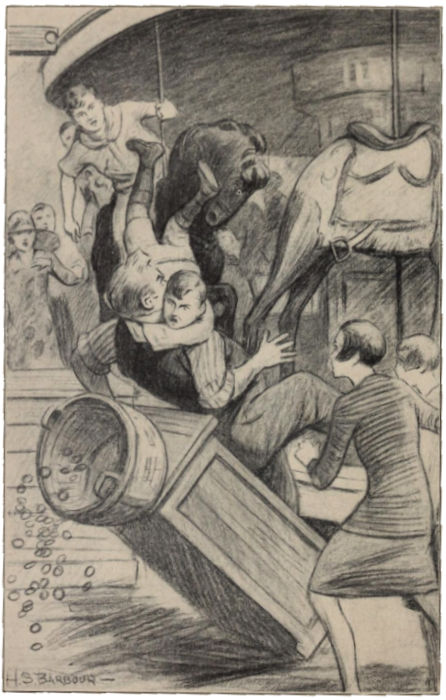

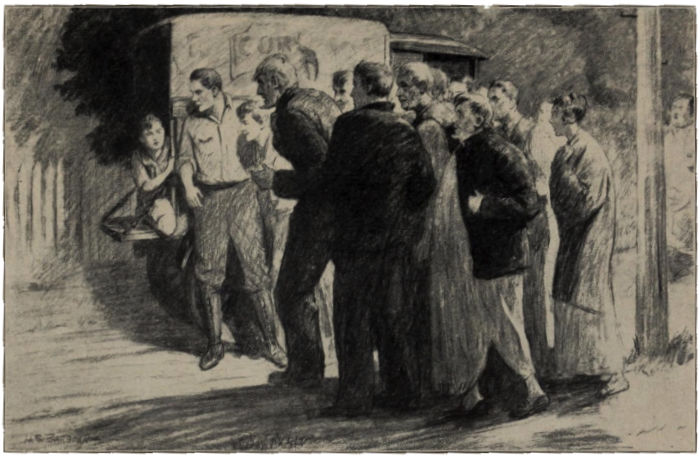

BEFORE ROY KNEW IT, PEE-WEE HAD GRABBED THE MAN

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Roy Blakeley's Go-As-You-Please Hike

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Sep. 10, 2019

Date last updated: Sep. 10, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190924

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

ROY BLAKELEY’S GO-AS-YOU-PLEASE HIKE

BEFORE ROY KNEW IT, PEE-WEE HAD GRABBED THE MAN

ROY BLAKELEY’S

GO-AS-YOU-PLEASE HIKE

BY

PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH

Author of

THE TOM SLADE BOOKS

THE ROY BLAKELEY BOOKS

THE PEE-WEE HARRIS BOOKS,

THE WESTY MARTIN BOOKS

ILLUSTRATED BY

H. S. BARBOUR

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1929

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Made in the United States of America

CONTENTS

| I. | First Comes the Noise |

| II. | It Sounds Good |

| III. | A Detour |

| IV. | You Can Never Tell |

| V. | A ‘Teckinality’ |

| VI. | The Uncovered Wagon |

| VII. | On Top of That |

| VIII. | Out of the Rut |

| IX. | A Dandy Offer—Almost |

| X. | Pee-wee Sticks |

| XI. | Marooned |

| XII. | And the Girls |

| XIII. | All Is Not Brass That Litters |

| XIV. | Taking Chances |

| XV. | A Warning |

| XVI. | A Message |

| XVII. | After the Smoke |

| XVIII. | A Sad Story |

| XIX. | A Big Moment |

| XX. | The Winner’s Picked |

| XXI. | Giddap |

| XXII. | Zeff Steps In High |

| XXIII. | Stalled |

| XXIV. | Swamped In the Swamp |

| XXV. | We Have Lots of Hard Luck |

| XXVI. | Model Scouts In a Model House |

| XXVII. | In Again Out Again |

| XXVIII. | And Gone |

| XXIX. | All for Gold |

| XXX. | This Is a Riddle |

| XXXI. | The Same Old Tune |

| XXXII. | That’s What We Get |

| XXXIII. | And Then |

| XXXIV. | Pee-wee Needs Sympathy |

| XXXV. | A Banana Story |

| XXXVI. | Who Said—Hay? |

ROY BLAKELEY’S

GO-AS-YOU-PLEASE HIKE

This is a hike that didn’t start out to be a hike. It just sort of happened, accidentally on purpose. That’s what I liked about it—it didn’t have any purpose but lots of nice accidents happened so I called it the go-as-you-please hike. We went as we pleased until Pee-wee came along and then we had to go as he pleased, so that’s how the accidents happened.

Anyway, I’ll write it for you if my fountain pen doesn’t break down in the middle of the story. The only thing holding it up (I mean my pen) is an elastic band. Everything will be fine as long as I remember not to forget that it will bust if I start chewing on it.

Pee-wee’s to blame for this sad condition of my precious pen. He’s to blame for everything whether he is or not. I don’t know who else to blame things on except myself and that won’t do because I get enough blame at home.

This time, though, the kid is really to blame because by mistake he almost let a famous horse chew up my pen into two parts while he was feeding it some hay. He used it to stir up some catnip in the hay and it got mixed up somehow so the horse found it before Pee-wee did.

Then we discovered some ink running out of the horse’s mouth and just in time I rescued my pen from the jaws of death. So now you’ll hear the story—it’s a long, hilarious tale. Pretty near as long as the horse’s.

Anyway, when I think of it now my pen didn’t do so bad. All I had to buy for it was the elastic band. We weren’t as lucky as that. We means Doc Carson, he’s in my patrol, and Pee-wee Harris, he’s a patrol by himself but on the quiet he’s supposed to be leader of the Chipmunk Patrol in our troop. He’s a leader in name only—one word from him and the kids do as they please. And last but not least, as they say in Siam, was Dub Smedley—he’s a nice feller and I’ll tell you more about him later.

As I said before we weren’t so lucky. I had to buy a new scout suit and hat and so did Doc Carson. Dub lost his shoes somewhere and Pee-wee—oh boy, he was lucky that he didn’t have to buy a new face and a few new bones. The only thing he had when he got back to camp was his voice and he didn’t have all of that because it was reduced to a whisper on account of him having to coax the horse for four hours straight.

Every time I think of it I have to laugh. My sister says she’s tired of hearing it and seeing it so I told her I could laugh just as loud up my sleeve. Jiminy, she ought to be glad I’m alive after that hike and am able to laugh. Another thing, I have to make up for the time I lost in those awful, dangerous moments when I was too scared to snicker.

I won’t begin from the beginning—I’m going to begin in the middle of it. That’s where Pee-wee came in. He always makes a good loud start so you’ll hear him before if not sooner. That depends on whether you skip any paragraphs. Pee-wee won’t care. The quicker you hear him the better he’ll like it.

One nice, sunny summer morning, Doc Carson and I were about a quarter of a mile from Temple Camp. It was sometime between July and September—I don’t mean Temple Camp, I mean the nice, sunny summer morning.

Temple Camp is in the Catskill mountains. It stays there all year round but we don’t. We just spend our summers there and all our money. We should worry about money as long as Pee-wee goes on our hikes.

Anyway, the reason I can’t tell you what time of the morning it was is because I always make a vow when I get to camp to never think of time. The only way I can tell the hour is by my stomach and the “eats” bell. Otherwise I don’t bother clocks as long as they don’t bother me.

I’m getting near the middle now so Doc and I were hiking from camp and we were glad to get away from the noisy bunch. We’d rather hear our own noise where it’s nice and quiet.

We were going along slow and easy and could hear ourselves talk fine. We didn’t know what we were going to do in Catskill—we weren’t even sure we were going there. But that doesn’t matter any to me. I can always think of something.

So while I was thinking about it, Doc and I heard a terrible noise that sounded like thunder and an earthquake all together. We looked up at the sky and all around at the mountains and down at our feet but everything was all right.

We started on and then we heard the noise again nearer and louder than before. So we turned around quick and looked back up the road. That’s where the noise was coming from.

We discovered the noise was Pee-wee. He was a little way behind and was running like anything to catch up to us. Every once in a while he yelled “WAIT!” Just as loud as that.

I told you you’d hear him in a minute. So now you can stop if you want peace and quiet because from now on we can’t get rid of Pee-wee. That means each chapter will be louder and crazier than the one before. It’s up to you.

Even when he was almost up to us he kept on shouting for us to wait. I called to him, “Don’t worry, we’ll wait. We’ll have to wait on account of the noise you’re making!”

And that was true because the noise was terrible and we were afraid that the birds all around would think the end of the world had come. They wouldn’t know it was only Pee-wee. So to do them a good turn Doc and I had to stop.

The kid ran up to us all out of breath. He said, “Where are you going?”

I said, “Somewhere in Catskill.”

“Where?” he wanted to know.

“How do I know till we get there!” I said.

“Are you going to hike all the way or catch the bus when it comes along?”

I said, “We’ll have nothing to do with the bus. We’re busted. What money we have we’re going to save for adventure. This is a go-as-we-please hike. We’re pleased to go anywhere.”

He said, “It’s lucky I saw you fellers and caught up to you.”

I said, “Yes, you’re lucky. We’re not. What did you do, go without your breakfast to catch up to us?”

“No, I didn’t,” he said. “I only saw you and Doc a few minutes ago. You don’t think I followed you on purpose, do you? I had to go to Catskill today on account of something important and I couldn’t find you and nobody else would go with me.”

“I don’t blame them,” I said.

“Who?” the kid said.

I said, “Nobody else.”

He said, “You’re so smart you won’t say so after I tell you something. You’ll be glad, because after I left camp and was walking along I was thinking it would be nice if I met a few fellers I liked. Then I happened to look up and saw you way ahead and I said to myself, ‘Now I’ll have company.’”

“Goodnight!” I said. “We’ll live to rue the time you looked up. You get the company and we get the nuisance.”

He scowled. “You wouldn’t say I was a nuisance if you knew how I intended to treat you and if you knew that you’d say I was good enough to hike to Catskill with,” he said all in one breath.

I said, “Ah-a! It’s a dark, black secret.”

Doc said, “It sounds more like a midnight blue to me.”

So I said, “All right, kid. Get it off your mind. Tell us the sad story.”

“It’s not sad, it’s something to be glad about!” he said. “You know how all last summer and the summer before that at Warner’s Drug Store they gave out tickets with everything we bought?”

I said, “Sure. And you got the tickets away from everybody in camp because you were saving them.”

“And from everyone in Catskill,” Doc added.

“I didn’t take them!” the kid shouted. “I asked everybody if they weren’t going to save them to give them to me.”

“They had to give them to you or you would have pestered them to death,” said Doc. “That’s the way you got a couple of dozen out of me.”

Pee-wee said, “If I didn’t ask, you’d have thrown them away. So would everyone else.”

I said, “Well, now that you have the tickets what are you going to do with them?”

“I have a hundred dollars worth,” he said sort of triumphant like. “That means I can have a dollar’s worth of anything free in that drug store. Today’s the last day to cash in the tickets.”

I said, “G-o-o-d night magnolia! You ought to treat everybody you got tickets from. Talk about getting something for nothing!”

“I’m asking you to let me hike with you so I can treat you, what more do you want?” he screamed. “Isn’t that fair enough if I treat you fellers? Gee whiz, you can’t ask everybody in camp on a dollar’s worth!”

“Not the way you eat,” said Doc.

“He’d starve to death on a dollar’s worth,” I said.

“Shall we start?” he wanted to know.

I said, “Wait a minute, here’s someone else coming along you’ll have to ask. That gives us twenty-five cents apiece.”

Doc said, “If we stand here talking much longer we’ll be lucky to get an almond out of an almond bar.”

Pee-wee said, “That’s your fault. You fellers should have said right away that you wanted me to hike with you. How did I know?”

I said, “We didn’t say we wanted you along but we can’t have your tickets without having you. In other words, we love you for your tickets alone.”

The kid smiled then. He said, “Didn’t I tell you you’d be glad you waited for me?”

By that time we could see it was Dub Smedley hiking down alone. He comes from Jersey City but it’s no fault of his—he’s a nice fellow, Dub is. He has freckles. Anyway, he likes nonsense so I was glad to see it was him.

I said, “You’re just in time to join our hike, Dub. We’re going as we please. But first the kid’s going to treat us to a dollar’s worth of anything free. One of us ought to buy a sponge so we can sponge up what’s left in the bottom of the dishes. We may need it before we get back. You can never tell with Pee-wee.”

Dub laughed and he said, “I’m game for anything. It pleases me if it pleases you and everybody else and if it doesn’t why it does just the same.

“Do you know what you’re talking about?” Pee-wee wanted to know.

I said, “You’re not supposed to know what you’re talking about on a hike with me. Dub’s been initiated.”

The kid said, “He’s crazy then too, but who’s going to be leader?”

I said, “No one. We’re all leaders but we must all be pleased to go wherever we go.”

“Gee whiz, that’s no kind of a hike,” the kid said. “I won’t have anything to say, I bet.”

“You will unless you get lockjaw or something,” Doc said. He’s always thinking about diseases and medicines, Doc is.

I said, “Chipskunk, are you pleased to go wherever we go or do you want to quit?”

Oh, boy, he was mad. “Did you ever hear me say I’d quit?” he yelled. “Did you?”

“If everyone’s pleased, hike on!” I said.

“Aye,” said Doc.

“Aye,” said Dub.

I said, “Good! We’re carried by a large minority. Everyone’s pleased.”

“Well, I’m not,” the kid grumbled.

Just the same he walked on.

Pretty soon Pee-wee got used to going as we pleased because he said, “We can each have a banana split at Warner’s, I just figured it all out. Mr. Warner makes peachy ones.”

I said, “Figures?”

He said, “No, banana splits. Maybe I’ll just get a soda though and buy some candy with the other ten cents. I don’t know.”

I said, “Neither do I. But why worry? We won’t be in Catskill for many moments to come.”

“How can it be moments when it’s an hour’s hike from here to Catskill?” the kid wanted to know.

Dub and Doc started to laugh. Then I said, “That’s what happens when you don’t study geography. Anyone can tell you that many moments means an hour, maybe two or three. I should worry.”

The kid stopped in the middle of the road and looked at me. “No fooling,” he said. “I wish I could get there quicker. I’m awful thirsty. I ate fish for breakfast.”

“The poor fish,” said Doc.

I said, “I knew a fish once—it was a gold fish....”

“Is this another gold fish story?” the kid yelled.

I said, “Posilutely, no. It’s about a gold fish that found the water in his bowl getting very hot and he went up to the top and began swimming around like sixty so he’d cool off.”

Pee-wee looked at me very suspicious like but Dub said, “Yes, yes go on, Roy.”

So I said, “And he kept going around but he didn’t get cool. He was getting warmer and warmer and the water kept getting so hot that it began to boil and simmer until it all boiled away and the bowl was dry. Do you know what happened?”

“No, what?” the kid asked with his mouth and eyes open.

“The poor fish fried,” I said in a very sad voice.

“Do you expect me to believe that!” he screamed. “It’s another fairy story just like you always tell.”

I said, “You can ask my sister if that honestly didn’t happen. Maybe it’s the same fried fish that you ate this morning and it’s still trying to get into cold water. Stranger things have happened.”

The kid gave me a disgusted look. “Only a lunatic could think of such a thing,” he said. “Just the same, I’d like to get a drink.”

I said, “It pleases me.”

Doc said, “And me.”

Dub said, “The same here.”

Pee-wee stood looking across the field, then he smiled, sort of. Anyway it was a bright look and I always know that means he’s thinking. That doesn’t happen very often—only when he’s not eating and talking. He eats and talks about twenty-three hours and fifty minutes out of twenty-four.

I said, “Hip, hip and a couple of hurrahs! The kid is thinking. Maybe he has an idea.”

“For once you guessed something sensible,” he said. “I was thinking how one time a couple of years ago I took a hike with Tom Slade. We took a trail off this road down a little further and in about ten minutes we came to a spring that has dandy water. It’s a short cut to Catskill too. Shall we take it?”

I said, “Sure, if you’re sure it’s the right way. But if you’re not sure, why as sure as can be I’ll start a friendly feud with you. The scouts may have pure food laws but there’s no pure feud law that wouldn’t let me start a feud with you if you bring us out the wrong way.”

He glared at me. “When I go on hikes with you don’t we always come out right at the end?” he yelled.

I said, “‘We!’ You mean you do. We don’t even come out right in the middle of it. The last hike we were on with you we didn’t get as far as where we started from.”

“Are you pleased to take that trail I just told you about?” he screamed.

“Now you’re talking,” I said. “A scout is obedient and you didn’t forget that I’m a patrol leader in good standing only I don’t stand around long enough. Anyway, I’m pleased to go.”

Doc and Dub were also pleased so we started after Pee-wee. In about five minutes we came to a trail that ran off the road and through some woods. It was all overgrown with weeds and we could tell that no one had been through there in a long time. But we never worry about underbrush or overbrush with Pee-wee along. He always carries his axe on a hike. He does that to convince the world he’s a boy scout in case people won’t believe what he tells them.

After we were on the trail I said to him, “For the last time, are you sure this is the right trail to the spring?”

He said, “You make me sick. Don’t I remember a trail when I see it? I remember this one just as if it was yesterday and Tom and I walked through here to the spring. Then after we had a drink we went on to Catskill. Gee whiz, I don’t forget that, you can bet!”

“It’s not my bet,” I said. “It’s yours.”

So we went on and pretty soon the kid said, “Even if it wasn’t the right trail and it is, it shouldn’t bother scouts. Scouts aren’t supposed to get lost. Not for long anyway.”

“Goodnight!” I said. “It won’t be long now!”

So we went along that trail and Pee-wee was as quiet as a mouse. He didn’t want to miss that spring. Anyway, no one said much until we had been walking more than ten minutes.

Then I said, “What I like best about the spring that we didn’t come to yet is that it’s a little more than ten minutes’ walk from the road. One thing, we won’t have to walk a mile for a drink of water.”

“And the water is as cool as anything, I bet,” said Doc. “It’s the most refreshing thing you can drink on a hot day.”

I said, “Maybe it’s hiding somewhere and we could call to it.”

“Maybe you could all keep still till we come to it!” the kid roared. “Everything’s got to be on the minute to satisfy you fellers. I didn’t say it was exactly ten minutes, did I? Gee whiz, lots of people sometimes say a thing will happen in a day or so and they really mean a week.”

“G-o-o-d night magnolia!” I said. “A week! Do you mean to tell me that we’re likely to hike for a week?”

Doc said, “Keep up your courage, Roy. Hikes have been known to last for years hunting for buried treasure and the like. And we’re hunting for something more precious than gold. I’ll leave that to Dub.”

“My father said lots of fellers lost their minds hunting for water in the desert,” Dub said, sort of chuckling.

I said, “You see, kid? This is dangerous business. It’s really more dangerous to hunt for water in the underbrush than in the desert. Maybe we passed the brush that it’s hiding under.”

The kid yelled, “Instead of talking like a lot of fools you ought to keep your eyes open like I am doing. Look for a lot of moss-covered rocks because under that is the spring.”

“To the left or right?” I asked the kid.

“Can I remember for years which side it’s on?” he wanted to know. “I’m just using my eyes like I told you.”

I said, “A smart scout like you ought to be able to walk to it blindfolded. Anyway, we’ll look for a spring with a lot of moss-covered rocks under it.”

“That shows how you listen,” Pee-wee screamed. “It’s under the rocks, not on top of them!”

I said, “All right, I’ll take a demerit for that. Let’s be observant like our little comrade Harris. We’ll now proceed with all diligence to look for a lot with some rocks and moss that has a spring.”

So Doc and Dub and I put our hands over our eyes like people do when they’re looking away in the distance. We made out we were very serious, looking north, south and east and west. Then we began turning over every rock we came to—even little pebbles.

“You’re crazy!” the kid shouted. “The whole bunch of you! Do you think you’ll find a spring under little pebbles and rocks like that? I meant great big ones like part of the mountain or something. You ought to have sense enough to know that.”

“I don’t need sense while you have it,” I said.

“I thought big rocks from little pebbles grew. Deny it if you dare!”

He just gave me a disgusted look and started on again and we followed him. Then we came to a very wide brook that separated the woods from a lot of big fields. Almost ready to fall across the overgrown trail was a great big poplar tree that must have been struck by lightning or broken in a storm. Anyway, it wouldn’t take many whacks with an axe to bring it down.

So I said, “That’s dangerous. It might fall on someone. Even us. If Pee-wee talked too loud the vibration might do it.”

Doc said, “Well, I’m pleased to take it down.”

Dub said, “I’ll help.”

The kid spoke up then and he said, “I betcha none of you know that if I chop that tree a certain way I can make it fall over that brook and we can keep on in the same direction to Catskill. We won’t have to swim across.”

“To Catskill?” I said.

“No, the brook,” he yelled. “I saw Mr. Ellsworth do it once when we were out on a hike and he says boy scouts could do things like that, when it would help strangers because not everybody can swim a brook like that. So I’ll chop it down so it’ll fall right across the brook and we can walk over it like a bridge. Want to see me do it, Dub?”

Dub said, “Sure!”

The reason the kid asked Dub, was because he knew Dub didn’t know him as well as Doc and I and he couldn’t show off in front of us. So I said, “What’s the matter with chopping the poplar tree down anywhere? It wouldn’t hurt any of us to swim across that brook and anyway we’re looking for a drink of water, aren’t we?”

The kid threw me another one of his disgusted looks and he said, “Gee whiz, you haven’t any pioneer instinct at all. While we’re chopping down that tree we might as well make a bridge for prosperity to cross hundreds of years from now. That’s the way the Romans did.”

“Not for prosperity, kid,” Doc said. “For posterity.”

“What difference does it make!” the kid said. “It almost means the same thing and anyway none of you fellers would know just how to notch that tree like I’m going to do because Mr. Ellsworth said I was the only one in the troop he ever showed how to do it.”

“What kind of a tree did he try you out on—a Christmas tree?” I kidded him.

Pee-wee got his axe into action and he said, “You think you’re so funny, you just watch how I do it. I’ll even carve my initials on it so that everybody that crosses here will know it was me that put it there.”

“Prosperity don’t know what they’re going to walk on,” laughed Doc, as we all sat down on the ground to watch the kid labor.

I said, “By the way, what about that spring?” Pee-wee said, “Well, what about it?”

“Do you think it is lost in that brook?” I asked him.

“Don’t talk like a fool,” he said. “It might be along that road through the woods the other side of those fields, I don’t know. It only seemed like ten minutes to me that day I was with Tom Slade but maybe it was longer on account of him and I talking.”

“As long as I know you were talking I won’t worry,” I said. “We’re likely to find it any time between now and January.”

So the kid kept on chopping and perspiring while we sprawled on the ground and were nice and cool. Doc said, “Don’t forget to let us know when that tree’s ready to fall over. We want a few seconds to scoot.”

“I told you it was going to fall straight across that brook and it is,” Pee-wee said.

So he kept on and pretty soon he yelled and we all jumped up and the tree started to topple over toward the brook. The kid ran back with us and we watched it go over with a loud crash—kerplunk into the water. It missed the opposite bank by about thirty feet and part of the trunk stuck way out of the water.

The kid stood and looked at the sad spectacle for about two minutes, then he said, “I can’t understand why that didn’t fall right across. ’T’s funny.”

“Prosperity won’t think so,” Doc said. “And they won’t understand it either.”

I said, “Well, now that that’s done we’ll wait till the kid carves his initials in it and then we’ll swim across so we can find that spring.”

Pee-wee looked at me and he said, “It won’t do any good now and another thing, Mr. Ellsworth said if it cracks like that when it falls it’s rotten in the center. So it wasn’t my fault that it was rotten, was it?”

I said, “You mean the way you did it?”

Well, Dub started up a howl, he laughed so. He had to sit down and hold his sides and the kid was getting madder by the minute when all of a sudden we heard a voice say, “Wa’al, ye made some mess on my property, didn’t ye?”

Goodnight, we all looked up and saw a farmer coming along in the brook with a pair of hip boots on. He was walking nearest the opposite bank and he stared at the tree in the water and then up at us again. None of us said a word we were so surprised.

Then the farmer said, “What right have ye to put a obstruction like that inter my property?”

So I found my voice then and I said, “Do you mean to say that brook is part of your property, mister?”

He said, “That’s what. So’s the woods yore standin’ in.”

Doc spoke up and he said, “Well, we weren’t doing any harm—we were ridding your property of an encumbrance. That tree was almost ready to fall and would have killed someone maybe. That’s why we chopped it down.”

“Boy scouts are supposed to do that,” the kid piped up. “They’re supposed to keep the woods clear of en-cum—anyway, they’re supposed to keep the woods clear of them, so do you call that doing harm to your property?”

“When ye throw it inter my brook it’s a-doin’ harm,” the farmer said.

“I didn’t throw it in,” the kid said in a scared voice. “On account of it being rotten inside it fell that way so could I help it? You can ask the scoutmaster of our troop, Mr. Ellsworth, if I could help it!”

The farmer stood there chewing on something in the corner of his mouth and every once in a while he would pull on the strap of his overalls. Jiminy, I thought he’d never talk until finally he looked at the kid and he said, “If ye couldn’t help ’bout that there tree ye still had no right a-trespassin’ on my property. I kin have ye fined for that alone.”

So I said, “Hey, mister, if it’s your property and you don’t want any trespassing why don’t you have a sign up saying so?”

The kid smiled at me and he said, “Yes, why haven’t you a sign up, mister?”

So the farmer chewed some more and then he said, “I have a sign nailed up there if ye want to know it.”

Doc said, “We’re willing to be shown.”

So he started walking downstream and we walked along on the bank and Pee-wee said, “Suppose he has us arrested for trespassing now?”

I said, “You’ll have a chance to carve your initials on paper then. Not everybody has that chance.”

He said, “How can you fool at a time like this?”

“There’s no time like the present,” I said. “We may not even have the chance to cry afterward.”

Dub said like a good sport, “If we have to go to jail there’s one good thing—we’ll all go together.”

I said, “You bet. United we stand....”

“Can’t you think of something else to say?” the kid wanted to know. “It’s all right to be united but who wants to go to jail when you really didn’t mean to trespass or do any harm? Gee whiz, if we do go I hope they’ll let me have a drink of water.”

“Don’t worry about that, kid,” I said. “They’ll even give you bread with it.”

“And a brand new cotton suit and your head shaved off free,” said Doc.

“It’s no joke,” Pee-wee said. “I’m sorry I bothered with the tree at all.”

Just then the farmer stopped and said, “That’s where it....” He was pointing his finger up to a tree on our side of the bank.

We looked up, but we didn’t see anything there and neither did the farmer because he stretched his neck and looked all around but, oh boy, there wasn’t a sign of a sign.

“That’s where ’twas,” he said in a disappointed voice and began wading toward the middle of the brook.

The kid went toward the edge of the bank and was looking over and all of a sudden he stooped over and he yelled, “It’s in the water! That makes a teckinality so we’re not guilty of trespassing or anything!”

Oh boy, but I was glad. I was really scared that he would have us arrested because he looked mean enough even when he knew we weren’t trespassing intentionally. Anyway, the kid nailed it up to the tree it had been on while the farmer looked on as disappointed as anything.

But we should worry. I’ll never make fun of Pee-wee’s teckinalities again. That one kept us out of jail!

We had to swim the brook anyhow because the farmer wouldn’t let us walk up any further. He wouldn’t even let us go through the fields so’s we could get right on the road to Catskill again. He made us go on a path that went northwest—he didn’t care as long as it wasn’t his property. I bet he wouldn’t let his own grandmother walk there.

Pee-wee said, “Anyway, we foiled him in a way and we can walk northwest until we strike a road or a trail going east. We’re sure to get to Catskill going east.”

“That’s the direction to China also,” Doc said.

“Gee whiz, you fellers are fine scouts,” the kid said. “A good scout shouldn’t get discouraged by distance or anything. Anyway, what do you care, we’re not in a rush, are we?”

So I said, “Maybe your tickets won’t be any good by that time.”

“By what time?” he wanted to know.

“By the time we strike a road going east,” I said. “Winter might overtake us.”

“Don’t talk like a fool,” he said. “If we don’t strike a trail going east soon, can’t we blaze one like they did in covered wagon days? Gee whiz, if you’re not resourceful, I am.”

I said, “Posilutely. Only you’ll have to do the blazing. You’re the cause of us going toward Seattle when we should be in Catskill now. When are you going to start blazing, kid?”

We came out onto a road going directly north. The kid said, “Not long now. Gee whiz, I’m as thirsty and hungry as you fellers are and I’m not complaining.”

Dub said, “Everything will be fine as long as we don’t try to hunt for any more springs.”

Pee-wee said, “Just the same we’d have a drink by now if it wasn’t for that farmer. I betcha that spring was only a little way down that road after you cross the field. You admit it wasn’t my fault that he came along, don’t you?”

Doc said, “That was a lucky break for you, kid. Maybe the spring dried up right after you and Tom Slade left it.”

I said, “Maybe Pee-wee didn’t leave any water there to dry up.”

“I won’t argue with you about such nonsense,” he said. Then all of a sudden he smiled. “Look! Some nice wild blackberries!”

We all looked and sure enough there were about skeentees thousand nice, ripe blackberries all waiting to be picked. So for about ten minutes we were very busy and didn’t talk because we were eating them. Especially Pee-wee, he didn’t even breathe. He was eating three mouthfuls at a time.

Just then we saw a big truck coming down the road. It was packed full of hay and we watched it until it came right up to us when the kid yelled, “G-go-ng t-t- C-a—ll?” He almost choked, his mouth was so full.

The driver looked down at the kid and laughed. “I pass right near it. Only a little walk for you. Climb in back, kids, and be comfortable!” he said.

Pee-wee grabbed off a few more berries and climbed up into the hay. We all went after him and almost fell backwards as the truck started off. Anyway, we sprawled all over and it smelled nice and sweet. That made me think of something, so I said, “What would Daniel Boone and the covered wagon days say if they could see you riding in an uncovered wagon instead of being resourceful and blazing a new trail to Catskill?”

The kid couldn’t answer right away. His mouth was still packed full and his lips and chin were smeared with blackberry juice. Finally, he swallowed some and he said, “Do you say it isn’t being resourceful that I thought of asking for a ride to Catskill? Do you think Daniel Boone wouldn’t ride on a hay truck if they had hay trucks in those days?”

I said, “That shows how much you know about botany. Daniel Boone wasn’t out for comfort, he was out for adventure and he wouldn’t ride a hay truck if he had the chance. He’d rather discover new trails and things. Ask Robinson Crusoe!”

“That shows you’re crazy and don’t know what you’re talking about,” he came back at me. “Do you mean to tell me if Daniel Boone was alive that he wouldn’t ask for a lift if he was in a hurry like we are? Gee whiz, it takes time to blaze a trail and isn’t it better to not be so pioneerish and get a lift when we only have till noon to turn those tickets in?”

I said, “Chipskunk, do you mean to tell me those tickets are only good till twelve o’clock?”

“That’s all,” he told me. “Mr. Warner says he’s too busy in the afternoons so he just set this morning as the time to turn them in.”

“My gosh!” said Doc looking up at the sun. “It must be after eleven now. It would be just our luck to get there too late.”

I said to the kid, “Goodnight, why didn’t you tell us this last night so we could have made an early start? Or you could have told us when you met us. We wouldn’t have followed you looking for a spring that sprung out of sight.”

“It isn’t noontime yet, is it?” the kid shouted. “Besides, I didn’t know I had enough tickets until this morning.”

I said, “Where are the tickets?”

The kid fished around in his pockets and brought out everything from a dried-up caramel to a bent safety pin. And just when we began to hold our breath he felt in his pocket and smiled. Then he pulled them out and they were all wrapped up in the tin foil from an eskimo pie.

He started unwrapping them and we went bumping along—that is, the truck did but we didn’t mind being thrown around in that nice soft hay. It was so high we couldn’t see the driver from where we were. All we knew was that we were riding along and all of a sudden we bounced up in the air and down again.

When I came up smiling once more I happened to look at the kid and he looked scared to death. So I said, “What’s the matter, little one?”

He said, “Gee whiz! I don’t know. I don’t know what happened to those tickets. When we were bounced up I had them but when I came down I didn’t.”

I said, “Excuse me while I faint!”

Doc sat up straight and he said, “What do you mean, you don’t know what happened to them?”

Dub started to laugh and the kid scowled. Then he said, “Is it so funny that I got bounced the same as the rest of you and lost track of the tickets? Gee whiz, it took a couple of years for me to get them together!”

Doc said, “Why didn’t you hold onto them?”

“Didn’t Roy ask me to show them to him?” he wanted to know.

Doc said, “Didn’t you see them go anywhere?”

“All I know is they went out of my hand when we struck that rut,” said the kid.

We looked back and could see that we were more than a block away from it then. “Maybe they landed in the hay,” said Dub.

Very thoughtful like, Pee-wee said, “That’s right, maybe.”

So we began looking for the tickets. It was just like hunting for a needle in a haystack—we didn’t find them. And by that time we couldn’t see the rut in the road any more. Then the truck stopped.

“All out!” the driver called. Then he stood up and looked over the top of the hay and laughed. “Sorry I can’t take you all the way but I’m in a hurry. Anyway, it’s not far for a bunch of scouts. S’long!”

Pee-wee was all set to tell his troubles to the driver but the engine started and the truck began to move so we all jumped off quick. Soon it was out of sight.

Pee-wee stood staring down the road for a second. Then he said, “What’ll we do next?”

I said, “We always leave that to you, kid. Just now we’re pleased to go without the tickets. You fixed it so we can’t do anything else.”

“And we’re dished out of a free banana split,” said Doc, very sad like.

I said, “Yes, it’s bad enough to be dished out of one dish but when there are four dishes that we’re dished out of it’s a very sad affair.”

“You fellers make me sick,” the kid said disgustedly. “You’d think you couldn’t buy a banana split if you wanted one. Can I help it because....”

“Why should we buy one when we can get it free from you?” I said. “Another thing we don’t know where a go-as-we-please hike may lead us to—especially with you along. We may have railroad fare to pay before we get back to camp tonight. You never can tell. Another thing we have to have money to eat because if we depended on your promises we’d starve to death.”

Gee, he was wild. He said, “Do you mean to say I’m stingy?”

I said, “Far be it from such. You have a heart like an elephant or is it a rhinoceros? Anyhow, it’s some wild animal whose heart is half the size of a human heart. Even arithmetic proves that less and less leaves nothing.”

He said, “I’m too hungry to get mad at your nonsense. We’ll eat as soon as we get to Catskill, hah?”

“Did you ever do anything else as soon as you get to Catskill?” Doc wanted to know.

He said, “Sure. I buy postcards there too, don’t I?”

I said, “Yes, while you’re eating ice cream cones.”

That kid doesn’t believe in three meals a day. He eats the whole day and three meals besides. And when he goes to bed he puts rock candy in his mouth so it will last all night.

It came to us all of a sudden that something was queer about the road that the driver directed us to. It ran west. So I said, “Since when did we hike west to Catskill? Have we been going east all the time?”

Doc said, “Gosh, it didn’t seem so to me. We were talking so much though, I just don’t remember.”

Pee-wee said, “We must have been going east all right because I can see the letter C on the signboard over there.”

So he walked over to it and began reading. I noticed that every once in a while he looked back to us in a funny way as if he was puzzled.

“What’s wrong now, kid?” I asked him.

He said, “I don’t know. There’s something funny about this whole business!”

“Again!” I said.

“It doesn’t say anything about Catskill on this sign,” he said, kind of quietly.

We started to walk over and Doc said, “What does it say, then?”

“It says, WELCOME TO CORNVILLE, ¼ mile from here,” said the kid.

“That’s what you get for talking with a mouthful of blackberries,” I said. “That driver thought you said Cornville, I bet.”

“Where’s Catskill then?” he wanted to know.

“You better get pioneerish again and find out,” I said. “Don’t ask for any more lifts. We’re likely to get out in Texas.”

“Anyhow, first I’m going to walk back to that rut and find out if I dropped those tickets anywhere around there,” he said.

“Go ahead,” I said. “The better the sooner. We’ll take a rest while we’re waiting.”

He said, “Won’t you come with me?”

I said, “I’m afraid the rut will disappear like the spring did.”

He said, “You’re a fine bunch of fellers for a hike. If I’m pleased to go back to that rut aren’t you supposed to be pleased too?”

Doc said, “In other words, it’s a go-as-Pee-wee-pleases hike, eh?”

“This is the first time I said I was pleased,” the kid yelled. “And if I found those tickets again you’d be pleased enough to say you were pleased too.”

I said, “Away, Sir Harris. Track down thy mistake while we rest under yonder tree.”

The poor kid was so rattled that he walked away. Then he looked back at me and he said, “You can’t deny it wasn’t my fault that the truck bounced.”

I looked at Doc and Dub and I said, “Who is pleased to look for the rut?” They both said aye so we started after Pee-wee.

We had walked quite a little way when we saw an old fashioned buggy and a gray horse. An old man was driving the horse along like a snail. So I asked him, “Mister, how many cubic feet do we have to hike before we get to Catskill?”

“Whoa, Elmer!” said the man to the gray horse. Then he looked at me. “Want ter know the way ter Catskill?”

I said, “Yes. We were looking for a spring and here we are, lost, lone and weary.” I read that in a magazine once about some pigs that wandered away from a sty. That’s how they felt.

Doc said, “He’s right, mister. The spring we were looking for sprung a leak and now it’s springing up in some other spring.”

The man looked at us as if we were all going crazy. He said, “Ye be a-goin’ the wrong way naow.”

“That’s on account of me,” the kid piped up. “We’re looking for something I lost.”

“It’s not his head, mister,” I said. “He lost that when he organized the Chipmunk Patrol.”

The man just stared and he said, “If ye want ter go ter Catskill yer hev ter git back the way yer jest came ’bout one mile. The road yuh come ter first on yer right is the road ter Catskill.”

“How many miles is it, mister?” Pee-wee asked him.

“’Bout fifteen mile. Giddap, Elmer!” said the man and he drove away.

“Bye-bye, Elmer,” said Dub, breaking out in hysterics again.

I said, “Well, after all it’s just a little hop to Catskill from here—in an airplane.”

Pee-wee said, “Gee whiz, how did we get so far away?”

“Ask me another,” I said.

“Which way shall we go?” the kid wanted to know.

“Foodward,” quoth I.

“Aye,” said Doc. “The sun is high in the heavens.”

“Anyway,” said Pee-wee, “Cornville isn’t far and we can eat there.”

“And phone there,” I said. “We better tell Mr. Ellsworth that on account of meeting Pee-wee we didn’t find a spring and we met a mean farmer and on account of him we’re fifteen miles from Catskill. I’ll tell him if we have to walk we’ll be back by Labor Day.”

So then we came to the rut but we didn’t find any tickets. Each one hunted in a different part of the road and the kid looked in the ditch. All of a sudden he let out a yell and he stooped and picked up something.

I said, “Is it them?”

“No,” he said. “It’s something better. Gee whiz, don’t say I’m not lucky! I found four good tickets to the carnival in Cornville and today is Royal Order of Lions Day for the benefit of Better Babies. They’re the ones who sold these tickets. I bet it will be peachy.”

“The carnival or Cornville?” Doc asked him.

“The carnival,” he said, still reading the tickets. “It says ticket entitled bearer to be admitted by the R. O. O. L.”

“Do we have to have a lion admit us?” I said.

“It’s no time for nonsense,” he said. “C’mon, we’ll hurry and eat first. Then we’ll spend all afternoon there.”

Doc said, “How are we going to get back to camp by night?”

I said, “We should worry about that. We’ll leave that to Pee-wee, too. He has lots of dandy ideas—for making mistakes.”

In about a half hour we made our grand entry into Cornville. Some entry, believe me. There was hardly anyone around except a few cows and two or three chickens.

Cornville measures about nine by twelve. That’s the size of the rug that’s in my sister’s bedroom. It isn’t on the map—I mean Cornville isn’t but it tried hard enough to get on that day with all the excitement that Pee-wee caused.

There’s about twenty houses in that town and two churches and five stores including the post-office and village green. They’re all painted yellow—all except the village green. That’s green with a white statue in the middle of it.

We came to the field where the carnival was being held. It wasn’t open for business yet a man told us. They didn’t open until one o’clock so we went around looking for a place to eat in.

Then we saw one of those traveling lunch wagons and it had a sign on it that read

HARRY’S FAMOUS HAMBURGERS.

It stood right on the edge of the field and smoke was coming out of the chimney.

Pee-wee said, “Oh boy! I’m going to have a regular dinner—soup to dessert. I might have two desserts even. I’ll see what he has.”

So we all piled in Harry’s famous lunch wagon. Believe me, it smelled good enough to eat. I mean the food that was cooking.

Harry stood behind the counter in a big white apron and he was short and fat and bald. We sat down at the counter and I said, “Can we have three regular dinners at a reduction, mister?”

Harry laughed but the kid frowned at me. “Whatcha mean, three?” he yelled. “Where do I come in?”

“Do you call your appetite regular?” I asked him. “You don’t fit in with nice, dainty appetites like ours. You need two regular dinners and four desserts so you can’t get a reduction. As it is, you’ll be a total loss to Harry. You’ll eat up all his profit.”

“You think you’re so smart,” the kid came back at me. “I bet if I went out and advertised how much I could eat in here it would help Harry’s business. I bet if I went out and told people that I ate two dinners and four desserts this place would be packed with customers!”

Harry was laughing like anything and he said to the kid, “If you can eat two regulars dinners and four desserts, I’ll let you have the whole business for the price of one.”

Make out that kid didn’t smile when he heard that. “It’s a go,” he said. “I’ll eat everything you give me.”

I said, “Hey, Harry, don’t give him anything on paper plates because he might eat them too! He’d eat tin cans if they were covered with chocolate ice cream.”

“Well, we’ll try him out and see,” Harry laughed. Then he started to get the dinners ready and Doc and I kept on kidding poor Pee-wee. Dub sat there laughing like he always does. That’s one of the reasons why I like to get the kid’s goat, because Dub has so much fun listening. The other reason is because I get fun out of it myself.

Dub hasn’t any mother and his family are poor. They live in Jersey City and he works hard all winter after school and on Saturdays so he can go to Temple Camp in the summer. I would work to get away too if I lived in Jersey City. But anyway, he’s a nice feller and a good scout you can bet.

While we sat there waiting the food kept on smelling nicer and nicer all the time. Harry set our places and all the time the kid watched him like a mouse. He wasn’t saying a word, he was so hungry.

Just as Harry started dishing up the soup a little thin man in a straw hat came into the lunch wagon with a big paper in his hand. He looked at us and then looked at Harry and he said, “You be Harry, proprietor of this here lunch wagon?”

Harry answered, “I sure am. What can I do for you?”

So the man said, “Wa’al, I be Mr. A. Tuck, d’ye know me?”

“I believe it,” I whispered to the kid.

“Believe what?” he wanted to know in a stage whisper.

“That he’s A. Tuck,” I said. “He isn’t wide enough to be A. Seam.”

So A. Tuck said then, “I be Sheriff of this here county and constable of this here village. I got a warrant here for to seize yore fixtures to satisfy the demands of yore creditors.”

I expected to see Harry look sad but he didn’t. His face looked red and mad as anything and he said, “Go to it, rube! The pleasure’s all yours.” So then he took off his big white apron and came from behind the counter and sat down on one of the stools.

A. Tuck grinned sort of like you see them do in the movies. “Yer ain’t got no permit for to transact business in this here county or in Cornville, have ye?”

“You know I haven’t!” Harry snapped. “And you’re the one that wouldn’t give me one, Mr. A. Tuck! You were afraid that I’d take some of the business away from the refreshment stand at the carnival. I found that out. Don’t think I’m so dumb. I found out you own that field the carnival’s on so it’s clear why you wouldn’t give me a permit!”

A. Tuck kept on grinning but it was a sickly grin and he didn’t look our way at all. Then he sort of turned and said to Harry, “Ye’ll have to move across the county line soon’s we take yore fixtures. Can’t stay here without a permit.”

He went to the door and called in a couple of Cornville men that looked like himself and they all went around gathering up everything—knives, forks and spoons and even the dishes. They carried them outside and put them in a truck and on the last trip they took the pots and pans away with the food in them.

The hungry kid spoke up and he said, “Can’t you think of some teckinality or something so he can’t do it?”

Harry smiled and he said, “Sure, I’ll get it all back soon’s I get some money from New York. He’s busted me up for the carnival trade anyway so I might as well take a rest while I’m waiting.”

We sat there so surprised at what had happened that we couldn’t speak. And the worst part of it, we almost ate! There wasn’t a sixteenth of a second between the soup and us.

That lunch wagon was emptier than the desert when A. Tuck got through removing the fixtures.

Anyway, Pee-wee kept alive longer than that and without food too. When he saw the last of the food gone he said to Harry, “How are we going to eat now?”

I said, “This is no time to be asking Harry riddles. He has troubles enough without you pestering him.”

“Who’s asking him riddles and who’s pestering him?” the kid yelled. “Don’t you think I feel as sorry for him as you do? All I’d like to know is how we’re going to eat! Gee whiz, even Harry has to eat I bet!”

Harry said, “Don’t worry about me. I had mine long ago. You kids will have to go out and buy something out of the general store, I guess.”

The kid’s face was all drawn up in a frown. He looked as disappointed as anything. I knew he was thinking of how near he had been to a lot of free eats. Then he said, “Is that money you told us about—is it on the way here?”

“Yes,” Harry said. “But I don’t know how long it will take. I’m not worrying though. A day out of business won’t kill me. What I’m mad about is that they’re going to hold over the carnival for two days more and now that mean old cuss has ordered me over the county line.”

“Don’t you care,” I said. “He’ll wake up some nice morning and find himself asleep.”

“Where is the county line?” Doc asked Harry. “Right across the road,” said Harry.

“If I stick with you do I still get the two dinners and four desserts?” the kid wanted to know.

“Absolutely,” said Harry. “Only you’re foolish to wait around, kid. It may be an hour and it may be the rest of the day before I get it.”

“I don’t care,” Pee-wee said. “I’ll wait for two hours and see. I’m not a quitter. Anyway, nobody else ever offered me all that for nothing. Gee whiz, I’ll stick. You see!”

I said, “Well, if Harry was sure, we’d stick too. But he’s not sure and he’s not worrying about what A. Tuck took away from him so I’m going and see what’s doing at the carnival. Whoever is pleased to go, say ...”

“Aye!” said Doc.

“Two ayes,” said Dub.

I think the kid was sorry right then that he had promised to stick to Harry and wait for the free meals. But he didn’t have courage enough to say so. He looked at us as we got up to go and I knew he was wishing he had kept his mouth shut. Then he said, “Don’t stay long, Roy. Just look around and see what they have over there and come back and tell me. Maybe by that time Harry’ll have his money and he’ll be cooking dinner again.”

Harry said, “Maybe is right. But if I do get the money I’ll give you the whole thing I promised you for nothing if you help me hitch up the horses and move across the county line. That will be a big help, kid.”

The kid was all smiles. For a few minutes then he changed his mind about being sorry. He was sorry for us that we hadn’t promised to stick. So he said to Harry, “That’s a go! Maybe I’ll stick for more than two hours even!”

Then he said to me, “You see what I’ll get for sticking and see what you won’t get? You’ll be sorry, I bet, when you see all the food I’m going to get afterward. Don’t you want to wait and stick too?”

I said, “No, I’m too hungry. Besides we want to see what’s doing at the carnival. If Harry’s got his money by suppertime and we’re still here, why, we’ll have supper here.”

Harry said, “Sure thing, kids. You’re wise. See you later!”

Well when Pee-wee heard Harry say that I knew he was sorry for sure because he said, “Don’t stay long like I told you before. Bring me back a hot dog, huh? If you can carry them bring me two! I won’t be so hungry then while I’m waiting.”

So I called back, “Do you want some nice dessert, too?”

Doc said, “Maybe you’d like some popcorn pastry?”

Dub said, “Would you like a custard or jelly filling?”

I said, “Say not so. The kid likes cement filling best of all. It lasts longer. Isn’t that right, Pee-wee?”

“You’re a pack of fools!” he yelled and went back in the lunch wagon and slammed the screen door behind him.

So we walked around the carnival grounds and they were just opening. We celebrated it by buying two hot dogs and a bottle of soda apiece and we got some for the kid too. Then we bought popcorn and salt water taffy for our dessert. After that we started back to find where Harry had moved.

When we got to the place where he had been before we saw a truck standing there that had

AUNT AGGIE’S HOME-MADE PASTRIES

printed on each side. There was a man standing right by it with his back turned to us and he was looking across the road. Harry’s wagon was standing in the center of it and a big crowd of people standing on either side of the road were all looking too.

When we got up to the man we could see there had been an accident. A big truck was turned over in the middle of the road and another one was lying alongside of it all smashed up.

I asked the truck man, “Did anyone get hurt, mister?”

He said, “Luckily, no. That’s one of those tank trucks all smashed up there. It had some kind of tar stuff in it and when the other big truck hit into it the tank burst or sprung a leak or something like that. Anyhow, it’s made a mess. Talk about a river of tar!”

I said, “Goodnight! Is it all over the road?”

“Is it!” he said. “Why, I’m supposed to deliver some pies to Harry’s lunch wagon that’s standing out there now and I just got here when the accident happened. It’ll be a month of Sundays before Harry gets out of it and besides, the horses were so frightened when the crash came that they broke loose and ran away across the field. I heard that no one’s captured them yet. Maybe he’ll never get ’em!”

Dub said, “How’ll Harry get his wagon out?”

“Don’t ask me!” said the pastry driver. “How’ll Harry get out for that matter! No one can walk in that stuff till it hardens. Then they’ll have to chop him out, I guess.”

“That may be years,” said Doc.

Dub started to laugh. He laughed and he laughed and he was almost hysterical when he said, “And nobody’s even thought about poor Pee-wee!”

There was nothing else we could do at the time so we bought a lot of pies from the pastry man. The crowd kept getting bigger and bigger so we decided to push our way down toward the edge of the road. We thought Pee-wee would feel better if he could see us anyhow.

About two inches separated us from the tar so we sat down at the edge of the field right where the kid could see us from the back door. It was facing us and we knew it wouldn’t be long before he’d look out to view the disaster from there. Anyway, it was just as the pastry man had said, you couldn’t approach that wagon from the north, west, south or east.

So we started to eat our hot dogs when Dub said, “Sh! He’s at the back door, now.”

I said, “Everybody take a mouthful before speaking and every second thereafter.”

So they did, myself included. Then we looked up together as if we were surprised to see Pee-wee standing there. I made my face look like I had forgotten about him being in that wagon at all. And at the same time I divided a juicy pineapple pie in half. Half stayed in my hand and half went in my stomach.

Dub and Doc did the same thing and all together we rubbed our stomachs and said, “Mm-mm-mm!” We said it good and loud and long and Pee-wee stood watching us with his mouth wide open as if he could almost taste it too.

But the more we ate the madder he was getting. And when I started on my second pie—peach, and the kid’s favorite, I yelled, “S’peach-piekid. Mm-mm!”

“You think you’re so smart!” he screamed. “I’d be out there eating pie too only I promised to stick and I’m not a quitter and besides when I say I’m going to stick, I stick!”

“Bet your life you’ll stick!” I said. “You can’t do anything else now. You’re stuck for fair. Otherwise you’d be out here eating your hot dogs and popcorn and taffy and pie and soda. I bought some for you but if you don’t get away soon why we’ll have to eat them because on a hot day like this they won’t keep!”

“Is that doing me any good?” the kid wanted to know. “Can’t you throw a pie over here or a hot dog or something?”

“It would land in the tar,” I said. “And another thing maybe Harry’ll be cooking in a little while.”

“Don’t talk like a fool,” he yelled. “If you can’t throw a pie here how can anything else get here?”

Doc said, “How does it feel to be shipwrecked on the Black Sea in a lunch wagon?”

I said, “Now he’s a jolly old tar!”

The kid yelled, “Say, are you going to eat up all those pies before I get rescued?”

“That depends on when you’re rescued,” I said. “They might melt—in my mouth.”

He said, “If you eat them all it isn’t fair. I’m hungry and I want to eat as well as you!”

Just then we heard a voice beside us say, “I thought you boy scouts were able to go for days and days without eating!”

Goodnight! When we looked up who should we see but two girls from Catskill that Doc knew.

He introduced them to us and the girl that spoke first, her name was Flora Flippant and the other girl’s name was Polly Pert. They were nice girls—nice and pretty.

So I said to Flora Flippant, “Say what you just said good and loud so the kid can hear you. Then you can listen for the thunder.”

So she did and the kid frowned over at her. “Sure boy scouts can go for days and days without eating,” he yelled. “But they’ve got to be prepared, don’t they? You have to eat for days ahead because, gee whiz, you can’t fast right away on an empty stomach. Even the pioneers had to get filled up first, anyone can tell you that and besides girls can’t understand those things anyway.”

Polly Pert laughed like anything. So did all the people standing around watching. Then Polly said, “Why, how absurd! Of course girls understand. Perhaps, better than you. I read in a book once that Daniel Boone could go for fifteen days without a mouthful of food.”

“I bet he had a whole lot to eat before that and I bet he drank lots of water,” the kid came back at her.

I said, “Sure, every time it rained in the desert and that’s as much as twice a year.”

The kid yelled, “Shut up! Who’s talking to you!”

Flora said, “My, what a snippy little scout!”

And Polly said, “He’s a little dear though.”

“All that talk isn’t getting me out of here,” the kid said in a disgusted tone.

Harry had come to the back of the wagon and he stood smiling and enjoying the mortal comeback between us and our hero of the Black Sea. So I said, “Look here, kid, Harry’s not complaining and he’s as much marooned as you are—even more so. Anyhow, between you and me and the tar there must be some way to get you out of there!”

The girls laughed loud as could be and so did all the people. In fact we were keeping the carnival from carnivalling so that goes to show you that people would rather hear the leader of the Sterling Silver Foxes and the leader of the Chipmunks in mortal comeback than ride a merry-go-round or a Ferris wheel.

When the laughter died down a little the kid yelled, “Do you think you were clever saying that? Anyone knows there must be some way to get Harry and me out of here. If you’d use your head for thinking instead of for nonsense you’d be better off.”

Just then I looked up and saw a worried face alongside of me. It belonged to A. Tuck.

“Hey, Mr. Tuck,” I said. “Can’t you help us rescue our brother scout from the tarry sea? He’s macarooned.”

“I wish I had some right now,” roared Pee-wee. “They’d keep me from starving to death.”

“See!” Doc said. “He admits he’s starving. He hasn’t had any lunch.”

“He’s had nothing to eat since breakfast,” I said. “And for breakfast he had some trout and a dozen pancakes and a half dozen crullers. No wonder he’s starving.”

Dub rolled over on the grass. Doc examined him and said it wasn’t hydrophobia or measles—it was just a chronic attack of laughter. A. Tuck looked at him and then over at Pee-wee and scratched his own head. Then he said, “How did that little feller get on that there wagon?”

I said, “He was waiting to get two regular dinners and four desserts for the price of one dinner. That is, he was waiting for Harry to get the money first so the dinner could be cooked and then he’d ’tend to the rest himself.”

“But now he anxiously awaits rescue from the black and tarry sea,” said Doc sadly.

I said, “Sure. Think kindly of our comrade, Mr. Tuck. He’s more to be pitied than scolded. He thinks they make tar out of tar bags.”

“Why don’t you shut up and let Mr. Tuck think?” the kid roared.

“You’re right, kid,” I said. “Two heads are better than none.”

Finally Mr. Tuck said, “Wa’al, if I want to hear the last of your nonsense, I spose I’d better think o’ something.”

Doc said, “Don’t exert yourself, Mr. Tuck. Give Pee-wee a chance to think. He’s some fixer. He knows how to fix everything for good—even himself.”

So then I told Mr. Tuck I thought he ought to get a ladder from the fire department, if they had one and stretch it from the field to the roof of the lunch wagon. I guess he thought it was a good idea because he went away and came back in a little while with the whole Cornville fire department. There were three and a half men including Mr. Tuck.

We all helped them to get the ladder onto the roof of the wagon and Harry climbed up first and steadied it. Then when it was safe the kid came down each rung backwards and every once in a while the girls would say “Ah,” and “Oh!” You know how they do. That’s when the ladder swayed a little bit and they thought Harry and the kid would slip down into the tar.

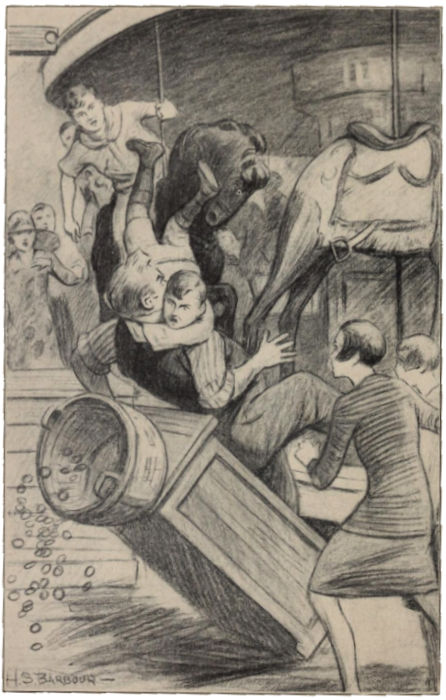

THE KID CAME DOWN EACH RUNG BACKWARDS

Polly Pert said, “That was just too clever of you, Roy, to think of that ladder. Otherwise they would have had to stay all night in there.”

“Like fun I would have,” the kid stopped to yell. “Do you think Roy’s the only one that can think of a ladder? I’d have thought of that too if I had to eat what he’s had. Gee whiz, a feller can’t think so quick on an empty stomach. Any doctor’ll tell you that.”

A. Tuck really smiled. It was his first offense and you could tell he wasn’t used to it. That’s the reason I never stop smiling. Once you get out of practice it’s hard to start again.

After Pee-wee and Harry were settled on terra cotta once more, why the carnival started and the people all went back. The fire department took the ladder back and Harry said he was going to see if he could telephone at the general store in the village.

He said he was going to sue the tar people for his horses and the damage it did to his wagon. Anyway he was happy-go-lucky about it and told the kid that if we were there when he got his money and his wagon out of the tar, why he’d keep his promise. So Pee-wee was satisfied and we started off for the carnival grounds.

After we had gone a little way the girls told us they’d meet us afterward because they had to go and tell their people where they were going to be. They said they wanted to show us around because they came to the carnivals at Cornville every year and knew them much better than we did.

Pee-wee didn’t like to hear that. He doesn’t like anyone to show him anything. Especially girls. He’d rather be the one to do the showing. Anyway he didn’t seem to like Flora Flippant and Polly Pert at all. He knew they were on to him, I guess.

Before they left us to help Pee-wee eat, Flora said, “We’ll meet you at the merry-go-round in ten minutes. We’ll show you what an adorable little thing it is!”

“Don’t you think I could show myself what it’s like?” the kid wanted to know in a very sarcastic way.

“Oh, of course we do,” said Polly. “But we want to ride it the same time you do because we know you’ve never seen any just like this one before. Won’t it be too funny for anything!”

“Funny!” the kid repeated disgustedly. “Gee, girls make me sick with their thinking things are funny when they’re not. What’s so funny about it? It’s fun if you can catch the brass ring and get another ride but girls can’t do that hardly ever because they think it’s funny just riding around and they’re laughing so they never catch the brass ring!”

“Oh, is that so!” said Flora. “I don’t know about that, Walter Harris! Do you catch the brass ring so much that you can afford to brag about it?”

“Sure, I do,” said the kid. “Most every time I catch it. You wait! I’ll show you how it’s done. It’s easy if you only know how.”

On account of thinking that the kid wouldn’t be rescued for hours we ate up what we had. Another thing, we had to help hold that ladder to rescue him and we wouldn’t have had any place to put pies and hot dogs so I thought the best place was in our stomachs. I figured all the time when he was rescued that we could get more where they came from.

But, goodnight! When we got to the refreshment stand why the man told us that he didn’t have a hot dog in the place and that the man they got their pies from had broken down somewhere along the road. Anyway he said he hoped they’d come along soon and that we should come back in about a half hour or so.

The kid was as mad as anything to eat a light lunch in his starving condition. He bought some popcorn and taffy and soda and he said, “This is a fine lunch all right. After you fellers have had all the pie you want I have to eat this stuff.”

I said, “You’re better off with something light. After anyone’s been as near starvation as you were, it’s not good to eat anything heavy. Any doctor’ll tell you that.”

He gave me an unfriendly look and he said, “Well, one thing, I’m going to fix it so that I won’t get left tonight. I’ll fix it so that I have a big meal I bet. Gee whiz, I’m even left for a hot dog.”

“Think of the starving children in Europe,” said Doc. “Do they get popcorn and salt water taffy and nice soda when they’re thirsty and hungry?”

I said, “Doc’s right. They only get black bread to eat, so don’t complain of your lot.”

“A lot you fellers care,” he said. “Just the same like I said before, I’ll fix it all right tonight. You’ll see!”

After that terrible threat we went over to the merry-go-round to meet Flora and Polly. They were all smiles when they saw Pee-wee even though he was snappy with them. They loved him for himself alone. All the girls do for some reason. But I should worry. If they don’t smile at me I can always smile at myself.

So then we bought the tickets and as soon as the music stopped we all made a dive for the horses. Goodnight, that was some rush we had on account of it being so crowded. The kid stopped to help put the girls on a couple of zebras that didn’t have all their stripes where the paint was rubbed off and by that time all the animals were taken except a camel.

Nobody wanted to sit on that because it was too high and hard to reach down from to catch the brass ring. So the kid stood alongside of it for a second and frowned back at me because I was sitting on a black horse that had lost its nose. Part of its right ear was missing too but I didn’t care. That’s all part of the game.

Anyway the kid said, “How do you expect me to get the brass ring on this thing?” He was speaking of the camel.

Polly Pert spoke up and she said, “I’d suppose that a smart scout like you could overcome any obstacle. You could stand in the stirrup, couldn’t you?”

Then Flora said, “Come on, Walter. Don’t you try and back out now on an excuse like that!”

Just then the music started and the thing began to move and the kid could hardly keep on his feet. The ticket man came around and helped to boost him up on the camel and from there he climbed out onto the head part and held tight to the brass pole. He sat facing us.

In a few minutes we were going good and a bunch of kids came in to wait for the next ride. Then the brass ring man climbed up on the little platform and he opened a box full of brass rings and stood them on the high desk beside him.

Just as I whizzed past him he took a nice bright ring out of the box to shove it through the long, black iron arm. So I yelled to the kid, “Hey Chipskunk, get ready now and show the girls what you can do!”

“Leave it to me,” he screamed back. “I’ll show you even in the face of Obsa—obstacles and camels.”

Polly Pert laughed in a little scream like and she called, “We’re watching, Walter!”

“All right, watch!” he roared. “That’s all girls can do is watch!”

So we came to the iron arm and we all watched but the kid just missed it. “If at first you don’t succeed,” laughed Flora.

“Who’s doing this?” the kid roared. “I was just practicing that time!”

Around we went again and the kid reached way out with his one hand. Just as he got up to it he made a grab and before I knew it he had grabbed the man on the platform and the desk went over kerplunk, brass rings and all. They were rolling all around us and I noticed that the kid had gone from his camel.

Everyone was laughing so, I couldn’t hear myself think. When we came around again the music was stopping and I saw the kid sitting on the floor kind of bewildered like. But in a second he jumped up and began helping the man put back the desk so I knew he wasn’t hurt.

The girls and Doc and Dub all found a brass ring—in fact everyone on that merry-go-round had one. I found mine alongside of my horse’s hind foot. Pee-wee was still helping to clear up the wreckage and the man was smiling so everything was all right.

Anyway the music started and we were whizzing around again before the kid was finished. Everyone that passed him smiled and held up their brass ring so he could see it. When I passed him I yelled, “Thanks for the free ride, kid. I’ll always leave it to you. Even in the face of camels.”

“Sure you will,” he screamed back. “If it wasn’t for me you wouldn’t be riding now! None of you!”

The kid didn’t try for any more brass rings and we left the merry-go-round. He said on account of having such a light lunch it made him dizzy and that’s how he fell.

The girls wanted to go and see an exhibition or something on the other side of the field so they left us for a while. Then we bought some more popcorn and Doc bought peanuts to help the kid’s stomach along.

After that we came to a booth that was all draped in flags and behind the booth was a great big tent. As we stood there looking at it a man came out and climbed into the booth and he said, “Would you scouts like to take a chance on an automobile? It’s in a good cause—for the benefit of defective children.”

I said, “Sure we will, mister. I think that’s the same disease our little Chipskunk has so if it helps him I’ll be glad to buy a chance. I’m poor but dishonest.”

The man laughed and the kid said, “Don’t listen to him. He doesn’t even know what defective means and he’s making fun of me. He thinks it means I’m crazy but it doesn’t, does it, mister?”

“That’s rich,” laughed the man. “But just the same it would be nice if you could all take a chance. One of you might win it.”

Doc said, “What kind of a car is it?”

And Dub said, “How much a chance is it?” Poor Dub doesn’t have a whole lot of money to spend but yet he isn’t a piker.

So I said, “Let the kid treat us to a chance. He was going to treat us to a banana split so now we’ll split the difference.”

Pee-wee looked at me and I winked so Dub couldn’t see me. So the kid said, “That’s a go. That’s only fair.”

And the man said, “You won’t be sorry, boys. It’s one of the best cars made. It’s a special made Krusher Super-Six and only twenty-five cents a chance. Cheap at half the price.”

We each took a chance and the man gave us tickets with numbers on. Then he took us around behind the tent where the car was standing and showed us all the important parts. Gee, it was one peachy car, I’ll say that!

The kid said, “If I win the car, how’ll we get it to Temple Camp?”

I said, “You can push it the first fourteen miles and we’ll push it into the garage.”

“If you won it,” the man said, “there’d be a licensed man to drive it wherever you wanted it delivered.”

“My father could get me a chauffeur as long as the car doesn’t cost him anything,” said Pee-wee, with it all planned out. “He wouldn’t have to keep him after I’m old enough to drive it.”

Doc said to the man, “You can deliver it to Pee-wee right now, mister. He’s just as good as won it.”

I said, “Maybe you’d better telegraph your father and ask him whether you can have the chauffeur up here by the time the car’s given away.”

The kid said, “You’re so smart, maybe you’ll win it yourself, how do you know? And if I win it, haven’t I as good a chance as anyone else, haven’t I?”

“Posilutely,” said I. “So has Doc and Dub.”

He said, “Sure, that’s what I mean. But anyhow, no matter who wins it we’ll get a ride home.”

I said, “I hope so, because if we have to hike back to camp again we won’t get there this summer. Maybe if we eat more popcorn and drink more soda we’ll puff up and be lighter than air and won’t have to walk. We’ll just blow into camp.”

“You’re crazy,” the kid said. “Another thing, I don’t want any more popcorn—I want to eat. The more candy I eat, the hungrier I get.”

The man told us to be back at the tent at seven o’clock. He said that was the time the car would be given away and he hoped it would be one of us. So I told him we’d be back with bells on to crush in on the Krusher.

Then Doc reminded us that we’d have to phone and get special permission from camp if we were going to stick around Cornville until seven o’clock. “I’ll tell Mr. Ellsworth what we’re staying for and tell him not to worry if we don’t show up by midnight. He’ll know we’re hiking it on all fours.”

“You fellers make me sick,” the kid said. “Can’t you say we will win it and that we won’t have to hike it back? Gee whiz, you haven’t any faith in yourselves or anything on earth, you haven’t!”

“You’re absitively mistaken, Scout Harris,” I said. “We have faith. We have the greatest faith in your mistakes. We know that eleven times out of ten you’ll make them. Isn’t that faith?”

“Shut up!” he said. “We’re not talking about mistakes, we’re talking about hiking back to camp.”

We found a phone booth and Doc went in to do the dirty work. While we stood outside arguing with Pee-wee the girls came along again and as soon as they saw us, Flora Flippant said, “Why, if it isn’t that clever little Walter Harris—the brass ring boy! The third time we meet, it’s up to you to treat.”

“That’s superstition,” said the kid, scowling like a dark cloud. “I don’t believe in things like that. I have more important things to think of, I have.”

“For instance,” said Polly Pert in that way that some girls have.

“First I want a regular meal tonight....” he began.

“And what’s second, Walter boy?” smiled Flora.

“Don’t call me, ‘Walter boy’,” he said. “I’m no baby and besides I’m a patrol leader so that shows you how much you don’t know and another thing I’m going to win the special Krusher Super-Six that they’re giving away tonight for the benefit of effective children.”

Well, the girls just about died—laughing. I hear my sister say that sometimes. Flora Flippant was almost hysterical when she said, “Now isn’t he just too funny! Effective children! Oh my, oh dear, I’m....”

“That’s right, laugh like a lunatic!” said the kid. “Girls are fools! Instead of being observant they laugh at nothing.”

Polly said, “Really! And what do you want us to observe, Walter boy!”

The kid gave her one of his dark black looks and he said, “That great big swell car that just came up in the field with the tall man in it—I bet you were laughing too much to observe it’s a Krusher car too. Gee whiz, I’d rather observe things than laugh like a fool!”

“What a perfect little imp you are,” said Polly. Then she and Flora turned around to look at the Krusher limousine.

When Flora saw it she smiled triumphant like and she said, “Why you’re so observant, Scout Harris, do you mean to tell me you don’t know who that man is? His picture’s forever in the papers.”

The kid stared at the man just getting out of the car and he said, “Do you think I ever look at pictures in the papers? I read more important things, I do. I read the news so I can learn things, so do you expect I should know who that man is?”

Flora smiled again and she said, “Well, Walter, if you want to learn important things it’s important to know who that man is because he’s famous. He’s no other than the President of Krusher Motors. He’s Mr. O. Stone Krusher, that’s who he is!”

Oh boy, that man’s worth an awful lot of money so you can just imagine how we watched him. Pee-wee especially. He stared until O. Stone Krusher disappeared inside the tent where they were selling the chances on his big Special Super-Six.

Sort of dreamy-like, the kid said, “Gee whiz, I only wish I’d get the chance to speak to him. Just once! I wish I could think of a question to ask him or something.”