* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Lincoln Frees the Slaves

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Stephen Leacock (1869-1944)

Date first posted: Nov. 23, 2017

Date last updated: Nov. 23, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20171138

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

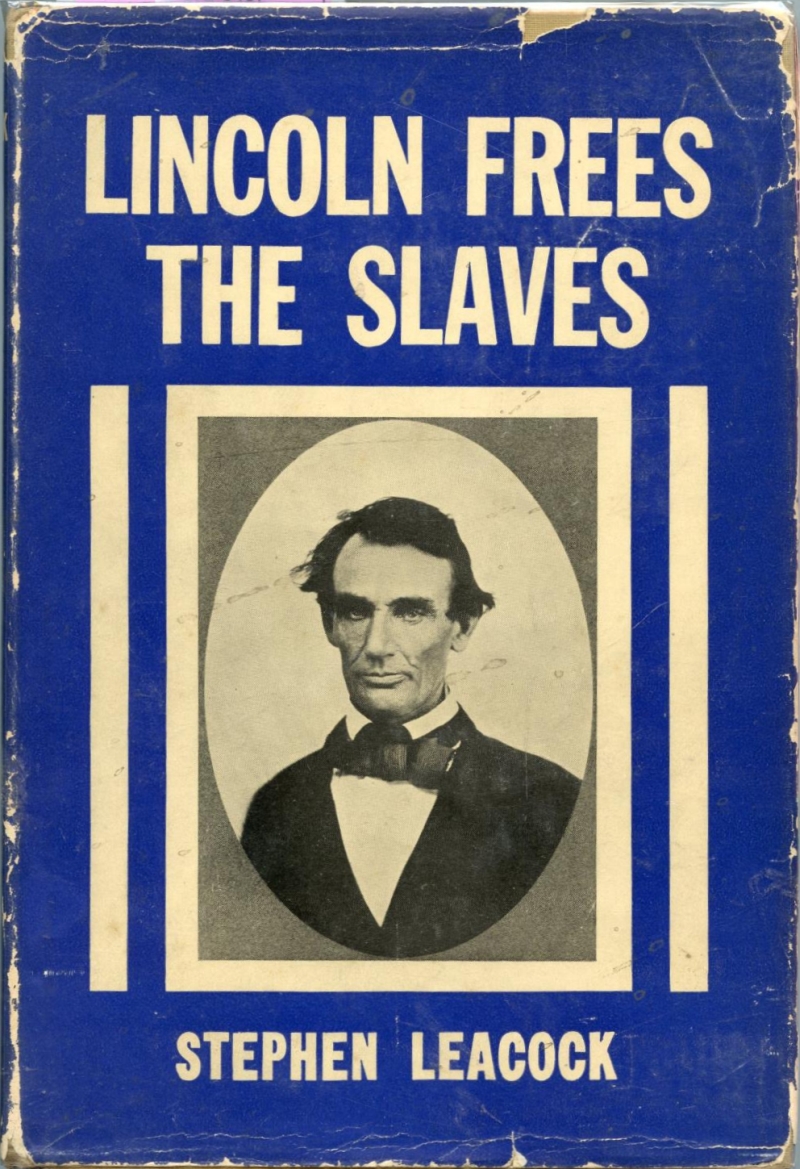

Reproduced by courtesy of Amos Pinchot, Esq.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

(At the time of the Douglas debates)

LINCOLN

FREES THE SLAVES

BY

STEPHEN LEACOCK

ILLUSTRATED

G • P • PUTNAM’S SONS

NEW YORK

MCMXXXIV

COPYRIGHT, 1934, BY STEPHEN LEACOCK

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must

not be reproduced in any form without permission.

MANUFACTURED

IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AT THE VAN REES PRESS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Slavery in America | 13 |

| II. | The Irrepressible Conflict | 33 |

| III. | Lincoln in Illinois | 51 |

| IV. | Towards the Abyss | 84 |

| V. | Secession | 107 |

| VI. | War | 126 |

| VII. | Emancipation | 149 |

| VIII. | Epilogue | 161 |

| Appendix—Final Emancipation Proclamation | 171 | |

| Index | 173 |

| Abraham Lincoln | Frontispiece | |

| (At the time of the Douglas debates) | ||

| Reproduced by courtesy of Amos Pinchot, Esq. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| What Will He Do With Them? | 53 | |

| (From Vanity Fair, October, 1862) | ||

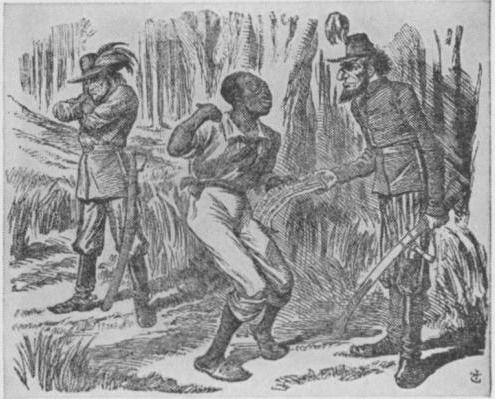

| Scene from the American Tempest | 77 | |

| (From Punch, January, 1863) | ||

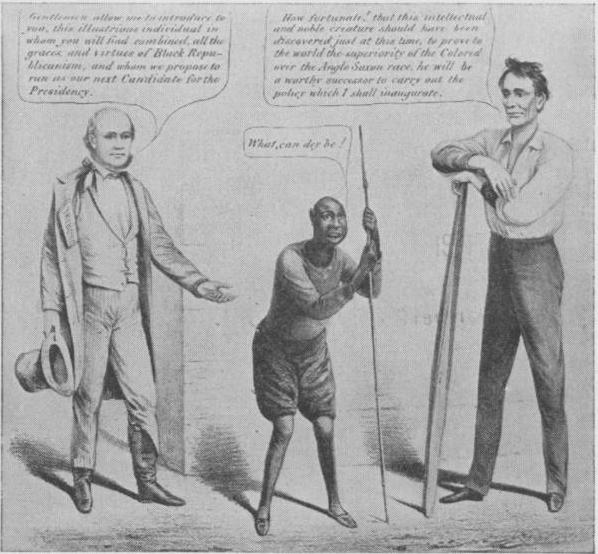

| An Heir to the Throne, or the Next Republican Candidate | 103 | |

| (A Currier and Ives print of 1860) | ||

| Contrabands Coming into the Union Lines | 137 | |

| (A contemporary drawing by Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly, 1863) | ||

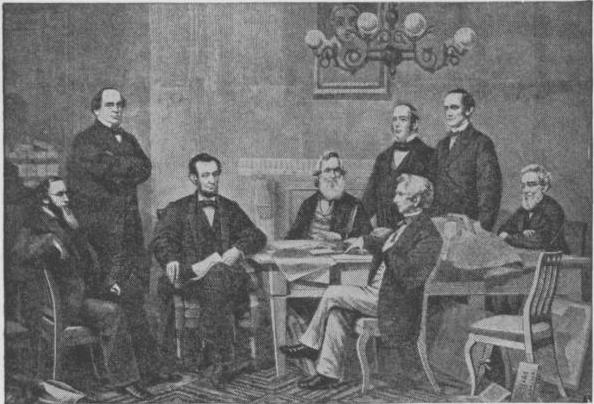

| Lincoln’s First Reading of the Proclamation to His Cabinet | 155 | |

| (From a contemporary engraving) | ||

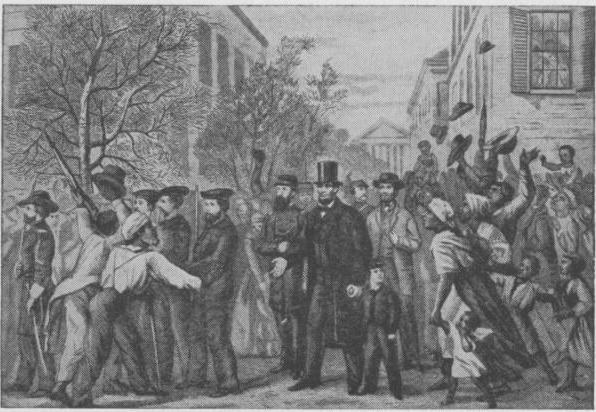

| Lincoln Entering Richmond, April 3, 1865 | 165 | |

| (From a contemporary engraving) | ||

| President Lincoln’s Funeral Procession | 169 | |

| (From Harper’s Weekly, May, 1865) | ||

Looking back on it, the existence of slavery seems one of the great facts, one of the dominating factors, in the history of America. In retrospect it looms large. But to the people of the time—at least until it had almost run its course—it did not seem a large fact or a particularly important fact at all. It was just part of life as they knew it. It was to them as poverty is to us. Those of us who are not poor, seldom think about it, and even the poor take it largely for granted. But if the time ever comes when poverty is eliminated, its existence will seem, to those who look back upon us, the great central fact of our history;—not our wars, our science, our machinery, our art, but the existence amongst us of poverty, of the slums, of people born into want and dying in penury. How we could have tolerated it, will seem a mystery to a generation that no longer has to do so. Why did not our hearts burn within us at the thought of it? The historian will record the peculiar callousness of our generation towards the suffering of the poor, and misinterpret it in our disfavor.

But such callousness to what we cannot change is the price at which we live. If we each tasted the sharp agony of others’ sorrows we could not long survive.

So with slavery in the past. Generations of people were born and died in America and gave no more thought to slavery than we do to poverty,—as much and as little.

Slavery had come down through the ages as part of the world’s history. There were slaves in the ancient world. The Greeks and Romans looked upon human suffering, at large and in the persons of those not dear to them, with cold neutrality. Students of classical literature will look in vain for tears shed over the slaves broken in the galley, over the slave gangs that built the pyramids beneath the lash, or over the cruel deaths in the arena. If Lucretius could write “the world is full of weeping” (sunt lachrymæ rerum) he meant it in a large philosophic sense in which it became a pleasure to contemplate it. Nor had Christianity ever condemned slavery. It opened for the slave the larger freedom of the Kingdom of Heaven. With that hope, the chains became an opportunity; “Slaves, obey your masters,” so ran the text (mistranslated into “servants” in King James’s time, to make it apply to footmen and gamekeepers in a nation that had no Africans).

Slavery was, so to speak, a part of human thought. The kindly Thomas More writing of a Utopia, full of light and happiness, put slaves into it,—the slave being a sort of ticket-of-leave man rescued from crime and singing in the kitchen.

Thus slavery was a part of life and, for those who must perforce think of it, the whole of life could be explained away as a vale of tears.

Slavery, it is true, had died out in Europe between the days of Rome and the time of Christopher Columbus. But there had been no condemnation of it and no legislation against it. It had not died out for moral reasons but from the simple fact that it had ceased to “pay.” The existence of slavery, indeed, is closely circumscribed in the economic sense. It can exist where great masses of men can be forced to a simple uniform task. Slaves built the pyramids. It can exist where the torrid heat of the climate and the enervating atmosphere undermine the energy of the individual man: where the soil can be tilled with driven labor, beaten to its task, brainless and without hope: or it can exist as an appanage of the tyranny of the palace or as a luxury of domestic life where subservience is more valued than efficiency. But as civilization advances slavery retreats. The task becomes too complicated for driven brains and beaten bodies. This is all the more so in a diversified and varied country, with never a wood or held exactly like another and where an invigorating climate stimulates mechanical genius. Here, sooner or later, work must depend upon freedom, or on the simulation of it. Looked at broadly, the medieval slave changed to the serf, and the serf to the hired laborer, as a means of keeping him going. By the time of Queen Elizabeth a slave in England would have been of no value,—except as a dusky Pompey in livery, an object rather of pride than of profit.

Slavery, therefore, died out in Europe for economic, not moral, reasons; a fact which made it all the easier for it to come to life again. Hence it came to life again with a rush when the colonization of the New World rendered it again a source of economic profit. There was no prejudice against it. When Queen Elizabeth honored the first English slave-catcher by making him Sir John Hawkins, there was no outcry. On the contrary,—the honor fell to him as it would today to any one who re-established an ancient industry.

Not that the people of the Middle Ages were worse, or very much worse, than we are. But they were much more callous to human physical suffering. We stand appalled at their cruel punishments, their dungeons, the savage brutality of their law. But they, if they could know us, would stand appalled at what they would think our crooked mentality, our universal cheating,—in a word, at what we call “business.” The honorable knight, or the pious abbot, or even the plain yeoman of the Middle Ages would regard us as a pack of unreliable crooks. No knight would have allowed himself, even if he could have understood the process, to buy International Armour Ltd. in the hope that it would turn out to be worth more than what he paid for it. To pick up for a few shillings, from a poor ignorant shopkeeper, an antique which proves to be priceless, would have seemed a hideous piece of dishonesty to a generation which thought nothing of the rack and the “question” and a dungeon sunk below the sunlight.

Underneath it all no doubt is progress, broad and slow and at the end of it, still unseen, is the Kingdom of Heaven on earth.

All the world is familiar with the story of how the nations of Europe, seeking the trade and treasure of the East, stumbled upon the empty continent of America. Slavery only came on the scene as an unforeseen consequence when the era of treasure hunting changed to that of colonial plantation. The first explorers wanted quick results. They wanted trade at the fabulous profits of ivory for beads, or the pillage of junks and temples and treasure houses at a profit higher still. Even when they reached out for the empty continent of America, their first thought was for gold and silver and precious stones. For the inhabitants their only care was to declare them all Christians, thereby saving them in millions, to take away their gold and to carry some of them home as a sort of certificate of discovery.

It is true that the idea of bringing the natives to Europe to make slaves of them did come up as an early incident of discovery. Columbus himself, in his voyage of 1493, in which he had a fleet of seventeen ships, brought home 500 Caribbeans. But Queen Isabella’s heart and conscience were troubled at it. The natives were sent back again. In any case there was little market for them in Europe. The Barbary and Algerian pirates used slaves but they caught enough among the Christians. For the other civilized countries the land economy left no place for slavery.

But it was natural that the Europeans should hit upon the system of catching slaves in Africa and taking them to America,—the source of woes unnumbered and still unfinished. The two continents were disclosed at the same time and it was soon found that on the American side of the ocean the natives of the West Indies were too soft, and the North American Indians too hard, to supply the labor demanded by the whites. The natives of the island paradise found by Columbus died under the lash.

On the mainland of North America the “Indian” proved of no use for the plantations. The red man would not work: he would rather die. The acceptance of death and the scornful tolerance of pain were among the redeeming features of a race whose fiendish delight in cruelty for cruelty’s sake forfeited their right to live. Those who know properly the history of such a tribe as the Senecas,—cruel, filthy and cannibal,—will harbor no illusions about the “noble red man.” But work the red man would not. The black man will work when he has to, but not otherwise. The white man cannot stop working. Take away his work as a necessity and he brings it back again under the name of “business” or golfs himself to exhaustion.

So it came to be the destiny of America that the whites cleared out the red men, and brought in the black men to work under white direction. Each race fulfilled its seeming destiny.

When the Portuguese discovered the western coast of Africa (1434-1500) they brought back black men to be sold to the Moors and to the Spaniards. This started a trade that was lucrative but limited. With the opening up of America, wider opportunities were presented. Negro slaves were sent out to Hispaniola as early as 1502. King Ferdinand especially ordered consignments of them for the mines. Pious bishops and clerics, such as the famous Las Casas, recommended the import of negroes as a substitute for the Caribbean race, sinking to death under European brutality. Private greed, the world’s greatest motive power, thus sheltered itself as usual behind a front of piety. African natives were brought over in thousands and presently in tens of thousands.

It must be understood that slavery did not grow up in the American colonies as the result of a plan. The promoters of the London Company that first permanently established Virginia were not thinking in terms of slave labor and of plantations. Their hope lay elsewhere. The earliest and liveliest was for a discovery of a quick route to the fabled wealth of the Indies. One early explorer carried with him letters addressed to the Khan of Tartary and looked for him up the Chickahominy River. He wasn’t there. A second hope was gold. The first returning ship brought to England a cargo of glittering dirt. It wasn’t gold. Beyond that was the idea of Indian trade and the easy production of silk and wine. Honest work came last.

The colony was hopelessly mismanaged. Of the first hundred settlers—all men—sixty died in the first year. There was no private land, no incentive to work. Then came tobacco, raised by John Rolfe in 1612. This changed everything. Next came the negroes, a bargain lot of twenty sold to the settlement at large by a Dutch privateer or pirate—in 1619. After that things moved forward. Wiser councils allotted land to the settlers. New people came in every year,—and more negroes. By 1649 there were 15,000 settlers and 300 blacks. The tobacco plantations spread up the rivers, each river an artery of settlement, each plantation a seaport in itself. The tobacco crop ravaged the land, left it as scrub and wilderness, and passed on. But the colony grew constantly. Tobacco held it up. England by this time was smoking seriously. Soon after the restoration of Merry King Charles II, 12,000 tons (50,000 hogsheads) of Virginia and Maryland tobacco went up each year in English pipe smoke. By the year 1671 there were 2,000 negroes in Virginia in a total population of 40,000. What their legal status was no one exactly knew. They were just servants forever. But after the restoration the law called them “slaves,” and whatever individual rights they once had disappeared in the slave codes of the Old Dominion of the eighteenth century. A slave was worth about £30 in Governor Berkeley’s day. Long-term white convicts sold at about £15. The negro was coming into his own. No doubt it all seemed natural enough at the time.

Slavery slid easily into its place in the rice-growing colonies of the Carolinas. The rice, brought from Madagascar in 1694, was a huge success. Black labor, impervious to heat and damp as the mist itself, was just the thing for it. Slaves were imported in shiploads to the great profit of the Royal African Company, the slave catchers of the day,—as respectable in the England of the eighteenth century as the Johannesburg mines and coolies were in the twentieth. By the middle of Queen Anne’s reign the Carolinas contained about 3,500 whites and over 4,000 black slaves. All through the first half of the eighteenth century the blacks outran the whites in number more and more.

Below the Carolinas in 1732 was born the gentle Georgia, the offspring of piety as a refuge for the oppressed, the debtors and the meek. There slavery was forbidden, and there rum was excluded. The noble founder, General James Oglethorpe, was at the same time one of the directors of the Royal African (Slave) Company. To understand this queer inconsistent fact, we must come down British history all the way to Cecil Rhodes.

Under these circumstances the import of negroes from Africa to America became one of the leading features of the world’s commerce. British energy shouldered itself into the new trade. It was for a hundred years as respectable as it was profitable. John Hawkins received as the emblem of his knighthood a crest with a negro in chains. When the slave ships came to Virginia the planters eagerly helped themselves. New England, with but little use for slave labor, entered gladly into the trade, a fine stimulus for a maritime coast with ships to build and cargoes to seek. In England the Royal African Company obtained under Charles II a monopoly of the trade in negroes. But under William and Mary (1698) it was thrown open to all British subjects, a broad generous gesture, comparable to the widening of the franchise.

Much humbug and hypocrisy surrounds the history of the British connection with slavery. After it was all over, somebody invented a characteristic song about the British flag, sung at a thousand Victorian pianos which declared:

“That fla-ag may float o’er a shot-torn wreck

But never shall float o’er a slave!”

As a matter of fact the flag probably floated over more slaves than any other flag, or two flags, in the world. British enterprise at sea reached out for the new trade. The Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 contained as one of its triumphs the Assiento clause, carrying over from the Dutch and the French to the British the right to supply 4,800 slaves yearly for thirty years to the Spanish colonies. To that was added an enormous importation into the British colonies themselves. To Jamaica alone over 600,000 negroes were brought during the eighteenth century. Virginia when the colonial days ended contained 200,000 slaves. About 20,000 blacks were brought from Africa each year during the eighteenth century—over 2,000,000 in all. There were nearly 200 British ships engaged in the trade. The British alone had forty depots along the African coast. They shared with the noble commerce of the Hudson Bay the honorable name of “factories”; and what they made, the world has not even yet cast out of its system.

The slave trade is one of the horrors of history. No palliation can excuse it. No arm-chair theory of gradual evolution and ultimate purpose can wipe it out. If such theory proves anything it tells in the other direction, as establishing the incurable sinfulness of humanity and the martyrdom of man. One cannot dwell upon its poignant details. The slaves, packed in narrow stifling holds, chained and stapled to the floor, groaning with suffocation and nausea; the dead thrown overboard each morning. Death, it is said, released one in eight, on the voyage; a third as many passed away on landing, too near death to be fit to sell.

It is hard to believe that public feeling was so slow, that it took a hundred years to rouse even the first gusts of public indignation. But private greed, the thing called “business interest,”—almost as cruel as medieval bigotry,—covered up the sin. And even a hundred years later the history of the Congo and the Putumayo was to show that private greed is not done with us yet.

In any case, let it be repeated, the slave trade began in rougher days than ours as regards this matter of human indifference to physical suffering. In the seventeenth century barbarous cruelties were still everywhere practiced upon criminals and heretics. Burning and torturing were still judicially used. Nor were such things alone the perquisite of the Inquisition and the Church of Rome. “In Scotland,” says the historian Lecky, “during nearly the whole period that the Stuarts were on the throne of England, a persecution rivaling in atrocity almost any on record was directed by the English government, at the instigation of the Scotch bishops and with the approbation of the English church. The Presbyterians were hunted like criminals over the mountains. Their ears were torn from the roots. They were branded with hot irons. Their fingers were wrenched asunder by the thumbkins. The bones of their legs were shattered by the “boots.” Women were scourged publicly through the streets. Multitudes were transported to Barbados, infuriated soldiers were let loose upon them and encouraged to exercise all their ingenuity in torturing them.”

The brutality of the criminal law was as great, or nearly as great, as the brutality of the law of religion. Even in the eighteenth century people, contrary to what is generally supposed, were still burned to death by law in England.

Our history has smothered up these things. Time’s ivy has grown over them, and on them falls the evening light of retrospect. The ever-living legend of the “good old times” spreads a kindly mantle over the horrors of the past. But the horrors were there just the same. So it comes that we single out the slave trade, ignorant of the setting in which it stood, the foul dungeon, the flaming stake, and the unspeakable torture room.

In such an age who could spare a tear for the dumb suffering of the transported African.

When the opposition to the slave trade at last arose, it came as a part of that inner light which presently illuminated England and mankind. It came as a part of the sentiment for humanity, which began in the eighteenth century, to replace the theological rigor of the days before. As theological controversy faded, it gave place to a new pity for mankind. As the Kingdom of Heaven retreated into the background it gave place to the hope of a kingdom on earth. The idea of salvation for eternity was replaced by that of salvation here and now.

This new current was a mingling of many streams. There was the new humanity of the Quaker, disclaiming persecution and turning the other cheek to war. The Quakers led in emancipating slaves, in deprecating cruelty, in casting out those who followed the trade (1761). There was added the new humanity of literature, the idealism of Pope and Thomson and Cowper, contrasting with the wholesale damnation of Milton.

All such writers decried and denounced the slave trade. Many of them, ignorant of the realities of savage life, carried their ideas to excess in the myth of the “noble savage.” Thus Pope from his garden at Twickenham sang of the “poor Indian whose untutored mind, sees God in clouds and hears Him in the wind.” In reality the “untutored savage” in America needed no tutoring in cruelty or cannibalism.

But even the myth of the noble savage and of the unsullied state of nature as taught by Rousseau, though false in fact, helped on the cause of humanity. To this was added the matter-of-fact reasoning of Adam Smith and the snorting indignation of Doctor Johnson.

The law followed its usual office of certifying a fact and locking a door already shut. Such was the famous judgment of Lord Mansfield in 1772 declaring slavery non-existent in England.

In time things reach even Parliament. A Mr. David Hartney, in 1776, moved that the slave-trade was contrary to the laws of God and the rights of man. The members failed to see it, but the thing was started. Then began a war of pamphlets and speeches. A certain Thomas Clarkson, competing, in Latin, for a Cambridge prize on the subject of the slave-trade, wrote so well that he convinced himself and devoted his life to the cause. He found associates in such men as Granville Sharp, William Wilberforce, and Zachary Macaulay. Business interest, having no conscience, began to shift sides. Planters in Virginia could raise and sell slaves at a bigger profit without the foreign slave-trade.

Then finally, the great tidal wave of the revolutionary era carried all before it and swept away in a flood a whole litter of dead laws, dead religions and dead iniquities, to give place to new ones.

In spite of the persistent opposition of the House of Lords, a British act of 1807 ended the British trade in slaves. French colonial slavery and the French slave trade, already denounced by Condorcet, Brissot, Lafayette and the other apostles of liberty and equality in 1789, was overwhelmed in the San Domingo rising and vanished. In the United States the slave-trade, already denounced in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence as an atrocious crime of George III, was prohibited by Act of Congress in 1807. The other nations (Sweden 1813, the Dutch 1814) followed suit. Even the Congress of Vienna condemned the trade in principle.

From the Europe and America that joined in the great peace of 1815, the slave-trade was gone forever.

All this, however, was not a matter of slavery, nor of the buying and selling of slaves, but only of the foreign trade in slaves with its attendant cruelty and horror. Of those who opposed the trade only a minority would have denounced slavery itself.

Even after Lord Mansfield’s judgment terminated slavery in the British Isles, slavery in the British dependencies went quietly on. There were slaves in all of the thirteen colonies that were soon to become the United States. At the moment of independence some 600,000 persons in a total colonial population of about three and a half million were held in bondage. Georgia, the youngest of the colonies, originally founded (1732) as a refuge for the meek and the oppressed, began its career as already said with neither rum nor slaves. But it found that even the meek, in those days, needed both. There were slaves, and always had been, in the British West Indies. There were slaves in the royal province of Nova Scotia. They helped, we are told, to build the settlement of Halifax. There were slaves in Canada when it was taken over in 1763 and their status continued undisturbed, even when the Loyalists moved in. There was a public sale of slaves in Montreal as late as 1797.

To the people of the later eighteenth century—to most people—the status of the slave still seemed more or less natural. Slave catching, the raiding of African villages, the wholesale slaughterings and burnings of the slave raiders, the hideous voyage across the equatorial ocean,—these things began to wear a different aspect. But not slavery. After all, the lot of a slave on a decent plantation could hardly be said to be worse in point of toil than the lot of a French peasant or an English laborer: no worse,—except in idea. And hardly any slaves and very few masters had any ideas. The few who had, deplored the thing but saw nothing to be done about it. Indeed presently, as the factory system arose, the lot of the English industrial workers was harder than that of many of the plantation slaves. At least, there was no “cry of the children” from the cornfields.

But the main thing was that before the great rise of the cotton trade, slavery was scarcely worth while. It was dying out. It came to an end, practically of itself, in British North America and in the Northern States. Free labor paid better. When the Massachusetts courts decided that slavery was incompatible with the Declaration of Independence and with the Constitution of 1780, this did not operate a social revolution. The emancipation laws which followed in all the states north of Mason and Dixon’s line occasioned no social upheaval.

But we are not to suppose that the new freedom of American independence brought about this emancipation. The statement of the Declaration of 1776 that “all men are created equal” was not intended to apply to negroes. It referred to men. A leading American historian tells us that “resistless logic of one burning sentence . . . wrought the downfall of slave institutions in the United States.” This is only true if we cut the sentence loose from the meaning given to it by those who set their names to it.

Yet slavery was a moribund institution.

Even in the South, the institution of slavery, in George Washington’s time, seemed to show signs of passing away. Not that it raised any social scandal. But in the main it was scarcely worth while. In most cases it was probably not cruel. It was at least free from the brutal grasp of machinery, speeding up the working power of man beyond man’s own endurance. It was machinery in Europe that presently reacted on slavery in America. Longfellow’s slave, who lay dead beside the ungathered rice and felt no more the driver’s whip, had been beaten to death, partly, by Lancashire. The train of slaves which cumbered a great household—George Washington had, in all, a hundred and eighty-eight indoors and out—must have been to a great extent idle chatterers, dear at the price. Slaves in America had to be supported in old age and in illness,—in Lancashire they could be turned out to die. Even in the field work out of doors, under decent or even half decent masters, the lot of the blacks—apart always from the idea of it—was not so bad. There was not as yet the hideous slave market of later days; the sales “down the river”; the transport in chains and fetters, the sight of which “put the iron” into the soul of young Abraham Lincoln; the moaning fugitives recaptured, all wounds and dust, that pierced John Hay to the heart; or the “chained slaves, the saddest faces I have ever seen” that inspired in the little boy who was to be Mark Twain a sullen anger against the world that never left him.

But all that represents the nineteenth century, when slavery had changed from a social institution to a social disease that must be extirpated with the knife.

The colonial slavery of Washington’s day gave at least a great appearance of wealth and social distinction. Washington’s domestic herd of a hundred and eighty-eight slaves was scarcely in the front rank. Charles Carroll of Carrollton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and the Rockefeller of his day, had twice as many: and various big planters of the Mississippi region twice that again. Slave-holding indeed seemed like wealth. Slavery permitted the efflorescence of the “gentleman,” the man who does not work—the ideal of the Greeks and the lost hope of today.

But it seems doubtful whether the great troops of slaves, were worth while in the economic sense. Free labor in North America, with the stimulus of liberty, the incentive of opportunity, and the magic of property, worked with an eagerness and efficiency never known to the serfs and laborers of Europe. Beside it the fettered negro was nowhere. All observers, from the days of Washington till the Civil War, noted the difference. Frederick Olmsted, writing in the closing days of slavery, said that the slaves “seemed to go through the motions of labor without putting strength into them.” He claimed that a New jersey farmer did as much work as four of them. Another visitor of the period, watching the slave at work with the hoe, said that their motion “would have given a quick working Yankee convulsions.”

Indeed during the period just preceding and just following the American Revolution there was spreading a wide feeling that slavery was scarcely worth the while. It must not be supposed that this feeling was inspired by the new emancipation of independence. As already said the assertion that all men are created equal was not meant for the negroes. Jefferson’s original draft contained an indictment of George III for having violated “the most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people, who never offended him, captivating them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” This remains as one of the supreme hypocrisies of history. Even at that, Jefferson struck out the clause out of deference to South Carolina and Georgia which still wanted the trade and because his “northern brethren” felt a “little tender” about the subject.

But many people, Jefferson among them, doubted whether slavery was right and wondered what would ultimately come of it. “I tremble for my country,” he wrote in his Notes on Virginia (1781), “when I reflect that God is just, that his justice cannot sleep forever.” Washington, writing in 1786, the year before the Constitution riveted slavery on the nation for three generations, expressed the wish that some way might be found “by which slavery may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees.” Gadsden of South Carolina called negro slavery a crime. Henry Laurens, whose slaves were worth £20,000, wrote to his son, “You know, my dear son, I abhor slavery.” He proposed to set free as many as he dared, balancing his duty to his family and to the community against his sense of righteousness, and calling on Providence to help him in his perplexity. The patriotic Macon of North Carolina said, “There is not a gentleman in North Carolina who does not wish there were no blacks in the country.”

In the North the case against slavery and its obvious economic futility was strong enough to terminate the institution. The Massachusetts courts read it out of the state by interpretation, but John Adams said that “the real cause was the multiplication of laboring white people.” Pennsylvania adopted a gradual emancipation act in 1780, Connecticut and Rhode Island in 1784, New York in 1799, New Jersey in 1804. In Delaware and Maryland abolition failed, but narrowly. Thus the North and South fell apart, but the line of division for the time had but little meaning and indicated no bitterness. That waited for the recrudescence of slavery half a century later.

If slavery could have passed away in Washington’s time it would have left no bitter memories. But it was not to be. On this world that seemed to be opening out into liberty, equality, and fraternity with the dreams of Rousseau, the enthusiasms of Brissot and Lafayette, the peace of Pitt and the pounds, shillings and pence of Adam Smith, broke the full fury of revolution and war. The question of liberty and slavery was overwhelmed for nearly a generation in what was called for a hundred years The Great War. When the storm passed the scene was all changed.

With the peace of 1815, Europe and America woke to a new industrial world. It is always thus. Forces which had been gathering before The Great War, ideas and policies that had been slumbering during the conflict, now broke over the surface of a liberated world.

We always speak of the industrial revolution as a phenomenon of the eighteenth century. This is true of its origins and its earlier stages. But the full reality of the changes it was to bring belong to the era after the Napoleonic war, the era of the great peace and the age of industry. Machinery and steam power were rapidly to transform the world. Capital took on an organization hitherto unknown. Industrial society was shaken into a new mobility. Migration moved in a flood. The exodus to America began.

It is true that the treaty of Ghent and the battle of Waterloo were followed by a severe “slump,” as had been, contrary to all expectations, the short-lived peace of Amiens in 1802. We are beginning now to understand, dimly, the economics of war, its initial economic prosperity, its marvelous and sustained impetus, its exhaustion, the collapse that follows its close, and the upward rush of prosperity that presently ensues. These phases the world witnessed a hundred years ago and will see again.

For America the consequences were colossal. Immigration moved in a flood. In Washington’s day we may estimate that about two or three thousand newcomers landed annually in America. When the tabulated returns begin (1820) they show 8,385 arrivals. In the year 1830 there came 20,000, and thirty years later the annual average stood at a quarter of a million. Famine and revolution drove out the distressed of Europe, while the hope of liberty attracted the brave.

This wave of migration profoundly affected the Northern States. It obliterated any lingering possibility of slavery. It reduced the negroes to an insignificant minority. And it stimulated further the great movement over the mountains to the Ohio Valley, the new land of promise. Settlement had begun immediately after independence. The States had wisely given the national congress the whole domain from the Ohio to the Mississippi: congress had thrown it open to settlement and, in accordance with the ideas of the day, kept slavery out of it.

The great epic of the moving frontier had begun. In the year when Napoleon first sat looking out over the waste of the South Atlantic, the little Abraham Lincoln, clinging to his mother’s hand, walked in the silent forest of Indiana, looking for a home. One age ended as the other began. The moving figures shifted on the screen.

In the Southern States a great change was going on, but of an opposite character. What happened there was destined to root slavery to the soil and to multiply the slaves. The industrial inventions in England in the eighteenth century had replaced domestic spinning and weaving by machine industry. Cartwright’s invention of the power loom (1785) had supplied the driving force. The stress was now on obtaining material. For in invention each process stimulates the others. No part must lag behind. Invention carries an increasing premium. It becomes conscious and deliberate. Mankind invents the idea of invention. Thus Edmund Cartwright, who was a clergyman and knew nothing of power and nothing of looms, sat down to invent a power loom. And thus did a young man called Eli Whitney set himself to invent a cotton gin, and therewith affected the destiny of the world.

The new textile industry in England wanted fibrous material. There was not enough wool, not enough flax, not enough of anything. Cotton was known in America but little grown and little used. It had been brought from the Orient to the Guiana coast of South America. It was tried out here and there in the Southern colonies. But the varieties used were short in the fiber, and the seeds clung to the lint, defying the slow labor of the fingers that plucked it out. After the peace of 1783 a few bags of United States cotton found their way to Liverpool.

But the opportunity offered by the straining industry was colossal. Once get a plant with long fibers, and find a way to get the seeds out of it,—and the consequences would be incalculable.

So it was done. Experiments began with new seeds from the Bahamas and new methods of cultivation. Many planters, like the famous General Moultrie, failed utterly. But success came. Before the end of the century they were raising 200 pounds of cotton to the acre. Each negro produced—in money, over his keep—$300 to $500 a year. Planters grew rich overnight.

Whereupon Eli Whitney, a graduate of Yale, invented the cotton gin (1793) because it had to be invented. Here again was conscious invention, and simple enough at that,—wire teeth on a sort of buzz-saw scraping into the cotton to tear the lint from the seeds and scraping itself clean against another saw.

Within a generation the raising of cotton overtook and surpassed all the other agricultural industries of the South put together. In the closing years of the slavery régime the census of 1850 showed some 75,000 cotton plantations as against 15,000 in tobacco. Of the slaves of the period almost three-quarters raised cotton as against only 14 per cent in tobacco and 6 per cent in sugar. Here began the economic union of Lancashire and the South with Cotton as King. Nothing hampered it but the deadweight of the northern connection crippling southern commerce with the ligaments of a mechanics tariff. So at least the Southerners saw it.

When secession came, it had with it an economic motive as powerful as political hatred. Secession, to the people of Charleston, meant a brief conflict in arms, or none at all, and then a wave of opulent commerce that would revive in the southern seaports the departed glory of Venice.

With cotton came sugar. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 opened up for the United States the raising of cane sugar in the Mississippi delta. There was a rush for sugar and slaves, the ocean trade in Africans being still open. The sugar plantations spread rapidly up the river. There were 308 of these estates soon after the peace of 1815, and by the year 1830 there were 691 with 36,000 working slaves and an output worth fifty million dollars.

The growth of the two great staples, cotton and sugar, restored prosperity to the other agricultural crops. Tobacco, rice and hemp were carried forward on the flood tide. With the closing of the Atlantic trade and the expansion of industry the market for slaves rose to pleasing proportions. Before the cotton gin, a first-class slave,—the kind listed for sale as a “prime field hand,”—was worth not more than $300: he fetched $800 in 1808 and $1,100 in the market boom of the years that followed. Virginia, not being a sugar or cotton State, went into the business of raising slaves for sale. It was estimated that from 50,000 to 100,000 were sold or taken out of the State in a year. A Richmond estimate in the banner year 1836 put the export at 120,000.

From now on there was no talk of abolition south of the Mason and Dixon’s line. Yet it was at this very time that slavery was assuming its most cruel features, was passing from the patriarchal to the commercial, and was breaking asunder the united commonwealth.

The outward and visible signs of the new disunion were not long wanting. As the Union expanded over the mountains and up the valley of the Mississippi, the question naturally arose, what about slavery? Its exclusion in 1787 from the Ohio Valley went without opposition. New states, it is true, had come into the Union balanced between slave and free; Vermont (1791) paired with Kentucky and so on. But there was nothing vital about the balance. But now times had changed. When the settlers went into Missouri and wanted to make of it a slave state facing, across the Mississippi, the free soil of Illinois, the nation burst suddenly into angry dissension. All the world has read of how the aged Jefferson said that the Missouri controversy had startled him like the sound of an alarm bell in the night. Foresight never carried further. Missouri was the beginning. For the moment, the controversy was settled on the fallacious principle of “this time but never again”—no more slavery, said Congress, north of the southern boundary of the State. Such a principle, as always, carried its own undoing. With the “Missouri Compromise” began the forty years of conflict that ended in secession.

For the time, political parties shunned the issue. The Democrats, once the Republican Democrats of the closing eighteenth century, were as old as the Union: they carried the slavery tradition as a part of it. The new party, that formed as the Whigs, aimed at progress, national improvements, canals, railroads and economic power. They could not disregard the South. In between the two were raised dissentient voices louder and fiercer as slavery hardened into the commercial exploitation of a sunken race and the internal traffic in slaves recalled in some measure the horrors of the ocean slave trade. These were the “abolitionists,” calling presently for martyrdom and defying the Constitution. They were repudiated on every side. Such honest men as Abraham Lincoln scoffed at them.

To Missouri succeeded the Texas annexation (1845) and the Mexican War and conquests with a vast new territory opened for slaves states. Southern enthusiasts dreamed of Cuba, of West Indian annexation—a very empire of slavery—as out of touch with the nineteenth century as the bygone empire of the Pharaohs. The rest of the world meantime was shaking off the contamination of slavery. England bought out its colonial slaves in 1833, and rustled with Victorian righteousness. France followed in 1848. Portugal after that. Only the Dutch retained slavery in their vast East Indian possessions till American emancipation. In Western Europe the semi-slavery called serfdom had been smashed to pieces in France and southern Germany by the French Revolution. Prussia ended it in 1807. After the great peace the remnants of it were cleaned out of Austria and the union states. Europe west of Russia was free after 1848,—if only free to starve. In America even the Federated States of Mexico, of which Texas was then one,—abolished slavery in 1824 and had gradual extinction written into the Constitution. Republican South and Central America had finished with slavery (Buenos Aires 1813, Colombia 1821, etc.) and even with the color line. The United States in the middle nineteenth century found itself lined up with monarchial Brazil, with Spanish Cuba, with the Dutch East Indies and with the slave continent of native and Arab Africa. It seems strange that any one could have believed in the expansion and duration of the slave empire of the South. Yet the people of the South did, and the people of the North in a limited and grudging way accepted it.

One turns to the contemporary record of the times to get some idea of what slavery seemed like in the days of its last conflict, to those who saw it and to those who lived among it. Only thus can we measure the forces that cast up Abraham Lincoln to the surface and made him a prime instrument of human destiny. Take a few of the typical judgments on American slavery. One turns to the outsiders first. Here to America in 1842 came the youthful Charles Dickens whose phenomenal success with the Pickwick Papers (1836) and the books that followed, had lifted him to a public notoriety and public affection never known before in the world of letters. Brilliant, ardent and captivating, he landed in Boston in January 1842 to meet a national reception only equaled by that of the Marquis de Lafayette, eighteen years before. He left America five months later sickened and disillusioned and longing for home. The disinterested radical longed for monarchy. Dickens never understood America. In the epic of the conquest of the frontier (he went as far as the Mississippi), he saw only the squalor of crowded steamers, the loneliness of log cabin settlements, the braggart voices, the lack of manners and the universal flood of tobacco spit. The genius that could turn to kindly amusement the filth of a London slum and could transform the brutality of a Squeers and the rascality of an Alfred Jingle,—utterly failed in America. Most of all he was repelled by slavery, not the fact of it, for he practically never saw it, but by the thought of it. The very idea of human bondage struck into his soul.

Charles Dickens, writes his latest biographer, “did not stop to ask, he did not care to know, whether the plantation slave was happier than the factory hand of Lancashire, whether the slave himself felt the degradation of his chain or only the weight of it.—Dickens wanted nothing of such talk. He felt, as Longfellow felt, or Channing, that the thing was utterly and hideously wrong in itself, and different from any form of want or suffering that might arise where at least the will is free. Like all the people of his day, he valued individual freedom, if only freedom to die of starvation. Many of us still share his view.

“His attitude towards slavery separated Dickens in thought and sympathy from the South. People who lived among slavery took it as they found it—a sort of way of living and working. There were good owners and bad, kind and cruel; but cruelty to any real extent was the exception, not the rule. A slave minded the whip as much and as little as did an Eton schoolboy. He measured it by the sting, not by the moral. People who owned slaves shuddered at the sight of an English factory—its close mephitic air, its clattering machinery, the pale, wan faces working at the looms in the gaslight, the hideous toll of the twelve and fourteen hours of work extracted from little children; the long lines of starving people clamoring for bread in the England of the hungry ‘forties and receiving as their answer the cold lead of the Waterloo musket. They contrasted this with the bright picture of the cornfield, bathed in wind and sun, the negroes singing at their work, and the little pickaninnies clinging to the red gowns of their mothers. On such people of the South in the days of the ‘forties descended a fury of anger when a pert Mrs. Trollope, or a prim old maid Harriet Martineau, or a young Mr. Dickens, fresh from the miseries of the English factory and the London slum, should hold up their hands in pious horror over the cheerful darkey of the sunny South. They were no doubt wrong. To many of us, one single family broken up and sold down the river outbalances the whole of Lancashire.”

But we must remember that Dickens represents the type of person who denounced slavery without seeing it, whose abhorrence arose from the idea of it and not from experience of it. We may place beside it the judgment of other foreigners who saw slavery on the spot and whose standing and eminence entitled their views to respect: among these one thinks of Sir Charles Lyell, the great geologist; Harriet Martineau, the Victorian spinster of a hundred works; Captain Basil Hall and Captain Marryat, as British naval men not overgiven to sentiment; Chevalier, French economist and official, visiting America (1836) on a government mission. All these came to America before the closing decade of the ‘fifties overwhelmed the slavery question in a maelstrom of prejudice and hatred. What did they think?

Sir Charles Lyell, the great geologist, visited America and traveled extensively in 1841 and in 1845. He was primarily interested in such things as the “retrogression” of Niagara Falls, the vegetation of the Dismal Swamp of Virginia and the alluvium of the Mississippi Delta. But he had an eye, also scientific and neutral, for manners and customs. Lyell noted the planters’ style of living, “like that of English country gentlemen,” the family pride of the planters; the cleanliness of the plantation hospitals for the sick slaves; the negro merriment at Christmas, “a kind of Saturnalia,” and sums it up that he saw “little actual suffering” in the South.

But almost at the same time with Sir Charles, there traveled in America a Mr. Alexander Mackay, correspondent of the London Morning Chronicle, reporting on the Oregon dispute. He agrees with Lyell about the dignity and pride of the older plantations but fiercely denounces the change wrought by the cotton plantation. There slavery “appears in its true light, in its real character, in all its revolting atrocities. In the practical working of slavery in the cotton growing districts, humanity is the exception and brutality the rule.”

Captain Basil Hall was a British naval officer of the Napoleonic war on active service from the peace of Amiens to Waterloo. After that he traveled the world over and wrote it up in about twelve volumes. He certainly should have known something. Of his travels in America in 1827 and 1828 he writes, “I have no wish, God knows, to defend slavery in the abstract but nothing gave me more satisfaction than the conclusion to which I was gradually brought that the planters of the Southern States, generally speaking, have a sincere desire to manage their estates with the least possible severity.” Nor did he think the work as hard as that of the “hired man” of the North. “In Carolina,” he writes, “all mankind appeared comparatively idle.”

Hall’s fellow naval officer, the famous Captain Marryat of the sea-stories, visiting America in 1837, takes slavery pretty much as he finds it with no great oratory. But he tells some appalling stories of exceptional cases of what slavery could mean.

Miss Harriet Martineau was a super-gifted English spinster, who embodied in herself the whole generation of Queen Victoria. She was as quick as a needle: she never stopped writing; and she had no more originality than a hen. Her mind, truly feminine, was just a reflection of the ideas of her time. But she wrote in all about a hundred books. In her account of her travels in the United States (Society in America, 1837) she paid full tribute to the charm and politeness of southern society, was fascinated by the languor and grace of Charleston, and its profuse hospitality. She admitted the care and kindliness of most southern masters and said that “nothing struck her more than the patience of the slave-owners with their slaves.” But the institution itself she could not tolerate: and people told her ghastly stories, probably untrue, of slaves worked to death on purpose on the sugar plantations.

Miss Martineau had a lot to say also about the status and lot of the negro woman. There she “got it all wrong,” confusing the ideas of a Victorian spinster with those of a rotund black woman only two generations out of equatorial Africa. Miss Harriet should have gone and lived for a while in the place where the negroes came from. After that she would have had no fear of the whites corrupting their morals. But most of all Harriet Martineau gave unpardonable offense to the South by openly espousing the cause of the abolitionists, whose treatment she described in the Westminster Review as the “martyr age of the United States.”

The name of Michael Chevalier, a by-gone authority on gold and free trade, still echoes in the gloomy Pantheon of political economy. The French government sent him to America to study the canal and transport system, a visit chronicled in his Society, Manners and Politics in the United States (1839). His judgment of slavery is interesting,—that it is physically all right, but morally and socially impossible and doomed. He thought that even the Americans still wanted to get rid of it,—“a scourge to all the countries in which it exists: of this the people of the United States in the South as well as in the North are convinced.” But he adds to this:

“It is just to observe that, in the United States, the slaves, though intellectually and morally degraded, are humanely treated in a physical point of view. They are less severely tasked, better fed, and better taken care of, than most of the peasants of Europe.”

This from a man of high intelligence, trained in observation, and biased in the other direction, is notable testimony.

Chevalier, however, never saw the cotton states. But even in Richmond, slavery hit him hard.

“There is something in Richmond,” he writes, “which offends me even more than its bottomless mudholes and shocks me more than the rudeness of the Western Virginians, whom I met here during the session of the legislature; it is slavery. Physically the negroes are well used in Virginia, partly from motives of humanity, and partly because they are so much livestock raised for exportation to Louisiana: morally they are treated as if they did not belong to the human race. Free or slave, the black is here denied all that can give him the dignity of man. The law forbids the instruction of the slave or the free men of color in the simplest rudiments of learning under the severest of penalties; the slave has no family; he has no civil rights; he holds no property. The white man knows that in secret the negro broods over hopes and schemes of vengeance and that the exploits and martyrdom of Gabriel, the leader of an old conspiracy, and of Turner, the hero of a more recent insurrection, are still related in the negro cabins.”

On this last point Chevalier was undoubtedly in error. The negro hoped for nothing and brooded over nothing.

Let it be noted, for what it signified, that the negroes, all through the slavery conflict, never rose, never even budged. The slave insurrection was a mere dream, a nightmare. The slaves went on playing the banjo and drowsily moving the hoe. They planned nothing. They harbored no hatred. The age-long children of destiny, they took their lot as they found it. They had no part in the fierce vindictive angers of the overfed white race, that passed in thunder over their heads. Even when the war came the slaves never rose and never thought of it. That large fact should never be forgotten in the record.

Set beside the foreign arguments, as typical of the lives and thoughts of millions of people in America, the words of one of the wisest men who ever lived with slavery and saw it go.

This is Mark Twain speaking of his mother,—

“My mother had been in daily touch with slavery for sixty years. Kind-hearted and compassionate as she was, I think she was not conscious that slavery was a bald, grotesque and unwarrantable usurpation. She had never heard it attacked in any pulpit, but had heard it defended and sanctified in a thousand....

“As a rule our slaves were convinced and content.... It was the mild domestic slavery, not the brutal plantation article.... The ‘nigger trader’ was condemned by everybody, a sort of human devil who bought and conveyed poor helpless creatures to hell.”

These all—the Dickenses and the Martineaus and the Basil Halls—were foreign travelers and observers. It is only fair to record that most foreigners, who stayed at home and never saw American slavery, accepted it easily enough. There was no international outcry against it. In England some people accepted it as other people’s trouble, easily borne; some, like the cotton spinning Gladstones, from business interest, as a part of the greatness of Lancashire; others as biblical and patriarchal fitting in with the squire and parson at home; others like Thomas Carlyle for the pleasure of disagreement and from the egotism of indigestion.

On one count or another there were plenty of pro-slavery, or pro-American slavery people in England.

At home the people in the South overwhelmingly accepted it. They lived too close to it to think of theories. It was their way of life. But naturally, as discussion multiplied they rallied to its defense. Argument, itself, presently deepened their conviction.

People of station, clergymen and college teachers of the South set forth the articles of their faith. There was Dr. Thomas Cooper of Carolina College who showed, as political economy (1826), that a slave who got his board and his keep and decent treatment got more than he was worth,—a woolly argument which led nowhere. Professor Thomas Dew of William and Mary did better by laying stress on the happiness of the slave, the “naturalness” of his condition and the scriptural warrant for it. Dew’s Essay (originally published in 1852) was followed by Harper and Hammond and other exponents and became the basis of the defense of the institution by all the honest pro-slavery men of the South, who wrote it fearlessly and defiantly into their constitution of 1861.

But Southern argument could no longer remain calm and academic when it was goaded to frenzy by the assaults of the rising abolitionists.

As the century wore on and the slave question ate into the national life, the abolition propaganda had changed from calm philosophy to fiery denunciation, from argument to martyrdom, from words to threats and blood. Abolitionists forgot the means in the end. They accused the Southerners of cruelty, lust and crime. They called on America to spurn the constitution as “a covenant with death and an agreement with hell.” Such men as the Reverend Stephen Foster denounced the Southern churches,—“every communicant worse than a pickpocket and an assassin.” The Reverend George Brown denounced the (imaginary) slave market, foul, drunken and obscene. In Boston Theodore Parker and Wendell Phillips urged the breaking of the law. “Accursed be the American Union,” rang out the Liberty Bell of 1845. William Lloyd Garrison, the patron saint of abolition, matched against the constitution the texts of Christ’s new testament and declared that the covenant of death must be annulled.

Others, the open incendiaries, went further still. John Hill, an escaped slave, called aloud for “blood, death and liberty.” Frederick Douglass, a negro, urged the slaves to rise in arms. This, ever since Nat Turner of Virginia, a negro preacher, a muttering mystic, had gone amuck (1831) with a cluttering of crazy followers, and butchered women and children,—this had been the slumbering dread of the South. To preach this was death.

The approaching convulsion of society was being made, said the Southerners, not by the slaves but by the abolitionists. Yet the abolitionists had begun as a people of the inner light. Were they wrong? Each must judge them for himself. But at least it can be noted that what they demanded was abolition, immediate and without compensation, and they claimed that slavery was contrary to the mind of God. This is exactly what Lincoln did in his proclamation of 1863, and exactly what he said in his second inaugural address.

Meantime, as the current moved faster towards the abyss, the politicians, after their manner, did nothing, or nothing real and final. The Democrats wouldn’t and the Whigs couldn’t. Both wanted votes and office. Neither could live except astride of slavery and freedom. They must ride two horses or fall. In 1850, as every reader knows, they patched up a “Great Compromise” that settled nothing; slavery in the South and at the capital, and perhaps in the Southwest, and a fugitive slave law,—and round it all a hedge of doubt and uncertainty. The compromise settled nothing. It carried down with it the reputation of Clay and Webster. But beyond that it merely shifted the scenes for the closing act of the ten years’ drama that was to end in secession.

Now there was living all this time in Illinois a tall, ungainly man whose name was Abraham Lincoln. And this was an inspired man, an instrument of human destiny. But the vision that was to make him so had not yet come.

Lincoln stood six feet four in his stockinged feet. He had a frame of great strength, proportionated after that of an ape, with hands swinging almost at his knees. He was, literally, one of the strongest men in all the world.

Round the name of Abraham Lincoln there has gathered one of the great myths of history. He is credited with capacities which he never had and with a foresight that he never showed. Nearly everything about his career is seen in a false light and glorified beyond recognition. The ignorance and ineptitude in which he assumed the presidency of the United States are now lost in the accumulation of panegyric and reverence. To say anything derogatory to his memory seems like the desecration of a grave.

But in reality the truth about Abraham Lincoln is better than the myth.

In his own day Lincoln was, till the very end, the object of hatred and mockery from millions who were his opponents: of contempt and ridicule, for years, from millions whom fate made his adherents: of doubt and distrust, for at least half his time in office, from many of those who worked beside him. But underneath this and through this, there grew the sublime faith of millions, the roaring plaudits of marching armies, whose voices went up in chorus to “Father Abraham,” the lamp of hope lit in the humble home, the pardons without hatred, the rebukes without anger, the wide humanity which in the end brought humanity to his feet,—and, at the last, martyrdom in the moment of achievement.

In the face of all this and the universal reverence that has grown out of it, it sounds like the babbling of a fool or the blasphemy of an idiot to cast doubt on Lincoln’s political career, of his fitness for the presidency or his policy towards secession. Who dares suggest that when he assumed the office he was lost, ignorant and incompetent, without a policy, without a plan, a man adrift upon a sea of trouble. Yet that is true. Not till he liberated the slaves in America did Lincoln liberate his own soul. Till then what is there to admire? Excepting always the inspiration of his soul, which in the end was to achieve his greatness.

For the truth about Lincoln is better than the myth about his prescience and capacity, his political foresight and diplomatic insight. He had little of these things and very little available for effective use in 1861. But the truth is that Lincoln was one of the elect of mankind. Underneath and unknown, he had an inspired soul. He was instinct with a love and pity for all mankind comparable to that which has carried the name of Jesus Christ down twenty centuries. He could not hate even a slaveholder.

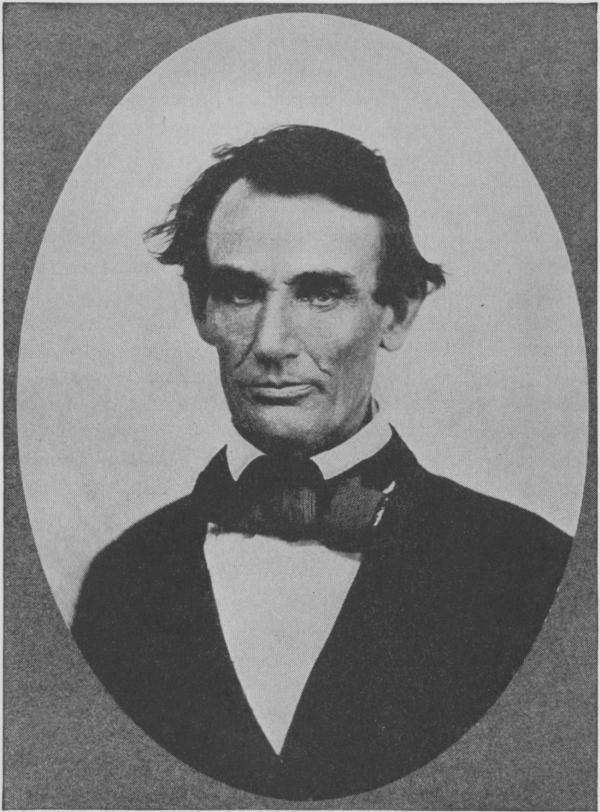

WHAT WILL HE DO WITH THEM?

(From Vanity Fair, October, 1862)

All of this was underneath, distant, unconscious, not yet realized. Yet there was a foreboding of it in the strange melancholy of Lincoln’s face, the deep lost meaning of his eye. It was this inner look that changed his whole aspect. For each of us there comes at times a sentience of the personality of others. It is the universal, the immortal part of us,—reaching across. In this hangs the art of mystic healing, the appeal of oratory and much else. Such was the “impression” conveyed by Abraham Lincoln.

Without this inner light Lincoln would have been a comic figure. At times he almost was. When they presently inaugurated him as the president of the United States, his clumsy gestures, his awkward clothes, his dilemma over his big Bible and his huge walking stick and his new hat, should have made him—almost did make him—ridiculous. There were those living not long ago who could remember seeing him riding beside his soldiers,—a grotesque figure in a stovepipe hat and an ill-fitting suit, his trailing legs too long for the horse,—a very Don Quixote of comicality,—but converted from ridicule to glory.

This impression that Lincoln gave, this saddened aspect, made people instinctively speak of him as old. “Honest Old Abe” was the name he carried in Springfield long before the world had heard of him. Yet he was not very old and not so desperately honest.

For honesty was not entirely his trade, at least not till later in life. As a lawyer Lincoln was absolutely and peculiarly honest, as honest as any one can be in that amiable profession which keeps its own moral department as the “ethics of advocacy.” But Lincoln was also a “politician.” In that capacity he was just like the rest. The politician learns to traffic in committees and platforms, caucuses and gerrymanders: office means too much to him: truth too little. The politician learns to confuse a platform with a principle, a unanimous vote with general agreement and a majority vote with a moral sanction. This was especially so in peace, in the formative era of democracy groping its way into the art of government. This was the cause of shipwreck of the Websters and the Clays.

Deep under the litter and rubble of the political surface lies, no doubt, the bed-rock of character and opinion. In time of peace, it is concealed. War lays it bare.

Thus naturally in a backwoods career like that of Lincoln “politics” played too large a place. He knew the tricks of the trade and he used them. Left to himself he would have been an abolitionist,—minus the hatred and invective. But backwoods politics dimmed the inner light. Lincoln thought of slavery in terms of parties and platforms. It was only when he was lifted up so high that he stood alone and isolated, with nothing between him and the infinite, that he found another vision.

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809. He came of the plainest sort of log-cabin people of the American frontier. His father moved from one shanty in the wilderness to another. His was the instinct of the frontiersman, building a cabin in the bush and then, as settlers came and the bush changed to farm and road and village, moving on again.

Such people as Thomas Lincoln lived in log huts, with holes for windows, with wooden slabs for chairs and tables, and with a few pots and pans brought with them from the “settlements.” Their sole treasured possessions, priceless beyond words, were their rifle and powder horn, and their ax. The men dressed in deerskins, foul and redolent in the damp, wore moccasins in place of shoes,—the dress of savages. Their food was game, plentiful but ill-cooked, without sauce or spice, corn from the patches among the trees. Sugar they had none, except as squeezed from wild honey. Their drink was water, and whisky crudely made, untaxed and deadly in its potency. All about them was the dripping malarial forest, the fierce dry heat of midsummer and the intermittent cold of winter, at times intense.

Theirs was not so much out-of-doors life as out-of-doors exposure. The men in spite of their iron frames and strong limbs were old at forty. Compare these types:—the Illinois pioneer of the backwoods, his tawny face lined and furrowed and ageless at forty years, and the English gardener of the same period on whose countenance the wind and the rain and the petals of the rose had fallen so gently as to leave it pink and white at seventy, his eyes a china-blue vacuity and his brain still undisturbed. Yet these were cousins. By a slight shift of circumstance either might have been the other.

Of intellectual life the settlers had and needed little or none. A few tattered books were trailed from cabin to cabin. Odd people taught the children their letters in a deserted shed, miscalled a school. Itinerant preachers moved through the bush, conducting domestic prayer in return for meals and a bed, and at times providing the settlers with the emotional hysteria of a “camp meeting.”

But no one can understand the circumstances of Lincoln’s life without realizing that this environment of the frontier was a moving, changing phenomenon. Within a little time it was, in any locality, all completely changed. First there was the unbroken forest, charted only by rivers,—silent, untenanted. The savages, except in little clusters here and there, were but few,—random hunters along the forest trails. Then came the earliest pioneers, floating down from the upper rivers on rafts or scows to find new homes. Thus floated (in 1816) Thomas Lincoln, with his pots and pans and kettles and tools and 400 gallons of whisky as the movable wealth of forest commerce. He was looking for a likely place—one lonely enough for a frontiersman.

After such first migrations came further settlers in a stream that spread and widened through the forest and out into the park land and the prairie. The forest fell before the ax. Great piles of timber, priceless today, went up in smoke. The rude cabins were replaced by frame houses. The clearings joined together to make fields. Roads struck through the woods. Crossroads, blacksmith shops, and river sawmills expanded into villages with courts, and schools and churches. The steamboat came, sending aloft the sparks of its wood fires, waking the wilderness by day and lighting it by night. And with the steamboat there poured in a flood of settlers, a tide of immigrants, good and bad, settlers and adventurers, pioneers on foot, with women and little children peeping from the wagon hoods.

It is a great epic in the history of America,—the invasion of the Mississippi valley and its transformation in one generation at the hands of man.

So it came that within the childhood and earlier life of Abraham Lincoln and his contemporaries the world about them was transformed. The Spring Creek in the wilderness of Illinois became the frontier village of Springfield, then a trim town, a rising city, a railroad center and the capital of the State. All this places behind the events of the time not a background but a moving picture. There was nothing of this in the Old World. But we cannot understand America and things American without it. The London to which the little Charles Dickens traveled in a coach from Chatham was, with no vital difference, the same town in which he lived and died. The Indiana to which was led through the forest the little Lincoln, Dickens’s contemporary, was a quite different place from the Indiana that sent its numbered regiments to Lincoln’s service in the Civil War.

Thomas Lincoln found a likely place on a forest stream,—Little Pigeon Creek in Indiana and went back and fetched his wife and his two children, Abraham and Sarah. He made a sort of shelter out of poles, three sides closed to the weather and one open. There the family lived for a year, while the father cut logs for a cabin and cleared a patch for corn.

For fourteen years the Lincolns lived in this cabin. It had for two years no doors, no windows. Little Abraham slept on a bed of leaves on the poles that made a “loft.” A few other settlers straggled to Pigeon Creek, among them Lincoln’s relatives, the Sparrows. In the second year came malaria and malignant fever, bred in the dripping woods. Among those who died were the Sparrows, husband and wife, and Lincoln’s mother (Oct. 5, 1818). Thomas Lincoln made three coffins “out of green lumber cut with a whipsaw” and buried the bodies in the clearing. It was little Lincoln’s first vision of death.

There was no burial ceremony till months later an itinerant preacher read the funeral service over the snow that covered the grave.

In such a place a man could not live alone. A year later Thomas Lincoln made a journey back to Kentucky and brought home a new wife. This Sarah Lincoln was a kind, energetic woman. She brought with her quite a stock of household goods. She made clothes for the little boy and his sister, and beds. She was a real mother.

Abraham Lincoln passed his childhood in this log cabin. He had a little schooling, from itinerant teachers in odd houses and shelters. To his last “school” the boy walked, to it and back, nine miles a day. He had, in all, perhaps a year of teaching. He learned to “read and write and cipher.”

Beyond that, all that he ever knew Lincoln taught himself. There were a few odd books in the settlement. Lincoln, by the firelight, pored over Æsop’s Fables, Robinson Crusoe, the Life of Washington (the cherry-tree one of Mr. Weems) and some forgotten History of the United States. His mind was slow, but an innate passion for learning drove it on. He wrote down sentences and phrases and learned them by heart. To save paper, a rarity, he wrote on a wooden shovel and shaved off the sums and the compositions to make place for the next ones.

All this time the settlement grew. There were “raisings” of new houses, the building of a church, the opening of a court. And with the settlement grew young Abraham, taller and longer with every year, rising to that incredible physical strength and the great height that marked him out even among frontiersmen. At eighteen he stood to his full height of six feet four. His strength was colossal. His feats became legendary. He could lift and carry away 600 pounds. He could pick up a barrel of whisky in his hands and drink out of the taphole: the whisky, they said, he spat out afterward. Liquor and tobacco, even in that age of drinking and chewing, he never touched.

His life and work were those of the bush farm: the clearing of trees, the breaking of the ground with yoked oxen, the plow, the harrow and the “cradle,” the care and watering of the stock. After the long day’s work came the long summer evening loud with insect and cricket; the long winter night with the bright silence of the moonlit snow; the hard, fresh call of spring with the frogs trilling in the marsh.

It was the routine of life, still remembered by many of us in old age, before the city and its apparatus laid its hand across our continent and claimed it.

As the settlement expanded, Lincoln’s life expanded with it. Near to his cabin home grew up the hamlet, the village, of Gentryville. Settlers moved in an unending procession down the rivers, heading west. Young Lincoln worked at a ferry crossing (Anderson’s Creek); he saw the world come and go. Not far away the famous English apostle Robert Owen had founded peace on earth at New Harmony on the Wabash. Lincoln saw Owen’s queer disciples float past.

Once, at sixteen years of age, he went right down the Ohio and far down on the Mississippi as a hand on a flatboat. He saw bush settlements and wharves and steamboats, towns rising out of clap-board lumber and “niggers” skulking in the bush.

All this was the difference between America and Europe. In America the life of the individual and the life of society moved together into the unknown.

But the settlements were becoming too crowded for Lincoln’s father. In the early spring of 1830 he moved on west, family and all. This time they passed over prairie like a park with cabins and farmsteads springing everywhere in the rich soil. Lincoln, a youthful giant, made the wagon, and hewed and hauled the logs for the new house. They settled in Coles County, Illinois, a district already loud with the hammer and the ax, with civilization closing in on it.

Again Lincoln went “down the river,” this time all the way to New Orleans. Here he had his first vision of a city, and with it his first real view of slavery. It is true that Lincoln’s eyes had opened upon slavery in his infancy in Kentucky. There were slaves even in the mean settlement where he was born. People who had one or two “niggers” as slaves were better than people like Thomas and Nancy Lincoln who had none. Slavery even there inserted the poison of social divergence among its masters. But in Indiana, in the bush clearing, there were no slaves and no use for them. Slaves cannot live in a one-room cabin where the children sleep in a loft.

But “down the river” Lincoln saw for the first time what slavery meant. “At New Orleans,” so wrote afterwards his kinsman, John Hanks, who went with him, they “saw negroes chained, maltreated, whipped and scourged. Lincoln saw it; his heart bled; he said nothing much, was silent, looked sad. I can say, knowing it, that it was on this trip that he formed his opinion of slavery. It run [sic] its iron in him there and then, May 1831. I have heard him say so, often.”

In the sympathetic sense no doubt this is true. But not in the political. Lincoln’s mind moved too slowly for that; his knowledge was too immature, his outlook too limited. He might sorrow for the slaves but he could tolerate the institution. As late as March 4, 1861, he would have kept every one of the five million slaves under what he called in 1865 the “bondsman’s unrequited toil,” rather than break the union of the States.

It is falsifying history to say that Lincoln was ever an active opponent of the institution of slavery, until his eyes opened upon his mission to destroy it. To “limit” slavery to a quarter of a continent, to prophesy its “ultimate extinction,”—there is nothing heroic in this. If the iron was in his soul, he carried it politically, for thirty years.

In short, it is not possible to straighten out Lincoln’s views on the place of slavery in American life without taking account of the gradual opening of his mind; the gradual awakening of his soul.

But all that great change was as yet latent and far away. For the time, as with each of us, his mind and thought and energy was set upon the little circuit of his own life.

It is beside the present purpose to follow in detail the stages of Lincoln’s earlier career, in farm and bush, and country store and village politics. It is a record shared with uncounted thousands of the unknown. Apart from his great strength, his tolerant good nature and a queer “something” about him, Lincoln was much like the rest.

He did not long remain on his father’s new place at Goose Neck Prairie in Coles County. He had no intention of being a farmer. Seeking a larger life Lincoln moved into New Salem, Illinois, a rising hamlet that as yet only meant a sawmill and a tavern and one or two frame shops. Lincoln started as a clerk in a store, tried storekeeping in partnership and storekeeping on his own account and failed at it all three ways.