* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Overland Trail

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Agnes C. Laut (1871-1936)

Date first posted: July 17, 2019

Date last updated: July 17, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190734

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

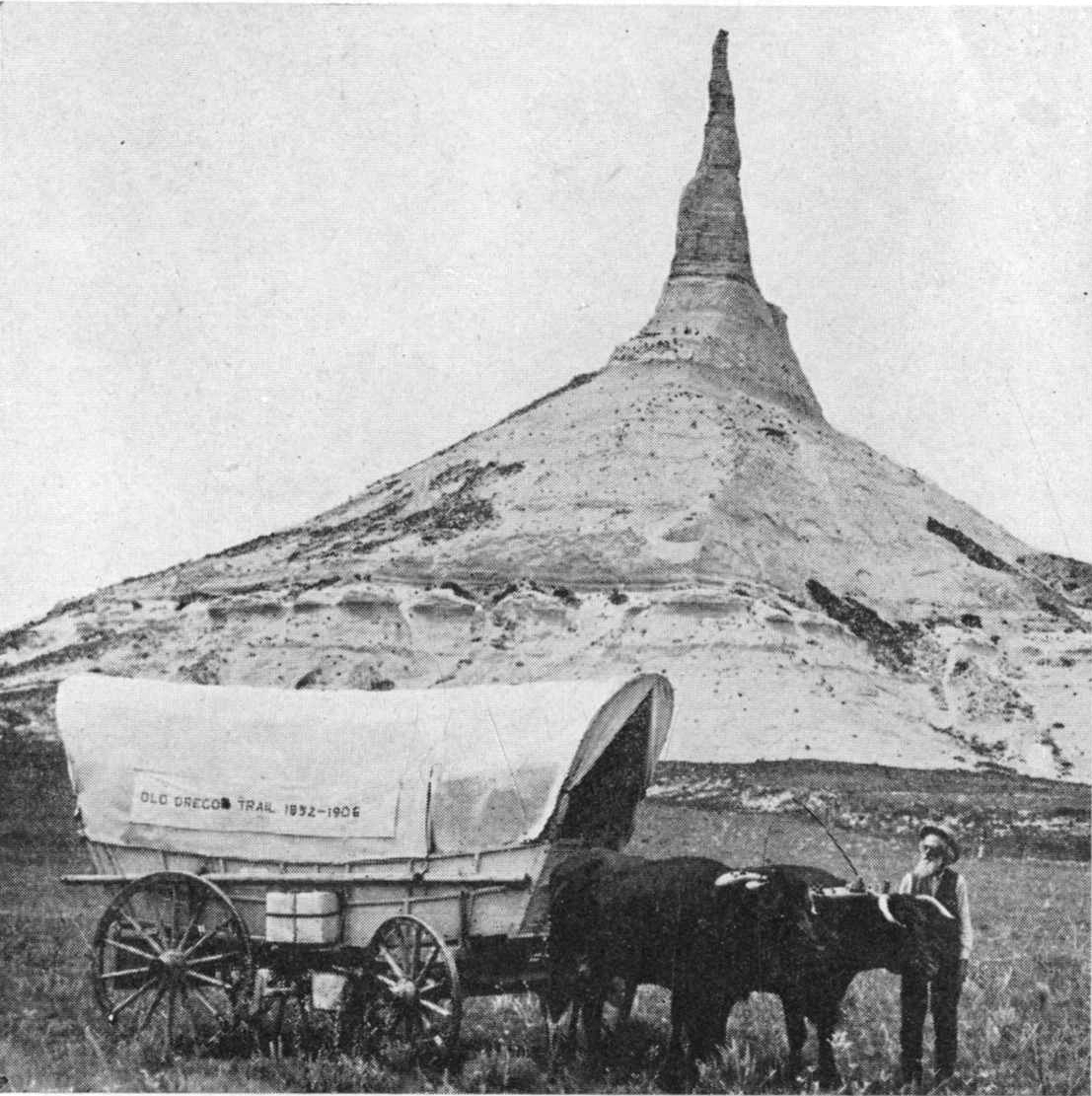

EZRA MEEKER RETRACING THE OREGON TRAIL IN 1910, AND CHIMNEY ROCK, THE FAMOUS LANDMARK OF THE PIONEERS

The

OVERLAND TRAIL

THE EPIC PATH OF THE PIONEERS TO OREGON

By AGNES C. LAUT

Author of “Conquest of the Great Northwest,”

“Pathfinders,” “Vikings,” etc.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS,

TWO MAPS AND TWO DIAGRAMS

GROSSET & DUNLAP

| Publishers | New York |

COPYRIGHT, 1929, BY AGNES C. LAUT

Printed in the United States of America

Dedicated

to

The Consecrated and Sacred Memories

of

The Pioneers on the Oregon Trail

and

That Doughty Champion

Ezra Meeker

Who Did So Much to Rescue the Epic

Highway from Oblivion

Humanized History

The story of America’s greatest trail moves vibrantly through the pages of this worthy book. It depicts with fidelity one of the most important phases of the master epic of the making of America.

Howard R. Driggs, President

OREGON TRAIL MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION, INC.

95 Madison Avenue, New York City

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | xxi |

| PART I | |

| From the Missouri to the Rockies up the Platte | |

| I—KANSAS CITY | |

| Kansas City—Westport—Independence—The Jumping-off Place into the Wilderness—Astoria Fur Traders—St. Louis Trappers—Missionaries—Oregon Pioneers—The Three Kansas Cities with Westport Now One | 3 |

| II—OLD FORT LEAVENWORTH | |

| Fort Leavenworth Becomes a Roving Patrol for Tribes North, South, and West—The Fort in the Indian Wars—Leavenworth a Century Ago and Today | 21 |

| III—OMAHA—“ABOVE THE WATERS” | |

| Omaha—Why Lincoln and Dodge Chose Omaha as Eastern Terminus of the First Transcontinental—What Has Built Omaha up and Ensures Its Future—Dodge’s Terrific Task—Episodes of Lincoln’s Life Here | 36 |

| IV—“AT LAST WE ARE OFF”—FORT KEARNEY | |

| Fort Kearney Where Troops Diverged to New Mexico and Mormons and Oregon Pioneers and Californian Gold Seekers All Foregathered—The Daily Perils of Life at Fort Kearney | 63 |

| V—FROM KEARNEY TO LARAMIE AND BEYOND | |

| Laramie the Last Safe Spot in the Ever Forward Procession to the Pacific Coast—All that Remains of the Old Fort—The Trail up Through the Black Hills to the Yellowstone—Frémont’s Great Indian Rally—His Climb of the Famous Peak | 82 |

| VI—LEGENDS OF SOUTH PASS | |

| Frémont and Jim Bridger and Joe Meek Heading for South Pass—Dodge’s Perilous Search for Good Mountain Pass | 100 |

| PART II | |

| Down Snake River Canyon to the Columbia River | |

| VII—ON TO THE NORTH DOWN SNAKE RIVER CANYON | |

| Fort Hall and the Famous Missionary Sermons to Wild Men of the Mountain Fur Brigade: Indians, Trappers, Immigrant Trains—Raiding Ground of Snakes and Plains Tribes—Old Hundred Sung in Pierre’s Hole and Jackson’s Hole | 129 |

| PART III | |

| Down the Columbia River to the Pacific | |

| VIII—WALLA WALLA, THE HALF-WAY HOUSE IN THE GREAT BEND OF THE SNAKE | |

| The Indescribable Suffering of the Astorians and Oregon Pioneers on Snake River Canyon—The Great Modern Growth from the Falls—An Empire out of a Wilderness | 157 |

| IX—WALLA WALLA, THE SHRINE OF THE WEST | |

| Walla Walla the Most Sacred Shrine of the Nation—A Haven for the Starving Pioneers, a Martyr’s Altar of Sacrifice for the Missionaries—Ground Consecrated by Blood and Heroism—Whitman and Narcissa and Helen Marr Meek and Bridger’s Daughter—Pete Pambrum and the Hudson’s Bay to the Rescue—Ogden’s Ransom of Captives | 173 |

| X—SPOKANE | |

| Spokane the Rialto of the Inland Empire—What Made Spokane a Unique City in the West—Old Fire-Eating Fur Traders Amid Flatheads, Nez Percés, Cayuses | 194 |

| XI—ON FROM WALLA WALLA TO THE DALLES | |

| The Beautiful Dalles and River Pirates of Wishram—How the Pioneers Ran the Rapids—Awful Loss of Life—The Applegate Boy’s Escape from the Whirlpool on a Feather Bed and Rescue of a Comrade Twice His Own Age | 210 |

| XII—“A PINCH OF SNUFF”—FROM THE DALLES PAST THE CASCADES ON TO FORT VANCOUVER | |

| On Down the Cascades to McLoughlin, the Father of Oregon—How McLoughlin’s Kindness Transformed Hate to Love—Help to Colonists Stranded on River | 232 |

| XIII—ON TO FORT VANCOUVER | |

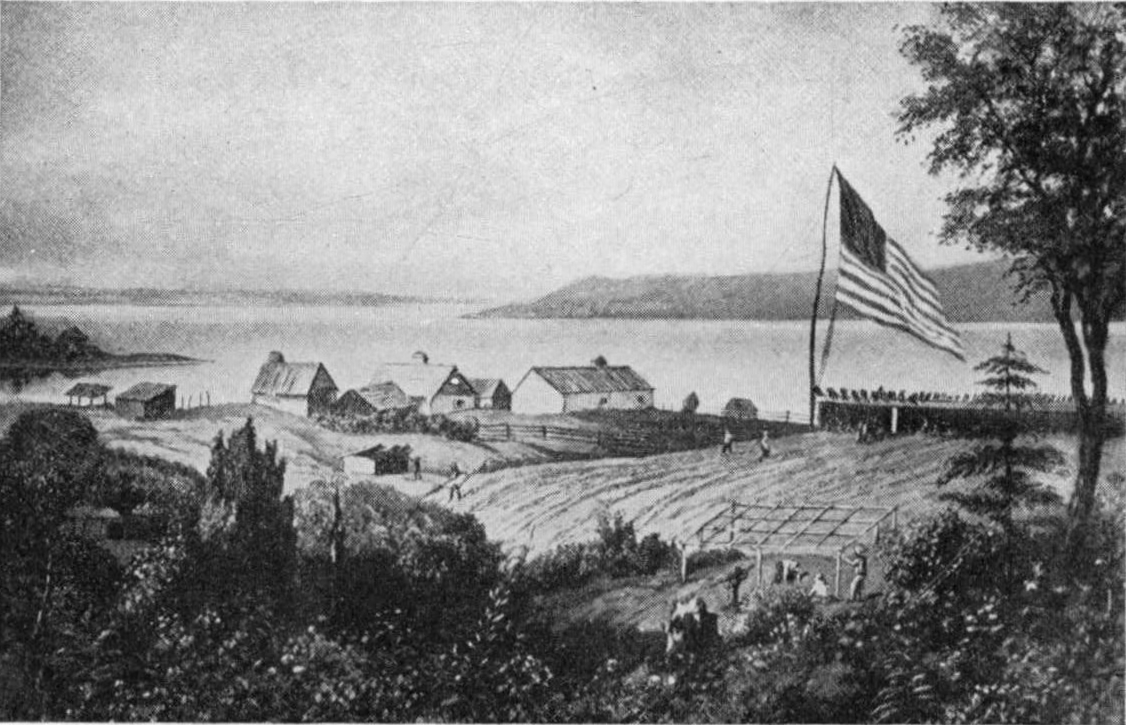

| Portland and Champoeg and the Promised Land—Condition of Pioneers—Expansion of Settlements far South and North to Puget Sound | 248 |

| XIV—ON DOWN THE HIGHWAY TO THE PACIFIC | |

| On to Seattle and Tacoma—Mountains and the Sea—The Old Seattle Chief’s Prophecy—Ghost Memories of Olden Days | 269 |

| XV—ON DOWN THROUGH LONGVIEW AND ASTORIA TO THE SEA | |

| New Cities from Portland to the Pacific—Longview the Utopia Dream City—Astoria’s Rise, Decline and Re-Growth to a Great Port—The Cockpit of Struggle for Forty Years | 285 |

| XVI—UP THE PACIFIC HIGHWAY TO OLYMPIA AND TACOMA AND SEATTLE | |

| The New Cities on Pacific Coast—Growth Beyond All Forecasts—Vancouver’s and Wilkes’ Predictions—Deep Sea Adventures of All Pioneers—Sounding of Depths at Seattle Changes a Sow Path to a Great City | 298 |

| XVII—ON TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH | |

| How to Reach Cape Flattery Today—The Olympic Highway—Mt. Baker, Mt. Rainier—How Mountains Blew Their Heads Off—Indian Mystics—What Destroyed Early Tribes—Poor Hancock’s Terrible Adventures—What Part Destiny in Great Overland Trail? | 313 |

| Ezra Meeker retracing the Oregon Trail in 1910, and Chimney Rock, the famous landmark of the Pioneers | Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

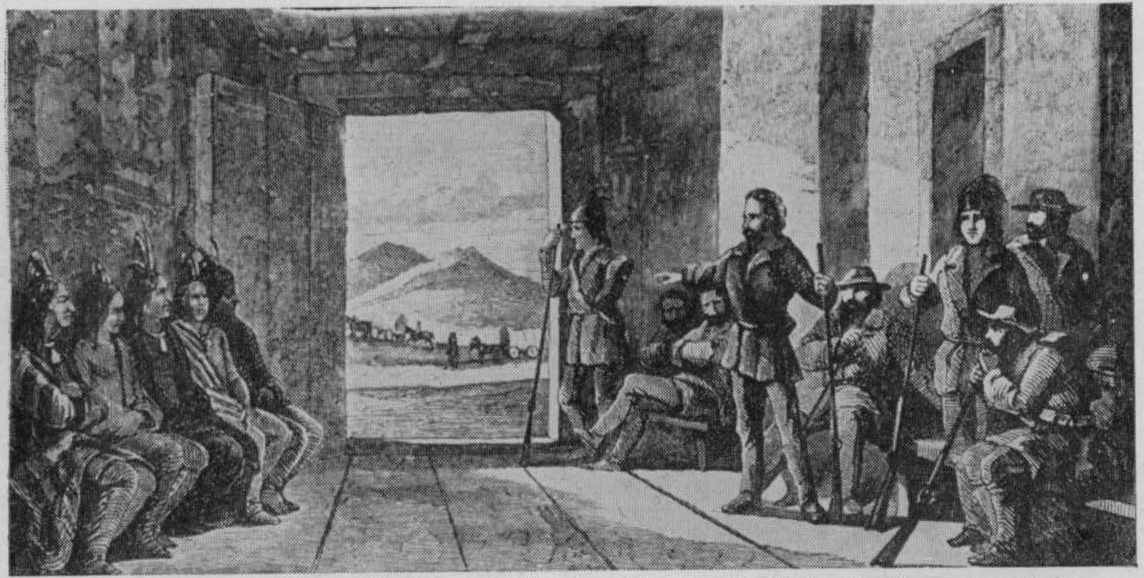

| Frémont addressing the Indians at Fort Laramie | 10 | |

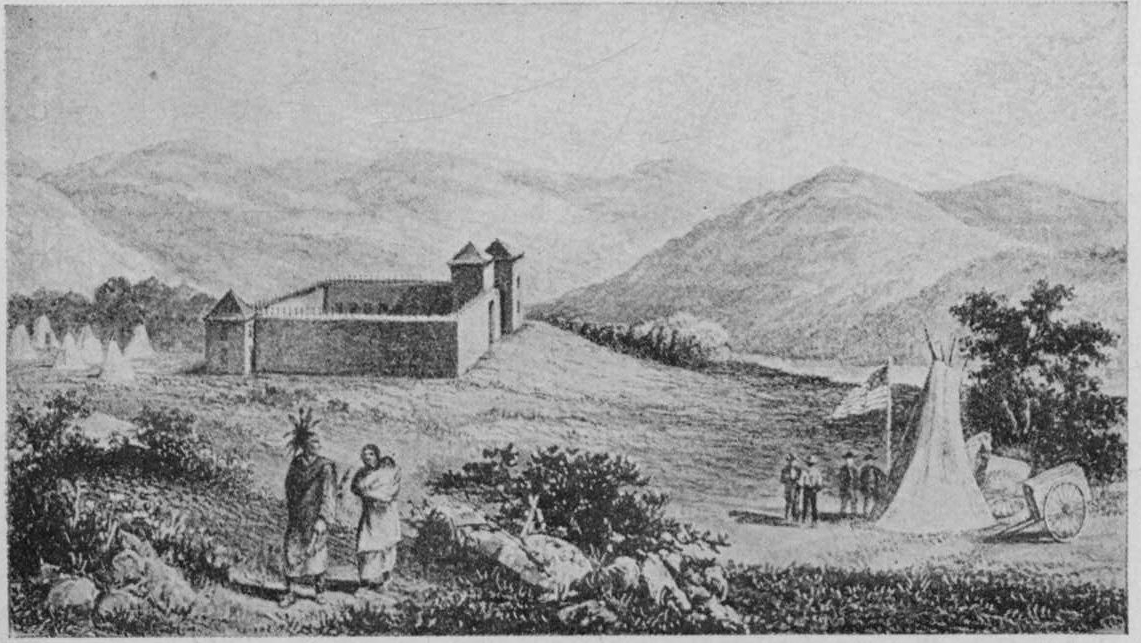

| Fort Laramie | 10 | |

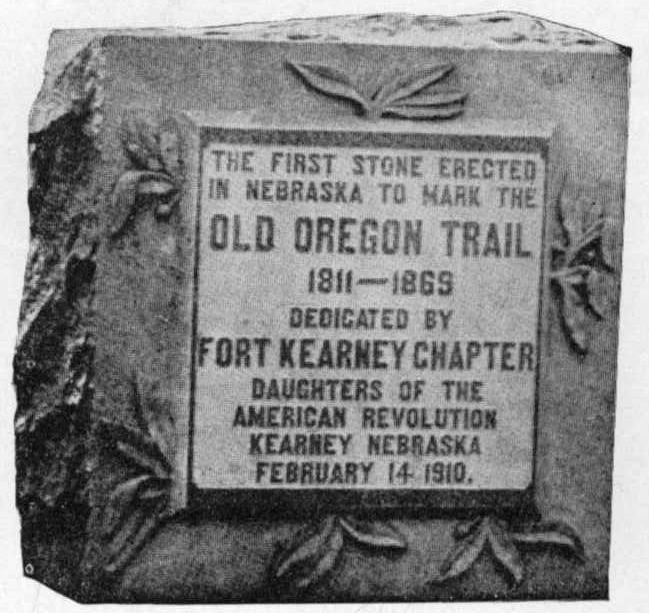

| First stone erected in Nebraska to mark the Overland Trail and famous U. S. Army heroes | 11 | |

| Union Pacific excursion train, 1866, at 100th Meridian | 11 | |

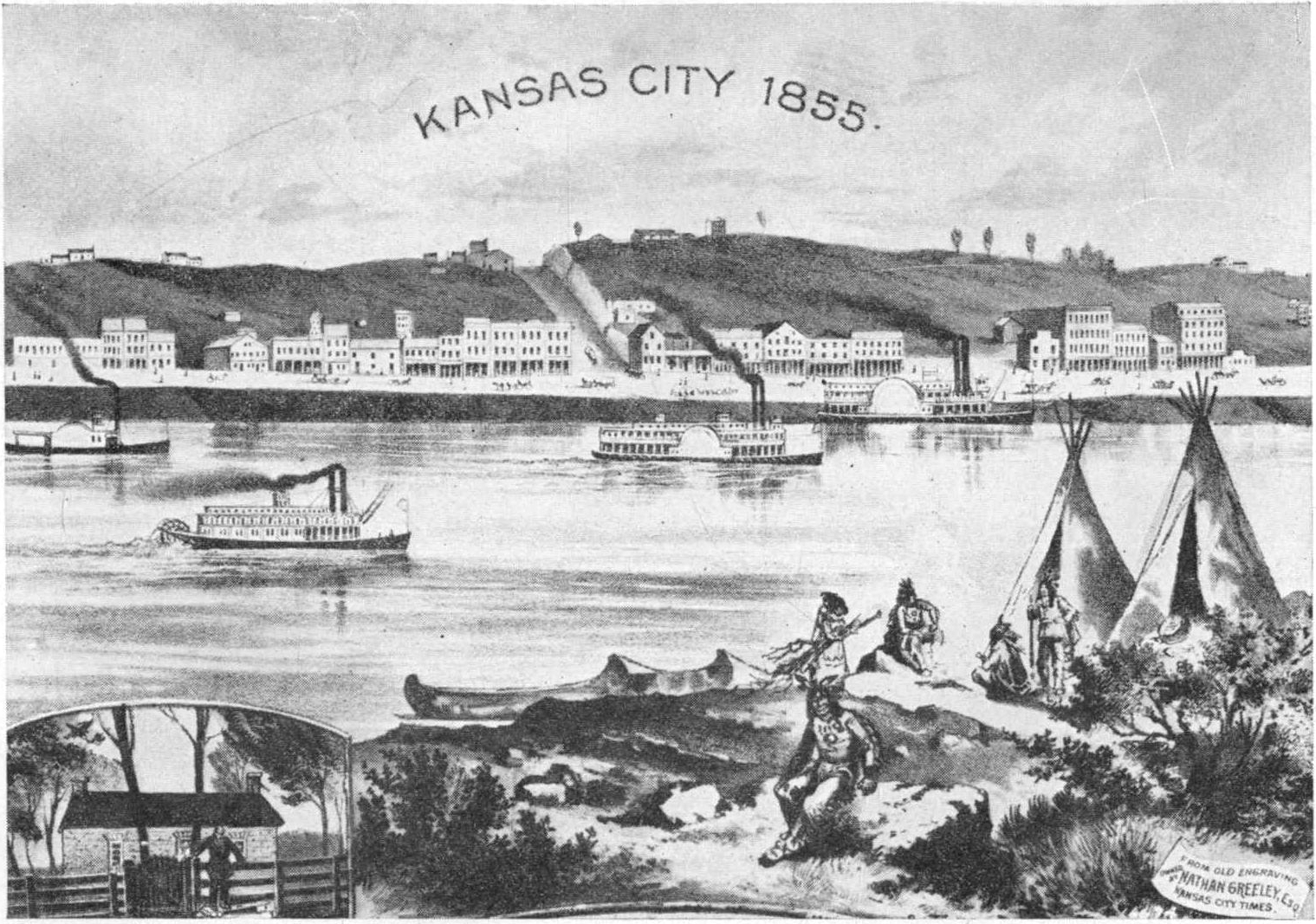

| Kansas City, 1855 | 58 | |

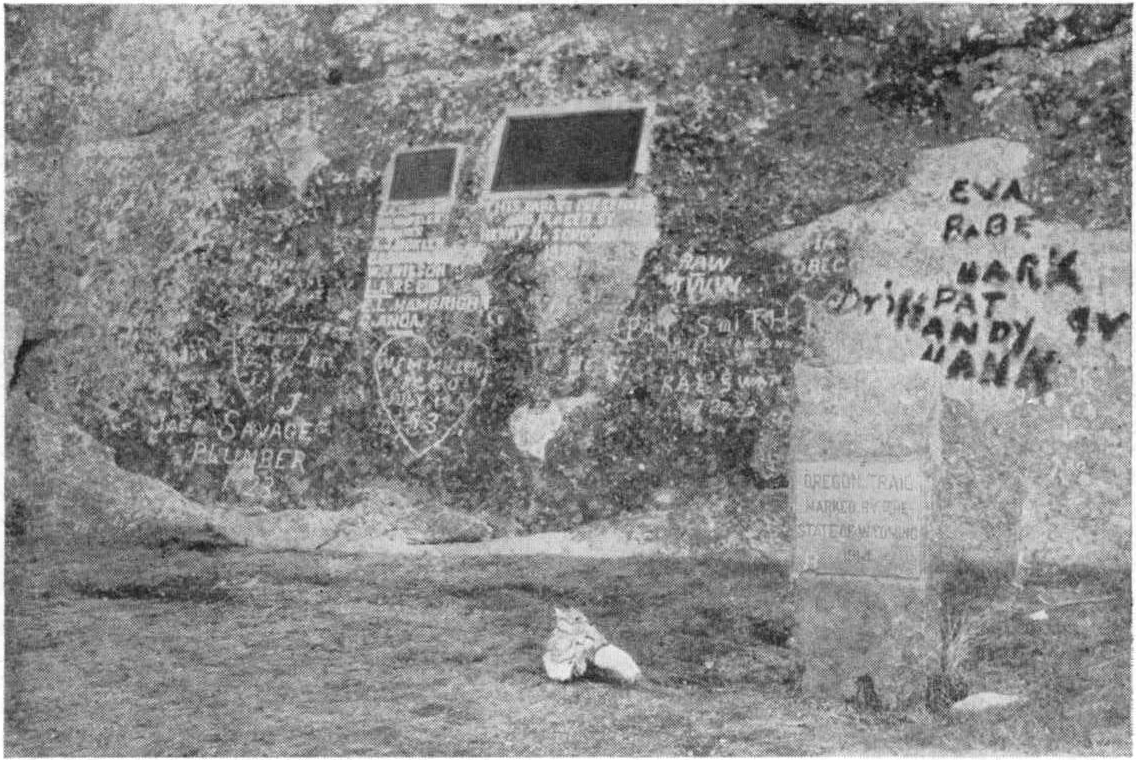

| Independence Rock, showing autographs of desert travelers and modern desecration | 59 | |

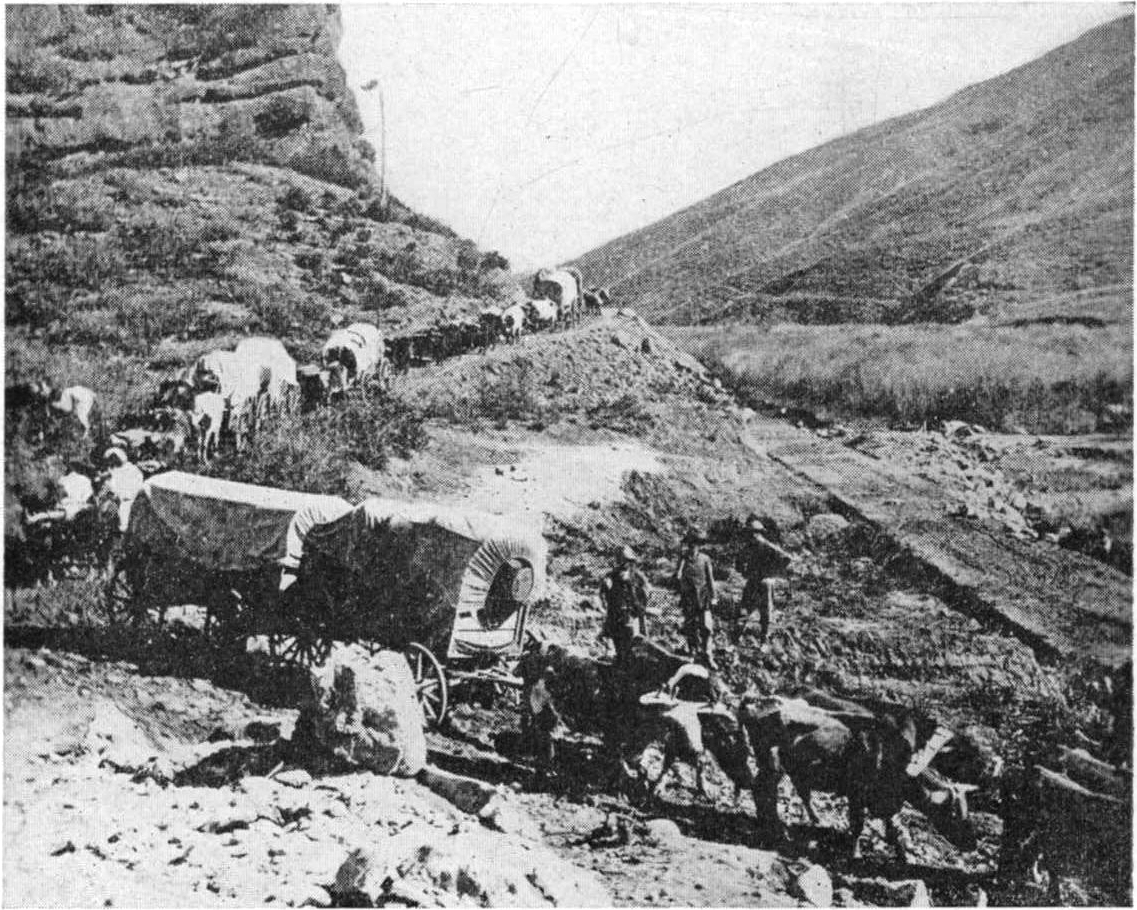

| Wagon train moving down Echo Canyon | 59 | |

| Freighting train known as “Bull of the Woods” | 106 | |

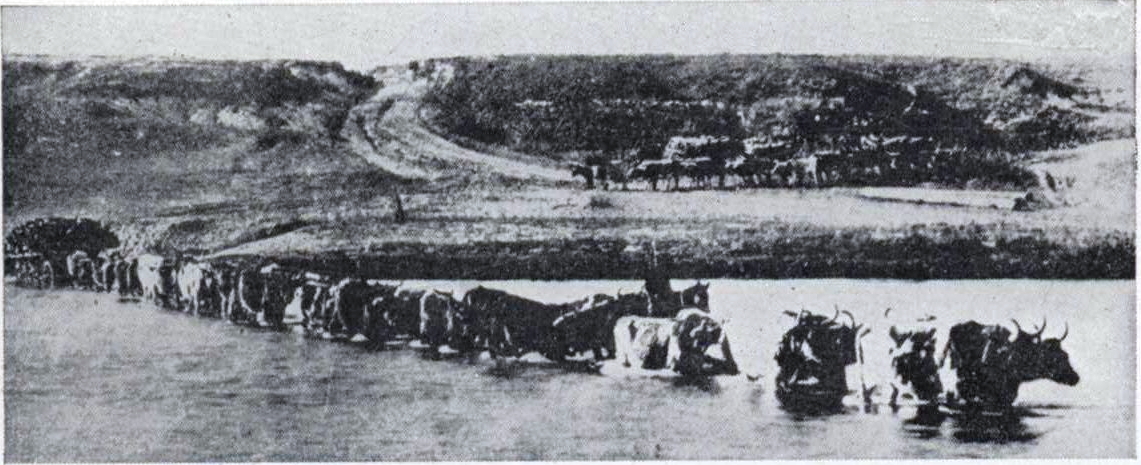

| Ox train fording a stream | 106 | |

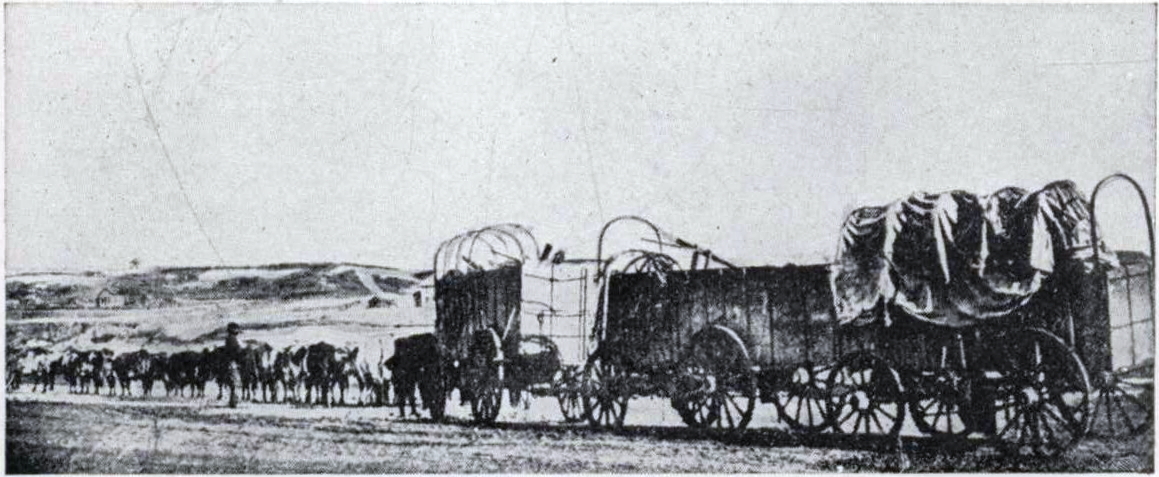

| Overland wagon train with oxen | 106 | |

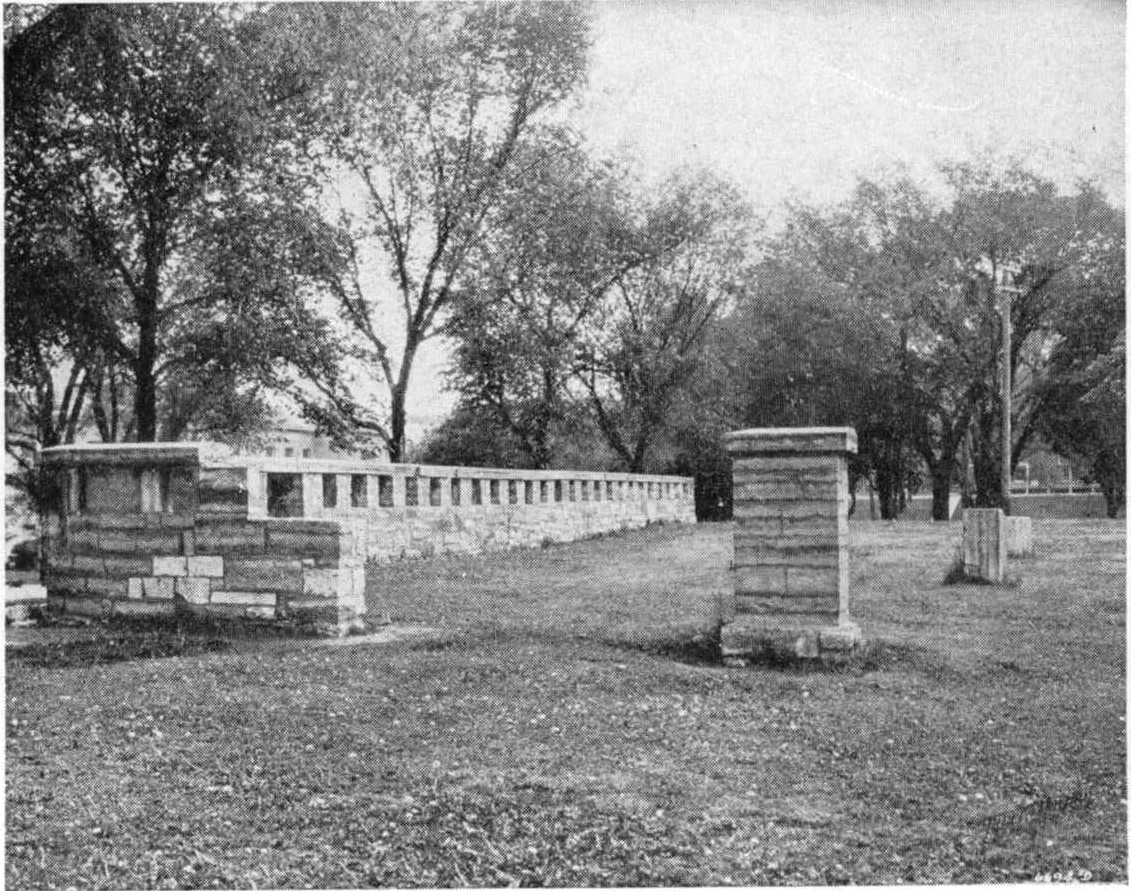

| Remains of wall of old Fort Leavenworth | 107 | |

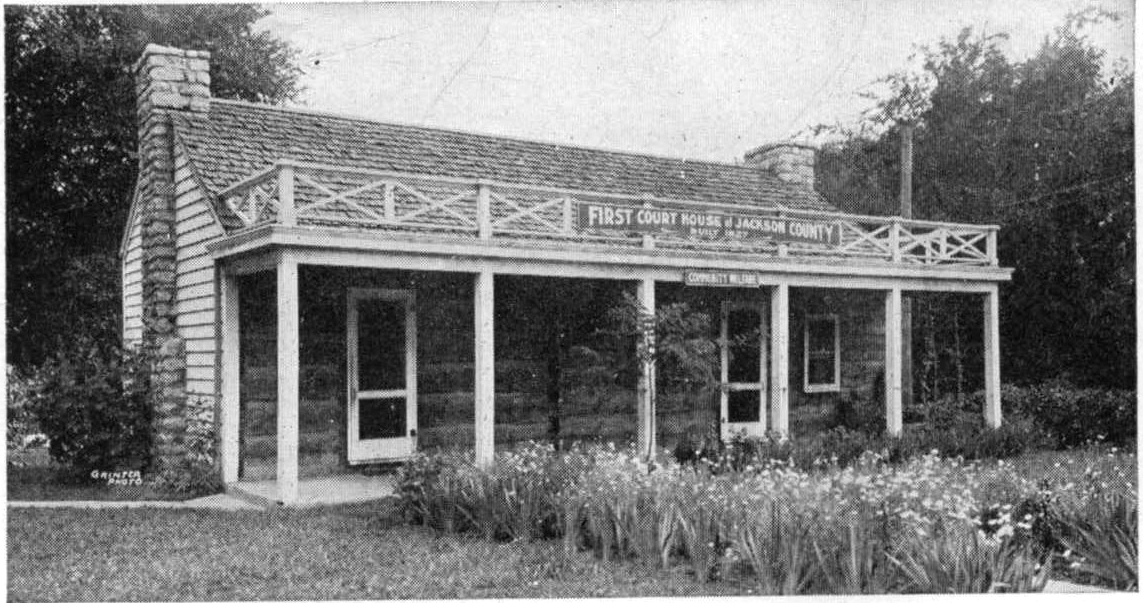

| First Court House of Jackson County, built 1827 | 107 | |

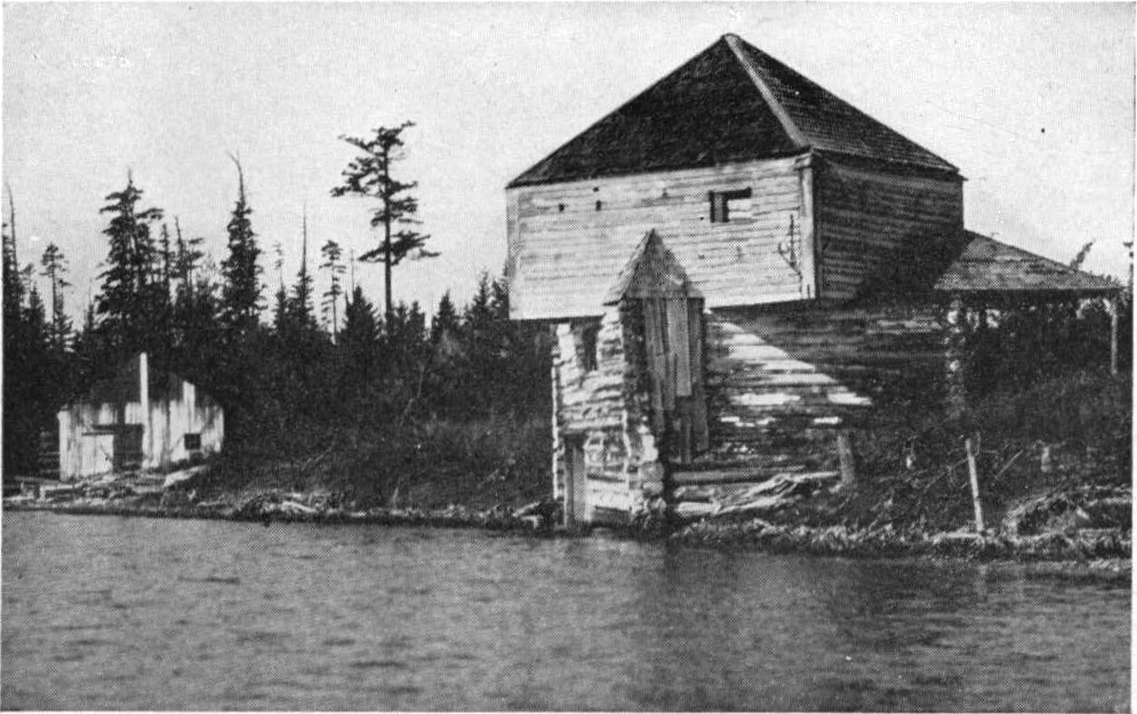

| Old block house used in Pig War, San Juan Island | 250 | |

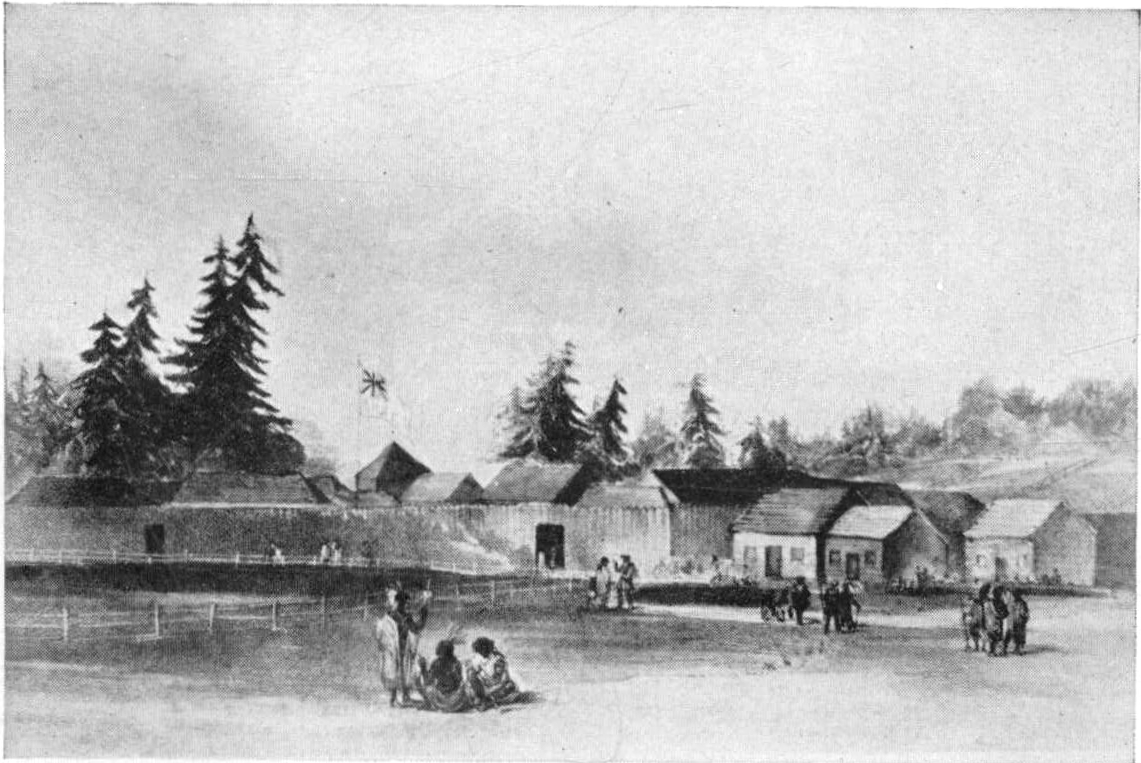

| Fort Vancouver | 250 | |

| An Umatilla Chief, 106 years old, whose father met Lewis and Clark | 251 | |

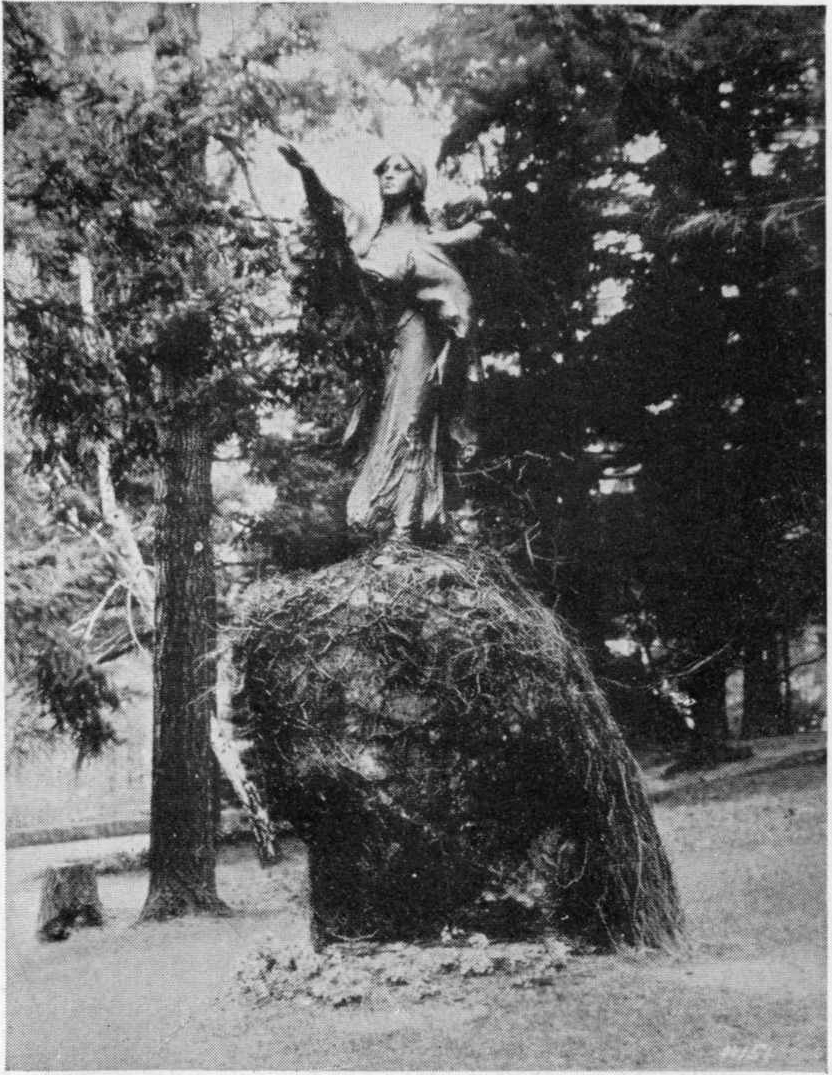

| Sacajawea Monument, at Portland, Oregon | 251 | |

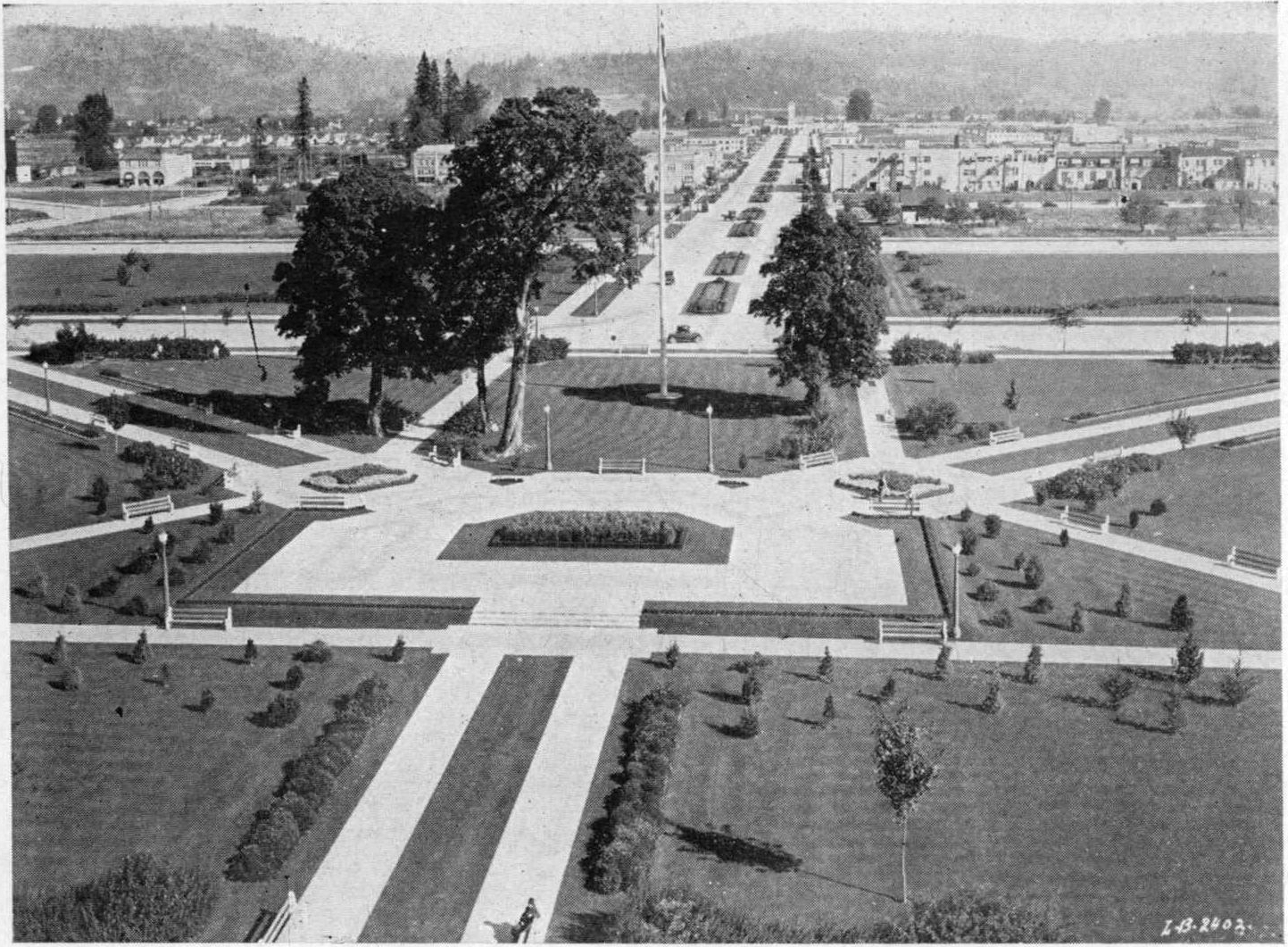

| View of Longview, looking across Jefferson Square | 266 | |

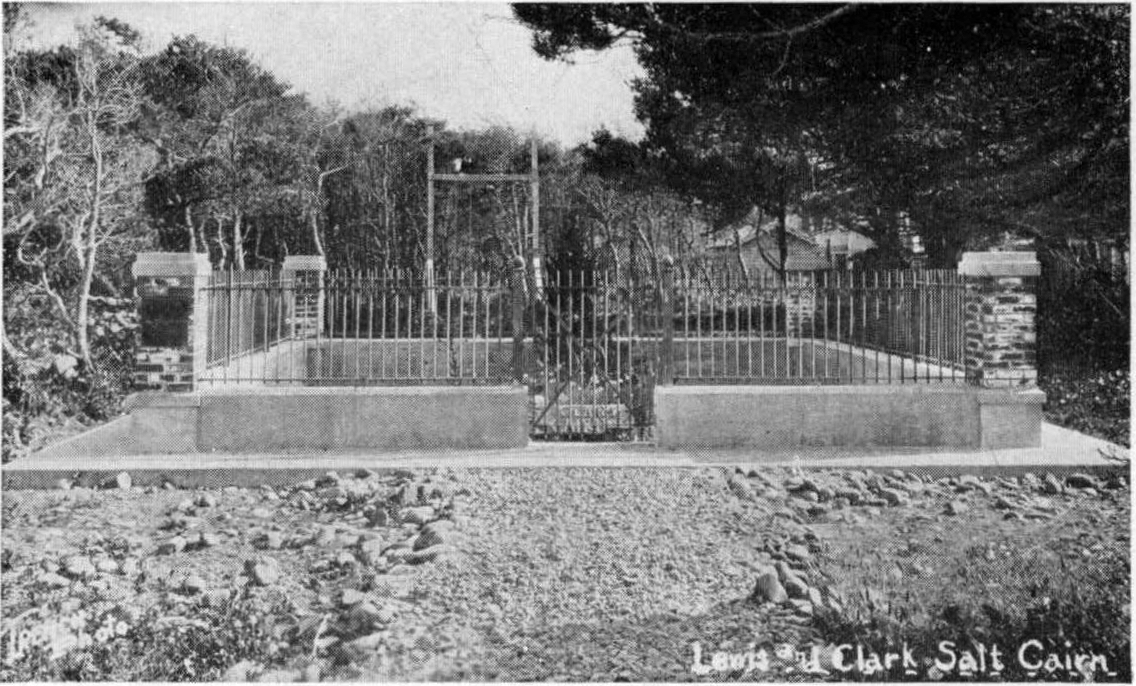

| Lewis and Clark salt cairn, at Sea Side, near Astoria | 267 | |

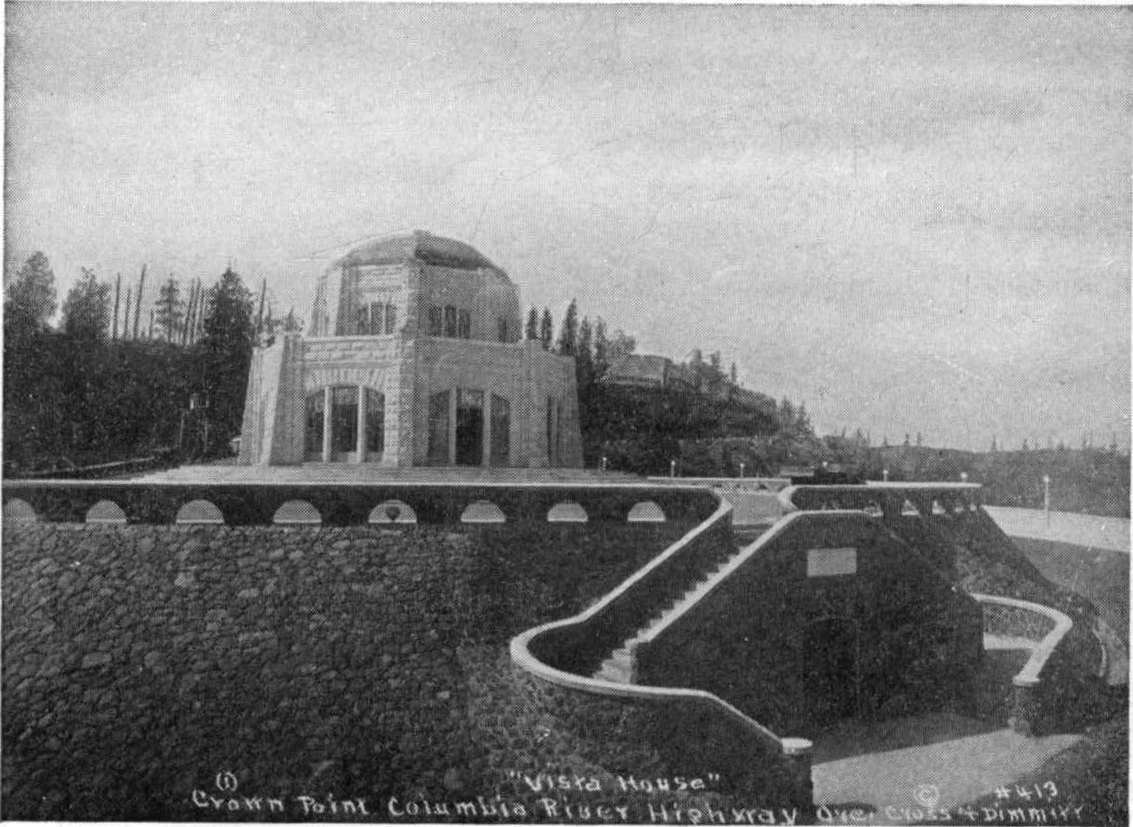

| Pioneer Monument, Columbia Highway | 267 | |

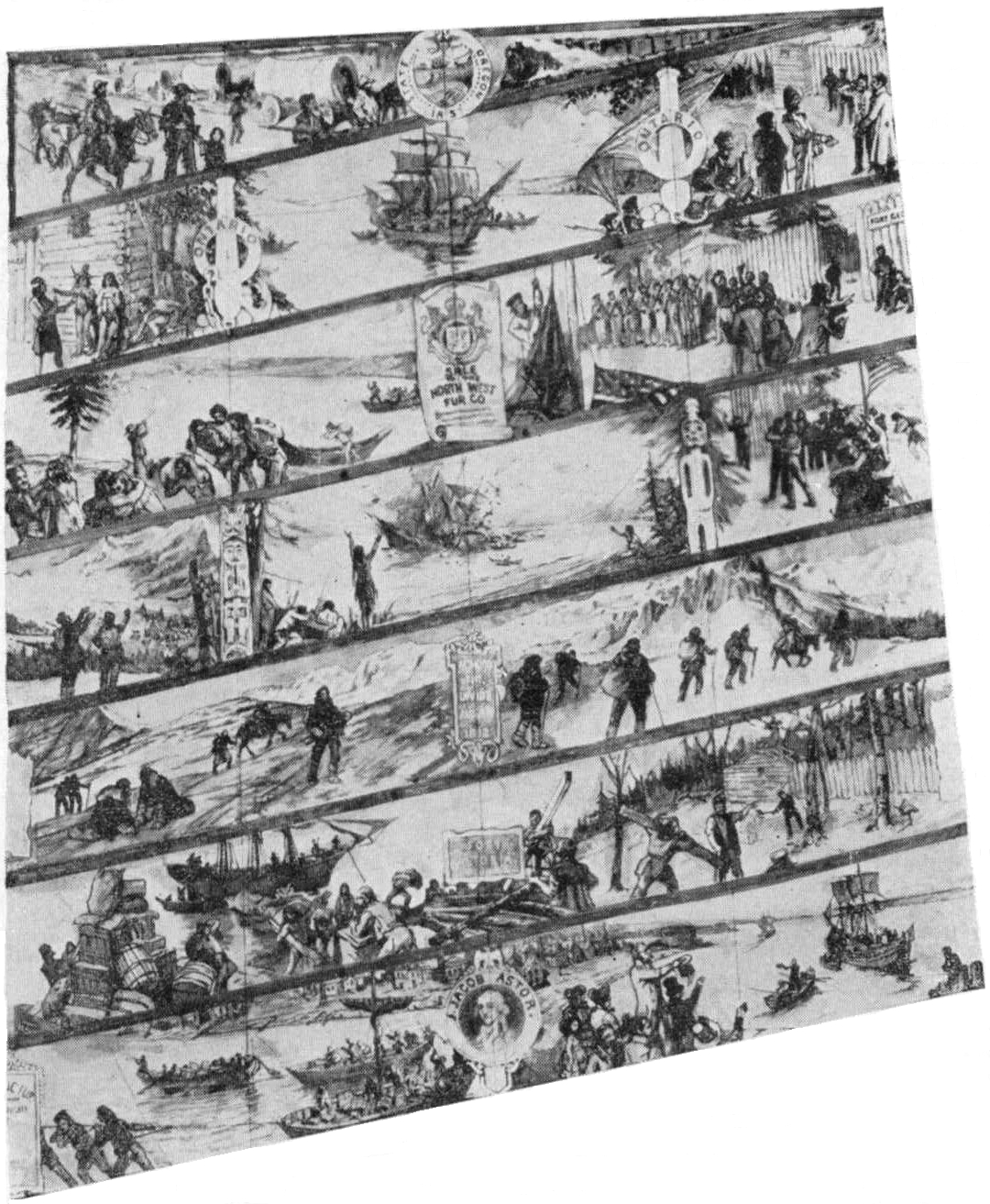

| Astor Monument, Astoria, telling whole history of the Northwest Pacific Coast. (Upper portion) | 282 | |

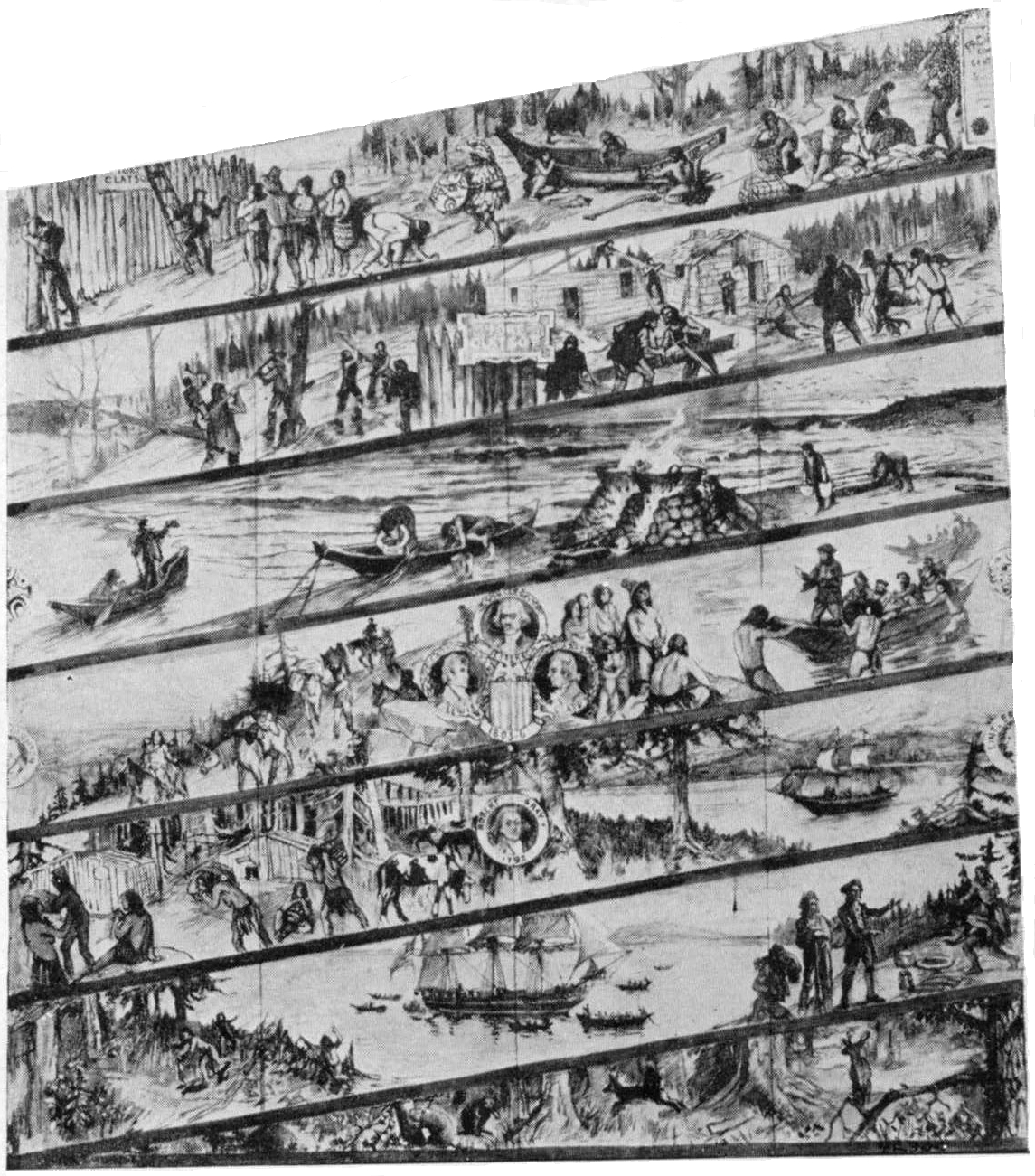

| Astor Monument, Astoria. (Lower portion) | 283 | |

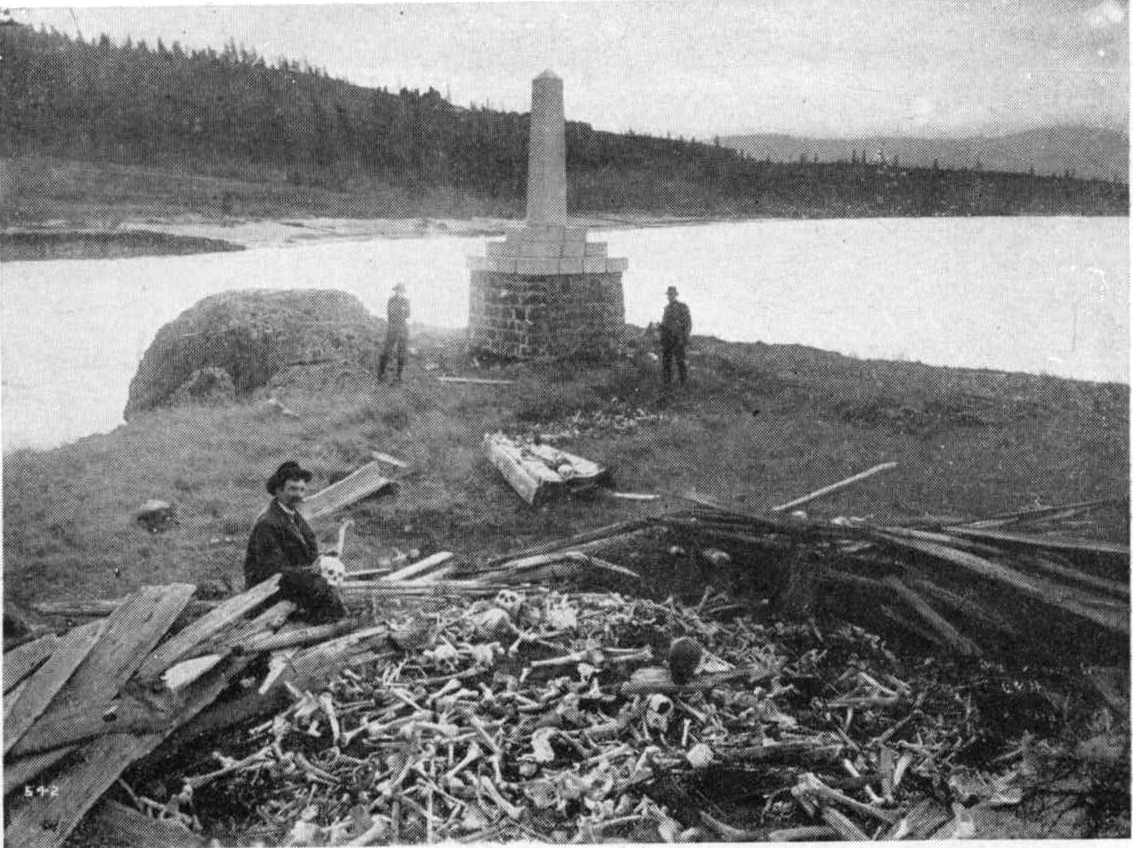

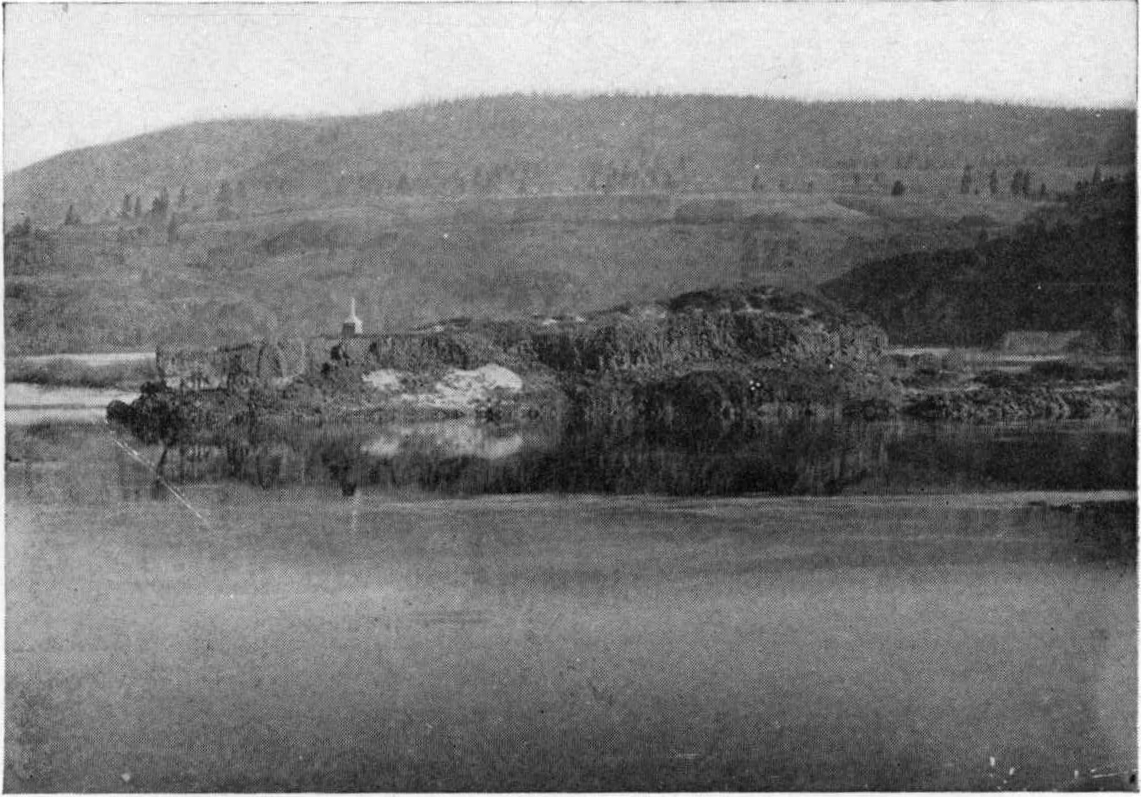

| Indian remains and Trevitt Monument on Memaloos Island in the Columbia River | 298 | |

| Memaloos Island, Columbia River | 298 | |

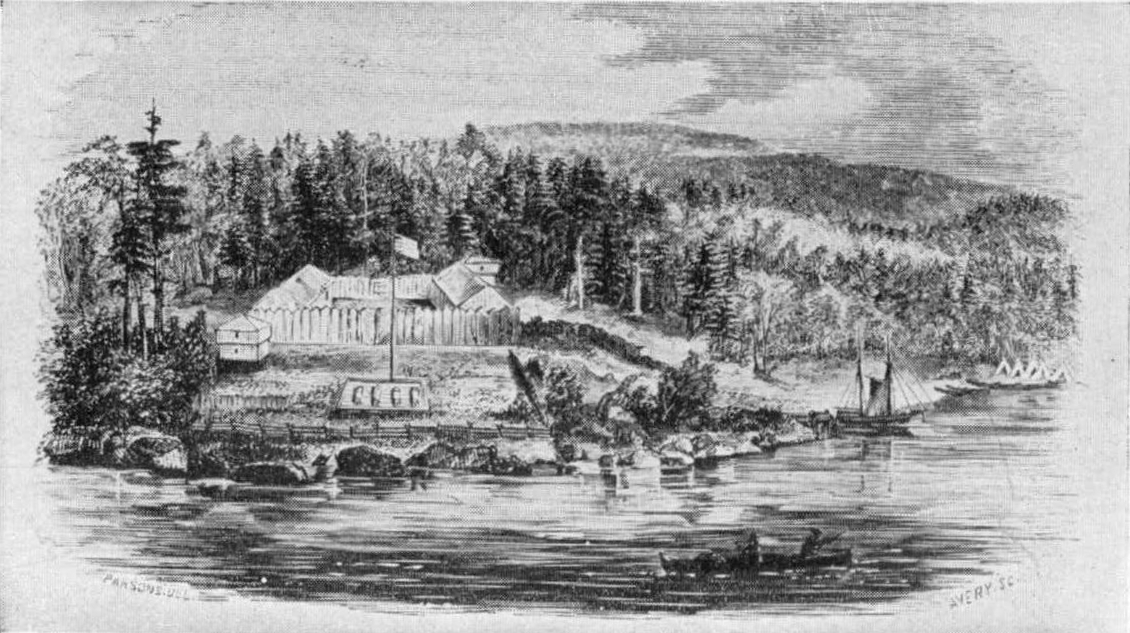

| Astoria, as it was in 1813 | 299 | |

| Astoria. From an Old Print published in 1861 | 299 | |

| Line Diagrams in Text | ||

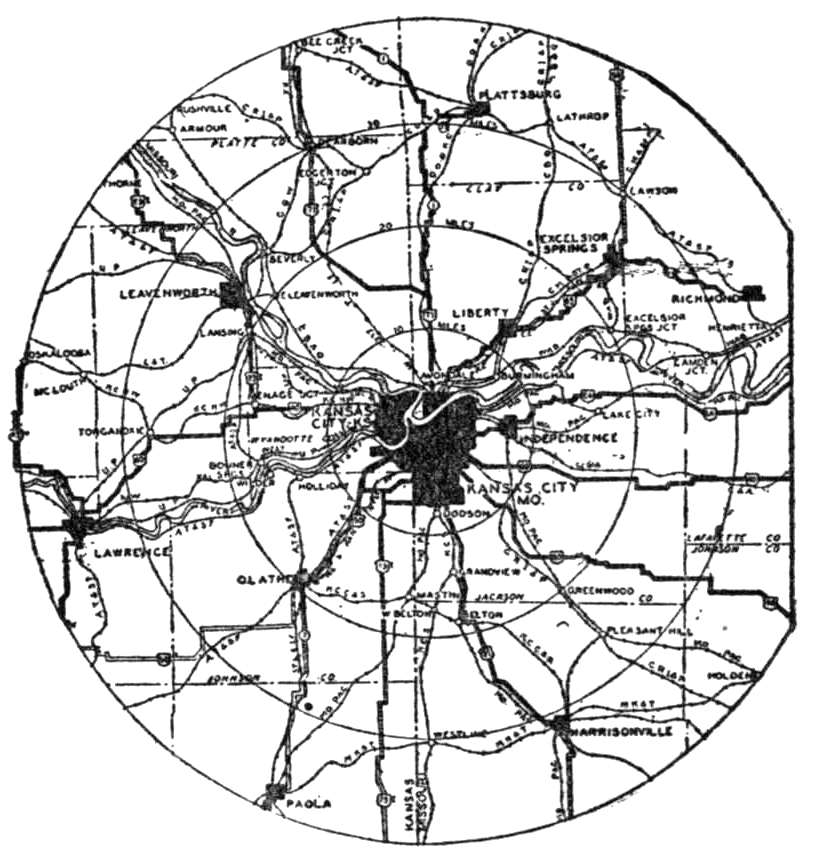

| Metropolitan Kansas City | 20 | |

| Metropolitan Omaha | 62 | |

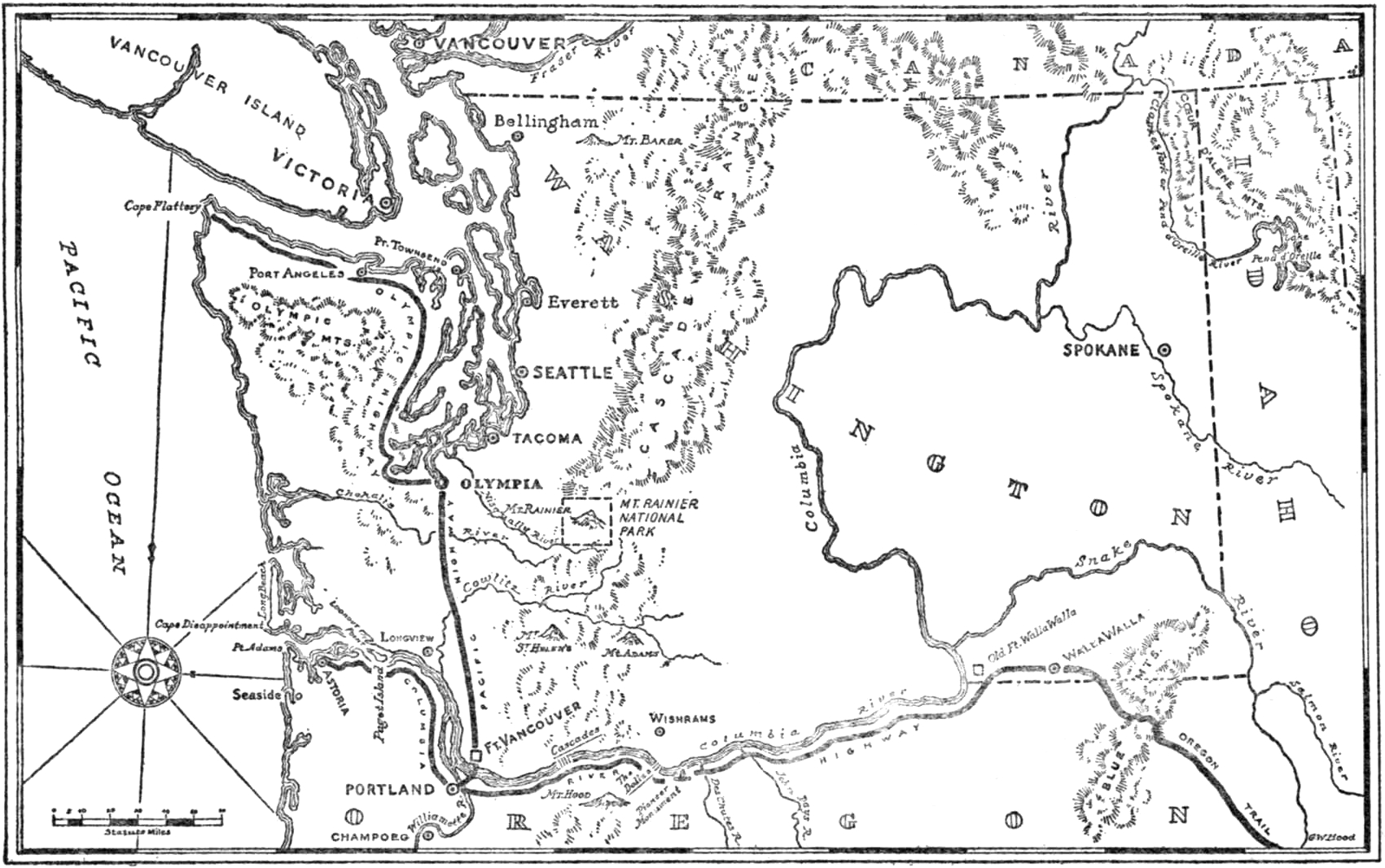

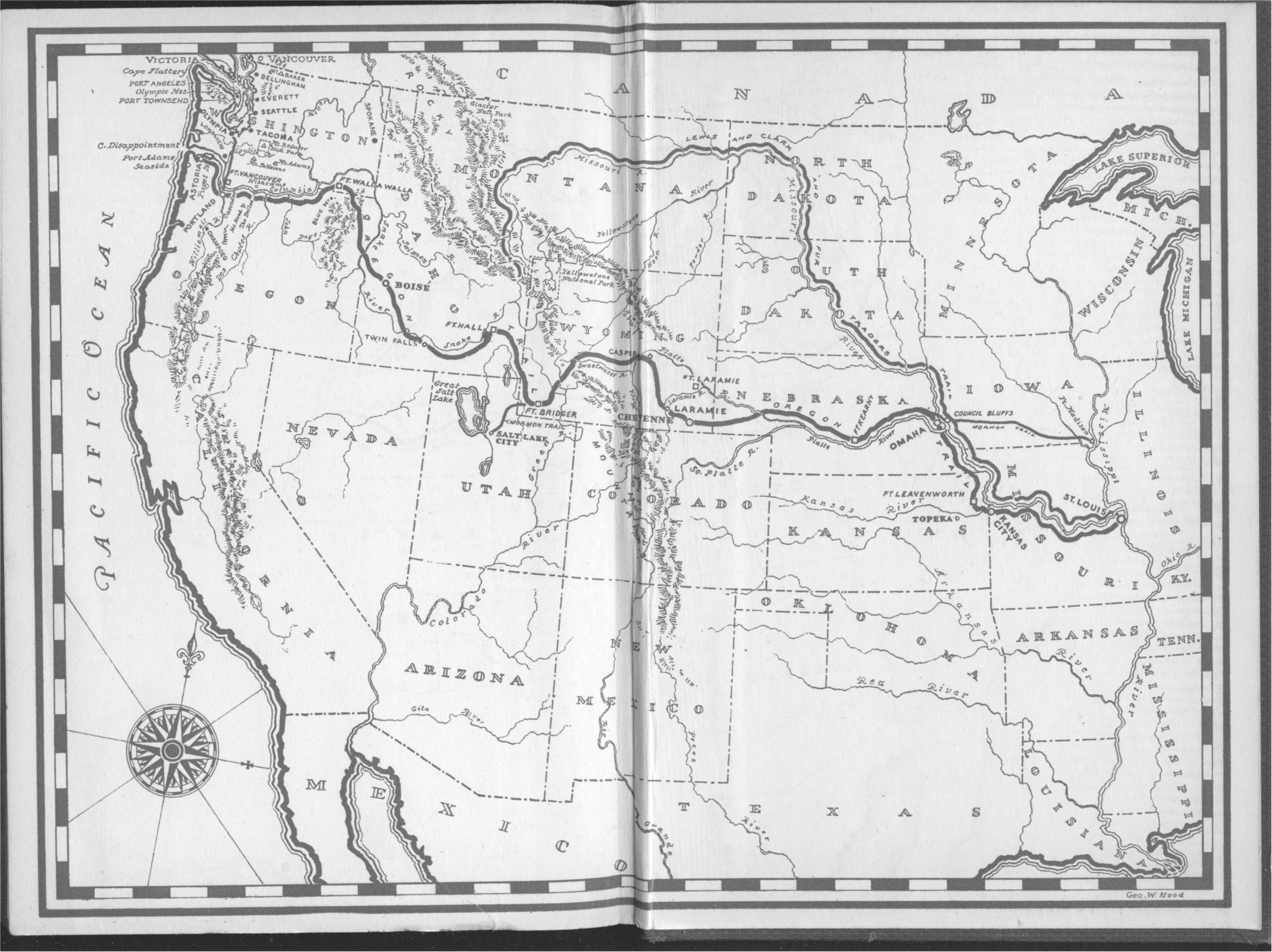

| The Columbia River, Pacific and Olympic Highway Country | 268 | |

One cannot better describe that great racial Highway of Humanity, that conquest of civilization over savagery, beginning its movement ever westward in the days of Abraham, going up the Euphrates from Ur on the Persian Gulf 2,000 B.C., and ending in our own days on the shores of the Pacific over the Pioneer Oregon Trail, than in the Memorial address given by Dr. Howard R. Driggs on the death of Ezra Meeker, one of the last of the Overlanders:

“It touches closely every part of our country, North, South, East and West. Every state in the Union has some heroic son or daughter who has played a valiant part in the trail-blazing, home-building story of the Far West.

“What is the West? It is merely the transplanted East. It is the blended North and South. We sometimes hear the song, ‘Out Where the West Begins.’ Frankly, I do not know where the West begins, but I do know where it began. It began along the shores of the stormy Atlantic. Our American pioneers were descendants of those who planted our thirteen American colonies and who afterward fought to establish this nation dedicated to freedom. It was the descendants of these stalwart defenders of liberty who carried America Westward. They followed the Indian trails through the passes of the Alleghenies along the national highways to the Mississippi; thence they wended their way over prairies and plains and mountains and deserts to the shores of the Pacific, there to plant our great Empire States beyond the Rockies. It is not commonly known how great this migration was. We get a mere suggestion of it when we learn from conservative estimates that fully three hundred and fifty thousand Americans took these trails during the days of the covered wagon—from 1836, when Marcus Whitman and his wife first made their way to Oregon, to 1869, when the Golden Spike linking the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific was driven at Promontory Point, at the north end of the great Salt Lake in Utah.

“We are brought a little closer to the tragic cost of it all when we realize that fully twenty thousand lost their lives in the effort to reach the Golden West. You can appreciate that I have a tender interest in the story when I tell you that somewhere among the velvety hills of old Iowa four of my great-grandparents lie in unmarked graves. They had no means of marking the graves of the dead in those prairie stretches. They might have put at the mound of the loved one laid away the skull of a buffalo, the end gate of a wagon or some other temporary marker, but mainly what they did was to scatter the ashes of their camp fires over these resting places to keep the bodies of their dear ones from being dug up by the wolves.

“Very few graves out of all the twenty thousand, so far as we know, are surely marked. One of these is the grave of the pioneer mother near Scott’s Bluffs, Nebraska. When Rebecca Winters passed away, one of the company had the happy forethought to pick up an old wagon tire that lay along the trail. Bending it into an oval he set the tire within the grave. On the top of the tire was chiseled the mother’s name and age. For more than three-score years it stood over the mound. Finally a party of surveyors laying out a railroad along the old North Platte, by mere chance happened to run their line right over the mother’s grave. As they read the inscription on the old wagon tire, they were touched by the love of a mother’s heart. They telegraphed into Salt Lake City, because it was on the old Salt Lake branch of the Oregon Trail, and relatives of the pioneer mother wired back who she was. Then the railroad builders protected the grave, erecting a neat, substantial fence about it. A monument, inscribed briefly with the story, was sent from Utah and set beside the old wagon tire, which still arches above the mound.

“Some years ago, I was in the Museum in Portland, Oregon, listening to George Himes, Secretary of the Oregon Historical Association, tell the story of the coming of the pioneers into the then Territory of Washington. I shall never forget the vivid recital of an experience he had as a boy of ten with the trail blazers into the far Northwest when they had to kill three of their oxen to use their hides to splice two ropes to let their twenty-nine wagons down a cliff that barred their way. Mr. Himes showed me during this visit one of the corners of the Museum in which he had relics that had come from every state east of the Mississippi River. ‘Here,’ said he, ‘is a clock that used to tick time in Vermont; here is a Franklin stove with which they used to warm themselves in Pennsylvania; here is a cradle in which they rocked the baby across the plains from Indiana and here is a scythe with which they mowed blue grass in Kentucky.’ ‘Yes, Mr. Himes,’ said I, ‘these people came bearing not only their scythes, and their stoves, their clocks and their cradles; they came carrying America across our continent; they came sprinkling the names of American towns and cities dear to their hearts upon the map of every state that they crossed; they came planting their school houses and churches; they came telling their children of the making of America; they came with American ideals throbbing in their hearts. They came, if you please, stretching the warp of our national life from one end of our country to the other. They stretched it stout and taut and true.’

“The vital question with you and me and with every American now is, ‘Will the warp hold?’ It will, provided we can keep alive the sacred stories of the pioneer builders of this nation in the hearts of American boys and girls. If we would save our country we must see to it that we save this invaluable heritage. An incident comes to my mind which would serve to make concrete the thought I would impress. It chances that recently I was giving an address in a high school in the Bronx, New York City, on America’s Greatest Trail. At the close of this address there came to me a young man, whose name was so foreign that I could not pronounce it, and he said with tears in his voice, ‘Mr. Driggs, if we could have our history taught to us like that, we would feel like saluting the flag. They tell us to salute the flag. We don’t know what they are talking about.’ ”

Could Americans grasp what an enormous achievement that was—accomplishing in a hundred years what neither Europe nor Asia had achieved in four thousand years—the Oregon Trail would be marked as one of the most famous in history. It would be regarded from end to end as the fulfilment of that Divine Prophecy “when His Dominions shall extend from the rivers to the ends of the earth.” It would be beautified, revered, consecrated as a Great National Highway. It would be visited and traversed by every traveler in the land. And it was not built by slave labor as were older highways in ancient lands. It was cut across the sand-blown desert, hewn through the solid rocks of the mountain passes, sculptured against the walls of river canyons by wagon rims of the penniless pioneer going West, ever West; of his Divine urge following the fantom hopes of his own heart to a Newer, Better, Promised Land.

Great epochs in history like mountain peaks in the receding sun lengthen their shadows as they recede. Tardily, very tardily, the Overland Trail is coming into its own. Its full history will never be told; it is lost in the dumb, inarticulate heroism of the dead; for pioneers did not ride “cock-horse on parade” like ancient conquerors. They marched on and died in silence as they marched, and the next band of marchers passed on; but enough of its heroism can be told to stir every heart. Enough of its dauntless adventuring can be recorded to keep its epic achievement fragrant and marvelous in memory. That is all attempted here—just enough to recall the shadowy figures of a Past that created the Present—ghost figures they may be but ghost figures that can never be degraded by cynic sneer; for these ghosts claimed no heroism. They just did their stint of work in life’s span and laid them down to sleep with good work well done.

A. C. L.

Old Spanish Explorers (1510-1542)

Crossed the country toward the mouth of the Missouri

before the voyages of Henry Hudson or Drake, or the

Settlement on the James River were made. A Spanish

stirrup of Coronado’s time was dug up in the streets of

Omaha.

Lewis and Clark (1804-1806)

Made a scientific exploration commissioned by Jefferson;

its results became important in the long quarrel between

Great Britain and the United States over the latter’s claims

to the Oregon country.

Astorians on the Way to or from the Pacific (1811-1813)

These were fur traders sent by John Jacob Astor to establish

a post on the Pacific Coast.

Missouri Fur Traders (1816-1840)

Adventurers from St. Louis who came up by the Platte

and Three Forks after the Astorians surrendered, to fight

the Hudson’s Bay men for the rich furs.

Later Exploring Parties (1842-1848)

The most noted were those of Frémont “the Pathfinder”

in 1842 and 1843. Frémont camped at Independence

Rock, and from there went on to the ascent of Frémont

Peak in August, 1842.

Pioneer Movements West (1835-1856)

Missionary, led by Dr. Whitman (1835-1843); Mormon,

led by Joseph Smith (1846 on); Santa Fé caravans, a

trade movement at its height in the late forties and early

fifties; the California Gold Stampede which in one year

(1849) raised the population of California from six thousand

to hundreds of thousands; the Oregon fever (1847 to

1856) caused by hard times.

Military Occupation (1823 to present)

From Col. Leavenworth’s expedition against the Aricara

Indians in 1823 through the eras of migration overland

and railway building down to that of Howard against

the Nez Percés in 1877, the army was called on to guard

the trail. The Fetterman and Wagon-Box fights took

place near Fort Kearney in 1866 and 1867.

Rail Pioneers (1856-1893)

Long and hazardous surveying preceded the era of actual

roadbuilding in the sixties. The Union Pacific advertised

in 1868: “track laid and trains running within ten miles

of the Rockies.”

There stand in America three great obelisks.

One is in Washington, the Federal Capital. It is the Washington Monument. It marks the beginning of a great nation in its expansion from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It commemorates also one of the noblest leaders, who ever guided that nation in its Destiny.

The second is in Kansas City. It commemorates the soldiers, who perished in the World War; but it also marks the beginning of a great racial path in that expansion from the Atlantic to the Pacific. That racial path is the Overland Trail. Here set out in the last trek of humanity westward, not an army of soldiers in rank formation, but an army of Pioneers, who conquered a wilderness and transformed a desert into a garden; and they accomplished in a little more than half a century, what the Old World did not achieve in sixty centuries. They conquered by sheer dogged dauntless courage an empire half the area of Europe. Five thousand people—men, women, children—perished from hunger, from hardship, from Indian raids, in a single year on the Oregon Trail. If you want to realize the epic heroism of such pioneer heroism, compare that mortality loss to the army death list of a single little war in Europe over some principality not the size of a single county in the states bordering the Overland Trail! Then you grasp what the great racial highway means in American history. You realize why to the West, it is sacred as the very altar stairs of a saint’s monument in Asia or Europe. It, too, is dyed in sacrificial martyr blood. It, too, is worn by the pilgrims’ feet in traces which time can never efface.

The third obelisk stands at the final outlet of Columbia River to the Pacific. It is known as the Astor Monolith. It marks the end of the Oregon Pioneer Trail. It commemorates far more. It symbolizes the final destination of man’s trek round the world from East to West for six thousand years.

One may grasp the significance of these things best, perhaps, by telescoping back from the present to the past and seeing how all evolved from simple beginnings.

Whether you travel by rail or by motor, pause midway above the long viaduct across the yeasty muddy floods of the river flats at Kansas City. Here shunt in a never-stop shuttle the trains of a dozen big rail systems. Ask yourself some questions.

Did the three Kansas Cities and their one suburb jump from a center of a few hundred thousands to a population of seven hundred thousand through man’s dauntless spirit or their own geographic position as the center of a Western Empire much vaster than all Central Europe or for that matter than all New England with New York and Pennsylvania included?

It is a mighty interesting question and its answer is an epic of human progress in a century unparalleled in the records of the race.

When I was there but a few years before the World War, and again just after the War, Kansas City was elated by a population of less than three hundred thousand. Here today are almost three-quarters of a million; and here tomorrow may be—what? I hesitate to answer—a Berlin, a Paris, a Chicago.

Less than seventy-five years ago, a man and his family with prophetic fore-vision might have sat down on a village lot sold at twenty-five dollars or given to anyone who would build and improve the property, and by sheer persistence in sitting on a little nest-egg without letting it go addled before it hatched, waken up to a fortune that would have left Rip Van Winkle rubbing his sleepy eyes, or King Midas feeling cheap. There are lots in Kansas City today as valuable as the best in New York, or richer far than any principality of the Old World. But the man would have needed more than prophetic fore-vision. He must needs have faith in his vision, faith based on facts.

Don’t regard Kansas City, Missouri, as the one Kansas City. Kansas City includes also Kansas City, Kansas, and Westport and suburbs beyond each, and Independence farther out, where many workers live and motor to and from home each day.

If you have eyes that see and comprehend what they see, the architecture tells the whole story of the city as it always does.

There are the most recent bank and public buildings and schools of the Grecian column and Chaldean lions with the wings of the spirit from the shoulders of power, with the acanthus leaves above the columns and not a line on the façade more or less than adds to beauty. Then there are the Gothic types, twenty stories with the towers and minarets cutting the clouds, resembling the highest structures of New York and Chicago. Older still are the good substantial red brick defying time in their squatty stolid ugliness—holding their own like good old burghers resisting change as a device of the devil and mighty useful in the wholesale and warehouse sections, where train smoke and the fogs of the rivers would blacken up my lady’s fine attire of frills now sported in the beautiful structures of the higher levels.

Take a look down from the causeway bridge, itself no mean viaduct of one and a quarter miles, where but a few years ago a bridge of one or two thousand feet was a marvel. Below the causeway, besides the ordinary freight car for general merchandise, lumber, coal, you see again the whole story of Kansas City’s growth. Oil from Oklahoma and Kansas. Cattle, sheep, hogs from the packing plants. Wheat from the great wheat plains north, south, west. Though oil will be piped for a century yet to the great oil distributing point of Kansas City which is the hub of a vast wheel, oil is a will-o’-the-wisp, which no science can foretell or forecast. It is a gusher today and an exhausted pool tomorrow. But the farm—the general farm of dairy, wheat, potato, fruit—there is the hub of Kansas City prosperity; and by the same token, that was what created Kansas as a rich state.

Apart from political plans to mend the farmers’ plight—and it is very real—put in a few lines the real farm problem of the fourteen states encircling Kansas City. Say the farmers—Give us a home market for all we sell and all we buy so we won’t be eaten alive by middlemen profits, and we’ll undertake to make ourselves prosperous. Say the manufacturers implored to come in and create such a home market—Give us a larger farming population to buy all we manufacture and to supply us with raw material, and we’ll come in. There is the eternal see-saw and Kansas City plans to meet both demands. Can she do it? She has in the past.

When the founder of the Santa Fé railroad—Halliday—came west and jumped off the back of nowhere, he found a place called Topeka—Indian word for “where potatoes will grow.” Where potatoes will grow, almost any staple farm product will grow; so he planted his meager fortune in the future capital of the State and incidentally, let it be added, quadrupled it and got him busy interesting friends in a rail line to center traffic in Kansas. The Civil War ditched his plans but did not stop them. When the first spadeful of earth was turned for the railroad and a little later a poor lame duck of a train came wabbling over twelve miles of rattling track bed and Halliday spread his arms and predicted his line would yet reach Chicago to the northeast and the Gulf of Mexico to the south and San Francisco to the west, a cowboy who had imbibed too freely of “tangle-foot” threw himself on the ground, kicked up his heels in the air and yelled “the blank old fool.” The old-in-head but young-in-years fool lived to see that cowboy become the mayor of Topeka.

Kansas City’s name tells its history much as its public buildings do. Before the squat brick structures were the warehouses of the fur traders on the flats and the French-Canadian little dormer-window cottages on the upper levels, of which only three remain today. The Indians who used to come padding in their moccasins up from the river flats where canoes lay beached called themselves Kon-zas. The French-Canadian voyageur had a trick of slurring his ins and awns and ons and called these Indians Kahns. Then when the Americans came, the Indians were known as the Kansas, and the Kaw River as the Kansas.

Or better still than the causeway as a look-out on the Kansas world, motor over to the Soldiers’ Memorial Column above the bluffs. You can ascend inside by an elevator. From its dome where flashes the most beautiful dark rose-red light each night, you see an empire fading on the horizon in the distance on all sides—literally an ocean of what was but yesterday sage brush and buffalo grass; but what is even more interesting than the marvelous growth of the city in its brief past is what may be its future.

Look down to the river flats. The Kansas River comes in here like a baby snake following its mother, the great looped python of the Missouri. From what looks like an island of sand in the broad mid-current but isn’t an island at all—rather an isthmus of sand accumulated in centuries by the two rivers, rise birds—the most beautiful birds in the world—sky-blue, blue wings of immense expanse, with the beautiful streamer lines of a gigantic aerial fish cleaving the air in whirls and spins, or poise like great hawks, with a roar of propellers that sets the atmosphere vibrating.

From “The Life of Frémont.” From collection Dr. G. C. Hebard, Wyoming Univ.

FRÉMONT ADDRESSING THE INDIANS AT FORT LARAMIE

From Dr. G. C. Hebard’s Collection

FORT LARAMIE

This is one of the great half-way stations across the continent for air flight. Will the air transportation do for Kansas City in the future what the steel rail has done in half a century? Quien sabe: as the Mexicans say. Remembering that “tangle-foot” cowboy’s derision and the crowd’s “boos” at the founder of the Santa Fé railroad, who can play prophet? Later, motor down to the Aviation Field. Now I know a little—very little—about aviation. I visited every great aeroplane factory during the War and once took a flight across one of the most dangerous sections of the Rockies. The improvements in aviation have left me gasping. War aeroplanes were built to kill or be killed—light of wing, too light for safety, light of cockpit, much too light for anything but war, but powerful of engine for speed. Now, the aeroplanes are built more powerful of engine, stronger in cockpit and body, with the wings of enormous spread in which may be carried extra gasoline to be tapped as needed. The take-offs are not the impossible bumpy-humpy land spots, which jarred going up and jolted the car to bits coming down, but long runways of concrete, smooth-surfaced as a billiard table; and experiments are in process whether these cannot be made softer to avoid jars in quick landing by the use of tars and asphalts and heavy fabrics as a binder. It is very much like the improvement of the railroad bed in a century, when granite ties and road beds jolted rail cars to wrecks and the nerves of passengers so that Boston papers pronounced all rails a positive menace to sanity. There are fourteen air lines now centering in Kansas City.

FIRST STONE ERECTED IN NEBRASKA TO MARK THE OVERLAND TRAIL AND FAMOUS U. S. ARMY HEROES

Courtesy Union Pacific Historical Museum

UNION PACIFIC EXCURSION TRAIN, 1866, AT 100TH MERIDIAN. LOCATED AT POINT 14.7 FEET EAST OF EAST FACE OF PRESENT DEPOT AT COZAD. NEBR.

Then coming up from the flats, pause midway on another viaduct and look down. Here are not switching yards but the dwellings of Mexican laborers—houses in adobé bricks with little yards and the usual assortment of children and puppy dogs and chickens. If you have ever visited a truly Mexican suburb for day labor of the unskilled sort, you know the smells are almost as variegated as the mosaic of colors but by no means so lovely. They assail you in a hot blast of anything but perfume. Look down on these Mexican workers’ dwellings—yards clean as a good kitchen floor, children in clean bright multicolored calicoes; no pulque drunks; no poverty. Kansas City does not entrust the Americanizing of her foreign unskilled labor to study-chair theory. She sends down either as public school teacher, or social settlement worker, or deaconess, or nun—according to the dwellers’ religion—someone to train these foreigners into American citizens; and of foreigners as foreigners, Kansas City today numbers less than eight per cent. The rest of her population has in a generation been so completely absorbed in American types, it cannot be distinguished from the home born and home bred type.

That is great work and it is more than talk.

Coming back one evening past a playground for children, I saw sitting banked against the green slope several thousand youngsters below a public school that looked like a university. It was as composite a group of what has made America as I have ever seen. The lank lean-horse type predominated; but what impressed most was that there was not a pasty faced weakling among them. These were fine little citizens and their children and their children’s children augur well for future Americans.

I wish I had space to tell of other things Kansas City is doing and what they mean in future growth.

Is it possible that only one city in what was called Indian Territory at the time of the Louisiana Purchase at fifteen million dollars has now an assessed property valuation of almost seven hundred millions? Was it gained by man’s dauntless spirit or was it the geographic position? People talk as though these two factors in human progress were distinct. The more you contemplate the opening and development of the West, the more you will be forced to the conclusion that with all our wild jumps hither and thither from the prods of necessity, with all our blind fumbling blunders following perhaps an illusion through fog and sunshine, with all our selfish brute instincts and all our fealty to an ideal that may resemble a rainbow and shifts from the glorious tints of heavenly light to the darkest shades of hopeless storm, something higher than self is shaping our zigzag course to a Divine Purpose. Shakespeare said this long ago. So has every prophet from Moses to John.

But keep on circling the city with both eyes open and your memory alert.

Where you come up from the viaduct across the river flats on a rocky ledge above the road stands a sentinel of the century—one of the finest bronze monuments in America of an Indian on horseback. It used to stand where now points the Soldiers’ Monument to the sky, but was appropriately moved here, above the very road where padded the fur traders in moccasins, the first Oregon Pioneers—missionaries and settlers—the gold-crazed hosts stampeding to California, later the Santa Fé traders in mule and horse-drawn covered wagon, and still later, after the Civil War, settlers of every nationality in swarms like locusts to take up homesteads preceding or following the lines of the transcontinental rails beginning to belt the land in loops of steel. Perhaps I should say in hoops of steel, for it was the rail bound East and West in unity.

What is the Indian, sitting so intent, thinking about? Fur traders—yes—he understood them. He had known fur traders from the time Lewis and Clark passed west early in the century. They wanted his peltries. He wanted their firearms. With these firearms, he could hold his own against Indian raiders from the south. He could raid the south tribes, himself, for more Spanish horses. He could defy the Crows and the Sioux and the Blackfeet on the north. He could pen the Snake Indians in the mountains and compel them to buy supplies from him as middleman between East and West. Who was this Indian? He might have been any one of a dozen tribes gradually moved by white man pressure from the East to the plains—a Shawnee, a Kaw, a Delaware, a Pawnee, an Osage, a Cherokee, a Sac, a Fox. A pathetic figure, too, he is. He knew what the coming of the white man meant. Kill or be killed, hold your ground or lose it—his code from times unrecorded—was to be applied to himself. Live by the sword and you die by the sword—an inexorable law. Should he resist these new comers? He could see where the traders left their canoes beached, or their flatboats moored to trees, or the puff puff “mill that walked on water,” the first steamboat snubbed up as close ashore as the sand flats would permit. In the billowing grass of the flats, horses pastured in thousands near water and carried up the fur traders’ packets for the traverse across the plains. No, he would not resist these traders, though he scalped and robbed them as he could. These fur traders had already gone west far as the Rockies. They had crossed the Rockies—they had a post just west of the Rockies, known as Henry’s Fort, on an upper branch of Snake River. To be sure, it was only a collection of tumbledown log huts; but it marked the fur traders’ advance across the Rockies.

But these missionaries and settlers. He could recall, perhaps, those Flatheads from the Far North going down to General Clark in St. Louis and asking for white men to teach them the Trail to Heaven from the Sacred Book. But these settlers on horseback, in covered wagons, on foot, with mountain men as guides, and women and children, with rifles on shoulders, rifles in cases and bullets in belt or pouch, who encamped in circles surrounded by their wagons, with cows for milk and oxen of broad spreading hoofs to ford the quicksand beds and not so likely to mix up in a buffalo stampede as horses—what did they mean? He knew only too well what they meant. To the rear of the Soldiers’ Monument, you will see another statue, finer than the Indian on horseback. It is the settler’s young wife on horseback with her husband on one side trudging doggedly, blindly into the unknown, the mountain man guide on the other side, alert for foe as a coyote for rabbit. Well, the Indian could rob and raid them, too. Their oxen and cows would give him winter beef. Sometimes they came in bands of a hundred, sometimes in bands of thousands, with cattle in thousands; but why did these mountain men out for furs guide these settlers, who would destroy hunting grounds? The mountain men wore red shirts or red handkerchiefs around their long hair. He knew why. Many had married Indian wives, partly to assure them of protection from the tribe, partly to have women to make and mend buckskin suits, tents, moccasins, to cure buffalo into pemmican, to gather berries and fruits to be dried and pounded to flour. While the red shirt or head gear was a good target for enemies, it was equally good protection for friendly raiders from mistaking a man for game on the dusky plains. Curious these mountain men befriended settlers. There was Boone, whose grandson lived out at Westport on the ridge above the river. There was a Joe Meek, who learned the white man’s letters by chalking them on a paddle and then learned to read from the Sacred Book and later—though the Indian didn’t know anything about that—from Shakespeare and Scott. Then there was Jim Bridger whose family lived at Westport. These men were all hunters and had married Indian wives. Why did they guide the settlers? The Indian was no fool. He knew what it meant. It meant the end of the hunting era. Particularly, he knew when the Civil War came on and these white men began fighting among themselves. That was the Indian’s last chance. From that time on, every plains tribe pot-shotted, raided, massacred where and what he could. He didn’t do it en masse. Indeed, their wise older chiefs opposed the younger rash warriors; but the chiefs could not control young bucks out on the war path; and the very contest they provoked hastened the end inevitable. But keep clear in your mind, the fault was not all with the Indian. White-man rum lashed up the worst in the Indian. No one compelled him to drink it; but tribes highly stimulated by an ozone atmosphere and diet too purely of concentrated meats had a passion for liquor from the first taste. White-men thugs pot-shotted Indians for the fun of seeing them spin. To them the only good Indian was a dead Indian. Of this you will get some terrible examples presently when you reach Omaha—and of the terrible nemesis that punished such acts. From Lewis and Clark’s day, the Washington Government had frowned on the use of liquor in Indian trade; but who was to enforce law in a no-man’s land? The profits were too great for the individual consciences of independent traders. Only four dollars value of liquor could be diluted with water, then “doped” with drugs of a maddening sort to sell for sixteen dollars; and the keg traded at five dollars a pelt worth twenty.

And right here from the look-out of the lone Indian, you get the very birth and growth of Kansas City. The river flats of the fur traders. Independence, where presently clustered and grew the blacksmith shops to shoe horses and oxen and repair wagons. Then the traders’ shops to supply goers and comers. Then some enterprising citizens took another jump to Westport to get the trade away from Independence. Thence, the city grew and spread from buckskin tents a century ago on river flats to seven hundred thousand people today.

Why did not the Oregon Trail jump into the unknown from St. Louis, from which Lewis and Clark had set out? Because Kansas City by the river’s windings was five hundred miles from the outlet of the Missouri. By cutting off the loops of the river, the Overlanders from the East could save some two to three hundred miles in their traverse across the plains. One was the circumference of the half circle. The other was the diameter.

Here in a steady stream every spring—usually in the months of April and May—from 1843 to 1853, converged lines of emigrant wagons in thousands. They came in neighborhood groups from various states and territories. One group might be from Missouri—one hundred, two hundred, to the group. Another band might be Illinois or Iowa families; yet another old South and Middle South frontiersmen; and in the Whitman Missionary era, from 1839 to 1849, families from as far east as New York State and New England. Motives were as various as the groups; but the lure was the same as from the beginning—the lure of the Western Sea. Missionary zeal, hard times back East, youth’s love of adventure, the chance of fortune in gold mine or land might be the bayonet prod of necessity; but the Oregon stampede had become what the New York Tribune called “an insanity.”[1]

|

To acknowledge all the authorities from whom data for the story of the Overland Trail have been drawn would be to cumber pages with a modern and ancient bibliography. Mrs. Paine, Stella Drumm, Doane Robinson, Grace Hebard, T. C. Elliot, Judge Carey, Mr. Himes, Professor Meaney, Ezra Meeker, Dr. Driggs, Alter,—the names of moderns are almost countless. I give these because they lived on the spot and knew descendants of the old heroes and the few of the old heroes who today survive, though nearing the century mark. I remember among my own personal friends two or three of these dear old people. One passed away, while I was writing this book. I spent the first twenty-five years of my life in the West, where many of the old fur traders had retired, and passed my school days with their children and grandchildren. The traditions of their descendants were already fading and it was comical to hear how many of the old generation differed as violently as to dates and spelling and this and that as modern study-chair critics. I have seen old fellows almost coming to blows over whom and what to blame; and I have tried in this narrative to take no sides but to set down as far as possible facts. On certain types of facts, the definite can never be set down and for obvious reasons, to anyone who has gone on long camping trips, whether by horseback or canoe. Down to at least the 1860’s, the daily brigades of fur traders, colonists, surveyors, dotted their notes on anything from dry parchment to tissue paper criss-crossed with a goose quill pen or carpenter pencil. Their notes could not be made daily as any traveler knows, and I myself, have found. They got in at night always dog tired, often drenched to the skin, frequently in haste to get up camps against an impending storm. Often notes had to be made a week after the places named were passed, or the day of the event happening to stamp their memory. This accounts for many of the differences as to places and dates. Take a man away from calendars for six months—yes, a month—and if absorbed by adventures of a life and death struggle, he will lose track of dates, even days of the week. If he didn’t you would have good ground for regarding his entire record as “doctored” afterward. Also what one man along the trail saw, another man in the same group missed. One man might be on the south shore of a river, the other on the north. Both were struggling through sage brush, over fallen trees,—perhaps running for dear life from a charging buffalo bull, or cocking a rifle at an ugly bear contesting the path. Would these two men remember the same episode? They would not. I say no more of that type of difference. More puzzling and confusing are the almost countless different names and sites given to the same forts. The reason is apparent, almost transparent on the spot. Sometimes, the first fort was so close to flood waters it had to be shifted back up the hill. Again, on the crest of the bank it was too easy and exposed a target for Indian raiders, or too vulnerable to violent storms; and the next fort would take the name of the army commander supervising the new structure, only to be razed for another later. In the majority of the cases, but not all, the name that emerged has been the old one, though the modern city may be from five to twenty miles from the first site. Laramie, Fort Hall, Boisé, Walla Walla are all examples of this; but monuments now mark most of the old sites but not all. That has been impossible. Farmhouses, barns, dam sites, water backed up by dam sites covered the old sites. I think of one great modern city, which in its history has had five different fort names. Again, I shall say no more of these differences. They are all along the Trail and do not detract in the least from the tremendous significance of this epic highway. Where I do not give the differences, it is only because they confuse the mind and needlessly cumber the memory, when what really matters is the intensely interesting document of heroism on the Trail. |

METROPOLITAN KANSAS CITY

Is it worth while to run out and see Fort Leavenworth?

That depends on what you want to see.

If you want to see things as they are, the answer is that of the canny Scot—“mebee yes—mebee no.”

If you want to see the shell of the acorn from which the mighty oak grew—decidedly yes.

Leavenworth is directly on the road to Omaha about forty or fifty miles north according to the road you follow. It is not properly on the Overland Trail, for here again the snaky rivers loop in countless coils and the Overlanders bound for the Platte ultimately took a short cut northwest from the Kansas to the Platte. On the way out you will see how Uncle Sam’s Treasury—the Army branch of it—spends tax money.

When I visited Leavenworth I was amused at my taxi driver’s insistence that I should stop and see the Penitentiary. I didn’t want to see the Penitentiary. This reminded me too much of a joke on King George of England when he was visiting Canada. He was asked what was the funniest thing he saw in Canada. He answered, the word “Welcome” in gorgeous coloring across the gate to a penitentiary. But the Soldiers’ Home and Hospital are certainly worth seeing. The Home did not know I was taking a look at it; so I was not displayed the bright spots, while the dark spots were hidden behind an official screen of discretion.

What I first saw was the men—few faces from the old Civil War era if any; some—fewer and fewer each year—of the Indian War era down to the 1880’s; a greater number from the Cuban and Philippine War; and still more from the last War—an invalid class. The faces were happy and contented. The clothing was neat, spick and span, as if in army service. Where not crippled by war, the figures were agile. The grounds—trees, lawns, flowers—in one of the most backward seasons the West has ever known, were a glory of beauty, peace, restfulness, repose. I do not believe any man could live in those surroundings and retain a permanent grouch—the inferiority complex. Nearly all the men have pocket money from pensions or savings for the little comforts of tobacco, knick-knacks and what not. The spotless hospital beds, the recreation halls, the reading-rooms, the bed and board are better than many a hotel for which I have paid five dollars a day. They are far and away better than the majority of the men ever knew in their own private homes. I hate to call those soldiers “inmates.” They are not. They are retired veterans from service for the public good. Some sat on the benches spinning yarns of the old days. I wish I could have sat down with them for a week without their knowing I was a writer so they would cut loose. When you hear two old fellows scrapping over a point, you may not take sides but you get a mighty human slant on exactly what did happen and how at that point. Others wandering among the flower borders pointed out with their jaunty canes especially fine pansies or pinks or spiræa. Others I saw pointing crutches at various trees—imported trees like purple beeches, or California pines, or silver maples. They were interested in life and that is the main thing to keep going and well.

The highway out from Kansas City is as good as Riverside Drive, New York, or Chicago’s Boulevard. In the rush hours from 7 A.M. to 5 P.M., it is pretty heavily traveled—tourists, workmen building bungalows reaching out from the city, army trucks en route to and from the fort; but toward the west is the same ocean of green prairies as from the beginning, now in fields of alfalfa and clover scenting the air as did the old prairie roses.

We had just had such a plunging rain as used to leave this road, then of log corduroy and mud holes, a horror; and where the sticky adobé mud had splashed across the pavement, the swerve of our car to the grease of soil and gasoline, gave me a guess at what the swerve of army mule-drawn wagon must have been.

Fort Leavenworth, itself, is a sleepy little old city of retired and resident officers and citizens. It is the only sleepy thing in Kansas. As a fort, it is not liked by Army men. Since the ending of Indian Wars, chances for promotion are slim. Ambitious men are transferred elsewhere and the fort sleeps away its drowsy tranquil days. The Great War brought it again to life when as many as a hundred thousand men were at times encamped on the rolling hills and plains. You can see the abandoned buildings now for the most part occupied by colored families of troopers. The stables that used to roof and train hundreds and thousands of the finest army horses in America, are like the fort—sad relics of glories that have departed. The few horses yet there are beauties—perfect mounts; but how few! I was both sorry and glad. Sorry the day of the most beautiful creatures in the animal world had passed; glad these noble brutes would no longer be mangled to torture in war but had been replaced by machines that could not feel, however much the men driving the machine might suffer. The men have a vote on war. The horse hasn’t.

It is rather ridiculous to have to set down that among the soldiers and minor officers, not a man but one lone sentry and one prison convict could we find to give us information as to the wall of the ancient fort. Sherman and Grant—yes—monuments and streets named after them, but we chased our car round in the futile circles of a kitten after its tail hunting monuments and streets in memory of General Leavenworth and Kearny and Miles and Crooks and Custer, Sheridan, yes, and Colonel Cody—Buffalo Bill—and a dozen others without whom the West could never have developed. It would have been the Great American Desert to this day. Pacifists or militants, we may hate that statement or like it; but as a fact of history it has to stand. Uncivilized people—yes, and some civilized, too—have to fear first and love second; and the love usually comes as the growth of reverence for the justice behind the fear.

I paused in our circling to watch a bunch of convicts brought in from field work by a detail of troopers. I looked over the marching line of convicts—with the exception of a dozen, perhaps, deserters or insubordinates or sub-morons, who ought never to have been in the army at all, where they would have been useless in action, a danger to themselves and others. They would have collapsed or gone wild. Some were colored, the majority white, only a few, I should say, unsafe brutes in human form—as Parkman called some Indians—men but not yet with souls. Many were well born, but from some trick of ancestry or environment—weaklings mentally or ethically, not to be trusted in ordinary life, much less in the wild action of ruthless war.

Will old Leavenworth’s departed glories ever return? Indian Wars are forever past and I never want to see another war mobilizing a hundred thousand men here; nor do I believe another war could. The aeroplanes and submarine explain that.

All the same, Leavenworth is worth the run out. It explains why neither Kansas City nor Omaha could ever have been here. The Missouri Flats are too wide here—eight miles in flood tide. A rail bridge here was for all time an impossibility; but here from 1827 were concentrated eight hundred troopers—the majority mounted with a pack mule for each horseman—besides officers for every unit of one hundred and two hundred men. The flats gave inland expresses pasture and water to prepare to cross to the Platte. The army units were detailed to keep order amid a million warring raiding tribes much more hostile to one another than to the whites. Cholera and sunstroke across the thousand miles of pathless plains patrolled were, down to the 1870’s, much more deadly than raiders’ arrows. We know now that much of what was called cholera was nothing more than the terrible effects of alkali water with a meat diet and heat to broil one’s brains. No white could stand up against day sweats that drenched in a Turkish bath and night chills called “ague” and the constant drainage of reserve strength by enteric disease. Much less could he withstand the drain if he could not resist the temptation to hunt buffalo in the heat of midday, when the buffalo clustered in the shade of the poplars and cottonwoods along stream beds. Hunters’ blood up, the troopers gave chase. The herds stampeded for the hot unshaded sand and lava plains. The white rider followed and paid for his folly. Of one group of eight hundred troopers sent west in all the panoply of war to impress the plains Indians during the 1830’s, fewer than two hundred came back alive. The dead were buried on the plains where they fell to be devoured by wolves scraping up graves. Only a few were brought back to be interred in some fort.

Telescope your memory back to old General Leavenworth so human, yet a great army man. He is described as a veteran of the 1812 War, but he couldn’t have been much of a veteran in years, for he came down in the prime of his powers from Ft. Snelling, St. Paul, to build Leavenworth—on the west bank of the Missouri in 1827-28. He passed Omaha, site of the grave of the famous Black Bird chief buried astride his war horse “to watch the French traders” passing up and down the river. It was Catlin the artist, in the 1830’s, who found the skeleton of Indian horse and chief. In his first trip west, Catlin had seen nothing in Indian life—except the tortures in the dances of the Mandan Lodges near modern Bismarck—to condemn. In his next trip, his clean sheet for Indian life had dimmed. He wasn’t quite sure the old chief hadn’t been “a murderous brute” in spite of courage. The courage of using poison on enemy chiefs and calling it “mystic medicine” wasn’t a brand of cunning liked by white men.

Leavenworth had been built as a sort of breakwater line between the Indian raiders—Cherokees, Shawnees, Tuskaroras, Delawares, south; and Omahas, Pawnees, Crows, Sioux, Blackfeet, north. Six or seven companies had been sent away up the Arkansas Southwest to arrange pow-wows of peace. Fifteen ladies dwelt at Leavenworth. Horseback riding was the great racing sport. Fires in the high dry grass of autumn were the awful danger. The Indians called those sweeps of livid flames “the Spirit of Fire” to create new pasture. The Kansas tribes now numbered about 1560, the Pawnees twelve thousand warriors, the Omahas fifteen hundred.

“Catlin,” said Leavenworth, as they came riding back across a thousand miles of heat-scorched plains in August from the Arkansas, “we are getting too old to hunt buffalo—we—” Just then the rise to the crest of a hill showed a herd of the shaggy buffalo moving across the plains in search of water. Leavenworth’s horse was off like an arrow on the chase. Leavenworth wanted a nice young yearling calf whose fur was in good form and meat would be tender. That calf was no dunce. He had a rabbit trick or two. He would let Leavenworth come right up where the rifle hot to the touch could be aimed—then he would double back over his tracks and Leavenworth’s horse would be thrown on its haunches in the sudden stop. Leavenworth laughed. “I’ll have that fellow if I have to break my neck for it,” he yelled. Catlin himself had been tossed astride a small tree. Catlin saw Leavenworth’s horse down and the general on hands and knees over its head. “Hurt?” shouted Catlin running up. “No, but I might have been,” answered the veteran of Indian Wars; and he fainted. He died a few hours afterward while catching up with his troopers. In that summer, more than a third of the troopers on the trail from Fort Leavenworth died.

I listened to the whippoorwills’ plaintive ditty, to the quails’ querulous note, to the bob-o-links’ joyous call in the clover fields and thought of the days in the middle of 1830’s when Narcissa Whitman and the dauntless doctor came ferrying across the Missouri to the whitewashed barracks of Fort Leavenworth high on the ledge above the flats. The soldiers must have gasped to see a woman coming as missionary to the back of beyond in this perilous land, where the only white women, up to 1830, dwelt inside fort walls. And the missionary hopes were yet so high, their faith so undiminished by failure, their zeal so unselfish! Hadn’t the Indians asked for missionaries? Didn’t they pray for instruction in the Sacred Book? And the way so far by steamboat had been so easy, warnings as to perils ahead seemed devices of some coward devil. The officers of Leavenworth looked sad; but Narcissa Whitman sang her beautiful hymns and looked at the gorgeous sunsets and smiled. She was divinely happy.

To the everlasting credit of the Daughters of the Revolution be it said, they finally restored the old crenelated wall of the first fort with its slit eyes for rifles to cover and protect ferry and steamboat below. On the flats often a thousand people were in promiscuous encampment—traders, rum runners, missionaries, Overlanders.

Pioneers from the Middle West were very religious and sang “Old Hundred” round the camp fires blinking above the yellow flood of the Missouri. Indians lounged about, stoically observing each party. Voyageurs gambled and sang and fiddled and danced. “Eat—drink—be merry—tomorrow we die.” Mormons, when their day came, though their chief jumping-off place was Omaha, were a bit grimmer and more fanatical than the Middle West and New England colonists. The Mormons had been hounded with persecutions; and martyrdom always acts as cement. It hardens into adamant unity. There were always Mexicans to swap saddles and horses and silver jewelry to traders and voyageurs and colonists. A great many wagons had come to grief and the blacksmith’s anvil above the ridge rang day and night to mighty blows. There were no lazy men in the camp. The Overland was not a trail for lazy men. Housewives rinsed out clothing in the river or baked bread in tin reflectors banked opposite the fire. I think it was at Leavenworth, Narcissa Whitman’s white hands did the first family washing on the Trail! Poor delicate hands—they were to know rougher, harder duty for delicate hands within three years; and they never flinched, however deep her hopes sank. Matches were few and bottled for security against damp. Butter had been packed in the middle of cornmeal sacks. So had eggs and sometimes the jars of travel had mixed an omelet all ready for the bake tin. Ready money was carried in a box or belt but was very sparse. Wages were from twenty-five cents a day to four dollars for good guides or as much as five dollars by clever fellows for each passage across a ferry. These men had calked their wagon-boxes with tallow and tracts sent out by misguided missionary societies in far lands, when, “the hell fire” missive was apt to be mixed with tar and tallow and serve a more immediate use. Many an Oregon Pioneer from 1843 to 1848 learned his first A B C’s from these “hell fire” tracts and they sent him to bed with such fright, as a boy, sleeping in the cabin loft above the grown-ups below, that he would awaken howling with a nightmare complex of too much pudding and too much imaginary sulphur.

It was well on in the 1860’s before stages were general as far as Leavenworth and these were so cramped that knees sat interlocked with knees, and husky travelers preferred horseback. When you consider that even the fastest stage travel of the 1850’s seldom exceeded ninety miles a day and often averaged twenty miles with upsets and broken axles and delays in quicksand fords—the discomforts of such travel can be guessed.

Prices were staggering from Leavenworth to Laramie—$1.50 for a pound of tea or coffee; so settlers contented themselves with kin-i-kin-nick—willow leaves steeped as a tea, which were a good purgative for too heavy a meat diet. Sugar, brown, was twenty-five cents a pound; so the Pioneers had brought maple sugar. Flour was $1.50 a pound; so travelers came to depend more and more on berries and roots dried and pounded to a flour.

The place has come to deal with two very controversial topics as to the Overland Trail. The disputes rage chiefly with study-chair trail markers—not Pioneers, nor the descendants of Pioneers, nor people who, themselves, have followed wild trails.

Can the Overland Trail be set down definitely as running always from here to there, and from this point to that?

How many people were on the Trail each year?

Remember there was first the fur traders’ migration West. Then there was the Missionary-Pioneer-Oregon migration. Then there was the gold stampede to California.

Parallel with these was the Mormon movement. Also the Santa Fé wagon travel. Five distinct migrations paralleling and diverging en route as each traveled westward. Just to state that fact is to show the absurdity of the disputes.

In some years there were as many as twenty thousand wagons following a road so dusty the wagons behind could not see the wagons ahead and many wagons moved five and eight abreast and, as each platoon of wagons formed for each day, self-imposed regulations compelled the dust-free leaders of yesterday to fall to rear today. It is nonsense to imagine the same fords could always be used, or the same ferries were in service. Fords and ferries depended on flood tides and dry seasons; and these varied each week and each day as they do today. I have been over these routes—all of them—in years when rail tracks were washed out by a cloudburst and in the very same season in the next year when the rails would gladly have paid the loss of a washout to help the scorched crops to increase traffic. I have been out in the month of June when sixteen-foot snow banks stopped us in a motor and we had to diverge to a lower road; and I have been out in April when you would have paid an extra fare for a whiff of snow air to lower the temperature. It has always seemed to me such disputes are a bit futile. Enough to set down that if you draw a broad belt from Kansas City and Omaha westward up the Platte to South Pass, you are on the Overland Trail, the epic road of human history.

Leavenworth is not on the Oregon Trail; but you have to know its position relative to the Overlanders’ highway. Else you will not understand the hopeless impossibility of moving troops westward fast enough to avert the awful tragedies of the 1847-49 era. Beyond Leavenworth every Pioneer took his life and law in his own hands; and in each covered wagon were more women and children and babies. One does not know whether to tremble at the temerity or applaud the courage. Perhaps both.

How many people were on the Trail each year?

What matters it?

When one Pioneer tells you he was in a band of two hundred and seven people and another tells you he was in a group of forty to fifty, and another tells you he saw five thousand wagons pass Laramie in a day, can such figures be checked up by the census of California or Oregon, when the census was guesswork and no census existed west of the Missouri and these birds of passage in movement across the plains were as varied in numbers as the wild geese winging overhead? As a wise guide of mine once answered in the North, “We don’t travel here as the crows and geese travel in an air line. We travel as the sand bars and head winds compel us.” Yet who has ever attempted to check up a census of the wild geese awing for the North?

I say no more. The best one can do is tell the story of various groups on the Trail. Then if you don’t take your hat off in reverence to hero Pioneers, and feel the tears choke your throat over the lonely graves, or the blood rush to your head in fury at the brutality of some thugs, both red and white, it is because you have lost the zest of real living. These people lived and died to create the West.

There is no mistaking the appropriateness of the Indian names from now on, “Omaha—Above the Waters,” “Nebraska—Shallow Waters,” and “the Platte—Flat-Muddy-Bottoms.” You realize that whether you go on from Kansas City over the Overland Trail by rail or motor; and Council Bluffs hardly needs its name explained. There, under the self-same oaks where Lewis and Clark spread their awning and met the Indian chiefs of a dozen tribes a hundred years ago, you can park your car below the high bluffs and think about the past and the future of the two cities on the heights above the flats. The rivers, themselves, here, are not wide, but from ledge to ledge where the cities stand, it is about eight miles. As in the Kansas Cities, the dividing state line between Iowa East and Nebraska West is right on the viaduct highway.

It is worth while to pause on this viaduct, too. You can see where the river below has shifted its tortuous course twice in a century—once in recent years, once in what became known as the great Madrid earthquake about a hundred years ago. No city was possible on the flats but it was feasible to find foundations for bridges, though you can see where one bridge planned had to be abandoned, with piers left standing, because engineers could not overcome the quicksand bottoms. It is plain, too, why General Dodge and President Lincoln had to choose this spot for the crossing of the first great transcontinental. Northwest, the Missouri Channel widens to a lake seven miles across. Though in two states with separate civic governments, commercially the two cities may be regarded as one, Omaha with over two hundred and sixty thousand people, Council Bluffs with more than sixty thousand.

Again telescoping the mind back to the old days, you can see why the Astorians, following soon after Lewis and Clark, avoided the great circle of the Missouri as well as the raids of Blackfeet north, and came to grief in the Rocky Mountain passes westward of the Platte. You see why missionary and colonist essayed to cross the plains overland rather than attempt any river route by canoe and rowboat. To have followed the river routes would have been akin to tracing the course of a long wriggling snake. The best air line was directly west.

Be it acknowledged frankly, both cities show signs of having suffered declines—perhaps I should say setbacks—following the War; but as the causes of the setbacks are also the causes of the comebacks, the swing of the pendulum is worth analyzing.

Let it be acknowledged frankly also—Panama is working a silent inevitable revolution in the Middle West. Chicago is not the Middle West. It is the western terminus of the East. Draw a line down equal distances from the Mississippi and the Pacific. The 100th Meridian marks the dividing line. That is the Middle West. Canals have never lastingly helped nor hurt any other section in America. Only where they deepened natural waterways to the ocean have they created new central cities by moving the ocean farther inland; but Panama is more than a canal. It is the shortest portage between two oceans; and ocean transport is cheaper than rail as one to seven. It must always be. There is no track bed to be built. There are no rails to be bought and replaced. There are no ties to be laid and replaced. There are no track crews to go out daily and clean up the cluttered highway. There are no spikes to be driven, no weeds to be sprayed out, no washout to be repaired, no bridges, no fill-ins, no sidings, no stations every few miles, no freight sheds, no round houses, no water tanks, no freight cars to be built, repaired, no tunnels. Compare these with any corresponding costs of ocean transport. The difference totals thousands of dollars a mile in places, millions in sections with long tunnels and long bridges.

Has, then, the Middle West suffered a vital final blow from Panama? By no means. Why not? Because in that Middle West dwell sixty million people, who must always be heavy buyers of all that the factories produce. Because that Middle West is the great producer of all the staples that the whole world eats. Across it must always shuttle the carriers of what is bought and sold. Can freight rates be reduced to meet ocean rates? They cannot. Such rates would throw every carrier in the Middle West into bankruptcy. Can the waterways of the Missouri and the Mississippi be deepened and improved to move the ocean inland as in the case of the St. Lawrence up to Montreal? There is a violent controversy over that right now. The Army engineers say the Missouri and the Mississippi cannot. The civil engineers say these river highways can be improved to become cheap feeders to ocean traffic. In other words—can the Missouri which is the longest water highway in the world be humanly controlled? It is a big job. It would cost as much as Panama and would be worth as much as its cost to the Middle West in a single year. Panama required a century to be conquered. Can the Missouri be conquered in this century? Will Hoover be the Saint George to slay the Dragon Snakes, the Pythons Missouri and Mississippi? Who can answer? Sixty million people buy and sell in the Middle West. Though the Atlantic and Pacific seaboard cities enjoy advantages no inland centers can, no inland centers that are the hubs of a wheel turning round such an empire can be sufferers from a final setback. From what are these prosperous Atlantic and Pacific cities prospering? From what the Middle West buys and sells.

Other causes that came as hard back-kicks from the Great War are another example in the swing of the pendulum from low to high. Try to see clearly here. There is no use doing anything else. It is a lesson for all time. A great deal of the Middle West was settled by the thriftiest, hardest-working type of German settlers in the immigration movement from 1848 to 1870. In fact, during the Civil War, St. Louis was known as a “Dutch town.” They did not love their native land less because they came to America, but they loved the freedom of America more. I, who am of British and American ancestry, acknowledge that the aspersions cast on these people during the War were unjust. When War Bonds came to be sold, their thrift enabled them to be eager and ready cash buyers. War prices had bulged their bank accounts and the proof of their fealty to Uncle Sam was that they bought War Bonds eagerly. But War prices had also sent up new factories for hides, beef, hogs, flour, sugar; and when bonds had to be floated to expand these factories, further proof of the German-American’s loyalty was demanded—may I say forced?—to buy the bonds of these factories. One of these in the beef-packing industry went into bankruptcy, another went so close to the bankrupt dead-line that its stock fell to seven and six from a hundred and reduced one of the biggest packing fortunes in America to such a residuum that the public gasped.

With the added pressure of the banks, the Middle West thrifty German-American, to prove his loyalty, had bought these inflated factory securities. He had not bought as Americans buy—for a quick profit. He had bought to hold and lock up; and when the smash came, he was locked up all tight in bad losses, in many cases, in total losses. Now recall, too, that in the inflated period of the War, even the canny stolid German-American had also lost his head and over-expanded his holdings of live stock and farm lands. Against those the banks held his paper.

When the smash in prices came after the War, fell tragedy, dire tragedy—terrible tragedy, for those in debt, more terrible for older folk past fifty and sixty years of age. They could not live long enough to recover and swing back with the ascending pendulum of the eternal balances. Those not in debt were safe. Those in debt were caught between the blades of two scissors—debts to banks for live stock and investments, and loss on live stock hurried to market on a glut of lowered prices and sold under pressure to pay interest overdue and overdue instalments on investments. The banks, themselves, were on no easy street. They had underwritten those bonds. They had advanced money on notes to expand factory and farm. Lands that ought to have been left in pasture had been plowed up for wheat. Now wheat from dry farm areas west of the Rockies is one thing and wheat on the eastern foot-hills of the Rockies is quite another. Wheat on the dry-farm areas of the Inland Empire, the country between the Rocky Mountains and the Cascades Range, grows from the glacial silt of millions of years. Give it moisture in winter rains or snowfall, and it will hold that moisture for summer use, but the eastern foot-hills will not. They have a top humus of thin soil that grows bunch grass (buffalo grass) forever; but they haven’t a depth of soil to hold moisture. It runs off to bottom lands, which are rich as the richest; but to let shallow land revert back to pasture requires from ten to twenty years. The interval is an era of weeds high as barb-wire fences drifting in terrible tumbling waves of dry seeds spreading ruin. Then back gradually comes the grass and back comes the pasture and back comes the vast herd of cattle or sheep. Both Nebraska and Wyoming have hinterlands in the Northwest belt with thousands, yes, millions, of such acres.

Now ride round Omaha and you will read the whole story in a moving human picture film ticked off by life’s balance wheel. It is a speaking human picture, too; but it ends well; and all’s well that ends well, as Shakespeare says. You see the oozing prosperity of the banking and hotel section, but on the bridges near the packing plants, the prosperity doesn’t ooze quite so noisily as it did. Circle round the stock yards. Not gloomy, but still distinctly disturbing—stock yards being ripped up; miles of little houses for workmen, needing paint if not empty; miles of little shops looking lame and moribund if not dead. Something forced these occupants to move away. It was necessity. The Pacific Coast got many of them and gained as the Middle West lost.

But wait a minute! What is happening now? The live stock beginning to come back is rising in price weekly from ten to twenty-four cents a hundred. Those hinterlands are beginning to ship again from Nebraska and Wyoming. I think of one little German burg of perhaps two hundred people, where a gruff old burly fellow, part farmer, part banker, who is now yearly sending to market for himself and his neighbors, a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of furs and six times that value in cattle and sheep. “What do the farmers chiefly need?” I asked one taciturn old chap. “To be let alone—to cut out the middleman—cheap water rates if we can get ’em.” I have no comment to add to his answer. He hit what is called “a problem” on its head and he hit it with a mallet from annealed experience. Only you must not be surprised if some folks in the Middle West are a little sore on their banking experiences and some politicians perfectly conscientiously a little muddled on remedies.

From the present let us turn to the past long before Lewis and Clark’s day.

It will jolt Eastern feeling of aged experience a bit to realize that Nebraska and Wyoming are two of the oldest sections in the United States. As Alfred Sorenson says in his admirable narrative of Omaha: eighty years before the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, sixty years before Hudson came poking into New York harbor, three years before Shakespeare was born, when Queen Elizabeth of England was yet a toddling baby—Nebraska and Wyoming had been discovered by Coronado with his three hundred Spaniards and eight hundred Indians seeking the Seven Mythical Cities of Indian lore. Proof? Coronado’s own record and the fact that an antique Spanish stirrup of that date was dug up on the very streets of Omaha.

We may hate to shatter some illusions here but truth compels it. From paintings and drawings on this Spanish period, one’s mental picture is of soldiers clad in mail from helmet to leg greaves and metal boot, with a flag held high aloft and a holy padre with cross upraised in one hand. Far different was the real scene. The soldiers were for the most part ragamuffin convicts wearing little but canvas shirts belted at the waist, broad hats of Indian weave and such foot-gear as would protect from cactus spines. They were—as we know from priest annals—both lawless and evil in all their relations with the Indians; but they were armed, heavily armed with bayonets and pistols and swords. They raided Indian camps for food for themselves and forage for their poor scrubs of starveling horses. This probably explains the perpetual enmity between Spaniards and all Indian tribes. The Indians had at first regarded the Spanish as gods. Too often the gods acted like evil demons of untellable cruelty; and the young Spanish officers could not control their mutinous convict troops.

The Overland Trail is not only the longest in history, but it is one of the oldest.