Worthington, sc.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Waverley Anecdotes, Vol I

Date of first publication: 1833

Author: anonymous

Date first posted: Nov. 6, 2018

Date last updated: Nov. 6, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20181105

This ebook was produced by: Iona Vaughan, Mark Akrigg, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

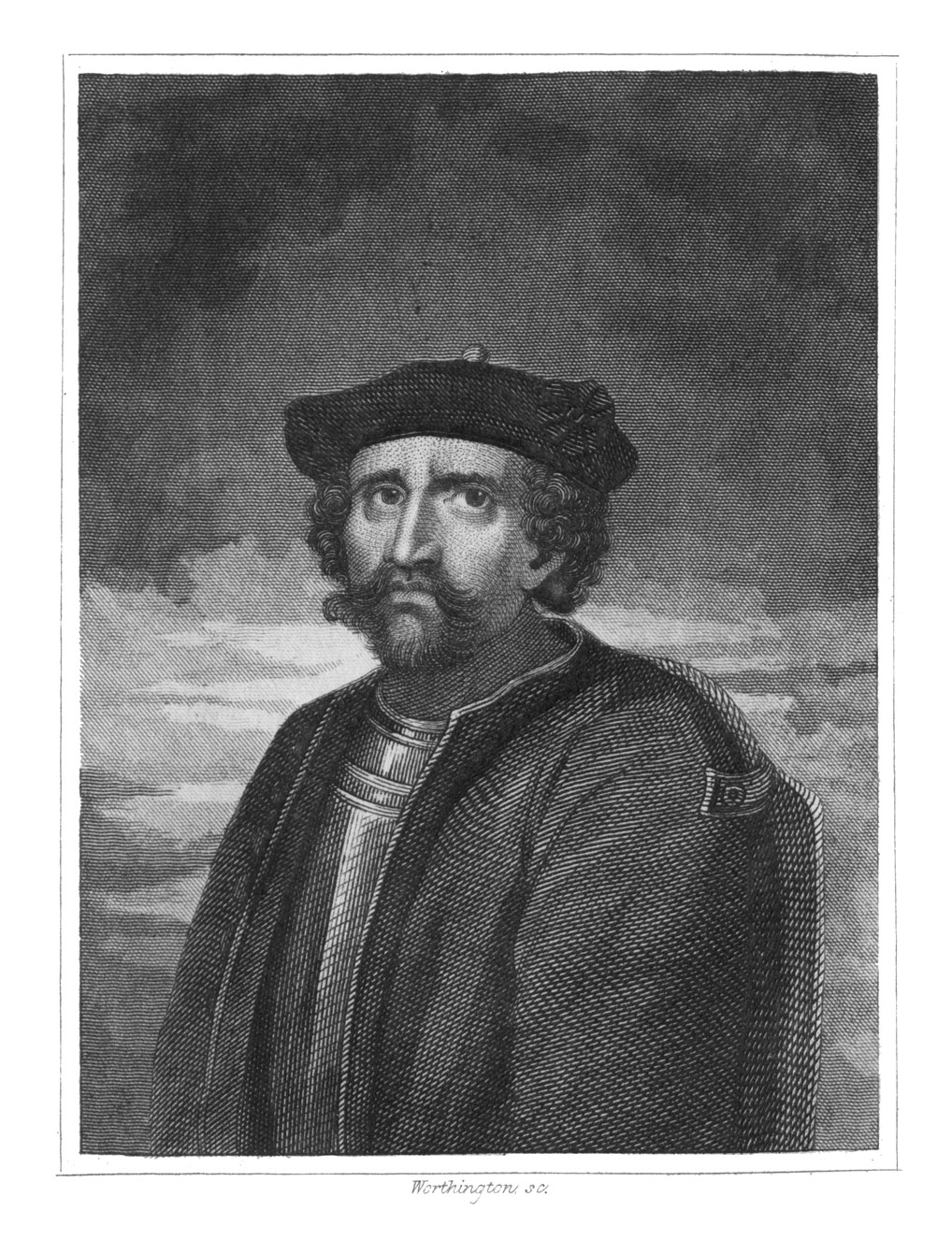

Worthington, sc.

ROB ROY.

FROM AN ORIGINAL DRAWING.

London, Published by James Cochrane & John Mc Crone.

1833.

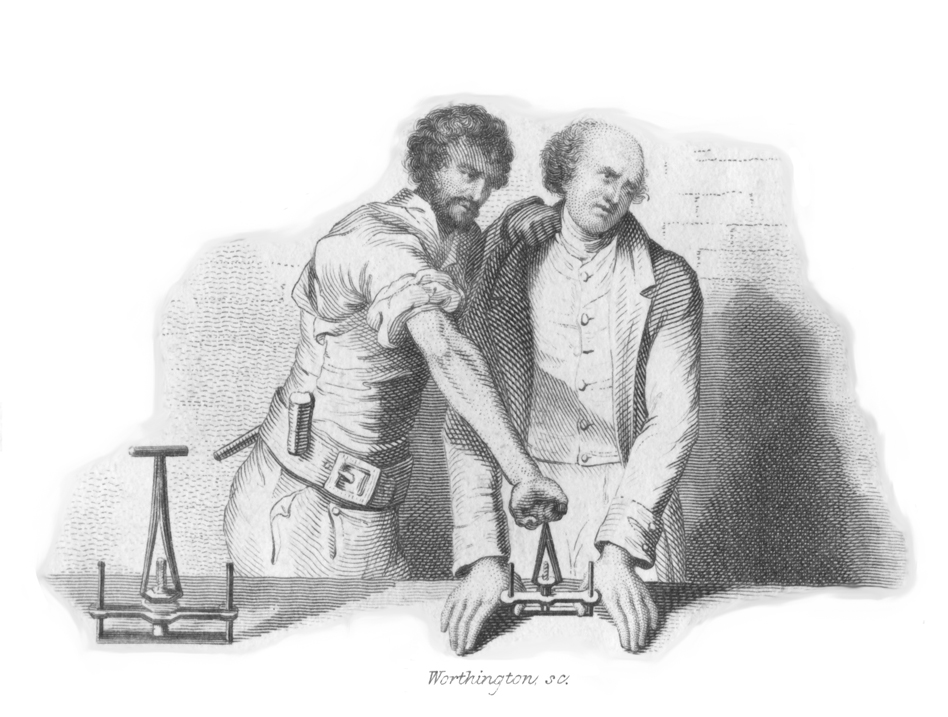

THE TORTURE OF THUMBEKINS.

LONDON:

PUBLISHED BY JAMES COCHRANE AND

JOHN Mc CRONE.

1833.

THE

WAVERLEY ANECDOTES,

ILLUSTRATIVE OF THE

INCIDENTS, CHARACTERS, AND SCENERY,

DESCRIBED IN THE

NOVELS AND ROMANCES,

OF

SIR WALTER SCOTT, Bart.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

J. COCHRANE AND J. Mc CRONE,

11, WATERLOO PLACE.

1833.

LONDON:

G. SCHULZE, 13, POLAND STREET.

| INTRODUCTION. | i |

| Domestic Manners, Costume, &c., of the Ancient Scots. | 1 |

| —Dress. Costume. | 4 |

| —Crimes, Superstitions, Credulity. | 7 |

| —Domestic Manners. | 10 |

| —Language, English and Scots. | 11 |

| —Diet, and Cookery. | 13 |

| —Field sports, Games and Diversions. | 14 |

| Anno Domini 1400 AD A.D. 1548. | 17 |

| Jurisprudence. | 20 |

| An Estimate of the Morals, Manners, &c., of the Scots and English. | 24 |

| —The Hamilton Faction. | 26 |

| —Manners of the Age. | 28 |

| Field of Stirling.—Death of James III. | 30 |

| Notes of Scottish Affairs, From the Year 1680 to 1701. | 40 |

| ——Paterson, Bishop of Edinburgh. | 41 |

| ——Royal Injunction. | 43 |

| ——Costly Coronation of Queen Mary. | 43 |

| ——Political State of Scotland. | 44 |

| ——A Parson fined for getting drunk. | 44 |

| —Torture of the Boots and Thumbiken. | 44 |

| Execution of Rumbold, the Projector of the Rye-house Plot. | 56 |

| ——Punishment for 'Mincing' the King's Authority. | 57 |

| ——Execution of a Drummer and a Fencing Master. | 58 |

| The Highland Fire-Cross. | 59 |

| The Covenanters.—Transactions During the Civil Wars.—Curious Entries. | 62 |

| State of the Scottish Army under General Alexander Leslie, in the Year 1641. | 73 |

| —His Majesties Passing Through the Scots Armie. | 75 |

| ——The Manner of the Scot's Departure. | 77 |

| Battle of Tippermuir. | 78 |

| —Reasons for the Surrender of Perth. | 82 |

| Waverley Novels.——Characters and Incidents, &c. | 90 |

| —Waverley Plot | 93 |

| —Sketches of Characters | 99 |

| Peveril of the Peak. | 107 |

| —Story of Fenella. | 115 |

| —Jeffery Hudson. | 118 |

| Originals. | 121 |

| —Davie Gellatley. | 121 |

| —Paul Pleydell. | 133 |

| —Driver. | 135 |

| —Driver's Shadow. | 143 |

| —Dominie Sampson. | 148 |

| —Dandie Dinmont. | 152 |

| —Meg Merrilies. | 154 |

| Rob Roy Macgregor. | 159 |

| The Antiquary. | 179 |

| —Andrew Gemmels. | 180 |

| —Old-Buck. | 186 |

| Gypsies. | 189 |

| —Elopement of the Countess of Cassilis with Johnnie Faa, the Gipsey Chief. | 189 |

| —The Bohemian. | 202 |

| Gipsey Colony. | 209 |

| Quentin Durward. | 218 |

| —The Revellers. | 235 |

| —The Flight. | 236 |

| —The Unbidden Guest. | 237 |

| —Uncertainty. | 237 |

| —The Sally. | 238 |

| The Borders. | 244 |

| —The English Border. | 250 |

| —Moss-Troopers. | 252 |

| Present State of the Borders, and the Character of the Inhabitants. | 257 |

| Cottages and Modes of Living of the Scottish Peasantry. | 259 |

| The Monastery. | 263 |

| —Visit to Melrose.—The Original Dominie Sampson. | 266 |

| —The Weird Hill, &c. | 278 |

| —Valley of Glendearg. | 279 |

| —The Fairey or Nameless Dean. | 281 |

| —Hislop Tower. | 282 |

| —Smailholm Tower. | 284 |

| —Ravenswood Castle. | 290 |

| —Ellangowan. | 291 |

| —Tillietudlem. | 292 |

| —Abbotsford. | 292 |

| Fairy-Land. | 302 |

| —Fairies Fagaries. | 312 |

| —Fairy Fragments. | 314 |

| —Brownies. | 321 |

| Witches. | 322 |

| —The Witches of Pittenween, in Fifeshire. | 325 |

| —Minutes of the committee of the privy counsel. | 337 |

| —Murder of a Reputed Witch. | 338 |

| —Approbation of the Report of the Committee. | 341 |

| —Report of Committee to Inquire Into the Murder. | 342 |

| Peveril's Castle of the Peak. | 345 |

| Kenilworth Castle. | 348 |

| Ivanhoe. | 359 |

| —Long-bow. | 361 |

| Tales of the Crusaders. | 368 |

| Redgauntlet. | 370 |

| —The Pride and Pleasure of a Lawsuit. | 372 |

| Errata to Vol. I. | end of book |

In no other part of the civilized world are the multiplicity of objects so calculated to invite poetic, romantic, or picturesque description, as the

"Land of brown heath and shaggy wood,

Land of the mountain and the flood!"

and, although these have met with their share of attention, local and general manners have been too frequently neglected or commingled with the caricature of romance itself, to convey adequate impressions of their real existence, either of the past, or during the present period. Had we a particular account of the manners of Scotland, and the changes that have taken place, from time to time, since the era of William the Conqueror, no history could be more entertaining. But those changes have been so little marked, that what knowledge we have of them, until the recent appearance of that great northern constellation in the hemisphere of romance, we owe more to the essay writers in Queen Anne's time, than to any other of the Scottish historians. Addison, Pope, and Swift, give us some ideas of the manners of the times they wrote in; since that period, the information we have had from our parents, and our own observation, only can instruct us.

It has long been a desideratum that some efficient writer would make his observations on this subject, during his own life, which, if carried down by others, would contain both useful and entertaining knowledge; and, in this respect, the tendency so lately manifested to depict the peculiarities of Scottish manners, have gone a great way in filling up a chasm in the literature of the country.

It is observable, that the spirit of a nation is subject to frequent and sudden vicissitudes; and that it passes from the extreme of religious phrenzy, or civil discord, to a state of inactive or cold indifference. Such, it must be acknowledged, has, at various periods, been the actual condition of the people of Scotland; though now they rank on the first scale of civilization, property, and independence. But even the love of liberty itself, may become the disease of a state, and the people may be enslaved the worst way by their own passions.

In Scotland, the methods of instruction have been on the increase since the rebellion, in the year 1745; and it has been started as a question, whether that lettered education, for which the Scots were noted by the neighbouring nations, was not of prejudice to their country, while it was of the utmost service to many of its natives. Their literature, however slight, rendered them acceptable and agreeable among foreigners; but, at the same time, it drained their nation of that order of men, who are the best fitted for forming and executing the great plans of commerce and agriculture, for the public emolument. The advances in Scottish literature keep pace, at least, with their corresponding attainments in the arts and sciences. Metaphysical speculation begins, perceptibly, to yield to the more seductive fascinations of national romance. At one period, however, and that too, in what has been called the golden age of British literature, the early part of the last century, our novels contained only the most depraved pictures of human life, and our romances were generally too wild or too amatory, to be read without imminent danger. To this style of writing succeeded another, whose distinguishing characteristic was monotonous simplicity; lives and adventures of lovesick ladies, or, what were still more tiresome and uninteresting, historical tales and rural stories. Such, however, was the taste of the age; and if, perchance, an historical novel or romance did appear, as soon it was eclipsed under the influence of some more amatory and feminine effusion. Yet all this time the fault lay rather with bad imitators of the style used by our best authors, whose merits had rendered it fashionable, than with the original inventors of it. Their peculiar mode of writing required the same ideas and feelings which they possessed, to soften their broad sketches of humanity, and to keep all parts of the picture in unison.

It was not then enough, any more than now, for novelists to imagine new Gullivers and Grandisons, but they must also place them in natural yet varied circumstances, to bring out their characters, and to show that their claims to eminence did not lay only in the similarity of a name, or in mere imitations of their predecessors; but that they also had looked into life for the materials of which their fictions were composed. The success of a few Gothic stories, as they were denominated, brought forward a whole host of others, written upon the same plan; and the metropolis was inundated with Lionels and De Montagues, and Red cross knights, and Seneschals, and pilgrims and warders, and a thousand other ancient fragments, all huddled together without order or arrangement.

This age of novel-writing fretted its hour and vanished, and we reached a new era in composition, for which, indeed, it would be difficult to find an appropriate term; the cacoethes scribendi raged like an epidemic, infecting all who inhaled its contagious influence. Some good works occasionally appeared, but those were like wandering stars which ran their erratic course in the sky, with those around, which could either follow the new tract, or quit the old one. The greatest darkness is before the dawning; in the midst of their literary gloom burst forth Waverley, and the astonishment awakened by that powerful production was kept in constant exercise by its no less celebrated successors. The latter of these were evidently founded on a broad historical basis, and while reading their pages, it seems as if the times they recorded had returned again, and we became actual spectators of the scenes they displayed. But, notwithstanding the admiration which these works excited, it was thought by many rather a daring, if not an improper, act, thus to bring forward the real actors of history, and to place them in the same scenes with fictitious personages; alleging against this system, that it would confuse such as were unacquainted with the true circumstances, by causing them to blend romance with history. This danger is now too old to excite alarm, any more than the apprehension that the works of Esop or Gay should cause the rising generation to believe that the inanimate subjects, without the aid of prosopopæia, can talk and reason, and hold "colloquy sublime," like an M.P. or a blue stocking. There is indeed not only no real danger attending these historical novels and romances, but if properly conducted, they produce actual good,—for such has been the care bestowed upon the Scottish series, that in many instances their composition must have required little less reading and research than that of a true history. Hence, as in the following pages, is induced a taste for biography and antiquities, and the consequent investigation of our ancient chronicles; for many would be led to turn to such scenes in order to learn more of the characters which had already interested them.

At a period, therefore, when the literary fame of Scotland has been raised to the highest pitch, when the verse of her poets, and the valour of her soldiers have equally astonished the world; and considering how great a mass of the population of this overwhelming metropolis alone is composed of natives of Scotland and their descendants, exclusive of the extended and general associations, abroad and at home, with those whose feeling and reminiscences are blended with the

"——Land, where the hardy green thistle,

The red blooming heath and the harebell abound;

Where oft o'er the mountains the shepherd's shrill whistle

Is heard in the gloaming so sweetly to sound.

——The land of the mountain and flood,

Where the pine of the forest for ages has stood;

Where the eagle comes forth on the wings of the storm,

And her young ones are rocked in the high cairn-gorm.

——Where the cold celtic wave

Encircles the hills, where its blue waters lave;

Where the virgins are pure as the germs of the sea,

And their spirits are light as their actions are free!"

* * * * * *

These endearing reflections, combined with the spirit of inquiry and research by which the present enlightened age is so strongly marked, open a fair prospect, to the presumption at least, that an agreeable and instructive miscellany of materials purely Scottish, designed to illustrate and record the manners, genius, and peculiarities of the Scottish people from the earliest period of their history down to the present period, will meet with a fair reception among the sons of Caledonia, their offspring, and the admirers of their talents and worth, either in public or private life, and of "A country," to adopt the words of an eloquent preacher, "where Providence seems to have repaid in moral advantages all that has been withheld in the indulgence of nature." Men (continues he) are ripened in these northern climes, and every country becomes tributary to that which by skill and industry knows how to draw from the stores of all. Strangers to luxury, undaunted by danger, unsubdued by danger, undismayed by hardships, your countrymen are found wherever arts, agriculture, and commerce extend; contributing to the improvement, and sharing in the prosperity of every civilized people under heaven. What country in the world scatters from a scanty population so numerous a train of hardy intrepid adventurers, who follow wherever gain or glory mark the way; braving all the extremities of climate, and every vicissitude of fortune? Nay, as if the accessible parts of the globe afforded too limited a sphere for enterprize, they embrace with eagerness every project for extending their boundaries. To the insatiable ardour and indefatigable perseverance of one of your countrymen, the Nile first disclosed its mysterious source; and who has yet forgotten, or remembers without the applauding or sympathetic sigh of deep regret, those who but lately went out from us, never to return—those who, in the ardour of unconquerable hope, promised not to return from Afric's burning and unfrequented wild, till they should have traced for us the pathless windings of that howling 'desert through which the Niger rolls its mighty and, at length, explored stream,' And even now, when hope seems to catch enthusiasm from danger, and many thoughts have been suspended on a perilous enterprise—when the torrid Zone darts its burning rays, and the northern blasts burst their icy fetters, unlock the bars of imprisoned seas, and break up the masses of its tremendous winter, the accumulation of centuries,—who have been, or are so ready as Scotsmen to dare the terrors of the equatorial summer, or the deadly blast of the nipping arctic winter, and impel their adventurous prows among the scorching and pestilential tropical heats, and betwixt the floating fields and frost-reared precipices that guard the secrets of the Pole?

The scientific spirit thus eulogized, characterises the Lowlander especially. The military spirit is common to him and the Highlander; if, indeed, it do not distinguish the latter in a full higher degree. The blended race of the Saxon and the Gael unites all the manly virtues. They are, truly, in the words of one of their own poets,

"A nation fam'd for song and beauty's charms;

Zealous, yet modest; innocent, though free;

Patient of toil; serene amidst alarms;

Inflexible in faith; invincible in arms."

BEATTIE.

The verse and valour of Scotsmen have also drawn from an English poet the following admirable eulogy:

"——And last, to fix thy faith and seal thy doom,

Her bugle note shall Scotia stern resume,

Shall grasp her highland brand, her plaided bonnet plume:

From hill and dale, from hamlet, heath, and wood,

She pours her dark, resistless battle flood.

Breathe there a race that from the approving hand

Of nature, more deserve or less demand?

So skill'd to wake the lyre or wield the sword;

To achieve great actions, or achiev'd record;

Victorious in the conflict as the truce—

Triumphant in a Burns as in a Bruce.

Where'er the bay, where'er the laurel grows,

Their wild notes warble, and their life-blood flows!

There truth courts access, and would all engage,

Lavish as youth, experienced as age;

Proud science there, with purest nature twin'd,

In firmest thraldom holds the freest mind,

While courage rears his limbs of giant form,

Mock'd by the blast and strengthen'd by the storm!

Rome felt: and freedom to their craggy glen

Transferr'd that title proud—the nurse of men—

By deeds of hazard high and bold emprize,

Trained like their native eagle for the skies.

Untam'd by toil, unconquer'd till they're slain,

Walls in the trenches—whirlwinds on the plain.

This meed accept from Albion's grateful breath,

Brothers in arms! in victory! and death![1]"

Scotland, of whose learning the fame is spread over every region of Europe—which forms in truth, the most enlightened empire, has, with the garb, had the courage of Romans transmitted to its soldiers. The Greeks excepted, no people on the earth perhaps, ever so eminently possessed at once the genius of learning[2] and of war. None ever excelled them in love of country and chivalrous obedience—that generous loyalty which once shook the empire from its verge to its centre, and now constitutes its noblest defence. They are destitute of no quality which fits men for the cold camp or sanguinary battle; nor does external aspect deny their capabilities of body or of mind. Their muscular forms denote their strength; their embrowned complexion, a disregard of storms and tempests; their bonnet, plaid and philibeg, the hardy mountaineer, whose welcome bed may be the heath, whose canopy the azure vault of heaven. What native of Caledonia has seen these martial bands in other countries, whose heart has not expanded to hail them; whose tears, in vain restrained, have not expressed his joy; whose soul has not risen in pride, that these men, his countrymen in any sense were his! It is these corporeal powers, these magical attractions, which render them invincible. From these in ancient times, the legions of Rome dared not attempt their mountains: by these in succession, have they driven the Gaul in succession over the boundless plains of Egypt, the wilds of Calabria, the rugged hills of Portugal and Spain, and the vine covered fields of France. Bound to them by every association, what native of northern Albion feels not united with these bands—the comrades of Abercrombie, of Moore, of Graham, all the invincibles of despotism would in an instant wither before them.

"'Twas there the son of Fingall towr'd along,

And midst his mountains roll'd the flood of song;

'Twas there the heroes of that song arose,

And Roman eagles found unvanquish'd foes;

The rugged cliff, the barren desert smil'd,

For I,[3] and loose rob'd freedom, walk'd the wild.

But now beneath a milder planet's reign,

No steely phalanx desolates the plain;

The gentler acts that polish human kind

Tread the soft lawn, and leave it bless'd behind;

Commerce and peace unlock their stores around

And choral muses sing on classic ground."

Never was the military character of Scotland better pourtrayed than in the following lines by Scott—

"And, oh! lov'd warriors of the ministrel land;

Yonder your bonnets nod, your tartans wave!

The ragged form may mark the mountain band,

And harsher features and a mien more grave,

But ne'er in battled field throbbed heart more brave

As that which beats beneath a Scottish plaid;

And when the pibroch bids the battle rave,

And level for the charge, your arms are laid,

Where lives the desperate foe, that for such onset staid?"

The antiquities of a country must be highly valuable to every one who would possess an intimate acquaintance with the ancient manners and customs of its inhabitants. The popular prejudices and superstitions enter no less forcibly than useful into the general delineation. The terrors of man in that rude state of society in which science had not yet begun to trace efforts towards their causes in the established laws of nature, seem every where to have laid the foundation of a multiplicity of popular creeds, of which the object is to connect man with mysterious beings of greater power and intelligence than himself. The light of Christianity and the progress of knowledge, which have done so much to rectify the judgment, as well as to purify the heart, by displaying the wisdom and goodness of the Supreme Being, have not yet altogether dispelled the illusions which had possessed the imagination during the infancy and helplessness of rational being.—These incidents, though of no great value in themselves, in conjunction with some general observations drawn from authentic historical sources, may not prove uninteresting to those who are curious to trace the history of national manners and popular superstitions of our own times; and, since it is as representations of Scottish manners, superstitions blended with historical incidents and characteristic traits, interspersed with scenery of the most romantic and picturesque hue, that the descriptions of the Waverley Novels are primarily intended, under which point of view, we apprehend that they ought to be chiefly considered by the judicious critic, our materials have been directed into the same, as well as other collateral channels as those of our great prototype, but without the smallest pretensions to a particle of his originality, manifestation or method. Principally but "a gatherer," in collating and arranging the following subjects without any arrangement at all, the object aimed at, founded on historical data, could not we conceive, have been better represented than under the attractive head of Anecdotes, to which the cognomen of "Waverley" is most deservedly promised for the great obligations we owe to that popular quarter; and, had it been the fortune of our labours to have fallen into the mighty and magnanimous hands of the author of Waverley himself, the case, we may suppose, to borrow a comparison, would nearly have resembled the reaper of Brobdignad, who lifted up between his finger and thumb the diminutive Gulliver, in order to examine near his eye the pigmy proportions of the creature, whom he found attempting to climb over the mountain of his shoe. Considering, however, the general intentions of our labours, we have perhaps not, on the whole so much to fear; since it is not our intention to depart from the author of Waverley, but to revive him if possible in the memory of a grateful public, by designing the "Waverley Anecdotes," as merely another stone added to the cairn, the mountain cairn of his literary honours.

Other writers, indeed, suppose some prevailing sentiment to influence their heroes, and every action they perform, and even every word which they utter, seems to be dictated by the ruling passion, and by that only. It is not thus, however, that human characters, even when under the influence of the strongest emotions, are actually displayed on the great theatre of life; and it is not thus, accordingly, that our great master of description has pourtrayed the characters which he employs. So much interest, in fact, has this excellency of our author's been thrown around them, that, if we rightly interpret the feelings of the generality of readers, from those manifested in some of our most popular periodicals, it has long been seriously believed and ultimately confirmed, that many of the portraits in novels have been copied from individuals, who either had lived, or were living at the time of their conception. This, no doubt, is a proud triumph of the author's genius, and nothing surely could have been more flattering to him, however much it may have amused him in another point of view, than to find himself so completely master of the imaginations of his reader, as to have invested with a living interest, whatever scenes he has chosen to fix upon, and to elevate into a gay resemblance of actual life the vivid creations of his own fancy. A little reflection, however, will at once evince what is the true secret of all this interest; and while there is a little doubt that the author has interwoven with his narratives whatever remarkable characters, or incidents or scenes, his keen observation of life may have pointed out to him as proper for this purpose, it must always be believed that the living likeness of his characters, has, in the generality of instances at least, been derived, not from their invaluable accordance with any substantial originals, but from that elasticity of talent which has enabled the author to enter into the very soul, and to speak with the very tone and meaning of every individual actor, whom he has thought proper to introduce.

F.

|

"Conflagration of Moscow," by the Rev. C. Colton. |

|

The following question has elicited some controversy as well as classical speculation. "Utrum apud Græcos an Scotos magis exalta fuerit civilis scientia?" Whether amongst the Greeks or Scots has civil science been most cultivated? |

|

The genius of Scotland. |

To enable the reader, on whatever side of the Tweed he may reside, to appreciate more sensibly many of the characters, incidents, and scenes, original and select, introduced into the following pages, from many popular and well authenticated sources, it is presumed that some brief historical notices, by way of prelude, of the state of society among the ancient Scots, at peculiar periods of their history, may not be unacceptable.

Among civilized people, hospitality has always been held in the highest estimation. It was, indeed believed, that the Gods sometimes vouchsafed to visit this terrestrial speck in the creation, in the disguise of distressed travellers, to observe the actions of man. The apprehension, therefore, of despising some deity instead of a traveller, induced people to receive strangers with respect, and thence the rights of hospitality were most sacredly and inviolably maintained. According to Macpherson[1] no nation in the world carried their hospitality to a greater extent than the ancient Scots. It was ever deemed infamous for many ages, in a man of condition to have the door of his house shut at all, lest, as the bards express it, "the stranger should come and behold his contracted soul." Some of the chiefs were possessed of this hospitable disposition to an extraordinary degree, and the bards, perhaps, upon a private account, have never failed to recommend it in their Eulogia.

The English noblemen and gentlemen who accompanied James I and his Queen to Scotland, introduced, it is said, a more luxurious mode of living into that kingdom than had been formerly known; and in consequence of an harangue against this, by a Bishop of St. Andrew, in 1433, an act passed, regulating the manner in which all orders of persons should live, and in particular prohibiting the use of pies and other baked meats (then first known in Scotland) to all under the rank of barons. It was the custom of great families to have four meals a day—namely, breakfast, dinner, supper, and livery, which was a kind of collation in their bed-chambers, immediately before they went to rest. They breakfasted at seven, dined at ten in the forenoon, supped at four, had their liveries between eight and nine, and soon after went to bed.

The barons not only kept numerous households, but very frequently entertained still greater numbers of their friends, retainers, and vassals. These entertainments were conducted with much formal pomp, but not with equal delicacy and cleanliness. The lord of the mansion sat in state, in his great chamber, at the head of his long clumsy oaken board; and his guests were seated on each side on long hard benches or forms, exactly according to their stations; and happy was the man whose rank entitled him to be placed above the great family silver salt in the middle. The table was loaded with great capacious pewter dishes, filled with salted beef, mutton, and butcher's meat of all kinds, with venison, poultry, sea-fowl, game, fish, and other materials, dressed in different ways, according to the fashion of the times. The side-boards were plentifully furnished with ale, beer, and wines, which were handed to the company when called for, in pewter and wooden cups, by the mareshals, grooms, yeomen, and waiters of the chamber, ranged in particular order. But with all this pomp and plenty, there was little elegance. The guests were obliged to use their fingers instead of forks, which were not yet invented. They sat down at table at ten in the morning, and did not rise from it till two in the afternoon.

The diversions of the people continued much the same; as tilts, tournaments, hunting among people of rank; boxing, quoit-throwing, pitching the stone, wrestling, constituted those of the common people. Such were among the early manners of the Scottish people, and which the author of Waverley has not failed to embody in a variety of shapes in the interesting series of novels from his distinguished pen.

|

Vide Ossian, Vol. II. p. 9. Edit. 1796. |

The dress of the Scots and English nobility during the reigns of Richard and Henry VII was grotesque and fantastical, such as renders it difficult at first to distinguish the sex.[1] Over the breeches was worn a petticoat; the doublet was laced like the stays of a pregnant woman, across a stomacher, and a gown or mantle with wide sleeves descended over the doublet and petticoat down to the ankles. Commoners were satisfied, instead of a gown, with a frock or tunic shaped like a shirt, gathered at the middle, and fastened round the loins by a girdle, from which a short dagger was generally suspended. But the petticoat was rejected after the accession of Henry VIII, when the trowsers or light breeches, that displayed the minute symmetry of the limbs, was revived, and the length of the doublet and mantle diminished.

The fashions which the great have discarded, are often retained by the lower orders, and the form of the tunic, a Saxon garment, may still be discovered in the waggoner's frock; of the trouse, and perhaps of the petticoat, in the different trowsers worn by smugglers and fishermen.

These habits were again diversified by minute decorations and changes of fashion: from an opinion that corpulence contributes to dignity, the doublet was puckered, stuffed, and distended round the body; the sleeves were swelled into large ruffs; and the breeches bolstered about the hips; but how are we to describe an artificial protuberance, gross and indecent in this age, if we may judge from the portrait of Henry VIII and others, a familiar appendage to the dress of the Sovereign, the knight and mechanic, at a future period retained in comedy as a favourite theme of licentious merriment? The doublet and breeches were sometimes slashed, and with the addition of a short cloak, to which a stiffened cap was peculiar, resembled the national dress of the Spaniards. The doublet is now transformed into a waistcoat, and the cloak or mantle, to which the sleeves of the doublet were transferred, has been converted gradually into a modern coat; but the dress of the age was justly censured as inconvenient and clumsy. "Men's servants," to whom the fashions had descended with the clothes of their masters, "have," says Fitzherbert, "such pleytes upon theyr brestes, and ruffles uppon theyr sleves, above theyr elbowes, that yf theyr mayster, or theymselfe, hadde never so greatte neede, they coulde not shoote one shote to hurte theyr ennemyes, till they had caste off theyr coats, or cut off theyr sleves."

The dress of the peasantry was similar, but more convenient, consisting generally of trunk hose, and a doublet of coarse and durable fustian.

The materials employed in dress were rich and expensive; cloth of gold, furs, silks, and velvets profusely embroidered. The habits of Henry VIII and his queen, on their procession to the Tower previous to their coronation, are described by Hall, an historian delighting in shows and spectacles. "His grace wared in his uppermost apparell a robe of crimsyn velvet, furred with armyns; his jacket or cote of raised gold; the placard embroidered with diamonds, rubies, emeraudes, greate pearles, and other riche stones; a greate banderike about his necke, of large bolasses. The quene was apparelled in white satyn embroidered, her hair hangying down to her backe, of a very greate lengthe, beweteful and goodly to behold, and on her hedde a coronall, set with many riche orient stones."

The attire of females was becoming and decent, similar in its fashion to their present dress, but less subject to change and caprice. The large and fantastic head-dresses of the former age were superseded by coifs and velvet bonnets, beneath which the matron gathered her locks into tuffs and tussocks; but the virgin's head was uncovered, and her hair braided and fastened with ribbons. Among gentlemen, long hair was fashionable throughout Europe, till the Emperor Charles, during a voyage, devoted his locks for his health or safety; and in England, Henry, a tyrant even in taste, gave efficacy to the fashion by a peremptory order for his attendants and courtiers to poll their heads. The same spirit, probably, induced him, by sumptuary laws, to regulate the dress of his subjects. Cloth of gold or tissue was reserved for the Dukes and Marquesses; if of a purple colour, for the royal family. Silks and velvets were restricted to commoners of wealth or distinction; but embroidery was interdicted from all beneath the degree of an Earl. Cuffs for the sleeves, and bands and ruffs for the neck, were the invention of this period; but felt hats[2] were of earlier origin, and were still coarser and cheaper than caps or bonnets. Pockets, a convenience known to the ancients, are perhaps, the latest real improvement in dress; but instead of pockets, a loose pouch seems to have been sometimes suspended from the girdle.

|

The Scottish was apparently the same with the English dress, at this period, the bonnet excepted, peculiar both in its colour and form. The masks and trains, and superfluous finery of female apparel, had been uniformly prohibited; but fashion is superior to human laws, need we learn from the satirical invectives of poets, that the ladies still persisted in retaining their finery and muzzling their faces. |

|

In 1571, it appears felt hats were not made in England, as a statute was then enacted, which ordered an English woollen cap to be worn in preference, by every person above the age of seven, on pain of forfeiting three shillings and four-pence; ladies, lords, and gentlewomen excepted. This restriction, however, we are told, had very little effect. |

Murders and assassinations are frequent in Scottish history about this period, for the people were cruel, fierce, and ungovernable; and to judge from the desperate crimes of the nobility, their manners were neither more softened, nor their passions better controlled and regulated. But whatever be the crimes of a people, there is in human nature a reforming principle, that ultimately corrects and amends its degeneracy; and history furnishes repeated examples of nations passing from even a mean effeminacy, to an enthusiasm that regenerates every virtue. Such a change was effected in a partial degree by the reformation; which, recalling its proselytes from the errors and abuses of the Romish superstition, taught them to renounce the dissipation and vices of the age, to assume the badge of superior sanctity and more rigid virtue, to suffer in adversity with patience, and to encounter persecution and death with fortitude. Sectaries, from the constant circumspection requisite in their conduct, contract an habitual and gloomy severity; and foreigners ever more observant than natives, discovered in the present period, symptoms of that puritanical spirit, which, at the distance of a century, was destined to give liberty to England, and law to kings.

The reformation might reflect discredit on recent miracles; but the period is still distinguished by excessive credulity. An Egyptian experiment, repeated by James IV exhibits the superstitious credulity of the Scots at this period: either to discover the primitive language of the human race, or to ascertain the first formation of speech, he enclosed two children, with a dumb attendant, in Inchkeith, an uninhabited Island of the Forth; and it was believed that the children, on arriving at maturity, communicated their ideas in pure Hebrew, the language of Paradise.

As another instance of credulity, we would mention the belief of a monstrous production of the human species, but the concurrence of grave historians attests and renders the fact indisputable. This monster was born in Scotland, and its appearance suggested the idea of twins fortuitously conjoined in the womb, united at the navel into a common trunk, and terminating below in the limbs of a male, but disparted above into two bodies; distinct and perfect in all their parts, each endued with separate members, and animated each by a separate intelligence. Their sensations were common when excited in the loins or inferior extremities; peculiar to one and unfelt by the other, when produced on the particular body of either. Their perceptions were different, their mental affections unconnected, their wills independent; at times discordant, and again adjusted by mutual concession. They received, by the direction of James IV, such liberal education as the times afforded, attained in music to a considerable proficiency, and acquired a competent knowledge of various languages. Their death was miserable; at the age of twenty-eight, the one expired, and his body corrupting, tainted and putrified his living brother.[1]

|

Examples of these monstrosities, as they are called, are nevertheless not so rare as might be supposed. The public curiosity of Paris was recently excited by the arrival of a biciphalous child, (Christina-Ritta), the destiny of which has been as unhappy as its birth was extraordinary. The Siamese boys a short time ago imported, were no less objects of attraction with the Londoners. How many monsters, indeed, have passed unremarked, in consequence of the negligence of midwives, or of the ignorance of nurses, or of the repugnance of families to call attention to those mal-formed births, which an absurd prejudice urges them to bury in the most profound oblivion? In 1665, the Journal des Savans states, that there had been sent to Oxford, in 1664, a child, who had two heads, diametrically opposite, four perfect arms, a single abdomen, and two lower extremities. In 1724, the Journal de Trevou relates the history of a girl, born at Domremy-la-Pucelle, who was equally double from the upper extremities to the navel, and who only presented, towards the left hip, something like the stump of a third thigh. This being lived for some time. Christina-Ritta was double from the head to the pelvis. The two vertebral columns were distinct to their lower extremity, that is, to the os coccygis. Before the pelvis it was simple. Thus there were two heads resting on two necks, the corresponding chests being so disposed, that the left arm belonging to the one (Ritta) naturally placed itself in the neck of the other (Christina), whose right arm placed itself in the same manner on the neck of its associate. The Siamese boys are perfect, being united, respectively at the ensiform cartilage of the sternum, by an intervening substance. |

The domestic manners of the Scots have seldom attracted historical notice, and their advances in refinement are to be collected or conjectured from their peculiar customs, their progress in the arts, and their improvement in the various comforts of life. Their morals, contrasted with those of their ancestors, are arraigned as degenerate, by the historian Bœthius, who accuses their intemperance, censures their luxury, and laments their departure from the frugal moderation and rugged virtues of the ancient Scots. His description, however, of these premature obdurate virtues is far from attractive: and what he denominates vicious intemperance, and excessive luxury, may be fairly interpreted an increasing refinement, and superior elegance of social life. The nobles, who resorted seldom to the cities, preserved in their castles their former rude, but hospitable magnificence, which increased their retainers, and strengthened their power, secured their safety, or enabled them to prosecute their deadly feuds. The people were divided into factions by those lords to whom they attached themselves, whose interest they espoused, and whose quarrels they adopted, and the clans peculiar at present to the Highlands were probably once universal in Scotland.

In the Highlands and on the borders clans were perpetuated by a constant warfare, that inured the people to the fierceness and rapine of a predatory life. As thieves and plunderers, their characters were proverbial; yet their depredations, committed generally on hostile tribes, assume an appearance of military virtue; and their mutual fidelity, their observance of promises, and in the Highlands, their inviolable attachments to their chieftains, are circumstances sufficient almost to redeem their character. The Clattan clan, during the minority of James V, had made a destructive incursion into Murray, but after their return were assailed and oppressed by superior forces; and two hundred of the tribe rather than betray their chieftain, or disclose his retreat, preferred and suffered an ignominious death.[1]

|

See Characteristic traits of the Ancient Scots Highlanders.—Passim. |

The mutability of language to the learned, whose fame depends on its duration, an incessant topic of serious regret, seems to be counteracted by the art of printing, which, in proportion as it disseminates a taste for letters, re-acts as a model on colloquial speech, and operates, if not entirely to repress innovation, at least to preserve the stability and perpetuate the radical structure of language. Such stability the English language has acquired from printing, and at the distance of three centuries, still exhibits the same phraseology and syntactical form varied only by those alterations essential to the progressive refinement of speech. The language of this period, if necessary to discriminate its peculiar style, was unpolished and oral; its character is rude simplicity, neither aspiring to elegance nor solutions of ease, but written as it was spoken, without regard to selection or arrangement; reduced to modern orthography, it is only distinguishable from the common colloquial discourse of the present period by a certain rust of antiquity, by phrases that are abrogated, or words that are either effaced or altered. These, however, are not numerous; and we may conclude from the composition of the learned, that the language of the people differed little from the present unless in pronunciation, which, to judge from orthography, was harsh, and such as would now be denominated provincial or vulgar. Whatever has since been superadded, either by a skilful arrangement, or the incorporation of foreign or classical words and idioms, is more the province of critical disquisition than historical research; yet it merits observation, that the first attempts at elegance in the English language are ascribable in poetry to Surry; in prose, perhaps to Sir Thomas More, whose English style, as it was modelled on his Latin, is constructed with art, and replete with invasions approaching to that which, in contra-distinction to the vulgar, may justly be denominated a learned diction.

Thus history has already furnished sufficient specimens both of the Scottish and English languages which descended from the same Gothic original, and nearly similar in former periods, divaricated considerably during the present. This is to be attributed to the alteration and improvement of the English, for the Scottish were more stationary; nor is there in the language a material difference between the compositions of James I, and those of Bellenden, Dunbar, and Douglas, each of whom by the liberal adaption of Latin words enriched and polished his vernacular idiom. But for the union of the crowns, which in literature rendered the English the prevalent language, the Scottish might have risen to the merit of a civil dialect, different rather in pronunciation than in structure; not so solemn, but more energetic, nor less susceptible of literary culture.

The diet of the Scots was worse and more penurious at this time than that of the English. The peasants subsisted chiefly on oatmeal and cabbages, for animal food was sparingly used even at the tables of substantial gentlemen.

An English traveller who experienced the hospitality of a Scottish knight, describes the table as furnished with large platters of porridge, in each of which was a small piece of sodden beef; and remarks that the servants entered in their blue caps without uncovering, and instead of attending, seated themselves with their master at table. His mess, however, was better; it consisted of a boiled pullet with prunes in the broth; but his guest observed, "no art of cookery," or furniture of household stuff, but rather a rude neglect of both.

Forks are a recent invention, and in England, the table was only supplied with knives; but in Scotland, every gentleman produced from his girdle a knife, and cut the meat into morsels, for himself and the women, a practice that first intermixed the ladies and gentlemen alternately at table. The use of the fingers in eating required a scrupulous attention to cleanliness, and ablution was customary, at least at court, both before and after meals. But the court and nobility emulated the French in their manners, and adopted probably their refinements in diet. The Scottish reader will observe that the knight's dinner was composed of two coarse dishes peculiar to Scotland; but others of an exquisite delicacy were probably derived from the French, and retained with little alteration by a nation otherwise ignorant of the culinary arts. The Scots, though assimilating fast with the English, still resemble the French in their mess tables. The English at this period were reckoned sober: the Scots intemperate; they are accused at least, by their own historians, of excessive drinking, an imputation long attached to their national character.

The sports of the field are in different ages pursued with an uniformity almost permanent. Hunting has ever been a favorite diversion both with the English and Scots, and hawking has only been superseded by the gun; but it was still practised with unabating ardour, and cultivated scientifically as a liberal art. Treatises were composed on the diet and discipline of the falcon; the genus was discriminated like social life, and a species appropriated to every intermediate rank, from an emperor down to a knave or a peasant; nor were gentlemen more distinguished by the blazoning of heraldry, than by particular hawks they were entitled to carry. The long-bow was also employed in fowling, a sport in which dexterity was requisite; but archery was a female amusement; and it is recorded that Margaret, on her journey to Scotland, killed a buck with an arrow in Alnwick park.

The preservation of the feathered game was enforced in the present age by a statute, the first that was enacted of those laws which have since accumulated into a code of oppression.

The Scottish monarchs hunted in the Highlands, sometimes in a style of eastern magnificence. For the reception of James V, the queen his mother, and the pope's ambassador, the Earl of Athol constructed a palace, or bower of green timber, interwoven with boughs, moated round, and provided with turrets, portcullis, and drawbridge, and furnished within with whatever was suitable for a royal abode. The hunting continued for three days, during which, independent of roes, wolves, and foxes, six hundred deer were captured; an incredible number, unless that we suppose that a large district was surrounded, and the game driven into a narrow circle to be slain, without fatigue, by the king and his retinue. On their departure, the earl set fire to the palace, an honour that excited the ambassador's surprise; but the king informed him it was customary with Highlanders to burn those habitations they deserted. The earl's hospitality was estimated at the daily expense of a thousand pounds sterling.

During the present period, several games were invented or practised to difuse archery, for the promotion of which, bowls, quoits, cayles, tennis, cards and dice, were prohibited by legislature as unlawful games. Tennis, however, was a royal pastime in which Henry VIII, in his youth, delighted much; but the favourite court amusements, next to tournaments, were masques and pageants: the one an Italian diversion subservient to gallantly, the other a vehicle of gross adulation.

The diversions of people of rank continued much the same for about five centuries after the Norman conquest. But in the course of this period card playing[1] was first introduced into Britain.

|

Playing cards were made, and probably first invented about the end of the fourteenth or beginning of the fifteenth century, by Jaquemain Gregonneur, a painter, in Paris, for the amusement in his lucid moments, of that unhappy prince, Charles VI as is evident from the following article in his treasurer's account: "Paid fifty shillings of Paris, to J. Gregonneur, the painter, for three packs of cards, gilded with gold, and painted with diverse colours and devices, to be carried to the king for his amusement." From this it appeared that playing cards were very different in appearance and price from what they are at present. They were gilded, and the figures painted or illuminated, which required no small genius, skill, and labour. The price as above for three packs, was a considerable sum in those times; a circumstance which perhaps prevented playing cards from being much known or used many years after they were invented. By degrees, however, cards became cheaper and more common; and we have the evidence of an act of parliament, that both card playing and card making were known and practised in England before the end of this period. On an application of the card-makers of London to parliament, A.D. 1463, an act was made against the importation of playing cards. But if the progress of card playing was slow at first, it has since become sufficiently rapid and extensive, to the ruin of many who have spent too much of their time in that infatuating amusement. |

Civilization indeed had not hitherto made such progress in England as entirely to abolish slavery. Yet few land-owners or renters were to be found who did not prefer the labour of free-men[1] to that of slaves. This circumstance diminished their number, and the perpetual civil contests enfranchised many, by putting arms in their hands. Within a few years after the accession of the Tudors, slaves were heard of no more[2]. Scotland was not so happy. The unfortunate death of the Norwegian Margate, had involved the realm in a long and bloody contest with its powerful neighbour; and, although the gallant and free spirits of the Scots had preserved the independence of their country, notwithstanding their inferiority in numbers, wealth, and discipline, it could not prevent the preponderance of a most odious and tyrannic aristocracy. Perpetual domestic war loosened every tie of constitutional government; and a Douglas[3], a Crichton[4], or a Donald of the Isles[5], by turns, exercised such despotism and inhumanity, as no monarch in the fifteenth century would have dared to practice.

|

The value of free-men who would labour in agriculture was so well known, that statutes were passed to prevent any person who had not twenty shillings a-year (equal to ten pounds sterling, modern money) from breeding up his children to any other occupation than that of husbandry. Nor could any one, who had been employed in such work until twelve years of age, be permitted to turn himself to any other vocation. Public Acts—The condition of the slaves in England was as completely wretched as the despot, who owned them, might please to make. His goods were his master's, and on that account were free from taxation; and whatever injuries he might sustain, he had no power to sue that master in any court of justice. |

|

A reflection made at the close of the 15th century is the more remarkable (by Philip de Comines) as it was given voluntarily, at the close of the longest and most bloody civil war with which the English annals can be charged. "In my opinion," (says the judicious observer quoted) "in all the countries in Europe where I was even acquainted, the government is no where so well managed, the people no where less obnoxious to violence and oppression, nor their houses less liable to the desolations of war, than in England; for there the calamities fall only upon the authors." |

|

Oppression, ravishing of women, theft, sacrilege, and all other kinds of mischief, were but dalliance. So that it was thought less on in a depender on a Douglas to slay or murder; for so fearful was their name, and so terrible to every innocent man, that when a mischevous limmer was apprehended, if he alleged that he murdered, and slew at a Douglas's command, no man durst present him to justice. Lindsay of Pettscotie. |

|

In consequence of James I opposition to the aristocracy he was induced to silence his ministers, officers, and counsellors, not from haughty nobles who rivalled his power, but among the lower class of barons or private gentlemen. From these James selected accordingly several individuals of talent, application, and knowledge of business, and employed their counsels and abilities in the service of the state without regard to the displeasure of the great nobles, who considered every office near the king's person as their own peculiar and patrimonial right, and who had in many instances converted such employments into subjects of hereditary transmission. Among the able men whom James thus called from comparative obscurity, the names of two statesmen appear, whom he had selected from the ranks of the gentry, and raised to a high place in his councils; these were Sir William Crichton the Chancellor, and Sir Alexander Livingston of Calender; both men of ancient family, though descended from Saxon ancestors; they did not number among the greater nobles who claimed descent from Norman blood. Both, and more especially Crichton possessed talents of the first order, and were well calculated to serve the state. Unhappily these two statesmen, on whom the power of a joint reigning devolved, were enemies to each other, probably from ancient rivalry; and it was still more unfortunate that their talents were not united with corresponding virtues; for they both appear to have been alike ambitious, cruel, and unscrupulous politicians. It is said by the Scots' Chronicles that, after the murder of the king, the parliament assigned to Crichton the chancellor, the administration of the kingdom, and to Livingston the care of the person of the young king. |

|

The Lords of the Isles, during the utter confusion which extended through Scotland during the regency, had found it easy to reassume the independence of which they had been deprived during the vigorous reign of Robert Bruce. They possessed a fleet with which they harrassed the main land at pleasure; and Donald who now held that insular lordship, ranked himself among the allies of England, and made peace and war as an independent sovereign. The Regent had taken no steps to reduce that kinglet to obedience, and would probably have avoided embarking in so arduous a task, had not Donald insisted upon pretentions to the Earldom of Ross, occupying a great extent in the north-west of Scotland, including the large isle of Sky, and laying adjacent to, and connected with his own insular domains. The regent Albany, however, after the battle of Marlow, compelled him to submit himself to the allegiance of Scotland, and to give hostages for his future obedience. "Donald," says Lindsay, "gathered a company of mischievous cursed limmers, and invaded the king in every airth, whenever he came, with great cruelty; neither sparing old nor young; without regard to wives, or feeble or decrepit women; or young infants in the cradle, which would have moved a heart of stone to commiseration; and burned villages, towns, and corn!" |

The endeavours of the First and Second James were turned towards improving the jurisprudence of the country, by engrafting on it the best parts of the English system; but the suddenness of their deaths and the weak reign of their successor James III, prevented these people from receiving much benefit from such laudable designs.

The parliament of Scotland at this period, had nearly monopolized all judicial authority. Three committees were formed from the house (for there was only one) soon after the members met. The first like the 'Friers' in England, examined, approved, or disapproved of petitions to the senate; the second constituted the highest court in all criminal prosecutions, as did the third in civil ones. And as every lord of parliament, who chose it, might claim his place in each of these committees, almost the whole administration of law, civil as well as military, resided in the breast of the Scottish nobility. There was another court, that of session, of which the members and the duration were appointed by parliament.

The justiciary (an office discontinued in England as too potent) was still nominally at the head of the Scottish law, and held courts which were styled 'justiciares,' as did the chamberlain, 'chamberlainaires:' from the courts there was allowed an appeal to a jurisdiction of great antiquity, styled, 'the four Bourroughs' Court. This was formed of burgesses from Edinburgh, and three other towns, who met at Haddington, to judge on such appeals.[1]

There was one abuse, however, which rendered every court of justice nugatory! It had become a custom for the Scottish monarchs to bestow on their favourites not only estates, but powers and privileges equal to their own. These were styled "Lords of Regalities:" they formed courts around them, had numerous officers of state, and tried, executed, or pardoned the greatest criminals. The good sense of James II prompted him to propose a remedy for this inordinate evil; but two admirable laws which he brought forward (the one against granting 'regalities,' without consent of parliament; the other to prohibit the bestowing of hereditary dignities) were after his decease neglected; and Scotland continued two centuries longer a prey to the jarring interests of turbulent, traitorous noblemen.

Although every obstruction had occurred which ruinous foreign wars, and still more detestable civil contentions, could cause, some advantage in the interim had been gained to the cause of general security. About the middle of the 16th century, the parliament appointed justices and sheriffs, in Ross, Caithness, the Orkneys, and the Western Isles, where none had been before, and appointed courts to be holden from time to time, in very remote districts. There was need of this attention if the preamble to the acts is to be credited, "Through lack of justiciaries, justices, and sheriffs, by which the people are become wild[2]."—Public acts, James VI.

James V, who could sometimes exert a just and people spirit, sailed in 1535 from Leith, and examined in person how far those wholesome regulations had been put in practice. He seized and brought away some of the most turbulent chieftains, and inspired the most ungovernable of his subjects with a decent respect for the laws.[3]

The parliaments were frequently and regularly called, particularly by James IV and V. Every thing which the nation could afford was granted by the house (for it was but single, the scheme which James I had planned, of forming two chambers, having unhappily miscarried) and all possible care was there taken, that the king should not alienate the demesnes of the crown. In some instances this branch of the legislative appears to have trenched upon the royal prerogative,[4] and even to have assumed the executive power.

It is certain (as has been remarked by a well informed historian) that this mixture of liberality and of caution in the Scottish representatives, at the same time that it maintained their kings in decent magnificence by the revenues of the crown lands, "prevented the subjects from being harrassed by loans, benevolences, and other oppressive acts, which were so often employed by the powers of Europe, their contemporaries." Yet as the government had very seldom sufficient strength to guard the unarmed members of society from assassination and pillage, arrayed under the banners of a factious nobleman, it may be doubted, whether the extortion and despotism of a Seventh or Eighth Henry, might not be more tolerable than the domestic tyranny[5] and murderous ravages committed by the satellites of a Douglas, a Home,[6] a Sinclair, or of a Hamilton.

|

Public Acts. |

|

"Justice," says Pennant, "was administered with great expedition, and too often with vindictive severity. Originally the time of trial and execution was to be within 'three suns.' About the latter end of the seventeenth century, the period was extended to nine days after the sentence; but since a rapid and unjust execution in a petty Scottish town in 1720, the execution has been ordered to be deferred for forty days on the south, and sixty on the north side of the Tay, that time may be allowed for an application for mercy." |

|

Ibid. |

|

As in 1503, when an act was passed for prohibiting the king from pardoning those convicted of wilful and premeditated murder; but this appears to have been done at the monarch's own request, and was liable to be rescinded at his pleasure. James IV, Act. 97. |

|

It appears that each great man had his courts, held by power delegated from the crown, with a soc sac, (a pit for drowning some offenders, particularly women) pit, and gallows, toill and paine, in-fang thief; 'he had power to hold courts for slaughter and doe upon ane man that is seized therewith in hand havand, or in back bearand.' |

|

The Homes were intrepid border chiefs; and their affrays were often taunted with that prevalent species of ferocity which characterised the times. Anthony d'Arcy, Seigneur de la Bastie, a French knight of great courage and fame, had been left by the regent (Albany) in the important situation of warden of the eastern marshes, and had taken up the duties of the office with a strict hand. But Home of Wedderburn, a powerful chief of the name, could not brook that an office usually held by the head of his house, should be lodged in the hands of a foreigner dependent on the regent, by whom Lord Home had been put to death. Eager for revenge, the border chieftain way-laid the new warden with an ambuscade of armed men. Seeing himself beset, the unfortunate d'Arcy endeavoured to gain the castle of Dunbar; but having run his horse into a morass, near Dunse, he was overtaken and slain. Home knitted the head of his victim to his saddle-bow by the long locks, which had been so much admired in courtly assemblies, and placed it on the ramparts of Home castle, as a pledge of the vengeance exacted for the death of the late lord of that fortress. |

As regards moral habits, the English generally were still brave, humane, and (at least among each other) hospitable. That their priests and monks[1] were luxurious and gluttonous, is known from their own prelates; and that their profligacy exceeded the usual natural bounds of licentiousness, we are but too well assured by the report of the visitation under Cromwell: but the faults of a singularly depraved and pampered race ought not to be laid to the door of a whole nation. The lower orders of the community were exceedingly ignorant; and as little attention was shewn to instruct them in the religious duties of life, they repaid the neglect by plundering their superiors. But although twenty-two thousand persons are said to have been executed chiefly for theft, in the time of Henry VIII, yet was murder almost entirely unknown, and England might, in the 16th century, proudly vaunt, that the taking away life in cold blood, at least without some legal colour of justice, was a practice almost unknown within her limits.

An unhappy species of political rivalry wherein each head of a party found it necessary to support its adherents in rapine and murder, lest he should be deserted by all, prevents the eulogy from being extended at this period to Scotland, wherein the example of the Douglas family, of the house of Hamilton, and many gallant but ferocious warriors, too plainly shewed that it was possible to unite in the same person intrepid bravery against the foreign foe and inexorable cruelty of the defenceless neighbour.

|

The monks in rich monasteries lived more luxuriously than any order of men in the kingdom. The office of chief cook was one of the greatest offices in these monasteries, and was conferred with great impartiality, on that brother who had studied the art of cookery with most success. The historian of Croyland Abbey speaks highly in praise of brother Lawrence Charteres, the cook of that monastery, who, prompted by the love of God, and zeal of religion, had given £40 (a sum equivalent to £400 now) "for the recreation of the convent with the milk of almonds on fast days." He also gives us a long statute that was made for the equitable distribution of this almond milk, with the finest bread and best honey. Nor were the secular clergy more hostile to the pleasures of the table; and some of them contrived to convert gluttony and drunkenness into religious ceremonies by the celebration of glutton-masses, as they very properly called them. These were celebrated five times a year, in honour of the Virgin Mary; and the bone of contention was who should devour the greatest quantities of meat and drink to her honour. |

The peace of the kingdom at this period was disturbed by the constant dissension kept up betwixt the parties of Hamilton and Douglas; that is, between the Earls of Angus and Arran. They used arms against each other without hesitation. At length (Jan. 1520) a parliament being called at Edinburgh, the Earl of Angus appeared with four hundred of his followers armed with spears. The Hamiltons not less eager and similarly prepared for strife, repaired to the capital in equal or superior numbers. They assembled in the house of the Chancellor Beaton, the ambitious Archbishop of Glasgow, who was bound to the faction of Arran by that nobleman having married the niece of the prelate. Gawin Douglas, Bishop of Dunkeld, a son of Earl Bell-the-cat, and the celebrated translator of Virgil, laboured to prevent the factions from coming to blows. He applied to Beaton himself, as official conservator of the laws and peace of the realm. Beaton laying his hand on his heart, protested upon his conscience he could not help the affray which was about to take place. "Ah! my lord," exclaimed the advocate for peace, who heard a shirt of mail rattle under the bishop's rochet, "methinks your conscience clatters." The Bishop of Dunkeld then had recourse to Sir Patrick Hamilton, brother to the Earl of Arran, who willingly attempted to exhort his kinsman to keep the peace until he was rudely upbraided with reluctance to fight by Sir James Hamilton, natural son to his brother, and a man for peace and sanguinary disposition. "False bastard!" exclaimed Sir Patrick, in a rage, "I will fight to-day where thou darest not be seen." All thoughts of peace had now vanished; and the Hamiltons with their friends and adherents rushed furiously up the lanes which lead from the Cow-gate, where the bishop's palace was situated, with the view of taking possession of the High street. But the Douglas party had been beforehand with them, and already occupied the principal street, with the advantage of attacking their enemies as they issued in disorder from the narrow lanes. Those of Angus's followers who were not armed were supplied with lances by the favour of the citizens of Edinburgh, who handed them through their windows. These long weapons considerably added to the advantages of the Douglases over their enemies; and rendered it easy to bear them down, as they struggled breathless and disordered out of the heads of the lanes. This was not the only piece of good fortune which attended Angus on the occasion; for Home of Wedderburn, also a great adherent of the Douglases, arrived on the spot while the conflict was yet raging, and, darting through the Netherbow gate at the head of his formidable borderers, appeared in the street in a decisive moment. The Hamiltons took to flight, leaving seventy killed behind them, one of whom was Sir Patrick Hamilton, the peace-maker, who had vainly attempted to prevent this sanguinary and disgraceful rencontre.

The Earl of Arran and his natural son were in such imminent danger that, in their flight, meeting a collier's horse, they were glad to throw off its burthen, and both mounting the same steed, they escaped through a ford in the lock which then defended the northern side of the city. The consequences of this skirmish which, according to the humour of the age, was long remembered, under the name of cleanse the causeway, raised Angus in a little time to the head of affairs.

Towards the 16th century the manners of the English became more humane than those of their ancestors had been, whom continual warfare, and an eager thirst for conquest and spoil had united to render ungentle and tremendous. Their exercises, sports and passion for feasting we have mentioned in another place. Dancing round the maypole, and riding the hobby-horse, were favourite country sports: but these suffered a severe check at the reformation, as did the humorous pageant of Christmas personified by an old man hung round with savoury dainties.

There is reason to think that gaming was the favourite amusement of the Scots in the sixteenth century. Sir David Lindsay, in a tragedy, makes Cardinal Beaton declare, that he had played with the king for 3,000 crowns of gold in one night, "at cards and dice;" and an anonymous bard (cited by the historian of English poetry) avers, that

'Halking, hunting, and swift horse rynning

Are changit in all his wrangus wynnin;

There is no play bot 'cartes and dice.'

As to the tables of the Scots, no particular remark occurs, unless it be that two national dishes (still cherished at the plentiful tables in the north) made in the sixteenth century, a part of the usual meal. Hospitality from one end of the island, seems to have been especially harboured at religious houses; and if the monk or 'holy friar' was to a proverb, fond of good living, jollity and conviviality of all, he was not backward in imparting a share of his dainties to the benighted or wandering stranger. The Scots afford, at this period, no materials for any particular observation on their dress. The ladies, in spite of a legal ordinance, 'that no woman cum to the kirk nor meriat with her face muffalit,' appear by the declamations of their contemporary poets to have continued to use the fashion which they thought most becoming.

Never was any race of monarchs more unfortunate than the Scottish; their reigns were generally turbulent and disastrous, and their own end often tragical. According to fabulous authors, more than one hundred had reigned before James VI, the half of whom died by violence; and of six successive princes, the immediate predecessors of that monarch, not one died a natural death. James III came to an untimely end in Stirlingshire.

A misunderstanding subsisted between this prince and several of the chief nobility, during a great part of his reign; a minute investigation of the various causes of which, would be foreign to our purpose. James did not possess those talents for government which had distinguished several of his predecessors; for, though some wise and useful regulators were established in his reign, and his errors have no doubt been much exaggerated by faction; yet it cannot be denied that marks of an imprudent and feeble mind are visible in the general turn of his conduct.

A natural timidity of temper, together with a foolish attention to astrology, filled his mind with perpetual jealousy and suspicion; a fondness for architecture, music, and other studies and amusements, which though innocent and useful, were too trifling to engage the whole care and time of one who held a sceptre over a fierce and turbulent people, rendered him averse to public business. Indolence and want of penetration led him to make choice of ministers and favourites who were not always the best qualified for the trust committed to them. The ministers of state had usually been chosen from amongst the nobility; but in the reign of James, the nobles, either from fear or hatred of them, or from a consciousness of his own inability to maintain his dignity among them, were seldom consulted in affairs of government, and often denied access to the royal presence.

This could not fail to excite the displeasure of the Scottish barons, who were naturally haughty, and who, in former reigns, had not only been regarded as the companions and counsellors of their sovereigns, but had possessed all the great offices of power and trust. Their displeasure arose to indignation when they beheld every mark of the royal confidence and favour conferred upon persons of mean rank, such as, Cochran, a mason; Hemonel, a tailor; Leonard, a smith; Rogers, a musician; and Torfifan, a fencing-master, whom James always kept about him, caressed with the fondest affection, and endeavoured to enrich with an imprudent liberality.

To redress this grievance the barons had recourse to a method altogether characteristic of that ferocity which had always distinguished them. Unacquainted with the slow and regular method adopted in modern times, of proceeding against royal favourites and evil counsellors, by impeachment, they seized upon those of James by violence, tore them from his presence, and, without any form of trial, executed them with a military despatch and rigor. So gross an insult could not but excite some degree of resentment, even in the most calm and gentle breast; but true policy would have suggested to a wise prince, as soon as the first impulse of passion was over, the necessity of relinquishing a behaviour which had given so great offence to subjects so powerful as the Scottish barons were at that time; for their power was become so predominant by a concurrence of other causes, beside the nature of the feudal constitution, that the combination of a few of them was able to shake the throne. The attachment of James to favourites was, notwithstanding, so immoderate, that he soon made choice of new ones, who became more assuming than the former, and consequently objects of greater detestation to many of the barons, especially those who, by their near residence to the court, had frequent opportunities of beholding their ostentation and insolence.

At length matters came to an open rupture; a party of the nobility, after a series of combinations amongst themselves, took to arms; and, having either by persuasion or force, prevailed upon the Duke of Rothesay, the king's eldest son, a youth of fifteen to join them, they, in his name, erected their standard against their sovereign, who, roused by the intelligence of such operations, quitted his retirement and also took the field. An accommodation at first took place; but upon what terms is not known. The transactions of the latter part are variously stated by historians, and but darkly by the best. Those who lived nearest the time and had opportunities of information, probably found that they could not be explicit without being obliged to throw reflexions upon either the father or the son; and, therefore, saw it prudent to be upon the reserve. Some affirm that the malcontents proposed, that James should resign his crown on behalf of his son; but this accommodation, whatever the articles were, as it appears to have been attended with no mutual confidence, was of very short duration. New occasions of discord soon arose: the malcontents asserted that James had not fulfilled his part of the treaty; but ignorance of the articles thereof, renders us unable to form any other opinion concerning the truth of this change. It is certain, however, that the confederacy began now to spread wider than ever, so as to comprehend almost all the barons, and consequently all their military tenants and retainers upon the south side of the Grampian mountains.