* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Dust of Dead Souls

Date of first publication: 1938

Author: Henry Bedford-Jones (1887-1949)

Date first posted: Apr. 20, 2022

Date last updated: Apr. 20, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220453

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Dust of Dead Souls

Warriors in Exile #9

By

H. Bedford-Jones

Illustrated by Jeremy Cannon

First published Blue Book Magazine, February 1938.

“Dust of Dead Souls,” ninth in this unique series, vividly pictures the tragic adventure of the Foreign Legion in the Franco-Prussian War.

“Have you need of anything, Sergeant?”

When news of the Hindenburg disaster broke, I was in Algiers. . . . Europe and Africa being tremendously air-minded, that calamitous news made a real impact. People talked about nothing else. My chauffeur talked about it, as he ran his rickety taxicab up the steep hill above the cemeteries, to the glorious church of Notre Dame d’Afrique on top of the headland. Two white-clad monks out on the church steps were evidently discussing it, too, with a little old gnarled, white-haired man who waved a newspaper in one hand and in the other held a stick, as a man holds a sword.

As my driver pulled up beneath the trees at the side, he jerked a thumb at the old bent figure.

“Regardez! A veteran of the Franco-Prussian war, m’sieur; the Colonel Wiart. He’s getting on to ninety, they say, and spry as an Arab boy!”

Not quite, perhaps; those little brown animals have the very devil in them. Old Wiart went into the church. Some kind of service was going on, and I followed him. The Black Virgin above the altar was lighted up, which seldom happens, and I studied her with some interest. This was a place of pilgrimage for all Algeria, and the walls were covered with votive objects of all sorts, from ship models to plaster casts and crutches. Among them were not a few medals. One, set high up, appeared to be a cross of the Legion of Honor, set behind glass.

I was looking up at this when Wiart came out. As he passed, he followed my glance, and I saw him smile and nod.

“Pardon me,” I ventured, “but you seem to recognize that cross. Of the Legion, I think?”

We had a few words; he spoke English perfectly, and seemed pleased by my request. We walked over beneath the trees and sat down at the verge of the great drop. Off to the left, the seminary, the villas and buildings running westward; below, the cemeteries; to the right, all Algiers dropping down its sweeping hillsides to the sickle-curve of the bay—and beyond all, the Mediterranean. A lovely spot, white with sun and green with the soft verdure of Africa, and vivid blue with sea and sky.

“Dust!” old Wiart snorted. “These scientists say that the blue of the sky comes from dust. Then it is the dust of men long dead.”

“That’s an idea, anyhow,” I said. “A charming conception.”

Wiart saluted. “Support—for the Legion.”

“These poor people who died with the Hindenburg airship—they are up yonder.” And he pointed with his stick. “They are the blue we see; the dust of souls. Conception? Not at all. It is fact. You asked me about the cross of the Legion, inside there. I’ll be glad to tell you the story. It is about a sergeant in the Foreign Legion, and what happened on the 15th of January, 1871.”

What all this had to do with the cross and its ribbon up there in the church wall, I did not see. The old fellow had a way with him, however. He mentioned Sergeant Wiart of the Legion, and this puzzled me; an old veteran, thirty years with the Foreign Legion—his father, I reflected. This man, approaching ninety, could not have been much more than a lad of twenty, back in 1871.

“You know,” he went on, accepting a cigarette and brushing back his white mustache as he held it to my lighter, “Bourbaki was the great hero, in those dark days. He had begun his career with the Legion in Africa; he was the finest soldier in all France; he had even refused a throne. Well, Bourbaki commanded the Army of the East; he was the hope of all France, when 1871 began. He had already beaten the Prussians once. Now he had one hundred and fifty thousand men and was advancing to relieve the siege of Belfort. Do you know why he lost his entire army and emptied a pistol into his own head?”

I shrugged; who knew, or cared, about those days of 1871? The old man caught my gesture, and sighed. Then he took a pencil and pad of scratch-paper from his pocket, and made a sketch. He dashed down a face, a ragged uniform, a man—an entire personality. The result was one of those astonishing trifles which say more than words can convey. . . .

A grizzled, unshaven man of iron, this sergeant of the Foreign Legion, wearing odd bits of various uniforms—anything to keep out the wintry blasts. The vivid intelligence of his face was held in check by his inbred habit of discipline, of respect for his superiors; if you ordered Sergeant Wiart to march and die, he might know you for a blithering idiot, but he would march to death in silence.

During the horrible march to capture the heights above Sainte Suzanne, this sergeant knew better than anyone else what it was all about. The Legion had been almost wiped out in previous fighting; now the gaps were filled by two thousand young Bretons. This entire army was composed of recruits, backed by a steely nucleus of a few old regiments.

The Foreign Legion was given one day in which to capture those heights. It was a mere detail of the marvelous plan Bourbaki had evolved to crumple the whole Prussian invasion; a plan so perfect that, despite all defects and failures, nothing could stop it. Bourbaki had spotted the one vulnerable point. General Cremer was to be hurled forward like a spearhead, all opposition rolled away—and the Prussian disaster would be inevitable.

As the Legion found, the plan was evolved from maps. The army had no intelligence service. Sergeant Wiart snorted through his mustaches that the Legion had to do what an entire division could not do—and it was literally true. But the Legion did it.

All that day, the Legion struggled ahead. Prussian batteries played upon them. Prussian troops occupied every height of land. Bridges no longer existed. The weather was bitter cold. There was no food; all service of supply had failed. The wintry air, throughout the whole Lisaine country, was hammering with artillery, spiteful with rifle-fire, clouded with the reek of powder.

Sergeant Wiart prompted the green officers, cheered up the men, scoffed at hunger and bloody feet. To him the colonel turned for some knowledge of what lay ahead. With admirable precision, Wiart sent on the advance scouts, sent back the word they bore, watched the Legion struggle grimly forward.

With afternoon, the plateau was dead ahead—the heights dark with Prussian battalions. They had reached the objective; they had only to take it. The harassed colonel and adjutant summoned Sergeant Wiart, who saluted stiffly.

“There is no reserve ammunition, sergeant. How is the supply?”

“Practically exhausted, my colonel.”

“Have you heard anything of supporting troops coming up?”

“There are none.”

“It is incredible!” muttered the colonel, his worried gaze searching the valley behind. “Already we have lost—how many, adjutant?”

“A few over five hundred, my colonel,” said the adjutant, and grimaced.

“Very well. The Legion has been ordered to take those heights and hold them. The quicker we do it, the better.”

The bugles shrilled. The orders rattled along the lines. Wiart had caught up a rifle, and fixed bayonet as the click of steel lifted on the wintry sunlight. Smoke rimmed the snowy heights ahead. Sergeant Wiart surveyed his weapon approvingly. Old model bayonet, new model rifle; the “fusil, 1866 model”—the famous chassepot.

Jests broke out. Wiart’s voice crackled into the chorus, dominating the others with its rasping, blasphemous profanity until the Legion howled with joy, all except the dark Breton recruits, who were religious fellows. There was nothing pious about the Legion in general, or about Sergeant Wiart in particular. He was noted for his hatred of anything clerical. He was as savagely blasphemous as his wife, in Algeria, was devout.

Oddly enough, the thing he most revered in life, aside from his wife and son, was the Cross of the Legion of Honor. He had won it years ago, and was wont to mourn over his wine-cup that the first Napoleon had not chosen another emblem than the Cross. . . .

A sudden order rattled. A wild yell burst forth; then Wiart was up and going with his company.

Fire rippled along the heights. Balls screamed and sang viciously, or thudded home. Grape shrieked and whistled; the cannon ahead were blasting away. Men stumbled, slipped in the snow; the charge left a bloody wake, yet, with never an answering shot, the figures wavered on and upward.

The heights came closer. The Prussian faces, bearded and staring, appeared through clinging smoke. Breastworks, by God! And then, suddenly, it was hand-to-hand work.

The sergeant was up and over. Wily old veteran that he was, he fought carefully and coolly, plunging the point home, warding threatening steel away. The guns were taken, the positions carried; the Prussians broke. The ferocity of the Legion swept everything before it, until the entire plateau was captured.

Now it had to be held.

The colonel paused beside Wiart, who was calmly bandaging a ragged gash across his upper left arm.

“So you caught it, eh?”

“A mere scrape of the bark, my colonel.”

“You’re able to travel. Go back to headquarters; give this note to General Barolle, chief of staff, and augment it by word of mouth. We must have cartridges, food and supports. Meantime, we shall hold the plateau as ordered. Now, sergeant, lift the lid off hell if you like—but reach headquarters!”

Within a quarter-mile of the hill, he drew rein. His errand had come too late.

Sergeant Wiart saluted, caught up his ragged coat, and started.

A dead Prussian provided a sound pair of boots, and emergency rations. A mile farther back, kindly fortune provided transport. A gallant and portly Bayonne wine-merchant, who had squeezed himself into captain’s rank and cavalry uniform, was frantically trying to find his regiment, when the ragged figure of Wiart came upon him, with revolver leveled. The major dismounted, cursing hotly, and Sergeant Wiart swung up into the saddle with a grin.

“Curses don’t hurt a Legionnaire, old sowbelly,” he retorted.

“I’ll have you shot for this, you scoundrel!”

“You’ll find me at headquarters,” said Wiart, and rode away.

Now he began to meet stragglers, officers, a torrent of marching men and transport. To anyone else, it would have been an involved and confused mess; to Sergeant Wiart, the news he picked up began to make the whole campaign look simple. Suddenly a shout halted him. He turned, to see a young staff officer, a captain, riding toward him. His scarred, brown features broke into joy. His gray mustaches quivered. Stirrup to stirrup, the two men embraced warmly, with open emotion.

It was the first time Sergeant Wiart had seen or heard of his son, since leaving home.

“Ah! You’re a fine fellow—and a captain!” Tears glittered on his unshaven cheeks. “Magnificent! On the staff, eh? What staff?”

“Headquarters, my father. I’m one of Barolle’s aides.”

“Good! We ride together,” and Wiart explained his mission. Voluble speech flowed from them both; joy at their reunion, wonder at the chance of it. The old sergeant called it luck; the young captain called it providence. He did not share his father’s atheism.

As they rode, their speech was torrential. Neither had heard from Algeria in weeks; with France prostrate and struggling vainly, everything seemed in chaos. Everything, except here. Under his son’s explanations, old Wiart understood the strategy of Bourbaki, and approved it. Simple enough; roll back the Prussians to right and left, let General Cremer smash through with his army corps to Belfort, and the war was over.

“But it’s not so simple,” said Captain Wiart, a worried look on his young face. “The chief of staff, Barolle, is a wonder. But General Bourbaki has a favorite aide, one Colonel Perrot, who has practically superseded Barolle; he’s a flashy fool.”

“Bah! Old Bourbaki knows his business,” growled the sergeant confidently. “I knew him thirty years ago when he came to the Legion as a shavetail. He’s all right.”

It was dark when they rode into the village that housed headquarters. The captain procured food and wine for them both, reported, and took in the sergeant’s note. Old Wiart noted with some astonishment that there was no particular tension here; couriers and aides were dashing about, but the general air was one of complacent assurance.

“Bourbaki knows how to run a battle!” he muttered. “Calm efficiency—that’s the ticket!”

Barolle appeared, a tall, thin man with the absolute precision which marks the born chief of staff. With a dozen words he appraised and ticketed Sergeant Wiart.

“No food, no ammunition, no supports—this must be remedied. God knows where the various corps are. Make yourself comfortable, until I see the general.”

The sergeant followed into a large room, blue with tobacco-smoke, littered with tables, maps, officers hard at work. Barolle vanished. Sergeant Wiart took a chair and relaxed gratefully.

“Poor Barolle!” remarked somebody. “They’ve raised hell with all his dispositions—”

The voice hushed abruptly. From an adjoining room came a laughing, jovial colonel, his face flushed, his eyes bright with wine.

“Captain Marcel! Send a telegram to General Belancourt at Verlans, instantly! At ten in the morning, he is to advance on the Mont Vaudois heights with every available man; instruct him that his job is to divert the enemy’s attention from the main attack against Hericourt.”

A dead silence fell. It was broken by the officer addressed, who spoke in dismay.

“But, my colonel, we do not know that Belancourt has yet reached Verlans! In fact, we received a report that the Prussians are there in force and have mined the bridges—”

“Nonsense!” exclaimed Colonel Perrot. “Belancourt was ordered to capture Verlans before six tonight; it has been done. Officers of France never fail. We’ve just had word that the Legion has taken the Sainte Suzanne plateau, as ordered. You see?”

With a twirl of his mustache, he turned and disappeared. Sergeant Wiart saw the flash of horror in the faces around.

“Colonel Perrot is always right,” some one muttered. “He counts the kilometers on a road—good! It should be marched in an hour. He does not stop to ask if the Prussians hold it, or if it is still a road.”

“It will not be a battle but a massacre, my son.”

“Anyhow,” said another, “we know that the great thing is accomplished: General Cremer has gone forward, the Prussians are pierced, the way’s open to him!”

“And there’s hell to pay everywhere else,” retorted the first officer.

Sergeant Wiart got out his pipe and lighted it, to choke down the spasm of emotion that gripped him. To his wise, cynical old eyes, the curtain had rolled back, revealing terrible things. A chief of staff superseded by an aide—that was bad enough. Worse, a telegram sent to Verlans on the assumption that a French general was there, because he had been ordered to be there! A telegram, not in code, revealing the whole strategy of the morrow’s battle! If that telegram reached a Prussian general[1]—well, Sergeant Wiart went cold at the very thought. He looked about for some sight of his son, but the young staff captain was nowhere to be seen.

|

As it did.—Editor. |

Colonel Perrot reappeared and summoned an aide.

“Make out a formal order, which the General will sign. Order Colonel Chauvez to march at once with the 115th Infantry and the 23rd Zouaves, to support the Legion at Sainte Suzanne. When it’s ready, Captain Wiart will take it.”

The aide saluted, and hesitated. “It is not known yet,” he blurted desperately, “if Colonel Chauvez and the reserve corps has reached the river—”

“Certainly he has reached it; he was to have been there by four this afternoon,” said Perrot brusquely. “Here’s an order for the quartermaster-general. Have food and ammunition sent the Legion at once, by a forced night march.”

Perrot disappeared. Sergeant Wiart again saw the officers look one at another, and from somewhere came a low, bitter comment:

“A fat chance the Legion has! Every corps living on its knapsack, and not a wagon of food to be found within twenty miles! And who knows where the ammunition is?”

Sergeant Wiart shivered with a chill that swept through his very soul—though he had always denied having a soul. A courier came stumbling in, and presently another; he could guess that they bore bad news. Telegrams were arriving. A funereal aspect settled on the big room, an air of consternation and dismay.

Suddenly it changed, all in a moment. The muttering talk ceased. General Barolle appeared, and his presence transformed the whole place; the man’s energy, his strength of character, was like a tonic.

“Sergeant! General Bourbaki wishes to speak with you.”

Old Wiart went into the adjoining room and stood at attention. More than anything in the world, just now, he wanted to see his son again; but orders were orders. A table was littered with maps and reports; orderlies at work with Captain Perrot; other officers all about. At the table was Bourbaki himself, with three other general officers.

“Ah! A sergeant of the Legion, and looks it!” exclaimed Bourbaki. He was swarthily handsome, for his father had been a Greek officer. “Here’s a glass of wine for you. What’s your name? Haven’t I seen you somewhere before now?”

“Thirty years ago, mon général.” Wiart downed the wine, put the glass on the table, and stood at attention again. He gave his name, pronouncing it in the German fashion.

“I seem to remember you,” Bourbaki said, frowning. “Thirty years ago? Where?”

“When the General joined us as a lieutenant at Algiers. He got into trouble about that Arab girl—”

Bourbaki broke into a roar of laughter, in which the others joined.

“So, I remember you now! Well, well, make yourself comfortable at that corner table, help yourself to food and wine; no ceremony, old campaigner! Rest a bit, eat, then return to your leather-bellies and congratulate them. The Legion has reached its objective, if no other corps has!”

“No other corps has!” Those words sent a jolt through Sergeant Wiart, but he settled himself at a corner table and began to eat and drink. An aide came in with a message. Bourbaki read it and uttered a delighted exclamation.

“Messieurs, all goes well! Cremer has driven the enemy from Chenebier. The Lure road is open before him. He has only forty kilometers to march, and France is saved!”

There was an outburst of voluble, joyous voices. Only one among them all uttered a hesitant word of disagreement.

“Forty kilometers? But, Bourbaki, that is a march!”

“Bah! Five years ago in Mexico, the Legion marched thirty leagues in a day. And Cremer can certainly throw his corps forward a mere forty kilometers, when the fate of France hangs in the balance! He must do so. He shall!”

Sergeant Wiart was actually stupefied by the fact that Bourbaki spoke in earnest. True, the Legion had marched something like a hundred and fifty miles in thirty-two hours; but not through ravened country, with every road mined, every bridge blown up. When Bourbaki rushed off half a dozen telegrams and couriers, the sergeant noted the messages, then wiped his gray mustache and fumbled for his pipe; his appetite was gone.

“The devil!” he told himself in dismay. “Army corps scattered everywhere. No information about the enemy. A general attack to roll back the Prussian armies, cut their rear, cripple them—and not a third of the job accomplished! And the old man gives an aide full charge of operations while the chief of staff is a mere messenger-boy. Well, if Cremer goes through, we still win the day, for nothing can save the Prussians then. If he doesn’t go through, the Army of the East will be wiped out like a burst of smoke.”

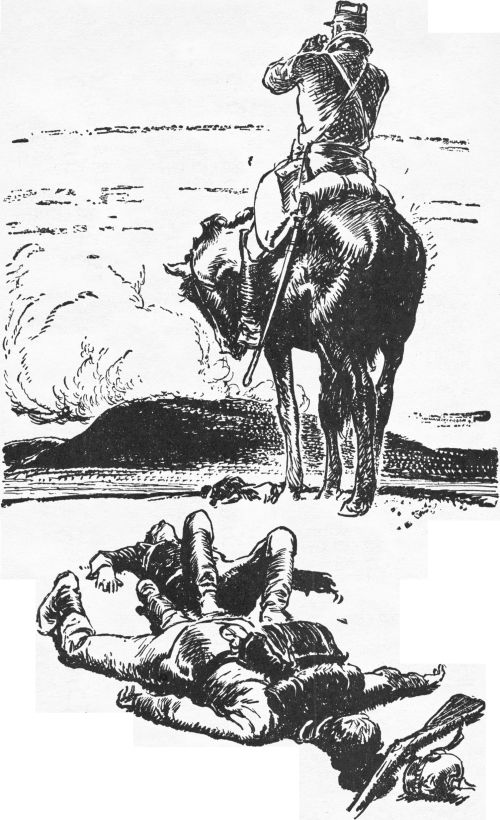

They had reached the objective; they had only to take it. . . . The charge left a bloody wake, yet the figures wavered on.

With his thirty years’ experience, he saw this in one flash—not of intuition, but of shrewd intelligence. He knew his business. At least, he had definite news that was good. Cremer had smashed through the Prussians and had a clear road before him. He tucked away his pipe and rose. Bourbaki caught sight of him.

“Leaving, Sergeant? Have you need of anything?”

Wiart saluted. “Food. Ammunition. Supports. For the Legion.”

“There’s a soldier for you, gentlemen!” And Bourbaki chuckled. “Well, my friend, I’ve sent food, ammunition and supports. You’ll probably join them en route back, for Chauvez and the reserves are down at the river, ahead. Perrot! Write out a pass for my friend the sergeant of the Regiment Étranger.”

Colonel Perrot scribbled the pass.

As Sergeant Wiart took it, the door suddenly burst open. Into the room hurtled an aide, pale, eyes staring. He struck against old Wiart, knocking him aside, and thrust the telegram in his hand at the General. He tried to speak, and could not.

Bourbaki seized the message. As he read it, his eyes distended.

“Mon Dieu! Mon Dieu!” he gasped. “Manteuffel and his army of sixty-five thousand Prussians are advancing on Cremer’s flank—an army supposed to be sixty miles away!”

The blood died out of his face; he was suddenly an old man, tragic, broken, hesitant, his fire exterminated. It was a frightful moment. Every man present knew what it meant; but only one man, of them all, knew what was to be done. Sergeant Wiart. The mad words rose in him—“Tell Cremer to hammer through!” They were on the very lips; and he might, in his momentary madness, have uttered them, had not General Barolle at this moment come into the room and saved him from the breach of discipline.

“Barolle!” The General swung around. “You know? You have heard? It is not true?”

“Apparently it is true,” said Barolle calmly. “You have not asked my advice. Pardon me for presuming; it is to tell Cremer to advance more quickly.”

Sergeant Wiart could have hugged the man, general or not, for those words.

“My God! It’s impossible. We haven’t any force at hand to meet Manteuffel—except Cremer’s army,” broke out Bourbaki, purple veins rising in his forehead. “He must halt, retire, and stop the gap. Once Manteuffel breaks through, our whole army is lost!”

“But my general!” said Barolle coldly. “If Cremer goes forward, if the army of Manteuffel does not strike his flank—then every Prussian in France is lost!”

“If! If!” cried out Bourbaki in a tragic voice. “Who could take such a chance? This is the one army remaining, the hope of all France— No, no! Send the order to Cremer at once, instantly!”

Barolle saluted and retired.

Sergeant Wiart went stumbling out of the room, out of headquarters, out to where he had left his borrowed horse. His pass took him through the sentries. He mounted, kicked in his heels, and sent his horse scrambling away.

He perceived, quite clearly, the truth of this whole business. The chances were ten to one that Cremer and his army would have gone through without sighting a Prussian—but the General dared not take that chance.

“And now, what happens?” reflected Wiart, as he rode under the cold stars. The crepitation of distant artillery fire crept down from far snowy hills. “What happens? Only one thing can happen. Cremer halts, checks the veterans of Manteuffel with his young recruits, and perishes. Meantime, the other Prussian armies are rolling in from all sides. The Army of the East is destroyed, its retreat is cut off, it ceases to exist. One of the great tragedies of history is happening around us.”

The night was bitter cold, and growing colder, but not nearly so cold as the heart of Sergeant Wiart, when he thought of the Legion awaiting him, up yonder on the heights. Not even his explosive roll of oaths could give any comfort. And by midnight the stars were hidden behind clouds, with a threat of snow.

The heights of Sainte Suzanne were only a couple of miles farther, when Sergeant Wiart overtook two wagons plodding along, with a little column of men. An Arabic oath crackled out; he responded with incredulous delight. Tirailleurs! Next moment a horse reined in beside him, and he was clasping the hand of his eager son.

“Your mother prates about miracles,” he said dryly. “Is this one?”

Captain Wiart laughed, and let the little convoy draw ahead lest they overhear him.

“Something of the sort, my father. I was ordered to take food, ammunition and supports to your corps. Well, I have bad news for you. There are no reserves, it seems. There is no food or ammunition. They have not come up with the army, and the Prussians have cut off the rear. I picked up a wagon of rations, another of ammunition, and a hundred tirailleurs under a lieutenant, who was lost; he consented to obey me and here we are.”

“Excellent,” said the Sergeant coolly.

With an access of emotion, his son caught him by the arm.

“My God! Don’t you realize what it means?”

“I realized that long ago. They’ve recalled Cremer to meet a fresh army of Prussians. If he’d gone on, their whole rear would have been cut. As it is, he’s turned back. Their armies are around us. We have only one possible retreat—across the Swiss frontier, to be interned. That is to say, if we can reach the frontier. Tomorrow, my son, all the upper air will be filled with the spirits of dead Frenchmen who have rejoined their Creator.”

“What!” exclaimed the other. “You have not suddenly become religious?”

“Not likely,” and Sergeant Wiart sniffed. “But I believe that when a man dies, what we call his spirit rejoins the Vital Force of nature, which you call God. It is quite simple, and satisfies me. Now, never mind theology. I’ll take these wagons on, and you get back to headquarters in a hurry.”

“No. I go with you,” said Captain Wiart.

The old sergeant flew into a furious cursing rage. He had no idea that the Legion would or could retreat. In any case, a few more hours would see the army a chaotic rabble striving desperately to reach the frontier, Prussian rifles and Uhlans and artillery hailing death into them from three sides; the headquarters staff would certainly be safe, and the Legion would as certainly be in the thickest of the hell. He said nothing of this, naturally.

“I stay with you,” calmly repeated his son. “It’s the first time we’ve met; and we can stay together now. Later, tomorrow, I can find my way back to headquarters—if there is one. Anyway, Colonel Perrot told me to inspect the conditions here and bring back a report later. That will cover my—”

“As your father, I tell you to clear out!” stormed the sergeant angrily. “It’s no place for you. There’ll be no report. We’re retreating at once, you fool!”

“I thought you said the Legion would not retreat? You certainly said so, when we first met and were talking.”

“It’s none of your damned business what I said,” furiously exclaimed old Wiart. “Get out! I order you—”

“I refuse. I’m your superior, an officer, and an aide of the General. March!” The younger man chuckled, then sobered. “Pardon, mon père; stop swearing and move on, will you? So far as I’m concerned, the argument’s ended. Let’s catch up with the wagons.”

He urged his horse on, and the sergeant followed. . . .

When they rode into the camp on the heights, Sergeant Wiart went straight to the colonel, who wakened to receive his report. Here was one man to whom he could speak his heart. The colonel was an old-timer. They were friends. In the blackness and chill, rank could be brushed aside.

Sergeant Wiart crouched beside the silent figure under the shelter, and told of everything he had seen and heard and feared. The colonel said nothing at all until he had finished. Then:

“You old fool, I hoped you’d stay gone!”

“Thirty years in the Legion, mon colonel.”

“I might have known it. Instead, you bring back a son and want me to send him off. I shall do nothing of the sort. We’ll need him. I suppose you think the Legion’s going to stick here unsupported—against all the armies of Prussia?”

“It’s the sort of thing the Legion does, certainly.”

“Not here. My orders are to fall back if unable to hold the heights. Turn in and sleep. We march at six in the morning; the food and ammunition you have brought will save us. Tomorrow the army will be destroyed, and the next day, and the next—”

He hung his head and muttered into his beard, in black despair and heartbreak. Old Wiart crept off, turned in among his comrades, and slept. He was dead beat.

Morning gave a gray sky, and the thunders of artillery from all the horizon; the Army of the East was encircled. A hero, who had suddenly turned into a broken old man, had flung away the whole splendid strategy of success. Sergeant Wiart found his son and sat apart with him, accepting the destiny he could not evade. He saw utter destruction for them all, and was desperate.

“France is dying,” he said to Captain Wiart, despairingly. “Men are dying. Half the army may reach the frontier and safety; the rest will perish. It will not be a battle but a massacre, my son. It is cold up there!”—and he glanced at the gray sky. The younger man smiled slightly.

“You’re still thinking of the Nature Force or whatever you call it?”

The sergeant nodded, gravely. “Yes; but I am not certain of anything. There is always a chance that your mother may be right about these things. Suppose I die, suppose what makes the life in me evaporates and goes up there, back to rejoin the divine force whence it came—well, after all one may reconcile that with Christ, or Allah, or what one likes. At all events, I have made a vow to the Virgin of Africa.”

Young Wiart stared in sharp surprise.

“Yes.” Old Wiart spoke with simplicity. “One never knows; your mother may be right. I have asked the Black Virgin—you know, the one in the church above Algiers, where your mother went on pilgrimage—I have asked her to bring you home safe; and if she does, I’ve vowed my Cross to her. You remember that. You tell your mother.”

“I?” Sudden tears suffused the keen dark eyes. “I, Father? You speak as though you weren’t coming back home.”

“I don’t think any of us are, my son; I hope you are.” Sergeant Wiart put out his hand to meet that of his son. “Good-by. There go the bugles. God bless you—well, I’m a damned old fool for saying so, but I mean it anyhow—”

They embraced, captain and sergeant, as the bugles spoke. Rifles were crackling; bullets were in the air.

The Legion began its retreat. If the advance had been difficult, this retreat was a horrible nightmare. The Prussians were everywhere. The hills were masked by smoke, the ground shook with the tremendous blasts of artillery fire. The colonel went to old Wiart and pointed down the valley.

“You remember that sharp, steep hill we passed on the way up—the little one? Take your company and get there; hold it, while we check these damned Uhlans who are coming down on us. If the enemy gains that hill, we’ll all be cut off. Otherwise—”

“Understood,” said Sergeant Wiart. He passed the word to his men, and they were off at the double.

The main body fought on grimly. As the morning wore on, it became more apparent that the colonel had hit the nail on the head; if the Prussians held the little hill off the road, they had the entire corps at their mercy. Smoke and rifle-fire now ringed that hill, however. Sergeant Wiart was holding it against a blasting attack.

The column slogged on, the Prussians were checked and fell back, only to come again as fresh troops reached them. Captain Wiart had field-glasses, and as he rode, trained them on the little hill. The colonel came to him.

“Your horse is fresh enough. Will you take word to Sergeant Wiart to retire his men at once? We’re past the danger-point now—we can’t be cut off, thank God!”

The captain saluted and thrust in his spurs, and was gone with a rush, across the snowy fields and away from the road.

He was within a short quarter-mile of the bald, bare little hill, when he drew rein. He was on a little rise of ground. His pulses suddenly leaped, as he sensed something wrong. Then he saw what it was: the firing had ceased. He drew out his glasses, focused them, and saw a flood of Prussian uniforms over the crest of the hill. His errand had come too late.

His heart stopped. Then, through the glasses, he discerned a little knot of struggling movement, off at one side of the crest. Figures were clumped there. For an instant, his glasses brought up a face and figure he was certain that he recognized. And then all was quiet; the group was dissolving.

The glasses slipped from his stiffened fingers, slid away. His straining, distended eyes lifted; sudden astonishment came into his face. For directly above the little hill, the gray sky showed a spot of blue. The blue widened. It became a circle of clear, open sky—and it was gone again. Only for the fraction of a moment. But enough to convince Captain Wiart, to send him riding back with fear and mystery stirring in his heart.

“And now the scientists have come along to say much the same thing,” said the old gentleman sitting beside me and looking down at Algiers and the Mediterranean. “It is very strange. The blue sky is only dust, they say. Well, it is not nearly so nice a thought as the one my father had! And there was something to his belief; perhaps that was why the gray sky opened and a little bit of blue showed to me, when he died there on the hill under the Prussian bayonets!”

I did not argue with him, of course. If the old chap believed it, if the thought pleased him, why argue it away? Besides, to be quite honest about it, I was by no means sure that I could argue it away even if I wanted to do so!

“Then,” I asked, “that story explains why the Legion of Honor decoration is hanging up there on the wall, silk collar and all!”

He nodded. “Bullets found me; but I reached home safe, though a little crippled. Still, that was not the fault of the Black Virgin. So my mother did as my father had desired, and his Cross hangs there as you see it. I had to leave the army, because of the bullets that crippled me. It was the great sorrow of my life. I had hoped to get transferred to the Foreign Legion, you see.”

“That’s all very well, about soul-dust making the sky blue,” I observed. “When you apply it in general, to poor folk such as those who perished with the German dirigible, it’s a nice thought. But what about people who go down under the sea with a ship and stay there? You can’t expect their vital essence or spirit or whatever it is, to get up through the water, can you?”

I had him there. He gave me a slow, serious glance, and then he pointed to the big block of stone out in front of the church, on the very tip of the high headland; the stone with its inscription for very pious folk, about the souls of those who were drowned in the sea below.

“No,” he said, “I can’t. But maybe the Black Virgin takes care of them, m’sieur. For, look down there!” And so saying, he swept his stick out at the Mediterranean. “What makes that ocean so blue, if it’s not the same thing that makes the sky overhead blue?”

Well, I was never good at theology!

Changed m’sieu to m’sieur.

[The end of Dust of Dead Souls by Henry Bedford-Jones]