* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Marlborough: His Life and Times--Volume V

Date of first publication: 1936

Author: Winston Spencer Churchill (1874-1965)

Date first posted: Jan. 3, 2024

Date last updated: Jan. 3, 2024

Faded Page eBook #20240102

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

MARLBOROUGH

HIS LIFE AND TIMES

VOLUME V

1705-1708

BY WINSTON S. CHURCHILL

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1911-1914

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1915

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1916-1918

THE WORLD CRISIS, 1911-1918

(Abridged, in one volume)

THE AFTERMATH

A ROVING COMMISSION

THE UNKNOWN WAR

AMID THESE STORMS

THE RIVER WAR

MARLBOROUGH

MARLBOROUGH

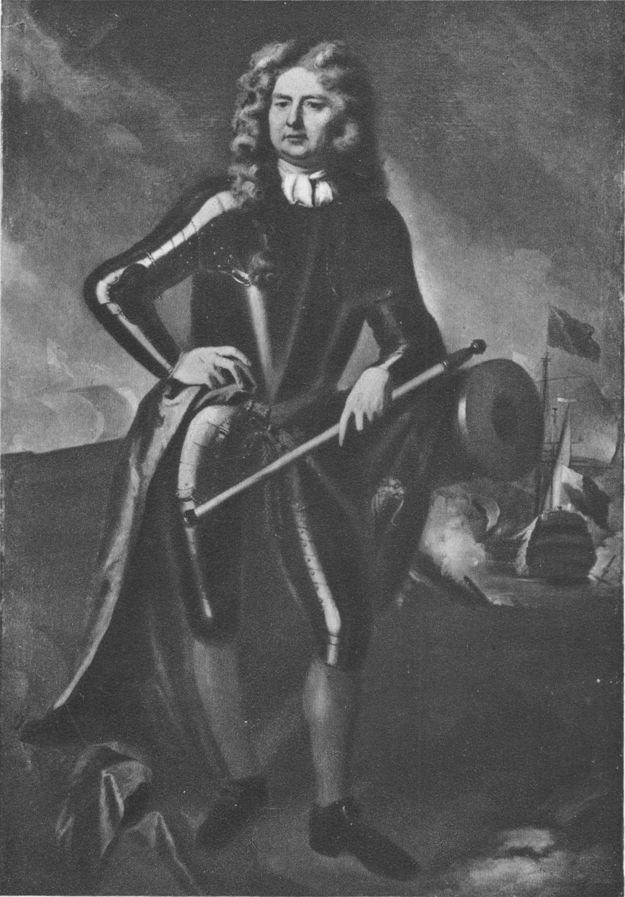

From a copy of a painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller

National Portrait Gallery

MARLBOROUGH

HIS LIFE AND TIMES

By

The Right Honourable

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL, C.H. M.P.

VOLUME V

1705-1708

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

MCMXXXVII

Copyright, 1936, 1937, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this book

may be reproduced in any form without

the permission of Charles Scribner’s Sons

I had purposed to finish the story of Marlborough and his Times in this volume; but as the massive range of the material came fully into view it was clear that this could not be done without altering the balance and proportion of the work and failing to give a level, comprehensive account. I have therefore ended this volume after the campaign of 1708.

At this point Louis XIV saw himself to be definitely defeated, and his whole desire was for peace, almost at any price. On the other hand, the Allies, although war-wearied and discordant, had extended the original objects of the war, raised their terms, and hardened their hearts. At the same time Marlborough’s power, triumphant in the field, and now accepted as paramount throughout the Grand Alliance, was completely undermined at home. He and his faithful colleague Godolphin had lost all effective hold upon Queen Anne, had no control of the Whigs, and were pursued by the malignity of the Tories. The Whig Junto had at last forced themselves upon the Queen, and established for the first time a powerful party Administration supported by majorities in both Houses of Parliament. Upon this rigid, tightly built, but none the less brittle platform Marlborough and Godolphin were still able to act, and Marlborough was to be furnished with greater means to conduct the war than he had ever before possessed. But the hollowness of his foundations was apparent to Europe, and especially to the enemy. It was known at Versailles that the Queen was estranged from Sarah, that she wished to extend her favour to the Tories, or Peace Party, as they had now unitedly become, and that she was in intimate contact by the backstairs through her bedchamber woman Abigail Masham with Harley, the leader of the Opposition. The knowledge of these deadly facts, coupled with the harsh demands of the Allies, encouraged France to struggle forward, until the fall of Marlborough broke the strength and blunted the action of the Grand Alliance, and brought it to a situation incomparably worse than that of 1708.

The constitutional and European issues debated in this present volume are peculiarly apposite to the times in which we live. At home they involve and portray, first, the Union of Great Britain; secondly, the establishment of party government as the expression of a Parliamentary Constitution; and, thirdly, the shaping of the Cabinet system, in the forms in which these arrangements were destined to survive for over two hundred years. By the Great Rebellion against Charles I, and by the Revolution of 1688, the House of Commons had gained the means of controlling policy through the power of the purse. But in the reign of Anne the Sovereign still preserved, not only in theory but in practice, the right to choose Ministers. Naturally the Crown, lifted above party, sought to maintain its own power by forming Court Governments, or, as we should now call them, national Governments, from both the organized political factions and from outside them. The stresses of a prolonged world war and the vast pre-eminence of Marlborough favoured such an inclination. He understood with his deep sagacity that only a peace party can make or wage a war with united national strength. His fears that a Tory Party in opposition would weaken, if not destroy, the war effort of England, and the Queen’s fears that, without the Tories in the Government, she would fall wholly into the hands of the Whigs, with all that that implied in Church and State, constituted a bond of harmony between servant and Sovereign which carried on our weak country and the loose confederacy of which it was the prop through the darkest, and at times apparently the hopeless, years of the struggle.

But after the glories of Blenheim had roused the martial enthusiasm of the English nation the Whigs, with their ardour for Continental war and leadership, obtained in very large measure, and in the end entirely, control not only of the Lords but of the Commons. It was not surprising that they insisted upon predominance in the Government. The dismissal of the high Tories, the intermediate system of the moderates of both parties which Harley rendered possible, and the steady incursion of the Whig leaders into the Cabinet Council comprised an evolution which in the compass of this volume led from a royal or national to a party administration in the height of a prolonged but successful war. Marlborough and Godolphin were forced step by step to yield to remorseless Parliamentary pressures, and make themselves the reluctant instruments of bringing them to bear upon the Queen. In so doing they, and still more Sarah—that keen Whig partisan—lost with the stubborn Queen the influence which alone had enabled them to cope with so many difficulties, and found themselves ultimately shorn of every source of organized domestic strength. All that remained was Marlborough’s universally acknowledged indispensability, whether for the victorious waging of war or the successful negotiation of peace.

The reader will be able to judge for himself whether they could have taken any other course. Upon the whole I incline to the view that greater risks should have been run in 1707 to preserve the coalition character of the Government, to placate the Queen, and to work with Harley. On the other hand, the House of Commons was master of the money, and no Minister, however magnificent and successful, could long withstand its hostility. Secondly, the Cabinet system in its rapid adolescence presented insoluble problems to its members. Great nobles and famous statesmen sat round the Council Board united by no party bond, and owing allegiance to rival factions engaged in bitter Parliamentary conflict. Once the Queen’s loyalties began to be in doubt, divergent personal and party interests manifested themselves in treacherous disclosures and intrigues. When Marlborough’s sword brought home the triumphs of Ramillies and Oudenarde, when all men saw the princes and states of Europe arrayed against France under his supreme direction, these disruptive tendencies were held in suspense, and all bathed their hands in streams of martial glory and growing British power. But a barren or adverse campaign relaxed all ties, and Marlborough’s defeat in the field, or even failure in a major siege, would have destroyed them. When in Marlborough’s conduct of war we see now violent and sudden action with armies marching night and day, and all hazards dared for a decision, now long delays and seeming irresolution, the dominating fact to be remembered is that he could not afford to be beaten. So he never was beaten. He could not bear the impact of defeats such as his warrior comrade Eugene repeatedly survived. Neither in his headquarters at the front nor behind him at home did he have that sense of plenary authority which gave to Frederick the Great and to Napoleon their marvellous freedom of action. It is the exhibition of infinite patience and calculation, combined upon occasion with reckless audacity, both equally attended with invariable success, which makes his military career unique. When British generals of modern times feel themselves hampered by the tardy or partial action of allies, or embarrassed by the political situation at home, let them draw from the example of Marlborough new resources of endurance, without losing his faculty of “venturing all.”

In these pages I also show the seamy side. A shorter account would, if justice were done, be compelled to dwell almost entirely upon the broad achievements. I have faithfully endeavoured to examine every criticism or charge which the voluminous literature upon this period contains, even where they are plainly tinctured with prejudice or malice, even where they rest on no more than slanderous or ignorant gossip. In the main Marlborough’s defence rests upon his letters to Sarah and Godolphin. It is strange that this man who consciously wrote no word of personal explanation for posterity should in his secret, intimate correspondence, which he expected to be destroyed, or at least took no trouble to preserve, have furnished us with his case in terms far more convincing than anything written for the public eye. The reader’s attention is especially drawn to these letters, not only those that have never been published, and which are now printed in their quaint, archaic style, but to the immense series drawn from Coxe’s Life and Murray’s Dispatches. I have sedulously endeavoured to reduce them, in the interests of the narrative, but in so many cases they are the narrative, and tell the tale far better than any other pen. They plead for Marlborough’s virtue, patriotism, and integrity as compulsively as his deeds vindicate his fame. Although no scholar, and for all his comical spelling, he wrote a rugged, forceful English worthy of the Shakespeare on which his education was mainly founded. He held the whole panorama of Europe in his steady gaze, and presented it in the plainest terms of practical good sense.

How vain and puerile seem the calumnies with which the Deputy Goslinga has fed Continental historians, and with which Thackeray’s Esmond has familiarized the English-speaking world, beside Marlborough’s plain day-to-day accounts of his hopes and fears in the long-drawn struggle for Lille! How base appear the slanders with which Tory faction assailed him in those vanished days! Everything Marlborough writes to his wife and cherished friends rings true, and proves him the “good Englishman” he aspired to be.

I have not sought to palliate his vice or foible in money matters. In his acquisitive and constructive nature the gathering of an immense fortune and artistic treasures wherewith to found and endow his family was but a lower manifestation of the same qualities which cemented the Grand Alliance and led England to Imperial greatness. His avarice never prejudiced his public duty. For the sake of petty economies, mostly affecting himself, he let himself become a joke among the officers and soldiers who trusted and loved him; while at the same time he made generous benefactions of which the world knew nothing to his children, friends, and subordinates, and to strangers in distress; or spent large sums upon buildings which would long outlast him. An instinctive hatred of waste in all its forms, private and public, and particularly where his own comfort was concerned, was his dominant motive. Narrowly he scrutinized the expenses of the army; but the soldiers praised the precision with which their food and rations reached them through all the long campaigns. With zest he collected the percentages for which he held the Royal Warrant on the bread contracts and on the pay of the foreign troops; but never was Secret Service money more lavishly or more shrewdly expended. Given only a small addition to the great authority he wielded, he would have brought the war to a victorious end with half its havoc and slaughter; would have made a wise and stable peace in harmony with the highest interests of England and of Europe; and at the same time blandly pocketed the largest possible commissions on these august transactions. We see him in the midst of his hardest struggles cheered by the prospect of a small perquisite of plate, and yet unhesitatingly brushing aside the revenues of a viceroyalty when his acceptance of that princely office would have impaired the cohesion of the Allies. Half the money which he gave in private kindness, if spent upon his table in camp, would have doubled his popularity. It would not have affected his worth.

Most of the English characters of the earlier campaigns present themselves again in this volume. Marlborough is everywhere attended at the front by his devoted friends Cadogan and Cardonnel, the former combining the functions of Chief of the Staff and Quartermaster-General, the latter presiding over and conducting a correspondence which extended from the Duke’s Headquarters to every capital in Europe. We find again Marlborough’s brothers—George managing the Admiralty, and Charles at the head of the Infantry; and his great fighting officers Orkney, Lumley, Argyll, and his younger men, Brigadiers Meredith and Palmes. The war in Spain introduces remarkable personalities. Peterborough, Galway, Stanhope, each in his own way shows the plethora of quality and ability at the disposal of the Crown in these famous years. Godolphin still guards Marlborough’s home base; Heinsius and Hop and Buys preserve his profound relations with the Dutch republic. Wratislaw is his contact with the Empire. There are some grand German princes and warriors in the heroic Hesse-Darmstadt, the Prince of Hesse, and the Prussian cavalrymen Rantzau and Natzmer. Always through the drama runs the brotherhood in arms of Marlborough and Eugene.

In one other main aspect the story of this volume has a peculiar interest for us to-day. We see a world war of a League of Nations against a mighty, central military monarchy, hungering for domination not only over the lands but over the politics and religion of its neighbours. We see in their extremes the feebleness and selfish shortcomings of a numerous coalition, and how its weaker members cast their burdens upon the strong, and sought to exploit the unstinted efforts of England and Holland for their own advantage. We see all these evils redeemed by the statecraft and personality of Marlborough, and by his military genius and that of his twin captain, Eugene. Thus the causes in which were wrapped the liberties of Europe were carried to safety for several generations.

In a final volume I design to describe the fall of Marlborough after his main work was done. Here again the tale is rich in suggestion and instruction for the present day; for it illustrates what seems to have become the tradition of Britain—indomitable in distress and danger, exorbitant at the moment of success, fatuous and an easy prey after her superb effort had run its course. Here we shall see harsh and excessive demands producing innumerable unforeseen reactions upon the defeated nations. Here in foretaste we may read the bitter story of how in the eighteenth century England won the war and lost the peace.

I have followed in these pages the method of the earlier volumes. The reader should consult the preface to Volume III for some comments upon the authorities to whom I have recurred. The bibliography has been extended to cover the new years through which the story now runs. It will be seen that I have drawn deeply upon the records of foreign archives and the writings of Continental historians. There is no doubt that they give a more vivid and vital picture of Marlborough’s life and times than anything which had appeared in the English language until the illuminating and impartial work of Professor Trevelyan.

I have tried as far as possible to tell the story through the lips of its actors or from the pens of contemporary writers, feeling sure that a phrase struck out at the time is worth many coined afterwards. Great pains have again been taken with the diagrams and maps in order that the non-military reader may without effort understand ‘what happened and why.’ I am again indebted to Brigadier R. P. Pakenham-Walsh in this respect, and for his assistance in the whole technical field. Commander J. H. Owen, R.N., has helped me in naval matters. I again renew my thanks to all those who have so kindly allowed me to reproduce pictures and portraits in their possession, and also to those who have placed original documents at my disposal. I make my acknowledgments in every case. I also record my thanks to the present Duke of Marlborough for continuing to me all that freedom of the Blenheim archives without which my task could neither have been begun nor pursued.

WINSTON SPENCER CHURCHILL

Chartwell

Westerham

August 13, 1936

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Whig Approach | 19 |

| II. | Prince of Mindelheim | 37 |

| III. | The War in Spain | 55 |

| IV. | The Tottering Alliance | 69 |

| V. | Fortune’s Gift | 83 |

| VI. | The Battle of Ramillies | 102 |

| VII. | The Conquest of Belgium | 130 |

| VIII. | The Reverse of the Medal | 151 |

| IX. | Madrid and Turin | 172 |

| X. | The Year of Victory | 196 |

| XI. | Sunderland’s Appointment | 215 |

| XII. | Marlborough and Charles XII | 241 |

| XIII. | Almanza and Stollhofen | 257 |

| XIV. | Toulon | 274 |

| XV. | Marlborough in Trammels | 291 |

| XVI. | Abigail | 311 |

| XVII. | The Fall of Harley | 334 |

| XVIII. | The Jacobite Raid | 359 |

| XIX. | Eugene Comes North | 373 |

| XX. | The Surprise of Ghent and Bruges | 388 |

| XXI. | The Battle of Oudenarde | 404 |

| XXII. | The Morrow of Success | 433 |

| XXIII. | The Thwarted Invasion | 446 |

| XXIV. | The Home Front | 463 |

| XXV. | The Siege of Lille | 483 |

| XXVI. | Wynendael | 502 |

| XXVII. | The Winter Struggle | 520 |

| XXVIII. | Culmination | 538 |

| Bibliography | 557 | |

| Index | 561 |

| PLATES | |

| PAGE | |

| Marlborough | Frontispiece |

| Admiral Sir George Rooke | 22 |

| John, Lord Somers | 36 |

| Charles Mordaunt, Third Earl of Peterborough | 58 |

| The Emperor Joseph I | 68 |

| Sicco van Goslinga | 104 |

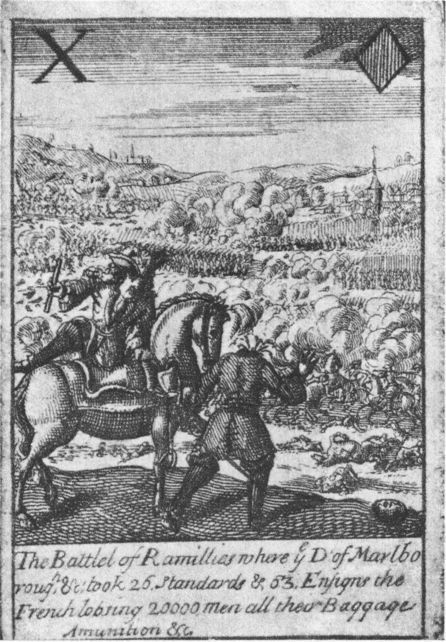

| The Ramillies Playing-card | 120 |

| Charles Montagu, Earl of Halifax | 168 |

| Sidney, Earl of Godolphin | 218 |

| Charles XII | 248 |

| Sir Cloudesley Shovell | 274 |

| Abigail Hill, Lady Masham | 316 |

| Matthew Prior | 328 |

| Admiral George Churchill | 336 |

| Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford | 350 |

| George Lewis, Elector of Hanover | 376 |

| Prince Eugene of Savoy | 384 |

| Tapestry of the Battle of Oudenarde | 408 |

| Colonel William Cadogan | 416 |

| Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, in 1708 | 478 |

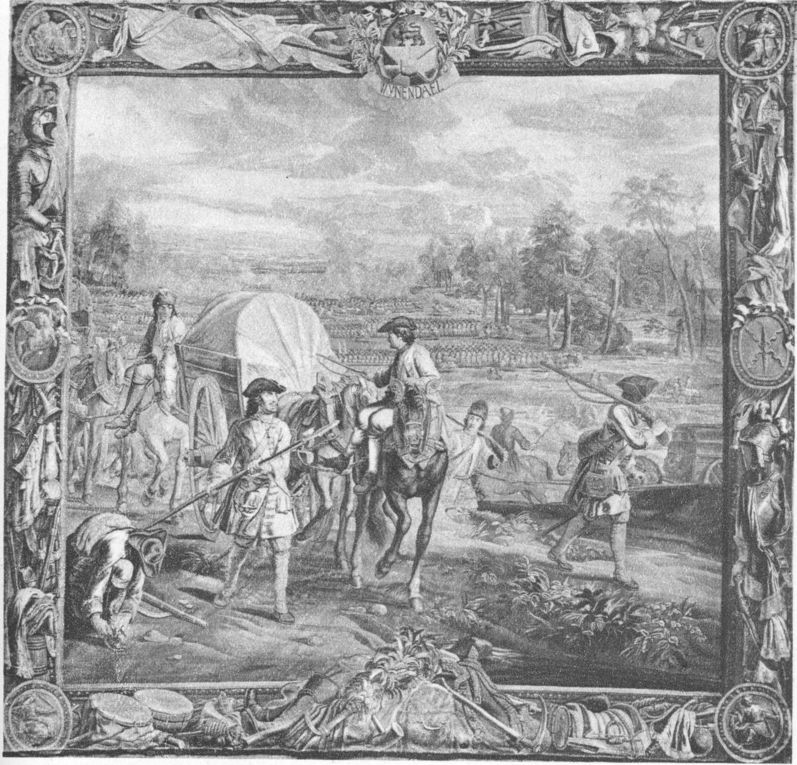

| Tapestry of the Action of Wynendael | 512 |

| General Overkirk | 518 |

| General James Stanhope | 534 |

| Prince George of Denmark | 544 |

| FACSIMILES OF LETTERS | |

| PAGE | |

| The Ramillies Letter | 134 |

| The Minorca Postscript | 446 |

| MAPS AND PLANS | |

| PAGE | |

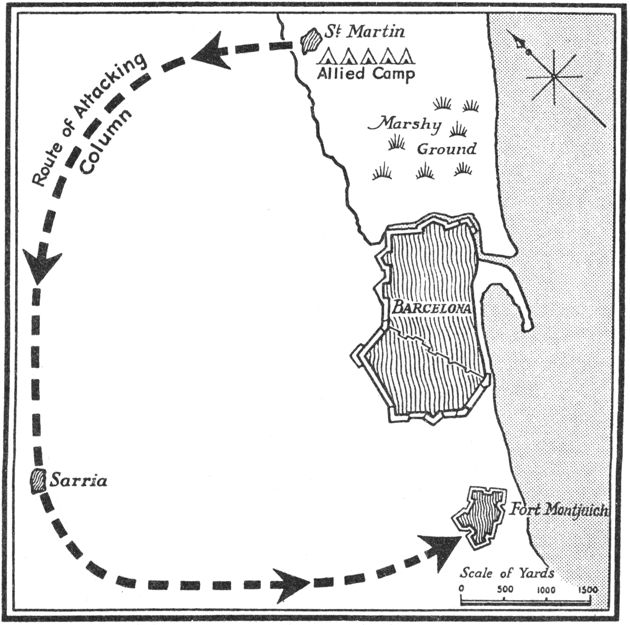

| The Capture of Barcelona | 63 |

| The Descent | 85 |

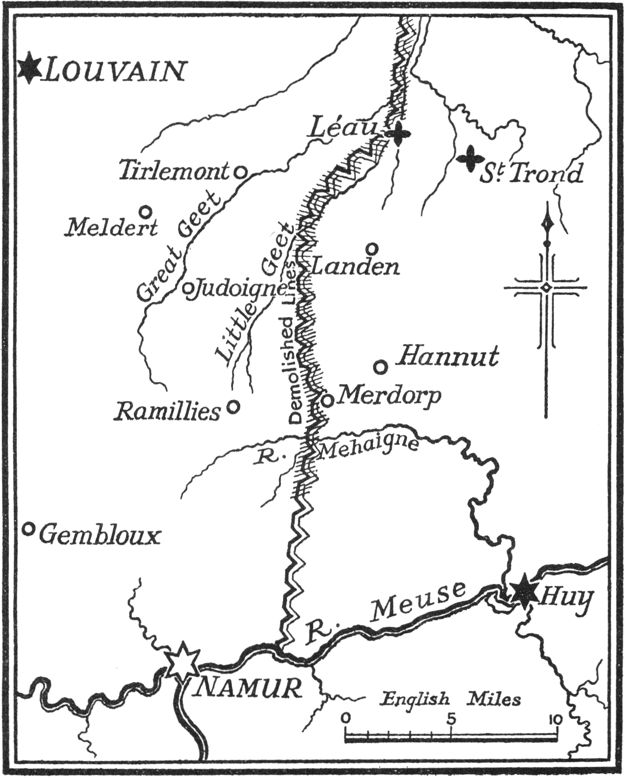

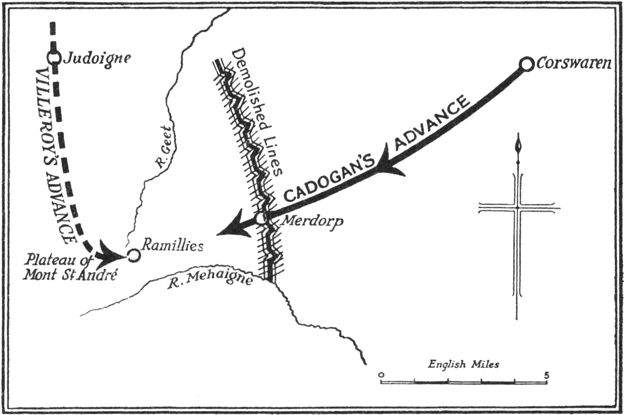

| The Northern Front (May 1706) | 96 |

| Villeroy’s Opening | 97 |

| Contact | 103 |

| The Horns | 107 |

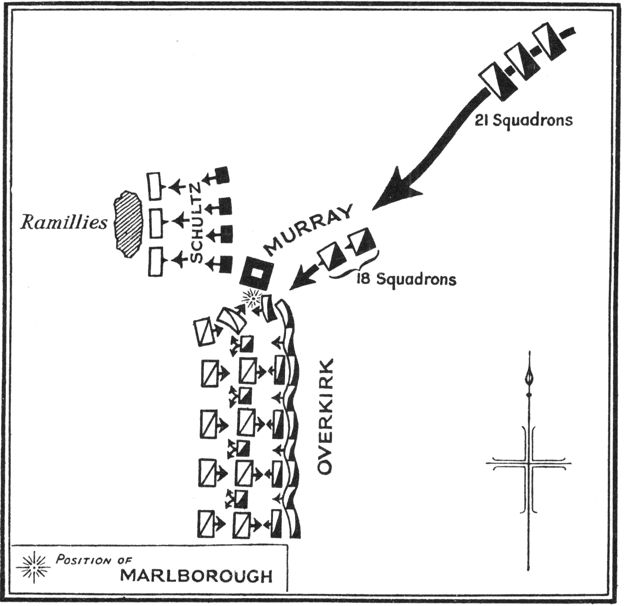

| The British Attack | 109 |

| The Combat by Taviers | 111 |

| The General Engagement | 114 |

| The Cavalry Battle | 115 |

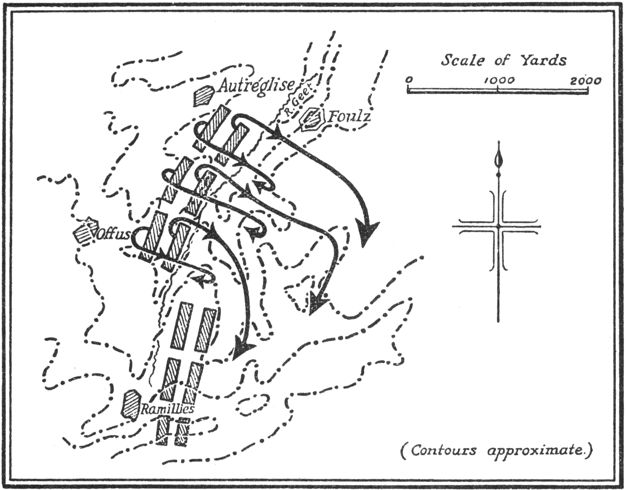

| Marlborough’s Intervention | 119 |

| Orkney’s Withdrawal | 121 |

| The New Front | 125 |

| The Pursuit | 127 |

| Contemporary Battle-plan of Ramillies | 128 |

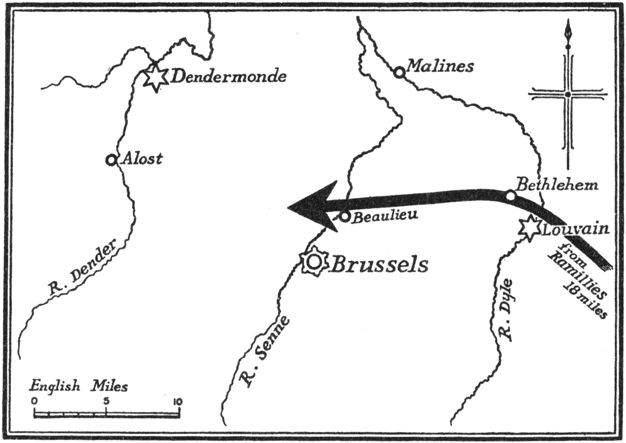

| The Direct Pursuit after Ramillies | 131 |

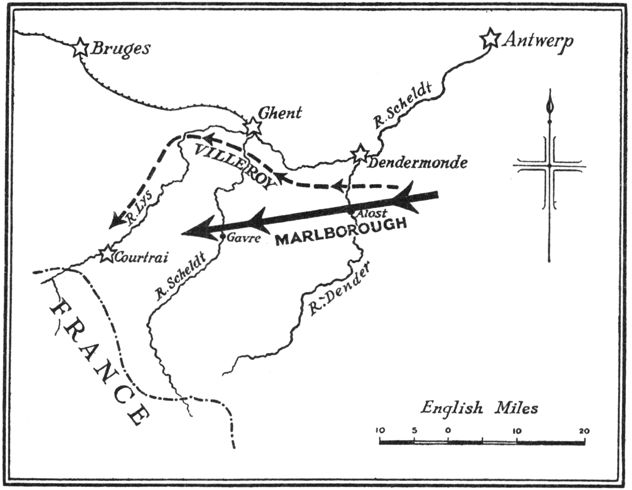

| Marlborough threatens Villeroy’s Communications (May 30) | 134 |

| The Capture of Madrid | 175 |

| Italy (May 1706) | 182 |

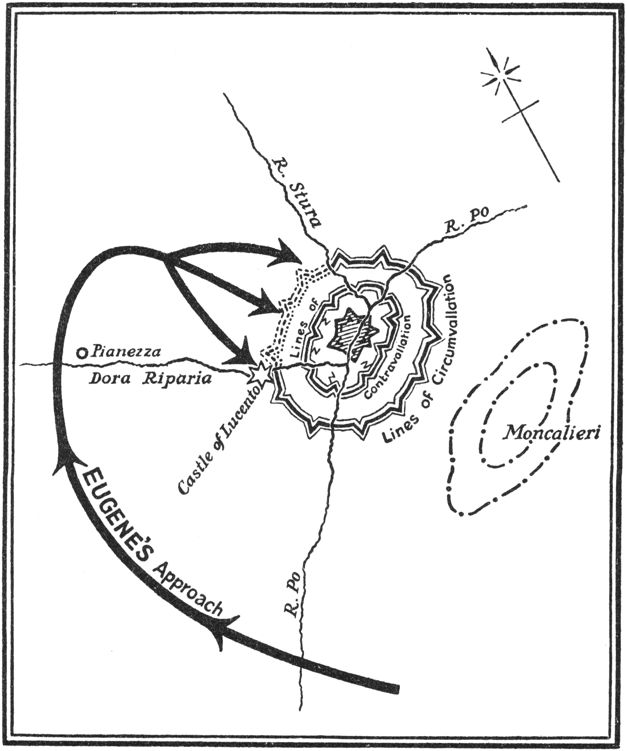

| Eugene’s March | 188, 189 |

| The Battle of Turin | 191 |

| The French Retreat from Italy | 193 |

| Flanders (July 1706) | 197 |

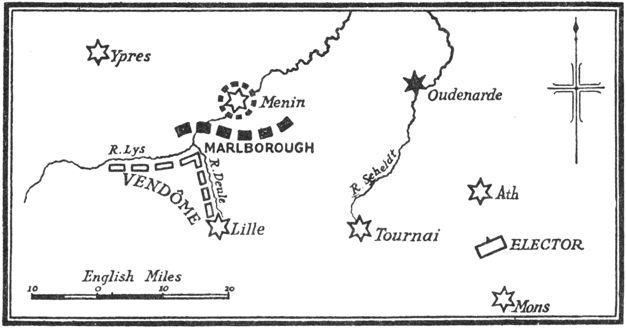

| The Siege of Menin | 200 |

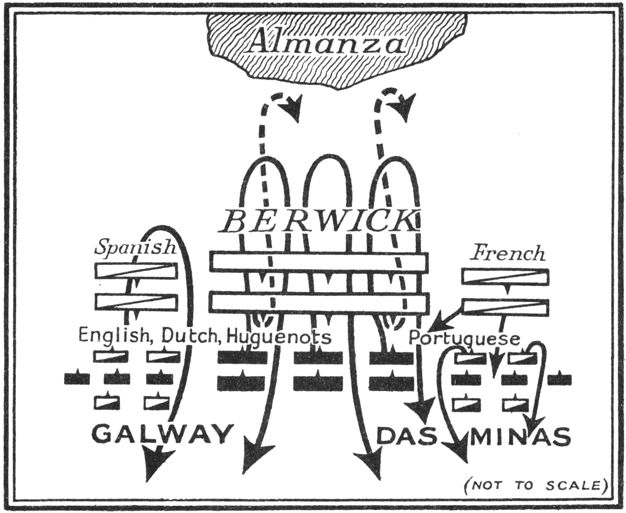

| The Battle of Almanza | 260 |

| May 1707 | 266 |

| Movements, May 23-26 | 267 |

| The Lines of Stollhofen | 271 |

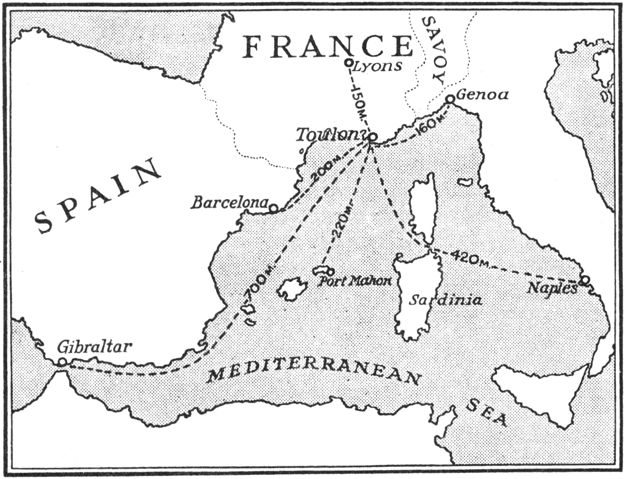

| Strategic Situation of Toulon | 275 |

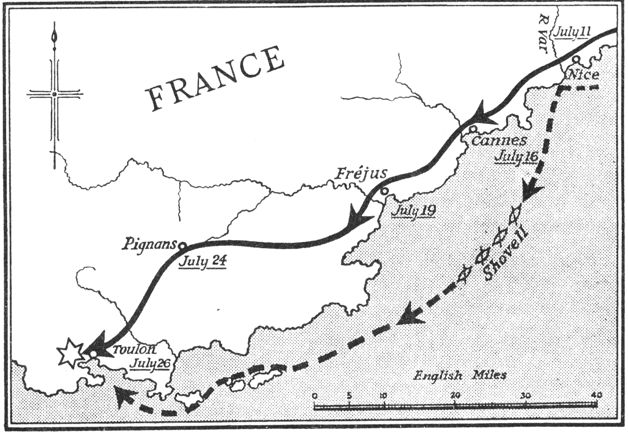

| Eugene’s March to Toulon (I) | 280 |

| Eugene’s March to Toulon (II) | 283 |

| The Siege of Toulon | 287 |

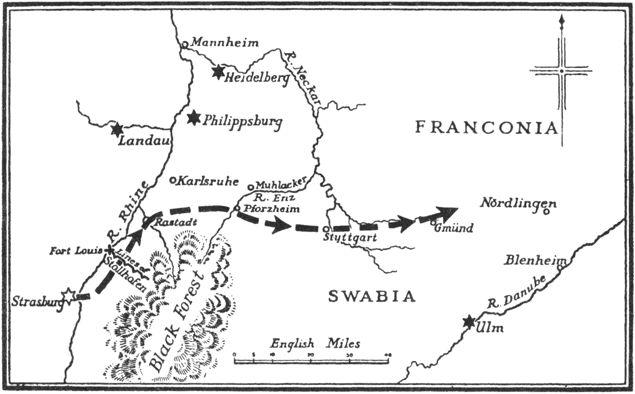

| Villars’s Invasion of Germany | 293 |

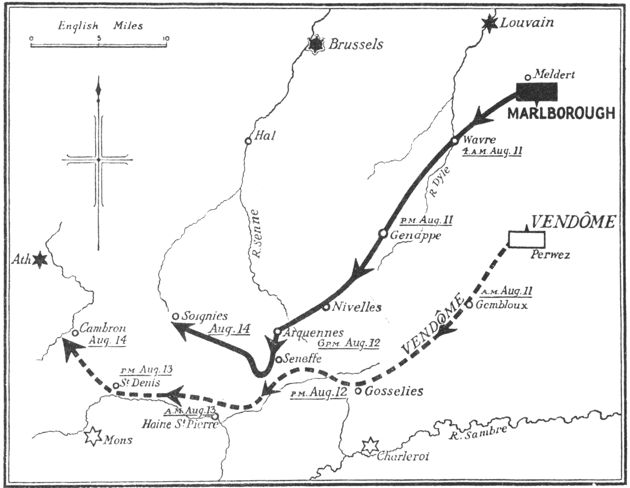

| August 11-14, 1707 | 303 |

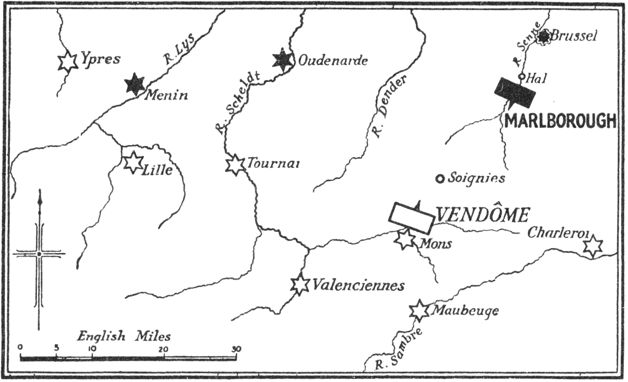

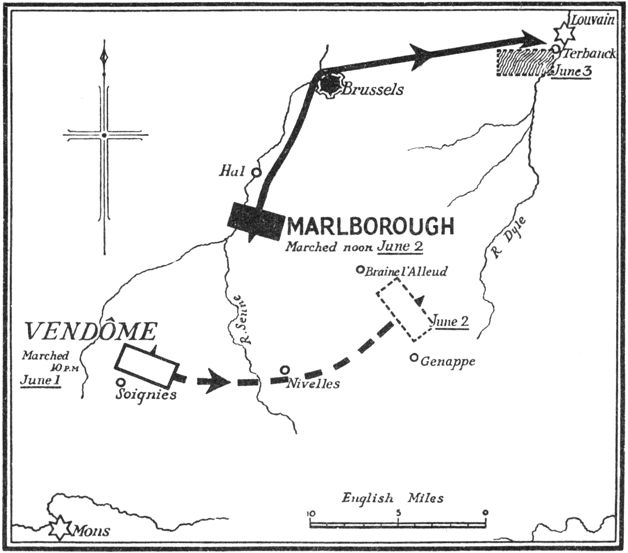

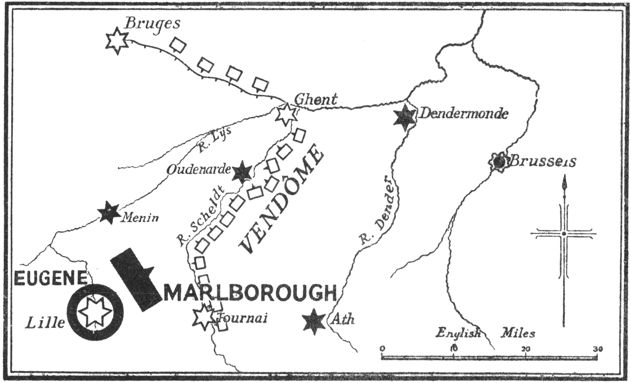

| Vendôme’s Choices (May 1708) | 381 |

| Movements in the First Week of June 1708 | 382 |

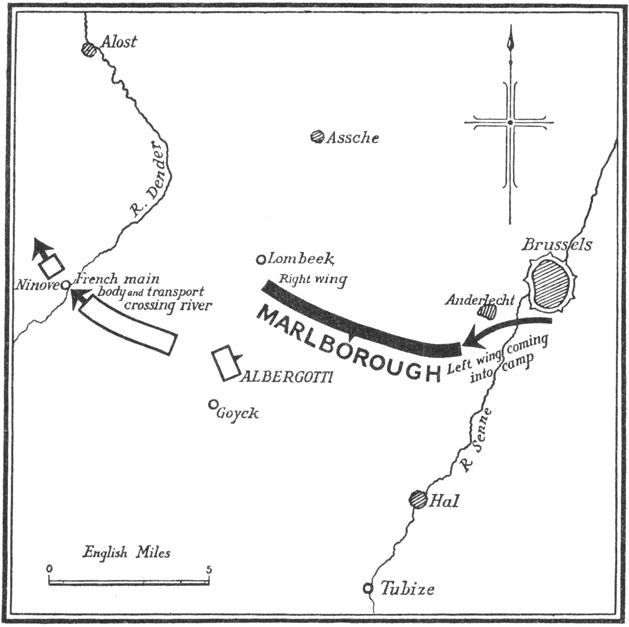

| Burgundy’s March | 389 |

| Evening of July 5, 1708 | 391 |

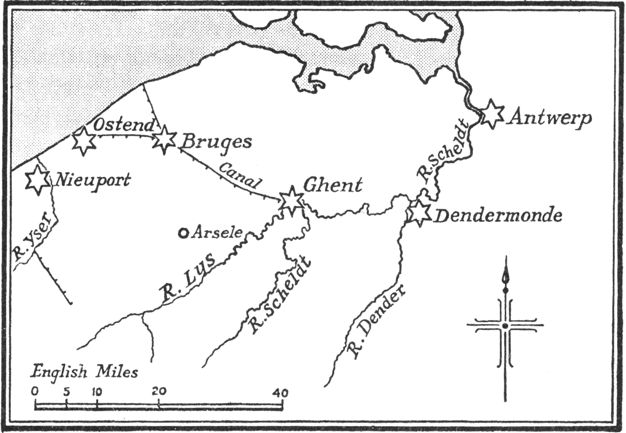

| French Control of the Waterways | 395 |

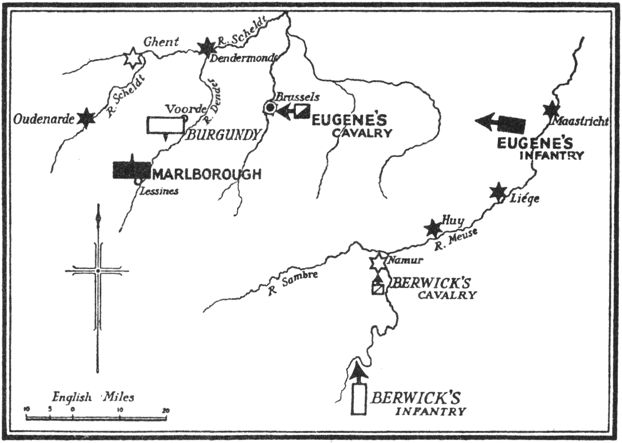

| The Main Armies (July 10, 1708) | 401 |

| General Situation (July 10, 1708) | 403 |

| Situation, Daybreak July 10 | 405 |

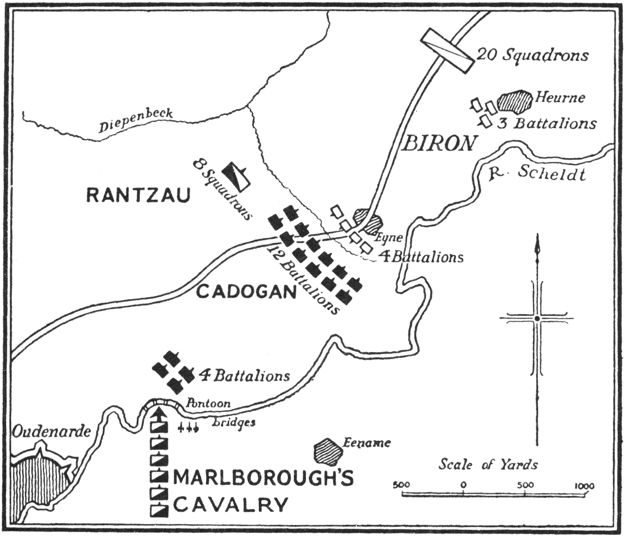

| Biron’s Discovery | 409 |

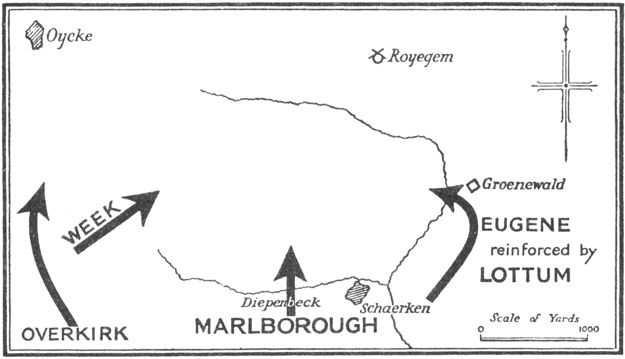

| Cadogan’s Attack, 3 p.m. | 412 |

| Rantzau’s Charge | 414 |

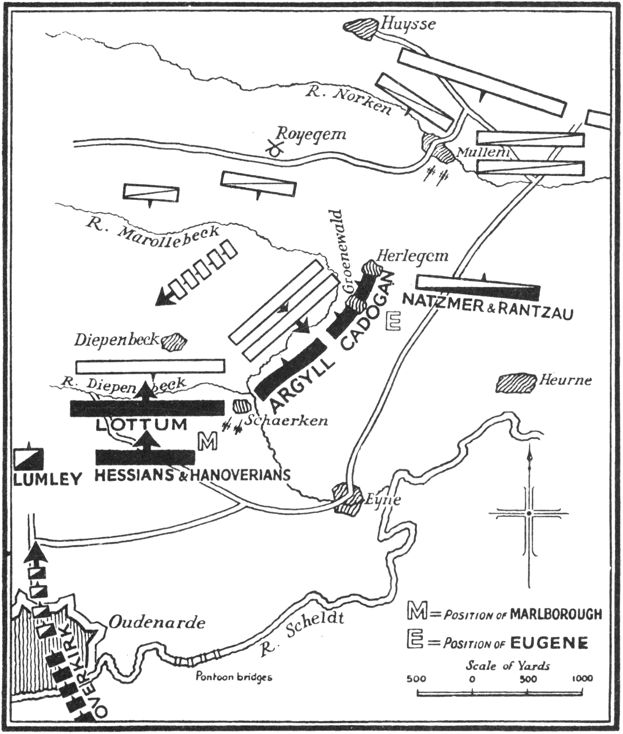

| Oudenarde, 5 p.m. | 417 |

| Oudenarde, 6 p.m. | 421 |

| The Encirclement | 423 |

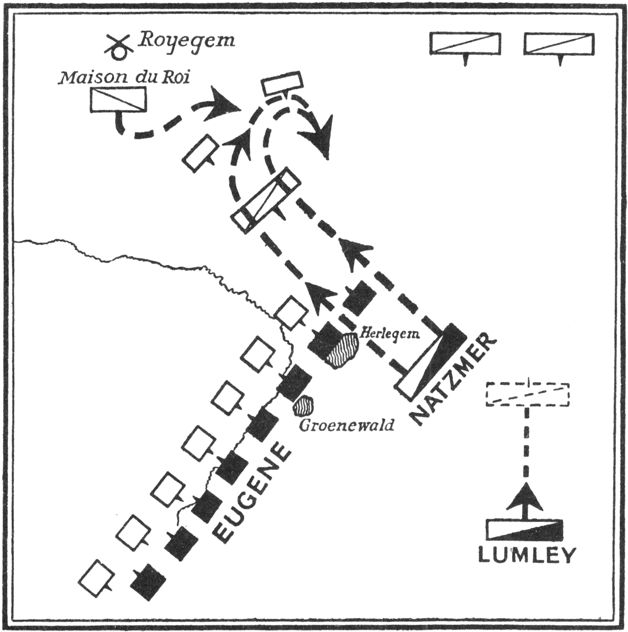

| Natzmer’s Charge | 425 |

| 8.30 p.m.: The Net Closes | 427 |

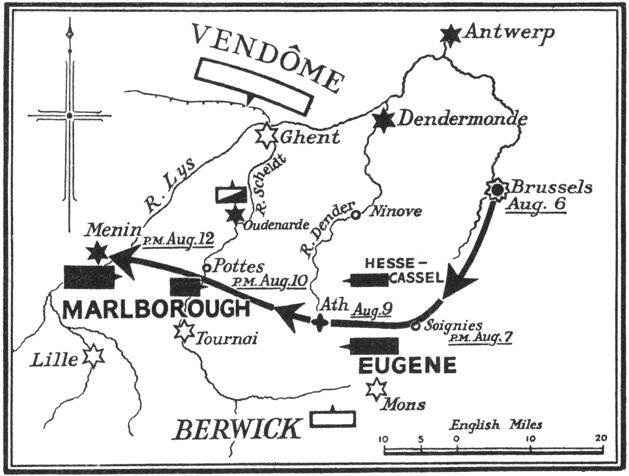

| The Battle of Oudenarde | 432 |

| Alternative Courses after Oudenarde | 435 |

| The First Convoy | 451 |

| The Thwarted Invasion | 453 |

| The Great Convoy | 461 |

| August 27-September 5, 1708 | 492 |

| September 5, 1708 | 493 |

| Vendôme cuts the Allied Communications | 503 |

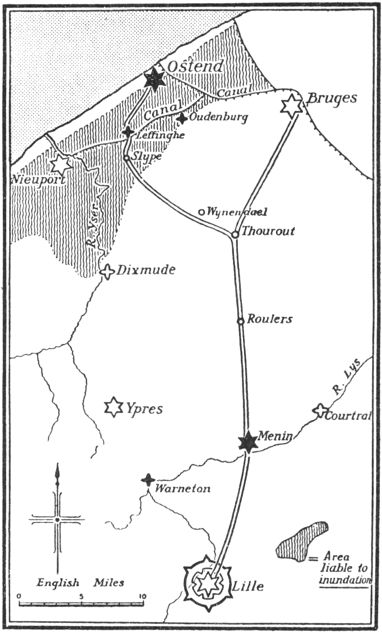

| Communications, Ostend-Lille | 505 |

| Situation, Morning, September 28 | 509 |

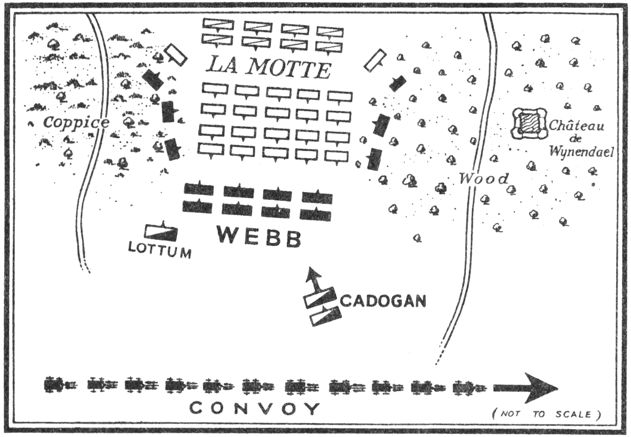

| The Action of Wynendael | 511 |

| October 7, 1708 | 515 |

| Marlborough forces the Scheldt | 525 |

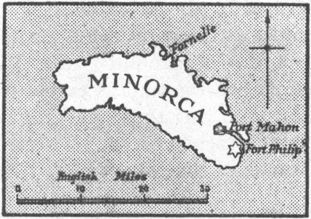

| Minorca | 535 |

| General Map of the Western Netherlands | 556 |

| General Map of Spain | 556 |

| General Map of Europe | 556 |

B.M. = British Museum Library.

H.M.C. = Report of the Royal Historical Manuscripts Commission.

Documents never before made public are distinguished by an asterisk (*) and left for the most part in their original form.

All italics are the Author’s, unless the contrary is stated.

In the diagrams, except where otherwise stated, fortresses held by the Allies are shown as black stars and those occupied by the French as white stars.

Until 1752 dates in England and on the Continent differed owing to our delay in adopting the Reformed Calendar of Gregory XIII. The dates which prevailed in England were known as Old Style, those abroad as New Style. In the seventeenth century the difference was ten days, in the eighteenth century eleven days. For example, January 1, 1601 (O.S.), was January 11, 1601 (N.S.), and January 1, 1701 (O.S.), was January 12, 1701 (N.S.).

The method used has been to give all dates of events that occurred in England in the Old Style, and of events that occurred abroad in New Style. Letters and papers are dated in the New Style unless they were actually written in England. In sea battles and a few other convenient cases the dates are given in both styles.

It was also customary at this time—at any rate, in English official documents—to date the year as beginning on Lady Day, March 25. What we should call January 1, 1700, was then called January 1, 1699, and so on for all days up to March 25, when 1700 began. This has been a fertile source of confusion. In this book all dates between January 1 and March 25 have been made to conform to the modern practice.

References in the text to pages in preceding volumes of MARLBOROUGH apply to the English edition. The following list gives the correct references to the American edition:

Page 9, line 7 from foot: for Vol. II, read Vol. III.

Page 43, footnote: for Vol. I, p. 463, read Vol. II, p. 162.

Page 57, footnote: for Vol. I, p. 463, read Vol. II, p. 162.

Page 57, footnote: for Vol. II, p. 217, read Vol. III, p. 217.

Page 69, footnote: for Vol. II, p. 569, read Vol. IV, p. 219.

Page 96. footnote: for Vol. II, pp. 568, 596, 604, read Vol. IV, pp. 218, 246, 254.

Page 98, footnote: for Vol. II, pp. 240-242, read Vol. III, pp. 240-242.

Page 99, footnote: for Vol. II, p. 423, read Vol. IV, p. 73.

Page 153, footnote: for Vol. II, pp. 251, 252, read Vol. III, pp. 251, 252.

Page 258, footnote: for Vol. II, pp. 555-559, read Vol. IV, pp. 205-209.

Page 316, footnote: for Vol. I, pp. 496-498, read Vol. II, pp. 195-197.

Page 337, footnote: for Vol. II, p. 118, read Vol. III, p. 118.

Page 436, footnote: for Vol. II, p. 301, read Vol. III, p. 301.

Page 469, footnote: for Vol. II, p. 38, read Vol. III, p. 38.

Page 559, Section IV, line 9: for Vol. II, p. 610, read Vol. IV, p. 260.

The General Election which began in May 1705 produced changes in English politics which at first seemed only slight and beneficial, but which set in train events of decisive importance to Marlborough and his fortunes. The Captain-General was capable of enduring endless vexations and outfacing extreme hazards. But he had one sensitive spot. In the armour of leather and steel by which in public affairs he was encased there was a chink into which a bodkin could be plunged. He sought not only glory but appreciation. When according to his judgment he had done well he yearned for the praise of his fellow-countrymen, and especially of those Tory squires—‘the gentlemen of England,’ as they styled themselves—to whom he naturally belonged, but with whom he was ever at variance. They were the audience whose applauses he sought to compel; and when instead of admiration he received their sneers and belittlings his indignation was profound. “Blenheim indeed!” quoth they. “What was that? A stroke of luck, and the rest the professional knowledge of Eugene.” Rooke was the man and the sea war the theme. The campaign of 1705, was it not a failure? All this Continental exertion and expense were follies which should be stopped. How much longer must the blood and treasure of England be consumed in European struggles while rich booty glittered neglected across the oceans and the Church was in danger at home? Thus the Tories. On the other hand stood the Whigs, logical, precise, resolute, the wholehearted exponents of the great war on land and of England rising to the directing summit of the world.

Sarah, as we can judge from John’s replies, must have confronted him with this contrast in many a letter. She saw, with a woman’s unsentimental discernment, that his illusions about the Tories were vain. They would ever be his foes, and would in the end work his ruin. Her hatred of them ran bitter and strong. With deft hand she picked and shot at him the Tory taunts that would sting him most; and others no doubt wrote in the same strain. Usually the Duke was proof against all minor assaults; but when the Moselle campaign was ruined by the desertion of the German princes and his fine conceptions in Brabant were one after another frustrated by the obstinacy and jealousy of the Dutch commanders, many shafts got home, and he palpably winced under the pangs.

The Parliamentary manœuvre of the Tories in trying to ‘tack’ the Occasional Conformity Bill to the main supply of the year was undoubtedly a breach of the solemn unwritten convention by which Whigs and Tories were alike bound—that, however party strife might rage, the national war effort must not be weakened. Reluctantly but remorselessly during 1705 Marlborough took the resolve to break with the Tories. His resentment burned through his letters to Godolphin from the front:

April 14

As to what you say of the tackers, I think the answer and method that should be taken is what is practised in all armies—that is, if the enemy give no quarter, they should have none given to them.[1]

And on June 24:

I beg you will give my humble duty to the Queen, and assure her that nothing but my gratitude to her could oblige me to serve her after the disappointments I have met with in Germany, for nothing has been performed that was promised; and to add to this they write to me from England that the tackers and all their friends are glad of the disappointments I meet with, saying that if I had success this year like the last the Constitution of England would be ruined. As I have no other ambition but that of serving well her Majesty, and being thought what I am, a good Englishman, this vile, enormous faction of theirs vexes me so much that I hope the Queen will after this campaign give me leave to retire and end my days in praying for her prosperity and making my own peace with God. . . . I beg you will not oppose this, thinking it may proceed at this time from the spleen; I do assure you it does not, but is from the base ingratitude of my countrymen. . . .[2]

Even before the scandal of the ‘tack,’ not only Marlborough and Godolphin but Harley too seem to have made up their minds to lean upon the Whigs, as Sarah ceaselessly urged. The first sign of this was Marlborough’s willingness in the spring of 1705 to demand the Privy Seal from the Duke of Buckingham, whose intrigues with the Tory leaders had become obvious. This might have seemed a delicate matter; for Buckingham had romantic, if faded, claims upon the Queen’s favour. He had been her first and sole flirtation. He was her personal appointment. Anne, however, seems to have made little difficulty about this. He was succeeded by the Duke of Newcastle, possibly the richest man in England and, though not a Junto stalwart, the fountain of Whig hospitality. On the night of March 28, 1705, when Buckingham retired, Portland (King William’s favourite and friend Bentinck, now become one of the most important sources of information on London affairs to the Dutch Government) wrote exultingly to Heinsius, “The liaison is thoroughly effective between the Whigs and 22 and 23 [Marlborough and Godolphin].”[3] A more significant step was the supersession of Admiral Rooke in the command of the Fleet. This ran directly counter to the resolution which the Tories had carried in the Commons, coupling his victory of Malaga with that of Blenheim, and may well have been the royal and ministerial rejoinder to it. Indeed, Harley’s agent Defoe described Rooke in one of his pamphlets in these blistering terms:

A man that never once fought since he was admiral: that always embraced the party that opposed the Government, and has constantly favoured, preferred, and kept company with the high furious Jacobite party, and has filled the Fleet with them.[4]

At the beginning of April the Lord-Lieutenancies, so important in elections, were shuffled in favour of the Whigs. On April 7, two days after the dissolution, political society was astonished to see the Queen sit down to luncheon with Orford (Admiral Russell) and other Lords of the Junto.[5] These steps showed, and were meant to show, the electorate which way the royal favour inclined.

Yet it is remarkable with what restraint Marlborough and Godolphin tried to measure the blow which must now be struck. There was no sense in weakening the Tories only to fall into the hands of the Whigs. Enough force must be used to beat them, but not so much as to produce a Whig triumph; for then the balance would be deranged, and the two super-Ministers and the Queen would but have exchanged the wrong-headed grumblings and intrigues of the Tories for the exacting appetites and formulas of the Whigs. Marlborough wrote to Sarah from The Hague (April 19/30):

[Neither] You nor anybody living can wish more for the having a good Parliament than I do, but we may differ in our notions. I will own to you very freely mine; which is, that I think at this time it is for the Queen’s service, and the good of England, that the choice might be such as that neither party might have a great majority, so that her Majesty might be able to influence what might be good for the common interest.[6]

Such sentiments were, of course, agreeable to the Queen. Thus the Cockpit circle, still intact, embarked upon the election with a desire to chastise the Tories, but not too much, and to procure a Parliament in which, the Whigs and Tories being equally matched, the “Queen’s servants,” as the placemen were called, and the moderates would hold the balance.

Such nicely calculated plans rarely stand the rough tests of action. The rank and file cannot fight hard to win only half a victory; and once the party forces were launched to the attack they strove with might and main. Everywhere the Tories proclaimed the Church in danger. Sir John Pakington rode to the hustings of Worcester under a banner which portrayed a toppling steeple. The highflying Tories were furious at what they called the Queen’s desertion of the Church, which they epitomized thus:

When Anna was the Church’s daughter,

She did whate’er that mother taught her;

But now she’s mother to the Church

She leaves her daughter in the lurch.[7]

ADMIRAL SIR GEORGE ROOKE

Michael Dahl

By permission of David Minlore, Esq.

A pamphlet called The Memorial of the Church of England, by Dr Drake, attributed this desertion of the Church to Marlborough and Godolphin. Everywhere the Tories railed against the expense of the Continental war and denounced the meanness of Britain’s allies and the mistakes of her leaders on the Continent and at the Admiralty. The oppressive land-tax upon the country gentlemen and the growing National Debt were contrasted with the fat profits of the upstart financiers and money interest of the City of London. Lust for war by those whom the war paid, and greed for self-advancement by those whose hypocritical conformity exposed the Church to mortal peril, were the Tory accusations.

To modern eyes this would seem a good platform. It marshalled all the prejudices of the Old England against the fighting effort of the New. But the vision of the English people was not clouded. Out of the brawl and clatter of the polls one dominating fact emerged—the battle of Blenheim. From the depth of the national heart surged up a glow of pride and of desire for British greatness. Mighty France, four times as populous, the Grand Monarch, tyrant of Europe in all his splendour, cut to the ground by island blades and English genius; his proudest regiments led off captive in thousands by the redcoats, his generals and nobles brought home in droves and tethered about the countryside; conquest, glory, the world to win and the man to win it—these scenes and thoughts stirred the English imagination.

Thus, although the Tories, both Tackers and Sneakers, as they called one another, fought with deep-rooted local strength, it was apparent by the beginning of July that the voting would carry their defeat beyond the calculations of the Ministry. Godolphin succeeded in breaking Sir Edward Seymour’s ascendancy in Cornwall. Cadogan was easily elected through Marlborough’s influence for Woodstock. The Tackers, indeed, though they suffered heavily, and all their names were on a special black list, returned seventy-five or eighty strong out of a hundred and thirty-four. But a good many moderate Tories fell, and the Whig Party gained at the expense of both. They had been but one-fifth of the old House of Commons. They were now nearly equal to the Tories. Hitherto, with their ascendancy in the House of Lords, they had been able to maintain themselves vigorously in the State. Now, with the Commons so much more evenly divided, their predominance became apparent. If they joined with the extreme Tories in a general opposition the new House of Commons would be unmanageable. If they supported the Government what price would they ask in return? This now became the crux.

The Queen scented the danger at once. To Godolphin, on the other hand, it seemed obvious that the Ministry would have to depend on Whig support. Marlborough, impressed by the toughness of the Tackers, was of the same opinion.

Marlborough to Godolphin

Lens les Béguines

July 6, 1705

* Upon my examining the list you sent me of the New Parl: I find so great a number of Tackers and their adherents that I should have been very uneasy in my own mind, if I had not on this occasion begged of the Queen as I have in my letter, that She shou’d be pleas’d for Her own Sake, and the good of Her Kingdom to advise early with You, what incoragement might be proper to give the Whigs, that they might look upon it as their own Concern, to beat down and oppose all such proposals as may prove uneasy to Her Maty’s government. . . . When I have said this, You know my opinion, and I am sure it is yours also, that all the Care imaginable must be taken that the Queen be not in the hands of any Party, for Party is always unreasonable and unjust.[8]

He wrote in this sense more at length to the Queen ten days later, adding at the end:

By the vexation and trouble I undergo I find a daily decay, which may deprive me of the honour of seeing your Majesty any more, which thought makes me take the liberty to beg of your Majesty that for your own sake and the happiness of your kingdoms you will never suffer any body to do Lord Treasurer an ill office. For besides his integrity for your service, his temper and abilities are such that he is the only man in England capable of giving such advice as may keep you out of the hands of both parties, which may at last make you happy, if quietness can be had in a country where there is so much faction.[9]

The Lords of the Junto surveyed the scene on the morrow of the elections with cool and determined eyes. They might well have been tempted to claim their rights with the same pedantic rigour with which they held their doctrines. Their turn, they felt, was coming. Why should not the war party wage the war? They had the strength, they had the talents, they had the experience, they had the Cause—why should they be proscribed? Why, indeed, should they not have the Government? Their wishes were no more than the workings of the Constitution would nowadays automatically concede. But at the beginning of the eighteenth century the Crown was still the prime factor in actual politics. The Queen might not be able to choose the policy of the State, but she could still choose the agents to conduct it. To entrust her beloved Church to the freethinking Whigs and their Dissenter supporters, to surround her person with men who in their hearts, as she believed, were the inveterate enemies of monarchy, to part with faithful Tory Ministers and household friends under Parliamentary pressure, was all against the grain to her.

The conflicts and disputations between Lords and Commons which had lasted since 1698 were now ended by Whig control and influence in both Houses. But in its place there opened a wearing struggle in which the Whigs, using all the resources and pressures of Parliamentary government, sought to force themselves upon the Queen. The Tory Party was splintered into four sections: the Jacobites, who claimed to be the only true exponents of the Tory creed; the anti-Jacobite Tories, generically dubbed the Sneakers, or more courteously “the Whimsicals”; the Tackers, whose embittered opposition was led by Rochester and Nottingham and found a new and eloquent mouthpiece in the converted Whig, Haversham; and the placemen, the “Queen’s Servants” and independent moderate forces who followed Harley and St John, deferred to the Court, and sustained the Government. Although the whole party had an underlying sense of unity, and felt alike on many questions of peace and war, they were for the time paralysed by their feuds. Indeed, in the Commons they could not find a single man of sufficient distinction and aptitude to be their leader. Their opposition was effectively vocal only in the Lords. Yet, resting as they claimed upon the Land and the Church, commanding as they did the support of the squires and parsons, they constituted the strongest political force in the realm. If at any moment Tory divisions were healed, their inherent power would assert itself.

The five Whig nobles, on the other hand, had the advantages of unity and leadership. They controlled a disciplined party, inspired by broad and logical principles, which in its most active branches, interests, and classes accepted their guidance with almost military obedience. Long and frequent were the conclaves of the Junto in their great country houses. They knew well the prejudices of the Queen against them. They acted at first with the utmost moderation and with admirable adroitness. They decided to put forward Sunderland, their youngest member—the only one who had not held high office under King William—as their candidate for official favour. Sarah, as usual, was ardent in their cause. Her influence both with the Queen and with her husband was regarded as irresistible. How could that influence be more easily and more naturally exerted than in pressing the claims of her own son-in-law? Sunderland would be the thin end of their wedge. Behind it were the sledgehammers of action in both Houses of Parliament.

The impact of all this fell, as the months passed, upon Godolphin. He had to procure a Parliamentary majority to carry on the war. From this there was no escape. It must be there, on the benches and in the lobbies of both Houses, from day to day. Without it there would be no Supply, the armies would wither, the Grand Alliance would crumble, and the war would be lost. Since he had broken with the Tory Party and the Queen was increasingly reluctant to admit the Whigs in numbers, his task soon became arduous and ungrateful to the last degree. His days were spent in begging the Whig Junto to forbear and the Queen to concede. Marlborough understood perfectly that his colleague’s vexations and anxieties at Whitehall were scarcely less wearing than his own distresses and dangers in the field. His letters breathed a lively sympathy, and again and again he assured the Lord Treasurer that he would stand or fall with him.

The idea of sending Sunderland to Vienna upon the mission of mediation between the Emperor and the Hungarian insurgents seemed to Godolphin the least difficult expedient. It was the wedge at taper-point. The Queen, relieved at not having this obnoxious politician obtruded upon her Council, accepted his employment abroad as a compromise. After all, Sunderland was Mr and Mrs Freeman’s son-in-law, and surely for the sake of old friendship they would keep him in his place and out of her sight. Thus in June 1705 one of the Lords of the Junto, formally representing the power and interest of the Whigs, became an envoy of Queen Anne. This was a considerable event. A minor appointment of a young Whig Member named Walpole to the Admiralty Board attracted little notice. But further encroachments upon the Queen’s peace of mind were in store. Sir Nathan Wright, the Lord Keeper, a Tory, was well known to be incompetent. His knowledge of Chancery business was woefully defective, and his praiseworthy efforts to acquaint himself late in life with the great profession of which he was the head, by studying a manual of practice compiled for his own use, evoked no confidence among his friends, and mockery from his foes. On the other side stood Cowper, the Whig, with far higher abilities and credentials. As the time for the meeting of Parliament approached the Whigs demanded with bluntness that Cowper should be appointed Lord Keeper. Under this pressure and that of the Parliamentary situation Godolphin recommended the change to the Queen. Anne was greatly distressed. The office of Lord Keeper was intimately concerned with Church patronage. To admit Whig influence in this sacred preserve was more than she could bear. Her letter of July 11 to Godolphin is well known.

. . . I cannot help saying I wish very much that there may be a moderate Tory found for this employment. For I must own to you I dread falling into the hands of either party, and the Whigs have had so many favours shown to them of late that I fear a very few more will put me insensibly into their power, which is what I’m sure you would not have happen no more than I. I know my dear unkind friend [Sarah] has so good an opinion of all that party that to be sure she will use all her endeavour to get you to prevail with me to put one of them into this great post, and I cannot help being apprehensive that not only she but others may be desirous to have one of the heads of them [the Junto] in possession of the Seal. But I hope in God you will never think that reasonable, for that would be an unexpressible uneasiness and mortification to me. There is nobody I can rely upon but yourself to bring me out of all my difficulties, and I do put an entire confidence in you, not doubting but you will do all you can to keep me out of the power of the merciless men of both parties, and to that end make choice of one for Lord Keeper that will be the likeliest to prevent that danger.[10]

Against this resistance Sarah strained her influence in vain. Stiff letters passed. The Queen refused. In a personal letter (now lost) she appealed to Marlborough. Marlborough’s reply of September 29, from which we may infer its character, deeply disappointed her.

Sept. 19/Oct. 10, 1705

Your Majesty has too much goodness for your servant in but thinking of an excuse for your not writing. . . .

Not knowing when I may have the honour of seeing your Majesty, I cannot end this letter without lamenting your condition; for I am afraid I see too plainly that you will be obliged by the heat and malice of some that would not stay in your service, to do more than otherwise would be necessary. What I say is from my heart and soul for your service; and if I had the honour of being with you, I should beg on my knees that you would lose no time in knowing of my Lord Treasurer what is fit to be done, that you might be in a condition of carrying on the war and of opposing the extravagances of these mad people. If your Majesty should have difficulty of doing this, I see no remedy under heaven, but that of sending for Lord Rochester and Lord Nottingham, and let them take your business into their hands, the consequences of which are very much to be feared; for I think they have neither courage nor temper enough to serve your Majesty and the nation in this difficult time, nor have they any support in England but what they have from being thought violently at the head of a party, which will have the consequence of the other party opposing them with all their strength.

As I am sure your Majesty has no thoughts but what are for the good of England, so I have no doubt but God will bless and direct you to do what may be best for yourself and for Europe.[11]

On this the Queen yielded, and the Great Seal was transferred to Cowper on October 11.

It was inevitable that this long, unceasing, day-to-day friction should destroy the relations between Anne and Sarah. The Queen’s friend became no more than the advance agent of the Whig Party, so ardent for tangible proofs of royal favour. She not only overrated her influence on public matters with the Queen, but she mistook its character. She sought to win by argument, voluble and vociferous, written and interminable, what had hitherto been the freehold property of love. She undertook to plead every Whig demand with her mistress. For Sunderland, her son-in-law—that might be understood. There the Queen could suppose a personal desire which in old friendship she still wished to meet. But the acceptance of a Whig Lord Keeper, guardian of the Queen’s conscience, adviser upon the Church patronage, seemed to Queen Anne not a matter for the judgment of her favourite and confidante. As for all the propaganda of Whiggery of which Sarah made herself the advocate, this only encountered an obstinacy, and in the end wore out a patience, which in conjunction were unique.

The result of the elections and its effect upon the Government manifested themselves as soon as Parliament met on October 25, and the House of Commons proceeded to choose a Speaker. The Tories put forward the pious ‘tacker’ Bromley, Member for Oxford University, long identified with the Occasional Conformity Bill. The Whigs found a respectable figure in a certain John Smith. The attendance was enormous for those days of difficult travel. Out of 513 Members 454 were in their places. It soon became evident that the Ministry would support Smith. Sir Edward Seymour, now desperately ill, could think of no better argument against him than that, being a Privy Councillor, he was ineligible for the Speakership. On this Harley was able to make a rejoinder which must have been effective. Seymour himself, he recalled, had been Speaker and Privy Councillor at the same time in the reign of Charles II. Smith was elected by 249 votes to 205 for Bromley. The majority of 44 did not represent the full combined strength of the Whigs and the Government. A number of Tory placemen were either genuinely unable to believe that the Court wished a Whig Speaker to be chosen, or else resented their instructions. They voted in the wrong lobby. They made haste, with many apologies for tardiness, to set their sails to the new breeze.

The Queen’s Speech dwelt upon the now familiar theme of Marlborough and Godolphin—“war abroad and peace at home.”

If the French king continues master of the Spanish monarchy, the balance of power in Europe is utterly destroyed, and he will be able in a short time to ingross the trade and the wealth of the world. No good Englishman [Marlborough’s phrase] could at any time be content to sit still, and acquiesce in such a prospect; and at this time we have good grounds to hope, that by the blessing of God upon our arms, and those of our allies, a good foundation is laid for restoring the monarchy of Spain to the house of Austria; the consequences of which will be not only safe and advantageous, but glorious for England.[12]

Such declarations went far beyond the original objects of the Grand Alliance, and proclaimed England’s direct interest in the most extreme form of victory. They confirmed the arguments and assurances which Marlborough had used to the Dutch a few weeks earlier in urging them to reject the peace overtures of France. War on the greatest scale with implacable spirit for the highest demands was the message. The second main appeal was for the union with Scotland. For these high purposes the Queen called for another union—a union of men’s spirits in England and the laying aside of party strife.

In every point except the last both Houses of Parliament cordially sustained the Sovereign. The addresses of the Lords and the Commons repeated the sentiments of the Queen’s Speech about the war in even stronger language. They overflowed with praise for the Queen’s person, her zeal for the Church, and her devotion to the harmony of her subjects. “We want words,” said the Commons, “to express the deep sense we have of the many blessings we enjoy under Your Majesty’s happy government.”[13] Although both addresses were tinctured with Whig censures against those whose wicked rumours that the Church was in danger had disturbed men’s minds, and thus acquired a partisan character, they were carried by large majorities. The Commons then proceeded to vote unprecedented supplies of money for the war, and to make large additions to the armed forces by land and sea.

The reactions of Whig pressure upon Godolphin affected Harley, and not only reveal the key to his future conduct, but form the true defence of his career. Harley knew the Tory Party alike in its temporary weakness and in its latent strength. He saw that it was his foundation in public life. He knew that his relations with the Queen were at this stage on an entirely different plane from those of the Cockpit circle. Godolphin and the Captain-General could perhaps, but only perhaps, afford to be careless of party attachments. That was their own affair. But Harley would never in any circumstances cut himself finally adrift from his Tory moorings. He might co-operate as an honoured colleague and as a real contributory force with a national Government such as the Queen and her two chief Ministers desired. He might even quarrel fiercely for the time being with the unreasonable elements of Toryism; but ever before his eyes there glinted the prospect of a Tory reunion at the head of which he would be no longer an agent, however indispensable, but the real, natural leader.

Therefore we find Harley from the very outset deprecating the Whig infusion. Large concessions must no doubt be made. As a House of Commons man and a master of that assembly, he recognized their practical necessity. He was prepared to give way step by step and month by month; but he meant it to be known both by the Queen and by the Tory opposition that he was a resisting force to Whig ambition. To the Queen the language he used was highly agreeable; indeed, it was her own. “Persons and parties must go to the Queen, not the Queen to them.” The Queen had chosen the Tory Party as her basis. There must be no party domination, certainly no Whig domination: “If the gentlemen of England [i.e., the Tory country gentlemen] are made sensible that the Queen is at the head and not a party [i.e., the Whig Party] everything will be easy, and the Queen will be courted, and not a party.”[14] In other words, Harley was prepared to serve in a national coalition provided it remained national; but he would not serve in a Whig Government veneered with Tory elements. Gradually, but at the same time decisively, Harley made this fact apparent to Godolphin and Marlborough. The differences which opened between the Lord Treasurer and the Secretary of State, though at present vague and veiled, were deep. Godolphin could never go back to the Tories: Harley had never left them. Godolphin was prepared to lean upon the Whigs and rule with their aid; Harley would never accept such a system. Godolphin sought always an effective, clear-cut majority upon which Marlborough could wage war triumphantly. Harley felt much more coolly about it all. The war would not go on for ever; it might even end disastrously. What would happen then? It was not his war. But it would be his Tory Party.

Nevertheless, at this stage the Whig assertion had not been pushed to such a pitch that he was seriously disturbed. On the contrary, he showed himself well disposed towards an accommodation with them. He soothed and reassured the Queen, who already found him expressing her instinctive thoughts, about the appointment of a Whig Lord Keeper. He was entirely favourable to the Sunderland mission. He it was who had tripped up Seymour in the Commons at the election of the Whig Speaker. In all this he served the Government, and at the same time made the Queen feel a certain measure of comradeship in the sacrifices which both must make for longer ends.

Their resentments now betrayed the Tory leaders into further acts of extreme unwisdom. Once again they tried by an insincere manœuvre to entangle the Whigs, and once again they were themselves upset. Their spokesman, Haversham, put forward in the Lords a proposal that, in order to ensure the Protestant succession, the Electress Sophia should be invited to take up her residence in England.[15] No one knew better than Rochester and Nottingham that this suggestion was insupportable to the Queen. Yet it seemed a plan for which no Whig could refuse to vote without repudiating the whole doctrines of his party. If the Whigs endorsed it, they made a new breach with the Queen. If they refused it, they falsified their principles, and staggered their party. Such was the plan upon which the Tories were led into the enemy’s lines masquerading in their uniforms.

This insidious form of attack naturally drew Godolphin, Harley, and the Whig lords into common consultation, and all were found equally desirous of pleasing the Queen. The political sagacity of the Junto and the discipline of their party enabled them easily to defeat the fantastic assault, and to turn it to their own advantage. They supported the Government in meeting Haversham’s motion with a plain negative. The Queen herself was encouraged to be present ‘incognito,’ as it was called, in the House of Lords during the debate. She heard the Tory orator putting forward the project most deeply repugnant to her. Buckingham, furious at his recent dismissal, wasted little sentiment. The Queen heard him at a few yards’ distance discuss the possibility of her soon being physically incapable of reigning. She heard the Whig debaters, whom she had so long regarded as her enemies, displaying all their brilliant gifts of argument and rhetoric upon her side. Never had the Whigs more nearly won the heart of Queen Anne than on this occasion. The motion was rejected by an overwhelming majority. The Queen returned to St James’s with the feeling that her lifelong friends had outraged her, and her lifelong foes had come to her rescue. How profoundly shaken she was alike in her faiths and her prejudices can be judged by the letter which she wrote to Sarah.

I believe dear Mrs Freeman and I shall not disagree as we have formerly done; for I am sensible of the services those people have done me that you have a good opinion of, and will countenance them, and am thoroughly convinced of the malice and insolence of them that you have always been speaking against.[16]

This royal mood might render possible the formation of a real national Government in which Harley and St John and many respectable Tories could work heartily with the Lords of the Junto, the whole under the auspices of Marlborough and Godolphin. Such a system would command ample Parliamentary strength for the vehement prosecution of the war. It was plain, however, that the Whig leaders could not rest upon the mere rejection of the disingenuous Tory proposal to bring the Electress Sophia into England. Had they done so they would have been disavowed by their party. They therefore in close accord with the Government brought forward their counter-plan for assuring the Hanoverian succession should the Queen die without a natural heir. This was the Regency Bill, by which upon the demise of the Crown a Council of Regency would automatically come into existence for the express purpose of placing the Hanoverian heir upon the throne. The Queen, in her relief from what she regarded as an odious proposal of the Tories, relegated into the background of unrealizable sentiment any compunction which she nursed about the “pretended Prince of Wales.” (“Maybe ’tis our brother.”[17]) She cordially welcomed the Regency Bill. It was carried without serious difficulty. The Whig leaders reassured their party, and the Tories lay like beetles on their backs.

At this time we must imagine the Tories, morose and chagrined by what they considered the unworthy defection not only of their own men, but of their own Queen, making every conceivable blunder, while the Whigs caracoled before the throne displaying their matchless skill in political equitation, and eager to persuade its occupant to make them her champions. One final exhibition remained. The Tories came forward with their cry, “The Church in danger.” Rochester, Nottingham, and the newly dismissed Buckingham set forth their threefold case. The Act of Security—which in that dark hour before the victory of Blenheim brought new life Godolphin had advised the Queen to sign—authorized the Presbyterian Government in Scotland to arm a fierce, fanatical anti-episcopalian peasantry. The Occasional Conformity Bill had been for three sessions handspiked. The invitation to the Electress Sophia had been rejected. Thus (moaned the Tories) Presbyterians and Dissenters had gained the upper hand both in England and in Scotland.

Anne again attended as an auditor, and sat impassive through eight hours of speeches, often directed at her. But neither the issue nor the ill-impression produced by the Tories upon the Queen was for a moment in doubt. Somers derided the Tory ex-Ministers. “Those lords who see the Church in danger take this view because they are excluded from office. They cannot, it seems, take their eyes off the danger, nor can the danger itself be removed until they are embraced in the Government, and an Act is passed to make their tenure of office eternal. But they are mortal: religion is immortal. The only final solution is to discover some means to make them immortal.”[18]

Upon this question of the danger to the Church and to the episcopacy the Bishops had a rightful say. King William’s bishops, still a majority, plumped for the Whigs and the Administration. By sixty-one votes to thirty the Lords declared that

the Church, which was rescued from the extremest danger by King William III, of glorious memory, is now, by God’s blessing, under the happy reign of her Majesty, in a most safe and flourishing condition; and whoever goes about to suggest and insinuate that the Church is in danger under her Majesty’s administration is an enemy to the Queen, the Church, and the Kingdom.[19]

The Commons at the request of the Lords made a similar declaration; and, the Queen assenting in cordial terms, it became a penal offence to speak of danger to the Church of England. Notwithstanding this threat, the country clergy and the fox-hunters continued to ingeminate their griefs with general impunity; and the pamphleteers were artful, virulent, hard to catch, and harder to convict.

JOHN, LORD SOMERS

Sir Godfrey Kneller

By permission of David Minlore, Esq.

|

Coxe, Memoirs of John, Duke of Marlborough (second edition, 1820), ii, 70. |

|

Coxe, ii, 127. |

|

Von Noorden, Europäische Geschichte im achtzehnten Jahrhundert (1870), ii, 248. |

|

Portland Papers, H.M.C., viii, 136. |

|

Dispatches of Spanheim (Prussian Resident in London), April 9, 1705; von Noorden, ii, 248. |

|

Coxe, ii, 232. |

|

Quoted by Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England, viii, 241. |

|

Blenheim MSS. |

|

Coxe, ii, 131. |

|

Godolphin Papers; Add. MSS. 28070, f. 12. |

|

Coxe, ii, 235. |

|

Parliamentary History of England (Hansard), edited by William Cobbett and J. Wright, vi (1810), 451. |

|

Ibid., vi, 455. |

|

Harley to Godolphin, September 4, 1705; Bath Papers, H.M.C., i, 75. |

|

Journals of the House of Lords, xviii, II, 19. |

|

Account of the Conduct of the Duchess of Marlborough (1742), p. 171. |

|

Vol. I, p. 272. |

|

Lords Debates, II, 161. |

|

Journals of the House of Lords, xviii, II, 43. |

The fruitless outcome of the campaign of 1705 in the Low Countries, the bitter controversies which it had aroused in all the camps, Courts, and Diets of Europe, and the revival of the French power on almost every front, might well have smitten Marlborough’s reputation on the Continent and in consequence impaired his strength. On the contrary, he emerged more obviously than ever before as the brain and impulse of the Grand Alliance. The victories which had been denied him in the field were to be gained during the winter by his personal influence in diplomacy. If the confederacy was to bear the strain of another year’s war its members must be regathered by a master-hand. There was but one, as all men could see. The island Power, which, though seemingly more detached from the struggle than its Continental allies, was making remarkable exertions, possessed in Marlborough an agent upon whom all eyes were turned, and to whose tent appeals from every quarter were addressed.

Once again the fortunes of the Alliance had ebbed.[20] Though the fame of Blenheim still resounded, its advantages had largely disappeared. The plight of the Empire, if not immediately desperate, seemed forlorn in the last degree. The Hungarian revolt had become monstrous. It dominated the life and swallowed the public revenues of four out of five of the hereditary provinces of the Austrian crown. It was the first call upon the Emperor’s men and money. The rebel leader, Rakoczy, bulked larger in the Emperor’s mind than Louis XIV. The Imperial armies on the Upper Rhine and in Italy were starved for the sake of the deadly intestine conflict. The failure of Marlborough’s design upon the Moselle and the lack of any victories in Brabant had wasted the superiority of the main allied army during the whole year. This had enabled the French to maintain an unrelenting pressure with numerous forces upon Savoy. Nearly a hundred and fifty thousand troops were acting continuously in the Italian theatre. Victor Amadeus, the reigning Duke of Savoy, was hopelessly outnumbered. His fortresses, stubbornly defended, had fallen one by one. The genius of Prince Eugene and the terror of his name could not make good the wants of his army in numbers, munitions, equipment, and money. His hazardous battle against Vendôme at Cassano[21] had yielded nothing more than a momentary diversion. His ragged, unpaid, disintegrated force, of which the eight thousand Prussians whom Marlborough had procured from the Court of Berlin in the previous year, now greatly reduced, were the core, could do no more than cling to the foothills of the Alps by Lake Garda. Victor Amadeus himself was at variance with Starhemberg, the Imperial general at his side. The French under Vendôme and La Feuillade were steadily overcoming every form of resistance. The total collapse of the Allies in the Italian theatre seemed to await only the return of spring. The French conquest of all Italy was imminent, after which the whole army of the two Marshals would be speedily transported to the northern fronts.

Godolphin was anxious that Marlborough should return to England, if possible in time for the meeting of the new Parliament, and assuredly the Duke himself was longing to be home. The state into which the Grand Alliance had fallen quenched these desires. All through September a series of letters from the Emperor, from Wratislaw, and from Eugene unfolded their new distresses and implored him to come himself to Vienna, and settle there, in the distracted capital of the Hapsburgs, whatever measures were possible to meet the dreaded opening of another campaign. Sunderland, now at Vienna, wrote urgently endorsing these requests. “If he does come,” he wrote to Godolphin, “there is nothing in the power of this Court that he will not persuade them to.”[22] Marlborough seems from the first to have been sure he ought to go. He laid his plans with his customary care. In forwarding the Emperor’s appeal to Godolphin and the Cabinet he represented himself as disinclined to undertake so arduous a journey. Certainly it would not be worth while making it if he were not armed with authority first from England and then from Holland to bring effective financial and military aid to the Emperor. Unless this were forthcoming, and both the Sea Powers felt such a mission to be his unavoidable duty, he would not go. If he went so far as Vienna, he would return by the Courts of Berlin and Hanover to The Hague and reach London early in the New Year, having done what he could, and at any rate with full knowledge upon which to advise the Cabinet. Thus he made himself begged from all quarters before he committed himself to the course he desired.

At this time his thoughts were centred upon the Italian theatre. “It seems to me,” he wrote to Wratislaw (October 5), “that it is high time to think seriously about this war in Italy, which employs so great a number of enemy troops, who would fall upon our backs everywhere if we were driven out of it.”[23] His prime object was to secure money from England and Holland, and men from Prussia and the German princes, to sustain the army of Prince Eugene. It may well be that he had already in his mind a design for a decisive campaign in Italy, in which after a march longer and more adventurous than the march to the Danube he would himself join his glorious and now beloved comrade upon the plains of Lombardy for a battle that should outshine Blenheim. At any rate, he began by every means and from every quarter setting the flow of troops and supplies towards the south.

He planned his tour of Germany so as to meet every one who mattered on the way. He must visit the Elector Palatine and the authorities of the Electorate of Trèves. At Frankfort he must find d’Almelo and Davenant, the Dutch and English financial agents, and Geldermalsen, the Dutch Deputy, whose removal at least from the front he had been promised before the new campaign, but who still held his office unwitting; and here too he hoped to conciliate the Margrave, if Prince Louis’s toe and temper would permit the rendezvous. To all these he wrote cordial letters specifying the business that must be transacted. Rantzau, the Prussian general, asked that his son might accompany the Duke upon his journey, and Marlborough invited the young man to join him at Ratisbon, “whence we will drop down the Danube together, and I will make it my task that his voyage shall be as agreeable to him as possible.” To Stepney, the English Ambassador, he wrote:

I must entreat the liberty when I come to Vienna to set up my field bed in your house, and if you find that preparations are making to lodge me elsewhere, I pray you will let the Prince of Salm . . . know that I expect this retirement as a particular mark of the Emperor’s favour, and cannot on any terms admit of being elsewhere.[24]

Meanwhile he remained at his headquarters with the army until the last possible moment, “spinning out the time” by the siege of Sandvliet “so that Prince Louis may not be interrupted in his operations on the Rhine,” and paying only flying visits to The Hague.

Bavaria had revolted against its conquerors of the year before. The Bavarian army had continued a local resistance after the battle of Blenheim. It had surprised and routed with heavy loss the small Imperialist force left to besiege, or rather to blockade, Ingolstadt. The treaty signed with the Electress was repugnant to the Bavarian generals, who, now that the main allied armies had left Bavaria, desired to continue fighting. It was, however, enforced throughout the country by the Munich Government, and the bulk of the Bavarian army was disarmed and disbanded, and all the fortresses, with one single exception, were garrisoned by Imperial troops. The reader will remember M. de la Colonie, the “Old Campaigner,” whose account of the Schellenberg is so valuable. It was due to La Colonie that Ingolstadt alone continued its resistance. This brave officer and his regiment of French grenadiers in the Bavarian service found themselves forgotten in the treaty, which covered only Bavarian subjects. They were without a military status of any kind, and opinion was divided upon whether they would be shot as deserters from the Empire, or hanged for the marauding for which they were notorious, or allowed to make their way back to France as unarmed individuals, with the certainty of being massacred by the infuriated Swabian peasantry. It would have gone hard with these men if they had not held together under their resolute leader.

In their desperation they animated the resistance to the terms of the treaty of all the Bavarian troops in Ingolstadt. Thus strengthened, they held the fortress, and declared themselves resolved to perish in their bastions unless they were granted honourable safe-conduct to France. The Allies in due course protested against the breach of the treaty. The Electress from Munich declared the recalcitrant garrison mutineers; but the deadlock continued. Superior forces at length arrived before Ingolstadt, and it seemed that a bloody event was inevitable. However, Prince Eugene, returning from the siege of Landau, took the matter into his own hands. He patiently inquired into the dispute. He treated La Colonie with soldierly respect, and entertained him at his table. He decided that the soldiers were entitled to their arrears of pay, and that the French grenadiers, together with the remaining French residents, should be escorted back to Strasburg as an armed force evacuating a foreign territory with the honours of war. Accordingly, La Colonie, after several private adventures, duels, legal processes, and a marriage, found himself by the end of 1705 commanding the remnants of his regiment under the Elector in the Low Countries.

The rancours in Bavaria had not ended with the dispersal of its military forces. The Bavarian nobility and people had not shared in their Elector’s guilt, but they had paid the penalty. The devastation of the countryside before Blenheim had roused a fierce, abiding hatred of the Allies. The efforts of Vienna to recruit Bavarians for the Imperial service met with sullen and often savage resistance from all classes. Disorder and bloodshed spread throughout the ravaged principality. The dragon’s teeth had been sown, and murder and revolt sprouted everywhere.

No enemy prince had suffered more at Marlborough’s hands than Max Emmanuel, Elector of Bavaria. His country had been laid waste; his armies had been destroyed in the Blenheim campaign; his remaining cavalry and personal adherents had been routed at Elixem. He was a fugitive ruler serving far from home and family in the Low Countries as a French Marshal. A crowning disaster impended upon him. But at least he must have his sport. The wild boar which infested the Forest of Soignies afforded him the prospect of a hunting season, and he wrote to Marlborough early in September asking various passport courtesies and, above all, facilities to pursue the chase undisturbed in regions which the Allies now controlled. The Duke answered on September 25 in his most ceremonious style:

Indeed I should be enchanted were it in my power to give the orders which His Highness desires to favour his hunting. When, however, he has thought the matter over carefully, he will see that it is not in my power to exempt so great a stretch of country from the movements of patrols; but as for the passports, they are at his service, and shall be couched in whatever terms he judges most convenient, there being nothing that I would not do to prove to his Electoral Highness the most submissive respect with which I have the honour to be Monseigneur’s devoted, humble, and obedient servant.[25]

The Elector persisted, and on October 4 Marlborough expressed his “despair” not to be able to give orders forbidding his patrols to enter the Forest of Soignies.

“I flatter myself,” he said,

that your Electoral Highness is convinced that if it depended upon me I should hasten with eagerness to accord everything he should ask, if only in order to mark the deference which I shall always have for his orders, begging him to do me the justice of believing that no one could be with more veneration and respect than I am Monseigneur’s devoted servant.[26]

Making all allowance for the manners of the period between opposing commanders, there was more in these exchanges than their trivial topic would warrant. We have seen the distrust with which Max Emmanuel in his capacity as Vicar-General of the Netherlands was viewed at Versailles. The possibility of his making a separate peace for Belgium at the expense of France was never excluded from the French precautions. Sometimes it is convenient for public men to keep up a correspondence on slight matters with their opponents in order to preserve a certain personal intimacy and an easy approach should it become desirable. The extravagant flattery and humility with which Marlborough caressed the Elector were not only characteristic of the age and of Marlborough, but a measure of the situation, with, as we shall see, a bearing on the future.

Ailesbury has given us a picture of Marlborough at this very time more intimate than any other which his campaign records provide. The old Jacobite Earl had made repeated requests to be allowed to go back to his native land. He felt he had claims of friendship upon Marlborough dating from the Fenwick trial.[27] The Duke pitied his plight, liked his company, used him with tender courtesy, but was inflexible upon reasons of State. At the end of 1703 they had dined together on two nights at the Albemarles’. “The last night,” says Ailesbury,

the Duke drinking to the Lord and Lady of the house to all that could give us most satisfaction, Mr Meredith [one of Marlborough’s rising brigadiers], who was diverting the company and ever towards me and my wife most obliging, cried out, “My Lord, I love deeds and not words. We are here all friends and in good humour, and pray let the whole company go to England in the same ship.” My poor wife, that knew better, let fall some tears, on which my Lord Marlborough said somewhat [something] obligingly, but what was taken for Court holy-water, the expression in French when Ministers say what they do not think to perform.

Ailesbury, still eating his heart out in exile, had refused to call upon the Duke either on his return from Blenheim (“Hockster” he calls it) or in the spring of 1705. But now in October Count Oxenstiern urged him to come to Headquarters, “for that I had sufficiently mortified my Lord Marlborough for going from his promise (the year before) given to my wife.” The Duke was quartered in a convent outside the gates of Tirlemont.