* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Lawrence of Arabia--Zionism and Palestine

Date of first publication: 1937

Author: Sir Ronald Storrs (1881-1955)

Date first posted: Mar. 22, 2020

Date last updated: Mar. 22, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200347

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Jen Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA

ZIONISM AND PALESTINE

BY SIR RONALD STORRS

Sir Ronald Storrs was one of Lawrence’s closest friends, and this personal sketch, written in 1937 has already become a classic. Of the chapters on Palestine which follow, the author himself says: “The estimate of Zionism will on the whole be found to have stood the test of time, and is, whatever its demerits, at least so balanced that each of the parties involved continues, as in the past, to accuse me of favouring the other.” For this edition it has been revised, and brought up to date by a postscript covering events down to March, 1940.

THE AUTHOR

(From a drawing by Eric Kennington in Seven Pillars of Wisdom)

Was born in Bury St. Edmunds in 1881 and educated at Charterhouse and Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he obtained First Class Classical Honours. He occupied several administrative posts in the Ministry of Finance of the Egyptian Government from 1904 until 1909, when he was appointed Oriental Secretary to the British Agency in Egypt. Sir Ronald was Assistant Political Officer with the E.E.F. in 1917, Liaison Officer in Baghdad and Mesopotamia, Military, (1917-1920) and afterwards Civil Governor of Jerusalem and Judaea, Governor and C.-in-C. of Cyprus 1926-1932, and Northern Rhodesia 1932-1934. He knew Col. Lawrence intimately, and has given many lectures on “Lawrence of Arabia” during his recent tour in America, as well as in this country.

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA

ZIONISM AND PALESTINE

BY

SIR RONALD STORRS

PENGUIN BOOKS

HARMONDSWORTH MIDDLESEX ENGLAND

41 EAST 28th STREET, NEW YORK, U.S.A.

The Contents of this book were originally published in “Orientations” (Ivor Nicholson and Watson) in 1937. This selection was first published in Penguin Books in 1940.

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR PENGUIN BOOKS LIMITED

BY PURNELL AND SONS. LTD., PAULTON (SOMERSET) AND LONDON

| CONTENTS | ||

| INTRODUCTION | v | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY | vii | |

| PART I--LAWRENCE OF ARABIA | ||

| I | 9 | |

| II | 14 | |

| PART II--ZIONISM AND PALESTINE | ||

| I | 41 | |

| II | 61 | |

| III | 78 | |

| IV | 98 | |

| POSTSCRIPT 7. viii. 37 | 121 | |

| P.P.S. 15. iii. 40 | 124 | |

I was pleased and proud when Mr. Allen Lane first suggested that my Lawrence chapters (IX and XVIII) in Orientations contained the makings of a Penguin. When, however, we came to compute we found that, assuming the quality, the quantity even after expansion (and revision) amounted to barely half a bird. I offered to build up the remainder by chapter XV, the Excursus on Zionism; and this also found favour in his eyes. The upper half, particularly when lengthened by a P.P.S. bringing it to the date of going to press, proved also much the larger; so that this particular Penguin will lurch and shuffle rather a top-heavy little fowl into the public eye.

I have tried to make each section “autarkic”, but I cannot deny that Lawrence, taken out of his appropriate setting of the Hejaz episode, and Zionism, unsupported by the four long Palestine chapters which it divides, may to such as have read Orientations both appear relatively isolated. Yet to hatch, and to hutch these extra chapters would demand (what the Oxford English Dictionary calls) a regular “Penguinery” or “colony of pen’gwins”.

The personal sketch of Lawrence would have been richer and better if I had from the first taken copies of his hundred odd letters, some ninety of which perished in the burning of Government House, Cyprus. The estimate of Zionism, which is reprinted as originally written (but brought up to 15th March, 1940, by a P.P.S.), will on the whole be found to have stood the test of time, and is, whatever its demerits, at least so balanced, that each of the parties involved continues, as in the past, to accuse me of favouring the other. I can only defend myself by accepting the double charge, and by likening my attitude (I hope with becoming reverence) to that of Hera towards Achilles and Agamemnon:

ἄμφω ὁμῶς θυμῷ φιλέουσά τε κηδομένη τε

For in her heart both of the pair

Did exercise her loving care.

The emblem on the obverse binding is my Arabic, on the reverse my Hebrew seal as Military Governor of Jerusalem (December 27, 1917, until July 1, 1920).

The unacknowledged quotations in these pages are from my diaries or private letters.

Thomas Edward Lawrence—always Ned to his family—was born the second of five sons at Tremadoc, in Wales, on August 16, 1888 (Napoleon’s birthday), of an Anglo-Irish father and a Highland Scottish mother. He was educated at the Oxford High School for Boys, where he was already developing “a passionate absorption in the past: in heraldry, arms and armour, monumental brasses, castles, ruins, church architecture, old coins, and every fragment of brick or pottery which might throw light on the social history and ways of living of mankind”.[1] He went on to Jesus College, Oxford, and gained a scholarship at Magdalen College which enabled him, under the famous archaeologist-arabist, D. G. Hogarth, to follow his bent in the Near and Middle East. In November 1914 he was appointed to the Intelligence Department of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, Cairo. The author, seven years his senior, had preceded him there by ten years, of which he had served five in the Egyptian Government and five as Oriental Secretary to the British Agency, latterly under Lord Kitchener. By the time of Lawrence’s arrival Great Britain, in retaliation for Turkish German-urged hostility, had declared Egypt (of which Turkey had been suzerain) a British Protectorate. The title of the Egyptian sovereign, Khedive, had been raised to Sultan; that of the British Representative from Agent and Consul-General to High Commissioner, his residence from Agency to Residency;[2] and this was the political status of Egypt throughout the Arabian campaigns. For Lawrence’s taking over and conduct of these, the major document must always be his Seven Pillars of Wisdom, until his death only available to the public in the abridged Revolt in the Desert; to both of which, but particularly Seven Pillars, the reader is referred.

After the British and Arab entry into Damascus Lawrence left the Army and served first in the Royal Tank Corps, then in the Royal Air Force, latterly as an Inspector (and perfector) of high-power motor-craft. He was retired in 1935 at the age of forty-six. On May 6, 1935, swerving his motor-cycle to avoid two boys riding abreast, he was violently thrown and met his death.

[1] Letters of T. E. Lawrence. Edited by David Garnett, p. 39.

[2] After the War all three were further promoted. The Sultan became King, the High Commissioner, Ambassador, and the Residency, Embassy.

Courage! build great works—’tis urging thee—it is ever nearest the favourite of God—the fool knows little of it. Thou wouldst be joyous, wouldst thou? then be a fool. What great work was ever the result of joy, the puny one? Who have been the wise ones, the mighty ones, the conquering ones of this earth? the joyous? I believe it not.

GEORGE BORROW, Lavengro, chap. xviii.

Into friendship with T. E. Lawrence I know not how I entered; not at first anyhow by direct official contact. I had never heard of him until the winter of 1914, when he became a member of the Intelligence Branch of the Egypt Defence Force, and then suddenly it seemed I must have known him for many years. Lawrence was of lesser medium stature and, though slight, strongly built. His forehead was high; his face upright and, in proportion to the depth of the head, long. His yellow hair was naturally-growing pre-War hair; that is parted and brushed sideways; not worn immensely long and plastered backwards under a pall of grease. He had a straight nose, piercing gentian-blue eyes, a firm and very full mouth, a strong square chin and fine, careful, and accomplished hands. His Sam-Browne belt was as often as not buckled loose over his unbuttoned shoulder strap, or he would forget to put it on at all. Once at least I had to send my servant Ismain running with it after him into the street. Augustus John’s first drawing is perfect of his Arab period; Kennington’s bronze in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral gives the plastic and Homeric simplicity of his lines and rhythm, and Howard Coster’s photograph, published in The Illustrated London News after his death, besides being a good likeness hints somehow at the unhappiness latent behind the eyes.

Save for official purposes he hated fixed times and seasons. I would come upon him in my flat, reading always Latin or Greek, with corresponding gaps in my shelves. But he put back in their proper places the books he did not take away; of those he took he left a list, and never failed to return them reasonably soon, in perfect condition. We had no literary differences, except that he preferred Homer to Dante and disliked my placing Theocritus before Aristophanes. He loved music, harmony rather than counterpoint, and sat back against the cushions with his eyes half-closed, enduring even that meandering stream of musical consciousness which I dignified by the name of improvisation. Ismain[3] told me that Lawrence used to ask at the door if I was alone, and go away if I was not, fearing (he told me when I complained) that he might be let in for the smart “or” the boring—he meant “and”, for the terms with him were synonymous. He angered me once by failing (without excuse) to appear at a dinner of four I had arranged for him; and only told me long afterwards that I had more than “got back on him” by explaining that I shouldn’t have minded if he had only warned me in time to get somebody else.

He must, it seemed, gulp down all I could shed for him of Arabic knowledge, then bounded for him by the western bank of the Suez Canal; yet never by the “pumping” of crude cross-examination. I told him things sometimes for the mere interest of his commentary. He was eager and unfatigued in bazaar-walking and mosque-hunting. I found him from the beginning an arresting and an intentionally provocative talker, liking nonsense to be treated as nonsense, and not civilly or dully accepted or dismissed. He could flame into sudden anger at a story of pettiness, particularly official pettiness or injustice. Of all men then alive I think he trusted and confided most in D. G. Hogarth who, by making possible his Travelling Scholarship, had given him his first chance in life.

Shortly after the Arab Revolution we found that its success was being denied or blanketed by the Enemy Press (which was of course quoted by neutrals), and we decided that the best proof that it had taken place would be provided by an issue of Hejaz postage stamps, which would carry the Arab propaganda, self-paying and incontrovertible, to the four corners of the earth. The High Commissioner was quick to approve; and the Foreign Office approved him. I had corresponded with King Husain on the project, and he sent me by return of mail a design purporting to typify Islamic architecture, but to the layman indistinguishable from the Eddystone Lighthouse. This I felt would never do, so wandered with Lawrence round the Arab Museum in Cairo collecting suitable arabesque motifs in order that the design in wording, spirit and ornament, might be as far as possible representative and reminiscent of a purely Arab source of inspiration. Pictures and views were avoided, for these never formed part of Arab decoration, and are foreign to its art: so also was European lettering. It was quickly apparent that Lawrence already possessed or had immediately assimilated a complete working technique of philatelic and three-colour reproduction, so that he was able to supervise the issue from start to finish. And it seemed only a few weeks before this young Hittite archaeologist was on the most intimate terms with machine-guns, with tulip bombs, even with the jealously forbidden subtleties of a Rolls-Royce engine. There still exists the last motor-cycle he had built, never ridden, never delivered, carrying ten improvements, all invented by himself.

These stamp designs (admirably carried out by the Survey Department of the Egyptian Government) drew him still more closely within the Arabian orbit and into meetings with some of my Egyptian friends, and I noticed that he grew more and more eager for first-hand knowledge. I sent my secret agent (who had assisted in the opening negotiations), to his office, to pass on all he had discovered about the Hejaz; the tribes, routes, wells, and distances. At last he asked me point blank to take him down on my next voyage to Jeddah. Nothing from any point of view could have pleased me more, and permission from his military superiors was (as he has explained) granted almost with relief. He has recorded[4] our mutual hope as we proceeded through the streets of Jeddah, that the other had not perceived that the back of his jacket was dyed bright scarlet from the leather backs of the Gun-room chairs. When Abdallah quoted Faisal’s telegram saying that unless the two Turkish aeroplanes were driven off the Arabs would disperse, “Lawrence remarked that very few Turkish aeroplanes last more than four or five days. . . .”[5] Abdallah was impressed with his extraordinary detailed knowledge of “enemy dispositions” which, being temporary Sub-Lieutenant in charge of “maps and marking of Turkish Army distribution”, he was able to use with masterly effect. As Syrian, Circassian, Anatolian, Mesopotamian names came up, Lawrence at once stated exactly which unit was in each position, until Abdallah turned to me in amazement: “Is this man God, to know everything?” My journal records that “I reminded Abdallah of the permission I had that morning extracted, in his hearing from the Grand Sharīf, for Lawrence to go up to Bir Abbas; and urged him to give L. letters of introduction to Ali and Faisal”. Abdallah was now so firmly gripped by Lawrence’s personality that he forthwith caused his father to write this eagerly desired letter of introduction to Faisal,[6] the letter that made his dream come true; and I can still see Lawrence three days later on the shore at Rābugh waving grateful hands as we left him there to return ourselves to Egypt. Long before we met again he had already begun to write his page, brilliant as a Persian miniature, in the History of England.

“A pardlike spirit beautiful and swift.”

SHELLEY

My Baghdad journal of 15 July 1917 unsupplemented alas, by memory, tells me: “Lawrence and Feilding to lunch. L.’s performance in Syria little short of miraculous and I hope he will get his V.C. Mentioned to me vague Damascus possibilities.”[7]

During my leave in London I heard nothing of him: on my return to Cairo at the end of 1917 he was—elsewhere.

Rūhi[8], whom I had instructed to watch over him in the beginning, told me that Lawrence came to him in Jeddah for further information about the customs and habits of the Hejaz Arabs. Rūhi compiled for him a vocabulary of vernacular Arabic expressions, accompanied him round the coast to Yanbo, Qaddīma, Umlej and Wajh, and there suggested to him that he should leave his uniform for Arab garments. At that time (according to Rūhi), Lawrence “spoke Arabic with horrible mispronunciation”; and though he greatly improved his accent, he never could have passed as an Arab with an Arab—a defect which renders his achievement the more remarkable.[9] He learnt the prostrations of the Moslem prayer, and for a time called himself the Sharīf Hassan, “born of a Turkish mother in Constantinople.”

There are other accounts, besides those in Seven Pillars, of the dynamiting of Turkish bridges[10] and culverts: none so far as I know giving the impressions of a dynamitee. This was the unsolicited introduction to Lawrence of Carl Raswan,[11] travelling on a Turkish train to Damascus:

“Somewhere near Deraa in Transjordan, as we approached a dry river bed, we were stopped, and as we looked out of the windows of our carriage, I suddenly saw and heard a terrible explosion, followed by several smaller ones. A bridge, several yards ahead of us, had been blown up with a train on it. It was ahead of our Military Convoy; our cars were shattered by falling debris, but I remember hardly anything, as we were taken away from the place of disaster and had to stay several days near Amman, until the bridge had been repaired.”

Early in January 1918 I was sitting in a snowbound Jerusalem, when an orderly announced a Beduin, and Lawrence walked in and sat beside me.[12] He remained for the rest of the day, and left me temporarily the poorer by a Virgil and a Catullus. Later on, when in Jerusalem, he always stayed in my house, an amusing as well as an absorbing if sometimes disconcerting guest. He had Shelley’s trick of noiselessly vanishing and reappearing. We would be sitting reading on my only sofa: I would look up, and Lawrence was not only not in the room, he was not in the house, he was not in Jerusalem. He was in the train on his way to Egypt.[13]

In those days and (owing to the withering hand of Monsieur Mavromatis’ Ottoman concession) for years after, there was no electric light in Jerusalem, and in my bachelor household the hands of the Arab servants fell heavy upon the incandescent mantles of our paraffin lamps, from which a generous volcano of filthy smuts would nightly stream over the books, the carpets and everything in the room. Lawrence took the lamp situation daily in hand, and so long as he was there all was bright on the Aladdin front. He said he liked the house because it contained the necessities and not the tiresomenesses of life; that is to say there were a few Greek marbles, a good piano and a great many books though (I fear) not enough towel-horses, no huckabacks, and a very irregular supply of cruets and dinner-napkins. Not all my guests agreed with Lawrence’s theory; but the Egyptian cook did, for my servant Said once observed: “When your Excellency has none other than Urenz in the house, Abd al-Wahhāb prepares ala kaifu—without bothering himself.”

He was not (any more than Kitchener) a misogynist, though he would have retained his composure if he had been suddenly informed that he would never see a woman again. He could be charming to people like my wife and sister, whom he considered to be “doing” something, but he regarded (and sometimes treated) with embarrassing horror those who “dressed, and knew people”. When at a dinner party a lady illustrated her anecdotes with the Christian names, nick-names and pet-names of famous (and always titled) personages, Lawrence’s dejection became so obvious that the lady, leaning incredulously forward, asked: “I fear my conversation does not interest Colonel Lawrence very much?” Lawrence bowed from the hips—and those were the only muscles that moved: “It does not interest me at all,” he answered.

I was standing with him one morning in the Continental Hotel, Cairo, waiting for Rūhi, when an elderly Englishwoman, quite incapable of understanding his talk, but anxious to be seen conversing with the Uncrowned King of Arabia, moved towards him. It was hot, and she was fanning herself with a newspaper as she introduced herself: “Just think, Colonel Lawrence, Ninety-two! Ninety-two.” With a tortured smile he replied: “Many happy returns of the day.”

In those days he spoke much of the press he would found in Epping Forest for the printing of the classics, where, he said: “I’ll pull you the Theocritus[14] of your dreams. I’m longing to get back to my printing-press, but I have two kings to make first.” He made the Kings if not the press: Faisal in Iraq, Abdallah in Transjordan stand indeed as in part his creations. But with his (and my) old friend Husain Ibn Ali of Mecca his relations were fated to fall tragically from bad to worse. That monarch was alas becoming less and less a practicable member of the Comity of Kings. Fully supported but wholly uncontrolled in his absolutism by the might of the British Empire, he dropped into the unfortunate habit of regarding the mere suggestion of anything he did not wish to do as an attack on his honour and his sovereign rights. An historian with the knowledge and the patience to go through the complete file of al-Qibla, for eight years the official organ of the Hāshimi Government in Mecca, could present to the world a state of mind—and of affairs—closer to the Middle Ages than to the twentieth century. In Jeddah money for the building of a mosque was collected by the simple process of the Qaimaqam sending for persons whom the King wished to subscribe, and presenting each with a receipt prepared in Mecca for the amount to be cashed in. As late as 1923 hands were being chopped off for theft in Mecca, as prescribed by the original Shari Law. When the telegraph cable between Jeddah and Suakin broke, His Majesty hoped that the Sudan Government would withdraw their request for the customary cash deposit for its repair. Finding them obdurate, he ordered that no ship in Jeddah harbour should use her wireless under penalty of being cut off from all communication with the shore, making no exception for owners engaged on the most important business, or for time-signals. The Jeddah wireless station was kept on the watch all night in order to jam even the receipt of messages by ships, and by sending out meaningless (and sometimes obscene) signals interfered with the daily time-indication from Massawa and the correction of ships’ chronometers up and down the Red Sea.

Such being the royal attitude abroad as well as at home, there was matter less for surprise than for sorrow that Lawrence’s last negotiations with the man he had helped to raise so high should have been broken off in anger. Time after time the King would go back on agreements made after hours of discussion the day before. More than once he threatened to abdicate.[15] (Lawrence “wished he would”.) I myself incline to doubt whether King Husain ever loved Lawrence. There were moments when he and his sons suspected him of working against them, and more than once let fall hints to confidants that he should not be allowed to mingle too much with the Arab tribesmen. Faisal spoke of him to me with a good-humoured tolerance which I should have resented more if I had ever imagined that kings could like kingmakers.

Towards the end of my time in Jerusalem I received the notice inviting subscriptions (“by approved persons”) for the original limited edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. I dispatched my cheque at once, to receive it again in a month neatly torn into four fragments, accompanied by the sharpest words I had ever known from Lawrence, to the effect that “in the circumstances” my letter was an insult, and that he was “naturally” giving me a copy, “your least share of the swag”. Later he professed a cynical indifference to his magnificent gift, and, when it became known as the Twenty Thousand Dollar Book, recommended me twice to sell quickly, while the going was good. When, with his (and some joint) notes, it was burnt, he immediately collected and sent me a complete set of the original illustrations.

AUTHOR WITH KING HUSAIN AT JEDDAH

December 12th, 1916

In the interval between Jerusalem and Cyprus I wrote to learn his plans and to suggest a meeting. He replied:

338171 A C Shaw,

Hut 105

R.A.F. Cadet College,

Cranwell, Lincs.

1. vi. 26

Dear R. S.,

Yes: I’m too far from London and from affairs to see many people now-a-days. Yet I hear of you and them, sometimes. If you want to see me you had better stay a week-end at Belton. We are about ten miles from it.

In August I’ll be away somewhere (no notion where). Sept.-October in Cranwell, November on leave, December on a troopship for I’m on overseas draft, probably to India for a five-year spell. One of the attractions of the R.A.F. is that you see the world for nothing.

Tonsils: yes, rotten things. I haven’t any. Lost them, like you.

The Sargent is reproduced and finished. The Kennington is still on the stones. The complexity and extravagance of my colour reproductions have put the Chiswick Press out of gear. They have been two years over them and are still hard at work. August, they hope to finish them. Till they do my book is held up. Yet it must come out, complete or incomplete, before I go abroad. So live in hope. Though what you will think of my personalities (yours and everybody’s!) God only knows.

Au revoir,

T. E. L.

In the autumn he resumed:

2. ix. 26.

Dear Ronald,

I’ll come over on Saturday the eleventh, to Belton. When? I can’t yet tell you. Just carry on with what programme the overlord of Belton has: and I’ll fit myself in. If Saturday is unfit for any reason (service life is highly irregular) I’ll come on Sunday, and will hang about till I see you. It might be tea-time on Saturday or late, after dinner, on Sunday: but God knows. Just carry on, and I’ll loom up sooner or later. I have a motor-bike, and so am mobile.

Book? November probably. Your copy will probably be posted to Colonial Office, and sent on thence by bag to the Governor and C.-in-C. of Cyprus (His Excellency; hum ha). I was exceedingly glad when I saw that news. The Sargent is at Kennington’s house (Morton House, Chiswick Mall), finished with. The Kennington has been the most difficult of all the pastels, and is not yet passed in proof. It keeps on falling to bits: looking butcherly-like, in raw-beef blocks of red. Very difficult. Kennington struggles hard with the colour-printers: and I hope not vainly. All over by 15 September, for that is “binding” day, when sheets are to be issued.

More when we meet,

Yours,

T. E. S.

My uncle forgot to warn the butler, who therefore announced that “an airman” was at the door. Strapped under the seat of his motor-cycle was the bound manuscript of Seven Pillars, one or two passages in which he wanted me to check. When, after tea, we were pacing up and down, round and about the lawns and gardens, I asked him point blank why he was doing what he was doing—and not more. He answered that there was only one thing in the world worth being, and that was a creative artist. He had tried to be this, and had failed. He said: “I know I can write a good sentence, a good paragraph, even a good chapter, but I have proved I cannot write a good book.” Not having yet seen Seven Pillars I could only quote the praise of Hogarth (which meant much to Lawrence) and agree that, compared with the glory of Hamlet or The Divine Comedy, career was nothing. Still, admitting these to be unattainable, there were Prime Ministers, Archbishops, Admirals of the Fleet, Press Barons and philanthropic millionaires, some of whom sometimes rendered service surely preferable to this utter renunciation? He allowed the principle, but refused the application. Since he could not be what he would, he would be nothing: the minimum existence, work without thought; and when he left the Royal Air Force it would be as night-watchman in a City warehouse.[16]

For all his puckishness, his love of disconcerting paradox, I believed then and am certain now that Lawrence meant what he said; though I thought there was also the element of dismay at the standard expected of him by the public; and I doubted how far even his nerves could ever be the same after his hideous manhandling in Deraa.[17]

I further believe that, though not given to self-depreciation, he did underrate the superlative excellence of Seven Pillars, and, as a most conscious[18] artist in words, ached to go further still.

13. ix. 34.

Dear R. S.,

I have been away for a while, during which your P.C. sat on the edge of Southampton Water, peacefully, in blazing sunshine. If all of the years were like this, no man would need to go abroad. . . .

Here are your K. articles,[19] which I return because I know how rare fugitive writings become in time. Once I did three or four columns in the same paper, but I have never seen them since; they gave me the idea that newsprint is a bad medium for writing. The same stuff that would pass muster between covers looks bloodless between ruled lines on a huge page. Journalistic writing is all blood and bones, not for cheapness’ sake, but because unnatural emphasis is called for. It’s like architectural sculpture which has to be louder than indoor works of art.

So I’d say that these articles of yours read too “chosen” for press-work; but that in a book they would be charming. You write with an air . . . and airs need the confinement of walls or end papers or whatnots to flourish. But do airs flourish? I think they intensify, suffuse, intoxicate. Anyhow they are one of the best modes of writing, and I hope you will try to write, not fugitive pieces, but something sustained or connected by the thread of your life.

. . . . .

I’ve often said to you that the best bit of your writing I ever read was your dictated account of the report of an agent’s interview, pre-revolt, with the Sharif of Mecca on his palace roof at night. If you could catch atmosphere and personality, bluntly, like that, it would be a very good book. These K. articles might be blunted. You’ll have to use the word “I” instead of the bland “Secretary” . . .[20] Forget the despatch and the F.O. and try for the indiscreet Pro-consul!

Yours,

T. E. S.

He loved discussing his own prose and, if convinced, was humble under criticism, whether of style or of fact. When I told him that he had been too generous to me in the beginning of his book but not quite just in the middle,[21] where, if I was “parading”, it was in order to teach him a business at which he was new and I was old, he exclaimed that he would have altered the passage had he known in time.

My wife and I came upon him early in 1929 returning from India by the Rajputana, where he spent his time, flat in his berth, translating Homer. He did not dissent when I thought that his Odyssey sacrificed overmuch to the desire of differing from predecessors: for instance in rendering ῤοδοδάκτυλος ἤως—rosy fingered dawn—in nineteen different ways. It is therefore an arresting rather than a satisfying version. Lawrence, though respectful almost to deference of expert living authority, lacked the surrender of soul to submit himself lowly and reverently, even to the first poet. Of Matthew Arnold’s three requisites for translating Homer—simplicity, speed and nobility, all dominating qualities of Lawrence’s being—he failed somehow in presenting the third, substituting as often as not some defiant and most un-Homeric puckishness of his own, so that Dr. Johnson’s criticism of Pope’s Iliad would be no less applicable to Lawrence’s Revised Version. The classical Arab could become in a trice a street Arab. Nevertheless, Lawrence’s Odyssey possesses two outstanding merits. It represents Lawrence as well as Homer, and it has by hero-worship or the silken thread of snobbishness led to Homer thousands that could never have faced the original, or even the renderings of Pope, Chapman, or Butcher and Lang; just as for countless Londoners the “approach” to the Portland Vase, visible but neglected for a century in the British Museum, was induced through its auctioning at Christie’s in the presence of the Prince of Wales.

Lawrence sent me in Cyprus, inviting comment, the typescript of The Mint, a remarkable and sometimes brutal picture of his early days in the Air Force. The narration was no less fine than the description, but the contrast between the lives and the language of all ranks was startling indeed. It seemed that they could only find relief from the cloistered rigour of their existence by expressing their emotions with an almost epileptic obscenity.[22] I offered, by a necessary minimum of blue pencil over a total of some thirty pages, to enable the book to emerge from the steel safe in which I had to guard it when not in use, into general reading: but Lawrence said the language was the life, sooner than falsify which he would rather not publish at all. (Part having appeared during his lifetime in an English newspaper, under a misapprehension that he had approved thereof, a copyrighting publication of 10 copies prohibitively priced was arranged in America; none other to appear until his earliest authorized date of 1950.)

He hated public attention save when impersonal enough for him to appear not to notice it, but was not disappointed when, as nearly always, his incognito broke down. One day he offered to take my wife and me to the Imperial War Museum “to see the Orpens”. When we came to his portrait by James McBey, I asked him to stand in front so that we might for a minute see him against McBey’s vision. In a flash the word went round the Staff that Lawrence was here, and for the rest of our visit we were accompanied by the rhythmic beat of a dozen martial heels. Lawrence was clearly not displeased, yet when on our departure I remarked upon the number of our escort, “Really?” he said “I didn’t notice any one.” He was indeed a mass of contradictions: shy and retiring, yet he positively enjoyed sitting for, and criticizing, his portrait. No one could have been more remote from the standard of the public school, and I can as easily picture him in a frock-coat or in hunting pink as in an old school tie. In action likewise he was an individual force of driving intelligence, but with nothing of the administrator; having about as much of the team spirit as Alexander the Great or Mr. Lloyd George.

In England we met (as might have been expected) more often unexpectedly than by appointment—in the street, on a bus, or at a railway station. Once, when I was choosing gramophone records, a hand from behind descended firmly upon my shoulder. I had only just arrived in England, and supposed for a moment that this must be an attempt on the part of an assistant at Brighter British Salesmanship. It was Lawrence, replenishing the immense collection of records arranged in volumes round a square of deep shelves in the upper room of his cottage. On another occasion he led me to his publishers where, walking round the room, he picked out half a dozen expensive books, and, as though he were the head of the firm, made me a present of them.[23] He was a loyal, unchanging and affectionate friend, and would charge down from London on the iron steed from which he met his death to visit me in a nursing home, or run up 200 miles from the West of England to say good-bye before I returned to Cyprus. After a convalescence voyage he wrote

338171 A/c Shaw,

R.A.F. Cattewater,

Plymouth.

5. v. 29.

Dear R. S.,

Maurice Baring told me you were back. Did it do good? Are you fit, or fitter even?

I’m down here, too far off to reach London even for a week-end: but the place is good, and the company. So all’s well with me.

Please give my regards to Lady Storrs. I hope she is contented with your improvement.

M. B. has given me a huge Gepäck[24] five times as fat as yours, and stuffed full of glory. I did not know there were so many good poems, in it, and outside it. Half of it is strange to me.

Yours,

T. E. S.

Leaving Southampton for Canada in 1934 we were “greeted[25] by C.P.R. officials and by T. E. Shaw. Him I found, healthier in appearance than ever before, capless in brown overalls and blue jersey. He came aboard and talked awhile of his retirement next March to a small cottage on a maximum of £100 per annum. He would provide bread, honey, and cheese for visitors, but could not put them up otherwise than in a sleepingbag (marked Tuum—his own Meum) on the floor. In order to side-slip the photographers he took me in his Power-boat Joker (£180, 25 knots, unupsetable) and allowed me to zigzag it about for 15 minutes. A permanent friend I shall always rejoice to see, with generosities of feeling for persons as well as for books.” I never saw him again alive.

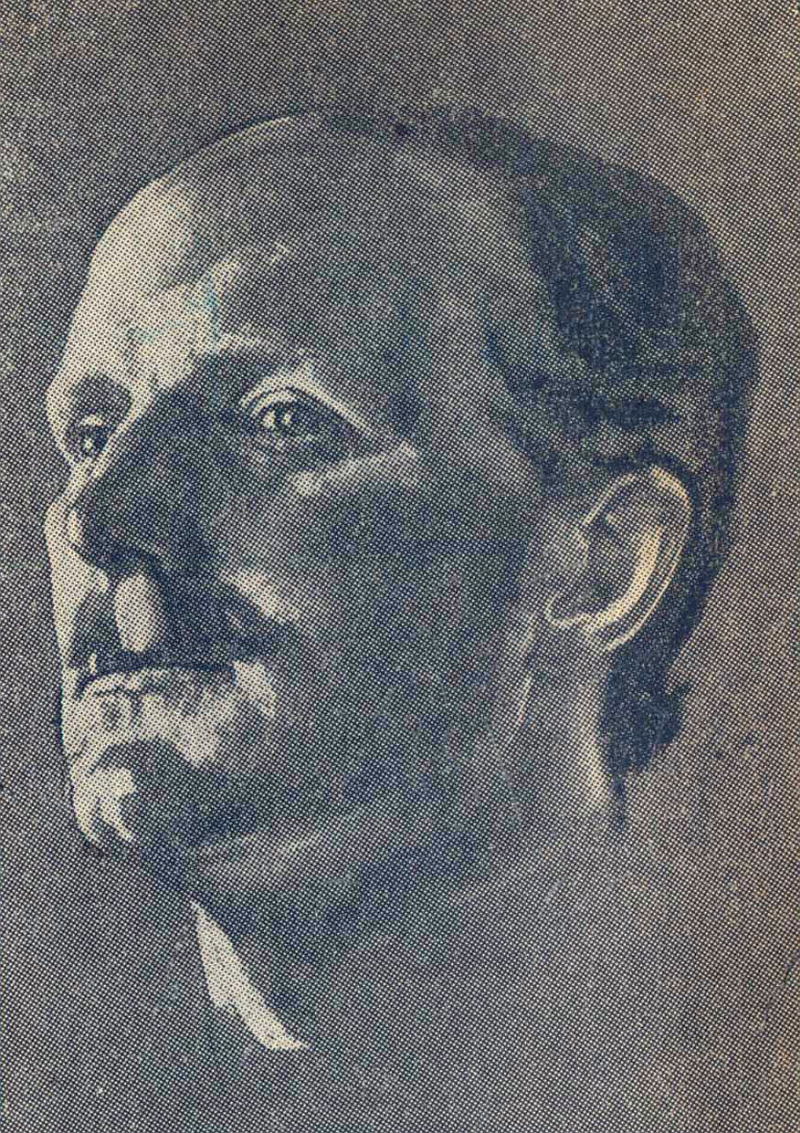

Nine-tenths of his letters to me have perished, and only a half-dozen, which never left England, remain. Even these few reveal his power and variety in that rarely mastered art. I had in a moment of weakness consented to ask him to write an introduction to a book on Beduin Life by an artist whose exhibition I had opened. I knew the request was hopeless, and had only written par acquit de conscience begging him at least to let me have an answer I could pass on. His reply, though admirable and richly deserved, hardly fell within this category.

Bridlington,

25. ii. 35.

No: I won’t; Forewords are septic things, and I hope never to do another. Bertram Thomas was like the importunate woman; but to strangers it is easy to say “No”: he must understand that he has no claim on me: nor do I even know what he has written, or why, or who he is. No, most certainly No.

Yours,

T. E. S.

I leave here to-morrow a.m. . . . and the R.A.F. that same moment εἰθε δὲ μήδ᾿ . . .[26]

LETTER FROM T. E. LAWRENCE

[Transcribed]

Bridlington

25.2.35

No: I won’t; Forewords are septic things, and I hope never to do another. Bertram Thomas was like the unfortunate woman; but to strangers it is easy to say “No”: he must understand that he has no claim on me: nor do I even know what he has written, or why, or who he is. No, most certainly No.

Yours

TES

I leave here tomorrow a.m. . . . and the R.A.F. that same moment εἰθε᾿ δὲ μήδ

Lawrence hated Society, but loved company. He refused the post of Director of Archaeology in Cyprus because of what he chose to imagine the social obligations of an official there. Those who knew him could have predicted the comparative failure of his Fellowship of All Souls, where it is reasonably expected of members to mingle with their fellows and—if not indeed to roll the ghost of an Olympian (a Cambridge accomplishment)—at least to present to the Common Room on occasion a polished spook of Horace. “Conversation”, says Gibbon, of the most famous Arab, “enriches and enlivens the mind, but solitude is the school of genius.”

Nevertheless, Lawrence liked sometimes to walk and talk with friends. The simplicity of his life was extreme. He smoked no tobacco, he drank no alcohol; but alas, he used a drug. His drug was speed, and speed was the dope which cost him his life. He once raced along the open road against an aeroplane, and led it for nearly a quarter of an hour.

Consider the variety of elements in his composition. It has been given to few to achieve greatness and also to enshrine that greatness in splendid prose: to which other of these few has been added the fastidious artistry to plan every detail of the setting up, the illustration, the printing and the binding of the material presentation of his genius? On any topic he was one of those who let fall, whether in speech or writing, the creative and illuminating idea or phrase—unmistakably his, signed all over—which held your memory and recharged your intellectual and spiritual batteries.

Lawrence suffered acutely from public exaggeration in all directions. Like Bassanio he had chosen the leaden casket—“Who chooseth me must give and hazard all he hath.” And his reputation when alive, and even after, has been subjected by some to a steady dribble of depreciation. There was a lack of understanding from moral as well as intellectual inferiors, who had occupied higher offices than his but had perhaps distinguished themselves less therein. And it was from such that he knew the bitterness, the contemptuous bitterness of irrefutable calumny. We are told that his military operations were on a small scale. So were those of Thermopylae and of Agincourt. We are told that anybody could have done what he did, with Allenby behind him, backed by the golden sovereigns of the British Treasury. But Paladins of the stamp and stature of an Allenby do not accord themselves, nor the resources of the British Treasury to an “anybody”. He was actually accused of a publicity engineered by intentional mystification; and indeed it must have irritated some other public servants to find a man without a handle before his name or letters after it, without a dress suit and with an income of under a hundred a year, nevertheless pursued and chronicled by an eager limelight which seemed in comparison to black out their particular merits. I have even heard his strong columns of English belittled as having been built, as he said himself, upon the foundation of Doughty; and true it is, that Doughty was no less his literary ancestor, than Gibbon Macaulay’s. Dante gloried in “taking his fine style from his master”, Virgil. If Lawrence lit his candle from Doughty’s flame, was the candle any less his own? There are two classes of public servant. Of one it is said: “What is he doing now?” Of the other: “Who is Minister of this or Governor of that.” The first category will interest and arrest and fascinate the world. Lawrence was one of those first. Mr. Winston Churchill is one of them, and so is Mr. Lloyd George. The second, a far more numerous category—will be identified as occupying most of the best places.

Lawrence was throughout the last months of his life oppressed by gloomy forebodings. In one of his later letters he spoke of “an utterly blank wall” after leaving his beloved R.A.F.; one of his latest to me[27] ends with the three hopeless words of the man of Tarsus.

Ozone Hotel,

Bridlington,

Yorks.

31. 1. 35.

Dear R. S.,

No; alas, Hythe will know me no more. I have only a month to do in the R.A.F. and will spend it up here, overseeing the refit of ten R.A.F. boats in a local garage. The name of the Hotel is real. So, I think, is the ozone, or is it the fishmarket that smells. It is empty, cold, and rather nice.

. . . . .

Alas, I have nothing to say at the moment. After my discharge I have somehow to pick up a new life and occupy myself—but beforehand it looks and feels like an utterly blank wall. Old age coming, I suppose; at any rate I can admit to being quite a bit afraid for myself, which is a new feeling. Up till now I’ve never come to the end of anything.

Ah well. We shall see after the Kalends of March. Indeed, I venture to hope we shall see each other, but I don’t know where I shall live, or what do, or how call myself.

. . . . .

Please regard me to Lady Storrs: and please make yourself again into fighting trim: or perhaps you are, now. Good.

Yours,

T. E. S.

Here is the second half of what was probably his very last letter, written on Jubilee Day to Eric Kennington:

You wonder what I am doing? Well, so do I, in truth. Days seem to dawn, suns to shine, evenings to follow, and then to sleep. What I have done, what I am doing, what I am going to do puzzle and bewilder me. Have you ever seen a leaf fallen from your tree in autumn and been really puzzled about it? That’s the feeling. The cottage is all right for me . . . but how on earth I’ll be able to put any one up baffles me. There cannot ever be a bed, a cooking vessel, or a drain in it—and I ask you . . . Are not such things essential to life . . . necessities? Peace to everybody.

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA

(By Eric Kennington in The Kennington Memorial at Dorchester Church)

Lawrence items carried a news value of hard cash, so that when at the end of his Air service he returned to the cottage at Clouds Hill, his welcome home was a row of strange faces blinking and dodging behind a battery of cameras. He fled the place awhile, then crept in, he hoped secretly, by night. They stoned his roof to make him appear. One forced his way in. Lawrence went for him, knocked him down and threw him out. His friend found him trembling—“so many years since I’ve struck a man”. There is no close season for heroes.

Every day, for the last three weeks of his life, a bird would flutter to his window, tapping incessantly with its beak upon the pane. If he moved to another window, the bird followed and tapped again. The strange insistence was so visibly fraying his nerves that one morning, when he had gone out, his friend shot the bird.[28] In that same hour, wrenching his handle-bars for the last time, Lawrence was flung over them sixty feet head first on to the granite-hard tarmac.

I stood beside him lying swathed in fleecy wool; stayed until the plain oak coffin was screwed down. There was nothing else in the mortuary chamber but a little altar behind his head with some lilies of the valley and red roses. I had come prepared to be greatly shocked by what I saw, but his injuries had been at the back of his head, and beyond some scarring and discoloration over the left eye, his countenance was not marred. His nose was sharper and delicately curved, and his chin less square. Seen thus, his face was the face of Dante with perhaps the more relentless mouth of Savonarola; incredibly calm, with the faintest flicker of disdain. The rhythmic planes of his features gradually became the symbolized impression of all mankind, moulded by an inexorable destiny. Nothing of his hair, nor of his hands was showing; only a powerful cowled mask, dark-stained ivory alive against the dead-white chemical sterility of the wrappings. It was somehow unreal to be watching beside him in these cerements, so strangely resembling the aba, the kuffiya and the aqàl of an Arab Chief, as he lay in his last littlest room very grave and strong and noble. Selfish, to be alone with this splendour; I was sorry, too late, that neither Augustus John nor Eric Kennington, though both within a few hundred yards, should have had the chance to preserve it for the world. As I looked I remembered that my first sight of death had been my beloved Arabic tutor at Cambridge, thirty-one years before, Hassan Tewfik ibn Abd al-Rahman Bey al-Adli—may God be well pleased with them both. Suddenly, in a flash, as by a bolt from the cloudless serene he had been wrapt into eternity, and we may well believe that his adventurous spirit leapt gladly to the call, as the trumpets sounded for him on the other side. As we carried the coffin into and out of the little church the clicking Kodaks and the whirring reels extracted from the dead body their last “personal” publicity.[29]

Some knew one side of Lawrence, some another. I wondered then if any knew him at all, or could imagine what had been his purpose, what the frontiers of his being. Could he have grown old? Had he ever been young? Some think he intended to resume action, for his country. Others that he would have created at least one more great work, for like Plato he felt deeply that what gives life its value is the sight, however revealed, of Eternal Beauty. In this he is with the great Elizabethans—Sir Philip Sidney; with the great Victorians—Charles Gordon—whose whole lives, free from fear and gain (those old perverters of mankind) are a protest against the guaranteed, the pensioned, the standardized and the safety-first existence. Like them Lawrence, even without his work, without his book, was and remains a standard and a touchstone of reality in life. That vast convulsion of human nature, the Great Four Years’ War, may have thrown up more important world-figures; none more gallantly yet practically romantic than the shy, slight, unaccountable emanation of genius who will live in universal as well as in English history as Lawrence of Arabia.

[3] My Egyptian servant, Ismail, pronounced in Egyptian Arabic, Ismain.

[4] Seven Pillars, p. 66.

[5] His telegram to the Arab Bureau, besides admirably resuming the discussion, foreshadows unambiguously his own plan, and future position:

“17th. For Clayton:

Meeting to-day: Wilson, Storrs, Sharif Abdallah, Azīz al-Masri, myself.

Nobody knew real situation Rābugh so much time wasted. Azīz al-Masri going Rābugh with me to-morrow.

Sharīf Abdallah apparently wanted foreign force at Rābugh as rallying point if combined attack on Medina ended badly. Azīz al-Masri hopes to prevent any decisive risk now and thinks English Brigade neither necessary nor prudent. He says only way to bring sense and continuity into operation is to have English staff at Rābugh dealing direct with Sharīf Ali and Sharīf Faisal without referring detail to Sharīf of Mecca of whom they are all respectfully afraid. Unfortunately withdrawal of aeroplanes coincided with appearance of Turkish machines but Azīz al-Masri attached little weight to them personally. He is cheerful and speaks well of Sharīf’s troops.”

[6] Seven Pillars, pp. 70 and 71, “. . . Storrs then came in and supported me with all his might. . . .”

[7] Both he and Haddād Pasha had thought of me for Military Governor there.

[8] My Bahai Persian secret agent, mentioned on p. 12.

[9] “I could never pass as an Arab—but easily as some other native speaking Arabic.” Liddell Hart, T. E. Lawrence, p. 24.

[10] The German General Staff pathetically records that “The destruction of 25 Railways Bridges on the Hejaz Railway line from May 1-19 shows how difficult it was to maintain the Hejaz Railway in operation.”

[11] A German-American traveller-photographer of unusual artistry.

[12] Seven Pillars, p. 524.

[13] In England also his best friends often knew least of his whereabouts. Hogarth answered my enquiries after my Sargent drawing, lent for Seven Pillars in 1924: “T. E. L. (or T. E. Shaw as he now calls himself) dumps his things all over the place. It is probably either with Griggs and Co., his reproducers, or at Baker’s house in Barton Street, where T. E. used to live and still I think goes from time to time. I can’t get any replies out of T. E. He sent me some weeks ago eight chapters of his book in paged proof and I returned them with comments, but I have heard no more. Two people, Sir Geoffrey Salmond and Sir M. de Bunsen, who had been in his neighbourhood of late, reported well of T. E. to me. Alan Dawnay tells me T. E. is coming here one day in his normal fashion—without notice and refusing to be put up—but days pass and no news of him so—voilà!”

[14] To the best of my knowledge there exists no beautiful Greek text of Theocritus.

[15] I wrote to my father during King Husain’s visit to Amman in 1924, some time before his final ruin, when Sir Herbert Samuel was straining to promote an understanding between him and Ibn Sa’ud: “We are just back from Amman, where we were caught in a cloudburst, and had to remain an extra day and to return by special train through French Syria past Deraa and Sámakh to Afúleh (near Endor) with eight cars on trucks, to the wonder of the countryside. King Husain embraced me several times. We talked with him for long hours in bitter cold, and he kept turning to Clayton and me, and repeating that we were the authors of all his troubles and difficulties: which consist, as you know, in a Crown for himself, a Crown for Faisal, and a coronet for Abdallah. He gave us a banquet with seventy different kinds of dishes: the waiters, walking up and down the tops of the tables à la Mecque. Lily, not happening to care about any one of the seventy, had to have a few sandwiches on our return to the house.”

[16] This attitude is said psychologically to represent a very rare manifestation of the Gottmensch Komplex.

[17] Seven Pillars, chap. xxxv. More than one member of his Staff told me that, after Deraa, they felt that something had happened to Lawrence which had changed him.

[18] Too conspicuous sometimes, as for instance in the effort to avoid ending Seven Pillars with the weak but natural phrase “how sorry I was”.

[19] On Lord Kitchener from The Times.

[20] Necessary because the articles were anonymous and therefore in the third person.

[21] Seven Pillars, p. 98.

[22] Perhaps on the precept of Catullus:

“Nam castum esse decet pium poetam

Ipsum, versiculis nihil necesse est.”

[23] They included that deservedly successful War book The Enormous Room which the firm had only published on his strong recommendation.

[24] Maurice Baring made some twelve Gepäcks: small square volumes of blank pages on which were pasted poems and extracts from poems cut from other books and forming polyglot anthologies.

[25] Canadian Diary.

[26] From the Greek epitaph of despair

ενθάδε κεῖμαι

Ταρσέυς · μὴ γήμας · εῖθὲ δὲ μήδ᾿ ὁ πάτηρ.

“Here lie I of Tarsus

Never having married, and I would that my father had not.”

Mackail, Select Epigrams, p. 172, 1911.

[27] P. 27.

[28] Virgilians will be reminded of the Diva which Jupiter sent in the shape of a little bird to dash herself against the shield of Turnus in his last fight with Aeneas (Aeneid XII, 861 . . .):

“Alitis in parvae subitam collecta figuram,

quae quondam in bustis aut culminibus desertis

nocte sedens serum canit importuna per umbras—

hanc versa in faciem Turni se pestis ob ora

fertque refertque sonans clipeumque everberat alis,

illi membra novus solvit formidine torpor. . . .”

E’en thus the deadly child of night

Shot from the sky with earthward flight.

Soon as the armies and the town

Descending, she descries,

She dwarfs her huge proportion down

To bird of puny size,

Which perched on tombs or desert towers

Hoots long and lone through darkling hours:

In such disguise the monster wheeled

Round Turnus’ head and ’gainst his shield

Unceasing flapped her wings:

Strange chilly dread his limbs unstrung:

Upstands his hair: his voiceless tongue

To his parched palate clings.

(Conington’s translation.)

Turnus was of the clan Laurens:

“non fuit excepto Laurentis corpore Turni.”

(Aen. VII, 650.)

[29] Immediately after his death a perverse cult was started, mainly by owners of the privately printed Seven Pillars and other monopolists in Lawrenciana, of horror at the desecration whereby that masterpiece was made available for the outside world; bringing back to me the protests of the Wagnerian fervent, when others beside the Bayreuth pilgrims were at last privileged to enjoy Parsifal.

Vere scire est per causas scire

I must warn those not interested in this question to beware. Though the territory involved is in extent negligible, though the inhabitants have produced nothing that has mattered to humanity, nevertheless, the problem of reconciling their rights and grievances with the promises made to and the aspirations cherished by an Israel that has meant and still means so much to the world, is apt to become an obsession, rarely accompanied by temperance, soberness or justice. So I summon up my heart to write dispassionately of Zionism under the three Military and the first two Civil Administrations, adding perhaps later comment; well aware that I may be risking thereby the toleration of my Jewish, the confidence of my Arab, the respect of my Christian friends.

Zionism is viewed from four different aspects. By enthusiastic supporters, minimizing difficulties and impatient of delay: these comprise I suppose a fair proportion of universal Jewry and many Gentiles outside Palestine. By declared adversaries, including all Palestinians who are not Jews, Roman Catholics (uninterested in the Old Testament) all over the world, and British sympathizers with Moslem or Arab views not concerned with formulation or maintenance of world policy. By persons unconcerned, or suspending or unable to form a judgment (I suppose about one thousand millions). By the official on the spot, loyal to the Mandate his country has accepted, yet wishing to justify his office to his conscience; and by persons connected with the British Government and Legislature, the League of Nations and the Press. I respectfully address myself to all four categories.

What does the average English boy know of Jews? As Jews, nothing. At my first school, between the age of seven and ten, I had met a Ladenburg, and a charmingly mannered Rothschild who seemed to know everything, in the sense that you could tell him nothing new, and who impressed me (as have other Jews later in life) with a sense of unattainable mental correctness. He did not come to school on Saturday (which I envied), and was not allowed to be flogged (which I resented). At Charterhouse were two pleasant brothers Oppé (very much cleverer than myself), who appeared in chapel at half-past seven every morning with the rest of us. At Cambridge Ralph Straus was one of my best friends but I do not think it ever occurred to either of us, that he was a Jew. There must have been other Jews in these institutions, but neither I nor my companions knew them as Jews. I never heard my father mention Jews save in connection with the Old Testament, outside of which apart from an occasional Rabbi he had hardly met one. My mother used to recall with relish how she had let our house at Westgate-on-Sea to a well-known Jewish family; excellent tenants, but so orthodox that they had taken down and inadvertently left in the cellar all our “sacred” pictures—including a reproduction of Van Dyck’s Infant Son of Charles the First. In Egypt I soon met and still enjoy the friendship of the leading Jews, a powerful colony of Sephardim originally from Italy, Damascus and Salonika. I was invited to the weddings and other festivals of the Suares, Rolo, Cattaui, Menasce, Mosseri and Harari; their Rabbis occasionally consulted me as Oriental Secretary—so much so that my appointment to Jerusalem was, according to Rabbi della Pergola, fêted in the Synagogue of Alexandria. Like their predecessor Joseph and like Sir Solomon de Medina, knighted by King William III at Hampton Court in 1700, they were loyal to the country of their adoption, and as bankers and Government officials enjoyed and deserved good reputations. As with all Jews, there was usually a crisis of some sort or other in the internal organization of their Kehilla—Jewish Community—of which you could hear widely differing versions in the bazaars and in the aristocratic Kasr al-Dubara. Their leaders were consulted with advantage, alike by Khedivial Princes and by British Representatives.

This then, apart from the Old Testament (Psalms almost by heart) and Renan’s Histoire du Peuple d’Israel,[30] was the sum of my knowledge of Jewry until the year 1917, a limitation which Providence was pleased to mitigate for me in middle life. My wife had never met a Jew until she reached Jerusalem after our marriage in 1923. I had much and still have much to learn. Nevertheless, having loved Arabic throughout my career—with the Egyptians, who speak it best, and the Palestinians, whose citadel of identity it is; having played a small part in the Arab National Movement; having studied and admired Jewry, having received much kindness from many Jews (and been pogromed in their Press as have few other Goys[31] or with less cause); above all, having been for the first nine years of the British Administration Governor of Jerusalem, striving according to my lights for the good of all creeds, I should feel it cowardly to omit my experiences of the early and the later working of Zionism. Being neither Jew (British or foreign) nor Arab, but English, I am not wholly for either, but for both. Two hours of Arab grievances drive me into the Synagogue, while after an intensive course of Zionist propaganda I am prepared to embrace Islam.

Europe had learned before, during and particularly after the War, the full significance of Irredentism (invented but unfortunately not copyrighted by Italy): practical Zionism, or Irredentism to the nth, was new to most and stood alone. I happened to have learned something of it from the chance of my few weeks in the War Cabinet Secretariat; but with 95 per cent. of my friends in Egypt and Palestine (as in England) the Balfour Declaration, though announcing the only Victory gained by a single people on the World Front, passed without notice; whilst the few who marked it imagined that the extent and method of its application would be laid down when the ultimate fate of Palestine (assuming the conquest of its northern half and final Allied victory) had been decided. Those who had heard of the Sykes-Picot negotiations in 1916 cherished vague hopes of Great Britain being awarded Haifa as a British Possession. Mandates were unknown, though President Wilson’s Fourteen Points seemed to indicate that Palestinians (then generally considered as Southern Syrians) would be allowed some voice in their political destiny. By the early spring of 1918 O.E.T.A.[32] was already beset with, and its seniors working overtime upon, new and strange problems.

When therefore early in March Brigadier General Clayton showed me the telegram informing us of the impending arrival of a Zionist Commission, composed of eminent Jews, to act as liaison between the Jews and the Military Administration, and to “control” the Jewish population, we could hardly believe our eyes, and even wondered whether it might not be possible for the mission to be postponed until the status of the Administration should be more clearly defined. However, orders were orders; and O.E.T.A. prepared to receive the visitors. Confidential enquiries revealed Arab incredulity of any practical threat. Zionism had frequently been discussed in Syria. Long before the War it had been violently repudiated by the Arab journal al-Carmel as well as officially rejected by the Sultan Abd al-Hamīd in deference to strong Moslem feeling;[33] to which it was presumed that a Christian Conqueror who was also the greatest Moslem Power would prove equally sensitive. The religious Jews of Jerusalem and Hebron and the Sephardim were strongly opposed to political Zionism, holding that God would bring Israel back to Zion in His own good time, and that it was impious to anticipate His decree.

DR. CHAIM WEIZMANN

(Bronze by Jacob Epstein)

The Zionist Commission travelled by train from Egypt, and after some contretemps whereby they were marooned awhile on the platform of Lydda Station, arrived by car in Jerusalem. I received in the Governorate Major Ormsby-Gore,[34] and Major James de Rothschild, Political Officers, Lieut. Edwin Samuel, attached, Mr. Israel Sieff, Mr. Leon Simon, Dr. Eder, Mr. Joseph Cowen and Dr. Chaim[35] Weizmann, President of the World Zionist Organization. Monsieur Sylvain Lévy, an anti-Zionist, was attached to the Commission as representative of the French Government. The party being under the official aegis of the British Government, I assembled in my office the Mayor of Jerusalem and the Heads of Communities in order that they and the visitors should meet, for the first time anyhow, in surroundings at once official and friendly. The Jerusalem faces were unassuring. I find among my letters home the plan of the dinner party with which I followed up this first meeting, annotated for my mother’s information:

| Mr. Abu Suan of Latin Patriarchate | Mūsa Kāzem Pasha al-Husseini, Mayor of Jerusalem | Mr. Silvain Lévy,[36] French Orientalist | The Mufti of Jerusalem[37] | Sa Grandeur Thorgom Kushagian, Armenian Bishop of Cairo (acting Armenian Patriarch) | Arif Pasha Daudi, ex-Ottoman Official of good family |

| Major Ormsby-Gore | Lt.-Col. Lord Wm. Percy | ||||

| Mr. D. Salāmeh, Vice-Mayor of Jerusalem (Christian Orthodox) | Major J. de Rothschild | His Eminence Porphyrios Archbishop of Mount Sinai, Locum Tenens Orthodox Patriarchate | Military Governor | Dr. Weizmann | Ismail Bey al-Husseini, Director of Education |

After proposing “The King” I explained that I had seized the occasion of so many representatives of communities being gathered in Jerusalem to clear away certain misunderstandings aroused by the visit of the Zionist Commission. Dr. Weizmann then pronounced an eloquent exposition of the Zionist creed: Jews had never renounced their rights to Palestine; they were brother Semites, not so much “coming” as “returning” to the country; there was room for both to work side by side; let his hearers beware of treacherous insinuations that Zionists were seeking political power—rather let both progress together until they were ready for a joint autonomy. Zionists were following with the deepest sympathy the struggles of Arabs and Armenians for that freedom which all three could mutually assist each other to regain. He concluded: “The hand of God now lies heavy upon the peoples of Europe: let us unite in prayer that it may lighten.” To my Arabic rendering of this speech the Mufti replied civilly, thanking Dr. Weizmann for allaying apprehensions which, but for his exposition, might have been aroused. He prayed for unity of aim, which alone could bring prosperity to Palestine, and he quoted, generalizing, a Hadith, a tradition of the Prophet, “Our rights are your rights and your duties our duties”.

It had been from a sense of previousness, of inopportunity, that Clayton and I had regretted the immediate arrival of the Zionist Commission; certainly not from anti-Zionism, still less from anti-Semitism. We believed (and I still believe) that there was in the world no aspiration more nobly idealistic than the return of the Jews to the Land immortalized by the spirit of Israel. Which nation had not wrought them infinite harm? Which had not profited by their genius? Which of all was more steeped in the Book of Books or had pondered more deeply upon the prophecies thereof than England? The Return stood indeed for something more than a tradition, an ideal or a hope. It was The Hope—Miqveh Yisroel, the Gathering of Israel, which had never deserted the Jews in their darkest hour—when indeed the Shechinah had shone all the brighter,

“a jewel hung in ghastly night”.

In the triumph of the Peace the wrongs of all the world would be righted; why not also the ancient of wrongs?

Zionism was created by the Diaspora; throughout the ages it has slept but never died. A remnant shall return[38], shall return with joy; “next year in Jerusalem”. In Russia, where Jewish suffering if not bitterest certainly lasted longest, there appeared in the last century the Hovevéi Tsiyón,[39] the Lovers of Zion, burning with the love of Zion, Hibbáth Tsiyón—to behold her face before they died. Disraeli, the first imperialist, wielding an Empire, creating an Empress, still yearned in his heart and cried in his lyric romance for Zion.[40] Before the end of his century there arose a giant in Israel, splendid to look upon as the bearded and winged deities of Assyria. The scandal of Dreyfus convinced Theodor Herzl that there was no refuge for the soul of Jewry, either from martyrdom or assimilation into nothing, save an individual land, state, and name: die letzte Anstrengung der Juden. What other land could there be than Eretz Yisroel, the Land of Israel? The spirit of world Jewry was moved by the grand conception, as the spirit of modern Greece used to be moved by the Μεγάλη ᾿Ιδέα—the Great Idea—of Constantinople, only more profoundly and far more justifiably; for the supreme intellects of Athens had lived and died five hundred years before the Roman built Constantinople, whereas the creative spirit of Judaism was of The Land, and ceased to create when The Land was taken from them. Therefore this Austrian Jew, Theodor Herzl, was able to stand before the Sultan of Turkey, empowered to buy back from him Palestine for the Jews. But that tremendous boon which the Sultan might have granted, the Caliph, fearing the anger of his Moslem Empire, refused; and once more hope seemed to die. There were already projects for colonization in South America when Joseph Chamberlain, the greatest Secretary of State of the greatest Colonial Empire, had the vision to offer Zion in exile a healthy, fertile and beautiful territory in East Africa. For many, including Herzl himself, the quest seemed to be ended; and the offer would have been accepted but for a small group headed by one strong Russian with the face and the determination of Lenin himself, and with Zionism coursing in his blood.[41] I remember Chaim Weizmann asking me as in a parable whether a band of Englishmen, banished for many years all over the world, would accept as a substitute for home permission to “return” to Calais: so felt he and his for the prospect of Zion in Uganda. Uganda was rejected, and Weizmann became a Lecturer in Chemistry at the University of Manchester, then in the constituency of Arthur James Balfour. The statesman whose heart was in science would take refuge from party routine with a scientist whose soul was in politics; and the first seeds of sympathy were sown. With the War came a demand for high explosives only less imperative than that for human lives, and Acetone, an essential ingredient of Trinitrotoluol—T.N.T.—was found to be unprocurable outside Germany. Its absence appalled the British Admiralty, but not the brain of the Jewish chemist. At his word the school-children of the United Kingdom were seen picking up horse-chestnuts by millions, and the Acetone famine ceased. Weizmann subsequently registered but did not press his claim for the invention, which was, on the skilful pleading of Sir Arthur Colefax, honoured, though none too generously, by the British Government.

But Acetone had registered another claim far more precious to the inventor; and the name and proposals of Weizmann and his colleagues, strongly supported by Arthur Balfour, Herbert Samuel and Mark Sykes, penetrated to the Supreme Council of the Nation and of the Allies.[42] On 2 November 1917, one week before the expected fall of Jerusalem, despite two formidable oppositions—British Jewry, preferring to remain “hundred per cent. Englishmen of ‘non-conformist’ persuasion”, and an India Office ultra-Islamic under a Jewish Secretary of State[43]—there was launched upon the world the momentous and fateful Balfour Declaration. By this instrument Lord Rothschild, bearer of the most famous name in world Jewry, was informed that “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of that object, it being understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by the Jews in other countries.” Mere promulgation by the British Cabinet of such a pronouncement would have been useless without the support of the principal Allies. Dr. Weizmann was fortunate indeed in his colleague Dr. Nahum Sokolow,[44] who obtained the adoption of the Declaration both from the French and Italian Governments, as well as from the Vatican, in letters addressed by those Governments to him personally; thus insuring its acceptance by the Peace Conference at Versailles. And it was Sokolow who as Head of the Zionist Delegation pressed for the British Mandate for Palestine.

The Declaration enjoyed an excellent Press, together with general and generous support from thousands of Anglican priests, Protestant ministers, and other religiously-minded persons throughout the Western Hemisphere; only the Central Powers bewailing their own delay in promulgating a similar document and the Church of Rome indicating early though not immediate reserve. In the numerous British constituencies enjoying a Jewish vote the Declaration was a valuable platform asset, and there was good reciprocal publicity in the almost apocalyptic enthusiasm telegraphed by politicians of standing to the Zionist Organization.

Behind the adoption of so novel a thesis by the most level-headed Cabinet in the world on the recommendation of a Russian Jew, there were alleged to lurk other considerations than mere eagerness for the fulfilment of Old Testament prophecy. British espousal of the Hope of Israel would, it was hinted, serve triply our interest as well as our honour by ensuring the success of the Allied Loan in America, hitherto boycotted by anti-Russian Jewish Finance; by imparting to the Russian Revolution, of which the brains were assumed to be Jewish, a pro-British bias; and by sapping the loyalty of the Jews fighting in scores of thousands on and behind the front of Germany. We may record with relief that even if these material inducements had influenced the decision, the Balfour Declaration was on results utterly clean from such profit.[45] The American Loan went much as had been anyhow expected; no sympathies for Britain accrued from the Soviets (which shortly denounced Zionism as a capitalist contrivance); and the loyalty of German Jewry remained unshaken—with the subsequent reward that the world is now contemplating.

In spite then of non-Zionist and anti-Zionist Jews, world Jewry was at last within sight of home. No more would an infinitesimal minority out of all her sixteen millions creep to Jerusalem for the privilege of being allowed to die on sufferance as in a foreign country. No longer would the Jews remain a people without a land, in exile everywhere; Consuls of the Spirit, bearing witness among aliens to the invisible glories of a vanished kingdom.[46] Civilization had at last acknowledged the great wrong, had proclaimed the word of salvation. It was for the Jews to approve themselves by action worthy of that confidence: to exercise practically and materially their historic “right”. The soil tilled by their fathers had lain for long ages neglected: now, with the modern processes available to Jewish brains, Jewish capital and Jewish enterprise, the wilderness would rejoice and blossom like the rose. Even though the land could not yet absorb sixteen millions, nor even eight, enough could return, if not to form The Jewish State (which a few extremists publicly demanded), at least to prove that the enterprise was one that blessed him that gave as well as him that took by forming for England “a little loyal Jewish Ulster” in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism.

The mainspring of the Zionist ideal being the establishment of a Hebrew nation, speaking Hebrew, upon the soil of the ancient Hebrews, an urgent though unpublished item in the duties of the Commission was to produce certain faits accomplis creating an atmosphere favourable to the project (and stimulating to financial supporters) before the assembly of the Peace Conference. Early in 1918 the twelve foundation stones—to every tribe a stone—of the Hebrew University were formally laid in the presence of a distinguished gathering which included the Commander-in-Chief. The intrepid Commissioners soon advanced (to our admiring sympathy) upon the organization of the Jewish Community, not without a measure of success. The exclusive use of the Hebrew language was imposed upon Jews with a severity sometimes irritating to others, sometimes indeed comic, but in my opinion entirely justified in theory and by results. It was perhaps vexing far a tax or rate collector who had heard a Jewish householder conversing with a Moslem friend in good Arabic to be informed that the speaker knew Hebrew only, and could not understand (or accept) a receipt printed and verbally explained in Arabic. But in this and many other matters Zionism was only applying the Turkish proverb Aghlama’an choju’a sud vermezler (“To the not-crying child they give no milk”) and thereby accelerating the tentative processes of the Military Administration. Again, a fervent Zionist from Central Europe or America might be daunted if his platform “message” in Yiddish was greeted and drowned by howls of “Dabér Ivrít”—“Speak Hebrew!” I myself was puzzled when, inspecting a Zionist Dental Clinic, I asked a man, whose face I thought I knew, what was wrong with him. To my surprise he signified in Hebrew that he could not understand me. The secretary of the Clinic was called from the room, when the patient added in a hurried undertone: “I’ve a terrible toothache, but if I say so in anything but Hebrew I shan’t be treated for it.” The anomaly was heightened by the absolute refusal of the orthodox Rabbis to converse in anything but Yiddish, reserving the holy language for sacred purposes. Many Gentile residents and most visitors derided this drastic revival of Hebrew, asking: “How far will Hebrew take a Jew? Not even as far as Beirut”; and only tolerating it on the explanation that it must entail a rapid diminution of the German language, Kultur and influence.[47] But what other language could a Jewish national revival in Palestine have adopted?