* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

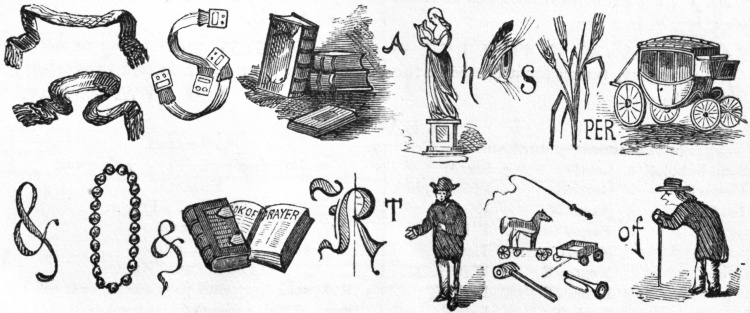

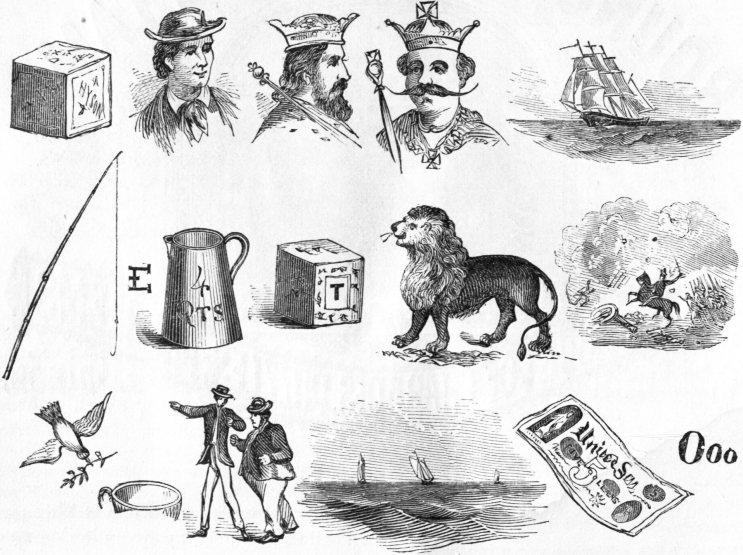

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 3, Issue 5

Date of first publication: 1867

Author: J. T. Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: July 17, 2018

Date last updated: July 17, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180786

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Delphine Lettau, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. III. | MAY, 1867. | No. V. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

DISCOVERING THE SCHOONER.

Drawn by S. Eytinge, Jr.] [See Too Far Out, page 271.

Engraved by W. J. Linton.

ound-the-World Joe sat on his front stoop,

moping; and as Charley Sharpe and I came up, he

turned his face the other way, so as to pretend not to

see us, and blew his nose, and began to whistle.

ound-the-World Joe sat on his front stoop,

moping; and as Charley Sharpe and I came up, he

turned his face the other way, so as to pretend not to

see us, and blew his nose, and began to whistle.

“I say, George,” said Charley, “something wrong with Joe this morning,—know by the way he blows his nose.”

“Pooh!” said I, “got a cold in his head.”

“Got a warm in his heart, you mean. Georgey, when you see a straightforward chap like that overdo it blowing his nose, and dodge with his handkerchief round the corners of his eyes, and begin to whistle (high old whistling!) like a sick bobolink that’s had too much green persimmons, it’s his feelings that are too many for him.”

“Think so, Charley?”

“That’s what’s the matter, Georgey.”

“Hello, Joe!” said Charley, “here we are again, as lively as a pair of polliwogs in a duck-puddle.”

“Good morning, lads,” said Joe, gravely; his eyes were red, his voice was husky, and his lip quivered.

I made a sign to Charley to stop joking. But, dear old fellow! he was as serious as I, only he had a different way of showing it.

“Feel badly, Joe?” I asked. “How’s your mother this morning?”

Then Joe jumped up, and turned his back to us, and stamped his foot, and said, “Con-found it! Confound it!” says he, “I don’t deserve to have any mother. If she was to die this very minute, serve me right. I’m no better than a piratical cannibal; that’s what I am,—a pi-rat-i-cal can-ni-bawl!”

“Look here, Joe Brace,” said Charley, “if you mean to say you’ve been mean enough—”

“Hold your tongue, Charley,” said I. “What’s the matter, Joe?”

Joe looked at Charley as if he didn’t know whether to knock him down or shake hands with him; and then he said: “Well, you see, lads, here’s how it is. This morning, at breakfast, the old man he begins to talk about getting the ‘Circumnavigator’ in trim for another voyage—to California, or Australia, or somewhere. And mother,—she says she hopes I’ll stay at home with her next time. And I says, ‘I’d look pretty staying at home, wouldn’t I? I’d like to know who’d bring him his coffee at four bells, or tell him how she heads. Why, mom,’ says I, ‘he’s no more fit to go to sea by himself than a hen.’ At that the old man he laughs, and his coffee goes the wrong way and chokes him. But mother, she looks steady into the teapot, the way she does when it’s drawing, and winks her eyes very hard,—’count of the steam, I guess; and says she, ‘It’s a long, long, lonesome time, my boy,—a lonesome, anxious time,—and you’re the last I’ve got,—and I’m getting old and foolish—’ Con-found it!” said Round-the-world Joe, and he stamped his foot and blew his nose again.

“Well?” said I.

“Well?” said Charley.

“Well,” said Joe, “of course I made a piratical cannibal of myself. ‘O, bother,’ says I,—‘don’t talk like that, mom; do be more manly; you’re worse than a sea-sick cook.’ And then I happened to cast an eye over towards the old man, and—well, he was just a-lookin’ at me,—that’s all, just a-lookin’ at me. You never caught my old man lookin’ at you, did you?”

“No,” said I.

“Well, you needn’t want to. ‘Youngster,’ says he, ‘do you know what day this is?’ ‘Friday, sir,’ says I. ‘Day of the month?’ says he. ‘Tenth of April,’ says I, mighty peert. ‘Tenth of April,’ says he. ‘And where were you last tenth of April, sir, about this time o’ day, if me and that sea-sick cook may make so bold as to ask?’ He was a-lookin’ at me, and I was a-thinkin’. ‘Straits of Malac—’ And then it all fell on me like a house, and I wished I was dead; but I didn’t say another word. Me and the old man just looked at one another, and I got up and kissed mother, and came out here.

“Lads,” said Joe, “last tenth of April, in the morning, we were in the Straits of Malacca, and a white squall struck the ‘Circumnavigator’ while we were taking in sail; and somehow my chum, Ned Foster, got knocked off the foreyard and fell on deck, hurt so he only lived an hour; and the last words he said were these: ‘Joe,’ (that’s me,) ‘take my chest home to mother,—she’s a widow, you know; and tell her I have read that Bible every day, accordin’ to promise; and it’s all right. And, Joe,’ says he, ‘I want you to make me a promise now.’ I couldn’t say anything, you know; but I looked straight into poor Ned’s eyes. ‘All right,’ says he. ‘You’ve got a mother, too, Joe,’ says he, ‘and she’s as good as gold, I know, if she ain’t a widow. Promise me, that you’ll keep loving her all the time, as if the very next minute was to be your last.’ I couldn’t say anything, you know; but I squeezed his hand, and he squeezed mine, and said it was all right. And it was all right—with him. Con-found it!”

“Well,” says Charley Sharpe (very shaky), “guess you do love your mother, don’t you? Guess she knows it, don’t she? If she don’t, she’s only got to send for one of them spiritual magnetic clearvoysters, and they’ll tell her all about it for a quarter.”

Of course, that made Joe laugh, (which was just what Charley was after,) and then he blew his nose again and began to sing:—

“Why, what’s that to you, if my eyes I’m a-wiping?

A tear is a pleasure, d’ye see, in its way;

’Tis nonsense for trifles, I own, to be piping,—

But they that ha’n’t pity, why, I pities they.

“If my maxim’s disease, ’tis disease I shall die on,—

You may snigger and titter, I don’t care—”

“Joe,” said I, “tell us some more about that funny spree you went on with Little Pigeon and the other Chinese chaps. What did you and Barney Binnacle do with all your sapecks?”

“Flung about a peck among the beggars,” said Joe. “Reckon there must have been a thousand to scramble for them.”

“Now, that’s what I can’t get through my hair,” said Charley.

“How’s that?” said Joe.

“Why should there be so many beggars in China,” said Charley, “when it takes fifteen sapecks to make one cent, and every sapeck will buy a handful of rice, and a handful of rice will keep one Chinaman going, and a cent’s worth will stuff his wife and children.”

“That’s just how it is,” said Joe. “It’s so much easier to ask for a sapeck than to work for it, and so much more pleasant to give the sapeck than to smell the beggar, or squirm at the sight of his sores, and so many more people have sapecks to spare, and a sapeck is such a small thing to give or to get, and rice is so cheap and filling, and Chinese beggars are so nasty and saucy,—that’s just how it is. It’s my opinion it’s the sapecks that make the beggars, and at first the beggars make their own sores on purpose to beg with, and then the sores spread and make more beggars, until at last there’s so many of them they breed a famine.”

“That’s it, Joe,” said Charley, “it’s the Political E-conomy; they get it just like the small-pox. Don’t they, Georgey? You know.”

“The Ex-ces-sive Cir-cu-la-tion,” said I, “of an In-fini-tesi-mal Cur-ren-cy by offering a Pre-mi-um to Idleness and Indifference diminishes the Number of Pro-du-cers on the one hand while it increases the Number of Con-su-mers on the other hence says Richard Cobden—”

“Hence,” said Charley, “no gentleman’s library is complete without your father’s Cyclopædia; and it must be a sweet consolation to John Chinaman, when he is starving to death, to know that you and that Cobden boy know what killed him.”

“Now, if you are going to talk Politics,” said Round-the-world Joe, “you may count me out; likewise Economy,—I didn’t ship for either of them. But there’s one thing I do know: when John Chinaman has made up his mind to die of starvation, somebody had better stand from under.”

“How so?”

“Why, when a dead Chinaman’s body don’t get buried, his soul gets mad, and turns into a devil, rampaging around and raising Cain generally. All China believes that gives fits to cats, pip to chickens, bots to horses, and hollow-horn to cattle, and afflicts the folks who neglected its carcass with crosses in love, miseries in their bones, and bad luck in their speculations. So somebody invented the Society for the Distribution of Gratuitous Coffins, to head off the spiteful ghosts of the beggars that die of hunger in the porches of pagodas, or freeze to death under the lee of graveyard walls; and nobody is safe from fits, pip, bots, hollow-horn, unrequited love, blanks in the lottery, or getting euchred, who doesn’t belong to the Society for the Distribution of Gratuitous Coffins.”

“Sho!” said Charley Sharpe.

“That’s so,” said Joe. “Then there is a King of the Beggars, enthroned on a dirty dog-mat at Pekin, who is as much of a monarch in his way as the tremendous ‘Son of Heaven’ and ‘Brother of the Sun and Moon’ himself. He reigns over all the gypsies, ragamuffins, rapscallions, and tatterdemalions in the Central Flowery Kingdom, and they acknowledge allegiance to him, and pay tribute into his treasury. On certain days, according to law, he lets loose upon the land the whole nasty swarm of them at once, and they go raiding upon cities and villages, gayly flourishing their monstrosities and deformities and leprosies and sickening sores, and all their crawling abominations; howling like wolves, and laughing and crying like hyenas, and grunting like hogs, and—”

“Ugh!—stop that, Joe,” said I, “do!”

“Away they go,” said Joe, “like all the plagues of Egypt boiled down to a pint; and they hop and crawl and wriggle and gnaw and blow, till the poor people in the towns begin to ‘call in their emergence upon countless saints and virgins,’ and dragons and ghouls, to come and help them; for no man dare strike one of them, or drive him from his door, on Beggar-day. Then up steps the King of the Beggars and calls a town-meeting, and offers to call off his frogs and lice and flies and locusts for so many cart-loads of cash, cash down. And the Board of Health pays the money, and away they go, hopping, crawling, wriggling, gnawing, blowing, to the next town. But all this time the King of the Beggars is personally responsible for every man of them; and if they are guilty of anything extra-outrageously outrageous,—such as scaring a prefect’s pony, or waking a judge’s baby,—the Mandarins seize his ragged Majesty by the tail of his head, drag him to the stocks, and then and there pound him with bamboos on the pit of the stomach till he squeals like a stuck pig.”

“That’s what I want to go to China for,” said Charley Sharpe.

“As how?” said Joe.

“To get bambooed. They say that when you have come to the worst of the hurting part, as if one more lick would kill you dead, then it begins to feel good.”

“I don’t know how that may be,” said Joe, “but I dare say Tea-Pot and Little Pigeon, if we had them here, could unfold a tale, as the ghost says, that speaks the theatre piece.”

“Who was Tea-Pot?”

“One of Little Pigeon’s friends that we went on the ten-cent spree with. He was a short, round chap, with very little legs and a great deal of stomach, and Barney called him Tea-Pot because he was built so squat. Tea-Pot and Little Pigeon both got bambooed tremendously when they went home, for losing so many sapecks that day.”

“How did they lose them?”

“Gambling,” said Joe; “but it was not for that that they were triced up, and caught their three dozen.”

“What for, then?” asked Charley.

“For not winning. Every man, woman, and child in all China ‘fights the tiger’ like the very old—John Morrissey; and is ready to go his whole pile on cards, dice, dominoes, chess, checkers, skittles, cock-fights, quail-fights, spider-fights,—any kind of a ‘lay out,’—as naturally as if they were all born on Mississippi steamboats, rocked in California cradles, weaned on Saratoga water, and had been running for Congress ever since. They’ll bet everything they can raise, from their fans and chopsticks to their wives and children. Tea-Pot’s old man had been an awful sport in his time, and when he got his hand in, and the game was lively, didn’t mind what he put up. He had lost Tea-Pot’s mother at Thimble-rig, and his own tail at Simon-says-Wiggle-Waggle, and the fingers of his left hand at All-fours; and once, at Shanghai, Little Pigeon’s father lost all his clothes in the dead of winter, spider-fighting, and had to run about among the bake-houses, and cuddle up to the warm walls, first one side and then the other, like a sick kitten to a hot brick,—that’s the naked truth.

“The way they play for fingers is funny: two of them sit down to a small table, with a flat stone, a small, sharp hatchet, a dish of nut-oil hot, with a lamp under it, and a pack of cards. As often as a game is lost and won, the loser lays one of his fingers down on the flat stone, and the winner takes the hatchet, chops the finger off and puts it in his pocket or his mouth. Then the loser sticks the stump in the hot oil to stop the blood, and takes another hand.”

“Now you Joe!” said I.

“Take my after-davit.”

“Certainly,” said Charley, “that’s one of the advantages that China offers to the traveller, over all other foreign parts; you can’t lie about it. If the last tough story is rather hard to swallow, the Chinese will make it all right for you next time. Like the Jerseyman that the wonderful Fakir of Blunderpore, in performing his celebrated gunpowder trick, blew through the roof of the theatre, all you’ve got to do is to wait till you come down, and wonder what they’ll do next. You pays your money, and you gets the worth of it.”

“But Joe,” said I, “when they’ve lost all their fingers, how do they work their chop-sticks?”

“Why, you see,” said Joe, “by the time they’ve got to that part of the game, they don’t generally have any more use for chop-sticks; for as long as they’ve a grain of rice left, they stump it down.”

“But what do they do with all the old fingers?”

“Sell them to the pickpockets and sleight-of-hand people,” said Charley, “or plant them, and raise presti-digit-taters.”

I can’t exactly see how that is!

“Tea-Pot and Little Pigeon,” said Joe, “lost all their sapecks on a cricket-fight. On the corner of Cream-jug Street and Slop-bowl Alley, a member of the Chinese Fancy had a lot of fighting crickets in bamboo cages, exactly like bird-cages, only smaller,—you can see them at the China shops on Broadway and Washington Street; and on a pretty lackered table he had a deep soup-plate. Little Pigeon and Tea-Pot cried ‘Hi-yah!’ when they saw him, and showed their sapecks, and called for a lay out; and Little Pigeon said, ‘Spose one piecee fights makee, too much fun can secure, Bul-lee!’

“Then he and Tea-Pot selected a pair of the peertest, that were well matched in size and weight,—regular game crickets, bred and trained, none of your common tea-kettle kind, that sing Peerybingle babies to sleep on the hearth. And Tea-Pot named his cricket ‘Fire-Dragon,’ and Little Pigeon’s was called Gong-Devil, and they set them down on the edge of the soup-plate, and asked the Fancy gentleman if he would be Umpire, and he said he would. Then Little Pigeon offered to bet the end of his thumb against one of Tea-Pot’s eye-teeth; but Tea-Pot said he couldn’t take it, because his teeth were all spouted, and he had to pay the pawnbroker so much a day for the use of them. So they were obliged to get along the best way they could, with sapecks. Then the old sport that was umpire said, ‘Gentlemen, make your game!’ and they both began to poke their crickets with sharp sticks, and call them names, to get their blood up. Tea-Pot called Fire-Dragon a sick donkey, and Little Pigeon called Gong-Devil an old woman, till they both got mad; for crickets are naturally quick on the trigger, and these two fellows were as gamy as Heenan and Sayers. The sick donkey began to rear up on his hind legs, and look round for something about his size; and the old woman began to claw and grit her teeth, as if she wished she knew what poked her. Presently they caught sight of each other, and with three cheers—”

“What?” said I.

“They jumped down into the soup-plate, and clinched in the middle of it, just where a blue man with a blue tree on his head was crossing a blue bridge on a blue umbrella. At it they went, give and take, nip and tuck, when, all of a sudden, before you could say Jack Robinson—”

“O, that won’t do at all,” said Charley; “you must say, ‘in even briefer time than this hasty, and I fear inadequate and incoherent description has occupied.’ ”

“Gong-Devil turned over on his back, groaned, shivered once, and then lay still,—dead as the mummy of Pharaoh’s mammy; and Fire-Dragon reared up on his hind legs and gave three—”

“Now stop that, Joe,” said I.

“But Little Pigeon snapped him up, turned him upside down, and hollered, ‘Foul!’ And, sure enough, there was a long pin sticking in his tail; Tea-Pot had put it there, to keep his pluck up. Little Pigeon and Tea-Pot both grabbed for the sapecks together; but the old sport that was umpire, he grabbed first and got it; and he said he’d hold it for them till the case was decided. But the case will not be decided in the reign of the present Emperor.”

“By the last advices from Pekin,” said Charley, “we learn that the cause has been carried up to the Supreme Court. But the Supreme Court has been occupied for the last three hundred years with the Great Green Cheese imbroglio, depending on the question whether the moon is in Hong Kong or Shanghai.”

Not far from the corner where the cricket-fight occurred was a show, where, as the bill announced, Signor Foo-Foo, the Champion Wizard of the Flowery World, from the Celestial Academy of Music at Nankin, would swallow his head and lift himself up by the tail; Signorina Poo-Poo, Fairy Fu-nam-bu-list, and Injin-rubber Rose of Loveliness and Elasticity, from the Imperial Cooper Institute at Pekin, would dance a break-down on a cobweb, and fling a double somerset through a finger-ring [☞This Establishment advertises in the Herald]; and Joe and Barney, with Little Pigeon and Tea-Pot and Young Hyson, and the rest of the Chinese boys, started to go there. But they hadn’t got far when they saw a pretty little girl, about five or six years old, running toward them, screaming with terror, and pursued by a Chinese madman of frightful aspect, who was yelling and cursing awfully, and stabbing the air with a great murderous dirk-knife. Joe and Barney sprang forward to rescue the poor little thing, but before they could reach her the madman caught her by the hair, plunged the horrid knife in her innocent bosom, and flung her body, quivering and bathed in blood, on the pavement. Joe and Barney stood for a moment, stunned and stupefied with horror, and almost turned to stone. But they recovered themselves quickly, and, Joe crying, “Come on, Barney!” and Barney crying, “I’m with you, shipmate!” they sprang upon the furious monster, and laid him on his back; and while Barney held him down by the throat, Joe wrenched the weapon from his grasp.

“Stick the knife in him, Joe, if he moves,” said Barney.

“Call the police,” said Joe.

“Po-lice! Po-lice!” bawled Barney. “Don’t be afraid, Police!”

“You can come up now, Police,” cried Joe; “it’s all over, and there’s no danger.”

But, instead of police, what should they see but the Chinese boys laughing as if they would go into fits. Little Pigeon was clapping his hands and dancing a crazy hornpipe with delight; Tea-Pot, rolling on the ground and red in the face, was behaving like an apoplectic dumpling; and another boy was slapping Young Hyson’s back to keep him from strangling. Even the murderer was grinning from ear to ear, and spluttering Pigeon-English as well as he could, with Barney choking him.

“Mi devil-man [conjurer]! Hi-yah! Mi makee one piece fine fun! Mi too muchee fine fun kin ketch, Hi-yah!”

And last of all, came the gory remains of the pretty little victim, holding out her shoe; and says she, in Chinese, “Please, sir, give me a cent to buy my grandmother a drink of water: she’s so hungry she don’t know where she shall sleep to-night.”

Then Joe looked at Barney, and Barney looked at Joe; and both said, “Chinese joke, I guess”; but Joe said, “Don’t see the point.”

Little Pigeon told Joe to “Look see one piece knife”; and then they did see the point. The handle of the dirk was hollow, and filled with sheep’s blood. When the point was thrust sharply against anything, the blade slid back into the handle, and at the same time a little valve flew open, and the blood spirted out.

Joe and Barney let the mad murderer up, and walked off, feeling very foolish. They filled the little girl’s shoe with sapecks, but they did not know Chinese enough to ask her not to say anything about it.

What with too much laughing and too many melon-seeds, Joe says, Tea-Pot was taken with the Chinese stomach-ache, and the other boys had to take him to a doctor. They found one on the corner of the street, perched on a high stool, with about a peck of red pills before him on a tray. His brother was a fortune-teller, and carried on business at the same table, with an old almanac, a calculating machine, a bottle of leeches, and a black cat; and as both of them wore long gray beards, and spectacles the size and shape of a saucer, and as they were both very deaf, and had to keep their heads close together, it was next to impossible to tell one from the other.

The doctor felt all of Tea-Pot’s different pulses twenty-four times, and played twenty-four different tunes on them with his fingers, as if they were two dozen pianos; and then he laid his head to the fortune-teller’s head, and they both stroked their beards, and both looked through their spectacles like a couple of owls, and both said, ‘H’m!—Hah!—Ho!’ And then the Doctor told Tea-Pot that his disease was in the vital spirits,—that the Ig-ne-ous Principle and the A-que-ous Principle inside of him had fallen out about something, and were fighting in his stomach like Kilkenny cats; that the A-que-ous Principle was getting the worst of it; that Reason required that something should be done to back up the A-que-ous Principle, for fair play; and that, as water-melons and soap-suds were friends and relations to the A-que-ous Principle, it was plain that Tea-Pot ought to eat a great many water-melons and drink a large quantity of soap-suds; and that it was his professional opinion, after playing the twenty-four tunes on the twenty-four pulses, according to Reason, that, if Tea-Pot did not continue to grow worse, he might, at the propitious hour, to be calculated from the seven moons and the seventy stars, begin to grow better, by virtue of the green medicine depending on the element of wood. “My compliments to your respectable mother,—Hi-yah! H’m!”

Then the other old owl told Tea-Pot’s fortune, to see whether he would pull through or not. He said that, according to Reason and the Tom-Cats, and according to the Leeches and the Rites, it appeared that two events personally concerning Tea-Pot might happen in the course of time,—Tea-Pot might die, and Tea-Pot might be a great-great-grandfather; and that, in order to avert the first, he must consult Doctor Owl, and in order to avert the second, he must take Doctor Owl’s opinion. “My compliments to your respectable mother,—Hi-yah! H’m!”

Then Round-the-world Joe paid the bill, Tea-Pot being broke; and Barney Binnacle tied the two owls’ tails together, and they all came away. And as it is not according to the Rites for one Chinese gentleman to pull, handle, or otherwise meddle with another Chinese gentleman’s tail, I presume those two old owls are still patiently waiting for the propitious hour, according to the Leeches and the Tom-Cats, when their respectable tails may be untied.

George Eager.

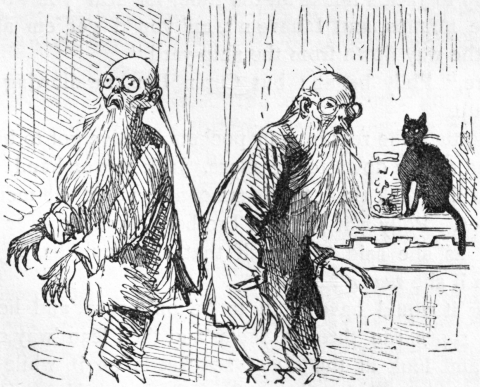

Captain Ben was in a hurry. To be sure it was only five o’clock in the morning, but he had been up since daybreak bringing ashore in the schooner’s boats everything he did not want to leave on board, and piling them into the wood-shed, till Mrs. Ben affirmed it would be as much as their lives were worth to try and get a stick of wood.

After long deliberation it had been decided that the Mary Ann could not go to sea again till newly copper-bottomed, and to-day Cap’n Ben and his men were to sail up the bay and leave her at the ship-yard. Polly and Nathan and Jimmy could hardly eat their breakfasts for joy at the idea that father would be at home at least a fortnight; and yet there was a small pout on Polly’s red lips. The boys were going up the bay with father, and coming home in the evening laden with fire-crackers, rockets, and pin-wheels, for to-morrow would be the Fourth of July.

Polly had begged to go, but as Cap’n Ben and the boys were coming down in an oyster-boat, and very likely might not run into the cove till late at night, mother had vetoed the plan, and Polly’s own sweet temper was struggling with a little natural indignation that the boys should do more than she could.

“Nathan’s had the measles, mother, and I haven’t, and I should think I could keep awake as long as he can; he ain’t but nine any way, and I’m seven and a month.”

“Good reason you didn’t have the measles,” shouted Nathan, “when they kep’ you up to Jack’s house all the time, for fear you would. Anyhow you’ve had the mumps, and I haven’t, an’ you’d get ’em again, sittin’ in dirty water all the way down from the ship-yard.”

“I don’t care,” Polly began; but Cap’n Ben, swallowing his last mug of coffee, rose up.

“Come, boys, tuck the rest in your pockets; we’ve got to be off.”

Polly followed slowly down to the shore. Jack was on hand, ready to bring back the boat which took them to the schooner, where the men were already weighing anchor. Polly watched her brothers climbing over the side, and heaved a sigh as she said to herself that she could have gone up just as easy as Nathan if she wasn’t a boy.

How exciting it would have been to be on board, and hear the blocks squeak as the ropes ran through them, and then lean ’way over as the anchor came up, and look at the queer sea-weeds on it, while the schooner tacked, and then with filled sails sped up the bay. Here was Jack coming back, though, and perhaps he was going to dig clams on their beach to-day, and she could have him to play with. Polly ran out to the very end of the point. It was only a rod or two from the big rock and the buoy where they moored the spare boats, though quite deep water lay between.

“I say, Polly,” said Jack as he came nearer, “I’m going to leave the boat here, and you get into the punt an’ come out to the rock, so ’t I can get ashore. I don’t want to swim, ’cause I can’t take time to dry my clothes.”

Polly ran back to the beach where the punt lay, half in and half out of the water, pushed off bravely, and rowed out to Jack, who, fastening his skiff carefully to the buoy, jumped into the punt and took the oars in his own hands.

“Good for you, Polly,” said he. “There ain’t many girls small as you be can row a boat, and not one ’longshore can swim a stroke but you.”

“I wouldn’t ’a’ learned,” said Polly, “but father said I wasn’t fit to be a sailor’s little girl if I didn’t, an’ I learned just as fast as Nathan. I can swim out to the big rock now, an’ not be tired one bit,” and Polly pointed to where they had left the large boat. “What you going to do to-day, Jack?” she added.

“Goin’ to dig like a streak, so’s to have time for fun to-morrow,” said Jack. “I left the big basket down to South Point as I came along; you come with me, Polly, if your mother’ll let you.”

Polly ran up to the house, where her mother was busy baking pies and gingerbread for to-morrow’s festivities.

“Do what you want till supper-time, so long as ’tain’t mischief,” she said, “for I have no time to look after you. Take enough in your pockets for you and Jack, and be off with you.”

“I’ll swim awhile, mother, mayn’t I?” said Polly. “The water’s good an’ warm, an’ Jack’s going to be round all day.”

“Not to-day, Polly,” answered her mother. “You’ve got a cold now, an’ you’ll get more if you go in a swimming, an’ then race round in your wet frock.”

“But, mother!” said Polly, “I wanted to go out to Black Rock an’ get some Job’s-tears off the sea-weed on the end: there’s beautiful ones there.”

“You can get ’em another day,” said her mother, “or may be Nathan’ll do it for you to-morrow; but you mustn’t think of it. Run off now, and play by Jack like a good girl.”

Polly shut the door hard as she went out. First to have to stay at home because she was a girl, and then not to go in swimming when she had set her heart on it. She could not feel good-natured, and went sulkily along towards the Point.

Half-way down, the rocks, thick enough anywhere alongshore, were piled up together, and one great one arched over, and formed what the children called their house. Here Nathan and Jimmy brought all treasures of smooth pieces of wood for boats, stray bits of bunting, curious shells and sea-weeds, and here in one corner, sacred to Polly, were her doll, and the wooden cradle manufactured for it by her father, gay bits of broken china, and a little wooden bench. Here, through spring and summer weather, the children played, and when autumn winds began to blow there was a grand moving time to the wood-house chamber, where through the winter they rioted till spring came again.

Polly felt too cross to meet Jack just then, and so stopped to take a look at Matilda Ann, her doll. The cradle was in sad disorder. Matilda must have been restless in the night; for the little patchwork quilt lay at one end of Polly’s corner, and the sheets at another. She made up the cradle smoothly, and then tried to play that Matilda Ann had kicked off the bedclothes, and made herself sick, and must have a doctor immediately.

“Jack!” Polly called, going out on the shore, “I want you to come and play you’re a doctor.”

“Couldn’t,” said Jack; “I’ve got to keep a doctoring these clams. I’m puttin’ ’em to bed in this basket fast as ever I can.”

Polly didn’t even laugh, but went back slowly, and settled down again to teach Matilda Ann her letters, and so passed away the time till nearly noon; but it grew harder and harder. All Matilda Ann needed was necklace and bracelets, which should by this time have been made from the Job’s-tears, as ornaments for Fourth of July.

“I can’t stand it,” said Polly. “Only to think how nice she’d ’a’ looked!” Then a new idea came. “I’ll go out in the punt,” thought she. “Mother only meant I mustn’t get wet, and I sha’n’t in the punt. It’ll be better than swimming, I do believe! If I’d ’a’ swum, I’d had to get into the big boat to get round to the very end where the best shells are, for father said I mustn’t go to the very end of the rock yet awhile, when I swum, ’cause it was too deep water, an’ that I mustn’t get into the big skiff, ’cause I couldn’t manage it; so the punt’s the very thing!”

Alas for Polly! Jack, finding the supply of clams on South Point running short, had taken the punt and was rowing down the shore to a beach where he knew they abounded. It was provoking. There lay the rock, hardly a stone’s throw from the shore, and there was Jack, pulling off over the smooth water, and only shaking his head a little as Polly screamed to him to come back.

“I can’t mind mother this time, anyhow,” said she, “for I’ve got to have those shells, and Jack’s gone off with the punt.”

Back she ran to the rock house, pulled off her clothes, and put on the old pink frock she wore as a swimming dress, and then down to the shore again, and into the water. How warm it felt, and how easily her little limbs made their way through it! She quickly reached the rock and sat down a moment to take breath. There were no shells near her, but at the other end Polly saw them shining on the great clusters of sea-weed. The skiff rocked softly up and down near her. “So much nicer,” thought Polly, “to just row round there an’ get all I want, than to crawl down the rock for ’em through all that nasty green slime and stuff.”

She stepped into the boat, untied the rope which fastened it, and rowed a stroke or two. “How easy it goes!” said she. “Father didn’t know, when he said I couldn’t manage it.”

Nevertheless, reaching the jagged point of Black Rock, just visible above water, it did not seem so easy to gather shells in this way as she had thought. The boat would not stay still, but bumped up against the rock, and then swung round in a very trying way. She caught at a trailing length of sea-weed, covered with the little gray and white shells, and pulled it in to her, sitting down in the stern to pick them off. This done, she moved back to her oars, intending to go round on the other side. One was there, but the other, knocked back and forth against the rock, had taken matters into its own hands, and was quietly floating off to sea. Polly’s impulse was to jump after it. “If I do,” said she, “the boat will get away, for it’s untied. I’ll have to get back to the buoy with one oar, and when Jack comes back, I’ll ask him what I’d better do.”

Getting back was not so easy. The current setting out to sea had made it possible for her to reach the end of the rock toward the shore, but as she had swung round on the ocean side, that same current, stronger than any force in her little arms, was surely drifting her away from rock and buoy. Polly pulled hard at her one oar, but two could have done her no good then. There was already quite a space of smooth green water between boat and rock,—farther than Polly had ever dared to swim. She stood up in the bow and screamed, “Mother! mother!” But mother, busy in her kitchen, far up on the shore, heard nothing, and Polly sat down, quite bewildered with fear. “Perhaps Jack will see me,” she thought; but Jack was only a little black speck on a distant beach, and no boat of oysterman or fisherman was in sight. The tide was going out, and Polly saw herself drifting, drifting, steadily out to sea. There we leave her.

Jack dug till two or three o’clock, filling his basket and the end of the punt with clams, and then rowed very slowly up to the cove. He was hot and thirsty; so, drawing his boat up on to the shore, he ran up to Cap’n Ben’s for a drink.

“Where’s Polly?” said Mrs. Ben.

“I don’ know,” answered Jack; “I thought she was here. I guess she’s down to the rock house playing with her doll.”

Mrs. Ben went quickly down to the shore, and on to the rocks. Jack heard her cry out as she reached them, and ran fast.

“Jack! O Jack!” she said. “Polly’s drowned! O my little Polly!”

Jack saw the clothes and shoes lying near her, but his quick eye had discovered, as he ran, that the boat was missing. “No, she isn’t,” he said; “she ain’t drowned at all. The boat’s gone from the buoy, and she’s in it, I know.”

Jack ran out to the end of the Point, where we first saw him, and looked out over the water. There was certainly a boat in the distance, and on it a little pink speck. “Polly’s out there!” he shouted. “I’ve been out farther’n that, an’ I’ll row hard’s I can, an’ bring her back. ’Taint so far”;—and he flew back to the punt, threw out his clams, and pulled off furiously.

“Save your strength, Jack,” called Mrs. Ben, “an’ I’ll send men off fast as I can find ’em”;—and she ran down the shore towards a fisherman’s house.

Every man and boy was away,—gone up the bay to sell off as much as possible before the Fourth, and there was nothing to do but to wait, patiently as might be, for Cap’n Ben’s return. She went up to the bluff and watched the two boats. Jack was pulling strongly; but how hard it seemed that there could not be some tough fisherman with him, to lengthen the strokes, and gain upon the fast-disappearing little boat! The sun was almost setting now, and they seemed sailing into a gold and crimson sea; but Mrs. Ben only thought that soon it would go down, and then her little Polly might die of fright in the darkness. The breeze blew up freshly, and there was a swish of water on the beach.

“Lord help us!” said Mrs. Ben; “the tide has turned, and Jack never can row against it”;—and she sank down crying on the bluff.

Jack too had watched the setting sun, and pulled more vigorously. His arms ached, and he trembled from head to foot with the effort. He was passing now a little island, hardly more than a rock, and the only one near the Highlands, and the current set in strongly towards it. He was nearing Polly too, and she evidently saw him, for she waved the skirt of her frock, and Jack heard her voice coming faintly across the distance.

He set his teeth and pulled fiercely. There was a snap, and he fell back sharply to the bottom of the punt. The slender oar had given way. Jack groaned, then pulled himself up, and examined the damages. The oar was useless, but he stood up and paddled the boat along till safely beyond the current. It was perilous work. The little flat-bottomed thing almost went over, time and time again, as Jack stepped from side to side; but Polly was in plain sight, wild with joy at being so near safety, and paddling with all her little might. A few minutes’ intense work, and Jack was near enough to throw the boat-line.

“Hold hard, Polly!” he shouted; “hold on for your life!”

Polly pulled in the rope, the boats drew nearer and nearer, till with a great jump Jack found himself safe in the skiff, while the little punt floated alongside, bottom up. Polly caught hold of him, and the two children sank down with a great burst of sobs. Jack had just strength enough to pick up the sound oar as it floated by, and tie the punt to the skiff, and then lie back.

“I never was so tired in my life, Polly,” said he, “and I can’t row another stroke. We sha’n’t come to any harm now, for the night’s still, and we’ll be picked up in the morning. Cuddle down close to me, and we’ll go to sleep.”

Polly, worn out with terror and crying, and Jack, with hard work, lay down in the bottom of the boat, and slept almost as their heads touched the jacket which Jack had rolled up for a pillow. A light wind came now and then from the south, but the skiff slid easily over the little waves, and the children did not stir.

Far into the night Jack awoke. The stars were still shining, and for a moment he thought himself in his own little bed under the roof. In the east was a faint streak of light, the first sign of coming day. Polly’s little brown head lay on Jack’s knee, and she still slept quietly.

“It’s lucky it’s hot weather,” thought Jack, “or she wouldn’t be so comfortable with nothin’ on but that frock. He drew her closer, and put his arm around her. To care for somebody in that darkness was a relief, and Jack sat looking steadily off to the east, watching the faint glimmer change and deepen into dawn. It seemed hours to him before the first gleam of sunlight came over the water, and Polly opened her eyes, first dreamily, and then half wildly, as she stretched out her stiff little arms and legs.

“Shake yourself, and get the wrinkles out, Polly,” said Jack, “an’ then you stand in the stern and steer, and I’ll pull ahead, some nearer that schooner that’s coming along so spry. Let’s see which’ll catch up with the other first.”

Polly stumbled over the seats, and took the rudder in her hand. Planks certainly were not as comfortable as the trundle-bed at home: she ached from head to foot. “If I’d only something to eat, Jack!” she said.

“I’m hungry too, Polly,” answered he, “but we’re going to have a Fourth o’ July breakfast on that schooner.”

Jack was right. An hour later a boat pulled from the schooner, manned by two sailors sent out by the captain, to whom it had been reported by the man at the helm, that two children were rowing for the schooner as hard as they could pull, though what they were doing out to sea, at four o’clock in the morning, he couldn’t tell.

Jack quickly told the story, and then Polly had the opportunity she had so longed for yesterday morning, of climbing up a schooner’s side. It wasn’t nice now, one bit, for she felt as if every sailor leaning over the railing knew every particular of her naughtiness, and was laying it up against her, and she looked hard on the deck as the captain came forward.

Jack knew him at once. It was Captain Brown, who had been the year before at Cap’n Ben’s, and since then had been down on the South Carolina coast, and now came from Charleston. He took both the children to his own cabin, gave them a good breakfast, and listened to Jack’s story.

“How came you afloat in such a rig?” he asked.

Polly grew crimson as she explained, and wanted to sink right through the cabin floor.

“Never mind,” said the good-natured captain; “mothers do know best pretty often, an’ I guess you’ll think so too after this. Your father’s been cruisin’ round for you all night, most likely, and thinks may be you’re drowned. We’ll be lookin’ out for him.”

Just then there was a shout from the deck, and Polly was sure she heard her father’s voice. Too timid to go on deck in her strange dress, she shrunk back, but Jack had darted up, and was looking over the water.

Two boats were pulling rapidly toward the ship, and in one Jack saw his father and Cap’n Ben.

“Hooray!” he shouted till he was hoarse, while Captain Brown, whirling Polly up to the deck, held her out like a flag.

What a meeting it was! Poor Cap’n Ben had not reached home till nearly midnight, and then had set out at once with Jack’s father, who was in great fear for his boy’s safety too. Three of the neighbors had already gone out; but in the darkness little could be done. They had thrown up rockets and shouted, but the worn-out children knew nothing of this, and it was not till Cap’n Ben, looking at the schooner through his spy-glass, had recognized his own boat towing behind, that he began to feel a little hope.

Now they were miles from home, and it would be a sad Fourth for mother and Nathan and Jimmy till they came sailing in again. Captain Brown crowded all sail, and they went swiftly on, while Jack and Polly, too tired to run about, sat and listened to the stories Captain Brown was telling of his year down South, of the Charleston people, and of a Mr. Calhoun in particular, who he said didn’t want the United States to be united any longer, and who, with a lot of other Nullifiers, would have had their way, if President Jackson hadn’t sent down troops and hindered them.

Polly, in her father’s arms, looked and listened, till Captain Brown’s voice seemed to come from away off, and then she slept again.

When she opened her eyes she was on deck. The stars and stripes were flying, gay bunting decked every stay, and the negro cook brought out his banjo and strummed Yankee Doodle as they sailed up to the cove. She could see the shore plainly, and there were her mother and Nathan and Jimmy and all the neighbors. Jack threw up his cap as he saw his mother among them, and could hardly stand still while the anchor was dropped, and the boats lowered in which all went ashore.

The two mothers cried together,—Jack’s mother over Polly, and Polly’s mother over Jack,—and then everybody went up to the little brown house, and after all didn’t get in, because, not having been built with such an end in view, the room couldn’t possibly hold more than half of them.

Not a word was said about Polly’s disobedience. Only in her little heart she had made a vow, when drifting away alone in the boat, that never again would she bring such sorrow to other people as she knew mother and father felt at her trouble. She kept close to her mother all day, only going away to press every good thing she could think of on Jack, who declared she meant to kill him.

At night they set off their fire-works, with the addition of some splendid ones which Captain Brown brought from the schooner. The last piece was “Union,” in great letters of red, white, and blue.

“Hooray for Union!” shouted Jack and Nathan and Jimmy together, and “Hooray for Union!” answered the lookers-on as the last spark went up.

“Secession’s no go for gals nor for States,” said Cap’n Ben. “Jack’s been our Jackson! Hooray for Jack!”

Helen C. Weeks.

Her father had gone to the village one night, and left her quite alone in that bit of a house; it was really very small,—it did not seem much larger than a dog-kennel; but it was large enough for two people, especially if one were such an atom as Ruby. It was a very lonely house, too, for it stood half-way up a mountain where the shadow of the pine forest was darkest, and the great white stretch of snow that sloped down through it lay still and untrodden,—still, except when the icicles clattered sharply down from the trees on it. Ruby could hear them often, when she sat alone; she could hear the wind too, sobbing around the house as if its heart were broken, and then wailing off over miles of mountain solitude. Sometimes she could hear the chirp of a frightened bird in its nest, or the mournful cry of the whippoorwill over in the swamp. Once she heard the growl of a distant bear that had lost his way.

But she never thought of such a thing as being afraid. Her father found and shot the bear, the next day, and it was the only one that had been seen on the mountain for years. As for the icicles, and the wind, and the whippoorwill, she had heard them ever since she could remember, and they did not disturb her in the least. On the contrary, she thought they were very pleasant company when her father was gone, and she used to sit at the window for hours together, listening to them.

But she had her playmates in-doors as well as out. Of these, her favorite was the fire. Now I do not believe there are many people who can build such a fire as Ruby could. She used to gather such piles of light, dry brushwood, and such branches of dead oak-leaves, which made the prettiest, quivering shavings, and she had such fragrant pine-cones for her kindling-wood!

When the hearth was all blazing and crackling with a fire about as tall as she was, she used to sit down before it, and stretch out her hands with the fingers close together, so that she could see the beautiful, brilliant blood in them; or take off her shoes and stockings, and put her pretty pink feet almost into the ashes to warm them; or sit with her eyes very wide open, and look and look into the pile of blazing fagots, till she made herself think that it was some great city in flames, towers falling, steeples tottering, churches crashing, and hundreds of houses in hundreds of streets turned to living fire.

Or she would watch the lights and shadows chasing each other all over the little low room. Where they flecked the ceiling, they painted rare fresco-work, that shifted and changed to some new pattern every moment; where they quivered over the bare plaster of the walls, they hung them with tapestry drooping and rich with quaint devices, and glittering with embroidery of black and golden threads. Every piece of the old, well-worn furniture,—the huge pine-bedstead, and Ruby’s little couch in the corner behind the chintz curtain, the rocking-chair and the cricket and the rough table,—all grew into the richest of foreign woods, with coverings of crimson and orange velvet, and the curtain waved itself into damask folds with jewelled fringes. As for the unpainted floor, that became the pavement of a palace, inlaid with ebony and gold.

At least, so Ruby used to think, and night after night, when her father had gone to the village to sell his wood, or the rabbits and squirrels that he shot in the forest, she would fancy, all the evening long, that she was not Ruby at all, but some beautiful, happy Princess.

Now how she came to be called Ruby I really do not know; but, after thinking of the matter two whole nights and a day, I have arrived at the conclusion that it was probably because her cheeks were as red as the reddest gem, and as soft as the sweetest of June roses, and her lips like beads of coral. I presume they were made so on purpose to be bits of crimson lights for her hair and eyes, which were as black as a summer’s night when the stars are hidden.

On this evening of which I started to tell you, she built up her largest and brightest fire,—for it was a very cold evening,—looked a few minutes at the towers crashing down through the city,—watched for the frescos, and the tapestries, and the gold and ebony pavements to flicker and glow into their places,—put upon her forehead her mother’s chain of gold beads that was kept so carefully in the drawer, and that served her for a princess’s crown; then she suddenly remembered another of her playfellows who would be in the room that night, and went to the window to look for it. Perhaps you will think it must have been a stupid companion, but I assure you that Ruby did not find it so. It was only the moonlight which had fallen silently in, and lay quite pale upon the floor.

The moon itself, looking very large and very lonely, was bright above the tops of the pines, against the blue of a far, faint sky. Every branch of every tree was tipped and edged with silver; all the foliage of the evergreens, and the dead leaves that had hung all winter shivering on their stems, flashed in the light like crystals; the footpaths stretched on through the woods, arched overhead and glittering, winding away and away like interminable fairy corridors, and the snow, like a mirror, caught all the pearly lights with which the air was filled, and threw them back. Ruby thought that they were little rainbow kisses tossed up at the moon.

She sat down on the floor right in a flood of light, with her hands folded, and her eyes looking up through the tree-tops, like a bit of a silver statue. And sitting so, she began to think—as Ruby loved to think when she was alone—about the rivers of molten pearl, and the diamond mountain, and the silver grass on silvered fields, and the trees with rainbows for blossoms and jewels for fruit, and the little ladies dressed in spun dew-drops, and—O, so many things that might be in the moon! If one could only find out for certain!

“O—I—really—why, what’s that? O, dear me!” said Ruby at last, scrambling to her feet in a hurry. For something or somebody was walking through the air, down upon the broadest of the moonbeams. Almost before she could draw a breath, it stood close upon the outside of the window,—something very large and very dark, but whether it was a man or an animal, Ruby could not decide.

“O, you can’t, you know,” she began, moving away a little, “you can’t possibly get through the window,—if you’ll wait till father comes, may be I’ll let you in at the door.”

But, to her unutterable surprise, the strange visitor at this came directly through the window without the slightest difficulty, or without making so much as a crack in the glass, and landed on the floor beside her.

“Oh!—if you please won’t!—why, I never did!” said Ruby, winking very hard, and looking around for a place to hide. But the stranger did not look in the least as if he had any thoughts of wringing her neck, or swallowing her whole, or doing her any harm whatever. He was only an old man,—a very odd old man, though. He was not so very much taller than Ruby; he had exceedingly white hands, and wore white satin slippers. His trousers were bright corn-color, and he had long pink stockings that came up to his knees. He wore a coat of white broadcloth, with sleeves a yard wide, and silver fringe and buttons. His vest was of faint, gray velvet,—whether it was faded or not, Ruby could not make out,—and on his head was a three-cornered cap of white tissue-paper, with a little black tassel on top of it. But by far the funniest thing about him was his face. It was as round as a dinner-plate, and perfectly white. His eyes were round, and his nose was round, and his mouth was round, and there was not a particle of color anywhere in them. His eyebrows and eyelashes, his hair, and his long, flowing beard, were like drifting snow.

He stood looking very solemnly at Ruby, and, after he had looked a minute without speaking, he made her so low a bow, that the tassel on the tip of his tissue hat touched the ground.

“Why—why, who are you?” stammered Ruby, with her eyes very wide open.

“Guess,” said he, setting his cap straight.

“Well, maybe,” began Ruby, trying very hard not to be frightened,—“maybe you’re one of the fairies that live in the rocks by the brook. I guess I saw you peekin’ out of a crack, last week.”

“No, you didn’t,” said the stranger; “guess again.”

“Or perhaps you’re some sort—some sort of a—sort of a king, you know,” said Ruby, hesitating, and feeling of the gold beads on her forehead; “and you’ve got a palace,—a real live one.”

“Guess again,” said the old gentleman.

“I shouldn’t wonder “—Ruby began to look again for a place to hide—“if you might be a—a ghost!”

The visitor burst into a laugh that echoed through the hut. “You’re a good Yankee! You haven’t come any nearer than you are to the moon.”

“I’m sorry I’m so stupid,” said Ruby, humbly. “Won’t you tell me?”

“O, certainly, with the greatest pleasure,—certainly, certainly, I’m the Man in it.”

“The Man in what?”

“The Man in the Moon.”

“O my!” said Ruby.

“Yes, I am,” continued he, growing suddenly very sober. “I have been ever since I can remember.”

“You don’t say so!” Ruby drew a long breath.

“I do,” asserted the Man in the Moon, with an air of gentle melancholy.

The crimson lights on Ruby’s cheeks fairly paled and glowed with curiosity. “If you wouldn’t mind telling me, I should like so much to know, sir, what—what on earth you came down for?”

“Your fire.”

“My fire!”

The old gentleman nodded. Ruby began to be afraid that he was going to make a bonfire of the house, or burn her at the stake.

“Cold!” said her visitor in an explanatory tone, shivering till every separate hair of his huge beard seemed to stand on end.

“What! don’t you have any fire up there, sir?” asked Ruby.

“Sat on a snow chair all last evening, and slept under one blanket of ice, and a frost bedquilt,—caught the worst rheumatism I’ve had this season,” said the Man in the Moon, sighing.

“O, how dreadful! and you don’t mean to say you saw my fire clear down here,—really?”

The old gentleman nodded again.

Ruby looked at the fire, then up through the window at the moon. “I don’t see how you could see so far, to save your life! Wouldn’t you like to come up and get warm, sir?”

The old gentleman had been seized with such a shivering fit just then, that Ruby thought he would shiver himself to pieces; which would not have been at all convenient, as she should not know what to do with the broken bits. She felt relieved, however, when he smiled the roundest of smiles out of his round mouth, and seated himself in the rocking-chair in front of the hearth, apparently with the greatest satisfaction.

“You—you are—really, you are very kind,” began her visitor, rubbing his hands. “I am not a thin man,” he proceeded, apparently giving himself no trouble about the want of connection between his sentences; “never was but once, and that was when I lived on putty and dew-drops for two years. We had a famine. I grew so small I got lost one day in my own coat,—couldn’t find my way out for four hours and a half.”

“Dear me!” said Ruby.

“Yes, you are very kind not to laugh, nor anything of the sort,” he continued, with an absent air,—“very, indeed; and it is very good in you to let me warm myself at your fire,—very. On the whole, I think it is exceedingly good.”

“Why, I shouldn’t think of doing anything else,” said Ruby, who had quite recovered from her fright; “but do tell me what you eat in the moon, when it isn’t a famine?”

The old man twirled his silver buttons, felt of the tassel on his cap, gave his head a little shake, and looked solemnly into the fire. “Depends on the season,—sand-cakes with hail-sauce are about as good as anything in their time. I have an excellent recipe for a sea-shell pudding; and for breakfast, I take fried snow-balls pretty much the year round.”

“O,” said Ruby. “Well, I should like to know if you weren’t cold, taking such a long journey in that hat.”

“O,” said the Man in the Moon, “I’m used to it.”

“But what do you wear it for?” persisted Ruby.

At this he looked very wise, and stared into the fire again, but said nothing. Ruby did not dare to repeat the question; so she stood with her eyes very black, looking at the funny, fat little figure and solemn white face beside her.

“Are there really little ladies up there,” she broke out at last, “with silver dresses, and diamond mountains, and castles with great pearl doors, and little princes riding white horses, and—”

“No, ma’am,” interrupted the Man in the Moon, “there isn’t anybody but me.”

“Don’t you get dreadfully tired of it?” said Ruby, beginning to feel very sorry for him.

He gave a little short groan, and, taking a black silk handkerchief out of his pocket, began to wipe his eyes. The handkerchief was so large that it dragged on the floor, and covered him quite out of sight, till he began to feel in better spirits, when he folded it up sixteen times, and put it back in its place.

“Who hems your handkerchiefs?” asked Ruby, suddenly.

“Hem ’em myself.”

“Why, how did you learn to sew?”

“O, I always knew how: first time I remember anything about myself, I was sitting on top of a thorn-tree, mending a pair of mittens.”

“You were?”

“Yes,” said the old gentleman, with a meditative air, “I was.”

Seeing how much enjoyment he appeared to take from the heat of the fire, Ruby suddenly bethought herself that he might also fancy some supper,—especially, poor man! as his bill of fare in his own residence was so uninviting. So she stole away on tiptoe to the closet, and brought out the remains of her supper,—a brown-bread cake, and a cup of goat’s milk. There was a bit of cold squirrel, too; but that was saved for her father. She spread them before her visitor on the table.

“Wouldn’t you like some supper, sir? It isn’t much; but I think it must be better than what you have at home.”

“Much obliged,” he said, looking first at the bread, then at the milk, then at her,—“very much indeed. Really, you are remarkably polite; but I never allow myself to eat away from home; it doesn’t agree with my constitution. The last time I did it,—I’d gone on a visit to my first-cousin, who lives in the planet Jupiter,—it gave me St. Vitus’s dance, and I had to walk on my head for a week afterwards.”

“Do tell!” exclaimed Ruby, who did catch some country expressions occasionally. “Well, I’m sure I wouldn’t have asked you, if I’d known.”

She put up the tea-things with a great clatter and hurry. Indeed, I am not sure but she was afraid the dyspeptic gentleman might be overcome by his appetite, and snatch a mouthful or two as she was carrying away the bread and milk. As for his exercising around the room on the tip of that tissue hat, though it might be a very interesting phenomenon, she thought she should, on the whole, prefer that he would not perform till her father came home.

She had no more than fairly locked up her dishes and come back to take a seat on the cricket, when she was attracted by a strange behavior on the part of her guest. He had been watching her, every step she took about the room, and now he folded both his little fat hands, and, looking at her very hard, gave her a solemn wink.

“What do you want?” asked Ruby.

Another wink; but he said not a word.

“I—I don’t exactly understand,” said Ruby.

Wink—wink—wink.

“Does the light hurt your eyes, sir?”

Wink—wink; but not a syllable did he say. Ruby was now really frightened. Perhaps he was a cannibal, and was going to make his supper out of her, after all! And, O dear! to think of being eaten up alive! And if she could only jump out the window and run away! And what would her father think when he came home, and found nothing but her dress and shoes and a heap of little white bones!

Wink—wink—wink—wink.

O dear! couldn’t she climb up the chimney?

And then he opened his mouth. Ruby screamed aloud, but she did not dare to stir.

“I say,” said the old man, “you’re a very polite young lady,—very polite; quite a sweet voice; and you’re very good-looking, too.”

“Dear no, sir,” said Ruby, drawing a long breath, and feeling very much relieved.

“What should you say,” continued the old gentleman, “to coming home with me? You might come back every Saturday night and see your father, you know.”

“O dear!” cried Ruby, turning pale, “I couldn’t think of it,—I couldn’t possibly.”

“O, it’s of no consequence,” replied the Man in the Moon, looking quite unconcerned,—“none in the world; it’s just as well. I think I must be going now. There won’t be anybody to ring the nine-o’clock bell if I don’t.” And before Ruby could find words to speak, he had walked with a serious air to the window and disappeared.

Ruby started, stared, and rubbed her eyes to look out after him. The forest was quite still; the wind had cried itself to sleep, and her father was just coming up the foot-path that led to the door.

Ruby, bewildered, looked up,—miles and miles away at the moon. The old gentleman’s solemn face was staring down out of it; and if it had not been for the branch of a little tossing birch-tree that came in the way just then, she would have been sure—perfectly sure—that he winked at her. Though I have been told that her father, with the stupidity common to parents, teachers, older sisters, and all ignorant people, continues somewhat sceptical on that point to this day.

It is reported, I believe, by a correspondent of a Patagonia paper, who found it in a Kamtschatkan exchange, which had it from the editor of a Boorioboola daily, who copied it from a popular magazine issued on the Mountains of the Moon,—where, of course, they ought to know,—that all this happened about the time when the Man in the Moon was hunting for a wife.

E. Stuart Phelps.

The eyes pertaining to Somebody opened very early, and very reluctantly, one bitter cold morning, in a front room on the third or fourth floor of a boarding-house “up town.” About the same moment, and perhaps the cause of that effect, the ears of Somebody became aware of a grating, scratching sound somewhere below. It might have been six o’clock, but the sun was not in the habit of getting up before that hour, probably because the weather was so cold, and, when inside shutters were partly closed, the hour seemed very doubtful. As before said, the eyes opened reluctantly, with a vague idea that it was somewhere about midnight, and the ears added to this impression sundry suggestions of burglars, and, listening intently to the mysterious pick, scratch, rattle, were almost convinced that some visionary thief was about to seek a fortune in a clerk’s boarding-house. But the unearthly whoop of a milkman, and the sound of his flapping arms, as he stood up in his cart, waiting for the tardy Bridget, put to flight such absurdities, and Somebody turned over for another nap. But for once curiosity was destined to overcome indolence, and a hasty rush to the window and a peep through the shutters solved the problem of what made that scratching.

In the next building was a bakery, and, as a natural consequence, there were plenty of ashes to be disposed of; and, not having the fear of the police before their eyes, the people had poured them in one heap in the gutter, instead of collecting them in box or barrel “as the law directs.” The accumulation was fast freezing into a solid mass, and growing to a mountain, quite enough to excuse the cart-men from taking it away. Thus much Somebody had seen and passed by, daily, but not till this particular morning had she seen the “atom of animated nature” which crowned the pile.

Where the last ashes were poured, and the warmth still lingered, stood the valiant little delver. No seeker for California treasure was ever more patient, more persevering, and scarcely more hardy. The yardstick would measure nearly all her height, but the belles of Madison Square might have envied her figure, had they ever been up early enough to catch a glimpse of it. The dirty worsted hood tied under her chin did not tie up all the pretty wavy brown hair, and the rosy cheeks with a dimple in each, or the roguish eyes. The ragged little woollen shawl was tied in a great knot behind, over the torn calico that left the little red knees bare to the tops of a pair of leggings that once doubtless warmed more tender limbs, and hands and arms were cased in old stockings with holes cut for thumbs. It is a wonder that those same thumbs were not frozen, for they were holding on to an iron rod, crooked at one end like a poker, with which she hammered away at the heap, only stopping to pick up a coal blacker than the rest, that, washed by the snow, looked as if it might be made to burn again. There were not many such, and the store in her basket was but scanty, for Jack Frost had laid his hand on them and was very loath to give them up.

Now you don’t suppose that Somebody noticed and thought of all this, standing in her night-dress of a December morning? Not a bit of it. She was not quite so romantic as that, though she was romantic enough to think poor children just as interesting as rich ones, and often a great deal better, because it is so much harder to be good amidst constant struggling and suffering than when life is made easier by every comfort that money can buy.

It did not require many mornings, however, to learn that the little maiden was always earliest of the cinder-pickers to visit that particular heap, so that, if there was anything to be got there, she had it long before less enterprising ones came along. The long windows of the warm dining-room were a good place to watch her, and, as the mornings grew lighter, Somebody didn’t mind getting up half an hour earlier. And the little one soon knew that there was a face at the window; and while she worked, she would look up with a shy smile that showed two rows of teeth like corn. Perhaps she was glad of company in the cold, lonely morning, there were so few to notice her among all the comers and goers of the great city.

Once a gentleman stood by Somebody, and the little girl knew that they were talking about her. Presently this gentleman opened the window and threw out a handful of somethings that rattled on the pavement and rolled down, trying to hide themselves in the snow and ashes. How her eyes danced, and her feet too, as she gathered them up, bowing and courtesying with life and grace in every movement!

Again the window opened, and the gentleman said, “Here, Kohlasche” (you know that is German for cinder), “I heard you singing the other day,—can’t you sing us a song?”

She looked a little frightened, and hesitated, but seemed to conclude that she ought to do something in return for his kindness; so she set down her basket, and, coming to the window-railing, sang such a pretty, plaintive song, all in German. And her voice was so sweet and childish! When she had finished, Somebody would have liked to send her away with a kiss, but was afraid of being laughed at. Perhaps it was as well, for kisses were so rare to her that she might not have understood its meaning.

On another morning a boy scarcely larger than herself, but carrying a heavy pail of garbage, set it down to rest, and, as he stood watching her, began to whistle the tune she was singing to herself, which made her stop singing and look at him, which was just what he wanted.

“Pretty hard picking, hey?” said he, by way of introduction. “Folks burn their coal awful close, these war times. Let’s help. I’ll scratch and you pick up. Give us your poke!”

So they began to work away together, the boy talking all the time, and stopping frequently to stand with arms akimbo as if he had accomplished a great deal.

“What does yer granny do with all these coals? How many cart-loads does she get in a day? Don’t yer have no fire but these? Sells ’em, eh! A shill’n a peck! Jim-me-nee! She must have heaps o’ money. We gives three shill’n a pailful for fresh coals, when we buys ’em by the pail, but Dad says folks is pretty hard up when they buys coals that way; it’s putting too much money inter other folkses pockets.

“Yes, I carry swill every morning, ’fore school, though. Bub or me goes to the Alhambra House, and t’other goes to the brewery. We likes to go to the hotel, ’cause yer see Dad’s sister is cook there, and that’s how we gets the swill; and ’most allers she saves something nice for Bub and me. See here, now!”

Carefully lifting a cabbage-leaf from the top of his pail, he brought forth in triumph the bones of a chicken, nearly picked.

“Have one?” he questioned, with good-natured generosity; and munching his, he added, with epicurean criticism, “Guess they lives pretty well at the Alhambra. Yer granny sells more ’n coals, I reckon? If she’s as dear on her rum as she is on coals, customers must be scarce. Cracky! there she comes now! Pick up yer basket. Won’t you catch it for stopping ter talk ter me!”

And shouldering his pail, he trudged off whistling—what do you think?—“No one to love.” It’s a fact. But then, you know, for a penny one can buy from off the Park railings almost any song in existence.

Up the street came trundling a large hand-cart piled with cinders, a dog harnessed to each side, and, pushing against the front bar, an old woman swathed, like a mummy, in every description of rag,—wrinkled, old, and ugly, with scanty locks of gray hair blowing about her weather-beaten face.

She stopped when she saw Kohlasche, who ran to her and held up her basket. The dogs stopped too, and tried to get nearer to the little girl, wagging their tails, and seeming glad to see her. Granny looked into the basket, emptied it upon the cart, scowled, handed it back to the child, and, with a shake and a cuff, pointed down the street to where ash-boxes and barrels bordered the way. Evidently glad to part from her taskmaster, she hurried off; but as the old woman disappeared to rummage an area, little Kohlasche turned, and, taking from the bosom of her shawl the chicken-bones which she and the little swill-carrier had been picking, she hastily gave one to each dog, bounding away before they could lick her hand, as they wished to do. Poor dogs! They had the quick instincts of children in knowing a friend. Weary as they were, and hating their bondage, they gladly and pantingly sat down to rest, uneasily glancing around, however, and the moment the old woman’s head appeared above the pavement they were alert with fear, and moving on.

So by these several steps it was that Somebody came to think her little romance about the pretty cinder-child. She could not belong to that old woman,—of course not. Never was such beauty born of such ugliness. It was a shame that she should be left to such a life,—that nobody came to the rescue. So it was. She might be a stolen child. Perhaps some lonely mother mourned as dead the innocence and loveliness which might better be buried under green earth and bright flowers than under poverty and wickedness. Something must be done! Something should be done!

Thus from watching little Kohlasche came talking to her, and from talking came visiting her home,—to find dirt, cruelty, wretchedness. A cellar, a gin-shop, a wicked old woman who beat and starved several children and two dogs, whom she lodged and held to do her bidding,—to pick, to gather, and even steal, in furtherance of her miserable trade.

No, the little girl was not hers. She thanked fortune she had no “gals,”—there was “more to be made on boys.” Six years before, the eyes of a hapless woman who lodged with her (and, alas! loved all too well the burning solace that made her forget life’s horrors) had closed upon them all for the last time as those of her baby-girl began to stare wide open in unmitigated wonder. Babies can sometimes be made useful, so Granny did not throw this one away or send it to the almshouse. Would she give her up now, to have a good home, to go to school, and be helped to grow up as good as she was pretty? Yes, if it was made worth her while,—if she was paid for her trouble—in letting her live, she must have meant.

Somebody remembered distinctly that she herself was once a child, a thing it is to be regretted that many forget; and well too she remembered the tears she shed over Cinderella, the despised but triumphant, and she longed to play “the fairy godmother” to all possible “Cinderellas” of these days.

Dear old Mother Lovechild! Blessed be her memory when she shall pass to Him who said, “Suffer little children to come unto me.” She not only suffered them; to her the words seemed a command to help them to come unto Him. Her heart was always good, and had a warm corner for children; but sorrow visited it early and left it more tender for bruising. Husband, children, all were gone,—last, the daughter who left three tiny children to their grandmother in her age and poverty. How could she send them away? The Lord gave them, and would help her to take care of them. So she prayed while she worked, and the Lord did help wondrously. Hearts as warm as her own prompted fuller hands to give. They gave house and food and fuel, and increased the little fireside group by ones and twos, till the little cottage and the mother’s hands were full. Some called it a ragged-school; but few rags were there, and cleanliness and plenty and love made it home. And all shared alike with the mother, for she called them all hers. Her eldest grandchild had grown old enough to help her teach the little ones and sing with them as year by year they came and went.

It was after weary days and disappointments, but at length “the fairy godmother’s” wand was lifted, and lo! “Cinderella” stood transformed in the midst of these. Her little brown hands were folded over a bright new dress and apron, and her hair was neatly combed and curled, as she stood up with her class to spell. And after they spelled, they sang; and it would have done you good to hear and to see how they knitted and sewed and played.

And here it would be pleasant to pause and say with satisfaction, “That is all.” But inexorable Truth says, “Go on.”

Somebody loved to call at Mother Lovechild’s now and then to refresh herself with a sight of the bright eyes, little sleeved aprons, and copper-toed shoes, just as other somebodies like to drop in at the florist’s and refresh themselves with camellias, tuberoses, and daphnes. But she came out one day with tears in her eyes, for little Kohlasche was gone. Yes, gone. Decoyed away, it was supposed, by the old cinder-woman, who, though diligently sought for, could not be found. Stolen, perhaps, for her clothes,—perhaps to hire out for her voice.

Dear children, “the fairy godmother” prays that, if anywhere you meet a little girl with brown hair and blue eyes, roaming the streets to beg, or digging in heaps of dirt and ashes, or you should chance to hear a sweet, childish voice singing to the sound of a wandering hand-organ, you will look kindly and searchingly to see if it be not her dear lost “Cinderella.”

Caroline A. Howard.

“Mamma, may Bessie and I have a silver wedding?”

Mamma looked up suddenly, with wonder in her beautiful eyes; and papa put down his paper, with his face all covered with summer lightning from the twinkling of mirth that afterwards broke out into the gentle thunder of his hearty laugh; and actually, after a little while, there was a shower in his eyes, he laughed so long.

The little girl felt the color spreading painfully over her face at this unexpected reception of her innocent question, and she looked appealingly at her mother to know what it meant. Mamma, with her quick instinct, saw the trouble in the young face, and began, with her usual affectionate sympathy, to explain the question of the silver wedding, and the merry answer it had received.

“O, don’t teach that child anything about it!” interrupted papa. “Do for once put your wisdom to bed, tuck it up, and let it sleep awhile. You know that Grace and Bessie are more united than a great many married people, and as their faith in each other is as pure as silver, I say let them have a silver wedding, after their own fashion! I shouldn’t wonder if we could learn a lesson from it some way, and it won’t hurt my dear little girls. Come, Grace, and tell me all about your plans. Your mamma is a very dear woman, but she knows very little about silver weddings,—never having had any of her own,—while papa knows this much about them, that—that he is invited to one next week.”