* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Lincoln's New Salem

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Benjamin P. Thomas

Date first posted: Mar. 4, 2019

Date last updated: Mar. 4, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190311

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

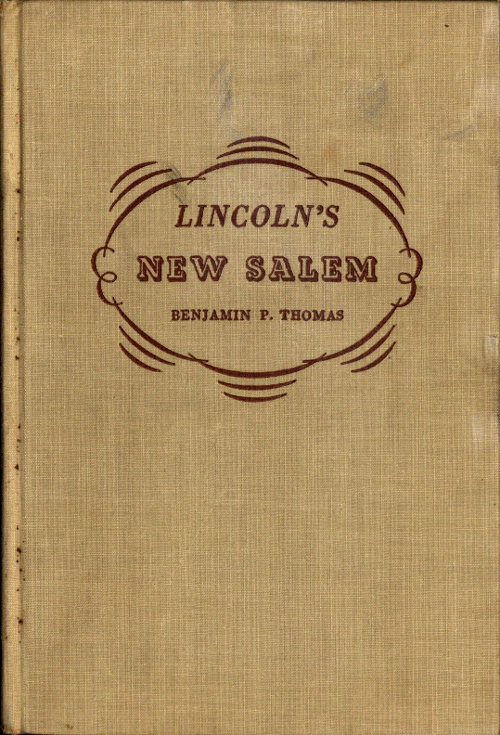

MAIN STREET, NEW SALEM, SHOWING SAMUEL HILL’S RESIDENCE, THE HILL-McNEIL STORE, THE LINCOLN-BERRY STORE AND PETER LUKINS’ HOUSE

BY

BENJAMIN P. THOMAS

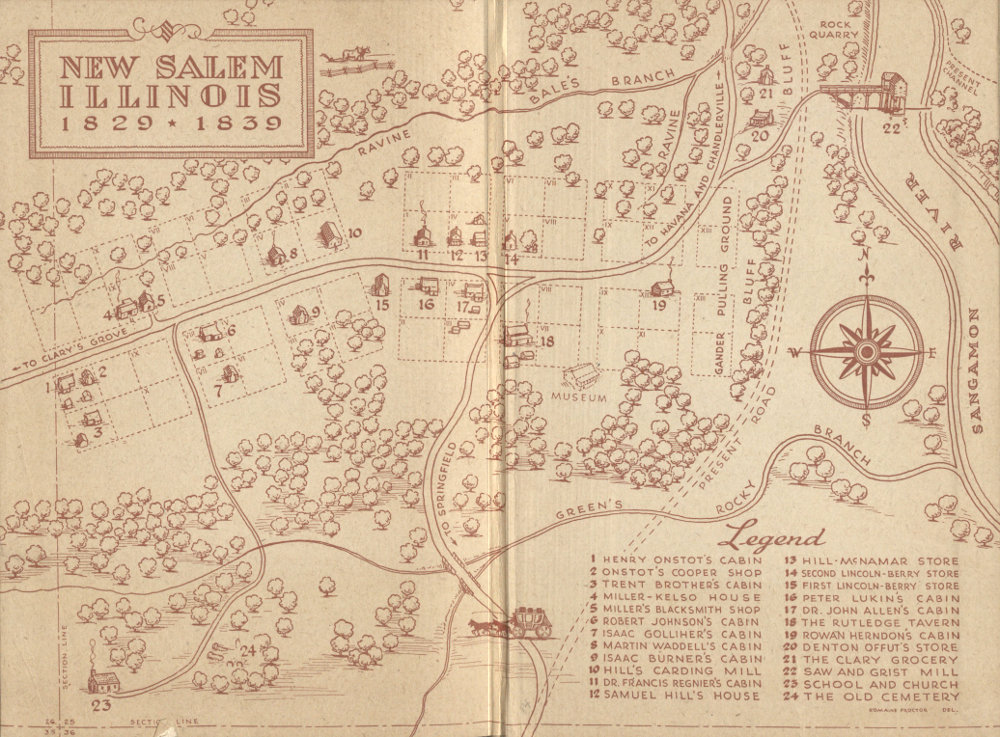

Drawings by Romaine Proctor

from photographs by the

Herbert Georg Studio, Springfield

Springfield, Illinois

The Abraham Lincoln Association

1934

COPYRIGHT, 1934, BY THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION

REPRINTED 1939, 1944, 1947

THE LAKESIDE PRESS, R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CRAWFORDSVILLE, INDIANA AND CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

TO MY MOTHER

For many years the surroundings in which Lincoln spent his boyhood, youth and early manhood were looked upon as drab, sordid, uninspiring; as an obstacle that he in some mysterious manner succeeded in surmounting. In recent years, however, American history has come to be interpreted largely in terms of the influence of the frontier as a factor in moulding our institutions and national character. With this interpretation comes a new conception of Lincoln as in a measure a product of his frontier environment.

Lincoln had less than a year of formal schooling. For the rest, he was self-made. He learned; he was not taught. What he read, he mastered; but he did not read widely. He learned principally by mingling with people and discussing things with them, by observation of their ways and their reactions—in short, from his environment.

This growing appreciation of the part that Lincoln’s environment played in shaping him is the reason for the State of Illinois’ reproduction of the village of New Salem, and is our reason for describing its people, their occupations, interests, customs, religion, manner of life and thought.

Some of New Salem’s residents had important and easily recognized influence on Lincoln. Denton Offut brought him to New Salem. Mentor Graham taught him grammar and mathematics, both of which were essential to his further development. Jack Kelso introduced him to Shakespeare and Burns. Jack Armstrong and his followers became his personal friends and political supporters. Others of the inhabitants touched his life at different points and even the humblest and most inconspicuous of them had some part in the making of the later, greater Lincoln. Lincoln’s success as a politician and president, for example, was due in no viii small measure to the fact that he knew how the common man would think. This he learned in large part at New Salem, where he worked on common terms with the humblest of the villagers. He learned how and what Joshua Miller, the blacksmith, thought, how Bill Clary, the saloonkeeper, Martin Waddell, the hatter, and Alexander Ferguson, the cobbler, viewed things. He knew the common people because he had been one of them.

No other portion of Lincoln’s life lends itself so readily to intensive study of his environment as do his six years at New Salem. His physical surroundings have been re-created. The names and occupations of practically all of his associates and something of the character of many of them are known. The village was small enough to make practicable a reasonably complete description of its people and its life.

Aside from its connection with Lincoln, New Salem is important as an example of a typical American pioneer village. There were hundreds like it. Some of them survived; others died, as it did. It is one of the few—perhaps the only one—whose founding, growth and decline can be minutely traced.

Part One of this book is devoted to the history of New Salem. It tells who the inhabitants were, how they lived, how they looked on life. Since many of those most active in the village lived in outlying settlements the account is not limited to the village, but provides a picture of the whole community. Part One sets the stage, so to speak, for Part Two, in which Lincoln’s activities are discussed, and the meaning of the New Salem years in his development is appraised. Part Three explains the growth of the Lincoln legend around the site of the lost town, and the changing conception of the significance of the frontier as a factor in Lincoln’s life. It explains how New Salem came to be restored, the manner in which the facts about the old cabins were secured, how the furnishings were acquired, and the problems that had to be solved in the restoration.

The New Salem period of Lincoln’s life has been difficult to treat with certainty, because the evidence is largely traditional in character. To exclude this type of evidence would make the story bare and incomplete. But by use of additional sources hitherto overlooked or unknown we have been able to use it with more discrimination, and to treat not only the Lincoln story but also the history of the village with more completeness and authenticity than was possible heretofore.

The files of the Sangamo Journal have yielded new facts. The letters of Charles James Fox Clarke, who lived in, and later near New Salem, published in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society for January 1930, but never used before in any book on New Salem, give a vivid picture of New Salem life. T. G. Onstot’s Pioneers of Menard and Mason Counties and Peter Cartwright’s Autobiography give the color of the pioneer days. County histories, reminiscences of old settlers, accounts of travelers, books and articles on pioneer life have been read. The records of land entries in Menard County, land transfers in New Salem and the records of the Sangamon County Commissioners Court have been examined.

The discovery of a copy of William Dean Howells’ Life of Lincoln, published in 1860, and corrected by Lincoln himself, enables us to write with assurance on several hitherto uncertain points. This copy was owned by Samuel C. Parks of Lincoln, Illinois. Parks, a native of Vermont, was educated at Indiana University and read law with the firm of Stuart and Edwards in Springfield. In 1848, he moved to Logan County, where he had many contacts with Lincoln. They were sometimes associated in the trial of cases in the Logan Circuit Court. Like Lincoln, Parks became a Republican. He spoke at Republican meetings in Logan County, and on one or two occasions introduced Lincoln when the latter spoke there. He worked for Lincoln’s nomination as the Republican candidate for President in 1860, x and Lincoln later appointed him Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Idaho. In the summer of 1860, Lincoln, at his request, read his copy of Howells and made corrections in the margins. Through the courtesy of Mr. Parks’ son, Samuel C. Parks, Jr., of Cody, Wyoming, the Abraham Lincoln Association was permitted to examine this book and make photostatic copies of the pages on which Lincoln’s corrections appear.

The research work done by the Division of Architecture and Engineering of the State of Illinois in connection with the restoration of New Salem has added to our knowledge of the village, especially with respect to the character and construction of the houses. This information, published in a mimeographed Record of the Restoration of New Salem, by Joseph F. Booton, Chief Draftsman, who had immediate charge of the research, has been of great help.

Anyone writing on New Salem must pay tribute to the Old Salem Lincoln League of Petersburg, Illinois, for collecting and preserving information about the town and its residents. Their material, published in Lincoln at New Salem by Thomas P. Reep, has been freely drawn upon. Mr. Reep has devoted years to the study of New Salem. But for his work and that of the League much of this information would now be lost beyond the possibility of recovery and a detailed history of the town could not be written. The League also initiated the movement for New Salem’s restoration and cooperated with the state in every stage of the work.

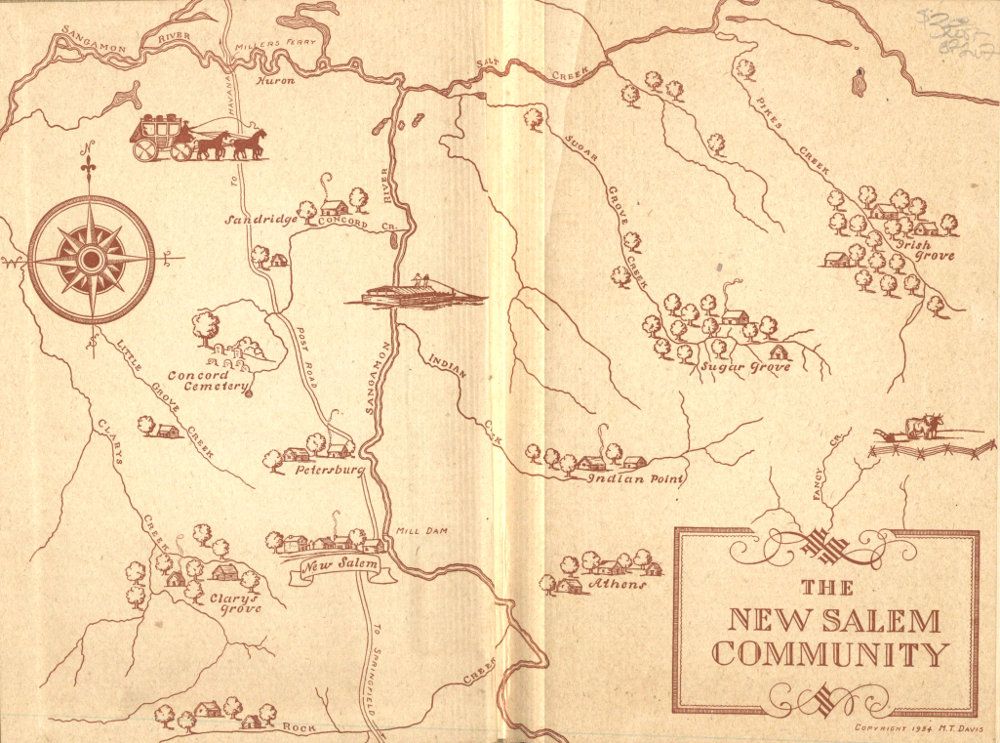

I wish to express my gratitude to Logan Hay, former President of the Abraham Lincoln Association, for constant encouragement and assistance. Mr. Hay gave freely of his time, and by his suggestions of sources and constructive criticism of content and form made this a better book than it would otherwise have been. Paul M. Angle, Librarian of the Illinois State Historical Library, has read the entire manuscript and has made many valuable suggestions with xi respect to material, manner of treatment and design. George W. Bunn, Jr., has also read the manuscript and has given helpful advice on design and format. Margaret C. Norton, Archivist of the State of Illinois, permitted me to use data collected by her on Lincoln’s activities in the State Legislature. The Herbert Georg Studio of Springfield kindly furnished the photographs used by Romaine Proctor in drawing the illustrations. Margaret T. Davis drew the map for the front endsheet, and Mr. Proctor made the drawing of the village used as the back endsheet. Many others have assisted me in one way or another, and to them go my sincere thanks. The loyal support of the members of the Abraham Lincoln Association has made possible the preparation and publication of the book.

Finally I wish to express my appreciation to the state officials who were responsible for the restoration of New Salem. Governor Louis L. Emmerson and Governor Henry Horner gave the project enthusiastic support. The State Legislature appropriated the necessary funds. H. H. Cleaveland and Robert Kingery, former Directors of the Department of Public Works and Buildings, had general charge of the work. C. Herrick Hammond, State Supervising Architect, supervised the research and the drawing of the plans for the restored cabins. They have given us a true reproduction of a pioneer town and a unique memorial to Lincoln.

Benjamin P. Thomas

Springfield, Illinois

The outstanding feature of Lincoln’s life was his capacity for development. Neither a born genius nor a man of mediocre talents suddenly endowed with wisdom to guide the nation through the trials of civil war, he developed gradually, absorbing from his environment that which was useful and good, growing in character and mind. “How slowly, and yet by happily prepared steps, he came to his place,” said Emerson.

No one seeing Lincoln at New Salem, would have predicted for him the high place he was to reach in public life and world esteem; yet at New Salem many of the characteristics which were to make him great were in process of development, while others were present in rudimentary form.

In New Salem Lincoln made his reputation for physical prowess and began the development of his talents of leadership. There he served his apprenticeship in business, made his first venture into business on his own account, and established the reputation for square dealing that stuck to him through life. While there he had his one brief experience as a soldier, and held his first state and first Federal office. He learned surveying, acquired the elements of law, improved his knowledge of grammar, mathematics and literature, and made his first formal efforts at speech-making and debate. There he made his first venture into politics, formed his first enduring friendships, and won—and lost through death—his first love. He came to New Salem an aimless pioneer youth; he left with an aroused ambition; and he took with him an abiding understanding of the thoughts and feelings of the common man.

The village of New Salem—Lincoln’s home from 1831 to 1837—was founded in 1829, by James Rutledge and John M. Camron. The former was born in South Carolina in 1781. Early in his life his family moved to Georgia. From there they moved to Tennessee, thence to Kentucky. There Rutledge married and had several children, among them a daughter, Ann. In 1813, he and his family moved to White County, Illinois. He was a man of medium height, quiet, dignified, sincerely religious, and fairly well educated. Camron, a native of Georgia, ten years younger than Rutledge, was a nephew of Rutledge’s wife. He accompanied his uncle on his migration from Georgia to White County. A man of great physical strength, a millwright by trade, Camron was an ordained Cumberland Presbyterian preacher as well.

In 1825 or 1826, Rutledge and Camron moved again, this time to Concord Creek, in Sangamon County, about seven miles north of the site of New Salem. There they entered land and planned to build a mill. But the volume of water in the creek was insufficient, and after an extensive search for a suitable site, on July 19, 1828, Camron entered a tract of land on the Sangamon River. There they were assured of a steady flow, so they applied to the State Legislature for permission to build a dam.

Anticipating favorable action, they left Concord Creek, probably in the fall of 1828, built new homes on the bluff above the river; and moved in before cold weather came. On January 22, 1829, the Legislature granted them permission to build the dam. Its construction was begun at once, farmers from the surrounding country furnishing oxen and horses to haul rocks with which to fill the wooden bins that had been placed in the stream.

The dam completed, a combination saw and grist mill, of solid frame construction, was erected beside it. The grist mill was enclosed and set out over the stream. The saw mill, with its old-fashioned upright saw, had a roof, but was open 5 on the sides, and stood on the west bank. A wooden trestle connected both mills with the steep bank.

Soon the grist mill was drawing trade from miles around. On busy days thirty or forty horses would be tied to the trees on the steep hillside, “their heads forty-five degrees above their hams.” In the fall of 1829, Samuel Hill and John McNeil, attracted by the growing business of the mill, opened a store on the hill above, at the point where the road from Springfield, ascending the slope from the south, curved toward the east. Soon a “grocery” or saloon, kept by William Clary, was dispensing liquor on the bluff.[1] Now, while waiting for their grain to be ground, men could stock up with supplies and lounge about the store, or drink and play “old sledge” at the grocery. When the boys were sent to mill they whiled away the time fishing or swimming or with feats of strength and skill on the bluff.

A mill, a store and a grocery were the usual beginnings of a pioneer village, and as the place became a center of trade Rutledge and Camron resolved to lay out a town and sell lots. The ridge above the mill provided a beautiful site. Extending westward from the river, it widens and gradually merges with the prairie. At the bottom of its steep southern slope, Green’s Rocky Branch ran eastward to the Sangamon. On the north the ridge sloped down sharply to another little stream, later called Bale’s Branch, which also flowed to the river. The steep bluff at the eastern end of the ridge deflects the Sangamon, flowing from the southeast, to the north. Groves of virgin timber crowned the rolling hills of the vicinity and lined the watercourses.

On October 23, 1829, Reuben Harrison, a surveyor whom Rutledge and Camron had employed, planned and laid out a town on the ridge. It was the first town platted within the limits of the present Menard County. The proprietors named it New Salem.

On December 24, the first lot was sold to James Pantier for $12.50. Ten days later Pantier paid $7.00 for a second 6 lot, adjoining his original purchase.[2] On Christmas Day, 1829, a post office was established, with Samuel Hill as postmaster. Up to that time the people in that part of the county got their mail at Springfield.

In 1830, Henry Onstot, a cooper, moved from Sugar Grove and built a shop and residence in the southeastern part of the village near the bluff. James and Rowan Herndon opened a store. Clary established a ferry, thereby making the village more accessible from the east, and extending its trading area in that direction. The County Commissioners allowed him the following rates:

| “For each man and horse | $ .12½ |

| For each footman | .06¼ |

| For each single horse | .06¼ |

| For each head of neat cattle | .03 |

| For each head of sheep | .02 |

| For each road wagon and team | .50 |

| For each two horse wagon and pleasure carriage | .25” |

When the river was out of its banks, or before sunrise or after sunset, he could charge double these amounts.

In 1831, the village continued to grow. In August, John Allen, a young physician from Vermont, bought Pantier’s lots, and built a house across the street from Hill’s store. Allen had received his medical degree from Dartmouth College Medical School three years before, and came west to seek a climate that might benefit his health. Early in September, Denton Offut, who had stopped in New Salem in April, when the flatboat that he was taking to New Orleans stranded on the mill dam, returned to the village, opened a store on the bluff near Clary’s grocery, and rented the mill.[3] With him came Abraham Lincoln, a young man who had worked for him on the flatboat, and whom he had hired to clerk in the store and run the mill.

The same year, David Whary purchased a lot in the eastern part of town.[4] Henry Sinco, the constable, opened a saloon.[5] Peter Lukins built a house and had a cobbler’s shop in one of its two rooms. George Warburton opened the 7 town’s fourth store, and secured a license to sell drinks. Later that year he sold out to two brothers from Virginia, St. Clair and Isaac P. Chrisman. In November, Isaac Chrisman succeeded Hill as postmaster; but he and his brother sold their store to Reuben Radford shortly afterward, and left town, and Hill again took over the post office. As immigrants came to the Sangamo country, Rutledge converted his house into a tavern and built an addition for guests.

Settlement in Illinois progressed from the south northward. The northern part of Sangamon County began to attract settlers about 1819, and at the time New Salem was founded the surrounding country, within a radius of ten or fifteen miles, already contained scattered farms and several smaller settlements. West of the river the nucleus of the population was the Armstrong-Clary-Greene-Potter-Watkins-McHenry-Kirby clan. These families had intermarried in Tennessee, Kentucky and southern Illinois as they gradually trekked north. In 1819, John Clary, who married Rhoda Armstrong while they were living in Tennessee, came to Sangamon County and settled in the grove that came to bear his name. He was the first settler within the area of the present Menard County. He was followed, in the early twenties, by most of the other members of the clan, who migrated north in groups.

These families, settling in and around Clary’s Grove and Little Grove, southwest of the site of New Salem, and along Rock Creek, to the south, dominated that part of the country. Early in the thirties, most of the Armstrongs and Clarys moved northward to Concord and Sand Ridge. East of the river, in Sugar Grove, Irish Grove, Athens and Indian Point, there was less relationship between the families.

New Salem, from the time it was founded until 1833 or 1834, was the trading point of all these settlements. The village and its surrounding area were really one community. No account of the village can be adequate unless it treats also of these outlying places, for many of those who 8 were important in the life of the village lived outside of it.

At the time New Salem was founded few villages of any size existed farther north. Peoria had been established, and at Dixon’s Ferry, where the trail from Peoria to the lead mines at Galena crossed the Rock River, and at other points along that trail there were clusters of cabins. At Hennepin there was a fur-trading post. Chicago had a population of about 100 people, living in a few log cabins huddled about Fort Dearborn. For sixty or seventy miles north of Sangamon County there were from two to six settlers to the square mile. Farther north were areas of trackless prairie, still roamed at times by hostile Indians, whose presence deterred settlers from coming too far north. As late as 1837, the country between Bloomington and Decatur was very sparsely settled. Springfield, twenty miles southeast of New Salem, contained about 500 people in 1830. Settlers built in the groves and along the streams, where timber was available for cabins, fences and fuel, where water for stock could be had, and where the land could be more easily broken. Away from timber the treeless, sun-baked prairie was almost uninhabited.[6]

Throughout the state, inns were to be found only in the larger villages, and along the more traveled roads. A traveler from Chicago to New Salem, in 1835, recorded that “the fare along the road was rather poor. We stopped one night at a house or rather it was a small cabin (one room only), where we were rather crowded there being twenty-seven lodgers, the landlord said he had often lodged that number we put out early in the morning feeling thankful that we had not been lost in the crowd.”

The greatest need of central Illinois was adequate transportation. The soil was rich, but it was difficult to get crops to market. Under “Hints to Immigrants” the Sangamo Journal of February 9, 1832, gave an impressive description of the difficulties of travel. “In the spring, the bottom-lands are overflowed, the channels of all streams are full, and the 9 travelling in any direction is impeded, and sometimes wholly stopped, by high waters.—The roads, generally speaking, are new; because the great channels of trade are not yet settled. Population is rapidly increasing, and trade fluctuating from point to point; the courses of roads are consequently often changed, before a permanent route is adopted. Few roads, therefore, have become so fixed, as to their location, as to have been beaten by travel, and improved by art; and the traveller who ventures out in the spring, may expect to be obliged to wade through mire and water—ancle deep, knee deep, and peradventure deeper than that. But the spring is, for the same reason, the most eligible season for travelling by water. . . The steam boat glides without interruption from port to port, ascends even the smallest rivers, and finds her way to places far distant from the ordinary channels of navigation. . . The traveller by water meets with no delay, while the hapless wight, who bestrides an ugly nag, is wading through ponds and quagmires, enjoying the delights of log bridges and wooden causeways, and vainly invoking the name of McAdam, as he plunges deeper and deeper into mire and misfortune.” In the autumn, on the other hand, streams were dry or shallow and roads were the better routes.

With roads poor and frequently impassable, the future of New Salem, and that of the Sangamon country as well, was believed to depend primarily on the possibility of making the river navigable for light-draft steamboats. A hundred years ago the volume of water in the Sangamon was greater than it is today, and great hopes were entertained of its navigability. On February 2, 1832, the Journal observed: “It would be folly, perhaps, ever to anticipate for our village [Springfield] advantages from steam boat navigation equal to those which St. Louis derived from that source. Yet such an anticipation can not be deemed more chimerical than was the project of running steam boats from the mouth of the Ohio to St. Louis in 1817.”

In the spring of 1832, the Talisman, a small cabin steamer from Cincinnati, actually managed to ascend the Sangamon as far as Portland Landing, a point near Springfield several miles above New Salem. “The result,” declared the Journal on March 29, “has clearly demonstrated the practicability of navigating the river by steamboats of a proper size; and by the expenditure of 2,000 dollars in removing the logs and drifts and standing timber, a steam boat of 80 tons burthen will make the trip in two days from Beardstown to this place.” On May 10, 1832, announcement was made that the steamboat Sylph would soon leave Cincinnati for Springfield, “and that, if the stage of water in the Sangamon permits, and business on the river will justify it, she will continue to run on the river during the ensuing season.”

The prospect of cheap and steady transportation started a boom. More settlers came. Prospective towns were laid out at strategic points along the Sangamon; and the Journal congratulated “our farmers, our mechanics, our merchants, and professional men, for the rich harvest in prospect.” The future of the country seemed assured.

Anticipation of New Salem’s becoming a thriving river town caused an inrush of new settlers; and in 1832 the village reached its peak. Isaac Burner and Isaac Golliher built houses.[7] Joshua Miller, a blacksmith and wagon-maker, and his brother-in-law, Jack Kelso, erected a cabin and blacksmith shop, which was soon one of the busiest places in town. From morning until night Miller’s anvil clanged, as he forged ox shoes, horse shoes, implements and household fittings.[8]

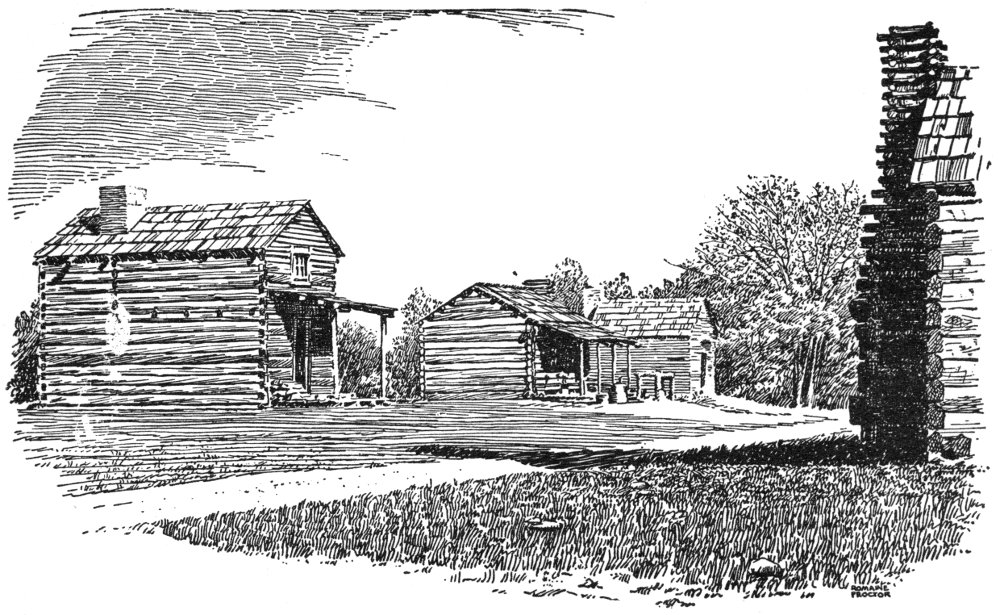

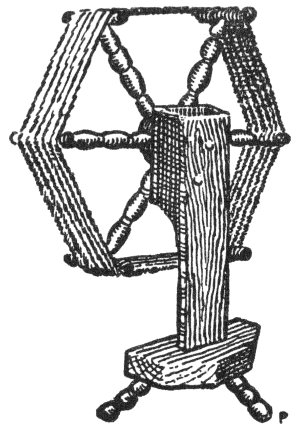

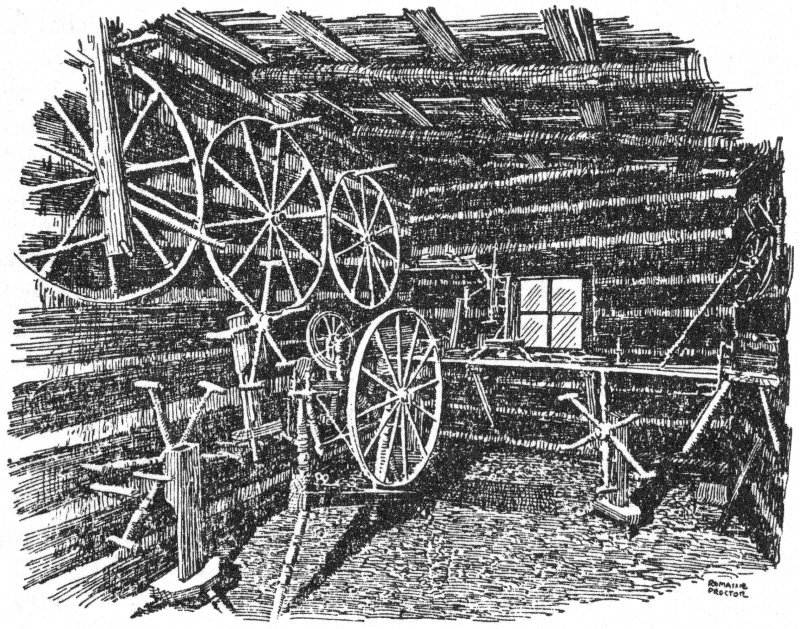

Francis Regnier, a young doctor from Ohio, bought the house that Sinco had used for a saloon, refitted it, and lived and had his office in its single room.[9] Martin Waddell built a house and made hats and caps for the community. Philemon Morris built a residence and tan yard. Robert Johnson, a wheelwright and cabinetmaker, settled in New Salem and made spinning wheels, wagon wheels and furniture.[10]

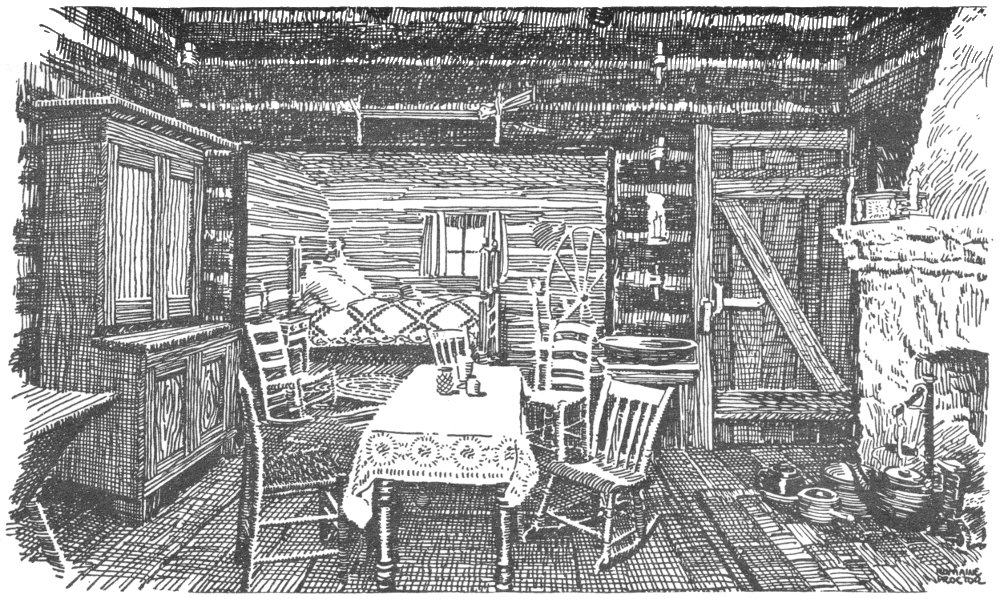

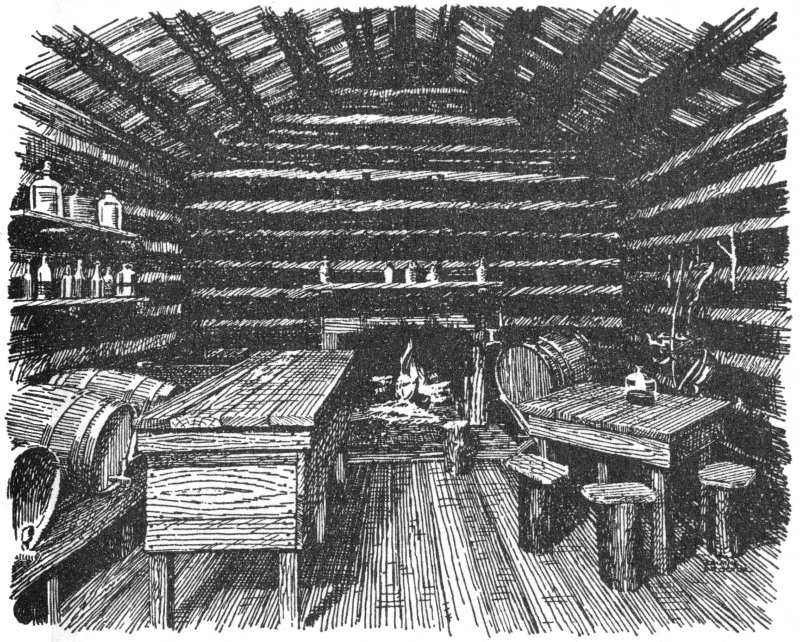

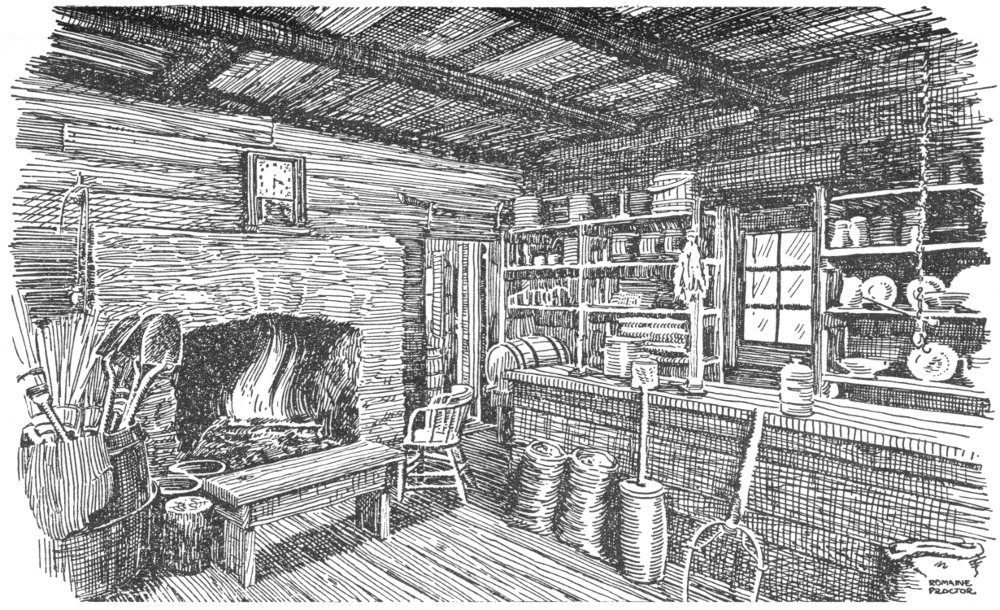

THE INTERIOR OF DR. FRANCIS REGNIER’S HOUSE

The population of New Salem, like that of many pioneer towns, was an ever-changing one. Settlers came, stayed a few months and moved on. Dr. Jason Duncan lived there for a short time, then moved to Warsaw, Illinois. Charles James Fox Clarke, a young man from New Hampshire, boarded at the tavern for awhile, then moved to a nearby farm. In the summer of 1832, William F. Berry and Abraham Lincoln bought the Herndon brothers’ store; and a little later, as the town continued to grow, they bought out Reuben Radford. This left Hill as their only competitor; for in the spring Offut had closed his store, given up the mill and moved away. In the autumn Jacob Bale, a Kentuckian, bought the mill. Bill Clary moved to Texas and Alexander Trent bought his grocery. When Lukins and Warburton founded the town of Petersburg, two miles down the river, in 1832, Alexander Ferguson moved into Lukins house, took his place as shoemaker, and soon had a thriving business. Farmers took their hides to Morris to be tanned, then brought the leather and the measurements of the family feet to Ferguson. Two or three weeks later they would come back with a two-bushel sack, and take home twelve or fifteen pairs of shoes.

The tavern changed hands several times. November 26, 1832, Rutledge sold it to Nelson Alley for $200; and in December, 1834, Alley sold it to Henry Onstot, the cooper. Onstot operated it for about a year, then built a new house and cooper shop in the western part of town and sold the tavern to Michael Keltner. Clary, Allen Richardson, John Ferguson, brother of the cobbler, Alexander Trent, and Jacob Bale and his son Hardin were successive owners of the ferry.

For four years after the coming of the Talisman, in 1832, rumors of the navigation of the river recurred at intervals. Most of the villagers still believed it could and would be navigated; but the more practical began to doubt. Settlers continued to take up the rich land of the surrounding country, 13 but by the spring of 1833, New Salem’s growth had stopped. Few new settlers came that year, and some old ones moved away. The Camrons went to Fulton County. James Rutledge moved to a farm on Sand Ridge.[11] Lincoln and Berry, disillusioned in their mercantile venture, sold out to Alexander and Martin S. Trent. On September 17, 1835, Mathew S. Marsh, who lived two miles southwest of New Salem, wrote to his brother: “You ask is there a prospect of my place growing rapidly. I suppose you mean New Salem—No; that stopped two years since.” On the whole, however, the village held its own until 1836.

New Salem was on the road from Springfield to Havana and in April, 1834, a stage line was established on that road. A four horse post coach, owned by Tracy and Reny, was scheduled to leave Springfield every Wednesday morning at six o’clock. It passed through Sangamontown, New Salem, Petersburg, Huron, Havana, Lewistown, Canton, Knoxville and Monmouth, and was due at Yellow Banks (the present Oquawka), on the Mississippi, 130 miles from Springfield, on Saturday at noon. It was scheduled to begin the return trip the same day, arrive at New Salem Tuesday morning, and reach Springfield that afternoon. More often than not, however, it was hours or even days late; and in very bad weather it didn’t run at all. The fare for through passengers was nine dollars; for way passengers, six and a quarter cents a mile. Since it cost about a dollar and a half to get to Springfield, Lincoln seldom rode the stage in his numerous trips back and forth.

In the spring of 1835, Samuel Hill built a carding machine and store house for wool west of Doctor Regnier’s house. He advertised in the Journal of April 24 that he would commence carding by May 1. “The machines are nearly new and in firm rate order, and I do not hesitate to say, the best work will be done. Just bring your wool in good order and their will be no mistake.” The cogs of the machine were made of hickory wood; and a yoke of oxen, 14 hitched to a forty-foot wheel, supplied the motive power. “Every person kept sheep in those days,” wrote T. G. Onstot, the cooper’s son, “and took the wool to the machine where it was carded by taking toll out of the wool or sometimes they would pay for it. They commenced bringing in wool in May and by June the building would be full. It was amusing to see the sacks of all sorts and sizes and sometimes old petticoats. For every ten pounds of wool they would bring a gallon of grease, mostly in old gourds. Large thorns were used to pin the packages together.”

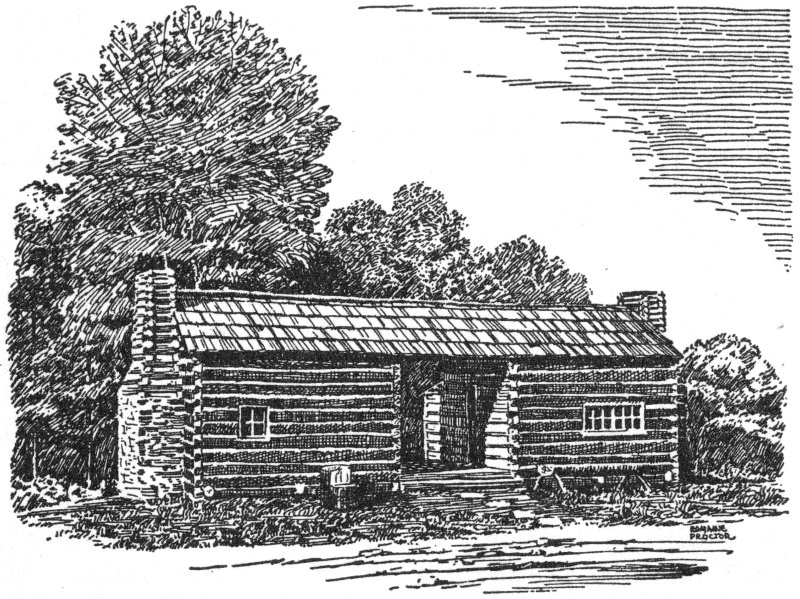

THE HILL-McNEIL STORE

Hill was the town’s leading business man. While other stores failed, his prospered as long as the village survived. On September 4, 1832, his partnership with McNeil was dissolved by mutual consent, and Hill continued in business alone. On July 28, 1835, he married Parthena Nance of Rock Creek.[12] Shortly before their marriage he built a two-story house beside the store. Hot-tempered and shrewd, 15 Hill was thrifty to the point of stinginess. Peter Cartwright, his inveterate enemy, claimed that he had always believed that Hill had no soul until he put a quarter to his lips and his soul “came up to get it.” Hill’s store was the center of village life. Throughout the day shoppers and gossipers came and went, or lounged on its porch, reading mail, exchanging news, or talking crops or politics. On election day the polls were located either there or at the Lincoln-Berry store or the tavern.

At the height of its prosperity New Salem had a population of some twenty-five families, with twenty-five or thirty log or frame structures, among them the saw and grist mill, the tavern, three or four general stores, the grocery, the cooper shop, the blacksmith shop and the tannery. It had no church, but services were held in the schoolhouse, across the Rocky Branch to the south of the village, near the cemetery, and in the homes of the inhabitants.

It was a typical pioneer town. Almost everything needed was produced in the village or the surrounding countryside. Cattle, sheep and goats grazed on the hillsides. Hogs rooted in the woods and wallowed in the dust and mud of the road. Gardens were planted about the houses; while wheat, oats, corn, cotton and tobacco grew in the surrounding fields. In August, 1834, C. J. F. Clarke described conditions to his relatives in the East. “I have been requested,” he wrote, “by all those that I have recd letters from to write what the people live in, what they live on etc. I will tell you. I should judge that nine tenths of them live in log houses and cabbins the other tenth either in brick or framed houses. The people generally have large farmes and have not thought so much of fine buildings as they have of adding land to land, they are now however beginning to build better houses. Many a rich farmer lives in a house not half so good as your old hogs pen and not any larger. We live generally on bacon, eggs, bread, coffee. Potatoes are not much used, ten bushels is a large crop and more than is used in a family in 16 a year. Sweet potatoes are raised here very easy. The wheat crop is very good, corn is very promising mother wishes to know what kind of trees grow here. We have all kinds except pine and hemlock, houses are built of white oak and black walnut and some linn. Almost all kinds of fruit grows here spontaneously among them are the crab apple, cherry, two or three kinds of plums, black and white haw, gooseberrys, etc., etc. The black walnut is a beautiful tree the wood of which is very much like mahogany. There is a considerable quantity of cotton raised here but none for expotation. Tobacco grows well here, etc. etc.”

Sunflowers bloomed profusely on the prairie. In the spring and summer, bass, sunfish, catfish and suckers could be caught in the river near the dam. Sometimes there was good seining below the mill, and occasionally fish could be gigged. Wild turkeys abounded in the woods; and deer, while becoming scarce, could still be had. Quail, prairie hens, ducks and wild geese were plentiful. Prairie wolves, a small species about the size of a fox, were rapidly being exterminated, but were still a menace to sheep.

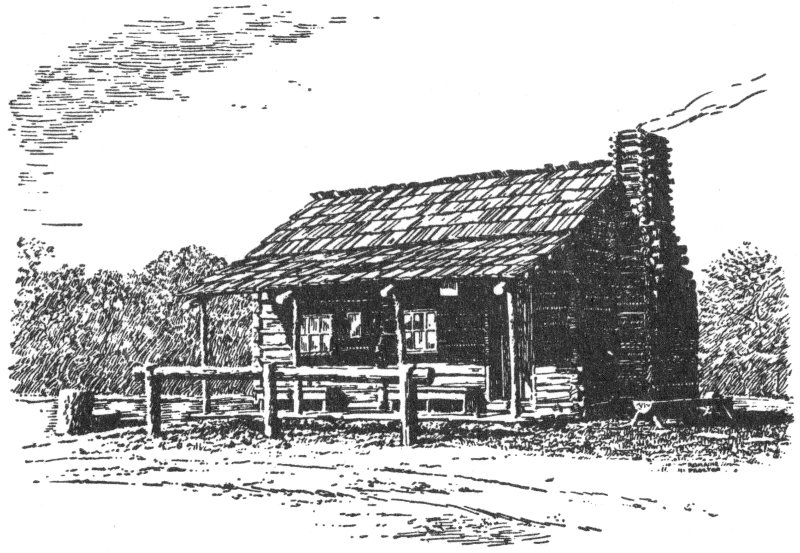

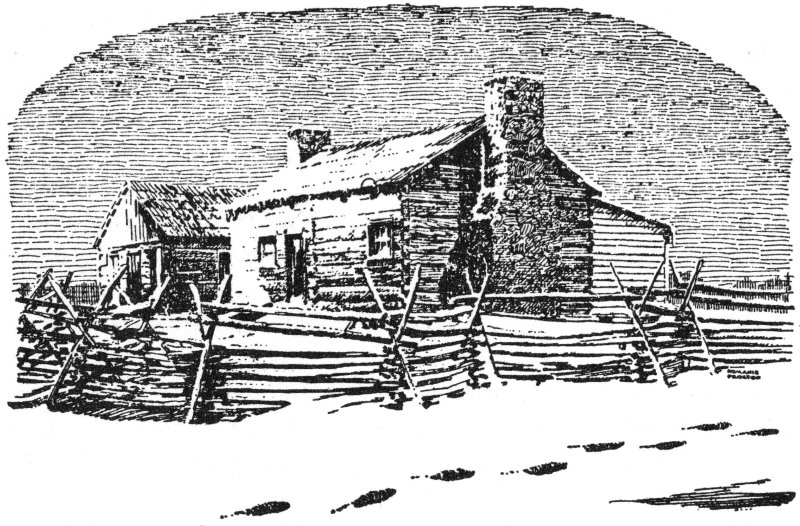

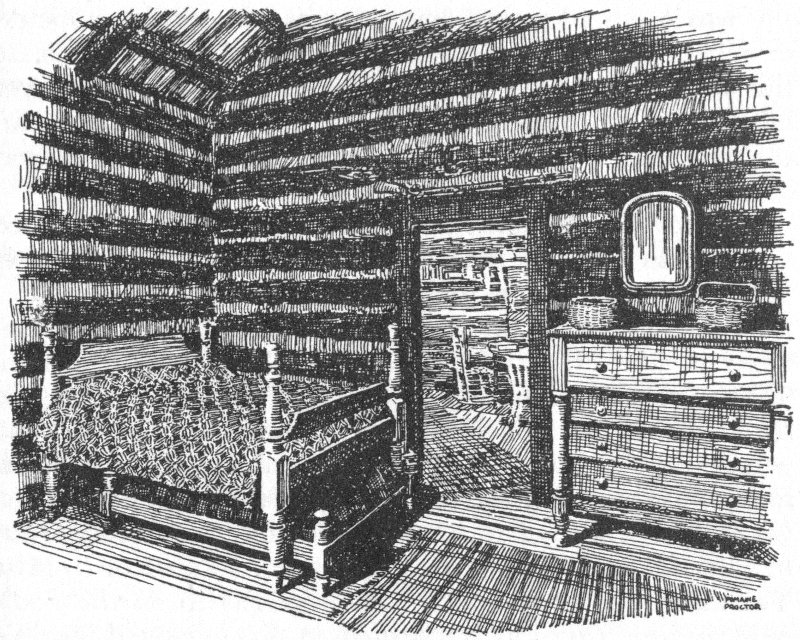

Although the neighboring farm houses were in many cases crude, the buildings in New Salem were fairly substantial and comfortable structures. Most of them were log houses rather than cabins. The frontiersman drew a distinction between these two types of structures. Peck’s New Guide for Emigrants (1837) says: “A log house, in western parlance, differs from a cabin, in the logs being hewn on two sides to an equal thickness, before raising; in having a framed and shingled roof, a brick or stone chimney, windows, tight floors, and are frequently clapboarded on the outside and plastered within. A log house, thus finished, costs more than a framed one.”

All the houses in New Salem, except Hill’s residence, were one story high. Occasionally they had a loft above. With few exceptions they had one or two rooms. Writing of the early one-room house, Onstot said: “At meal time it was all kitchen. On rainy days when all the neighbors came there to relate their exploits, how many deer and turkeys they had killed, it was the sitting room. On Sunday when the young men all dressed up in their jeans, and the young ladies in their best bow dresses, it was all parlor. At night it was all bed-room.”

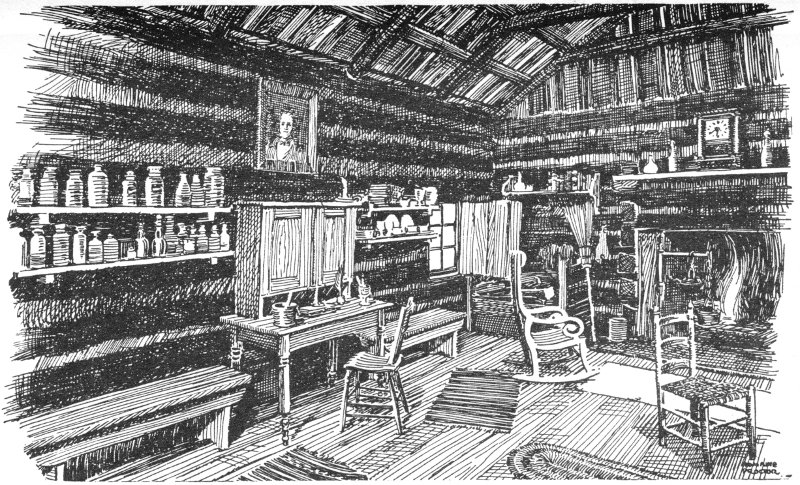

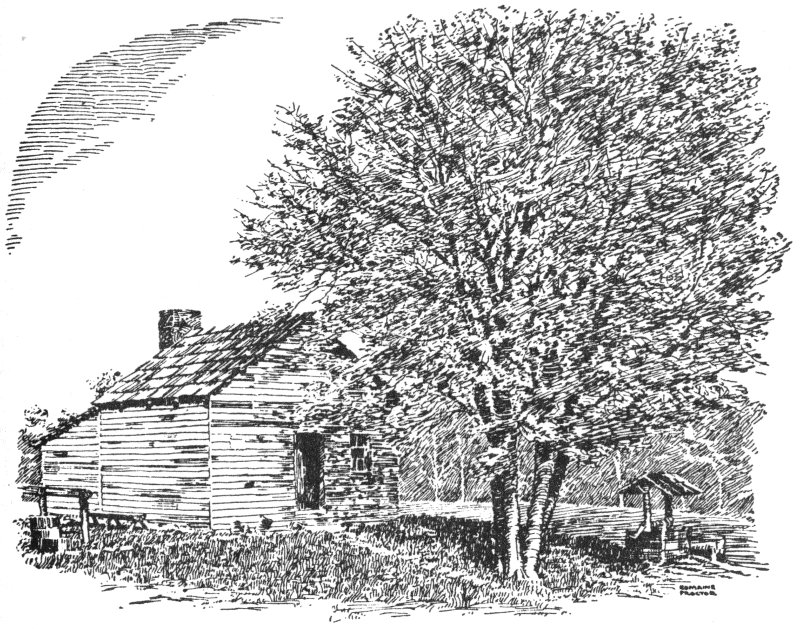

THE INTERIOR OF PETER LUKINS’ HOUSE

Houses built before the coming of Joshua Miller, the blacksmith, had wooden hinges, latches, and locks. In those built later, these fittings were often of iron. Those antedating the mill had puncheon floors, and were of cruder construction than those for which planks for floors, ceilings and siding could be sawed at the mill. Fireplaces were made of stone or brick; chimneys of stone or of the “cat and clay” type—logs and sticks chinked with mud or plaster. When a chimney was built on the inside of a cabin, between two rooms, it was invariably made of stone because of the danger of fire. On windy days persons with “cat and clay” chimneys had to go outside frequently and look at them to be sure they were not on fire.

Roofs were built of clapboards or shingles—sometimes called “shakes”—held in place by nails or by logs, known as “weight poles,” laid across them. Walls were of logs, notched and fitted together at the corners, and chinked with sticks and plaster made of mud and hair. Doors were of frame construction. Those with wooden latches had buckskin latchstrings, which were tied to the latch and passed outside through a hole above it. When only friends were about “the latchstring was always out,” but in time of danger it could be pulled in through the hole.

Two of New Salem’s stores were of frame construction. Hill’s store, his residence, and Offut’s store had porches. Almost all New Salem structures had glass windows; for there was a glazier at Springfield at least as early as 1832, and glass and nails were available at St. Louis before that time. Usually windows were situated near the fireplace where cooking was done and near which most family activities 19 were carried on. Because the prevailing winter winds were from the north and west, windows were almost always cut in the south or east walls. The first house in the New Salem neighborhood to have glass windows, instead of the greased paper variety, was that of George Spears, built in 1830 at Clary’s Grove. Spear’s house was also the first to be built of brick. The mud for the bricks was trampled by oxen. None of the houses in New Salem was of brick, although there were some brick houses close by.

On the bluff above the river, the New Salem settlers were more exposed to the elements than their neighbors in the lowlands. Clarke recorded that in the summer of 1835 “a violent tornado past over this part of the country and blew down all the fences and destroyed much timber.” Biting winds swept the hill in winter time. Occasionally snow sifted down the wide chimneys, deadened the coals in the fireplace, and spread a thin white covering on the floor. At times the wind drove the stinging wood smoke back into the room. On bitter winter days, even with a roaring fire, the unplastered cabins were often cold.

The winter of 1830-31—the winter of the “deep snow”—was especially severe. In December a raging storm piled up the snow three feet deep on the level. Then came rain, which froze and formed a crust of ice. On top of this was deposited a layer of fine, light snow. The storm ended with a cutting northwest wind, which drove the snow across the prairie in a blinding, choking swirl. Tracks made one day were obliterated by the next. Feed was still in the fields, and on some of the newer farms sheds had not yet been erected for the stock. The crust would support a man; but horses broke through. Deer were a helpless prey for wolves, for their sharp hoofs cut through the crust and prevented them from running. Day after day the thermometer got no higher than twelve below, and for three weeks there was no thaw. For nine weeks snow covered the countryside. When it melted all the streams were swollen out of their banks.

HENRY ONSTOT’S COOPER SHOP AND RESIDENCE. THE COOPER SHOP IS THE ONLY ORIGINAL BUILDING AT NEW SALEM

The winter of 1836-37 was also hard. That was the year of the “sudden freeze,” when a quick shift of the wind caused the temperature to take a precipitate drop. It had been raining for some time, and water and slush turned almost instantly to ice. Geese and chickens were frozen to the ground. Several people, caught on the open prairie, died. Clarke told of a drove of 900 hogs that were overtaken on the prairie four miles from house or timber. “The men left the hogs and made out to get to a house alive although they were very much frozen one was not expected to live. The hogs piled themselves up into a heap and remained there three days before the[y] could be got away and then they were hauled on sleds, twenty only were found dead.” Washington Crowder, riding into Springfield, attempted to dismount at a store, “but was unable to move, his overcoat holding him as firmly as though it had been made of sheet iron. He then called for help, and two men come out, who tried to lift him off, but his clothes were 21 frozen to the saddle, which they ungirthed, and then carried man and saddle to the fire and thawed them asunder.” Sun and rain, wind, snow and cold were important factors in the lives of the pioneers.

Most settlers in the New Salem vicinity made their living from the soil. To break the hard-baked, untilled prairie, covered with long, thick-rooted, matted grass, with oxen—sometimes several yoke—was arduous labor for the strongest men. Twenty to forty acres was all that could be broken in a year. James McGrady Rutledge, of Sand Ridge, owned three yoke of oxen, which he hired out to break land. Even after the land was broken, plowing was hard work. The plows had steel shares; but the mouldboards were made of wood, and scoured poorly in the sticky soil. A plow with a long, sloping mouldboard was best suited to the hard or muddy prairie loam. Corn was cultivated by hand with a hoe, or with a “bull tongue” plow. Grain was cut with a sickle, threshed with a flail, and winnowed by tossing it in a sheet so that the wind would blow away the chaff. A few settlers, like Tom Watkins, of Clary’s Grove, tried stock raising on an extensive scale, letting their stock run at large on the prairie.

The women worked harder than the men. Clarke wrote that “a man can get corn and pork enough to last his family a fortnight for a single day’s work, while a woman must keep scrubbing from morning till night the same in this country as in any other.” Women prepared the food, bore and cared for the children, spun thread, wove cloth and made clothes, churned the butter, made soap and candles, and performed most of the humble, humdrum, necessary tasks. An English traveler noted that central Illinois was “a hard country for women and cattle.”

Marriageable girls did not stay single long. Clarke told of one who arrived from the East in June and by August had “had no less than four suitors, . . . three widowers and one old batchelor.” A man often outlived two wives, 22 and sometimes three. Families were large, and babies came in annual crops. James Rutledge had nine children, and Camron was the father of eleven girls. Mathew S. Marsh, writing from New Salem to his brother in 1835, complained that he had “one objection to marrying in this State and that is, the women have such an everlasting number of children, twelve is the least number that can be counted on.” “Granny” Spears of Clary’s Grove, a little old woman whose chin and nose nearly met, officiated at more than half the births in the community. “When weaned, usually by the almanac, youngsters began to eat cornbread, biscuits, and pot likker like grownups. The fittest survived and the rest ‘the Lord seen fitten to take away.’”[13]

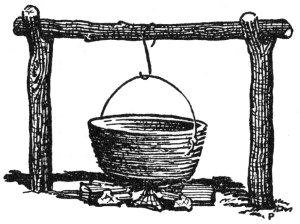

Cooking was done over the open fire, sometimes on a “flat oven,” or in a “Dutch oven”; and with skillet, frying pan, iron pot and kettle. Stoves were unknown, and matches were just coming into use. The basis of the diet was corn meal, prepared in every way from mush to “corn dodgers,” the latter being often hard enough “to split a board or fell a steer at forty feet.” This was supplemented by lye hominy, vegetables, milk, pork, fish and fowl. Honey was generally used in place of sugar. In summer grapes, berries and fruit were added to this fare. The women made preserves, but most families used them only on special occasions or when company came. Ned Potter had a sugar camp and Mrs. Potter’s maple sugar “was legal tender for all debts.”

Men wore cotton, flax or tow linen shirts, and pants of the same material or jeans or buckskin. In winter they wore hats or caps of wool or fur, sometimes with the tail of the animal dangling down behind; while in summer plaited hats of wheat straw, oats or rye were the style. Boots and shoes were supplanting the moccasins formerly worn by both sexes, although moccasins were still to be seen. Women were supplementing their dresses of wool, flannel and flax with cotton and calico clothes. Cotton handkerchiefs, sunbonnets and straw hats were all used for feminine headgear. 23 Children were often clad only in a long tow linen shirt. In summer most of them—and sometimes their elders as well—went barefoot.

Each family produced most of what it used, although the presence of craftsmen in the village indicates some division of labor. But even craftsmen had gardens, and some of them bought farms; while farmers occupied the winter months with some sort of handicraft, producing articles for personal use or for sale. Almost every family kept a cow. Beside the houses gigantic woodpiles mounted during summer and fall, and dwindled as winter passed. Rain barrels caught the “soft” water that dripped from eaves. Lye for soap-making was leeched from wood-ashes in hoppers in back yards. Drinking water was obtained from wells, one of which was dug beside the Rutledge tavern and another near the Lincoln-Berry store.

Furniture was of the simple pioneer sort. Some of it had been brought from former homes, often with great difficulty; other pieces were homemade or made by Robert Johnson in New Salem. Poor families had tables made of puncheons or unplaned boards, crude chairs, and “scaffold” beds, the framework for the latter being made by erecting a forked upright in a corner of a cabin about six feet from either wall and laying a pole from the upright to each wall. Families of moderate means had rush seat chairs, cord and trundle beds, chests of drawers of plain but skilful workmanship. The boys were delegated to keep the woodbox, always found beside the fireplace, filled with logs. Corner cupboards were adorned with glass and chinaware. For those who could afford them, Seth Thomas clocks were the style. Rifles and shotguns hung on wooden pegs or brackets, or on deer or cow horns, over doors and on the walls. Tongs, spurs, bootjacks, candle-moulds hung beside the mantels. At night candles in brass or iron holders shed soft light through the rooms.

Merchants stocked their shelves with dry goods, furs, 24 mittens, seeds, hides, tallow, lard, bacon, cheese, butter, bees wax, honey, eggs, hops, vegetables, firearms and ammunition, saddles, ox yokes, tools. In every store barrels of liquor stood along the wall. A few traders bought commodities from the farmers and sold them in St. Louis and New Orleans; and occasionally a farmer, having accumulated a surplus, loaded it on a raft or flatboat and floated down the Sangamon to Beardstown, thence down the Illinois and Mississippi to St. Louis, or even to New Orleans. The few commodities brought from afar—sugar, salt, coffee—came by boat from New Orleans or Cincinnati to St. Louis or Beardstown, and from there were distributed overland.

Some money came into the village through trade and some was brought by immigrants; but for the most part money was scarce and of uncertain value. Currency was chiefly bank notes, issued by banks good, bad and indifferent, which passed at various discounts depending on the reputation of the bank of issue. Counterfeit notes were common. Trade was carried on largely through long term credit. A man would bring his wool, for instance, to Hill’s wool house, and instead of cash would receive a credit at Hill’s store. He would draw on this from time to time throughout the year. Another individual might be “carried” by Hill until he sold his crops. The craftsmen of the village exchanged their wares for products of the farms and struck a balance with the farmers at the end of the year. Doctor Allen accepted dressed hogs, bacon and lard in payment of bills, barrelled up his products and shipped them to Beardstown and St. Louis.

Writing of the people of the West generally and of Illinois in particular, Peck said (1834): “They have much plain, blunt, but sincere hospitality. Emigrants who come amongst them with a disposition to be pleased with the people and country,—to make no invidious comparisons,—and to assume no airs of distinction,—but to become amalgamated with the people . . . will be welcome.” This characterization 25 was applicable to the people of the New Salem community. They were of the third wave of migration, having been preceded by the roving hunters and trappers and the restless squatters, who stayed a few months and moved on. They were mostly farmers, many of them with some stock and capital, who bought land, or hoped to do so soon. They were home builders, who expected to remain and eventually to attain to a standard of living comparable to that of the regions whence they came. They too were restless, however, and many of them moved on, hoping to find better locations farther west.

The backbone of the community was the Southern pioneer element, represented by the Clarys, Armstrongs, Kirbys, Watkins, Potters, Rutledges, Camrons and Greenes. The Chrismans were Virginians; Peter Lukins and his brother Gregory came from Kentucky; the Grahams and Onstots, from Kentucky and Tennessee; the Berrys, from Virginia through Tennessee and Indiana.

Interspersed with the predominant Southern element were a few Yankees—C. J. F. Clarke and Mathew S. Marsh, who entered land southwest of New Salem, and Doctor Allen, who represented the New England reformer type. Sam Hill was from New Jersey, John McNeil from New York, and Doctor Regnier was of French extraction. The Southerners came by families; the Yankees and Easterners were individuals, who left their families to seek health, wealth or adventure.

Like Westerners in general, the people of New Salem were young, enthusiastic, self-reliant, willing to take a chance. Equality of opportunity was in large degree a fact, and courage, endurance and ingenuity were the requisites of success. Wealth, “kin and kin-in-law didn’t count a cuss.” Government was of, by and for the people, with public opinion as the most effective force.

There were two elements in the place: a happy-go-lucky, rough and roistering group, typified by the Clary’s Grove 26 boys, and men of a more serious turn like Allen, Rutledge, Onstot, Regnier and Graham. But social lines were not drawn. Preacher and ne’er-do-well, doctor and laborer took part together in the village life. Grocery keeper and temperance advocate; farmer, craftsman, merchant; Yankee and Southerner rubbed elbows with each other. Diverse types were represented in the groups that idled at the stores. Discussions in such groups brought out conflicting opinions and differences in point of view. Men learned what other men were thinking.

Most notorious of the roistering, sporting crowd were the boys from Clary’s Grove. They were always up to mischief of some sort. “They trimmed the manes and tails of horses, cut girths, put stones under saddles so as to cause riders to be thrown mounting.” Favorite sports of this crowd were cock-fighting, gander-pulling and wrestling. The cock pit was across the road from Clary’s grocery, and the gander-pulling ground was at the eastern end of town, along the bluff. In this sport, a tough old gander, its neck thoroughly greased, was tied, head down, to a limb of a tree. Then the contestants rode at full speed under the limb, and the one who could snap off the gander’s head as he dashed by, got the bird.

On the frontier men settled their disputes with fists, feet and teeth as often as they resorted to the courts; or fought first and sued each other afterward. Sometimes they fought for the sheer love of fighting. Sam Hill, a small man himself, once offered a set of china dishes to John Ferguson, who had considerable local renown as a “scrapper,” if he would whip Jack Armstrong, with whom Hill had had a quarrel. Ferguson accepted, and being larger than Armstrong, finally won; but he took such punishment that he later declared that the dishes would have been dear at half the price. On one occasion two incorrigible enemies fought out their differences on the other side of the river while the whole population watched from the bluff. Finally, when 27 both men were down, a party crossed the river and pulled them apart. One of them was so severely beaten that he died of his hurts within a year.

But these ultra-virile aspects of the community life should not be overstressed. T. G. Onstot, relating the story of this fight, described it as typical of the frontier civilization of that day, but he added, “many of the old citizens never had to contend with its barbaric customs. Only those who trained in that school were subject to its conditions.” Besides the rough sports of the Clary’s Grove boys there were social events of a milder nature. Clarke recorded: “I attended an old fashioned Kentucky barbecue last week . . . where they had feasting and drinking in the woods, the people behaved very well. There were many candidates present and each one made a stump speech. . . . I have an invitation to a wedding next thursday and expect to have a real succor wedding. It is to be in a log cabin with only one room, we shall probably stay all night as the custome is in this country, and the probability is, the floor will be the common bedstead of us all.”

This custom of all sleeping together on the floor was necessitated by the size of the houses and the distance that people had to travel to social functions. Peck said of it: “On the arrival of travelers or visitors, the bed clothing is shared with them, being spread on the puncheon floor, that the feet may project towards the fire. . . . All the family, of both sexes, with all the strangers who arrive, often lodge in the same room. In that case, the under garments are never taken off, and no consciousness of impropriety or indelicacy of feeling is manifested. A few pins, stuck in the wall of the cabin, display the dresses of the women and the hunting shirts of the men.”

Dances, house-raisings, wolf hunts, militia musters and camp meetings made life at New Salem far from dull. Clarke wrote that at the frequent quilting bees each of the guests would “take his or her needle as the case may be for 28 any man can quilt as well as the women.” Guests came shortly after breakfast, quilted until about two o’clock, then had a “good set down” until ready to go home. Once there was a circus at Springfield, and several New Salem men, loading wives, children, neighbors and food into farm wagon or buckboard, jounced twenty miles over the rutted road to see it. Impromptu footraces and horse races provided amusement and thrills; and every year there were formal race meets in each county under the sponsorship of local jockey clubs. The horses for these events were imported from Kentucky and Tennessee “by gentlemen that do nothing else for a livelihood and some of them have as high as fifteen and twenty horses.” The jockey clubs provided the purses, and betting was private.

A favorite pastime was shooting for a beef. Some one, wishing to make a little money, would announce that at a certain time and place a beef would be shot for. The word would spread, and settlers from miles around would gather at the appointed place. A subscription paper was then passed around stating, for example, that “Tom Watkins offers a beef worth twenty dollars at twenty-five cents a shot.” The contestants subscribed their names with the number of shots they would take.

| Jack Armstrong | puts in four shots | $1.00 |

| Royal Clary | “ “ eight “ | 2.00 |

| Jack Kelso | “ “ two “ | .50 |

Finally the twenty dollars would be made up.

Judges were then chosen, and each contestant made a target—usually it was a board with a cross in the center. Each man’s target was placed in turn against a tree as he shot. The judges then took the boards and graded the shots, and the five best shots each got a part of the beef. The best one got the hide and tallow. The next best had his choice of the hindquarters. The third took the other hindquarter. The fourth got his choice of the forequarters, and the fifth took the remaining forequarter. The sixth got the lead in 29 the tree against which the targets had been placed. An expert marksman, if he bought enough shots, could sometimes win the whole beef.

On the Fourth of July and during political campaigns, barbecues were held. Some one would donate a heifer, another a shoat; still others turkeys, chickens, pies and loaves of bread. Long trenches were dug in which the fires were lighted a day or two before the event, so that a bed of red-hot coals would be ready for the cooks. The beef and pig were quartered and hung over the fire on long iron rods. Every few minutes, as the rods were turned, the cooks basted the meat with melted butter. After dinner came patriotic orations or political speeches, followed by athletic feats. T. G. Onstot recalled that they had a heavy old cannon, and the boys “nearly strained their gizzards out” to see which ones could shoulder it.

There was even a budding intellectuality in the place. James Rutledge is said to have had a library of twenty-five or thirty volumes. Doctor Allen was a graduate of Dartmouth. Jack Kelso, a lazy dreamer, who knew where to catch the best fish, how best to snare small game, and who was an expert rifleman, was familiar with the works of Shakespeare and Burns, and could quote long passages. Rev. John M. Berry, who lived on Rock Creek but often preached at New Salem, John Camron, Doctor Regnier and James Rutledge were fairly well educated. Rutledge organized a debating society in 1831. David Rutledge, his son, William F. Berry, son of John M. Berry and Lincoln’s partner for awhile, William G. Greene and his brother, L. M. Greene, and Harvey Ross, who carried the mail to and from New Salem, attended Illinois College at Jacksonville, about thirty miles away. In Clarke’s Opinion that institution was “doeing more for this country than any eastern man could expect,” and its students “almost astonish the old folks when they come home.”

The school at New Salem was taught by Mentor Graham, 30 a serious, self-educated man in his early thirties, who lived in a brick house about a mile west of town. He came to Sangamon County from Kentucky in 1828, and first taught school at the Baptist Church on the Felix Greene farm about a mile southwest of New Salem. Referring to the subject of school teaching, Clarke informed his relatives back East that it was “good business worth from eighteen to twenty-five dollars pr. month clear. Schools are supported here different from what they are in N. England every one pays for the number he sends, there is no tax about it.” A statement submitted by Graham to Jacob Bale, covering tuition for the latter’s children from 1833 to 1840, shows that Graham’s subscription rates ranged from thirty to eight-five cents a month for each pupil, evidently depending on the child’s age. Five cents per pupil was his rate by the day.

New Salem had a relatively healthy site; but it was not immune to the malarial fever, typhoid and ague with which the Sangamon country was afflicted. The latter disease was so common on the frontier that settlers hardly regarded it as a disease at all. “He ain’t sick,” they said, “he’s only got the ager.” In the early thirties there were cholera epidemics in the vicinity and in 1836, smallpox was prevalent. But settlers consoled themselves with the argument that these diseases occurred only in the summer months, and that there were no “lingering complaints like the consumption” with which so many Easterners were afflicted.

Pioneer remedies were a combination of domestic experience, superstition and lore. Whiskey, purgatives, bitters made from roots and barks, brimstone, sulphur, scrapings from pewter spoons, gunpowder and lard, and tobacco juice were tried for various complaints. Cayenne pepper in spirits on the outside, and whiskey within, were good for stomach ache. A piece of fat meat, well peppered, and tied around the neck was a common treatment for colds and sore throat. A bag of pounded slippery elm over the eye was supposed to draw out fever. Raw potato poultice was tried for headache. 31 The breaking out of eruptive diseases was hastened by doses of a concoction made from sheep dung known as “nanny tea.” A seventh son could supposedly cure rash by blowing in children’s mouths.

With many communities entirely dependent upon such homemade remedies or upon the prescriptions of local “yarb and root” doctors, New Salem was fortunate in having Doctor Allen as a resident. Young Doctor Regnier, stout, witty, eccentric, the son of a French physician, was a capable colleague of Allen’s. Their judgment and experience were invaluable to the community. Like most pioneer doctors, they worked under handicaps, for the self-reliant frontiersmen called the doctor only when home remedies had failed, and drastic treatment was demanded. There was reason for their reluctance, for even educated doctors like Allen and Regnier used treatments of appalling severity. They “purged, bled, blistered, puked, and salivated.” Twenty to one hundred grains of calomel was a common dose. Pills were often as big as cherries. Wet sheets were wrapped around a sufferer to counteract fever. Severe types of ague were combatted by treatment designed to bring on the shakes. “Carry then your patient into the passage between the two cabins . . . and strip off all his clothes that he may lie naked in the cold air and upon a bare sacking—and then and there pour over and upon him successive buckets of cold spring water, and continue until he has a decided and pretty powerful smart chance of a shake.”[14]

Allen was as much interested in saving men’s souls as in ministering to their bodies. He organized a Temperance Society in which he was assisted by John M. Berry. There was need for such an organization, for New Salem was a hard-drinking place. George Warburton, one of the town’s first merchants, a thrifty, capable man when sober, was found face down in the shallow water of the river after a drunken debauch, and Peter Lukins, another heavy drinker, 32 also died after a Spree. Few even of the better citizens were teetotalers, and Onstot recorded that Allen, in his temperance enterprise, “found his worst opponents among the church members, most of whom had their barrels of whiskey at home.”

Much of this whiskey was made in or near the town. Lincoln said that he worked the latter part of one winter “in a little still-house, up at the head of a hollow.” In all grain growing regions where transportation was difficult whiskey was distilled on a wholesale scale. A horse could carry about four bushels of corn in the form of grain, and the equivalent of twenty-four bushels in the form of liquor. Besides the economic motive, there were other reasons for whiskey making. Whiskey was a standard remedy and preventive of disease. Some people regarded alcohol as a necessity for persons engaged in strenuous work. While temperance agitation had made some headway and was destined to spread rapidly during the next decade, Allen was somewhat ahead of the times, for in the thirties the making and drinking of whiskey was not generally condemned. The prevailing attitude toward liquor is illustrated by the fact that a man was dismissed from a Baptist church near New Salem for joining Doctor Allen’s temperance society. At the same time another member was dismissed for drunkenness; whereupon a third member, rising excitedly to his feet and shaking a flask in his hand, shouted: “Brethering, it seems to me you are not sistenent [consistent] because you have turned out one man for taking the pledge and another for getting drunk. Now, brethering, how much of this critter have a got to drink to have good standing amongst you?” Camp meetings, funerals, weddings and house-raisings were often enlivened by the strange conduct of drinking men.

Besides leading the temperance movement, Allen organized the first Sunday School in New Salem. A strict Sabbatarian, for years he refused to practice on Sunday. Finally he compromised by giving all his Sunday fees to the church. In his home all the Sunday food was cooked on Saturday.

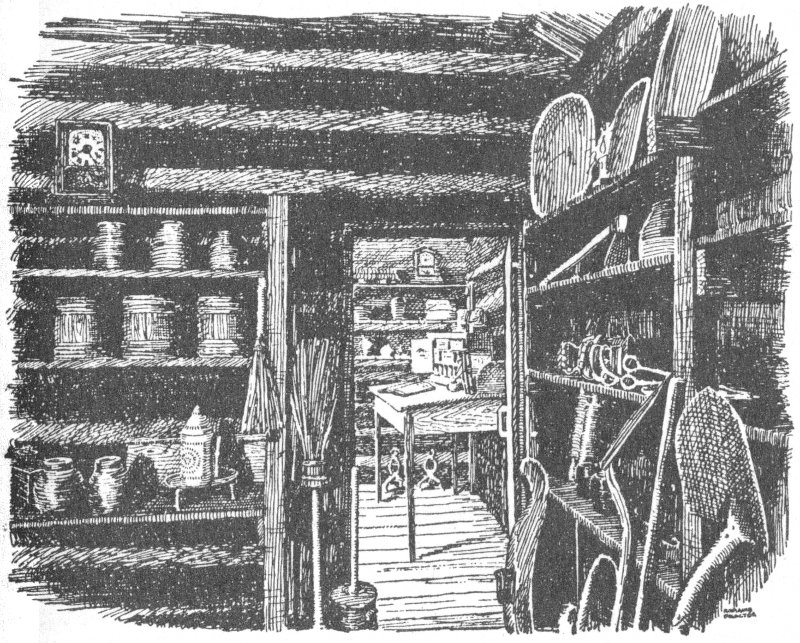

THE INTERIOR OF DOCTOR ALLEN’S HOUSE

The strongest religious sects in the New Salem neighborhood were the “Hardshell” Baptists, Cumberland Presbyterians and Methodists. Strange new sects were continually forming, however, as the self-reliant pioneer—usually with untrained mind and faulty logic—exercised the prerogative of interpreting the Scriptures for himself. Clarke noted that besides the denominations mentioned there were many others “that deserve no name.” Mentor Graham and Joshua Miller were leading Baptists. Onstot, Allen, Berry and Camron were Presbyterians. Every year camp meetings were held at Concord and Rock Creek. The Rutledges, Onstots and Berrys were enthusiastic “campers.” So was James Pantier of Sand Ridge, an eccentric “faith doctor,” noted for his ability to cure snake bites. “Uncle Jimmy,” as the latter was called, sat on the front row and repeated the sermon after the preacher. If he disagreed with the doctrine expounded, he would shake his finger and exclaim, “Now, brother, that ain’t so.”

Peter Cartwright, the famous Methodist circuit rider, whose home was at Pleasant Plains, ten miles from New Salem, often preached at these camp meetings, which were of the old-fashioned, emotional sort. Sometimes as the preacher warmed to his work and “swung clear,” members of the congregation, overcome with hysteria, would be seized with the “jerks.” Cartwright told of having seen five hundred persons jerking at one time. “Usually persons taken with the jerks,” wrote Onstot, “to get relief would rise up and, dance, some would try to run away, but could not, some would resist, and on such the jerks were very severe.” The women especially were addicted to this hysteria. The first jerk would loosen bonnets, caps and combs, “and so sudden would be the jerking of the head that their long loose hair would crack almost as loud as a waggoner’s whip.” Mrs. Robert Johnson, wife of the New Salem wheelwright, 35 was particularly susceptible to the exhortation of the frontier preachers, being seized with the jerks almost every year.

There were smaller gatherings in the schoolhouse, in Doctor Allen’s residence and other homes, where James Camron and John M. Berry preached and prayed. Onstot described “Old John Berry,” a veteran of the War of 1812, as tall and well formed, “the noblest Roman of them all,” who, “like Paul among the prophets stood head and shoulders above his brethren.” Well versed in the doctrines of his faith, a leader in the Rock Creek lyceum and in the New Salem community life, Berry, said Onstot, “did as much to civilize and christianize the central part of Illinois as any living man.”[15]

The ruffians of the neighborhood were a constant tribulation to the religious element. When the Baptists immersed their converts in the Sangamon below the bluff, they were wont to throw in logs and dogs and otherwise to disturb the proceedings.

There were also some free thinkers in the community, who read Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason and Constantine de Volney’s Ruins of Empire, and who questioned the pronouncements of the preachers. According to Herndon, Lincoln belonged to this skeptical group.

The church members had little hope for them. Preachers threatened hell and damnation for those who had the gospel offered to them, but rejected it, and “could hold a sinner over the pit of brimstone till he could see himself hanging by a slender thread.” Clarke observed that the Baptists “preach the hardest election doctring that I ever heard. They say they were created for Heaven (the church members) and such as die in their sins were created for Hell, or in other words, God made a part of mankind for eternal happiness and the ballance for endless misery. This is a kind of doctering I cant stand.”

The Methodists and Baptists looked askance at preachers 36 who were college trained. Preachers of the old school suspected college men of having no religion in their hearts and knowing nothing about it except what they learned at school. Peter Cartwright rejoiced that he had not spent four years “rubbing his back against the walls of a college.” Written sermons were taboo; and even preparation was frowned upon by some. A true preacher got his inspiration directly from the Lord as he spoke. Preachers often “made up in loud hallooing and violent action what they lacked in information.”

Deeply concerned with creeds and the externals of religion, church members despaired not only of unbelievers and skeptics, but of those of different faiths as well. Julian Sturtevant, coming from Yale to teach at Illinois College, wrote: “In Illinois I met for the first time a divided Christian community, and was plunged without warning or preparation into a sea of sectarian rivalries, which was kept in constant agitation.” Methodists and Baptists argued endlessly “about the way to heaven, whether it was by water or dry land,” while both scorned the “high toned doctrines of Calvinism” and the “muddy waters of Campbellism.” Cartwright told of a mother who, at one of his revivals, forcibly tore her daughters from the altar to prevent their becoming Methodists.

Yet religion was a potent force for good, and in some respects an intellectual stimulus. Sermons, poor as they often were, gave many people their only examples of creative mental work, while discussions of salvation, baptism, morals and faith provided a sort of intellectual free-for-all.

Such was New Salem in its day; but its day was brief. Seven years after its birth its decline had already begun. In 1836, a last attempt was made to navigate the Sangamon, when the steamboat Utility ascended the river as far as New Salem and tied up at the dam. But the river fell rapidly, and there she stuck. All attempts to float her failed, and she was finally sold and dismantled. The most optimistic 37 now admitted that New Salem had no future as a river town.

Meanwhile, as Springfield grew it restricted New Salem’s trading area on the south and southeast. The growth of Athens narrowed it on the east. Beardstown, Chandlerville and Jacksonville encroached upon it to the west and southwest. New Salem might have been compensated by increased trade with the growing settlements to the north; but trade expansion in that direction was prevented by the founding of Petersburg.

The original efforts of Lukins and Warburton to found a town, in 1832, had not gone very far; but in 1836, John Taylor took over the Petersburg project, had Lincoln re-survey the town, and promoted it vigorously. As settlers filled up the Sand Ridge and Indian Creek neighborhoods, Petersburg and not New Salem became their trading center. The removal of the post office from New Salem to Petersburg, on May 30, 1836, foretold the former’s doom.

Even before 1836, several of New Salem’s first residents had moved away; after that an exodus took place. Doctor Regnier moved to Clary’s Grove, and then to Petersburg. Whary, Burner, Waddell, Morris, Kelso pulled up stakes and tried their luck again farther west. Alexander Ferguson and Joshua Miller bought farms in the vicinity. In 1837, John McNeil, who had bought the Lincoln-Berry store when the Trent brothers failed, moved it to Petersburg. Doctor Allen, who had been an inactive partner of McNeil, followed soon afterward. Lincoln moved to Springfield. Hill sold the carding machine and wool house to the Bales. As people moved away the Bales bought their land, and eventually owned the whole village site.

By 1836 there were almost 4,000 people in the northern part of Sangamon County, and demand for the establishment of a separate County was becoming more and more insistent. Petersburg was the prospective county seat. On January 15, 1837, Clarke wrote: “When I first came here 38 there was but one store and two dwelling houses in Petersburg. There are now seven stores and the number increasing this has all ben don within the last year, the place would grow much faster if they could get carpenters to do the work. The town lots . . . were sold a little more than a year ago for ten to twenty dollars each, they now sell for fifty to one hundred and fifty, the reason of this is we are about to get a new county here and this place will undoubtedly be the county seat.”

On February 15, 1839, the Legislature set Menard County off from Sangamon; and as had been anticipated, Petersburg was made the county town. To New Salem this was the final blow. Hill, Onstot and its few remaining residents now deserted their old homes and established themselves in the more promising place. By 1840, New Salem had ceased to exist.

One day in late April, 1831, a crowd gathered on the river bank near the New Salem mill. They were watching four men who were working over a flatboat that had stranded on the dam. The men had tried to float the boat over the dam; but halfway across it had stuck. Now, with its bow raised in the air and shipping water at the stern, it was in danger of sinking.

One of the crew, a long, ungainly looking individual, took charge. He was dressed in “a pair of blue jeans trowsers indefinitely rolled up, a cotton shirt, striped white and blue, . . . and a buckeye-chip hat for which a demand of twelve and a half cents would have been exorbitant.” Under his direction the cargo in the stern was unloaded until the weight of the cargo in the bow caused the boat to right itself. The young man then went ashore, borrowed an auger at Onstot’s cooper shop, bored a hole in the bow and let the water run out. He then plugged the hole; and the boat, with lightened cargo, was eased over the dam.

Poling the flatboat over to the bank, the crew came ashore, where the onlookers congratulated them. The owner of the boat introduced himself as Denton Offut. The others were John Hanks, John Johnston and “Abe” Lincoln. The latter was the ungainly youth who had directed operations, and the villagers looked at him with interest. Well over six feet tall, lean and gangling, raw-boned and with coarsened hands, he was a typical youth of the American frontier. He had been born in Kentucky, and had lived there seven years. Then he had gone with his parents to Indiana where they had lived for fourteen years. About a year ago they had moved to Macon County, Illinois. He was now twenty-two. Johnston was his step-brother and Hanks was his 42 cousin. Offut had hired them to take the flatboat to New Orleans.

During their brief stay in New Salem, Offut looked about appraisingly. He believed the place had possibilities, for the tide of immigration to the Sangamo country was rising steadily. He was convinced that the Sangamon could be navigated by steamboats, and loudly announced that he would build a boat with rollers to enable it to get over shoals and runners for use on ice. With Lincoln in charge, “By thunder, she would have to go!” He made arrangements to open a store on his return from New Orleans and to rent the mill.

A strange combination, Offut was enterprising and enthusiastic, but also boastful and vain. “He talked too much with his mouth.” He was dreamy, impractical, too fond of drink. In a sense, however, he was the discoverer of Lincoln. “During this boat enterprise,” as Lincoln later said, “he conceived a liking for Abraham, and believing he could turn him to account, he contracted with him to act as clerk for him on his return from New Orleans.”

The remainder of the voyage was uneventful. At New Orleans cargo and boat were sold, and the crew returned by steamboat to St. Louis. From there Lincoln walked to New Salem, while Offut stayed behind to purchase a stock of goods.

Lincoln reached New Salem in late July, 1831. Shortly after his arrival, on August 1, an election was held. The polls were at John Camron’s house. Here Lincoln voted, probably for the first time. His selections were Edward Coles for Congress, Edmund Greer and Bowling Green for magistrates, and Jack Armstrong and Henry Sinco for constables. The three last named were elected. Lincoln did not serve as clerk at this election, as has been often stated.[16] Throughout the day he loitered about the polls, talking, gossiping and making acquaintances. By evening he had met most of the male inhabitants of the precinct.

At slack moments during the election he amused the bystanders with stories. Among others, he told of an old preacher in Indiana who was accustomed to appear before his congregation dressed in a coarse linen shirt and old-fashioned pantaloons with baggy legs and a flap in front, which buttoned tightly about his waist with a single button, thus making suspenders unnecessary. His shirt was also held together by a single button at the collar. Rising in his pulpit, he announced as his text: “I am the Christ, whom I shall represent today.” About that time a small lizard ran up inside his baggy trousers. Continuing his discourse, the preacher slapped at the lizard, but without success. As it continued to ascend, the old man loosed the button on his pantaloons, and with a swinging kick divested himself of them. But the lizard was now above the “equatorial line of waist band,” exploring the small of his back. The sermon flowed steadily on, but in the midst of it the preacher tore open his collar button and with a sweep of his arm threw off his shirt. The congregation was dazed for an instant; but at length an old lady rose, stamped her foot and shouted: “Well! If you represent Christ, I’m done with the Bible!”

Rowan Herndon, one of those who listened to Lincoln, recounted this story years afterward to his cousin, William H. Herndon. It was evidently the kind of story that appealed to Lincoln’s audience. It also tells something of the Lincoln of this period. Lincoln had already some of the knack of story-telling for which he was later famous. Here, however, he was telling stories merely for the amusement of the bystanders and to win their good-will. He later used stories to illustrate a point or drive home an argument. This is but one instance of his growth between the New Salem days and the presidential period.

While waiting for Offut Lincoln lounged about town getting better acquainted. He boarded at John Camron’s. As days passed and Offut did not come he picked up a little money by piloting a family, bound for Texas, down the Sangamon to Beardstown on a raft, and returned to New Salem on foot.