* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXX, No. 6 (June 1847)

Date of first publication: 1847

Author: George R. Graham (editor)

Date first posted: Feb. 7, 2018

Date last updated: Feb. 7, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180212

This ebook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXX. June, 1847. No. 6.

Table of Contents

Fiction, Literature and Articles

Poetry and Fashion

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

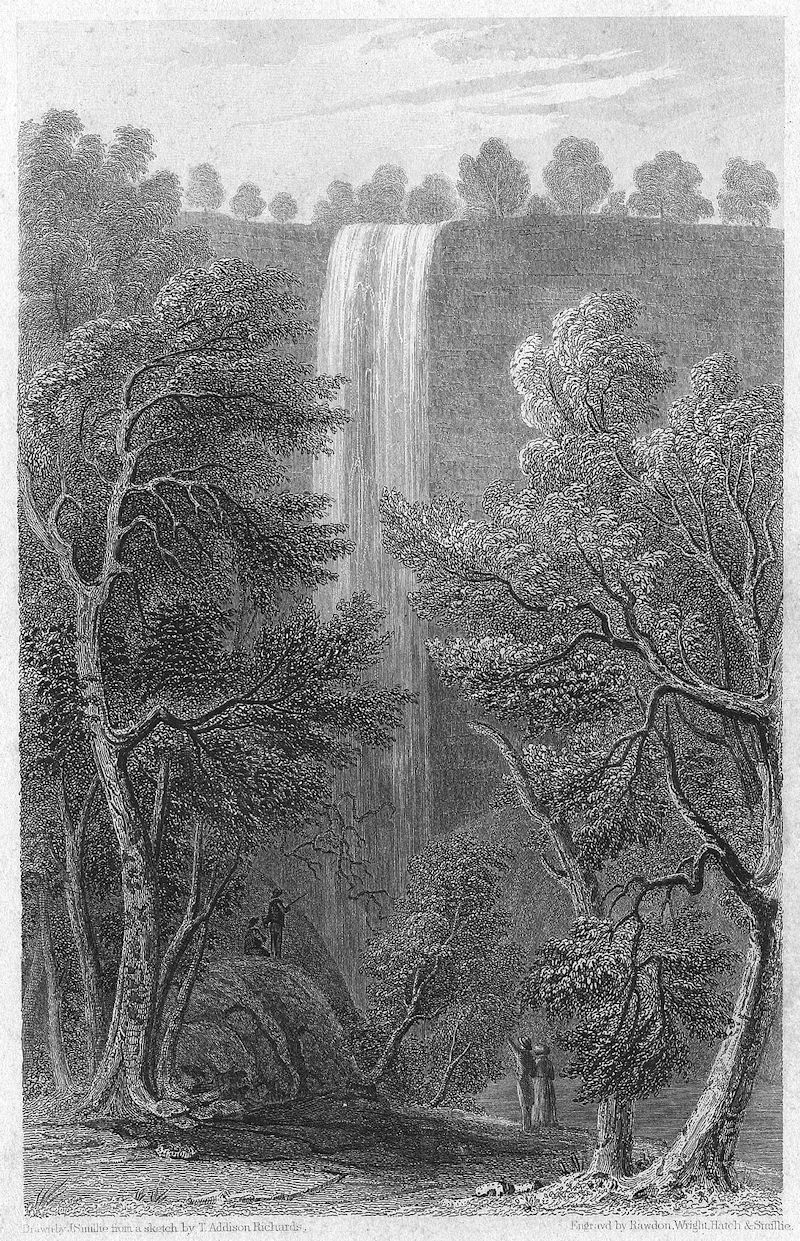

Drawn by J. Smillie from a sketch by T. Addison Richards. Engraved by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Smillie.

FALLS OF TOCCOA.

Graham’s Magazine 1844.

Painted by J. W. Wright. Engraved by A. L. Dick.

THE HOME BIRD.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXX. PHILADELPHIA, June, 1847. No. 6.

OR THE MISFORTUNES OF PETER FABER.

———

BY JOSEPH C. NEAL.

———

It was a lovely autumnal morning. The air was fresh, with just enough of frost about it to give ruddiness to the cheek and brilliancy to the eye. The rays of the sun streamed brightly up the street; knockers, door-plates and bell-handles, beamed with more than usual lustre; while they who had achieved their breakfasts and had no fear of duns, went, according to the bias of their musical fancy, either whistling or singing through the town, as if they had finally dissolved partnership with care, and had nothing else to do for the remainder of their natural lives but to be as merry as grigs and as frolicsome as kittens. Every one, even to the heavy-footed, displayed elasticity of step and buoyancy of motion. There were some who seemed to have a disposition to dance from place to place, and evidently found it difficult to refrain from a pirouette around the corner or a pigeon-wing across the way, in evidence of the light-heartedness that prevailed within. The atmosphere had a silent music in it, more delicious than orchestral strains, and none could resist its charm, who were not insensible in mind and body to the innocent delight which is thus afforded to the healthful spirit. There are mornings in this variable climate of ours, more exhilirating than the wines of the banquet. There are days which seem to be a fête opened to all the world. The festive hall with its blaze of chandeliers and its feverish jollity has no pleasure in its joys to equal Nature’s holyday, which demands no hollow cheek or haggard eye in recompense. Enjoyment here has no remorse.

No wonder, then, that young men slapped their comrades on the back with a merry laugh, and dealt in mirthful salutations. Nor could it cause surprise that old men poked their cronies with a stick, and thought that it was funny. Ay, there are moments when our frail humanity is forgotten—when years and sorrow roll away together—when time slackens its iron hold upon us—when pain, tears, disappointments and contrition cease to bear down the spirit, and, for a little moment, grant it leave to sport awhile in pristine gleefulness—when, indeed, we scarcely recognize our care-worn selves, and have, as it were, brief glimpses of a new existence.

Still, however, this is a world of violent contrasts, and of painful incongruities. Some of us may laugh; but while we laugh, let us be assured of it that there are others who are weeping. It is pleasant all about you here, within your brief horizon, but the distance may be short to scenes most sadly different. Smiles are on your brow, as you jostle through the street, yet your elbow touches him whose heart is torn with grief. Is there a merry-making in your family—are friends in congregation there with mirth, and dance and song? How strange to think that it is scarce a step to the couch of suffering or the chamber of despair! The air is tremulous perchance with sighs and groans; and though our joyous strains overwhelm all sorrow’s breathings, yet the sorrow still exists even when we hear it not.

And so it was on this autumnal morning. While the very air had delight in it, and while happiness pervaded the atmosphere, there was a little man who felt it not—poor little man—poor grim little man—poor queer little man—poor little man disconsolate. Sadness had engrossed the little man. For him, with no sunshine in his heart, all outward sunshine was in vain. It had no ray to dispel the thick fogs of gloom that clouded round his soul; and the gamesome breezes which fluttered his garments and played around his countenance, as if to provoke a smiling recognition, met with as little of response as if they had paid courtship to the floating iceberg, and they passed quickly by, chilled by the hyperborean contact. The mysterious little man—contradictory in all his aspects to the order of the day—appeared as he walked toward the corner of Fifth and Chestnut streets—justice’s peculiar stand, where “Black Marias” most do congregate, and where his Honor does the honors to that portion of society who are so unfortunate and so maladroit as to be caught in their transgressions and to be arrested in their sins—he appeared, we say, as he approached this awful corner, to be most assuredly under duresse, as well as an enlistment under general affliction—a guard of functionaries—a body-guard, though not of honor, seemed to wait upon him—the grim little man and the queer little man. There was a hand too—ponderous in weight—austere in knuckle—severe in fist—resting clutchingly upon the collar of the little man, as if to demonstrate the fact that he only was the person to be gazed at—the incident, the feature, the sensation of the time—though the little man resisted not. He had yielded to his fate, sulkily, it may be, but submissively. Pale was the little man’s face—most pale; while his hat was generally crumpled in its circumference, and particularly smashed in the details of its crown, having the look, abused hat, of being typical of its owner’s fortunes—an emblem, as it were, of the ups and the downs, the stumbling-places and the pitfalls wherewith its owner’s way through life is diversified. He had a coat, too—though this simple fact cannot be alluded to as distinctly characteristic—most men wear coats whose aspirations go beyond the roundings of a jacket. But our little man’s coat was peculiar—“itself alone,” speaking of it merely as a coat. There were two propositions—either the coat did not belong to him, or else he did not belong to the coat—one of these must have been true, if it were proper to form an opinion upon the usual evidences which go to settle our impression as to the matter of proprietorship in coats. The fitness of things is the great constituent of harmony in coats, as in all other matters; but here was a palpable violation of the fitness of things, a coat being a thing that ought always to fit, or to come as near to that condition as the skill of the tailor or the configuration of the man will allow. It may possibly be that mischance had shrunk the individual’s fair proportions, and had thus left his garments in the lurch—the whole arrangement being that of a very small kernel in an uncommonly extensive shell. It may be mentioned also in the way of illustration, that the buttons behind were far below their just and proper location—that its tails trailed on the ground; while in front, the coat was buttoned almost around its wearer’s knees—not so stringently, however, as to impede progression, for its ample circumference allowed sufficient play to his limbs. Thus the little man was not only grim, and queer, and sorrowful, but was also picturesque and original. There was at least nothing like him to be seen that day, or any other day; and, as he walked, marvelous people held up their hands and wondered—curious people rubbed their eyes and stared—sagacious people shook their wise heads in disapproval; and dubious people, when they heard of it, were inclined to the opinion that it must be a mistake altogether, and “a no such thing.” A boy admiringly observed that it was his impression that “there was a good deal of coat with a very small allowance of man,” like his grandmother’s pies, which, according to his report, were more abundantly endowed with crust than gifted with apples; as if the merit of a pie did not consist mainly in its enclosures. To confess the truth, it might as well be candidly granted at once, that but for the impediment of having his arms in the sleeves, the little man might have turned round in his coat, without putting his coat to the inconvenience of turning round with him.

The case—we do not mean the coat, but the case, in general and inclusive—offered another striking peculiarity. In addition to the somewhat dilapidated pair which already adorned his pedal extremities, the little man, or Mr. Peter Faber—for such was the appellation in which this little man rejoiced, when he did happen to rejoice,—for no one ever was lucky enough to catch him at it—Mr. Peter Faber carried another pair of boots along with him—one in each hand—as if he had used precaution against being sent on a bootless errand, and took the field like artillery, supplied with extra wheels. But it was not that Mr. Peter Faber had feloniously appropriated these boots, as ill-advised persons might be induced to suppose. But each man has his idiosyncrasy—his peculiarities—some trait which, by imperceptible advances, results at last in being the master-passion, consuming all the rest; and boots—an almost insane love of boots—stood in this important relation to Mr. Peter Faber. In happier days, when the sun of prosperity beamed brightly on him, full of warmth and cheeriness, Peter Faber had a whole closet full of boots, and a top-shelf full of blacking—in boxes and in bottles—solid blacking, and that which is diluted; and Peter Faber’s leisure hours were passed in polishing these boots, in admiring these boots, and in trying on these boots. Peter knew, sadly enough, that he could not be regarded as a handsome man—that neither his face nor his form were calculated to attract attention as he passed along; but his foot was undeniably neat—both his feet were—and his affection for himself came to a concentration at that point.

Some men there are who value themselves upon one quality—others may be discovered who flatter themselves on the possession of another quality—each of us is a sort of heathen temple, with its peculiar idol for our secret worship. There are those who pay adoration to their hair. Whiskers, too, have votaries. People are to be met with who attitudinize with their fingers, from a belief that these manual appendages are worthy to be admired, because they are white or chance to be of the diminutive order. Many eyes have double duty to perform, that we may be induced to mark their languishing softness or to note their sparkling brilliancy. To smile is often a laborious occupation to those who fancy they are displayed to advantage in that species of physiognomical exercise; and there are persons of the tragic style, who practice frowning severity in the mirrors, that they may “look awfully” at times. Softnesses of this kind are innumerable, rendering us the most ridiculous when most we wish to please. The strongest have such folly; and the weak point in Peter Faber’s character lay in his foot. Men there are who will make puns, and are yet permitted to live. Peter Faber cherished boots, and became the persecuted of society! Justice is blind.

On the previous night, in the very hours of quietness and repose, there came a strange noise of rattling and bumping at the front door of the respectable house of the respectable family of the Sniggses—people by no means disposed to turbulence themselves, or inclined to tolerate turbulence in others. It so happened, indeed, on this memorable occasion, that Sniggs himself was absent from the city; and the rest of the family were nervous after dark, because his valor had temporarily been withdrawn from their protection. Still, however, the fearful din continued, to the complete and terrified awakening of the innocent Sniggses from the refreshment of balmy slumber. And such a turmoil—such hurrying to and fro, under the appalling influence of nocturnal alarm. Betsy, the maid of all-work, crept in terror to the chamber of the maternal Mrs. Sniggs. Betsy first heard the noise and thought it “washing-day,” but discovering her mistake, Betsy aroused the matron with the somewhat indefinite news, though rather fearful announcement, that “they are breaking in!”—the intelligence, perhaps, being the more horrible because of its vagueness, it being left to the excited imagination to determine who “they” were. Then came little Tommy Sniggs, shivering with cold and fear, while he looked like a sheeted ghost in the whiteness of his nocturnal habiliments. Tommy and Betsy crawled under the bed that they might lie hid in safety. Nor were Mary and Sally, and Prudence and Patience slow in their approach; and they distributed themselves within the bed and beneath, as terror chanced to suggest. Never before had the Sniggs family been stowed away with such compactness—never before had there been such trembling and shaking within the precincts of that staid and sober mansion.

“There it goes again!” shivered Mrs. Sniggs, from beneath the blankets.

“They’re most through the door!” quivered Betsy, under the bed.

“They’ll take all our money!” whimpered Prudence.

“And all our lives, too!” groaned Patience.

“And the spoons besides!” shrieked Mary, who was acting in the capacity of housekeeper for that particular week.

“Pa!” screamed Tommy, under the usual impression of the juveniles, that as “pa” corrects them, he is fully competent to the correction of all the other evils that present themselves under the sun.

“Ma!” ejaculated the others, seeking rather for comfort and consolation, than for fiercer methods of relief. But neither “pa” nor “ma” seemed to have an exorcising effect upon the mysterious bumpings and bangings, and pantings, and ejaculations at the front door.

In process of time, however, becoming a little familiarized to the disturbance, Mrs. Sniggs slowly raised the window, and put forth her nightcapped head, it having been suggested that by possibility it might be a noise emanating from Mr. Sniggs, or “pa” himself, returning unexpectedly.

“Who’s there?” said Mrs. Sniggs.

“Boots!” was the sepulchral reply.

“Is it you, dear—you, Sniggs?”

“If you mean me by saying you, it is me—but I’m not ‘dear’—boots is ‘dear’—Sniggs, did you say? Who’s Sniggs? If he is an able-bodied man, send him down here to bear a hand, will you?” and another crash renewed the terrors of the second story, which sought vent in such loud and repeated shrieks, that even the watchman himself was awakened, and judiciously halting at the distance of half a square, he made his reconnoisance with true military caution, concluding with an inquiry as to what was the matter, that he might know exactly how to regulate his approaches to the seat of war. An idea had entered his mind that perhaps a ghost was at the bottom of all this uproar; and though perhaps as little afraid of mere flesh and blood as most people of his vocation, he had no fondness for taking spectres by the collar, or for springing his rattle at the heels of a goblin, holding it—the principle, and not the ghost—as a maxim that if such folks pay no taxes and are not allowed to vote, they are not entitled to the luxury of an arrest; for the ordinances of the city do not apply to them.

“Even if it is not a ghost nor a sperrit, and I’m not very fond of any sort of sperrits but them that comes in bottles,” said he, having now approached near enough to hear the knocking and to see a dark object in motion at the top of Mr. Sniggs’s steps; “perhaps it’s something out of the menagerie or the museum—something that bites or something that hooks; and I cannot afford to have my precious corporation used up for the benefit of the city’s corporation. The wages is too small for a man to have himself killed into the bargain.”

“But maybe it’s a bird,” continued he, as he caught a glimpse of Peter’s coat-tail fluttering in the wind. “Sho-o-o-o!”

But no regard being paid to the cry, which settled the point that there was no bird in the case—“sho-oo!” being a part of bird language, and only comprehensible by the feathered race—the watchman slowly advanced until he saw that the mysterious being was a man—a little man—apparently leveling a blunderbuss and pulling at the trigger.

“Who said shoe, when it’s boot?” inquired the unknown figure, still seemingly with a gun at its shoulder, and turning round so that the muzzle appeared to point dangerously at the intruder.

“Halloo! don’t shoot—maybe it will go off!” cried the watch, as he ducked and dived to confuse the aim and to avoid the anticipated bullet.

“Don’t shute! I know it, don’t shute—that’s what I want it to do—I’m trying to make it shute with all my ten fingers,” was the panting reply, as the apparently threatening muzzle was lowered for an instant and raised again—“and as for its going off, that’s easy done. What I want, is to make it go on.”

Luckily for Charley’s comfort, he now discovered that the supposed blunderbuss was Peter Faber’s leg, and that the little man had it leveled like a gun, in the vain attempt to pull a Wellington boot over that which already encased his foot. He sighed and tugged, and sighed and tugged again. The effort was bootless. He could not, to use his own words, make it “shute.” The first pair, which already occupied the premises, would not be prevailed upon to admit of interlopers, and Peter’s pulling and hauling were in vain.

It was the banging of Peter’s back against the front door of Mrs. Sniggs’s mansion that had so alarmed the family; and now as he talked, he hopped across the pavement, still tugging at the boot, and took his place upon the fire-plug.

“Pshaw!—baint it hot!” said Peter. “Drat these boots! they’ve been eating green presimmings. I guess their mouths are all drawed up, just as if they wanted to whistle ‘Hail Kerlumby.’ They did fit like nothing when I tried ’em on this morning; but now I might as well pull at the door-handle and try to poke my foot through the key-hole. My feet couldn’t have growed so much in a single night, or else my stockings would have been tore; and I’m sure these are my own legs and nobody else’s, because they are as short as ever and as bandy. Besides, I know it’s me by the patches on my knees. That’s the way I always tell.”

“Are you quite sure,” inquired the watch, “that you didn’t get swopped as you came up the street? You’ve got boot, somehow or other. But come, now,” added he authoritatively, and putting on the dignity that belongs to his station, “quit being redickalis, and tell us what’s the meaning of sich goin’s on in a white man, who ought to be a credit to his fetching up. If you’re a gentleman’s son, always be genteel, and never cut up shindies or indulge in didoes. What are you doing with them ’are boots? That’s the question, Mr. Speaker.”

“Doing with my boots? What could I do without my boots, watchy?” added Peter, in tones of the deepest solemnity, as he laid his boots upon his lap and smoothed them down with every token of affection. “Watchy, though you are a watchy, you’ve got a heart with the sensibilities in it—nothing of the brickbat about you, is there, watchy? If you are ugly to look at, it’s not your fault, and it’s not your fault that you’re a watchy. I can see with half an eye that you’re a man with feelings; and you know as well as I do that we must have something to love in this world—you love your rattle—I love my boots—better nor they love me, I’m afraid,” and Peter grew plaintive.

The watchman, however, shook his head with an expression of “duberousness,” which, like the celebrated nod of Lord Burleigh, seemed to signify a great deal relative to the thoughts existing within the head that was thus shaken. It vibrated, as it were, between opinions, oscillating to the right, under the idea that Peter Faber was insane from moral causes, and pendulating to the left with the impression that he was queer perchance from causes which come upon the table of liquid measure.

Peter’s thoughts, however, were too intent upon the work he had in hand and desired to get on foot, to pay attention to any other insinuation than that of trying to insinuate his toes into the calf-skin. Sarcastic glances and nods of distrust were thrown away upon him. He asked no other solace than that of bringing his sole in contact with the sole of his new boot. On this his soul was intent.

“It’s not a very genteel expression, I know,” said the nocturnal guardian, “and it may seem to be rather a personal insinivation, though I only ask it in a professional way, and not because I want to know as a private citizen—no, it’s in my public campacity, that I think you have been drinking—I think so as a watchman, not as David Dumps. Isn’t you a leetle corned?”

“Corned! No—look at my foot—nor bunioned either,” replied Peter, as he commenced another series of tugging at the straps; and with a look of suspicion, he added, “That tarnal bootman must have changed ’em. He’s guv me some baby’s boots. But never mind—boots was made to go on, and go on they must, if I break my back a driving into ’em. Hurra!” shrieked our hero, “bring on your wild cats!”

With this exclamation—which amounts with those who use it, to a determination to do or die—Peter screwed up his visage and his courage to what may be truly denominated “the terrible feet,” and put forth his whole strength. Every nerve was strained to its utmost tension; the tug was tremendous; but alas! Cæsar was punctured as full of holes as a cullender, by those whom he regarded as his best friends; many others have been stuck in a vital part by those who were their intimate cronies, and how could Peter Faber hope to escape the treachery by which all great men are begirt? When exerting the utmost of his physical strength, the traitorous straps gave way. Two simultaneous cracks were heard; a pair of heels, describing a short curve, flashed through the air, and Peter, with the rapidity of lightning, turned a series of backward somersets from the fire-plug, and went whizzing like a wheel across the street. Now the half-donned boot appeared uppermost, and again his head followed his heels, as if for very rage he was trying to bite the hinder part of his shins, or sought to hide his mortification at his failure, not only by swallowing his boots, but likewise by gobbling up his whole body.

“Why, bless us, Boots!” said the Charley, following him like a boy beating a hoop, “this is what I call rewarsing the order of natur. You travel backerds, and you stop on your noddle. I thought you was trying to go clean through the mud into the middle of next week. A’n’t you most knocked into a cocked hat?”

“Cocked fiddlesticks!” muttered Peter. “Turn us right side up, with care. That’s right—cocked hat, indeed! when you can see with half an eye—if you’ve got as much—it’s my boots vot vont go on. A steam engine—forty horse power—couldn’t pull ’em on, if your foot was a thimble and your legs a knitting-needle. Don’t you see it was the straps as broke? Not a good watchy!” continued Peter, as he dashed the boots on the pavement, and made a vain attempt to dance on them, and “tread on haughty Spain.”

“Well, now, I think I am a good watchy; for I’ve been watching you and your boots for some time.”

“What’s a man if he a’n’t got handsome boots; and what’s the use of handsome boots, if he a’n’t got ’em on? As the English Gineral said, what’s beauty without bootee, and what’s bootee without beauty? Look at them ’are articles—fust I bought ’em, and then I black’d ’em, and now they turn agin me, and bite their best friend, like a wiper. Don’t they look as if they ought to be ashamed?”

“Yes, I rather think they do look mean enough.”

“Who cares what you think? Have you got a boot-jack in your pocket?—no, not a boot-jack—I want a pair of them ’are hook-em-sniveys, vot they uses in the shops. I don’t want a pull-offer; I want a pair of pull-on-ers.”

“If you’ll walk with me, I’ll find you a pair of hook-em-sniveys in less than no time.”

“If you will, I’ll go, because I must get my boots on somehow, and hook-em-sniveys will do it if anything will. There’s no fun in boots what wont go on; you can’t make any thing of ’em except old clothes-bags and letter-boxes, and I a’n’t got much use for articles of the sort—seeing as how clothes and letters are scarce with me.”

“Can’t you use ’em for book-keeping by double-entry? That’s the way I do. I put all my cash into one old boot, and all my receipts into the other. That’s scientific double-entry simplified,—old slippers is the Italian method.”

“No, I can’t. I does business on the fork-out system. I don’t save up, only for boots; and as soon as I gets any money, I speculates right off in something to eat, and lives upon the principal.”

Peter gathered up his boots, and half reclining upon the watchman, wended his way to the common receptacle, where, after discovering the trick played upon him, and finding that the “hook-em-sniveys” were not forthcoming, he shared his wrath between the boots which had originally betrayed him, and the individual who had consequently betrayed him. At length,

“Sweet sleep, the wounded bosom healing,”

restored Peter to himself and that just estimate of the fitness of things, which teaches that it is not easy—even for a man who is as sober as a powder-horn—to pull a pair of long boots over another pair; particularly if the latter happen to be wet and muddy. Convinced of this important truth, Peter put his boots under his arm, and departed to get the straps repaired, and try the efficacy of hook-em-sniveys where the law could not interfere.

And such was the close of this remarkable episode in the life of the grim little man and the queer little man, whose monomania had boots for its object.

There is a lowly mountain home

That nestles near a clear blue stream,

A shady nook—a fitting spot

For pilgrim rest, or poet’s dream.

Two tall elm trees their branches fling

Across the humble roof-tree there

While fearlessly the robins sing,

And woodland flowers perfume the air.

Not ten yards from the cottage door

A rocky wall the streamlet meets,

And wildly, quickly dashing o’er

With its rude song the valley greets.

While far and wide the glittering spray

Like showers of diamonds fill the air,

The golden sunbeams with them play

And arch the beauteous rainbow there.

A shelving rock, like semi-bridge,

From the rude bank hangs jutting o’er,

While round the rough and frowning ridge

Twine moss and vine and creeping flower.

A winding pathway, near the stream,

Leads to this wild and dizzy height;

Once gained the waters flash and gleam

Like jewels on the gazer’s sight.

Beyond, the hills, in robe of green,

Mount upward to the calm blue sky,

While at their feet the silver sheen

Of a broad river meets the eye.

Here in this cot, a space below,

A widow dwells in silent grief,

Earth has no balm to sooth her wo,

No magic song, no healing leaf.

Long weary years have slowly fled

Since death first filled her home with gloom.

Numbered her husband with the dead

And traced for her a widow’s doom.

One sunbeam there, one ray of joy

On that low cottage shed its light,

A fair-haired child, an idiot boy

Was to her heart like stars to night.

I’ve seen a vine, a fragile vine,

When strong support had failed,

Around a weaker cling and twine,

Till drooping both in dust they trailed.

I’ve seen a lonely captive find

Sweet solace in his hours of grief,

Yea food for heart, and thought for mind,

In a frail plant—one pale green leaf.

From the damp earth in his lone cell

It sprung to life, sad life awhile,

But there, alas! it could not dwell,

No sunshine shed its cheering smile.

’Twas tended well mid hope and fear,

And watched with all a parent’s care,

Yea, watered daily with a tear,

But could not stay in darkness there.

So in this cot that idiot boy

Was like that leaf to captive sad,

His guileless ways, and childish joy,

Oft made the broken-hearted glad.

Beside him she on earth had nought,

For him all labor, love and prayer,

And he no other playmates sought,

Save birds and flowers, sunlight and air.

Speech was denied him, and not one

Save she who gave him birth alone

His uncouth gestures e’er could read,

Or learn his sorrows, joy or need,

And as, amid the quiet sleep

Of summer noon, a storm will sweep

In sudden wrath, and blackness cast

O’er skies serene a moment past;

So in the spirit of this child

Dark passion, fitful, quick and wild,

Such inward storm would sometimes wake,

Naught but her gaze its power could break;

Her words could bid its fury cease,

The mother’s voice could whisper peace.

Not often thus, but the long hours

Of summer day mid birds and flowers

He’d cheerful spend, or watch the spray

Of dashing waves in their wild play.

And this, indeed, his chief delight,

When airs were bland and skies were bright.

So fixed his gaze, you wondered why,

A child should look so earnestly.

It seemed as if he longed to be

A wave amid those waters free.

His thoughts we know not, but perchance

Some spirit dream was in that glance!

Such as when reason leaves her throne

And fancy reigns supreme alone,

Will lead the helpless captive on

To deeds we fear to think upon.

Some thought as strange, some wish as wild,

We deem possessed this idiot child.

One day he climbed the pathway, where

The rocky bridge seemed hung in air;

Awhile he looked with strange delight

On sparkling wave and rainbow bright;

Then, with a scream so wild and shrill

It made the distant hearer thrill,

He plunged amid those waves and foam,

Like Naiade seeking its lost home.

A moment, and it all was o’er —

He sunk, to rise with life no more.

A schoolboy saw but could not save

The idiot from his watery grave.

Few were the mourners, and some there

With hard heart said, “the widow’s care

Would now be less,” yea, thought that she

From a great burthen thus was free.

Ill judging ones! ye could not know

The depth of that fond mother’s wo.

He surely was not loved the less

Because of his great helplessness —

Nor can we in our weakness tell

He was not loved by God as well —

The smallest bird and flow’ret share

His holy watch and daily care.

That broken link in Nature’s chain

May after death unite again.

The fettered mind! Ah! who can tell

What mysteries in that casket dwell,

When God, alone who holds the key

Shall set the darkened captive free?

One gleam of that electric thought,

Which beauty out of chaos wrought;

One touch of that creative hand

Which loosed prime Nature’s iron band,

To feeblest mind can give the power

On seraph’s wing to mount and soar.

We know not but the soul that lay

Like folded flower in feeble clay,

May open beneath purer skies,

And, fanned by airs of Paradise,

May bloom in beauty fresh and fair

Amid the richer glories there.

E. P.

———

BY ALICE G. LEE.

———

“Child no longer. I love, and I am Woman!”

When first thy face blent with my youthful dreaming,

I loved thee fondly, madly, e’en as now;

Yet to a mossy bank, with careless seeming,

I pressed a woman’s heart, a girl’s young brow.

I did not dream that thou couldst ever love me,

One that was fondled as a very child!

But as the glorious stars that beamed above me,

I worshiped thee, with love as deep and wild.

Then bending low, thy face was by my pillow:

A kiss was pressed upon my burning cheek —

As floats a flower upon the foamy billow,

Uprose my heart, and yet I could not speak.

I sat beside thee in that pulseless hour,

And gazed into the cloudless vault above.

I learned that o’er thy heart was cast the power —

E’en as on mine—the fatal spell of love.

Unto my soul it came a torrent rushing,

And brought wild thoughts unknown to it before.

Bright hopes and dreams within thy heart were gushing

Of joys the future held for thee in store.

I only knew that, seated now beside thee,

My hand lay trembling, nestling in thine own;

I only felt thy dear voice did not chide me —

Oh, how I treasured every careless tone.

Another hand in fancy thou wert pressing;

Another voice fell softly on thine ear:

And looks of love came—with a low-voiced blessing —

From beaming eyes, that memory brought so near.

While thoughts of a bright meeting on the morrow

Had chased a transient shadow from thy brow —

Unto my heart came the first thrill of sorrow;

An omen of the weight it beareth now.

We parted: I those mournful thoughts to smother

Within a breast till then unknown to care.

I knew thou lovedst only as a brother —

A sister’s love I had no wish to share.

In that short hour I had lived many years;

And now, alas! must share the common lot —

The lot of woman—suffering and tears;

While yet a child to those who knew me not.

The wreath of Fame e’en then for thee was twining;

High aspirations urged thee proudly on:

The light of love upon thy path was shining,

A dear hand would be thine when fame was won.

I bade God speed thee; though my heart was breaking

My pale cheek flushed beneath thy parting kiss —

Hope from my soul a final leave was taking —

The future hath no trial worse than this.

———

TRANSLATED BY ALICE GREY.

———

Where is the brow that, with the slightest sigh,

Moved my fond heart, its most devoted slave?

Where the fair eye-lid, and those stars divine,

Which to my life its only lustre gave?

Where is the worth, the wise, accomplished mind;

The prudent, modest, humble, sweet discourse?

Where are the beauties which, in her combined,

So long of all my actions were the source?

The shadow of that gentle countenance

To which the weary soul for rest might flee?

And where my thoughts were written; where is she

Who held my willing life within her hands?

Alas! for the sad world! alas! for my

Still weeping eyes, that never shall be dry.

PART I. (THE PHILOSOPHY AND USES OF EATING.)

———

BY FRANCIS J. GRUND.

———

Brillat Savarin, the immortal author of “The Physiology of Taste,” among his axioms has the following: “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai qui tu es.” (Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are.) If any one doubt the truth of this remark, or has the least objection to it, he must not read my essay; for I judge him utterly incapable of understanding what follows. It was an equally wise saying of Sir John Hunter, that man was what his stomach made him; but he did not carry his investigations far enough. He had reference to the capacity, and, in case of damage, to the recuperative faculty of the stomach, and did not take into consideration the gentle persuasions of the palate—the sense which is slowest of development, but the most faithful companion of old age. The worthy Englishman had drawn his inferences from the stomachs of the livery and aldermen of London; and his beau ideal, in this respect, was no doubt the stomach of the Lord Mayor. But turtle and venison, though excellent things in themselves, are not the only criterion of rank, fashion, and capacity, though they are the necessary concomitants of magisterial dignity. Brillat Savarin went much further; he classified men according to their dinners; judging thereby of their tastes, their accomplishments, their refinement, and their scientific pursuits. There is, indeed, no function that man performs in common with the beasts, in which he differs so widely from the brute creation, as in eating, which led Brillat Savarin to another not less important axiom: “L’animal se repait, l’homme mange, l’homme d’ésprit seul sait manger,” (which, translated into elegant English, means, animals feed, man eats, but the man of education and refinement alone knows how to eat.)

The savage merely wants his meat coagulated—civilized man wants it cooked; but it requires taste to discriminate between gravies. Gravy is to meat what dress is to man, or rather woman; it not only hides deformities, but sets off and enhances beauty. It dissolves the dissonance which might otherwise exist between boiled and roasted into harmony; it establishes the balance of power between the joints and the petits pieds. Talk of man, in his savage state, appreciating gravy; or the man without refinement discriminating between a common sauce aux capres and one aux truffes, or au vin de champagne! Men, in civilized countries, have immortalized themselves by gravies; and Very—I mean the old man, not his son, who has done nothing in the world to entitle him to respect, except marrying a pretty woman, who never peeled a mushroom—has made gravies with which, as Puckler Muscau said, “a man could eat his grandfather!” The prince, being of half royal descent, meant by his grandfather the beau ideal of toughness.

But I must not shoot ahead of my argument. I am to show that we, in this country, lay too little stress on what we eat—do no justice whatever to cooks, and thereby deprive ourselves of a vast deal of enjoyment that would not interfere with our neighbors. A man who tells you he does not care what he eats, might just as well tell you he does not care with whom he associates. You may depend on it that man cannot appreciate beauty. To him one woman is just as good as another—prose just as good as poetry—the sound of a jews-harp equal to that of a harpsichord. Avoid that man, by all means, or your associations will become vulgar, your taste corrupted, and your appreciation of beauty and elegance as dull as a pair of cobbler’s spectacles.

But there are those who boast of caring naught for a good dinner. They are so etherial, scientific, or Spartan-like, as to be just as well satisfied with a piece of beef as with a pair of canvas-backs. Well, what does it mean? Might a man not, for as good a reason, boast of his blindness, and his stoic indifference as to the color of woman’s eyes, or the incarnation of her cheeks? Might he not as well boast of liking the smell of tobacco as much as that of a rose or a violet? The man who has no taste, has only four senses instead of five, and is therefore defective in organization. What notion has he of a sweet face, a sweet disposition, or a sweet voice?

Taste may be cultivated as much as every other sense. The man who has never exercised his eyes, cannot be a judge of painting, of statuary, or of architecture. The man who has not cultivated his ear, will not easily distinguish between the harmony of Mozart and the tuning of the instruments, which set a musician’s teeth on edge; and a man who has not practiced his sense of touch, will take no more pleasure in taking a lady’s hand, than in handling her glove. Would, can, ought, a lady to give her hand to such a man?

But there is yet another still more remarkable philosophical consideration, which ought to induce us to investigate this subject. What we eat assimilates with us, becomes our own flesh and blood, influences our disposition, our temper, and consequently our amiability. Every living thing in nature longs for incarnation, aspires to become human—to move from its apogee to its human perihelium. But the lord of creation makes his selection; he consults his taste, and admits but few of the aspirants to his intimacy.

Nothing but want is an excuse for bad living—for not restoring ourselves in the best manner possible. Only think that every seven years we are made entirely new! Our whole frame is consumed, and new particles of matter accrue in place of the old ones, during that period. Then to reflect that we are made up of half boiled potatoes, raw meat, and doughy pie-crust! The very thought of it is enough to lower our self-respect, and to diminish very sensibly the regard we owe to others.

It is intended by nature that we should have taste—that we should select our food and make it palatable. The infinite variety of plants and animals subject to the human stomach, testify to the superiority of man. Without the power of assimilation, what sympathy could there exist between him and the rest of Creation? To say we are fond of trout, of grouse, of venison, is but another way of expressing our affection for fish, bird, and deer. What would these animals be to us if we did not eat them? What we to them? And does not our love often partake of the same characteristics? Do we not frequently crush that which we tenderly press to our bosoms?

The Germans have a terrible idiom for expressing the highest paroxysm of affection. They say “they love a woman well enough to eat her.” The idea is monstrous; and yet can it be denied that the greatest intimacy imaginable is the identity produced by assimilation. The idea, in spite of its apparent coarseness, is purely transcendental. And is not the converse of this principle admitted by all civilized nations? What do the terms “distasteful,” “disgusting,” “nauseating,” “sickening,” signify? What else but that these things do not agree with our stomachs? there are no stronger similes in the English language. Mark the climax; “distasteful,” referring to the tongue; “disgusting,” having reference to the palate; “nauseating,” applying to the throat; and “sickening,” proceeding, ex profundis, from the stomach! Here you have the whole gamut of human pathos—in which the stomach is, after all, the key-note—the heart being nothing but the sounding-board.

Even knowledge borrows its terms from the stomach. Our scientific acquisitions are “crude” and “undigested,” when they have not been systematized; and a man is “raw,” when he has neither tact or experience in the common pursuits of life. One half of our vocabulary is taken from the palate and the stomach—the milky-way of that microcosm of which man is the universe. Nor have we as yet properly watched that wonderful economy of nature, by which we are constantly consumed and restored—those unceasing pulsations between life and death, which, when undisturbed, are the cause of so much enjoyment. We watch the heavenly bodies, we rejoice over the discovery of a new planet, or an asteroid; we espy comets, and endeavor to account for their movements and perturbations, while a much more wonderful process is going on every day before our eyes, without exciting our astonishment. How comes it that the stomach, out of the most heterogeneous matters treasured up in it, is daily preparing flesh, bones, brains, the enamel of the teeth, the horny substance of the hair and nails, &c.? Can any philosopher explain how the particles of inanimate matter are vivified and thrown from the womb of life—the stomach—into circulation, to perform with the blood those rapid revolutions which mark our existence, and bear such a close analogy to the revolution of our planet round the sun? We look for wonders to the stars, and are a living wonder ourselves—a microcosm much more astonishing and interesting than all above and beneath us. The stomach is the great laboratory of the world, and yet how indifferent are the greater part of mankind to the gentle affinities of that much abused organ! We cultivate a good appearance—a healthy complexion—a clear eye, handsome teeth, and all that, but entirely neglect the gentle admonitions of that organ which alone can impart these virtues. Men talk of hereditary blood; but of what possible use is it without an hereditary good stomach? Give me a good stomach, and the blood will follow as a matter of course.

We talk of improving the breed of cattle, of horses, sheep, &c. But how is it done? By what other principal means than by improved feeding, and taking care that nothing shall interfere with the proper digestion of the improved food. You may use every possible means of improving the breed, without improved feeding the race will degenerate. And so it is with man. Whole nations, as, for instance, the English, wear a better aspect than others, merely because they are better feeders. Meat-eaters have generally a more florid complexion, and, on an average, a greater development of brains. They are, usually, not easily wrought; but when excited, “perplexed in the extreme;” and as slow to back out of as they are to commence a fight. We imagine these qualities inherent in the race; but they are the offsprings of the stomach, and nothing else. Change the diet of that nation, and she will soon lose her distinguishing characteristics. And so it is with certain classes of society. Why is the mob of England cowardly? Because it is badly fed. Increase the wages of the laboring man so that he can obtain beef once a day, and no soldiery in the world will be able to cope with him. He would soon show symptoms of animation; he would, in very characteristic language begin “to feel his oats.” Nothing is equal to the contempt which well-fed people have for those who are badly fed. The former are called respectable, the latter are thought capable of any mischief that can be conceived of. Pauper ubique jacet.

Between the stomach and the highest faculty of our souls there is a very close connection, though men have vainly endeavored to disprove it. Heavy food, which calls for undue action of the stomach, paralyzes, for a time at least, all mental action, and destroys the highest power of the mind—imagination. By gentle stimulants, however, we may increase both—provided we are temperate. You see better with a spy-glass than with the naked eye, provided you do not draw it out beyond the proper focus. Again; good cheer promotes cordiality, friendship, benevolence, and charity. Only the highest paroxysm of love is capable of triumphing over the stomach. But how long does it last? And does it not, in the end, warm itself at the chemical fire of good cheer, or die for the want of it? Love does very well during the hey-days of the blood; while the stomach, with its even sway, governs until death, with a power which increases as it goes on. Every passion fades as we pass the meridian of life, or dwells only in that great faculty of the soul, reminiscence, until that even becomes palsied by the gnawing tooth of time; but the sensitiveness of the palate increases—a regular gourmandizer scarcely existing before the age of forty. Our taste becomes matured with our judgment; when reason waits upon the tender passions, they have already flown. Every other passion has a regular rise and fall, and a culmination point, the pleasures of the palate alone are fixed and immovable as the eternal stars in the firmament. The fiery youth may “sigh like furnace,” and make “ballads to his mistress’ eyebrow,” and man “may seek the bubble reputation even at the cannon’s mouth;” but the sober justice is “capon lined;” he is the only sensible person among them, and guards against the bowels of compassion, by that completeness about the region of the stomach which is generally received as prima faciæ evidence of good nature. The Chinese—the oldest civilized people on earth—require that their justices should be fat; and the popular idiom of our own language corresponds to it; for we expect from a judge, gravity of deportment, and sedate manners. Lean men seldom inspire the confidence which fat men do. “I wish he were fatter,” says Cæsar, of Cassius; for a man who feeds well, and grows fat, has given “hostage to fortune.” Corpulency, like marriage, being “a great impediment either to enterprise or mischief.”[1]

There is yet another reason for conceding the ascendancy of the palate over the other organs. The palate and the stomach have had more to do with the establishment of civil liberty than is even suspected by those who have neglected this important study. The custom for magistrates to feed their clients, is as old as the Roman empire, and has been preserved in all civilized countries. Our Saxon and Anglo-Saxon ancestors were accustomed to do every thing important over a dinner; and to that circumstance, as Alderman Walker, of the English metropolis, very justly remarked, must be ascribed the preservation of English liberty, as contradistinguished from that of France. A people, accustomed to civic festivals, will not easily be reduced to slavery. Good cheer enlivens our attachment to the country, enhances patriotism, and calls for those expressions of sentiment which I look upon as the main pillars of liberal institutions. And if public liberty is consolidated by public feastings and Lord Mayors’ dinners in England, where the people only partake of the good cheer, by a liberal construction of the constitutional charter, that is to say, through their legal representatives, how much more conducive to public liberty must be those public dinners in our country, where people enjoy the privilege of assisting in person at the banquet! Instead of hearing the herald proclaim, “Now the Lord Mayor is helping himself to turtle—now the Lord Mayor has commenced upon venison—now the Lord Mayor drinks to the queen!” they themselves eat the turtle, the venison, and drink success to popular governments;—with this difference only, that they have less patriotic cooks—cooks who, in most cases, have scarcely an interest in common with those to whose patriotism they minister. This is radically wrong, and ought to be looked to. If our Fourth of July dinners have somewhat fallen into disrepute with the fashionables, it is, I trust, not from a want of patriotism on their part, but on account of the atrocious manner in which some of them are prepared. Let venison and turtle, or if these be out of season, the best that the market affords abound, and the beau monde of our Atlantic cities will excuse the sentiments for the cook’s sake, and wash them down with Champagne and Madeira!

The custom to invite men whom we respect and honor to a public dinner, is as old as the hills, and ought to be carefully handed down to our children. No higher distinction ought ever to be claimed by our public men, and none granted. Political feasts are the highest stimulants to action I know of—but in order to ensure their success, an act of Congress ought to prohibit set speeches, and impromptus prepared for the occasion. The awkward manner of taking public men by surprise, was strikingly exhibited in the speech of Lord Brougham, at a dinner of the members of the National Institute, which began thus: “Non-accoutumé que je suis à parler en publique,” and extorted some smiles even from the furrowed countenances of the French savants. The reading of written addresses, concealed under the plate during dinner, for the purpose of being let loose after the cloth is removed, is a breach of hospitality, and ought to be voted a nuisance; but the greatest latitude might, without danger to public safety, be allowed in regard to toasts, especially when they refer to the Eagle, who from his royal toughness has nothing to fear from the barbarism of the cooks. By the by, English writers and reviewers need not feel so squeamish about “that Eagle,” as “the British Lion” is quite as tough, if not more so, and when he is finished, there still remains the Unicorn, as a corps de reserve. They have two beasts to our one; neither of which is fit to be exhibited in a drawing-room.

Dinners serve scientific and artistical purposes quite as well as they do political ones. Every learned society of England has its annual meetings, at which a public feast is prepared for its officers and members. Turtle and venison are the only means of bringing the members together, just as the suppers at our Philadelphia Wistar parties season the scientific conversation of our own men of learning, and render their entertainments more attractive and cheerful. Dinners and suppers act as the attraction of cohesion among members of the same family. Why should they not promote a feeling of fraternity among men of science and literature?

The practice of patronizing literary men and artists by dining them, has, it is to be regretted, not yet been generally adopted in this country. In England and France it is quite common; but since the remuneration of artists exceeds all bounds in the latter country, the artists, in turn, invite their patrons. There is no better means of spreading useful information than these interchanges of hospitality. Knowledge in general is dry,[2] and would have few votaries if the stomach did not act as interpreter between the learned and the tyro. At table you may bring the most opposite characters together, and they will agree—as long as they are eating—on most subjects, provided they are but half bred. The elective affinity of viands and gravy, mushrooms and truffles, will establish harmony among them, which may last even for an hour after dinner; but at tea you must be careful. All beverages are deceptive, and are rather apt to exhibit differences than to equalize them. A true diplomat will press you to drink; but he will seldom taste any thing but ice water and lemonade.

What important part the stomach plays in diplomacy, is known to the whole world. Napoleon, when sending the Abbé de Pradt to Poland, gave him no other instruction than this: Tenez bonne table et soignez les femmes, (keep a good table and take care of the women.) I wonder whether the late administration gave similar instructions to Colonel Todd, when it sent him to St. Petersburg! Our ministers abroad may take care of the women, after a fashion, but I defy them, unless they are rich, to keep a good table.

It is a vulgar error to suppose that ladies are most attractive at a ball. I prefer to see a woman at dinner. The dinner is the touchstone of her attractions. If she be graceful and agreeable there, she will be so in every position in life, and you may say of her what Napoleon said of Josephine: elle a de la grâce même en se couchant. It was whimsical affectation in Lord Byron to pretend that ladies ought not to eat at all. A woman who has no appetite, or is indifferent as to the manner of gratifying it, is but a poor companion for life, whose good nature and agreeable temper will scarcely last through the honey-moon. Byron had in his mind’s eye an English woman, who breakfasts on chops and dines on raw joints, which is detestable. But fancy an artistically arranged salle à manger, a partie quarrée, (two ladies and as many gentlemen) at breakfast, and the servants handing round côtelettes à la Maintenon, (little lambs’ ribs that look as innocent as new-born babes, artistically set off and coupled with historical associations of the golden age of French literature!) and you have quite another picture. Then the abandon which follows the little cup of Mocca—the sallies of wit and humor—the little attractions of graceful hands and mouths, and fine teeth—the flow of conversation, and the embarrassing intervals and flaws filled up with wine! Then the dessert, which ought never to fail, even at breakfast,—flowers decorating the table, and the women as in the Hesperian garden, touching the forbidden fruit! There you see woman in all her grace, and in all the attractions of her sex,—calm, collected, dignified, observing, listening and perhaps—consenting. What is a ball in comparison? Ladies and gentlemen do not move as ballet-dancers, and make at best but an impression inferior to the latter. Their dilettantism in that respect is no better than that of music, compared with regular performers. At breakfast and dinner, a woman may study attitude, and remain longest in those which are attractive. At the ball-room, she is hurried along, and depends for success on her partner. A clumsy, ungraceful partner in a dance, is enough to ruin her—comparisons will wound her pride—she is agitated, angry, and it is only the queen of a ball who enjoys it and is capable of giving pleasure. At dinner, you possess a woman altogether to yourself,—the impressions which you receive and make are lasting, and you are, by the pleasant occupations of the table, prepared to relish them. You cannot become intimate with a woman unless you have taken a meal with her. And then how many thousand opportunities you have of showing your attention, your being captivated by her charms—how much resignation you can practice in entertaining her! The impressions made at dinner are indelible; those of a ball are evanescent, for you do not receive them in a proper state of mind, and forget them after a night’s rest. The dance deranges a woman’s toilet, makes her gasp and pant for breath, and is apt to exhibit those faults which a skillful toilet would have concealed, and which we would have been happier in not knowing. Ladies after a dance look like victims that have been tortured; and oh! gentle reader, may you never have the misfortune to be behind the scenes at a ballet! The first ballerina, after the greatest storm of applause, looks then but like a fallen angel scourged by furies. No, no! give balls and routes to boys and girls. A sensible man scorns at that, and takes it as no mark of respect for him to be invited to them. Let me lead the woman I fancy to dinner, and give me an hour’s conversation with her afterward, in the boudoir, and I will gladly resign meeting her in a crowd. Let the cook but half do his duty, and I will not be deficient in mine.

A word, before I part, to the Blue Stockings—(I would whisper it if I could do so in print)—It’s very well to quote Shakspeare, and Byron, and Milton, (whom nobody reads,) and Mrs. Hemans, who had much better written sermons. But if you want to acquire a lasting reputation, and choke off envy and detraction, have an eye to your cook. The most fastidious critic would sooner forgive a misquotation than the want of seasoning in a favorite dish. As much literary reputation may be acquired by dining literary men, as by imitating or plundering their writings.

|

I hope that in a chapter on eating I may quote “Bacon.” |

|

“Gray, my friend, is all Theory, and Green the Tree of life,” says Mephistophiles to the student, in Goethe’s Faust. |

———

BY THE PRIVATE SCHOLAR.

———

Let us go to the dewy mountain, love,

’Tis the time of the Maying weather;

The lark is up in the blue above,

The thrush in the briery heather;

From the cottage elm the robin calls —

List, love, to the gentle warning —

We’ll away to the mountain waterfalls,

And drink the dew of the morning.

Let us go to the tangled greenwood fair,

The scented buds invite us;

The young red deer will gambol there,

And a thousand songs delight us.

Thy hand in mine, and mine in thine,

In the wood-path we will linger,

Where the dew is bright on the eglantine,

As the jewel on thy finger.

Let us go to the moor and the virgin lake —

I hear the call of the plover;

And the fisherman’s song comes over the brake,

With the perfume of the clover.

A bonny boat with a pennon gay,

Like a nymph on the blue is sleeping —

To the fairy lake, oh, let us away,

While the sun from the hills is peeping.

Let us go to the upland airy lea,

Where the silent flocks are browsing;

We’ll pass the dale where the honey-bee

His early store is housing.

Our path shall lead through the meadow lane,

Its daisy blooms will meet us;

And the reed-pipe strain on the distant plain,

With the herd-boy’s song will greet us.

Let us go abroad at the early dawn,

With the blue sky bending o’er us;

While the mingled music of grove and lawn

Goes up in a grateful chorus;

For sweet is the breath of the morning, love,

And sweet are the opening flowers;

And sweet shall our communion prove,

In the fields and woodland bowers.

Let us go while Nature’s holy strain,

O’er the joyous earth is pealing;

My pulse has caught its youth again,

And throbs with the rural feeling.

Each bird, and brook, and dripping bud,

Invites with a gentle warning;

Then let us away to the field and wood,

And drink the health of the morning.

———

BY MRS. C. E. DA PONTE.

———

Weary of earth, and tossed

Amid the storms which ever wreck my way,

Thou who canst save the wretched and the lost,

O hear me pray.

Weary of time, which brings

Little of comfort to my bosom now,

Feeble and worn, to Thee my bosom clings,

To Thee I bow.

Deep is the inward strife,

Thou knowest consumes my sick and weary soul,

Deep is that grief still agitates my life,

Beyond control.

Here joy is o’er,

Earth cannot soothe, for life can nothing give,

Take me, then, Father, to that mighty shore,

For Thee I’ll live.

Watch me where’er I go,

Guide my faint footsteps through this valley drear;

Father, I weep with more than mortal wo,

But yet can bear.

A TALE OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION.

———

BY P. HAMILTON MEYERS.

———

(Concluded from page 274.)

The ensuing evening was cold, dark, and stormy. The commandant of Fort Constitution was faithful to his appointment. He was received at the door of Captain Wilton’s cottage by Arabella, and conducted silently to the drawing-room. A single light faintly illuminated the interior, and scarcely served to reveal the figure of an individual, plainly dressed, and enveloped in an overcoat, seated beside a table in the centre of the apartment. He rose on the entrance of Gansevoort, and advancing hastily to meet him, with extended hand, and a cordial manner, said, “I rejoice to meet you, Mr. Gansevoort, or rather Sir Francis, if you will permit me thus, in anticipation, to address you.”

The commandant drew back with evident emotion, and declining the proffered hand of the other, replied; “If I mistake not, I have the honor of addressing Sir Philip Bender. We will waive courtesies for the present, until we more fully understand the relation in which we stand to each other.”

“We meet no longer as enemies, Mr. Gansevoort, but as fellow-subjects of the same most gracious sovereign.”

“You and I are, indeed, subjects of one sovereign, Sir Philip, but it is that Sovereign whose empire is the universe.”

“Very true,” replied the other. “My remark, perhaps, was not properly applicable until our business is accomplished.”

“If there is business to be transacted between us, Sir Philip will have the kindness to disclose the nature of it.”

“Come, come, Colonel Gansevoort,” replied Major Bender, with a smile, “let us have no unnecessary formality. I have come to consummate, in every particular, the negotiation already pending between us, through my fair plenipotentiary here, and to learn from you at what hour you will be prepared to deliver formal possession of the fortress under your charge to its rightful and royal proprietor, whom I have the honor to represent.”

“You then recognize this lady as your authorized agent in what has heretofore passed between her and myself on this subject, and now renew her propositions.”

“I do,” eagerly replied Sir Philip; “I see we are fast coming to the point.”

“Yes, Sir Philip Bender, we are coming to the point; but it is one of which you do not seem to dream. In the name, and by the authority of the Congress of the United States, I arrest you as a spy.”

Simultaneously with these words, which were spoken in a tone sufficiently elevated to be heard without, the door opened, and a serjeant, followed by a dozen men, entered the room. A deadly palor overspread the countenance of Sir Philip. Surprise and consternation for a moment paralyzed his faculties. He made no attempt at escape, but dropping silently into a chair, covered his face with his hands, and remained speechless. Had not Bender considered his success in this intrigue as nearly certain as any human project can be rendered before its fulfillment, nothing would have induced him to run the hazard of a personal exposure. But, notwithstanding his certainty, he had still done all that he could do, to be prepared for what he considered the very remote contingency of a mistake. He had landed thirty men, under command of Wiley, and concealed them at the edge of a wood, about a third of a mile distant; it being impossible to bring them into the village without instant detection. A faithful servant alone had accompanied him to the house, and had received instructions, in case of need, to hasten, if possible, and bring them up in time for a rescue. At the moment of his arrest, Miss Wilton, trembling with terror, had slipped from the room, and hastened to notify the servant of his master’s danger. Sir Philip’s horse stood saddled at the door, and the clatter of his hoofs, as he dashed down the street, now caught the ear of the prisoner. Hope, therefore, had not entirely deserted him. If by any means he could detain his captor fifteen or twenty minutes, he was yet safe, and not only so, but would have accomplished no slight enterprise in capturing the commandant of the fort. Gansevoort manifested a becoming respect for the feelings of his prisoner, and allowed him to remain some minutes undisturbed. When the latter, however, saw that preparations were making to depart, he resorted to another artifice to gain time. He sought to draw the commandant into a debate on the propriety of his arrest, alledging that if he had been guilty of any offence, he had been decoyed into it by the latter.

“Not so,” replied Gansevoort, indignantly. “Did I decoy the Dragon into this harbor, or your emissaries into my presence? If I have made use of strategy, it has been to counteract strategy; to undermine the miner, and ‘blow up the engineer with his own petard.’ But why should I waste words in justifying myself to a man who has shown himself to be beyond the influence of every honorable feeling. Extraordinary, indeed, must be those measures which I should not have been justified in using, to prevent the accomplishment of an outrage so great, that I can scarcely refrain even here from inflicting signal vengeance for its contemplation. Base, perfidious, cowardly man! the mantling blood upon your cheek tells me that I am understood.”

“He rails with safety, who rails at a prisoner,” replied Bender, “but let me ask you,” he continued, rising and speaking slowly, and with an abstracted air, “let me ask you whether —”

“Another time and place must suffice,” said the other.

“One word,” rejoined Sir Philip, “only one word!” He paused suddenly, and threw back his head in a listening attitude. A distant tramp was heard. It came nearer—nearer—until a loud “halt!” resounded in front of the house. Then, with an air of indescribable exultation, he shouted, “Now, Colonel Gansevoort, the tables are turned. You are my prisoner! What think you now of ‘undermining the miner, and blowing up the engineer with his own petard?’ ”

“Stand to your arms, my men!” shouted Gansevoort, hastily drawing his sword, “Let one fly and alarm the garrison. Quick! barricade the doors!”

It was too late. The doors were flung violently open, and panting with haste, rushed into the room—not a British officer, but the Count Louis De Zeng! “We heard that you were in danger,” he exclaimed, hastily, to the commandant. “A hundred men at the door await your orders.”

“Your aid is timely,” was the reply. “Take half of your men, and conduct the prisoner immediately to the fort. The rest will remain with me to receive our approaching visiters.”

These orders were immediately put into execution. Wiley, however, became apprized of the state of affairs, and retreated with his men rapidly to their boats. They were not pursued.

A few words will explain the secret of Count De Zeng’s unexpected appearance. When Arabella gave her orders to the servant of Major Bender, Alice, unperceived, stood trembling by. She was terrified beyond measure at the peril of Gansevoort, in whom the gentle girl was interested to a degree that she would not own, even to herself and which nothing could have induced her to exhibit to another. She could not give the alarm within, without exposing her predilections, besides which, she supposed the British force to be much nearer than they were, and that nothing but an immediate alarm of the garrison would afford the slightest chance of escape. She ran, therefore, as soon as she was unobserved, hastily to the fort, which was scarcely forty rods distant. A sentinel on duty conducted her immediately to Count De Zeng, to whom, after exacting a promise of secrecy in regard to her agency in the matter, she briefly communicated the state of affairs at her father’s house. The count lost not a moment in acting on her information, with the result which has been described.

——

We will not follow the prisoner to the place of his confinement, or dwell upon his dismal reflections behind the grated bars of a felon’s cell. He was not a prisoner of war, entitled to the courtesies and respect due to a brave but unfortunate soldier. He was a criminal, guilty of a most base and ignominious act, for which his thorough knowledge of military law told him he must die. He had landed without a flag, entered the enemy’s quarters in disguise, and there sought to bribe an officer to the betrayal of his trust. There was no hope. He felt it. He must die upon the scaffold. In vain, with impotent rage, did he heap curses upon the heads of his imbecile agents. They were at liberty, and he was the victim. If any thing could aggravate his wretchedness, it was the reflection that the day of his arrest was the day of his expected nuptials. No time was lost in his trial. A military court was convened on the ensuing day, before which the prisoner made an ingenious but useless defence. He was convicted, and sentenced to death, and the sentence was immediately forwarded to the commander-in-chief for approval.

The minutes of the trial, which were also sent to General Washington, were fully explanatory of the particulars of his arrest, and of the personal reasons which had influenced Gansevoort in resorting to measures for its procurement, which the latter would otherwise have considered objectionable. To these, the commandant added his express desire, that if the circumstances afforded any ground for a mitigation of punishment, the prisoner might have the full benefit of it.

During the few days that elapsed before a return could be expected, no exertions were spared by the unhappy man that seemed to offer a chance for his escape. At times, inflated with the idea of his personal importance, he indulged the hope that Washington would not dare to proceed to extremities against him. If that distinguished leader entertained any idea of compromising the national quarrel, it certainly would be bad policy to widen the breach between the opposing parties, by unnecessary rigor. He did not, therefore, neglect to magnify his own importance by allusions to his family connections, his expected promotion to the peerage, and, stretching a point for that purpose, his intimacy with royalty itself. He succeeded so well by these means, in at least convincing himself of his security, that he soon began to resent even the indignity of a personal confinement. His first expostulations on this point, addressed to an officer on guard, were met by the assurance that his cause of complaint would be speedily removed. The order for his execution had arrived. Blanched with terror, he refused to believe the tidings. He had not entertained a doubt that whatever the decision of the commander-in-chief should be, the importance of the transaction would at least induce the personal attendance of that officer. When, however, pursuant to his request, the report of his trial and sentence was shown to him, bearing the simple endorsement, “Approved—Geo. Washington,” his humiliation was complete. Losing at once all sense of personal dignity and fortitude, he begged his life in the most abject terms. Resolutely refusing any personal interview with the prisoner, Gansevoort was importuned by letter. Entreaties, threats, and promises, mingled together, and urged with all the energy and earnestness of despair, formed the staple of his epistles. They were read and returned with the simple reply that his execution would take place on the ensuing day at sunset. We will pass over that dreadful interval, in which hope had entirely forsaken the breast of the doomed. Coward-like, he died a thousand anticipatory deaths.

The day and the hour approached. The giant shadows of the western mountains began to stretch toward the environs of Fort Constitution. As the declining sun lingered above the summit of the hills, its rays were reflected by the bayonets of a military guard, encircling a scaffold, a prisoner, and a coffin. To that sun the executioner looked for his signal. Its disk was resting on the horizon, and a hundred eyes were watching its motion. At this moment there was a sudden movement in the crowd—a parting to give way to some new comer, and a messenger, breathless with haste, placed a letter in the hands of Count De Zeng. Not heeding that it was addressed to the commandant, he hastily opened and perused it. The blood forsook his cheeks, as with a trembling hand he passed the note to Gansevoort, and made a signal to the executioner to forbear. As the eyes of the other ran rapidly down the page, mingled rage and terror shook for a moment his manly frame. Recovering himself with an effort, he directed the serjeant in command to approach.

“Remand the prisoner to his cell,” he said, “the execution must be deferred.”

Before explaining the cause of this sudden change in the aspect of affairs at the fort, it will be necessary to travel back a short period, and take up another clew of this singular history.

——

Miss Gansevoort’s week of dreadful expectation had passed away, and the day of her expected sacrifice arrived. Her father in the meantime had used every means both to persuade and frighten her into a peaceable compliance with his wishes. Fancying he perceived an increased docility in her conduct, he relaxed a portion of his severity, and tried the effect of kindness. Although closely watched, she was no longer confined to her room. When the appointed day arrived without bringing Sir Philip, she felt a temporary relief; but she then had the additional agony of suspense to endure. Hope, vague and indefinite, began to dawn in her breast; but its light was scarcely more than sufficient to reveal the depth of her despair. Every foot-fall alarmed her. Every voice quickened her pulsation.

In this state of mind, she was astonished and delighted by the unexpected reception of a letter from her brother. It was delivered in the evening to a servant at the door, by a man cloaked and muffled, who immediately departed. It informed her that, having heard of her situation, he had provided means for her immediate rescue; that at the hour of nine in the ensuing evening, a carriage would be in attendance at the corner of the street, displaying a single light in front; and that if she could escape her father’s surveillance long enough to reach the vehicle, she would be safe. A confidential friend of her brother would there receive her, and convey her before morning to the fort. Every thing, he said, was arranged to avoid detection or arrest upon the route.

There were no bounds to the ecstasy of Miss Gansevoort on the receipt of this letter. She resolved to brave every danger, for the purpose of escaping the one which she dreaded most. Never did time travel so slowly as on the ensuing day. Every moment was an age of fear and suspense. Could she manage to make her escape? Would not Sir Philip arrive? Would there be no failure or mistake on the part of her brother’s friend? Who was that friend? These, and a thousand similar questions, continually passed through her mind, and kept it in a state of the most violent agitation. She was obliged to confide her secret to one of her maids, who readily promised all the aid in her power, and even consented to be the companion of her flight. Through her agency, when the appointed hour arrived, she was enabled to transfer a few indispensable articles to the carriage; and when she herself tremblingly prepared to depart, it was without an article of dress about her which could create a suspicion of her design. As the clock struck nine, she rose from her seat in the drawing-room, and with careless air approaching the outer door, suddenly opened it, and darted, fawn-like, down the street. She heard the alarm behind. She heard the clattering steps of her pursuers; but she saw the signal-light at hand. The carriage-door stood open, and a cloaked stranger at its side. Without a word he lifted her in—followed—closed the door—and the cracking of the coachman’s whip, and the rattling of the wheels, mingled with the shouts and execrations of the pursuers.

“My maid! my maid!” exclaimed Ellen, “she is left!”