* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 3, Issue 9

Date of first publication: 1867

Author: J. T. Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Aug. 31, 2018

Date last updated: Aug. 31, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180892

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Delphine Lettau, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. III. | SEPTEMBER, 1867. | No. IX. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

WHAT DR. HARDHACK SAID TO MISS EMILY.

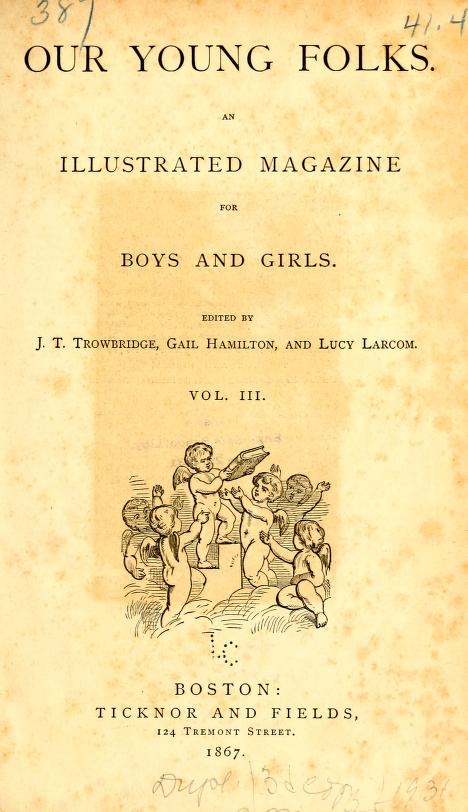

ENTERING THE ICE.

Drawn by Harry Fenn, from the Original Painting by F. E. Church.] [See Cast Away in the Cold, page 524.

he two days which the “Ancient Mariner” and

his young friends had passed together had so

completely broken down all embarrassment between

them, that the children felt as if they had

known the old man all their lives. It was therefore,

perhaps, not unnatural, that, when they went

down next day, they should feel inclined to give

the Captain a surprise. So they concerted a

plan of sneaking quietly around the house that

they might come upon him suddenly, for they

saw him working in his garden, hoeing up the

weeds.

he two days which the “Ancient Mariner” and

his young friends had passed together had so

completely broken down all embarrassment between

them, that the children felt as if they had

known the old man all their lives. It was therefore,

perhaps, not unnatural, that, when they went

down next day, they should feel inclined to give

the Captain a surprise. So they concerted a

plan of sneaking quietly around the house that

they might come upon him suddenly, for they

saw him working in his garden, hoeing up the

weeds.

“Now let’s astonish him,” said William.

“That’s a jolly idea,” said Fred, while Alice said nothing at all, but was as pleased as she could be.

The little party crawled noiselessly along the fence, through the open gate, and sprang upon the Captain with a yell, like a parcel of wild Indians; and sure enough they did surprise him, for he sprang round his hoe, as if preparing to defend himself against an attack of enemies.

“Heyday, my hearties!” exclaimed the Captain, when he saw who was there. “Ain’t you ashamed of yourselves to scare the old man that way?” And then he joined the laugh that the children raised at his own expense, and enjoyed it as much as they did.

“That’s a trick of William’s, I’ll be bound,” said he; “but no matter, I’ll forgive you; and I’m right glad you’re come, too, for it’s precious hot, and I’m tired hoeing up the weeds. There’s no wind, you see, to-day, or we might have a sail; but come, let us get out of the sun, into the crow’s nest.”

“The crow’s nest!” cried William. “What’s that?”

“Why, the arbor, to be sure,” said the Captain. “Don’t you like the name?”

“Of course I do,” answered William. “It’s such a cunning name.”

It was but a few steps to the arbor, and the happy party were only a few moments in reaching it. Once seated, the Captain was ready in an instant to pick up the thread where he had broken it short off when they had parted in the golden evening of the day before, and then to spin on the yarn.

“And now, my lively trickster and genius of the quill,” said he to William, “how is it about writing down the story? What does your father say?”

“O,” answered William, “I’ve written down almost every word of what you said, and papa has examined it and says he likes it. There it is”;—and he pulled a roll of paper from his pocket and handed it to the Captain.

The old man took it from William’s hand, looking all the while much gratified; and after pulling out a pair of curious-looking, old-fashioned spectacles from a curious-looking, old-fashioned red morocco case, which was much the worse for wear, he fixed them on his nose very carefully, and then, unfolding the sheets of paper, glanced carefully over them, growing more and more gratified as he went along.

“That’s good,” said he; “that’s shipshape, and as it ought to be. Why, lad, you’re a regular genius, and sure to turn out a second Scott, or Cooper, or some such writing chap.”

“I am glad you like it, Captain Hardy,” said William, pleased that he had pleased his friend.

“Like it!” exclaimed the Captain. “Like it!! that’s just what I do; and now, since I’m to be immortalized in this way, I’ll be more careful with my speech. And no bad spelling either,” ran on the Captain, as he kept on turning back the leaves, “as there would have been if you had put it down just as I spoke it. But never mind that now; take back the papers, lad, and keep them safe; we’ll go on now, if we can only find where the yarn was broken yesterday. Do any of you remember?”

“I do,” said William, laughing. “You had just got out into the great ocean, and were frightened half to death.”

“O yes, that’s it,” went on the Captain,—“frightened half to death; that’s sure enough, and no mistake; and so would you have been, my lad, if you had been in my place. But I don’t think I’ll tell you anything more about my miserable life on board that ship. Hadn’t we better skip that?”

“O no, no!” cried the children all together, “don’t skip anything.”

“Well, then,” said the obliging Captain, glad enough to see how much his young friends were interested, “if you will know what sort of a miserable time young sailors have of it, I’ll tell you; and let me tell you, too, there’s many a one of them has just as bad a time as I had. In the first place, you see, they gave me such wretched food to eat, all out of a rusty old tin plate, and I was all the time so sick from the motion of the vessel as we went tossing up and down on the rough sea, and from the tobacco-smoke of the forecastle and all the other bad smells, that I could hardly eat a mouthful, so that I was half ready to die of starvation; and, as if this was not misery enough, the sailors were all the time, when in the forecastle, quarrelling like so many cats and dogs, or wild beasts in a cage; and as two of them had pistols, and all of them had knives, I was every minute in dread lest they should take it into their heads to murder each other, and kill me by mistake. So, I can tell you, being a young sailor isn’t what it’s cracked up to be.”

“O, wasn’t it dreadful!” said Alice, “to be sick all the time among those wicked people, and nobody there to take care of you.”

“Well, I wasn’t so sick, may be, after all,” answered the Captain, smiling,—“only sea-sick, you know; and then, for the credit of the ship, I’ll say that, if you had nice plum-pudding every day for dinner, you would think it horrid stuff if you were sea-sick.”

“But don’t people die when they are sea-sick?” inquired Alice.

“Not often, child,” answered the Captain, playfully; “but they feel all the time as if they were going to, and when they don’t feel that way, they feel as if they’d like to. However, I was miserable enough in more ways than one; for to these troubles was added a great distress of mind, caused by the sport the sailors made of me, and also by remorse of conscience because I had run away from home, and thus got myself into this great scrape. Then, to make the matter worse,—as if it was not bad enough already,—a violent storm set upon us in the dark night. You could never imagine how the ship rolled about over the mountainous waves. Sometimes the waves swept clear over the ship, as if threatening our lives, and all the time the creaking of the masts, the roaring of the wind through the rigging, and the dashing of the seas, filled my ears with such awful sounds that I was in the greatest terror, and I thought that every moment would certainly be my last. Then, as if still further to add to my terror, one of the sailors told me, right in the midst of the storm, that we were bound for the Northern seas to catch whales and seals. So now, what little scrap of courage I had left took instant flight, and I fell at once to praying (which I am ashamed to say I had never in my life done before), fully satisfied as I was that, if this course did not save me, nothing would. In truth, I believe I should actually have died of fright had not the storm come soon to an end; and indeed it was many days before I got over thinking that I should, in one way or another, have a speedy passage into the next world, and therefore I did not much concern myself with where we were going in this. Hence I grew to be very unpopular with the sailors, and learned next to nothing. I was always in somebody’s way, was always getting hold of the wrong rope, was in fact all the time doing mischief rather than good. In truth, I was set down as a hopeless idiot, and was considered proper game for everybody. The sailors tormented me in every possible way. One day (knowing how green I was) they set to talking about fixing up a table in the forecastle, and one of them said, ‘What a fine thing it would be if the mate (who turned out to be the red-faced man I had met in the street, and who took me to the shipping-office) would only let us have the keelson.’ So this being agreed to in a very serious manner (which I hadn’t wit enough to see was all put on), I was sent to carry their petition. Seeing the mate on the quarter-deck, I approached, and in a very respectful manner thus addressed him: ‘If you please, sir, I come to ask if you will let us have the keelson for a table?’ Whereupon the mate turned fiercely upon me, and, to my great astonishment, roared out at the very top of his voice, ‘What! what’s that you say? say that again, will you?’ So I repeated the question as he had told me to,—feeling all the while as if I should like the deck to open and swallow me up. I had scarcely finished before I perceived that the mate was growing more and more angry; if, indeed, anything could possibly exceed the passion he was in already. His face was many shades redder than it was before,—and, indeed, it was so very red that it looked as if it might shine in the dark; his hat fell off, when he turned round, as it seemed to me, in consequence of his stiff red hair rising up on end, and he raised his voice so loud that it sounded more like the angry howl of a wild beast than anything I could compare it to. ‘You lubber!’ he shouted. ‘You villain!’ he shrieked; ‘you, you!’—and here it seemed as if he was choking with hard words which he couldn’t get rid of,—‘you come here to play tricks on me! You try to fool me! I’ll teach you!’—and seizing hold of the first thing he could lay his hands on (I did not stop to see what it was, but wheeled about greatly terrified), he let fly at me with such violence that I am sure I must have been finished off for certain had I not quickly dodged my head. When I returned to the forecastle, the sailors had a great laugh at me, and they called me ever afterwards ‘Jack Keelson.’ The keelson, you must know, is a great mass of wood down in the very bottom of the ship, running the whole length of it; but how should I have learned that? One day I was told to go and ‘grease the saddle.’ Not knowing that this was a block of wood spiked to the mainmast to support the main boom, and thinking this a trick too, I refused to go, and came again near getting my head broken by the red-faced mate. I did not believe there was anything like a ‘saddle’ in the ship. And thus the sailors continued to worry me. Once when I was very weak with sea-sickness and wanted to keep down a dinner which I had just eaten, they insisted upon it that, if I would only put into my mouth a piece of fat pork, and keep it there, my dinner would stay in its place. The sailors were right enough, for as soon as my dinner began to start up, of course away went the fat pork out ahead of it.

“But by and by I came to my senses, and, upon discovering that the bad usage I received was in some measure my own fault, I stopped lamenting over my unhappy condition, and began to show more spirit. Would you believe it? I had actually been in the vessel five days before I had curiosity enough to inquire her name. They told me that it was called the ‘Blackbird’; but what ever possessed anybody to give it such a ridiculous and inappropriate name I never could imagine. If they had called it Black Duck, or Black Diver, there would have been some sense in it, for the ship was driving head foremost into the water pretty much all the time. But I found out that the vessel was not exactly a ship after all, but a sort of half schooner, half brig,—what they call a brigantine, having two masts, a mainmast and a foremast. On the former there was a sail running fore and aft, just like the sail of the little yacht ‘Alice,’ and on the latter there was a foretop-sail and a foretop-gallant-sail, all of course square sails, that is, running across the vessel, and fastened to what are called yards. The vessel was painted jet-black on the outside, but inside the bulwarks the color was a dirty sort of green. Such, as nearly as I can remember, was the brigantine Blackbird, three hundred and forty-two tons register. Brigantine is, however, too large a word; so when we pay the Blackbird the compliment of alluding to her, we will call her a ship.

“Having picked up the name of the ship, I was tempted to pursue my inquiries further, and it was not long before I had possessed myself of quite a respectable stock of seaman’s knowledge, and hence I grew in favor. I learned to distinguish between a ‘halyard,’ which is a rope for pulling the yards up and letting them down, from a ‘brace,’ which is used to pull them around so as to ‘trim the sails,’ and a ‘sheet,’ which is a rope for keeping the sails in their proper places. I found out by a diligent inquiry and exercise of the memory, that what I called a floor the sailors called a ‘deck’; a kitchen they called a ‘galley’; a pot, a ‘copper’; a pulley was a ‘block’; a post, a ‘stancheon’; to fall down was to ‘heel over’; to climb up was to ‘go aloft’; and to walk straight, and keep one’s balance when the ship was pitching over the waves, was to ‘get your sea legs on.’ I found out, too, that everything behind you was ‘abaft,’ and everything ahead was ‘forwards’; that a large rope was a ‘hawser,’ and that every other rope was a ‘line’; to make anything temporarily secure was to ‘belay’ it; to make one thing fast to another was to ‘head it on’; and when two things were close together, they were ‘chock-a-block.’ I learned, also, that the right-hand side of the vessel was the ‘starboard’ side, while the left-hand side was the ‘port’ or ‘larboard’ side; that the lever which moves the rudder that steers the ship was called the ‘helm,’ and that to steer the ship was to take ‘a trick at the wheel’; that to ‘put the helm up’ was to turn it in the direction from which the wind was coming (windward), and to ‘put the helm down’ was to turn it in the direction the wind was going (leeward). I found out still further, that a ship has a ‘waist,’ like a woman, a ‘forefoot,’ like a beast, besides ‘bull’s eyes’ (which are small holes with glass in them to admit light), and ‘cat-heads,’ and ‘monkey-rails,’ and ‘cross-trees,’ as well as ‘saddles’ and ‘bridles’ and ‘harness,’ and many other things which I thought I should never hear anything more of after I left the farm. I might go on and tell you a great many more things that I learned, but I should only tire your patience without doing any good. I only want to show you how John Hardy received the rudiments of his marine education.

“When it was discovered how much I had improved, they proposed immediately to turn it to their own account; for I was at once sent to take ‘a trick’ at the wheel, from which I came away, after two hours’ hard work, with my hands dreadfully blistered, and my legs bruised, and with the recollection of much abusive language from the red-faced mate, who could never see anything right in what I did. I gave him, however, some good reason this time to abuse me, and I was glad of it afterwards, though I was badly enough scared at the time. I steered the ship so badly that a wave which I ought to have avoided by a dexterous turn of the wheel, came breaking in right over the quarter-deck, wetting the mate from head to foot. He thought I did it on purpose, (which you may be sure I did not do,) and once more his face increased its redness, and his mind invented hard words faster than his tongue would let them out of his ugly throat.

“I tell you all this that you may have some idea of what a ship is, and how sailors live, and what they have to do. You can easily see that they have no easy time of it, and, let me tell you, there isn’t a bit of romance about it, except the stories that are cut out of whole cloth to make books and songs of. However, I never could have much sympathy for my shipmates in the ‘Blackbird,’ for if they did treat me a little better when they found that I could do something, especially when I could take ‘a trick at the wheel,’ I still continued to look upon them as little better than a set of pirates, and I felt satisfied that, if they were not born to be hanged, they would certainly drown.”

“I don’t think I’ll be a sailor,” said Fred.

“Nor I either,” said William. “But, Captain,” continued the cunning fellow, “if a sailor’s life is so miserable, what do you go to sea so much for?”

“Well, now, my lad,” replied the Captain, evidently at first a little puzzled, “that’s a question that would require more time to explain than we have to devote to it to-day. Besides,” (he was fully recovered now,) “you know that going to sea in the cabin is as different from going to sea in the forecastle as daylight is from darkness. But never mind that, I must get on with my story, or it will never come to an end. I’ve hardly begun it yet.

“Now you must understand that, while all I have been telling you was going on, we were approaching the Arctic regions, and were getting into the sea where ice was to be expected. A man was accordingly kept aloft all the time to look out for it; for you will remember that we were going after seals, and it is on the ice that the seals are found. The weather was now very cold, it being the month of April.

“At length the man aloft cried out that he had discovered ice. ‘Where away?’ shouted the mate. ‘Off the larboard bow,’ was the answer. So the course of the ship was changed, and we bore right down upon the ice, and very soon it was in sight from the deck, and gradually became more and more distinct. It was a very imposing sight. The sea was covered all over with it, as far as the eye could reach,—a great plain of whiteness, against the edge of which the waves were breaking and sending the spray flying high in the air, and sending to our ears that same dull, heavy roar which the breakers make when beating on the land.

“As we neared this novel scene, I observed that it consisted mostly of perfectly flat masses of ice, of various sizes (called by the sealers ‘floes’); some were miles in extent, and others only a few feet. The surface of these ice floes or fields rose only about a foot or so above the surface of the water. Between them there were in many places very broad openings, and when I went aloft and looked down upon the scene, the ice-fields appeared like a great collection of large and small flat, white islands, dotted about in the midst of the ocean. Through these openings between the ice-fields the ship was immediately steered, and we were soon surrounded by ice on every side. To the south, whence we had come, there was in an hour apparently just as much ice as before us to the north, or to the right and left of us,—a vast immeasurable waste of ice it was, looking dreary enough, I can assure you.

“I have said that the pieces of ice now about us were called ‘floes,’ or ice-fields; the whole together was called ‘the pack.’ We were now in perfectly smooth water, for you will easily understand that the ice soon breaks the swell of the sea. But the crew of the ship did not give themselves much concern about the ice itself; for it was soon discovered that the floes were covered in many places with seals, lying in great numbers on them near their margins.

“Now you must understand that seals are not fish, but are air-breathing, warm-blooded animals, like horses and cows, and therefore they must always have their heads, or at least their noses, out of water when they breathe. When the weather is cold, they remain in the water all the time, merely putting up their noses now and then (for they can remain a long time under water without breathing) to sniff a little fresh air, and then going quickly down again. In the warm weather, however, they come up bodily out of the sea, and bask and go to sleep in the sun, either on the land or on the ice. Many thousands of them are often seen together.

“As we came farther and farther into the pack, the seals on the ice were observed to be more and more numerous. The greater number of them appeared to be sound asleep; some of them were wriggling about, or rolling themselves over and over, while none of them seemed to have the least idea that we had come all the way from New Bedford to rob them of their sleek coats and their nice fat blubber.

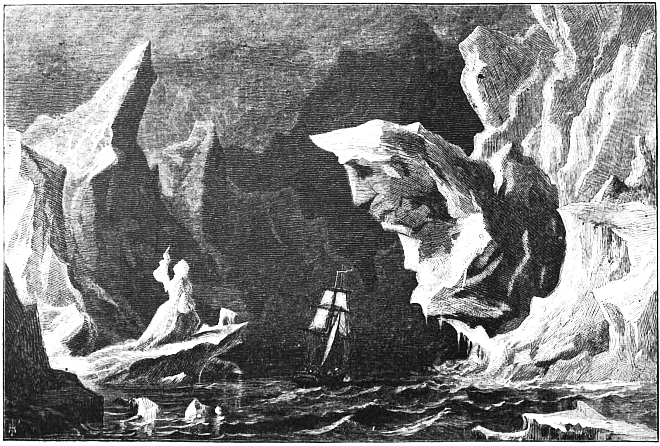

“We were now fairly into our ‘harvest-field,’ and when a suitable place was discovered the ship was brought up into the wind, that is, the helm was so turned as to bring the ship’s head towards the wind, when of course the sails got ‘aback,’ and the ship stopped. Then a boat was lowered and a crew, of which I was one, got into it, with the end of a very long rope, and pulled away towards the edge of a large ice-field, pulling out the rope after us, of course, from the coil on shipboard. As we approached the ice the seals near by all became frightened, and floundered into the sea as quickly as they could, with a tremendous splash. In a few minutes they all came up again, putting their cunning-looking heads up out of the water, all around the boat, no doubt as curious to see what these singular-looking beings were that had come amongst them, as the Indians were about Columbus and his Spaniards, when they first came to America.

“As soon as we had reached the ice, we sprang out of the boat on to it, and, after digging a hole into it with a long, sharp bar of iron, called an ice-chisel, we put into it one end of a large, heavy crooked hook, called an ice-anchor, and then to a ring in the other end of this ice-anchor we made fast the end of the rope that we had brought with us. This done, we signalled to the people on board to ‘haul in,’ which they did on their end of the rope, and in a little while the ship was drawn close up to the ice. Then another rope was run out over the stern of the ship, and, this being made fast to an ice-anchor in the same way as the other, the ship was soon drawn up with her whole broadside close to the ice, as snug as if she were lying alongside of a dock in New Bedford.

“And now began the seal-hunt. It would not interest you to hear all about the preparations we made, first to catch the seals, and then to preserve the skins and try out the oil from the blubber, and put it away in barrels. For this latter duty some of the crew were selected, while others were sent off to kill and bring in the seals. These latter were chosen with a view to their activity, and I, being supposed to be of that sort, was one of the party. I was glad enough, I can assure you, to get off the vessel for once on to something firm and solid, even if it was only ice, and at least for a little while to have done with rocking and rolling about over the waves.

“Each one of the seal-catchers was armed with a short club for killing the seals, and a rope to drag them over the ice to the ship. We scattered in every direction, our object being each by himself to approach a group of seals, and, coming upon them as noiselessly as possible, to kill as many of them as we could before they should all take fright and rush into the sea. In order to do this we were obliged to steal up between the seals and the water as far as possible.

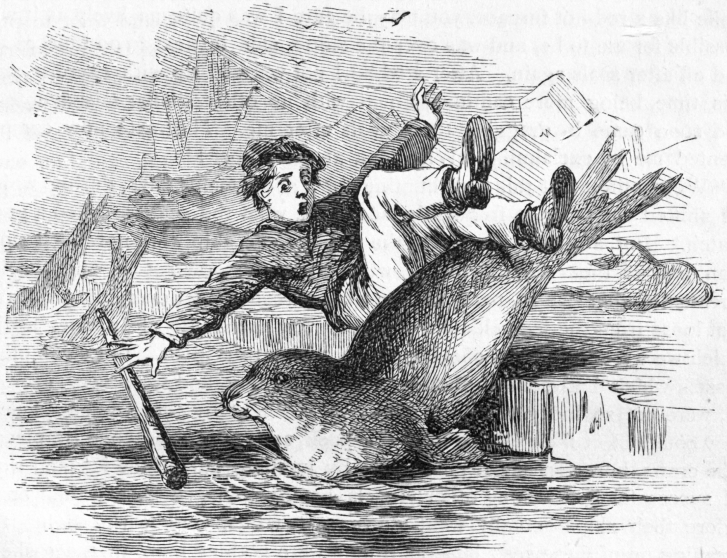

“My first essay at this novel sport, or rather business, was ridiculous enough, and, besides nearly causing my death, overwhelmed me with mortification. It happened thus. I made at a large herd of seals, nearly all of which were lying some distance from the edge of the ice, and before they could get into the water I had managed to intercept about a dozen of them. Thus far I thought myself very lucky; but, as the poet Burns says,

‘The best laid schemes o’ mice and men

Gang aft a-gley,

And leave us naught but grief and pain

For promised joy,’—

so it fell out with me. The seals of course all rushed towards the water as fast as they could go, the moment they saw me coming. But I got up with them in time, and struck one on the nose, killing it, and was in the act of striking another, when a huge fellow that was big enough to have been the father of the whole flock, too badly frightened to mind where he was going, ran his head between my legs, and, whipping up my heels in an instant, landed me on his back, in which absurd position I was carried into the sea before I could recover myself. Of course I sunk immediately, and dreadfully cold was the water; but, rising to the surface in a moment, I was preparing to make a vigorous effort to swim back to the ice, when another badly frightened and ill-mannered seal, as I am sure you will all think, plunged into the sea without once looking to see what he was doing, and hit me with the point of his nose fairly in the stomach.

“I thought now for certain that my misfortunes were all over, and that my end was surely come. However, I got my head above the surface once more, and did my best to keep it there; but my hopes vanished when I perceived that I was at least twenty feet from the edge of the ice. It was as much as I could do to keep my head above water, without swimming forward, so much embarrassed was I by my heavy clothing, the great cold, and the terrible pains, (worse than those of colic), caused by the seal hitting me in the stomach. I am quite certain that this would have been the last of John Hardy’s adventures, had not one of my companions, seeing me going overboard on the back of the seal, rushed to my rescue. He threw me his line for dragging seals (the end of which I had barely strength to catch and hold on to), and then he drew me out as one would haul up a large fish.

“I came from the sea in a most sorry condition, as you can well imagine. My mouth was full of salt water. I was so prostrated with the cold that I could scarcely stand, and my pains were so great that I should certainly have screamed had I not been so full of water that I could not utter a single word. But I managed, after a while, to get all the water spit out, and then, after drawing into my lungs a few good long breaths of air, I felt greatly refreshed. I could still, however, hardly stand, and was shivering with the cold. But I found there was strength enough left in me to enable me to stagger back to the ship, where I was greeted in a manner far from gratifying. The sailors looked upon my adventure as a great joke, never once seeming to think how near I was to death’s door, and the mate simply cried out, ‘Overboard, eh? Pity the sharks didn’t catch him!’ It was clear enough that this red-faced and unpitying tyrant would show me no mercy; and when, pale and cold and panting for breath, I asked him for leave to go below for a while, he cried out, ‘Yes, for just five minutes. Be lively, or I’ll warm your back for you with a rope’s end.’

“The prospect of a ‘back warming’ of this description had the effect to make me lively, sure enough, although I was shivering as if I would shake all my teeth out, and tumble all my bones down into a heap. As soon as I reached the deck, the mate cried out again for me to ‘be lively,’ and when he set after me with an uplifted rope’s end, his face glaring at me all the while like a red-hot furnace, you may be sure I was quite as lively as it was possible for me to be, and was over the ship’s side in next to no time at all, and off after seals again. After a while I got warmed up with exercise, and this time, being more cautious, I met with no other similar misadventure, and soon came in dragging three seals after me. The mate now complimented me by exclaiming, ‘Why, look at the lubber!’

“We continued at this seal-hunting for a good many days, during which we shifted our position frequently, and made what the sealers called a good ‘catch.’ But still the barrels in the hold of the ship were not much more than half of them filled with oil, when a great storm set in, and, the ice threatening to close in upon us, we were forced to get everything aboard, cast loose from the ice-field, and work our way south into clear water again, which we were fortunate enough to do without accident. But some other vessels which had come up while we were fishing, and were very near to us, were not so lucky. Two of them were caught by the ice-fields before they could effect their escape from the pack, and were crushed all to pieces. The crews, however, saved themselves by jumping out on the ice, and were all successful in reaching other vessels, having managed to save their boats before their ships actually went down. It was a very fearful sight, the crushing up of these vessels,—as if they were nothing more than egg-shells in the hand.

“This storm lasted, with occasional interruptions, thirteen days, but the breaks in it were of such short duration that we had little opportunity to ‘fish’ (as seal-catching is called) any more. We approached the ice repeatedly, only to be driven off again before we had fairly succeeded in getting under way again with our work, and hence we caught very few seals.

“By the time the storm was over the season for seal-fishing was nearly over too; so we had no alternative, if we would get a good cargo of oil, but to go in search of whales, which would take us still farther north, and into much heavier ice, and therefore, necessarily, into even greater danger than we had hitherto encountered. Accordingly, the course of the vessel was changed, and I found that we were steering almost due north, avoiding the ice as much as possible, but passing a great deal of it every day. The wind being mostly fair, and the ice not thick enough at any time to obstruct our passage, we hauled in our latitude very fast.”

“Excuse me, Captain Hardy,” here interrupted William, “what is hauling in latitude?”

“That’s for going farther north,” answered the Captain. “Latitude is distance from the equator, either north or south, and what a sailor makes in northing or southing he calls ‘hauling in his latitude,’ just as making easting or westing is ‘hauling in his longitude.’ ”

“Thank you, Captain,” said William, politely, when he had finished.

“Is it all clear now?” inquired the Captain.

“Yes,” said William, “clear as mud.”

“Clear as mud, eh! Well, that isn’t as clear as the pea-soup was they used to give us on board the Blackbird, for that was so clear that, if the ocean had been made of it, you might have seen through it all the way down to the bottom; indeed, one of the old sailors said that it wasn’t soup at all. ‘If dat is soup,’ growled he, ‘den I’s sailed forty tousand mile trough soup,’—which is the number of miles he was supposed to have sailed in his various voyages.

“But no matter for the soup. The days wore on none the less that the soup was thin, and still we kept going on and on,—getting farther and farther north, and into more and more ice. Sometimes our course was much interrupted, and we had to wait several days for the ice to open; then we would get under way again, and push on. At length it seemed to me that we must be very near the North Pole. It was a strange world we had come into. The sun was shining all the time. There was no night at all,—broad daylight constantly. This, of course, favored us; indeed, had there been any darkness, we could not have worked among the ice at all. As it was, we were obliged to be very cautious, for the ice often closed upon us without giving us a chance to escape, obliging us to get out great long saws, and saw out and float away great blocks of the ice, until we had made a dock for the ship, where she could ride with safety. We had many narrow escapes from the fate which had befallen the poor sealers.

“At first, when we concluded to go after whales, there were several vessels in company with us. At one time I counted nine, all in sight at one time; but we had become separated in thick weather, and whether they had gone ahead of us, or had fallen behind, we could not tell. However, we kept on and on and on; where we were, or where we were going, I, of course, had not the least idea; but I became aware, from day to day, that greater dangers were threatening us, for icebergs came in great numbers to add their terrors to those which we had already in the ice-fields. They became at length (and suddenly too) very numerous, and not being able to go around them on account of the field-ice, which was on either side, we entered right amongst them. The atmosphere was somewhat foggy at the time, and it seemed as if the icebergs chilled the very air we breathed. I fairly shuddered as we passed the first opening. The bergs were at least three times as high as our masts, and very likely more than that, and they appeared to cover the sea in every direction. It seemed to me that we were going to certain destruction, and indeed I thought I read a warning written as it were on the bergs themselves. Upon the corner of an iceberg to the left of us there stood a white figure, as plain as anything could possibly be. One hand of this strange, weird-looking figure was resting on the ice beside it, while the other was pointing partly upwards towards heaven, and backwards toward the south whence we had come. I thought I saw the figure move, and, much excited, I called the attention of one of the sailors to it. ‘Why, you fool,’ said he, ‘don’t you know that the sun melts the ice into all sorts of shapes. Look out hard, if there isn’t a man’s face?’ I looked up as the sailor had directed me, and, sure enough, there was a man’s face plainly to be seen in the lines of an immense tongue of ice which was projecting from the side of a berg on the right, and under which we were about to pass.

“I became now really terrified. In addition to these strange spectral objects, the air was filled with loud reports, and deep, rumbling noises, caused by the icebergs breaking to pieces, or masses splitting off from their sides and falling into the sea. These noises came at first from the icebergs in front of us; but when we had got fairly into the wilderness of bergs which covered the sea, they came from every side. It struck me that we had passed deliberately into the very jaws of death, and that from the frightful situation there was no escape.

“I merely mention this as the feeling which oppressed me, and which I could not shake off. Indeed, the feeling grew upon me rather than decreased. The fog came on very thick, settling over us as if it were our funeral shroud. The noises were multiplying, and we could no longer tell whence they came, so thick was the air. We were groping about like a traveller who has lost his way in a vast forest, and has been overtaken by the dark night.

“It seemed to me now that our doom was sealed,—that all our hope was left behind us when we passed the opening to this vast wilderness of icebergs; and the more I thought of it, the more it seemed to me that the figure standing on the corner of the iceberg where we entered, whether it was ice or whatever it was, had been put there as a warning. How far my fears were right you shall see presently.

“The fog, as I have said, kept on thickening more and more, until we could scarcely see anything at all. I have never, I think, seen so thick a fog, and it was with the greatest difficulty that the ship was kept from striking the icebergs. Then, after a while, the wind fell away steadily, and finally grew entirely calm. The current was moving us about upon the dead waters; and in order to prevent this current from setting us against the bergs, we had to lower the boats, and, making lines fast to the ship and to the boats, pull away with our oars to keep headway on the ship, that she might be steered clear of the dangerous places. Thus was made a slow progress, but it was very hard work. At length the second mate, who was steering the foremost boat, which I was in, cried out, ‘Fast in ahead.’ Now ‘fast in’ is a belt of ice which is attached firmly to the land, not yet having been broken up or dissolved by the warmth of the summer. This announcement created great joy to everybody in the boats, as we all supposed that we would be ordered to make a line fast to it, that we might hold on there until the fog cleared up and the wind came again. But instead of this we were ordered by the mate to pull away from it. And then, after having got the vessel, as was supposed, into a good, clear, open space of water,—at least, there was not a particle of ice in sight,—we were all ordered, very imprudently, as it appeared to every one of us, to come on board to breakfast.

“We had just finished our breakfast, and were preparing to go on deck, and then into the boats again, when there was a loud cry raised on deck. ‘Ice close ahead! Hurry up! Man the boats!’ were the orders which caught my ear among a great many other confusing sounds; and when I got on deck, I saw, standing away up in the fog, its top completely obscured in the thick cloud, an enormous iceberg. The side nearest to us hung over from a perpendicular, as the projecting tongue on which I had before seen the man’s face. It was very evident that we were slowly drifting upon this frightful object, and directly under this overhanging tongue. It was a fearful sight to behold, for it looked as if it was just ready to crumble to pieces; and, indeed, at every instant small fragments were breaking off from it, with loud reports, and falling into the sea.

“We were but a moment getting into the boats. The boat which I was in had something the start of the other two. Just as we were pulling away, the master of the ship came on deck, and ordered us to do what, had the mate done it an hour before, would have made it impossible that this danger should have come upon us. ‘Carry your line out to the fast ice,’ was the order we received from the master, and every one of us, realizing the great danger, pulled the strongest oar he could. The ‘fast ice’ was dimly in sight when we started, for we had drifted while at breakfast towards it, as well as towards the berg. Only a few minutes were needed to reach it. We jumped out and dug the hole and planted the anchor. The ship was out of sight, buried in the fog. A faint voice came from the ship. It was, ‘Hurry up! we have struck.’ They evidently could not see us. The line was fastened to the anchor in an instant, and the second mate shouted, ‘Haul in! haul in!’ There was no answer but ‘Hurry up! hurry up! we have struck.’ ‘Haul in! haul in!’ shouted the second mate, but still there was no answer. ‘They can’t hear nor see,’ said he hurriedly; and then, turning to me, said, ‘Hardy, you watch the anchor that it don’t give way. Boys, jump in the boat, and we’ll go nearer the ship so they can hear.’ The boat was gone quickly into the fog, and I was then alone on the ice by the anchor,—how much and truly alone, you shall hear.

“Quick as the lightning flash, sudden as the change of one second to another, there broke upon me a sound that will never, never leave my ears. It was as if a volcano had burst forth, or an earthquake had instantly tumbled a whole city into ruins. A fearful shock, as of a sudden explosion, filled the air. I saw faintly through the thick mists the masts of the ship reeling over, and I saw no more;—vessel and iceberg and the disappearing boat were mingled as in a chaos. The whole side of the berg nearest the vessel had split off, hurling thousands and hundreds of thousands of tons of ice, and thousands of fragments, crashing down upon the doomed ship. Escape the vessel could not, nor her crew, the shock came so suddenly. The spray thrown up into the air completely hid everything from view; but the noise which came from out the gloom told the tale.

“Presently there was a loud rush. Great waves, set in motion by the crumbling icebergs with white crests that were frightful to look upon, came tearing out of the obscurity, and, perceiving the danger of my situation, I ran from it as fast as I could run. And I was just in time; for the waves broke up the ice where I had been standing into a hundred fragments, and, crack after crack opening close behind me, I fled as before a devouring fiend.

“I had not, however, far to run before I had reached a place of safety, for the force of the waves was soon spent. And when I saw what had happened, I fell down flat upon the ice, crying, ‘Saved, but for what? to freeze or starve! O that I had perished with the rest of them!’

“So now you see that I was really and truly cast away in the cold. In almost a single instant the ship which had borne me through what had seemed great perils was, so far as appeared to me, swallowed up in the sea,—crushed and broken into fragments by the falling ice; and every one of my companions was swallowed up with it. And there I was on an ice-raft, in the middle of the Arctic Sea, without food or shelter, wrapped in a great black, impenetrable fog, with a lingering death staring me in the face.”

The Captain paused as if to take breath, for he had been talking very fast, and had grown somewhat excited as he recalled this terrible scene. The eyes of the children were riveted upon him, so deeply were they interested in the tale of the shipwreck; and it was some time before any one spoke.

“Well!” exclaimed William at last, “that was being cast away in the cold for certain, Captain Hardy. I had no idea it was so frightful.”

“Nor I,” said Fred, evidently doubting if Captain Hardy was really the shipwrecked boy; but Alice said not a word, for she was lost in wonder.

“I should not have believed it was you, Captain Hardy,” continued William, “if you had not been telling the story yourself, this very minute; for I cannot see how you should ever have got out of that scrape with your life. It’s ever so much worse than going into the sea on the seal’s back.”

The Captain smiled at these observations of the boys, and said: “It was a pretty hard scrape to get into, and no mistake; but through the mercy of Providence I got out of it in the end, as you see, otherwise I shouldn’t have been here to tell the tale; but how I saved myself, and what became of the ship and the rest of the crew, you shall hear to-morrow, for it is now too late to begin the story. The evening is coming on, and your parents will be looking for you home; so good by, my dears. To-morrow you must come down earlier,—the earlier the better, and if there’s any wind we’ll have a sail.” And now the children once more took leave of the Ancient Mariner, with hearts filled with thanks, which they could never get done speaking, and with heads filled with astonishment that the Captain should be alive to tell the tale which they had heard.

Isaac I. Hayes.

Blunder was going to the Wishing-Gate, to wish for a pair of Shetland ponies, and a little coach, like Tom Thumb’s. And of course you can have your wish, if you once get there. But the thing is, to find it; for it is not, as you imagine, a great gate, with a tall marble pillar on each side, and a sign over the top, like this: WISHING-GATE,—but just an old stile, made of three sticks. Put up two fingers, cross them on the top with another finger, and you have it exactly,—the way it looks, I mean,—a worm-eaten stile, in a meadow; and as there are plenty of old stiles in meadows, how are you to know which is the one?

Blunder’s fairy godmother knew, but then she could not tell him, for that was not according to fairy rules and regulations. She could only direct him to follow the road, and ask the way of the first owl he met; and over and over she charged him, for Blunder was a very careless little boy, and seldom found anything, “Be sure you don’t miss him,—be sure you don’t pass him by.” And so far Blunder had come on very well, for the road was straight; but at the turn it forked. Should he go through the wood, or turn to the right? There was an owl nodding in a tall oak-tree, the first owl Blunder had seen; but he was a little afraid to wake him up, for Blunder’s fairy godmother had told him that this was a great philosopher, who sat up all night to study the habits of frogs and mice, and knew everything but what went on in the daylight, under his nose; and he could think of nothing better to say to this great philosopher than “Good Mr. Owl, will you please show me the way to the Wishing-Gate?”

“Eh! what’s that?” cried the owl, starting out of his nap. “Have you brought me a frog?”

“No,” said Blunder, “I did not know that you would like one. Can you tell me the way to the Wishing-Gate?”

“Wishing-Gate! Wishing-Gate!” hooted the owl, very angry. “Winks and naps! how dare you disturb me for such a thing as that? Do you take me for a mile-stone! Follow your nose, sir, follow your nose!”—and, ruffling up his feathers, the owl was asleep again in a moment.

But how could Blunder follow his nose? His nose would turn to the right, or take him through the woods, whichever way his legs went, and “what was the use of asking the owl,” thought Blunder, “if this was all?” While he hesitated, a chipmunk came skurrying down the path, and, seeing Blunder, stopped short with a little squeak.

“Good Mrs. Chipmunk,” said Blunder, “can you tell me the way to the Wishing-Gate?”

“I can’t, indeed,” answered the chipmunk, politely. “What with getting in nuts, and the care of a young family, I have so little time to visit anything! But if you will follow the brook, you will find an old water-sprite under a slanting stone, over which the water pours all day with a noise like wabble! wabble! who, I have no doubt, can tell you all about it. You will know him, for he does nothing but grumble about the good old times when a brook would have dried up before it would have turned a mill-wheel.”

So Blunder went on up the brook, and, seeing nothing of the water-sprite, or the slanting stone, was just saying to himself, “I am sure I don’t know where he is,—I can’t find it,”—when he spied a frog sitting on a wet stone.

“Mr. Frog,” asked Blunder, “can you tell me the way to the Wishing-Gate?”

“I cannot,” said the frog. “I am very sorry, but the fact is, I am an artist. Young as I am, my voice is already remarked at our concerts, and I devote myself so entirely to my profession of music, that I have no time to acquire general information. But in a pine-tree beyond, you will find an old crow, who I am quite sure can show you the way, as he is a traveller, and a bird of an inquiring turn of mind.”

“I don’t know where the pine is,—I am sure I can never find him,”—answered Blunder, discontentedly; but still he went on up the brook, till, hot, and tired, and out of patience at seeing neither crow nor pine, he sat down under a great tree to rest. There he heard tiny voices squabbling.

“Get out! Go away, I tell you! It has been knock! knock! knock! at my door all day, till I am tired out. First a wasp, and then a bee, and then another wasp, and then another bee, and now you. Go away! I won’t let another one in to-day.”

“But I want my honey.”

“And I want my nap.”

“I will come in.”

“You shall not.”

“You are a miserly old elf.”

“And you are a brute of a bee.”

And looking about him, Blunder spied a bee, quarrelling with a morning-glory elf, who was shutting up the morning-glory in his face.

“Elf, do you know which is the way to the Wishing-Gate?” asked Blunder.

“No,” said the elf, “I don’t know anything about geography. I was always too delicate to study. But if you will keep on in this path, you will meet the Dream-man, coming down from fairy-land, with his bags of dreams on his shoulder; and if anybody can tell you about the Wishing-Gate, he can.”

“But how can I find him?” asked Blunder, more and more impatient.

“I don’t know, I am sure,” answered the elf, “unless you should look for him.”

So there was no help for it but to go on; and presently Blunder passed the Dream-man, asleep under a witch-hazel, with his bags of good and bad dreams laid over him to keep him from fluttering away. But Blunder had a habit of not using his eyes; for at home, when told to find anything, he always said, “I don’t know where it is,” or, “I can’t find it,” and then his mother or sister went straight and found it for him. So he passed the Dream-man without seeing him, and went on till he stumbled on Jack-o’-Lantern.

“Can you show me the way to the Wishing-Gate?” said Blunder.

“Certainly, with pleasure,” answered Jack, and, catching up his lantern, set out at once.

Blunder followed close, but, in watching the lantern, he forgot to look to his feet, and fell into a hole filled with black mud.

“I say! the Wishing-Gate is not down there,” called out Jack, whisking off among the tree-tops.

“But I can’t come up there,” whimpered Blunder.

“That is not my fault, then,” answered Jack, merrily, dancing out of sight.

O, a very angry little boy was Blunder, when he clambered out of the hole. “I don’t know where it is,” he said, crying; “I can’t find it, and I’ll go straight home.”

Just then he stepped on an old, moss-grown, rotten stump; and it happening, unluckily, that this rotten stump was a wood-goblin’s chimney, Blunder fell through, headlong, in among the pots and pans, in which the goblin’s cook was cooking the goblin’s supper. The old goblin, who was asleep up stairs, started up in a fright at the tremendous clash and clatter, and, finding that his house was not tumbling about his ears, as he thought at first stumped down to the kitchen to see what was the matter. The cook heard him coming, and looked about her in a fright to hide Blunder.

“Quick!” cried she. “If my master catches you, he will have you in a pie. In the next room stands a pair of shoes. Jump into them, and they will take you up the chimney.”

Off flew Blunder, burst open the door, and tore frantically about the room, in one corner of which stood the shoes; but of course he could not see them, because he was not in the habit of using his eyes. “I can’t find them! O, I can’t find them!” sobbed poor little Blunder, running back to the cook.

“Run into the closet,” said the cook.

Blunder made a dash at the window, but—“I don’t know where it is,” he called out.

Clump! clump! That was the goblin, half-way down the stairs.

“Goodness gracious mercy me!” exclaimed cook. “He is coming. The boy will be eaten in spite of me. Jump into the meal-chest.”

“I don’t see it,” squeaked Blunder, rushing towards the fireplace. “Where is it?”

Clump! clump! That was the goblin at the foot of the stairs, and coming towards the kitchen door.

“There is an invisible cloak hanging on that peg. Get into that,” cried cook, quite beside herself.

But Blunder could no more see the cloak than he could the shoes, the closet, and the meal-chest; and no doubt the goblin, whose hand was on the latch, would have found him prancing around the kitchen, and crying out, “I can’t find it,” but, fortunately for himself, Blunder caught his foot in the invisible cloak, and tumbled down, pulling the cloak over him. There he lay, hardly daring to breathe.

“What was all that noise about?” asked the goblin, gruffly, coming into the kitchen.

“Only my pans, master,” answered the cook; and as he could see nothing amiss, the old goblin went grumbling up stairs again, while the shoes took Blunder up chimney, and landed him in a meadow, safe enough, but so miserable! He was cross, he was disappointed, he was hungry. It was dark, he did not know the way home, and, seeing an old stile, he climbed up, and sat down on the top of it, for he was too tired to stir. Just then came along the South Wind, with his pockets crammed full of showers, and, as he happened to be going Blunder’s way, he took Blunder home; of which the boy was glad enough, only he would have liked it better if the Wind would not have laughed all the way. For what would you think, if you were walking along a road with a fat old gentleman, who went chuckling to himself, and slapping his knees, and poking himself, till he was purple in the face, when he would burst out in a great windy roar of laughter every other minute?

“What are you laughing at?” asked Blunder, at last.

“At two things that I saw in my travels,” answered the Wind;—“a hen, that died of starvation, sitting on an empty peck-measure that stood in front of a bushel of grain; and a little boy who sat on the top of the Wishing-Gate, and came home because he could not find it.”

“What? what’s that?” cried Blunder; but just then he found himself at home. There sat his fairy godmother by the fire, her mouse-skin cloak hung up on a peg, and toeing off a spider’s-silk stocking an eighth of an inch long; and though everybody else cried, “What luck?” and, “Where is the Wishing-Gate?” she sat mum.

“I don’t know where it is,” answered Blunder. “I couldn’t find it”;—and thereon told the story of his troubles.

“Poor boy!” said his mother, kissing him, while his sister ran to bring him some bread and milk.

“Yes, that is all very fine,” cried his godmother, pulling out her needles, and rolling up her ball of silk; “but now hear my story. There was once a little boy who must needs go to the Wishing-Gate, and his fairy godmother showed him the road as far as the turn, and told him to ask the first owl he met what to do then; but this little boy seldom used his eyes, so he passed the first owl, and waked up the wrong owl; so he passed the water-sprite, and found only a frog; so he sat down under the pine-tree, and never saw the crow; so he passed the Dream-man, and ran after Jack-o’-Lantern; so he tumbled down the goblin’s chimney, and couldn’t find the shoes and the closet and the chest and the cloak; and so he sat on the top of the Wishing-Gate till the South Wind brought him home, and never knew it. Ugh! Bah!”—and away went the fairy godmother up the chimney, in such deep disgust that she did not even stop for her mouse-skin cloak.

Louise E. Chollet.

I know a little theatre

Scarce bigger than a nut.

Finer than pearl its portals are,

Quick as the twinkling of a star

They open and they shut.

A fairy palace beams within:

So wonderful it is,

No words can tell you of its worth,—

No architect in all the earth

Could build a house like this.

A beautiful rose window lets

A ray into the hall;

To shade the scene from too much light,

A tiny curtain hangs in sight,

Within the crystal wall.

And O the wonders there beside!

The curious furniture,

The stage, with all its small machinery,

Pulley and cord and shifting scenery,

In marvellous miniature!

A little, busy, moving world,

It mimics space and time,

The marriage-feast, the funeral,

Old men and little children, all

In perfect pantomime.

There pours the foaming cataract,

There speeds the train of cars;

Day comes with all its pageantry

Of cloud and mountain, sky and sea,

The night, with all its stars.

Ships sail upon that mimic sea;

And smallest things that fly,

The humming-bird, the sunlit mote

Upon its golden wings afloat,

Are mirrored in that sky.

Quick as the twinkling of the doors,

The scenery forms or fades;

And all the fairy folk that dwell

Within the arched and windowed shell

Are momentary shades.

Who has this wonder holds it dear

As his own life and limb;

Who lacks it, not the rarest gem

That ever flashed in diadem

Can purchase it for him.

Ah, then, dear picture-loving child,

How doubly blessed art thou!

Since thine the happy fortune is

To have two little worlds like this

In thy possession now,—

Each furnished with soft folding-doors,

A curtain, and a stage!

And now a laughing sprite transfers

Into those little theatres

The letters of this page.

J. T. Trowbridge.

And so it was settled that our elegant young friend, Miss Emily Proudie, was to go and stay at the farm-house with Pussy Willow. Dr. Hardhack came in to give his last directions, in the presence of grandmamma and the aunts and mamma, who all sat in an anxious circle.

“Do pray, dear Dr. Hardhack, tell us just how she must be dressed for that cold mountain region. Must she have high-necked, long-sleeved flannels?” said mamma.

“I will make her half a dozen sets at once,” chimed in Aunt Maria.

“Not so fast,” said Dr. Hardhack. “Let’s see about this young lady,” and with that Dr. Hardhack endeavored to introduce his forefinger under the belt of Miss Emily’s dress.

Now the Doctor’s forefinger being a stout one, and Miss Emily’s belt ribbon being drawn very snugly round her, the belt ribbon gave a smart snap, and the Doctor drew out his finger with a jerk. “I thought so,” he said. “I supposed that there wasn’t much breathing room allowed behind there.”

“O, I do assure you, Doctor, Emily never dresses tight,” said her mother.

“No indeed!” said little Miss Emily. “I despise tight lacing. I never wear my clothes any more than just comfortable.”

“Never saw a woman that did,” said the Doctor. “The courage and constancy of the female sex in bearing inconveniences is so great, however, that that will be no test at all. Why, if you should catch a fellow, and gird his ribs in as Miss Emily wears hers all the time, he’d roar like a bull of Bashan. You wouldn’t catch a man saying he felt ‘comfortable’ under such circumstances; but only persuade a girl that she looks stylish and fashionable with her waist drawn in, and you may screw and screw till the very life leaves her, and with her dying breath she will tell you that it is nothing more than ‘comfortable.’ So, my young lady, you don’t catch me in that way. You must leave off belts and tight waists of all sorts for six months at least, and wear only loose sacks, or thingembobs,—whatever you call ’em,—so that your lungs may have some chance to play, and fill with the vital air I’m going to send you to breathe up in the hills.”

“But, Doctor, I don’t believe I could hold myself up without corsets,” said Miss Emily. “When I sit up in a loose dress, I feel so weak I hardly know what to do. I need the support of something around me.”

“My good child, that is because all those nice strong muscles around your waist, which Nature gave you to hold you up, have been bound down and bandaged and flattened till they have no strength in them. Muscles are nourished and strengthened by having blood carried to them; if you squeeze a muscle down flat under a bandage, there is no room for blood to get into it and nourish it, and it grows weak and perishes.

“Now look there,” said the Doctor, pointing with his cane to the waist of a bronze Venus which adorned the mantel-piece,—“look at that great wide waist, look at those full muscles over the ribs that moved that lady’s breathing apparatus. Do you think a woman with a waist like that would be unable to get up stairs without fainting? That was the idea the old Greeks had of a Goddess,—a great, splendid woman, with plenty of room inside of her to breathe, and to kindle warm vital blood which should go all over her with a glow of health and cheerfulness,—not a wasp waist, coming to a point and ready to break in two in the middle.

“Now just there, under Miss Emily’s belt, is the place where Nature is trying to manufacture all the blood which is necessary to keep her brain, stomach, head, hands, and feet in good condition,—and precious little room she gets to do it in. She is in fact so cooped up and hindered, that the blood she makes is very little in quantity and extremely poor in quality; and so she has lips as white as a towel, cheeks like blanched celery, and headaches, and indigestion, and palpitations of the heart, and cold hands, and cold feet, and forty more things that people have when there is not enough blood to keep their systems going.

“Why, look here,” said the Doctor, whirling round and seizing Miss Emily’s sponge off the wash-stand, “your lungs are something like this, and every time that you take in a breath they ought to swell out to their full size, so that the air that you take in shall purify your blood and change it from black blood to red blood. It’s this change in your lungs that makes the blood fit to nourish the whole of the rest of your body. Now see here,” said the Doctor, squeezing the sponge tight in his great hand,—“here’s what your corsets and your belt ribbons do,—they keep the air-vessels of your lungs matted together like this, so that the air and the blood can hardly get together at all, and consequently it is impure. Don’t you see?”

“Well, Doctor,” said Emily, who began to be frightened at this, “do you suppose if I should dress as you tell me for six months my blood would come right again?”

“It would go a long way towards it, my little maid,” said the Doctor. “You fashionable girls are not good for much, to be sure; but yet if a Doctor gets a chance to save one of you in the way of business, he can’t help wishing to do it. So, my dear, I just give you your choice. You can have a fine, nice, taper little body, with all sorts of pretty little waists and jackets and thingembobs fitting without a wrinkle about it, and be pale and skinny, with an unhealthy complexion, low spirits, indigestion, and all that sort of thing; or you can have a good, broad, free waist, with good strong muscles like the Venus up there, and have red lips and cheeks, a good digestion, and cheerful spirits, and be able to run, frisk, jump, and take some comfort in life. Which would you prefer now?”

“Of course I would like to be well,” said Emily; “and in the country up there nobody will see me, and it’s no matter how I look.”

“To be sure, it’s no matter,” chimed in Emily’s mamma. “Only get your health, my dear, and afterwards we will see.”

And so, a week afterwards, an elegant travelling-carriage drew up before the door of the house where Pussy’s mother lived, and in the carriage were a great many bolsters and pillows, and all sorts of knick-knacks and conveniences, such as sick young ladies use, and little Emily was brought out of the carriage, looking very much like a wilted lily, and laid on the bed up stairs in a chamber that Pussy had been for some weeks busy in fitting up and adorning for her.

And now, while she is getting rested, we will tell you all about this same chamber. When Pussy first took it in hand, it was as plain and dingy a little country room as ever you saw, and she was very much dismayed at the thought of putting a genteel New York young lady in it.

But Pussy one day drove to the neighboring town, and sold her butter, and invested the money she got for it,—first in a very pretty delicate-tinted wall-paper, and some white cotton, and some very pretty blue bordering. Then the next day she pressed one of her brothers into the service, and cut and measured the wall-paper, and contrived the breadths, and made the paste, and put it on the paper as handily as if she had been brought up to the trade, while her brother mounted on a table and put the strips upon the wall, and Pussy stroked down each breadth with a nice white cloth. Then they finished all by putting round the ceiling a bordering of flowers, which gave it quite an air. It took them a whole day to do it, but the room looked wonderfully different after it was done.

Then Pussy got her brother to make cornices to the windows, which she covered with bordering like that on the walls, and then she made full white curtains, and bordered them with strips of the blue calico; she also made a bedspread to match. There was a wide-armed old rocking-chair with a high back, that had rather a forlorn appearance, as some of its slats were broken, and the paint wholly rubbed off, but Pussy took it in hand, and padded and stuffed it, and covered it with a white, blue-bordered dress, till it is doubtful whether the chair would have known itself if it could have looked in the glass.

Then she got her brother to saw out for her a piece of rough board in an oblong octagon shape, and put four legs to it; and out of this foundation she made the prettiest toilet-table you can imagine. The top was stuffed like a large cushion, and covered with white, and an ample flowing skirt of white, bordered with blue, like the bedspread and window-curtains, completed the table. Over this hung a looking-glass whose frame had become very much tarnished by time, and so Pussy very wisely concealed it by looping around it the folds of some thin white muslin that had once been her mother’s wedding-dress, but was now too old and tender for any other usage than just to be draped round a mirror. Pussy arranged it quite gracefully, and fastened it at the top and sides with some smart bows of blue ribbon, and it really looked quite as if a French milliner had been at it.

Then beside this, there was a cunning little hour-glass stand, which she made for the head of the bed out of two old dilapidated spinning-wheels, and which, covered with white like the rest, made a handy little bit of furniture. Then Pussy had arranged vases of blue violets and apple-blossoms here and there, and put some of her prettiest books in the room, and hung up one or two pictures which she had framed very cleverly in rustic frames, and on the whole the room was made so sweet and inviting that, when Emily first looked around it, she said two or three times, “How nice! How very pretty it is! I think I shall like to be here.”

Those words were enough to pay Pussy for all her trouble. “O mother, I am so sorry for her!” she said, rushing down stairs; “and I’m so glad she likes it! To think of her being so weak, and I so strong, and we just of an age! I feel as if I couldn’t do too much for her.”

And what the girls did together we will tell you by and by.

Harriet Beecher Stowe.

“Well, boys, here we are at Bartlett’s!” said Mr. Craig, as his boat, closely followed by another, grounded on a little beach at the foot of a soft-swelling green knoll.

When the guide, as the boatman is called in the Adirondacks, had dragged the boat a little farther up out of the water, Mr. Craig jumped on shore, followed by his son Harry, a tall, bright-eyed, rosy-cheeked boy of about fifteen. The other boat held two more boys, one his son Frank, a lad of twelve, and the other his nephew Herbert.

Mr. Craig was a benevolent, kindly-looking man, an eminent lawyer in New York, who had brought the boys for a hunting and fishing trip to the Adirondacks. He wore a thick, dark hunting-coat and trousers, and the boys were dressed in bright flannel shirts, soft black felt hats, and tall boots, all of them carrying knapsacks, swung at their sides by leather straps passing across their shoulders, and containing powder-flasks and cartridge-boxes, and each boy had a tin cup hanging at his waist, and carried a gun.

The guides took from the boats the “traps,” consisting of a tent and blankets and other furniture for camping out, then pulled the boats from the water and carried them up the bank on their shoulders, placing them bottom side up to dry.

The Saranac boats are about twelve feet long and very narrow, made of pine boards about a quarter of an inch thick, carefully lapped over one another, and painted a dark blue both outside and in. They are made very light, to be transported easily over the carries, and hold three persons, a guide who sits in the bow to row, a passenger in the stern with a high backboard behind him, and another in the middle seat.

“Now, boys, come up to the house!”

At the top of the knoll stood a long, two-story, unpainted frame-house, with a piazza running its entire length, on which several men sat, some reading, and others examining their guns and fishing-flies, while on the green before it three or four young men, gay in red flannel shirts, were practising firing at a target.

Several guides were clustered at the open door of a log cabin in which the hunting implements were kept, a little at one side, with three or four gaunt fox-hounds standing about them. On the outside wall of the hut fishing-nets and a dead heron dangled, besides two or three deer-skins stretched out to dry.

The presence of the neighboring hills threw the whole place into deep, cool, gray shadow, but the beams of the setting sun lighted up, almost with a rose-color, the range of the Ampersand Mountains on the other side of the clearing, and brilliant orange and rosy clouds filled the sky. At the foot of the knoll the narrow river Saranac was sleeping, dotted with pond-lilies, and the distant sounds of the cow-bells on the hills mingled with the noise of the falls or rapids at the side of the Carry beyond the house.

“Shall the boats go over the Carry, or wait till morning?” asked a guide coming up from the river-bank.

“O, either time will do,” answered Mr. Craig. “I must arrange with Bartlett about our outfit and guides to-night, to be ready for an early start.” So saying, followed by the boys, he entered the house.

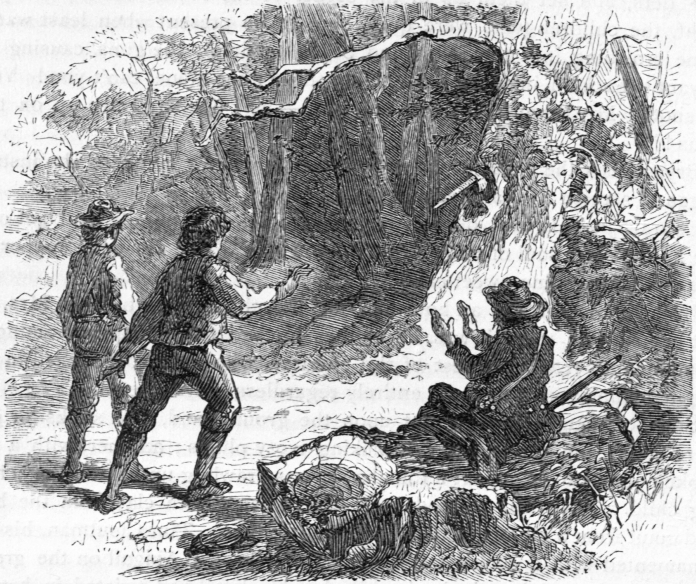

The mountains were yet in deep shadow when the boys arose the next morning. Little wreaths of white mist curled up their steep sides, and a steam from the river ascended into the thin, cool morning air.

“It is a glorious day for our start,” said Harry, running down stairs to the piazza. The guides were lounging about, and a pack of hounds in a large enclosure on the other side of the river barked and yelped as they watched the approach of a man bringing them their breakfast. At the door of the guides’ house a fire was smouldering, and several of them overhauled their fishing nets as they stood around it.

Breakfast over, three guides, Sam Williams, Dan Wood, and Paul Johnson, with a couple of dogs, and followed by three boats in a long wagon, accompanied Mr. Craig and his party over the short Carry.

“Cut some brakes for the dogs’ beds, Paul, as you come along over the Carry,” said Williams, who acted as leader of the party, stalking along to the place of embarkation on the Upper Saranac Lake.

The waves danced bright and blue in the crisp wind, gently rocking the slender little boats, whose keels grated on the small beach.

Williams was a square-set, brawny fellow, in a dark flannel shirt. Each of the other guides had an English fox-hound in leash, who jumped about and whined to be off to the hunt. Tents, guns, and knapsacks were scattered about on the ground ready to be packed in the boats.

Paul Johnson, a tall, Indian-looking fellow, with the eye of a hawk, cut armful after armful of the coarse fern-like brakes, and deposited them on the shore, while Williams proceeded to arrange them in thick beds in the middle of one of the boats for the dogs to lie on. “Here Tige, come along! Don’t pull him by his ears,” he said to the guide, who was helping the dog into the boat. Tige seemed to know what was going on, and, giving a whine of satisfaction, coiled himself up quietly in the boat, and, though he kept his eyes and head up, attentively looking about, he did not move a leg for fear of tipping over the little craft in which he was lying.

“Now give me another dog,” said Williams, “and now a couple of the guns. There, that will do. Now, Dan, you get in here and take Frank Craig along with you. Here, slip in, Frank. Sit quiet in the stern and don’t rock the boat. Now be off.”

Dan gave the boat a shove, and, as she moved from the shore, sprang into the bows himself, and in a moment was rowing swiftly down the bay which the Saranac makes here, bordered on each side by dense forests of pine and maple coming down to the water’s edge.

“Now put in the tent snugly in the middle of your boat, Paul, and then Mr. Craig will go with you, and I will take Herbert and Harry with me.” Mr. Craig had been giving the boys many cautions about the use and care of their guns, and now as he left them, said, “Be sure neither of you have your guns capped in the boats.”

After a few minutes, guides, dogs, and all were safely stowed away in the boats, and were skimming up the lake to the Indian Carry.

“ ’Tis not quite so rough as it was last night coming up Round Lake,” said Frank Craig to Dan, as they moved along. “Why, off the little islands in the middle of the lake, a squall struck us, and in two minutes the white caps were so high that they sent the spray flying in our faces. For my part, I never had such a rocking and ducking before.”

“That’s a great lake for squalls,” answered Dan, “but to-day I think the water will be quiet enough here for any one.” And indeed, after they passed the point that divides the bay from the lake, long bands of still water reflected the deep green and blue of the opposite shores.

“There’s a heron,” said Dan, as a large gray bird rose slowly from the edge of the bank and flapped awkwardly over the tops of the trees into the woods. “Plenty of them here, and loons too,—only I don’t like to hear the loons laugh when I am out on a hunt, for that always brings rain, and there’s an end to deer-driving, for the dogs are no use, there’s no scent when the ground is wet. There’s a good view yonder up the lake!”

The scene was indeed lovely. High hills, densely covered with forests to their summits, sloped in long lines to the edge of the water, the trees brilliant with light, or black with shadow as the clouds chased each other above them, while the more distant mountains had every lovely hue, from rich purple to soft azure.

“There’s the Indian Carry,” said Dan, as he rounded a little point, and a small clearing on the edge of the lake a mile distant came in sight. He lifted the oars out of the rowlocks, and dipped them in the water to make them run smoother, then, replacing them, rowed vigorously for a few minutes till the keel of his boat scraped on the pebbly beach.

Another guide, who had first reached the carrying-place, had already unloaded his boat, and placed it in an ox-team to be drawn across the Carry. The men shouldered the traps, and taking the dogs by their chains, lest they should be off to the woods unawares, straggled along to the other side, over a rough, miry road, bounded by raspberry-bushes. “O, you have brought your boat along with you, have you?” said one of the boys, as Dan appeared with his boat on his shoulders, looking much like a long turtle covered with its shell.

“Yes, Frank here, though he is the youngest, thinks we may catch the first trout if we can get to Ampersand Brook before the rest of you come along to disturb the waters; but any way I didn’t want to wait till the team can go back for my boat, as it will be near on to an hour, so I have brought it myself, and can go back for the traps in half that time; so Master Frank and I will have the first chance to try our luck.”

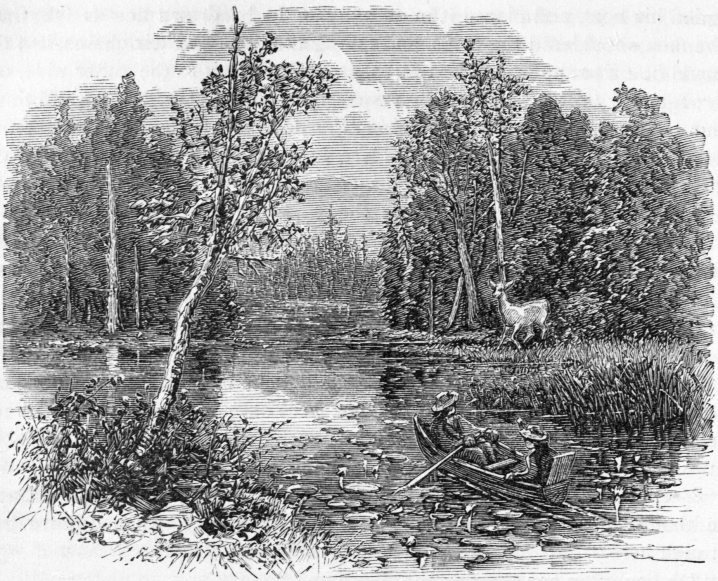

Frank and his companion were soon launched on a smooth little pond, the first of the three Stony Ponds, and were skimming swiftly over its mirror-like surface.

“Are those pond-lilies that cover so many acres?” asked Frank.

“Yes, and here is where the deer come down to feed o’ nights. Many is the time I have heard them champing the lily-pads, when I have been through here.”

“Do you often see them in the day-time?”

“Seldom enough, except when the dogs chase them into the water; for if they catch a glimpse of a boat, they are off before one can so much as seize his gun to aim at them.”

“I should like to see one, if nothing more,” said Frank.

“Well, keep a sharp lookout, and perhaps you may.”

They now wound into a little creek, so narrow that the shores were scarcely an oar’s length from the boat, and the pond-lilies grew so thick that the keel pushed them aside as the boat moved along.

“Here are fresh deer-tracks in the mud,” said Dan, nodding his head towards the bank; and indeed there were plenty of little hoof-marks all along up and down. The silence was profound. Grassy banks bordered the creek, and a few rods back from the stream rose the tall forest-trees, their front unbroken, except where here and there a tall pine towered above the rest into the still summer air, or an occasional white skeleton of a tree, long ago scathed by fire and bleached white by the snows and rains, stood sharply out from the dark woods behind it. The stream turned and twisted, but at each bend showed only a new phase of the same solitude. Kingfishers dipped occasionally into the water, and now and then Dan left off rowing to turn aside some log that had floated across the stream.

Presently they entered another pond, covered with pond-lilies like the first, and then again passed out by a winding creek.

“Hush, Dan, I see a deer; see, quick, quick,—shoot him!” Dan turned his head, and there, not many rods up the creek, stood what looked to Frank like a large deer, gazing attentively at them. He did not move, and Dan, giving the boat a pull up to the side, pushed along under the overhanging grass. He took his rifle and snapped it,—the cap was a bad one. Frank was so excited he could hardly breathe as he kept his eye fixed on the motionless animal. The next time Dan was more successful. His aim was sure, and the creature fell. With a few oar-strokes Dan reached the spot where it lay dying. But now poor Frank’s joy at “killing a deer” was turned into grief, for the creature on the grass was a pretty little fawn, about half grown.