* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Book of Talbot

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Violet Mary Clifton (1883-1961)

Date first posted: June 29, 2025

Date last updated: June 29, 2025

Faded Page eBook #20250611

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Lending Library.

THE BOOK OF TALBOT

★ ★ ★

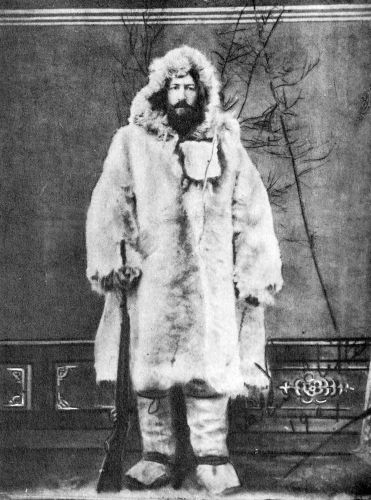

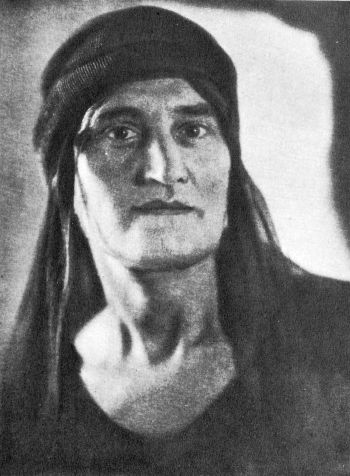

TALBOT CLIFTON

IN SIBERIA, 1901

THE

BOOK OF TALBOT

BY

VIOLET CLIFTON

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY

NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1933, BY

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY, INC.

All rights reserved, including

the right to reproduce this book

or portions thereof in any form.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE POLYGRAPHIC COMPANY OF AMERICA, NEW YORK

TO

GOD

FOR TALBOT

★ ★ ★

CONTENTS

★ ★ ★

| I. | THE LITTLE BOOK OF ALASKA | 3 |

| II. | THE BOOK OF THE BARREN LANDS | 37 |

| III. | THE BURDEN OF AFRICA | 143 |

| IV. | THE BOOK OF BOREAS | 155 |

| V. | BURDEN OF TIBET | 257 |

| RHYTHM OF BURMA | 260 | |

| VI. | THE BOOK OF BARUCHIAL | 265 |

| VII. | THE LAST JOURNEY | 393 |

| NOTES | 428 |

ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

★ ★ ★

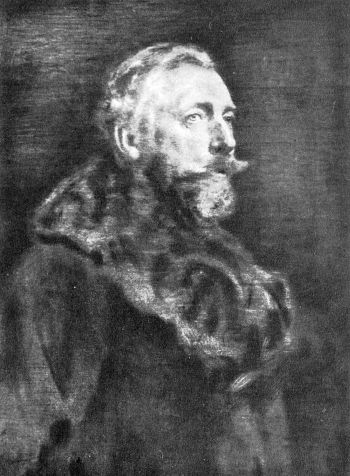

| TALBOT CLIFTON | |

| In Siberia, 1901 | |

| ALLIANI AND TALBOT | |

| In Yakutsk, 1901 | |

| TALBOT CLIFTON OF LYTHAM | |

| After a painting at Lytham Hall, by F. Copnall, 1908 | |

| VIOLET CLIFTON | |

| Widow, 1929 | |

★ ★ ★

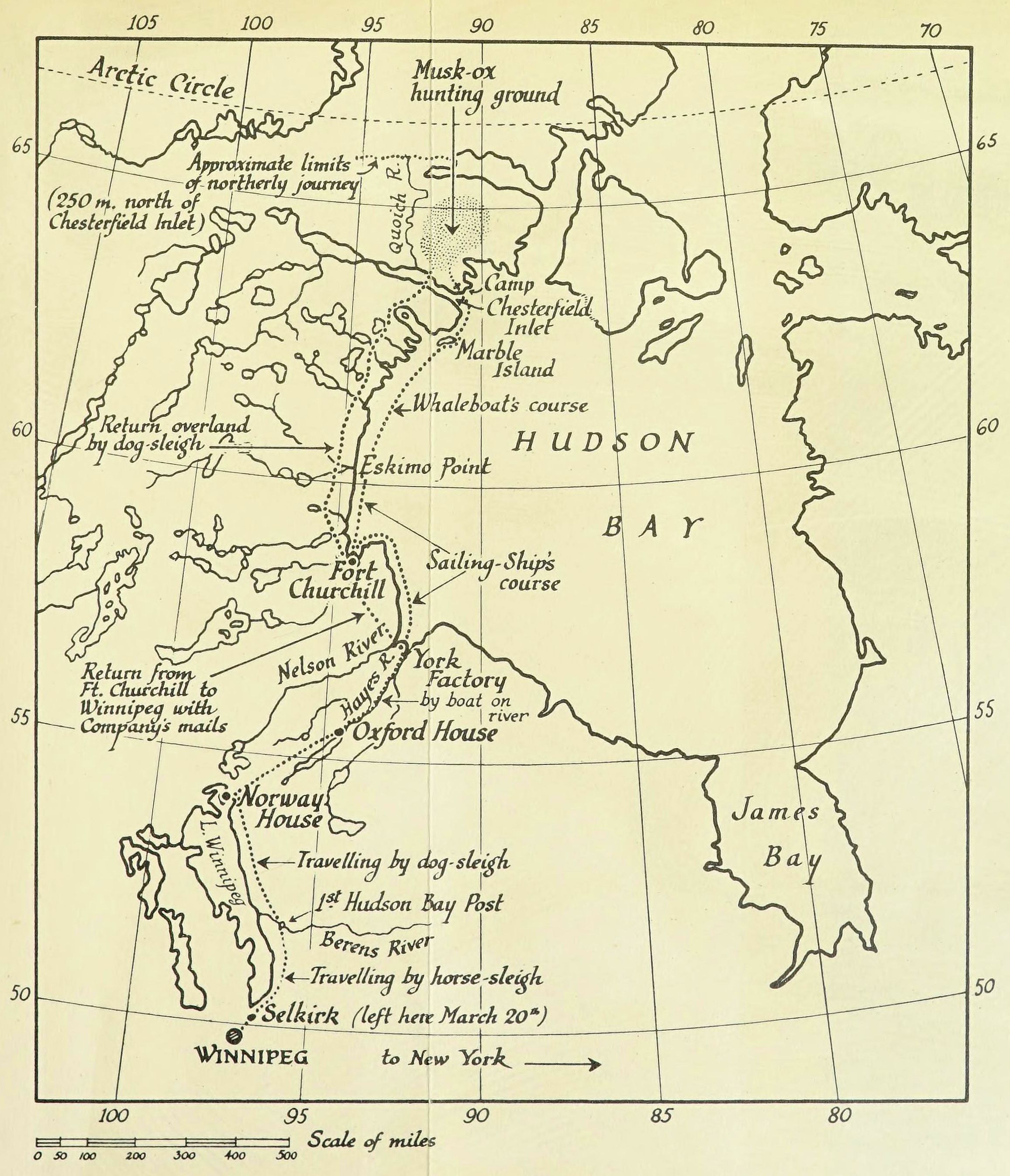

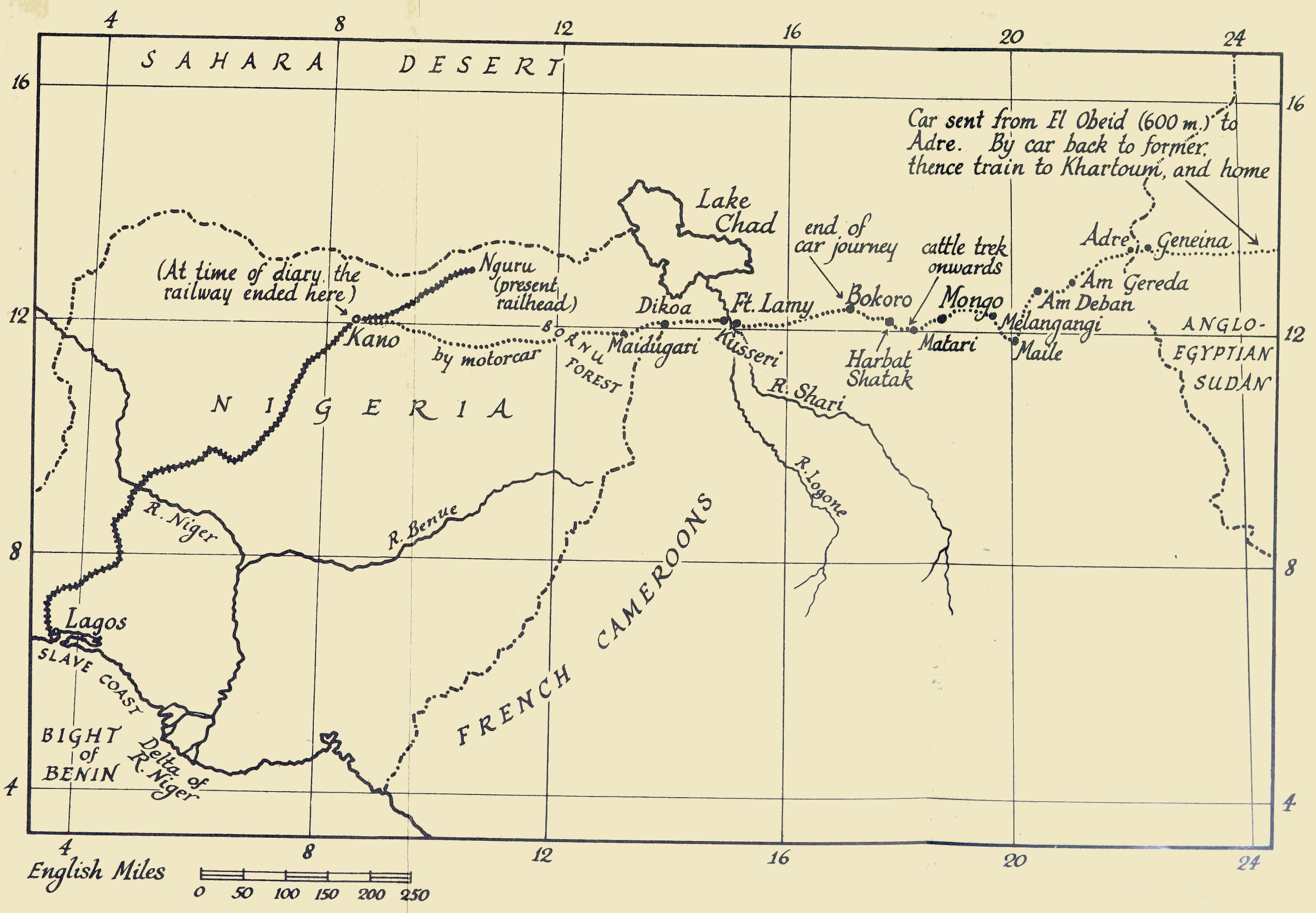

| A SKETCH MAP OF HUDSON BAY | |

| To illustrate The Book of the Barren Lands | |

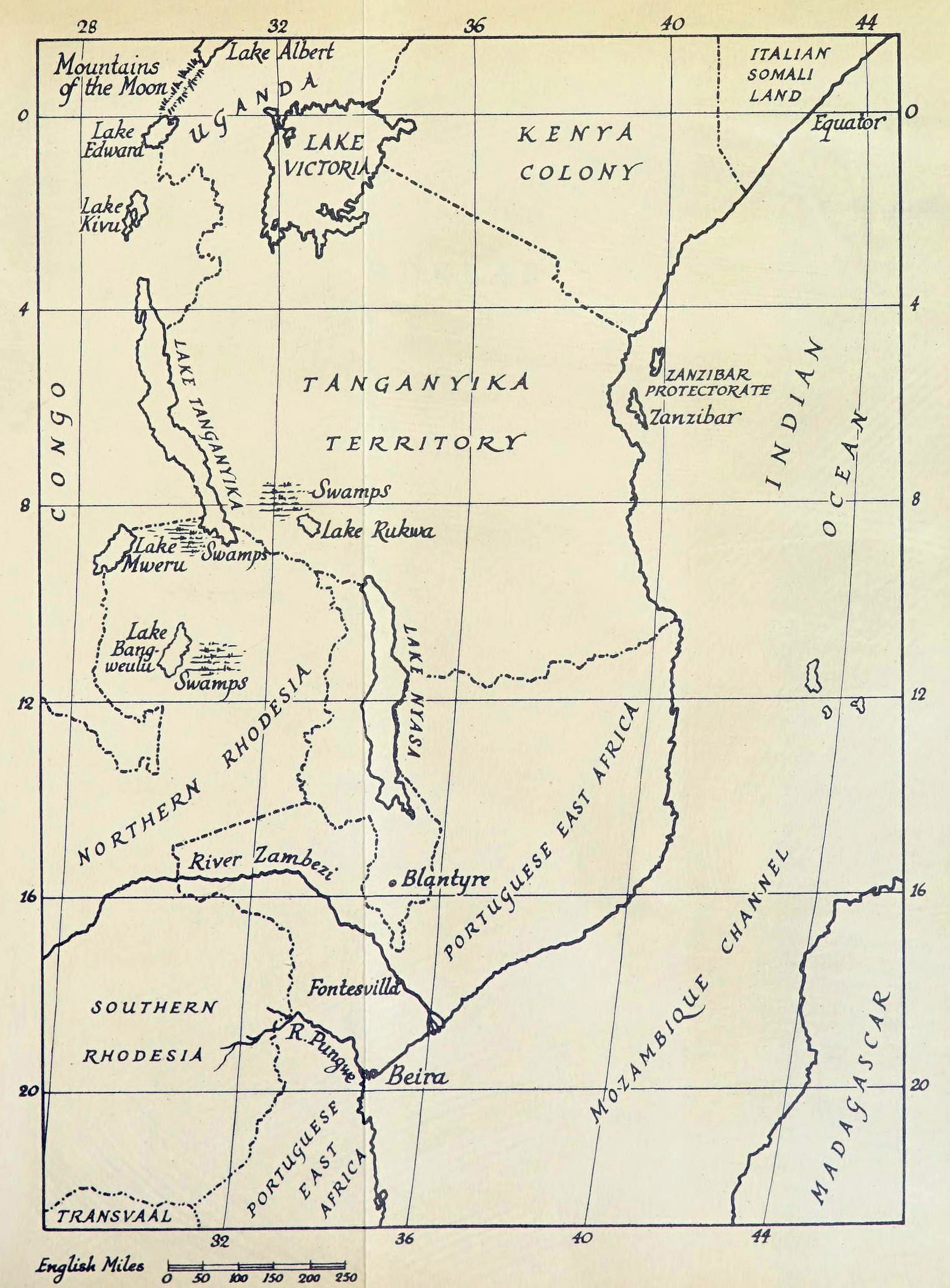

| A SKETCH MAP | |

| To illustrate The Burden of Africa | |

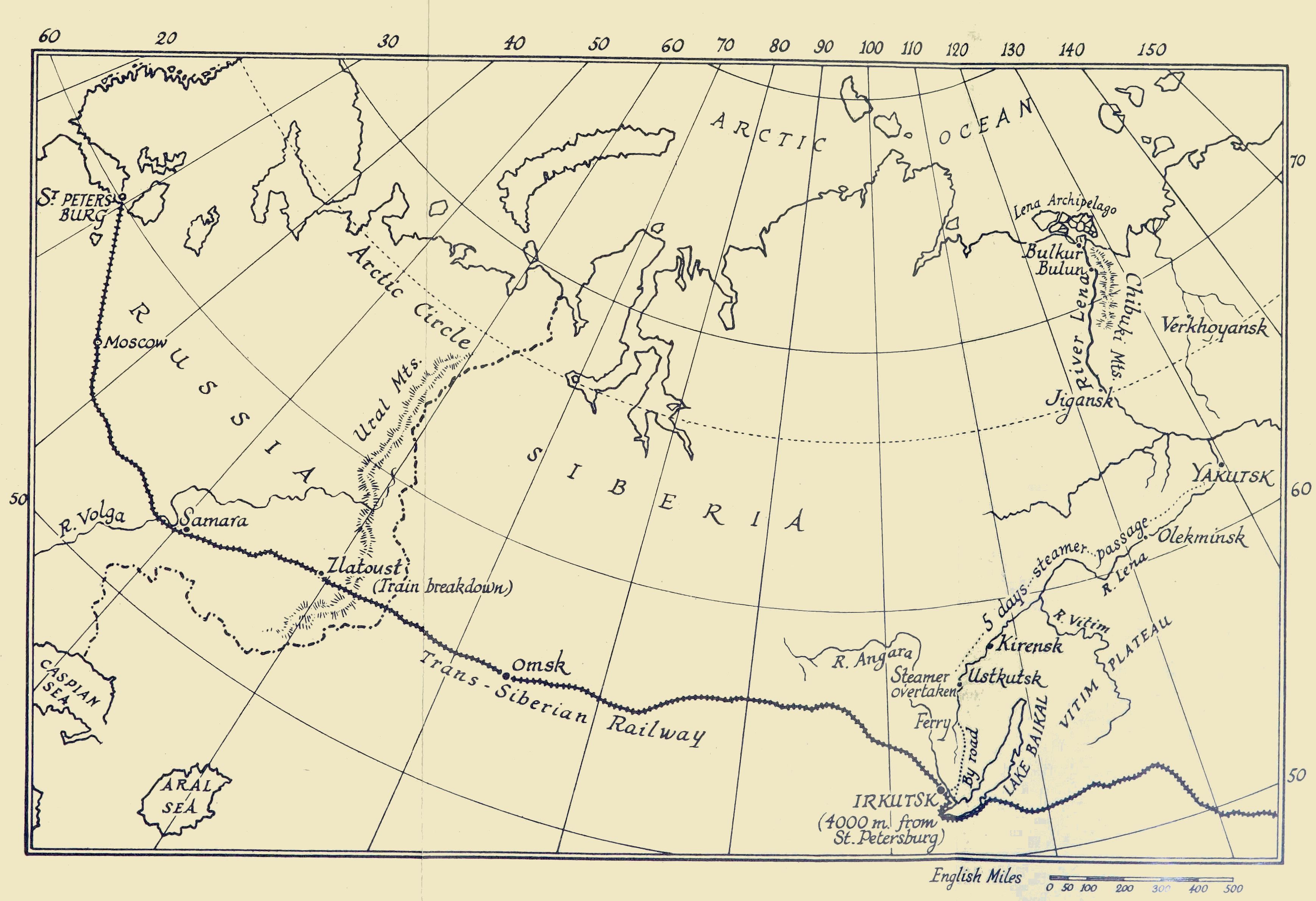

| A SKETCH MAP OF SIBERIA | |

| To illustrate The Book of Boreas | |

| A SKETCH MAP | |

| To illustrate the African journey in | |

| The Book of Baruchial | |

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

Begin at the beginning.

But indeed when is the beginning?

Is it when soul and unborn body mysteriously meet in a womb?

Then the soul is launched into time: ‘Such and such a treasure from out of matter, and from out of time this venture shall bring Me.’ That may be the expectation of God.

The beauty of God to be increased, somehow, by the adventures of this being, of this thing welded of soul and of body. The body fashioned by time, and by race, and by generation following generation; the soul emerging after its age-long enfoldment in the Thought, in the Beauty.

Begin at the beginning.

Talbot Clifton was born in 1868, and he suckled his mother so fiercely that she had a wound in her breast. ‘That’, said Nurse Patch from Devonshire, ‘that was the start of the discord between them.’

He went to Eton and to Cambridge and then, for eighty days he was on the sea, sailing to Australia. The schooner was nearly overcome by gales.

Talbot learned the signs that are in the clouds: promise of fair, and threat of foul weather.

Before he was twenty years old he had been twice round the world, choosing adventure rather than the enjoyment of the ancient vast estates in the Fylde, which wealth had come to him when his grandfather died. Talbot was then but sixteen years of age; his father had died when he was a child.

After that there was a time in Wyoming when he learned to throw the lasso, and learned the signs that are in the eyes and in the ears of a horse. Bucking horses, and men whose hands went quickly to their hip pockets, these were his teachers. He nearly forfeited his life because, serving his turn as cook, he forgot to Hunting in Mexico clean the roasted birds and set them down upon the table, stinking under the pie-crust.

Then came the year 1894.

With a revel begins the diary of that year, with a revel the diary ends.

After leaving Liverpool, he had written that he was pleased to go, but that it was a curious feeling to leave England for five or six years.

At Los Angeles, for three months he played polo, rode steeplechases and drove a coach; the first man there to do so for pleasure.

Then with a boy, Santiago, with ten mules, one horse, and with provisions for four months, he started for Durango in Mexico.

The journey was rough; there was lack of water; there was vermin; the mules bolted and were caught. “These mountains have never been shot.” Bear and deer were the quarry, but soon, because he had an abscess on his chest, the hunter was bound to lie in a ranch and to send the boy Santiago to hunt for food. “Did nothing all day. Lay on my back. Learnt Spanish, sketched, and Shakespeare.”

That went on for days, till, maddened by pain, he wrote: “I can do nothing to relieve my chest. I can’t move, damn it, and chest is worse than ever. Wish it would get right into my heart and kill me.”

Mario, owner of the ranch, went in and out. Sometimes he was beneficent, procuring milk and ointment; at another time he took all Talbot’s whisky and vomited in his room.

Then Talbot, suffering still, rode on, and he met a man who had been bitten by a snake; he had been bitten in the head and it had swelled up; Talbot could pity him. So he lent him a mule and the three men rode together. “I cannot sleep at night so I learn Spanish and the speech of Antony.” By perilous paths in the mountains by moonlight, and by lovelier dawn, so the men gained Durango.

“Very ill, wrote thirty pages of my novel.” And again: “Chest aching. Sat up all night writing poems like a demon a-blood-curdling; these relieve my mind.”

Later on, Talbot stayed in Mexico City; was inebriated by Faith of his forefathers the life, and painted picture after picture as though the sun and the colour so demanded. At the end of July he was back in San Francisco. “July 29. Rode Guadaloupe three days ago. Guadaloupe broke another man’s collar-bone. One death, two collar-bones and several more casualties, but will ride him at the races in Monterey. Drove to the park to the Heads in my drag. It went beautifully and everyone seems pleased with it. Had a charming day.” He went to Monterey. “Magnificent trees but gloomy. Wandered about, then went to bed.” And next day: “Dismal outline of trees blacker than ivory-black, yet not black.”

Some days later August had come, and he wrote: “Went in the evening to see a water-party supposed to be like Venice, but in this quarter of the globe like hell. Female got us drunk. Don’t know what I am coming to.”

★ ★ ★

These words were the last to be written in that year’s broken diary. But it is known that in the autumn Talbot joined the Church for which his forefathers had suffered. It may be that the low aims and the self-seeking of the men about him drove him sheer and sudden to the God self-sacrificed. “It was like finding an orchid on a dung heap.” That is what he said of a Mass heard in a low part of the city. He was at variance with himself; he was cast down by hollow-hearted women. So he turned to where was enshrined that Lady who is clean as the scent of apple-blossom, as the scent of the bean-flower. Virgin and Mother, she, Mary, could make good to him the lack of mothering, which lack had frozen[1] his boyhood.

★ ★ ★

The following year Talbot sailed from England to return to California; and it was in the summer that he reached Montreal.

The day after his arrival: ‘Come and hunt with us in Quebec,’ some Canadians said. Talbot was ready to start, but he fell ill. After delaying for a day or two, the hunters went off whilst miserably he remained behind. In the same hotel with himself was staying a company of actors and actresses whose looks and performances were equally pitiable. One evening, feeling less ill, Talbot went downstairs to talk to them. He took with him Bob, his dog—then remembered that upstairs he had left his handkerchief. “Go and get handkerchief,” he ordered, and Bob scampered off, for that was a service sometimes asked of him. From the half-open drawer he took one in his mouth and reappeared with it in the hall below. The leading actress thought this delightful; and without sense, pushing past Talbot, she swept down upon the dog which bit her twice in the leg.

“There was the deuce to pay, and the doctor,” who feared hydrophobia. The poor lady left the next morning, “after having cried all night at the cruel marks the bite would leave on her little leg. Pity, that she was not bitten in the face instead, as that might have taken off an inch of rouge.”

But Talbot fell ill again and the doctor visited him twice a day: “Although his visits are expensive it is a great relief to see anyone.” Loneliness in a hotel was more bitter than in wild places, where would be at least a brook or a tree for company, or, failing these, the wind to hear and the clouds to watch. From this room no sky was visible and man had tampered with the very air. What wonder was it that such a place should be—to Talbot—terrible. He suffered a double distress, for added to his own dislike of towns there was in his nature the long-inherited usage of the country. For some eight hundred years, from their home windows, the Cliftons had looked out upon their lands, as far as eye could reach. The houses in which they were reared, century after century, were set about with lawns and woods, so that trees had served those Cliftons for neighbours—trees always, never human beings.

The Montreal newspapers were so puritanical that Talbot ‘The grandest bargain ever made’ flung them away, owning the while that those of San Francisco were not puritanical enough. On Sunday Talbot went to Mass and Benediction, then, thankful to leave Montreal, he travelled on to San Francisco.

In 1894, Talbot had been the summer hero of San Francisco, and that partly because he had been the owner and the rider of the horse ‘Guadaloupe’. Before he bought the splendid chestnut it had been gelded that it might become tamer, but it was still untamed. What price Talbot paid for the creature is not known. ‘It’s the grandest bargain ever made,’ was all his friend ‘White-Hat’ McCarty would say, reflectively boring more holes in his white hat.

At the Country Club at Del Monte Talbot would take his seat for dinner at the table of Dick Tobin who rode better than he: Tobin who, with Hobart and Baron, was a most expert gentleman rider. A newspaper of the day recorded that as Clifton sat down there would be a great hush and people would nudge each other whispering: ‘That’s the man who’s going to ride Guadaloupe.’

‘Every morning at eleven o’clock Clifton held a reception at the stables where young ladies had thrills as they watched Guadaloupe endeavouring to bite the tips of his owner’s fingers, whilst Clifton would quote McCarty’s opinion that ‘he’s a cannibal but he’s a winner’.’

On the Bay District Track that year was held the first race ridden by gentlemen, and the newspapers were filled with news of ‘gentlemen riders climbing into pigskin, riding for glory only’; ‘aristocrats who ride in the first gentleman’s steeplechase held in California’. ‘One rider represented San Francisco’s noble Four Hundred, another Canada’s untallied élite. Talbot Clifton on Guadaloupe upheld the chivalry of England.’

Riding so for England.

‘Twenty to one against you,’ shouted a bookmaker, as Talbot entered the betting ring, clothed in ‘all the glory of the Clifton The horse Guadaloupe and the Press yellow-and-brown racing colours’.

‘Twenty to one against you!’ again yelled the man, leaning out of his box.

Talbot parted with one of his twenty-dollar pieces and put the ticket in his pocket.

‘Bet you ten to one you don’t show,’ cried the man in the next box.

The English gentleman yielded up another gold piece. Then the crowd lifted him overhead and carried him from box to box, at each of which he left a twenty-dollar piece, receiving a ticket in return. The laughing crowd carried him to the Club House balcony and cheered him three times.

Guadaloupe came in third, but, always treacherous, veered round in front of the judge’s stand and threw Talbot over his head. Talbot, though bruised, held on to the reins and remounted, and again the great crowd, pleased at his nerve, cheered him.

‘Training down amid the aristocratic seclusions afforded by the track of the Burlingame Club in San Mateo County, Talbot Clifton, the day before he negotiated for Guadaloupe, bought a filly out of a selling race which he sought to pay for with a draft on Coutts’ of London. Norman Brough, clerk of the scales, begged for more negotiable local currency, and then learned that Clifton was a blood of the first water. With a well-bred sigh of regret, Clifton called a coloured boy who was loafing around the scales.

‘ “Boy,” he said, “will you please go down to my room at the Palace Hotel? Here’s the key. When you enter my room you will find two silver boxes. The one on the right has cigarettes in it. Leave it alone. The other contains about nine hundred pounds in English notes and American gold. Bring me about—how much did you say I’d bid for that filly, Mr. Brough? Seven hundred dollars, eh? Well, my boy, bring me about seven hundred dollars.”

‘Then Brough interrupted. ‘My dear sir,’ he said, ‘don’t you know that coloured boys are only human? Better arrange with the owner and bring him down to that silver box.’ ’

Talbot nearly won a great race for which he entered Guadaloupe. He was leading, but the animal threw him at the water Guadaloupe and the son of Stamboul jump, and, though no part of him was broken, Talbot was stunned and had to go back. Later, in Monterey at the hurdle race, Guadaloupe did break Talbot.

‘He’s a vicious brute. Don’t ride him,’ said his friends.

‘He jumps out of control,’ added Tobin.

All the same Talbot rode.

So that day at Monterey they cleared a stone wall, but Guadaloupe, headstrong, crossed another horse at the water jump and fell, throwing Talbot. Weeks of pain followed, because the doctor who first attended him was an estate agent whose spare time was given to doctoring and surgery. This man set his shoulder blade and dressed his lacerated tongue, but failed to notice that his collar-bone was broken. Another doctor was called in by Talbot’s friends and, with agony, the first operation was completed. Next day in the sick man’s room was furious contention, the first doctor storming at the second one, and Talbot and his friends in chorus cursing the fool. The villain attached Talbot’s buggy and horses, which attachment was released on a bond. A big law suit followed.

When that year Talbot was leaving San Francisco a man came to him wishing to buy Guadaloupe: “I’d prefer not to sell him,” said Talbot, “I’d rather shoot him. He’s not fit for anyone to ride.” The man pressed him; Talbot put the price high to stave him off.

“A horse that takes the bit in his teeth and bolts deliberately through temper (and not through fear) is useless to a man. Nothing will stop Guadaloupe when he gets frenzied, and he will kill himself some day.” Still the man insisted and Talbot, getting angry at his obstinacy, let him have the horse. Within a week Guadaloupe had killed his new owner.

On the day before leaving, Talbot had a wild drive which a local newspaper reported in this manner:

‘White-Hat McCarty and Talbot Clifton, in a buggy behind a runaway horse going at one-minute gait, was what people on Golden Gate Avenue saw Thursday afternoon. The horse was a son of Stamboul, and it was the first time he had ever been on any thoroughfare more lively than a stock farm. The car bells frightened him and he bolted.

‘For several weeks Lord Clifton had been anxious to possess a White-Hat McCarty drives son of Stamboul, and during a recent trip to Southern California he found what he was seeking—a genuine son of the great horse. After purchasing the horse Clifton was anxious to try him out on the Park speed track. He knew that his animal was a wild, strong horse, but Clifton boasts that he has never yet seen the horse he would not drive. The son of Stamboul was therefore put aboard a car and sent to this city.

‘HEARD THE CAR BELL RING

‘Thursday afternoon Clifton and McCarty were preparing to drive out to the race track. Nothing would suit the Lord but to have his new horse put in harness. McCarty protested, but in vain. Lord Clifton would drive, and McCarty could take the cars if he preferred; but McCarty would not allow it to be said that he was less plucky than Lord Clifton, and both men were seated in the buggy when it left the stable.

‘McCarty handled the reins and managed to keep the fiery horse in check till a car crossed the Avenue with its bell ringing loudly. That was something too metropolitan for the son of Stamboul from the country, and it frightened him. He ran off at a gait never before seen on Golden Gate Avenue, and McCarty, by heroic exertions, kept him straight till Baker Street was reached. On one side of Baker Street is a board fence, and McCarty managed to head the animal straight for it.

‘On flew the buggy, and it did not stop until several feet of the fence was torn away and the buggy badly scraped. The horse was trembling in every limb and McCarty concluded he had had enough of Stamboul’s son for one afternoon.

‘But not so Lord Clifton. He insisted upon driving his new horse to the track. The buggy was squared up and the two men made the remainder of the trip in safety.

‘THE WILDEST RIDE OF HIS LIFE

‘ ‘It was the wildest trip of my wild life’, said McCarty that night. ‘That horse has not had a strap on him for five months. He has never been in the city in his life and is a strong animal with a 2.23 record. I thought ‘Lord’ was joking when he proposed to take him out, but Clifton is dead game and is afraid of The son of Stamboul nothing. I never saw a horse in all my life go at the speed we made along the avenue. One of my arms has been paralysed since, and I do not expect to be able to use it for several days. But what commands my admiration was Clifton insisting on driving the horse after it had once bolted and was completely frightened. Not another man that I know would have dared to do such a thing, but Clifton is not an ordinary man. It was fortunate that we were able to drive into that fence as the animal was thoroughly unmanageable by that time. I am sure when we struck that fence the horse jumped sixteen feet into the air. And Clifton just laughed.’ ’

★ ★ ★

This year Talbot stayed for four months in San Francisco. Those months moved to the sound of galloping feet of horses and the click of polo stick and ball. Talbot in these spring and summer months was gay. Gay, as when he rode, feeling his eye ‘as keen as a hawk’s’. Gay, as when driving a Gaiety Girl behind the Crown Prince she cried out: ‘I’ve never been so fast before, darling!’

“I’m surprised at that from you,” he said, amused by her expression. Then he touched up the horse.

There were crazy scenes in San Francisco. At such a one the judges of a race were hissed by a set of rogues, at another Colonel C., and Harry Simpkins, nicknamed sometimes the Duke, sometimes the Earl, sat up all night trying with empty cartridges to shoot out the light of a candle. Colonel C. going home fell over the Embankment and the Earl took him back to the club and had him put to bed. The Earl after that was melancholy for he knew that he would have to pay the Colonel’s bills; the Colonel never drank anything except champagne, and now he complained that his mouth had been too much bruised for him to eat anything but pâté de foie gras.

Polo and riding, steeplechasing and driving a coach filled the days. The horse, Ormond, was bought “looking finer than silk,” but the jockeys had been bribed: “So no one even with a string of Ormonds can win unless he be of the corrupters.”

Talbot got a fast, neat, small pony, grey-coloured; and then, from the Earl, “A clinking little broncho buck called ‘Jumping Jumping Jack Jack’, not less than fourteen years old. The Earl told me he is about the best pony here.” Jumping Jack was at the height of his perfection and from this pony Talbot gained another view of horses’ ages. The broncho had been caught one spring, trained and used, and then, each year, freed to go back to the plains and hills until late spring, when it would be caught again. It had made its growth, slow and strong, and had not been too much fed, or cleaned, or pampered, nor broken too young. The creature had grown in accordance with its nature, and in its fourteenth year was still at its best, not having, like many of the racehorses, been worn out before it had fulfilled its promise.

The diary gives two lively presentments. The first: of Talbot teaching Miss Wheeler to drive four horses in his drag, and finding her a quick learner. But his pleasure in her was spoilt because she looked on horses as so much mechanism, creatures that all day and all night should go on, wound up by the mere click of a whip.

The other: that of a long drive on a rainy day that cleared at noon. Talbot went in his coach and four to a ranch in the country, taking with him some friends. The roads were very heavy for the horses, and up-country they came on two men who were perhaps drunk, perhaps merely insolent. They would not, by drawing to the side of the road, give the coach room to pass. So, after calling an unheeded warning, Talbot drove straight at them and forced them to give way. One man jumped out and levelled a gun at him, but did not fire.

But in his diary Talbot did not record what befell one night at dinner; his friend Tobin, in a letter[2] to the Duke told the tale this wise:

‘My recollection of the incident that you refer to is as follows: I was present at the dinner that you gave to celebrate the steeplechase which you had won. There was a large party present, racing men and others. Among them were Talbot Clifton and Jack Chinn—the latter I remember as one of the most formidable-looking men I have ever seen. He had piercing black eyes and his dark, menacing countenance was rendered even more alarming by powder burns, the evidences of his narrow escape from someone who had tried to kill him. He bore the reputation of being one of the most dangerous men in the Horses and Jack Chinn country, was known to be ready to shoot on the slightest provocation and to be at all times heavily armed.

‘I remember that we discovered on that occasion that he was carrying a pistol in his trouser pocket and a large knife up his sleeve.

‘My attention was suddenly attracted to Talbot Clifton who said to Chinn across the table, in a loud clear tone, “You are a liar.” We all knew enough of Chinn to feel that he was almost certain to meet this uncompromising challenge in the way that he had always been accustomed to, namely with his pistol, and quite expected to see him shoot Talbot Clifton dead.

‘Clifton must have realized his danger. He was not armed, and he knew enough of Chinn and of his record to be aware that he was likely to kill any man who insulted him.

‘I think that the fact that Clifton was not killed was due to two things—I think Chinn, himself, was impressed by Clifton’s extraordinary courage and that he knew Clifton was unarmed. If he had known that he was armed, and especially if he had made any movement to draw a pistol, I feel confident Chinn would have killed him. Much was due also to your intervention in getting between them.

‘I remember the incident as a most impressive display of courage and nerve. I do not think there is anybody in the country who would have dared to challenge Chinn the way that Clifton did. It was the more impressive because Clifton had come to the defence of an absent friend, a picturesque adventurer by the name of McCarty.

‘Clifton was undoubtedly one of the most courageous men I had ever seen. He did not know what fear was[3].’

Into the diary come a few words which show that in July Talbot was beginning to get tired of all the fun and the folly of the picnicking girls and of the horse-besotted men: “Went for a picnic by the sea. Very pretty but most of the best places had been taken up. Went along to a cove on the beach and watched the sea-gulls. In spite of them the afternoon was tame.”

Tame, in spite of the sea-gulls: over the page, next day, “Alaska” is written. Then came the fourth of July and a “polo match, fireworks display, buffoonery and every imaginable vice which I believe is thought befitting to the day”.

On the morrow he was sailing towards Alaska; the Earl and Sailing for Alaska—The dog Bob Talbot’s manservant, Betts, and the dog Bob, accompanied him. Bob liked being on board—was indeed happy anywhere with Talbot, notwithstanding he was a moody dog and independent. On land he would run off on amorous mischief and be gone for hours or for days. But on his good days: “Look after it, Bob,” Talbot would say, and put his books, or pipe, or flute, before the dog, and all day Bob watched the things and no one would be so foolish as to near the growling animal. Or—“Look after him,” Talbot would say, and leave Bob alone with a man in a room. Bob would be gentle enough, but if the man went towards the door then Bob sprang at him and by his clothes held him captive.

“What sort of weather is it, Bob?” Talbot in the morning would ask his dog, and Bob, leaping off the bed would go to the window—always open—always with curtains drawn back. Were the day to be fine he would wag his tail and show joy, were it wet he would slink back. To please his master, at a word he yawned, or sneezed, or rolled over on the floor, danced, or trod along a table laid for dinner. Master and pupil these such as made people gape: but the tricks were in fact nothing; it was rather the rare quality of Bob’s understanding, of Bob’s heart, that mattered.

★ ★ ★

The Captain was a jolly man, and he allowed Bob to sleep in Talbot’s cabin. His only evident fault was the love he had for a fiddle on which he tried to play ‘Annie Laurie’ and many another tune. All the first day the sea was calm and everybody was on deck. They passed many whales, and from the ship, sailing near the shore, the beauty of the coast was seen to be bewitching. At Port Lamont they found a “hotel like a barber’s shop with food fit only for pigs”. The steamer Quebec came in, but she was so full of passengers that Talbot and the Earl slept in one of the ship’s boats, which “the Earl thought was an awful discomfort”. Next day they were both black with smoke, and there was no cabin in which to wash. “The Earl and I seem to do the drinking for the rest of the sardines on board!”

Past lovely mountainous scenery and past Vancouver they sailed. Black bear-skins costing about forty dollars apiece were put on board. Next night Talbot “sat up half the night singing”, and the following morning he saw with pleasure the fine forms and faces of Indians of this country. They made their canoes from the trunk of a tree, scooped out; boiling water and hot bricks served them to stretch the wood.

In heavy mist Talbot, the Earl, and Betts the manservant, landed at Juneau. They walked down streets miry as bogs, and went to the hotel built of pasteboard. Juneau was enveloped in fog and rain, and smoke from the Treadwell Mines. Every second week a ship sailed in, but here was no telegraph or telephone office. Yet Juneau boasted three newspapers a week: “But I think the editors must be very small men or else very bad shots for they are not at all aggressive!” A man called Maas befriended Talbot and gave him written directions as to how to go down the Yukon River. Talbot hoped that the directions were exact; but, in spite of what Maas said, Talbot did not believe Juneau that he had been down the river. “People seem to fight shy of him, but he is small and can do me no harm as my purse is very carefully guarded.” The next day passed in fishing and shooting and Maas, getting out of a boat, “shot a bit off his foot with his rifle.” “Very careless,” is the laconic comment, “I hear that he is always doing something like that.”

In the creeks up-country, men were washing out gold dust; working so all day, a man might earn two and a half dollars. Juneau now was lamentable; in the days when miners only had reached it the place had been pleasant, but this year a lot of adventurers and tenderfoots ruined the town. Every man carried a ‘sack’ of gold dust. The dust was the town’s currency.

The customs in the town were based on the supposition that men are honest. A miner going into a store with his sack of gold dust would not watch the weighing of the price of his purchases, for did he do so he was ‘no gentleman’. The miners till now had enforced their own laws[4] and lately, for cheating, a salesman had been shot.

There was trout and salmon fishing in the country, and cod could be caught from the end of the pier at Juneau. Talbot found it difficult to keep the low newcomers from asking impertinent questions. When they could not be prevented from doing so it was difficult to resist fighting the lot.

Some days later he and Betts and Bob started for Dyea. Here Simpkins said good-bye to them. To reach Dyea by river they took two boats, two guides, and packed a load that weighed twelve hundred pounds. The scenery was dismal but grand. They passed a rich mine where worked some two hundred men, and also a salmon cannery where in five years its owner had made a fortune. To this factory fish were sold at five cents each. The price did not depend on the weight of the fish. Five cents was paid for a twenty-pound salmon or for a small one.

The travellers spent twenty-one hours wayfaring ninety miles. They loaded the boats, but afterwards unloaded them whilst they waited for the tide. Finally they took four hours to go a bare mile to the village. Talbot and the Indians arrived at the place exhausted. One store and six Indian huts—that was Dyea, yet it was very pretty. The steamer now and again brought fresh meat, for in Dyea no cattle could live, the place was a Dyea—The Indian Ajibnee swamp. Cranberries and bilberries grew and but little else: the Indians were fevered and sickly—only the streams were beneficent, rich in trout and salmon.

For two days the men rested whilst awaiting pack Indians to come from Chilcoot. They would leave their boats at Dyea and travel to Sheep’s Camp and to Lake Lindeman.

Talbot watched the Indians playing blind poker; the best of their players gambled with white men. The Indians cheated a great deal, the white men cheated more. “I think it hardly right for white men to play for money with Indians.” Later, with surprise, Talbot watched the red men playing harmless hunt-the-slipper, which they had changed into a gambling game.

Early next day an Indian squaw beckoned to Talbot, for in the net, which she had set overnight, she found six salmon-trout. Talbot gave her a quarter for one of the fish, and he was as pleased with the fish as she with the money. By the water an old Indian “sat eating a ground-hog with all its hairs on, just singed, and guts not taken out”.

Talbot had to leave his boats at Dyea and obtain others. On July 24th, the Indian, Ajibnee, started for Sheep’s Camp, taking four thousand pounds’ weight of goods in three canoes. That same day Talbot broke camp and sent his things a mile up-river whilst he remained dining and sleeping in a store. “At half-past six in the morning ‘good-bye to Dyea’. Started for Sheep’s Camp on horseback, crossed the River to my Camp. All the horses swam, awful current. (Place where Frenchman got drowned.) Loaded packs, off at 10 a.m. after crossing river twenty times, very deep and dangerous, arrived at Sheep’s Camp 4.30 p.m.” Now and then Bob, in front of Talbot, had balanced on the saddle; before they plunged into the river, at a given word, he would jump on to Talbot’s shoulder and from there would envisage the heavy swim.

After ten hours of travel they reached Sheep’s Camp and supped on salmon and bacon and marmalade. The pack Indians with Ajibnee afterwards came in. Then they all pitched camp. There were in Sheep’s Camp about seven miners and twenty Indians.

“Two inches of water lying in the blankets”—so observed Talbot when he was awakened early by the miners who, in the Chilcoot Pass next tent, were singing ‘God save the Queen’. As Talbot changed the clothes that had been drenched whilst he slept, he wished that the miners would propitiate, instead, the god of the weather. All that day the rain fell, and at night the blankets were still wet.

In the evening Talbot and Ajibnee saw a glacier break off the cliff before them. The cliff was nature’s calendar, the ice a used sheet which had recorded winter. On this, almost the last day of July, the winter’s record, the great green slab of ice, was torn away. It broke off and slipped down the rock, and was shivered on the stones in the water.

★ ★ ★

Talbot was now making for Lake Lindeman where he would build a boat and go to the Yukon; but hours of trial were between the man and the Lake. “God forbid that I should ever try again such a desperate feat,” he wrote when he had reached the Lake; “if I had known what the last ten miles were to be I should have stopped.” At ten in the morning they started up the awful Chilcoot Pass. Sixteen Indians carried the twelve hundred pounds of goods that Talbot was taking; the gun, the rifle, the tent, and blankets, and the food. Men, women, children and dogs had burdens tied to them, and according to the weight carried so was the charge exacted. “Words cannot express what the pass was like. Climbing over torrents, scrambling through trees over huge rocks, sliding down a hill one hour, balancing along a precipice the next.” Two hours after noon they reached the summit of a range of hills; between the travellers and Timber Camp, towards which place they were pressing, lay five miles “over rocks innumerable and mountains. Did not arrive till half-past ten at night, more dead than alive. Twelve and a half hours of the hardest walking a man can do.”

★ ★ ★

Talbot walked in the hills seeking for trees to fell: below him lay Lake Lindeman. Grayling jumped in the water and now and again a pack of grouse flew across the Lake. No breeze blew, and with the advancing day the bite of the mosquitos became an anguish.

For eighteen days Talbot and Betts camped by Lake Lindeman. Two miners, Jock and Jim, unable to pan gold in this the summer, helped him to build a boat in which they would all go to Forty Mile Town. Grain of men’s flesh against this obdurate grain of the fir wood; first the felling, then the lugging—dogs sometimes helping—and the sawing of the trunks, plank by plank. The sweat running down his body, Talbot liked to think how the woodenness of these dull evergreen trees, by nature rooted and fixed, was being changed by whip-saw and by hatchet, into something which should be, a body moving, responsive to hand and to sail—mistress of the water.

As the men fingered the resin of the fir wood Jock explained that the resin was protection to the fir tree against the saw-flies that sought to burrow into the tree-trunks when all else around would be covered by snow—an Indian, coming into camp, with a haunch of wild sheep, had just been bitten in the face by such a fly, of which the cruel fangs had nipped out a quarter of an inch of flesh.

One day Ajibnee, with his canoes, paddled away under a blue sky. “Seven boats have left us since we came here. We were rather mournful as we saw the last three go off. No one has any idea of the meaning of loneliness unless he travel where the high road ends.” Close to Talbot’s tent an Indian squaw was dying of consumption. He tried to ease her misery—“many Indians die that way from exposure.”

A miner named Antelope Dock arrived alone in a canvas boat. He went always alone—he was a hermit. In the evening, The building of the boat with a pack, another lone man came; the camp that had been isolated filled up with men staying here to make their boats. Three boats were being built, a scow, a skiff, and Talbot’s boat. Four of the newcomers had a boat apiece, of which they carried the pieces and screws, and now on Lake Lindeman they built them up. Other men brought in timber from as far as three miles, carrying it upon their shoulders or dragging it with dogs. The miners were sick men, tortured by the mosquitos. Although the wind, when it rose, blew icily cold, yet every man preferred its flail to the tease of the flies. Half an inch beneath the earth’s surface water lay.

“Miners’ camps are very peaceful till worthless men, adventuring, come in and spoil these new countries. A blackguard came in yesterday with a bear. He tried to escape from paying his Indians but was forced to do so. Had he refused we should have sent him back to Dyea. Afterwards he played cards with the Indians and won back the wages he had paid them.” The next day the ruffian was off in his boat.

On the twelfth of August the scow departed. Talbot had watched her being built, and some of his provisions were put on the flat ferry-like boat. She was called the Negress and she weighed six tons. The men could hardly steer the unwieldy thing; she had no sail. She went off at midday “in an awful blue fit of fear”. Half a dozen times she veered round to the wind because she could not be steered, but at last went yawing out of sight. At four o’clock the skiff, which also Talbot had helped to build, danced off under a trysail. Talbot’s own boat was still unfinished; but on the thirteenth of August, after eighteen days of labour, the last strake laid, the last seam caulked, the mast and stays and rigging set, away they went.

★ ★ ★

Four days in the boat, days of sailing, of rowing, and sometimes of rolling the boat overland. Talbot, Jim and Jock seem to have been at strife; Talbot was ever for pushing on, beyond all endurance, but by eight at night or it might be later the men insisted on stopping. “Jock is trying to make himself captain, to this I disagree. At eight o’clock we camped in a very pretty place. They refused to go on any later—poor babies.”

The next night they did not camp till eleven, having started at seven in the morning—“almost got beat”, Talbot owned. The wind all day had been high, and of Jock and Jim was written: “They are both frightened of the water, and the water by night has an awful aspect to them.”

Next day, the sixteenth of August, there was no wind, so for twelve hours they rowed.

“Saturday, 17 August, 1895. (Thirteen hours rowing.) Started at seven in the morning. Other boat just ahead. Reached end of Lake Marsh at two in the afternoon. Ten hours—doing twenty miles—very hot. Then started down river, four-mile current, for Grand Canyon. At times we went twelve miles an hour; at others caught in eddy and completely stopped for a couple of minutes. All the time we were listening for the noise of the waters in the Canyon and looking out for a danger post the book says it has. It was getting dark and we were looking for a camp ground when we saw smoke and made for it. By this time we were going like a racehorse. Turned a narrow corner. There in front of us was the Miles Canyon. Our rudder lost its power and the boat went stern first, but two of us pulled like hell and we got into the backwater. Very exciting. The steersman, Jock, got whiter than snow.

“Sunday, 18 August, 1895. Up at eight in the morning. Took boat by overland—four and a half hours; awful pull one mile. Grand Canyon and White Horse Rapids Rained a little, then very hot. Worked all day carrying packs up and down steep places. The Canyon is five-eighths of a mile; very narrow except in the middle where there is a whirlpool. There is an old fellow with a boat here and I offered to go with him through it. After six hours’ deliberation he said ‘Yes’, so to-morrow at five in the morning we will go through. I don’t look at the water much as it makes my nerves shaky. It is about eight in the evening; am still packing. The sand-flies and mosquitos are awful.

“Monday, 19 August, 1895. (Eight hours’ rowing.) Went over to the old man and to my surprise he had packed. We started our own boat between the Canyon and went on to White Horse Rapids which is worse than Canyon. Jock, a stranger and myself took it through twice. The people on shore thought we were gone. The last few leaps turned our boat broadside. In a moment we were almost full of water. Curious experience. Sometimes the boat would stop a quarter of a second, then shoot on faster than ever—one mile in two and a half minutes was the pace. Wet through. We then rowed to the end of the Lewes River, twenty-six miles, camped on an island and am fairly bitten all over. Shot a widgeon.”

Although the diary does not record it, yet Betts used to tell a tale of the White Horse Rapids. Talbot had determined that he would not again endure the toil of carrying packs up and down over the rocks that rose from the rapids, and because, overnight, Jim and Jock had refused to take the boat over the White Horse Rapids, Talbot prevailed upon the old man to say a long-deferred ‘Yes’. But the elder slunk off in the dawn, grey as his fears. He did not dare to meet the mock in Talbot’s eyes nor the great waters. Then Talbot laughed Jock and the stranger into going; the twinkle in his eye and his gibes spurred to assent. Jock did frown, though he half laughed too, when Talbot beckoned to Betts to pull the dog Bob out of the boat.

“Go back, old manny, it’s too risky for you,” said Talbot to the spaniel; and Bob was led away to do the dangerous part of the journey on foot in company with Betts, Jim and some miners.

★ ★ ★

After that for six days they sailed and rowed or dragged the boat overland until they reached Forty Mile Town. The chart Bob and the rapids had been faulty, and the men were joyfully surprised when Ninety Mile River[5] was reached, with a current running at a five- or six-mile speed, and the Lakes were left behind. To bake bread, and to fry with bacon the dried bean—the ‘Alaskan strawberry’, to catch trout, to shoot a goose, a duck, to see the splendour of the country—all this was good.

Then came Five Finger Rapids[6] which Talbot’s boat took first, the scow followed and both shipped water. Rink Rapids came next, and the men took them clumsily. After were islands innumerable amongst which the boats lost their way, and then came fourteen hours of rowing, with all the felicity of excitement.

The next day they passed a place of wreckage—the wrecks of miners’ boats, and they thought sadly of the drowned men. Just then a wind rose up and blew away the fog so that was revealed country magnificent with leaf of red and gold, whilst in earth, and in river-bed, lay the alluring gold.

Through Talbot’s mind flashed apprehension of the strange quality of gold. The being of God, the worth of man, of woman, the right to war, and a thousand things beside disputed throughout time, but the preciousness, the value, of this rare, pure, strong and uncorroding metal, ever agreed upon by all people under the golden sun.

In the evening of the twenty-fifth of August, the five canoes of the surveying party stopped where Talbot and his men had struck camp, so they all put up their tents among the trees, pine, and spruce, and birch, with here and there bushes of red currants. How silent were the woods! No song of birds; once the croak of a raven, and twice seen, but not heard at all, a grey bird—the Canadian jay, the whisky-jack.

‘That is the camp robber, a thieving pest,’ someone said. On the evening air sounded the inharmonious voices of the miners. ‘Pay-streak’ . . . ‘Low-grade diggings’ . . . ‘Gold pan’ and ‘Strike it rich’: such fragments of talk moved the air; the air that was goodly with the smell of four loaves being baked and of the goose which, after boiling for an hour, was now being fried in fat.

Next day they passed the Negress—her crew was so disheartened at being passed that she would not race again. Then Good-bye to the boat came a very hard pull, and a race with the small boat—her of the trysail. Three hours after noon they reached Forty Mile Town, winning the race against the small boat by eighty yards. For seven hundred and fifty miles, during sixteen days they had raced her. She had left a day before they had left, so also indeed had the Negress—it was good to have beaten her.

Talbot showed some letters of introduction that he had been given, and he was put into a hut “with a very nice fellow and a bar-owner”. The bar-owner’s name was Bob Miley.

Standing by the side of the water that evening of his arrival Talbot, in thought, went over the course of his travel. His mind recalled the great effort to surmount the Chilcoot Pass: the building of his boat on Lake Lindeman: the two hundred miles of lake, and river, and of rapids. The portaging from one lake to another, each man burdened by heavy weights, a hundred pounds or more upon his back; the cutting down of trees to use as rollers for the overland passage of the boat. Then, unseen of any other, Talbot took leave of his boat. He stooped down and caressed her—the boat that he had built, and that ill-built would have been his doom.

★ ★ ★

Talbot stayed for nine days in Forty Mile Town, because the steamer which he awaited was long delayed. The shack was built of logs, one lying on another. The rifts between the logs were filled with moss, a mud roof was piled upon the top. The windows of this shack were of glass, though in some shacks linen steeped in oil served for panes. “Three of us and a squaw had meals together.” At dusk another Indian woman would come in and the two talked together in “their very ugly language”. So seemed to him the speech of these Indians whilst he listened only; but he thought otherwise when afterwards, from squaws and from hunters, he learned a little of the language.

During this time of waiting, Talbot went sometimes to Fort Cudahy, a small place standing where Forty Mile River joins the River Yukon. Whether it belonged to the United States or to Canada was debated. The Mounted Police, “nice fellows”, had lately arrived and were building barracks. Uncommon leisure was the portion of an Englishman, who all and every day fished for pleasure. He sent to Talbot a basket of fine grayling. To fill the time of waiting Talbot started a newspaper: “We are working hard at it. We are all disappointed because we cannot find any scandal. Twenty-five copies are to be issued at five dollars each. It is not too dear as the papers will all be written by hand.”

Forty Mile Town, this early autumn, was wildly disordered. A year before Bob Miley, Englishman, had arrived with fifteen dollars in his pocket. In four days he had paid five hundred dollars for a year’s outfit. He bought a saloon; gambling, he won a gold-mine and from it panned ten thousand dollars. Now a new saloon was being opened by him; this was the base of the town’s Life in Forty Mile Town excitement. Prosperous too was the bar-keeper, for in his claim a seventeen-ounce gold nugget had been found. A dance was given to celebrate the open doors of the new saloon. Miners, storekeepers and Indians came. Twelve o’clock struck somewhere; just then Talbot danced a waltz with an Indian girl. He could feel that this was more to her than just a waltz. Her feet, her body, all of her moved as a bird’s throat moves in song. Generations of people, who by firelight had danced to show the hunters’ joy and the warriors’ delight, a whole past of such a people, quiet now in their graves, a whole line of such forefathers, had been needed to produce the joyful easiness of this midnight waltz.

Mrs. ——, full of sudden pomp and wealth, debarred Indians from her private dance given a few days later. That she should be so eclectic aroused comment.

The wife of the storekeeper, Mrs. Healy, of a like mind, had amused Talbot ten days before the dance in the saloon. He had called on the wife of Captain Constantine and “Mrs. Healy was there, but when the representatives of the other store came in she took up her cloak and hat and bundled out of the room—an absurd phase of rudeness.”

The steamer Weir had just come in. She brought miners, but no stores. She had had a collision with the Arctic, which ship, long overdue, was eagerly awaited by miners and Indians. Medicine stores and spirits were getting scarce. The Arctic, hampered by the damage done, would be yet later than had been feared.

‘Whose fault was the mishap?’ every man questioned, and though none vouched for the truth of the surmise, yet suspicion sneaked around Healy, the store-owner.

‘There has been foul play,’ was whispered, for a chain of events could be foreseen. Soon indeed, just as had been expected, prices in the store surged up. The tongues that scandalized the store-owner grew sharper. One day Healy had no butter; the next day it was salable, at a price. Healy had no medicines but, the need sharpening and the price rising, an odd bottle could be found. Healy was an affliction-monger. The town was full of miners who had arrived in the Weir—nearly everyone was drunk.

A miners’ meeting was held in the saloon. ‘Whose wife is Antelope Dock is judgedshe?’ was the case tried, and on an immediate scandal some judgment was passed.

A dance was started in Bob’s saloon—at three hours after midnight every dancer was rolling over another, and it lasted till eleven o’clock next morning. “One man was wounded with a knife, that was all.” Talbot had left soon after midnight. He had watched a game of poker that had been going on for thirty-six hours. Bob Miley and Barker went back to the hut late next afternoon, but did not, till eight in the evening, seek their beds, to which for forty hours they had been strangers. There was another dance on the following night, but none of the women went to it, so the men danced with one another.

The talk of the town was of one Curly who, coming up in his boat, had smashed a man over the head with his six-shooter. The wounded ruffian sought the police and Curly was looked for in his hut, but he had gone away by two o’clock in the morning. “Both men were in the wrong, but I am on Curly’s side, as miners are the most damnably irritating beings under the sun,” wrote Talbot.

In a canvas boat “the absolute hermit, Antelope Dock”, arrived from Lake Lindeman and the coast. He carried a mail, but he had been about three months coming. “He expected to collect a dollar a letter, which was absurd. Because he was not paid anything he called a meeting in the Alaskan Store, but instead of being paid he was rebuked by all for not having come here in good time. His delay has been a catastrophe to several men who had expected remittances and who, not being able to buy provisions, have left the country. Antelope Dock was nearly fined; he was almost sent out of the country, but for some reason he was dealt with gently.”

For no clear reason that day, “all the dogs seem to be mad; any amount of fights. One Manuas squaw was nearly pulled down, but threw a bucket of water over the two fighters which had a good effect. Men here talk about dogs as elsewhere about horses. Whether strength or speed is best, raises many discussions.”

Often in the streets by day Talbot, of necessity, carried Bob upon his shoulders—otherwise the dogs would have torn him to A ‘Chink’ pieces. At night, as soon as the sun set, “they howled like wolves, from which they are descended”. Up and down the Yukon the dogs had many uses: they hauled the wood to be burned in the stoves, they ploughed, they were beasts of all burdens. Men travelled in sleighs drawn by the creatures. The dogs were fed only at night, to be hungry made them zealous—so thought their masters. They were always penned outside the ‘shacks’; every time the door of a hut was opened, fighting each other, they would rush to look for food. A dog would snatch a bag of food from under a sleeping man’s head; they ate even one another.

Learning Indian from two squaws; gambling at faro; watching money endlessly changing hands at poker—so the days passed.

“This place will soon kill me; the muck we get to drink plays havoc with me,” sighed Talbot in his diary. The ship not coming caused whisky to be scarce, and drink called hooch was taken instead. It was made of molasses, and of spirit of various berries; even old leather was thrown into the cauldrons; the whole was fermented and was drunk hot. The talk turned often upon drink. One man would boast that he had gone all day without having paid for a drink. ‘Tossed double or quits and won each time’, he would laugh. Another would complain that he ‘had dropped in for a chink and that had cost him one hundred dollars’. A ‘chink’ entailed paying for a drink for every man within sight in the whole saloon. “A drunkard has been following me all day to give him a drink. The saloon-keepers will not sell him any more, so he got a box of cigars at two dollars each and gave me one. Then he tried to start a fight; not allowed. Then he said he wanted to talk over the Home Rule question. He was at once turned out of the saloon for naming the subject.”

One night, the night before Ajibnee left for Dyea, he and Barker and the doctor and Talbot found some good whisky in the store. “The glasses all cracked afterwards without being touched—unused to such a quality.”

On the night before Talbot went off to hunt, the Indians gave a ‘potlash’, a dance with an exchange, between themselves, of presents. Rifles, blankets and lesser goods A-hunting changed hands; each man trying to get the better of his neighbour, but fortunes were even when the dawn broke. There was still no sign of the boat. On the sixth of September, after nine days of waiting for the ship, with men of the tribe of Tinné[7], Talbot, intent on hunting, left Forty Mile Town.

★ ★ ★

In the diary the pencil records of the hunting days have been blotted out by rain or by sea-spray. But this is known, that Talbot, hunting with the Indians, was diverted by watching a mink. It was feeding upon frogs near some water. From it came an oppressive smell at variance with the sweet evening. Lustrous was the soft glossy coat that made the creature the prey of the trapper; its bushy tail was comely.

He caught a heavy silver fish, and shot a bear, and with the Indians for hours went thirsty in the fierce sun; at night the frost set in. The caribou, the fat small caribou of the woodlands, grazed on the high grounds above the blue-berries; moose browsed on the lowlands and ate the leaves of willows. The hunters watched a bull-moose wallowing in a pool, seeking escape from the besetting flies. They heard the hornlike challenge of a far bull; they listened to the moose of the pool grunting back to the call. Then they saw him rush recklessly towards the rival beast. ‘We could kill him now; he is blind with anger,’ whispered an Indian; but Talbot was set on watching the moose. At evening they heard against the trees the banging of a bull-moose, ridding himself of the velvet on his antlers. They heard in the woods a cow answering a bull. They saw the young spruce trees ridden down, straddled over and broken by the moose that were hungry for the green food. They saw, too, last winter’s ‘parks’, where the beasts had herded together, in places of trampled snow. (On the untrampled snow their feet slipped, and their weight endangered them in drifts. Herded together amongst the trees they could feed in safety; could defy the wolves.) Talbot delighted in the primal look of the creatures, in their noble elklike horns, in the great solid over-lip. What acute scent endowed those wide nostrils; what acute hearing endowed those upright ears!

But, that he might have a trophy, he killed a beast and sent Mink, caribou, and the moose its head to England.

On the last night in the woods Talbot was surprised by the moon-dogs—five luminous circles hung in the figure of a cross above him: they were the fivefold image of the moon, reflected in the sky. Not having heard that such appearances sometimes distract the Northern skies, Talbot was the more perplexed.

Pity it was that he did not regard the five moons as heralds of fortune; emboldened by the image in the sky he should have snatched bravely at his chance. Instead, next day, he let go a life’s occasion, and that, when on the river bank, at morning he met two miners. It seemed that they were at their fag-end; travelling wearily to Forty Mile.

‘We have been on the pups of the Klondyke River; heard of Hayne being there; we’re certain that miners there will soon strike it rich.’ But the wife of one of the two men was dying, so he must travel by the next steamer down the Yukon; the other miner was crippled by rheumatism.

‘It is a commanding illness,’ he said. Both men had staked big claims; they were certain the Klondyke was rich; all the same they wished to sell their claims. Talbot could see they were sincere. Unless these were low-grade diggings, the claims were bound to be worth more than the men were asking. Talbot got up and walked away to think: he decided that the men were honest and that they knew their claims were good; he decided that here was the chance of a fortune. He could not afford to buy the men out by himself; he could afford a third share. In London he would see B——, who might be able to raise the remaining two-thirds of the money. Talbot would return straight to London, and would cable to the men refusing or assenting. He told the miners of his decision; then the three men smoked a pipe before rowing to Forty Mile. Through Talbot’s mind chased thoughts and feelings somewhat thus: that by his travel and the hard living he had saved money; that he must travel again, and often, where he could pay for his living in work and sheer muscle rather than with money. In the green of his youth he had abused wealth; now he would try to regain, by living hard and poor, some of what he had lavished on races and on foolery. Though he left his heritage often, yet he never quite forgot that—according Talbot remembers the lands in Amounderness to tradition—it was William Rufus who had bestowed on a Clifton knight ‘ten carucates of land in Amounderness’. His farmers might, did indeed, complain that John Talbot—bluntly naming him so—too seldom ‘had a look at them’, yet Talbot knew there was not a faulty window or a leaking shippon in the hundred or more, solid, red-brick farms that stood upon his lands.

When, later, he returned to London he tried vainly to interest business friends, but ‘who has ever heard of the Klondyke?’ they laughed. Regretfully then, though partly unaware, Talbot signed away in a cable his chance of a fortune. Next year the Klondyke was discovered to the world.

★ ★ ★

At last Talbot sailed “through a luxuriant storm”, and “after struggling with the night and its gloomy surface”, after “another wild senseless intoxicating night of horrors”, came this entry: “The weather grew hot, the stars were in all glory. There are things to think about at sea which a man ashore does not consider—why that should be I don’t know, but so it is. Thinking takes the place of reading.”

Talbot read Shakespeare. One morning he was reading, but left the book and, going aloft, he watched the sea-birds. A miner picked up the book, glanced, then read. At school he had heard of Shakespeare, and had thought that he was a writer acclaimed by schoolteachers—one whom the learned might enjoy, but who was beyond the understanding of the simple. Clifton was reputed reckless, was the builder of a boat, hale huntsman and pioneer—what Clifton read might have meaning. The miner read and was convinced. When Talbot went back to his book he was surprised to see the man lost in the poetry and to hear him, in the language of his calling, acclaim the passage he was reading as though it were a seam of gold, a rich streak that he had come upon. In terms of nuggets found, and of ore panned, he praised the book. Talbot gave him the volume. It was bound in red and gold; many of the passages were pencil-marked. The book was battered, a little, by the roughness of river travel.

On October the twenty-first the journey was ended: “Sighted land northward of Point Orena. The stars in their glory are making the heavens blush. Point Orena itself was sighted at midnight. Alas, my journey to Alaska is over.”

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

At the end of February, 1897, Talbot Clifton, then aged twenty-eight, wrote in his diary, “Left Liverpool for the Barren Lands”. He hoped to go by the unmapped tracts near Chesterfield Inlet, hoped too, that in spite of searchers, and explorers, and whalers, some further trace of Franklin might be found, for after all endeavour the body of the hero had never been come upon. Talbot’s provision was belief in himself, and in his aim, besides some knowledge of travel. Afterwards he wrote: “How little did I think as we walked over the wet slippery quay to the Cunarder that was to carry us three thousand miles towards our goal, how little did I think what scant new knowledge regarding Franklin would accrue to me (if indeed any). . . . My quest was to find if possible where the great Northern explorer had his last resting-place. I so much admired his intrepid courage that I felt I must pay this tribute to his name.” Talbot hoped also to capture some musk-ox, because none had yet been brought alive to England.

He sailed off in a storm that destroyed two of the ship’s life-boats and so harassed the steamer that she arrived at New York three days late. One of his brothers, Arthur, was with him and the same man, Betts, who had been with Talbot in the Yukon: thin and quick, the outward and the inward man very upright. But to Bob he said good-bye. “I miss Bob very much and keep thinking of him. We have never been separated for more than one week in a period of eight years. It seems wicked to leave the old chap behind.” But now Bob was too old for a journey such as this might be, so he was left in Scotland. Then the dog ran fifty miles from Elgin to Ross-shire looking for Talbot in his home in the deer forest, led back there by his loving instinct over all the way he had covered by train. He was sent back to Elgin and he died there before Talbot returned from the Barren Lands.

From New York they went to Winnipeg, carrying letters to From Winnipeg to Norway House the heads of the Hudson Bay Company, and the men of the Company advised him as to his necessities: from matches to a muzzle-loader or even a breech-loader, the Company would supply everything—so bacon, salted pork, beans, flour, and other things were bought. “I move here: tailor, bootmaker, gunmaker, cartridges out of Customs, watchmaker, cards to leave at Club, bills to pay, clothes to try on, good-byes to say.”

At Winnipeg, Mr. Chipman helping him, Talbot studied maps and charts, and deliberated whether to go east or west. Then he decided to go to Norway House, Oxford House, and York Factory, stations of the Hudson Bay Company, and thence to Fort Churchill. Farther than that he could not now foresee. There were nine hundred miles to cover between Winnipeg and Fort Churchill, so there would be time for thought.

On the twentieth of March they left Selkirk and spent twelve days going thence to a Hudson Bay Company settlement, called Norway House. Their way was four hundred miles long. At first they travelled with sleighs and horses; they ran too on snow-shoes. Later, they changed horses for dogs with sleighs. By night the Aurora Borealis flashed in the sky as though angel combatants unsheathed celestial swords. By day sometimes they passed other sleighs and met Indians, and now and then a Scotsman, travelling. They slept in tents, and ate moose and caribou. On the third day they saw a wolf, a cave that had just been dug out of the snow by a bear, and, on the lake, a broad fissure[8] spreading for about a hundred miles. One of the men told how these clefts sometimes went to the bottom of the lake, and so were dangerous. They unharnessed the horses, pushed the sleighs over, and then jumped the horses, but the take-off was bad. The drivers were in mortal terror; nevertheless the danger was surmounted. Later, in a snow-drift, the horses were up to the girths in snow and were spent when, at Berens River, the first Hudson Bay post was reached.

One day: “The track is a foot and a half broad. Go off it and you will be up to your middle in snow; crawl out as best you can. Moccasins take hours to dry and it is necessary to be dry-shod.” Thus they travelled, sometimes on the great lake, sometimes From Winnipeg to Norway House near it. When they stopped for the night the Indians cut the fir trees down for fuel, but so wastefully that Talbot twice prevented this destruction.

As they neared Norway House an Indian went ahead to test the ice with a pole. Once the pole went through. In the deep water of the ice-holes a man could be drowned[9]. “Thank God no fog came on last night, for I was long by myself with unmanageable dogs. I thought the Indian ahead had been drowned in a hole and Betts behind was clean out of sight. The night grew darker, clouds came up, with dogs tired and the track lost—not much fun.”

The radiance of the snow dazzled Talbot into snow-blindness[10], “a slight attack—which is hell”. After a day’s rest they went on again and now Talbot wore glasses. Instead of horses they had five teams of dogs. ‘Norway House is a hundred and sixty miles by our way,’ said William of the Company: he was half white, half Indian, and spoke with a strong Scots accent. That part of the journey lasted seven days.

On the second day of April William said: ‘In an hour we should reach Norway House,’ and Talbot was glad for the sake of the dogs.

A flock of buntings flew past him. They were sharp-winged and white as snow. After them came a raven; strong-winged and swift he needed no cover, and on his sable no cover was bestowed. In a just balance his strength had been weighed against the weakness of the smaller birds; it had been found sufficient; in a world of white the raven remained black, pointing the care that encompassed the ptarmigan and the snow-birds. Quick and new, although Talbot long had known of the merciful colouring of the Northern creatures, quick and new then came, with the immediate seeing of these buntings, the sureness that God is good. ‘The buntings know some gay songs,’ said William, but Talbot did not heed what was said of their singing because, with their silent passage, had glittered a faith that was gay enough.

★ ★ ★

“Reached Norway House, dogs’ feet leaving a trail of blood upon the snow.” Twelve days had passed since the travellers had left Selkirk.

It was early in the morning when they arrived, but not too early for Chute, who was in charge, to receive them hospitably. “Found Chute in bed, woke him up; he kindly gave us breakfast and beds and a much-needed bath. I had the itch badly.” For some days they rested; the thaw added delay. Indians who had tried to reach Oxford House came back unable to pursue the trail, for in such a thaw a man might, in a treacherous place, be waist-deep in water.

The feet of the sleigh dogs must be healed before there could be further travel, so moccasins were made for them to wear. There was gear that must be bought in the store. Talbot bought snow-shoes five feet long, the hunting shoes of the Cree Indians. To every tribe its own shoe. Three-foot shoes would suffice for the trail, but for chasing deer over unbeaten snow these were made five feet long, sometimes six, with narrow frames of hickory filled in with thongs of plaited hide. The tribal enemies of the Crees had dreaded the speed of these shoes. He also bought isinglass goggles.

The days were sunny, at night there was frost. Often the traders played football and, in the evening, tales were told by the fireside. The store of whisky was broached in celebration of the arrival of the visitors. ‘I was starving, just about to die, when I got a shot at a pike in the river, killed it, and so am here.’ Such a tale a man would tell, and another would match it with equal adventure.

One of them who talked and drank was a ‘free-trader’, that is, not a member of the great Hudson Bay Company, but a trader buying and selling for himself. Anathema in former From Winnipeg to Norway House days, such men now, with the opening of the Western country, found access to the interior less difficult and, with custom, had become tolerable to the servants of the Company.

Then from Behring’s River came MacDonald, the head of the station. He had done the journey in four days. ‘Good,’ said the other Scotsmen. On the day of departure MacDonald gave Talbot a pair of sleeping-boots and a rabbit-skin rug. ‘Safe journey,’ he called out as the two brothers and Betts started for Oxford House—that was the sixth of April.

They travelled five days, at an average of forty miles per day, over portages hard and long, in some places dangerous. They shot rabbits and woodland caribou for food. In many parts there was deep snow; always there was frost.

One night they slept round a fire that burned away all too quickly, but not before their blankets had been set on fire by the sparks. Another night, because of the snow, they put up a tent.

But the night of comfort was one passed in the hut of an Indian. Eight Indians, some of them Talbot’s men, and two Indian women and the three white men slept in a little house the length of which Talbot covered in eight strides, its breadth in seven.

Oxford House is one hundred and eighty miles by the trail from Norway House, and the day that they reached it they had run for hours with the dogs.

Campbell, the head of the station, saw them nearing Oxford House but, when they hailed him, he could hardly hide his disappointment because he had been hoping that the approaching sleighs were bringing flour, of which his need was great.

‘There is our little father,’ said an Indian as they passed the Company store.

From the mirror on the wall of his bedroom, Talbot saw the reflection of his face which was burned and blistered by sun and snow; the whites of his eyes seemed strangely white, like those of a negro gleaming out from the dark skin. Running with dogs had made him hard, strong and swift. “I can run three and a half miles in sixteen and a half minutes,” he wrote. “In a week I have gained eleven pounds.”

At Oxford House all the clocks and the watches had stopped, They reach Oxford House yet the meals were served to a set time. Talbot’s four watches all told different hours. A man, Simpson, arrived and he had a watch with yet a fifth variant of the time.

Indians came in to the settlement, bringing fox-skins and lynx-skins. Soon would come the spring, thinning out the winter coats of the creatures and putting an end to the bartering in furs. Busy too were the Indians catching fish in their nets, and white fish and heavy trout were brought in to the settlement. The dogs were fed upon fish—the troublesome noisy dogs. They were thin and quarrelsome; some of them had just killed one of the few cats of Oxford House.

‘I’m glad to see those beggars going away,’ said Campbell one morning as he watched his own team of dogs being led in the direction of Goslake, a place where fish abounded more than at Oxford House and where the husky dogs would pass the summer.

Snow-birds going north sang a few notes of sweetness. ‘They are of the finches,’ one of the Scotsmen said. Next the badger woke up and was seen, and put forth on to the south wind its smell so loathsome to man, to its own kind so alluring. William took Talbot to its earth and this was a great place—such a dwelling as only a brock with its high courage and its strong paws will make. Then, in his own tongue but with many a deviation, with English sentences and with Scottish words, William told Talbot about the badgers, and this was the gist of his talk: A fox, he said, shares that earth with the badger; his hole is an offshoot of the brock’s tunnel. Each has his own dwelling, though the badger alone made the mansion. The fox—and William laughed—knows well enough that he will not get mange if he shares the badger’s earth, for the badger three times a week cleans out his own as also the fox’s earth; he puts fresh bedding for the fox and for himself. The badger asks of the fox only that his vixen shall not let the cubs disgust him by droppings at the mouth of the earth, nor by foolish play with him if he passes near them. If they get in his way he will kill them with one bite across the breast.

William and Talbot spent hours watching the musk-rats that now went abroad, after their winter concealment in the common dwelling which also was a storeroom, and which had been Spring and the creatures built under the water. The creatures were akin to voles and to water-rats, but they had their own ways. William knew where, on the bank, was the vent. By suddenly breaking it open and letting the light in I could dazzle and then kill them and that is what I am going to do; their pelt is of value, brown shaded from blue-grey. This was the sum of William’s talk. But Talbot would not allow him to kill the musk-rats. He liked to watch the small creatures roll off with sailor gait as though a life spent so much in, and beneath, the water ill fitted them for terrestrial journeying. He liked to smell the coming of the spring in the amorous message which the cloying scent of the musk conveyed—liked to wonder at this elastic beast, smaller than grown rabbit, bigger than rat, made with such suppleness that it could squeeze its way into a hole smaller than itself.

Talbot took upon himself to provision the station with food; he went about always with his Indian. They lay in wait for wild-geese coming up from the south, and for duck which were late that year. Ruffled grouse he shot, and a snipe which he long remembered because he had to run over not very solid ice so as to snatch it up before the crows could sweep down upon it. Always this race with the hungry crows when anything was shot.

William taught him to make pemmican from wild-duck. They skinned the bird, and cut it into small pieces that were boiled so that the meat should lose its fishy taste. Then the pieces were mashed with boiled potato on which was heaped pepper and salt. When the mess was cold they fried it with bacon—and it was good.

The fishy taste that the duck had at this season proved that they too must be hard pressed for food, and must eat fish instead of the weed of their seeking.

Talbot learned many other things from William the half-Indian. He learned to speak Cree. He saw it as the perfect quickness of a man’s expression: a way of saying that constantly surprised him. He saw the verbs unfolded into sense upon sense, into meaning after meaning. He delighted in those Indian verbs, so many times richer and ampler than his own. Little by little he understood how pliant and enfolding are the Cree words, and how a single one might compass a meaning where the English The language of the brave speech would demand upwards of seven. It pleased him, as a game of skill would please, to puzzle out the many meanings that one root-word could mother[11]. Oratory and courage, these, of every chieftain, of every brave had been demanded. No written language had the Cree, but the spoken word was conserved with piety; heirloom of the warriors. Perfection of the spoken word; perfection in the mastery of the body; these the two wings of their ascendance.

Talbot learned to track down the ruffled grouse and to follow a spoor as though the snow were a book. The Aurora Borealis too he must see with a difference, not only as beautiful, but as harbinger of wind.

Talbot now held in his memory long poems of Byron, and Tennyson, and passages from Shakespeare. Sixty lines a day he set himself to learn, and this with a double purpose. He must strengthen his memory so as to learn quickly the Eskimo tongue—if once he should reach that people—also he must carry in his mind spiritual provision against the emptiness of the Barren Lands. A harvest gathered, a harvest garnered would be his store of poetry; though his body might go hungry, he would be provisioned with nourishment for thought.

★ ★ ★

Cunningly William made some decoys, the best that Talbot had seen. He shaped a piece of burned wood into a rough ellipse and to each of these he nailed two wings—ducks’ wings. The decoy floated, the incoming duck were deceived, and so the hunger of the station was appeased.

It was, for the brothers, the last Sunday to be spent at Oxford House; the pemmican, what little was left of it, was being cleared away, the Scotsmen were praising it and talking of one thing and another; but Talbot could not talk much because he was hoarse with grunting, for all Saturday he had hidden in sedges and grunted to attract passing geese.

After smoking a clay pipe, and learning various tricks for colouring it, Talbot in spite of his sore throat recited poetry: ‘for we don’t play cards on the Sabbath,’ said Campbell, and dropped into silence—thinking perhaps of Sunday in his native island of Skye.

‘Soon we’ll sit in darkness, for the oil is nearly finished, and there are only ten more candles in the house,’ said Simpson.

‘The thaw, the geese, the duck, everything is late this year,’ they grumbled, as they settled down to drink the last few drams of the whisky.

The talk hinged awhile on Scottish Sabbaths. One of the Company said that the gloom of the Sabbath, the only free day in the week, was the cause of his being in Canada. ‘Same here,’ came the answer. Talbot remembered being sent to bed in the afternoon one Sunday, because, at Locknaw as a boy, he had whistled. “But I would never shoot anything on Sunday unless I were really hungry,” he said.

Whatever the five contrary watches might prove, the time passed pleasantly at Oxford House. For fifty days the brothers stayed there. If, sometimes at night, a man dozed off after a game of poker, leaving the talk to languish, Talbot would rouse the Water-faring and portaging from trader into wakefulness by defaming the Company, for at that its most lethargic servant awoke to defend it.