* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 3, Issue 12

Date of first publication: 1867

Author: J. T. Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Sep. 21, 2018

Date last updated: Sep. 21, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180933

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Delphine Lettau, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. III. | DECEMBER, 1867. | No. XII. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

MISS EMILY PROUDIE MAKES A DISCOVERY.

IN TIME’S SWING.

[See In Time’s Swing, page 748.]

The Ornamental Border, drawn by C. H. Jenckes; The Vignettes, by H. Fenn; and the Figures, by George G. White.

Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Vol 3, Issue 12: December 1867

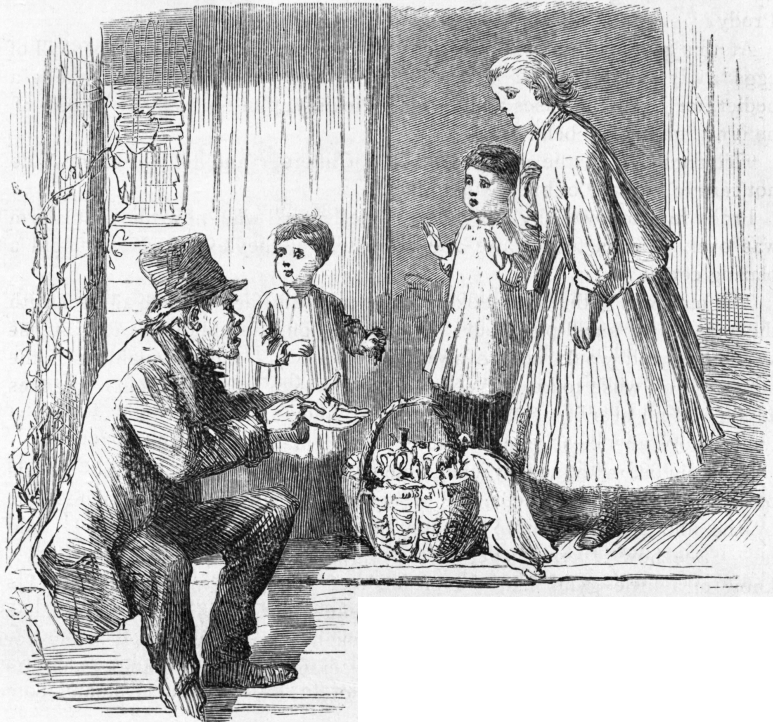

he next day being Sunday, the Captain’s

little friends did not go down to see him,

and the day after being stormy, they could

not. So, when Tuesday came, they were all

the more eager for the visit that it had been

delayed; and accordingly they hurried off

at a very early hour. Indeed, the old man

was only too glad to have them come down

at any time, for he had during these past few

days become so used to their being with him,

and had, withal, taken such a fancy to them,

that he felt himself quite lost and lonely when

a day passed by without seeing them. Like

most old men, he was at first somewhat

afraid they might disturb him if he said,

“Come at any hour you please,” instead of

“Come at four o’clock”; but he had discovered

them to be such well-behaved and

gentle children, that he had made up his

mind they could never worry or annoy him.

So when last they parted, he said to them,

“Come in the morning, if you like, and play

all day about the grounds, and if I have

something else to do you must not mind.

Nobody will disturb you”;—and, in truth, there was nobody there to disturb

them, for besides the old man and his boy, Main Brace, there was no

living thing about the house, if we except two fine old Newfoundland dogs

which the Captain had brought home with him from his last voyage, and

which he called, “Port” and “Starboard.” He had also a flock of handsome

chickens, and some foreign ducks. “And now,” said he, “when you

have seen all these, and Main Brace, and me, you have seen my family, for

this is all the family that I have, unless I count the birds that hop and skip

and sing among the trees.”

he next day being Sunday, the Captain’s

little friends did not go down to see him,

and the day after being stormy, they could

not. So, when Tuesday came, they were all

the more eager for the visit that it had been

delayed; and accordingly they hurried off

at a very early hour. Indeed, the old man

was only too glad to have them come down

at any time, for he had during these past few

days become so used to their being with him,

and had, withal, taken such a fancy to them,

that he felt himself quite lost and lonely when

a day passed by without seeing them. Like

most old men, he was at first somewhat

afraid they might disturb him if he said,

“Come at any hour you please,” instead of

“Come at four o’clock”; but he had discovered

them to be such well-behaved and

gentle children, that he had made up his

mind they could never worry or annoy him.

So when last they parted, he said to them,

“Come in the morning, if you like, and play

all day about the grounds, and if I have

something else to do you must not mind.

Nobody will disturb you”;—and, in truth, there was nobody there to disturb

them, for besides the old man and his boy, Main Brace, there was no

living thing about the house, if we except two fine old Newfoundland dogs

which the Captain had brought home with him from his last voyage, and

which he called, “Port” and “Starboard.” He had also a flock of handsome

chickens, and some foreign ducks. “And now,” said he, “when you

have seen all these, and Main Brace, and me, you have seen my family, for

this is all the family that I have, unless I count the birds that hop and skip

and sing among the trees.”

Main Brace did all the work about the house, except what the Captain did himself. He cooked and set the Captain’s table, and kept the Captain’s house in order generally. As for the house itself, there was not much of it to keep in order. We have already seen that it was very small, and but one story high. There was no hall in it, and only five rooms upon the floor. Let us look into it more particularly.

Entering it from the front through the little porch covered over with honeysuckle vines that are smelling sweetly all the summer through, we come at once into the largest of the rooms, where the Captain dines and does many other things. But he never calls it his dining-room. Nothing can induce him to call it anything but his “quarter-deck.” On the right-hand side there are two doors, and there are two more on the left-hand side, and directly before us there are two windows, looking out into the Captain’s garden, where he has fruits and vegetables of every kind growing in abundance. The first door on the right opens into a little room where Main Brace sleeps. This the Captain calls the “forecastle.” The other door on the right opens into the kitchen, which the Captain calls his “galley.” The first door on the left is closed, but the second opens into what the Captain calls his “cabin,” and this connects with a little room behind the door, that is closed, which he calls his “state-room,”—and, in truth, it looks more like a state-room of a ship than a chamber. It has no bed in it, but a narrow berth on one side, just like a state-room berth. All sorts of odd-fashioned clothes are hanging on the walls, which the Captain says he has worn in the different countries where he has travelled. Odd though this state-room be, it is not half so odd as the Captain’s cabin.

Let us examine this cabin of the Captain. There is an old table in the centre of it. There are a few old books in an old-fashioned bookcase. There is no carpet, but the floor is almost covered over with skins of different kinds of animals, among which are a Bengal tiger, a Polar bear, a South American ocelot, a Rocky Mountain wolf, and a Siberian fox. In a great glass case, standing against the wall, there is a variety of stuffed birds. On the very top of this case there is a huge white-headed eagle, with his large wings spread out, and at the bottom of it there is a pelican with no wings at all. On the right-hand side there is an enormous albatross, and on the left-hand side there is a tall red flamingo, while in the very centre a snowy owl stands straight up and looks straight at you out of his great glass eyes. And then there are still other birds,—little ones and big ones, and birds bright and birds dingy, scattered about wherever there is room, each sitting or standing on its separate perch, and looking, for all the world, as if it were alive and would fly away only for the glass.

On the walls of this singular room are hanging all sorts of singular weapons, and many other things which the Captain has picked up in his travels. There is a Turkish scymitar, a Moorish gun, an Italian stiletto, a Japanese “happy despatch,” a Norman battle-axe, besides spears and lances and swords of shapes and kinds too numerous to mention. In one corner, on a bracket, there is a model of a ship, in another a Chinese junk, in a third an old Dutch clock, and in the fourth there is a stone idol of the Incas, while above the door there is the figure-head of a small vessel, probably a schooner.

When the children came down, running all the way at a very lively rate, the Captain was in his cabin overhauling his treasures, and dusting and placing them so that they would show to the very best advantage. Indeed, there were so many “traps,” as he called them, hanging and lying about, that the place might well have been called a “curiosity shop” better than a cabin. In truth, it had nothing of the look of a cabin about it.

When the Captain heard the children coming, he said to himself, “I’ll give them a surprise to-day,” and he looked out through the open window and called to them. They answered with a merry laugh, and, running around to the door, rushed into the “quarter-deck,” and were with the Captain in an instant.

“O what a jolly place!” exclaimed William; “such a jolly lot of things! Why didn’t you show them to us before, Captain Hardy?”

“One thing at a time, my lad; I can’t show you everything at once,” answered the old man.

“But where did you get them all, Captain Hardy?”

“As for that, I picked them up all about the world, and I could tell a story about every one of them.”

“O, isn’t that splendid?—won’t you tell us now?” inquired William.

“And knock off telling you what the Dean and myself were doing up there by the North Pole on that island without a name?”

William was a little puzzled to know what reply he should make to that, for he thought the Captain looked as if he did not half like what he had said; so he satisfied himself with exclaiming, “No, no, no,” a great number of times, and then asked, “But won’t you tell us all about them when you get out of the North Pole scrape?”

“May be so, my lad, may be so; we’ll see about that; one thing at a time is a good rule in story-telling as well as in other matters. And now you may look at all these things, and when you are satisfied, and I have got done putting them to rights, we’ll go spinning on our yarn again.”

The children were greatly delighted with everything they saw, and they passed a very happy hour, helping the Captain to put his cabin in “ship-shape order,” as he said. Then they all crowded up into one corner, and the Captain, seated on an old camp-stool, which had evidently seen much service in divers places, came back once more to his story.

“And now,” said he, “what was I doing when we knocked off the other day, after the storm?”

William, whose memory was always as good as his words were ready, said the Captain was “just going to sleep.”

“True, that’s the thing; and I went to sleep and slept bravely, I can tell you. And this you may well enough believe when you bear in mind how much I had passed through since the last sleep I had on board the ship,—for since then had come the shipwreck, the saving of the Dean and carrying him ashore, the walk around the island, besides all the anxiety and worriment of mind in consequence of my own unhappy situation and the Dean’s uncertain fate.

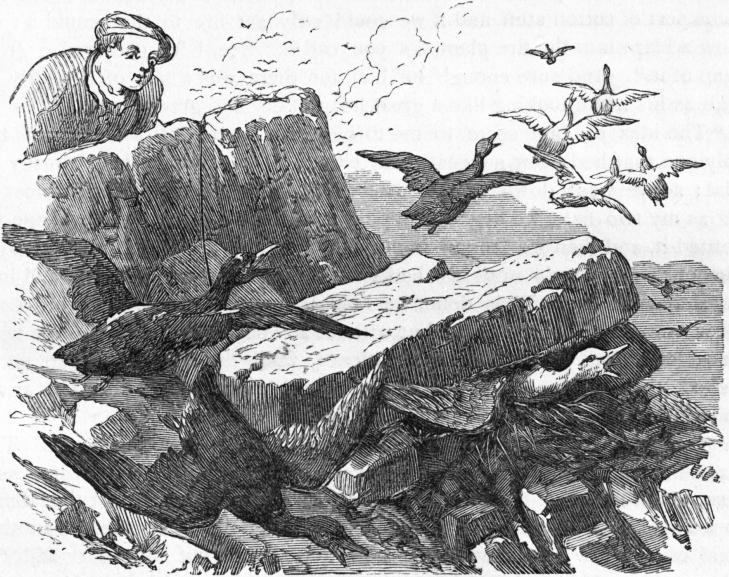

“More than twenty-four hours had elapsed since the shipwreck, and if I slept full twelve hours, without once waking up, you must not be in the least surprised. When I opened my eyes again, we were in the shadow of the cliffs once more; that is, the sun had gone around to the north again. The Dean was already wide awake. When I asked him how he was, he said he felt much better, only his head still pained him greatly, and he was very thirsty and hungry.

“I got up immediately and assisted the Dean to rise. He was a little dizzy at first, but after sitting down for a few minutes on a rock he recovered himself. Then I brought him some water in an egg-shell to drink. And then I gave him a raw egg, which he swallowed as if it had been the daintiest morsel in the world. ‘It’s lucky, isn’t it,’ said he, ‘that there are so many eggs about.’ After a moment I observed that he was laughing, which very much surprised me, as that would have been about the last thing that ever would have entered into my head to do. ‘Do you know,’ he inquired, ‘what a very ridiculous figure we are cutting. Look, we are all covered over with feathers. I have heard of people being tarred and feathered, but never heard of anything like this. Let’s pick each other.’

“Sure enough we were literally covered over with the down in which we had been sleeping, and when I saw what a jest the poor Dean, with his sore, dizzy head, made of the plight we were in, I forgot all my own troubles and joined in the sport which he was inclined to make of it. So we fell to work picking each other in good earnest, and were soon as clean of feathers as any other well-plucked geese. By this time the Dean’s clothes had become entirely dry; so each dressed himself in the clothes that belonged to him, and then started over to the nearest brook, where we bathed our hands and faces, drying them on an old bandanna handkerchief, which I was lucky enough to have in my pocket. I had to support the Dean a little as we went along, for he was very weak; but notwithstanding this his spirits were excellent, and when he saw, for the first time, the ducks fly up, he said, ‘What a great pair of fools they must take us for,—coming into such a place as this.’

“After we had refreshed ourselves at the brook and eaten some more eggs, we very naturally began to talk. I related to the Dean more particularly than I had done before the events of the shipwreck, and our escape, and what I had discovered on the island, and then made some allusion to the prospect ahead of us. To my great surprise, the Dean was not apparently in the least cast down about it. In truth, he took it much more resignedly, and had a more hopeful eye to the future, than I had. ‘If,’ said he, ‘it is God’s will that we shall live, He will furnish us the means; if not, we can but die. I wouldn’t mind it half so much, if my poor mother only knew what was become of me.’ This reflection seemed to sadden him for a moment, and I thought I saw a tear in his eye; but he brightened up instantly as a great flock of ducks went whizzing overhead. ‘Well,’ exclaimed he, ‘there seems to be no lack of something to eat here anyway, and we ought to manage to catch it somehow, and live until a ship comes along and takes us off.’

“The Dean took such a cheerful view of the future that we were soon chatting in a very lively way about everything that concerned our escape, and the fate of our unfortunate shipmates; and here I must have expatiated very largely upon the satisfaction which I took in rescuing the Dean, for the little fellow said: ‘Well, I suppose I ought to thank you very much for saving me; but the truth is, all the agony of death being over with me when you pulled me out, the chief benefit falls on you, as you seem so much rejoiced about it; but I’ll be grateful anyway, and show it by not troubling you any more, and by helping you all I can. See, I’m almost well. I feel better and better every minute,—only I’m sore here on the head where I got the crack.’

“To tell the truth, in thinking of other things, I had neglected, or rather quite forgotten, the Dean’s wounded head; so now, my attention being called to it, I examined it very carefully, and found that it was nothing more than a bad bruise, with a cut near the centre of it about half an inch long. Having washed it carefully, I bound my bandanna handkerchief about it, and we once more came back to consider what we should do.

“Of course, the first thing we thought of and talked about was how we should go about starting a fire; next in importance to this was that we should have a place to shelter us. So far as concerned our food and drink, our immediate necessities were provided for, as we had the little rivulet close at hand, and any quantity of eggs to be had for the gathering, and we set about gathering a great number of them at once; for in a few days we thought it very likely that most of them would have little ducks in them, as, indeed, many of them had already. Another thing we settled upon was, that we would never both go to sleep at the same time, nor quit our present side of the island together; but one of us would be always on the look-out for a ship, as we both thought it possible that, since our ship had come that way, others would be very likely to, though neither of us had the remotest idea in the world as to where we were, any more than that we were on an island somewhere in the Arctic seas.

“But the fire which we wanted so much to warm ourselves and cook our food,—what should we do for that? Here was the great question; and fire, fire, fire, was the one leading idea running through both our heads;—we thought of fire when we were gathering eggs, we talked of fire when, later in the day, we sat upon the rocks, resting ourselves, and we dreamed of fire when we fell asleep again,—not this time, however, under the eider-down where we had slept before, but on the green grass of the hillside in the warm sunshine, under my overcoat, for we had turned night into day, and were determined to sleep when the sun was shining on us at the south, and do what work we had to do when we were in the shade.

“Every method that either of us had ever heard of for making a fire was carefully discussed; but there was nothing that appeared to suit our case. I found a hard flint, and by striking it on the back of my knife-blade I saw that there was no difficulty in getting any number of sparks, but we had nothing that would catch the sparks when struck; so that we did not seem to be any better off than we were before; and, as I have stated already, we fell asleep again, each in his turn,—‘watch and watch,’ as the Dean playfully called it, and as they have it on ship-board,—without having arrived at any other result than that of being a little discouraged.

“When we had been again refreshed with sleep, we determined to make a still further exploration of the island; so after once more eating our fill of raw eggs, we set out. The Dean, being still weak and his head still paining him very much from the hurt, remained at the look-out. He could, however, walk up and down for a few hundred yards without losing sight of that part of the sea from which quarter alone were we likely to discover a ship. This brought him up to where I had discovered the dead seal and narwhal lying on the beach, when upon my first journey round the island. I had told him about them, as indeed I had of everything I had seen, and he was curious to see if he could not catch a fox; but his fortune in that particular was not better than mine.

“For myself, I had a very profitable journey, as I found a place among the rocks which might, with a little labor in fixing it up, give us shelter. I was searching for a cave, but nothing of the sort could I come across; but at the head of a little valley, very near to where I left the Dean, I discovered a place that would, in some measure at least, answer the purpose of sheltering us. Its situation gave it the still further advantage, that we commanded a perfect view of the sea from the front of it.

“I have said that it was not exactly a cave, but rather an artificial tent, as it were, of solid rocks. At the foot of a very steep slope of rough rocks there were several large masses piled together, evidently having one day slid down from the cliffs above, and afterwards smaller rocks, being broken off, had piled up behind them. Two of these large rocks had come together in such a manner as to leave an open space between them. I should say this space was ten or twelve feet across at the bottom, and, rising up about ten feet high, joined at the top, like the roof of a house. The rocks were pressed against them behind, so as completely to close the outlet in that direction; and in front the entrance was half closed by another large rock, which was leaning diagonally across the opening. I climbed into this place, and was convinced that, if we had strength to close up the front entrance with a wall, we should have a complete protection from the weather. But then when I reflected how, if we did seek shelter there, we should keep ourselves warm, I had great misgivings; for there came up the great question of all questions, ‘What were we to do for a fire?’

“Although this place was not a cave, yet I spoke to the Dean about it as such, and by that name we came to know it; so I will now use the term, inappropriate though it is. I also told the Dean about some other birds that I had discovered, in great numbers. They were very small, and seemed to have their nests among the rocks all along the north side of the island, where they were swarming on the hillside, and flying overhead in even greater flocks than the ducks. I knew they were called little auks, from descriptions the sailors had given me of them.

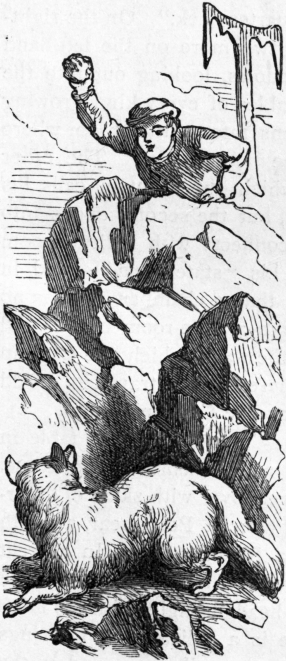

“ ‘But look here what I’ve got,’ exclaimed the Dean, as soon as I came up with him. ‘See this big duck!’

“The fellow had actually caught a duck, and in a most ingenious manner. Seeing the ducks fly off their nests, the happy idea struck him that, if he could only contrive a trap, or dead fall, he might catch them when they came back. So he selected a nest favorable to his design, and piled up some stones about it, making a solid wall on one side of it; then he put a thin narrow stone on the other side, and on this he supported still another stone that was very heavy. Then he took from his pocket a piece of twine which he was fortunate enough to have, and tied one end of it to the thin narrow stone, and, holding on to the other end, hid himself behind some rocks near by. When the duck came back to her nest, he jerked the thin narrow stone away by a strong pull on the twine string, and down came the big heavy stone upon her back. ‘You should have heard the old thing quacking,’ said he, evidently forgetting everything else but the sport of catching the bird: ‘but I soon gave her neck a twist, and here we are ready for a dinner, when we only find a way to cook it. Have you discovered any way to make a fire yet?’

“I had to confess that on the subject of fire I was yet as ignorant as ever.

“ ‘Do you know,’ continued he, ‘that I have got a brilliant idea?’

“ ‘What’s that?’ said I.

“ ‘Why,’ replied he, ‘you told me something about people making fire with a lens made of glass. Now, as I was down on the beach and looked at the ice there, I thought, why not make a lens out of ice,—it is as clear as glass?’

“ ‘But,’ said I, ‘what will you set on fire with it?’

“ ‘In the first place,’ he answered, ‘the pockets of my coat are made of some sort of cotton stuff, and if we could only set fire to that, couldn’t we blow a blaze into the fire plant, as you call it. See, I’ve gathered a great heap of it.’ And sure enough he had, for there was a pile of it nearly as high as his head, looking like a great heap of dry and green leaves.

“The idea did not seem to me to be worth much, but still, as it was the only one that had been suggested by either of us, it was at least worthy of trial; so we went down to the beach, and, finding a lump of ice almost as big as my two fists, we began chipping it with my knife into the shape we wanted it, and then we ground it off with a stone, and then rubbed it over with our warm hands until we had worn it down perfectly smooth, and into the shape of a lens. This done, we held it up to the sun, relieving each other as our hands grew cold; but without any success whatever. We tried for a long time, and with much patience, until the ice became so much melted, that we could do nothing more with it, when we threw it away, and the experiment was abandoned as hopeless.

“Our disappointment at this failure was in proportion to our hopes. The Dean felt it most, for he was, at the very outset, perfectly confident of success. Neither of us, however, wished to own how much we felt the failure, so we spoke very little more together, but made, almost in silence, another meal off the raw eggs, and being now quite worn out and weary with the labors and anxieties of the day, we passed the next twelve hours in watching and sleeping alternately in the bright sunshine, lying as before on the green grass, covered with the overcoat. We did not even dare hope for better fortune on the morrow. We had, however, made up our minds to struggle in the best manner we could against the difficulties which surrounded us, and mutually to sustain each other in the hard battle before us. Whether we should live or die was known but to God alone, and to his gracious protection we once more commended ourselves; the Dean repeating, and teaching me a prayer which he had learned, as was very evident, from a pious and careful mother, who had brought him up in the fear of Heaven, and taught him, at a very early age, to have faith in God’s endless watchfulness.

“And now, my children,” concluded the Captain, “I have some work to do in my garden, to-day, so we must cut our story short this time. When you come to-morrow, I will tell you what next we did towards raising a fire, besides many other things for our safety and comfort.”

And now the party scattered from the “cabin,”—the Captain to his work, and the children to play for a while with the Captain’s dogs, Port and Starboard, out among the trees, and to talk with Main Brace, whom they found to be the most singular boy they had ever seen; after which they went to the Captain to say “Good evening” to him, and then ran briskly home,—William eager to write down what he had heard, while it was yet fresh on his mind, and all of them to relate to their parents, over and over again, what this wonderful old man had been telling them, and what a dear old soul he was.

Isaac I. Hayes.

Fourteen years ago, I spent a winter in Africa. I had intended to go up the Nile only as far as Nubia, visiting the great temples and tombs of Thebes on the way; but when I had done all this, and passed beyond the cataracts at the southern boundary of Egypt, I found the journey so agreeable, so full of interest, and attended with so much less danger than I had supposed, that I determined to go on for a month or two longer, and penetrate as far as possible into the interior. Everything was favorable to my plan. I crossed the great Nubian Desert without accident or adventure, reached the ancient region of Ethiopia, and continued my journey until I had passed beyond all the cataracts of the Nile, to the point where the two great branches of the river flow together.

This point, which you will find on your maps in the country called Sennaar, bordering Abyssinia on the northwestern side, has become very important within the last twenty or thirty years. The Egyptians, after conquering the country, established there their seat of government for all that part of Africa, and very soon a large and busy town arose where formerly there had only been a few mud huts of the natives. The town is called Khartoum, and I suppose it must contain, by this time, forty or fifty thousand inhabitants. It is built on a sandy plain, studded here and there with clumps of thorny trees. On the east side the Blue Nile, the source of which was discovered by the Scotch traveller Bruce, in the last century, comes down clear and swift from the mountains of Abyssinia; on the west, the broad, shallow, muddy current of the White Nile, which rises in the great lakes discovered by Speke and Baker within the last five years, makes its appearance. The two rivers meet just below the town, and flow as a single stream to the Mediterranean, a distance of fifteen hundred miles.

Formerly all this part of Africa was considered very wild, barbarous, and dangerous to the traveller. But since it has been brought under the rule of the Egyptian government, the people have been forced to respect the lives and property of strangers, and travelling has become comparatively safe. I soon grew so accustomed to the ways of the inhabitants, that by the time I reached Khartoum I felt quite at home among them. My experience had already taught me that, where a traveller is badly treated, it is generally his own fault. You must not despise a people because they are ignorant, because their habits are different, or because they sometimes annoy you by a natural curiosity. I found that by acting in a kind yet firm manner towards them, and preserving my patience and good-nature, even when it was tried by their slow and careless ways, I avoided all trouble, and even acquired their friendly good-will.

When I reached Khartoum, the Austrian Consul invited me to his house; and there I spent three or four weeks, in that strange town, making acquaintance with the Egyptian officers, the chiefs of the desert tribes, and the former kings of the different countries of Ethiopia. When I left my boat, on arriving, and walked through the narrow streets of Khartoum, between mud walls, very few of which were even whitewashed, I thought it a miserable place, and began to look out for some garden where I might pitch my tent, rather than live in one of those dirty-looking habitations. The wall around the Consul’s house was of mud like the others; but when I entered I found clean, handsome rooms, which furnished delightful shade and coolness during the heat of the day. The roof was of palm-logs, covered with mud, which the sun baked into a hard mass, so that the house was in reality as good as a brick dwelling. It was a great deal more comfortable than it appeared from the outside.

There were other features of the place, however, which it would be difficult to find anywhere except in Central Africa. After I had taken possession of my room, and eaten breakfast with my host, I went out to look at the garden. On each side of the steps leading down from the door sat two apes, who barked and snapped at me. The next thing I saw was a leopard tied to the trunk of an orange-tree. I did not dare to go within reach of his rope, although I afterwards became well acquainted with him. A little farther, there was a pen full of gazelles and an antelope with immense horns; then two fierce, bristling hyenas; and at last, under a shed beside the stable, a full-grown lioness, sleeping in the shade. I was greatly surprised when the Consul went up to her, lifted up her head, opened her jaws so as to show the shining white tusks, and finally sat down upon her back.

She accepted these familiarities so good-naturedly that I made bold to pat her head also. In a day or two we were great friends; she would spring about with delight whenever she saw me, and would purr like a cat whenever I sat down upon her back. I spent an hour or two every day among the animals, and found them all easy to tame except the hyenas, which would gladly have bitten me if I had allowed them a chance. The leopard, one day, bit me slightly in the hand; but I punished him by pouring several buckets of water over him, and he was always very amiable after that. The beautiful little gazelles would cluster around me, thrusting up their noses into my hand, and saying, “Wow! wow!” as plainly as I write it. But none of these animals attracted me so much as the big lioness. She was always good-humored, though occasionally so lazy that she would not even open her eyes when I sat down on her shoulder. She would sometimes catch my foot in her paws as a kitten catches a ball, and try to make a plaything of it,—yet always without thrusting out her claws. Once she opened her mouth, and gently took one of my legs in her jaws for a moment; and the very next instant she put out her tongue and licked my hand. There seemed to be almost as much of the dog as of the cat in her nature. We all know, however, that there are differences of character among animals, as there are among men; and my favorite probably belonged to a virtuous and respectable family of lions.

The day after my arrival I went with the Consul to visit the Pacha, who lived in a large mud palace on the bank of the Blue Nile. He received us very pleasantly, and invited us to take seats in the shady court-yard. Here there was a huge panther tied to one of the pillars, while a little lion, about eight months old, ran about perfectly loose. The Pacha called the latter, which came springing and frisking towards him. “Now,” said he, “we will have some fun.” He then made the lion lie down behind one of the pillars, and called to one of the black boys to go across the court-yard on some errand. The lion lay quite still until the boy came opposite to the pillar, when he sprang out and after him. The boy ran, terribly frightened; but the lion reached him in five or six leaps, sprang upon his back and threw him down, and then went back to the pillar as if quite satisfied with his exploit. Although the boy was not hurt in the least, it seemed to me like a cruel piece of fun. The Pacha, nevertheless, laughed very heartily, and told us that he had himself trained the lion to frighten the boys.

Presently the little lion went away, and when we came to look for him, we found him lying on one of the tables in the kitchen of the palace, apparently very much interested in watching the cook. The latter told us that the animal sometimes took small pieces of meat, but seemed to know that it was not permitted, for he would run away afterwards in great haste. What I saw of lions during my residence in Khartoum satisfied me that they are not very difficult to tame,—only, as they belong to the cat family, no dependence can be placed on their continued good behavior.

Among the Egyptian officers in the city was a Pacha named Rufah, who had been banished from Egypt by the Viceroy. He was a man of considerable education and intelligence, and was very unhappy at being sent away from his home and family. The climate of Khartoum is very unhealthy, and this unfortunate Pacha had suffered greatly from fever. He was uncertain how long his exile would continue: he had been there already two years, and as all the letters directed to him passed through the hands of the officers of government, he was quite at a loss how to get any help from his friends. What he had done to cause his banishment, I could not ascertain; probably he did not know himself. There are no elections in those Eastern countries; the people have nothing to do with the choice of their own rulers. The latter are appointed by the Viceroy at his pleasure, and hold office only so long as he allows them. The envy or jealousy of one Pacha may lead to the ruin of another, without any fault on the part of the latter. Probably somebody else wanted Rufah Pacha’s place, and slandered him to the Viceroy for the sake of getting him removed and exiled.

The unhappy man inspired my profound sympathy. Sometimes he would spend the evening with the Consul and myself, because he felt safe, in our presence, to complain of the tyranny under which he suffered. When we met him at the houses of the other Egyptian officers, he was very careful not to talk on the subject, lest they should report the fact to the government.

Being a foreigner and a stranger, I never imagined that I could be of any service to Rufah Pacha. I did not speak the language well, I knew very little of the laws and regulations of the country, and, moreover, I intended simply to pass through Egypt on my return. Nevertheless, one night, when we happened to be walking the streets together, he whispered that he had something special to say to me. Although it was bright moonlight, we had a native servant with us, to carry a lantern. The Pacha ordered the servant to walk on in advance; and a turn of the narrow, crooked streets soon hid him from our sight. Everything was quiet, except the rustling of the wind in the palm-trees which rose above the garden-walls.

“Now,” said the Pacha, taking my hand, “now we can talk for a few minutes, without being overheard. I want you to do me a favor.”

“Willingly,” I answered, “if it is in my power.”

“It will not give you much trouble,” he said, “and may be of great service to me. I want you to take two letters to Egypt,—one to my son, who lives in the town of Tahtah, and one to Mr. Murray, the English Consul-General, whom you know. I cannot trust the Egyptian merchants, because, if these letters were opened and read, I might be kept here many years longer. If you deliver them safely, my friends will know how to assist me, and perhaps I may soon be allowed to return home.”

I promised to deliver both letters with my own hands, and the Pacha parted from me in more cheerful spirits at the door of the Consul’s house. After a few days I was ready to set out on the return journey; but, according to custom, I was first obliged to make farewell visits to all the officers of government. It was very easy to apprise Rufah Pacha beforehand of my intention, and he had no difficulty in slipping the letters into my hand without the action being observed by any one. I put them into my portfolio, with my own letters and papers, where they were entirely safe, and said nothing about the matter to any one in Khartoum.

Although I was glad to leave that wild town, with its burning climate, and retrace the long way back to Egypt, across the Desert and down the Nile, I felt very sorry at being obliged to take leave forever of all my pets. The little gazelles said, “Wow! wow!” in answer to my “Good by”; the hyenas howled and tried to bite, just as much as ever; but the dear old lioness I know would have been sorry if she could have understood that I was going. She frisked around me, licked my hand, and I took her great tawny head into my arms, and gave her a kiss. Since then I have never had a lion for a pet, and may never have one again. I must confess, I am sorry for it; for I still retain my love for lions (four-footed ones, I mean) to this day.

Well, it was a long journey, and I should have to write many days in order to describe it. I should have to tell of fierce sand-storms in the Desert; of resting in palm-groves near the old capital of Ethiopia; of plodding, day after day, through desolate landscapes, on the back of a camel, crossing stony ranges of mountains, to reach the Nile again, and then floating down with the current in an open boat. It was nearly two months before I could deliver the first of the Pacha’s letters,—that which he had written to his son. The town of Tahtah is in Upper Egypt, near Siout; you will hardly find it on the maps. It stands on a little mound, several miles from the Nile, and is surrounded by the rich and beautiful plain which is every year overflowed by the river.

There was a head wind, and my boat could not proceed very fast; so I took my faithful servant, Achmet, and set out on foot, taking a path which led over the plain, between beautiful wheat-fields and orchards of lemon-trees. In an hour or two we reached Tahtah,—a queer, dark old town, with high houses and narrow streets. The doors and balconies were of carved wood, and the windows were covered with lattices, so that no one could look in, although those inside could easily look out. There were a few sleepy merchants in the bazaar, smoking their pipes and enjoying the odors of cinnamon and dried roses which floated in the air.

After some little inquiry, I found Rufah Pacha’s house, but was not admitted, because the Egyptian women are not allowed to receive the visits of strangers. There was a shaded entrance-hall, open to the street, where I was requested to sit, while the black serving-woman went to the school to bring the Pacha’s son. She first borrowed a pipe from one of the merchants in the bazaar, and brought it to me. Achmet and I sat there, while the people of the town, who had heard that we came from Khartoum and knew the Pacha, gathered around to ask questions.

They were all very polite and friendly, and seemed as glad to hear about the Pacha as if they belonged to his family. In a quarter of an hour the woman came back, followed by the Pacha’s son and the schoolmaster, who had dismissed his school in order to hear the news. The boy was about eleven years old, but tall of his age. He had a fair face, and large, dark eyes, and smiled pleasantly when he saw me. If I had not known something of the customs of the people, I should have given him my hand, perhaps drawn him between my knees, put an arm around his waist, and talked familiarly; but I thought it best to wait and see how he would behave towards me.

He first made me a graceful salutation, just as a man would have done, then took my hand and gently touched it to his heart, lips, and forehead, after which he took his seat on the high divan, or bench, by my side. Here he again made a salutation, clapped his hands thrice, to summon the woman, and ordered coffee to be brought.

“Is your Excellency in good health?” he asked.

“Very well, praised be Allah!” I answered.

“Has your Excellency any commands for me? You have but to speak; you shall be obeyed.”

“You are very kind,” said I; “but I have need of nothing. I bring you greetings from the Pacha, your father, and this letter, which I promised him to deliver into your own hands.”

Thereupon I handed him the letter, which he laid to his heart and lips before opening. As he found it a little difficult to read, he summoned the schoolmaster, and they read it together in a whisper.

In the mean time coffee was served in little cups, and a very handsome pipe was brought by somebody for my use. After he had read the letter, the boy turned to me with his face a little flushed, and his eyes sparkling, and said, “Will your Excellency permit me to ask whether you have another letter?”

“Yes,” I answered; “but it is not to be delivered here.”

“It is right,” said he. “When will you reach Cairo?”

“That depends on the wind; but I hope in seven days from now.”

The boy again whispered to the schoolmaster, but presently they both nodded, as if satisfied, and nothing more was said on the subject.

Some sherbet (which is nothing but lemonade flavored with rose-water) and pomegranates were then brought to me, and the boy asked whether I would not honor him by remaining during the rest of the day. If I had not seen his face, I should have supposed that I was visiting a man,—so dignified and self-possessed and graceful was the little fellow. The people looked on as if they were quite accustomed to such mature manners in children. I was obliged to use as much ceremony with the child as if he had been the governor of the town. But he interested me, nevertheless, and I felt curious to know the subject of his consultation with the schoolmaster. I was sure they were forming some plan to have the Pacha recalled from exile.

After two or three hours I left, in order to overtake my boat, which was slowly working its way down the Nile. The boy arose, and walked by my side to the end of the town, the other people following behind us. When we came out upon the plain, he took leave of me with the same salutations, and the words, “May God grant your Excellency a prosperous journey!”

“May God grant it!” I responded; and then all the people repeated, “May God grant it!”

The whole interview seemed to me like a scene out of the “Arabian Nights.” To me it was a pretty, picturesque experience, which cannot be forgotten: to the people, no doubt, it was an every-day matter.

When I reached Cairo, I delivered the other letter, and in a fortnight afterwards left Egypt; so that I could not ascertain, at the time, whether anything had been done to forward the Pacha’s hopes. Some months afterwards, however, I read in a European newspaper, quite accidentally, that Rufah Pacha had returned to Egypt from Khartoum. I was delighted with the news; and I shall always believe, and insist upon it, that the Pacha’s wise and dignified little son had a hand in bringing about the fortunate result.

Bayard Taylor.

Well, my dear girls, who read this story, I want now just to ask you, seriously and soberly, which you would rather be, as far as our story has gone on,—little Miss Pussy Willow, or little Miss Emily Proudie.

Emily had, to be sure, twice or three times as much of all the nice things you ever heard of to make a girl happy as little Pussy Willow; she had more money, a larger and more beautiful house, more elegant clothes, more brilliant jewelry,—and yet of what use were these so long as she did not enjoy them?

And why didn’t she enjoy them? My dear little girl, can you ever remember, on a Christmas or Thanksgiving day, eating so much candy, ice-cream, and other matters of that nature, that your mouth had a bitter taste in it, and you loathed the very sight of cake or preserves, or anything sweet? What earthly good did it do, when you felt in that way, for you to be seated at a table glittering with candy pyramids? You could not look at them without disgust.

Now all Emily’s life had been a candy pyramid. Ever since she was a little girl, her eyes had been dazzled, and her hands filled, with every pretty thing that father, mother, aunts, uncles, and grandmothers could get for her, so that she was all her time kept in this state of weariness by having too much. Then everything had always been done for her, so that she had none of the pleasures which the good God meant us to have in the use of our own powers and faculties. Pussy Willow enjoyed a great deal more a doll that she made herself, carving it out of a bit of white wood, painting its face, putting in beads for eyes, and otherwise bringing it into shape, than Emily did the whole army of her dolls, with all their splendid clothes. This was because our Heavenly Father made us so that we should find a pleasure in the exercise of the capacities he has given us.

So when the good fairies which I have told you about, who presided over Pussy’s birth, gave her the gift of being pleased with all she had and with all she did, they knew what they were about, and they gave it to a girl that was going to grow up and take care of herself and others, and not to a girl that was going to grow up to have others always taking care of her.

But now here at sixteen are the two girls; and as they are sitting, this bright June morning, up in the barn-chamber, working and reading, I want you to look at them, and ask, What has Miss Emily gained by her luxurious life of wealth and ease, that Pussy Willow has not acquired in far greater perfection by her habits of self-helpfulness?

When the two girls stand up together, you may see that Pussy Willow is every whit as pretty and as genteel in her appearance as Emily. Because she has been an industrious country girl, and has always done the duty next her, you are not to suppose that she has grown up coarse and blowsy, or that she has rough, red hands, or big feet. Her complexion, it is true, is a healthy one; her skin, instead of being waxy-white, like a dead japonica, has a delicate shade of pink in its whiteness, and her cheeks have the vivid color of the sweet-pea, bright and clear and delicate; and she looks out of her wide clear blue eyes with frankness and courage at everything. She is every whit as much a lady in person and manners and mind as if she had been brought up in wealth and luxury. Then as to education, Miss Emily soon found that in all real solid learning Pussy was far beyond her. A girl that is willing to walk two miles to school, summer and winter, for the sake of acquiring knowledge, is quite apt to study with energy. Pussy had gained her knowledge by using her own powers and faculties, studying, reading, thinking, asking questions. Emily had had her knowledge put into her, just as she had had her clothes made and put on her; she felt small interest in her studies, and the consequence was that she soon forgot them.

But this visit that she made in the country opened a new chapter in Emily’s life. I told you, last month, that she had a new sensation when she was climbing down the ladder from the hay-mow. The sensation was that of using her own powers. She was actually so impressed with the superior energy of her little friend, that she felt as if she wanted to begin to do as she did; and, instead of being lifted like a cotton-bale, she put forth her own powers, and was surprised to find how nicely it felt.

The next day, after she had been driving about with Pussy in the old farm-wagon, and seeing her do all her errands, she said to her: “Do you know that I think that my principal disease hitherto has been laziness? I mean to get over it. I’m going to try and get up a little earlier every morning, and to do a little more every day, till at least I can take care of myself. I have determined that I won’t always lie a dead weight on other people’s hands. Let me go round with you, Pussy, and do every day just some little thing myself. I want to learn how you do everything as you do.”

Of course, this good resolution could not be carried out in a day; but after Emily had been at the farm a month, you might have seen her, between five and six o’clock one beautiful morning, coming back with Pussy from the spring-house, where she had been helping to skim the cream, and a while after she actually sent home, to her mother’s astonishment, some little pats of butter that she had churned herself.

Her mother was amazed, and ran and told Dr. Hardhack. “I wish you would caution her, Doctor; I’m sure she’s over-exerting herself.”

“Never fear, my dear madam; it’s only that there’s more iron getting into her blood,—that’s all. Let her alone, or—tell her to do it more yet!”

“But, Doctor, may not the thing be carried too far?”

“For gentility, you mean? Don’t you remember Marie Antoinette made butter, and Louis was a miller out at Marly? Poor souls! it was all the comfort they got out of their regal life, that sometimes they might be allowed to use their own hands and heads like common mortals.”

Now Emily’s mother didn’t remember all this, for she was not a woman of much reading; but the Doctor was so positive that Emily was in the right way, that she rested in peace. Emily grew happier than ever she had been in her life. She and her young friend were inseparable; they worked together, they read and studied together, they rode out together in the old farm-wagon. “I never felt so strong and well before,” said Emily, “and I feel good for something.”

There was in the neighborhood a poor young girl, who by a fall, years before, had been made a helpless cripple. Her mother was a hard-working woman, and often had to leave her daughter alone while she went out to scrub or wash to get money to support her. Pussy first took Emily to see this girl when she went to carry her some nice things which she had made for her. Emily became very much interested in the poor patient face and the gentle cheerfulness with which she bore her troubles.

“Now,” she said, “every week I will make something and take to poor Susan; it will be a motive for me to learn how to do things,”—and so she did. Sometimes she carried to her a nice little print of yellow butter arranged with fresh green leaves; sometimes it was a little mould of blancmange, and sometimes a jelly. She took to cutting and fitting and altering one of her own wrappers for Susan’s use, and she found a pleasure in these new cares that astonished herself.

“You have no idea,” she said, “how different life looks to me, now that I live a little for somebody besides myself. I had no idea that I could do so many things as I do,—it’s such a surprise and pleasure to me to find that I can. Why have I always been such a fool as to suppose that I was happy in living such a lazy, useless life as I have lived?”

Emily wrote these thoughts to her mother. Now her mother was not in the least used to thinking, and new thoughts made a troublesome buzzing in her brain; so she carried her letters to Dr. Hardhack, and asked what he thought of them.

“Iron in her blood, my dear madam,—iron in her blood! Just what she needs. She’ll come home a strong, bouncing girl, I hope.”

“O, shocking!” cried her mother.

“Yes, bouncing,” said Dr. Hardhack, who had a perverse and contrary desire to shock fine ladies. “Why shouldn’t she bounce? A ball that won’t bounce has no elasticity, and is good for nothing without a bat to bang it about. I shall give you back a live daughter in the fall instead of a half-dead one; and I expect you’ll all scream, and stop your ears, and run under beds with fright because you never saw a live girl before.”

“Isn’t Dr. Hardhack so original?” said mamma to grandmamma.

“But then, you know, he’s all the fashion now,” said grandmamma.

Harriet Beecher Stowe.

was sitting at the window reading, when

Charley Sharpe came in with Round-the-World

Joe.

was sitting at the window reading, when

Charley Sharpe came in with Round-the-World

Joe.

“More useful knowledge, I’ll bet,” said Charley.

“Yes,” said I, “and entertaining as well as instructive,—something nice for Joe about his Eden of islands in the Indian Ocean.”

“Reel us off a turn or two,” said Joe.

“Do what?” said I.

“Read it out.”

“Oh! Why don’t you speak polite English when you’re ashore?” said I.

“Because fokesel lingo slips smoother, and coils snugger,” said Joe; “you can stow more sense in a few fathoms of it,—not so much slack. But bear a hand, Georgey, and pay out your log.”

“ ‘Busragon stretched along—’ ”

“I know where that is,” said Joe; “sou-west side of Mindoro Straits.”

“ ‘Busragon stretched along—’ ”

“Who’s preaching?” said Charley.

“Bayard Taylor,” said I; “now hush! ‘Busragon stretched along, point beyond point, for forty or fifty miles. The land rose with a long, gentle slope from the beaches of white sand, and in the distance stood the vapory peaks of high mountains. The air was deliciously mild and pure, the sea smooth as glass, and the sky as fair as if it had never been darkened by a storm. Except the occasional gambols of the bonitos, or the sparkle of a flying-fish as he leaped into the sun, there was no sign of life on those beautiful waters.’ ”

“That,” said Charley, “is what my Big Brother with the Literary Turn of Mind calls the Genial Style. All Style is either ‘Genial’ or ‘Incisive.’ ‘The Genial Style,’ says my Big Brother with the Literary Turn, ‘may be described as—’ ”

“O, belay that!” said Joe; “you must take a fellow for a Young Man’s Own Letter-Writer, or a Cooper Institute.”

“Well, as this is not a Debating Society,” said I, “Mr. Taylor and I will try it again.”

“ ‘Toward noon the gentle southeast breeze died away, and we lay with motionless sails on the gleaming sea. The sun hung over the mast-head, and poured down a warm tropical languor, which seemed to melt the very marrow in one’s bones. . . . . The night was filled with the glory of the full moon,—a golden radiance, nearly as lustrous, and far more soft and balmy, than the light of day,—a mystic, enamored bridal of sea and sky.’ ”

“Ah-h-h-h!” said Charley.

“That’s so!” said Joe,—both together.

“ ‘The breeze was so gentle as to be felt, and no more; the ship slid as silently through the water as if her keel were muffled in silk; and the sense of repose in motion was so sweet, so grateful to my travel-wearied senses, that I remained on deck until midnight, steeped in a bath of pure, indolent happiness.’ ”

“Now I know,” said Charley, “where all the good travel-writers go to when they die,—where the wicked critics cease from troubling and the weary readers are at rest. But jump into your bath again, Georgey; don’t mind me.”

“ ‘Retreating behind one another, until they grew dim and soft as clouds on the horizon, and girdled by the most tranquil of oceans, these islands were real embodiments of the joyous fancy of the poet Tennyson in his dream of the Indies. Here, although the trader comes, and the flags of the nations of far continents sometimes droop in the motionless air,—here are still “the heavy-blossomed bowers and the heavy-fruited trees,” “the summer isles of Eden in their purple spheres of sea.” ’”

“Oh!” said Charley, “if I only owned an Old Man, and my Old Man only owned a Circumnavigator, I’d leave this weary world, where school forever keeps, and climb one of those heavy-fruited trees—with a basket.”

But Joe said it was not all palms and banyans, heavy-blossomed bowers and heavy-fruited trees, in the Indian Ocean. Not far from the island of Cagayan, in the Sooloo Sea, there is a small, lonely coral bank,—a patch of glaring white sand, without tree, or shrub, or blade of grass, and surrounded by a belt of coral so steep that the Circumnavigator might have rubbed her sides against it, although no bottom could be reached with the hand-leads. The centre of this corpse of an island was stirring with an endless variety of sea-birds, from little naked, gaping, peeping chicks to the full-fledged screaming cocks and hens, that flapped and slapped the air overhead, and so boldly and obstinately disputed the landing of a boat’s crew from the ship that Joe and Barney Binnacle and Toby had to knock them down with sticks by the dozen. On this grim and dismal coral strand, with no requiem but the roar of Old Ocean, and no visitors more gentle than those savage sea-birds, was the solitary grave of a Mussulman, with its turban, the symbol that marks the last resting-place of every follower of the “Prophet,” rudely carved from a block of wood. Joe thinks it would be hard for even the most pious Mohammedan, standing by such a grave in such a place, to “envy the quiet dead,” as his Koran advises, and exclaim, “Would to God I were in thy place!” But for a true Mussulman any grave is better than the bottom of the sea, because, as Washington Irving says, they believe that the souls of the Faithful hover in a state of seraphic tranquillity near their own tombs.

But, of course, such barren banks are very rare and strange in the Indian Ocean,—almost all the islands, with their cones of never-fading green, “draped to the very edge of the waves, except where some retreating cove shows its beach of snow-white sand,” looking, from the sea, like great emeralds set in silver; or the larger ones, with their woody valleys folded between the hills, and opening upon long slopes, “overgrown with the cocoa-palm, the mango, and many a strange and beautiful tree of the tropics; island after island fading from green to violet, and from violet to the dim, pale blue that finally blends with the sky,”—showing like mounds of changing velvet that the giant genii of the sea have piled there to charm the fairies of the air.

Joe says, wherever the Circumnavigator came to anchor in this coral harbor, or off that bamboo village, the people put off from the shore, with great bustle, in their proas and canoes, and were soon alongside with fowls, quails, rice, yams, plantains, sweet pumpkins, and bread-fruit, cocoa-nuts, oranges, pine-apples, the “stinking” but delicious dorian, the fragrant and more delicious mango, and the melting and most delicious mangosteen; besides a perfect Barnum’s Museum of curiosities to satisfy the imaginations of the expectant young folks at home,—such as dwarf monkeys, golden paroquets, green pigeons, tufted doves, Java sparrows, and a great variety of curious and beautiful shells. All these were bought, not with dollars, but with glass beads, looking-glasses, gaudy handkerchiefs, pieces of red or blue cotton, bright brass buttons, lucifer matches, and empty bottles.

“At Samarang,” said Joe, “on the north coast of Java, some of the fishermen had bird’s-nests to sell.”

“Do you mean the edible sort?” I inquired.

“The sort,” suggested Charley, “that the Chinese make soup of when the Nanking Fire Department gives a dinner at the Celestial Hotel to the Peking Seventh Regiment?”

“Exactly,” said Joe; “only when you trade for that kind, your buttons must be silver, and your bottles must be full.”

“But, Joe,” said I, “is it really a bird’s-nest? And what is there in it to make soup of?”

“It is the nest of the sea-swallow,” said Joe. “The Java traders call it the lawit, and on the Philippines it is the salangane,—a dark-gray bird, greenish on the back and bluish on the breast, and with a short, strong bill. There are two species; one smaller than a wren, the other double the size of a martin. They are found—both the large and the small—in swarms of countless thousands among the limestone caves of the Philippines, and in deep, sea-swashed, roaring caverns on the coasts of Java and Borneo. Karang Bollong (the ‘Hollow Reefs’), on the south coast of Java, is famous for them.

“From coral rocks and stones on the sea-shore, these birds gather and swallow fish-spawn, glutinous weeds, and jelly-like animals, such as are seen floating on every coast; and this mixture of vegetable and animal matter is digested in their stomachs into a transparent glue, slimy and very adhesive,—such slippery, sticky stuff, as you young land-lubbers find along the shore on stones that are alternately covered and left bare by the tide. The bird has the power of disgorging this glue at pleasure; and when it is ready to build its nest, it begins by expertly plastering with its trowel-like beak the walls of thundering caverns on the coast, and dreadful, sunless dungeons of awful depth, where it has its strange and dismal home. It is employed during two months in the preparation of the nest, which is bowl-shaped, about the size of a common coffee-cup, and composed of waxy-white or transparent shreds, like isinglass, cemented together by that stomach-glue; but from the time the eggs are laid until the young are fledged, it grows continually darker and dirtier. On the rocky walls, millions of these nests adhere together, in regular rows and tiers, without a break. In each nest two eggs are laid, and hatched in about a fortnight; and the chicks are found lying softly on feathers, which have evidently been shed for the purpose from the breasts of the parent-birds.

“The value of the nest to the Javanese, Malays, and Chinese engaged in gathering them depends on its age. The best are those which are newly made, and nearly transparent; those that contain eggs, and are darker and mixed with feathers, are of the medium quality; and those from which the young birds have flown, and which are defiled with food and dirt and streaked with blood, are classed as inferior; some of the nests are of coarser texture, originally, than others. When they are gathered, they are dried in the shade, assorted according to quality, and packed in wooden boxes, holding a picul each,—that is, about one hundred and thirty-three pounds. They are then shipped in the junks,—a fleet of which waits to receive them twice a year,—taken to China, and sold in the principal markets for from $1,250 to $4,500 per picul, according to quality; the very best fetch double their weight in silver, or about forty dollars a pound.

“The caverns in which the nests are gathered are dreadful pits and dungeons,—deep, dark, and dangerous. The caves of Karang Bollong open in the face of a sheer wall of rock five hundred feet to the top; from mouths twenty feet wide and thirty feet high, they expand within the rock until they attain the tremendous dimensions of one hundred and twenty feet in width and four hundred and fifty feet in height; and far, far back in their black recesses the waves of the Indian Ocean furiously dash and roar, as if struggling to break from those cells and tombs of midnight horror back to their dazzling noons and tender moonlight again.”

[“Well!” said Charley Sharpe. “Wishimaynever!”

“What’s the matter?” said I.

“Well! Wishimaynever if he ain’t trying his hand at Fine-Writing! Why, George Eager! I shouldn’t have thought it of you. If that’s what you’ve come to, you’d better resign, and let my Big Brother with the Literary Turn edit us. Joe didn’t say it that way, and the Young Folks will know it.

“O, that’s all right, Charley!” said Joe; “let him show his colors and fire a gun when he runs into Port Hyfalutin. What’s the use of being a Celebrated Author if you don’t spread yourself now and then? Proceed with the pretty talk, Georgy.”]

“The rows and tiers of nests in the caves are found at different depths, from fifty to five hundred feet; and the nest-gatherers, who are trained to their dreadful trade almost from infancy, descend to them by means of ladders of bamboo and reed, or of rope, when the depth is alarming. Down, down, down,—utterly out of sight and almost out of hearing from above, the foolhardy fowler gropes by the light of a torch through the pitchy darkness for his prize,—now clinging desperately to his slender ladder, now feeling with his cunning toes for a foothold on the dripping, slippery ledges, whence a single false step would plunge him into the greedy, fretting surf, or impale him on the spear-like spires of rock. Sometimes he drops his torch! and as it flashes down some devil’s-spout, and hisses in the boiling pot below, he can only crouch and tremble.”

[Joe says he dropped his torch once, in an idol-cave in Burmah; and though it still makes him shiver to think of it, he’ll try to tell the Young Folks the story, when he comes to it in the regular course of his travels.]

“The gatherings take place in April, August, and December; and as each expedition, so romantic in its peril, is an exciting event,—especially to the women whose husbands or lovers are to descend into the caves,—its departure is celebrated with strange ceremonies and stirring sports. A bimbang, or feast, is spread; and there are wayangs, or games in mask. The flesh of buffaloes and goats is distributed among the guests, and a pretty young Javanese girl, dressed in fantastic costume, represents an imaginary patroness, named Nyai Ratu Kidul, ‘the Lady-Queen of the South,’ to whom offerings are made, and her favor and aid invoked. There is an understanding, that, without her approval, the expedition cannot proceed, and that the ‘nesting parties’ must not move until she has given the word. But as the leaders of the expedition are always the judges of the omens, and have the appointment of the season, the Lady-Queen takes her cue from them, and is sure to give the required signal at the right time.”

“And all this trouble, expense, danger, and superstitious tomfoolery,” said Charley, “serves no better purpose than to help a lot of Chinese swells and office-holders to have a curiosity for dinner. Did you ever taste bird’s-nest soup, Joe?”

“Yes,” said Joe.

“What did it taste like?”

“An editor’s paste-pot, warmed up.”

“Trepang,” said I,—“that’s another queer thing that the Chinese make soup of. What’s Trepang, Joe?”

“Trepang?” said Joe,—“tre-pang? O, that’s the sea-cucumber: bêche de mer, the Frenchmen call it,—the sea-spade.”

“Do you mean a real cucumber, that grows in the sea?”

“O, no! It’s an animal,—rather more so than the sponge, for it gives signs of sensation.”

“Then why do you call it a cucumber?”

“Because, although there are several species, they generally resemble a cucumber in form. They are very curious creatures,—usually about eight or nine inches long, and one inch thick; but sometimes they are found two feet long and eight inches round the middle. In the water the sea-cucumber displays its full length; but if you touch it, it suddenly contracts and thickens, like a leech, so as to completely alter its shape and appearance. But, long or short, thick or thin, it is always an ugly dirty-brown thing,—hard, stiff, and with scarcely a sign of animal life; though at one end of its body it has a mouth with shelly teeth, set in a circle, and surrounded by many feathered tentacles, or feelers.”

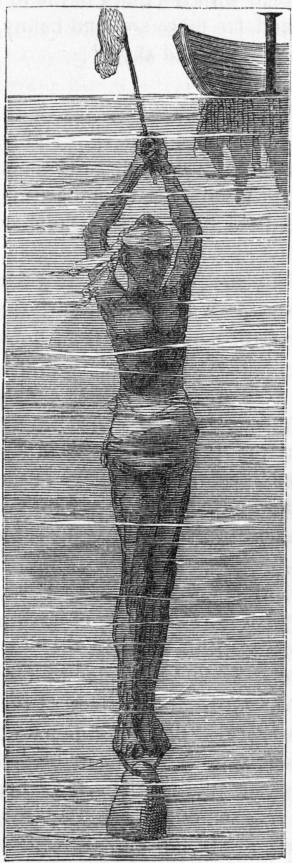

Charley said he had read about it in Gosse’s “Ocean.”

“The sea-cucumber is found in shallow waters, on coral reefs, or in those lovely, calm lagoons, that shine like looking-glasses just inside the breakers,—sometimes exposed on the bare rocks, sometimes half buried in the coral-sand, its tentacles floating on the surface of the water. The natives often capture the larger kinds by spearing them on the rocks; but the usual mode of taking them is by diving, where the water is four or five fathoms deep, and gathering them by hand, as the pearl-oyster is taken. A good diver will bring up a dozen at a time.

“To prepare them for market, they are split down one side, boiled, and pressed flat with stones; then, stretched on bamboo slips, they are dried in the sun, and afterwards smoked; and so they are shipped aboard junks, and sent to China, to tickle the whimsical palates of dainty prefects and epicurean mandarins. And you may imagine how fond of trepang soup those luxurious fellows are, when I tell you, that although the finest sea-cucumbers sell in Fuhchow and Nanchang for about a dollar and a half a pound, fleets of from sixty to a hundred proas, carrying from fifteen hundred to two thousand men, leave Macassar in company to gather them.”

Joe says that of all the curious and beautiful forms of animal life that float or sail or row on the surface of the Indian Ocean, covering the sea for miles in all directions, the most curious and beautiful are the Violet Janthine, the Portuguese Man-of-War, the Sallee-man, and the Glass-Shells.

The Janthine is a snail with a shell which in form and size resembles the little house that the common garden snail carries on its back; but its color is pearly-white above, and violet beneath. It is provided with a curious oblong “float,” about an inch in length, composed of a delicate white membrane, inflated, and puckered on the surface into small bladders or bubbles; and supported by this the Janthine floats on the convex side of its shell. Three or four drops of a blue liquid are always found in its body; and some naturalists have imagined that the use of this is to conceal the pretty little creature, when danger threatens it, by imparting to the water around it a color like its own. But this can hardly be so, since the whole quantity found in even the largest Janthine is barely enough to stain half a pint of water. In the spawning season, the eggs of this sea-snail are hung by pearly threads under the float; yet these tiny bladders are found in great numbers, separate from the mother, but with the eggs attached; so the Janthine must have the power of casting off its float, and forming a new one,—leaving its eggs, and probably its young also, to be warmed and cradled on the billows, in the heat and light of the sun.

Then there are those exquisitely lovely and fragile “Glass-Shells,”—little living row-boats, the bustling shallops of invisible sea-fairies, like the mussel-shell the poet Drake describes in his charming story of “The Culprit Fay”:—

“She was as lovely a pleasure-boat

As ever fairy had paddled in;

For she glowed with purple paint without,

And shone with silvery pearl within.

A sculler’s notch on the stern he made;

An oar he shaped of the bootle-blade;

Then sprung to his seat with a lightsome leap,

And launched afar on the calm blue deep.”

The two prettiest of these are the Hyalea and the Cleodora. Both have glassy, colorless shells, extremely delicate and brittle, with a pair of fins, or wings, which the elfin within uses as oars. In the dark the Cleodora is vividly luminous; its tiny glass lantern shining and bobbing on the top of a wave, like a fairy floating beacon for the Portuguese Men-of-War, and the Sallee-men, and its own consorts in the Glass-Shell fleet, to steer by.

“Ah!” said Charley, “that’s what I want to know about,—the Portuguese Man-of-War. I read of it in all my ‘Voyages’ and ‘Adventures,’ but I never yet did clearly know whether it was a boat or a bug.”

“Like the Glass-Shell,” said Joe, “it is a living boat, only it carries sail instead of oars; and the Sallee-man is like it. Its build is very simple,—merely a bag of semi-transparent membrane, round at one end and sharp at the other,—that is the hull. Along one side of this bag it carries a puckered membrane, which it can spread wide, or take in,—that is the sail. From the other side hangs a thick fringe of blue tentacles, among which are a few that are crimson or purple, and very long, and with these tentacles it can sting severely any living thing that comes within its reach; small fishes, benumbed and helpless, are often found attached to it.”

Joe says a fleet of these Portuguese Men-of-War, some thousands of them together, as he has many a time seen them in the tropics, with their blue hulls, and pink-edged sails, all on a pygmy scale, bearing down before a tender, playful breeze on the long lazy-swelling slopes of sea, is just the prettiest and most engaging sight on all the world of waters. And of all the marvellous displays of God’s power that those behold who go down to the deep in ships, there is nothing so wondrous and so sweet as that tender Providence which keeps His little Men-of-War afloat and tight in seas where man’s big men-of-war go down like stones.

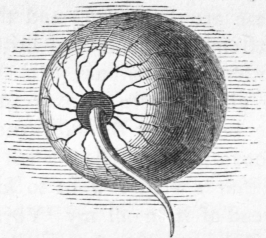

Joe says that, on a clear moonless night, when the Circumnavigator has been dancing over the water gayly, he has seen the Indian Ocean all ablaze, ahead and astern, to windward and to leeward, with countless billions of luminous microscopical creatures, the makings without end of Him who made Leviathan and Mastodon, and cares for all alike,—lines of light, belts of light, globes of light, flakes of light, spangles and sparks of light, churned and curdled milky-ways of light, mists and clouds of light, whirls and eddies of light, spouts and waterfalls of light, flashes and steady glows of light, meteors and auroras of light, ripples and billows and long swells of light, fountains and wheels and whirligigs of light, tapers and calcium-lights of light, glow-worms and planets of light, lamps and laboratories of light, sweet smiles and fierce troubles of light, light white and sharp, light yellow and dull, light blue and vivid, light red and dead. For God has sown the sea thick with luminous life,—the darting Cyclop, the whirling Medusa, the sparkling Entomostraca, the globular Noctiluca,* the glowing Cephalus (the sun-fish), the ghostly Heterotis, the ghastly Squalus fulgens. And to all these He has said, Let there be Light! And there is Light, compared with which the Pope’s illumination of St. Peter’s at Easter is a mere lucifer-match.

George Eager.

|

A picture of the Noctiluca, greatly magnified, follows this article. |

Next to the fishes and amphibious quadrupeds as swimmers come the aquatic or water birds. In some respects the latter beat the best of the amphibious quadrupeds. They can swim faster, though they cannot as divers stay under water as long as the otter, the beaver, the hippopotamus, and the alligator. The quadrupeds that are not amphibious are all inferior to the aquatic birds as swimmers. In the water they are almost wholly immersed, and if they can keep their heads up, it is about all they can do. On the other hand, the floatage of the birds is great. They swim on, rather than in, the water, and skim over its surface at a rapid rate. Their feathers serve to buoy them up in some measure, and the hollow structure of their bones is another aid. But the principal thing is the make of the bird. The next time you have duck for dinner (and a most savory thing roast duck is), observe the shape of the breast. It is nearly flat, and beautifully moulded, not sharp, and deeply let down, as the breasts of turkeys and barn-door fowls are.

The duck is not a favorite of the poets. I only know of one who alludes to it; and he, in describing the graceful measure of a fat young lady in a dance, says that she circled about “like a duck round a daisy.” But I know of nothing more easy and graceful than a duck on a fine sheet of water. It has passed into a proverb with the sailors, who say of a good ship in heavy weather, “She rides like a duck in a cove.”

Very few, if any, of you young folks have seen the albatross, the largest of the great sea-birds. Off Cape Horn, and, indeed, all round the world in those southern latitudes, these noble birds are seen in immense numbers. They do not swim much, for their power on the wing is immense; but they must mostly sleep on the water, as they are found hundreds of miles from any known land. Besides, they are not making a passage towards the land, but circling and sweeping about “day after day, for food or play.” And that reminds me that, in Coleridge’s poem of “The Ancient Mariner,” there is a mistake about the albatross. In speaking of the one he afterwards killed, the Mariner says,—

“In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine;

Whiles all the night, through fog smoke-white,

Glimmered the white moonshine.”

No albatross would perch on mast or shroud. It is not a perching bird, but rests and sleeps upon the heaving waves. It is very broadly web-footed, and so made that it cannot rise and fly off from a flat, solid surface. Even in getting on the wing from the water, it paddles with its feet in the water, while giving quick strokes with its wings, for a considerable distance. But once fairly afloat between sea and sky, nothing can exceed the power and grandeur of its flight. We caught many of them during a passage to New South Wales. Some measured sixteen feet from tip to tip of wing, when extended. Our method was to rig a long line with a flat piece of pine board to float it out astern; and on this board there was a piece of fat pork on a good, stout fish-hook. This, being paid away astern, soon attracted the notice of an albatross, which would hover, take the bait, and settle on the water. When hooked, it was drawn up to the stern, hand over hand, and then lifted on board. I brought home the skull and bill of a very fine one. We tried the flesh of the albatross, but it was not as good eating as cutlets of shark. The latter is almost as good as some halibut.

The albatross carries hardly any flesh, except on the thighs; and this part seems to be nearly all sinew, and almost as hard as brass. No other bird that I know of goes so far out to sea for sport, except it be the stormy petrel. So you see that the albatross, which is the largest of the sea-birds, and the stormy petrel, which is the smallest, roam farthest over the ocean.