* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Maple Leaf, Volume 1, No. 1, July 1852

Date of first publication: 1852

Author: Robert W. Lay (1814-1853) and Eleanor H. Lay (18??-1904) (editors)

Date first posted: Sep. 11, 2020

Date last updated: Sep. 11, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200928

This eBook was produced by: Iona Vaughan, Susan Lucy, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

MAPLE LEAF.

A Juvenile Monthly Magazine.

Volume 1, No. 1.

July 1852

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR MRS. E. H. LAY BY J. C. BECKET, MONTREAL

| CONTENTS | |

| Column of Freedom | 1 |

| The Railroad Flower | 3 |

| Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or Life Among the Lowly | 4 |

| The Foundling of the Storm | 13 |

| The Mother’s Lament | 15 |

| Leopold of Brunswick and his Writing Master | 16 |

| African Chief | 23 |

| Anecdote of Lord Nelson | 24 |

| Socrates | 26 |

| Cottage Plan | 27 |

| Things Useful and Agreeable | 28 |

| Publisher’s Letter | 30 |

| Editorial | 31 |

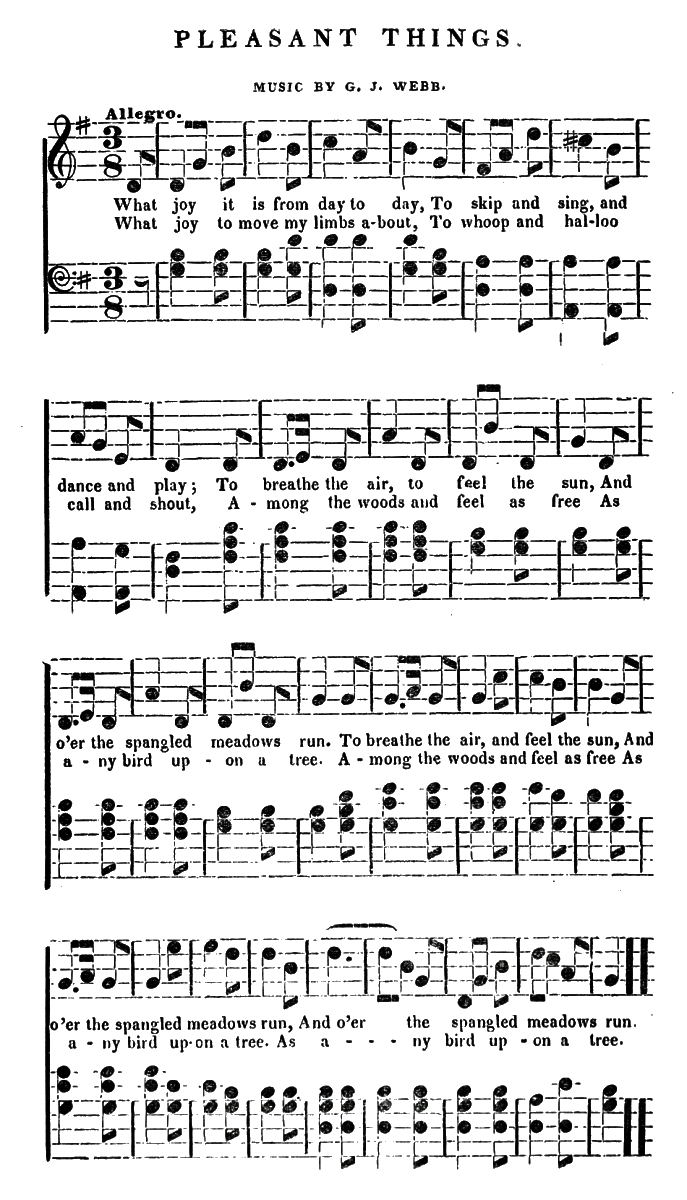

| Pleasant Things | 32 |

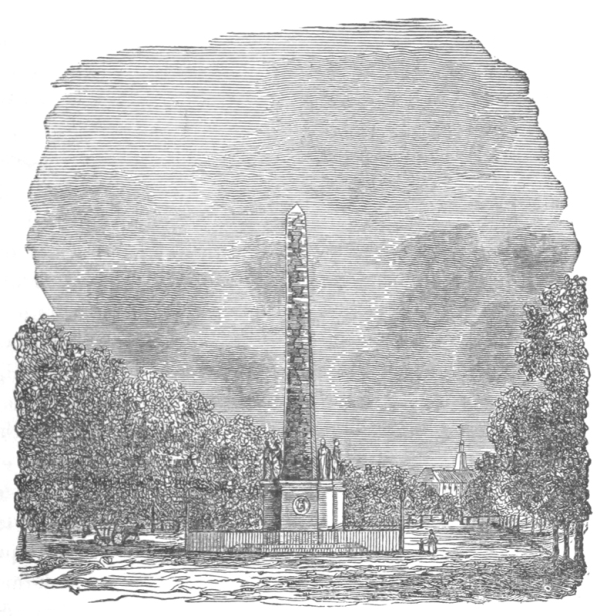

COLUMN OF FREEDOM.

The column of Liberty, or Freedom, was erected to commemorate the emancipation of the peasants of Denmark. This great measure of justice was commenced in 1766, when Christian VII. freed the peasants of the royal domains; it was completed when, during the nominal reign of the same king, his son, the Crown Prince, in the year 1787, by the advice of the younger Bernstorff, gave to all the peasants of the kingdom their liberty.

The material of this column is Bornholm free-stone, of a reddish color. The pedestal is of greyish marble. It is 48 feet in height. It bears on its four sides suitable inscriptions. On the east side there is, in basso-relievo, the figure of a slave in the act of bursting his feudal fetters; whilst on the west side, the goddess of Justice is represented, also in basso-relievo. At the four corners of the base are four emblematical figures of white marble, of Fidelity, Agriculture, Valor, and Patriotism. The expense of erecting this monument was defrayed by subscription. The late king, Frederick VI., then Crown Prince, has had the chief reputation of having accomplished this great measure of justice. But much is due, in the estimation of those who know, to Counts Stolberg and Bernstorff, who took the deepest interest in the matter. They had been for many years endeavoring to accomplish this humane and just measure.

The advantages which have resulted to the peasants are immense, as any one will perceive, who considers what was their former state and what their present. Formerly the peasants were considered as appertaining to the soil, and were sold with it. They enjoyed but few rights, and were in fact not considered as differing much from the brute creation. They were called upon to render services of the most unreasonable kind. If the sovereign chose to go a-hunting, in the time of harvest, not only did he traverse, with his dogs and horses, and many attendants, their fields ready for the sickle, and trample down their grain and their hay, but even demanded the aid of the peasants themselves, to beat the bushes and drive up the game. Sometimes a fortnight was thus spent; in the meanwhile their harvest went to ruin. Nothing was done to promote education among them. They had no encouragement to work, no stimulus to endeavor to elevate themselves in society. Now it is far otherwise. They feel that they are freemen. What property they possess is respected, and they know that it is their own. They are allowed to purchase lands and do purchase them. They are the small farmers of Denmark. Some of them are becoming rich. They have fine horses, cows, sheep, &c. Those who own no land rent from a rich proprietor. Their children are universally sent to school some portion of the year; and they are now a happy people.

A little flower of lustrous hue

Within a public rail track grew.

A poet, passing, in surprise,

Fixed on it his reproachful eyes.

“Oh wherefore here, in dust and heat,

Should dwell a thing so pure and sweet?

Thy home, thou gentle flower, should be

Far off beneath some green wood tree;

Within some soft and perfumed glade,

All spread with dew, and cool with shade;

Where thou no ruder sound shouldst hear,

Than winds and waters murmuring near;

Where birds should sing to thee, and bees

Should bear thy sweets upon the breeze.”

The flower with earnestness replied,

“Where God has placed me, I abide,

Content in some way to impart

Pure feeling to one worldly heart;

Proud, if the merchant, worn with gain

Through me a backward glance obtain,

A retrospect of joyous youth,

And simple wants and artless truth;

Prouder, if folly in the maid

Assume for me a thoughtful shade;

If sorrow, weeping, lift her eye

By my example, to the sky.

“And, Poet, now one word to thee;

Where should thy home and labor be?

Art thou repining in the heat

For some more lone and cool retreat?

Some refuge from the careless throng,

Where thou canst feed thy soul with song?

Oh be content where God requires

To wake thy harp, and feed thy fires;

And if some worldly notes float in,

Some echoes of the ceaseless din,

Some groans from bleeding slaves, and cries

From infancy, that, starving, dies,

Oh deem not that thy strain, young bard,

By these discordant notes is marred;

The Master Minstrel’s hand through such

Achieves, they say, its mightiest touch;

And thou mayest shake the sturdiest wrongs,

By some bold outbreak of thy song.

Then be content, where God requires,

To wake thy harp, and feed thy fires!”

The Poet stooped and kissed the flower

Wiser and better from that hour.

S. C. E. M.

E think we cannot better promote the interest

and pleasure of our readers than to

commence with this number to reproduce, in a

consecutive series of chapters, a work which is

doing more to move the soul of the American people than any other

production on the same subject; more than all the thunderings,

denunciations and missiles ever launched forth by the abolitionists.

This work, entitled, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or life among the

lowly,” is from the pen of the celebrated authoress, wife of the

Rev. Professor Stowe, and daughter of Dr. Beecher, who is

known to many of our readers as a distinguished divine. Dr. B.

has long labored in the cause of human progress, and defended

the rights of the oppressed slave in a signal manner. Mrs.

Stowe, instructed by such a father, caught his fervor, and availing

herself of peculiarly favorable circumstances for observing

the different phases of slavery, has, with the fire of her genius,

traced the wrongs of the race in living colors. Her work first

appeared in the columns of the National Era, a weekly abolitionist

newspaper, published in Washington, that nursery of the

slave trade. Unmoved as the heart of the American people has

seemed to be upon this most difficult subject, Mrs. Stowe has

touched its sympathetic chord, and that heart is now pulsating

mightily throughout the length and breadth of that proud and

powerful nation.

E think we cannot better promote the interest

and pleasure of our readers than to

commence with this number to reproduce, in a

consecutive series of chapters, a work which is

doing more to move the soul of the American people than any other

production on the same subject; more than all the thunderings,

denunciations and missiles ever launched forth by the abolitionists.

This work, entitled, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or life among the

lowly,” is from the pen of the celebrated authoress, wife of the

Rev. Professor Stowe, and daughter of Dr. Beecher, who is

known to many of our readers as a distinguished divine. Dr. B.

has long labored in the cause of human progress, and defended

the rights of the oppressed slave in a signal manner. Mrs.

Stowe, instructed by such a father, caught his fervor, and availing

herself of peculiarly favorable circumstances for observing

the different phases of slavery, has, with the fire of her genius,

traced the wrongs of the race in living colors. Her work first

appeared in the columns of the National Era, a weekly abolitionist

newspaper, published in Washington, that nursery of the

slave trade. Unmoved as the heart of the American people has

seemed to be upon this most difficult subject, Mrs. Stowe has

touched its sympathetic chord, and that heart is now pulsating

mightily throughout the length and breadth of that proud and

powerful nation.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” has been brought out in book form in Boston, and such is its unparalleled popularity, that the publisher has found it difficult to supply the demand. It has been reprinted in England, and read with all the eagerness so unique a production is calculated to elicit.

We think the sketches which will, from time to time, appear in this Magazine will be highly interesting to our readers, as allusion is often made to this country, which is in fact the only asylum for the fugitive from slavery in the western world. It is hoped that the sympathy of our Canadian readers will be awakened in behalf of this unfortunate people, who, while they possess many repulsive traits, are our brethren, since God has declared that He hath “made of one blood all nations of men.” Even the Americans respond to this breath of inspiration, and declare “That all men are created free and equal,” and “endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights,” among which are “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” and yet they have not had the courage to remove the stigma of slavery from their otherwise lustrous fame. Lest we should feel too much indignation towards our neighbors, when we see that it is on British soil that the immortal sentiments put forth in their declaration of independence are realized, we must remember that it is but a few years since philanthropic England proclaimed with the trumpet voice the decree which broke the shackles of thousands of the blacks then her bondmen.

In the preface to her work, Mrs. Stowe has conveyed to the world an idea of the warmth of her heart, and has so touchingly and graphically portrayed her motive in penning these truthful sketches, that we cannot do better than transcribe it here:—

PREFACE.

The scenes of this story, as its title indicates, lie among a race hitherto ignored by the associations of polite and refined society; an exotic race, whose ancestors, born beneath a tropic sun, brought with them, and perpetuated to their descendants, a character so essentially unlike the hard and dominant Anglo-Saxon race, as for many years to have won from it only misunderstanding and contempt.

But, another and better day is dawning; every influence of literature, of poetry and of art, in our times, is becoming more and more in unison with the great master chord of Christianity, “good will to man.” ...

The hand of benevolence is everywhere stretched out, searching into abuses, righting wrongs, alleviating distresses, and bringing to the knowledge and sympathies of the world the lowly, the oppressed, and the forgotten.

In this general movement, unhappy Africa at last is remembered; Africa, who began the race of civilization and human progress in the dim, gray dawn of early time, but who, for centuries, has lain bound and bleeding at the foot of civilized and Christianized humanity, imploring compassion in vain.

But the heart of the dominant race, who have been her conquerors, her hard masters, has at length been turned towards her in mercy; and it has been seen how far nobler it is in nations to protect the feeble than to oppress them. Thanks be to God, the world has at last outlived the slave-trade!

The object of these sketches is to awaken sympathy and feeling for the African race, as they exist among us; to show their wrongs and sorrows, under a system so necessarily cruel and unjust as to defeat and do away the good effects of all that can be attempted for them, by their best friends, under it.

In doing this, the author can sincerely disclaim any invidious feeling towards those individuals who, often without any fault of their own, are involved in the trials and embarrassments of the legal relations of slavery.

Experience has shown her that some of the noblest of minds and hearts are often thus involved; and no one knows better than they do, that what may be gathered of the evils of slavery from sketches like these, is not the half that could be told, of the unspeakable whole. ...

It is a comfort to hope, as so many of the world’s sorrows and wrongs have, from age to age, been lived down, so a time shall come when sketches similar to these shall be valuable only as memorials of what has long ceased to be.

When an enlightened and Christianized community shall have, on the shores of Africa, laws, language and literature, drawn from among us, may then the scenes of the house of bondage be to them like the remembrance of Egypt to the Israelite,—a motive of thankfulness to Him who hath redeemed them! ...

CHAPTER I.

IN WHICH THE READER IS INTRODUCED TO A MAN OF HUMANITY.

Late in the afternoon of a chilly day in February, two gentlemen were sitting alone over their wine, in a well furnished dining parlor, in the town of P——, in Kentucky. There were no servants present, and the gentlemen, with chairs closely approaching, seemed to be discussing some subject with great earnestness.

For convenience sake, we have said, hitherto, two gentlemen. One of the parties, however, when critically examined, did not seem, strictly speaking, to come under the species. He was a short, thick-set man, with coarse, commonplace features, and that swaggering air of pretension which marks a low man who is trying to elbow his way upward in the world. He was much over-dressed, in a gaudy vest of many colors, a blue neckerchief, bedropped gaily with yellow spots, and arranged with a flaunting tie, quite in keeping with the general air of the man. His hands, large and coarse, were plentifully bedecked with rings; and he wore a heavy gold watch-chain, with a bundle of seals of portentous size, and a great variety of colors attached to it,—which, in the ardor of conversation, he was in the habit of flourishing and jingling with evident satisfaction. His conversation was in free and easy defiance of Murray’s Grammar, and was garnished at convenient intervals with various profane expressions, which not even the desire to be graphic in our account shall induce us to transcribe.

His companion, Mr. Shelby, had the appearance of a gentleman; and the arrangements of the house, and the general air of the housekeeping, indicated easy, and even opulent circumstances. As we before stated, the two were in the midst of an earnest conversation.

“That is the way I should arrange the matter,” said Mr. Shelby.

“I can’t make trade that way—I positively can’t, Mr. Shelby,” said the other, holding up a glass of wine between his eye and the light.

“Why, the fact is, Haley, Tom is an uncommon fellow; he is certainly worth that sum anywhere,—steady, honest, capable, manages my whole farm like a clock.”

“You mean honest, as niggers go,” said Haley, helping himself to a glass of brandy.

“No; I mean, really, Tom is a good, steady, sensible, pious fellow. He got religion at a camp-meeting, four years ago; and I believe he really did get it. I’ve trusted him, since then, with everything I have,—money, house, horses,—and let him come and go round the country; and I always found him true and square in everything.” ...

“Why, last fall, I let him go to Cincinnati alone, to do business for me, and bring home five hundred dollars. ‘Tom,’ says I to him, ‘I trust you, because I think you’re a Christian—I know you wouldn’t cheat.’ Tom comes back, sure enough; I knew he would. Some low fellows, they say, said to him—‘Tom, why don’t you make tracks for Canada?’ ‘Ah, master trusted me, and I couldn’t,’—they told me about it. I am sorry to part with Tom, I must say. You ought to let him cover the whole balance of the debt; and you would, Haley, if you had any conscience.”

“Well, I’ve just got as much conscience as any man in business can afford to keep,—just a little, you know, to swear by, as ’t were,” said the trader, jocularly; “and, then, I’m ready to do anything in reason to ’blige friends; but this yer, you see, is a leetle too hard on a fellow—a leetle too hard.” The trader sighed contemplatively, and poured out some more brandy. ...

“Well, then, Haley, how will you trade?” said Mr. Shelby, after an uneasy interval of silence.

“Well, haven’t you a boy or gal that you could throw in with Tom?”

“Hum!—none that I could well spare; to tell the truth, it’s only hard necessity makes me willing to sell at all. I don’t like parting with any of my hands, that’s a fact.”

Here the door opened, and a small boy, between four and five years of age, entered the room. There was something in his appearance remarkably beautiful and engaging. ...

“Hulloa, Jim Crow!” said Mr. Shelby, whistling, and snapping a bunch of raisins towards him, “pick that up now!”

The child scampered, with all his little strength, after the prize, while his master laughed.

“Come here, Jim Crow,” said he. The child came up, and the master patted the curly head, and chucked him under the chin.

“Now, Jim, show this gentleman how you can dance and sing.” The boy commenced one of those wild grotesque songs common among the negroes, in a rich, clear voice, accompanying his singing with many comic evolutions of the hands, feet, and whole body, all in perfect time to the music.

“Bravo!” said Haley, throwing him a quarter of an orange.

“Now, Jim, walk like old Uncle Cudjoe, when he has the rheumatism,” said his master.

Instantly the flexible limbs of the child assumed the appearance of deformity and distortion, as, with his back humped up, and his master’s stick in his hand, he hobbled about the room, his childish face drawn into a doleful pucker, and spitting from right to left, in imitation of an old man.

Both gentlemen laughed uproariously.

“Now, Jim,” said his master, “show us how old Elder Robbins leads the psalm.” The boy drew his chubby face down to a formidable length, and commenced toning a psalm tune through his nose, with imperturbable gravity.

“Hurrah! bravo! what a young ’un!” said Haley; “that chap’s a case, I’ll promise. Tell you what,” said he, suddenly clapping his hand on Mr. Shelby’s shoulder, “fling in that chap, and I’ll settle the business—I will. Come now, if that ain’t doing the thing up about the rightest!”

At this moment, the door was pushed gently open, and a young woman, apparently about twenty-five, entered the room.

There needed only a glance from the child to her, to identify her as its mother. ...

“Well, Eliza?” said her master, as she stopped and looked hesitatingly at him.

“I was looking for Harry, please, sir;” and the boy bounded toward her, showing his spoils, which he had gathered in the skirt of his robe.

“Well, take him away, then,” said Mr. Shelby; and hastily she withdrew, carrying the child on her arm.

“By Jupiter,” said the trader, turning to him in admiration, “there’s an article, now! You might make your fortune on that ar gal in Orleans, any day.” ...

“I don’t want to make my fortune on her,” said Mr. Shelby, dryly; and, seeking to turn the conversation, he uncorked a bottle of fresh wine, and asked his companion’s opinion of it.

“Capital, sir,—first chop?” said the trader; then turning, and slapping his hand familiarly on Shelby’s shoulder, he added—

“Come, how will you trade about the gal?—what shall I say for her—what’ll you take?”

“Mr. Haley, she is not to be sold,” said Shelby. “My wife would not part with her for her weight in gold.”

“Ay, ay! women always say such things, cause they ha’nt no sort of calculation. Just show ’em how many watches, feathers, and trinkets, one’s weight in gold would buy, and that alters the case, I reckon.”

“I tell you, Haley, this must not be spoken of; I say no, and I mean no,” said Shelby, decidedly.

“Well, you’ll let me have the boy, though,” said the trader; “you must own I’ve come down pretty handsomely for him.”

“What on earth can you want with the child?” said Shelby.

“Why, I’ve got a friend that’s going into this yer branch of the business—wants to buy up handsome boys to raise for the market. Fancy articles entirely—sell for waiters, and so on to rich ’uns, that can pay for handsome ’uns. It sets off one of yer great places—a real handsome boy to open door, wait, and tend. They fetch a good sum; and this little devil is such a comical, musical concern, he’s just the article.”

“I would rather not sell him,” said Mr. Shelby, thoughtfully; “the fact is, sir, I’m a humane man, and I hate to take the boy from his mother, sir.”

“O, you do?—La? yes—something of that ar natur. I understand, perfectly. It is mighty onpleasant getting on with women, sometimes. They are mighty onpleasant; but, as I manages business, I generally avoids ’em, sir. Now, what if you get the gal off for a day, or a week, or so; then the thing’s done quietly,—all over before she comes home. Your wife might get her some ear-rings, or a new gown, or some such truck, to make up with her.”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Lor bless ye, yes! These critters an’t like white folks, you know; they gets over things, only manage right. Now, they say,” said Haley, assuming a candid and confidential air, “that this kind o’ trade is hardening to the feelings; but I never found it so. Fact is, I never could do things up the way some fellers manage the business. I’ve seen ’em as would pull a woman’s child out of her arms, and set him up to sell, and she screechin’ like mad all the time;—very bad policy—damages the article—makes ’em quite unfit for service sometimes. ... It’s always best to do the humane thing, sir; that’s been my experience.” And the trader leaned back in his chair, and folded his arms, with an air of virtuous decision, apparently considering himself a second Wilberforce. ...

There was something so piquant and original in these elucidations of humanity, that Mr. Shelby could not help laughing in company. Perhaps you laugh too, dear reader; but you know humanity comes out in a variety of strange forms now-a-days, and there is no end to the odd things that humane people will say and do. ...

“Well;” said Haley, after they had both silently picked their nuts for a season, “What do you say?”

“I’ll think the matter over, and talk with my wife,” said Mr. Shelby. “Meantime, Haley, if you want the matter carried on in the quiet way you speak of, you’d best not let your business in this neighborhood be known. It will get among my boys, and it will not be a particularly quiet business getting away any of my fellows, if they know it, I’ll promise you.” ...

Perhaps the mildest form of the system of slavery is to be seen in the State of Kentucky.

Whoever visits some estates there, and witnesses the good-humored indulgence of some masters and mistresses, and the affectionate loyalty of some slaves, might be tempted to dream the oft-fabled poetic legend of a patriarchal institution, and all that; but over and above the scene there broods a portentous shadow—the shadow of law. So long as the law considers all these human beings, with beating hearts and living affections, only as so many things belonging to a master,—so long it is impossible to make anything beautiful or desirable, in the best regulated administration of slavery. ...

Now, it had so happened that, in approaching the door, Eliza had caught enough of the conversation to know a trader was making offers to her master for somebody. ...

She thought she heard the trader make an offer for her boy;—could she be mistaken? Her heart swelled and throbbed, and she involuntarily strained him so tight that the little fellow looked up into her face in astonishment.

“Why, Eliza, child! what ails you?” said her mistress.

“O! missis, missis,” said Eliza, “there’s been a trader talking with master in the parlor! I heard him.”

“Well, silly child, suppose there has.”

“O, missis, do you suppose mas’r would sell my Harry?” And the poor creature threw herself into a chair, and sobbed convulsively.

“Sell him! No, you foolish girl! You know your master never deals with those southern traders, and never means to sell any of his servants, as long as they behave well. Why, you silly child, who do you think would want to buy your Harry? Do you think all the world are set on him as you are, you goosie? Come, cheer up, and hook my dress.” ...

“Well, but, missis, you never would give your consent—to—to—”

“Nonsense, child? to be sure, I shouldn’t. What do you talk so for? I would as soon have one of my own children sold. But really, Eliza, you are getting altogether too proud of that little fellow. A man can’t put his nose into the door, but you think he must be coming to buy him.” ...

Mrs. Shelby was a woman of a high class, both intellectually and morally. To that natural magnanimity and generosity of mind which one often marks as characteristic of the women of Kentucky, she added high moral and religious sensibility and principle, carried out with great energy and ability into practical results. Her husband, who made no profession to any particular religious character, nevertheless reverenced and respected the consistency of hers, and stood, perhaps, a little in awe of her opinion. ...

The heaviest load on his mind, after his conversation with the trader, lay in the foreseen necessity of breaking to his wife the arrangement contemplated,—meeting the importunities and opposition which he knew he should have reason to encounter.

Mrs. Shelby, being entirely ignorant of her husband’s embarrassments, and knowing only the general kindliness of his temper, had been quite sincere in the entire incredulity with which she had met Eliza’s suspicions. In fact, she dismissed the matter from her mind, without a second thought; and being occupied in preparations for an evening visit, it passed out of her thoughts entirely.

Eliza had been brought up by her mistress from girlhood, as a petted and indulged favorite.

She had been married to a bright and talented young man, who was a slave on a neighboring estate, and bore the name of George Harris. ...

(To be continued.)

WRITTEN BY MRS. SUSANNAH MOODIE.

My Young Canadian Friends,—This is the first time that I have ever sought your acquaintance through the medium of the pen, though I feel a deep and maternal interest in your happiness and future prosperity; for I am myself the mother and grandmother of Canadian children, and as members of one common country, I cannot separate their welfare from yours.

I have been asked to tell you a story to amuse and interest you, and as I love all good children, it is with pleasure I comply with the request.

It has often been said that “truth is more wonderful than fiction,” and the following affecting circumstance, which I extract from a recent number of the New York Albion, cannot fail to impress this fact upon your minds.

“An infant was recently picked up at sea, off Yarmouth, England. It was lashed to a plank lying fast asleep, and almost benumbed with cold. There was no trace of any ship in sight, or for miles around, and it was supposed that the vessel from which it had been thrown had sunk, and that all hands perished. The Captain who picked it up, lives at Yarmouth, and intends to rear the child as his own.”

Now my young friends, if this circumstance does not fill your eyes with tears, I must confess that it did mine.

Born and brought up on that dangerous, shallow line of coast, and having from infancy been accustomed to see the German Ocean rolling its tremendous surges on that shore, and knowing all its horrors, having myself been exposed with a young infant in my arms to its fury during a storm, I can fully realize the situation of this forlorn babe—now buried in the trough of the sea—now carried like a feather on the crest of those awful billows—the leaden sky pouring down its torrents, the cold, pitiless north-west wind roaring in thunder above his hard pillow, and covering his little form with sheets of foam—and yet he slept—slept amidst all this uproar of winds and waves, of dashing spray and the huge din of conflicting billows. Yes, he slept. The protecting arm of God, the great Father, was around this orphan child, and he slept in peace, safe in His holy keeping, and as tranquilly as if his little head rested on his dead mother’s fond breast.

Never, my dear children, after reading this pathetic story, doubt the protecting care of God. When you say your prayers at night, lie down in the firm belief that He hears you, that your well-being is dear to Him, that His mercy enfolds you, and that His sleepless eye watches over your slumbers. Little children are His peculiar care, “for of such,” He has said, “are the Kingdom of Heaven,” of which this marvellous incident is a striking illustration.

Tossed on the wide and raging deep,

Unconscious of the tempest’s sweep;

The boiling surge, and bursting wave,

And deafening blasts that round him rave,

A little infant gently sleeps,

Although no mother vigil keeps;—

Alone that helpless prostrate form,

Poor foundling of the Ocean’s storm!

His bed a plank, his canopy,

The dark clouds of yon lurid sky.

Like weed cast forth on ocean’s foam,

Far from the land, his friends, his home,—

Or feather floating on the sea,

An atom in immensity;

Now borne upon the topmost crown

Of some huge surge, now plunging down

Where the chaff’d waves in wrath retreat,

Once more in madd’ning shock to meet;

Yet the pale outcast could not rest

More sweetly on his mother’s breast.

His mother! where, oh where, is she?

Ask the loud winds that sweep the sea.

They bore the last convulsive sigh

Of that young mother’s heart on high,

When ’mid the din of waters wild,

To heaven she gave her darling child,—

Launched his frail plank upon the wave,

Strong in her faith that God could save!

He sleeps—the tempest cannot harm,

While round him lies the eternal arm.

He sleeps—the elemental strife

That ’whelmed the bark, has saved his life;

The voice that calmed the raging deep

Has lull’d the orphan child to sleep.

Oh wonder of Almighty love!

That sight the coldest heart should move,

To kneel upon the surf beat shore,

The God of mercy to adore!

Oh! pale at my feet thou art sleeping my boy,

Now I press on thy cold lips in vain the fond kiss;

Earth opens her arms to receive thee my joy,

And all my past sorrows are nothing to this:—

The day-star of hope ’neath thy eyelids is sleeping,

No more to arise at the voice of my weeping.

Oh how art thou changed! since the light breath of morning,

Dispersed the light dew-drops in showers from the trees;

Like a beautiful bud my lone dwelling adorning,

Thy smiles called up feelings of rapture in me;

I thought not the sunbeams all gaily that shone

At thy waking, at eve, would behold me alone.

The joy that flashed out from thy death shrouded eye,

That laughed in thy dimples, and gladdened thy cheek,

Is vanished; but the smile on thy cold lip that lies,

Now tells of a joy that no language can speak.

The fountain is sealed—the young spirit at rest,—

Ah! why should I mourn thee, my loved one, my bless’d!

F all the young princes who, in their

early years, were remarkable for

kindness of heart, none is more deserving

of notice than Prince Leopold

of Brunswick,—a prince whose

name is engraven on the hearts of

thousands. The manner of his

death has added to the interest with

which he was regarded when living.

In the terrible inundation of the

Oder, in 1785, he perished whilst

attempting to save some poor persons,

who were in imminent danger

from the flood. Honor be to his

memory!

F all the young princes who, in their

early years, were remarkable for

kindness of heart, none is more deserving

of notice than Prince Leopold

of Brunswick,—a prince whose

name is engraven on the hearts of

thousands. The manner of his

death has added to the interest with

which he was regarded when living.

In the terrible inundation of the

Oder, in 1785, he perished whilst

attempting to save some poor persons,

who were in imminent danger

from the flood. Honor be to his

memory!

The very pleasing anecdote now about to be related, is not only interesting as an illustration of the prince’s real kindness of disposition, but is instructive, since it shows us what may be accomplished, in the way of surmounting difficulties, by a good will, determined resolution, and invincible patience of purpose.

Prince Leopold, as a child, was distinguished for his exuberant spirits. He possessed that engaging and fascinating liveliness which usually accompanies a good disposition and a happy temperament. He had already learned to read, and a portion of every day was agreeably employed in this amusing and instructive occupation. A book that at once informs and delights us is a true friend. We can leave off and return to it at our pleasure. It can accompany us wherever we go, and will occupy but little space. To be able to read, therefore, what others have thought and said, is doubtless very pleasant, but to be able to write down what we ourselves think, and so to converse with distant friends,—a beloved mother, sister or brother,—is a far greater pleasure. Leopold anxiously wished to learn to write.

With great zeal and energy he commenced this new study, in which he was instructed by a respectable old gentleman named Wagner. This gentleman was kind and amiable—a perfect master of his art—and possessed of a patience that nothing could overcome. And much, indeed, was his patience tried by his ardent and impetuous little pupil. The novelty of his new occupation having worn away, the young prince’s natural vivacity rendered him impatient of the restraints that were necessarily laid upon him. He ceased to be industrious and attentive to his tutor’s directions. Sometimes he complained that he was made to write the same letter over and over so often, that he was quite tired of it: then, that the words given him to copy were too long and too hard. In short, there was no pretence that he did not make use of to excuse the dislike which he had now taken to writing. The venerable Wagner was almost in despair of seeing his pupil make any progress in the art in which it was his business to instruct him. How could he be otherwise? When he saw him intentionally go above the line in writing, he would say, “Now, my prince, you are going above the line.” “Do you think so, Mr. Wagner?” he would indolently reply; and then, out of impatience or mere gaiety of heart, he would run to the opposite extreme.

“Now, my prince, you are below the line.”

“Ah, you are right;” and then he would write still more awkwardly and perversely than ever. Then he would find fault with his pen, which he would require to be mended, perhaps, twenty times in the course of one lesson, on the plea that it would not write well. Then the ink was thick, or he was tired, or his head ached, or he wished to do something else; and often, could he have done so without incurring his tutor’s severe displeasure, he would fairly have run away to his ball, or his rocking horse, or some other amusement.

One day he observed that his tutor, Mr. Wagner, was unusually thoughtful and sorrowful. His natural kindness of disposition at once led him to endeavor to discover the cause; and when he remembered his waywardness, his idleness, and inattention, he thought it must be his conduct that had vexed the good old man, and caused him anxiety. He therefore, on this day, did all that he could to please him. He wrote as well as he was able, and exactly followed his directions. He was submissive and pliable, affectionate in his manner towards him, and he even endeavored to anticipate his wishes in everything. But all was in vain. His attentions could not dispel his tutor’s gloom, or rouse him from the melancholy that oppressed him.

As soon as he was gone, the young prince made inquiries of his attendants as to the cause of his writing-master’s sorrow; and from them he learned that the good old man had placed too much confidence in a deceitful friend. Naturally of an obliging disposition, he had incautiously, at the knave’s urgent request, and to relieve him from a pressing difficulty, signed a bill for 500 crowns. His pretended friend had told him that this was only a form, that no risk was incurred, and no danger to be apprehended; and then, when he had obtained the money, he absconded, and left the poor unfortunate writing master to be responsible for the whole. He had made every exertion to meet this bill, which would be due in about six weeks; but, notwithstanding all his efforts, there was still a sum of 200 crowns deficient; and this he could not raise, except by means that would utterly impoverish him—namely, the sale of his furniture and goods, perhaps at ruinously low prices.

Leopold, at the time, appeared to pay but little attention to this important discovery. Perhaps at first he was even pleased at finding that he himself had not been, as he supposed, the cause of his writing-master’s trouble; but in reality, and upon reflection, he felt deeply for him, and thought seriously how he might relieve him from a difficulty to which only his amiability of temper had exposed him. He knew that, by simply mentioning the circumstances to his father, who rejoiced in every opportunity of doing good, the poor man’s sorrows would soon be at an end. But the impression made upon his mind during the morning by the thought that he had been the cause of so much anxiety to one so kind, was so deep, and clearly showed him the ingratitude and folly of his behavior, that he determined to make use of this circumstance as an inducement to himself to subdue his fault. If he could at once relieve Wagner’s distress, and overcome his own failings, a double end would be answered, and both he and his tutor would be gainers at the same time.

On the following day, therefore, while Leopold was conversing with his father, he adroitly turned the conversation to his writing lessons.

“Ah, dear papa,” he said, “if you only knew how tiresome it is!”

“I confess, my dear child,” said his father, “that the rudiments of this art are very tedious; but consider, since it is absolutely necessary that you, as a prince, should be able to write, would it not be better for you to apply yourself boldly and manfully to surmount these difficulties, than to increase them by murmuring?”

“Yes, certainly, papa,” returned Leopold; “and I assure you I will work courageously if you will but promise me something.”

“What is it that you want, my child?”

“Well, I wish that as often as my writing master says I have done well, you would give me a carl d’or, and leave me to do as I like with the money.”

“On such a condition I am not afraid of making the agreement. I consent, my dear child; and gladly will I empty my whole purse under such circumstances, if there should be occasion.”

The agreement thus formally made was sealed with a hearty kiss. Leopold was delighted at the promise which his father had made him, and his face beamed with smiles. His father in vain endeavored to unravel the mystery which enshrouded his son’s behavior; at the same time he would not question him too closely: he resolved rather to wait patiently the result.

At the next writing lesson the young prince was so teachable, so industrious, so careful, that his instructor was quite surprised. The child who had hitherto been so idle, so full of fun and frolic, was now most sedate and serious. He did not now rock his chair, or play his usual antics, but seating himself properly at the table, he sedulously gave his attention to the task before him. Instead of wantonly writing above or below the lines, requiring his pen to be frequently changed or mended, and finding fault with the ink or the paper, he diligently set himself to improve by his tutor’s instructions, insomuch that Mr. Wagner, in the course of the lesson, frequently encouraged him: “Good, my prince! very good!”

The following lesson was marked by the same industry and attention on the part of the young prince, and the same surprise and satisfaction on the part of his tutor.

“Indeed, my prince,” said the latter at last, “I cannot understand the change that has taken place in you; you are so different from what you were?”

“You are pleased, then, with me, Mr. Wagner?” returned the little boy.

“Pleased is not the right word,” said the tutor. “I am delighted; I am highly gratified to see you at length doing justice to yourself.”

“Then will you write two or three lines, saying how pleased you are with me, that I may show them to papa, who always seems to think that I do nothing?”

“Willingly, my dear prince; and I will do the same every time you are so industrious.”

The delighted teacher, in the fullness of his heart, prepared a very flattering testimonial. Leopold took it to his papa, and received the promised reward, and how valuable to him was the first piece of gold he received! He had fairly earned it; it was justly and honestly gained. He placed it in a pretty little purse, and secretly determined that he would add another every day. Indeed, he was so industrious, and made such rapid progress, that in a short time he left off writing the long uninteresting words which had displeased him at first, and came to sentences, and at length little tales, which either pleased him from their interest, or amused him from their simplicity. And now his writing lesson became at once an instructive and a pleasing and delightful occupation.

Every morning when Leopold embraced his kind father he gave him the testimonial which he had received the day before, and every day he saw his treasure increase. His father, though much gratified at receiving such repeated testimonials of his dear son’s good conduct and improvement, reflected that he had now paid him the promised reward upwards of thirty times; and he began to fear that good Mr. Wagner might be treating him with too much consideration. He therefore desired his son to bring him his writing-book, that he might judge for himself. Leopold, with much alacrity, obeyed, and showed him what astonishing progress he had made within the last six weeks. In short, his father was satisfied; and the prince rejoiced in finding himself in possession of some five-and-thirty pieces of gold, which he had so earnestly desired in order to relieve his tutor’s necessity.

The bill signed by Wagner was now due within three days, and still the worthy man was at a loss to complete the sum. In vain had he implored his creditor, a covetous and hard-hearted usurer, to afford him a little delay. No mercy was shown him; and the poor tutor, his anguish visible in his face, had resolved as a last resource to take his little plate and few trinkets to a jeweller’s in the course of the day, to raise what he could upon them; and then, if necessary, to sacrifice his all to meet the demand so unjustly made upon him.

Deeply absorbed with the trying sacrifice he was about to make, he came upon this occasion rather later than usual to the instruction of the prince, and excused himself on account of important business. Whilst the old man’s face was anxious and sorrowful, that of the child beamed with joy and happiness.

“What is the matter, dear Mr. Wagner?” inquired the prince. “You are not so cheerful as usual.”

“It is true, my prince, in this life every one must expect trouble and vexation.”

“Are you then in trouble? O tell me all about it; you do not know how much I love you!”

These affectionate words almost induced Mr. Wagner to lay open his secret to his little pupil. He well knew that one word would be sufficient to procure him all that he needed. The father of the prince both could and would have supplied him readily with the means of discharging himself from his liability; but his pride and independence of spirit constrained him. The very idea of using his influence over the prince, in order to procure a favor for himself, was painful, and wounded the honorable feeling of the good old man. The better to conceal his secret, he attempted to turn the conversation.

“You are not so anxious as usual, my prince, to take your lesson to-day?”

“What makes you think so, Mr. Wagner?”

“You are not so attentive as you were yesterday?”

“That is because I am thinking of something more important.”

“What can it be? Your hand trembles; you are agitated.”

“Mr. Wagner,” returned the little boy, “you alone are the cause.”

“I, my prince?”

“Yes, you! I can write no longer.” With these words he rose, and opened the drawer of his writing desk, where he had deposited his treasure; then throwing his arms round the old man’s neck, he said, as he gave him the money: “Take it, Mr. Wagner, and pay your bill. I hope you have not sold your silver plate?”

Wagner at once perceived that his secret was known. He could not, however, at first accept the money. Strong as was his emotion, gratified and delighted as he was, both at his own prospect of deliverance from ruin, and at his pupil’s noble behavior, he yet hesitated to receive it till he had heard the whole of the story. The young prince at length told him of the agreement he had made with his father, and how the five-and-thirty pieces of gold were the rewards that he had received for his industry and improvement.

Upon hearing this, the old man could not restrain his tears. He seized Leopold’s hands, pressed them to his lips, and said with the deepest emotion: “What, my prince! to rescue me from calamity, have you for more than a month restrained your sports, defied your weariness, and conquered your disinclination to your task? I accept with pride and gratitude this touching, this honorable memorial. It not only restores comfort and happiness to my dwelling, but it excites the deepest feelings of love, admiration, and respect for my amiable pupil and preserver. It is sweet indeed to owe this favor to you.”

The joy of giving and the pleasure of receiving may be universally diffused. It is not the greatness of the gift that imparts to it its value. One may be much less than a prince, and yet rejoice many a sorrowful heart by trifling gifts, well-timed, and affectionately and delicately bestowed, and when the gifts thus presented are obtained by the giver’s self-denial and self-discipline, he not only does good to the person to whom he gives, but acquires for himself a satisfaction, an elevation of mind and of principle, that to the good is more valuable than the greatest treasures or the costliest self-indulgence.

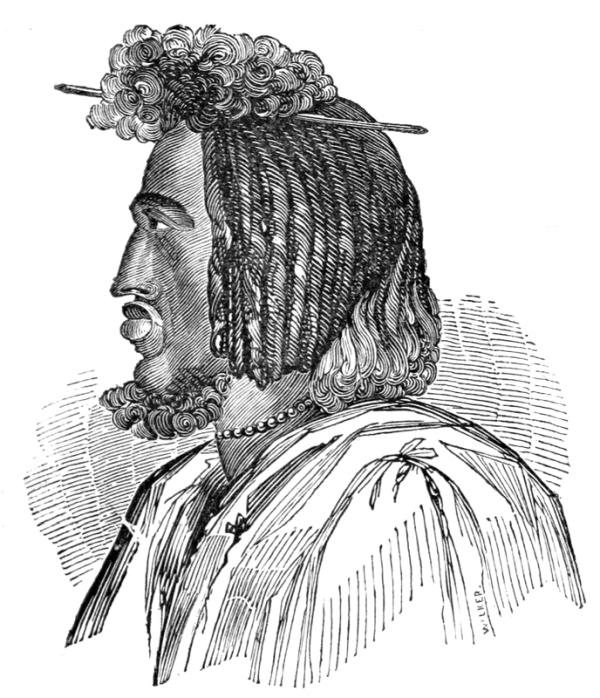

AFRICAN CHIEF.

The above is an excellent likeness of an African Chief. We are sure that no one who examines this peculiarly striking and interesting countenance can fail to see strong lineaments of humanity, and apparently just as great susceptibility of intellectual and moral advancement, as may be seen in the descendants of Japheth, or Shem. Great sternness and resolution, as well as physical strength, are characteristics of the people which he represents. These are the qualities which they cultivate, but in ancient times some of the African nations were considered among the most enlightened in the world. They still have a written language, but rank among the lowest of the half civilized nations. Astonishing efforts, attended with great sacrifice of life and means are now being put forth by Christians and philosophers in England and America to explore this vast country, and to enlighten and Christianise the people.

According to report, a white Christian community exists in the centre of this, the hottest region on the globe. It is supposed that 150 languages are spoken in the known parts of Africa. The imports of this country are ivory, gums, spices, drugs, dyes, teak, timber, cotton, rice, skins, oils and fruits. The most wonderful animals in Mr. Barnum’s menagerie, recently exhibited in Canada, such as the lion, rhinoceros, camel, leopard, zebra, antelopes, and monkeys, came from Africa.

BY MRS. TRAILL.

It used formerly to be the custom in many of our maritime towns and villages in England, to offer up prayers in the churches for seamen, preparatory to their embarking on any long voyage. This practice, like many of the simple usages of our forefathers, has, for the most part, fallen into disuse;—perhaps, through the want of fervour in the priest, whose office it was to call the attention of his flock, to join together in asking a blessing for those men who occupy their business in great waters, or possibly through the indifference of the seafaring people themselves; yet, even at this very day, among the crowded churches of the metropolis, there are a few instances of men who, feeling their dependence upon Him who holdeth the waters in the hollow of his hand; who alone ruleth the winds and waves in their fury, are inclined to call upon their God to keep them under the shadow of his wings, and to ask all Christian people to add their supplications at the throne of mercy in his holy temple. I was, myself, one of a congregation thus exhorted some years ago:

It was on Palm Sunday that I accompanied a friend and her family, to the church in Longham Place. The prayers were read with great reverence of manner by the venerable Bishop of St. Asaph’s. Before commencing the litany, the Bishop made a longer pause than usual, insomuch that every eye was turned inquiringly upon him, as if silently asking the cause of the delay. He had evidently desired his silence to produce this effect,—then in a distinct voice, and with deep solemnity of manner, he said, “The prayers—the earnest prayers of this whole congregation, are desired by two young seamen about to embark on a perilous voyage.”

There was again a solemn and impressive pause, as if the good prelate was himself engaged in silent but earnest prayer, and as if he desired that all present should have time to offer up one heartfelt petition for those two brothers;—who shall say that such supplication would be unheard. A feeling of sudden interest was awakened in my mind, and my eye glanced over that gaily dressed congregation, (for it was one of the fashionable churches,) and many of the fair, and proud, and noble, were before me, but vain was my search—there were none to realise the two young seamen.

Some accidental cause made our party almost the last to quit the church, and I was not sorry for the delay, for near the altar rails, as the dense mass of waving feathers and flowers moved off, my eye fell upon a group that I felt were those whose simple act of devotion had so moved my heart that day. They were a pale-faced widow in mean and faded black garments, a sickly child of some seven or eight years old, and two fine manly youths, attired in new blue jackets, and coarse white trowsers; they were evidently twins from the striking likeness between them. The face of the mother was composed though sad,—the boys—hopeful, eager, almost joyous. The contrast was painfully striking,—I would have given much to have known something of the history of those boys and their widowed mother, and the meek child; but they mingled in the throng, and I saw them no more, though I did indeed pray earnestly that the God in whose never failing arm they put their trust, would restore them to their pious widowed parent, to be a comfort to her in old age.

I noticed to my friend, the Bishop’s impressive manner. It had passed almost unheeded by her,—she regarded the matter as a piece of harmless superstition,—it was in vain to argue with her, or to awaken feelings that had no corresponding warmth in her heart.

“Perhaps you do not know,” she said, “that it was a constant practice of Lord Nelson, to have prayers offered up in the Foundling church, when he was about to embark, especially during the hottest part of the war. These prayers were asked in the same simple, unpretending manner, as you heard this day; no titles or name mentioned, merely this: “The prayers of the congregation are earnestly desired for a seaman about to enter on a perilous voyage.” Few knew who it was that thus humbly solicited the prayers of all good Christians; “still, I regard it merely as a piece of superstitious form in Lord Nelson or in any one else.”

I was sorry that such should be the opinion of a person for whom I entertained a regard, but of such are the world. I would rather have held the lowly, trusting faith of that pale widow, and of England’s gallant champion, than the lukewarm show of religion that led my fashionable friend to bow her knees in the Church in Longham Place.

In like manner, Lord Nelson used to return thanks in the Church for mercies vouchsafed during the perils of a voyage—“for having been preserved from perils of the deep, and perils of the enemy,”—so it used to be worded. Few were aware when they heard these words that they had been suggested by the greatest Naval Captain of this, or any age, Horatio Nelson.

I was much pleased with this anecdote of Nelson—it was new to me, as I dare say it will be to many of my readers.

He surely acknowledged by this simple act of piety that it was wiser to trust in the Lord than in any arm of man,—and did he not, like the Samaritan, “return to give glory to God!”

Socrates.—It is said of Socrates, the great Grecian philosopher, that he never allowed his temper to overcome him, but displayed the utmost tranquility on all occasions. Feeling at one time displeased with one of his servants he said, “I would beat thee if I were not angry.”

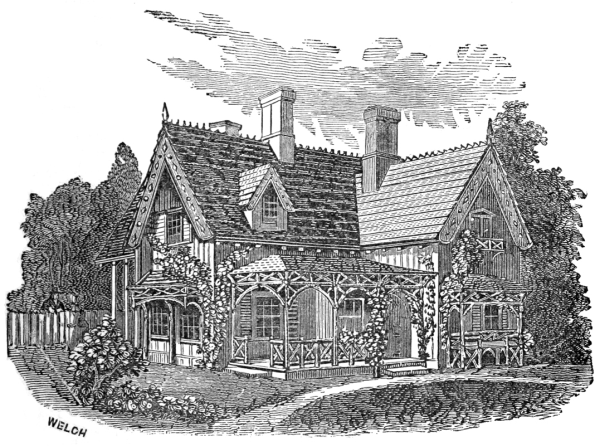

COTTAGE PLAN.

The natural scenery of our country is as fine and captivating as that of any other land. We need hardly except wide-awake England, la belle France, or staid and sober Germany. We certainly can boast of greater inland seas or lakes, larger rivers and more extended and fertile valleys. God has blessed our country with smiling features, which we may look upon, and rejoice that our lot has “fallen to us in pleasant places.” We have, however, deformed our fair landscapes by shabby towns and villages, not miserable and shabby from the poverty and wretchedness of their inhabitants, for we exult in peace and abundance, but shabby looking from the want of a nicely cultivated taste for symmetry and order. We may repeat the sentiment of Pope with propriety: “God made the country, but man made the town.” It must be evident to an observing community that there is a growing interest upon the subject of architectural improvement. But those who would improve their houses, find it difficult to obtain modern and tasteful plans to guide them. We shall therefore occasionally give a plan, with description of the most convenient and approved styles, for the construction of country and suburban residences. Our next will contain the ground plan of the above cottage, with specifications.

Our sorrows are like thunder clouds, which seem black in the distance, but grow lighter as they approach.

Gratitude is the music of the heart when its chords are swept by the breeze of kindness.

Some hearts, like evening primroses, open most beautifully in the shadows of life.

Truth.—The open, bold, honest truth is always the wisest, always the safest, for every one, in any, and in all circumstances.

Mother.—What a comfort there is in the name which gives assurance of a love that can neither change or fail.

The Robin.—I am sent to the ant to learn industry—to the dove to learn innocency—to the serpent to learn wisdom—and why not to the robin redbreast, who chaunts it as cheerfully in winter as in summer, to learn equanimity and patience?

Effect of climate and cultivation on vegetables.—The myrtle tree, which with us is a small shrub, grows in Van Diemen’s Land to the height of two hundred feet, and has a trunk from thirty to forty feet in circumference. The wood resembles cedar.

————

A few books well chosen are of more value than a great library. A knowledge of our duties is a most useful part of philosophy. A bad wound heals—a bad name kills. A truly great man borrows no lustre from splendid ancestry. A bad workman quarrels with his tools. An idle brain is the devil’s own workshop. Among the base merit begets envy; among the noble, emulation. A bitter jest is the poison of friendship. Avarice generally miscalculates, and as generally deceives. A blithe heart makes a blooming visage.

Favor is deceitful and beauty is vain; but a woman that feareth the Lord she shall be praised. She stretcheth out her hand to the poor, yea, she reacheth forth her hands to the needy, she openeth her mouth with wisdom, and in her tongue is the law of kindness. She looketh well to the ways of her household, and eateth not the bread of idleness.

Definitions of vanity.—A very small bottle with a very long neck; the less there is in it the greater noise it makes in coming out. A talking peacock looking with contempt upon the rest of his species. An empty mind turned inside out.

Definitions of cleanliness.—A life preserver—A personal index—A first-rate house decorator—The most complete medicine chest—The best garb poverty can wear—The home of comfort, and the comfort of home. As virtue is to the soul, so is cleanliness to the body.

Management of children.—Young children are generally good judges of the motives and feelings of those who attempt to control them; and if you would win their love, and dispose them to comply with your reasonable requests, you must treat them with perfect candor and uprightness. Never attempt to cheat even the youngest into a compliance with your wishes, for though you succeed at the time, you lessen your influence by the loss of confidence which follows detection.

A person, meeting a coal merchant, enquired what a chaldron of coals would come to? The coal merchant began to consider, and knowing that the question was put to him from mere idle curiosity, deliberately answered, “Sir, if they are well burnt they’ll come to ashes.”

Prisoner stand up. Are you guilty or not guilty? “Faith, do you think I’d be doing the work of the jury for ’em when they’re paid for it? Let ’em find it out themselves.”

An eminent and witty prelate was once asked if he did not think that such a one followed his conscience. “Yes,” said his grace, “I think he follows it as a man does a horse in a gig—he drives it first.”

A man down east has invented yellow spectacles, for making lard look like butter. They are a great saving of expense, if worn when eating.

A poor poet wished that a sovereign, like a piece of scandal, would grow bigger every time it circulated.

Jars of jelly, jars of jam,

Jars of potted beef and ham,

Jars of early gooseberries nice,

Jars of mince meat, jars of spice,

Jars of orange marmalade;

Jars of pickles all home made:

Would the only jars were these

That occur in families.

————

Mock preserved ginger.—Boil as if for table small, tender, white carrots; scrape them free from all spots, and take out the hearts. Steep them in spring water, changing it every day, until all vegetable flavor has left them. To every pound of carrot so prepared, add one quart of water, two pounds of loaf sugar, two ounces of whole ginger, and the shaved rind of a lemon. Boil for a quarter of an hour every day until the carrots clear, and when nearly done, add red pepper to taste. This will be found equal to West India preserved ginger.

A black man’s receipt to dress rice.—Wash him well; much wash in cold water, the rice flour make him stick. Water boil all ready very fast. Throw him in; rice can’t burn, water shake him too much. Boil quarter of an hour, or little more; rub one rice in thumb and finger; if all rub away, him quite done. Put rice in collander, hot water run away; pour cup of cold water on him, put back rice in saucepan, keep him covered near the fire; then rice all ready. Eat him up!—Correspondent.

To dress cold fish.—Dip a flat dish in hot water to prevent cracking, smear it with butter, and sprinkle white pepper on it; then a thick layer of stale bread, grated fine; a layer of the fish, picked from bones, and broken small; a little melted butter—prepared without milk—poured over another layer of bread—then of fish—with butter as before. Repeated as often as required for quantity of fish, and size of dish. Smooth the surface with a spoon, and sprinkle slightly fine bread, mixed with white pepper, on the top. Place it for twenty or thirty minutes—according to thickness—before a brisk fire, with a tin shade at back of dish, to refract the heat. Cold washed mutton may be redressed same way; first wiping the meat quite free from gravy, in a napkin.

Invaluable Dentifrice.—Dissolve two ounces of borax in three pints of boiling water; before quite cold, add one teaspoonful of tincture of myrrh, and one tablespoonful of spirits of camphor; bottle the mixture for use. One wine-glassfull of this solution, added to half a pint of tepid water, is sufficient for each application.

An excellent yellow dye for silks, ribbons, etc.—Take a large handful of horseradish leaves, boil them in two quarts of water for half an hour, then drain it off from the leaves, and soak the article you have for dying in it; when you think the color deep enough, take it out, wash it in cold water, and spread it out to dry.

Cologne Water.—The “Der Freychuetz,” a German newspaper, thus speaks of the city of Cologne:—“Cologne is principally inhabited by the editors of the ‘Cologne Gazette,’ and by 90,000 Germans, each of whom claims the name of ‘Jean Maria Farina,’ and to be the only first and original distiller of Cologne Water.”

Montreal, June 28th, 1852.

Dear Editor,—Since you have kindly offered me a space to devote to my business and correspondence with you, I have endeavored to show my appreciation of your thoughtfulness by designing a title page, which I hope may please you, and be considered appropriate by your readers. However, by so doing I have brought myself into close quarters as far as the first page is concerned. You see that bears, beavers, canoes, and ships of ancient date environ it on one side; Niagara Falls in miniature, appear in the distance pouring a ceaseless volume of water into the basin below, and Montreal, the rallying point of commercial interests, to our Province, will be easily recognised by her spires and her various emblems of commerce, with the figure of liberty guarding that most powerful engine of human progress—The Press.

As I am a man of modest aspirations, and limited acquirements, it accords with my feelings to confine myself to a small space, but I trust you will, in this instance, be quite willing to give me all the room I may require, as I wish to make some suggestions, which will, I trust, be for our mutual good and the best interests of the “Maple Leaf.” Our position is one of great importance: circulating books is a very responsible pursuit, because whether decidedly good or otherwise, they are generally retained and read, and a salutary or hurtful influence will be exerted over future generations. A sermon may be preached or a lecture given of a doubtful tendency, and the mind for a time disturbed, but favorable influences will bring it back to a healthful train of thought, and no great injury be done. Not so with a bad or foolish book,—it can be reperused, and the baneful impressions strengthened. With these facts impressing my mind, I must beg you to co-operate with me fully in making this magazine unexceptionable. Admit no articles but those of a refined and improving character, that while it shall be adapted to the young it may be edifying to older, and more cultivated minds. We must provide profitable and pleasant employment for the hands as well as the head, and introduce chapters on Botany, gardening, or patterns for knitting, netting, or crotchet work. In short, we must, with a nice taste, and discriminating judgment, select from the vast storehouse of useful knowledge, everything proper to embellish a periodical of such pretensions, and thus render it emphatically a Canadian Family Magazine.

It may here be proper for me to advert to my former relations to the “Snow Drop,” as you have seen an advertisement which somewhat criminates me. I will simply say that the work would not probably now be in existence if I had not taken hold of it, and for two years labored with considerable zeal and no small sacrifice to give it publicity. After superintending its publication for the proprietors one year, they informed me that they could not go on with it, and urged me to assume the pecuniary responsibility of the work, and pay them a salary to edit it, which I accordingly did; and, as they transferred their subscription list to me, and the perpetuation of the magazine depended on my efforts, I could only conclude that it was my own. All my arrangements were made to continue it, but just at the period when the “Snow Drop,” promised well, I was informed that by virtue of a copyright the work must revert to the original proprietors, who felt that they could proceed without any further assistance on my part. I was therefore obliged to publish a new magazine, “The Maple Leaf,” which occupies a somewhat different field, and is far from being an opponent to that truly valuable Juvenile Magazine, which I wish all success. I might obtain many subscribers to it while laboring for my own work, but the proprietors have declared that they will have no connection with any enterprise in which I may engage.—I must therefore content myself with good wishes, and push my own work with all the more vigor. I here take leave of you, promising not to encroach upon your time and patience for at least one month, when I hope I may be able to tell you many encouraging things.

Yours, truly,

The Publisher.

————

As soon as we get fairly started with the “Maple Leaf,” we shall introduce a few things to amuse, in the form of charades, puzzles, &c. We hope some of our readers will exercise their ingenuity to good advantage in preparing some fine enigmas, particularly geographical ones, as they exercise the mind, and fix the names of places and their localities upon the memory.

The Netting, Knitting, or Crochet Patterns we shall introduce on the 3rd and 4th pages of the cover, for several reasons. Some may object to occupying valuable space with what cannot interest them, others may not like the patterns, but if the cover is used, they cannot complain; then frequent use of the pattern will not soil the reading portion, and it can be removed entirely without injuring the book.

We regret that we have not space to call attention to some valuable books received from the publishing house of Gould and Lincoln, Boston; also from John and Frederick Tallis, London, through their agent, Mr. J. Smyth, No. 26, Great St. James Street, Montreal, who keeps an extensive assortment of valuable illustrated works, which are issued in numbers. We hope next month to do justice to the liberality of those publishers who have kindly favored us.

What joy it is from day to day,

To skip and sing, and dance and play;

To breathe the air, to feel the sun,

And o’er the spangled meadows run.

To breathe the air, and feel the sun,

And o’er the spangled meadows run,

And o’er the spangled meadows run.

What joy to move my limbs about,

To whoop and halloo, call and shout,

Among the woods and feel as free

As any bird upon a tree.

Among the woods and feel as free

As any bird upon a tree.

As any bird upon a tree.

TRANSCRIBER NOTES

Misspelled words and printer errors have been corrected. Where multiple spellings occur, majority use has been employed.

Punctuation has been maintained except where obvious printer errors occur.

[The end of The Maple Leaf, Volume 1, No. 1, July 1852 edited by Robert W. Lay and Eleanor H. Lay]