* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Crusades (Volume 2) The Flame of Islam

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Harold Lamb (1892-1962)

Date first posted: Mar. 22, 2019

Date last updated: Mar. 22, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190348

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

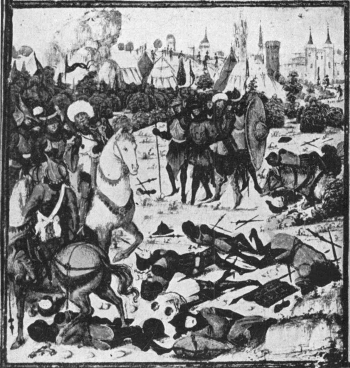

BLESSING THE SWORDS OF THE CRUSADERS

FROM THE PAINTING BY GEORGES CLAIRIN

THE CRUSADES

The Flame of Islam

SALADIN, THE VICTORY BRINGER;

BAIBARS, THE PANTHER; RICHARD THE LION HEART;

SAINT LOUIS; BARBAROSSA

BY HAROLD LAMB

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

GARDEN CITY PUBLISHING CO., INC.

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

printed at the Country Life Press, garden city, n. y., u. s. a.

COPYRIGHT, 1930, 1931

BY HAROLD LAMB

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

This book is complete in itself. It tells the story of the first Christian kingdom in the Moslem world, until its overthrow.

We are apt, all of us, to think of the crusades as a series of armies marching to war in the East. The reality is otherwise. Two separate movements made up the crusades. First the conquest, the invasion of the East by our forefathers who founded a kingdom there. With this movement the first volume, Iron Men and Saints, deals.

The second movement began with the rousing of the Moslem powers which brought about the hundred-year struggle for supremacy that spread from East to West. With this phase the present volume, The Flame of Islam, is concerned.

These two phases of the crusades are different in nature. The first was a mass movement, a march of inspired multitudes. The second was a world conflict in which individual leaders arose to take command on both sides.

And these leaders, from Saladin to De Molay, the last master of the Templars, are fully revealed to us by the chronicles and the letters of their day. They shaped, by their efforts and sacrifices, the beginnings of the modern world.

H. L.

| CONTENTS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Author’s Note | v | |

| PART I | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | The Frontier | 3 |

| II | The Land of the Arabs | 6 |

| III | Islam | 11 |

| IV | The Knights of the Prophet | 16 |

| V | The Assassins | 22 |

| VI | The Kalif’s Curtain | 26 |

| VII | Saladin | 31 |

| VIII | The Path of War | 39 |

| IX | Exiles | 46 |

| X | Saladin Pays a Visit | 53 |

| XI | A King is Crowned | 63 |

| XII | Hattin | 68 |

| XIII | Jerusalem | 74 |

| PART II | ||

| XIV | The Army of Islam | 85 |

| XV | The Gathering Storm | 93 |

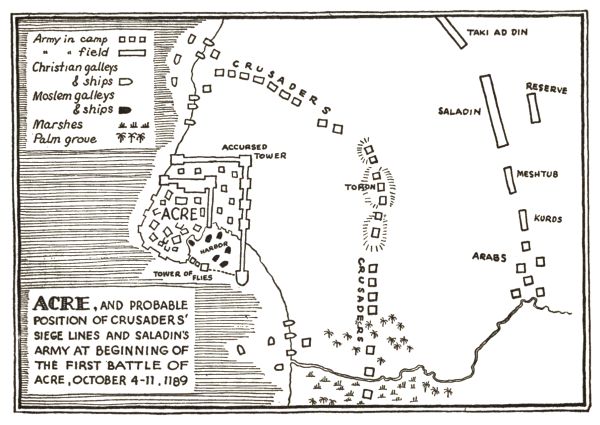

| XVI | Guy Marches to Acre | 98 |

| XVII | The Siege Begins | 104 |

| XVIII | Karakush Burns the Towers | 111 |

| XIX | The Full Tide | 121 |

| XX | Richard at the Wall | 131 |

| XXI | The Massacre | 140 |

| XXII | Richard Takes the Field | 149 |

| XXIII | The Barrier of the Hills | 158 |

| XXIV | The Caravan | 167 |

| XXV | Baha ad Din’s Tale | 173 |

| XXVI | Saladin Strikes | 178 |

| XXVII | Richard’s Farewell | 188 |

| XXVIII | Ambrose Visits the Sepulcher | 199 |

| XXIX | The Dream of the Hohenstaufen. An Interlude | 207 |

| PART III | ||

| XXX | Innocent Speaks | 217 |

| XXXI | The Conspirators | 226 |

| XXXII | The Doge Sails | 231 |

| XXXIII | What Ville-Hardouin Saw | 239 |

| XXXIV | At the Sea Wall | 246 |

| XXXV | Byzantium Falls | 257 |

| XXXVI | The Master of the World | 269 |

| XXXVII | Innocent’s Call to Arms | 276 |

| XXXVIII | The Road to Cairo | 283 |

| XXXIX | Mansura | 290 |

| PART IV | ||

| XL | The Child of Sicily | 299 |

| XLI | Frederick’s Voyage | 307 |

| XLII | Vae, Caesar! | 315 |

| XLIII | At the Table of the Hospital | 324 |

| XLIV | Beauséant Goes Forward | 331 |

| XLV | The Black Years | 336 |

| XLVI | The King’s Ship | 342 |

| XLVII | The Miracle | 347 |

| XLVIII | Shrove Tuesday’s Battle | 353 |

| XLIX | St. Louis at Bay | 363 |

| L | Joinville’s Tale | 370 |

| LI | Farewell to Palestine | 382 |

| PART V | ||

| LII | The Tide Ebbs | 391 |

| LIII | Hulagu and the Kalif | 398 |

| LIV | The Panther Leaps | 404 |

| LV | A Letter to Bohemund | 412 |

| LVI | Asia Sends Forth Its Horde | 421 |

| LVII | The Last Stand | 426 |

| Afterword | 437 | |

| Selected Bibliography | 471 | |

| Index | 479 | |

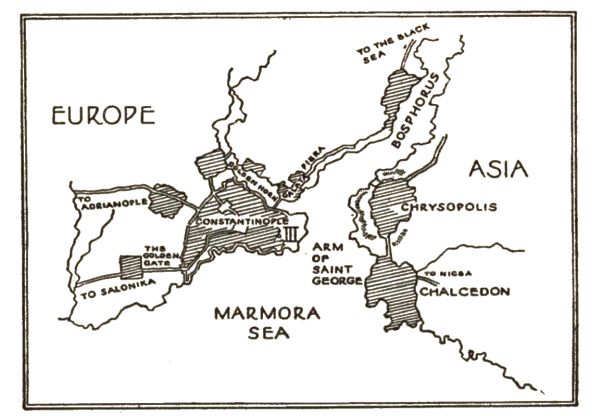

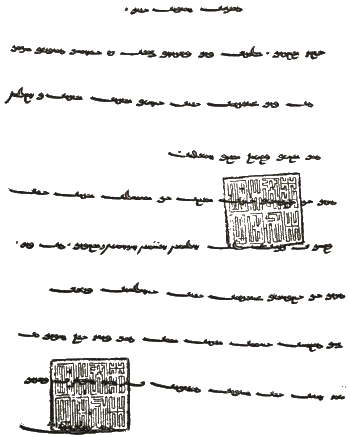

[Click on map to enlarge]

When the Sun shall be folded up, and when the stars shall fall.

And when the wild beasts shall be gathered together,

When souls shall be paired with their bodies . . .

And when the leaves of the Book shall be unrolled.

And when Hell shall be made to blaze, and when

Paradise shall be brought near—

Every soul shall know what it hath produced.

And by the Night when it cometh darkening on,

And by the Dawn when it brighteneth . . .

Whither then are ye going?

Verily this is no other than a warning to all creatures:

To him among you who willeth to walk in a straight path.

the koran.

HE year 1169 dawned upon a quiet East. Along this

frontier of Christianity nothing unusual was taking

place. Nothing ominous, that is. And in that part of

the East known as the Holy Land the crusaders went about

their affairs without misgivings.

HE year 1169 dawned upon a quiet East. Along this

frontier of Christianity nothing unusual was taking

place. Nothing ominous, that is. And in that part of

the East known as the Holy Land the crusaders went about

their affairs without misgivings.

There was, of course, no actual peace in the Holy Land—or in the rest of the world, at this time. And the harvest had been bad. During the last summer the rains had failed, and the wheat and barley crops in consequence had been poor. The cattle had suffered, and the fruit yielded little. At such times men often gave way to the temptation to harvest a neighbor’s crops across the border, sword in hand. Both Christians and Moslems were accustomed to such raids.

For seventy years the Holy Land, around the city of Jerusalem, had remained in the hands of the victorious crusaders. They had settled here, and here they meant to stay. They had built their little cathedrals on the sacred places where Israel had prayed before them; they had crowned the rocky summits of isolated hills with their castles, and they were the lords of the land. Their sons knew no other land than this, which they called Outremer—Beyond the Sea. And their grandsons were growing up here.

The Moslems accepted the presence of the conquerors as one of the inevitable things ordained by fate. They mourned the loss of Jerusalem, and they awaited the hour when the wheel of fortune would turn again and the holy city would be restored to Islam. Meanwhile, they were occupied with their own concerns beyond the border.

No boundary post marked the invisible line where Christianity ceased and Islam began. Only a watcher standing in the bell tower of the church of the Sepulcher could look toward the east, over the flat gray roofs of Jerusalem, over the parapet of the massive wall, past the haze of the Jordan gorge to the hard blue height of Moab’s hills.

Beyond that line, he would be told, lay the lands of the paynims, the men of Islam. If he rode down with the pilgrims through the waste lands of clay and rock, to gather reeds at the edge of the muddy Jordan, he would see a squat tower with a stone corral around it, for the horses, and perhaps some men-at-arms in the shade of the olive trees.

If he dared cross the ford by the tower and ride on toward the east, he might come upon the stained black shelters of a Bedawin tribe, with its sheep and dogs. Instead of a tavern or hospice, he would find only the rough stone wall and cactus hedge of a caravan serai, in which to spend the night. Nowhere would he find any visible sign of the borderline.

It was invisible. But it lay, enduring and forbidding, between the men themselves. It separated Nazarene from Moslem—knight of the cross from the warrior of Islam. To cross it in reality a Christian must become a renegade. He must renounce his own faith to enter the world of Muhammad, the prophet. And few were the renegades on either side.

At this time, late in the Twelfth Century, men lived by the faith within them. To the wearers of the cross, the cross was the visible sign of an everlasting truth. They were the children of God, striving to follow the Seigneur Christ. Upon no other path would they set their feet.

To the Moslems, they were merely the People of the Book. True, Muhammad had said that the Messiah Jesus was one of the prophets. But Allah was God indeed, and Muhammad had been his prophet. Upon the day when all souls would be weighed by the chains of judgment, they who believed would taste of Paradise, and they who believed not would know oblivion. No middle path existed—the Moslems were fiercely certain of that.

This gulf between Moslem and Christian could not be bridged by any bridge. They might live together in friendship, as many did live, but between them the breach stood as wide as ever. Muhammad had admonished his people never to make lasting peace with the unbelievers.

And the crusaders had taken Jerusalem. They meant to remain there, to tend the Garden of Gethsemane and to guard with their swords the Rock of Calvary over which they had built their churches. Jerusalem was the spot to be cherished above all others in the world.

But to the Moslems also Jerusalem was sacred. They called it Al Kuds, The Holy, and they held only Mecca and Medina in greater veneration. Muhammad’s home had been in Mecca, and once he had fled to Medina—they dated the years of Islam from that flight. From the rock in Jerusalem, they believed, he had ascended from the earth, upon the back of his steed Burak. Now the crusaders had built a marble altar over the rock, and had placed a cross upon the dome that sheltered it. . . . The Moslems waited for the turning of the leaves of the book of fate.

They were not aware, nor were the crusaders aware, that in this year 1169 events were shaping that would break the long deadlock between them. The change came imperceptibly, and it began out of sight of the frontier, within the depths of Islam.

HE world of Islam was restless as wind-swept sand.

It stretched, in fact, over all the deserts and barren

ranges between Jebal at Tarik—Gibraltar—and the

great heights of central Asia. Its people for the most part

were nomads moving with their animals wherever grass

grew. Such were the Bedawins, who clad themselves in the

camel’s hair and wool woven by their women. The children

watched their flocks and black goats, while the women did

all the work, even kneading rings of camel dung to dry for

fuel. The men did the ploughing, with a wooden spike hitched

by long ropes to a camel, followed by a harrow drawn by

mules. These were the farming implements of Solomon’s

day, and the Bedawin cared for no better, so long as Allah

sent rains from the sky. They knew every well of the waste

lands, and they plundered every stranger who came to the

wells.

HE world of Islam was restless as wind-swept sand.

It stretched, in fact, over all the deserts and barren

ranges between Jebal at Tarik—Gibraltar—and the

great heights of central Asia. Its people for the most part

were nomads moving with their animals wherever grass

grew. Such were the Bedawins, who clad themselves in the

camel’s hair and wool woven by their women. The children

watched their flocks and black goats, while the women did

all the work, even kneading rings of camel dung to dry for

fuel. The men did the ploughing, with a wooden spike hitched

by long ropes to a camel, followed by a harrow drawn by

mules. These were the farming implements of Solomon’s

day, and the Bedawin cared for no better, so long as Allah

sent rains from the sky. They knew every well of the waste

lands, and they plundered every stranger who came to the

wells.

To the common men of Islam, water was the veritable giver of life. Grass failed when the rains did not come. At such a time pools and cisterns became dry, or poisonous, and the herds were thinned. Pestilence followed a dry season. On the other hand abundant flowing water created a kind of earthly paradise—from the mass of date palms around an oasis, to a hill garden fed by an underground channel. The stone tanks of the great mosques served for washing and drinking alike, and it was a poor palace that did not have a fountain of some kind.

About the rivers such as the Nile and Tigris whole peoples clustered, thriving in the flood periods, and sickening when the waters sank low. To these folk of the desert, coming in from the glare and the driven dust of the dry lands, the sheltered shadow, the soft greenery and cool air of an oasis or river gave relaxation and new life. Muhammad had assured them that Paradise would be one immense garden, where water miraculously never failed.

During the five centuries of Islam, the Arabs had become the aristocracy of the Moslems—the chosen people, dominant over Bedawin and Berber, black Sudani and patient Tajik. Victorious from Spain to China, they had held the lands and trade of half Asia in their hands. And, like the Romans, they had the pride of conquerors. Being both curious and adaptive, they had learned much from the culture of elder Greece and Persia. And as Latin had become the language of scholars and kings in Europe, Arabic had become the speech of educated men in western Asia. The Koran—the Book To Be Read—could be copied into no other language.

But in five centuries the Arabs had changed from the fanatical tribesmen who rode from Mecca under Khalid and Muavia with no other possessions than their swords and the memory of the exhortation of a dead prophet. As the Romans had done before them, they settled down in the conquered lands, to dispute fiercely among themselves. Unlike Rome, Mecca changed little. It remained the sanctuary of Islam, sheltering the great black stone, the Kaaba, and the sacred well of Zem-zem—the goal of the devout, where prayer availed a hundredfold and even the barren stones were blessed. In worldly splendor, however, the great cities of Cordoba and Alexandria, Damascus and Baghdad outgrew the desert city of the Prophet’s birth. The Arabs had a taste for splendor.

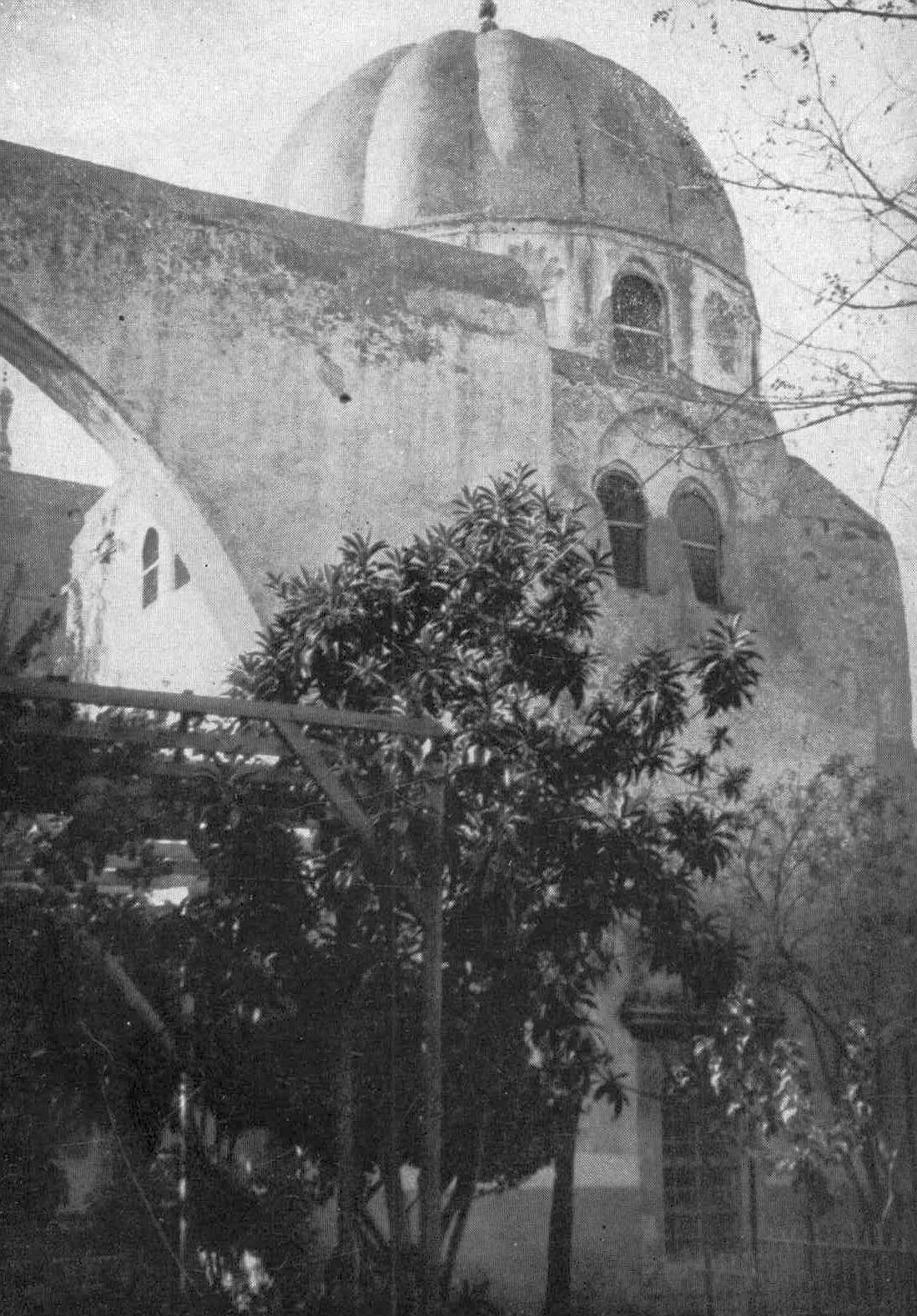

In Damascus the descendants of Omar built a mosque that was a veritable wonder. An Arab traveler has described it as it was at this time.

Nowhere else is such magnificence. Its outer walls are of squared stones, and crowning the walls are splendid battlements. The columns supporting the roof of the mosque consist of black polished pillars in a triple row. In the center of the building is a great dome. Round the court are lofty colonnades above which stand arched windows, and the whole area is paved with white marble. For twice the height of a man the inner walls of the mosque are faced with variegated marbles, and above this, even to the ceiling, are mosaics of various colors and gold, showing figures of trees and towns and beautiful inscriptions, all most exquisitely worked. The capitals of the columns are covered with gold, and the columns around the court are all of white marble, while the walls that enclose it are adorned in mosaics.

Both within the mihrab and around it are set cut-agates and turquoises of the size of the finest stones that are used in rings. On the summit of the dome of the mosque is an orange and above it a pomegranate, both in gold. Before each of the four gates is a place for ablution, of marble, wherein is running water and fountains which flow into great marble basins. . . . The Kalif al Walid spent thereon the revenues of Syria for seven years, as well as eighteen shiploads of gold and silver.

But within the mosque over a sealed entrance that had been the door of the great Roman basilica upon the foundations of which the mosque had been built, remained an inscription worn by time—“Thy Kingdom, O Christ, is an everlasting kingdom, and thy dominion endureth throughout all generations.”

Indeed wealth flowed through the hands of the Arabs. They had become heritors, by virtue of their swords, of the vast palaces of Yazdigird and Samarkand; the sweep of their conquest had brought to their feet all the riches stored in the jeweled basilicas of Byzantium and the immense treasuries of Egypt. Their kalifs—the successors to Muhammad—lived in a golden haze of luxury. Haroun ar Raschid was dead, but the new Commanders of the Faithful rode through courtyards as wide as open fields, attended by regiments of guards whose black-and-gold cloaks gleamed against the blue of the sky, and the plumed heads of the horses were like tawny wheat, tossing under the wind. And when the wind blew, the bronze lions roared by the gates.

Lovely Zenobia lay in her tomb, but the Bedawin spread their black tents within the white marble columns of her theater, in the shadow of the temple of Balkis where the palms nodded over the steaming sulphur springs.

Meanwhile wealth had changed the Arabs from single-minded warriors to shrewd merchants. Many a Sindbad sought his fortune in new lands. Caravans came down the slow, long road from Cathay, the laden camels bearing sacks of rhubarb, silk, or camphor and the musk of Tibet. Over the barrier ranges of India came spices, cinnamon, and precious stones. From the deserts of Arabia the caravans brought incense and dates. Where the trade routes crossed, as at Baghdad or Damascus, enormous markets exchanged the furs of the North for the precious stuffs of the East, and skilled workmen wrought fine fabrics—damask, brocades, or camelet.

In a single voyage a merchant made his fortune by bringing porcelain from China to Byzantium; there he took ship with a cargo of Greek brocade, for India. He sold this and bought Indian steel, conveying it overland by caravan to Aleppo, whence he took glassware to Yamen, going back to Persia with embroidered stuffs.

Their long open boats with towering lateen sails drifted down the wide rivers, and ventured overseas. The Arab masters knew the trade routes, and had, besides, serviceable maps and compasses at this time when European seamen felt their way along the northern coasts from headland to headland.

But in the last century a new power had entered Islam, displacing the Arabs to a great extent. From that immense reservoir of men beyond the heights of central Asia the pagan Turks appeared with their women and children and cattle. They had wolf heads on their standards, and a lust for war in their hearts. They were the brood of the steppes and the lofty snow-filled valleys, and their strength was the untiring strength of barbarians. Some of them, Hungarians and Kazars, turned toward Europe; others wandered down the rivers, dwelling for a time at Bokhara and Samarkand, then pressing on to warmer lands. These, the Seljuks and Turkomans of the White and Black Sheep, made themselves lords of the eastern frontier of Islam. Under Mahmoud of Ghazni they penetrated India, while other Seljuks drifted into the service of the kalif of Baghdad.

Whereupon the race of Haroun ruled no more, and the Seljuks rode on to the west, until they could look across the waters at the walls of Constantinople. They became devout Moslems, and this new wave of conquest touched Christianity so near that it helped launch the crusades to free Jerusalem from the yoke of Islam. Fortunately for the crusaders, the last great sultan of the Seljuks, Malik Shah, had perished before their coming, and Islam remained divided among a dozen princes. In such a chaos the authority of the kalifs went unheeded.

But the Turks had brought new blood into the thinning veins of Islam; they made up the bulk of its armies. While the Turkish sultans ruled, the Arabs remained the intellectual class, with the threads of affairs under their capable fingers. And for generations they had followed a new policy, of conversion instead of conquest. Their imams, leaders, and kadis, judges, penetrated the Far East to make converts.

For the present this had no perceptible effect in the nearer East, yet they had tapped the reservoir of the barbaric clans, and had set new forces in motion. They had extended the dominion of Islam over vast territories, and as far as the guard posts of China the muezzins called the multitudes to prayer.

HEN the muezzin called from his balcony, hundreds

of thousands hastened to cleanse themselves and

kneel toward Mecca. “Allah is Almighty—Allah is

Almighty . . . I witness that there is no other god but Allah—I

witness that Muhammad is his prophet . . . Come to

prayer—come to prayer . . . Come to the house of praise.

Allah is Almighty—Allah is Almighty . . . There is no god

but Allah!”

HEN the muezzin called from his balcony, hundreds

of thousands hastened to cleanse themselves and

kneel toward Mecca. “Allah is Almighty—Allah is

Almighty . . . I witness that there is no other god but Allah—I

witness that Muhammad is his prophet . . . Come to

prayer—come to prayer . . . Come to the house of praise.

Allah is Almighty—Allah is Almighty . . . There is no god

but Allah!”

Islam—submission—bound together the unruly multitudes which had become Muslimin—Moslems, as the Christians called them—those who had submitted. Islam fed their cravings, and ordered the hours of their day. It put the sword in their hands, and bade them use it against the unbelievers. It made of them a gigantic brotherhood, apart from the other men of the world.

They were all wanderers at heart—why not, when God’s earth was wide, with so much for their eyes to see within it? Islam enjoined upon them the duty of the pilgrimage, and of hospitality to other Moslems. The visitor within the bonds of Islam did not make a gift to his host; instead the master of the house rewarded the guest. All property belonged to Allah, and they were but the keepers of it.

Islam assured them that all happenings were written down in the book of fate, even the hours of their deaths. But fatalism brought its anodyne. If the props of a weak dwelling collapsed and the roof fell in, and perhaps someone was killed—who could avert his fate? The house was rebuilt no stronger than before. When pestilence visited them, and hundreds of bodies were carried out of a single city gate in a day, the survivors bore the dead upon their shoulders and sat down to await what fate would bring them. It was all written, and what was written would come to pass.

These men of the desert had a code as rigid as any Christian law. The Bedawin who would club a stranger to death on the road to take his horse would not lift hand against the man who had eaten of his salt. Tribesmen who would rather kill than loot and would much rather loot than eat would pass without a glance the goods of another clan left for safekeeping by the grave of a holy man.

Lying was an ancient art with them, but they would hold with few exceptions to a spoken promise. “What is profit without honor?” they said.

The brotherhood of Islam had a strange and restless freedom within it. Its rulers were all autocrats, as the patriarchs of the clans had been before them. The sultan or prince was answerable only to Allah for his deeds, but his servants would sit by his bed and worry him out of sleep if they disapproved of his conduct. His deeds must be weighed in the scales of the Koran, and if the balance were against him, a venerable kadi would appear to exhort him to better things.

A prince might seize the property of his followers, but if he did they could haunt his doorstep and beg for charity. All the goods and gear of the dead, indeed, went into his hands by right; yet woe to the lord who did not provide for widows and orphans. Like the baron of feudal Europe, he bestowed grants of land and dwellings on his vassals who must come at his summons—after their fields were planted—to serve in his wars. In their turn, they must make annual gifts of money, horses, weapons, or slaves to the prince. The spoil taken in war was divided between the prince and his vassals.

Besides this levy of the vassals, the greater princes of Islam had what may be called standing armies. Masterless warriors enlisted in his pay, and ate of his salt. Sometimes he bought outright slaves trained to arms who were known as mamluks—“the possessed.” These mamluks were of Turkish origin, and since they were both loyal and formidable in arms, they became the flower of the armies. Usually they composed the bodyguards of the princes, and their sons succeeded to their position and pay. Like the Cossacks of a later day, they could turn their hands to other work, training horses, building bridges, or caring for falcons or messenger pigeons. They followed the hunt as eagerly as their masters.

Already most of the reigning princes of this portion of Asia between the sands of the Sahara and the hill barriers of Persia were atabegs, Father Commanders—Turkish captains of war who had first served and then displaced the powerful Arab families. Mahmoud of Ghazni had been born a slave.

Moslem slaves had little to regret. They could, of course, be sold in the open market, and their lives rested upon the pleasure of their masters. But the position of slaves was an honorable one in this brotherhood of Islam, since the master had the obligation to protect and care for his servitors, and many a lord was ruled in reality by his domineering slaves, especially if they were mamluks. Women and infidel slaves were entitled to no more care than the beasts.

All this motley world of Islam came together in fellowship upon the Hadj, the Pilgrim Road. Gaunt Turkomans in sheepskins from the north sheathed their yataghans and trotted quietly beside their feudal foemen the Kurds of the hills. Black slaves from Egypt clad in flaming crimson guarded the tall, swaying dromedaries that bore within screened hampers the women of some amir or prince.

Learned kadis, sitting sidewise on donkeys under the parasols held by their disciples, discoursed of the merits of the road of salvation, and barefoot pilgrims thronged around to listen. Somber warriors, shields swinging upon their shoulders, stared through the dust at a passing cavalcade of merchants in striped khalats with heavy purses swaying at their girdles—and forbore to plunder. Fly-infested beggars thrust out their bowls unreproved.

Veiled women, as sturdy as the warriors, with all the pride of poverty and suffering, tugged at the halter ropes of mules upon which old grandsires clung, on their last journey to the city of salvation. They all gathered together in the serais at night to share fire and food and to watch the antics of the dervishes who circled slowly and chanted to the thrumming of the drums. Holy men with shaven skulls sat patiently in the dirt and dung by the beasts, waiting to accept the leavings of the food. They were all sons of the road, and it was good to be upon the road of salvation.

They could not go to Jerusalem, where the crusaders barred the way, but they knew every tradition of that holy city—how lost souls wailed of nights in the Valley of the Damned under the Golden Gate. How the white marble height of the Noble Sanctuary[1] awaited the final day of judgment, when the souls of the faithful would gather in the Cavern of Souls under the rock of Muhammad’s ascension, and Solomon himself would sit in judgment before the chains, with David and the Messiah Jesus at his side. They even knew just where the chains hung, from the great arches. They had built, before the coming of the infidels, a dome over the sitting place of Solomon, in readiness for this ultimate event.

They cherished old customs, but their restless minds led them off after new soothsayers and would-be prophets, for they were as changeable as children. Credulous and impulsive, they could be fired by an idea. A strong man could lead them easily, but only a saint of Islam could restrain them or hold them together for any time.

Ceaselessly they disputed among themselves about the details of their faith, yet they were more than ready to tear the limbs from a mocker of their faith. The only thing capable of welding them together was war—the holy war against unbelievers. Muhammad had exhorted them never to fail in the holy war, the jihad. At such a time all Islam would unite, burning with the fever of martyrdom, and who could stand against Islam?

But, until now, they had found no one to lead a jihad against the crusaders. For a time they had rallied to Zangi, the atabeg of Mosul who captured Edessa from the Christians and so brought down upon them the second of the crusades. In their anger they had mobbed the pulpit of Baghdad where the kalif behind his black veil remained impotent against the crusaders. Yet the leader had not come forth.

Now, in the year 1169, Nur ad Din, the great sultan of Damascus, preached the jihad. Nur ad Din, however, was old—a man of sanctity incapable of forcing the issue against the Christian knights. Another leader must be found.

[1] The Haram, the quarter sacred to the Moslems in Jerusalem, lies above the site of Solomon’s temple. The rock from which they believed Muhammad ascended is thought to have been the altar of burnt offerings of the Israelites. In the vaulted chambers under the El Aksa mosque at the end of the Haram, remnants of Herod’s temple are still to be seen. Even to-day under British control, Christian visitors are admitted to the Haram only upon sufferance. During the Arab-Jewish troubles in August and September 1929, the Golden Gate and the underground chambers as well as the Cavern of Souls were closed to visitors. The present writer was allowed to inspect them by permission of the mufti of Jerusalem.

S in Christendom, the youth of Islam went to a hard

school. Boys grew up under rigid authority, taught

by khojas and hadjis, sitting in the wide courtyards

of the mosques. For the aristocracy of Islam was one of

learning as well as the sword, and the Arab and Turkish

youngsters swayed in unison as they memorized the sonorous

verses of the Koran, even if they did not master reading.

S in Christendom, the youth of Islam went to a hard

school. Boys grew up under rigid authority, taught

by khojas and hadjis, sitting in the wide courtyards

of the mosques. For the aristocracy of Islam was one of

learning as well as the sword, and the Arab and Turkish

youngsters swayed in unison as they memorized the sonorous

verses of the Koran, even if they did not master reading.

Old mamluks taught them the use of the bow, handled from the saddle, not from the ground. They practised in the riding fields with slender bamboo lances, and became adept at sword play—the swift strokes of the pliant curved blades. They raced their ponies and longed for the battle-wise thoroughbreds of the stern lords their fathers. The richest of them found diversion in the favorite game of mall, in which the riders drove a ball about the field with mallets—the game that is polo to-day.

Wine was forbidden them, and dalliance with women denied them until full manhood. Their teachers frowned upon gaming, and even chess was a sport reserved for the elder men. True, they could watch the exciting magic lantern that cast its shadow figures upon the wall, or a rare puppet show in which the ageless Punch cracked obscene jokes and beat his wife. Yet laughter touched them seldom and most of them grew up somber, intent on the affairs of men.

They shared, of course, in the hunting that was half the life of the Moslem nobles—hunting with falcon, panther, bow, or spear. One of them, Ousama, a son of the lord of Shaizar, has left us a tale of his hunting in the beginning of the Twelfth Century.

In the house of my father, by Allah, we had about twenty captive gazelles, with brown coats and white coats. Also young gazelles, born in his house, and stallions and goats. He would send his men to far-off lands to buy falcons, even to Constantinople.

I have taken part in the hunting of great lords, but I have never seen hunts like those of my father—may Allah have mercy upon him. He spent all his time during the day in reciting the Koran, in fasting and in hunting; during the night he copied down the Book of Allah the Most High. He made two copies written from one end to the other in gold.

Now we had at Shaizar two places good for the chase—one on the mountain where partridges and hares were plentiful, the other by the banks of the river where waterfowl, grouse, and antelope were to be met.

Falcons became as common as chickens with us, and the servants of my father—may Allah have mercy on him—were mostly falconers and saker keepers and men who looked after the dogs. He taught his company of mamluks the art of caring for falcons.

As for him, he went out to hunt accompanied by his four sons, and we ourselves brought along our esquires, our led horses and weapons—because we were not safe from encounters with the Franks,[2] our neighbors. We brought more than a dozen falcons with us each time, and pairs of men to look after the sakers, the hunting leopards and the dogs. One man went with the greyhounds, the other with the brach-hounds.

On the way to the mountain, my father would say to us, “Scatter. Whoever has not yet finished his reading of the Koran, let him fulfil his duty.” Then we, his sons, who knew the Koran by heart, would separate one from another and would recite until we reached the meeting place.

Then my father gave his orders to the squires who went off to look for partridges. Still there remained with my father, between his companions and the mamluks, forty horsemen, experienced hunters. As soon as a bird took flight, or a hare or antelope stirred up the dust, we were off after them, ready to loose the falcons at them. So we arrived at the top of the mountain. The ride lasted until the afternoon. Then we went back, after feeding the falcons and let them down at the mountain springs where they drank and bathed themselves.

Whenever we mounted our horses toward the place of waterfowl and grouse, it was an amusing day. We left the hunting leopards and sakers outside the reed beds, and only took the falcons with us into the marshy ground. If a grouse flew, a falcon was after it. If a hare jumped up we cast a falcon at it, which took it or drove it toward the leopards. Then the keeper loosed a leopard at it. If a gazelle jumped out toward the leopards, they were sent after it. Often they captured it.

In these swampy reed beds, there were numbers of wild boars. We rode at a gallop to fight and kill them, and then our joy was intense.

One of the falcons, although still quite young, was large as an eagle. The head falconer Gana’im used to say, “This one called al Yashur has not its equal among the falcons. It will not leave any game without taking it.” At first we doubted him.

Gana’im trained al Yashur. It became like one of our household. In the hawking, it served its master, unlike other birds of prey that pursue the quarry for themselves. Al Yashur lived beside my father, and was well able to look after itself. If it wished to bathe, it moved its beak in the water to show what it desired. Then my father ordered a tub of water to be placed near it. When it came out, my father put it on a wooden gauntlet made especially for it, and set the gauntlet by a lighted brazier. Then the falcon was combed and rubbed with oil, and they rolled up a fur cloak for it, on which it settled down and slept. If my father wanted to go off to the women’s chambers, he would say, “Bring the falcon,” and it would be brought asleep as it was, and the cloak placed beside the bed of my father—may Allah have mercy on him.

In the winter, the waters flooded the ground near Shaizar, and waterfowl gathered in the pools. My father himself would take al Yashur on his wrist and go up to the citadel to show it the birds. The citadel lay to the east, while the birds were to the west of the town. As soon as the falcon had seen the birds, my father let it go, and it flew over the town until it reached the quarry and seized its booty.

When the pursuit was lucky, the falcon came down again near us. If not, it took shelter in one of the caves along the river—we did not know where. The next morning the falconer would go to look for it, and would bring it back.

Mahmoud, lord of Hamah at that time, would send over every year to ask for the falcon, which was sent to him with a keeper, and was used in his hunting for twenty days.

But al Yashur died at Shaizar.

One morning I went to visit Mahmoud at Hamah. While I was there, the readers of the Koran came into view, with mourners crying, “Great is the Lord!” I asked who was dead, and they replied, “One of Mahmoud’s daughters.” I wanted to go with them to the funeral, but Mahmoud forbade me.

They all went out and buried the body, and when they came back Mahmoud asked me, “Knowest thou who the dead person was?” I made answer, “It was told me—one of thy children.” He answered, “Nay, by Allah, it was the falcon al Yashur. When I heard that it was dead, I sent for it and ordered a shroud and a funeral, and buried it. Indeed, it was worth all of that.”

One hunting leopard also lived in our house, in a shed built for it with hay in it. A hole was made in the wall by which the leopard could go in and out. This unusual animal had a servant to care for it.

Among the guests of our house at that time was the old and wise Abou Abdallah of Toledo. He had been director of the House of Science in Tripoli. When the Franks captured this town, my father took the shaikh Abou Abdallah for himself. I studied grammar under him for ten years.

One day I found him with the following texts in front of him—the Book of Sibawaihi, the Particulars of ibn Jinni, the Elucidation of al Farisi, and also the Examples and the Flowers of Speech. I said to him, “O shaikh hast thou read all of these books?” He answered, “Indeed I have read them, or rather, by Allah, I have copied them out. Dost thou wish to be convinced? Choose any text, open it and read to me the first line of the leaf.”

I took up one of them; I opened it and read a line. He resumed reading from memory until he had finished the part. That was a remarkable phenomenon. At another time I saw Abou Abdallah. He had been hunting with this hunting leopard. He was mounted on a horse, with his feet wrapped in bloodstained bandages. While he had been following the leopard, thorns on the ground had torn his feet. Yet he did not feel the hurt at the time because he had been absorbed in watching the leopard seize the gazelles![3]

Men of letters like Abou Abdallah were welcome guests in the houses of the nobles. “The ink of the learned”—so a proverb ran—“is as precious as the blood of the martyrs.”

And beside them sat the scientists, astronomers, physicians, and engineers. Because the astronomers interpreted omens and calculated fortunate days, they were important personages and usually received large salaries from the princes.

On the flat roofs of the palaces they had their spheres of bronze, their zodiacs and horizons, carefully made. Already they had set down in tables the orbits of the planets, and had calculated the vagaries of the moon’s motion—six centuries before Europeans did so. They had even worked out an exact calendar, but the expounders of the Law would have nothing that altered Muhammad’s choice of the months of the moon. They had translated the books of the Greeks, and compared them with the Ptolemaic and Hindu theories, and had learned much.

The Arabs had been wise enough to study the Roman ruins that they found scattered through their conquests. Dikes and aqueducts and hydraulic works seemed good to these avid intellects of the dry lands, and they copied them while Europeans made quarries out of them.

Someone translated Aristotle, and he became for better or worse the ideal of Moslem philosophers. Natural law and the dicta of logic he made clear to them.

Their mathematicians—who were at home with algebra and the decimal system—worked out latitude and longitude. And, having noted down the tidings brought by travelers and seamen, made excellent maps. A certain Idrisi completed a silver chart of the Mediterranean etched on a silver shield.

Cairo, as well as Baghdad, had its House of Science, with an observatory and a library. A cool and quiet place the library, with its manuscripts arranged in cubicles up the walls, and its cushioned rugs where men of letters could sit, reading the volumes on the stands in front of their knees and sipping sherbet. In the cubicles lay Greek texts of Archimedes and Galen.

Paper had been known to the Arabs for some time—paper made of cotton, at first in Samarkand, then in Damascus. The secret of making it had come from China over the caravan road with many other things.

The Arab physicians had secrets of their own. They knew of more than simple remedies, having studied a bit of chemistry and the course of the blood. Most ills they treated by diet and hygiene, while the Christians of Europe still searched for malignant demons.

And a few years before, Nur ad Din, the enlightened sultan of Damascus, had built a public hospital where physicians made examinations and gave out drugs. Only in surgery were the men of medicine deficient—because the expounders of the Law forbade them to cut or alter human bodies.

The keen minds of the Arab scientists probed into the causes of things. They followed Aristotle into the mysteries of Nature, and pondered. And out of their pondering grew disbelief in religion. About the philosophers gathered groups of doubters, invoking the mantle of Pythagoras. Mysticism went hand in hand with scepticism.

A century before, the wine-loving court mathematician of the last great Seljuk sultan had written:

Myself when young did eagerly frequent

Doctor and Saint, and heard great argument

About it and about; but evermore

Came out by the same door where in I went.

[2] The crusaders. Ousama lived in the foothills near Hamah, and to the west of his castle stretched the mountains. Two of the crusaders citadels, the great Krak des Chevaliers and Marghab, lay across this borderline, within raiding distance of Hamah.

[3] From the memoirs of Ousama, translated from the Arabic by M. Hartwig Derenbourg—“Souvenirs historiques et récits de chasse par un émir syrien du douzième siècle.”

N echo of Omar’s plaint was heard within Cairo,

where the free-thinkers gathered together. Cairo

itself lay beyond the authority of the orthodox kalif

of Baghdad and the idlers in its courtyards dared mock at

Islam while they nourished secrets of their own. They were

known as Ismailites, and they built a lodge of their own,

sending out into the East their missionaries of unbelief.

And thereby hangs a tale so strange that, although the truth

of it was established long ago, it has the seeming of a myth.

The tale is of the Old Man of the Mountain, as the crusaders

called him.

N echo of Omar’s plaint was heard within Cairo,

where the free-thinkers gathered together. Cairo

itself lay beyond the authority of the orthodox kalif

of Baghdad and the idlers in its courtyards dared mock at

Islam while they nourished secrets of their own. They were

known as Ismailites, and they built a lodge of their own,

sending out into the East their missionaries of unbelief.

And thereby hangs a tale so strange that, although the truth

of it was established long ago, it has the seeming of a myth.

The tale is of the Old Man of the Mountain, as the crusaders

called him.

During the lifetime of Omar lived one Hassan ibn Sabah, a free-thinker, an Ismailite, and a man of consummate ambition. This extraordinary soul was not content to be a missionary of scepticism; he dreamed of a new power. He said that with a half-dozen faithful servants he could make himself master of the world.

It is related that after he said this, one of his friends fed him meals of saffron and a certain wine—supposed to be remedies for madness. Later, Hassan sent a message to this friend: “Which of us is mad now?”

Because, in a way, he made good his prophecy. At least he became the Old Man of the Mountain.

In the beginning, undoubtedly, Hassan possessed great personal magnetism. The half-dozen allies that he desired he acquired readily enough by his boldness. He preached a very simple creed, “Nothing is true, and all is permitted.” And he gained attention by ridiculing some of the rather absurd traditions of orthodox Islam.

He formed his followers into a secret order, divided into preachers, companions, and fedawi—devoted ones. These became the real key of his success. They were the Assassins. Garbed in white, with blood-red girdle and slippers, each of them carried a pair of long curved knives. They were young, and Hassan initiated them into the secrets of hemp eating and the virtue of opium mixed with wine until they became in reality the blind instruments of his will. He convinced them that death was verily the door to an everlasting delight, of which the drug dreams gave them only a foretaste.

To these youths Hassan appeared to be a prophet more potent than any figure of Islam; to discontented souls he presented himself as a liberator; only to the few subtle minds of his order did the master reveal his real purpose—to win power by instilling fear, and wealth by upsetting the existing order of things.

“Bury everything sacred,” he explained, “under the ruins of thrones and altars.”

And he began a schedule of assassination, to create fear. Usually three fedawis would be sent to kill the appointed victim, often at the hour of public prayer in a mosque. The first Assassin would leap at the condemned man and stab him; if he failed, the second and third would make their attempt in the ensuing confusion. Since they themselves rather sought than avoided death, they rarely failed in their mission. At other times they would disguise themselves as servants, or camelmen—water carriers, anything. In the crowded streets of Muhammadan cities such folk throng past their betters.

His first victim was the wisest soul in Islam, Omar’s patron and his own benefactor, Nizam al Mulk, the minister of the great Seljuks. Nizam’s death hastened the break-up of the Seljuk empire—and Hassan profited from the chaos. He dared assassinate Maudud, the ghazi of the North.

Shrewdly, he profited more from the fear caused by his daggers than from the killings. Who cared to refuse him an annual tribute to escape the daggers? Hassan was punctilious about his word. If he promised a victim immunity, the man went unharmed.

Naturally, many amirs and sultans made open war on him. In whole districts the mulahid, heretics—as his followers were called—were searched out and slain. But Hassan himself proved elusive. And other lords, who were afraid of the daggers, protected him. One influential teacher preached against him, cursing him publicly, and before long an Assassin knelt upon the chest of the too-daring preacher, in the seclusion of his study. A long knife pricked the soft skin of his stomach. After the fedawi had vanished, the preacher no longer cursed the heretics, and his disciples asked him why.

“They have arguments,” said the great man, who was not without humor, “that cannot be refuted.”

And then, again, an enemy of the order would awake to find two daggers thrust into the carpet beside his head. The resulting dread of overhanging peril would sap the courage of a man who did not fear the open shock of battle. No one was immune. A kalif of Cairo fell under the daggers.

But Hassan’s greatest conception was his castles. Usually a Moslem lord had his citadel on some height within a town. The grand master of the new order of death sought out sites upon the mountains overlooking a city. Existing castles he bought or intrigued for, and in the wild mountain districts he built strongholds of his own. These were of stone, and almost impregnable—so that a few men could hold them. So Hassan came to be called the Shaikh al jebal—the Old Man of the Mountain. And no old man of the sea was ever such a burden as he. To his strongholds flocked all unruly spirits, and he made a place for all. Few cities in the hill regions of Persia and Syria did not have a castle of the Assassins to reckon with.

At the end of his life Hassan had managed to lay the foundation for his strange new imperium. He ruled an empire of his own, from Samarkand to Cairo—wherever stood the mountains. His plan after all was simple: he had laid the governing powers under contribution, and enlisted the revolutionary powers of the people. Having established a perpetual reign of terror and profited much from it, he died and another grand master headed the order.

And at this time, paradise was built. Tales of it filled all nearer Asia, and generations passed before the outer world knew the secret of it.

Alamut—the Eagle’s Nest—was the headquarters of the order. Here, on the summit of an unclimbable mountain, a walled garden had been built—a garden filled with exotic trees, with marble fountains that tossed wine spray into the sunlight, with silk-carpeted pavilions and tiled kiosks. The melody of invisible musicians hung upon the air, and all men who entered were wrapped in the dreams of opium, or yielded the bodies of beautiful girls.

And only the young Assassins could enter this paradise. First, they were given a drug and carried in a coma to the garden, where they awakened to every delight of the senses. Then, after two or three days they were drugged again and carried out into the castle of Alamut, where they were told that, in reality, they had been allowed to visit the unearthly paradise—the place that awaited them at death. No island of lotus eaters quite compared to the garden of the Eagle’s Nest. Above the entrance gate was written:

AIDED BY GOD

THE MASTER OF THE WORLD

BREAKS THE CHAINS OF THE LAW.

SALUTE TO HIS NAME!

Just how the Assassins managed to appear to be all things to all men is one of the mysteries of elder Asia, wherein the straight path often went roundabout, and prophets spoke in parables, and sanctuaries were veiled, and men were led by ideas instead of rules.

HE Assassins were in fact very much like vultures,

perched in their rocky eyries, watching the movements

of human beings in the crowded valleys below.

No one knew in what place the shadow of the vultures’ wings

would fall—although they were most often seen in the

mountain region of Persia far to the east, and in the hills

north of Lebanon that divided the crusaders and the Moslems.

During the chaotic conditions of the last hundred

years they had risen to the height of their power. They were,

however, by no means supreme.

HE Assassins were in fact very much like vultures,

perched in their rocky eyries, watching the movements

of human beings in the crowded valleys below.

No one knew in what place the shadow of the vultures’ wings

would fall—although they were most often seen in the

mountain region of Persia far to the east, and in the hills

north of Lebanon that divided the crusaders and the Moslems.

During the chaotic conditions of the last hundred

years they had risen to the height of their power. They were,

however, by no means supreme.

For one thing the kalifs still reigned in Baghdad—no more than specters of the early kalifs, but still with the black veil and the mantle of the prophet upon them. North of Baghdad, up the ancient Tigris and Euphrates, extended a network of little dominions ruled by the atabegs—the war lords whose chief citadels lay in the gray rock of Aleppo above the red wheat fields, and in mighty Edessa with its ruined churches standing desolate. Still farther north the warlike Armenians clung to their mountain villages in the barrier range of the Taurus.

Beyond them lay Asia Minor, its lofty plateau a grazing ground for the sultan of Roum, Kilidj Arslan by name. He was almost the only surviving prince of the Seljuk line, and he was gradually pushing the Byzantines back, within the shelter of the walls of Constantinople.

And one man was patiently tracing a pattern of order through this kaleidoscope of the Near East. Nur ad Din, the son of Zangi, had made himself supreme over the minor chieftains and he ruled over the beginning of an empire, from Edessa in the north to the Arabian desert in the south. Light of the Faith, they called him—a just man, rigorous and devout, but too old to follow the path of war in the saddle. He had lieutenants more than willing to do this for him, Shirkuh the Mountain Lion, and Ayoub his brother—Kurds who made a hobby of statesmanship and a pastime of war.

Nur ad Din reigned in Damascus, the Bride of the Earth, and he was loath to leave its fruit gardens where lines of willows and poplars kept out the desert dust, and swift waters murmured under old bridges. He prayed in the great mosque, with white turbaned hadjis sitting by the opened windows of colored glass, ceaselessly intoning the verses of the Book To Be Read. Beside the mosque clustered the tombs of Islam’s elder champions, in the rose gardens under the dark mulberry trees. Through the four gates pattered the bare feet of children hastening to a teacher’s desk, and the limping feet of the sick, and the firm feet of the lords.

He had brought peace to Damascus. Under the latticed arcades of the alleys gray heads bent over chessboards of inlaid ebony and ivory while bearded lips muttered the gossip of the roads; at night upon the terraces stately figures scented with civet knelt about the banquet cloth, sipping sherbet while the pungent smoke of burning ambergris drifted up, and lutes wailed. Against the marble fretwork of balconies overhead, fair faces pressed and dark eyes searched the shadows of the narrow streets, watching the torches of an amir’s cavalcade go by, or the plodding lantern of a drowsy donkey.

It was due to Nur ad Din, the son of the atabeg, that comparative quiet prevailed in the Near East in this year 1169, because, while he held the unruly north in rein, he had made a truce with the crusaders.

These indomitable fighters lay within Islam but not of it—separated by the long natural barrier of Lebanon, beside which the Jordan descended into the Dead Sea.

There was, however, a third power to be reckoned with, in Cairo.

El Kahira, men called her, the Guarded. Others knew her as the City of the Tents. She was mistress of the Nile, luxuriant and fecund and ageless. Toward her gates rode the merchants of all Asia, and from her port of Alexandria went forth the ships of all the seas. Within her coffers lay wealth incalculable.

But she was harassed and bereft. Too much blood had been shed in the halls of her palaces by the great Gray Mosque; the tombs of her mighty ones had fallen into neglect, and down by the river the tents of the Bedawin stood among smoke-darkened ruins. “The mark of the Beast,” devout Moslems said, “is upon her.” For the kalif of Cairo was apart from orthodox Islam, a schismatic, his adherents devotees of Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad. He wore white instead of traditional black and his unruly congregation believed passionately in the coming of El Mahdi, the Guided One, who would be a second Muhammad.

This Fatimid kalif lived in guarded seclusion. Sudani swordsmen filled the corridors of the Great Palace, and paced the mosaic floors of the antechambers, by the marble fountains where peacocks strutted and parrots screamed. The audience hall glistened like a gigantic treasure vault with its ceiling of carved wood inlaid with gold, and its inanimate birds fashioned of silver and enamel feathers and ruby eyes. But the kalif was hidden from the eyes of the curious by a double curtain of gilt leather. Men said that he ate from gold dishes and drank from amber cups—he and the bevy of his women. When he went from the city a pavilion wrought of gold and silver thread accompanied him; when he wished to enjoy the cooler air upon the river, a silver barge awaited him.

Rumor said more than this. Within the foundation of the palace, fair girls had been walled in, alive, as a sacrifice. A gilt cage was kept in readiness to receive the kalif of Baghdad as a captive, if the arms of Cairo should ever prevail over the host of orthodox Islam. And up the river—so rumor insisted—there was a hidden pleasure kiosk built in the semblance of the sacred Kaaba of Mecca, and a marble pool filled with wine, to mock the holy well of Zem-zem. Darker whispers could be heard in the seclusion of the harim—of a kalif who had poisoned his son, and a wazir who had been cut to pieces by the palace women.

The kalif ruled Egypt only in name, the real power in the hand of his wazir, or minister. The kalif had become a figurehead, the wazir a dictator. Between them they had bought off the enemies of Egypt for years, while the kalif amassed new treasures. They had managed to play the invincible Christian knights against the victorious armies of Nur ad Din. Once they had paid the crusaders to beat off an attack by Shirkuh, and then they had summoned Shirkuh to defend the city against a foray of the king of Jerusalem.

A dangerous game, this of buying protection. The knights of Jerusalem and the mamluks of Damascus had both tasted the honey pots of the Great Palace, and had seen with their own eyes the weakness of the men of Cairo. This taste only whetted their appetite for more.

Amalric, king of Jerusalem, was a fighter and an aggressive fighter. Clearly he saw that the capture of Cairo and the line of the Nile would bring final triumph to the crusaders, and would break the deadlock between Jerusalem and Damascus. The possession of the kalif’s treasures alone might do that, but if the crusaders could hold Cairo and the narrow isthmus of Suez (where the canal now lies) they would separate the Moslem of the Near East from those on the African coast.

And Shirkuh saw the situation just as clearly. He pointed out to Nur ad Din that the crusader castles below the Dead Sea made a salient that almost cut off Damascus from Cairo. Moslem caravans had to feel their way through the desert, to steal past the watchful eyes of the Christians. With Cairo in his hands, Nur ad Din could pinch out this salient, and then attack Jerusalem from two sides.

Amalric started the race for Cairo as the year 1168 ended. Having the shorter distance to go, he was first upon the scene. But the fiery general of Nur ad Din was close on his heels with a greater host, and Amalric, having failed to surprise Cairo, was forced to withdraw as quickly as he had come, to his own lands. Thence he journeyed to Constantinople to beseech aid from the Byzantine emperor.

Not so did Shirkuh. He saw his chance and took it. Riding triumphantly into the gates of Cairo, he boldly claimed the reward of a rescuer and the kalif received him with outward rejoicing and inward misgiving. At once the Mountain Lion pounced upon the hapless wazir who had played the double game of intrigue for so long, and the kalif agreed that it was full time the wazir died. Whereupon Shirkuh was invested in a robe of honor and duly declared wazir of Egypt.

It became apparent that Shirkuh meant to be dictator in fact as well as in name. The swaggering Kurd overrode the Fatimid officials and collected his own taxes, to the mingled fear and admiration of the watching Cairenes. The kalif stayed behind his curtain. Whether he was served by convenient poison or not, Shirkuh died almost in the moment of his triumph.

His death left Nur ad Din’s army without a head, and the kalif without anything to protect him from the army. The situation was precarious and the amirs of the army agreed with the kalif that a new wazir should be chosen at once. They debated among themselves and named Shirkuh’s nephew—to win the loyalty of Shirkuh’s mamluks—a young officer who was a general favorite. And the kalif agreed at once, seeing in the officer a man too young to be experienced—an easier soul to deal with than Shirkuh.

So the kalif sent a new robe of honor out to the camp, with an escort of kadis to salute the hitherto obscure officer and to bestow upon him his name title—El Malik en Nasr, the Conquering King.

The officer was Saladin.

HIRKUH’S nephew thus became administrator of Egypt

at a time when the kaleidoscope of the Near East was

shifting in even more than its wonted fashion. He

discovered himself to be at once the wazir of a schismatic

kalif and the general of the orthodox army of Damascus; he

must be pacifier of an unruly country, and defender extraordinary

against that veteran warrior, Amalric of Jerusalem.

Some of the older amirs, jealous because a little-known

youth had been placed over them, left the army and went

back to Damascus with their men. Others remained expecting

that Nur ad Din would appoint someone else in his place.

It would be hard to conceive of a more trying situation.

HIRKUH’S nephew thus became administrator of Egypt

at a time when the kaleidoscope of the Near East was

shifting in even more than its wonted fashion. He

discovered himself to be at once the wazir of a schismatic

kalif and the general of the orthodox army of Damascus; he

must be pacifier of an unruly country, and defender extraordinary

against that veteran warrior, Amalric of Jerusalem.

Some of the older amirs, jealous because a little-known

youth had been placed over them, left the army and went

back to Damascus with their men. Others remained expecting

that Nur ad Din would appoint someone else in his place.

It would be hard to conceive of a more trying situation.

Yet Saladin[4] emerged from it undisturbed. And in the end he made a name for himself greater than that of the two giants of his day, Frederick Barbarossa and Richard the Lion Heart.

Even in the beginning he had the gifts of patience and firm determination. By birth he was a Kurd, of the northern hills where the patriarchs still led the clans. Like the Scottish Highlanders, the Kurds of that day knew the law of the sword and of loyalty. They were like the Arabs but apart from them. Lean and dark and passionate, they had all the pride of the elder Greeks. The spoken word was their bond, and he who had shared their salt was safe from harm at the hand of the giver of the salt. All Kurds were soldiers by inclination, and devout Muhammadans by tradition. But Saladin—strangely, in a Kurd—had no love of fighting for its own sake.

Slight in body, subject to intermittent fever, he lacked the energy that makes a sport of war. Courteous and shy and self-contained, he avoided quarrels. He had a taste for fine horses and rare wine, and books. He played polo well, and he sought leisure rather than public honors.

He had not wanted to come to Egypt this time. “By Allah,” he had said, “if you offered me the kingdom of Egypt, I would not go. I have suffered at Alexandria ordeals which I will never forget.”

But go he did, at the request of Nur ad Din—he who once had held Alexandria for Shirkuh against the siege of the crusaders for seventy-five days. Rumor has it that the Christian knights esteemed him and welcomed him into their company.

“No man may escape his fate,” the jesters of the bazaar pointed out. “Lo, here is this same Saladin now master of Egypt.”

Only this much is known of Saladin. The shadowy outline is that of a recluse and a scholar more than a warrior. Yet Saladin was sought after by the lords of Islam, and the men of the army accepted his leadership. That he was able to command he proved at once, when the throngs of Cairo rioted, and he hung the worst of them. He defended Damietta against the Byzantine fleet that came down later in the year.

He even struck a counter-blow at the Christians, raiding with his mamluks across the sands, and plundering Amalric’s outposts. Still, he was not reconciled to Cairo and its endless responsibility. When his father Ayoub—a shrewd and impetuous statesman, then governor of Damascus—joined him in the city, he offered to yield the wazirship to him. The old Kurd refused.

“Am I,” he said, “to alter what hath been done by fate? Nay, thou art the wazir!”

Whereupon Saladin plunged into the task of creating an orderly government in Egypt out of the prevailing chaos. He had been chosen dictator and dictator he would be.

Cairo, blackened by fires, scarred by plague, rotted by bad water, had not known a firm hand for generations. Only the newer part of the city with its palaces and mosques lay within the massive brick wall; the rest of it, between the bare brown hills and the distant peaks of Ghizeh’s pyramids, was a half-ruined waste where Bedawins prowled and looted dismantled tombs, when the mist hung over the river.

But the life of the bazaars went on apace, and wealth gleamed amid the débris. Under the arches of the souk, carpets were piled high and hemp bales pressed against jars of olive oil—colored lamps burned through the night above chests of spices and pearls from the Indies watched by swordsmen from Marghrab or Rayi. In this labyrinth crowded a multitude of buyers and sellers; Jews in blue robes bargained shrilly with Armenians and Venetians who wore bells about their necks to show that they were despised Nazarenes. If they rode donkeys they had to sit face to tail.

For this was the true city of the Thousand and One Nights, sleepless, indolent, and very wise. Arab shaikhs in dark robes strode among crimson-clad negroes; Circassian slaves, veiled from forehead to toe, rode past in a cluster of black eunuchs with their long staves. Fair and indifferent Greek girls stood in the slave market under the insolent eyes of Turkish officers. Mamluks in jeweled khalats built themselves palaces of half-dried bricks in a month, and feasted on the carpets of slain enemies.

From this tumult Saladin held aloof. While he displaced the Fatimid officials with his own men—and gave the vacated palaces to them to plunder—he lived in a small house near the mosques. He discovered a great library within the city—120,000 volumes—and while he had some of the manuscripts sent to his own house, he entrusted the mass of them to a distinguished man of letters, the kadi El Fadil, thereby making one firm friend for life.

He gave up wine and sports, and settled down to a routine of labor. At sunrise he rose from his mattress and washed his face and hands before making the dawn prayer. After his servants came in to salute him, the new wazir ate a little fruit washed in clear water. His sleeping mattress was rolled out of the way, and he held a morning levée, listening to the reports of his officers and the complaints of the mullahs and merchants of the city. When they had taken their leave, the young Kurd went out to make his daily inspection before the heat grew too great.

At such a time he became a stately figure—a slender man, erect in bearing, with quiet, meditative eyes. He wore a black tarboush, or long fez, wrapped round with a white turban cloth, and a black cloak, its wide sleeves trimmed with gold thread. Into his girdle was thrust a long Arab scimitar with a gold or jade hilt. His horses were the best of the Arab thoroughbreds, their reins and headstalls heavy with silver or gilt coins. About him clustered his guards in yellow cloaks. Before him went riders beating upon silver kettledrums, and black Sudanis running barefoot, who cried,

“ ’Way for the Conquering Lord, the favored of Allah!”

For the East demands splendor in its masters. And the throngs that salaamed to Saladin or ran beside him to beg would have drawn their knives to loot him if for one moment he had relaxed the rein of authority.

But that moment did not come. Ayoub gave him wise counsel, and Shirkuh’s mamluks transferred their allegiance to him. One of them, Karakush by name, knew all the arts of fortification, and planned with him, after a devastating earthquake, a new citadel on the spur of the overhanging hills. They meant to run a wall from the city to the citadel, and all the way down to the Nile.

All Saladin’s kinsmen rallied to him—Taki ad Din, his nephew, a youthful and warlike soul, leader of the wild horsemen of the north, and Turan Shah, his brother, an experienced man but uncertain and overrash.

And Nur ad Din, the sultan, sent him congratulations with fresh troops and suggestions. The conquest of Egypt delighted Nur ad Din, who wished to have the kalif of Cairo deposed, after which Saladin was to march to aid Nur ad Din to overthrow the crusaders.

Saladin, however, did not obey at once. He knew that Nur ad Din had one foot on the edge of the grave. If he left Egypt to its own devices and joined the sultan, he would become an officer of the army again, with others more than ready to take his place. So Ayoub and Saladin played their parts in a real comedy. When Nur ad Din was far in the north with his army, the young Kurd would march against the salient of the crusaders, raiding the castles of the knights down in the desert. The sultan, hearing of this, would hasten back joyfully to aid him, and Saladin upon one pretext or another would decamp and recross the sands to Egypt.

The comedy did not long deceive the astute sultan, and rumor said that he meant to come in person and dispossess the young master of Egypt.

Saladin assembled his small council to discuss the situation—sitting down by Ayoub on a carpet with the leading amirs, the officers of the mamluks, and his own kinsmen. He asked them what they would do if the sultan, Nur ad Din, marched on Egypt.

“When he comes,” cried Taki ad Din, “we will give him battle and drive him from the land.”

The others assented, saying that they had eaten the salt of Saladin. But Ayoub lifted his gray head angrily. “I am thy father,” he said, “and here is Al Harimi thine uncle, and for the rest, I am certain of their loyalty to thee. Who would wish thee better than we?”

“I am sure of that,” Saladin assented.

“Well,” Ayoub went on, “by God, if I and thine uncle should see the sultan Nur ad Din, we would lower our heads and kiss earth before him. If he orders us to cut off thy head with a saber stroke, be sure we will do it. That is how we are. And these others—if one of them saw the sultan Nur ad Din, he would not dare to remain sitting in the saddle. He would get down to kiss the earth. All this country is the sultan’s and if he wishes to name another in thy place, he will do it, and we shall obey his commands!”

All the officers of the council cried assent, saying that they were the slaves and mamluks of the sultan. Saladin dismissed them, and Ayoub, when he sat alone with his son, said bitterly:

“Thou art a fool, an idiot! To bring together all these men, and tell them what thou hast at heart! When Nur ad Din learns of thy plan, he will march to attack this land, and thou wilt not have one of these men to defend it. Nay, more—some of them will write to him concerning thee. Write thou also, saying, ‘Why march against me, to bring me to obedience? For that, it will be sufficient to take a towel and pass it around my neck.’ When he reads thy letter, he will put aside thinking of thee, and will occupy himself with the more important matter of his kingdom—so thou wilt gain time. God is great and all-wise!”

Ayoub had spoken the truth. The Egyptian army was loyal enough to the young Kurd, but the appearance of the great sultan in the field would cause a general desertion. Saladin realized this. He gave an order that took a good deal of courage.

When the multitude gathered in the great mosque on the following Friday for prayer, the mosque was as usual, the unlit lamps hanging from the lofty ceiling, the carpets clean and brushed, and the very shadows inviting meditation. But when the preacher advanced from the alcove to the carved wooden steps of the minbar, there was a turning of heads and the sound of heavy breathing. Attentive eyes saw that he was clad not in the customary white but in the black of the orthodox preachers—even his turban was black, and about his hips a sword had been girdled, as in the days of Muhammad and the Companions. Thrice he paused in his ascent of the steps to strike the sword sheath upon the wood for silence, but there was no need of that.

He lifted his long arms, and his voice echoed against the high arches. “Blessed be the Companions, the Followers, and the Mothers of the Faithful . . . and the kalif Al Mustadi!”

The prayers went on, after an instant of amazement. For the preacher had invoked the name of the kalif of Baghdad, in the great mosque of Cairo, within an arrow’s flight of the palace where that other kalif, the Fatimid, lay behind his curtains. Saladin had virtually dethroned the kalif of Cairo, thereby making a host of new enemies for himself. But he had made his own position clear. He was a follower of the lawful kalif of Baghdad, and acknowledged no other lord.

By the same stroke Saladin gained possession of the kalif’s treasure—gold and silver ingots ranged along the walls as high as the ceiling, with caskets of matched pearls and great, uncut precious stones almost beyond the counting. As well as the famous enamel peacocks and a leopard made of ebony spotted with pearls. With this trove in his hands, he could set Karakush to work in earnest, taking massive stones from the pyramids to build the new walls, and an aqueduct to bring good water from the hills, and a dam to keep out the stagnant river water. As Nur ad Din had done in Damascus he planned an academy for the men of letters, and a hospital.

He appointed over it [said an Arab from Spain, who saw it years later] a man of knowledge with a provision of drugs. In the chambers of this palace couches have been set, with bed clothes and servants who inquire into the condition of the sick morning and evening. Opposite this hospital is another for the women. Adjacent is a spacious court where the chambers have iron gratings for the confinement of those who are mad. He himself investigates everything, verifying what is told him with the uttermost care.

Meanwhile his court was growing. Moslems went far to seek out a man who had been fortunate. Fatalists, they believed that achievement came only from the will of God, and a man who had achieved much was beyond doubt favored of God.

The kadi, El Fadil, was now administrator in general. New figures appeared at Saladin’s side—a certain Hakhberi, an old Arab jurist, and Aluh, the Eagle, who was poet, astrologer, and debater in one. Saladin liked to listen to their talk. But he was careful to send Turan Shah afield to search for a place of safety into which they could retreat if the sultan marched against them. Turan Shah rode up the Nile, only to return disgusted with tales of half-naked blacks who laughed when he spoke to them. He fared better when he explored the Arabian desert.

But Saladin had no need of this pied à terre. Sturdy Ayoub could counsel him no more—the old Kurd, riding recklessly through a gate of Cairo, was thrown from his horse and killed. Amalric of Jerusalem followed him to the grave. And in the act of preparing to invade Egypt, the sultan Nur ad Din died.

This was in 1174. The embryo empire of Damascus cracked into fragments under the hands of the leading amirs of the army. And Saladin, after a survey of the situation, took upon himself the task of keeping the dominion intact, himself to be the sultan. Undoubtedly he was the man most fit to succeed Nur ad Din. And to this task he brought all his quiet patience, as unbending as tempered steel.

[4] Salah ad Din. Moslems in general addressed him by his official title, Malik en Nasr. The crusaders wrote down his name as Saladin and by this name he has been known to Christendom for more than seven centuries.

T is clear that Saladin planned the jihad from the first.

He knew that only in the jihad, the holy war, could he

unite the factions of the Near East. Turkoman, Kurd,

and Arab would follow the standards to war against the unbelievers;

the atabegs, of the north, the shaikhs of the

desert clans, and the amirs of Egypt would ride to such a

summons—given the sultan to lead them.

T is clear that Saladin planned the jihad from the first.

He knew that only in the jihad, the holy war, could he

unite the factions of the Near East. Turkoman, Kurd,

and Arab would follow the standards to war against the unbelievers;

the atabegs, of the north, the shaikhs of the

desert clans, and the amirs of Egypt would ride to such a

summons—given the sultan to lead them.

He wrote to the kalif of Baghdad, recalling the many times in which he had opposed the crusaders, and pledging himself to the holy war that would free Islam from the invaders. He had already united Cairo to Baghdad; eventually he would regain Jerusalem.

But twelve years passed before the victorious Kurd was able to declare the jihad.

Twelve years of almost ceaseless campaigning and siege and pacification. “Only a hand that can wield a sword may hold the scepter,” said the proverb of Islam. And Saladin had need of all his tact and clear judgment to weld together the fragments of Nur ad Din’s dominion.