* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

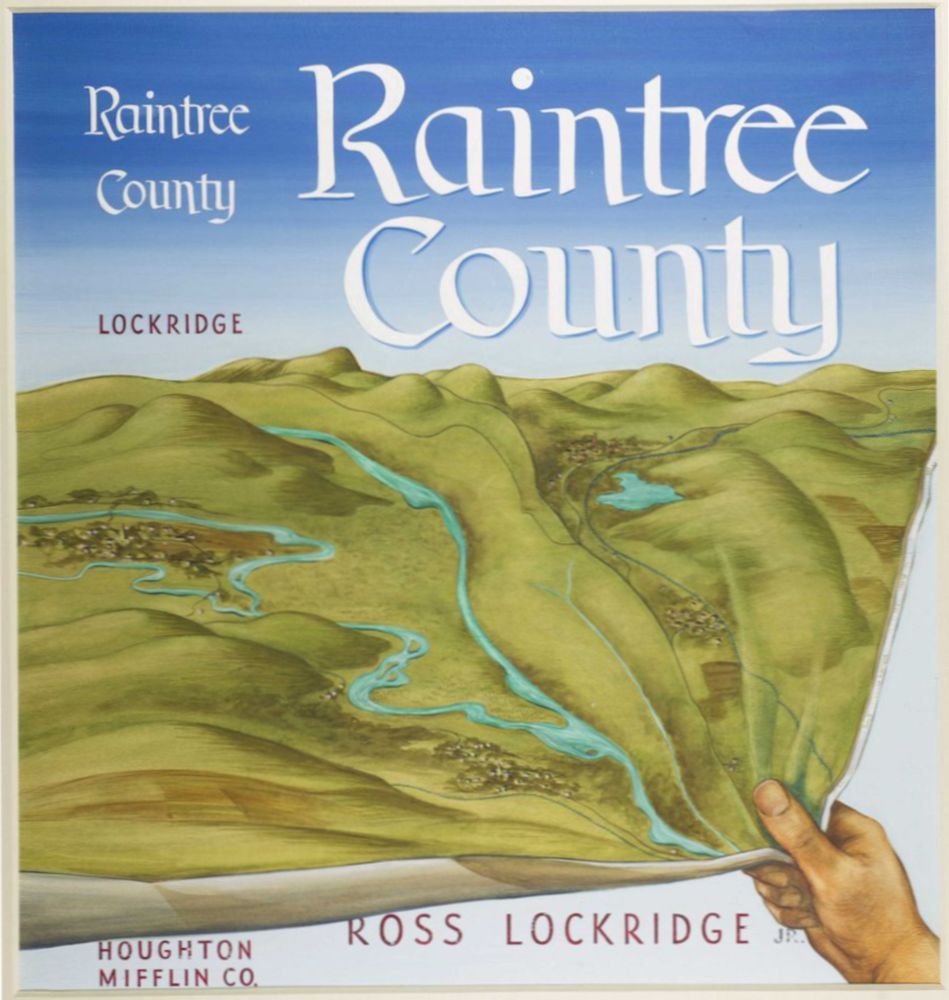

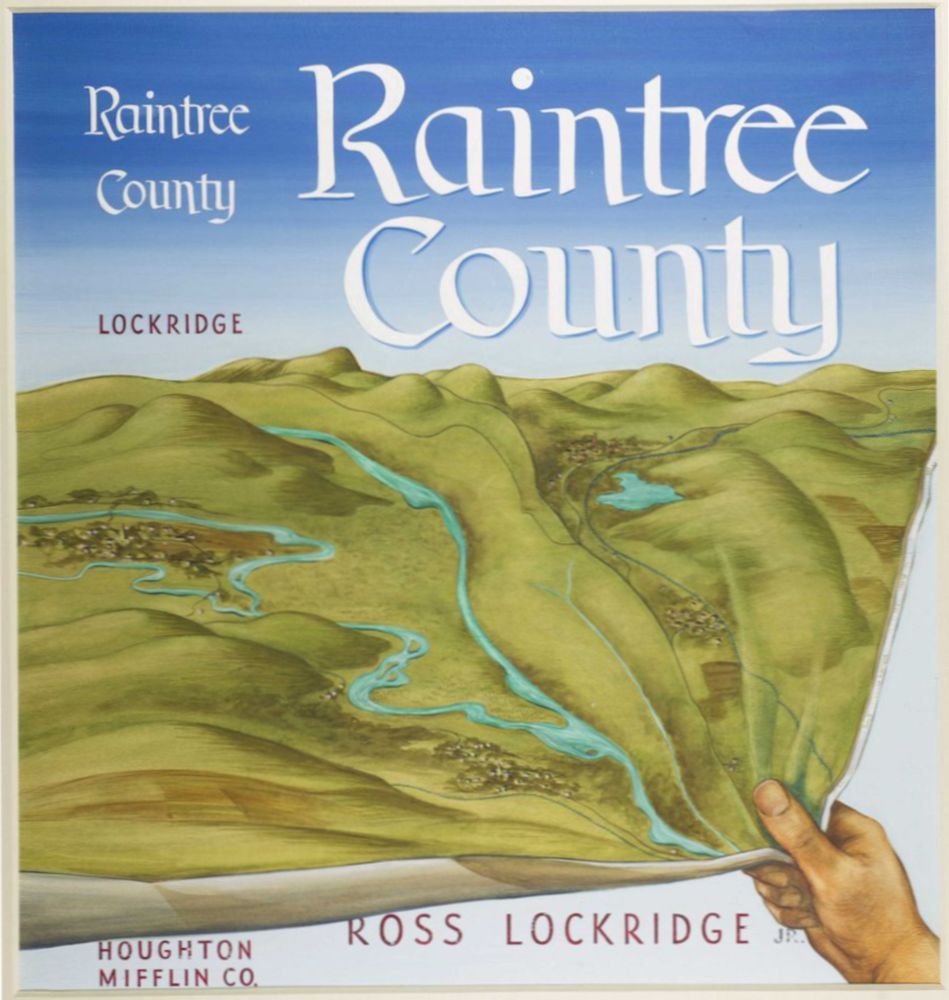

Title: Raintree County

Date of first publication: 1948

Author: Ross Lockridge Jr. (1914-1948)

Date first posted: Jan. 28, 2023

Date last updated: Jan. 28, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230143

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

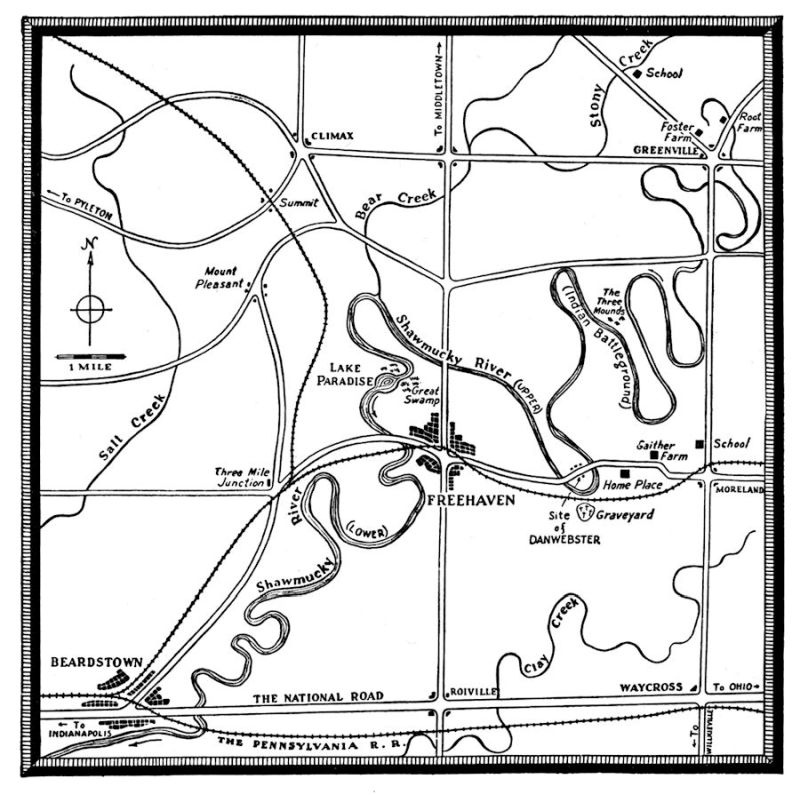

Map of Raintree County

THERE IS NO INTENDED RESEMBLANCE

BETWEEN THE CHARACTERS OF THIS

NOVEL AND ANY PEOPLE LIVING OR DEAD

Hard roads and wide will run through Raintree County.

You will hunt it on the map, and it won’t be there.

For Raintree County is not the country of the perishable

fact. It is the country of the enduring fiction. The clock in

the Court House Tower on page five of the Raintree County Atlas

is always fixed at nine o’clock, and it is summer and the

days are long.

COPYRIGHT, 1947 AND 1948, BY ROSS F. LOCKRIDGE, JR.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO REPRODUCE

THIS BOOK OR PARTS THEREOF IN ANY FORM

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE HADDON CRAFTSMEN, SCRANTON, PA.

For My Mother

Elsie Shockley Lockridge

This book of lives, loves, and antiquities.

I wish to acknowledge the assistance of my wife, VERNICE BAKER LOCKRIDGE, whose devotion to this book over our joint seven-year period of unintermitted labor upon it was equal to my own. Without her, Raintree County would never have come into being.

Ross Lockridge, Jr.

For the Reader

Raintree County is the story of a single day in which are imbedded a series of flashbacks. The chronologies printed here may assist the reader in understanding the structure of the novel. At the back of the book may be found a chronology of historical events with bearing on the story.

Chronology

of

A GREAT DAY

for

RAINTREE COUNTY

July 4, 1892

Morning|

Dawn—MR. JOHN WICKLIFF SHAWNESSY awakens in the town of Waycross. (page 3)

6:00—The Shawnessy family leaves Waycross by surrey.

6:45—In the Court House Square of Freehaven, Mr. Shawnessy enters a Museum of Raintree County Antiquities.

7:45—Across the site of the vanished town of Danwebster, Mr. Shawnessy carries a sickle and a box of cut flowers.

8:30—Approaching the town of Moreland, EVA Alice Shawnessy reads the last page of Barriers Burned Away. (page 235)

8:45—Re-entering THE GREAT ROAD OF THE REPUBLIC in Waycross, Mr. Shawnessy is engulfed in wheels and faces. (page 253)

9:30—Senator Garwood B. Jones arrives by special train in Waycross Station.

10:00—Three men tip their chairs back against the General Store for a talk.

10:05—Esther Root Shawnessy enters the Revival Tent to hear THE OLDEST STORY IN THE WORLD, the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey officiating. (page 358)

10:30—Mr. Shawnessy hands Professor Jerusalem Webster Stiles a copy of the News-Historian, containing the legend of a HOUSE DIVIDED. (page 421)

11:15—A photographer, a preacher, a lady in a Victorian mansion, a chorus of men only, and A WHITE BULL prepare respectively to take pictures, glorify God, distribute pamphlets, see an Exhibition for Men Only, and affirm life. (page 553)

Afternoon

12:30—In the intersection of Waycross, General Jacob J. Jackson presents Mr. Shawnessy with a copy of a manuscript entitled FIGHTING FOR FREEDOM, and the G.A.R. parade forms to march on the schoolhouse for a banquet. (page 595)

2:30—The Grand Patriotic Program begins in the schoolhouse yard.

4:30—Eva Alice Shawnessy muses in WAYCROSS STATION, where Statesmen, Soldiers, Financiers, and Poets arrive and depart by train. (page 753)

4:35—As Senator Garwood B. Jones prepares to entrain for the City, Mr. Shawnessy recalls a SPHINX RECUMBENT in his gilded years. (page 765)

5:05—Financier Cassius P. Carney descends from the Eastbound Express in Waycross Station.

6:00—BETWEEN TWO WORLDS in contest for her soul, Esther Root Shawnessy passes the intersection in Waycross as a train bears Financier Cassius P. Carney from Waycross Station. (page 869)

Evening

7:30—On the porchswing at Mrs. Evelina Brown’s mansion, an informal meeting of the Waycross Literary Society opens a discussion on THE GOLDEN BOUGH. (page 885)

9:30—Esther Root Shawnessy watches a cluster of torches approach the garden east of Waycross.

9:35—From the tower of Mrs. Brown’s mansion, Eva Alice Shawnessy beholds a celestial conflict.

10:50—The last Fourth of July rocket explodes over Waycross.

Midnight—Professor Jerusalem Webster Stiles departs by train from Waycross Station.

(Page numbers show actual order in text.)

| Election Day, 1844 | How on the morning of Election Day | 9 |

| July 20, 1848 | Everything was still on the wide fields | 22 |

| 1848-1852 | A fabulous and forgotten secret was written | 43 |

| July 4, 1854 | A big crowd of people | 65 |

| Summer, 1856 | Flowing from distant to distant summer, the river | 93 |

| September 6, 1856 | ‘Father, Come Out of That Old Saloon’ | 124 |

| 1857-1859 | How a quaint visitor arrived | 145 |

| May 26, 1859 | The plateglass window of the Saloon | 168 |

| June 1, 1859 | Legends in a Class-Day Album | 186 |

| June 18, 1859 | The romantic, illstarred, wonderful, wicked Class Picnic | 200 |

| June 18, 1859 | Two creatures playing whitely in a riverpool | 212 |

| July 4, 1859 | The race to determine the fastest runner in Raintree County | 891 |

| July 4, 1859 | Bare except for a chaplet of oakleaves | 917 |

| Summer 1859 | How that was a summer of drought | 258 |

| October 19, 1859 | A letter at the Post Office was always a big event | 283 |

| November, 1859 | How the rock had lain there always | 297 |

| November 22, 1859 | The scent of withered summers hovered | 308 |

| December 1-2, 1859 | Dawn and its day of long farewell | 318 |

| December 2, 1859 | —Down the river for you, my boy | 334 |

| 1859-1860 | Far, far away to an everblooming summer | 430 |

| 1860-1861 | The house, Susanna’s tall house | 458 |

| April 12-14, 1861 | In the dawn, in the red dawn | 480 |

| 1861-1863 | ‘All’s quiet along the Potomac’ | 496 |

| July 2-4, 1863 | Lost children of a lost republic | 515 |

| July 4, 1863 | An Old Southern Melodrama | 934 |

| 1857-1863 | How in her oldest awareness of being alive | 366 |

| July 13, 1863 | Johnny Shawnessy’s departure for the war | 602 |

| Summer, 1863 | What faces he saw in the camps | 621 |

| September 19-21, 1863 | —Chickamauga, the staff officer said | 637 |

| November 22, 1863 | War had come to this hollow between hills | 657 |

| November 25, 1863 | —Hurraaaahhhh! The cry smote him | 670 |

| November 14-16, 1864 | Progress through doomed Atlanta | 680 |

| November 26, 1864 | Fifty thousand strong on the earth of Georgia | 696 |

| February 17, 1865 | Hands pointing and gesturing, Flash Perkins | 721 |

| April 14, 1865 | Wearing a battle wound, scarce healed | 949 |

| May 24, 1865 | From the last encampment in a hundred fields | 738 |

| May 31, 1865 | When Johnny came marching home again | 1033 |

| May 1, 1866 | The soft spring weather of Raintree County | 373 |

| June 1, 1876 | The New Court House was by far the most | 380 |

| 1865-1876 | How the first eleven years following the Great War | 770 |

| July 4, 1876 | On the morning that America was a hundred years old | 794 |

| July, 1876 | Pleasant to the eyes during the Centennial Summer | 389 |

| 1876-1877 | How he came to the City of New York | 817 |

| July 21-22, 1877 | How the Great Strike came upon the land | 831 |

| July 25, 1877 | Before the Footlights and Behind the Scenes | 851 |

| July-August, 1877 | A message for him to come back home | 989 |

| August, 1877 | ‘COME TO PARADISE LAKE’ | 394 |

| 1877-1878 | A contest for her soul | 871 |

| July 4, 1878 | Waiting for Pa to come home | 998 |

| Pre-Historic | A strange light was over everything | 1010 |

| 1880-1890 | How once upon a time a little girl | 238 |

| 1890-1892 | The Road, the great broad Road, the National Road | 755 |

Yes, sir, here’s the Glorious Fourth again. And here’s our special Semicentennial Edition of the Free Enquirer, fifty pages crowded with memories of fifty years since we published the first copy of this newspaper in 1842. And, friends, what a half-century it has been! While the Enquirer has been growing from a little four-page weekly to a daily paper of twice the size, the population of these United States has quadrupled and the territory governed under the Institutions of Freedom has been extended from sea to shining sea. In those fifty years the Great West has been conquered, and the Frontier has been closed. The Union has been preserved in the bloodiest war of all time. The Black Man has been emancipated. Giant new industries have been created. The Golden Spike has been driven at Promontory Point, binding ocean to ocean in bands of steel. Free Education has been brought to the masses. Cities have blossomed from the desert. Inventions of all kinds, from telephones to electric lights, have put us in a world that Jules Verne himself couldn’t have foreseen in 1842.

Folks, it has been an Era of Progress unexampled in the annals of mankind, and all of it has been made possible by the great doctrines on which this Republic was founded on July 4, 1776.

During those fifty years, we haven’t exactly stood still here in Raintree County. Freehaven has grown from a little country town to a bustling city of ten thousand. The Old Court House of 1842 could be put into the court room of the present imposing edifice, one of the finest in the State of Indiana. And we challenge any section of comparable size in this Republic to show a more distinguished progeny of great men than our own little county has produced.

If anybody doubts the above statement, let him take a look at what is going on in the little town of Waycross down in good old Short-water Township. The eyes of the whole nation are fixed on that little rural community today. The celebration there to honor the homecoming of Senator Garwood B. Jones is a striking testimonial to the vitality of our democratic institutions. While we have often opposed Senator Jones on political grounds, we would be the last to diminish the lustre of his name or the distinction he has brought upon the county of his birth. We had hoped that the Senator would see fit to make his homecoming address here in the County Seat, but no one can doubt the political wisdom of Garwood’s decision to speak in his birthplace, a town of two hundred inhabitants, as the opening move in his campaign for reelection. It’s a dramatic gesture, and the Senior Senator from Indiana needs all his vote-winning sagacity, not only to defeat the rising tide of Populism this year, but to further his well-known ambition to achieve the Presidency in 1896.

Nor is the Senator the only nationally known figure in Waycross today. His friend and ours, another Raintree County boy, Mr. Cassius P. Carney, the famous multimillionaire, is expected to be there. And our own great war hero, General Jacob J. Jackson, is going to lead a march of G.A.R. veterans to point up the pension issue. There are rumors of other celebrities coming on the Senator’s special train, and all in all it looks like the little town of Waycross will have dern near as many famous people in it today as Washington, D. C. If the celebrated Stanley set out to explore this dark continent tomorrow for the Greatest Living American, he could do worse than get off a train in Waycross to ask his famous question. . . .

I presume?

—Yes?

His voice was tentative as he looked for the woman who had spoken from the dusk of the little post office. The whole thing seemed vaguely implausible. A short while ago, he had left his house to take part in the welcoming exercises for the Senator, whose train was expected momentarily in the Waycross Station. Walking west on the National Road, he had joined the crowd that poured from three directions into the south arm of the cross formed by the County and National roads. A swollen tide of parasols and derby hats blurred and brightened around the Station. Except on Sundays, he had never seen over ten people at once along this street, and he had been afraid that he might not be able to reach the platform where he was to greet the Senator. Near the Station, the crowd had been so dense that he could hardly move. Women in dowdy summer gowns jockeyed his nervous loins. Citizens with gold fobs and heavy canes thrust, butted, cursed. A band blared fitfully. Firecrackers crumped under skirts of women, rumps of horses. From the struggling column of bodies, bared teeth and bulgy eyes stuck suddenly.

Then he had found himself looking into the glass doorpane of the Post Office, where his own face had looked back at him, youthfully innocent for his fifty-three years, brows lifted in discovery, long blue eyes narrowed in the sunlight, dark hair smouldering with inherent redness. He had just begun to smooth his big mustaches and adjust the poet’s tie at his throat when the crowd shoved him against the door. It had opened abruptly, and stepping inside on a sudden impulse, he had heard the woman’s question.

Now he shut the door, drowning the noise of the crowd to a confused murmur.

—I was expecting you, Johnny, the woman said in the same husky voice. Where have you been?

—I was just on my way to greet the Senator, he said. Is there—is there some mail for me?

He walked slowly toward the distribution window, where in the darkness a face was looking out at him.

—Some letters carved on stone, the voice said. The fragments of forgotten language. I take my pen in hand and seat myself——

The woman was lying on a stone slab that extended dimly into the space where the window usually was. She lay on her stomach, chin propped on hands. Her hair was a dark gold, unloosened. Her eyes were a great cat’s, feminine, fountain-green, enigmatic. A dim smile curved her lips.

She was naked, her body palely flowing back from him in an attitude of languor.

He was disturbed by this unexpected, this triumphant nakedness. He was aroused to memory and desire by the stately back and generously sculptured flanks.

—How do you like my costume, Johnny? she asked, her voice tinged with mockery.

—Very becoming, he said.

Her husky laughter filled the room, echoing down the vague recess into which she lay. He hadn’t noticed before that the slab was a stone couch, curling into huge paws under her head. He was trying to understand what her reappearance meant on this memorial day.

Watching him with wistful eyes, she had begun to bind up her hair, fastening it behind her ears with silver coins.

—What creature is it that in the morning of its life——

She paused and opened her left hand, color of the pallid stone on which she lay. The hand was excitingly feminine, though perhaps too broad, too fleshy for perfect beauty. She put her arm on his shoulder. Then with her hand gently plucking and pulling at the base of his neck, like one wishing to uproot a little tree without hurting it, she pressed his head down to hers. Reminding himself that she was an old friend of the family and perhaps even a relative, he was about to kiss her.

Just then she turned her face aside and handed him a rolled newspaper.

—Our Semicentennial Edition, dear, she said, with a special column devoted to the history of the County. The fragments from your own unfinished epic occupy a prominent place on page one. You’ll find a picture of the authentic Raintree——

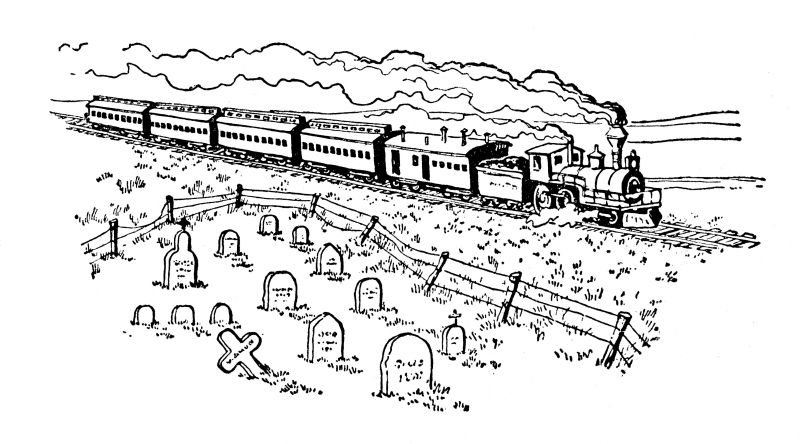

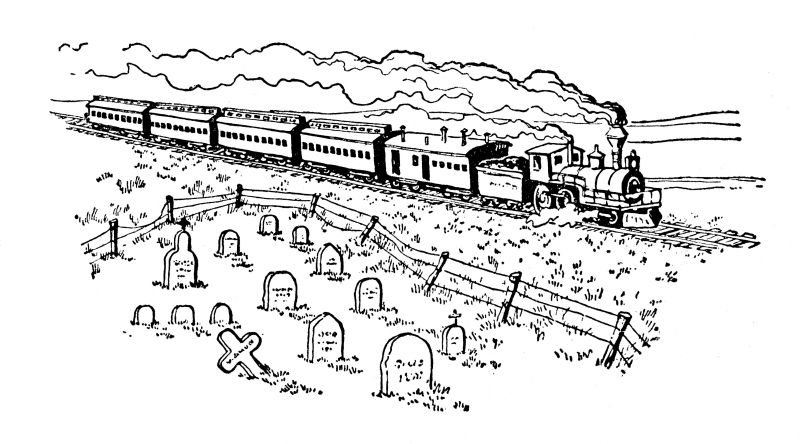

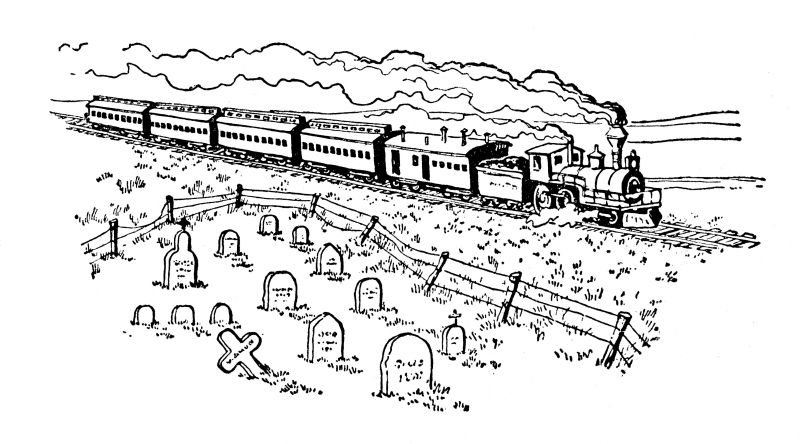

Opened, the paper was a parchment warm to the touch, engraved with a map of Raintree County so exquisitely made that the principal landmarks showed in relief with living colors. In the middle of the County, Paradise Lake was a pool of shimmering green. Its shore eastward where the river entered dissolved into the steaming substance of the Great Swamp. The roads crisscrossing on the flat earth were brown and gravelly. Tiny shiny carriages moved on the National Road, which, side by side with the Pennsylvania Railroad, cut across the County close to the southern border. Westward on the railroad, a darkly lovely little locomotive pulled a chain of coaches covered with patriotic bunting. The intersection at Waycross was dense with human faces. All over the County, the bladed corn swayed softly in the fields. In the Square of Freehaven, a mile and a half southeast of the lake, the Court House stood in a lawn of slender trees. A flag fluttered from the brave brick tower, and the four clock faces told the time of day. From the northeastern to the southwestern corner of the County, the Shawmucky River lay in loops of green, halved into upper and lower segments by the lake. On the road east from Freehaven two bridges spanned the upper river’s great south loop, and in the halfcircle formed by the road and the river, relics of the vanished town of Danwebster lay in deep grass. Across the river was the graveyard, a mound of pale stones. And somewhat beyond the bridge on the south side of the road was the Old Home Place, a little collection of farmbuildings on a gentle hill, the ancestral Shawnessy home in Raintree County, where Mr. Shawnessy had been born fifty-three years before. So precise was the map that he could see the great rock half sunk in the earth at the limit of the South Field.

He was certain that in the pattern of its lines and letters this map contained the answer to the old conundrum of his life in Raintree County. It was all warm and glowing with the secret he had sought for half a century. The words inscribed on the deep paper were dawnwords, each one disclosing the origin and essence of the thing named. But as he sought to read them, they dissolved into the substance of the map.

With a feeling suspended between erotic hunger and intellectual curiosity, he looked for the young woman. She was no longer lying on the stone couch. Her voice was passionate, musical, receding.

—Johnny! Tall one! Shakamak!

He could see her pale form turning over and over in a slow spiral floating away on green waters. From time to time, one hand rose beckoning while the other untwined her hair. The loose gold cord of her hair was at last all he saw of her, untwisting, prolonged in the water to a single shimmering thread.

Holding a branch of maize loaded with one ripe ear, he stood on the threshold of the door, about to lunge into the delirious crowd. The ceremonial day that he had spent a lifetime preparing, a web of faces and festive rites, trembled before him. The girls in their summer dresses were twirling their parasols and shouting hymen. The official starter of the Fourth of July Race was raising his pistol. A path was opening through the crowd to a platform erected in a distant square. Beyond, beside a sky-reflecting pool, he saw white pillars and a shrine. He heard a far voice calling. The sound was shrill, appealing, with a note of sadness. . . .

He awoke. The whistle of a train at the crossing had at last pressed its way into his sleep. It was early dawn. He lay in bed, among the glowing fragments of the dream. The dream had been vivid with the promise of adventure, consummation. He rewove its tantalizing web, contrasting it with the simple reality into which he had awakened.

His wife, Esther, eighteen years younger than he, lay beside him, her Indianblack hair screwed into curlpapers, her regular features composed by sleep into a look of stony, almost mournful serenity. In the next room slept the three children, Wesley, Eva, and Will, thirteen, twelve, and seven years old. The family slept in the two upstairs rooms of the plain white wooden house. There were four main rooms down—parlor, middle room, dining room, and kitchen, running in that order from front to back. A pumproom adjoined the kitchen, and a small spare bedroom was annexed to the dining room. A cellar with outside entrance was under the kitchen. A porch extended along the front and halfway down the east side of the house. The house was set well forward in a trimly kept yard, fenced in with white pickets in front and on the two sides. Almost against the house behind was a small frame building of two parts, smokehouse and woodshed. A path started at the backdoor and ran along a garden to the outhouse. At the rear of the lawn was a small barn. A narrow field planted in corn extended a hundred yards back to the railroad.

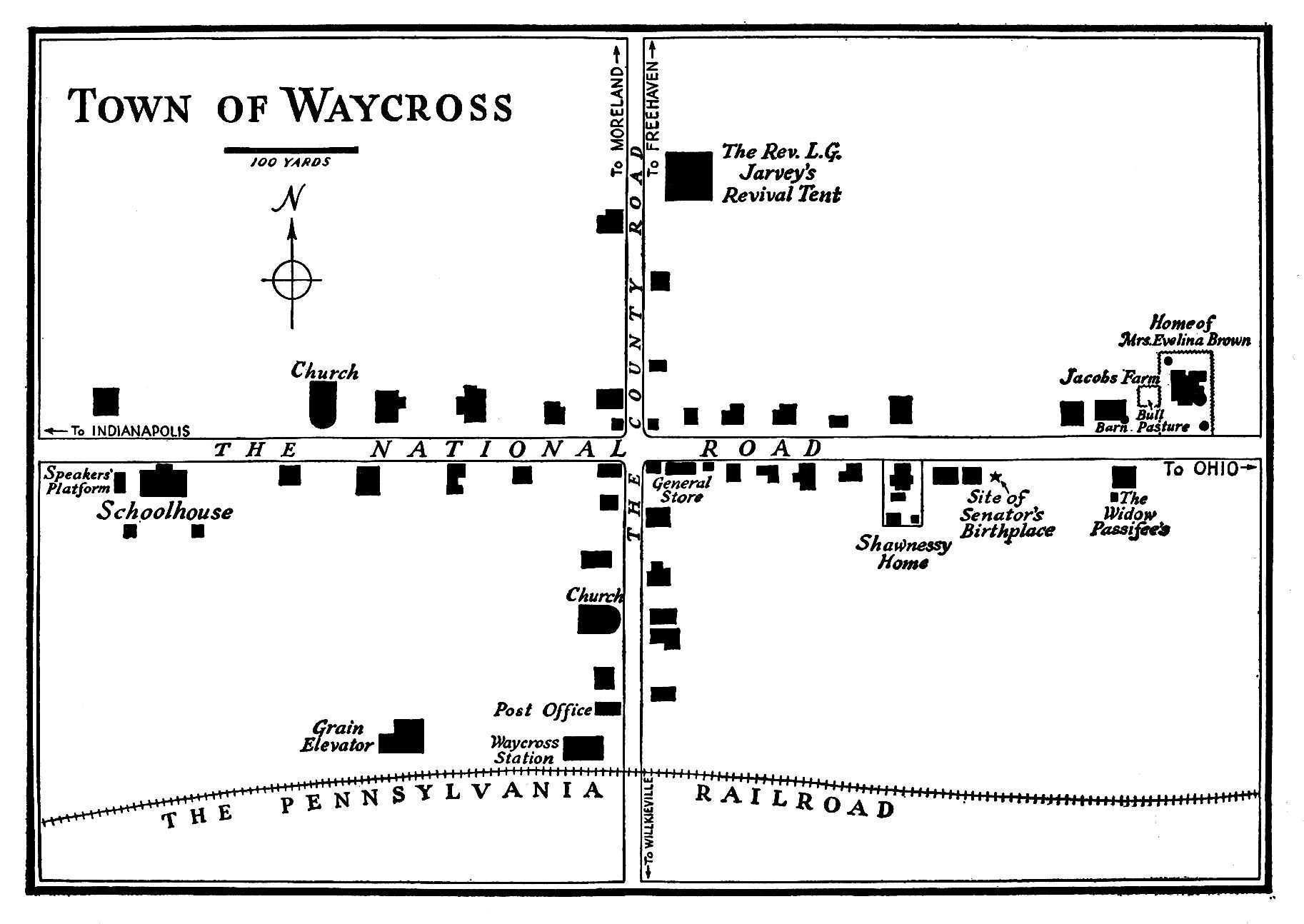

The town of Waycross, where Mr. Shawnessy had lived for two years, had an equally austere pattern. The business buildings were at the intersection of the roads—general store, barber shop, bank, feedstore, blacksmith shop. Half a hundred houses were scattered along the four arms of the cross. On the south arm were a church, the Post Office, and the Railroad Station. The Schoolhouse, where Mr. Shawnessy and his wife were the only teachers, was on the west arm. On the north arm was a huge tent where the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey had been conducting his Summer Revival Series. Among the dwellings on the east arm were the Shawnessy house, lying on the south side of the National Road, and the mansion of Mrs. Evelina Brown somewhat beyond the town proper.

In the naked pallor of dawn, Waycross seemed to him devoid of visual complexity, as if to reduce the problem of place to its basic ingredients. And Raintree County also aspired to spatial symmetry, being a perfect square twelve miles to the side. What could be more certain than the location of Raintree County, whose western border was sixty miles from Indianapolis and whose eastern border was fifty miles from the neighboring state of Ohio? And yet, the dream had left him with an uneasy feeling of being anchorless, adrift on an unknown substance. The formal map of Raintree County had been laid down like a mask on something formless, warm, recumbent, convolved with rivers, undulous with flowering hills, blurred with motion, green with life.

He mused upon this mingling of man’s linear dream with the curved earth, couched in mystery like a sphinx.

Had the woman of his dream, whose face had been teasingly familiar, known the answer to this riddle? And what token could she have given him of himself, he who also escaped name and definition in his long journey through time, a traveller from dawn to darkness, and all at once a child, a man, an old man?

He should have asked this gracious lady about time past. He should have followed her beckoning hand down the mystic river of the years back to the gates of time, the beginning of himself. He should have traced a tangled thread to the source of a life on the breast of the land.

It was dawn on Raintree County, and in a little while he would have to yield himself to the ritual day. Past midnight, he had lain awake thinking about the big Fourth of July Program, in which, as principal of the local school and an old friend of the Senator, he had a leading responsibility. First he would drive to Freehaven, where he had some matters to see to before the Senator arrived. Despite the necessarily early hour of the trip, the whole family planned to go along as usual. On the way back, he would stop at the Danwebster Graveyard for his annual visit to the family lot. At nine-thirty the Senator’s special train was due in Waycross, and the substance of Mr. Shawnessy’s dream would be repeated—minus, no doubt, the interesting lady in the Post Office. Then he would entertain the Senator until the G.A.R. parade and banquet at twelve-thirty. The main program was planned for two-thirty, and after that he would see the Senator off at the Station. In the evening there was to be a lawn party sponsored by the Literary Society at the home of Mrs. Evelina Brown. It promised to be the most exciting day since his second marriage fourteen years ago.

He could still hear the thunder of the train on distant rails receding. Its passing echoed in the eastern valleys of his sleep. The lone shriek of it at the crossing had been like a calling of his name. The sound of it ebbing down gray lanes of dawn into the west was the lonely music of a century, awakening memories of himself and the Republic. He would lie awhile and chase a phantom of himself that was always passing on a road from east to west. He would hunt for the earliest mask of an elusive person, a forgotten child named Johnny, the father of a man.

What creature is it that in the morning of its life . . .

It was dawn now on Raintree County, and he would begin with things of the dawn. He would pursue awhile his ancient pastime of looking for the mystic shape of a life upon the land, the legend of a face of stone, a happy valley, an extinct republic, a memory of

| Election Day— | How | —1844 |

on the morning of Election Day

the mother and the little child were waiting

before the cabin. At the bottom of the yard, a rudely sculptured head stood on the gatepost by the road. Johnny had helped T. D. make it, and they called it Henry Clay, maybe because it had been made out of clay from the river bank.

—Henry Clay, T. D. had said, is the Greatest Living American.

T. D. had also said that Henry Clay was running for President, a matter of interest to Johnny, who for his age was considered a very fast runner himself.

The head on the gatepost had had an ugly, eyeless look when T. D. and Johnny first made it, but now at this distance it had an expression of greatness and distinction.

A few days ago when Johnny was in the yard by himself, a man had driven past in a covered wagon. He was a bearded man in a big hat, his wagon was pulled by two big oxen, it was all stuffed up with things, there was a thinfaced woman on the seat beside him, and a pretty little girl with vivid brown eyes kept peeping out of the wagon and shaking her pigtails at Johnny.

—Hello, son, the man said, stopping the wagon.

Big white teeth flashed through the thick bush of his beard.

—Hello, Mister.

—You look like a smart boy, son. Maybe you could tell me if this here is the road to Freehaven.

—Yes, sir, this here is it.

—How fer is it, son?

—You go on down the road, Johnny said, pointing west, and you git there after a while. They’s a court house and a lots of people.

—Ain’t he a smart boy! the man said, winking at his wife. Maybe you can tell me, son, what that there head is on the fence there.

—Henry Clay, Johnny said.

—Who’s he?

—The Greatest Living American, Johnny said.

—You don’t say, the man said. Who tole you so?

—T. D. did.

—Who’s T. D.?

—My pa. He’s a doctor and a preacher.

—Well, you go tell T. D. that that there head ain’t Clay. It’s mud. Anyhow it’ll be mud after the Election.

—It ain’t mud, Johnny said. It’s clay. It was made out of clay, and it’s Henry Clay.

—It’s mud, dad burn it! the man said. You tell your pappy somethin’ else. You tell him a man passed said Henry Clay ain’t the Greatest Livin’ American. He’s nothin’ but a goddern Whig protectionist. Can you say that?

—Yessir. A goddern Whig protectionist.

The man roared, and the woman said something to him. The man leaned out again.

—You tell your pa you saw a man, and he told you the Greatest Livin’ American was James K. Polk. Yessiree, James K. Polk is the man that’s goin’ to win that election. James K. Polk.

The man was motioning big and violent with a whip.

—James K. Polk. The Lone Star Republic and the Oregon Trail. Can you say that, son?

—The Lone Star Republic and the Oregon Trail, Johnny recited.

—Listen to him say that, the man said. How old are you, son?

—Five.

—You’re a smart boy, son. You’ll amount to somethin’ some day. Don’t fergit that slogan. James K. Polk is the man that’ll win the Election, and he’ll make Clay’s name mud.

—It ain’t mud, Johnny said. We got it down along the river. Mud’s black. This here’s red, and it’s clay.

—O.K., son, the man said. But all the same, don’t fergit to tell your pa what I said. The Oregon Trail. That’s where I’m a-headin’ right now, and if your pappy was half a man, he’d be a-goin’ there with me to settle out there and git that land fer America instead of votin’ fer Harry Clay and Protection.

The man made his whip lash over the backs of the oxen.

—Oregon, here we come!

As the oxen pulled away, the girl with the pigtails leaned from the wagon and waved her hand. She waved a long time, and Johnny waved back.

It seemed to him then that he had always been a small boy who stood beside a road and waved to people going west.

Later when he had told his father about it, T. D. had laughed and said to his mother,

—I wonder what they were doing off the main road.

—Where is the Lone Star Republic and the Oregon Trail? Johnny had asked.

His father told him something about them.

—Are there Indians out there?

—Yes, I reckon there are, T. D. said.

The Indians used to live right around the Home Place before T. D. and Ellen Shawnessy had come there in 1820. The Indians were naked and had red skins, and they lived in tepees, and they killed and scalped you with tomahawks. They were marvellous people, and they had lived all over America before the pioneers came and made the stumps. Now all the Indians had gone out West, where the man in the covered wagon was heading.

Next to the Indians, the most interesting people were probably the Negroes. Men would get together in front rooms and around the Court House at Freehaven, shake fists, spit tobacco, and talk in loud voices about the Negroes and the Election and Polk and Clay and Texas and the West.

The Negroes were black slaves in the South. It was a bad thing to keep them slaves and make them work. Johnny had walked through the South Field once and had gone a long way back hoping to see a Negro. He never did see one.

But that same day he kept on going and wound around back north until he crossed a road and came out at the Gaither farm. Nell Gaither was playing in the orchard under an appletree. She was a thin, serious girl with long golden hair, big blue-green eyes, and a freckled nose. She had a quiet, grave way of talking in contrast with Johnny’s older sisters, who were very giggly and loud.

—You’re Johnny Shawnessy, she said.

—Yes, I am.

—I’m Nell.

—Is the river back of your house?

—Yes, I’ll show you.

The river was a big mystery to Johnny. Now he and Nell walked a piece and pushed through some trees and came right out at the edge of the river. It was wide and pale green, and it had a cold green odor. He and Nell had played a long time by the river building little mud and stick huts. They both waded out looking for craw-dads and frogs. Johnny forgot all about the time until he noticed that long shadows were falling on the river.

—Your folks’ll be after you, Johnny, Nell said.

—Let ’em, Johnny said.

You had to run away from home to have a good time like that.

When he started down the road that evening, he ran into a lot of people, and they all rushed at him and grabbed him and took him home.

Later his mother had come home on a horse, all hot and dusty and her dark red hair in strings down her face. She began to cry when she saw Johnny in the front yard surrounded by people. She hugged him very hard and kept saying, Thank God! and laughing and crying at the same time. Johnny cried too from sheer excitement. It appeared that he had been lost and found again. People said that his mother had ridden all over Raintree County looking for him.

—Poor Ellen! people said. Johnny, you pretty near killed your poor mother.

They never let him go back and play along the river again with Nell because it was too much fun.

That was when he learned that he was a person of great importance and that his exact location in Raintree County was a matter of intense concern to everyone.

Ellen Shawnessy, his mother, was short and slight. Though not pretty, she had a young girlish look. Her hair, dark with glints of red like Johnny’s, was entirely ungrayed. Johnny was the last of her nine children, four boys and five girls. Two of the girls had died in an epidemic that swept through Raintree County in the early forties, and they lay beneath two stones with letters on them in the Danwebster Graveyard, across the river from the board church where T. D. preached.

—What is a great man, Mamma? Johnny asked as they waited in front of the cabin for T. D.

—A great man is somebody everyone looks up to. He’s a good man who does things for other people.

—Like Pa?

Ellen Shawnessy smiled. Her smile was like Johnny’s, quick and affectionate. More often than not she smiled for no other reason than that she felt animated and happy.

—Well, T. D. is a mighty good man, she said, and he’s smart too. But usually a great man is a wellknown man. That is, he’s famous.

Johnny’s father, T. D. Shawnessy, preached and wrote poetry and delivered babies and made sick people well. He was very tall and thin, and his head looking down at Johnny from a great height always nodded blondly and benignly and smiled confidently and spoke very hopefully of God and the future.

—I aim to be a great man, Johnny said. Is God a great man?

—God isn’t exactly a man, Ellen Shawnessy said. He’s—well—he’s just God. He’s a divine being. That is, he’s greater than any human being.

God was the biggest puzzle of all to Johnny. He had begun to worry about God during the summer when the Millerites were camping out in Raintree County. When the family would be riding down the road, they would see at night the bonfires burning on a distant hill.

—There’s them plaguey Millerites, T. D. would say.

The Millerites were out there on the hill waiting for the End of the World. T. D. said that in his opinion it wouldn’t come for quite a while yet.

In those days, God was a whitebearded giant who lived up in Heaven but had a sneaky way of being everywhere else at the same time. He could do anything he wanted and just waited around for you to make a mistake, whereupon he would land on you and whop you good. Johnny used to wonder if it would do any good to go out and hunt for God. But God was just as scarce as the Indians and the Negroes in Raintree County. There were times when Johnny wondered if God was just a big story, the kind that big people were always telling little people.

Later on that day when T. D. came home, they all got into the wagon, the older ones sitting on chairs in the wagon bed, and went into Freehaven. There was a big crowd around the Court House Square, people talking loud and waving banners. Later the older children took Johnny down to the Polls. Johnny looked around for some tall sticks, but it turned out that the Polls was a place where a lot of people were trying to put papers into a box.

Several big barrels were hoisted on sawhorses and wedged into the crotches of trees, and men kept going over and turning on the taps and getting brown stuff out of the barrels. Johnny got lost from the other children for a while and was swept up in a crowd of people marching and chanting:

—Vote, vote, for James K. Polk!

The Lone Star Republic and the Oregon Trail!

Johnny marched and chanted too, until T. D. spied him and striding into the middle of the parade carried him off.

—Don’t you know them’s Democrats, John? he said.

A lot of men went around swatting people on the back and laughing fiercely. T. D. put a paper in the ballot box. Things got louder as the night came on. Bonfires burned on the Court House Square. The family had a big feed in the wagon, and after that Johnny slipped off into the crowd with his brother Ezekiel, who was two years older than he and a lot bigger. They watched some men hitting each other and yelling things about God, Polk, and Clay over in front of the Saloon. A man was knocked down and had his coat torn off. A woman came up shrieking and grabbed at the man lying on the sidewalk, so that Johnny didn’t see how he could get up if he wanted to. Zeke disappeared for a while, and when he turned up again, he was grinning all over his face and said he had just beaten up on a goddern kid that admitted he was a Democrat. Zeke showed his knuckles all skinned and bruised.

Late at night, the family started back to the Home Place in the wagon. Johnny lay for a long time awake with his head in his mother’s lap, looking up at the stars. He hunted the heavens until he saw one big star low in the west. He thought it might be the Lone Star. Somewhere out there in the Far West, under the night and the shining stars and across the Great Plains, was the Lone Star Republic and the Oregon Trail. Right now maybe the little girl with the pigtails was out there.

Johnny Shawnessy decided that some day when he was big enough to go away from home by himself, he would go over and get Nell Gaither, and they would get into a big covered wagon and go down and find the National Pike, and they would ride off together toward those big plains and those far western mountains beneath the shining stars, where the land was fair and free, where the Indians lived in tepees, and the streams were full of fish, in the country called the United States of America, which was somewhere in Raintree County.

For in those days, he didn’t very well understand the boundaries of Raintree County or of his own life. Raintree County was simply the place where people lived, it was the earth, and you might go anywhere and never leave it. He had heard people talk of a time when there was no Raintree County. He used to think back and back to see if he could remember such a time, and he would come to a place where all his memories fading reached a green wall of summer. Sometimes he would attempt to cross that wall, vaguely wondering at the murmurous world beyond it from which his being had been ferried up some summer long ago to be deposited in Raintree County. He had some dim intuitions and memories of it, all drenched in green and gold. Nameless, and neither child nor man, he had lived in a beautiful garden where stately trees dripped flowers on the ground. And somehow that life was longer than all the rest of his life together. But long ago that summer of wordless forms had been lost to him, or rather the forms had been subtly changed and hidden by a veil of words.

Now in the still night, Johnny Shawnessy was carried in a wagon over the dark earth of Raintree County, which had no boundaries in time and space, where lurked musical and strange names and mythical and lost peoples, and which was itself only a name musical and strange.

And lying in his mother’s arms, he went to sleep and dreamed that he was riding in a ribbed and canvas-covered wagon down a road at night toward a lone star palely shining over fields of summer.

—Look there! everyone said. The Greatest Living American!

In the red far light of the star, he saw an immense face of clay, and he and all the other people were running for President as fast as they could go. So in the still night

he dreamed a fair young

dream of

going

Westward, the National Road pursued its way, a streak of straightness to the flat horizon. As the surrey approached the intersection, Mr. Shawnessy was thinking of his dream. Although he had since risen, dressed, eaten breakfast, and set out for Freehaven, he was still haunted by the riddle of a naked woman in the Waycross Post Office. The dream had distilled the conundrum of his life into one image, delightful and disturbing.

She had reminded him of his plural being. He had presented to her Mr. Shawnessy, a dutiful citizen of the Republic calling for his mail. She had addressed herself to mr. shawnessy, a faunlike hero, poised on the verge of festive adventures.

Mr. Shawnessy, meet mr. shawnessy. Hail and farewell! Farewell and hail!

Just now, the majuscular twin, Mr. Shawnessy, was sitting upright in the front seat of the surrey beside his wife, Esther, while the three children, Wesley, Eva, and Will, occupied the back seat. It was a characteristic Mr. Shawnessy attitude, for Mr. Shawnessy was eminently a family man and a respectable citizen. When he called at the Waycross Post Office later in the morning, he wouldn’t find a naked woman on a stone. Instead he would receive the Indianapolis News-Historian from a fat-faced functionary named Bob.

Only the adventurous twin, mr. shawnessy, could achieve naked women in post offices. For mr. shawnessy was a lower-case person, disowning all proper names, including his own, and many other proprieties. Yet it was convenient to call him mr. shawnessy since he was always moving in and out of Mr. Shawnessy with pleasant alacrity, using his obliging companion as a kind of depot for incessant arrivals and departures. In fact, mr. shawnessy used Mr. Shawnessy as a straw man, a large comfortable mask that he had spent a lifetime adapting for public performances.

Mr. Shawnessy, the straw man, was now driving the family westward through Waycross, an inseparable part of the Shawnessy landscape. At the intersection, he would turn due north, being a creature bounded by severe alignments.

He was bounded by the Nineteenth Century and knew only one way to escape—by living his way out moment by moment.

He was bounded by a box, the County, inside a box, the State, inside a box, the Nation, inside a box inside a box inside a box.

He was sartorially bounded by his one good suit, a cloth of light black wool, newly pressed for the day, a white shirt, a black poet’s tie, knobtoed black shoes, dark soft hat. A hundred dollars would not have persuaded him to walk down the street of Waycross in an Elizabethan doublet, a woman’s bonnet, or naked.

He was linguistically bounded by the English language, which he spoke with a Hoosier accent, though, when he pleased, with precision, wit, and eloquence.

He was morally bounded by a certain code of right and wrong that Moses had brought down from Sinai into Raintree County. He had a way of lingering wistfully on thresholds without crossing.

He was a completely legal person. On April 23, 1839, his birth had been accomplished from an inkwell in the Raintree County Court House. His marriage to Esther Root in 1878 had achieved a whole column of print on the first page of the Raintree County Free Enquirer. The children who occupied the back seat of his surrey on trips around the County were what was known as legitimate. He enjoyed certain rights of citizenship under the Constitution of the United States and certain inalienable rights under the Declaration of Independence, among them, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.

He was a creature of amazing certainties. He had his infallible Saturdays and his relentless Mondays. He almost never went to bed in the middle of the night or rose at noon. And every year the Fourth of July came and bestowed on him firecrackers, patriotic programs, and a drive with the family to the middle of Raintree County where he placed some flowers on a grave.

He lived in a precariously poised world of taboos, pomps, and games called American Society—with no spectacular triumphs, it is true, but in a manner to inspire confidence and respect. In fact he was one of the priests of the temple, being responsible for teaching the communion to others, for he had spent a lifetime instructing the young of Raintree County in what is known as the rudiments of education.

In a world convulsed with war, famine, industrial unrest, and public and private vice, Mr. Shawnessy was a citizen of the American Republic, living quietly on the National Road of life where it intersected with Raintree County, and tacitly involved in a confused course of human events that the newspapers and people in general agreed to call American History.

The versatile twin, mr. shawnessy, on the other hand, was a fugitive from boundaries. No sooner did he appear to be caught in a definition than he somehow turned inside out to include the includer. He was always pressing beyond the confines of himself, yet could never go anywhere that wasn’t himself.

His seeming foothold in the Nineteenth Century was illusory. His face peered furtively from a frieze of the Parthenon, passed in mob scenes in the reign of Justinian, crossed with crowds on Brooklyn Ferry ever so many centuries hence.

His landscape was an infinitely potential number of Raintree Counties past, present, and to be. He was always arriving in train stations from parts unknown to meet himself departing for unknown parts.

In him, the word and the thing almost rejoined each other at the source. His words were dreams of things; his dreams were things of words.

He had a way of joyfully crossing the thresholds at which Mr. Shawnessy lingered.

He had no legal existence whatsoever. His birth was recorded, if anywhere, in the first chapter of Genesis and his death was foreseen only in Revelation. Eve was his mother, his daughter, and his wife, and he was the citizen of a republic that never was on sea or land.

Of course, his being was all tangled up in that of Mr. Shawnessy. The two were always colliding with each other as Mr. Shawnessy went his ritual way through conversations and thoroughfares, and mr. shawnessy carried on his eternal vagabondage through a vast reserve of memories and dreams. But even in dreams the carefree twin had to do devotion in strange ways to Raintree County and its gods. It was clearly the whim of mr. shawnessy to prepare a naked woman on a stone slab in the Post Office, but it was Mr. Shawnessy who timidly asked for a newspaper, trying his best to adapt himself and his puritan conscience to the bizarre world of his twin.

Yet doubtless there was really only one John Wickliff Shawnessy, one Raintree County, one Republic, one riddle with plural masks. That was what the young woman with the catlike eyes had meant by the half-given line from a legend of antiquity:

What creature is it that in the morning of its life . . .

Mr. Shawnessy had made the turn north onto the County Road. But the insouciant twin had kept the westward bias.

Westward the star of empire. Westward the Great Companion takes his way. Shirt open at the neck, broad hat pushed back on matted, vital hair, he walks the boulevards of westward cities, crosses the wide windrippled plains, ferries the Mississippi, and strikes out strongly through the sagebrush mesas. He climbs the sunblaze summits of the Rockies, descends deep passes to the Golden Shore.

O, Californy!

That’s the place for me!

I’m off for . . .

Firecrackers crumped in backyards. A smell of patriotism tinged the early morning air.

—How long before we get back, Papa? Wesley asked.

—About nine o’clock. We have to be back by then.

—What yuh readin’, Eva? little Will asked.

—Book, Eva muttered, absorbed.

—I want to be back in time for the service, Esther Shawnessy said, as the surrey passed the Revival Tent.

—We’ll be in time, Mr. Shawnessy said. We won’t be stopping in Freehaven long. And I only mean to leave a few flowers at Mamma’s grave.

—Papa, what’s Senator Jones look like? Will asked.

—I haven’t seen him for twenty years. When I last saw him, he was a big heavyset man, broadshouldered, deepchested, with blue eyes, dark brown hair, and a voice like a bull.

—What’s General Jackson like?

—The General looks like a fighting man. Of course, he’s pretty old now, but in his prime he was a fine figure of a man.

—Will he have his uniform on?

—I imagine so.

—Will he have a sword?

—A dress sword maybe.

—O boy! Jiminy! A sword! How many wars did he fight in?

—Just two. The Mexican War and the Civil War.

—The Mexican War. When was that?

—Eighteen forty-six to eighteen forty-eight. I was about your age then, Will.

Are you Johnny Shawnessy? Yes, sir. Can you read, son? Yes, sir. Well, read this then.

—Did they have a Fourth of July when you were a boy, Papa?

—Sure.

—Did they have firecrackers and things?

—Big ones.

Bang! Forward, boys, all along the line! Kill the damn greasers! Westward the star of empire.

The Fourth of July was the memory of a lone white rocket rising in the purple sky above a town in Raintree County long ago. The rocket burst and feathered into burning spray and floated softly on the fields of night. The Fourth of July was the memory of a new republic, a bloody babe of destiny, waiting to be filled with soul. The Fourth of July was a war on sunbaked plains, a fighting in the high passes and in California. It was the pasteboard red of firecrackers, the blue of armies charging stiffranked in steel engravings, the white of flowers flung by girls in summer dresses for the boys who fought at Buena Vista. It was the fury and the fighting heart of a young republic, fledgling of the nations, conceived in battle and confirmed in battle. It was a lone star rising in the east and westward tending. It was a million faces pressing westward, the harshvoiced dreamers of a strange, disordered dream.

Mr. Shawnessy jingled the reins over President’s back, passing the last houses of Waycross. Meanwhile mr. shawnessy roamed on other roads. There had been a wagon shrugging down a road to westward years ago. It had gone on for days creaking across the vast plain. Where were all the days of the travellers in that wagon?

But those days had passed, and the girl with the pigtails had grown up, no doubt had married and borne children. The burly charioteer of the westward sun, who had driven his oxdrawn car through Johnny Shawnessy’s life, had died long ago, and the wagon itself was ribs of weathering wood in a far lone valley of the West.

A small boy had wandered out into the morning of America and down far ways seeking the Lone Star Republic and the Oregon Trail. A small boy had dreamed forever westward, and the dream had drawn a visible mark across the earth. But the boy had never gone that way. He had only dreamed it.

He saw the face of a girl fading among the vehicular tangle of the years. All the evenings of a life in the West dyed the sunset peaks with purple—the lost years ebbed with waning voices in the cuts where the little trains passed, crying. Yes, he had been fated to stay after all, chosen for a task that called for more than ordinary strength. He and only he had stood on the earth of Raintree County in an early summer dawn and had had that deep vision of the Republic, the passionate, westward dream.

I had a dream the other night,

When . . .

| July 20— | Everything | —1848 |

was still on the wide fields

and sleepy stream of summer, and the days

were long in the hot weather that summer, and the world of Raintree County seemed fixed around him like paintings on a wall. Then one day a horse thundered up the road from Freehaven and into the yard of the Home Place, and a young man got off. He had long blond hair under a broad hat.

—This where Doctor Shawnessy lives?

—Yes, sir, Johnny said.

He and the man went to the Office behind the house.

—What’s the trouble, son? T. D. said.

—Why, my wife’s gonna have a baby, sir, the man said. We got into this here town of Danwebster over here last night, and she was took sudden and before her time. Some fellers in town said as how you was the best baby doctor around here. I’d be mighty obliged to git some help for my wife.

While T. D. was getting his medical kit, Ellen came out and talked with the young man, who said that he was from Tennessee and was on his way to California. He and his wife had left the National Pike intending to stop with friends in Middletown, but the woman had come down unexpectedly with labor pains. It was her first baby.

Johnny was pleased when he was permitted to go along with his mother and father to Danwebster.

—It’s the house right aside of the General Store, the man said, getting up on his horse. Name is Alec Doniphant.

While they were driving to Danwebster, Ellen said,

—Courteous young feller. It must be awful hard on ’em having their first baby on the road thisaway. There’s so many of ’em these days. Anything to get out West.

When they got to Danwebster, T. D. and Ellen went into the house with Mr. Doniphant. There were several men sitting on a bench in front of the General Store. Just as Johnny got settled on the bench, he heard a low sound from the house, musical like a mouth rounded. The men on the bench listened without turning their heads.

—She ain’t a-hollerin’ loud enough yet, a man said.

He was a fat old man everyone called Grampa Peters. Those days, he always seemed to be sitting on the bench before the General Store in Danwebster. A Democrat of the old Jacksonian breed, he was reported to have Southern sympathies and was the only person in town who received a newspaper regularly.

—I seen them come in last night, a thin man said. She was in considerable pain then and kept a-cryin’ out all night.

There was another low moan from the house.

—She’ll have to bear down harder than that, Grampa Peters said. She ain’t puttin’ herself into it yet. She’ll have to make up her mind to have that baby.

A cry of pain lay suddenly on the quiet street.

—That’s the first real loud one I’ve heard her give, Grampa Peters said. That was a good loud one.

His flesh stirred a little as if pleasantly goaded by this fierce contact with life. He fumbled around in a coat pocket and drew out a newspaper.

—Son, can you read?

—Yes, sir, Johnny said.

—I heard you could, Grampa Peters said. They say you read as good as a grown person. Well, I want you to read me somethin’ here. I fergot my specs.

Grampa Peters spread out a copy of a newspaper. At the top it said

THE INDIANA COURIER

—Read that there righthand colyum for me, Grampa Peters said.

Johnny read outloud how the Whig Nominating Convention meeting on June 7 had nominated General Zachary Taylor for the Presidency. While he was reading, T. D. and Mr. Doniphant came out of the house.

—How’s she comin’? Grampa Peters asked.

—She’s pretty little and of course it’s her first one, T. D. said absently. But she’s young and strong, and I take a hopeful view of the situation. After all, having a baby is the most natural thing in the world.

—I hope it comes soon, young Mr. Doniphant said.

—I think it’ll be a while, T. D. said. My wife’s going to stay with her. You look fagged out, young feller. You better relax awhile.

—Git us that there banjo of yours, the thin man said, and play us some music.

—I reckon it might take my mind off of it, the young man said, and he went back of the house.

—What about it, T. D.? Grampa Peters said, when Mr. Doniphant was gone.

—It’s a hard case, T. D. said. She hasn’t really got anywhere with it yet, and she’s very narrow. There isn’t anything to do but wait. However, as I said before——

His voice trailed off.

—What you got there, John?

—Newspaper.

—The boy was just readin’ it to us, the thin man said. He’s a bright boy.

—How’d you learn to read, son? Grampa Peters said.

—I learned at school.

—John learned at this here school in Danwebster, T. D. said. He can read anything. What’s in the news these days? I haven’t seen a paper for mighty near a month.

—I see where your danged Whigs nominated old Blood and Thunder, Grampa Peters said.

—Yes, so I hear, T. D. said. Well, I guess he’d make a good President.

—Maybe that’s what we need, a military man, the thin man said. The country’s so all tore up. Winnin’ the war pretty near wrecked us.

—Pretty near wrecked us! Grampa Peters snorted. What are you talkin’ about, boy? Some folks don’t reason things out. Who made this glorious victory possible and added all this here new land to the Republic? The Democratic Administration—that’s who.

—Couldn’t have done it, hadn’t of been fer ole Zach Taylor whippin’ the damn greasers, the thin man said.

—What’s Taylor’s stand on the slavery question? T. D. said.

—Probly, he ain’t got no stand, Grampa Peters said. Call it a straddle rather.

Johnny read some more from the paper. It appeared that General Taylor had avoided the slavery question. There was a good deal in the paper about the old veteran of many a hardfought campaign who had personally inspired his stalwart troops on the windy plains of Buena Vista.

Johnny was glad that General Zachary Taylor was going to be the Whig candidate for President because he was the Greatest Living American.

Zachary Taylor was a rugged, whitehaired old man standing in the middle of a wall engraving. Stiff ranks of soldiers dressed in blue advanced across a plain through volleys of bounding cannonballs. In the background of the picture a darkskinned horde, color of the earth, dissolved in flight.

The War with Mexico was a pageant of names that made your flesh tingle. The names were Rio Grande, Monterey, Buena Vista, Vera Cruz, Cerro Gordo, Cherubusco, Molino del Rey, Chapultepec, Mexico City. The names were Zachary Taylor, Winfield Scott, John C. Frémont. The names were the Santa Fe Trail, Oregon, New Mexico, and California. The names were color of the sun on deserts and treeless mountains, color of buckskin breeches and blue coats, streaming South and West in a perpetual Fourth of July.

The Mexican War was a memory of orators, long hair combed back lush behind their ears, frock coats flapping, standing on the platform in the Court House Square, raising and dropping their arms and bellowing the names of battles and heroes. Johnny remembered the recent Fourth in Freehaven, when the County had turned out to welcome back its boys who had fought in Mexico. Marching at their head was the young hero, Captain Jake Jackson, who had distinguished himself in the attack on Chapultepec and been three times wounded as he led his men over impregnable defenses. The girls of Raintree County had flung flowers on the marching soldiers.

Johnny wished the men in front of the General Store would talk more about the real war, but instead, as usual, they talked about slavery.

Grampa Peters kept saying that the best thing to do was just to leave the whole question alone and not get the South all excited about it and that the territories to be carved out of the new land would settle the question of slavery for themselves. He said there never would have been all this fuss and fidget if it hadn’t been for the Wilmot Proviso. The thin man said that the South was all for throwing over the Missouri Compromise and that they never would be satisfied to let California come in as a free state.

—Damn them! the thin man said, getting excited, as people always did sooner or later when they talked about the new lands and slavery, that’s what they fought the damn war for—slavery.

T. D. was inclined to take a hopeful view of the situation.

—It was destiny, he said. We was going in that direction.

Mr. Doniphant came back, carrying his banjo. He sat down and sang some songs in a soft whanging voice, and while he was singing, Ellen came out of the house to listen, and some other people gathered around.

—Sing that one you sang last night, Grampa Peters said.

Mr. Doniphant sang:

—I come from Alabama

With my banjo on my knee,

I’se gwine to Louisiana,

My true love for to see.

It rained all day the night I left;

The weather it was dry.

The sun so hot, I froze to death,

Susanna, don’t you cry.

The chorus went:

—O, Susanna,

Do not cry for me;

I come from Alabama

With my banjo on my knee.

The best verse was the second:

—I had a dream the other night,

When everything was still;

I thought I saw Susanna dear,

A-comin’ down the hill.

The buckwheat cake was in her mouth,

The tear was in her eye.

Says I, I’se comin’ from the south,

Susanna, don’t you cry.

—That’s a good one, Grampa Peters said.

They had him sing it again.

—Where’d you learn it? T. D. said. I don’t recollect ever hearing it before.

—O, I picked it up in a camp of folks over in Ohio. We had a different way of singin’ it too that they made up around there. They was some of ’em singin’ it thisaway:

—O, Californy!

That’s the place for me!

I’m off for Sacramento

With my washbowl on my knee.

—Reckon you intend to git some gold out there, eh, son? Grampa Peters said.

—Well, sir, Mr. Doniphant said. I didn’t know if all them stories about there bein’ gold there was true. Most people just said they heerd it from somebody else. I thought I’d git me some land. If they is gold to be got, maybe I could git some of it too. I ain’t worryin’ none about it. All I want is to git out there.

—What d’yuh think about this here slavery question, son? Grampa Peters said. Do you think they’d ought to keep slavery out of them new lands?

Young Mr. Doniphant strummed softly on his banjo.

—Well, he said softly, I don’t know how you folks feel about it around here. Me and the folks I been travellin’ with goin’ West don’t want no slave labor to compete with in the new lands.

—But have they a constitutional right to prohibit it? Grampa Peters said. That’s the question. There ain’t any right under the Constitution to prohibit it. That’s all I say.

—Maybe they ain’t, the young man said. But I don’t figger there’ll be any slavery in the new lands.

He strummed softly on the banjo, humming,

—O, Californy!

There’s the land for me.

I’ve tooken quite a journey from

My home in Tennessee.

—If we keep slavery from spreading, T. D. said, it will die natural of its own accord. Slavery’s a wrong, and nothing can make it right. I take a more or less hope——

Something bit and tore the mildly spoken words. Young Mr. Doniphant stood up, ashamed and scared.

—D’yuh think——

—She’s all right, T. D. said. It’s natural. The pains are getting sharper.

—No good baby was ever got without a lot of yellin’, Grampa Peters said.

Ellen and some other women went back into the house.

—Take it easy, son, T. D. said. This may go on all day.

—By the way, T. D., Grampa Peters said, could you let me have another bottle of them pokeberry bitters sometime? My stummick’s been actin’ up on me agin. Sometimes I think I can’t hardly stand it.

Mr. Doniphant sat down slowly and kept picking nervously at the banjo and humming,

—O, Californy!

That’s the place for me!

—What route do you figure on takin’ to git out there? the thin man said.

—Why, I don’t know yet. I aim to take the safest.

—After what happened to them Donners, Grampa Peters said, I reckon you can’t be too careful. I wonder if you ain’t goin’ to have to winter over somewhere before you try it.

—Maybe so, the young man said.

—Have you seen any Mormons along the way? T. D. said.

—Not as I know of. They say the Mormons has all gone out and got them a place out there somewheres.

—I seen a book, Grampa Peters said, and it had a picture in it of a Mormon goin’ to bed with his wives. That there bed was simply swarmin’ with women pullin’ each other’s hair and feedin’ babies.

—One woman’s more’n enough fer me, the thin man said. They’d ought to take and burn all them Mormons at the stake.

Those days, people were always going West. Johnny had heard it said that along the National Pike there was a wagon every hour regular and at times a whole train. Nothing could stop the people from going West. They had babies along the way, like Mr. and Mrs. Doniphant. They died in the snow on the mountains and ate each other to keep from starving, like the Donners. They had a scad of wives in one bed like the Mormons. Most of them were slightly crazy some way. But they kept right on going. Perhaps it had something to do with the sun that made an arc day after day above the National Pike. Johnny thought of the western land under the far setting of the sun, wide plains in purple evening through which on softly thundering hooves the buffalo herds were running, he thought of Indians, riding swift ponies toward the flanks of purple mountains, wagontrains streaming thinly westward, he thought of shining rivers, green slopes, blue ocean on the distant shore of evening.

Those days, Johnny thought much of gold, Indians, great rivers, buffalo, and men who carried guns. Before the war, the West was a vagueness, a direction, a place of few names that belonged mostly to someone else. Now, however, it was good to think that the Nation extended from sea to shining sea.

—Here’s an interesting item, T. D. said, shaking the newspaper. It tells here how they laid the cornerstone for the Washington Monument.

—I wonder will they ever git that thing built, Grampa Peters said. Seems to me I’ve heard talk of it for a long time now.

—O, I guess they’ll get it built some——

A cry cut across T. D.’s sentence. This time it lasted longer than usual, and Mr. Doniphant got up and went into the house.

—Now that’s what I call a good loud one, Grampa Peters said. Sounds like the real business, T. D.

—How do you stand listenin’ to ’em all the time, T. D.? Just this one’s drivin’ me crazy, the thin man said. But I suppose you git use to it.

—I never will get use to it, T. D. said. But the Lord requires it of Woman for her Sin, and so it must be.

—I guess it must hurt ’em somethin’ awful, the thin man said.

Grampa Peters belched complacently.

—By God, I got to git me another bottle a them bitters.

Each time the woman cried, Johnny wanted to crawl off somewhere and hide. His pleasant landscape of Raintree County revolved dizzily, running with rivers of blood. Life was not what he had supposed it to be. When his mother appeared at the door, he turned his face away. He and all his brothers and sisters had entered life by an incredible wound inflicted on that slight beloved form. This was what the word ‘woman’ really meant.

—Daniel Webster, Grampa Peters was saying, much as I oppose him in most questions, has the right idea about this whole slavery thing. Stand upon the Constitution, and all will be well.

In those days, people were always standing on the Constitution. The Constitution was like the Bible. When you appealed to the Constitution, you had made the ultimate appeal. If you could quote the Constitution to support your argument, you had quoted God. People who quoted the Constitution always did so solemnly and as if that finished the matter. The majority of arguments ended by each man appealing to the Constitution, and the man who did it oftenest and in the loudest voice was adjudged the winner.

Not that anyone ever really won.

It seemed as though Grampa Peters’ remark about the Constitution set the argument going again. More men gathered around, and as the woman in the house cried more often, the men talked more loudly and profanely about slavery, westward expansion, and presidential candidates. There appeared to be a contest between the men before the General Store and the woman in the house to see which could get the best of a furious debate in which the two contestants were determined to ignore each other. But to Johnny, only the cry of pain was real. It filled up the street. It drew a bloodred streak across the day. And at last it compelled silence and respect.

After a particularly loud cry, Ellen came to the door and said,

—You better come now, T. D.

—Must be the breakin’ of the waters, Grampa Peters said.

—O, my God! a woman’s voice cried from the house. O, dear God!

—That’s all right, honey, Ellen Shawnessy was heard saying. Go right on and holler, honey. Just holler as loud as you want to, if it helps.

The men sat cowed. Johnny hated them and himself. He hated especially Grampa Peters. He hated the portly bulk of Grampa Peters, squatting majestically before the General Store; he hated the male complacency of Grampa Peters, which never had to be torn open and rent by such an anguish, the trousered fatness of Grampa Peters, who only sat before the General Store on his big dumb behind and made words about politics while life shrieked in an upstairs room. He hated all men in the person of Grampa Peters, because men caused this awful thing to happen and then could do nothing about it.

After the screaming had gone on for a while, the men began to curse softly.

—Well, Jesus God, I wish she’d hurry up and git it over with.

—Goddammit! Grampa Peters said once. I don’t remember my wife yelled that loud, though God and Jesus knows she always yelled loud enough.

—They sure git the raw end of things, the thin man said.

After a particularly frightful yell,

—Well, Jeeeeeeeeeesus God in Heaven, Dear Lord! said Grampa Peters, git rid of it, sister!

The men began to act as though they were being abused in some way. As for Johnny, each time the shrieking came, the skin of his face drew tight, his chest heaved, tears came to his eyes, he wanted to scream, roll on the ground, and yell with laughter. The desire to laugh became so strong that he had to get up and walk away. He went to the big wagon that was in back of the house where Mr. Doniphant had gone for the banjo. He got behind the wagon and tried to laugh, but instead he was sobbing. Apparently that was what he had been wanting to do.

After a while, the shrieking stopped and was followed by a series of moans and then a silence. The men got up and stood looking at the house. Johnny felt strangely calm. He dried his eyes and walked back to the road and stood with the men.

There was a new sound, which was like an echo of the other, a piping, insistent little echo, helpless and shameless as the other. But after that sound began, the other sound never did return.

The men in front of the General Store began to smile, at first a little sheepishly, then broadly.

—By God, listen to that little pipsqueak howl a hisn.

—That ain’t no pipsqueak howl. He’s got a good loud yell fer a baby.

—He ought to have, if he takes after his maw.

After a while, the door opened, and Ellen Shawnessy came out.

—They want you all to come in and see it, she said.

—I reckon they’d better leave us see it, said Grampa Peters. I never worked harder to have a baby in my life.

The men all removed their hats and walked sheepishly into the house. Johnny brought up the rear. In a room upstairs, a woman was lying on the bed. Her cheeks were flushed, and her hair was all strung around on the pillow. She was looking at something lying on her arm. Her husband was standing beside the bed looking at it too.

It was a little hairless monkey with a scalded skin, the ugliest thing Johnny had ever seen.

—It’s a boy, said Mr. Doniphant tentatively.

—It’s a fine boy, Grampa Peters said, lying magnificently.

The mother only lay looking at the baby. The baby was yelling again, and T. D. said,

—A perfect baby. The beginnings of a fine family, my boy.

Some of the men hit Mr. Doniphant solidly between the shoulders, and others pumped his hand. He looked bewildered and kept saying,

—Thank ye, sir, thank ye.

—Well, Missus, Grampa Peters said, how do you feel?

—All right, said the woman on the bed. I’m sorry if I caused y’all trouble by carryin’ on so. I never knowed what it’d be like.

All of them lied, saying they didn’t notice a thing, and anyway it didn’t bother them the least bit.

—What you goin’ to call it, Missus? Grampa Peters asked.

—Well, the young woman said very slowly, looking at it, we was aimin’ to call it, iffen it was a boy, Zachary Taylor Doniphant, but I done change my mind, and my husband and I would like to give him the name of this kind gentleman here who help us out and maybe save my life and the baby’s.

—O, I assure you—— T. D. started to say.

—No, sir, Mr. Doniphant said, we talked about it while you was all out of the room just now, and we’re a-goin’ to christen ’im Timothy Shawnessy Doniphant, if the doctor don’t mind.

—Mind! T. D. said. I would be delighted. But, I assure you——

Johnny thought it was a terrible insult to his father because the baby was a monstrous-looking object, but T. D. seemed to be delighted.

—T. D., one of the women said, I think that calls for a little prayer.

T. D. blew his nose and put his head down. The baby kept on crying.

—Dear Father in Heaven, T. D. said, these good young people have come a long way across the great continent of America and have suffered many hardships. So far Your kind providence has been upon them. We ask You now to continue to favor them with the benign light of Your countenance and take a hopeful view of their future, far-wandering across the land. May this little child that is this day born unto them live and prosper in the far land to which they are journeying. Dear Lord, preserve him and his father and his mother in the trials that await them. May they reach that far-off beautiful land of California and may they find all of their desires fulfilled until they arrive as all of us must, after much wandering, on that Golden Shore where there is no distinction between here and hereafter. We ask it, Lord, in Jesus’ name. Amen.

Outside, everyone made a little contribution for the new baby, and T. D., who had already donated his services, gave two dollars. The baby was yelling again when they went in to give the money to the Doniphants. One thing you could say for it: it had a lot of life in it.

Johnny was very quiet until they were on their way home. Then he found that he was humming a song:

—O, Susanna,

Do not cry for me.

—I wish I could get the words to that song, Ellen said. How much do you remember, Johnny?

Johnny started in, and it turned out that he knew the whole song.

—It pays to have a good memory, T. D. said. With your mind for remembering things, John, you ought to go far.

The tune had a fine gaiety, but the words filled Johnny Shawnessy with delicious sadness, and the name Susanna haunted him even into his sleep, for that night he dreamed that he was hunting through the Court House Square for a mysterious woman, whose stately name he couldn’t remember. Meanwhile the Square darkened; people were rushing by him in wagons going west.

—It’s the breaking of the waters, they said solemnly.

And indeed he could see the cold waters of the Shawmucky rising in the cornfields. He himself, trying to escape, wandered all night through familiar landscapes. They had an empty, joyless look

like paintings on a wall

or pictures

in

AN

ILLUSTRATED HISTORICAL

ATLAS

OF

RAINTREE COUNTY

INDIANA

1875

In the back seat of the surrey little Will had the book open.

—Who is that lady above the door, Papa?

He pushed the book over into Mr. Shawnessy’s lap. The title was stamped in gold on a black clothbound cover, eighteen by fifteen inches. The Atlas was an inch deep, corners and spine reinforced in tooled black leather. The fullpage lithograph of the Court House showed a rectangular brick and stone building. A tall tower set into the west end contained the Main Entrance, an American flag stood stiff out from the peak of the tower, and two clock faces visible in the sloped roof read nine o’clock. Two ladies, bustled, bearing parasols, walked on symmetrical paths of the court house lawn. Over the Main Entrance a draperied woman stood in a niche, blindfolded, leaning on a sheathèd sword, holding bronze scales.

—Justice, Mr. Shawnessy said.

—What are those things in her hands?

—Scales. To measure the exact difference between right and wrong.

—Why do they call it an atlas? Will asked.

—An atlas, Mr. Shawnessy said, is a book with maps—pictures of the earth. In the old Greek stories, a giant named Atlas held the world on his shoulders.

—Hercules came and held the world for him once, Wesley said, while Atlas went to the Garden of the Hesperides and got the golden apples for Hercules.

—What did Hercules want with the apples? Will asked.

—It was one of his twelve labors. And when Atlas came back, he just laughed at Hercules and said he was going to leave Hercules there holding the world forever. He didn’t want to take the world back.

—You can’t exactly blame him, Mr. Shawnessy said.

—But, Wesley said, Hercules played a trick on him. He fooled Atlas into taking the world back just long enough so he could fix his lion skin on his shoulders to keep the world from chafing them. And as soon as Atlas had the world back on his shoulders, Hercules just laughed at Atlas and took the apples and beat it, leaving Atlas to hold the world.

—He isn’t still holding it, is he? Will asked.

—No, of course he isn’t, Wesley said. It’s just a Greek myth.