* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Death on the Prairie

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Paul Iselin Wellman (1895-1966)

Date first posted: Aug. 17, 2022

Date last updated: Aug. 17, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220835

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

DEATH ON THE PRAIRIE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO • DALLAS

ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

OF CANADA, Limited

TORONTO

DEATH ON THE

PRAIRIE

The Thirty Years’ Struggle

for the Western Plains

BY

PAUL I. WELLMAN

NEW YORK

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1934

Copyright, 1934, by

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and printed.

Published September, 1934.

Reprinted, December, 1934.

To

LYDIA I. WELLMAN

pioneer on two continents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many books have of a necessity been consulted in the writing of this one. I wish to acknowledge particularly my indebtedness to the following:

Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston, for permission to use quotations and references from Stanley Vestal’s “Sitting Bull, Champion of the Sioux.”

Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, for permission to quote and use material from George Bird Grinnell’s “The Fighting Cheyennes.”

Mrs. Olive K. Dixon, Amarillo, for permission to use data, names and incidents from her biography “The Life of Billy Dixon.”

Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis, for permission to quote from Colonel Homer W. Wheeler’s “Buffalo Days.”

Mrs. Alice V. Schmidt, of Houston, and Charles A. Maddux, of Los Angeles, for permission to use material from John R. Cook’s “The Border and the Buffalo.”

Captain Robert G. Carter, U.S.A., retired, Washington, D. C., for information and the permission to use material from his “The Old Sergeant’s Story; Winning the West from Indians and Bad Men in 1870-76.”

The State Historical Societies of Kansas, Nebraska and Minnesota for their generous furnishing to me of material from their records.

A. C. McClurg and Company, Chicago, for the use of quotations and incidents from E. B. Bronson’s “Reminiscences of a Ranchman.”

Hunter-Trader-Trapper Company, Columbus, for permission to use certain statistics from E. A. Brininstool’s “Fighting Red Cloud’s Warriors.”

The Century Company, New York, for quotations from magazine articles, “Besieged by the Utes,” by Colonel E. V. Sumner, and “Chief Joseph the Nez Percé,” by Major C. E. S. Wood, published in Century Magazine.

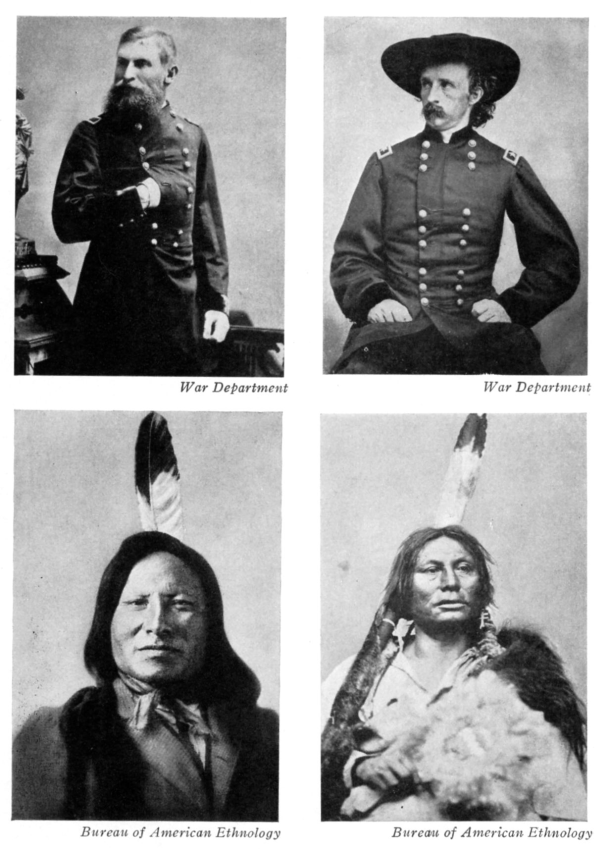

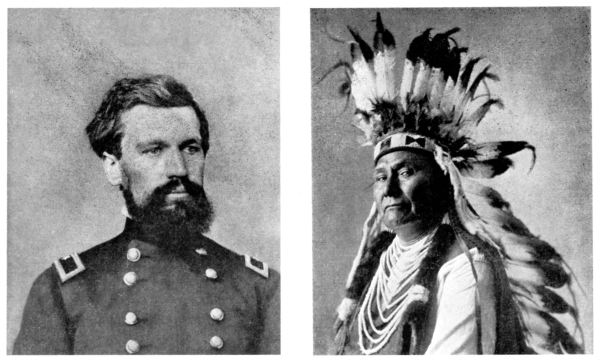

Thanks are also extended to the Bureau of American Ethnology, the War Department, and Professor C. W. Grace, Wichita, for valuable photographs used, and hereby acknowledged.

Paul I. Wellman

FOREWORD

In the old West the beginnings of the Machine Age met the last vestiges of the Stone Age. The white man had just embarked upon the great industrial era; the red man still used the flint arrow point.

Between these two extremes of human culture there was no common ground. The Indian could not understand the Anglo-Saxon’s land hunger. To him the earth and its creatures belonged to all, the free gift of the Great Mystery. That one should build a fence about a little corner of it and say “This is mine,” was repugnant.

His ideas on war were equally at variance with those of the white man. To him war was a dangerous game, but still a game. It was a glorious, exciting field of honor, as it was to the knights-errant of medieval Europe. The grim, dour Anglo-Saxon attitude that war was something unpleasant to be gotten over quickly by scientifically exterminating the enemy, was new and often appalling.

The white man’s greed added to the tension. Seeing the fair land, he reached forth to take it. His conquest of the West was iniquitous in its conception and its execution. Not even the excuse that it permitted the spread of civilization is moral justification.

In the inevitable wars which followed this clash of ideas and interests, the Stone Age was foredoomed to defeat. The white man had the repeating rifle, the telegraph, and the railroad. The Indian had only his primitive weapons and his native courage. Remorselessly the Machine Age engulfed the wilderness.

But it was not without a struggle. There was manhood in the red race. For thirty years the Indian fought a sometimes heroic, often spectacular, always futile war for the possession of his hunting grounds. And it is the purpose of this volume to try to picture for the reader the moving panorama of that struggle; to catch for him a little of the glamour of those days, the action, the vivid color, the heroism and the despair.

Paul I. Wellman

| CONTENTS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| FOREWORD | ix | |

| I. | ||

| MASSACRE IN MINNESOTA | ||

| 1862-1863 | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | THE STORM BREAKS | 3 |

| II. | THE WHITE MAN STRIKES BACK | 14 |

| II. | ||

| WAR SPREADS TO THE PLAINS | ||

| 1864-1869 | ||

| III. | A CHIEF OF THE OGALALLAS | 27 |

| IV. | FORT PERILOUS | 34 |

| V. | THE LAST DAYS OF FORT PHIL KEARNEY | 48 |

| III. | ||

| THE STRICKEN FRONTIER | ||

| 1864-1869 | ||

| VI. | THE GRIEVANCE OF THE CHEYENNES | 59 |

| VII. | AN ISLAND IN THE ARICKAREE | 66 |

| VIII. | THE CHEYENNES PAY | 81 |

| IV. | ||

| THE SOUTHERN TRIBES RISE | ||

| 1873-1874 | ||

| IX. | THE IRRECONCILABLES | 95 |

| X. | BEFORE THE ADOBE WALLS | 102 |

| XI. | THE ARMY TAKES THE FIELD | 112 |

| V. | ||

| THE STRUGGLE WITH THE SIOUX | ||

| 1875-1877 | ||

| XII. | THE DIPLOMAT AND THE WARRIOR | 129 |

| XIII. | ON THE BANKS OF THE ROSEBUD | 139 |

| XIV. | THE GREATEST VICTORY | 147 |

| XV. | WANING OF THE RED STAR | 162 |

| VI. | ||

| THE LONG TRAIL | ||

| 1877 | ||

| XVI. | “NEVER SELL THE BONES OF YOUR FATHER” | 183 |

| XVII. | ACROSS THE MOUNTAINS | 191 |

| XVIII. | “FROM WHERE THE SUN NOW STANDS” | 199 |

| VII. | ||

| THE BUFFALO HUNTERS’ WAR | ||

| 1877 | ||

| XIX. | WITHOUT BENEFIT OF MILITARY | 211 |

| XX. | THE BATTLE OF POCKET CANYON | 217 |

| VIII. | ||

| THE ODYSSEY OF THE CHEYENNES | ||

| 1878 | ||

| XXI. | LITTLE WOLF’S RAID | 227 |

| XXII. | DULL KNIFE’S LAST FIGHT | 235 |

| IX. | ||

| MURDER IN THE MOUNTAINS | ||

| 1879 | ||

| XXIII. | THE MEEKER MASSACRE | 249 |

| XXIV. | OURAY’S PEACE | 258 |

| X. | ||

| THE WAR WITH THE MESSIAH | ||

| 1889-1891 | ||

| XXV. | THE GHOST DANCERS | 265 |

| XXVI. | THE LAST INDIAN BATTLE | 272 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 283 | |

| INDEX | 285 | |

The soft green hills of Minnesota lay placid in the August sun. Oak and birch and pine scarcely stirred in the breeze which brought a hint of coolness to the drowsy atmosphere, and the woodland lakes, which are the northland’s chief charm, were barely ruffled.

Quiet was the forest which stretched its leagues on leagues of feathery tops to the northward. Even the birds were silent, for this was August. In the few small fields which the industry of the backwoodsmen had cleared out of the woods, no farmer moved. Scythe and hoe hung idle on their hooks. It was Sunday.

At the Lower Sioux Agency near Fort Ridgely, the morning of August 17th, 1862, services were held as usual in the little Episcopal church. The rector addressed his simple words of faith to a mixed congregation—English and German farmers, a few agency employees and traders, and a handful of converted Sioux Indians. But his eyes probably wandered most frequently to a single dark figure which sat, morose and alone, in the shadows at the back of the church.

We have a photograph of him as he must have looked then—that silent communicant. He was a tall and splendid figure in his neat black broadcloth, with white collar and dark cravat; dressed as well as the best garbed white man among them. Only his head and feet were in sharp contrast. His feet were covered with doe-skin moccasins, beaded according to the highest art of the Indian race. His head was bare and the swarthy bronze of his face was framed in two gleaming black braids of hair which swept downward over his shoulders, to fall across his broad chest in front.

If anybody in the church felt a shrinking from his dark presence, they gave no sign, for they all knew him. He was Little Crow, the great chief of the Santee Sioux, the steadfast friend of the white man, their guarantee of peace with the dark people of the forests.

The service ended. With perfect courtesy he greeted the white men and women assembled. Suavely he complimented the rector’s eloquence; shook hands with everybody; strode out, mounted his horse and rode off—never to return.

Little Crow attended church that Sunday morning. By evening of the next day he was elbow-deep in the blood of those with whom he had worshipped.

Why did Little Crow attend that last service? Nobody will ever know. Many have held it was for the purpose of cloaking the treachery which must already have been planned and ordered. But the reason may have been more human. Perhaps the dark chief came to be once more with the friends from whom he was to part forever.

Little Crow was an unusual Indian. He affected the white man’s garb and ways, but was at heart an utter barbarian. His manners were those of a refined gentleman. His diplomatic talent and oratorical ability were very marked. And events were to prove him a patriot.

His friendship for the whites had once been genuine, but it was blasted long ago. An endless list of his people’s grievances cried out to him. Rascally traders, using government red tape to withhold food from the starving red men, to sell them wormy flour and spoiled bacon at exorbitant prices; the seduction of Indian women by degenerate white men and the multiplication of half-breed children, a reproach and indignity to every honorable Sioux; Inkpaduta in the north, counting the spoils of his Spirit Lake raid and inciting to the war path; these and many other things fanned the smouldering flame.

Above all his tribe, Little Crow felt the wrong and the dishonor. A son and grandson of chiefs, he had known the days of his people’s glory. Then came the shameful Mendota treaty of 1851, when the Sioux ceded most of their hunting grounds. He played his own part when, after a drunken fight with his brother, he nursed a crippled wrist and swore to banish firewater from the tribe. He sent for a Christian missionary to “teach the people the white man’s way.” Reverend Williamson, the man of God, won a place in Little Crow’s heart, but now his goodness was all forgotten in the rascality of those other white men, the traders.

Only a week before the Sioux received the final insult. Their chiefs went to the agency to plead for the long-promised government stores. Andrew J. Myrick, a trader, listened with a sneer.

“If they’re hungry, let them eat grass for all I care,” was his callous reply.[1] The Sioux heard—and remembered.

. . . . . . . . .

Forty miles from the agency three German farmers and the wife and daughter of one of them, sat at Sunday dinner. Four Indians entered the cabin. A crash of rifles, a flurry of knives—the happy dinner party lay dead. The Indians rode into the forest.

It was a signal. Up and down the Minnesota River stealthy bands of warriors set forth.

Monday dawned. With the first peep of the sun, the little community of traders at the Lower Agency was awakened by a gunshot, followed by a hideous war whoop. The people ran out of their homes into the streets to be shot down at their doors by Sioux posted in ambush. Myrick, whose cruel taunt had stirred the Indians’ hatred, was killed in front of his store. When his body was found, days later, the mouth was stuffed full of grass.[2]

Other traders met ends as bloody. Francois La Bathe was slain on his counter. Henry Belland, James W. Lyndy and five other traders and clerks died similarly. Every soul in the agency would have perished but the Sioux began looting the ammunition stores and food boxes, permitting about fifty to reach the river. There a heroic ferryman, Hubert Millier,[3] plied his boat until as he returned for the last load he was killed. Those cut off from crossing were all massacred and the Indians pursued the refugees, slaying seven more in the terrible fifteen-mile race to Fort Ridgely.

The arrival of the haggard vanguard of that fleeing band must have been a terrific shock to the people of the fort. The whole world was shocked by the events which followed.

The agency massacre was not the only tragedy of the morning.[4] While the Sioux were killing the traders, smaller parties swept through the surrounding settlements. The country was a shambles. The Indians took the farms as they came, slaughtering the men, carrying the young women off as captives, and butchering the children or allowing them to follow their mothers, according to the whim of the moment.

Lake Shetek and Renville County were especially bloody. In the first day alone more than two hundred white persons were killed in the vicinity of the Lower Agency. How anybody escaped is a mystery. Some of the experiences of the refugees are almost unbelievable. Tales of heroism also come down to us from that massacre. Men and women, even children, sacrificed themselves to save their friends.[5]

The exact number massacred will never be known. Minnesota state records list six hundred and forty-four.[6] There were hundreds, mostly women, taken captive. After the Battle of Wood Lake, two hundred and sixty-nine of these were recovered. Scores were rescued at other times. And the record of those who were never heard of again will never be complete.

And what were the soldiers at Fort Ridgely, fifteen miles from the Lower Agency, doing all this time?

Captain John S. Marsh, 5th Minnesota, was in command. As the first of the refugees burst into the fort with their frightened story, Marsh acted quickly. Sending a courier to Fort Snelling for help, he started promptly for the agency with forty-six men and the post interpreter, Peter Quinn, leaving only a skeleton guard behind. They went in wagons but dismounted a mile from their destination. On the way they met a stream of fugitives. Here and there they passed dead bodies. They began to realize that they were in the midst of a great disaster—an Indian uprising of nightmare proportions.

Unused to Indian fighting but supremely confident, young Marsh led his men down to the ferry. The Agency opposite was in flames. Not a soul could be seen. Had the Sioux left? No—at the very moment more than two hundred warriors were hiding behind saw logs and bushes with rifles cocked and aimed, ready to pull the triggers at a signal.

Now an Indian appeared among the burning buildings, walking toward the ferry. The soldiers recognized him—White Dog, a sub-chief and a frequent visitor at the fort. He motioned them to come across. Marsh hesitated. While he parleyed, a party of Sioux crossed unobserved farther down the river, and crept up on his flank.

Then White Dog made a gesture which must have been a signal. Clouds of smoke sprang up from a hundred apparently untenanted places. Marsh and his men suddenly found themselves fighting for their lives.

Half a dozen soldiers were killed in the first volley, including Quinn who was pierced by at least a dozen bullets. At the same moment the Indians on the flank opened fire. Marsh tried to charge into the thicket, saw it was useless, and ordered a volley fired instead. His men were falling fast. A retreat was finally ordered. They threw themselves into the timber near the river and for an hour fought an unequal battle with overwhelming numbers of Sioux, gradually retreating down the stream.

At length the captain decided to cross over. To show his men it was feasible, he tried to swim the swift current himself. The eddies caught him and he drowned—youthful, gallant, but utterly unfit to cope with Indian warriors.

The Sioux harried the rest of the soldiers almost to the fort. What was left of the command which had marched out so gallantly that morning, straggled in late in the evening. Of the forty-eight men who started, exactly half, including the captain, were dead.

That was a night of terror at Fort Ridgely. Lieutenant Thomas P. Gere, now commanding, had only a handful of soldiers left and scores of women and children to protect. The women hysterically begged their friends to shoot them rather than let the Indians get them. There were a dozen alarms which set the post frantic with fear. But nothing happened that night.

Next morning refugees still poured in, demoralized with fright. Should Little Crow attack now, nothing could prevent the massacre of every soul in the fort. But for some reason the attack was delayed. Why? The nervous young lieutenant paced the fort with anxious steps. About noon a challenge from a sentry changed to a shout of joy. Coming down a road from the north, at the double-quick, was a detachment of soldiers—Lieutenant Timothy J. Sheehan with the first reinforcements. Five hours later a second detachment came in from the south, after an all-night march of forty miles. There were more than two hundred and fifty refugees at the fort now. Among them were some resolute men who would make good fighters. Including these settlers, Sheehan, now the senior officer, marshaled about one hundred and eighty men, mostly raw recruits.

Still the Indians did not attack.[7] Every moment was used in strengthening the defenses.

Without warning on the morning of the 20th, a tall warrior, mounted on a splendid horse, rode up from the west and demanded a conference. It was Little Crow himself. He wanted to divert attention from his attack which was forming on the opposite side.

A sudden burst of firing announced the onslaught and the Sioux leader rode for cover. With wild yells the Indians stormed the first line of defenses, outside the regular limits of the fort. Helter-skelter fled the soldiers for safety, with Sioux tomahawks flashing in their rear. So fierce was the charge that the redskins actually burst through the second line of defense, a row of log houses which formed the north wall of the fort and took possession of these barracks.

Still the defense reeled. Working like mad, Sheehan rallied his men on the parade ground. If they did not hold fast here, the fort was doomed. Two or three soldiers, hit, fell thrashing on the ground. The undisciplined troops began to waver. Simultaneously the Sioux came out from the buildings and formed for another charge. Sheehan’s men began to retreat. The day seemed hopelessly lost.

And then came aid—aid so unexpected as to seem miraculous.

Among the few veteran soldiers at the fort was an old artillery sergeant with the unromantic name of Jones. Fort Ridgely had once been an artillery post and a few old cannon of various patterns and calibres were still parked there. Like all old gunners, Sergeant Jones loved his field pieces. To vary the monotony of garrison life, he had asked and received permission to drill some of the infantrymen in the principles of artillery practice. The soldiers took it up for fun. None of them had any idea that their lives and the lives of hundreds of others would ever hang upon their skill.

At this critical moment in the Sioux attack, Jones bethought himself of his amateur artillerymen and rusty old cannon. Here and there he hastily collected members of his gun squads and ran to where the ancient field pieces stood. There was some delay in getting things ready. The men were, after all, only infantrymen, and the old sergeant probably did some royal swearing before three guns were loaded. This was finished just as Sheehan’s line began to melt before the Sioux fire and the threatened attack.

Now was the time. Everything depended upon the old artilleryman. His own wife and children were among the helpless noncombatants crowded in the south buildings of the fort.

“Aim in their center and fire as rapidly as possible,” was the order.

Just as Sheehan, in despair, saw his recruits breaking for cover; just as Little Crow’s warriors, with triumphant yells, began their final advance; just as the women in the south fort gave a concerted cry of terror, the ancient cannons spoke.

“Boom! Boom! Boom!”

Across the parade ground hurtled a heterogeneous collection of misfit cannon balls, canister and solid shot. Dismayed, the Indians halted.

Working like mad, the sergeant and his men rammed home a second round. Again the rusty field pieces spoke. It was too much for the Sioux. They could stand rifle fire—had done so right bravely. But the “wagon guns” appalled them. They wavered, began to retreat, and as a third discharge thundered among them, fled in panic, followed by the hysterical cheering of the soldiers.

Fort Ridgely was saved and Sergeant Jones was the hero of the day. The Sioux kept the fort surrounded, and even attempted another attack the following morning. But the age-worn cannon now were masters of the situation. Before the charge was well started, Sergeant Jones sent several shots among the hostiles and scattered them.[8] Little Crow had been wounded the first day. A sub-chief, Mankato, led that final abortive assault. The Indians quickly withdrew.

The defeat at Fort Ridgely was a solar-plexus blow to the Indians’ hope of sweeping the white man out of Minnesota. They had suffered serious losses and the moral effect had been most discouraging.

[1] William Watts Folwell, “A History of Minnesota,” p. 233, by permission of the Minnesota Historical Society.

[2] Folwell, “A History of Minnesota,” p. 233.

[3] The name is also given as Mauley.

[4] There are tales of frightful brutality during these raids. Governor Ramsey said in a speech: “But massacre itself had been mercy if it could have purchased exemption from the revolting circumstances with which it was accompanied—infants hewn into bloody chips of flesh, or nailed to doorposts to linger out their little lives in mortal agony . . . rape joined to murder in one awful tragedy . . . whole families burned . . .”

The above statement sounds like some of the anti-German propaganda circulated in this country during the World War. It is only fair to the Indians to say that these atrocities occurred only in isolated instances if at all. Most of the settlers were mercifully killed at once. The Indian viewpoint is well summed up by Dr. Folwell: “From the white man’s point of view these operations amounted simply to massacre, an atrocious and utterly unjustifiable butchery of unoffending citizens . . . The Indian, however, saw himself engaged in war, the most honorable of all pursuits, against men who, as he believed, had robbed him of his country and his freedom . . . He was making war on the white people in the same fashion in which he would have gone against the Chippewa or the Foxes. There are a few instances of . . . mutilation . . . There are also cases of tenderness and generosity to captives.” (“A History of Minnesota,” pg. 125.)

[5] The story of 11-year-old Merton Eastlick and his devotion to his baby brother Johnny is worth re-telling. When the Indians struck Lake Shetek settlement, the Eastlick family hid with other settlers in the rushes of a stream bed. The Sioux found them, killed John Eastlick, the father, and three of the five boys. Mrs. Eastlick was captured. Before they found her, she hid her baby, Johnny, and charged his only surviving brother, Merton, never to leave him until he died. Mrs. Eastlick eventually escaped from the Indians and was found by August Garzine, a mail carrier, crazed with the belief that her whole family was dead. He took her to New Ulm. On the way, forty miles from the scene of the massacre, they found Merton and Johnny! The lad had carried the baby every foot of the way, hiding from Indians and subsisting on berries. He was an emaciated skeleton, with the flesh worn off his bare feet and was unable to speak for days afterward. But the baby was safe and sound.

[6] The Minnesota Historical Society’s figures on the massacre are as follows:

| Citizens Massacred | ||

| In Renville County (including reservations) | 221 | |

| In Dakota Territory (including Big Stone Lake) | 32 | |

| In Brown County (including Lake Shetek) | 204 | |

| In all other frontier counties | 187 | |

| —— | ||

| 644 | ||

| Soldiers Killed in Battle | ||

| Lower Sioux Ferry, Capt. Marsh’s command | 24 | |

| Ft. Ridgely and New Ulm | 23 | |

| Wood Lake | 17 | |

| Birch Coulie | 26 | |

| Other engagements | 23 | |

| —— | ||

| 757 | ||

[7] Sioux Indians afterward said Little Crow could not get his warriors to stop plundering long enough to follow him to the attack. Whatever the cause, the delay was fatal to the Indian plans.

[8] Jones was mentioned in the dispatches for his spectacular part in the battle. As for the modest hero himself, however, his only thought was of the workmanlike manner in which the guns were handled. In his terse report, still preserved, he stated that his amateur artillerymen and rusty cannon “gave much satisfaction . . . to all who witnessed the action.”

Sharing the post of greatest danger with Fort Ridgely was the little German frontier town of New Ulm, a few miles down the river. The morning after the agency massacre a small party of Indians were seen near the town but were driven off in a brief skirmish. Not much damage was done on either side but it threw New Ulm—already panic-stricken because of the inpouring hundreds of refugees with their tales of horror—into still greater terror.

Judge Charles E. Flandreau of the supreme court and Ex-sheriff Boardman of St. Peter’s rode with a company of volunteers to the threatened settlement. The Indians had gone when they arrived, and next day the town was not molested for Little Crow was busy with his attack on Fort Ridgely. But the Sioux had by no means forgotten New Ulm. In spite of their defeat at the fort they moved toward it. Early Saturday the smoke of burning buildings up the river showed that they were on their way.

Judge Flandreau, a man of great force of character, was elected commander of the defending forces. At the approach of the Sioux he formed his two hundred and fifty fighting men on the prairie a half mile west of the town. By ten o’clock they were skirmishing with Little Crow’s advance guard.

Suddenly a brilliant spectacle unfolded itself. Five hundred Sioux warriors, in all the color and movement of feathered head dresses, war paint and brilliant beadwork, rode out of the woods and spread like a giant fan over the prairie. As they reached long rifle shot, they charged. The Sioux, yelling like fiends, looked so horrible that Flandreau’s rookies began to retreat. A few more whoops and, in spite of the judge’s efforts, the whole line fell back leaving the outer tiers of houses of the town undefended. The Indians were soon shooting at New Ulm’s citizens from the shelter of their own homes. Flandreau rode wildly up the hill and succeeded in rallying his men. There they halted the Sioux advance. The crackling of rifle fire became incessant. The white men were hard pressed, but they held.

Then smoke came floating up from the lower end of the town. The Indians had slipped behind the defense and set some buildings ablaze. Now they advanced through the smoke. In a few minutes the whole lower part of New Ulm was burning. Bullets whined, in ever-increasing chorus, up the streets. Captain William Dodd, Flandreau’s second in command, was killed. Captain Saunders was critically wounded with a ball through his body.

Under cover of the smoke, Little Crow massed his warriors in the shelter of some houses near the river. The charge in the morning had been so nearly a complete success that the Sioux believed a second attack would crush the whites. But by now New Ulm had been under fire for several hours and the men were steadying down.[9] The Sioux charge came, but a withering fire drove them back. Then, as the Indians withdrew, Flandreau led a fiery counter-charge. It caught the Indians by surprise and drove them clear out of the city limits. Evening was falling and the firing shortly stopped.

During the night Flandreau ordered more than forty outlying buildings on the outskirts burned to the ground to prevent them from becoming rallying places for the savages on the morrow. A system of trenches was dug, and a large brick house made into a redoubt, garrisoned and munitioned. But there was no battle Sunday. The Sioux contented themselves with some long-range shooting. By noon Little Crow’s warriors were in retreat.

Fort Ridgely and New Ulm definitely ended any probability that the Sioux would push the settlers out of eastern Minnesota. But Little Crow was not discouraged. The northeast, the north and even the south, down into Iowa where Inkpaduta had left a trail of blood years before at the Spirit Lake massacre, offered an unlimited field for his operations.

He withdrew his war parties into the wilderness for the present, content for a time to count his scalps and gloat over his booty. They had been repulsed, it is true, but, even so, the success of the weeks’ raiding exceeded the Indians’ most sanguine dreams. At one swoop the Sioux had won back much of their richest hunting country. Their camps were full of prisoners and plunder. Little Crow was a bigger man than ever among his people.

But a new figure was entering the picture. Colonel Henry H. Sibley, an old soldier in middle life, took command of the Minnesota troops. He had had wide experience, spoke French and the Dakota tongue and possessed a profound knowledge of Indian character.

Sibley reached the frontier in three days, and in four more his call for volunteers was answered by fourteen hundred men. They were raw, undisciplined and ill-equipped, but they were the only force on which Sibley could lay his hand. With them he marched toward Fort Ridgely. It took several days to reach the fort. On the way he kept his fatigue details busy burying the bodies of slaughtered settlers. He reached the fort on the afternoon of August 28th, to be received with transports of joy by the people, who, he said, “seemed mad with excitement.”

Next day he moved toward the Lower Agency, reaching it the last of August. His men buried Marsh’s soldiers, together with more than twenty dead citizens. Traces of the handiwork of the Sioux were plentiful, but thus far not an Indian had been seen. Major J. R. Brown with two hundred men moved west along the river looking for hostiles and burying the dead. They camped at Birch Coulie the night of September 1st.

Little Crow was not asleep. His scouts watched, unseen, every movement of the army. Brown’s movement was a beautiful opportunity for the Sioux. As dawn broke there was a war whoop, followed by a sudden volley which swept into the camp from the birch woods near at hand. Dead and dying men, and kicking, screaming horses, littered the ground. The survivors of that deadly volley threw themselves behind their wagons and fought back. It was a short but terrific little battle. The Sioux poured into the camp such a storm of bullets that nearly every horse was killed or disabled, and annihilation threatened the whole command.

But Sibley at the agency heard the distant firing and marched immediately to Brown’s assistance. The reinforcements reached Birch Coulie in the nick of time. As Sibley’s column appeared, the Sioux withdrew up the valley. A picture of bloody wreckage was presented by Brown’s camp. It was strewn with dead and dying men and horses. Some of the wagons were riddled like sieves. Of Brown’s two hundred soldiers, twenty-four were dead and sixty-seven wounded, nearly fifty percent. Sibley retreated to Fort Ridgely to care for the wounded.

Birch Coulie wiped out the sting of New Ulm and Fort Ridgely for the Sioux. They considered honors even now. Sibley, on the other hand, saw that his raw levies were not ready for the job before them and went into camp to drill them into some sort of a coherent military body. It was a big task and took time. Meanwhile Little Crow ranged far and wide.

He led one marauding expedition deep into northeastern Minnesota, with Hutchinson as its objective. Captain Richard Strout and a company of soldiers met him and were chased for miles, the Sioux almost riding into Cedar Mills on the strength of the wild retreat. But Hutchinson, now a fortified post like every frontier town, was too strong for the Indians. Little Crow, with more scalps and loot, returned to the old reservation camp.

While Sibley’s army was learning its business, its commander took up wearisome days in a long-drawn negotiation with Little Crow. Hundreds of prisoners, mostly women and children, were in the hostile camp and great fear was held for their safety. Sibley, knowing Indians, feared that these helpless hostages would be murdered wholesale should he march against the Sioux.

The wily red chief proved more than his match in diplomacy, and Sibley finally gave up the negotiations.[10] Little Crow was making constant raids and keeping all Minnesota in an uproar. Finally, on September 18th, with sixteen hundred men and two pieces of artillery, Sibley marched northwest toward the Yellow Medicine River where the hostile village was reported to be.

Little Crow knew this march was in deadly earnest. He felt his handicaps. His warriors were fine natural fighters, but they completely lacked organization. They would not stand up to artillery fire. To maneuver them in battle was practically impossible. On the other hand, they were superior in mobility and were expert in scouting and ambush. In planning the fight with Sibley, the chief kept all these things in mind.

The road to the Sioux village lay through the deep timbered gorge of the Yellow Medicine. Sibley had to pass through it. As he marched past Wood Lake down this canyon, a volley of shots rang out half a mile ahead. Indians had fired into a party of foragers. Three men were down, one mortally wounded.

Major Welsh’s command went at the double to the rescue. The foragers were saved, but heavy firing which broke out from the woods ahead showed that they were swarming with Sioux. Bullets were cutting the leaves from the trees overhead so that they fell in showers.

Little Crow had thrown a cloud of warriors across the road in front. Although the whites did not yet know it, two other large bodies of Indians lay hidden in ambush—one along the east side of the road, the other in a ravine to the right.

It was strange fighting for Sibley’s men. The woods ahead looked deserted except for the spurts of rifle smoke and the sight of an occasional flitting figure. The constant piping of bullets overhead and the occasional smack as one found its mark, made the raw troops nervous. Welsh decided to charge. Into the woods went his men but the foe they expected to meet had disappeared. Using the same tactics which were so fatal to Braddock a hundred years before, the Sioux slipped away from the direct front and poured in their fire from the flank. Welsh was forced to halt.

A staff officer came riding like the wind across the field with an order from Sibley to retire, but the stubborn major did not at once comply. Sibley sent another, this time peremptory, message to fall back at once. Then Welsh ordered a retreat.

Sibley’s main body was formed on a low hill. Toward it Welsh started, carrying his wounded. The Sioux leaped in pursuit. There was a moment of hand-to-hand fighting. Then the soldiers began to run. Here was Little Crow’s big chance. Had he been able to press home a charge at the backs of the fleeing troops, he might have cut Sibley’s line in two. But Sibley rushed forward five companies under Colonel Marshall and the Indians were beaten back.

Then, too late, after the soldiers were formed and ready, the Sioux attacked in deadly earnest. For two hours they tried valorously to take the hill. Once a headlong charge on the extreme left came very near carrying home, but Major R. N. McLaren, with two companies of recruits, repulsed it.

Just then the Indians in the ravine were discovered. Backed by shells from the two guns, Marshall charged and drove them out. The Sioux had been roughly handled and were losing their zest for the fight. As the day wore on, the fire from the woods slackened. Finally, as if at a signal, the Indians disappeared. Sibley, hampered by his many wounded, camped where he was.[11]

That must have been a gloomy night in the Sioux village. Little Crow recognized the completeness of his defeat in a final stand on a chosen battle ground. He could no longer hold his people together. The Sioux broke up their great camp and scattered all over the plains. Sibley said he permitted their escape because he knew that if pressed too closely they would slaughter their white captives. As a matter of fact, Little Crow did try hard to have the prisoners killed after the battle. But the chiefs saw their doom and wanted to soften the punishment. They refused. Little Crow’s influence had ended.

Days passed. Through friendly Indians, Sibley got in touch with three trustworthy chiefs, offering amnesty and pardon if they would bring the prisoners to him. The offer was accepted. On the afternoon of September 26th, two hundred and sixty-nine captives were delivered, most of them women and children. All wore Indian clothing. There were some refined and educated women among them. Others were ignorant immigrant settlers. But their consideration for each other was beautiful to see as they helped the sick and assisted with the young children. Most of them cried with joy and relief. But some merely gave vacant stares. The scenes and experiences through which they had passed had left them dazed and stolid.

That night the rescued captives slept in the tents of the soldiers, the men taking the hard ground outside. They were sent down to Fort Ridgely the following day and their relatives—if any were left living—claimed them.

. . . . . . . . .

The war in Minnesota was over. But there still remained to be written the punishment of its chief figures.

Sibley rounded up fifteen hundred of the Sioux and placed them in prisons at Fort Snelling and Mankato. The rest scattered far and wide over the plains, carrying the seeds of their grievance to the other tribes, the results of which will be noted later.

At a great court martial, three hundred and ninety-two prisoners, accused of extreme barbarity, were tried. Of these three hundred and seven were sentenced to death and sixteen to prison. President Lincoln commuted the death sentences of all but thirty-nine whose cruelties had been too clearly shown, and on December 28th a great concourse witnessed the execution of these unfortunates on a special gallows built for the purpose.

Little Crow was still at large. Although his followers had all deserted him, there were reports that he was gathering new strength and preparing for another invasion. Every day or so fresh rumors were printed in the newspapers and so much fear was attached to his name that it was practically impossible to get the settlers to return to their homes.

Nathan Lampson and his son Chauncey were deer hunting in the north woods on July 3rd, 1863. Stealing through the thickets, they surprised two Indians picking berries. Hostiles were still scattered all over the country. No Sioux was a friend. The elder Lampson fired, wounding one of the Indians. The other tried to help him on a horse. As the wounded Sioux attempted to fire at his father, Chauncey Lampson shot him dead. The other Indian mounted and escaped.

The Lampsons scalped the body and carted it to the neighboring town of Hutchinson. Nobody could identify it. Some claimed they noted a resemblance to Little Crow, but the complexion seemed too light. The mortifying corpse was thrown into the offal pit of a slaughter house.

Then came an unexpected revelation. A party of Indians was captured on Devil’s Lake, among whom was a sixteen-year-old boy. He said he was a chief and asking for the commander of the troops by whom he was captured, made a statement of which the following is a part:

“I am the son of Little Crow; my name is Wo-wi-nap-sa. I am sixteen years old. . . . Father hid after the soldiers beat us last fall. He told me he could not fight against the white men, but would go below and steal horses from them . . . and then he would go away off. Father . . . wanted me to go with him to carry his bundles. . . . There were no horses . . . we were hungry . . . Father and I were picking red berries near Scattered Lake. . . . It was near night. He was hit the first time in the side, just above the hip. . . . He was shot the second time . . . in the side, near the shoulder. This was the shot that killed him. He told me he was killed and asked me for water. . . . He died immediately after.”

Sibley read the statement and at once concluded that the Indian killed by the Lampsons was Little Crow. The corpse was hauled out of its noisome resting place and there was observed a mark of identification which could not be mistaken. A deformity of his right wrist, caused by a gunshot wound received in a family feud when he was a youth, was the mark.

So died Little Crow, at the height of his power the most feared red man in America; leader of the greatest massacre in history; a scholar and a gentleman after his way. He started on the white man’s path but left it when his people’s wrongs cried out to him. Reduced to stripping red berries to keep life in his frame, he was at last shot by wandering hunters and his body thrown into the stinking offal pit of a slaughter house.

[9] “White men fight under a great disadvantage the first time they engage (the Indians). There is something so fiendish in their yells and terrifying in their appearance when in battle that it takes a good deal of time to overcome the sensation that it inspires!”—Judge Flandreau’s story of the battle.

[10] Sibley was the center of a storm of abuse and criticism as he waited. The newspapers grew restive. One dubbed him a “a snail who falls back on his authority and assumed dignity and refuses to march.” Another referred to him as “the state undertaker with his company of grave diggers,” an allusion to his burial of hundreds of dead settlers.

[11] An interesting sidelight, showing the character of Sibley, is the following: Several dead Sioux were found after the battle, although most of them were carried away. Next day Sibley published a general order expressing extreme pain and humiliation over the scalping of these Indians and threatening punishment for a repetition of the offense. “The bodies of the dead,” read the order, “even of a savage enemy, shall not be subjected to indignities by civilized and Christian men.”

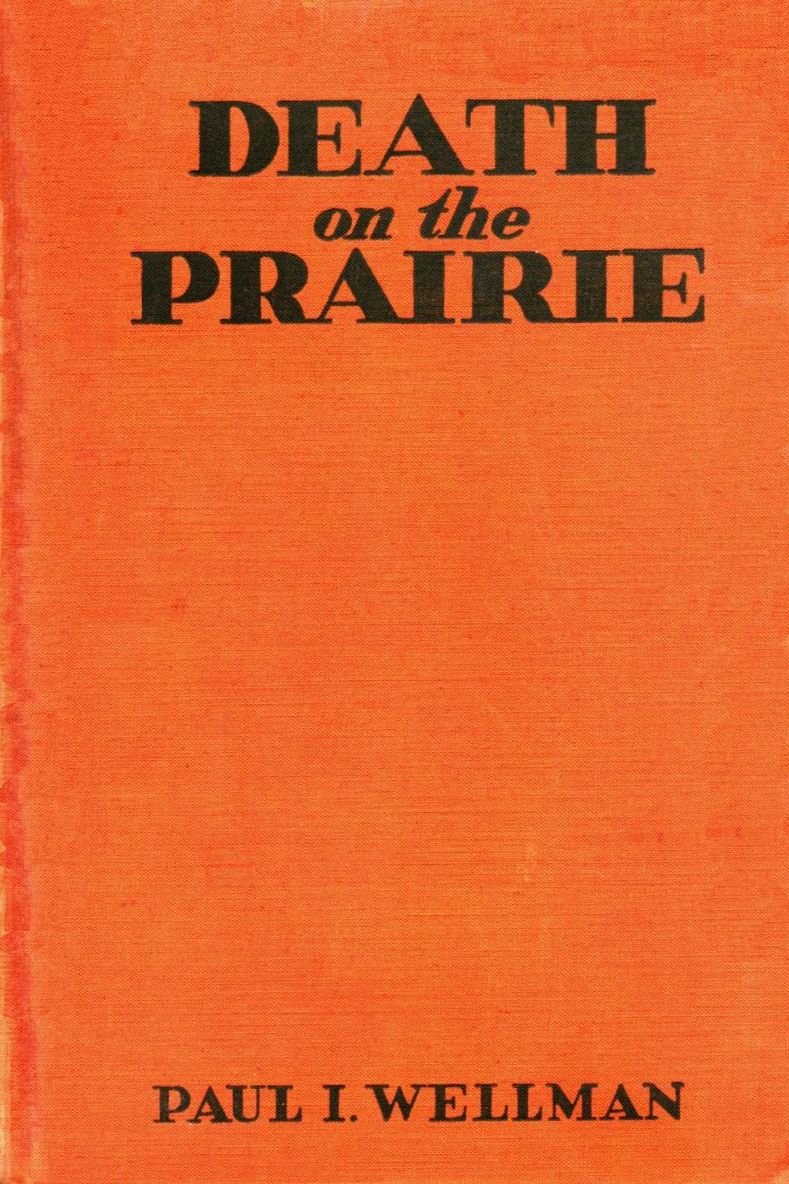

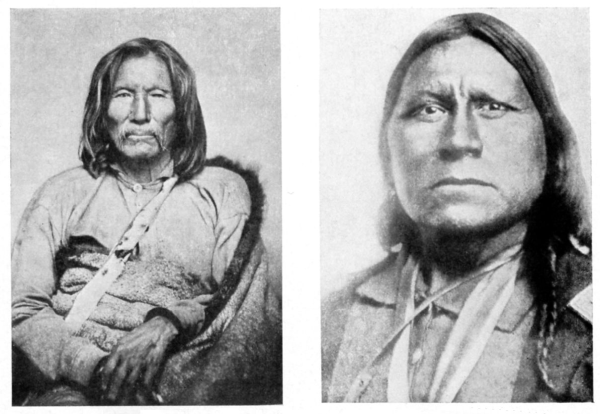

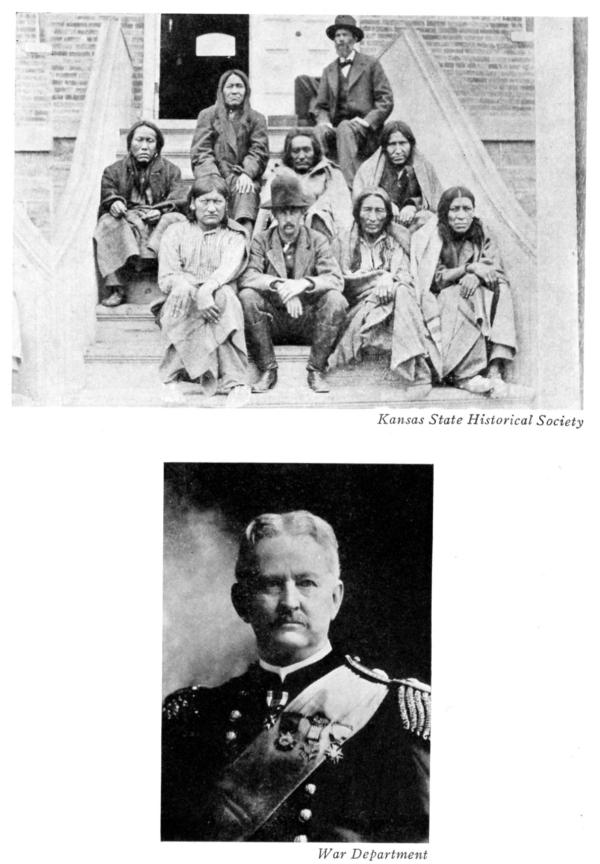

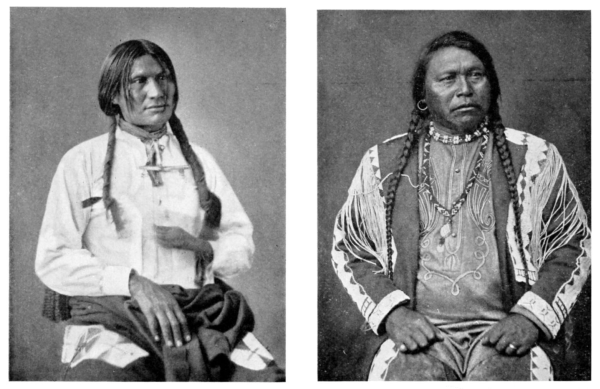

| Bur. of Am. Ethnology | Bur. of Am. Ethnology |

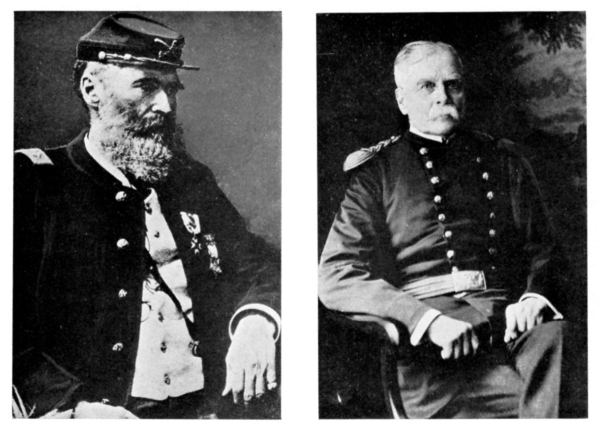

Left: Cutnose, one of Little Crow’s subordinates in the Minnesota uprising. Center: Little Crow (Cetan Wakan Mani), chief of the Santee Sioux in the Minnesota uprising in 1862. Right: Gen. H. H. Sibley, commanding U. S. forces opposed to the Sioux in Minnesota, 1862.

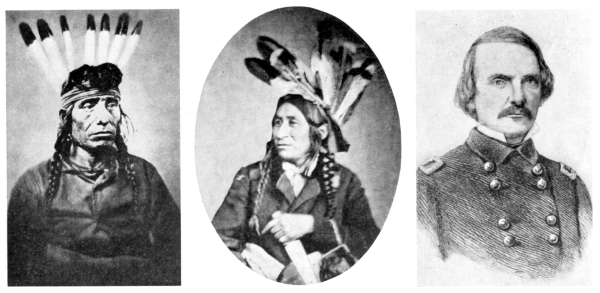

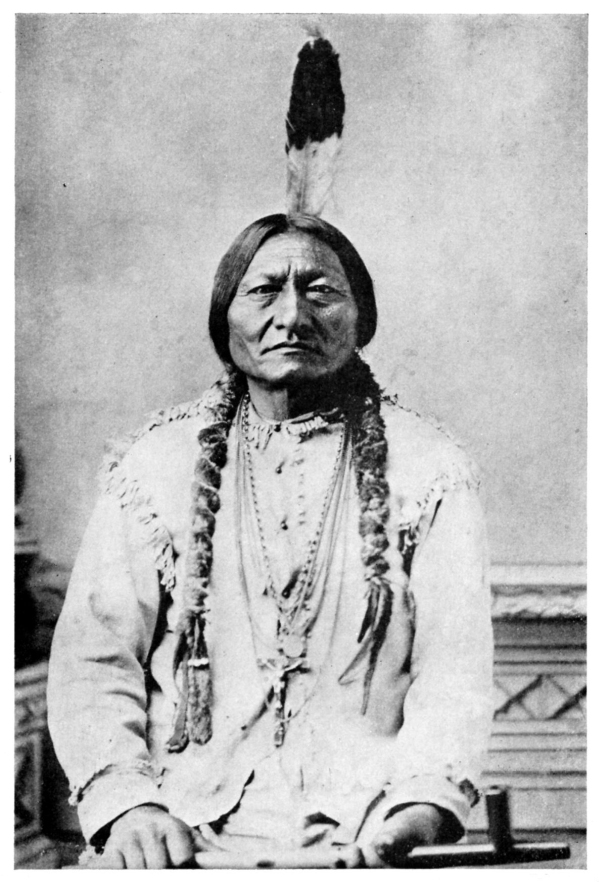

Bureau of American Ethnology

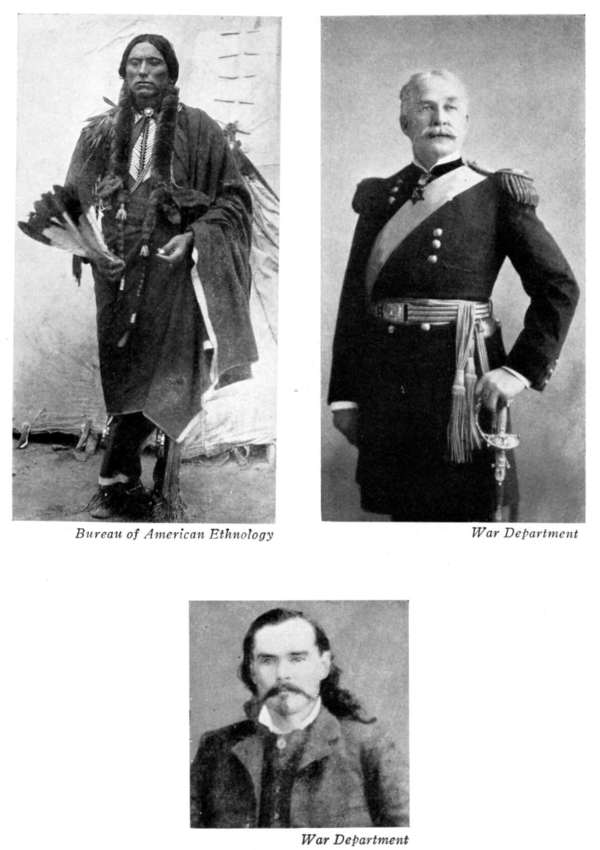

Red Cloud (Mahkpiya Luta), leader of the Sioux in their siege of Fort Phil Kearney.

Life was good on the high plains of the Dakotas before the white man came. The Teton Sioux wandered in leisurely, light-hearted fashion wherever the whim moved them. Buffalo moved in dark masses on the grasslands; the Black Hills and the Rockies were populous with deer, beaver, bear and other game. The Sioux were great hunters, and starvation was usually far from their teepees. They were great warriors and near at hand were their traditional enemies, Crows, Pawnees, Flatheads, Shoshones and Blackfeet, who were so necessary to them, for how else should the Sioux braves win honor? Everything was ideally arranged for the simple happiness of this people. The skill of the squaws provided every necessity. The world was full of pleasant valleys; Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery, smiled on his children.

In an Ogalalla teepee, about 1822, was born a baby boy. His father had no particular distinction, except that he died a drunkard. What the boy, Red Cloud, made of himself was due to his own personal traits, not to any family influence. There has never been a satisfactory explanation of how he got his name. No matter; he made it notable in history. His early years were typical of the boys of his tribe. He became a skillful hunter, a magnificent horseman, and could hold his own with any in feats of skill, speed, strength and agility. Very early he gained fame as a warrior and leader. Even in his early twenties he had his following.

The Teton Sioux loved fighting. Their five great tribes, the Ogalallas, Unkpapas, Sans Arcs, Brulés and Minneconjous, had frequent war parties in the field. Red Cloud had plenty of chances to distinguish himself.

The whole theory of war among the Sioux was different from that of the civilized white man. It resembled in many respects the feudal system of the middle ages. There was a certain wild chivalry, for example. A brave enemy was often spared rather than ruthlessly killed.[12] The warriors looked upon war as an opportunity to win honor. There was always greater rivalry to do some deed of stark daring, than merely to inflict damage upon the enemy.

Some of their exploits seem quixotic to our modern standards. The brave who charged into battle and struck his armed, unwounded enemy with his coup-stick or open hand, received more distinction for it than did the man who killed and scalped his enemy. The man who stole into a hostile camp and crept out leading a single horse whose lariat he had cut among the teepees was applauded more than the man who ran off a whole herd of ponies grazing unguarded outside of the village.

The analogy goes farther. Instead of definite military divisions, such as regiments, companies and squads, each with its appropriate officers, the Sioux fighting units were based on the prestige of various chiefs, exactly as medieval lords ranked according to the number of retainers they could muster. Renowned Sioux leaders had big bands of warriors. Each of these bands operated separately and retained the characteristics of an autonomous nation. It levied its own wars, moved to suit itself and was generally independent. Occasionally two or three bands would combine in a grand war party. But the idea of massing three or four thousand fighting men in the field and keeping them at it for months at a time was yet to come.

Living in this atmosphere of constant action, few of the Sioux noticed the black cloud, heavy with portent, which loomed on the horizon. The white man was beginning to seep across the plains in his strange, hysterical stampede over the mountains; was beginning to wander among the hills grubbing in the dirt, spoiling the little springs, for the dull yellow metal he prized above food and drink, above the love of his women, above honor even. There would be fighting—bitter, bloody fighting, not the glamorous, exciting battling of the Indian paladins—and the Sioux were to learn a new name, Red Cloud.

There had been war for some time in the south. The settlers in Kansas resented the presence of the Cheyennes and Kiowas on their frontier. The Indians were angered by the constant streams of immigrants who moved down the Santa Fé and Platte River trails on their way to California and Oregon. The caravans of covered wagons made much noise, what with the creaking wheels, the shouts of mule skinners, the cracking of whips, the bellowing of cattle, and the general hubbub which always accompanies the white man wherever he goes. As a result the buffalo and antelope moved out of the country. It was ruined as a hunting ground.

The exasperated Indians made more than one attack on these wagon trains. And the white men in revenge fired upon the next band they met—often killing Indians who knew nothing of any former attack and who approached them with the friendliest of intentions. This aroused still deeper enmity among the Indians and the vicious circle continued until all of western Kansas and Colorado were in a state of warfare.

In the summer of 1857, Colonel E. V. Sumner campaigned against the Cheyennes. There were several clashes with troops in later years. And on the morning of November 29th, 1864, Colonel J. M. Chivington, a fanatical ex-preacher, with a regiment of “hundred days men,” led the notorious Sand Creek massacre, in which he destroyed the friendly Cheyenne villages of Black Kettle and White Antelope, although they were under the protection of Major Wynkoop of Fort Lyon.

The Sand Creek massacre had far-reaching effects. The Cheyennes carried the war pipe to the Sioux, and Sitting Bull and other Sioux chiefs smoked it with them.[13] But Red Cloud was already definitely on the war path. Streaming westward, harried out of Minnesota, had come the Santee Sioux by hundreds, telling of Little Crow’s war and the causes of it. Red Cloud and the Tetons heard and sympathized.

When, in the summer of 1865, Major General G. M. Dodge, commanding the Department of the Missouri, sent four columns of troops up the Missouri to further punish the Santees, the Teton Sioux joined their relatives in the war. Red Cloud rode and skirmished with the soldiers under Generals Sully, Conner, Cole and Walker. He joined the Cheyennes in an attack on Colonel Sawyer’s military train which was marching up the Niobrara River to open a wagon train to the Montana gold fields. The fight was inconclusive. Sawyer paid Red Cloud an indemnity of a wagon load of sugar, coffee and rice on his promise to withdraw. The chief was true to his promise but some other Sioux came up who had not shared in the provisions and the soldiers had to fight in spite of the indemnity.

The Harney-Sanborne treaty was signed in 1865. Spotted Tail, Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses[14] and other chiefs conceded the white man a safe passage through their lands. Red Cloud was not present. He was in his teepee critically wounded by a Crow arrow. Shortly before, on a raid against the Crows, an arrow fired from ambush had struck him squarely in the middle of the back and passed completely through so that its barbed head stuck out from his breast. He was carried out of danger and a medicine man had tried to draw the arrow out. The feather at the back and the barbs in front prevented the shaft from being withdrawn. At length the medicine man had cut off the head, after which the arrow was drawn out. By a miracle no vital organs were pierced and Red Cloud eventually recovered.

He was set against allowing the provisions of the Harney-Sanborne treaty to be carried out. More far-sighted than his fellows, he saw the inevitable disaster to his country if ever the white man were allowed to set foot firmly in it. With Red Cloud urging them on, the turbulent younger warriors of the Sioux kept up a series of depredations which at length forced the government to send out a second treaty commission in the spring of 1866 to offer the Sioux new terms.

The great council was held at Fort Laramie. Red Cloud was present. He was now the foremost warrior of his nation and his influence was steadily thrown against the white man’s proposals.

A spectacular incident broke up the council, precipitated war, and made Red Cloud, for the time at least, supreme arbiter of his people. While the council was in session, a column of troops, led by General Henry B. Carrington, rode up. They were on the way to the Powder River Country, in defiance of the very spirit of the peace council, to erect a row of forts, and apparently did not even know the council was in session.

Carrington rode up, dismounted, and was being introduced to the members of the commission, when Red Cloud dramatically leaped on the platform under the shade of the pine boughs, pointed to Carrington’s colonel’s shoulder straps[15] and shouted that he was the “White Eagle” who had come to steal a road through the Indians’ land. The dramatic suddenness of the gesture riveted the attention of the Indians. Then he turned and, followed by every eye, sprang from the platform, ordered his teepees struck and led his band out on the prairie, openly announcing he was going on the war path.

That broke up the council. For some days the older chiefs of the other Sioux bands remained sullenly in conclave, but their young men were melting away like snow in summer, to join the standard raised in such spectacular manner by Red Cloud. Finally in sheer self-defense, to protect their own prestige, the older chiefs followed. Red Cloud was the greatest figure in the Sioux Nation. He had made the Sioux come to him. Now they looked to him for orders.

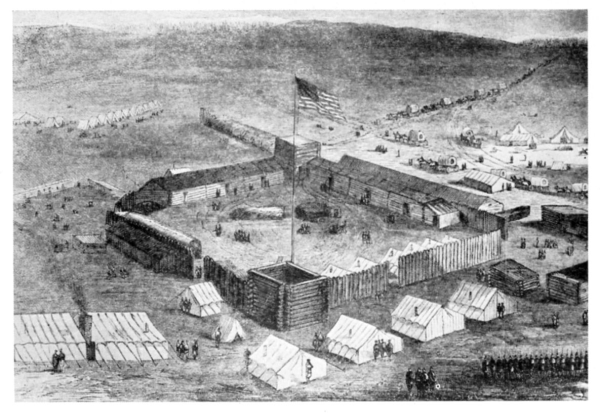

In the meantime Carrington marched into the Powder River country looking for a spot to erect a fort. The government wanted a string of posts built to protect the Bozeman trail over which thousands of emigrants were ready to travel to the new gold districts of Idaho and Montana. Carrington found an ideal location on the banks of Piney Creek, a branch of the Powder River and began construction of Fort Phil Kearney. Later a second post, known as Fort C. F. Smith was built ninety-one miles to the north.

The establishment of Fort Phil Kearney was equivalent to a declaration of war, if any such declaration was needed. Red Cloud smoked with many chiefs and tribes in those days. He was the prime mover in the hostilities against the white man. But there were many who saw eye to eye with him in the matter. Crazy Horse, the young paladin of the Ogalallas was one. There were Black Shield and High Backbone of the Minneconjous, who were just as eager as he to fight. They knew that the white man was eating up their land, driving away their buffalo, destroying their forests.

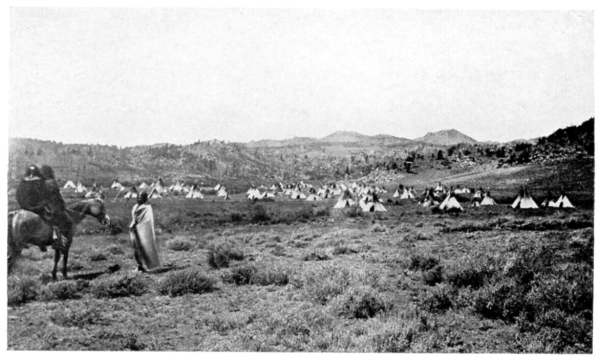

The Sioux gathered in magnificent response to Red Cloud’s call. At times their huge encampment extended for miles up and down the Little Goose River. Estimates of as high as fifteen thousand Indians were made for this camp, with upward of four thousand fighting men. This number is probably too high. But, even so, it was the most imposing fighting force the Sioux had ever put into the field.

[12] Sitting Bull’s preservation of Frank Grouard and Little Assinboine (Jumping Bull) are good examples of this frequent habit among the plains Indians. Yellow Nose, one of the most famous of the Northern Cheyenne warriors, was a Ute who had been captured and adopted into the tribe.

[13] Stanley Vestal, “Sitting Bull, Champion of the Sioux,” p. 70. References to this work hereafter are by permission of the publishers, Houghton-Mifflin Co.

[14] “His Sioux name, Tashunka Kokipapi, is not properly interpreted; it really means that the bearer was so potent in battle that the mere sight of his horses inspired fear.”—Frederick W. Hodge, “Handbook of American Indians,” Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 30.

[15] Although a general officer in the Civil War, Carrington held a colonelcy in the regular army. As everybody knows the colonel’s insignia is a silver eagle on the shoulder strap. This was the figure to which Red Cloud alluded in his dramatic charge.

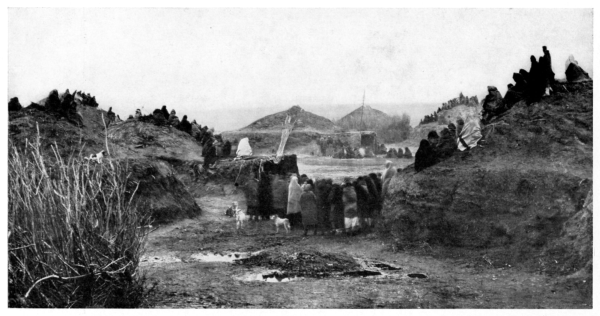

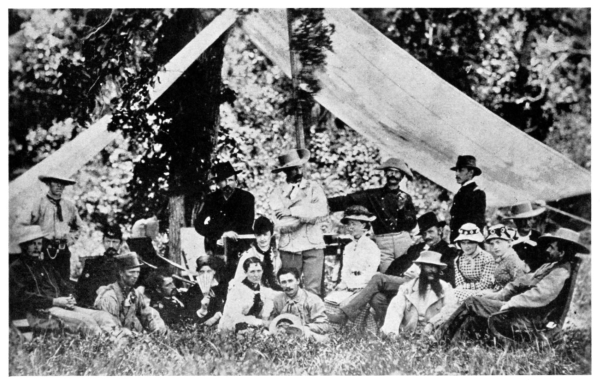

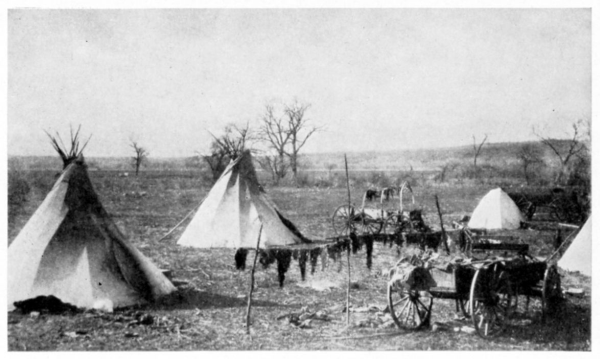

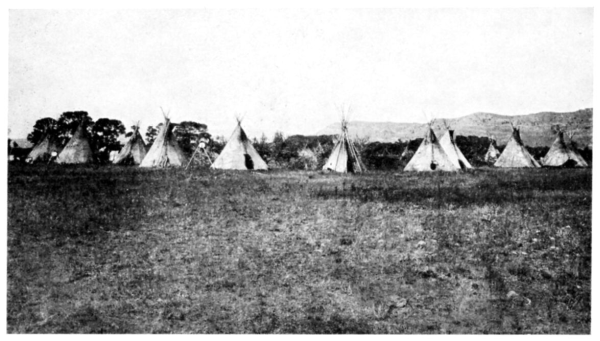

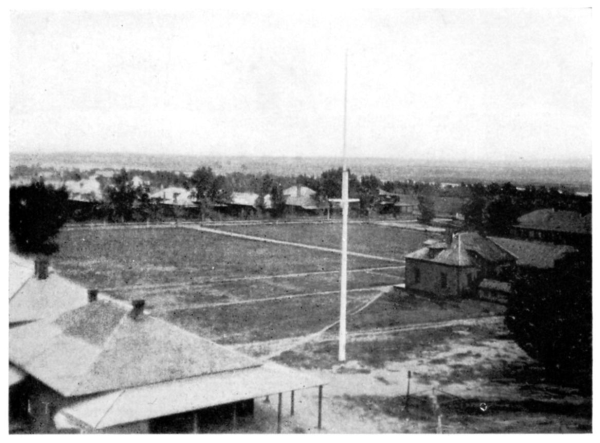

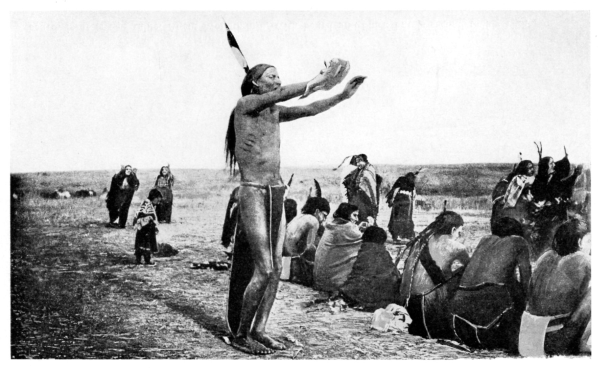

Courtesy of Prof. C. W. Grace

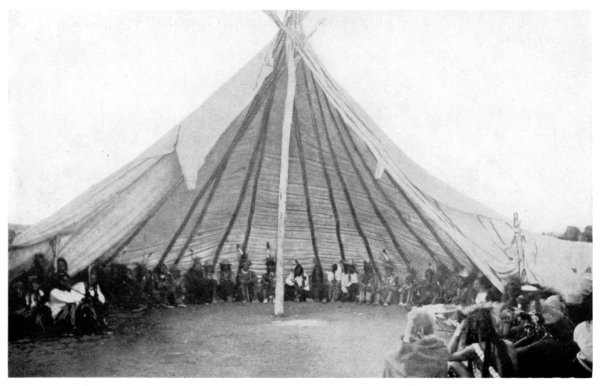

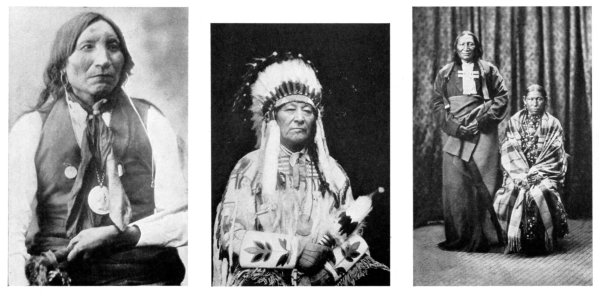

A Big Sioux council in session. This gives a good view of the chiefs and head men in the council lodge of the old days. The rank and file sat outside.

Courtesy of Prof. C. W. Grace

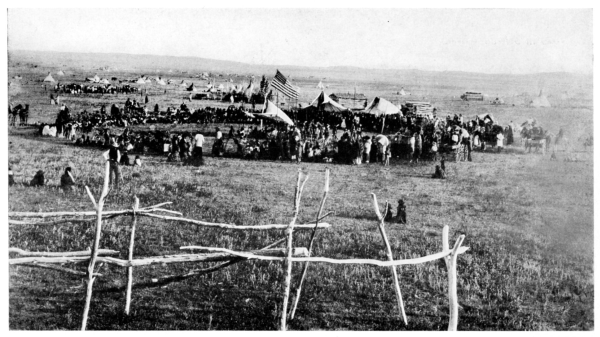

Sioux in council with government representatives. Note the flag flying over the council lodge.

No finer natural cavalry ever existed than the Sioux, according to such authorities as General George Crook and General Frederick Benteen. Yet they were unfitted for conducting a sustained siege. Their ideas of organization were the most rudimentary, discipline was utterly lacking as our modern armies know it, and they had no knowledge of scientific warfare. In spite of this, the Sioux, largely because of the leadership of Red Cloud, besieged Fort Phil Kearney for more than two years. There are writers who have denied that Red Cloud played the dominating role ascribed to him in the campaign. It is true that Indians are prone to exaggerate not only their own importance but that of the leaders of their individual bands, so that it is often difficult to discover who was the actual commander in a given encounter. Still the impression of Red Cloud’s importance and of the part he played is too well established to be dismissed from history.

General Carrington began building the fort on July 15th. Less than forty-eight hours later, at daybreak of the 17th, the Indians made their first attack. Part of the post horses were stampeded, and in a brisk little fight two soldiers were killed and three wounded. Later that day, the same war party scooped up the outfit of Louis Gazzous, a traveling sutler, and killed six men. In the next twelve days five wagon trains were attacked, fifteen men killed and much livestock run off. On July 24th Carrington wrote for reinforcements. He already knew the implacability of his enemy.

The Sioux did not formally invest the fort. But they planted scouting parties everywhere about it. The soldiers found they had a foe who never slept. Did a herder stray from his guard? He was cut off and killed. Did a sentry expose himself on the palisade during a moonlit night? A bullet from the bush laid him low. Did a detachment of soldiers set out without an imposing display of power? They straightway had to fight for their very existence.

Even during the long, bitter cold spells the Indians kept the circle of death about the post. That was not like the Sioux, whose custom was to withdraw to their camps during cold weather. Better than anything else that showed the grim purpose of their leader.

There was an atmosphere of constant dread about the fort, reflected in the letters the soldiers wrote home. And the feeling was justified by the circumstances. In the first six months from August 1st to December 31st the Sioux killed one hundred and fifty-four persons at or near Fort Phil Kearney, wounded twenty more and captured nearly seven hundred head of livestock. Fifty-one times they made hostile demonstrations. It was a hectic existence for the garrison.

In spite of this constant pressure the men worked on the building of the fort with dogged courage. The country about was hilly but barren, and the nearest forests from which stockade posts could be obtained were seven miles away. An enormous amount of wood was required for the huge rectangular palisade, eight hundred feet long by six hundred feet wide, to say nothing of the corral for several hundred horses and mules and the forty-two buildings in the post. Large parties of men continuously felled timber and hauled it to the fort. At times this “wood train” numbered one hundred and fifty members.

All through those six months not a man left the stockade without knowing that he might never see it again. They worked with their rifles close at hand and a guard stood constantly under arms. Even so, men were frequently cut off and killed. Sometimes soldiers disappeared and no trace of them was ever found. That meant one thing: they had been captured and carried away for torture.[16]

Captain William J. Fetterman was a soldier by birth, instinct and profession. His Civil War record was brilliant. He went to Fort Phil Kearney because it promised plenty of action. From the first he disapproved of Carrington’s tactics. Fetterman arrived in November. On December 6th he had a chance at the action he craved and an opportunity to test the mettle of his tawny foe.

On that day frantic signalling from the lookout on near-looming Pilot Hill showed that the wood train was attacked two miles from the fort and forced to corral. Fetterman, with forty men, including Lieutenants Grummond, Bingham and Wands, and Captain Fred H. Brown, dashed to the rescue, while Carrington and twenty-five troopers rode over the Piney to take the Indians in the rear.

Down the valley galloped the eager Fetterman. Dust rose ahead and they saw horsemen—Sioux. Guns began to speak and bullets kicked up little clouds of dirt around their horses’ feet. But Fetterman’s carbines were crackling too. The Sioux whipped their horses and rode hard down the valley. Five miles Fetterman chased them, his men shooting but not hitting any of the Indians. The wood train made its way on in to the fort unmolested.

Thus far the affair was fun. The pursuit turned a spur of the Sullivant Hills and the fort was shut out of view. In a twinkling the whole aspect of things changed. The Sioux stopped running. Other mounted warriors joined them. And now, yelping and shooting, they turned and charged.

At the Indian rush some of Fetterman’s troopers whirled their horses and spurred as hard as they could for safety. He had only about twenty-five men left and the Sioux were four to one, but he held his ground. It looked as if it would be hand-to-hand in a minute, with the odds in favor of the enemy, when there was a clatter of hoofs, and Carrington, his sabre flashing, galloped around the spur at the head of his detachment.

Not knowing how many soldiers were following Carrington, the Sioux rode off. Fetterman was saved. But for the timely arrival of the post commander it would have been all over but the scalp dance. As it was, Lieutenant Bingham and Sergeant Bowers were dead. Lieutenant Grummond barely escaped with his life from the circle of barbaric foes. Five other soldiers were wounded.

It was a clever ambuscade and almost worked. The plan was a favorite one with the Sioux and Cheyennes—a small decoy party to lead the foe into the reach of the main body of warriors. In this case Indian lookouts were observed on the hills signalling the troop movements. Red Cloud’s plans miscarried but were later put into effect.

As for the fire-eating Fetterman, it would be supposed that he should have derived some wisdom from the episode. But the opposite appears to have been the case. Only a short time after the fight he said: “Give me eighty men and I’ll ride through the whole Sioux Nation.”

If that remark ever got to Red Cloud’s ears, it probably caused him considerable grim amusement.

Two weeks passed. The morning of Friday, December 21st, dawned bright and cheery, the sun gleaming on the snow in the hills. Carrington surveyed the almost completed fort with a creator’s pride. One more consignment of logs, he estimated, would finish the hospital building, the last structure to be built.

That morning a wood train of fifty-five men started to the hills. At eleven o’clock the Pilot Hill lookout began violently signalling. The wood train had been attacked again.

“Boots and Saddles,” sounded the bugles. Carrington quickly told off forty-nine men from the 18th Infantry and twenty-seven from the 2nd Cavalry for the relief. He ordered Captain James Powell, experienced and cool-headed, to take command, but Fetterman came up and begged so hard for the assignment, urging his seniority, that the general gave in. Lieutenant Grummond volunteered to lead the cavalry. Captain Brown, soon to be transferred to Fort Laramie, asked to go along. He considered Indians a sort of game to be hunted and was crazy “to get a scalp.” A couple of old Indian fighters, Wheatley and Fisher, likewise went, with their new Henry breech-loading rifles which they “wanted to try on the redskins.” Every man was mounted, including the infantry, and they carried Spencer carbines and revolvers or Springfield muskets. Ammunition was low so they were not very well supplied. Still, they looked formidable enough as they rode out of the fort, eighty-one officers and men. Now was the time for Fetterman to “ride through the Sioux Nation.”

Carrington, who knew his reckless subordinate, seems to have feared that some such thought was in his mind. He gave Fetterman specific orders: “Relieve the wood train, drive back the Indians but on no account pursue the Indians beyond Lodge Trail Ridge.” To make sure he was not misunderstood, he repeated the orders to Grummond.

Instead of heading south of the Sullivant Hills where he heard the firing, Fetterman rode north of the hills toward Lodge Trail Ridge, which he occupied with his men in skirmish order shortly after noon. As he did so, the lookout signalled the wood train was no longer being attacked.

Now an alarming thing happened. Fetterman’s command, after a brief halt on the ridge, disappeared on the other side. He had deliberately disobeyed orders.

. . . . . . . . .

Fetterman perhaps merited all the censure that has been heaped on his head for that disobedience. But a wiser man than he might well have fallen victim to the uncanny skill of the trap which was prepared for him.

As he mounted the ridge he saw a handful of Indians below him, riding so daringly near that the hot impulse to pursue could not be denied. How was he to know that, in the ravines running from each side of the draw, hid the Sioux and Cheyennes in hundreds, their mounted men clustering at the mouth of the ravine, to close the door of the trap, while others in scores lay in the grass across the line of march?

The handful of warriors who so tantalized Fetterman were ten picked men, chosen as a high honor for this tremendously dangerous post. One of them was the famous Big Nose, brother of the great Cheyenne chief Little Wolf. As the soldiers started after the audacious decoys, Big Nose, greatly daring, whipped his horse back and forth in front of the troops, so close he seemed to be right among them, yet escaped from the hail of bullets unscathed.

At last the ten Indians divided into two groups, riding apart then criss-crossing. It was the signal to close in.

A wild whooping, a rush and the Cheyennes charged. Then the whole mass of Indians swept around the little band of soldiers. Some rode clear through the blue line. The troops grew rattled. Fetterman, Brown and the infantry stopped and became separated from Grummond’s cavalry. These men died in the first fierce rush of the savages, stabbed and clubbed to death as they stood. But Grummond gathered his troopers around him on the ridge, surrounded by the yelling horde. Arrows glinted like a swarm of grasshoppers flashing across the sky.[17]

Suddenly, according to the Indian account, the officer commanding the cavalry (Grummond) went down, shot or beaten out of his saddle. The troopers grew panicky. Remorselessly the Indians followed them as they tried to retreat up the ridge. There was a final great rush, a desperate smother of flashing lances, tomahawks and clubs. Then all was quiet except for the whooping of the victors. Fetterman’s command was dead to a man. His boast had proved empty and bitterly tragic.[18]

Back at the fort, Carrington, noting with alarm that Fetterman had disobeyed orders, looked around for somebody to send after him. Five minutes after the command disappeared heavy firing broke out. The roar of many guns was continuous and increased in volume. Everyone knew a hard battle was in progress. Surgeon Hines was sent with an orderly, with instructions to join Fetterman if possible. Hines quickly returned. There were too many Indians in the hills.

At that Carrington ordered Captain T. Ten Eyck, with every man who could be spared, to follow Fetterman. Followed by fifty-four soldiers, the captain galloped down the trail and began to ascend the ridge. It was noticed that the firing was diminishing in volume. What had happened? Were the Indians driven off? Or were the soldiers beaten? Carrington was nearly crazed with anxiety. He knew the men were ill supplied with ammunition. Then, just before Ten Eyck reached the summit, with three or four scattered shots the firing abruptly ceased altogether.

Ten Eyck in turn disappeared beyond the ridge. In a few minutes an orderly came spurring down the hill at the dead run. He rode into the fort with a message which filled every listener with dread.

“The valley on the other side of the ridge is filled with Indians, who are threatening me,” wrote Ten Eyck. “The firing has stopped. No sign of Fetterman’s command. Send a howitzer.”

Back went the orderly with word that reinforcements were coming. Forty men followed hard at his heels. At the same time Carrington armed every non-combatant man in the post, even released prisoners from the guard house to man the palisades. No howitzer could be sent for lack of horses.

When Ten Eyck crossed the ridge, more than two thousand Indians were in the valley he estimated. There was no fighting going on. The warriors were dashing back and forth, yelling, their war bonnets flying in the breeze, the dust rising. It was cold. The temperature was falling, presaging the blizzard soon to come. Ten Eyck did not descend the hill until the reinforcements arrived. By that time the Indians were gone.

Cautiously Ten Eyck moved down the road. Quite without warning he came upon the ghastly evidence of a terrible disaster. In a little space enclosed by huge rocks were the bodies of Fetterman and Brown and forty-seven of their men. This was where the infantry had been overwhelmed. It was a horrible sight. The bodies of the dead were stripped, scalped, shot full of arrows and mutilated.[19]

Fetterman and Brown had bullet holes in their left temples from weapons held so close that the powder had burned their faces. They had “saved their last shots for themselves,” to escape capture and torture.

Ten Eyck brought the forty-nine corpses to the fort in wagons. It was now bitter cold and night was setting in. With darkness, preparations were made to resist the expected Indian attack. Double guards were placed and in every barrack a non-commissioned officer and two men stood watch. The surviving officers did not sleep. But the night passed without attack.

Morning dawned cold and blustery with a blizzard threatening. Carrington, disregarding the advice of his officers, took eighty men and went to learn the fate of Grummond and the thirty-two missing men. As he left, he ordered every woman and child placed in the magazine with an officer sworn not to allow a single one to fall into the Indians’ hands alive. If the Indians captured the fort, he was to blow up the magazine.

Evidences of the fight multiplied as Carrington reached the fatal ridge. Dead cavalry horses were scattered along the trail. Here and there they found bodies of slaughtered soldiers. A quarter of a mile beyond the scene of greatest carnage lay Grummond. Still farther were the corpses of a dozen men, grouped together with many empty cartridge shells about them. To one side were the dead frontiersmen, Wheatley and Fisher, with a heap of empty shells as evidence that they had sold their lives dearly.[20] All of the bodies were scalped and mutilated.

Every man was now accounted for. Eighty-one were dead. After the peace treaty the Indians admitted twelve killed and about sixty wounded on their side. But years later the Cheyennes said that the dead warriors, laid out side by side, made two long rows, perhaps fifty or sixty men.[21]

There has been much dispute as to who led the Indians in this battle. Red Cloud said he commanded. High Backbone, the Minneconjou, has also been named as have Black Leg and Black Shield. But it is probable that the real commander of the Indians was Crazy Horse who was just beginning to build his reputation as the greatest fighter the Sioux Nation ever produced.

Carrington brought the dead back to the fort. That night the threatening sky fulfilled its portent. A terrific blizzard broke loose. The thermometer fell to thirty degrees below zero. Snow piled up so rapidly against the stockade that details of men had to work constantly to shovel it away lest it pile high enough to allow the Indians to climb over. Sentries could stand the intense cold only twenty minutes at a time. Even with quick reliefs there were many frozen feet, ears, noses and fingers.

But for the blizzard the Indians might have followed their advantage by attacking the fort itself. According to their own account this was a part of the plan.[22] To the people at the fort arrival of cold weather was providential.

Southward, two hundred and thirty-six miles, lay Fort Laramie, with reinforcements, ammunition and supplies. Word must be gotten through. There was no telegraph, so a courier had to take it. Carrington called for volunteers.

Several old plainsmen were in the post and many veteran soldiers, but they shook their heads. That ride, over a broken, snow-covered country, even in times of peace, meant almost certain death by freezing, with the temperature where it was and the blizzard raging so it was hard to see a hundred yards ahead. With the country swarming with hostile Indians it was odds of a hundred to one against any man rash enough to attempt it.

But there was one man willing to take the risk. John Phillips, commonly known as “Portugee,” was an Indian fighter, trapper and scout. He knew the country and offered to go.[23] Carrington gave him his own horse, a blooded Kentucky runner, the swiftest animal in the post. Wrapping himself in a huge buffalo coat, with a little hardtack for himself and a sack of grain for his horse, he passed out through a side gate into the swirling storm.

Nobody ever got the full details of that ride but it will always remain one of the epics of the West. At first he walked in the blackness of the night storm. For hours he led his horse, stopping at suspicious noises. He expected to be seen in the first half mile but no Indian yelled. With the howling wind whipping the snow around him, he mounted at last and spurred his horse along, across the Piney and past frozen Lake De Smet. Behind him the lights of the fort grew dim and disappeared.

Gallop—gallop—on through the storm, plunged Portugee Phillips. The miles fell behind him like the snow-flakes he shook from his furry shoulders. The Indians were in their teepees, not dreaming that any white man would face the fury of this storm. And Portugee Phillips rode on and on.

Day dawned and still the wind whirled the snow. A short stop to feed his horse and cram a few crackers down his own throat, a handful of snow for a drink, and Portugee Phillips was in the saddle again. How he guided his horse across that wilderness, is explained only by the instinct which is sometimes possessed by those perfectly attuned to the wilds. From the Big Horn Mountains the blizzard swept with unslackened fury, piling in drifts from five to twenty feet deep. The storm prevented his seeing any landmarks. The trail itself was covered by the drifts. Yet on he rode, as unerring as a hound on the slot.

Night fell, and still the good steed breasted the snow. In the homes of civilization happy families gathered around their hearths in the light and warmth of their homes. But alone, a dot in the icy waste, Portugee Phillips was riding for the lives of the women and children at Fort Phil Kearney. Just at dawn he reached Horse Shoe station, forty miles from Laramie, and one hundred and ninety miles from Phil Kearney. He telegraphed his news to Laramie. Fortunately he did not trust the telegraph. The message never got through. After a brief rest he rode on.

Icicles formed from his beard. His hands, knees and feet were frozen. He looked more like a ghost than a man. But still, with indomitable purpose, he urged his failing horse over the trail.

It was Christmas Eve and they were holding high revel at Fort Laramie. A grand ball was in progress at “Bedlam,” the officers’ club. Beautiful women, garbed in silks and satins, and gallant officers, in brilliant dress uniforms, made the interior a splendid kaleidoscope of changing color. The sound of violins, the laughter of the ladies, and the gay banter of the brave men who were taking holiday from military cares, created a symphony of cheery sound.

Above this happy noise came suddenly the sharp challenge of a sentry. It was followed by the shouting of men in the fort enclosure and a rush of running steps outside, coupled with a ringing call for the officer of the day. The dancing stopped. Officers and ladies grouped themselves at doors and windows, gazing out at the snow-covered parade ground. A horse lay there, gasping its last, fallen from exhaustion. And reeling, swaying like a drunkard, a gigantic, fur-clad figure staggered toward the hall. In through the door he stumbled and stood for a moment, supporting himself on the lintel while his eyes blinked in the unaccustomed light. Then seeing the post commander, he told a story of horror which put a period to the festivities that night—the story of the Fetterman disaster.

As he gasped out his story and appeal for reinforcements, he swayed, then fell crashing to the floor, unconscious from over exposure and exhaustion. Kind hands lifted him and carried him to a bed. Even with his rugged physique it took him weeks to recover from the terrible ordeal. To this day his ride remains unparalleled in American history.

[16] “A favorite method of torture was to ‘stake out’ the victim. He was stripped of his clothing, laid on his back on the ground and his arms and legs, stretched to the utmost, were fastened by thongs to pins driven into the ground. In this state he was not only helpless, but almost motionless. All this time the Indians pleasantly talked to him. It was all a kind of a joke. Then a small fire was built near one of his feet. When that was so cooked as to have little sensation, another fire was built near the other foot; then the legs and arms and body until the whole person was crisped. Finally a small fire was built on the naked breast and kept up until life was extinct.”—Colonel Richard I. Dodge, “Our Wild Indians,” p. 526.