* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Lady-with-the-Crumbs

Date of first publication: 1931

Author: Flora Klickmann (1867-1958)

Date first posted: July 26, 2019

Date last updated: July 26, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190752

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Dianne Nolan & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE LADY-WITH-THE-CRUMBS

First Published October 1931

Printed in England at

The Westminster Press

411a Harrow Road

London, W.9

CONTENTS

| Chap. | page | |

| i | The Little White Dog Arrives | 1 |

| ii | How the News went Round | 8 |

| iii | A Mysterious Disappearance | 14 |

| iv | Mrs. Starling Obliges | 19 |

| v | Mrs. Starling Sees Things! | 29 |

| vi | The Lost One Returns | 37 |

| vii | Everybody Explains | 43 |

| viii | Bobbie Decides to Travel too | 50 |

| ix | Bushy Tail makes Himself Useful | 59 |

| x | The King Comes Back! | 69 |

| xi | The Little Dog has a Sorrow | 80 |

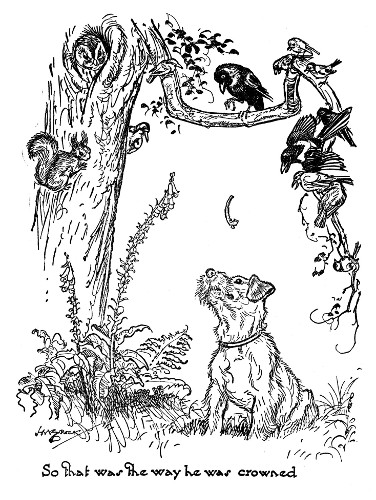

| xii | The Real King is Crowned | 89 |

The Lady-with-the-Crumbs

The little white dog stood at the top of the Ferny Path―the path that goes down the hillside, right through the middle of the Windflower Wood.

In addition to wearing a silky coat and soft brown velvet ears, the little white dog wore a really very superior look on the end of his nose.

He only came to the Flower-Patch House for part of the year. The rest of the time he lived in London. And he knew quite well how highly the postman in town thought of him, also the dustman, and the tramps, and the butcher’s boy, and the man who came to look at the gas meter, and the coal man, and the old gentleman who bought Cook’s bottles and bones―I don’t mean her own bones, you know, but the meat bones.

And though he was only a small dog, he realized that he was a Very Important Person. Why, even the plumber was so afraid of him that he wouldn’t let so much as a tool come inside the house, to say nothing of himself, till he was sure it was perfectly safe. And to make quite certain, he would put his head cautiously round the door, and inquire anxiously:

“Is that bloodhound chained up?”

No wonder Mac felt himself to be an altogether superior dog. Any dog whose full name was “The Mackintosh of Mackintosh” naturally would feel superior!

As he stood at the top of the Ferny Path, he pretended that he was hunting for burglars, and wild beasts, and anything else that would be likely to hurt his master and mistress, in the Flower-Patch House just above the wood. But in reality he was anxious to let all the other Little People of the Forest see that he had arrived.

He hoped they would notice how extra white he was. He had had a bath in town only the day before: and though he didn’t like being washed―said dreadful things and hid under the easy chair in the dining-room when he saw Cook getting out that horrid tub―he knew it was necessary for a Very Important Person.

Besides, people always patted him after this trying event, and said, “Doesn’t he look nice!”

The day before, however, he had a lovely surprise. After his bath, Cook had brought down his travelling basket from the attic, and said to him, “There now! what does that mean?” Whereupon he ran round and round like a top gone crazy, and went up to everybody, putting his front paws on them, and saying with his tail, his eyes, and his ears, “Are we really going away to the Flower-Patch? Oh, won’t it be jolly!”

Then he jumped into his travelling basket (he could open the lid himself, and get in, and let it shut down again with him inside it!); and he refused to budge for meals or at bed-time, lest they should go off and leave him behind, as had happened once upon a time. Oh it was dreadful that other time to see the luggage being brought down, and no sign of his basket! And it was more than dreadful to be shut up in the kitchen and hear the luggage being carried out, and hear the car drive off, and to know they had gone! Gone!―and left him behind!

On that sad occasion he went into his sleeping box and hid his face in his blanket and cried.

No use for Cook to bring him dainty bits, he couldn’t touch them. It was his master and mistress he wanted. Next morning he crept up to the front door, and lay on the mat with his nose on his paws, just waiting till they should return. And not a bit of food would he eat till he heard them coming up the steps to the door. Then he rushed round and round, and down to the kitchen: gobbled a bit of his dinner, which was on a plate near his box. But he couldn’t wait to eat it all. Back again to the front hall. Round and round his dear friends he raced, then upstairs at a rush to find everybody and tell them all about it. And then he never left his master’s side for the rest of the day.

So affectionate and faithful was the little white dog with the brown ears.

Then there was another time, when he saw some luggage in the hall, and his basket not among it―and when they went to find him he had disappeared! Everywhere they hunted and called that day; indoors and out. No reply. No little dog rushed up joyfully, saying, “What can I do for you, master?”

Fortunately, they were not leaving till the next day. But, of course, everyone was very worried.

Then when Cook was going to bed that night she fancied she heard a little sound in the attic. Taking a light, she went to investigate.

There, sitting up in his travelling basket, with a most anxious expression, was the little white dog! He evidently thought that if he sat there in readiness, they would be certain to take him with them.

And of course they did.

However, he had not been left behind this time. He had arrived from London that very afternoon. And as one of his many duties was to go carefully round the Flower-Patch (as the garden is called), and the barns, and outhouses, and orchards, and fields, so as to make sure that every gate-post, and bush, and stone―particularly those at the corners―were just where he left them last time, he had started off at once to attend to this, his own special business.

In the course of his tour of inspection he reached the top of the Ferny Path―as I have already mentioned. And there he stood with everything about him, saying, “I am a Very Important Person. And don’t you forget it!”

He was just thinking that supposing lions or elephants were hiding in that wood he would soon clear them out, and teach them to attend to their own affairs, and make them sorry they had troubled to take a railway ticket from Africa in order to get there!

He was so pleased with his brave thoughts that he went on picturing giraffes and tigers and bears lying dead all around him, with his master and mistress patting his head and saying, “Good boy! Good old Mac! What a wonderful dog to have saved our lives like this.”

Then he knew what would come next―he was sure it would be a very big bone. And――

But just here his beautiful dreams were interrupted by a sharp little voice that called out:

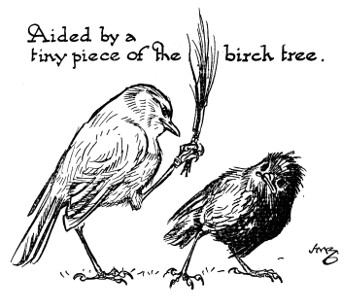

“Hello! Cockie! So you’re back again, are you? Have you brought a little of your London salt to put on my tail? Ha! Ha! You haven’t caught me yet, although you’re so clever.”

And a ball of fur came out from among the brambles close beside him; right under his very nose, so to speak! And then up a big oak tree scampered a saucy squirrel.

His fur was reddish brown; his eyes were bright and full of mischief; his long bushy tail was all fluffed out as he trailed it after him up the rugged trunk.

But the curious thing about him was his face. At first sight it looked as though it was terribly swollen, poor thing, with toothache. In reality he was taking home a meal to his family; and as squirrels use their mouths for pockets, he had stuffed some nuts and one or two young larch cones in his cheeks. Squirrels are very fond of young larch cones.

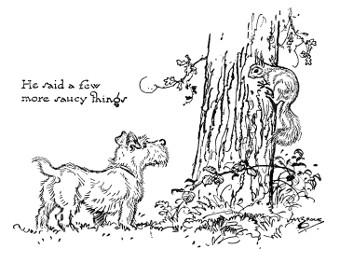

But evidently he wasn’t in a hurry; at any rate he kept his family waiting for their tea, while he said a few more saucy things to Mac, who was most indignant to think that, though he was willing to settle giraffes and elephants, he couldn’t catch a squirrel, a silly animal like that, who was not so big as himself! Most annoying!

And he knew it was useless to argue with the creature; he had learnt that from past experience. So he merely said, with a dignified air, “In London, the animals of my acquaintance do not talk with their mouths full!”

“Ha! Ha! I don’t suppose they do,” said the squirrel. “There is nothing to put in them up there! Not a single walnut rattling down from a tree in all the streets. Not a mushroom growing on any of the pavements. Not a brook with watercress for tea running by the side of the tramlines. Never a plum or cherry tree for miles; no strawberries by the roadside―I know! The swallows have told me what a wretched place London is. How could anyone talk with his mouth full up there? London is where your friend Mother Hubbard lives. A nice state of affairs her cupboard is in!”

But Mac declined to waste any of his precious time on this exasperating creature, who was really worse than a cat, because it would leap from bough to bough above his head, and just out of his reach. So he turned his back upon the squirrel and looked the other way, with his tail in the air.

Whereupon the tiresome little animal in the tree barked out: “Do you call that wispy thing of yours a tail! A tail!! Oh my! Look at it everybody. Just look at it!”

Mac was always annoyed when the squirrels gave their funny, scolding little bark. He thought no animal should presume to bark excepting a dog. He was conscious, however, that his own tail wasn’t much to boast of in comparison with the bushy thing dangling from the tree above him. So he carefully lowered his, and tucked it away behind him.

Then Bushy Tail, the Saucy Squirrel, called out:

“I’ll sing you a song, my young friend, about a dog who came to a sad end because he was so up-shus! Now you just take warning!” And he started to sing:

“Oh! Hi! Diddle Diddle!

Did you ever see the fiddle

Being played by the Man in the Moon?

Did you ever hear the cow

Singing out ‘Bow-wow! Bow-wow!’

While the cat ate the dish and the spoon?

“Oh, Diddle, Diddle Di!

But I really nearly cry

When I think of the little dog that laughed;

For his mouth he opened wide,

Letting all the cold inside,

And they say―he died next morning from the draught!”

But long before the squirrel had finished Mac had stumped off in disgust, wondering whether all the Little People of the Forest were ridiculing him like that aggravating creature up in the tree.

But down in the Windflower Wood, the Little People Who Live There had something far more exciting to talk about. From one end of the wood to the other the tidings went flying around―

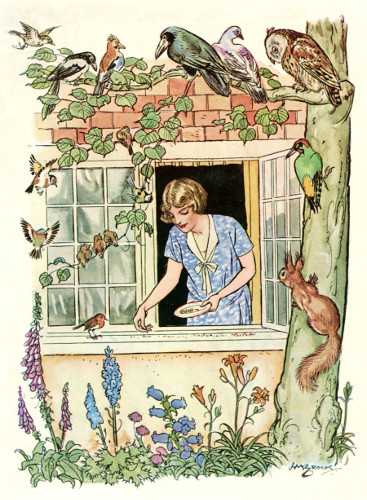

“The Lady-with-the-Crumbs is here!”

Everybody started to tell everybody else the news.

“She’s here! She’s here! She’s here!” the thrush sang, over and over again.

“Who-o-o? Who-o-o?” inquired an owl, who had been fast asleep in the hollow beech, only the clamour woke him. “Who-o-o is it?” he asked again. “Who-o-o is it?”

“It’s the Lady-with-the-Crumbs,” replied an obliging linnet. “You know her, don’t you? Oh, but of course you don’t, because you always go to bed by day, when all sensible birds get up.” But seeing that the owl was beginning to look fierce, he added hurriedly, “I mean―er―hum―I mean, when all unfortunate birds who haven’t the dole have to turn out and work for their living. Of course things are different for an aristocratic gentleman like you.”

“Oh, do get on with it,” said the owl, “and tell me Who-o-o is it?”

“Well, the Lady-with-the-Crumbs doesn’t live here always, but when she comes and stays in the Flower-Patch House she gives everybody the loveliest things to eat. Puts crumbs on all the window ledges, and on the three bird-tables,―cake crumbs and rolled oats and currants and raisins and cheese (only Bushy Tail gobbles that up, first go). We have a garden-party there every day. Why don’t you come and join us like a sociable bird?”

“Any mice there?”

“Certainly not! What a question!”

“No good to me then. My doctor doesn’t allow me to take anything else. But how do you know she’s here?”

“We saw her dog just now. That’s a sure sign.”

“Chut! Chut! Chutter! Chut!” said a blackbird, as he always does when he’s cross. “Won’t someone pat that poor old owl on the back and send him to sleep again? or he’ll be asking conundrums all night. I woke up in a fright last night, thinking there was an air-raid, only to find it was that noisy wretch talking to his cousin across the river.”

“Well, if you won’t come,” said the linnet, “there will be all the more for us. Good-night and happy dreams,” as the owl was settling down again into its Cosy Corner.

“Much chance of happy dreams!” he grumbled. “Just listen to the cackle!”

And, sure enough, everything that lived in the wood was having a say on the subject.

The pigeons were planning to be up at the house as soon as it was daylight, and they were telling their children all about it. As a rule they send their little ones to sleep by cooing: “Take two pears, Tommy; take two pears, Tommy; take two more, Tommy, do!”

But, to-day, all they could say was “Oh the Cr-r-rumbs! the Cr-r-rumbs! the Cr-r-rumbs! You’ve no idea how delicious they are!”

Then there was Mr. Rook, who had been left in charge of the children while Mrs. Rook went to visit her sister, who lived across the valley in a lovely grove of oaks. Mrs. Rook had said she would be back before bed-time, and would bring the children something nice for supper if they were good.

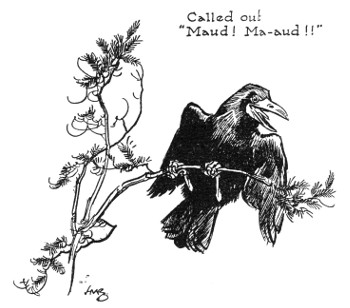

But Mr. Rook couldn’t wait till supper-time to tell her the great news. He simply flew to the topmost branch of the tallest tree in the wood and called out “Maud! Ma-aud!! Mau-au-d!!” as loud as ever he could, and Mrs. Rook (whose name was Maud), hearing her husband calling her, was quite sure that one of the little Rooks had fallen out of the nest on top of his head. So she hurried home as fast as her wings could carry her, and entirely forgot to bring any treat for supper!

Great disappointment, of course! For there the children were, with their beaks wide open, expecting her to drop a tit-bit in. Naturally!

“Ah me! It’s a sad world,” was all they could say to each other, when they found their beaks were still open, and nothing doing, because father and mother were simply talking, talking, talking!

Mrs. Robin was also very excited, and only wished her husband would come home so that she could tell him all about it. But he was off, as usual, having a little disagreement with the black and yellow tits.

He said they were not to come hunting caterpillars on his Oak Tree.

They inquired who gave it to him, and what right he had to it more than they?

That was the way the quarrel started. But by the time it wasn’t nearly ended they had found such a number of fresh things to argue about that no one remembered exactly how it began. That’s often the way with squabbles, I’ve noticed!

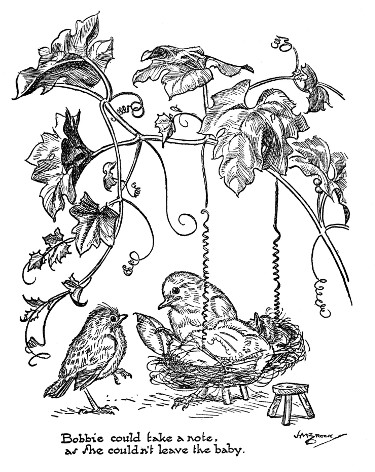

However, Mrs. Robin didn’t intend the great news to be wasted. At least she would send word to her sister, Mrs. Twitter. Bobbie could take a note, as she couldn’t leave the baby, who was rather delicate. Bobbie, the eldest of the children, was beginning to be quite useful. Though his father said if he would only stop asking questions for one day the world wouldn’t be so short of breath!

Mrs. Robin was a very particular lady, and she liked her children to be well-mannered. She used to say to them, “Of course you can’t sing like your father; he has the most wonderful tenor voice of any robin that ever lived. But at least you can speak nicely.” And in order to show them how to do it, she talked to them in poetry (except when she was in a great hurry and forgot).

Having written a note on the back of a laurel leaf with a pointed twig from a blackthorn tree (and it’s quite easy to do this, you just try), she called Bobbie, and told him exactly how to get to his Aunt Twitter’s house.

This was the way she told him he had to go:

“Round the shady corner

By the hart’s-tongue fern;

Past the bank of strawberries.

Then you take a turn

Down the lane with nut-trees

Where the rabbits play;

Over clover where the bees

Buzz about all day.

When you reach the foxgloves,

Ring their bells and wait.

Auntie will unfasten

The prickly bramble gate.

Say ‘Good-morning’ nicely;

Mind you raise your hat!

And―oh! be sure you wipe your feet

Upon the oak-leaf mat!”

Do you know that robins usually put a few oak leaves for a mat outside their front-door when their nest is made in a bank, or on the ground? They do! So look out for it.

Bobbie found his way quite easily, and was hoping that his Aunt would give him something very nice to eat. But to his surprise she burst out crying when she opened the door, hardly looking at the note on the laurel leaf. And instead of telling him how pleased she was to see him, and how he had grown, and what a smart child he was to have come all that way by himself, and how was his mother and the baby?―all she said was:

“Your Uncle Twitter is gone! Clean gone!”

“Oh, Auntie! Where’s he gone?”

“How can I tell? If I knew where he’s gone, he wouldn’t be gone, would he, he’d be there!”

“Where would he be, Auntie, if he was there?”

“Where he isn’t, of course.”

“But, Auntie, if he isn’t where he is―I mean if he’s not where he isn’t―no, that’s not right―I mean, if he’s where he’s gone and he’s not there, why did he wash himself clean? It wouldn’t have mattered if he hadn’t washed behind his ears, would it, if his ears aren’t there?”

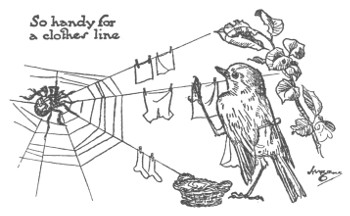

“Oh, for mercy’s sake, do stop asking questions, or I shall go out of my senses.” And poor Aunt Twitter mopped her eyes with her best handkerchief―a lovely silky one, which the spider next door had made specially for her, and given her on her last birthday, because she had persuaded Uncle Twitter to leave him alone, and not to turn him into Breakfast Food. You see Aunt Twitter found the long threads of his web so handy for a clothesline.

“Now go straight back to your mother,” she sobbed, “and tell her ‘Auntie says Uncle Twitter is gone, and she doesn’t suppose we shall ever see him again.’ Now, can you remember that?”

“Oh yes; that’s quite easy. ‘Auntie says Uncle Twitter says he doesn’t suppose he’ll ever see her again.’ ”

“No! No! That’s not it!” And she went all over it several times; till at last Bobbie had got it quite right. She gave him a currant to suck on the way home, and told him not to stop to play with any other little robins he might meet.

He felt very important when he flew back to his mother, because he knew he had some interesting news. He began at once:

“Auntie Twitter says he isn’t there; and he washed himself very clean, and he――”

“Who do you mean

Washed himself clean?”

his mother asked in surprise.

“Uncle Twitter, of course. He isn’t there because he isn’t. And Auntie says I was ‘specially to tell you that if he was there he wouldn’t be and she wouldn’t know it, and if she knew why he was there, he wouldn’t be gone. She’s crying like anything into her party handkerchief, and she says we’ll never see it again, and, Mother, can I have my tea? Auntie only gave me a currant, and it was a very teeny-weeny one. Can’t I have some of the Lady’s Crumbs?”

“No, they won’t be put out for us till the morning. She’s always busy unpacking them the day she gets here. You shall have some to-morrow. But I’m dreadfully worried about Auntie. Evidently something is wrong!”

And so it was!

Mr. Robin happened to come in at that moment.

“I’m so very anxious about poor Auntie,” said his wife. “It seems that Uncle Twitter has disappeared!”

“Disappeared? Twitter disappeared?”

“Yes, Father: gone clean where he isn’t.” Bobbie didn’t wish to be left out of it, being the one who had brought the news.

“Clean gone, has he! And he owes me three grasshoppers!” Mr. Robin was decidedly upset. “Borrowed them that evening―why it must be months ago, when they had unexpected company to supper, you remember. Promised faithfully to return them the next week. And now he skips off without paying his debts. A nice state of affairs to go robbing a hard-working father of a family!”

“Mother, why is he robbing father of his family?” But no one had any time to listen to Bobbie.

“Oh, don’t worry about the three grasshoppers, dear,” Mrs. Robin said. “Probably Auntie Twitter will see to all that. But”―lowering her voice―“I am so afraid it’s the Cat! You remember, Mrs. Chaffinch’s cousin disappeared, and Mr. Greenfinch’s father, and young Wren. I simply dare not let the youngsters out of my sight, or I would have flown over to hear all about it. I must see her in the morning. It’s too late now.―Children! Look at the sun! It will be behind the hill in a minute!”

Whereupon all the small robins hurried home.

For it is a fixed law of the Flower-Patch and the Forest that, so soon as the sun drops out of sight behind the opposite hills, every little bird must be safely in bed, even though the fathers and mothers stay up for just a tiny five minutes longer. And it is another fixed law that, when the youngsters are settled for the night, the Little People of the Forest sing an Evening Song.

Every wood has its own Evening Song. They are not all alike. But you can always hear it being sung by birds and bees, and brooks and trees, if you stand quite still among them when the sun is setting on any summer evening.

This is the Evening Song that they sang that night:

THE EVENING SONG OF THE WINDFLOWER WOOD

“Hush, Baby, hush!”

The Mother Bird is saying.

“Bed-time is Sleep-time―

It isn’t time for playing.

Shut both your little eyes;

The nest is nice and cosy;

Then wake up in the morning light,

All fresh and bright and rosy.”

“Hush, Baby, hush!”

The Bubbly Brook is chattering.

“Don’t be afraid if

You hear the Rain-drops pattering.

Some children like a Brolley―

―Brella always dry;

But little fishes love the wet

To drop down from the sky!”

“Hush, Baby, hush!”

The Silver Birch is sighing.

“Star-time is Quiet-time,

It isn’t time for crying!

Sleep till to-morrow comes,

Then wake, all smiles and sunny.

For children with a Criss-Cross face

Do look so very funny!”

“Hush, Baby, hush!”

The Nightingale is singing.

“All about the Windflower Wood

Are bluebells softly ringing.

Leaves whisper overhead,

And say the moon is peeping

To see our baby in its bed,

And watch it sweetly sleeping.”

As day after day went by and no Uncle Twitter appeared, everyone looked more and more at the cat: and the cat looked more and more the other way. But, though they were all very sorry for Mrs. Twitter, work had to go on as usual. So one bright sunny day Mrs. Robin said to Mr. Robin: “As you and Bobbie are going up the river with Mr. Kingfisher to-morrow, it will be a good chance for me to get on with the spring cleaning. I’ve sent for Mrs. Starling, and we’ll start nice and early.”

I should explain that Mrs. Starling is the charlady. She’s a well-meaning bird, and all that sort of thing. But she isn’t refined like the most exclusive Mrs. Thrush, and she isn’t prettily dressed like the tits and the chaffinches and the exquisite goldfinches. While her voice―oh dear! I really can’t describe it! Though I dare say most of you know what it is like. For even in towns you can hear her loud shrill calls.

Then again, the way she gobbles her dinner is painful to witness―so unlike the blue tits, who take one tiny flake of rolled oats, and make three dainty, polite little bites of it.

However, Mrs. Robin sent her a note:

“Please come by Nine,

If it is Fine.

Then we can Spring-

Clean everything.”

Mrs. Starling said, “Right-o! That’ll suit me to a T.” And she arrived next morning at a quarter to eleven.

Now I dare say you know that birds build a new house for themselves every year. Some of them build two houses in a year―one in the spring and one in the summer. Birds don’t go back to the old nest once the little ones have left it. Yet they like to keep in the same district, and usually build the new house somewhere quite near their old one.

Mrs. Robin was particularly fond of a bank below a hedge that had all sorts of lovely ferns and flowers and wild strawberries growing over it, with blackberries, and purple sloes, and crab-apples hanging over it from the hedge above. Robins often prefer to build their nests on the ground, rather than in a tree.

Mr. Robin, however, had been anxious to move. He said the Windflower Wood was getting too crowded with nobody-knows-who! The birds, from miles around, were trying to get houses and flats there, so as to be near the Lady-with-the-Crumbs. It saved them such a lot of trouble if they could get those delicious things to eat without working for them. In fact, if the Lady-with-the-Crumbs had only lived in the Flower-Patch House all the year round, there would have been an extra one million seven hundred thousand four hundred and thirty-one added to the Unemployed. For all the birds in the valley would have given up work.

But when Mr. Robin spoke about moving, Mrs. Robin pointed out that it would mean the children missing all the nice meals―ready cooked too, a lot of them were―up at the Flower-Patch House. Why should they leave all these for the nobody-knows-whos to enjoy, while they (Mr. and Mrs. Robin) had to start life over again, and scrape and scratch for a living? Especially as they weren’t quite so young as they were last week!

Mr. Robin realized the wisdom of this. He remembered, when she reminded him, how thankful he had been last year to take the children up there, and dump all three of them down on the window ledge, leaving them there, to eat and eat and eat until they were quite full inside―while he went off for a chat with his friends.

So, in the end, they simply moved farther along the wild strawberry bank, and started another new house only a yard or two from the last one. It was this new house that was to be spring-cleaned.

“Is this where you’re thinking of living?” asked Mrs. Starling, taking off her hat, made from an old tulip which had been just her size, but was battered and the worse for wear, as she sometimes forgot to take it off when she went to bed, after the brook water had been a little stronger than usual. She hung up her hat on one of the hundreds of little pegs in the hawthorn. Have you noticed the tiny spikes? So convenient the Little People of the Forest find them.

Then she put on her overall, made from some gaily-coloured autumn leaves, but getting a bit tattered by now, and further inspected the new premises.

“Can’t say I think much of it, mum”―with a sniff. “Never did fancy these basement flats meself. But my fambly always was high-minded. We’re used to being up in the world, you know; usually build near the chimney pots.”

“Yes, of course. That must be a very pleasant locality too,” said Mrs. Robin politely. But, all the same, she was anxious to get on with the work. Because, you see, she had been waiting since nine o’clock for the Right-o lady.

So she said, “Now I think we’ll start on the walls.”

“Humph! Yes! Not much to look at, are they? And the room’s dreadful small, isn’t it? And stuffy! Makes one quite thirsty to look at it, don’t it? By the way, do you happen to have a drop of coffee lying about anywhere that you could oblige me with the loan of? I didn’t stop to have me breakfast this morning, knowing as how you were in a hurry, and I never keep my ladies waiting.”

“Oh! Then I expect you would like a little something to eat now,” said kind Mrs. Robin.

“Well, mum, seeing as it’s time for lunch, I should think I would.”

Mrs. Robin quickly put some food on the corner of the table―that is, the flat grey stone they always used. She didn’t stop to lay the cloth of course, but just put a couple of ivy leaves for doyleys, with some little pieces of food collected early in the morning from the window ledges of the House, that made a really tasty lunch.

“I’ll start on the walls,” she said, “while you’re having this.”

“That’s right,” Mrs. Starling replied with her mouth full of bread and cheese, “I can’t a-bear to waste time.”

So Mrs. Robin worked away, and got the walls clean and tidy, while Mrs. Starling did herself very well in the matter of refreshments.

Just as Mrs. Robin was starting to brush the ceiling with a dandelion seed-ball for a mop she noticed a teeny trickle of water coming through. Evidently there was a spring somewhere in the bank. It would have to be stopped.

The water reminded her of Mrs. Starling. She had been so happy in thinking of the pretty little home she was making that she had forgotten that individual. Surely she had finished her lunch before this! Why she must have been sitting there a good half-hour at least! She went out to look, and behold there was Mrs. Starling fast asleep and snoring after her good meal, with her head resting comfortably on a clump of violets!

Mrs. Robin was very annoyed! Naturally! And woke her up. Mrs. Starling said she wasn’t asleep; indeed! In fact, never could sleep in the day time! Wouldn’t dream of such a thing! She was only smelling the violets!

When she saw the damp ceiling she got interested.

“Ah! That’s a plumber’s job, that is. Bill, my sister’s husband, is a plumber. He might be able to advise you. He’s working up at the Flower-Patch House now. Filling up a hole in the roof.”

“Really! A hole in the roof! Did the water come in on the Lady-with-the-Crumbs?”

“I should think it did! Poured in something cru-wel.”

“What a pity! How did the hole get there?”

“Bill made it.”

“Made it? I thought you said he was filling it up?”

“Yes; but he had to make it first, hadn’t he? or there wouldn’t have been a hole there for him to fill up, would there now!”

“How did he come to make it?”

“With his beak. He just hammered and hammered and hammered till he had ever such a fine big hole. He’s got the best beak in the fambly, except my husband’s.”

“But how is he going to fill it up?”

“With a nest, of course. That’s what he made it for. You may take it from me, Bill isn’t one to work unless he’s bound to. And if you don’t mind, mum, I see it’s close on dinner-time. And as I feel a bit faint-like, I think I’ll have something before I really start with the work. Spring-cleaning’s a nawful hard job; and one has to be strong to do it. And after all, how can one get strong if one starves?”

Mrs. Robin looked at the shadows made by the sun, which is the way all wild things tell the time, and she saw that it certainly was nearly one o’clock. So she got the dinner on the table, and they sat down to it together.

Mrs. Starling looked at the doyleys rather contemptuously while Mrs. Robin was carving the suet.

“I thought these common ivy leaves had gone out of fashion long ago,” she said. “You should see Mrs. Bullfinch’s new ones. Scented geranium leaves. All cut up and lacy and ever so stylish, and scent the whole place. And Mrs. Greenfinch has a set of apple-blossom petals for hers, pink and white. Very original she is. And they go with her dress too. I don’t think dark green, like the ivy, goes with your sort of complexion at all. I should try a change if I were you.”

Mrs. Robin’s feathers turned redder than ever, and it quite took away her appetite. But she determined not to lose her temper. And as she finished her dinner long before Mrs. Starling was anywhere near the end of hers, Mrs. Robin said: “I’ll get on with the floor now, while you are finishing.”

“Yes, mum; that would be a good idea. And, by the way, I don’t suppose you want that oak-leaf mat outside? It looks rather shabby. I should be glad of it, as there’s a hole coming in the bottom of our nest, and it would be the very thing to patch it up.”

“Oh, but that’s a new mat! Mr. Robin wouldn’t like it to be given away!”

“I see. He’s just like my husband; wonderful contrary. But it’s no odds. Mrs. Lark has several mats she’s not using. I know she’ll say ‘Take one by all means, Mrs. Starling. You know you’re always welcome.’ Very generous she is.”

After Mrs. Starling had eaten up everything within sight, including Mr. Robin’s and Bobbie’s supper, she sighed a very full sigh.

“There now. I feel better for that little snack. It will carry me on nicely till dinner-time. And when I’ve rested a bit I’ll give you a hand with that new moss carpet. It wants a lot of brushing, so you had better get on with it till I’m ready.”

“But you’ve just had your dinner,” said Mrs. Robin in surprise.

“Dinner? D’you call that scrap a dinner? Why, I’ve only had a bit of bacon rind, and a lump of suet (which I don’t think was quite fresh), and some bread and cold potatoes, and a mutton bone without too much on it, and a piece of sausage, and a cold sardine-head, and the end of a roly-poly pudding without much jam in it, and some stale cake, and you surely don’t call that a dinner? Why, Mrs. Chaffinch gives me the most aristocratic dinners when I go there. She wouldn’t expect me to do a day’s work on odds and ends! But, of course, she’s connected with very high-up people, who always build near the top of the tree, so she knows what’s what. Still, if that’s the best you can do, it can’t be helped. But I wish that Cook at the Flower-Patch House had been a little more liberal. I thought that at least you would have given me a taste of roast chicken. I could have eaten that with a relish. My appetite’s very poor and wants encouraging.”

Mrs. Robin felt quite mortified to think that her dinner wasn’t as good as the one Mrs. Chaffinch provided. But she wanted to get on with the spring cleaning, so she said: “Hadn’t we better scrub the floor before the carpet goes down?”

“As you please, mum. I leave it to you. I always say, ‘Let ladies do as they like. It’s their work, not mine. And as they’re paying for it, and not me, let ‘em do it how they like.’ You do the same, mum. I shan’t interfere nor I shan’t take no offence. And, while you’re doing it, I’ll have the ten minutes’ complete rest the doctor says I must always have after my dinner to digest it―and he’s most particular about it being complete.”

So Mrs. Robin got on with the work, while Mrs. Starling got on with her digestion.

Presently she appeared at the door of the new house. “I’ve been thinking,” she said, “you won’t want that old moss carpet now you’ve got a new one. So, as I expect it’s only in your way, I may as well have it. My Mabel is wanting one badly. She’s going to be a prima donna. Sings wonderful, and never had a lesson in her life. Everyone admires her voice. Only yesterday she was practising her top notes, standing on the roof of the farm. A lady passing was very complimentary and said, ‘They ought to wring that bird’s neck.’ ”

“What did she mean?” Mrs. Robin asked.

“She meant, they ought to put a diamond ring round her neck, of course, because she’s so wonderful. Prima donnas always wear diamond necklaces. I know, because I lived with one once. For, silly like, I made a nest in a chimney pot belonging to one; I didn’t know then that it was a hole that hadn’t any beginning nor ending. You should have heard her top notes when the nest, and all the lot of us, arrived down the bedroom chimney suddenly, in the middle of the night. And that reminds me of what I came along to ask you: Don’t you have a cup of tea after your dinner? I do―and as you’re so busy, I don’t mind making it to save you the trouble. Always lend a helping hand, is my motto. And you’re getting on so nicely with that floor it would be a pity to interrupt you.”

When Mrs. Starling brought the tea in acorn cups, Mrs. Robin said:

“I must get you to help me shake these sycamore-leaf curtains. They are rather heavy.”

“Well, mum, I’d be only too pleased to oblige, but school will be out directly, and I must be home in time to get my Jimmie’s tea. I’m so sorry, but I must fly. And if you don’t want that piece of haddock that’s hanging up in the holly bush, I’ll have it. My Jimmie’s so fond of it, especially when it’s a bit high like this is!”

But Mrs. Robin was looking for her purse, and did not happen to hear this last remark.

“We’ve done a nice day’s work, haven’t we?” Mrs. Starling went on. “So if you’ll give me my money, I’ll be off before your good gentleman returns. They’re all alike; can’t bear to see a bit of housework being done. My husband’s just the same. And though I work as hard as I do, I have to keep it very quiet, and pretend I don’t, so that he shan’t know nothing about it. I never dare let my right claw know what my left claw’s doing. And you did say I was to take away these ivy-leaf doyleys, didn’t you? They are awful ugly, aren’t they? And send for me whenever you want help. I’m always pleased to oblige. Good-bye.”

Mr. Robin came in almost immediately.

“Well, my dear, you’ve had a nice restful day I know,” he said, rubbing his hands. “No one to cook for, with Bobbie and me away. And Mrs. Starling to do all the work. And now we’re quite ready for our supper. I hope you’ve something special after the lovely day’s holiday you’ve had.”

“I’m afraid there’s only a bit of haddock, dear,” she said. “You see Mrs. Starling has such a big appetite and cleared us out of everything except the haddock. But I’ll soon have that ready.”

She went to look for the haddock. But alas! she never found it!

Mrs. Starling was on her way home, carrying the old moss carpet, the ivy-leaf doyleys, an acorn cup which she had cracked when washing-up. Also the piece of haddock wrapped up in a primrose leaf, and placed for safety inside her hat. And just as she was thinking how very useful the fish was, as it would save her having to use any hair tonic that day, in addition to making them all a nice supper―the wonderful thing happened!

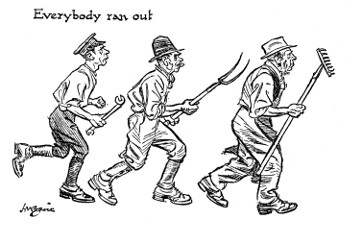

Not that any bird knows exactly what did happen, because accounts vary considerably, as I will show you. But it is a fact that when she was nearly home she gave a wild shriek, threw her bundle into the air―which sent doyleys, hat, carpet, haddock and acorn cup all anywhere―and sank into a heap on the ground. I repeat―a―HEAP!

Of course the whole neighbourhood rushed to her assistance, dozens of them; and they all talked at once, asking what was the matter, where it hurt her, and how she came to do it? Though there wasn’t much need to ask her, because, apparently, everyone knew what was wrong. Only they didn’t all say the same thing. Some were sure she had been stung by a wasp; some were certain the carpet had been too heavy for her, and carrying it had been bad for her heart; some, when they smelt the haddock, felt convinced she had caught appendicitis. While all of the older ones remembered that her grandfather and grandmother had both died once upon a time; therefore it didn’t look as though there was much chance for her to go on living for ever.

They held the haddock to her nose to see if it would restore her. It had a little effect, because she did just wake up enough to gasp:

“He’s blue and green―Oh! Oh!―and yellow!”

“No! No!” they told her. “It isn’t as far gone as that yet, dearie! Why it isn’t a day more than a month since it was in the water!”

She continued to moan, “Oh!―Oh!―and awful red―I saw him plainly―and he will eat us all up―Oh!―Oh! Don’t let him get me―Take me home!” With that she closed her eyes, and never uttered another syllable. Not another single one, or a double one either, so far as that goes.

They carried her to her nest. As soon as Mabel saw her mother’s silent form she flew to the very highest part of the farm-house roof, and let out all the top notes she had, and some that were quite new.

More starlings were soon hurrying up from the Elm Grove, three fields off, to inquire about it. The neighbours told them that she had been struck by a wild animal, that was red and green and blue and yellow, and ghastly white with black eyes; and she had never smiled again!

Next all the Beechwood cousins arrived, and the Elm-Grovers explained that a great monster had suddenly dropped down from the clouds, who was pink and purple and orange and lemon and scarlet and red and crimson and blue and pea-green and magenta. And he had clutched her so hard that it was all they (the Elm-Grovers) could do to get her out of his claws!

By this time the starlings from across the river had turned up. And although they are not on speaking terms with any of their family connections our side of the river, as a rule, they consented to let bygones be bygones for the minute, while the Beechwood cousins told them how a great dragon had appeared. With fire and smoke coming out of his nose. And green hair done in long plaits. And blue claws. And a red tail two yards long that rattled something awful as he approached Mrs. Starling. And an orange tongue, two feet three and a half inches in length, that he had to tie to his tail to keep it from getting in his way as he walked. And this terrible monster had got her in his mouth, and was that very moment going to swallow her, when they (the Beechwood cousins) happened to arrive in the nick of time. And after a fierce and most terrible struggle, in which Mrs. Starling lost her best hat, they succeeded in rescuing her from his foaming jaws.

And they all shivered from beak to the endest tail feather, as they thought about it.

By this time there was a fair-sized crowd, as you will readily understand.

But still she didn’t move.

Then someone said, “Let’s send for the plumber.”

Bill came. But he only looked at her and shook his head sorrowfully. “Not in my line,” he said. “The Undertakers’ Trade Union wouldn’t let me touch it!”

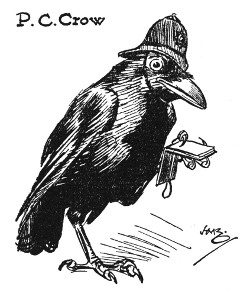

“What about fetching the policeman?” said another bright bird.

Dozens hurried off in search of him.

But there was no sign of flurry or hurry or undignified haste about Police Constable Crow when he arrived. In a stern black voice he said:

“Now then! What’s all this about? Move on there.”

And he stalked through the crowd up to the family tree. “Oh! I thought it was a row at an election meeting. I see!” looking thoughtfully at the poor evidently-lifeless-body lying there so silent with closed eyes. Then turning to the crowd: “Did anyone take the number of the motor-car?”

“She wasn’t run over,” every starling began to tell him excitedly. “She saw things, and――”

But P.C. Crow held up a warning claw, and, taking out his pocket-book, he informed the evidently-lifeless-body that she must be very careful what she said, because he was entering every word in his note-book, and it might be used against her.

As she still lay silent with closed eyes, he felt he needn’t write any more. Besides, having heard all the facts of the case, and a lot that weren’t facts, from the dozens who had fetched him, he had an idea that he would like to get home before dark, if that dragon was still anywhere about. So after shutting up his pocket-book with a snap and putting the elastic band round it, he said, “You’d better send for the doctor,” and walked away majestically.

Of course each starling wondered why all the other starlings hadn’t thought of that before, and explained that he, or she, was at that very moment going to suggest sending for the doctor.

Before very long Dr. Magpie’s aeroplane was seen in the sky, and was soon moored fast to the tallest fir tree. A car would have been quite useless to him, of course, seeing that he had to visit patients who lived up in the air. Therefore he had an aeroplane. And if you look up, when a magpie is flying overhead, you can see the aeroplane’s long tail and wings quite clearly.

Everybody stepped back, immediately, when he arrived, looking very learned and serious.

“She needs air!” he said (being an aeroplane doctor). “Fan her instantly.”

In rushed several butterflies and fanned her hard with their wings.

Then her next-door neighbour, who had run in, as soon as they brought home the evidently-lifeless-body, to take charge of her, explained to the doctor: “She’s seen an awful monster, yellow ochre and gamboge” (her little boy was starting brush-work at school) “and indigo and Prussian blue――”

“Drumsticks!” said the doctor. “She’s been having a drink out of that brook over there by the spotted cow. I’ve strictly forbidden her to touch it, because it’s far too strong for her. She’ll come round presently, however, if you keep on fanning her.”

“But it was vermilion and crimson-lake and rose-madder――” the neighbour went on.

“Ah! I expect she saw her own nose reflected in the brook! But keep on fanning her.” (The butterflies kept on.) “I’ll look in again to-morrow if she isn’t better.”

And with a whirrrrrr his aeroplane went skywards, and in a minute he was half-way to his next patient, old Granny Hawk, who was feeling a bit all-overish, after having swallowed the china egg she found in a fowl-house, in mistake for a real one―her sight not being as good as it might be.

Then the other starlings, who had kept most respectfully in the background while the doctor was in the sick room, crowded round to hear his verdict, after he had gone.

“High fever!” said the kind neighbour. “He doesn’t give any hope” (sobbing into the corner of her apron). “May linger till to-morrow with care, but it’s uncertain, poor dear; and she’s the best neighbour I ever had.”

“That she is,” with sobs from the other neighbours.

“And he says she can’t last more than a couple of hours. Fetch Mabel,” the kind neighbour continued.

They all fetched the prima donna.

“Oh, my dear,” wept the kind neighbour, “I’m to break it to you gently: he told me your darling mother will probably be gone in less than an hour. And you and Jimmie will be poor orphans―perhaps in half an hour.” (Every starling was weeping quarts, excepting those who had left their hankies at home, and couldn’t borrow one.) “If only she would speak,” wailed the kind neighbour, “and say one―only one―last long loving word for us all to remember, I should feel better about it. But it seems so sad for her to have started out this morning―

‘All happy and gay,

So anxious to do

Her good deed for the day.’

And after working so hard―” (“Ah! and she was a worker!” murmured the crowd) “to come nearly home―and end―like―this!”

Choking sobs all round.

And Mabel, not to be outdone by the others, cried so loudly that all the owls in the valley woke up―and the cocks and hens and turkeys and geese and ducks at the farm set up ever such a hubbub.

Now I can’t say whether it was due to the butterflies or to Mabel’s voice, but at that moment one of Mrs. Starling’s eyelashes flickered.

“She’s moved!” they all exclaimed.

Then she opened her left eye, merely a trifle. Seeing a nice large crowd, she closed it again.

“She’s recognised us!” three hundred and twenty-nine starlings announced in one breath.

Then she opened both her eyes.

“Oh speak! Mother, spe-e-e―e―ak!” sang Mabel, running up the scale right beyond the top of her voice this time.

Her mother smiled a heavenly smile.

Everybody said “ShSh! ShSh! ShSh!” to everybody else―and listened breathlessly.

Then she opened her beak the merest trifle, and only sufficient to enable her to murmur:

“I really think I could enjoy a kipper’s tail for me supper.”

That seemed to remind her of something. For she sat up so suddenly that she almost upset the nest as she inquired, “Where’s that piece of haddock I brought home?”

No one knew excepting Jimmie, and he said nothing. Besides, he had had a pain under his feathers ever since he ate it; and he had enough to do to think about that. No one offered to go and look for the haddock because―the dragon might still be there. Indeed, several of the company had remarked that the air seemed very hot and sultry, almost as though there was fire in the wood. And seeing that poor Mrs. Starling had now recovered, it might be as well to hurry home―in case of a storm, they were all careful to add.

And they weren’t long in reaching home either!

Yet―in spite of everything―the blue and green and red and yellow mystery remained unsolved.

Since the sad disappearance of her husband, Auntie Twitter had shut up her house very early each evening, fastening the door most securely, while it was still light, for fear of burglars. Because, as she said, “You never know!”

She had heard all the riot and racket of the starlings, but as they are always a noisy crew, she didn’t bother to go up the lane to find out what it was all about. They weren’t quite her style; and she didn’t want to get mixed up with any of their hullabaloos!

She merely took a look up the lane before she finally locked the door, when―to her surprise―she saw an extraordinary-looking bird hopping along cautiously, and keeping as much out of sight as possible. He had blue wings, a yellow back, a green head, a green tail, and a red breast.

She had never seen anyone like it in all her life before. Even the parrot at the farm was only pink and green. Then a dreadful thought occurred to her―this was a BURGLAR! Disguised, of course, to take her in! And he was coming up the path, too! She was on the point of slamming the door in his face when a familiar voice said:

“Here I am, dear. Back again at last. I expect you wondered what had become of me.”

And though she certainly couldn’t believe her own eyes, it was Uncle Twitter’s voice, and Uncle Twitter’s red waistcoat. She would have known that anywhere, because there was a feather missing on the front that she had intended to sew on again the very day he went away.

But―as for the rest of him―!! Well there!! All she could manage to say was:

“What―in―the―world―!!!”

And he replied, “Yes, I thought you’d say so. That’s why I waited till it was nearly dark before coming home. As it was I happened to run into that old woman Starling, and she shrieked so loud that the people along the road thought it was the train in the station, and ran like anything to catch it! But I’m awfully hungry, my dear―haven’t had a bite for hours.”

She quickly got him some supper. And then, after they had shut the door, and pulled down the clematis blind, so that no one could look in, he told her his sad, sad story.

This is what had really happened.

He had been caught in a trap by one of those wicked men who go about the country stealing poor little birds. He was taken to town, and there they coloured his feathers to make him look like some rare and uncommon bird―hich he certainly did! After that he was put in the bird-shop window. And all this while he had been cooped up in a tiny cage. Oh, it was awful! It made him ill to talk about it.

Before long a little boy, who was out with his mother, saw him and wanted him. So the mother bought Uncle Twitter, telling her little boy that he must look after his bird himself.

He was taken home―but still in the dreadful cage.

He tried to explain to them that he wasn’t a Rotto-tott-o lundo-rum-car-deer bird―very rare indeed, from the thickest jungle in the centre of Africa―as the man in the shop said; but just a poor little English robin, who had been stolen from his home near the Windflower Wood. And please, oh please, would they open the door, and let him out of that terrible cage?

But all they said was, “Just listen how nicely he sings!”

Yet the poor little bird was really crying fit to break his heart.

He had food and water, however, when the little boy didn’t forget about it. It wasn’t much at the best of times, only in two tiny glasses, one each side of the cage, for water and a little bit of seed. There was never any left over for to-morrow. On the days when the little boy did forget, poor Uncle Twitter nearly died of starvation. And he would sit all of a heap on his tiny perch, hardly able to hold up his head or keep his eyes open. But he could just see the sunset out of the window, from between those horrible cage wires. And his tiny body would shake with sobs; he did so long for the lovely wood and to join in with all the other birds in singing the Evening Song of the Windflower Wood.

He did once try to sing it to himself. He thought it might make him feel better if he could hear it. But his lovely voice was almost gone, with hunger and his sad life. He could only whisper. And they all said, “The robin is going to sing again, see how happy he is!” when he was nearly dead with misery!

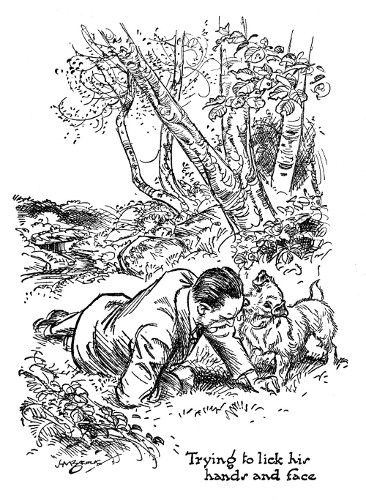

But one day he found the cage door wasn’t fastened. He pushed it, and got out. Fortunately the window was open, and away he flew!

Oh the joy of being able to fly again, and stretch his wings, instead of being cramped up in that awful cage!

His troubles weren’t quite over, however, for his wings were slightly injured, with beating against those dreadful cage wires, trying to get out. He couldn’t fly without pain.

Fortunately he met a swallow whom he knew.

“Hello, Twitter!” he said. “Hurt your wing? Just lean on my shoulder. We’ll soon get you home. But, I say, where did you get that new suit? Quite gay, aren’t you? They dress like that in some of the countries I’ve been visiting, but I didn’t know the fashions had got down here yet!”

“I had to run up to town on business,” said Twitter, not wishing him to know he had been in a cage. Birds consider it such a disgrace to be caught. They call it being in prison. “And I thought I would get a new rig-out. Not that I mind old togs myself, rather like them, in fact; comfortable you know, and all that sort of thing. But the wife said I was getting so shabby she was ashamed to go out with me. My tailor said this was the very latest style. Rather neat, don’t you think?”

The swallow said all the polite things necessary. And in this way Twitter got back home.

Of course Auntie Twitter was overjoyed to see him safe and sound. But she did wonder whatever the neighbours would say about his strange appearance.

“You leave all that to me,” her husband said. “I’m a travelled gentleman now, and shall know exactly how to deal with them. So don’t have any anxiety on that score――”

“And, perhaps, if I put a little extra soda in the tub next washing day,” she said hopefully, “you might try a bath, and see if some of it would come off.”

“What! and be hung out on that wretched spider’s web to dry? Not a bit of it!” He was feeling much more courageous, and so very, very glad, now that he was safely at home again, and after his good supper! “You’ve got a distinguished and most remarkable husband now. Don’t you dream of putting him into the bath overnight to soak, or there will be trouble in this happy home, my dearest.”

So she didn’t.

Next morning the Twitters set off first thing to tell Mr. and Mrs. Robin the good news. And you can understand the commotion it made when all the colours of the rainbow suddenly appeared in their midst.

“Good gracious, Twitter, is that you?” said Mr. Robin. “Where in this whole universe did you find that box of paints you’ve got on your back? and where have you been hiding?”

So of course he went over it all again, and told them not the true story he told Auntie Twitter, but the story that he told the swallow, with more added to it to make it sound grander. And he puffed himself out while he told it, too, and did his best to look as accustomed to travelling as the swallows and wild geese, who go away every year to a warmer climate.

Naturally, the robins had to think of something important to tell him, in return for all he had told them, and so they mentioned the fact that the Lady-with-the-Crumbs had come again, and they described the lovely meals that could now be got merely by hopping about on her bird tables.

You may remember that Uncle Twitter had disappeared before the Lady-with-the-Crumbs arrived; so it was news to him to hear that she was at the Flower-Patch House. They thought he would be very excited about it; but he pretended he wasn’t.

“It’s all very well to talk so much about the Lady-with-the-Crumbs,” he said in a lordly, I-know-everything way. “But, ‘smatter of fact, you country people don’t know what a decent meal is, having to scratch around and peck about as you do for every morsel of food! It positively makes me laugh; or it would do, if I wasn’t so sorry for you!”

“But, Uncle, how can we get our dinner if we don’t get it?” Bobbie asked.

“In town they bring it to you,” his uncle explained majestically. “You don’t even have to ask for it. It comes! A sort of footman brings it, and puts it in a crystal bowl all ready beside you.” (Uncle had seen the glasses in the town shops marked “Beautiful Crystal.”)

“A crystal bowl!” the family repeated. “Just think of that now!” And they gasped with wonder.

“But, Uncle, what is a crystal bowl?”

“It’s the thing they put the food in, of course. There are two; one each side of the ca―I mean, the flat in which I resided.” (He was thankful he remembered in time not to say cage! What would they have thought of him?) “One crystal bowl held a most choice selection of eatables―I mean viands; the other contained pure water―er―that is to say, it was supposed to be pure when it was put there; but you understand bathing does sometimes discolour it a trifle, and I never miss my bath, as you know. Altogether it was a life of luxury that I lived in town. Why, they almost fed one with a spoon!”

“Mother, what is a spoon?”

Uncle Twitter kindly explained. He told Bobbie that people are not like birds, whose beaks can do everything they need. People are so helpless that they have actually to be provided with a separate tool for anything they want to do! Just think of it! They have a knife and fork to divide their food; a spoon to get it into their mouths; a pair of scissors if they want to cut something; a comb to do their hair; a tool to crack their nuts; more tools to build their houses―and so on. And all because they haven’t beaks, poor things!

“But, Mother, they’ve got noses. Aren’t they beaks?” Bobbie inquired.

“Don’t ask such ridiculous questions,” said Mrs. Robin:

“Have you ever seen a boy brush his clothes

With his nose?

Or ever seen a girl take her tea

With her toes?

Of course it’s quite absurd!

Yet any little bird

Could do all this quite easily

And never say a word!”

“Quite so! Quite so!” said a voice above, in the oak tree. “And a very bright family too. Wonderfully talented.”

Everyone looked up, to see who was interrupting the conversation, though they knew quite well it was the saucy squirrel. But before anyone could think of something suitable to answer back―very polite of course, but explaining clearly and precisely what they thought of him―he started to sing at the top of his voice, only in a mocking imitation of Mrs. Robin:

“Have you ever seen a boy comb his hair

With his tail?

Or climb the tallest tree with his little

Finger nail?

Have you ever seen a girl wear her bed-clothes

All the day?

Or run along the tree-tops when she wants

A little play?

Of course it’s quite absurd!

Yet I’m certain I have heard

Of a squirrel that just uses

His tail for what he chooses!

At night it keeps him warm in bed

Curled gracefully above his head.

It’s also handy as a brush.

And when that squirrel has to rush

Right up the very tip-top-tree

He holds on by his blanket! See?

Who is he? Why he’s Me! Me! Me!”

“And now, ladies and gentlemen, after that beautiful poetry, I’ll wish you good afternoon――” And as he skipped away from branch to branch he called out, in a voice that imitated Bobbie, “Mother! I’ve lost my lov-erly tail! And it was my best Sunday tail, too! Oh, why ever didn’t you sew it on stronger?”

“I can’t think why you don’t move,” said Uncle Twitter. “This neighbourhood has gone down terribly since I went on my travels. Now in London that vulgar creature would not be tolerated for a moment, except in the Zoo; where, of course, they are a very mixed lot. Where I stayed not a squirrel was to be seen.”

“If I had my way,” said Mr. Robin, “they wouldn’t be seen here!”

“But what can you expect in such an uncivilized place as this!” Uncle Twitter went on. “Just look at the furniture! Did anyone ever see such ridiculous, old-fashioned, uncomfortable perches as these twigs and branches you use here―all rough and knobbly and uneven? Why in the beautiful flat they placed at my disposal in town the perches were quite round and smooth and polished, not a twig, or thorn, or leaf on them anywhere. I had three in my flat, two downstairs and one higher up.”

“I shouldn’t care to have only three,” said Mr. Robin, who was beginning to be a little jealous as he listened to Uncle Twitter’s description of the grandeurs. “I like a fresh one every day to sharpen my beak upon. Not the same dirty old perches.”

“But they weren’t dirty. They were taken out and cleaned―sometimes. Did you ever find anyone taking down our branches here, and cleaning them, and putting them back again on the trees all nice and tidy? Ah! Town life is wonderful,” he said.

“But, Uncle, why did you come back and leave such a lovely place――?”

“I expect they got sick of him, and turned him out,” said a cheeky voice up above. And a beech nut descended on Uncle Twitter’s nose!

At that moment there was a sound of a window being opened in the Flower-Patch House. Instantly every bird flew up to the house, for this was the sign that the crumbs and other delicacies were being put out for them. No one bothered about the grandeurs of town, or gave another thought to Uncle Twitter’s new suit.

The squirrel went scampering over the trees, calling to his sister: “Hurry up, Flossie! she’s putting out the nuts.”

And in less time than it takes to write about it scores of birds of all sizes, from pheasants down to tiny cole tits and gold-crested wrens, were flocking to the window ledges and bird tables and lawns, where the Lady-with-the-Crumbs had spread the most delicious meals―of rolled oats, canary-seed, hemp-seed, suet, oats, cake and biscuit crumbs, wheat, maize, raisins and currants; with nuts and cheese in the food boxes fixed to the squirrels’ breakfast-tree.

Such a banquet! And as though that wasn’t enough, one robin came and perched on the Lady’s shoulder, and then ate out of her hand.

Everybody seemed pleased except the yellow-hammer. He always was annoyed because the squirrels gobbled the cheese before he could get it―and to this day you can hear him airing his grievance, because all he could get was “a little, little, little bit of bread and no che-e-e-se!”

A ROWDY RHYME

When we’re having a game―

It is always the same―

We make a consider’ble noise!

But, you see, it’s the way

We enjoy all our play,

So long as we’re girls and boys.

We cannot keep still,―

Though you say what you will,―

Our toes are all twists and twirls.

We jump and we dance,

If you give us the chance,

So long as we’re boys and girls.

For what we like best

Is not a nice rest,

But making a beautiful noise!

We do love a riot,

And hate to be quiet,

So long as we’re girls and boys.

So long as we’re girls and boys

Of course we can play with our toys,

But what we prefer

Is to make a great stir,

And a floor-shaking, earthquaking NOISE!

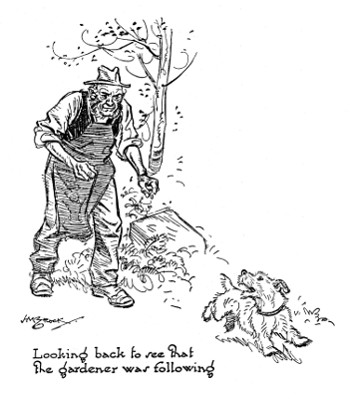

The robins were playing Hide and Seek, a game they are very fond of; but they don’t play it quite as we do. Instead of hiding in some out-of-the-way spot, they wait till they see the gardener at work sweeping the paths. Then they simply drop down from a branch, among the red and brown leaves that have blown off the trees. And so exactly do they match the leaves, and the red and russet apples that are rolling about the orchard and the paths, that it is exceedingly difficult to detect them, unless you are very used to robins―any number of them.

They seem to enjoy it hugely when the gardener gets taken in, and finds he is sweeping up a bright-eyed little bird when he thought it was a red leaf from the pear tree. A robin will wait silently, and keep still, until the broom nearly swishes against him. Then up he flies into a bush or tree and whistles out to all the others in the garden:

“I’ve done the gardener again; took him in completely! That’s another game to me.”

While the other robins answer back that they don’t believe he played fair. And they all start to argue about it.

Robin No. 1 says he will fight anyone who dares to say it isn’t his game. And he’ll show them exactly how he did it.

Silence in Birdland for a minute. They all watch him carefully.

Down drops a little brownish red streak from the trees again. The gardener, if he is thinking about other things, merely concludes it is another autumn leaf, and he goes on sweep, sweep, sweeping.

His broom seems to move to a tune, as though it were singing:

Brown leaves,

Red leaves,

Yellow, green, and gold,

Whirling leaves,

Curling leaves―

That robin’s very bold!

“Hello!” says the gardener, “there’s that bird again! He’ll find himself in the bonfire one of these days, if he isn’t careful!”

But robin knows better! And by this time he is carolling away at the very top of the syringa bush, and inquiring if anyone now doubts whether he won? And if so―will they kindly speak out plainly, and he will soon explain?

But if by any chance you do notice the little ball of feathers among the leaves, and you say to him: “You rascal! I see you! What are you doing down there?” he looks up with a most innocent expression. “Me?” he seems to say. “Were you speaking to me? I’m only hunting for my dinner. Look! Here’s a lovely worm――” and he brandishes it in the air for you to see.

But all the other birds laugh aloud, because, according to the rules of their game, he has lost this time, and the game counts one to them.

Bobbie was very good at this game, he usually had the highest score. In fact, he was smart at most things―when he liked. But he didn’t always like, that was the trouble.

He was playing with the other young robins in the Flower-Patch one day after Uncle Twitter had told them about his wonderful travels―and he won every game. But just as he was in the middle of a very exciting sweep-up he heard his mother calling him. Dreadfully annoying, of course, when he was at the most exciting part of the game, and wanted to win it badly in order to prove himself the Champion of the Wood.

But young birds are obedient, and though he did not look over-amiable, he went to his mother at once. She was on one of the window ledges busily collecting food for the family supper.

“I want you to take some of these lovely cake crumbs down to baby,” she said. “Then come straight back and help me carry home the supper.”

Now if there was one thing Bobbie hated doing, it was carrying home the provisions. And especially did it annoy him to have to spend valuable time feeding the baby, when he might have been the Champion of the Wood by then! He met some of the other robins as he was going home sulkily with the baby’s supper, and they called after him, mockingly:

“Hello, Nursie, are you going to give baby its bottle?”

It was silly of him to take notice of course; because they were only jealous that he was nearly the Champion. But he was in such a cross mood at the minute that he didn’t stop to think. He merely pitched the food into the nest, right over the poor baby’s head, and then he flew out of the wood, across the river, and half-way up the opposite hill. Here he paused for breath.

But his mind was quite made up. He was thoroughly sick of this place. He would go right away to that wonderful town Uncle Twitter had told them about, where no one had to take food to the baby, or help to carry it home for suppers. But a footman brought delicious everythings in crystal bowls. It seemed a lovely idea―nothing to do but eat all the―what was it Uncle called them?―viands! Yes! that was the word―viands.

He didn’t know what viands were, but they sounded most aristocratic and tasty. And that was the sort of meal he liked.

The very thought of it was so delightful that he wouldn’t rest another minute on the tree, but set off to find the town. He hadn’t the least idea where it was. Being only young, he didn’t know anything about the world outside the Windflower Wood and the Flower-Patch. He thought there would be only one way to go, and that way would be sure to lead to the town! So he flew on and on and on.

Foolishly, he never thought to notice the way he was going. He never once looked back (as one ought to do, so as to know the way if one has to return). He just rushed on and on and on some more!

And still no town was in sight.

Sometimes he stopped to take a drink at a brook: but he wouldn’t wait to find anything to eat. He was so anxious to get to those lovely viands in crystal bowls.

At last it began to get dark; and he was feeling very tired. Also, everything seemed very strange, with no one he knew to speak to.

He tried to think he wasn’t really afraid. He told himself he was a brave explorer―going a long journey, thousands of miles long―such as he had heard the swallows describe.

But, all the same, he felt very lonely and little; and he did wish he knew the way back to the nest. Just for the night, of course. He didn’t want to stay there. But it would be so very nice to have his father beside him now that it was getting dark.

He didn’t sleep in the nest, at home, now that he was growing up. The younger ones slept there, with Mother to take care of them, while he and Father slept in such a cosy place among some very thick ivy that grew against the wall at the corner of a barn. The cold wind never touched them there, and the thick overhanging ivy kept the rain off them, and sheltered them like ever so many umbrellas.

Father had shown him this lovely place the first night after he came out of the nest. And he had slept there with Father to take care of him every night since.

Birds usually go to the same sleeping place every night―but it isn’t easy to find them! You have to watch very carefully to discover where they go, and if they see you watching they will fly off in another direction, and pretend they are going to sleep somewhere else. They will wait and wait, till they see you go away―and then, with one quick dart, they slip into their usual corner, and hide themselves so cleverly that it would be most difficult to find them.

The parents teach the little ones how to do this. And the youngsters soon learn to be as quick at hiding themselves as their elders are.

You can understand, therefore, how miserably lost and lonely poor Bobbie felt when it got dark and he didn’t know where to look for his usual sleeping corner. Neither could he hear his father fluffing out his feathers beside him, or his mother settling the children for the night, in the nest just a little way off.

He decided he had better creep into some ivy that was climbing up a tree near by. He flew over to it, and began to look for a secluded spot, where he would be out of the wind (birds don’t like wind as a rule), when suddenly a large white head poked itself out of the ivy close beside him, and a big owl said in a loud voice:

“Who―who―who―who―are you? Who―who―who―who―are you?” And it looked so fierce!

He was terrified. His mother had told him to be very careful and never go too near Mr. Owl in their wood because owls liked small birds for their supper. Yet here he was walking right into the owl’s mouth, almost!

He tumbled off the tree, in his haste to get away, and landed on a lower branch. But that was still too near his enemy. Yet, if he went to another tree there might be another owl there. He was frightened.

Fortunately, the big white owl took no more notice of him, but flew away in search of his friends. At last little Bobbie put his head under his wing and went to sleep. Though he soon woke up again, for a storm had come on, and he was dripping wet, and cold with the wind. How he did long for his snug sleeping corner at home.

Morning came at last. He was thankful to see the sun. Being very hungry, he realized that he must search for his own breakfast now, as there was no mother or father to get it for him. This wasn’t quite as pleasant as going to the Flower-Patch House and finding lovely cake crumbs and all sorts of tit-bits on the window ledges and bird tables. But he consoled himself with the thought that, when he got to town, he would have wonderful meals brought to him by footmen. Then he would enjoy himself!

That reminded him that he had better be getting along, as there was no sign of the town yet! He wished he knew which was the right way. There seemed such a lot of different ways when he began to look around.

A pigeon chanced to be passing by―great travellers some pigeons are, and very obliging, friendly birds. The pigeons are really the A.A. men of the bird world (you know, the polite men in uniform who look after people in cars, who are travelling along the roads). They tell other birds the way.

Bobbie asked the pigeon to direct him to the town. The pigeon kindly told him which turnings to take, and about midday he arrived there.

But he was surprised! Never had he seen such a strange place. No fields of grass, no nice haystacks to play around. No trees! He wondered where he ought to go?

He waited on a lamp-post (it was the nearest thing to a tree he could find), hoping someone would come along with the crystal bowls of dinner, and take him to a lovely flat, such as Uncle Twitter had described. But no one seemed to bother about him. He just sat there, wondering what to do next, when some unkind boys came along. One shouted out:

“Look! There’s a robin! Let’s see if we can get him.”

And they tried to climb up the lamp-post.

Bobbie was so frightened, because one was throwing stones at him, and they were all making a great noise, he flew away in terror, anywhere―he didn’t know where―just to get away from them, and in his plight he banged his head against something he hadn’t seen in his fright, and fell, stunned and senseless.

Up above the fields adjoining the Windflower Wood the lark was singing at the top of his voice. This was his song:

“Green and brown go well together,

In the fields this sunny weather.

Green is the grass, but brown is my nest;

So brown is the colour I love the best.

Brown and gold is the autumn wood;

Reddy brown apples are very good.

The sky is blue, but brown is my nest;

So brown is the colour I love the best.”

“Can’t someone tell that rowdy creature up there to move on into the next street, instead of disturbing the whole neighbourhood like this?” inquired the bullfinch, bulging out his chest, indignantly. “Why, I can’t hear myself speak!” (which wasn’t surprising, for the bullfinch has a very small voice). “Besides,” he went on, “what he says is perfectly ridiculous, since everybody knows that red and black and grey are the only colours a refined and really aristocratic gentleman would deign to notice. If he had said that a crimson waistcoat and a black velvet cap――”

But no one heard the rest of his wise remarks, for the lark sang louder than ever.

“Around my house are buttercups yellow,

And a tall moon daisy―a splendid fellow―

Stands at the door.

While over the floor

The speedwell has laid down a carpet of blue―

A lovely hue

When the sun shines through.

And the clover is pink. But brown is my nest;

So brown is the colour I love the best.”

“And quite right too,” said the squirrel. “In fact, why take notice of any other colour? I am brown, and nuts are brown. That settles it, what more can anyone need?”

“Why, black and orange, of course,” replied the blackbird, who had a beautiful orange bill. “And what about the grey squirrels in Regent’s Park? Relations of yours, aren’t they?”

“Only very distant,” replied the squirrel. “Some foreign connections, I fancy. But we don’t visit them. And we hope they won’t call on us, for our families have never got on well together.”

“And serve you right, too,” said the jay. “You need taking down a peg or two. You are far too top-loftical!”

“Oh, do be kind everybody. Do be kind everybody, do!” said the wood-pigeon, who is always anxious for peace and pleasantness, and hates to hear any quarrelling. Then, as a bright idea occurred to him, he said, “Do sing us a song, squirrel dear, do sing us a song, now do!”

The squirrel had meant to say something cheeky to the jay. But he was very pleased to be invited to sing. For as a rule the birds told him his voice was like the lawnmower when it needs oiling! So he started off at once without waiting to settle accounts with Mr. Jay. And this was what he sang:

“Jack and Jill went up the hill

To fetch a pail of milk;

Jack was dressed in his Sunday best,

And Jill was all in silk.

They tied the pail to Brindle’s tail,

And clambered on her back;

Which made her jump and sadly bump

Miss Jill and Master Jack.

She leapt so high they knocked the sky,

And bashed into a star;

It blinked its eyes in mild surprise,

And said, ‘How rude you are!’

The milk upset, they all got wet,

The clouds, indeed, were soaking: