* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Grey Steel. J. C. Smuts A Study in Arrogance

Date of first publication: 1937

Author: Harold Courtenay Armstrong (1891-1943)

Date first posted: Nov. 22, 2019

Date last updated: Nov. 22, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20191142

This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, Al Haines, Jen Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GREY STEEL

J. C. SMUTS

A Study in Arrogance

BY

H. C. ARMSTRONG

Author of “Grey Wolf,” “Lord of Arabia,” etc., etc.

LONDON

ARTHUR BARKER, LTD.

12 ORANGE STREET, W.C.2

| First Published | • | • | April 1937 |

| Second Impression | • | • | May 1937 |

Copyright Reserved

Made and Printed in Great Britain by

Hazell, Watson & Viney Ltd., London and Aylesbury

I wish to thank many friends and acquaintances who have placed their personal knowledge at my disposal, but must remain unnamed, and:

Mr. A. S. Owen, of Keble College, Oxford, for much sage advice also.

I use punctuation as some people use pepper from a pot, with closed eyes, held nose, and a liberal gesture. Mr. Owen has sorted my dots and dashes and made my English as readable as he can.

Mr. B. K. Long, lately Editor of the Cape Times, for looking through the proofs with a jaundiced eye and marking them with a blue pencil.

The Royal Institute of International Affairs.

The Royal Empire Society.

The Bodleian Library, Oxford.

The Rhodes Library, Rhodes House, Oxford.

And many South African libraries.

In addition, for courteously placing much material at my disposal:

African World

Daily Mail

Daily Telegraph

Manchester Guardian

New Statesman and Nation

Nineteenth Century and After

Observer

Round Table

Spectator

Sunday Express

Sunday Times

The Times

Cape Argus

Cape Times

Natal Mercury

Rand Daily Mail

Sunday Express, Johannesburg

Sunday Times, Johannesburg

Le Journal

Le Temps

Le Matin

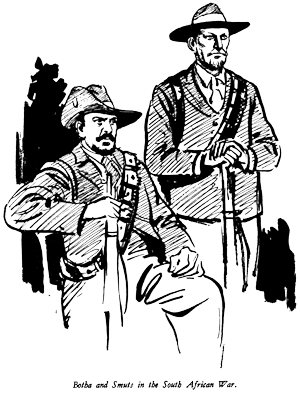

| BOTHA AND SMUTS IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| JAMESON AND CECIL RHODES | 52 |

| MILNER | 77 |

| SMUTS AND KRUGER | 78 |

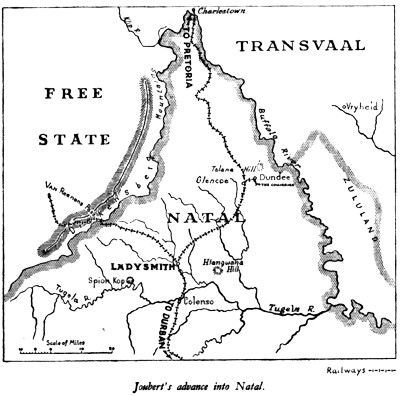

| MAP: JOUBERT’S ADVANCE INTO NATAL | 95 |

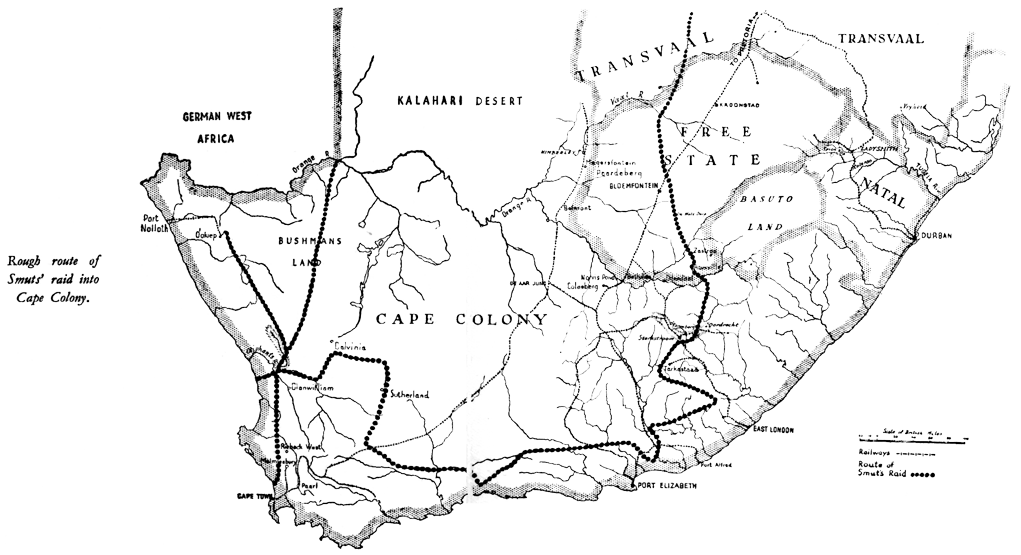

| MAP: ROUGH ROUTE OF SMUTS’ RAID INTO CAPE COLONY | 123 |

| LOUIS BOTHA | 223 |

| DE LA REY | 235 |

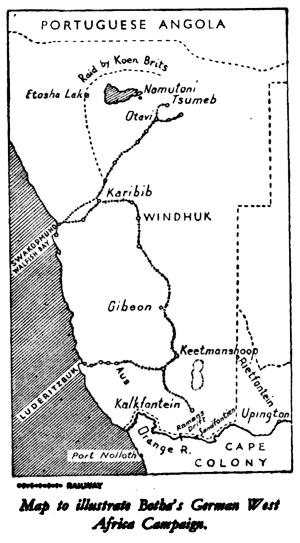

| MAP TO ILLUSTRATE BOTHA’S GERMAN WEST AFRICA CAMPAIGN | 250 |

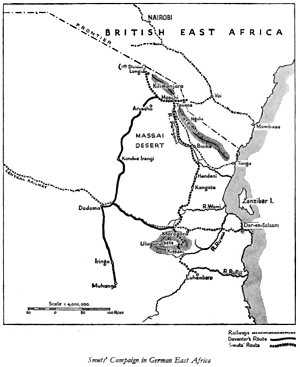

| MAP: SMUTS’ CAMPAIGN IN GERMAN EAST AFRICA | 262 |

| JAMES HERTZOG | 337 |

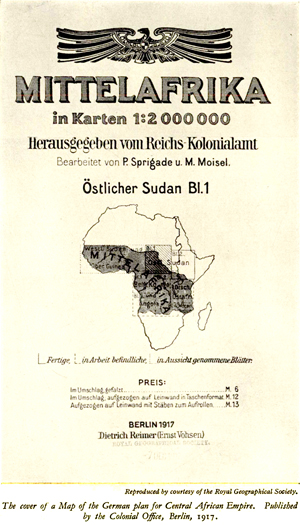

| MAP OF GERMAN PLAN FOR CENTRAL AFRICAN EMPIRE | facing page 218 |

In this book I have described the development of the character of an unique personality given exceptional opportunities, of Jan Christian Smuts, the South African.

I have described frankly and without bias. I claim no close friendship with Smuts. The friendship of a biographer with his subject is a disadvantage. It ties his hands. It biases his opinions. It gives him a view out of perspective, because it is too close. If he knows him only at one particular stage of his life, and not from birth to death, he sees the whole man in terms of this one stage, which is probably when he is already a grown man, and successful and set in his ways.

Without it I have been able to stand well back and to study Smuts with an unprejudiced eye. I have worked through vast quantities of books and documents, together with his own writings and speeches. I have visited South Africa and watched him in the House of Assembly, at dinners, at receptions, at private luncheons. I have visited his birth-place, his school and college, the houses he has lived in, and his places of work. I have discussed him with his associates and with his opponents, with his admirers and with his detractors in England, France, and South Africa. I have been able to talk with men and women who have known him at each stage of his career, and so to give me vivid and authentic descriptions of his manners and actions.

In South Africa politics are a personal, a family affair, and produce the intense hostility and the equally intense advocacy of a family. As coming from the outside I was, in South Africa, able to study him without being influenced by local politics or local feeling; and I have refused to be influenced by the hatred of his enemies or the homage of his admirers.

Much of what I have written will not please his admirers, but Jan Christian Smuts is a great man. The history of modern South Africa is the story of Jan Christian Smuts battling with his enemies. His influence in England, in Europe, in the British Empire, and in International Affairs has been immense.

Out of the Great War little remains. The peace treaties have been dishonoured; the ideals for which my generation died physically and morally have been found to be follies, Dead Sea fruit, ashes in the mouth; the generals, admirals, and statesmen have been written off as fools or knaves: out of all that tremendous struggle there remain untouched by the fury of the iconoclasts only four men—T. E. Lawrence of Arabia, Marshal Foch, Mustafa Kemal of Turkey, and Jan Christian Smuts.

Much flabby nonsense has been written about him, but as a great man he does not need to have his reputation shored up, as some showy but rotten building needs to be shored up with beams, with fables of virtues he does not possess, or with unreal sentiment and unreasoning partisanship. His reputation can stand on the firm foundations of his real qualities and achievements, and those foundations are of steel.

Of documents used I have given a list at the end. Verbal informants—who were legion—I cannot quote or thank personally, for in many cases this would prejudice their interests. But if any reviewers of this book or private critics should doubt the evidence of my facts, I am willing to supply them with chapter and verse if they will write to me.

I have avoided any use of the word Boer. Literally it meant “Farmer,” but in the war of 1899 it was used as a term of opprobrium for the Dutch, and its use in this book would therefore to-day confuse the reader. Afrikander is the modern term for a South African born of Dutch parents. This too begins to change, and the people of South Africa call themselves English- or Dutch-speaking South Africans.

In order to render them into intelligible English, here and there I have had to adjust the wording of quotations of translations from Dutch documents. These have been done in collaboration with a Dutch-reading professor.

The Orange Free State was for a short time called the Orange River Colony. To avoid confusion I have called it throughout the “Free State.”

At one time there was an English party called the Unionists. They had no similarity with the party of that name in England, and I have called them “the English Party” to avoid confusing the reader in England.

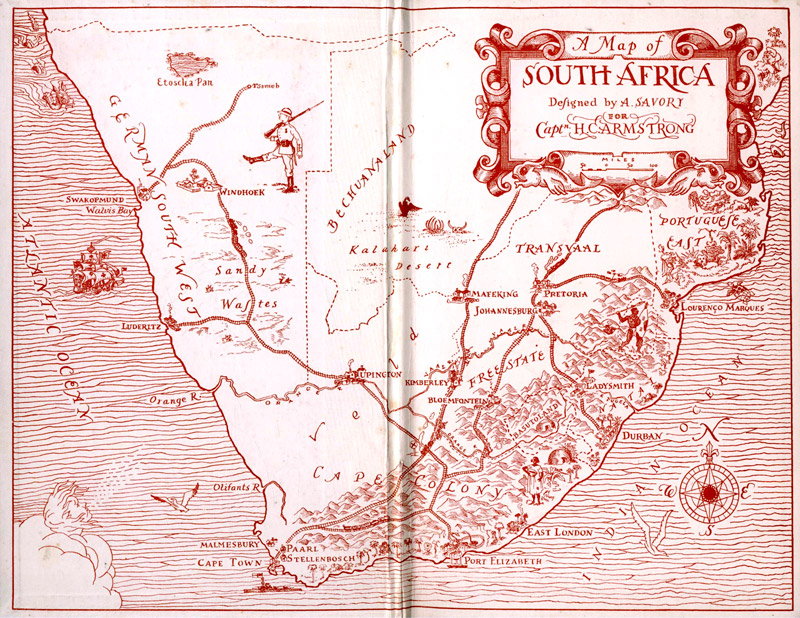

To the ancients Africa beyond and below the equator was an old land, but unknown: so immeasurably old that, wrinkled and shrivelled like some witch, it had never been young: unknown like the gods themselves and veiled in mysterious twilight; and in that twilight moved horrors and monstrous primeval things.

The Arabs had tales of vast hordes of elephants; of caverns full of ivory; of gold worked by the Chinese; and mines that produced the fabulous wealth of Ophir and of the Queen of Sheba.

The Phœnicians went exploring, but their ships did not return until one, long given up as lost, came sailing in past Gibraltar, and the crew told how they had set out southwards from Aden down a barren coast, how they had been driven before great storms of angry seas until they came to the end of all land, where the sky was full of strange stars, or the old stars inverted, and the sun circled from their right to their left. Rounding a great cape they had sailed northwards, until once more, after three long years, they had come to the Pillars of Hercules and sailed into the Mediterranean. But this story was treated as a sailor’s tale.

The Greeks and the Romans and the Byzantines knew little of South Africa. Even in the fifteenth century after Christ, geographers held that beyond the equator was the Sea of Darkness, which was the running together of many seas and which lay in a steep inclined plane, so that any ships that ventured on to it would slide down into a bottomless abyss.

In Central Asia there had been fierce drought. All across Asia from the Great Wall of China and the Gobi Desert the tribes had been on the move, marching westwards looking for pasture for their starving flocks; among them were the Tartars and the Turks. As they came they had conquered all the lands from the Caucasus to Egypt, and from the Black Sea down the Eastern shore of the Mediterranean to Cairo, and by the fifteenth century they had blocked all the old trade routes to the East.

With the trade routes blocked, the maritime nations of Europe were being ruined, and they sent out expedition on expedition to look for some new road to the Indies. First came the Portuguese. In their frail wooden galleys they crept cautiously down the Atlantic coast of Africa until they found the Cape of Good Hope, and, making it a station for call and to revictual, they went on to India; but they treated the Cape as of small value. It was for them a liability only and they quickly evacuated it, leaving little trace of their occupation.

Next came the Dutch, and the Government of Holland took over the Cape and turned it into a half-way house to their empire in the Indies, and finally into a colony, built a fort to protect it, settled Dutch colonists, sent out a Governor from Holland, and imported black slaves.

In France a Catholic king was persecuting his Protestant subjects, the Huguenots, and these took ship and came to the Cape to look for a new home. The Dutch welcomed them and quickly absorbed them.

And then came the English, just beginning to build up their Empire. First they conquered the Cape of Good Hope by force of arms, but handed it back to the Government of Holland; and then bought it again for six million pounds in gold.

GREY STEEL

When the Dutch, and after them the English, came to the Cape of Good Hope, they found it and the country round it good and fruitful, and they settled, calling the place Cape Town.

The Dutch built themselves—and the English copied them—white, sturdy houses with open, wide verandahs, which they called stoeps, and with roofs of deep thatch supported by heavy black beams of stinkwood and oak. They constructed pointed gables as in Holland, windows framed in dark wood, shady rooms tiled with red brick and panelled to the ceilings, and walls so solid that they held out the heat and the cold alike and could be used as forts for defence.

They laid out open streets and gardens and vineyards, and planted trees until Cape Town became a little city and the country round rich and pleasant—a blest land smiling in its soft air, with abundant rain, beautiful with many green hills and a luxuriant, kindly sun, and along its coasts warm seas.

Beyond the Cape the country climbed from the coast plains up to a plateau that, vast and treeless and fierce-sunned, the immense veld, stretched barren or covered with a little sparse pasturage away a thousand miles and more to the north, to the Limpopo and the Zambesi rivers.

At first, few of the settlers pushed out far into the hinterland, for the savage tribes, the Bushmen and Hottentots, lived there and attacked all strangers; but thirty miles to the north of Cape Town they built the village of Malmesbury, and nine miles to the north again, on a mountain, they constructed a fort to form an outpost. On the lower slopes of the mountain grew up a dorp, a hamlet, which they called Riebeek West.

Little by little they pushed back the natives, hunting out the Bushmen, as if they were wild animals, and conquering the Hottentots, until the whole district became safe and Riebeek West settled down into a quiet hamlet of houses standing each in its own garden, and with roads of red gravel flanked with tall trees. All round were cornfields and vineyards, and to Riebeek West the farmers came riding in from their scattered farms to see their friends and relations, or on their way to market in Malmesbury. A pleasant, sleepy, placid life of easy-going people.

Close outside the dorp was the farm of Bovenplatz, where lived Jacobus Abraham Smuts and his wife; and there in May of 1870 was born to them a boy, the second in the family, whom they christened in the Dutch Reformed Church with the names Jan Christiaan.

Jacobus Abraham Smuts was a well-to-do yeoman farmer, great-handed, ruddy-faced, solid yet jovial, and active-witted with the rude, powerful health of one who lived in the open and dealt with primitive things, but large girthed, for among the Dutch it was still a tradition, as it was in Holland, that an ample paunch was a proof of standing and prosperity; and Jacobus Smuts was both a man of standing and prosperous. His farm was wide and well-conducted. In Riebeek West and in all the farms round were his relations, and in this area there were no poor: all were well-to-do and self-supporting. Many came to him for advice, for he was steady, sober and religious, and wise in judgment: a typical conservative Dutch farmer of the Cape.

When he had been a boy there had been much ill-feeling between the Dutch and the English. The Dutch were a dour people made even more dour and uncompromising by their intermarriage with the Huguenots. They held no allegiance to Holland or to anyone else. They were not even a people, but a holding together of individuals, each intensely proud, each refusing to accept any man as his superior and searching at any price for complete individual freedom.

The English Government was the legal ruler, but had little interest in the country except as a port of call to India, and to see that no other nation should have it. The local English had the urge to control and direct. The Dutch refused to be ruled by them and the English sturdily refused to be absorbed by the Dutch.

It was a quarrel as of relations who had different temperaments but so much in common that their likenesses increased the friction between them, and their quarrel was sharpened by a hundred little disagreements. A quarrel over the slaves: from England came missionaries who interfered and persuaded the English Government to release all slaves for compensation. The Dutch grew angry, for the slaves were their private property and they were cheated even over the compensation. A quarrel over schools, over the official language, and over religious teaching: Calvinist pastors sent from Scotland increased the ill-feeling. The English Government claimed political supremacy. The Dutch, awkward, obstinate, refused to compromise: the English officials were tactless and brusque. These quarrels had increased until at last many of the Dutch of the Cape had taken their cattle and their goods and set out northwards, and they had gone not in a spirit of adventure, but in a spirit of resentment and, as the Jews went out of Egypt to escape the tyranny of the Pharaohs, so they went to escape the interference of the English officials. Some had crossed the Orange River and founded the Orange Free State—the Free State. Others had gone farther across the Vaal River and made the Transvaal Republic. Still others had turned into Natal, but found the English there before them.

As they went the English officials came pressing up behind them, and from the north, out of Central Africa, came pressing down in hundreds of thousands the Black Men, the Bechuana, the People of the Crocodile, and the Bantu tribes on their way southwards.

The Dutchmen fought the Black Men. They fought the English. And not satisfied with that they quarrelled continuously amongst themselves, split up into parties, and each party founded a new republic of its own and then split again and made other republics, so that by the year 1870 South Africa was all but in ruins. Away to the north the two republics of the Free State and the Transvaal, though established, were bankrupt. The Black Men had been overrunning all and destroying as they came. The Transvaal was split with civil war and threatened by the Zulus. The Free State was swamped with Basutos. In Natal, an English colony, the colonists were fighting against the Zulus, for their existence. The Cape, an English colony also, was alone prosperous, but growing poor, for the Suez Canal had been opened and the shipping to the East was going that way instead of by the Cape, and its prosperous wine trade was being killed by a treaty between England and France. The English and the Dutch were even more bitter in their quarrelling. All South Africa was sour with distress.

And Jacobus Smuts had not understood the anger nor the bitterness of the Dutch against the English. He bore the English no ill-will. He was a Dutchman first, but the English were fellow countrymen with whom he wished to live at peace. For him the country beyond the Cape was vast and inhospitable and barren, and the men who had gone there had become not farmers, but poor shepherds. They had grown, they and their vrouens, their wives, into unkempt, difficult people, uneducated takhara, shaggy-heads, dour and sullen and rancorous and sullen-browed from their life on the harsh veld. He found them completely unlike his neighbours, the placid and prosperous farmers of the Cape.

The boy, Jan Christiaan—very soon Christiaan became plain Christian, and he was called Jan or Jannie—puked and puled his way slowly into life, for he was a weak, sickly child and only with difficulty did his mother wean him and teach him to walk, and she never believed that he would live long.

She was a capable, clever woman of strong character, come of an old French Huguenot family, very religious and tenacious of her beliefs, but lighter handed and more buoyant than the usual Dutch housewives, the solid, immense-hipped, and full-uddered vrouens, with their hair brushed severely back from their foreheads and their shrewd eyes set in wide faces. She was more cultured, also, for she had been to school in Cape Town and had learned music and to read and write French, and these were accomplishments in those isolated farms when thirty miles in a carriage or on a horse was a long journey. She brought up her children strictly and religiously as a good mother.

The Bovenplatz was a family farm, and, as an elder brother wanted it, Jacobus Smuts found himself another, some miles to the north, known as Stone Fountain, and moved.

Bovenplatz had consisted of vineyards as well as wheat, but the farm at Stone Fountain was all corn-land with a little pasturage, for it lay well out in the Zwartland, the Black Land, and the Zwartland consisted of hills rolling in long, smooth, bare curves like an ocean heaving in long swell after a storm, broken here and there with outcrops of jagged rock: in the summer dusty and hot; in the winter cold with sweeping winds; but at the first rains covered with emerald-green grass and myriads of tiny, sweet-scented flowers which died and turned grey quickly under the thirsty sun. The soil was rich: close at hand red to look at but at a distance black; and it was the best land in all South Africa for wheat.

The farm stood on a hill-side, the farmhouse—a low building, thatched and whitewashed and with wooden shutters to the windows—painted red. Though Jacobus Smuts was well-to-do and lived baronially with large-handed hospitality, yet the house and its arrangements were primitive and crude, without conveniences, baths, or lavatories, and the life very rough and ready and haphazard. On one side was a square, with cattle sheds round it and a few smooth-trunked eucalyptus trees to give a little shade, and on the other, a kraal, a yard with a mud wall; and the crops grew close up to the walls of the buildings.

Behind the farm the hills climbed up towards the mountain above Riebeek West, which showed as a range of bare dark rock, except when the wind blew out of the south-east, when it was covered with white clouds which piled on to it and spilled down over it like the curve of a breaking wave.

Below the farm the hills, broken here and there with abrupt gorges torn out of them by the winter rains, ran down to the plain of the Great Berg River. The plain flat, yellow with corn in the harvest or grey-fallow in the winter, with here and there a dark patch of trees, the white gleam of a distant farmhouse, and the scar of a track leading up to it from where in the sunset rose columns of dust as the cattle came home, stretched mile after mile into the soft distance, away to the foot of the Drakenstein mountains. The mountains heaved themselves up sheer out of the farther edge of the plain, steep slopes into precipices and precipices into crags to peak after peak far up into the sky, peaks purple with distance, up till they reached the crest of the Winterhof, which like a cathedral spire stood out against the clear steel-blue sky, and from which at times a cloud would stream, blown out like a grey banner, from its summit.

There was in this Zwartland a great sense of freedom. Holland had been crowded, a bee-hive life. From this these Dutchmen had migrated, for they had resented its restraints and restrictions, the cheek-by-jowl crowded existence of minute farms and miniature gardens, joined like the pattern in a close-woven cloth. Here they found in the Zwartland great space, immense distance, freedom, and also the loneliness which they sought.

Bovenplatz had been close to the village, but Stone Fountain was isolated. The roads to it were tracks, deep dust in the summer, quagmires in winter. The only means of travel was by horses or by two-horsed buggy. Transport was by ponderous wooden wagons on wooden wheels with eight or more yoke of oxen to heave them laboriously along. The only contacts with the outside were a journey to the nearest church for service when the predikant, the Calvinist pastor, came visiting; four times a year a general gathering in the dorp for the nagmaal, the Holy Communion, to which all came; a formal visit to another farm; now and again a trip into Riebeek West or a pilgrimage into Malmesbury.

The whole life was that of the farm and the seasons: the ploughing, sowing, harvesting, and the threshing of the corn; the cattle; the lambing and sheep-shearing; the poultry and the pigs which rooted and fed and quarrelled noisily and sunned themselves in the kraal, close in against the house, in the porch or on the stoep, and even in the living-rooms.

It was the boy’s work to look after these: at first the geese and the pigs and to herd the sheep. He helped the farm labourers, who were a black man or two, but the rest half-castes, coloured people they were called, the offspring of Hottentots and Bushmen who had mated with Malay immigrants and black slaves from the Guinea coast and some white blood from the early settlers mixed in. Most of his time he spent with Old Adam, the shepherd, an ancient, shrivelled Hottentot, who was full of the weird tales and the strange lore of the native people. When he grew older he helped to drive the cattle to pasture and round them up as it grew to dusk, and to lead the farm wagons down to the fields.

From a sickly baby he had grown up into a thin, rickety child, silent and reserved, listless and white-faced, with pale-blue, staring eyes. He mooned about, taking little interest in anything, dirty, untidy and unwashed, dressed in ragged clothes, a blanket round his shoulders, either going barefoot or wearing velskoene, shoes made of hide.

When he was ten his father decided that he must learn his letters and that he should go to a school in Riebeek West; and as it was too far to go and come daily, he should board in a house known as Die Ark, which the headmaster kept for a few boarding scholars.

Jannie went to school reluctantly. The idea terrified him. He was shy with a shyness that terrorised him. When he saw people coming his way, people very often whom he knew well, he would hide rather than meet them. If spoken to by a grown-up he would, without reason, blush a bright scarlet from his neck to his temples, so that almost at once he began to close in on himself and instinctively developed a reserved manner to avoid any chance of being hurt, as a crab develops a hard shell to protect its sensitive body.

He found school worse than he had dreaded. The discipline, the restraints, the fixed hours, the wearing of clothes, irked him after the casual life of the farm, where he could moon without interference, and the happy-go-lucky ways of the coloured labourers. He resented the discipline and, as his master said in a report, he was like “a wild bird newly caught beating its wings against the bars of its cage.” At the end of the first term he had made no progress.

In his second term he began to give in. In his third term, like an inrush of water into an empty dyke, almost like a madness, there rushed in on him a desire for knowledge, and knowledge out of books. He could already read a little and was studying English—at the farm they talked only Dutch—and he began to read books, to devour books with an amazing greed, books of every sort and description and on any subject. Not on any plan or particular subject, but books, any books he could lay his hands on. As a boarder in Die Ark he did not have to go home and work on the farm each evening as did the other scholars, and he had the run of the headmaster’s library. He read all there was there, early in the morning before the classes and late at night until the hour for bed. He never went out if he could avoid it, nor did he play with the other scholars. He made no friends. He kept rigidly to himself, and the others looked on him as a stuck-up little swot.

The school was a mixed one and he was put in a class with two girls and another boy, the children of neighbouring farmers who had all been already three years in the school. He caught them up and passed them. He had a firm memory, which was like a plain sheet of paper, so that whatever he read was imprinted on it in clear capital letters without crosslines or corrections or blurred portions.

Hitherto the headmaster had looked on him as an abnormal and difficult scholar and no more, but one day he set a geography paper to the whole school and he was amazed to find Jannie Smuts far away at the top. He began to take an interest in him, and finding him above the average, he moved him up several classes in one move, and into his own special scholarship class.

The weedy, puny boy went on reading continually. He did not appear to have any particular interests nor any object or ambition except to collect facts and more facts, facts from books, facts that he saw in words on printed paper. He was solemn far beyond his age. A visitor wanted some information about Riebeek West. Jannie Smuts sent her a long and learned essay on “The Advantages of living in Riebeek West,” with a wealth of local facts and dates.

When he went home for the holidays he took books with him and he read. His father grew annoyed with him. The eldest son had died of typhoid and he wanted Jannie to take over the farm after him, but the lad was useless. If he was sent with a wagon he took a book, and hours later he would be found sitting on the shafts, having forgotten all about the animals or his business. At meal times he sat silent or dreaming or was surly, would eat his food without a word, or would get up and walk out abruptly on to the stoep, where he would sit reading or walk up and down talking to himself.

To solid old Jacobus Smuts, wise in men and from his experience in practical things, this son which he had produced was a freak. Letters and figures were useful things to be learned and for practical use. Books too were good, but this was too much of a good thing. He talked with his wife and they agreed. The boy was staid and religious. If he wanted to live on books he had best be a predikant, a pastor. The pastors lived on books.

Still the boy worked, absorbed in absorbing knowledge, his nose always in a book. He had no boyhood. He was born old and serious. There was nothing of the boy about him, no high spirits, no playing, no misdeeds, no practical joking or laughter, only dogged, persistent grey work—reading. But he was the headmaster’s prize pupil and he was to sit for the entrance examination for Victoria College, the Dutch college in the town of Stellenbosch. He increased his hours of work, cutting short his sleep, working with complete and, for a boy, abnormal concentration. The strain began to affect his health. He became even more skinny, lean, and rickety. He grew queer in his manner, his pale-blue eyes often set in a wide distant stare, and when spoken to he did not seem to hear. The doctor was afraid that his mind was being affected. He was forbidden to read, but he persisted. To keep him under his own eye, the headmaster moved him out of the general dormitory into his own side of the house, made up a bed for him in his sitting-room, and locked away his books. Still the boy persisted. He persuaded the headmaster’s son to get him books from his father’s library and smuggle them in to him, hiding them under his pillow, reading them when no one was about; until he was caught and finally forced to stop, for a month. But he fretted and wandered aimlessly about, lost without books or work, having no hobbies or outside interests to fill his time, until he was allowed to study again.

He passed the examination and was accepted for Victoria College.

Going to Stellenbosch filled Jan Smuts with some of the same fears as when he went to school in Riebeek West; and he prepared himself methodically. He took himself with an immense and portentous seriousness. Life was a grave and serious affair, and he must not lose or misuse a minute of it. He wrote to a professor at the college, asking his advice and his help. . . . “I trust you will,” the letter ran, “favour me by keeping your eye on me. . . .” for he considered Stellenbosch “as a place where a large and puerile element exists,” and so “affords scope for moral, and, what is more important, religious temptation, which if yielded to will eclipse alike the expectation of my parents and the intentions of myself. . . . For of what use will a mind, enlarged and refined in all possible ways, be to me if my religion be a deserted pilot, and morality a wreck?”

Stellenbosch, this sink of possible iniquity as the boy thought of it, was a quiet old town centred round the College. It lay in a valley full of vineyards and gardens of flowers. In the centre was a square where the ox-wagons on trek down to Cape Town outspanned, and from which the streets branched off, each bordered with giant oaks which arched and met so that the streets, even in the hot midsummer days, were always in deep shadow, and down each, in the gutters, ran, from the hills above, rivulets of water which gurgled and laughed their way through the town on their way to a river beyond. It was a cloistered, peaceful old place of picturesque thatched houses and professors and scholars and schools and religious missions, and it slumbered placidly in the drowsy, languid shade under its great trees. Jan Smuts found it very different from the bare, treeless sweeps of the Zwartland, but he refused to allow it to make him relax or to become lazy.

He worked as he had worked at school, poring always over books, absorbing knowledge and retaining it, for his memory had become photographic in its exactness, in its power of retention and of reproduction. There were no regulated games and no compulsory communal life. The professors were nearly all Scotsmen who encouraged work, and work to the exclusion of all else, so that he could work without interruption. For his degree he took Literature and Science. He studied the English poets, especially Shelley and Keats, and Walt Whitman the American, and, though he did not appreciate the beauty of the words or of the metres, he sought out their ideas. He learned German and studied the German poets, especially Schiller, in the same way. And he learned High Dutch, the Dutch of Holland, fluently and exactly.

He wrote articles for the college magazine and even for the local papers, articles on subjects such as Slavery, Scenery, the Rights of the Individual—dull articles without originality; and some doggerel poetry, such as all youths write some time or other.

He was, however, still painfully shy and nervous. His physical weakness and his spindly body gave him a sense of inferiority; but he refused to be crushed down by it and he determined to overcome it. To cover his shyness he continued to develop an artificial manner which became abrupt and gauche, and the other students, not realising that he was shy, looked on him as conceited. He, in turn, avoided them, took no part in their social lives or their amusements. When asked to a dance he refused because he was too self-conscious and he was afraid of making an exhibition of himself, and his manner of refusing the invitation caused offence. But if anyone became flippant or tried to rag him or to waste his time with frivolities, his shyness disappeared; he was on his dignity at once and became indignant, short-tempered, and ill-natured.

For recreation he walked over the hills, usually alone, thinking, and often talking to himself. On Sundays he held a Bible class for coloured men and solemnly propounded to them the Word of God; and with the same immense seriousness he joined the volunteers.

So much did he shut himself away from the life of the college that he would not live in a general boarding house with the other students, but lodged in a private house, that of Mr. Ackermann, because, as he explained to a professor, he wished “to avoid temptation and to make the proper use of my precious time . . . which in addition will accord with my retired and reserved nature.”

With one person, however, he could relax and be natural—with a girl, a Miss Sibylla Margaretha Krige, known for short as Isie Krige, who was a fellow student, for at Victoria College co-education was encouraged.

The Kriges were an old family which had come from Cape Town and lived in Stellenbosch. Some of them had trekked away to the north. Many of them were politicians. All of them—in contrast to old Jacobus Smuts—were opponents, and bitter opponents, of the English and English ways. In this tradition Isie Krige was brought up.

She was a little, quiet girl with a round white face, who dressed simply and brushed her hair severely back from her forehead. She was very solemn, passed all her examinations, was steady and plodding without brilliance or attracting much attention—in every way a satisfactory student: and she was very prim and proper.

Jan Smuts fell in love with her in his own stilted way and they “walked out” together. The Kriges lived at the bottom of Dorp Street, on the corner where the road turned east to the sea, and they farmed some land that ran along the river-side below the town. Mr. Ackermann’s house, where Smuts had his lodging, was half-way up the same street, where the oak trees were thickest. Every morning Jan Smuts waited at his door until the girl came by and then joined her, and each evening he saw her to her home. A queer couple they made, the little prim girl with the white round face and the lanky, spindly youth with the unsmiling cadaverous jowl, sedately side by side, their books tucked under their arms, silent or in solemn discussion, walking in the shade under the avenue of oaks up to the college gate. They found Life a very serious concern.

They were young to walk out—he was seventeen and she was sixteen—but they were not exceptional, as it was customary amongst the Dutch to marry early. Smuts made love to her in his dry way—as a fellow scholar. He did not lack sex and virility, but he repressed these as he repressed enthusiasm and any other natural youthful inclination. Being egocentric he talked of what interested him primarily—his work. He taught her the things that interested him: Greek, which he had learned out of a textbook: German, in which they read the poets together: Botany, and especially grasses, for that was his hobby.

And the girl adored him. She hero-worshipped. She worked for him. When he translated some Schiller, she wrote it out in copy-hand. But she gave him far more than that; he knew he was unpopular: he wanted to be liked, but he could not unbend, be normal and natural; but with her he could be natural. He was at heart a schoolmaster with the itch to teach and direct the lives of others: she was a ready and willing pupil. He needed applause: she gave him applause and with it self-respect.

Jacobus Smuts, however, was not so satisfied. The jovial, good-natured old man with his practical knowledge saw that he had, in some strange way, produced a son who was just all grey brain and little else. He wanted him on the farm, but Jannie was incompetent with his hands; he had no practical abilities or farm sense. He was a book-worm, and that was all there was to it. The old man accepted the fact: Jannie must be a pastor.

But Jan Smuts’ outlook had changed. He was not so solidly religious as he used to be. His studies, especially of Shelley and Walt Whitman, and his new experiences had altered his outlook and he was doubtful whether he had the call to the ministry. At last he decided that he wished to read not theology, but the law and to complete his studies in England, and at Cambridge. His tutors encouraged him, for he had shown himself to be one of the cleverest students at the college. He had passed his matriculation and his first intermediary examinations with success and he was second on the passing-out list for the local degree of Bachelor of Arts.

To go he needed money, and, though he was never actually poor, he had not enough for this and his father was by no means inclined to help him in this new venture; but he won a scholarship, the Ebden, which was worth a hundred pounds a year and a number of small bursaries. Then, in 1891, taking his local degree, he collected all the spare cash he could lay his hands on, borrowed some from a tutor, shut down his Bible class, said good-bye to Isie Krige and took ship for England.

The England to which Jan Smuts came was the England of the early nineties of the nineteenth century—rich, imperially expanding, haughty and powerful, but it was also England at its most florid and turgid; overfat with money and self-satisfaction; a land of dowager duchesses; of top-hats and high collars; the working classes, servants, and such like kept out of sight and out of mind; the upper classes very exclusive, nose-in-air and select. It had little interest in or welcome for a colonial, and especially for a poor and unknown colonial. For Jan Smuts, with no ability at making friends, it was a very inhospitable place, but in his own lonely way he ferreted round and learned much.

At Cambridge he went to Christ’s College, but he got little out of university life; he did not like it or the undergraduates. He did not understand them. He was older than the average and had another viewpoint. He came to work with a specific object. They, with their lackadaisical drawling ways, appeared to him to have come just to pass time. He did not understand that no man in England of their class should be openly serious or show that he was making an effort: he must succeed without apparent effort or there was no virtue in his success; the undergraduate who worked openly was a “nasty little swot”; he might work as hard as he liked, but he must not be caught working. To Smuts, not knowing these things, these languid young men seemed to be only frivolous time-wasters, wasters of “my precious time.” He kept away from them lest they should corrupt him. He worked hard and openly. He remained lonely, aloof, and lost, reserved even to ill-nature. He repelled or ignored advances and attempts at friendship or intimacies. He wished to be noticed, but if anyone took any interest in him he played the part of being unconscious of the interest. His original sense of inferiority and his shutting himself in himself had made him introspective and self-centred.

He was still thin and weedy, with a big forehead, a long jowl, a slight chin, and pale-blue eyes in a pasty, drawn face; and he grew pastier, for he worked all day and far into the night. Like many of the Dutch of South Africa, he had a flair for the law, for its intricacies and its dry subtleties.

Of the joy of living, of the pride of the body and of physical fitness, of the thrill of sport and of competition with others—he shrank from competition—he knew nothing. The heart-leap of revolt against accepted things, the fire in the blood, the follies and the inconsequentials which are the privileges of youth and which if a man has not felt and suffered he has never lived, were outside his comprehension: he despised them.

In return the undergraduates disliked him, this lanky, stand-offish, nose-in-air, self-opiniated colonial with the amazing accent—he had the broad accent of the Dutch from the Malmesbury district, which was nasal and sing-song—who was either silent or spoke with an air of contempt; a brusque, uncouth fellow; a dull dog, a prig. They felt that some kicking and bullying in the rough and tumble of an English public school would have done him good. They would have liked to rag and torment him, but there was something about him which made them sheer off, and they left him alone.

At his work Smuts was very successful. He had no difficulty in passing examinations, for when asked a question he could, with the eye of his memory, see the answer with page open in front of him, the exact wording with chapter and verse. And he could, if it was necessary, still in the eye of his memory, turn over a page and read on.

He took superlative honours in the Cambridge finals. Maitland, the Professor of Law, said of him that he was far the best student he had ever examined. He was admitted to the Middle Temple in May 1894 and passed the Honours Examinations with exceptional success and won a number of special prizes. He was offered a professorship at Christ’s College, but refused it, without waiting to be called to the English Bar he set out back to Cape Town.

He went back to South Africa with joy in his heart. He was homesick. Africa was his home and Africa called him back insistently.

One who stood near him as the ship came into the harbour of Cape Town told how the silent, reserved young man became suddenly alive and vibrating as he saw before him the city along the shore and behind it Table Mountain towering up with the clouds spilling down over it and collecting towards the peaks of the Twelve Apostles. For a while he stood staring out, his blue eyes shining and alive, rejoicing. For a minute he had ceased to repress himself. He was natural and unconscious of anyone looking at him. He was human and a young man rejoicing simply. Then quickly, like the sudden dragging down of a steel shutter over a lighted window, the light went out of his eyes and the joy out of his body, and as if he were ashamed that, even for one minute, he should have shown himself and his inner feelings, he turned abruptly away and went below deck.

When Jan Smuts landed in Cape Town, the local newspapers welcomed him back. They spoke of him as a brilliant young man: a credit to South Africa. They quoted his success at Stellenbosch and his phenomenal success in England, at Cambridge and in the Middle Temple; and they predicted a great future for him as a barrister. He was called to the Bar in Cape Town, went into Chambers, and began to practise in the Supreme Court. He was for a while a big splash in the small pool of Cape Town life, and then, as time passed and people grew used to him, he became an unnoticed member of the community—and, despite all that the newspapers had predicted, no briefs of importance came his way.

For a barrister, especially in South Africa, a pleasing personality and an engaging manner were more important in getting clients and briefs than academic and examination successes—and Jan Smuts had a bad manner. He worked as hard as ever, searching out and absorbing knowledge out of books and musty documents, but he could not hob-nob with the other junior counsel, do the casual passing-the-time things they did, playing cards, swapping drinks, sitting in the casual, sociable manner of Cape Town to talk by the hour. He was constitutionally unable to get on to familiar or intimate terms with the other men. He had a hesitating and reserved manner, with a haughty look, and his pale-blue eyes looked past or through people and held them at arm’s length, so that the juniors liked him as little as the Cambridge undergraduates. The older men and the solicitors wanted someone more human and pleasant to handle the cases of their clients and one who could influence juries—and this Smuts could never do.

Having little legal work he undertook odd jobs. For a fee he examined in High Dutch, in which he was very proficient. He wrote articles for the Dutch and the English newspapers, and especially for the Cape Times, on all manner of subjects—on the Native Problem, the Scenery of the Hex Valley, on A Trip to the Transvaal, on Immigration, a review of a book on Plato, a criticism of the Transvaal Government because it employed Dutchmen from Holland instead of local Dutchmen in its government offices, and he demanded that young South Africans should be given a chance before foreigners; and a study of Walt Whitman, about whom he had written a book, for which he could not find a publisher.

The Cape Times was going through a bad period. The editor had given himself an indefinite holiday. After a time the staff met and elected a temporary editor from amongst themselves—one Black Barry, one of the journalists. Black Barry had been a trainer of fleas in a circus and knew much more about training fleas than editing newspapers, so that the Cape Times became a burlesque of a newspaper and was rapidly going bankrupt when a committee of important men took it over and engaged a number of young men to write for it. Amongst these they engaged Jan Smuts. He worked conscientiously, producing a steady stream of ponderous leaders on such subjects as The Moral Conception of Existence, and The Place of Thrift in the Affairs of Life. As part of his work he attended in the Press gallery and reported the parliamentary debates, for Cape Colony had become a self-governing colony and had its own parliament.

At first he did this work as part of the routine of journalism. Then he became mildly interested. His interest increased and grew rapidly until it began to absorb him. All other interests became secondary. His religious convictions had become weaker. The idea of being a pastor had long since faded out of him. The law was his profession, but he had had no success in it. Philosophy and learning appealed to him, but he needed more action and not the life of a student or a professor.

Steadily politics took a grip of him. They became the centre and the co-ordinating force of all his thoughts and all his actions. He had worked at school, at Victoria College, at Cambridge, in London, and in his chambers in Cape Town hard, but without a concentrated central plan. He had been wandering. Now he had concentrated on to one point. He had a definite objective—politics.

At that time politics in South Africa were electric with possibilities. While Jan Smuts had been growing up all had been changing. Away back in 1870, despite its troubles, South Africa had been a sleepy old land, and the people, whether of the Cape or of Natal or of the Dutch Republics, the Transvaal and the Free State, had been farmers, traders, and shopkeepers—all decent, solid folk. The English and the Dutch had continued to quarrel, but had kept their quarrels as those of relatives. They had stood together against the common enemies, the invading Black Men, to establish their common safety. They had intermarried and worked together and defrauded each other in amicable rivalry. They had disagreed, but lived side by side in disagreement. England had been far away and the English Government had had little interest in the country except in the Cape as a naval base, and it begrudged any money it had to spend on administration.

But in 1871 diamonds had been discovered in Kimberley; and then in the Interior, a thousand miles from the Cape, was found gold: gold in quantities near the surface; reefs of gold in the Witwatersrand, and the Witwatersrand was a bare ridge of hills high up on the veld, in the territory of the Dutch Republic of the Transvaal.

With the finding of gold South Africa changed and woke from sleep into a vicious mood. The gold begat trouble. Instead of the farmers and the traders, all solid, ordinary folk, there came gangs of adventurers from all parts of the world and of all nationalities—Turks, Greeks, many English, Germans and Americans, and the worst type of internationalised Jews, with their noses close down on the gold trail. The Dutch of the Transvaal resented their coming, called them Uitlanders, Outsiders, but they themselves became greedy for quick wealth and their officials became corrupt and dishonest. Foreign governments became interested: the Dutch of Holland; the Germans, who annexed Namaqualand, some four hundred miles to the west on the Atlantic seaboard, and who planned to make themselves a great African empire which should contain the gold area. And the English Government suddenly realised that South Africa was valuable and made up its mind to control its gold. The quarrels of the English and the Dutch ceased to be the squabbles of relations and became a vicious quarrel for wealth, with the English Government behind the local English. The Dutch, convinced that the English Government had decided to annex their republics, though not looking to Holland for help, were equally determined to defend their independence to the bitter end. The leader of the Dutch was Paul Kruger, an old Dutchman and the President of the Transvaal Republic.

Amongst the first adventurers had come a young Englishman—by name Cecil Rhodes. He was from a good middle-class English family, but in England he had few opportunities, for the England of 1870 was rigid in its social classes and even more rigid in its distribution of wealth and opportunities, so that a young man without money or family connections had few chances of getting out of the rut in which he was born, however capable or ambitious he might be, and Cecil Rhodes was born with vast ambitions and exceptional capabilities, though with weak health and diseased lungs.

He had come to South Africa for his health and to find a career. At once he had shown a remarkable ability for choosing useful friends, for business and for gambling; and in an incredibly short time he had amassed a vast fortune out of diamonds and gold and an equally enormous reputation. He had amalgamated the diamond industry into a company, the De Beers, and become the managing director, and he had gained control of a large portion of the gold output of the Transvaal. With this wealth behind him he had gone into politics, with wide views and high aims, and become Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

His aims were clear cut and defined. His methods were vigorous and he was held back by no scruples. He believed that South Africa, consisting of the two colonies of the Cape and Natal together with the two Dutch Republics of the Transvaal and the Free State, must remain as one indivisible whole, and that within it, the Dutch and the English should work shoulder to shoulder as one white nation. Such a South Africa should rule itself, free of the government in England and of the politicians in Downing Street, but, above all, free of the officials in the government offices. Beyond this again he saw a tremendous vision, not merely of a united white South Africa, but of all Africa away up far to the north, to Egypt and the Mediterranean coast, as one great state still within the British Empire. Money, as the means of buying luxury or ease, meant nothing to him, but it meant power. And above all things he loved power, the power to achieve his ambitions and realise his vision.

But in his way, across his path, preventing expansion to the north, preventing a union of South Africa, controlling the gold that Rhodes needed, and in touch with the Germans—thwarting all his schemes and thwarting them with deliberate and bitter pugnacity, was Paul Kruger.

Paul Kruger hated the English. He had been taught to hate them since he was a child. He had been born in the Cape as a British subject, but his father had been one of those who had trekked away north to get away from the control of the English. As a youth he had lived hard. Naturally dour and a strict, an extreme Calvinist with a harsh outlook, his life had soured him so that his hatred of the English had become part of his mentality.

Paul Kruger had aims as clear as those of Cecil Rhodes; he was equally unscrupulous and as determined to succeed. He too believed in a united South Africa, but one that was wholly Dutch, and he hoped to drive all the English into the sea. Finding that impossible, he set to work to unite the two Dutch republics and to make them into an isolated Dutch country, independent of the English-ruled Cape Colony and Natal, and with its own government, laws, tariffs, customs, and its own separate railway system and its own seaport.

For Rhodes he had a special hatred. As the Englishman who was Prime Minister of the Cape, Rhodes was the agent of the interfering English Government. He hated him also as one of the foreigners, the Uitlanders, the Outsiders, who were profiting from the gold of the Transvaal—of his Transvaal. Aasvogel, dirty vultures, Kruger called them, who had found a dainty morsel in the Transvaal and sat down to gorge themselves. Rhodes was the King of the Aasvogel, with his evil Jewish assistants; his evil friends who made his money for him. He was, for Kruger, the incarnation of Capital, of Evil: of Capital lying, bribing, treacherous, bullying without conscience or moral sanction, using politics to rig the market and then using the money so foully made to debauch politics. Rhodes had already with his bribes debauched many of the officials of the Transvaal. The gold itself was a cancer rotting the heart of the people, and Rhodes and his friends were no more than stinking corruption and a vital danger to the liberty of his state. He could not see Rhodes’ virtues, mighty though they were, but only his gigantic vices.

At first Rhodes tried to come to terms with Kruger, to persuade him, to buy him into complaisance—and Rhodes believed that, if offered enough, any man could be bought—but Kruger would neither be cajoled nor bribed, and he drove Rhodes to fury. To Rhodes the President was a dirty, uneducated old Dutchman, backward, primitive, and impossible, an anachronism, a throw-back to the times of Moses, who ought to be cleared away, and who blocked all his great schemes and all progress and advance.

Like two primeval monsters they faced each other. Kruger hard, rugged, a fighter, brutal, dictatorial and overbearing: a fanatic, who ruled his people as a patriarch by the power of his personality. The Old Testament taken literally with its exact wording was his guide. Rhodes, ruthless, unscrupulous, an ourang-outang of a man, unkempt in appearance, uncouth in manner, huge head with sleepy eyes, turbulent and volcanic in his rages, tearing at opposition and tearing it down without pity with great, grasping hands.

At the time that Jan Smuts was reporting the parliamentary debates from the Press gallery in Cape Town and learning the elements of politics, across the hard brutal land of South Africa these two immense, primitive men straddled, squared up, face to face, grim, hostile, and snarling; they dominated all South Africa and their quarrel dwarfed all other issues.

The quarrel between Rhodes and Kruger appeared to be identical with the quarrel between the Englishmen and the Dutchmen of South Africa—for domination. In reality, many of the Dutch were not behind Kruger. In the Transvaal many thought that the old man—he was now well over seventy—had grown so obstinate and dictatorial that it would be good to replace him with a younger man. Martinus Steyn, the President of the Free State, a big-bearded Dutchman, jealously proud of his race and their independence, did not want close union with the Transvaal: the Transvaal was becoming rich and the Free State was poor, and he was afraid of being absorbed by his neighbour or at least overlaid; and in the Free State the English and the Dutch lived happily together and had no reason for disagreement. In the Cape a large percentage of the Dutchmen, solid, sound men of standing, like old Jacobus Smuts, had no ill-feeling against their English neighbours.

These Dutchmen, the Dutchmen of the Cape, had formed an organisation known as the Afrikander Bond—the Bond—to look after their interests. It was led by W. P. Schreiner, the son of a German missionary, but the organiser and the real director from behind was a Dutchman, J. H. Hofmeyr. The Bond members also wanted a united South Africa; to them Kruger’s policy of creating an isolated Dutch country cut off from the Cape was folly. It would injure the Cape and the trade of Cape Town and it would ruin all the Dutch.

Hofmeyr and Rhodes found much in common. Both were enthusiastic South Africans: Hofmeyr by birth, Rhodes by adoption. Both were convinced that South Africa could exist only in union, with common laws, tariffs, customs, and a common railway system. Both were imperialists, wishing South Africa to remain part of the British Empire so long as the English Government did not interfere in its local affairs. Hofmeyr had proposed a tariff in favour of England and against other nations, the proceeds to be paid as an annual contribution to the British Navy.

The two men became close friends. Hofmeyr brought the Bond in behind Rhodes, and backed him both inside and outside the House. When Parliament was sitting they met almost daily and discussed all problems without restraint. Each morning they rode for exercise on the downs outside Cape Town. Rhodes relied on Hofmeyr’s judgment and consulted him on all occasions, and Hofmeyr believed in Rhodes. Both he and Schreiner realised that if Rhodes succeeded it would mean a South Africa ruled by the Dutch, for they were in the majority. Rhodes on his side encouraged Dutchmen to take office and position under him—there were several Dutchmen in his cabinet. And he showed an open preference for men born in South Africa and employed young Dutchmen born in South Africa, Afrikanders they were called, whenever he could.

Hand in glove, Cecil Rhodes and Hofmeyr, with Schreiner and the members of the Afrikander Bond, with their English and Dutch supporters, ruled the Cape and worked for a united South Africa.

Jan Smuts joined the Bond. Already he had become a strenuous and restless politician. Politics were in his blood as they were in the blood and in the mouth of every Dutchman. His father had been elected member for the Malmesbury district and was a whole-hearted supporter of the Bond and a follower of Hofmeyr—and he encouraged his son to join. Between himself and Jannie he had at last found an interest in common.

Though Jan Smuts was of little importance, both Rhodes and Hofmeyr were glad to have him as a recruit. Rhodes had already marked him down some years before, when he had gone on an official visit to Stellenbosch—it was part of his policy to encourage the Dutch colleges and schools—and Smuts was a junior student there. Smuts had been chosen to reply to the address which Rhodes had given, and Rhodes had been so struck by his speech—which echoed all Rhodes’ own ideas—that he had asked Hofmeyr to keep an eye on the young man for future employment. Rhodes knew too his record at Cambridge and in London. He was exactly the type of clever, serious young Afrikander he wanted working for him, and one who had been to England, knew something of the outside world and what the British Empire meant: a man with the right ideas, as his articles in the newspapers showed. “Keep an eye on that young man,” he said one day to Alfred Harmsworth; “he will do big service for the Empire before he is finished.”

Hofmeyr knew him too. He had a great respect for old Jacobus Smuts and he recommended young Smuts in the strongest terms to Rhodes. To help him and to put him financially on his feet, Rhodes was thinking of employing him as one of the legal advisers to De Beers, his diamond combine.

For Jan Smuts it was his chance. As a barrister he had done no good. Briefs still did not come his way. The little work which had come had been haphazard and unsatisfactory, a little devilling, pot-boiling, and without any future. Politics! It was politics he wanted. As a lawyer and a journalist he had been unsure and hesitating, but when dealing with politics he was becoming sure of himself and confident. He had found the thing he could do. He knew he would succeed. His ambition woke: he determined to become great. The Bond and its policy appealed to him. Paul Kruger’s policy of isolation was mean and little: he despised it. The idea of a united South Africa caught his imagination. It was the big idea, the big conception; and the big thing, together with power and success, appealed to him. Rhodes spelt success and power: he was the symbol of the big idea: the Colossus over-riding, towering above everyone else.

He became an ardent admirer and supporter of Rhodes. He opened out, loosened the stiff joints of his awkward manner, became more human, began to warm with enthusiasm. He supported Rhodes the man, and the ideas and aims of Rhodes. He worked whole-heartedly for Rhodes, absorbed his ideas, and expounded them in articles. He had in England seen the might and power of the British Empire. He wrote and spoke in favour of the English, the people from whom Rhodes came. He compared Afrikaans, the local dialect of Dutch used by the Dutchmen of South Africa, unfavourably with English as a language. He explained in an article in the Cape Times that the English were unpopular “not because of their pharisaism but because of their success,” especially their success as organisers of colonies.

Rhodes! He became obsessed with Rhodes. He lived Rhodes. He made Rhodes his hero and his leader. He saw an assured future with Rhodes leading the way. He worked and talked Rhodes and the climax was a meeting in October of 1895 in the Town Hall in Kimberley, where he made a long speech on his behalf.

To this meeting he was sent by Hofmeyr, who primed him. There was trouble brewing in Kimberley, the centre of the diamond industry. It was encouraged by Olive Schreiner, a South African novelist. She suspected that Rhodes was preparing some treachery against the Dutch, that the Uitlanders in the Transvaal were up to something, preparing something also: all through South Africa there was talk that Rhodes and the Uitlanders were plotting together against Kruger and the Transvaal Government, and about to take some action, a coup de main of some sort. The Dutch were becoming suspicious and awkward. The De Beers’ Political and Debating Society were holding a meeting in Kimberley, in the Town Hall, and wanted someone direct from headquarters to speak for Rhodes and contradict the rumours. Hofmeyr schooled Smuts in what he was to say and he went with enthusiasm. He was no more the dull, reserved student. He had found an inspiration. He was in his element. He was on the high road in politics.

In the Town Hall in Kimberley, before a large audience, he defended Rhodes against all criticism: his Native Policy, which had many faults; his scheme to unite all English and Dutch into one people. Some said that Rhodes had no right to be the Prime Minister of the Cape, an English Colony, and to hold vast interests in the Transvaal, an independent Dutch republic, which might conflict with his political duties: Smuts stoutly defended the dual position. Others attacked Rhodes’ private character, charged him with corruption, bribery, and dishonest opportunism: Smuts denied these vigorously, and criticised the handling by the Transvaal officials of the foreigners who worked in the mines; and ended off with an enthusiastic panegyric of Rhodes.

He was attacked and laughed at by some of the newspapers and by Olive Schreiner, but he did not care. The future was assured. He was on the road to success, with Rhodes leading the way. And he returned to Cape Town full of enthusiasm.

But Olive Schreiner and her supporters were right. Rhodes was plotting with the Uitlanders and there was trouble ahead. His quarrel with Kruger was coming to a climax, for he was in a hurry. He was agitating to get his aims quickly. His lungs were growing worse. He knew he had not long to live, and he trusted no one to carry out his work, once he was gone. A dozen new difficulties had arisen. Steyn of the Free State had at last made an agreement with Paul Kruger to protect both republics against the English. The centre of South Africa was shifting from Cape Town to the Transvaal, to Johannesburg, which had been the camp for the gold-miners and was now rapidly growing from a town into a rich city, and Rhodes wanted to control Johannesburg. The Germans had come interfering in earnest. They were at work on their plan for a great central African empire from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean which would cut the Cape off from the north and have control of the republics and the gold mines. They had come to some terms with Kruger, though no one knew exactly what, and Kruger was using them—as Sultan Abdul Hamid in Turkey at that same time was using the Germans—to counterbalance the English and so protect himself. He had given the Germans special freight rates for their goods. He had allowed them to open banks in the Transvaal. He had engaged German officers to train his regular soldiers and his State artillery. He was building a ring of forts round Pretoria with the technical advice of Germans. He boasted that he had the promise of help from Germany if he called for it and that he would welcome such help—and to back up his statements there were lying in the harbour of Delagoa Bay, the harbour he proposed to use instead of Cape Town, two German cruisers.

As Rhodes grew impatient, Kruger sat back. He put his trust in God and so had unlimited patience. “I wait,” he said, “until the tortoise puts out its head, and then . . .” Rhodes put his trust in no one but himself and hence could not wait. Again he tried to negotiate with or to bribe the old Dutchman, but Kruger would have nothing to do with him. And as the precious days went by, Rhodes became maddened with impatience. He was not used to being opposed. He was used to elbowing men roughly on one side, but Kruger remained impassive and immovable and would not be elbowed aside. At last Rhodes determined to defeat Kruger by force.

The Uitlanders, the foreigners who owned and worked the mines in the Transvaal, were also at loggerheads with Kruger. They had many legitimate complaints: they paid seven-eighths of the taxes, but they had no political rights and no say in the expenditure of the money. For the Dutch children there were State schools, for their children none; the State officials were greedy and corrupt, the municipal officials of Johannesburg even worse; the administration was very inefficient; they were harassed by vexatious taxation; the concessions which Kruger gave his relatives, bled them of their profits; they were allowed no freedom of Press, public meeting, or speech. When they complained to Kruger he told them to go to the devil. He hated and despised—and he feared—the Uitlanders. He was convinced that if he gave them any political power, they would swamp the republic and probably call in the English Government as well. They were in the Transvaal, he told them, on sufferance: they said that they could not get justice in the courts or from the police, that they were being fleeced. Well! they could go away when they liked. He would not stop them, but, if they stayed, they must put up with what they got.

The Uitlanders saw that they could get no redress by bribery or persuasion, and they too decided to upset Kruger and his Government by bluff, or, if necessary, by direct action.

They combined with Rhodes, but they had different objects. They wished to eject Kruger and replace him by another government which would be more amenable and in which they would have a share—perhaps the dominant share. The last thing in the world that they wanted was for the English Government to take over or to fly the Union Jack in Pretoria. They wanted to be like the foreign subjects in the Turkish Empire—to live under a weak foreign government and to have special privileges, their own consuls to help them, and even their own consular courts to try them. In this way they would get the best of both, being able to flout the local government and yet not be hindered by their own nationality.

Rhodes wanted to get rid of Kruger and his government, for they were the stumbling-block to his plans, to his great dreams, to his vision of the great united Africa of the future, and now he was convinced that he must force the hands of the English Government. He must jockey the English Government into taking a hand direct. The Germans were too close and too ready to interfere at the first opportunity. He knew that there was a definite treaty of defence between them and Kruger. A weak move, and they would be in the Transvaal as champions of the Dutch and the way to the north would be blocked for ever. They were already acquiring land, buying concessions, and getting control of the railway that ran from Delagoa Bay through Portuguese East Africa to the Transvaal. The English Government must be forced to come in to keep the Germans out.

He sent help and encouragement to the Uitlanders, and he sent to Pitsani, a village on the Transvaal frontier close to Mafeking, his most intimate friend, Dr. Jameson, with four hundred armed police, on the pretext that they had gone there to protect the workmen on a new railway that was being built up to Bechuanaland; but with orders to be ready to cross the frontier if necessary.

The general scheme was simple. On a fixed date the Uitlanders should march out of Johannesburg on to Pretoria, the capital of the Transvaal and only thirty miles away, take the arsenal and forts and eject Kruger, and form a new government in the Transvaal. If Rhodes thought it necessary and gave the order, Dr. Jameson should advance over the border from Pitsani and join the Uitlanders.

The plot was a complete fiasco. The Uitlanders boasted and talked openly. The scheme became an open secret. When Smuts was in Kimberley in October defending Rhodes in the Town Hall, the preparations were being freely discussed in every club and bar and public place throughout South Africa. Olive Schreiner had a shrewd suspicion of the facts. Kruger knew and waited his chance. The plotters could not agree. The Uitlanders had little desire to use force. They wished by the threat of force to bluff Kruger into giving way. They also wanted to be sure that the English Government was not going to interfere and that Rhodes was not going to use them for his own plans. Every arrangement was so mismanaged that it was more like a crowd of schoolboys playing at Red Indians than grown men risking their lives for big stakes. Rhodes, not understanding the attitude of the Uitlanders, went on arranging details, but found himself continually held up. He asked what flag the Uitlanders intended to fly when they reached Pretoria: he wanted the Union Jack. After much discussion they decided on the Transvaal republican flag, but flown upside down. He tried to fix the date. They kept postponing and finally refused to act on Christmas Day, not for religious reasons, but because there was a race-meeting that day in Johannesburg and they wished to attend.

Jameson and Cecil Rhodes

Meanwhile Dr. Jameson sat at Pitsani. He was naturally hot-headed. He was ill. His nerves were on edge. He had imagined himself to be a second Clive or Warren Hastings adding a province to the Empire with a bold advance. His men were getting weary of the delay and deserting, and he grew angry. Colonel Willoughby, the senior officer with him, constantly urged him to act. He decided to force the issue. Anyhow he refused to go tamely back to Cape Town and be laughed at. Rhodes sent him orders to stand fast, as he was still arranging details. He believed that Rhodes was bluffing and meant him to go ahead. Sending a message to the Uitlanders to tell them that they were cowards, on the twenty-ninth of December of 1895 he crossed the frontier from the Cape into the Transvaal.

Kruger was ready for him. The tortoise had put out its head, and he cut it off. He rounded up Jameson with his men, and turning to Johannesburg he arrested the leaders of the Uitlanders. All the Transvaal went up. The commandos came hurrying out, the men with their rifles ready to fight. Every Dutchman in South Africa blazed up with anger. They believed that England was behind the raid, England and Rhodes, and had meant to destroy the independence of the Dutch republics and make the English dominant in all South Africa.

Smuts had gone to Riebeek West, to his father’s house, for Christmas and the New Year. He was sitting on the stoep of the house, when the news was brought in—vague, excited news that had increased in the telling. An army of English soldiers was said to have marched from Mafeking on Pretoria. Johannesburg was up in revolt. . . . All the Dutch of the Transvaal were out, and the commandos on the move. There had been fighting. Many had been killed and hundreds wounded.

At first Smuts did not believe it. A scare story! One of the many that were flying round at that time. He knew, as everyone knew, that the trouble between the Uitlanders and Kruger had become very bitter, but it was full of big words and threats and there was little danger of any real action. There was no English army near Mafeking. But as more reports came in, he realised that something serious had happened.

Cape Town was buzzing with excitement. The facts were clear. Dr. Jameson with a party of police had raided into the Transvaal, been surrounded, and, after some fighting, captured by the Transvaal General, Cronje, and was likely to be shot in Pretoria. Prominent Uitlanders from Johannesburg had been arrested for plotting to join with Jameson to upset the Government by force, and were in the civil prison in Pretoria charged with treason. And Rhodes must have known all about it. He must, in fact, have himself, and secretly, organised the whole plot and the raid. That became more obvious as more facts came out. He had sent his brother to help organise the Uitlanders. Arms had been smuggled to them by the officials of the De Beers company under his orders, in cases and tins addressed to the company, and had been stored in the mines. The secretary of the company had been his principal confidant and had handled the correspondence and used special codes to send instructions. Dr. Jameson was his closest friend, and letters and telegrams showing his part, with most of the details of the scheme, had been captured by the Dutch amongst Jameson’s luggage. The sending of Jameson to Pitsani to protect the railway had been just bluff. Men sent by Rhodes had mapped out the route from Pitsani to Pretoria and made depots for food and fresh horses, and one party had made a depot at Irene, a farm a few miles from Pretoria. Without a doubt it was a plot by Rhodes to make the English dominant in the Transvaal, and he had not given one word of warning to his Dutch friends and supporters.

The Bond met. The leaders, Hofmeyr and Schreiner, boiled with indignation. They had been fooled and betrayed by Rhodes: they had believed his talk of a united South Africa with Dutchmen and Englishmen working together as brothers. Brothers! And all the time he had been plotting this thing with Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary of the English Government, and with the Imperialists in England, to smash the Dutch Government of the Transvaal with English soldiers and to make England supreme in all South Africa! He had planned it right under their noses while he was leading them the other way with his talk of co-operation. It was treachery! Black treachery! They became again simple Dutchmen and angry Dutchmen, hating the English. They demanded that Rhodes be hounded out; that all the English be ejected from South Africa. They must get clear of Rhodes, denounce him, cut all connection with him as quickly as possible and before they were themselves involved in his ruin.

Hofmeyr cursed Rhodes publicly. “Now he has done this thing,” he said, “he is no friend of mine,” and telegraphed his congratulations to Kruger and demanded that the High Commissioner should repudiate Rhodes and outlaw Jameson.

The Bond followed their leaders; but this did not explain their close friendship and their enthusiastic support of Rhodes either to their followers or to the rest of the Dutch. In the heat of the moment, with tempers rising, they were attacked from every side and treated as traitors.

For Smuts it meant more. He had followed Hofmeyr, but of Rhodes he had made a leader and a hero. He had overcome his natural reserve, allowed himself to become enthusiastic openly, publicly, exposed himself, come out of his shell; and being still very thin-skinned, he had suffered accordingly. His hero had shown himself an unprincipled and treacherous adventurer. His hero-worship had been destroyed as by a sudden, scorching flame. His pride was hurt, for he had been publicly made a fool of, and he had been cheated. His enthusiasm for Rhodes, which had been the drive and the spur for months of all his actions, dried up and shrivelled. He tore Rhodes out of his life and out of his consciousness, but it left him empty and lost and leaderless.