* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Canada and its Provinces Vol 12 of 23

Date of first publication: 1914

Author: Adam Shortt (1859-1931) and Arthur G. Doughty (1860-1936) (editors)

Date first posted: Jan. 20, 2021

Date last updated: Jan. 20, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210155

This eBook was produced by: Iona Vaughan, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Archives Edition

CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES

IN TWENTY-TWO VOLUMES AND INDEX

| (Vols. 1 and 2) | (Vols. 13 and 14) |

| SECTION I | SECTION VII |

| NEW FRANCE, 1534-1760 | THE ATLANTIC PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 3 and 4) | (Vols. 15 and 16) |

| SECTION II | SECTION VIII |

| BRITISH DOMINION, 1760-1840 | THE PROVINCE OF QUEBEC |

| (Vol. 5) | (Vols. 17 and 18) |

| SECTION III | SECTION IX |

| UNITED CANADA, 1840-1867 | THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO |

| (Vols. 6, 7, and 8) | (Vols. 19 and 20) |

| SECTION IV | SECTION X |

| THE DOMINION: POLITICAL EVOLUTION | THE PRAIRIE PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 9 and 10) | (Vols. 21 and 22) |

| SECTION V | SECTION XI |

| THE DOMINION: INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION | THE PACIFIC PROVINCE |

| (Vols. 11 and 12) | (Vol. 23) |

| SECTION VI | SECTION XII |

| THE DOMINION: MISSIONS; ARTS AND LETTERS | DOCUMENTARY NOTES GENERAL INDEX |

GENERAL EDITORS

ADAM SHORTT

ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

| Thomas Chapais | Alfred D. DeCelles | |

| F. P. Walton | George M. Wrong | |

| William L. Grant | Andrew Macphail | |

| James Bonar | A. H. U. Colquhoun | |

| D. M. Duncan | Robert Kilpatrick | |

| Thomas Guthrie Marquis | ||

VOL. 12

SECTION VI

THE DOMINION

MISSIONS; ARTS AND LETTERS

PART II

Photogravure. Annan. Glasgow.

THOMAS CHANDLER HALIBURTON

From an engraving in the Dominion Archives

Copyright in all countries subscribing to the Berne Convention

| PAGE | |||

| THE HIGHER NATIONAL LIFE. By W. S. Milner | |||

| INTRODUCTORY | 403 | ||

| EDUCATION | 406 | ||

| THE PRESS | 426 | ||

| OTHER FACTORS | 429 | ||

| FRENCH-CANADIAN LITERATURE. By Camille Roy | |||

| I. | LITERARY ORIGINS, 1760-1840 | 435 | |

| II. | LITERARY DEVELOPMENT, 1840-1912 | 451 | |

| History—Poetry—Fiction—Political, Philosophical and Social Literature—Miscellaneous | |||

| ENGLISH-CANADIAN LITERATURE. By T. G. Marquis | |||

| I. | INTRODUCTORY | 493 | |

| II. | HISTORY | 496 | |

| III. | BIOGRAPHY | 506 | |

| IV. | TRAVELS AND EXPLORATION | 511 | |

| V. | GENERAL LITERATURE | 520 | |

| VI. | FICTION | 534 | |

| VII. | POETRY | 566 | |

| PAINTING AND SCULPTURE IN CANADA. By E. F. B. Johnston | |||

| I. | PAINTING | 593 | |

| General Survey—History—Contemporary Painters—Portraiture—Black and White | |||

| II. | SCULPTURE | 632 | |

| III. | ART SOCIETIES | 634 | |

| IV. | THE ART SITUATION IN CANADA | 636 | |

| MUSIC AND THE THEATRE IN CANADA. By J. E. Middleton | |||

| I. | MUSIC IN CANADA | 643 | |

| II. | THE THEATRE IN CANADA | 651 | |

| CANADIAN ARCHITECTURE. By Percy E. Nobbs | |||

| GENERAL CONDITIONS | 665 | ||

| FRENCH-CANADIAN ARCHITECTURE | 667 | ||

| ENGLISH-CANADIAN ARCHITECTURE | 671 | ||

| THOMAS CHANDLER HALIBURTON | Frontispiece | ||

| From an engraving in the Dominion Archives | |||

| JOSEPH QUESNEL | Facing page | 440 | |

| From a portrait in the Château de Ramezay | |||

| MICHEL BIBAUD | „ | 450 | |

| From a portrait in the Château de Ramezay | |||

| FRANCOIS XAVIER GARNEAU | „ | 454 | |

| From the painting by Albert Ferland | |||

| HENRI RAYMOND CASGRAIN | „ | 458 | |

| From a portrait in the Château de Ramezay | |||

| PHILIPPE AUBERT DE GASPÉ | „ | 472 | |

| From a portrait in the Château de Ramezay | |||

| RESIDENCE OF THOMAS CHANDLER HALIBURTON AT WINDSOR, N.S. | „ | 542 | |

| From a drawing by W. H. Bartlett | |||

| WILLIAM KIRBY | „ | 546 | |

| From the painting by J. W. L. Forster | |||

| SIR GILBERT PARKER | „ | 552 | |

| From the painting by J. W. L. Forster | |||

| CHARLES HEAVYSEGE | „ | 570 | |

| From a portrait in the Château de Ramezay | |||

| ISABELLA VALANCY CRAWFORD | „ | 586 | |

| From the portrait in 'The Collected Poems of Isabella Valancy Crawford,' reproduced by permission of Mr J. W. Garvin, Toronto | |||

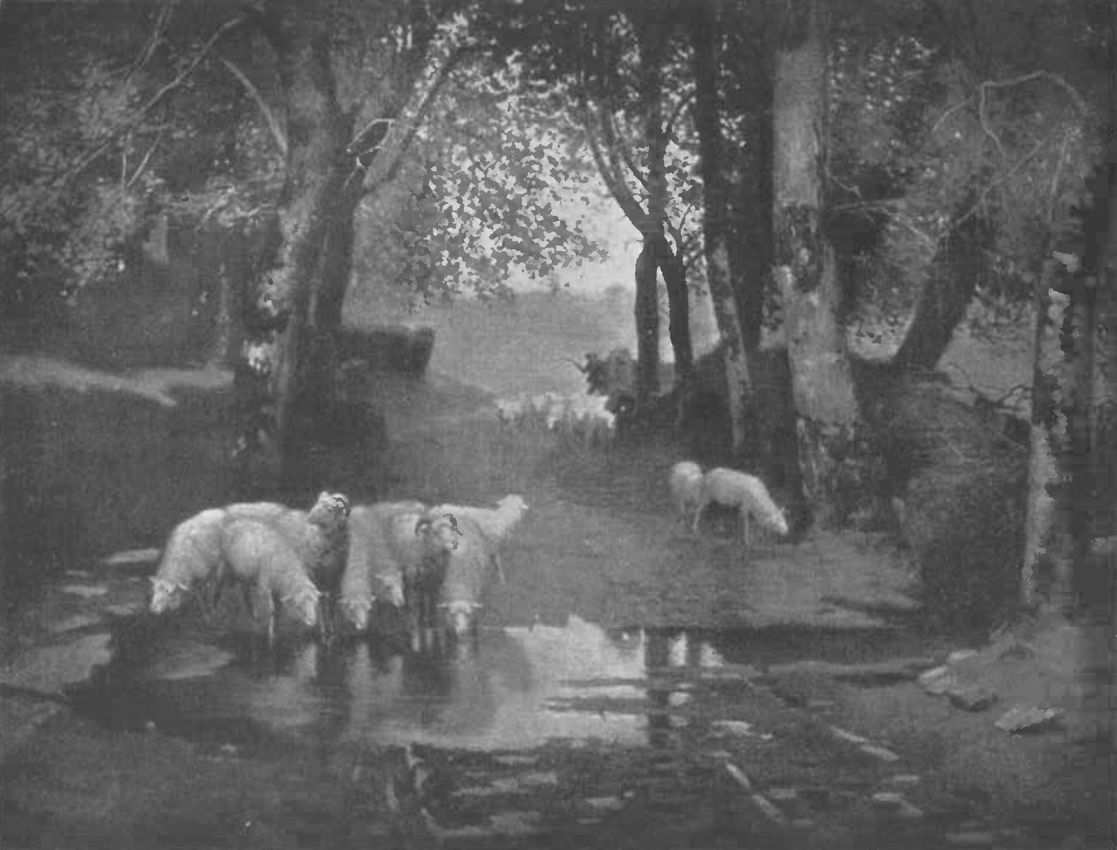

| THE RETURN OF THE FLOCK | „ | 594 | |

| From the painting by Paul Peel | |||

| A HARVEST SCENE ON THE GRAND RIVER | „ | 598 | |

| From the painting by Lucius R. O'Brien | |||

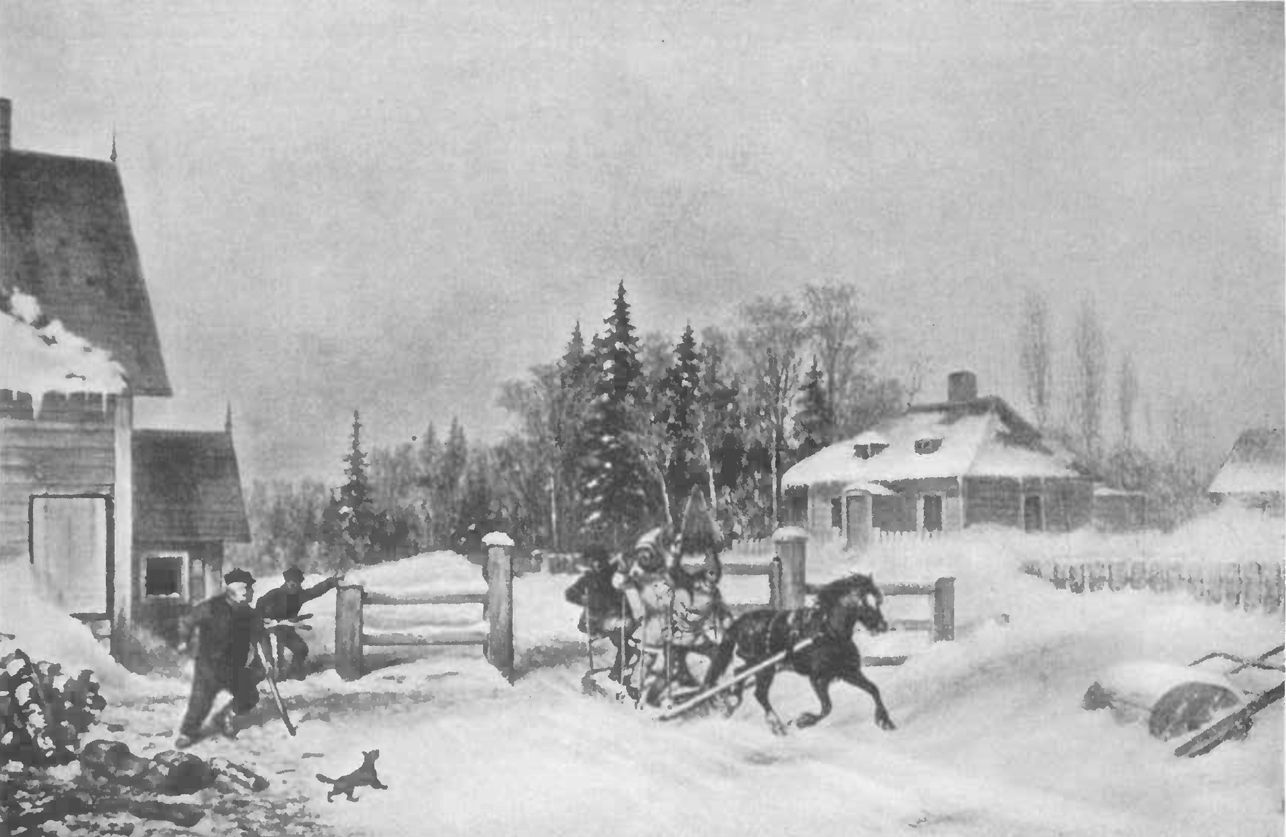

| THE TOLL GATE | „ | 602 | |

| From the painting by Cornelius Krieghoff, by courtesy of the owner, Mr Alex. Buntin, Toronto | |||

| ON THE ST LAWRENCE | „ | 604 | |

| From the painting by O. R. Jacobi | |||

| A ROUGH ROAD | „ | 606 | |

| From the painting by John A. Fraser, by courtesy of the owner, Lieut.-Col. J. B. Miller, Toronto | |||

THE HIGHER NATIONAL LIFE

A Grecian temple and a Canadian Pacific railway have a common factor. They are alike the product of national intelligence. A Parthenon may conceivably, indeed, be the work of an inspired fool, but not of a nation 'mostly fools.' So, too, with the social, economic and political problems of our Western world. Far greater is the demand they make for trained and powerful intelligence. Neither passion for beauty, nor material resources and industrial energy, nor love of country and fellow-men is wholly sufficient for these things. In so far as the ultimate fund of power for great achievement is controllable by men, the sacred keep must be erected, in our modern world, in its highest institutions of learning and research. If culture—and we intend the word in no narrow sense—must remain the property of the few, it is not their privilege, but a prime necessity of a nation that would be great.

It is a simple plea for foundations that this chapter has to make. If 'we must educate our masters' we must find and train our leadership, that core of guidance and initiative which constitutes the soul of progress. For the supreme trial of our New World institutions is only now approaching. Were a Burke among us he would couple with chivalry obedience and rule as vanishing landmarks in the language of our race. Let us cherish the hope that they are being slowly transmuted by a new order of things into loyalty and authority. But should we ever enter upon a period of moral eclipse, authority will be the first to wane. For 'lead and I follow' is eternal in the hearts of men. The urgent call, then, is not for 'scientific efficiency' alone—it need not be thought that this will remain intact, if we drop to lower spiritual levels—but for intellectual leadership in the higher values of life, for sound knowledge, for the highest training, rigid, unstinted, of the highest natures wherever they may be found.

There is of course in Canada no intellectual tradition, no genuine product of revolt from an old social system, such as was the doctrine of laissez-faire, or such as is the long reaction which continues into the present century in the motherland. There has been no fresh struggle with secular antinomies, as was the Tractarian movement, nor any fruitage of an age of great action. Everything is still inchoate. To say this is not to neglect the literary activity of Quebec, nor a fine note in a group of young Ontarian poets, nor a sinewy intelligence in the Eastern provinces, which has produced a striking series of academic workers and public men. But the actual achievement which succeeding chapters will portray, however full of promise, may be set to one side in any broad and faithful survey of the character and possibilities of our intellectual life.

To be broad and faithful such a survey must be continental. For it cannot be too strongly insisted upon that, however conscious we may be of deep contrasts with the great people to the south of us, we share a common life. Our fundamental problem is the same, the problem of a commercial democracy feverishly busy in the development of half a continent. Where our neighbours have succeeded we too may hope to succeed, where they have failed we too shall fail at first. The toils in which they struggle to-day will be ours in large measure to-morrow. We stand where they stood a generation after they crossed the Ohio. If it is a great advantage that we have brought our institutions with us and are not creating our democracy anew, it is equally true that unconsciously we shall follow far in their steps. It is, indeed, not for nothing that we carry with us into our West our schools, and banks, and colleges, and religion and law. We may hope, against great odds, to escape thereby the long results of frontier life. But we too have opened an asylum for the nations and we give freely the sacred rights of citizenship as though we were treading the beaten track of history, while we lack as yet the tide of national sentiment in which the comers from all nations are submerged across the border with so astonishing success. But if we have been knit together by no great convulsion, we have made enormous efforts to create a united people, and, apart from commercial intercourse, it goes for much that the lines of religious and educational activity run east and west. A short study of the newspapers of fifty years ago, whose outside world lay mainly to the south, will bring home to any Canadian how profound a diversion of interest has been created by our great transcontinental lines.

Perhaps the sharpest intellectual contrast between Canada and her neighbours is in the national conception of law. When we reflect upon the long struggle of nations through the ages to erect an august impersonal authority, to detach a sacred deposit of rule for the intercourse of men, above the passion of the hour and the tug and sway of the human struggle, one cannot but feel that the inner meaning of law is but feebly developed with our neighbours as a people. This is not to make the easy reproach of their law's delay and uncertainty, or odious hints of the power of money and influence—we may yet know the bitterness of these faction cries—nor is it to comment upon the election and recall of judges, nor to smile from on high upon attempts to enforce habits by a show of hands, but it is to say that we neither conceive law as an experiment, a thing that we may try to-day, and if we like it not, change to-morrow, nor as the mere will of the many (how soon a mob!) which, at a pass, they may carry out themselves.

On the other hand, though the change which ten years have made in the United States in this regard is very hopeful, we share with them a sense of the futility of the expression of individual opinion. We need reflect on this alone to realise how deep is the unity of spirit in this North-American life. In leaving the motherland we brought with us our ideals of liberty and our institutions, to enter a land of immensities where, if the vastness of our heritage inspires the many with optimism, it likewise creates a kind of fatalism in the individual. Oppressed, as it were, by mere vastness of scale in these great democracies, we start at the sound of an isolated voice as at the discharge of a gun in our great solitudes, and cling fanatically to party and organization as to something human and tangible. The correspondence with which the great British newspapers are deluged appears to us as something quaint and inscrutable. The newspaper editorial replaces the spoken word and appeals more often to the crowd than to the man. To express personal conviction, to create public opinion, and to ascertain what public opinion is, constitute the great task for citizen and statesman, with ourselves as with our neighbours. To achieve it is to have transformed a crowd into a people.

We share again with our neighbours the danger of a great class-embitterment. He is, indeed, wilfully blind who cannot see the idealism with which that great people is imbued. Again and again we seem to hear among them the ancient doctrine that the state is not a commercial enterprise but a spiritual partnership, a moral organism for the making of men. We know nothing, it is true, of the ferocity with which the struggle of capital and labour is being waged across the border. But we do know the danger of class-division. It is a singular spectacle that the continent presents at the moment, with its marvellous agricultural resources worked extravagantly or listlessly, its stupendous increment in natural values intercepted by the drones and pirates of the industrial world, and its wealth of organizing ability assailed as the great menace of society. The demagogue had never a wider scope. If we are to escape a serious check to our civilization, it can be only through an education that does even more than diffuse information—that produces sane leadership.

But we too, as our neighbours, have fixed our hopes upon education, upon a state-system, co-educational, which proceeds from the common school to the university, which includes training for our greatest industry, farming, and which will, in the near future, not neglect a manifold technical and artistic training. With trivial deviations this education is throughout free. This was unerring instinct rather than reasoned theory, but it has crystallized into a first principle of the two democracies. We hold together a deeply seated belief, which, however it may at times or in sections be obscured, more and more affects our national life, in 'equality of opportunity'; and we believe in common that the state cannot leave education in any of its stages to private initiative. If the first results have been a chaos of standards recalling the compliment once paid to a railway magnate, that he had within a short time brought the stock of his railway within reach of the poorest inhabitant of the United States, both peoples are slowly reaching the point when they will demand that the education for which the state pays shall secure to the people the highest type of service and hallmark its products.

But it is not merely the state that does all this. Men of vast wealth and great religious bodies hasten to duplicate the system in its higher grades. So familiar is this spectacle to the people of North America, that we rarely stop to consider the idealism which this implies.

The chapters devoted to education will show that, as a result of government supervision and definite professional training, the qualifications of primary and secondary teachers are much more uniform in Canada than in the United States. But this professional training and state regulation raise questions of national importance. An observer must find indications that in England certain difficulties are slowly arriving which our North-American system develops. We cannot have centralized government control without the defects of its virtues. Something of vital spontaneity is lost beyond recall. But if we really face the inherent dangers we may greatly reduce them. The weakness of professional training is the development of a corporate consciousness and self-interest that come presently to seize control of the system. The danger of government control is that of all organization. It is quite possible to organize the life out of an educational system and to cut off the supply of teachers of any marked type of intelligence and character. These things are quite consistent with a very high level of skilful teaching, as a mere art, and given the end set up for achievement, but they may be slowly robbing a people of idealism and the power of initiative and adjustment to changing conditions. Canada has gone further than her neighbour in government regulation and possibly in the professional education of teachers. The great arguments for this professional training are not those of the generation of Squeers and Bradley Headstone, when primary teaching was largely given over to the failures of other walks in life. It may be speciously defended as magnifying the office of the teacher, raising salaries, and creating permanency. But it is possible for society to lament this permanency, if the final result is to merge the citizen in the teacher. There is little real analogy between the professional training of a teacher and that of a lawyer or physician. Professional training of teachers will have justified itself when it presents something to which an earnest teacher would voluntarily return for help after discovering the difficulties of his vocation and his special needs, in the only way in which he can ever discover them, by doing what physicians and lawyers do, plunging into his work. There is an element of unfairness in the naked statement of this position, for no system is quite devoid of common sense. But it is not as unfair as the analogy used to justify this training. More and more the professional qualifications tend to rise not in substance but in length, until an anæmic guild is created, jealous of intruders, and cut off from wider interests. This little world is further driven in upon itself by unconscious arrogance in the class above it. Like the absolute potentates of the Orient, its rulers withdraw themselves from men, with complete success, behind the mysteries of educational psychology. The only remedy is to open the doors of such a system at both ends. Demand any number of years of sound education sufficient to produce a thoughtful man or woman—nothing but generous education will produce such a man or woman—and take down artificial barriers to character and genuine culture from any part of the Dominion or Empire. Keep the direction of the system, primary and secondary, inspectorships and the like, in the hands of men of wide and liberal training, the best product obtainable from the highest education the country affords. This, too, is the sole safeguard against over-organization. Ministers of education and superintendents should be of the same high type and non-professional. It may well be that the higher education of a country cannot at times provide such leadership, but a country is then in the unhappy case of having no leadership. The Province of Ontario has taken the all-important step of handing over the professional training of the highest grade of teachers to the Universities of Queen's and Toronto—a tacit and wholesome admission that the guidance of primary and secondary education, so far as it is a matter of subjects and content, is no function of government. It remains to be seen how far these universities will realize their great opportunity.

'The power which controls the schools in this generation will control public opinion in the next,' said Coleridge. If ever a nation may be said to have deliberately embodied this Greek ideal in practice, it is the American people in their primary schools. We have much to learn from them. If public interest in the common school is less striking with us, it is because our problem is only beginning. It is a question not of subjects and grants of money, but of living spiritual forces, of the making of citizens. The young life of this continent is a living unit, a palpitating mass of nervous human energy which reacts from end to end with marvellous speed to a patter of language, a trick of sport, of dress, of vandalism, of jest. Can the influence of the schools prove stronger? But we must further remember that the given material is no longer our own. By the time this work is in the reader's hands one in every four of our population will have been an immigrant, and more than half of these will have come from the United States. The power of our national life must indeed be living and intense, our energies definite, if we are to absorb them. The fertility of device, the human enthusiasm and devotion with which our neighbours set themselves to the task of primary education especially, not merely of the child but of the adult, deserve our deep consideration. They strike at first principles: first the language, then the flag. With their practical ingenuity they abandon all language theories in teaching adults. They turn their rural schools into community centres. Their underlying idealism is manifested in the remarkable experiment now being made in illustrated lessons in morals. Yet there are not wanting signs that civic enthusiasm has been born in Canada, and that a great force only waits for leadership.

We have described the influences which tend to drive our primary and secondary systems into guilds. There is a further separating force operating in the latter, the effect of which may be seen over the whole continent. A genuine teacher, in proportion to his human instinct, feels that his work is in the main not to feed the university, but to give the widest training possible to his pupils, for the majority of whom education must now cease. He makes a mistake in demanding that the subjects with which he rounds out their training should find recognition in university examinations. Universities must be trusted to know what they want. There is no other hope for our higher intellectual life. The whole system suffers when once the bond of sympathy is broken. But the secondary teacher is right in considering his school as an end in itself. Those familiar with the extraordinary civic interest that centres in an American high school, whatever their criticism of it, must have reflected that we have a great force here lying comparatively unutilized. Our high schools and collegiate institutes should be the outposts of culture and national intelligence. It holds true here as elsewhere that, as all civic leaders know, leadership is conceded in a higher degree than it is even deserved. The naïve and unwholesome social functions of some of our city schools contrast poorly with the intelligent efforts at larger civic usefulness of which occasional note is made in small centres.

The organization of studies in the secondary system probably presents the most serious and unsettled questions in the whole range of education. Other provinces will do well here to study the system of Ontario, where the attempt is being made, while commencing language study three years later, to carry on in combination types of education which in Germany are allotted to three classes of schools. The total impression left is of a turbid fret of contending aims and subjects and standards and examinations, in which men forget to ask what education is. The system, from no fault of individuals, has become an intellectual and bureaucratic tyranny, which would exclude an Arnold or a Thring, unless he could pass successfully through some round of professional training. And in truth no Arnold or Thring could probably work in the system with the same skill as its best exponents. For it is not lack of skill from which the system suffers, but lack of humane and cultured leadership and dearth of men.

This dearth of men is a subject that should cause national concern. It is undoubted that the personnel of the teaching profession is deteriorating, and the difficulty of obtaining teachers at all is a commonplace. The difficulty extends to the churches and the universities and is a great continental question. In the United States it is a matter of common knowledge that important professorships have gone for years unfilled. The causes for this condition of things are not all on the surface. Undoubtedly the main cause is our commercialism and material prosperity. Not only do other walks of life present greater attractions and hold out higher material rewards, but our people as a whole are so immersed in developing the country that from pure lack of consideration they are slowly impoverishing mentally and starving out their teaching class. The astonishing rise in standards and cost of living leaves all efforts to grapple with the problem far behind. The Presbyterian Church in Canada is contemplating the raising of the minimum stipend of its married clergy to $1200. This is about the average salary of a secondary teacher in Ontario and Saskatchewan, and twice what the average secondary teacher in Ontario received ten years ago. The rhadamanthine character of the professional qualifications for teachers in Ontario is largely due to the deliberate belief that the problem of raising the type of teachers is, at bottom, a question of remuneration. The task set for itself by government is therefore to reduce the supply by steadily increasing the difficulty of entering the profession, and this policy has been adhered to honestly and courageously. But the result is that in the year 1911-12, out of 262 students in the faculty of education in the University of Toronto only 93 were men. The lure of the West is great. For years to come the male teacher especially will go to the West, only to be absorbed presently in some form of speculative activity. It is the same general process that denuded the Eastern States and is now operating in the American West. It is open to any one to say that if the average salary were doubled and communities were compelled by law to pay the same salary to women as to men, the problem would be solved. But insufficient remuneration, if the main, is not the only cause. There is, indeed, a minimum, which we are far from reaching yet, below which intellectual efficiency cannot be maintained. But it is the high distinction of teaching that it has never been in any age devoid of a spirit of service. The question is, at final analysis, one of driving men with the teaching instinct into other fields. Many a woman teacher or forlorn pedagogue in the outskirts of Quebec or our eastern provinces, urged by some fine human impulse, toils on a smaller income than that of a good domestic servant elsewhere. The church, perhaps, as well as the teaching profession, may well consider whether the office of the ministry and the teacher makes quite the same appeal as formerly to the whole man. It is undoubtedly the fact that such a system as that referred to in Ontario repels the most desirable men, but Ontario has taken a step, as we have pointed out, towards vitally connecting the whole system with the university and the highest culture of the province, the significance of which is not yet realized.

Women have a place in teaching which men cannot fill. But it is equally true that men have a place for which women are unfitted. This disproportionate influx of women into the profession of teaching cannot go on for another twenty-five years without having a distinct and serious effect upon national life. The rapid growth of residential schools outside the state system, particularly for boys, is significant. Their ideal is noble and human, but they cannot pay salaries sufficient to attract teaching equal to the best in the state system. There is always the difficulty, moreover, of retaining a good man beyond a certain age, and they raise in an acute form the question once asked by Balfour in an address before the Leys school in Cambridge: Is it the boys or the masters who make the school? They wage an unequal war against the spirit of the continent. One can understand how great is the temptation under this increasing pressure to surrender scholarship to character. If this were the alternative, a training-ship would be a still better school of discipline. But a man-of-war is not a school. The state system, on the other hand, draws from village and farm the soundest and most hopeful material that any educational system in the world has to deal with. From this material the city absorbs the best, to create in the next generation the problem, so intractable with our neighbours, of training the children of wealth without the traditions of culture. This will be more and more the educational problem of Canada. We may hope, however, that our problem will be less acute. For the purely intellectual side of school work is with us its strongest feature, and, even if we do not train the whole boy or girl, and if they are over-stimulated, they do respect learning. It would be interesting to speculate upon how much of the educational difficulties of our neighbours is traceable to the absence of intellectual competition which largely characterises their whole educational system and distinguishes it in a remarkable manner from that of Canada, but this would take us too far afield.

A tabular statement illustrating some of the foregoing features of primary and secondary education in the various provinces, which we conceive to have bearing upon an intellectual life, would be valuable. But it is impossible to make such a comparison with any degree of accuracy. The very words 'primary' and 'secondary' are not in general use, some of the provinces borrowing their terms from the American system, and all differing in countless details. The time may have arrived when a Dominion bureau of educational statistics might perform a useful service.

But it is to the university that a modern nation must look for the ultimate forces which shall mould its intellectual life. A Darwin, a Fabre, a Gauss, a Jacobi may appear to arise outside of the system, but without it they were impossible. It is here that democracy must find its highest direction and its ultimate justification. The student of popular government cannot watch the development of higher education on this continent during the last half-century without a certain exhilaration. Cut off from any vivid remembrance of what mighty movements have had their first beginnings in the university, we have continued the work begun by the church and by private initiative on a scale unparalleled. It is true that the direct connection between the university's activities in pure science and material progress is brought home to us in a thousand ways. There is no knowing when the work of some patient investigator in a laboratory may make its appearance in terms of wheat. But we are also conscious of his ideal value. As we follow this development in those laboratories of democratic institutions in the states to the south of us we see no failure of idealism. The people may be trusted to maintain the university and to give it what constitutes its very soul—freedom. State after state, province after province, repeats the process. Imitation, amour propre and the pride of prosperity are no explanation of this wonderful movement which disturbs in so many ways deep prejudices and convictions. They operate, for we are only men, but some may discern below the surface a democratic faith that, while authority may seem to melt away in a coming grey materialism, the unfettered pursuit of truth may yet be trusted to make a vaster synthesis in a spiritual interpretation of the world.

It must, however, be admitted, that in the United States signs are visible of disillusionment with the results of university education. Its many critics, however, are in the main attacking only symptoms. As a system of to-day it is deliberately borrowed. Aware of a certain 'condescension of foreigners,' our neighbours determined to have scholarship and science, and they have achieved a success that is the admiration of the world. It was natural that they should turn to Europe rather than England. The German university ideal, libertas docendi, fell into fertile ground. It seemed to carry the great assertion of the equality of men into the field of knowledge. Throughout the whole system of school and university, it may be broadly said, all attempt to discriminate values has been abandoned and helplessly replaced by a scheme of a minimum of units of teaching hours. Manifestly the animating idea is incapable of extreme extension in the high schools, but with isolated protests and attempts at some correction, it prevails in the universities and has reached the point in one great university when an 'arts' student may avoid Latin and mathematics entirely and take but one year of French. The field is swept from side to side by violent winds of doctrine. An extreme application of the 'vocational' idea, and the demand from high quarters that 'marked individuality' in high school teachers be allowed to choose its own subjects, would appear to complete a picture of educational anarchy. When the student repairs to the university he makes up his tale of 'hours' by some sense which enables him to judge of the unknown. In any real use of the word there is no competition. The system is throughout what the British university knows as that of the 'pass' man. It is a game that is done, not played, without medal play, bogey or par, the majority of the students looking at the curriculum with the critical judgment with which a hunter surveys the inequalities of a hedge. But the finer spirits work and presently fall under the power of an able instructor, it may chance, in some minute field, to disappear in the ranks of graduate workers and presently themselves become instructors and repeat the process. When a fine college, recently founded in the West under hopeful auspices, 'knows history too well to prescribe the essentials of a liberal education,' it need not dumbfound us that one of those humiliating travesties of learning which the American Bureau of Education is at present investigating should have expressed its understanding of the system in a programme which 'offers' astrology, aviation, Bahaism, bill-collecting and Esperanto. Every tragedy must have its fool.

Thoughtful Americans very well know that this description catches the general spirit of their system. It is a caricature only because it is in vacuo. If it were completely true it would imply that a people as a whole was cut off from critical standards and from the past that animates and explains and directs its social and political institutions. But great disciplines remain for the making of men, such as law, and it must be said at once that, if the guidance of primary and secondary education were frankly trusted to the university, if it were realized that the 'expert,' bred and thrown up by corporate systems detached from the highest culture of the country, is the last person to whom education can be safely entrusted, great educational forces would presently be released. For knowledge is one. It needs no muezzin to make this call to a great American university. Scholarship and scientific attainment have their sanity as well as genius, and men of real distinction do not stand far apart in ultimates. Some arrive at last, if the many fail in a system which leaves genuine culture to be, in the main, the uncertain by-product of the graduate school: uncertain, from the very nature of the work, but produced, as witnesses the splendid roll of scholars in so many fields, with whom Canada has few, as yet, to put in comparison.

In turning to the Canadian university we shall find strong reasons for believing that a system of higher education is quietly developing which is destined to exert a deeper influence upon the higher life of the Dominion than any other body of forces. Uniformity is not to be expected. To aim at it is to sow at once the seeds of future decay. Yet it may be asserted with reasonable confidence that a type of university has arisen in Toronto, as the result of seventy years' struggle, which is destined to prevail over a large part of the Dominion. The noble foundations of Queen's and McGill will be repeated, we earnestly hope, as the wealth of the Dominion increases. It is well that the state should have its competitors. They will form invaluable strongholds of political criticism. But the provincial universities will, we believe, conform more or less to the type of the University of Toronto, for the background of ideas and the general conditions that produced it are present everywhere except in Quebec. As a people we are deeply Puritan, and we have brought with us the age-long struggle of ideals that produces so deep a cleavage in the motherland. The Province of Ontario has only fused in education contending principles which make the history of education in Nova Scotia painful reading. The situation there to-day is what it was in Ontario two generations ago. Manitoba repeats in a most striking way conditions in Ontario on the eve of university federation. In Saskatchewan and Alberta (though in the latter there is some dissipation of energy) the framework of higher education is being laid far in advance of present conditions with the true statesmanship that will allow the ideals the people have carried with them full opportunity of embodiment, and we can already observe in these provinces in outline a foreshadowing of the Ontario plan. The scheme outlined in the recent act for British Columbia follows that of Ontario up to a certain point, without rendering impossible at some future time a feature of the Ontario system which is all-important. The growth of this feature in the great Western provinces will depend upon the vitality of the college ideal. If it is fundamentally sound, the unbounded resources of the West will make its realization a mere matter of time. Quebec, in spite of the great university of McGill, obviously presents difficulties so serious that its educational problem becomes European rather than American. But it is worth the consideration of other Canadian universities whether some interchange of academic life would not tend to bring together conflicting currents in our national life. Some of our academic pilgrimages might well be diverted from Europe to Laval, a seat of unworldly culture which we too contentedly ignore.

Another chapter will detail the long contention and debate which gave the University of Toronto its present form. But the essential meaning of what was accomplished in 1890, 1904 and 1906 is not too well understood by members of the university itself. Men do not lay aside their prepossessions in the first generation, and the inquirer would be happy who should come away with a satisfactory understanding. For the purposes of this chapter there are three features which claim the careful attention of all Canadians to whom the fostering of our intellectual life is a matter of deep concern—the grouping of theological schools about a university centre, the scheme of undergraduate studies in arts, and the confraternity of arts colleges.

If the system went no further than the plan outlined for the Province of British Columbia, it would be hard to overestimate the far-spreading results of this clustering of the theological schools of the great religious bodies, including the Roman Catholics, about a common university. The churches of Canada show unmistakable signs of having been too long cut off from the great currents of modern thought. The process of readjustment which is being accomplished in Great Britain, with renewal of spiritual life and activity, is hardly begun in Canada. It was high statesmanship which brought the theological school to the university. As the walls separating the sciences wear rapidly thinner, may we not likewise hope for some greater spiritual comprehension, a more vivid hold upon truth catholic? The immediate result cannot fail to be a wider citizenship and a more vital contact of the church with the flower of young manhood.

The principles upon which this tangle of conflicting ideals and interests, passionate loyalties and genuine fears, was solved were the paramount responsibility of the state and the academic autonomy of the university and colleges. The state asserted as fundamental that, whether it had discharged its duty in the past or not, it could not relinquish its right to support in a system of its own every step in the educational process from the primary school to the university. This much accepted by all parties, the colleges were then given an equal voice in working out the academical programme. The result is that liberal culture is practically entrusted to the 'Council of the Faculty of Arts,' an absolute democracy, where all members of the arts staff in the university and the arts colleges have a voice, and all above the grade of lecturers an equal vote. The various departments of study are organized in smaller groups upon the same footing of equality. It requires no prophet to forecast the difficulties of this academic democracy in the first generation: many an officious hand will be put out to stay the ark of learning, but it will achieve in the end an enforced continuous reflection upon the meaning of higher education of inestimable value.

This clear definition of first principles went little further. With the British instinct that destroys nothing, the former senate was retained with narrowed functions, which constitute it, in the main, a revising and registering board; but, as it gives representation to the various faculties, the federating units, the secondary system of education, and the graduate body, it provides a centre for debate on questions of large policy, and power is dormant in it which might on occasion find proper exercise.

The same thing is true of the division of subjects between the university teaching body and the arts colleges. The broad intention was to hand over the 'humanities' to the arts colleges, and to give to the university the sciences and some special subjects such as might be expected to attract a limited number of students. But the illogical inclusion of modern history, political science and philosophy among the university subjects must appear to the outsider to leave the arts colleges pretty much in the position of higher schools of language teaching. Whether this is true depends of course upon how the study of language is conceived. The more serious of these anomalies will doubtless slowly disappear. Victoria College is already contemplating the addition of tutorial work in modern history.

As we proceed, some influence of the American state university will appear. The university includes, besides arts, faculties of medicine, education, applied science and forestry, with affiliations in agriculture, music and other subjects for which it examines and grants degrees. It is matter for regret that, with such an outstanding precedent as the splendid school at Harvard, no faculty of law appears as yet. Ontario has thus placed herself in line with such a state as Wisconsin. But while the university has much to learn from the enlightened civic spirit of the institution of that state, it has something also to avoid. The final value of a university is incapable of being expressed in terms of material progress.

What has been said of education is equally true of the great professions of medicine and law. The growth of the corporate spirit is a weakness in the professions and a public danger. The emancipation of medicine in Ontario is still incomplete, and, while legal education in Ontario is much advanced, there are indications in the West of the rise of what may become nothing more or less than the guild. It is to the universities alone that the Dominion should turn for standards, and the public interest would be greatly served by the creation of professional qualifications valid throughout the Dominion. The temper that handicaps a higher training as against an inferior, either by heavy fees or by sophistical educational devices, is that of a mediæval guild, unworthy of a great people, and degrading to the professions themselves. For a professional body only too soon forgets that the privileges accorded to it by law are granted solely in the public interest.

But, to continue our attempt to detach the essence of the Toronto system, more vital is the second feature, the quite distinctive scheme of arts studies. It is manifestly an extension of the Oxford and Cambridge 'schools.' But of conscious borrowing there was none, for a 'nativism' inevitable to the lusty youth of a country, and still mindful of the days of the 'Family Compact,' would have rendered that impossible. Moreover, it is not the type of college training which was first imported into North America, and which still survives in many small institutions in Canada and the United States, the genius of which is mental discipline. Your ruthless modernist, who protests against the mediævalism which he sees in Oxford, would have assassinated Pompey for Cæsar. He takes fright in the wrong direction. For the two outstanding features in mediæval education were surely first, that it scoured the very hedges for ability; and second, that it treated the mind as a bundle of faculties, for each of which a special discipline could be devised. This discipline of the trivium and quadrivium nowhere persisted more unchallenged than in Scotland, where, in the form of a training in mathematics, Latin and philosophy, with some concession to science in the shape of natural philosophy, an education was given, the power of which is undeniable. But this is a mental training without content. Whether the man so trained becomes a social force depends upon what he afterwards analyses and digests. Moreover, if we put to one side the philosophy—the real power of the Scottish system—and the genius of the born teacher, this education of discipline fails to weigh sufficiently a first principle of the philosophy of education and of the world's general progress, that all great achievement starts from a core of interest.

Now the system which has grown up in Toronto began with a disciplinary scheme of studies for the 'pass' man, upon which it superimposed for the 'honour' man a gradually extending list of what is known in England as 'schools,' until a scheme of studies has been formed in which the student takes either a 'general' course, as it is now called, or as thorough a training as four years of undergraduate life permit in mathematics or classics or political science or modern history and so on, in some cases making combinations, as English and history with a basis of modern languages or classical studies, in other cases, such as the natural sciences, narrowing his field as his course proceeds. Obviously the departments differ in their social and educational value, but, when every deduction is made for failure, the failure cannot be complete, for the system has an organic life of its own. As we have seen, it differs toto caelo from the Germanized type of education prevailing in the United States, where knowledge spreads out her wares in random profusion. In essence it makes a simple but great affirmation: Immerse a student, when once the years of reflection begin, in a great and worthy subject of his choice. Let him follow it as it ramifies, adding what subsidiary studies he finds necessary, studies which are meaningless when pursued in isolation. He will slowly gather judgment, an energy of continuous inquiry, concentration, a sense of the unity of knowledge; and in the end you may hope for a serious reflecting man, generously critical, with power and outlook.

It may be asked with some justice, whether all this does not describe the essential characteristics of the graduate school in some fields of knowledge, if for a moment we may regard its ideal as educational. We must reply that, even so, this is to organize culture too late in a national system and to organize it simply for a professional class. Moreover, even if all roads lead to Rome, how few may hope to arrive, when it is of the essence of the itinerary that the point of departure shall never have been used before! But more than all, sophisticate the case as we will, the temper and motive of graduate work are different from that of any true scheme of liberal culture, which must follow the main march of humanity, the beaten road. The genius of the one is synthetic, synoptic; the other aims to advance knowledge.

It was only natural that, as the possibilities of this scheme of studies came to be better appreciated, the methods of Oxford in her schools of 'Greats' and 'Modern History' should come to be scrutinized more closely, and that some tentative efforts should be made to apply the Oxford tutorial methods. The question probably was never formulated, but in many quarters it is observable that the university is asking whether the unexampled power of Oxford 'Greats' is not capable of extension to other fields of study. For if the method of liberal culture is one, its application is, after all, a question of more or less. Such education can begin only when the powers of reflection assert themselves in early manhood, and the outlook upon life which it gives is conditioned by the depth to which it strikes its roots into the past. It is an enormous advantage to approach the great problems of the life of to-day in their simplest form, retracing them from the starting-point of the race. This is the genius of Oxford 'Greats,' but it requires a preparation attainable only by the very few. Indeed, of late years a project is said to have been discussed in Oxford to construct a new 'school,' which shall carry over the essential power of the old, but take a point of departure nearer ourselves. In any case, once admitted to a university, the student must be taken as he is. The system of Ontario (for Queen's practically repeats the Toronto plan) simply asserts that true culture is produced only by placing the student in a large and noble field and allowing his development to proceed from pivotal points, fundamental books, periods or ideas.

But manent vestigia ruris, the notion still persists in many quarters that this is specialization, so little is known in Canada as yet of the graduate school; and in the university itself, as a concession to supposed popular feeling, the term 'special' has been unfortunately applied to what has been heretofore known as 'honour' departments, and these carry with them in their early stages a trail of 'general' subjects, often unrelated, and, to the extent that they are compulsory, educationally valueless. But no belief is more deeply fixed in the university body than this, that any success which the university has attained is due to these 'special' courses, and there is no feature more characteristic of the student body than its aversion to the 'general' course, which by the latest statistics contains in the graduating year but twenty-seven per cent of the students of that year. The problem of the future would seem to lie in a study of the power, value and method of the various 'honour' courses.

We now come to the third outstanding feature of the Toronto system, the group of arts colleges. This detailed examination is given without apology, for if we are right in forecasting the reproduction of the system in greater or less detail throughout the West, its effect upon the intellectual life of the Dominion will be profound. This is the critical hour in our development. Ideals are happily combined in this product of genuine evolution, which in other countries still more or less contend with each other. In Oxford the college lacks the stimulus of a great centre of higher university activity, the smaller English universities tend to become the educational homes of nonconformity and to divide the national life, the students in the great German and American universities are lost in the crowd or gather in anti-social groups, the solitary college, in proportion to the very nobility and intenseness of its life, suffers somewhat in intellectual outlook.

Now we conceive the soul of the system which we have analysed to be the arts college. The college is an end in itself. It is here that we must organize the culture of the nation in a system maintained by the state. The college does not exist to feed the graduate school, to man the professions, to make scholars or experts, to teach mere languages, or to give four years of blissful life to its inmates, though some or all of these things it may also do, but to make men and citizens of all its students, and sane and noble leaders of a few. Quod semper quod ubique is the criterion of values in its scheme of studies. It teaches the great books for what they contain, not for their documentary antecedents, and literature, not literary literature or literary history. It is no breeding-ground for the doctrinaire or the 'intellectual.' It should devote great energy to historical and political studies, because as the child of the state it seeks the largest social returns, and because upon history and philosophy in some form or other all culture is ultimately based. It does all this amid the vital human relationships of a living social unit which is a fragment of life itself, instinct with activities, a nursery of citizenship, itself a member of a group where a generous competition intensifies the life of the whole. In short, it aims to impart not information, but wisdom. What remains in a few years to the man of scientific training, who does not pursue science through life, but the scientific method and spirit? In like fashion, the economics or political studies of liberal culture subside presently into platitudes in the eyes of the specialist or the commonplaces of the rhetorician. This is true of all the truth there is: once perceived, it is hopelessly obvious. But to the man so trained these platitudes have been reinforced by a wealth of experience and become permanently vitalized. This result is not achieved by text-books or the tepid effort of the average man, but only by teaching of the highest creative type and the 'souls well disposed' for which it calls.

The product of such a training has been called the amateur, and if, to put it simply, to have understood the aspirations of an age from a fundamental work in literature, to have felt the significance to our continent of the Reformation or the French Revolution, to have seen in the politics of Aristotle the primal human forces at work in our own democracy, constitute the amateur, may he abound! It is he who maintains the great monthlies and reviews of the motherland, who repairs to her foreign service, depleting the country of some of its best intellect, who finds his way into her cabinets, or, while engaged in the business of life, pursues learning or philosophy for its own sake, and who is altogether that which the political and intellectual life of this continent most sorely needs.

But will the college ideal in this system remain unshaken? The amazing growth of the university since federation of itself raises the question. With eleven hundred students the state college would already appear to have passed the bounds of corporate life, and Victoria with five hundred is confronted with similar difficulties. One can only register the conviction that the splendid vitality and idealism of the church colleges will lead to imitation and eventually enforce a duplication also of the state unit. It may, moreover, be predicted that the system of co-education is not destined to continue indefinitely. The creation of a college for women would give temporary relief.

What does the Province of Ontario not owe to the generous breadth of view that brought these denominational colleges into the common system! Nothing has so deeply imbedded the university in the affections and confidence of the people, nothing so humanized the university or strengthened its scientific efficiency. The American people are beginning to scrutinize more closely the power of the college. Of this there is no better evidence than the movements at Princeton and Amherst. The latter is an effort to reorganize the college on humanistic lines, but reverting overmuch possibly to the disciplinary ideal, and it is doubtful whether Princeton, in turning to the Oxford tutorial idea, really caught the whole genius of the tutor's activity at Oxford. There appears also to be growing up at Princeton a scheme of studies which foreshadows the 'schools' of Oxford and Cambridge, or the 'honour courses' of Toronto and Queen's.

One cannot dismiss the subject without a final word. Canada is, for its population, among the richest countries of the world. We are only beginning a period of immense growth in population and literally unparalleled material development. The danger that confronts education in the next twenty years is that the material will have run away with the system, that the pressure of the prospering multitude for the form of culture without the effort—for a culture that will come as quickly as wealth and comfort—will have so reacted upon educational methods as to endanger liberal culture and the highest pursuit of science alike. For science, pure and applied, is not less threatened than the so-called liberal arts. Moreover, while making every effort to bring the universities to the people, we may play the demagogue, and the revenge will be severe. The laboratory may, indeed, make vast material promises, but there will be barren years, when its output will dwindle into a thin rill. Men will then remember that they have souls. For, after all, the greatest aim which our educational system as a whole can have is the creation of national like-mindedness—in short, public opinion. The indictments of social injustice, of which we see the unhappy beginning, have no value in a society where all the members are pursuing the same ends. They are not opinion but sentiment—and mean sentiment. The public opinion which really preserves the state is a combination of character and knowledge, and created by leadership, and this leadership the higher education of the state must supply if it is to justify itself.

Apart from an educational system as an organized force in the creation of public opinion, the disciplined intelligence of a people, nothing would appear comparable in its possibilities to the Press. Probably no people of its size is better served by its Press. It must be said with satisfaction that, as a whole, it traffics little in scandal, and the invasion of the private life of a public man is an offence almost unknown. Its code of professional honour is high. Every prominent editor possesses information which he refuses to use. The first criticism passed by the British traveller is of the paucity of important news, particularly foreign news, and it must be confessed that the supply of news from abroad is very inadequate. Our greatest papers may be detected, in a crisis, referring to previous information which has never been chronicled. Some exception, however, must be made as to British news. The efforts made in recent years to keep the country in touch with British politics are noteworthy, and it is significant of our future that the average man is probably kept better informed of what is really important in British politics than in the politics of the United States. The faults of the Canadian newspaper are, on the whole, those of the average citizen. Apart from the disgusting comic supplement imported by some papers, which poisons society at the well-head, the country contains as yet no paper which exercises a force distinctly pernicious. The Press of Canada no more preaches publicity as its raison d'être with the naked absolutism of a Pulitzer or a Hearst, than its statesmen find it their sole function to give the people only what is good for them or only what the majority want. It may justly refuse to be impaled on the dilemma: lead or follow. To do both is the common lot of all professions, and for none is the task more difficult than for that of the Press, which is really called upon to find its material subsistence outside its actual work, that is in its advertising. For democracy will not pay enough for its newspapers to give them independence. They are asked to undertake a mission at their own charges. We need a party Press to preach those ultimate principles which, in conflict, maintain the life of society. But if the Press is partisan, so is the citizen. If it tends to keep out of public life the growing class of men who should be drawn into it, so do we, the public. Highly again as we must rate its moral force, its integrity and intelligence, we cannot fail to observe that its greatest failing is that of the politician. It accurately knows the crowd, but the nation not so well. It is a poor judge of public opinion and ineffective in producing it. In the last analysis, the politician believes with intensity that the great appeal is to immediate self-interest. Like the politician, the Press devotes its energies rather to converting the converted than to the question itself. Partly, as has been said before, this is a national characteristic. As a people we have yet little conception of how great is the power of deliberate opinion that has no personal ends to serve. Liberal or conservative, we do not believe in the possibility of persuading an opponent. Our first impulse is not to resort to the merits of the question. But more, perhaps, it is due to the lack of great issues. Since Confederation we have gone through a barren period, lit up, it is true, in 1878 by an appeal directed to the idealism of the country, but, on the whole, without the stuff in it which compels men to go to fundamentals. Our neighbours went through such a period after the Civil War. If we take our stand at the eve of the Spanish-American War, or perhaps the Venezuela episode, it would have seemed that the days of Webster, Clay, Calhoun and Lincoln were irretrievably gone. But splendid examples are again appearing of men who know the power of direct appeal on the ground of the public interest. For the force of such appeal is a matter not of belief, but of knowledge, and it is the secret of permanent power in a democracy. But it must further be said with regret that our newspapers, even the greatest, are not wholly exempt from the charge of demagogism. We cannot appeal to the prejudices of west as against east, of province against province, or producer against consumer, of farmer against manufacturer, of capital against labour, and that in a period of unexampled prosperity, without endangering our future and without ignoring the first two axioms of politics, that men are actuated by the same motives, and that they would not form into societies if they were not capable of working together.

As civilizing factors our best papers are immensely superior to any in the United States, with some few exceptions such as the New York Evening Post, the Boston Transcript and the Springfield Republican. It is doubtful whether the editorial page of some of them is not equal to that of the Evening Post. But no paper in Canada interpreted the results of the elections on the Reciprocity issue with the same acute political insight as that paper in its issue of September 22, 1911. This political insight is not quickly acquired, and if we ask the reason for the discouraging failure of a series of attempts at independent journalism—the Bystander, the Week, the News, all of Toronto—the answer must be that we have not yet developed a sufficient body of educated opinion either to conduct such an enterprise over a lengthened period or to support it. Democracy must pay the price, and those who lead such forlorn hopes must wait—and be able to wait—for the growth of the opinion they seek to create.

In the University Magazine we have at last produced a quarterly periodical which may have a future of much power. At times quite equal, if not superior, to the best work on the American continent, it reveals occasionally the limited circle of contributors from which it has to draw, and it is edited for the love of the thing. Independent journalism will begin in this missionary fashion. Its clientèle will be limited, but so is genuine opinion, and it is in opinion far more than interests that real power is vested.

Early in this chapter attention was called to the extreme importance of the fact that the life of the churches flows east and west. The project, which will be noted in this volume, to effect a union of the Presbyterian and Methodist bodies has equally great national significance. Men cannot unite on this vast scale for purposes which transcend themselves without quickening the intellectual life of the country. So too the civic enthusiast, the town-planner, the social worker have arrived, and will contribute each in his own degree. The affiliations of the higher range of professional workers are largely international, but the growth of societies such as the Royal Society of Canada, the Canadian Institute, the Literary and Scientific Society of Quebec, the Nova Scotia Historical Society, the Champlain Society, and the increasing interest in the great British scientific associations are all indications of accelerated national consciousness.

Nor should mention be omitted of the Young Men's Christian Association as a humble but genuine force in our intellectual development. This is particularly true from Ontario out to the Pacific. The statesmanship with which its leaders place these New World monasteries of manly development strikes the thoughtful traveller with admiration.

Finally, in the Canadian Club we have an indigenous institution destined to exert an increasing and continued influence in the Dominion. It is a curious example of how little a fertile idea depends upon mere organization. It has almost no organization. Conceived by C. R. McCullough and launched in Hamilton, it presently repeated itself in Toronto. Beginning as a group of young men, engaged mainly in active life, undertaking to lunch together weekly and discuss public questions without bringing in party issues, it has gradually spread, with absolutely no propaganda, from Halifax to Vancouver. In large centres mere numbers presently made debate impossible, and men of prominence began to be invited to address the clubs without discussion. With like rapidity youth ceased to be the characteristic of its members. It has now become a very remarkable instrument for the diffusion of intelligent opinion throughout the whole country. Its larger branches bring men of world-wide prominence, and the publicist, the philanthropist, the born leader find here an incomparable opportunity to 'state their case.'

Much of the best intellect of Canada will long continue to be drawn into commercial and financial and organizing activity. We need not lament this overmuch so long as it is the best intellect, much less need we sequester it by the play of petty instinct from which neither the professional man nor the man in the street is exempt. It lies with our universities and with all who have the instinct for affairs to forestall the arrival of the idle rich and barbarous profusion by the appeal to duty and the public interest, and by holding out ideals of simple and noble living. A witty Frenchman once expressed his admiration of the genius in the Anglo-Saxon that in the course of centuries had transformed his conquerors into public slaves. We shall be conquered on this continent by the exploiter of its unbounded resources only if we hive the genius and vision and incomparable energy of the captains of our industry and material development, instead of giving them scope in the field of public service. For it is a poor analysis of this activity which finds its only motive in mere wealth or even power. And we shall yet continue to lose young poets and artists and intellectual workers to the great republic to the south of us, and now also to the motherland—the tally of these is long—for the exhausting force of a neighbouring nation more than twelve times as large, and speaking our own language, is enormous.

But the turn of the tide has come. How far intellectual greatness is impossible apart from great issues and a sense of national responsibility may contain some matter for speculation, but it is idle to deny the connection. In this period of expectant pause we do well to inquire whether we have not been influenced more than we were aware by our history and the consciousness of membership in the greatest human family. One of the most vital characteristics of the English people is what has been called its 'clubbableness.' This perpetual conflict and interchange of ideas in natural groups keeps alive the soul of the nation. It is our task to give vitality to such diffusive centres of national life as have been described, to foster their growth, and to bring under their power the inpouring tide of immigrants from the sister democracy, with aspirations not wholly ours, from Great Britain, with much to unlearn, and from Europe, 'wild hearts' often 'and feeble wings that every sophister can lime.' The roll of names which have stood, and still stand, for higher life in the American Republic is a moving study in nationality. In Canada, too, British stock and the Puritan strain constitute the warp into which the web of our national life is to be woven if it is to endure.

FRENCH-CANADIAN LITERATURE

The literary history of the French Canadians may be said to date from the year 1760, or, if one prefers, from the cession of Canada to England. Before that time, indeed, there had been certain manifestations of literary life in New France: there had been accounts of travel, like those of Champlain; interesting narratives, like the Relations of the Jesuits; histories like that of Charlevoix; studies of manners like those of the Père Lafitau; and instructive letters, full of shrewd observations, like those of the Mère Marie de l'Incarnation. But these works were, for the most part, written in France, and all were published there. Their authors, moreover, belong to France much more than to Canada, and France, rather than Canada, is entitled to claim their works as her patrimony.

During the hundred and fifty years of French domination in Canada the colonists were unable to devote much attention to intellectual pursuits. All the living forces of the nascent people were engrossed by the ruder labours of colonization, commerce and war.

Nor was it even on the morrow of 1760—the morrow of the treaty that delivered New France to England—that the first books were printed and the first notable works written. There was other work to be done, and the French under their new rulers betook themselves to action. While repairing the disasters to their material fortunes, they numbered themselves, consolidated themselves, and set themselves to preserve as intact as possible their ancient institutions and the traditions of their national life.

From this effort to preserve their nationality the first manifestations of their literary life were soon to spring; and it was through the newspaper—the most convenient vehicle of popular thought—that the French-Canadian mind first found expression. Only colonial literature could begin in the newspaper article. The older literatures were born on the lips of the ædes, the bards or the troubadours: it was the human voice, the living song of a soul, that carried to attentive ears these first untutored accents. But in Canada, in America, where machinery is at the beginning of all progress, the Press is naturally the all-important instrument for the spread of literary ideas. In the years immediately following the Cession there were established in Quebec and Montreal several periodicals, in which the unpretentious works of the earliest writers may be found.

The following are some of the journals that appeared at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, and that mark the true origin of French-Canadian literature:

La Gazette de Québec (1764); La Gazette du Commerce et littéraire, of Montreal, named almost immediately La Gazette littéraire (1778); La Gazette de Montréal (1785); Le Magasin de Québec (1792); Le Cours du temps (1794); Le Canadien, of Quebec (1806); Le Courrier de Québec (1807); Le Vrai Canadien, of Quebec (1810); Le Spectateur, of Montreal (1813); L'Aurore, of Montreal (1815); L'Abeille canadienne, of Montreal (1818).

These journals were not equally fortunate. Most of them—La Gazette littéraire, L'Abeille canadienne, Le Magasin de Québec, Le Courrier de Québec, Le Vrai Canadien—struggled for life for a few months or a few years, and disappeared one after the other. With the exception of La Gazette de Québec, La Gazette de Montréal, Le Canadien, and Le Spectateur, the first newspapers succumbed after a valiant struggle for existence. To reach the greatest possible number of readers, several of these journals—La Gazette de Québec, La Gazette de Montréal, Le Magasin de Québec and Le Cours du temps—were written in both English and French.

The French newspapers may be divided into two distinct categories. There were those that were mainly political, or contained political news, like La Gazette de Québec and La Gazette de Montréal; and the periodicals that were distinctly literary, such as La Gazette littéraire of Montreal and Le Magasin de Québec. This last-named journal contained little but reproductions from foreign literature.

La Gazette littéraire of Montreal, published by Fleury Mesplet, on whose staff Valentin Jautard, a native of France, was an active collaborator under the pseudonym of 'Le Spectateur tranquille,' is noteworthy as having given the French Canadians their first opportunity of writing on literary and philosophical subjects. Much literary criticism, sometimes of a decidedly puerile nature, also appeared in it. In this paper, too, are encountered the first manifestations of the Voltairian spirit that had permeated many minds in Canada during the latter part of the eighteenth century.

The first political journals were literary in but a small degree, and it was seldom that they published French articles of any value. Apart from a few occasional poems—of little merit, however—the French contents of La Gazette de Québec were, for the most part, merely translations of its English articles. The political literature of this journal is dull and unimportant. William Brown, who, with Thomas Gilmour, was its founder, characterized his journal only too well when he wrote (August 8, 1776) that it 'justly merited the title of the most innocent gazette in the British dominions.'

Nevertheless it was Quebec that became, in 1764, the cradle of Canadian journalism. Before the end of the French régime Quebec was already the centre of a civilization that was polished, elegant—refined even—and often very fashionable. Peter Kalm, the Swedish botanist—who visited New France in 1749, and left such a curious, instructive and faithful record of his journey—observed that Quebec then contained the elements of a distinguished society, in which good taste was preserved, and in which the people delighted to make it govern their manners, their language and their dress. Quebec, moreover, prided herself not only on gathering within her walls the most important personages of the political and the ecclesiastical world, but also on being the chief seat of intellectual life in the new country. From Bougainville[1] we learn that in 1757, towards the end of the French régime, there was a literary club in Quebec. Besides this, the Jesuits' College and the Seminary had for more than a century drawn to Quebec the studious youth of the entire colony. Michel Bibaud, who visited the city in 1841, noted there 'the agreeable, affable manners of her leading citizens, and their French urbanity and courtesy.'[2] For this reason he called her 'the Paris of America.'

It was at Quebec, too, after 1791, when parliamentary government was accorded Lower Canada, that political oratory—timid at first, and modest in expression—was born. There the first groupings of intellectual forces were afterwards organized: the Club constitutionnel (1792); the Société littéraire (1809); the Société historique et littéraire (1824), founded at the Château Saint-Louis, under the presidency of Lord Dalhousie; and the Société pour l'encouragement des Sciences et des Arts (1827), which soon amalgamated, in 1829, with the Société historique et littéraire.

Montreal, in the nineteenth century, was not backward in seconding, propagating and developing those movements of intellectual life which were gathering force in Quebec. At Montreal people read both poetry and prose. Joseph Mermet, a French military poet, who came to Canada in 1813 and took part in the war then in progress, had a large number of admirers in the city. There Jacques Viger pursued his historical studies on Canada; and Denis Benjamin Viger, who at certain moments thought himself a poet, published his ponderous verses in Le Spectateur. In 1817 H. Bossange established in Montreal a fairly considerable bookselling business. The City Library is said to have contained eight thousand volumes in 1822.[3] The inhabitants might also nourish their intellectual curiosity in the newspapers and the literary miscellanies published about the middle of the nineteenth century, such as—La Minerve (1827), L'Ami du Peuple (1832), Le Populaire and La Quotidienne (1837), L'Aurore des Canadas (1839), and Le Jean-Baptiste (1840). To these may be added the miscellanies of Michel Bibaud—La Bibliothèque canadienne (1825 to 1830), L'Observateur (1830), Le Magasin du Bas-Canada (1832), and L'Encyclopédie canadienne (1842).

At this period Quebec and Montreal, with their associations, their journals and their literary miscellanies, were not as yet, of course, powerful centres of intellectual life, nor was the energy they radiated either very active or brilliant. In tracing the real origins of a literature, however, it is not unprofitable to indicate briefly the historical environment in which that literature was to have its birth. By this means the relative value of its earlier efforts is more justly appreciated.

With the French Canadians, song appears to have been the first form of poetry. Some verses written in 1757 and 1758[4] are still to be found; many may be read in the journals which made their appearance later. The popular song flew quickly from mouth to mouth when, in 1775, or again in 1812, the people were fired with a fine patriotic ardour to defend the soil of their invaded country. New Year's Day also supplied the rhymesters with matter for a few verses, mainly intended for newsboys' addresses. Needless to say, these poems—interesting as they are from the point of view of literary origins—have in themselves scarcely any literary value. The same may be said of many lyrical, pastoral and satirical pieces that appeared anonymously in the early journals.[5]

At this period, however, two poets stand out from all others—Joseph Quesnel and Joseph Mermet. Although they were of French origin, they so deeply impressed Canadians of their time, and exercised such an influence upon later writers of verse and men of letters, that we cannot but take account of them in a history of the beginnings of French-Canadian poetry.