* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 3, Issue 11

Date of first publication: 1867

Author: J. T. Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Sep. 8, 2018

Date last updated: Sep. 8, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180913

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Delphine Lettau, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. III. | NOVEMBER, 1867. | No. XI. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

WILL CRUSOE AND HIS GIRL FRIDAY.

SOUND ASLEEP!

ound-the-world Joe was paring apples for his

mother to make pies of; and, being one of those boys

that give all their mind to a thing, and even pare apples

with enthusiasm, he had thrown off his jacket and rolled

his shirt-sleeves up to the shoulder.

ound-the-world Joe was paring apples for his

mother to make pies of; and, being one of those boys

that give all their mind to a thing, and even pare apples

with enthusiasm, he had thrown off his jacket and rolled

his shirt-sleeves up to the shoulder.

“What’s that, Joe?” inquired Charley.

“Which?—where?”

“On your arms,—blue things,—pictures.”

“O, that!” said Joe; “that’s what I call my classmark,—stands for “A. B.,” Able-Bodied Seaman,—means I’ve been Round. When the second mate sees that, he knows I’ve got my sea-legs on, and don’t look for me to wriggle through the lubber’s hole, or spit to windward.”

“Let’s see!” said we too; and Joe took what he called a “close reef” in his sleeves and “squared his yards”; that is, he held out one arm to me, and the other to Charley.

Mine had a picture of a ship under full sail, with blue hull and spars and red rigging, and, underneath, the words,—

“Circumnavigator—Joe.”

She had blue sails, and was dashing through red water; and there was a blue angel with red wings and a pink trumpet flying over her, blowing.

Charley’s arm—that is Joe’s, you know—had a blue eagle with a red tail, perched on a blue anchor, and under it the glorious motto of our native land:—

“E Pluribust Unam!”

“O, isn’t it splendid?” said I, “and so natural! Who did it, Joe? and how did he do it?”

“Pshaw!” said Joe, “that’s nothing; if you want to see richness, look here!” and he tore open the bosom of his shirt, and slapped his breast proudly, like the sailor-man in the play, when he tears his shirt before the judge, and says, “If your Honor wants witnesses to the pre-vi-ous carakter of Cutlash Jack, your Honor can jest overhaul these here!” and then he shows a “gridiron” of ghastly wounds that impart to his manly chest the appearance of having been ploughed over when he was asleep. And the judge says, “Your hand, my brave lad! Britannia needs no bulwarks, no towers along the steep,” &c.

[But Mrs. Brace only said, “Joseph, my child, didn’t I hear a button?”]

Well, as Joe so triumphantly remarked, there was richness! A blue sailor with red hair, dancing a hornpipe with a red sweetheart with blue hair, on a red cloud, surrounded by a blue rainbow, and both of them waving the Star-Spangled Banner! Below was this proud inscription:—

“Long may she wave!”

“O Joe! how do you do it?”

“Stick it,” said Joe.

“Spaulding’s glue?” said Charley.

“Needles,” said Joe, and he laughed.

“Hurt?” I asked.

“Smarts some,” said Joe; “but what’s that to a chap that’s been ROUND? Besides, quids cures it.”

“Joe,” said Charley, “may I speak with you a moment in private, if Georgey will excuse us?”

[We bowed, with dignity.]

“What’s the matter now, chum?” said Joe, stepping aside.

“Joseph,” said Charley, “could you stick her—here?” tearing the buttons off his shirt, and poking his hand under the left side of his jacket.

“Who?”

“Hush! You know,—Kate!”

“Well, you see, chum,” said Joe, “that’s a touch above me; I’m not in the high lines yet. If a star now, or a heart, or even her name, with an anchor to it, would do you any good, why, I’m ready to stick you; but portraits are Science, you know. Hows’ever, I’ve got a shipmate, Toby Splice,—everybody knows Toby,—he’s been ROUND three times, and his father’s a ship-carpenter,—Toby’ll put you through beautiful.”

“Would she have to sit for it, Joe?” inquired Charley, very anxiously.

“Do which?” said Joe.

“Sit for it,” said Charley,—“so that Toby can get her expression correct, you know?”

“O, not at all,” said Joe, “I’ll do that myself.”

“Do what?” said Charley.

“Sit for her expression,” said Joe. “Why, I’ve sat for seventeen Long-may-she-waves, and every one was a perfect likeness. O, that’s all right!”

“O Joe,” whispered Charley, “I’m so much obliged to you! I’m your friend forever! It’s such a relief! Always next your heart, you know,—never can fade,—stern father can’t take it from you, and lock it up in his burglar-proof,—spiteful sister can’t steal it, and show it to all the other girls, and make fun,—nobody can harrow your feelings, you know. O, it’s such a relief!”

“That’s all right,” said Joe, and then they rejoined me. I was chewing apple-parings, and they thought me deceived. But I shall advise my sister to retire to a nunnery.

“But, Joe,” said I, “what do you do it with?”

“Injin Ink, Old Useful Knowledge!” said Joe. “But here’s all about it, in a ballad that I made myself; and if it isn’t poetry, why it’s true, that’s all.”

THE BALLAD OF INJIN INK.

It is a Tarry Sailor-man

Doth shift his quid and sigh;

And, moping o’er his Injin Ink,

He spits, and pipes his eye:

In all their queer variety,

Perusing, one by one,

Spars, anchors, ensigns, figure-heads,

His fokesel chums have done.

Around his arms, all down his back,

Betwixt his shoulder-blades,

Are Peg and Poll and Patsy Ann,

And mer and other maids;

And just below his collar-bones,

Amidships on his chest,

He has a sun in blue and red,

A-rising in the west.

A bit abaft a pirate craft,

Upon his larboard side,

There is a thing he made himself,

The day his Nancy died.

Mayhap it be a lock of hair,

Mayhap a kile o’ rope:

He says it is a true-love knot,—

And so it is, I hope.

He recks not, that bold foremast-hand,

What shape it wear to you:

With soul elate, and fist expert,

He stuck it,—so he knew.

To “Ed’ard Cuttle, Mariner,”

His sugar-tongs and spoons

Not dearer than that rose-pink heart,

Transfixed with two harpoons;

And, underneath, a grave in blue,

A gravestone all in red:—

“Here lies, all right, Poor Tom’s delight:

God save the lass,—she’s dead!”

Permit that Tarry Sailor-man

To shift his quid and sigh,

Nor chide him if he cusses some,

For piping of his eye.

Few sadder emblems are the heart’s,

Than, traced at first in pink,

And pricked till all the picture smarts,

Are fixed with Injin Ink.

“Now you know all about it,” said Joe.

“But what kind of poetry do you call that?” Charley asked. “Sort of mixed, isn’t it? I was just going to laugh, when we came to the grave.”

“Why, you didn’t imagine it was funny,—did you?” said Joe.

“At first I did,—a little.”

“Sich is Life,” said Joe. “As my old man says, ‘Laughing or crying, it’s all the same hyena.’ ”

“But let’s get back, aboard the ‘Circumnavigator’; for by this time she’s half-way down the Indian Archipelago, on her way to Borneo and Java for camphor, spices, and gutta-percha. As Captain Cuttle—‘Ed’ard Cuttle, Mariner’—used to say, ‘Overhaul your chart, and, when found, make a note on it.’ Down the China Sea, passing Luzon and Manilla; through the Straits of Mindoro, and down the Sooloo Sea; then through the Straits of Basilan, past the great pirate-island of Mindanao, and across the Sea of Celebes, with a southwesterly slant to the Straits of Macassar; and so along the east coast of Borneo, and through the Java Sea, to Batavia. And O, boys! but it’s a cruise of wonders, every furlong of it, from the last grinning Chinaman you leave at Hong Kong, with his own tail wagging at the small of his back, to the first Sea-Dyak you spy at Labuan, with the fresh head of his victim reeking in his hand,—an Eden of beauty and romance and enchantment, and with the biggest and ugliest kind of a serpent squirming and hissing and thrashing through it.”

“Yes,” said I, “and don’t we school-boys know it? Why, the dullest Geography reads like Sinbad and Marco Polo in one, when it comes to the Indian Ocean; and the boy that isn’t ‘up’ in his lesson then must be stupider than one of those ‘Booby-birds’ that you saw scrambling and squawking round the ‘Circumnavigator’ in the Gulf Stream, or nodding, gorged, on mangrove logs off the Straits of Malacca! His only excuse must be that he stopped to look at the pictures. I tell you, Joe, some of us are at home in the Indian Ocean,—aren’t we, Charley? For instance, there’s where the trade-winds blow, that bowl you along steady, straight on your course, for a month at a time, without sea enough to spill a passenger’s soup.”

“Yes,” said Charley, “and there’s where the typhoons strike you like a thunderbolt, out of a clear sky and a calm sea, and tear you plank from plank, grinding like a coffee-mill.”

“And there,” said I, “is where everlasting rainbows span the flashing straits from island to island,—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet arches, arch within arch, like a cathedral in heaven.”

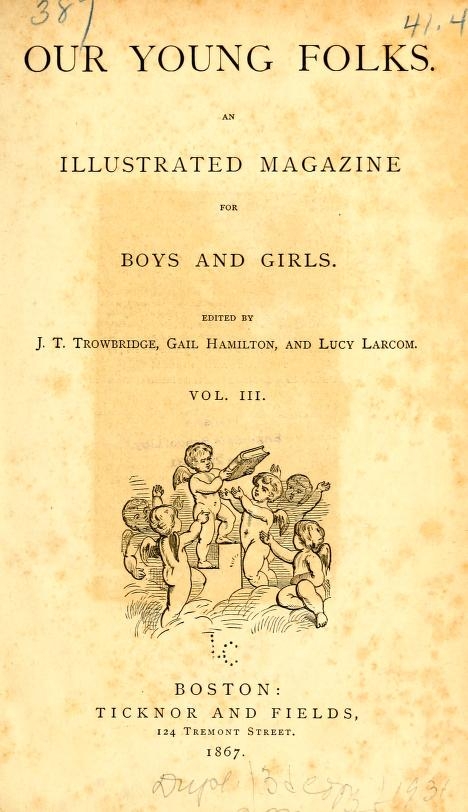

“And there,” said Charley, “is where everlasting water-spouts are let down from the black and growling clouds to join with other water-spouts growing from the churned and frothy sea, bubbling, whirling, frosted columns, column upon column, column crossing column, to uphold the bursting, falling roof of sky.”

“Rosy groves of coral,” said I.

“Wrecking reefs of coral,” said Charley.

“Skimming swallow-fleets of fishermen,” said I.

“Dodging vulture-fleets of pirates,” said Charley.

“Proas like butterflies,” said I.

“War-canoes like scorpions,” said Charley.

“The confiding, child-like harvesters,” said I.

“The cunning, fiend-like freebooters,” said Charley.

“Curious, picturesque junks from China,” said I.

“Rascally, meddlesome rogues from China,” said Charley.

“Proud, intrepid Malays,” said I.

“Snaky, revengeful Malays,” said Charley.

“Grateful, affectionate Hill-Dyaks,” said I.

“Treacherous, remorseless, Coast-Dyaks,” said Charley.

“Honey-hunters,” said I.

“Head-hunters,” said Charley.

“Chameleons, cockatoos, and birds-of-paradise,” said I.

“Snakes, buzzards, and vampire-bats,” said Charley.

“Life-saving drugs,” said I.

“Death-dealing poisons,” said Charley.

“Spicy breezes,” said I.

“Sickly blasts,” said Charley.

“Mermaids,” said I.

“Sharks,” said Charley.

“The Lotos,” said I.

“The Upas,” said Charley.

“Moonlight and enchantment,” said I.

“Diabolical conjuration and midnight murder,” said Charley.

“The sea glowing with luminous animals,” said I.

“The land illuminated with burning villages,” said Charley.

“Nutmegs and cloves, frankincense and camphor, diamonds, rubies, and opals, gold, silver, silks, tortoise-shell, feathers, pearls, and sandal-wood,” said I.

“Earthquake, Pestilence, Slavery, and Death,” said Charley.

“Where they ‘whistle back the parrot’s call, and leap the rainbows of the brooks,’ ” said I.

“ ‘Like a beast with lower pleasures, like a beast with lower pains,’ ” said Charley.

“ ‘Where all the prospect pleases,’ ” said I.

“ ‘And only man is vile,’ ” said Charley.

“Is that a game you’re playing,” inquired Joe, “or are you only showing off your wisdom?”

“Joe,” said Charley, “it’s a sermon!”

“You don’t tell me so!” said Joe. “Well, I thought it sounded funny.”

“Joe,” said I, “what’s a proa?”

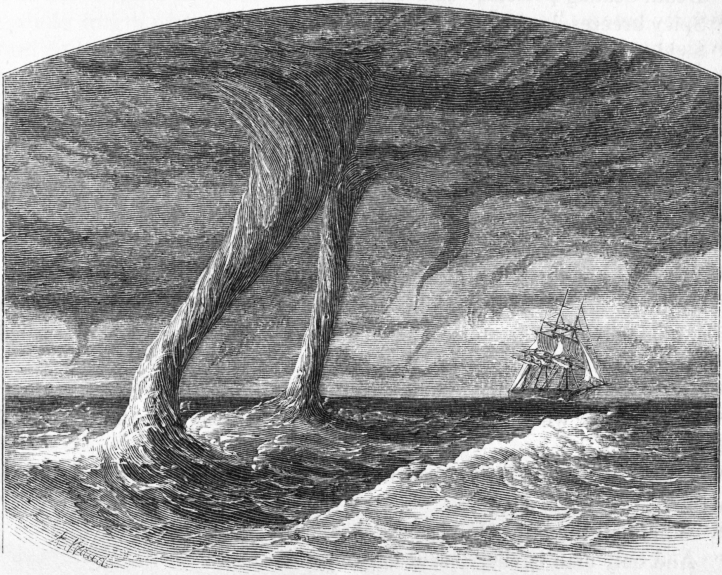

“A proa,” said Joe, “is a boat built like the handle of a jug or a political editor,—all on one side. Instead of having the stern round or square, as our craft have, and the two sides alike, it has stem and stern alike,—both rather sharp and high out of the water; and while one side is round, as in European and American vessels, the other side is flat, and nearly perpendicular. It has but one mast; and that, instead of being ‘stepped,’ as sailors call it, amidships, or exactly between the sides, rises, with very slight ‘rake,’ from the round edge of the proa. The hull is long and narrow; and as it is much deeper than it is broad, and carries a sail that covers the whole boat, you can readily imagine that the least puff would capsize it, if it were not for a very ingenious contrivance, not to be found on any other craft in the world except some of the fishing canoes of the Polynesian Islands. From the edge or ‘rail’ of the round side, a bamboo frame, very light, elastic, and strong, is run out over the water; and from the outer edge of this a hollowed log, shaped like a small canoe, hangs just on the surface of the sea. Over the ‘leeward’ or flat side, and exactly in the middle of it, they run a simpler ‘outrigger,’—that is, a heavy beam or pole, projecting over the water. The inner end, or ‘heel,’ of this is made fast under the round side of the proa, just where the mast is stepped. The sail, which is made of matting, and of great spread, is triangular,—one angle being at the mast-head, one at the bow, and the other at the stern; of course, the lower side stretches the whole length of the craft. The after edge of the sail is free, but the for’ard edge works on a bamboo yard, which is slung near the mast-head, so that the foot of it falls diagonally into the proa near the bow, where it fits in a socket. The lower edge of the sail is stretched on a bamboo boom, one end of which projects over the stern. The outrigger, or bamboo frame, which supports the little canoe, is itself supported by tackling of coir rope—that is, rope spun from the fibre of the cocoa-nut—slung from the mast.

“Now,” said Joe, “I have taken pains to describe all that (and Mr. Waud says he will take pains to draw it) very accurately for you, because a Ladrone proa is really the most remarkable craft afloat, not only in respect of her shape, but in the way she is worked, and especially in the way she goes. In the first place, she is built and rigged from first to last, never to be turned round, but always to present the same side to the wind. Either end is bow or stern, according to the course she happens to be on; but the round side is always the windward, and the flat side always the leeward side. When they wish to ‘go about’ on another tack, they turn the sail, not the boat, around. All they have to do then is to lift the foot of the yard from its socket in the bow, and carry it round to leeward, with the boom, till it falls in the stern socket; at the same time letting fly one ‘sheet,’ and hauling in another. Thus the bow is in an instant converted into stern, and stern into bow, and away she goes, trimmed! No matter how fresh the wind, or how rough the sea, she never can upset,—her outrigger keeps her in perfect balance. Should she need more weight on either side, a man stands on the outrigger. By her extreme narrowness and sharpness, and her wonderful power of lying near the wind,—that is, of sailing nearly toward the points from which the wind is blowing,—the proa is the swiftest craft on all the waters of the world. She can run from twenty to thirty miles an hour. With the right breeze, nothing slower than a frigate-bird or a sea-swallow can catch her.”*

“Speaking of birds,” said Charley, “I should really like to know the honest truth, without prejudice, about the Booby. For I cannot believe that anything (unless it might be a lover, or a young hen with her first chickens) was ever such a chuckle-headed fool as the ornithology books make out that poor fowl to be.”

“Well, chum,” said Joe, “that’s all right. A fellow that’s been Round shouldn’t be above doing justice even to a shark or a cockroach; and if he has got a spite against a critter, he shouldn’t be mean enough to backbite it. Nobody can say I’m down on the Booby; I feel as friendly disposed towards that amiable stoopid as there’s any call for. Still, if you put me on my after-davit, why, then I’m bound to say it ain’t talented. To be sure, in its own line it’s spry enough—just so far: it’s a pretty smart fisherman—just so far; and when it prances for a minute or two over a school of silver-bellies, and then drops down among them ker-chunk, like a bullfrog on business,—why, then somebody’s scales have got to go under somebody’s feathers, that’s all. But whose feathers? that’s the question. If you think I don’t do justice to Booby, whose feathers, then?”

“Well, whose?” said Charley.

“Why, sir,” said Joe, “by the time your Booby friend has got the water out of his eyes, taken one long breath, and swallowed Silver-Belly whole, who should come along but Frigate-Bird,—seven feet across the wings, sir, and with a swoop like a thunderbolt,—Frigate-Bird, that sleeps in the air, and, though he neither swims nor dives, is never in want of fish for his dinner. No use for Booby to run, he hasn’t got the wings; no use for him to fight, he hasn’t got the weight; no use for him to dive, he hasn’t got the wind. But Frigate-Bird wants that Silver-Belly he has just swallowed. ‘Throw down that fish!’ roars F. B.; and Booby throws it up. Before Silver-Belly can reach the water, Frigate-Bird has reached Silver-Belly. Now whose feathers, do you think? You see, Booby is a smart fisherman—just so far.

“As I said before,” continued Joe, “I haven’t got anything against Booby; he never did me any harm. But when I see a fellow that’s just been knocked down with a belaying-pin come right back to be knocked down again, as if he liked it; when I see a fellow with a mighty pair of pinions, and the broad ocean to flap them over, prance up to have his legs grabbed by the cook; when I see a fellow that can dive from over the main-truck plump down among the bonitos and the albicores, and come up dry out of any sort of a sea,—when I see him staggering and floundering around on the poop-deck, the passengers making game of him, and him making faces, sea-sick!—if I’m on my after-davit, I’m bound to say that fellow ain’t talented.

“But,” said Joe, “here’s the beauty of it. When I see a double-ended line towing over the stern, with each end baited with a chunk of fat pork, and a couple of boobies in the wake of the ship, spending the whole blessed day gobbling down the two chunks, and then jerking them up again out of each other’s stomach, as if they were on a wager which can first turn the other inside out, while the world of waters under them is all alive with fresh fish,—when I see that,” said Joe, “if I’m on my after-davit, I’m bound to declare that, compared with such a pair of ornithological idiots, a lover, or a hen with her first chickens, is a perfect Martin Tupper for wisdom.”

“Well,” said Charley, “I don’t seem to know what to make of them, unless they’re a parable; in which case, Sich is Life.”

“Speaking of fishes,” said I, “what are Chætodons?”

“Lovely little things!” said Joe; “the Straits of Macassar swarm with them, and they are plentiful in the Sooloo Sea. From their beak-like mouths they shoot flies with drops of water, and if you drop your hand in the sea they will come and play around it. Then there are the Parrot-fishes and the Rock-wrasses, glowing like tiny rainbows among the coral reefs, their bodies brilliant with bands and stripes of crimson, yellow, and silver; and the Gurnard flying-fishes, with great prominent fins, pencilled and variegated like the wings of a butterfly; and the Toad-fishes, or Anglers, with pectoral and ventral fins not unlike the feet of a tortoise, so that they can come out of the water, and crawl over the land: on their heads they have a sort of horns, from which a shining fringe plays freely in the ripples, by its brightness and its pretty changes continually attracting smaller fishes within reach of the slow and clumsy ‘Angler.’

“In the Sooloo Sea, European sailors sometimes haul huge seines; and the sport is full of excitement and fun, such surprising draughts of strange ‘outlandish’ creatures are taken in the net,—sharks, sword-fish, flying-fish, dolphins, young alligators, turtles, and snakes.

“There’s a fish called the Puttin,” said Joe, “which the people around the Sampun River in Borneo will never eat; and this is the reason why. Once upon a time a good Dyak was fishing in the Sampun, and he caught one Puttin. Presently he wanted a light for his pipe; so he landed at the house of a Malay on the shore, taking his Puttin with him; and when he had lighted his pipe he returned to his boat, but forgot the fish. When the sun had gone down, he drew in his lines, and returned to the Malay’s house for his Puttin. But, lo! instead of the fish, in the calabash where he had left it there was a beautiful dwarf-maiden, with tiny golden wings like fins, and skin like scales of rosy pearl. And when the good Dyak recovered from his astonishment he took her home, and brought her up in his family very tenderly. She grew to be a woman, like any other Dyak woman, and she was married to the fisherman’s son, and made him a good wife,—pounding the rice, and drawing the water, and mending the nets, and plaiting the mats. Then she gave birth to a son, and suckled him till he could run about. At last, one day, being on the river-bank with her husband and the little lad, suddenly she said, ‘Here, take the child, and be kind to him for my sake. I have tried to be a good wife and a good mother; but now my finny folk call me, and I must go to them.’ And so she plunged into the river, and was changed back into a Puttin!”

George Eager.

|

[While Joe was speaking, I remembered there was some Useful Knowledge about proas in Lord Anson’s “Voyage Round the World,” and when I went home I looked for it. Here it is: “So singular and extraordinary an invention would do honor to any nation, however dexterous and acute; since, if we consider the aptitude of this proa to the navigation of these islands, which, lying, all of them, nearly under the same meridian, and within the limits of the trade-wind, require the vessels made use of in passing from one to the other to be peculiarly fitted for sailing with the wind upon the beam,—or if we examine the uncommon simplicity and ingenuity of its fabric and contrivance, or the remarkable velocity with which it moves,—we shall in each of these particulars find it worthy of our admiration, and deserving a place among the mechanical productions of the most civilized nations, where arts and sciences have most eminently flourished.”] |

Whistle once more, whistle once more,

Whistle again, little Willie;

What body knows but he’s under the rose

Or fast asleep in the lily?

Dreaming his wee bit dream, my lad;

Fighting his battles again;

Leading his men with a conqueror’s pride

On through the fiery rain.

His grape and canister, peas and beans;

His arrows, needles and pins,—

Sharpest of steel,—and steal them he will,—

That’s how the fairy sins.

He grows his silk on the waving corn;

His doubtlet is cut from its leaves;

His bonnet is hid in the kernel’s heart

He gives us the useless sheaves.

The milk-weed’s pod is his fishing-boat,—

It has weathered many a gale;

And a stolen bodkin forms the mast,

Where floats a gossamer sail.

A butterfly’s wing is his lady’s fan,

Her plume the willow-tree bears;

The spider weaves her Honiton lace,

And gay are the gowns she wears;

All sparkling with jewels, and powdered with gold,

And streaked with the rainbow’s hue,

And (tell not your sister, my wise little lad)

Her bravery always is new.

But whistle no more, whistle no more,

My darling! be watchful and wary!

Hush! hear the birds singing, the happy news bringing,

“Day breaks!”—so good by to the fairy.

Mary Leonard.

Again? But you have never seen him before! You do not remember, I suppose, what happened longer ago than yesterday. Never mind! Jamie will be just as well pleased as if you had been thinking about him ever since he made you his first bow.

In the cold country where Jamie lives the frost lies thick on the windowpanes all day long. A great fire rushes roaring up the chimney, and calls out constantly, “Be off, Jack Frost! Be off, Jack Frost!” But Jack perches saucily on the window-seat, and snaps his fingers at the fire. And how do you think Jamie can set out-doors? Why, his mamma takes a knife, and scrapes a little hole through the curtain which Jack Frost has hung there. The hole is about as big as Jamie’s eyes, and a little higher than his nose, and through it he sees everything that is going on. Once Jamie took a sleigh-ride. O, it was a sleigh-ride indeed! They went straight across the fields, over the tops of fences, upsetting a little now and then, and not minding it, till one of the horses, whose name was Charley, grew cross and tired, and got down on his knees, and said, as plainly as a horse could speak, that, as for going any farther on such a road as that, he would not. But Jamie’s papa got out, and made a track for him a little way, and then Master Charley grew ashamed of his ill-temper and his weak legs, and went about his business. But Jamie quite shook with fright. He was afraid Charley was going to “get dead.”

One thing Jamie wanted very much was a pair of boots to tuck his trousers into. But he had no trousers to speak of,—little snips of things that only came down to his knees. Then he said his feet were tired, and he wanted a pair of slippers like papa’s. So his mamma went to her bag of pieces, and found a bit of red merino, and made Jamie a pair of slippers. The soles were cut from an old buffalo-robe. Jamie grew tall as soon as he stuck his little feet into these new slippers. Now, when evening comes and papa begins to take off his boots, out come Jamie’s slippers too. The bail of a little tin pail he sets on his nose for spectacles; takes a book, though he cannot read a letter,—the little know-nothing!—and places himself in his chair with one foot on the opposite knee, so that one slipper at least shall be in plain sight.

I think myself Jamie is rather fond of fine clothes. He laments his papa’s old coat; he thinks it “looks awful.” When his tired mamma happened to sit down without noticing that her dress was awry, he cried, in distress, “O mamma! you look like old gobbler with your dress all that way; it doesn’t look nice at all.” If she puts on a new dress, his last words in bed are, “Be careful of your new dress, mamma.”

I would not have you think it is always winter where Jamie lives. Sometimes the summer is warm and bright and green, and we take long walks. Once in our walk we saw a bull coming bellowing towards us, and Jamie and I thought we would run and climb over the fence. When we were quite beyond reach of the bull, Jamie grew very brave. “Why,” said he, “when I was a little boy,—last summer, once,—I was out here, and a dozen bulls came along, and I wasn’t afraid!”

“Weren’t you?”

“No; and, O, a good while ago, when I just begun to walk, there was thirty bulls come along! I b’lieve there was ’bout thirty bulls!”—but I don’t myself believe there were more than twenty-eight, or at the utmost twenty-nine.

Once we went fishing. You should have seen Jamie with his rod on his shoulder, a pail of water in his hand for the fishes he was going to catch, and his curls tossing in the wind; at the river he set his pail on the ground, and sat down on the bank, and dropped his line into the water. The fishes were not hungry, but Jamie was patient. “Bring up the pail,” he called cheerily, after waiting I don’t know how long, “I may catch a fish by and by.” And sure enough he did catch a fish, and after he got it home the cat caught it too,—so we were none the richer for it. When we could catch no more fish, Jamie thought we might at least catch toads; for he declared, “Benny caught a toad,—shot him with his bow and arrow, and killed him, and pulled him right out of the water, and he’s ’live yet!”

One day Jamie came rushing into the house, shouting at the top of his voice that he had found a nest of kittens: “Ten,—four black ones, and four gray ones.” We went out-doors, and there indeed was a nest with eleven of the dearest little kittens,—two families of cousins. Nine of them presently went out into the world to seek their fortune, and only two remained. These two Jamie was very fond of; and he handled them so much that Mother Puss feared they would become spoiled kittens, and she hid them in the hen-coop. Foolish Puss! As if Jamie did not know the hen-coop through and through. Then she hid them again under the barn-floor, and in two days there was Jamie’s saucy nose poking under the barn-floor. Then she hid them again; and for nearly a week Jamie could not find them, and Mistress Puss had a little peace of her life. At the end of that time Jamie got the better of her again. He had found the kittens! And nothing would do but we must go and see them. Jamie ran ahead, and made his little legs go so fast that we could hardly keep up with him; and he squeezed his little self between rails and through cracks just about large enough for a mouse, and then up on the fence, and up on the hen-house, and up on the shed-roof, and at last on the top of the barn! And there, in a snug little hole in the thatch, were the two little kittens curled up in the sunshine. But the cat did not look happy. She really scowled at Jamie.

Jamie has another pet,—a beautiful white rabbit, with pink eyes and long ears. But the rabbit is bashful, and they are not yet on the best of terms. Jamie has just come in quite sorrowful to say, “I just been out to give my rabbit a turnip; and I called ‘Bunny, Bunny,’ four, four times, and he didn’t come out.”

“Didn’t he?” says Nano. “Well, come here a minute. Your face is dirty, I know; but give me a kiss.”

“O no!” says Jamie, with an expression of disgust.

“But your lips are clean,” says Nano;—whereat he just lays his thumb and forefinger round his mouth, and drops a kiss daintily through these defences.

His Bunny takes the place of a dog. Jamie does not much like dogs. A big one ran at him once, and came near biting him. “I tell you,” says Jamie, “I had a drefful scare that time. It makes me shake yet.”

One Sunday Nano was telling him about the flood and Noah. He was very still and attentive. “Were they all drowned?” he asked, when she had finished.

“Yes.”

“All of them?”

“Yes, all.”

He paused a moment, then shook his head: “I don’t believe that. That’s too big a story.”

Jamie is very fond of using grown-up words. When his baby cousin lost his ball, he was kind and patient; but after she was gone he asked his mamma if she did not think Aunt Molly’s baby was a real nuisance! When Nano wanted him to go home with her, “O no, he could not afford to.” He does not wish to go to the Episcopal church because he “does not like the services.” He is still as a mouse while we are driving in the lake, and after we come out, he draws a long breath, and says, softly, “O, how I did enjoy that ride in the water!” When the wind blows his brown curls in his face at the picnics, he says he “believes he shall get a habit of eating hair.” But sometimes he goes a little beyond his depth. There is steamed bread on the table for breakfast, and he hears his mamma say that some one has inordinate self-esteem; so he puts the two together in his dear little brain, and presently says, “Thank you, mamma, for some of that self-esteem bread.”

We were speaking one day of the Good President. Jamie said, solemnly, “He is dead.”

“What made him die, Jamie?”

“Naughty man shoot him, and throw him up to God in the sky”;—and Jamie flung up his arms as if he were throwing something up very high, so that we could see just how the beloved President went; and if you want to know what he is doing up in the sky, there is a little boy whose name is Eddie who can tell you all about it.

Gail Hamilton.

Sad times had come for Polly Ben. “ ’Most seven years old,” mother had said that very morning, “an’ don’t know how to sew yet.”

“I do, mother,” Polly had answered. “I can make a whole square of patchwork.”

“Can’t do it with your thimble,” said mother. “You can’t take a stitch as you ought to. You go play, an’ I’ll call you at ten o’clock, an’ then you must sew till dinner-time.”

Polly went out sadly and down to the rock house. Matilda Ann was still in bed, and Polly sat down on her small stool and began to think. “I shouldn’t wonder if it was ’most ten now,” said she, “and there won’t be time to dress her or anything.”

She took Matilda out and looked at her. Poor Matilda! One leg was entirely gone, and the paint had all been scrubbed off, till her head was nothing but a wooden knob, with some ink eyes which her father had made on it the last time he had taken down the inkstand from the cupboard over the mantel-piece.

“I want a new doll,” said Polly. “I’m tired of old Matilda Ann. I’ve a good mind to pull off her other leg.”

At this moment Nathan appeared under the rock. He and Polly were so nearly of an age, that they enjoyed playing together, though Nathan was growing to look upon it as something of a favor, and was inclined to remind Polly of the things he might be doing with Jimmy or Jack, out in the oyster boat, or digging clams. Jimmy, being nearly eleven, supplied the family with fish, and the four children were not much together except on Saturdays and stormy days.

This morning Nathan had come running to tell Polly he was going far out in the skiff with Jack and Jimmy to fish for rock-fish, and to ask her if she didn’t want to go with them and help bait the hooks. He stopped, quite astonished, for Polly, generally so careful with all her dolls, was holding Matilda Ann by the leg in a very reckless manner.

“I say, Polly, what you going to do?” said Nathan.

“Nothing,” said Polly. “Yes, I am, too. I’m going to pull Matilda Ann’s other leg off, ’cause I’m tired of her.”

“Cracky!” said Nathan. “Won’t mother scold you though? Give me a pull too?”

“I don’t want to,” said Polly, “ ’cause then you’ll want to do it to the two rag ones. Mother won’t care, either, ’cause she lets me do what I’m a mind to with my own things.” Spurred on by this thought, Polly gave a little pull, and a delicate stream of sawdust began to run slowly down.

“Hi!” said Nathan. “Ain’t it fun?” and he gave a harder pull.

“Let’s play she’s got a dreadful cut, and’s all bleeding to death,” said Polly; “you be a doctor, Nathan.”

“Yes, I’ll be a doctor,” said Nathan. “Now you see this leg’s got to come off right away, quick, ’cause she’ll die in a minute if it don’t. Hold on, Polly, and I’ll pull.”

Dolly was put together strongly, but Nathan pulled till crack went the last stitch in the leg, and Polly almost fell off her stool with the shock.

“Now let’s pull her arms off too,” said Nathan. “ ’Tain’t healthy for her to have arms when she hasn’t got any legs.”

Here Jack’s head appeared in the door-way. “I say, Nathan, why don’t you come?”

Then, as he looked at the little pile of sawdust, and from that to Matilda Ann and Polly’s red face, he burst into a laugh. “That’s one way to play baby,” said he. “I thought you was fond o’ Matilda.”

“So I am,” said Polly, beginning to cry. “I am fond of her, and I’m going to mend her this very minute.”

“No, you ain’t,” said Nathan, “ ’cause I’m goin’ out fishin’ with it”;—and, snatching the leg, he ran out.

“Bring that leg back,” shouted Jack, who always stood up for Polly. “Bring it back, or you sha’n’t go out in my boat.”

Nathan came back, laughing, and threw the leg down, but too late for Polly, who, bursting into loud sobs, had clasped Matilda Ann, and rushed home to her mother. Mrs. Ben was frying doughnuts, and turned in surprise, as Polly ran in, holding up the mutilated doll.

“The land!” said she, “what have you done to Matilda?”

“She was dreadful sick,” sobbed Polly, “an’ we was doctorin’ her, an’ Nathan pulled too hard, or I held on too tight, an’ it just come off.”

“I should think it did,” said Mrs. Ben. “You go put her on the best bed, an’ I’ll sew on her leg by’m by.”

“You can’t,” said Polly, with a fresh burst. “Nathan runned away with it. He said he wanted it to go fishing with.”

“Served you right, I do most believe,” said Mrs. Ben, “treating your poor doll so. Tell Nathan I want him.”

Polly walked down to the rock house. Nathan was invisible, but the leg lay there all right. She picked it up, with all the sawdust she could, and carried it up to her mother, who restuffed it, and sewed it on again better than ever.

“I’ll never doctor her any more,” said Polly, “only for measles, may be. We was dreadful to pull her leg off.”

“I should think you was,” said Mrs. Ben. “Now the clock’s going to strike ten in a minute, and there’s your thimble and everything all ready.”

Polly sat down with a very long face, and took the nicely basted towel into her hand. This subject of sewing with a thimble had been a sore one. She was certain she never could learn; if she pressed her needle into one of the little holes, it was sure to push the thimble off, or, if it didn’t do that, the thread knotted, or caught in some mysterious way, and pulled out of the needle; and then, do what she would, she could not get it into the eye again, till it was so dirty one would have said it began life as brown thread. This morning all these difficulties came up, one after the other, till at last Polly began to cry again. “ ’Tisn’t any use at all,” said she. “The old thimble plagues me the whole time.”

“You’ll have to be more patient,” said her mother. “Look at me now, and see how I do it.”

Polly looked, and then tried again; but this morning it was of no use. Her face was very red as she went on, and she drew such a long breath that Mrs. Ben laughed.

“You may stop now,” said she, “and set the table for dinner; for you’re tired, and it’s ’most half past eleven. To-morrow morning we’ll try again.”

Polly sighed as she laid the towel in her mother’s big basket, and she sighed again next morning when she heard the clock strike ten. She was putting tiny gold and silver shells into a bottle of water, and then holding it up to the light to see the sparkle; and it was very trying to leave such lovely play, and sit for two hours poking her finger into a little brass thimble as fast as it tumbled off. To-day’s work was not much better than the day before.

“What’s got into the child?” said Mrs. Ben. “Seems to me I never had no trouble learning to sew with a thimble.”

“If you only was a boy,

Wouldn’t you have lots o’ joy?”

sang Jimmy, who had been watching the operation from the corner where he and Nathan sat mending a fish-net.

One big tear rolled over the bridge of Polly’s nose, and fell on her towel.

“There, there!” said Mrs. Ben; “don’t do any more now. Put it all away.”

Polly put the thimble in her pocket, and ran fast to her rock house.

“Polly cries all the time, now’t she’s learning to sew,” said Nathan.

“It’s hard work,” said his mother, “and six year old ain’t as patient as nine year can be.”

Nathan turned red, for he felt very certain patience and he had but little to do with each other; and, to change the subject, he slid out of the door, and down to Polly, who sat hugging Matilda Ann, and looking very thoughtful.

“It makes my stomach ache to sew,” said she, “an’ I’ll wear my finger all out with that hateful thimble.”

“Throw it away,” said Nathan.

“No,” said Polly, “ ’cause mother gave it to me. I’m a great mind to hide it though.”

“I’ll hide it,” said Nathan. “You give it to me, an’ then, when mother asks, you can say you don’t know where it is.”

Polly took out the thimble, and Nathan, snatching it, ran up to the head of the cove. When he came back his hand was quite empty, and Polly said not a word.

Somehow or other, play that day was not as nice as usual, and Polly went to bed very early. Next morning and ten o’clock came very soon; and Polly sat down on her stool, and took her little box of spools and needles into her hand.

“Where’s your thimble?” said Mrs. Ben, seeing her sit idle.

“I don’t know,” said Polly, turning very red.

“Look all round for it,” said her mother, and Polly began a search through the room.

“It’s very queer,” said Mrs. Ben, too busy to notice Polly’s red face. “I thought I saw you put it in your box, certain. So long as you can’t find it, though, you may go out again, and I’ll look by’m by.”

Nathan, going down to the rock house after a time, found Polly sitting by Matilda Ann, and crying aloud.

“What’s the matter now?” said he. “Been sewing some more?”

“Where’s my thimble? I’m an awful girl, I do believe,” sobbed Polly. “I want to find it, and tell mother.”

“She’ll give it to you for cheating,” said Nathan. “Mother can’t stand cheating, an’ she’ll give it to me too for doing it for you.”

“No, she won’t,” said Polly, “for I sha’n’t tell about you. Get it for me, now, Nathan.”

Nathan marched after the thimble; but, seeming to forget he was to hand it to Polly, ran up to the house.

“Stop, Nathan!” screamed Polly. “I want it myself.”

But Nathan didn’t stop, and Polly ran after him, just in time to hear him say: “Here’s Polly’s thimble, mother. I hid it for her, ’cause she was tired o’ sewing, an’ she didn’t know where I put it exactly, an’ I wouldn’t ’a’ told her, if she hadn’t been a crying ’cause she’d cheated!”

“I let him, mother,” said Polly; “I’m the baddest. I’ll sew all the afternoon.”

“Well, if I ever!” said Mrs. Ben; and then smiled a little as she looked at them. “You’re good children to own up,” said she, “an’ I guess I’ll let it square our account. Off with you! and I shouldn’t wonder if Polly sewed better to-morrow for having been an honest gal to-day.”

Sure enough, for that or some other reason, the sewing went on so well that Polly at last took a dozen stitches, one after the other, with very little trouble, and in a week or two could sew much better with than without a thimble.

“How much money is there in my tin box?” said Polly, one day.

“ ’Most a dollar, I guess,” answered her mother. “Why?”

“ ’Cause I want a new doll,” said Polly; “a real good one, and not wooden, like Matilda Ann. One with hair like that we saw down to Shrewsbury.”

“They cost a deal,” said her mother, “and father isn’t home to get you one.”

“Couldn’t I earn some money?” said Polly.

Mrs. Ben thought awhile. “There’s all the over-hand seams to them new sheets,” said she. “If you’ll do ’em nice, Polly, I’ll pay you two cents a yard.”

Polly looked grave. Over-hand seam she could but just bear to do. “How many are there?” said she.

“Ten of ’em, and every one three yards long.”

“Ho!” said Polly. “That’s thirty yards. I never could.”

“Yes, you could,” said her mother. “Do a yard a day, and ’t wouldn’t take you much more ’n a month. I’ll give you three silver quarters for the whole.”

Polly’s eyes shone. “I’ll do it,” said she, and raced off to tell Nathan and Jimmy.

So through all the hot August days Polly sewed away at the long seams. It was very trying work sometimes, and her small nose would have a whole line of little beads of perspiration standing on it before she ended. The rows of stitches too, were of every shade, from gray and brown to a lively black, from Polly’s little, hot, sweaty hands; but Mrs. Ben said to herself, ’t would all wash out, and Polly was working hard, sure enough.

Finally came a day when the last stitch was taken, and Polly danced about like a wild child. Her mother had put the three shining silver pieces on the table by her, and Nathan, very much interested, had pried up the side of the money-box so that it wouldn’t take a minute to turn all out together. There was quite a pile, and Polly began to count with a very eager face. “Five quarters, an’ a sixpence, an’ two dimes, and there’s twenty pennies and a five-cent piece. How much does it all make?”

“One dollar and seventy-six cents,” said Jimmy, who did the arithmetic for the family.

And Polly shouted, “There’s a beauty little one for a dollar and a half. O mother, do come along right away!”

Mrs. Ben had made her preparations, and, though Polly didn’t know it, Jack was waiting up on the bluff with the old horse and fish-wagon.

Polly never forgot that ride over the sandy road to Shrewsbury, with the September sun shining down on them, and a soft haze resting over the sea, towards which they often looked, to see if, by any chance, Cap’n Ben’s schooner might be sailing in. Polly had no difficulty in choosing her doll; for there were but three in the store, and only one within her means. Such blue eyes, and red lips, and curling, yellow hair, have never in her opinion been seen on any doll since; and she hugged it all the way home in a perfect transport of affection. Even the scoffing and unbelieving Jimmy and Nathan admitted that it was “kinder pooty,” and treated it with more respect than they had ever shown Matilda Ann.

“I am going to call her Seraphina,” said Polly; “that’s the handsomest name I can think of. Mother used to know a girl, and her name was Seraphina Simmons.”

So time went on. Matilda Ann was altogether neglected, and every stray bit of silk and muslin in the house was turning into mysterious fixings for Seraphina. Jimmy and Nathan were no less busy. They were finishing a little schooner, begun under their father’s eye, and an exact model of his. Polly had been hired with four red apples and a jews-harp to hem the sails, and the little thing was all ready for launching. Jack had gained a holiday by extra work; and the last Saturday afternoon in September the four children, with a supply of doughnuts and apple turn-overs, took up quarters in the rock house, while Jack put the last nail in the little ways down which the schooner was to slide. It was only a board, with a cleet, or narrow strip, nailed to each side, and one end fastened to another piece of board to raise it two or three feet from the ground, and so enable the schooner to slide down easily to the water.

Jack carried the board to the head of the cove, where the sand was smooth and the water not very deep, and set it so that the lower end was just in the water. Then Jimmy and Nathan put the schooner on it, and placed a little block of wood underneath to hold it steady till they were ready, while Polly, carrying Seraphina, looked on with admiration.

“Now, boys,” said Jack, “I’ve got the hammer; when I knock the block out, and the schooner begins to go, you hurrah loud as ever you can.”

Jimmy and Nathan took off their hats to have them all ready for a toss, and Polly almost choked, keeping back her hurrah till just the right moment. Jack gave a little knock, the block flew out, and the schooner started,—stopped a moment, as if it hadn’t made up its mind, and then slid down faster and faster, till it touched water, dipped a moment, and then skimmed along like a bird to the other side of the cove. Such a shout from the three boys that Polly forgot entirely she was to take part in it, and came out with a little shrill hurrah when all the others were through.

Jimmy had raced to the other side of the cove, and now the three boys, with trousers rolled up above their knees, sailed the little schooner back and forth with more and more enthusiasm.

“Won’t father be tickled?” said Nathan. “I say, Polly, let’s give Seraphina a sail. Play she’s the captain’s wife, come to the launch.”

“O my!” said Polly, “I wouldn’t dare. S’posin’ she was to get upset.”

“O, but she won’t,” said Nathan. “Don’t you see how she goes? There ain’t any upset to that schooner.”

“She’s steady as a rock,” said Jimmy;—and Polly, who had great faith in Jimmy’s judgment, allowed Seraphina to be seated on the deck and started off to the other side.

Certainly it was a very pretty sight, and they might have kept it up all night, if Jack, looking up suddenly, had not said: “My! there’s the sun setting, an’ I’ve got to drive the cows home. We’ll send her across once more.”

Seraphina’s curls blew out as the little schooner got half-way across.

“Look out, boys!” shouted Jimmy, “there comes a flaw!”

The water darkened and rippled up as the quick breeze swept over it; the sails swelled, and the schooner keeled over almost to the water’s edge, then righted, and went on safely. Seraphina slipped, caught against the mast, then slid, and was in the water before the little vessel had reached the shore.

“O my doll, my doll!” screamed Polly, as Seraphina, weighed down by the heavy string of great glass beads Polly had put on her that very afternoon in honor of the day, bobbed up and down once or twice and then sank.

Nathan began to cry, and Jimmy and Jack looked on in consternation.

“Never mind,” said Jack, “I’ll get her up again. Where’s the punt and the oyster-tongs? No, I’ll swim out and dive.”

Jack and Jimmy both swam out, and both searched, but the doll was not to be found. Polly stood on the shore pale and quiet, and not shedding a tear till Jack said, “It’s no good. I guess she’s gone into some hole.” Then she started and ran fast to the house. Mrs. Ben turned, quite frightened at her pale face, and Polly ran into her mother’s arms.

“O mother, mother! O mother!” sobbed Polly, “what shall I do? Seraphina’s dead! she’s drownded!”

“Land o’ Goshen!” said Mrs. Ben, “what will happen next? Tell mother about it.”

So Polly, in tears and misery, told the sad story, while Jimmy and Nathan, who had followed her, stood looking on in silent sympathy.

“I guess Jack means to do something, mother,” said Jimmy, “for he said he’d take the cows home, and come back like a streak. He can do most anything, you know, Polly.”

Polly, a little comforted, raised her head, but laid it down with a fresh burst a moment after. “He can’t get her, I know,” she said. “Her clothes are all spoiled, an’ her hair’ll soak off, and all her beautiful red cheeks!—Oh!”

There was no comfort for this. Mrs. Ben sat and held her till bedtime, and then undressed her herself, and tucked her into the trundle-bed, and there we will leave her.

Jimmy and Nathan stood on the shore, looking off to the path over which Jack would come. The moon was up clear and full, and shining over the water, and, as the boys tried to remember the exact spot where poor Seraphina had gone down, Jack came like a flash, carrying the biggest oyster-tongs he had been able to find.

“I told Mis’ Green all about it,” said he, “and she told me to bring the doll right up there, if I found it.”

Jack stepped into the punt which the boys had brought round, and rowed out as nearly as he could remember to the exact place. Then he stood up and slowly lowered the great tongs. There was dead silence on the shore while he groped about, and at last carefully raised them.

“Bosh!” said Jack, as he shook off a great clump of shells and sea-weed, and put them down again. This time he was longer, and the boys half lost patience, when—

“Hurrah!” all three shouted, for there was Seraphina,—nothing but a lump of mud to be sure, but still Seraphina, for they could see her scarlet skirt.

“Now,” said Jack, when he had gone back to shore, “let’s have a race to Squire Green’s.”

Jimmy got there first, and stood outside the gate waiting for the others to come up. Mrs. Green was in the porch, and a fair, sweet-looking lady was walking up and down the wide hall.

“That’s the one that’s going to fix her,” said Jack; “that’s Mis’ Green’s daughter.”

The lady laughed a little as she saw poor Seraphina. “Take off her clothes, if you can, Jack,” said she, “and then we’ll see what can be done.”

Jack got them off after a fashion, and then the lady washed dolly in some water, till the mud was off. After all, it was not so bad. Her pink cheeks and lips were gone, and her hair soaked into a little dripping tail, but she was still whole and uninjured. Mrs. Lane (that was the lady) wiped her carefully, then combed her hair smoothly, and brought forward some curious little tongs, such as the boys had never seen.

“Those are too large,” said she: “they are curling tongs, but I think a pipe-stem will do better for Miss Dolly.”

Squire Green handed her one of his pipes, and Mrs. Lane heated it in the lamp, and then, brushing the hair smoothly around it, and pulling it out, there was a more charming curl than dolly had before. This work done, she turned to the table and took up a little brush from a saucer standing there. Seraphina’s red cheeks and lips were back in a twinkling.

“Now,” said Mrs. Lane, “my little Lotty has some dolly’s clothes which will, I think, fit Seraphina exactly.”

So from the stand in the corner came little things, one after the other, till Seraphina was better dressed than ever.

“Now carry her very carefully,” said Mrs. Lane, “and put her where she can dry all night. In the morning she will be just as good as before her ducking.”

The boys could hardly wait to say, “Thank you,” and dashed home. Polly was fast asleep, for it was after nine now. Mrs. Ben laid Seraphina on the table by the bed, and gave Jack such a piece of pie that it came very near being a whole one.

Polly opened her eyes brightly next morning, and then, remembering her loss, sat up sadly in the trundle-bed, and looked about. What a squeal she gave! for there on the stand lay Seraphina, in such a pretty pink dress that Polly felt quite crazy. Mother looked down from the big bed. “Well, Polly, what do you think o’ that?”

Polly heard the whole story in silence, hugging Seraphina tighter and tighter, and was hardly willing to let go of her one moment all day.

That afternoon Jack and she went up to Squire Green’s. There were three children there,—the little Lotty, and two boys, Paul and Henry, one older and one younger than Jack. Mrs. Lane was with them, and Polly at once fell in love with her sweet face and pleasant voice. By and by Squire Green came out.

“Here’s a boy,” said he to Paul, taking hold of Jack, “who’ll show you all the ins and outs ’long shore,—a good boy, too, that won’t be getting you into mischief.”

Paul looked as if he didn’t care to be shown, and Polly felt indignant that anybody should stare at Jack in such a manner.

“Jack fished up my Seraphina,” said she, “an’ he knows more than any other boy in the world.”

There might have been hard words here, but Mrs. Lane gave each one a cake, and Jack and Polly ate theirs as they walked home.

“Good by, Jack,” said Polly, as they reached her door. “I wonder if it’s wicked, when you ain’t any relation; but I love you just as much as I do Jimmy and Nathan, I do believe.”

Helen C. Weeks.

“I say, Sue, ain’t it splendid?” asked Will, laying down the book, and turning to his companion.

“Don’t you like that part where Robinson crawled up and saw ’em eating each other? Don’t it just make you sort of creep all over,—so nice?”

“Yes, that’s nice; but I liked it better where Robinson saw the print of the foot in the sand. O, just think how scared he was then!” replied Sue, her great brown eyes opening wide in sympathy with Crusoe’s supposed dismay.

Will did not pursue the subject. A new and wonderful idea had suddenly entered his curly head, and it took all his mental force to grapple with it. He laid down the book, went to the window, through which came the pleasant sights and sounds of a summer day in the country, stood there a minute, and then came back to the sofa where his pretty playmate still sat, her feet curled under her, her curls drooping over her rosy face, and her eyes fixed upon the picture of Robinson intent upon the footprint in the sand.

“Sue,” said Will, softly, “let’s us run away!”

Sue looked up in astonishment and a little doubt. “Would you?” asked she; “what’s the use?”

“Why, so as to be like Robinson, you know. We’ll have a cave, and I’ll make a palisade all round it, so no one can get in, and we’ll have a parrot. I know a fellow that’s got one, and I guess he’ll give it to me for my jack-knife, and we’ll have goats.”

“Where’ll we get goats?” asked Sue, already warming with enthusiasm, but not yet beyond doubt.

“O, we’ll get ’em—somewhere. May be we’ll find one running about in the woods; or, if we don’t, I might get a calf out of father’s yard some night. And then you’ll sew my clothes, and we’ll have an umbrella made of skin, and I’ll teach you to read and write—”

“I know how to read already, and you can’t write very well yourself,” interposed Sue, rather indignantly.

“Well, just play, you know; because if I’m Robinson, you must be the man Friday, of course.”

“But I ain’t a man,” objected Sue.

“Well, then, you shall be a girl Friday, and instead of Robinson I’ll be Will Crusoe, and then some day, when we get tired of it, and come back to live among folks, I’ll write a book, and tell all about it.”

“Well, I will if you will,” consented Sue, still a little aghast at the size of the idea, but confiding, as was her habit, in Will’s superior judgment and experience, not to mention his physical strength, which, with bigger girls than Susy, carries its weight. Besides, Will was ten years old, and Sue only eight,—a superiority upon which that young man was a good deal in the habit of insisting, as in the present instance, when he said,—

“Of course you will, Susy. I’ll take care of you like everything, and keep off all the creatures and savages, and make a nice bower for you out in another part of the woods, and tell you all about the world: we’ll play, you know, that I’ve been everywhere and you haven’t, and we’ll have lots of fun, you see if we don’t.”

“But how will we get to an island? There isn’t any sea here,” suggested Sue, after some moments of profound consideration.

“Why, we needn’t have it an island. We’ll go off in the woods ever so far, and make believe it’s an island. And, Sue, I do declare if that ain’t an idea!—we’ll take the doctor’s horse and chaise!”

“My gracious!” gasped Sue.

“Yes. He’s just driven up and hitched it. He’s going in to see grandpa, and he always stays ever so long when he gets in there. Now, you see, we’ll just get in, drive straight ahead till we come to a forest, and then we’ll get out, and turn old Whitefoot toward home, and set him off. He’ll come back all right; and we might send a letter by him to tell our folks that they needn’t worry, and that we ain’t ever coming back.”

“How’ll we write the letter out there in the island?” asked Sue, meditatively.

“I’ll carry a pencil and a piece of paper, and I can write enough to say just that, I know. Any way, I sha’n’t have to print, same as you would, Susy. Never mind, though, I’ll teach you after we get the cave built, and the palisade, and all. Now you get your hat, and some picture-books, and the box of dominos, and some paper and a pencil, and I’ll go into the but’ry and get something to eat. Mother said, you know, we might have as much as we wanted of that gingerbread; so I guess I’ll take it all, and some bread and butter, and cheese, and a pie. You see we shall want such things for a day or two, and then we shall get to eating—What did Robinson eat mostly?”

“Fish and clams and cocoa-nuts, till the rice and wheat grew,” said Sue, obviously doubting the supply of shell-fish in the forest island she was about to set forth to seek.

“O well, we’ll get something,—checkerberry-leaves and spruce-gum, any way,—and pretty soon there’ll be chestnuts,” asserted Will, recklessly, and bustled off to his mother’s well-stocked larder, whence he presently returned with a basketful of eatables.

Sue was ready also, her round arms and white apron full of books, toys, a gray kitten, and the tiny work-box given her upon her last birthday by her kind aunt, Will’s mother. For Susy was an orphan, and had come about a year before to live with her uncle and aunt, and be a playmate and companion for Will, their only child. This fine summer day had been selected by the parents for a distant and long-deferred visit; and the children had been left to their own care and that of Melissa, the young woman in the kitchen, who, having given them their dinner, and seen them settled with their books in the cool, old-fashioned parlor, considered her duty accomplished, and went to her own room to “fix up” for the afternoon.

The doctor, closeted with grandpa in the bedroom at the back of the house, was deep in one of his favorite theories, and Jotham, the hired man, was busy in the cornfield, so that no one was at hand to see or prevent the elopement of our youthful couple, who, divided between joy and terror at their own success, bestowed their housekeeping preparations in the bottom of the chaise, unhitched Whitefoot from the paling, and set forth.

“There, Sue, what do you say to that?” asked Will, after they were fairly started; and, settling himself in his seat, he looked round in triumph upon his companion, who answered, tremulously,—

“It’s real nice, only are you sure you know how to drive, Will?”

“Drive! Of course I do! Don’t father let me drive ’most always when we go out to ride in the carry-all?” asked vainglorious Will.

“Yes; but then he’s right there himself, and he always keeps a-looking at you.”

“Well, Sue, I do say you’re too bad! When I’m going to make you a cave and a palisade, and catch goats, and everything, you talk all the time as if you thought I couldn’t do anything, and you didn’t want to go. If you’re scared, do say so, and we’ll go home again.”

As he spoke, Will made a pretence of drawing the rein to turn Whitefoot’s head toward home; but, as he knew in his boy-heart would be the case, Sue prevented him, protesting, with tears in her eyes and in her voice, that she had no idea of being scared, that she was quite sure Will knew how to drive, that she didn’t mean to say anything, and—and—

So Will resumed his conquering airs, comforted his little cousin, promised renewed protection, and drove on; she smiling with all her might, and concealing her quaking heart under assurances of the most unbounded confidence.

If the man who wrote it down that “the boy is father to the man,” had said, instead, that the girl is mother to the woman, he would have shown more sense; but perhaps he thought, as the French have it, “that goes without saying.”

The summer day was almost done; Whitefoot, Susy, and even Will himself, were beginning to grow tired; black clouds were rolling up for a thunder-storm;—and still the forest was not reached, nor had any desert island, either real or make-believe, presented itself. Susy had long ceased to speak, except in answer to Will’s remarks or questions, and even these were growing rare, as the young Crusoe found the practical questions of his undertaking pressing more and more closely upon him, and did not find any ready answers to them.

The first low thunder-peal rolled along the horizon, heralded by the first blue flash of lightning. Whitefoot pricked up his ears, tossed his head, and quickened his pace.

“May be he’s afraid of lightning, Will!” exclaimed Sue, sitting upright, and turning very pale.

“Sho! No, he isn’t,” said the boy, tightening his hold upon the reins, and looking uneasily about him.

“There’s some woods over there,—may be it’s the forest,—and we’ll get out, and send Whitefoot home, if you say so,” suggested he, presently.

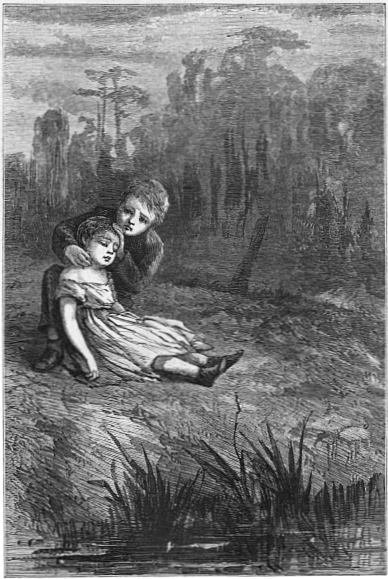

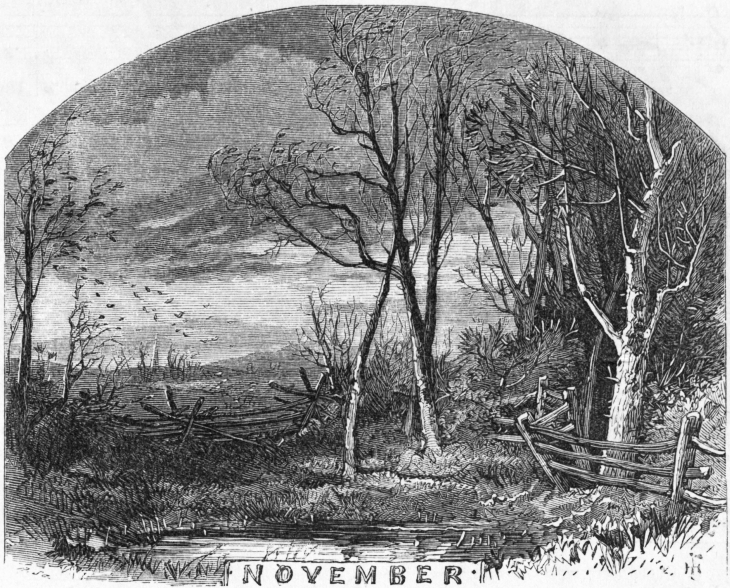

AFTER THE ACCIDENT.

Drawn by S. Eytinge, Jr.] [See Will Crusoe and his Girl Friday, page 668.

“Yes, do. O Will!” and the little girl clung convulsively to her cousin’s arm, while a vivid flash and rattling peal seemed to fill the whole atmosphere.

Whitefoot, answering to the challenge, flourished his sandy tail, letting it fall within the dasher, uttered a shrill neigh, and set off at speed. Will tugged at the reins, but might as well have tugged at the Atlantic cable. Sue, too thoroughly frightened for disguise, covered her face with both hands, and sobbed piteously.

Another flash, and another, and Whitefoot, missing the doctor’s steady hand and soothing voice, gave full play to the “nerves” he did not often get an opportunity of indulging, and snorted, plunged, and tore madly on, making the chaise bound and rock behind him, until poor little Sue, too frightened now for tears, could only cling to the hand-strap, and hold her breath in an agony of suspense.

A final peal crashing through their very heads, accompanied by a blinding flash, and Whitefoot, springing to the side of the road, tilted one wheel into a ditch, upset the chaise, and rushed madly on, dragging it behind him.

The children lay where they were thrown for a minute; and then Will, sternly refusing himself the luxury of tears, gathered up what seemed at first but the bruised fragments of a body, but proved, upon inspection, to be the whole, shook himself together, and looked round for Susy. She, poor little thing! had fared worse. Her forehead was cut and bleeding, her eyes were closed, and her pretty face, white and cold as snow, looked more like that of a statue than that of Will’s rosy and merry little playmate.

He stood and gazed at her in awe for a moment; then, smoothing down her little frock, and laying his handkerchief across the wound upon her forehead, he sat quietly down beside her. “She’s dead,” said he, softly, “and I shall sit here to keep the wolves off till I am dead too. Then they will eat us both, unless some angels come first to carry her off. I should think they would, she was such a good little girl!”

Then poor Will fell to wondering forlornly, if any angels should come for Susy, whether they would charitably help him, who had not been, as he now became painfully aware, a particularly angelic boy, and, even if they were so disposed, how they would be able to do so; and, with these questions yet unsolved, fell fast asleep, his head drooping lower and lower until it lay upon Susy’s lap.

“Sakes alive! what’s this?” exclaimed Mrs. Hoskins, as she went out at her back-door the morning after the thunder-storm to set her shining milk-pans in the sun.

“What’s what, mother?” asked a blithe voice; and Bessie Hoskins, dish-towel in hand, followed her mother to the door.

“Why, them young ones coming down the lane,” said the farmer’s wife, pointing to two forlorn little figures approaching the house from the direction of the wood-lot.

“Sure enough! Well, that beats me, I do declare,” returned Bessie, staring with all her might.

Approaching nearer, the strange guests showed themselves to be a fine-looking boy, without cap or jacket, but otherwise well dressed, and a lovely little girl, her head bound with a handkerchief, her face deadly pale, and wearing above her summer frock the jacket of her companion. Both children were so torn, stained, weather-beaten, and disorderly in appearance, that Bessie felt moved to suggest,—“They’re walkabouts,—ain’t they, mother? Come to see what they can carry off.”

“For shame, Bessie Hoskins! Don’t go to suspecting folks just because they’re poor and ragged. Not that these young ones seem so dreadful poor, neither. They look sort of used up, but they’ve got on shoes and stockings, both on ’em,—summer time, too,”—said the shrewd and kindly mother, going a few steps down the garden-path to meet the children, who were just unlatching the little gate.

Bessie, somewhat abashed at the rebuke she had received, followed silently.

“Good morning, ma’am!” said hatless Will, as prettily as possible.

“Good morning to yourself, sir. What can I do for you?” replied Mrs. Hoskins, smiling good-naturedly.

“Why, you see, ma’am, we—Sue and me—are going a little way farther, only she’s hurt her head, and I’m awful hungry, ’cause Whitefoot ran away with the basket; and if you’d give us something to eat, and fix Sue’s head a little, I’ll send word to my folks, and they’ll come and give you something, ’cause we ain’t beggars,”—and Will, a little flushed and uncomfortable, but withal glad to have delivered himself of the speech so carefully prepared, stood looking gravely into the kind face of Mrs. Hoskins, while poor little Sue laid her head upon his shoulder, and closed her eyes with a look of patient suffering very pitiful to the kindly heart of the farmer’s wife.

“Well, if ever I did see the beat of this! Here, you come right in, and set up to the fire. You’re all of a muck with dew and dust, and—Guess you laid out all night, didn’t you?”—and as she spoke the dame brought in her guests, placed them in front of the crackling fire, and began to take off the jacket Will had buttoned over Susy’s bare neck and arms.

“Yes’m, we had to sleep on the ground, ’cause Susy was dead, I thought, and I didn’t look for any cave; but in the morning she woke up, and then I thought we’d find a house, and get something to eat, and I guess I’d better leave her with you a little while, till I get a place fixed.”

“A place, child! What kind of a place do you calc’late to fix?” asked Mrs. Hoskins, with a side glance at Bessie, who hovered near, divided between astonishment and admiration.

“Why, a cave, or a hut, or something; I’ll fix it,” replied Will, a little uneasily; for he began to fear his new friend might try to interfere with the project still so near his heart.

“Just you hear that, will you, Bess?” exclaimed Mrs. Hoskins; and then, acting upon the womanly impulse of relieving suffering before inquiring too curiously into the deserts of the sufferer, she sent Bessie for two mugs of the rich new milk she had just strained, and, taking the poor little “girl Friday” into her lap, began to strip off the wet and torn clothing from her shivering limbs, uttering the while such exclamations as, “Poor little lamb! If ever I saw the beat! I declare for ’t, it’s enough to make a mother bawl right out, to see a poor little innocent creter so put upon. There, my pretty, drink the nice warm milk right down. It’ll kind o’ set ye up. That’s a beauty! Now she’s a little lamb-pie; and we’ll wash that great ugly cut all off nice, and get her to bed.”

So, soothing and caressing the pretty child she had already taken into her motherly heart, Mrs. Hoskins fed, clothed, and placed her in her own bed, then returned to the kitchen to find the great Will Crusoe fast asleep upon the settle, a big doughnut in one hand and a piece of cheese in the other, and the tears he had so bravely kept back while he waked creeping from under his closed eyelids. Bessie still stood admiring him, her neglected towel hanging from her arm.

“My! ain’t he a beauty?” whispered she, as her mother approached. “Just see his curls! and what a pretty mouth he’s got!” And Bessie stooped to kiss the bright lips quivering in sympathy with the tears.

Her mother grasped her by the shoulder, saying, “You go and mind your work, Bess Hoskins! Kissing the boy when he’s asleep ain’t going to do him no good, nor you either. Wait till he wakes, and then see what you can do about making him comf’table. Kissing ain’t much account, if that’s where it stops.”

But before poor Will’s nap was over, before Bessie’s dishes were washed, or Mrs. Hoskins’s cream well in the churn, a chaise drove rapidly up to the door, and from it sprang Doctor Morland’s well-known form.

“I’m powerful glad to see you, Doctor,” began Mrs. Hoskins, untying her apron, and going to meet him.

“Can’t stop a minute, mother; only called to ask if you’d seen—Hallo! There’s my young horse-stealer, safe and sound; but where’s the little one? where’s Sue?”

“There! I reckoned you’d know about ’em. Well, if this ain’t just the beat of everything ever I see yet! Here, Doctor, come right into the bedroom. I ha’n’t had time to fix up much this morning, but—there, that’s her you’re looking for,—ain’t it?”

The Doctor bent over the dozing child, laid a finger on her pulse, then on her brow and cheek, and said gravely, “Yes, and a sick child enough she’ll be before to-morrow morning. We must get her home. Here, Mother Hoskins, you put on your bonnet, and come along with me to hold her in your lap. I can’t wait to go for her aunt, and Will isn’t big enough.”

Mrs. Hoskins cast one look at her churn, another at the meat Bessie was just bringing out of the cellar, then hesitated no longer. Giving a few comprehensive directions to her daughter, she hurriedly changed her dress for a better one, tied on her bonnet, and, seating herself in the chaise, took upon her lap and gathered to her heart the poor little orphan, who lay there dozing and unconscious. The fifteen miles between the Hoskins farm and Will’s home were soon passed; and before noon Sue lay in her own little bed, with her pale and tearful aunt bending tenderly over her. The Doctor did not leave her, but put Whitefoot in the barn, while Will’s father, returning from his search in another direction, took his own horse, and set off to find his truant boy, with a mind divided between joy and displeasure.

“It would do him good to have a sound flogging,” remarked he to himself more than once on the road.

“But you know you won’t give it to him,” replied himself to him, with a knowing smile, and himself proved right; for when Will came running to the Hoskinses’ gate, his face all flushed with joy at the meeting, even while his eyes were full of tears as he eagerly asked for Sue, the father took him in his arms, and kissed him tenderly.

Sue was very, very ill for many days, and not strong again for many months, yet at last she recovered, and became as gay and active and beautiful as before; but although she still believes very much in Will, and loves him better than any one else in the world, I do not think even he could tempt her to set off again to find an island in the forest, or to accept the part of Will Crusoe’s girl Friday, even if the island were found.

Jane G. Austin.

The June morning dawned beautifully; the settlers, leaving the rangers to protect the garrison, came, men and boys, to their work. Placing their dinners, and a pail of water, beside the pine stump, they freshened the priming of their guns, and, leaning them against the wall of the breastwork, plied their labor.

That morning, William McLellan, who was now eighteen, and James Mosier, who was much younger, were put upon the stump as sentinels,—William on the side next to the rock, James on that next to the men, who, with their backs to the rock, were nearly at the other end of the piece. The sun was getting hot, and the boys began to grow sleepy. It had been some weeks since they had been alarmed by Indians, and in that field they felt quite secure. William, with his hands on the muzzle of his gun, and his chin upon his hands, was almost dozing. The Indians, whose keen eyes were fastened upon the boys, were preparing for a spring, and had already loosened their tomahawks in their belts, when James exclaimed, “Bill, here comes the Captain!”

They straightened themselves up, and brought their guns to a “shoulder-arms,” as he came near. Thirsty with his work, he had come in quest of water.

“James,” said he, after he had drank, “give me your gun, while you put that water where it will keep cool. It is going to be a very hot day, and it will be as warm as dish-water if it stays there. Put it under the side of that big rock, and be sure and set it level, for, if it is spilt, it will take one man to go after more, and two more to guard him.”

This was a trying moment for the Indians, as James was approaching the very place of their ambush; but, with that unrivalled self-command which the savage possesses, they remained without the motion of a muscle, trusting that the bright glare of the sun without would so dazzle the eyes of the boy as to prevent him from seeing them in their dark retreat, especially as the color of their bodies harmonized so perfectly with the charred logs under which they lay. James placed his pail by the side of the rock; but as it was nearly full, and the ground fell off, he began to hunt for a stick or stone to put under the side of the vessel. In thus doing he looked into the hole, and his eyes encountered those of an Indian.

With a yell that reached the ears of the men at the other end of the field, he tumbled over backwards, and, clapping both hands to his head, as if to save his scalp, uttered scream upon scream. The Indians, hatchet in hand, sprang over the body, and, hurling their weapons at their foes to confuse their aim, turned to flee. The guns made a common report, and two of the savages fell dead, when Captain Phinney, catching a musket from the wall, brought another down with a wound in the hip. The remaining savage, catching up the screaming boy, flung him over his back as he ran, thus shielding himself from William’s fire, (who had provided himself with another gun,) as he was afraid of hitting his comrade. The moment he was out of gunshot, he flung down his burden, and fled to the shelter of the woods. The wounded savage was despatched by a blow from the breech of Captain Phinney’s rifle. James, now relieved from his fears, had screamed himself so hoarse that he made a noise much like a stuck pig in his dying moments.