* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

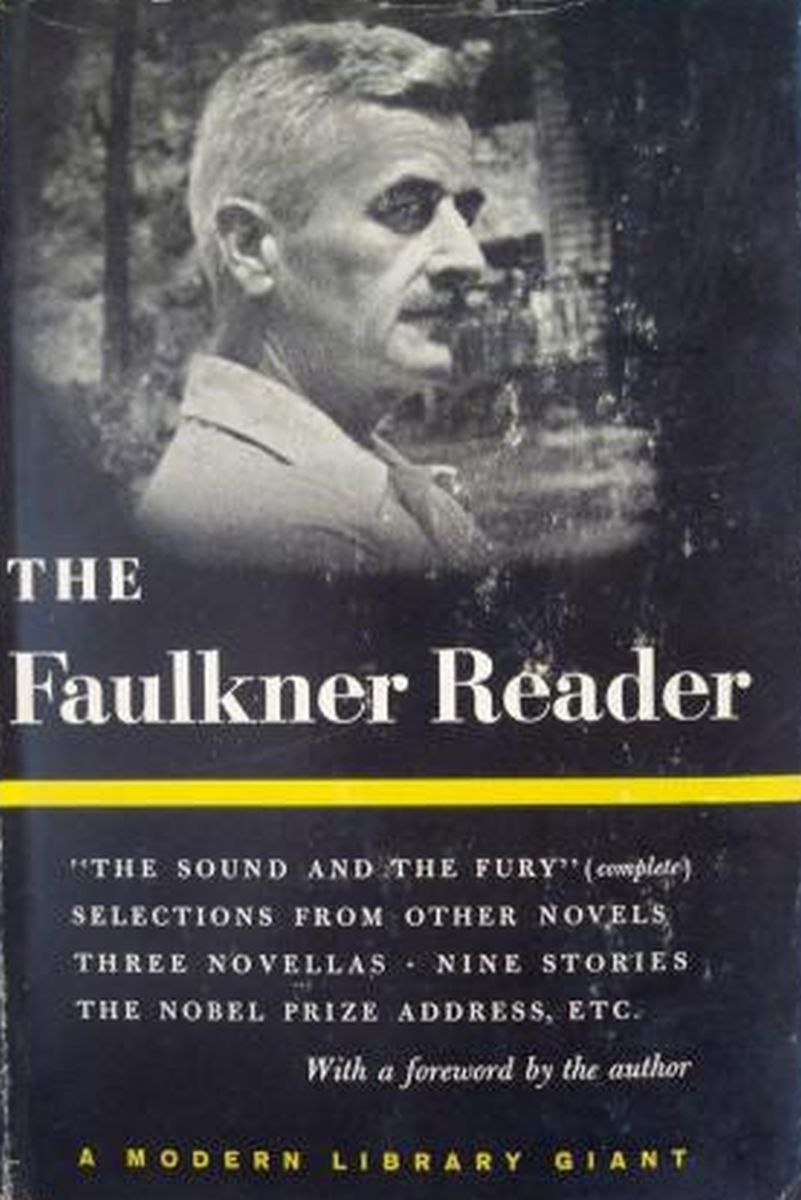

Title: The Faulkner Reader

Date of first publication: 1954

Author: William Faulkner (1897-1962)

Date first posted: Mar. 4, 2020

Date last updated: Mar. 15, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200304

This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

FAULKNER

READER

Selections from the works of

WILLIAM FAULKNER

THE MODERN LIBRARY • NEW YORK

First Modern Library Giant Edition, 1959

Copyright, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1932, 1934, 1938, 1939, 1951, 1954 by William Faulkner

Copyright renewed, 1956, 1957, 1958 by William Faulkner

Copyright, 1931, 1939, 1946, by Random House, Inc.

Copyright, 1932, 1942, 1943 by The Curtis Publishing Co.

Copyright, 1930, by Forum

| Contents | |

| FOREWORD | vii |

| Nobel Prize Address | 3 |

| The Sound and the Fury | 5 |

| The Bear (Go Down, Moses) | 253 |

| Old Man (The Wild Palms) | 353 |

| Spotted Horses (The Hamlet) | 433 |

| A Rose for Emily | 489 |

| Barn Burning | 499 |

| Dry September | 517 |

| That Evening Sun | 529 |

| Turnabout | 547 |

| Shingles for the Lord | 575 |

| A Justice | 589 |

| Wash | 603 |

| An Odor of Verbena (The Unvanquished) | 615 |

| Percy Grimm (Light in August) | 643 |

| The Courthouse (Requiem for a Nun) | 655 |

My grandfather had a moderate though reasonably diffuse and catholic library; I realize now that I got most of my early education in it. It was a little limited in its fiction content, since his taste was for simple straightforward romantic excitement like Scott or Dumas. But there was a heterogeneous scattering of other volumes, chosen apparently at random and by my grandmother, since the flyleaves bore her name and the dates in the 1880’s and ’90’s of that time when even in a town as big as Memphis, Tennessee, ladies stopped in their carriages in the street in front of the stores and shops, and clerks and even proprietors came out to receive their commands—that time when women did most of the book-buying and the reading too, naming their children Byron and Clarissa and St. Elmo and Lothair after the romantic and tragic heroes and heroines and the even more romantic creators of them.

One of these books was by a Pole, Sienkiewicz—a story of the time of King John Sobieski, when the Poles, almost single-handed, kept the Turks from overrunning Central Europe. This one, like all books of that period, at least the ones my grandfather owned, had a preface, a foreword. I never read any of them; I was too eager to get on to what the people themselves were doing and anguishing and triumphing over. But I did read the foreword in this one, the first one I ever took time to read; I don’t know why now. It went something like this:

This book was written at the expense of considerable effort, to uplift men’s hearts, and I thought: What a nice thing to have thought to say. But no more than that. I didn’t even think, Maybe some day I will write a book too and what a shame I didn’t think of that first so I could put it on the front page of mine. Because I hadn’t thought of writing books then. The future didn’t extend that far. This was 1915 and ’16; I had seen an aeroplane and my mind was filled with names: Ball, and Immelman and Boelcke, and Guynemer and Bishop, and I was waiting, biding, until I would be old enough or free enough or anyway could get to France and become glorious and beribboned too.

Then that had passed. It was 1923 and I wrote a book and discovered that my doom, fate, was to keep on writing books: not for any exterior or ulterior purpose: just writing the books for the sake of writing the books; obviously, since the publisher considered them worth the financial risk of being printed, someone would read them. But that was unimportant too as measured against the need to get them written, though naturally one hopes that who read them would find them true and honest and even perhaps moving. Because one was too busy writing the books during the time while the demon which drove him still considered him worthy of, deserving of, the anguish of being driven, while the blood and glands and flesh still remained strong and potent, the heart and the imagination still remained undulled to follies and lusts and heroisms of men and women; still writing the books because they had to be written after the blood and glands began to slow and cool a little and the heart began to tell him, You don’t know the answer either and you will never find it, but still writing the books because the demon was still kind; only a little more severe and unpitying: until suddenly one day he saw that that old half-forgotten Pole had had the answer all the time.

To uplift man’s heart; the same for all of us: for the ones who are trying to be artists, the ones who are trying to write simple entertainment, the ones who write to shock, and the ones who are simply escaping themselves and their own private anguishes.

Some of us don’t know that this is what we are writing for. Some of us will know it and deny it, lest we be accused and self-convicted and condemned of sentimentality, which people nowadays for some reason are ashamed to be tainted with; some of us seem to have curious ideas of just where the heart is located, confusing it with other and baser glands and organs and activities. But we all write for this one purpose.

This does not mean that we are trying to change man, improve him, though this is the hope—maybe even the intention—of some of us. On the contrary, in its last analysis, this hope and desire to uplift man’s heart is completely selfish, completely personal. He would lift up man’s heart for his own benefit because in that way he can say No to death. He is saying No to death for himself by means of the hearts which he has hoped to uplift, or even by means of the mere base glands which he has disturbed to that extent where they can say No to death on their own account by knowing, realizing, having been told and believing it: At least we are not vegetables because the hearts and glands capable of partaking in this excitement are not those of vegetables, and will, must, endure.

So he who, from the isolation of cold impersonal print, can engender this excitement, himself partakes of the immortality which he has engendered. Some day he will be no more, which will not matter then, because isolated and itself invulnerable in the cold print remains that which is capable of engendering still the old deathless excitement in hearts and glands whose owners and custodians are generations from even the air he breathed and anguished in; if it was capable once, he knows that it will be capable and potent still long after there remains of him only a dead and fading name.

New York

November, 1953

THE FAULKNER READER

delivered in Stockholm on the tenth of December,

nineteen hundred fifty

I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work—a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will some day stand here where I am standing.

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed—love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

Through the fence, between the curling flower spaces, I could see them hitting. They were coming toward where the flag was and I went along the fence. Luster was hunting in the grass by the flower tree. They took the flag out, and they were hitting. Then they put the flag back and they went to the table, and he hit and the other hit. Then they went on, and I went along the fence. Luster came away from the flower tree and we went along the fence and they stopped and we stopped and I looked through the fence while Luster was hunting in the grass.

“Here, caddie.” He hit. They went away across the pasture. I held to the fence and watched them going away.

“Listen at you, now.” Luster said. “Aint you something, thirty-three years old, going on that way. After I done went all the way to town to buy you that cake. Hush up that moaning. Aint you going to help me find that quarter so I can go to the show tonight.”

They were hitting little, across the pasture. I went along the fence to where the flag was. It flapped on the bright grass and the trees.

“Come on.” Luster said. “We done looked there. They aint no more coming right now. Lets go down to the branch and find that quarter before them niggers finds it.”

It was red, flapping on the pasture. Then there was a bird slanting and tilting on it. Luster threw. The flag flapped on the bright grass and the trees. I held to the fence.

“Shut up that moaning.” Luster said. “I cant make them come if they aint coming, can I. If you dont hush up, mammy aint going to have no birthday for you. If you dont hush, you know what I going to do. I going to eat that cake all up. Eat them candles, too. Eat all them thirty-three candles. Come on, let’s go down to the branch. I got to find my quarter. Maybe we can find one of they balls. Here. Here they is. Way over yonder. See.” He came to the fence and pointed his arm. “See them. They aint coming back here no more. Come on.”

We went along the fence and came to the garden fence, where our shadows were. My shadow was higher than Luster’s on the fence. We came to the broken place and went through it.

“Wait a minute.” Luster said. “You snagged on that nail again. Cant you never crawl through here without snagging on that nail.”

Caddy uncaught me and we crawled through. Uncle Maury said to not let anybody see us, so we better stoop over, Caddy said. Stoop over, Benjy. Like this, see. We stooped over and crossed the garden, where the flowers rasped and rattled against us. The ground was hard. We climbed the fence, where the pigs were grunting and snuffing. I expect they’re sorry because one of them got killed today, Caddy said. The ground was hard, churned and knotted.

Keep your hands in your pockets, Caddy said. Or they’ll get froze. You don’t want your hands froze on Christmas, do you.

“It’s too cold out there.” Versh said. “You dont want to go out doors.”

“What is it now.” Mother said.

“He want to go out doors.” Versh said.

“Let him go.” Uncle Maury said.

“It’s too cold.” Mother said. “He’d better stay in. Benjamin. Stop that, now.”

“It wont hurt him.” Uncle Maury said.

“You, Benjamin.” Mother said. “If you dont be good, you’ll have to go to the kitchen.”

“Mammy say keep him out the kitchen today.” Versh said. “She say she got all that cooking to get done.”

“Let him go, Caroline.” Uncle Maury said. “You’ll worry yourself sick over him.”

“I know it.” Mother said. “It’s a judgment on me. I sometimes wonder.”

“I know, I know.” Uncle Maury said. “You must keep your strength up. I’ll make you a toddy.”

“It just upsets me that much more.” Mother said. “Dont you know it does.”

“You’ll feel better.” Uncle Maury said. “Wrap him up good, boy, and take him out for a while.”

Uncle Maury went away. Versh went away.

“Please hush.” Mother said. “We’re trying to get you out as fast as we can. I dont want you to get sick.”

Versh put my overshoes and overcoat on and we took my cap and went out. Uncle Maury was putting the bottle away in the sideboard in the dining-room.

“Keep him out about half an hour, boy.” Uncle Maury said. “Keep him in the yard, now.”

“Yes, sir.” Versh said. “We dont never let him get off the place.”

We went out doors. The sun was cold and bright.

“Where you heading for.” Versh said. “You dont think you going to town, does you.” We went through the rattling leaves. The gate was cold. “You better keep them hands in your pockets.” Versh said, “You get them froze onto that gate, then what you do. Whyn’t you wait for them in the house.” He put my hands into my pockets. I could hear him rattling in the leaves. I could smell the cold. The gate was cold.

“Here some hickeynuts. Whooey. Git up that tree. Look here at this squirl, Benjy.”

I couldn’t feel the gate at all, but I could smell the bright cold.

“You better put them hands back in your pockets.”

Caddy was walking. Then she was running, her booksatchel swinging and jouncing behind her.

“Hello, Benjy.” Caddy said. She opened the gate and came in and stooped down. Caddy smelled like leaves. “Did you come to meet me.” she said. “Did you come to meet Caddy. What did you let him get his hands so cold for, Versh.”

“I told him to keep them in his pockets.” Versh said. “Holding onto that ahun gate.”

“Did you come to meet Caddy.” she said, rubbing my hands. “What is it. What are you trying to tell Caddy.” Caddy smelled like trees and like when she says we were asleep.

What are you moaning about, Luster said. You can watch them again when we get to the branch. Here. Here’s you a jimson weed. He gave me the flower. We went through the fence, into the lot.

“What is it.” Caddy said. “What are you trying to tell Caddy. Did they send him out, Versh.”

“Couldn’t keep him in.” Versh said. “He kept on until they let him go and he come right straight down here, looking through the gate.”

“What is it.” Caddy said. “Did you think it would be Christmas when I came home from school. Is that what you thought. Christmas is the day after tomorrow. Santy Claus, Benjy. Santy Claus. Come on, let’s run to the house and get warm.” She took my hand and we ran through the bright rustling leaves. We ran up the steps and out of the bright cold, into the dark cold. Uncle Maury was putting the bottle back in the sideboard. He called Caddy. Caddy said,

“Take him in to the fire, Versh. Go with Versh.” she said. “I’ll come in a minute.”

We went to the fire. Mother said,

“Is he cold, Versh.”

“Nome.” Versh said.

“Take his overcoat and overshoes off.” Mother said. “How many times do I have to tell you not to bring him into the house with his overshoes on.”

“Yessum.” Versh said. “Hold still, now.” He took my overshoes off and unbuttoned my coat. Caddy said,

“Wait, Versh. Cant he go out again, Mother. I want him to go with me.”

“You’d better leave him here.” Uncle Maury said. “He’s been out enough today.”

“I think you’d both better stay in.” Mother said. “It’s getting colder, Dilsey says.”

“Oh, Mother.” Caddy said.

“Nonsense.” Uncle Maury said. “She’s been in school all day. She needs the fresh air. Run along, Candace.”

“Let him go, Mother.” Caddy said. “Please. You know he’ll cry.”

“Then why did you mention it before him.” Mother said. “Why did you come in here. To give him some excuse to worry me again. You’ve been out enough today. I think you’d better sit down here and play with him.”

“Let them go, Caroline.” Uncle Maury said. “A little cold wont hurt them. Remember, you’ve got to keep your strength up.”

“I know.” Mother said. “Nobody knows how I dread Christmas. Nobody knows. I am not one of those women who can stand things. I wish for Jason’s and the children’s sakes I was stronger.”

“You must do the best you can and not let them worry you.” Uncle Maury said. “Run along, you two. But dont stay out long, now. Your mother will worry.”

“Yes, sir.” Caddy said. “Come on, Benjy. We’re going out doors again.” She buttoned my coat and we went toward the door.

“Are you going to take that baby out without his overshoes.” Mother said. “Do you want to make him sick, with the house full of company.”

“I forgot.” Caddy said. “I thought he had them on.”

We went back. “You must think.” Mother said. Hold still now Versh said. He put my overshoes on. “Someday I’ll be gone, and you’ll have to think for him.” Now stomp Versh said. “Come here and kiss Mother, Benjamin.”

Caddy took me to Mother’s chair and Mother took my face in her hands and then she held me against her.

“My poor baby.” she said. She let me go. “You and Versh take good care of him, honey.”

“Yessum.” Caddy said. We went out. Caddy said,

“You needn’t go, Versh. I’ll keep him for a while.”

“All right.” Versh said. “I aint going out in that cold for no fun.” He went on and we stopped in the hall and Caddy knelt and put her arms around me and her cold bright face against mine. She smelled like trees.

“You’re not a poor baby. Are you. You’ve got your Caddy. Haven’t you got your Caddy.”

Cant you shut up that moaning and slobbering, Luster said. Aint you shamed of yourself, making all this racket. We passed the carriage house, where the carriage was. It had a new wheel.

“Git in, now, and set still until your maw come.” Dilsey said. She shoved me into the carriage. T. P. held the reins. “ ’Clare I don’t see how come Jason wont get a new surrey.” Dilsey said. “This thing going to fall to pieces under you all someday. Look at them wheels.”

Mother came out, pulling her veil down. She had some flowers.

“Where’s Roskus.” she said.

“Roskus cant lift his arms, today.” Dilsey said. “T. P. can drive all right.”

“I’m afraid to.” Mother said. “It seems to me you all could furnish me with a driver for the carriage once a week. It’s little enough I ask, Lord knows.”

“You know just as well as me that Roskus got the rheumatism too bad to do more than he have to, Miss Cahline.” Dilsey said. “You come on and get in, now. T. P. can drive you just as good as Roskus.”

“I’m afraid to.” Mother said. “With the baby.”

Dilsey went up the steps. “You calling that thing a baby,” she said. She took Mother’s arm. “A man big as T. P. Come on, now, if you going.”

“I’m afraid to.” Mother said. They came down the steps and Dilsey helped Mother in. “Perhaps it’ll be the best thing, for all of us.” Mother said.

“Aint you shamed, talking that way.” Dilsey said. “Dont you know it’ll take more than a eighteen year old nigger to make Queenie run away. She older than him and Benjy put together. And dont you start no projecking with Queenie, you hear me, T. P. If you dont drive to suit Miss Cahline, I going to put Roskus on you. He aint too tied up to do that.”

“Yessum.” T. P. said.

“I just know something will happen.” Mother said. “Stop, Benjamin.”

“Give him a flower to hold.” Dilsey said, “That what he wanting.” She reached her hand in.

“No, no.” Mother said. “You’ll have them all scattered.”

“You hold them.” Dilsey said. “I’ll get him one out.” She gave me a flower and her hand went away.

“Go on now, ’fore Quentin see you and have to go too.” Dilsey said.

“Where is she.” Mother said.

“She down to the house playing with Luster.” Dilsey said. “Go on, T. P. Drive that surrey like Roskus told you, now.”

“Yessum.” T. P. said. “Hum up, Queenie.”

“Quentin.” Mother said. “Dont let”

“Course I is.” Dilsey said.

The carriage jolted and crunched on the drive. “I’m afraid to go and leave Quentin.” Mother said. “I’d better not go. T. P.” We went through the gate, where it didnt jolt anymore. T. P. hit Queenie with the whip.

“You, T. P.” Mother said.

“Got to get her going.” T. P. said. “Keep her wake up till we get back to the barn.”

“Turn around.” Mother said. “I’m afraid to go and leave Quentin.”

“Cant turn here.” T. P. said. Then it was broader.

“Cant you turn here.” Mother said.

“All right.” T. P. said. We began to turn.

“You, T. P.” Mother said, clutching me.

“I got to turn around somehow.” T. P. said. “Whoa, Queenie.” We stopped.

“You’ll turn us over.” Mother said.

“What you want to do, then.” T. P. said.

“I’m afraid for you to try to turn around.” Mother said.

“Get up, Queenie.” T. P. said. We went on.

“I just know Dilsey will let something happen to Quentin while I’m gone.” Mother said. “We must hurry back.”

“Hum up, there.” T. P. said. He hit Queenie with the whip.

“You, T. P.” Mother said, clutching me. I could hear Queenie’s feet and the bright shapes went smooth and steady on both sides, the shadows of them flowing across Queenie’s back. They went on like the bright tops of wheels. Then those on one side stopped at the tall white post where the soldier was. But on the other side they went on smooth and steady, but a little slower.

“What do you want.” Jason said. He had his hands in his pockets and a pencil behind his ear.

“We’re going to the cemetery.” Mother said.

“All right.” Jason said. “I dont aim to stop you, do I. Was that all you wanted with me, just to tell me that.”

“I know you wont come.” Mother said. “I’d feel safer if you would.”

“Safe from what.” Jason said. “Father and Quentin cant hurt you.”

Mother put her handkerchief under her veil. “Stop it, Mother.” Jason said. “Do you want to get that damn loony to bawling in the middle of the square. Drive on, T. P.”

“Hum up, Queenie.” T. P. said.

“It’s a judgment on me.” Mother said. “But I’ll be gone too, soon.”

“Here.” Jason said.

“Whoa.” T. P. said. Jason said,

“Uncle Maury’s drawing on you for fifty. What do you want to do about it.”

“Why ask me.” Mother said. “I dont have any say so. I try not to worry you and Dilsey. I’ll be gone soon, and then you”

“Go on, T. P.” Jason said.

“Hum up, Queenie.” T. P. said. The shapes flowed on. The ones on the other side began again, bright and fast and smooth, like when Caddy says we are going to sleep.

Cry baby, Luster said. Aint you shamed. We went through the barn. The stalls were all open. You aint got no spotted pony to ride now, Luster said. The floor was dry and dusty. The roof was falling. The slanting holes were full of spinning yellow. What do you want to go that way for. You want to get your head knocked off with one of them balls.

“Keep your hands in your pockets.” Caddy said, “Or they’ll be froze. You dont want your hands froze on Christmas, do you.”

We went around the barn. The big cow and the little one were standing in the door, and we could hear Prince and Queenie and Fancy stomping inside the barn. “If it wasn’t so cold, we’d ride Fancy.” Caddy said, “But it’s too cold to hold on today.” Then we could see the branch, where the smoke was blowing. “That’s where they are killing the pig.” Caddy said. “We can come back by there and see them.” We went down the hill.

“You want to carry the letter.” Caddy said. “You can carry it.” She took the letter out of her pocket and put it in mine. “It’s a Christmas present.” Caddy said. “Uncle Maury is going to surprise Mrs Patterson with it. We got to give it to her without letting anybody see it. Keep your hands in your pockets good, now.” We came to the branch.

“It’s froze.” Caddy said, “Look.” She broke the top of the water and held a piece of it against my face. “Ice. That means how cold it is.” She helped me across and we went up the hill. “We cant even tell Mother and Father. You know what I think it is. I think it’s a surprise for Mother and Father and Mr Patterson both, because Mr Patterson sent you some candy. Do you remember when Mr Patterson sent you some candy last summer.”

There was a fence. The vine was dry, and the wind rattled in it.

“Only I dont see why Uncle Maury didn’t send Versh.” Caddy said. “Versh wont tell.” Mrs Patterson was looking out the window. “You wait here.” Caddy said. “Wait right here, now. I’ll be back in a minute. Give me the letter.” She took the letter out of my pocket. “Keep your hands in your pockets.” She climbed the fence with the letter in her hand and went through the brown, rattling flowers. Mrs Patterson came to the door and opened it and stood there.

Mr Patterson was chopping in the green flowers. He stopped chopping and looked at me. Mrs Patterson came across the garden, running. When I saw her eyes I began to cry. You idiot, Mrs Patterson said, I told him never to send you alone again. Give it to me. Quick. Mr Patterson came fast, with the hoe. Mrs Patterson leaned across the fence, reaching her hand. She was trying to climb the fence. Give it to me, she said, Give it to me. Mr Patterson climbed the fence. He took the letter. Mrs Patterson’s dress was caught on the fence. I saw her eyes again and I ran down the hill.

“They aint nothing over yonder but houses.” Luster said. “We going down to the branch.”

They were washing down at the branch. One of them was singing. I could smell the clothes flapping, and the smoke blowing across the branch.

“You stay down here.” Luster said. “You aint got no business up yonder. Them folks hit you, sho.”

“What he want to do.”

“He dont know what he want to do.” Luster said. “He think he want to go up yonder where they knocking that ball. You sit down here and play with your jimson weed. Look at them chillen playing in the branch, if you got to look at something. How come you cant behave yourself like folks.” I sat down on the bank, where they were washing, and the smoke blowing blue.

“Is you all seen anything of a quarter down here.” Luster said.

“What quarter.”

“The one I had here this morning.” Luster said. “I lost it somewhere. It fell through this here hole in my pocket. If I dont find it I cant go to the show tonight.”

“Where’d you get a quarter, boy. Find it in white folks’ pocket while they aint looking.”

“Got it at the getting place.” Luster said. “Plenty more where that one come from. Only I got to find that one. Is you all found it yet.”

“I aint studying no quarter. I got my own business to tend to.”

“Come on here.” Luster said. “Help me look for it.”

“He wouldn’t know a quarter if he was to see it, would he.”

“He can help look just the same.” Luster said. “You all going to the show tonight.”

“Dont talk to me about no show. Time I get done over this here tub I be too tired to lift my hand to do nothing.”

“I bet you be there.” Luster said. “I bet you was there last night. I bet you all be right there when that tent open.”

“Be enough niggers there without me. Was last night.”

“Nigger’s money good as white folks, I reckon.”

“White folks gives nigger money because know first white man comes along with a band going to get it all back, so nigger can go to work for some more.”

“Aint nobody going make you go to that show.”

“Aint yet. Aint thought of it, I reckon.”

“What you got against white folks.”

“Aint got nothing against them. I goes my way and lets white folks go theirs. I aint studying that show.”

“Got a man in it can play a tune on a saw. Play it like a banjo.”

“You go last night.” Luster said. “I going tonight. If I can find where I lost that quarter.”

“You going take him with you, I reckon.”

“Me.” Luster said. “You reckon I be found anywhere with him, time he start bellering.”

“What does you do when he start bellering.”

“I whips him.” Luster said. He sat down and rolled up his overalls. They played in the branch.

“You all found any balls yet.” Luster said.

“Aint you talking biggity. I bet you better not let your grandmammy hear you talking like that.”

Luster got into the branch, where they were playing. He hunted in the water, along the bank.

“I had it when we was down here this morning.” Luster said.

“Where ’bouts you lose it.”

“Right out this here hole in my pocket.” Luster said. They hunted in the branch. Then they all stood up quick and stopped, then they splashed and fought in the branch. Luster got it and they squatted in the water, looking up the hill through the bushes.

“Where is they.” Luster said.

“Aint in sight yet.”

Luster put it in his pocket. They came down the hill.

“Did a ball come down here.”

“It ought to be in the water. Didn’t any of you boys see it or hear it.”

“Aint heard nothing come down here.” Luster said. “Heard something hit that tree up yonder. Dont know which way it went.”

They looked in the branch.

“Hell. Look along the branch. It came down here. I saw it.”

They looked along the branch. Then they went back up the hill.

“Have you got that ball.” the boy said.

“What I want with it.” Luster said. “I aint seen no ball.”

The boy got in the water. He went on. He turned and looked at Luster again. He went on down the branch.

The man said “Caddie” up the hill. The boy got out of the water and went up the hill.

“Now, just listen at you.” Luster said. “Hush up.”

“What he moaning about now.”

“Lawd knows.” Luster said. “He just starts like that. He been at it all morning. Cause it his birthday, I reckon.”

“How old he.”

“He thirty-three.” Luster said. “Thirty-three this morning.”

“You mean, he been three years old thirty years.”

“I going by what mammy say.” Luster said. “I dont know. We going to have thirty-three candles on a cake, anyway. Little cake. Wont hardly hold them. Hush up. Come on back here.” He came and caught my arm. “You old loony.” he said. “You want me to whip you.”

“I bet you will.”

“I is done it. Hush, now.” Luster said. “Aint I told you you cant go up there. They’ll knock your head clean off with one of them balls. Come on, here.” He pulled me back. “Sit down.” I sat down and he took off my shoes and rolled up my trousers. “Now, git in that water and play and see can you stop that slobbering and moaning.”

I hushed and got in the water and Roskus came and said to come to supper and Caddy said,

It’s not supper time yet. I’m not going.

She was wet. We were playing in the branch and Caddy squatted down and got her dress wet and Versh said,

“Your mommer going to whip you for getting your dress wet.”

“She’s not going to do any such thing.” Caddy said.

“How do you know.” Quentin said.

“That’s all right how I know.” Caddy said. “How do you know.”

“She said she was.” Quentin said. “Besides, I’m older than you.”

“I’m seven years old.” Caddy said, “I guess I know.”

“I’m older than that.” Quentin said. “I go to school. Dont I, Versh.”

“I’m going to school next year.” Caddy said, “When it comes. Aint I, Versh.”

“You know she whip you when you get your dress wet.” Versh said.

“It’s not wet.” Caddy said. She stood up in the water and looked at her dress. “I’ll take it off.” she said. “Then it’ll dry.”

“I bet you wont.” Quentin said.

“I bet I will.” Caddy said.

“I bet you better not.” Quentin said.

Caddy came to Versh and me and turned her back.

“Unbutton it, Versh.” she said.

“Dont you do it, Versh.” Quentin said.

“Taint none of my dress.” Versh said.

“You unbutton it, Versh.” Caddy said, “Or I’ll tell Dilsey what you did yesterday.” So Versh unbuttoned it.

“You just take your dress off.” Quentin said. Caddy took her dress off and threw it on the bank. Then she didn’t have on anything but her bodice and drawers, and Quentin slapped her and she slipped and fell down in the water. When she got up she began to splash water on Quentin, and Quentin splashed water on Caddy. Some of it splashed on Versh and me and Versh picked me up and put me on the bank. He said he was going to tell on Caddy and Quentin, and then Quentin and Caddy began to splash water at Versh. He got behind a bush.

“I’m going to tell mammy on you all.” Versh said.

Quentin climbed up on the bank and tried to catch Versh, but Versh ran away and Quentin couldn’t. When Quentin came back Versh stopped and hollered that he was going to tell. Caddy told him that if he wouldn’t tell, they’d let him come back. So Versh said he wouldn’t, and they let him.

“Now I guess you’re satisfied.” Quentin said, “We’ll both get whipped now.”

“I dont care.” Caddy said. “I’ll run away.”

“Yes you will.” Quentin said.

“I’ll run away and never come back.” Caddy said. I began to cry. Caddy turned around and said “Hush.” So I hushed. Then they played in the branch. Jason was playing too. He was by himself further down the branch. Versh came around the bush and lifted me down into the water again. Caddy was all wet and muddy behind, and I started to cry and she came and squatted in the water.

“Hush now.” she said. “I’m not going to run away.” So I hushed. Caddy smelled like trees in the rain.

What is the matter with you, Luster said. Cant you get done with that moaning and play in the branch like folks.

Whyn’t you take him on home. Didn’t they told you not to take him off the place.

He still think they own this pasture, Luster said. Cant nobody see down here from the house, noways.

We can. And folks dont like to look at a loony. Taint no luck in it.

Roskus came and said to come to supper and Caddy said it wasn’t supper time yet.

“Yes tis.” Roskus said. “Dilsey say for you all to come on to the house. Bring them on, Versh.” He went up the hill, where the cow was lowing.

“Maybe we’ll be dry by the time we get to the house.” Quentin said.

“It was all your fault.” Caddy said. “I hope we do get whipped.” She put her dress on and Versh buttoned it.

“They wont know you got wet.” Versh said. “It dont show on you. Less me and Jason tells.”

“Are you going to tell, Jason.” Caddy said.

“Tell on who.” Jason said.

“He wont tell.” Quentin said. “Will you, Jason.”

“I bet he does tell.” Caddy said. “He’ll tell Damuddy.”

“He cant tell her.” Quentin said. “She’s sick. If we walk slow it’ll be too dark for them to see.”

“I dont care whether they see or not.” Caddy said. “I’m going to tell, myself. You carry him up the hill, Versh.”

“Jason wont tell.” Quentin said. “You remember that bow and arrow I made you, Jason.”

“It’s broke now.” Jason said.

“Let him tell.” Caddy said. “I dont give a cuss. Carry Maury up the hill, Versh.” Versh squatted and I got on his back.

See you all at the show tonight, Luster said. Come on, here. We got to find that quarter.

“If we go slow, it’ll be dark when we get there.” Quentin said.

“I’m not going slow.” Caddy said. We went up the hill, but Quentin didn’t come. He was down at the branch when we got to where we could smell the pigs. They were grunting and snuffing in the trough in the corner. Jason came behind us, with his hands in his pockets. Roskus was milking the cow in the barn door.

The cows came jumping out of the barn.

“Go on.” T. P. said. “Holler again. I going to holler myself. Whooey.” Quentin kicked T. P. again. He kicked T. P. into the trough where the pigs ate and T. P. lay there. “Hot dog.” T. P. said, “Didn’t he get me then. You see that white man kick me that time. Whooey.”

I wasn’t crying, but I couldn’t stop. I wasn’t crying, but the ground wasn’t still, and then I was crying. The ground kept sloping up and the cows ran up the hill. T. P. tried to get up. He fell down again and the cows ran down the hill. Quentin held my arm and we went toward the barn. Then the barn wasn’t there and we had to wait until it came back. I didn’t see it come back. It came behind us and Quentin set me down in the trough where the cows ate. I held on to it. It was going away too, and I held to it. The cows ran down the hill again, across the door. I couldn’t stop. Quentin and T. P. came up the hill, fighting. T. P. was falling down the hill and Quentin dragged him up the hill. Quentin hit T. P. I couldn’t stop.

“Stand up.” Quentin said, “You stay right here. Dont you go away until I get back.”

“Me and Benjy going back to the wedding.” T. P. said. “Whooey.”

Quentin hit T. P. again. Then he began to thump T. P. against the wall. T. P. was laughing. Every time Quentin thumped him against the wall he tried to say Whooey, but he couldn’t say it for laughing. I quit crying, but I couldn’t stop. T. P. fell on me and the barn door went away. It went down the hill and T. P. was fighting by himself and he fell down again. He was still laughing, and I couldn’t stop, and I tried to get up and I fell down, and I couldn’t stop. Versh said,

“You sho done it now. I’ll declare if you aint. Shut up that yelling.”

T. P. was still laughing. He flopped on the door and laughed. “Whooey.” he said, “Me and Benjy going back to the wedding. Sassprilluh.” T. P. said.

“Hush.” Versh said. “Where you get it.”

“Out the cellar.” T. P. said. “Whooey.”

“Hush up.” Versh said, “Where’bouts in the cellar.”

“Anywhere.” T. P. said. He laughed some more. “Moren a hundred bottles left. Moren a million. Look out, nigger, I going to holler.”

Quentin said, “Lift him up.”

Versh lifted me up.

“Drink this, Benjy.” Quentin said. The glass was hot. “Hush, now.” Quentin said. “Drink it.”

“Sassprilluh.” T. P. said. “Lemme drink it, Mr Quentin.”

“You shut your mouth.” Versh said, “Mr Quentin wear you out.”

“Hold him, Versh.” Quentin said.

They held me. It was hot on my chin and on my shirt. “Drink.” Quentin said. They held my head. It was hot inside me, and I began again. It was crying now, and something was happening inside me and I cried more, and they held me until it stopped happening. Then I hushed. It was still going around, and then the shapes began. “Open the crib, Versh.” They were going slow. “Spread those empty sacks on the floor.” They were going faster, almost fast enough. “Now. Pick up his feet.” They went on, smooth and bright. I could hear T. P. laughing. I went on with them, up the bright hill.

At the top of the hill Versh put me down. “Come on here, Quentin.” he called, looking back down the hill. Quentin was still standing there by the branch. He was chunking into the shadows where the branch was.

“Let the old skizzard stay there.” Caddy said. She took my hand and we went on past the barn and through the gate. There was a frog on the brick walk, squatting in the middle of it. Caddy stepped over it and pulled me on.

“Come on, Maury.” she said. It still squatted there until Jason poked at it with his toe.

“He’ll make a wart on you.” Versh said. The frog hopped away.

“Come on, Maury.” Caddy said.

“They got company tonight.” Versh said.

“How do you know.” Caddy said.

“With all them lights on.” Versh said, “Light in every window.”

“I reckon we can turn all the lights on without company, if we want to.” Caddy said.

“I bet it’s company.” Versh said. “You all better go in the back and slip upstairs.”

“I dont care.” Caddy said. “I’ll walk right in the parlor where they are.”

“I bet your pappy whip you if you do.” Versh said.

“I dont care.” Caddy said. “I’ll walk right in the parlor. I’ll walk right in the dining room and eat supper.”

“Where you sit.” Versh said.

“I’d sit in Damuddy’s chair.” Caddy said. “She eats in bed.”

“I’m hungry.” Jason said. He passed us and ran on up the walk. He had his hands in his pockets and he fell down. Versh went and picked him up.

“If you keep them hands out your pockets, you could stay on your feet.” Versh said. “You cant never get them out in time to catch yourself, fat as you is.”

Father was standing by the kitchen steps.

“Where’s Quentin.” he said.

“He coming up the walk.” Versh said. Quentin was coming slow. His shirt was a white blur.

“Oh.” Father said. Light fell down the steps, on him.

“Caddy and Quentin threw water on each other.” Jason said.

We waited.

“They did.” Father said. Quentin came, and Father said, “You can eat supper in the kitchen tonight.” He stopped and took me up, and the light came tumbling down the steps on me too, and I could look down at Caddy and Jason and Quentin and Versh. Father turned toward the steps. “You must be quiet, though.” he said.

“Why must we be quiet, Father.” Caddy said. “Have we got company.”

“Yes.” Father said.

“I told you they was company.” Versh said.

“You did not.” Caddy said, “I was the one that said there was. I said I would”

“Hush.” Father said. They hushed and Father opened the door and we crossed the back porch and went in to the kitchen. Dilsey was there, and Father put me in the chair and closed the apron down and pushed it to the table, where supper was. It was steaming up.

“You mind Dilsey, now.” Father said. “Dont let them make any more noise than they can help, Dilsey.”

“Yes, sir.” Dilsey said. Father went away.

“Remember to mind Dilsey, now.” he said behind us. I leaned my face over where the supper was. It steamed up on my face.

“Let them mind me tonight, Father.” Caddy said.

“I wont.” Jason said. “I’m going to mind Dilsey.”

“You’ll have to, if Father says so.” Caddy said. “Let them mind me, Father.”

“I wont.” Jason said, “I wont mind you.”

“Hush.” Father said. “You all mind Caddy, then. When they are done, bring them up the back stairs, Dilsey.”

“Yes, sir.” Dilsey said.

“There.” Caddy said, “Now I guess you’ll mind me.”

“You all hush, now.” Dilsey said. “You got to be quiet tonight.”

“Why do we have to be quiet tonight.” Caddy whispered.

“Never you mind.” Dilsey said, “You’ll know in the Lawd’s own time.” She brought my bowl. The steam from it came and tickled my face. “Come here, Versh.” Dilsey said.

“When is the Lawd’s own time, Dilsey.” Caddy said.

“It’s Sunday.” Quentin said. “Dont you know anything.”

“Shhhhhh.” Dilsey said. “Didn’t Mr Jason say for you all to be quiet. Eat your supper, now. Here, Versh. Git his spoon.” Versh’s hand came with the spoon, into the bowl. The spoon came up to my mouth. The steam tickled into my mouth. Then we quit eating and we looked at each other and we were quiet, and then we heard it again and I began to cry.

“What was that.” Caddy said. She put her hand on my hand.

“That was Mother.” Quentin said. The spoon came up and I ate, then I cried again.

“Hush.” Caddy said. But I didn’t hush and she came and put her arms around me. Dilsey went and closed both the doors and then we couldn’t hear it.

“Hush, now.” Caddy said. I hushed and ate. Quentin wasn’t eating, but Jason was.

“That was Mother.” Quentin said. He got up.

“You set right down.” Dilsey said. “They got company in there, and you in them muddy clothes. You set down too, Caddy, and get done eating.”

“She was crying.” Quentin said.

“It was somebody singing.” Caddy said. “Wasn’t it, Dilsey.”

“You all eat your supper, now, like Mr Jason said.” Dilsey said. “You’ll know in the Lawd’s own time.” Caddy went back to her chair.

“I told you it was a party.” she said.

Versh said, “He done et all that.”

“Bring his bowl here.” Dilsey said. The bowl went away.

“Dilsey.” Caddy said, “Quentin’s not eating his supper. Hasn’t he got to mind me.”

“Eat your supper, Quentin.” Dilsey said, “You all got to get done and get out of my kitchen.”

“I dont want any more supper.” Quentin said.

“You’ve got to eat if I say you have.” Caddy said. “Hasn’t he, Dilsey.”

The bowl steamed up to my face, and Versh’s hand dipped the spoon in it and the steam tickled into my mouth.

“I dont want any more.” Quentin said. “How can they have a party when Damuddy’s sick.”

“They’ll have it down stairs.” Caddy said. “She can come to the landing and see it. That’s what I’m going to do when I get my nightie on.”

“Mother was crying.” Quentin said. “Wasn’t she crying, Dilsey.”

“Dont you come pestering at me, boy.” Dilsey said. “I got to get supper for all them folks soon as you all get done eating.”

After a while even Jason was through eating, and he began to cry.

“Now you got to tune up.” Dilsey said.

“He does it every night since Damuddy was sick and he cant sleep with her.” Caddy said. “Cry baby.”

“I’m going to tell on you.” Jason said.

He was crying. “You’ve already told.” Caddy said. “There’s not anything else you can tell, now.”

“You all needs to go to bed.” Dilsey said. She came and lifted me down and wiped my face and hands with a warm cloth. “Versh, can you get them up the back stairs quiet. You, Jason, shut up that crying.”

“It’s too early to go to bed now.” Caddy said. “We dont ever have to go to bed this early.”

“You is tonight.” Dilsey said. “Your pa say for you to come right on up stairs when you et supper. You heard him.”

“He said to mind me.” Caddy said.

“I’m not going to mind you.” Jason said.

“You have to.” Caddy said. “Come on, now. You have to do like I say.”

“Make them be quiet, Versh.” Dilsey said. “You all going to be quiet, aint you.”

“What do we have to be so quiet for, tonight.” Caddy said.

“Your mommer aint feeling well.” Dilsey said. “You all go on with Versh, now.”

“I told you Mother was crying.” Quentin said. Versh took me up and opened the door onto the back porch. We went out and Versh closed the door back. I could smell Versh and feel him. “You all be quiet, now. We’re not going up stairs yet. Mr Jason said for you to come right up stairs. He said to mind me. I’m not going to mind you. But he said for all of us to. Didn’t he, Quentin.” I could feel Versh’s head. I could hear us. “Didn’t he, Versh. Yes, that’s right. Then I say for us to go out doors a while. Come on.” Versh opened the door and we went out.

We went down the steps.

“I expect we’d better go down to Versh’s house, so we’ll be quiet.” Caddy said. Versh put me down and Caddy took my hand and we went down the brick walk.

“Come on.” Caddy said, “That frog’s gone. He’s hopped way over to the garden, by now. Maybe we’ll see another one.” Roskus came with the milk buckets. He went on. Quentin wasn’t coming with us. He was sitting on the kitchen steps. We went down to Versh’s house. I liked to smell Versh’s house. There was a fire in it and T. P. squatting in his shirt tail in front of it, chunking it into a blaze.

Then I got up and T. P. dressed me and we went to the kitchen and ate. Dilsey was singing and I began to cry and she stopped.

“Keep him away from the house, now.” Dilsey said.

“We cant go that way.” T. P. said.

We played in the branch.

“We cant go around yonder.” T. P. said. “Dont you know mammy say we cant.”

Dilsey was singing in the kitchen and I began to cry.

“Hush.” T. P. said. “Come on. Lets go down to the barn.”

Roskus was milking at the barn. He was milking with one hand, and groaning. Some birds sat on the barn door and watched him. One of them came down and ate with the cows. I watched Roskus milk while T. P. was feeding Queenie and Prince. The calf was in the pig pen. It nuzzled at the wire, bawling.

“T. P.” Roskus said. T. P. said Sir, in the barn. Fancy held her head over the door, because T. P. hadn’t fed her yet. “Git done there.” Roskus said. “You got to do this milking. I cant use my right hand no more.”

T. P. came and milked.

“Whyn’t you get the doctor.” T. P. said.

“Doctor cant do no good.” Roskus said. “Not on this place.”

“What wrong with this place.” T. P. said.

“Taint no luck on this place.” Roskus said. “Turn that calf in if you done.”

Taint no luck on this place, Roskus said. The fire rose and fell behind him and Versh, sliding on his and Versh’s face. Dilsey finished putting me to bed. The bed smelled like T. P. I liked it.

“What you know about it.” Dilsey said. “What trance you been in.”

“Dont need no trance.” Roskus said. “Aint the sign of it laying right there on that bed. Aint the sign of it been here for folks to see fifteen years now.”

“Spose it is.” Dilsey said. “It aint hurt none of you and yourn, is it. Versh working and Frony married off your hands and T. P. getting big enough to take your place when rheumatism finish getting you.”

“They been two, now.” Roskus said. “Going to be one more. I seen the sign, and you is too.”

“I heard a squinch owl that night.” T. P. said. “Dan wouldn’t come and get his supper, neither. Wouldn’t come no closer than the barn. Begun howling right after dark. Versh heard him.”

“Going to be more than one more.” Dilsey said. “Show me the man what aint going to die, bless Jesus.”

“Dying aint all.” Roskus said.

“I knows what you thinking.” Dilsey said. “And they aint going to be no luck in saying that name, lessen you going to set up with him while he cries.”

“They aint no luck on this place.” Roskus said. “I seen it at first but when they changed his name I knowed it.”

“Hush your mouth.” Dilsey said. She pulled the covers up. It smelled like T. P. “You all shut up now, till he get to sleep.”

“I seen the sign.” Roskus said.

“Sign T. P. got to do all your work for you.” Dilsey said. Take him and Quentin down to the house and let them play with Luster, where Frony can watch them, T. P., and go and help your pa.

We finished eating. T. P. took Quentin up and we went down to T. P.’s house. Luster was playing in the dirt. T. P. put Quentin down and she played in the dirt too. Luster had some spools and he and Quentin fought and Quentin had the spools. Luster cried and Frony came and gave Luster a tin can to play with, and then I had the spools and Quentin fought me and I cried.

“Hush.” Frony said, “Aint you shamed of yourself. Taking a baby’s play pretty.” She took the spools from me and gave them back to Quentin.

“Hush, now.” Frony said, “Hush, I tell you.”

“Hush up.” Frony said. “You needs whipping, that’s what you needs.” She took Luster and Quentin up. “Come on here.” she said. We went to the barn. T. P. was milking the cow. Roskus was sitting on the box.

“What’s the matter with him now.” Roskus said.

“You have to keep him down here.” Frony said. “He fighting these babies again. Taking they play things. Stay here with T. P. now, and see can you hush a while.”

“Clean that udder good now.” Roskus said. “You milked that young cow dry last winter. If you milk this one dry, they aint going to be no more milk.”

Dilsey was singing.

“Not around yonder.” T. P. said. “Dont you know mammy say you cant go around there.”

They were singing.

“Come on.” T. P. said. “Lets go play with Quentin and Luster. Come on.”

Quentin and Luster were playing in the dirt in front of T. P.’s house. There was a fire in the house, rising and falling, with Roskus sitting black against it.

“That’s three, thank the Lawd.” Roskus said. “I told you two years ago. They aint no luck on this place.”

“Whyn’t you get out, then.” Dilsey said. She was undressing me. “Your bad luck talk got them Memphis notions into Versh. That ought to satisfy you.”

“If that all the bad luck Versh have.” Roskus said.

Frony came in.

“You all done.” Dilsey said.

“T. P. finishing up.” Frony said. “Miss Cahline want you to put Quentin to bed.”

“I’m coming just as fast as I can.” Dilsey said. “She ought to know by this time I aint got no wings.”

“That’s what I tell you.” Roskus said. “They aint no luck going be on no place where one of they own chillens’ name aint never spoke.”

“Hush.” Dilsey said. “Do you want to get him started?”

“Raising a child not to know its own mammy’s name.” Roskus said.

“Dont you bother your head about her.” Dilsey said. “I raised all of them and I reckon I can raise one more. Hush now. Let him get to sleep if he will.”

“Saying a name.” Frony said. “He dont know nobody’s name.”

“You just say it and see if he dont.” Dilsey said. “You say it to him while he sleeping and I bet he hear you.”

“He know lot more than folks thinks.” Roskus said. “He knowed they time was coming, like that pointer done. He could tell you when hisn coming, if he could talk. Or yours. Or mine.”

“You take Luster outen that bed, mammy.” Frony said. “That boy conjure him.”

“Hush your mouth.” Dilsey said, “Aint you got no better sense than that. What you want to listen to Roskus for, anyway. Get in, Benjy.”

Dilsey pushed me and I got in the bed, where Luster already was. He was asleep. Dilsey took a long piece of wood and laid it between Luster and me. “Stay on your side now.” Dilsey said. “Luster little, and you don’t want to hurt him.”

You can’t go yet, T. P. said. Wait.

We looked around the corner of the house and watched the carriages go away.

“Now.” T. P. said. He took Quentin up and we ran down to the corner of the fence and watched them pass. “There he go,” T. P. said. “See that one with the glass in it. Look at him. He laying in there. See him.”

Come on, Luster said, I going to take this here ball down home, where I wont lose it. Naw, sir, you cant have it. If them men sees you with it, they’ll say you stole it. Hush up, now. You cant have it. What business you got with it. You cant play no ball.

Frony and T. P. were playing in the dirt by the door. T. P. had lightning bugs in a bottle.

“How did you all get back out.” Frony said.

“We’ve got company.” Caddy said. “Father said for us to mind me tonight. I expect you and T. P. will have to mind me too.”

“I’m not going to mind you.” Jason said. “Frony and T. P. dont have to either.”

“They will if I say so.” Caddy said. “Maybe I wont say for them to.”

“T. P. dont mind nobody.” Frony said. “Is they started the funeral yet.”

“What’s a funeral.” Jason said.

“Didn’t mammy tell you not to tell them.” Versh said.

“Where they moans.” Frony said. “They moaned two days on Sis Beulah Clay.”

They moaned at Dilsey’s house. Dilsey was moaning. When Dilsey moaned Luster said, Hush, and we hushed, and then I began to cry and Blue howled under the kitchen steps. Then Dilsey stopped and we stopped.

“Oh.” Caddy said, “That’s niggers. White folks dont have funerals.”

“Mammy said us not to tell them, Frony.” Versh said.

“Tell them what.” Caddy said.

Dilsey moaned, and when it got to the place I began to cry and Blue howled under the steps. Luster, Frony, said in the window, Take them down to the barn. I cant get no cooking done with all that racket. That hound too. Get them outen here.

I aint going down there, Luster said. I might meet pappy down there. I seen him last night, waving his arms in the barn.

“I like to know why not.” Frony said. “White folks dies too. Your grandmammy dead as any nigger can get, I reckon.”

“Dogs are dead.” Caddy said, “And when Nancy fell in the ditch and Roskus shot her and the buzzards came and undressed her.”

The bones rounded out of the ditch, where the dark vines were in the black ditch, into the moonlight, like some of the shapes had stopped. Then they all stopped and it was dark, and when I stopped to start again I could hear Mother, and feet walking fast away, and I could smell it. Then the room came, but my eyes went shut. I didn’t stop. I could smell it. T. P. unpinned the bed clothes.

“Hush.” he said, “Shhhhhhhh.”

But I could smell it. T. P. pulled me up and he put on my clothes fast.

“Hush, Benjy.” he said. “We going down to our house. You want to go down to our house, where Frony is. Hush. Shhhhh.”

He laced my shoes and put my cap on and we went out. There was a light in the hall. Across the hall we could hear Mother.

“Shhhhhh, Benjy.” T. P. said, “We’ll be out in a minute.”

A door opened and I could smell it more than ever, and a head came out. It wasn’t Father. Father was sick there.

“Can you take him out of the house.”

“That’s where we going.” T. P. said. Dilsey came up the stairs.

“Hush.” she said, “Hush. Take him down home, T. P. Frony fixing him a bed. You all look after him, now. Hush, Benjy. Go on with T. P.”

She went where we could hear Mother.

“Better keep him there.” It wasn’t Father. He shut the door, but I could still smell it.

We went down stairs. The stairs went down into the dark and T. P. took my hand, and we went out the door, out of the dark. Dan was sitting in the back yard, howling.

“He smell it.” T. P. said. “Is that the way you found it out.”

We went down the steps, where our shadows were.

“I forgot your coat.” T. P. said. “You ought to had it. But I aint going back.”

Dan howled.

“Hush now.” T. P. said. Our shadows moved, but Dan’s shadow didn’t move except to howl when he did.

“I cant take you down home, bellering like you is.” T. P. said. “You was bad enough before you got that bullfrog voice. Come on.”

We went along the brick walk, with our shadows. The pig pen smelled like pigs. The cow stood in the lot, chewing at us. Dan howled.

“You going to wake the whole town up.” T. P. said. “Cant you hush.”

We saw Fancy, eating by the branch. The moon shone on the water when we got there.

“Naw, sir.” T. P. said, “This too close. We cant stop here. Come on. Now, just look at you. Got your whole leg wet. Come on, here.” Dan howled.

The ditch came up out of the buzzing grass. The bones rounded out of the black vines.

“Now.” T. P. said. “Beller your head off if you want to. You got the whole night and a twenty acre pasture to beller in.”

T. P. lay down in the ditch and I sat down, watching the bones where the buzzards ate Nancy, flapping black and slow and heavy out of the ditch.

I had it when we was down here before, Luster said. I showed it to you. Didn’t you see it. I took it out of my pocket right here and showed it to you.

“Do you think buzzards are going to undress Damuddy.” Caddy said. “You’re crazy.”

“You’re a skizzard.” Jason said. He began to cry.

“You’re a knobnot.” Caddy said. Jason cried. His hands were in his pockets.

“Jason going to be rich man.” Versh said. “He holding his money all the time.”

Jason cried.

“Now you’ve got him started.” Caddy said. “Hush up, Jason. How can buzzards get in where Damuddy is. Father wouldn’t let them. Would you let a buzzard undress you. Hush up, now.”

Jason hushed. “Frony said it was a funeral.” he said.

“Well it’s not.” Caddy said. “It’s a party. Frony dont know anything about it. He wants your lightning bugs, T. P. Let him hold it a while.”

T. P. gave me the bottle of lightning bugs.

“I bet if we go around to the parlor window we can see something.” Caddy said. “Then you’ll believe me.”

“I already knows.” Frony said. “I dont need to see.”

“You better hush your mouth, Frony.” Versh said. “Mammy going whip you.”

“What is it.” Caddy said.

“I knows what I knows.” Frony said.

“Come on.” Caddy said, “Let’s go around to the front.”

We started to go.

“T. P. wants his lightning bugs.” Frony said.

“Let him hold it a while longer, T. P.” Caddy said. “We’ll bring it back.”

“You all never caught them.” Frony said.

“If I say you and T. P. can come too, will you let him hold it.” Caddy said.

“Aint nobody said me and T. P. got to mind you.” Frony said.

“If I say you dont have to, will you let him hold it.” Caddy said.

“All right.” Frony said. “Let him hold it, T. P. We going to watch them moaning.”

“They aint moaning.” Caddy said. “I tell you it’s a party. Are they moaning, Versh.”

“We aint going to know what they doing, standing here.” Versh said.

“Come on.” Caddy said. “Frony and T. P. dont have to mind me. But the rest of us do. You better carry him, Versh. It’s getting dark.”

Versh took me up and we went on around the kitchen.

When we looked around the corner we could see the lights coming up the drive. T. P. went back to the cellar door and opened it.

You know what’s down there, T. P. said. Soda water. I seen Mr Jason come up with both hands full of them. Wait here a minute.

T. P. went and looked in the kitchen door. Dilsey said, What are you peeping in here for. Where’s Benjy.

He out here, T. P. said.

Go on and watch him, Dilsey said. Keep him out the house now.

Yessum, T. P. said. Is they started yet.

You go on and keep that boy out of sight, Dilsey said. I got all I can tend to.

A snake crawled out from under the house. Jason said he wasn’t afraid of snakes and Caddy said he was but she wasn’t and Versh said they both were and Caddy said to be quiet, like Father said.

You aint got to start bellering now, T. P. said. You want some this sassprilluh.

It tickled my nose and eyes.

If you aint going to drink it, let me get to it, T. P. said. All right, here tis. We better get another bottle while nobody bothering us. You be quiet, now.

We stopped under the tree by the parlor window. Versh set me down in the wet grass. It was cold. There were lights in all the windows.

“That’s where Damuddy is.” Caddy said. “She’s sick every day now. When she gets well we’re going to have a picnic.”

“I knows what I knows.” Frony said.

The trees were buzzing, and the grass.

“The one next to it is where we have the measles.” Caddy said. “Where do you and T. P. have the measles, Frony.”

“Has them just wherever we is, I reckon.” Frony said.

“They haven’t started yet.” Caddy said.

They getting ready to start, T. P. said. You stand right here now while I get that box so we can see in the window. Here, les finish drinking this here sassprilluh. It make me feel just like a squinch owl inside.

We drank the sassprilluh and T. P. pushed the bottle through the lattice, under the house, and went away. I could hear them in the parlor and I clawed my hands against the wall. T. P. dragged the box. He fell down, and he began to laugh. He lay there, laughing into the grass. He got up and dragged the box under the window, trying not to laugh.

“I skeered I going to holler.” T. P. said. “Git on the box and see is they started.”

“They haven’t started because the band hasn’t come yet.” Caddy said.

“They aint going to have no band.” Frony said.

“How do you know.” Caddy said.

“I knows what I knows.” Frony said.

“You dont know anything.” Caddy said. She went to the tree. “Push me up, Versh.”

“Your paw told you to stay out that tree.” Versh said.

“That was a long time ago.” Caddy said. “I expect he’s forgotten about it. Besides, he said to mind me tonight. Didn’t he say to mind me tonight.”

“I’m not going to mind you.” Jason said. “Frony and T. P. are not going to either.”

“Push me up, Versh.” Caddy said.

“All right.” Versh said. “You the one going to get whipped. I aint.” He went and pushed Caddy up into the tree to the first limb. We watched the muddy bottom of her drawers. Then we couldn’t see her. We could hear the tree thrashing.

“Mr Jason said if you break that tree he whip you.” Versh said.

“I’m going to tell on her too.” Jason said.

The tree quit thrashing. We looked up into the still branches.

“What you seeing.” Frony whispered.

I saw them. Then I saw Caddy, with flowers in her hair, and a long veil like shining wind. Caddy Caddy

“Hush.” T. P. said, “They going to hear you. Get down quick.” He pulled me. Caddy. I clawed my hands against the wall Caddy. T. P. pulled me.

“Hush.” he said. “Hush. Come on here quick.” He pulled me on. Caddy “Hush up, Benjy. You want them to hear you. Come on, les drink some more sassprilluh, then we can come back if you hush. We better get one more bottle or we both be hollering. We can say Dan drunk it. Mr Quentin always saying he so smart, we can say he sassprilluh dog, too.”

The moonlight came down the cellar stairs. We drank some more sassprilluh.

“You know what I wish.” T. P. said. “I wish a bear would walk in that cellar door. You know what I do. I walk right up to him and spit in he eye. Gimme that bottle to stop my mouth before I holler.”

T. P. fell down. He began to laugh, and the cellar door and the moonlight jumped away and something hit me.

“Hush up.” T. P. said, trying not to laugh, “Lawd, they’ll all hear us. Get up.” T. P. said, “Get up, Benjy, quick.” He was thrashing about and laughing and I tried to get up. The cellar steps ran up the hill in the moonlight and T. P. fell up the hill, into the moonlight, and I ran against the fence and T. P. ran behind me saying “Hush up hush up” Then he fell into the flowers, laughing, and I ran into the box. But when I tried to climb onto it it jumped away and hit me on the back of the head and my throat made a sound. It made the sound again and I stopped trying to get up, and it made the sound again and I began to cry. But my throat kept on making the sound while T. P. was pulling me. It kept on making it and I couldn’t tell if I was crying or not, and T. P. fell down on top of me, laughing, and it kept on making the sound and Quentin kicked T. P. and Cad put her arms around me, and her shining veil, and I couldn’t smell trees anymore and I began to cry.

Benjy, Caddy said Benjy. She put her arms around me again, but I went away. “What is it, Benjy.” she said. “Is it this hat.” She took her hat off and came again, and I went away.

“Benjy.” she said, “What is it, Benjy. What has Caddy done.”

“He dont like that prissy dress.” Jason said. “You think you’re grown up, dont you. You think you’re better than anybody else, dont you. Prissy.”

“You shut your mouth.” Caddy said, “You dirty little beast. Benjy.”

“Just because you are fourteen, you think you’re grown up, dont you.” Jason said. “You think you’re something. Dont you.”

“Hush, Benjy.” Caddy said. “You’ll disturb Mother. Hush.”

But I didn’t hush, and when she went away I followed, and she stopped on the stairs and waited and I stopped too.

“What is it, Benjy.” Caddy said, “Tell Caddy. She’ll do it. Try.”

“Candace.” Mother said.

“Yessum.” Caddy said.

“Why are you teasing him.” Mother said. “Bring him here.”

We went to Mother’s room, where she was lying with the sickness on a cloth on her head.

“What is the matter now.” Mother said. “Benjamin.”

“Benjy.” Caddy said. She came again, but I went away.

“You must have done something to him.” Mother said. “Why wont you let him alone, so I can have some peace. Give him the box and please go on and let him alone.”

Caddy got the box and set it on the floor and opened it. It was full of stars. When I was still, they were still. When I moved, they glinted and sparkled. I hushed.

Then I heard Caddy walking and I began again.

“Benjamin.” Mother said, “Come here.” I went to the door. “You, Benjamin.” Mother said.

“What is it now.” Father said, “Where are you going.”

“Take him downstairs and get someone to watch him, Jason.” Mother said. “You know I’m ill, yet you”

Father shut the door behind us.

“T. P.” he said.

“Sir.” T. P. said downstairs.

“Benjy’s coming down.” Father said. “Go with T. P.”

I went to the bathroom door. I could hear the water.

“Benjy.” T. P. said downstairs.

I could hear the water. I listened to it.

“Benjy.” T. P. said downstairs.

I listened to the water.

I couldn’t hear the water, and Caddy opened the door.

“Why, Benjy.” she said. She looked at me and I went and she put her arms around me. “Did you find Caddy again.” she said. “Did you think Caddy had run away.” Caddy smelled like trees.

We went to Caddy’s room. She sat down at the mirror. She stopped her hands and looked at me.

“Why, Benjy. What is it.” she said. “You mustn’t cry. Caddy’s not going away. See here.” she said. She took up the bottle and took the stopper out and held it to my nose. “Sweet. Smell. Good.”

I went away and I didn’t hush, and she held the bottle in her hand, looking at me.

“Oh.” she said. She put the bottle down and came and put her arms around me. “So that was it. And you were trying to tell Caddy and you couldn’t tell her. You wanted to, but you couldn’t, could you. Of course Caddy wont. Of course Caddy wont. Just wait till I dress.”

Caddy dressed and took up the bottle again and we went down to the kitchen.

“Dilsey.” Caddy said, “Benjy’s got a present for you.” She stooped down and put the bottle in my hand. “Hold it out to Dilsey, now.” Caddy held my hand out and Dilsey took the bottle.

“Well I’ll declare.” Dilsey said, “If my baby aint give Dilsey a bottle of perfume. Just look here, Roskus.”

Caddy smelled like trees. “We dont like perfume ourselves.” Caddy said.

She smelled like trees.

“Come on, now.” Dilsey said, “You too big to sleep with folks. You a big boy now. Thirteen years old. Big enough to sleep by yourself in Uncle Maury’s room.” Dilsey said.

Uncle Maury was sick. His eye was sick, and his mouth. Versh took his supper up to him on the tray.

“Maury says he’s going to shoot the scoundrel.” Father said. “I told him he’d better not mention it to Patterson before hand.” He drank.

“Jason.” Mother said.

“Shoot who, Father.” Quentin said. “What’s Uncle Maury going to shoot him for.”

“Because he couldn’t take a little joke.” Father said.

“Jason.” Mother said, “How can you. You’d sit right there and see Maury shot down in ambush, and laugh.”

“Then Maury’d better stay out of ambush.” Father said.

“Shoot who, Father.” Quentin said, “Who’s Uncle Maury going to shoot.”

“Nobody.” Father said. “I dont own a pistol.”

Mother began to cry. “If you begrudge Maury your food, why aren’t you man enough to say so to his face. To ridicule him before the children, behind his back.”

“Of course I dont.” Father said, “I admire Maury. He is invaluable to my own sense of racial superiority. I wouldn’t swap Maury for a matched team. And do you know why, Quentin.”

“No, sir.” Quentin said.

“Et ego in arcadia I have forgotten the latin for hay.” Father said. “There, there.” he said, “I was just joking.” He drank and set the glass down and went and put his hand on Mother’s shoulder.

“It’s no joke.” Mother said. “My people are every bit as well born as yours. Just because Maury’s health is bad.”

“Of course.” Father said. “Bad health is the primary reason for all life. Created by disease, within putrefaction, into decay. Versh.”

“Sir.” Versh said behind my chair.

“Take the decanter and fill it.”

“And tell Dilsey to come and take Benjamin up to bed.” Mother said.

“You a big boy.” Dilsey said, “Caddy tired sleeping with you. Hush now, so you can go to sleep.” The room went away, but I didn’t hush, and the room came back and Dilsey came and sat on the bed, looking at me.

“Aint you going to be a good boy and hush.” Dilsey said. “You aint, is you. See can you wait a minute, then.”

She went away. There wasn’t anything in the door. Then Caddy was in it.

“Hush.” Caddy said. “I’m coming.”

I hushed and Dilsey turned back the spread and Caddy got in between the spread and the blanket. She didn’t take off her bathrobe.

“Now,” she said, “Here I am.” Dilsey came with a blanket and spread it over her and tucked it around her.

“He be gone in a minute.” Dilsey said. “I leave the light on in your room.”

“All right.” Caddy said. She snuggled her head beside mine on the pillow. “Goodnight, Dilsey.”

“Goodnight, honey.” Dilsey said. The room went black. Caddy smelted like trees.

We looked up into the tree where she was.

“What she seeing, Versh.” Frony whispered.

“Shhhhhhh.” Caddy said in the tree. Dilsey said,

“You come on here.” She came around the corner of the house. “Whyn’t you all go on up stairs, like your paw said, stead of slipping out behind my back. Where’s Caddy and Quentin.”

“I told her not to climb up that tree.” Jason said. “I’m going to tell on her.”

“Who in what tree.” Dilsey said. She came and looked up into the tree. “Caddy.” Dilsey said. The branches began to shake again.

“You, Satan.” Dilsey said. “Come down from there.”

“Hush.” Caddy said, “Dont you know Father said to be quiet.” Her legs came in sight and Dilsey reached up and lifted her out of the tree.

“Aint you got any better sense than to let them come around here.” Dilsey said.

“I couldn’t do nothing with her.” Versh said.

“What you all doing here.” Dilsey said. “Who told you to come up to the house.”

“She did.” Frony said. “She told us to come.”

“Who told you you got to do what she say.” Dilsey said. “Get on home, now.” Frony and T. P. went on. We couldn’t see them when they were still going away.

“Out here in the middle of the night.” Dilsey said. She took me up and we went to the kitchen.

“Slipping out behind my back.” Dilsey said. “When you knowed it’s past your bedtime.”

“Shhhh, Dilsey.” Caddy said. “Dont talk so loud. We’ve got to be quiet.”

“You hush your mouth and get quiet, then,” Dilsey said. “Where’s Quentin.”

“Quentin’s mad because he had to mind me tonight.” Caddy said. “He’s still got T. P.’s bottle of lightning bugs.”

“I reckon T. P. can get along without it.” Dilsey said. “You go and find Quentin, Versh. Roskus say he seen him going towards the barn.” Versh went on. We couldn’t see him.

“They’re not doing anything in there.” Caddy said. “Just sitting in chairs and looking.”

“They dont need no help from you all to do that.” Dilsey said. We went around the kitchen.

Where you want to go now, Luster said. You going back to watch them knocking ball again. We done looked for it over there. Here. Wait a minute. You wait right here while I go back and get that ball. I done thought of something.

The kitchen was dark. The trees were black on the sky. Dan came waddling out from under the steps and chewed my ankle. I went around the kitchen, where the moon was. Dan came scuffling along, into the moon.

“Benjy.” T. P. said in the house.

The flower tree by the parlor window wasn’t dark, but the thick trees were. The grass was buzzing in the moonlight where my shadow walked on the grass.

“You, Benjy.” T. P. said in the house. “Where you hiding. You slipping off. I knows it.”

Luster came back. Wait, he said. Here. Dont go over there. Miss Quentin and her beau in the swing yonder. You come on this way. Come back here, Benjy.

It was dark under the trees. Dan wouldn’t come. He stayed in the moonlight. Then I could see the swing and I began to cry.

Come away from there, Benjy, Luster said. You know Miss Quentin going to get mad.

It was two now, and then one in the swing. Caddy came fast, white in the darkness.

“Benjy,” she said. “How did you slip out. Where’s Versh.”

She put her arms around me and I hushed and held to her dress and tried to pull her away.

“Why, Benjy.” she said. “What is it. T. P.” she called.

The one in the swing got up and came, and I cried and pulled Caddy’s dress.

“Benjy.” Caddy said. “It’s just Charlie. Dont you know Charlie.”

“Where’s his nigger.” Charlie said. “What do they let him run around loose for.”

“Hush, Benjy.” Caddy said. “Go away, Charlie. He doesn’t like you.” Charlie went away and I hushed. I pulled at Caddy’s dress.

“Why, Benjy.” Caddy said. “Aren’t you going to let me stay here and talk to Charlie awhile.”

“Call that nigger.” Charlie said. He came back. I cried louder and pulled at Caddy’s dress.

“Go away, Charlie.” Caddy said. Charlie came and put his hands on Caddy and I cried more. I cried loud.

“No, no.” Caddy said. “No. No.”

“He cant talk.” Charlie said. “Caddy.”

“Are you crazy.” Caddy said. She began to breathe fast. “He can see. Dont. Dont.” Caddy fought. They both breathed fast. “Please. Please.” Caddy whispered.

“Send him away.” Charlie said.

“I will.” Caddy said. “Let me go.”

“Will you send him away.” Charlie said.

“Yes.” Caddy said. “Let me go.” Charlie went away. “Hush.” Caddy said. “He’s gone.” I hushed. I could hear her and feel her chest going.