PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND | 537 | |

| HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN NEW BRUNSWICK. By G. U. Hay | |||

| EDUCATION IN PIONEER DAYS | 545 | ||

| THE MADRAS SCHOOLS | 548 | ||

| ESTABLISHMENT OF COMMON SCHOOLS | 550 | ||

| THE FREE SCHOOL SYSTEM | 552 | ||

| HIGHER EDUCATION | 557 | ||

| THE ATLANTIC FISHERIES OF CANADA. By John J. Cowie | |||

| THE FISHING GROUNDS | 561 | ||

| THE PIONEER FISHERMEN | 562 | ||

| BEGINNINGS OF CANADIAN FISHERY | 563 | ||

| EARLY DEVELOPMENTS | 565 | ||

| THE INSHORE FISHERY | 567 | ||

| THE DEEP-SEA FISHERY | 568 | ||

| GROWTH OF THE FISHERIES | 569 | ||

| THE COD FISHERY | 570 | ||

| THE HADDOCK, HAKE, AND POLLOCK FISHERIES | 572 | ||

| THE HALIBUT FISHERY | 573 | ||

| THE HERRING FISHERY | 574 | ||

| THE SARDINE FISHERY | 576 | ||

| THE GASPEREAUX FISHERY | 578 | ||

| THE SHAD FISHERY | 578 | ||

| THE SMELT FISHERY | 578 | ||

| THE MACKEREL FISHERY | 579 | ||

| THE SALMON FISHERY | 581 | ||

| THE LOBSTER FISHERY | 582 | ||

| THE OYSTER FISHERY | 585 | ||

| CLAMS | 588 | ||

| OTHER FISH | 588 | ||

| SEAL HUNTING | 589 | ||

| RECENT DEVELOPMENTS | 589 | ||

| STEAM-TRAWLING | 591 | ||

| FOREST RESOURCES OF THE MARITIME PROVINCES. By R. B. Miller | |||

| I. | NEW BRUNSWICK | 597 | |

| Character of the Forests—History and Progress of the Timber Trade—Lumbering Operations—Forest Conservation | |||

| II. | NOVA SCOTIA FOREST SURVEY | 621 | |

| III. | THE CHIEF COMMERCIAL SPECIES | 624 | |

| Conifers—Hardwoods | |||

| IV. | MINOR FOREST INDUSTRIES | 630 | |

| AGRICULTURE IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES. By M. Cumming | |||

| I. | CLIMATE AND SOIL | 637 | |

| Geographical Situation—Topographical and Geological Features—Geology of Nova Scotia—Geology of New Brunswick—Geology of Prince Edward Island | |||

| II. | AGRICULTURE IN NOVA SCOTIA | 644 | |

| Types of Farming | |||

| III. | AGRICULTURE IN PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND | 657 | |

| History of Agriculture in Prince Edward Island—Types of Farming—Fruit-growing | |||

| IV. | AGRICULTURE IN NEW BRUNSWICK | 663 | |

| History of Agriculture in New Brunswick—Types of Farming—Crops—Fruit-growing in New Brunswick | |||

| MINES AND MINING IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES. By F. H. Sexton | |||

| EARLY DISCOVERIES | 671 | ||

| A PROVINCE WITHOUT MINES | 673 | ||

| COAL-MINING IN NOVA SCOTIA | 673 | ||

| COAL-MINING IN NEW BRUNSWICK | 683 | ||

| IRON AND STEEL INDUSTRY IN NOVA SCOTIA | 685 | ||

| IRON AND STEEL INDUSTRY IN NEW BRUNSWICK | 689 | ||

| GOLD-MINING IN THE MARITIME PROVINCES | 691 | ||

| GYPSUM DEPOSITS | 694 | ||

| MISCELLANEOUS MINERALS | 696 | ||

| SIR CHARLES TUPPER, Bart. | Frontispiece | ||

| From a photograph by Elliott and Fry, London | |||

| OLD WHARVES AT HALIFAX | Facing page | 398 | |

| (1) MILLER'S DOCK AND MORAN'S WHARF | |||

| (2) OLD WHARF ON THE HARBOUR FRONT | |||

| (3) OLD WHARF AT THE FOOT OF SLATER STREET | |||

| From original etchings by Leo Hunter in the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library | |||

| THEODORE HARDING RAND | Facing page„ | 420 | |

| From a photograph | |||

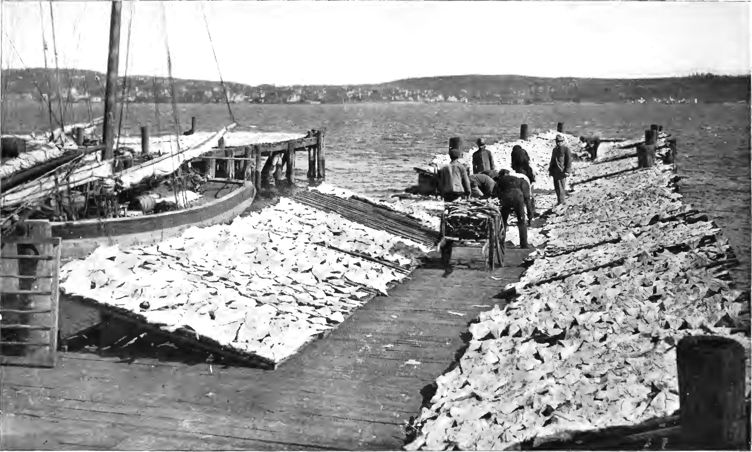

| FISHERMEN AT ISLE PERCÉ AT THE MOUTH OF THE ST LAWRENCE | Facing page„ | 566 | |

| From original paintings by John A. Fraser | |||

| COD-FISHING IN NOVA SCOTIA | Facing page„ | 570 | |

| LUMBERING IN NEW BRUNSWICK | Facing page„ | 602 | |

| (1) A 'JAM' AT GRAND FALLS ON THE ST JOHN RIVER | |||

| (2) A SNOW-COVERED YARD | |||

| LUMBERING IN NEW BRUNSWICK | Facing page„ | 606 | |

| (1) A TYPICAL SHANTY | |||

| (2) A DRIVING SCENE | |||

| LUMBERING IN NEW BRUNSWICK | Facing page„ | 608 | |

| (1) UNLOADING AT THE LANDING | |||

| (2) LOG-DRIVING | |||

| LUMBERING IN NEW BRUNSWICK | Facing page„ | 614 | |

| (1) A LOG-JAM ON A SMALL STREAM | |||

| (2) LOGS ON THE BANK OF A STREAM READY FOR THE SPRING FRESHET | |||

| FARMING NEAR CHARLOTTETOWN, PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND | Facing page„ | 642 | |

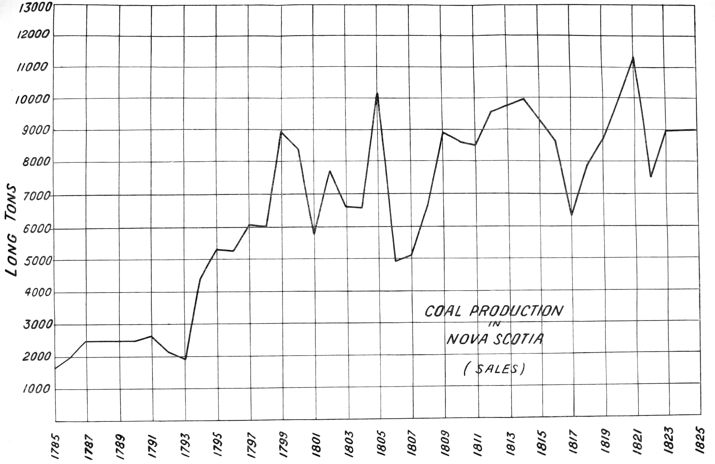

| COAL PRODUCTION IN NOVA SCOTIA, 1785-1825 | Facing page„ | 674 | |

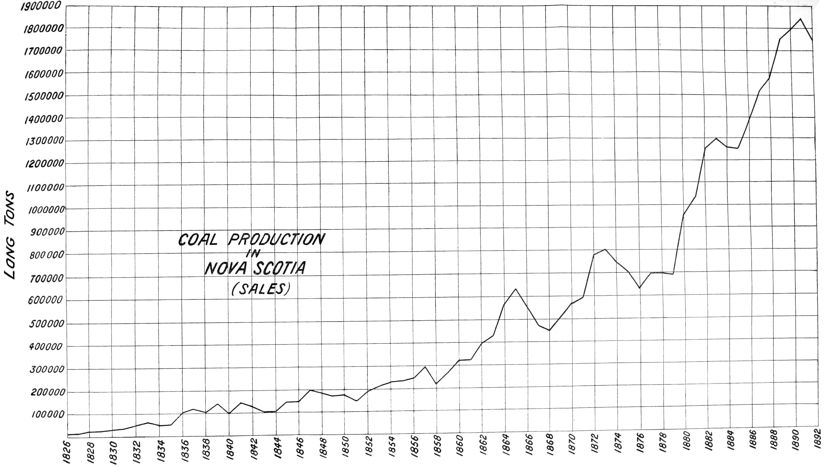

| COAL PRODUCTION IN NOVA SCOTIA, 1826-1892 | Facing page„ | 678 | |

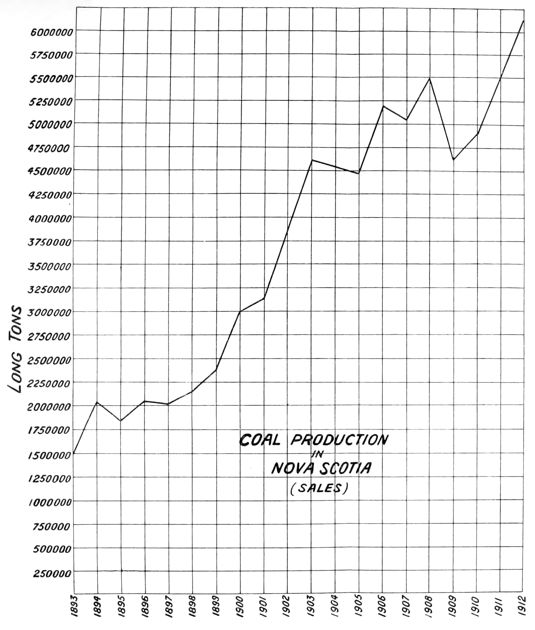

| COAL PRODUCTION IN NOVA SCOTIA, 1893-1912 | Facing page„ | 680 | |

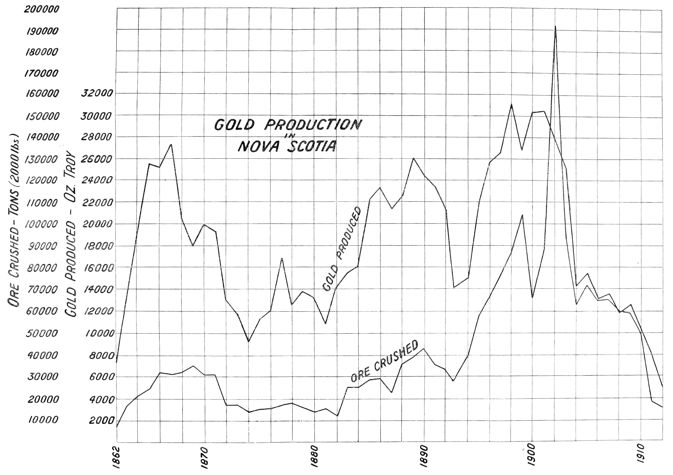

| GOLD PRODUCTION IN NOVA SCOTIA | Facing page„ | 690 | |

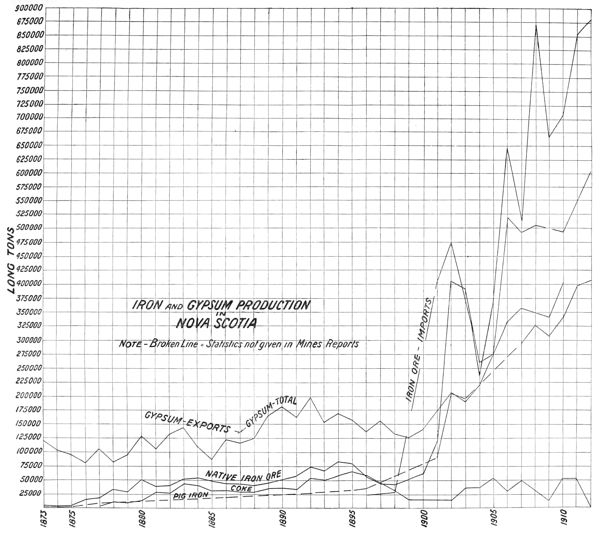

| IRON AND GYPSUM PRODUCTION IN NOVA SCOTIA | Facing page„ | 694 | |

NOVA SCOTIA: POLITICAL

HISTORY, 1867-1912

'Not Confederation itself, but the way it was brought about,' say Nova Scotians, 'was our reason for fighting Confederation.' How real their objection, how strong their opposition, is manifest from what took place immediately after the dissolution of the assembly. On July 1, 1867, by the fiat of the imperial parliament, the union of four scattered colonies was consummated; a new nation had come into being; and new elective bodies must be chosen to carry out the new constitution. Nova Scotia had ceased to be a quasi-independent state. Against the will of its people it had been forced into a new political combination, to which public feeling was actively hostile. On such a momentous question as a complete change of status the people directly affected should surely have been consulted; the consent of the governed should have been obtained; but in his brief span of power a strong-willed man carried this radical measure by the weight of his majority in the local parliament. Even if he be credited with broader patriotism, wiser statesmanship and deeper vision than his opponents, still, to overturn the whole constitution of a quasi-independent state and alter all its relations without a mandate from the people was dead in the teeth of every principle of free self-government. It provided one political party with a grievance that lasted for thirty years.

Nothing could be more free from doubt or ambiguity than the pronouncement of Nova Scotia on the question as soon as she could make her voice heard. In the first Dominion elections the only Confederate returned was Dr Tupper himself. For the assembly only two Confederates were elected: of these one was immediately unseated and an anti-Confederate elected in his place. In the first Dominion parliament Howe headed a solid party of seventeen opposed to Confederation, while his friend Annand became premier of the local house of thirty-eight members with just one lonely Confederate for the entire opposition.

In winning such a victory Howe had, of course, the prime part. His 'Letters to the People of Nova Scotia,' which constitute his apologia, tell of his labours through that strenuous campaign. The battle with Tupper in the joint debate at Truro was the talk of the province. It was a war of giants. But Howe was not alone, and to attribute the liberal triumph solely to his eloquence and energy is a grave error. The consistent opposition of W. Garvie, an able writer, in the Citizen must be reckoned with. Annand of the Chronicle was only one of a number of irreconcilables who never accepted the new order, and worked tooth and nail against it long after their efforts were plainly hopeless. The agitation and discussion in the newspapers from 1864 to 1867 convinced the people of Nova Scotia that the contemplated change was undesirable and had effected a complete cleavage between them and the majority in the assembly. It is also an error to attribute the result to mere faction and the wiles of the demagogue. Subsequent events showed solid grounds for objection, and Nova Scotians are not the sort of people to be stampeded by an empty cry.

Steps were at once taken to induce the British government to reconsider its action so far as to permit Nova Scotia to recover her ancient status and relation to the Empire. Howe, Annand and Hugh McDonald formed another delegation to England. These men left no stone unturned to effect their purpose. But the great public was indifferent, the House of Lords could not be interested, and Bright's motion for mere inquiry in the Commons was defeated. Britain had her own difficulties. Her relations with the United States were strained. An American politician actually demanded the whole of British North America in settlement of the Alabama claims. To disrupt the newly formed Dominion as soon as it was formed looked like an act of folly. The delegates could not even obtain a hearing, and, sick at heart, they came back to the province.

On the return of the disappointed men an anti-Confederate council of war was held in Halifax. It consisted of the members of the Dominion and of the local house. All sorts of wild schemes were suggested—blocking the wheels of the constitution by wholesale resignation, armed resistance, even the intervention of the United States and annexation. Howe pointed out the hopelessness of fighting. 'There are the British bayonets,' he said. But it was no mere flourish when he talked of dying with his boys on Tantramar marsh. As for calling the United States to aid, it was unthinkable to a patriot like Howe. He would none of it. Resignation in a body meant the loss of place and salary, and for such a sacrifice the office-holders were not prepared. This conference justified the proverb that a council of war never fights, and it broke up without any concerted plan of action.

At the very same time Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir G. É. Cartier came to Halifax to listen to complaints, to hear both sides, and, if possible, to placate the party of disruption. Howe had to write a chivalrous letter to the Chronicle bespeaking a courteous reception for the Canadians. The party lodged at Government House and conferred with all who would do so. Irreconcilables like Annand refused to meet them at dinner. But 'Old To-morrow' employed all his well-known powers of diplomacy and persuasion. With Howe, as the acknowledged leader of the anti-Confederates, he discussed the whole question. He was willing to do anything in reason to win over his opponents, to conciliate local feeling and to preserve the Union. He succeeded in winning over Howe, who was already convinced of the futility of further opposition, and at a heavy price devoted himself to obtaining 'better terms.' In a conference at Portland with Sir John Rose, the finance minister, the final details were arranged. On his return to Halifax the whisper ran round that Howe was a 'traitor,' that he had been 'bought.' In January 1869 he was appointed president of the council in the Macdonald government. Sir John had invited him to assist in working out the plan of 'better terms,' for he needed a man of Howe's ability to overcome the opposition of the other provinces to further money grants to Nova Scotia. The 'better terms' meant a further subsidy of $80,000 for a period of ten years and the assumption of a million more of the provincial debt.

It is difficult to see what else Howe could have done. Repeal was hopeless. The only course that remained open was to make the best of what he regarded as a bad bargain. Howe's action benefited Nova Scotia, but it cost him almost every friend he had left. After more than thirty years of comradeship Annand turned against him and filled the Chronicle with venomous attacks upon his old chief. The hatred of the anti-Confederates for their leader's defection was shown in his next political campaign. That same winter Howe had to contest Hants County with Monson Goudge, the president of the legislative council. It was the old lion's last fight and his hardest. The anti-Confederates put forth every effort to defeat him. He won, but he was never the same man again. The Hants election killed him. At a joint meeting in the schoolhouse at Nine Mile River his physical agony made it impossible for him to stand. He lay on the floor of the platform, wrapped in his cloak, while his adversary, nicknamed 'Roaring Billows,' stood over his prostrate form 'bellowing like a bull of Bashan.' That night he took to his bed and did not stir out again for a month, but he could still command the support of loyal friends who carried the canvass through and won the seat for him.

Howe's career was over. An old and broken man, he sat in the Macdonald cabinet as secretary of state for the Provinces for some three years, and then, in May 1873, the dying man was paid the compliment of being placed at the head of the province he loved so well and had served so loyally and long. He was sworn in as lieutenant-governor on May 10, but he enjoyed the honour less than a month. On June 1 he was dead. It was fitting that he should die in Government House, and it was characteristic that he should die on his feet. The night before his death he was in great pain and unable to sleep: he spent it in his study, sitting in his chair, or restlessly pacing the floor. Towards dawn he was induced to go to his bedroom. As he neared the bed he staggered and fell into his son's arms. In ten minutes he was gone.

Over his grave the parties made a truce. Even his bitterest foes paid tribute to his greatness. As the years go by the figure of Howe will detach itself more and more from the clouds of detraction and party enmity and reveal its towering height and massive strength, for the generations to come will learn to know him from the printed record of his own words, and they retain their vital heat. It is impossible to read Howe's state papers, his public letters, his speeches, and refuse him the epithet 'great.' For breadth of view, for piercing insight, for firmness of grasp, for raciness and energy of style, they stand absolutely alone. Howe served his country well. He attacked and defeated single-handed the banded respectabilities of his time; he gave his province a new constitution; he fostered her material progress in every way; he educated British statesmen in the principles of popular government; he was the first of Canadian leaders to think imperially; he lived in the constant close companionship of great ideas; he had strange power of speech to move the hearts of men as the wind sways the fields of wheat; he embodied and intensified the strong local feeling that glorified the province of his birth. His story is fascinating, enigmatic, tragic. It offers the solitary case of hero-worship in Canadian history. Men remember his words, his characteristic gestures, his grey suit, his white hat, his jaunty walk, the way he would open and throw back his coat as he took the platform. The province is full of anecdotes about him. Even now, men take sides and dispute regarding his motives and his actions. Faults he had not a few. He was egotistic, he was careless about money, his debts mined his independence; he was not the kind of politician that fattens on politics; he could shock the prudes; at the great crisis of his life he was weak, jealous, untrue to himself. But he had puissant and splendid excellences to put on the other scale: his courage was above proof, he was unselfish, he was chivalrous even in his hardest fights, he gave without reserve his whole marvellous strength to the public service; he was a true patriot—Nova Scotia's faulty, generous, great-hearted tribune of the plebs. His monument stands beside the Province Building which so often rang to his eloquence. The bronze effigy seems alive. It will be level with the dust before Nova Scotia can forget her favourite son.

The aftermath of Confederation in Nova Scotia is now to be considered. The strife of parties was the fiercest, the question at issue was the most important, the leaders were the ablest and best matched, in all the provincial history. Men's strongest passions were aroused. The very children shared their fathers' animosities and fought, Confederates and anti-Confederates. The intensity of the struggle is seen in the fact that less than twenty years later it was possible to raise once more the cry of 'Repeal' and carry the country on it. To pretend that the battle of 1867 was the ordinary party sham-fight of the ins and the outs is to misread history and human nature.

If Confederation was not an immediate and dazzling success the student of history will not be surprised. It was a daring experiment. Howe's keen criticism of the 'Botheration Scheme' read forty years later brings out a truth he did not intend—the brilliant audacity of the men who tried to form a new nation out of such disparate elements as the four original provinces. More clearly than any one Howe points out the dangers and difficulties. Now Canadians forget that they existed. For a generation the Canadian union was in the experimental stage. It might succeed, or it might fail. Now that the experiment has succeeded, to the admiration of the world, no one remembers by what toil success was guaranteed and with what tremors its progress was watched. There was friction still between French Catholic Quebec and English Protestant Ontario. Nova Scotia came in with a deep sense of injury. Her autonomy had been roughly disregarded. Between the seaboard provinces and the inland centres of population there was a wilderness to be crossed, and between the English-speaking provinces stood the solid French wedge. A statesman might well have doubted if such an experiment in nation-building would come to aught.

Once more in the history of Nova Scotia a completely new orientation was necessary. Now, instead of England with her stately past, the eyes of the province must be turned to 'Canada,' which had only a future. Ottawa unknown, in the making, somewhere in the inaccessible interior, had nothing to compare with London's thousand years of vivid, varied, historic interest. London was much nearer to Halifax than Bytown was. There was a feeling, too, that Nova Scotia 'belonged' to Canada, a country known only for rebellion, deadlocks and debt, and did not 'belong' any more to Britain. The ancient, deep-rooted loyalty to the mother country protested against the sudden, forcible transfer of allegiance. The new national ideal was neither well defined nor specially attractive, and Nova Scotia was slow in responding to the appeal. To this day the Canadian tourist in Nova Scotia is astonished at being asked if he comes 'from Canada.' The question is an unconscious indication of the old separatist feeling.

At the same time, it must be remembered that the whole influence of the conservative party in the province has been given steadily and loyally to the support of the national idea. That party, however, has only held power for four years out of forty-five.

Confederation did not make any province suddenly rich, and it was considered a failure in Nova Scotia for several post hoc, propter hoc reasons. Hard times set in. The Reciprocity Treaty with the United States expired, after it had been renewed through Howe's Detroit speech. At first it was rather resented in Nova Scotia, and its benefits to the province were slight. When the American Civil War broke out, however, the States offered an eager market for every bushel of provincial produce. Water carriage was cheap and easy; the natural line of trade was open once more for the first time since 1775. Halifax, as ever, profited greatly by war. Before the blockade of the Confederate ports became effective, the Halifax merchants sent in cargoes of fish and lumber and brought back cotton. When the Federal cruisers shut the South from the sea, Halifax harbour was thick with blockade-runners, low-built, speedy, mouse-coloured iron steamers with collapsible funnels. They would load in Halifax and sail out boldly under the British flag to Nassau. All goods were paid for in gold. There were no accounts and no bad debts. If they succeeded in slipping past the Federal cruisers into Wilmington, they would buy cotton at sixpence a pound, contract price, which sold in England for three and sixpence. The captains, naval officers under assumed names, got a thousand pounds a trip, in and out, and the privilege of bringing out, on their own account, ten bales of highly compressed cotton. But the war came to an end, blockade-running ceased, war prices returned to normal, and, with the expiry of the Reciprocity Treaty in 1867, the trade of Nova Scotia with its natural market stopped abruptly.

Another pinch was the ruin of a staple crop. About 1860 the weevil came to Nova Scotia and attacked the wheat. It was impossible to stop the plague, and 'bread corn' ceased to be cultivated. Some years ago an artist in Nova Scotia, wishing to paint mural decorations representing the four seasons, was hard pressed to find a wheat-field as his model in his autumn scene. On the rich intervale land of Pictou wheat had been grown for two generations, often with a yield of forty bushels to the acre. That phase of farming passed away definitely. The loss to the farmers and millers may be readily understood.

Another reason for the unpopularity of Confederation in Nova Scotia was the decay of wooden shipbuilding. That indecisive fight in Hampton Roads between the Merrimac and the Monitor decided one thing—warships and merchant ships should henceforth be of iron. Now the tramp steamer has driven sails from the sea. Nova Scotia had a huge capital invested in ships, and owners were slow to realize the revolution that had come about in the carrying trade. Only the irresistible logic of dwindling profits and dead losses forced them out of the business. The marked decay set in about 1874, and in thirty years Nova Scotia's chief industry was dead. This was the heaviest blow ever dealt to provincial prosperity. It speaks volumes for the recuperative power of the province that it is recovering from such a blow.

One direct effect of Confederation that distinctly injured the business of the capital was the building of the Intercolonial Railway. This was really a violent attempt to overcome nature and geography by establishing a new trade route. As a maritime province the trade of Nova Scotia had been from the first water-borne to England, to the West Indies and to the nearest American colonies. Now the nation-builders of Canada, confident of her future and greatly daring, ran an iron road through a wilderness and linked Halifax with Quebec. This ready means of communication had an unforeseen effect upon the trade of the province. The wholesale merchants of Toronto and Montreal sent their travellers in and secured a large part of the trade that had so long been the monopoly of the wholesale merchants of Halifax. It was a reversal of the ancient order of things. In the good old days the retail merchant came from the country to the city. He approached the wholesale magnate humbly, and after a glass of wine in the office and a chat on general topics, he would request permission to see the goods he might order. To go after business, to drum it up, to employ ambassadors of commerce to visit the country merchants and solicit orders for goods was a most unheard-of, undignified proceeding, and the indignation of the old-fashioned Halifax merchants at 'those Canadians' poaching on their preserves was extreme. Halifax lost her pre-eminence, but the country towns profited. They began to import for themselves, and so became independent of the capital.

All these things came together after Confederation, and for them, illogically enough, Confederation was held to blame. There were other changes, inevitable but none the less to be regretted, which arose from the changed status of the province. The battle over Confederation is the fiery climax of Nova Scotia's one hundred and ten years of independent political life and of her unrelaxing efforts to govern herself. The final struggle left the province exhausted. Death claimed Johnston and Howe. Tupper found scope for his ambition in the wider field of Dominion politics. These men left no successors to their strength or their policies. The provincial arena was so shrunken, the interests involved were so narrow, that inevitably the men of outstanding ability were drained off into national politics. Tupper, Fielding, Thompson, Borden are examples of the strong drag towards the centre. The general assembly, with its ancient and worthy tradition of great principles and great debating, can never be what it once was. Henceforward its activity must be limited to the bounds of a county council, labouring over the honest disposal of the provincial revenue, and meticulous details of expenditure for roads and bridges, for education and public charities.

And with the glamour of the Province Building has passed the glory of Government House. It is in thorough accord with every democratic theory and tendency that the office of lieutenant-governor should be filled by the native-born. But in practice it is difficult to find the combination of qualities that are desirable in the official head of the province. Little remains to the modern lieutenant-governor but to maintain the dignity of his province on public occasions and to act as a social centre. The constitution leaves him very narrow range of action. The choice in candidates is limited. When the lieutenant-governors were really intended to govern, men of distinction were selected for the office. The old order was doomed, but the lover of the picturesque may be permitted a sigh for the days of Wentworth and Sherbrooke, Dalhousie and Kempt.

One of the last and not the least distinguished 'royal governors' was a native of Nova Scotia. Sir William Fenwick Williams was born at Annapolis Royal in 1800. He entered Woolwich in 1815 just as the long peace began. The Crimean War found him a middle-aged officer of the Royal Artillery, who had spent fourteen years in assisting the organization of the Turkish army. His opportunity came late in life, like Havelock's, when he was shut up in Kars, a city on the eastern border between Turkey and Russia, by a greatly superior Russian army under Mouravieff. By sheer skill, courage and sagacity he held the Russians at bay for six terrible months. In one desperate battle outside the city walls his Turks accounted for six thousand of the enemy, killed and wounded. Cholera and starvation decimated the garrison; the soldiers shared their scanty rations with the famishing townspeople. At last, when word came that the relieving force could not reach him, Williams thought of surrender. He stipulated for the honours of war; otherwise he would burst every gun, destroy every standard and trophy, and allow Mouravieff to wreak his will on the garrison. The chivalrous Russian accorded the most honourable terms. The defence of Kars was the most brilliant episode of the Crimean War, the admiration of all professional soldiers. England showered distinctions on the hero—a baronetcy, a pension of a thousand pounds a year for life, the freedom of the city of London, a sword of honour, and the degree that Oxford reserves for men of mark. His native province also voted him a sword of honour, the last time that knightly compliment was paid. He was appointed lieutenant-governor in 1865 and valued the honour highly. His portrait hangs in the council-chamber of the Province Building to remind coming generations what Nova Scotians have achieved.

Another notable son of the province to be named for this office after Howe's death was Johnston. He was travelling for his health in the south of France at the time of his appointment, but he died before he could reach home and is buried in Cheltenham. It was only fitting that both these ancient rivals should be paid the high compliment of being placed at the head of the province they had done so much to distinguish. Such memories cling to the time-stained walls of Government House.

After the Heroes, the Epigoni! A smaller race of provincial politicians succeeded. Annand died still unreconciled, and was followed by the government of P. C. Hill, which was turned out by the one conservative administration that has governed the province in forty-five years. The leader was Simon Holmes, a native of Pictou County, editor of the Colonial Standard. He had for second-in-command a young Catholic lawyer, John Sparrow Thompson, whose father had been Queen's Printer. He was destined to become prime minister of Canada and to find death in Windsor Castle. The Holmes-Thompson government was noted for its careful, economical use of the provincial revenue, by which it was able to reduce the outstanding debt and to increase the efficiency of the school system by enlarged grants. Owing to ill-health Holmes was obliged to retire from politics in 1882, and Thompson was soon after raised to the bench. This solitary instance of the conservative party obtaining power since Confederation is a remarkable political fact. Majorities in Canada are strangely permanent. The Canadian people are not lightly given to change; but four years out of forty-five is entirely disproportionate. There is the fact, interpret it who may.

To the Holmes-Thompson government succeeded that of W. T. Pipes and W. S. Fielding, who entered political life almost by accident as a compromise candidate by way of the Chronicle office. As provincial secretary Fielding reigned without intermission from 1884 until the liberal victory of 1896, when he became minister of Finance in the Laurier government. His long term of office is noteworthy for two measures, which diversify the monotonous record of parish legislation.

On May 10, 1886, just before the provincial elections, W. S. Fielding, from his place as provincial secretary, moved a remarkable series of resolutions, which form a sort of epilogue to the struggle of 1867. These contrasted the state of the province before and after Confederation. Before, 'the Province of Nova Scotia was in a most healthy financial condition.' 'Nova Scotia, previous to the Union, had the lowest tariff and was, notwithstanding, in the best financial condition of any of the Provinces entering the Union.' Now, 'the commercial as well as the financial condition of Nova Scotia is in an unsatisfactory and depressed condition.'

The resolutions assigned the reasons for the 'unsatisfactory and depressed condition.' By the terms of the Union the chief sources of revenue were transferred to the federal government. Further, they pointed out that the promises contained in Sir John Macdonald's letter to Howe, dated October 6, 1868, had never been fulfilled. They also asserted roundly and without any qualification that 'the objections which were urged against the terms of Union at first apply with still greater force now than in the first year of the Union.' Taken all together, they form a severe arraignment of Confederation, and justify every criticism Howe made of the pact. After giving the new idea a trial of nineteen years, those in charge of the provincial affairs declared deliberately, in their official capacity, as representatives of the people, that the experiment had failed so far as Nova Scotia was concerned.

The remedy proposed was the old object of the Charlottetown conference—Maritime union, the peaceful detachment of the three Atlantic provinces from the Dominion; in other words, a reversion to the old boundaries of Acadie, prior to 1784. If Maritime union is not possible, the government of Nova Scotia 'deems it absolutely necessary' to 'ask permission from the Imperial Parliament to withdraw from the Union with Canada and return to the status of a Province of Great Britain, with full control over all fiscal laws and tariff regulations within the Province, such as prevailed previous to Confederation.'

The final resolution runs: 'That this House thus declares its opinion and belief, in order that candidates for the suffrages of the people at the approaching elections may be enabled to place this vital and important question of separation from Canada before them for decision at the polls.' The English might easily be improved by the pen of Howe, but the intention is unmistakable. After debate the repeal resolutions were carried by a vote of fifteen to seven.

Outside the house the resolutions were bitterly assailed. The liberals were accused of insincerity, of sectionalism, of making merely a party move. Elsewhere in Canada the cry of Repeal aroused something like consternation. In Ontario the new national idea was so completely accepted that the outspoken protest from the Atlantic was regarded as a piece of incomprehensible ingratitude. That any province could possibly object to its rôle in Confederation was a novel and unwelcome idea to the generation of Canadians growing to manhood since 1867 and knowing nothing but one country stretching from the centre to the sea. And yet Nova Scotia was declared in unmistakable official terms to be discontented.

The decision of the people at the polls in regard to the 'vital and important question' was free from any doubt. Fielding was returned to power with a large majority. Nova Scotia had given him what he asked, a mandate to take his province out of the Union, and his natural course would have been to petition the British government and head delegations to England as Howe did in 1866 and 1868. It is quite conceivable that Nova Scotia, a quasi-island with its own tariff, might flourish as does Newfoundland in its old status as a colony. Its natural resources are very much greater, and its power is much more evenly diffused. It is also conceivable that, however pained and grieved by the defection, the rest of Canada would never think of opposing separation by force, though it would pay handsomely to preserve the Dominion ring-fence intact. But Fielding did nothing. Two of his party, W. T. Pipes and T. R. Black, frankly refused to contest their seats on the separation cry. Pipes retired from politics altogether, and Black was returned at the head of the poll. On his return to office, in 1887, Fielding passed other resolutions alleging further action impossible in view of the fact that in the Dominion elections, held at the same time, a majority of conservatives had been elected. Nothing was done further to obtain repeal, but the agitation had one material result. Once more Nova Scotia obtained an increase to the subsidy from the Dominion. His political opponents held that Fielding had stultified himself.

Those repeal resolutions remain on record for the instruction of students of Canadian history, and for the warning of Canadian statesmen. They testify to Howe's foresight. What he predicted came to pass. The modern vulgar reverence for the merely big, megalomania, and the vulgar admiration of mere wealth have led the larger states of Canada to look on the smaller, poorer states with something akin to contempt. Such phrases as 'the shreds and patches of Confederation' and 'Ontario the milch-cow of the Dominion' are straws that show the direction of a steady wind of political opinion. The popular conception of Nova Scotia approaching Ottawa for an increased subsidy is a mendicant holding out his hand for alms. The true conception is of a partner in a going joint concern demanding his lawful share of profits. As Andrew Macphail truly says: 'The Fathers of Confederation never intended that the Dominion should be rich and the provinces poor.' No matter which party has held the purse-strings at Ottawa, the Dominion government has never erred on the side of liberality to the member of the Confederacy that sacrificed most for the ideal of national unity.

A striking physical feature of Nova Scotia is its mineral wealth. Within its borders almost every species of ore is found—gold, iron and coal—but the chief of these is coal, the indispensable basis for the age of steam. Coal is found in many parts of the province—in Cumberland, in Pictou, and, above all, in Cape Breton. In Cape Breton some four hundred square miles of desolate country are underlain by seam below seam of rich bituminous coal. The exploitation of this vast wealth began in a feeble way as early as the seventeenth century. Denys mentioned the coal of Cape Breton in his Description and Natural History of Acadia of 1672, and five years later was authorized by the French government to collect a tax of twenty sous per ton on all coal exported from the island. The ships at first were loaded from the cliffs. When the French began to fortify Louisbourg in 1720, the first attempt at mining was made on the north side of the island, to meet the needs of the workmen engaged. The first mining after the English occupation dates from 1766, when four Halifax merchants—Gerrish, Lloyd, Armstrong and Bard—for the sum of £400 paid to the government were granted the privilege of mining three thousand chaldrons, on condition of their sending half the quantity to Halifax and not charging more than twenty-six shillings per chaldron. These enterprising men began mining at Spanish River, now Sydney. Very little was done to follow up the work. In 1826 the total average annual yield of all Cape Breton was only 7500 tons. In 1872 it was 383,000 tons; in the same year Pictou produced 5000 tons more. This was a considerable advance in forty-six years, but still it was only scratching the surface of these enormous deposits. Small companies, feebly capitalized, with antiquated machinery, were competing with one another, and far from prosperous. This was the situation of coal-mining in Nova Scotia up to the year 1893.

By very ancient English law all minerals are deemed to be the personal possession of the crown, and this law was embodied in the constitution of Nova Scotia. That is the reason that Gerrish and his partners had to pay so handsomely for the privilege of digging the Spanish River coals, now the favourite 'Old Sydney.' George IV took the law literally and transferred the coal-mines of Nova Scotia to his brother the Duke of York to pay his debts. The duke in turn made them over to the once well-known London firm of jewellers, Rundell, Bridge and Rundell. For some time they worked the mines and held Nova Scotia in tribute. It is one of Johnston's great public services that he recovered, by his legal knowledge and diplomacy, Nova Scotia's rights to her own coal-mines. The coal areas were never sold outright, but were leased for a term of thirty years, and the lessees paid the government a royalty of seven and a half cents for every ton raised, and the proviso of this ancient law had far-reaching results.

About the year 1889 it occurred to B. F. Pearson, a lawyer of Halifax, that this situation might be improved. Pearson came from Colchester, and he had already promoted considerable local enterprises. His project was to combine and work the coal-mines of Cape Breton on an entirely modern business plan. It was a large conception. He was able to interest H. M. Whitney, a prominent capitalist of Boston, and, working with him, bought out nine Cape Breton collieries. The result was the formation of the Dominion Coal Company. In the necessary legislation passed at a special session in January 1893 important modifications were made in the old law: the term of the lease was increased from thirty to ninety-nine years, and the royalty from seven and a half to twelve and a half cents per ton. This increase brought in 1912 the total amount of coal royalties up to $800,000. Thanks to this law and the enterprise that consolidated the coal industry, the province is sure of a yearly revenue, which must steadily grow.

Another important result was the formation of a sister industry, the Dominion Iron and Steel Company, in order to find a steady customer for the huge quantities of coal that would be raised by improved modern methods and management. Again H. M. Whitney supplied the money and floated the company. Sydney, des Barres' old capital, was selected as the site of the huge complex of buildings, wharves and roads necessary for the production of steel on an enormous scale. Millions were spent in the necessary first outlay, and a great deal of it was wasted. As soon as the furnaces began to produce the first billets, Dominion Steel stock rose on the market. Every one bought; the value of the stock steadily mounted; and then came a drop, and hundreds of Nova Scotians lost heavily. The truth is that the company was used for the purpose of speculation and was nearly brought to ruin. Strikes and an expensive lawsuit hampered its development, and 'American enterprise' nearly wrecked it. Under Canadian management it is gradually coming back to a sound financial basis.

Another great concern with an entirely different origin and history is the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company of New Glasgow. In 1872 it began in a small way as the Hope Iron Works, with a capital of four thousand dollars. In thirty years it had grown to a corporation with a capitalization of fourteen millions and six thousand persons on its payrolls. In Cape Breton it acquired from the General Mining Association fourteen square miles of coal areas at the mouth of Sydney Harbour. It draws its ore from Bell Island, Newfoundland, which consists almost entirely of red hematite, part of which it sold to the Dominion Steel Company for a million dollars. This native company has made haste slowly, but its progress has been sure. No one can examine these two industries, or survey even what strikes the eye, without being convinced that the future of Nova Scotia is industrial. Great as are her fisheries, her forests and her orchards, their yield is even now insignificant compared with the actual output of coal and steel. Around the 'plants' at Sydney and New Glasgow ancillary and derivative manufactories are springing up. It seems impossible that they shall not grow and add immensely to the wealth of the province.

In 1896 W. S. Fielding was one of the provincial premiers called to form the Laurier cabinet. He resigned his office as provincial secretary and stood for the constituency of Shelburne and Queens. He was elected and became minister of Finance. His first budget speech, in 1897, made him famous for the significant clause according a preference to English manufactures coming into Canada. This measure was regarded in England as a sign of the growing feeling of unity among the scattered members of the Empire, and it had a result probably unique in the history of budget speeches—it produced a poem, much misunderstood by Canadian journalists, 'Our Lady of the Snows.' Fielding's successor in the assembly was a young lawyer from North Sydney, named George Murray. He has remained in control ever since, with hardly sufficient opposition, until recently, to ensure competent criticism of government measures. The Murray administration has been noted for its honesty and economy. It has also the honour of extending a broad scheme of industrial education which must greatly increase the efficiency of the working classes.

One line of Kipling's glowing and prophetic characterization of Canada ran, 'I, I am first in the battle,' and this event was soon to prove true. Two years later the Boer War broke out, and in October 1899 Canada sent her first force of a thousand men to the war. Nova Scotia did her part and soon recruited the number of men required to fill a company, which was designated 'H' in the second battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment. The captain chosen was a young graduate of Dalhousie, H. B. Stairs, a lawyer and an officer in a local volunteer regiment. He belonged to a Halifax family that had been firmly established in the city for more than a century. His grandfather, a fine type of the old-fashioned merchant, was the lifelong friend of Howe and the first opponent of Confederation. His cousin, John F. Stairs, represented the city in the Dominion House for years. His brother, Captain W. G. Stairs, was Stanley's right-hand man in the Emin Pasha expedition.

Canadians did not expect very much of the 'First Contingent,' as it was commonly called. They would be put on garrison duty, it was supposed, in order to set the regular British regiments free for the front. The First Contingent themselves entertained other views. They were jealous of their honour and they would have hotly resented any difference in treatment from that meted out to the most famous battalion in the whole Army List. There was no difference in their treatment. They were rushed to the front, they were worked hard, they made forced marches on quarter-rations, and, to their joy, they found that they were depended on. They were tested under fire over and over again, and they stood the test like veterans. Their great opportunity came in the night attack on Cronje's camp at Paardeberg.

A long-strung-out line of Canadians moved forward silently from their trenches in the darkness of February 27, 1900, to assail a position of unknown strength; Shropshires and Gordons were in support. The Canadians were at right angles to the river, and H company was at the very right of the line and next to the stream. Their orders were to advance until fired on and then to entrench. They did so. After some firing an unknown person shouted 'in an authoritative tone': 'Retire, and bring back your wounded.' The whole battalion fell back for some distance, with the exception of H company and part of G company which was next to it. The fusillade continued until dawn revealed the situation. When Brigadier Smith-Dorrien crawled into the donga which the two Canadian companies and some Royal Engineers who accompanied them had improved into a rude trench, he found it was parallel to the T trench at the end of Cronje's long main trench following the bank of the Modder. From their position, sixty measured paces from the T trench, H company was able to enfilade the main trench, and for two hours they took their revenge for what they had suffered in the night. Then the white flag was raised over Cronje's camp and the bugles sounded 'Cease firing.'

OLD WHARVES AT HALIFAX

1) MILLER'S DOCK AND MORAN'S WHARF

2) OLD WHARF ON THE HARBOUR FRONT

3) OLD WHARF AT THE FOOT OF SLATER STREET

From original etchings by Leo Hunter in the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library

For his steadfastness Captain Stairs was mentioned in dispatches and awarded the Distinguished Service Order, and on the old Lower Parade of Halifax, north of the Province Building, stands a monument to the dead of H company. It is a bronze soldier, in the uniform and equipment of the First Contingent, signalling with his rifle the approach of the enemy. The soldier balances the figure of Howe on the other side, who once said: 'A wise nation preserves its records, gathers up its muniments, decorates the tombs of its illustrious dead, repairs its great public structures and fosters national pride and love of country by perpetual references to the sacrifices and glories of the past.'

The history of that territorial division of North America known as Acadie or Nova Scotia according to the European nation that owned it covers three eventful centuries. At first the haunt of the romantic explorer, seeking riches, trading in furs, striving to transplant the feudal system to the New World, the province was bandied to and fro for a century between the soldiers and diplomats of two great European powers. At last one held tenaciously to what she had gained by the sword, and gradually broke and drove her rival from the field. Then, from the opening of the eighteenth century, the population began to expand naturally and to take possession of the soil. English occupation ensured an outline sketch of free government, which was later more clearly defined and completely filled in. Colonized effectively by two immigrations from the sister American colonies, Nova Scotia developed a strong individual life and marked local patriotism. At the same time the double pressure of war and exile strengthened the feeling of loyalty and affection to the motherland. In many ways and in many places that sentiment has shown itself, from the bloody deck of the Shannon to the snow-bound trenches of Sebastopol and the bullet-swept plains of Paardeberg. At one time of stress the province was split in two, a fission that the logic of time has proved to have been a political blunder. Although the ancient paternal system of government lasted far into the nineteenth century, the long familiarity of a law-abiding people with constitutional methods enabled a native leader of genius to work out by peaceful means the problem of a modern, democratic, self-governing state. Geographical conditions produced the industries of lumbering, fishing and seafaring; and these industries have reacted on the character of the people. When the time came for merging the province in a larger national unity, the great change was attended by friction, which all must regret; but the strife of that time has become merely a picturesque memory. In the new orientation there was loss and there was gain, but no one would now think seriously of returning to the old status. World-wide economic changes injured the province severely. One great industry, shipbuilding, was wiped out altogether by the discovery that an iron ship was better than a wooden ship and that steam was better than sails. But Nova Scotia has shown extraordinary recuperative power. The steel plants at Sydney and New Glasgow point out the way of future industrial progress. To the life of the new nation Canada, Nova Scotia brought her valuable contribution of a strong, well-defined individuality. The influence of politicians from the province in the central parliament has been out of all proportion to its mere size and population. Three have been premiers, while a fourth, the same leader who advocated taking his province out of the Union, had the honour of giving the mother country preferential treatment in her commerce with Canada. Time was needed for Nova Scotia to adjust herself to new political conditions, but that adjustment is now complete. Adjustment to new industrial conditions will follow. At the opening of the twentieth century Nova Scotia, while mindful of her distinguished and honourable past, looks forward to the part she is to play in the future of Canada with confidence and hope.

NEW BRUNSWICK: POLITICAL

HISTORY, 1867-1912

A glance at the conditions existing in New Brunswick on the eve of Confederation will serve as an introduction to the period we are here to consider. It was not until 1855 that a full measure of responsible government, as we now understand it, prevailed in the province. This was somewhat later than was the case in the sister provinces, but there was ample compensation in the fact that in New Brunswick the struggle over this burning question was attended by little of the turmoil that prevailed in other parts of Canada.

The agitation for responsible government did not begin in good earnest until 1840. From that time it was continued under the leadership of Lemuel Allan Wilmot, Charles Fisher, William J. Ritchie and their associates until 1854, when the reins of power were wrested from the grasp of the Family Compact, which had retained control for seventy years. Under the new system the members of the executive government no longer held office during pleasure or good behaviour, but only so long as they retained the confidence of a majority of the representatives of the people in the house of assembly, the criterion of their fitness for office being their performances as advisers of the lieutenant-governor and originators of sound measures for the betterment of the country. Many of the men who were destined to play an important part in the promotion of Confederation were trained for leadership in the struggle for responsible government.

The decade that preceded Confederation was one in which New Brunswick made rapid progress in wealth and population. Immigration reached its largest proportions in the forties and then began to decline, but new settlements continued to spring up in various parts of the province. Irish navvies came to work upon the railways that were in course of construction, and many of them became settlers. More than seventy per cent of the total immigration to New Brunswick came from Ireland.

To stimulate the settlement of the waste places the government passed a Labour Act, under which settlers were to pay for the lands on which they settled by labour on the roads in and near their settlements. Most of the settlements from 1850 to 1872—whether of immigrants or natives of the province—were made under the provisions of the Labour Act. A large number of the settlements were on the upper St John in the counties of Victoria and Carleton. Several tracts were laid out for companies of settlers organized upon a religious basis. An association of Scottish Presbyterians, under the leadership of the Rev. Charles Gordon Glass, settled Glassville; a Baptist association, led by the Rev. Charles Knowles, settled Knowlesville; and a Roman Catholic association, of which the Right Rev. John Sweeney, Bishop of St John, was patron, settled Johnville. All these settlements are in the county of Carleton.[1] This fine county is a highly developed farming region, sometimes termed the Garden of New Brunswick.

In recent years the men born in the province have continued to establish new settlements and to consolidate and expand those already existing. In this way the valley of the Tobique and many other places in the province have been occupied by an almost purely native population, as fine a body of people as any part of the Dominion can boast of.

Another very important native expansion is that of the Acadians. In Madawaska the first settlements on the banks of the St John have been extended to the back lands. In Westmorland the Acadians have greatly extended their early settlements, especially in the vicinity of Cape Pelee. In Kent County they have filled up the back lands and made new settlements along the coast. They have formed large communities at Rogersville and other places in the county of Northumberland. In the county of Gloucester, which is almost entirely French, their expansion has been even more remarkable, for in the census of 1911 this county stands third in the number of its inhabitants, whereas at the time of Confederation it stood ninth. In some parts of Eastern and Northern New Brunswick the Acadians are gradually superseding the English-speaking people, occupying the ungranted lots in the English settlements and taking up the farms of those who remove to the Canadian West. This process is going on extensively in the counties of Gloucester, Kent, Restigouche and Madawaska.

In 1872 the provincial government, under the influence of the lessening immigration and the increasing exodus, passed a Free Grants Act whereby lands were offered free of cost to companies of actual settlers. Under this act some sixty settlements have been established. With the exception of the Danish and Scottish colonies in Victoria County, these new settlements have been effected almost entirely by native-born people. This was not the intention of the promoters of the Free Grants Act, which was passed with the view of inducing a large number of immigrants from the United Kingdom to settle in New Brunswick. Unfortunately for the success of the experiment, the lure of Western Canada has prevailed, not only with the English immigrant, but with the home-born. Experience has shown that those best fitted for pioneer work in a forest country are the native-born—men who can wield an axe and understand the conditions of life that exist. The provincial government is now wisely attempting to place well-to-do British immigrants on cultivated farms.

The ungranted crown lands are administered by the provincial Crown Lands department. They comprise about seven million acres, or one-quarter of the entire area of the province. The crown lands are chiefly in the central and northern parts of New Brunswick. They are now being explored and examined with the view of selecting suitable tracts for settlement. The policy of concentrating settlers on good farming lands at different points instead of permitting them to locate indiscriminately is having a beneficial effect. It enables the settlers to assist one another and minimizes the danger from forest fires.

The railway from Campbellton to St Leonards, completed in 1910, has opened for settlement some of the very best farming land in the province. The National Transcontinental Railway from Moncton to the Quebec border also passes through a tract of country suitable for farming, and much of it is unsettled.

|

Most of the early settlements in Carleton County have become towns and villages, and the word 'settlement' in many instances has been altered to 'ville.' In addition to Glassville, Knowlesville and Johnville, mentioned above, we find in this county: Chapmanville, Gordonville, Jacksonville, Bellville, Somerville, Speerville, Grenville, Florenceville, Centreville, Waterville, Lakeville, Ferryville, etc. |

At the period when Confederation became an issue the government of New Brunswick was engrossed in railway construction. It is claimed that this comparatively small province has more miles of railway in proportion to its population than any other country in the world. It certainly was early in the field. Ten years after the first railway was in operation in England there was an agitation for the construction of a railway in New Brunswick. The agitation had its birth at a meeting held in St Andrews, on October 5, 1835, to discuss the construction of a railway to Quebec.[1] The road was surveyed in 1836 by Captain Yule of the Royal Engineers, who estimated the cost at £10,000,000 sterling. This evidently frightened the promoters, and nothing further was done until 1850. In that year a great international railway convention was held in Portland, Maine. The oratorical honours of the convention were carried off by a son of New Brunswick, the Hon. L. A. Wilmot, who in an eloquent and memorable address referred to his native province as a country hardly known beyond its borders, but whose people would not rest until they had by railway construction brought themselves into connection with the outside world. As the outcome of its early ambition New Brunswick has to-day two thousand miles of railway.

After many vicissitudes the St Andrews and Quebec Railway was pushed as far north as Canterbury—sixty-four miles—in 1858, and to its temporary terminus at Richmond—twenty-three miles farther—in 1862. Connection was made with St Stephen in 1866 and with Woodstock in 1868.

Appeals had meanwhile been made to the mother country for assistance in the construction of a railway, through New Brunswick, from Halifax to Quebec. Captain Pipon and Lieutenant Henderson of the Royal Engineers were appointed by William Ewart Gladstone, secretary of state for the Colonies, to survey the route, but the home government was not prepared to give any definite assurance of assistance. A correspondence ensued—and it became voluminous in the course of years—but the project remained in abeyance until the time of Confederation.

New Brunswick devoted its energies to building a railway from St John to Shediac on the Straits of Northumberland. The turning of the first sod of the railway on September 14, 1853, by Lady Head, was an event long remembered in the province. Railways and Confederation were even at this early period inseparably associated in the minds of thinking people. The address presented to Sir Edmund W. Head, lieutenant-governor of the province, by the directors of the railway company contained the following passage: 'Our sister colonies and ourselves, though under the same flag and enjoying the same free institutions, are comparatively strangers to each other, our interests disunited, our feelings estranged, our objects divided. From this work, from this time, a more intimate union, a more lasting intercourse must arise and the British Provinces become a powerful and united portion of the British Empire.' His Excellency in his reply cordially endorsed this sentiment, and expressed the hope that the people of Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island would speedily realize that their interests were identical and be inspired with a unity of purpose and of action such as had not yet existed. He added: 'If these sentiments prevail, I have no fear for the future greatness of British North America.' The triumphal procession through the streets of St John on this occasion was a remarkable demonstration for a comparatively small community. In it there marched ten hundred and ninety shipwrights, representing seventeen shipyards. At least a dozen other trades were splendidly represented. Firemen, millmen, patriotic societies, public officials, bands, etc., helped to form a procession two miles in length which occupied a full hour in passing a given point. The presence of more than a thousand stalwart shipwrights, representatives of seventeen shipyards, was a feature which it would be impossible to reproduce in a trades procession in Canada to-day.

The new railway was called the European and North American Railway. Its construction was part of a plan to connect the great cities of the United States with an eastern port in the Atlantic provinces in order to shorten the voyage to Europe. The steamships of those days made slow passages in comparison with the modern greyhounds of the Atlantic. The European and North American Railway was not finished until 1860. Later it was continued from St John westward, connecting with Fredericton and McAdam in 1869. On October 19, 1871, the 'last spike,' making connection with the United States railway system, was driven at Vanceboro. The event was deemed of international importance and the ceremony was honoured by the attendance of General Grant, who was then president of the United States, and Hannibal Hamlin, the vice-president. The short line to Montreal was not opened for traffic by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company until 1889.

During the years that preceded Confederation the principal policy of the government of New Brunswick was always a railway policy, and it was largely the desire for the speedy construction of an intercolonial railway that led the Atlantic provinces to consider the question of federal union. Meanwhile the railroad promoter was abroad in the land. At every session of the legislature charters were applied for and were granted. Some of the roads were built, but fortunately for the finances of the province a good many projects did not materialize. At one time the government sought relief from its tormentors by the introduction of a bill providing $10,000 a mile for the construction of seven different lines of railway. As the proposed lines extended to all parts of the province few members of the house dared to oppose the bill. The act was facetiously called the 'Lobster Act.' The railways proposed penetrated every county save three, and, as a consequence, the legislature found itself in the grasp of the claws of the lobster. Several of the railways were built under the provisions of this act and others have since been constructed under less liberal subsidy acts.

In 1861 delegates from Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia went to England to press upon the imperial authorities the importance of aiding in the construction of an intercolonial railway. While they were in England news of the Trent affair reached that country. Messrs Mason and Slidell, two representatives of the Southern Confederacy, were forcibly taken from on board the British mail-steamer Trent by the captain of a United States warship. This incident seemed likely to lead to war between Great Britain and the United States, and there was intense excitement both in England and America. British soldiers were sent in haste to Canada. Winter was at hand and most of the troops had to proceed through New Brunswick overland to Quebec. The winter was cold and stormy, rendering their progress somewhat arduous and difficult. The troops were among the best in the British army—Grenadier Guards, Scots Fusiliers, London Rifles, Royal Artillery and Transport Corps. They were warmly clad and were forwarded to their destination in comfortable sleds provided by the farmers of the country. Every village and town along the route thrilled with excitement as day after day the bugle notes were heard on the frosty air announcing the approach of a procession of from fifty to one hundred sleds, filled with soldiers of the imperial army. They made the journey with little discomfort, many of them wearing sheepskin coats and fur caps.[2] The difficulty and delay attending such a mode of transportation served as an object-lesson to British statesmen on both sides of the Atlantic, and led the home government to consider more seriously the construction of an intercolonial railway for military reasons. But there was to be further delay. Canada hesitated to embark on so costly an undertaking, and the English government continued to temporize in the matter.

|

See 'National Highways Overland' in section V. |

|

One or two transport ships were able to land at Rimouski, on the lower St Lawrence, but the greater number of the troops were sent to Quebec by way of the St John River. The following corps proceeded from St John via Fredericton to Rivière du Loup, en route to Quebec, between January 9 and March 15:

In addition to the above, about 1250 officers and men of the 62nd Regiment and of the Royal Artillery were landed at St Andrews with some Armstrong guns, ammunition and stores. These were sent to Woodstock by the railway and thence in sleds to Quebec. The troops were fortunate in escaping the intense rigour of February 8 of the previous winter, a day of unparalleled severity, still spoken of in New Brunswick as 'The Cold Friday,' but they encountered cold weather and snow-storms. |

The Atlantic provinces now began to consider the idea of a Maritime union, and their proceedings were watched with interest by the statesmen of Canada. It seemed but natural that colonies of similar origin, owning the same allegiance and with many interests in common, should dream of political union.

A leading New Brunswick historian makes the statement that the British government was to be blamed for doing little or nothing to promote the union of the colonies until compelled to move in the matter by the logic of events. But it is questionable whether Great Britain would have been wise in bringing any pressure to bear upon the colonies. Anything in the nature of compulsion would have been resented. In Nova Scotia the people were committed to the details of the scheme by their own leaders before the question had been submitted to popular approval. The dissatisfaction and turmoil that followed there are a very good indication of what might have occurred everywhere if the mother country had attempted to force Confederation as an issue in British America. The fact, however, remains that the colonial office did not at the outset display much enthusiasm over the proposed union.

In New Brunswick the people were not of one mind as to the desirability of Confederation. In every community there are persons who see in any new movement a host of difficulties. It is their nature to cling to old systems and to look for precedents for any step of a political character, forgetting that precedents must be created some time or another, and that the century in which they live has as good a right to create a precedent as any of its predecessors. We need not, however, doubt the honesty or loyalty of those who were the anti-Confederates, or consider that they were opposed to British connection or to the building up of the Empire.

The discussion of the union of the provinces had been heard at intervals during the American Civil War, and most people who gave any attention to the subject approved of it. It was when the matter came up in a practical form that opposition was manifested.

At the time when the Atlantic provinces began to discuss Maritime union the people of Canada and the people of New Brunswick, owing to the lack of the means of intercourse, were almost unknown to each other. In fact, the people of New Brunswick knew much more of their United States neighbours than they did of their fellow-subjects in Canada.

The New Brunswick legislature in 1864 agreed to negotiate with Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island as to the best means of effecting a Maritime union. A convention was held at Charlottetown in September. The New Brunswick delegates were Samuel L. Tilley, W. H. Steeves, J. M. Johnson, E. B. Chandler and John H. Gray. The first three were members of the government, while Chandler and Gray were members of the opposition. A delegation of the leading statesmen of Canada sought admission to this convention to discuss with the Maritime Province men the question of a federation of all the British provinces in North America. The story of the conference at Charlottetown and of the subsequent conference at Quebec is told elsewhere in these volumes.[1] At the Quebec conference the New Brunswick delegates were the same as at Charlottetown, with the addition of the Hon. Charles Fisher and the Hon. Peter Mitchell.

No strong feeling was at first evinced in New Brunswick against Confederation, but when the details were submitted to the people their interest grew amazingly until the question was debated in every village store and blacksmith's shop throughout the country. Many honest-minded men opposed Confederation because they feared it would alter the relations existing with the mother country. 'Let well enough alone,' was the cry. Others there were who felt that they were not sufficiently informed upon the question to vote in its favour. Professional politicians embraced the opportunity to advance their own ends and helped in fomenting the opposition. There was, too, an element, not large but of some influence, that regarded political union with the United States as the destiny of New Brunswick, and opposed union with Canada as likely to defeat their wishes.

It had been agreed at the Quebec conference that the first trial of the Confederation scheme should be made in the Province of New Brunswick, the legislature of which was about to expire. Accordingly the question was submitted to the people and the elections were held in March 1865. The time for consideration was short, and the votes of the electors were cast in accordance with prejudices and misconceptions which the advocates of the measure had not sufficient opportunity to dispel. Increased taxation was perhaps the greatest deterrent.

The result of the election was that the friends of Confederation went down to the most overwhelming defeat that till then had been suffered by any political party in New Brunswick. In the new house of assembly their supporters numbered only six in a house of forty-one members. Tilley and all his colleagues in the government but one shared in the defeat. The entire block of counties on the River St John, with the exception of Carleton, proved hostile to Confederation. The rest of the province was equally emphatic in its condemnation, only the outlying counties of Restigouche and Albert returning members who favoured the scheme. Not only this, but in many of the counties the majorities were so large as to make it appear hopeless to expect any change in the general verdict.

And yet it was only fifteen months later when the anti-Confederates were as badly beaten as the advocates of Confederation had been in the previous election. The effecting of such a revulsion of political sentiment in so short a time was undoubtedly the greatest personal triumph of Sir Leonard Tilley's career. Immediately after the defeat of his party in March 1865 he began a campaign for the purpose of educating the people on the merits of the question. Being free from official duty and having plenty of time on his hands, he was able to devote himself to the task of explaining the advantages of the proposed union throughout the province, and during 1865 and the early part of the year following he spoke in almost every county. He was then in the prime of manhood, his appearance on the platform attractive, his manner dignified and impressive and his voice clear and ringing. As he spoke his evident sincerity, the logic of his reasoning and his enthusiasm were so convincing that the current of public opinion soon began to set in favour of Confederation. It is quite safe to assert that Confederation would not have been carried in New Brunswick at so early a day had it not been for Tilley's personal efforts. As leader of the government that had approved the Quebec scheme he was very properly regarded as the chief of his party, and in his native province his name will go down to future generations identified with this great achievement of colonial statesmanship.

While the Dominion was struggling to its birth, influences from without combined to render their unwilling aid. The United States government gave the provinces notice of its intention to terminate the reciprocity treaty. It was hoped by some that for the sake of free trade the Maritime Provinces would ere long consent to political union with their neighbours to the south. Congress even went so far as to pass a bill providing for the admission of the provinces on the most favourable terms as states of the American Union. This only served to draw the provinces closer together. The threatened Fenian invasion had a like effect. It was noticed that all who were disposed to talk lightly of British connection seemed to have got into the anti-Confederate camp. This helped to strengthen the hands of the friends of Confederation.

In 1861 Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon, a son of the Earl of Aberdeen, had succeeded Manners-Sutton as lieutenant-governor. Gordon was at first a strong advocate of the union of the Maritime Provinces. After his advisers had decided at the Charlottetown conference in favour of the larger union of all the British provinces, he seems to have hesitated as to his course. He repaired to England, and after consultation with the home authorities returned convinced of the propriety of doing all in his power to promote the general union of the provinces.