* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Postmaster-General

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953)

Date first posted: Sep. 12, 2019

Date last updated: Sep. 12, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190931

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

CRANMER

WOLSEY

RICHELIEU

JAMES THE SECOND

The Right Hon. Wilfrid Delescue Halterton, M.P., born 14th January, 1905. Father, John Halterton of Reldwell Hall, Essex. Mother, the Hon. Sarah Woolley. Educated Eton and Merrion College, Cambridge: 3rd Class Honours, Botany, 1936. Postmaster-General in Mrs. Boulger’s second administration (1960). Recreation, golf. Unmarried. No s., no d.

Copyright, 1932, by

Hilaire Belloc

Manufactured in the

United States of America

TO

ORIANA HAYNES

Wilfrid Halterton, Postmaster-General in Mrs. Boulger’s second administration—that of 1960—sat before the wireless electric heater in the study of his new flat, at the top of the new Clarence block overlooking Hyde Park from the north. He was waiting for a visitor. He was waiting for McAuley, the younger McAuley, James (not his elder brother Andrew, the Attorney-General). The appointment had been made for five o’clock on that Tuesday afternoon, to give plenty of time for the Minister to come up after questions from the House of Commons to this flat north of the Park. There was nothing on but that eternal dull recurrent business of the Succession, and he could be free in the later afternoon.

He was a tall, patient-looking man in his fifty-fifth year, with a rather troubled face, long grey lax moustaches that drooped, and somewhat anxious about the mouth and eyes. He was looking rather more anxious than usual as he sat there. He half dreaded the interview which faced him—but it had to be gone through, and it was worth while doing. It was, of course, but one issue in the greater public affairs which a Postmaster-General controls. It was about a contract, and his own connection therewith was satisfactory enough.

Yet nervous he was. James McAuley—“J.,” as they called him in the City—was of a sort which Wilfrid Halterton had come to know well enough during his now long acquaintance with public life, yet his uneasiness in the presence of which he could never quite master: the decisive men, the men who knew beforehand what they were going to say, who have all their forces marshalled and their reserves well in hand. Yes, he was nervous, though he had grown intimate with James McAuley during the last few months, since the Socialist Party had come in due rotation to its regular term of office again under Mrs. Boulger, who had led it so long. The Anarchist Party were of course again in opposition, having for their most forcible personality, though not their leader, Lady Caroline Balcombe, the wife of “Posh” Balcombe the banker, the big noise in the Anglo-American.

James McAuley, “J.,” having a brother as Attorney-General in Mrs. Boulger’s Government was a familiar with both front benches, and a man of consequence; a financier who was the prime mover in a number of great commercial interests.

Nothing but good should come of close friendship with such a man, and Wilfrid Halterton had no reason to worry about the coming interview, so far as its fixed results for himself were concerned. He had already arranged them with “J.,” and there was nothing left to do but read over and sign the letter they had agreed upon.

Television, which had for long been an expectation, then an experiment, then a toy, had approached more and more during the past ten years to a commercial proposition. Television was already working at short ranges. It seemed just at the stage of being practicable over very long distances and having high commercial value.

Just before the Anarchists had gone out, some six months before the election designed to that effect, things were already ripe for the chartering of a television monopoly, and there had been talk of setting one up; but it was thought better to leave things over to the coming Socialist administration, which would have a clear run before it and plenty of time to organize the new public service.

Of course, the Television Service when it should be in working order would have to be under the control of the Government. It would, equally of course, have to be worked in connection with the Post Office. With the Post Office the decision would lie as to which of the two chief competing companies should be granted the monopoly.

Neither group had the least objection to Public Control. It was recognized as a necessity—and, what counts much more with public men—a duty. Each group therefore had negotiated with the permanent officials of the Post Office—pending the final decision of its political chief—on the basis of an arrangement with the authorities whereby whichever company worked the new system of Television as a monopoly should be granted a subsidy, the right to enforce rates fixed by themselves, to let out private machines at their own price, and to make whatever charges they thought fit for installation; with a guarantee from the Treasury against loss.

Whichever of the rival groups should obtain the management of this public service would also, of course, have the right to nominate its own directorship and management and to fill all posts. Finally, there was to be special legislation by schedule attached to the bill, providing that in case of dispute recourse could not be had to the ordinary Courts of Justice, but that the decision of an official of the Company called “the Arbitrator” should be final. To those few cranks who may quarrel with this system and complain that Public Control was imperilled by it, we have a self-evident reply, which is that we are not a logical people; we have a genius for compromise. The test of any system with us is not its theoretical perfection, but whether it works. This system of what may be called “modified Public Control” would certainly work by the only available test, which is the production of a profit for the monopoly which held the Charter.

Durrant’s and Reynier’s were the popular names of the two competing groups. The so-called “Reynier crowd” had their names from the screen they used, which was the invention of the late Hector Reynier, an admitted genius who had died in great poverty. The other (which was more talked about) was the Durrant Imperial Television Company. It was so called after Durrant, the name of the original inventor, who had lately died in embarrassed circumstances; an admitted genius. Its finance was in the hands of James McAuley—James Haggismuir McAuley to give him his full name, which bore record of family distinction on his mother’s side.

Both Reynier’s lot and Durrant’s had manufactured short range private instruments for domestic use since 1953, each Company was well established and the shares of each stood at a premium; but when long-range Television was a fact—already arrived at experimentally over nearly a hundred miles and with prospects of indefinite extension—much larger developments were in prospect. The political—and City—interest of the movement centred upon which of the two rivals should obtain the contract and Charter.

Durrant’s Television shares were known as “Billies.” They had first been called “Tells,” then “William Tells,” then “Williams”; then Capel Court had settled down into this form of “Billies,” and “Billies” they now were and would remain. They stood on this Tuesday, March the 3rd, 1960, the £1 shares, at 23s. 6d.—24s.

A final decision upon the matter was still awaited—and one great difficulty stood in the way of such a decision. There was not much to choose between the Reynier system and Durrant’s so far as sending or receiving were concerned. The difficulty in deciding lay in who should ultimately prove possessor of a gadget called “Dow’s Intensifier.”

Dow’s Patent was the only Intensifier which had been found to work satisfactorily. With it you got tolerably clear reproductions. None of the other very numerous competing types had successfully solved what is, as everybody knows, the chief difficulty in the practical use of Television at long range; for with the experimental and unsatisfactory Intensifiers that were in use, though the picture was then all right, it was all but invisible.

Durrant’s used, and talked a lot about, a certain Murray’s Intensifier; but that was bluff (said the people in the know). It didn’t work and it couldn’t ever: it was on a false principle.

Dow’s was—to those who could judge—indispensable. Reynier had hitherto used the old Keeling Intensifier, which could not of its nature suit long ranges. But it was rumoured on all sides, it was even affirmed by a good many responsible people, that Reynier’s had a secret agreement which secured them Dow’s Patent for the future—or at any rate could take it for granted that they would get it once they had the charter. But the Dow’s Company (Dow, an admitted genius, had died two years before—financial embarrassment had hastened his end) always asserted their complete independence, and denied everything that was going about to the contrary.

None the less, the committee of experts which had been appointed by the Post Office to report on the two systems had reported in favour of Reynier’s. They had done so mainly because they were convinced that Reynier’s would mean Dow’s Patent. They were satisfied that Murray’s totally different system which Durrant’s talked of would never do. Dow’s alone could make the long-range Television practicable.

I have said that James McAuley was behind Durrant’s—one might put it more strongly and say that he was Durrant’s. He was the complete master of that group. And it was largely because of the trust men had in him that Billies stood thus at 23s. 6d.—24s. and were being talked higher, in spite of the Committee’s report in favour of their rivals. For, after all, the report of the Committee was as yet private, and, what was much more important, it could be overruled by the Secretary of State at the head of the department. One thing was certain, whichever got the charter—that is the monopoly—would have Dow’s at their service. For Dow’s could have no other market, and the new market would be immense. Even if Reynier’s did have already some pull or claim, they would have to sell it to Durrant’s if Durrant’s had the P.M.G. in its favour.

And there was Wilfrid Halterton sitting and waiting for James McAuley.

The Postmaster-General knew that this close but direct fellow McAuley was coming to complete a sound proposition; on that sound proposition Halterton had already been approached in a series of interviews from the first days of the session, of which conversations this coming one was to be the last and decisive. He had said as much to Halterton when they had met only twenty-four hours before in the Postmaster-General’s room at the House of Commons and arranged the last details by word of mouth—yet did that statesman hesitate and still dread what was coming. He was still in that mood when he heard the rumble of the lift, a discreet voice at the door asking if Halterton were in, and the light but determined step of his visitor in the passage.

He got up to receive the familiar figure as it entered: the short contained figure of a man much the same as himself in years—but how different in aspect: hands ready to grip, lips under firm control, eyes searching but fixed, and all this modified by a voice that was at once courteous and suave.

“You don’t find it cold, J., do you?” said the host. “If you do I’ll turn on the other one.”

“Nay! Not cold!” said McAuley. “I’ve been walking. A man ought to walk this weather. I’m thinking I’m a touch late,” he added. He pulled out his watch. “I’d hate to be late.”

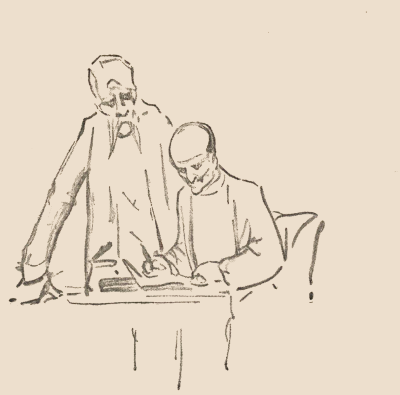

Then he sat down, and with a lack of preliminaries that was native to him sharply pulled out a bunch of papers from his pocket, looked at one of the sheets, and spread it out before him on the table. It was a large quarto sheet of the best thick paper, with the Royal Arms on it and the heading of the Postmaster-General’s Office. It had on it perhaps twenty lines of clear typescript.

The Postmaster-General had always heard that in critical moments of negotiation it was important to stand up and make the other man sit down. He had always heard that it gave one a dominating position. It was part (he had been told) of the A B C of success. But all this knowledge, though sound enough, availed him nothing; for McAuley said, gently enough, “Sit ye down, Wilfrid. Ye can read it the better so. We can run through it together in a trice.”

So Halterton sat down, drew up his chair, and joined his visitor in studying that typewritten sheet. It was addressed to the Directors of the Durrant Imperial; it began, “Gentlemen,” and it ended, “Your obedient servant.”

When Halterton had read the letter he sighed, and McAuley, by way of contrast, gave a sharp little cough—a cough of half-insinuating command.

“All the main points are there, ye’ll be noting,” he said. “All the main points. ’Tis quite simple. Just a word o’ memorandum. Now ye’re agreeing to give us the contract—oh! quite general. And it’s sufficient—oh! we shall be quite content with that to go on with.”

“Yes,” answered Halterton. “Yes. . . . Yes. . . . I think I shall see better with my glasses.”

He pulled out his spectacle case, rubbed the lenses carefully with his handkerchief, put them on, took them off again, rubbed them over a second time, once more put them on very carefully, got the right hook wrong and spent quite a second or two curling it round his ear, while his visitor chafed restrainedly. Then Wilfrid Halterton settled down, not too certainly, to business.

“Yes, it’s quite clear,” he said. “All that you were saying yesterday; it’ll be quite enough for you to act on . . . when I’ve signed it.” And he sighed again. Then he got up slowly and began pacing the room, keeping his eyes vaguely as he did so on the sheet which McAuley still held down before him with a careful but firm hand and with watchful eyes fixed on the other’s face.

“You see, J.,” said the Postmaster-General, “the Committee have decided against you . . .”

“We’ve had that out before,” took up McAuley quietly and not unkindly. “We’ve had that out several times already.”

“Of course, the Committee’s report in favour of Reynier’s isn’t public yet . . . not public. . . .”

“Well, well, it was public enough to make t’other lot jump a shilling the day.” And Mr. McAuley laughed a subdued laugh.

“Well, what I mean. . . . The way I want to put it,” said Halterton, “is that . . . of course you’ve pretty well convinced me, but what I mean is, if I decide to go against the Committee. . . . No, what I mean is, if we, the Department, should finally decide to go against our own Committee . . . why. . . .”

J. McAuley pulled out his watch again.

“It’s a pity to waste time over these things, Wilfrid,” he said shaking his head, but without emphasis. “Ye’ll not hear anything more, I think, for there’s even nothing more to add. I take it, ’tis settled. Have you got it on the Order Paper yet?”

“It goes in to-night,” said Halterton.

“Well! There ye are! Didn’t I tell ye it was settled?”

“Yes, but one could always hold it up . . . delay debate, I mean.”

“Oh! Come man!” said McAuley, still gently, “all this is great waste o’ time, surely. ’Twas all fixed yesterday.”

“McAuley,” said the Postmaster-General, sitting down again and putting his spectacles away, and looking towards the door a moment, “have you brought anything in writing? I mean . . . something for me? We’ve had nothing in set terms as yet, you know. Not on that point. My point.”

“No . . . no,” said J., more slowly than he had yet spoken. He sifted his papers a moment, and then turned again to the sheet of paper on which stood those twenty lines of typescript with the Post Office heading at the top. “This note from you to us is what comes first, naturally,” he continued.

“I say, J. . . .”—the Postmaster-General gave a little nervous laugh—“you ought not to have written it on the official paper, you know. You should have left me to do that.”

“Eh, man, but ye do beat about the bush!”—there was a faint hint of irritation in McAuley’s even voice—“what would ye have me write it on? ’Twas no good making another draft for a simple thing like that, and it saved time to put it on your paper, from the office there. I took some with me last time I saw ye.”

“Oh, did you?” said the statesman. “All right.”

Then he put his spectacles on again with deliberation and slowly read the matter before him. He looked up.

“Oh, I say, this isn’t quite what I meant. This to be from me—of course?”

“Aye, of course,” said McAuley, “what else should it be? And if ye’ll just sign ’twill all be right and ready and we can all go ahead.”

“Well, no doubt sooner or later there will have to be some memorandum of this kind . . . but after all, it was for me to write it, wasn’t it?”

McAuley was so provoked that he went too far; clicked his tongue impatiently.

“Ye’re difficult, man!” he said, “very difficult!” He half frowned as he said it. “Come now,” more cheerfully, “I canna get to work till ye’ve signed; we settled that yesterday, didn’t we?”

“All right,” said Halterton, “all right. . . . But I want to put it this way. I think we ought to exchange memoranda, eh? Simultaneously, eh? Don’t you?”

“What d’ye mean—exactly?” said McAuley doubtfully.

“Why,” answered Halterton, “when I give you this acceptance of the proposal . . . if I sign . . . why that’s giving you the contract, isn’t it? . . . Virtually? You’ve put it clear enough.”

“Of course it’s enough for us to start work on the strength of it. That’s why I brought it.”

“Yes, but. . . . But there’s the other side to it, you know.”

“Oh,” said J. genially, leaning back for the first time in the conversation, “ye mean that ye’d have me to put down in writing here and now what I’ve been saying to you lately about y’r own position in the Company—if so happen ye should resign and go into the City, for instance?”

“Well . . . yes . . . Something of that kind, you know . . . something of that kind.”

“Hey! ’Tis not the time for that yet! Ye’re still in office, ye know. See now that it’s all right, before you sign, I’ve to-day’s date on it.”

“Yes, I know, I know. Quite. But still, I should feel . . . what shall I say. . . ? I should feel a little more . . . regular.” He stood up with this and watched the talker.

“Oh, regular!” admitted the persuasive J., still seated, and he gave a very slight half-smile. He sat silent for a moment, still keeping that half-smile and rapidly considering the full consequences. It would tie him. It would leave a record to have the Postmaster-General’s share in the arrangement written and undersigned by J. himself. It would give Halterton a hold on him. But then, Halterton seemed to insist, and it was necessary to have Halterton’s signature now, at once.

“Very well,” he said at last. “It might have been better to leave that part of it as a gentleman’s agreement, and verbal, but perhaps you’re right.”

He drew out from among the papers a blank sheet, headed it with no date or address of any kind, and with the fine, hard nib of his neat fountain pen—symbolic of the man—he wrote rapidly for several minutes, covering the large sheet of paper with his stiff handwriting. Then he pushed the note over to the Minister. Halterton took it up and read it slowly, half aloud:

Mr. James McAuley, financier, makes everything regular for Mr. Wilfrid Halterton, Statesman and Postmaster-General.

“My dear Halterton. . . .”

“I put it like that, Wilfrid,” interrupted J., “it’s not likely that they’ll give ye more than a Baronetcy and of course I couldn’t call ye Wilfrid. And whether you choose to be Sir Wilfrid or whether you don’t, ’t’ll work either way.”

“All right,” sighed Halterton, and he began reading again:

My dear Halterton,

I am going to approach you with a proposition which I do sincerely hope you will smile on. I know what a modest view you take of your own talents, especially in the business line; but you are the only man in England who does; and what is more, your administration while you were at the Post Office not only gave you just the kind of experience we want, but earned you the respect and admiration of everybody. So what I want to ask you is simply this: “Would you, now that you are out of public life, and I suppose enjoying plenty of leisure, consent to take up the Managership of our Corporation?” Since my appointment as Chief Permanent Commissioner was settled there has been a great deal of discussion on the board as to who should be called in; but I don’t like these long discussions, and I don’t like a vacant place. Still less do I like having to do two jobs at once. I need hardly tell you that when your name was mentioned we were unanimous about it. The only trouble was whether you would consent. For we know how you value your leisure. But do say yes! It would be a personal favour to me; and, what I am afraid I value even more, you would make all the difference to what is now a great public service. I am putting my whole heart into this, and I do beg you not to refuse.

Yrs. ever,

Jas. Haggismuir McAuley

It was a fine clear signature, worthy of the man whose mother had been born a Haggismuir of Haggismuir.

Mr. Wilfrid Halterton finished his reading of it, and looked up. There was, what is odd in a man well over fifty, and especially in a man over fifty whose genius had raised him to one of the greatest public positions in the world, a faint tinge of colour upon either cheek.

“I think, J.,” he said, “I think it would be more . . . er, regular, wouldn’t it, if you were just to write a . . . a postscript with a word or two about . . . well, about the salary?”

“Regular again, Wilfrid!” said J., with that same faint momentary half-smile of a few minutes before. “All right. What was it I said the other day?”

There was a long pause. At last, almost in a whisper, came the words:

“You said ten thousand, J.” Then, in a still lower tone, “Free of tax.”

“All right, Wilfrid,” replied J., in a cheerier tone than he had yet used. He scribbled off the postscript, and after that the figures, then the phrase, “Free of tax,” he added, “and official residence, of course, if you care to use it.” And the neat initials followed: “J.H.M.”

The Postmaster-General was not quite sure; he had always understood that an initialled addendum to a memorandum or habendum ridendum, or any other official binding thing, “went,” as the saying goes. At any rate, he felt he could not ask for anything more.

“Now,” said J., in a more business-like tone than he had yet used, “ye’ll keep that—and date it when the time comes.”

“I suppose it will need some address, won’t it?” asked Halterton.

“Hey? What does that matter? Ye can add it. Ye can write in whatever you like. That’s not what counts. ’Tis my name at the end that counts. Ye can write in wherever I happen to be at the time.”

“Very well, very well,” said Halterton.

James Haggismuir McAuley got up and stretched himself. He also yawned, which, with him, was a gesture of satisfaction and completeness: but he was careful to put his hand in front of his mouth.

“Now,” said he, “we must get them in their envelopes, and we’ll each take his own. . . . I’ve brought the envelopes to fit—not that it matters much. Do you sign yours—your typewritten one.”

Wilfrid Halterton brought out his little fountain pen mounted in gold and slowly inscribed his name. McAuley blotted the same: folded the fateful document which gave the contract, stuck it in the open envelope; gummed it carefully down and put it in the inner pocket of his coat.

Halterton, always influenced by example, more slowly pocketed James McAuley’s generous and as yet undated offer. But he added something of his own, under a vague feeling that it rendered him more secure. He took up a pencil and wrote, in his rather straggling hand, across the top of the paper which James McAuley had given him:—

“James McAuley’s letter. Handed to me March 3, 1960. W.H.”

He could always rub it out when the time came to use it, and meanwhile there it was as a sort of record. McAuley watched him as he wrote and folded it with too much deliberation, and put it into its corresponding envelope, making only one boss shot. Then, licking the flap and pressing it down, to keep state secrets hidden from all profane eyes, Wilfrid Halterton, Postmaster-General, put the envelope into the pocket of the morning coat he was wearing—the side-pocket away from Mr. McAuley.

“Now,” said that great captain of industry—or, at least, of applied science—or anyhow, of finance; “I must be off.” He looked at his watch for about the fourth time. “Aye, man! I must be off. I’m in a hurry—I shall be late.”

He shook hands warmly with his host as the Postmaster-General showed him to the door, walking at his side. James Haggismuir McAuley stopped a moment in the passage, looked up at the wall, and said:

“That’s a fine etching, Wilfrid!”

Wilfrid turned his long thin neck round to follow the connoisseur’s gaze. As he did so, in the tenth of a second James Haggismuir McAuley had removed the envelope from the side-pocket, passed it in a flash round his back into his other hand, and got it into that breast-pocket of his where its little brother already lay.

Mr. James McAuley, financier, effecting a conveyance of property from Mr. Wilfrid Halterton, Statesman and Postmaster-General.

That business transaction did not take five seconds all told. It had taken Wilfrid Halterton ten to move his neck.

He began the story of the etching, of its value, of its acquirement by him, when he felt his hand warmly grasped again by his friend from the outer, non-political world; he heard the door slam; he sighed, stooped his head somewhat forward, and shuffled back into his study.

As Wilfrid Halterton once more sat by himself in front of his wireless heater, he was filled with that powerful impression men receive but once or twice in the course of a lifetime; the impression that a whole tide about them has changed; that they have passed out of one long phase, during which the current has carried them in one direction, and that now they have come to a second phase, in which the current is to carry them the opposite way. He felt that he had achieved—or, as the phrase goes among statesmen, “made good.”

His own position in the negotiation just concluded was but one out of many such. The deal about his future salary was of a commonplace sort, something we have all come to expect in political arrangements. But it was the first one he had made in all his years of Parliament, and it impressed him accordingly. He had always been far too timid a man, in a profession where timidity is sometimes fatal, and always a handicap. Some women (and men) had blamed Mrs. Boulger for giving him Cabinet rank at all. But we know that if a man attains such a position it cannot be without high talent, which his eminent colleagues have recognized. Such talents he had abundantly shown during his tenure of office. He himself had now been for more than six months at the head of a vast machine; he had delivered daily 264,748,942 letters; 968,477,321 postcards; 7,263,402 telegrams; stamps of all denominations to the value of £6,923,410 6s. 3d.—more than the entire yearly revenue of Guatemala—and at the same time carried parcels and issued licenses for armorial bearings, dogs, and male servants.

Wilfrid Halterton had managed all this for now over half a year, and there had been no hitch. It should have given him a better opinion of himself. Besides which, he should have remembered that a man is not given powers of this exalted kind unless he be also competent to deal with many other activities. Having shown his capacity for handling this huge, intricate business of the Post Office, he would be naturally chosen to direct in turn the finances of the nation, its Foreign Affairs, its Navy, its immense Police machine, public and secret, and perhaps its Museums, or even the London Parks. For it is a presumption in our constitution, and a wise one, that the talents sufficing for a Cabinet Minister in one Department will suffice for him in any other and a statesman must shift around.

Wilfrid Halterton should, I say, therefore have been less modest in the first months of high office. None the less, his original mood remained with him, and he was glad to think that his first considerable political success, this negotiation of his with James McAuley, would enable him to re-enter private life. He was content to leave to others the glory of public fame, and to take in its place a largely increased income.

He would make the delay as short as possible. There would have to be an interval, of course, between the establishment of the new Television Corporation and his taking over the prepared place and the salary agreed upon: convention demanded that, and convention must always be observed. No man in the House of Commons was more sensitive upon such points. No man knew better the decencies of public life; no man shrank more sensitively from censure in these matters. Such delicacy went naturally with his character; it was the more laudable side of that in him which also produced his hesitations. When these things are done too quickly there is—illogically enough—a savour of something indecent about them.

He pondered for a moment as he leant back in his low chair and gazed fixedly down his long legs at the glowing grid of the heater; he was estimating what exactly the interval ought to be between this moment and his taking his salary at the head of the new Television Corporation.

Better too long than too short. J. would set to work without delay. The vote establishing the Television Corporation would come on almost immediately. It would be in public use not long after the Easter recess, and earning by the end of the summer at latest. There had been some talk of nominating young Collum to the first Chief Commissionership for a year or more, to give him time and an income for marrying Joan Bailey—who had nothing—for buying his furniture and all that—before taking up the new post at the League of Nations. Then J. would naturally succeed, and the Managing Directorship would be open—say an interval of little more than twelve months all told.

His own resignation ought to take place, then, in about six months, so that when he accepted the management it should be with an air of leisure quite unconnected with the Post Office. This delay of six months is generally understood to be the least required between a man’s ceasing to take an official salary and beginning to receive the larger private City emolument which is the natural reward of political services. Well, if the Charter came into effect in the late summer, that would mean his own resignation, say, about next Easter, in rather more than a year. He could make use of J.’s letter then, date it six months after that, say in the autumn of next year, eighteen months all told.

He made all these calculations for his own satisfaction, and through them all ran the substantial prospect of which he was now assured.

Wilfrid Halterton had been born to considerable wealth; the only son of old John Halterton of Reldwell Hall in Essex. The Halterton Library, at his old college at Cambridge—Merrion—was witness to the family fortune and generosity.

But things had not gone well since his father died, now twenty-five years ago. He had managed ill; he had suffered badly from one big crash in investment; he had grown embarrassed. He had mortgaged. He had got into arrears. Some years of increasing difficulty had preyed upon him. The more relieved was he at the new prospect: that document with J.’s firm signature to it, the certitude of ample security, the old income of his early manhood and more.

He meditated on that document. He recalled J.’s face and gesture while it was being drafted, and the light on the paper. He would not, of course, fill in the date as yet; there was plenty of time for that. Then, not for any useful purpose, but from that sort of itch we all have to read again a letter which has filled our thoughts, he felt in his coat-pocket for the envelope. He would pull out McAuley’s offer and go through its terms again exactly—though the only thing of moment was clear enough in his brain—the salary; free of tax.

For a second or two he wondered why his hand did not meet any envelope in that pocket, and he still groped. Then he woke up, with a start, leant forward and thrust into the pocket three or four times, as if he were looking for some small object like a coin. No. There was nothing there.

Memory of a recent instinctive movement is nearly always accurate; but one never knows. He plunged his other hand into the pocket on the other side. Ah, there it was! No . . . that envelope was one which had been there all day. It was the note from his tailor. It was of a different size, too.

He grew half curious and half alarmed. He got up out of his chair. He actually took off his coat. He took everything out of his pockets and turned the linings inside out. There was not a sign of the thing.

Then he went down on his knees and lit a match to explore the darkness under the table. He drew blank. He went out of the room and searched all the short way to the front door, along the passage. There was nothing. He stood in a quandary, his eyes fixed again upon that etching which McAuley had praised. It brought the movements of that quarter of an hour back to him as vividly as though he were still living in those moments. How could the thing have gone? He spent another futile five minutes back in the room, crawling about the carpet on all fours; lifting the corners in the vain idea that it might be lurking there.

Then he stood up again and pondered fruitlessly. He had heard no servant in the hall outside; no one had come in by the front door. If anyone in the house should find that envelope it would be awkward . . . but that was impossible . . . there had been no time for such a thing; no one could have known what he had had upon him.

Further search seemed useless. Things do disappear in this extraordinary way. The bother about this particular thing was the unpleasantness of knowing that such a letter might be lying about loose. He said to himself that there was no time to be lost: the essential thing was to communicate with J. at once.

He had had time to get home to his flat by this time, surely? He must telephone. He went to the little room at the back where his private telephone stood, and when he had got on to McAuley’s flat in Marble Arch House at the top of Park Lane, not half a mile off, he heard, even as the servant answered, another voice speaking which he could have sworn was that of McAuley himself.

It was not a voice near the instrument—it could not quite certainly be made out—but he thought he caught certain words.

The voice that presently did answer him clearly and directly was that of McAuley’s secretary: he knew her well—an efficient gentlewoman, of like nationality with her employer, Rose Fairweather by name. That voice said, in singularly distinct tones, that J. had been in for a moment, and had gone out again.

Halterton was almost positive he had heard J.’s voice, and that, in spite of its faintness and his inability to catch all the words, one patch of those words had been: “If it’s him,” and another, “You don’t know when.”

In answer to a second more nervous questioning there had come the still more distinct reply, that not only had J. just gone out but that he would not be back for dinner, and that Miss Fairweather did not know where he had gone or when he would return. . . . No, he might not be back till long after midnight. . . . No, he had not dressed, and he hadn’t taken a bag. . . . Oh yes, he would be back some time next morning at latest . . . yes, he would get his post. . . . And with that Wilfrid Halterton had to be content. But it left him in an agony.

As he walked slowly back to his study from the private instrument in the little room he asked himself what a man ought to do in such circumstances.

A Statesman and Postmaster-General looking under a carpet.

Here he was, with a document which no one else must see, lying about lost and to be found by heaven knows who. It was a document vital to him, and he himself was deprived of its use and without guarantee. J. would certainly act very soon; hardly, perhaps, next day, but certainly within a few days; and then all the world would know that the Charter was as good as granted. And he, Wilfrid Halterton, would be there without his side of the affair secure under his own keeping. Obviously there was only one thing to be done. He couldn’t make out why he hadn’t thought of it at once. Since J. was not on the telephone, he must write to him. He could not help thinking that J., for some reason or other, had wanted not to be bothered. He was almost certain he had heard that voice, and nearly as certain that he had heard those two fragmentary phrases. He quite understood that McAuley should want not to be bothered, but still he ought, after such an important transaction, to have come to the instrument. Anyhow, it was too late now. He must write, and he must send it round at once, or even take it himself, to make certain.

He did it in only a few lines.

My dear J.,

An extraordinary thing has happened. That letter of yours has disappeared. No doubt it will be found, but as it may not be for some time or even perhaps never at all, of course the only thing is for you to write me another. You remember the terms, I am sure. I do not know when you will get this, but your secretary tells me you will be back some time to-night, and I am sure you will send me a message first thing to-morrow morning—by hand if possible. I shall be at home till ten.

Wilfrid Halterton re-read these simple words, was satisfied with them, and then spent another ten minutes of indecision, as to how they should be delivered. It was really imperative that J. should get them certainly, and get them as soon as possible. He was in such an anxiety that he was half inclined to take them himself, had he not feared almost any movement of which record could remain. Besides which, if he stayed at home he could spend some more time looking after that strangely truant bit of paper. He would trust to the post.

So he went down to the street and posted off his note to McAuley with his own hand at once. Then he passed something like two hours searching over and over again, with what, in a less eminent man, might have been called fatuity, making certain and re-certain and counter-certain that the envelope was nowhere to be found.

There was nothing on for him at the House. He had paired in anticipation of that important interview. He dined at home, and went to bed early. He read for half an hour before sleeping, but he could not remember what he read. He felt as though he had been reading the missing letter. And twice in the night when he woke he could see its contents before him with extraordinary clearness—he could have recited it by heart.

Oddly enough, when Wilfrid Halterton sat down to his breakfast the next morning—Wednesday the 4th of March—and took up his newspaper, he made no search for an item which was to prove of more interest to him than any other. It did not occur to him that such an item would be there. He solemnly read his first leader, then his second and his third, after barely glancing at the big head-lines, which told him nothing more than he had seen in the evening papers of the night before. He went through the rest of the paper in no hurry; until he came to the financial page, and there it was that he saw what suddenly checked the wandering of his mind.

There was a paragraph about the position of Billies. It was rumoured that the report of the Committee appointed by the Postmaster-General had been unfavourable to Billies and favourable to Reynier’s; of course, nothing certain was known, but the report would doubtless be published shortly. That was all. The rest of the paragraph was only a few lines of the usual anodyne sort, mentioning vaguely the rival companies and their claims.

Halterton frowned. His dignity was offended. This kind of leakage could not be allowed. It was also exceedingly awkward now that J. held that signature of his. It was torturing. He wondered who had talked.

I could have told him. It was the sharp little page boy who goes in and out during the Committee meetings announcing people and taking messages. He had talked. He had got half-a-crown from the porter, and the porter had got a sovereign from Mr. Gamble, who had received fifty pounds in five ten-pound notes in an envelope from Miss Rose Fairweather’s own dainty hands when he had called there the day before at Mr. McAuley’s flat. Mr. Gamble had gone on gaily to his newspaper, and received another twenty pounds from the Financial Editor, to whom Miss Fairweather had specially recommended him. The Financial Editor had got no money indeed, but hearty thanks when next he met his proprietor—I use that word in its fullest sense. Also the Financial Editor had promptly sold his Billies before writing a line.

Anyhow, there the paragraph was, and after all, it could not be contradicted because it was true. There was nothing to be done now, the thing was printed, and it would be known, anyhow, when Parliament met that afternoon: so there was nothing to be done. And Wilfrid Halterton was far too much a gentleman to have words with his permanent officials, anyhow.

He looked at his watch. It was just on ten o’clock. J. would probably be ringing him up any moment now. He waited, and waited, his nervousness increasing; no ring came. It was fully a quarter-past when he could bear the suspense no longer, and himself rang up the flat near the Marble Arch.

Once more the clear accents of Miss Rose Fairweather, delicately balanced between the soft Glasgow and the more lapidary Edinburgh—reflecting therefore, perhaps, an origin in Whitburn—replied like chiselled silver.

Yes, Mr. McAuley had been in for a time that morning, and had worked with her for an hour; but he had gone out again, saying that he would walk to his office, in the City, because he wanted the exercise. He would hardly be there till well after eleven, he had one or two things to do on the way.

At eleven-thirty Wilfrid Halterton, now slightly feverish, took the risk of ringing up the Imperial Durrant’s crowd by the number of their palatial building. It was not very regular, the Postmaster-General was not supposed to do that sort of thing—but after all, it was most unlikely anyone would know his voice, and if by a miracle they did, why—everybody knew that he was a friend of McAuley’s, and that McAuley was a brother of his colleague the Attorney-General. He might be ringing up about anything.

Anyhow, he need not have been in such a stew, for the answer was simple enough.

Yes. . . . Mr. McAuley had been in, and had attended to a little business. . . . No, he had gone out again. . . . He wouldn’t be back till after lunch. They did not know where he had gone to. They couldn’t say when.

Once more did the sorely harassed Wilfrid Halterton challenge the gods—once more, before he went down to his own office at noon. And this time it was again the flat near the Marble Arch which he attacked. And once more did the pellucid, sweetly-divided syllables of Rose Fairweather inform him that Mr. McAuley had indeed rung up his flat, from the Carlton Hotel, where he had happened to be for a moment in the course of the morning, but that it was only about some papers he wanted sent on to him there by messenger, and that he would have left the hotel long ago.

The Postmaster-General had no desire to increase this stream of records, or to emphasize his tracks. He must possess his soul in patience until McAuley should come to him in his rooms at the House, or until in some other way they should meet again. It could not be long. And if he did not see McAuley after a sufficient delay he would write him another letter. But all that day there was no sign of McAuley.

* * *

What did happen that day, and what the Postmaster-General himself discovered from the evening papers, and from the tape, and also, to his no small annoyance, from a certain amount of conversation around him, was a smart little fall in Billies. They had opened well below yesterday’s level, at 21s.—22s. They had sunk to 20s.—21s., rallied again at 22s. and closed at 22½s. The rally, it may interest my readers to know, was due to the purchase of a fairly large block in the interest of a Mr. Charles Marry—a relative of Miss Rose Fairweather’s, whom she had herself introduced to James McAuley, and who was now devoted to the interests of that great man.

A whole day having thus passed without news having reached the Postmaster-General from his good and intimate friend James McAuley, it was necessary to take action.

There are situations which act marvellously as a spur to the intelligence, and Wilfrid Halterton that very evening acted as he had never acted before in his life. He did what is called, “taking steps”; he “cast about,” in half-a-dozen quite indirect, discreet, indifferent remarks dropped here and there, in the dining-room of the House and in the lobbies, and succeeded by half-past eight in getting hold of J.’s momentary whereabouts.

“Who’s dining at Mary’s to-night?”

“Do you know whether Johnny’s at Angela’s to-night?”

“Hullo, I thought you were dining with McAuley?”

And so on; with such phrases he traced McAuley to his lair. He heard at last that the financier was dining with the Balcombes. At that time of night which Victor Hugo so finely calls the desert hour when lions gather to drink, that is, at a quarter to nine, when the lions lift the first cup of champagne to their lips in the houses of our great democracy, Wilfrid Halterton caused J. to be summoned to the telephone: he used a ruse: he summoned J. in the name of his secretary—“Say Miss Fairweather wants him—urgently.” James McAuley, who had but just sat down and exchanged his first words with his hostess, Lady Caroline, in the very ugly grand new house of the Balcombes in Hill Street, cursed under his breath, left the dinner, went out and sat down to the telephone in Balcombe’s private room; with the thick door carefully shut. He lifted the receiver and said, rather testily:

“Well, Miss Fairweather?”

But it was not Miss Rose Fairweather’s voice that he heard in reply. It was the voice of Wilfrid Halterton.

“I’m sorry to trouble you, J. . . .”

“What d’ye mean? They told me ’twas my secretary.”

“The servant must have made a mistake—it’s me.”

“Yes, I can hear that. What about it? What do ye want?”

“You got my letter?”

“Yes, I got your letter. But I didn’t understand it. I think ye’d better explain when I see ye.”

“How do you mean, you didn’t understand it? I told you I’d lost the letter you gave me last night, and asked you whether you could send me another.”

There was a pause, and Wilfrid Halterton at the other end of the wire wondered why there should be a pause. He was not left long in doubt. There came at the end of that pause, in strong virile accents, Scots in timbre, the following words:

“I can’t understand what ye mean! I never gave ye a letter. You gave me a letter. I’m sorry. I can’t wait now. I’ve had to come away from the dinner table. I must get me back. Try and see ye to-morrow.”

And the wire went dead.

There is a row of semi-detached villas in the suburb of Streatham known (I know not why) as Eliza Grove. Of these semi-detached villas, one (known officially and to the gods as Number 5, but to mortals and on the front gate in white letters on a green ground, as Myrtle View) is the dear home of a small building contractor, by name Nicholas Clarke. As he has nothing whatever to do with this story and, for all his efforts, will not be allowed to appear upon these pages again, we may leave it at that. But the other villa of this Siamese twin, tied on to it, rib to rib, Number 7, also with a green door, has no particular name; for its owner has discovered in his social advance that the giving of names to small suburban houses is not done. It is plain Number 7, to gods and men alike.

Here resides that strong, humorous, kindly, thoroughly efficient, healthy man, just on sixty years of age, known to the world as Jack Williams, for the moment Home Secretary—but there, he might be anything he pleased. The ball is at his feet. He had been offered the Presidency of the Council and had refused it; partly because the opportunities were insufficient—no contracts—partly because it was not a leg up. As like as not he would have the Dominions before the end of the year, for the present Secretary of State for the Dominions, like others before him, found his job a very thankless one.

Anyhow, Jack Williams is for the moment Home Secretary, pleased with his work, as he has been pleased with everything he ever had to do, and doing it well, as he has done well everything he ever had to do.

You would notice him anywhere, for though he was but a rather short man, with heavy, undistinguished features, and those rendered common by an undignified small moustache, his carriage and still more his expression would have struck you. His twinkling steel grey eyes, intermittently narrowed as he gazed sharply at you in conversation, had a sort of fire in them: they saw everything that was going on about him. His big shoulders had strength and endurance, his deep chest vitality, and his step was solid. Also there was this about him, that when he spoke he spoke with zest, entertainingly, full of life, and yet said nothing which could betray what was in his mind. The very man for politics!

He was an early riser, and this Thursday, March 5th, at 8 o’clock, he was sitting at his breakfast table, with his admirable wife opposite him, in the little front room of Number 7.

It was the morning after that strange, abrupt conversation which had passed on the telephone during the dinner between James Haggismuir McAuley and the distracted Halterton. Jack Williams was reading his newspaper, propped up against the coffee pot, and anyone who had seen him would have said: “Here is a man who has risen from very small beginnings to a modest, but, for his station, prosperous middle age. This little semi-detached villa with its spare bedroom, its parlour and its dining-room, and its one neat servant—this humble suburban home—is for him comfort and even luxury. He contrasts it in his own mind with his origins in that miserable muddy slum up North where he passed his starved childhood under a mother broken with childbearing and a father alternately drunk and sober, and bringing in, as luck served him, about a pound a week, in the old days before the Great War when the poor were really poor.”

Anyone who had passed such a judgement would have been right. Jack Williams did feel exactly like that. He had risen, he had prospered. Indeed, he had prospered more than the observer would have imagined. He was worth about a quarter of a million pounds.

He had risen simply and naturally, as such men do, something of a hero among his fellow-boys in his teens in the mill, finding he had facility with his tongue, joining in debates, as a young man, when he was shop steward: then advancing in his Union, then secretary to it: then elected to Parliament, when he was thirty years of age, not long after the Great War. All the regular routine, the cursus honorum which is happily still the public life of England in 1960, and which blends so well with the remains of our old aristocratic policy.

He had been cordially received as he rose. He had made his mark in the House of Commons. He had first had office of a minor sort before he was fifty. He had entered the Ministry in Mrs. Boulger’s first administration. He had used his opportunities well, investing shrewdly, getting to know all he could about men, and using all that he knew, to their praise or shame, making the right friendships with rich men—real friendships upon all sides. It was a point with the young bloods to boast that they knew him. There was competition among the great hostesses to get him into their houses—and he went.

The Right Hon. John Williams, Esq. (“Honest Jack Williams”), M.P., Secretary of State for Home Affairs in Mrs. Boulger’s second administration (1960).

Among his many talents were two which just fitted such a position: he played billiards admirably—he had discovered his ability therein before he was twenty years of age in the dingy billiard-room of the “Percy Arms,” whilst he was yet a lad in the mills, but already earning good money. And he had a quick, racy sort of repartee. He never tried to lose the accent of his native town and province. If anything he exaggerated it, though whether consciously or not I cannot say.

There he sat, reading his newspaper. But he was not one of those men who read their newspapers to the discomfort of their wives. If she had helped to make him, as she had, it was not only because she was a woman of such capacity (he had married her when he was still a very young man—they both worked in the same mill and earned between them less than four pounds a week), but because he had always respected her, always cherished her, and always depended upon her judgement in a way which she could feel and be proud of. She was a woman much after his own mould in features as in bearing, equally resolute though more demure: not provided of course with the small moustache: and I am afraid, not humorous about the eyes, but steady in her gaze. Upon business affairs she had never advised him. She never interfered with any decision of his to do this or that, as he went up in his career, save now and then quietly and at critical moments, but she gave judgements usually negative, against what might have been a false move. He was careful of her, and he was right. Their one child had died while they were still poor in the North, in the old days. That grave had strengthened the bond between them, and no man and woman in England were to-day less lonely.

So he was reading his paper this morning, not selfishly to himself, but with a running commentary to her as he read, telling her the news.

“Sammy’s been at it again. He talks too much. . . . Hullo! Jack’s got a letter. . . . All about the currency, and saying nothing.”

“That Lord John never does say anything worth hearing,” commented Mrs. Williams.

“Oh, but he thinks a lot,” answered her husband; and he added, “That’s how he’s got where he is.”

“And where is he?” said Mrs. Williams superciliously. “In the soup!”

“He may be now,” answered the master of the house, nodding sagaciously, “but he’s one as crawls out of the tureen. Don’t you forget that, Martha. Now, you be kind to him!”

“Oh, I’ll be kind to him, Mr. Williams; I’ll be kind to him,” said Martha, a little ruffled.

“Yes, my dear, you always were. You always know what to do.”

There was a pause. And during that pause the husband turned over the paper and looked towards the back pages. His wife knew what that meant. He was glancing at certain high matters in stocks and shares, with which she was far too wise to interfere.

Mrs. Honest Jack Williams, one of our leading political ladies, giving her judgement that Lord John is in the soup.

He had done admirably at that game, and she knew her limitations. Always in her heart when she heard (for he sometimes blundered) of such and such a big thing brought off, or when he told her in a general way (for he did that also) how they stood before the world, how he would cut up, she remembered that there might have been a son to which all this should have gone. But she never spoke of that. She knew well enough what would happen if she survived him. It would all be at her disposal. And if he survived her, why, she knew well enough that what time might be left to him would not then matter to him much. She had a vague feeling, which people often have when they have had so close a companionship for so many years, that somehow neither would survive the other. It does not exactly happen like that; but it often happens nearly like that. . . .

And even as Honest Jack Williams (Secretary of State for Home Affairs) looked at those stocks and shares, and even as the eyes which she could just see above the propped-up paper got a look of concentration in them, while he fastened on the figures he was following, she admired him more for his excellent judgement of the market, which she well knew to be the chief glory of a public man.

There had been ups and downs, though he had told her frankly of certain misjudgements or bits of bad luck; but on balance he had always been going upwards—and to what a height! For of all that large solid income nine-tenths was saved and went to swell the pile. There was the salary as well, so long as he was in office. And as for Number 7, Eliza Grove, slavey and all, and the taxis they were always taking, and the visits and the rest, the whole thing didn’t come to fifteen hundred a year. She had good reason to be proud of him.

In these few moments of concentration during which he interrupted that conversation with his wife, which he was very careful to maintain, Jack Williams had captured with his bright sharp eyes one point after another in the financial news before him. He had seen that the Indian Loan was steady, he had been a little annoyed at the head-lines on the Third Central Bank; there had been a half-smile on his face for half a second at an absurd puff of the New Guaranty Loan, which he had heavily sold forward upon good official knowledge, shared by not more than half-a-dozen other men. Then his expression changed again and became arrested and almost excited. His wife noticed the expression, but she could not tell what caused it.

What had caused it had been something very small but very significant. It was a line in the middle of the industrial shares, the line concerning Billies on the New York Exchange after London had closed the evening before. That line said simply:

“Durr. Imp. Tel. Ord. 29s. 6d.—31s. 6d.”

The Home Secretary gave a very low whistle, for which he politely begged his wife’s pardon. He put the paper down, and asked Mrs. Williams what she thought on a vexed question which had been a good deal debated between them: whether they should make a bid for the cottage in Surrey on the fringe of the park palings which they had hitherto leased from their very good friends and constant hosts in the big house at Henbury.

Mrs. Williams was always voluble on that subject; she knew that her husband was against buying, while she was in favour. Mr. Williams therefore expected—and got—a good long re-statement as usual of all her reasons. As she made it he nodded, taking in every point, though he had heard it twenty times before—and it gave him leisure to think without her knowing how his mind was working.

He was not bothering about the cottage. He was wondering about Billies. It would perhaps be too strong to say that he was cursing himself inwardly for not having watched the tape; he had been glued all night to the Treasury Bench, right up to the cry of “Who goes home?” ringing through the vaults of the House of Commons, he had come home too tired to think of anything, he had gone to bed at once, and meanwhile he had missed his opportunity. Lord! How Billies had jumped in New York! Nearly eight bob! Twenty-nine bob, thirty-one, from twenty-two. . . . What on earth had made them jump like. . . .

The voice of his wife came to him across the table (for men like this can attend to two things at once).

“You’re always saying as you don’t want the place—saying it’s always better to look tenants of theirs anyhow—more friendly-like, and doesn’t make people call us forward. But that’s all nonsense, Mr. Williams. You never know what’s going to happen in this world, and we’ve been there now all those weeks every summer for these five years, and I couldn’t abear to part with it.”

“If they was to take it away we could buy them out big house and all,” said Mr. Williams proudly.

“Not open, we couldn’t,” answered his wife.

“My dear, there’s a great deal in what you say, but they won’t turn us out.”

Mr. Williams spoke gently and kindly—but the words that were passing through his mind were quite different: he was saying to himself:

“It’s still early, I can arrange for Gunter to get my packet before that broker leaves his house for the City: but it’s nearly ten bob a share lost already anyhow, dammit!”

Then he continued aloud, to Mrs. Williams: “I shall always do what you want in the matter, my dear—you know that: I shall always do what you want.”

And the sentence running in his mind was more like this: “They’re blazing! I’ve missed the first eight shillings, but I’ll bet they’ll go to forty and over!”

“Thank you, Jack,” said Mrs. Williams. She called him Jack every time she got her way. She rose, with a little difficulty, waddled round the table, and kissed him on the forehead. He fondled her hand, murmuring: “Anything you want, dear, I allus do say, anything you want.”

But in his mind there was running something like this:

“I’m that sure, I think I’ll cover fifty thousand.”

He pulled out his watch and sprang from his seat.

“Hullo, it’s later than I thought,” he said. “I must telephone.”

He went off to the telephone in the narrow hall. He heard his wife’s slow and heavy step proceeding to the kitchen to give her orders for the day to the unique servant, the symbol of their humility. And then, taking off the receiver, he talked to one of the gentlemen with whom he dealt—indirectly—for some at least of his business affairs.

“Is that you, Gunter? . . . yes, Jack speaking. Fifty thousand. . . . No, I know what I’m saying. . . . Yes, I know all about that. . . . Never mind what I missed. Perhaps I didn’t miss it. Anyhow, that’s what I say. . . . No, it’s not too much. . . . Yes, I do know best. Yes, fifty thousand. The second name, the one we agreed on last week. . . . No, no top figure. There’ll be time enough for selling. I’ll tell you when.”

He hung up the receiver again.

The Rt. Honourable Jack Williams, M.P., one of H.M. Ministers, Secretary of State for Home Affairs, loved exercise, as any healthy, successful Englishman will. And though it threatened rain upon this early March day, he would walk, as was his custom, from Victoria to Whitehall. He would be at the office by ten.

As the train took him up to Town his mind was full of that which so often mixes with public affairs in the minds of great statesmen. He was wondering why Billies had kangarooed.

Obviously they had jumped because someone had wind, or believed he had wind, of the contract’s going to Durrant’s. But what was the nature of the information? What was its value? By the time he got to Victoria he had it well sorted out in his mind.

There were four possibilities:—

First, McAuley and his crowd, the Durrant crowd, might have had an assurance; they might have that assurance in their pockets now, and however much they wanted to conceal the fact in order to give them time to buy before the rise, it might have leaked out through a servant or a spy, or someone through whose hands the document had passed: in the typewriting as like as not—if anyone had been fool enough to have it typewritten.

That was one possibility. The second possibility was that James Haggismuir McAuley, having got his assurance solidly in writing, had deliberately released the knowledge of it indirectly, having already bought at the lowest during the little slump of yesterday, Wednesday morning, and desiring to catch a profit in passing before the big business began.

The third possibility was that there was no assurance at all, and that James, in a laudable effort to catch the same quick profit, had let it be thought that he had an assurance, though he had it not. In that case the shares would slump badly sooner or later, and must be watched. For the moment they were bound to be blazing, because all London would be reading the quotation from New York in the paper this morning.

The fourth possibility was that someone in New York had lied brazenly for his own purposes, and that there was as yet no assurance given to Durrant’s at all, or, if there was, no leakage of the assurance voluntary or involuntary, no funny business on this side at any rate.

He had got that far in his analysis, he was out of the train and on his way to walk straight to his office in Whitehall, when he suddenly remembered another factor, and he went round by back streets to the river so as to have time to think it over. The factor he had remembered was the Committee’s report—adverse to Durrant’s. Someone had set aside that report. No mere rumour would have raised the shares in face of the news that had leaked out—the news that the Committee had reported in favour of Reynier’s and against Durrant’s. Only one man could set aside that report, and that one man was the Postmaster-General.

He saw it clearly now. At some hour of the yesterday, Wednesday March the 4th—or possibly late on Tuesday the 3rd—McAuley had squared the P.M.G.

Jack Williams grew more and more convinced as he walked briskly up the river side from Horseferry Road, with the rain still threatening but not falling, and the brave south-west wind ruffling the water against the tide. As he passed the Houses of Parliament his conclusion was fixed. It was a good omen that he should have arrived at it just as he passed those august walls, which shed so benign an influence over meditations of this kind. Yes, he was absolutely certain. James Haggismuir McAuley had got his assurance in black and white with Halterton’s name on it and had released the knowledge through his own channels. Billies would blaze and soar. He was glad he had given the order! He possessed his soul in peace.

All the morning the Rt. Honourable John Williams attended to the business for which he was paid by a grateful nation his £100 a week. His rapidity of decision, his excellent manner with subordinates, the health of his presence, pervaded the place. He commuted the sentence of one man, decided to hang another (on competent advice, of course), and read with real care the report on the trouble in the “C” division, summoned the clerk who had written the minute, grasped every detail, came to a wise decision, devoted all the rest of his time to the great Police Reform, and then went out to cross the Park toward the Club at lunch time feeling that he had earned his money—which indeed he had: he was a good workman.

He glanced at the general tape as he went in, holding it up to his face, paying particular attention to the news of the Royal Wedding in Italy, but with his right eye he was shooting glances at the other ribbon to catch the price of Billies. He had to wait a little time till they came round.

“12.56 p.m.; Pelham Pref. 108—109, Reefers 79 ex.” so and so, and so on and so on . . . then, at last, Billies:—

“Dur. Imp. Tel. Ord. 35s.—36s.”

Another man would have smiled. Jack Williams put on a troubled look as of slight grief, bent again for a moment over the news of the Italian Royal Wedding, sighed, and went on into the dining-room.

Just when Jack Williams was finishing his breakfast, his colleague, Wilfrid Halterton, was determining far off that he must ring up James McAuley, for the sixth time.

He was a little ashamed to be going on like this—but what was he to do? There was some misunderstanding, and it must be cleared up. If James Haggismuir McAuley could meet him face to face the extraordinary situation would straighten out—but James Haggismuir seemed so difficult to find just now. The telephone was never very satisfactory, but there it was. So after five early efforts—before nine o’clock—all failures, Wilfrid Halterton once more rang up the flat at the Marble Arch. He heard from the voice of a manservant that the great financier was in his bath. Wilfrid Halterton, who was himself not very far advanced in dressing, went back to his bedroom, sat on the bed, and thought matters over. At first he came to no conclusion—save this, which he reached in about ten minutes—that somehow, something had gone wrong. Then he went off again to the telephone, and this time the voice of the manservant answered that Mr. McAuley would be at the instrument at once. Next came the decisive voice, for once in a way irritated.

“Look here, Wilfrid, man, what’s all this? Don’t keep on ringing me up at these godless hours! I’m not dressed yet! What d’ye want? It is you, isn’t it?”

“Yes. I want to see you. I must see you. There’s some misunderstanding. I don’t think you quite caught what I was saying to you last night at the Balcombe’s—at least, you were at the Balcombe’s—I was talking from the House, as I told you. I don’t think you quite understood what I was saying, did you, eh? Something went wrong. Can I come round and see you this morning—now? In a quarter of an hour?”

There was a good long interval, in which no answer came, though Halterton filled it up with a few remarks such as “Eh? What?” and “I say—Exchange!” Then came J.’s voice again, a little lower, and with the irritation gone out of it.

“Look ye here, Wilfrid, all this is just a tangle. You get ye round here just after ten. Ye’ll find me at breakfast. I don’t understand what it’s all about. Ye seem to have lost some letter from someone? Isn’t that it? But no matter. . . . Come you round and see me at a quarter-past ten.”

Before the Postmaster-General could say another word J. rang off. As for Wilfrid Halterton, he mused for a moment, standing before his wireless radiator, staring down at the glowing grid; he shook his head twice, and muttered: “Most mysterious!”

The short interval seemed interminable, and he got to the Marble Arch a little before his time, sauntered through the lounge, and did not ring for the lift until his watch assured him that it really was ten o’clock. He did not want to seem in a hurry, though if ever haste and anxiety were imprinted on drawn face and unquiet fingers they radiated from the various corners of that Minister.

He found J. sitting comfortably alone at his breakfast table. J. could not trouble to get up, but just nodded him towards a chair and asked him if he would care for a cup of tea. Wilfrid Halterton thanked him. It afforded a moment’s reprieve during which he could pull himself together. He did so, and then, avoiding McAuley’s eye, he said:

“I say, you know—you know what I’ve come about?”

“No, I’m damned if I do!” McAuley, abandoning his sausage, laid down his knife and fork and looked up squarely, compelling his guest to turn his face towards him.

“I’m damned if I do! I suppose ye want my advice about something? Ye spoke about some letter having gone wrong. Spit it out.”

“My dear J.,” said Halterton, glancing at the door and a little frightened by the loud voice, “it’s quite simple. All I have come for is to ask you whether I could have another letter in the place of the one I had from you yesterday evening. I’ve mislaid it. It’s very unfortunate. A thing like that ought not to be left lying about. Someone might find it. But anyhow, I must have a duplicate. You can see that, can’t you?”

“I don’t in the least understand you!” James Haggismuir McAuley pronounced these words very deliberately, with his sharp eyes trained upon the Postmaster-General like two small calibre gun-muzzles. “What letter?”

“Why,” faltered the other, “the letter you gave me, of course.”

“My dear Wilfrid, there have been plenty of letters between us.”

The Postmaster-General suddenly got up and strode towards the door rather more rapidly than was customary to his step. He opened it, peeped round, satisfied himself that there was no one about, shut it again, came back, and said:

“Look here, I don’t understand, either. . . . I must have a duplicate of that letter.”

James McAuley put a clenched hand down on the table, either side of his plate, and cried:

“We’re at sixes and sevens, man, somehow! Ye were talking last night on the telephone o’ somewhat you thought I knew; but I don’t—now, there! I don’t know what it’s all about.”

Wilfrid Halterton’s mind turned a somersault, and left him bewildered. It dazed him, and he hadn’t yet found his feet. However, he acted with complete simplicity. He said:

“Why, the letter you gave me Tuesday night, J. After you got my letter accepting the contract. I took your letter, didn’t I? That undated one, you know . . . you remember what was in it? Well, anyhow, that undated letter. You remember. The one signed by you. I put it in an envelope. . . . I put it in my pocket. . . .”

“This is all Greek to me,” sighed J. “I’ve got your letter all right, of course. We both of us know that. And I’m sincerely grateful to ye for it, Wilfrid. It’s made all the difference. And apart from that,” he went on, as Halterton seemed about to interrupt him, “I think you’ve done well by the country. I’m sure”—this emphatically—“I’m as sure as I am of the daylight that ours is the only system that will work the thing as it should be worked. I don’t deny it’s to my advantage. Of course it is. Everybody knows it is, and that I’ve been urging for it. But you’ve done the right thing by the public, and they’ll thank you, and so do I.” He held out his right hand, open. Halterton took it, rather weakly.

“Thank you, J.,” he said, “thank you. Thank you very much. But now look here. There’s some grievous misunderstanding. You must let me have a duplicate of that lost letter.”

“There is some misunderstanding,” answered J. in a voice now half an octave below that which he had used even at his deepest in this pathetic interview. “ ’Tis a very grave misunderstanding. Ye’ve been mixing things up.”

Then, before Halterton could interject a contradiction, a master thought struck the presiding genius of Durrant’s Imperial Television Company.

“Look ye here, man, the best thing for ye to do is to get ye home and write down just what it is ye want. Somehow or other, mayhap, ye’re mixing me up with some other body—or mayhap ye’re getting confused between one document and another. Anyhow, ye think there was a letter, given you—by me. ’Twas not by me. It must a’ been by someone else just before or after. ’Tis easy to get mixed up in such things. But there’s no harm done. If there’s something ye want me to do in connection with your contract, get ye home, I say, and put it all down fair on paper. Then we’ll talk it over with all the facts before us.”

Wilfrid Halterton was taken aback, breathless.

“You want me to write to you about what . . . what was offered me? You want it in my own handwriting? You want me to do that?” he said, in rising but somewhat tremulous accents. “In my own handwriting?”

J. shook his head.

“There’s no making anything of all this!” he said.

He put his hand on his friend’s shoulder. His friend dared not shake it off, though he would have liked to do so.

“Get ye home and put down whatever it is in black and white, sign it, and send it along to me; then I’ll answer you. That’ll be all square, won’t it?”

“You deny that you gave me that letter?” answered Wilfrid, in tones higher up the scale than he had yet used. Then he jumped three notes, into B flat, and repeated: “You deny you. . . .”

“My dear fellow,” implored the financier, “don’t shout!” (Squeak would have been more accurate, for shriek is too grand.) “Just write it down, as I say. Write it down here, if you like.”

Wilfrid Halterton had grown white and passionate.

“Very well,” he said in a lower voice, half muttering, half hissing. “Very well. Very well. My word! I think I’m beginning to understand. But don’t you make too sure! I shall find it, J. . . . Remember. . . . I shall find it!”

By way of answer J. caught the tall man’s two hands and held them closely in his firm grasp.

“Look here, Wilfrid,” he said, as he gazed wisely and benignly at him, but with great gravity in his expression, “I’ve known ye for some months now, and we have been good friends, I think? There’s no one admires ye more than I do. But one can’t have a fine brain working double pressure like yours without paying the price. Be advised by me. Get you back home. Get that brain of yours quiet again, and, as I say, put down on paper what you think happened; or if you don’t like to do that, write down what you want me to do, anyway. You may be sure I’ll meet you. There!”

Still holding the wrists of those two hands in his own firm right grasp, he again put his left hand on the Minister’s shoulder.

“Do what I tell ye,” he said. “Ye are your own worst enemy, sometimes, Wilfrid. But no one wishes ye well more than I do.”