* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Nelson's History of the War Vol. 12

Date of first publication: 1915

Author: John Buchan

Date first posted: July 10, 2023

Date last updated: Sep. 22, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230715

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

| CONTENTS. | |

| LXXXIV. | The Bagdad Expedition |

| LXXXV. | The Situation in the Ægean |

| LXXXVI. | The Evacuation of Gallipoli |

| LXXXVII. | Some Sidelights on the German Temper |

| LXXXVIII. | The Second Winter in the West |

| LXXXIX. | The Second Winter on the Russian Front |

| XC. | The Breaking-point in War |

| XCI. | The Derby Report |

| APPENDICES. | |

| I. | The Evacuation of Gallipoli |

| II. | The Letter of the Belgian Bishops |

| III. | The Work of the Munitions Department |

| IV. | Lord Derby’s Reports |

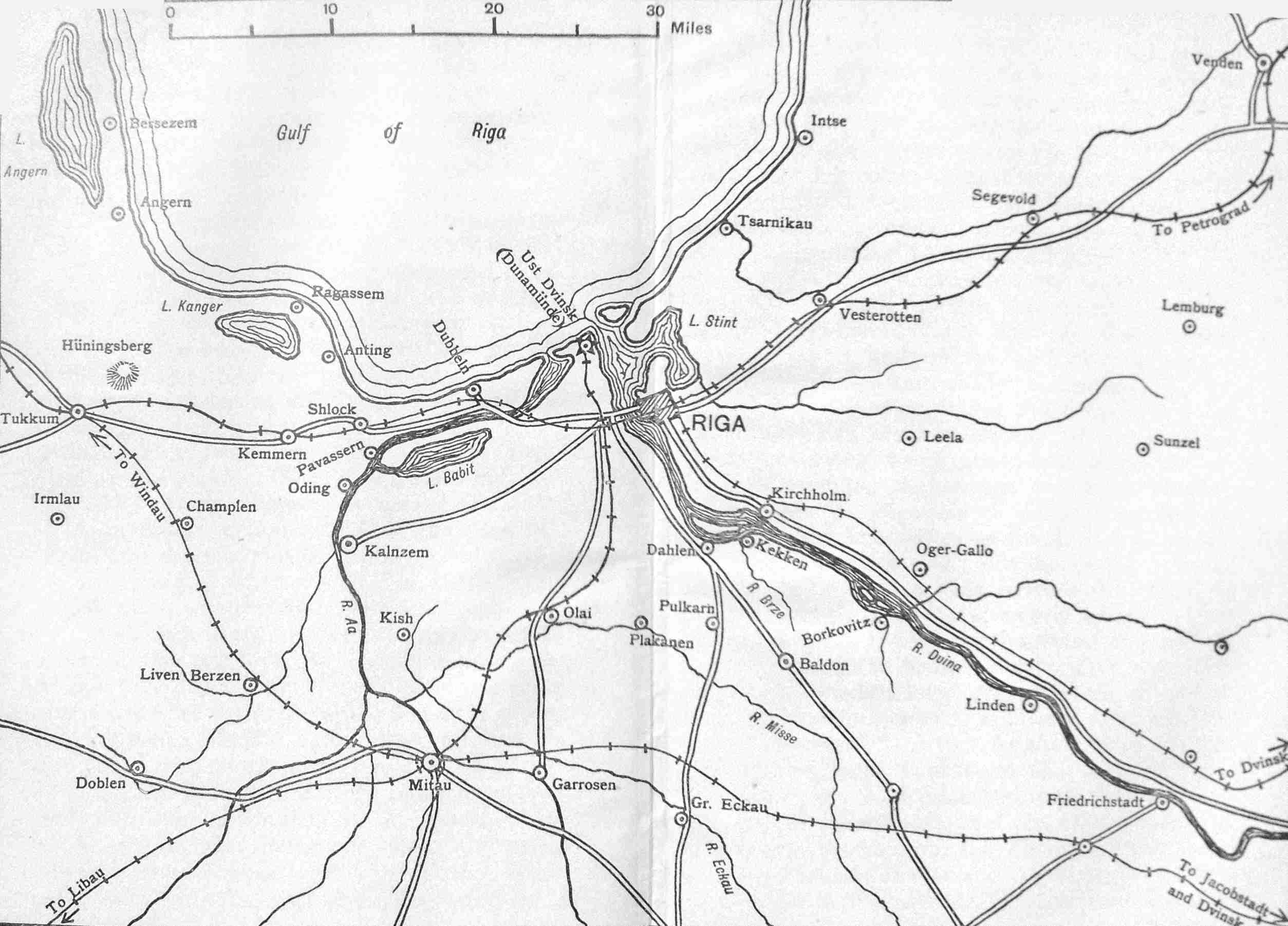

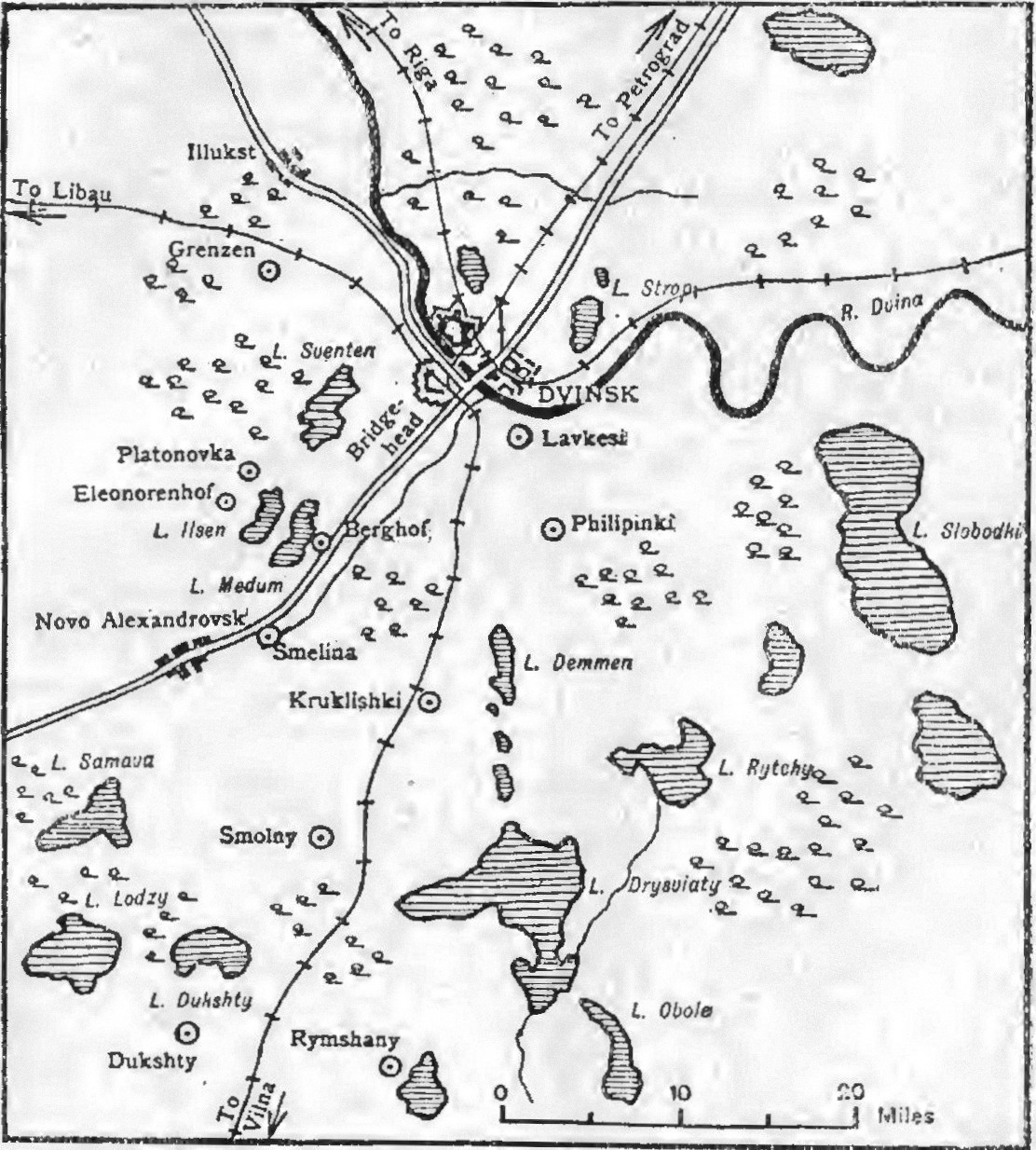

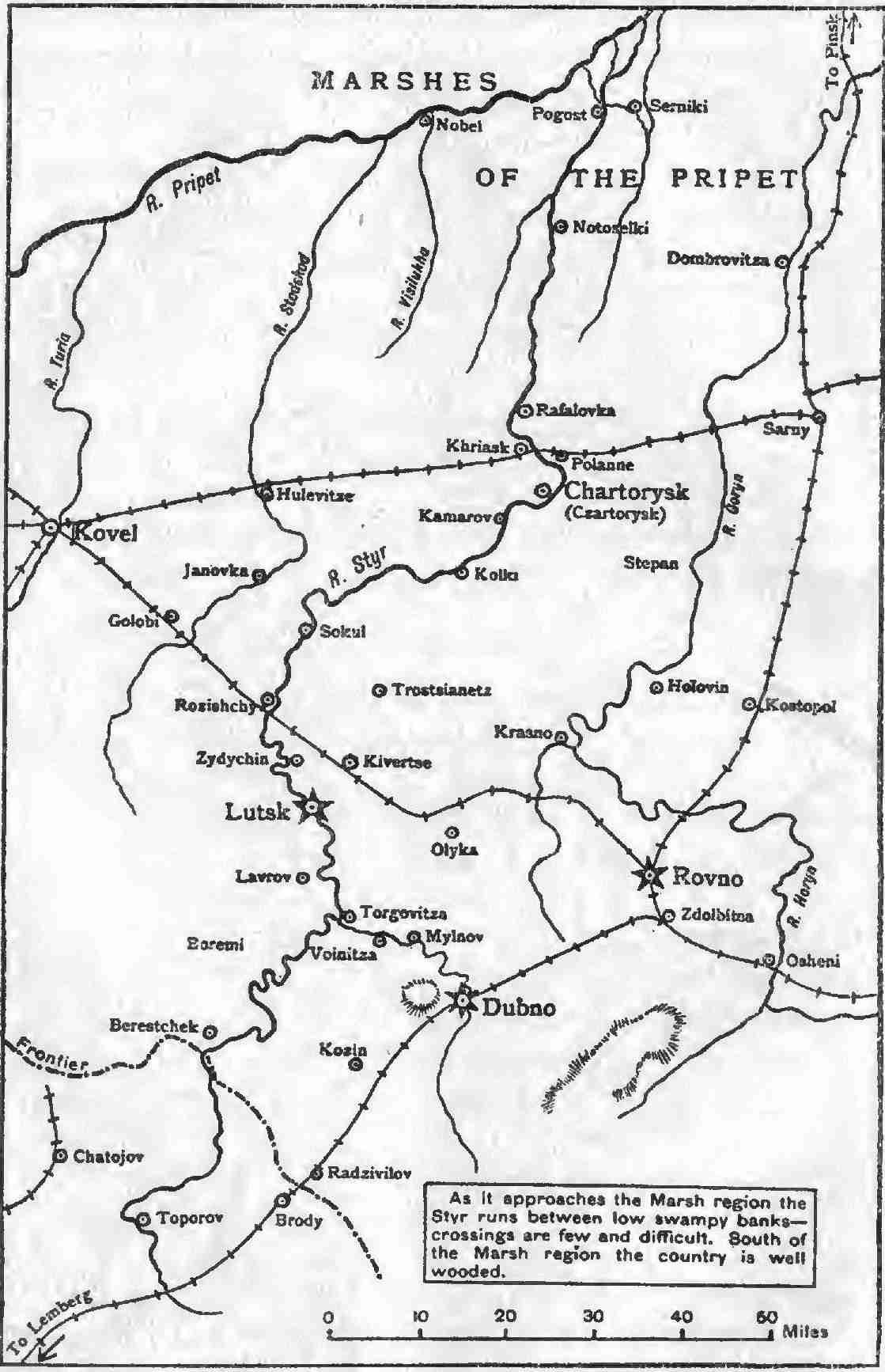

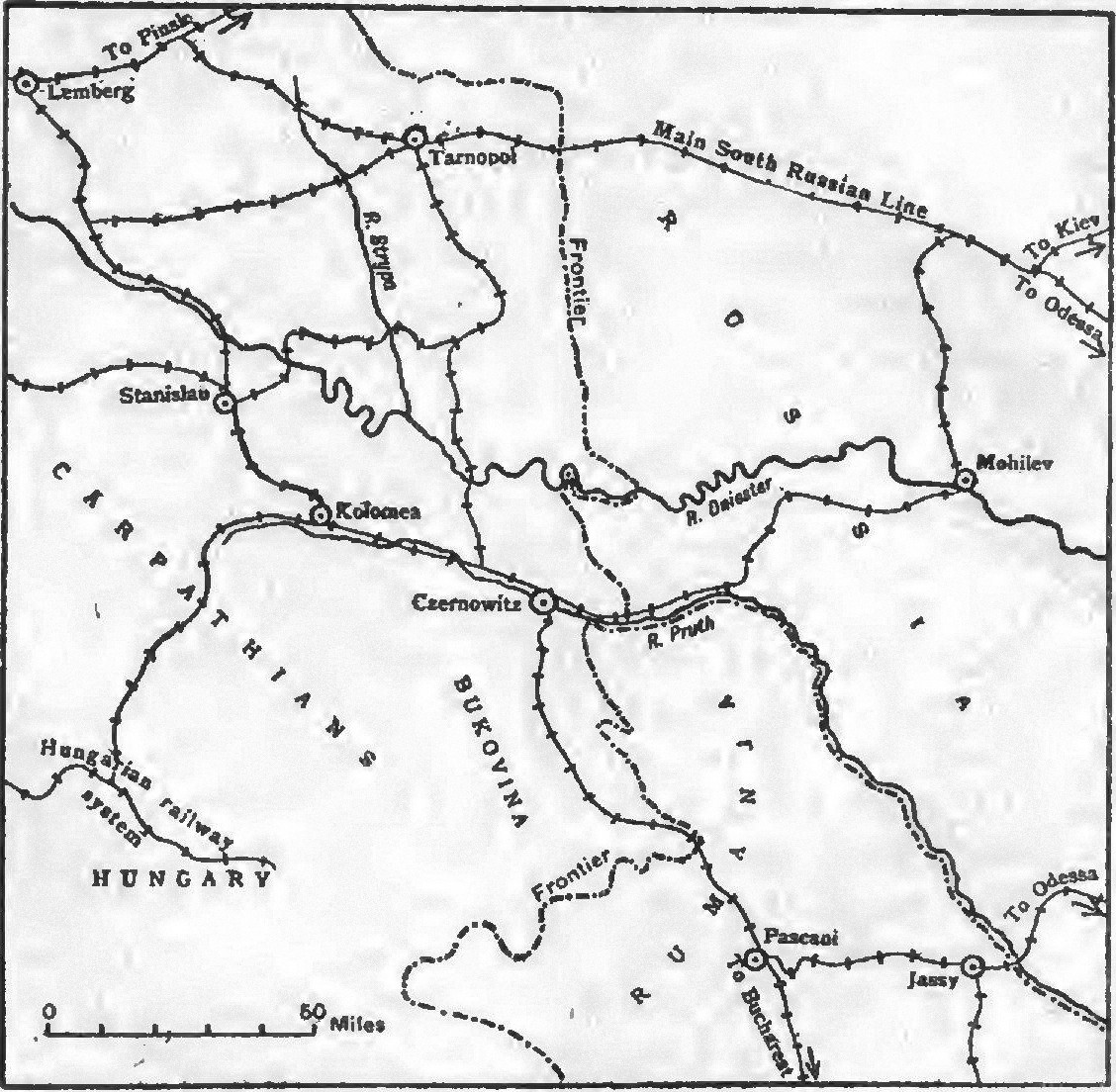

Western Theatre of the War.

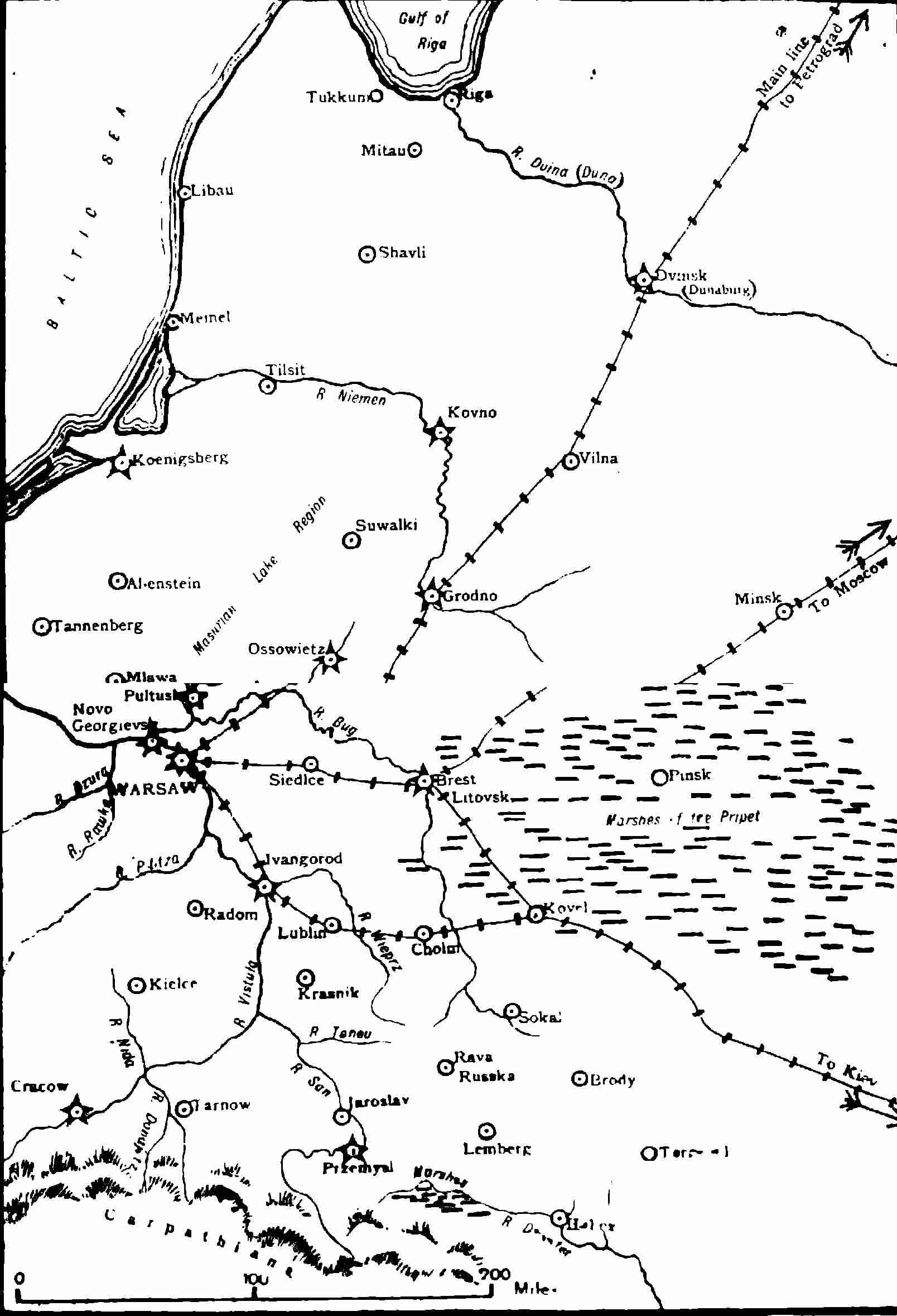

Eastern Theatre of the War.

NELSON’S HISTORY OF THE WAR

VOLUME XII

Reasons for the Advance to Bagdad—Dangers of the Enterprise—Mr. Asquith’s Statement—The Opposing Forces—The Advance up the Tigris—Nature of Ctesiphon Position—The British Plan—The First Day’s Fighting—British capture Turkish First-line Trenches—Arrival of Turkish Reinforcements—General Townshend’s Retreat—Kut surrounded—Von der Goltz at Aleppo—The Situation in Northern Persia—Prince Reuss’s Doings—Revolt of the Gendarmerie—Russians take Hamadan and Kum.

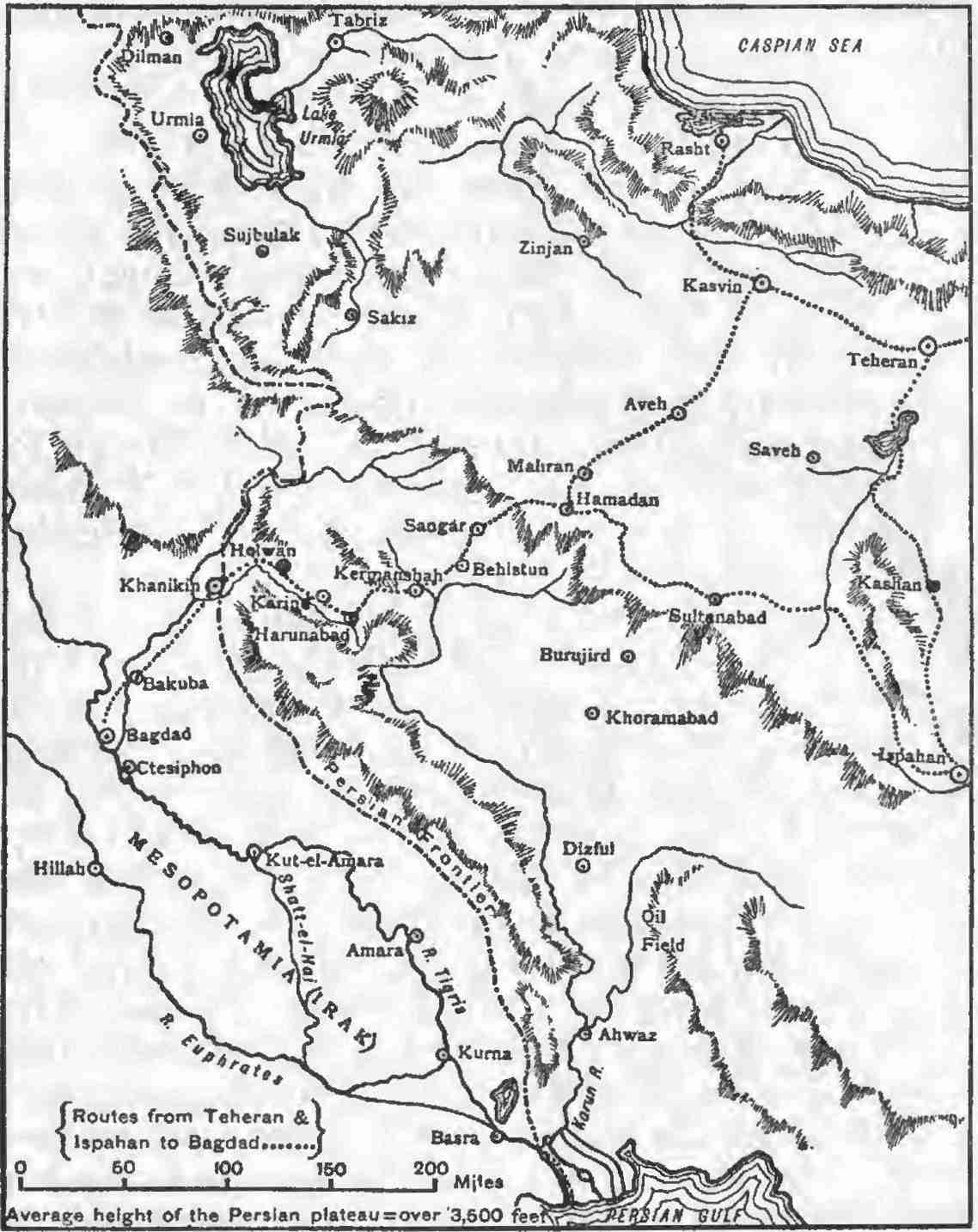

When, at the end of September, the Turkish defence was broken at Kut-el-Amara, the British force began its advance on Bagdad. General Townshend was now in the position in which many British generals have found themselves since the days of Elizabeth. He commanded little more than a single division, and was outnumbered by the enemy’s forces directly opposed to him, and vastly outnumbered by their potential levies. He was well over three hundred miles from his base on the sea. He had a river for his sole communication, and, after our amphibious fashion, was assisted by armed vessels from the water; but that river was full of shallows and mudbanks more formidable than the cataracts of the Nile. All around him lay a country ill-suited for operations by white troops—sparsely-watered desert and reeking marshes, baked by the hottest of Asian suns, and brooded over by those manifold diseases which heat and desert soil engender. The local tribes were either treacherous or openly hostile, and might at any moment strike at his long, straggling connections with the coast. Before him, a hundred miles off by the short cut across the loop of the Tigris, lay one of the most famous cities of the world. That a little British army, wearied with ten months’ incessant fighting, should advance to conquer a mighty province of a still powerful empire might well seem one of the rashest enterprises ever embarked upon by man. It was the war in the Sudan undertaken under far more difficult conditions, for the fall of Bagdad would not mean, like the fall of Khartum, the end of serious resistance, and no Sirdar had planned a Sudan railway to bring supplies and reserves more quickly than the route of the winding river.

It may well be asked why an advance was ordered. The Turkish army which we had beaten at Kut-el-Amara could be readily reinforced. They had the Mosul Corps to draw upon; by the Tigris troops could be brought from Kurdistan; and from Damascus and Aleppo, by the caravan routes through the desert, reserves could be sent from the Army of Syria. Turkey had by no means used up all her supplies of men. The fronts in Gallipoli and Transcaucasia were stagnant, and the Allied embarrassments in the Balkans made any immediate pressure there unlikely. The British, on the other hand, could only add to their army by drafts from India or the Western front, a matter of weeks in one case and months in the other. In the face of a demoralized enemy a bold dash for the capital might succeed. But the Turks, as we well knew, were not demoralized. If they had failed at Kut they had to all intents succeeded at Gallipoli, and there stood by their side their German taskmasters to keep them to their business.

Moreover, Bagdad was no easy problem. The Tigris for some miles below the town loops itself into fantastic whorls, which meant that at many parts any land force, whose aim was speed, would be deprived of the co-operation of its flotilla. Again, some twenty miles below the city, the river Diala, entering the main stream on its left bank, provided a strong line of defence. Finally, Bagdad was an open city, and, even if won, would be hard to defend. In fact, it was an impossible halting-place. Once there, for the sake of security we should have been compelled to go on seventy-five miles to Samara, on the Tigris, the terminus of the railway from Bagdad. We should also be obliged to occupy Khanikin, where the Diala crosses the Persian frontier. From Samara it would soon be necessary to advance another hundred miles to Mosul. Indeed, there was no natural end, save exhaustion, to the progress which the need of security would impose on us. There was no attainable point where that security could be assured, for between the Tigris valley and the Russian front in Transcaucasia lay the wild mountains of Kurdistan. And all the while our communications would be lengthening out crazily. At Bagdad we should be 573 miles by river from the Gulf, and between 300 and 400 by the shortest land route. We should be hopelessly out of touch with our sea-power. On every ground of strategy and common sense the advance was indefensible.

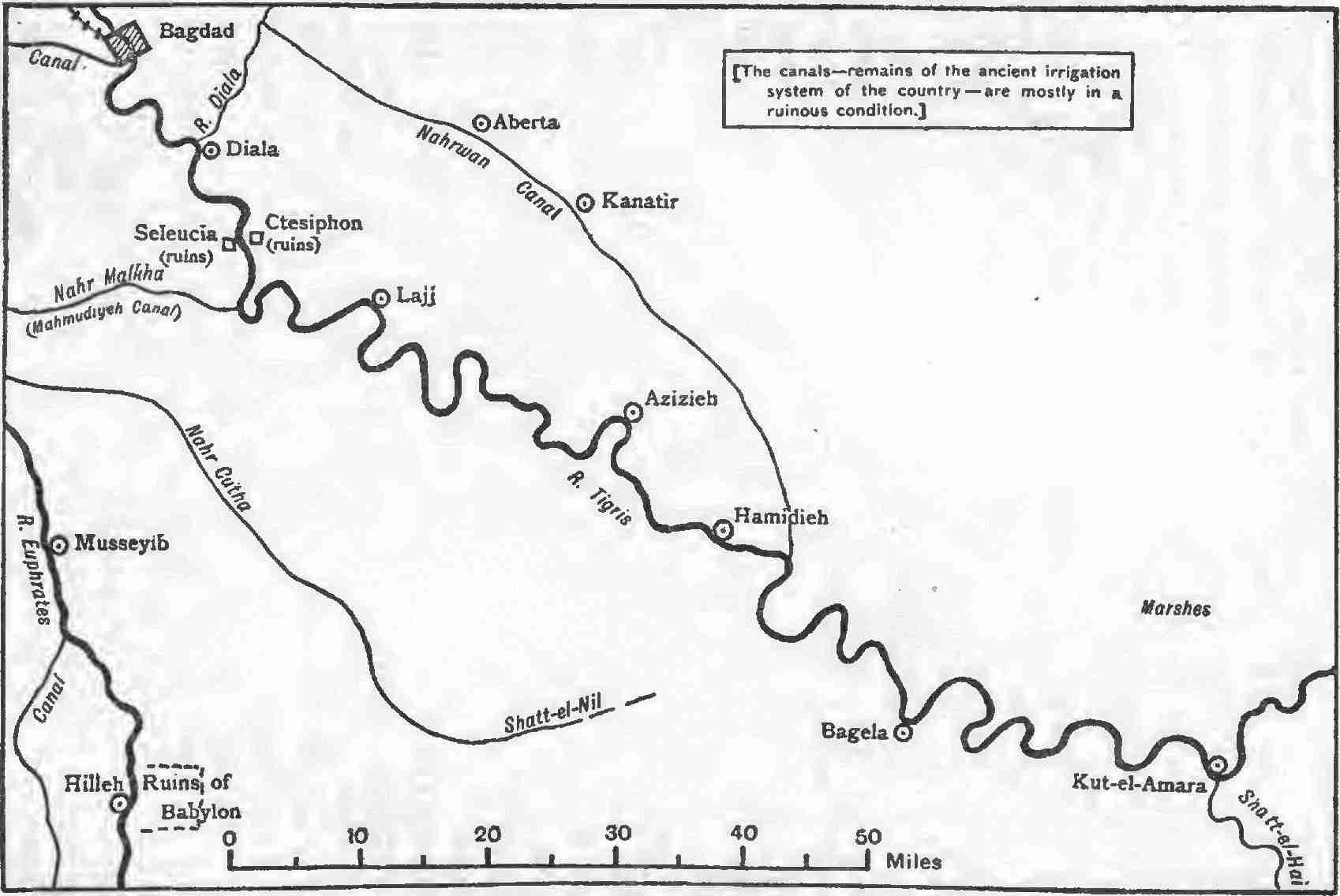

The Country between Bagdad and Kut-el-Amara.

On the other hand, it was undeniable that the conquest of Bagdad would have great political advantages—if it could be achieved. As we have argued in an earlier chapter, its fall would be a makeweight to the German domination at Constantinople. It would cut at their nodal point the principal routes of German communications with Persia and the Indian frontier. But even this success would not be final. There would remain the great caravan routes of the Northern Shammar desert, which followed the projected line of the Bagdad railway to Mosul, and thence to Rowandiz on the Persian frontier. Full success in our objective really demanded the control of the whole of Northern Mesopotamia. Such a control might have been won, but it required an adequate force—at least two army corps fully equipped, and not one weary division.

The British Prime Minister, in his speech in the House of Commons on 2nd November, defined the objects of the Mesopotamia Expedition as “to secure the neutrality of the Arabs, to safeguard our interests in the Persian Gulf, to protect the oil-fields, and generally to maintain the authority of our Flag in the East.” Of these aims the first may be dismissed as trivial. The Arab tribes of Mesopotamia were a much overrated folk, notable rather for low cunning than for military virtues. Their hostility and their friendship alike were worth little. The third we secured when we held Amara and the desert route to Ahwaz; the second when we won Basra. The fourth was a vague aspiration which did not involve any specific military operations, but which did demand that we should not get ourselves into impossible situations. All the objects defined by Mr. Asquith were, in fact, realized when General Townshend took Kut-el-Amara, and, by holding the northern end of the Shatt-el-Hai, prevented the enemy cutting his communications by a flank march. At Kut the extreme purpose of the original expedition was fulfilled. The advance to Bagdad was a new scheme involving a new policy.

If we remember the situation at the end of September we shall find a possible clue to the reasons for the adventure. The great advance of the Allies in the West had reached its limit without a decision. The Balkan affair had gone from bad to worse, Serbia was about to be isolated, Bulgaria was entering the field on Germany’s side, and von Mackensen’s guns had begun to sound on the Danube. Our diplomacy, justly or unjustly, had suffered a serious loss of credit. Looking round the globe for something to restore our drooping prestige at the moment, the eyes of soldiers and statesmen naturally fell on Mesopotamia. The expedition there had been up to date a brilliant success. No mistakes had been made. Miracles had been performed with a handful of troops. But the names of Kut-el-Amara and Nasiriyeh were not familiar to Europe. Now Bagdad was known to all the world. If the old city of the Caliphs fell to British arms there would be a resounding success wherewith to balance our failure in the Ægean. Our much-tried diplomacy would have something to point to in its painful negotiations with suspicious neutrals. Therefore let us make a dash for Bagdad, and trust to the standing luck of the British army. It was commonly assumed in Britain at the time that the enterprise was primarily conceived by the politicians, and that we had embarked on a scheme politically valuable without counting the military cost. It was urged that we had forgotten one of Jomini’s most pregnant aphorisms: “The choice of political objectives ought to be subordinate to the interests of strategy, at any rate until the great military issues have been decided by arms.” But for this most natural assumption there was in fact no warrant. The advance to Bagdad was advocated by the soldiers chiefly concerned, and on the information at our disposal we believed it to be a practicable undertaking. General Townshend was understood to have protested against an advance with such inadequate forces, but Sir John Nixon and the Indian military authorities thought differently.

In October Turkey had in the field as many men as the British Empire. She was fighting nominally in four theatres of war—Transcaucasia, the Egyptian frontier, Gallipoli, and Mesopotamia. Of her four theatres three were virtually in a state of stagnation. Probably not more than 150,000 men were mobilized along the Russian frontier; there was nothing doing on the Egyptian borders; the enemy in Gallipoli had shot his bolt; and in Mesopotamia alone was there any urgent question of defence. It was therefore open to Turkey, given a little time and some assistance from Germany in the way of supplies, to deploy on the Tigris little short of a quarter of a million men. To meet this possibility Sir John Nixon had his Anglo-Indian division and an extra brigade—all told, perhaps, 15,000 bayonets. One-third of the force were white soldiers, including such regular battalions as the 2nd Dorsets, the 2nd Norfolks, and the 1st Oxford Light Infantry, and territorial battalions of the Hampshires and Sussex. The remainder were Indian troops, including a number of Punjab battalions, the 103rd, 110th, and 117th Mahrattas, the 7th Rajputs, two Gurkha battalions, and four regiments of cavalry. The accompanying flotilla was composed of every conceivable type of boat, from ancient Admiralty sloops to Burma paddle-steamers, the river-boats of the firm of Lynch, motor launches, and the flat-bottomed native punts of the Delta. The whole British force was battle-worn and weary. Large numbers had contracted ailments and diseases, and all were jaded by the incessant struggle of the hot summer. But to cheer them they had a record of unbroken success. Wherever and in whatever numbers they had found the enemy they had soundly beaten him.

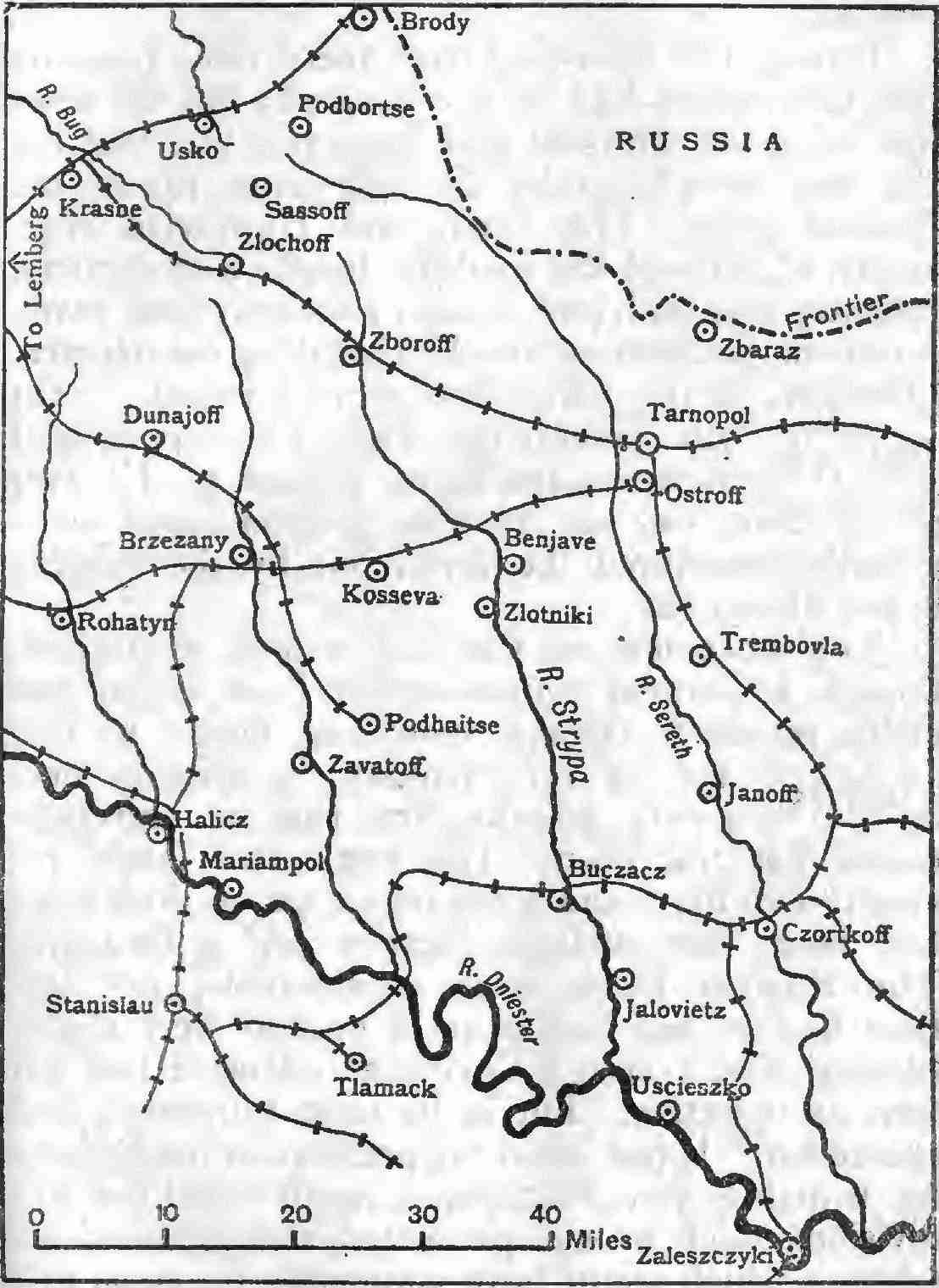

In Mesopotamia in October the days are bright and clear and the nights cold. It is the beginning of that bracing and clement winter which in subtropical deserts is the atonement for the arid summer. The normal period of floods was past, and the marshes were drying. It was the best season of the year for an advance, and no time was lost in making a start. After the victory of Kut the flotilla had pursued the enemy up the river, but the multitude of sandbanks made progress slow, and the chase was soon relinquished. Our aeroplanes watched the retreating Turks, and reported that they were falling back in hot haste, and were not halting short of the Ctesiphon line, which was their last defence south of Bagdad. They seem to have moved at the rate of twenty-five miles a day, and, though they shed quantities of ammunition and rifles by the roadside, they got away all the guns which we had not captured on the field of Kut. Reconnoitring parties were sent forward on steamers by General Townshend. In the early days of October the advance began, partly by land and partly by river. On 4th October there were troops already fiftyOct. 4. miles up river from Kut, and only sixty by road from Bagdad. By 23rd October the bulkOct. 23. of the British force had reached Azizie, more than halfway to the capital. There had been a few skirmishes with raiding Arabs, but no serious rearguard fighting. At Azizie, however, we found the Turkish advanced guard in position, and for a few days our progress halted. Then by a flank attack we routed the 3,000 or 4,000 of the enemy, and pushed them back to their main Ctesiphon standing-ground. In the first week of November our movement began again. On the 12th GeneralNov. 12. Townshend was encamped at Lajj, seven miles from Ctesiphon, and about thirty miles from Bagdad. His outposts were almost in touch with the prepared Turkish positions.

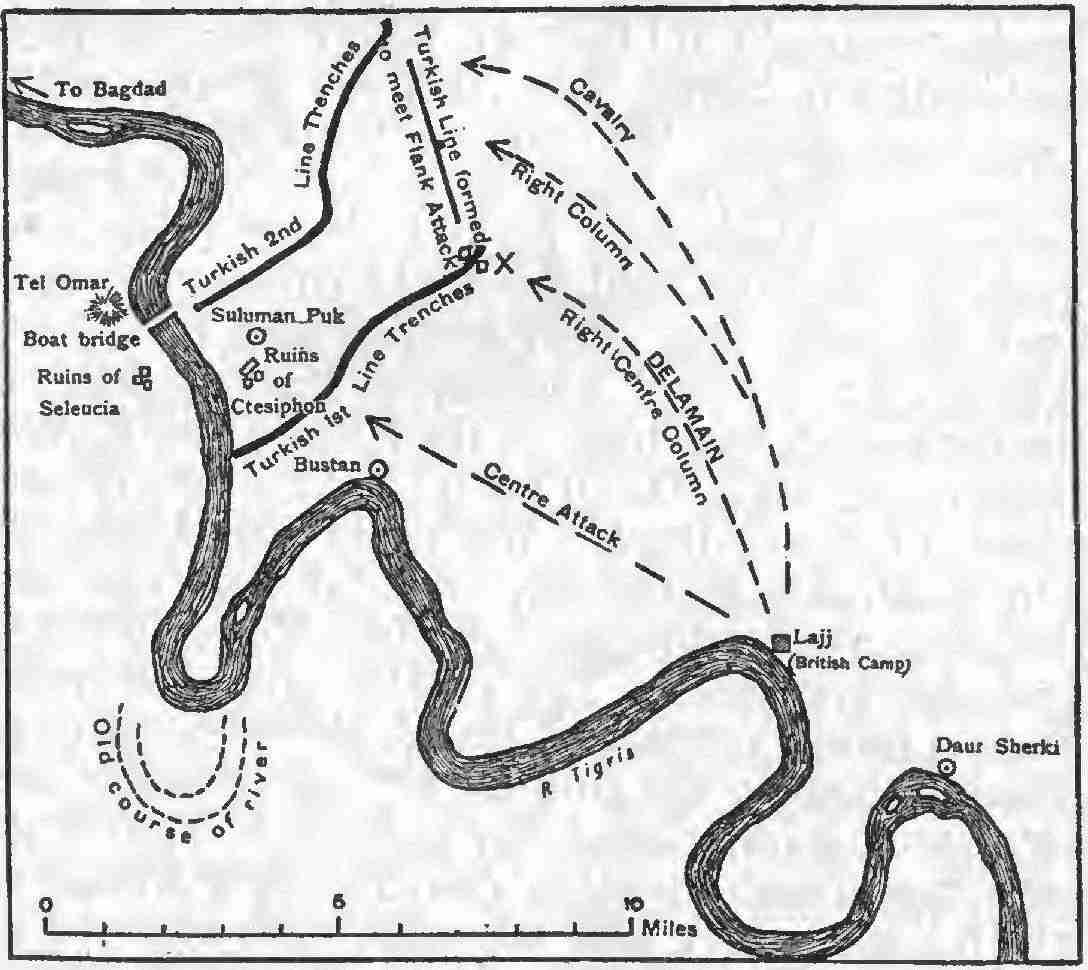

The map will show the nature of the ground. At Ctesiphon the Euphrates and the Tigris approach within twenty miles of each other. Such a position was obviously well chosen, for the Turks’ could bring reinforcements down the Euphrates from Aleppo and the Army of Syria. Had we been in sufficient force to send an expedition up that river, we should have won a double line of communications, and been able to adopt an enveloping strategy. But the enemy was perfectly familiar with our numbers, and knew that of such a movement there was no possible danger. Ctesiphon, the old Sassanid capital, had been the battle-ground of Romans and Parthians, but only the massive brick shell of the “Throne of Chosroes,” rising above the squalid Turkish village, remained to tell of its former grandeur. Beyond the river lay the ruins of Seleucia, the old capital of the Seleucidae, for at this point Parthia and Syria had faced each other across the Tigris. The Turkish first position ran from the angle in the Tigris, with a second line about half a mile in the rear. The whole place had been strongly fortified according to the latest German fashion, and the wastes of old débris furnished admirable shelters for machine guns, of the same type as the redoubts on the Western front. The Turkish right wing was beyond the Tigris, but their centre and left, comprising three-fourths of their army, were on the left bank.

Battle of Ctesiphon.

On the evening of 21st November GeneralNov. 21. Townshend advanced from Lajj. His force, as at Kut, was divided into three columns. tactical plan was almost the same as that at Kut. One column was to advance against the centre of the first Turkish position. A second column, under Delamain, was to envelop the left of that position; while a third was to make a wide detour, and come in on the left rear of the main Turkish force, and co-operate with Delamain in driving them back towards the river. We may call these columns the Centre, the Right Centre, and the Right. Behind the main Turkish position lay the village of Sulman Puk and the ruins of Ctesiphon. On the right flank of the second Turkish position was a bridge of boats across the Tigris, and it was towards this bridge that our Right Centre and Right columns were directed. The cavalry was sent round to the left of the Turkish reserve trenches in order to hinder any retirement. The scheme was an admirable one, but our numbers were barely adequate. All told we had, perhaps, 12,000 men. The Turks had the remains of the three divisions which had fought at Kut, little less than 20,000 men, and they had reinforcements at hand.

The British troops marched seven miles in theNov. 22. bright moonlight, till they saw before them the ruins of Ctesiphon casting blue shadows on the yellow plain. Before dawn the Centre column had dug itself in in front of the main enemy line, Delamain’s Right Centre had done the same on the flank, and the Right column had covered ten miles and taken ground well to the left rear of the enemy. The cavalry had wheeled to the north-east, and hung on the flank of the Turkish reserve trenches. Dawn broke, and the enemy were aware of our advent. We could see bodies of Turks moving northward, and our first idea was that they were relinquishing Ctesiphon and falling back on the Diala. The cavalry and the British Right promptly attacked the flank of the retreat, which formed in line to meet us, and revealed itself as a force several times our strength. The Turks were now drawn up along two sides of a square, of which the northern side was their reserve trenches, the western the Tigris, the southern their main position, and the eastern the force with which our Right and our cavalry were engaged. At the point marked X in the map was a group of buildings, forming the junction of the eastern and southern sides.

About a quarter to nine the great attack began. Our Centre moved against the main line, Delamain’s Right Centre attacked at X, and the Right and the cavalry assaulted the east side. The last, being greatly outnumbered, at first made no progress. Indeed they lost ground, and Delamain was compelled to detach some of his battalions to support them. At eleven he carried X by artillery fire, and about half-past one the Centre, with Delamain’s assistance, succeeded in piercing the main Turkish front. These successes gave us the first position; but the Turks, assisted by their eastern flank, which defied our Right and our cavalry, were able to retire in good order to their reserve lines. Our success so far had been brilliantly achieved, but there was to be no rout such as had followed the same tactics at Kut. Nur-ed-din had learned his lesson, and the real kernel of the position was the second line.

At half-past two in the afternoon we advanced against the second position. The eastern side of the former square was still intact, and our three columns drew together in an attempt to roll it up. But now we found out the true numbers of the enemy. Another division had joined him, and he counter-attacked with such force that he recovered the guns he had lost, and before evening had driven us back to his old first trenches. Delamain, however, managed to hold the village of Sulman Puk in advance of these lines. Both sides were utterly wearied, and about 11.30 p.m. the battle died away.

Next day we saw fresh reinforcements arrivingNov. 23. for the enemy, and all morning the two forces shelled each other. The Turkish attack came at three o’clock in the afternoon, and lasted till long after dark. It was now that they suffered their severest losses. Our men, being well-entrenched, beat them back time and again, but all night long there were intermittent assaults. Next day, the 24th, they fellNov. 24. back to their second line, and that day was filled with bombardments and counter-bombardments. Our force was badly disorganized, so we spent the day in consolidating our ground, and next day we received by river some much-needed supplies. Our aeroplanes reported that reinforcements were still reaching the enemy. Obviously we could now do nothing more. Our casualties were about a third of our force—some 4,500, with 800 killed, and the losses among officers and staff had been specially heavy. We had handled the enemy severely, for the prisoners in our hands were over 1,300, and the killed and wounded we reckoned at some 10,000. But his strength was being replenished, and ours was waning. There was nothing for it but to fall back. We had won his first position and encamped on the battlefield, but we were very far from having broken his army.

At midnight on the 25th we marched back toNov. 25-26. Lajj. Our wounded went by river, and reached Kut on the 27th. All the 26th we halted at Lajj to rest our men, and that evening we retreated twenty-three miles over a villainous road to Azizie. Four days later, on the 30th, we left Azizie and beganNov. 30. to get news of the enemy. Tidings travel fast in the East, and the word of our retirement encouraged the riverine Arabs to make an attempt on our communications between Kut and Amara, an attempt frustrated by a watchful gunboat. Early in the evening of 1st DecemberDec. 1. General Townshend’s little army reached camp ten miles below Azizie, where they were much sniped, and where next morning they saw the smoke of the Turkish fires all around them. The slowness of the enemy’s pursuit is a proof of how severely he had suffered at Ctesiphon, for, had he been able to follow our trail at once, the whole British force must have perished. We counter-attacked and beatDec. 2. him off, losing only 150 men to the enemy’s 2,500, but all that day we fought rearguard actions and marched twenty-seven miles before we dared to halt. We rested for three hours and then moved on for fifteen miles more. We were now only four miles from Kut, but we could not go a yard further. Both men and beasts were utterly leg-weary. Next morning, 3rdDec. 3. December, the remains of the Bagdad Expedition, which had set out with high hopes six weeks before, staggered into Kut. From north, east, and west the enemy closed in upon us, and the siege of Kut had begun. It had been a brilliant and memorable episode in the history of British arms, but, judged from the standpoint of scientific warfare, it had been no better than a glorious folly. Once again, as in the Nile Campaign, a beleaguered town far up an Eastern river became the centre of the anxious thought of our people.

British reserves were on the way. The twoNov. 24. Indian divisions, which for a year had been on the Western front, had reached Egypt en route for the Persian Gulf. By a wise decision Mesopotamia was selected as the terrain for the concentration of our Indian fighting strength. But Turkey was also awake, and her German masters saw in the check at Ctesiphon a chance for a blow which should drive the British from the Delta. The veteran Marshal von der Goltz had been for months in Constantinople, and had prepared the first Turkish armies for the field. He was now sent to take general charge of the Mesopotamia armies, a fitting honour for one who had been the chief military instructor of modern Turkey. On 24th November he was at Aleppo, and at a banquet given in his honour announced that in the appointment of so old a man to so great a command he recognized the hand of God. “I hope that, with God’s help, the sympathy of the Ottoman Empire and the friendliness of the whole people will enable me to achieve success, and that I shall be able to expel the enemy from Turkish soil.”

Meanwhile things were going ill in northern Persia. The German Minister, Prince Reuss XXXI., had won over to his side many of the Persian Ministers, a number of the local tribes, and the 6,000 men of the Gendarmerie, officered by Swedes, which had been established by Russia and Britain to police the country. The standstill of the Russians in the Caucasus and the British retirement from Ctesiphon brought these intrigues to a head. There were numerous local risings, and the British civilians at Yezd and Shiraz were made prisoners. In the capital, Teheran, things presently rose to the pitch of crisis. In the second week of November a detachment of the Russian Army of the Caucasus moved upon that city. The German, Austrian, and Turkish corps diplomatique left on 14th November for the villageNov. 14. of Shah Abdul Azim, on the Ispahan road, and frantic efforts were made to induce the Shah to accompany them, and so put himself into German hands. Prince Firman Firma and one or two of his advisers resisted the proposal, and after much wavering the boy-king resolved to remain. It was a difficult decision, for he had no troops to rely on against the Gendarmerie and the Turkish irregulars except the Persian Cossack Brigade, which remained true to its salt.

Map of the Scene of the Russian Operations in Persia, showing its relation to the Mesopotamian region.

Prince Reuss now showed his hand. He raisedDec. 7. the standard of revolt, and with the 6,000 men of the Gendarmerie, a number of tribesmen, and at least 3,000 Turkish irregulars from Mesopotamia—a total strength of some 15,000—endeavoured to hold the key points, which would allow him to keep in touch with his friends on the Tigris. One was Kum, eighty miles south of Teheran, on the Ispahan road, which, being a telegraph junction, tapped all the communications with southern Persia. The other was Hamadan, near the ancient Ecbatana, two hundred miles from Teheran, on the Bagdad road. Prince Reuss divided his forces between these two places, and also held the pass which led to Hamadan from the north. By the end of November the Russians were in Teheran. One detachment marched south towards Kum, but the main force was at Kasvin, moving on Hamadan. On 7th December the rebels were driven out of Aveh, and two days later were routed at the Sultan Bulak Pass and forced back upon Hamadan. On the 11th Hamadan submitted,Dec. 11. and on 17th December the Russians were pursuing the enemy through the mountains towards Kermanshah. The rebel strength at Hamadan was estimated at 8,000 irregulars and 3,000 gendarmes, all plentifully supplied with rifles and machine guns. Prince Reuss departed for Kermanshah to take counsel with the emissaries of von der Goltz. On the 20th the Russian leftDec. 20. took Saveh and Kum, and put an end to rebel activity in that notorious centre of intrigue. Five days later the PersianDec. 25. Government fell, and Prince Firman Firma, a staunch friend of the Allies, was appointed Premier.

For a moment the air was clear. But all Persia was in a ferment; the rebels who had been driven towards Kermanshah were in touch with the Turkish Army of Mesopotamia, and could call upon reserves which might gravely embarrass the far-flung Russian detachments. Germany had succeeded in one of her purposes. She had kindled a fire in the inflammable Middle East, and she was whistling for a wind to fan it.

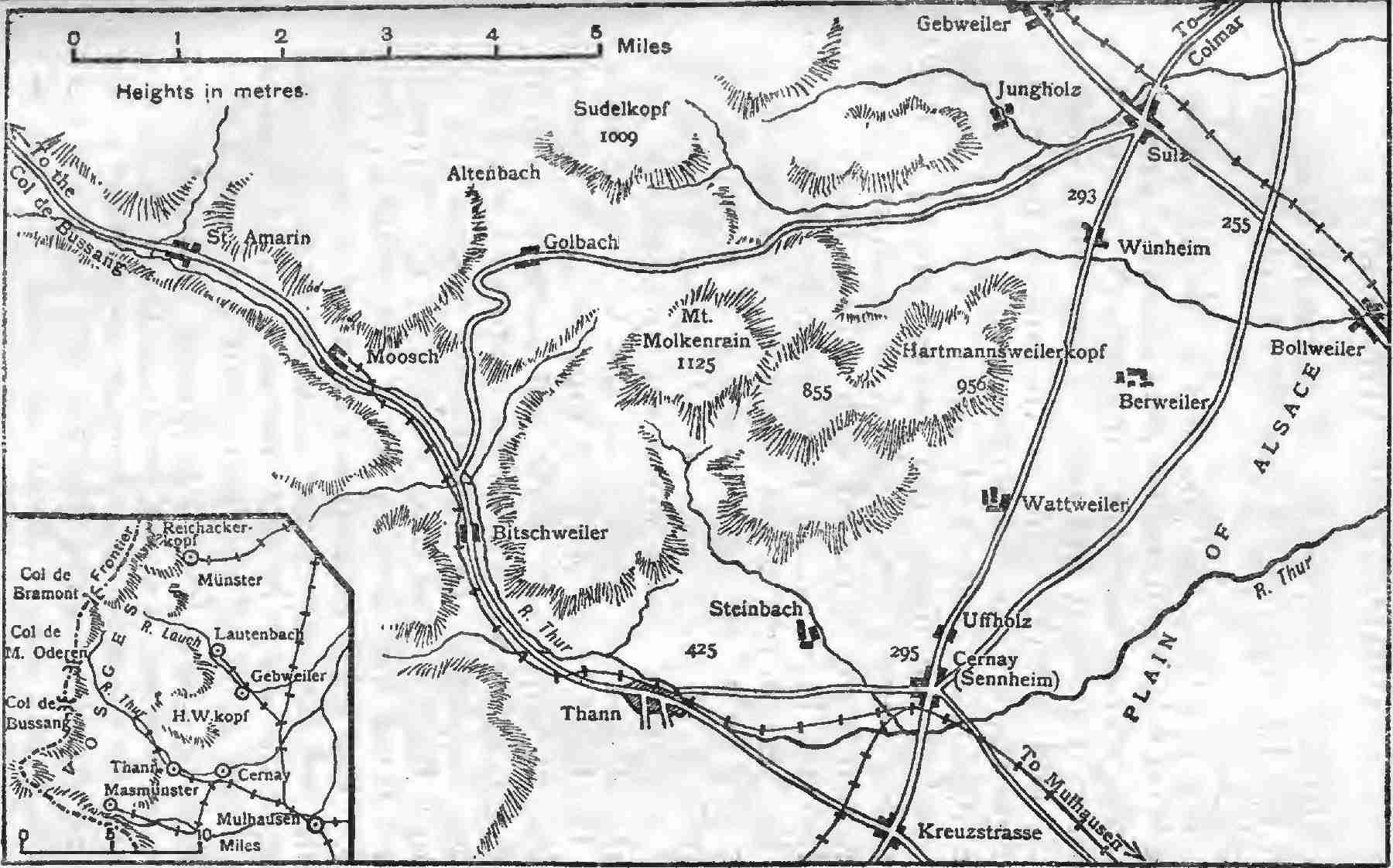

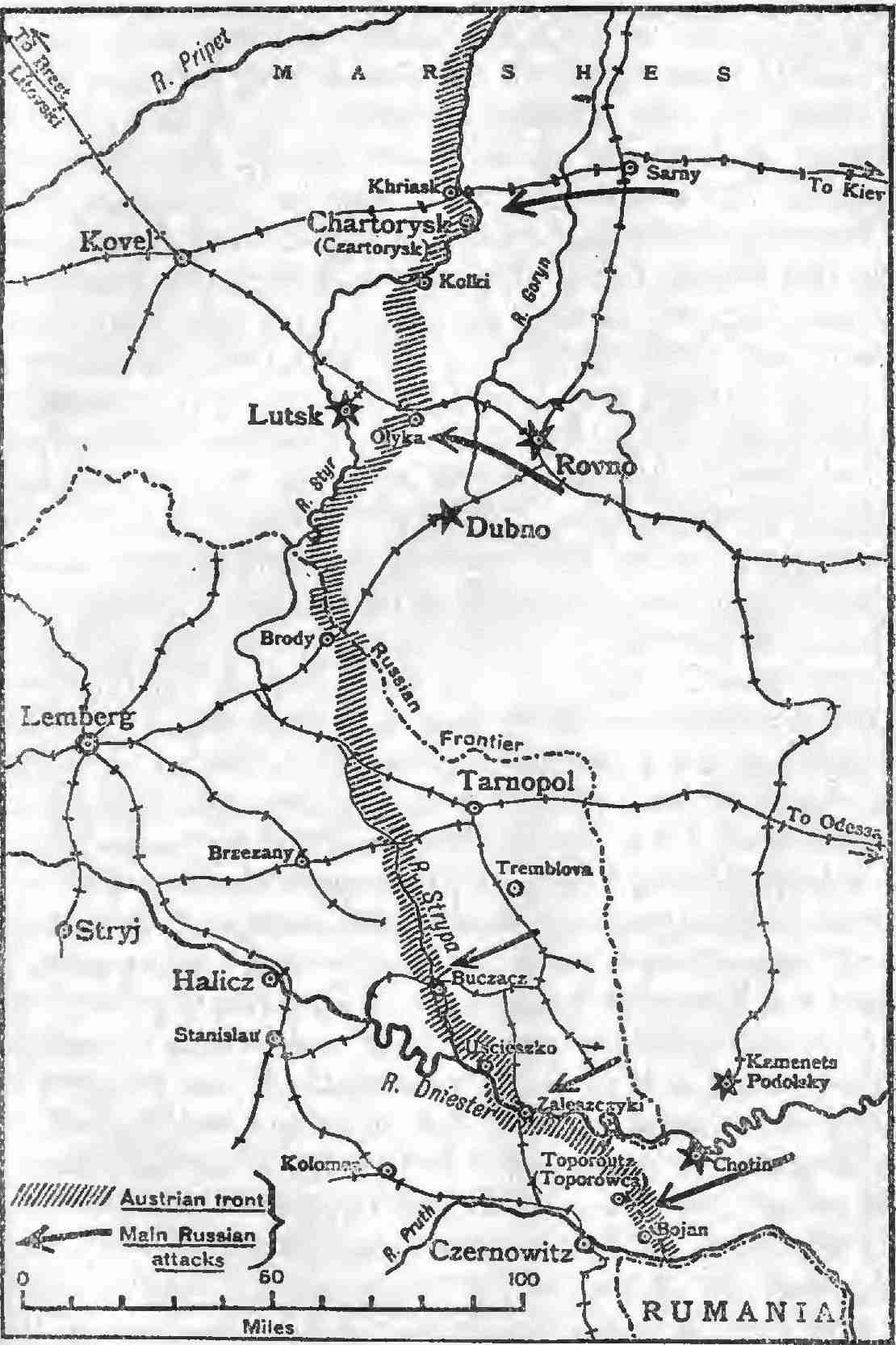

The Serbian Retreat—Essad Pasha—The Work of Italy—King Peter’s Journey—Monastir entered—Sarrail’s Retreat from Kavadar—British Retreat from Lake Doiran—Work of the 10th Division—Allies reach Salonika Zone—The Conduct of Greece—Decision to hold Salonika—Nature of the Adjacent Country—The Allied Lines—The Christmas Air Attack—Arrest of Enemy Consuls—The Overrunning of Montenegro—Fall of Mount Lovtchen—Behaviour of King Nicholas—Austrians enter Scutari—French occupy Island of Castelloriza—German Division in Constantinople—Meeting of Kaiser and King Ferdinand—The Situation in Egypt—Chances of Invasion—The Western Frontier—The Senussi—Withdrawal of Frontier Posts to Matruh—Fighting on the Libyan Plateau.

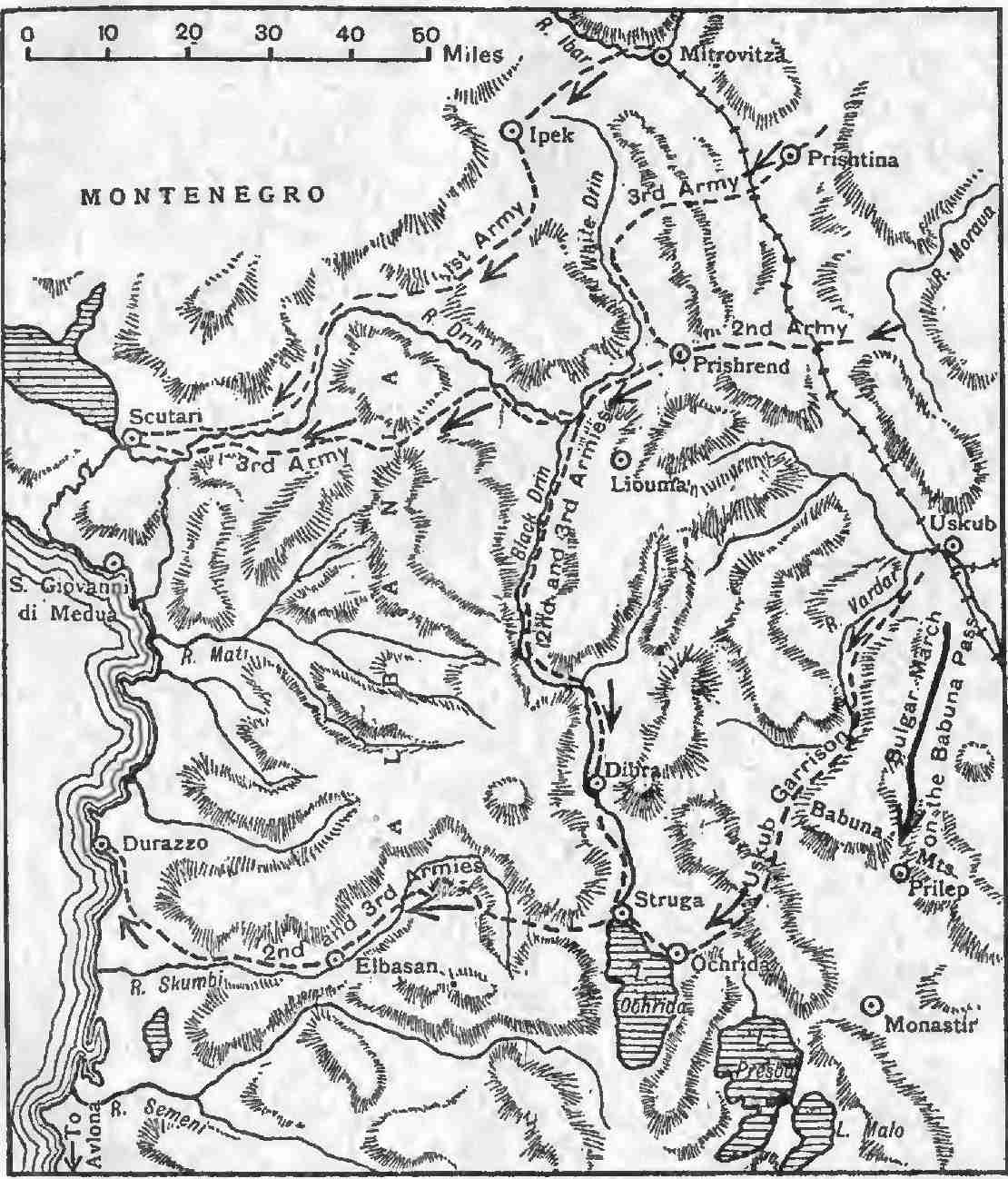

By the middle of November fighting had ceased through Serbia, save in the far south, where the Allied contingent was holding the gorge of the Vardar. The Serbian remnant was straining westward by every hill road which led to Montenegro and Albania. The tale of that strange migration is confused, as all such tales must be, for it was not only the retreat of an army but the flight of a people. The weaker and poorer fugitives were left behind in the foothills; but many women and children struggled on, cumbering the infrequent roads and suffering untold privations, till they reached the shores of the Adriatic. The campaign had already shown great national dispersions—the evacuation of Belgium, the move of the Russian Poles eastward; and it had shown the retirement of mighty armies—from the Meuse to the Marne, from the Vistula to the Dvina. But no army in retreat and no people in flight had ever sought a city of refuge through so inhospitable a desert. The stony ridges of the Coastal Mountains were already deep in snow. The few roads were tracks which led over high passes and through narrow gorges beside flooded torrents. The Albanian tribes were eager to profit from the misery of the fugitives. If they sold food it was at a famine price, and they lay in wait, like the Spanish guerillas in the Peninsula, to cut off stragglers. At the end of the journey was a barren sea-coast with few harbours, and between it and Italy lay the Adriatic, sown with enemy mines and searched by enemy submarines.

The main lines of the retreat are clear. Mishitch’s 1st Army and the detachment which had held Belgrade retreated by the upper glens of the Ibar to the little plain of Ipek, which is tucked away among the Montenegrin hills. Thence they made their way through the land of the Black Mountain to Scutari. Yourashitch’s 3rd Army fell back upon Prishtina, whence they moved to Prisrend on the Albanian border. They then tramped down the White Drin to its junction with the Black, and while a portion followed the river to Scutari, the majority went south by the Black Drin to Dibra, and made their way by Struga to Elbasan, and so to Durazzo. Stepanovitch’s 2nd Army followed much the same course, concentrating on Prisrend; and the Uskub garrison, after it had been driven from the Babuna Pass, moved straight by way of Ochrida upon Elbasan. The peculiar difficulty of the retreat for the southern armies lay in the fact that the Bulgarians, after the success at Katchanik and Babuna, had cut the route from Prisrend southward, and so forced the Serbians, in order to reach Elbasan, to make the journey on Albanian soil among the wild ravines of the Black Drin.

Few of the guns got away. Many reached Ipek, where they were destroyed and abandoned, since the paths west of Prisrend were only for foot travellers lightly burdened. Every hour of the retirement was a nightmare. The hill roads were strewn with fainting and starving men, and the gorges of the two Drins found their solitude disturbed by other sounds than the angry rivers. Happily the conditions which made the retreat so hard imposed discretion upon the pursuit. The German armies took no part in the chase. They were busy repairing the Orient railway, and getting ready to enter the country of their new allies. But the Bulgarians pressed the pursuit hard, and, had the land been more practicable, and had they occupied Struga and Elbasan, they might have cut off at least one-half of the Serbian force. But the time was too short, and the Serbians were well on the way to Durazzo before the Bulgarian advanced guards had entered Albania.

The Retreat of the Serbian Army.

One other piece of good fortune attended theDec. 21. retreat. Essad Pasha, who after many vicissitudes had made for himself a little Albanian kingdom after the flight of the ill-fated Prince of Wied, declared himself on the side of the Allies. He expelled all Austrian and Bulgarian subjects from the territories under his control, and gave to the Teutonic agents who appeared in December to stir up the northern tribes a taste of Albanian justice. He did his best to welcome the fugitives, and loyally assisted the efforts of the British, French, and Italian missions to prepare for their reception. These efforts were made in the face of immense difficulties. Food was sent by Britain and France, and Italy provided the shipping. It was necessary to bring the Serbian remnant to Durazzo, and for this purpose jetties had to be built, rivers and marshes had to be bridged, and roads had to be repaired and constructed. Italian troops arrived at Durazzo from Avlona on 21st December, to provide a rallying point. In one way and another nearly 130,000 men of the Serbian army were brought to the coast in safety. The civilian refugees went for the most part to Southern Italy.

King Peter himself had a journey of strangeJan. 1, 1916. vicissitudes. He reached Prisrend with his troops, and then pressed on to Liuma, across the Albanian border. Thence he set out incognito, accompanied by three officers and four soldiers, and journeyed on muleback and horseback through the hills held by the Albanian Catholic tribes. After four days he reached Scutari, where he rested for a fortnight, and then continued along the coast by San Giovanni di Medua, Alessio, and Durazzo to Avlona. He crossed to Brindisi, and remained there six days unrecognized. Then he took ship to Salonika, and arrived there on New Year’s Day, crippled with rheumatism and all but blind, but undefeated in spirit. If his country was for the moment lost, he had sought the nearest camp of its future deliverers. “I believe in the liberty of Serbia,” he said, “as I believe in God. It was the dream of my youth. It was for that I fought throughout manhood. It has become the faith of the twilight of my life. I live only to see Serbia free. I pray that God may let me live until the day of redemption of my people. On that day I am ready to die, if the Lord wills. I have struggled a great deal in my life, and am tired, bruised, and broken from it; but I will see—I shall see—this triumph. I shall not die before the victory of my country.”

The chronicle of the war is now concerned onlyNov. 16. with the southern border of Serbia and the fifty miles of Greek territory between it and the port of Salonika. On 16th November Vassitch and the remnant of the Uskub garrison which had held the Babuna Pass retired on Prilep. Teodorov’s forces at first moved slowly, but on 2nd December Vassitch was forced back on Monastir, and evacuated that town on 5th December. To begin with, Monastir was administered by German officers, in order to avoid rousing the jealousy of Greece; but in a few days the farce was dropped, and it was handed over to the Bulgarians.

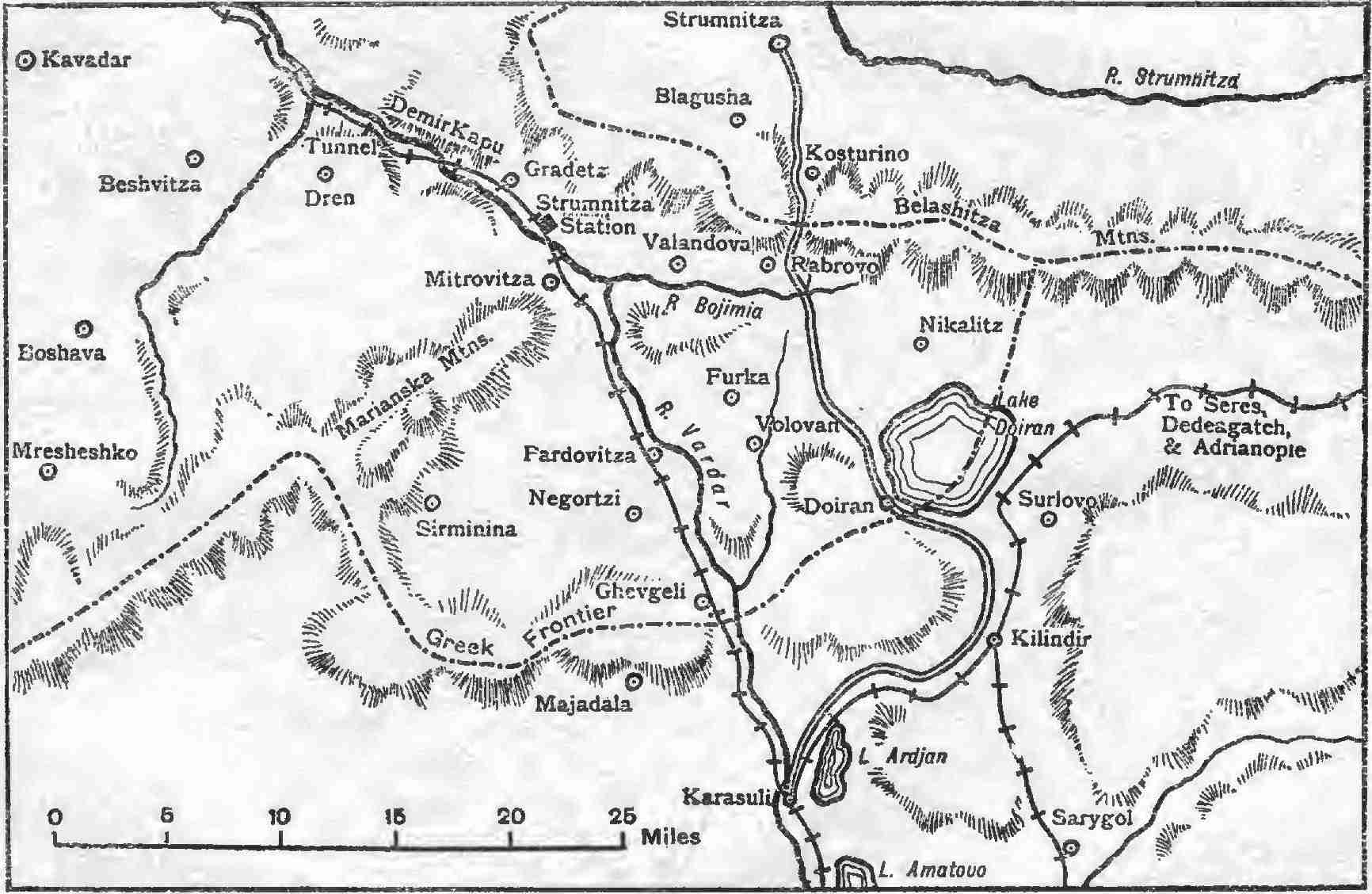

The position of Teodorov’s armies made itNov. 27. dangerous for Sarrail to remain longer in the camp of Kavadar, and compelled him to begin his retirement to the Greek frontier. As early as 27th November the troops holding bridgehead at Vozarci, on the left bank of the Tcherna, were withdrawn to the right bank. On the 2nd of December, while a detachment feinted eastward from Kara Hodjali, the French drew in their lines from the Tcherna to the railway, and began their retirement. The passage of the Demir Kapu ravine was not attained without hard fighting. The railway and bridges were destroyed behind them, and by 10th December the French were clear of the gorge and in position along the little river Bojimia, which enters the Vardar from the east. On their right lay the British 10th Division, which had been protecting the right rear of the advance to Kavadar.

Meantime the British had been seriously engaged.Dec. 6. They held the ground among the hills west and south of Lake Doiran, with their right crossing the railway which runs from Salonika by Dedeagatch to Adrianople. Teodorov struck at them with his left wing, which contained the equivalent of two army corps. On 6th December the British were driven out of their first trenches, and the weight of the enemy made retreat imperative. Next morning the attack was repeated, and slowly, at the rate of about two miles a day, they were pressed back from Lake Doiran towards the Vardar valley. We exacted a heavy penalty from the attack, and lost ourselves some 1,300 men, as well as eight guns, which in that rugged country could not be moved in time. The Irish battalions of the New Army showed fine stamina in rearguard fighting, and the Connaught Rangers, the Munster Fusiliers, the Dublin Fusiliers, and the Inniskillings added to the regimental laurels which their other battalions had won at Gallipoli and in the West. The Allies were now disposed from the mouth of the Bojimia south-eastward towards the village of Doiran. On the 4th the Bulgarians drove hard against their centre at Furka, but were beaten off with the loss of several thousands.

There was little time to waste if Sarrail was toDec. 12. avoid having his flanks turned. By 12th December the French under Bailloud and the British under Mahon had crossed the Greek frontier. The fourteen miles of the retreat had been completed methodically; transport and stores were got clean away, and no foodstuffs remained in the countryside for the enemy. Railways and roads were wrecked, and the frontier village of Ghevgeli was left in flames. Such a retreat, with casualties which scarcely exceeded 3,000, was an achievement of which any commander might well be proud. Sarrail had ventured his force into as ugly a strategic country as could be conceived. That he was able to withdraw it intact spoke volumes for the skill of his generalship and the resolution of his men.

The Allies were now in position about thirty miles from the port, on a line running from Karasuli, on the Vardar and on the Nish railway, to Kilindir, on the Salonika-Dedeagatch railway. A branch railway connected the two points, and gave the Allies lateral communication. It was a strong position, since it covered the main routes to Salonika, and could be reinforced at will. There were now in this theatre eight Allied divisions—three French, and the 10th, 22nd, 26th, 27th, and 28th British. Any Bulgarian invasion could be held long enough to provide for the creation of a new Torres Vedras based on the sea.

The Positions on the Serbo-Greek Border (Ghevgeli, Lake Doiran, etc.).

The retreat from Kavadar brought to a headNov. 23. the unsettled problems between Greece and the Allies. M. Skouloudis had succeeded M. Zaimis as Premier, and it was his opinion that any Allied troops which were driven across the Greek frontier must be disarmed and interned. On 23rd November France and Britain presented a Note to Greece, asking for assurances that this should not happen, and guaranteeing that all occupied territory would be restored and an indemnity paid for the use of it. The first Greek reply was vague, and a second Note on the 26th reiterated the demand. Meantime the Allies acted without waiting for an answer, and when the reply came, a fortnight later, it was a friendly compliance. Most of the Greek troops were removed from Salonika, and the whole “zone of manœuvre,” together with the roads and railways, was handed over to the Allies. Undoubtedly it was not an easy position for Greece, if she sought a correct neutrality, but it was the inevitable consequence of her acquiescence in the Allied landing. The Bulgarians waited on the frontier, but for the moment did not cross. Greece had announced with a certain voice that she would not permit her ancestral rivals to tread her soil; and caution was enjoined on Bulgaria by Germany, who did not want at the moment to have a belligerent Greece on her hands.

The Allied statesmen had decided that Salonika should not be relinquished. Though the purpose for which its occupation had been designed had failed, there were insurmountable objections against letting it fall into German hands. It would provide a formidable submarine base in the Eastern Mediterranean. It would give Austria that Ægean port to which her tortuous policy had so long been directed. Accordingly preparations were made at once to defend it, as Verdun had been defended, by far-stretched lines.

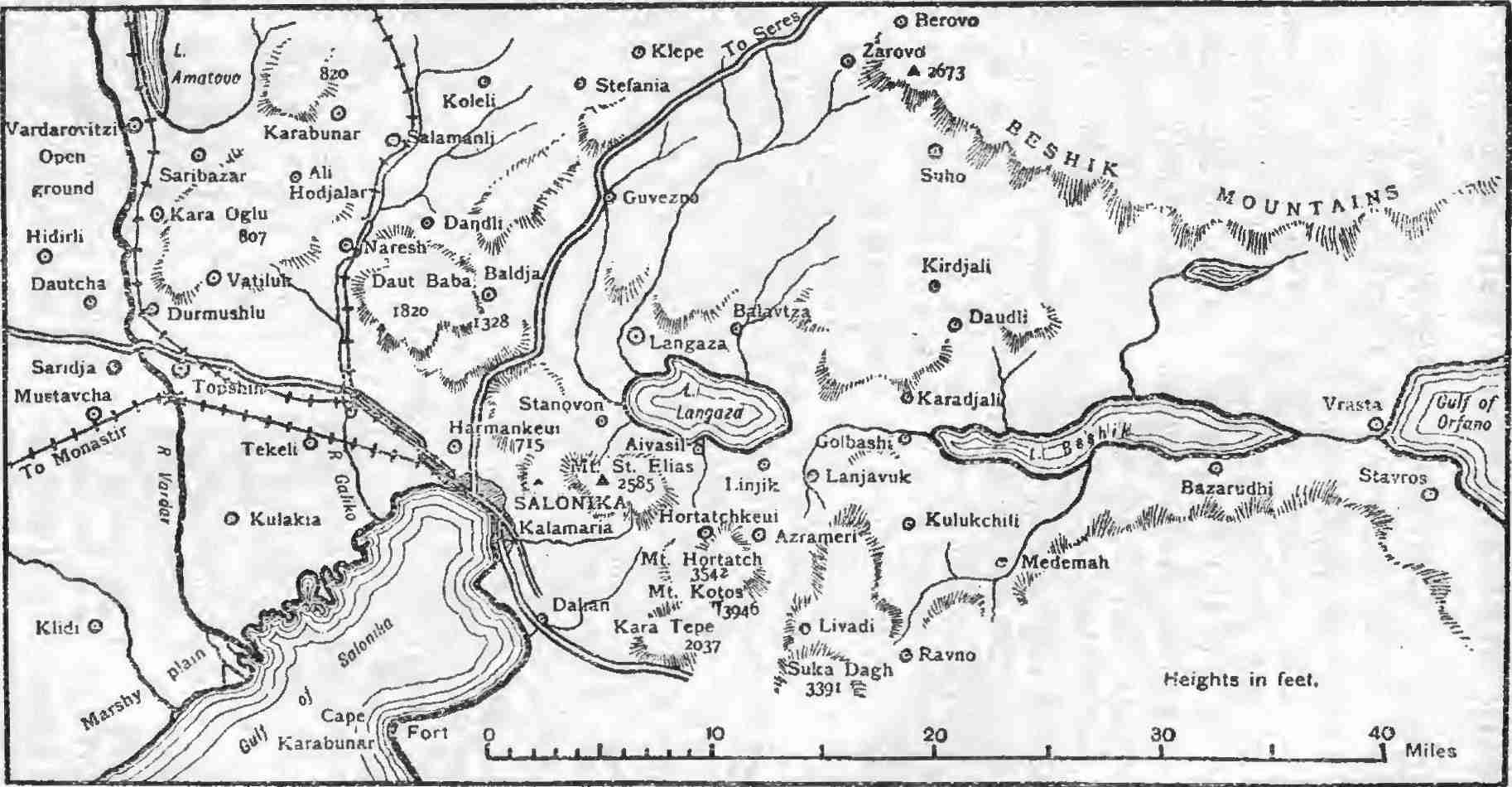

Salonika was, after Athens and Constantinople, the most famous city of the Near East. It had been the chief port of the kings of Macedon, and in its vicinity the fate of the Old World had been decided when Antony and Octavian defeated the murderers of Julius. Under the early emperors it was a free city, and the emporium of all the country between the Adriatic and the Marmora—the halfway house between Rome and Byzantium. It had seen many vicissitudes—the massacres by Theodosius, for which he did penance in Milan Cathedral; the sack by Berber pirates in the days of Leo the Wise; the capture by the Normans, with the short-lived rule of Boniface of Montferrat; the Turkish conquest under Murad the First; Venetian rule; the second Turkish dominion, which was destined to endure for centuries; the arrival of the Jews of the Sephardim from Spain, which was the key to its modern history; the inception of the Young Turk movement; the conquest by the Greeks in the Balkan War, and the murder in its streets of the Greek king.

In fortifying such a base it was necessary to find suitable points on the sea to form the flanks of the lines. Salonika lies at the head of the long gulf of the name, and, to prevent a turning movement of the enemy, a large tract of country had to be brought into the defended zone. West of the city is a swampy level extending to the mouth of the unfordable Vardar. Due north is a treeless plain rising to a range of hills, which are continued up the Vardar valley, but farther east sink into flats, where lie the two large lakes Langaza and Beshik. The trough which holds the lakes is continued in a wooded valley to the Gulf of Orphani. The country between the Vardar delta and the gulf was an admirable position for defence. At the Vardar end the deep and wide river with its salt marshes constituted a formidable barrier to envelopment, and any attack from Orphani was made difficult by the mouth of the Struma and the long Tahiros lake. Further, at Seres, at the north end of that lake, a portion of the Greek garrison of Salonika lay, thereby providing an awkward diplomatic obstacle to any Bulgarian attack. No narrower zone could give security. It was necessary to draw the Allied lines from the Vardar to the Gulf of Orphani, a distance of over sixty miles. Such a position included not only the immediate neighbourhood of the port, but the whole three-pronged peninsula of Chalcidice.

The Salonika Position.

The preparation of the lines and the communications behind them was pushed on with surprising speed. The now considerable numbers of the Allied troops, and the hosts of refugees which poured ceaselessly into the city, made labour plentiful. The French held the western section from the Vardar mouth to east of the Dedeagatch railway. The coast part of their line did not need to be defended by entrenchments; indeed, in the marshes trenches could not have been dug. The true defence lay in artillery fire. The lines bent back from the Vardar some ten miles above its mouth, and crossed the plain to the low ridges along the Dedeagatch railway. Here the position was very strong. The field of fire was perfect, and immense barbed wire entanglements cloaked all the possible points of attack. The British section included several parallel ridges of hills, and then the long trough of the lakes, which acted as a natural bulwark. A correspondent described the position: “Our trenches guard the northern slopes of one of the lines of hill that rib the plain. Our principal trenches lie deep and well-sandbagged, and from the front they are invisible. Three hundred yards after you have passed them and look back there is nothing but the blue smoke of camp fires behind them, mingling with the mists that rise from the clayey soil, to mark the lines on which they lie. Farther on, across the brown flats that stretch in unbroken treeless monotony to where the next hill ridge rises six or seven miles away, there are more earthworks, outworks, and advanced posts, covering possible lines of approach along the folds of the ground, with machine guns and trenches buried so flush with the surface that even the sun cannot find enough disturbance in the earth to cast a shadow. It is a most shelterless plain; but its very flatness and absence of cover make it a stout stronghold.”

By Christmas Day the defence of Salonika wasDec. 30. virtually complete. At the nearest point the lines ran ten miles from the city, following the analogy of Verdun, Dvinsk, and Riga. General de Castelnau, now chief of the French General Staff, visited the place on 20th December, and approved the plan. The 30th of December saw the first act of war. At ten o’clock in the morning enemy airplanes appeared, and dropped several bombs, one of which fell close to a Greek general who was parading a body of troops. Little damage was done, but the French airplanes which went up in pursuit failed to catch the invaders. That afternoon General Sarrail put into effect the scheme he had decided on in case of such an event. Salonika was a nest of spies, and the polyglot mob in the poorer quarters of the city offered dangerous material for the agitator to work upon. Accordingly, quietly and methodically, the German, Austrian, Bulgarian, and Turkish Consuls and Vice-Consuls, with their staffs and families, were gathered in, and taken on board a French warship. Search at the various consulates revealed ample warrant for this drastic step. The Austrian Consulate in especial was an arsenal of rifles and ammunition, stored for some sinister purpose. The measure was wholly correct and judicious. Military necessities were urgent. The enemy had boasted that Salonika would be his by 15th January, and it behoved General Sarrail to see that he had no foes in his own household.

The scene now changes to the shores of the Adriatic. Early in December Italy had landed the better part of two divisions at Avlona, and, as we have seen, had pushed forward troops to Durazzo. Serbia having fallen, it remained for Austria to overrun the little kingdom of Montenegro, the last of the Balkan Allies which still held the field. For this purpose she had her armies in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the troops which had taken Ushitza and were now on the eastern Montenegrin border, and the support of the Bulgarians on the Albanian frontier. By the end of the year the plain of Ipek was in her hands, and the towns of Plevlie and Bielopolie, and she was advancing up the Tara and the Lim, the upper streams of the Drina. More important, Mount Lovtchen, the fortified height up which the road to Cettinje climbs from the fiord of Cattaro, was being resolutely bombarded by warships in the gulf. If Lovtchen fell Cettinje must follow, and with the enemy pressing in from the east the days of the little kingdom were numbered. The Montenegrin fortification of Lovtchen was old and rudimentary, and there was much speculation at the time why Italy, whose immediate business it was, did not take steps while there was yet time to secure this vital position. The explanation seems to have been that she had her hands full with providing for the Serbian retreat on the Albanian coast, and that the activity of Austrian submarines made the transport of troops and stores so difficult that the task was beyond her. The fortification of Lovtchen should have been done six months before. It was another case where in Balkan matters the foresight of the Allies was to seek.

Lovtchen fell on 10th January to an infantryJan. 10, 1916. attack supported by ships’ fire. It had been held by a few thousand men, lamentably short of food, guns, and munitions. Three days later the Austrians entered Cettinje. Then followed a curious comedy. Berlin and Vienna announced with great jubilation the unconditional surrender of Montenegro. Silence followed, and it was assumed that King Nicholas, making the best of a bad business, had come to terms with the conqueror. But gradually it came out that there had been no surrender. The Montenegrin army was retreating towards Podgoritza and Scutari; King Nicholas was on his way to France; the Black Mountain had fallen, but with its flag flying. It is idle as yet to seek for an explanation. King Nicholas may have treated with the enemy, and then broken off negotiations, either because he could not carry his army and people with him, or because he was indignant at the harshness of the Austrian terms. In any case his principality was gone. On 23rd January the enemy occupiedJan. 23. Scutari; on the 25th, San Giovanni di Medua, and moved south against the Italian lines at Durazzo. The Teutonic League had secured a third little country to add to its trophies, and rouse the enthusiasm of those of its subjects who measured success in geographical terms.

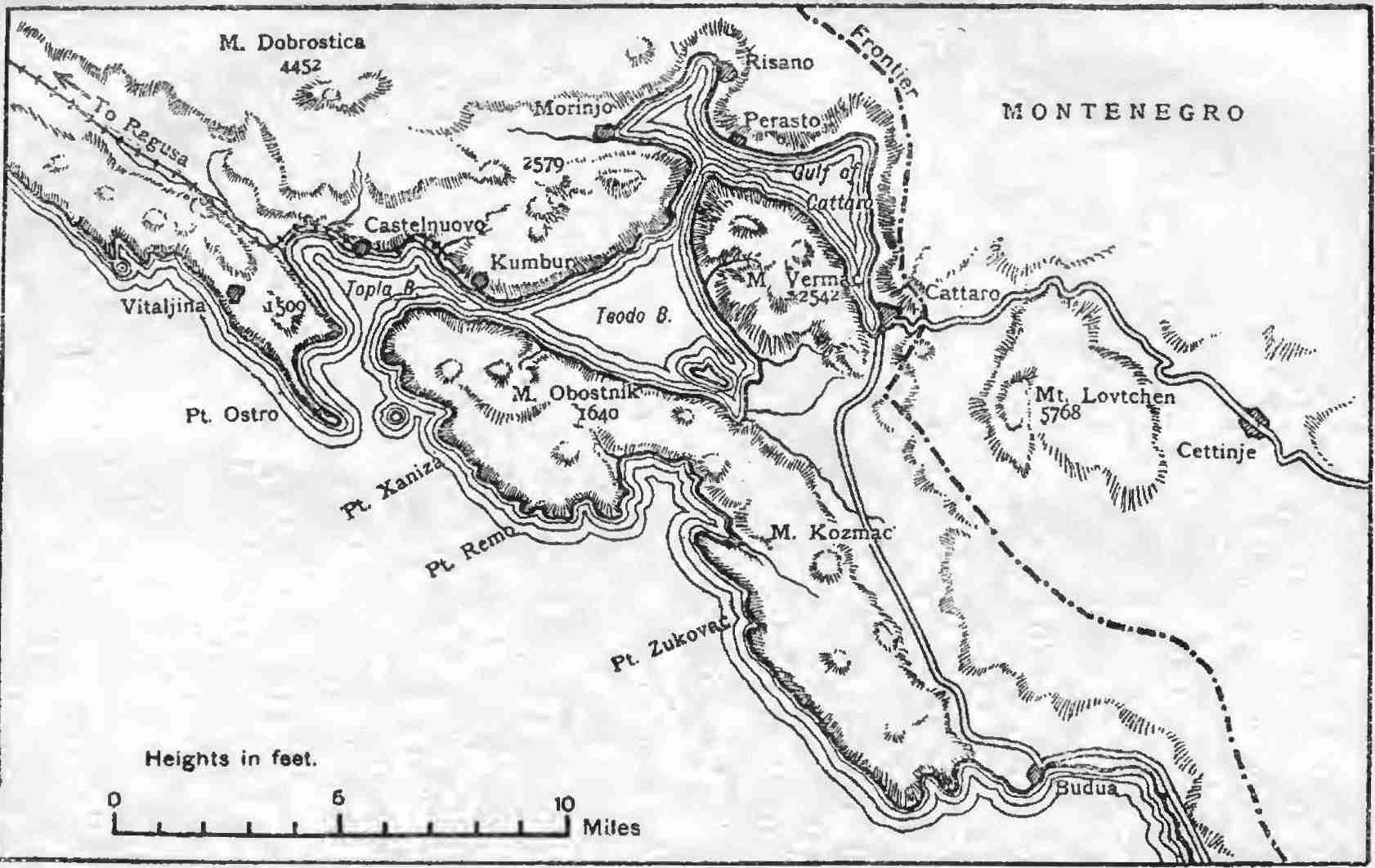

The Bocche di Cattaro, Mount Lovtchen, and the Road to Cettinje.

Elsewhere in the Near East there was little toDec. 29. record. The most significant event, the offensive of Ivanov in the Bukovina, belongs to another chapter. On three occasions the Bulgarian port of Varna was bombarded by Russian warships. On 29th December the French occupied the island of Castelloriza, in the Dodekanese group, east of Rhodes, which might be useful as a base for operations against Adalia. Greece protested, but with little reason, for since the Tripoli war the group had been nominally occupied by Italy. Meantime, to guard against possible danger from Rumania and Russia, the main Austro-German forces had entered Bulgaria, and were watching the Danube line and preparing to resist any landing on the Black Sea coast. Germany was making haste to reap the fruits of her conquest. The Belgrade bridge and the Ottoman railway were being repaired, special rolling-stock was being sent out for the Constantinople journey, and time-tables were prepared for the through route from Berlin to Bagdad. If these doings seemed to argue a complete confidence in the future, there were others which betokened some uneasiness as to Turkey’s position. Undoubtedly there was a growing hostility among the Ottoman people to the new régime. Turkish and German soldiers came often to blows, and Enver remained in power solely by terror. Secret murder became the order of the day, and the fame of Abdul Hamid in this respect was wholly eclipsed. At the end of the year it was believed that two divisions of German troops were in Constantinople, and, since the Egyptian expedition was hanging fire and was none too favourably regarded by von Falkenhayn, their presence could only have a political explanation.

The Kaiser himself visited Bulgaria in the beginningJan. 18, 1916. of the year. At Nish on 18th January he hailed his ally as an illustrious War Lord, and praised “the sublime leaves of glory” which he had added to Bulgarian history. The grateful Ferdinand returned the compliment in doubtful Latin, greeting his guest as “imperator gloriosus,” the redeemer of a stricken people. It was a strange piece of mock-heroic. Times had changed since, two years earlier, one of the official spokesmen of Prussianism had contemptuously dismissed the monarch of Bulgaria as a “hedge-king.” The Kaiser declared that he could expect no greater honour than to be honorary colonel of a Bulgarian regiment. It was the language of courtesy, but it had an ironical truth. Megalomania makes strange bed-fellows, and the tragedy-king, grandiosus et gloriosus, was reduced to hobnob with Pantaloon.

The situation in Egypt, since that day a year before when a British Protectorate had been proclaimed and Sultan Hussein placed on the throne of the deposed Khedive, had been one of internal tranquillity. Great masses of British troops had been under training, a Turkish force had reached the banks of the Suez Canal, and later the place had been the base for the Gallipoli operations; but these military doings had small effect on the serenity of the land. Nationalism, in the old bad sense, was quiescent. Its leaders were either in detention camps or in exile, and the attempts on the life of the Sultan and one of his Ministers were the only flickering of what Germany had hoped would be a consuming fire. The secret of this tranquillity is not to be sought only in the firm hand of the British Military Governor, but rather in the very real economic prosperity of the country. Egypt was in the rare position of being untouched, so far as her pockets were concerned, by the world war. The presence of great armies brought money into the country, and provided an inexhaustible market for local produce. Her crops were good; even her cotton crop, which at one moment gave cause for disquiet, belied her fears. The peasant farmer of the Nile valley might owe a shadowy allegiance to the Khalif, but he was first and foremost a man who had to get his living. Lord Cromer had long before discovered that the centre of gravity was economic, and that political stability would be assured if among the labouring masses there was a modest security and comfort.

By the end of the year the German threats of invasion were very generally discounted. The so-called “Army of Egypt” was watching the Bulgarian frontier; and its former commander, von Mackensen, was at grips with Ivanov on the Dniester. Had Turkey been in earnest, preparations for the great assault should have been begun in early December. But in spite of rumours of pipe lines and light railways being built westward from Beersheba, it was clear that no serious effort was being made to prepare the ramshackle Syrian railways for the transport of a great army. The invasion could only succeed if it were conducted on a colossal scale with the most elaborate preliminaries, and these neither Djemal at Damascus nor Enver at Constantinople had seriously envisaged. Part of the Syrian army had gone to reinforce Bagdad; part, it was clear, might soon be called for in Transcaucasia. The Turkish aims were distracted; and Germany, having locked up eight Allied divisions at Salonika, showed some disposition to rest on these laurels. The Drang nach Osten had not had the popular success which its promoters expected.

But it behoved the Allies to be ready for all emergencies. Their position in the Eastern Mediterranean was roughly that of an army holding interior lines, and, with the command of the sea, their communications were simple. From a proper base they could reinforce Salonika and Gallipoli at will. That base must clearly be Egypt, which had the further advantage that it was the most convenient base for the Mesopotamia campaign. Accordingly the defence of the Nile valley could be combined with the provision of a base for all the other activities in the Near East. Egypt, said one of the characters in Mr. Kipling’s stories, was “an eligible central position for the next row.” Britain was fortunate in controlling a territory which was at once a training-ground and a starting-point.

The only cloud which threatened immediately—and it was a very small one—came from the west. The western frontier of Egypt, seven hundred miles long, adjoined the Italian possessions in Tripoli, and Italy was an ally. But the writ of Italy ran feebly in the interior. After the Tripoli war the Italian suzerainty, formally acknowledged in the Treaty of Lausanne, was not made effective beyond the coast line. Turkish regulars and Turkish guns remained behind to help the Arab and Berber tribes to resist the alien rule. When Italy declared war on Austria the Italian force of occupation fell back to the coast, and the inland tribesmen were left to their own devices. Stirred up by German and Turkish agents, these tribesmen prepared for action. They hoped to gather to their standard the Bedouins of the Libyan plateau, and to win the support of the great Senussi brotherhood. The Senussi form one of those strange religious fraternities common in North Africa. Their founder had been a firm friend of Britain, and had resisted all overtures from the Mahdi. He had preached a spiritual doctrine which Islam for the most part regarded as heterodox, and his followers were outside the main currents of the Moslem world. In especial they were untainted with Pan-Islamism, and had held themselves aloof from politics. Their headquarters were the oases of the North Libyan desert, and they had no fault to find with British rule in Egypt. Their Grand Sheikh, Ahmed Sherif, had given assurance of friendliness to the Anglo-Egyptian authorities, and his official representatives lived on the Nile banks in cordial relations with the Government. But a mass of tribesmen called themselves Senussi who were only loosely attached to the main organization; and there was the danger that these, whatever the attitude of the Grand Sheikh, might join hands with the Tripolitan Berbers and the less reputable of the Bedouins in an assault from the west, which would disarrange our military plans.

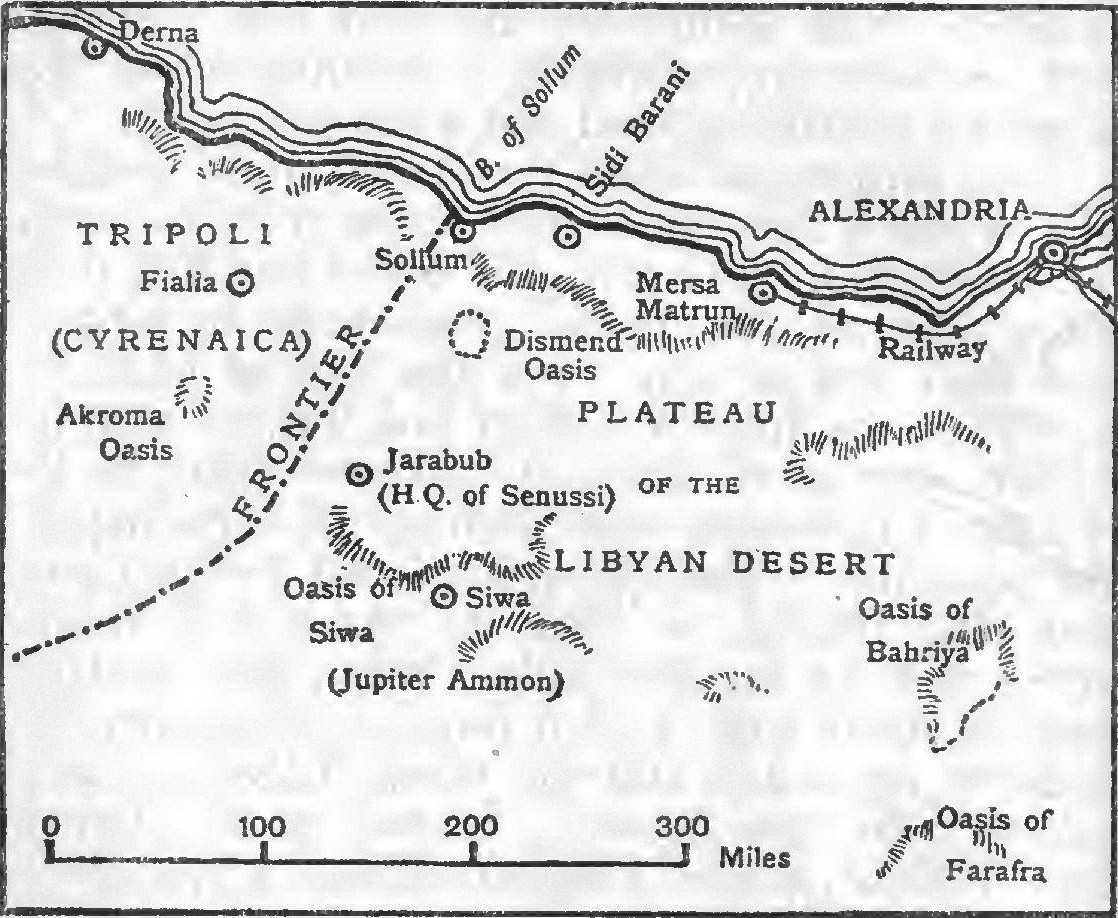

The Western Frontier of Egypt.

It was only at the north end that the Tripoli frontier had to be guarded. South lay the endless impassable wastes of the Libyan desert. But along the coast ran the Libyan plateau, with many little oases linked up by caravan tracks. A railway runs from Alexandria as far as Mersa Matruh, a port on the coast, and beyond that were Egyptian forts at Sidi Barani and at Sollum close to the Italian border. When trouble began to threaten, the posts at Sollum and Sidi Barani were drawn in, and Matruh was held in some strength. With the railway behind it and the sea at its doors it was amply equipped to defend the marches.

The first hostilities began on 13th December,Dec. 13. when 1,300 Arabs were driven back with heavy losses. Towards the end of the month a force of 3,000 gathered on the outskirts of Matruh. A British force, consisting of part of a new New Zealand Brigade then training in Egypt, the 15th Sikhs, and detachments of the Australian Light Horse and British Yeomanry, went out against this, the first invasion of Egypt from the west since the Fatimites in the tenth century. The enemy was located in a donga some eight miles from Matruh, and was completely routed by the British infantry with a loss of over 500 killed and prisoners. Our own casualties were inconsiderable. The mounted troops swept up most of the transport and supplies of the raiders.

The invasion was handicapped from the start.Jan. 13, 1916. It had no sea bases by which to receive reinforcements from Turkey, and it was confined by the nature of the land to certain well-marked routes. There was another attempt on 13th January, and the tribesmen after their fashion still hung around our camp. On 23rd January our forces, under General Wallace, now increased by part of General Lukin’s South African Brigade, marched out in two columns, fell on the tents of the enemy, now 4,500 strong, and drove them westward in utter rout, with losses of over 600. After this the attack languished. The eastern and western tribesmen took to quarrelling, refugees came in in starving mobs, and the tribes on the Egyptian side, notably the Walad Ali, petitioned the British Government and the Grand Sheikh of the Senussi for protection against their former allies. The affair soon degenerated into little more than frontier brigandage. If Germany hoped to make of the Arabs and Bedouins of the Tripoli hinterland, a fanatical horde which should sweep to the gates of Cairo, she had wholly misjudged their temper. To build up armies from such material was like an attempt to make ropes of desert sand.

Meanwhile, as this skirmishing proceeded, the troops in Egypt received a sudden accession. By one of the miracles of the war the forces in Gallipoli had been safely withdrawn from the peninsula, and with scarcely a casualty the wildest adventure of the campaign had come to a fortunate close.

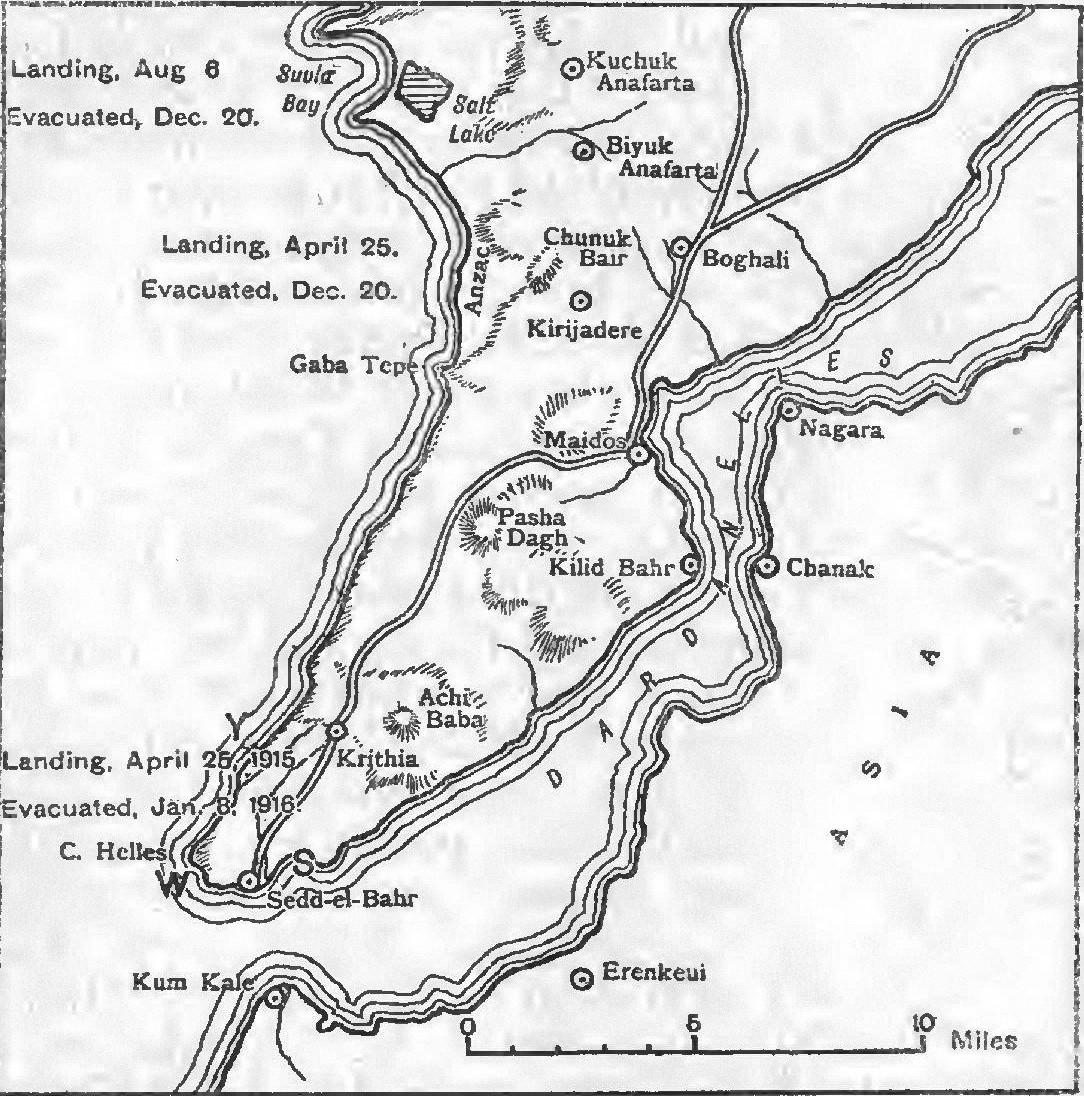

Autumn Fighting at Gallipoli—A Great Storm—Casualties up to 11th December—Evacuation decided upon—Difficulties of the Decision—The General Plan—The Final Days at Suvla and Anzac—All Troops embarked—The Great Bonfires—The Succeeding Gale—Special Difficulties at Helles—The Covering Attack of 19th December—Fighting on 7th January—The Evacuation—A Storm rises—Total Casualties—Nature of the Achievement—General Monro’s Order—An Exploit without Parallel—The “Sporting Chance” in War.

While the Serbian army were in retreat toNov. 15. the Adriatic and the Allies at Salonika were slowly falling back to the coast zone, the campaign at Gallipoli languished. Neither side had any inducement to a great attack. The Allies had shot their bolt and failed; the Turks were still awaiting the new munitionment which Germany’s success in the Balkans had ensured to them. There were minor affairs on both sides which came to nothing, such as the attack on 15th November by the 156th Brigade of the 52nd (Scottish Lowland) Division—4th and 7th Royal Scots, 7th and 8th Scottish Rifles, and Ayrshire Yeomanry—which captured nearly 300 yards of front-line trench at the Krithia nullah. As November wore on it became apparent that the Turks were getting bigger guns and an ampler supply of shells. New roads were being made, as we learned from prisoners, to facilitate the progress of the Krupp and Skoda monsters, and the six-inch batteries on the Asiatic shore became unpleasantly industrious in the bombardment of the Helles beaches. It must be remembered that the Turkish possession of the high ground forming the spine of the peninsula gave excellent observation posts, and in the circumstances it was a miracle that their artillery did so little damage. But any increase in their batteries could not but be viewed by the Allied command with grave disquiet.

The weather of late autumn was mild and equable,Nov. 27. but towards the end of November our men had a taste an Ægean winter storm. On the 27th it rained without ceasing for twelve hours. The trenches became canals, the dug-outs cisterns, and every nullah held a raging torrent. Next day the wind shifted to the north, and there was a spell of bitter frost. This was followed by a snow blizzard, which recalled the worst days of the Crimea. “Frozen, buffeted by wind and sleet, with hardly a possibility of motion to keep the circulation alive, the men endured agonies. Sentries watching through the loopholes in the parapets were found dead at their posts when their turn came to be relieved, frozen solid, their stiff fingers still clutching the rifle in an iron-fast grip, the blackened face still leaning under its sackcloth curtain against the loophole.” This weather bore especially hard on the Australian Corps, many of whom had never seen snow before, and who longed now for the dust and stifling heat of the August battles. The force of the storm was felt chiefly at Suvla, where there were over 200 deaths from exposure. Over 10,000 sick were evacuated in the succeeding week as a further consequence.

The gale lasted three days, and was followed byDec. 11. a spell of mild weather which gave us leisure to repair the damage. But the experience was ominous; the Dardanelles winter had scarcely begun, and the worst storms might be looked for in the first months of the new year. Our troops were dependent for every necessary of life and war on seaborne supplies, and it became a question how our ships could keep the water if the gales were frequent. Without the aid of the warships we had no real answer to the Turkish bombardment, and without the transports and cargo-boats we should certainly starve. The publication of the Gallipoli casualties up to 11th December enabled the world to judge of the cost of the enterprise. In seven months over 25,000 officers and men had perished, over 75,000 were wounded, and over 12,000 missing—casualties nearly twice the number of the force which landed on 25th April. Sickness had been rife, and over 96,000 cases had been admitted to hospital. The chief causes were dysentery and para-typhoid, and the prevalent type of the former was one which demanded careful nursing and a long convalescence if it were not permanently to impair the constitution. An enterprise which had shown such unparalleled losses, and which, what with the probability of ill weather and the certainty of an increased enemy strength, boded so ill for the future, ought clearly to be relinquished, if relinquishment was possible.

The decision to evacuate Gallipoli was made in the course of November by the British Government in deference to the clearly expressed opinion of General Monro. It was not an easy decision. It meant in the view of all concerned a considerable loss, and even those who took the optimistic side put that loss at not less than a division. Historical precedents were clear on the point. An embarkation in the face of the enemy had always meant a stiff rearguard fight and many casualties. Corunna was a typical case. There we succeeded well, but in most instances the cost had been far greater. Take, for example, an almost forgotten episode in the Seven Years’ War. In 1758 a British expedition attacked St. Malo. The troops disembarked six miles west of the town and tried to cross the Rance to the south of the place. This movement was prevented by the numbers of the enemy, and we fell back on the bay of St. Cast, where we re-embarked after heavy losses. It was the accepted military doctrine that re-embarkation without disaster was only possible after a victorious battle with the enemy, and that even then a considerable price must be paid for getting away.

The difficulty was increased by the fact that the evacuation of Gallipoli must be lengthy and must be piecemeal. It was not a question of shipping a division or two, but three army corps. It was impossible to move them all at once with our existing transports. There must be a gap between the operations, and this meant that with regard to the later movements the enemy would be abundantly forewarned. Moreover, a protracted embarkation put us terribly at the mercy of the winter weather. Even a mild wind from the south or south-west raised such a groundswell as to make communication with the beaches precarious. Those who looked for the loss of a third of our strength had good historical warrant for their pessimism. Few more anxious decisions have ever fallen to the lot of a British commander than that on which Sir Charles Monro was required to pronounce the final word.

The problem fell into three parts: Suvla, Anzac, and Cape Helles. From Suvla the 10th Division had already gone to Salonika, as well as one French division from Cape Helles, and the 2nd Mounted Division had left for Egypt. But in each zone there remained a matter of three or more divisions to be moved. The whole thing was a gigantic gamble with fate, but every precaution was taken to lessen the odds. The plan, which was mainly the work of General Birdwood, was to remove the matériel, including the heavy guns, by instalments during a period of ten days, working only at night. A large portion of the troops would also be got off during these days, certain picked battalions being left to the last. New lines of trenches would be constructed to cover the embarkation points in case a rearguard action became necessary. Everything must be kept normal during the daylight—the usual artillery shelling and spurts of rifle fire. Every morning before daybreak steps must be taken to hide the results of the night work. Any guns brought nearer the shore must be covered up so as to be unrecognizable by an enemy airplane. Success depended upon two things mainly—fine weather and secrecy. The first was the gift of the gods, and the second was attained by sheer bluff. It was a marvellous achievement, considering that every man in the British force had been talking for three weeks about the coming “rest camp.” Its success may have been due partly to the curious apathy which at the moment had seized the Turks and made them disinclined for the offensive. The new big howitzers were arriving and settling down on their concrete emplacements. Enver proposed to wait till these could be used to blow the British off the peninsula. Unfortunately for him these pledges of German friendship arrived too late for the fair.

Before the end of November the battalions holding the firing lines were conscious of great nocturnal activity in their rear. Stores which had been accumulated at advanced bases were shifted nearer the coast, and at Suvla, especially on the two flanks, trenches and entanglements were being created which seemed irrelevant to any military purpose. On the 8th of December it was whispered that orders for the evacuation had arrived, and night after night our men watched the shrinking of their numbers. There was a generous rivalry as to who should stay to the last—a proof of spirit when we remember that every man believed that the rearguard was almost certainly doomed to death or capture. Presently only those in the prime of physical strength were left. All the weak and sickly had gone to the transports, which nightly stole in and out the moonlit bay. Soon it became clear that the heavy batteries had also gone. To the ordinary observer in daylight they still appeared to be in position, but the guns in the emplacements were bogus. Then the field guns began to disappear, leaving only a sufficiency to keep up the daily pretence of bombardment. It was an eery business for the last battalions as they heard their protecting guns rumbling shorewards in the darkness. The hospitals were all evacuated, and their stores moved to the beach. New breakwaters had been built there, and all night long there was a continuous procession of lighters and motor boats. Soon the horses and motor cars were also shipped, and by Friday, 17th December, very few guns were left. To the Turkish observers the piles of boxes on the beaches looked as if fresh supports had been landed, and we were preparing to hold the place indefinitely. These beaches were shelled all day, principally by the heavy howitzers behind the Anafarta ridge. But at night, fortunately for us, the shelling ceased.

The weather was warm and clement, with light moist winds and a low-hanging screen of clouds. Coming in the midst of an Ægean winter it seemed to our men a direct interposition of Providence. It was like the land beyond the North Wind which Elizabethan mariners believed in, where he who pierced the outer crust of the Polar snows found a country of roses and eternal summer. No fisherman ever studied the weather signs more anxiously than did the British commanders during those days. Hearts sank when the wind looked like moving to the west. But the weather held, and, when the days consecrated to the final effort arrived, the wind was still favourable, the skies were clear, and the moon was approaching its full. Nature had joined the wild conspiracy.

On Saturday, 18th December, only picked battalionsDec. 18. held the front. The final embarkation had been fixed for the two succeeding nights, and it was believed that if the first night was successful the whole enterprise would go through. Evening fell in a perfect calm. The sea was as still as a quarry-hole, and scarcely a breath of wind blew in the sky. Moreover, a light blue mist clothed all the plain of Suvla, and made a screen against the enemy observers, while a haze also shrouded the moon. At 6 p.m. the crews of the warships went to action stations, and in the darkness the transports stole into the bay. Not a shot was fired. In dead quiet, showing no lights, the transports moved in and out. Every unit found its proper place. By 1 a.m. on the morning of Sunday, the 19th, all had gone, and the bay lay empty in the moonlight.

That Sunday was one of the most curious in the war. Our lines lay to all appearances as they had been for the past four months, but they were only a blind. We kept up our usual fire, and received the Turkish answer, but had any body of the enemy chosen to attack they would have found the trenches held by a handful. There were 20,000 Turks on the Suvla and Anzac fronts, and 60,000 in immediate reserve. Had they known it, they had before them the grand opportunity of the campaign. But our warships plastered their front and they “watered” our routes of transport as methodically as they had done since the August battles. Lala Baba came in for a heavy bombardment, but there was no longer a gun on the little hill. An attack by our troops at Helles on that day distracted the enemy’s mind from their immediate opponents. Night fell with the same halcyon weather. The transports—destroyers, trawlers, picket boats, every kind of craft—slipped once again into the bay, and before midnight the last guns had been got on board. At 1.30 a.m.Dec. 20. on Monday morning the final embarkation of the troops began. Platoon by platoon they filed in perfect order down the communication trenches, a detachment occupying one of the new defensive positions till the other had passed. Strange receptions were provided for the first enemy who should enter the deserted trenches in the way of mines and traps and automatic bomb-throwers. There were messages left, too, congratulating “Johnnie Turk” on being a clean and gallant fighter, and expressing hopes that we might meet him again under happier conditions. By 3.30 the last of the troops were on the beach, and long before the dawn broke all were aboard. One man had been hit by a bullet in the thigh; that was the only casualty. The Highland Mounted Brigade acted as the rearguard to fight the expected action which never came. Among the last to embark were 200 men who had been the foremost to land in August. They left from the very spot where they had first set foot ashore.

The operations at Anzac were conducted on the same lines. The beaches at Suvla were five miles or so from the enemy, and open to his observation. At Anzac they were less than two miles in places, but concealed from view under the steep seaward bluffs. But the intricate Anzac lines, and the exceeding precariousness of many of the positions, made the movement of guns and troops far more difficult. Some of our gun positions there were on dizzy heights, down which a gun could only be brought part by part. This work was brilliantly performed. Half the guns and half the men of the New Zealand batteries disappeared in a single night. As at Suvla, only picked battalions were left to the end, and there was desperate rivalry as to who should be chosen to act as rearguard. On the Saturday night three-fifths of the entire force was got on board the transports. On Sunday night the rest left, with two men wounded as the total casualties. By 5.30 a.m. on Monday morning the last transports moved from the coast, leaving the warships to follow.

Then on the twelve miles of beach from Suvla Burnu to Gaba Tepe began one of the strangest spectacles of the campaign. All the guns but four 18-pounders, two old 5-inch howitzers, one 4.7 naval gun, one anti-aircraft and two 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns had been removed, and these were rendered useless;[1] ammunition and the more valuable stores had been cleared, but there was a quantity of supplies, chiefly bully-beef, which was not worth the risk of human life. These were piled in great heaps on the shores and drenched with petrol. Before the last men left parties of Royal Engineers set them on fire. About 4 a.m. on the Monday morning the bonfires began, blazing most fiercely near Suvla Point. The Australians at Anzac about 3.30 had exploded a big mine on Russell’s Top, and this called forth from the Turks an hour’s rifle fire. As the beach fires blazed up the enemy, thinking that some disaster had befallen us, shelled the place to prevent our extinguishing the flames. The warships shelled back, and all along that broken coast great pharoses flamed to heaven, like giant beacon-fires in some strife of the Immortals. At 4.30 a.m. a motor lighter at Suvla, which had been wrecked some weeks before, was blown up, and added to the glare. Watchers on the Bulgarian coast, looking seaward, saw the peninsula wrapped in flames, as if its stony hills had become volcanoes vomiting fire.

It was not till dawn that the Turkish guns ceased. Even then they did not know what had happened. They shelled the bonfires still blazing in the bright sunrise; they searched the solitudes of Lala Baba and Chocolate Hill with high explosives, and the British warships fired a final volley. Picket boats at Anzac and Suvla up to eight o’clock were still collecting a few stragglers from the beaches. By 9 a.m. it was all over, and the last warship steamed away from a coast which had been the grave of so many high hopes and gallant men.

We were just in time. That night the weather broke, and a furious gale blew from the south, which would have made all embarkation impossible. Rain fell in sheets and quenched the fires, and soon every trench at Suvla and Anzac was a torrent. Great seas washed away the landing-stages. The puzzled enemy sat still and waited. They saw that we had gone, but they distrusted the evidence of their eyes. History does not tell what fate befell the first Turks who penetrated our empty trenches, what heel first tried conclusions with the hidden mines, or with what feelings they viewed the parting Australian message left on Walker’s Ridge—a gramophone with the disc set to “The Turkish Patrol.”

The success, the amazing success, of the Suvla and Anzac evacuation made the position at Cape Helles the more difficult. Few observers in the West believed that there was any chance of a similar operation there. At the most they looked to see a new Torres Vedras fortified at the butt-end of the peninsula, where, with the help of the ships, the enemy might be held off till the situation cleared. It was true that Helles was ill placed for such a policy. It was too well commanded by the heights on the European and Asian shores, and it was doubtful how the Torres Vedras plan would work in the face of the big Austro-German howitzers, of which the departing Australians at Anzac had seen the first shots. But there seemed no other way. The first bluff had worked to admiration; but it is of the nature of bluff that it can scarcely be repeated against the same opponent. Moreover, the Turkish aerial reconnaissance had now become active over all our positions.

Sunday, 19th December, the second last day of theDec. 19. Suvla and Anzac embarkation, saw a covering attack of the troops at Helles. At two in the afternoon the ships opened a bombardment of the enemy’s front, which was soon taken up by all the land batteries, including those of the French, which had remained after most of their infantry had been withdrawn. Under this cover a brigade attacked up the Krithia nullah, and with some 250 casualties won 200 yards of trench, and left the Turks with an awkward salient to defend. After that came the storm, and then another spell of fine weather. The Turks did not press their advantage, though they now outnumbered the British by more than three to one. They did not occupy the old Anzac lines, and men from Cape Helles made excursions there, and brought back among other things some welcome cases of champagne. Perhaps the enemy was still busy getting his new big guns in place. Perhaps he thought that he had us at his mercy, and could finish the business at his leisure. What is certain is that he never dreamed that the Suvla and Anzac enterprise could be repeated.

Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula.