* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

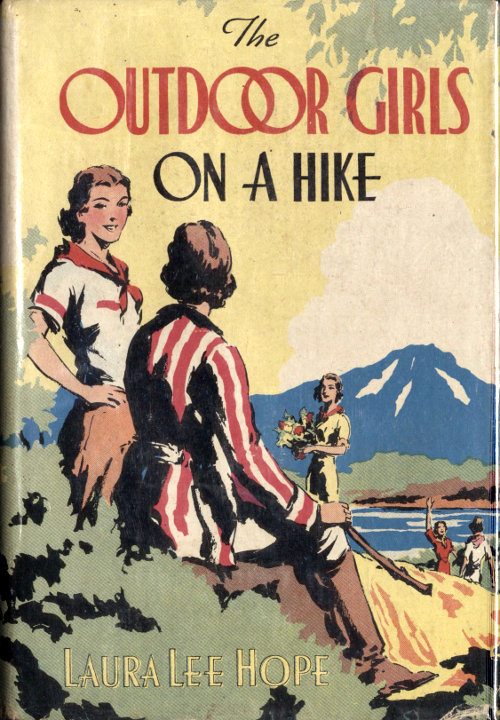

Title: The Outdoor Girls on a Hike

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Edward Stratemeyer (as Laura Lee Hope)

Date first posted: May 31, 2018

Date last updated: May 31, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180533

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

By

LAURA LEE HOPE

Author of

“The Outdoor Girls of Deepdale,”

“The Outdoor Girls at New Moon Ranch,”

“The Blythe Girls: Helen, Margy, and Rose,”

“The Bobbsey Twins,” Etc.

WHITMAN PUBLISHING CO.

RACINE, WISCONSIN

Copyright, MCMXXIX, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

“Hand me that book, Carolyn, will you? There’s a dear!”

Carolyn Cooper, blond and pretty and delightfully lazy, regarded the speaker reproachfully.

“Always, just when I am comfortable, you think up something for me to do, Lota Bronson. Here—take your old book!”

“Thanks for the manner,” laughed Lota, catching the book as it was flung toward her. “If you ask for the truth, Carolyn——”

“Which I don’t and never did,” sighed Carolyn.

“I’d say you were getting abominably lazy.”

“Speak for yourself,” retorted Carolyn. “I don’t see you dancing any Highland fling yourself!”

“It’s the weather,” said Irene Moore, wrinkling her funny little nose. “We’ve all got spring fever.”

Stella Sibley sat up with sudden energy.

“How convenient it is to blame the weather,” she said. “But I’ll tell you what’s the matter with us, girls. It isn’t spring fever. It’s just plain laziness, spelled with a large L.”

“It’s a plot,” protested Carolyn, from the mass of pillows in the porch swing. “She’s trying to stir up something, girls. Don’t let her!”

But Stella found support from an unexpected quarter.

“I think Stella is exactly right.” This from Meg, the second of the Bronson twins. “We are all getting soft, sitting around eating candy and going to dances——”

“We play tennis sometimes!” Irene protested.

“How often?” Meg sniffed. “Once or twice a week. And I noticed after that last singles set I beat you——”

“Ouch! Don’t remind me!” begged Irene. “The memory hurts!”

“You were puffing like a fat little——”

“Don’t say it!” begged Irene. “Not if my friendship means anything to you!”

“Just the same,” Stella Sibley took up the theme where she had left off, “the fact remains that as athletic girls and members of the Outdoor Girls Club, we haven’t been exactly living up to our reputation.”

“Well, what do you want us to do?” Carolyn definitely abandoned her pillows and regarded Stella with the air of one who is willing to be reasoned with. “Are we to start skipping rope or making passes at a punching bag?”

“Not so bad for exercise,” chuckled Stella. “But hardly what I had in mind. I was thinking that what we needed was more road work.”

“Girls,” giggled Irene, “she wants to make us into lady pugilists.”

“Oh, well,” said Stella, offended, “if all you can do is laugh——”

“I’m not laughing,” said Carolyn Cooper virtuously. “I think it’s a mighty fine idea.”

“Listen who’s talking!” mocked Irene.

“But I really am in earnest,” protested Carolyn. “Hiking is the best kind of exercise and it’s apt to prove mighty interesting, too.”

“The trouble is that you can’t go far enough in one day to have any real fun,” Lota Bronson objected. “By the time you reach new, interesting places you have to turn round and trot home again. Not so good.”

“Oh, but I’ve an idea!” Irene clapped her hands. “A perfectly scrumbumptious idea! Why not take a real hike—an overnight hike?”

“A several overnights hike,” amplified Carolyn, slightly incoherent in her sudden enthusiasm. “Then we shouldn’t have to turn around and come home just when things began to get interesting.”

“And we could camp overnight wherever we happened to be,” added Irene. “We could pick out a route that wouldn’t be too lonely and where there would be plenty of farmhouses that would take us in for the night.”

Stella considered the idea seriously.

“That would be fun, girls, real fun. We would be gypsies for a while. What a lark to start out in the morning without knowing where we would end up at night.”

“Or how!” finished Meg, with a chuckle. “I’m right with you, girls, although Lota and I are more used to traveling on horses’ feet than our own. We ought to be good, though, for a considerable cross-country hike.”

The Outdoor Girls were holding their meeting at the beautiful Deepdale home of Stella Sibley. They had chosen the summerhouse in the garden because it was the coolest spot anywhere about. The summerhouse was completely and comfortably furnished with its swing, its small tables and inviting chairs, and the girls were fond of holding their meetings there.

“I think it’s a marvelous idea,” agreed Lota, continuing the discussion of the proposed hike. “Only I don’t think we ought to leave too much to chance. We ought to agree to hike so many miles a day for a certain number of days.”

“We could make it a two-weeks’ hike,” Stella suggested, “and we could cover, well, say something like ten miles a day.”

“Lovely!” cried Carolyn. “Fourteen days at ten miles a day makes something like one hundred and forty miles in the two weeks. Not bad for girls who have grown ‘soft’!” She made a face at Stella.

“We haven’t done it yet,” Stella quickly reminded her.

“I have another idea,” Irene announced suddenly.

“She’s running mad with them to-day,” observed Lota, with a lazy grin.

“Why wouldn’t it be possible to visit the married girls while we’re about it?”

“Great!” exclaimed Stella approvingly. “Mollie and Roy have that darling bungalow in the woods——”

“Newlyweds!” chuckled Irene Moore. “Maybe they wouldn’t be glad to see us.”

“Maybe they wouldn’t!” scoffed Stella. “I’d be willing to take a chance on that.”

“Then we could go on to the seashore and stay overnight with Grace and Amy and the boys,” Carolyn proposed. “And then travel on to Betty’s.”

“Up in the hills,” agreed Irene contentedly. “I call that a pretty nice itinerary, if you ask me.”

“Then it’s settled?” asked Stella, in her capacity of president. “There is no dissenting voice?”

“Not one dissenting voice!” the others assured her in a solemn chorus.

“Then,” added Stella, assuming a very businesslike manner, “I think it’s about time we called the meeting to order and got on with the business of electing officers. That’s what we are here for, you know.”

“Oh, bother business,” protested Carolyn Cooper. “I move we save time by reëlecting the same officers we had last year. I’m sure we all want Stella to go on being president——”

“Hear! Hear!” cried Irene, the irrepressible. “Second the motion!”

“Carried unanimously,” added Meg Bronson, grinning.

“And I’m sure,” Carolyn continued, looking prettier than ever as she twinkled at them mischievously, “Irene has made a most excellent, honest, and praiseworthy treasurer——”

“Irene for treasurer!” was the clamorous cry, while Stella rapped in vain for order. “We’ll have no one else! We want Irene!”

“Unanimously elected!” laughed Carolyn. “For myself,” she lowered her eyes modestly, “I say nothing. As your secretary, I have honestly tried to give satisfaction. It is for you to decide whether or not I have succeeded.”

“We want Carolyn!” the others chorused obligingly. “We want Carolyn! Carolyn Cooper for secretary!”

Carolyn rose and bowed gravely about the circle.

“I thank you all,” she said.

“Well, I must say,” cried Stella indignantly, “I never saw such an unbusinesslike meeting in my life! What I want to know is, am I the president of this——”

“Didn’t you just hear yourself elected?” asked Carolyn, with much gravity.

“You must have been asleep or something,” giggled Irene.

“Well, of all the unbusinesslike——”

“Oh, bother!” drawled Meg. “Who wants to be businesslike on a day like this? Listen!” she added, sitting at attention. “Do you hear an airplane or am I imagining things?”

Silence descended on the summerhouse; a silence invaded by the unmistakable roar of an approaching plane.

“Oh!” Carolyn jumped to her feet and ran out into the open. “Maybe it’s Hal. Oh, I hope it is!”

The rest of the girls joined Carolyn and gazed up at the plane, now directly overhead.

“What do you mean by ‘maybe it’s Hal’?” Lota Bronson demanded. “Don’t tell me Hal has taken up flying!”

“Oh, hadn’t you heard?” Carolyn tried to look innocent. “Hal has gone crazy over aviation. He has been up in a plane several times and he told me that he is considering taking up flying—seriously, you know.”

“You little wretch!” cried Lota. “Of course you wouldn’t tell us about it!”

Hal Duckworth was a nice lad, who had become interested in the Outdoor Girls—in general; and in Carolyn Cooper—in particular. It would not be giving away a secret to admit that Carolyn returned this interest.

“I think it’s thrilling,” observed Irene. “If Hal gets to be a demon air pilot, maybe he’ll take us for a ride once in a while.”

The plane winged its swift way into the distance, the whine of its motor died on the soft summer air.

As the girls turned to reënter the summerhouse they saw that some one had come into the garden. An unprepossessing old crone, dressed in the colorful garb of a gypsy, shuffled along the gravel drive. Two younger women with dark, brooding faces, followed her.

They saw the girls standing at the entrance to the summerhouse and came toward them. The old crone’s face lighted with what was evidently intended to be an ingratiating smile.

“Have your fortunes told, pretty ladies?” she mouthed, showing toothless gums. “Pretty fortunes for pretty ladies. Come, cross my palm with silver and you shall look into the future.”

“Send them away!” Carolyn whispered to Stella. “I don’t like the looks of them. Do send them away!”

Stella Sibley did not like the looks of the gypsies any more than Carolyn Cooper did. There was something in the old crone’s smile, in the sullen faces of the other two that repelled her. She knew, however, that kind words are often more effective than threats. So she said, answering the gypsy’s smile:

“We don’t care to have our fortunes read just now. We are busy with something else.”

The eyes of the old crone roved to the summerhouse, luxuriously appointed and with every evidence of recent occupation. She leered at Stella, again displaying toothless gums.

“We can wait,” she said, “until you are finished with your—business.”

Stella glanced swiftly at the other girls. She could see that they were all half-dismayed, half-angered by the gypsy’s presumption.

“No,” said Stella, with a decided shake of the head. “We thank you very much, but we shan’t want our fortunes read to-day. You would only be wasting your time by staying here.”

Instead of retreating, the gypsy shuffled closer.

“To a gypsy time is nothing, pretty lady,” she persisted. “We will wait.”

“No; you will go,” said Stella quietly. “I’ve told you we don’t want our fortunes read and I mean it. If you do not go at once, I shall have to call some one from the house.”

This threat appeared to have no effect upon the old crone. She stretched out her skinny old hand toward Stella.

“The pretty lady would not do that,” she whined. “She has too kind a heart. I am an old, old woman, but I can see into the future—aye, better than most. Give me your hand, dearie, and I will tell your fortune.”

Stella shrank back, her hands outflung in a gesture of unconscious loathing.

“Go away!” she cried. “Go away!”

While Stella Sibley is wondering how she can drive the impertinent gypsies from the garden, it may be well to take a moment to introduce the Outdoor Girls to those who are not already acquainted with them.

The adventures of the Outdoor Girls had been interesting and varied from that first, never-to-be-forgotten camping and tramping trip, in which the girls had many thrilling and exciting events befall them before they arrived home safe and sound. There had been later adventures in Florida, at Wild Rose Lodge, at Cape Cod and other interesting places. A summer spent at Spring Hill Farm carried with it adventures that would long live in the girls’ memory.

Just the previous summer the Outdoor girls had made the acquaintance of two charming girls, Meg and Lota Bronson, and had spent a thrilling vacation as the guests of Daniel Tower on the latter’s Western ranch. Daniel Tower was the guardian and self-styled uncle of Meg and Lota Bronson, recent members of the Outdoor Girls Club.

Of the four original Outdoor Girls, Betty Nelson, Molly Billette, Grace Ford and Amy Blackford, there was now none left in the club, they having all deserted it in favor of marriage.

One by one, during the years, they had dropped out. First, Betty Nelson, the much-loved Little Captain, had married Allen Washburn, a young Deepdale lawyer. Then Amy Blackford had married Will Ford, Grace’s brother. Still later Grace had paired off with Frank Haley, another Deepdale boy.

But as the older girls had dropped out, new members were initiated; first Irene Moore and Stella Sibley, then Carolyn Cooper and the Bronson twins. So when Mollie Billette finally decided to take the “big step” and had married Roy Anderson, long her fervent admirer, there were still five Outdoor Girls, though none of the original number remained in the club.

Naturally, as new Outdoor Girls took the place of old, new boys were admitted to the magic circle.

First there was Clem Field, a cousin of Stella Sibley. Clem was a likable lad and from the first had been attracted to the Outdoor Girls and to all that their club stood for. He had liked Mollie Billette particularly well, and for a time their close friends had found themselves unable to predict whether Roy or Clem would be the lucky one chosen by dark-eyed, dark-haired, vivacious Mollie. Since Mollie had definitely turned to Roy Anderson, however, Clem had seemed to find it possible to transfer his admiration to Irene Moore.

Then there was Hal Duckworth, a fine lad who made no secret of his admiration for Carolyn Cooper.

Dick Blossom, a young giant of a fellow, with great hands that seemed continually to get in his way, was another good friend of the Outdoor Girls. During the previous summer he had appeared greatly taken with both the Bronson twins and had created great merriment for the rest of the young folks by his inability to tell them apart.

Deepdale, where the Outdoor Girls lived, was a thriving city of some twenty thousand inhabitants and was situated on the banks of the Argono River. This river emptied into Rainbow Lake, some miles below.

Now to return once more to the Outdoor Girls as they face the impertinent gypsies in the Sibley garden.

The aspect of the three gypsies had grown threatening. The leer had faded from the lips of the ancient crone. She mouthed wrathfully, muttering something beneath her breath.

One of the younger women said angrily:

“Make them do as you say, Hulah, or call down the curse of the tribe upon them!”

The woman called Hulah raised a skinny arm above her head. Her sunken eyes fixed themselves upon Stella with a disconcerting intensity.

“For the last time,” she shrilled. “Will you let us read your fortune?”

“No!” cried Stella, frightened but thoroughly angry. “Go away, you horrible old woman!”

The old crone raised both arms above her head. The expression of vindictive hate on her withered old face was horrible to see.

“Then,” she cried, in a shrill, piercing voice, “may the curse of——”

“Dick!” shouted Meg suddenly, in a round full young voice that drowned out the shriek of the gypsy. “Dick Blossom! Come here! Quick!”

A stalwart young fellow had been passing along the side street. Meg had seen his head and shoulders above the hedge that guarded the Sibley property.

Her shouted command was received and obeyed instantly.

Dick vaulted the hedge lightly, for all his bulk, and loped across the lawn with the grace of a young elephant. He stopped beside the girls and regarded the queer scene with a look of bewilderment.

“For the love of Pete—” he began, but paused as the gypsies, after one good look at his height and breadth of shoulder and the ham that served him as a fist, turned and scuttled down the pathway, the old crone muttering and mouthing savagely at those in the summerhouse.

“Well,” said Dick whimsically, “I may be dumb; but tell me, somebody, what it is all about.”

“Oh, those horrible gypsies!” cried Stella, clinging to Dick’s arm. “They wanted to read our fortunes, Dick, and when we wouldn’t let them they got nasty and threatened to put a c-curse upon us.”

“Nervy beggars!” cried Dick. “Wish I’d known that a few seconds earlier. I wouldn’t have let ’em get off so easily.”

“All we wanted them to do was to get off,” Stella explained, with a nervous giggle. “And they wouldn’t. Oh, Dick, I’m glad you came!”

Dick grinned.

“For once I’m really welcome,” he said. “Think I’ll stroll down to the gate, ladies, and see if those gypsies have really taken themselves off.”

He returned a few moments later to report that the gypsy women were mere specks in the distance.

He was all for going on about his business then, but the girls would not part with him so easily. Quite apart from their genuine liking for the young fellow, they found his stalwart presence extremely reassuring and comforting at that time. The evil influence of the gypsies still seemed to hover above the garden.

Carolyn linked her arm within Stella’s as the Bronson twins and Irene dragged Dick into the summerhouse.

“That horrible old crone!” she said, with a shudder. “I may be silly, Stella, but I’m glad she didn’t have time to finish that curse!”

Dick Blossom was told about the Outdoor Girls’ proposed hike and listened with flattering attention.

“Bully!” he said, and added, with a grin: “Nothing better for reducing, I’ve been told.”

Lota and Irene made a dash for him and he ducked adroitly from the summerhouse.

“I was going, anyway,” and he grinned as he avoided their laughing attack. “Don’t hurry me! It isn’t polite!”

As he dodged among the bushes, Stella called after him:

“Come on over to-night, Dick. I think Hal and Clem will be here.”

Dick paused and glanced back.

“Will you treat me right?” he demanded.

“We’ll pet and pamper you to your heart’s content,” Stella promised recklessly. “Only come.”

Dick nodded.

“Try to keep me away,” he retorted, and vaulted over the hedge.

After he had gone, the girls exchanged uncomfortable glances. Stella went to the doorway of the summerhouse and stood there uncertainly.

“It’s time for refreshments, girls,” she said, in what she hoped was a matter-of-fact voice. “Shall we have them here or up at the house?”

“At the house!” was voted unanimously, and then all exchanged shame-faced glances.

“We’ll feel better about those gypsies to-morrow,” said Irene Moore, as though trying to find an excuse for their “attack of nerves.” “But that old hag they called Hulah is something you don’t see except in nightmares. And after all, she might come back.”

In the house, refreshed by crisp lettuce sandwiches, small cakes, and tall glasses of iced lemonade, the girls were more inclined to laugh at their fear of the gypsies.

“Those wandering tribes never pitch their camps long in one place,” Meg Bronson pointed out. “Probably by to-morrow they will be gone and we’ll never hear of them again.”

“A consummation devoutly to be wished!” murmured Lota, who had recently discovered a certain famous poet named William Shakespeare and was proud of her ability to quote—or misquote—him on certain occasions.

“Especially now that we are planning our hike,” added Meg. “I wouldn’t enjoy meeting Hulah and her pleasant friends—on a dark night, for instance.”

Carolyn Cooper gave a little shriek and covered her ears with both hands.

“Make her stop!” she implored. “I don’t want to give up our glorious hike, but I will if any one mentions that horrible Hulah woman to me again!”

This dire threat temporarily banished the name of Hulah from the conversation of the Outdoor Girls.

A short time later they parted, promising to meet again directly after dinner.

So, about eight o’clock of this particular evening, the girls began to drift back toward their leader’s house. They had changed into frocks more appropriate for evening and the soft hues gave them the appearance of a bouquet of flowers.

At Stella’s they found that Hal Duckworth had already arrived. He and Stella were engaged in an earnest conversation when the girls burst in upon them.

“Here, you two!” cried Irene. “What are you up to, conspiring in a corner?”

Hal got up and came toward them. He was a good-looking youth and possessed a certain charm. Older people were apt to say that young Hal Duckworth had “a way” with him.

Now he greeted all the girls pleasantly, but his last and most lingering look was for Carolyn Cooper. One could scarcely blame him. Carolyn always sparkled at night. On this particular evening she was lovelier than usual in a pale blue frock with her bright hair fluffed out about her face.

“We weren’t conspiring,” he declared. “We were merely having an interesting conversation. Isn’t that right, Stella?”

“Perfectly,” agreed Stella gayly. “Tell them your news, Hal. They’ll be thrilled.”

“News!” drawled Meg. “I didn’t think anything ever happened in Deepdale these days. What is it, Hal? Murder or theft?”

“Theft,” returned Hal.

The girls found seats for themselves and Hal, at a corner of a massive table, faced them.

“I don’t know whether you girls will be as interested as I am,” he began. “But the robbery occurred under somewhat curious circumstances.”

“Tell us,” begged Carolyn. “We’ll all promise to be pleasantly thrilled.”

“I imagine poor old Fennelson was thrilled, too,” said Hal. “Though not so pleasantly.”

“Fennelson,” repeated Stella thoughtfully. “I don’t recall the name.”

“He has a curio shop on Maple Street, pretty well back from the main street,” Hal explained. “I’ve passed the place once or twice and I remember wondering how the old fellow ever managed to do any business. His shop is dingy and stuffed with curious junk and cheap jewelry.”

Carolyn leaned forward in her chair. She looked startled, but no one seemed to notice.

“Hal!” she breathed. “Was it Fennelson’s place that was robbed?”

“I’ll say so,” returned the young fellow. “The poor old man was found gagged and bound in the cellar under his shop. He had evidently been beaten about the head, for he was unconscious when they discovered him.”

“Is he going to die?” gasped Lota.

“They don’t think so. He recovered consciousness in the hospital; but unfortunately he was unable to describe his assailants. The scoundrel—or scoundrels—attacked him from behind. When the police found him he was blindfolded.”

“And he never saw the robbers!” mused Irene.

“Only felt them,” agreed Hal, with a grim smile.

Carolyn interrupted again and this time her agitation was apparent to them all.

“You haven’t said a word, Hal, about what was stolen from the shop,” she said, and looked at him with a sort of strained eagerness.

“About two thousand dollars’ worth of jewelry and curios, they say.”

“Oh!” gasped Carolyn, and sank back in her chair, limp and white.

Carolyn Cooper’s collapse took her companions completely by surprise. They had been so interested in what Hal Duckworth was saying that, up to the moment that she had fallen back in her chair, looking white and ill, they had no notion that the robbery of the Fennelson Curio Shop was of any more personal interest to Carolyn than to the rest of them.

Now, the other girls ran to her. Hal jumped to his feet and looked conscience stricken.

Irene ran to the kitchen for a glass of water.

“Bring smelling salts, some one,” called Lota distractedly.

“Might better stand back and give her a little air,” Meg suggested practically.

At this Carolyn sat up and took a firm grip on the arms of the chair. She shook her bright hair back from her face with an impatient gesture.

“I’m all right, girls,” she said. “If you think I’m going to faint, you’ll have a disappointment.”

“A very pleasant disappointment, Carol,” said Stella gently.

“I should say!” added Irene, returning with the glass of water. “Drink this, anyway. It can’t hurt and it might help.”

Carolyn drank the water and then looked appealingly at the girls. She smiled at Hal, hovering penitently in the background.

“You needn’t look as if you’d murdered somebody,” she told him. “It’s only that your news sort of—knocked me out for a moment.”

“But why should it?” Meg asked, mystified.

Irene added, with a nervous giggle:

“Yes, tell us! What was Mr. Fennelson to you?”

To this flippant remark Carolyn returned only an injured glance.

“It isn’t Mr. Fennelson I’m worried about, silly—though I’m sorry enough for the poor old man. I was thinking of my family heirlooms.”

After much persuasion and many interruptions that served only to delay the narrative, they finally coaxed the tale from Carolyn.

“I don’t suppose the heirlooms are worth a great deal in actual cash,” she told them. “But they were trinkets that have been in the family for—oh, I don’t know how long. Some of them were mother’s and so,” her voice lowered and her eyes filled with tears, “they were very valuable to me——”

“We know, dear,” said Stella soothingly, gently patting her hand.

“Some of the settings were loose,” Carolyn continued, “and so Uncle Joe thought I’d better take them to Fennelson’s and have them fixed before they were lost—the stones I mean, of course. Mr. Fennelson is an expert at such work.”

Stella continued to pat her hand.

“And you took them?” she queried.

“That’s the worst of it,” wailed Carolyn. “I took them right away. You know that isn’t like me! I usually wait a week before I actually get anything done. If I’d been true to my worse nature this time, I might still have the family heirlooms.”

“When did you take these trinkets of yours to Fennelson?” Hal asked. He frowned at Carolyn, but she knew he was thinking not of her but of a raided curio shop, of an unconscious old man found on the floor of his cellar, bound, gagged and brutally beaten about the head.

“Yesterday,” she said, in response to his question.

“And the robbery was pulled off to-day. But even at that,” he added, “you are merely assuming that these heirlooms of yours were among the loot carried off by the thief.”

“No,” said Carolyn mournfully, “I’m counting on my bad luck, Hal. If any one has to suffer because a cowardly scoundrel or two needed a little extra pin money, your little friend Carolyn is bound to be it!”

“Just the same, I wouldn’t be too sure,” Hal insisted. “Wait till Mr. Fennelson recovers from that crack on the head. Then he will be able to take an inventory of his stock and tell exactly what goods have been lost.”

“How soon do you suppose he will be able to do that?” Carolyn asked, brightening.

“Neither the police nor the doctors seem to be very clear on that point,” he said. “A hard blow on the head of a man of Fennelson’s age isn’t a thing to be taken lightly. As a matter of fact, there’s some danger that, in this case, brain fever may result. In that event, of course, the poor old fellow will be laid up for an indefinite time with the possibility of death at the other end.”

“Which would turn plain thieves into murderers,” Meg observed.

Hal nodded gravely.

“It would that,” he said. “And of course, Fennelson’s being laid up in this way, the police are hampered at the very start of their investigation. If they knew just what type and quantity of goods had been stolen, they would be able to follow along that track, searching pawn shops and such places, in the end, almost certainly turning up a clue that would lead to the thieves. As it is, they must search for other clues—which are chiefly conspicuous by their absence.”

He made this last observation under his breath as though speaking to himself.

Meg, who had been watching him shrewdly for some time, asked suddenly:

“You are very much interested in this case, aren’t you, Hal?”

He looked at her, surprised; but, as he met her steady glance, the girl imagined that a veil fell across his own. He said, lightly:

“Why, yes, of course I’m interested, especially so now that Carolyn appears to be involved.”

An interruption occurred now in the form of Clem Field, who has already been introduced as Stella Sibley’s cousin, and Dick Blossom. It appeared that Clem had overtaken Dick on his way to the same rendezvous and had given him a lift in his car.

The other two boys had heard of the robbery and expressed their sympathy to Carolyn upon hearing that she was, or might be, involved in it.

“However, we hope that your property was not among the stolen stuff,” Clem said, and Hal added:

“That’s what I’ve tried to tell her. There’s no use anticipating bad fortune. And, in the meantime, why not enjoy the evening?”

The revived gayety was infectious. Carolyn was gradually won over to a more optimistic view of the robbery and, in the end, entered into the fun of the evening with much of her usual light-hearted zest.

It was a lovely party, as all parties at the home of the Outdoor Girls’ leader were bound to be.

“Turn on the radio, some one,” Stella cried. “You boys, take up the rugs, will you, and throw them into the corner? We want plenty of room to dance.”

The request was promptly complied with. Rugs were removed, furniture thrust into corners, while music from one of New York’s most famous jazz bands filled the room with irresistible syncopation.

After a while Clem, dancing with Irene close to the radio, turned it off. Silence descended upon the dancers. They stopped and looked indignantly at the perpetrator of the outrage.

“S O S,” announced Clem, grinning. “Everybody off the air for ten minutes while we have some real music by Miss Stella Sibley with a possible dance by the young lady at my right.”

“The young lady at his right,” by name, Irene Moore, made a face at him.

“Bother!” she cried. “Who wants to clog dance when she might Charleston? Don’t take the joy out of life, Clem. Turn on the radio, do!”

But Stella was already at the piano, her fingers busy with an Irish jig. Irene’s feet could not resist it. She danced out into the middle of the room, hands on hips, and leaped into a roguish clog, her short hair bobbing, merry eyes flashing.

Irene’s audience urged her on, clapping in time to the rhythm until she was out of breath and Stella’s clever fingers refused to strike another note.

Then they gathered around their leader and she played for them tender little ballads and they sang in fresh, clear, untrained voices that nevertheless caught the meaning of the melody, rendering it more truly than many a trained chorus could have done.

They sang “The Rosary,” with Dick’s deep voice carrying the bass. When the last rich chord melted away and became part of the vibrating stillness of the room, some one said, “Bravo!”

They turned to see Mr. Sibley sitting in a deep chair, the picture of content.

“Why, Dad,” cried Stella, “when did you come in?”

“Don’t stop,” urged her father. “Sing it again. It sounded good!”

The young people sang again and yet again until they had exhausted their small repertoire.

Mr. Sibley sat back in his chair, the tips of his fingers pressed together, nodding with contentment.

When they stopped for lack of more material he smiled and got slowly from his chair.

“I’m glad you young folks can sing like that,” he said. “I’d begun to believe that all any of you cared for these days was jazz——”

“Oh, Dad, you know better than that!” Stella reproached him. “We love jazz, of course. How else could we dance? But this sort of thing,” with a gesture toward the scattered music, “is what we always come back to.”

“Good!” said Mr. Sibley gravely. “No very great harm can come to you as long as ‘that is the sort of thing you always come back to.’ Good night, you rogues. Now I’m going away so that you can turn on jazz. Good night.”

But somehow, the jazz had temporarily lost its charm. In response to a general request Clem Field tuned in to some fine organ music. To the poetry of a Bach fugue Stella alternately served refreshments and joined in a discussion of the proposed hiking trip.

Clem and Hal were inclined to be dubious when they heard of the plan, made by the girls only that afternoon. The incident of the gypsies as related to them by Irene—with all the trimmings that Irene could invent—only served to strengthen them in their belief that a hike of the sort the girls proposed was at best a hazardous undertaking.

“Five girls have no business hiking alone through all sorts of country,” said Clem. “I don’t like the idea at all.”

“But you see,” said Stella, as she passed the cake, “it isn’t as though it were just any group of girls starting out on any sort of hike. It’s the Outdoor Girls, you know, and there’s a difference.”

“Oh, of course,” said Hal, with elaborate scorn. “It’s a protection, I suppose, a sort of invisible armor. You should carry a banner with you. ‘We are the Outdoor Girls of Deepdale. Harm us at your peril.’”

“Might be a good idea, at that,” chuckled Irene. “They say advertizing always pays.”

When the party broke up at last, some two hours later, the determination of the girls to continue plans for the hike were not in the least affected by the out-spoken disapproval of the boys. If anything, they were the more determined to start as soon as the inevitable details could be arranged.

When Stella’s guests turned from her door, Clem offered to give them a lift home, an offer which was accepted by all but Hal and Carolyn.

“It’s such a heavenly night,” said the latter, “we think we’ll walk.”

Carolyn and Hal waved to Stella and to the gay crowd in Clem’s car, then turned down the dark street that led to Carolyn’s home.

The girl sighed, and Hal said quickly:

“Tired? Perhaps we should have gone in the car, after all.”

Carolyn shook her head.

“I’m not the least bit tired,” she said. “It’s lovely to be out in the fresh air. I feel as if I could walk for hours.”

“What is it, then?”

Carolyn hesitated, then said impetuously:

“I’m terribly worried, Hal. I hated to spoil the party, and so I pretended to forget all about that poor old man—Mr. Fennelson—and those things I left with him.”

“But you didn’t forget,” said Hal quickly. “I knew it, Carol, and I thought what a game little sport you were.”

A short silence fell between them while Carolyn looked up at the stars and thought of a packet containing precious things.

“There was a locket,” she said, in a hushed voice. “It was only a very little locket, Hal, but it was mother’s and there was a picture of her in it——”

Hal squeezed her hand in quick sympathy.

“Don’t get to thinking that those things are gone,” he admonished her. “In a day or two Fennelson may be able to check up on his goods. Then we’ll know definitely. The probability is,” he added, “that your things are safe.”

They had reached the house of Mr. Joe Cooper, where Carolyn lived. The girl paused at the foot of the steps and held out her hand to him.

“We’ll hope so,” she said. “And in the meantime, you will do all you can to find out for me, won’t you, Hal?”

The boy took her hand in a firm grip.

“I guess,” he said, “you know you can count on me, Carol—for anything.”

But the next day came and the next. Several days passed, and the proprietor of the Fennelson Curio Shop lay raving in delirium. It became increasingly uncertain whether the thief, or thieves, when caught, would be arraigned for just plain theft or murder.

Carolyn haunted the shop where the robbery had taken place. The heirlooms, left her by a mother now dead, had always seemed precious to her. Now that there was a possibility that they might be lost to her forever, they assumed a double importance.

The Fennelson store was guarded by detectives. Nothing could be added to or taken from the stock until the proprietor’s recovery.

“But if I could just glance over what things are left,” said poor Carolyn again and again, “I could tell at once whether my heirlooms were among them!”

“Can’t be done, Miss.” The detective, though kindly, was firm. “What’s fair for one, is fair for all. If we let you have your way we would probably have half of Deepdale rummaging over Fennelson’s stock.”

“I’m not ‘half of Deepdale,’” Carolyn protested faintly. But the detective continued to shake his head and Carolyn walked away, discouraged.

Meanwhile, the Outdoor Girls went on with their plans for the hike. There were parental objections to be overruled; but this hurdle once taken successfully, they turned a totally deaf ear to the continued objections of Clem Field and Hal Duckworth.

They had one ally on their side, and this was Dick Blossom. Dick stoutly maintained his faith that the Outdoor Girls were amply able to look out for themselves.

“I don’t believe there is any more danger to them than there would be to five boys starting out on the same adventure,” he said. “The girls have proved often enough that they don’t need any one to think for them in case of an emergency. Why not leave them alone?”

“What a comfort you are, Dick,” Meg and Lota chorused.

Dick gave them a mystified look and shook his head.

“You not only look alike,” he complained, “but you even talk together. Now, I ask you! how is a poor fellow to know?”

Plans for the hike were at last matured to such an extent that the girls considered it safe to set the date of departure.

“Day after to-morrow, if it’s a nice day,” Stella announced, and her comrades shouted with glee.

“Two more sunrises will see us on our way,” sang Lota.

“There is just one thing we haven’t decided definitely, yet,” Stella continued. “That is the matter of baggage. Lota and Carolyn still insist that we shall need more clean things than we can carry in our knapsacks. The rest of us don’t care to be burdened with too much dunnage. Now, what shall we do?”

“As you say,” returned Irene promptly. “You are the leader, Stella, and, as far as I’m concerned, what you say goes.”

The others echoed the sentiment, though Carolyn and Lota looked a bit doubtful.

“Well,” said Stella, “if you really want my opinion, I think that the lighter we travel, the better it will be for us. We shan’t need any heavy camping outfit because we intend to stop at some hotel or farmhouse every night. We will carry a camp kit along with us and a few provisions. We can replenish when we pass through villages on our way.”

“Day after to-morrow is too far away,” sighed Lota. “I don’t know how I am going to wait that long!”

“We’ll have room in our packs for several changes of clothing,” Stella continued, with a smile for Lota. “And if we feel a crying need for clean things, there will always be brooks and streams along the way——”

“Where we can do a little dab of washing and hang things up on the bushes to dry,” finished Carolyn. “The way you tell it, Stella, makes it sound fascinatingly hoboish. Was I the one who spoke of luggage? Perish the thought!”

So another question—the last of any importance—was settled with satisfaction to every one. There was nothing left now but to wait for the day of the start.

This dawned clear and bright, with a cool breeze to temper the sun’s heat.

“Ideal! A day made to order,” said Meg, as she regarded the pleasant prospect from the window of her bedroom. “Hurry up, Lo. We mustn’t keep the others waiting!”

They had agreed the day before to meet at Farmers’ Tavern, an old deserted house on the edge of the woods.

“It’s a sort of central point for all of us,” Stella had pointed out “and as good a place as any to start from. We’ll meet there at nine o’clock sharp. Don’t any of you dare be late!”

The girls remembered that admonition when they were all gathered at the rendezvous—with the exception of Stella herself!

“She reminds us to be on time—and then turns up late,” remarked Lota.

“It’s one thing to preach, and another to practice,” returned Irene flippantly. “Anyway,” with a chuckle, “here come the boys.”

“Hal and Dick,” counted Carolyn. “But I don’t see Clem. I wonder if he isn’t going to get here to see us off.”

“Much you care,” said Irene mischieviously, “as long as Hal Duckworth is among those present!”

There was a burst of merry greetings as the boys reached them.

Hal went directly to Carolyn’s side—a fact which did not pass unremarked by the mischievous eyes of Miss Irene Moore.

“Straight as a homing pigeon,” she murmured, quite loud enough for Carolyn to hear.

“Listen, Carol,” said Hal, “I’ve word of Fennelson——”

“Yes?” breathed Carolyn. “What, Hal?”

“Nothing much yet. But the old chap is getting better. His recovery will probably be slow, but the authorities hope that they will be able to get some badly needed information from him before long.”

Before Carolyn could reply a motor car swept about a curve in the road and came to a stop within a few feet of them. Clem was in the driver’s seat with Stella beside him.

Stella jumped to the ground and ran toward them.

“Sorry to be late,” she called. “But it was all Clem’s fault. He told me to wait for him. I——”

Hal came forward suddenly and caught her wrist.

“What have you got here?” he demanded.

Taken by surprise by Hal Duckworth’s strange action and the eager tone of his voice, Stella Sibley stammered:

“This—oh, I forgot—nothing, really. Just a little brooch I picked up near the summerhouse. I thought it was a curious design and brought it along to show——”

“Let me see it, please.”

There was still something in Hal’s tone that caused Stella to look at him curiously. She handed the brooch to him without comment.

“What is it, Hal?” she asked, as the lad turned it over and over in his fingers. “You can’t possibly think it is anything important.”

“Have you any idea how it came to be near the summerhouse?” Hal asked.

“Not a very clear one,” returned Stella. “I was quite sure none of the girls had dropped it, for they don’t wear such stuff. I asked the cook and the upstairs maid, but they disowned it. I can’t imagine unless one of those gypsies dropped it the other day—” she paused, making the suggestion a question addressed to Hal.

The latter nodded.

“That might be the answer,” he agreed. “At any rate, you won’t mind my keeping this trinket, will you?”

Although somewhat surprised, Stella agreed to the request readily enough.

“Why, of course not,” she said lightly. “I can’t think of any occasion when I would be likely to wear it. I simply brought it along as a curiosity—and a memento of the gypsies’ visit.”

“All right, thanks,” said Hal, and pocketed the trinket.

It was only Meg who noticed that the simple action was accompanied by a very thoughtful look. She noticed, too, that Hal stared straight over Stella’s head, like one who looks into the future and sees visions. Meg decided, however, for reasons of her own, to keep these observations to herself for the present.

Now that their leader had joined them, the Outdoor Girls were eager to be off.

“If we expect to make ten miles before sundown we’ve got to be at it,” stated Lota. “’Bye, boys,” she said, waving to them. “See you next Christmas, if we have luck!”

But they were not to be rid of the boys so easily. The latter accompanied them for a considerable distance along the first lap of their journey, and even then turned back with marked reluctance.

“We should be going with you,” Clem said.

“Which wouldn’t do at all,” laughed Irene. “Think how disgustingly safe and protected we would be with three stalwart youths along to smooth the path for us. No, thanks! We’ll write you a letter about it!”

But after the boys had finally turned back and were crunching along the hard-worn trail toward Deepdale, the Outdoor Girls, for all their vaunted independence, felt suddenly lonely and deserted. For some unknown reason, the woods appeared to have lost some of its friendly sparkle. They stood for some time, looking back toward the place where they had last seen the boys.

“Well, come on,” said Stella finally. “We’ll not get anywhere by standing still.”

“Do tell,” giggled Irene. “Lead on, and we’ll suit our pace to yours!”

Gradually, as they pressed farther and farther into the heart of the woods, the old zest for adventure returned to them. They felt gloriously free. They were no longer dependent upon street cars, automobiles, railroad trains. As long as their feet held out they were reasonably certain to get where they were going, without recourse to artificial means of locomotion.

However, they were to find that, after several hours of travel, even the stoutest pair of feet will grow tired and demand a rest.

“The very next place we come to that looks good, we’ll stop and have lunch,” Stella promised. “I don’t know about the rest of you, but I feel hollow from my head clear down to my toes.”

“I’ve been seeing visions of ham sandwiches for the past two hours,” Carolyn confessed. “If we don’t eat soon I’ll start chewing grass.”

Meg and Carolyn had been walking in advance. Now Meg stopped and pointed through the trees. Her expression was one of extreme disgust.

“Look!” she cried. “We are back on the road again!”

The girls in the rear joined her. Looking ahead, they also saw the thin, dusty, ribbon of road. Its parched glare contrasted unpleasantly with the cool comfort of the woods.

“Bother! Now what shall we do?” cried Irene discontentedly.

“Well, we knew the path would lead us out onto the road sooner or later,” Stella remarked philosophically. “Only, it happens to be sooner, that’s all.” She pushed past Meg and Carolyn and went on along the path.

The girls came out upon the road and looked about them with interest. Although they had been over this same route quite frequently by automobile; afoot, it all looked new to them. Now they noticed many pleasant details; the almost tropical luxuriance of the verdure that flanked the road, the rock-studded bank, the wild flowers that grew between the crevices of the rock, making even that harsh surface beautiful.

The girls picked the flowers as they walked until each had gathered an armful of fragrant color.

“Now we’ve got them, what do we do with them?” Meg wanted to know. “Wild flowers aren’t particularly practical on a cross-country hike.”

“I’ll make me a chaplet for my brow,” sang Irene. She broke off and added with a chuckle; “That’s an excellent idea. We’ll make wreaths and crown each other——”

“That’s saying it with flowers,” giggled Lota. “All right, I’m game, if the rest are.”

So they sat down at the side of the dusty road and busied themselves with the flowers. They were glad to sit down, for their feet were protesting again. And their task was a pleasant one.

When the wreaths were finished they “crowned” each other with a good deal of ceremony and giggles and so-called compliments that did not compliment.

“Our heads don’t match the rest of us,” complained Irene. “A crown of posies certainly deserves something better than a knicker suit beneath it.”

“I suppose we should be garbed in flowing Grecian robes,” giggled Lota, “with girdles of gold about our lissom waists and sandals on our fairy feet——”

“Stop her, some one,” protested Meg. “She may be my twin, but there are limits to what even a twin should be asked to stand!”

Lota looked pained.

“Can’t I be poetical if I want to?” she inquired. “A hike like this should be full of poetry——”

A scream from Carolyn temporarily diverted their attention. She was pointing wildly into the woods.

“I saw something!” she cried. “It was an animal. I think it was a w-wolf!”

At Carolyn Cooper’s preposterous statement Irene giggled heartlessly.

“Poor girl! She thinks she’s Little Red Riding Hood. Where,” in a coaxing tone, “did you see your wolf, dear?”

Carolyn became suddenly indignant.

“I’m not joking,” she said. “I did see an animal, a big one, over there among the trees. When I screamed, it disappeared.”

“No wonder!” observed Meg dryly. “You scared the poor thing.”

“Oh, well, come on,” cried Lota impatiently. “We were going to eat half an hour ago and I can’t see that we’re any nearer it now.”

“All right,” agreed Stella. “The first likely spot we see, that’s where we camp.”

“I only hope it’s far enough away from that—beast,” said Carolyn nervously. “Oh, you may laugh, if you like,” in response to the amused glances of the girls. “But I tell you I did see something in the woods and I didn’t like the looks of it, either.”

Of course none of her companions believed Carolyn’s “wolf story.” But they did imagine more than once during the next few moments that something was trailing them among the bushes and shrubs along the side of the road. The snapping of a twig, some loose stones rolling down into the road; slight sounds but significant to the woods-wise girls.

When they paused for a moment to make a survey of the landscape, these sounds stopped, too. When they moved on again, so did their shadowy trailer.

Of course they all knew that Carolyn’s tale of a wolf was preposterous. Wolves did not roam the woods near Deepdale. Still, what was it that trailed them so persistently and mysteriously?

All this time they had kept an eye out for a convenient place in which to rest and refresh themselves before continuing on the second heat of the day’s hike.

Lota discovered it, a miniature plateau among the rocks, so high above the road that one had to climb to reach it.

The girls hailed it with approval and, like monkeys, clambered up the steep bank. Stones, loosened by their feet, rolled down into the road, but they never noticed.

Once settled, they explored their knapsacks hungrily. True to agreement, they carried few provisions, each girl having packed her own lunch of a few sandwiches, a piece of cake, fruit and a pint thermos bottle containing hot coffee or milk. Most of the girls had chosen milk, for they knew the value of that nourishing food.

They ate ravenously, for the hours in the open had made them as hungry as a pack of wolves. The available supply of food vanished like dew beneath a summer sun.

Stella viewed this ruthless demolition with a rueful eye.

“We’ll have to do a good five miles more this afternoon,” she observed, “or something tells me we will go hungry to bed to-night.”

“The way I feel now, that won’t worry me,” Meg said lazily. “I think I could lie down right here and sleep the clock around.”

“Well, don’t,” retorted Stella unfeelingly. “We’ve a long hike ahead of us before we can call it a day, you know.”

Something stirred in the bushes behind them. The girls started and faced the sound. There was a moment of breathless silence while they listened, every sense alert.

Only silence rewarded their strained attention. They relaxed, exchanging sheepish glances.

“What’s the matter with us, anyhow?” Meg demanded irritably. “Is it possible that we are all ‘hearing things?’”

“Carolyn’s wolf story has upset us,” Irene suggested. “I’ve been ‘hearing things’ ever since,” she confessed impulsively.

“So have I,” confessed Lota, staring, wide-eyed, at Irene.

“And I,” added steady-nerved Stella. “I know it sounds silly, but it is as if something’s been trailing us through the woods.”

“Well, it wasn’t a wolf, anyway,” said Meg Bronson crossly. “That’s too silly.”

“I wonder—oh, it couldn’t be—still, it might—” Irene paused and flushed uncomfortably as she found the girls staring at her.

“What are you talking about?” demanded Lota.

“I was wondering if those gypsies up at Stella’s—if they could have followed us,” she explained disjointedly. “That horrible Hulah——”

“Hush!” cried Carolyn sharply. “If they should be about——”

“Oh, nonsense!” Stella jumped to her feet and began to gather up the remains of her lunch. She spoke loudly and with unusual vehemence, proving that mention of the impertinent gypsies had not left her entirely unmoved. “I think we are all acting like perfect simpletons. It’s time we moved on!”

The other girls followed their leader’s example, hastily packing knapsacks, picking up bits of paper and drinking cups so that their camp site might be left neat and in good order. They were eager to leave a place that was suddenly filled for them with shadows and a mysterious dread. After all, something had been following them. They had all heard it. They could not all be mistaken!

In a suddenly valorous mood, Irene Moore suggested that they search the woods in the immediate vicinity. But Stella shook her head.

“It’s a waste of time,” she said. “And we can’t afford to waste a minute, not if we hope to get our stint of hiking done to-day.”

“Besides,” added Carolyn, “what we don’t know won’t hurt us.”

“I’m not so sure of that!” returned Irene. Suddenly she straightened up. Her look became concentrated, intent. “Girls, what—is—that?” she demanded.

All came to a sudden halt. Carolyn gave a little shriek and clapped her hand over her mouth.

“What did I tell you?” she cried for the second time within the space of a few minutes. “It’s the wolf!”

What they all saw was a large, bushy brush that stood up above a clump of stunted bushes close to them, a brush that waved gently to and fro!

It was the tail of some animal, no doubt of that!

“But a wolf doesn’t wag its tail!”

Irene dashed forward, parted the bushes.

“Hesper, you rogue!” she cried. “Come out of that!”

The Outdoor Girls stared.

The waving brush suddenly drooped, disappeared. From between the bushes, held aside by Irene Moore’s hand, crept a beautiful, shaggy beast. Its proud head was lowered, its tawny, magnificent coat swept the ground, its brown eyes begged forgiveness.

Irene did not melt before that appeal. Her expression was stern and disapproving.

Behind her, the other girls were trying to digest the fact that Carolyn’s wolf was none other than Irene’s thoroughbred collie dog, Hesper.

Some one giggled. Irene held up a warning hand.

“This is not a laughing matter,” she said, in a solemn tone. “Hesper has been a wicked, wicked dog! He has disobeyed his mistress. I have no use for bad dogs!”

Poor Hesper’s brush drooped lower. He was the picture of doggish distress. His eyes implored.

“Oh, Irene, don’t be cruel,” laughed Stella. “The poor dog has apologized the best he knows how.”

“And one should always accept a gentleman’s apology,” added Carolyn Cooper demurely.

“Yes, but what am I going to do with him?” Irene wanted to know.

“Take him along as a protection against the gypsies,” suggested Lota Bronson.

Although this was said jokingly, the idea more than half appealed to the girls. It would be pleasant to have a protector as big and strong and willing as Hesper on their hike.

It was Stella who shook her head.

“Not so good. There are a great many places, hotels and farmhouses and such, where we would be welcome and a dog would not,” she reminded them. “He is bound to be in the way.”

Irene stretched out a hand and the collie came to her. He thrust his cold muzzle against her palm, the beautiful brush began a faint hopeful wig-wag.

“You’re bad, but I can’t help loving you,” Irene scolded, and the wig-wag became more pronounced. “What am I going to do with you?”

“Why not take him along as far as Mollie’s?” Meg suggested. “Then we could get her to ship him back home again.”

This suggestion pleased the girls. Even Stella nodded approval.

“I guess that’s the best way,” she said. “If we took him back to Deepdale now we’d lose a whole day. Let him come with us as far as Mollie’s, anyway.”

The hikers started on again, uncomfortably aware that they had lost time and must make up for it by an extra burst of speed. They scrambled down to the road and swung off at a merry pace, Hesper galloping at their heels.

The girls had marked Draketown, a village some ten or eleven miles from Deepdale, as the end of the first day’s hike. They knew that Draketown boasted a hotel of sorts where they could probably be accommodated for the night, and it was toward this refuge that they now eagerly turned their steps.

However, after the first two or three miles had been covered, they began to slow down a little. Their feet were tired, the heat was oppressive.

They found a path that ran for some distance through the woods, parallel to the road. This they took, grateful for the shade and the sweet, pungent smell of the damp earth.

Once they came to a brook. Without comment Irene sat down and began to pull off her shoes and stockings.

The others paused and Stella said resignedly:

“Would you mind telling us what is the big idea?”

“I’m going to cool my feet if we never get to Draketown,” Irene retorted resolutely. “If you girls want to go on without me, suit yourselves. I’ll still have Hesper.”

But her companions did not go on without her. Instead, they sat down and removed their own shoes and stockings and paddled blissfully in the cold water.

Hesper ran down into the water and barked and splashed and misbehaved himself like any riotous puppy, instead of the full-grown dog he was.

After a while the girls dried their feet and reluctantly pulled on their shoes again.

“We should be able to get on faster now,” observed Stella. “And Draketown can’t be very much farther off.”

But though the girls tramped steadily on for a long time, it seemed to them that they came no nearer to their goal.

At last they began to pass farmhouses—a hopeful sign. These habitations became more and more frequent. At one of them a small white terrier came dashing out to yap at Hesper’s heels. The collie gave the little dog one disgusted glance and trotted on his way with an air of dignified detachment.

“You could almost see his lip curl,” chuckled Carolyn. “If there’s one thing I envy you, Irene Moore, it’s that dog.”

“He is a darling,” Irene admitted. “Though bad!”

The hikers soon found that the signs were not deceitful. At the foot of a low hill Draketown lay spread out before them, a straggling little village with two or three stores, a blacksmith’s shop, an auto repair shop, and what was called, by courtesy, a “hotel.”

However, in their present mood the girls were not critical. Ahead of them lay food, shelter, a place to lay their heads for the night. That was all they cared about.

As they passed down the crooked main street of the village two or three children paused in their playing to stare at them curiously. The girls showed the effect of the long hike; their faces streaked with perspiration and the grime of the road, their short hair touseled by the wind, their shoes covered with dust. But for all that, they were gloriously happy.

“I expect we look like tramps,” observed Carolyn. “And the funny thing is, I don’t care a bit.”

“We’re turning into gypsies already,” added Lota. “Gypsies and the dust of the road belong together.”

“They’re always dirty, if that’s what you mean,” Meg said prosaically.

The Outdoor Girls paused before a weather-stained building whose door bore the sign, Draketown Inn. It was not an inviting looking hostelry, but the travelers knew they must make the best of it. They went up on the porch and, seeing no one about, Stella rang the bell.

After a considerable delay there was the sound of shuffling footsteps and a woman appeared inside the screen door.

She was a very thin woman, the type sometimes described as “scrawny,” and her glance was habitually suspicious. Her glance passed over the girls, then fastened, with marked dislike, upon Hesper. The collie, seeing himself thus observed, thumped a friendly greeting with his tail.

“Take that dog away from here!” cried the woman in a shrill voice. “I won’t have dogs about the place!”

“But this is a very nice dog!” said Irene Moore demurely, in response to the words of the woman who had come to the door of the hotel. “Hesper won’t make a bit of trouble. You see what a sweet disposition he has!”

Hesper eyed the woman ingratiatingly and thumped his tail.

The thin woman behind the screen door looked increasingly suspicious. With a warning glance at Irene, Stella Sibley ventured to explain.

“We’ve been hiking since early morning,” she said. “We really had no intention of bringing the dog with us, but he followed without our knowing. We are sorry if you don’t like dogs, but if you would put up with him for just one night—We are going on again the first thing in the morning.”

This was only the beginning of a long, tiresome argument. But finally the hikers won. Hesper should be tied securely in the yard where he could not worry the cow or kill the chickens.

The Outdoor Girls, after another suspicious scrutiny on the part of the thin woman, were admitted to the house.

“I think she would like to tie us outside with Hesper,” Lota whispered to Stella.

However, when the woman finally led them to the second floor and opened the doors of two adjoining rooms the girls saw that they could expect to be fairly comfortable for the night.

Two double beds and a cot, together with austere dressers, tables, and chairs, furnished the two rooms. Rag mats were on the floor and the pitchers on the washstands were soon filled with sparkling cold water. Everything was immaculately clean.

The girls washed their hands and faces, brushed their hair until it was once more sleek and orderly, and removed as much dust as possible from their outer garments.

“Maybe our landlady will view us with more favor now,” laughed Carolyn. “We do look a little more respectable.”

They went down to a well cooked, old-fashioned dinner. There were several others at the table besides themselves. These were almost all elderly people and their interest in the young hikers was so frank and their curiosity so openly expressed that the girls were glad to make their escape as soon as possible after dinner.

They found a sad and chastened Hesper tied to a staple outside the barn. He jumped up eagerly at sight of the girls, but slumped down again when Irene made no move to release him.

“Can’t do it, old boy,” she said, twining her fingers in the thick white ruff about his neck. “I’ve promised to keep you tied up until morning. But at daybreak we’ll be off again.”

At the kitchen door, they wheedled a plate of scraps from the cook—who was a plump, comfortable-looking girl and not in the least suspicious of them—and set it down before Hesper. The dog gulped the food ravenously and thereafter appeared more resigned to the ignominy of an imprisoning rope.

The girls sat about on the grass, talking over the events of the day until dusk descended like a thick mist, blurring outlines and filling the place with fantastic shadows.

“I think maybe we’d better go to bed,” said Stella, after a while. “We want to get up at the crack of dawn to-morrow, you know.”

“Yes, come on, everybody,” said Lota, yawning. “I could fall asleep right here.”

Irene delivered a parting pat upon the head of the despondent Hesper, bade him be a “good dog,” and followed the others toward the house.

Half an hour later the last of the Outdoor Girls had drifted into dreamland. But out in the lonely yard, Hesper mourned long and audibly. His world had deserted him and he was inconsolable.

How many hours later it happened, the girls did not know. They were dragged from an exhaustion-drugged sleep to sudden and violent wakefulness.

A dreadful commotion was going on in the hall outside their rooms. Shouts of “Help! Murder! Thieves!” resounded in their startled ears. There was a terrific thumping and banging, a muttered imprecation, a sharp thud.

“Now I’ve got you!” cried a masculine voice.

“Hold him, Bud,” in a woman’s determined tones. “Hold on to him now, while I fetch a light.”

The girls rushed to the door and flung it open. They stared, open-mouthed, at the oddest tableau they had ever seen. A small group had gathered, composed of the cook, the waitress, a few of the guests of the inn. In the center of this excited group a man lay prone upon the floor. He appeared to be grappling with something.

“The thief!” cried Lota, excitedly.

“Be quiet, you goose!” said Meg. “It isn’t a thief he’s got hold of. It isn’t even a man. It’s a—” as the light in the hands of the landlady wavered closer—“dog!”

The man on the floor appeared to realize this at the same time. He struggled to his feet amid a chorus of half-smothered chuckles from the audience. His stubby blunt fingers were entwined among the coarse hairs of a collie’s white ruff.

“Here’s your burglar,” he said sullenly, as the landlady raised the oil lamp high above her head. “Here’s your thief and murderer! Pity you had to make such a fuss about a bloomin’ dog!”

The landlady bent forward and stared at a very much dejected collie.

“Well, how was I to know?” she replied tartly. “I wake in the dark and hear something come soft-like up the stairs. It stops somewhere in the hall here and seems to be trying to open a door. What was I to think? A dog, eh?” She bent a grim look upon the collie. “Out upon you!” In her anger she took a step forward, her hand upraised.

The collie did not move nor growl, but the hairs began to stiffen on his neck.

“Hesper!” said Irene sharply. “Come here to me!”

The collie shook himself free of the hand that still gripped his ruff. He came and sat down close to his mistress, looking up at her. It was evident that he awaited further instructions.

The group in the hall had melted away, some tittering, some growling because of rest unnecessarily disturbed. Only the grim landlady and the broad-shouldered youth who had wrestled with Hesper remained. The latter was probably a hired helper. The girls remembered having seen him working about the place that evening.

Now he looked in scowling uncertainty at his employer.

“Want I should put the brute out?” he inquired.

“Oh, please,” Irene spoke entreatingly, her hand on Hesper’s head, “let him stay in here with us the rest of the night. I promise he won’t make any trouble.”

The thin woman snorted.

“Humph! Trouble enough he’s made already, scaring the life out of honest folk. Knew I was a fool, taking in a dog.”

“He was just trying to find me,” Irene pleaded. “He will be all right with us.”

The woman shrugged her thin shoulders.

“Keep him where you like as long as he’s out from under my feet,” she retorted tartly. “And I’ll not have him here another night. To-morrow he gets out!”

In the morning the hikers found the proprietress of the Draketown Inn quite eager to get rid of Hesper as soon as possible. And since neither the Outdoor Girls nor Hesper had discovered any great love for the disagreeable landlady, they did nothing to thwart this ambition.

They ate an early breakfast while, at their request, a lunch was put up for them in the kitchen. The girls paid well for all these accommodations, beside being taxed liberally for two dead chickens and a ruined screen door, these damages being the result of Hesper’s midnight escapade.

Hesper hung his head while the list of his villainies was being compiled, but for all that, the girls doubted that he was sincerely penitent.

“He had a look in his eyes that said he wished he had killed another chicken while he was about it, just to make it a good night,” Meg Bronson chuckled. “What a time he must have had before he decided to come into the house and look up Irene!”

“And then had to ruin a door screen just for good luck!” Lota added.

“Well, how else could he get in?” retorted Irene. “Be reasonable, do, and look on the poor dog’s side!”

The hikers were free of Draketown Inn at last. With a substantial lunch to last them through the day—with all her faults, the grim landlady did know about food—with a delicious breakfast in the background and the prospect of seeing Mollie and Roy Anderson before the day was out, it is small wonder that they found their spirits soaring.

The hikers stepped out buoyantly, reveling in the crisp air of early morning, in the dew still sparkling on shrub and bush, in the long, long road that stretched out endlessly before them and which they had sworn to conquer.

“How queer it seems to think of Mollie Billette as Mollie Anderson,” said Irene to Stella as they swung along the highway.

They made good time through the hours of the morning. As Meg put it, they had “got on their striding legs.” Stella encouraged this sudden burst of energy and herself led the pace, “stepping out” bravely.

“If we can break the back of the hike in the morning while we’re fresh and the air is cooler,” she explained, “then we can afford to linger a little over lunch and set an easier pace down the last long stretch.”

This seemed to them all a sensible contention; so they continued the hike until the sun was not only high in the heavens but had begun its slow progress toward the west.

Presently Stella paused. For some time they had been following an old, disused wagon trail through the woods. They knew that if they followed it long enough it would lead them to a small, woodland lake and—Mollie Anderson’s bungalow.

But just at this point the road widened. Trees had been chopped down here and there, leaving only blackened stumps. At its base a steep slope revealed a sparkling, silvery pool.

“I bet we’d find good fishing there,” said Meg Bronson. “A splendid place to lunch, anyway, Stella. What do you think?”

“We have made well over six miles this morning,” Stella returned. “I should say we deserve some food!”

Stella, Meg, and Carolyn sat down at once on the soft ground and spread out the lunch between them while Irene and Lota went down to the pool.

“For a drink,” Irene flung back. “We’ll bring you all some.”

Hesper followed, excited, as always, by the water. When the two girls and the dog reached the banks of the pool, Irene and Lota stopped. Not so, Hesper! He plunged straight in, shaking himself and snorting and behaving in an altogether ridiculous manner.

“Better make the best of this day,” Irene said, shaking a finger at him. “It’s the last you will have with this crowd. Oh, you bad dog, stop it!” as he came closer and some sparkling drops fell upon her and Lota. “We are not ready to take a bath yet. All we want is a drink.”

“I don’t like to drink this,” Lota said, drawing back. “It looks as if it had been standing too long. Let’s hunt about and see if we can’t find a spring.”

Further back in the woods they did find a spring, just a thin trickle of water, but as clear and pure as sunlight. They took long, delicious drinks of this, then filled their canteens and started back.

When they neared the spot where they had left the rest of their party they were surprised and a little startled to hear the sound of voices, several voices, raised in angry altercation.

“Seems to me this will bear looking into!” Irene said, and hurried forward.

Irene Moore paused suddenly, gasped, and took a step backward. Lota caught her arm and whispered:

“What is it?”

There was no need for Irene to answer the question. In a moment Lota saw for herself.

“The gypsies!” she cried.

Irene quickly put a hand over her mouth to silence her.

“Please wait a minute,” she commanded. “Listen!”

There were two gypsies in the clearing. Irene recognized Hulah, but the other’s back was toward her so that she could not make sure of her identity.

Evidently, the gypsies had come upon the girls just when they were in the act of distributing the lunch. Now the one called Hulah moved forward. Mouthing and grinning, she held out her hand.

“Just a bite to eat, pretty ladies,” she whined. “Just a bite for a poor old hungry woman who has touched no food since yesterday morn.”

The girls knew this was untrue, for, besides seeing that she looked exceedingly well fed, they noticed a half loaf of hard rye bread protruding from the old woman’s sagging pocket.

“If you have not eaten, it is your own fault,” said Meg boldly, and pointed to the bread.

The leer on the face of the old hag faded. Her thin lips pressed together in an ugly line.

“You say I lie!” she shrieked at them. “Hulah does not lie! You shall pay for that.”

She advanced upon them, hands outstretched, clawlike fingers crooked.

“I have asked for a bite to eat,” she said, in a voice that shook with fury. “You have refused an old woman bread. You tell me I lie. Now I will take your food from you.”

“Take it all,” urged the younger woman. “Let the impudent ones know what it is to go hungry!”

The girls swiftly gathered up the lunch and jumped to their feet, backing away from the menacing gypsies.

But Hulah advanced, followed by the other woman. The old hag shrieked imprecations.

Lota started forward, apparently determined to come to the rescue of her chums. But Irene caught her arm.

“Don’t!” she whispered excitedly. “I know a trick worth two of that!”

She pointed to Hesper, who had found the burrow of a rabbit and was nosing at it rapturously. He was still wet from his gambols in the stream.

Irene whistled, a shrill note that pricked Hesper’s ears forward and then brought him dashing up the bank. When Irene and Lota broke from cover and confronted the startled gypsies, the collie was close at their heels.

Carolyn cried out in relief. Meg and Stella relaxed and sighed audibly.

Hesper, blissfully unconscious of anything unusual in the situation, dashed into the center of the group and shook himself. It happened that he was nearest the old hag, Hulah, so that the latter was treated to a generous shower bath.

Hulah cried out at the dog, scowling at him furiously.

Surprised, Hesper paused in the act of another shake and looked at the old woman. It was evident that he did not like what he saw. The old person in the queer-colored rags who snarled at him like one of his own kind was a suspicious character, he felt. Certainly, she would bear watching.

This inward feeling found outward expression in a low growl. Hesper ceased to grin. His jaws began to look like a wolf’s jaws; long-fanged, vicious. He moved forward a pace or two, the long hairs on his neck bristling.

“Irene, look out!” cried Stella. “He’ll spring on them!”

Irene leaned forward and inserted her fingers firmly beneath the dog’s collar. Then she looked up at the cowering gypsies.

“You’d better go,” she advised gently. “I can’t tell how long I can hold the dog—nor how long I shall want to,” she added significantly.

This was enough. One parting look at the bared fangs of the collie and the gypsy women turned and fled. Hesper growled savagely and made a lunge for them, but Irene did not relax her hold upon his collar.

“Easy does it, boy,” she coaxed. “They are going, going, gone! That’s all right, as long as they go,” she added, impressing the lesson upon him. “But, if they come back, you know what to do!”

Hesper growled deep down in his throat, a sign that he knew precisely what was expected of him. Then Irene released her hold on his collar. The dog trotted over to the spot from which the gypsies had disappeared, and sat down, ears cocked forward, eyes watchful. An occasional low growl assured his friends that Hesper was on guard. No harm would come to them while he was at his post!

Though reassured, the girls found that their woodland glade had lost a good deal of its charm for them. Every snapping twig, every rustle of leaves, spoke to them of the gypsies and their possible return.

“What shall we do?” Stella hesitated in the act of redistributing the lunch. “Shall we eat here, anyway, or go on and find another place?”

Carolyn was all for following this latter suggestion. But the other girls, being exceedingly hungry, cried her down.

“Let’s eat first,” said Meg. “I’m starved.”

“Nothing very frightful can happen to us with Hesper on guard,” added Lota.

“He certainly did look savage,” chuckled Irene. “With those bared fangs he was more wolf than collie.”

“He had no liking for those gypsies,” added Stella, “and he didn’t care who knew it either!”

So it was decided that they would eat where they were and move on out of the gypsies’ neighborhood as quickly as they could after lunch.

The meal over, they lingered no longer than was absolutely necessary in the pretty glade. The gypsies had robbed it of all glamour and they were eager to be on their way again.

“Besides, we’ll see Mollie soon,” Stella Sibley added. “And maybe she won’t be surprised!”

“I only hope we find her at home,” Meg observed. “She and Roy may have gone out——”

“And they’ll come home to find us perched, like a row of little sparrows, on the front doorstep,” chuckled Irene.