* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Music of Bach: an Introduction

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Charles Sanford Terry

Date first posted: Feb. 3, 2018

Date last updated: Feb. 3, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180204

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

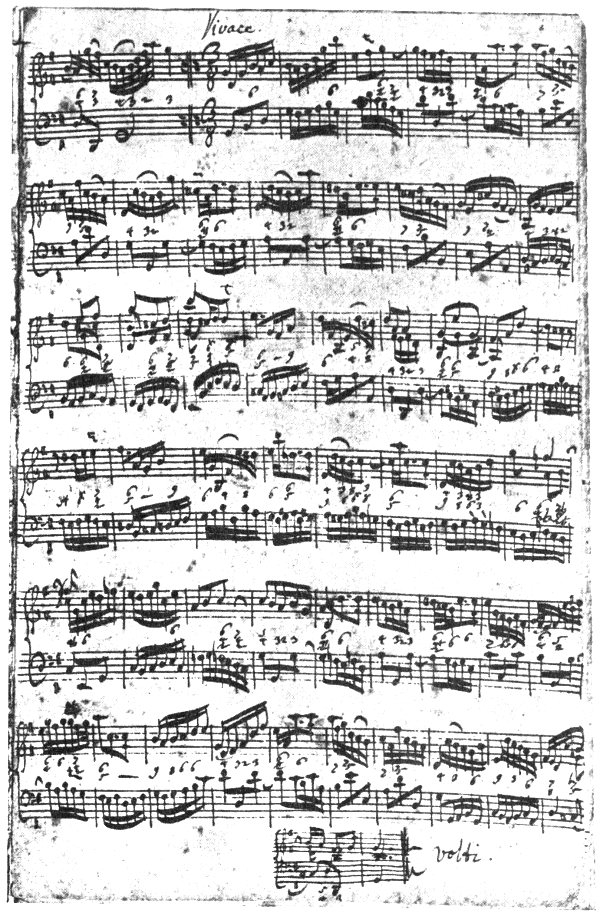

THE G MAJOR VIOLIN SONATA (Bach’s autograph)

AN

INTRODUCTION

By

CHARLES SANFORD TERRY

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company Limited, 10 Orange Street, London W.C. 2.

This Dover edition, first published in 1963, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the work first published by the Oxford University Press in 1933. This edition is published by special arrangement with the Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-19516

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc.

180 Varick Street

New York 14, N.Y.

ii‘She played Bach. I do not know the names of the pieces, but I recognized the stiff ceremonial of the frenchified little German courts and the sober, thrifty comfort of the burghers, and the dancing on the village green, the green trees that looked like Christmas trees, and the sunlight on the wide German country, and a tender cosiness; and in my nostrils there was a warm scent of the soil and I was conscious of a sturdy strength that seemed to have its roots deep in mother earth, and of an elemental power that was timeless and had no home in space.’

From ‘The Alien Corn’

by W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM

To

ALBERT SCHWEITZER

THIS INADEQUATE EXPRESSION OF PROFOUND REGARD

A century and a quarter have passed since Samuel Wesley, Bach’s ecstatic propagandist, wrote to Benjamin Jacob: ‘I knew that you had only to know Bach to love and adore him, and I sincerely assure you that, in meeting so true an Enthusiast in so good a Cause (and depend on it that nothing very good or very great is done without enthusiasm), I experience a warmth of Heart which only enthusiasts know or can value.’

The enthusiasm and the demand in 1809 were for Bach’s organ music—‘The Organ is King, be the Blockheads never so unquiet’ Samuel boasted jubilantly. Other aspects of him were shrouded by the mists of ignorance. To-day enthusiasm is general, the public appetite omnivorous. Bach, formerly frowned upon by the generality as academic, ‘high-brow’, ‘a cold mathematical precisian’, is now the idol of a widening public, which finds in his music the very qualities in which it was once supposed deficient.

These pages fill the gap deliberately left open in my Bach: a Biography. They offer a plain, non-technical guide to one of the largest expanses of musical thought planned by a human brain. I use the word ‘guide’ advisedly. For my purpose is indicative rather than expositive, to relate Bach’s music to the circumstances of his life, unfold its extent, offer guidance for a more intensive study of it, and incidentally engender the ‘warmth of Heart’ of true enthusiasm.

I am much indebted to Herr Manfred Gorke for permission to reproduce the facsimile of Bach’s autograph of the G major Violin Sonata, one of the principal treasures of his remarkable collection of Bachiana.

C. S. T.

WESTERTON OF PITFODELS,

Summer, 1932.

In a general way, the music of every composer in any age is the mirror of his circumstances, and more or less faithfully reflects them. Certainly this is so with Bach and his period. For the art of musical invention was not yet admitted to be the province of inspired minds, but was deemed the normal accomplishment of official musicians in executive posts. The Capellmeister at the princely court, the Cantor in his parochial church, were equally charged to furnish the organization they controlled with music of their own contriving. By no other means, indeed, could its needs be satisfied. Little instrumental music was in print and circulation, and of church music such as Bach wrote there was none. Nor were manuscript scores readily exchangeable. Bach was strongly disinclined to lend his own, and his prejudice was shared by others with less cause to deem them valuable, but equal reason to preserve them for their own occasions. Recognition outside their immediate circle consequently was the lot of few. The concert-room only afforded a platform for public music late in the eighteenth century, and at Leipzig Bach held himself aloof from it. Only rarely was he induced to provide music not required by the conditions of his office: the Brandenburg Concertos, the Musical Offering (Musicalisches Opfer) dedicated to Frederick the Great, and, perhaps, the funeral music for Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, are the rare exceptions to an otherwise invariable rule of abstinence. Hence his music was almost exclusively ‘official’. It is not the least testimony to his character that, though ordered by routine, it bears from first to last the hall-mark of noble inspiration.

But if Bach’s Muse was subservient to the situations he filled, the career he followed almost uninterruptedly was his early and deliberate choice. By becoming an organist and Cantor he deserted the traditions of his direct ancestry. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were members of secular guilds of musicians, whose duties were not exclusively 2 musical. Had his father lived, he probably would have followed their example. But the premature death of Johann Ambrosius removed an impediment which might have frustrated the career on which his son early set his heart. For, already as a schoolboy Sebastian learnt to regard music as primarily the handmaid of religion, in his own words, ‘a harmonious euphony to the glory of God’. It was therefore no sudden impulse that moved him, when little more than twenty, to dedicate himself and his art to God’s service. Only once in his purposeful career he divorced himself from it.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Thuringian Eisenach on Saturday, 21 March 1685, the youngest child of Johann Ambrosius Bach and Elisabeth Lämmerhirt. His mother, daughter of an Erfurt furrier, contributed nothing to his genius—she died soon after his ninth birthday. His father, after similar service at Erfurt and Arnstadt, had since 1671 been town’s-musician (Stadtmusicus) at Eisenach, where he also chimed the hours and alarmed the community when fire threatened its inflammable roofs. Greatly esteemed by his fellow townsmen, and generally competent in the technique of all the instruments of his craft, he was especially gifted on the violin and viola, for both of which Sebastian was his pupil. At the Eisenach Gymnasium the lad pursued the normal curriculum with precocious success, while he absorbed the romantic associations of the locality. His relative, Johann Christoph Bach, the town’s organist, was another potent influence. In after life Sebastian praised him as ‘a profound composer’, whose motet I wrestle and pray (Ich lasse dich nicht) was once supposed to be the younger Master’s composition. His brother, Johann Michael Bach, of Gehren, also was a composer of uncommon merit. In their scores, not improbably, Sebastian found his first models of church music. Both brothers were organists, another bond between them and their young relative; and with Johann Michael he was more intimately associated: he married his daughter. It is curious that, neither as organist nor composer, Sebastian drew inspiration from his immediate ancestry.

Sebastian’s frequent absences from school at Eisenach 3 betoken a juvenile constitution not robust, and domestic griefs clouded his youthful sky. He lost his mother in 1694, received a stepmother before the year was out, and, just short of three months later (1695), followed his father’s coffin to the grave. He was within a few weeks of his tenth birthday. In this crisis of his life good fortune took him to Ohrdruf, where his eldest brother, recently married, was organist. This younger Johann Christoph, fourteen years Sebastian’s senior, was a musician whose competency is declared by the successful careers of his sons, every one of whom received his instruction. He was, moreover, a pupil of Pachelbel, and transmitted to them and to his brother the technique of that Master of the organ. For five impressionable years Sebastian lived under his brother’s roof and received his tuition in a branch of their art they alone of their father’s sons adopted. At Ohrdruf’s school, as at Eisenach, he showed precocious ability, and in its class-rooms imbibed the sturdy faith which fortified him throughout his life; the bias of the school was sternly orthodox. At Ohrdruf, too, his genius for composition began tentatively to declare itself, and he left his brother’s roof already drawn to dedicate it to the service of religion.

Sebastian was now fifteen and of an age to find employment. Disinclination for a secular career prevented him from seeking an apprenticeship at Erfurt or elsewhere where his relatives were in office. Providence opportunely opened a door at Lüneburg, far remote from his Thuringian homeland. In the school attached to St. Michael’s Church Thuringian voices were in request, and, through the good offices of one of the Ohrdruf masters, Sebastian was summoned to fill a vacancy there. At Easter 1700, after a long and venturesome journey, he was enrolled as a discantist of its select choir, in surroundings singularly apt to fit him for his vocation. Neither Eisenach nor Ohrdruf was equipped fully to reveal the potentialities of music as an adjunct to public worship. That instruction he owed to Lüneburg, whose musical resources exceeded those of which he so far had experience. The choir’s repertory was wide and 4 eclectic, its library rich in the scores of the masters of polyphony, German, Dutch, Italian, and no less representative of the critical century that stretched back from his own birth to that of Heinrich Schütz. Thus, though his sojourn at Lüneburg was brief, it was of first-rate importance in the enlargement of his experience.

But the organ was his absorbing interest. And here, too, Lüneburg afforded him exceptional opportunities. The famed Georg Böhm, whose music, among others, he had transcribed at Ohrdruf, was organist of St. John’s Church. Though a quarter of a century separated their births, Sebastian could not fail to seek the acquaintance of one whom he greatly admired. At Hamburg, too, some thirty miles distant, Böhm’s master, the veteran Jan Adam Reinken, was still in service, patriarch of the brilliant school of North German organists. More than once in a summer vacation Sebastian tramped the weary miles to hear one whom in after years his own mastership deeply impressed. Celle, too, was another magnet and instructor. At its ducal court French music and French musicians were the vogue and introduced him to an idiom his own art so greatly enriched later at Cöthen.

Sebastian bade farewell to Lüneburg in the late summer or early autumn of 1702, after more than two years of fruitful experience. Not yet eighteen, fortune so far had befriended him; at no time had he been distant from masters of the instrument on which he desired to excel. Disappointment met him, however, on the threshold of his professional career. In the autumn of 1702 he presented himself at Sangerhausen, a town in Saxony some thirty miles west of Halle, whose Market (St. James’s) Church required an organist. He submitted to the customary tests, treated a prescribed melody, accompanied a Choral, extemporized a fugue on a given subject, and so impressed the assessors that, notwithstanding his youth and inexperience, his selection was recommended. Higher authority, however, favoured an older candidate, who received the post in November 1702. Bach’s disappointment may have been tempered by the prospect of an imminent and 5 similar opening in his native Thuringia. Meanwhile, being without means, he needed to earn a livelihood, if not as an organist, then in some other capacity. Opportunely employment was offered at Weimar, where in April 1703 he entered the chamber orchestra of Duke Johann Ernst, younger brother of the reigning sovereign. His service there was not prolonged, for on 9 August 1703, as he had probably anticipated, Arnstadt gave him an organ. His apprenticeship was over. He was in his nineteenth year.

The restored New (St. Boniface’s) Church at Arnstadt, to which Bach was now attached as organist, had just installed an organ by the Mühlhausen builder Johann Friedrich Wender. It comprised a Pedal Organ of five speaking stops, three of 16-foot tone; an upper manual (Great Organ: Oberwerk) of twelve stops, strong in diapason tone; and a brilliant lower manual (Brustwerk) of nine stops. As an organist, Bach never had at his peculiar disposal an instrument worthy of his skill. But now, for the first time, an organ was at his exclusive use. His official duties left him ample leisure to perfect his technique; indeed concentration upon it eventually displeased his employers, who, though proud of his talent, deplored his evasion of other tasks which threatened to curtail his arduous practising. He was induced to compose a cantata, probably for Easter 1704, but refused to write another unless he received the assistance of a choirmaster. His thoughts turned often to Lübeck and its organist Dietrich Buxtehude, whose eminence as composer and player urgently attracted him. Even in the maturity of his powers the neighbourhood of a fellow artist always drew him to seek his acquaintance and, haply, his instruction. But Lübeck was 300 English miles distant! In October 1705, however, he obtained a month’s leave to make the pilgrimage, and prolonged it without sanction till the end of the following January (1706). He brought back to Arnstadt from his contact with Buxtehude a newly acquired virtuosity which greatly perturbed his congregation. He accompanied the hymns with unconventional freedom, and set his hearers agape at the audacity of his improvisations. The Consistory vainly 6 admonished him, and his relations with that body became increasingly uncordial. He had, moreover, outgrown the meagre opportunities for self-expression the situation afforded, and in June 1707 gladly accepted the post of organist in the Church of St. Blaise at Mühlhausen.

Bach remained at Mühlhausen for almost exactly twelve months. He succeeded a musician of eminence, was attached to a church whose beauty contrasted with the unlovely fabric at Arnstadt, and served a community of greater culture and resources. Moreover, he was no longer a bachelor, having taken his Gehren cousin Maria Barbara Bach to wife. Circumstances therefore promised a prolonged residence in Mühlhausen. But his visit to Lübeck had left him no longer resigned to function simply as an organist. He coveted a post which would allow him to dedicate his genius more generously to the service of religion. Mühlhausen impeded his new resolve; for the battle between the Puritan Pietists and orthodox Lutherans raged there with particular fury, and the propriety of elaborate church music was in debate. So, on 25 June 1708, he tendered his resignation. It had been his aim, he complained, to employ music as a vehicle for the exaltation of God’s glory, and yet he had encountered vexatious opposition. He had therefore accepted another situation, in which he would be at liberty ‘to pursue the object which most concerns me—the betterment of church music’. He begged, and with regret on the part of his employers received, permission to resign.

Bach’s new occupation was at Weimar. He described it to his Mühlhausen friends as membership of the Duke’s musical establishment (Capelle) and of the more select body of string players who performed in the ducal apartments. But from the first, or after a brief interval, he functioned as Court Organist. The Duke’s serious and religious nature promised to support his plans for the improvement of church music, and though, at the outset, he exerted no wider authority than at Arnstadt and Mühlhausen, he correctly anticipated promotion to a post which would effectually enable him to pursue them. Meanwhile his 7 Weimar period conclusively revealed him as an organist of unrivalled technique, a composer for his instrument of the most inventive genius, an architect of contrapuntal form whose like had not and has not appeared. Nurtured in the traditions of German polyphony, but gifted to endow it with new life, he combined a felicity of melodic utterance with harmonic inventiveness and resource never excelled or equalled. A very large proportion of his masterpieces for the organ were first heard on the instrument incongruously placed in Duke Wilhelm’s bizarre chapel. Before he was thirty the foremost German critic dubbed him ‘famous’, and his profession conceded him a supremacy which only Handel contested. Had he wished, he might in 1713 have succeeded Handel’s master, Friedrich Wilhelm Zachau, as organist of the Church of Our Lady at Halle, whose new organ of sixty-three speaking stops strongly attracted him. He seriously entertained the prospect. But his Duke at length placed him in a position to realize the high purpose declared at Mühlhausen six years before. In March 1714 he received appointment as ‘Concertmeister’, with the obligation to compose cantatas at regular intervals for the ducal chapel.

Preoccupied with the organ, and holding situations which imposed no other routine service upon him, Bach had to this point written little vocal church music. Inadequate material at his disposal made him obstinate in refusing to compose a second cantata at Arnstadt. Impediments of another kind had obstructed him at Mühlhausen. But his visit to Lübeck and experience of its famous performances of church music made him eager to express himself in that form, and the success of his Gott ist mein König (No. 71) at Mühlhausen in 1708—its parts were printed at public expense and the work was repeated in 1709 under his direction—fortified the resolve he formed in that year. Prior to his appointment as Concertmeister in March 1714, however, no more than seven church cantatas can be attributed to his pen. But from thenceforward he poured out an astonishing stream, which, with a single intermission, flowed uninterruptedly for thirty years. The bulk of it belongs to Leipzig. But the stream had its 8 source at Weimar, and in that period was decisively grooved in channels from which thereafter it never wandered.

The year 1717 blazed Bach’s name throughout Germany and also, ironically, recorded his disgrace. His contest with the Frenchman Marchand at Dresden, unreasonably hailed as a victory for German art, heightened his resentment at his Duke’s failure to give him the post of Capellmeister, which had fallen vacant at the close of the previous year (1716). For no other discernible reason, in August 1717, a few weeks before his meeting with Marchand, he accepted the invitation of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen to enter his service. For a time the irate Duke refused to release him. But, before the New Year of 1718, with his wife and children, the eldest of them nine years old, Bach opened a new chapter of his career as Capellmeister to the princely Court at Cöthen.

Bach’s Cöthen years stand aloof from the main thoroughfare of his life. His active interest in church music was in abeyance. For the Cöthen Court was ‘reformed’, its chapel a bare vault in which only stern Calvinist psalms were heard. The deprivation of an adequate organ at the zenith of his renown as a player was another disadvantage. Only the exceptional friendliness of his young music-loving master reconciled him to so long an exile from the path he had deliberately chosen, and to it he returned when the Prince’s marriage cooled his interest in his Capellmeister’s art. Meanwhile, Bach’s Cöthen years display another aspect of his embracing genius. The musical establishment he directed consisted of a small body of instrumentalists, whose duty was the entertainment of their sovereign in his apartments. Bach was already versed in the secular music of France and Italy, and his office now required him to express himself in that idiom. He did so with amazing fertility and gusto, in Suites, Ouvertures, and other pieces. That the organ was not wholly neglected is evident in the Great G minor Fugue performed at Hamburg in 1720. One or two church cantatas also were added to his store. But his Cöthen music was otherwise exclusively secular and instrumental.

The death of his wife Maria Barbara in July 1720 inclined 9 him to remove from the scene of his loss, and stirred again the ambition she had shared with him at Mühlhausen. Hamburg could have secured him for the vacant organ in St. James’s Church there, and the Concertos he dedicated to the Markgraf of Brandenburg in the following year (1721) were probably designed with a view to his migration elsewhere. His second marriage, with Anna Magdalena Wilcken, brought happiness again to his motherless house. But Prince Leopold’s subsequent union with one whom Bach disparaged as an ‘amusa’ diverted him from the interests he had shared with his Capellmeister. Other motives supported Bach’s resolution to find employment elsewhere. Cöthen provided inadequate facilities for his children’s education: his stubborn Lutheranism would not allow them to attend the more efficient Calvinist school, and a desire to give his elder sons the University education denied to himself may also have moved him. But, above all, the inclination to return to his early and normal associations urged him, and opportunely the death of Johann Kuhnau, Cantor of St. Thomas’s School, Leipzig, assisted his inclination. On Quinquagesima Sunday (7 February) 1723 he underwent his trials at Leipzig. More than two months elapsed before he received the appointment, and, after further delay, on Tuesday, 1 June 1723, he was formally inducted. He was a few months beyond his thirty-eighth birthday, and for the rest of his life devoted his ripest genius to the declared purpose of his earlier manhood.

St. Thomas’s School, on whose staff Bach functioned as Cantor, was an ancient institution dating from the thirteenth century. Its foundation students (alumni), as was the German custom, furnished the civic churches with choirs, receiving in recompense their board and education. The staff comprised a Rector, Conrector, Cantor, and Tertius, who constituted the senior body and taught the foundationers. A similar number of junior masters instructed the non-foundationers, who, as day-boys, were restricted to the lower classes. The alumni, Bach’s singers, numbered fifty-four, of ages from fourteen to twenty-one, and gave him his immature tenors and basses as well as his sopranos and altos. Divided into 10 separate bodies, they provided choirs for four city churches. In two of them the music was of simple character and employed Bach’s least competent singers, whose instruction and direction he left to his prefects. The music which we particularly associate with him—his cantatas, Oratorios, and Passions—was heard only in the two principal churches, St. Thomas’s and St. Nicholas’s, in both of which a generous feast of public worship was spread on Sundays and certain festivals. To only one of the many services, however, the principal one (Hauptgottesdienst), was ‘music’, as Bach’s generation understood the term, admitted. It began at seven in the morning and lasted till about noon. In the course of it a cantata was performed by the choir, organ, and orchestra. At the other services the music was simple and sung to organ accompaniment. At the afternoon service (Vespers) on the three high festivals, however, it was customary to render a Latin Magnificat with full orchestral accompaniment, and, on Good Friday, Passion music was performed in similar conditions. For his orchestra Bach drew upon the small company of professional musicians maintained by the municipality, augmented by amateur players drawn from the School and University.

The School had a repertory which successive Cantors had enlarged. But the vogue of new-style music, such as Bach’s congregations expected to hear, was comparatively recent, and for its provision he depended in great measure on his own pen. The composition of church music consequently was his absorbing occupation at Leipzig over a period exceeding a quarter of a century. Yet he found time to express himself in other forms. As an organist he had no official status at Leipzig. But he was in much request elsewhere, and some of his greatest music for the instrument belongs to this period. The needs of the University Musical Society (Collegium Musicum), which he conducted for a number of years, and perhaps his obligations as Composer to the Saxon Court at Dresden, account for the orchestral music he wrote in the later years of his Cantorship. To the literature of the keyboard he contributed the four parts of the Clavierübung and 11 the second part of the Well-tempered Clavier (Wohltemperirtes Clavier), and enriched the technics of his art with The Art of Fugue (Die Kunst der Fuge) and Musical Offering (Musicalisches Opfer) presented to Frederick the Great.

Apart from the music it inspired, Bach’s Leipzig career invites little notice in this outline. His independence of character and insistence upon the prerogatives of his office frequently involved him in conflicts, in which he more than held his own. But his home life was singularly placid and happy, his sons were talented, and only in the last years of his life illness dulled his activities. He died on 28 July 1750 and was buried in the graveyard of St. John’s Church, beneath whose altar his ashes now rest.

NOTE

The fullest narrative of Bach’s career is afforded in the present writer’s Bach: a Biography (Oxford University Press, 1928; new edition 1933). See also his Bach: the Historical Approach (Oxf. Univ. Press, New York and London, 1930). The standard works by Parry, Pirro, Schweitzer, and Spitta deal principally with Bach’s music.

There is no musical field in which Bach is not dominant and indispensable. Music emanated from him with apparently equal ease in all its forms, but not, one is sure, with equal satisfaction. Inadequate material, vocal and instrumental, too often alloyed his pleasure, particularly in the rendering of his larger concerted works. On that account, if for no other, he was happiest at the organ, on which his supreme virtuosity completely expressed his design. Of all others it was the medium most responsive to the emotion that swayed him. In its company he soared in free communion with the high intelligences that inspired him. To it he confided his most intimate thoughts, and, could he have foreseen the immortality posterity bestowed on him, he would undoubtedly have associated it with his favourite instrument.

It is therefore surprising that, proportionately to his total output, his organ music is meagre in quantity. The complete tale of his labour is summed in fifty-seven volumes of the Bachgesellschaft edition, of which no more than four (XV, XXV (2), XXXVIII, XL) and a fraction of a fifth (III) contain his organ music. Their contents are displayed in Table I.

The Table records all the organ music accessible to the editors of the Bachgesellschaft volumes. Nor has any important discovery been made since. But it does not represent all that Bach wrote for the instrument. For the extreme paucity of his organ autographs is remarkable, and significant. They are extant for the Little Book for the Organ (Orgelbüchlein), the six Organ Sonatas, and the Eighteen Choral Preludes. We also have his autograph of four Preludes and Fugues (the ‘Great’ G major, the ‘Great’ B minor, the ‘Great’ C major, the ‘Great’ E minor), the Fantasia in C minor, two Choral Preludes, and the Canonic Variations on Vom Himmel hoch.

But the originals of his other organ compositions are lost. They circulated among his pupils, are known to us in large 13 measure only in their transcriptions of them, and, falling eventually into heedless hands, too often met the fate from which the Violin Solo Sonatas were providentially snatched. The paucity of Bach’s autographs, however, is not attributable solely to the ignorance or carelessness of others. He was a severe critic of his work and undoubtedly destroyed much that fell below his maturer standards. The statement is not challenged by the fact that a quantity of his earlier music survives; for it is not extant in his autograph. In his own script we have nothing earlier than the Little Book for the Organ, with the possible exception of the ‘Great’ Prelude and Fugue in G major. His youthful essays had long been extruded from his portfolio and memory.

Bach’s perpetually improving technique was instructed by the most laborious and consistent study of accessible models, and his equipment as a composer for the organ advanced with it. At an early age he invited reprimand for his midnight study of the great Masters of the instrument, particularly Dietrich Buxtehude, who represented the traditions of German art at their highest. Celle and its French music revealed to him another idiom, and at Weimar Italy added the last contribution to his self-planned curriculum. Here he studied the scores of Legrenzi, Corelli, Vivaldi, and Albinoni. Here, in the year of his promotion (1714), he copied out the Fiori musicali of Frescobaldi, an autograph of 104 pages happily extant at Berlin. From these models he acquired the organized clarity combined with elastic freedom which distinguish him from his German forerunners, whose musical utterance had tended either to looseness of thought or extreme rigidity of form.

In his instrumental, as in his vocal, music Bach expressed himself in the forms convention prescribed. His genius ennobled them all. But the Fugue it transformed into an art-form of the utmost expressiveness. Based on the contrapuntal method of vocal polyphony, a Fugue exhibits a rigid thematic subject, first presented in orderly succession in each part, and then treated by the composer with the skill at his command, in such a way as to impose 14 it on the whole movement as its vivid and pervading thought. In Parry’s words, the Fugue is ‘the highest type of form based on a single thematic nucleus’. For that reason it can easily degenerate into mechanical rigidity. But in Bach’s hands, prefixed by the conventional Prelude, or more showy Fantasia or Toccata, the Fugue was endowed with the richest artistic qualities. Modelled with consummate craftsmanship, constructed on themes of genuine melody, and treated with intuitive contrapuntal skill, the Fugue became the most nervous form of self-expression at his command. The processes of his mind, singularly logical and orderly, delighted in a quasi-mathematical problem. But, exhibiting a unique combination of constructional ingenuity and poetic expression, he was able to impose upon the exercise the qualities of pure music. His name and the Fugue are inseparably associated. None before him and none after him has been able to confer on it so consistently the attributes he has taught us to expect and admire. As Beethoven to the Sonata or Haydn to the Quartet, Bach stands to the Fugue as its classic and unrivalled exemplar.

It was at Weimar, in his middle period, that Bach most persistently practised Fugue form. Of the forty-one that are extant nearly thirty (27) are assigned to that period, and among them are six which display his genius at its zenith, and which the admiration of posterity has crowned with the appendant appellation ‘the Great’: the Fantasia and Fugue in G minor, whose jovial fugal theme Bach borrowed from a Dutch folksong; the Prelude and Fugue in G major, whose Fugue is an extended version of the opening theme of Cantata No. 21, composed in 1714; the Prelude and Fugue in A minor; the Prelude and Fugue in C minor; the Toccata and Fugue in F major; and the Toccata and Fugue in C major, with its tremendous pedal solo.

To the Weimar decade also belong a few isolated movements in forms Bach did not employ again. The Allabreve in D major is a four-part fugue in the strict style. The Canzona in D minor exhales the same atmosphere as the Allabreve, and, like it, reveals their composer’s 15 sympathetic study of Frescobaldi. Both are ‘congruous with a solemn and majestic fabric’ and calculated ‘to stimulate devotional feeling’, qualities Forkel especially discerned in Bach’s organ style. The Pastorale in F major has the rustic charm and character of its counterpart in the second Part of the Christmas Oratorio. The Trios and Aria in F major we can associate with the maturer Sonatas composed at Leipzig for Bach’s eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann, of which Forkel declared it ‘impossible to overpraise their beauty’. All were designed for a harpsichord with two manuals and pedals, rather than a church organ, and are in the nature of chamber music. Not so the Passacaglia in C minor, in its mighty architecture one of the greatest pieces in the literature of the organ. It is built upon a recurring ‘thema fugatum’ of eight bars:

Bach borrowed the theme from André Raison, a Paris organist in the reign of Louis XIV—a further example of his omnivorous study. On it he constructed a fabric of overpowering grandeur. Set on granite foundations, it rises tier by tier, majestic, proportionate, and capped with glorious brilliance. As an architect of form Bach is unsurpassed and unapproachable.

When Bach left Weimar in 1717 his official career as an organist ended. The Leipzig churches had their own; to none of their instruments he had access, save of another’s courtesy. His office was that of choirmaster, his duty to conduct choir, organ, and orchestra in the performance of the weekly cantata. When the cantata was his own work, the organist would naturally permit the composer to displace him in movements whose accompaniment was not fully scored. But otherwise Bach’s office neither required him to function as an organist, nor is it likely that he ever claimed to do so. 16 That he often was heard in St. Thomas’s, St. Nicholas’s, and St. Paul’s is not doubtful, but not officially. Forkel expressly states that, though Bach often gratified visitors by playing to them, he did so always between the hours of service. But his skill as an organist continued to be sought by communities elsewhere, who desired his advice before erecting a new organ, or invited him to display its qualities when completed. If the instrument pleased him, says Forkel, he readily consented to exhibit his talent on it, partly for his own satisfaction, partly for the pleasure of those who were present.

These circumstances throw light on Bach’s compositions for the organ at Leipzig. Apart from the Sonatas, which were not composed for the instrument, and five Preludes and Fugues, three of which are ranked among his greatest, all his Leipzig organ compositions are of the kind known as ‘Choral Preludes’ (Choralvorspiele), that is, short movements treating the melody of a congregational hymn. Very nearly half the total sum of Bach’s organ music is of this character. In the Bachgesellschaft volumes the whole extant of it fills nearly 800 large quarto pages, of which so many as nearly 300 display the Choral Preludes. What is the explanation of this preponderance?

The explanation is twofold. In the first place, Germany’s unrivalled fund of church hymnody was the foundation of German organ technique. This was natural; for its tunes were universally beloved, the hymn-book was the most accessible collection of printed music, and the organ was dedicated exclusively to the same sacred use. Consequently the hymn-book was the organist’s earliest lesson-book. So Bach had used it. His first composition was a simple exercise on a hymn-melody, and when the finger of death touched him he was still at work on the same theme.

A second and equally practical reason explains the prominence of the Choral in Bach’s organ music. During divine service custom required the organist to ‘preambule’. His interludes were not invariably based on a hymn-tune. But at some point he would mark the ecclesiastical season by an appropriate piece of that character, particularly before the 17 seasonal (de tempore) hymn, which, at the principal service (Hauptgottesdienst), was sung immediately before the Gospel. Bach wrote his Choral Preludes in large measure for this purpose. Hence, his organ music includes preludes on nearly eighty congregational hymn-tunes, simple and elaborate, short and long, suited to every season of the ecclesiastical year.

Of Bach’s Choralvorspiele there are extant 143 examples, besides four sets of Variations on hymn-melodies. A number of them have come down to us in transcripts by his pupils and others, notably the collection made by Kirnberger of Berlin. The majority, however, reach us in Bach’s own autograph, or in copies engraved under his supervision and published with his authority. Unlike the former, they are not haphazard in their contents, but represent four separate collections arranged by Bach himself for a particular purpose. The earliest of them, the Little Book for the Organ (Orgelbüchlein), was compiled in 1717. The other three—the Schübler Chorals, the Eighteen Preludes, and the Catechism Preludes—belong to Leipzig.

The autograph of the Little Book for the Organ, a small quarto in paper boards, bears the following title:

A Little Book for the Organ, wherein the Beginner may learn to perform Chorals of every Kind and also acquire Skill in the Use of the Pedal, which is treated uniformly obbligato throughout.

To God alone the praise be given

For what’s herein to man’s use written.

Composed by Johann Sebast. Bach, pro tempore Capellmeister to His Serene Highness the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen

Although Bach describes himself as in the service of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, the book was planned at Weimar, was relevant to his duties there, and of no practical use to him thereafter. For that reason it remained incomplete. Upon its ninety-two sheets Bach planned to write 164 Preludes on the melodies of 161 hymns. Actually he composed only 46. They are not inserted consecutively, and upon the intervening leaves he placed only the titles of the melodies he intended 18 to treat there. Thus, the Little Book for the Organ contains 46 Choral Preludes and the bare titles of 118 unwritten ones. It forms a condensed Hymnary, based on the hymn-book authorized for use in the Grand Duchy of Weimar in 1713. The latter followed general usage in the arrangement of its contents—First, hymns relative to the Church’s seasons and festivals, and, in a second Part, hymns illustrating the various aspects and aspirations of the Christian life. The Little Book for the Organ follows the same order. But only the first Part of it, illustrating the Church’s seasons, is even approximately complete. Bach planned it to contain 60 Preludes, of which he composed only 36. Part II was designed to include 104, of which only ten actually were written. All are short—no more than ten of the forty-six exceed twenty bars in length—and true examples of the Organ Choral (Orgelchoral). They treat the tune in its complete form, uninterrupted by interludes between its several strophes, and decorate it with the composer’s richest devices of harmonization and ornament.

Throughout his life the Lutheran hymn-book unfailingly stimulated Bach’s interpretative faculty. For his affection for the Choral was not simply a personal inclination. It was in the blood of his nation, a prop of their faith, as essential an adjunct of their devotional equipment as the Bible itself. Indeed, Luther gave Protestant Germany a hymn-book thirty years before he formulated her Creed, and she sang vernacular hymns for generations before she read a vernacular Bible. Both, as M. Pirro writes, ‘passed from the inner temple to the outer court, like the reading of Holy Writ’, the Bible as ‘the book of the family’, the hymn-book as ‘its musical Breviary’. Thus Bach’s treatment of the Chorals in the Little Book for the Organ gives an impression of homely intimacy, of a fire-lit interior enclosing a gently-sounding harpsichord. The tunes and their hallowed verses meant so much to him, that his music mirrors the simple faith that sustained him.

A gap of more than twenty years separates the Orgelbüchlein from Part III of the Clavierübung, which Bach engraved and published in 1739. It includes, its title-page declares, ‘various Preludes [Vorspiele] on 19 the Catechism and other Hymns for the Organ’. Bach was never deterred from planning a large design by the objection that it could serve no practical use. In the present case it interested him to employ a number of Luther’s hymns to illustrate the Lutheran Catechism. For the purpose he selected six hymns: 1. Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’ (The Ten Commandments); 2. Wir blauben all’ an einen Gott (The Creed); 3. Vater unser im Himmelreich (Prayer); 4. Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam (Baptism); 5. Aus tiefer Noth schrei’ ich zu dir (Penitence); 6. Jesus Christus, unser Heiland (Holy Communion). With characteristic reverence he prefaced his exposition of Lutheran dogma with an invocation to the Trinity, for which he chose two more melodies, those of the Litany, Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit, and the Trinity hymn Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’. Moreover, it pleased him to treat each of the Catechism melodies in two forms, first in a lengthy and elaborate movement, and then in short and simple guise. Perhaps he had in mind to distinguish in this way the longer and shorter Catechisms, for such a design was in keeping with his bent. Each of the three clauses of the Kyrie also he duplicates, and the hymn to the Trinity is treated thrice, in homage to the Three Persons. So there are in all twenty-one movements, which exhibit diverse types of treatment and reveal Bach’s devotional purpose. Eleven are for the manuals alone, generally in simple counterpoint. The larger movements display Bach’s inventiveness and resource, and three are particularly distinguished—the Choral Fantasia on the Lord’s Prayer (Vater unser), for its scale and harmonic richness; the Aus tiefer Noth, which is scored in six parts with double pedal; and the Choral Prelude on the Creed (Wir glauben all’), wherein the pedals move with confident strides which have given the movement its popular title, ‘The Giant’s Fugue’.

The six Schübler Chorals take their name from Johann Georg Schübler, of Zella, near Gotha, to whom Bach sent them to be engraved in or soon after 1746. They are described on the title-page as ‘Six Chorals in various forms for an Organ with two Manuals and Pedal’. In fact they 20 were not composed for the instrument, but are arrangements of vocal movements selected from church cantatas composed at Leipzig. We detect no plan or design in their association, and can only infer that, being favourites with him in their original form, Bach desired to give them a wider currency in the only one which would secure it. The first (Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme) is particularly lovable for its association of the Choral melody with a spacious counter-subject in what Sir Henry Hadow has called ‘one of the most beautiful and melodious interplays that even Bach has ever entwined’.

After 1744 Bach appears to have ceased from composing church cantatas, and devoted himself to the revision of his organ music with a view to its publication. When he was seized by his fatal illness he was at work upon a series of movements conveniently known as ‘Eighteen Chorals in various forms for an Organ with two Manuals and Pedal.’ For the most part they date from his Weimar period, when he was still under the spell of Buxtehude, Pachelbel, and Böhm. But he selected them as worthy of revision, and, as his hand left them, they are, in Mr. Harvey Grace’s words, ‘as nearly flawless as we have a right to expect from a mere human’. The first fifteen in the manuscript are Bach’s holograph. Nos. 16 and 17 are in his son-in-law’s handwriting. In No. 18 the manuscript breaks off abruptly in the middle of the twenty-sixth bar. It was Bach’s swan-song.

Very early in his career Bach was attracted to the art of varying a given theme and of presenting it with diverse embroidery. His Goldberg Variations are the classic example of his genius in this form. But it was natural that the hymn-book also should supply him with themes for this purpose, and it did so for almost the first and last of the organ music that he wrote. Among the compositions we associate with his years at Lüneburg are three sets of variations on hymn-tunes—Christ, der du bist der helle Tag; O Gott, du frommer Gott; and Sei gegrüsset, Jesu gütig. Over all of them is an air of ingenuous simplicity. In the closing years of his life he turned again to the same form, a set of 21 five canonic variations upon the Christmas Carol Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her, published in 1746 and presented in 1747 to the Mizler Society, of which he had just been elected a member. His object was technical—to illustrate the art of canon—and his exposition culminates in a veritable tour de force in the final movement. The melody is passed from the treble to the bass, from the bass to the pedals, and from the pedals back again to the treble, while another part is in canon with it at varying intervals. The last five bars are in five parts, and into them Bach contrives to introduce all four lines of the melody, and to decorate them with a profusion of little canons in diminution, which, as Parry remarks humorously, seem to be tumbling over each other in their determination to get into the pattern ‘before the inexorable limits of formal proportion shut the door with the final cadence’.

Three things are necessary for the understanding and enjoyment of Bach’s Organ Chorals—familiarity with the hymn-tunes he uses, knowledge of the text of the hymns to which they belong, and the key to his musical idiom and language. The first and second are now easily accessible. The third has been fully expounded by Schweitzer and Pirro; unless it is apprehended, much of the significance of Bach’s music will be lost, and the range of his thought be missed. Briefly, his language is one of realistic symbolism, and the Little Book for the Organ is its pocket lexicon. He was not its originator; for the method was typically German. But it came to maturity with him, and in his usage of it he was consistent from earliest youth to mature old age. As his art developed, his symbols acquired manifold shadings and inflexions. But the master-symbols themselves do not exceed some twenty-five or thirty in number. Some are directional, denoting ascent or descent, height or depth, width, distance, and so forth. The act of hastening or running, and, conversely, the idea of rest or fatigue, are indicated by appropriate symbolic formulas. The moods, again, are distinguished by themes diatonic or chromatic to express joy or sorrow. The thought of laughter, of tumult, of terror, and the forces of nature, the winds, waves, clouds, and thunder have their indicative 22 symbols, which do not vary. Bach was one of the tenderest and most emotional of men, with the eye of a painter and the soul of a poet. But the fact is only fully revealed to those who are at the pains to translate him.

NOTE

The best and most helpful guide to Bach’s organ music is Harvey Grace’s The Organ Works of Bach (London, 1922). Eaglefield Hull’s Bach’s Organ Works (London, 1929) covers the ground less profitably. Pirro’s Johann Sebastian Bach the Organist, translated by Wallace Goodrich (New York, 1902), is valuable. Analyses of the organ music are in Schweitzer, vol. i, chaps. 13 and 14, Spitta passim, and Parry, chaps. 12 and 14. For the hymns and hymn-tunes of the organ works see the present writer’s Bach’s Chorals, vol. iii (Cambridge, 1921), and Bach’s Four-part Chorals (Oxford, 1929). The most instructive edition of the Orgelbüchlein is published by the Bärenreiter-Verlag, Cassel (ed. Hermann Keller, 1928). Besides the Novello and Augener editions of the organ works, interest attaches to the Schirmer (incomplete) and Peter’s editions, from the association of Schweitzer and Widor with the former, and of Karl Straube with the latter.

In his generation Bach was no less remarkable as a clavier and cembalo (harpsichord) player than as an organist. ‘Admired by all who had the good fortune to hear him,’ writes Forkel, ‘he was the envy of the virtuosi of his day.’ At his service were three kinds of stringed instrument played at a keyboard: the (1) clavicembalo, or, shortly, cembalo; (2) clavichord, or clavier; (3) Hammerclavier, or Fortepiano. They differed in the mechanism which vibrated their strings, and consequently in their tone; their finger technique was not uniform, and music composed for one was not equally suited to all.

The clavicembalo resembles the modern wing-shaped grand piano in appearance; whence the name ‘Flügel’ by which the Germans know it. Its strings are vibrated by quill-points set up on wooden jacks, which pluck or twitch the strings when the keys are depressed. Larger specimens have two manuals and a set of pedals, and their tone quality is controlled by stop-levers, which regulate the number of strings in action.

Externally the clavichord resembles a shallow rectangular box, much smaller than the clavicembalo, easily transported, and, when in use, resting on its own supports, or on a table. In Bach’s period its range was about five octaves. Its strings are excited by upright brass blades or tangents inserted in the key-levers, which, rising to the strings when the keys are depressed, mark off, and at the same time excite, a length of vibrating string, whose tone the player’s finger controls so long as the key is held down. The instrument has no pedals or mechanical device affecting its delicate tone. But, Mr. Dolmetsch observes, ‘it possesses a soul, or rather seems to have one, for under the fingers of some gifted player it reflects every shade of the player’s feelings as a faithful mirror. Its tone is alive, its notes can be swelled or made to quiver just like a voice swayed by emotion. It can even 24 command those slight vibrations of pitch which in all sensitive instruments are so helpful to expression’—an instrument of very intimate character in a domestic setting.

The Hammerclavier—Beethoven’s pianoforte—was immature even in Bach’s later years. Its strings were vibrated by hammers, but its mechanism lacked the regulated perfection of the pianoforte. When Bach visited Frederick the Great at Potsdam in 1747 he found in the palace several instruments the king had recently acquired from Gottfried Silbermann, a pioneer in their construction, and on one of them astonished Frederick by his treatment of a theme composed by the monarch. But he had no liking for the instrument, found it coarse in tone, shrill in its upper octaves, and unsuited to his finger technique; he nowhere associates it with his keyboard music.

As between the clavicembalo and clavichord, Forkel asserts Bach’s preference for the latter: ‘Both for practice and intimate use he regarded the clavichord as the better instrument, and preferred it for the expression of his finest thoughts. The clavicembalo, or harpsichord, in his opinion, was incapable of the graded tone obtainable on the clavichord, an instrument of extreme sensitiveness, though feeble in volume.’ Forkel, no doubt, is correct in a statement which had the authority of Bach’s sons. But it must not be inferred that the clavichord completely displaced its fellow instrument in Bach’s usage. For the louder-voiced cembalo universally accompanied concerted music in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Bach’s cantata scores, sacred and secular, constantly name it, and for concerted chamber music its use was no less imperative. The weak tone of the clavichord disqualified it for these purposes and reserved it for pure keyboard music. The respective provinces of the two instruments are clearly indicated in Bach’s manuscripts. Das wohltemperirte Clavier is the title of the instructional exercises he composed for his pupils. For his eldest son he arranged the Clavier-Büchlein vor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach. He devised his two-part and three-part Inventions and Symphonies for ‘Liebhabern [lovers] des Clavires’. The early 25 Suites in A minor and E flat major are described in the Autograph as ‘pur le Clavesin’. Bach’s specification of the clavicembalo is no less precise. The Chromatic Fantasia in D minor is entitled Fantasia chromatica pro Cimbalo, as its structure reveals. The Passacaglia in C minor is marked ‘Cembalo ossia Organo’. The Italian Concerto, the Partita in B minor, and the Goldberg Variations are allotted to a two-manual clavicembalo. So (with pedal) are the four early Preludes and Fughetta, and much music included in the organ works—the Sonatas, early Choral Variations, Preludes and Fugues. True, some of these are found in a publication bearing the title Clavierübung (Diversions for the Clavier). But Bach borrowed the word from his predecessor Kuhnau with a purpose, and it has so loose a connotation that in Part III it covers the Catechism Preludes, which are definitely ‘vor die Orgel’. Thus Bach’s preference for the clavichord, which Forkel correctly asserts, did not exclude the other instrument from uses for which it was better equipped. The clavier was the more responsive to his touch and more sensitively interpreted his emotions. But in his keyboard music of larger design or more showy intention, as in his concerted music, the clavicembalo better fulfilled his purpose.

As Table II reveals, Bach’s keyboard music is associated with every period of his active career. Besides the larger works, it exhibits a considerable number of detached pieces which represent his assiduous self-discipline, and, at the same time, afforded him agreeable relaxation from the major tasks which constantly preoccupied him. In his early years a small number of extant pieces—Fantasias, Fugues, Preludes, Toccatas, a couple of Capriccios, and a Sonata in D major—reveal his maturing genius. The Capriccio in B flat is specially notable, a vivid piece of program music, which Parry does not hesitate to call ‘the most dexterous piece of work of the kind that had ever appeared in the world up to that time’. It was written at Arnstadt, about 1704, to mark the departure of the composer’s brother, Johann Jakob, who was entering the Swedish service as an oboist. We hear the traveller’s friends dissuading him from 26 the hazardous journey. In a short fugal movement they depict the dangers ahead. Then (Adagissimo) we hear their lamentations, till the postilion’s horn sounds, and off goes the coach to a brisk and entertaining fugue! The Capriccio in E major, less interesting musically, is equally so as a token of fraternal regard. For the piece is inscribed ‘in honorem Johann Christoph Bacchii’, the Ohrdruf brother to whom Bach owed his first lessons on the keyboard. Probably it was composed soon after his return from North Germany to demonstrate his progress along a path on which his brother was his earliest guide. It consists of a single fugal movement on a somewhat uninteresting theme. But it sufficiently displays the youthful composer’s deftness in the treatment of his material to please the eye for whose observation it was intended. The Sonata in D major, like the Capriccio in B flat, reveals the influence of Johann Kuhnau, whom Bach succeeded twenty years later at Leipzig, and whose Biblical Sonatas, recently (1700) published, were now his model. For the moment their descriptive method attracted him: the last movement of the Sonata is on a subject quaintly indicated as ‘A theme in imitation of a clucking hen’!

At Weimar Bach was preoccupied with the organ and, latterly, with the composition of church cantatas. Consequently the tale of his keyboard music is meagre—a few arrangements, notably the Violin Concertos by Vivaldi and others, a couple of Fantasias, five Fugues, some early Suites, and the Aria variata in A minor. They all evidence the Italian influences in which at this period Bach was steeping himself. Vivaldi attracted him both as a violinist and composer. Only seven of the adapted Concertos, however, are by him: three of them were composed by the talented young Duke Johann Ernst of Weimar. Two of the Fugues, also, are on themes borrowed from the Italian Tommaso Albinoni. The Aria in 27 A minor, again, is ‘variata alla maniera italiana’, on a tender theme, which, in Spitta’s words, ‘seems to wander like a shade through the variations, but blossoms out again in the full beauty of intoxicating harmony in the last’. But Weimar inspired no music for clavier or cembalo to equal the organ masterpieces there brought to birth. To match them Bach’s genius awaited the next step in his career.

A double duty rested on Bach at Cöthen. The Suites we owe to his function as Capellmeister. With other works of large design, of which the Chromatic Fantasia and the Toccatas in C minor and F sharp minor are most noteworthy, they represent the response of his official Muse. But circumstances imposed on him a more domestic duty. In November 1719 his eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, kept his ninth birthday. Bach at that age had received his first lesson on the clavier, and he introduced his children to it at the same period. His youngest son’s ninth year was marked by the composition of the second Part of The Well-tempered Clavier at Leipzig. And now, at Cöthen, on 22 January 1720, his eldest son, received his first lesson in an exercise-book prepared with meticulous care. For the occasion was one of solemnity to a father who destined his son for his own profession, and that profession semi-sacred. First in his Clavier-Büchlein Friedemann found explanations of the clefs and ornaments—the trill, mordent, cadence, and so forth. Next, under the reverent ascription ‘In the Name of Jesus’, came his first finger exercise:

Among the exercises that follow are fifteen two-part pieces (Praeambulum) arranged in key-sequence; fourteen three-part 28 pieces (Fantasia) similarly marshalled; eleven Preludes (Praeludium) in order of tonality; six more, not entered consecutively, but fitted into the key-plan of the whole and entitled Praeludium or Praeambulum; and a Minuet-Trio, added to a Partita by another composer. The fifteen two-part and fourteen three-part pieces are known to us in another autograph as the Inventions and Symphonies; the eleven Preludes are found also in The Well-tempered Clavier; and the six scattered Preludes and Preambules and Minuet-Trio are among the Twelve Little Preludes. Along with the Six Preludes for Beginners these titles name the ‘Clavier School’ on which Bach brought up his sons and pupils.

As a complete and separate collection, the Inventions and Symphonies come to us in an autograph written in 1723 on the eve of Bach’s migration to Leipzig. Its prefatory title declares the uses it was designed to serve:

A faithful Guide, in which Lovers of the Clavichord, particularly such as are truly anxious to learn, may find a clear System for clean playing in two Parts, and for correct and finished playing in three; and, at the same time, a Model on which they may learn how to form Inventions and develop them, and, above all, acquire a cantabile Style in their playing, and receive an incentive and taste for Composition.

Bach’s choice of the uncommon definition ‘Invention’ affords another example of his familiarity with contemporary Italian music. The Bachgesellschaft edition prints four ‘Inventions’ extant in his autograph, which were believed to be his compositions. In fact they are by Francesco Antonio Bonparti, who wrote them when Bach was in service at Weimar. They do not resemble his own genuine Inventions. But he was grateful for the word, and deemed it more applicable to his contrapuntal two-part pieces than the title he had given them in Friedemann’s book. For Forkel correctly defined Bach’s Invention as ‘a musical theme so constructed that by imitation and inversion it can provide the material for an entire movement’. He commended the fifteen as ‘invaluable exercises for the fingers and hands, and sound 29 models of taste’. Such was their primary purpose. But they are far removed from the dull literature of the schoolroom. For here, as in all his instructional music, Bach had an ulterior purpose, which his prefatory title reveals. His intention was to shape the pupil’s artistic sense, and to stimulate his latent faculties as a composer, a motive that seems extravagant till we remember that his students were embryo Cantors and organists, and that in his eyes music was the most worthy homage man could offer to his Maker. He aimed also to inculcate the cantabile style, possible on the clavier alone, but then too little practised. Both Inventions and Symphonies are arranged in the 1723 autograph in the ascending order of the scale, from C major to B minor. But there is a definite relation of mood or material between each Invention and its corresponding Symphony: indeed, in another manuscript each pair is brought together in this way. All are perfect miniatures in form and content, as satisfying to the accomplished player as they are instructive to the youngest. ‘Only an infinitely fertile mind’, Schweitzer remarks with truth, ‘could venture to write thirty little pieces of the same style and the same compass, and, without the least effort, make each of them absolutely different from the rest. In face of this inconceivable fertility it seems almost a superfluous question to ask whether any other of the great composers has had an inventive faculty so infinite as Bach’s.’

Unlike the Inventions and Symphonies, Bach’s instructional Preludes reach us in haphazard association. Seven of them are found in Friedemann’s Clavier-Büchlein—Nos. 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 of the Twelve—and five more—Nos. 2, 3, 6, 7, 12 of the Twelve—in the manuscripts of Johann Peter Kellner (1705-72), who was personally known to Bach, but not his pupil. These are printed under a single title in the Bachgesellschaft edition, and are universally styled the Twelve Little Preludes. The other six were first published by Forkel, and the title he gave them—Six Preludes for Beginners—has been generally adopted. Consequently, neither set exhibits a completely ordered plan. In the larger one the keys of E major, G major, A major, and B minor are 30 not illustrated, and those in C major, D minor, F major, and G minor are duplicated. In the smaller, no examples are provided for the keys above E. But all are fresh and fragrant, especially the delicate Minuet-Trio Bach added to J. G. Stöltzel’s Partita in his son’s Little Book.

The crown and glory of Bach’s instructional music is The Well-tempered Clavier, which, in Spitta’s opinion, ‘reflects the whole of the Cöthen period of Bach’s life with its peace and contemplation, its deep and solemn self-collectedness’. The Berlin autograph bears the title:

The well-tempered Clavier; or, Preludes and Fugues on every Tone and Semitone, with the major third Ut, Re, Mi, and minor third Re, Mi, Fa. For the Use and Profit of young Musicians anxious to learn, and as a Pastime for others already expert in the Art. Composed and put forth by Johann Sebastian Bach, presently Capellmeister and Director of Chamber-Music at the princely Court of Anhalt-Cöthen. Anno 1722.

At Leipzig, in later years, Bach played the whole work through thrice to his pupil Heinrich Nikolaus Gerber, who probably then received the story of its inception published many years later by Gerber’s son. As an illustration of Bach’s invariable independence of the keyboard when composing, the latter records that The Well-tempered Clavier was written when Bach was idle in a spot lacking musical instruments of every kind. The story is not improbable. Bach was wont to accompany Prince Leopold on his journeys, and returned from one of them in 1720 to find his wife dead, a tragic close to a journey in whose course The Well-tempered Clavier may have been compiled. He appears to have solaced an earlier period of confinement by arranging The Little Book for the Organ. And his independence of the keyboard is otherwise authenticated. Forkel remarks on his derision of ‘Harpsichord Riders’, ‘Finger Composers’, whose uninspired hands ran up and down the keyboard in hope to strike an idea worth capturing.

Bach deliberately chose the title he prefixed to the twenty-four 31 Preludes and Fugues. It registered his approval of an innovation in the European scales system, without which the avenues modern music has since explored must have remained closed. Bach’s purpose was to demonstrate the practicability of ‘equal temperament’ by providing pieces in every key, major and minor, for the clavier tuned on that principle. The controversy was ancient. Composers of old-style music, content with a few keys—in general such as had not more than three sharps or flats in their signature—were willing to sacrifice all others to secure theoretical correctness of intonation in the few. The more progressive realized the limitations this ‘mean-tone’ or ‘unequal temperament’ imposed upon their art: it rendered modulation outside the preferred scales impossible. They therefore advocated the method of tuning known as ‘equal temperament’, which proposed to make all the semitones in the scale equal. Hence, each octave would be divided into twelve equal semitones; every scale, instead of a few, would be approximately correct; and the bar to free modulation would be removed. The twelve-semitoned scale has become universal, and by practical demonstration Bach’s Well-tempered Clavier assisted to establish it.

There is no doubt that, besides the public service the twenty-four Preludes and Fugues were designed to fulfil, Bach intended them for his children’s instruction. He made copies of them for Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel. And twenty-two years later (1744), when his youngest son Johann Christian was starting on the road they formerly had traversed, he compiled another set of twenty-four on the same principle, but not under the same title. For the controversy over temperament was no longer active, and further propagandism was not required. Bach apparently entitled the set ‘Twenty-four new Preludes and Fugues’, forming, with the original collection, the immortal ‘48’. There are other indications of his aloofness from the circumstances which produced the earlier set. It is observed by Professor Tovey that the later twenty-four are less evidently written in terms of the clavichord than the first series, with which instrument their title definitely associates them. Further, Mr. Fuller-Maitland 32 remarks that the second set is less obviously instructional; Bach was thinking less of ‘young Musicians anxious to learn’ than of ‘others already expert in the Art’. That he incorporated in both sets pieces of earlier date than the autographs is immaterial. They hold their place worthily in a galaxy of exceptional lustre. ‘Both Parts’, Forkel boasted sixty years after the appearance of the second, ‘contain artistic treasures not to be found outside Germany.’ Nor has their like been seen since Forkel proclaimed Bach’s grandeur to his countrymen. Their technical skill is matchless, but so controlled that they chiefly stir us as the noble diction of great literature, the vehicle of lofty thought.

As Capellmeister, Bach’s Cöthen keyboard music was almost exclusively in Suite form. Occasionally he displayed his virtuosity as a player in movements of more brilliant texture—the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, the Fantasia and Fugue in A minor, and the Toccatas in F sharp minor and C minor. But, in general, he provided music agreeable to the general taste. And of all forms of chamber music the Suite was the most popular, whether for solo instruments or orchestral ensemble.

The Suite comprises a few—generally seven or eight—short movements bearing the name, and in the distinctive rhythm, of characteristic national dances. The universal employment of a French designation for this, the earliest, cyclic art-form declares its original source, and Bach most usually employed it. But the seven he wrote at Leipzig bear the title ‘Partita’, and occasionally the term ‘Sonata’—as in those for Solo Violin and Solo Violoncello—covers a composition of similar character. ‘Ouverture’, again, is the alternative name for the orchestral Suites.

Under whatever title it passed, the Suite comprehended a string of dance measures of international currency and diversity. Their contrasts, no doubt, originated the idea of stringing them together, and at first no rigid principle selected those admitted. But, long before Bach was born, four established a preferential claim for inclusion—the Allemande, Courante (or Coranto), Sarabande, and Gigue (or Jig); while 33 the Gavotte, Bourrée, and Minuet were also popular. The Allemande expressed the solemn nature of the German, the Courante the fervid temperament of the Italian, the Sarabande the courtly dignity of Spain, the Gigue the robust jollity of the Englishman, and the Minuet or Gavotte the refined gaiety of France. Consequently, the Suite was well adapted to the purposes it served: it was varied in its contents, melodious, neither too long to be irksome, nor too short to appear trivial. Only in one particular it was monotonous: convention required all its movements to be pitched in the same key, a blemish of which its public was less conscious than our own. Only in the English Suites, the detached Suite in E flat, and the Partita (or French Ouverture) in B minor, is the persisting key sequence interrupted. In these eight instances usually the penultimate movement, or another, is in two divisions, one of which changes to the relative major or minor. Throughout the whole twenty-six Bach’s inclination to satisfy the champions of unequal temperament is evident. The last of the French Suites is in E major: otherwise their signatures do not exceed three sharps or flats. All of them are suited to the harpsichord rather than the clavichord, for they invite the tonal contrasts which only the former could afford.

Fourteen of the nineteen keyboard Suites belong to Bach’s Cöthen period. One is unfinished. Another (in B flat) is not certainly authenticated. The other twelve have come to us in two sets of six, distinguished popularly as the ‘French’ and ‘English’. The titles lack the sanction of Bach’s authority, but were evidently used by his sons. Forkel, in intimate touch with both of them, explains that the ‘French Suites’ were so called ‘because they are written in the French style’, and that the others were known as the ‘English Suites’ ‘because the composer wrote them for an Englishman of rank’. Of both sets autographs have survived. The French Suites are found, though imperfect, in Anna Magdalena Bach’s earlier Note-book, which places their composition before 1722; and on an early manuscript of the English set the inscription ‘composed for the English’ (fait pour les Anglois) heads the 34 first Suite. No reason is apparent why the French set should be particularly distinguished by the name: their measures are not characteristically French. Nor is Forkel’s statement regarding the English Suites convincing. The Prelude of the first introduces a theme by Charles Dieupart, a popular French harpsichordist in London during Bach’s early manhood. But the coincidence, though interesting, does not explain the words ‘composed for the English’. The conjecture that the Suite was written for the English public is, of course, untenable. The inscription must therefore refer to particular Englishmen, and, if the date of the set is accurately placed, to visitors at Cöthen. Between the Anglo-Hanoverian Court and the petty German principalities conventions were not infrequent, and the ‘old Dessauer’, Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau, Marlborough’s sometime colleague, was still living. A military Commission perhaps visited Cöthen, was entertained by the Prince, and received from his Capellmeister the compliment of a composition specially dedicated. To such an audience the composer would wish to display his familiarity with English practice by borrowing a theme from London, and also by framing the Suite—and subsequently the remaining five of the set—in a distinctively English form. For they differ from the French set in the fact that each is prefaced by an elaborate Prelude, like those of Henry Purcell and his precursors.

Bach’s keyboard Suites contain not far short of two hundred movements. They exhibit extraordinary fertility of invention, vivid imaginative power, and complete technical mastery of the forms they employ. Some are of poignant beauty—the Sarabandes of the first, fifth, and sixth French Suites, and, above all, of the second English Suite. But their pervading tone is of happy humour and exuberant good nature, especially the fifth of the French and fourth of the English. It has been suggested that Bach was a disgruntled revolutionary, beating his wings with angry futility against the circumstances which confined him. The picture is out of drawing. He was an incorrigible optimist, and so his Suites proclaim him.

The secular character of his Cöthen duties afforded Bach opportunity and incentive to cultivate the Flügel, which most closely approached the organ in its technique. Forkel particularly records his meticulous care of his instrument. No hands but his own were suffered to tune it or his clavichord, an operation in which he was so skilful that he accomplished it in a quarter of an hour. He tuned the strings always to equal temperament, and consequently used the whole twenty-four scales, major and minor. But the finger technique of his early manhood was inadequate for the complete expression of his complex harmonies and brilliant passagework. Equal temperament, also, brought the neglected black notes on the keyboard into action, and, along with the new forms in which music was expressing itself, insistently demanded a more adequate keyboard technique. As his abnormal power developed, Bach was conscious of the restraint imposed upon him, and, before his meeting with Marchand in 1717, jettisoned the accepted system of fingering, which found no use for the thumb or little finger, and little for the first. Bach, on the contrary, gave the thumb regular duty in the scale and compelled the idle little finger to pull its weight.

These changes had important consequences. The thumb having become their active partner, the fingers could no longer lie flat and extended over the keyboard, but needed to withdraw their extremities in order to accommodate themselves to its shorter length. Consequently, they assumed a curved shape, their tips poised above the keys, giving the player the utmost facility for rapid passages, and also adapted to the cantabile or legato style Bach impressed upon his pupils as proper to the harpsichord no less than to the organ. His hands, like Handel’s, maintained their bunched shape even in the most intricate passages, and his fingers were so controlled that they appeared hardly to move.

Prince Leopold was an amateur musician for whose abilities Bach had sincere respect. The Prince, on his side, was attracted to his Capellmeister as much by his executive powers as by his felicity as a composer, which, in fact, before 1718 had been expended on forms to which a Calvinist Court 36 was indifferent. There is every reason, therefore, to suppose that the brilliant keyboard ‘show-pieces’ composed at Cöthen were performed by Bach himself at the soirées which periodically entertained the princely audience in the Ludwigsbau of the Schloss. Prominent among them is the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue in D minor. From the first it was one of Bach’s most popular compositions; Forkel, who received a copy of it from Friedemann Bach, observed truly that, ‘if performed even tolerably, it appeals to the most ignorant hearer’. In the Fantasia, which has the brilliance of the Great Fantasia in G minor for the organ, Bach adventures daring feats of modulation. The general effect, as Spitta observes, is of ‘an emotional scena’, in which the chromatic fugue pulses forward in ‘a mighty demoniacal rush’. Worthily Forkel’s copy bore the inscription, ‘Glorious for all time!’

The Fantasia in A minor is not less bold and spirited, and its Fugue—the longest Bach ever wrote (198 bars!)—exhibits his boundless resource. Built on a spirited theme in semi-quavers, it spins its course in a whirling perpetuum mobile. The Toccatas in F sharp minor and C minor complete this quartet of Cöthen exhibition pieces. Sir Hubert Parry declares the Toccata ‘a branch of art which has been more piteously discredited than any in its whole range, save and except the operatic aria’. These two exhibit the form, and Bach’s handling of it, at the zenith. In that in F sharp, after a bravura introduction, we pass to a nobly expressive interlude (Adagio), after which, in Spitta’s graphic words, ‘it is as though spirits innumerable were let loose, whispering, laughing, dancing up and down, teasing or catching each other, gliding calmly and smoothly on a translucent stream, wreathed together into strange and shadowy forms; then suddenly the phantoms have vanished, and the hours of existence are passing as in everyday life, when the former turmoil begins afresh’. The C minor also, opening stormily, passes to a meditative Adagio, from which a strong fugal theme emerges, ‘a proud and handsome youth, swimming on the full tide of life, in delightful consciousness of his strength’.