* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Facts for Everybody

Date of first publication: 1863

Author: Robert Kemp Philp (1819-1882)

Date first posted: June 6, 2020

Date last updated: June 6, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200608

This eBook was produced by: Iona Vaughan, Ron McBeth, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

FACTS FOR EVERYBODY:

An Encyclopædia of Useful Knowledge.

BY THE EDITORS OF “THE FAMILY FRIEND.”

LONDON:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

Edinburgh; and New York.

1863.

“Is it a Fact?” Such is the question we daily ask of matters occurring or suggested. Is it a truth—a reality—a thing of which our senses or intellect can take firm grasp? Is there no delusion about it? Does it stand out clear of all shadows—a point of actual existence—in short, is it a Fact?

The importance of Facts cannot be overrated. Canning once said that he knew nothing so sublime as a Fact. They constitute our universe—our existence. They comprise all that we are, all that we have, and all that we can hope to be.

Knowledge is nothing more than the comprehension of Fact; well, therefore, may it be said that knowledge is power,—for he who knows the most of what is, must be able to make the best use of it. And knowledge is justly said to be “the solace and delight of the human mind;” for the mind was created for it. By knowledge man stands pre-eminently distinguished amidst creation, and to him alone is given the privilege of viewing all the beautiful varieties of nature, and all the works of human ingenuity and art.

But the realms of Fact are vast and limitless, and those things which conduce most to the usefulness and happiness of man’s daily life, are the things which concern him most.

Useful Facts, as they are commonly termed, are, therefore, most properly the demand of the age; and this demand it is the object of the present work to supply. Besides Facts about the Food we Consume, the Clothes we Wear, and the House we Live in, we have herein—

Facts from Arts, Sciences, and Literature: As,—The Liberal and Mechanical Arts—Philosophical and Musical Instruments—Chronological Divisions—Architectural Orders—Months and Days—Poetical and Literary Terms—Telegraphs and Railways—The Stereoscope and Photography—Drawing, Music, and Oil Painting. Our

Facts from Commerce and Manufactures, deal with Metals, Minerals, Woods and Alkalies—Gems and Precious Stones—Colours and Paints—Curious Trees—Silk, Flax and Cotton, Pottery, Glass, and Paper—Bleaching and Dyeing—Gold Ores and Manufactures—Weights and Measures. While our

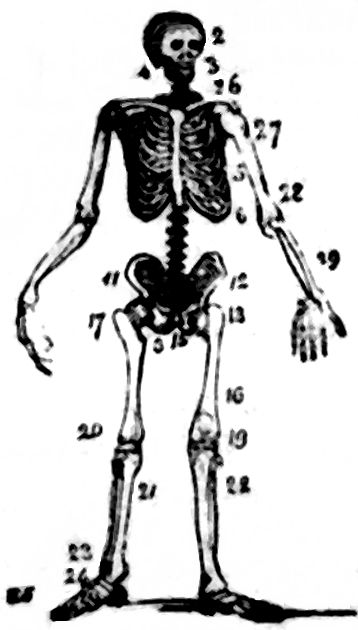

Facts from Anatomy and Physiology, relate to the Bones, Muscles, Nerves, Arteries, and Blood—The Laws of Health: How to Preserve and How to Restore it—Ventilation and the Sanitary Laws, &c. We also present

Facts from the Garden and the Field:—As, the Culture and Management of the Favorite Flowers, Weeds, Grasses, Vegetables and Agricultural Operations. We have, indeed, gleaned

Facts from all Subjects and for Everybody; Including Etiquette—The Philosophy of Eating, Drinking, and Cooking—Popular Science of Common Things—Laws of Chess, Draughts, Billiards, Whist, Cribbage, and Cricket—Calendar of the Months—Domestic Natural History—Education—Police Regulations—Railway Signals—Signification of known Christian Names—In short, all those things which have the magic power of metamorphosing “bleak houses” into happy homes. And thus we claim for the work universality of scope as well as utility of aim; and present it, with confidence, as comprising in a pre-eminent degree—“Things not generally known; Things that ought to be known; and Things worth knowing;” the whole collated and condensed with most scrupulous anxiety for accuracy as well as originality.

In the treatment of our book, care has been taken to give the plainest and clearest definitions of whatever is described, or set before the reader, so as to be neither tedious in explanation, nor so compressed as not to be intelligible and practically useful.

Abacus, 22

Abattoir, 22

Abbreviations, 23

Ablution, 17

Aborigines, 21

Absolution, 25

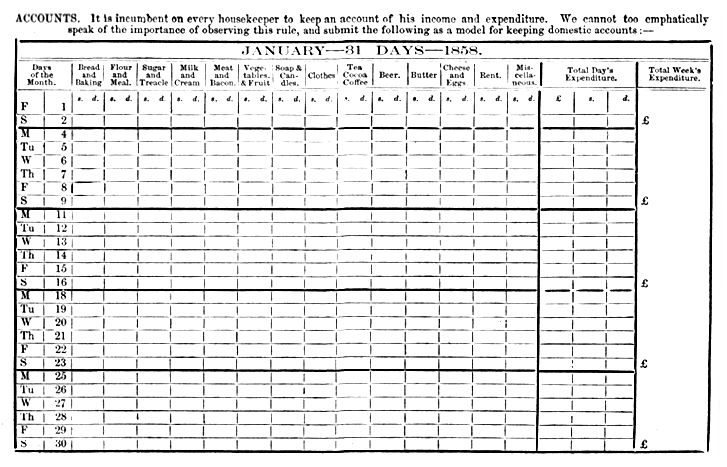

Accounts, Method of Keeping, 37

Acorns, Germination of, 17

Acidulated Drops, 126

Acre, 72

Acrostic, 290

Adhesive Composition, 99

Adjective, 234

Adverbs, 235

Agate, or Achat, 326

Air, Change of, 313

Air, Elasticity of, 126

Air-Pump, 160

Alabaster, 340

Albert, Prince, 227

Alcohol, 313

Alder, 317

Ale and Beer Measure, 274

Aliquot Parts, 173

All-hallow Eve, 257

All Saints, 285

All Souls 285

Allspice, 77

Aloes, 160

„ , Wood, 317

Alphabet, 43

„ , Deaf and Dumb, 43

„ , Hebrew, 307

Altimetry, 157

Amazon, 65

Ambulance, 147

Amethyst, 326

Anagram, 128

Anatomy, 52

Anchovy, 203

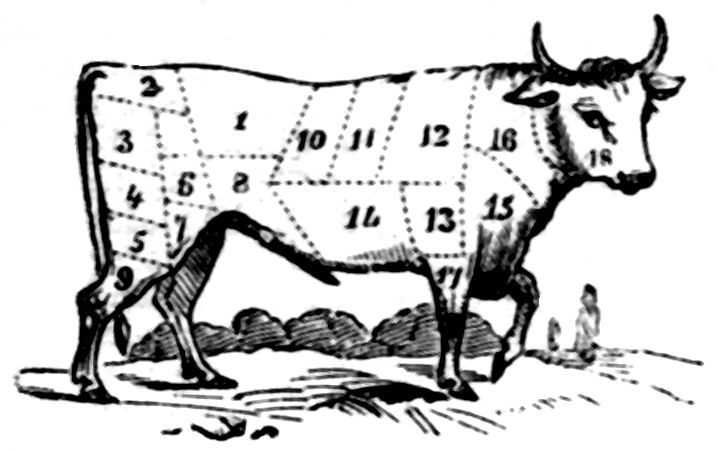

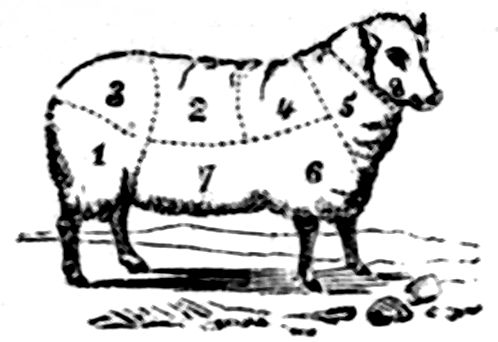

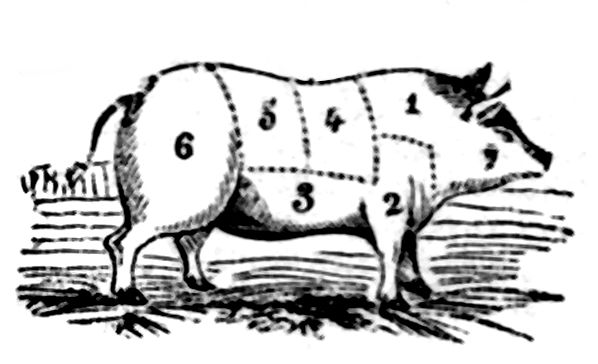

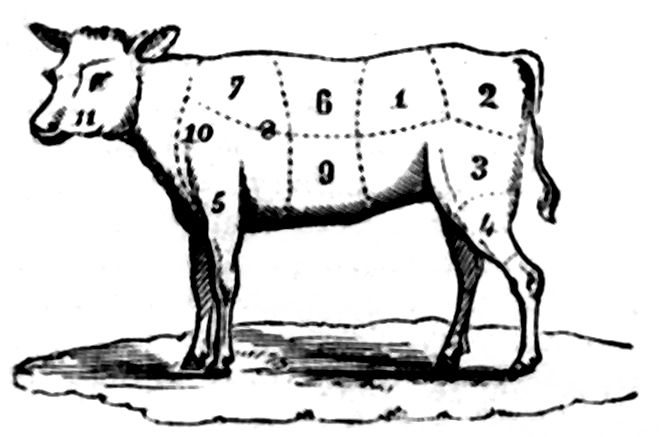

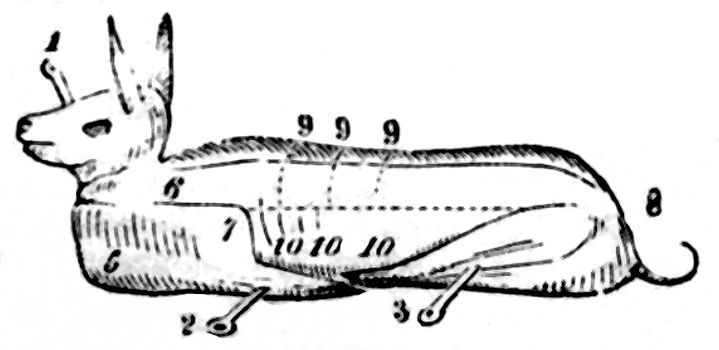

Animals, Names of the Various Parts in, 66

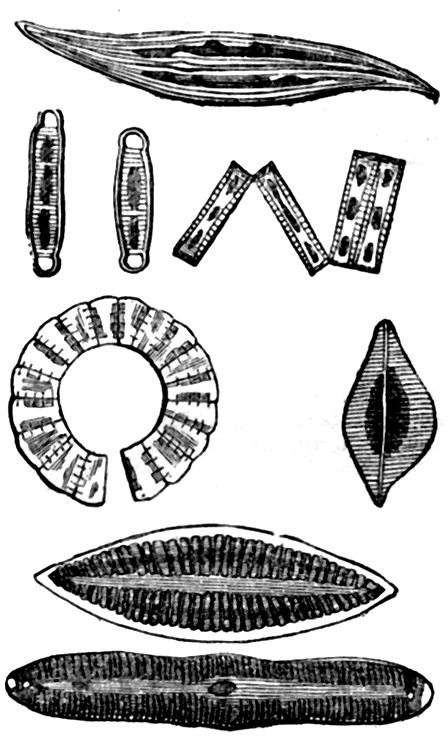

Animalculæ, 80

Annatto, 322

Annealing, 117

Annunciation Day, 136

Antediluvian, 72

Anthracite, 68

Ants, White, 81

Apartments, to Perfume, 227

Aphorism, 291

Apophthegm, 291

Apothecary, 136

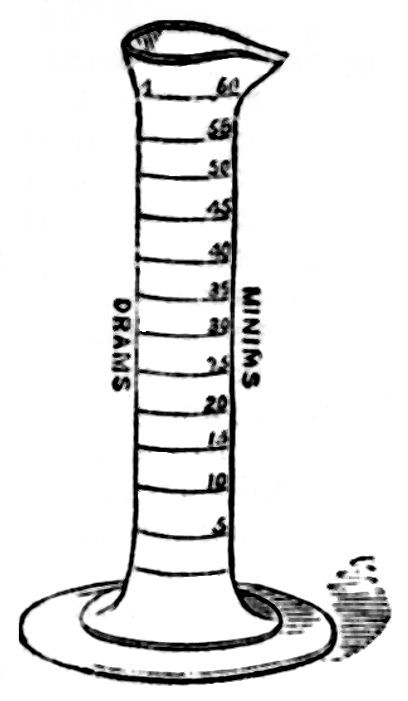

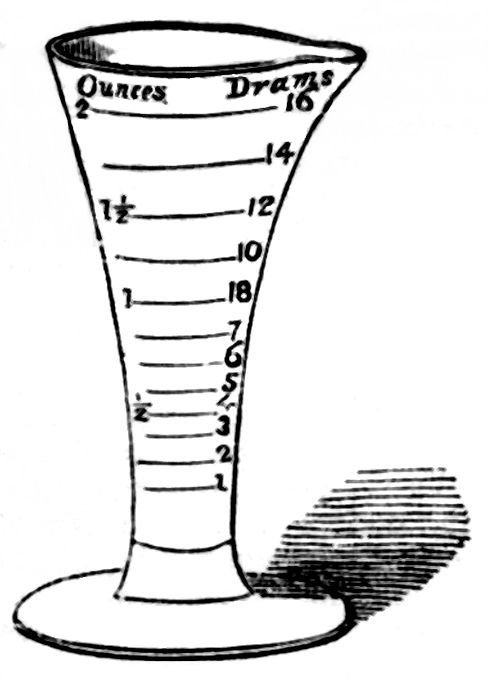

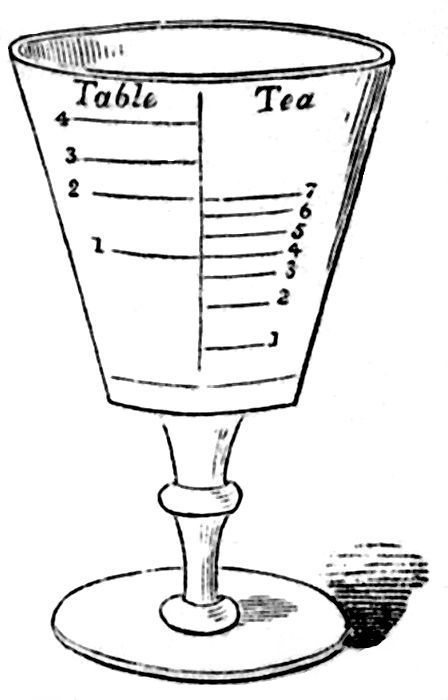

Apothecaries’ Weights and Measures, 136, 274

April, 165

April Fools’ Day, 51

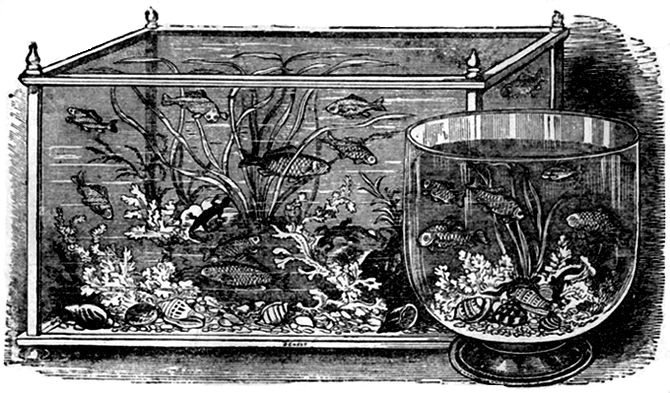

Aquaria, Parlour, 355

Aquarius, 153

Aqueous, 304

Architecture, 52

Ariosto, 197

Arrow-root, 107

Arsenic, to Detect, 23

„ , Antidote for, 31

Artesian Wells, 216

Ascension Day, or Holy Thursday, 196

Ash, 317

Ashlar, 66

Aside, 66

Asp, 71

Aspect, 71

Aspen, 68

Athanasian Creed, 71

Athenæum, 61

Athwart, 52

Attraction, Electrical, 81

August, 226

Auscultation, 87

Auspices, 71

Autographs, to Preserve, 192

Avalanches, 312

Ave Maria, 71

Avoirdupois Weight, 274

Axles, 69

Azote, 62

Azure, 51

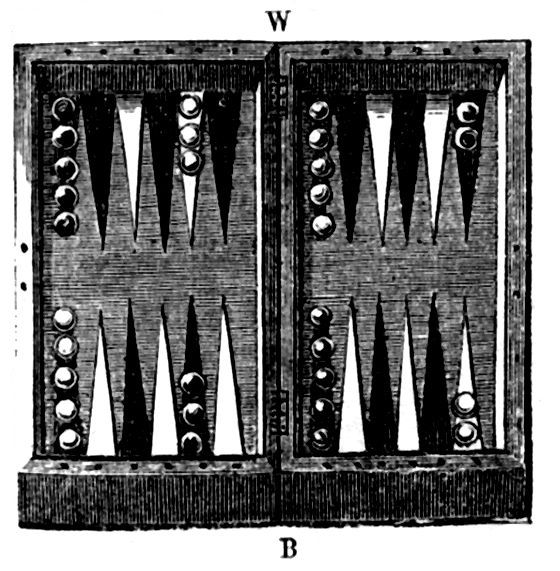

Backgammon, 349

Bagatelle, 374

Baking, 85

Balloon, 51

Balm of Gilead, 126

Banana, or Plantain Tree, 200

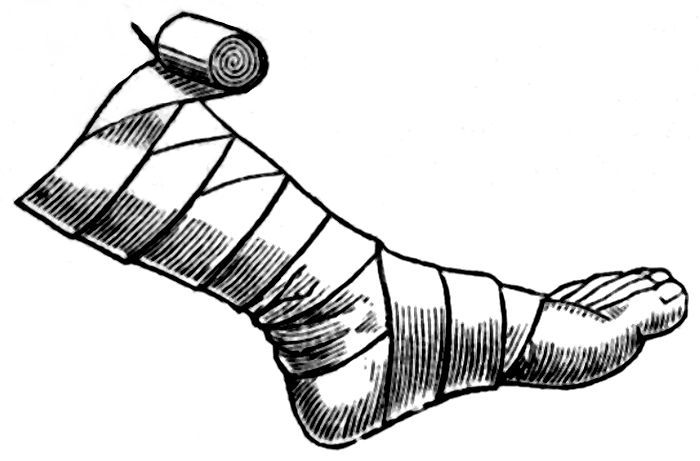

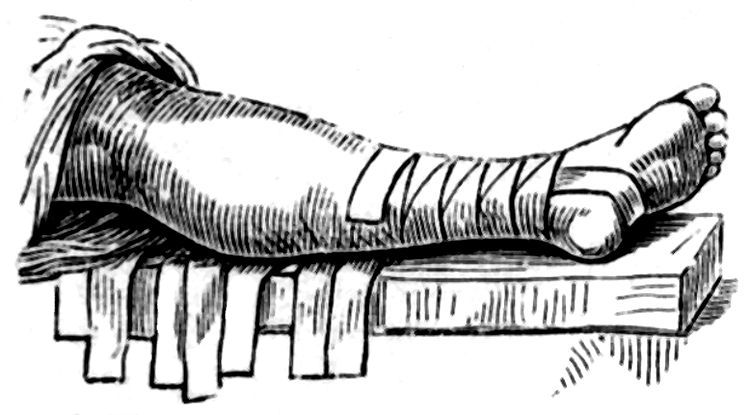

Bandages, 351

Bandanas, 130

Bank of England, 190

„ Note, 286

Banks, Sir Joseph, 197

Barbers’ Poles, Origin of, 34

Barley, 219

Barometers, Leech, 29

„ , how to Consult them, 21

Baron, 141

Baronetage, 184

Barons of the Exchequer, 194

Barons by Letters Patent, 184

Bassoon, 231

Baths, 127

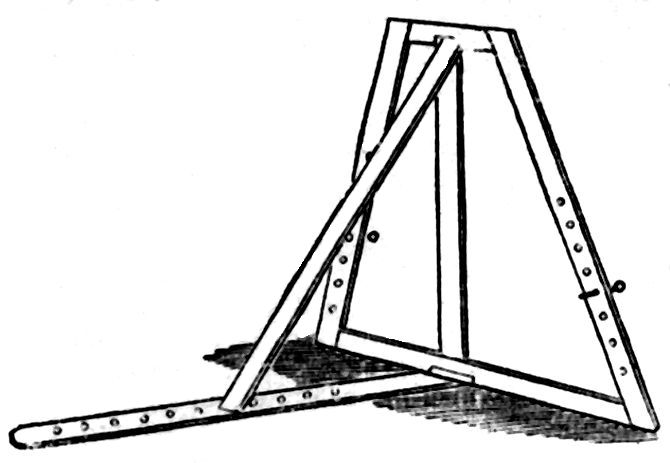

Battering-Ram, 81

Beads, Glass, 168

Beans, 77

Beaver, 186

„ Hats, 171

Beds, 100

Beef-Eaters, 56

Beer Measure, 274

Bees, 287

„ , Sting of, 30

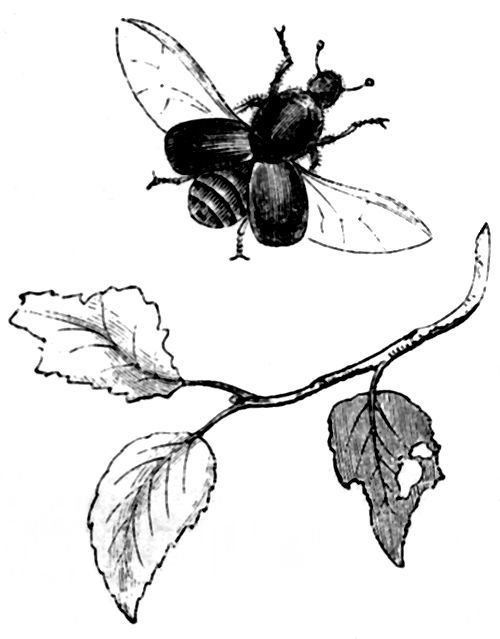

Beetle, 80

Beetle-Traps, 30

„ Truffle, 190

Beetroot Sugar, 160

Belles Lettres, 291

Beryl, 326

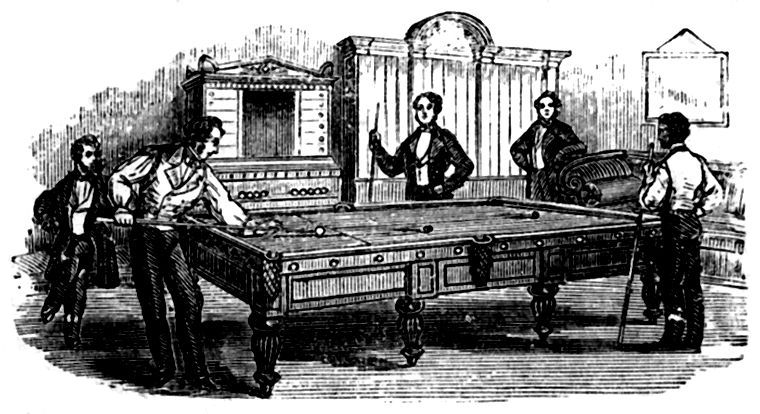

Billiards, 379

Billion, 306

Binding-knots, 16

Birch Tree, 317

Bird Stuffing, 146

Birds, Diseases of, 63

„ , Rapid Flight of, 273

Births, Registration of, 150

Bistre, 323

Bissextile, or Leap-Year, 130

Black, 323

Black Chalk, 323

Blackberry Bramble, 170

Blacklead Pencils, 67

Bleed, How to, 115

Bleeding at the Nose, 38

Blood, 52

„ Stone, 323

Blowpipe, 80

Blue, 319

Blue Stocking, 160

Blue Verditer, 320

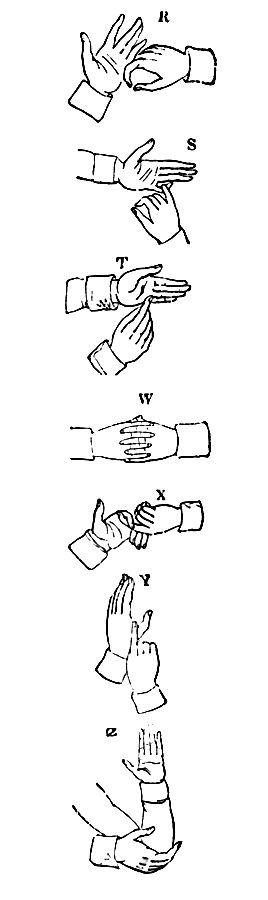

Bodies, Regular, 46

Boiling, 82

Bomb Ketches, 42

Bomb Vessels, 42

Bonaparte, Napoleon, 227

Books, to Preserve, 125

Boots and Shoes, Waterproofing, 33

Bottles, to Extract Corks from, 103

Bouquets, 162

Bouts-Rimes, 56

Boxwood, 315

Brass Coins, 275

Brazil Wood, 315

Bread, Etymology of Word, 188

„ , Assize of, 167

Bread-Fruit Tree, 130

Breath, to Sweeten, 80

Bride Cake, 193

Brig, 42

Brigantine, 42

Britain, 151

Broiling, 84

Bronzing, 261

Bruises, and their Treatment, 34

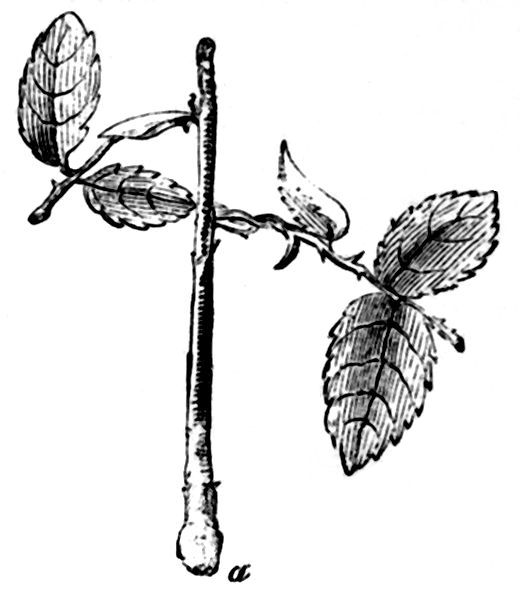

Budding, 169

Bulbous Roots, 193

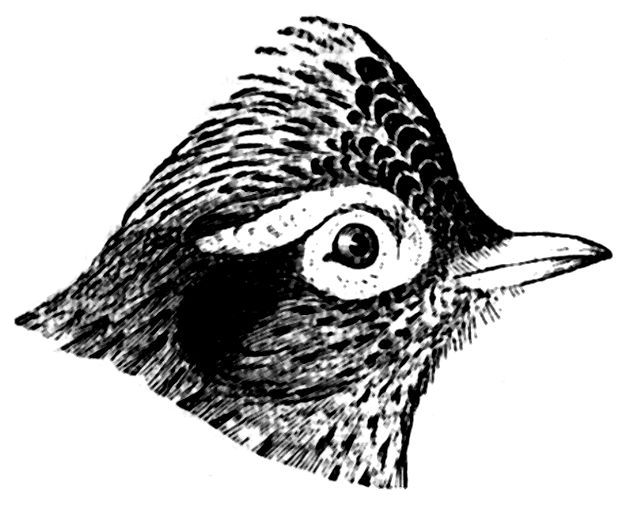

Bullfinch, the, 269

Burning, to Protect Children from, 41

Burns and Scalds, 41

Butter, 277

Butter, to Cure, 146

Buttercups and Daisies, 122

Butterfly, 85

Cage Birds, 63

Cake, Bride, 193

Calisthenic Exercises, 57

Cameleopard, 100

Camera Obscura, 22

Camomile, 161

Canaries, 94

Candles, Economy in, 91

„ , How to Make Good, 251

Candlemas Day, 105

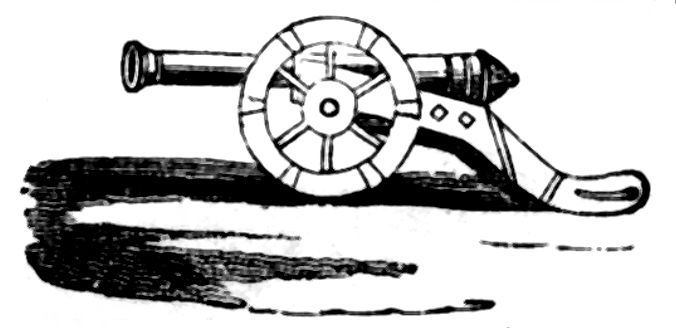

Cannon, 65

Capillaire, 116

Capacity, Measures of, 276

Carbon, 202

Cardinal, 74

„ Points, 74

„ Virtues, 56

Cards, 56

Carmine, 320

Carnelian, 327

Carols, 287

Carpets, Management of, 79

Carving, 270

Casks, to Sweeten, 47

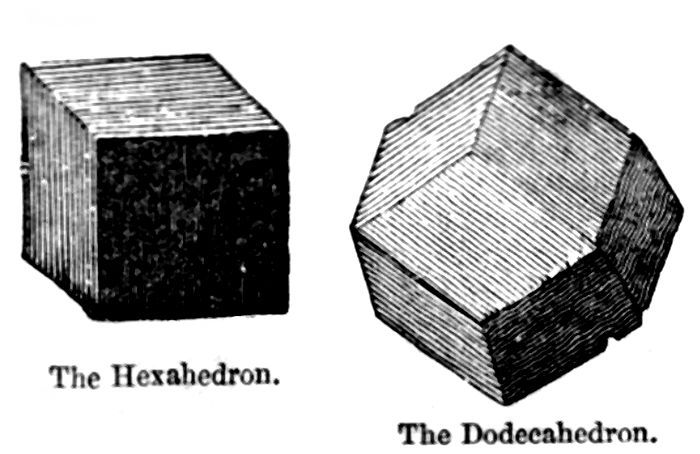

Catherine Wheel, 47

Cats’ Whiskers, Use of, 159

Cedar of Lebanon, 316

Celery, 143

Cements, Manufacture and Use of, 131

Centre of Gravity, 55

Ceres, 141

Chains, 161

Chalcedony, 327

Chameleon, 61

Champagne, 160

Charade, 128

Charcoal, 202

Charles I., 75

Chaplain, 56

Cheese, 277

Chemical Transmutations, 141

Cherries, 131

Chesnut Tree, 317

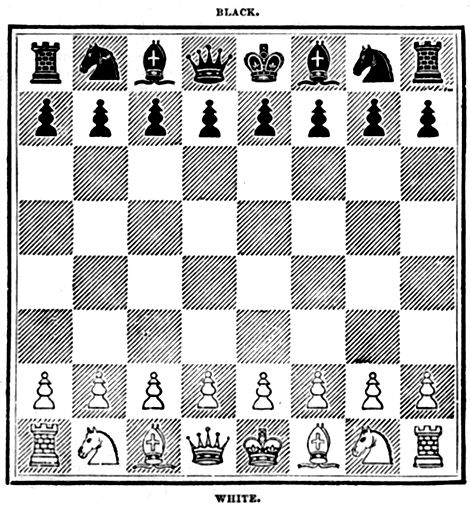

Chess, 179

Chicory, 129

Chimneys, Smoky, 366

China and Earthenware, to Clean, 74

China, Dresden, 123

China or Glass, to pack, 253

Chiromancy, 117

Chlorine, 203

Chocolate, 102

Christian Names, 187

Christmas Customs, 287

„ Day, 287

Christian Names, Signification of, 308

Chromatype, 365

Churching, 131

Churches and Chapels in England, 168

Chrysididæ, 216

Chrysolite, 325

Cinque Ports, 56

Cinnabar, 319

Clarion, 231

Clarionet, 231

Classes of Flowers, 188

Climate, 130

„ of England, 24

Clocks and Watches, 290

Cloth Measure, 274

Clothes, to Brush, 245

Clouds, 130

Clove Tree, 100

Cloves, Syrup of, 116

Clove-hitch Knot, 16

Coach Accidents, 41

Coal, 60

Coat, to Fold for Packing, 245

Coats of Arms, 155

Cochineal, 320

Cockatoos, 148

Cockroaches, to Destroy, 30

Cocoa, 102

Cocoa-nut Tree, 156

Cod Liver Oil, 38

Coffee, 102

„ , French Method of Preparing, 102

„ , Milk, 102

„ , Syrup of, 116

„ , To Make with Hot Water, 102

Coin, Gold and Silver, 305

Coins, to take Impressions from, 192

Cold Cream, 124

Colossus of Rhodes, 67

Colours and Paints, 319

Columbus, 196

Complexion, to Improve, 80

Copper Plate Printing, 246

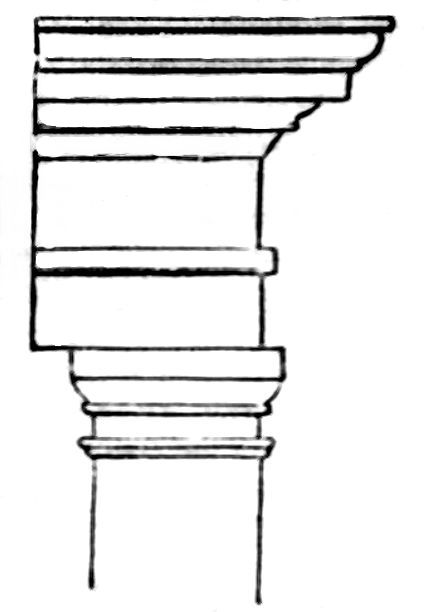

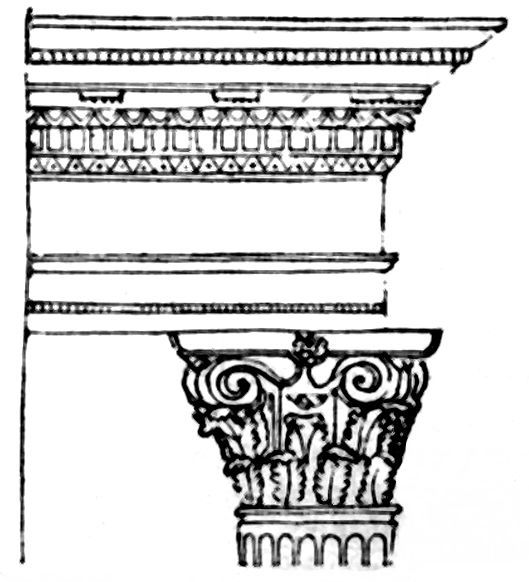

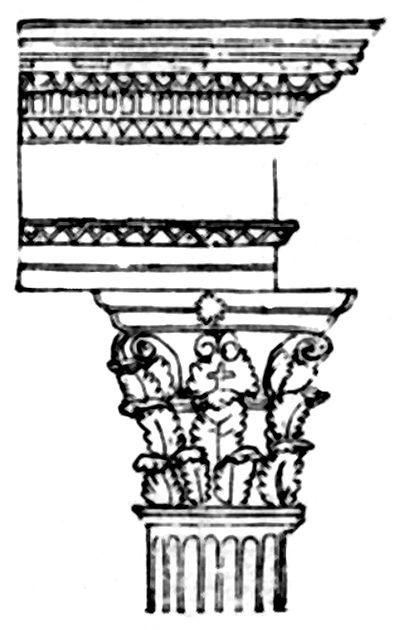

Composite Order, 123

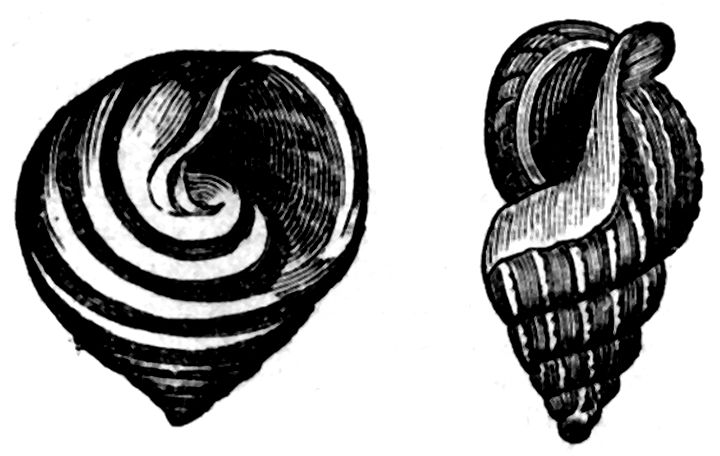

Conchology, 140

Condiments, 146

Cone, 92

Conjunction, 236

Consanguinity, 128

Conversation and Writing, Modes of Address in, 184

Convex Lens, 93

Cookery, Rudiments of, 81

Cooking in a House, to remove the Smell of, 72

Copernicus, 76

Coral, 99

Corinthian Order, 134

Cork, 181

Corns, Cure for, 74

Cornet à Piston, 231

Corundum, 326

Corrosive Sublimate, 32

Cosmetics, 124

Court Plaister, to Make, 259

Crescent, 163

Crests, 131

Cribbage, 372

Cricket, Laws of, 227

Cromwell, Oliver, 166

Crucifixes, 287

Cruth, 232

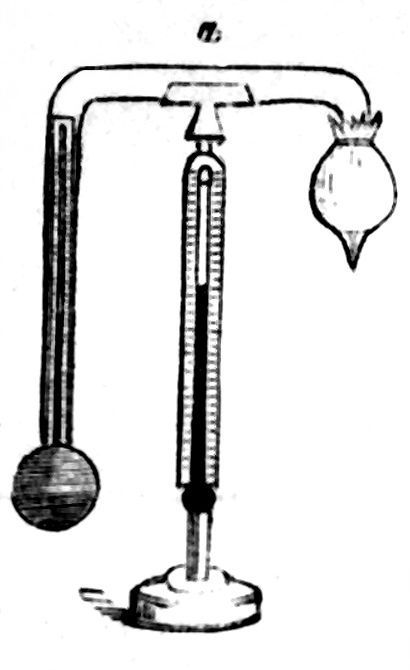

Cryophorus, 38

Crystal, 324

Cubic Measure, 274

Cuckoo, 314

Cucumbers, 131

Cups in Pies, 33

Cutter, 42

Cymbal, or Cymbalum, 282

Dahlia, Cultivation of the, 236

Daisies and Buttercups, 122

Damp Walls, 53

Dandelion, 35

Dante, 256

Day, Division of the, into Hours, 65

Days, Difference of, 177

Days of the Week, Roman names of, 351

Deaf, Axioms for the, 73

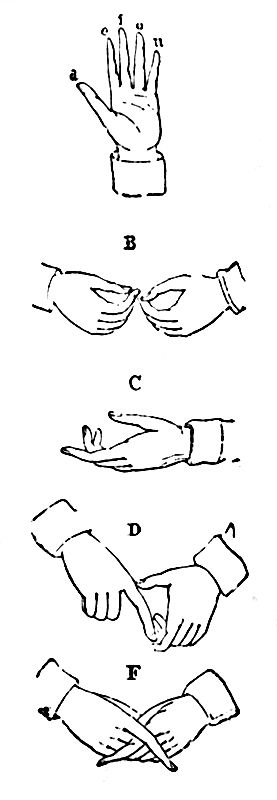

Deaf and Dumb Alphabet, 43

Death Watch, 33

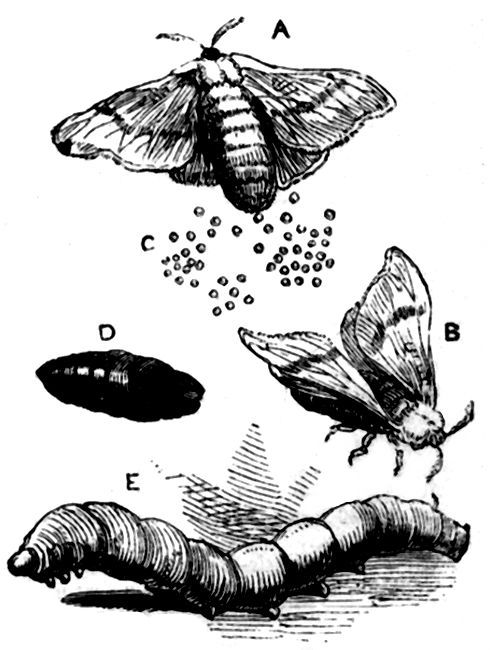

Death’s-Head Hawk-Moth, 194

Decanters, Cleaning, 22

Decanting Liquids, 181

December, 45

Deck, 167

Diadelphia, 140

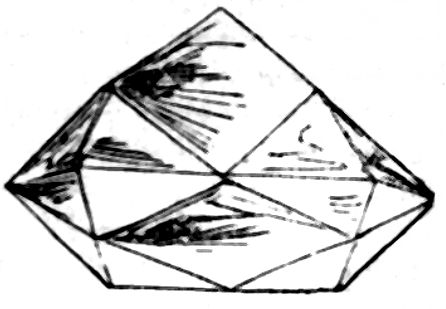

Diamonds, 32

Diamond Beetle, 164

Diana, 164

Diaphanie, 261

Dilettanti, 164

Disinfecting Liquid, 290

Dissolving Views, 242

Distilled Waters, 131

Distillation, 175

Dividing, Powdering, and Grinding, 50

Diving Bell, 163

Dog Days, 106

Dogs, Distemper in, 219

Domesday Book, 112

Door Mats, 34

Doric, 100

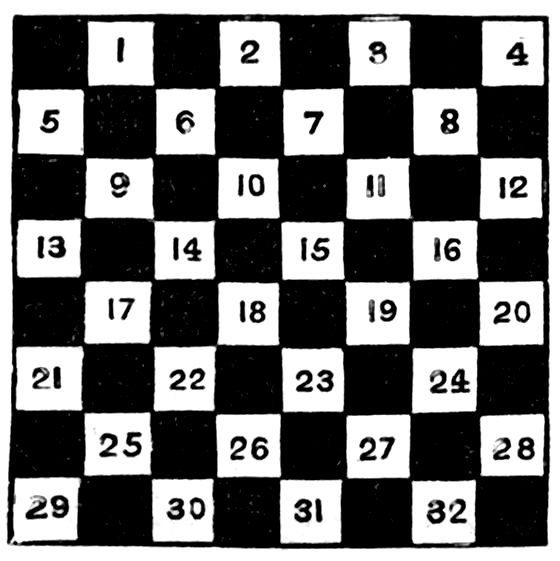

Draughts, 359

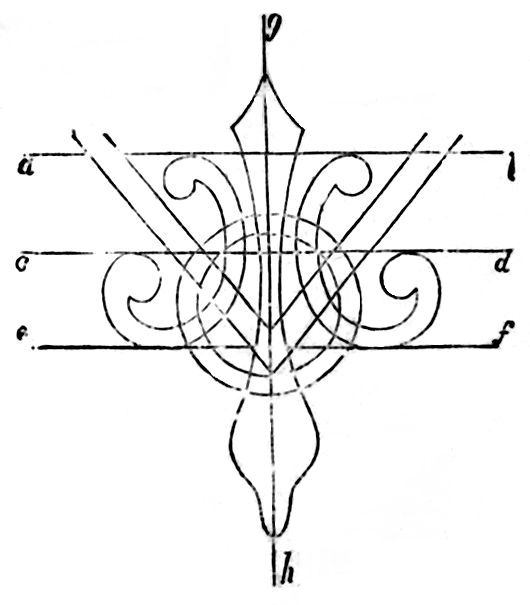

Drawing, Practical Lessons in, 292

Dresden China, 123

Dress, On Proper Taste in, 369

Dresses, to Preserve the Colours of, 253

Dromedary, 104

Drowning and Suffocation, 27

„ , Prevention of, 27

Drum, 232

Dun, 67

Dulcimer, 232

Dry Measure, 274

Dyeing, Art of, 54

Eagle, 284

Early Rising, 143

Earthenware and China, to Clean, 74

Earrings, 123

Earthquakes, 312

East India Company, 112

Easter Sunday, 165

Ebony, 315

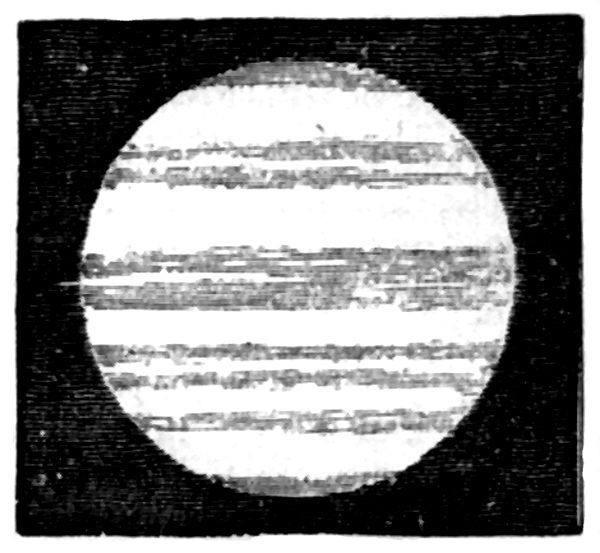

Eclipses and Moons, 211

Eclogue, 290

Eggs, Ornamental, to make, 33

Eggs, to Preserve, 125

Egg Shells, Etching upon, 24

Egyptian Architecture, 101

Elder Flowers, 124

Electric Telegraph, 18

Electricity, 176

„ and Magnetism, 151

Electrotyping, 310

Election Ribbons, 155

Elgin Marbles, 154

Elm, 317

Elm destroying Scolytus, 166

Emblem, 290

Emerald, 325

Emery, 181

Enamels, 66

England, Climate of, 24

Enigma, 128

Epic Poem, 291

Epigram, 290

Epilogue, 291

Epitaph, 290

Epitome, 291

Epode, 291

Esquire, 185

Essence of Flowers, to Extract, 188

Et, 287

Etching upon Ivory, 24

„ Egg Shells, 24

„ Glass, 30

Evaporating Dishes, to Make, 156

Excelsior, 219

Exercises, Indoor, 24

Eye, Substances in the, 25

Eyes, Preservation of the, 282

Faith, 257

Falcon, 170

Farthing, 130

Feathers, to Dye Blue, 260

February, 105

Feet, to remove the Offensive Smell of, 220

Ferguson, James, 286

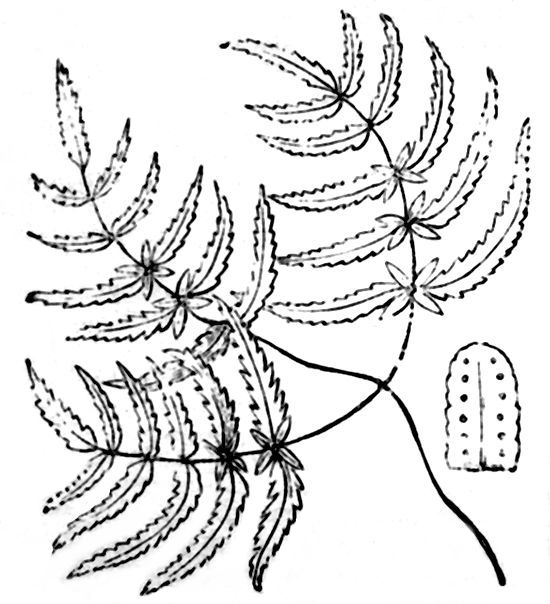

Ferns, 216

Fife, or Fiffars, 231

Fig tree, 187

Figs, 359

Filberts, 359

Filtering Liquids, 181

Filters, 22

Fir, 318

Fire, Precautions in, 25

Fire Ships, 42

Fires, how to Light them, 60

Fish Ponds, 34

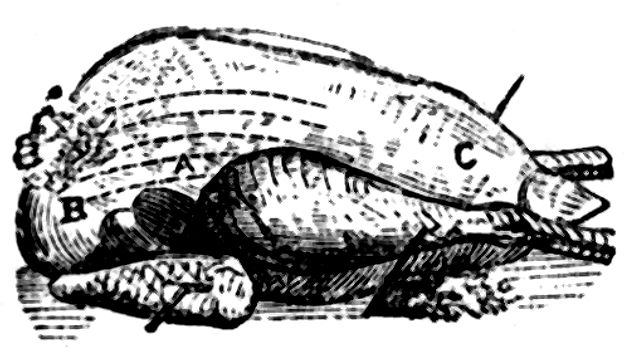

Fish, to Carve, 270

Flannel Shirts, 161

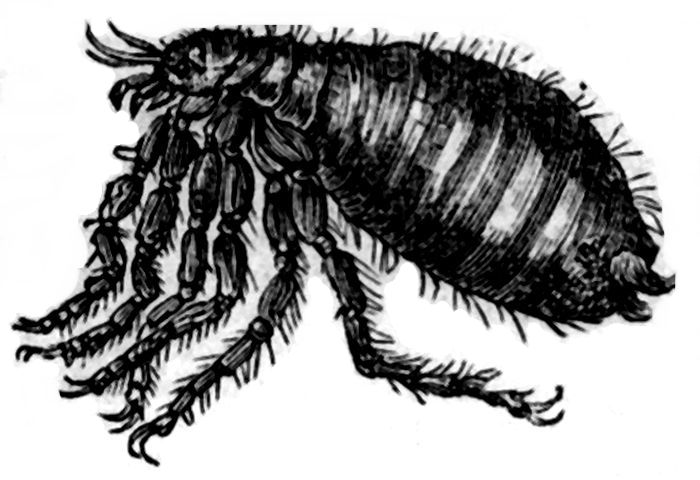

Flea, 366

Flint, or Silex, 340

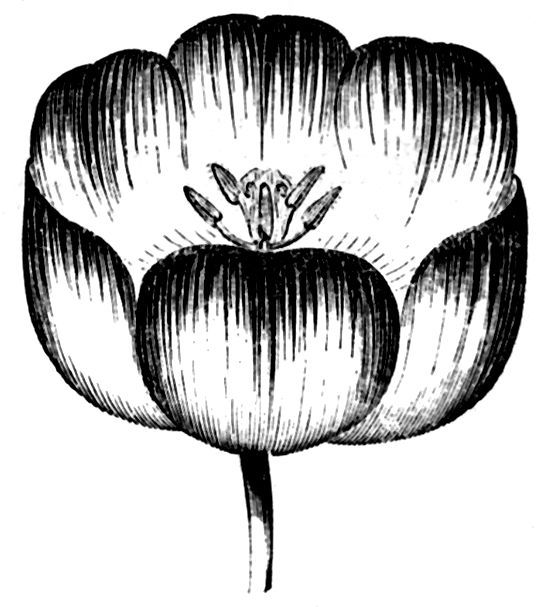

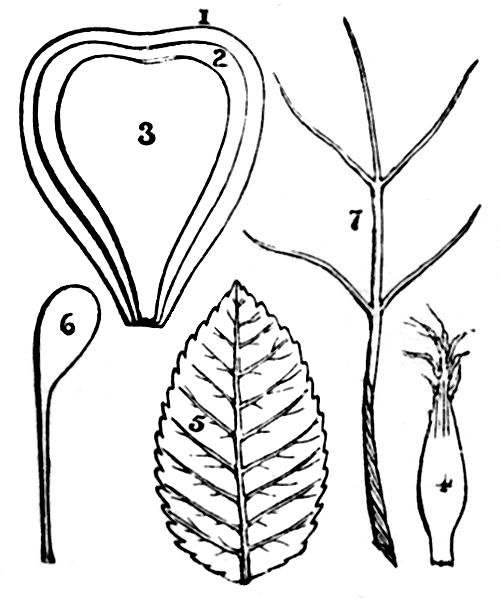

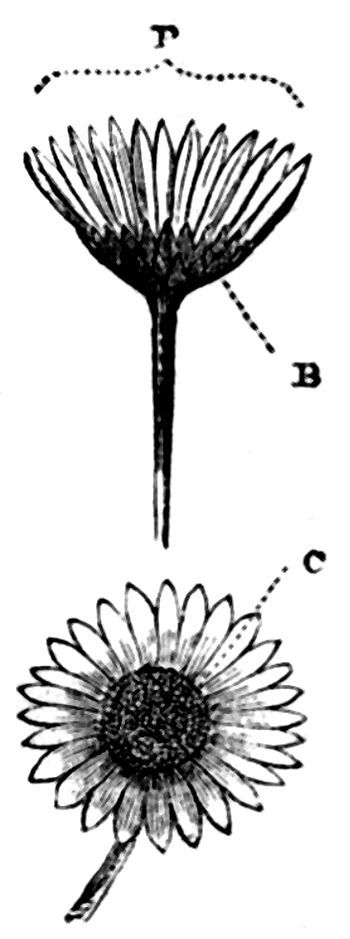

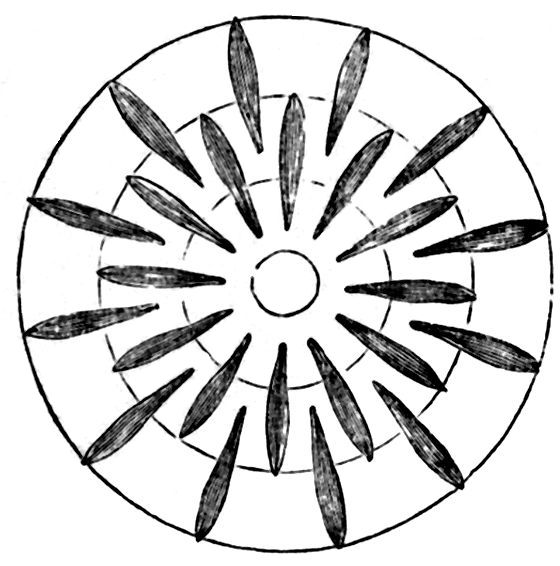

Flower, the, 258

Flowers, Classes of, 188

„ , Language of, 280

„ , Essence of, to Extract, 188

Flute, 232

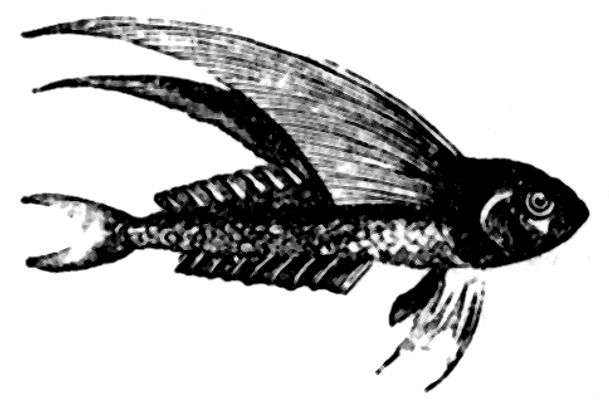

Flying Fish, 167

Food in Season, 35

„ Nutritious, 273

Forces, the Resolution of, 157

Fountain Cheap, How to Make, 131

Fowls, How to Keep, 311

Fox and Geese, Game of, 260

Frankincense, 161

Freckles, to Remove, 101

French Horn, 231

Freestone or Sandstone, 340

Frieze, 314

Frigate, 42

Frog, 100

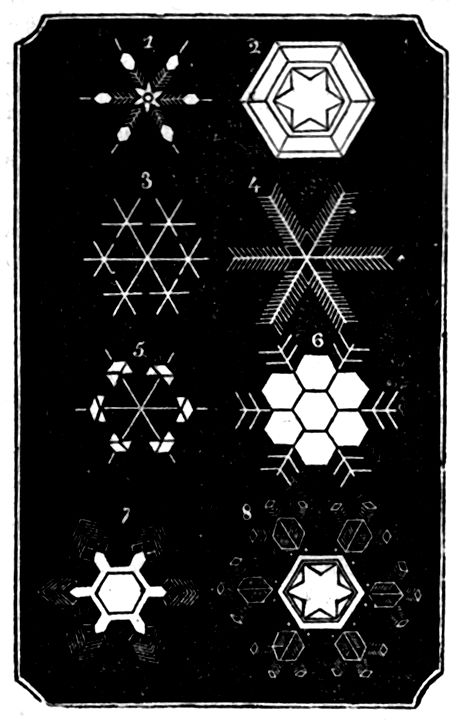

Frost and Snow, 114

Fruit, Best time for Eating, 38

„ , Syrups of, 116

„ , Digestive properties of, 137

„ to Pack for Carriage, 261

Frying, 84

Funnel, to make a, 157

Fur Clothing, 158

Furniture Polish, 254

Fustic, 322

Gall Nuts, 273

Galvanic Battery, 115

„ Coil, 53

Galvanism, 213

Gamboge, 322

Garnet, 326

Gas, 47

„ , Economy of, for Domestic Purposes, 191

Gasometer, 171

Gelatine, 134

Gems and Precious Stones, 324

Gendarmerie, 127

Gentleman, 186

Gipsies, 155

Glaciers, 155

Glass, 307

„ Ware, to Clean, 254

„ to Join, 260

„ or China, to Pack, 253

„ Etching upon, 30

„ Cracking by Hot Water, to Prevent, 168

„ Painting, Transparent, for Windows, 207

„ for using ordinary Engravings on, 263

Glowworm, 155

Glue, Rice, 261

„ , Common, 133

„ , Marine, 133

„ , Liquid, 133

„ , Mouth, 132

„ , to Resist Moisture, 129

Gnats, 31

Gobelin Tapestry, 129

Gold Coins, 275

Gold Wire Leaf, 161

Goldfinch, 109

Gold Fish, 113

Gordian Knot, 151

Grate Papers, Ornamental, to make, 263

Granite, 339

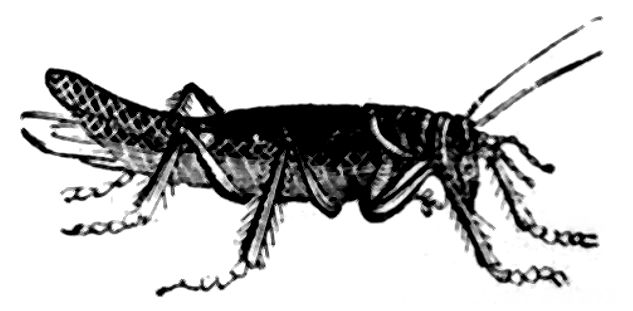

Grasshopper, 170

Gravity, Centre of, 55

Greenwich Observatory, 157

Guaiacum, 316

Guitar, 232

Guillotine, 126

Gum Arabic, 193

Gums and Loose Teeth, to Strengthen and Fasten, 77

Gun Barrels, to Brown, 192

„ , Varnish for, 192

Gunpowder Plot, 285

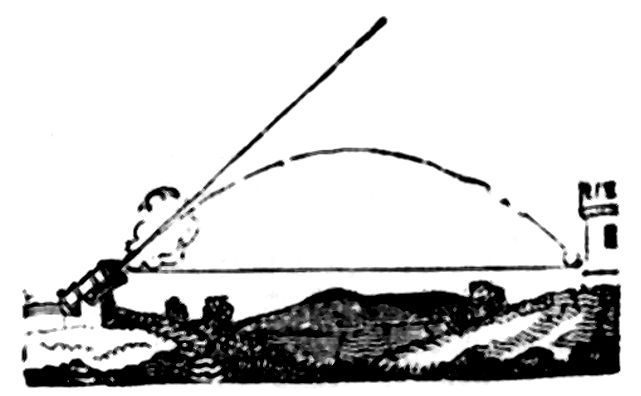

Gunnery, 171

Gutta-Percha Soles, 36

Haberdashers, 140

Hackney Coaches, 159

Hair Oil, 124

„ , Pomatum for the, 124

„ , Dyeing the, 124

„ , Black, to Dye, 125

„ , Brushes, to Wash, 129

„ , Structure of the, 278

„ , Management of the, 280

Hand, 104

Handel, George Frederick, 166

Handkerchief, to Perfume, 47

Hare, to Carve, 273

Harmonium, 230

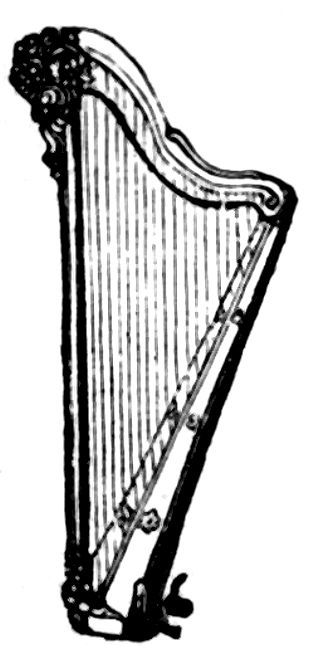

Harp, 230

Harpsichord, 230

Harrow, 104

Harvey, William, 166

Hautboy, 232

Hay Measure, 274

Headache, Cure for, 61

Heat and Cold, 54

Hebrew Alphabet, 307

Heraldry, 67

Hermetic Sealing, 154

Herschel, Sir William, 227

Hidage, 159

Hieroglyphics, 354

Hives, Cottage, 24

„ , Fumigating, 24

Holy Thursday, 196

Holly, 318

Holyrood, Origin of, 146

Hone, 341

Honeymoon, 113

Honey Soap, 209

Horse, 306

Horse Power, 160

Hosiery, 143

Hotchpot, 114

Hotte, 224

Houses, Transposition of, 141

Hour Glass, 147

Hoy, 42

Hulks, 42

Hunter, John, 226

Hurricanes, 198

Hyacinth, 327

Hydrogen, 202

„ Gas, 224

Hygrometers, 29

Icebergs, 307

Impressions, to Copy, 81

Inclined Plane, 186

Indian-Ink, 251

„ Rubber, 324

Indigo, 113

Ink, Black, 125

„ , Blue, 125

„ , Green, 125

„ , Marking, 125

„ , Sympathetic, 88

„ , Invisible, 304

Inorganic, 305

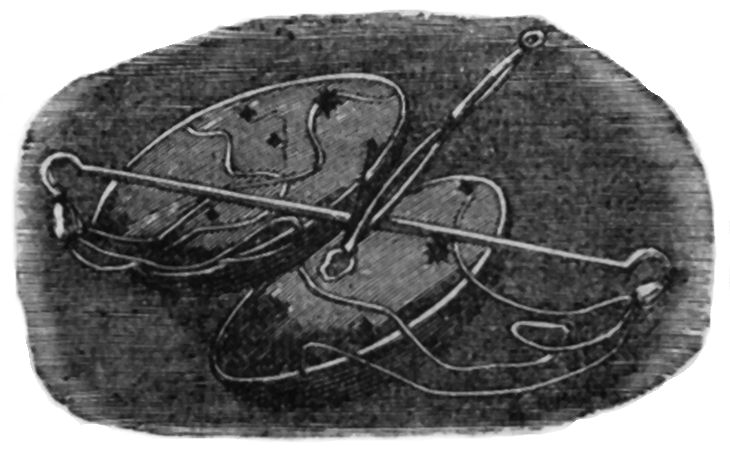

Insect’s Wings, 159

„ , to Prepare for Cabinets, 116

Interest, 116

Interjection, 236

Iodine, 203

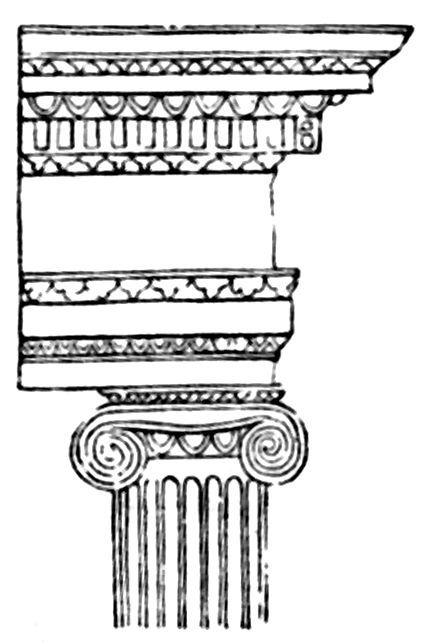

Ionic Order, 111

Isinglass, 169

Ivory, 323

„ , Black, 323

Ivory Etching upon, 24

Lac, 321

Lace, to Wash, 245

Lake or Lacca, 321

Lammas Day, 227

Lamp-Black, 323

„ , to Prevent the Smoking, 131

Land and Sea Breezes, 198

Larch Tree, 318

Laudanum, Antidote for, 31

Laurel, 287

Lavender Water, 221

Leaden Cisterns, to Neutralize the Effects of, 103

Leather, Morocco, 177

Leaves, Functions of, 222

Leech Barometers, 29

Leeches, to make Bite, 113

Lemon, 103

Length, Measures of, 276

Letters, 46

Leyden Jar, 106

Libra, or the Balance, 114

Light, 161

Light House, 187

Lightning Stroke, 23

„ Conductors, 23

Lip Salve, 197

Liquids, Decanting, Straining, and Filtering of, 181

Literary Terms, 290

Lithographic Stones, to Pack, 259

Liveries, 167

Logwood, 315

Long Measure, 274

„ Sight, 104

Lords, Spiritual and Temporal, 169

Lories, 149

Lotteries, 71

Lunar Month, 275

Luther, Martin, 286

Macaws, 148

Madder, 320

Madrigal, 291

Magic Lantern, 104

„ and Dissolving Views, 242

Magnetic Needle, 114

Magna Charta, 197

Magnitude, 365

Mahogany, 316

Mahogany, Artificial, 263

Mamalukes, 238

Mammalia, 177

Man-of-War, 42

Marble, 339

Marble Appearance to Plaster Figures, 100

Marbles, 114

March, 135

Masks, 163

Mast, 211

Massicot, 319

Matter, Divisibility of, 162

May, 195

May-Day Festivities, 195

Measures of Length, Roman, 276

„ Capacity, 276

Medallion Wafers, 151

Medicine, the Nauseous Taste of, Prevented, 51

Medicines, Aperient, 355

Meerschaum, 79

Mensuration, 190

Merchant Ships, 42

Mercury, 101

Metallic Trees, 35

„ Pens, to Prevent Ink Damaging, 210

Michaelmas Day, 256

Micrometer, 158

Microscope, 92

Microscope Glasses, to Clean, 354

Milk, 277

„ of Roses, 124

„ , to Prevent Turning Sour, 103

Mill Stones, 340

Milton, John, 286

Miniatures, to Prepare Ivory for, 160

Mistletoe, 72

Mists, 123

Mite, 216

Mitre, 200

Mnemonics, 219

Models, 189

Mohair, 142

Mole, 314

Monkey, 314

Monsoons, 198

Moon and Eclipses, 211

Month, 192

Morocco Leather, 177

Moss, Formation of, 145

Moth, 221

Mother-of-Pearl, 181

Mule, 284

Muses, the Nine, 140

Mushrooms, to Distinguish from Poisonous Fungi, 49

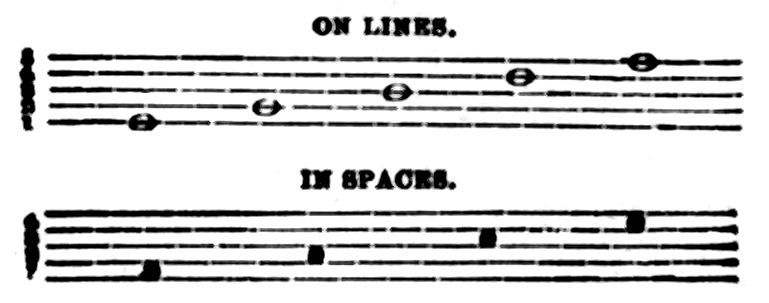

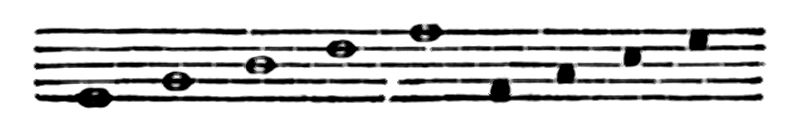

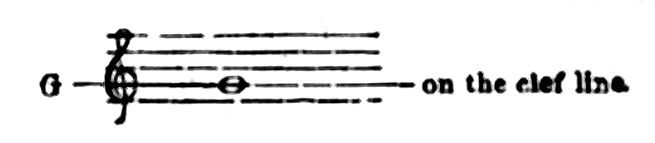

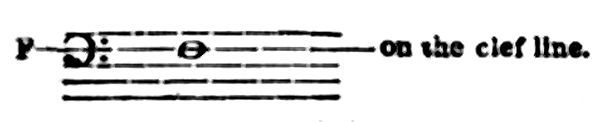

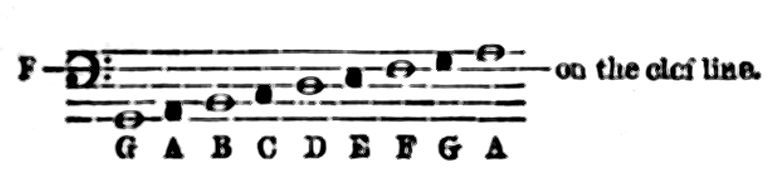

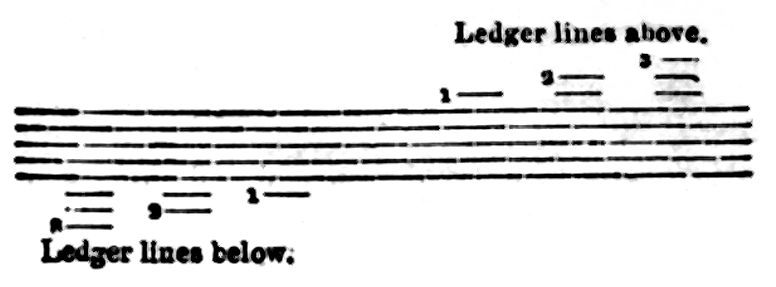

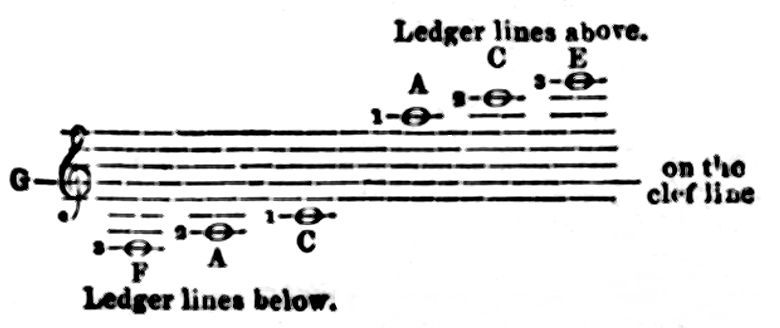

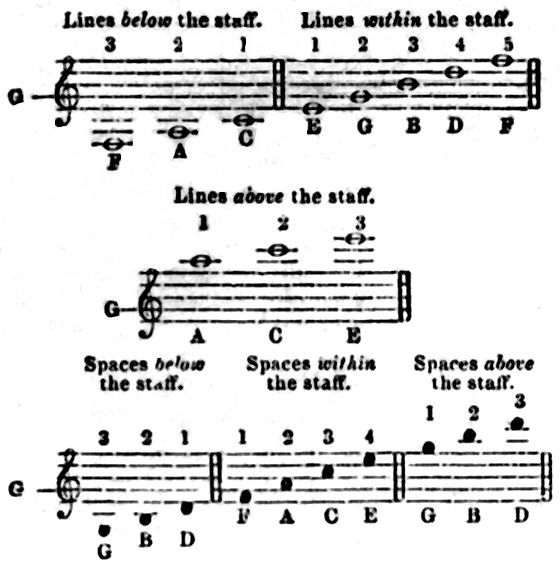

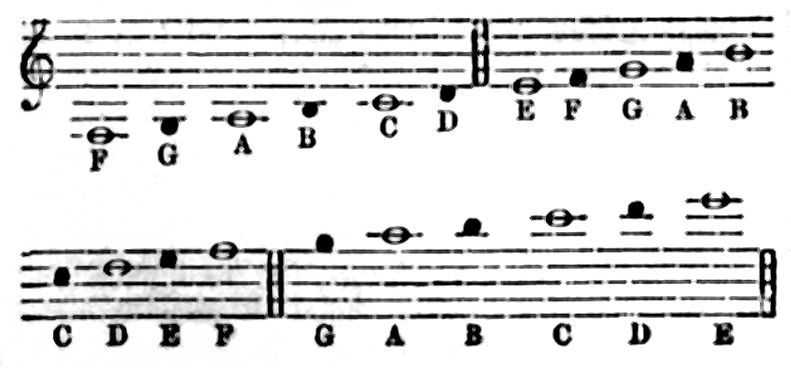

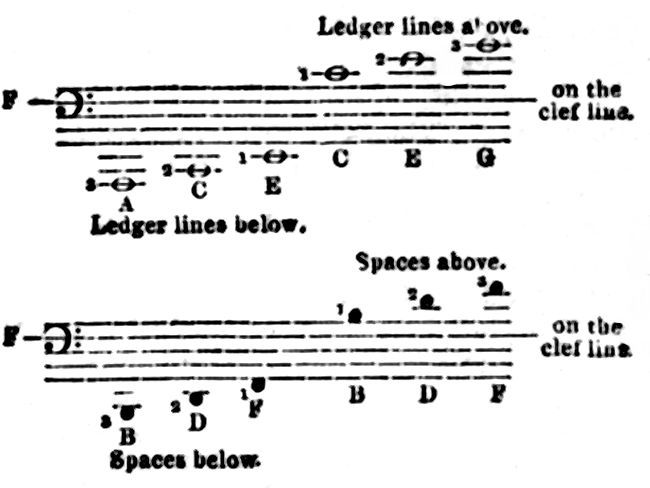

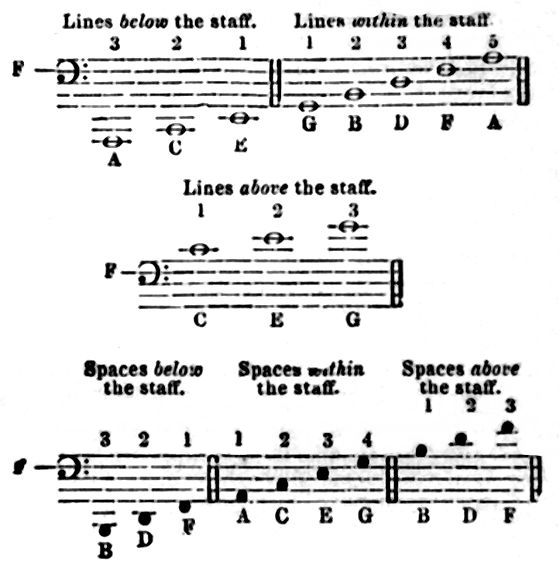

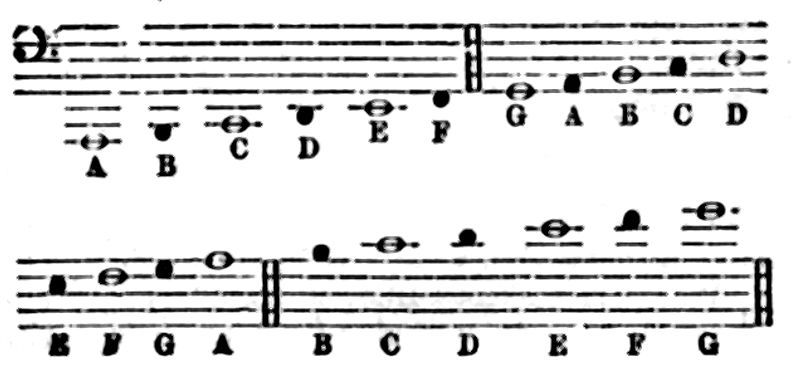

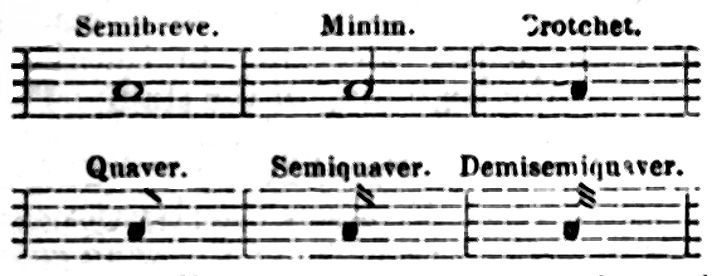

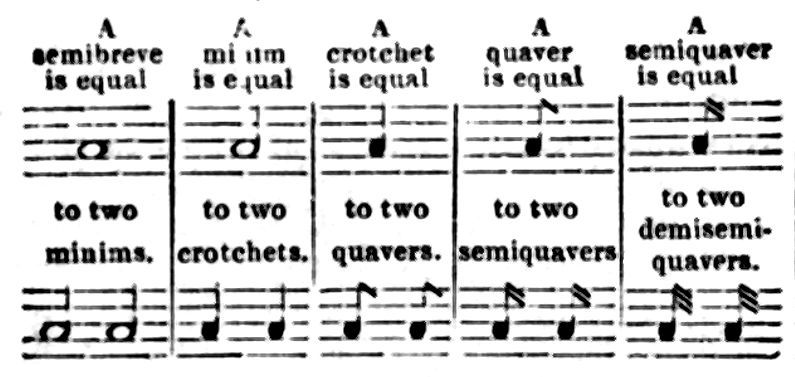

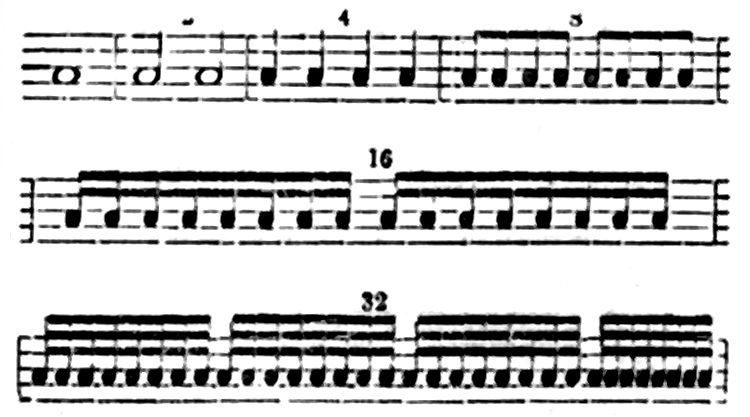

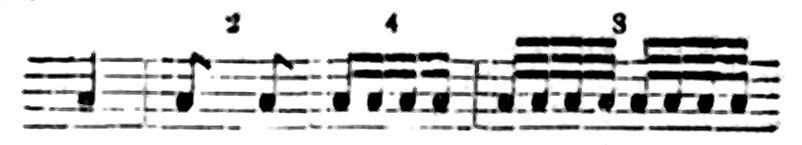

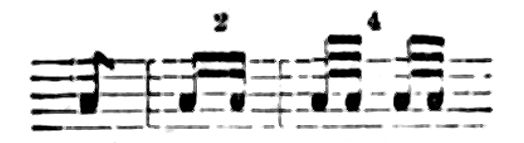

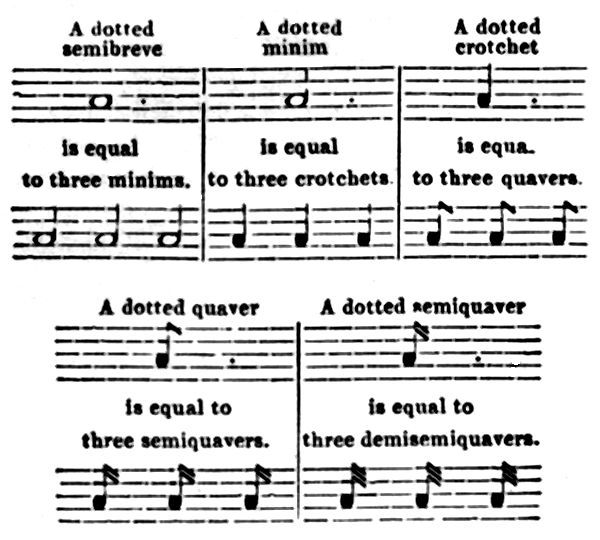

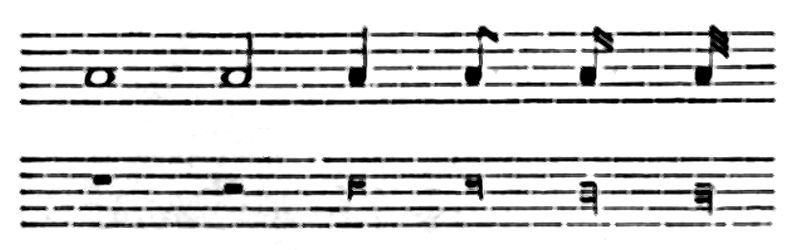

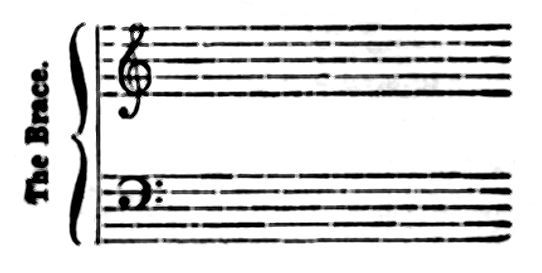

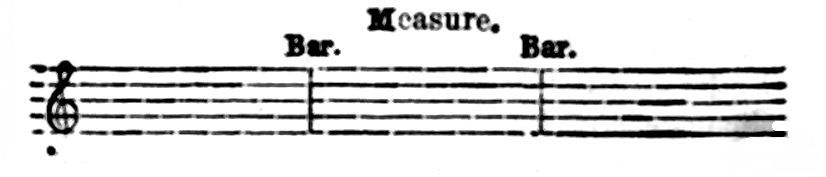

Music, an easy Method of Teaching the Rudiments of, 246

Musical Instruments, 229

„ to Stain, 265

Muslin, Painting upon, 262

„ in Water-Colours, 262

Musk, 142

Nails, Care of the, 85

Names, Christian, 187

Napkins, How to Fold, 173

National Debt, 305

Naval Officers, 48

„ Terms, 48

Necks, Support for Stiff, 25

„ , Swelling in the, 25

Neptune, 187

Net making, 284

Newspapers, 287

New Year’s Day, 75

Nile, Source of the, 128

Nitrogen, 202

Nose, Bleeding at the, 38

Noun, 234

November, 285

Numerals, 310

Nursery Pictures, to Preserve, 365

Nutmeg, 92

Nutritious Food, 273

Oatmeal, 142

Ochre, 323

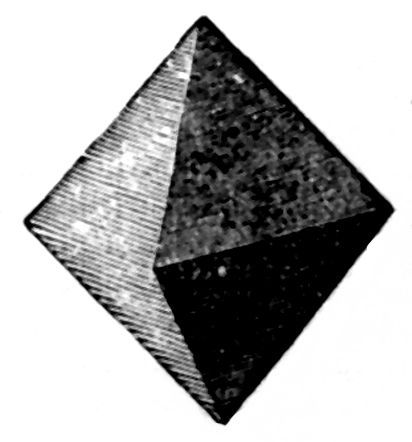

Octahedron, 216

October, 256

Ode, 290

Oil Cloths, to Preserve, 103

Oil Paintings, to Clean, 26

Oleaginous, 304

Onyx, 327

Opal, 327

Optical Effects, 127

„ Illusion, 134

Orange Tree, 93

Organ, 229

„ , Mechanism of an, 204

Ornamental Eggs, 33

Osier, or Willow, 318

Ottoman Empire, the, 151

Ourang Outang, 254

Oxygen, 202

Oyster Grottoes, 117

Paint, to Remove Smell of, 47

„ , to Mix, 274

„ , White House, to make, 266

Paints and Colours, 319

Painting, Oil, 344

„ on Velvet, 143

Paintings, Oil, to Clean, 26

Palm Sunday, 165

Palms, 164

Pan, 284

Paper, 359

Paper Hangings, 189

„ , to Clean, 259

Paper Table, 275

„ , Transparent, 187

Paper into Parchment, How to Make, 314

Papier Maché, 314

Papyrus, 251

Parachute, 134

Parakeets, 149

Parcels in Paper, to Tie up, 16

Parrots, 148

Parts of Speech, 234

Passion Flower, 159

Passing Bell, 189

„ , Permanent, 132

Pastilles, 36

Pawnbrokers’ Signs, 286

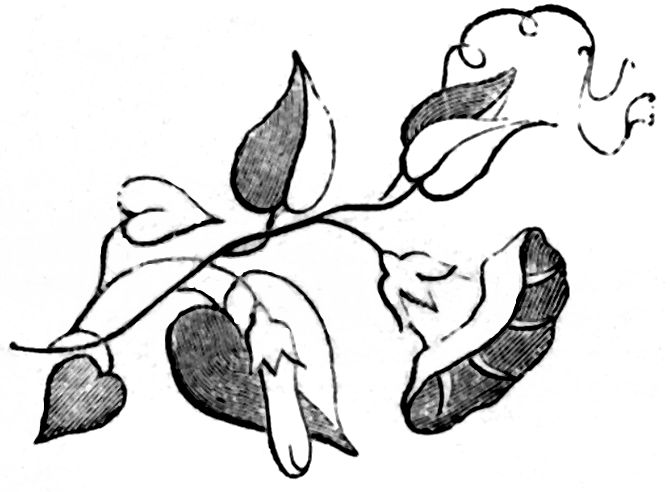

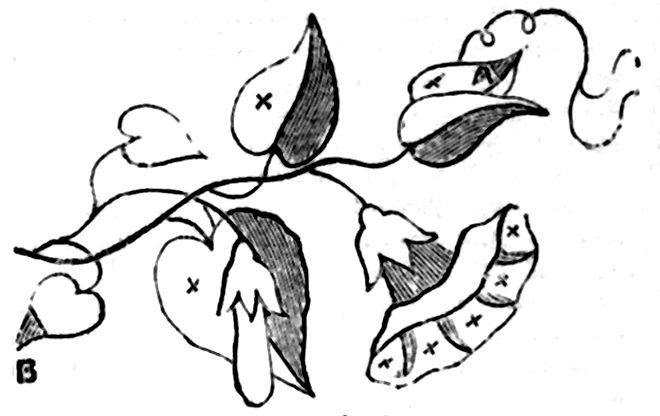

Pea, the, 163

Pearl, 328

Peers, Spiritual, 186

Pencil Marks, to Preserve, 209

Pendulum, 169

Pens, Metallic, 177

Pepper, 126

Phonography, 354

Phosphorus, 203

Photography, 303

Pianoforte, 230

Pies, Cups in, 33

Pigeon Houses, 31

„ Law, 158

Pimples, 103

Pinchbeck, 355

Pindaric, 291

Pine, 318

Pin Money, 66

Plants, Nourishment of, 152

„ , Water for, 251

„ in Cultivation for the Use of Man and Cattle, 336

Plaster Casts, 34

Plate Glass, Discovery of, 307

Plated Ware, 146

Pliers, 254

Pluto, 104

Pneumatic Apparatus, 194

Poetical and Literary Terms, 290

Poisons, Accidents from, 31

Poisonous Vegetables, 31

Police, 378

Polished Iron, to Preserve, 253

Polypi, 93

Pomade for Baldness, 124

Pomatum, White, 124

„ , Colouring and Scenting, 125

Pope’s Hat, 106

Poplar, 317

Porcelain, 65

„ or Glass Ware, to Clean, 254

Pores of the Human Body, 305

Porphyry, 339

Post Office Rates, 39

Postage, Penny, 47

Potatoes, Mealy and Waxy, 181

Potichomanie, 86

Poultice, Bread-and-Water, 49

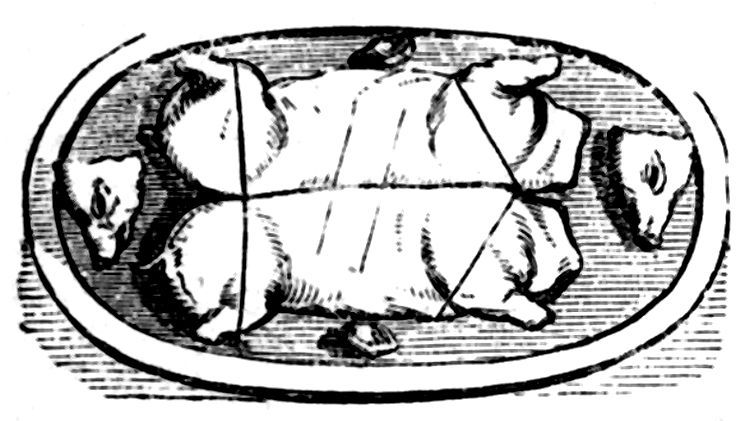

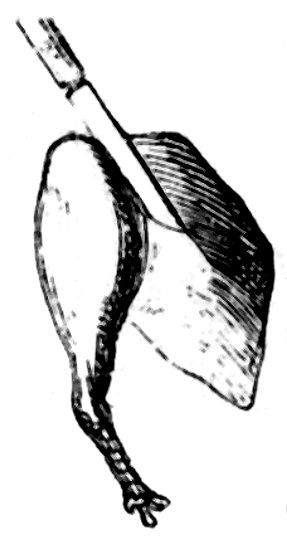

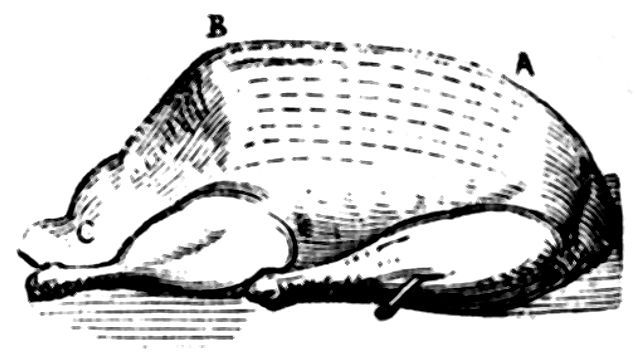

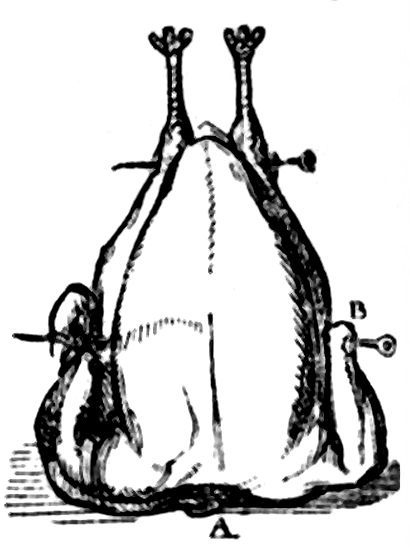

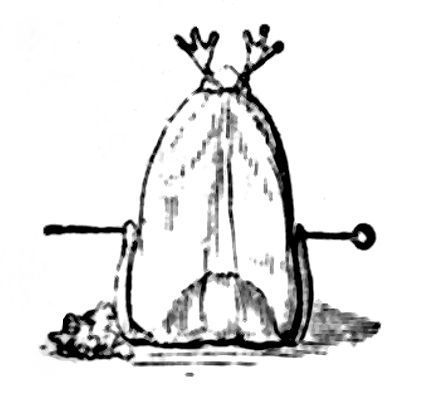

Poultry, to Carve, 271

Pound Sterling, 155

Pounds, Shillings, and Pence, 65

Practical Science, 156

Preposition, 235

Preserves, Covering for, 251

Prints, to transfer to Wood, 154

Prism, 221

Profiles in Black, Method of Taking, 283

Prologue, 291

Pronoun, 235

Proteinaceous, 305

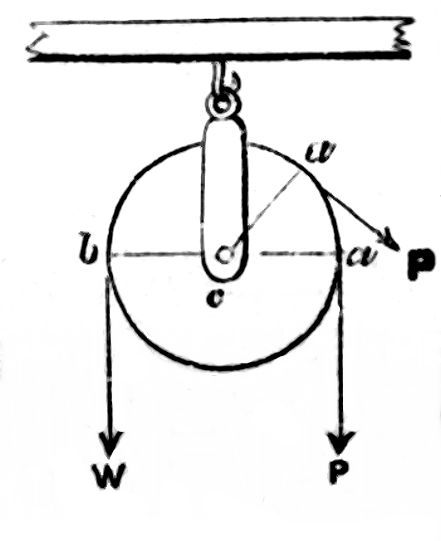

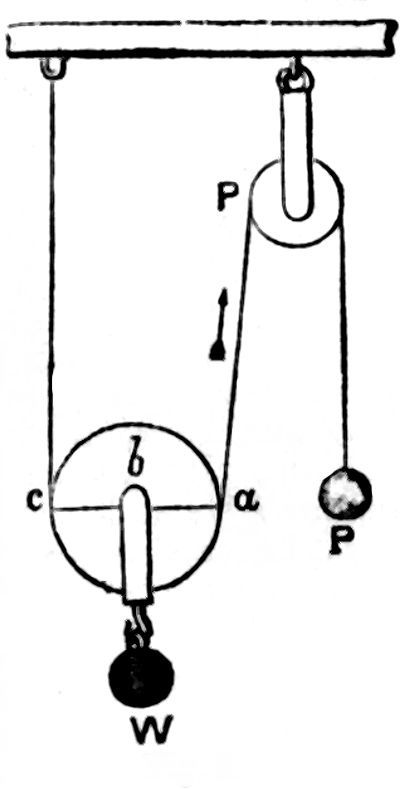

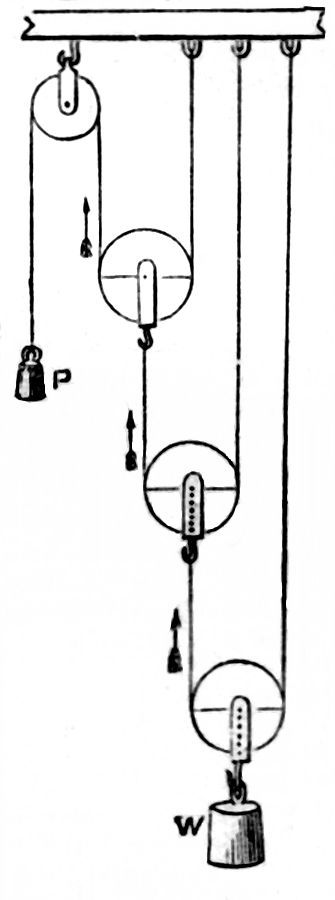

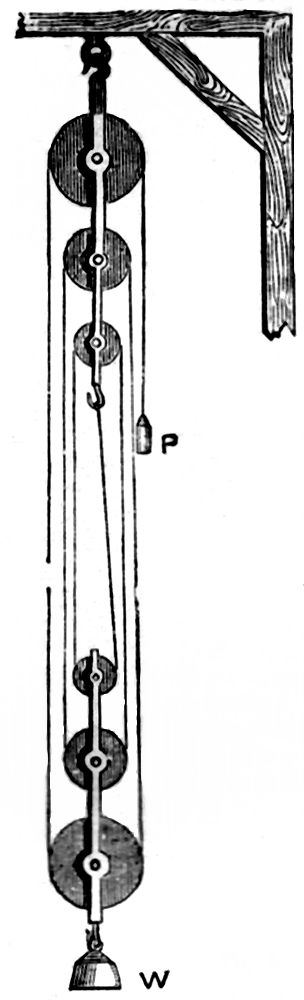

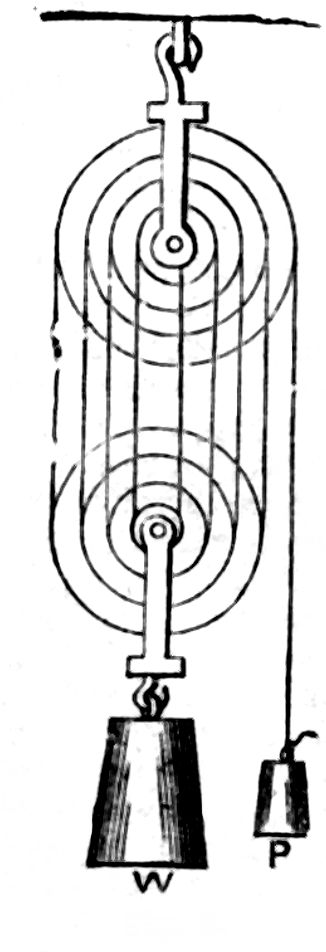

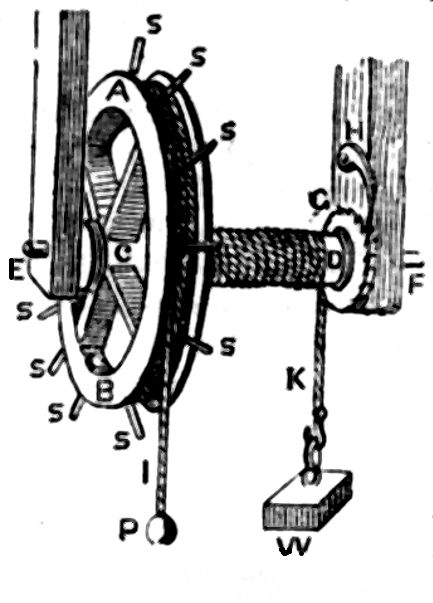

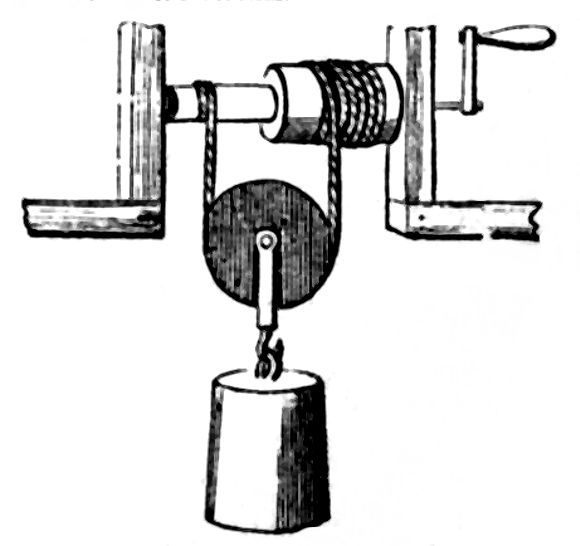

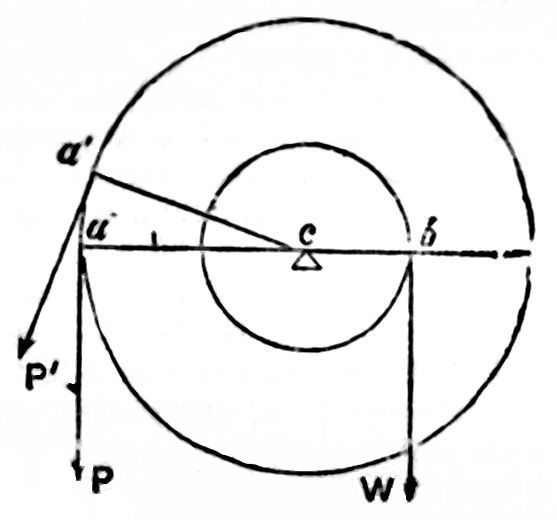

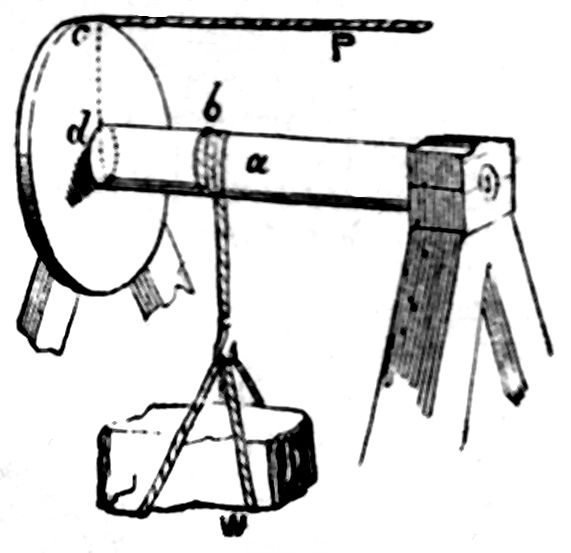

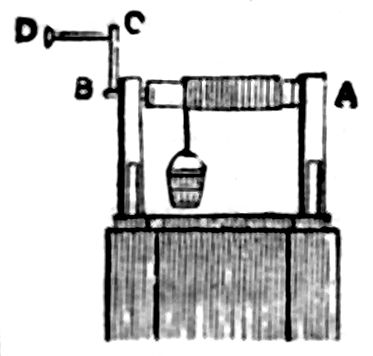

Pulleys, 68

Pumice Stone, 341

Pump, 76

Punctuation, 76

Puzzle, 128

Pyramids, 374

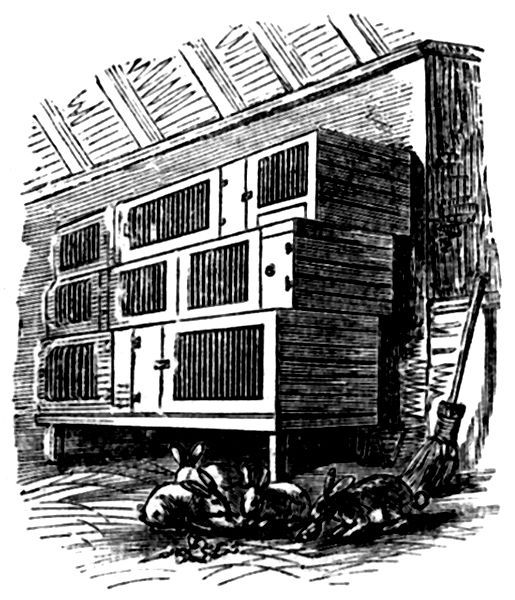

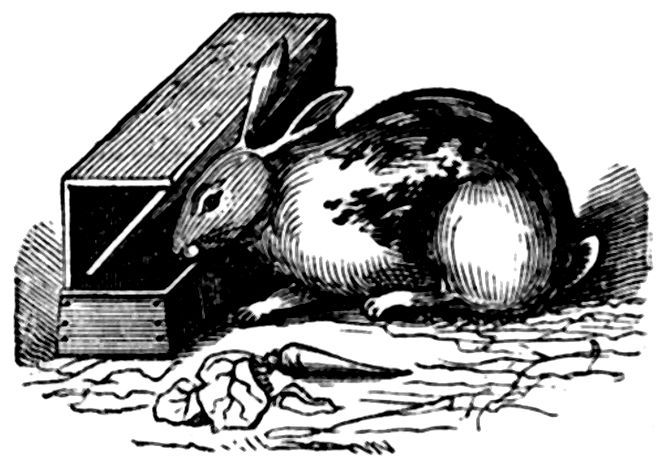

Rabbits, 341

„ , to Carve, 271

Radiated Animals, 115

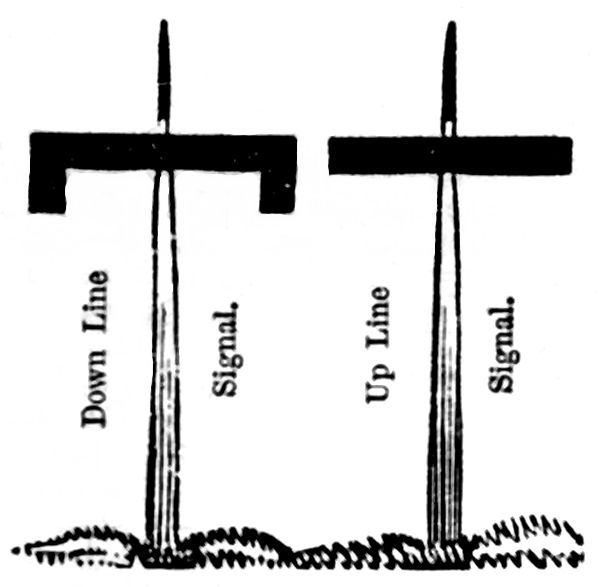

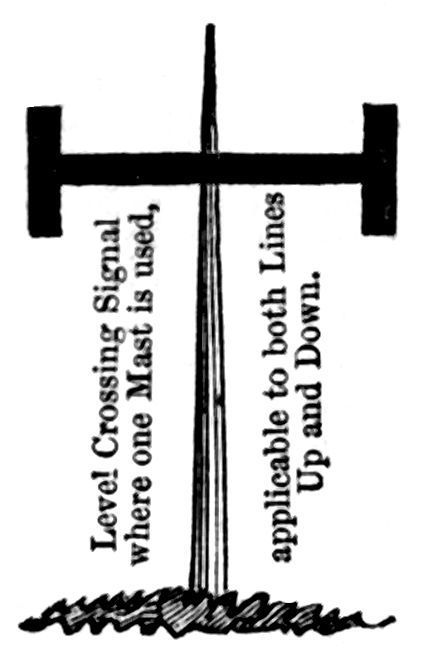

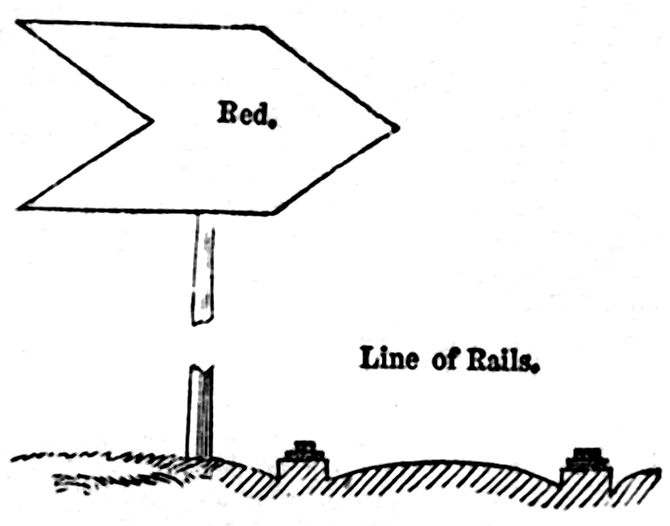

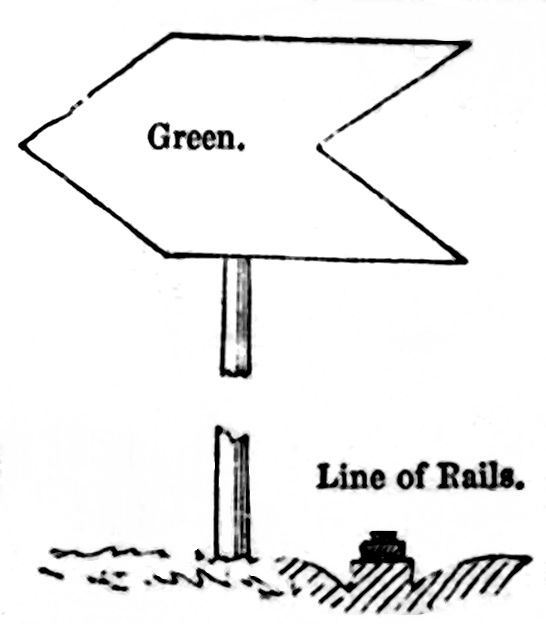

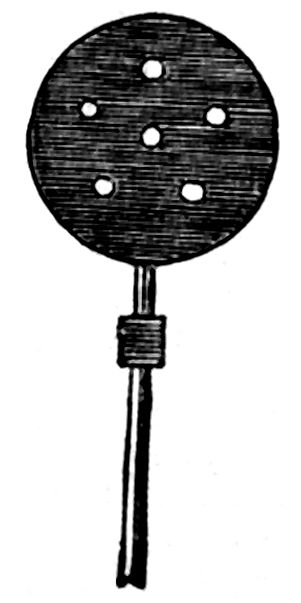

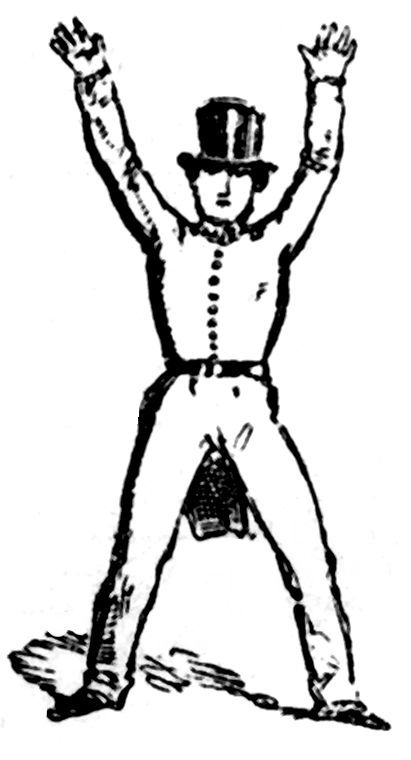

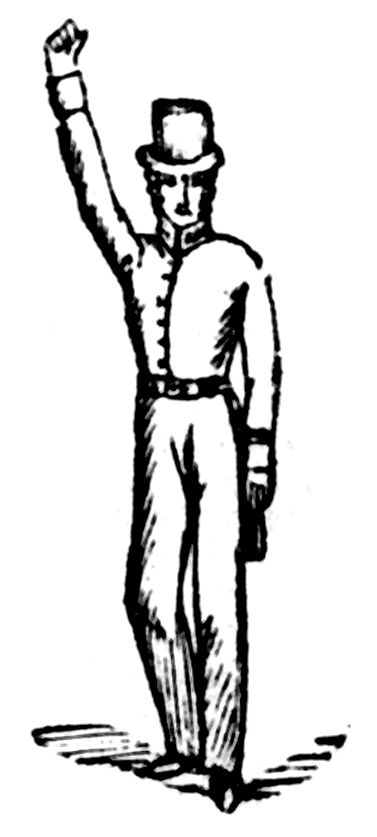

Railway Signals, 88

Rain, 67

„ Water, 163

Rainbow, 217

Raleigh, Sir Walter, 257

Reading Aloud, 140

Rebus, 128

Red, 320

„ Chalk, 321

„ Lead, 319

„ Sealing Wax, to Make, 111

Reef Knots, 15

Respiration, 73

„ , Agents which Increase, 115

Restoration Day, 196

Retort, 216

Reynolds, Sir Joshua, 226

Rice-Paper, to Model in, 146

Riddle, 128

Rigging, 212

Ring Fast on the Finger, 365

Roasting, 83

Rocks, Transition of, 284

Rogation Sunday, 195

Rolling Blinds, 351

Roman Money, Weights, and Measures, 275

Room Papers, to Clean, 259

Roots, 199

„ , Bulbous, 193

Rose of Wood Shavings, to Make, 311

„ Pink, or Rose Lake, 321

Roses, Propagation of, 212

„ , to Restore Faded, 254

Rotten Stone, 111

Royal Mottos, 128

Rubens, Paul, 197

Ruby, 325

Ruddle, or Blood Stone, 323

Sabbath, 77

Saccharine, 305

Sackbut, 233

Safety Lamp, 17

Saffron, 322

Sago, 108

Salamander, 254

Salt Water, to Make Fresh, 28

Sandal Wood, 316

Sap, the, 252

Sapphire, 326

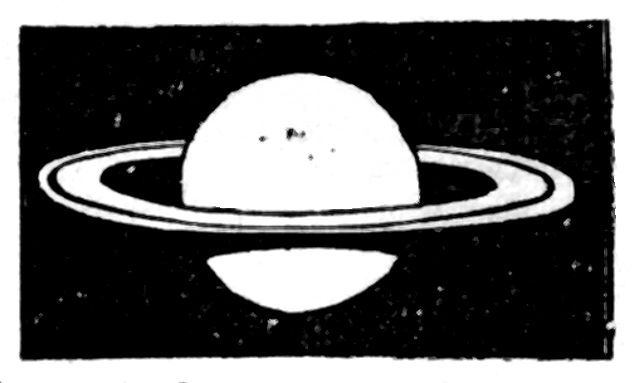

Saturn, 76

Saucepans, Danger from Copper, 85

Savings’ Banks, 167

Scalds and Burns, 41

Scurf Skin on Face, 124

Scent Jar, 151

Scratching out Ink Marks, 365

Scripture, Tables of Weights and Measures mentioned in, 276

Scrubbing Floors, 73

Sealing Wax, Red, 111

Seasons, the, 210

Sea Water, to Make Fit for Washing Linen, 28

„ , to Make Artificial, 28

Sedan Chairs, 169

Seed, 258

September, 255

Serpent, 231

Serpentine, 339

Seven Wonders, the, 211

Shakspeare, William, 166

Shamrock, how it came to be the National Emblem of Ireland, 33

Shaving Soap, 263

Shells, to Polish, 253

Shilling, 142

Ships, Description of, 42

Shirts, to Fold, 284

Shoes, 365

Shop Tickets, Composition for, 131

Shorthand, 307

Shrove Tuesday, 106

Shuttle, 261

Sick-rooms, to Fumigate, 54

Silk, to Keep, 238

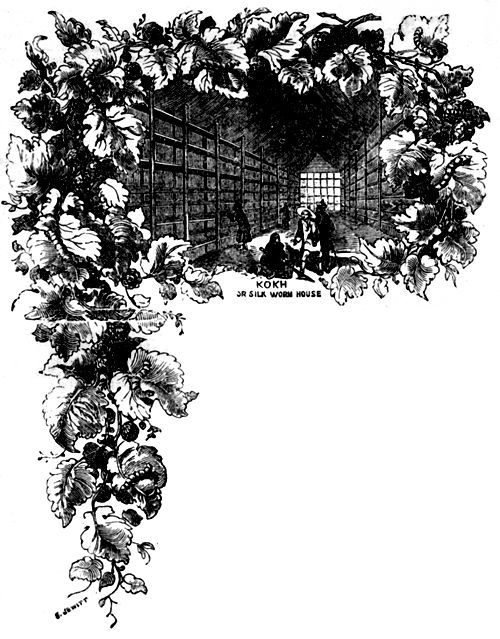

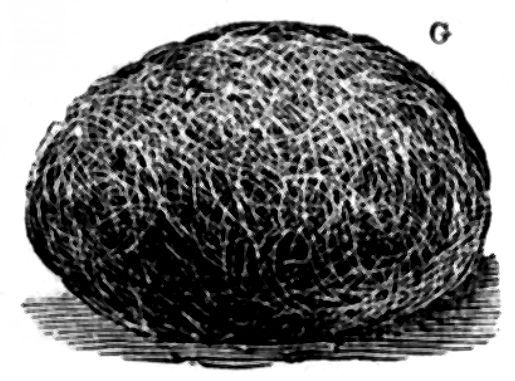

Silkworms and their Products, 239

Silkworms’ Eggs, 129

Silver Coins, 275

Silver Spoons, 365

Simple Bodies, 202

Skin, Olive, to Dye, 124

„ , to Clear a Tanned, 124

„ , Dark Colour of the, 188

Skylark, the, 177

Slate, 340

Sloop, or Shallop, 42

Smacks, 42

Smalt, 320

Snails, 188

Snakes, Bites of, 41

Snow and Frost, 114

Snuff-taking, 147

Soap Bubble, 193

„ , Shaving, 263

Sore Throats, 61

Sound, 93

South Sea Bubble, 74

Spanish Black, 323

„ Brown, 323

Spasms, 131

Spinnet, 230

Spirit Lamp, 156

Squadron, 43

Stains (To Remove From the Hands), 263

Stammering (Cure for), 146

Steam Navigation, 304

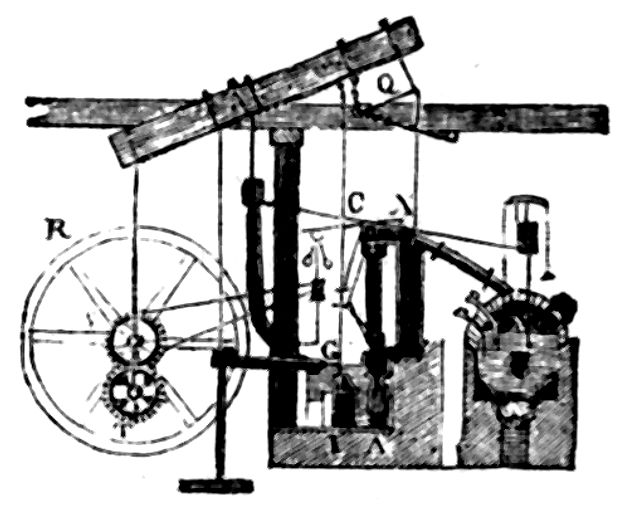

Steam-Engine, 166

Steel (To Preserve from Rust), 92

Steel-Yard, 254

Stems, 221

Stereoscope (The), 375

Stereotyping, 153

Sticking-Plaster, 254

Still, 56

Sting of Bees, 30

Stones, 339

Storm Glasses, 36

Stroke of Lightning, 23

Sub-Rosa, 172

Sumac, 322

Summer, 200

Sunbeams, 158

Sun-Dials, 29

Sunflower, 65

Sun-stroke (Protection Against), 25

Swimming (Safe and Easy Method of), 28

Swimming-Belts, 38

Symbol, 200

Syrups, 116

Tamarinds, 163

Tambourine, 232

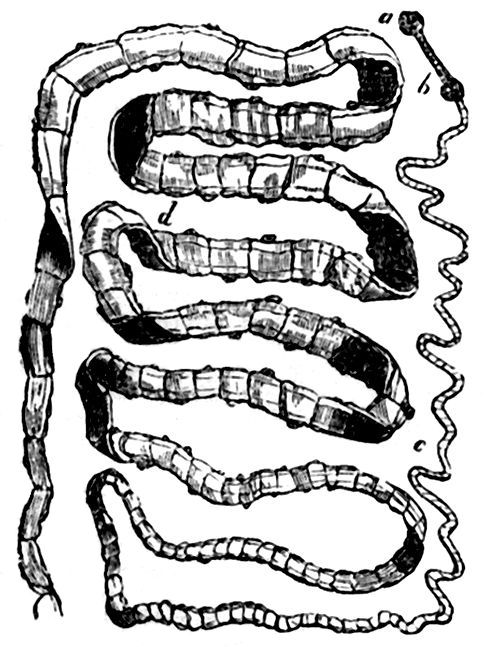

Tape-Worms, 305

Tapioca, 108

Tea (Tea Cream), 102

Tea-Plant, 101

Teasel, 171

Teeth (To Make Them White), 80

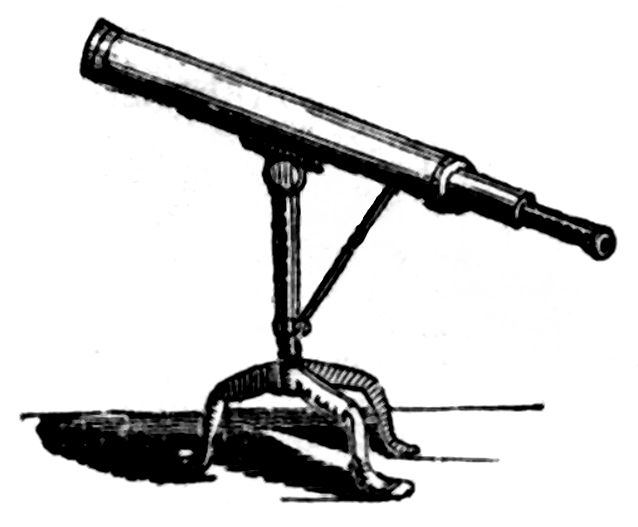

Telescope, 62

Tetrahedron, 166

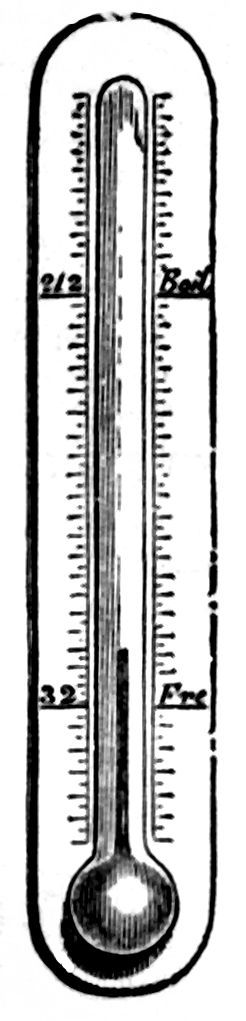

Thermometer, 54

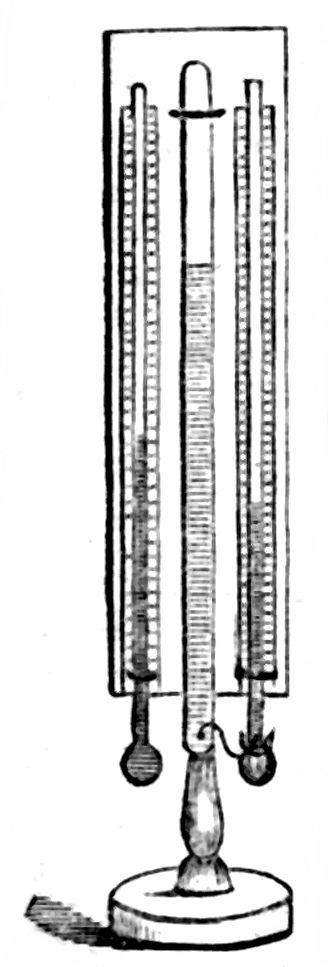

Thermometers for Comparison, 147

Thimbles, 159

Thirst, 143

Thorns (How to Extract), 29

Tides (The), 201

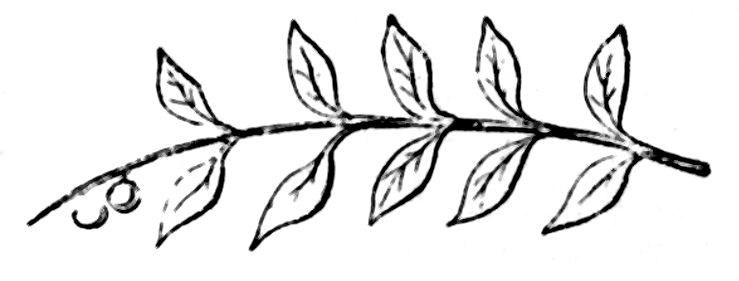

Timber Trees, 317

Time, 62

Tivoli, or Chinese Billiards, 265

Toast and Water, 188

Toothache, 142

Topaz, 325

Tortoise, 261

Tortoiseshell (To Mend), 266

Tracing-Paper, 151

Trance, 187

Transfer Paper (To Make), 266

Transparent Paper, 187

Transplanter (The), 153

Triandria, 221

Triangle (musical instrument), 232

Triangle, 190

Truffle Beetle, 190

Trumpet, 230

Trustee, 284

Tulip (Cultivation of the), 266

Turmeric, 321

Turnpikes, 151

Turpentine, 142

Tuscan, 74

Tying up of Parcels in Paper, 16

Walking, 177

Wallflower, or Gilliflower, 117

Walnut, 317

Warts, 87

Watch, 191

Water (To Determine whether Hard or Soft), 28

Water, 189

Water Gleanings, 28

Water Louse, 251

Waterproofing Boots and Shoes, 33

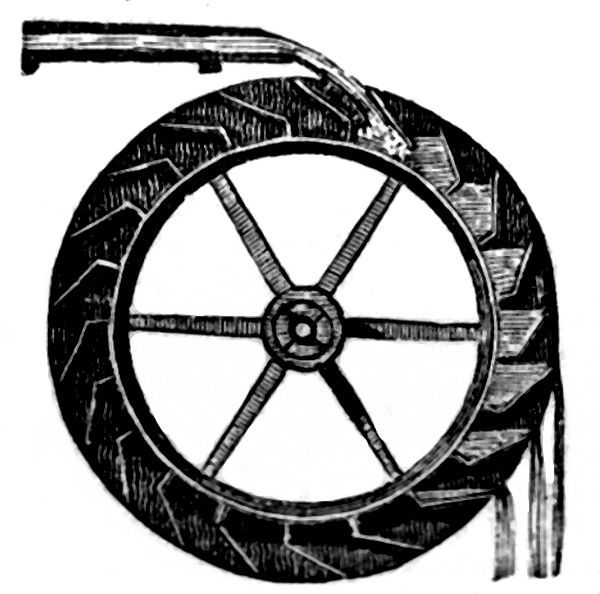

Water-Wheel (Overshot), 74

Water-Wheel (Undershot), 224

Wax and Wafers, 193

Waxen Flowers and Fruit, 329

Wedding Ring, 161

Wedding Rings (Origin of), 142

Wedding-Ring Finger, 169

Wedge, 26

Weeds (Utility of), 365

Weights and Measures, 274

Weld, 322

Whey, 221

Whist, 361

White House-Paint (To Make Economical), 266

White Lead, 319

Wills, 46

Windlass, 73

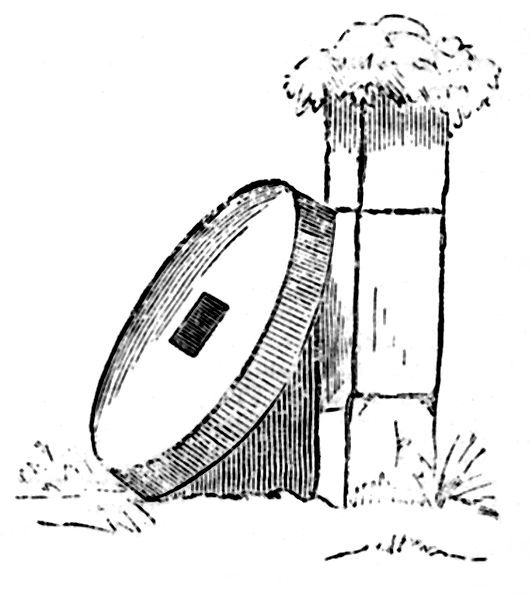

Windmill, 194

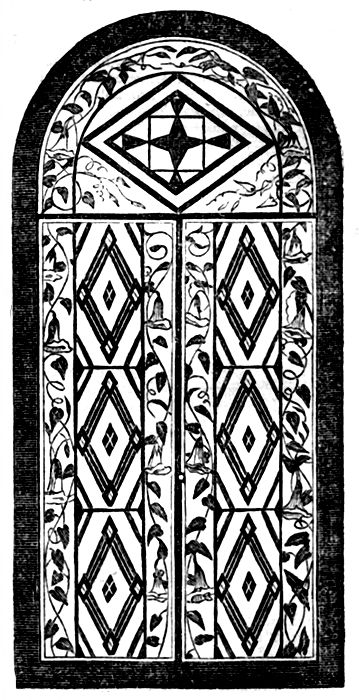

Windows (To Paint to Resemble Stained Glass), 172

Winds, 197

Wine (How to Choose), 188

Winter, 200

Woad, 319

Wood (To Give a Fine Black Colour to), 253

Woods (Fine, etc.), 315

Writing, 224

Writing and Conversation (Modes of Address in), 184

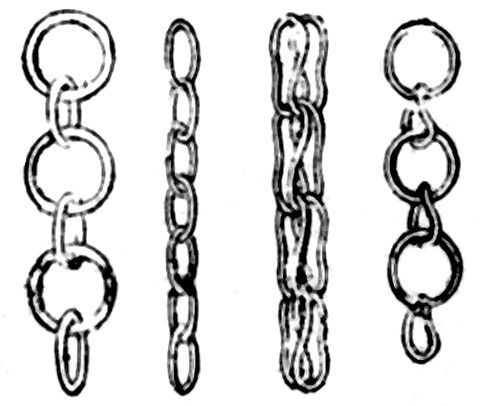

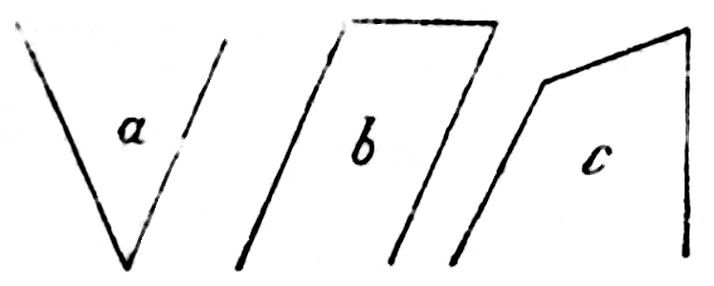

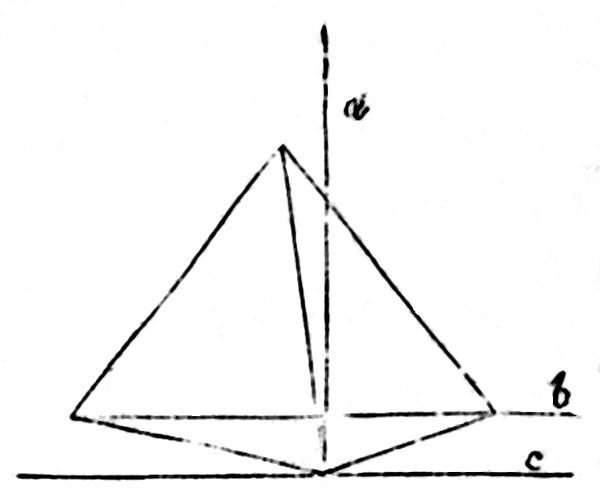

KNOTS. The most simple purpose for which a knot is required, is the fastening together of two pieces of string or cord: the knot selected for this purpose should possess two important properties;—it should be secure from slipping, and of small size. Nothing is more common than to see two cords attached together in a manner similar to that shown in Fig. 1. It is scarcely possible to imagine a worse knot; it is large and clumsy, and as the cords do not mutually press each other, it is certain to slip if pulled with any great force.

Fig. 1.

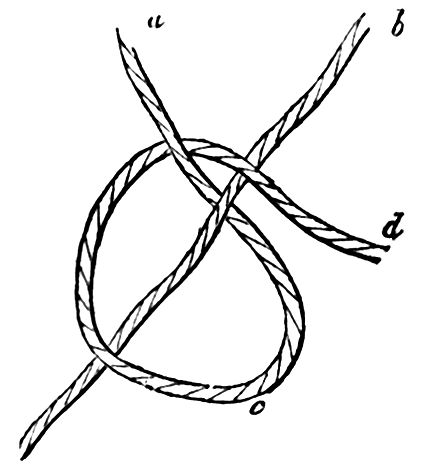

In striking contrast to this—the worst of all, we place one of the best; namely, the knot usually employed by netters, and which is called by sailors “the sheet-bend.” It is readily made by bending one of the pieces of cord into a loop (a b, Fig. 2),

Fig. 2.

which is to be held between the finger and thumb of the left hand; the other cord c is passed through the loop from the farther side, then round behind the two legs of the loop, and lastly, under itself, the loose end coming out at d. In the smallness of its size, and the firmness with which the various parts grip together, this knot surpasses every other: it can, moreover, be tied readily when one of the pieces, viz., a b, is exceedingly short, in common stout twine less than an inch being sufficient to form the loop. Of the knot, Fig. 2 is the simplest method to describe, although not the most rapid in practice; as it may be made in much less time by crossing the two ends of cord (a b, Fig. 3) on the tip of the forefinger of the left hand, and holding them firmly by the left thumb, which covers the crossing; then the part c is to be wound round the thumb in a loop, as shown in the figure, and passed between the two ends, behind a and before b; the knot is completed by turning the end b downwards in front of d, passing it through the loop, securing it under the left thumb, and tightening the whole by pulling d. As formed in this mode, it is more rapidly made than almost any other knot; and, as before stated, it excels all in security and compactness, so firmly do the various turns grip each other, that after having been tightly pulled, it is very difficult to untie.

Fig. 3.

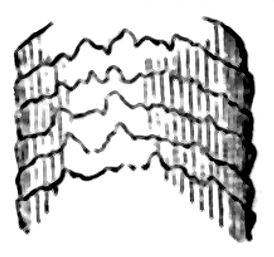

Reef-Knots. The only precaution necessary in making a reef-knot is, to observe that the two parts of each string are on the same side of the loop; if they are not, the ends (and the bows, if any are formed) are at right angles to the cords; the knot is less secure, and is termed by sailors a granny-knot. Other knots are occasionally used to connect two cords, but it is unnecessary here to describe them, as every useful purpose may be answered by those already mentioned.

Fig. 4.

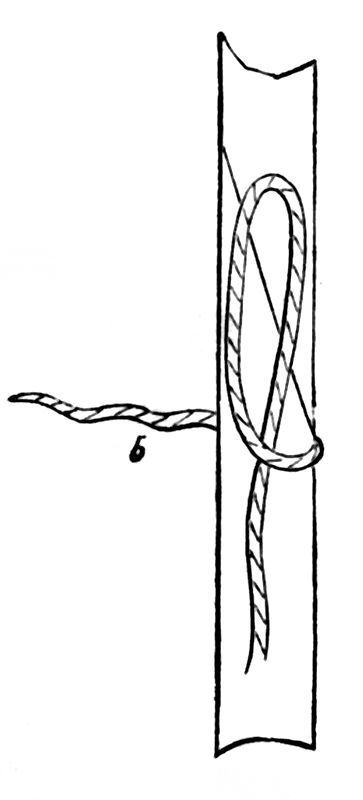

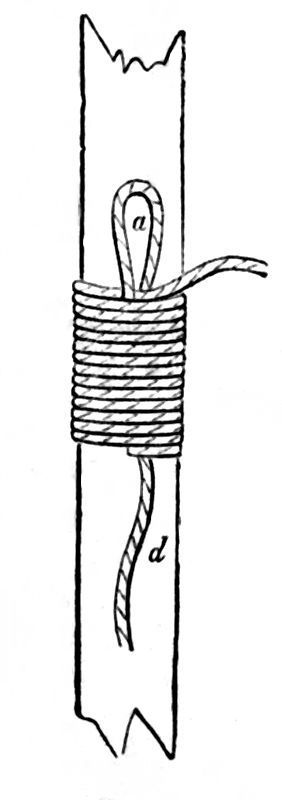

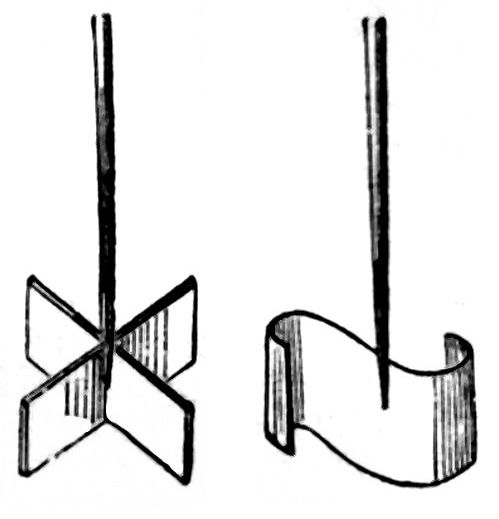

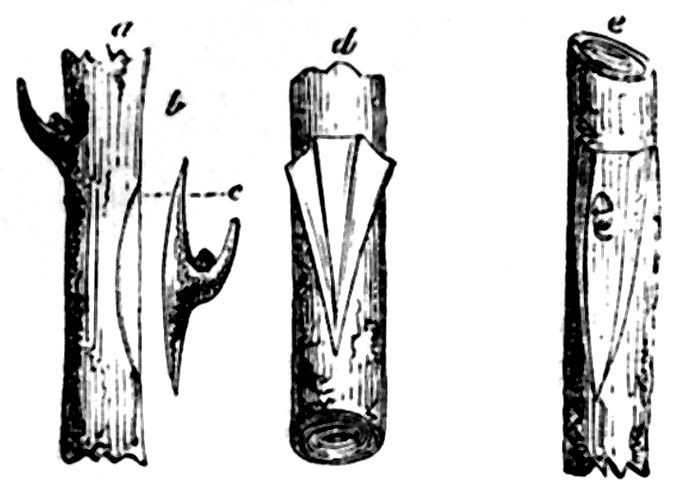

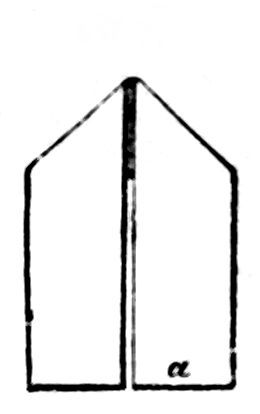

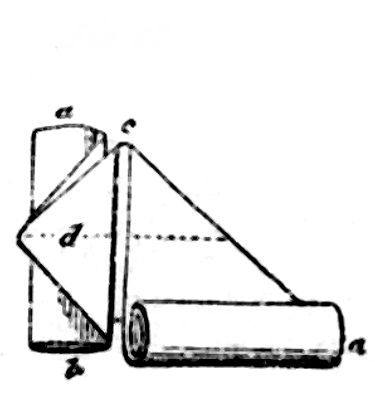

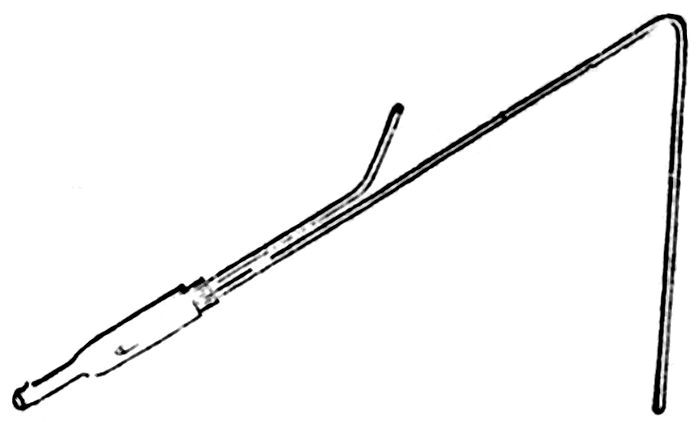

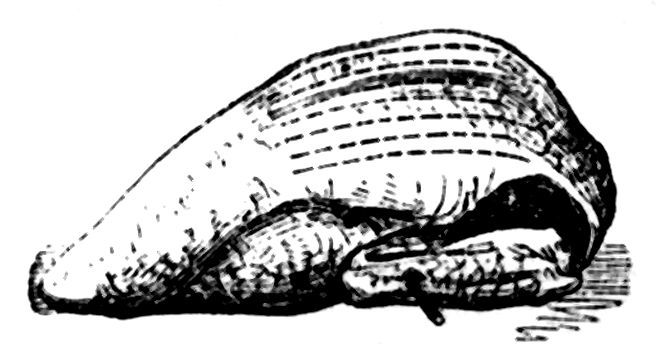

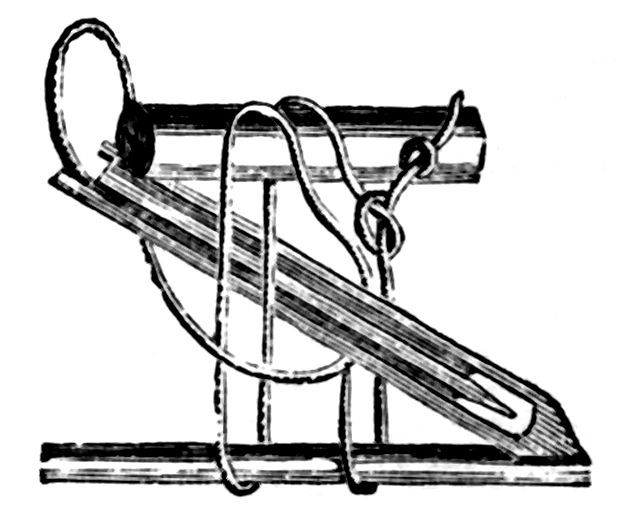

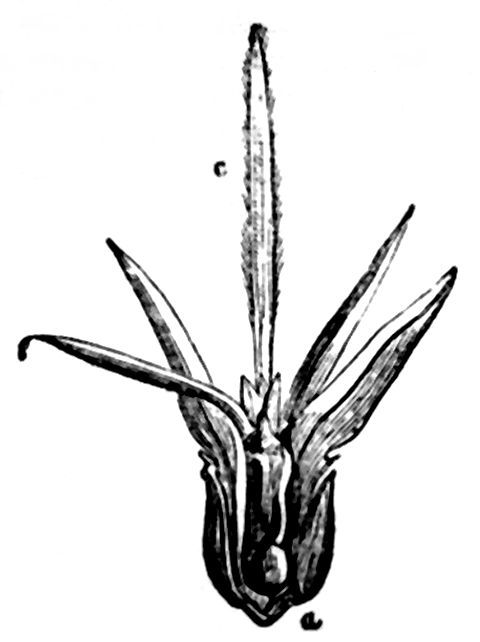

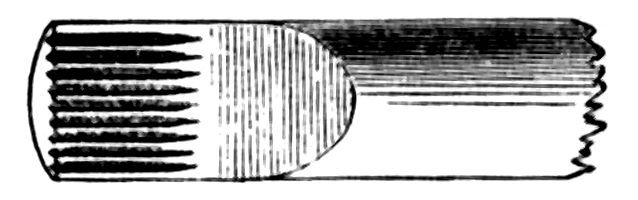

The Binding-Knots (Figs. 5 and 6) are exceedingly useful in connecting broken sticks, rods, &c., but some difficulty is often experienced in fastening it at the finish; if, however, the string is placed over the part to be united, as shown in Fig. 5, and the long end b, used to bind around the rod, and finally passed through the loop a, as shown in Fig. 6, it is readily secured by pulling d, when the loop is drawn in, and fastens the end of the cord.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

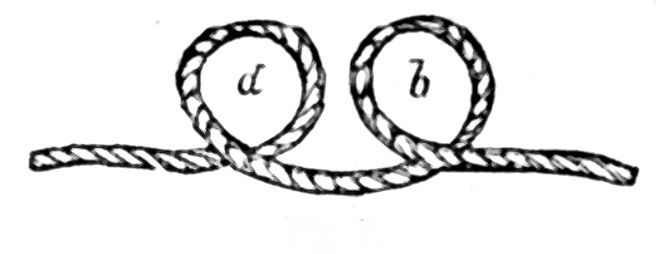

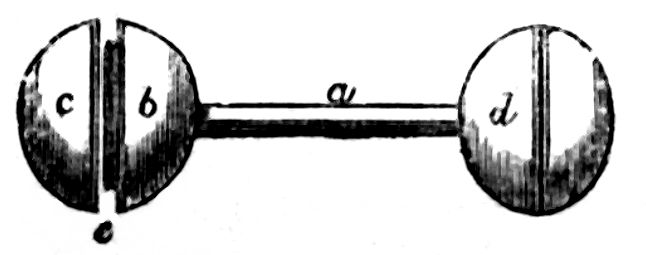

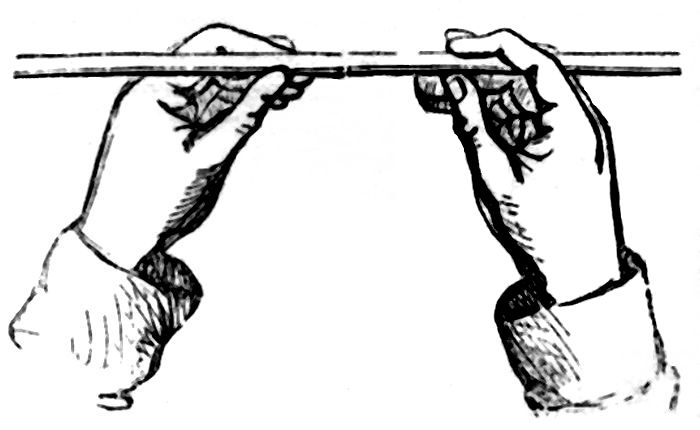

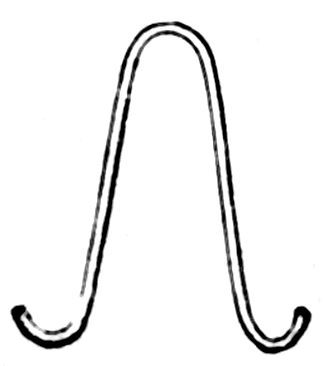

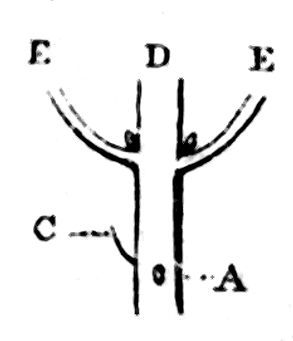

The Clove-Hitch Knot. For fastening a cord to any cylindrical object, one of the most useful knots is the clove hitch, which although exceedingly simple and most easily made, is one of the most puzzling knots to the uninitiated. There are several modes of forming it, the most simple being perhaps as follows:—make two loops, precisely similar in every respect as a and b, Fig. 7, then bring b in front of a, so as to make both loops correspond, and pass them over the object to be tied, tightening the ends; if this is properly done, the knot will not slip, although surrounding a tolerably smooth cylindrical object, as a pillar, pole, &c.

Fig. 7.

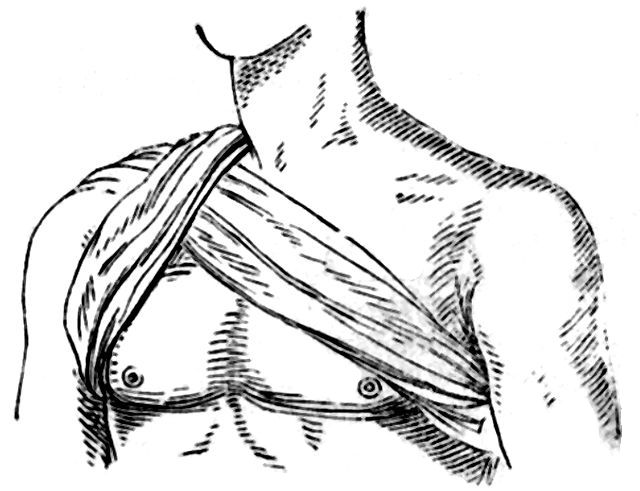

This knot is employed by surgeons in reducing dislocations of the last joint of the thumb, and by sailors in great part of the standing rigging. The loop which is formed when a cable is passed around a post or tree to secure a vessel near shore, is fastened by what sailors term two half hitches, which is simply a clove hitch made by the end of the rope which is passed around the post or tree, and then made to describe the clove hitch around that part of itself which is tightly strained.

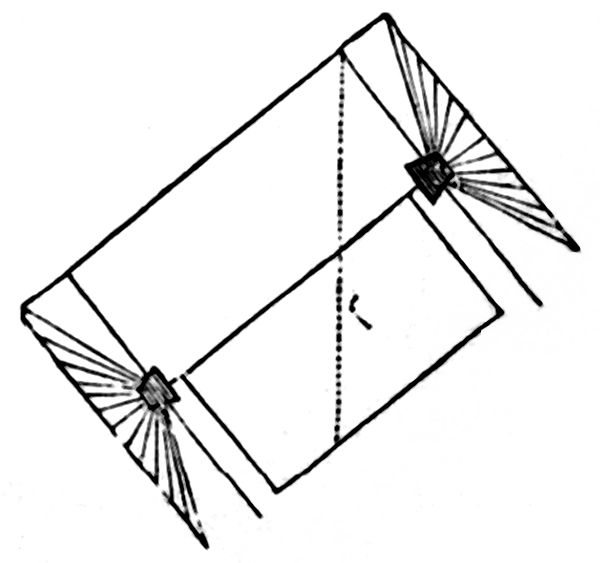

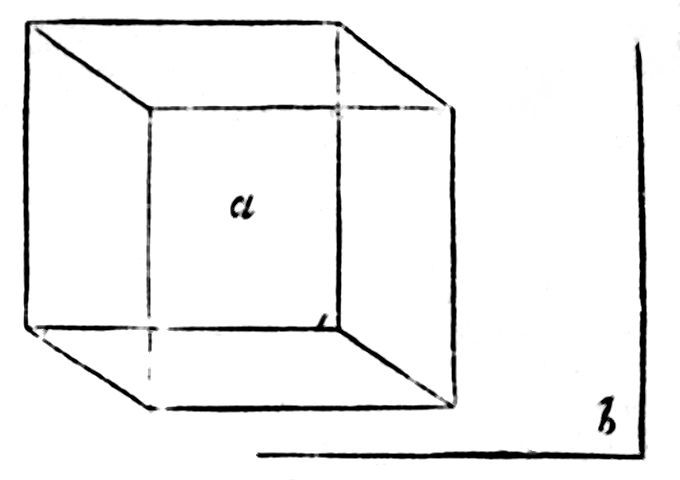

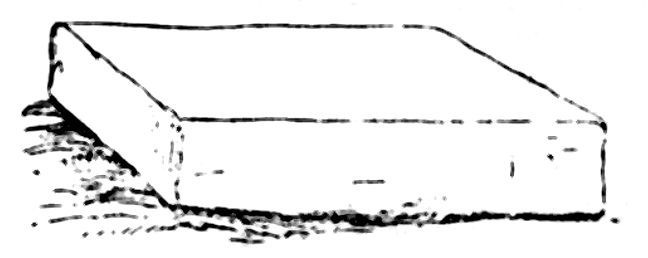

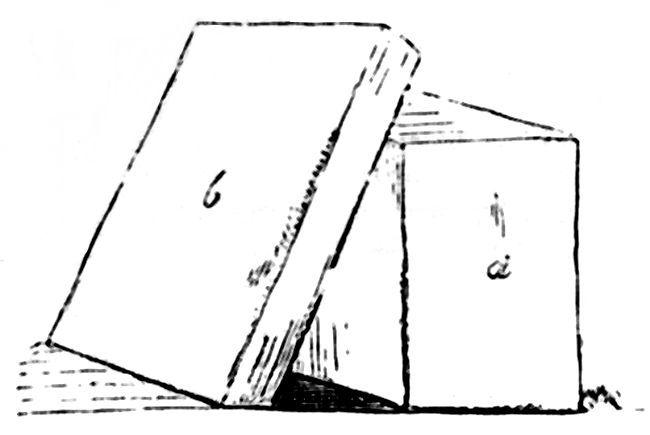

The Tying Up of Parcels in Paper is an operation which is seldom neatly performed by persons whose occupations have not given them great facilities for constant practice. Whether the paper be wrapped round the objects, as is the case usually when it is much larger than sufficient to enclose them, or merely folded over itself, as is done by druggists, who cut the paper to the required size, it is important that the breadth of the paper should be no longer than sufficient to enable it to be folded over the ends of the object enclosed, without passing over the opposite side. It is impossible to make a neat or close parcel with paper which is too broad; excess in length can be readily disposed of by wrapping it round; the excess of breadth should be cut away. With regard to turning in the ends, the mode adopted by grocers is the best. The most common cause of failure in parcels is their being badly corded. We will therefore (however unnecessary the description of so simple a performance may appear to those already acquainted with it), describe the most readily acquired mode of cording.

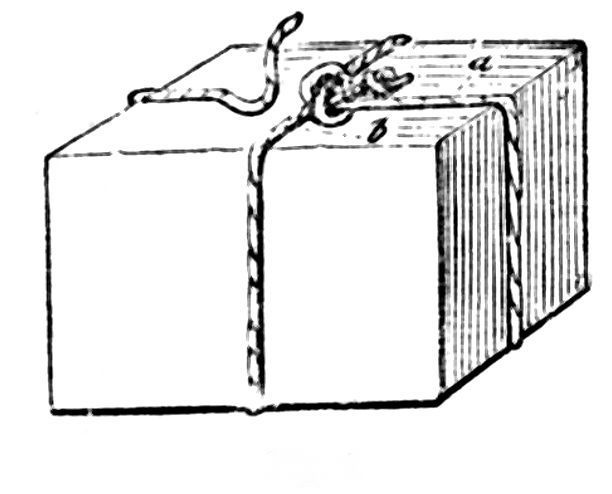

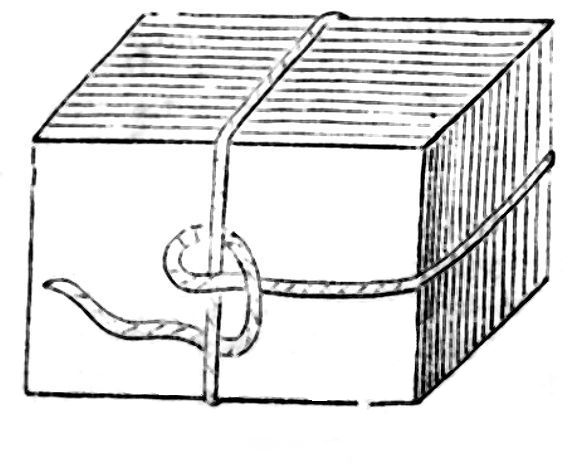

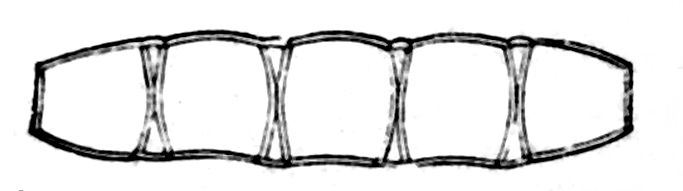

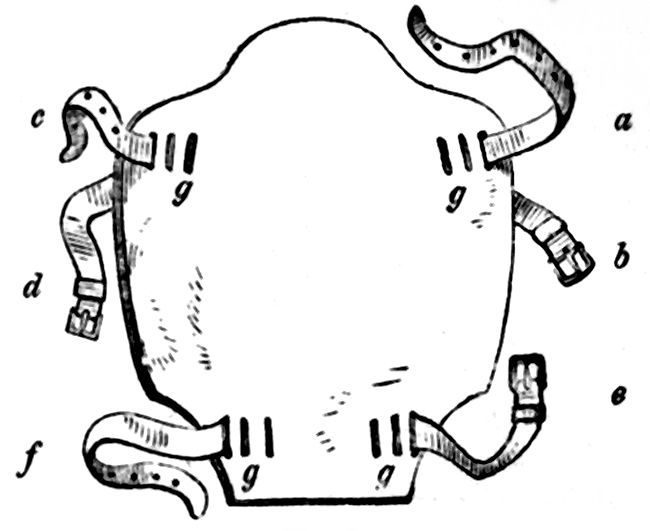

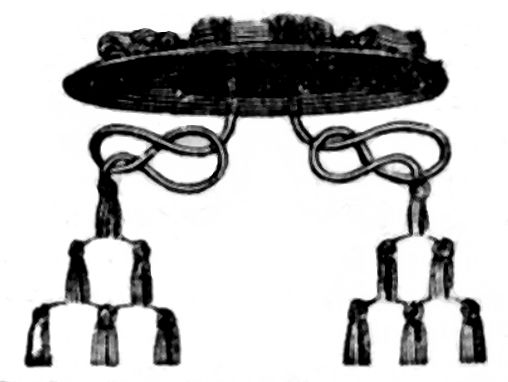

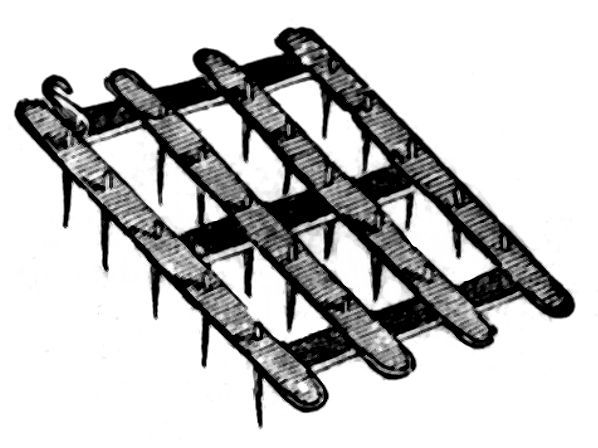

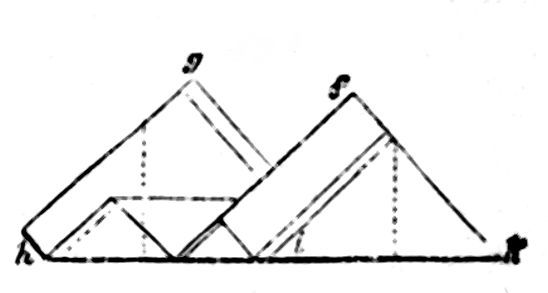

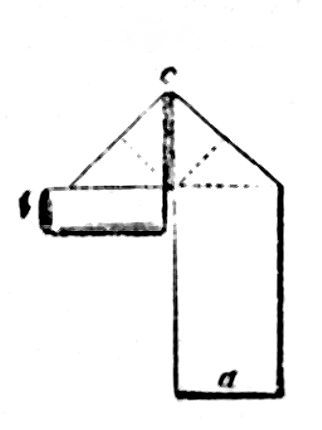

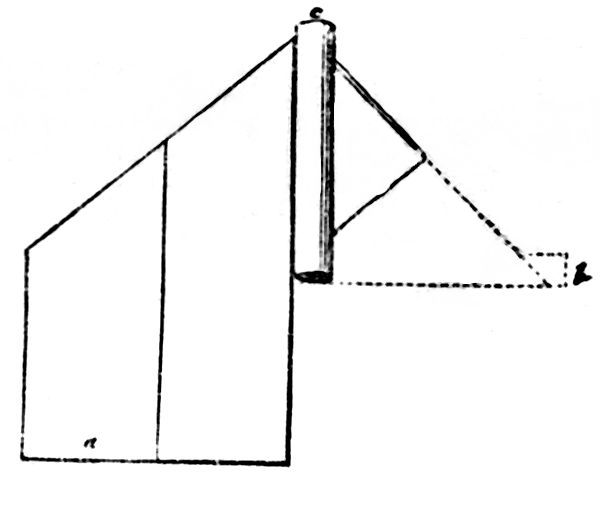

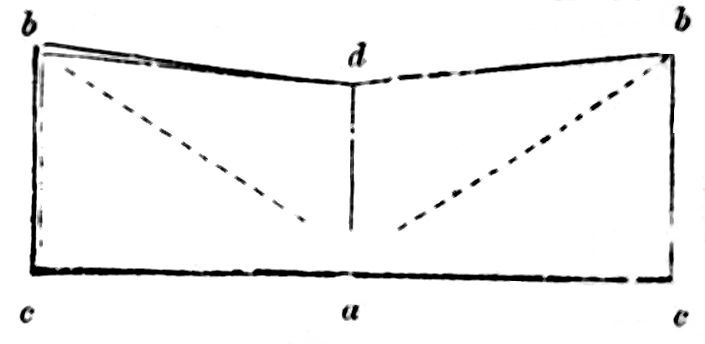

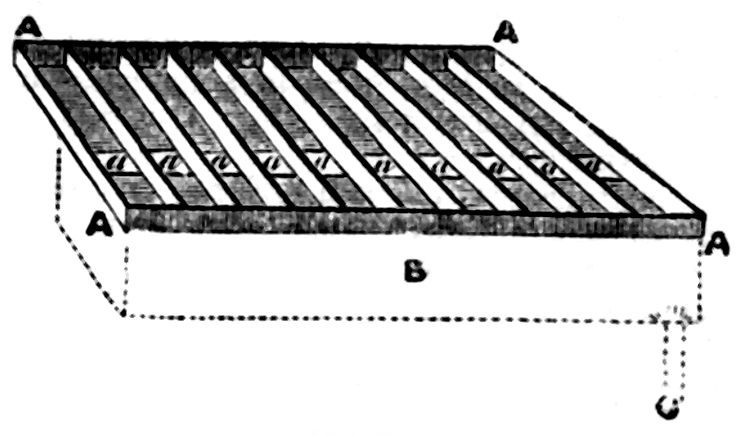

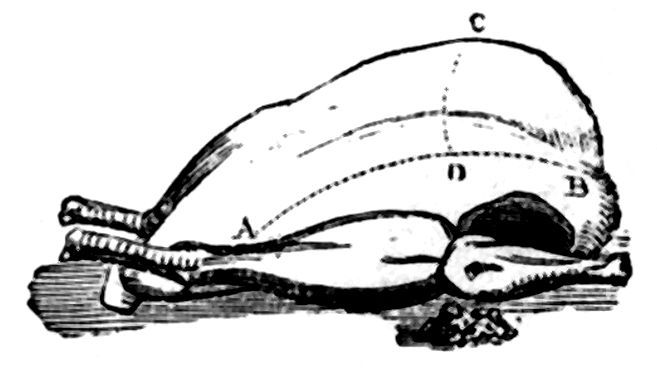

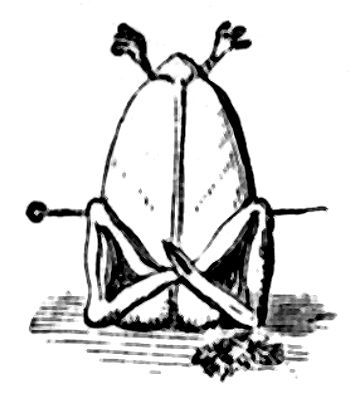

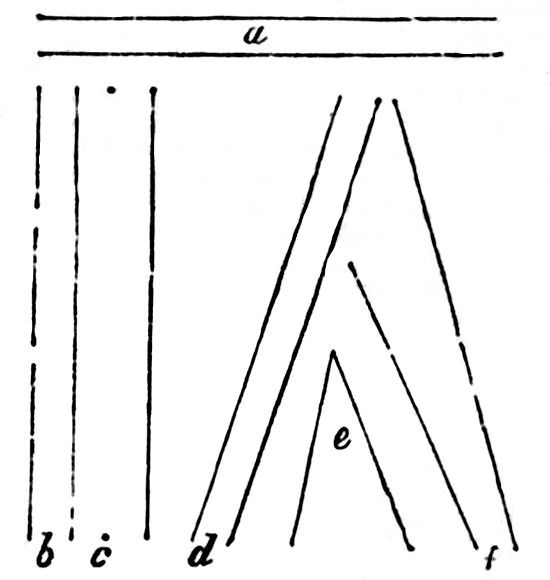

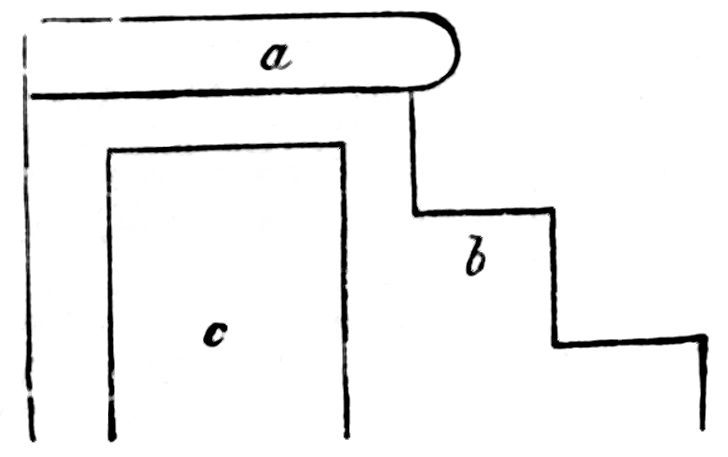

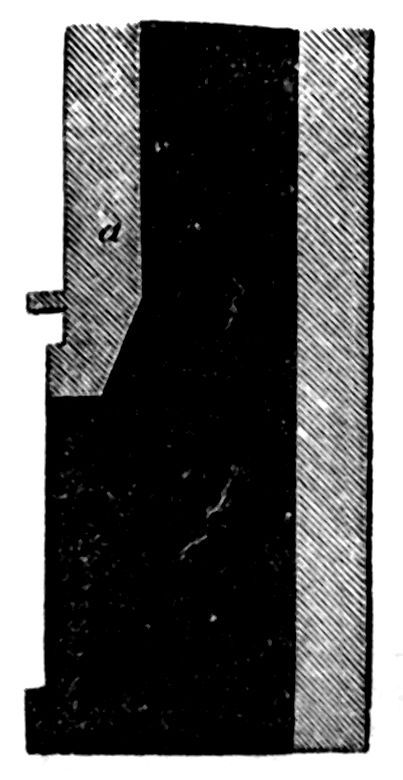

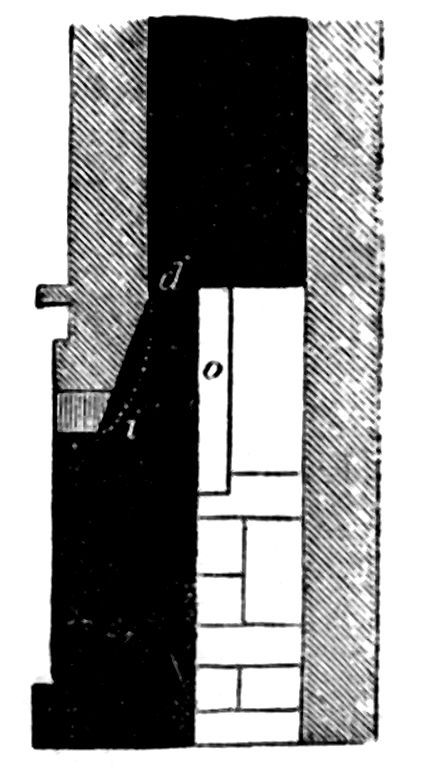

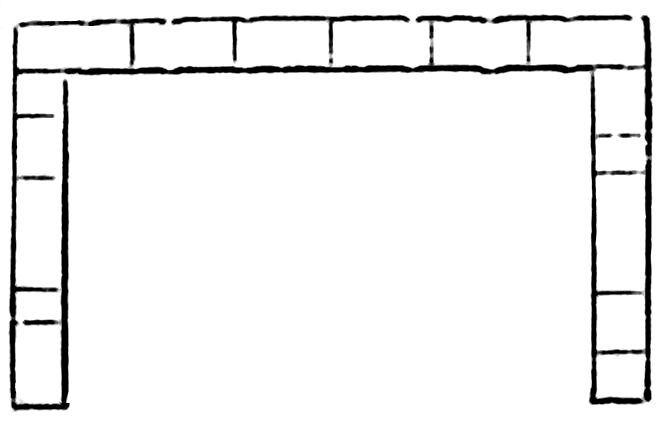

Let a single knot be made in the end of the cord, which is then passed round the box or parcel. This knotted end is now tied by a single hitch round the middle of the cord (Fig. 8) and the whole pulled tight. The cord itself is then carried at right angles round the end of the parcel, and where it crosses the transverse cord on the bottom of the box (Fig. 9), it should (if the parcel is heavy and requires to be firmly secured) be passed over the cross cord, then back underneath it, and pulled tightly, then over itself; lastly, under the cross cord, and on around the other end of the box.

Fig. 8.

When it reaches the top it must be secured by passing it under that part of the cord which runs lengthways (a, Fig. 8) pulling it very tight, and fastening it by two half hitches round itself. The great cause of parcels becoming loose is the fact of the cord being often fastened to one of the transverse parts, (as b, Fig. 8) instead of the piece running lengthways, and in this case it invariably becomes loose.

Fig. 9.

The description may perhaps be rendered clearer by the aid of the figures, which exhibit the top and bottom of a box corded as described. The cords, however, are shown in a loose state to allow their arrangements to be perceived more easily.

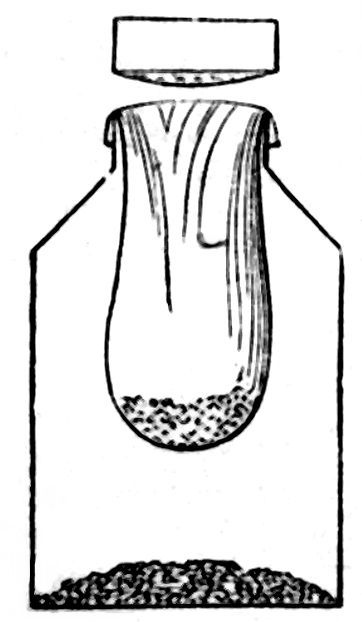

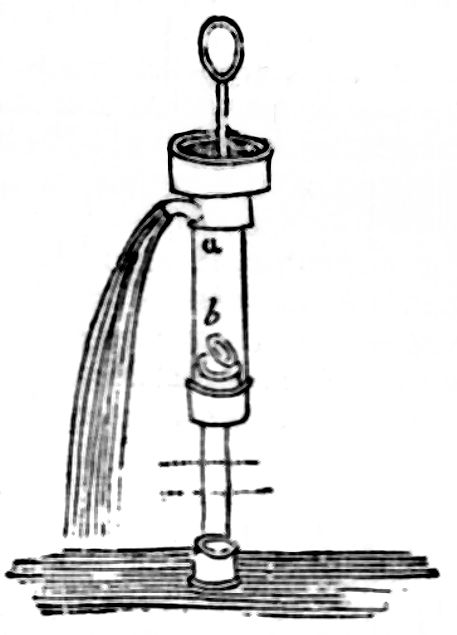

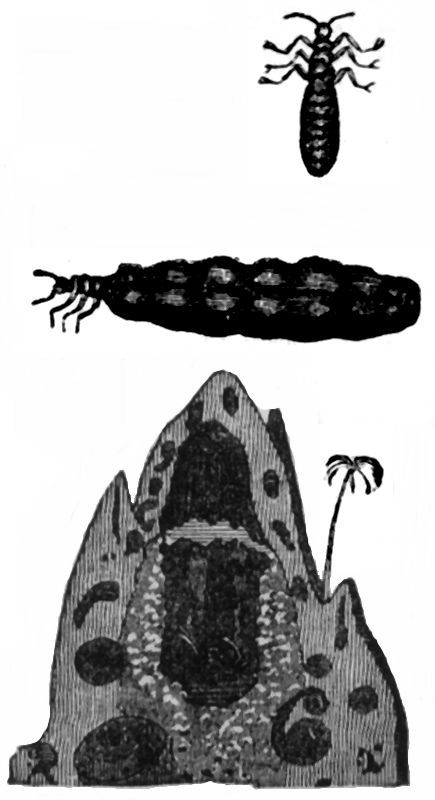

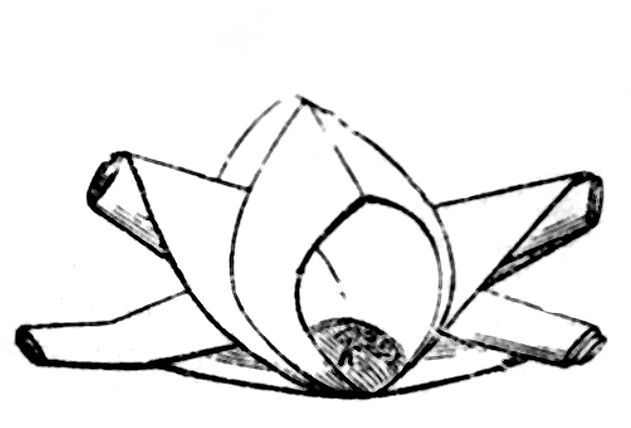

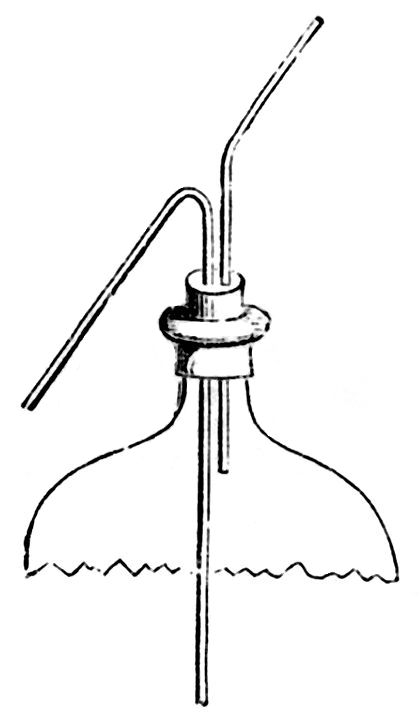

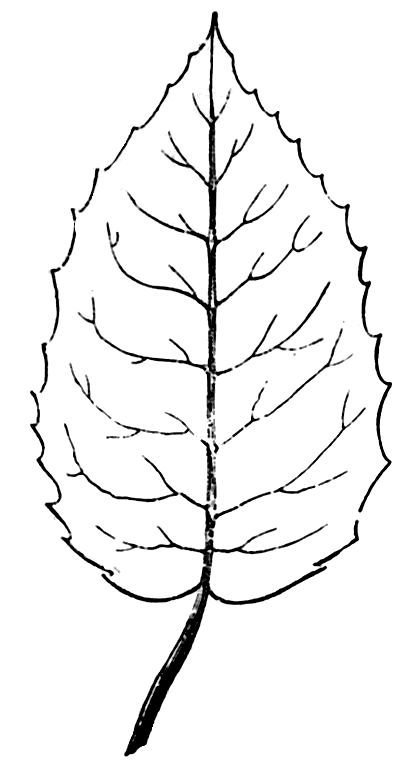

GERMINATION OF ACORNS. Take a hyacinth glass, or a broad-mouthed bottle, and fill it about-one-third with water. Cut a piece of stiff cardboard, or tin, to fit closely the opening of the glass or bottle, and from the centre thereof suspend an acorn by a piece of thread just long enough to let the acorn descend nearly to the water. It will be advantageous to drop the acorn until it touches the water, and then to draw it up very gently as far as may be done without overcoming the attraction which holds the water to the base of the acorn.

Keep it now on the mantel-piece over the fire, and in a few weeks the germ will burst the shell, and a little root will appear and descend to the water, where it will become more fully developed. Steep the acorn in water a day before suspending it. Soon afterwards, another germ will be seen to strike upwards until it reaches the covering of the glass, where a contrivance may easily be made for its escape, still keeping the acorn in the same relative position. And thus a sapling oak may be produced—a curiosity for the parlour.

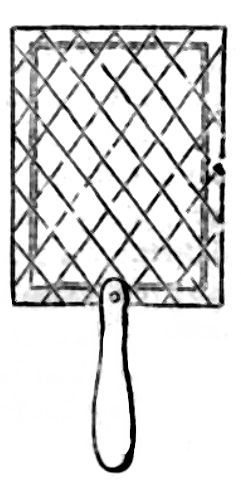

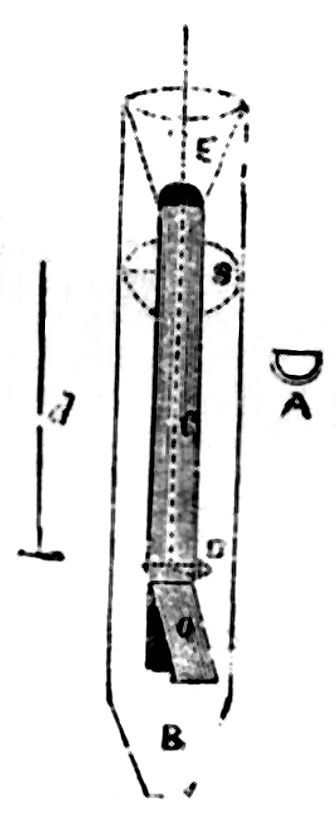

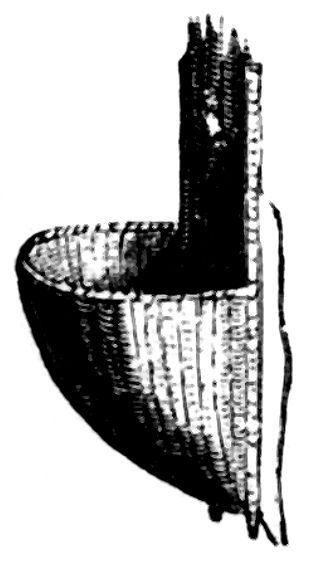

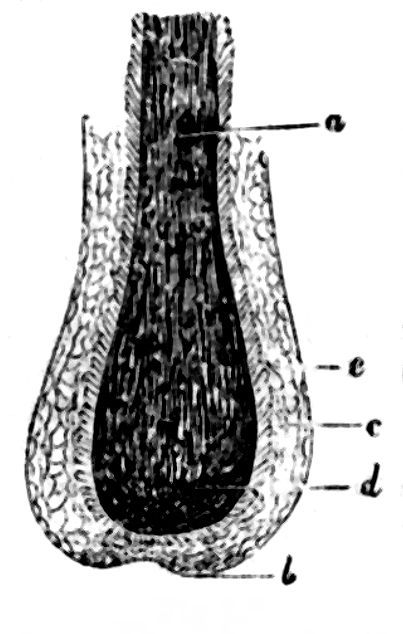

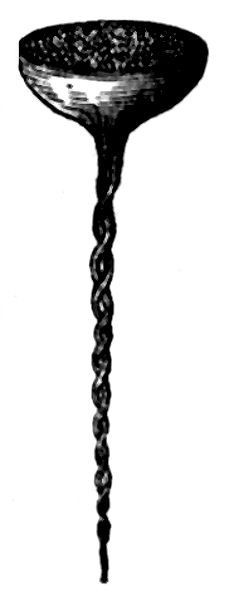

THE SAFETY LAMP was invented by Sir Humphrey Davy, and was constructed so as to burn without any danger in an explosive atmosphere. It is merely a common oil-lamp, the frame of which is enclosed in a cylindrical cage of wire gauze, sometimes made double at the upper part where the hottest portion of the gas collects, and containing about 400 apertures to the square inch. The wick is trimmed by means of a bent wire, passing tightly through the body of the lamp, so that when the lamp has been supplied with oil, the wick may be kept burning for any length of time without unscrewing the cage.

When this lamp is immersed in an explosive mixture of marsh-gas or coal-gas and common air, the gauze cylinder becomes filled with a blue flame, arising from the combustion of the gas within; but the flame does not communicate to the outside, even though the gauze may be heated to less redness.

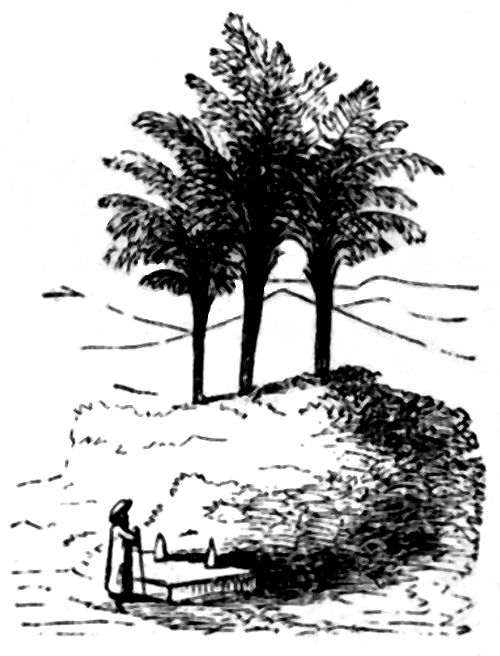

ABLUTION, or a Washing Away—a religious ceremony, which has been practised more or less by the followers of all creeds. The Mohammedans and Brahmins are very strict in their ablutions; and they occupy an important rank amongst other religions of India. The Ganges is considered by the natives as possessing a power of purification so great even, that if a votary cannot reach that river, and who calls upon it while bathing in another to cleanse him, he will be freed from all his sins.

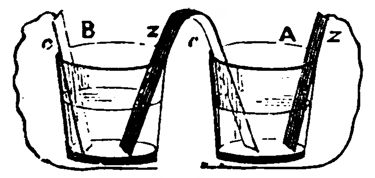

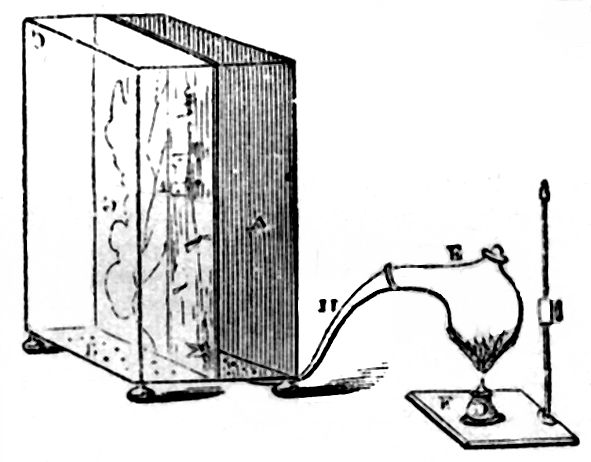

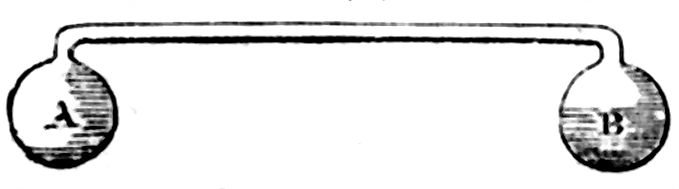

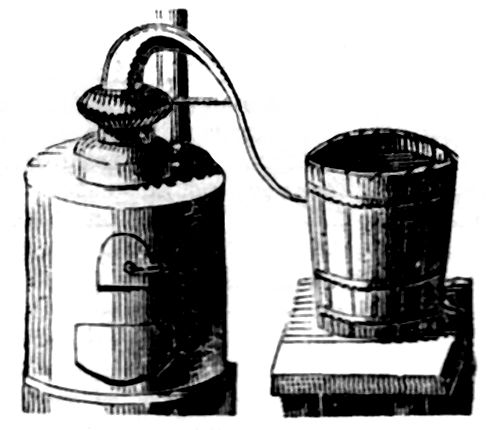

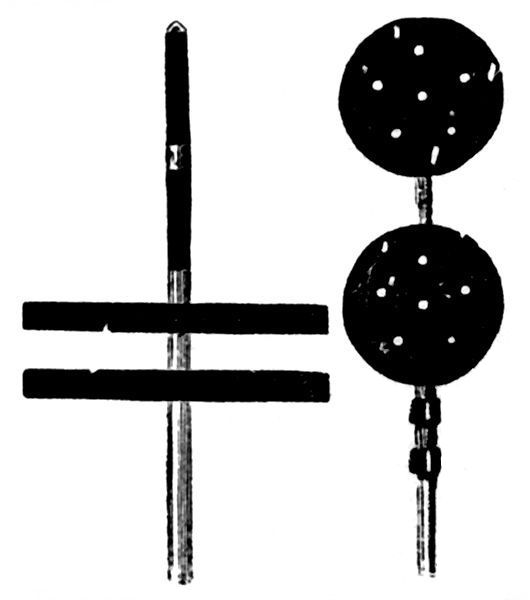

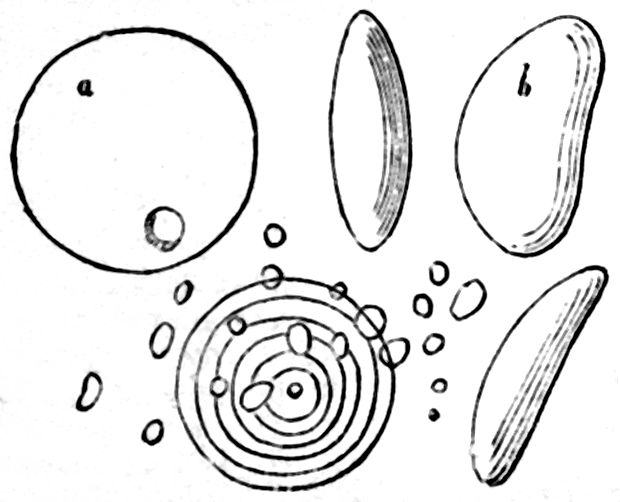

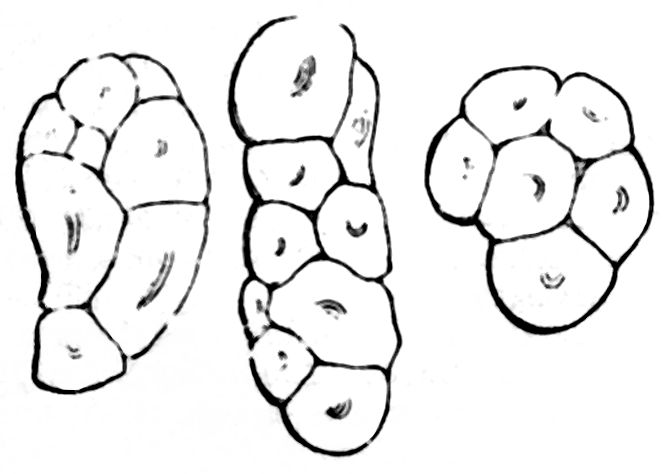

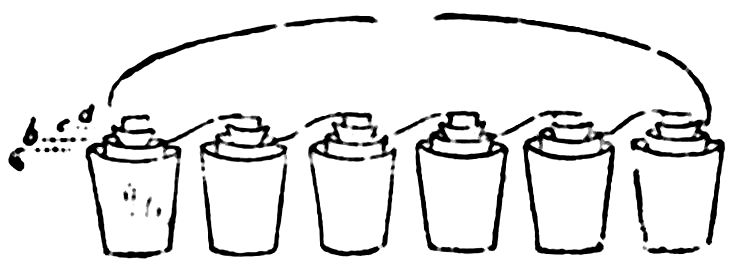

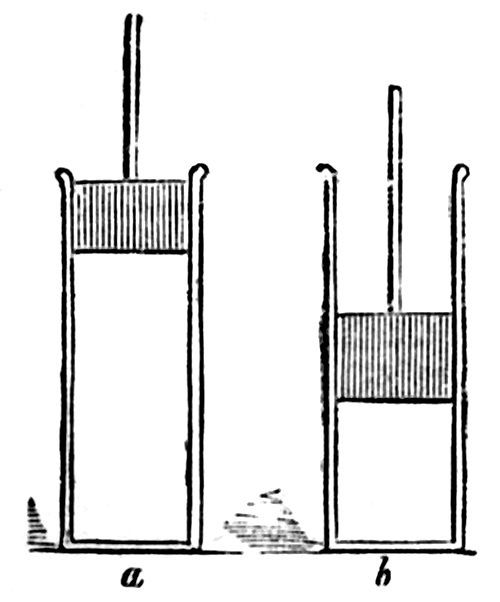

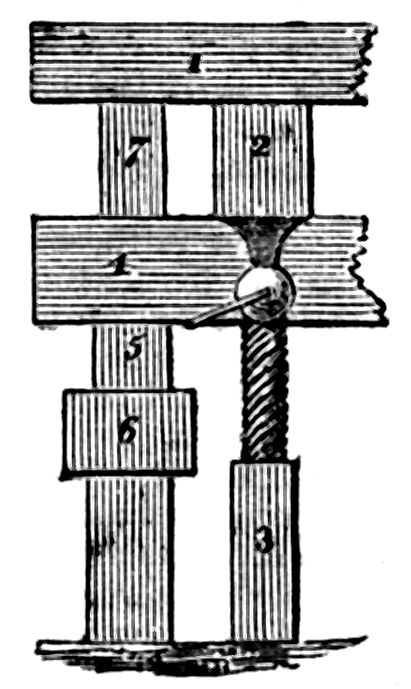

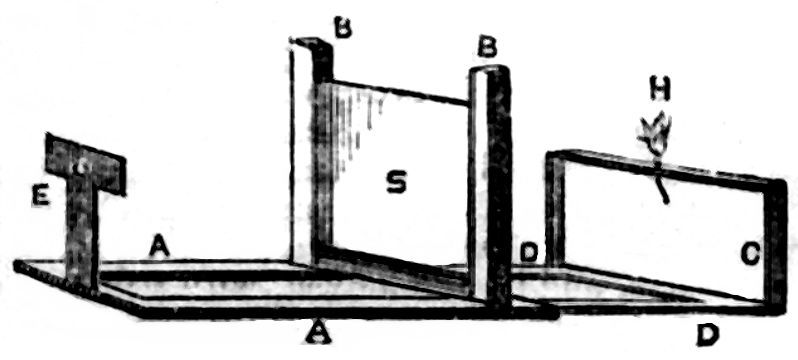

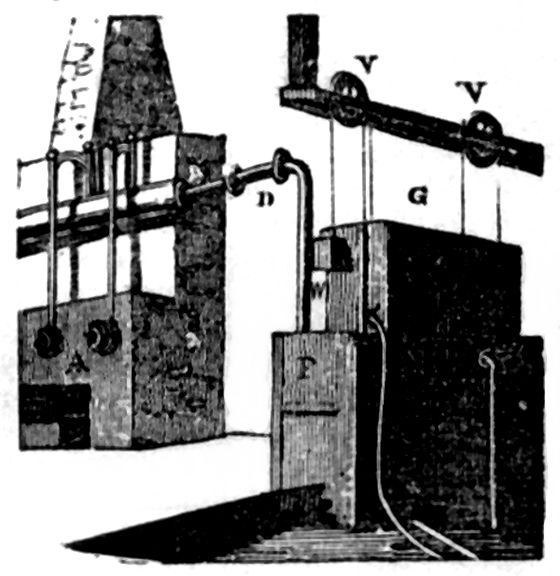

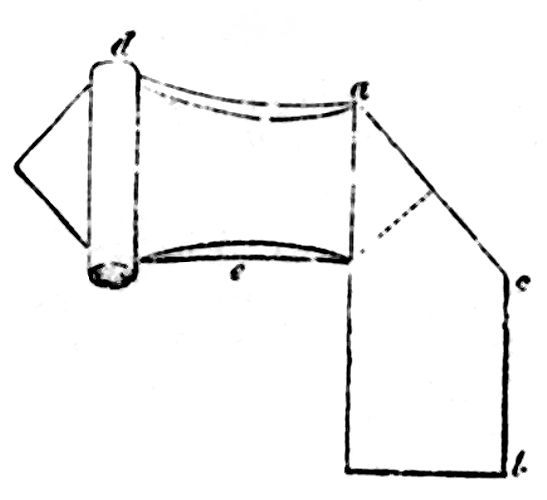

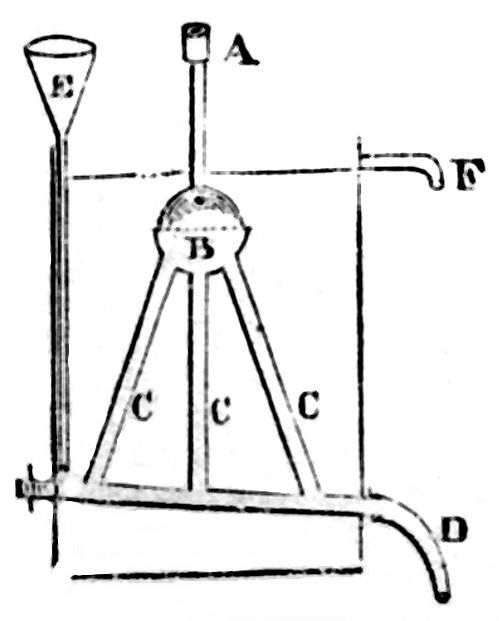

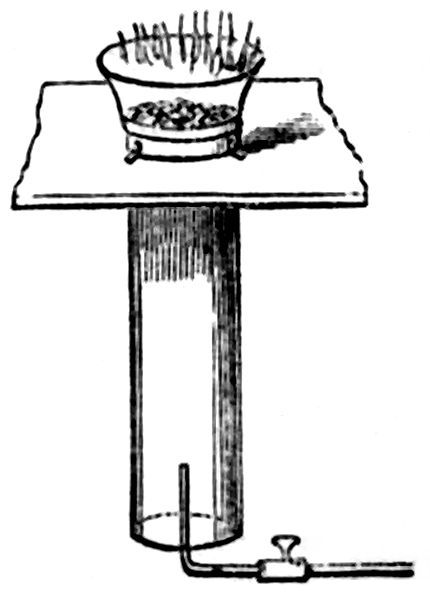

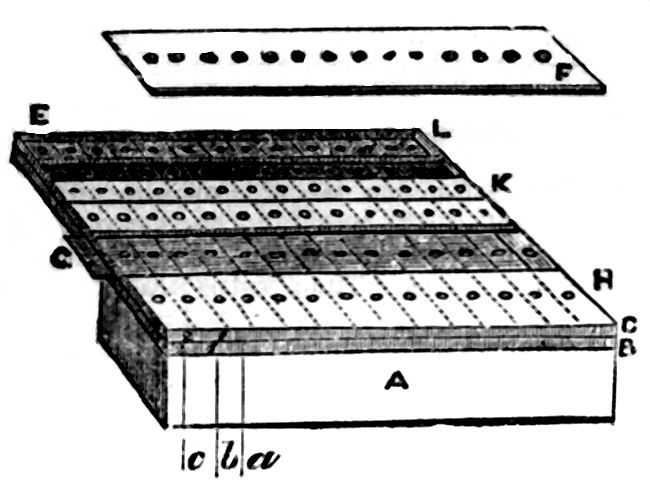

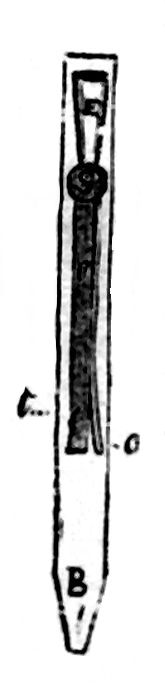

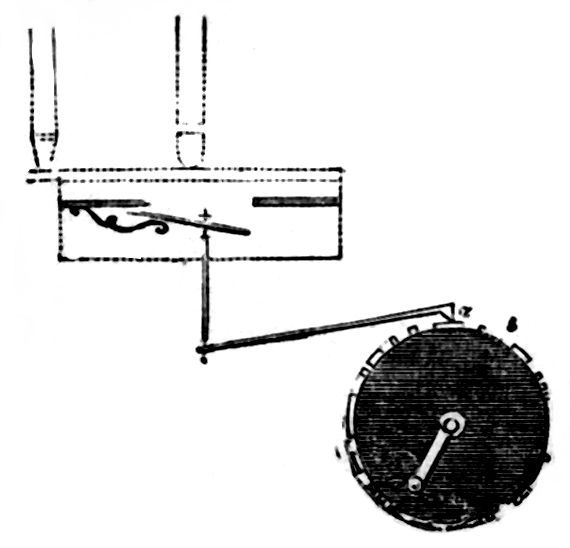

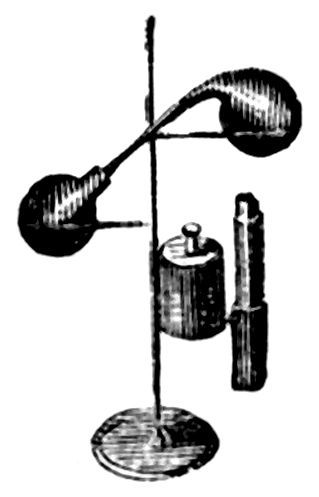

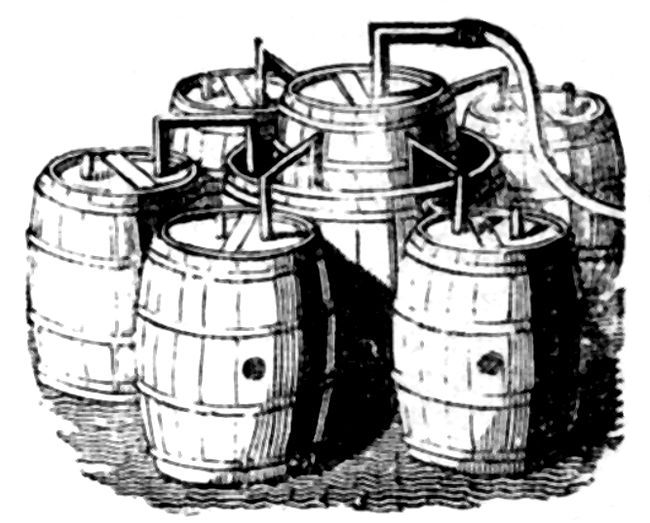

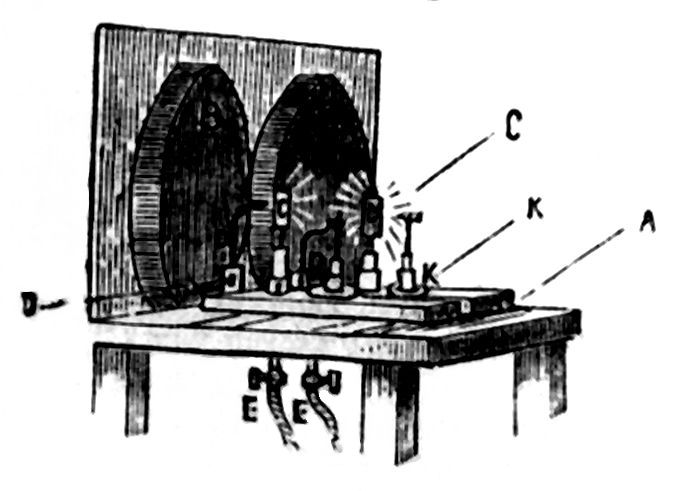

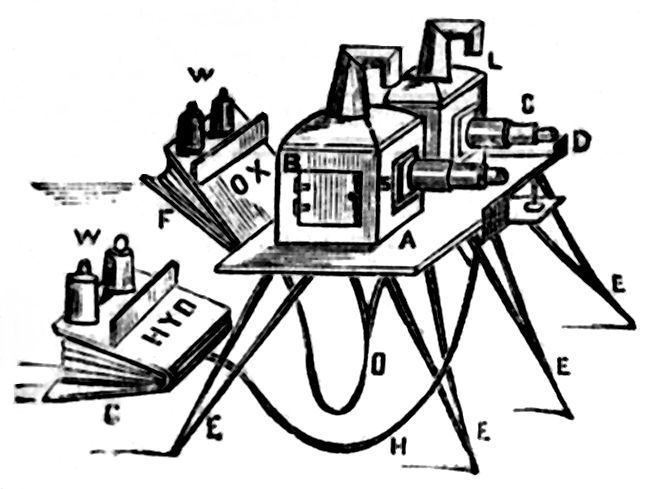

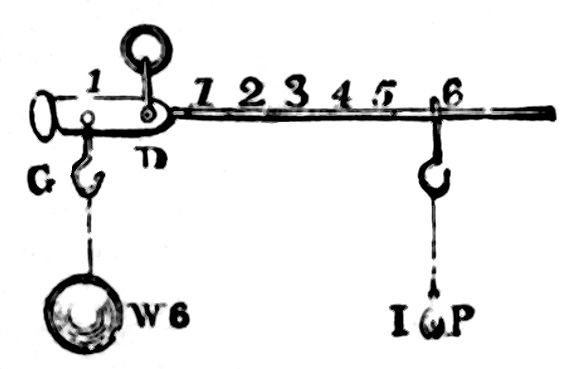

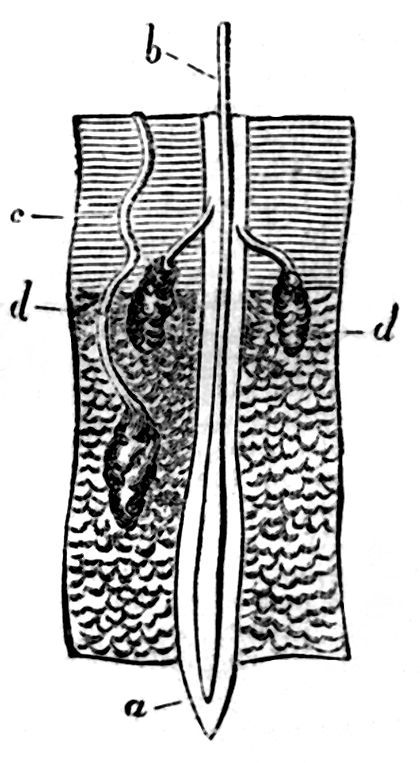

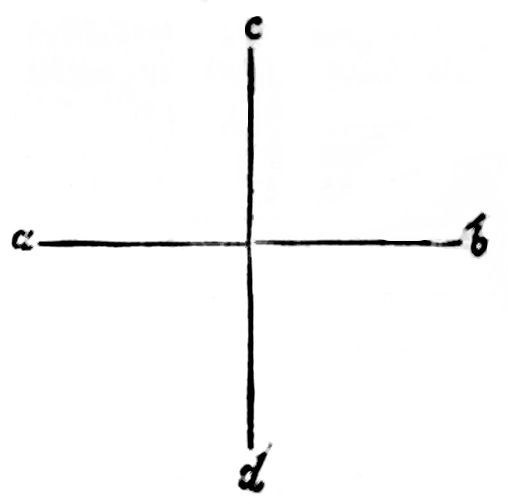

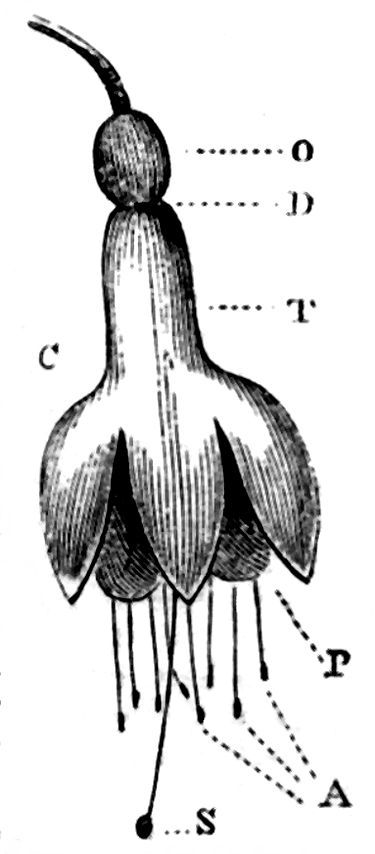

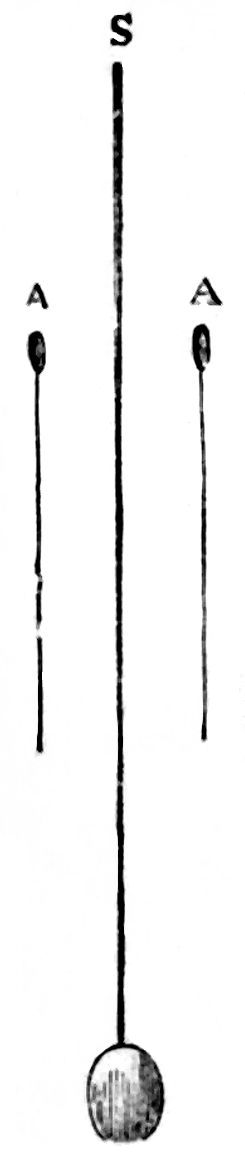

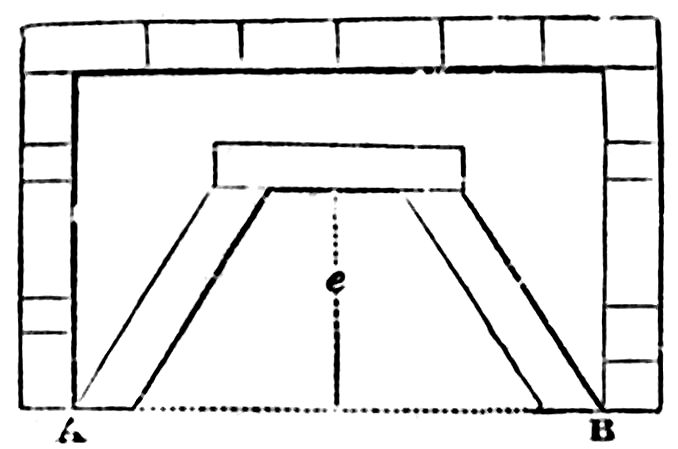

ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH. In the description of the electric telegraph, we will lay aside all technical and scientific terms, and explain clearly this greatest wonder of our day. The source of the electricity used requires our first attention. This is what is called a voltaic, or galvanic battery; and it is so called from Volta and Galvani, its originators. We can make a very simple battery by means of two tumblers, a little salt and water, two small pieces of zinc, and two of copper, united in the following manner:—A and B are the tumblers, c c the pieces of copper, z z the pieces of zinc; the tumblers being partly filled with the salt and water, the battery is complete.

Fig. 1.

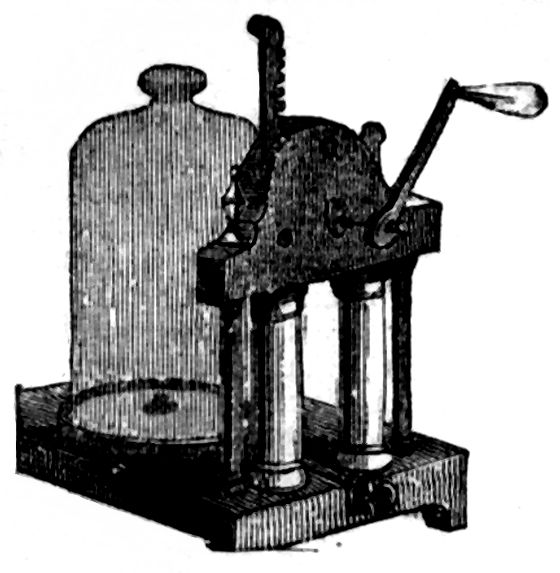

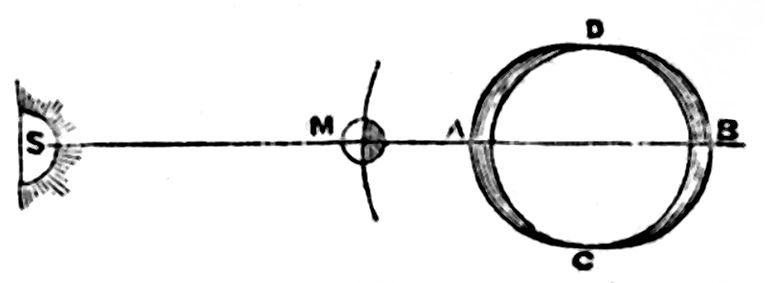

It may be observed that the metals used are dissimilar; that a plate of copper and one of zinc unite at e, and that there are wires fixed to the other two plates, which as yet are in no way connected. Whilst things are in this state, nothing will take place; the battery is at rest, and no electricity is evolved by it; but if we join the two wires, a current of electricity will immediately pass, and this current will continue till we again separate the wires. If two plates of metal are placed in a solution which will only dissolve one of them, and their upper edges are brought into contact, whilst the others are kept apart, a current will pass from one to the other through the solution, and, passing also from one to the other at the point of contact, will continue thus circulating, till either the soluble matter is consumed, or the liquid itself is saturated—that is, has dissolved as much metal as it is capable of dissolving. This is always the case; but often the effect is so slight, that it is rarely perceptible. Take a piece of silver, and a piece of zinc the size of a half-crown; place one upon the tip of the tongue, the other under it; bring their edges into contact, and what is called a shock will be perceptible; that is, the saliva acting upon the zinc and not upon the silver, a small battery is made, and the electricity passes from the zinc through the tongue to the silver, thence to the zinc again, and thus circulates till you part the edges of the metals. The shock is very slight, being chiefly known by an acid taste; nor would it be felt at all, but that the tongue is so acutely sensitive. We have called this a small battery, but it is scarcely a correct term; it is a single voltaic pair—a battery, in its proper sense, being made up by a union of two or more such pairs, as in the case of the one above. In practice, a battery consists of twelve or more such pairs; and the following sketch represents one commonly used in working the electric telegraph:—

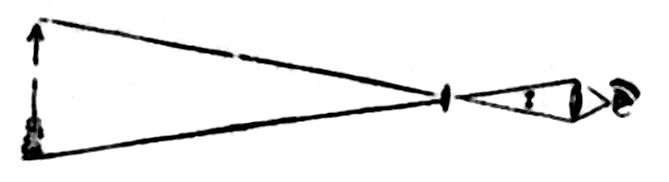

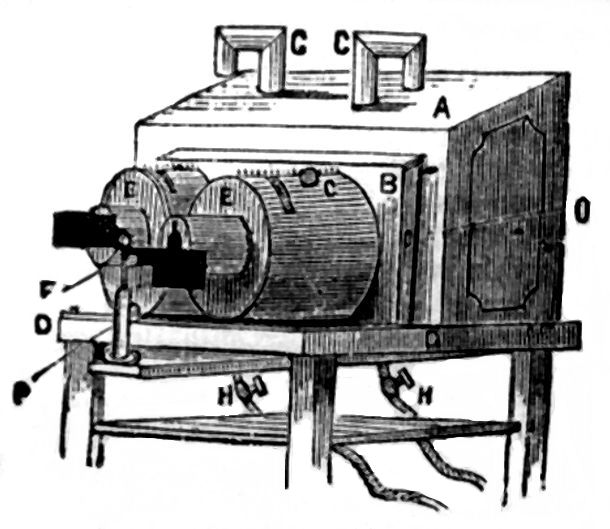

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

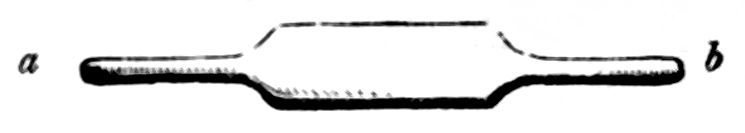

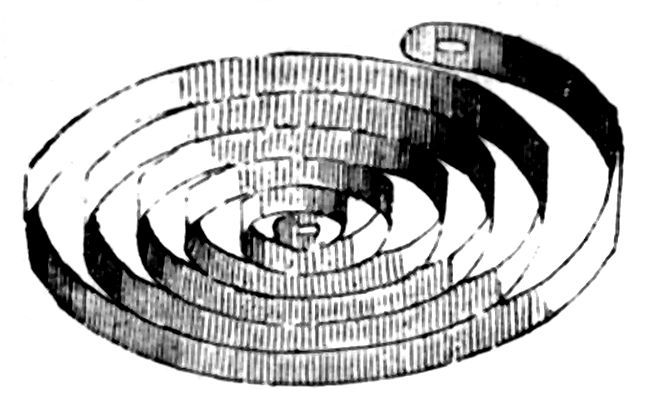

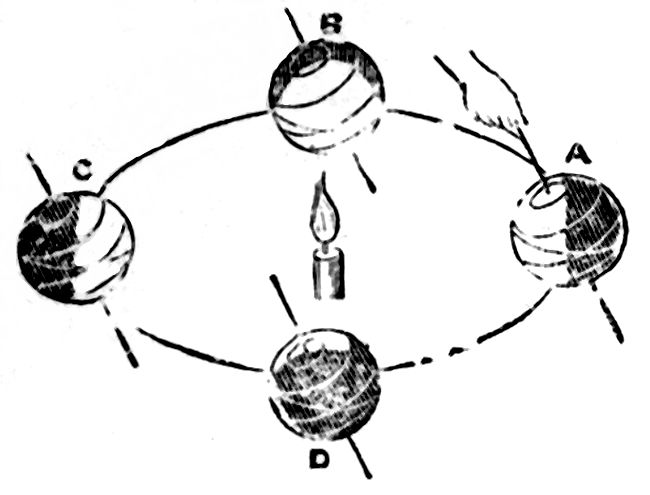

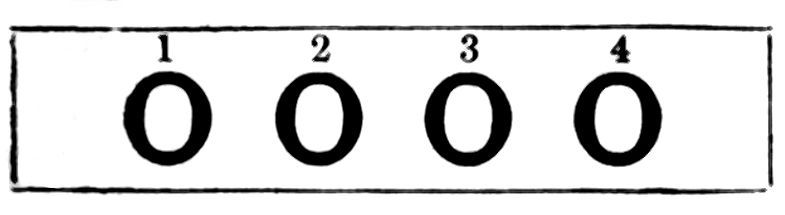

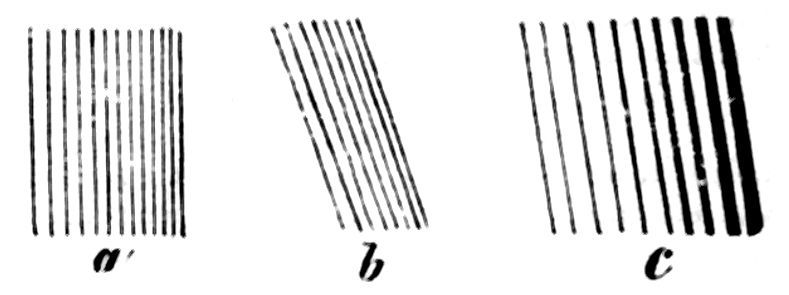

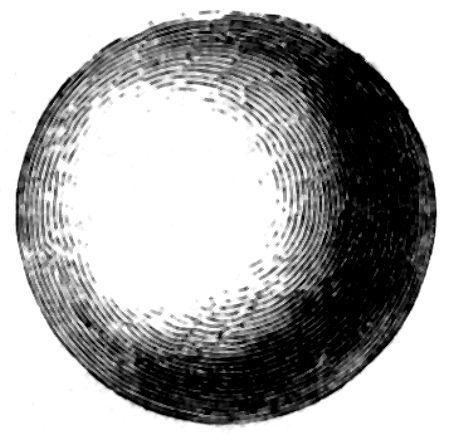

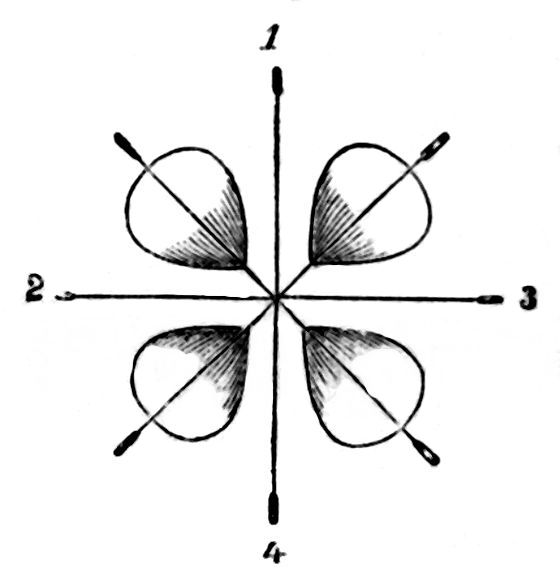

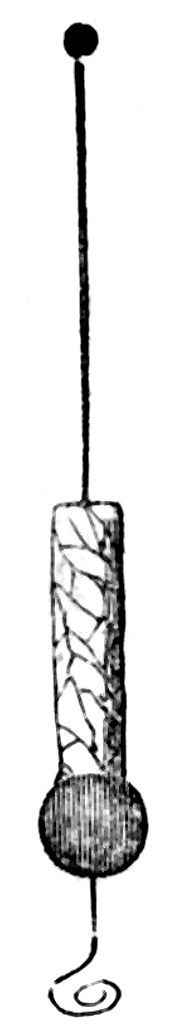

It contains twenty-four pairs of zinc and copper plates, about four inches square. Each pair are soldered together by means of a strap of metal, as in Fig. 3. To make it quite clear, we have drawn but twelve pairs in section, and lettered the alternate plates, z standing for zinc, and c for copper. The trough in which they are placed is either made of baked wood, glass, earthenware, or gutta percha; the only requisite being that it is a non-conductor of electricity—that is, such a substance as electricity will not readily pass through. The last plate at one end is zinc, and the other copper, and a wire is soldered to each. If these wires are joined, a current of electricity will pass from the zinc plate to which one is attached, through the exciting liquid, which is here sulphuric acid and water, to the copper plate in the same cell, thence by the metal strap to the zinc of the next cell, and thus through the whole series to the other single plate, whence it passes by the wires to the first zinc plate again. But as each pair of plates produce similar currents, their combined power is very great, and a large quantity of electricity passes through the terminal wires. So much for the battery. We will now go a step further, and learn an extraordinary effect which it is capable of producing. You know what a magnet is, and many of you have, we dare say, seen a mariner’s compass—if not, we must briefly tell you what it is. It consists of a flat piece of steel, of this shape, which is called a needle.

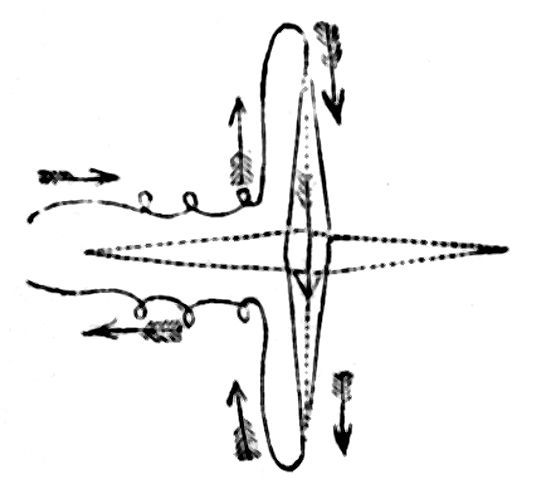

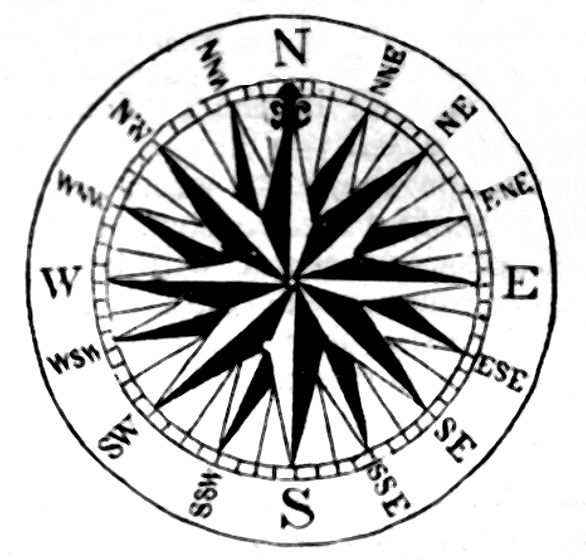

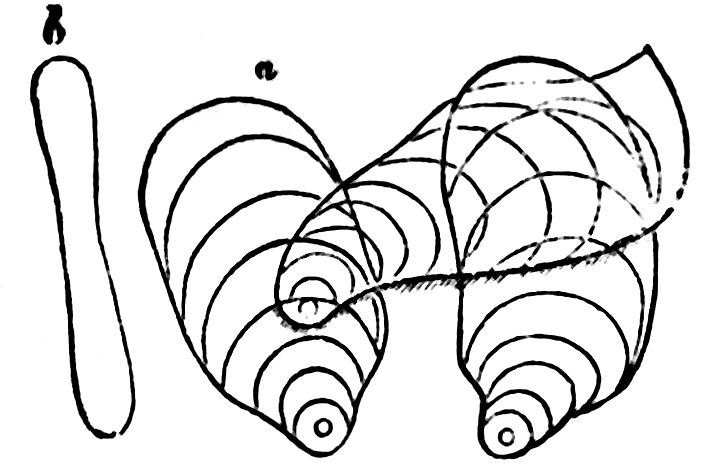

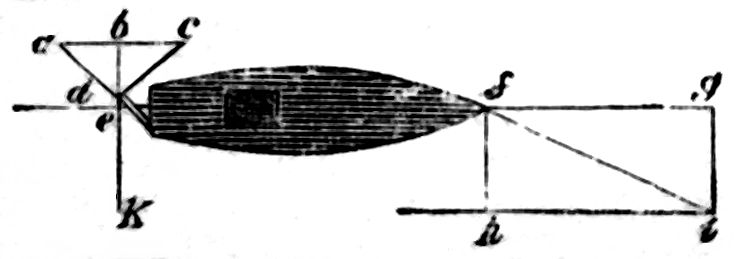

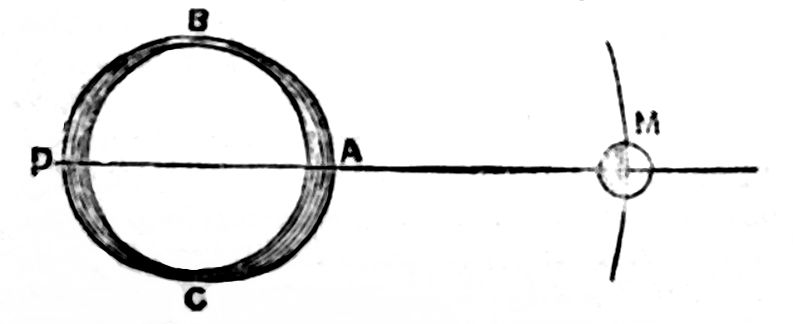

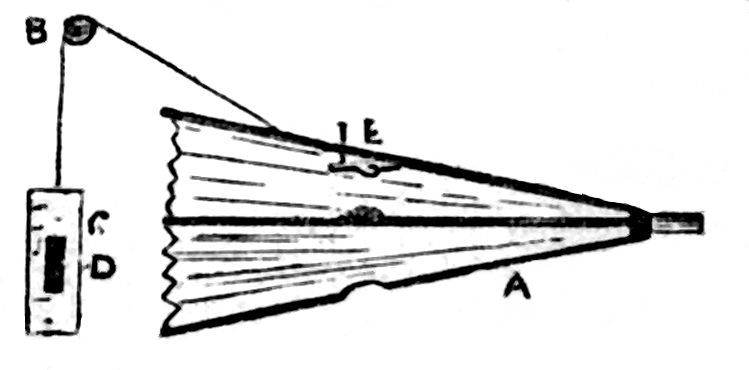

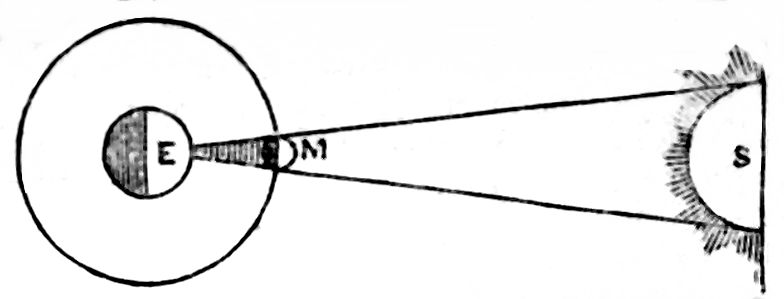

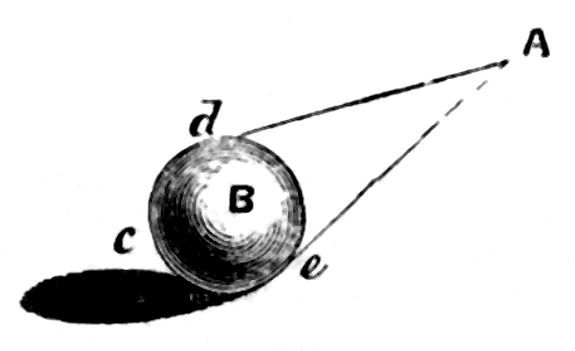

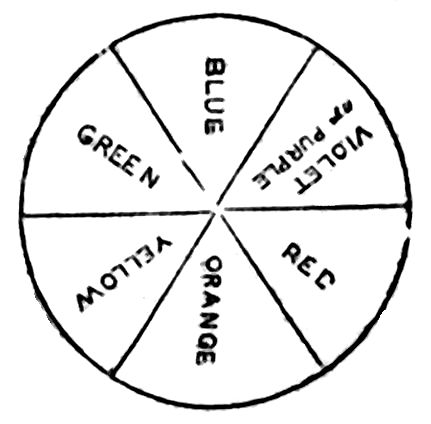

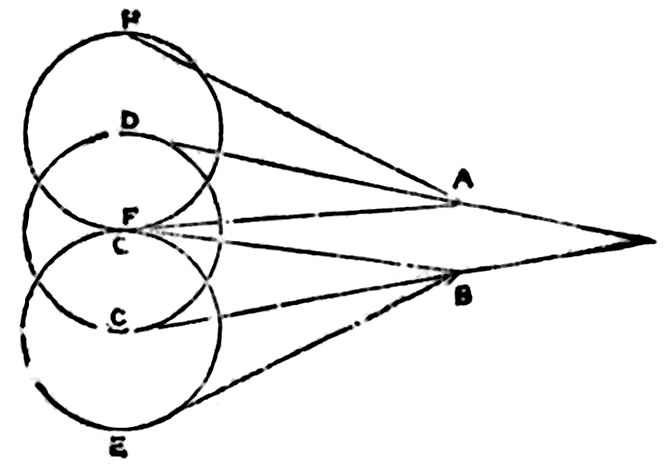

This is suspended on a point, by means of a small hole, or rather conical indention made in its centre. This needle being magnetised, and thus suspended, will always point in the same direction, one end being directed to the north, the other to the south; and it thus enables the sailor to go in any direction he may desire. For if he knows where these points are, he can tell the east and west; and if, as is always done, a card is placed below the needle, with the intermediate points carefully marked upon it, he has no difficulty in steering exactly to any place of which he knows the position; and thus the compass is to the sailor on the pathless deep just what the direction post is to the traveller. Now, if we take such a needle as we have described, and suspend it vertically on an axis passing through its centre, and then, by means of a wire, pass a current from our battery round it thus, the needle will take up a new position at right angles to that which it maintained before, indicated by the dotted lines.

Fig. 5.

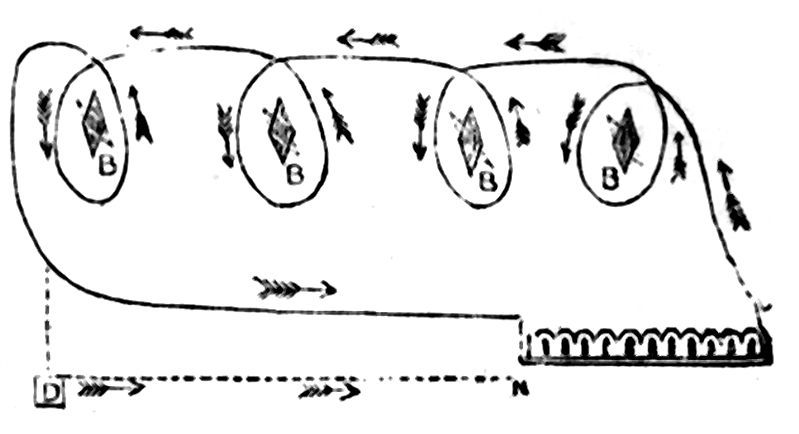

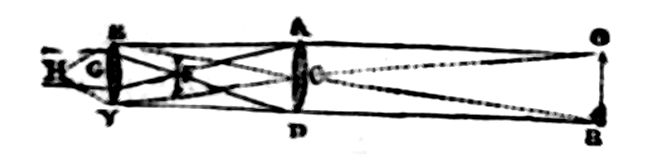

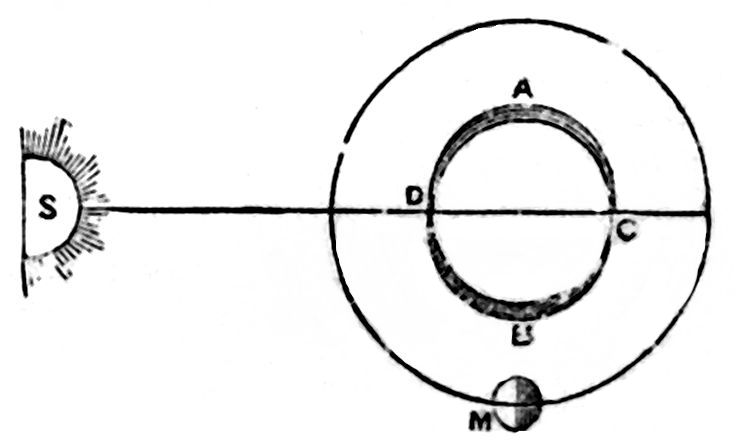

Whether the upper point, or north pole, of the needle moves to the right or left in order to attain this position depends on the direction of the current. Thus we have arrived at the principle of an electric telegraph. We have but to agree upon a set of signals that the deflection of the needle shall signify; and if we can contrive to send the current in the direction we wish, so as to move the north pole of the needle to the right or left at will, the apparatus will be complete. But, in practice, it is necessary that we should be able to move, as we please, a similar needle to our own, at the station to which we desire to send the message. In order to accomplish this, we have but to conduct the current from one station to the other by means of an insulated wire. This will be easily understood by the following diagram, where the battery is represented at A, and the different stations at B, at each of which the needles have their north poles upwards; and the wire conveying the current passes in the same direction round all, and lastly returns to the other pole of the battery; thus the current, leaving the battery by the copper or positive end, c, will traverse the wire in the direction of the arrows, deflect the needles in the same direction at the different stations, and return to the zinc or negative end of the battery by the same wire.

Fig. 6.

We will now tell you a very curious fact about the return of the current. The return wire is not necessary, nor is it now put in practice; for a man named Sternheil proved, in 1837, that if we buried deep in the ground the end of the wire, attaching it to a plate of metal, the earth itself would conduct the current back again, thus saving the cost of a return wire. Thus, in the figure above, we have represented this by dotted lines, and marked the direction of the return current by double arrows, N O being the plates of metal, and having the wires attached to them.

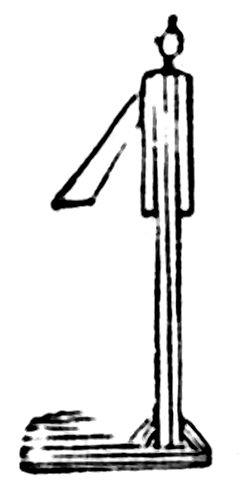

Fig. 7.

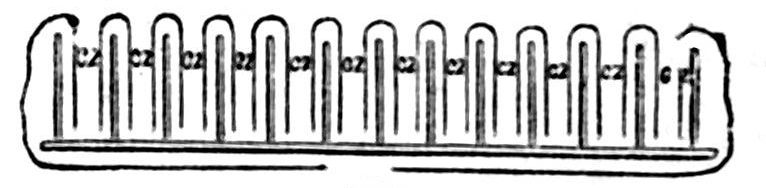

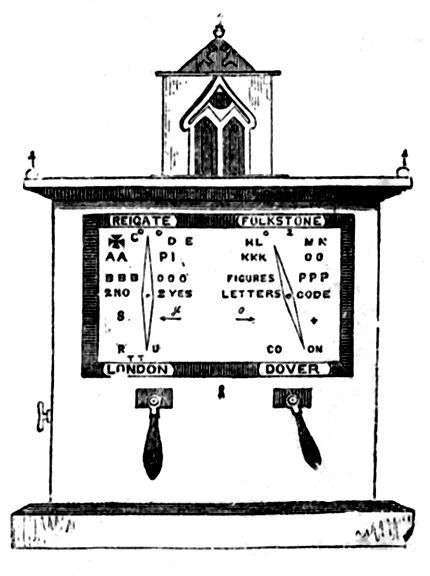

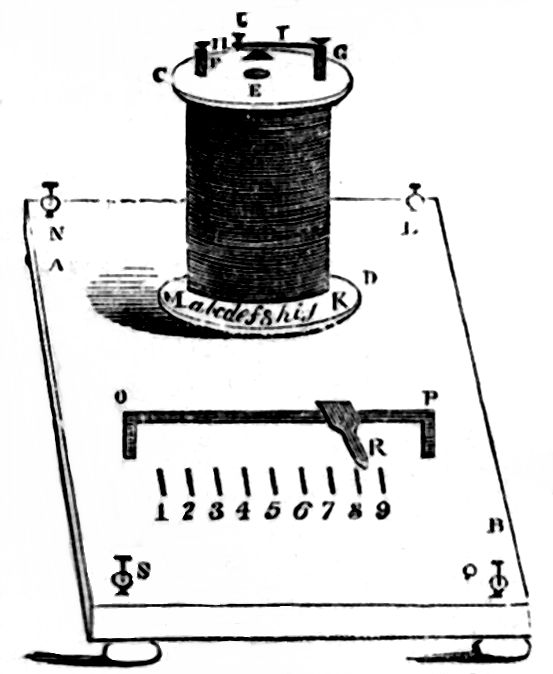

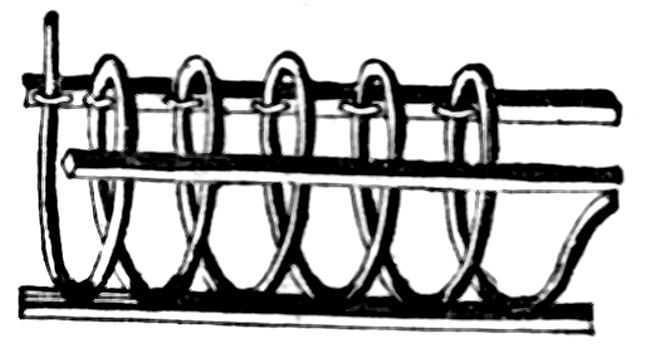

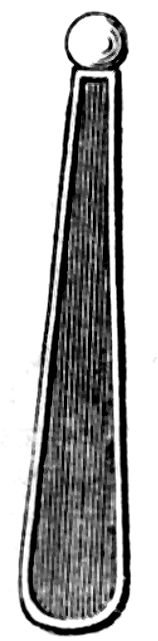

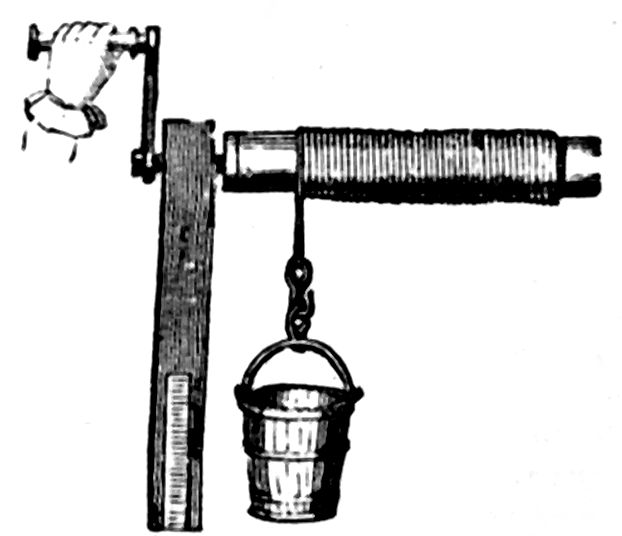

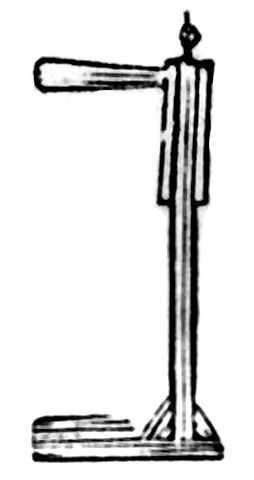

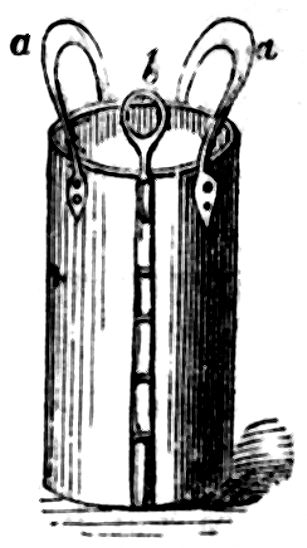

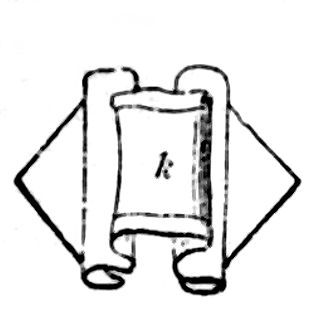

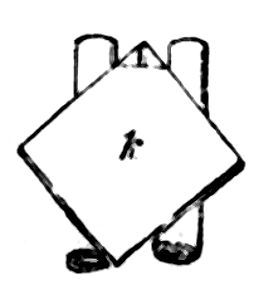

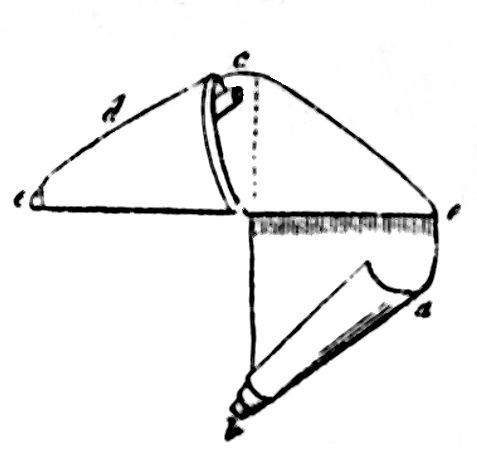

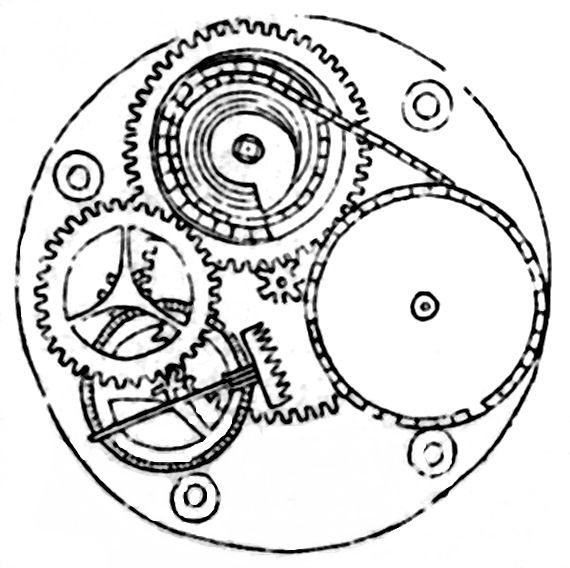

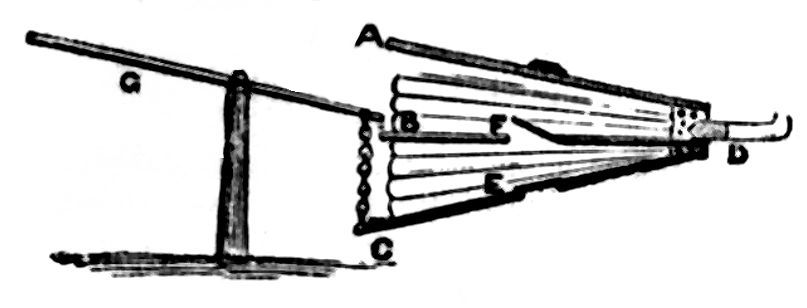

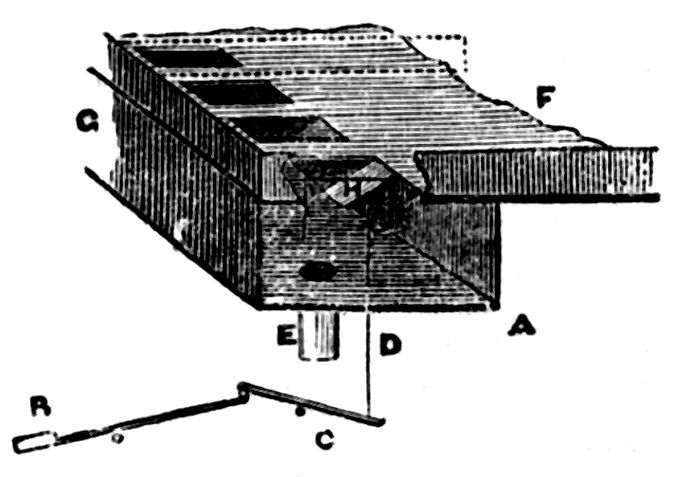

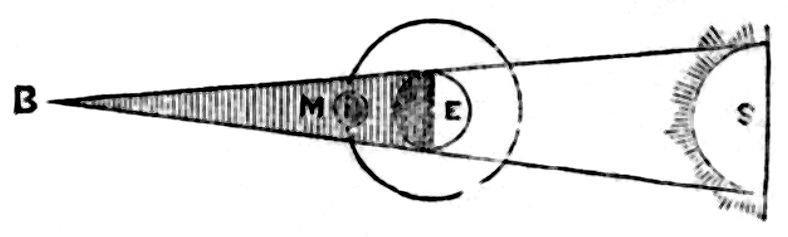

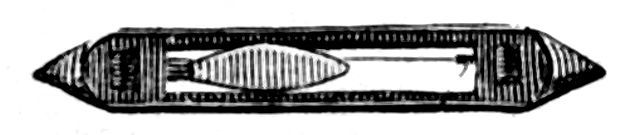

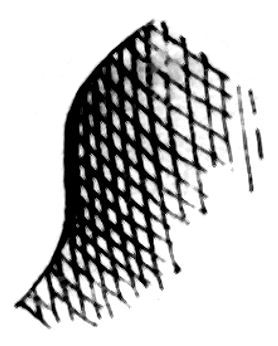

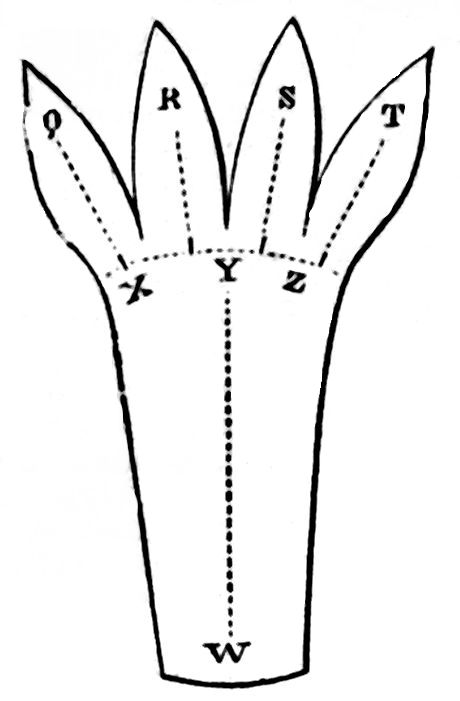

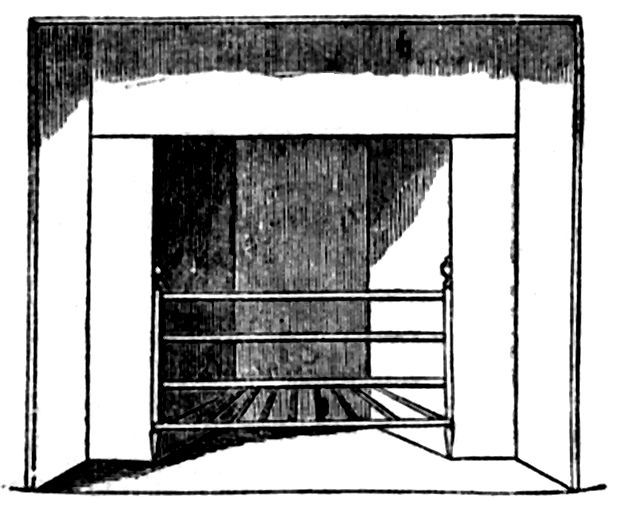

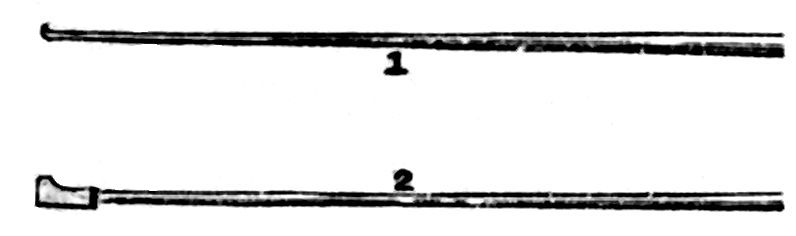

We will now explain the instrument by which communication is made with the battery, and which is qualified not only to send, but also to receive signals. It is represented by Figs. 7 and 8; Fig. 7 being the exterior, and Fig. 8 the interior. The needles in Fig. 7 (for there are usually two) are on the same axis as the ones on which the electric current acts, only their poles are reversed,—the north pole of the one being opposite the south pole of the other, by which the effect of the earth’s magnetism is annulled, and they are the more powerfully influenced by the electric current. It is by means of these outer needles that the signals are read: they are prevented from deflecting too far from their vertical or upright position by two ivory studs, one on each side; and thus the signalling is rendered more certain and rapid than if they were allowed to oscillate further. The handles at the lower part of the instrument are for moving the barrel in the interior, the one at the side for ringing a signal bell, which is also effected by electricity.

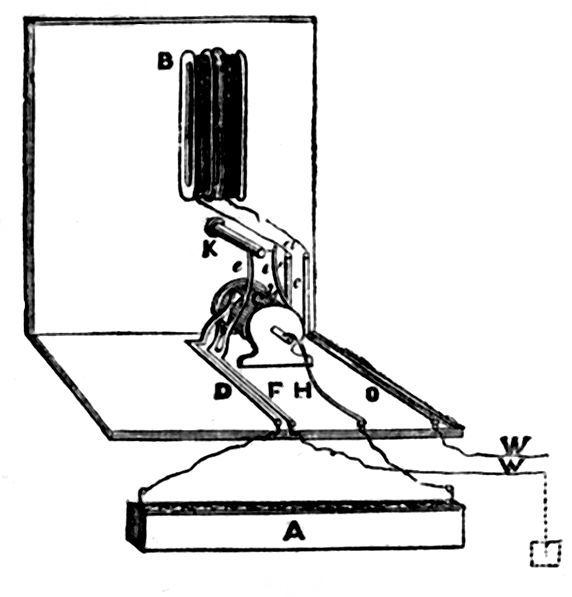

Fig. 8.

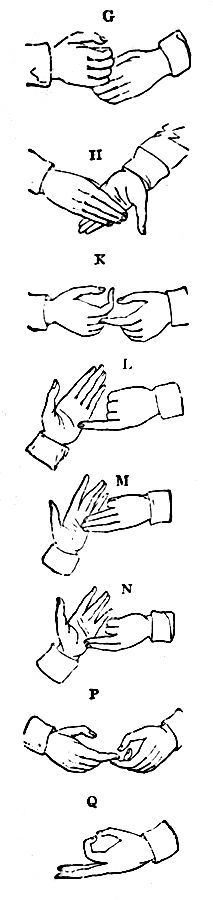

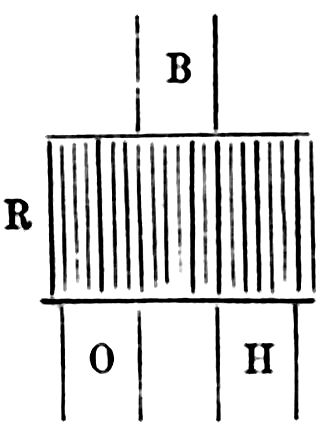

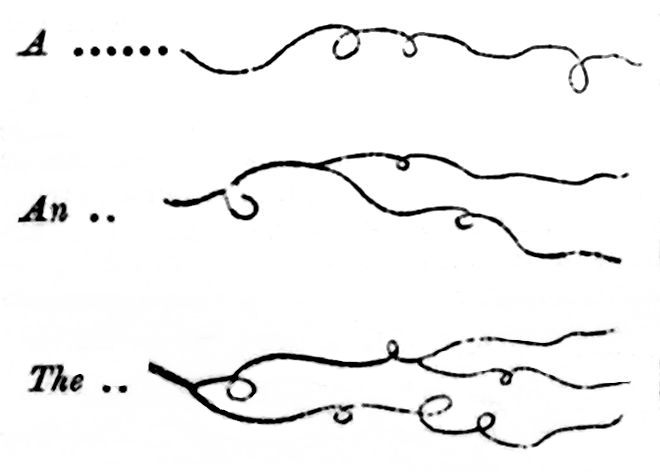

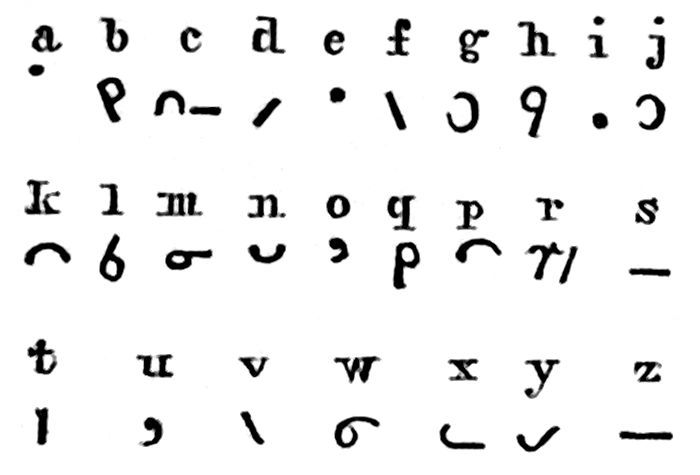

In Figure 8, we are looking at the back of the instrument, the case being removed. B is the coil of wire for passing a current of electricity round a magnetic needle suspended in it by its axis. In the former drawing, the wire passes but once round the needle; but by winding it round several times, as here shown, the effect is greatly increased. W, W, are the wires which transmit the current to and from the distant station. We will now see, first, how the instrument is calculated to receive signals. C is a cylinder of box-wood, capped at each end with brass; D, F, H, O, are slips of metal, the shape of which is seen clearly on the left side of the barrel; a piece of wood, K, projects from the front of the case, having a metal bar, about an inch in length, inserted through the end, standing across it, as in the figure. Now, if W, W″, are connected at the distant station with the two poles of a battery, a current will pass along one of these wires, W, and along the slip of metal, O, to the coil, B, having, in its passage round this, deflected the needle, thereby making a signal; it will descend by a, down the slip of metal, x, thence to the spring, e (which is a part of the same slip), through the metal bar to e, and thence by F to W″, and to the other pole of the battery. We have told you that this return wire, W″, is not used in practice: nor is it; but by supposing it to exist here, the direction of the current is more easily understood. We have, by the dotted lines, shown the buried plate attached to this wire. You should look well at the figure, and read this description of receiving signals several times, till you see it clearly; for though at first sight, the apparatus appears very complicated, it is not so; these slips of brass, so curiously shaped, being all that is required to receive signals; to send them, the cylinder C is added, the action of which we will now explain. The furthest end of it is joined to one of the handles seen in Fig. 7, by which it is made to revolve in either direction. Supposing, then, we move this handle so as to cause the small metal pin z to press against the spring e, we can thus remove the end of this spring from the short bar against which it rested, whilst the pin y at the other end of the cylinder will touch the curved end of the slip F (both these pins are fixed into the metal caps at the ends of the cylinder). The current will now pass from the battery by the spring H to the brass cap of the cylinder, thence by the pin z to é; é being removed from the short bar, and the current thus cut off in that direction, it will pass to x, which is a part of the same slip as é, thence round the coil deflecting the needle, and passing to the next station by the slip o, and wire W, will deflect the needle there, and return by the earth-current to W″. Although it is a crooked path, the electric current traverses it so quickly that no perceptible time elapses between the movement of the needle at our own instrument and the various needles of all the telegraphs on the line. Each handle has a separate cylinder, and each needle a separate coil, one only being represented for the sake of clearness. Every word of the message sent is spelt letter by letter, according to the number of times that each needle moves. The following is one of the usual alphabets, and (as in Fig. 7) this is commonly inscribed on the face of the instrument. It is the code of a single needle:—

A—One movement to the left.

B—Two left.

C—Three left.

D—Four left.

E—One left, one right.

F—One left, two right.

G—One left, three right.

H—Two left, one right.

I—Two left, two right.

J—Two left, three right.

K—Three left, one right.

L—Three left, two right.

M—Four left, one right.

N—One right.

O—Two right.

P—Three right.

Q—Four right.

R—One right, one left.

S—Two right, one left.

T—Three right, one left.

U—One right, two left.

V—Two right, two left.

W—Three right, two left.

X—One right, three left.

Y—Two right, three left.

Z—One right, four left.

With two needles the alphabet is somewhat different; but you will now understand how the movement of the needles can signify words; and we think you must now have a very good idea of the machinery of an electric telegraph. We shall now show you how the alarum is rung by electricity, to give the clerk at the instrument notice that a message is about to be sent to him, that he may be at his post, and ready to watch the needles, and read.

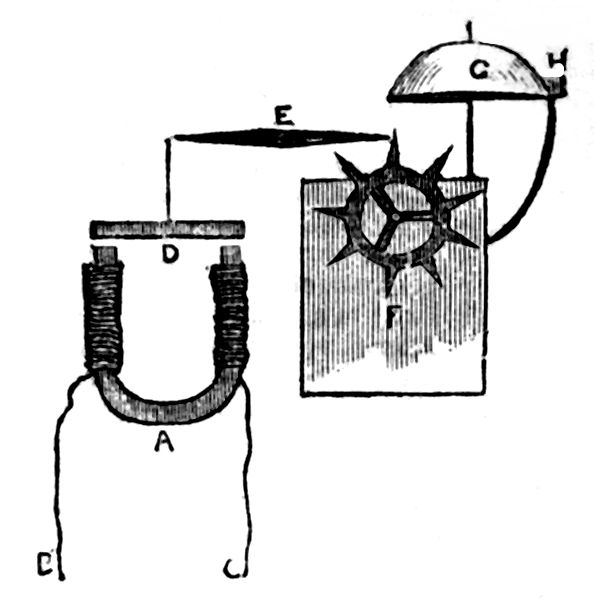

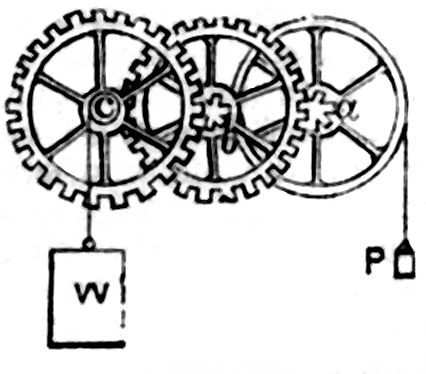

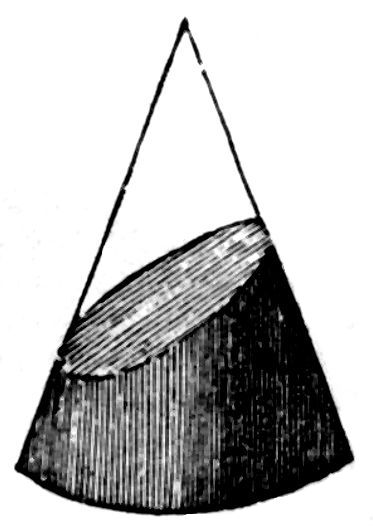

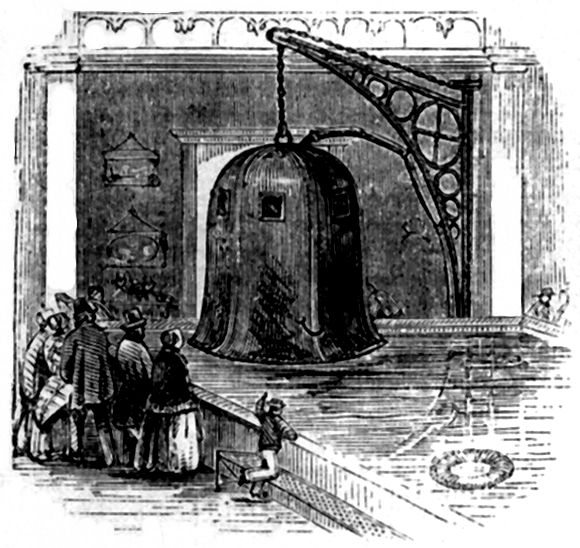

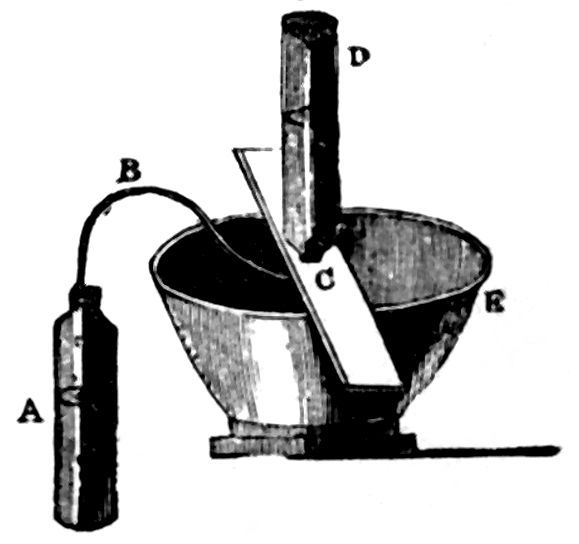

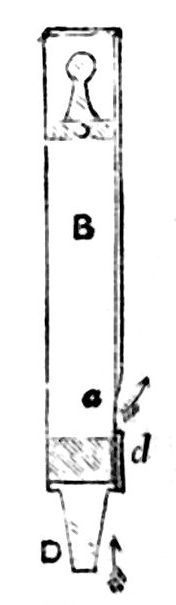

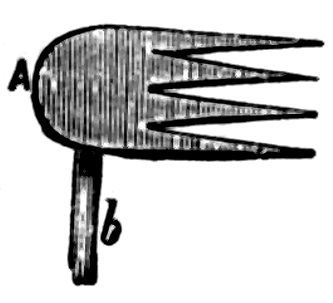

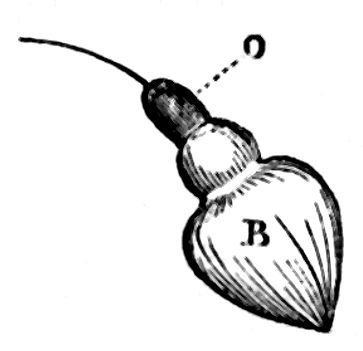

Wonderful as it may appear, an electric current passing round a piece of soft iron will instantly convert it into a magnet; but its magnetic properties cease as soon as the current stops. In the telegraph alarum this effect of electricity is thus applied:—A is a piece of soft iron, bent into the form of a horse-shoe; some covered copper wire is wound round it, the ends, B and C, being left loose for the purpose of connecting them with the battery. D is a piece of steel, connected with the lever, E; the other end of which forms a detent or catch, which falls into one of the notches in the wheel, F. This wheel, when the catch is removed, will revolve by a spring, and, like the movement in a common clock, acts on the hammer, H, which strikes the bell, G. B and C are connected with the distant station by a wire, as the needle apparatus. When the operator, therefore, at that station sends a current from his battery along this wire, A will become a magnet, and attract the keeper, D; this, by means of the levers, will release the wheel, F, and the clock-work will cause the hammer to strike the bell. This will call the attention of the operator, who will return the signal and watch the movement of the needles, read the message, and send the reply in the same manner.

Fig. 9.

BAROMETERS, (HOW TO CONSULT THEM.) In very hot weather, the fall of the mercury denotes thunder. Otherwise, a sudden fall denotes high wind.

In frosty weather, the fall of the barometer denotes thaw.

If wet weather happens soon after the fall of the barometer, expect little of it.

In wet weather, if the barometer falls, expect much wet.

In fair weather, if the barometer falls much, and remains low, expect much wet in a few days, and probably wind.

N. B.—The barometer sinks lowest of all for wind and rain together; next to that for wind—(except it be an east or north-west wind.)

In winter, the rise of the barometer denotes frost.

In frosty weather the rise of the barometer indicates snow.

If fair weather happens soon after the rise of the barometer, expect but little of it.

In wet weather, if the barometer rises high, and remains so, expect continued fine weather in a day or two.

In wet weather, if the mercury rises suddenly very high, fine weather will not last long.

ABORIGINES. A term by which we denote the primitive inhabitants of a country.

FILTERS. The employment of a common flower-pot, of large dimensions, which may be suspended to a beam, or otherwise secured in an elevated situation, makes a good and inexpensive filter. Into this pot lay a mixture of clean sand, and some charcoal broken into bits about the size of peas, and into the hole of the flower-pot place a small plug, drilled through the centre, by which the filtered water may be conducted to the pitcher below. The water may be doubly filtered by employing two flower-pots, one suspended over the other, with a piece of sponge in the hole of the pot, the under one being prepared as directed. The sand and charcoal should occasionally be taken out and well washed, or be replaced by new materials.

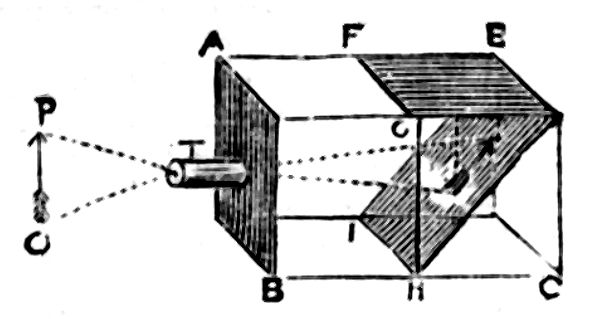

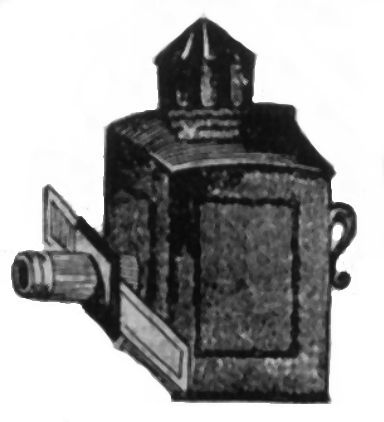

CAMERA OBSCURA. The simplest form of the Camera Obscura consists of a darkened room, with a round hole in the window-shutter, through which the light enters. Pictures of opposite objects will then be seen, inverted, on the wall, or on a white screen placed so as to receive the rays.

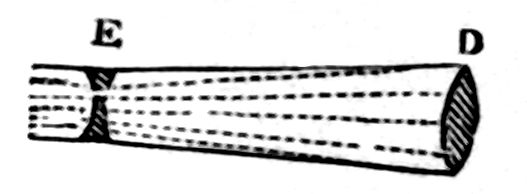

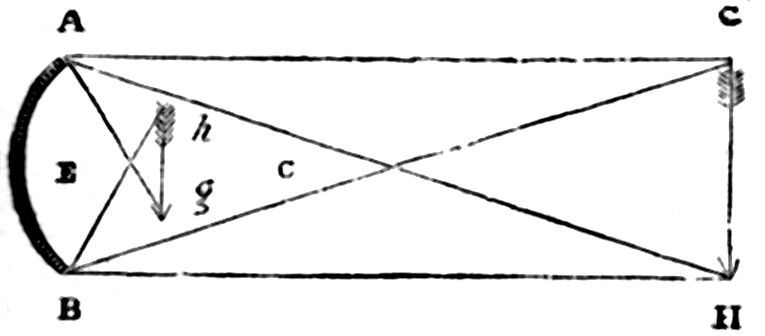

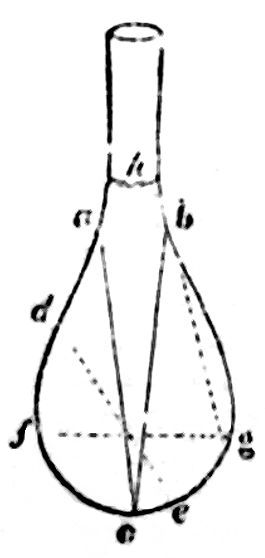

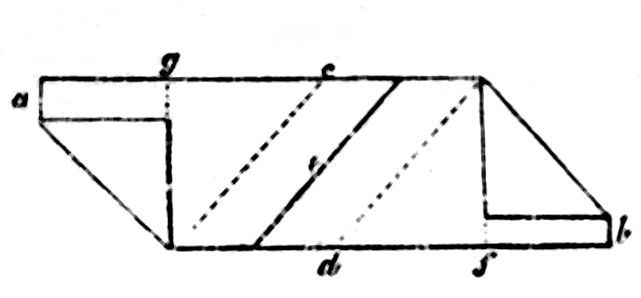

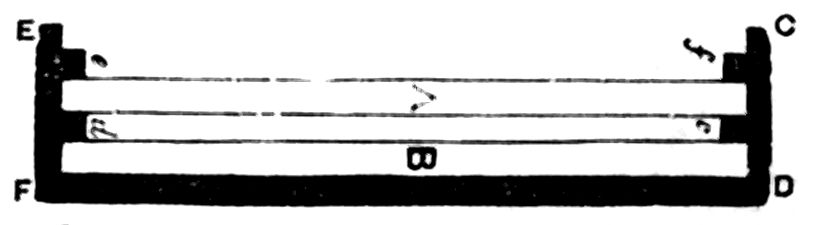

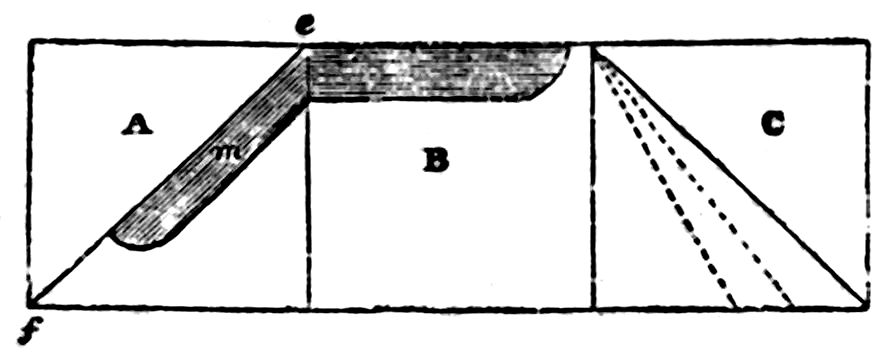

We give here a very simple form of Camera, which our readers may easily construct. A B C D is a small rectangular box, closed on all sides, except the space E F G D, which is covered with a piece of ground glass. In the other end is a moveable tube, T, with a proper lens; and in the body of the box is a mirror, E I H D, set to an angle of 45 deg. Upon this mirror the image of the object, P Q, falls, and is reflected upon the ground-glass plate.

CLEANING DECANTERS. Those encrusted with the dregs of port wine, will be readily freed from stain by washing them with the refuse of the tea-pot, leaves and all, whilst warm. Dip the decanter into a vessel containing warm water, to prevent the hot tea leaves from cracking the glass, then empty the tea-pot into the decanter, and a few strokes will clean it. The tannin of the tea has a chemical affinity for the crust on the glass.

TO CLEAN PAPER OF ROOMS. Few things can be devised better for this purpose than the old-fashioned one of rubbing the paper with stale bread; but where the paper is greasy, occasioned by persons reclining their heads against the wall, it is advisable to use a piece of flannel, wetted with spirits of wine, or Smith’s scouring drops, a mixture of turpentine and essence of lemon.

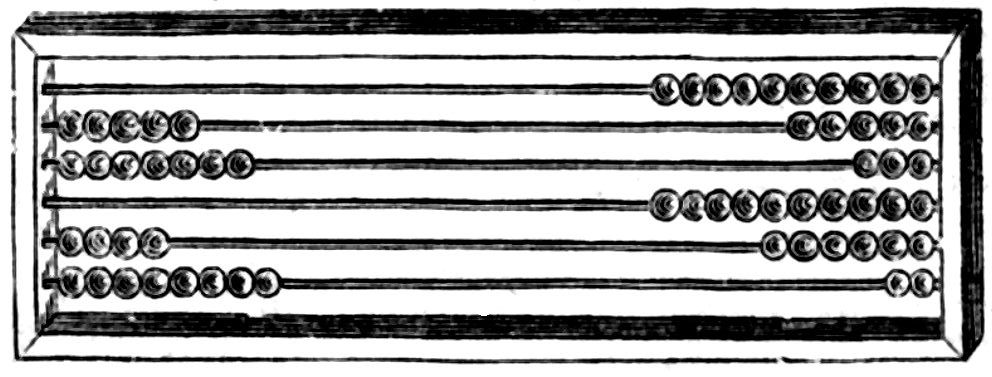

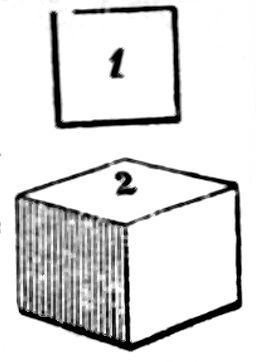

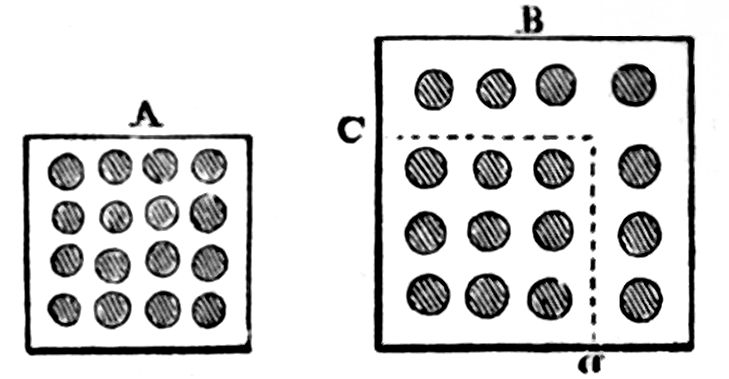

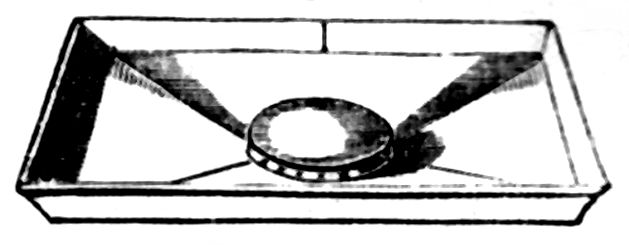

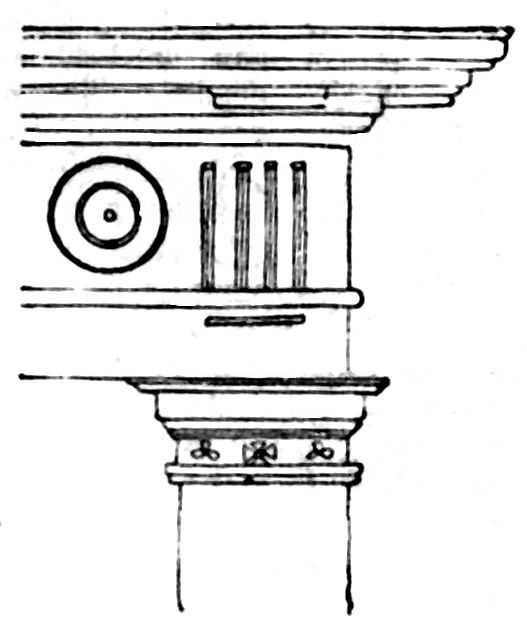

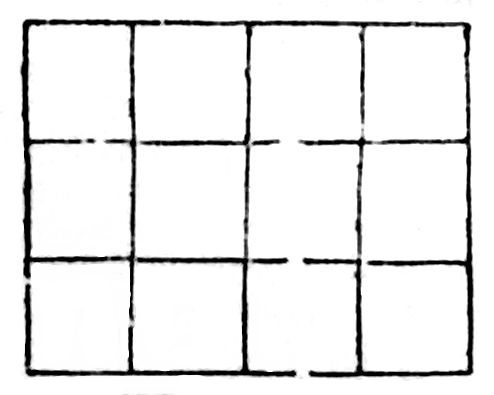

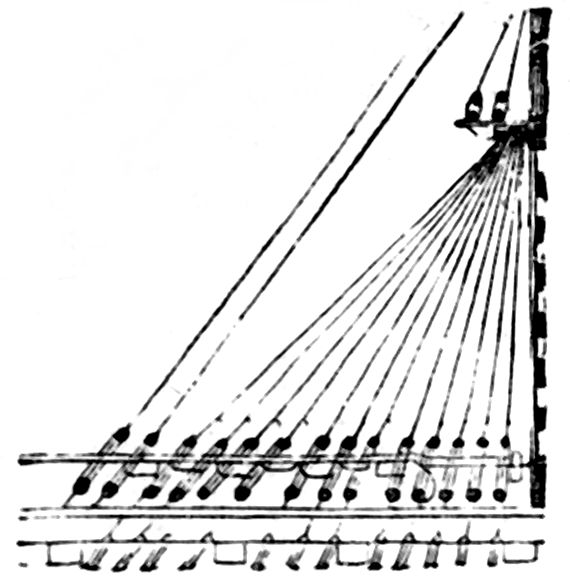

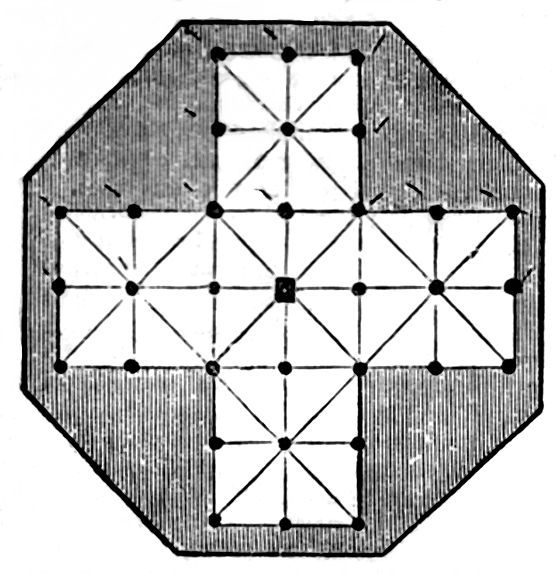

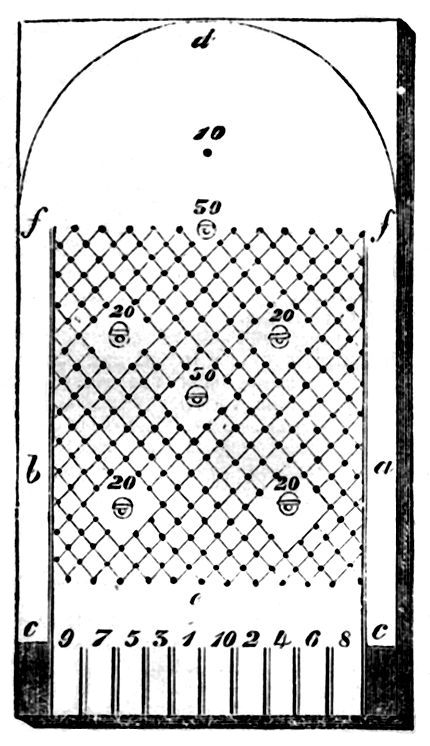

ABACUS. An instrument employed to facilitate arithmetical calculations. The name may be given with propriety to any machine for reckoning with counters, beads, &c., in which one line is made to stand for units, another for tens, and so on. We have here given the form of an abacus, such as we may recommend, for the purpose of teaching the first principles of arithmetic, the only use, as far as we know, to which such an instrument is put in this country. Its length should be about three times its breadth. It consists of a frame, traversed by stiff wires, on which beads or counters are strung so as to move easily. The beads on the first right hand row are units, those on the next tens, and so on. Thus, as it stands, the number 57048 is represented upon the lower part of it.

There is an instrument sold in the toy shops with twelve wires, and twelve beads on each wire, for teaching the multiplication table, and for this purpose much used in our National Infant Schools. The Russians are also much in the habit of performing calculations by strings of beads. In China, however, where the whole system is decimal, this instrument, called in Chinese shwanpan, is universally used. The word Abax was the Greek term for this instrument. Their abacus differs from that described in having only five beads on each line, one of which is distinguished by colour or size from the rest.

ABATTOIR. The name given by the French to the public slaughter-houses, which were established in Paris, by a decree of Napoleon, in 1810, and finished in 1818. These buildings, which are of very large dimensions, consist of slaughter-rooms, built of stone, with every arrangement for cleanliness, and with ample mechanical aids. An endeavour was made to establish them in England, but it failed.

ARSENIC (TO DETECT). Arsenic is not freely soluble in any organic mixtures, and may generally be found as a white sediment, which, when thrown upon a red-hot cinder, gives out a strong odour, like that of onions, and a thick white smoke. The best test is the following:—Pour two tablespoonsful of the suspected fluid into a six ounce bottle, and add seven tablespoonsful of water. Then pour in one tablespoonful of sulphuric acid. Having prepared a cork with a piece of tobacco-pipe run through it, drop into the bottle a few scraps of zinc. Hydrogen gas will be evolved, which, after waiting two or three minutes, may be lighted. If arsenic is present, the onion smell will be detected, and the flame will have a blueish-white colour. Upon holding a piece of glass, or a white saucer, over the point of the flame, black metallic arsenic, in fine crystals, and white arsenic, will be deposited. Common arsenic cannot be detected by the taste.

LIGHTNING. To avoid accidents from lightning during a thunder-storm, sit or stand as near the middle of the room as possible. Avoid going near the windows or walls, and put knives, scissors, and all kinds of steel utensils out of the way. Avoid standing near pipes, iron-railings, and metallic bodies, and if caught in a storm in the country, do not shelter yourself by any means under trees. On a wide and open heath, where no house shelter can be obtained, the safest plan is to lie down flat on the earth.

Stroke of Lightning. Throw cold water upon a person struck by lightning. It is said to be of very great benefit, if not a positive cure.

Lightning-Conductors should be made of copper, or preferably of iron; if of the latter metal, the pointed extremity should be gilded to prevent rust: they should be of sufficient diameter; should project some feet above the highest point of the building, and sink some feet into the ground, till they meet with moisture; and should be perfectly insulated from the building they are designed to protect, by being made to pass through glass rings wherever they come in contact with it.

ABBREVIATIONS are of two kinds; first, those which are used in familiar speech, by which two words are made one, as can’t for cannot, won’t for will not, and those which are employed in writing only. The Rabbins carried this practice to a great extent; thus for Rabbi Levi ben Gerson, they took the first letters, R. L. B. G. In the middle ages the practice of abbreviating increased, insomuch that many writings became unintelligible, and in matters of law and government the difficulties thus created demanded prompt legislative interposition; accordingly, in the fourth year of George II., an act was passed forbidding the use of abbreviations in legal documents. Within a year or two this act was so far modified as allowing the use of those of common occurrence, but the old practice was never completely revived. The most important are:—

titles.

A.M. Master of Arts.

Abp. Archbishop.

Bp. Bishop.

Bt. Baronet.

B.A. Bachelor of Arts.

B.C.L. Bachelor of Civil Law.

B.D. Bachelor of Divinity.

C.B. Companion of the Bath.

Dr. Doctor.

D.C.L. Doctor of Civil Law.

D.D. Doctor of Divinity.

Esq. Esquire.

F.G.S. Fellow of the Geological Society.

F.L.S. Fellow of the Linnæan Society.

F.R.S. Fellow of the Royal Society.

F.S.A. Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.

G.C.B. Grand Cross of the Bath.

Kt. Knight.

K.B. Knight of the Bath.

K.C.B. Knight Commander of the Bath.

K.C.H. Knight Commander of Hanover.

K.G. Knight of the Garter.

K.G.H. Knight of Guelph of Hanover.

K.M. Knight of Malta.

K.P. Knight of St. Patrick.

K.T. Knight of the Thistle.

LL.D. Doctor of Laws.

Messrs. Gentlemen.

M.A. Master of Arts.

M.D. Doctor of Physic.

M.P. Member of Parliament.

R.A. Royal Academician.

Rt. Hon. Right Honorable.

R.E. Royal Engineers.

R.M. Royal Marines.

R.N. Royal Navy.

H.E.I.C. Honourable East India Company.

W.S. Writer to the Signet.

commercial.

Cr. Creditor.

Dr. Debtor.

Do. or ditto, the same.

No. Number.

Fo. Folio.

4to. Quarto.

8vo. Octavo.

L.S.D. Pounds, Shillings, and Pence.

A.R.P. Acres, Roods, and Poles.

Cwt. Qr. Lb. Oz. Hundredweights, Quarters, Pounds, and Ounces.

miscellaneous.

A.D. the year of our Lord.

A.M. the year of the world.

A.M. before noon.

B.C. before Christ.

i.e. that is to say.

ib. in the same place,

id. the same.

H.M.S. Her Majesty’s ship.

MS. Manuscript.

N.B. Observe.

N.S. New Style (after the year 1752).

O.S. Old Style (before 1752).

Nem. con. without contradiction.

P.M. Afternoon.

P.S. Postscript.

ult. the last month.

viz. namely.

F.D. Defender of the Faith.

D.G. By the grace of God.

EXERCISES, (INDOOR). Females much confined within doors often suffer ill health from the want of exercise. Nature demands it, and health cannot exist without it. The skipping-rope, dumb-bells, battledoor and shuttle cock, &c. are all aids to the required end. Dancing is one of the best preservatives of health, when enjoyed at proper hours, and not carried to excess. But this exercise can only be obtained upon particular occasions, when there are many to share it, and glad music contributes to heighten the enjoyment. Really the best indoor exercise for developing a graceful bearing, and for diffusing its healthful influence over the whole frame, is that of throwing balls dexterously, according to any of the contrivances of fancy. Persons who become expert in this practice may throw from one to eight balls with astonishing dexterity, the exercise being sufficiently stimulating to encourage its frequent repetition; quickening the eye, and imparting a healthful vigour to every muscle of the system. A few neat leather balls are all that are required, and a room of moderate size will afford sufficient space. Dumb-bells are cumbrous and inelegant things, and the exercise they afford is monotonous and wearisome; besides which, they exercise but one part of the body.

CLIMATE OF ENGLAND. The mortality of Great Britain, its cities, and its hospitals, is greatly inferior to that of any other country in Europe; it is also incontestable that Great Britain is at present the most healthy country with which we are acquainted; and that it has been gradually tending to that point for the last fifty years. It has been long the fashion, both abroad and at home, to exhaust every variety of reproach on the climate of our country, and particularly on the atmosphere of London; and yet we find that the most famed spots in Europe, the places which have been selected as the resorts of invalids, and as the fountains of health, are far more fatal to life than even this great metropolis.

ETCHING UPON IVORY. Cover the ivory with wax, hard varnished, or an etching ground, execute the required design, border with wax, and pour on sulphuric acid, hydrocloric acid, or a mixture of equal parts of both acids; when etched sufficiently, wash well, remove the wax, varnish, or etching ground with oil of turpentine, and rub well with old linen rag. Some persons rub a black varnish into the etched parts to give a greater effect. The varnish is made of lamp-black and common turpentine varnish, and the surface is rubbed clean off, leaving only the dark parts visible.

Etching (Upon Egg shells). Cover the shells with appropriate designs in tallow, or varnish, and immerse in strong acetic acid; they will then come out in strong relief.

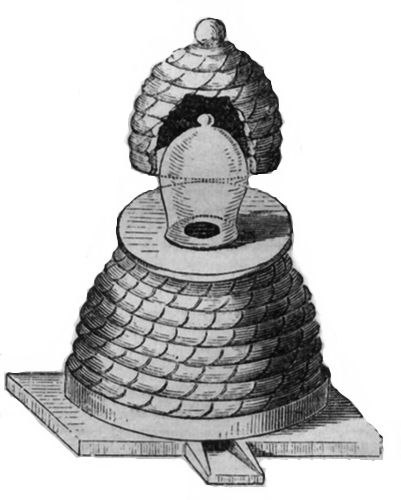

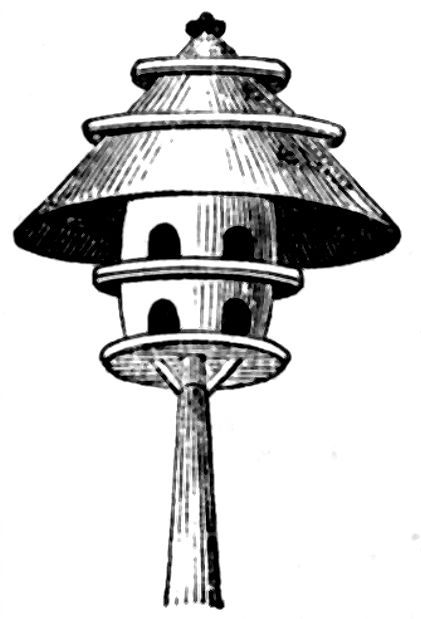

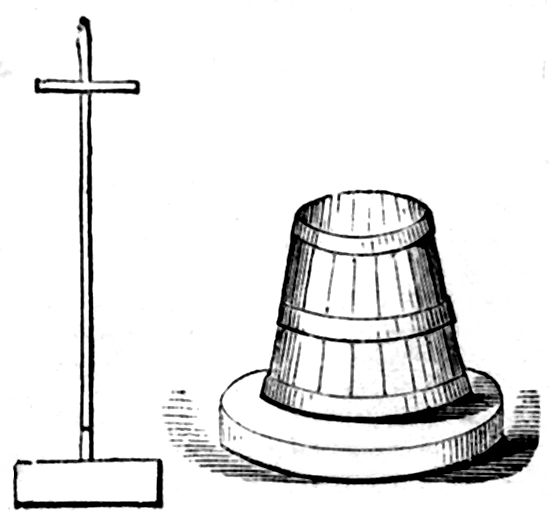

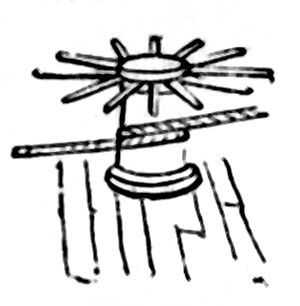

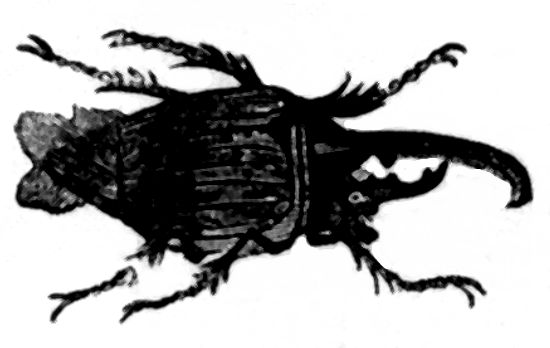

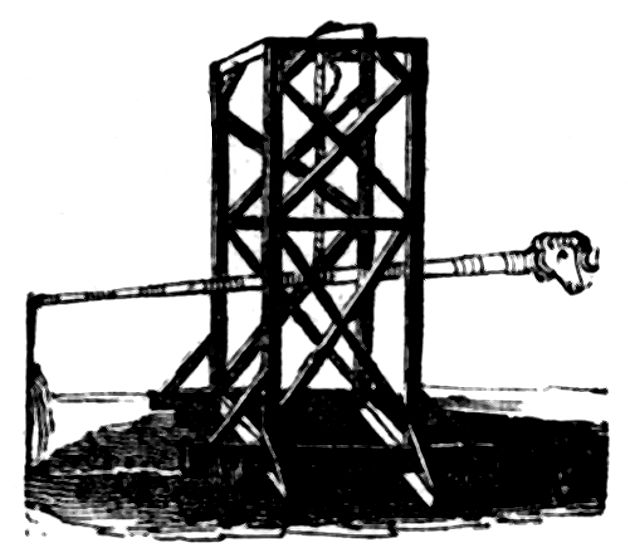

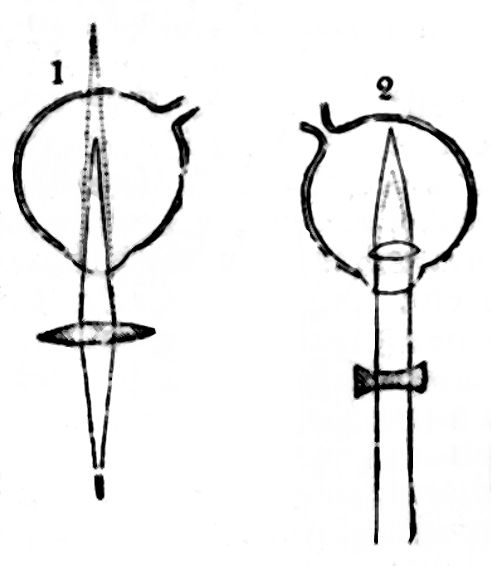

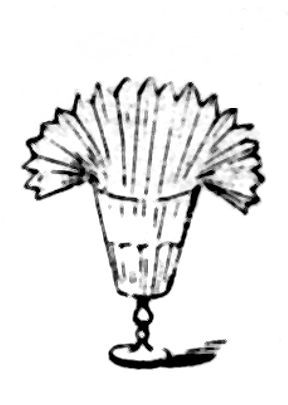

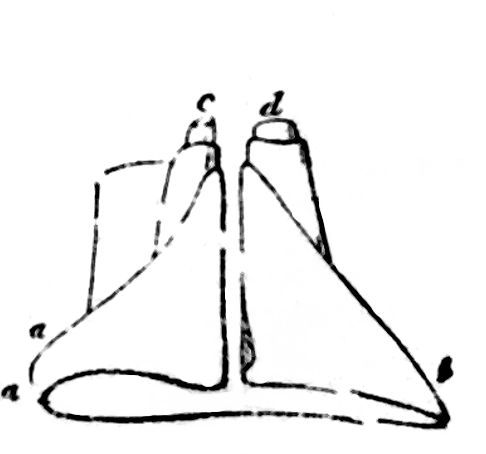

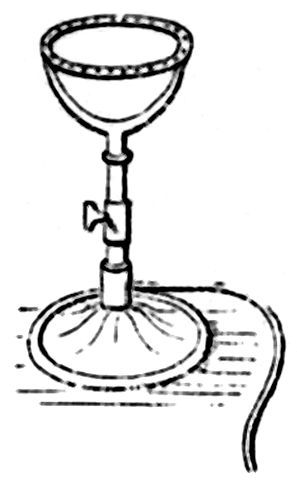

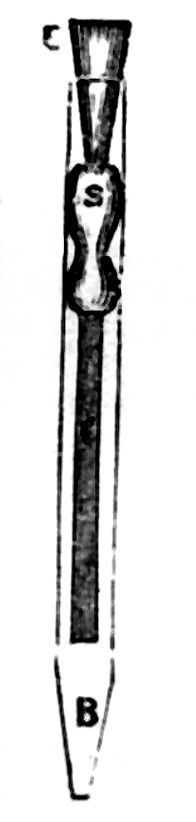

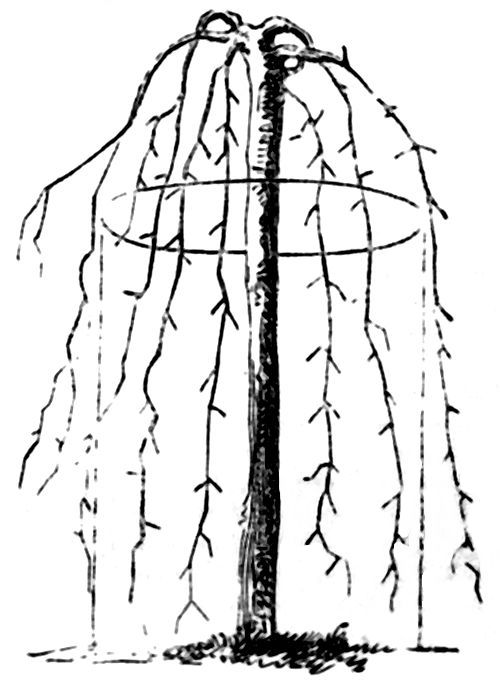

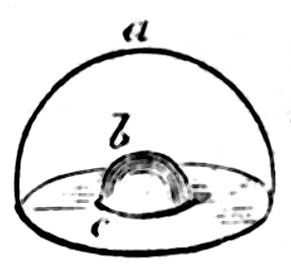

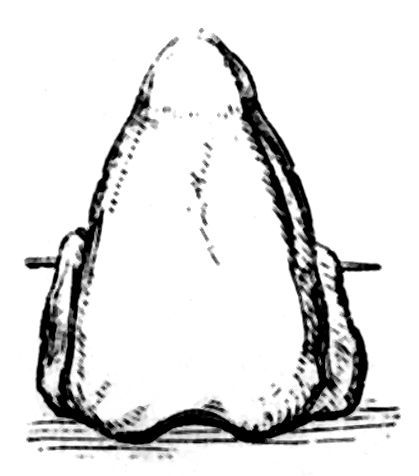

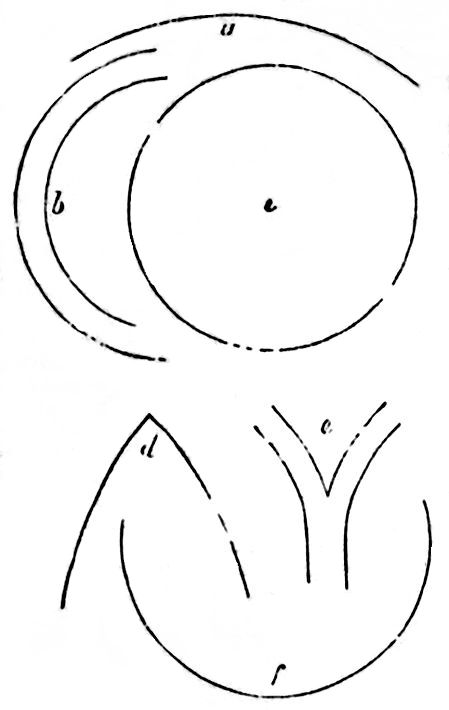

HIVES, (COTTAGE). There are various descriptions of hives in general use. Without recommending any particular kind, we give a representation of one which is simple and effective. This is capped with a bell-glass; the small hive used as a cover for which is raised, and has part of the side cut away to show the bell-glass. The dome shape is preferable to a square or cylinder, as affording more perfect ventilation, and as being more in accordance with the clustering position of the bees themselves, either in winter or during swarming.

FUMIGATING BEE-HIVES. Fumigation is a word employed by bee-keepers to express the process in which, by the aid of certain intoxicating smoke, the insects become temporarily stupified in which state they are perfectly harmless, and may be deprived of their honey without any risk or trouble. They subsequently soon recover from their stupification, and are none the worse for it. Rags steeped in a solution of saltpetre, or a few tobacco leaves wrapped in brown paper, will do.

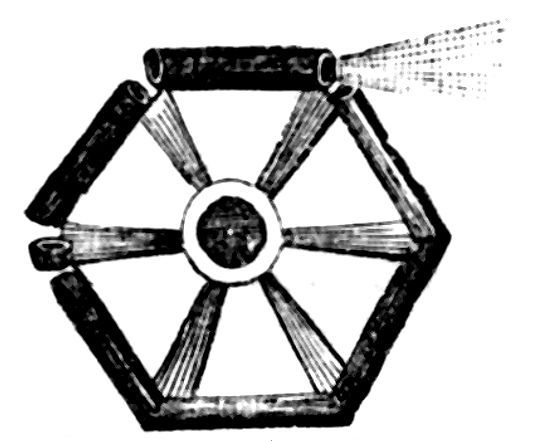

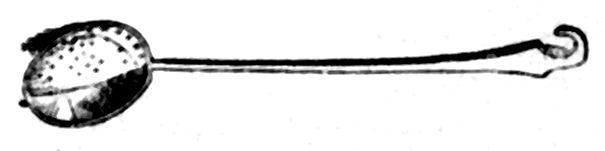

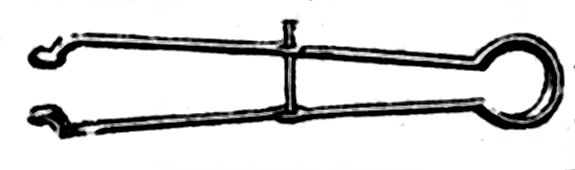

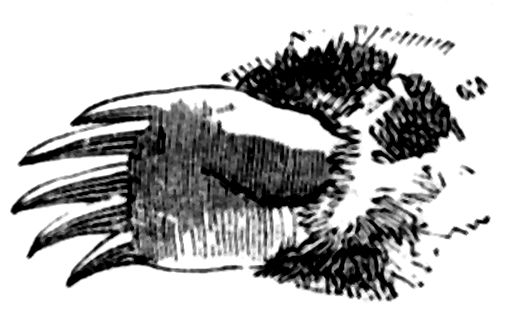

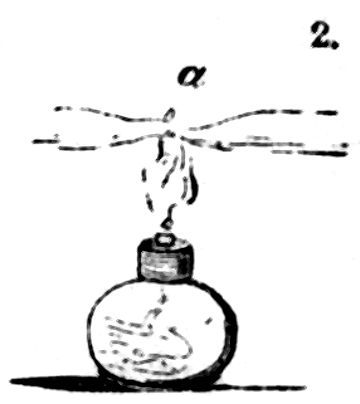

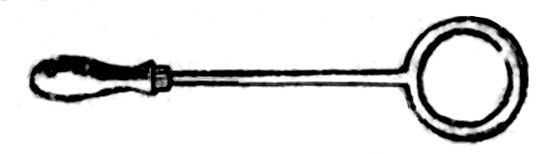

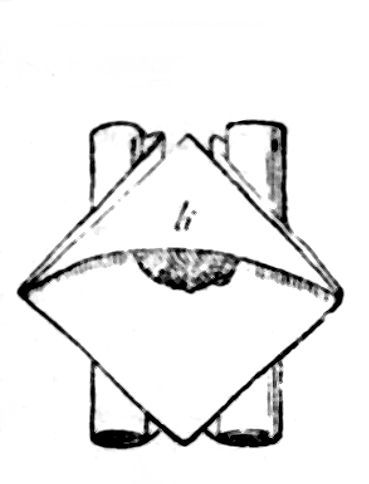

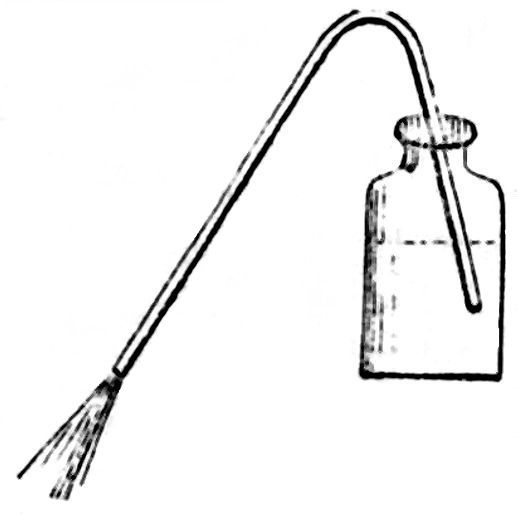

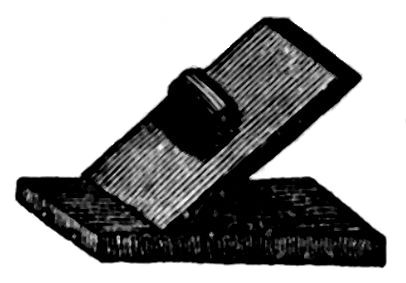

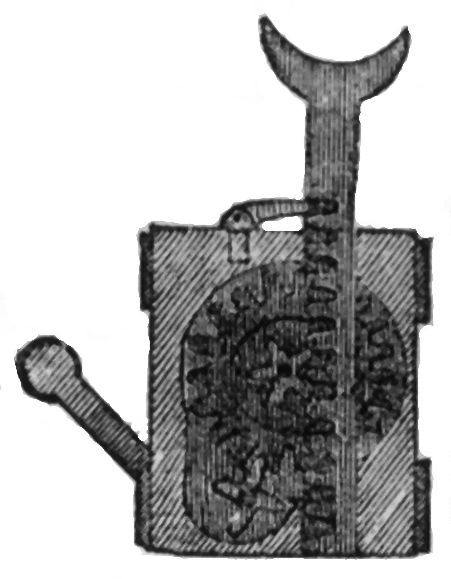

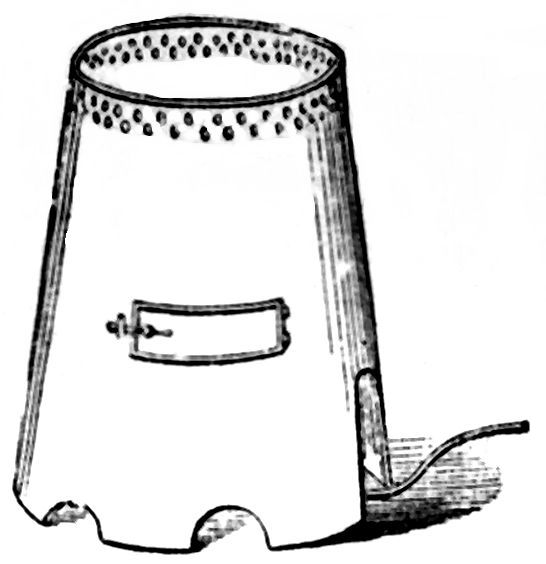

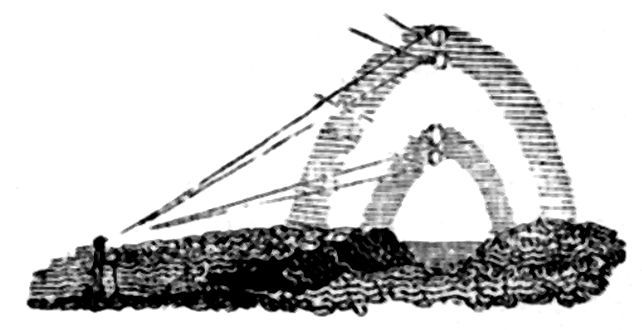

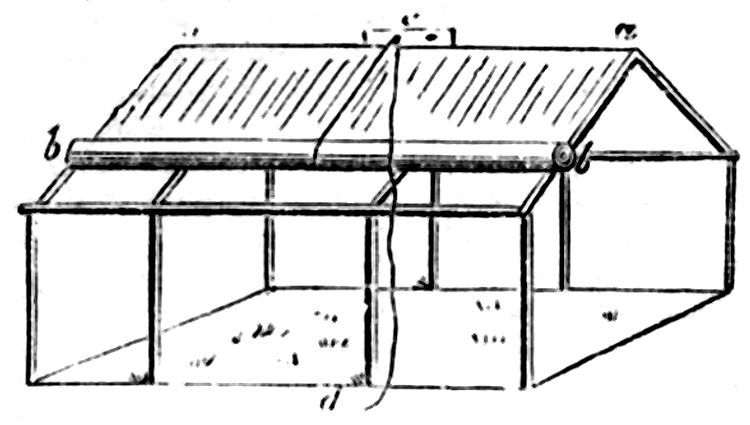

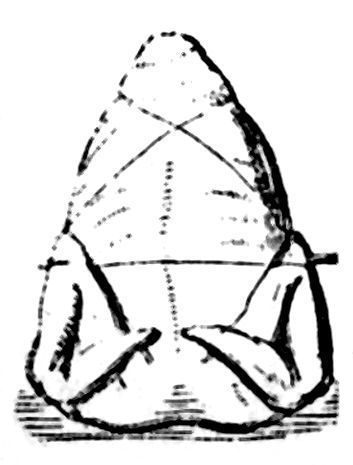

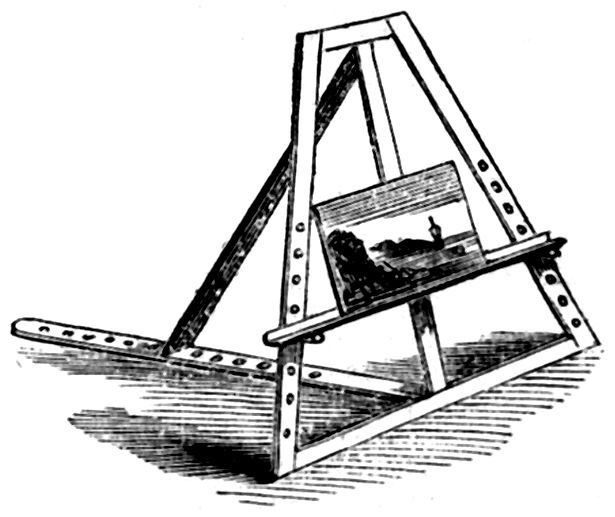

If, however, tobacco is used, care is necessary, lest the fumigation be carried to too great an extent, so as to cause the death of some of your stock. Persons not accustomed to deal with bees should wear an overall of thin gauze over the head and breast, and gloves on their hands. With this, and a little bottle of aqua-ammonia, or aqua-potassæ, to be used in case of their being stung, they have no cause for trepidation. For the process of fumigation, you should have a small tin box, with a tube extending from each of the two opposite ends; one end of this tube being so fashioned that it can readily be inserted into the hive, and the other so formed that it can readily be attached to the tube of an ordinary bellows, as in the annexed engraving.

EYE, (SUBSTANCES IN THE). To remove fine particles of gravel, lime, &c., the eye should be syringed with lukewarm water till free from them. Be particular not to worry the eye under the impression that the substance is still there, which the enlargement of some of the minute vessels makes the patient believe is actually the case.—Or, bathe the eye with a little weak vinegar and water, and carefully remove any little piece of lime which may be seen, with a feather. If any lime has got entangled in the eyelashes, carefully clear it away with a bit of soft linen soaked in vinegar and water. Inflammation is sure to follow; a smart purge must therefore be administered.

FIRE. The following are among the best Precautions in Cases of Fire. 1. Should a fire break out, send off to the nearest engine or police station. 2. Fill buckets with water, carry them as near the fire as possible, dip a mop into the water, and throw it in showers on the fire until assistance arrives, 3. If a fire is violent, wet a blanket and throw it on the part in flames. 4. Should a fire break out in a chimney, a blanket wetted should be nailed to the upper end of the mantel-piece, so as to cover the opening entirely, the fire will then go out of itself; for this purpose, two knobs should be permanently fixed in the upper ends of the mantel-piece, upon which the blanket may be hitched. 5. Should the bed or window-curtains be on fire, lay hold of any woollen garment, and beat it on to the flames until extinguished. 6. Avoid as much as possible leaving any door or window open in the room where the fire has broken out, as the current of air increases the force of the fire. 7. Should the staircase be burning so as to cut off all communication, endeavour to escape by means of a trap-door in the roof, a ladder leading to which should always be at hand. 8. Avoid hurry and confusion. 9. In case a lady’s dress takes fire, she should endeavour to roll herself in a rug, carpet, or the first woollen garment she meets with. 10. A solution of pearlash in water, thrown upon a fire, extinguishes it instantly; the proportion is a quarter of a pound dissolved in some hot water, and then poured into a bucket of common water.

STIFF NECKS, (SUPPORT FOR). This valuable support should be made of black moreen if it be worn with a black neckerchief; and of white ditto, (or mohair,) if with a light one. It is formed of a number of pieces, each one being bound with ribbon only, and being joined in the middle of each piece by a few stitches. The binding must be carried all along the top and bottom but must be sufficiently loose between the segments to give the neck a comfortable freedom.

SWELLING IN THE NECK, or Goitre, is a disease peculiar to the natives of some of the Pennine Alps, particularly Aosta and Martigny, and is allied to a species of idiotcy called cretenism.

ABSOLUTION, a religious ceremony in use in different Christian communities, by which the priest declares an individual, on repentance and submission to the requisite penance, to be absolved from his sin.

SUN-STROKE, (PROTECTION AGAINST.) A piece of silk, which is a non-conductor, worn as the lining of hat or bonnet, is a very safe protection against sun-stroke.

OIL PAINTINGS, (TO CLEAN). The art of cleaning oil paintings has been very much neglected, and several valuable pictures have been destroyed in consequence of the persons operating upon them employing the same means for removing all kinds of dirt, as they do for dust and varnish commingled, so that frequently a valuable painting has actually been scoured away.

Most paintings are varnished, and as the nature of the varnish differs, so also must the means by which they are removed. In some cases it is better to allow the varnish to remain untouched, than to interfere with it, as the painting might be damaged in the latter instance.

The materials required consist of water, olive oil, pearlashes, soap, spirits of wine, oil of turpentine; sponge, woollen and linen rags; essence of lemons, and stale bread crumbs.

Soluble Varnishes, such as sugar, glue, honey, gum arabic, isinglass, white of egg, and dirt generally, may be removed by employing hot water. To know when the painting is varnished or coated with such materials, moisten some part with water, which will become clammy to the touch. To clean the picture, lay it horizontally upon a table or some convenient place, and go over the whole surface with a sponge dipped in boiling water, which should be used freely until the coating begins to soften; then the heat must be lowered gradually as the varnish is removed. If, however, the coating is not easily removed, gentle friction with stale bread crumbs, a damp linen cloth, or the end of the forefinger, will generally effect it, or assist in doing so. White of an egg may be removed (if not coagulated by heat), by using an excess of albumen (white of egg), and cold water; but if coagulated, by employing a weak solution of a caustic alkali as potash.

Coated dirt is removed by washing with warm water, then covering with spirit of wine, renewed for ten minutes, and washing off with water, but without rubbing. The process is to be repeated until the whole is removed.

Spots should be washed with warm water dried with soft linen rags, and covered with olive oil warmed; after the oil has remained on the spots for twenty minutes, gentle friction with the finger should be used, the foul oil wiped off and fresh laid on, until the spot disappears. Should this fail, spirits of wine, essence of lemons or oil of turpentine may be carefully applied, observing that only such parts as are dirty must be covered with them; they are to be cleaned off first with water and then with olive oil. Sometimes even these means fail, and then strong soap-suds, applied directly to the spots, and retained there until they soften or disappear, will prove effectual. The spots must then be washed with water.

In employing these means, as indeed throughout the whole process of cleaning, the greatest care should be taken in removing any coating upon the surface of a painting, and it is therefore better to employ mild measures first, then if they fail, to use stronger; or in the event of these not succeeding, to very carefully apply the strongest. For our own part, we prefer leaving the painting in a half-cleaned state, as it sometimes happens that, with the most scrupulous care, under experienced persons, some of the fine touches or delicate tints of a painting are damaged by the process. When we state this, we mean only such pictures as are covered with insoluble varnishes—varnishes of gum-resins, or old oil varnishes, which cannot well be removed without injury to the painting.

Varnishes of long standing are very difficult to remove, as they generally consist of linseed oil combined with gum-resins, and if not easily taken off by the means given below, it is better to leave them as they were.

To remove these varnishes, use spirits of wine in the manner recommended for coated dirt; or, oil of turpentine, which requires greater care than the spirits of wine; or, warm olive oil: but if the varnish is very hard, the painting should be washed by means of a sponge, with a warm solution of pearlash (an ounce to a pint of water), until the coating is removed, when the surface must be washed well with fresh water frequently.

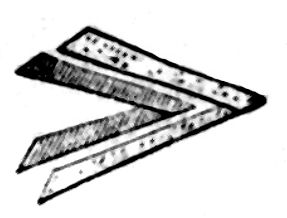

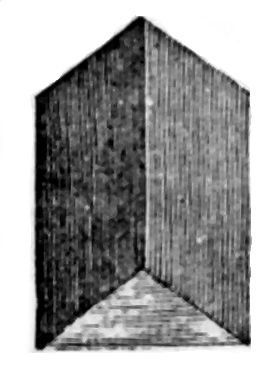

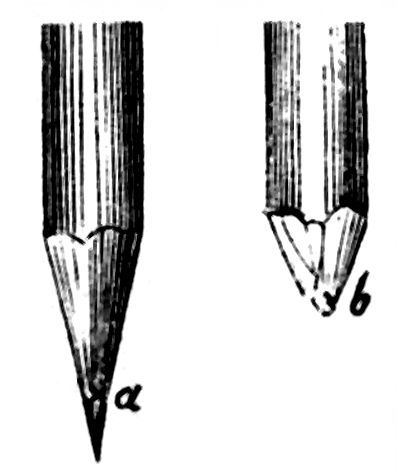

THE WEDGE. When the compression of a block of wood is completed by the means of driving in a wedge, it then splits, and it is on this principle that the action of the wedge is founded. In the annexed diagram the explanation of the law may be seen. The point of the engine has been inserted by the blow of a hammer into a block of wood, and the wood by compression, has been displaced, and the block is rending because it can suffer no more compression. All the various kinds of cutting and piercing tools, as axes, knives, scissors, nails, pins, awls, are modifications of the wedge. The angle, in these cases, is more or less acute, according to the purpose to which it is applied.

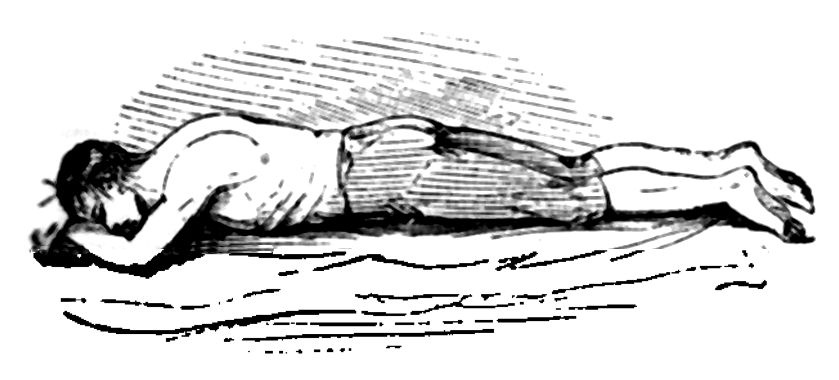

DROWNING and SUFFOCATION. Dr. Marshall Hall, after careful research, shews that to induce the act of breathing is the first thing to be attended to in drowning or suffocation. And the reason is: the lungs refuse to act, not so much because the common air with its oxygen cannot find entrance, but because the carbonic acid remains in the blood. Let us look at the mode of treatment which Dr. Marshall Hall recommends. Suppose the body to be taken from the water, it is to be at once laid on the face, not on the back, and in the open air, if houses be so far distant as to cause long delay in the removal. Every minute is precious. Being laid on the face, with the head towards the breeze, the arms are to be placed under the forehead, so as to keep the face and mouth clear of the ground. In this position the tongue falls forward, draws with it the epiglottis, and leaves the glottis open. In other words, the windpipe is open, and the throat is cleared by fluids or mucus flowing from the mouth.

The reason for placing the body in the prone position, on the face, will be better understood by noticing what takes place when it is on its back. The tongue then falls backwards, sinks, so to speak, into the throat, and closes up the windpipe, so that no air can possibly find its way to the lungs, except by force.

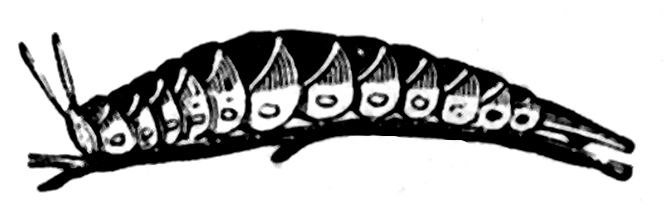

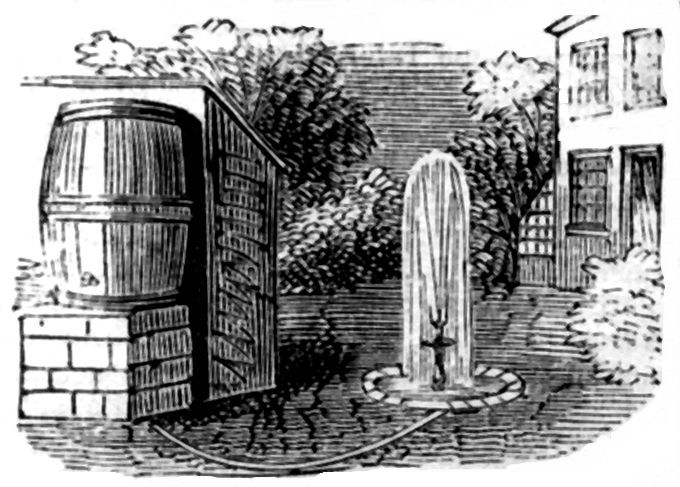

The body, therefore, being laid on its face, there is a natural pressure of the chest and abdomen which causes an expiration. This may be increased by some additional pressure. Then if the body be lifted by an attendant placing one hand under the shoulder, the other under the hip, and turning it partly on its left side, there will be an inspiration. The air will rush into the lungs with considerable violence. Then the expiration may be repeated by letting the body descend, and so on, up and down alternately. And thus, without instruments of any kind, and with the hands alone, if not too late, we accomplish that respiration which is the sole effective means of the elimination of blood poison. It is worthy of notice that by this means a really dead body may be made to breathe before it has become stiff—as experiment fully demonstrates.