* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Two Worlds of Music

Date of first publication: 1946

Author: Berta Geissmar (1892-1949)

Date first posted: Apr. 6, 2021

Date last updated: Apr. 11, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210405

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

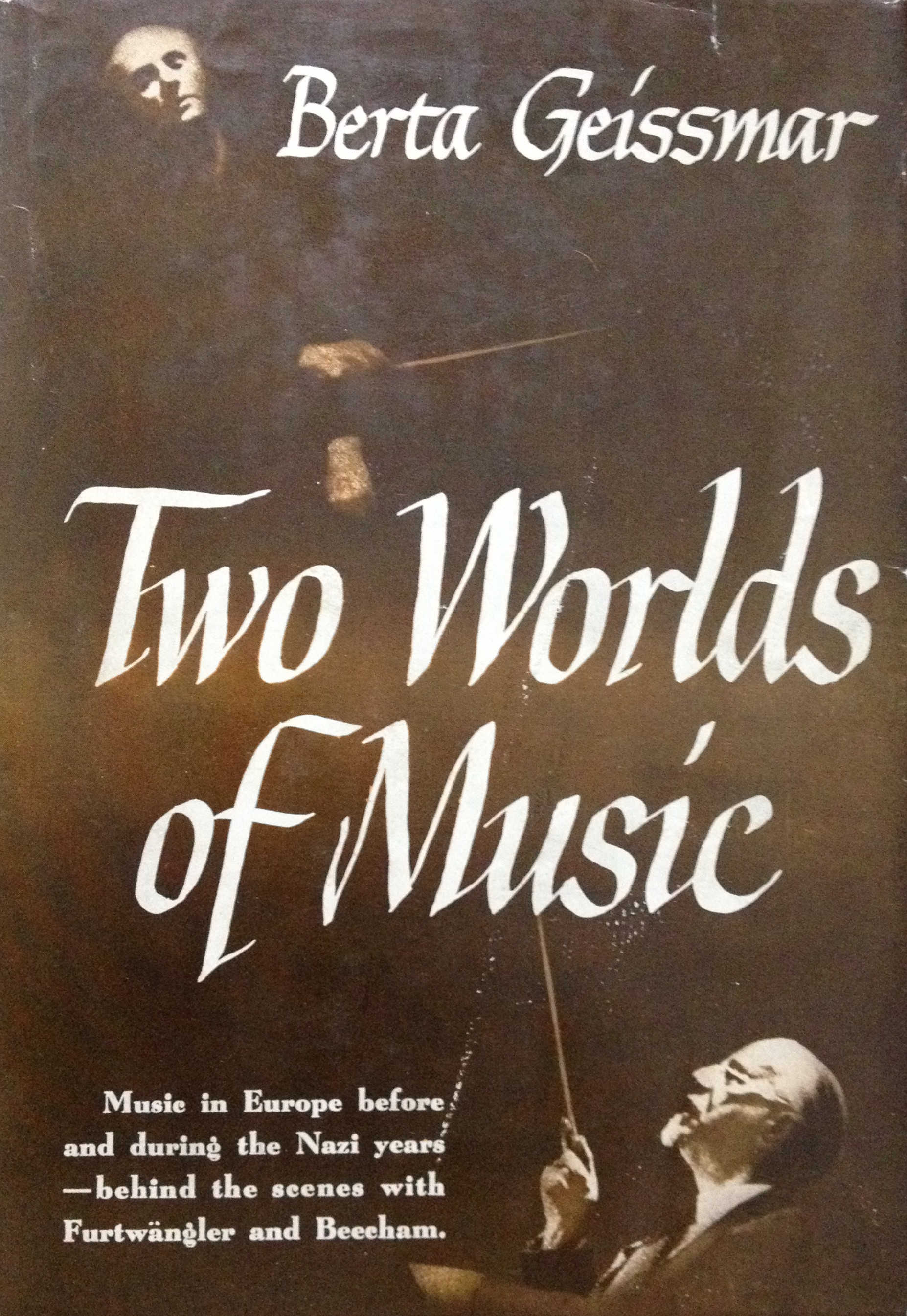

The Author in her office at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Berta Geissmar

TWO

WORLDS

OF

MUSIC

NEW YORK

Creative Age Press, Inc.

Copyright 1946 by Berta Geissmar

All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this

book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever

without written permission except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AMERICAN BOOK—STRATFORD PRESS, INC., NEW YORK

| CONTENTS | |

| Part One | |

| Germany Before Hitler | |

| Part Two | |

| Hitler Germany, 1933—1935 | |

| Part Three | |

| American Interlude, 1936 | |

| Part Four | |

| Pre-War England, 1936-1939 | |

| Part Five | |

| England in War Time, 1939—1945 | |

| Epilogue | |

| Index | |

This book touches on the musical life of seventy years ago and dwells on it for the last thirty. Music, as every other part of cultural life, is, to a certain extent, connected with the current social and economic conditions, but never before has it been seized and exploited for the purposes of the “absolute state” in which art ceased to be independent.

The events of this book have actually happened. It is a document of the problems that arose out of the circumstances of an epoch, of men behaving according to their disposition and character. It intends to be an honest record of a period in which tradition, evolution and freedom fought their battle against dictatorship; of music in Germany fettered to Hitler’s huge machine, and music in England, neglected perhaps, but free.

B. G.

A town of character bequeathes a rich heritage to its children.pre-1914 I was born in Mannheim, a town which since the reign of art-loving Elector Karl Theodor had endowed its citizens with a love of music and of drama, and had established a great cultural tradition which persisted through the years. The young Goethe admired its collections of art and literature; Mozart’s visit to Mannheim was a milestone in his artistic development. Charles Burney, Dr. Johnson’s friend, wrote in praise of Mannheim’s Electoral band in 1773: “. . . Indeed, there are more solo players and good composers in this, than perhaps any other orchestra in Europe; it is an army of generals, equally fit to plan a battle, as to fight it.” Lessing very nearly became director of Mannheim’s theater, and the beginnings of Richard Wagner’s career were influenced by his friend and early enthusiast, Emil Heckel, a citizen of Mannheim, founder of the first Richard Wagner Society in June 1871.

Mannheim was my native town.

My mother descended from one of the venerable families which had made Mannheim its home for almost two hundred years. Both my paternal grandfather and my father, his junior partner, were well-known lawyers. My father, in addition, was extremely musical. Business was never mentioned at home, but his passionate love for music constantly invaded his office. The concert society that he founded was run from there, and he even kept a violin there to play at odd moments.

My father played the violin and viola extremely well, and was a respected connoisseur of string instruments whose judgment was consulted by people from all over Germany and even from abroad. He carried on a wide, fascinating correspondence about instruments. In 1900 the collector’s dream came true. He was offered the Vieuxtemps Stradivarius. When he consulted Joachim, the famous violinist, about the instrument, he received a post card saying, “This Antonio is not a cardboard saint!” That decided him. He bought the Vieuxtemps, so called because it had been owned by the famous virtuoso.

The violin was made in 1710 which is considered Stradivarius’ best period. It has always been in careful hands and is still in a fine state of preservation. The golden-orange color for which it is noted, and which most Strads of that time share, is reminiscent of the golden hue of Rembrandt’s best period. The late Alfred Hill, world renowned London connoisseur, considered it among the handsomest Stradivarii that exist.

The violin was the delight of my father’s life, and he hardly ever parted from it. After his death my mother and I kept the instrument, for we cherished it far beyond all the tempting offers that we got for it. When I had to leave Hitler Germany, the export of such instruments was not yet forbidden, so the Strad was tucked under my arm, a symbol of all I had loved and was forced to leave behind. Except for a brief period in 1936 when I was in America, I kept it with me, until I placed it in the care of the Messrs. Hill during the blitz. It was removed from the danger zone during the blitz to one mysterious place after another. “Don’t you worry,” said Mr. Hill, “your fiddle is in the most illustrious company.” The roster of other instruments removed to safety with my Vieuxtemps was indeed impressive, and for a while, by one of those strange coincidences of an emergency, the Vieuxtemps Guarnerius was sheltered with the Stradivarius with which it had formerly alternated.

After my father had acquired his Stradivarius, his collecting zeal abated. He always kept a floating population of instruments in the house, however, at least enough for a quartet; and once a week during his entire life, his own quartet which he had organized gathered to play at our house. Nor was his enthusiasm for chamber music satisfied with those superlative amateur evenings of music. In those days, innumerable concert societies flourished all over Germany, supported, for the most part, by music-loving amateurs, many of whom were competent musicians themselves. With a few others, my father had guaranteed the money to found a concert society which, in the course of its four annual winter concerts, engaged all the famous quartets.

Concert days of “our concert society” were always exciting. The artists were often our guests, so the rehearsals were almost always held at our house, and after the concert we invariably entertained the musicians and a group of friends.

The life of the family was inextricably bound up with music. We were constantly entertaining famous musicians. We loved and respected the works of the great masters, but at the same time were keenly aware of the newest aspects of that brilliant era of German musical development. When Brahms’ works, particularly in chamber music, became more widely known, a big Brahms community sprang up in Mannheim. My family knew him personally and supported him ardently from the beginning, but their inherent devotion was to music, not to individuals, and for that reason they were able to accept Wagner too. Controversy raged about the work of the two men, but my family listened to them both with enjoyment.

Mother loved to illustrate the degree of that controversy with an account of her visit to Karlsruhe to hear Felix Mottl conduct the first local performance of Brahms’ Third Symphony which had had its premiere under Hans Richter in Vienna in December 1883. Mottl was frankly a Bayreuth man, a champion of Wagner, which in those days logically implied a sworn enemy of Brahms. After the Karlsruhe performance of the Third Symphony, Mottl burst into the artist’s room quite out of breath, exclaiming, “Thank God! We made short work of that!” He had falsified Brahms’ tempi to spoil the effect of the symphony.

Even Brahms himself was not a good interpreter of his work. When he played his concerto in B flat in the historic Rokokosaal of the Mannheim Theater, his clumsy fingers often hit the wrong notes, but in spite of it, the concert left a deep impression on the audience.

Mother went to Bayreuth, too. In 1889, when she was seventeen, she made the long, tiring journey to a Bayreuth far different from the one I was to know later. That year, royalty, musicians and people from all over the world flocked to hear Felix Mottl conduct Tristan with Alvary and Rosa Sucher, Hans Richter conduct Die Meistersinger and Hermann Levi, Parsifal with the incomparable Van Dyck in the title role and Amalie Materna and Therese Malten alternating as Kundry. And afterward they congregated in the restaurant to give further acclaim to the singers as they entered.

My childhood was full of such stories, people and the music that was behind them. As I quietly sat and listened to my father and his friends playing quartets, I got to know a great deal of chamber music by heart, and one of my greatest delights was to sit with him at the Society concerts, following his score with him while he pointed out the passages he loved and told me how they should sound. I became so involved in his correspondence about instruments, that I gained a considerable knowledge of the subject. I can never be grateful enough for that heritage. It makes a person strong in himself, gives him a kind of armor against all mishap, something which no circumstances can ever take away.

There was a perfect companionship between my father and myself. He would have preferred that I stuck to music as I grew up, and was not really in favor of a university career for me. But he was as responsible for my love of philosophy as for my love of music, and when I was 18 I overcame his protests and entered Heidelberg.

Heidelberg in 1910 was a wonderful place for a young and ardent student. The great scholars teaching there inspired a feeling of rapt discipleship, and the romantic surroundings of the old university town encouraged lasting friendships. I was the only woman at the University majoring in philosophy, and at father’s insistence concentrated first on the Greek. From the beginning, my family was concerned lest I neglect my violin, and lose my interest in the outside world in my concentration on philosophy and everything concerned with it. At first father simply selected my courses with care, but when I seemed to be growing overstudious, he interrupted my studies and sent me to England.

I adored England from the first. As a paying guest in a family in Harrow, I explored the world. I learned for the first time what it meant to live in a really free country, and my months of contact with unself-conscious Englishmen helped me overcome much of my shyness and quick embarrassment. I visited museums in London, waited in the pit queues of the theaters, saw all the Shakespeare I could, and for the first time in my life saw a ballet And what a ballet! The Pavlova Season at the Palace Theatre—the season during which Pavlova slapped her partner Mordkin’s face when he dropped her during Glazunof’s Bachanale, the climax, I learned years later, of jealousies because a woman mad about Mordkin had called for him after every number to Pavlova’s great irritation. Little did I think as I sat there, thrilled by that new world, that I would be working for the man who was to bring the Russian Ballet to England and be largely responsible for making London ballet conscious.

When I returned to the University, my time was divided between my studies and music. Then came the war. Mother was soon busy in one of the military hospitals, and I worked in an emergency hospital at the huge Heinrich Lanz plant. The ranks of Heidelberg were depleted, and since I could not go often, I confined myself to a private course at the home of my venerable teacher, Wilhelm Windelband, who read Kant’s Prolegomena and The Critique of Pure Reason with his eight students.

During those four war years, cultural and artistic life was kept up in Germany. Those really indispensable for the maintainance of cultural life, of opera, drama and concerts, were exempt from full-time war work. People met frequently for simple pleasures. An opera or a good play seemed even more enjoyable than in normal times. At home we played more chamber music than ever. Whether the news was good or bad, life was always stimulating.

After the first year of the war, Bodanzky, the Hofkapellmeister of1914-18 Mannheim, was appointed to the New York Metropolitan Opera. The choice of a successor in the great musical tradition of the town would have been difficult enough without the limitations imposed by the war. But the Theater Commission which was responsible for all questions concerning the Mannheim Theater and orchestra, selected a few likely candidates, and sent a small committee accompanied by Bodanzky to Lübeck to hear one of them. The young conductor was barely 28. He conducted Fidelio. Without further hearings, he was unanimously chosen. The Theater Commission had recognized his genius. He was Wilhelm Furtwängler.

In September 1915, Furtwängler took up his duties as first conductor of the opera and Musikalische Akademien concerts that date back to 1779. His first performance was Der Freischütz, conducted in the presence of his predecessor, who sat in the center box with my mother. It was full of promise of what was to come, and his first concert, which included Brahms’ First Symphony, gave Mannheimers the satisfactory feeling that in spite of his youth the new man in charge of their musical life was well able to carry on the fame of their old tradition.

For a young man as painfully shy as Furtwängler, it was disconcerting to discover that the Mannheim public looked on its Hofkapellmeister as a kind of demi-god; he was common property and everything he did and said was the talk of the day. Fortunately, Oskar Grohé, the intimate friend of lieder composer Hugo Wolf, was a member of the Theater Commission, was sympathetic to the young conductor’s position, and was well able to look after him and offer him the protection of a broad back behind which to hide.

One afternoon shortly after the Freischütz performance, our bell rang. Mother called down to the maid, “I am not in,” but was too late. Furtwängler stood in the hall—a very tall young man in an enormous black hat and a Loden cape.

It was not his first visit to our house. As a little boy he had spent his holidays with his grandmother who had lived in Mannheim, and who had been a friend of our family for years. Even then he had begun to compose, and when he was a boy of fifteen, my father and his friends played his first quartet. The parts were hardly readable and Furtwängler, with his head of golden curls, went from one stand to the other to explain what he meant. Now the youth returned as a man and the old friendship was renewed. My father took him under his wing, and soon he was at home with us, and found a sympathetic hearing for all the problems of his new life.

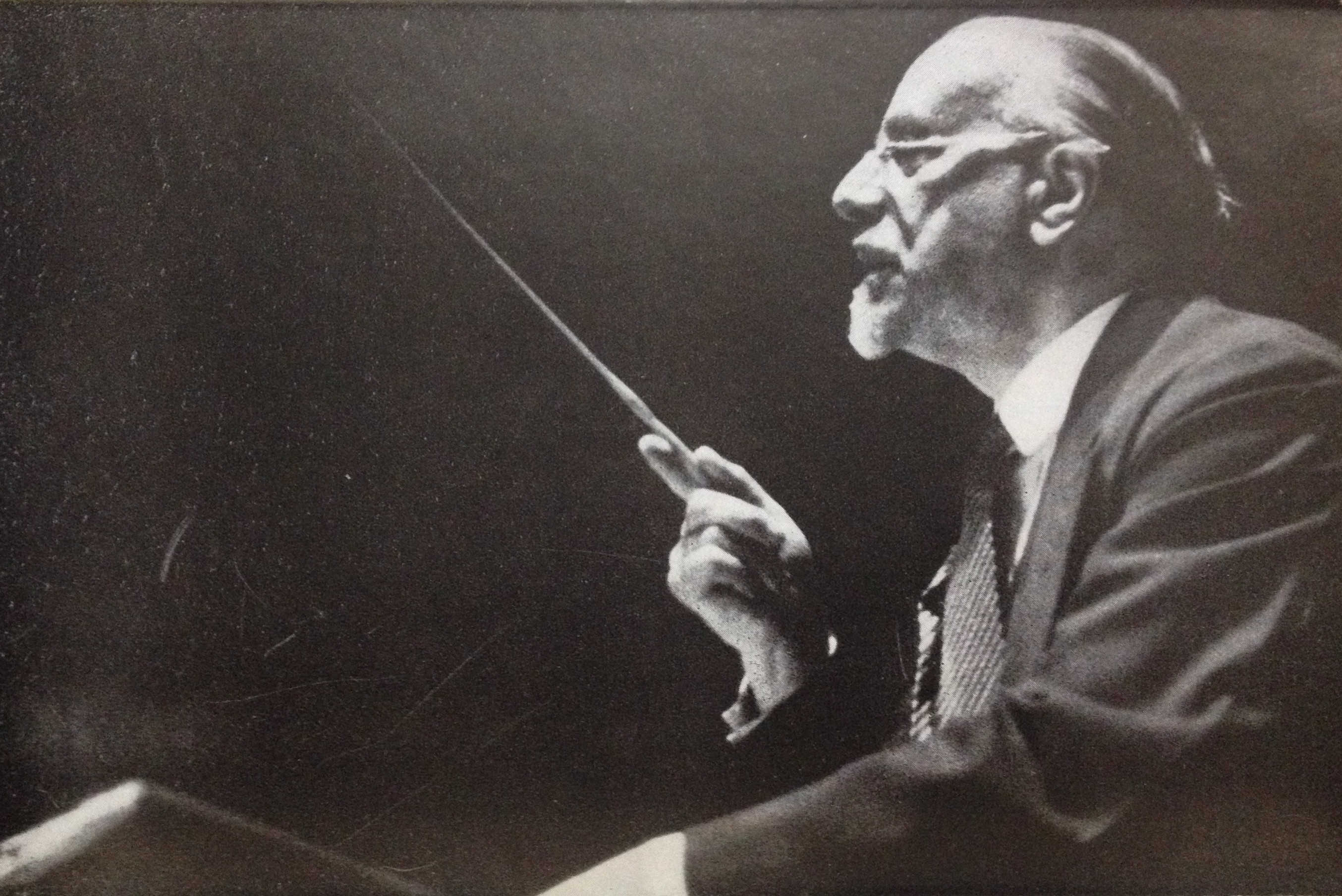

Furtwängler was tall, slim and fair. The most arresting features of his fine artist’s head were the high and noble forehead and the eyes. His were the eyes of a visionary, large, blue and expressive: when he conducted or played the piano, they were usually veiled and half closed, but they were capable of widening and emitting a tremendous vitality when he entered into an argument or a conversation which interested him, and they could grow tender and radiant when he was in a softened and happy mood.

His character was involved. He had a logical and persistent mind, direct and forceful: at the same time, particularly in his youth, he was shy to the point of extreme sensitiveness. Sometimes it seemed that he was only completely at ease with his enormous dog “Lord,” which followed him everywhere, even occupying his room at the theater during rehearsals, with the result that nobody else could ever get in.

He was not then, nor did he ever become, an homme du monde; but he brought to bear on life not only his musical genius but his other fine mental equipment. He had been carefully brought up by parents both of whom came from scholarly and musical families. From them he inherited, among other things, his love of beauty and his appreciation of art. His mother was a gifted painter, who painted charming portraits of her four children; his father was the well-known archaeologist, Adolf Furtwängler, a great authority on Greek vases and coins, Director of the Munich Glyptothek and Professor at the Munich University, where he was adored almost as much by his students as by his children, of whom Wilhelm was the eldest. During his youth he travelled with his father to Greece and Italy, opening his eyes to the glories of ancient Greece and Rome and the Renaissance, which meant so much to him during his whole life. On tour, his first excursion in any town was to its museum. On our first visit to London we went to look at the Elgin Marbles and the unique collection of Greek vases in the British Museum, which represented for him the world in which he had grown up.

This love of art provided him with one of his favorite pastimes, one in which he often indulged as a relaxation from his strenuous and busy life. Reproductions of famous paintings were spread out on a table and covered up except for some small detail, from which one person who had been sent out of the room was called upon to identify the picture. Furtwängler himself never missed. His knowledge was uncanny.

Furtwängler’s father was one of the first German skiing enthusiasts, and he often took his young sons on tours in the Bavarian Alps. Furtwängler attained almost professional skill at the sport, and he still tries to take a winter holiday where he can ski. Almost every sport appealed to him; he loved tennis, sailing and swimming. The family’s country house on the beautiful Tegernsee was a paradise for the children. He was a good horseman, but too dramatic a driver when he acquired a car. His passion for passing everything on the road occasionally landed him in serious trouble. Hardly had he obtained his driver’s license and a wonderful Daimler-Benz, when he offered to drive Richard Strauss to the Adlon Hotel. As they drove through the Linden after a rehearsal at the State Opera, the two famous musicians were so deep in conversation, they ran straight into a brand-new white car and entirely smashed it. Furtwängler and Strauss were unhurt, and escaped with a shock, but not without considerable trouble.

His love of sport, and the training he received from his father has stood Furtwängler in good stead all his life. By no means a faddist, he is careful of his health, and no day is too busy to interrupt his routine of two walks and an “air bath” before he goes to bed. Because of this, perhaps, he hardly ever has had a cold.

He maintains the same discipline over food. He is practically a vegetarian, never smokes and never drinks. Before a concert his meal is always especially light—a couple of eggs, a little fruit, or some biscuits perhaps, though during the interval of long operas, like Die Götterdämmerung, he eats sandwiches, nuts and fruit, and drinks quantities of fruit juice.

This, then, was the young man who came into my mother’s hall in his long cape, and around whom my life was to center for so many years: the genius compounded of intellectual directness and an almost excessive shyness, whose timidity made him efface himself in any gathering, but who had so great an attraction for women that, if they did not fall victim to his musical genius, they were fascinated by his personality. It used to be said that there was something of the Parsifal about him, with his limpid blue gaze and his voice that could be so caressing that the most ordinary sentence could sound like a passionate declaration of love.

Yet nobody, not even the most beloved woman, could ever deflect him from his work. His music always came first. When he was going to be married, he wrote to me expressing his anxiety as to whether his future wife, whom he dearly loved, would understand it.

When Furtwängler came to Mannheim in 1915, I was a young student. Little wonder that I was fascinated by his personality, found his music a revelation, and discovered sympathetic understanding in his sincerity and modesty. But I was so impressed by his wide knowledge on all subjects that it took me a long time to bridge the gulf which my respect for him created. Furtwängler himself, always simple and natural, was in no way responsible for adding to my constraint; it was entirely in my own mind.

One day, however, my shyness was overcome. We had met by chance at a party at a Heidelberg professor’s house and went home together. It was early summer, and when we came to the ancient bridge near the Neckar facing the castle ruin, a little shriveled old woman sat selling the first cherries of the season. Furtwängler bought a bagful and said, “Now let’s see who can spit the stones farthest.” So we stood there spitting our stones into the Neckar, and suddenly I was on common ground, and our lifelong friendship was sealed. For the sake of that friendship it was perhaps just as well that his stones went farthest as we leaned on the parapet of the Neckar bridge. I learned afterwards that such competitions were a favorite sport of the Furtwängler family, and that father and sons were all addicts. Among them, Wilhelm considered himself a champion!

Soon we shared many interests. Furtwängler was at home in university circles and often came to Heidelberg while I was there for a walk along the Neckar or on the Königstuhl. Or we spent the evening with one of the professors—the Geist von Heidelberg—Ludwig Curtius, the famous archaeologist who had assisted the elder Furtwängler and tutored the younger; Rickert and Jaspers, the philosophers; Max Weber, the famous economist; and Friedrich Gundolf, the young romantic friend of the poet, Stefan George. And when he came to dine with my family, he often came an hour earlier to talk about my studies, about music, and about books in my little sitting-room. There too, he began to tell me about his own work and troubles, and soon I was on the way to becoming a kind of confidential secretary.

In Mannheim, the theater became the center of attraction for me. From the box which my family had occupied since the time of my great-grandparents, I heard all the operas for the first time. I went to Furtwängler’s rehearsals whenever possible, and life, already rich, was enhanced by his friendship and our mutual interests.

Yet it was a grave time, and in spite of our full life, the war weighed heavily upon us. My private life was also shadowed; my father had begun to show signs of a serious illness from which he was not to recover. My parents had been very happily married, and I had been devoted to my father. When he died in July 1918, both mother and I felt that life had stopped, and sought the seclusion of the Black Forest.

Furtwängler was on holiday when my father died. I knew he was my friend, of course, but it seemed to me that his interest focused in my father and I was not at all sure that our friendship would not be greatly limited by his death. But one day he wrote to me. He was back in Mannheim and wanted to discuss various things with me. Could I come? I could. We met in our house—our house which seemed dead and deprived of its real spirit. That evening Furtwängler put me on my feet. His confidence that I would face anything in life bravely inspired me with courage which I had entirely lost. He drew me into a discussion of his own problems, and in sharing them I felt that I was needed. It was a new mainspring of my life.

Soon another problem arose. My father had been the soul of his own concert society; who could take his place? I was recommended to succeed him on the committee but I hesitated. In those days few women served on committees. Again Furtwängler encouraged me. He declared that I was the only possible successor to my father, little guessing how much the knowledge and experience I was to gain in the post would eventually mean to him.

Meanwhile the fateful month of November 1918 had come, and with it the Armistice. The relief was so tremendous that few realized the implications of the peace.

When Furtwängler came to Mannheim there was no doubt that1920 he was unusually talented, but he himself was the first to realize that he still lacked experience. Yet every performance he gave was so outstanding, it was no wonder that more and more invitations from other towns were extended to him.

Unlike many gifted young conductors, however, he remained aloof from all these tempting offers. He had the self-control to wait, and was determined to continue to work towards the ripening of his own musical experience. However, during the two last years of his Mannheim contract, he found it difficult to adhere to this determination.

The first year after the war, rail travel was so complicated that Willem Mengelberg felt unable to keep up his work with the Frankfurt Museum concerts, which he conducted in addition to his traditional Concertgebouw concerts in Amsterdam. Nothing was more logical than that Furtwängler be asked to combine the Frankfurt concerts with his work in Mannheim. However, although he occasionally went there as a guest conductor, he considered that his work in Mannheim excluded him from assuming further permanent responsibilities.

To refuse a similar offer from Vienna was far more difficult. As an entirely unknown conductor he had gone there in December 1918 for a concert with the Wiener Symphonie Orchester, at which he performed Brahms’ Third Symphony, and had been immediately acclaimed by the Viennese press and public as the greatest and most interesting conductor of the younger generation. From that moment Vienna sought him whenever possible. The first invitation for a cycle of concerts with the Symphonie Orchester—the Tonkünstlercyclus—he accepted in 1919 and annually thereafter. He was fascinated by Vienna. He was thrilled by the understanding of Vienna’s musical public; he made friends who had known Bruckner, Brahms, and Mahler; he basked in the atmosphere of tradition and sympathy. With iron self-control, however, he kept to his decision of sticking to the Mannheim work as the necessary basis of preparation for his future activities. He went to Vienna from time to time, but travel made the few visits he permitted himself more and more difficult, and he wrote me resignedly, during an unexpected breakdown on one of these journeys, that he was afraid he would not be able to keep them up.

Meanwhile, his career went its meteoric way. He had given some concerts in Berlin, and, like the Viennese, the Berliners acclaimed him. When Richard Strauss left the Berlin State Opera concerts in 1920 to settle in Vienna, Furtwängler was invited to conduct, as a possible successor. He was unanimously elected by the orchestra, in the interval of the first rehearsal, and was appointed for the coming season (1920-21). Nothing stood in the way. His Mannheim contract expired in June 1920, and the Berlin contract in October.

While Furtwängler was having his triumphant success with the Berlin1921 Staatskapelle, I submitted my thesis in philosophy: “Art and Science as Concepts of the Universe.” As was the custom, the Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at Heidelberg knew my subject, but I had never discussed what I was writing with him, and had worked quite on my own. He rejected my thesis as being too independent, and proposed that I re-edit it under his supervision for another year. I was utterly defeated. I felt as if I would never be able to complete my Ph.D., so many obstacles always arose.

However, I took courage. There were many schools of philosophy in Germany, and it was quite possible that one philosopher might welcome what another rejected. I went to Frankfurt. My thesis was accepted, and I got my degree.

The move to Frankfurt had another advantage. Furtwängler had decided to accept the Directorship of the Frankfurt Museum concerts, in addition to the State Opera concerts, and travelled regularly between Berlin, Frankfurt, and Vienna, where he had also agreed to do some conducting. When he came to Frankfurt we always had a great deal to discuss. I shared his general work as much as possible, and in January 1921 he asked me to consider coming to Berlin, the center of Germany’s musical life and, for Furtwängler, the most exciting place of all. I accepted.

That summer my mother and I went to the Engadine for the first time after the Great War. My parents and grandparents had gone there every summer, and had regularly met the same group of friends, for many well-known people went to the Engadine to enjoy the clear air and the wonderful sun. Among them, in my mother’s day and during the time of the Brahms controversy, were Simrock, the famous Brahms publisher, and Hanslick, his great supporter and the enemy of Wagner, made immortal by Wagner as Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger.

Furtwängler joined us that year. For once he gave himself a holiday of three weeks without work. He fell under the spell of the beautiful landscape. He was a marvellous mountaineer, trained to it from childhood by his father. He loved nature, and soon knew every summit of the area. He liked to climb the mountains without using the better-known paths, and on our many trips together we frequently took our food with us and spent the day on some mountain top. On real climbs through snow and ice, we observed a kind of ritual. We climbed in silence, almost grimly, till we had reached our objective—then we relaxed. Furtwängler threw off his coat and breathed deeply in the crystalline air, and then, sitting in solitude and peace, with the chain of snow-peaked mountains and glaciers facing us, we discussed and planned much of our future work.

We spent many holidays in the Engadine after that, and a few years later, in 1924, he bought his own house there. Situated on a lovely and lonely slope between St. Moritz and Pontresina, the house had every comfort. It had been a painter’s chalet, and the studio made a wonderful music room. Later Furtwängler’s first wife, with her Scandinavian hospitality, never counted the heads of those who sat down to meals, nor did she care how many slept, tucked away somehow in that house. Furtwängler was usually invisible and “not to be disturbed” while working, but at meals he always sat at the head of his table.

In the autumn of 1921, I went to Berlin. The political situation was desperate, but the city was full of life. Old friends were kind, and I quickly made new ones. I attended many concerts, and, of course, all the Staatsoper concerts. They were given on Thursdays and, like the concerts of the Vienna Philharmonic, were purely the concern of the orchestra, which was the Opera Orchestra as well. This series had been in charge of such noted conductors as Muck, then Weingartner from 1891-1908, and finally Richard Strauss from 1908-20. Though there was hardly ever a seat to be had, I was lucky enough to get into one of the boxes above the orchestra where the famous Berlin painter, Max Liebermann, was regularly to be found making sketches of the orchestra and its conductor.

Berlin was exciting. There was a flood of concerts to which everybody came, and there was an enormous competition between the various conductors. Each concert was a new battle for maintaining a reputation. The political depression of the nation was grave, but it is significant, in considering the cultural situation of pre-Hitler Germany, that whatever the material misery, there was a free intellectual and spiritual life.

Looking back on Germany’s musical life in those years, it is amazing how much went on in spite of the adverse times. In the spring of 1921 the first Brahmsfest after the war was held in Wiesbaden. These Brahms festivals had been founded by the Deutsche Brahms Gesellschaft in 1909, and attracted their own special community, a community of real music lovers from all parts of Germany and from abroad. The artists considered it a great privilege to be invited to participate, for these occasions had become a traditional feature of German musical life. I remember at Wiesbaden in 1921 and at Hamburg in 1922 meeting old friends of the Schumann-Brahms Kreis, Professor Julius Röntgen, born in 1855, and Fräulein Engelmann, from Holland; Eugenie Schumann, born in 1851, daughter of Robert and Clara, and the nonagenarian Alwin von Beckerath, who had been an intimate friend of Brahms.

The Brahms festivals were not the only music festivals held after the war. There were the famous Schlesische Musikfeste, there were the Handel festivals, and there were the festivals of small groups for the International Society for Contemporary Music. Somehow they all managed to get financial support from admirers and from the towns where they were held, and the festival spirit was always such as to make everybody temporarily forget that the outside world existed.

In Berlin I looked after Furtwängler and worked for the Artists’ League, a league run on an honorary basis, formed by the musicians themselves for the protection of artists’ interests. It gave advice and ran a concert department which took less than the professional agency fee, and gave me much valuable experience.

Furtwängler became more and more popular in Vienna during this time, and in 1921 after a performance of the Brahms Requiem, which he conducted there, he was appointed a director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde founded in 1812. He traveled a lot, but in those days I did not always accompany him; I sat in Berlin and held the fort.

During that winter, 1921-22, it was definitely necessary to hold the fort. There was a boom in musical life and a first-rate phalanx of conductors—Busch, Furtwängler, Klemperer, Nikisch, Strauss, Bruno Walter, Weingartner, and others. I went to every possible concert and reported daily to Furtwängler when he was absent.

Furtwängler was then director of the Berlin Staatskapelle, a magnificent orchestra with a splendid tradition. Yet an Opera House is not always suitable for concert purposes, and although Furtwängler highly appreciated the orchestra, he was often depressed after a concert because he had been unable to realize his artistic intentions—the acoustics in the Opera House, with the orchestra sitting on the stage, damped the sound of a big heroic symphony. He considered this fact in the choice of his programs but once could not resist including one of the big Bruckner symphonies. The performance left him unsatisfied, and as we walked down the Linden afterwards, he poured out his despair over the impossibility of achieving what he wanted.

While Furtwängler was worrying about the problem of the Staatskapelle Concerts, things moved unexpectedly to an exciting climax. On January 9, 1922, Arthur Nikisch conducted a Berlin Philharmonic concert for the last time. He had been permanent conductor of these concerts since 1895, of the Hamburg concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic since 1897, and had been in charge of the Leipzig Gewandhaus since 1895 as well. On January 23, Max Fiedler conducted in place of Nikisch, who was ill with influenza. Nikisch was still advertised on the program at the general rehearsal on February 5th, but on February 6th Wilhelm Furtwängler conducted the concert: In Memoriam Arthur Nikisch. A great artist had passed away.

The Leipzig Gewandhaus was immediately offered to Furtwängler. It was alleged to be Nikisch’s last wish. The decision about the Berlin post was not taken immediately. Furtwängler fully realized that this was the opportunity of his life, and that only if, in addition to the Gewandhaus, he could obtain the direction of the Berlin Philharmonic concerts with their acoustically perfect hall, could he fully live up to his artistic ideals.

Shortly afterwards, in spite of several competing conductors of rank, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra unanimously voted for Furtwängler, and he became successor to Nikisch in both Leipzig and Berlin. His talent, the instinct of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, and a kindly fate, had made his dream come true.

Furtwängler was thirty-six. Within a short time he had attained some of the highest musical positions that Europe had to offer.

In life and in his relation to the world, Furtwängler may have seemed to have had a wavering and mutable attitude—but this is not so where music is concerned; here he knows exactly what he wants. Even in the days when his name on a bill was sufficient to sell out the house at once, Furtwängler was always striving to improve his technique, and was keenly interested in that of other conductors.

In his work Furtwängler was a curious mixture of artistic instinct and intuition, and deliberating intellect. These two main qualities can be traced all through his development, until they achieved a balance in his more mature years. He was always so obsessed by, and intent on, his music that everything else was pushed into the background. Even as conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, he used to rush to the platform for his rehearsal, raising his baton aloft, as if he could hardly wait to begin. I well remember how the famous orchestra resented it at first, and complained to me that he never even said “Good morning.” When I cautiously tried to explain this to him he was completely surprised and full of consternation; and from then on he always remembered to begin his rehearsals with a friendly word.

The incident, trivial in itself, is symbolic of an ever-varying and inexhaustible problem: the relation between conductor and orchestra. From the very beginning Furtwängler had the respect of the orchestras he conducted; there could never be any doubt about his sincere and earnest musicianship; but until the ideal stage of things was reached, until he knew his job not only musically but also psychologically, there were many phases in his relationship to orchestras which are perhaps typical of any conductor’s relation to his orchestra, even if his authority is not supported by world-wide fame.

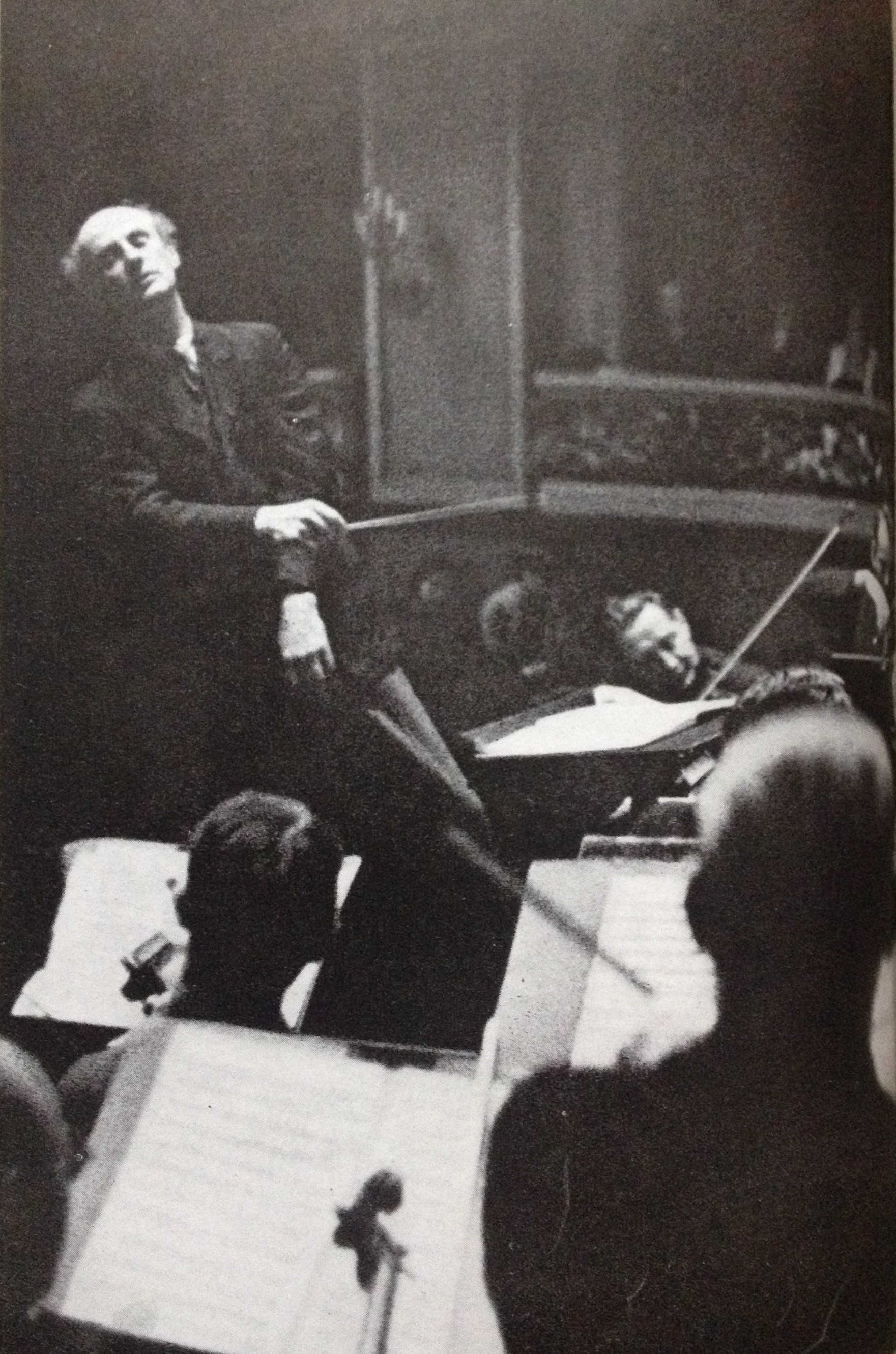

While Furtwängler was learning he was often handicapped by conflicts between technique and vision. With his relentless self-criticism he was perfectly aware of his shortcomings, and tried to overcome them. During this phase his conducting was restless and unbalanced, and was not easy for the orchestra to follow. One thing, however, was all right from the beginning—the expressive directing movements of his wonderful hands, which seemed to paint the music on an invisible screen or form it out of an unseen piece of clay. But apart from this, he gesticulated in all directions, shook his head constantly, walked about on his rostrum, made faces when something went wrong, stamped, sang, shouted, and even spat (so that a joke came into being that the first desks must be armed with umbrellas). Furtwängler worried deeply when occasional difficulties arose with the players who complained that they could not understand his indications. All his life he has worked on his beat, and has never ceased to try to improve it. I remember him coming off the platform in some European capital one evening during the applause and saying to me that he had “just found out the beat” for a certain passage. Furtwängler’s beat—as orchestras all over the world know—is an absolute nightmare to all players until they get used to it. A member of the London Philharmonic Orchestra once declared that it is “only after the thirteenth preliminary wiggle” that Furtwängler’s baton descends. It has always been a riddle for the outsider how, with his peculiar beat, he gets results of exactitude as well as of richness in sound.

Furtwängler realized that he had two different things to watch—his own technique and his relationship with the orchestra as an understanding medium and friend. He fully appreciated that there is nothing more delicate and sensitive, more relentless and clear-sighted than an orchestra, and that its handling requires the greatest skill, subtlety, human kindness and an undisputed authority. In the course of time he mastered the approach. His orchestras worshipped him though he often asked the impossible, seldom praised them, hardly ever said a word of thanks; his players got to know that a nod given half in a trance during the performance was a greater acknowledgment from him than any spoken word of praise.

While he is preparing to conduct a work, Furtwängler clearly and distinctly identifies himself with it: he absorbs it, and, deeply concentrating on it, he re-creates it as the composer intended. This he does again and again, even if he has performed the work a thousand times before. Nothing disturbs him while he works, that is, while he is walking up and down the room, his hands beating time and his lips silently singing. He fixes the piece before his spiritual eye with intense concentration. An infinite painstaking is always behind every performance that Furtwängler gives, and even in later years he has never taken advantage of his famous name to save himself trouble. He would never risk skimping the conscientious preparation of any concert, and in this may perhaps be found the clue to his artistic fascination. No unrest of the day ever touches him while he works; nothing on earth can induce him to speed up his working time in order to be finished an hour earlier to be free for something else. His whole organism is attuned to this exact conscientiousness, and never would he allow himself to be forced out of it by some exterior pressure. He needs time to live through a great masterpiece again and again in all tranquillity. Only in this way can he feel himself ready, and sure of himself. When he finally arrives at a rehearsal his main work is already done, and he has only to transmit his intentions to the orchestra. When the concert begins, he seems to leave all earthly things behind: he is conscious neither of audience nor of score. With half-closed eyes he seems to mesmerize the orchestra, and owing to his deep musical feelings he relives the creative process of the composer, while the orchestra hangs on his movements.

If the audience leaves such a concert with a feeling of having lived through an extraordinary experience, it is because it has been made to feel the tension and the thrill of a truly visionary process of re-creation. Only if his vision of how a work should sound has been realized does Furtwängler relax after the strain of the concert; otherwise, he is nearly demented, and most difficult for those nearest to him, even if the public has acclaimed the performance with fanatical applause.

Even on the piano, Furtwängler had the gift of calling music to life in a monumental yet plastic way. His velvety touch was envied by many professionals, and to hear him play one of the great Beethoven sonatas, the “Moonlight” or the Hammerklavier Sonata, was a real experience. Never will I forget the first time he demonstrated to me from beginning to end the true spirit and inner meaning of the Choral Symphony. He knew the whole repertoire of piano and chamber music, and it was through him that I got to know the true inwardness of the late Beethoven quartets which he played magnificently—volcanic and lucid at the same time.

Since its foundation in the days of the monarchy, the Berlin Philharmonic1922 Orchestra[1] has been a little republican island. It is the child of a spiritual revolution, a revolution in the presentation of musical masterpieces, a revolution connected with a man with whom the history of modern concert life really begins: Hans von Bülow.

In January 1882 Bülow had come to Berlin with his Meininger Hofkapelle. He conducted in the Sing-Akademie the music of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Brahms. First Brahms himself played his Second Piano Concerto under Bülow’s direction; then Bülow played the First Concerto with Brahms conducting. Berlin was overwhelmed. They did not recognize “their” Beethoven and Mendelssohn and for the first time realized the greatness of Brahms.

Twelve years after the second Reich had been founded, its young capital had neither a competent symphony orchestra nor an adequate concert hall. Ever since 1868, however, there had existed among the different musical organizations the Bilse’sche Kapelle, a collection of excellent musicians, especially of wind and strings, who gave concerts and made little tours under the worthy Benjamin Bilse, a former municipal musician from Liegnitz.

Early in 1882 there was a disagreement between the players and the patriarchal, despotic Bilse, and overnight the orchestra of fifty-four members found that they were left to themselves. Under the leadership of the second horn and a second violin, they constituted their own republic, and drew up their own constitution. From the beginning the orchestra was an independent creation of its own members, who held the shares of their limited company, and appointed the conductor and new players by popular vote. By legal deed they pledged themselves to remain inviolably together. This first constitution was enlarged in 1895, but it has never been greatly changed.

On May 5, 1882, they played their first concert as an independent body, and during that summer their concerts in Berlin and the provinces met with great success but little material profit. During that summer of 1882 this first self-governing orchestra in Germany got its name: The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

In the same year an adequate hall was found for it. The old skating rink, which till then had been devoted to roller-skating, was taken over to be devoted to music. Its name was changed to “Philharmonie” and the ugly, but acoustically perfect, hall remained the home of the Berlin Philharmonic till it was destroyed by a bomb.

The orchestra began by giving three or four popular concerts a week in its new hall. Soon the great choirs gave concerts with them, and soloists began to engage them and finally on October 23, 1882, the first of the great Berlin Philharmonic concerts took place. They combined tradition and a progressive outlook, and were enlivened by the cooperation of famous soloists.

Several conductors officiated that first winter, among them Joseph Joachim. From the beginning he was the patron and friend of the orchestra. He sent them his best pupils, and in 1883 he procured some summer engagements for them, the first of which he conducted himself. He contrived their presence at official functions, and conducted six concerts of a series of twelve. When a financial crisis threatened, he got support from the Mendelssohn and Siemens families. It was exactly fifty years before the Berlin Philharmonic could count on a regular subsidy from Berlin and the Reich, and after both had turned a deaf ear to its early needs, it was Joachim who suggested a Society of Friends of the Orchestra to contribute to its maintenance.

The first five years of the orchestra’s activities had proved the necessity of its existence, but what it lacked was a leading personality. Hans von Bülow filled the need. On March 4, 1884, Bülow, who had left Meiningen in 1882, had conducted one of the great Berlin Philharmonic concerts. Subsequently he had conducted a series of concerts in Hamburg and Bremen, but had not been satisfied. He came to the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. The first great trainer of a great orchestra in the history of conducting, he was the real founder of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, for it was he who prepared the ground for its tradition.

Bülow was the initiator of the great age of conductors which has lasted for eighty years. Through him the technique and position of a conductor gained their importance and became independent and influential. It was only, in fact, from Bülow’s day that the work of a conductor was taken seriously. He is the founder of modern orchestral culture.

The first of the ten Philharmonic concerts planned under Bülow took place on October 21, 1887. By November, the idea of admitting the public to the final rehearsal was adopted. It was an important innovation, the beginning of a lasting tradition. In the season 1890-91 Bülow conducted the first concert for the newly organized Pension Fund of the orchestra to found another permanent institution, the Pension Fund concert. He conducted in all fifty-one Berlin Philharmonic concerts. At the fiftieth, March 28, 1892, he made a famous speech after a performance of the Eroica, dedicating it to Bismarck; the speech and the dedication were intended as a protest of Bismarck’s brusque dismissal as the First Chancellor of the Reich by the young Kaiser.

In the winter of 1892-93, Bülow was already so ill that he could conduct only the last Philharmonic concert of the season, at which he made a speech praising the artistry of the orchestra. Hans Richter, Raphael Maszkowski, Felix Mottl, and Hermann Levi had conducted the previous concerts of that winter.

The winter of 1894-95 saw a memorable combination of conductors at the Philharmonic desk: Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. Strauss conducted the ten Berlin, Mahler the eight Hamburg concerts. But the winter could only be an interregnum, for Strauss, the creative artist, could never submerge himself entirely in the direction of an orchestra. Meanwhile, the right man was found: Arthur Nikisch.

Some people consider it wrong to identify the history of an orchestra with its great conductors. But it seems to me that only in combination with dynamic leadership and a vital personality can the artistry of an orchestra be molded into truly inspired creative performances.

There was no doubt that Arthur Nikisch had that leadership and personality, and the ten Philharmonic concerts under his direction were the highlights of the enormous activity which the orchestra now assumed. He was, in his art, the extreme opposite of Bülow; he gave the orchestra, in addition to Bülow’s discipline, what he himself had to give as a conductor—a great elasticity and a most sensitive adaptability. The orchestra was increased to ninety.

Until January 9, 1922—a full twenty-seven years—Nikisch conducted1922 the Berlin Philharmonic concerts without interruption. He must have conducted about three hundred and fifty great concerts in Berlin, concerts which gave him an even greater prestige than the famous Gewandhaus concerts, which he conducted over the same period. His programs included a constant succession of new works and great soloists.

On January 9, 1922, Nikisch conducted the Berliners for the last time, and a new epoch began with their new chief, the young and idealistic Wilhelm Furtwängler.

|

I am indebted to Dr. Alfred Einstein’s brochure, 50 Jahre Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester, for much of the information about the Berlin Philharmonic’s history. Though he quotes me as a source, I could not have written what I have without his booklet, which he wrote on the occasion of the Orchestra’s fiftieth anniversary in 1932. |

At Furtwängler’s first Philharmonic Concert in October1922 1922, I sat in a box with Marie von Bülow, the widow of the former conductor of these concerts. It was she, his second wife (his first was Cosima Liszt), who had edited his letters and writings to provide nine valuable volumes of great musical history. She seemed deeply moved on this occasion, and said to me, “Not since Bülow’s day has music been so conducted to give me that thrill down the spine.”

Furtwängler’s appointment as the successor to Arthur Nikisch was also the turning point in my own work. He had given up the State Opera concerts and the direction of the Frankfurt concerts, but he had to move about continuously between Berlin, Leipzig, and Vienna. Each of the musical organizations of those towns had its own management, but the core of Furtwängler’s whole work, the arrangement of his year’s activity, the coordination of his concerts and programs were worked out with me. The amount of work Furtwängler had to cope with was considerable. Although the war was just over, the Berlin Philharmonic and Gewandhaus concerts played an important part in European musical life. There was an endless number of soloists, composers, publishers, music agents, and other visitors from all over the world who had continually to be dealt with. Life was fascinating and full to overflowing. The young successor to Nikisch was, of course, of interest to the international musical world, and so negotiations soon began to develop with concert institutions abroad.

Except for a series of concerts in Stockholm, the first venture of this kind was a visit to the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, an engagement which, in a way, was decisive to my whole career. The Berlin Philharmonic concerts had been founded by Hermann Wolff, the director of the noted concert agency, Wolff und Sachs. Wolff had not only been an impresario but also a friend of his artists and had been intimately connected with Hans von Bülow, Anton Rubinstein, and others. After his death his widow, Louise Wolff, carried on the business with her daughters until Hitler’s day. Louise Wolff was an exceedingly capable woman and a dynamic personality. She was a most popular figure in Berlin’s social life, and was to be found in every salon, political or artistic. She was equally at home with Reichspräsident Ebert as with the Hohenzollerns, and every Embassy was open to her. There were innumerable tales of the strings she pulled, and the people with whom she had her regular telephone conversations early in the morning before she went to her office.

Yet, in spite of all her cleverness, she failed to see in which direction1923 the tide was turning. The firm and the family came first with her, and her consideration of everything solely from the point of view of Wolff und Sachs was gradually becoming incompatible with public interests. It was impossible that a private enterprise should pocket seventy-five per cent of the profit of an orchestra like the Berlin Philharmonic which had to count on public support.

Not only the orchestra but also its new conductor had to face this situation of monopoly. The Wolffs of course had had their say in Furtwängler’s election as Nikisch’s successor, but the orchestra had cast their vote too. Yet, in the beginning, Furtwängler was considered as a kind of private property of the Wolffs and was expected to do all his business through them. The first important outside offer, however, these Concertgebouw concerts, came through me, as executive of the Artists’ League. Furtwängler expressed a doubt as to whether he would be free to sign the contract through the League. He had no “sole right” contract with the Wolffs but felt that it was taken for granted. I, of course, objected. I had gotten the engagement, I wanted to sign it, and I declared that if things were going to be like that I did not care to work in Berlin at all. Furtwängler, probably secretly amused and possibly wishing to dampen my ambitious ardor, said he was going to think it over, and next morning told me over the telephone that perhaps I was right, but he did not sound wholly convinced. I had thought it over too, and said, “Please leave the matter to me and wait.”

Frau Wolff had always been extremely kind to me, and when I telephoned her, she agreed to see me immediately. I remember that she produced some marvellous Russian cherry brandy, an unheard-of luxury in post-war Germany. I sipped a little of the lovely golden-red stuff and then plunged in medias res. “I want to ask you something, Frau Wolff,” I said, and then proceeded to recite the case without mentioning names. “But there’s no question at all about this,” she declared, “the person who made the offer must conclude the business.” “That’s just what I thought,” I replied, and told her that it was she, Furtwängler, and myself, who were involved. At first her consternation was evident. But she was a superior woman, remarkable in many ways, and at the moment may have felt that she could not maintain her privileged policy forever and that I represented a young generation and a new era. She put her arm round my shoulders and said, “You are a wonder! I am going to tell Furtwängler about this conversation myself.” She did, next day. Furtwängler never referred to the incident, but he casually instructed me to sign the Concertgebouw contract. Although my heart leapt, I behaved as if it were the most natural thing in the world, and from then until Hitler parted us, almost always acted as Furtwängler’s intermediary. I was dubbed “Louise II.” It was an important step to break this monopoly, and later, the monopoly on the Philharmonie hall itself, which was shared by its proprietor Landecker and Wolff und Sachs, and excluded the orchestra from direct transactions.

But a powerful new monopoly was in the making—that of Hitler1924 and the Third Reich.

I accompanied Furtwängler on this first tour abroad, and on a subsequent one which I had arranged in Switzerland with the Gewandhaus Orchestra.

He was to marry at the end of May. His future wife was Scandinavian and was only to arrive from Copenhagen on the day before the wedding, so I helped him to prepare his home, and even went along to buy the wedding rings. The salesman, naturally assuming that I was the bride, proceeded to try the ring on my hand, to the utter dismay of Furtwängler!

I then left for Mannheim, and Furtwängler was married. Directly after the wedding, he had to attend a Congress of the Allgemeine Deutsche Musik Verein at Kassel. A few days later at 3 a.m. my telephone rang. It was Furtwängler, who had arrived in Mannheim from Kassel, and informed me that he was on his way to our house. He had to leave for Italy the next day to conduct there for the first time. I had always gone with him on important journeys, but this trip to Italy was a kind of honeymoon, and I certainly had not anticipated accompanying him. However, he had taken it for granted that I would, so I had to get ready quickly. We left for Stuttgart, where we were joined by his wife.

The visit to Milan proved most interesting, for among other things, I met Arturo Toscanini. Toscanini was then director at La Scala, and lived in Italy surrounded by the veneration and love of the Italian people. His operatic performances were famous all over the world, and people from everywhere, especially musicians, flocked to attend them.

My visit to Toscanini was arranged by his right hand and secretary, Anita Colombo, who later on became director of the famous Opera House. While I waited for him in Signorina Colombo’s office at La Scala all sorts of people went in and out, and I—still a greenhorn—noted with envy the respect with which they talked to her.

Quick steps outside, the door opened, Colombo introduced me, “La signorina, Maestro,” and the great Italian led me in to the adjoining room. Nobody who has talked to Toscanini can ever forget the extreme intensity of expression in his strikingly handsome face. His brilliant, flashing eyes are full of fire and temperamental intentness, of vitality mixed with a strange obsessed wistfulness. He has an intense manner of speaking and he accompanies his words with quick and decisive gestures. The conversation did not last long, and centered round musical matters. Toscanini seemed interested to hear about the different conductors working in Germany at the time—but he did not discuss Furtwängler.

Toscanini’s memory is famous: since his vision is poor, he conducts and rehearses without a score, relying entirely on his knowledge of the piece. Apparently his memory for other things is just as acute, because when I met him again at Bayreuth during the great season of 1931 when he and Furtwängler both conducted, the first thing he did was to remind me of what must have been to him a trivial incident—my visit to La Scala so many years ago.

Toscanini, when not speaking Italian, generally spoke English, hardly ever German. That summer in Bayreuth while rehearsing the orchestra, he used to convey his wishes by gestures rather than by words, and when a passage was not yet as he intended it to be, made hypnotic movements with his hands, accompanied by repeated exclamations of “No! No! No!” The orchestra called him “Toscanono.”

The first concerts of Furtwängler’s in Italy provided the initial meeting of the two conductors. During one of the innumerable rehearsals that Furtwängler, according to the Italian custom, had to conduct, Toscanini, who had been sitting unnoticed at the back, suddenly rushed forward and shook him warmly by the hand. Throughout the entire visit Toscanini and his family were extremely friendly, and the following year, Furtwängler visited La Scala to attend some of Toscanini’s own operatic productions.

In the winter of 1924, Furtwängler made his English debut conducting the Royal Philharmonic Society. From his first performance, the English public took him to their hearts, and only Ernest Newman, the dean of British musical criticism, raised a dissenting voice. His unfavorable review in the Sunday Times was delivered to me on our way to the train, and knowing how amazingly touchy Furtwängler was about press criticism, I sat on it throughout most of the journey just to keep peace. After that first success, Furtwängler appeared regularly in England until the gulf between Germany and the rest of the world grew too wide.

Times were difficult as far as finances were concerned, and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra did not know how they were going to get through that summer of 1924. “Let’s try a tour,” said Furtwängler, and we forthwith sent telegrams to several towns in Germany and Switzerland. They all accepted. Everywhere we went the orchestra was asked to repeat its visit, and so began the Berlin Philharmonic tours with Furtwängler.

At the end of June, Furtwängler went to Mannheim. It had become his custom to conclude the season with some concerts there, combined with a visit at my mother’s house. During that time we finished up his remaining correspondence and went over the scores sent to him for approval. Then he proceeded to his house in Switzerland.

I was to go to the Engadine with him that year to help plan for the coming year, as was our habit on our tramps through the mountains. Just as we were leaving for the station I received a letter from Otto Müller, charter member and chairman of the Berlin Philharmonic. In his sprawling hand, he wrote that the orchestra had decided to entrust the management of its tours to my “proven hands”; he hoped I would be willing to accept the task. I was indeed. Not only was this token of confidence a source of tremendous personal pride, but working as I would be with both Furtwängler and the orchestra would permit me to unify my activities as well.

For many years following there was uninterrupted activity. With our unique team we all served the cause with zest. Times were hard but we were free to work as we liked and with whom we liked. In those days orchestras had not started their extensive tours of Europe. Beyond an occasional visit to a neighboring town there was no large-scale traveling at home or abroad. The idea came to me as a sort of inspiration and I sat down and thought it all out. But it was only gradually that I developed my technique for an orchestral tour. It was like the invention of a new battle strategy, and as the years went by I made more and more improvements which added to its smooth running.

I always began work on a tour a year ahead. First I listed towns to be visited. Then the sequence was planned. The first draft of programs—often for thirty to fifty concerts—had to be made by Furtwängler. That was always a complicated task because, although an orchestra on tour has little time for rehearsing, Furtwängler disliked repeating a work too often; nor could he always play just what he wanted for various cities had various requests, and local taste was always a major consideration. To simplify it, from 1924 on I kept a program book for reference.

Besides the business and musical sides of the tours there were other considerations. The itinerary had to be planned in detail. I was hopeless at looking up trains but Lorenz Höber, a viola player and also one of the executives, was a genius with a timetable. I may have invented and organized the tours, but without Höber I could never have carried them out successfully. For not only did we have to plan railroad transportation for the personnel of the orchestra, but we had to arrange for the transportation of their luggage and instruments as well—seventy-seven cases which required a van all their own. Often it could not be coupled to the express on which we traveled and had to be sent on in advance immediately after the concert. Lists of the contents of the well-designed instrument cases and the huge specially constructed wardrobe trunks full of the numbered dress suits of the players had to be forwarded to the customs with an indication of when we should pass their frontier. Two members of the orchestra were responsible for the luggage, assisted by Franz Jastrau, the attendant, who managed to make friends wherever he went even if he occasionally did not understand the language. It was a strenuous job for it was of vital importance that each player find his clothes with his instruments on arrival.

There were fairly good halls all over the Continent, but the different sizes, and especially the varying acoustics, required different seating arrangements for the orchestra. At first a short “seating rehearsal” was held two hours before each concert. But then one of the players with a special talent for that sort of thing began to make a platform plan for every hall in which we appeared. We kept the diagrams on file and, when the orchestra returned again, the seating could be quickly settled.

At first the billeting of the orchestra in each town was also a complicated problem, but in that, too, experience led to efficiency. Snorers and non-snorers had to be well separated. It was important to get the players quickly settled when they arrived.

But it was not I who did all the organizing. The orchestra members themselves became very ingenious. Often they had to travel for weeks in railway carriages, and so they started to organize a seating plan to which each member had to submit. There were the smokers and the non-smokers, there were the skat players and there was the Rummy Club, there were the readers, and there were the talkers. They were all placed according to their various interests. Occasionally I was invited by a particular group, a welcome honor on those long and often tiring journeys.

The organization and building up of these tours was for me a wonderful combination of friendship and of work. I knew to what Furtwängler aspired, and I knew the orchestra’s ambitions. The relation between the orchestra and their conductor, in whom they had absolute faith, was the basis of my own position with them. From the moment that they had confided to me the management of their tours they gave me their complete confidence. This perfect relationship between Furtwängler, the orchestra, and myself lasted until I had to leave them all and they were forbidden to have any more to do with me—when, under Hitler, I became persona non grata.

When I first took over, the orchestra had no offices. The three executive members divided their different duties among themselves, and dealt with them at their respective homes. Otto Müller, the chairman, always carried everything in his wallet, in which he fumbled as soon as a question arose. I had no office either, merely a combination bedroom sitting-room and a typewriter. Eventually I was given a typist on three afternoons a week—the beginning of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s office.

Step by step the orchestra organization was built up, and one of the first milestones of its road to glory was a special agreement between Furtwängler and the orchestra—they would always give each other the first option on their time. This “marriage” of orchestra and principal conductor was for many years the core of the orchestra’s life, and around this they grouped their engagements under other conductors, and with soloists, and their popular concerts.

Meanwhile, Furtwängler had received several invitations to visit America. Tied up between Berlin, Leipzig, and Vienna, he had little time to spare, yet finally it was agreed that he should accept four weeks as a guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra at the end of December 1924. We went on a Hamburg-Amerika liner, and nothing was left undone in Furtwängler’s honor.

Germany was poor in those days, while the United States was flourishing. The hospitality of the Americans was indescribable. From the moment we landed, when an unknown person packed us into a magnificent car to sweep us away to our hotel, until we left, and could hardly enter our cabins for presents, this first American visit was a unique experience. How interesting it was to hear the magnificent American orchestras—the Boston and Philadelphia Orchestras, as well as the New York Philharmonic; or to sit in the Golden Horseshoe of the Metropolitan and hear the performances of that famous Opera House.

Furtwängler was conducting exclusively for the New York Philharmonic. His first appearance was one of the great successes which are milestones in an artist’s life, and after it there was not a single ticket to be had for his New York concerts. The orchestra took to him, and so did the public. Furtwängler was immediately offered the directorship for the whole season of the following year, but because of his European commitments he could not undertake more than two months’ activities in America. Many of the great international artists were in the United States at that time, and we saw them frequently. At the house of Frederick Steinway, the venerated chief of the famous music firm, such a galaxy of musical genius and brilliance used to assemble as I have never seen elsewhere. I remember a dinner where Casals, Furtwängler, Gabrilowitsch, Landowska, Kreisler, Rachmaninoff, Stokowsky and other famous people were present. Mr. Steinway’s hock was memorable too! Our stay in New York was exciting and strenuous but rushed past us like a dream, and on a quiet and peaceful English boat, where we were treated as “ordinary folk,” we slept our way back to Europe.

For the next two years Furtwängler worked intensely hard. There1927 was an annual visit to America, and the Berlin Philharmonic made several successful tours on which I accompanied them.

Then in the winter of 1927 the Berlin Philharmonic went to England for the first time. The orchestra and I had frequently discussed our aspirations and desires, and once I suggested, “Why don’t we go to England?” They all laughed at me, and said that I might as well propose a visit to the moon. That was challenge enough, my determination stiffened, and in due course I arranged the tour. We had two concerts in London, and between them went to Manchester. The enthusiasm of the British public was enormous; there was no feeling against the orchestra of their former enemies. Long paragraphs appeared about the wonderful Berlin Philharmonic and great interest was shown in the organization of the tour. For the second London concert Albert Hall was filled to the last seat. I think that except for the Paris success one year later, it was the orchestra’s greatest triumph. After that they went to England every year, their English tours becoming more and more extensive, until Hitler at last estranged the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from its British public.

It is astonishing to me even now to look back and remember how1927 rich was the musical life in cities like Berlin and Vienna in the years after 1918, and how culture flourished in Germany and Austria. While in France and England the capitals were more or less the principal centers of all cultural and social life, in Germany, towns like Dresden, Leipzig, Munich, Hamburg, Cologne, and Breslau all had their own individual life. The musical field was full of men of outstanding merit, and there was ample opportunity for all of them.

While his activities were actually centered in Berlin and Leipzig, Furtwängler had for many years been a favorite in Vienna. The romantic Viennese worshipped the passionate young conductor, and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra always found a way to arrange an “extraordinary Philharmonic Concert” or “Furtwängler Concert” when he came to conduct his choral concerts with the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. The first performance with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1922—a Brahms Concert, a memorial on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Brahms’ death—had established a lifelong artistic relationship. In Berlin and Leipzig he was the successor to Arthur Nikisch. Now Vienna, too, claimed him for the post of first conductor of its orchestra, founded in 1842. The Vienna Philharmonic knew that in offering Furtwängler the position, it fulfilled the ardent wish of the Viennese.

Furtwängler could not resist the dream of every conductor on the Continent. The 1927-28 season found him in charge of the Berlin Philharmonic, the Leipzig Gewandhaus, and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, besides his other commitments.

In retrospect Furtwängler’s great success in Vienna can only be appreciated in the light of Vienna’s musical life at that period. He had come there in 1919, at a moment when its musical life had reached a new climax. The Vienna Opera, after years under the direction of Gustav Mahler, was now under the joint direction of Richard Strauss and Franz Schalk, and was considered one of the most distinguished Opera Houses in Europe. The Vienna Philharmonic, which was at the same time the Opera Orchestra, gave performances thrilling to any musician. Puccini had been moved to tears when he heard the orchestra play at the first Tosca performance in Vienna, November 20, 1907. The new great Strauss operas from Rosenkavalier to Ariadne auf Naxos had been first given there as “festival performances” during that period.

The Vienna Philharmonic, which, since Gustav Mahler’s day had played under the batons of Nikisch, Mottl, Muck, and Schuch, had for the last nineteen years been under the direction of Felix Weingartner. Weingartner had been a pupil of Liszt. When he conducted Brahms’ Second Symphony in the presence of the composer, he had been kissed in enthusiasm by Brahms, and he gave to the Vienna Philharmonic that great “everything” which only a classical conductor of his caliber could give. While he was their permanent chief, they had played under other conductors: Furtwängler, Kleiber, Krauss, Mengelberg, Nikisch, Schalk, Strauss, and Bruno Walter.

No wonder that this orchestra, with its outstanding artistry and unique tradition, enthralled a young conductor like Furtwängler. With enthusiasm he began his first Philharmonic Concert in the autumn of 1927 with the Freischutz Ouverture, and he felt keenly the historic atmosphere of the Musikvereinssaal where Brahms and Bruckner had so often attended concerts. This period, during which he occupied, besides his other commitments, two prominent positions in Vienna, was certainly a milestone in Furtwängler’s career, and definitely influenced his musical development.

Furtwängler’s activities in Vienna began another phase in my work with him. Of course the Vienna Philharmonic had its own office and management, but there was a large correspondence with Furtwängler when he was in Berlin. There were countless things to attend to, and a new world opened for me when dealing with the famous orchestra on his behalf.

The Rosé Quartet, a group of prominent members of the orchestra, whom I had known in Mannheim, were a link between me and the other players, and I soon became devoted to the chairman, the oboist Aleseander Wunderer, one of the most “Viennese” and lovable musicians imaginable.

Frequently Furtwängler required me to accompany him to Vienna,1928 and I was always delighted to go. We usually had to leave Berlin the morning after a Philharmonic Concert, on an 8 A.M. train. It was a peculiar old train with one old-fashioned Austrian carriage containing a half coupé, a one-sided compartment of three seats only. Since it was essential for Furtwängler to work undisturbed on these journeys, he always coveted that special compartment, and since by a bureaucratic decision it could not be reserved in advance, I used to get up early to be on the platform when the train pulled in to secure those seats.

Later on Furtwängler always went by plane, but for years we used that 8 o’clock train. The day of such a long journey was always methodically planned. First we had breakfast, then there was “silence.” Furtwängler either read a new book or studied his program, taking advantage of the remoteness from the world for concentration. I remember that he read Spengler’s Decline of the West, which had just been published and stirred intellectual circles, and that he learned Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps on such a journey, while I—though a welcome guest in his compartment—was not allowed to break the spell of silence until he gave the sign. Lunch was always a happy interruption; usually we waited until we had passed the Czech frontier because the Czech diner gave such excellent fare. After lunch we relapsed again into silence until, towards evening, Furtwängler declared himself ready for talk.