* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Condemned to Devil's Island

Date of first publication: 1928

Author: Mary Blair Rice (as Blair Niles) (1880-1959)

Date first posted: Dec. 22, 2020

Date last updated: Dec. 22, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20201256

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

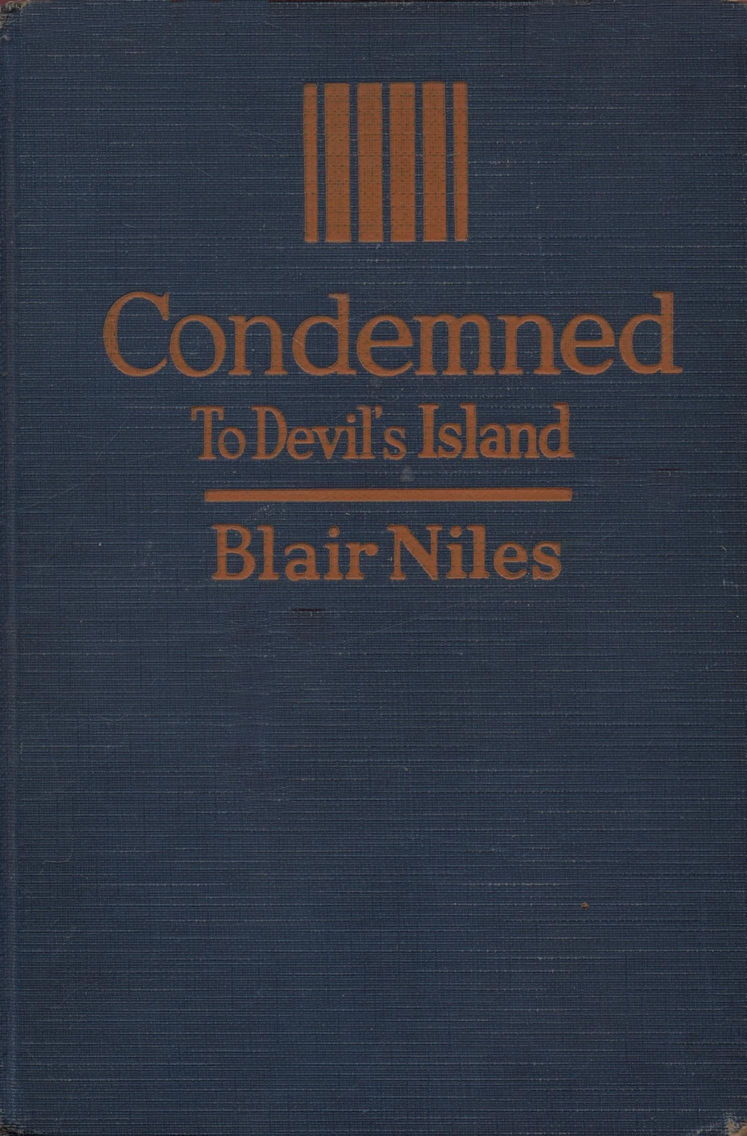

Photo Copyright by Robert Niles, Jr.

FRENCH CITIZENS CONDEMNED TO PENAL SERVITUDE IN GUIANA.

CONDEMNED

TO DEVIL’S ISLAND

The Biography of an

Unknown Convict

BY

BLAIR NILES

Illustrated by

BETH KREBS MORRIS

and from photographs by

ROBERT NILES, JR.

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY, INC.

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A.

Dedicated to

MY HUSBAND

ROBERT NILES, JR.

In different form certain parts of this narrative have appeared over the author’s signature in The Forum and The New York Times

In telling the story of The Devil’s Island Penal Colony in French Guiana, I have adopted the method of a fictional biography, instead of a personal narrative. This method made it possible to write of Devil’s Island as it appears to the men condemned to live and to suffer there as prisoners and as exiles. It did not seem to me important how I personally felt about this tragic Penal Colony but immensely important how the convicts themselves feel about it.

And so I chose to tell the story as the biography of an unknown convict whom I have called Michel.

The character of Michel is thus based upon a real person; altered in the story only sufficiently to conceal his identity.

The created characters of the book are similarly founded upon existing types and in many cases actual prisoners have been brought into the narrative. Life aboard the convict ship and the breathless dangers of convict escapes, I have related as they were told me by the men who took part in them. The prisons and the prison life have been described from my own observation. I was present at the arrival of the convict ship which brought 687 new victims to Guiana. And, in order to complete the cycle of convict life, I journeyed through the interior, following the jungle streams and trails used by escaping convicts.

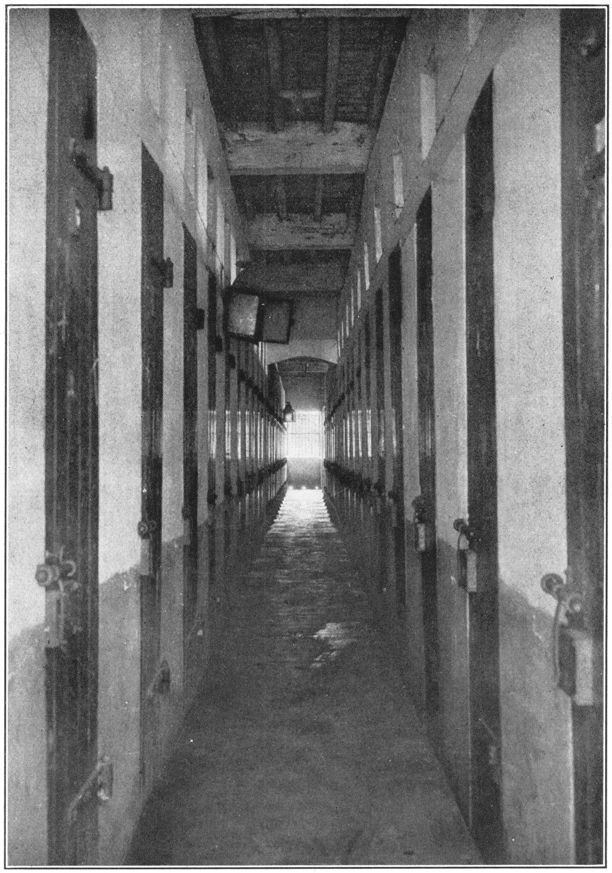

The material for my story has thus been obtained at first hand. No other foreigner has ever had such opportunity to study these famous prisons. I was permitted, not only to visit Devil’s Island itself, but to penetrate to the solitary cells of the Ile St. Joseph. And we kept house in the heart of the Penitentiary Concession, with, as servant, an old convict who had been thirty-nine years in the Guiana prisons.

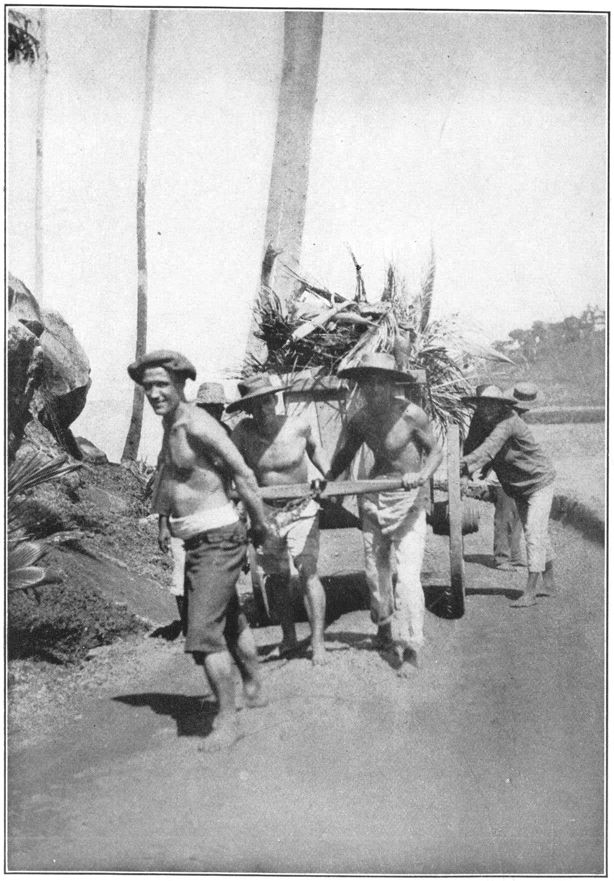

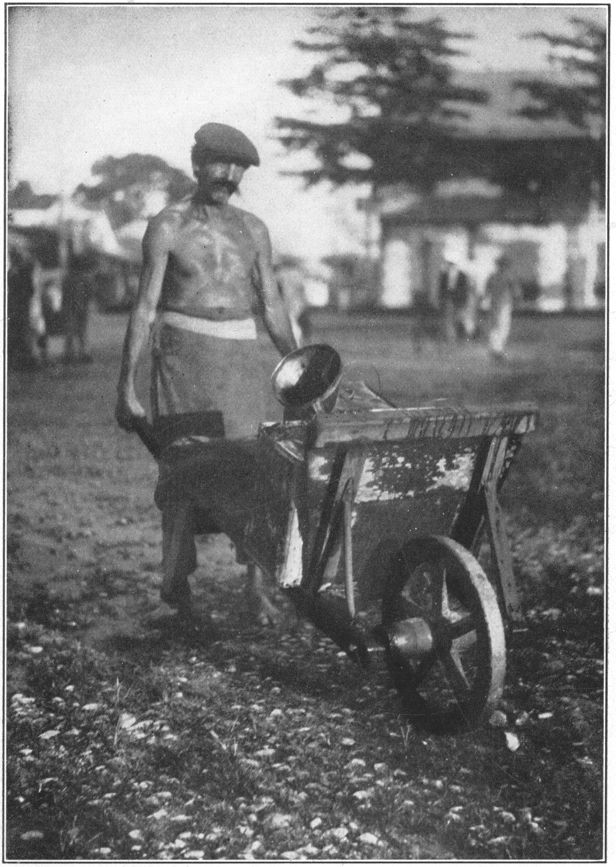

My husband, Robert Niles, Jr., secured more than four hundred unique photographs which include a prisoner in solitary confinement; pictures taken on Devil’s Island which are the first ever brought to this country and photographs of the convict burial at sea, which we were allowed to attend. In such a burial the dead man is, as the convicts express it, “given to the sharks.”

The drawings by Beth Krebs Morris owe their authenticity of detail to my husband’s camera record of our expedition. The photographic illustrations appear here and on the jacket of the book, with his permission, and are copyrighted by him.

Two points I should like to make clear to the reader are:

First, that Devil’s Island is devoted entirely to political prisoners. The thousands of convicts convicted of general crimes—murder, burglary, forgery, counterfeit money-making, etc., etc.—are imprisoned either on the mainland or on the Islands of Royale and Joseph. But I have used the term “Devil’s Island” to stand for the whole French Guiana Penal Colony, the famous Dreyfus case having established it in the public mind.

Second, that in writing the book I had no idea of muckraking. I realized that in many of our own prisons, conditions are shocking. The recent outbreaks prove that to be true.

I selected the notorious Devil’s Island Penal Colony as the place where I would make my investigation, because there the drama of the criminal is staged against a background of tropical jungle, where descendants of escaped negro slaves live the jungle life of Africa; dancing the African dances and worshiping the African gods. While, locked behind the bars of prison, are criminals sent from highly civilized France. The Devil’s Island Colony thus offers a startling contrast between the primitive and the civilized.

And since the French possess to an extraordinary degree the gift of self-expression, it is my hope that through the French mind, we may come to understand better the condemned of all other nationalities.

And now, through Michel, the young professional burglar whom I first saw standing ragged and barefoot, his toes curling over my doorsill, you may look into the strange, tragic prisons of the Devil’s Island Colony.

Blair Niles.

New York City, September 10th, 1929.

“Prison has its atmosphere, its spirit, its body. . . . And none can sound the profound misery of the convict.”

From an unpublished poem, “L’Enfer,” by Roussenq, the “Incorrigible.” Written in a solitary confinement cell on Ile Joseph of the Devil’s Island Penal Colony in French Guiana.

The day had come at last!

In the great square courtyard seven hundred men waited in column of fours. Each in heavy gray woolen trousers, a heavy gray wool blouse, a black skull cap, and clumsy black wooden-soled shoes; while lying at the feet of each was the canvas sack into which he had stuffed his belongings. All were thus ready for the voyage.

“I am afraid!” Félix whispered to Michel, who stood beside him in one of the units of four. “I am afraid—”

And the thought back of the words drove the blood from his chubby peasant cheeks. With that look on his face, only the dimples remained of the warm youngness which he had brought to the cold moldy walls of the prison. Not that St. Martin lacked youth. Michel, for example, was only twenty, with a slender, boyish body and big, innocent, clear brown eyes, guarded by long, dark lashes. But Michel fancied himself wise in the strange philosophy of that stealthy prowling world which had drawn him into itself; whereas Félix was but a bewildered child, whispering, “I am afraid!”

“Careful, kid,” Michel warned, for just in front of them old Pierre had turned at the almost imperceptible vibration of the terrified whisper. And of the many things that Félix feared, Michel knew that he feared most of all—Pierre.

Pierre’s hairy tattooed body was horrible to the smooth young boy. The muscles beneath skin weathered by years of African sun seemed to Félix to writhe like serpents making ready to spring. He found Pierre’s very age a thing of disgust.

Michel had, out of his sorry wisdom, cautioned against accepting part of Pierre’s food ration. But to Félix acceptance was easier than refusal, and daily he had expected commutation of his sentence. His mother, he explained, would certainly do something. Because of his youth she would convince them that he ought not to be deported to serve a term of hard labor. Why didn’t Michel’s mother do the same? But Michel protested that he never had one. “If your mother had run off to Moscow with an army officer when you were three months old, and if you’d never heard from her, would you say you’d had a mother?”

Well, wasn’t there some one else?

No, his father had given him to his grandparents to bring up. He’d hardly ever seen his father, who was the captain of a freighter and away for months at a time. The grandparents kept a boîte de nuit in Montmartre. The women who frequented it were delighted with the child, always small for his age, who regarded them with so candid an admiration. “When we are no longer beautiful to Michel,” they said, “then we shall know that the game is up.”

They looked into the mirror of his eyes, and, when what they saw there made them happy, they tossed him francs so lavishly that he early formed the habit of spending.

First he discovered that money bought sweetmeats, then that it bought amusement—merry-go-rounds and ingenious toys; later that it purchased fuel for the flame of self-respect, that it brought a boy homage, the obsequiousness of tradespeople and waiters; finally it was the price of strange new thrills which people called love.

Then the grandparents had died. The money which his father sent for schooling had some time ago ceased to come. From his mother there had never been a word since the day when she’d left his father with the three-months-old baby on his hands. Michel had been all sorts of things since then; assistant to a jockey—he liked that and would have been a jockey himself if the war hadn’t come along and made a soldier of him instead. Oh, the war! He didn’t like to think about the war. Fortunately, he’d not had to go through all the ghastly four years of it, being too young to have been involved at the beginning.

When it was over he’d gone into what was an entirely new life for him; he’d secured a position as valet de chambre in a princely establishment. That experience convinced him that luxury was for him the essential ingredient of life. It was almost by chance that he’d hit upon a way of securing it which put the champagne of adventure into the pursuit. Then he found that he loved his new profession quite as much as he did the life which it made possible.

And so Félix must see that there was no one to be interested in urging commutation of Michel’s sentence. For all he knew, his father might even be dead. And as for the women—well, they weren’t the sort who could afford to open negotiations with law courts.

And he looked so extraordinarily innocent, so pathetically young, while he outlined to Félix the events of his twenty years, that only his presence in the prison of St. Martin de Ré gave the color of reality to his story.

But in all their conversations it was Michel who urged recognition of their plight.

They were to sail on a convict ship. They had been sentenced to servitude in the Devil’s Island Penal Colony in Guiana. They must concentrate upon how best to adjust themselves to that situation and how eventually to get the best of it.

Félix would never look at it squarely. He would say that it didn’t matter what he did, because always in the end he was going to be saved. So every day he had shared Pierre’s food. It was the way of least resistance. After working-hours keepers marched him off to one dormitory, Pierre to another. And he was convinced that before it was too late, his commutation would arrive. So the months slid by.

Then information had drifted through the prison that at the end of March or early in April the convict ship was again to sail. And now two men in uniform were walking up and down the lines, counting to make sure that the numbers tallied with the roll-call. Yes, the numbers checked up. A receipt was made out and signed. And the seven hundred passed from the custody of the prison warden into that of the Commandant of the convict ship.

Discipline suddenly relaxed. The silence of months was broken; not furtively, but openly. Men began to talk among themselves. The fours split up into groups. A few brought out cigarettes, and actually there was smoking in the prison yard of St. Martin de Ré.

“God,” some were saying, “it will be good to get out of this place!”

And their voices, so long suppressed, sounded to them as unfamiliar as when one hears one’s self shout into the trumpet of the deaf.

“God, but it will be good. . . .”

“Yes, but don’t forget we go to Guiana. And they say that’s death.”

The older men spoke out of the memory of all they’d heard of Dreyfus and of Devil’s Island.

Their words made the others remember how, when sentence had been passed, doom had seemed to echo in the very word.

Why, Guiana was the “dry guillotine”! Everybody knew that.

Seven hundred men in the courtyard. Didn’t even the official figures admit that at least half of them would die in the first year of prison in the Guiana climate? Half? Three-quarters, they’d heard, would be nearer the truth!

Which of the seven hundred would it be? But with the tenacity of the will to live each thought it would be his neighbor. And in the months at St. Martin, Guiana had little by little lost its terror for them. It had gradually become part of an accepted destiny to which the mind had at first slowly adjusted itself, until at length, in the horror of St. Martin, Guiana had come even to be desired.

“But,” a frail old voice realized, “it’s leaving France forever.”

“Forever?” Pierre jeered. “Wait and see if it’s forever.”

“Well,” Michel spoke with the fatalistic courage which sat so oddly on his thin colorless face; too young to know so much, too delicate for its brave acceptance of stern realities. “Well, at least Guiana’s not St. Martin de Ré.”

The grim massive walls gave back the pale echo of a stifled cheer. Men instinctively stretched the limbs in the baggy gray garments, as though stone and mortar and iron bars had pressed against flesh and bone.

The boy was right. Guiana would at least not be St. Martin de Ré. Their speech there in the courtyard, the smoke drifting in transparent wisps from their cigarettes, would, the day before, have meant punishment cells and blows. Guiana might not be so bad after all. And in any case all would, of course, soon escape. Upon that they were determined.

“But what shall I do?” Félix was whispering again.

“Don’t give in. Then after a while he won’t plague you any more.”

The boy caught a little of Michel’s surprising hardness, and for a moment reflected it, like an image in a cloudy mirror.

“Oh, I shall resist with all my force, Michel. You may be sure.”

Then came the sudden order to reassemble. The fours formed. Men raised their sacks from the floor to their backs. At last the hour so long awaited . . . so greatly dreaded . . . and finally, after all, so desired . . . the hour had come!

The monstrous iron doors moved. Opened. Laboriously, ponderously, as if reluctant to let go their guarded prey. But they opened, for they, too, had to obey the Law’s decrees. They opened. And the fresh, moist April air rushed in, to be in its turn imprisoned by inflexible walls.

Slowly the column of fours passed out. You would have said they went to their death, so slowly did they move forward. Yet few went sorrowfully.

They passed out, their wooden soles clumping heavily on the courtyard floor. They advanced between a double line of fixed bayonets. Michel’s square little chin went up. “Ah,” he said, “see the precautions they have taken for us! Are we then so terrible?”

Outside in the mist of a light fog they saw that a crowd had gathered. “Are we then so beautiful,” Pierre grumbled, “that people come to see us off?”

In the waiting group there was a cry, a commotion. A mother, recognizing her son, was fainting. Félix’s mother, perhaps. A wife with a white face was holding up a baby in her arms. Accomplices in crime were there, too, scanning the advancing column to isolate the familiar features of some luckless partner. Two or three photographers ground the cranks of their cameras. Some one put up an umbrella. The salt mist was turning to fine gray drizzle.

But the moving column looked straight ahead. For there was the sea! And there like a vague ghost the solitary ship rode at anchor.

No need to hurry. No danger that she would leave one of them behind. Barges, rising and falling with the movement of the water, rubbed their wet sides against the slimy pier. All in good time they would convey seven hundred men across the drab stretch of water to the ship, whose only passengers were to be convicts.

The moment had at last come!

In the barges the men were crowded standing. Even in the rain, how wide the horizon seemed after months of prison! The focus of eyes lengthened. The air seemed to possess a quality extracted from it when filtered through iron bars. The lungs expanded, and hearts unreasonably lightened.

Then some one, catching sight of the brawny convict whose task at St. Martin had been to strike the punishment blows, shouted, “Death to him!”

“Death!”

The cry went from barge to barge and from barge to dock. The man should pay for their miseries. They would wait their opportunity, but he should pay.

“Death to him!”

But Michel shouted, “Death to Society!” It was Society which he vowed was to pay for the bitter moments of his life. He would not soil his hands with blood. That revolted him. It was, besides, a stupidity. And in all he did, Michel had the instinct of the artist; in his vengeance as well as in his calling.

“Society!” The men on the barge laughed. They were more concrete than that.

But, though they often scoffed at him, Michel, for all his youth, had their respect. They liked the absurd lack of fear which he, so small a creature, showed in the presence of burly, hardened men from the battalions of Africa. They admired, and sometimes secretly envied, the decision of his personality. He knew so well what he wanted, and could never be made to follow any path but his own. He was so fearless that they believed him to be fundamentally honest. In spite of his boy’s body they felt him to be a man, with all a man’s aloofness and inviolability of ego. So Michel said what he liked and went unmolested.

The barges put off and the Ile de Ré retreated. It became not a dock to which lighters had been moored, but an island—long and narrow, turning a rocky and forbidding face to the sea. There was the lighthouse on the northwest point. And there were Vauban’s old fortifications guarding the harbor of St. Martin. Back of that the land was flat, and but for its orchards of pears and figs, it was treeless; lying like a raft of floating salt-marshes which had drifted a little way off the mainland shore.

So it appeared to the moving barges, from which it was possible to look beyond the great grim silent prison which is the depot of the transportation of convicts to Guiana; to look beyond that to the cottages of peasants who live upon the oyster and salt industries and upon the fruit of trees which would now soon be blossoming. And then, beyond the island, there came into view the profile of France.

But they might not look longer, for already the lighters were bumping against the ship. Single file they must climb the gangway, and, under the eyes of armed keepers, march up, and then down; down two steep iron ladders to barred cages in the hold.

From the low black ceiling of the cages hammocks hung side by side and end to end, without an unnecessary inch between; for in each cage more than a hundred men were to be crowded.

Michel chose a hammock near a port-hole. There would be need of what air you could get, when they were all packed in there like herrings.

Putting himself and his sack into the hammock he proceeded to look about. Only six port-holes—small ones. He had been wise to take up a claim near one of them. No furnishings but the hammocks. A worn cement floor; at one end of the cage a toilet, up a couple of steps. Another cage opposite—a duplicate of that in which he found himself. A little passageway between, where stood two water-barrels. You helped yourself through the bars, using a tin cup chained to one of them. Coils of rubber hose out in the passageway, by which the cages were flooded and cleansed; or, Michel had been told, the hose might be turned on the men in case of disorder. Also outside were several large electric bulbs enclosed in protective wire frames, and a couple of candle lanterns for emergency use. Nothing but the hammocks inside.

Bringing his eyes back to his immediate surroundings, Michel saw that Pierre was arranging Félix’s sack in a hammock near his own. It was an end which Michel had seen from the beginning. He shrugged and lit a cigarette. It would be an hour at least, he thought, before the embarkation could be finished. He was tired after the excitement of the morning. That’s what the monotony of prison did for you; excitement tired you. How many months had he been at St. Martin? . . . Four. . . . Four months, and now that at last something had happened, he was tired. They’d stood so long in the courtyard and in the barges. He smoked slowly to make his one cigarette last. Yes, he was really worn out. He blew the smoke into rings and watched them with a quaint, elfish smile. He was thinking of that double line of soldiers, bristling with bayonets. “They did us that much honor,” he thought.

And then the siren cut short his casual scraps of memory. The siren whistled. Engines pulsed. They were off. The impossible and the inevitable had happened. The judge had said, “Seven years’ penal servitude in Guiana.” But until the siren blew, that had never seemed real.

The ship was moving. They had, then, actually sailed. And unseen by them, Michel knew that slowly France grew dim and finally disappeared. The lighthouse would be the last thing you could see.

“May I tell you about it again?” Félix asked.

“Oh, I don’t mind.”

The two boys sat in niches formed by frames which divided the ship’s side into eighteen-inch segments. A narrow ledge connecting the frames furnished seats for a fraction of each cage’s quota. A similar ledge ran along the barred side, but the niches were the coveted places, and many convict shipments had left on the paint the dark smudge of heads and shoulders.

In their stiff regularity these niches seemed to Paul Arthur a travesty of the choir of some medieval monastery. They faced the tragedy of bars, as such a monks’ choir often faced a sculptured cross; or looked, perhaps, upon some soft old picture, whose mellow creams and blues, crimsons, and rich dark browns like oiled shadows, portrayed a life-sized Christ hung between two thieves, whom He planned that day to meet in Paradise.

From the opposite ledge under the bars near the water-barrel, this ironic symbolism crossed Paul’s mind, as he sat, a silent prisoner, moving in that strange company as though he were merely an on-looking spirit; as though he were a philosopher who but temporarily occupied the suffering physical body of a convict bound for Guiana.

But Michel, unconcerned with symbolism, stared absently straight ahead, through the bars of their cage, across the narrow passage and through the bars of the next cage, whose occupants he saw as though longitudinally divided by the repetition of vertical bars. He thought how odd it looked to see half a face, half a body, then the inch of bar, followed by the continuation of face and body, then by another bar, with possibly nothing left over, or only just a narrow slice of a man.

Yesterday the sea had been rough, and Félix a limp yellow thing, too sick for speech.

For twenty-four hours the ship had heaved and tossed, her frames groaning under the strain. Ports had been closed and hatches shut down. Waves had hurled themselves against the six circles of glass. Many were seasick, and with each hour the close air had become more and more foul. When the sick opened their eyes they saw that through the bars men traded clothing for the packets of tobacco which the sailors offered in exchange. They saw, but were indifferent as to whether or not the bartered garments belonged to them.

Closing their eyes, they listened to the rhythmic groan of the ship and waited for the waves which broke in measured beat. And always memories like colossal shadows moved through their brains, only to reappear, to pass out, and to return in dizzy procession.

To the seasick there is no future. There is only a ghastly present and an immediate past; a monstrously distorted past, wherein every emotion, every experience, is magnified and multiplied, to recur again and again with the repetition of the complaining frames and of the slapping spray.

On such a ship, a remembered corpse would take on gigantic proportions, a judge would appear of heroic size, a prostitute move with an allure greater than any reality, and lost moments of joy or pain would vibrate with an intensity they never actually possessed, while with closed eyes men waited for the deathly sinking and the wrench of the recovery as the creaking ship rolled and tossed with the measure of the sea.

And in the hold of a convict ship seasickness is stripped of all alleviations. No bells to summon attentive stewards murmuring, “Very good, sir. Coming directly.” No “Get out into the air, sir; it’ll do you good.” No lounging in deck-chairs, before which officers pause to predict better weather. No friends or relatives to suggest that you try this or that. No one who cares a damn whether you live or die. Perhaps no one ever again who cares.

In those black hours all of Michel’s past had seemed to him wiped out, except the sound of the prévôt whipping prisoners in the disciplinary cells of St. Martin. It was that sound which had beat upon his brain, assuming the rhythm of the angry sea. At the lowest depths of his misery he had heard some one exclaim:

“What do we expect? Aren’t we traveling free?” And those who were not ill had laughed loudly.

But today was calm. Under charge of the armed guard they’d been taken in squads for a fifteen-minute walk on deck, while the sailors hosed out the cages. The air and the calm had brought back speech to Félix.

“May I tell you again, Michel, how it all happened?”

Félix had been to a fête in a near-by village. He had more to drink than he was used to. So had the two friends with whom he’d gone. That was how, on the way home, they’d come to think of going to a cabaret for just a little more. And Félix paused to wonder why it is that when you have had too much is always the time when you want one more. The cabaret, he went on, had been closed for the night, but the door had been easy to force. Yes, Michel remembered that he had already told him how all would have gone no further than that, if only the patron had not got out of bed and accused them of coming to steal. So they had fallen upon him and given him a beating, a thing which, of course, they wouldn’t have done but for having had more than enough to drink. After that they had made themselves free of the bar and had robbed the box of four hundred francs.

But it had been their first offense, and the patron had had only five days in the hospital. What did Michel think about it? How did he think young fellows, who had never before broken in to steal, had come to do such a thing? And the sentence . . . five years’ hard labor and deportation. Was it not excessive? And why hadn’t his mother been able to get him commutation? Perhaps she hadn’t done all she could. If she could know what prison is . . . but who ever understands who has not heard the key turn in the lock? The horror of St. Martin, and now this ship . . . and the terror of what was to come!

Félix grew tearful with pity for himself.

“But you don’t mind, Michel. Not as I do. Sometimes I think you are almost happy!”

It was the first time that Félix had seemed aware of any state of mind but his own. And Michel, his reserve relaxed with the lowered resistance of the past twenty-four hours, began to explain:

“You see,” he said, “I have my profession. You want your mother. You want to go on raising artichokes. You’re willing to grow old raising artichokes. But I . . . I want to stand at the top. I want to do the things that take skill and daring!”

Michel spoke rapidly. He had the Latin gift of expression, and he had so often analyzed for himself the end he sought, that he did not need to grope for clarification of word or thought.

“For the big jobs,” he continued, “you have to foresee everything. Your eyes must be quick—and your hands—so that you never make a useless movement, or an unnecessary sound. Never make a mistake. At the crisis you must be as cool as ice.

“Then it’s just as though you weren’t inside yourself at all . . . but somewhere out in the audience looking on and thinking how wonderfully the fellow is doing it.

“And the greater the danger, Félix, the greater your joy. You’re playing with your life and you’re playing in the dark. Any minute—even if you haven’t made one blunder—any minute it may be all up with you. You can never be certain how the cards are going to fall.”

“But, Michel, how can you like it? They’ve caught you and you’re on your way to seven years’ hard labor—and seven years’ exile after that. You’re even worse off than I am. I’ve got only five. So how can you be so cheerful? What’s the use of a profession if it ends you in prison the same as me?”

“Yes, prison is terrible.” Michel conceded it. “But I’m what you call cheerful because I’m not going to waste my time while I’m there. I’m going to learn. Why, some of the greatest of us are in Guiana. I’ll learn all they can teach—and then, of course, I’ll escape.”

In the afternoon, stripped to the waist, two men fought in the cage . . . Pierre and David. Both men were elaborately tattooed in indigo against the yellow brown of bodies tanned in the service of the Public Works in Morocco.

Pierre was covered with a close pattern of the African fauna and flora—elephants and lions, baboons and strange birds with enormous beaks. At the base of his throat was etched a magnified human eye. Pierre called it the “eye of the police.” Just below the eye and on each shoulder was a pansy, which in the symbolism of tattoo signifies “thoughts of mother.” All was drawn with Egyptian feeling—straight lines and elimination of detail.

David was done in flourishes and curves. His taste had run to the heads of ladies of the era of Pompadour and picture hats; to an angel with a trumpet; to a ship, which typified escape; while across his chest ran the motto whose translation reads, “My food is tobacco,” followed by the Arabic word “Barkat,” meaning, “That is all.” As the finishing touch a blue band of tattoo circled his neck, with instructions to “cut on the dotted line.”

Men were betting their clothes on the outcome of the combat; even odds at first, for Pierre and David were well matched, hardened by the same rough life.

Scared and pale, Félix looked on. He knew that they fought for the possession of his body, and tensely he watched the victory pass from Pierre to David and back to Pierre. He saw blood, a thing which had never happened among his mother’s artichokes. He didn’t know that the fight would not be to the death, nor that each had decided that if vanquished a certain girl-faced boy named Louis was to console him for the loss of Félix.

So with numb horror Félix watched the figures thrust and parry, while the ring of on-lookers sang, that the keepers above decks might hear nothing of the battle. It began to matter to him that Pierre should win. After all, he had eaten Pierre’s food. He would be, perhaps, a little less afraid of Pierre than of David. With David he could never forget that gruesome “Cut on the dotted line.”

Thus with a sense of relief he saw David go down, and heard the shout, “He’s yours, Pierre!” But Pierre, wiping a little streaming trickle of blood from the pansy at his throat, paid no immediate attention to his prize.

“Bah, what a place!” And Michel turned to the port for air.

That night from the opposite cage a shriek woke all the hammocks. It started high and shrill, and slowly diminished in power until it died away in a low, terrible gurgle.

In the morning it was found that a man had been assassinated, and sailors brought the report of two mortal combats in the aft cages. The bodies of the dead, they said, would be thrown into the sea.

That was the day when at the early promenade Gibraltar had been sighted. Within twenty-four hours the ship would touch at Algiers to take on Arab convicts. There was talk of attempting escape at Algiers. One of the prisoners had succeeded in unscrewing a port-hole. And Félix, who had sat all day speechless, weeping in his niche, raised his head to listen. Men were saying that while officers and keepers were busy with the embarkation, the port would be removed, and one by one all who could squeeze through might escape. But at five o’clock a sailor coming in to make fast the ports had discovered the loosened screws. Never mind, escape was merely postponed until they reached Guiana.

And Félix went back to his quiet weeping.

“He’s not a bad man,” Michel comforted. “He will, I think, be good to you. He’s only following the custom, you know.”

Still Félix wept. What consolation was it to him to know that Pierre simply carried on the custom of the battalions of Africa? All his hopes, all his futile little plans, were finished. Without will-power, he had trusted to the successful intervention of his mother—and failing that, he had relied on chance, on being perhaps assigned to a different cage on the ship, and at the end of the voyage being sent to a different prison.

“But if it hadn’t been Pierre, it would have been some one else,” Michel reminded. “There’s no way out of this sort of thing unless you stand against it yourself.”

And Michel realized that the quality of strength was not in Félix.

After Algiers there would be, in fourteen days, Guiana. Life settled down to the routine of the voyage: coffee and biscuits at six; six-thirty, fold up the hammocks; at seven, walk on deck; at ten, soup and meat or soup and fish; four o’clock, soup and beans; six o’clock, hang the hammocks.

And all the hours between to kill; herded in iron-barred cages in the hold of a ship.

Little groups were formed, made up of men who had met in other prisons, or whose specialty happened to be the same, or who chanced to come from the same city or village. More of the strange prison “marriages” were arranged; some amicably and some settled by force.

Félix had become calm and strangely listless. But at least he no longer sat silently weeping. Michel thought he had adjusted himself to what he’d not had the moral fiber to avoid. And Michel’s brain was in the grip of his own thoughts. He was resolving to control his destiny. But how? And he fluctuated between detailed schemes and a certain superstitious confidence in a predetermined fate. He remembered the prophecy of an uncle;—made long ago when he was still a child. The uncle had predicted that he would grow up to become one of the greatest of rascals. A chief of police had later corroborated it: “Oh, I’ll see you again,” he’d said. “This is only the beginning for you.” Michel had thought often of their prophecy.

If they were right, then his career was not to be snuffed out in any foul prison of the Devil’s Island Colony. His uncle, now dead, he recalled as a very intelligent man. As for the chief of police . . . Yes, surely he was to escape from Guiana.

So he sat apart with his thought, identifying himself with none of the groups. Listening sometimes when they bragged of their deeds. This one had robbed a jeweler to the value of many thousand francs. That one had made a fortune in the manufacture of counterfeit money.

Paul Arthur also listened. “It is significant,” he thought, “that no one boasts of murder. If life has been taken, it has somehow to be justified.” And of course a woman was the most romantic way of justification, self-defense the most convincing.

“This is all very well,” Michel said to Félix, “but none of the real Aces are on board. Those I hope to meet in Guiana.”

With the passing days all thoughts turned more and more to Guiana—from the past to the future. Like the Ile de Ré and the coast of France, the past seemed to recede. The ship sailed into a space where life hovered between what had gone before and what was to come. In that no-man’s space it was enough to be free from the cruelty of St. Martin. It was enough to be able to smoke, to gamble, and to sing in the hold of a convict ship.

Then on the sixteenth day out from St. Martin, tropical heat, like some exotic bird blown out to sea, boarded the ship. On the morning promenade flying-fish were seen, darting in and out of an oiled sea, where only the light spray of their movement disturbed the viscid calm. The cages had become suddenly unbearably hot. Several men had died in the infirmary. The news trickled from prisoner to prisoner until all knew that the decimation of the seven hundred had already begun.

On the seventeenth day the sailors promised, “In three more days you’ll see Guiana!” The period of suspension between past and future was over. Men now spoke only of Guiana. Three days. How the time dragged. They were eager to reach the prisons of Guiana in order to escape from them. All the talk was of escape. Guiana was seen in rose. They had forgotten completely that it was known as the “dry guillotine.” No one believed any longer in the ominous mortality figures. Dreyfus and Devil’s Island were no more mentioned. They were nervously impatient to arrive—that much sooner to escape to liberty.

Meanwhile the heat increased. Michel could never decide whether the minutes on deck were a relief or not, for upon return to the cage the stifling air seemed more unendurable than when they left it to go on deck. When the sailors turned the hose into the cages, the men undressed and stood in the salt spray. Sleep was impossible. From Michel’s hammock he could see Pierre’s naked chest with the light from the bulb outside streaming over it, as though by intention the spotlight had been thrown upon the “eye of the police” and the pansy which meant “thoughts of mother.”

On the eighteenth day the sailors said that tomorrow they would land in Guiana. But not until six o’clock on the afternoon of the nineteenth was land seen. Land! The news came from a convict at a port-hole, and at once there was a rush to see.

What?

Only twelve had places. They relayed their observations to the less fortunate.

Nothing but trees. The jungle, of course.

The ship seemed to be at the entrance of a river. That would be the Maroni.

The anchor rattled down.

So they would not get up to St. Laurent until the morning. The sailors had predicted this.

A canoe passed close to the ship.

There were two . . . no, three . . . black men in the canoe. They were practically naked.

And in the bottom of their boat was a big bunch of yellow bananas.

The canoe paddled out of the line of vision. Light failed, and then all at once it was dark. And very quiet. The stillness of the engines was as startling as sudden noise; and from the shore no sound came to fill the void they left. But in the cages there was no silence. Throughout the sweltering night men talked. And all their talk was of Guiana and of how they would soon, of course, escape—even if they had to live naked in the forest, like the blacks who had passed in the canoe.

In the morning the port-holes were to the strong. If a man of frail force found a place, it was by grace of a powerful patron. For at the ports only two faces might be pressed against the dingy glass; thus only twelve men might look upon the land with which all were so vitally concerned. In the mind of French convicts Guiana has long stood next to the ultimate horror. And now through eight-inch port-holes it might at last actually be seen. . . .

“What is it like?”

“Tell us what it is like.”

Behind the faces flattened against glass, men crowded, questioning.

“What do you see?”

“Only trees. Nothing is different from what we saw last night.”

“Trees and more canoes full of black men.”

“Ma foi! How wide they open their mouths when they laugh!”

“Oh, là! là! but they have white teeth!”

“Now here comes a launch.”

“Frenchmen on board.”

“No, blacks in white men’s clothes.”

“The pilot, perhaps.”

The twos at the port-holes gave their places to other twos. They reported that men from the launch were climbing up the ship’s ladder; then, that the launch had gone away.

“Yes, it must have brought the pilot.”

Somehow the morning passed. Nothing more was to be seen from the ports. Even the canoes had disappeared. All now had a turn at the windows. But there was only the amber water which the Maroni pours into the sea, and a little distance off, a bank of motionless green forest. Jungle-stained water and an unbroken wall of vivid green.

“Why . . . it’s beautiful!” Michel murmured to himself. He hardly knew what he’d expected. Jungle would naturally be green. Yet it was so amazingly green!

Back in the cage was hot seething impatience.

“If that was the pilot, why, in God’s name, don’t we start?”

“And why of all days have they cut out our walk on deck this morning? What harm would it have done to let us out of this for a little air?”

“Yes, and why not give us a chance to see what sort of place they’re shipping us to?”

From an old man who had been a seaman came the conclusion that they must be waiting for the tide.

“Well, while they wait they might let us out of this hell . . . we’ve a right to fifteen minutes on deck.”

“Right?”

“Mon dieu! Who talks about rights? Convicts don’t have rights.”

Then there had come the grinding sound of pulling in the anchor.

The strong again possessed the ports. From the comments of the few who peered through the dirty circles of glass, those in the cage must construct the voyage up the Maroni.

But all were aware that engines had begun again to throb, and that the ship moved. They did not need the sight of the bank sliding by to tell them that they were off. And hearts contracted with sudden realization of the fact. In two hours, a passing sailor had said they would be at St. Laurent—at the distributing center of the great Devil’s Island penitentiary system which was to absorb them into itself. What would it be like? What did the comrades at the ports see?

Again only trees—miles of jungle—a twisting river—green deserted islands—trees.

Some one cried out, “Monkeys!”

“Monkeys? Where?”

“Like hell he saw monkeys!”

In the unbelievable heat of the cages, men dripping perspiration packed their canvas sacks and dressed themselves in the gray wool of the St. Martin prison. Some one had a mirror. It was passed around. “Coquetterie!” Michel laughed, combing his hair until it lay quite smooth, flat and damp, like yellow corn-silk, against his hot little head. He felt possessed by a bizarre, mocking gayety. His blood pulsed with the engines which drove them to the end of their long journey. It was enough to know that they were arriving, that they would soon be in Guiana, to which all were going with the fixed purpose of escaping from its prisons.

The boat gave two long melancholy whistles. The vibration died on the air. But there came no answering salute from the shore. A convict ship announces its arrival, but no siren condescends a response. In the cages this went unremarked, for some one was shouting that he could see the dock.

“And people—a lot of people. A few on the dock. Many on the river bank.” There were women in light dresses—bright colors under the trees.

The anchor went down, rattling over the ship’s side, until it came to rest in the thick deep mud of the river bottom.

“Now we’re coming up to the dock.”

“We’re alongside.”

“What are they waiting for? Why don’t they let us off?”

“They’re putting the gangway down.”

“Men—officers and keepers—are coming on board. They’re all in white—with helmets.”

Finally the doors of the cages opened. Keepers gave the order, and one by one the prisoners filed out, each bearing his sack upon his back.

They streamed up the two flights of iron ladders to the deck and then down the gangway to the wharf. And all, as they reached the deck, blinked in the strong white tropic light, and all, half blinded, stumbled down the gangway; hurrying as though propelled from the rear, shot, as it were, out of the bowels of the ship. Their progress seemed a flight from the sick crowding discomforts of the voyage, from the prisons of France, from trial and arrest. And yet on their faces was more than the bewilderment of sudden, blinding light; there was a groping curiosity on the threshold of their new life.

Keepers stationed at intervals barked commands:

“Not so fast.”

“Faster than that.”

On the deck Michel halted, as though there were no armed guard, as though he were merely a voyager before whom the spectacle of St. Laurent had suddenly unfolded.

Stems of cocoanut palms, graceful as the swaying bodies of nude dancers with green plumed headdresses trembling against a strangely exciting blue. Dark massed foliage of mango trees. Under the trees strong reds, pinks, blues, and greens of women’s dresses. Beyond were white houses set in green. And white foam-clouds drifting across the gorgeous blue.

No one had ever told him that Guiana was like this. He gave a little gasp. Whatever he was to feel here, he knew he was to live intensely.

A rough hand pushed him forward with a curse. He came quickly to himself. That was familiar. That was what a convict expected. The curse hurried him forward down the gangway. On the wide, sloping bottom step he slipped and fell.

Was it an evil omen, he wondered, as, flushed and confused, he scrambled to his feet?

No, he would not think of it. Besides, others were slipping and falling too. It was a bad step—unexpectedly sloping like that. Several men had gone flat. Why didn’t the keeper at the foot of the gangway warn them?

Now there came a fellow with a crutch; his leg had been amputated near the hip. Would he be able to make it?

The gangway rope was so low as to be useless. To steady themselves, the men put out one hand against the ship’s side; the other hand grasped the sack under which their back stooped.

There was a prisoner carrying a one-legged comrade on his back. On the dock he stood him up carefully, as though he’d been some great, mutilated toy which might be so balanced as to stand alone.

Thus, like gray gnomes hurrying from some dark dungeon, they poured from the ship to the wharf, where they were quickly formed in rows of four. There, keepers moved up and down the always lengthening line; counting, and comparing the numbers with the ship’s records.

In their rows of four the men stared silently. From the moment the doors of their cages had opened, dumbness had fallen upon them. There had been no sound but the heavy thumping of wooden-soled shoes, and the surly shouts of the keepers.

Now in the long, blinking line not a word was spoken. They stared in silence; their eyes gradually adjusted to the light opened wide as if in an effort to take in more than is possible to any normal range of vision.

They saw French women on the dock. They must be the wives of officials with special permissions, for obviously the crowd was kept to the river bank. Most of these women were fat, but one was pretty—in a thin yellow dress, and carrying a rose-flowered parasol. To men just driven out of the hold of a convict ship she had an unearthly cool daintiness.

The fours slowly moved forward as men were added to the rear line. Those in front saw that the women in gay colors on the bank were black, brown, yellow—negro, mulatto, Chinese. And Michel’s eyes traveled back to the fair girl under the blossoming parasol. Ah, St. Laurent might not be so bad!

He noticed perhaps a dozen men—barefoot, in soiled white trousers and blouses, across which were stamped numbers—long numbers, like 47,950, or 46,320. They had been making fast the ship’s ropes, and now they stood about, watching the drab stream. Michel concluded that these numbered men were convicts who had preceded him to Guiana, and he smiled tentatively. They returned a blank stare, and he quickly withdrew his greeting. Of course, he reasoned, they could not smile because of the guards who passed up and down the line. He extracted encouragement from the fact that one or two were smoking. It might not be so bad a life, and then in a few months he would have escaped. It did not occur to him to wonder why, if it were so simple, Number 47,950 or 46,320 had not done so.

He looked again for the woman under the bright parasol, but with a gesture of disgust she had moved away; out of range of the pungent odor of heavy flannel drenched with the perspiration of nearly seven hundred men, and away from the odor of nearly fourteen hundred leather shoes, also soaked with perspiration.

Michel returned to the contemplation of what might be seen of St. Laurent.

“Forward!” The word echoed along the silent staring line. Sacks were lifted. As he stooped to his, Michel sent a fleeting thought back to the ship. “You have brought me here, but a more beautiful ship than you shall soon carry me away.”

“En avant!”

The line advanced.

The hundreds of wooden soles clattered deafeningly over the plank flooring of the wharf. The rows were at first wavering, for men moved stiffly, uncertainly, after so many days of inaction. But gradually the column straightened to follow the stout khaki official who led the way.

They thus passed along the river-front. And always they were silent, always staring with eyes greedy to absorb St. Laurent before they should be marched through the prison gates for which they knew they must be headed.

Strange ugly black birds hopped awkwardly out of the way of their advance; flying up to perch on the roof-tops, where they sat in dumb rows of rusty black. There was a cart drawn by oxen with huge, flat, spreading horns, and bodies gray like elephants.

On the right was the river—the wide coppery river which separates French and Dutch Guiana. On its farther side they saw a little village, very white in the sun. The Dutch bank hung like a bright curtain-drop beyond the broad stream, which was in its turn the back-drop for a foreground where on piles of logs sat groups of men more haggard, more devastated, than any tramp ever seen in the Paris slums. They were white men, gaunt and ill, whose beards grew like weeds in an abandoned lot; rags of men, who sat staring at the marching column.

On the left, brick walls enclosed little gardens like green flowered aprons in front of small wooden houses. There were people on the steps and on the walls—many negro girls in dresses as brightly scarlet or purple as the hibiscus or the bougainvillea of the gardens. A negro woman threw kisses and cried, “Have courage, my boys!”

“Without doubt a prostitute,” they concluded.

At a small dock, opposite the white Dutch village across the river, the column turned left. Now they saw the great walls of the Penitentiary. They saw its iron gates over which stood the words, “Camp de la Transportation.” Of course they had expected it. For what else had the convict ship brought them so far? And yet . . . coming with that sudden turn upon high walls and an iron gate, and seeing the irrevocable words, the column unconsciously slowed down in rhythm with the momentary interruption of its heart-beats. And the wooden soles dragged under the arching roof of trees.

The great gates opened. They showed low buildings in a courtyard carpeted with long afternoon shadows—shadows of breadfruit trees. An old man fell fainting against the gate-posts. A turnkey helped him to rise. The column marched into the courtyard. Half a dozen of the sick and dying were borne in on stretchers. And the gates closed.

Prison possessed Michel. St. Martin had been but a clearing house, a place where one awaited transportation. But Guiana was permanent. Guiana was the land of the deported. And Michel was there to serve his seven-year prison sentence, to be followed by an equal term of exile. Of course it was far from his intention to submit to any such period of servitude. He constantly reminded himself of that. Yet he would do nothing prematurely. While he was learning all that prison had to teach he would be perfecting his plans.

On board ship, lying wakeful in his hammock, watching the great tattooed eye thrown into relief by the shaft of light which fell across Pierre’s chest, he had thought out what was to be his policy.

And now overwhelmingly the prison had possessed him. He was an explorer in that strange world whose avowed reason for existence was set down as “expiation of crime, regeneration of the guilty, and the protection of Society.” This world had its own code, its own customs, its distinctive slang, its abiding tragedy, its frail pleasures. And Michel’s curious, adventuring mind would investigate it all.

This attitude of inquiry carried him through the dreadful day when he had stood stripped in the office where authorities registered finger prints and made inventories of men’s bodies, recording every distinguishing mark, every wart or mole, every birth blotch and every tattooed design, making measurements, and adding these things to one’s name and age and birthplace, and to the individual crime histories and sentences sent over by the French courts—all indexed and cross-indexed to facilitate emergency reference.

In that office, Paul Arthur thought, part of a man seemed amputated and preserved in card catalogues; much as entomologists impale upon pins all that is mortal of once-living insects, classifying as hymenoptera, lepidoptera, and so on and so on, the brittle remains of creatures who had known life. With the same conscientious precision the prison files catalogued something which was vitally part of a man’s being. They robbed him of inviolability of personality, of privacy of body, privacy of possessions and of correspondence; collecting, as it were, his human rights.

And standing naked in the room, man after man looked on with a sense of horror while that which had been an integral part of his ego was inventoried; impaled for all time in the criminal archives of Guiana; impaled while it still lived. It was as though it struggled there on its merciless pin.

And man after man submitted, each in his own way. Michel burying his hot resentment under an inquisitive bravado, a questioning “What next?” Pierre with a strong hatred, Félix with mute terror, Paul Arthur with the detachment which was his refuge. He drove his spirit out of the unclothed body which officers of justice examined, itemized, and recorded. He forced it to occupy itself with impersonal reflections. As convicts seated in niches along the side of a barred cage had suggested to him monks gazing at some dim stained-glass-lit painting of a Christ hanging between thieves, so now Paul thought of entomologists scrupulously arranging their collection.

He saw himself as but one in the procession of men stripped to the “body, parts, and passions,” about which theologians once argued with futile violence. And he pictured the hundreds of such bodies, parts, and passions which are yearly cast into the prison vortex; to be starved for the protection of Society, for their own reformation, and for the expiation of deeds known as crimes.

Looking thus upon the physical man, he realized for the first time the marvel of creation there unveiled; man in his erect position above all four-footed things, a being of inalienable dignity even in his humiliation.

“A convict,” he thought, “but still a man. Remove their uniforms and revolvers, and are these officials more than that? Why are they then officials? While I . . . I am a convict? Why? What has happened to make that enormous difference in the fate of bodies cast in the same mold; with the same extraordinary motors propelling blood through the same intricate pipes and valves; with the same amazing factories converting vegetable, mineral, and animal substances into energy and tissue; with the same perfect mechanical appliances for self-expression; bodies each with directing brains, with telegraphic nervous systems, and with organs of miraculous creative powers?

“Evolved into the same image, why then are some of us convicts and others officials? What happened to bring that about?”

These were questions which Paul often put to himself, emphasizing the unbelievable word “convict.” Thus he fluctuated between devices for forgetting and attempts to accustom himself to the fact.

There were vacancies in one of the dormitories of seasoned convicts. Half a dozen of the new arrivals were to be transferred to fill the empty places, and among them were Michel and Paul. This would plunge them immediately into the reality of the Guiana prison, and Michel, with his resolve to learn as soon as possible all that there was to know, considered the change a great piece of luck.

They found their new quarters a boiling caldron. Outside, while the turnkey fumbled at the lock, they heard loud, excited voices. But the door opened upon a sudden silence in which words seemed congealed upon the lips of a group whose very gestures appeared solidified by the unexpected opening of the door. The prisoners had been as usual locked in for the noon hour, and the reappearance of the turnkey was startling.

What was up?

“Bah, just a lot of the new gang.”

The door was closed, locked, and the turnkey went away.

The six looked about. No one offered to show them a place. No one, in fact, took any sort of notice of them. The men went back to their interrupted discussion, but speaking now in lowered voices.

Along each side of the room, in groups of three, were ranged planks facing end on, out from the wall into the center of the room; each group roped to a supporting frame and separated from its neighbor by perhaps twelve inches. Between the two rows an aisle some six feet wide ran the length of the room.

Each convict was entitled to one of these groups of planks, to the segment of wall to which it was attached, and to a corresponding portion of a single wall-shelf. The planks formed his narrow bed. Upon the wall and the shelf he might keep his few possessions.

Michel and his companions established themselves in the scattered places which appeared to be unclaimed. Michel unrolled his blanket, put on the shelf the small canvas knapsack containing his extra blouse and cotton trousers, placed his wide-brimmed, flat-crowned straw hat on top of the knapsack, and on two unappropriated nails hung his tin cup and bowl.

These, with a pair of wooden sandals, he had received from the prison in exchange for all of which it had robbed him. Also, as the scientist’s beetle has its tag, so he had a number, stenciled large and black across his blouse and below the waist-line of his trousers.

Having disposed of his equipment, he lay down on his blanket to rest until the bell should order work squads to gather in the courtyard. He didn’t venture to join the men crowded at the far end of the room. But now that he was settled he would listen.

The door had opened again, this time to admit two men delayed at the sawmill which rented them from the penitentiary administration. They were now being let in on the discussion. It seemed that some one named Darnal had hanged himself that morning.

“Dead?”

“Certainly, dead. Isn’t that what happens to you when you hang yourself?”

“Well, I’m glad of it.”

“Much good it does us except to prove what everybody knows.”

“What of that? Who does it prove it to? They’ll just put another like him in his place.”

“Yes, and maybe the next bird won’t have the grace to swing himself.”

“If it could get back to France!”

“You know damn well it won’t do that!”

“There’s one thing that seldom leaves prison—the truth. It’s exiled—en perpétuité, like the rest of us.”

“We can prove that our bread is watered.”

“And that boxes of sardines and condensed milk disappear from the cargo.”

“And beans and rice and sugar out of our storehouses.”

“We know what sort of meat we get, while the difference in price goes into somebody’s pockets.”

“And we know the doctors haven’t proper medicines.”

“But what good does it do us to know all that?”

“Hasn’t the Director laughed at the idea that there’s such a thing as public opinion?”

“Much good it would do us if it did get back to France!”

“Much good anything does pariahs! And that’s what we are.”

A wasted little man, with singularly bright eyes which seemed to have burned two deep holes under his bristling iron-gray brows, jeered:

“Ho! You all forget that at least they teach us how to steal. We should be grateful!”[1]

Michel raised himself on one elbow. “Are you saying that the keepers steal from us?” he asked.

“Good God!” some one shouted. “Hear the infant! Hear him!”

“Steal from us?” The gray man turned the fiery embers of deep-sunk eyes upon the boy, who sat up now, waiting for the answer, with scarlet spots of excitement burning on his cheeks.

“Steal from us? How do you think they’re able to live in this God-damned, God-forsaken country? Do you suppose they’re drawing magnificent pay? Not a bit of it. They’re getting a good part of their living out of us—out of the food we’re entitled to, little enough as that is, heaven knows. Their houses . . . those are free, too. And we do their work. Cook for them. Grow their vegetables and raise their chickens. They pay us in some favor which costs them nothing. And when their time is up, they retire on a pension. Whatever they do here, they know we’re afraid to tell. We’re craven, and they know it. They’ve all got revolver courage, you understand.

“Now here’s the first time one of them has gone so far that the authorities had to jail him. Misappropriating some thousands of francs belonging to the Administration. That’s all. But could he face what we’ve marched to, revolvers at our backs? No, the cur couldn’t see a prison sentence through!

“Knew too much about prison, that was his trouble.”

The group dissolved; four to play belote, some to smoke, others to sleep on their planks until the two o’clock bell sounded. Only Eugène Bassières, still smoldering, remained talking in a high nervous voice.

“Do they steal? Yes, they steal and we steal. Pretty nearly every cursed one of us, from the top straight down to the bottom and back again, steals. But we—” his tone was dry with the dregs of his bitterness—“we steal because otherwise we’d die!

“Can a man live and work on a cup of black coffee at daybreak; at noon half a loaf of bread with only enough flour in it to make it stand up, a chunk of boiled meat—a hundred grams, to be exact—and at night a cup of rice or beans? Yes, and we get the water they’ve boiled the rice and the meat in. I mustn’t forget the water. They call that bouillon. Sounds well, doesn’t it? Bouillon! Sounds like a menu. Waiter, bring me bouillon!

“Can you live on this sort of fare, you think? Not for a week, with the strength of France still in your blood; but live on it for months and then years? With disease in you, too. Try fighting hookworm and dysentery and fever with our seven hundred and fifty grams of bread and our hundred grams of meat and our quarter of a liter of rice—always remembering the water they’ve been cooked in!”

“Listen to Eugène!” The man dealing three cards to each, twice around, held up the game. “Listen to Eugène! He’s found a new pair of ears.”

“Can you live on that?” Eugène shouted. “Try it and see. Ten centimes a day spending money. That’ll have to do you until you get promoted out of class three up to the first class, where, if you’re lucky, they may hire you out to a civilian and let you earn fifty francs a month. That’s the limit of your ambition, and you’ve got to have ‘good behavior’ to get it. Wait and see whether it’s easy to get ‘good behavior’ here. If you’re a tale-bearer, yes. If you’re a spineless jelly-fish, perhaps. Always remember to say nothing but ‘Oui, monsieur’ and ‘Non, monsieur.’ That’s their idea of a good convict.”

“Everybody passes. Deal again.”

“One, two, three; one, two, three; one, two, three; one, two, three.” The cards fell in little crimson heaps before each player.

“Not so much noise over there, Eugène.”

But Eugène went on as though he’d not heard:

“Now you see, don’t you, that if you’re honest you can’t do much more than keep yourself in tobacco? That’s why we steal. Because it’s the only way we can live. You’ll soon learn how . . . that is, if you don’t know already.

“You’ll steal wood if you work in the jungle. If they send you to the coffin factory you’ll steal enough timber to make paper-knives and boxes and what not in your spare time. Maybe you’ll be able to sell them, and maybe you won’t. If you’re a clerk you’ll steal paper and pencils. Or if you work in the kitchen or the store-house you’ll steal some of our food. You’ll have to. It is the mode of the prison. That is, unless you are willing to sell your body and be some man’s brat,[2] and then he’ll steal for you as well as for himself. Look around, and wherever you see a young convict who seems better fed and better dressed than the rest, put him down as somebody’s brat.

“You’re young yourself and not ill-looking. That may be your way.”

“Never that,” said Michel. “I’m clever enough to steal for myself.”

Eugène looked at him searchingly and then raised his voice to announce:

“Here’s a boy who isn’t going to be brat to any of you.”

“Who says so?” A derisive hoot from the belote game.

“I do. I know character when I see it. No use wasting your time. He’s not that sort.”

And from the corner where he turned the pages of a book, Paul said, “You’re right there. I crossed in the same cage with him. He’ll only go his own way—and it’s not that way.”

Michel wondered how he knew. On board ship he’d scarcely noticed the quiet man with the deep, level voice. Only his horn-rimmed spectacles had registered with Michel.

It had rained in the afternoon.

While they waited in the courtyard for the final roll-call before dormitories were locked for the night, the convict work squads shivered in clammy wet garments. So little stood between their bodies and the Guiana rain.

Looking across the yard, Michel had caught sight of Félix and left his place in the line to go over to speak to him.

“How do you get on?” he asked—anxiously, because the skin of Félix’s face seemed pale and drawn, taut like a drumhead. “How goes it with you?”

And out of dazed, blurred eyes Félix had recognized Michel.

“Oh, I’m in Pierre’s dormitory now. He bribed the turnkey to get me moved.”

There was no more, for, angrily waving his umbrella, the short-legged, long-waisted, rampant-mustachioed Corsican keeper ran up to curse Michel back to his place.

“If you weren’t a damned greenhorn you’d be reported for this,” he bellowed.

Michel stepped into line.

“These keepers are dogs,” he heard an Arab convict mutter.

And Michel, prison-broken to silence, mentally chalked the incident up in the long score which he kept against what he called Society.

The keeper moved away.

“Your friend over there looks good for the bamboos,” whispered Eugène Bassières, who stood next Michel in the waiting squad.

“What?”

“Your friend—the boy you went over to speak to—he looks, as we say, good for the bamboos.”

“What does that mean?”

“The bamboos? That’s the cemetery—at least the part of it where they throw us when we’re finished. No frills like funeral rites and tombstones, you understand. Why should a Guiana convict expect a blessing? Has he any money to pay for the rest of his soul? Nobody’s going to say a mass to get him out of purgatory. No, when you go to the bamboos you’re just dumped somewhere in a piece of ground set aside for the condemned. It’s the prison of the dead, and instead of a wall, it’s got bamboos growing around it. . . . That’s the end— Deceased; ‘D.C.D.’ in blue pencil on your registration card. And it’s all over with you. . . .”

So Félix was going to die. . . . Poor Félix wasn’t much more than a child. It couldn’t be possible that he would die.

“Yes,” Eugène continued, “prison has shocked your friend. I’ve seen a lot go off that way. . . . They go fast. No special disease. Just prison.”

“What’s your name?”

“Michel Arnaud.”

“Where from?”

“Paris.”

“What did you do?” The man on the plank bed to his left put the questions to Michel that night after they’d both stretched out to sleep. “I mean why are you here?”

“Because I wanted the things money buys,” was Michel’s prompt reply.

“Oh, I see. And you tried to get them?”

“Yes, in the only way I could. Once I lived in a prince’s house—a Russian prince. I suppose you don’t know what a prince’s house is like?”

Michel took in the big young figure which lay next him. A heavily built man, not more than twenty, with the slow, mild manner of the country-bred.

“A prince’s house? No, I couldn’t say what that was like. How did you happen to be there?”

“I was valet de chambre. I picked up the trade after the war. It’s easy enough, and any other sort of work was scarce. This prince had been living for years in France. That’s how the revolution didn’t hit him. He had everything—money and honor. And he never earned a sou of it himself.

“It seemed as if I was born for the luxurious life that man lived. I loved everything about it—the silver, the wine out of red and gold glasses, the smell of flowers in the rooms, the soft carpets, and at night candles everywhere—the way they are on the altars of a church. I liked the women, too. The scent they used and the way they kept their bodies like silk.

“The prince had all this, and I knew he’d never earned it. My way of getting a little of what he had was more honest than the way it had all come to him. What he had was the life’s blood of the poor.”

“Well, you’re here, and I suppose he’s still a prince?”

“Yes.” Then after a silence: “And now what’s your name?”

“Antoine Godefrey . . . Matricule 46,207.” He added the number as though it were an address.

“You’re from?”

“Avignon.”

“And you’re here for?”

“Murder.”

Then Antoine Godefrey turned his back and closed his eyes as though he slept. His left arm lay along the brown blanket and Michel saw that the forefinger was missing. He wondered how that had happened.

On the right Michel’s neighbor lay staring mutely at the ceiling. He’d not seemed to observe the presence of a newcomer on the planks next him. Looking straight ahead, with apparently unseeing eyes, he’d eaten his cup of rice, and then stretched out on his planks, lying on his back and staring up, as stiff as a corpse but for the rise and fall of his chest and an occasional twitching of the lines of agony drawn about his finely-modeled mouth. The grief on his upturned face seemed permanently carved, as unalterable as the expression of an effigy in marble; forever looking up with unchanging expression.

Outside, dull, steady rain fell. It had begun in the afternoon; at first a light, pearly drizzle, then, with a rush of wind through the palms of the Avenue des Cocotiers, it had come roaring like a waterfall. Wrapped in wings like shiny black waterproof coats, vultures had perched on the roofs, gargoyles of wretched resignation. The gutters of the village streets had run red like blood. And there’d been a faint, derisive whistle in the wind.

How cold and wet they’d all been, Michel remembered. Perhaps that was what had made Félix look, as Eugène had said, “good for the bamboos.” It must have been the rain, and not what Eugène had thought. Yet in the first year—he suddenly recalled that even the Administration figures admitted that of every shipment, at least half died in the first year. . . .

There was no break in the thud of rain on the roof. The man across the aisle snored faintly. What had he done? Michel wondered. For that matter, what had all the others in the room done? Ninety men stretched on planks, with twelve inches separating convict from convict. Eugène Bassières, for example, and Paul Arthur, the man with the low, even voice, who so seldom spoke, so that when he did, you listened. What had they done to be locked in behind bars while they slept?

The rain checked his flickering speculations. He wouldn’t have thought there was so much water in the sky. He’d heard some one say that this being the month of May, rain was to be expected every day. Something about the way it fell made him horribly nervous. He felt as though he could stand it if it would only let up just a minute. Then he could pull himself together, and it might go on again. This, he thought, is how you feel about the ocean when you’re seasick. And the thing that’s so awful to you is knowing you’re helpless, that nothing you or anybody can do will stop it.

Prison, he decided, is something like this; something you want to have stop for just a minute. But could anybody stop it? he wondered. Or would it be just as impossible as stopping rain or the sea? Now the rain sounded as though endless buckets of water were being dumped on the roof. And that would go on, no matter what anybody did. He could hear it sliding off the roof into the great puddles on the ground. And he couldn’t think why it made him so nervous.

Antoine Godefrey seemed to sleep. The rigid man who stared up at nothing breathed slowly, and the number stamped on his blouse rose and fell with the measure of his heart.

“Ah,” Michel thought, “I didn’t know there could be so sorrowful a place.”

|

An authority for instances of official graft in the Guiana prisons is George Le Fèvre, a French journalist who visited the penal colony under the aegis of Ex-Governor Chanel. He published the result of his observations in a book whose title is Bagnards et Chercheurs d’Or. |

|

In the womanless world of the Guiana prisons the men who satisfy Adam’s desire for Eve are called mômes. The English “brat” is of course necessarily an inadequate rendering of the local significance of môme. |

The turnkey handed Michel a bit of paper many times folded. Faintly penciled inside, Michel read:

“Félix died in the night. They will bury him this afternoon.”

It was signed “Pierre.”

Michel crumpled the paper into the pocket of his cotton trousers, joined his work squad, and was marched out through the gates under the words, “Camp de la Transportation.”

The village streets were deserted but for convict corvées filing out of the prison and branching off to the right and left to pass along streets named for Rousseau and Voltaire and Victor Hugo; to pass also the official building which flaunts the familiar “Liberté, Fraternité, Egalité”; and the blue and white Palace of Justice, where four times a year convicts are tried for the various crimes they commit as prisoners.

In this direction and that the squads proceeded to their assigned tasks; to workshops where they produce chairs and tables, wooden spoons and bowls; to shops where it is their duty to keep the supply of coffins equal to the demand; to sawmills and lumberyards, and to the river-front where they land the logs floated downstream on rafts.

Their exodus did not disturb the sleeping houses, quiet behind scraps of gardens and little walls with bricks arranged in geometric pattern like the colored designs on boxes of children’s building-blocks. The citizens of St. Laurent may sleep in the dawn, for the convict corvées are for the most part barefoot, walking humbly like Trappist monks—finding it less painful to accustom themselves to bare feet than to the irritation of the clumsy wooden sandals provided them.

So on silent feet they leave the prison. And on their lips there are few words, for one wakes tired after a night in a Guiana prison.

Michel’s squad moved straight along the Rue Maxime du Camp. It moved toward the rosy flush of sunrise. Yet the air was heavy with possible rain, for it was still the month of May, and the dry season not due until after the middle of June.

Passing St. Laurent’s solitary church, the men heard priests intoning early mass. In the branches of the mangos and the flamboyants, birds twittered, invisible among the leaves. Cocks crowed everywhere, and on the roofs vultures unfurled their wings, showing light buff bands across the black. In spread-eagle position they dried their rain-soaked plumage, occasionally giving a wing-flap to hurry the process, and then soaring off to circle hopefully above the village streets where soft-footed convicts wearily dragged themselves to work.

Behind each squad sauntered ruddy keepers, placidly smoking cigarettes. With big black umbrellas on their arms, sun-helmets on their heads, and heavy revolvers on their hips, they were ready for any emergency—rain, sun, or disobedience.

“What time do they bury the dead?” Michel asked, in a voice so low that he had twice to repeat the question before Eugène replied.

“In the afternoon—about five o’clock.”

The squad turned left to the river where a pair of oxen stood ready to drag the great chain by which a waiting locomotive would haul floating logs. It was a small locomotive, mutilated at Verdun, but since cobbled into sufficient repair for the job of pulling logs up the steep bank of the Maroni.

Standing in the water, Michel, armed with a heavy iron prong, helped steer the logs to the river’s edge. There, others attached the chain and gave the signal that set the engine in motion. Then slowly the logs mounted. The oxen returned the chain to the workers at the river’s brink; it was fastened to other logs, and the signal was again shouted to the locomotive. This process, many times repeated, made up the forced labor of a convict’s day.