* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Ghost of Melody Lane

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Lilian Garis

Date first posted: Sep. 30, 2018

Date last updated: Sep. 30, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180952

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

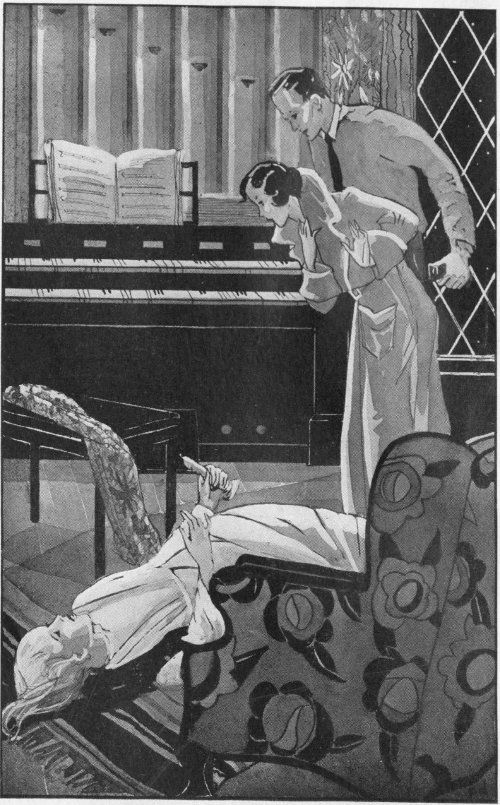

“I—FELL. MY HIP, I GUESS——” (Page 56)

MELODY LANE MYSTERY STORIES

BY

LILIAN GARIS

Author of

NANCY BRANDON’S MYSTERY,

THE FORBIDDEN TRAIL,

JUDY JORDAN, ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

PELAGIE DOANE

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

BOOKS BY LILIAN GARIS

MELODY LANE MYSTERY STORIES

Copyright, 1933, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

The Ghost of Melody Lane

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

TO THE REAL CAROL

There was only one way to go home, though to Carol it did not seem to matter which way she went. Just outside the marbleized lobby of the moving picture theatre she stood, looking first down Cedar Street, which would lead her home, and then over Fourth Street, which wound out of town toward the trolleys, busses, and a railroad station.

But Carol did not sigh as she took the road to her little home. Instead she squared her fine shoulders and perked up her head until another blue-black tangle of hair shot out from the side of her small hat.

“And yet,” she was remembering, “I knew it was coming.”

The early afternoon performance had just dislodged its few patrons, for money was scarce in Oakleigh, just as in other places, and few were reckless enough to spend any on picture matinées. That was why this had happened to Carol.

“I’ve lost my job.” She could not help telling herself the cruel fact. “And now what are we going to do?”

Oakleigh’s cozy little theatre, the Silvertone, had kept its organ and kept Carol on, playing it, long after other places had substituted the sound music that came with the films. People liked Carol’s playing, and she studied hard to please them. But now the management could no longer afford the extra expense and Carol’s eighteen dollars per week. The very last pay check was tucked into her brown purse with some business cards she was wondering about.

“I’ll have to go right over to Long Hill,” she was deciding. “And, worse yet, I’ll have to buy gas. Good thing we have the old flivver. I never could get out of town twice a day without that. Providing,” she mocked herself, “I get the job.”

In the late afternoon few persons stop to say hello. They merely call a hasty greeting and run along, as they did now, while Carol rushed past them because she just had to hurry.

There were her father and Cecy to confront. Her father, poor dear, would try to cheer her up, but she dreaded that beaten look in his tired eyes, the look that had come there and had remained ever since he lost his splendid position last year because of his poor health which, somehow, did not seem to improve in spite of doctoring.

“Dad will want to start right off again tomorrow on the everlasting looking which just wears out hearts and shoes,” mused Carol as she almost bumped into a man barging along as if the whole sidewalk were his. But the dreaded look in her father’s dear, loving eyes would not be as hard to deal with as would Cecy. She was a trial, always. Younger than Carol, she had played baby; always shirked, except in cooking, for she liked to cook. She read just because she loved to read; had to wear glasses because she had not taken care of her eyes; had to see a doctor once in a while because she ate candy and shouldn’t. In fact, Cecy was as unlike Carol as a sister possibly could be. Even the mother who had spoiled Cecy admitted before she closed her eyes that long, dark evening, which brought no morning to her: “Cecy should try to be more practical.”

“I suppose I’ll find her making fudge with the last of the sugar,” Carol was desperately telling herself as she hurried along. Then came a sudden revulsion. She stopped short, turned down a side street, and with a new look on her face murmured:

“I just can’t stand it! I’m not going to stand it! I’m not going home with the bad news—just yet. I’m going to see Cousin Kitty and have a last, mad, grand riot of music on her wonderful pipe organ before I have to come down to earth again. Yes, I’ll go see Cousin Kitty and play and play and play——”

With a new objective, Carol swung along, her head up, her eyes brighter, and with that same stray lock of her blue-black hair streaming in the wind she hurried on, managed to catch one of the infrequent busses and sank into a seat. It was rather a long distance to Melody Lane, that picturesque, strange, tree-shaded thoroughfare where Oak Lodge added to its mysteriousness.

Mrs. Katheryn Becket, once “Kitty Adair,” known to a large and delighted public because of her singing and acting, lived in a big, gloomy old mansion, Oak Lodge, on the other side of town. The old house was set in a large estate, at least it had once been an estate, though it had now rather fallen into ruin and was difficult to care for.

“Cousin Kitty” Carol and many of her girl friends called the beautiful, elderly lady, who though no longer an actress, had still her passion for music. She had formed and trained the girls’ Choral Club and had given Carol all her organ lessons without charge. At times Mrs. Becket had delightful entertainments at her big house, based on “home talent” and fortified by that always alluring professional talent, willing to come out from the city to help.

But lately something had been wrong. Since Mr. Becket’s sudden death, about a year and a half ago, a change had gradually come over the fine old place he had bought for his wife.

There had been rumors that the house was haunted—that ghosts came in the wee hours and played mournful music on the great organ. No one quite believed these stories, but many did begin to feel that there was something strange about the house on Melody Lane.

However, it was always a relief for Carol to go to Mrs. Becket’s, for the often tired girl always found surcease around the great organ whose deep notes seemed to be a voice from the sky. Carol loved Mrs. Becket as she loved her music, and the thought, now, that at least for a little while she could sense the flow of melody around her, not hampered by having to play something to fit trite films, made a brief break in the tension of worry.

“Oh, Carol! How nice of you to come and see me!” greeted Mrs. Becket as she opened the door.

“I—I just had to come!” was the murmured reply.

“You had to come? Is anything the matter? Oh, you mean you are hungry for music, is that it?”

“Yes, part of it!” Carol laughed a short, little laugh that had less of mirth in it than she could have wished. “Do you mind if I go to the organ—just for a little while?”

“Not at all—only you can’t go just yet. You see——”

Mrs. Becket paused and seemed to be listening. From a distant part of the old mansion, where the organ loft was built, there came a few harsh notes vibrating through the half-darkness, for Mrs. Becket never did seem to care for bright lights.

“Some one is playing!” Carol exclaimed, and she wondered, for she knew neither Jacob, the grouchy man of all work, nor Mrs. Becket’s maid were ever allowed near the great organ.

“No, not playing, Carol, dear, just mending. I suppose he accidently touched a key, for I left the power on so he could see if anything else was wrong.”

“Something wrong with the organ?” Carol almost gasped. “Oh——!”

“Nothing serious, my dear. That is, nothing wrong with the keys, the motor, or the pipes, or the stops. But part of the railing seemed to me to be weak, and the bench of late has developed a tendency to be ‘wobbily,’ to quote Mr. Bancroft.”

“Mr. Bancroft?” repeated Carol, wonderingly.

“Yes. Mr. Lenton Bancroft, but, as he says himself, ‘everybody around these here parts allers calls me Len,’” and Mrs. Becket imitated so well the garrulous tones of an old, crabbed man, that Carol laughed almost like some of the higher, tremulous notes of the great organ.

“Who is Len Bancroft?” asked Carol, when she and Cousin Kitty had finished their mutual mirth.

“A carpenter I had to call in,” was the answer. “He’s a strange, queer old man. I don’t like him. There’s an odd look in his eyes, sort of stupid, probably.”

“Why did you call him in?” asked Carol. “Does he live around here? I don’t remember the name.”

“No, he comes from Burrtown. Jacob knew of him and got him for me. He seems to be a good carpenter, but I don’t know whether or not he knows anything about organs, though Jacob says he does and Mr. Bancroft, himself, admits the charge,” Mrs. Becket explained. “I left him and Jacob in the loft, to come and answer the door,” she went on. “The carpenter has been here nearly all day and he has just finished. So if you want to come along——”

“I’d love to,” murmured Carol, her fingers longing to touch the shining ivory keys.

“Come along then.” Mrs. Becket led the way to the tower room, almost a complete ell built off the great hall, where the massive organ had been installed. In the first hall they passed Jacob Vroom, who was furnace man, gardener, butler, and whatever else seemed to be called for in the way of help around Oak Lodge.

“Has the carpenter finished, Jacob?” asked Mrs. Becket.

“Yes’m, jest about. He says it ain’t what he’d call a good job, but it’s good an’ firm.”

“That’s what I wanted,” Mrs. Becket responded. “Was that him or you trying to play, Jacob?” Her voice was sterner now.

“You know I wouldn’t, Mrs. Becket,” Jacob seemed hurt. “I never put a finger on the keys. But Len might have; couldn’t say.”

“I suppose so. Well, I’m glad he’s finished.”

A tall, lanky man, with a seamed, lined nutcracker kind of face, arose from a little clutter of shavings and sawdust, dusting off his overalls as he stood up with a chisel in his hand. He had suddenly appeared from the rear of the great organ, like some gnome who had been engaged in putting new and sinister notes into a perfect melody.

“Is everything all right, Mr. Bancroft?” asked Mrs. Becket.

“Yes’m, I’ve got th’ rail solid now. A elephant could lean ag’in it now an’ not bust it.”

“But I don’t allow elephants in here,” was the quick retort. “I hope you haven’t one in prospect.”

“What, ma’am?” Len seemed a bit taken aback, and Mrs. Becket, seeing he had no sense of humor, let it go.

“About the bench?” she asked.

“Oh, yes’m, I tightened that, too. This is a mighty fine organ, ain’t it, ma’am?”

“It has always been considered so.”

“That’s what I thought.”

“Do you know anything about organs, Mr. Bancroft?”

“Well, not what you could really call knowin’. But I know wood, Mrs. Becket. Wood’s my specialty. I couldn’t put back in the busted rail jest the same kind of wood it had in it original, but I done the best I could. The bench I jest had to tighten.”

“Well, I’m glad everything is all right. You touched some of the keys, didn’t you?”

“Oh, you heard that, did you?” and Len seemed a bit surprised.

“The organ carries to the farthest part of the house,” said Mrs. Becket, while Carol looked at the crabbed old carpenter, looked again, and decided she didn’t like him. Not that it mattered.

“Yes’m, I saw you had the power on an’ I jest sort of wanted to see how one of these things sounded close by. So I touched a few keys. I hope I didn’t do no harm.”

Mrs. Becket did not answer. She sat down at the bench, assured herself, by rocking to and fro, that it was now firm, and then she put her feet on the great lever keys that emitted the trembling notes, pulled out a few stops and, touching the ivory black and white keys, sent a burst of wild, haunting melody vibrating through the mansion.

“That’s grand, ma’am, jest grand!” complimented the strange carpenter as he gathered up his tools. “Shall I clean up this mess or——”

“Jacob will clean it up, thank you. And let him have your bill, Mr. Bancroft.”

“Yes’m, I will. But there’s no hurry about that. I’ll have to come back in a couple of days, anyhow.”

“Come back? What for? I thought you said you had finished.”

“Wa’al, I have, sort of.” Len Bancroft’s face was bent over his chest of tools. “But I might want to look an’ make sure them joints ain’t slipped none. The glue has to set, you know.”

“Oh, by all means come back if you need to,” said Mrs. Becket.

“Yes’m, I shall,” promised Mr. Bancroft. “You see, it’s all in knowin’ wood—all in knowin’ wood!” and he seemed to chuckle like a sardonic gnome as he went behind the organ for a moment.

Then, with another promise to come again in a few days, “to sorter look things over,” the strange carpenter melted away in the darkness that, save for a few dim lights, shrouded the organ loft.

“Well, I’m glad he’s gone,” murmured Mrs. Becket with a sigh of relief as she and Carol were left to themselves.

“So am I. So you think I might play now?”

“Surely, Carol. Just look and see if the air motor is full on. There is no telling what that silly man might have done—trying a few keys.”

Carol went behind the instrument, looked at the indicator, listened to the dull, almost silent hum of the motor, and was about to come back in front to the repaired bench, where Mrs. Becket awaited her, when she saw some peculiar marks on the corner of the great organ.

“Just as if some one had been cutting slivers out,” Carol mused. “I wonder if that ugly gnome of a carpenter could have done some damage, by accident, and be afraid to speak of it,” she asked herself.

Delaying a moment, she looked again at the strange marks—cuts and slashes they seemed to be in the very woodwork of the organ itself.

“Is anything wrong?” called Cousin Kitty.

“Wrong? Oh, no!” Carol made a sudden resolve not to mention what she had seen. It might make Mrs. Becket worry and, as Carol well knew, she had troubles enough as it was. “If it’s anything, which I can see by daylight,” Carol mused, “I can tell her then, and she can force that ugly little man to make it good. But perhaps it isn’t anything.”

“Come and play,” Mrs. Becket invited. “I believe I am hungry for music, and I don’t feel like making it myself. Come and play, my dear,” she urged again.

As Carol sat down at the bench, adjusted her feet to the pedal stops, and ran her fingers softly over the smooth ivory keys, old Jacob was letting Len out of the side door.

“Yes, I know wood!” chuckled the nutcracker face to himself. “I sure do, an’ if that old organ is what I feel certain it is—why—” He went into a mirthless chuckle.

He turned to look up at a lighted window on which was the shadow of Carol Duncan at the organ bench, and as she swung into the pealing notes of a soothing melody, old Len Bancroft shuffled down the road.

The deepening twilight cast his shadow before him, a ghostly, sinister shadow that appeared to dance up and down in unholy glee.

“Feel better, Carol?”

“Much better, Cousin Kitty!”

The girl, her black hair now a tangle over her eyes, for she had thrown herself body as well as soul into interpreting the music she loved, swung around on the bench the strange carpenter had repaired. It creaked the least bit.

“Oh, I must be careful!” Carol murmured. “He said the glue wasn’t quite set. Funny man!”

“Yes, he was a bit odd,” admitted Mrs. Becket. “I didn’t quite like him.”

Carol didn’t say she had the same feelings. She was thinking of those strange marks back of the organ. It would be time enough later, if anything developed, to chime in her feelings with those of the dear “Cameo lady.”

“I’m so glad you feel better.” Mrs. Becket arose from the deep chair beside the organ.

“Music always makes me feel better,” said the girl. “Now I must run along home. I just came from the picture place—isn’t it strange they call them pictures when so many of them aren’t that?”

“Aren’t what?”

“Aren’t really pictures, you know. I mean—well, I suppose you could call it art.”

“Yes, it is strange. Carol, you’re in trouble, child! Tell me!” Carol seemed to shrink away from the thin, outstretched hands.

“No! Cousin Kitty. I’m all right, really.”

“You mean you aren’t in trouble or that you won’t tell me?” Mrs. Becket smiled warmly.

“I’m not in trouble—not really. You might call it a temporary embarrassment, but——”

There was a moment of silence.

“If I can help, you must be sure to let me know.” Mrs. Becket was too wise to insist.

“I shall, Cousin Kitty. And thanks, just heaps and heaps, for letting me come here to work off one of my moods.”

“Are you sure it’s only a mood, Carol, dear?”

“Quite sure, Cousin Kitty. Now I must run along. I hope——”

“You hope what?” for Carol had not finished.

“I hope I don’t meet that queer carpenter. He might—he might think I was a piece of—wood and try to glue me fast!”

“You are far from being woodeny, Carol. Your playing alone would prove that. Come soon again, dear.”

“I shall, Cousin Kitty. And, thanks again.”

Carol, at home finally, found her sister in the living room reading some sort of document.

“Cecy, what is that paper?” she demanded.

“A contract.” The blonde girl with the big glasses, which made her eyes seem extraordinarily large, waved a crackling sheet.

“A contract? What for?”

“The car. The flivver. Pet Lizzie.”

“The car?”

“Exactly. It’s going to look like new. I’ve decided on pigeon blood for the color.”

“Cecy Duncan!” Carol grasped the paper. “What are you talking about?”

“If you’ll just listen a second and cut out the dramatics, I’ll tell you, my dear.”

“But a contract—?”

“It’s for painting our family car.” Cecy’s mocking tones rang through the small room so near the kitchen where some gas burners sent out a little heat.

Carol dropped into the rocker. Her face was white. She pulled off her hat.

“Whatever ails you?” Cecy demanded. “You look like——”

“I feel a darn sight worse.” Carol was on the verge of sighing. “You little idiot!”

“Idiot nothing! I didn’t sign this contract. Dad did!”

“Where’s the car?”

“At Crawford’s, all cleaned down to the pin feathers by this time, I hope.”

“Do you mean it’s already scraped?”

“I should hope so. It’s only a flivver, and he started on it this morning. What’s all the row? Didn’t we all agree it should be done?”

“We did a week ago,” admitted Carol, in that hopeless tone. “But it’s different now.” She turned toward the window, outside of which the rocking shadows of the horse-chestnut tree seemed to be threatening her. Like the shadows of the man with the carpenter kit in his hand. “But now—now—I’ve lost my job!”

“Carol Duncan! You never!” That woke Cecy up.

“I certainly did, and I didn’t chuck it either. They merely fired me.”

“What ever will you do now?”

“Whatever will I do? Whatever will you do?”

“I!”

“Yes, you. It’s time you stopped reading library books at five cents a day extra. And movie magazines——”

“You can just mind your own business——”

“I intend to. What’s Crawford’s number? I’ve got to have that car if it looks like a Mexican Hairless. I’ve got to go over to Long Hill.”

Cecy had washed her glasses under the faucet, the better to see this awful situation.

“It’s even worse than that. A major operation, Dad said—it would have to be turned inside out to be a good job.”

“Where is Dad?”

“Over at Crawford’s, holding Lizzie’s hand. He was so tickled, he took the bus over to see how they did it. I was glad when he went out.”

“You would be.” Carol’s tone was scathing. “Poor Dad! But we can’t starve.”

“You’re right, we can’t. And that lamb stew is two days old.”

“It may have whiskers before we finish it. You don’t seem—” she stopped. After all, Cecy was not more than a child. “You just don’t seem to realize the enormity of our situation.”

“Don’t I, though. And I counted on a new coat before I freeze to death.”

“Please try to think of— What’s Crawford’s number?”

“Union, two hundred, a neat little number. But don’t go calling up, Caro. Dad might be there——”

“Yes, that’s so. But why ever did you rush it so? Couldn’t you wait until I came home?”

The two sisters, so unlike in temperament, were bound to clash under excitement. It was their way of adjusting differences; of getting to a spot where they could agree. Even Cecy, who was ever on the defensive because she had so much to defend, was now settling down to something like common sense.

“Darling,” she said to Carol, “I’ll make you a cup of tea. You certainly need it.”

“Oh, don’t bother, Sis. You see, I needed the car at once. They still run an organ in Long Hill, and the man who played it has gone or is going West. I might get it. But it won’t wait.”

“Why don’t you phone?”

“They hardly listen——”

“But they know your name. We all sang there and you played a solo at Mrs. Becket’s fest.”

“Yes, that’s right.” Carol was on her feet again, she needed to move about. “They might happen to remember.”

“Try it.” Cecy had the tea ready, poured in Carol’s favorite black and white cup, with a fruit cracker on the side. “You can be sipping this. I’ll get the number.”

A long, anxious wait. What is slower than slow telephoning? Finally Cecy had it, and had reached the manager’s office, who was not only manager, but treasurer and general boss besides.

Carol spilled her tea, but Cecy caught it up noiselessly—just a little puddle on the pretty table oilcloth. Not an extra sound, lest the conversation might be interrupted, for Carol was talking eagerly.

“Well—” Cecy asked, breathlessly. “The place isn’t taken?”

“No, and he’ll see me soon. How can I get over there?”

The problem of the stripped car was seething in Carol’s mind. How could she reach Long Hill?

“Why, Glenn will take you over!” burst out Cecy. “He’ll be tickled pink.”

“Glenn?”

“Sure, Glenn! You don’t give that boy half a chance, Carol. He’s a peach!”

“I know it.”

“And you act it—not!”

“Cecy—please! I’ve got to think this out. Dad may be in any moment now. We’ve got to do something.”

“But what are you going to do, Carol?” Cecy’s voice was just the least bit impatient.

“It’s about your turn to do something, Cecy!” Carol retorted somewhat vehemently. “Why don’t you go into the Vienna bakeshop? See if they could give you anything to do. That’s a fine place for fancy baking.”

In answer Cecy piled a mound of crumbled cheese over on a palisade of bread, with expertness akin to the movies.

“Me in a bakeshop!” she muttered.

“Why not? It’s a lot cleaner than a mouldy old organ loft and not so hard on your feet, either. My shoes are just shedding their soles. Another expense!”

“Oh, well!” sighed Cecy indecisively.

A step was heard outside.

“It’s Dad!” murmured Cecy. “Let’s not tell him—just yet.”

“It’s only putting off the evil day,” Carol sighed. “But I suppose there’s no use worrying him tonight.”

Mr. Duncan entered, and it either speaks well for the dissimulation of the girls or not so well for his observation, for he did not notice their perturbed looks. Flashed glances passed between Carol and her sister and then, as if by common consent, they began a conversation in which Mr. Duncan could join.

Muddled, worried, and uncertain, Carol did not sleep well that night. As for Cecy—well, she was just Cecy and, as she boasted, it took more than that to keep her awake. Mingled with Carol’s wakefulness were worries which seemed involved in the wailing organ and the strange carpenter’s work upon it.

It was raining hard when morning broke, and this put a most effectual damper on any plans Carol had for herself or for Cecy. They remained indoors most of the day, slipping out, still indecisively, when the rain ceased for a moment or two.

The storm continued, intermittently, for two days more, during which Carol could do nothing to advance her own plans nor those of her sister. She wondered what was happening at Oak Lodge.

It was on an evening after the long storm when a red sunset gave promise of a fair next day that Carol and Cecy were again talking in the absence of Mr. Duncan. Carol had been speaking to Glenn on the telephone. Somewhat jokingly he had asked her if she had seen or heard anything more of the ghosts in the organ.

“I never said there were ghosts in the organ, and I don’t believe anyone else did!” countered Carol. “As a matter of fact, I don’t believe in ghosts.”

“I do—certain kinds!” chuckled Glenn. “I’ll tell you about them when I come over for you.” He had promised to run her to Long Hill in his car. Carol hung up and went back to join her sister. Mr. Duncan had gone out for a walk, he was moody and depressed, Carol thought, sadly.

“Well,” began Cecy belligerently, “I’m not going to——”

The tingling of the telephone startled them both. It might mean any one of so many important things.

Thalia Bond was speaking. She was all but breathless, Carol noted, as she listened.

“Oh, Oh, Carol!” Thalia almost gasped.

“Yes! Yes. What is it?”

“It’s Mrs. Becket. They just called and told me that she is ill—very strangely ill, it seems. They tried to get you, but—”

“I know. I was talking to Glenn. Oh, what is it?”

“She seems to be ill.”

“Ill?” Carol was much disturbed. “Why,” she said, “I saw her just for a moment this morning. She was all right then. What can be the matter?”

“If you ask me,” drawled Thalia’s voice, “I think she’s just scared, Carol.”

“Frightened! Of what?”

“That’s it—what? If she knew, she wouldn’t be scared. Can you run over with me?”

“I can’t! I’d love to, but I am going out with Glenn to Long Hill. It’s important to me.”

“I can imagine that. But——”

“Cecy can go.”

“Go where?” snapped Cecy, overhearing. “Are you making dates for me?”

“It’s all right, Cecy,” Carol explained in an aside. “Mrs. Becket is suddenly taken ill—or alarmed. Thalia is going over. You’ll go with her, won’t you—please?”

“Oh, I suppose so. Is it more—ghosts?”

“I don’t know. You’ll have a chance to find out.”

“Then I’ll go. But not until I’ve had tea. Here’s Dad coming back. We can eat together. Shall we tell him—all the news?”

“Not yet,” Carol decided. And she was glad of this decision when her father, at his tea, enthused over the prospect of the repainted and all but rebuilt car—which refurbishing might now be indefinitely postponed.

Both girls listened with somewhat guilty knowledge as he rambled on so happily. It might have been kinder to tell him at once about Carol’s loss of position. It seemed, now, little short of cruel to let him talk on so eagerly. But, having thus started, the matter had to run its course now.

It was almost half-past seven, the hour when Glenn was to call.

“But,” mused Carol, “what could have happened to Mrs. Becket?”

There was small time to wonder. She must go with Glenn. Cecy must accompany Thalia to Oak Lodge. What would she find there?

In their room, while both girls were getting ready to go out, Cecy was all excited about Mrs. Becket.

“It’s that old organ,” she insisted, exuding mystery in gobs of breath.

“Silly! What could be scary about that marvelous organ?”

“What couldn’t be? Stubby told me——”

“Cecy, you haven’t been talking to that horrid boy again!” Carol stopped pondering to ask.

“Carol, how quaint! Horrid boy. You sound like an old woman. Besides, what’s horrid about a boy that knows all the ghost stories of Melody Lane? I think he’s fascinating.” Cecy’s laugh belied that. She was agreeing secretly with Carol about that Stubby—the queer boy that worked for Mrs. Becket because she had to take him with the house, like the old black dog Rover, who never roved, so died conveniently. Stubby was not fascinating, except at a good, safe distance. He was ugly, unkempt, and hard to understand. Cecy herself had once caught him trying to tie a tin can to old Tommy’s tail. And Tommy was a good, quiet cat, if ever there was one.

“Please, Cecy, don’t be seen talking to that——”

“I won’t. But he told me the organ plays of ‘its ownself’! He says Mrs. Becket is so scared she stays up nights.”

“Now listen, Sis. I just beg of you not to go on that way with Thally. You know how stuff like that spreads around here. And Mrs. Becket is our best friend.”

“Don’t worry. I’m out to listen, not to talk,” and for once Carol felt she might depend upon some discretion from the flighty Cecy.

Then Glenn called. He didn’t honk outside, but dashed in, hatless and handsome, bringing a sweep of the pure outdoor air in along with him.

“I’ll be ready in a jiff.” Carol had only to pick up a few sheets of music. They might ask her to play.

“No hurry, we’ve got all our lives. How are you, Mr. Duncan?” The father had come into the living room.

He liked Glenn. When the boy asked that sort of personal question, he seemed interested in the answer. Most boys only listened to their own voices. So Mr. Duncan told Glenn about the car.

“Seems to me well worth the money,” he was saying, while Carol winced at the mention of money. “And we all enjoy the car. As a matter of fact, Carol needs it.” He seemed trying to justify the expense. Mr. Duncan certainly was good-looking. Black hair like Carol’s, with a wonderful “white wing” in the front like an actor’s. And his eyes still blue through his glasses. Clean shaven and of soldierly carriage, any daughter might well be proud of so fine a father. It was dreadful that he had had to lose his position, and now that so many fine men were going through the despond of the depression, Felix Duncan was no exception.

Finally Carol and Glenn got away. Cecy and Thalia had gone to Oak Lodge.

“I’m petrified,” Carol began as she and Glenn took the wide road out to Long Hill. “I’m just scared to death.”

“Hold on to me.”

“Glenn, I mean it. We’re in an awful jam.”

“Who isn’t?”

“Please be serious.”

“At your attention. Can I help, Carol?”

Instinctively she slipped down closer to Glenn. He was protective.

“I’ve lost my job. I’m going over to the Keystone to try there. I couldn’t tell you before Dad.”

“That’s tough, Carol. But if there’s a vacant chair or bench in front of that old Keystone organ, it’s yours.”

“Why so sure?”

“I know Mr. Cameron. He’s in Dad’s bank company. If you can’t charm him into giving you the job, I’ll threaten him. They say I look like my dad.”

“Honest, Glenn, do you know him?”

“Certain thing, and he isn’t so bad either. Rather pleasant. He gave Mother twenty-five smackers for her poor kids.”

“Glenn, I’m hopeful now. I was terribly sunk. You see, there’s Dad and Cecy.”

“I know. But you’ll pull out, Carol. My dad had to lay off three men today, and I’m going in the factory.”

“Oh, no, Glenn!” Carol’s voice.

“Why not? Am I so good? Saves Dad twenty-five a week. Not that I’m worth all that, but the other fellow had to get it.” They were rounding a curve with high banks on all sides and Glenn slowed down. The extra lights at the dangerous point flickered in the late September uncertainty. It was darker than it looked, Glenn had remarked, which was true if trite.

“There’s the glimmering Keystone. See if you can make out anything in my favor,” suggested Carol as they swung into the village centre.

“Sure I can. The lights. Carol dear, the lights are always in your favor,” which served to give them the green traffic signal, allowing them to speed on without further delay.

Glenn reminded Carol he was within reach if she needed influence with Mr. Cameron, the manager who was on the board of Glenn’s father’s bank.

“All right,” Carol told him with the rare smile which was sweeter for its wistfulness. “But I always like to try my own hand first.”

“Now, Carol,” he had secured her hand in a playful little grasp, “my hand’s pretty good too. You have no idea.”

“Haven’t I?” Which of course meant she had.

Then Glenn took up a waiting spot while Carol went to the small door marked private.

Just as Cecy had reminded her, the manager had remembered Mrs. Becket’s music festival the year before, and he was sure Carol would be satisfactory at the organ. Mr. Cameron was a quiet, pleasant little man, more like a country storekeeper than a movie manager. He was most agreeable, and Carol felt quite elated until he said, as if he was ashamed to say it:

“Trouble is, no patronage. Can’t tell when we’ll have to close up.”

“Oh, of course.” Carol fought back, in a surge of bitterness that this run of hard times seemed to spare no corners. “But no one can help that,” she said finally. “I’d be glad to go with you as far as you could go.”

“That’s fine.” Mr. Cameron answered. But he showed no enthusiasm, Carol wondered why.

“Do you have afternoon shows?” she asked hesitantly.

“That’s just it. We have only afternoon shows where the organ is used, and we have to take the sound music at night. Three afternoons weekly. I’m afraid, Miss Duncan, it will hardly pay you,” he faltered.

“Oh, but I’m glad to take anything,” she hurried to assure him, while her heart felt heavier. “You see, Father——”

“Yes, I know your father, Felix Duncan. A fine man. Pity the Standard Works couldn’t take him back after his illness. He knows more about that company than all those youngsters put together,” Mr. Cameron declared, warmly.

“You know Father? Yes, it was too bad he had to lose his place. It’s so hard to get a new one in these times.”

“Yes. But he’ll be taken back. I suppose these college boys in the owners’ families have to be put somewhere, and that’s right enough, too. But a man like Felix Duncan is going to be missed.” He paused for a moment as Carol bit a lip pulled into a defiant line. “But about your salary,” Mr. Cameron went on. “That is, if I can call it that,” and he smiled grimly. “I can’t promise more than twelve dollars a week.”

“Oh, that’s all right,” Carol quickly gulped, her brain instantly at work upon the loss of the six dollars from the Silvertone. But this, at least, she must make sure of.

So it was arranged, and she had not needed Glenn’s kindly offered influence. Neither did she mention to Glenn, when she joined him, the small salary she had promised to take.

“I told you that you’d get it,” Glenn chuckled as she sat beside him.

“Yes, thanks.” Then she said, impulsively. “But the plucked car! How am I to get over here without it?”

“When will it be ready?”

“It’s the money I mean.”

“Oh,” mused Glenn. “Well, we might manage that quicker than the painting.”

“You’re kind, Glenn,” sighed Carol. “But— Oh, I don’t know! Why did Cecy pick such a time to turn in our car?”

Glenn didn’t answer. It may have seemed an unanswerable question to him. Certainly it was to Carol. The sudden accumulation of troubles had stirred in Carol every ounce of her determination to fight them. But there were so many. What was far from a minor one was means of getting back and forth to Long Hill, now that she had a job there. Even the afternoon performances with Carol at the organ would mean arrival at the movie house early, so that she would have to cut school classes beyond repair. The things she had to think of just now were those she had to do, not those she hated doing, although they were, just now, identical.

Glenn swerved the car to avoid a bump in the road, and when they were running steadily again he remarked:

“You say Cecy had to hurry over to Mrs. Becket’s? I didn’t pay much attention at the time. What’s wrong?”

“I don’t know. I was so excited about getting this job, I didn’t give it much thought myself. But it seems that Mrs. Becket was taken suddenly ill—frightened, Thalia said—she begged me to go over with her, but I didn’t dare.”

“Didn’t dare? You don’t mean you were afraid?”

“No, but I didn’t dare pass up this chance for a job. I might not get another opportunity.”

“Oh, I guess you would, all right. But what could have frightened Mrs. Becket?”

“It’s hard to say. Oh, Glenn, do you know they tell the craziest things about Mrs. Becket’s place?”

“Sure, I do. Who doesn’t? The old organ seems to harbor a ghostly Saint Cecilia.”

“It’s terribly silly, of course——”

“But Jane Jackson is no fool, and she stopped going there for lessons. Says it’s too spooky.”

“Jane Jackson has stopped her lessons? Why, Glenn, that’s awful.”

“Why is Jane so important?”

“Because she’s rich, and all the girls follow her. It might even break up our Choral Club.” Carol was now truly dismayed.

“What can I do about it?” Jane Jackson was not exactly a rival of Carol’s, but everybody knew Jane liked Glenn.

“Maybe you could do something about it, Glenn,” Carol told him. “If it’s all a trick, we’ve got to run it down, that’s all. Certainly Thally seemed worried about Mrs. Becket being sick. She wanted me to go right over there, and when I couldn’t, she took Cecy.”

“Well, Cecy’ll know all about it,” he answered good-naturedly. “She surely loves detective stories.”

“Yes, too much. She just thinks of nothing but mysteries and reading silly movie stuff. But she’s got to do something now.” Carol meant that.

“She will; you’ll see. Cecy’s all right, but maybe not busy enough.” Glenn wasn’t the boy to say more than that about any girl.

“But she talks to that awful boy, Stubby. I’m afraid her interest in mysteries may lead her too far.”

“Stubby is not good company,” Glenn grudgingly agreed.

“But, Glenn, haven’t you any plans for running down the organ ghost? We can’t let Jane’s scare get all over town.” Carol returned to that important subject as they neared home.

“Maybe I could get Jane to reconsider.” Glenn was being “foxy” about Jane. But Carol didn’t mind, at least she pretended she didn’t. Her hand still on the open door of the roadster, she smiled her sweetest into Glenn’s eyes and assured him that he could do just that very thing about Jane if anyone could, adding:

“I hope you will!”

Glenn burst into a roar of laughter at what Carol said, covered her hand with his own firm clasp, and called her a good little sport.

“But, Carrolla,” he teased, “don’t worry about everything. The ghost is O. K.; that’s a good healthy worry, and I’ll bet it’s an all right ghost too. We’ll get after that if we have to bust the famous organ of Melody Lane.”

“Nothing could be hidden in the organ,” Carol insisted.

“Oh, mice and things, bats maybe, or some sort of gibbering animals——”

“No, nothing so simple,” Carol again insisted. “But wait until we hear Cecy’s story. Maybe she’s home. Come along in and hear the ghostly details.”

“If you insist——”

“There’s Thally’s car coming now. We’ll make a fine audience for them, for they’re sure to have a thrilling story.”

Cecy sprang out of the car, but Thalia couldn’t wait. Had to go right off with no more than hellos and good-bys. But Cecy would make up for the loss. In fact, she had already started.

“What happened?” asked Glenn.

“Oh, you’d never guess——”

“Come inside. I’m cold,” urged Carol. “Besides, we’re all tired. Let’s get sitting down.”

They found the living room empty, only the low light awaiting them.

“Dad’s asleep. Don’t let’s talk loud.” Again it was Carol who admonished them.

“But oh, really,” Cecy had flopped down, was tossing off her hat and all but kicking up her heels, the way she swung herself back in a big easy-chair. “Honest, poor Mrs. Becket!”

“No parking, Cecy,” ordered Glenn. “Put out your hand and keep going. What does the ghost look like?”

“Look like? Who knows! But you ought to see poor Mrs. Becket. She looks like a ghost, all right,” Cecy was not to be stampeded into telling her story too rashly.

“Is she really sick?” Carol asked.

“I’ll say she’s sick. I would have stayed with her if I hadn’t been afraid to.”

“Does she need someone tonight?” Carol pressed.

“Well, she didn’t say she did. But Thally said she hated to leave her.”

“What happened?” Direct-action Glenn.

“She wouldn’t say just what happened. But she did say that things were happening around there—things hard to understand.”

“Now, Cecy, don’t be silly. You know she didn’t say anything like that,” Carol objected.

“Well, she said she hadn’t slept for nights. And Stubby won’t pump the organ any more, and the electric thing is disconnected. And all the girls are quitting their lessons.” Cecy’s feet both went up and down so violently at that statement, her left pump almost dropped off.

Glenn and Carol were talking in glances. Plainly they both agreed something should promptly be done about the beloved Mrs. Becket, who was worse than alone because she seemed to be among enemies. There was that crabbed old caretaker, Jacob Vroom, who lived in the gate house, and his wife Lena, who acted as though afraid to draw her own breath without his permission. The queer episode of the carpenter was still Carol’s secret. Then there was a girl at the Vroom cottage, a niece or some relative of Lena’s, but no one ever saw her around unless she was shaking a rug or hanging up clothes. And now Cecy had just said that Stubby, the queer boy who always had pumped the organ in spite of some other indefinite mechanical arrangement, was on a strike. Wouldn’t go near the thing because it was too spooky, as he said.

“Well, what do you think?” Cecy demanded impatiently, for the language of their glances was not entirely lost upon her, although Carol was keeping things quiet, lest her father might be awakened. “Isn’t it simply terrifying?”

“What?” asked Glenn exasperatingly.

“Ghosts, of course,” snapped Cecy.

“Ghosts,” repeated Carol scornfully.

“Ghosts!” echoed Glenn whimsically.

After that chorus and refrain they all subsided into a silence that might mean anything. But to Carol it meant just one thing. She must go to Mrs. Becket at once.

“I guess I’ll go over and stay with Cousin Kitty tonight,” she said with as much indifference as she could assume. “I have a lot to tell her, anyhow. Things have happened to me since I saw her for a moment this morning.”

“Carol Duncan! It’s a wonder you wouldn’t stay home and tell me,” accused Cecy. “Besides, I’ve got some extra school work to do and with breakfast——”

“I wouldn’t kick if that were all I had to do,” Carol reminded her. “And from my latest financial reports you had better consider the plan we mentioned.” She referred to the idea of Cecy getting some extra hours in the pretty yellow and white Vienna Bakery, where any girl who had had domestic science at school might have been glad to show off.

But Cecy glared at Carol. She wouldn’t even mention that before Glenn. Her working in a bakery!

“Take me over, Glenn,” begged Carol.

“To Cousin Kitty’s? Certainly. Maybe we can run down the ghost on the way.”

Which wild idea did more to make Cecy satisfied with Carol’s absence from home that night than all Carol’s promises to let her have a night off very soon.

“No lights!” Carol was at the heavy front door of the mansion which was Kitty Becket’s home.

“Maybe a fuse burned out.” Glenn was always reassuring.

Carol pushed the bell button again and they waited. Still no answer.

“That’s queer. Let’s try the side door,” Glenn suggested.

The night was now dark and dreary, as fall nights are apt to be, and the massive trees with heavy shrubbery seemed to weave sinister figures into the very darkness.

Carol drew her coat around her. “You should have worn a sweater, Glenn,” she remarked to the boy who so gallantly stood beside her.

“Oh, I’m all right,” he declared. “But I would just like to know why we can’t get in.” He rattled the door thoroughly.

They tried the windows; all locked and perhaps even bolted, for Mrs. Becket had lately been having trouble to keep even one maid with her; the spook story had frightened several away.

“Isn’t Lizzie Towner here?” Glenn asked.

“She was yesterday, but who knows? Oh, Glenn, I am afraid something really serious has happened.”

“Maybe Kitty went away for the night.”

“Not likely. I was here this afternoon and Cecy was here an hour ago. Do you suppose there is any possible window unlocked?”

“We’ll try them all. But old windows seem locked when they ain’t,” he tried to joke.

“The pantry is above the cellar door,” Carol remembered.

“Wait, I’ll get my flash light from the car.”

The few moments Carol stood alone on the great wide porch seemed to add to her fears. What could be wrong around that place? What could have happened to dear Kitty Adair—Mrs. Becket? She had done so much for so many girls, including Carol, herself.

Memories of her many kindnesses flashed into Carol’s mind, like a shaft of light cutting through the hideous black night, as she waited for Glenn with his flash light.

They tried the pantry window, Glenn standing on the slanting cellar door, but it did not budge.

“We’ll have to break something, I guess,” he said finally. “Are you sure it’s best to get in?”

“Oh, yes, we must. Glenn, she may be very ill.”

“All right. Never mind windows,” he concluded. “That old French door in the library shouldn’t be hard to convince. Let’s try it.”

“You mean—batter it down?”

“Or bust it in. I don’t care which. Do you?”

“No.” But she didn’t lighten her voice to match his. It was heavy with keen anxiety.

“Why didn’t she ever keep a dog?” he asked, as they again tramped around to the side porch.

“Old Jacob Vroom is a crank about dogs.”

“And about a lot of other things. But no lone woman should ever stay in a place like this without a good watchdog.”

“Oh, she never did intend to be alone. She always had visitors, and her maid Tillie was very faithful. But lately—oh, I don’t know,” sighed Carol. “It does seem to me everything comes at once.”

“Now for the door.” Glenn was edging his shoulder against it with premonitory tests.

“Suppose we ring the bell once more,” suggested Carol, disliking the possibility of hearing that glass door splinter. “She might just hear us.”

“All right. But don’t let’s waste too much time.”

First they rang the side doorbell and could hear it plainly. But there was no step inside; no answer. Then they raced around to the front, having to leave the porch to do so; but neither was that attempt successful.

“Looks like busting the old door,” Glenn decided, and down the steps they trotted again, wasting no time now on other possibilities.

A step from the back gate was crunching up the gravel path.

“Someone coming,” whispered Carol.

“Yes,” Glenn had her arm and she was instinctively crowding nearer to him.

“A man—it’s Jacob,” Carol whispered. “He may be ugly.”

“Will be,” Glenn corrected. “But maybe he has a pass-key. Easier than breaking the door.”

“Who’s that?” came a gruff command. “What you doin’ here?”

“I’m Carol Duncan and we are here to see Mrs. Becket,” Carol promptly answered. “She does not answer the door. Do you know if she is at home?”

“I don’t. Maybe she ain’t. If she don’t answer, so why make all that noise? It’s nighttime, ain’t it?”

He was ugly, his voice almost snarling. The few times Carol had spoken to him before he had been like this, she remembered. He always growled and snarled, and Mrs. Becket would have sent him away long ago but for some legal angle that seemed to give him a home on the old estate as long as he should want it. He had taken care of an invalid son of the original owner, and while well paid for his services, the home idea was evidently a matter of extreme gratitude. Carol remembered hearing all this, and she hoped Glenn would not argue with Jacob Vroom. Glenn could answer quickly enough, and what he was saying just now showed the very danger Carol was hoping to avoid.

“You can get yourselves out of this,” Jacob began when Glenn paused for breath. “How’s this your business, I’d like to know?”

“I came to spend the night with Mrs. Becket,” Carol tried to explain.

“And we are not going away till we see her,” fired back Glenn. “Have you got a key or shall I break in?”

“You break in! Want to go to jail? I’ll call Tim Clark just this minute——”

“Never mind Tim Clark, he’s a friend of mine and a good cop. You just open a door or I’ll call him myself after I get through investigating, maybe,” Glenn retorted.

Which had the effect of cooling Jacob’s anger, for he at once changed his tone.

“’Tain’t no use gettin’ so mad——”

“But I must get inside quickly,” pressed Carol. “If Mrs. Becket is in, she must be dreadfully ill.”

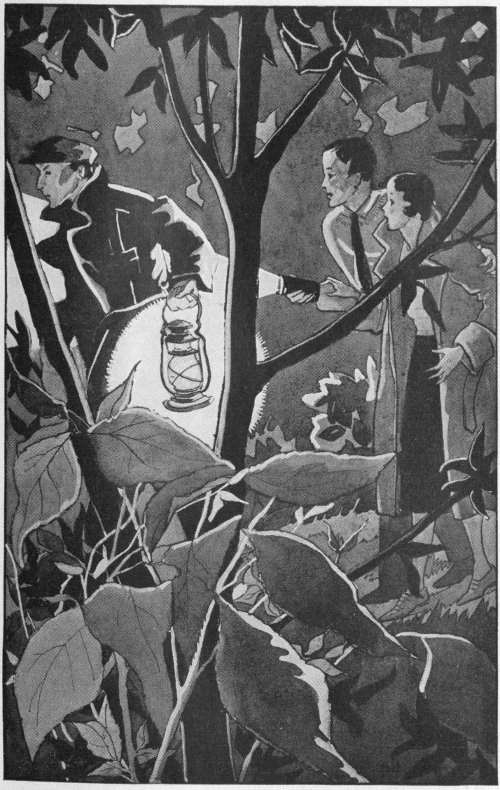

“I ain’t seen no light since maybe eight o’clock. I can go in by the back door, the ice house door.”

They followed him, with his dingy lantern, all around the house, for the ice house door was on the extreme end. Trees and bushes were thick about the old door, for it was no longer used, and Carol as well as Glenn wondered Jacob did not use a more convenient entrance. Near the little round extension that bulged out back of the kitchen he suddenly stopped.

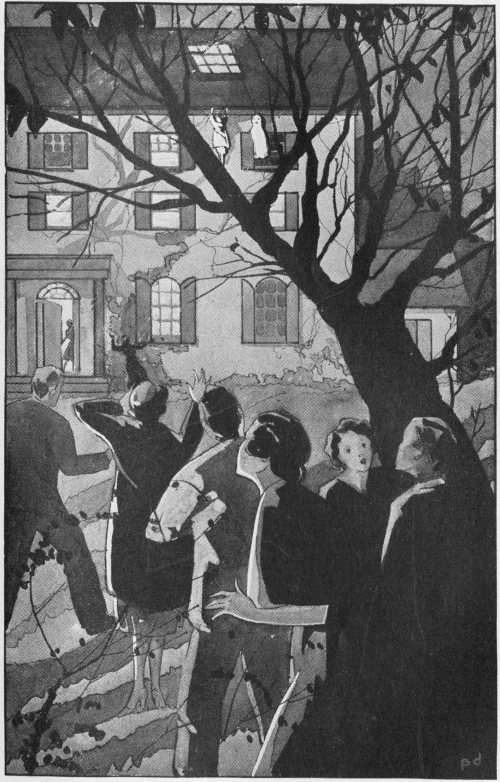

THEY FOLLOWED HIM WITH HIS DINGY LANTERN.

“You wait here. I’ll open the door when I get in.”

“We can just as well go in the door you use,” Glenn urged quickly. He wondered why they shouldn’t.

“’Tain’t necessary, and it’s dark. I’ll open the kitchen way for you. You stay here.” Jacob was ordering them now.

“Let’s wait,” Carol asked, as if fearful of further complications. Also, she was pretty well used up and didn’t feel like prowling around dark corners.

Glenn made a way for her to follow. If there ever had been a path that way, it must have been a long time ago, for the underbrush was in a terrible tangle.

“Why didn’t he park us in a clearing?” Glenn wondered. “Maybe he’s trying to lose us.”

“Lose us?” Carol repeated.

“I mean slip away from us. But fat chance. Here, hold on to me, Carol, dear. I’m your hero.”

She did hold on to him and refused to notice the hero joke. Comic hero business was farthest from her thoughts just then.

“This is the door he will open, I suppose,” she said, going up another little flight of steps to a door almost hidden in the arch of a window.

“More doors than keys,” Glenn added. “Say, Carol,” he changed to seriousness, “don’t worry so. After all, Kitty may really have gone out for the night, you know.”

“If only I could think so. Listen, here comes Jacob.”

They listened, waited, but the step they had heard coming was now apparently going away from the door.

“He’s calling. Hear him yell! Calling Mrs. Becket,” Glenn said, as the rough, raucous voice of the man sounded through the big dark house. “Wonder he wouldn’t scare her, yelling like that.”

“She may be glad to hear his voice. Oh, Glenn, why doesn’t he open the door!” Carol was shuddering.

“I’ll find out why. Hey there, Vroom!” Glenn yelled himself this time. “Let us in!” and he pounded on the door as if he meant business. “Open up here! If you don’t soon, I’ll go after Tim Clark, pretty quick. Get a move on,” ordered Glenn. “I’ve got a good little car here, you know.”

They waited after that and, yes, the step was coming down the stairs again. Jacob Vroom had stopped calling out Mrs. Becket’s name. Couldn’t he find her?

A new dread seized Carol. Her nerves were on edge from the anxieties of the afternoon, and this seemed like the last straw. Still, if only nothing serious had happened to her dear, good friend Mrs. Becket, she would be glad and willing not to complain of anything else.

A sound of stumbling and more growls within told them what they could not help knowing. Jacob was stumbling about in the dark, trying to reach the door, for no light showed, and the dingy lantern could be little use as a guide.

Finally, after many knocks and bumps, the bolt was shot back and the door pulled open.

“Come in,” the man uttered, “but she ain’t here.”

“Isn’t here!” They had stepped quickly into the dark hall that Carol knew so well under more pleasant circumstances. “Where can she be? Have you looked everywhere?”

“And yelled my t’roat sore. She ain’t nowheres.” They saw now that Jacob, too, was scared, for he was holding the lantern high and its faint glow cast a queer pallor over his hardened face. “I don’t see what she could do—” he went on. “She was here at supper time.”

“Let’s look,” ordered Glenn sensibly. “What’s wrong with the lights?”

“That’s funny, too, they’re off. Not a button works.” Jacob Vroom may have been mean and ugly, but he showed deep concern now. “I takes as good care of her as she’ll let me,” he defended himself, “but she’s queer.”

“I don’t think she’s a bit queer,” Carol exploded. “But queer things are happening around here lately. I know that much. Come along, Glenn, let’s try her bedroom first.”

“I was in there,” Jacob declared.

“Well, we’ll take another look,” Glenn answered. “It’s a pretty big house and we have only my flash light and your lantern. So let’s get going. Wait for me, Carol. You can’t see without some light,” for Carol was rushing up the stairs, fearing she knew not what, and wishing every button she touched would answer presently with at least a friendly light. But her wish was vain; it was in darkness they went first to the big bedroom, where that delicate perfume Carol had always loved flooded about in the darkness now, friendly enough but not reassuring.

“Cousin Kitty!” Carol called softly. “Are—you—here!”

Glenn flashed his light first on the bed. Its pretty satin coverlet had been neatly turned back, and the dainty little pink head pillow Carol had given Cousin Kitty at Christmas showed the crush of a head only lately withdrawn.

But there was no sign of the owner. Jacob was opening the closet doors, Carol was looking everywhere while her heart sank to deeper fears, as she realized the enormity of their quest.

They were not arguing now, even Jacob had stopped growling; Glenn would say a cheerful word when he stumbled in the dark or kicked his shins against a chair, but Carol was silent. She knew this handsome, big old house so well, and loved it. Her happiest hours had been spent here with the girls Mrs. Becket assembled about her, determined to pass on to them as much of her musical knowledge as they could absorb, for both Kitty Adair the actress and musician, and her late beloved husband, Wilmer Becket, had been known for their quiet charities, their individual philanthropies. Music was their passion.

When they had bought this house, Oak Lodge, after it had been standing unoccupied for more than a year, people, friends, advised them against it.

“You’ll have no luck there,” they argued.

“Since that poor boy came back to the lodge with his back broken—a mere youngster from some junior college—there’s been nothing but trouble and mystery in that end of Melody Lane.” This was the general opinion of people in Oakleigh.

But the real attraction for the Beckets was the great organ. This had been built in by the original owner for his young wife, whose early death had added one more tragedy to the history of Melody Lane.

Far and near the organ was known. Famed artists had come to try out its unbounded melody, but it was found, on account of its intricate building, too expensive to move from its original setting. That was why Wilmer Becket had bought the great old place, Oak Lodge, with the famous organ built in.

But the weird, menacing history of its mysterious power was working the old-time disaster tonight.

Where was Kitty Becket? What could have happened to her?

The searching party had not yet looked in the organ loft. That was set out in a circular wing off the great staircase, and there could be no reason, at least not much reason, to expect to find her there.

“If only the lights would come on,” sighed Carol as all three searchers stood, beaten, discouraged.

“But them buttons—don’t strike no more of them. What must I do if they all blaze up later maybe?” growled Jacob, not unreasonably. “I now go after you Miss, Miss——”

“Carol,” the girl supplied.

“Yes. And I turn out all I can find. But this house is all lights——”

“And doors,” Glenn added.

They were on the first floor again, in the wide hall beneath the grand stairway, where jutting out in a tower, with stained glass windows on all sides, the great organ was now hidden in cruel darkness.

“Listen!” whispered Carol, “I heard——”

“So did I. Give me the lantern, Jacob,” Glenn demanded, “it’s better than my flash.”

“Come on,” begged Carol. “I know I heard—There it is again! In the loft.” She was going up the broad stairs ahead of Glenn, following the sound that now seemed positively to come from somewhere near the organ. “If only those lights——”

“Look out! Don’t trip,” warned Glenn, for her foot had slipped sharply.

“But that is Kitty. Kitty!” she called out, “we’re coming. Where are you?”

“Here, here,” came back the beloved voice, feeble and strangely constrained. “Here—by—the—organ!”

“Wait; I go first,” ordered Jacob, gruff and coarse again. “It is my business——”

“It is our business,” retorted Glenn, “Come along—after us!”

Carol was not listening to the men arguing, her light shoes scarcely tapped the steps as she hurried up, past the alcove where the red leather seats had so often enticed the girls of the Choral Club—they looked black, not red, now in the darkness—then up four more steps and out into the tower where the giant organ was so majestically built.

“I’m coming, Kitty darling,” she kept calling. “If only these lights—” She put her finger to the spot where she knew a button marked the way, and instantly the whole place was flooded with light.

“Oh, the lights!” she breathed thankfully, “now we will be all right.”

Yes, the lights were indeed welcome and now, one more step, a turn——

“Kitty!”

“Dear Carol!”

“What happened?”

“I—fell. My hip, I guess——”

“Don’t try to move. Glenn, Jacob——”

“Jacob,” repeated the prostrate woman in a queer way. Then, “Oh, yes, Jacob.” She was lying almost under the long organ bench and still holding a candle, a futile, foolish little candle in a little silver stick. Its light was out, of course, but evidently the helpless woman had clung to it in vain hope that some light might be brought into her prison of darkness.

Her blue silk gown, her wavy white hair, white as platinum, and her now too white face made a strange picture there in the organ’s shadow. The golden pipes above and the gleam from the gold dome did something heavenly to the scene, and Carol recalled the famous painting of Saint Cecilia—this was a prostrate Saint Cecilia.

Glenn and Jacob were lifting her, Carol cautioning at every touch.

“Does it pain much, dear?”

“Frightfully. I must have fainted. I could hear sounds but—could not—call——”

“Don’t talk. What a mercy the lights are on. This way, Glenn. Can you keep her hip from jarring?”

“Yes, we’re as good as a stretcher. Aren’t we, Jake?” He was so relieved at finding Mrs. Becket, for even this injury was not as bad as a head blow might have been, that he felt much more friendly now toward Jacob. Perhaps, after all, it was a mere mean suspicion that had caused him and Carol to blame the caretaker in a vague way for the uncanny tricks of a night of terror, without lights, in the big house, the site of the mystery of Melody Lane.

On the bed, in that beautiful room of ivory and old blue, Kitty Adair looked the actress she once was, as if again acting a part; a part of a lovely lady in a lovely room, surrounded by an anxious boy, an anxious girl, and that other figure, alien to the group but lending drama to the picture, Jacob Vroom.

“We must get a doctor at once,” Carol said aside to Glenn. “I hope the telephone is all right.”

“I’ll test it. What doctor? Want a nurse too?”

“I wonder—but the doctor will tell us. The phone is under the stairs, in the alcove. Kitty always has Doctor Hadley.”

“O. K.” Glenn was making for the telephone. Jacob stood in the doorway, awkward and puzzled. He kept looking at the woman on the bed, but he said scarcely a word. And occasionally she would look at him, her look also questioning and bewildered. As Carol noticed this exchange of glances, she wondered. Jacob had come with the place, he appeared odd as many hard-working men are apt to, but he had been faithful, according to Mrs. Becket, and would send his wife Lena over to stay with her any night she might be alone and want Lena’s company.

Glenn was back. “Be right over,” he said quietly. “Lucky I found him in.”

And Doctor Hadley was right over. Carol felt a new importance in assuming the duties of a nurse, but when the doctor’s opinion rendered a verdict of nothing more serious than strains and sprains, the erstwhile nurse was happy enough to take the hot water Glenn was so expertly toting in from the bathroom, hand the doctor his bandages, using scissor tips to keep the antiseptic qualities intact, and generally fulfilling her new duties with promptness, if not with professional skill.

“Feel better, dear?” Carol had suddenly grown up enough to call Mrs. Becket dear, instead of the usual Cousin Kitty.

“Oh, I’m in heaven now! If you knew what it was to lie there so—helpless!” Mrs. Becket bit her lip to suppress further complaint.

“If you could only tell us about it,” suggested Carol, trying not to show any alarm.

“I heard a noise,” was the faltering reply.

“What has been frightening you?” again Glenn asked in his direct way.

“I don’t know; I’m not a bit timid usually. My dear husband and I have braved many dangers, traveling and even exploring. That is why I have been determined not to let any foolish tricks or—well,” she stopped suddenly, as if not knowing how to go on.

“We’ve heard all sort of rumors,” Carol helped out, “but believed none of them. I wouldn’t be afraid to stay alone here tonight,” she declared bravely.

“You did come to stay with me, didn’t you, Carol?”

“Certainly did. And Glenn, you had better be moving on,” Carol suggested. “Even injured ladies and beautiful nurses must sleep, you know.”

“Leave you two alone! I guess not.”

“Surely not thinking of staying as special night watchman, are you?” Carol asked in surprise. Mrs. Becket was merely smiling at the youngsters’ squabble.

“I might at that. But I have a better plan. Know my nice, big, fat, lusty Aunt Mary?”

“Yes.”

“Well, she declares she adores nursing and never gets a whack at it. How about my going for Aunt Mary?” Glenn was smiling at Carol in such a way as to beg her to agree. He must have known that Mrs. Becket’s strained hip might cause sudden pain, and he knew that Carol was scarcely able to take care of everything. Aunt Mary would be so much more congenial and less alarming than a regular nurse.

Carol was hesitating, looking to the lady on the bed to offer an answer. But Mrs. Becket was waiting for Carol. Finally Mrs. Becket said she thought having Glenn’s Aunt Mary would be splendid, if she would like to come.

“Sure, she will,” declared Glenn. “Aunt Mary is the guardian angel who spoiled me, according to my folks. So I take her at her word, that she will always be my best friend. This is just one more chance.”

But when Glenn had gone and Carol busied herself to get Mrs. Becket fixed for the night, slipping things on and off without stirring that injured hip, she was not thinking entirely of the accident, but of what had caused the accident. Knowing she should ask Cousin Kitty no more questions that night, she also knew that her own fears were crowding her to a new sort of anxiety. It had not been the loss of her organ at the Silvertone, although that was indeed serious, neither had it been Cecy’s foolish mistake in inducing her father to have the old car painted, although that too was mildly tragic, but it was this sinister influence, this unknown cruel power that had suddenly developed upon Oak Lodge. And Mrs. Becket’s accident tonight was too real to laugh at, too serious to attempt to ignore.

But there were many strange things happening in Melody Lane and more were to follow.

Jacob Vroom, who had followed the doctor to the front door, had watched him get into his car. Then, with a shake of his head, sparing of words even when communing with himself, Jacob shuffled off down the path that led to his own cottage. Something—a shadow or that which made a shadow—startled him as he moved past a bulky bush. Jacob saw first a crouching figure, then one that became upright.

“Who’s there?” he demanded.

“Oh, is that you, Vroom?” asked a human voice, and Jacob’s heart began to slow its rapid beating.

“Bancroft!” exclaimed Jacob, recognizing the tones of the carpenter. “What are you doing back here?”

“Lost my best saw. It must have slipped out of my box when I left here this afternoon. I come to look for it.”

“Hum! Queer time to be looking for a saw. Did you find it?”

“No, but I found somethin’ else!”

“What?”

“A ghost, I think.”

“A ghost in Melody Lane! Stuff and nonsense!”

“Ho! Not so much nonsense, Vroom, an’ enough stuff t’ scare me. Didn’t you see it?”

“See what?” Jacob’s voice was clearly skeptical.

“Suthin’ white an’ wavylike, sort of floatin’ or flyin’ through the trees an’ then vanishin’ jest like ghosts! I tell you it scared me for a minute!”

“Stuff and nonsense! Just a bit of fog—night mist. I’ve often seen that here in the Lane. You can’t locate a saw after dark. I’ll look for it in the morning. Good night!”

“All right. Reckon I can’t locate it now. But I did see somethin’ white,” and with that the carpenter with the nutcracker face shuffled away as Jacob went on to his cottage.

Darkness and silence shrouded Melody Lane, but sinister influences were at work there. Carol seemed to sense them as she ministered to Mrs. Becket.

Carol wondered why every family in the world was not blessed with an Aunt Mary. So soothing and kind without any silly “my dear and my darling,” so really authoritative without being a bit bossy, and so cheering without straining common sense.

Just now Aunt Mary was actually laughing, as Carol told her a discreet part of the spook stories that had been circulated about the big place they were visiting.

“I’ve been in this town of Oakleigh quite a long time,” she said in that velvet voice that seems to go with generous physical build, “and I’ve never met up with a ghost yet, although I have heard some thrilling ghost stories,” she told Carol. Mrs. Becket’s door was closed and Carol was with Aunt Mary in the big room next Mrs. Becket’s. Carol had insisted upon taking the yellow room at the end of the long hall, because that was her room by right of habit. She had slept there the night of the big party, when Mrs. Becket entertained the Choral Club and their friends. Also the night of the awful windstorm, when Mrs. Becket wouldn’t let her go home even in a big closed car. And other nights, a number of them. So tonight she would take the same place.

“You are not afraid to be so far away from me?” Aunt Mary teased.

“Not a bit. I’d just like to meet up with that ghost and settle his or her hash,” declared Carol, shaking her head until the hair, loosened by long service of that night, fell all but free from its last few hairpins.

“Exactly what Glenn said coming over.” Aunt Mary’s ready smile returned for a moment, and her fine, fair face assumed a questioning expression. “I have heard rumors, of course,” she went on in a very low voice, lest Mrs. Becket might overhear a single syllable, “but folks who have little to do usually do it in other folks’ affairs,” she finished wisely.

“What rumors have you heard, Aunt Mary?” Carol asked, directly.

“Oh, about the big organ, of course. How it plays, is played they say, by ghost hands. Also the passing of a white vision about the place. That’s silly, of course. But Melody Lane always did seem mysterious. My mother—she’s gone now, used to tell me when I was a child to stay out of Melody Lane, for some queer reason.”

“Was it called Melody Lane then?”

“Before this house was built with the big organ in it? Yes, it was; I think that was why the Fenton family chose this spot to build the big house for their big organ.”

“Fenton was the name of the first family here?”

“Yes. Robert Fenton was a wealthy manufacturer. He came in here, according to my childhood stories, with a beautiful Spanish wife. And when they say a Spanish beauty, you know all that means.”

“Oh, yes,” Carol agreed, who looked a little bit Spanish herself. “The dark lady, with the silky lashes, rosy lips, wide smile, flashing eyes——”

“White rose between her teeth. Don’t forget the rose,” Aunt Mary suggested, her smile coming back again.

“Oh, yes, the rose they always carry between their teeth in dancing,” went on Carol, seeming to enjoy the romantic idea. “The shawl they always seem to be going to commit suicide with and—oh, why bother. Go on, Aunt Mary, please tell me what happened to the Spanish bride of Robert Fenton.”

“Something tragic, indeed. She fell from her horse on the West Hill——”

“Where the drive is cut through?”

“Exactly. Mr. Fenton had the hill torn down and a road cut through its very heart, after the lovely lady died from the fall when her horse stumbled on the hill.”

Both Carol and Aunt Mary were silent then, picturing the scene, perhaps, of that beautiful young woman lying dead in one of those very rooms—Which room? Carol was wondering. It did not seem superstitious, but uncanny, weird, and all but malevolent, that the young Spanish beauty should have died, been killed on those grounds, and that the strange house had ever since refused to be silent, but had seemingly tried to wake the very dead by its unaccounted for organ peals.

Neither Aunt Mary nor Carol could forget this, as again a beautiful woman, Mrs. Becket, not young but middle aged, not a bride but a widow, was lying in a room, fortunately not dead, but suffering from some sinister influence that had cast its spell over Oak Lodge.

“You don’t believe in real ghosts, Aunt Mary?” Carol broke the prolonged silence.

“Yes, real enough, when things happen that should not happen, and when people or things can stay out of sight, even vanish without our being able to know why. That’s real ghost enough for me,” the pleasant woman declared emphatically.

“Yes, and for me,” assented Carol.

“Nobody likes Jacob nor Stub,” Aunt Mary went on in a hushed voice, “but they came in a sort of deed to the place, so Mrs. Becket keeps them on.”

“Yes, I understand that. I don’t like Jacob, but he acted really alarmed tonight when we discovered Cousin Kitty lying there like death.”

“Yes?” It was a question.

“But at first Glenn and I were both suspicious; the way he acted about letting us in.”

“I can imagine that. He’s very jealous of his place here. When the Guild comes for flowers for the hospital during summer, they always expect Jake to count the thorns on the rose stalks they cut. He tags at their heels as if he owned the place.”

“He’s that way always. When the girls come, he just spoils everything, watching lest they break a blade of grass. But Cousin Kitty says all good gardeners are that way; they love their gardens so much they make fools of themselves over everything growing.”

“We must get to bed, but I felt a talk would straighten out your nerves. You have been through so much today and tonight; Glenn told me about the organ.”

“Yes, that’s one of my own troubles. And the old car. Did he tell you about that?”

“He did. Glenn’s a great boy,” his Aunt declared proudly. “But don’t worry about the car. He’ll help you with that, I’m sure.”

Carol said nothing in answer to the kind assurance, but her smile was a little restrained. She didn’t see just how Glenn was going to help her get back the “plucked” car.

They were now moving toward bed, Aunt Mary was out in the hall in her soft slippers, and Carol had taken her own shoes off.

“We’ll leave this light burning,” Aunt Mary pointed out to the side wall bracket under the picture of Mozart.

“Leave it burning, but how long will it go?” Carol asked, remembering the darkness of the earlier hours.

“I’ve got Glenn’s flash light for you; I forgot it. I’ll bring it down to your room.” She turned to go back, when a noise, a soft, shuffling sound, arrested them.

“What’s that?” whispered Carol.

“I wonder.”

They naturally both thought of the ghost, of their boasts they would like to “meet up with it,” but now they were not so sure of that.

“It’s at the back stairs.”

“I’ll get the flash.”

“Yes, if the lights went out now—” Carol shuddered at the thought.

Aunt Mary was back almost instantly. How glad Carol was to have the big, strong, courageous woman at her side now! She was going softly toward the back stairs. The noise was stilled, just the merest sound like something slipping, slithering.

They waited. No further sounds. But they had both heard it. And they would have to find out what it was. They moved stealthfully down the red-carpeted hall to the bolted door that separated the rear from the front of the house and led to the lonely back stairs.

“Don’t open the door—yet,” whispered Carol. She had a fear that perhaps someone, something would spring in upon them.

Aunt Mary stood there; the lights were on and she had no present need for the flash.

“But we had better find out—” She stopped as another sound rustled behind the bolted door. But not near it; it was shuffling down the stairs.

“Let it go,” begged Carol. “It can’t get to the front. All the house is bolted at the back.”

“All right,” Aunt Mary agreed, glad, seemingly, that whatever was there surely now was running away. “In a strange house, it may even be a servant.”

“No, Lizzie Towner went away today. But let us go back. No one can get through.” Carol was unmistakably glad of all those bolts that completely separated the back from the front of the house. She had had Glenn try every one of them before he left.

“Spooky, all right,” whispered Aunt Mary, as they went up the hall again. “Good thing the doctor gave Mrs. Becket that quieting powder.”

“I’ve been wondering—should we peek in?” They were about to pass the door where the injured woman had lain so quietly.

“No, better not; she might just wake. I can see from my door. That’s open a crack.”

“I’ll wait. I want to be sure she’s all right.”

Both went into the room next Mrs. Becket’s.

“That you, Carol?” It was her voice, soft, almost weak.

“Yes, dear, we’re here. Want us?” Both were beside her instantly.

“Oh, I’ve had such a dreadful dream—” Her hand went to her head in a gesture of fearful memory.

“That’s all right, Mrs. Becket,” Aunt Mary promptly assured her. “You would be sure to have bad dreams after your accident.” Carol was now gently rubbing the white hand with its long, tapering fingers.

“Yes, I suppose so. I have been terribly frightened. I believe now—” She paused, looked about her with that wild glance peculiar to those just emerging from a drugged sleep. “I believe I should not have stayed there. The place—it——”

“Now don’t talk, dear,” Carol begged. “Everything will be all right, I know.”

“I wonder,” murmured the unsteady voice.

But there was something stirring around the place; queer sounds, too faint to be positive, but sounds, fluttering, eerie, creeping sounds. Carol made her way to the very small window down over the kitchen. She pulled aside the useless scrim curtain and peered out into the darkness.

There was something fluttering in that tree at the gate; something white! There must have been a light near by, for she could see that waving, cloudlike mass moving amid the branches. Fascinated, she stood there while the queer thing disappeared suddenly, like a light extinguished.

“A rose! A beautiful, waxy white bridal rose!”

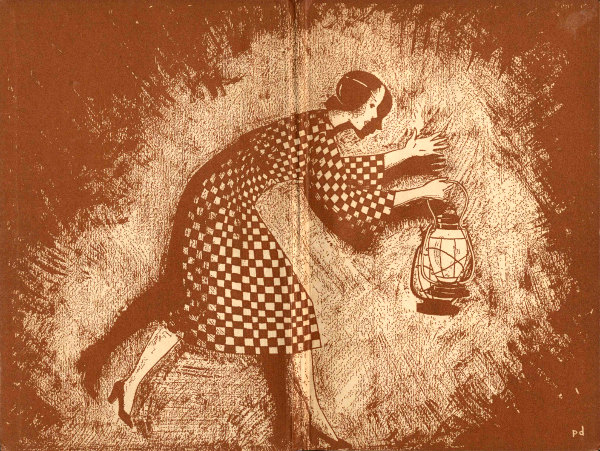

It was the morning after that eventful night. Carol was alone in that darkened back stairway where the strange, unearthly rustle, that seemed more like a wild wind than could any noise made by human agency, had so startled Aunt Mary and her when they were preparing for bed. She was now investigating, secretly going over the whole place, and had picked up the flower.

Carol held in her hand the waxy white bridal rose. It too seemed unreal, it was so frail, so lovely. The white bloom was perfect and not wilted, although it must have been in the damp darkened place all night.

She counted the shining deep-green leaves, one rose with five perfect green leaves. These too seemed waxed, so heavy was their texture. Even the thorns were tender, not sharp, not rough, but like bits of wax exuding from the waxy stems.

“All wax,” she was thinking, “and a bride rose. However could it have come here?”

Naturally she thought of that Spanish bride killed some years before; at her death they would have brought her bride roses like this one. But who now, about that strangely unhappy house, could care for or have such a flower? Where could it have come from? There were none of this precious variety about Oak Lodge. The conservatory of a few years before had never been used by Mrs. Becket, nor was it even heated to give out so beautiful a bloom. It would never have bloomed out of doors and this was the blustery weather of early fall, death to all vagrant roses.