* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Maple Leaf, Volume 1, No. 3, September 1852

Date of first publication: 1852

Author: Robert W. Lay (1814-1853) & Eleanor H. Lay (18??-1904)

Date first posted: Oct. 6, 2020

Date last updated: Oct. 6, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20201015

This eBook was produced by: Iona Vaughan, Susan Lucy, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Volume 1, No. 3.

September 1852

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR MRS. E. H. LAY BY J. C. BECKET, MONTREAL

| Kom Ombus | 65 |

| Ursuline Convent, Quebec—1641-1650 | 68 |

| The Island Home | 70 |

| The Beaver | 77 |

| Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or Life Among the Lowly | 78 |

| Sounds of Summer | 85 |

| The History of Canada | 86 |

| Things Useful and Agreeable | 90 |

| Precepts Inviting and Important | 92 |

| Editorial | 94 |

| Design for a Cottage | 96 |

he monuments of man’s astonishing

skill, preserved through ages, strike

the traveller with a solemn awe.

Ancient Egypt, with its pyramids,

and tombs, the grandeur of whose

dimensions, only equals the delicacy

and beauty of their finish, still presents

attractions to the lovers of antiquarian

research. In spite of every inconvenience arising

from the peculiarities in the customs of the people,

and the climate of that country, men of learning and

talent, are constantly employed in bringing its wonders

to light, exploring its ruins, and even penetrating far beyond

Egypt, into the heart of Africa. We have been

much delighted with the perusal of a work published by

Gould & Lincoln, of Boston, entitled, “A Pilgrimage

to Egypt with Illustrations,” by J. V. C. Smith,

Editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal,

from which we have taken the following extract:—

he monuments of man’s astonishing

skill, preserved through ages, strike

the traveller with a solemn awe.

Ancient Egypt, with its pyramids,

and tombs, the grandeur of whose

dimensions, only equals the delicacy

and beauty of their finish, still presents

attractions to the lovers of antiquarian

research. In spite of every inconvenience arising

from the peculiarities in the customs of the people,

and the climate of that country, men of learning and

talent, are constantly employed in bringing its wonders

to light, exploring its ruins, and even penetrating far beyond

Egypt, into the heart of Africa. We have been

much delighted with the perusal of a work published by

Gould & Lincoln, of Boston, entitled, “A Pilgrimage

to Egypt with Illustrations,” by J. V. C. Smith,

Editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal,

from which we have taken the following extract:—

“At four o’clock in the afternoon, we had drifted down to Kom Ombus, sixteen miles. Going on shore, we examined the gigantic columns, and parts of a great temple, dedicated to Ptolemy and Queen Cleopatra, his sister, &c.,—a ruin that bids defiance to all description. There is not a house, shanty, or even the habitation of a human being, to be seen, where was once a city; and this temple, which has withstood the assaults of ages, and of barbarous men and travellers, excites the liveliest sentiments of admiration. The attainments of the artisans and architects of the remote epoch when this magnificent structure stood in all its classical proportions and beauty,—the object of admiration for a series of ages,—were very extraordinary. This massive and very costly building—that must have required the constant and indefatigable labor of thousands of the first artists of the time, for forty or fifty years—contained two holies of holies. It was raised wholly at the expense of the infantry that was quartered, during its erection, at Ombus, which was one of the eminent military stations, and the centre of an extensive military district, during the joint reigns of the brother and sister. Under the ceiling of the magnificent portico of this imposing creation of men, some of the designs in coloring were never completed; but the outlines, in red chalk, are still fresh and distinct, as though but just made. I was so full of astonishment at the sight of these ancient ruins, that have outlived everything else, that it quite destroyed all the veneration that had previously been acquired for the antiquities of Rome. Pompeii and Herculaneum, with all their wonders and buried treasures, which I had wandered over with feverish eagerness, melted into utter insignificance in comparison with Kom Ombus.

We spent some time in reflection over two beautifully-sculptured stones, twenty feet long, eight in width, and nearly eight thick. How they had been transported from the quarry is a matter of speculation; for, even in our modern improvements in derricks, and boats for burden, it would be very difficult to handle these enormous blocks. But the next query was this: How were they raised up the steep bank of the river, and then elevated to their position in the structure? In regard to the great blocks of which the roof was composed, the same perplexity arises. Many of them would weigh—so thought all of us—from twenty to fifty tons, if not more. This is, indeed a marvellous story to relate.

The propylon, the imposing gateway,—lofty enough for the entrance of the gods,—is fast going into the river. The current has undermined the advance sub-structure, and some massive and unequalled specimens of ancient sculpture, and primitive outline drawing in colors, have already been swallowed up by the insatiable Nile. Thirty years will wholly obliterate the last remains of this magnificent, wonderful, and unique edifice, unless the government speedily lends a helping hand, and defends them against the steady assaults of the river, and the ruthless devastation of foreign visitors. Monster temple as it was, it has diminished in volume; and, though it holds itself erect and dauntless between two never resting foes,—the sands of Arabia upon its back, and the swift flowing waters of the river in front,—it must, at no very remote period, give way after a resistance of many a century of abandonment.

A grand prospect of distant mountain scenery opened upon our excited vision from the top of the old temple, and the walls that enclosed the sacred edifice. In another direction, the aspect was desolate; for there was a wide waste of millions upon millions of acres of arid, heated sand, that defied vegetation, and is now threatening the concealment, in its constrictor embrace, of one of the finest specimens of architecture the world can boast. One of our sailors picked up the cast skin of a serpent six feet in length, indicating that loathsome reptiles are the permanent, undisturbed occupants of a spot once sacred to the gods of Egypt. A solemn worship, in the darkness of paganism, was instituted and practiced where we were standing: but the smoke of the altars has gone out; the holy vestments and priestly apparatus are nowhere to be found; and the stillness of death marks the locality where the voices of thousands were heard, in the ecstasies of heathen enthusiasm, in praise of imaginary deities, whose attributes were the passions of men, with the character of devils.”

“No radiant pearl, which crested fortune wears,

No gem, that twinkling hangs from beauty’s ears,

Not the bright stars, which night’s blue arch adorn,

Nor rising sun, that gilds the vernal morn—

Shine with such lustre as the tear, that flows

Down virtue’s manly cheek, for other’s woes.”

“ ’Tis wrong to sleep in church—’tis wrong to borrow

What you can never pay—’tis wrong to touch

With unkind words the heart that pines in sorrow—

’Tis wrong to scold too loud—eat too much;—

’Tis wrong to put off acting till to-morrow,

To tell a secret, or get drunk.”

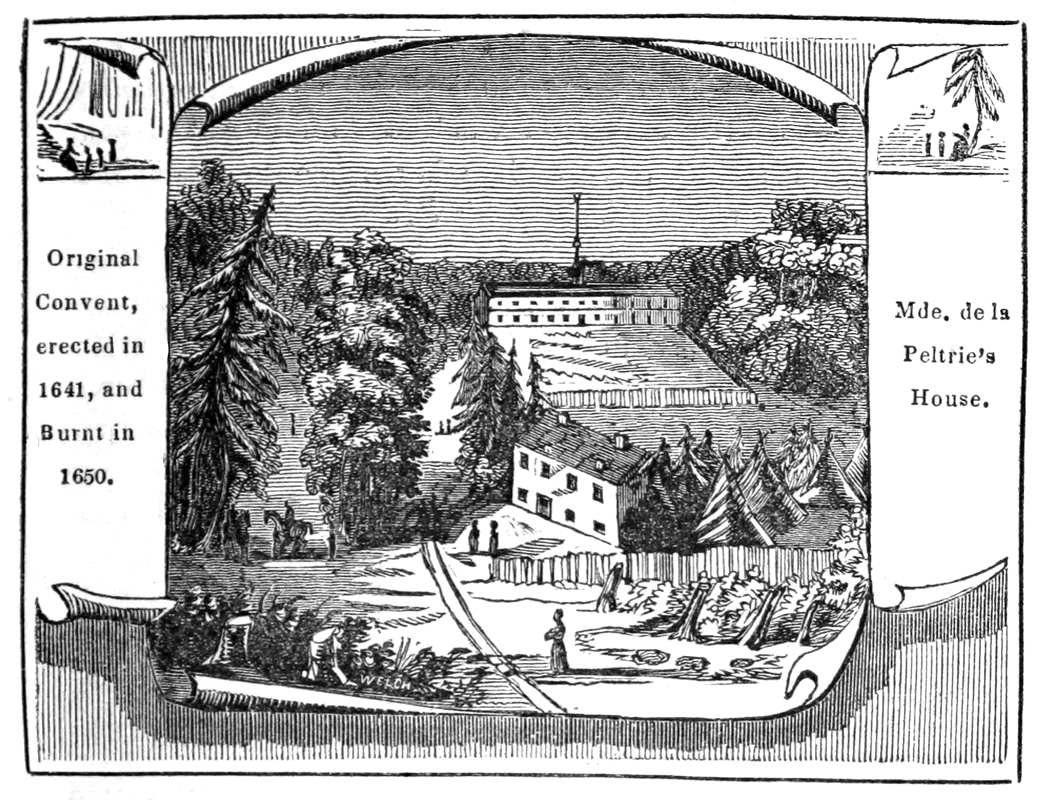

ublic institutions, whether religious or secular, are alike, the common property of a country, and the history of their establishment should be preserved, because the peculiarities of such institutions, give us a fair idea of the views and opinions of the era in which they existed. An excellent and respected friend has sent us an exquisitely finished drawing, from which our engraving is taken. It is a small landscape representing the Ursuline Convent Quebec. The drawing is the work of a young pupil of that institution, and is an exact copy of a larger painting. This engraving brings history home to us, and places before the mind, times when men had need of courage and heroism. It represents venerable trees, roads short, and lost in the deep forest shade, and groups of human beings, who once inhabited those houses and wigwams, and acted their part in life’s busy allotments. Dim and shadowy is the imagery with which we are wont to invest such scenes, since we see them through the long vista of departed years, but the picture before us, has a touch of reality about it,—as we look, our fancies of the far off past begin to assume a more definite shape, and we can conceive the whole with the vividness of ideal presence. Centuries have passed since those grand arcades echoed the first sounds of aggressive civilization. The lofty monarchs of the woods yielded slowly to the axe, and years of toil were endured before the little settlement of Quebec wore a prosperous appearance. The following interesting description accompanied the drawing:—“This institution was founded in Quebec, under the auspices of an illustrious widow, Mde. De la Peltrie, at a very early period after the foundation of Quebec. The first building, completed in 1641, nearly two years after the arrival of the nuns, was of wood, two stories high, and solid, says Mde. De l’Incarnation, (the first lady superior of the house) in her letters, under date of 1644. She adds that the said house, was 92 feet in length, by 28 broad, in which was the chapel at one end measuring 17 feet by 28. It contained four chimnies for heating the house in winter, and consumed 175 cords of wood each year.

Original Convent, erected in 1641, and Burnt in 1650.

Mde. de la Peltrie’s House.

The late J. C. Fisher, Esq. in his valuable notes on Quebec, its edifices, monuments, &c., as identified in Hawkins’ Picture of Quebec, thus gives account of the curious pictorial plan of the establishment:—A very curious pictorial plan or map of the original convent is still in existence. In this, St. Lewis Street, appears merely a broad road between the original forest trees, and is called La grand allée, without a building immediately on either side.—At a little distance to the north of La grand allée is a narrow path called Le Petit Chemin, running parallel, and leading into the forest. . . . The house of Mde. De la Peltrie, the founder of the convent, is described as occupying, in 1642, the corner of Garden Street. . . . The Ursuline Convent stood at the north west of Mde. De la Peltrie’s house, abutting on Le Petit Chemin, which ran parallel to St. Louis Street, and fronting toward Garden Street. It is represented as being a well proportioned and substantial building, two stories high, with an attic, four chimnies, and a cupola or belfry in the centre. The number of windows in front was eleven, on the upper story. . . . In other compartments of this singular map, are seen La mere de l’Incarnation instructing the young Indian girls, under an ancient ash tree, and other nuns proceeding to visit the wigwams of the savages. . . . In La grande allée, the present St. Louis Street, we see Mr. Daillebout, the Governor on horseback. . . . And Mde. de la Peltrie entering her house, &c.”

“The plan we have attempted to describe, is probably the most ancient, as it is the most interesting representation extant of any portion of Quebec in her early days.”

B.

he Island Home is the title of a book recently published by Messrs. Gould and Lincoln, of Boston. It purports to be an authentic narrative of six young adventurers, who, left by their ship’s crew in a yawl, without compass or provisions, were driven out upon the broad ocean, and exposed for several days to great peril and imminent danger of starvation, but at last escaped these trials and reached a “desert island,” “where, after the fashion of Robinson Crusoe, and other shipwrecked worthies,” they appear to have led quite a romantic, holyday kind of life. It would seem that a diary was kept by these “islanders,” which furnished the materials for one of their number to fill out a manuscript, from which the book has been compiled. The circumstances under which the manuscript came to light are curious. It is said that an American Captain, while cruising among the islands of the Pacific ocean, found a miniature ship drifting with the winds and tide, and as there was no well-appointed crew on board to offer resistance, he captured the tiny vessel, and upon opening the hatches (which were most ingeniously secured and made impervious to water by a coating of a resinous substance,) he found her whole cargo to consist of a roll of papers. On examination, this proved to be a closely written manuscript, in a cramped hand, calculated to discourage any very extended investigation of its contents. Sufficient could be understood to show that it had been deposited in the hold of the liliputian ship and set adrift, in the hope that it would be made a prize by some one who could appreciate its importance, and by publishing it as a book of remarkable adventures, convey to the world the history of the wonderful preservation of these lads. It contains graphic descriptions of many wonders of the ocean, and interesting accounts of objects of nature. “The Island Home” was published not only to amuse and instruct those who may read it, but at the same time to apprise the relations of the castaways, (if any such should survive,) of their fate, and perhaps interest the government to fit out an exploring expedition for the discovery of the new desert island, and the relief of the exiles.—“Upon a loose half sheet of the manuscript,” says the editor, “was found the following memorandum of the names and former places of residence of these unfortunate young persons, probably designed for the information of their friends.” The editor says—“Having received no answer to the letters of inquiry which I thought it my duty to forward to these addresses, (such of them, at least, as are visited by mail,) I publish the memorandum, in the hope that it may thus reach the eyes of the interested parties”:—

John Browne, of Glasgow, Scotland.

Arthur Hamilton, of Papieti, Tahiti.

William Morton, of Hillsdale, New York.

Max Adeler, of Hardscrabble, Columbia County, N. Y.

Richard Archer, of Norwich, Connecticut.

Johnny Livingston, of Milford, Mass.

Eiulo, Prince of Tewa, his (X) mark, South Sea.

As near as can be gathered from the mutilated manuscript, these lads left their homes and engaged to an American Manufacturing Company, established in Canton, China, and while on their way the ship stopped at an island to procure supplies, where a mutiny took place, and the mutineers escaped with the ship, leaving them to make the best of their position. A most interesting fact connected with the history of these young men, as we infer from the tone of the work, was a cheerful humorous harmony which always prevailed in their little circle, and what is most pleasing to see, an implicit confidence in Him who holds “the sea in the hollow of his hand,” thus evincing to a certainty their early and excellent religious training. As many of our readers may not obtain the book, we will extract a chapter or two from it, which will give a fair idea of the character of the work:—

ISLAND HOME, OR THE YOUNG CASTAWAYS.

LAST HOPE, WITHOUT IMMEDIATE RELIEF—MUST PERISH.

SANGUINARY ENGAGEMENT BETWEEN THE WHALE AND SWORD FISH.

“Strange creatures round us sweep;

Strange things come up to look at us,

The monster of the deep.”

“The first thought that flashed through my mind with returning consciousness in the morning, was, ‘This is the last day for hope—unless relief comes to-day in some shape, we must perish.’ I was the first awake, and glancing at the faces of my companions lying about in the bottom of the boat, I could not help shuddering. They had a strange and unnatural look—a miserable expression of pain and weakness. All that was familiar and pleasant to look upon, had vanished from those sharpened and haggard features.

“There was still no indications of a breeze. A school of whales was visible about a quarter of a mile to the westward, spouting and pursuing their unwieldy sport; but I took no interest in the sight, and leaning over the gunwale, commenced bathing my head and eyes with the sea-water. While thus engaged I was startled by seeing an enormous cachelot suddenly break the water within fifteen yards of the boat. Its head, which composed nearly a third of its entire bulk, seemed a mountain of flesh. A couple of small calves followed it, and came swimming playfully round us. For a minute or two, the cachelot floated quietly at the surface where it had first appeared, throwing a slender jet of water, together with a large volume of spray and vapor into the air; then rolling over upon its side, it began to lash the sea with its broad and powerful tail, every stroke of which produced a sound like the report of a cannon. This roused the sleepers abruptly, and just as they sprang up, and began to look around in astonishment, for the cause of so startling a commotion, the creature cast its misshapen head downwards, and throwing its immense flukes high into the air, disappeared. We watched anxiously to see where it would rise, conscious of the perils of such a neighborhood, and that even a playful movement, a random sweep of the tail while pursuing its gigantic pastime, would be sufficient to destroy us. It came to the surface at about the same distance as before, but on the opposite side of the boat, again it commenced lashing the sea violently, as if in the mere wanton display of its terrible strength, until far around, the water was one wide sheet of foam. Meantime, the entire school seemed to be edging down towards us. But our attention was soon withdrawn from the herd, to the singular and alarming movements of the individual near us. Rushing along the surface for short distances, it threw itself several times half clear of the water, turning after each of these leaps, as abruptly as its unwieldy bulk would permit, and running a tilt with equal violence in the opposite direction. Once, it passed so near us, that I think I could have touched it with an oar, and we saw distinctly its small, dull eye, and the loose wrinkled folds of skin about its tremendous jaws. For a minute afterwards, the boat rolled dangerously in the swell caused by the swift passage of so vast an object. Suddenly, after one of these abrupt turns, the monster headed directly towards us, and came rushing onward with fearful velocity, either not noticing us at all, or else mistaking the boat for some sea-creature, with which it designed to measure its strength. There was no time for any effort to avoid the danger; and even had there been, we were too much paralyzed by its imminence, to make such an effort. The whale was scarcely twelve yards off—certainly not twenty. Behind it stretched a foaming wake, straight as an arrow. Its vast, mountainous head ploughed up the waves like a ship’s cutwater, piling high the foam and spray before it. To miss us, was now a sheer impossibility, and no earthly power could arrest the creature’s career. Instant destruction appeared inevitable. I grew dizzy, and my head began to swim, while the thought flashed confusedly through my mind, that infinite wisdom had decreed that we must die, and this manner of perishing had been chosen in mercy, to spare us the prolonged horrors of starvation. What a multitude of incoherent thoughts and recollections crowded upon my mind in that moment of time! A thousand little incidents of my past life, disconnected and trivial—a shadowy throng of familiar scenes and faces, surged up before me, vividly as objects revealed for an instant by the glare of the lightning, in the gloom of a stormy night. Closing my eyes, I silently commended my soul to God, and was endeavoring to compose myself for the dreadful event, when Morton sprang to his feet, and called hurriedly upon us to shout together. All seemed to catch his intention at once, and to perceive in it a gleam of hope; and standing up, we raised our voices in a hoarse cry, that sounded strange and startling even to ourselves. Instantly, as it seemed, the whale dove almost perpendicularly downwards, but so great was its momentum, that its fluked tail cut the air within an oar’s length of the boat as it disappeared.

“Whether the shout we had uttered, caused the sudden plunge to which we owed our preservation, it is impossible to decide. Notwithstanding its bulk and power, the cachelot is said to be a timid creature, except when injured or enraged. Suddenly recollecting this, the thought of undertaking to scare the formidable monster, had suggested itself to Morton, and he had acted upon it in sheer desperation.

“Our reprieve from danger was only momentary. The whale came to the surface at no great distance, and once more headed towards us. If frightened for an instant, it had quickly recovered from the panic, and now there was no mistaking the creature’s purpose: it came on, exhibiting every mark of rage, and with jaws literally wide open. We felt that no device or effort of our own could be of any avail. We might as well hope to resist a tempest, or an earthquake, or the shock of a falling mountain, as that immense mass of matter, instinct with life and power, and apparently animated by brute fury.

“Every hope had vanished, and I think that we were all in a great measure resigned to death, and fully expecting it, when there came a most wonderful interposition.

“A dark, bulky mass, (in the utter bewilderment of the moment, we noted nothing distinctly of its appearance) shot perpendicularly from the sea twenty feet into the air, and fell with a tremendous concussion, directly upon the whale’s back. It must have been several tons in weight, and the blow inflicted was crushing. For a moment the whale seemed paralyzed by the shock, and its vast frame quivered with agony; but recovering quickly, it rushed with open jaws upon its strange assailant, which immediately dove, and both vanished. Very soon, the whale came to the surface again; and now we became the witnesses of one of those singular and tremendous spectacles, of which the vast solitudes of the tropical seas are doubtless often the theatre, but which human eyes have rarely beheld.

“The cachelot seemed to be attacked by two powerful confederates, acting in concert. The one assailed it from below, and continually drove it to the surface, while the other—the dark bulky object—repealed its singular attacks in precisely the same manner as at first, whenever any part of the gigantic frame of the whale was exposed, never once missing its mark, and inflicting blows, which one would think, singly sufficient to destroy any living creature. The first glimpse which we caught of the second antagonist of the whale, as it rose through the water to the attack, enabled us at once to identify it as that most fierce and formidable creature—the Pacific Sword-fish.

“The other, as I now had an opportunity to observe, was a fish of full one third the length of the whale itself, and of enormous bulk in proportion; it was covered with a dark rough skin, in appearance not unlike that of an alligator. The cachelot rushed upon its foes alternately, and the one thus singled out invariably fled, until the other had an opportunity to come to its assistance; the sword-fish swimming around in a wide circle at the top of the water, when pursued, and the other diving when chased in its turn. If the whale followed the sword-fish to the surface, it was sure to receive a stunning blow from its leaping enemy; if it pursued the latter below, the sword-fish there attacked it fearlessly, and, as it appeared, successfully, forcing it quickly back to the top of the water.

“Presently the battle began to recede from us, the whale evidently making towards the school, which was at no great distance. The whale must have been badly hurt, for the water which it threw up on coming to the surface and spouting, was tinged with blood. After this I saw no more of the sword-fish and his associate; they had probably abandoned the attack. After awhile the school of whales appeared to be moving off, and in half an hour more, we lost sight of them altogether.

“All this while, Johnny had continued to sleep soundly, and his slumbers seemed more natural and refreshing than before. When at length he awoke, the delirium had ceased, and he was calm and gentle, but so weak that he could not sit up without being supported. After the disappearance of the whales, several hours passed, during which we lay under our awning without a word being spoken by any one. Throughout this day, the sea seemed to be alive with fish; myriads of them were to be seen in every direction; troops of agile and graceful dolphins; revolving blackfish chased by ravenous sharks; leaping albacore, dazzling the eye with the flash of their golden scales, as they shot into the air for a moment; porpoises, bonito, flying-fish, and a hundred unknown kinds which I had never seen or heard of. At one time we were surrounded by an immense shoal of small fishes, about the size of mackerel, so densely crowded together that their backs presented an almost solid surface, on which it seemed as if one might walk dry-shod. None, however, came actually within our reach, and we made no effort to approach them.”

The wonderful escape of our heroes, and the sanguinary battle between the Cachelot, or sperm whale, and its adversaries, the Thresher and Sword Fish, may look to our readers like a veritable “fish story,” particularly when taken in connection with the account of the multitudinous variety of strange fish with which at this time they were surrounded. However, those who sail in the tropical seas, and especially those engaged in the whale fishery, often relate far more astonishing things which they have seen, than those recorded by the young castaways. We landsmen know but little of the wonders of the deep. Many an old tar can give more real information about the marvels of the ocean, and the natural history of its inhabitants, “than all the books and bookish men in the world.”

Our next number will also contain a chapter from the “Island Home,” of more absorbing interest, and will be accompanied with a fine engraving of the yawl and the young crew, as they appeared in their exhausted and famished state, after their wonderful escape from the whale.

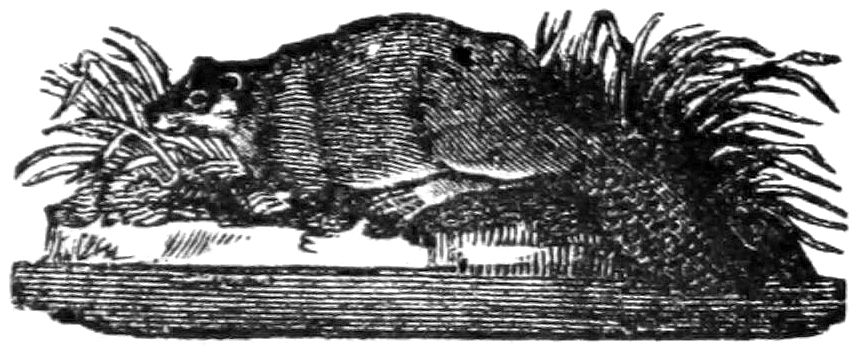

Up in the north if thou sail with me,

A wonderful creature I’ll show to thee,

As gentle and mild as a lamb at play,

Skipping about in the month of May;

Yet wise as any old learned sage

Who sits turning over a musty page!

And yonder, the peaceable creatures dwell

Secure in their watery citadel!

They know no sorrow, have done no sin;

Happy they live ’mong kith and kin—

As happy as living things can be,

Each in the midst of his family!

Ay, there they live, and the hunter wild

Seeing their social natures mild,

Seeing how they were kind and good,

Hath felt his stubborn soul subdued;

And the very sight of their young at play

Hath put his hunter’s heart away;

And a mood of pity hath o’er him crept,

As he thought of his own dear babes and wept.[1]

I know ye are but the Beavers small,

Living at peace in your own mud-wall;

I know that ye have no books to teach

The lore that lies within your reach.

But what? Five thousand years ago

Ye knew as much as now ye know;

And on the banks of streams that sprung

Forth when the earth itself was young,

Your wondrous works were formed as true

For the All-Wise instructed you!

But man! how hath he pondered on,

Through the long term of ages gone;

And many a cunning book hath writ,

Of learning deep, and subtle wit;

Hath encompassed sea, hath encompassed land,

Hath built up towers and temples grand,

Hath travelled far for hidden lore,

And known what was not known of yore,

Yet after all, though wise he be,

He hath no better skill than ye!

Mary Howitt.

|

A fact. |

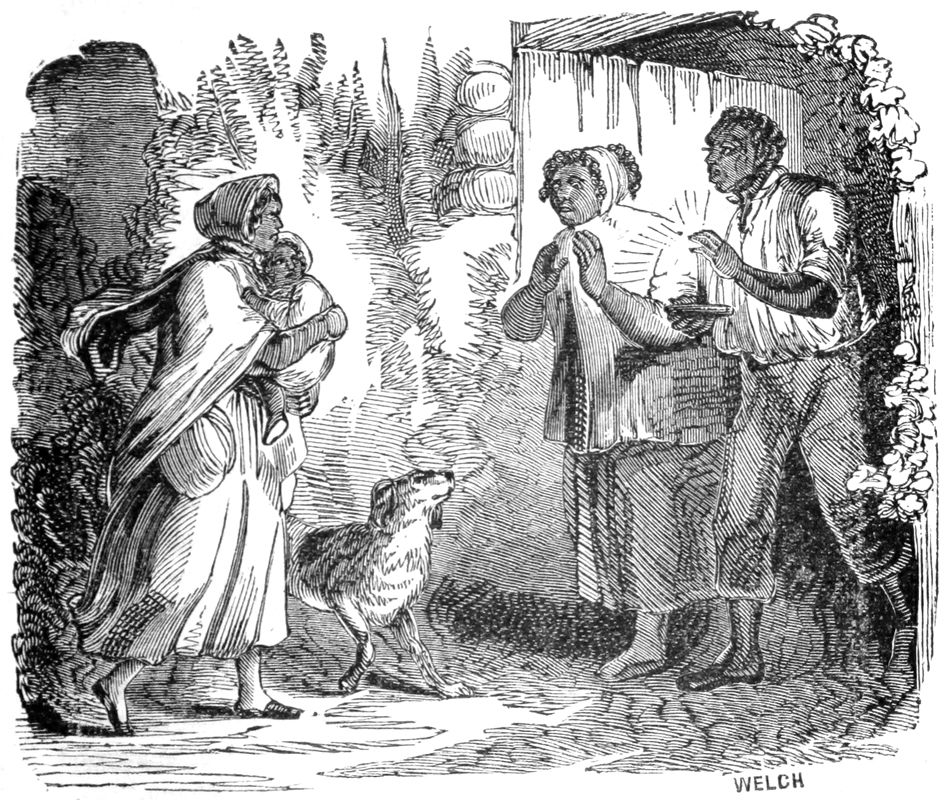

hat’s that?” said Aunt Chloe,

starting up and hastily drawing the

curtain. “My sakes alive, if it

an’t Lizy! Get on your clothes,

old man, quick!—there’s old

Bruno, too, a pawin’ round; what

on airth! I’m gwine to open the

door.”

hat’s that?” said Aunt Chloe,

starting up and hastily drawing the

curtain. “My sakes alive, if it

an’t Lizy! Get on your clothes,

old man, quick!—there’s old

Bruno, too, a pawin’ round; what

on airth! I’m gwine to open the

door.”

And, suiting the action to the word, the door flew open, and the light of the tallow candle, which Tom had hastily lighted, fell on the haggard face and dark, wild eyes of the fugitive.

“Lord bless you!—I’m skeered to look at ye, Lizy! Are ye tuck sick, or what’s come over ye?”

“I’m running away,—Uncle Tom and Aunt Chloe—carrying off my child—Master sold him!”

“Sold him?” echoed both, lifting up their hands in dismay.

“Yes, sold him!” said Eliza, firmly; “I crept into the closet by Mistress’ door to-night, and I heard Master tell Missis that he had sold my Harry, and you, Uncle Tom, both, to a trader; and that he was going off this morning on his horse, and that the man was to take possession to-day.”

Tom had stood, during this speech, with his hands raised, and his eyes dilated, like a man in a dream. Slowly and gradually, as its meaning came over him, he collapsed, rather than seated himself, on his old chair, and sunk his head down upon his knees.

“The good Lord have pity on us!” said Aunt Chloe. “O! it don’t seem as if it was true! What has he done, that Mas’r should sell him?”

“He hasn’t done anything,—it isn’t for that. Master don’t want to sell; and Missis—she’s always good. I heard her plead and beg for us; but he told her ’twas no use; that he was in this man’s debt, and that this man had got the power over him; and that if he didn’t pay him off clear, it would end in his having to sell the place and all the people, and move off. Yes, I heard him say there was no choice between selling these two and selling all, the man was driving him so hard. Master said he was sorry; but oh, Missis—you ought to have heard her talk! If she an’t a Christian, and an angel, there never was one. I’m a wicked girl to leave her so; but, then, I can’t help it. She said, herself, one soul was worth more than the world; and this boy has a soul, and if I let him be carried off, who knows what’ll become of it? It must be right: but, if it an’t right, the Lord forgive me, for I can’t help doing it!”

Welch

“Well, old man!” said Aunt Chloe, “why don’t you go, too? Will you wait to be toted down river, where they kill niggers with hard work and starving? I’d a heap rather die than go there, any day! There’s time for ye,—be off with Lizy,—you’ve got a pass to come and go any time. Come bustle up, and I’ll get your things together.”

Tom slowly raised his head, and looked sorrowfully but quietly around, and said,

“No, no—I an’t going. Let Eliza go—it’s her right! I wouldn’t be the one to say no—’t an’t in natur for her to stay; but you heard what she said! If I must be sold, or all the people on the place, and everything go to rack, why, let me be sold. I s’pose I can b’ar it as well as any on’em,” he added, while something like a sob and a sigh shook his broad, rough chest convulsively. “Mas’r always found me on the spot—he always will. I never have broke trust, nor used my pass no ways contrary to my word, and I never will. It’s better for me alone to go, than to break up the place and sell all. Mas’r an’t to blame, Chloe, and he’ll take care of you and the poor—” . . .

“And now,” said Eliza, as she stood in the door, “I saw my husband only this afternoon, and I little knew then what was to come. They have pushed him to the very last standing place, and he told me, to-day, that he was going to run away. Do try, if you can, to get word to him. Tell him how I went, and why I went; and tell him I’m going to try and find Canada. You must give my love to him, and tell him, if I never see him again,”—she turned away, and stood with her back to them for a moment, and then added, in a husky voice, “tell him to be as good as he can, and try and meet me in the kingdom of heaven.” . . .

A few last words and tears, a few simple adieus and blessings, and, clasping her wondering and affrighted child in her arms, she glided noiselessly away.

Mr. and Mrs. Shelby, after their protracted discussion of the night before, did not readily sink to repose, and, in consequence, slept somewhat later than usual, the ensuing morning.

“I wonder what keeps Eliza,” said Mrs. Shelby, after giving her bell repeated pulls, to no purpose.

Mr. Shelby was standing before his dressing-glass, sharpening his razor; and just then the door opened, and a colored boy entered, with his shaving-water.

“Andy,” said his mistress, “step to Eliza’s door, and tell her I have rung for her three times. Poor thing!” she added, to herself, with a sigh.

Andy soon returned, with eyes very wide in astonishment.

“Lor, Missis! Lizy’s drawers is all open, and her things all lying every which way; and I believe she’s just done clared out!”

The truth flashed upon Mr. Shelby and his wife at the same moment. He exclaimed,

“Then she suspected it, and she’s off!”

“The Lord be thanked!” said Mrs. Shelby. “I trust she is.”

“Wife, you talk like a fool! Really, it will be something pretty awkward for me, if she is. Haley saw that I hesitated about selling this child, and he’ll think I connived at it, to get him out of the way. It touches my honor!” And Mr. Shelby left the room hastily. . . .

Never did fall of any prime minister at court occasion wider surges of sensation than the report of Tom’s fate among his compeers on the place. It was the topic in every mouth, everywhere; and nothing was done in the house or in the field, but to discuss its probable results. Eliza’s flight—an unprecedented event on the place—was also a great accessory in stimulating the general excitement.

Black Sam, as he was commonly called, from his being about three shades blacker than any other son of ebony on the place, was revolving the matter profoundly in all its phases and bearings, with a comprehensiveness of vision and a strict look-out to his own personal well-being, that would have done credit to any white patriot in Washington.

“It’s an ill wind dat blows nowhar,—dat ar a fact,” said Sam, sententiously, giving an additional hoist to his pantaloons, and adroitly substituting a long nail in place of a missing suspender-button, with which effort of mechanical genius he seemed highly delighted.

“Yes, it’s an ill wind blows nowhar,” he repeated. “Now, dar, Tom’s down—wal, course der’s room for some nigger to be up—and why not dis nigger?—dat’s de idee. Tom, a ridin’ round de country—boots blacked—pass in his pocket—all grand as Cuffee—who but he? Now, why shouldn’t Sam?—dat’s what I want to know.”

“Halloo, Sam,” said Andy, cutting short Sam’s soliloquy. “Mas’r wants Bill and Jerry geared right up; and you and I’s to go with Mas’r Haley, to look arter Lizy, she’s cut stick and clared out, with her young un.”

“Good, now! dat’s de time o’ day!” said Sam. “It’s Sam dat’s called for in dese yer times. He’s de nigger. See if I don’t cotch her, now; Mas’r’ll see what Sam can do!”

“Ah! but, Sam,” said Andy, “you’d better think twice; for Missis don’t want her cotched, and she’ll be in yer wool.”

“High!” said Sam, opening his eyes. “How you know dat?”

“Heard her say so, my own self, dis blessed mornin’, when I bring in Mas’r’s shaving-water. She sent me to see why Lizy didn’t come to dress her; and when I telled her she was off, she jest ris up, and ses she, ‘The Lord be praised;’ and Mas’r, he seemed rael mad, and ses he, ‘Wife, you talk like a fool.’ But Lor! she’ll bring him to! I knows well enough how that’ll be,—it’s allers best to stand Missis’ side the fence, now I tell yer.”

Black Sam, upon this, scratched his woolly pate, which, if it did not contain very profound wisdom, still contained a great deal of a particular species much in demand among politicians of all complexions and countries, and vulgarly denominated “knowing which side the bread is buttered;” so, stopping with grave consideration, he again gave a hitch to his pantaloons, which was his regularly organized method of assisting his mental perplexities. . . .

At this moment Mrs. Shelby appeared on the balcony, beckoning to him. Sam approached with as good a determination to pay court as did ever suitor after a vacant place at St. James’ or Washington.

“Why have you been loitering so, Sam? I sent Andy to tell you to hurry.”

“Bless you, Missis!” said Sam, “horses won’t be cotched all in a minit.” . . .

“Well, Sam, you are to go with Mr. Haley, to show him the road, and help him. Be careful of the horses, Sam; you know Jerry was a little lame last week; don’t ride them too fast.” . . .

“Let dis child alone for dat!” said Sam, rolling up his eyes with a volume of meaning. . . . “Yes, Missis, I’ll look out for de hosses!”

“Now, Andy,” said Sam, returning to his stand under the beech-trees, “you see I wouldn’t be ’t all surprised if dat ar gen’lman’s crittur should gib a fling, by and by, when he comes to be a gettin’ up. You know, Andy, critturs will do such things;” and therewith Sam poked Andy on the side, in a highly suggestive manner.

“High!” said Andy, with an air of instant appreciation.

“Yes, you see, Andy, Missis wants to make time,—dat ar’s clar to der most or’nary ’bserver. I jis make a little for her. Now, you see, get all dese yer hosses loose, caperin’ permiscus round dis yer lot and down to de wood dar, and I spec Mas’r won’t be off in a hurry.”

Andy grinned.

“Yer see,” said Sam, “yer see, Andy, if any such thing should happen as that Mas’r Haley’s horse should begin to act contrary, and cut up, you and I jist lets go of our’n to help him, and we’ll help him—oh yes!” And Sam and Andy laid their heads back on their shoulders, and broke into a low, immoderate laugh, snapping their fingers and flourishing their heels with exquisite delight.

At this instant, Haley appeared on the verandah. Somewhat mollified by certain cups of very good coffee, he came out smiling and talking, in tolerably restored humor. Sam and Andy, clawing for certain fragmentary palm-leaves, which they were in the habit of considering as hats, flew to the horse-posts, to be ready to “help Mas’r.”

Sam’s palm-leaf had been ingeniously disentangled from all pretensions to braid, as respects its brim; and the slivers starting apart, and standing upright, gave it a blazing air of freedom and defiance, quite equal to that of any Fejee chief; while the whole brim of Andy’s being departed bodily, he rapped the crown on his head with a dexterous thump, and looked about well pleased, as if to say, “Who says I haven’t got a hat?”

“Well, boys,” said Haley, “look alive now; we must lose no time.”

“Not a bit of him, Mas’r!” said Sam, putting Haley’s rein in his hand, and holding his stirrup, while Andy was untying the other two horses.

The instant Haley touched the saddle, the mettlesome creature bounded from the earth with a sudden spring, that threw his master sprawling, some feet off, on the soft, dry turf. Sam, with frantic ejaculations, made a dive at the reins, but only succeeded in brushing the blazing palm-leaf afore-named into the horse’s eyes, which by no means tended to allay the confusion of his nerves. So, with great vehemence, he overturned Sam, and, giving two or three contemptuous snorts, flourished his heels vigorously in the air, and was soon prancing away towards the lower end of the lawn, followed by Bill and Jerry, whom Andy had not failed to let loose, according to contract, speeding them off with various direful ejaculations. And now ensued a miscellaneous scene of confusion. Sam and Andy ran and shouted,—dogs barked here and there,—and Mike, Mose, Mandy, Fanny, and all the smaller specimens on the place, both male and female, raced, clapped hands, whooped, and shouted, with outrageous officiousness and untiring zeal. . . .

Nothing was further from Sam’s mind than to have any one of the troop taken until such season as should seem to him most fitting,—and the exertions that he made were certainly most heroic. . . .

At last, about twelve o’clock, Sam appeared triumphant, mounted on Jerry, with Haley’s horse by his side, reeking with sweat, but with flashing eyes and dilated nostrils, showing that the spirit of freedom had not yet entirely subsided.

“He’s cotched!” he exclaimed, triumphantly. “If’t hadn’t been for me, they might a bust theirselves, all on ’em; but I cotched him!”

“Well, well!” said Haley, “you’ve lost me near three hours, with your nonsense. Now let’s be off, and have no more fooling.”

“Why, Mas’r,” said Sam, in a deprecating tone, “I believe you mean to kill us all clar, horses and all. Here we are all just ready to drop down, and the critters all in a reek of sweat. Why, Mas’r won’t think of startin’ on now till arter dinner. Mas’r’s hoss wants rubben down; see how he splashed hisself; and Jerry limps too; don’t think Missis would be willin’ to have us start dis yer way, no how. Mas’r we can ketch up, if we do stop. Lizy never was no great of a walker.”

Mrs. Shelby, who, greatly to her amusement, had overheard this conversation from the verandah, now resolved to do her part. She came forward, and, courteously expressing her concern for Haley’s accident, pressed him to stay to dinner, saying that the cook should bring it on the table immediately. . . .

“Soft winds murmuring as they pass,

Locusts singing in the grass,

Rivers through the meadows rushing,

Fountains in the woodlands gushing,

Insects humming ’mid the flowers,

Sudden falls of sunny showers,

Cascades leaping from the rocks,

Tinkling bells among the flocks,

Blackbirds whistling in the glen,

Songs of sturdy harvest men,

Rustlings of the golden grain,

Creakings of the loaded wain,

Robins singing round the porch,

Swallows twittering on the church,

Wild ducks plashing in the lakes,

Croaking frogs among the brakes,

Little children at their play,

Shouting through the livelong day,

Echo screaming from the hills

Every idle sound it wills,

Flutterings of the leafy vines,

Hollow sighing of the pines,

Low sounds from the porous earth

Where the insects have their birth,

Distant boomings from the rocks,

Far off groans of thunder shocks,

Rushings of the sudden gale

Loaded with the rattling hail,

Soft subsidings of the rain,

Dripping o’er the prostrate grain,

These, and countless sounds like these,

Load the languid summer breeze,

Coming from the cool blue seas;

These throughout the growing year,

With their rich abounding cheer,

Thrill the ear and flood the heart.”

y Dear Young Friends,—Some time since you perhaps read in the “Snow Drop,” a series of letters on the History of Canada from its discovery by Jacques Cartier in 1535, to its capture by England in 1759, and to the treaty signed at Paris, (which is the capital city of France,) in 1763, by which treaty the French King, Louis the Fifteenth, transferred all his rights over this country to Great Britain. I trust, my young friends, that you found those letters instructive, and as it is very important that we should all be acquainted with the history of our country, I now propose to continue those letters, in telling you the events which happened here from 1763, up to the present time.

I may here remark that I shall try to avoid saying anything in my epistles which I may think untrue or partial, or that may wound the religious or national prejudices of any of my young readers.

The present letter will be occupied with a brief sketch of the events which took place from 1763 to 1774.

By the law of nations, when one country is captured by another, the conqueror has a right to place those who are conquered under his laws and government, unless it is otherwise expressly agreed. Consequently as soon as Canada became a British Province, the French laws which were formerly in force here became, by the conquest, abolished. But as the King of England was desirous of being kind to his new Canadian subjects, he commanded, by his Royal Proclamation in 1763, that the French Canadians should continue to enjoy their own laws and customs with regard to all matters except crime; that the English who settled here should have the English laws; and because the criminal law of England was milder than that of France, and because both the English and French settlers liked it best, he likewise ordered that it should govern the people of both races.

It is very important that the laws of a country should be clearly defined and thoroughly understood, for without this knowledge it would be very difficult to settle disputes about the rights of property, or to punish the disorderly and the wicked. You will remember, that this Proclamation of the English King, who was George the Third, introduced the French law for the French Canadians, and the English law for the English Canadians, in certain cases. These two different systems of law produced much difficulty, because in a dispute between a person of French origin and a person of English, it was difficult to decide whether the dispute should be settled by the French law or by the English law. Then again, the English Judges who were then here, did not know much about the French law, and the French inhabitants from whom they asked information gave different opinions, and in these uncertainties, a particular dispute would sometimes be settled in one way sometimes in another.

Canada was from 1759 to 1774 under the administration of a Governor, and two or three other officers, without any particular form of Government. Imperfect as such a government may appear now, it seemed to have then given satisfaction to the inhabitants.

But with a view to improve the Government of Canada, an act or law was passed in 1774, in the Parliament of England, which is called “the Quebec act,” because at that time the whole of Canada was one Province, and was called “the Province of Quebec.” This law, after stating the extent or size of this country, and that the Proclamation of 1763 was abolished, declared, 2ndly, that the Roman Catholic Clergy were to have the exercise of their religion, subject to the supremacy of the Crown. 3rdly. That all Canadian subjects, except religious orders and communities, were to hold all their property, and that all disputes respecting property were to be regulated by laws which then existed here, or by such other laws as the Governor and the Legislative Council might afterwards make; and that all persons might dispose of all their property by will, in any way they liked, a right which they had not by the French law. 4thly. It declared the criminal law of England to be in force, and that the Government of Canada could alter it, as it might see fit. 5thly. It ordered that the Province should be governed by a Governor General and a Legislative Council, which was to consist of not less than 17 nor more than 22 of the respectable inhabitants of the Province, who were to be appointed by the Crown, and to hold their offices as long as they lived. They could not make the inhabitants pay any taxes, and they were ordered to send every law they made to the King in England, and if he and his Councillors did not like it, he caused it to be abolished. Nor could the Legislative Council pass any law which interfered with religion, or which would inflict any punishment greater than a fine or imprisonment for three months, until the Government of England had given consent. (See Annual Register for 1774, vol. 17, from whence the above extract was taken.)

This law did not remove the conflicts which continued between the French laws and the English laws. That evil was not cured until 1791, by an act of the English Parliament, which I shall speak more about in my next letter. But the present law conferred some privileges, upon which I would offer a word or two. In the first place, it gave permission to the Roman Catholic clergy to exercise their religion, a privilege which they had not, by the laws which were then in force in Great Britain. For in those days, I am sorry to say, the English Government oppressed the Roman Catholics in a similar manner as many Roman Catholic Governments oppress the Protestants in the present day. Such conduct is both foolish and unchristian. No convert can be made by intolerance. And as England and the United States and Canada now give to every person the free exercise of religion, we must pray and hope that religious freedom will soon be enjoyed all over the world. The treaty of Paris, which I have alluded to, stipulated that the Roman Catholics of Canada should enjoy their religion “as far as the laws of England would permit,” but as those laws did not then give permission for the free exercise of that religion, the stipulation was valueless, and the religious freedom granted by the English Government was therefore voluntarily given to Canada.

Another instance of the liberality of the English Government to Canada is shewn by the fact, that although this law of 1774 deprived all Roman Catholic societies, such as convents and monasteries, &c., of their lands, because it thought that such possession might be injurious and opposed to the interests of the English Crown; yet, notwithstanding, all of these societies have been allowed to keep possession of their lands, with the exception of that land which belonged to the Jesuits, which is now used for paying the education of the little boys and girls in Lower Canada. And these lands of the Jesuits would have been taken away from them by the King of France, if Canada had then belonged to him, because at this time he banished them from France, and deprived them of their property there.

There was another cause than that I have mentioned, which induced the British Government to pass this “Quebec act,” which I have described. About this time, the country now called the United States, were English Colonies, such as Canada, New Brunswick, &c., are now. These Colonies were dissatisfied with England, because she wanted them to pay taxes for the support of the English Government, and they refused to pay any taxes but those required for their own Governments. The disputes which arose from this opposition, caused the Americans to declare themselves independent of England, and they tried to get the Canadians to assist them in making war against her. Accordingly, on the 26th of October, 1774, they sent an address to Canada, saying, that England was trying to deprive all her subjects in America, of a share in their own Government, of trial by jury, of freedom of the press, and of other privileges, and begging the Canadians to assist them in fighting against England. But, it is said, that this address was not seen by many here, because a great number of our colonists could not read—there was only one printing press and newspaper then in Canada—and if any one had been found circulating it, he would have been severely punished. It was partly, therefore, to gain the good-will of the Canadians, to prevent them from assisting the Americans, that England passed this Bill, because she thought the Canadians would be pleased at having more power placed in their own hands, to govern themselves, than they had before. Nor did the Canadians rebel against her. They remained loyal to the British Crown throughout the war between her, and the American colonists.

I must now conclude this long letter. In my next I shall speak of the further changes which this law produced here.—In the meantime, I remain, my dear young friends, yours sincerely,

J. Popham.

As joy rises to the greatest height at the removal of some violent distress of body or mind, so sorrow is felt most acutely at the removal of what makes us happy.

Paternal love is the same in every bosom, and in every country. The caresses bestowed by the lowest gradation of Arabs, in a mud hut, on their children, are as pure and cordial as the tenderest exhibitions in a Christian family. A mother is always true to the instincts of her nature. She cherishes and defends her child, and death alone can limit the extent of her efforts.

“Affairs must suffer when recreation is preferred to business. Affectation in dress, implies a flaw in the understanding. Affectation in wisdom often prevents our becoming wise. A man had better be poisoned in his blood than in his principles. A virtuous mind in a fair body, is like a fine picture in a good light. A burden which one chooses is not felt. A careless watch invites a vigilant foe. Acquire honesty; seek humanity; practice economy; love fidelity. Against fortune oppose courage; against passion reason. A fop is the tailor’s friend, and his own foe. A thing worth doing at all, is worth well doing.”

Golden Treasure; Book Divine!

Simple, beauteous, pure, sublime

Eloquence and Poesy

Find their richest gems in thee:

Truth and love in flaming light

Burn upon thy pages bright.

Ages hidden in the past

Are upon thy mirror cast.

Oh thou art a glorious guide

O’er life’s dark and boisterous tide.

For when doubts and mysteries reign

In the troubled human brain,

And eternity doth seem

Only as a wondrous dream—

Then thy spirit o’er the night

Gives the mandate, “Let be light!”

Then be mine thou precious boon

Light my pathway to the tomb,

And when life’s short reign is done,

Give me to a higher home.

“The Earth is the Lord’s and the fulness thereof; the world and they that dwell therein. For He hath founded it upon the seas, and established it upon the floods. Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord? Or who shall stand in His holy place? He that hath clean hands and a pure heart; who hath not lifted up his soul unto vanity, nor sworn deceitfully.”

There was sent from China to the Great Exhibition at London, a set of Early Cups and Saucers, with the gilding laid on,—by a process unknown to English manufacturers, in solid gold plates; of these plates each cup contains no less than 961, and of these 260 are ornamented with imitation rubies. Each cup is also enriched with 269 solid silver plates, of which 31 bear small emeralds. The saucers are still more highly enriched, each being inlaid with 1,035 plates of pure gold, and of these 415 bear imitation rubies. They have also 432 solid silver plates inserted in each, in 56 of which are emeralds. This unique set belonged to a mandarin of the highest rank, and is the first specimen of the kind ever imported.

Fuller’s Earth.—Fuller, the well-known author of British Worthies, wrote his own epitaph as it appeared in Westminster Abbey. It consists of but four words, but it speaks volumes:—

“Here lies Fuller’s earth.”

The term “We.”—The plural style of speaking (we) among Kings was begun by King John of England, A. D. 1119. Before that time, Sovereigns used the singular person in their edicts. The German and the French Sovereigns followed the example of King John in 1200. When editors began to say “we,” is not known.

Laconic.—A remarkable example of the laconic style has recently taken place, which would put Lemidius and his countrymen to shame. An Edinburgh Quaker sends, to a brother Quaker in London, a sheet of letter paper, containing nothing whatever in the writing way, save a note of interrogation, thus (?); his friend returned the sheet, adding, for a sole reply, a (0). The meaning of the question, and answer, is as follows:— “What news?” “Nothing.”

Is a lion in the way!

Keep calm:

Tell him you respect his pride,

But that you may go ahead

He must please to stand aside,

Keep calm.

Can’t you find your guardian friends?

Keep calm.

You have only lost your cash—

They will all come dancing back,

When they see the dollars flash

Keep calm.

Are your virtues not admired?

Keep calm:

Rest assured if they exist,

They will never sue for praise;

On their own wealth they subsist.

Keep calm.

Let things jostle as they will,

Keep calm.

Outward evils need a check:

But the greatest curse of all,

Is the stiffening in your neck.

Keep calm.

Talents in a napkin.—A gentleman once introduced his son to Rowland Hill, by a letter, as a youth of great promise, and likely to do honor to the University of which he was a member; “but he is shy,” added the father, “and I fear buries his talents in a napkin.” A short time afterwards, the parent, anxious for his opinion, inquired what he thought of his son. “I have shaken the napkin,” said Rowland “at all the corners, and there is nothing in it.”

“Nobody likes to be nobody; but every body is pleased to think himself somebody. And everybody is somebody: but where anybody thinks himself to be somebody, he generally thinks everybody else to be nobody.”

Windsor Soap.—To make the celebrated Windsor Soap, slice the best white bar soap as thin as possible, and melt it over a slow fire; then take it off, and when luke warm, add sufficient oil of carraway to scent it, or any other fragrant oil. Pour it into moulds, and let it remain five or six days in a dry place.

To extract the essential oil of flowers.—Take a quantity of fresh, fragrant leaves, both the stalk and flower leaves, cord very thin layers of cotton, and dip them in fine Florence oil; put alternate layers of the cotton and leaves in a glass jar or large tumbler; sprinkle a very little fine salt on each layer of the flowers; cover the jar close, and place it in a window exposed to the sun. In two weeks a fragrant oil may be squeezed out of the cotton. Rose leaves, mignonette, and sweet scented clover, make nice perfumes.

Cheap family cake.—To one egg and four ounces of butter well beaten together, add a tea-spoonful of allspice, half a tea-spoonful of pepper, pint of molasses, tea-spoonful of saleratus dissolved in a cup of cream or milk, and flour enough to make the consistency of fritters; set it where quite warm to rise, and when perfectly light bake moderately.

We have chosen the above motto, and intend devoting two or more pages each month to subjects in keeping with its import. We wish to show that in almost every condition of life there is an opportunity for study and self-culture, and for those ardently desirous of improvement, “there is a way.” Past history shows that the most learned have often acquired their knowledge and celebrity under circumstances of the most discouraging nature. As we so frequently hear from the young, particularly those engaged in commercial houses and mechanical occupations, a description of their trying situation in regard to early advantages, and present opportunities for improvement, we are led to present what we hope may prove incentives to earnest effort after knowledge, excellence and usefulness. There are many motives which might be mentioned to stimulate us all to activity. For the sake of our own happiness let us look away from ourselves into the grand and wonderful world which God has spread before us, until, by becoming acquainted with its resources, so varied and beautifully adapted to all its phenomena, we feel our hearts swelling, and great and good thoughts and desires gushing forth. The best incentive to self-improvement is an honest wish to be useful to our fellow beings. We owe a duty of love and self-denial to the suffering sons of misfortune and misery, who, with sorrowful voices, implore our aid. There are evils growing rank around them, and increasing, because we, who are now happily situated, neglect to exert ourselves to ameliorate their condition. We owe a duty to the future of our country. Nobly overcoming every obstacle, each one of us should advance with the heroism of determined resolution, and a will that knows no backward wavering, or longing for ease and indulgence, to high attainments in all that is “lovely and of good report.”

“Life is real! life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

Art is long, and time is fleeting,

And our hearts, tho’ stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,—act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead.

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime!

And departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time.

Footprints that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, may take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.”

Socrates was probably the greatest and best philosopher of antiquity. His motto, Esse quam videri, i.e., be rather than seem, is worthy of our adoption, for as this illustrious man used to say, “The only way to true glory is for a man to be truly excellent—not affect to appear so.” In the defence of Socrates before the Judges, we find these words:—“I never wronged any man, or made him more depraved, but contrarywise, have steadily endeavored throughout life to benefit those who conversed with me, teaching them to the very utmost of my power, and that, too, without reward, whatever could make them wise and happy.” If this heathen philosopher, without the word of God and its sanctifying influences to guide him, was actuated by such principles, certainly there can be no reason why we should rest supinely contented in selfish indolence. The excuses, “no time,” “no ability,” “too much advanced in life to accomplish anything,” &c., will appear futile, if we familiarize our minds with the lives of the world’s benefactors, who have been esteemed for their learning and talents, not the less because they bravely surmounted obstacles to attain that knowledge and develope those talents. A distinguished merchant and philanthropist (Sir Thomas Fowel Buxton) said:—“The longer I live the more I am certain that the great difference between men,—between the feeble and the strong, the great and the insignificant,—is, Energy, Invincible Determination,—a purpose once fixed, and then Death or Victory. That quality will do anything that can be done in this world; and no talents, no circumstances, no opportunities, will make a two-legged creature A Man without it.”

We have grouped together the following remarkable instances, which prove that even old age need not exempt man from the necessity and advantage of cultivating his intellectual powers:—Socrates learned to play on a musical instrument in his old age. Cato at eighty learned Greek, and Plutarch almost as late in life Latin.—Theophrastus began his admirable work on the characters of men at the age of ninety. The great Arnauld translated Josephus at the age of eighty. Sir Henry Spelman, whose early years were chiefly devoted to agriculture, commenced the study of the Sciences at the age of fifty, and became a most learned antiquary and lawyer. Tellier, the Chancellor of France, learned logic merely for an amusement to dispute with his grand-children. The Marquis de St. Aulaire, whose poetry has been admired for its sweetness and delicacy, began his poetical compositions at the age of seventy. Ogilby, the translator of Homer and Virgil, knew little of Latin or Greek till he was past fifty. Franklin’s philosophical studies began when he was near fifty.

Believe not that your inner eye

Can ever in just measure try

The worth of hours as they go by:

For every man’s weak self, alas!

Makes him to see them while they pass,

As through a dim or tinted glass:

But if in earnest care you would

Mete out to each its part of good,

Trust rather to your after-mood.

Those surely are not fairly spent,

That leaves your spirit bowed and bent

In sad unrest, and ill content:

And more—though free from seeming harm

You rest from toil of mind or arm,

Or slow retire from pleasure’s charm—

If then a painful sense comes on

Of something wholly lost and gone,

Vainly employed, or vainly done—

Of something from your being’s chain

Broke off, nor to be link’d again

By all mere memory can retain—

Upon your heart this truth may rise—

Nothing that altogether dies

Suffices man’s just destinies:

So should we live, that every hour

May die as dies the natural flower—

A self-reviving thing of power;

That every thought and every deed

May hold within itself the seed

Of future good and future meed.

The following singular calculation was made by Lord Stanhope:—“Every professed inveterate snuff-taker, at a moderate computation, takes one pinch in ten minutes. Every pinch, together with the agreeable ceremony of wiping the nose, and other incidental circumstances, consumes a minute and a half. One minute and a half out of every ten, allowing 16 hours to a snuff-taking day, amounts to two hours and twenty-four minutes out of every natural day, or one day out of every ten. One day out of ten amounts to thirty-six days and a half in a year. Hence, if we suppose the practice persisted in forty years, two entire years of the snuff taker’s life will be dedicated to tickling his nose, and two more to blowing it. The expense of snuff, and snuff-boxes, and handkerchiefs, will form the subject of a second essay,” he says, “in which it will appear that this luxury encroaches as much on the income of the snuff-taker as it does his time.” If so much time is lost by the habitual snuffer, what shall be said of the habitual smoker? His hours pass away in a kind of reverie, ere he is aware. There are many who consume six hours every day in fumigating their pipe or cigar. This will be disputed by the guilty persons, because time passes so insensibly under the influence of smoke. If they wish to be convinced of the truth, let them ask some friend to note the hours they pass in smoking, when they feel themselves under no restraint. When an habitual smoker quits his pipe or cigar, one considerable source of uneasiness is, that he has so much spare time. Let any habitual smoker, who is a man of business, throw away his pipe or cigar, and employ the time which he has been accustomed to waste, diligently in business, and he may literally add hundreds, perhaps thousands, to his yearly income.

With this number our subscribers have another proof of our existence, as well as a testimony of our fidelity. We promised in our first to make the “Maple Leaf” unexceptionable, particularly in a moral point of view. As we have not seen in the public prints any disparaging reflections, or heard any expressions of disapprobation in this respect, we hope that it has generally pleased. If any of our subscribers have been dissatisfied, but from respect to our feelings have adopted the old adage, “speak well of a person or not at all,” we assure them we can fully appreciate such a sentiment, and we are quite sure none of us will ever regret taking such a stand in regard to our neighbors. It is common to hear people freeing their minds when things do not suit them, but it is more lovely and admirable to govern the tongue which, unrestrained by Christian principle, often gives pain to ourselves and others.

If the first numbers of our Magazine have not attained the mechanical excellence which may have been expected, we think all will be pleased with the improvement in this. It is, however, but an approximation to what we wish to bring the “Maple Leaf,” when an extended circulation shall enable us to beautify its pages by contributions and embellishments still more attractive. Our subscribers can be sure that the publisher will not be backward in improving it, since he is very desirous that it should become truly welcome, interesting, and instructive. We have been so engaged with our multifarious duties that we can hardly realise that three months have sped since we presented our little Magazine to the Canadian public. As to the editorial work, we can say that it brightens and grows really charming as we engage in it. A hearty good will is the key to success, and we have not only brought that to the editorial table, but many other resources, from which we shall draw from time to time, as we ply the pen or arrange the subjects which we select.

We would assure our friend who has so kindly suggested that there should be more original matter in our Magazine, that every word has originated from some source! Those articles not expressly prepared for its pages, we intend to be very particular in crediting to their proper source. We were very sorry to have inadvertently omitted to acknowledge our indebtedness to Chambers’ Miscellany for the description of the ‘Voyage of an Elephant,’ which appeared in our last number. If, by originality, is meant a faculty to give thrilling descriptions of imaginary adventures, or write histories of wonderful characters figuring in love scenes, escaping most astonishingly all the dangers and horrors of the battle field, and living in an ideal world far above the stern principles of life, we cheerfully grant that there is not, nor will there appear, much original matter in our pages. We leave that department undisturbed to those whose tastes lead them in that direction. Fictions writings have long flooded the country. The Magazines, and works in other forms, now in circulation, in which this branch of literature is handled in a masterly style, amount almost to legion. Certainly, those whose palate is not satisfied with the true and substantial, can obtain a surfeit from them. There is so much information, of the most enticing character, so many interesting things really existing, which we can collect, collate, and write about, and make a magazine of this size valuable, that we do not wish to enter much upon the unreal.

Our neighbours on the other side of the line have adopted the republican plan, that of a sovereign right to draw from the productions of others. If we reprint from some of their works, they will have no cause of complaint. For this number we have drawn largely from some of the “smart folks down east,” and we can, with confidence, recommend the purchase of those books from which we have taken extracts. They are from a large publishing house in Boston, Gould & Lincoln. We mention, as coming from the same house, ‘Plymouth and the Pilgrims,’ ‘Novelties of the New World, or the Adventures and Discoveries of the first Explorers of America,’ ‘The excellent Woman, as described in the Book of Proverbs,’ with an introduction by William B. Sprague, D.D. This last is very interesting, and gives some views of woman’s character, and the dignity of her station, that we should like to see generally understood. We have also received from the same house, ‘The Principles of Zoology,’ for schools and colleges, by Agissiz and Gould. The mechanical execution of these works is praise-worthy, and both the religious and secular press give high encomiums in regard to their merit.

We are sorry to observe that the publisher has been so misrepresented, in regard to his former connection with the “Snow Drop.” We cannot understand why it is not proper for him to issue as many books and periodicals as he sees fit. Unless much mistaken in the man, the statement which he has caused to appear on the second page of the cover of this Magazine, WILL BE FOUND CORRECT AND NECESSARY, from the circumstances of the case.

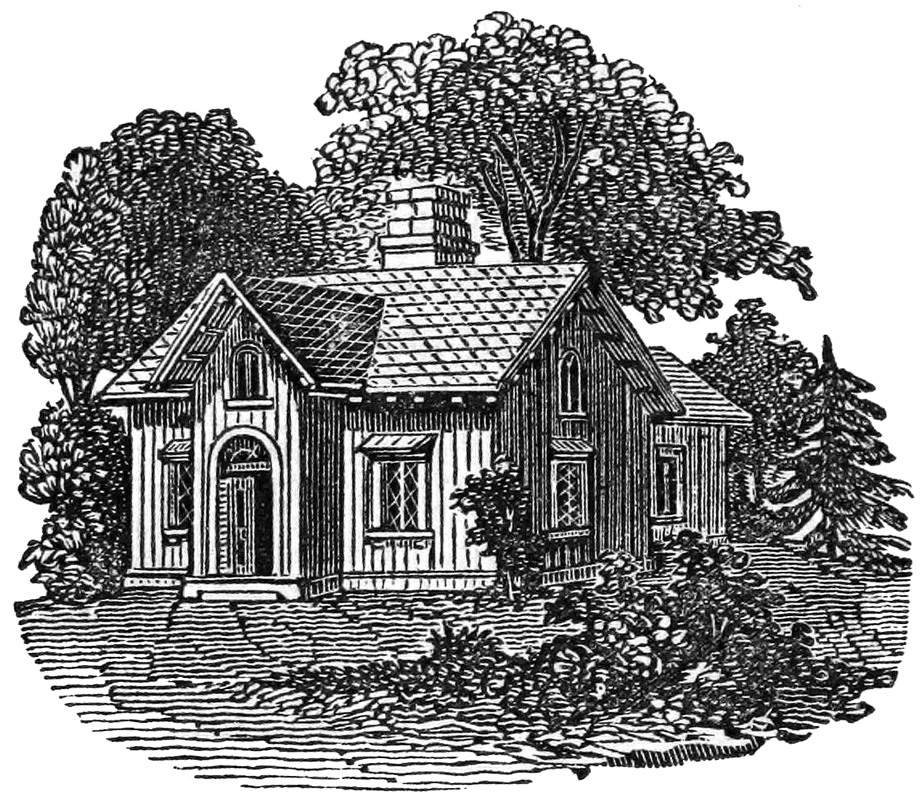

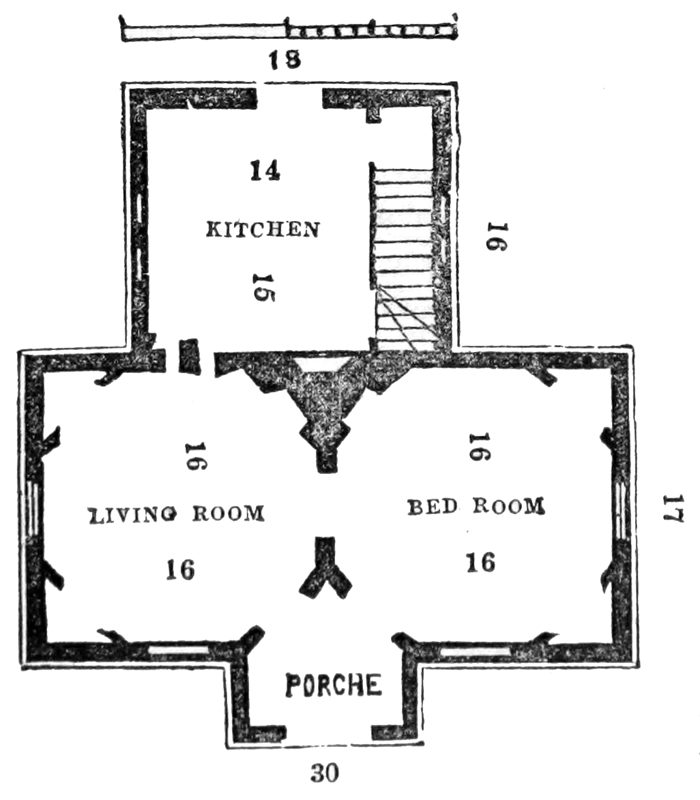

The accompanying design of a small cottage, in a simple and yet ornamental style, we think best adapted for the purpose, in which wood is the material to be employed in building.

The roof projects two feet, showing the ends of the rafters as brackets. The exterior is covered with the vertical weather boarding. For a cottage of this class, we would be content with unplaned plank, the joints covered with the necessary strip or fillet, and the whole painted and sanded.

A glance at the plan of the first floor will show that its accommodation is very compactly arranged. By placing all the flues in one stack, no heat is lost in winter; and by cutting off the corners of the two principal rooms, convenient closets are afforded. As, in a house of this class, the kitchen is usually the room most constantly occupied by the family, there is no objection to the entrance to the stairs being placed within it.

The plan of the second floor shows four good bed-rooms, which, with the best bed-room on the first floor, makes five sleeping apartments. This would enable a family, consisting of a number of persons, to live comfortably in a house of this size.

In portions of the country where timber is abundant, this cottage may be built at a cost of from £100 to £150.

Mis-spelled words and printer errors have been fixed.

[The end of The Maple Leaf, Volume 1, No. 3, September 1852 by Robert W. Lay & Eleanor H. Lay]