* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Tom Slade on Mystery Trail

Date of first publication: 1921

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Aug. 19, 2019

Date last updated: Aug. 19, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190844

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

TOM SLADE

ON MYSTERY TRAIL

BY

PERCY K. FITZHUGH

Author of

TOM SLADE, BOY SCOUT, TOM SLADE AT TEMPLE

CAMP, ROY BLAKELEY, ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

R. EMMETT OWEN

Published with the approval of

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1921, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| I | The Three Scouts |

| II | Another Scout |

| III | The “All But” Scout |

| IV | Hervey Learns Something |

| V | What’s in a Name? |

| VI | The Eagle and the Scout |

| VII | The Streak of Red |

| VIII | Eagle and Scout |

| IX | To Introduce Orestes |

| X | Off With the Old Love, on With the New |

| XI | Off on a New Tack |

| XII | As Luck Would Have It |

| XIII | The Strange Tracks |

| XIV | Hervey’s Triumph |

| XV | Skinny’s TriumpH |

| XVI | In Dutch |

| XVII | Hervey Goes His Way |

| XVIII | The Day Before |

| XIX | The Gala Day |

| XX | Uncle Jeb |

| XXI | The Full Salute |

| XXII | Tom Runs the Show |

| XXIII | Pee-Wee Settles It |

| XXIV | The Red Streak |

| XXV | The Path of Glory |

| XXVI | Mysterious Marks |

| XXVII | The Greater Mystery |

| XXVIII | Watchful Waiting |

| XXIX | The Wandering Minstrel |

| XXX | Hervey Makes a Promise |

| XXXI | Sherlock Nobody Holmes |

| XXXII | The Beginning of the Journey |

| XXXIII | The Climb |

| XXXIV | The Rescue |

| CHAPTER THE LAST. | Y-Extra! Y-Extra! Y-Extra! |

TOM SLADE ON MYSTERY TRAIL

At Temple Camp you may hear the story told of how Llewellyn, scout of the first class, and Orestes, winner of the merit badges for architecture and for music, were by their scouting skill and lore instrumental in solving a mystery and performing a great good turn.

You may hear how these deft and cunning masters of the wood and the water circumvented the well laid plans of evil men and coöperated with their brother scouts in a good scout stunt, which brought fame to the quiet camp community in its secluded hills.

For one, as you shall see, is the bulliest tracker that ever picked his way down out of a tangled wilderness and through field and over hill straight to his goal.

And the other is a famous gatherer of clews, losing sight of no significant trifle, as the scout saying is, and a star scout into the bargain, if we are to believe Pee-wee Harris. I am not so sure that the ten merit badges of bugling, craftsmanship, architecture, aviation, carpentry, camping, forestry, music, pioneering and signaling should be awarded this sprightly scout (for Pee-wee is as liberal with awards as he is with gum-drops). But there can be no question as to the propriety of the music and architecture awards, and I think that the aviation award would be quite appropriate also.

Yet if you should ask old Uncle Jeb Rushmore, beloved manager of the big scout camp, about these two scout heroes, a shrewd twinkle would appear in his eye and he would refer you to the boys, who would probably only laugh at you, for they are a bantering set at Temple Camp and would jolly the life out of Daniel Boone himself if that redoubtable woodsman were there.

Listen then while I tell you of how Tom Slade, friend and brother of these two scouts, as he is of all scouts, assisted them, and of how they assisted him; and of how, out of these reciprocal good turns, there came true peace and happiness, which is the aim and end of all scouting.

It was characteristic of Tom Slade that he liked to go off alone occasionally for a ramble in the woods. It was not that he liked the scouts less, but rather that he liked the woods more. It was his wont to stroll off when his camp duties for the day were over and poke around in the adjacent woods.

The scouts knew and respected his peculiarities and preferences, particularly those who were regular summer visitors at the big camp, and few ever followed him into his chosen haunts. Occasionally some new scout, tempted by the pervading reputation and unique negligee of Uncle Jeb’s young assistant, ventured to follow him and avail himself of the tips and woods lore with which the more experienced scout’s conversation abounded when he was in a talking mood. But Tom was a sort of creature apart and the boys of camp, good scouts that they were, did not intrude upon his lonely rambles.

The season was well nigh over at Temple Camp when this thing happened. Not over exactly, but the period of arrivals had passed and the period of departures would begin in a day or two—as soon as the events with which the season culminated were over.

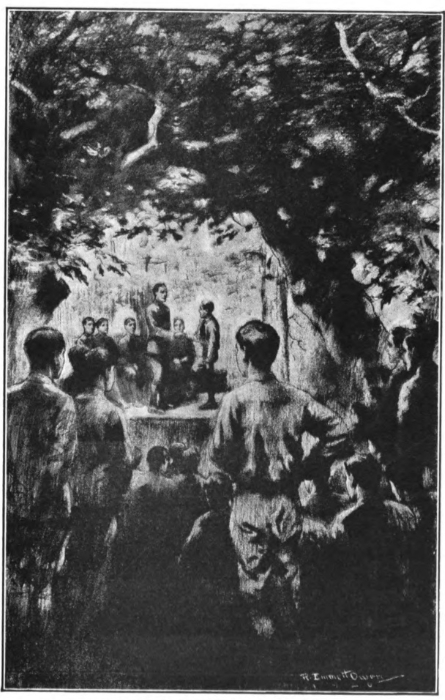

These were the water events, the tenderfoot carnival (not to be missed on any account) and the big affair at the main pavilion when awards were to be made. This last, in particular, would be a gala demonstration, for Mr. John Temple himself, founder of the big scout camp, had promised to be on hand to dedicate the new tract of camp property and personally to distribute the awards.

These events would break the backbone of the camping season, high schools and grammar schools would presently beckon their reluctant conscripts back to town and city, until, in the pungent chill of autumn, old Uncle Jeb, alone among the boarded-up cabins, would smoke his pipe in solitude and get ready for the long winter.

It was late on Thursday afternoon. The last stroke of the last hammer, where scouts had been erecting a rustic platform outside the pavilion, had echoed from the neighboring hills. The usually still water of the lake was rippled by the refreshing breeze which heralded a cooler evening, and the first rays of dying sunlight painted the ripples golden, and bathed the cone-like tops of the fir trees across the lake with a crimson glow.

Out of the chimney of the cooking shack arose the smoke of early promise, from which the scouts deduced various conclusions as to the probable character of the meal which would appear in all its luscious glory a couple of hours later.

A group of scouts, weary of diving, were strung along the springboard which overhung the shore. A couple of boys played mumbly-peg under the bulletin board tree. Several were playing ball with an apple, until one of them began eating it, which put an end to the game. Half a dozen of the older boys, who had been at work erecting the platform, sauntered toward the scrub shack, leaving one or two to festoon the bunting over the stand where the colors shone as if they had been varnished by that master decorator, the sun, as a last finishing touch to his sweltering day’s work. The emblem patrol sauntered over to the flag pole and sprawled beneath it to rest and await the moment of sunset. Several canoes moved aimlessly upon the glinting water, their occupants idling with the paddles. It was the time of waiting, the empty hour or two between the day’s end and supper-time.

Upon a rock near the lake sat a little fellow, quite alone. He was very small and very thin, and his belt was drawn ridiculously tight, so that it gave his khaki jacket the effect of being shirred like the top of a cloth bag. If he had been standing, he might have suggested, not a little, the shape of an old-fashioned hour glass. A brass compass dangled around his neck on a piece of twine as if, being so small, he was in danger of getting lost any minute. His hair was black and very streaky, and his eyes had a strange brightness in them.

No one paid any attention to this little gnome of a boy, and he was a pathetic sight sitting there with his intense gaze, having just a touch of wildness in it, fixed upon the lake. Doubtless if his scout regalia had fitted him properly he would not have seemed so pathetic, for it is not uncommon for a scout to want to be alone in the great companionable wilderness.

Suddenly, this little fellow’s gaze was withdrawn from the lake and fell upon something which seemed to interest him right at his feet. He slid down from the rock and examined it closely. His poor little thin figure and skinny legs were very noticeable then. But he picked up nothing, only kneeled there, apparently in a state of great excitement and elation.

Presently, he started away, looked back, as if he was afraid his discovery would take advantage of his absence to steal away. Again he started, hurrying around the edge of the cooking shack and to the little avenue of patrol cabins beyond. As he hurried along, the big brass compass flopped about and sometimes banged against his belt buckle, making quite a noise. Several boys laughed as he passed them, trotting along as if possessed by a vision. But no one stopped him or spoke to him.

In the patrol cabin where he belonged, he rooted in great haste and excitement among the contents of a cheap pasteboard suit case and presently pulled out a torn and battered old copy of the scout handbook. He sat down on the edge of his cot and, hurriedly looking through the index, opened the book at page thirty. He was breathing so hard that he almost gulped, and his thin little hands trembled visibly....

In that same hour, perhaps a little earlier or later, I cannot say, Tom Slade, having finished his duties for the day, strolled along the lake shore away from camp and struck into the woods which extended northward as far as the Dansville road.

He had no notion of where he was going; he was going nowhere in particular. For aught I know he was going to ponder on the responsibility which had been thrust upon him by the scout powers that be, of judging stalking photographs preliminary to awarding the Audubon prize offered by the historical society in his home town. Perhaps he was under the influence of a little pensive regret that the season was coming to an end and wished to have this lonely parting with his beloved hills and trees. It is of no consequence. About all he actually did was to kick a stick along before him and pause now and again to examine the caked green moss on trees.

When he had reached a little eminence whence the view behind him was unobstructed, he turned and looked down upon the camp. Perhaps in that brief glimpse the whole panorama of his adventurous life spread before him in his mind’s eye, and he saw the vicious little hoodlum that he had once been transformed into a scout, pass through the several ranks of scouting, grow up, go to war, and come back to be assistant at the camp where he had spent so many happy hours when he was a young boy.

And now there was not one thing down there, nor shack nor cabin nor shooting range nor boat nor canoe, nor hero’s elm (as they called it), nor Gold Cross Rock, which had the same romantic interest as had this young fellow to the scouts who came in droves and watched him and listened to the talk about him and dreamed of being just such a real scout as he. He moved about unconsciously among them, simple, childlike, stolid, but with a kind of assurance and serenity which he may have learned from the woods.

He was singularly oblivious to the superficial appurtenances of scouting. He had passed through that stage. The pomp and vanity of the tenderfoot he knew not. The bespangled dignity of the second-class and first-class scout, these things he had known and outgrown. His medals were home somewhere. And out of all this alluring rigmarole and romantic glory were left the deeper marks of scout training, burned into his soul as the mark is burned into the skin of a broncho. The woods, the trees, were his. That, after all, is the highest award in scouting. It is a medal that one does not lose, and it lasts forever.

As Tom Slade stood there looking down upon the camp, one might have seen in him the last and fullest accomplishment of scouting, stripped of all else. His face was the color of a mulatto. He wore no scout hat, he wore no hat at all. It would have been quite superfluous for him to have worn any of his thirty or forty merit badges of fond memory on his sleeves, for his sleeves were rolled up to his shoulders. He wore a pongee shirt, this being a sort of compromise between a shirt and nothing at all. He wore moccasins, but not Indian moccasins. He was still partial to khaki trousers, and these were worn with a strange contraption for a belt; it was a kind of braided fiber of his own manufacture, the material of which was said to have been taken from a string tree.

As he resumed his way through the woods he presently heard a cheery, but rather exhausted, voice behind him.

“Have a heart, Slady, and wait a minute, will you?” Tom’s pursuer called. “I’m nearly dead climbing up through all this jungle after you. Old Mother Nature’s got herself into a fine mess of a tangle through here, hey? Don’t mind if I come along with you, do you? Look down there, hey? Pavilion looks nice. I’ve been wondering if I stand any chance of being called up on that platform on Saturday night. Looks swell with all the bunting over it, doesn’t it?”

The speaker, who had been half talking and half shouting, now came stumbling and panting up over the edge of the wooded decline where the thick brush had played havoc with his scout suit but not with his temper.

“Some climb, hey?” he breathed, laughing, and affecting the stagger of utter exhaustion. “I bet you knew an easier way up. The bunch told me not to beard the lion in his den, but I’m not afraid of lions. Here I am and you can’t get rid of me now. I’m up against it, Slady, and I want a few tips. They say you’re the only real scout since Kit Carson. What I’m hunting for is a wild animal, but I haven’t been able to find anything except a cricket, two beetles and a cow that belongs on the Hasbrook farm. Don’t mind if I stroll along with you a little way, do you? My name is Willetts—Hervey Willetts. I’m with that troop from Massachusetts. I’m an Eagle Scout—all but.”

“But’s a pretty big word,” Tom said.

“You said it,” Hervey Willetts said, still wrestling with his breath; “it’s the biggest word in the dictionary.”

They strolled on through the woods together, the younger boy’s gayety and enthusiasm showing in pleasing contrast to Tom’s stolid manner.

He was a wholesome, vivacious boy, this Willetts, with a breeziness which seemed to captivate even his sober companion, and if Tom had felt any slight annoyance at being thus overhauled by a comparative stranger, the feeling quickly passed in the young scout’s cheery company.

“They told me down in camp that if I need a guide, philosopher, and friend, I’d better run you down, or up——”

“If you’d gone a little to the left you’d have found it easier,” Tom said, in his usual matter-of-fact manner.

“Oh, I suppose you know all the highways and byways and right ways and left ways and every which ways for miles and miles around,” Hervey Willetts said. “I guess they were right when they said you’d be a good guide, philosopher, and friend, hey?”

“I don’t know what a philosopher is,” Tom said, with characteristic blunt honesty, “but I know all the trails around here, if that’s what you’re talking about.”

“Oh, you mean about guides?” Hervey asked, just a trifle puzzled. “That’s an expression, guide, philosopher, and friend. It comes from Shakespeare or one of those old ginks; it means a kind of a moral guide, I suppose.”

“Oh,” said Tom.

“But I need, I need, I need, I need a friend,” Hervey said.

“You seem to have lots of friends down there,” Tom said.

“A scout is observant, hey?” Willetts laughed.

“I mean you always seem to have a lot of fellows with you,” Tom said, ignoring the compliment. “Everybody likes your troop, that’s sure. And your troop seems to be stuck on you.”

“Good night!” Hervey laughed. “They won’t be stuck on me after Saturday. That’ll be the end of my glorious career.”

“What did you do?” Tom asked, after his customary fashion of construing talk literally.

“Oh, I didn’t exactly commit a murder,” the other laughed, “but I fell down, Sla—you don’t mind my calling you Slady, do you?”

“That’s what most everybody calls me,” Tom said, “except the troop I was in. They call me Tomasso.”

“Sounds like tomato, hey?” Hervey laughed. “No, my troubles are about merit badges. I’ve bungled the whole thing up. When a fellow goes after the Eagle award, he ought to have a manager, that’s what I say. He ought to have a manager to plan things out for him. I tried to manage my own campaign and now I’m stuck—with a capital S.”

“How many merits have you got?” Tom asked him.

“Twenty,” Hervey said, “twenty and two-thirds. Just a fraction more and I’d have gone over the top.”

“You mean a sub-division?” Tom asked.

“That’s where the little but comes in,” Hervey said. “B-u-t, but. It’s a big word, all right, just as you said.”

“Is it architecture or cooking or interpreting or one of those?” Tom asked.

Hervey glanced at Tom in frank surprise.

“Maybe it’s leather work, or machinery, or taxidermy or marksmanship,” Tom continued, with no thought further from his mind than that of showing off.

“Guess again,” Hervey laughed.

“Then it must be either music or stalking,” Tom said, dully.

His companion paused in his steps, contemplating Tom with unconcealed amazement. “Right-o,” he said; “it’s stalking. What are you? A mind reader?”

“Those are the only ones that have three tests,” Tom said. “So if you have twenty merits and two-thirds of a merit, why, you must be trying for one of those. Maybe they’ve changed it since I looked at the handbook.”

Hervey Willetts stood just where he had stopped, looking at Tom with admiration. In his astonishment he glanced at Tom’s arm as if he expected to see upon it the tangible evidences of his companion’s feats and accomplishments. But the only signs of scouting which he saw there were the brown skin and the firm muscles.

“They change that book every now and then,” Tom said.

Still Hervey continued to look. “What’s that belt made out of?” he asked.

“It’s fiber from a string tree,” Tom said; “they grow in Lorraine in France.”

“Were you in France?”

“Two years,” Tom said.

“How many merit badges have you got, anyway, Mr.—Slady?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Tom said; “about thirty or thirty-five, I guess.”

“You guess? I bet you’ve got the Gold Cross. Where is it?” Hervey made a quick inspection of Tom’s pongee shirt, but all he saw there was the front with buttons gone and the brown chest showing.

“I couldn’t pin it on there very well, could I?” Tom said, lured by his companion’s eagerness into a little show of amusement.

“Where is it?” Hervey demanded.

“I’m letting a girl wear it,” Tom said.

“Oh, what I know about you!” Hervey said, teasingly. “You can bet if I ever get the Gold Cross or the Eagle Badge (which I won’t this trip) no girl will ever wear them.”

“You can’t be so sure about that,” said Tom, out of his larger worldly experience, “sometimes they take them away from you.”

“You’re a funny fellow,” Hervey said, while his gaze still expressed his generous impulse of hero-worship. “I guess I seem like just a sort of kid to you with my twenty merits—twenty and two-thirds. Maybe some girl is wearing your Distinguished Service Cross, for all I know. But we fellows are crazy to have the Eagle award in our troop. I suppose of course you’re an Eagle Scout?”

“I guess that was about three or four years ago,” Tom said.

“Once a scout, always a scout, hey?”

“That’s it,” Tom said.

They strolled along in silence for a few minutes, Hervey occasionally stealing a side glimpse at his elder, who ambled on, apparently unconscious of these admiring glances. Now and again Tom paused to examine a patch of moss or some little tell-tale mark upon the ground, as if he had no knowledge of his companion’s presence. But Hervey appeared quite satisfied.

“I’ll tell you how it is,” he finally said, selecting what seemed an appropriate moment to speak; “I was elected as the one in our troop to go after the Eagle award. We want an Eagle Scout in our troop. We haven’t even got one in the city where I live.”

“Hear that?” Tom said. “That’s a thrush.”

“A thrush?”

“Yop; go on,” Tom said.

“So they elected me to win the Eagle award. Some choice, hey? I had seven badges to begin with; maybe that’s why they wished it onto me. I had camping, cooking, athletics, pioneering, angling, that’s a cinch, that’s easy, and, let’s see—carpentry and bugling. That’s the easiest one of the lot, just blow through the cornet and claim the badge. It’s a shame to take it.”

“You mean you’ve won thirteen more since you’ve been here?” Tom asked.

“That’s it,” said Hervey. “First I got my fists on the eleven that have got to be included in the twenty-one, and then I made up a list of ten others and went to it. I chose easy ones, but some of them didn’t turn out to be so easy. Music—oh, boy! And when I started to play the piano, they said I wasn’t playing at all, but that I really meant it. Can you beat that?”

Tom could not help smiling.

“So you see I’ve been pretty busy since I’ve been here, too busy to talk to interviewers, hey? I’ve piled up thirteen since I’ve been here; that’s a little over six weeks. That isn’t so bad, is it?”

“It’s good,” Tom said, by no means carried away by enthusiasm.

“I thought you’d say so. So now I’ve got twenty and I know them all by heart. Want to hear me stand up in front of the class and say them?”

“All right,” Tom said.

“No sooner said than stung,” Hervey flung back at him. “Well, I’ve got first aid, physical development, life saving, personal health, public health, cooking, camping, bird study——”

“That’s a good one,” Tom said.

“You said it; and I’ve got pioneering, pathfinding, athletics, and then come the ten that I selected myself; angling, bugling, carpentry, conservation or whatever you call it, and cycling and firemanship and music hath charms, not, and seamanship and signaling. And two-thirds of the stalking badge. I bet you’ll say that’s a good one.”

“There’s one good one that you left out,” Tom said. “I thought you’d think of it on account of that last one.”

“You mean stalking?”

“I mean another that has something to do with that?”

“Now you’ve got me guessing,” Hervey said.

“Well, how do you want me to help you?” Tom asked, thus stifling his companion’s inquisitiveness.

“Well,” said Hervey, ready, even eager to adapt himself to Tom’s mood, “all I’ve got to do is to track an animal for a half a mile or so——”

“A quarter of a mile,” Tom said.

“And then I’m an Eagle Scout,” Hervey concluded. “But if I want to be in on the hand-outs Saturday night, I’ve got to do it between now and Saturday, and that’s what has me worried. I want to go home from here an Eagle Scout. Gee, I don’t want all my work to go for nothing.”

“You want what you want when you want it, don’t you?” Tom said, smiling a little.

“It’s on account of my troop, too,” Hervey said. “It isn’t just myself that I’m thinking about. Jiminies, maybe I didn’t choose the best ones, you know more about the handbook than I do, that’s sure, and I suppose that one badge was just as easy as another to you. Maybe you think I just chose easy ones, hey?”

“Well, what’s on your mind?” Tom said.

“Do you know where there are any wild animal tracks?” Hervey blurted out with amusing simplicity. “I don’t mean just exactly where, but do you know a good place to hunt for any? A couple of fellows told me you would know, because you know everything of that sort. So I thought maybe you could give me a tip where to look. I found a horseshoe last night so maybe I’ll be lucky. All I want is to get started on a trail.”

“Sometimes there are different trails and they take you to the same place,” Tom said.

No doubt this was one of the sort of remarks that Tom was famous for making which had either no particular meaning or a meaning poorly expressed.

Hervey stared at him for a few seconds, then said, “I don’t care whether it’s easy or hard, if that’s what you mean. Is it true that there are wild cats up in these mountains?”

“Some,” Tom said.

“Well, if you were in my place, where would you go to look for a trail? I mean a real trail, not a cow or a horse or Chocolate Drop’s[1] kitten. If I can just dig up the trail of a wild animal somewhere, right away quick, the Eagle award is mine—ours. See? Can you give me a tip?”

Tom’s answer was characteristic of him and it was not altogether satisfactory.

“I’m not so stuck on eagles,” he said.

[1] Chocolate Drop was the negro cook at Temple Camp.

“You’re not?” Hervey asked in puzzled dismay. “You can bet that every time I look at that little old gold eagle on top of the flag pole I say, ‘Me for you, kiddo.’”

“I like Star Scout better,” Tom said, unmoved by his companion’s consternation.

“Why, that means only ten merit badges,” Hervey said.

“It’s fun studying the stars,” Tom added.

“Oh, sure,” Hervey agreed. “But star and eagle, they’re just names. What’s in a name, hey? Is that the badge you meant that I forgot about? The astronomy badge?”

“No, it isn’t,” Tom said. “You’re too excitable to study the stars. It’s got to be something livelier.”

“You’ve got me down pat, that’s sure,” Hervey laughed.

Tom smiled, too. “Well, you want the Eagle badge, do you?” he said.

“You seem to think it doesn’t amount to much,” Hervey complained.

“I think it amounts to a whole lot,” Tom said.

“When I get my mind on a thing——” Hervey announced.

“That’s the trouble with you,” Tom said.

“There you go,” Hervey shot back at him; “you’ve been through the game and walked away with every honor in the book, and you know the book by heart and you can track with your eyes shut and you’ve been to France and all that and you think I’m just a kid, but it means something to be an Eagle Scout, I can tell you.”

Doubtless Tom Slade, scout, was gratified to receive this valuable information. “And there’s just the one way to get there, is that it?” he answered quietly, but smiling a little. “I always heard that a scout was resourceful and had two strings to his bow.”

“You just give me a tip and I’ll do the rest,” said Hervey.

“It must be about tracking, hey?”

“That’s it; test three for the stalking badge. Track an animal a quarter of a mile.”

“Well, let me think a minute, then,” Tom said.

“Up on that mountain, maybe, hey?” Hervey urged.

“Maybe,” Tom said.

So they ambled along, the elder quite calm and thoroughly master of himself, the younger, all impulse, eagerness and enthusiasm. His generous admiration of Tom, amounting almost to a spirit of worship, was plainly to be seen. It would have been hard to say how Tom felt or what he thought. At all events he had not been jostled out of his stolid calm.

“Did you ever hear any one say that there is more than one way to kill a cat?” he finally inquired, pausing to notice some bird or squirrel among the trees.

“I don’t want to kill a cat,” Hervey said. “I want to find some tracks, I——”

“You want to be an Eagle Scout,” Tom concluded; “and you’ve got your mind set on it. That it?”

“That’s it; but it’s for the sake of my troop, too.”

Still again, they strolled on in silence. A little twig cracked under Tom’s foot, the crackle sounding clear in the solemn stillness. Some feathered creature chirped complainingly at the rude intrusion of its domain by these strangers. And, almost under their very feet, a tiny snake wriggled across the trail and was gone. The shadows were gathering now, and the fragrance of evening was beginning to permeate the dim woods. And all the respectable home-loving birds were seeking their nests.

And so these two strolled on, and for a few minutes neither spoke.

“Well then, suppose I give you a tip,” Tom said. “Will you promise that you’ll make good? You claim to be a scout. You say that when you get your mind set on a thing, nothing can stop you. That the idea?”

“That’s it,” Hervey answered.

“You wouldn’t drop a trail after you once picked it up, would you? Some animals take you pretty far.”

“You bet nothing would stop me if I once got the tracks,” Hervey said. “I wouldn’t care if they took me across the Desert of Sahara or over the Rocky Mountains.”

“Hang on like a bulldog, hey?” Tom said.

“That’s me,” said Hervey.

“All right, it’s a go,” Tom concluded. “I’ll see if I can give you a pointer or two down near camp in the morning. Ever follow a woodchuck—or a coon? Only I don’t want any badge-getter falling down on a trail, if I’m mixed up with it. That’s one thing I can’t stand—a quitter.”

“I wouldn’t anyway,” Hervey said with great fervor; “but as long as I’ve got you and what you said to think about, you can bet your sweet life that not even a—a—a jungle would stop me—it wouldn’t.”

“That’s the kind of a fellow they want for an Eagle Scout,” Tom said; “do or die.”

“That’s me,” said Hervey Willetts.

And so these two strolled on. And presently they came to a point where the wood was more sparse, for they were approaching the rugged lower ledges of a mighty mountain, and the last rays of the dying sun fell upon the rocks and scantier vegetation of this clearer area, emphasizing the solemn darkness of the wooded ascent beyond.

Few, even of the scouts, had ever penetrated the enshrouding wilderness of that dizzy, forbidding height. There were strange tales, usually told to tenderfeet around the camp-fire, of mysterious hermits and ferocious bears and half-savage men who lurked high up in those all but inaccessible fastnesses, but no scout from Temple Camp had ever ascended beyond the lower reaches of that frowning old monarch.

At Temple Camp, when the cheery blaze was crackling in the witching hour of yarn telling, the seasoned habitués of the camp would direct the eye of the newcomer to a little glint of light high up upon the mountain, and edify him with dark tales of a lonesome draft dodger who had challenged that tangled profusion of tree and brush to escape going to war and had never been able to find his way down again—a quite just punishment for his cowardice. But time and again this freakish glint of light had been proven to be the reflection of that very camp-fire upon a huge rock lodged up there and held by interlacing roots.

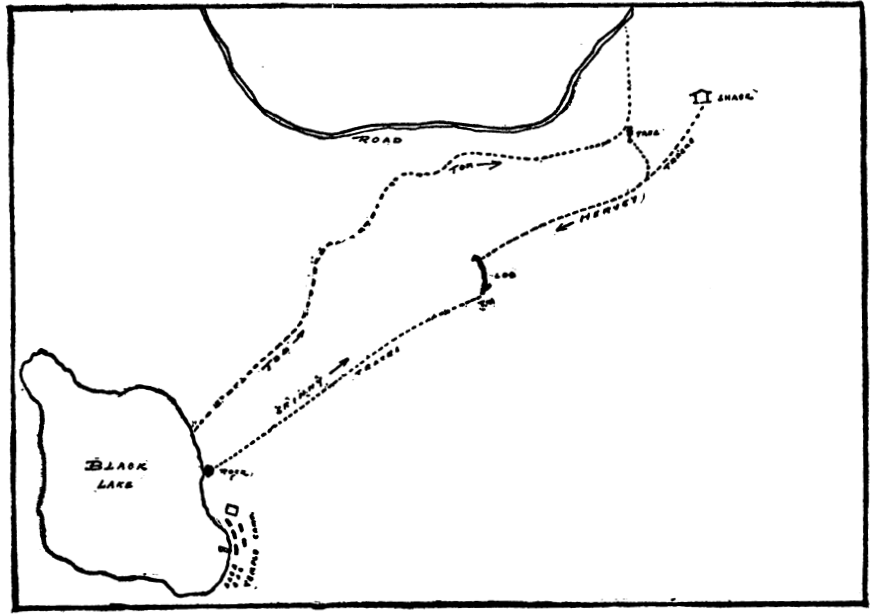

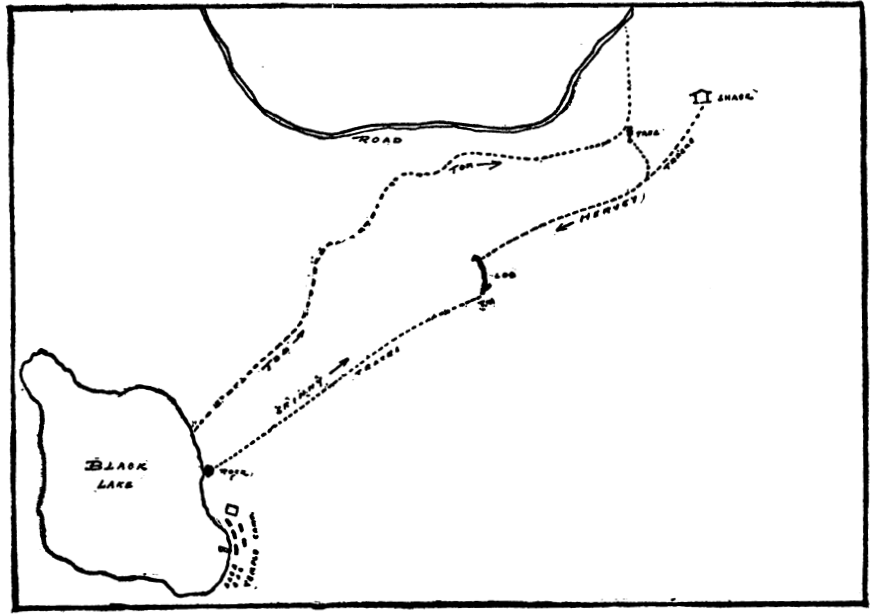

Tom and Hervey stood upon a ledge of rock just outside the area of a great elm tree, and as they looked down and afar off, Black Lake seemed a mere puddle with toy cabins near it.

“I bet there are wild animals up there,” Hervey said.

“Here’s one of them now,” commented Tom, pointing upward.

High above them in the dusk and with a background of golden-edged clouds, which gave the sun’s last parting message to the earth, a great bird hovered motionless. It seemed to hang in air as if by a thread. Then it descended with a wide, circling swoop. In less than ten seconds, as it seemed to Hervey, its body and great wings, and even its curved, cruel beak, were plainly visible circling a few yards above the tree. It seemed like a journey from the heavens to the earth, all in an instant.

“Watch him, watch him,” Hervey whispered.

But Tom was not watching him at all. He knew what that savage descent meant and he was looking for its cause. Stealthily, with no more sound than that of a gliding canoe, he stole to the trunk of the tree and looked about with quick, short, scrutinizing glances, away up among its branches.

Then he placed his finger to his lips, warning Hervey to silence, and beckoned him into the darker shadow under the great tree.

“Did you see anything beside the bird?” he whispered.

“No,” said Hervey. “Why? What is it?”

“Shh,” Tom said; “look up—shh——”

It was the most fateful moment of all Hervey Willetts’ scout career, and he did not know it.

“Look up there,” Tom said; “out near the end of the third branch. See? The little codger beat him to it.”

Looking up, Hervey saw amid the thicker foliage, far removed from the stately trunk, something hanging from a leaf-covered branch. Even as he looked at it, it seemed to be swaying as if from a recent jolt. At first glimpse he thought it was a bat hanging there.

“See it?” Tom said, pointing up. “You can see it by the little streak of red. I think the little codger’s head is poking out. Some scare she had.”

Then all in an instant Hervey knew. It seemed incredible that the great bird, hovering at that dizzy height, could have seen the little songster of the woods which even he and Tom had failed to see. And the thought of that smaller bird reaching its home just in time, and poking its head out of the opening to see if all was well, went to Hervey’s heart and stirred a sudden anger within him.

“I didn’t know they could see all that distance,” he said.

“Well, that’s one thing you’ve learned that you didn’t know before,” Tom said in his matter-of-fact way.

Scarcely had he spoken the words when the foliage above shook and there was a loud rustling and crackling of branches, while many leaves and twigs fell to the ground.

The monarch of the mountain crags, having circled the elm, had found a way in where the foliage was least dense, and had thus with irresistible power carried the outer defenses of that little hanging citadel.

And still the little streak of red showed up there in the dimness of those invaded branches, and one might have fancied it to be the colors of the besieged victim, flaunting still in a kind of hopeless defiance. Down out of the green twilight above floated a feather, then another—trifling losses of the conqueror in his triumphal entry.

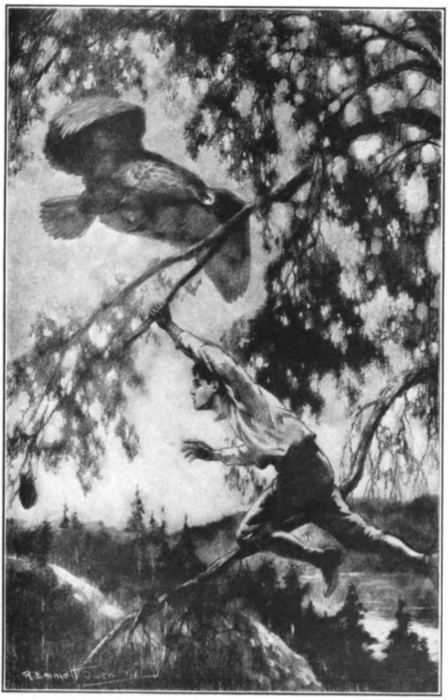

“You’re not going to get away with that,” said Hervey in a voice tense with wrath and grim determination; “you’re—you’re—not——”

What happened then happened so quickly as almost to rival the descent of the destroyer in lightning movement. Before Tom Slade realized what had happened, there was Hervey’s khaki jacket on the ground, his discarded hat was blowing away, and his navy blue scout scarf was plastered by the freshening breeze flat against the trunk of the tree.

Hervey Willetts, who had dreamed and striven all through the vacation season of “capturing the Eagle,” as they say, was on his quest in dead earnest.

Up, up, he went, now reaching like a monkey, now wriggling like a snake. Now he loosed one hand to sweep back the hair which fell over his forehead. Again, unable to release his hold, he threw his head back to shake away the annoying locks. Tom Slade, stolid though he was, watched him, thrilled with amazement and admiration.

The great bird was embarrassed in the confines of the foliage by its big wings. But the freedom and strength of its cruel beak and talons were unimpaired and every second brought it nearer to the hanging nest.

But every second brought also the scout nearer to the hanging nest. Up, up he went, now straddling some bending limb, now swinging himself with lightning agility to one above. Once, crawling on a horizontal branch, he slid over and hung beneath it, like an opossum.

Twisting and wriggling his way out of this predicament, he scrambled on, handing himself from branch to branch, and once losing his foothold and hanging by one hand.

Tom Slade watched spellbound, as the agile form ascended, using every physical device and disregarding every danger. More than once Tom almost shuddered at the chances which his young companion took upon some perilously slender limb. Once, the impulse seized him to call a warning, but he refrained from a kind of inspired confidence in that young dare-devil who by now seemed a mere speck of brown moving in and out of the darkened green above him. Once he was on the point of shouting advice to Hervey about what to do in the unlikely event of his reaching the nest before the eagle, or in the more serious contingency of an encounter with that armed warrior.

For, thrilled as he was at the young scout’s agility and fine abandon, he was yet doubtful of Hervey’s power of deliberation and presence of mind. But no one could advise a creature capable of being carried away in a very frenzy of nervous enthusiasm, and Tom, sober and sensible, knew this. Hervey Willetts would do this thing or crash his brains out, one or the other, and no one could help or hinder him.

Amid the crackling sound of breaking limbs and a shower of leaves and smaller twigs, the mighty bird of prey, extricating himself from every obstacle, tore his way into the leafy recess where his little victim waited, trembling. Every branch seemed agitated by his ruthless, irresistible advance, and the hanging nest swayed upon its slender branch, as the cruel talons of the intruder fixed themselves in the yielding bark. The weight of the monster bird upon the very branch which his little victim had chosen for a home caused it to bend almost to the breaking point, and the hanging nest, agitated by the shock, swung low near the end of the curving bough.

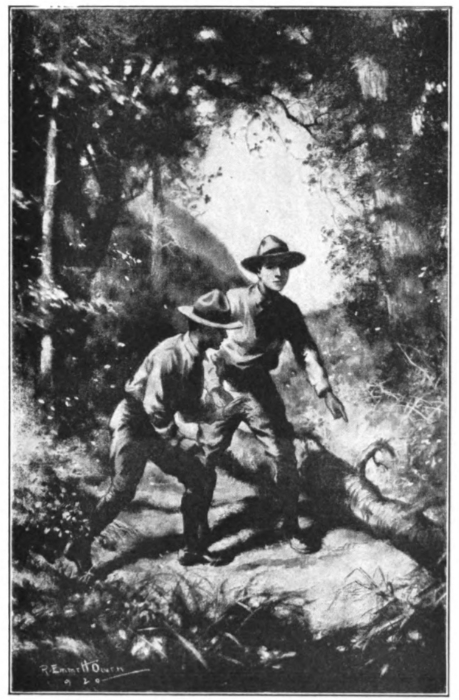

HERVEY SAVES THE LITTLE BIRD FROM THE EAGLE.

That was bad strategy on the part of the invader. As the end of the bough descended under his weight, there was the appalling sound of a splitting branch, which made Tom Slade’s blood run cold, and he held his breath in frightful suspense, expecting to see the form of his young friend come crashing to earth.

But the boy who had ventured out so far upon that straining branch had swung free of it just in time, and was swinging from the branch above. The great bird had played into the hands of his dexterous enemy when he had placed his weight upon the branch above, from which the nest hung.

Hervey could not have trusted his own weight upon that upper branch, and he knew it. But even had he dared to do this he could not have passed the enraged bird who stood guard within a yard or two of his little victim. When the weight of the bird’s great body bent the branch down, Hervey, close in toward the trunk just below, saw his chance. He did not see the danger.

Scrambling out upon that slender branch, he moved cautiously but with beating heart, out to a point where the bending branch above was within his reach. If the eagle had left the branch above, that branch would have swung out of Hervey’s reach and he would have gone crashing to the ground when his own branch broke. He knew that branch must break under him. He knew, he must have known, that the chances were at least even that the eagle would desert the branch above in either assault or flight.

Hervey’s chance was the chance of a moment, and it lay just in this: in getting far enough out on the branch before it broke to catch the branch above before it sprang up and away from him. Also he must trust to the slightly heavier branch above not breaking.

It would be impossible to say by what a narrow squeak he saved himself in this dare-devil maneuver. His one chance lay in lightning agility.

Yet, first and last, it was an act of fine and desperate recklessness—the recklessness of a soul possessed and set on one dominating purpose. This was Hervey Willetts all over. And because he had a brain and the eagle none or little, he thus used his very enemy to help him accomplish his purpose.

In that very moment when Tom Slade heard with a shudder the appalling sound of that splitting branch, something beside the brown nest was also dangling from the branch which the baffled eagle had suddenly deserted. Right close to the swaying nest the boy hung, his limbs encircling it, his two hands locked upon it, trusting to it, just trusting to it. It bent low in a great sweeping curve, the nest swayed and swung from the movement of the swing downward, a little olive-colored, speckled head peeking cautiously out as if to see what all the rumpus was about.

It must have seemed to those little frightened eyes that the familiar geography of the neighborhood was radically changed. But there was nothing near to strike terror to it now. There was nothing near but the green, enshrouding foliage, and the brown object hanging almost motionless close by.

This was Hervey Willetts of the patrol of the blue scarf, scout of the first class (if ever there was one) and winner of twenty-one merit badges....

No, not twenty-one. Twenty and two-thirds.

Hervey moved cautiously in along the limb to a point where he felt sure that it would hold his weight, and as he did so it moved slowly up into place. What the little householder thought of all this topsy-turvy business it might be amusing to know. For surely, if the world war changed the map of Europe, the little neighborhood of leaf and branch where this timid denizen of the woods lived and had its being, had been subject to jolts and changes quite as sweeping. Now and again it poked its downy speckled head out for a kind of disinterested squint at things, apparently unconcerned with mighty upheavals so long as its little home was undisturbed.

Hervey Willetts straddled the branch and calculated the thickness of it.

“You all right?” he heard Tom call from below.

“Yop,” he called back; “did you see his nobs fly away? Back to the crags for him, hey? Wait down there a few minutes, I’m going to bring a friend.”

Hervey had now a very nice little calculation to make. In the first place he must not frighten his new acquaintance by approaching too near again. Neither must he make any sudden and unnecessary noise or motions. He knew that a nest of that particular sort was more than a home, it was a comparatively safe refuge, and he knew that its occupant would not emerge and desert it without good cause. One of those precious twenty badges was evidence of that much knowledge.

His purpose was to cut the branch as near to the nest as he dared, both from the standpoint of the bird’s peace of mind and his own safety. The further from the nest he cut, the thicker would be the branch, and the more cutting there would be to do. To cut too near to the nest might frighten his little neighbor on the branch, and endanger his own life.

Yet if he cut the branch where it was thick, how could he handle it after it was detached? How would he get down with it through all that network of lower branches?

In his quandary he hit on a plan involving new peril for himself and doubtless some agitation to his little neighbor. He would not detach the nest from its branch, for how could he ever attach it to another branch in a way satisfactory to that finicky little householder? He knew enough about his business to know that no bird would continue to live in a nest which had been tampered with to that extent.

So he advanced cautiously out on the branch again till he could reach the nest. Then very gently he bound his handkerchief about the opening. Having done this, he cut into the branch with his scout knife within about six or eight inches of the nest. When he had cut the branch almost through it was a pretty ticklish matter, straddling the stubby end, for he had the tip of the branch with the nest still in his hand and was in danger of losing his balance.

Sitting there with his legs pressed up tight against the under side of the branch so as to hold his balance on his precarious seat, he held the end in one hand while he carefully pulled away the twigs from the end beyond the nest. Thus he had a piece of branch perhaps twenty inches long, with the nest hanging midway of it. This he held with the greatest care, lest in turning the branch the delicate fabric by which it hung should strain and break away. You would have thought that that little prisoner of the speckled head owned the tree, which in point of fact was owned by Temple Camp, notwithstanding its distance from the scout community. So it was really Hervey’s more than it was little downy-head’s if it comes to that.

It is not every landlord that goes to so much trouble for a tenant.

“All right, we’re coming down; kill the fatted calf,” Hervey called with all his former gay manner. “No more up and down trails for me. This is moving day.”

When he had descended a little nearer, Tom heard the cheery voice more clearly. “It’s no easy job moving a house and family. I have to watch my step. Oh, boy, coming down! This tree is tied in a sailor’s knot.”

“Are you bringing the bird?” Tom called.

“I’m bringing the bird and the whole block he lived in,” Hervey called back merrily. “I’m transplanting the neighborhood. He’s going to move into a better locality—very fashionable. He’s coming up in the world—I mean down. O-o-h, boy, watch your step; there was a narrow escape! I stepped on a chunk of air.”

So he came down working his way with both feet and one hand, and holding the precious piece of branch with its dangling nest in the other.

“Talk about your barbed wire entanglements,” he called. Then, after a minute, “This little codger lives in a swing,” he shouted; “I should think she’d get dizzy. No accounting for tastes, hey? Whoa—boy! There’s where I nearly took a double-header. If I should fall now, I wouldn’t have so far to go.”

“You won’t fall,” said Tom with a note of admiring confidence in his brief remark.

“Better knock wood,” came the cheery answer from above.

And presently his trim, agile form stood upon the lowest stalwart limb, as he balanced himself with one hand against the trunk. His khaki jacket was in shreds, a great rent was in his sleeve, and a tear in one of his stockings showed a long bloody scratch beneath. In his free hand he held the piece of branch with its depending nest, extending his arm out so as to keep the rescued trophy safe from any harm of contact.

“Some rags, hey?” he called down good-humoredly, and exposing his figure in grotesque attitude for sober Tom’s amusement. “If mother could only see me now! Get out from under while I swing down. Back to terra cotta—I mean firma. Here goes——”

Down he came, tumbling forward, and sprawling on the ground, while he held the branch above him, like the Statue of Liberty lighting the world.

“Here we are,” he said. “Take it while I have a look at my leg. It’s nothing but an abrasion. It looks like a trail from my ankle up to the back of my knee. What care we? I’ve got trails on the brain, haven’t I?”

Tom took the branch and stood looking admiringly, yet with a glint of amusement lighting his stolid features, at the younger boy, who sat with his knees drawn up humorously inspecting the scratch on his leg.

“Well, what do you think of eagles now?” Tom asked, in his dull way.

“Decline to be interviewed,” Hervey said, with irrepressible buoyancy. “What kind of a crazy bird is this that lives upside down in a house that looks like a bat. It reminds me of a plum pudding, hanging in the pantry. What’s that streak of red, anyway? His patrol colors? You’d think he’d get seasick, wouldn’t you?”

“You’ve got the bird badge,” Tom said, smiling a little; “can’t you guess?”

What Tom did not realize was that this merry, reckless, impulsive young dare-devil, whose very talk, as he jumped from one theme to another, made him smile in spite of himself, could not be expected to bear in mind the record of his whole remarkable accomplishment. He was no handbook scout.

There is the scout who learns a thing so that he may know it. But there is the scout who learns a thing so that he may do it. And having done it, he forgets it. Perhaps there is the scout who learns, does, and remembers. But Hervey was not of that order. He had made a plunge for each merit badge, won it and, presto, his nervous mind was on another. It takes all kinds of scouts to make a world.

Perhaps Hervey was not the ideal scout, but there was something very fascinating about his blithe way of going after a thing, getting it, and burdening his mind with it no more. He lived for the present. His naïve manner of asking Tom for a tip as to a trail had greatly amused the more experienced scout, who now could not understand how Hervey had used the handbook so much and knew it so imperfectly.

“Didn’t you ever see one before?” Tom asked.

“Not while I was conscious,” Hervey shot back, “but if he likes to live that way it’s none of my business. He’s inside taking a nap, I guess. He had some rocky road to Dublin coming down. I wonder what he thinks? That wasn’t the right kind of a trail, was it?”

“Wasn’t it?” Tom queried.

“No; I want a trail along the ground.”

“Still after the Eagle, huh? Do you realize what you have done?”

“I’ve torn my suit all to shreds, I know that. Right the first time, hey? I’d look nice going up on the platform Saturday night? Good I won’t have to, hey?”

“I thought you were going to,” Tom said soberly.

“So I am,” Hervey shot back at him; “trails up in the air don’t count. Never mind, I’ll find a trail to-morrow. It’s my troop I’m thinking of. I’ll land it, all right. When I get my mind on a thing.... Hey, Slady, what in the dickens is that streak of red in the nest? Is it a trade mark or something like that? You’re a naturalist.”

“It’s an oriole’s nest,” Tom said, with just a note of good-humored impatience in his voice. “I thought you’d know that.”

“You see my head is full of the Eagle badge just now,” Hervey pleaded, “but I’m going to look up orioles.”

Tom smiled.

“I’m going to look up orioles, and I’m going to get Doc to put some iodine on my leg, and I’m going to do that tracking stunt to-morrow. There’s three things I’m going to do.”

Tom paused, seemingly irresolute, as if not knowing whether to say what was in his mind or not. And presently they started toward the camp, Hervey limping along and carrying the branch.

“An oriole picks up everything he can find and weaves it into his nest,” Tom said; “string, ribbon, bits of straw, any old thing. He likes things that are bright colored.”

“He’s got the right idea, there,” Hervey said.

Tom tried again to interest the rescuer in this little companion, imprisoned within its own cozy little home, whom they were taking back to camp. He could not comprehend how one who had performed such a stunt as Hervey had just performed, and been so careful and humane, could forget about his act so soon and take so little interest in the bird which had been saved by his reckless courage. But that was Hervey Willetts all over. His heart went where action was. And his interest lapsed when action ceased.

“Somebody in a book called the oriole Orestes, because that means dweller in the woods,” Tom ventured.

“He dwells in a sky-scraper, that’s what I say,” Hervey commented. “In a hall bedroom upside down, twenty floors up.”

Tom tried again. “What do you mean to do with her now that you’ve got her?” he asked.

“I’m going to turn her over to you, Slady. You’re the real scout; none genuine unless marked T. S. You’ve got the birds all eating out of your hands.”

“You didn’t tear the nest from the branch,” Tom said. “You must have had some idea.”

“Well,” said Hervey, “my idea was to stick it up in an elm tree down at camp. Think she’d stand for it?”

“Guess so,” Tom said.

“You see I’m all through bird study,” Hervey said with amusing artlessness, “so I think you’d better adopt Erastus—is that the way you say it?”

“Orestes,” Tom corrected him.

“Pardon me,” Hervey said.

“Maybe you don’t even care if I tell them what you did?” Tom queried.

“Tell them whatever you want,” Hervey said. “I don’t care. What I’m thinking now is——”

“The next stunt,” Tom interrupted him.

“You said it,” Hervey answered cheerily; “just about a mile or so of tracks. I guess you think I’m kind of happy-go-lucky, don’t you?”

“I don’t blame you for not remembering all the things you’ve done,” Tom said, “and all the rules and tests and like that. But most every scout goes in for some particular thing. Maybe it’s first aid, or maybe it’s signaling. And he keeps on with that thing even after he has the badge.”

“That’s right,” Hervey concurred with surprising readiness. “You’ve got the right idea. My specialty is the Eagle badge. See?”

“Well, that’s twenty-one badges,” Tom said.

“Right-o, and all I need to do now is test three for the stalking badge and I’m it. And if I can’t go over the top between now and this time Saturday, I’ll never look the fellows in my troop in the face again, that’s what.”

Tom whistled to himself a moment as they strolled along. Perhaps he knew more than he wished to say. Perhaps he was just a little out of patience with this sprightly, irresponsible young hero.

“Well, there isn’t much time,” he said.

“That’s the trouble, Slady, and it’s got me guessing.”

It is doubtful if ever there was a scout at Temple Camp for whom Tom felt a greater interest or by whom he was more attracted than by this irrepressible boy whose ready prowess he had just witnessed. And the funny part of it was that no two persons could possibly have been more unlike than these two. Hervey even got on Tom’s nerves somewhat by his blithe disregard of the handbook side of scouting, except for what it was worth to him in his stuntful career.

The handbook was almost a sacred volume to sober Tom. Still, he was captivated by Hervey, as indeed others were in the big camp.

“Well, you were after the Eagle and you got an oriole,” he said, half jokingly. “That’s what I meant when I said that sometimes you don’t know where a trail will bring you out. You got a lot to learn about scouting. What you did to-day was better than tracking a half a mile or so.”

“The pleasure is mine,” said Hervey, in bantering acknowledgment of the compliment, “but if there’s anything higher in scouting than the Eagle award, I’d like to know what it is.”

“How much good has it done you trying for it?” Tom asked. “Nobody is supposed to go after a thing in scouting the same as he does in a game. He’s supposed to learn things why he’s going after something,” he added in his clumsy way. “You went through the bird study test and you didn’t even know it was an oriole’s nest that you rescued. And you forgot all about something else too, and it makes me laugh when I think about it; when I think about you and your tracks.”

“You think I’m a punk scout,” Hervey sang out, gayly.

“I think you’re a bully scout,” Tom said.

“If I win the Eagle you’ll say so, won’t you?”

“Maybe.”

“And do you mean to tell me that a scout can be any more of a scout than that—an Eagle Scout?”

“Sure,” said Tom uncompromisingly.

For a few seconds the young hero of the lofty elm was too astonished to reply. Then he said, “Gee, you’re a peachy scout, everybody says that, but you’re a funny kind of a fellow, that’s what I think. I don’t get you. The Eagle award is the highest award in scouting. It means, oh, it means a couple of hundred stunts—hard ones. You can’t get above that. You’re one yourself, you can’t deny it. No, sir, you can’t get above that—no, siree.... Do you mean to tell me that there’s anything higher in scouting than the Eagle award?” he asked defiantly, after a pause.

“Yop, there is,” said Tom, unmoved.

Hervey paused in consternation. “Well, I’m for the Eagle award, anyway,” he finally said. “That’s good enough for me. And I’m going to get it, too; right away, quick.”

“You’ll get it,” Tom said.

“Think I will?”

“I don’t think, I know.”

“You mean you’re sure I will?”

“That’s what I said.”

“Positive?”

“That’s what I said.”

“Well, then I’d better get busy hunting for some tracks, hadn’t I? I’ve got to make good to you as well as to my troop, haven’t I?”

“You ask a lot of questions,” said Tom in his funny, sober way. “You don’t need to make good with me.”

“Believe me, I’ve got you and my troop both on my mind now. Are you going to give me a tip about some tracks?”

“Maybe—to-morrow,” Tom said.

“Do you know what I think I’ll do, Slady?” Hervey suddenly vociferated as if caught by an inspiration. “I think I’ll follow this ledge around a little way and see if there are any prints. Good idea, hey?”

This was too much for Tom. “Aren’t you coming back to camp with me?” he asked. “They’ll want to hear about your adventure. It’s getting pretty late, too.”

“Oh, I’m a regular night owl,” Hervey said. “You take Asbestos back to camp and hang him up in a tree and I’ll blow in later. I’m going on the war path for tracks. So long.”

Before Tom had recovered from his surprise, Hervey was picking his way along the rocky ledge at the base of the mountain, apparently oblivious to all that had happened, and intent upon a rambling quest for tracks. It was quite characteristic of him that he based his search upon no hint or well considered plan, but went looking for the tracks of a wild animal as one will hunt for shells, along the beach.

And there stood Tom, holding the memorial of Hervey’s heroism in his hand. Hervey had apparently forgotten all about it....

Hervey picked his way among the rocks, looking here and there in the crevices and upon the intervening ground as if he had lost something. A more random quest could scarcely be imagined. Tom watched him for a few minutes, then took the shorter way to camp with his little charge.

Hervey followed the rocky ledge for about fifty yards to a point where the dry bed of a stream came winding down out of the mountain. It ran in a tiny canyon between two rocks and so out upon the level fields to the south where the camp lay.

The twilight was well advanced now, the last vivid patches were mellowed into a pervading gray, which seemed to cover the rocks and woods like a mantle. Clad in this somber robe, the wooded height which rose to the north seemed the more forbidding. Not a sound was to be heard but the voice of a whip-poor-will somewhere. Even Hervey’s buoyant nature was subdued by the solemn stillness.

Suddenly something between the two rocks caught his eye. The caked earth looked as if a narrow board had been drawn over it. Bordering this broad line, about half an inch from it on either side, were two narrow fancy lines—or at least that is what Hervey called them. Examining these carefully, he saw that they were made up of tiny, diagonal lines. In the place where this ran between the rocks, in the deep shadow, these singular marks were surprisingly legible, and bore not a little the appearance of a border design. The big stones formed a sort of shadow box, causing the markings to appear in bold relief.

Hervey knew nothing of the freakish influence of light on tracks and trails, but he saw here something which he knew had been made by a moving object. The continuous design was so nearly perfect that it seemed like the work of human beings, but Hervey knew that it could hardly be this.

What, then, was it?

Where the lines emerged from between the rocks the marking was less regular and less clear, but plain enough in the damp, crusted earth which covered the mud in the old stream bed.

With heart bounding with joy and elation, Hervey followed the bed of the stream. The tracks, or whatever they were, were so clear that he could keep to the side of the muddy area and still see them.

It was characteristic of him that having made this great discovery, he did not trouble himself about the direction he was taking. In point of fact he was going in a southwesterly direction toward the camp.

For perhaps a quarter of a mile the strange markings were clearly legible in the dusk, running as they did in the yielding caked surface of the stream bed. They were as clear as tracks in caked snow. Then the path of the dried up waterway petered out in an area of rocks and pebbles and beyond that there was no clearly defined way; the brook had evidently trickled down into the lower land taking the path of least resistance among the rocks.

No doubt Tom Slade could have followed that water path to its end, but Hervey was puzzled, baffled. Yet the enthusiasm which carried him, as though on wings, to his triumphs was aroused now. He had the prophecy of Tom Slade to strengthen his determination. He must make good for Tom’s sake now, as well as for the sake of his troop. He had told Tom that if he only once found a trail, nothing would stop him—nothing. Very fine. All that talk about there being something higher than the Eagle award was nonsense, and Tom Slade knew it was nonsense. “He said I’d do it, and I’m going to,” Hervey muttered to himself.

Hervey had no patience with obstacles, he must be always moving, so now he began frantically scrutinizing the ground to see if he could find some sign of the marks which had eluded him. Since he could no longer distinguish the stream bed, he looked for some sign of those marks outside the stream bed.

And presently he was rewarded by the discovery of tracks, animal tracks sure enough, without any ribbon, so to speak, printed between them. There they were upon the hard, bare earth, two lines of claw marks, continuing to a point where they disappeared again at the edge of a close cropped field. Evidently his mysterious predecessor had known just where he wished to go and had forsaken the stream bed when it no longer went in his direction. These were no aimless tracks, they were the tracks of a creature that had particular business in the southwest, and that knew how to get there.

Hervey had not the slightest idea in which direction he was going, but in point of fact he was heading straight in the direction of Temple Camp. But he had found his precious tracks and nothing would stop him now. He would go over the top in a blaze of glory next day, and then perhaps a telegram could be sent to scout headquarters to have the Eagle badge sent up immediately so that he could receive the very award itself on Saturday night. He was on the home stretch now, as luck would have it, and nothing would stop him—nothing....

Nothing! He would send a line to his mother that very night and tell her all about it, and put E. S. after his name. Eagle Scout. The bicycle his father had promised him when he should attain that pinnacle of scout glory, he would now demand. That would be where dad lost out....

If Tom Slade knew some secret about a higher award, that meant more stunts, Hervey would do those stunts, too; the more the merrier. He should worry....

Yes, he was on the trail at last, and at the end of that trail was the stalking badge—and the Eagle award. Hervey Willetts, Eagle Scout. It sounded pretty good....

He realized now that this discovery of his was just a streak of luck, that the chances would have been altogether against his finding real tracks in these two remaining days. “I’m lucky,” he said. Which must have been true, else he would have lost his life long ere that....

Darkness was now coming on apace, and it must be long past supper-time. But this was no time to be thinking of eating. Nothing would stop him now, nothing. When he set his mind on a thing....

The tracks changed again in traversing the fields. They were not tracks at all, in fact, but a narrow belt of trampled grass, which was not visible close by. It was only by looking ahead that Hervey could distinguish it. Half way across the field he lost it altogether, but, remembering the fact that it could be seen better at a distance, he climbed a tree and there lay the long narrow belt of trampled grass running under the rail fence at the field’s edge and into the sparse woods beyond. He had not to follow it, only pick out the rail of the fence near where it passed and hurry to that spot.

And there it was, waiting for him. If Hervey had been well versed in tracking lore and less of a seeker after glory, he would have scrutinized the lowest rail of the fence, under which the track went, for bits of hair. But Hervey Willetts was not after bits of hair. It was quite like him that he did not care two straws about what sort of animal he was tracking. He was tracking the Eagle badge.

In the sparse woods the tracks appeared as regular tracks again, sharply cut in the hard earth. Where the ground was bare under the trees, the tracks were as clear as writing on a slate, but in the intervening spaces the vegetation obscured them and he found them with difficulty. This tracking in the woods was the hardest part of his task because it required patience and deliberation, and Hervey had neither.

But he managed it and was beginning to wonder how far his tracking had led him and whether he was near to covering the required distance. When he felt certain of that, he would drive a stake in the ground, fly his navy blue scarf from it to prove his claim, and go back to camp in triumph. He had made up his mind that he would at once report his feat in Council Shack, and offer to escort any or all of the trustees back over the ground in verification of his crowning accomplishment. The only Eagle Scout at Temple Camp, except Tom Slade; and Tom Slade didn’t count....

Still, as he looked back, the base of the mountain seemed almost as near as when he had made his discovery, the fields and wood which had seemed so long to the tracker were but small to the casual glance and he realized that his whole journey was yet far short of a quarter mile.

The tracks now ran, as clear as writing, across one of those curious patches of damp ground with a thin, slippery skin, which was torn straight across in a kind of furrow. Hervey was so intent on studying this that he did not notice in the shadow about a hundred feet ahead of him a log directly in line with the tracks. When suddenly he looked up, he paused and stared ahead of him in consternation.

Some one was sitting on the log.

As soon as Hervey’s dismay subsided he approached the log, and as he did so the figure appeared familiar to him. There was something especially familiar in the scout hat which came down over the ears of the little fellow who was underneath it, and in the hair which straggled out under the brim. The belt, drawn absurdly tight around the thin little waist, was a quite sufficient mark of identification. It was Skinny McCord, the latest find, and official mascot of the Bridgeboro troop, one of the crack troop of the camp. Alfred was his Christian name.

The queer little fellow’s usually pale face looked ghastly white in the late dusk, and the strange brightness of his eyes, and his spindle legs and diminutive body, crowned by the hat at least two sizes too large, made him seem a very elf of the woods. At camp or elsewhere, Skinny was always alone, but he seemed more lonely than ever in that still wood, with the night coming on. Nature was so big and Skinny was so little.

“Hello, Skinny, old top!” Hervey said cheerily. “What do you think you’re doing here? Lost, strayed, or stolen?”

Skinny’s eyes were bright with a strange light; he seemed not to hear his questioner. But Hervey, knowing the little fellow’s queerness, was not surprised.

“You look kind of frightened. Are you lost?” Hervey inquired.

For just a moment Skinny stared at him with a look so intense that Hervey was startled. The little fellow’s fingers which clutched a branch of the log, trembled visibly. He seemed like one possessed.

“Don’t get rattled, Skinny,” Hervey said; “I’ll take you back to camp. We’ll find the way, all right-o.”

“I’m a second-class scout,” Skinny said.

“Bully for you, Skinny.”

“I—I just did it. I’m going to do more so as to be sure. Will you stay with me so you can tell them? Because maybe they won’t believe me.”

“They’ll believe you, Skinny, or I’ll break their heads, one after another. What did you do, Alf, old boy?”

“Maybe they’ll say I’m lying.”

“Not while I’m around,” Hervey said. “What’s on your mind, Skinny?”

“I ain’t through yet,” Skinny said. “I know your name and I like you. I like you because you can dive fancy.”

“Yes, and what are you doing here, Alf?” Hervey asked, sitting down beside the little fellow.

“I’m a second-class scout,” Skinny said; “I found the tracks and I tracked them. See them? There they are. Those are tracks.”

“Yes, I see them.”

“I tracked them all the way up from camp and I’ve got to go further up yet, so as to be sure. You got to be sure—or you don’t get the badge. So now I won’t be a tenderfoot any more. Are you a second-class scout?”

“First-class, Skinny.”

“I bet you don’t care about tracks—do you?”

Hervey put his arm over the little fellow’s shoulder and as he did so he felt the little body trembling with nervous excitement.

“Not so much, Skinny. No, I don’t care about tracks. I—eh—I like diving better. How far up are you going to follow the tracks?”

“I’m going to follow them away, way, way up so as I’ll be sure. They might say it wasn’t a half a mile, hey?”

The hand which rested on the little thin shoulder, patted it reassuringly.

“Well, I’ll be there to tell them different, won’t I, Skinny, old boy?”

“Will you go with me all the way up to where the mountain begins—will you?”

“Surest thing you know.”

“And will you prove it for me?”

“That’s me.”

“Then I won’t be a tenderfoot any more. I’ll be a second-class scout.”

“Is that what you have to do to be a second-class scout, Skinny? I forget about the second-class tests. You have to track an animal, or something like that? I’ve got a rotten memory.”

“And I’ll—I’ll have a trail named after me, too; it’ll be called McCord trail. These are my tracks, see? Because I found them. Only maybe they’ll say I’m lying. Anyway, how did you happen to come here?” he asked as if in sudden fear.

“I was just taking a walk through the woods, Skinny.”

Skinny continued to stare at him, still with a kind of lingering misgiving, but feeling that gentle patting on his shoulder, he seemed reassured.

“I was just flopping around in the woods, Skinny; just flopping around, that’s all....”

And that was the triumph of Hervey Willetts, who would let nothing stand in his way. “Nothing!”

A hundred yards or so more and the stalking badge would have been won, and with it the Eagle award. The bicycle that he had longed for would have been his. The troop which in its confidence had commissioned him to win this high honor would have gone wild with joy. Hervey Willetts would have been the only Eagle Scout at Temple Camp save Tom Slade, and, of course, Tom didn’t count.

Yet, strangely enough, the only eagle that Hervey Willetts thought of now was the eagle which he had driven off—the bird of prey. To have killed little Skinny’s hope and dispelled his almost insane joy would have made Hervey Willetts feel just like that eagle which had aroused his wrath and reckless courage. “Not for mine,” he muttered to himself. “Slady was right when he said he wasn’t so stuck on eagles. He’s a queer kind of a duck, Slady is; a kind of a mind reader. You never know just what he means or what he’s thinking about. I can’t make that fellow out at all.... I wonder what he meant when he said that a trail sometimes doesn’t come out where you think it’s going to come out....”

Hervey had greatly admired Tom Slade, but he stood in awe of him now. “Well, anyway,” said he to himself, “he said I’d win the award and I didn’t; so I put one over on him.” To put one over on Tom Slade was of itself something of a triumph. “He’s not always right, anyway,” Hervey reflected.

He was aroused from his reflections by little Skinny. “I followed them from camp,” he said. “They’re real tracks, ain’t they? And they’re mine, ain’t they? Because I found them? Ain’t they?”

“Bet your life. I tell you what you do, Alf, old boy. You just follow them up a little way further toward the mountain and I’ll wait for you here. Then we can say you did it all by yourself, see? The handbook says a quarter of a mile or a half a mile, I don’t know what, but you might as well give them good measure. I can’t remember what’s in the handbook half of the time.”

“You know about good turns, don’t you?”

“’Fraid not, except when somebody reminds me.”

“I’m going to keep you for my friend even if I am a second-class scout, I am,” Skinny assured him.

“That’s right, don’t forget your old friends when you get up in the world.”

“Maybe you’ll get that canoe some day, hey?”

“What canoe is that, Alf?”

“The one for the highest honor; it’s on exhibition in Council Shack. All the fellows go in to look at it. A big fellow let me go in with him, ’cause I’m scared to go in there alone.”

“I haven’t been inside Council Shack in three weeks,” Hervey said. “I don’t know what it looks like inside that shanty. I’m not strong on exhibitions. I’ll take a squint at it when we go down.”

“The highest honor, that’s the Eagle award, isn’t it?” Skinny asked.

“I suppose so,” Hervey said; “a fellow can’t get any higher than the top unless he has an airplane.”

“Can he get higher than the top if he has a balloon?” Skinny wanted to know.

“Never you mind about balloons. What we’re after now is the second-class scout badge, and we’re going to get it if we have to kill a couple of councilmen.”

“Did you ever kill a councilman?”

“No, but I will, if Alf McCord, second-class scout, doesn’t get his badge. I feel just in the humor. Go on now, chase yourself up the line a ways and then come back. I’ll be waiting at the garden gate.”

“What gate?”

“I mean here on this log.”

“Do you know Tom Slade?”

“You bet.”

“He likes me, he does; because I used to steal things out of grocery stores just like he did—once.”

“All right,” Hervey laughed. “Go ahead now, it’s getting late—Asbestos.”

“That isn’t my name.”

“Well, you remind me of a friend of mine named Asbestos, and I remind myself of an eagle. Now don’t ask any more questions, but beat it.”

And so the scout who had never bothered his head about the more serious side of scouting sat on the log watching the little fellow as he followed those precious tracks a little further so that there might be no shadow of doubt about his fulfilling the requirement. Then Hervey shouted to him to come back, and shook hands with him and was the first to congratulate him on attaining to the dignity of second-class scout. Not a word did Hervey say about the amusing fact of little Skinny having followed the tracks backward; backward or forward, it made no difference; he had followed them, that was the main thing.

“They’re my tracks; all mine,” Skinny said.

“You bet,” said Hervey; “you can roll them up and put them in your pocket if you want to.”

Skinny gazed at his companion as if he didn’t just see how he could do that.

And so they started down for camp together, verging away from the tracks of glory, so as to make a short cut.

“I bet you’re smart, ain’t you?” Skinny asked. “I bet you’re the best scout in this camp. I bet you know everything in the handbook, don’t you?”

“I wouldn’t know the handbook if I met it in the street,” Hervey said.

Skinny seemed a bit puzzled. “I had a bicycle that a big fellow gave me,” he said, “but it broke. Did you ever have a bicycle?”

“Well, I had one but I lost it before I got it,” Hervey said. “So I don’t miss it much,” he added.

“You sound as if you were kind of crazy,” Skinny said.

“I’m crazy about you,” Hervey laughed; and he gave Skinny a shove.

“Anyway, I like you a lot. And they’ll surely let me be a second-class scout now, won’t they?”

“I’d like to see them stop you.”

That Hervey Willetts was a kind of odd number at camp was evidenced by his unfamiliarity with the things that were very familiar to most boys there. He was too restless to hang around the pavilion or sprawl under the trees or idle about with the others in and near Council Shack. He never read the bulletin board posted outside, and the inside was a place of so little interest to him that he had not even seen the beautiful canoe that was exhibited there, and on which so many longing eyes had feasted.

Now as he and Skinny entered that sanctum of the powers that were, he saw it for the first time. It was a beautiful canoe with a gold stripe around it and gunwales of solid mahogany. It lay on two sawhorses. Within it, arranged in tempting style, lay two shiny paddles, a caned back rest, and a handsome leather cushion. Upon it was a little typewritten sign which read:

This canoe to be given to the first scout this season to win the Eagle award.

“That’s rubbing it in,” said Hervey to himself. “That’s two things, a bicycle and a canoe I’ve lost before I got them.”

He sat down at the table in the public part of the office while Skinny, all excitement, stood by and watched him eagerly. He pulled a sheet of the camp stationery toward him and wrote upon it in his free, sprawling, reckless hand.

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

This will prove that Alfred McCord of Bridgeboro troop tracked some kind of an animal for more than a half a mile, because I saw him doing it and I saw the tracks and I came back with him and I know all about it and it was one good stunt I’ll tell the world. So if that’s all he’s got to do to be a second-class scout, he’s got the badge already, and if anybody wants to know anything about it they can ask me.

HERVEY WILLETTS,

Troop Cabin 13.

After scrawling this conclusive affidavit and placing it under a weight on the desk of Mr. Wade, resident trustee, Hervey sauntered over to the cabins occupied by the two patrols of his troop, the Leopards and the Panthers. They were just getting ready to go to supper.

“Anything doing, Hervey?” his scoutmaster, Mr. Warren, asked him.

“Nothing doing,” Hervey answered laconically.