* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Paxton's Magazine of Botany and Register of Flowering Plants Vol. 1

Date of first publication: 1834

Author: Joseph Paxton (1803-1865)

Date first posted: Aug. 17, 2022

Date last updated: Aug. 17, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220833

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

MAGAZINE OF BOTANY.

PAXTON’S

MAGAZINE OF BOTANY,

AND

REGISTER OF FLOWERING PLANTS.

————————

God Almighty first planted a garden; and, indeed, it is the purest of human pleasures; it is the greatest refreshment to the spirits of man; without which buildings and palaces are but gross handiworks: and a man shall ever see, that, when ages grow to civility and elegance, men come to build stately, sooner than to garden finely; as if gardening were the greater perfection.—Lord Bacon.

————————

VOLUME THE FIRST.

LONDON:

ORR AND SMITH, PATERNOSTER ROW.

——

MDCCCXXXIV.

LONDON:

BRADBURY AND EVANS, PRINTERS,

WHITEFRIARS.

TO THE MOST NOBLE

WILLIAM SPENCER CAVENDISH,

DUKE OF DEVONSHIRE, K.G., &c. &c.

This First Volume

OF

THE MAGAZINE OF BOTANY

IS,

WITH THE GREATEST RESPECT AND GRATITUDE, AND BY HIS GRACE’S KIND

PERMISSION,

MOST HUMBLY DEDICATED,

IN TESTIMONY OF

HIS GRACE’S ENTHUSIASTIC LOVE OF BOTANY, AND HIS EARNEST ENDEAVOURS TO

PROMOTE SCIENCE IN GENERAL;

AND ALSO

AS AN ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF THE INNUMERABLE FAVOURS

CONFERRED ON HIS GRACE’S

OBLIGED AND MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT,

JOSEPH PAXTON.

ADVERTISEMENT.

The object and design of the Magazine of Botany being stated at length in the Introduction, renders it needless to repeat them here. Yet the Author may be allowed to say, that as a guide to the lover of Flowers, both as regards culture and selection, he can, without fear of being charged with vanity, state that the work will be found valuable.

The Author has studiously endeavoured to render everything as plain and intelligible as possible. The botanical descriptions of the plants are therefore written in English, and, as much as possible, without the use of scientific terms.

The methods of culture are written in short paragraphs, to assist the memory; and these paragraphs are, in most cases, numbered, to render each easy of reference.

In the Calendars of work to be done in each month, no useless repetitions of the methods of culture are entered into; but after stating it to be the season for performing certain operations, reference is given to page and rule, where the mode is detailed.

The volume contains one hundred illustrations in wood, cut by persons eminent in that branch of business.

The coloured plates, of which there are nearly fifty, were drawn and coloured by some of the first artists. The plants represented are all really valuable, and some of them entirely new.

The great and increasing demand for this work, which has far exceeded the Author’s expectations, stimulates him, at the close of this first volume, to persevere in his humble but constant endeavours to render the Magazine of Botany a sure guide to every admirer and cultivator of FLOWERS.

Chatsworth,

Dec. 20, 1834.

WOOD-CUT ILLUSTRATIONS.

VOLUME THE FIRST.

GARDENS AND GARDEN STRUCTURES.

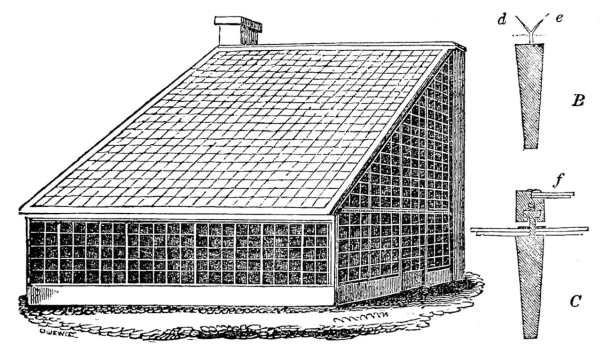

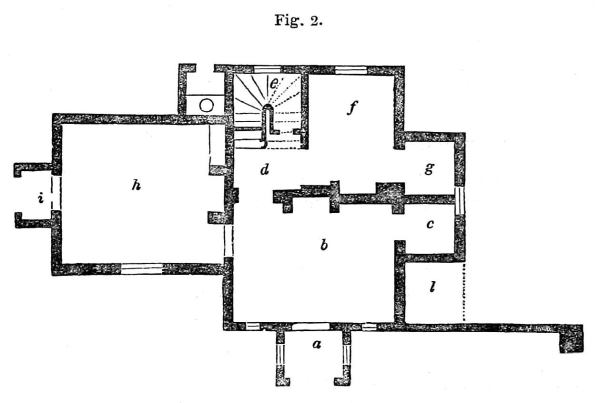

Greenhouse, glazed on Mr. Saul’s principle, 130

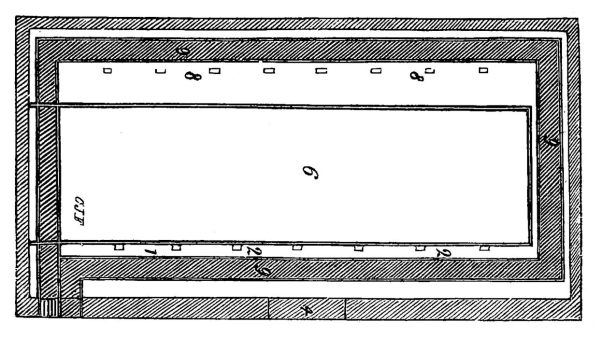

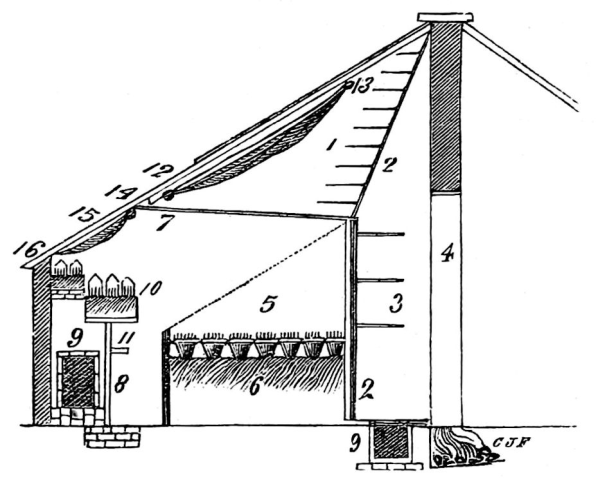

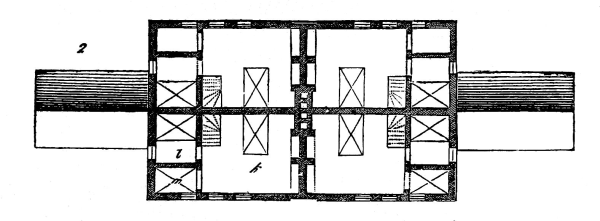

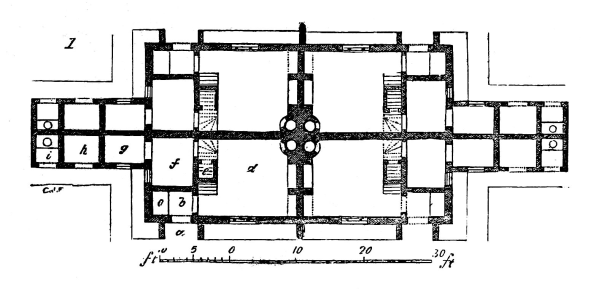

House for striking cuttings. Plan and section of one, 112

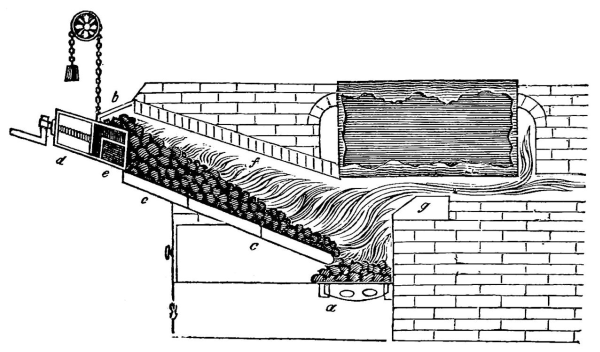

Hot-water apparatus on Mr. Saul’s principle, 136

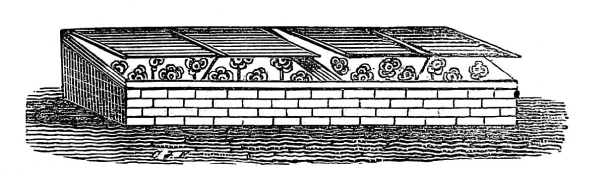

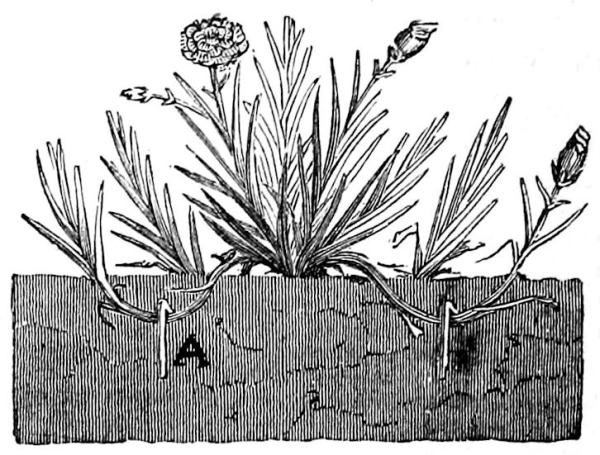

Pit for sheltering Auriculas, &c., 9

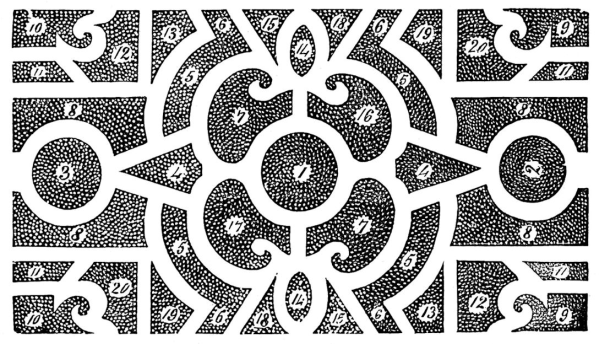

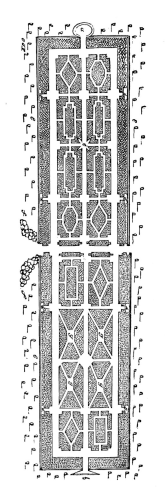

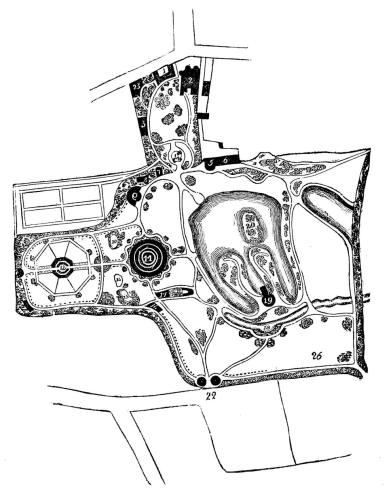

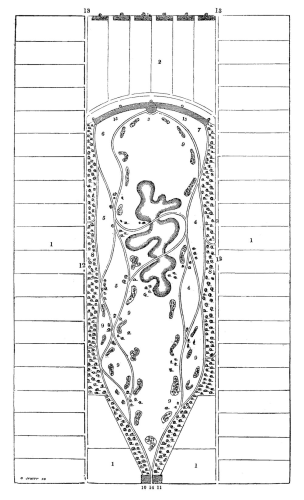

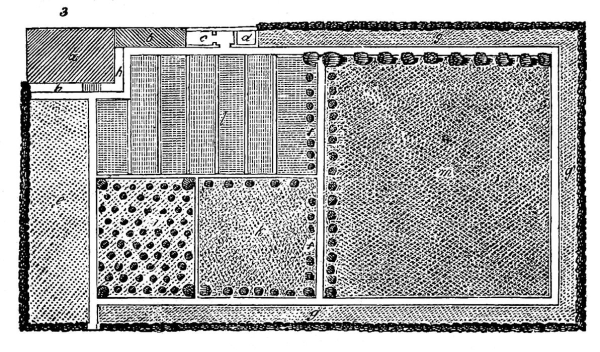

Public Subscription Gardens. Design for, 215

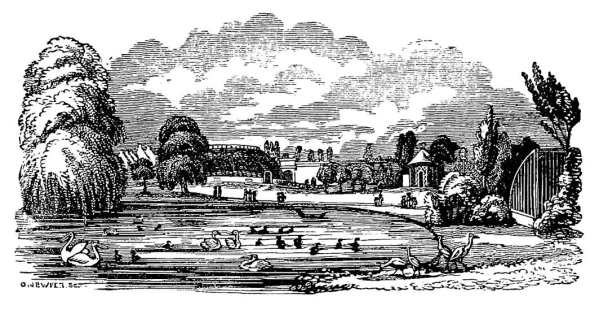

Surrey Zoological Garden, 185, 186

Witty’s Patent Gas Furnace, 133

EDIFICES.

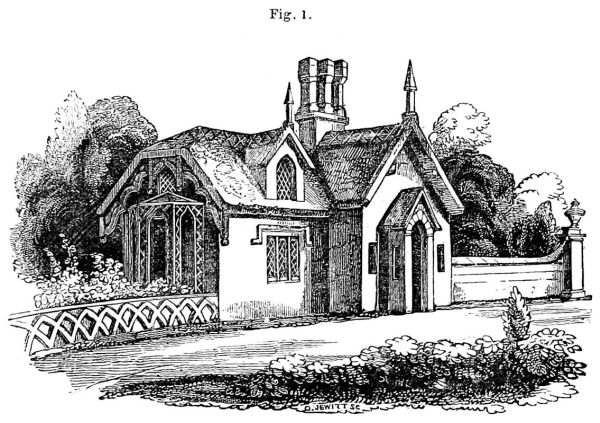

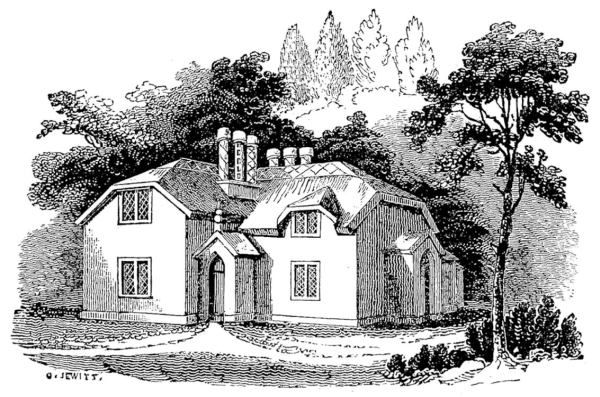

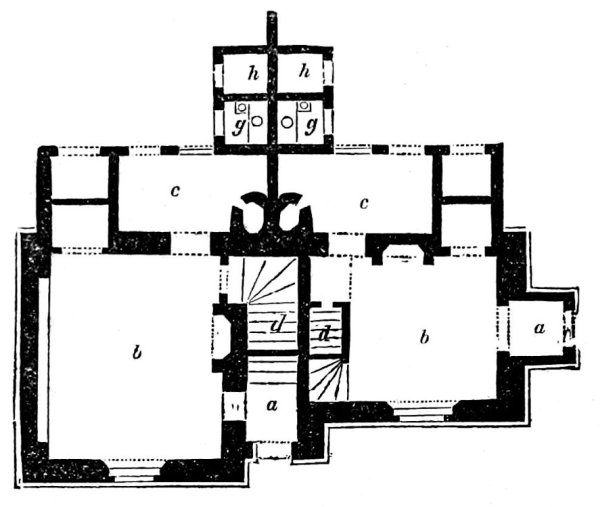

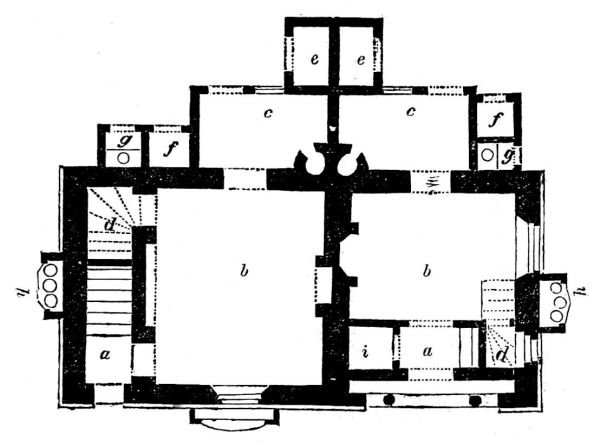

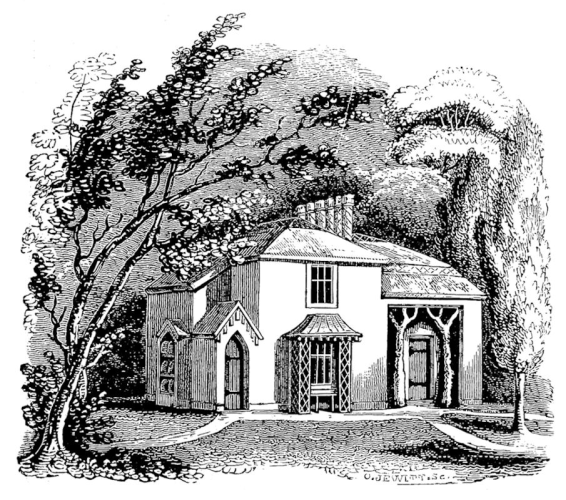

Cottages for ornament on Gentlemen’s Estates, 251-255

Old English Gate Lodge, 178

OPERATIONS.

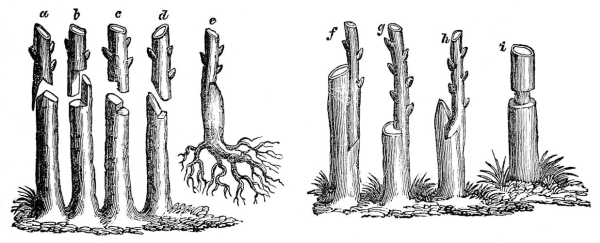

Abscission; propagation by, 92

Auricula seed; mode of sowing, 10

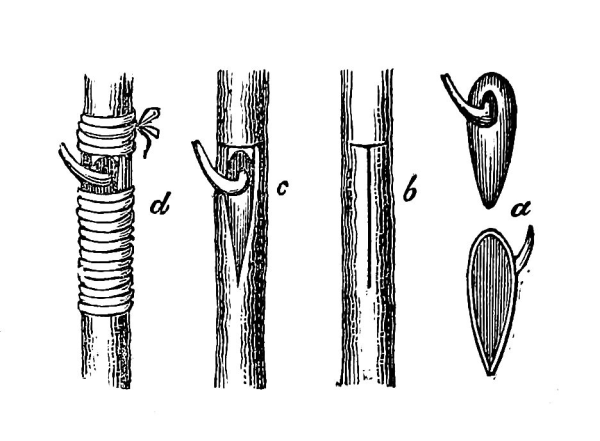

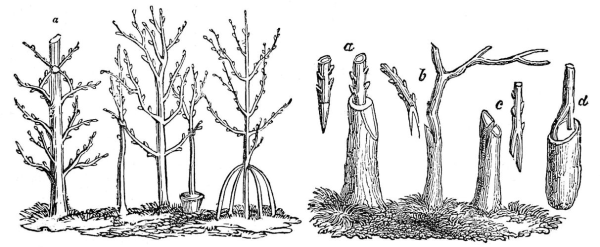

Budding; propagation by, 37

Camellias; new mode of propagating, 36

Flowers; mode of packing, 12

Grafting Camellias by approach, 36

Grafting Camellias by approach, new mode of, 36

Grafting, many modes of, 93

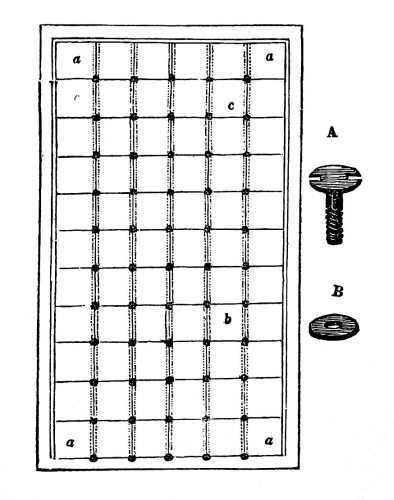

Glazing on Mr. Saul’s principle, 130

Glazing on Mr. Harrison’s principle, 131

Inarching, 36

Layers; propagation of Carnations by, 72

Layers; propagation of Oranges by, 92

Potting; peculiar method of, 6

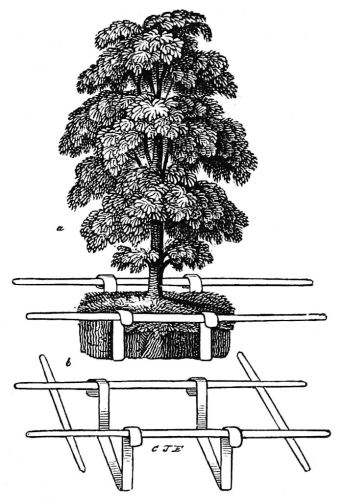

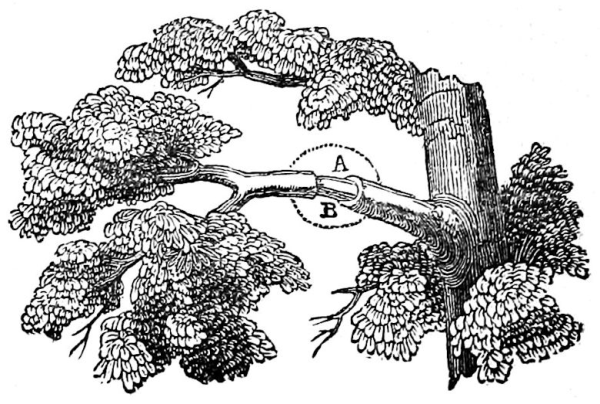

Trees; method of removing large ones, 47

Trees; method of supporting without bands, 47

DIAGRAMS.

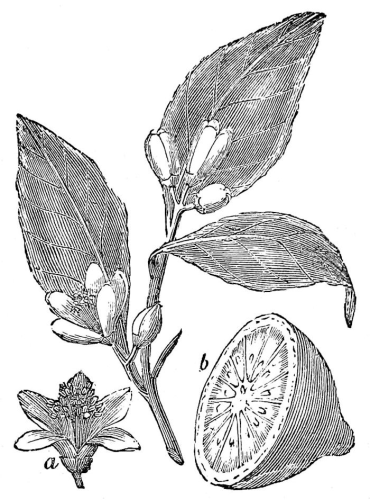

Lemon Fruit, 89

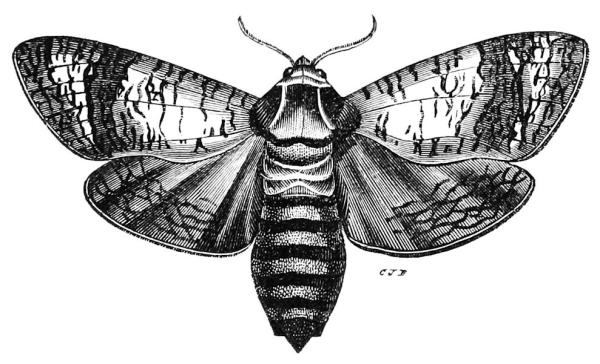

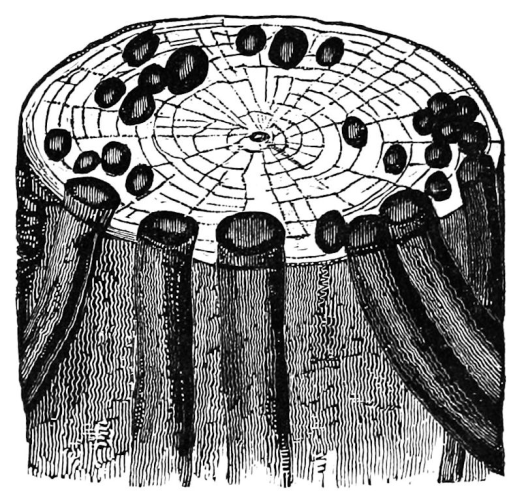

Piece of wood perforated by the Goat Moth, 48

Rafter on Mr. Saul’s mode of glazing, 130

MACHINES, INSTRUMENTS, AND UTENSILS.

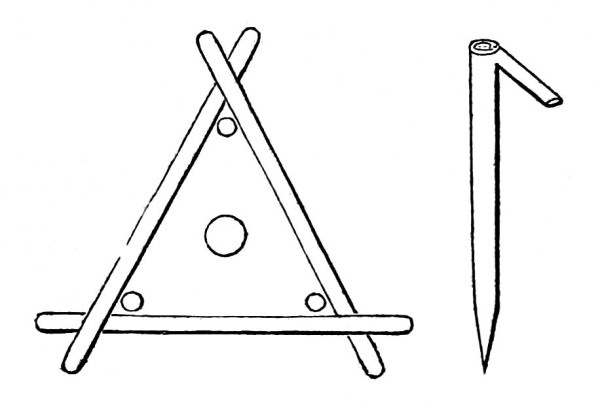

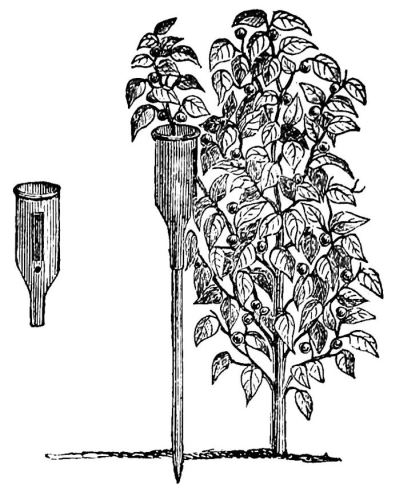

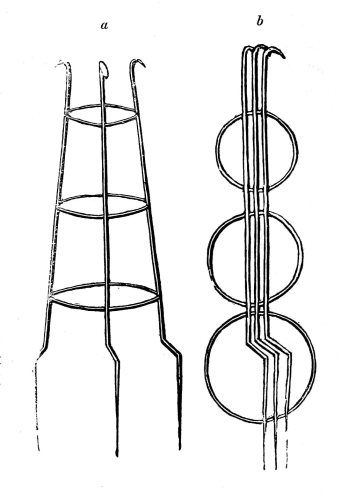

Basket for growing Orchideous Epiphytes, 15

Bygrave Plant Preserver, 17

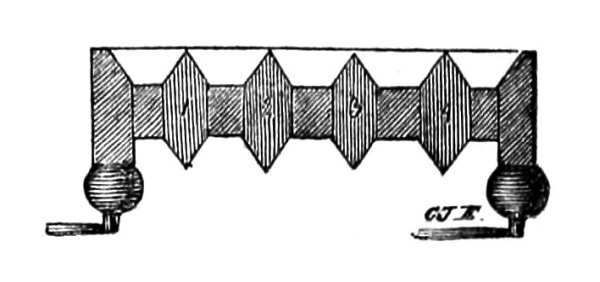

Bygrave Slug Preventer, 17

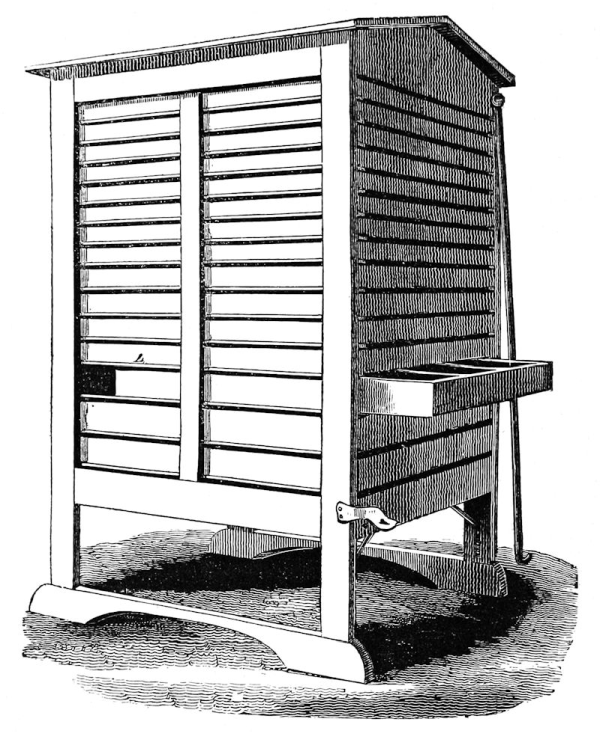

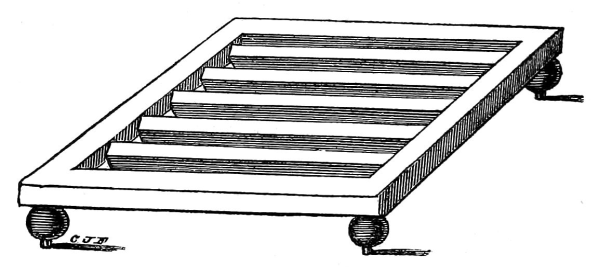

Case of drawers, in which to keep Bulbous Roots, 44

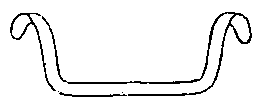

Collar to support the flowers of Carnations, 71

Daisy Extractor, 274

Flattener of Florists, 11

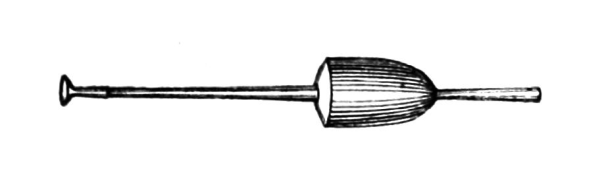

Fumigator, 24

Implements for removing large trees, 46

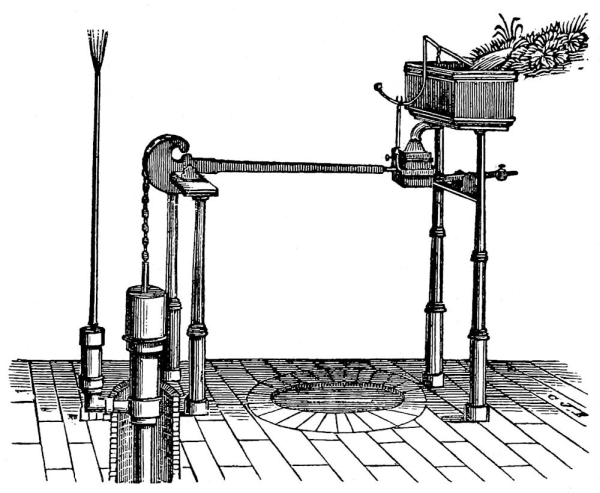

Lucas’s Self-acting Force-pump, 156

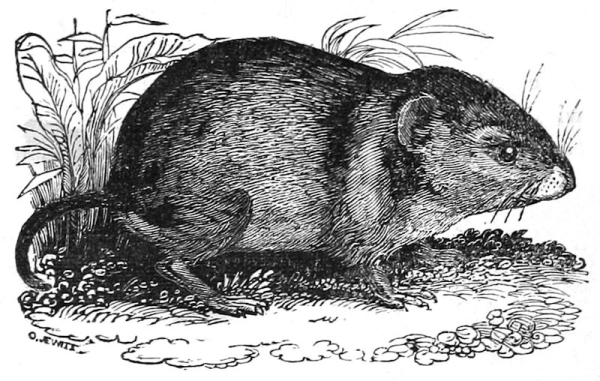

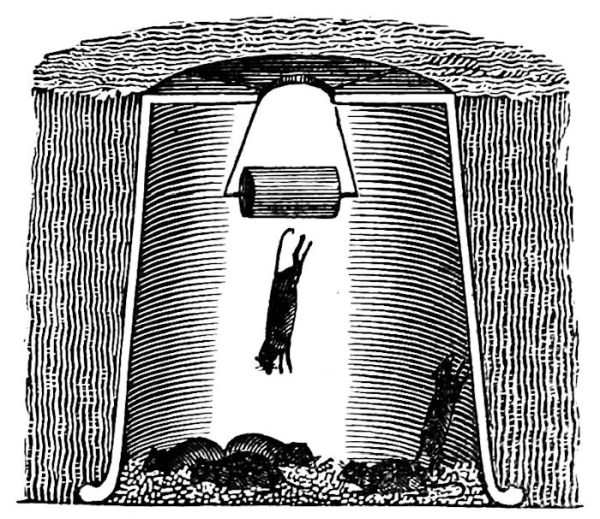

Mouse-trap, 24

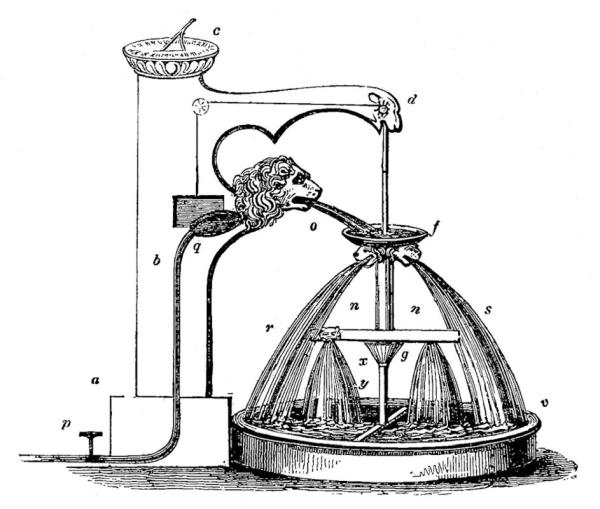

Musical Dial Fountain, 250

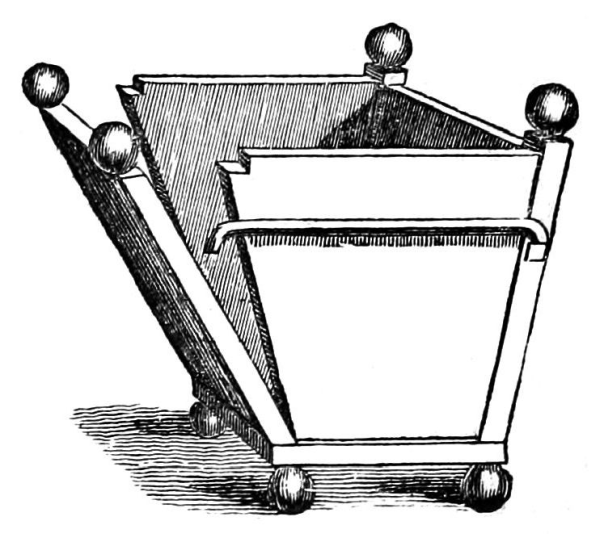

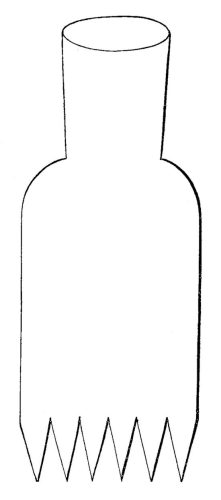

Orange Tub, 94

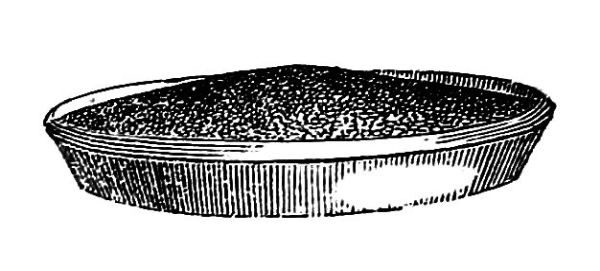

Pan for sowing small seeds, 10

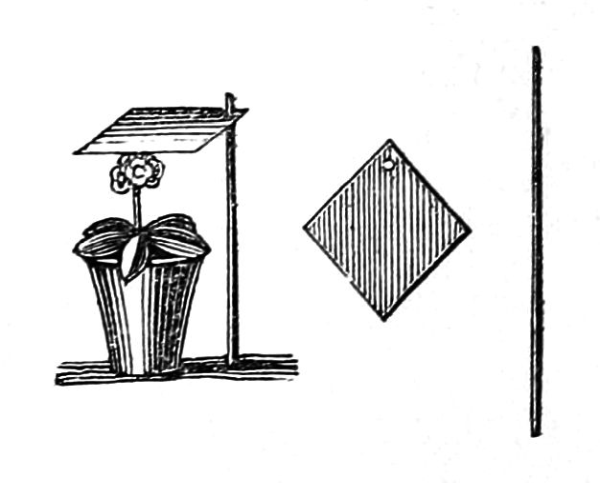

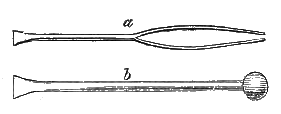

Pliers used by Florists in transplanting small seedlings, 11

Propagating Pot, 92

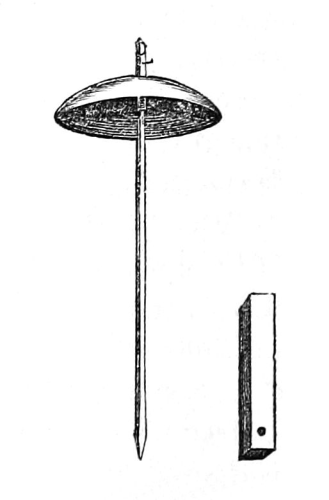

Shade used by Florists for Auriculas and Polyanthuses, 10

Shade used by Florists for Carnations, 70

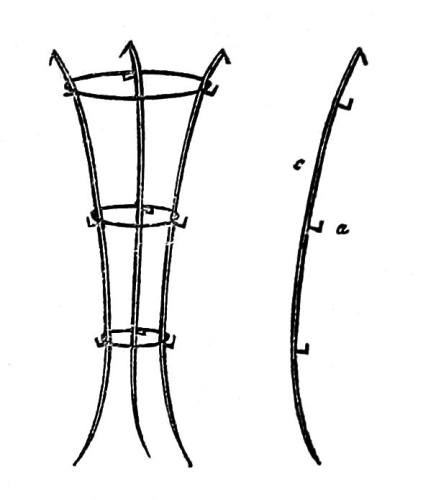

Stands for supporting Dahlias, 106, 107

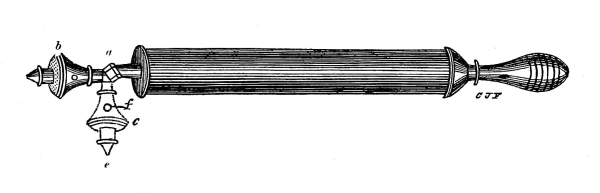

Syringe, Siebe’s new invented, 23

Transplanter or Dibber, for planting seedling Auriculas, 11

INSECTS.

Goat Moth, 48

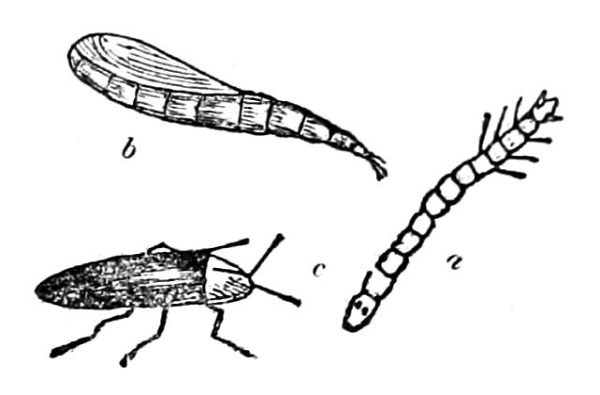

Wire Worm, in its three stages of existence, 74

PLANTS.

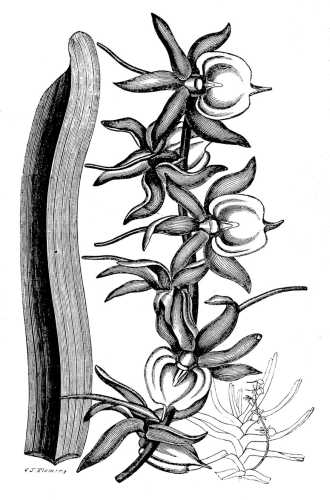

Aerides paniculata, 15

Angræcum eburneum, 258

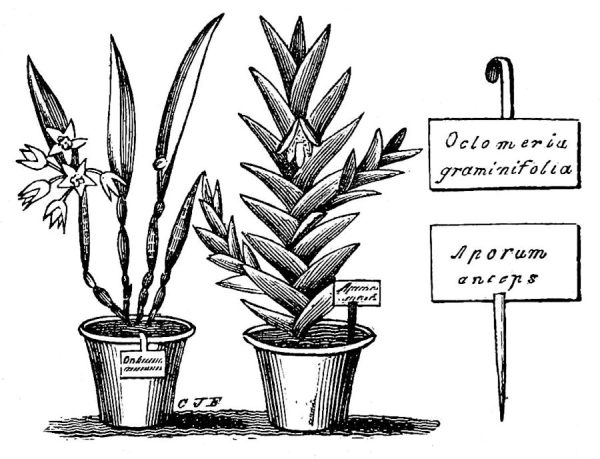

Aporum anceps, 155

Camellias, 36

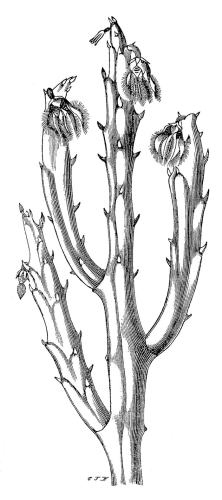

Caralluma fimbriata, 216

Cacti, grafting of, 51

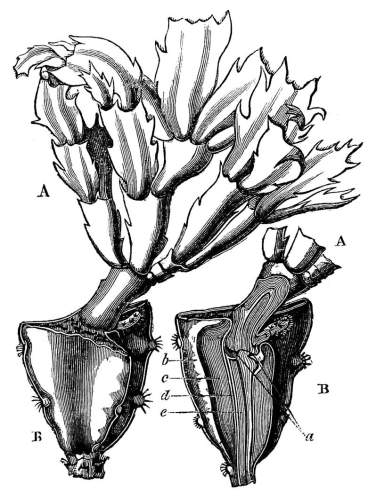

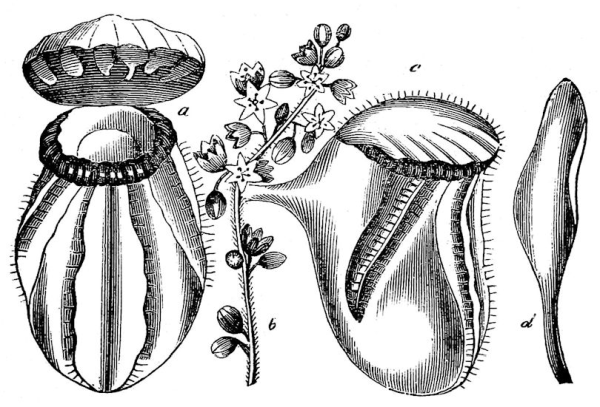

Cephalotus follicularis, 59

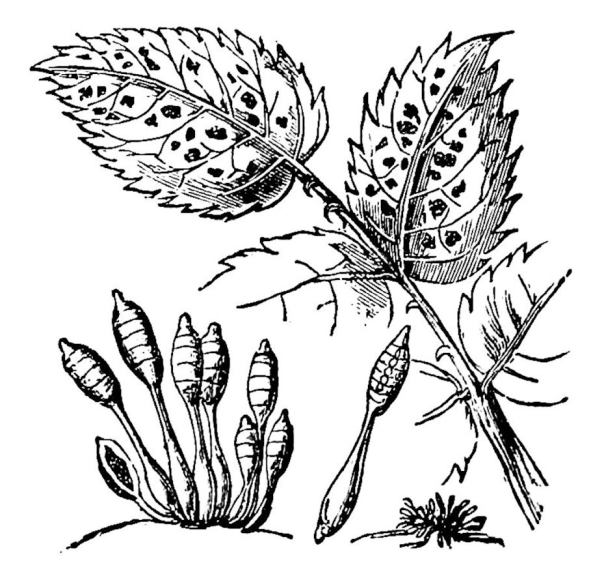

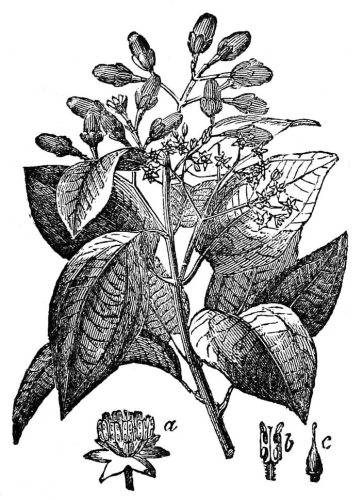

Cinnamon Tree, 147

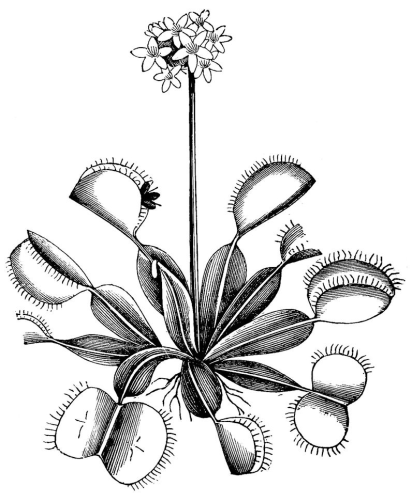

Dionœa muscipula, 61

Dipsacus fullonum, 60

Francoa sonchifolia, 234

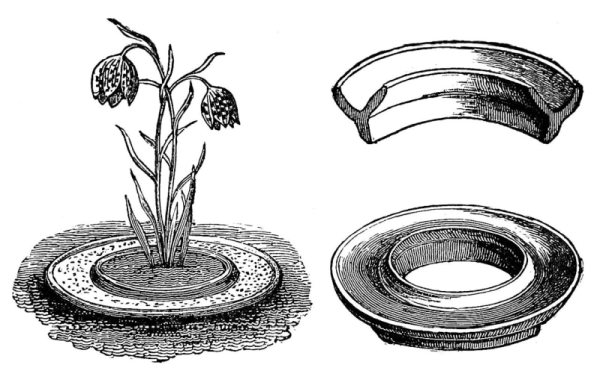

Frittillaria Meleagris, 17

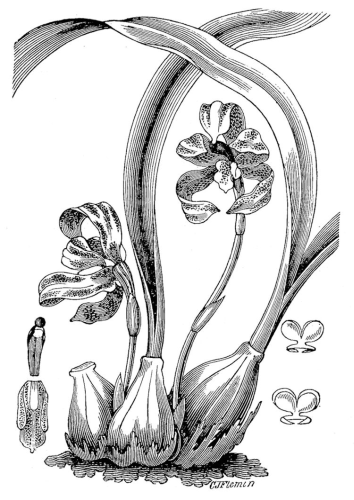

Hermodactylus longifolia, 242

Lemon Tree, branch of, 89

Maxillaria picta, 228

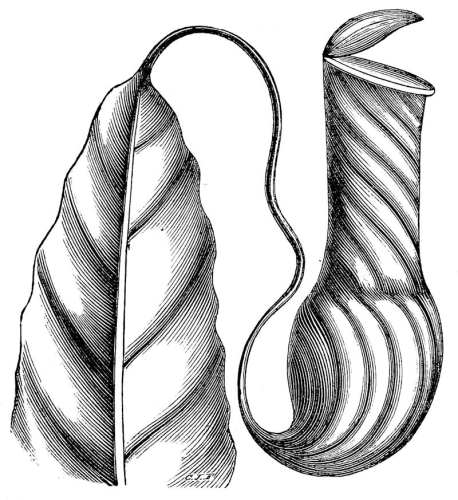

Nepenthes distillatoria, 57

Octomeria graminifolia, 155

Oncidium bifolium, 234

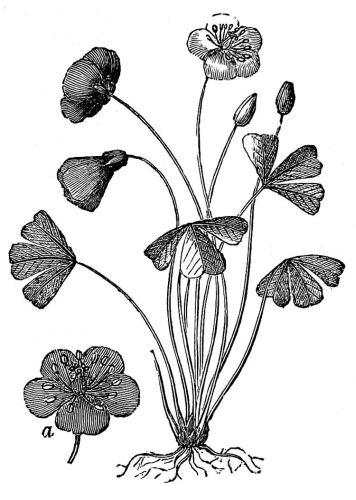

Oxalis acetosella, 229

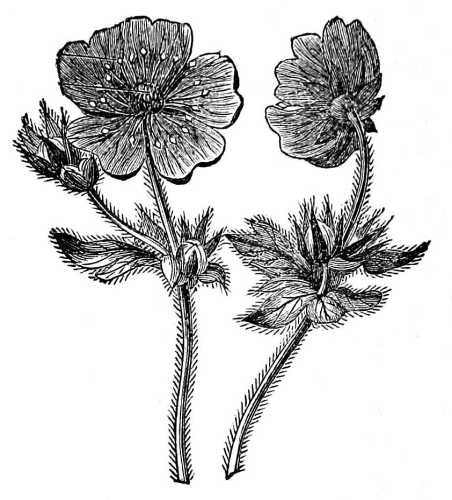

Potentilla Nepalensis, 170

Polyanthus, Geo. IV., 110

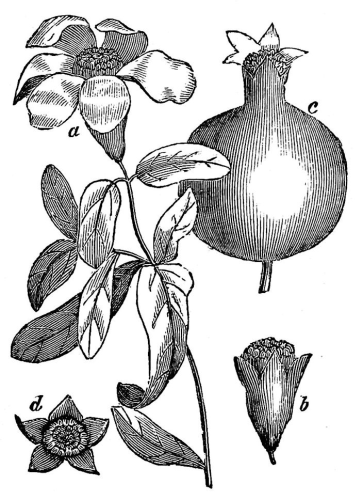

Pomegranate Tree, 65

Psidium Cattleyanum, 119

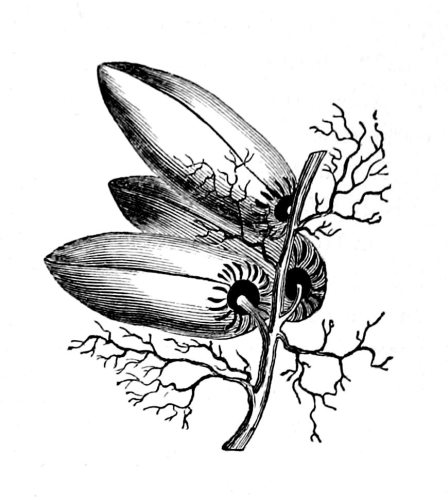

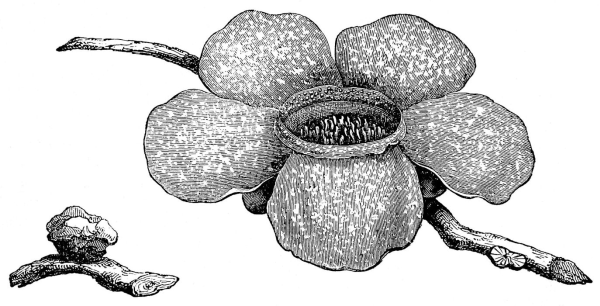

Rafflesia Arnoldi, 153

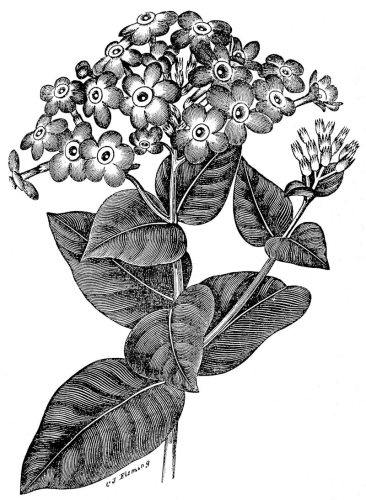

Rondeletia speciosa, 158

Sarracenia flava, 55

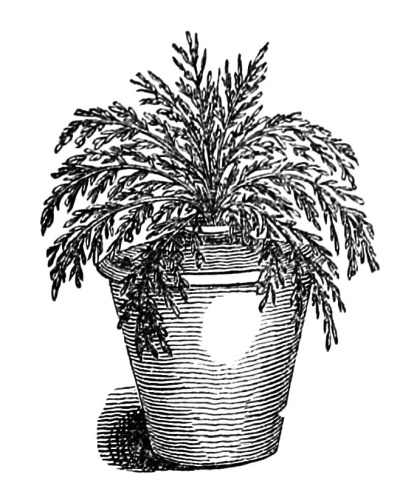

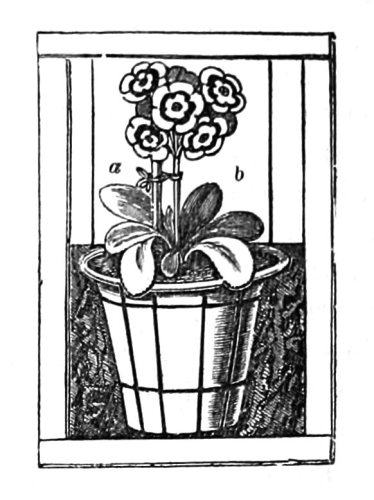

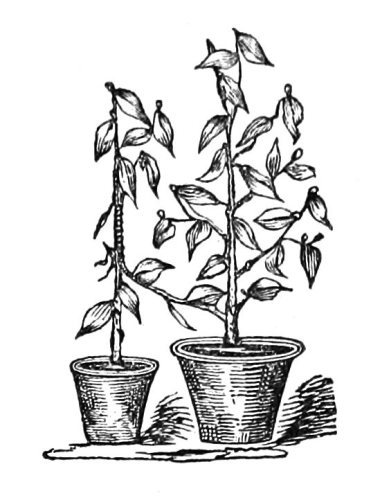

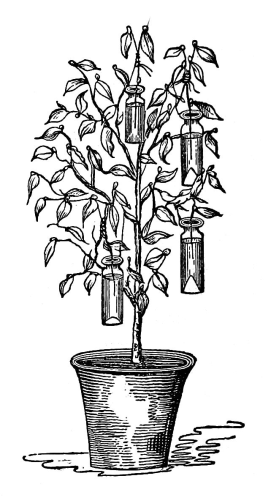

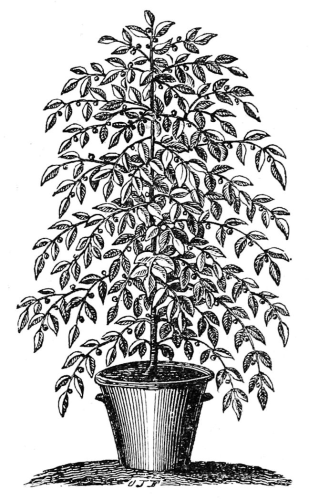

Schizanthus in a pot, 6

Scutellaria macrantha, 234

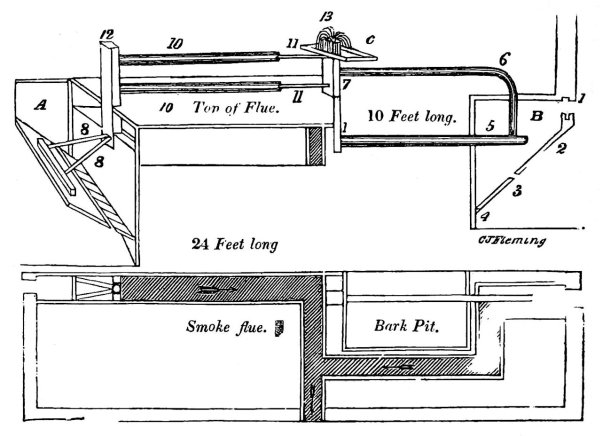

Smut on Roses, 146

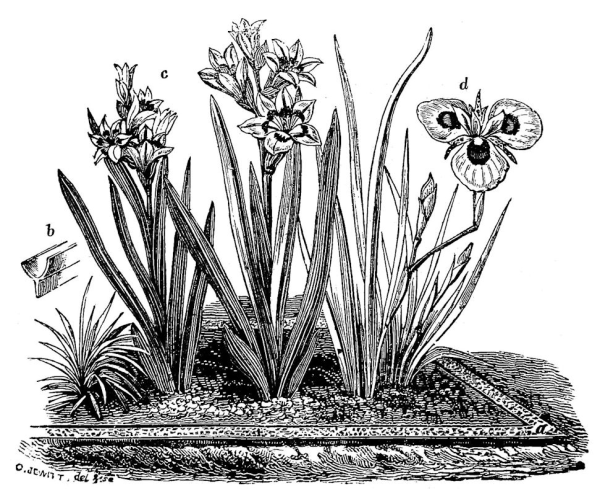

Sparaxis lineata, 17

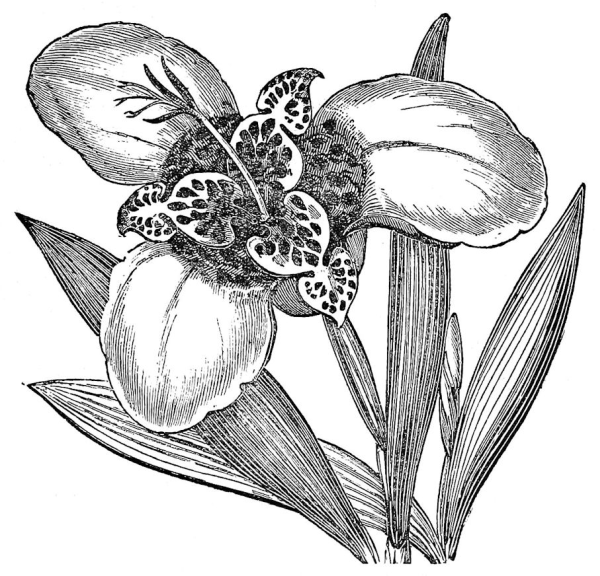

Tigridia pavonia, 85

Vieusseuxia glaucopis, 17

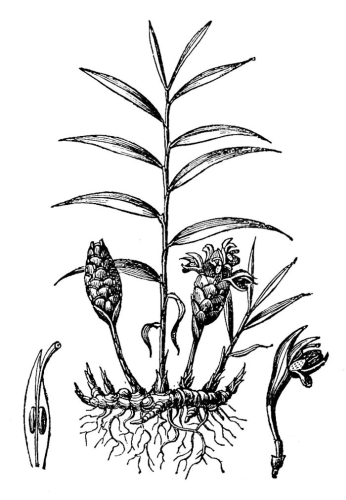

Zingiber Officinalis, 200

LATIN INDEX

TO

THE COLOURED FIGURES OF PLANTS

Alstrœmeria pelegrina alba, 199

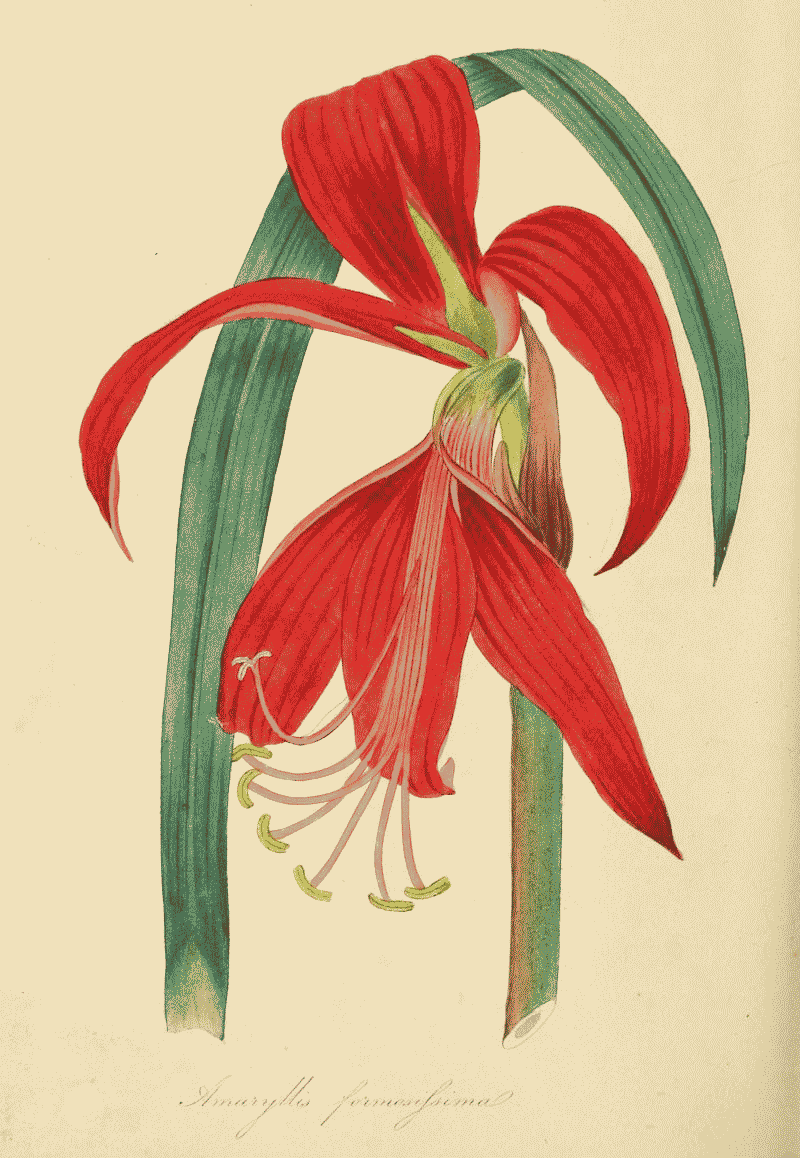

Amaryllis formosissima, 149

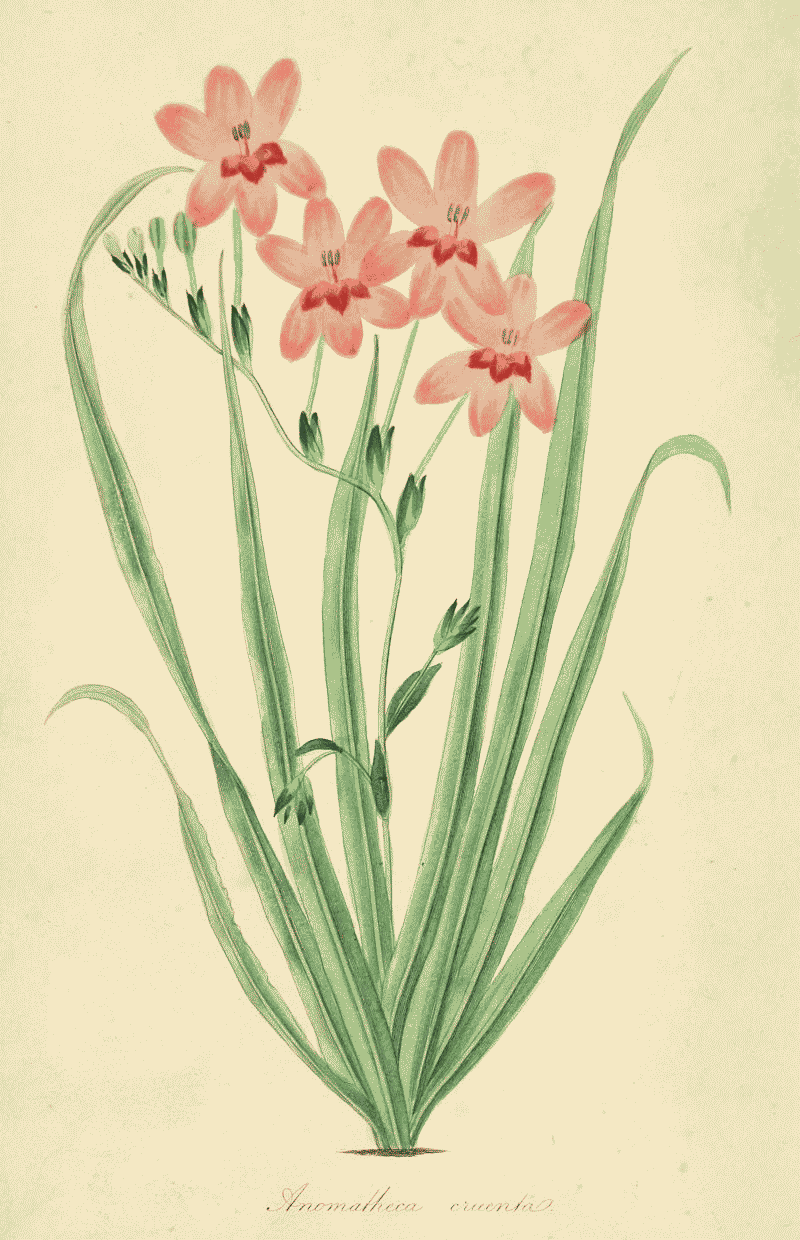

Anomatheca cruenta, 103

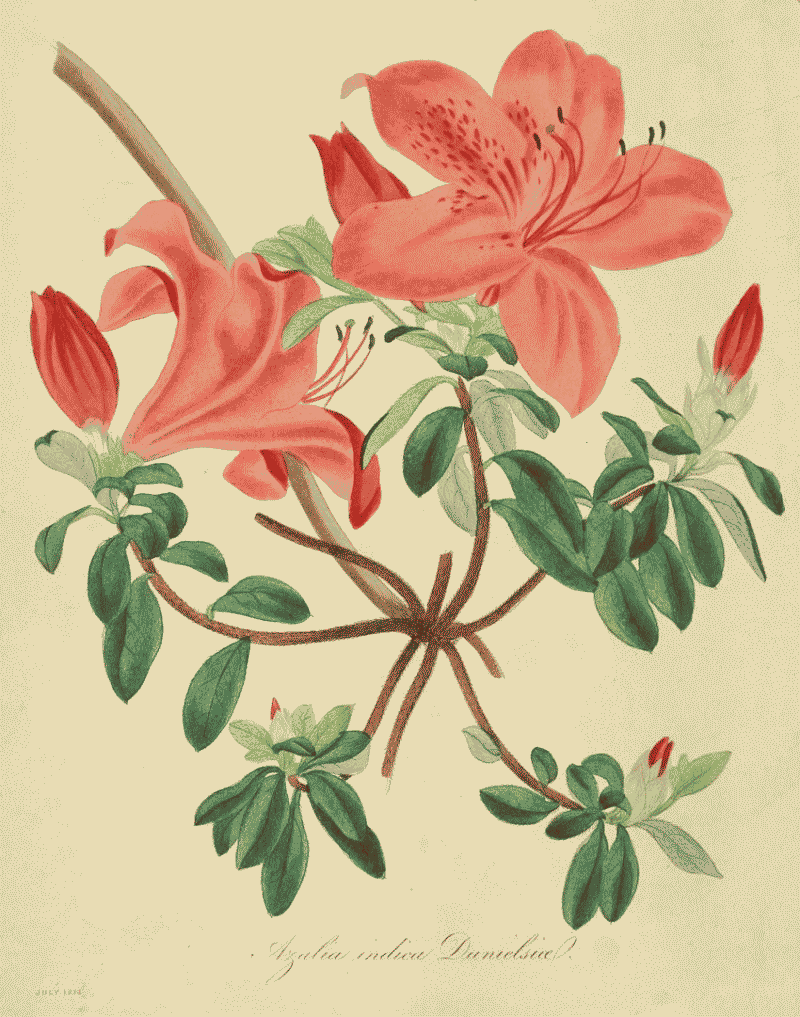

Azalea Danielsiana, 129

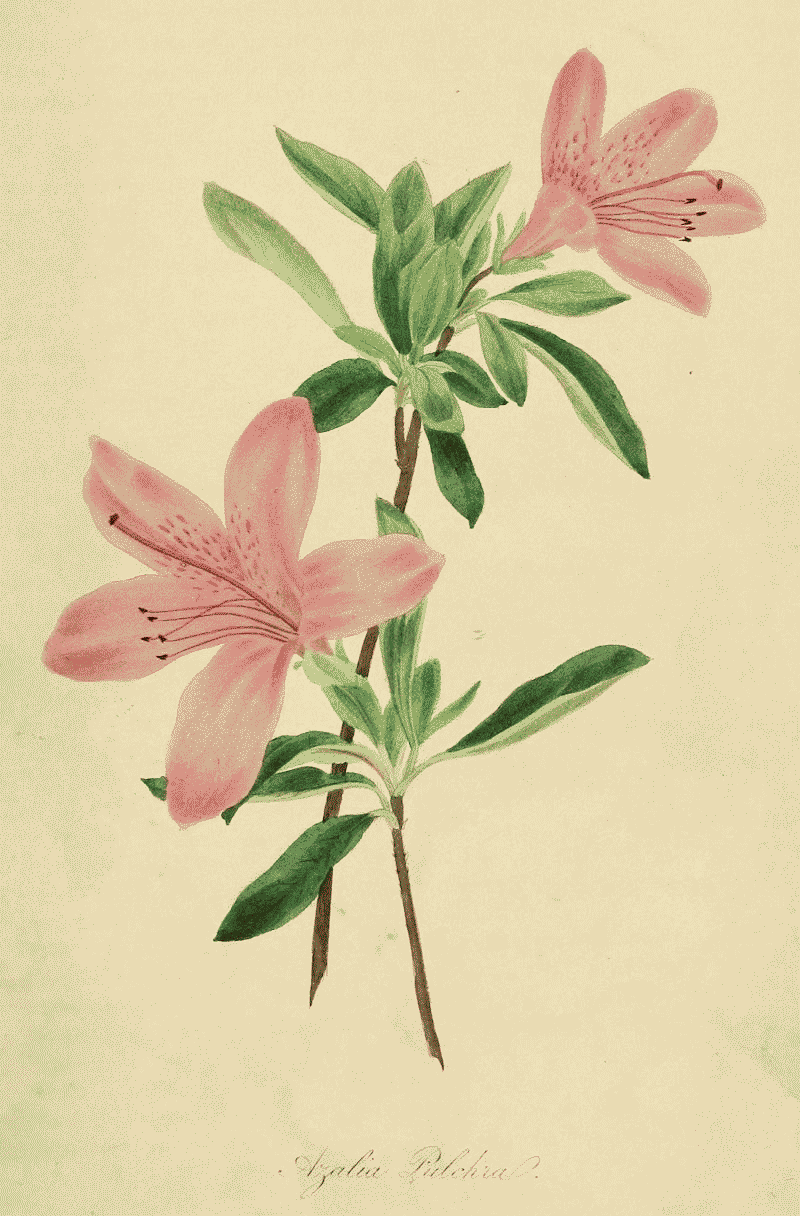

Azalea pulchra, 126

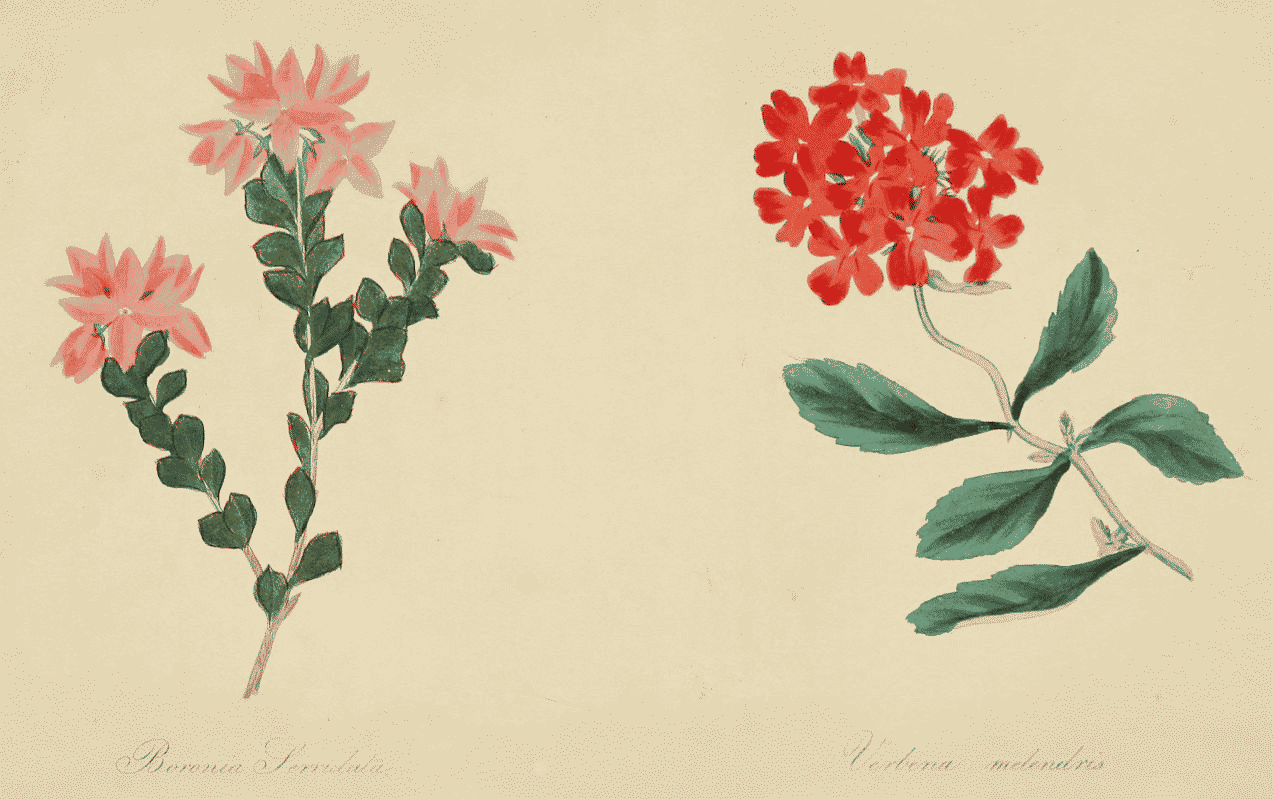

Boronia serrulata, 173

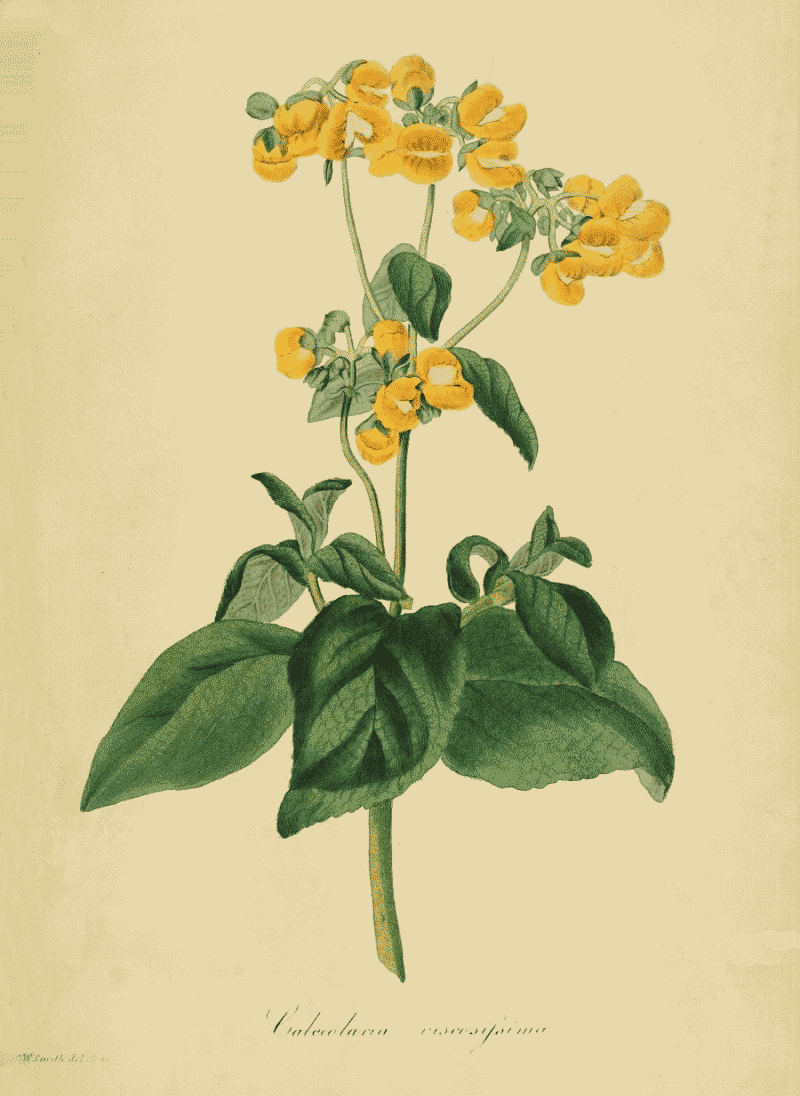

Calceolaria bicolor, 246

Calceolaria integrifolia viscosissima, 269

Calochortus luteus, 221

Calochortus venustus, 175

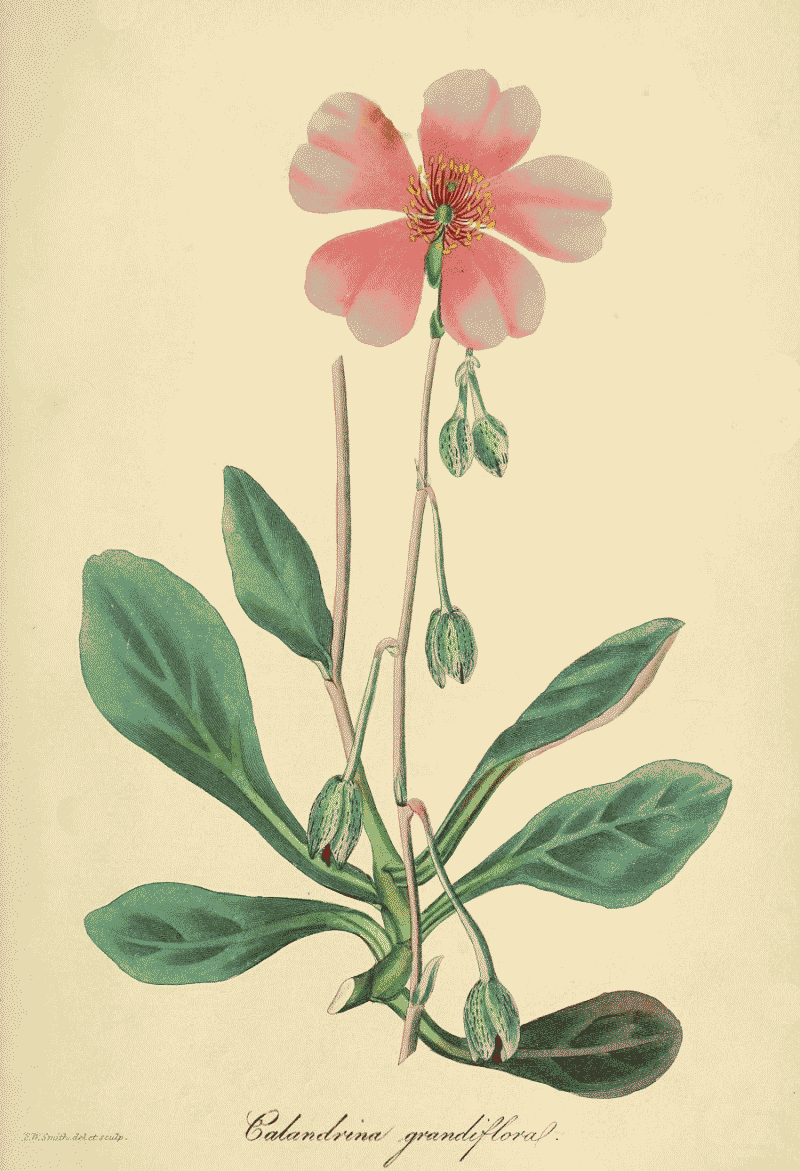

Calandrinia grandiflora, 222

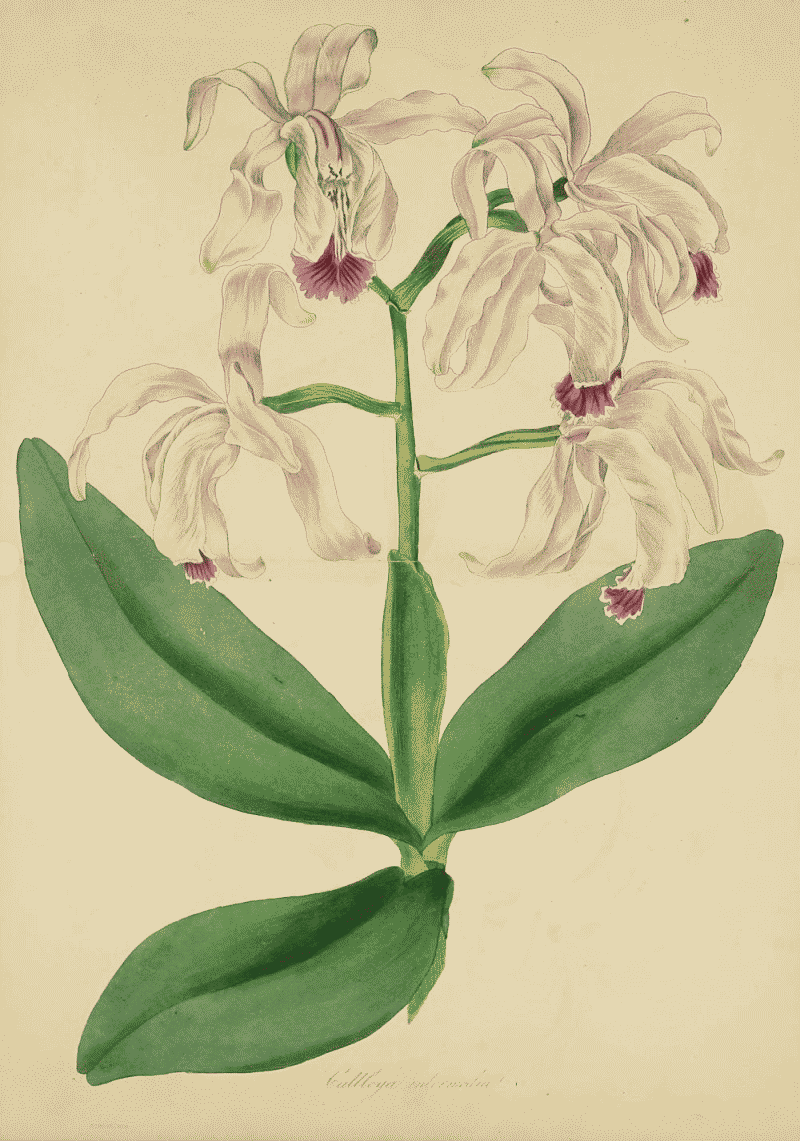

Cattleya intermedia, 151

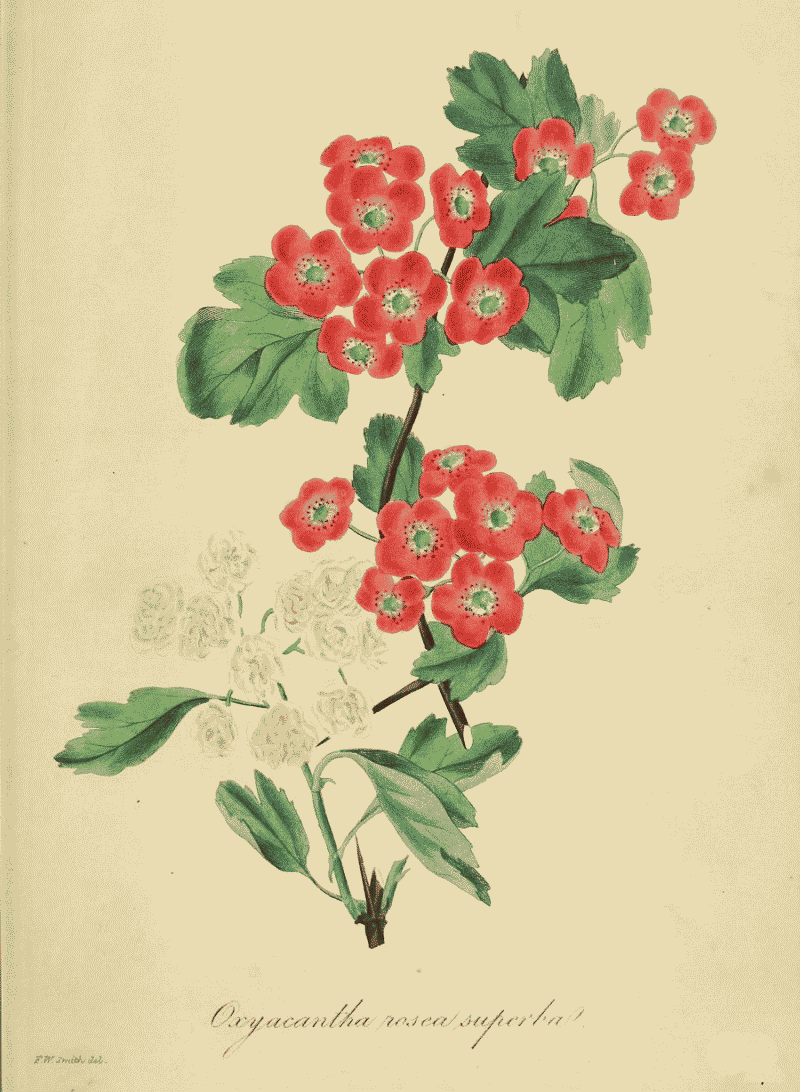

Cratægus Oxyacantha rosea, 198

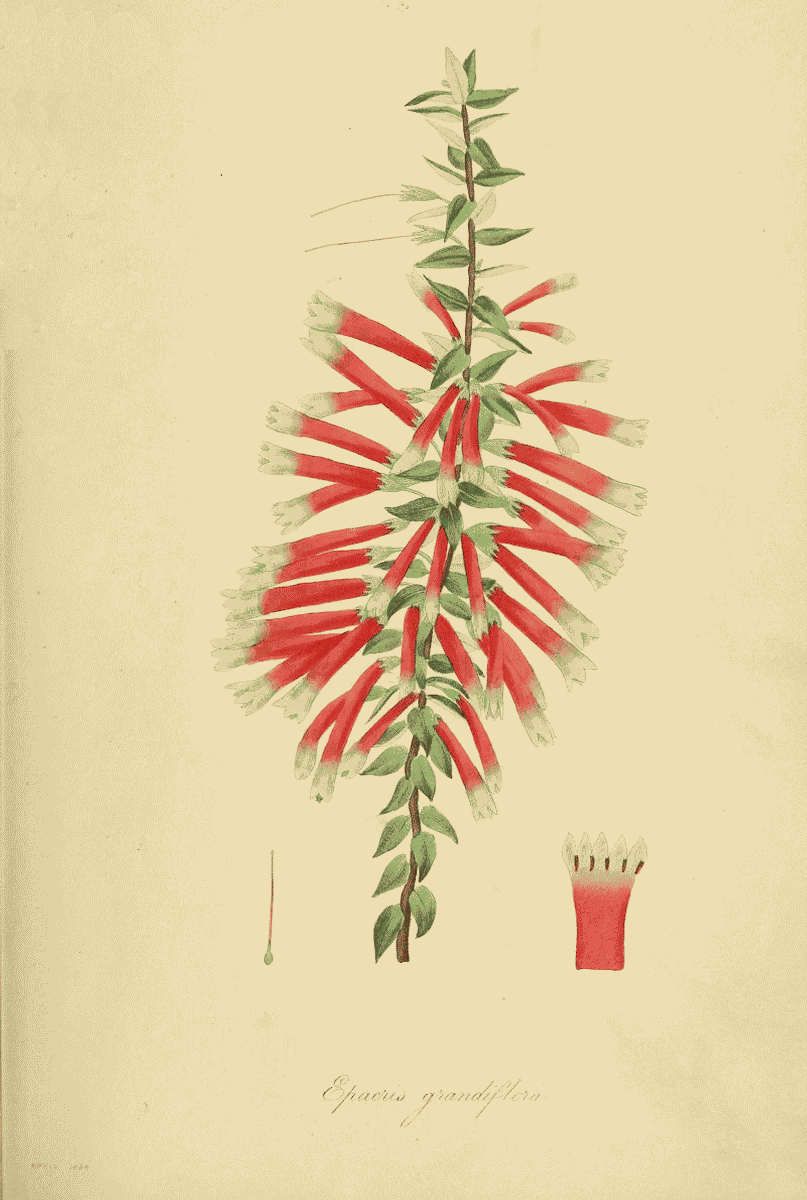

Epacris grandiflora, 52

Epiphyllum splendidum, 49

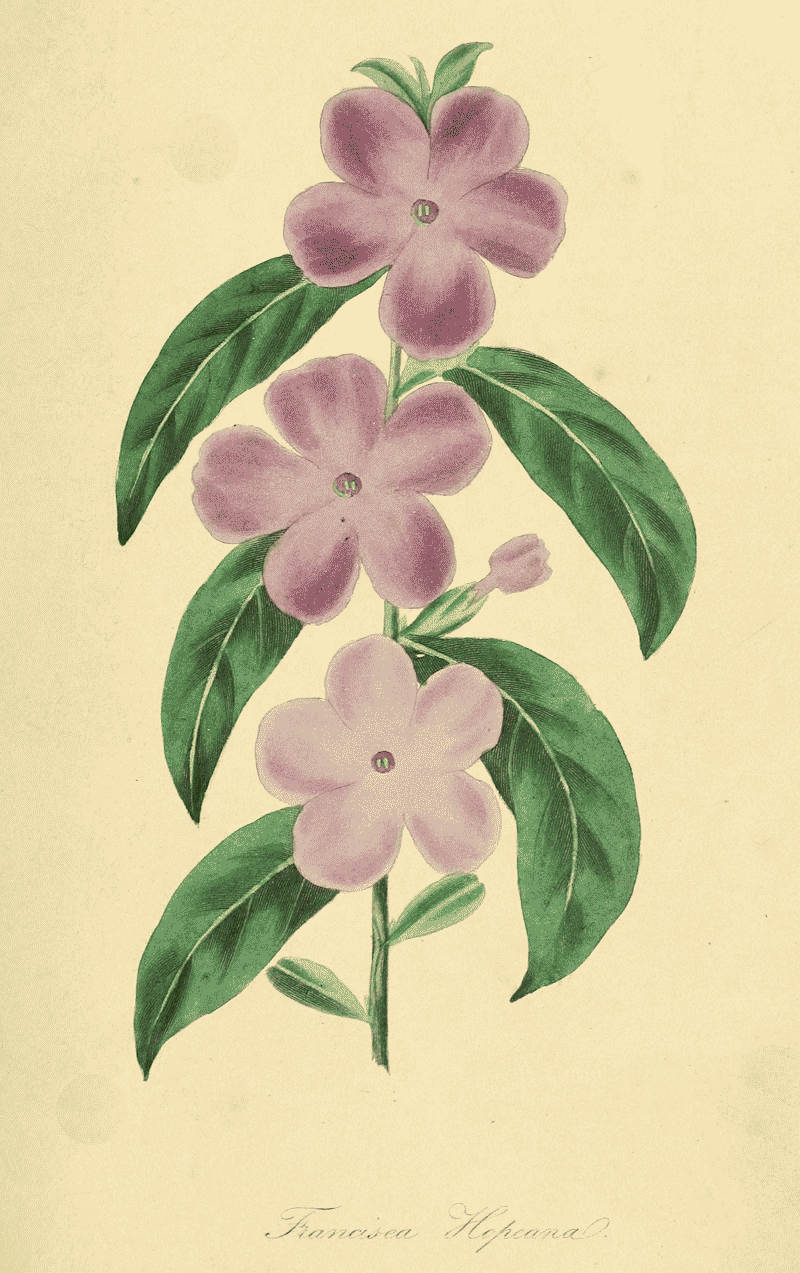

Francisea Hopeana, 80

Gesneria Cooperi, 224

Gilia Achillæfolia, 150

Gilia tricolor, 150

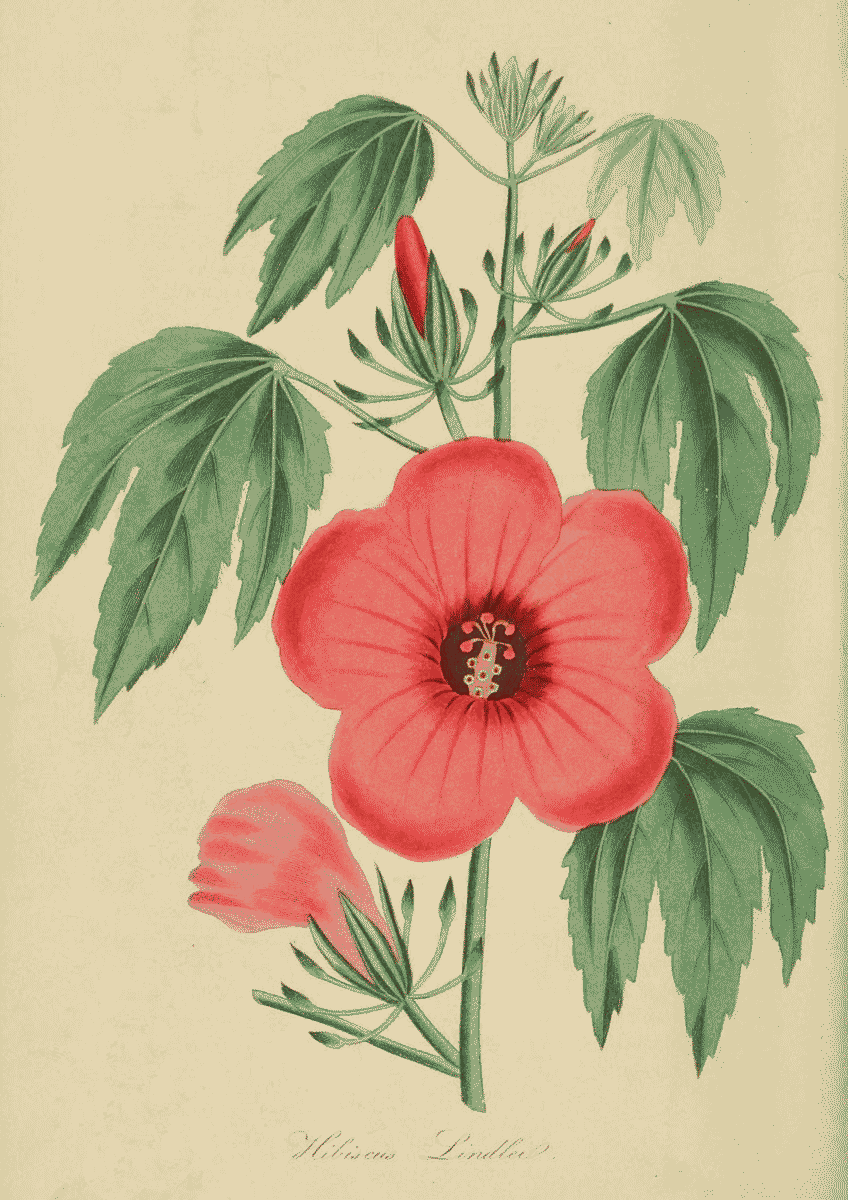

Hibiscus Lindlei, 77

Ipomopsis elegans, 27

Ipomopsis picta, 245

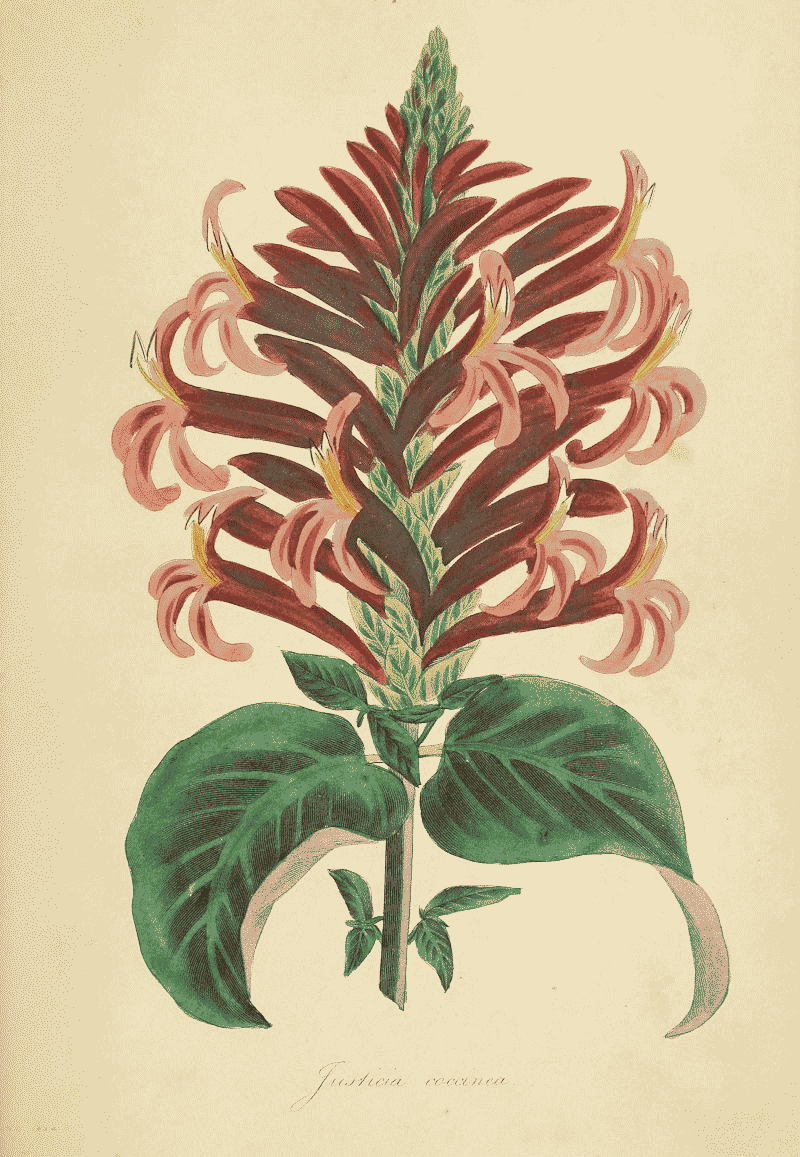

Justicia coccinea, 102

Kæmpferia rotunda, 125

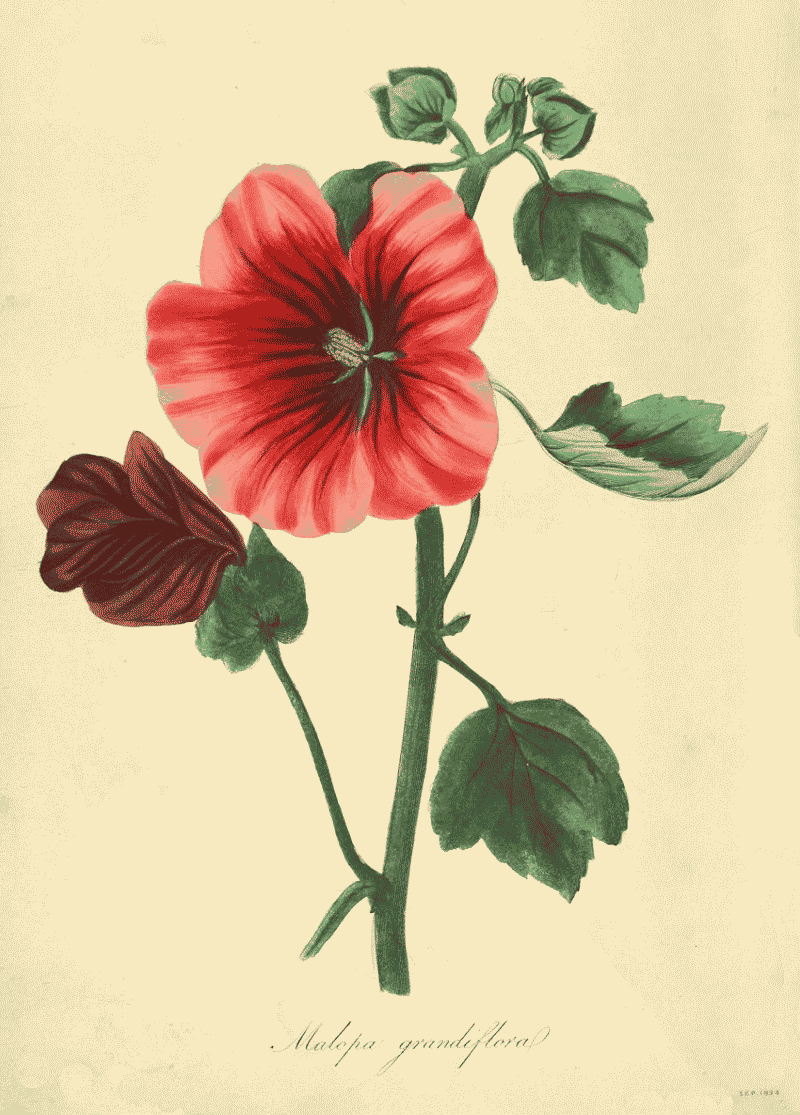

Malop trifida grandiflora, 177

Marica cærulea, 128

Marica Sabini, 81

Mimulus roseus, 29

Mimulus Smithii, 54

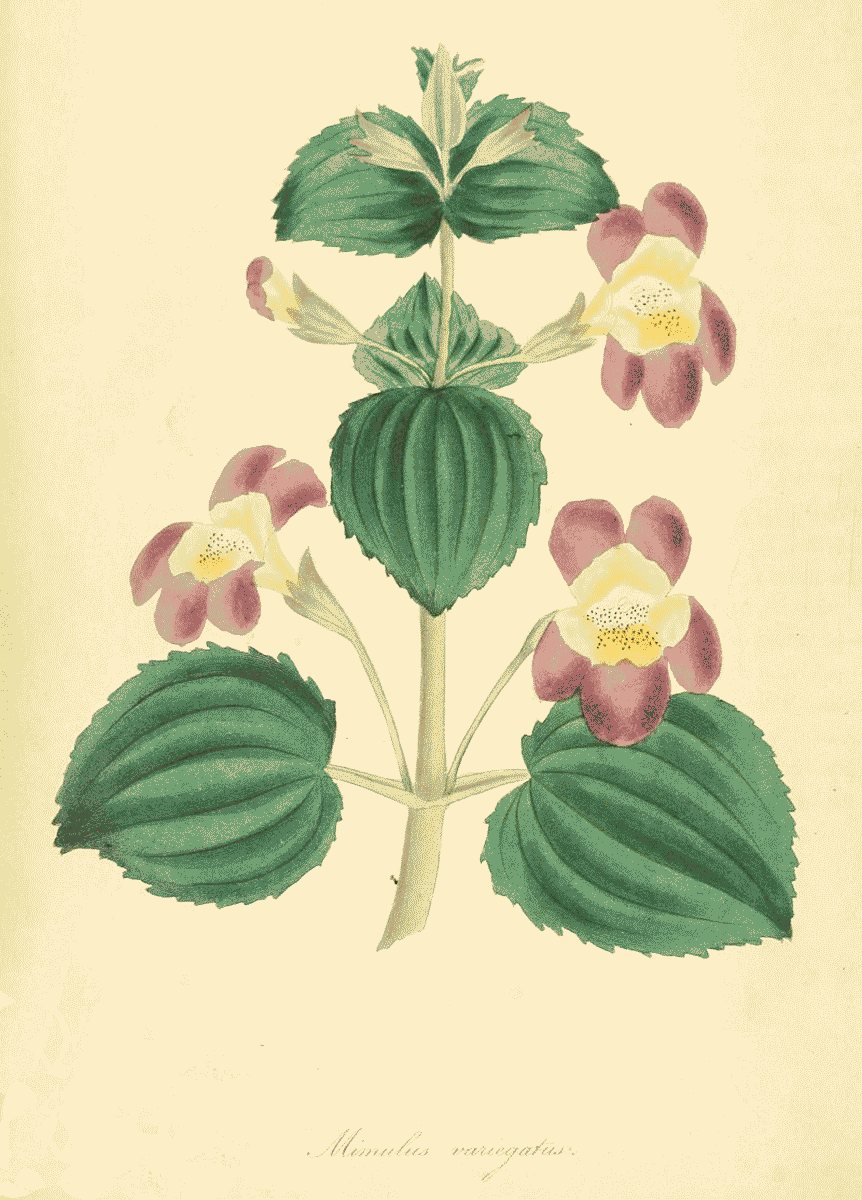

Mimulus variegatus, 79

Pæonia edulis Reevesiana, 197

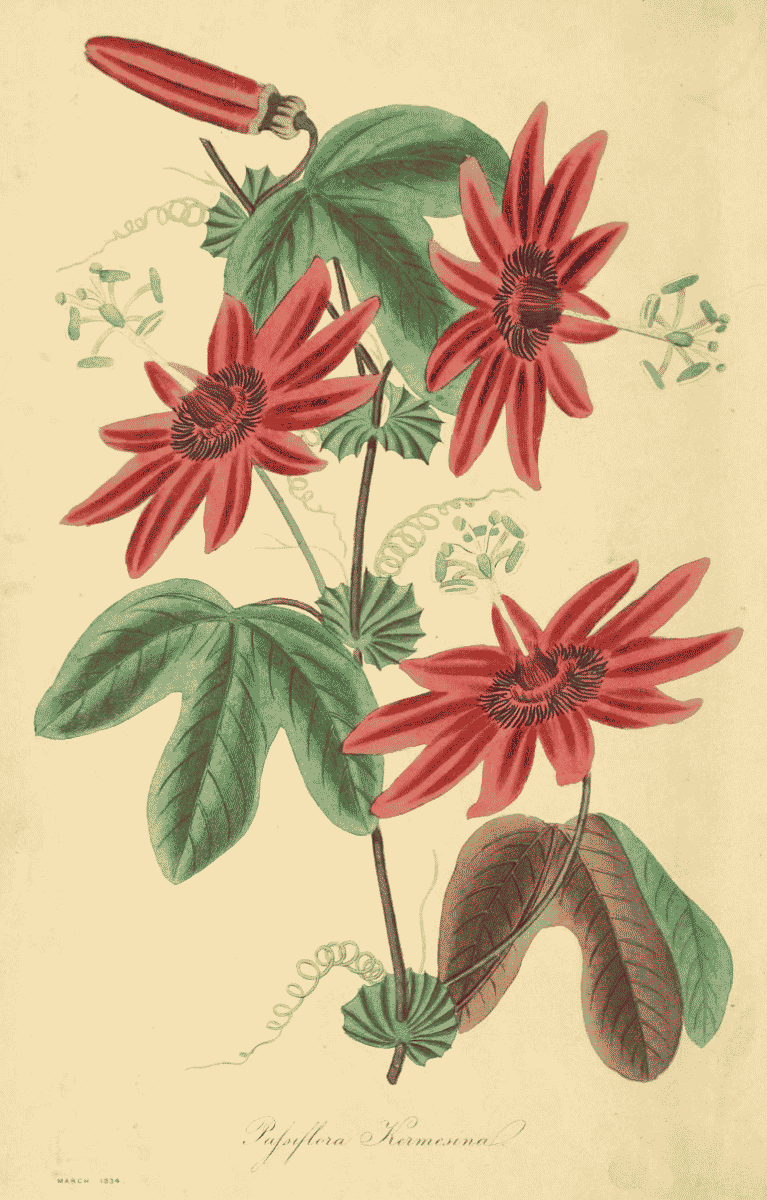

Passiflora Kermesina, 25

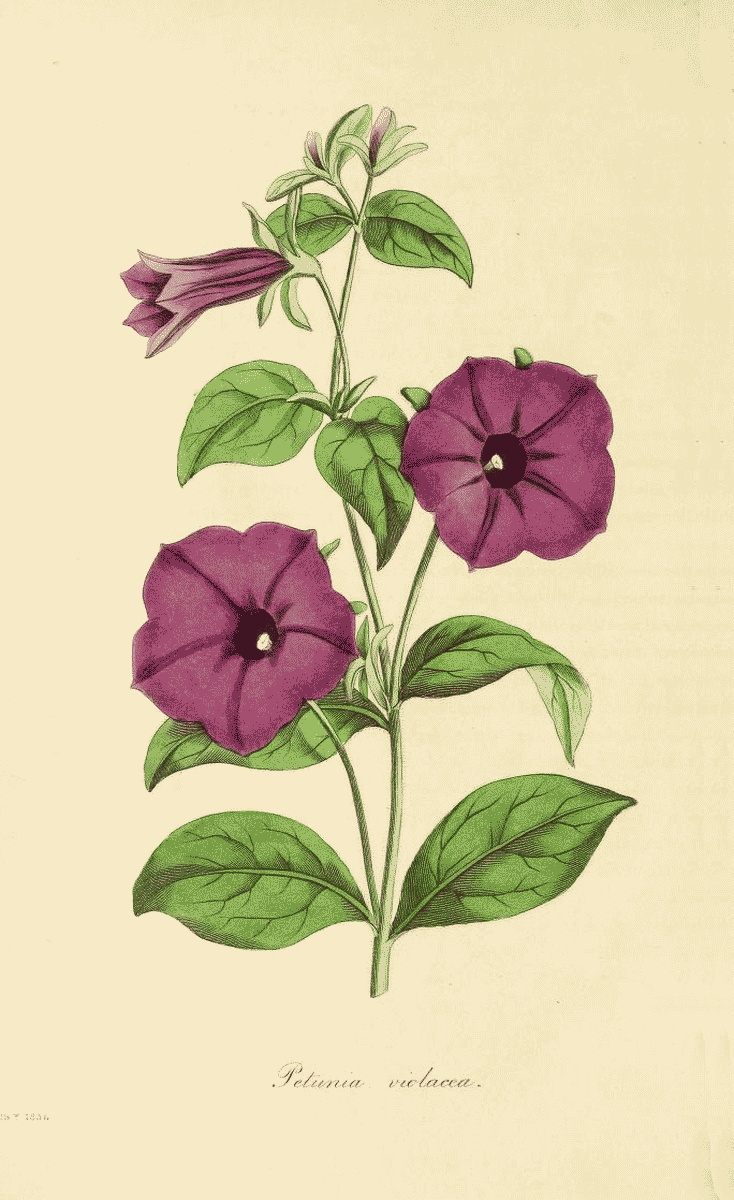

Petunia violacea, 7

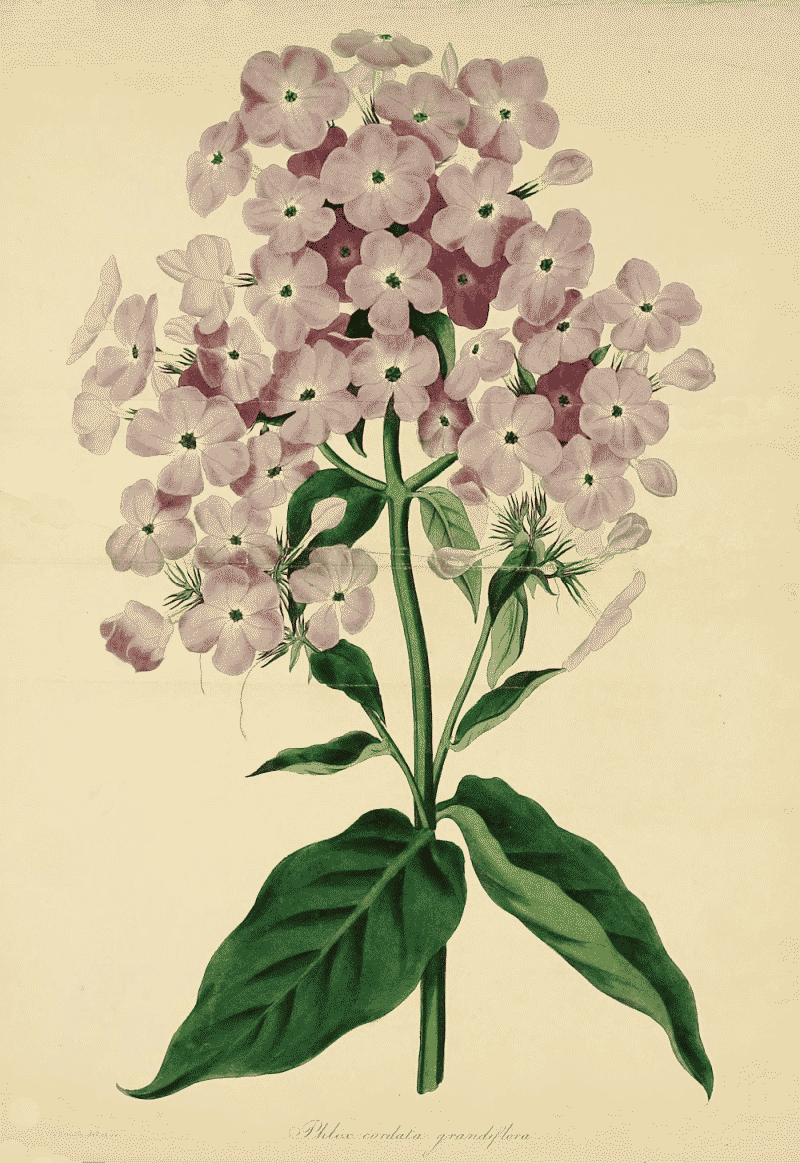

Phlox cordata grandiflora, 268

Rhododendron arboreum, 101

Rhododendron pulchrum, 126

Ribes sanguineum, 3

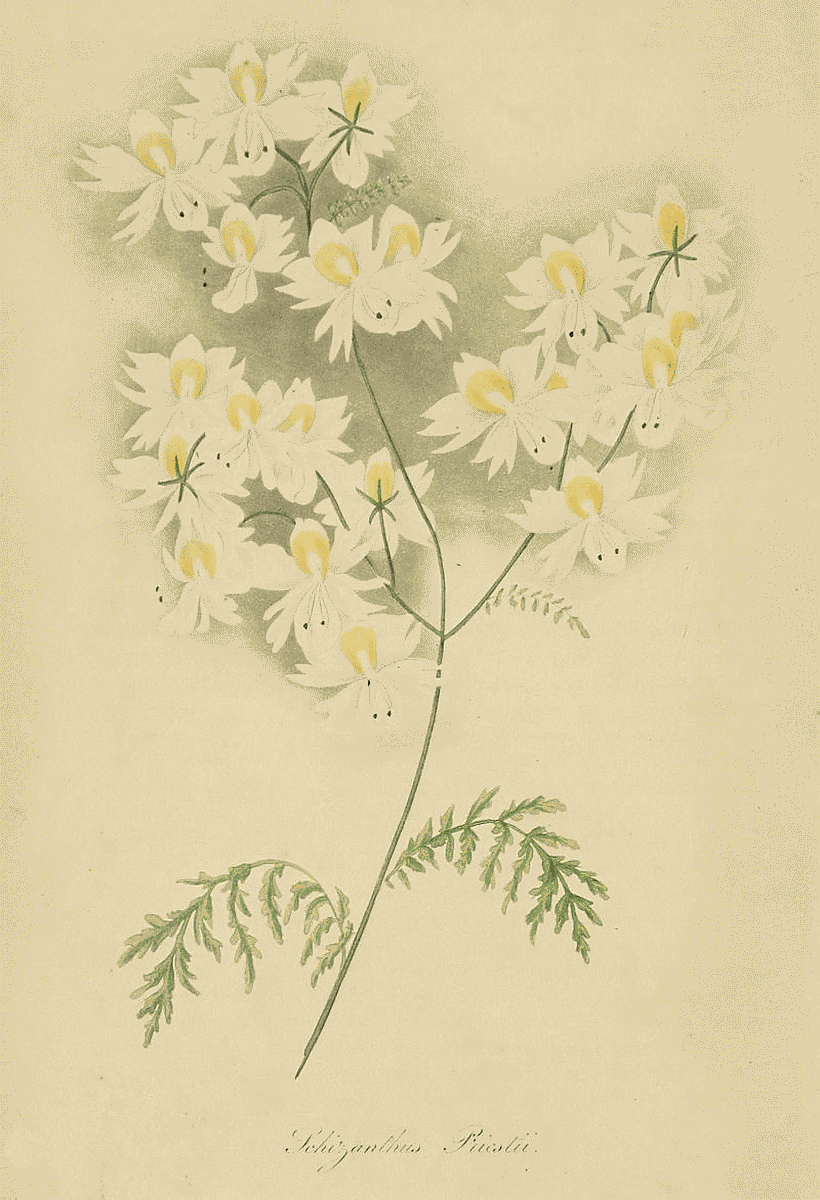

Schizanthus Priestii, 31

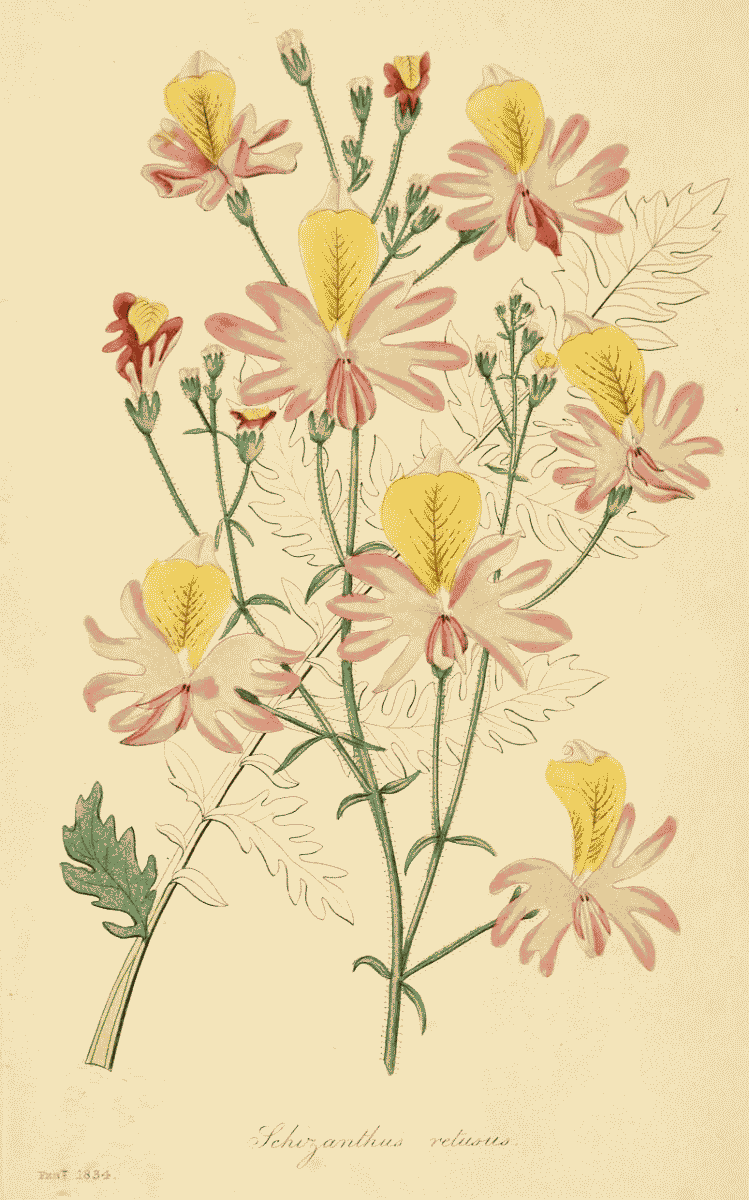

Schizanthus retusus, 5

Silene laciniata, 267

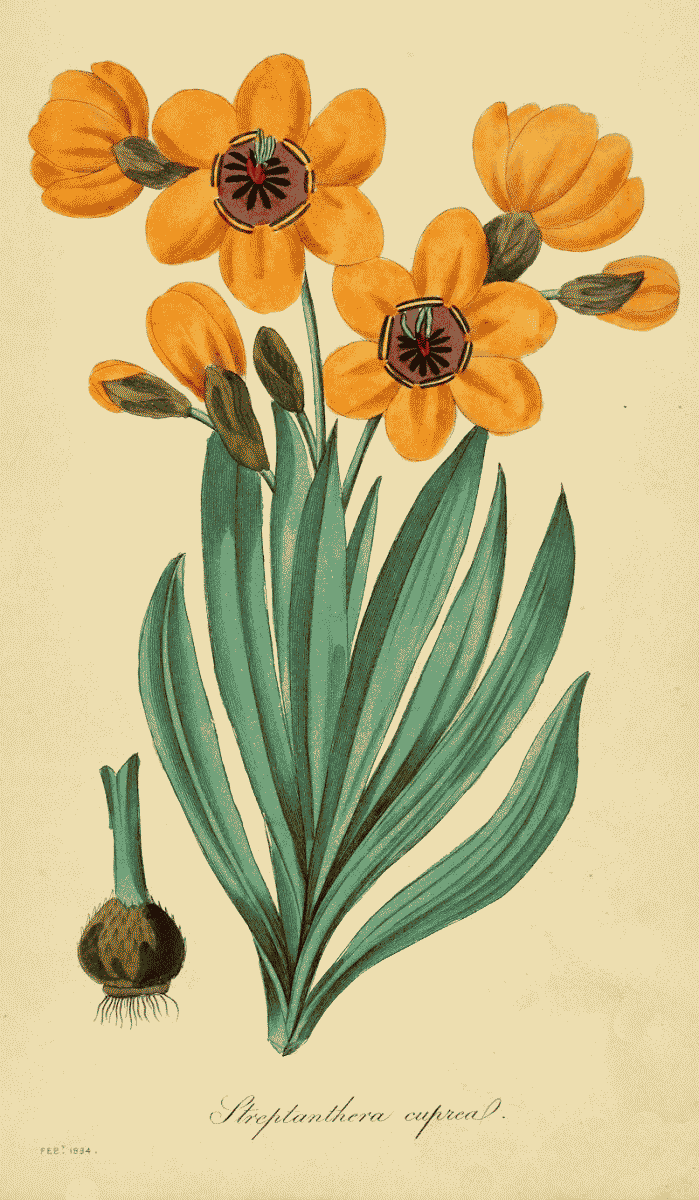

Streptanthera cuprea, 8

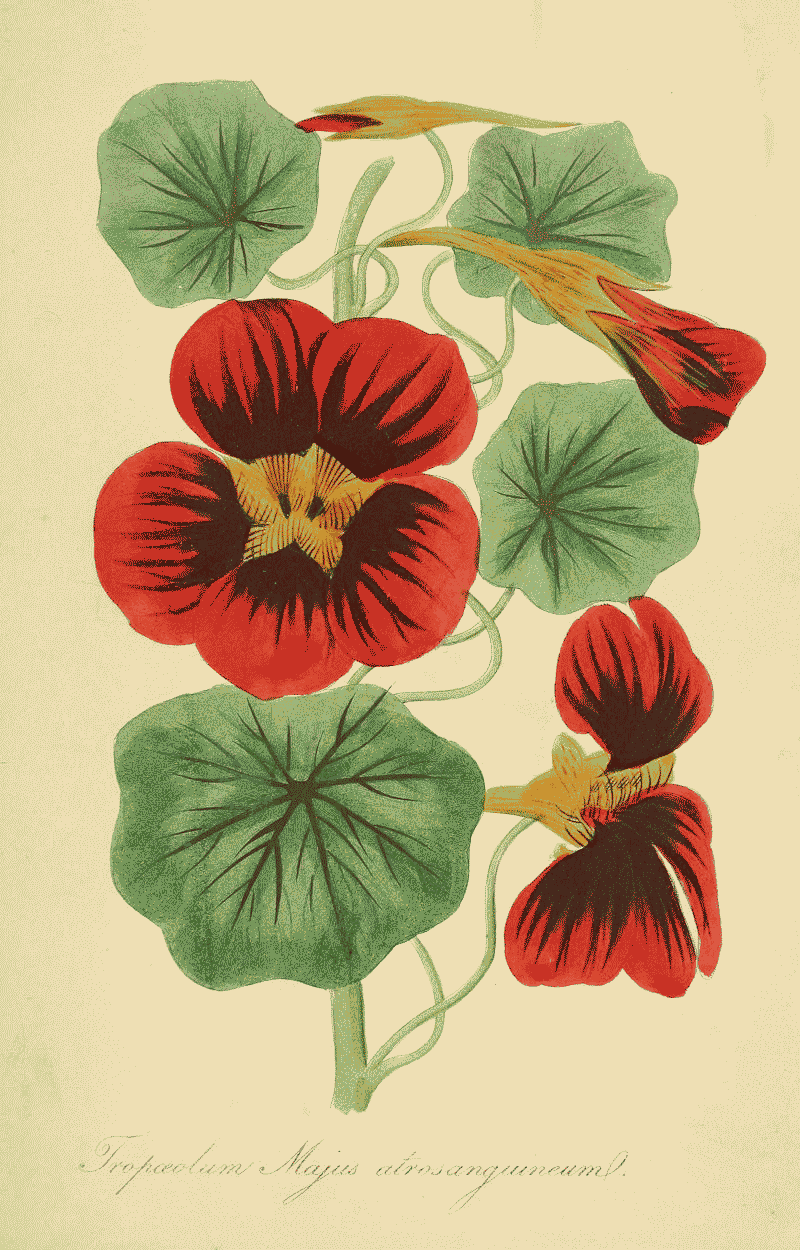

Tropæolum majus atrosanguineum, 176

Verbena Melindres, 173

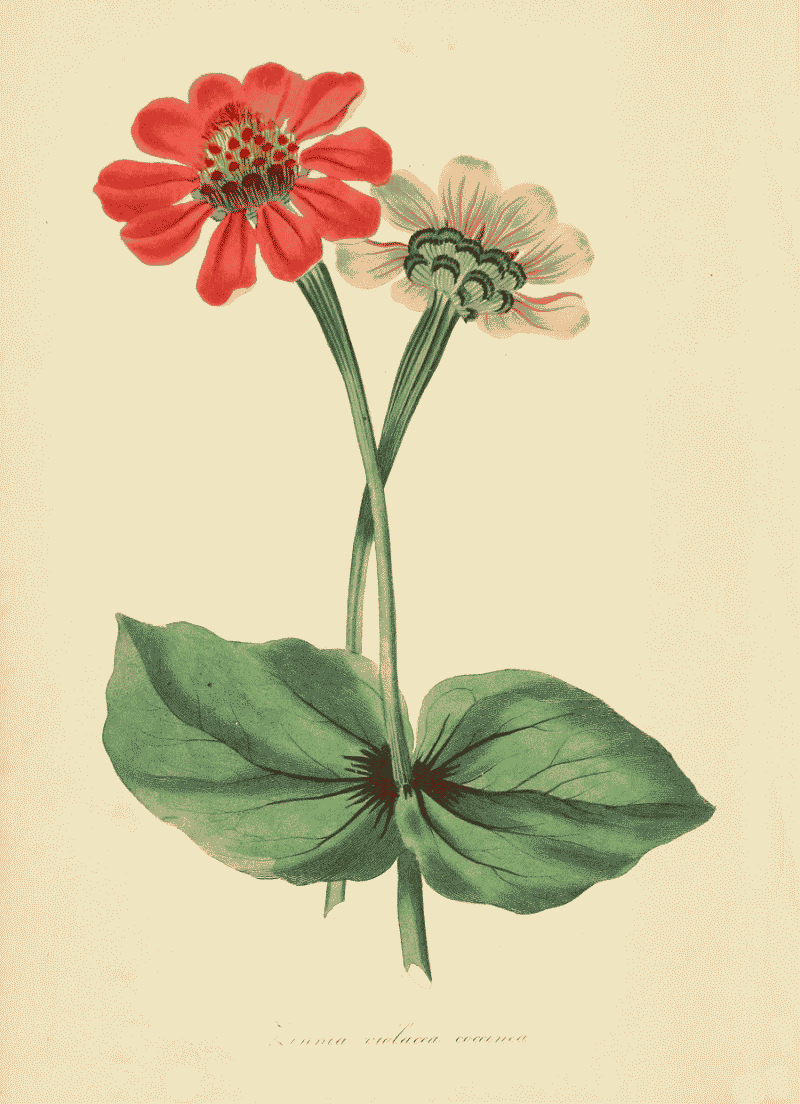

Zinnia violacea coccinea, 223

ENGLISH INDEX

TO

THE COLOURED FIGURES OF PLANTS.

Alstrœmeria, white variety of spotted flowered, 199

Anomatheca, blood-spotted, 103

Azalea, Mrs. Captain Daniels’, 129

Azalea, pretty, 126

Boronia, saw-leaved, 173

Calandrinia, great-flowered, 222

Calochortus, beautiful, 221

Calochortus, yellow-flowered, 175

Cattleya, middle-flowered, 151

Currant, red-flowering, 3

Epacris, great-flowered, 52

Epiphyllum, splendid-flowering, 49

Francisea, one-flowered, 80

Galangale, round-rooted, 125

Gilia, three-coloured, 150

Gilia, milfoil-leaved, 150

Gesneria, Mr. Cooper’s, 224

Hawthorn, dark rose-coloured, 198

Hibiscus, Mr. Lindley’s, 77

Indian Cress, dark red, 176

Ipomopsis, painted flowered, 245

Ipomopsis, elegant flowered, 27

Jacobea Lily, 149

Justicia, scarlet-flowering, 102

Lychnidea, large flowered cordate, 268

Malope, great-flowered, 177

Marica, Captain Sabine’s, 81

Marica, blue-flowering, 128

Monkey Flower, rosy-flowered, 29

Monkey Flower, Mr. Smith’s, 54

Monkey Flower, variegated, 79

Passion Flower, crimson, 25

Petunia, purple-flowered, 7

Pæony, Reeves’, 197

Rose Bay Tree, 101

Rose Bay, pretty flowered, 126

Schizanthus, blunt-petalled, 5

Schizanthus, Mr. Priest’s, 31

Slipper wort, two-coloured, 246

Slipper wort, very viscous, 269

Streptanthera, copper-coloured, 8

Tacsonia pinnatistipula, 249

Vervain, scarlet-flowering, 173

Zinnia, scarlet flowered, 223

INTRODUCTION.

From time immemorial Flowering Plants have been objects of especial care and delight; but probably at no period was there a greater interest exhibited, both as regards the introduction of new ones, or the cultivation of those we already possess, than at the present. Botanical collections are to be found in almost every part of the globe, from the torrid regions of India to the cold and icy poles.

In consequence of these exertions great numbers of new plants are annually introduced; and in a few years, should these additions continue, our present extensive collections will appear comparatively scanty and meagre.

That these valuable introductions may be rendered of general utility, several splendid botanical works, containing coloured figures, are published periodically; and during the past year nearly two hundred new plants have been figured in them, some of which are exceedingly beautiful.

This regular annual increase, added to the stock already in this country (nearly thirty thousand), does not merely swell the size of our botanical catalogue, but renders indispensable the existence of a work which will be an unerring guide in the selection and nurture of such as are worthy of extensive cultivation; and yet of so low a price as to be within the reach of all classes.

This selection, it is true, might be made from the botanical works already in course of publication; but, it must be confessed, the high price of these places them beyond the reach of most flower cultivators: while the cheap periodicals, although unobjectionable in this respect, are manifestly defective in other points of greater importance; the plates they contain bearing but little resemblance to the plants they are intended to represent.

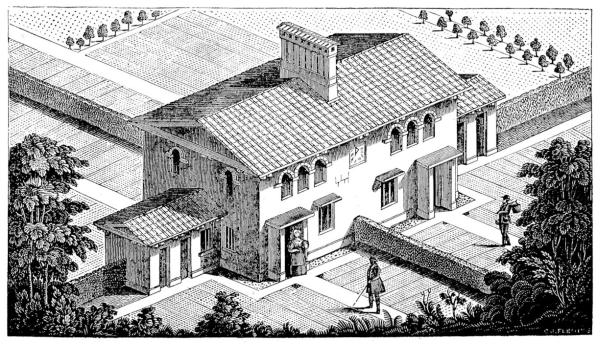

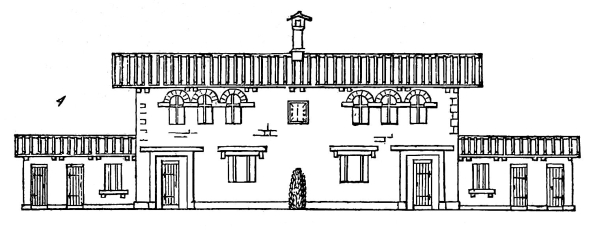

To obviate these objections, each Number of the Magazine of Botany will contain Four Engravings of Plants, of the natural size, beautifully coloured, from original Drawings. The letter-press will be illustrated by numerous Wood-cuts of Plans of Flower Gardens, Elevations of Garden Structures, Utensils and Instruments necessary for Florists and others who take delight in the cultivation of Flowers: and also of Figures representing the practical operations necessary for the proper management and full development of their several beauties; without which figures it is hardly possible to render intelligible the peculiar and requisite mode of operation.

The text will comprise Botanical Descriptions of the Plants figured; the Time of their Introduction; the best Mode of Culture; and every other particular essential to their perfect growth. Every beautiful plant, newly introduced, if considered worthy of notice and general cultivation, will be described, and, if of sufficient importance, accurately figured.

As great confusion often exists amongst cultivators, in consequence of our very eminent Botanists so frequently changing the names of Plants after their introduction, great care will be taken to constantly adhere to the names first given, if at all consistent. In some cases the change is indispensable.

Each Number will also contain a Calendar of the Work to be done in each Month in the Flower Garden, including Descriptions of all kinds of Insects which infest Flowers, with the most efficient methods for destroying them, or preventing their depredations; together with such other information as is requisite for the successful propagation of Plants.

The object of the author being to render the work practically useful, and one on which implicit reliance may be placed, the modes of culture recommended will be given from his own daily experience and observation. And as a medium of conveying sound practical instruction,—its utility increased by the beauty of its illustrations,—he hopes to render it deservedly popular with every one interested in this highly pleasing and interesting pursuit.

Chatsworth,

January, 1834.

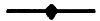

Ribes sanguineum.

| CLASS. | ORDER. | |

| PENTANDRIA. | MONOGYNIA. | |

| NATURAL ORDER. | ||

| GROSSULACEÆ. |

Generic Character.—Calyx superior, in 5 coloured divisions. Corolla, petals 5, inserted in the top of the calyx. Stamina 5, inserted opposite to the petals; Anthers compressed, and inclining. Germen simple; style 1; Stigmas 2; berry round, umbilicated, of one place, containing many seeds.—Lindl. in Bot. Reg.

Specific Character.—Leaves heart-shaped of from 3 to 5 serrated lobes, linearly veined, rough, above hairy, downy white beneath; branches flexible and nodding; flowers aggregated; petals oblong; bractea ovally spatulate, somewhat longer than the footstalk; ovarium covered with glandular hairs—D. Don, in Brit. Flower Garden.

This present species of Ribes far surpasses in beauty any of previous, or, we believe, of subsequent, introduction. It is a native of North-west America, and, according to Mr. Douglas, Archibald Menzies, Esq. discovered it near Nootka Sound in 1787, when on his first voyage round the world; and in 1792, on his second voyage with the celebrated Vancouver, he found it again in various parts of North-west America. From the time of its first discovery until its introduction in 1826, comparatively nothing was known of it in this country; but in the last mentioned time Mr. Douglas forwarded seeds to the Horticultural Society’s garden. He says it usually grows on rocky situations, or on the shingly shores of streams, in partially shaded situations.

It is perfectly hardy, and nearly as easy of culture as the common currant bush of our kitchen gardens; it requires to be planted in a dry situation and a light soil, when it produces abundance of beautiful purplish-red flowers about the beginning of May, and continues flowering for two or three weeks successively. It is increased by cuttings, after the manner of the common currant, which should be planted in light sandy soil, either in September (which is probably the best time) or in spring. The colours of this, as well as many other plants, are subject to considerable variation, some bearing flowers of a light rosy colour, others of a dark carmine, and others with deep purple tints. These variations are evidently the effects of situation, soil, and other circumstances; this we are the more confirmed in by observing the flowering of some plants at Chatsworth the last year, and we think there is little doubt but the remark of Mr. Douglas, in the Transactions of the Horticultural Society, vol. vii. part 4, may be perfectly correct—“That if the bushes were planted in soil having a portion of lime rubbish mixed with it, the blossoms would be more profuse, and probably of a deeper colour;” a circumstance he states to have observed in the limestone districts of its native woods.

Previous to the introduction of this species, the R. aureum was the favourite of this genus; it is certainly a pretty shrub, though very far inferior to the R. sanguineum. Its very easy culture, thriving in almost any situation, its numerous racemes of bright yellow flowers, and the peculiarly pleasant fragrance they emitted when in perfection, rendered it a desirable inhabitant of our gardens. In North America, its native country, it is highly prized for its fruit, which is said to be of an excellent quality, and superior in size to any of our common garden sorts, although in this country it rarely, if ever, produces fruit at all.

The generic name Ribes originated in the supposition that our currant and gooseberry were the plants to which the Arabian physicians of the eleventh and twelfth centuries gave the name of Ribas, but which has since been discovered to be a kind of rhubarb, called Rheum Ribes. The specific name, sanguineum, alludes to the colour of the flower, being purple-red or blood-colour.

Feby 1834.

Schizanthus retusus.

| CLASS. | ORDER. | |

| DIANDRIA. | MONOGYNIA. | |

| NATURAL ORDER. | ||

| SCROPHULARINEÆ. |

Generic Character.—Calyx 5-parted, somewhat unequal. Corolla, limb in 4 parts, lobed, irregular, plaited while expanding; tube narrow and short. Stamina 4, two upper ones barren, filaments all adnate. Anthers inserted below in two places, confluent at the top. Ovarium of 2 locaments placed on a smooth fleshy disk. Stigma compressed, obtuse, of 2 united lobes. Capsula of 2 places containing many seeds; valves divided. Dissepiments parallel. Placenta 2, spongy. Seeds simple, shell-like, having a hard wrinkled integument; albumen fleshy. Embryo arched; the rostel roundly obtuse and twice as long as the seed leaves.

Specific Character.—Fruit on footstalks erect; Corollæ tubes longer than the calyx; lips variously cut or slashed, middle one arrow-shaped, upper one somewhat square and abrupt.—D. Don, in Brit. Flower Garden.

This is without doubt the most strikingly beautiful species of Schizanthus that has yet appeared. We are indebted to Dr. Gillies for its introduction, who discovered it on the Chilian Andes, and sent seeds to the late Mr. Barclay, who raised the first plants in 1831 at Bury Hill. It is an annual of great beauty, and of tolerable easy culture, growing from seeds which ripen freely, if the plants be kept in an airy situation at the time of flowering.

Those intended for the principal flowering we would recommend to be sown the previous summer, or early in the autumn; and in February and March two more sowings should be made to succeed each other. The autumn sowings, or rather those of the previous summer, should be sown in the middle of July and beginning of August. Light rich mould is the most suitable for the purpose. As soon as the plants have formed two proper leaves, pot them in small sixty-sized pots, drained so as to allow the water to pass off freely. They should remain in these pots in a cool airy part of the green-house, or dry frame, during the winter; and about the beginning of March be shifted into pots a size larger, which shifting should be repeated as often as the roots reach to the sides of the pots. The soil should be composed of about equal parts of peat, well rotted dung, and light sandy loam.

Their roots are very tender, and easily injured; the first effects of injury visible, is the drooping of the leaves of the plants, as if for want of water, which is too often administered as a remedy: very shortly after drooping, the plant falls over the pot, the stem having cankered just above the soil. We have more than once experienced this; and as a remedy we recommend the pots to be very well drained, and the plants to be rather elevated in the centre of the pots, judicious waterings, and light soil.

Last year we made a sowing in May, from which we grew extraordinary fine plants, but only a few of them flowered, and those indifferently; we have, however, preserved about fifty fine plants, from which we anticipate a dazzling display of flowers in May or June. We kept them in a frame, and gave them abundance of air; they were shifted into larger pots about every fortnight or three weeks; and in September many of them threw up eight or ten fine flowering stems, but owing to the unfavourable weather in this part of the country, they did not come to perfection. We have not yet tried whether it will flower well in the open air, though we have little doubt but that it will grow equally well with other half-hardy annuals.

Mr. Hugh Cuming has lately discovered another beautiful sort, which is found to be a variety of the pinnatus, and is therefore named pinnatus humilis; this and all the other species may have similar treatment to the retusus. If planted in the borders, always select situations where they will be dry and airy, but not exposed to strong winds.

The generic name is derived from the Greek words schizo, to cut, and anthos, a flower, alluding to the flowers having the appearance of being deeply cut.

J. P.

Feby. 1834.

Petunia violacea.

| CLASS. | ORDER. | |

| PENTANDRIA. | MONOGYNIA. | |

| NATURAL ORDER. | ||

| SOLANEÆ. |

Generic Character.—Calyx, shortly tubular, leafy, leaflets lacinated. Corolla, tube cylindrical, bellying, limb plaited and divided into 5 unequal lobes. Stamina 5 unequal, inserted in the middle and within the tube of the corolla. Ovarium on a disk having one tooth on each side. Stigma capitate. Capsula with 2 valves. Seeds spherical and netted.

Specific Character.—Stems prostrate, clammy and hairy; leaves oval, with short footstalks. Corolla bellying, lips cut into sharp divisions.—Lindl. in Bot. Reg.

There are few plants in our gardens which surpass this in brilliancy of blossoms and general beauty. It is a native of Buenos Ayres, from whence seeds were sent to the Glasgow Botanic Garden, in 1830, by Mr. Tweedie. It succeeds extremely well in the open border, during summer, but must be treated as a hardy green-house plant in winter; the flowers show to the greatest advantage if a whole bed be devoted to them, and where the branches are allowed to spread over the whole surface, and become entangled with each other. Under these circumstances the flowers will be produced from July until the end of October, or, at least, as long as the weather will permit. Some beds so planted at Chatsworth, last summer, had a very splendid appearance: if trained under a wall or to a trellis, it is also a great ornament. Whether planted in a bed or trained on trellis, it is necessary that the situation be somewhat sheltered from winds, but fully exposed to the influence of the sun.

Cultivated in a green-house, we would recommend it always to be trained to trellis; where, as was the case with some in our houses last year, it will extend from four to six feet square, continue flowering until quite winter, and commence again early in spring.

It thrives in almost any sort of soil, but prefers one that is rich and light. It produces seeds by which it may be increased, but also grows very freely from cuttings, which may be taken off at almost any season, and planted, and otherwise treated, like those of Geraniums.

The generic name is derived from petum, a Brazilian name for one of the species.

| CLASS. | ORDER. | |

| TRIANDRIA. | MONOGYNIA. | |

| NATURAL ORDER. | ||

| IRIDEÆ. |

Generic Character.—Spatha of 2 valves, membranaceous, somewhat cut, dry. Perianthemum like a corolla in 6 divisions; tube very short; limbs regularly wheeled. Stamina 3, inserted in the tube; filaments erect; anthers twisted round and including the style. Stigmata 3, dilated into 2 fringed lobes. Seeds round.

Specific Character.—Leaves sword-shaped, acute, channelled and cut in the middle. Flower stem bearing from 2 to 4 flowers. Perianthii cut ovately obtuse; keel having two spots upon the base.—Sweet, in Brit. Flower Garden.

This is a very elegant species, introduced in 1825 by Mr. Synnot, from the Cape of Good Hope. The generic name is derived from streptos, twisted, anthera, anther, alluding to the twisted form of the anthers; and the specific name is given in consequence of the copper colour of the flowers. All the Cape Irideæ require one general mode of treatment, which, with a few exceptions, may be stated as follows:—

1. Pot the roots, or plant them in a border in front of a stove or green-house, or other sheltered place, during the month of October. Let the soil be composed of equal parts of leaf-mould, sandy loam, and peat, well mixed.

2. If planted in pots, set them in a cold frame, and protect them from severe weather, till the pots are pretty well filled with roots; then remove them to the green-house, or room where they are intended to flower.

3. When potted they must be watered very sparingly, until they have produced leaves and begin to show their flower stems. And after flowering, when the leaves are dead, keep the roots perfectly dry in the pots. If planted in a border or frame, they must be completely preserved from rains, snow, or frost, particularly during their dormant state: in the former case a good thickness of litter will answer the purpose; and in the latter, the frame may be covered with lights.

4. The usual flowering season is April, May, and June, but some species flower somewhat earlier, others later. The plants at that time require to stand in light airy places, and should receive a good supply of water.

5. It is not well to take up the bulbs in less than two or three years, at which times all the offsets should be taken off; but such as are in pots, must be invariably repotted every October.

No person who cultivates Cape bulbs should be without Streptanthera cuprea and elegans; Sparaxis lineata, grandiflora and tricolor; Ixia Heleni, flexuosa, and viridiflora; Trichonema rosea, and some others.

Feby. 1834.

Streptanthera cupreal.

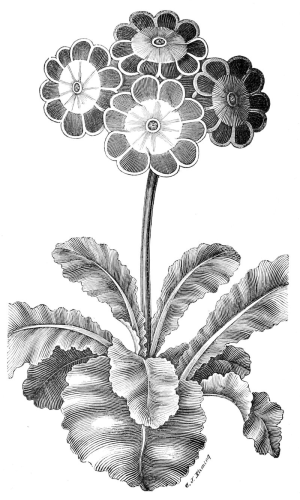

It is evidently as important for a cultivator to know the climate and altitude natural to a plant, as the soil in which it will grow; for if the latter be ever so suitable, and the temperament be not agreeable, the plant will never grow to any degree of perfection. The name Primula is derived from primus, first, in allusion to its early flowering, and Auricula, from auris, an ear, on account of the leaves resembling the ears of an animal. It is a native of the mountains of Switzerland, Austria, Syria, and the Caucasus.

With regard to the culture, daily observation has convinced us that a plain and simple mode of treatment is the best for all plants, providing they thrive and flower well in the use of it. “Strong stimulative manures, however beneficial they may be for the time, in producing large flowers and vivid colours, too frequently leave the plants in a state of exhaustion, if not of premature and gradual decay[1].” With this view of the subject we will describe the mode of cultivating auriculas, under fifteen heads:—

[1] Hogg’s Supplement on Horticulture.

1. With regard to a suitable soil, those persons who use only such as is rich, wholesome, porous, and of simple mixture, usually have the best success. Bone dust is an excellent ingredient, and its decomposition being slow, the volatile alkali passes off slowly, which is very advantageous, because the stimulus is of long continuance. Some good new turfy loam, well rotted, mixed with one fourth of vegetable mould, either made from leaves, or gathered from the interior of a hollow tree; one fourth well rotted dung, one eighth river sand, and a portion of bone dust, are all the ingredients necessary to grow them to the greatest perfection. In using bone dust a very small portion of lime will be of great utility mixed with it in the soil, as the animal matter will by this means be decomposed, and immediately fitted for the use of plants. This, must, however, be in a very small proportion, or it will be injurious.

2. All auriculas, to be grown to perfection, must, previous to flowering, stand in an airy, sunny situation; but afterwards, that is, from the end of May to the beginning of September, in one somewhat shaded.

3. From the beginning of September to the end of April, the plants must be sheltered, in a frame or brick pit, sunk or built two feet below the level of the ground; so that when placed upon a platform of boards six inches from the floor, and in flower, they will not reach higher than the surrounding surface. This frame or pit should be covered with wooden shutters, instead of glass lights, to secure the plants from the effects of sudden frosts during the night.

4. Never allow auriculas, either before, at the time of, or after, flowering, to be exposed to heavy dashing rains. When the flower stems begin to rise in February, they may be exposed now and then to a gentle shower, but after the flowers begin to expand, this practice must be discontinued; and be repeated again, but seldom, after they have done flowering until the succeeding February, watered carefully with a small watering-pot, and the leaves kept as dry as possible.

5. Auriculas, while in their winter quarters, must receive as much air and light as the weather will permit. And during the month of March, when the flower stems are rising up, the shutters must be entirely removed in fine days, but replaced again at night; and, in case of frost, be closely covered down with mats or straw. Never expose the plants too hastily to the sun in a morning after frost, but allow every symptom of it to disappear before you open them.

6. During mid-winter, that is, throughout December and January, give auriculas little or no water; but in February and March, water them at least once a week with diluted liquid manure.

7. Any time from the beginning to the middle of February, the plants must be top-dressed with the soil recommended for potting, taking off a sufficient portion of the old soil, to admit the new. The same process must be performed again in September.

8. When the flower buds begin to swell, thin out all the small ones, never leaving more than ten buds to flower.

9. Although the plants at the time the buds are swelling, must be exposed to gentle rains and the full influence of the sun, the buds themselves must be exposed to neither: the former will cause the colours of the flowers to run into, and mix with, each other; the latter will cause them to be faded and dull. On the other hand, if the buds are never exposed to the sun at all, the colours of the flowers will be much less vivid. To obviate these difficulties, shade the flowers with small boards, about five inches square, placed upon sticks, as in the figure. And to attain brilliancy of colours, expose the buds to the influence of the sun for an hour, or more, every morning, and at all other times: from the buds beginning to swell until they are expanded, and wanted for the show, keep them carefully shaded.

10. Place the plants intended to produce seed under a south wall as soon as the flowers begin to fade, and give them a good supply of water. As soon as the seed is ripe, sow it in pans or feeders, filled with the compost in which the plants are grown, having previously placed a quantity of it in a hot oven, that all the seeds of weeds, &c. may be destroyed. Fill the pans to within half an inch of the top at the edges, but something higher in the middle. Sprinkle the soil with water, sow the seed, and cover it lightly with the same compost, finely sifted. Place the pans on an eastern or south-eastern aspect; and shelter them from heavy rains, and water lightly as often as they require it.

11. Transplant seedlings as soon as their seed-leaves become pretty strong. Take each up with a small pair of tweezers made of ivory, with very narrow points, so as to raise each by the seed-leaf, and the other end somewhat flat, to loosen them previous to raising (a). And likewise a piece of ivory, not more than one-eighth of an inch broad (b), to make a small cleft in the soil, to admit the roots of the plant. Transplant as often as the plants require it, placing them in the first instance one inch asunder, and increasing the distance every time, until they are large enough to place in the pots used for flowering.

12. Always pot the plants immediately after the flowering season, that is, about the end of May, or beginning of June, except such as are to produce seed, which must not be potted until the seed is gathered. The proper sized pot for a good flowering plant is ten inches deep, and eight inches wide, at top (inside measure). Good drainage of broken pot is indispensable.

13. In potting never shake off all the soil from the roots, unless the roots be decayed. In taking off the decayed parts, never use a knife to cut them, but always break them off with the hand, for a plant rarely thrives after being so cut.

14. Remove all the large offsets from the plants, some time in March, because they grow the quickest in the spring.

15. Great care is indispensable to secure auriculas from the attack of slugs, particularly in April and May; also it often happens that small caterpillars are secreted in the hearts of the plants; this may be known by the appearance of webs. These depredators must be destroyed, or all cultivation will be useless.

16. All plants, to be healthy, must be kept free from weeds and dead leaves. The former occasion disease, by depriving the plants of nourishment; and the latter, by infection. Great care is requisite never to strip off a leaf, until it is thoroughly dead; for by doing so, a wound is made, which will absorb more water than the plant is able to evaporate. This causes a decay to commence in the wounded part, which soon spreads throughout the whole plant. Whenever this decay is perceived, scratch out the rotted part with the finger, and fill up the place with a little tallow, to keep out the moisture, until the wound heals.

If the flowers when expanded do not lie flat and even, florists use an instrument called a flattener, made of ivory: this instrument, if the flower is cupped, is pressed upon the pip until the petals become quite flat. If, on the contrary, the petals bend backward, the flattener is placed under the pip, betwixt the calyx and the corolla, drawing it through the opening, in the eye of the flattener; then each petal is properly straightened by a camel hair pencil.

Many experienced florists place the flowers in perfect darkness for two or three days previous to their being shown, and usually in a cellar, fixing the cut flowers in bottles, and often changing their water. This is found to improve their colours wonderfully. In sending flowers in pots to a distance, a light box should be made to fit the pot; place some moss betwixt the pot and sides of the box, to prevent the pot being broken, bind some upon the top to keep the soil from falling out, and tie the flower to a stick to preserve it from shaking. Then take two pieces of wood (a, b), just the length of the distance betwixt the pot and the lid, place them upon the edges of the pot close to the side of the box, nail them fast to the lid, after it is placed on the box, and the lid being well fastened down, with common care, no injury whatever can happen to the plant.

Amaryllis Kermesina (Carmine Amaryllis).—A beautiful plant. The roots were brought from Brazil in the early part of 1833, by Lieutenant Holland, of the Royal Marines, who presented them to Miss Street, of Penryn. The flowers are a rich deep carmine colour. The soil it thrives in is a mixture of loam, peat, and sand. It has hitherto been kept in a warm vinery, and has shown no disposition to increase by offsets.—Bot. Reg. Of late years this genus has been greatly increased by a number of hybrids, many of which far surpass the originals, both in the production of their flowers, and the rich variety of their colours: for the most part, they require the temperature of the stove, although A. pumilio, pudica, blanda, &c. do very well in the greenhouse, and a few species, as A. belladonna, &c. will do in a frame, or even out of doors in warm situations. They are in general easy of culture, and are readily increased by offsets, and many ripen plenty of seeds, if some pollen be shaken on the stigma at the proper time. A shell peeled off the bulb will grow very freely. The strong growing species must be plentifully supplied with water during their time of flowering and growing; they also thrive best if planted in large pots. Mr. Sweet found it an advantage to turn them out of the pots when the bulbs were ripe, and, after shaking all the soil from them, lay them upon a shelf in a dry situation, until they began to show flowers; he then had them potted in a compost of light turfy loam, rather more than one-third of white sand, and turfy peat, well chopped together, but not sifted. But this system of turning them out of the pots will not do for a general rule, as A. reticulata and striatifolia, or the mules raised from them, will flower much better by remaining in the pots all the year, as do also A. aulica, calyptrata, solandræflora, all of which require to be kept dry during their dormant state. A. regina, crocata, rutila, acuminata, fulgida, Johnsoni, psittacini, and the mules between them, flower much better if turned out of their pots, and treated after Mr. Sweet’s system. Each requires a good drainage.

Pancratium pedale. (Long-flowered Pancratium.) One of the most beautiful of the Amaryllis tribe, excelling them all in the extraordinary length of the flowers, which measure a foot from the base of the tube to the tip of the segments. The latter are very narrow and wavy, and of a delicate white. The bulb was sent by Mr. Barnard from near Truxillo, and of course requires the stove.—Bot. Reg. All the species of this genus are free flowerers, and the greater part of them inhabitants of our stoves. P. Canariense and Carolinianum, however, thrive well in the green-house; and P. maritimum, and Illyricum are perfectly hardy: the P. rotatum also is nearly so, requiring only a slight shelter in cold or wet weather. They all flower freely in rich turfy soil, mixed with a small portion of sand and leaf mould, to keep it open. The stove species grow much finer if plunged in a hot-bed until the flowers begin to expand, than they do grown upon the old system of constantly standing in the stove. When the pots become filled with roots, the plants should be shifted into larger; by doing so, the flowering season is greatly prolonged. During their growing, it is necessary to give a good supply of water, but when in a dormant state they should be kept dry, or nearly so. Previous to their beginning to grow again, they should be repotted, removing about three parts of the soil from the old ball: when potted, plunge them in a hot-bed as above directed. They ripen seeds, by which, together with suckers and offsets, they are readily increased.

Gesnera Suttoni (Captain Sutton’s Gesnera). We owe the introduction of this fine plant to Captain Sutton, of his Majesty’s packet establishment at Falmouth, who informs us that he found it growing in a wood on a sloping hill, near the Bay of Bomviaga, Rio de Janeiro, at an elevation of between thirty and forty feet above the level of the sea, and not exceeding forty yards from the water. Its beautiful bright scarlet flowers attracted his attention, and induced him to dig up the plant and bring it home. It has some resemblance to Gesnera bulbosa, but is evidently distinct from that species. It requires the constant heat of the stove, and flourishes in a strong rich soil, and may probably be increased by cuttings. Bot. Reg. All the species of Gesnera require the heat of the stove, and should be potted in a light rich soil. Part of them are tuberous rooted, and the others have somewhat of a half-shrubby habit. Most of them will increase by the leaves, although in some cases, as in G. Douglasi, &c., it is attended with considerable difficulty. Those with tuberous roots may occasionally be propagated by division of the roots; and the latter, and indeed all, will grow readily from cuttings taken off at the second joint from the top, and planted in sand under a bell-glass, placed upon a warm flue, and shaded after the manner of other tender cuttings with a sheet of thin paper. When they have struck roots, pot them in sixty-sized pots, in a mixture of equal parts of sandy peat, leaf mould, and rotten dung, well chopped together but not by any means sifted. After being potted, plunge them in the bark bed, in a shady part of the stove, until they have begun to grow, when they may receive the full force of the sun. In watering them let the leaves also be slightly sprinkled; but be careful that the water is about the temperature of the house, or the leaves and roots are liable to be injured. If this be attended to they will soon till their pots with roots. When this is the case, shift them into others, about four inches wide at top, and the same deep.

When they have done flowering, they must receive very little water: this decrease of water, however, should be gradual, so that at the time the leaves are decayed, the soil in the pots should be kept quite dry. After the tops are dead, place them in a cooler situation, where they will receive no moisture, until about the beginning of February, when they should be potted and again plunged in the bark bed, where they will flower beautifully.

Combretum grandiflorum.—(Large-flowered Combretum.)—This is one of the many noble plants with which the once-fatal colony of Sierra Leone abounds. It is a scrambling plant, raising itself by means of a very curious kind of hook with which nature has ingeniously supplied it. At first sight, one would wonder what this hook can be; for nothing like spine, or prickle, or tendril, can be discovered upon the branches: for want of these, it is necessary that their place should be supplied by some special provision, which is of the following kind. When the leaves are first fully formed, they are seated upon a footstalk of a very common appearance; but, after a time, they fall away, leaving the leaf-stalk behind: the latter does not wither up, but gradually lengthens, hardens, sharpens, and curves, till at last it becomes a powerful hook, admirably adapted for catching hold of the branches of any tree that it may be near, and thus elevating the plant from the earth. These hooks, however, are not to be found on those grown in our stoves, but only in the woods of Sierra Leone, its native habitation.—Bot. Reg. t. 1631.

The C. comosum, purpureum, and all the other species of this genus, require similar treatment to the grandiflorum: they are all very beautiful, particularly the purpureum, which makes a most splendid show at the time of flowering. They all thrive well in a mixture of loam and peat: cuttings will root freely if planted in a light soil or sand, and covered with a hand-glass, and placed in the moist heat of a good hot-bed. A good way, also, to obtain fine plants in a short space of time, is to layer some of the branches, which will soon strike root. After they are rooted, pot them off in 60-sized pots, and place them in a shady part of the stove.

Cychnochis Loddigesii is a beautiful and an extraordinary plant. The flowers are large and beautifully spotted with red. It is a native of Surinam, whence it was sent to Messrs. Loddiges, by Mr. Lance, in 1830, in whose stove it flowered in May, and again in the winter of 1832. Dr. Lindley gave it the present name, and published it in his excellent work on the “Genera and Species of Orchideæ.” It requires the stove, and thrives if planted in moss and broken pieces of pot, and is suspended from a rafter.—Bot. Cab. t. 2000.

Cirrhæa Warreana.—This is a native of Brazil, and was discovered by Mr. Warre. It bears a strong resemblance to the other species: they are all highly interesting and curious plants, well deserving every possible care in cultivation. It succeeds very well in the stove, planted in moss with potsherds, and a little sandy peat soil. Like the rest, it will admit of occasional increase, by dividing the bulb.—Lod. Bot. Cab. The C. viridipurpurea should be treated precisely the same as the Warreana; but the C. Loddigesii will do very well, if potted in a light vegetable mould, providing the drainage be complete. All the species require a very humid atmosphere to bring them to flower in perfection. Indeed, all the Orchideous Epiphytes of the stoves require a similar treatment in this particular, although in others they may somewhat differ. The whole genus of Dendrobiums, for instance, hang in their native woods upon the trees, in a pendent manner; they, therefore, cannot be cultivated with success, unless some means of this kind are resorted to. The usual mode, therefore, is to suspend the pots in which they are planted to the rafter, or merely hang the plants themselves upon trees, covering the roots with a little moss, so arranged that the branches can shoot freely in their natural way. The D. secundum, chrysanthemum, cuculatum, &c., grow very freely, if planted in perfectly rotten wood and moss; also in pots, covered over the outside with moss. The D. moniliforme, longicorni, pulchellum, &c., grow best in moss, mixed with a little vegetable mould and broken pot, and suspended like the other.

The genus Aerides will thrive with a treatment somewhat different to Dendrobium. A. cornutum has a most delightful fragrance when in flower, not very dissimilar to that of the tuberose. A. paniculata will grow and flower, if cut off from all nourishment except what it receives from the air. It does not, however, flourish so well in this way as if planted in a basket, having a mixture of chopped moss and vegetable mould at the bottom. After the plants are placed in the baskets, spread a little moss over the roots, and hang them up to the rafters, by means of a few twigs, formed as the figure. The Renanthera Coccinea is a splendid plant for this purpose; its beautiful crimson flowers hang in a most graceful manner: but it flowers equally well, if a bit of moss be tied round the stems, and kept constantly damp. After it comes into flower, it may be taken down, and hung up in a warm room of the dwelling house, where, if treated with care, its flowers will continue for a long time. It is readily propagated by cuttings.

The season is now fast approaching when slugs and other crawling depredators commence their ravages in our flower gardens, and, unless prevented, may destroy all our choicest productions. Many are the remedies which have been prescribed; but none are so generally applicable as could be desired; although most, under certain circumstances, are found to answer.

Some persons make a few holes about one inch deep round the plants infected, the slugs taking shelter in these holes are easily destroyed by dropping a bit of salt or quicklime upon them. This method, however, will not answer for valuable plants, as the slugs might probably destroy the plants before they sought shelter in the holes.

Others water the ground and plants with the drainings of the dunghill, or cow-house, diluted with a little water. Clear lime-water also effectually destroys them. It is made by adding two pecks of quicklime to about sixty gallons of water, and well stirring them together in a large tub, and pouring off the clear liquor into a watering pot, with a rose. If the ground be well saturated with either this or the urine, the slugs will disappear; but the application is fatal to all delicate and tender plants.

Some spread lime upon the ground, or dig it in, neither of which is of much avail, unless the operation be performed when the slugs are on the surface. Mr. Corbett’s system, as noticed in the “Horticultural Register,” page 166, is probably one of the best, if not one of the very best, remedies of this kind. “Lightly cover the ground over with good quicklime, at ten o’clock at night, and about three or four o’clock in the morning, in still fine weather, repeat the operation for a few times, and most of, if not all, the slugs, will be destroyed.” This, however, can be scarcely considered safe for delicate plants, as an injudicious application will be very likely to destroy them.

Another method is enticing them by baits: if cabbage leaves are warmed before the fire until they become quite soft, and are then rubbed with fresh butter or dripping, and placed on different parts of the ground infested, they prove an excellent decoy. Also a turnip, cut into halves and hollowed out, and laid on the ground with the hollow part downwards, proves a good place of shelter. Both the leaves and turnips should be examined every morning, and the slugs sheltered under them killed.

Another system is to prevent them from coming near the plants. To accomplish this, many means have been used: dry hulls of oats, saw-dust, or sifted coal ashes from an iron foundry, or smithy, strewed upon the ground where the plants are placed, or spread round any particular plant, are impassable barriers, so long as they remain dry; the two latter in particular, because they abound in innumerable sharp points, which no slug can pass over, owing to the extreme delicacy of that part of their bodies upon which they move. But the efficiency of all these is lost after a heavy shower of rain, either from being washed into the soil, or entirely away, as is generally the case with the saw-dust and hulls of oats.

To remedy these deficiencies, a circular earthenware pan has been invented to protect single plants, by Miss Bygrave[2], an ingenious lady, in the Isle of Wight. It is placed round the plant nearly even with the surface of the soil, and the hollow part is filled with water, over which the slugs cannot pass. If the plant to be preserved stands in a pot, and the pot be set in a pan or feeder, the “Bygrave Plant Preserver” might be filled with salt, instead of water, which will be much more effectual; but if the pot in which the plant grows be not placed in a feeder, and even then, if the plant be small, there will be great danger of its being destroyed, by a sudden shower of rain washing the salt, either to the roots or leaves.

[2] Horticultural Register, vol. i. p. 150.

But if all the choice plants were formed into beds, either by placing the pots together, or otherwise, as might be the most convenient, they might very readily be protected with the greatest safety, by another invention of the same lady, called the “Bygrave Slug preventer.” It is a leaden gutter, a, b, an inch and a quarter broad, having a keel an inch and a half deep, and made in pieces of any desired length, which, when set completely round the hedges of a bed and staunted at the edges with soft solder, or putty, and filled with salt, forms a totally impassable barrier. When the article is used, either slices of turnip, or any other decoy, should be placed here and there on the ground inclosed, for the vermin to harbour under, from whence they ought every morning to be hand-picked and destroyed. Persevering thus for a few days, will completely clear the space within the boundary of salt; and any delicate plants may be placed, or seeds sown, without any danger of being destroyed by this class of depredators.

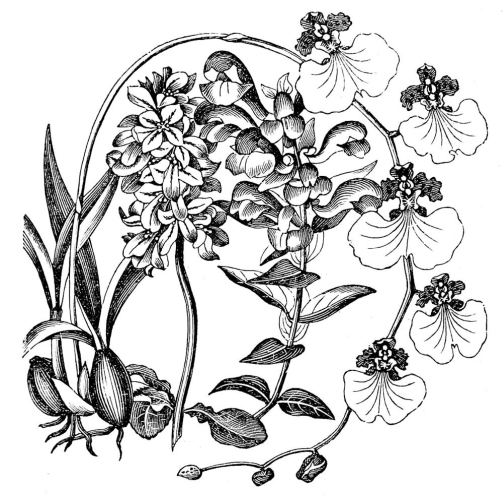

The plants introduced into the engraving are:—c, Sparaxis lineata. A bulbous plant, requiring a pit, or warm border of sandy loam and peat, and to be covered with a mat in case of frost. The flower is white, with a yellow throat, marked with brown; each petal marked with a red line; d, Vieusseuxia glaucopis. This is a native of the Cape of Good Hope, has delicate white flowers, with a bright blue, or rather purple eye, not unlike the spots on the tail of a peacock. It appears to thrive best in a sandy peat earth, and from the changeable climate we experience in this country, it will not prosper without some means of artificial heat, although it does not appear to enjoy the greenhouse; but if planted on a vine border, close under the front wall of a stove, it will generally thrive and flower freely. The only means of propagation is by offsets; the seeds with us very seldom ripening.

All Annuals are raised from seeds, and are either hardy, and may be sown in the open border; half-hardy, requiring to be sown on a hot-bed, and afterwards transplanted; or tender, requiring to be kept during the summer in the green-house, or stove. The first thrive well in any common light soil, with little attention, except keeping them free from weeds; the second require rather more care during their early growth, although afterwards they grow well in the same soil as the hardy ones; the third want considerable attention all summer, the soil most suitable for them generally, is about two-thirds of light rich loam, and one-third of rotten dung, or leaf mould.

Treatment of hardy annuals.—About the end of February, or beginning of March, commence sowing the seeds after the following manner: stir up the soil and make it fine with the hand, if it be light; if not, with a small hand hoe, or fork, then with the finger draw a circular drill, of about six inches in diameter in the circle, and one inch or less deep, according to the size and habit of the plant intended to be sown: cover the seed lightly with moist soil, and place an inverted flower pot over them (if convenient to do so); allow the pot to remain until the seeds have begun to grow, then prop it on one side two or three inches high, until the plants are able to bear the weather; afterwards remove it altogether. Covering the seeds with a pot answers several good purposes: First, it keeps the soil moist until the seeds have vegetated. Second, the sun shining on the pot causes a reflection of considerable heat, and brings up the seeds much sooner than under other circumstances. Third, it screens them from the spring frosts. Fourth, it prevents the soil from being washed off the seeds, or the seeds themselves being washed away by heavy rains; and, Fifth, it preserves them from birds and mice. When the plants are about an inch high, they must be thinned out according to the kind, that those remaining may be able to grow and flower strong: the height the plants grow must also guide the person as to what part of the border they ought to occupy, which (where the selection is choice) may be known by referring to the list annexed. If sown successively through the summer, there will be a constant supply of flowers, till the autumnal frosts kill them. In mild winters they may be kept till towards Christmas, staking, tying, and occasionally stirring the soil; and in dry summers gentle watering in an evening, is then all that is necessary.

Treatment of half-hardy annuals.—These require to be raised in a hot-bed, and when an inch or two high transplanted in pots, and placed where they will receive abundance of air, and be protected from frosts. If a frame could be spared it would be preferable to pots, for transplanting them in; and if the frame be placed upon a declining hot-bed, which would communicate a little heat, it would be very beneficial to them, taking care to give plenty of air and moderate waterings. But if the season is so far advanced that all danger of spring frosts is gone, they may be transplanted where they are intended to flower.

The bed for raising the plants should be about two feet thick in front, and two feet six inches at the back; beat it down pretty level with a fork, but do not trample it, set on the frame, cover it with lights, and allow it to stand three days to settle, then level it properly, and lay on about four inches thick of soil, composed of two-thirds of light sandy loam, and one-third of leaf mould well beaten together, but not sifted; rake the surface smooth and level, and with the hand draw some shallow drills about three inches apart; then thinly scatter the seeds of each sort in the drills, and cover them lightly over with some finely sifted soil, being cautious not to cover them too deep, or they will be liable to perish. Some of the half-hardy sorts will flower early in the spring, if sown in pots the preceding autumn; amongst these may be named the varieties of ten-week stocks, the different species of Schizanthus, China asters, Tsotoma axillaris, &c.: the latter should be sown in forty-eight sized pots, in September, or as soon as the seeds are properly ripe. Protect them during winter in a dry frame, and keep them clean and free from dampness; these will come into flower about the end of May. The different species of Schizanthus must be treated in a similar manner; these, however, with the exception of S. pinnatus, are not very free at producing seeds, unless some pollen be shook on the stigmas when in bloom. Ten-week stocks may be sown at the same time, and treated after the same manner. It is not advisable to transplant any of them at this season of the year: sow but a small quantity in each pot, and when about half an inch high, thin out all the weakest, for it often happens, when transplanted at this time they are never able to make good roots again; and, during the dark months of November and December, are almost sure to perish. When they are grown about two inches high remove a little of the soil from the top, and give them a shallow top-dressing; this will be sufficient until the following March, when they should be shifted into thirty-two sized pots, without disturbing the roots. In May time thin out into the borders, with the balls entire; part, however, may be kept to succeed them in the general sowing in March. The spring sown ten-week stocks are also much forwarded if transplanted in pots, and afterwards turned into the borders. Calceolarias do best when transplanted singly into sixty-sized pots, and turned out at the same time as the stocks.

Treatment of tender annuals.—These are sown in pots in February or March, and plunged in a hot-bed. When they are up and have attained one or two proper leaves, they should be pricked out into thimble pots, filled with the compost mentioned in the beginning of this paper; as they advance in growth remove them into larger sized pots until they begin to show blossom, when they may be removed to the houses appointed to receive them. They are divided into two sections, 1st, those which require a powerful heat to make them flower to high perfection, called stove annuals; and, 2nd, such as will flower to perfection with a much less heat, called green-house annuals.

I. Those requiring strong heat.—The Globe Amaranthus (Gomphrena globosa,) Cockscomb (Celosia cristata), Centroclinium reflexum, Indigofera endecaphylla, Martinia lutea, Cleome rosea, &c., &c. The Globe Amaranthus should be transplanted first into thimble pots, and shifted regularly, until finally they are placed in forty-eights, and in these they will flower: the soil most suitable is a mixture of peat, loam, and leaf-mould or rotten dung; they should be allowed to stand near the glass, and be subjected to a moist heat of not less than seventy-five degrees.

Cockscombs may be grown with strong short stems, and very large heads, if they are allowed to remain in small pots until the flowers are formed, then potted in larger pots, and supplied with as much liquid manure, and moist heat, as possible. Sow the seeds in pots, filled with a compost of three quarters leaf-mould, and one quarter sand, and place them in a frame in a good hot-bed. When they are up, and have become large enough to transplant, pot them singly into sixty-sized pots, adding to the above compost a good portion of rich loam; subject them to a very close humid heat, and by no means allow them to stand more than a foot and a half from the glass roof, and occasionally syringe them over head with clear water. When the roots begin to show themselves through the bottoms of the pots, shift the plants into forty-eights, and let them stand in these until they show flowers; then select some of the best shaped, and pot them in thirty-twos, in a compost of one half rich loam, one fourth leaf-mould, and one fourth sand, well mixed and broken together, but not sifted. When the roots have grown considerably, shift the plants into a size larger pots (twenty-fours), in this size they will flower. Give them a strong moist heat, and plentifully supply them from the time they show flower, until they come to perfection, with water, in which dung, of either sheep, fowls, or pigeons, is dissolved.

When the flowers are come to perfection, they may be removed out of the strong heat, and placed with the other green-house annuals, where their colours and beauty will remain throughout the whole summer.

II. Requiring only a moderate heat.—Amongst these, the Lobelia hypocrateriformis, Manulea argentia, Nierembergia linariæfolia, &c., require to be potted in sandy peat: the Salvia foliosa, Browallia grandiflora, Commelina cucullata, &c., thrive in a mixture of peat, loam, and a small portion of well rotted dung. Salpiglossis linearis, Loasa volubilis, &c., do best in a light sandy loam, with a little well rotted dung, without any mixture of peat. Capsicum should be potted in a good rich loam, mixed with about one quarter peat, and one quarter rotten horse-dung.

Balsams attain to greatest perfection, if grown by themselves, under the following treatment. When there are plenty of frames, and one can be spared until the end of May, the superior show of flowers, that will be obtained, will probably more than repay for the extra trouble and sacrifice.

As soon as the plants are fit to transplant from the seedling pots, make up a bed of good horse-dung, about three feet thick, and after allowing it to settle for a few days, lay about six inches of rotten bark on it. Then transplant the blossoms singly into sixty-sized pots, filled with a mixture of half light sandy loam, one quarter peat, and one quarter of rotten dung. When potted, plunge the pots up to the rim in the bark, and allow a considerable portion of air, by propping up the glasses. Shift them into larger pots as often as they require it, each time diminishing the quantity of peat, and adding more rich loam, so that at the last potting (which must be just after they have shown flower), the compost is nothing more than three quarters of rich strong loam, and one quarter of good rotten dung. Give them occasional waterings with liquid sheep manure, and keep a constant brisk heat to their roots until the time they are removed.

As the season advances, and the plants grow, give a proportionate increase of air, until the beginning of May; the glasses may then be entirely taken off during the day, and nearly put on at night to preserve them from frost. By this mode of treatment, a very great number of blossoms are produced: it will therefore be necessary to thin out the weakest as soon as they are formed. If these rules are attended to, and the sort be good, a most splendid show of large rich coloured double blossoms may be anticipated. We do not wish to convey an idea that balsams will not grow and flower under different treatment. We are satisfied they may be brought to flower very well, with the common treatment of green-house annuals, and perhaps their stems may exceed in size those grown in the manner we have recommended; but the blossoms will be inferior in colour, and in many cases scarcely double, although the sort, under other treatment, might have proved a very excellent one.

| Feet. | Inches | ||

| high. | |||

| White. | |||

| Omphalodes linifolia (Venus’s Navel Wort), growing | 0 | 6 | |

| Iberis odorata | 0 | 6 | |

| Andosace macrocarpa | 9 | 0 | |

| Delphinium Ajacis (Rocket Larkspur) | 1 | 0 | |

| Œnothera tetraptera | 1 | 0 | |

| Prismatocarpus Speculum Album | 1 | 0 | |

| Iberis Lagascana | 1 | 0 | |

| Calendula hybrida | 1 | 0 | |

| Purple. | |||

| Valerianella congesta | 0 | 6 | |

| Iberis spatulata | 0 | 6 | |

| Prismatocarpus speculum | 1 | 0 | |

| Eutoea multiflora | 1 | 0 | |

| Cleome speciosissima | 1 | 6 | |

| Blue. | |||

| Nolana paradoxa | 0 | 6 | |

| Lupinus bicolor | 0 | 9 | |

| Lupinus— micranthus | 1 | 6 | |

| Convolvulus tricolor | 1 | 6 | |

| Yellow. | |||

| Lotus arenarius | 0 | 6 | |

| Madia elegans | 1 | 6 | |

| Calliopsis bicolor | 2 | 0 | |

| Calliopsis— Atkinsoniana | 2 | 0 | |

| Helianthus lenticularis | 3 | 0 | |

| Helianthus— petiolaris | 3 | 0 | |

| Lupinus luteus | 2 | 0 | |

| Rose or Pink. | |||

| Mathiola tricuspidata | 0 | 6 | |

| Palavia rhombifolia | 1 | 0 | |

| Delphinium Ajacis | 1 | 0 | |

| Silene Armeria | 1 | 6 | |

| Elsholtzia cristata | 1 | 6 | |

| Scarlet and Crimson. | |||

| Saponaria calabrica | 0 | 6 | |

| Eucroma coccinea | 0 | 6 | |

| Amanthus hypochondriacus | 2 | 6 | |

| Amanthus— caudatus | 3 | 0 | |

| N.B. The varieties in the colours of sweet peas, and rocket larkspurs, are so numerous, that they are purchased generally in mixed colours. | |||

| HALF-HARDY ANNUALS. | |||

| White. | |||

| Argemone grandiflora | 1 | 6 | |

| Nicotiana multivalvis | 2 | 0 | |

| Petunia nyctaginiflora | 2 | 0 | |

| Purple. | |||

| Gentiana humulis | 0 | 4 | |

| Clarkia Pulchella | 1 | 6 | |

| Œnothera Romanzovii | 1 | 6 | |

| Convolvulus Major (creeper) | 10 | 0 | |

| Yellow. | |||

| Calceolaria pinnata | 2 | 0 | |

| Anthemis Arabica | 1 | 6 | |

| Zinnia multiflora flava | 1 | 6 | |

| Blue. | |||

| Clintonia elegans | 0 | 6 | |

| Isotoma axillaris | 1 | 0 | |

| Callistema Indica | 1 | 0 | |

| Trachymene cœrulca | 2 | 0 | |

| Ipomœa hederacea (creeper) | 10 | 0 | |

| Scarlet and Crimson. | |||

| Zinnia violacea coccinea | 2 | 0 | |

| Zinnia— multiflora rubra | 2 | 0 | |

| Eccremocarpus scaber (creeper) | 10 | 0 | |

| Variegated Flowers. | |||

| Schizanthus retusus | 1 | 6 | |

| Schizanthus— Hookeri | 1 | 6 | |

| Schizanthus— pinnatus humulis | 1 | 0 | |

| * | Schizanthus— pinnatus | 2 | 0 |

| * | Schizanthus— Priestii | 1 | 0 |

| * | Schizanthus— Grahami | 2 | 0 |

| * | Schizanthus— porrigens | 2 | 0 |

| Salpiglossis picta | 1 | 6 | |

| Salpiglossis— atropurpurea | 1 | 6 | |

| China and German asters; Russian, ten-week, and German stocks, are not enumerated in the above, in consequence of the very numerous varieties. Seeds of each variety may usually be obtained in the seed shops, mixed together in one paper. | |||

| TENDER ANNUALS. | |||

| White. | |||

| Gomphrena globosa alba | 1 | 0 | |

| Nierembergia lineariæfolia | 0 | 6 | |

| Blue. | |||

| Salvia foliosa | 1 | 6 | |

| Browallia grandiflora | 2 | 0 | |

| Commelina cucullata | 1 | 0 | |

| Purple. | |||

| Gomphrena globosa | 1 | 6 | |

| Lobelia hypocrateriformis | 1 | 0 | |

| Rose or Pink. | |||

| Cleome rosea | 1 | 6 | |

| Centroclinium reflexum | 2 | 0 | |

| Yellow. | |||

| Salpiglossis linearis | 1 | 0 | |

| Martynia lutea | 1 | 6 | |

| Loasa volubilis | 1 | 6 | |

| Loasa— hispida | 2 | 0 | |

| Manulea argentea | 1 | 6 | |

| Scarlet. | |||

| * | Indigofera endecaphylla | 1 | 0 |

| Variegated. | |||

| * | Gomphrena globosa striata | 1 | 0 |

| The varieties of the balsam, cockscomb, and capsicum, are very numerous, and are generally to be purchased with the different colours mixed. | |||

Annuals (Tender) may be sown about the end, in pots filled with a mixture of two-thirds light rich loam and one-third leaf mould. Cover the seeds very lightly, and plunge the pots into a hot-bed. In watering, either do it with a very fine rose watering pot, or with a syringe.

Auriculas about the middle of the month should be top-dressed with a mixture of one-half good new turfy loam; one fourth vegetable mould, either made from leaves or gathered from the interior of a hollow tree; one-fourth well rotted horse dung; a portion of river sand, to keep it open; and a handful or two of bone dust. Take off about two inches of the soil from the top previous to adding the new. Begin also to water with liquid manure about once or twice a week.

Dahlias. A few of the old roots should be now plunged in tan, to excite them to grow. The seeds should also be sown in pans or feeders, and placed in a hot-bed till up.

Polyanthuses should be top-dressed in the same manner as Auriculas; but the soil need not be so rich. Also sow the seed in the same manner.

Pinks, Carnations, and Hyacinths, if taken into the forcing houses, will come early into flower. All plants of this kind, as well as roses, lilacs, &c. &c., will, during forcing, require a little water sprinkling over their leaves about three times a week. This is best done by means of a syringe; and none, perhaps, will answer the purpose better than Siebe’s.

It consists of only one apparatus, which can instantly, by turning a pin, be applied so as to serve the purpose of four different caps. By means of an universal joint (a) the cap or head (b) may be turned in any direction and to any angle (c). The pin, by which the alterations in the rose head are effected, works in a groove (d) in the face of the rose; and by it a very fine shower, a coarse shower, or a single jet, from one opening (e) may be effected at pleasure. The valve (f), by which the water is admitted to the syringe, is in the side of the rose. Reid’s is also a very excellent syringe; but if the cultivator possesses neither, a watering pot with a very fine rose may be used for the purpose.

Rose Trees in pots, now brought into the forcing house, will flower about the beginning of May. These plants, when forced, are very often much troubled with the aphis. If only one or two plants are infested, a sprinkling of tobacco water with a syringe will destroy them; but if the insects have spread through the whole house, it is better to fumigate. This may be either done with a detached fumigator, fitted on a common pair of bellows, or merely with a pair of bellows and a flower pot, to contain fire and tobacco, with a hole in the side, at which to use the bellows.

Schizanthus retusus, and other species, should be sown about the middle of the month.

Tuberoses, about the end, should be planted in small pots filled with rich loam, placing a root shallow in each pot; and then plunging the pots in a hot-bed or pine pit.

During February, mice are often very troublesome in the flower garden, particularly the short-tailed field-mouse (Mus arvalis), which devours many of the bulbous roots. Perhaps no trap is more efficacious and simple than one invented by Mr. Howden, gardener at Heath House, Staffordshire. It merely consists of a large flower-pot, inverted on a board or slate, and sunk in the ground nearly level with the surface. Opposite to the hole in the bottom of the pot, and about two inches from the surface or entrance, is suspended on a crooked piece of wire a smooth wooden roller, like the castor of a bed-post; this the mouse will leap upon, and from thence be precipitated to the bottom, from whence it can never escape. The surface may be sprinkled with chaff or short straw, and a mixture of grass and clover seeds about the hole. The roller may be besmeared with lard, and dusted over with flour or oatmeal. In wet weather a rough tile may be set over the hole to keep it dry.

MARCH 1834.

Passiflora Kermesina.

| CLASS. | ORDER. | |

| MONADELPHIA. | PENTANDRIA. | |

| NATURAL ORDER. | ||

| PASSIFLOREÆ. |

Generic Character.—Calyx inferior, in five divisions, coloured. Corolla five petals inserted in the calyx. Nectarium, a crown. Fruit a fleshy, smooth, berry, rarely hairy, containing many seeds.

Specific Character.—The whole plant smooth; leaves, heart-shaped, cut into three lobes, slightly toothed; leaf-stalks, each having two glandular hairs; flower-stalks solitary, much longer than those of the leaves; calyx and corolla carmine colour; corona or crown purple;—a very beautiful slender climber.

In speaking of this splendid species, we cannot do better than give the words of Professor Lindley:—“This is beyond all comparison the most beautiful species in cultivation, except racemosa. Its flowers have a richness of colour which art cannot imitate; they are produced in very great abundance at almost all seasons; and in consequence of the length of the slender stalks from which they singly hang, the whole plant has a graceful aspect, which is unrivalled even among passion-flowers.” It was introduced to the Horticultural Society garden in 1831, from Berlin.

It thrives well with us at Chatsworth, potted in a mixture of loam and peat, and placed in the orchidea stove, where it obtains plenty of heat and moisture.

If cuttings be made of the firmest of the previous season’s wood in May, and they be planted in pots well drained with potsherds, and filled up with sand, and afterwards placed in a temperature of from 70 to 80 deg. Fahr., drying them occasionally to prevent their damping off, but little difficulty will be found in striking them. These will make fine plants by autumn.

The greater part of this genus require the heat of the stove; the P. quadrangularis, in particular, seldom does well except it be grown in the corner or side of a bark bed. Either, therefore, make a square partition with bricks or boards, one foot wide and two feet deep, or make a box for the purpose, and plunge it on one side of the tan pit; leave in this box or division several holes round the sides, for the egress of the roots; fill the box with good rich loam, and place in the plant. Every autumn shorten the stems of the plant in a similar manner to cutting a vine: that is, if the young shoots are found weak, shorten them to two or three eyes off the old wood, and the stronger ones proportionally. In February, just before it starts growing again, raise it, if convenient, out of the box, and trim its roots, and after having put in a supply of new soil, replace it; if not convenient to raise it, take out as much of the old soil as can be got round the sides of the box, reduce the ball about one-third, and add a fresh supply of loam. Abundance of water is also requisite during the flowering season, or the fruit will set very shy, even with impregnation. Fruit are produced from the end of June till Christmas. This, in connexion with edulis, alata, ligularis, incarnata, maliformis, and lancifolia, are grown for their fruit in America, where they are known by the name of Granadillas, because the fruit bears a resemblance to the Granada, or Pomegranate.

Passifloras are sometimes rather shy at setting their fruit; this may be remedied by impregnating with the pollen of other species in preference to their own pollen.

The quadrangularis is much cultivated in the West Indies as an ornamental climber, especially for arbours and covered walks. The fruit is somewhat watery, rather fragrant, with a grateful taste, betwixt sweet and acid: the bloom is very large and handsome. It is frequently grafted upon the cærulea in France, where it flowers and fruits the same season it is grafted, sometimes when not above two feet high.

The alata will grow under the floor of a hot-house, and in other situations where most of the stove species will not live; only it is necessary to keep the roots quite moist. The racemosa will bear fruit if impregnated with the pollen of alata, or other species, but shows no disposition to do so when confined to its own stamens.

The maliformis is plentiful in the woods of Jamaica, where its fruit forms a principal part of the food of wild swine. The hard shell-like rind is manufactured into snuff-boxes and toys of various kinds.

The vespertilio is remarkable for its hours of flowering, being from ten o’clock at night till towards seven or eight o’clock the next morning. The fœtida is called in the West Indies, “Love in a Mist,” because its unexpanded flowers are curiously enclosed in a feathered involucre. Of rubra an intoxicating drink is made which is said to be a safe narcotic.

All the stove species require cutting in more or less every autumn.

MARCH 1834

Ipomopsis Elegans

| CLASS. | ORDER. | |

| PENTANDRIA. | MONOGYNIA. | |

| NATURAL ORDER. | ||

| POLEMONIACÆ. |

Generic Character.—Calyx in five divisions, tubulous and membranaceous. Corolla funnel-shaped; much longer than the calyx, coloured, deciduous. Stamina five, inserted within the tube of the corolla. Capsule three-celled, and many seeded. Seeds angular.

Specific Character.—Stem erect, the top somewhat pendulous, clothed with abundance of soft hairs. Leaves deeply pinnatifid, and spear-shaped. Flowers growing in clustered panicles. Corolla funnel-shaped, carmine colour, tube narrow, limb five-cleft. Segments terminating in a sharp point, marked round the mouth of the tube with irregular white spots.

Synonyms.—Gilia aggregata, Sw. Br. Fl. Gard., fol. 218. G. pulchella, Douglas. Cantau aggregata Pursh.

This beautiful plant is a native of the North-west coast of America, whence is was introduced to the garden of the Horticultural Society, by Mr. Douglas, in 1827.

Whether it is naturally a perennial or not is uncertain; it seldom with us survives two years, being very impatient of cultivation. We have seen individual plants of it thrive and flower beautifully, whilst their neighbours of the same sowing, and apparently experiencing the same treatment, have fallen over just above the ground when about to flower, without any apparent cause.