* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

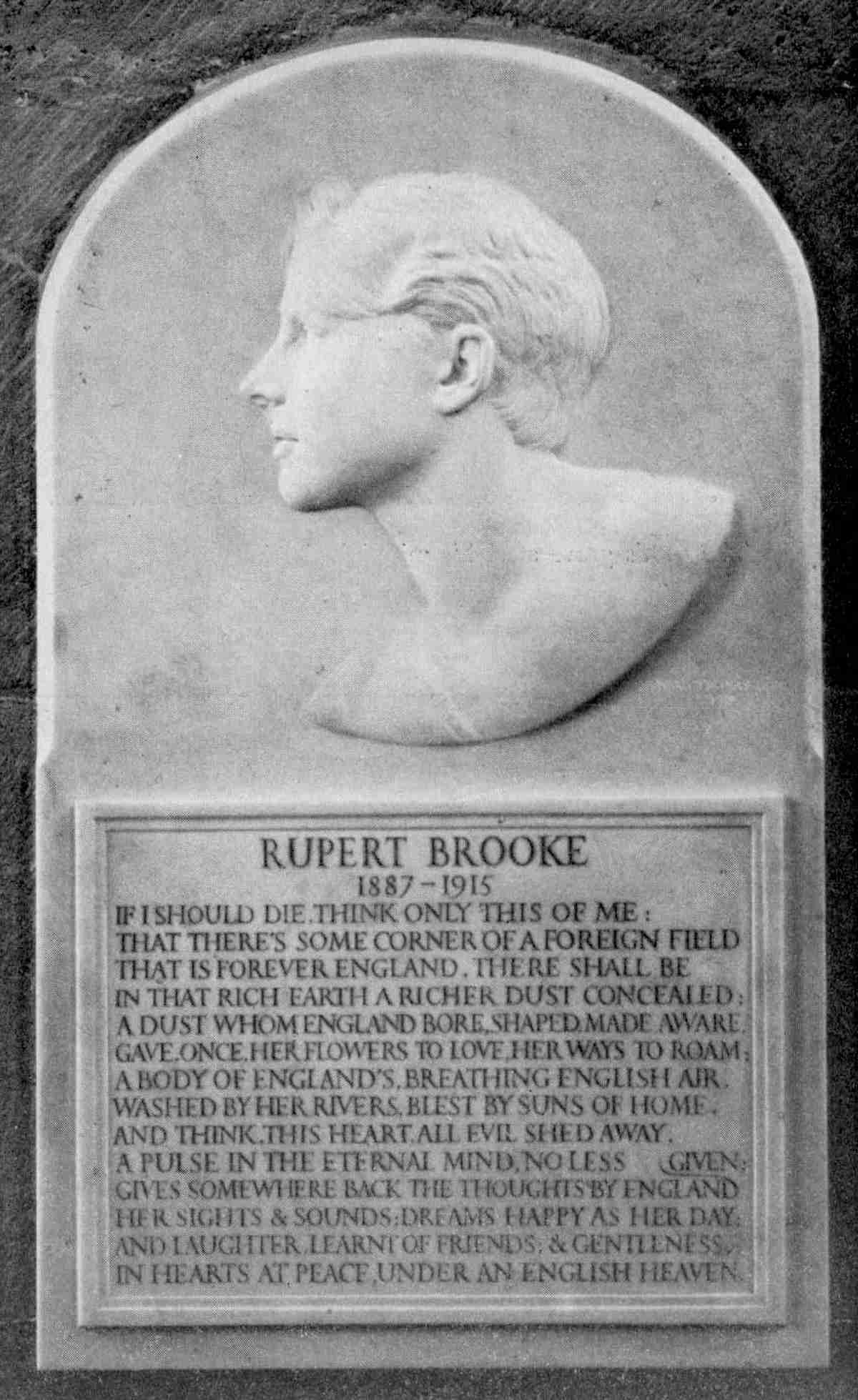

Title: Red Wine of Youth, A Life of Rupert Brooke

Date of first publication: 1948

Author: Arthur Stringer (1874-1950)

Date first posted: Jan. 13, 2023

Date last updated: Jan. 13, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230120

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

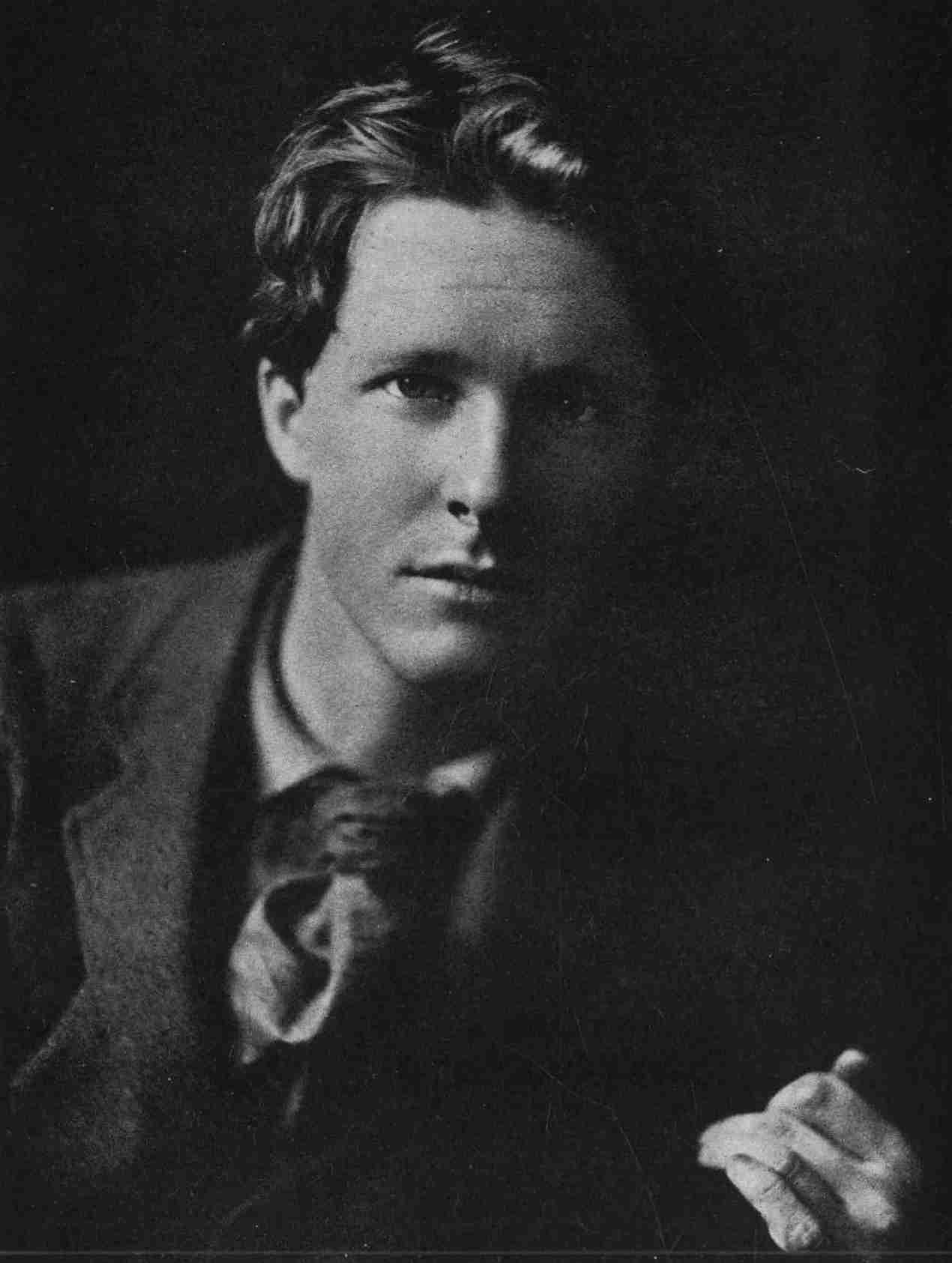

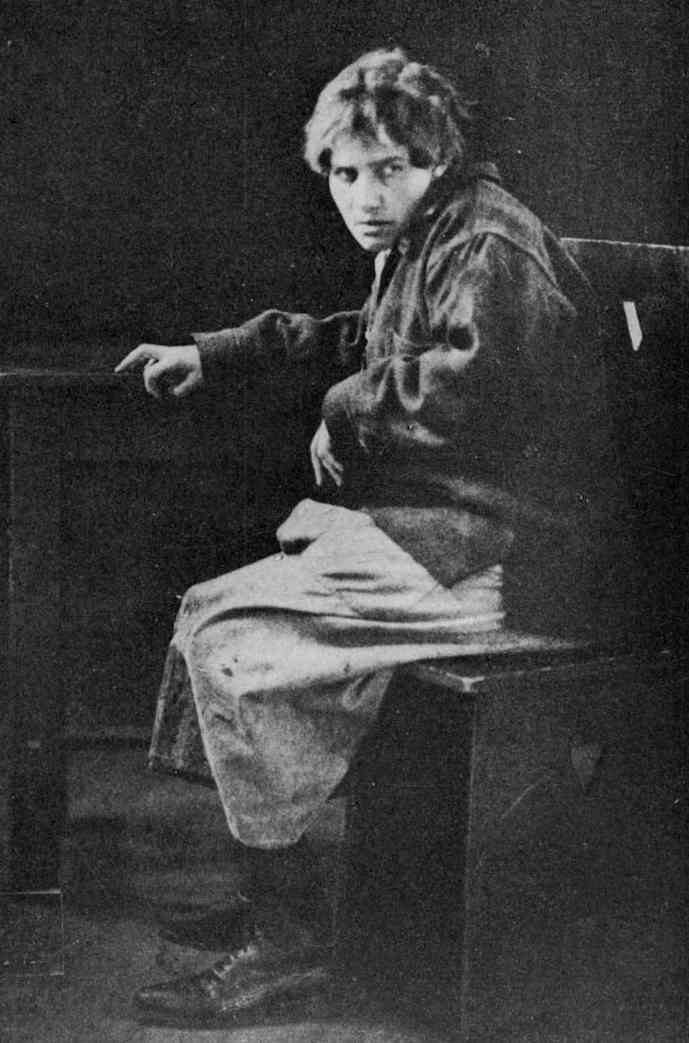

Photo by Sherill Schell.

Rupert Brooke at twenty-five.

COPYRIGHT, 1948, BY ARTHUR STRINGER

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

I must express my indebtedness to Dr. Geoffrey Keynes for his permission, on behalf of Rupert Brooke’s Literary Executors, to quote from many of the poet’s letters, a permission doubly gracious in view of Dr. Keynes’s own projected and more definitive volume of Brooke correspondence. I am, too, greatly indebted to Sir Edward Marsh not only for authorization to use extracts from his Diary and portions of his letters but also for kindly help in other ways. Mr. Maurice Browne I must thank for allowing me to quote from his Recollections of Rupert Brooke and for numerous more personal impressions of the subject of this biography. My deep gratitude goes to Miss Cathleen Nesbitt both for permission to quote from letters and for much elucidating data regarding her dead friend. Equally generous was Canon Henry Foster, late chaplain of the Second Royal Naval Brigade, who permitted me to quote from his At Antwerp and the Dardanelles, a volume with many vivid pictures of the twin expeditions in which Rupert figured.

To Dr. Edward Dent, John Masefield, Wilfrid Gibson, Duncan Campbell Scott,[1] Reginald Pole, Eugene Hutchinson, Ellen Van Volkenburg and Christopher Morley must go my thanks for the use of letters and pictures and numerous copyrighted extracts. The author also expresses his gratitude to the following American and English publishers for license to quote from duly copyrighted material: Dodd, Mead & Company; The Macmillan Company; Charles Scribner’s Sons; Houghton Mifflin Company; J. B. Lippincott Company; Elmer Adler; Alexander Greene; Macmillan & Company (London); Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd.; and Mills & Boon Ltd.

And my acknowledgments would not stand complete without including the names of those who earlier extended permission to the late Richard Halliburton to quote from letters written by Rupert. Among these are: Frances Cornford, St. John Lucas, Erica Cotterill, Jacques Raverat, Katharine Cox, Ben Keeling, Gwen Darwin, Geoffrey Fry, Violet Asquith, Helen Verrall, Edmund Gosse and John Drinkwater.

A. S.

|

Since these lines were written Duncan Campbell Scott passed away in the city of Ottawa, December 15, 1947. He died at the age of eighty-three, after writing his own valorous L’Envoi: He that cowers now is not the less a varlet. I know I’ll brave them well—I know not why; Toss me my proudest cloak of green and scarlet; Fellows—old friends—good-bye! |

RED WINE OF YOUTH

A Life of Rupert Brooke

A China-built junk, with three torn bat-wing sails above her hull of carved and lacquered teakwood, went down in the storm-lashed wastes of the mid-Pacific. Just where and when she foundered, with all on board, remains a secret of that speechless sea. The last message came from her on the morning of March 24, 1939. Her captain, still gallantly blithe, radioed that he was facing southerly gales with his lee rail under and was having a wonderful time.

The rest is silence; silence, and wonder and mystery.

But when that ill-starred junk, the Sea Dragon, went to the bottom she took with her a man who had given his life to adventure and discourse on the adventures of other men. Several years before his untimely death in the Pacific, Richard Halliburton had decided to write the life of a fellow nomad who had followed the Red Gods and traversed the waterways of the world even as he himself had done.

The author of The Royal Road to Romance, it is true, had never met Brooke in person, and had never seen “Shelley plain.” But the two had come together in the spirit world of the written word. When a mere schoolboy at Lawrenceville, Richard had fallen under the spell of the still youthful poet’s fearlessly intimate lyrics. The small volume he carried about with him became his Bible.

He placed Rupert Brooke on an adolescent list of heroes, side by side with Alexander the Great and Lord Byron and Richard Coeur de Lion. When he learned of the poet’s death and burial at Skyros his one wish was some day to make a pilgrimage to his idol’s island grave.

In the years that intervened, before that pilgrimage was undertaken, Richard read and pondered the later war poems. He found his own youthful moods exultantly expressed in the earlier lyrics and proceeded to glean every morsel of information he could as to his hero’s life and background.

But it was more than a case of mere hero worship. For the two men had much in common. Both were endowed with physical appeal and charm of manner. Both were born romantics. Both in their college days tramped and camped in the byways of the world. Both were sedulous readers of poetry and both believed, with Keats, that the fullness of life lay in living with gusto. So both, in time, sought the open trail and adventure in far-off lands. Though both saw boyish fragility eventually merge into the calisthenic strength of manhood, they nursed a common dread of old age and a dislike for the thought of passing away without progeny. Yet both lived and died unmated, just as both, in the end, faced the Final Adventure and passed on when life had so much to give them.

It was but natural that Rupert’s untimely death at the front and the heroizing circumstances of his midnight burial on far-off Skyros should deepen his worshiper’s resolve for that projected journey to the Upper Cyclades. It was a determination that was finally carried out. How Richard went to the Aegean, landed on Skyros and visited the poet’s grave, has already been told in The Glorious Adventure.

“I stood beside the grave alone,” Richard wrote at the end of his Aegean wayfaring. “The silence of the night enfolded land and ocean in dim mystery. The stars crept close to illuminate the name carved across the marble tomb—a tomb that was to me a sacred shrine. . . . In his most poetic fancy Brooke could have desired no lovelier spot. On three sides the marble mountains shield it; seaward there is a glorious vista of the island-dotted ocean, bluer than the sky itself which looks straight down through the wreath of olive trees upon the tomb. The flowering sage that perfumes all of Skyros grows thickest here. There is a sweetness in the air, a calmness in the ancient trees, a song in the breeze through the branches, a poem in the picture of the sea. . . . Twilight had gone, and the stars were gleaming. . . . I stood beside the grave and thought how safe Brooke was here. He had a beautiful burial place; he had the brightest sky and the best sunsets in the world; and the whispering olive grove, and the view of the sea.”

All night long, while the moon rose from behind the mountains’ rim and paled again with the breaking dawn, the silent watcher dreamed and brooded beside the marble tomb. When a shadow moved under the silvered trees the startled watcher studied it, half expecting it was Rupert Brooke’s specter confronting him. But it proved to be only the shifting shadow of a low-hanging olive branch.

During that vigil, however, a second resolve took shape in Richard’s mind.

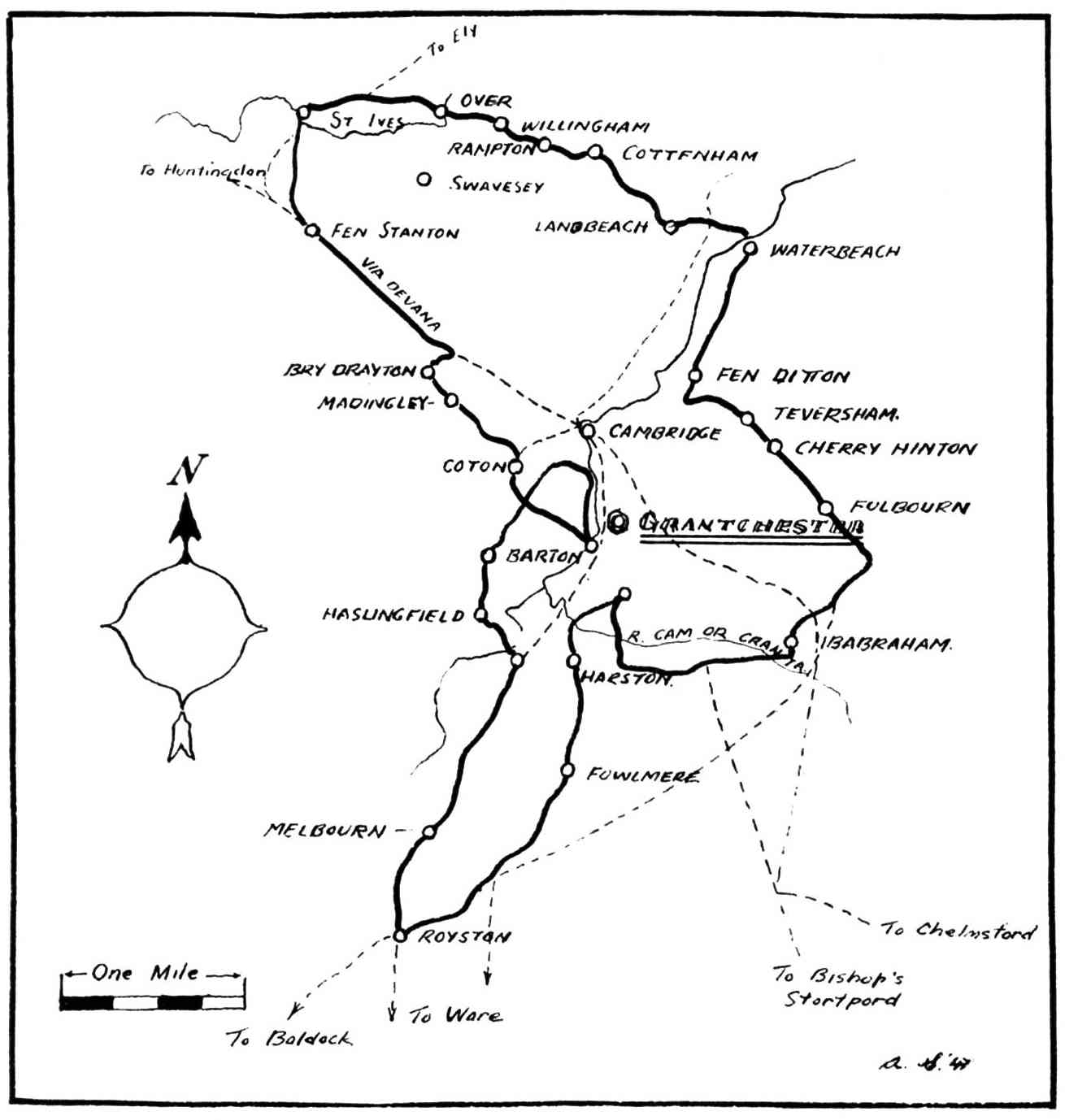

“Then the splendid idea came to me that I might go to England on my way home, and try to meet Brooke’s mother and his friends at Rugby, to report to them that his grave was still as beautiful and peaceful as they would want it. I realized I’d rather meet Mrs. Brooke than the Queen of England. . . . And why not Cambridge also? I could go there from Rugby, and walk across the meadows to Grantchester, and call upon the Old Vicarage where Brooke spent the happiest days of his life.”

From Naples, on his devious journey westward, the modern Ulysses wrote to Mrs. Brooke explaining he had taken some interesting photographs of her son’s tomb on Skyros and expressed the hope he might show these to her on his arrival in England toward the year end.

In December 1925, in response to a coolly formal note that came to him in his London hotel from Mrs. Brooke, he went to Rugby to meet the poet’s mother. He had been warned that she might prove as unapproachable as royalty. But the intrepid adventurer who had emulated Byron by casually swimming the Hellespont was not daunted by English reticence.

His two-hour visit with that sorrowing mother who had lost three sons did not open auspiciously. She listened quietly to Richard’s expressions of sympathy and seemed genuinely interested in his Skyros pictures. But beyond that her responses were disappointingly reserved. She remained sternly opposed to any plan of publicizing her Rupert’s career. The would-be biographer went back to London feeling he had gleaned nothing of importance to write about his idol.

So disappointing was the encounter with Rupert’s mother that two years elapsed before Richard returned to Rugby, determined to overcome an opposition he still failed to understand. But his assault on that citadel of reserve was not an easy one. He still found Mrs. Brooke one of the most formidable persons he had ever met. “She’s very discouraging, very set, very unsympathizing,” he wrote of his second encounter with her. He was conscious of barriers that were phantasmal yet firm.

There were, it may be deduced, certain reasons for reticence. Like many another star-gazer, Rupert had not always followed the paths of what his puritanical-minded mother regarded as rectitude. With all his fineness of feeling and his wind-harp responsiveness to the urges of the flesh, he had not escaped those human frailties which according to Saint Luke could even win the pity of God. There was a chapter or two in his book of life that called for silence.

But this second Richard the Lion-Hearted, who claimed that he always liked resistance, was not easily discouraged. Even when his hostess confronted him with a curt “Ask your questions, young man—one—two—three—four,” he saw no reason for making a retreat. When his questions exceeded the allotted number, in fact, and seemed to be probing too deeply into personal issues he was only temporarily halted by the acid announcement: “I happen to belong to a family that was never in the habit of taking its baths in public.” That passionate curiosity and craving for knowledge which had carried him over many a rough road left him patient in the face of passing disapproval. He did his best to explain that he merely wanted to understand the man he was determined to write about. Any skeletons that lurked in the family closet could remain there.

The strong-minded lady relented a little. Perhaps she detected in the New World intruder a personal charm reminiscent of her own adored and beautiful son, though any reference to Rupert’s physical attractiveness invariably awakened her anger. Perhaps she was won over by her visitor’s obvious sincerity. The ice walls went down. It was not long before Richard, sitting on a hassock at her feet, was listening as she talked quietly about her son who slept in a far-off grave.

Yet there were definite reservations in that surrender. Mrs. Brooke was willing to hand over an early photograph or two and impart some of the essential facts of Rupert’s life at Rugby and Grantchester. But any information as to his interests and activities was given only on condition that no single word of it was to be committed to print until after her death.

“Sensitive poets,” the would-be biographer concluded, “often have such mothers, vital, dominating, strong.”

That stern and sorrowing mother, who had already lost her husband and sons, followed them to the grave in 1931.

There were, of course, other sources to be delved into. After visiting Rugby and Cambridge and wandering about the Grantchester countryside and interviewing friends and relatives of the dead poet, Richard went on to London, where he sought out still more of Rupert’s associates and from them obtained letters and reminiscences that could throw new light on his idol’s character and career.

Some of the poet’s acquaintances, the presumptive author of the biography found, stood unwilling to surrender to other hands, and especially American hands, any information that carried the threat of disturbing a posthumous tradition already approaching sanctification. The mythopoeists were intent on merging the man into the myth, almost evangelical in their ardor to keep the picture one of knightly probity, as simplified as a stained-glass angel in a chapel window. For, unlike an American Whitman who fabricated his own rather legendary figure, Rupert Brooke was being transfigured into a sort of Arthurian angel by a coterie of over-zealous friends who remained blind to his faults. He was not the gilded gargoyle those friends tried to make him. That there should be discrepancies between the legend and the recorded facts may be ascribed to a human enough tendency to dramatize into sanctity what was once dear to the heart. The magnetic Rupert, being human, was not without his failings. The one extenuating circumstance was that he never entirely grew up. He remained, to the end, very much of a boy. He poured out the sweet red wine of youth before he was given a chance to fulfill his destiny.

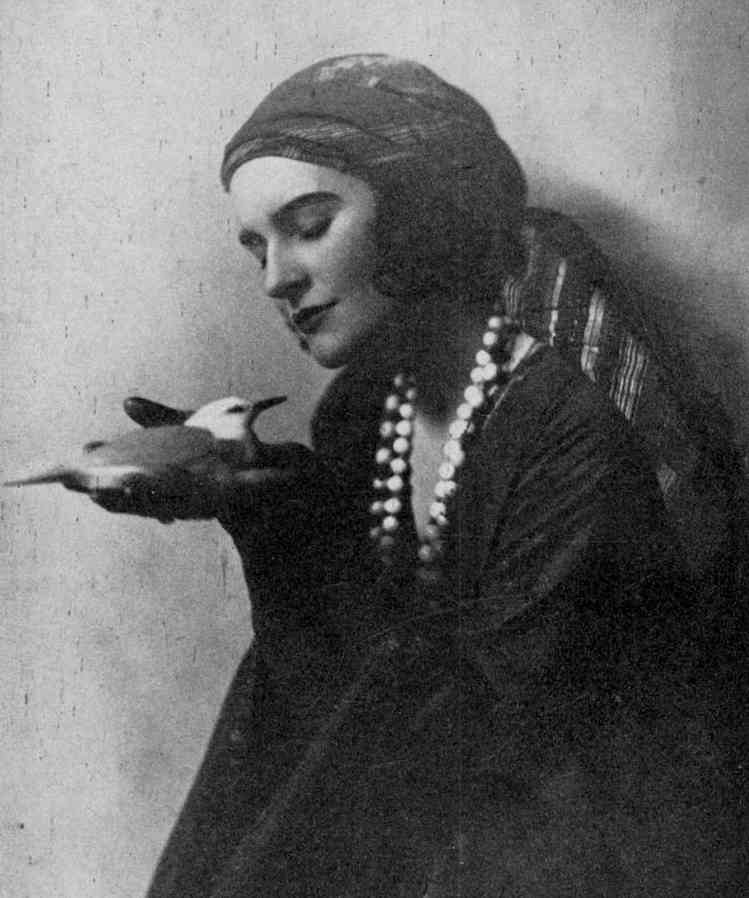

But those blindly loyal friends who preferred Bowdlerizing to Boswellizing were in the minority. Men of letters, from John Masefield to Edmund Gosse and Wilfrid Gibson, were liberal in their surrender of letters and memorabilia and as yet unpublished bits of prose and verse. Cathleen Nesbitt, the talented Irish-born actress who had first come to America with the Abbey Theatre players, permitted a judiciously edited number of Rupert’s letters to be copied. For those letters, ardent and intimate, were documents in evidence of a rhapsodic love affair that was both idyllic and destined to be ill-starred. Violet Asquith, the brilliant daughter of the then Prime Minister, was also willing to lift the curtain a little on her dead friend’s life.

But by far the most co-operative, once the situation had been made clear to him, was Edward Marsh,[1] Private Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty, now Sir Edward Marsh. For eight long years he had been Rupert’s friend, had watched over him like a father, and after the poet’s death had written the invaluable Memoir that stood the only intimate recountal of his all-too-brief career.

The warmhearted and affable “Eddie”—for as such he was known, significantly enough, to countless friends—gladly came to Richard’s help and, infected with the younger man’s enthusiasm, not only directed him to other sources but gave him access to the Marsh diary and notebooks. What is more, he allowed the would-be biographer to make copies of letters to and from Rupert, released to him a number of the latter’s unpublished poems and talked over and corrected sporadic data already in Richard’s hands. In doing this he was ready to acknowledge that his own Memoir was necessarily incomplete and in no way definitive. Perspective and scale would be less difficult to adjust, he knew, after the stabilizing lapse of years.

Yet the task of assembling the material duly harvested by the later investigator carried the promise of being no easy one. The era of deification may have passed but there was still the nebulous line between dicenda and tacenda to be remembered. The patina of time may have dimmed the luster of the legend, but both the voice and the vivid personality of the Apollonian youth who sang and died for his country was still a jealously cherished memory with his compatriots. The new interpreter, as well, found himself confronted by many contradictions.

Some friends remember Brooke as shy and modest; others describe him as willfully self-assertive and given to exhibitionism. Some speak of his golden voice and his genius for interpreting his own verse; others claim that his reading (like his acting) was as unimpressive as his voice was monotonous. Some maintain he was always gentle and kindly and considerate; yet he could be curt in his criticisms, violent in his dislikes, and sometimes guilty of “the superb insolence and the lovely brutality of youth” which he had once detected in Marlowe. He was a lover of beauty yet lived in continual protest against beauty. He was a Romantic who detested romanticism, and an apostle of carpe diem enjoyment who was obsessed with the thought of death. He is reported as solemnly leading Rugby Chapel in prayer yet proving as vocal as the youthful Marlowe of the Elizabethans in his opposition to established religion. He had no belief in a future life. On this earth, however, he hungered for enchantment. For the world, to him, remained a playground, where such a thing as manual labor was foreign to his interests and any thought of hardening toil was remote from his intentions. His heritage may not have been a markedly aristocratic one but the aristocratic attitude persisted in his Athenian aloofness and his impatience with the barbarian. He could lose himself, at times, in a love for all humanity and claim fellowship with the raggedest derelict that drifted about a village street, but his affiliations with the lower classes were tenuous and he could be as intolerant as Coriolanus with democracy, especially with American democracy.

Some who claim to have known him expatiate on the ease with which he wrote, while the laboring artist himself has explained how he pondered and brooded and patiently filed and revised, confessing that he spent three long months on his three-page poem “The Fish.” Some associates contend he remained platonic and mentally austere, claiming amorous adventure was merely a side issue in his all-embracing zest for life. Others accept the belief he merited the epithet of the “Great Lover” and, agreeing with Goethe that the world is moved not so much by the love of God as by the love of woman, did not and could not escape the voluminous soft protection of many mothering spirits anxious to shield over-sensitive youth from the world. Erotic experience and its aftermath, it is true, afforded material for much of his verse. But he left behind him scant record of either abandoned Byronic romances or tragic Shelleyan misalliances. His final interest was in his versifying. He himself may have claimed a Celtlike inability to recognize the spiritual glory of work, but he toiled so assiduously at his job of writing that he fell a victim of nervous prostration and was twice bundled off to the Continent for a summer-long rest. He has been described, in some quarters, as abstemious and frugal-living and fond of plain food, yet his letters abound in references to his beer drinking and his consumption of stout and his delight in divers Lucullan repasts. Some reminiscent admirers speak of his lithe and athletic figure, while others attest to his carelessly awkward carriage, his disregard of dress and his habit of lounging against any furniture at hand.

It all merges into an oddly conflicting picture, nonetheless interesting, perhaps, because of its very contradictions. For intimacy, often enough, can be a handicap to final judgment. With so enigmatic a character it is not easy to probe beneath the surface and detect the motive behind the movement and the impulse behind the occasional defiance of convention. The life of genius, conditioned by inner and elusive influences, is not readily understandable. On one point, however, the evidence is clear and the chorus of voices united.

Rupert Brooke was one of those rare poets who looked the part. With his vivid coloring and his almost womanly smoothness of skin, with his mop of fair hair, with a golden tint, crowning an almost godlike beauty of face, with his English blue eyes that could glow with unanglican ardencies and with his casually responsive and carelessly radiant spirit, he invariably cast a spell over those who came in contact with him. From Henry James and John Masefield to Ian Hamilton[2] and Winston Churchill, they all succumbed to the charm of this dangerously endowed youth who expected so much of life and embodied so much of a now-fading English tradition. With him and his poetry it was not an instance of the ailing oyster producing the pearl. As one long-range victim of his pulchritude observed: “He is a poem himself!”

This challenging physical attractiveness may at times have left him the prey of those predaceous Dulcineas whose litanies are vocal with the claim that the youthful poet must live ardently before he can sing impressively. He could not entirely escape them, perilously blessed as he was with beauty of feature and boyish charm of manner. But, young as he was, he sought and found his salvation through an escape into intellectuality. It was a retreat to the subjective that tended all too soon to temper his mood into moroseness and presaged that later post-orgastic listlessness which crept into so many of his lyrics. It is the mood that runs through “Menelaus and Helen,” that dominates the poem first called “Lust” and later called “Libido,” that gives a sort of agonized and contrapuntal ugliness to the lines under the slightly fallacious title of “Jealousy.”

Women, it must be assumed, played a profound part in the life of this overardent and over-sensitive young Epicurean. But, as has been said before, there is no record of Casanovian adventures along the way, no whisper of Shelleylike disasters, and no catastrophic surrender to the voluptuary issues that marred the life of the frustrated hero of Missolonghi. The truth is, indeed, that Rupert Brooke won and held the friendship of many women who could attach the stabilizing tail of discretion to the kite of romantic affection. They were his helpers and counselors, his companions and his comforters, sometimes his critics and sometimes his inspiration. His letters to loyal friends of their sex are both numerous and enlightening, though by no means as numerous as his letters to men. He spilled much ink, in his too-brief life, in trying to bind closer to him the companions he valued and the friends he craved to keep in this calamitously changing world. Because of these outpourings that brief but beautifully vocal life has fewer secrets than one finds in the customarily tangled-up career of genius.

Richard Halliburton was, of course, attracted by that career. But he confessed to an ulterior motive in his proposed recountal of it. What he was actually in search of was a divorce from the personal, an escape from the perpendicular pronoun, the “I” that had to repeat itself so disturbingly in all his self-revealing books of travel. There was the danger, he claimed, of those volumes being accepted as an exercise in personal glorification. And from any possible charge of self-exploitation he proposed to rescue himself by the objective exploitation of a life not his own.

It was his expressed intention to make the first half of the book gay and vivid, the second half scholarly and interpretative.

But the book was never written. The amassed letters and notes were never made use of. The adventurer who once braved the Sahara and once climbed Mount Olympus met a death at sea as untimely and tragic as the earlier death he had proposed to write about. And the accumulated material was passed on to other hands.

|

Edward Marsh, son of the master of Downing College, Cambridge, has long been close to the seats of the mighty. In 1900 he was private secretary to Chamberlain, in 1903 private secretary to Lyttelton, and still later private secretary to Churchill, accompanying the latter to East Africa and Uganda. In 1915 and 1916 he was Asquith’s secretary and for five years after that resumed his secretarial duties under Churchill, filling the same position with the Duke of Devonshire from 1922 to 1924. |

|

“I have seen famous men and brilliant figures in my day, but never one so thrilling, so vital, as that of our hero. Like a prince he would enter a room, like a prince quite unconscious of his own royalty, and by that mere act put a spell upon every one around him. In the twinkling of an eye gloom changed into light; dullness sent forth a certain sparkle in his presence. . . . Here was someone who was distinguished by a nameless gift of attraction, head and shoulders above the crowd; and it is the memory of this personal magnetism more even than the work his destiny permitted him to fulfill that adds strength to the roots of his ever growing fame.” Sir Ian Hamilton at the unveiling of the Rupert Brooke Memorial in Rugby School Chapel, as reported in the Rugby Observer. |

The gray old market town of Rugby, on the Warwickshire tableland sloping up from the south bank of the Avon, has long been known as the home of one of England’s most illustrious public schools. It is spoken of as a hamlet in Domesday Book. The first Rugby Chapel, eight centuries before its successor was made memorable by Matthew Arnold, goes back to the reign of Stephen. For four long centuries Rugby School has shaped and colored the character of England’s youth.

In the shadow of these historic walls a poet first saw the light of day. At Rugby on the third of August in the year 1887 a son was born to William Parker Brooke and his wife, Mary Ruth Cotterill. This son, who was later christened Rupert Chawner Brooke, was the second of three brothers, all of whom were unhappily destined to die before they reached the age of thirty.

William Parker Brooke, a canon’s son, was then a teacher in Rugby School, where a master’s remuneration was still rather modest. Rupert’s mother, fortunately, had funds of her own, funds which, though dispensed with Spartan frugality, eventually permitted her gifted son to share in what she regarded as the better things of life. She was considerate, but never indulgent. She was strong-willed and sternly critical, but she was willing, when necessary, to make sacrifices for the restless youth who demanded so little and yet so much. He was never ashamed of his background. And if he was not born with a silver spoon in his mouth he at least made his appearance in the midst of considerable time-mellowed Sheffield plate. He was not denied the Englishman’s customary Grand Tour of the Continent. But he was able to boast, later in life, that he could dress on three pounds a year.

When Rupert was five years old, in fact, his father was promoted to Housemaster of School Field. There, for the next eight years, the family made its home. It was a modest home with a formalized but slightly unkempt garden where the youthful Rupert wandered and played and in the old pergola essayed his first ventures into the world of the written word. He was not happy when he was sent off to a small preparatory school at Hillbrow, where his more formal-minded brother Dick had preceded him.

Little record remains of Rupert’s Hillbrow days. Life there was embryonic and objectively uneventful. It became more animated when he met and fell under the influence of a much older youth who answered to the name of St. John Lucas—a name which in the free masonry of boy life was soon converted into Jack Lucas. This older youth was already a dabbler in literature, not unaffected by the wearied perversities of the Naughty Nineties.

His appeal to Rupert was immediate. Contact with a more mature aspirant for literary honors must have awakened, or at least deepened, the younger lad’s interest in expressing himself on paper. Instead of scribbling censurable rhymes in the blank pages of his textbooks the schoolmaster’s son pioneered into less frivolous exercises in rhythmic expression. He ventured a serious poem or two. But he kept the matter a secret from his family.

There was nothing robust about Lucas. But he was understanding and articulate. His patter about literature and his increasing facility in turning out light verse left him one of the elect in the eyes of the younger groper after self-expression. To Rupert he stood for sophistication and things of the spirit, proving a tolerant comrade with whom one could talk over the problems of adolescence and discuss the intricacies of prosody. Lucas, for all his tendency to walk with the decadents, was destined to become a sympathetic counselor and critic of Rupert during that earlier formative period when he was so in need of help. Years later, when Lucas abjured law to produce a novel entitled The Marble Sphinx, his younger disciple was much impressed by its morbid cleverness.

But the son of the Rugby schoolmaster, in those earlier and lighthearted years, was living his poetry more than writing it. He was a dreamy boy, more interested in insects and animals than in the monotony of classroom study. It is safe to assume that any homesickness he may have experienced in his exile from Rugby was softened by the knowledge of his escape from parental supervisions already clouding his carefree quest of unscholastic diversions.

There is a picture of him in his boyhood garden, patiently trying to teach his fat old bull terrier (known as “Mister Pudsey Dawson” in dubious honor of a previous owner) to retrieve timorous toads from the long grass into which they attempted to escape. He was equally attentive to a pair of pink-eared rabbits and a cage of white mice that made one corner of his play yard as odoriferous as a neglected horse stall. He always had what his nurse called an itching heel. From the first he was a wanderer. More than once he strayed away from his home district and was found only after hours of search. The suggestion of music lessons, when there was so much to be explored in neighboring meadows, left him with the determination to abandon his home circle for life in a tinker’s van. For he was always happiest out of doors, a brooding blue-domer who rambled along streams and hedgerows, yet, oddly enough, was never what might be called a close student of nature.

Even as a child he showed a reluctance to conform. At the age of twelve he was independent-minded enough to sit on the platform at a local pro-Boer meeting. When upbraided by his indignant mother for resorting to bullying tactics with his younger brother, he demanded to know what was wrong with his conduct. His exacting parent none too patiently explained that he was older and bigger than his brother and that when one imposes one’s will on a smaller person he could be written down as a bully.

Rupert, after viewing his mother with a youthfully sagacious eye, announced that she was older and bigger than he was and since she was imposing her will on him it was plain enough that she was the bully.

He was equally dissident in his abhorrence of clothes, always happiest when he could go barefoot and always wanting his throat uncovered. His room was chronically untidy and littered with books. His appetite was capricious and his dietary experiments were the cause of many reprimands. His practical-minded and stern-spirited mother found much to deplore in her son’s gypsy-like idleness and often had cause to be disturbed at both his restlessness and his too early tendency to toss stones, figuratively, through stained glass windows. This led to a monitorial attitude that lasted into the years.

It largely accounts, indeed, for his Shelleylike lack of sympathy with his own family and his repeated claim that his mother never really understood him. His love for her was always more vocal when he was far away from the home roof. That odd relationship between the occasionally unruly Rupert and his occasionally choleric mother remained a variable one. There was an obvious divergence of aim and outlook that often enough put a strain on affection, a grim reserve that clashed with careless and exuberant youth. If any deeper basic devotion existed between mother and son, it was a devotion that became more voluble, as has been implied, when they were not within the same walls.

For his more stable-spirited brother Alfred, who was to precede him at King’s College, Rupert had both respect and admiration. There was a real bond between the two. And a common understanding of home conditions made them partners in campaigning to keep the domestic picture a tranquil one. Unless Alfred is put in that picture, the Provost of King’s reported, the depiction of the family life would be out of focus. The contrast of the three characters was remarkable, acknowledged this onetime visitor at Bilton Road, but the dominant impression he harvested was that, with all their differences, the three were basically close to one another in an unparaded sort of understanding.

Yet a gulf remained between Rupert and his mother. We even find him more voluble in his expressions of affection for his nurse than for his parent, to whom was later attached the humourously tolerant epithet of “The Ranee.” And if that managerial lady’s love for the son on whom she pinned such high hopes was tangled up with repeated frustrations it must be written down to fundamental differences in character which even adoration could not bridge. Throughout his youth he remained a square peg in the round hole of British conformity, always thinking more of his family when beyond the periphery of parental authority.

The male head of that family, preoccupied with school duties as he was, seems to have given only perfunctory attention to the volatile boy who perplexed him by his changing moods and dismayed him by dissidences obviously unpalatable to the pedagogic mind. Yet William Parker Brooke was not entirely without humor. He could break into a parody of Swinburne when inviting a Miss Tottenham, who was his son’s ex-governess, to come and spend Christmas week with them, where

With puns that leave you smarting

And hair that knows no parting

Rupert your soul will vex!

The gulf here was not often bridged, however. And later in life Rupert could confess that he was without ancestor worship. He felt curiously unlike his parents and was often puzzled by a sense of remoteness from their aims and ideas, consoling himself with the claim that as an individualist he had his own way to go.

This conviction obviously left him a bit of a problem child. Notwithstanding his mental brightness and his ebullience of spirits that left him alternating between laughter and tears, he was far from robust. Throughout his youth, his mother tells us, he suffered from a throat ailment that left him allergic to dust and was the source of much family concern. And during his early years he had his fair share of the passing tribulations of childhood, from croup and mumps to influenza and measles and pinkeye.

At the age of fourteen he entered Rugby, that historic school where a great granite slab on what is known as its Doctor’s Wall describes a lighter phase of its history. “This stone,” it reads, “commemorates the exploit of William Webb Ellis who with a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time, first took the ball in his arms and ran with it, thus originating the distinctive feature of the RUGBY GAME. . . . a.d. 1823.”

Rupert was installed as a student in School House, where his father was Master, to pass back and forth through the same doors where “Tom Brown” was once carried shoulder-high on the last night of his life as a Rugby boy. And in that school the new boy was confronted by traditions as fixed as the names of earlier Rugbeians carved deep in the dark oak of the desks and dining-hall tables. There were many things to be done, and many not to be done. No lowly member of the school might ever cross the Quad on the stone paths that bisected the greensward; that path was sacred to masters and visitors.

The free-ranging Rupert had much to unlearn. He had by this time developed into a somewhat bookish boy, impressing his fellow students as shy and quiet, preferring to slip off to the Temple Library to lose himself in literary reviews rather than join in the games and junketings of his schoolmates. But he could leave his fellow Rugbeians pop-eyed by demonstrations of his remarkably prehensile toes, with which he could play marbles or toss a stone. At Rugby, it is recorded, he showed how with one simian foot he could take a match out of a matchbox and nonchalantly light it.

In the give and take of school life in a colony of six hundred unruly youths, in the fagging and ragging that persisted long after the Tom Brown era, the bashful boy lost a little of his once fixed tendency toward introversion. Although he had little enthusiasm for athletics he did his required stint on the playing fields of Rugby. His deeper interests were along other lines. He was never what might be called a school hero. He played tennis passably well, it is true, and in time could participate creditably enough in cricket and football, playing on the School Cricket Eleven and the Football Fifteen. In the latter two sports he even had a hand in promoting the School Field players to “Cock House,” which meant school championship. But he did not lose himself in the fanaticism for sports that surrounded him. He had a preference for more leisured walking tours and in later years developed a love for swimming, though his ambitions at diving remained a source of mixed anxiety and amusement to his more accomplished friends. He became, without distinction, a Cadet Officer in the Corps. But when, later on, a Cambridge associate suggested a mountain-climbing holiday in Switzerland, Rupert declined with thanks, protesting such rugged exercises were not for him. Yet his fondness for an open-air life was deep and enduring. Summer by summer, that golden-brown hair of his was invariably bleached to a lighter tone by the sun. And he remained boyishly proud of the tan which gave a much-desired touch of masculinity to an almost womanly peaches-and-cream complexion.

Religion, it is worthy of note, had little influence on him. In the School Chapel he could sing with ardency, though, as his discomfited fellow choristers kept reminding him, persistently out of tune.

Rupert’s love for Rugby did not blind him to some of its anachronisms. He saw something incongruous in the weird architecture of the older buildings with their mock battlements and fifteenth-century castellated towers—making a wonderful place for clambering boys to hide—yet he learned to accept the general effect as one of solid and stolid impressiveness. The School Chapel with its Georgian Gothic, he saw, might fail to harmonize with the surrounding buildings, but there too the aura of tradition combined with the mellowing influence of time to soften earlier ugliness. For time went far back at Rugby, where boyish anglers who fished at Brownsover Mill could remember they were whipping a stream once whipped by Izaak Walton himself.

Changes were taking place in the young Master’s son who both loved and laughed at Rugby. He may have stood ready to make protests against what he called the conventional hypocrisy of the public school but he could not escape its influence. The stream caught him up and carried him along with his fellows. He became a member of that select circle dignified by the classic title of “Eranos,” made up of only twelve members, restricted to the Sixth Form, more energetic spirits who filled up vacancies by “co-opting” and met regularly to read papers on literary subjects. The Lower Bench, as the Junior Class was termed, had an “Eranos” of its own, a larger and less-ardent group given over, not to creative writing, but to the mere reading of the poets.

It was natural that Rupert should become more bookish than ever. His reading, though not desultory, was centered more on the English poets than on the classics. After delving into Donne—a diversion that left its influence on him for many a year—he fell under the spell of the more decadent moderns, reveling in Oscar Wilde and Ernest Dowson and Swinburne. From these he came up to clearer air with Yeats and Kipling and Henley and Pater. But even in that transitional period when Beardsley and The Yellow Book seemed the final word in sophistication a salvaging sense of humor kept Rupert from altogether losing himself. With the catharsis of irony he could cleanse his spirit, as he did in the imaginary dialogue quoted by Edward Marsh in his Memoir (page xviii). In this narcissistic exercise in aestheticism, which originally came to light in a letter to Arthur Eckersley, he playfully pictures himself as an ennui-drenched victim of the current decadence.

“The Close in a purple evening in June. The air is full of the sound of cricket and the odour of the sunset. On a green bank Rupert is lying. There is a mauve cushion beneath his head and in his hand E. Dowson’s collected poems bound in pale sorrowful green. He is clothed in indolence and flannels. . . . ‘You talk wonderfully,’ he says to his ghostly companion. ‘I love listening to epigrams. I love to think of myself seated on the greyness of Lethe’s banks and showering ghosts of epigrams and shadowy paradoxes upon the assembled wan-eyed dead. We shall smile, a little wearily, I think, remembering.’ ”[1]

He emerged, in time, from the Narcissism of the Naughty Nineties, but, like a fever, that immersion in aesthetic morbidity had its after-effects. He confessed that, when he should have been busy with schoolbooks, he had written the first five chapters of an enormous romance, the opening sentence of which describes the moon as looking like an enormous scab on the livid flesh of a dropsical leper.

The budding poet, it is true, could burlesque the momentary cult of the morbid and satirize the vogue for arresting ugliness. It is equally true that his early intimacy with the authentic insurgents left him with an insurgency of his own. To the end of his life he liked to shock the Philistines and disturb the pious by unexpected profanities. His revolt against orthodoxy was not as fundamental as Shelley’s; he had a housemaster father to be loyal to. But he early formed the habit of salting his porridge with Elizabethan coarsenesses, of acidulating his honeyed lyrics with unlooked-for cynicisms.

Rupert was already writing poetry at Rugby. He was associate editor of a typical school paper there called The Phoenix (which later became The Venture) and in its pages appeared a steady flow of adolescent verse from his pen. Those early efforts, naturally enough, show themselves as largely experimental and derivative.

“Intense surroundings,” he wrote in April 1906 to St. John Lucas, “always move me to write in an opposite vein. I gaze on the New Big School, and give utterance to frail diaphanous lyrics, sudden and beautiful as a rose-petal. And when I do an hour’s work with the Head-Master, I fill notebooks with erotic terrible fragments at which even Sappho would have blushed and trembled.”

Behind this facade of irresponsibility, however, the young versifier was deep in a study of the older poets. Here and there in his outpourings one finds a golden line attesting to the sensitiveness of his ear. During his second year at Rugby, in fact, he publicly read a poem on “The Pyramids,”[2] a poem which just failed to achieve the school prize.

It was a schoolboy effort, marked by immaturities, halting in rhythm and a trifle overfacile as to rhyme. Yet in it was a sonorous sort of bigness, a youthful stretching toward the cosmic. In it too were passages that carried the promise of better things.

Where on Egyptian sand the lone sun fades

Hotly, and in the purple distance dies,

Near the eternal Nile old Memphis lies

Forgotten, and those three lone aeon-scarred

Monuments, keeping immemorial ward,

Dream of departed splendour and the shades

Of old Regalities . . . .

Thus will they stand and watch the mad world away

Pulsing in endless haste,

Till the red dawn of that last day

When Earth shall vanish and the pale-starr’d waste

Of Heaven, a robe out-worn, be cast away.

From the apocalyptic solemnity of its final lines we catch an echo of that prematurity which marked so much of this poet’s adolescent verse and gave a note of world-weariness to many of his later efforts.

Ah, when we muse upon the weight of years

That cover these grey tombs, how petty seem

The little things we dream,

The tissue of our loves and hopes and fears

That wraps us round and stifles us, till we

Hear not the slow chords of the rolling spheres,

The eternal music that God makes, nor see

How on the shadow of the night appears

The pale Dawn of the glory that shall be!

This early prize did more than leave him a marked man in that army of Philistines which thought more of Rugger and cricket than it did of iambic pentameter. It was a young tiger’s first taste of blood. It sealed a decision that his life was to be devoted to song. While the Philistines were engrossed with football, which he deemed “a senseless game,” he slipped away to his room and struggled with sonnets. After a series of them had appeared in the school paper he seems to have agreed with Schopenhauer that there was small virtue in groundless modesty.

|

By permission of Sir Edward Marsh and Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd.; copyright 1918. |

|

After the public reading of “The Pyramids” on Speech Day at Rugby the young poet’s mother, who had earlier rather opposed his addiction to writing verse, relented sufficiently to have Rupert’s poem privately printed, as an unbound pamphlet, for presentation copies. |

Rugby Chapel could boast of the best organ in all the Midlands. Many an afternoon, during school term, a dark and slender-bodied youth could be seen at that organ, lost in the sonorous music with which he was filling the empty and gray-walled chamber.

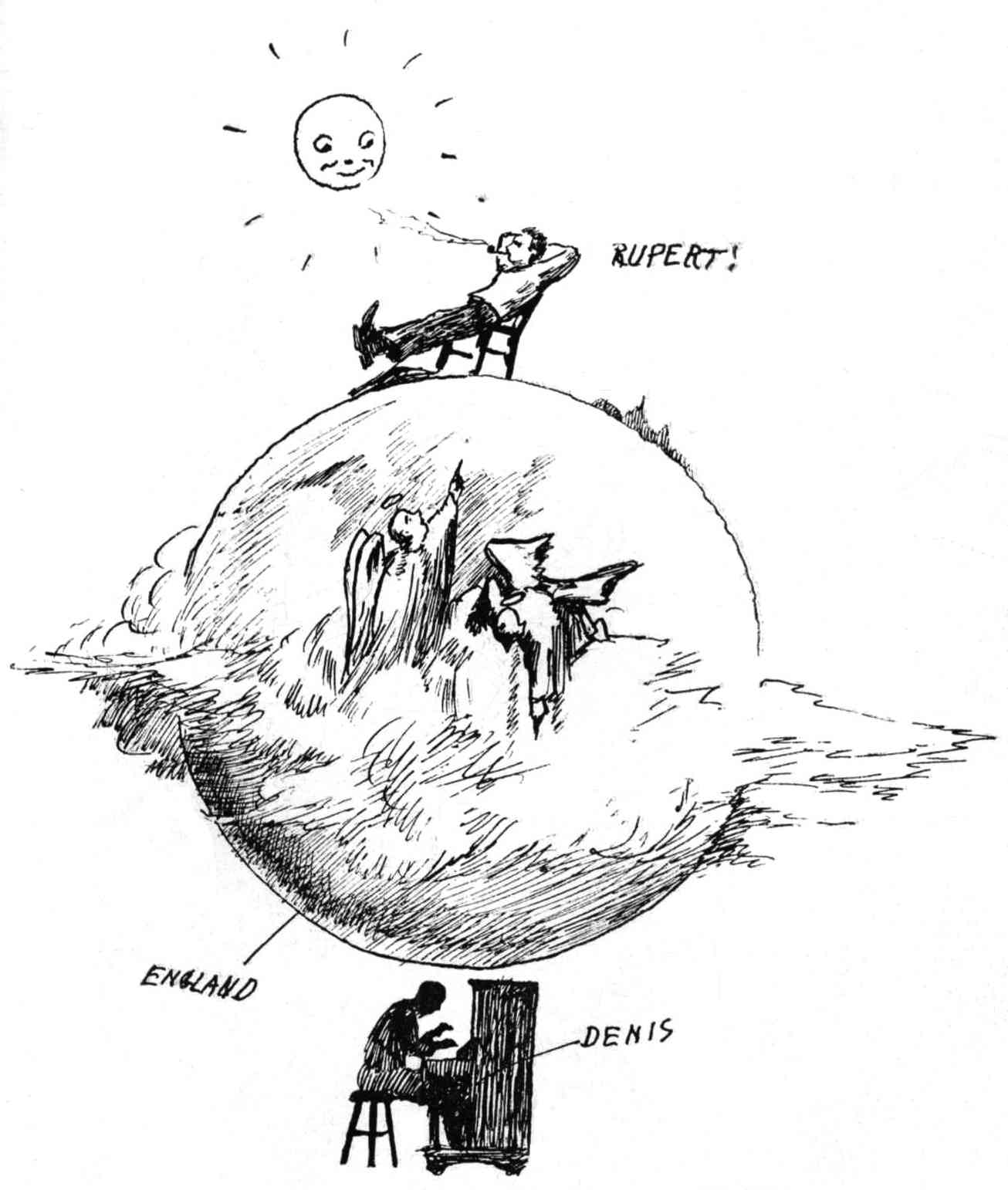

That youth was Denis Browne, who, as a close and lifelong friend of Rupert, must not be dismissed with merely a passing word. Denis, in his way, was as gifted as his golden-haired schoolmate. What the one expressed with words the other expressed with music. Both, when they were on the brink of becoming master of their chosen art, were struck down by the hand of death.

Denis, the son of a music-loving Irish mother, at the age of five was able to play hymns on the home piano. His great joy, when he was little more than twice that age, was to make the rounds of the various churches in his home town of Leamington and coax the organists to let him play. He was so small that he had trouble in reaching the pedals, but his mastery of the keys was unimpeachable. He had been born with a perfect ear. By the time he was fifteen he was able to take over the choir practices and the entire services of his family church. When he entered Rugby he was well equipped to furnish the organ music for either Evensong or the more exacting Sunday service.

Denis was remarkable for more than his musical genius. He was a youth of rare charm, gentle and understanding and modest. He was clean-minded and idealistic, yet wholesomely mirthful and always companionable. It was foreordained, once he and Rupert got to know each other, that a Damon and Pythias relationship should bind them together to the end of their tragically brief lives. Denis did settings for many of his friend’s poems. He composed the music for Rupert’s “Easter-Song,” which was duly performed at morning chapel, as a voluntary, with Denis at the organ. Chapel, that Easter Sunday, was not so loathsome as usual to Rupert. The solemn setting for his words, in the manner of Elgar, so held him that he resented the steady clump of young boots up the aisle, making clamor enough to drown out the opening movement.

That partnership in creating beauty bound him closer to the quiet and sensitive Denis who, a year later, was to follow him to Cambridge and advance to the position of organist in the Clare College Chapel. He was also to furnish incidental music for the Marlowe Society productions in which Rupert was involved. Later, on the blindly blithe voyage to the ill-fated Dardanelles, it was Denis who pounded out cheering music on the battered old piano of the Grantully Castle. Before that final voyage to the Eastern Mediterranean he had won scholarships and given concerts and achieved recognition in London, where he was organist at Guy’s Hospital when war broke out. Like Rupert, he brushed aside his one aim in life and responded to his country’s call, only to be cut off, as was his friend and fellow artist, in his hour of greatest promise.

When on Speech Day at Rugby, in June of 1905, Rupert read a more successful prize poem before the assembled dons and distinguished visitors, Denis sat at a piano within ten feet of him, whispering reassuring words to the none-too-happy speaker. More than once a prize winner himself, he was elated that his running mate’s poem “The Bastille,” had carried off the honors for the year and its author was to be solemnly rewarded with a volume of Browning and one of Rossetti.

In that shyly read poem we see the craftsman a little surer of his tools, the prosodist a little airier in his lyrical interludes, though the optimistic note of the finale wakens the suspicion of a monitorial housemaster looking over the young poet’s shoulder.

Sullen athwart the freedom of the skies

It frowned and mocked the sun’s high pageantry,

Dawn of the cloudy hair and pleading eyes,

And the green sunset light,

With the dark threat of its immensity

And sinister portent of all-shrouding night.

. . . Still we grope

Blind in the utter night, yet dimly gleams

The star of an infinite tremendous hope

That there shall come an ending, that at last,

Somewhere beyond our dreams,

The Eternal Day, the Ultimate Goal shall be,

All mystery revealed, the old made new;

Where, the quest over, sin and bondage past,

Men shall be Gods, and every vision true.

It was not poetry, but a prose essay dealing with “The Influence of William III on England” that a year later brought Rupert his final school prize, the King’s Medal For Prose, a triumph he was to repeat when he went up to Cambridge with a scholarship.

Notwithstanding these accruing honors Rupert was never entirely happy at Rugby. That restless spirit was never perdurably happy anywhere. He had his moments of ecstasy, his poet’s moods of rhapsody. But he was always looking before and after and sighing for what was not. He was in Berlin, be it remembered, when he wrote his immortal “Grantchester.” When in the grayness of London, he longed for the country. When in the country, he pined for the companionable excitement of the city. When seemingly happy in Samoa he hungered for England, and when back in his Warwickshire home he craved the South Seas again, just as he lamented the loss of Rugby after entering Cambridge.

In all his enthusiasms lurked a touch of the radical. He refused to accept life at the valuation of others. The objective world never quite lived up to his subjective ideals. He was eager for knowledge, but any canalized or classroom method of acquiring it went against the grain. He had little love for Latin grammar, but his discovery of Theocritus was a joy to his youthful heart. He preferred pioneering through the past in his own elective way. He could heap scorn on the solemn pedagogues of Rugby, yet in a characteristic mood of melancholic nostalgia he could speak of the receding scene, so soon haloed by time, as the one bright spot in his life.

“I have been happier at Rugby,” he confessed in a letter to Frances Cornford, “than I can find words to say. As I looked back at five years there, I seemed to see almost every hour golden and radiant, and always increasing in beauty as I grew more conscious; and I could not, and cannot, hope for or even imagine such happiness elsewhere. And then I found the last days of all this slipping by me, and with them the faces and places and life I loved, and I without power to stay them. I became for the first time conscious of transience, and parting, and a great many other things.”[1]

It is a feeling, of course, not uncommon in many a graduating class in many a corner of the world.[2] In this case the idealizing tendency of the poet, one suspects, is coloring the picture to suit a passing mood. The note struck in an earlier letter was not so lyrical. He enviously asked how London was and announced that in Rugby the slushy roads and gray skies and epidemic mumps made New Big School almost bearable. Still later he wrote to Eddie: “The Rugby masters are beginning to return. They ask me what I have been doing . . . and illuminated by a kind of twilight knowledge look shocked, blush, and go away. And these are the people who have charge of my unconscious tender youth—and bid me read Pater! There are two classes of Rugby schoolmasters, those who insult Beauty by ignoring it, and those who insult Beauty by praising it!”

The adolescent disdain of this schoolmaster’s son for teachers in general is discernible in the four brief lines he wrote under the picture of another schoolmaster:

For forty years he has taught Greek;

He gets about four pounds a week.

He speaks in patient monotones;

His name is Jones.

He was restless with an intransigency all his own. Though still in his teens, his tumultuous teens, he decided he had lost all the vain knowledge he had ever possessed and proposed going to London or Paris and “living for one year a life like a great red flame.” As he knew nothing, he contended, he would have nothing to fear; and as he sought for nothing, all things would flock to him. He pictured himself as wreathing scarlet roses of passion round his brow and drinking the purple wine of beauty from the polished skull of some dead archbishop.

Then he remembered he was in England, and had a cold in the head and a heap of reading to do for his entrance to Cambridge.

Before Rupert went up to King’s with his scholarship considerable changes had taken place in both his outlook and his activities. He lost his boyhood shyness and eventually discovered he had a genius for friendship. He still disdained the swimming and walking tours of his classmates. He became more of a favorite with the masters who knew and condoned his industrious idleness and was respected by the more bookish students, being notably active in the Eranos Society, where he read papers on modern poetry and led inconsequential debates on the merits of Swinburne and Dowson.

It was by this time common knowledge that he was dedicating himself to the esoteric paths of poetry and the admiration of more material-minded associates prompted him to affect certain singularities of dress. There was, at Rugby, a strict injunction against colored neckties, but Rupert evaded the issue by taking to Byronic puff scarves that were arresting in their amplitude even though burdensome in their bigness. He resorted to blazers and flannels that would have delighted the bobby soxers of a later generation. He let his hair grow long, a mop of bleached and bright golden brown that crowned a singularly vivid face almost classical in its regularity of feature, and so perpetuated the time-honored tradition of poetry’s relationship to pilosis. That crown of wavy gold, in fact, remained with him and marked him off from run-of-the-mill youths until he joined his country’s fighting forces. Then Army regulations ordained a Samsonlike clipping of the tawny locks.

But Rupert, notwithstanding his efforts at self-derogation, was designed to be a conqueror. That sheer physical beauty, combined with a developing spirit of fun and an ever-radiant charm of manner, became a magnet that drew friends close about him.

In the summer of 1905 he went to Aldershot, where in the Public Schools’ Camp he faced a short but strenuous course in military training, with much mud and discomfort, and a discipline more rigid than that of Rugby masters.

In the spring of 1906 his general health was impaired by an attack of ophthalmia. “I started this disease,” he wrote to Erica Cotterill (April 1, 1906), “together with another lad in the House, rather badly. And as the San was full we were put into a room in the House. Our cases were obstinate and for a week we never improved. So Father got annoyed and one day when Dukes (the family doctor) was paying us his hurried visit, rushed in and accused him practically of being a fool and a careless ass, and many other things. Dukes replied in suitable terms. And the pair almost came to blows at the door. The other lad and I sat up in bed and cheered.”

That quarrel, Rupert contended, did his eyes a lot of good. But his general condition remained so below normal that a change of scene and climate was indicated. When spring vacation came along he was given parental permission to join what he termed “a large British band” of thirty rather jolly young people, mostly females, who journeyed to the Continent on a sort of circular return ticket that limited them to sixty days in Italy and fifteen more in France.

“Here,” he wrote from 3 Via Bonifazio Lupi, Firenze, to St. John Lucas (February 10, 1905) “I am enjoying myself more than I thought I should. I have been spending much time in the galleries trying to cultivate an artistic eye. But . . . I have achieved nothing except a certain admiration for Botticelli, and even that I am bitterly disappointed to find fashionable. On Tuesday night we went out into the streets to watch the Carnival rejoicings. It was a peculiar sight, full of colour and noise, and very Italian. In the distance the scene had a certain fantastic charm. But when one saw the figures at close quarters they became merely vulgar. . . . The Piazza del Duomo was full of rather pathetic incongruity. Giotto’s Tower swung upward grimly into the darkness, the summit invisible, the base surrounded by coloured lights and gay quick-moving figures and clouds of confetti.”

If he was unhappy at times in Italy he found his dolor increased by a visit to Venice, which he described as full of stertorious Germans and Americans and crowded hotels and electric launches and the other evils that civilization seems to give. If he could admire the Giottos and muse contentedly in the vaporous gloom of St. Mark’s he could be correspondingly restless in the galleries of Venezia.

“I was really miserable, being modern and decadent,” he later wrote to Lucas (August 13, 1906). “And I hated all the Venetian painters, who are of the flesh and yet do not know that the most lovely flesh is that through which the soul shines. The stolid and respectable damsels of Bellini developed into the ponderous carnalities of Titian and Paolo. . . . The Venetians were never purely young and never beautifully decadent, but always in a tawdry middle-age.”

One can overlook his indictment as to the “carnalities of Titian” just as one can condone the adolescent proclamation of decadence. Rupert’s letters, it must be remembered, were always keyed to the temper of their recipient. He strikes a more lyrical note after a side excursion to Fiesole, a Fiesole already romantic to his poet’s heart through his reading of Robert Browning.

“I am filled by a cruel desire to torture you,” he had written to his fellow poet, Lucas (February 10, 1905), “by describing at length an expedition we made yesterday to Fiesole. How we had tea on the hillside and squabbled over Browning and others. How the sun had begun to set over the plain and beyond Florence; and the world was very quiet; and we stopped talking and watched; and how the Arno in the distance was a writhing dragon of molten gold; and the sky the most wistful of pale greens.”

To his own family, apparently, he was less communicative. That family had exacted from him a promise to write regularly. To fulfill his promise Rupert purchased a stack of picture postcards, which day by day he mailed to the home address, with his initials on one corner and on the other a brief comment as to the weather. When the indignant family demanded impressions more personal and details more explicit, the young traveler, always the individualist, invested in a local guidebook from which he could extract safely appropriate facts and satisfactorily worded enthusiasms.

He was glad to head homeward by way of Verona, with a stop-off at Paris, where he waywardly longed for a glimpse of night life and a visit to Oscar Wilde’s grave. Neither wish was gratified. Paris, at that time, was disturbed by labor riots and much loose talk about revolution. The young traveler’s overanxious parents, remembering their son’s occasional anarchical tendencies, sent word for his prompt return to England. The entire party, in fact, was hurried back to the assured safety of their precious stone set in a silver sea, after two meager days of holidaying in the French capital.

If Rupert’s reports on this qualified “grand tour” were spasmodic and inconsequential it must be remembered he was still a schoolboy, though an increasingly articulate one. Notwithstanding his claims of indolence, and the abbreviated family postcards, he always found time to write to those friends from whom he could expect understanding and to whom he could enlarge on both his mental troubles and his rhapsodic moods. It was not merely that he had the gift of words, and the further gift of wit. The voluminousness of his correspondence, even in his Rugby days, seems to be wrapped up with his rare power of winning friends—friends he hungered to hold close amid the shifting currents of life. A congenial craving for companionship persuaded him that estrangement could be written down as one of the greatest evils in a world that threatened to be as variable as his own altering moods. For a tendency to reverse earlier impressions, to dramatize some passing situation, to heighten the colors and deepen the shadows, is conspicuous enough in the letters written during his adolescence. Apparent, too, is his trick of burying boyish emotion under a meringue of cynicism, of shielding passing ardencies behind the mask of boredom. This touch of the histrionic is evident in letter after letter. In some he is plainly making an effort to sustain his reputation as a wit; in others he is intent on producing an impression of disillusionment with life and lost hope in the value of love. At one time he mourns that he may once have been a poet but is one no longer, contending that instead of being high and proud and hard he is actually small and shy and tired and old. Being both voluble and volatile, he naturally varied his note in response to the varied temperaments to which those letters of his were directed.

Typical of that transitional period between boyhood and manhood is the letter (April 14, 1905) he sent from Hastings to his school friend Geoffrey Keynes, who later became one of his literary executors:

“For the most part I have been leading the tranquil yet beautiful existence of a vegetable, eating much, sleeping much, thinking—not much! Tomorrow my eyes will be soothed by the sight of Rugby’s vivid towers once more. As a matter of fact I have roused myself sufficiently to write this that I may express in delicately chosen polysyllables my deep gratitude for your so kind criticism and reports on the feelings of the populace.” (The reports were on his poem “The Bastille,” which had been published in the school paper The Phoenix a few weeks before.) “Though of some literary merit, the poem was too long. . . . The only tolerable thing at Hastings are the dinners at the hotel. They are noble. I had some soup tonight that was tremulous with the tenseness of suppressed passion; and the entrees were odourous with the pale mystery of star-light. . . . I am writing a Book. There will be only one copy. It will be inscribed in crimson ink on green paper. It will consist of fifteen small poems, each as beautiful, as perfect, and as meaningless, as a rose-petal or a dew-drop. When the book is prepared I shall read it once a day for seven days; then I shall burn the book—and die.”

He did not die, of course, just as he did not write the book. But he revealed how he was still in that green-sick interregnum when imaginative youth is moodily experimenting with reality and floundering in uncertainties, both somatic and psychic.

|

From Edward Marsh’s Memoir, page xi-xii, published by Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd.; copyright, 1918. Quoted by permission of Sir Edward Marsh and the publishers. |

|

Richard Halliburton on the eve of leaving Princeton had written in a kindred strain: “How alarmingly close the time is coming! How I would like to hold the sun in the sky and delay the summer a month or two! I’m so happy here now, more than I ever realized I could be.” Like Rupert, Richard could contemplate age without enthusiasm. “. . . I can look forward to no joy in life beyond thirty. I see there the end of my ability to enjoy and love and live—it’s only existence for me after that.” |

The newcomer to King’s, introspective and self-absorbed, was not entirely happy in that clamorous new circle so deep in its own absorptions. The characteristic nostalgia for the receding scene made him think with envy of his Rugby days, and for friendship he leaned most heavily on two fellow students from the old school. A little of his earlier playfulness slipped away from him and a plaintive note crept into his letters. To his cousin Erica, with whom he had much in common, he sent a warning never to let his family know how miserable he was. If the knowledge that he loathed Cambridge ever reached his mother’s ears, he confessed, it would mean worry to him as well as to his parents. One cause for his dislike of his new associates was their parade of cleverness which, ironically enough, kept them always dull and rarely wise.

The freshman at King’s, after achieving a limited celebrity at Rugby, was temporarily subjugated by the larger life of the university. The newcomer’s feeling of being an outsider, an invader of indecipherable traditions, put him on the defensive. He had small interest in the playing field and, for a time, little inclination for outdoor activities.

But a spirit so active could not be repressed. He still found classroom work obnoxious and the classics dreary. Required reading was a burden. Professors were a bore. Cambridge seemed like an underworld into which he had descended from the light and laughter of happier days. He was, as usual, looking before and after and sighing for what was not.

“At certain moments,” he wrote to St. John Lucas from Cambridge’s Union Society, “I perceive a pleasant kind of peace in the grey ancient walls and green lawns among which I live, a quietude that does not recompense for the things I loved and have left, but at times softens their outlines a little. . . . At the end of last week I went down for two days to Rugby and found that already I am very far away from them. So I have returned with a little disappointment to the hermit life here. These people are often clever and always wearying. . . . Here across the Styx we wander about together and talk of the upper-world, and sometimes we pretend we are children again, a little pitifully.”

But the exile from Rugby was not as segregative as he pretended. Notwithstanding his unrest, essential adjustments were taking place. He was no longer sporting his oak. He could triumphantly inform his cousin Erica that if she came to Cambridge at the end of the month she would see a performance of the Eumenides in which an aged and gray-haired person called Rupert Brooke would be wearily taking the part of the “Herald.” Slowly but surely, as had happened at Rugby, the roots were striking deeper in the new soil. He shook off a little of his earlier contemplative egoism and made an effort to adapt himself to his new environment. He gave less thought to the past and more to the future. For by now he had only one view in life. That was to be a writer. He began to learn the value of good connections, the need for knowing the right people, especially the right people in the preoccupied world of letters which he stood determined to invade. He decided to concentrate, with Keatslike grimness, on the business of being a poet.

The decadent posture still persisted. He could boast of being still deep in Verlaine and Baudelaire and Dowson and Swinburne, just as he could boast of his college “digs” being decorated with Beardsley drawings. He confided to Geoffrey Keynes that he was busy draping his study, which was to be the Eighth Wonder for the coming term, covered with rugs and draperies in various shades of green, pale and sorrowful in effect. All the bookshelves were to be filled with volumes of minor poetry.

To his other good friend, St. John Lucas, he sent a letter reiterating his leaning toward the dark flowers of decadence. “My room,” he wrote, “is a quaint Yellow Book wilderness with a few wicked little pictures scattered here and there. The bookshelves are numerous and half empty. But it was rash in you to inquire what books I still needed. . . . I want, for instance, to complete my set of the three great decadent writers, Oscar Wilde, St. John Lucas, and Rupert Brooke. Of the last and the most infamous of the three I possess most of the works, but of the other two I have less. But perhaps those would have a too bad influence on me. I have none of Belloc’s ridiculous works; the madder Elizabethans would please me; and if you dare find some of your evil Frenchmen of the more decadent sort they would delight my wicked mind. A complete set of the most infamous of Beardsley’s drawings might be purchased for about fifty guineas in Paris and would certainly bring a stream of faint interest in my wan eye.”

That the moody and emotional freshman at King’s was still at loose ends was evidenced by a later letter to Geoffrey Keynes, who, remembering the natural gaiety behind his friend’s mask of gloom, had advised Rupert to give up the pose of discontent and take to optimism. The advice, obviously, was not accepted, the budding poet claiming he was pleased with his “pessimistic uncertainty.”

“A week today I return to Cambridge,” he wrote Geoffrey Keynes, “and then I shall find all the witty and clever people running one another down again. And I shall be rather witty and rather clever and I shall spend my time pretending to admire what I think is humourous or impressive in me to admire and attempt to be ‘all things to all men’, faintly athletic among athletes, a little blasphemous among blasphemers, slightly insincere to myself. However, there are advantages in being a hypocrite, aren’t there? One becomes Godlike in this at least: that one laughs at all the other hypocrites.”

That he was still adrift in the indecisions of adolescence is made plain by his moody declaration that he had finally given up all kinds of writing, except the writing of letters. There were, he decided, only ten beautiful words in the language, and he had used them all. Since there remained only one subject on which he could write, and he had written on that too often, he felt it was time to abandon letters and devote the rest of his life to being a parish beadle or a pork butcher, if not a mere M.P. or a suicide.

At Cambridge, as at Rugby where the classics and field sports were still regarded as more important than the test tube and the T square, he had to harvest any knowledge of his own ethereal art in the hard way, lamenting the curricular diffidence to modern literature and the absence of any official guidance in the intricate maze of versification. He could complain with Osier that he was climbing Parnassus in a fog. Poetry writing, in a circle where classes were spoon-fed on the syntax and prosody of dead languages until striplings loathed Xenophon and Homer and until Cicero and Livy became merely tasks, turned into a sort of personal campaign in which he learned through trial and error and grew wiser through tangled defeat and triumph. His one help, he found, was to resort to a careful study of those who had already fought their way up the slope, from Webster to Watson and from Donne to Davidson.

When bedridden during the Christmas vacation (1906-1907) he confessed, in a letter to his cousin Erica, that he was as bored by idleness as by college work. “I have just read through Plays Pleasant again and feel more certain than ever that Candida is the greatest play in the world. These holidays have been paltry and pottering as usual. The only thing of interest is that Gertrude Lindsay has been drawing me. . . . It represented me as of a round, fat, youthful, chubby, and utterly contented face, instead of the gaunt, sallow, aged, haggard, thin expression at which I always aim.”

Rupert and his younger brother Alfred with their boyhood pet known as Trim.

Rupert at Rugby.

As a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Division.

There was, plainly, a touch of exhibitionism in Rupert’s lapses into world-weary listlessness. He hungered for enchantment, yet he was ready to toy with the macabre. He was willing to agree with Sir Thomas Browne, in his overardent plea for incineration, that he would rather be reduced to ashes and put in an urn than have his skull turned into a drinking cup and his shinbone made into a pipe.

It is not easy to unveil the cause of Rupert’s cyclic psychoses of depression and exaltation. The Aprilian melancholy of youth may be far from the autumnal gloom of age, but to dismiss the poet’s addiction to morbidity as mere play acting would be as unsound as placing too much stress on the therapeutic value of self-dramatization. Impulsive, overstrung, always fearless, yet bewildered to the end, he faced the double frustration of a body not robust enough to withstand the emotional demands of a heart and mind that expected too much of life. He tried to learn from Pater the trick of passing from point to point and always being present at the focus where the greatest vital forces united in their purest energy, of maintaining ecstasy and burning with a hard and gem-like flame. But he learned too early the impermanence of passion. Life too abandonedly lived had its reactions of ennui. One inner tragedy of his career seems to repose not so much in the clouded penalties of promiscuity as in the embittering cynicism that all but turned him into a misogynist and weighed early and heavy on his impulses of lyricism. Another and deeper tragedy was his youthful surrender to a belief in the purposelessness of life. Rebellious and undisciplined, he became increasingly restless and increasingly in search of wider personal experience. He moved by indirection, but he was never torpid. The virtues of placidity he was always willing to bequeath to those who were satisfied with Buddhistic inaction. He confessed that he was a mere hand-to-mouth liver, but his enormous appetite for sensation faced him with the ironic discovery that he was peeling the onion of life until little remained in his hands. He was to find nothing aimless in the world—except the world itself. Relief he sought from time to time in those preliminary excursions to reality spoken of as returns to nature. But with the wayward irreverence of youth he continued to mock at the gods who had given him so much. Only two things, beyond all the adolescent indecision and misdirection, remained sacred with him. One was his Mother England; the other was the art to which he had dedicated his young life. And it took a World War to save him from the disaster of insincerity.

One extramural activity that earlier helped to normalize Rupert a little was his awakening interest in drama. Equally influential in bringing the brooding aesthete temporarily down to earth was his ever-growing participation in undergraduate dramatics. His interest in the stage stayed with him through all his years. His one great wish was to write a play and see it produced. Yet his only professional production was the one-act entitled Lithuania, which was put on by his friend Maurice Browne at the Little Theatre in Chicago and later had a brief run at His Majesty’s Theatre in London.

Opinion is divided as to Rupert’s acting. When he joined Cambridge’s Amateur Dramatic Club he was consigned to the unimportant part of “Stingo” in She Stoops to Conquer. Equally small, during his first term, was his part in the Eumenides, where he was first assigned to the role of “Hermes” but was soon demoted to the part of the “Herald,” in which he made a brief appearance in cardboard armor and a red wig. His task was to stand in the middle of the stage and blow a prop trumpet while somebody in the wings produced the necessary sound. His costume of vivid red and blue and gold may have made him look like a page in the Riccardi Chapel but his nervousness and his limited knowledge of stagecraft made him a none too persuasive buccinator.

His Cambridge friends were united in their opinion that Rupert was not a second Irving. Some reported that he had an expressive quality of voice and an exceptional power of employing it, but was without any definite talent for acting. As in his public speaking, an audience embarrassed him. Any charm perceptible in rehearsals was lost when it came to actual performance. Yet he refused to accept defeat as a thespian.

Reginald Pole, Rupert’s friend and fellow student at King’s, who later became an actor and director of eminence, acknowledged that the youth from Rugby was not a good actor but claimed no one could more impressively deliver a poetic line. “He had no essentially histrionic gift,” Pole concluded, “but he delivered poetry quite beautifully. When he played ‘Mephistophilis’ in the first performance of Marlowe’s Faustus the dramatic passages were poorly done but the lyric ones were always sufficiently effective. Also when he played the Attendant Spirit in Milton’s Comus at the New Theatre in Cambridge, he triumphed more in the declamation of poetry than in drama.”